Portland’s new eastern cityscape

Development was part of a larger plan, city says

ANALYSIS BY CLARKE CANFIELD PHOTOS BY MICHELE STAPLETONIf you happen into the east end of the Portland waterfront for the first time in a long time, you might look around and ask yourself this: Where am I?

This area at the base of Munjoy Hill was historically industrial, known for railyards, heavy manufacturing, industrial warehouses, and a monstrous drydock called “The Hog” that was used to overhaul and modernize huge Navy destroyers.

But today, what’s known as the eastern waterfront has been transformed into an entirely new neighborhood with new streets, hotels and condos, parking garages, and steel-framed office buildings with dazzling amounts of glass.

The changes have come about incrementally over the past 15 years. Over time, the landscape has changed so much that you just might feel like you’re on a movie set.

Paul Stevens, a senior architect at SMRT, an architectural and engineering firm, lived near the eastern waterfront neighborhood for a number of years

decades ago. His firm’s offices were in an aluminumsided building (once used as railroad-era warehouse) in the waterfront zone for 26 years. The building is still standing, but today it’s surrounded by glistening office buildings that would have been unimaginable a generation ago.

When SMRT moved into the eastern waterfront building in the mid-1990s, it was essentially surrounded by dirt parking lots, Stevens said. On

the nearby waterfront, BIW worked on ships and Cianbro Corp. constructed two massive oil rigs that towered 300-plus feet for shipping elsewhere.

The area is now barely recognizable compared to the old days, he said. When he drives down Hancock Street from partway up Munjoy Hill, he’s awestruck by the upscale condos, offices, and other development all the way down to the waterfront. When he reaches

continued on page 2

The next generation of workers are here

Mid-coast School of Technology offers diverse, hands-on programsBY TOM GROENING

Want an antidote to your gloomy thoughts about the worker shortage and the long waiting lists to hire plumbers, electricians, and

carpenters, and the equally long wait time to schedule car repairs and medical appointments? Then tour a facility like Rockland’s Mid-coast School of Technology where the next generation of workers is already getting their hands dirty.

The facility’s vibe is more software design than vocational school, with its bright, airy spaces. The students are engaged, cheerful, and comfortable chatting about the work they are immersed in, from grinding steel to preparing croissants, from testing computer systems on a truck to studying nursing protocols, from applying finish to bookshelves to writing computer code.

The investment is paying dividends.

“A majority of our students stay, or at least stay in Maine,” he said.

“A majority of our students stay, or at least stay in Maine.”

Clearly, this isn’t your father’s trade school.

The facility is the result of a $26 million bond approved by Knox County voters in 2016. Director Robert Deetjen is grateful, he said during a tour of the school, for the community’s support, and also is grateful that construction concluded in 2019 just before the pandemic.

A typical day will see as many as 300 students in the building, which serves students who attend from Camden Hills Regional, Oceanside, and Medomak Valley high schools. But in all, the facility serves over 500, including those working remotely from their high schools on Vinalhaven, North Haven, and Islesboro, and students at Pen Bay Christian School in Rockland and homeschoolers.

There is far more interest in the diverse programs the school offers than it can accommodate, Deetjen says, with, for example, 60 applying for the small engine program which can only

continued on page 11

EASTERN WATERFRONT

continued from page 1

Thames Street, which runs parallel to the waterfront, he’s greeted by those large glistening office buildings.

“It’s very, very different. It’s amazing to me,” said Stevens. “When we moved our offices down there 30 years ago, there was literally nothing down there. It was just a huge dirt parking lot out in front of us.”

PLANNED DEVELOPMENT

Portland essentially has three waterfronts. The central waterfront with its 19th-century piers and wharves is the heart of Portland Harbor and supports commercial fishing, marine research, tourism, and nonmarine uses. The western waterfront, which has undergone its own transformation over the past decade, is dedicated to freight and industrial uses.

The eastern waterfront extends east from the Casco Bay Lines ferry pier, past Portland’s cruise ship terminal, and on to the former Portland Co. marine complex, which is now under development.

The area’s transformation was prompted by Bath Iron Works’ decision to end its repair yard operations in Portland. BIW leased the repair yard from 1982 to about 2001 from the city. The yard included two floating dry docks, one 844 feet long.

When BIW told the city in the late ‘90s that it was leaving, the city had to ask itself: What do we want to do with the city-owned property on that section of the waterfront?

The city council appointed a committee of more than 30 people with diverse interests who came up with a master plan for redevelopment of the eastern waterfront, looking at both city-owned land and adjacent privately owned property.

One part of the plan looked at marine infrastructure for international ferry vessels and cruise ships, and the other part was devoted to associated upland development, said Bill Needelman, Portland’s waterfront coordinator.

primarily by cruise ships and for a time served ferries that traveled between Portland and Nova Scotia.

To allow vehicles to get to the ferry, the city built Thames Street, an extension of Commercial Street from India Street to the east. And Hancock Street was built perpendicular to Thames Street to connect to Fore Street. Later, Thames Street was extended and another section of Hancock Street was built that runs from Fore Street to Middle Street, where it links to an older section of the original Hancock Street.

“ When we moved our offices down there 30 years ago, there was literally nothing down there.”

“This was all done on purpose,” he said while showing printouts of two aerial photos comparing the area in 2006, before the development, and 2021, when new streets and buildings had taken hold. “It was a plan.”

As a result, the Ocean Gateway marine terminal was built, opening in the spring of 2008. It’s used

Along Thames Street, the first block east of India Street feels like an extension of Commercial Street, with a mix of smallerscale condos, offices, some ground-floor retail stores, and the AC Hotel Portland, which opened in 2018.

But the next block is a head-turner, with its four-story, 100,000 square-foot, glass-sided building that opened in 2019 and serves as the headquarters for the paymentprocessing company WEX Inc.

Beyond the WEX building stands another fourstory glass-sided building that houses both WEX and the Roux Institute, a graduate school of Northeastern

University. Last summer, Sun Life opened its own four-story building—this one with lots of glass and gray brick—in the neighborhood.

Those buildings use contemporary architectural styles, a stark contrast to the smaller red-brick buildings that dominate the central waterfront and the nearby Old Port.

The waterfront side of Thames Street includes the cruise ship terminal, a small harborside city park, the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad, and the Eastern Promenade Trail pedestrian and bicycle corridor, which runs from Commercial Street to the city’s East End Beach.

THE HILL

With its contemporary architectural styles and upmarket development, the eastern waterfront stands out from the older clapboard-sided and multi-unit houses on the nearby streets of Munjoy Hill, parts of which retain a grittiness from bygone years even when being encroached upon by million-dollar condos. Munjoy Hill, or simply “the Hill,” was once dominated by poor and lower middle-class Italian and Irish immigrants who lived in densely populated neighborhoods with single-family houses and

triple-deckers. Many consider the neighborhood’s official boundary to begin at Washington Street, but others recognize anything east of Franklin Street to be part of the Hill.

The neighborhood today has become one of the most desirable—and expensive—areas to live in Portland, but at one time it was a place many avoided.

While having gorgeous views of Portland Harbor and the Casco Bay islands, the Hill in the ‘60s and ‘70s was dismissed as downright dodgy, a place to be avoided with its crime and alcohol and drug abuse. Munjoy Hill still retains a sense of neighborhood, but it’s also become gentrified over the past 25 years, with

trendy restaurants, shops, and condos coming in, old corner neighborhood stores going out.

You know Munjoy Hill is a popular place when the local paper’s featured properties in its real estate section carries the headline “Condos under $1 million on Munjoy Hill.”

URBANIZATION OR SUBURBANIZATION?

While some may call the eastern waterfront a continuation of the urbanization of Portland’s waterfront area, others look at it as more of a suburbanization.

Barbara Vestal, who has lived on nearby Fore Street since 1978, thinks the area has the feel of a business

park. Vestal is a retired lawyer who has been involved in planning matters for decades and served on the waterfront committee that developed the plan for the eastern waterfront more than 20 years ago.

The scale of the larger buildings, she said, seems overblown and is far different from what she envisioned while serving on the waterfront committee that developed the eastern waterfront master plan in the early 2000s. She was hoping for smaller buildings with individual owners, a variety of tenants and perhaps another cross street to break up the expanse of land. Instead of a lively urban

continued on next page

neighborhood, she says the eastern waterfront has a generic suburban feel that could be anywhere—suburban Boston, Pittsburgh, or Kansas City. Or Westbrook, she adds for good measure.

“I think to people who have been in Portland for a long time it’s not really recognizable as Portland,” she said. “When you’re in the middle of the new development, some buildings seem to me they belong in a suburban office park. There’s nothing that really says this has been influenced by Portland.”

Change, of course, is inevitable, and Portland has experienced many changes through the decades that transformed neighborhoods. Interstate 295 opened in the ‘60s, breaking up neighborhoods and providing easy highway access to the city.

Franklin Street was transformed into the four-lane Franklin Arterial throughway from I-295 to downtown and the waterfront in the ‘60s as part of an urban renewal project that razed dozens of homes and decimated neighborhoods.

A plan to redesign the road has been in the works for years, with the aim of transforming it back into a lively residential neighborhood with

multi-use plazas instead of just a wide urban access road that gets cars into and out of the city. That plan, dubbed “Reclaiming Franklin Street,” is now moving forward; the city plans to work with a consultant to update its master plan beginning this summer and assess federal funding opportunities for a final design and construction in the fall of 2025. A construction timeline is still up in the air.

The waterfront, too, has gone through many changes. Trains still rumbled down Commercial Street and the Grand Trunk railyard in the eastern waterfront was busy with activity when Stevens moved back to his native Portland in 1966 to join the family architectural firm (founded by his great-grandfather, renowned architect John Calvin Stevens). The trains stopped running those routes in the early 1980s.

Along the eastern waterfront, even more changes will come. A development company plans to build hundreds of housing units, retail space, a luxury hotel and a huge parking garage on land that formerly housed the historic Portland Co. at the end of Thames Street. The complex has been dubbed Portland Foreside and basically transforms what was once a huge factory complex that manufactured steam locomotives and ship propulsion

systems from the mid-1800s until 1982. Developers have already built a modern 150-slip marina at the site and opened an upscale restaurant named Twelve, so named because the building it’s in was named “Building 12” when it was part of the manufacturing complex at the Portland Co. in days of yore. The Sun Life building is also part of the development.

On the water, the city is planning to build a 152-foot public dock for this boating season where transient recreational and island boaters can tie up for

up to six hours while they’re in Portland. The city also plans to build a new public waterfront park where a parking lot is now located near India Street.

It remains to be seen what the impacts of the eastern waterfront will be on the city once it’s fully developed. Vestal says while the eastern waterfront has transformed the land, it hasn’t necessarily been transformational for the city.

“It’s kind of its own little world down there,” she said. “It’s not a place I tend to go. It’s not a destination.”

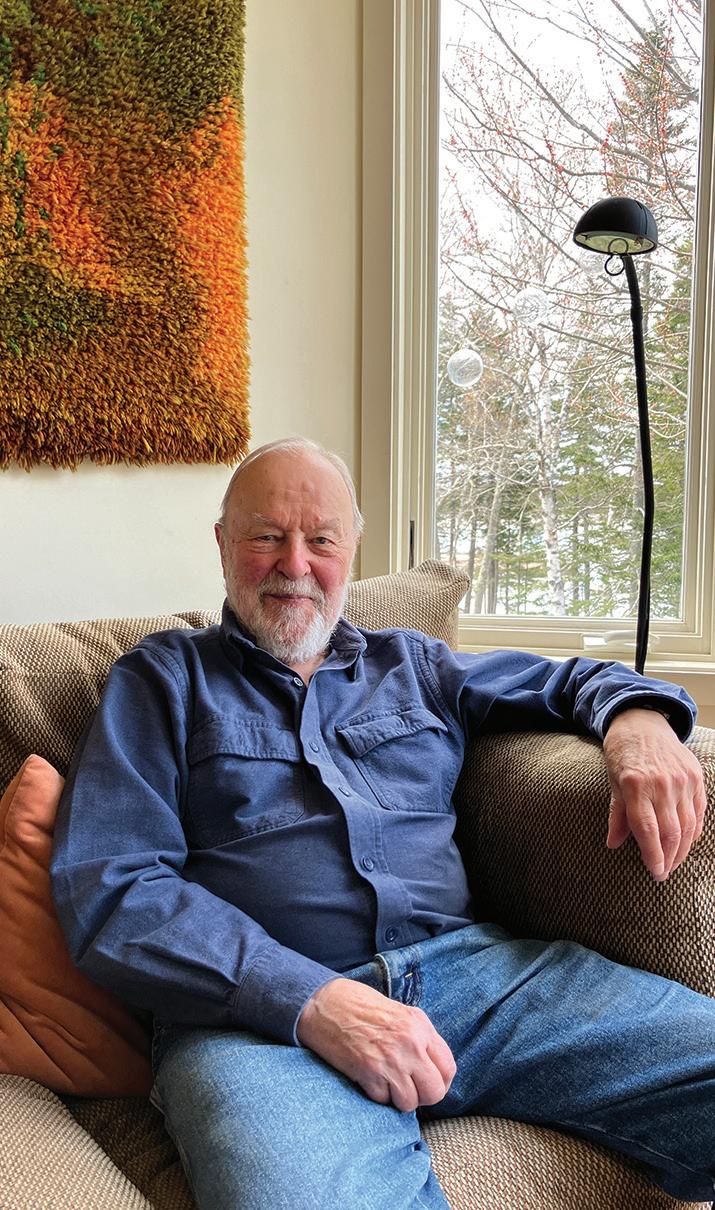

That New England spirit in literature Islandport Press marks 25 years of publishing

BY DORATHY MARTELDean Lunt founded Islandport Press, a Yarmouth-based publisher now celebrating its 25th year, in his basement in 1999. The press is rooted in New England and suffused with family history.

The company’s logo depicts the home of its founder’s grandmother, Vivian Lunt Davis, an amateur historian who grew up on Frenchboro. The press’s first publication, Hauling by Hand: The Life and Times of a Maine Island, arose from Vivian’s writings about the Frenchboro, where Lunts have lived for hundreds of years. Hauling’s cover features a photo of his grandfather, Sanford “Dick” Lunt.

Writing, producing, and selling Hauling by Hand was a crash course in publishing. Lunt said, “We used that book to learn about book design, cover design, distribution, sales.” A revised, 25th anniversary edition will soon be released, marking the book’s importance in the press’s founding.

Lunt started Islandport Press in his basement in 1999. He was working as a journalist, but he had concerns about the future of the industry.

“You could sort of see the beginning of the decline of newspapers,” he said.

“Local books, local authors are really important for culture, for heritage.”

—DEAN LUNT

Needing a job, but not wanting to be deskbound, he weighed up his skills and interests— editing, writing, history. Publishing seemed like a good way to incorporate all three.

Heading north for an assignment for the Portland Press Herald, he recalls, “I pulled over and sketched out the plan.”

The plan was, and still is, to publish books that “capture and explore the grit, heart, beauty, and infectious spirit,” as the website copy puts it, of New England.

What makes a book a “New England book”? Lunt said it requires “a sense of place, the voice of the place that speaks to it, the jobs, the environment, the people.”

Islandport Press collaborates closely with its contemporary authors—“people with stories and a voice,” Lunt said—to craft books that people will want to read and keep on their shelves, rather than selling them at a yard sale. “We want people to know it’s an Islandport book, not a widget.”

They also publish older books that might otherwise be forgotten.

“We’ve had a lot of success finding great books or classics that have gone out of print and bringing them back,” Lunt said. “That’s been from day one, finding those gems that just get lost to time.”

Rather than simply reprinting older books, Islandport redesigns them to make them look and feel more modern, and updates the language, when necessary, to increase their appeal to today’s readers.

“A confused reader stops reading the book,” Lunt said. The Islandport Press catalog includes a wide range of books, including novels by the early 20th century Maine writer Ruth Moore, children’s picture books, art and photography books, memoirs, and mysteries. Islandport’s mission goes beyond publishing and selling books, however.

“It’s critical for a state to have a literary culture. One of our goals is to maintain that culture,” Lunt said. “Local books, local authors are really important for culture, for heritage. People have to support them.” He worries about an attrition of the necessary skills to publish quality books, given that training grounds like newsrooms are disappearing.

“It takes eight to 10 people to publish one book,” Lunt said, describing a “community of professionals” that includes the author, multiple editors, proofreaders, designers, and sales reps. “Down the road the problem for this industry is that so many people were trained at newspapers or magazines.” With the number of print outlets shrinking, “Who’s going to train the next generation? Where are they going to come from?

For now, though, Lunt said, “We’re still out there kicking.”

As for the 25th anniversary, it is still a work in progress and partially under wraps. “We’ve got some exciting news coming soon,” Lunt said, alluding to new investments, events, and partnerships.

Learning from one town’s pioneering spirit

High-speed internet is big deal for small towns

BY KIM HAMILTONDOWN THE PEMAQUID Peninsula and bordering Muscongus Bay sits the small coastal town of Bremen.

According to the town’s website, Bremen was “founded in 1828 by pioneers and fishermen.” I can’t fully picture what those early pioneers encountered along the coast or what they imagined their futures to be. I can say with certainty, however, that high speed internet was not on their minds.

In the context of broadband expansion in Maine, the people of Bremen stand out again as pioneers. Last month, I had the honor of joining a celebration of the completion of the town’s universal fiber-to-the-home project, which Island Institute has supported.

On its face, an internet party might sound like a dry affair. In reality, it was anything but. It turns out that connecting more than 400 households to this fundamental technology is a glass-raising, community-focused, future-building milestone.

Local businesses that depend on reliable internet for sales and marketing now have it. The technology supports students, parents, and adult learners who

want easy access to online educational material. Older people with limited mobility can now access services virtually and maintain their social, physical, and spiritual health. Connectivity will strengthen the town’s ability to attract and retain year-round families. These are big wins for a small town.

These are exactly the kinds of community enhancements that Island Institute envisioned when we launched our broadband initiative in 2015. Grounded in an in-depth feasibility study that looked specifically at 14 island communities, we learned that high speed internet was a crucial public service, just like clean water, electricity, public ports, and piers.

Based on what was happening across the country, we knew broadband could become a bridge to employment, education, and healthcare and a solution for loneliness and isolation.

In retrospect, this seems astoundingly obvious. At the time, the aspiration to bring broadband to every home on the coast and on islands was audacious.

Since the launch of our broadband initiative, Island Institute has made over $450,000 in planning grants and provided thousands of hours of expertise and guidance in support of community

broadband aspirations. On the Blue Hill Peninsula alone, we invested over $55,000 in planning grants and helped secure over $10 million in public and private funding to connect thousands of residents and businesses to broadband.

We’ve done this in close partnership with the state’s former Connect Maine Authority and its new Maine Connectivity Authority, internet providers, town committees, the Maine Broadband Coalition, Grow Smart Maine, and many others.

Along the way, we’ve learned an important lesson: the opportunities fostered by high-speed internet are not shared equally, especially when the cost of accessing broadband is out of reach. For a time, the federal government’s Affordable Connectivity Program helped nearly 96,000 Mainers. Now out of money, that program is no longer a viable option, and its future is unclear. This means that many people are at risk of being left out or left behind. These exclusions are even more acute for rural communities or islands. Known as “digital equity,” this is the new frontier for broadband expansion.

Back in Bremen, digital equity has always been part of the plan. In

For our towns, when are the ‘good old days’? Change is a constant, but retaining livability is possible rock boundBY TOM GROENING

ON MAY 4, I took part in Belfast’s version of “Jane’s Walk,” an event inspired by community activist and author of 1961’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities Jane Jacobs. She critiqued, quite presciently, the urban renewal impetus of that era.

The concept of a Jane’s Walk, loosely coordinated by the nonprofit Maine Preservation, is to host volunteer-led “walking conversations” in which participants take in a town while “personal observations and local history” are discussed. A couple of years ago, I attended Stonington’s Jane’s Walk in which a tour of the village area had various players stepping out of buildings to share local history.

In Belfast, former mayor and city councilor and downtown booster Mike Hurley based his 90-minute talk on his recollections of the community’s business history, all from the perspective of the intersection of Main and High streets.

A self-described hippie who arrived here in the 1970s, Hurley became a serial entrepreneur, a newspaper columnist, a civic improvement subversive, and finally a city official. Having arrived in town in the mid-1980s, I was struck by

how many of the businesses and local characters that Hurley brought to life in story were those I had never known.

And that’s something to reflect on— change is a constant in our communities, but is there a point at which they evolve away from an ideal, away from a vitality and healthy social and economic stratification?

I’ve heard some in Belfast who grew up here lament that they no longer know many of the people they now pass on the sidewalk. Is the town losing its heart and soul, or are the old-timers not making an effort to stay in touch?

More questions: Do communities have their “good old days?” Do they peak? And if so, how do we measure the qualities that contribute to that status?

In recent years, my wife and I have had to drive her parents to Logan and then pick them up there several weeks later. To break up the long trips, we’ve begun planning visits to Massachusetts coastal towns. The first two visits, to Newburyport and Ipswich, were sort of pilgrimages to This Old House project houses, having become curious about those host communities on seeing them on TV.

Even in April, Newburyport was a busy town with beautiful 19th century

partnership with the National Digital Equity Center, the town will continue to pay $30 a month service fee through its Bremen Broadband Benefit for households below a certain income threshold. This is the same amount provided through the ACP and will guarantee that no resident falls through the digital divide.

This makes Bremen the first town in the state to provide a local affordability option for its residents. That is a commitment worth celebrating and yet another example of its pioneering spirit we can learn from.

We’d love to hear how access to high-speed internet is affecting your community. Send us a note. Christa Thorpe, who leads our broadband and digital equity efforts, can be reached at cthorpe@islandinstitute.org

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

architecture and a long waterfront walkway. We found the TOH project house and—just between us, dear reader—saw that some of the exterior paint had peeled back to bare wood. Maybe they had rushed to complete the project.

Ipswich, I learned from the TV show, had the most First Period homes in the U.S., those built in the 1625-1725 era. We didn’t have a lot of time that day, and we did find a nice walk that let us see some of those old houses, but the main drag through town was quite busy with midday traffic.

That visit had me wondering about the “past their prime” idea. Would locals walking those same streets recognize each other, or had it become a bedroom community for those who work closer to Boston?

Marblehead, with streets that looked like they’d been drawn by throwing chop sticks on a map, was a visual delight. The central square with its looming public building was like a lighthouse for us as we wandered the winding streets, gawking at the colorfully painted old homes. The snug harbor is probably chockful of boats in summer.

Rockport also had a central, waterfront square and a small, very protected

harbor. What probably had been a commercial wharf is now lined with tourist-oriented businesses; nice in April, but probably jammed in summer.

On one of the trips, we stopped in Portsmouth, N.H., a city we never think to visit. Since it is circumscribed by the river and I-95, it has a pleasing orderly and compact center, and may give Portland’s Old Port a run for its money.

The oral history focus of the Jane’s Walk events is one way to keep us connected with our past while making us mindful of what forces bring change.

Next year, Jane’s Walk in Maine will be held Saturday, May 3. Consider organizing or at least attending one in your town.

Tom Groening in editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

THE PALM BEACH OF MAINE—

This image, probably from the late 1930s, shows Main Street in Wells. The sign hanging from the telephone pole at left reads “14 ML Sanford The Palm Beach Mills.” The line of cars heading south suggests either a traffic jam or a parade of some kind. Can readers shed more light on this image? Contact editor Tom Groening at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

Do ‘fishing, fowling, and navigation’ ring a Bell?

Landmark waterfront access decisions must be reversed

BY RICHARD QUALEYAT A TIME when the working waterfront faces converging external threats like never before—increased property values along the coast, rising seas, and a changing ecology—those who rely on the sea and, by extension, the intertidal lands, must be adaptable to sustain their business and their livelihoods.

The biggest threat to adaptability is uncertainty, and under current Maine law, uncertainty pervades. We are working to change that.

In the words of former Chief Justice Saufley, under current Maine law, a member of the public is “allowed to stroll along the wet sands of Maine’s intertidal zone holding a gun or a fishing rod, but not holding the hand of a child.”

Why? Because in 1986, the Maine Supreme Court held, in Bell v. Town of Wells, that by virtue of the 1641-1647 Colonial Ordinance, title to intertidal lands is held by the upland owner, subject only to the public’s right to use the intertidal zone for fishing, fowling, and navigation.

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kristin Howard, Chair

Doug Henderson, Vice-Chair

Shey Conover, Secretary, Chair of Governance Committee

Carol White, Chair of Programs Committee

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Chair of Finance Committee

Bryan Lewis, Chair of Philanthropy Committee

Megan Dayton, Ad Hoc Marketing & Comms Committee

Mike Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Mike Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Michael Sant

Mike Steinharter

Donna Wiegle

Tom Glenn (honorary)

Joe Higdon (honorary)

Bobbie Sweet (honorary)

John Bird (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

What is fishing, fowling, and navigation? Courts look at each activity on an individual basis, leaving people who rely on access to the shore in a position of uncertainty.

Walking, running, and general beach-going may be the examples that jump most readily to mind, but what about the working waterfront? Can you access the intertidal zone to support your own livelihood?

In 2011, in a case which involved a commercial scuba diving business that took clients on shore dives in Passamaquoddy Bay, the Maine Supreme Court held that the public has the right to walk across the intertidal lands to enter the water and scuba dive. However, in 2019, the Court held that harvesting rockweed was not a right the public held in the intertidal lands.

Recognizing the need for certainty, in 1985 the Maine Legislature tried to solve this problem. The Public Trust in Intertidal Land Act provided that the intertidal lands could be used by the public for fishing, fowling, navigation,

recreation, and “[a]ny other trust rights to use intertidal land recognized by the Maine common law.”

Only four years later, in Bell II, the Maine Supreme Court held that the act was unconstitutional.

Thirty-five years later, we find ourselves wrestling with the same questions. The Maine Supreme Court has heard a number of cases since the Bell decisions, each of them addressing a specific activity or circumstance.

Each time the Court declines to overrule Bell and instead tells Mainers whether that specific activity falls into the public trust rights.

But what if “fishing, fowling, and navigation” was never intended to be so restrictive? What if the long-abandoned Colonial Ordinance was only ever intended to preserve the public’s right to use the intertidal land in a way that balances the upland owners’ interests in accessing the sea with those same interests shared by the public?

That is what we will be arguing at the Maine Supreme Court in the latest case in this long running saga.

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront. For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209

E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

Rather than seeking a decision by the Maine Supreme Court that a specific activity should be allowed, we are attacking the very heart of the problem in a way that has not been directly attempted since the Bell decisions.

The Colonial Ordinance expired by its own terms prior to Maine statehood. Though its mandate lives on in the common law, the common law is intended to be fluid and adaptable, adjusting to the society it serves. The Court has acknowledged that reality in the context of the Colonial Ordinance before, yet the law remains—for now.

You can follow this case, Peter Masucci et al. v. Judy’s Moody, LLC, et al., at ourbeaches.me, or on the Court’s website at courts.maine.gov/news/ high-profile.html.

This case isn’t about fishing, fowling, and navigation; it’s about certainty in public rights—it’s about your rights to access and enjoy the intertidal lands.

Richard Qualey is an attorney at Archipelago in Portland and represents the plaintiffs in this pending matter.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org (207) 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

Maine Maritime crew will deploy ‘drifter’ devices

Buoys will follow currents and transmit weather data

BY STEPHEN RAPPAPORTWhen the Maine Maritime Academy training ship State of Maine sailed from Castine May 8 for the start of the annual summer cruise, she carried 202 students, 25 faculty members, and a crew of 20 professional mariners. She also carried a unusual cargo: six high-tech drifter buoys to be launched along her cruise track through the Atlantic for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s global Argo weather research project.

NOAA describes Argo as an international program to collect information from the sea using floating buoys that drift freely with the ocean currents and move up and down in the water column at regular intervals, measuring water temperature and salinity between the surface and a depth of 2,000 meters (about 6,600 feet.) Data from these floats—transmitted by satellite—are incorporated into weather forecasting models worldwide.

The day before the training ship sailed from Castine, Dr. Pelle Robbins, a physical oceanography research specialist at Cape Cod’s Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), delivered a half-dozen of the drifters to the MMA waterfront, each packed in a heavy cardboard box, and explained their use and how they should be deployed to a group including the State of Maine’s master, Capt. Gordon MacArthur, and Dr. Kerry Whittaker, assistant professor of coastal and marine environmental science in the academy’s ocean studies department.

Atlantic.” The middle of the Atlantic is exactly where the State of Maine will be as it travels to Spain. Besides the convenient cruise track, there was also an existing link between MMA and Woods Hole.

Before coming to Castine, Whittiker was an assistant professor of oceanography at the Woods Hole-based Sea Education Association, an experiential education program that takes college students to sea for a semester of scientific research aboard a pair of purposebuilt sailing vessels. A WHOI colleague of Robbins with a connection to SEA contacted Whittaker who put her in touch with MacArthur.

“It’s really because of him” that the ARGO-MMA connection came to fruition, Whittaker said.

She anticipates that the product of that connection will offer several educational opportunities to MMA students. Midshipmen aboard the training ship will have the practical experience of deploying the ARGO drifters while at sea. That process should be relatively easy, Robbins said, because the drifters are encased in special cardboard containers with bottoms that essentially dissolve in the water. After the crew hoists the container back on board the training ship the drifter floats free and begins its work.

“ We have targeted the deployment of these floats for regions important for the formation and growth of hurricanes.”

The event marked a milestone both for Argo and MMA. Robbins said the program depends almost entirely on commercial ships and deep-sea fishing vessels to distribute its drifters throughout the world’s oceans. The venture with Maine Maritime Academy is the first time in its 25-year history that the Argo program has partnered with a state maritime academy to launch drifters from a training ship.

The choice of MMA was somewhat fortuitous.

“We try to maintain a fleet of 4,000,” Robbins said. “Currently, there’s a little bit of a thinning in the middle of the

Whittaker plans to use data from the drifters in MMA’s ocean studies program, which offers both advanced courses for students majoring in that discipline and an introductory course for non-ocean studies majors. Groups of students, some of whom may well have been on the training cruise, might “adopt” individual buoys, she said, and trace their journey through the sea and track the data they transmit. She also hopes to establish an ocean studies seminar each semester and, perhaps, get Robbins back to MMA for a final presentation regarding the ARGO program.

“It’s really exciting,” Whittaker said. When Robbins prepared the drifters for loading onto the ship in Castine, he said they were set in a “pressure activation mode” in which they “wake up” at 10-minute intervals and measure the pressure in the environment. “If it’s atmospheric pressure, they go back to sleep,” Robbins said. But, if the pressure is more than five times greater

than normal atmospheric pressure at sea level, “that is a signal they are in the ocean and they commence their mission,” to measure ocean temperature and, when they periodically rise to the surface, transmit that data via satellite through channels that feed into weather forecasts.

“We have targeted the deployment of these floats for geographic regions important for the formation and growth of hurricanes,” Robbins said. “Our initial hope was for these new floats to be in place for the 2024 hurricane season and we are still on track for that goal.”

1/2ʹ and 11ʹ plywood and lapstrake

in plain sight

A photographer who captured artists

Peggy McKenna was a master portrait maker BY KEVIN JOHNSONIF ONE WERE to go out to Monhegan Island in the summer or fall, it’s quite common to see groups of artists gathered on Fish Beach or other shoreline outcroppings with their easels and canvases painting the seascape or lobster boats. While this scene is replicated all along the Maine coast, Monhegan island is a hotspot. The dramatic light on the water and the beautiful, ragged shoreline of the Maine coast have lured artists here for more than a century.

In the 1980s, Belfast stood in stark contrast to the state’s more idyllic stretches of coastline. That’s what makes the photograph of Rackstraw Downes included here so unusual and interesting. Rather than facing out to the ocean (or river mouth, in this case), he has his back to it, facing a gritty working waterfront.

He stands in front of the railroad tracks, now a walking/bike trail, with junk piled on the other side. You can see what was the Penobscot Frozen Food factory building, which processed potatoes, on his canvas and the footbridge (formerly the Route 1 bridge) behind it. Belfast was a different town than it is now. The sardine factory was still operating and the poultry industry, while

winding down, still had a presence. A saying that was popular in this time was “Camden by the sea, Rockland by the smell, but if you want to go to hell fast, then go to Belfast.” This unflattering description did not, however, deter artists from coming. It didn’t hurt that rent and properties were cheap, but the allure of the place was more than mere economics. Artists like Downes saw beauty in the aged and run-down infrastructure. There is a patina in the peeling paint and rusted metal. It represented lifetimes of hard, dirty work and basic survival by the men and women who made their livings in these old factories.

Peggy McKenna, who made this photograph, was one of the artists who was drawn to this part of the state in the 1970s. She settled in Montville along with other artists and “back to the landers” and worked as a photojournalist for The Republican Journal and then The Waldo Independent. Her specialty was portraiture.

McKenna had the technical chops, but she also had a unique ability to connect with her subjects; she disarmed them and inspired trust.This was not an act or front, but a sincere interest that McKenna had in people and an empathy that was palpable to them.

An exhibition of her artist portraits, including the one featured here, will be on display this summer at Waterfall Arts at 256 High Street in Belfast: “McKenna and Her Camera: The Midcoast Maine Art Scene: 1987–2002” opens on Thursday, June 27 and runs through Labor Day Weekend.

Kevin Johnson is photo archivist for the Penobscot Marine Museum in

Searsport, whose photograph archives include more than 300,000 images which can be searched at its website, penobscotmarinemuseum.org. This season the museum, whose campus is on Route 1, is featuring: “Powering Up: The Evolution of the Maine Lobster Boat,” “Jim Steele Peapod Shop,” “Music in Our Lives,” “If You Give a Girl a Camera,” and “Faithfully Yours, Joanna C. Colcord.”

The 2024 College of the Atlantic Summer Institute will examine democracy in the United States during one of the most consequential years of our times.

Struggles for democracy traverse our lives and society, from ballot boxes to inboxes, from the corridors of Congress to the halls of schools, from kitchen tables to city streets. Questions of democracy confront us in our debates over freedom of the press, voting rights, and artistic freedom, in struggles against authoritarianism, and in conversations about how to effectively engage with disagreement and conflict across a range of topics.

Dating to the second century BCE, the kleroterion (pictured at right) was an early tool used in Athenian democracy to select members of the boule, or local council.

Join us from July 29–August 2 as elected officials, authors, analysts, and community organizers discuss what democracy means to them, the threats it faces, and how our individual and collective efforts can fortify democracy now and for future generations.

Free and open to all Registration required

‘Taking’

Quebec by boat

Anniversary of Arnold expedition revives Maine roleBY STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

“You can take Quebec City on a Saturday,” declares Rob Stevens, who is standing beside a wooden boat he’s in the process of completing behind the home of Maine’s First Ship along the Kennebec River in Bath.

Depending on your definition of what it means to “take Quebec City,” you could say the shipwright from Woolwich is talking from experience. In 2017, he and four other men followed the grueling route Benedict Arnold and 1,100 men (and a couple of women) took through Maine’s wilderness to Quebec in 1775 with the intention of capturing the city from the British.

The “taking” of Quebec City by Stevens and his four comrades more than 240 years later on Saturday, Nov. 4, 2017, involved an “assault” by river on the Canadian Coast Guard’s icebreaker, the Pierre Radisson. After banging on the side of the 322-footlong ship with an oar, “Nothing happened,” Stevens says, “and that’s why I say you can take Quebec City on a Saturday.”

The assault then included an arduous climb up the “secret path nobody knows about” (a.k.a. the Cap-Blanc stairs) to the Plains of Abraham, and a “storming” of La Citadelle, capped by the five drunk men exposing their bare arses in the direction of the barracks representing the long-ago British enemy .

“I’m not kidding when I say I was not drunk,” declares a straight-faced Stevens, “but the other four guys were smashed.”

The bateau Stevens built for that 2017 trip serves as a model for the one he is building today. This bateau, at 22 feet and made mostly of pine, will be used not for a repeat of the 350-mile journey to Quebec (although Stevens is game for another go at it) but as the basis for other bateaux Stevens and members of the Arnold Expedition Historical Society hope will be built as part of the society’s celebration next year of the 250th anniversary of the Quebec campaign.

As a little history refresh: At the start of the American Revolution—a year before the Declaration of Independence—Benedict Arnold proposed to George Washington that he take a force through the Maine wilderness via the Kennebec and Dead rivers to seize Quebec and thwart the British.

Arnold and his army were outfitted with funds and supplies, including 220 bateaux made at the home and shipyard of Reuben Colburn (now a state historic site and museum) in present-day Pittston.

To say the expedition to Quebec that began in late September 1775 on the Kennebec River outside Colburn’s home was miserable is an understatement.

The expeditionary force faced whitewater in the rivers which bashed their bateaux (and themselves) to pieces, snow and freezing temperatures, and a massive storm that resulted in the loss of supplies and provisions.

Disease, injury, death, and the decision by some of the expedition leaders to turn around meant that fewer than half of those who began the expedition made it to Quebec, says Tom Desjardin, a Mainebased author who wrote the book Through a Howling Wilderness about the expedition.

“People died of about everything you can die of in the Maine woods,” he says. “They died of freezing, they died of drowning, they died of disease, they died of everything but a bear attack.”

Despite the reduced force, Arnold and his army still made it to Quebec and attempted capturing the city, but both attempts failed (in deference to Rob Stevens, it must be noted that each of those attempts began on a Sunday).

The “failure” to seize Quebec for the Americans really wasn’t a failure at all when placed in the context of all that followed, says Desjardin, but the story of the expedition—essentially the first major military campaign of the American Revolution— doesn’t get the attention it deserves because of

Arnold’s later betrayal when he switched sides to support the British.

“The reason there was a Saratoga was because Arnold and his army tried but failed to walk to Quebec and take the city,” Desjardin says. And if it wasn’t for Saratoga—when the American military captured an entire British army, which convinced the French to provide support—the Americans would likely not have prevailed against the British, he notes.

The Arnold Expedition Historical Society has been trying to raise the profile of the Quebec campaign through Maine since its founding in 1973. With the 250th anniversary coming up and the Reuben Colburn House still closed due to a need for major renovations, the society is hoping to bring attention to the expedition and Maine’s role in it, and to raise funds, says Mike Holt, one of the society’s members.

Part of that effort will be next year’s events. Those are still in the planning stages, says Holt, but members are talking about holding poling and rowing competitions, including some more strenuous challenges such as portaging around obstacles, and maybe even a cooking competition to include creative recipes such as “right-shoe soup,” jokes Holt, in reference to the starving men of the 1775 expedition who did resort to eating their shoe leather.

The society is also partnering with Maine Maritime Museum in Bath to sell bateau kits. The boatshop at the museum has offered to create the kits based on Stevens’s design for those who want to build a bateau but don’t have the resources to do so. Society members hope that a handful of nonprofit organizations will build bateaux that can later be placed on public display at a variety of locations.

Those interested in a bateau kit or in participating in next year’s events should contact the Arnold Expedition Historical Society at arnoldexpedition250th@gmail.com

MID-COAST SCHOOL

continued from page 1

include 16. Staff interview prospective students and must turn away most.

“That’s the hard part,” he says. Students list ranked choices when they apply, so they may land in a second or third requested class.

The programs typically run for two years, beginning in the junior year, and students sometimes switch out of one, realizing the work is not for them. This is a win, Deetjen says, since time isn’t wasted pursuing a career that won’t be satisfying.

On our tour, we see scenes that may align with the images we have of vocational education—students grinding steel under the watchful eye of their instructor, another applying finish to newly built bookshelves, and others working dough for what will become croissants.

But there are some surprises, like students working with representatives of Shepard Toyota in nearby Thomaston. Two new large pickups are in the shop—one retailing for $100,000, the other for $80,000— and students are learning to connect diagnostic equipment to the vehicles’ various computer systems.

Deetjen notes that several private sector businesses are involved in the education at the Mid-coast School of Technology, providing tools, materials, and actual job opportunities.

Instructor Tom Vannah says the realworld work “takes the ‘scary’ out of it,” and allows students to see the jobs that exist in this realm: automotive technician, parts manager, body shop work, and sales.

Though hands-on is key, students spend considerable time in a small classroom adjacent to the large shop area, where they attend lectures. This component is part of almost all the programs.

And the work isn’t random. Vannah says students perform 200 assigned tasks on vehicles over their two years.

Deetjen observes that dealerships hire diagnostic engineers who identify problems and assign the work to mechanics. It’s problem solving, he says, and adds that almost all the programs boil down to this sort of critical, analytic thinking.

Computer design is another surprise, with students hunched over laptops writing code. Many are aiming for careers creating video games, though they also learn to do audio and video editing, so one of these students may work on a movie you stream on Netflix in a few years.

Students in the outdoor leadership program have just returned from a two-night camping trip on Black Island in Penobscot Bay and under their teacher’s direction, are unpacking and inventorying their gear.

They are aiming for guide licenses; some will end up in the military, or working for land trusts, and some

will pursue a degree in the field at Washington County Community College. Local outdoors outfitter Maine Sport works with the class.

Seth Walton, the instructor, says the overnight trips are not unusual.

“We’re probably out of the building 75% of the time,” he says.

There aren’t many students in the medical program’s classroom, Deetjen explains, because half of them are doing “clinicals,” actually working in area nursing homes and hospitals to learn skills. Most achieve CNA licensing by the time the program ends, but most go on to become RNs, he says.

In the building, they sit through fiveand-a-half hours of lectures.

The culinary program students are preparing croissants when we stop by.

The program serves lunch for six weeks each semester, serving 70 people a day with four entrees and dessert.

In the marine program, a young man proudly shows visitors a boat he finished. The hull was developed by a student who has since graduated, a passing of the baton that’s common here.

Deetjen, who taught in a traditional school before this job, heartily confirms the observation that students here seem engaged and, well, happy to be here. National statistics show that career students graduate at higher rates than those in traditional high schools.

See photos on the following two pages.

provisions

Garden & Market

• Freshly made sandwiches & salads

• Hot entrees: soups, chili, and chowders

• Large selection of wine, craft mixers, and Naut-E botanical spirits

• We also now make pizza. Call to order: (207) 326-0781

• Free wine/beer tastings every 1st/3rd Friday at 4:30

We also have wonderful unique gifts, from finely crafted Japanese teacups, award-winning Folkmanis puppets, and our iconic coffee mugs and sweatshirts—this year’s line being in Pantone’s 2022 color of the year, Peri.

Open Daily 10-5

5 Castine Road • Castine, ME

windmillhillprovisions@gmail.com • https://windmillhillprovisions.store INSTAGRAM: windmillhill.provisions FACEBOOK: Windmillhillprovisions

The next generation of workers

PHOTOS BY JACK SULLIVAN

Our Island Communities

Righting a wrong—Monhegan’s women artists get their due

Show featuring their work at museum through September

REVIEW BY CARL LITTLEAs curator Emily Grey relates in the catalogue for “Woman Artists of Monhegan Island: A Common Bond” on view at the Monhegan Museum of Art and History, Elena Jahn (1938-2014) and Frances Kornbluth (1920-2014) founded this collective in 1990 “as a way for women artists on the island, with greater intention than in previous generations, to create a space for collaboration and ‘mutual support’ in a newly invigorated Monhegan art community.”

Grey goes on to explain that membership in the collective was limited to 15 artists “based on exhibition and storage limitations” and that the artists were required to be actively showing in galleries and to spend at least six weeks on Monhegan each year.

“In a spirit of egalitarianism, common in many contemporary women’s cooperatives and groups,” she notes, the members “used identical frames of the same size.”

Over the years, Women Artists of Monhegan Island, or WAMI, held exhibitions in a variety of venues, on and off Monhegan. The “pinnacle” of these shows, notes Grey, was “On Island: Women Artists of Monhegan” at the University of New England Gallery in 2007. Co-curated by WAMI member Kate Chappell and gallery director Anne Zill, the exhibition, wrote the latter, was an opportunity “to right a wrong” and “demonstrate that women’s artistic talents are just as good as their male counterparts.”

“Woman Artists of Monhegan Island: A Common Bond” offers another excellent demonstration of this collective’s praiseworthiness. With a couple of exceptions, all 18 artists in the show are represented by three works. The images range from realist to abstract, with many variations in between.

Inspired by their mentor and fellow Monhegan painter Reuben Tam (1916-1991), Kornbluth and Jahn brought expressionist energy to their island paintings. Kornbluth’s “Changing Light, Monhegan Ice Pond,” (1989) evokes a shimmering cascade of what might be moonlight on the water framed by colorful foliage.

Jahn’s “Red Rocks, Monhegan,” (1959) is bold and fiery.

A view of the Eider Duck cottage on Fish Beach beneath an array of clouds by Sylvia Alberts (1928-2015) has a Magritte-like feel— real yet surreal. By contrast, Natalie Minewski (1927-2017) responded to the landscape by way of a dynamic collage that mixes night and day and island elements.

Yolanda Fusco (1920-2009), Beth Van Houten (1945–2022), and Evelyn Davis (1905–2000) bring impressionist/expressionist energy to their arrangements of fruit and flowers. An untitled watercolor still life by Susan Rosenthal (1905–1997) features a simple bouquet in a tall pitcher—a lovely evocation of summer. In translucent watercolors Ruth Boynton (19152003), Joanne Scott (1928-2021), and Joan Rappaport (1941-2019) found poetry in beach stones, pebbles, rocks, shells, and seaweed. Also notable is “Tangled Nets II,” a wild and colorful mixed-media piece by

Nancy Thompson Brown (1926–2019), and the Thiebaud-esque “Men Cigarettes” by Arline Simon (1927–2020).

Various print techniques come into play. Frankie Odom (1941–2019) turned to ink print embossment to create “Spawning,” a flurry of fish that brought to mind Morris Graves’s “Flight of Plover.”

The images range from realist to abstract, with many variations in between.

A lithograph by Jacqueline Hudson (1910–2001), “Maine Morning,” captures the calm of a new island day.

The sole sculptor in the show, Lucia Taylor Miller (1928–2019), delighted in the figure in her work. Her charming painted terra cotta “Best Friends” shows WAMI cofounders Jahn and Kornbluth, all smiles in sunglasses and scarves, driving a four-wheeler.

The Monhegan Museum has produced an enlightening catalogue to accompany the exhibition. Art historian Susan Danly’s essay provides a history of women artists on Monhegan. Artist Kate Chappell writes about her personal connection to the island—it became her “soul place” after a visit in 1987—and the challenges of presiding over a sometime unruly group.

“At a particular time in a rare place,” Chappell writes, “we supported one another as a community through our stories, our resilience, and our mutual passion for art.”

WAMI came to a close in 2018. In “I Am a Daughter of Monhegan Artists,” Lisa Jahn-Clough offers a timeline of her mother, Elena Jahn’s, and her own connection to the island. She acknowledges the influence of the artists in the show and how they “forged the way

11 x 14½

for younger women artists to expect more, to demand more, and to remain true to their artistic souls.”

The Monhegan Museum has a policy that it only shows deceased artists, but it has reproduced work by former WAMI artists Chappell, Dyan Berk, Judy Shepard Gomez, Joan Harlow, Sylvia Murdock, Elaine Reed, and Robin Young in the catalogue. Together, this group of “groundbreaking individuals,” writes museum director Jennifer Pye, “offered a source of camaraderie and critique”—and some finest kind of art.

“Woman Artists of Monhegan Island: A Common Bond” runs through September. For days, hours, and other information, visit www.monheganmuseum.org.

Carl Little is the author of The Art of Monhegan Island. He provided some of the narrative for the documentary Women Artists of Monhegan (2007).

SEA LIFE

SPONSORED BY from a new perspective

Bigelow Laboratory’s Café Sci is a fun, free way for you to engage with ocean researchers on critical issues and groundbreaking science. Join us at The Opera House at Boothbay Harbor for these in-person-only events. Register at bigelow.org/cafesci.

book reviews

A librarian weaves a surprisingly tangled web

Novel set in Maine rich in plot twists

Bad Animals

By Sarah Braunstein (W.W Norton, 2024) REVIEW BY TINA COHENI’M NOT SURE if “a novel” is a subtitle or an aside for Sarah Braunstein’s Bad Animals, but the story might also be described as a mystery and a romance, a book that seems to delight in pointing out how quirky librarians can be.

The story is told by one: Maeve Cosgrove, who works in a library in an unidentified place in Maine. Braunstein lives in Portland and teaches at Colby College and the story references both Portland, Southern Maine, and the Midcoast.

Maeve loved her job and programming for library events, but she gets canned for a contested reason. Was it an adolescent girl, trying to make trouble by reporting her as a “peeping Tom,” or was it budget cuts, the official reason she was given?

Maeve agrees to a new “job,” that of “facilitating” the telling of the life story of Willy, fiancé of a former colleague, Katrina (still at the library), as told to famous author Harrison Riddles (we are left to wonder who his real-life equivalent would be).

Riddles, having heard of Willy in fan letters Maeve wrote him, as well as letters he received from Willy, now wants to make it his next book.

A book club would have a lot of fun with this, as it can be understood multiple ways.

As with Misery, Stephen King’s story about how a besotted fan can actually hurt the author she adores, Maeve seems capable of ill will at the same time as “doing anything” for Harrison. No longer the meek librarian but a thrill-seeking mid-career empty nester, she even ingests part of a mystery plant, part of her college daughter’s botanical experiment, which seems to provide a kind of mind-altering experience. And Maeve ventures into therapy, which also seems mind-altering; she accepts that her depression needs help from a source other than illicit romance.

The novel reminds me of the film Adaptation, based on the book by Susan Orlean, The Orchid Thief, where a nonfiction writer researches rare orchids in Florida jungles. The movie has her character ingesting mind-altering drugs, and having a sensational, torrid romance that is, on the face of it, highly unlikely.

We can even wonder if Maeve is the book’s imagined author, conjuring up adventures and a sexy author’s erotic interest in her. You may never look at a librarian the same way and assume anything “boring.”

The work takes place at Riddles’ summer home on the Maine coast. Willy is a “New Mainer,” having resettled in the U.S. from Sudan during high school, now proficient in English and studying in college.

Bad Animals is thoughtful and enjoyable, combining memorable characters, a twisty plot, and lots of good loose ends. Richard Russo is quoted on the back cover: “...a dazzling high-wire act. Absolutely chilling.” A book club would have a lot of fun with this, as it can be understood multiple ways.

The complicated case of Melvin Fuller Supreme Court justice from Maine had role in race law

Calm Command: U.S. Chief Justice

Melville Fuller in His Times, 1888-1910

By Douglas Rooks Maine Authors Publishing (2024) REVIEW BY DANA WILDEIN FEBRUARY 2022, a statue of Melville Fuller, the Augusta native who served as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1888-1910, was quietly removed from its spot on the grounds of the Kennebec County Courthouse where it had stood for nearly nine years. Everyone who’d been paying attention knew what this was about.

Fuller presided over the court in 1896 when the now infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case was decided. He voted with the 7-1 majority ruling against the claim by Homer Plessy, a black man who could nonetheless pass for white, that he should have been allowed to use a railroad car designated for white people. The ruling upheld the practice of separate but equal facilities for different races of people.

One hundred twenty-eight years and the overruling of the separate but

equal principle in Brown v. Board of Education in 1955, we think we have a pretty clear picture of right and wrong in America’s sorry, bloody racial history. Fuller voted to uphold a principle that would underpin oppressive Jim Crow laws for decades. Shame on him. His statue must come down.

We learn in Douglas Rooks’ new book about Fuller’s life, Calm Command, that reality is nowhere near so simple.

Fuller was born in Augusta in 1833 and participated, like others in his family, in Maine politics. He moved to Chicago in his 20s, established a successful law practice, and became an important figure in Illinois politics. Although a Democrat, he supported Lincoln’s position in the election of 1860, which was not to end the practice of slavery, but to limit its expansion into Western states.

In keeping with that aim, Fuller backed the effort through the Civil War to keep the union together but, like many at the time, thought the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 was a political mistake.

fill the vacancy for chief justice of the Supreme Court.

Fuller did not write the majority opinion in the Plessy case, which at the time, Rooks explains, was not considered to be of much consequence. Several similar cases had been decided along those lines.

Justice Henry Billings Brown spelled out the persuading issues for the majority in the 7-1 decision (one justice was absent for the case). While agreeing that the Constitution and the laws following from it grant the government oversight of civil and political rights, Brown wrote, trying to legislate social rights would be extremely problematic.

“Brown’s bland assurance that there was something natural about racial prejudice offends us today but was widely accepted then.”

Rooks details how Fuller’s integrity, universally praised good nature, and keen knowledge of law won him many allies in Washington. In 1888, President Grover Cleveland persuaded him to

Separate but equal accommodations for the races seemed fair to the justices as well as many, if not most people who opposed slavery following the Civil War. As expressed in the Plessy opinion, Rooks says, “Brown’s bland assurance that there was something natural about racial prejudice, or that one race could be ‘inferior,’ offends us today but was widely accepted then.”

Here in the 21st century, we know that the conclusions in Plessy were used to

What a perfect character a librarian is for a mystery—we assume the character knows everything or at least how to find anything, like a detective, and that all their thrills are vicarious ones. They seem so fact-bound; how often do we wonder at their own inner life and imagination?

Tina Cohen is a former librarian who left mid-career to become a therapist, and spends most of the year on Vinalhaven, reading and writing.

underpin Jim Crow laws, but the justices had no way of knowing that in 1896. Deference to states’ rights arguments on social issues seemed the more hopeful course. Rooks quotes Supreme Court Justice David Souter in 2010 reflecting that “members of the court in Plessy remembered the day when human slavery was the law of the land. To that generation, the formal equality of an identical railroad car meant progress.”

Rooks’ clearly written, meticulously researched book gives the background of Fuller’s life and of the Plessy case, and also the historical backdrop of the Constitution and the political and social machineries of the 19th century, in tandem with discussions of cases in constitutional, labor, and maritime law.

A point that returns again and again is that Fuller was viewed as an extraordinarily capable administrator who shepherded the federal court system through a major, necessary overhaul and expansion. There are reasons why we may want to remember Fuller favorably, despite a serious mistake rooted in the ethos of his time rather than the individual himself.

Calm Command is a careful, wellwritten book that throws light on not only Melville Fuller, but the boiling history he helped guide the U.S. through, for better and worse.

Dana Wilde is a former newspaper editor and college professor. He lives in Waldo County.

Lobster Institute names new director

MAINE NATIVE and University of Maine alumna Christina Cash has been named executive director at the UMaine Lobster Institute, effective May 17.

Cash has been with the Lobster Institute since 2021, serving as assistant director of communication and outreach, and more recently as interim director. Before joining the organization, Cash served as an advancement officer at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Boothbay Harbor, as well as program and development director at the Frances Perkins Center, and director of outreach at the Institute for Broadening Participation, both in Damariscotta.

research, workforce and other focus areas.

“We are excited about the next stage for the Lobster Institute, broadening its reach and impact across the UMaine campus, state, and national and international lobster fishery partners,” said Dean Diane Rowland of the College of Earth, Life, and Health Sciences, where the Lobster Institute resides. “I know Chris will help effectively lead this broad coalition with strategic vision and continue the legacy of the Lobster Institute into the future.”

Cash will be based at UMaine’s Darling Marine Center.

Castine Historical Society tells story through objects

HISTORICAL SOCIETIES exist to tell a community’s history through objects and archival records. The Castine Historical Society’s new exhibition, “A History of Castine in 40 Objects,” opens June 10 and will remain on view through Oct. 14. The exhibition highlights aspects of the town’s history through never-before-displayed objects from its permanent collection.

“It is an honor to be in this position as a liaison between industry and the university,” Cash said. “There’s so much going on in the lobster world right now and I look forward to collaborating with partners from industry, management, and academia on research that can help the fishery. I hope to expand Lobster Institute’s programs and student opportunities based at the Darling Marine Center.”

Cash is a former first mate, captain, and lobster boat owner/operator and holds an active captain’s license. In her new role, Cash will oversee the creation of a new executive committee, with subcommittees planned for outreach,

“In her time at the Lobster Institute, Chris has already proven adept at fostering communications within the industry and advancing research to help benefit the lobster fishery as a whole,” said Marianne LaCroix, executive director of the Maine Lobster Marketing Collaborative and chair of the Lobster Institute advisory board stated. “She is ideally suited to furthering the Lobster Institute’s mission of supporting a sustainable and profitable lobster industry.”

Since 1987 the Lobster Institute has been a center of discovery, innovation and outreach at UMaine with the goal of promoting, conducting, and communicating research focused on the sustainability of the American lobster fishery in the U.S. and Canada.

Owning a home or business on the coast of Maine has many rewards.

A close working relationship with your insurance agent is worth a lot, too.

We’re talking about the long-term value that comes from a personalized approach to insurance coverage offering strategic risk reduction and potential premium savings.

Generations of Maine families have looked to Allen Insurance and Financial for a personal approach that brings peace of mind and the very best fit for their unique needs.

We do our best to take care of everything, including staying in touch and being there for you, no matter what.

That’s the Allen Advantage. Call today.

(800) 439-4311 | AllenIF.com

We are an independent, employee-owned company with offices in Rockland, Camden, Belfast, Southwest Harbor and Waterville.

Forty unexpected and compelling artifacts in the exhibition weave together almost 400 years of Castine history. Organized by a team of community members and staff, the objects selected for exhibition tell Castine stories which are both familiar, like the town’s Revolutionary War history, and unexpected, such as its African American history.

The exhibition is divided into themes that help visitors dive into these fascinating stories of the past and present.

“Castine at War” looks at why major world powers fought over the peninsula and also examines how subsequent wars—including those not fought in town—affected the average Castine citizen.

“Castine at Sea” not only delves into the careers of wealthy ship captains but also the people who worked on the docks to support this maritime trade.

“Castine at Work” explores how politics, community organizations, and occupations helped shape the town. The

exhibition ends with “Castine and the Arts,” which examines the significant role the arts, artists, and writers played and continue to play in this community.

The Historical Society exhibits are free and open from June 10-Sept. 2, Monday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-4 p.m.; Sunday, 1-4 p.m.

Fall hours are Sept. 7-Oct. 14, Friday, Saturday, Monday, 10 a.m.-4 p.m.; Sunday, 1-4 p.m. Free one-hour walking tours of Castine are offered Friday, Saturday, and Monday at 10 a.m. beginning June 22. No reservations are needed to take a walking tour.

Exhibitions are housed in CHS’s Abbott School gallery at 17 School Street, where visitors will also find a gift shop and a community meeting space. The neighboring Grindle House at 13 School Street houses offices and a research library, where visitors are welcome by appointment year-round. For further information visit castinehistoricalsociety.org, call 207-326-4118, or email info@castinehistoricalsociety.org.

saltwater cure

Unexpected awe in life’s big moments

Eclipse, aurora borealis, and new book move me

BY COURTNEY NALIBOFFBY THE TIME you read this, the book I co-authored, Your Postpartum Body, will be out in the world.

For ten years I’ve been throwing manuscripts at the wall of literary agents to see what might stick and have often richly imagined the moment when a book with my name on it might be a tangible reality. Now that it’s almost here, I find that I might not be big enough to hold all my feelings. I think of myself as cool, calm, collected, a veritable Vulcan in the face of the big life moments, but it’s time to face facts: I’m as susceptible to awe as the next tiny speck in the universe.

There have been plenty of opportunities to experience the majesty of the cosmos and find those big feelings in a less personal, more global way this year, and I was fortunate enough to experience both eclipse totality and the aurora borealis.

The eclipse opportunity came about when my colleague and friend invited Penrose and me (because I badgered her relentlessly) to join her family in

Rangeley at a house they had rented months earlier through foresight and good planning.

High on a hill above Rangeley Lake, we had a perfect, almost private viewing spot. We had snacks, a playlist, Adirondack chairs carried to the top of a snowplow pack, and plenty of eclipse glasses.

Everything felt fun and festive until totality neared. The sky grew dim, colors faded, the temperature dropped several degrees. All things that had been predicted and described but which in the moment I found unnerving.

A sense of dread built in my stomach as the sun entered the diamond ring stage and shortly thereafter vanished. I was my distant ancestor, gazing at the sky, desperately hoping for the return of the beloved sun. I was a small mammal, confused and aggrieved, awakened for my nocturnal cycle unexpectedly, or driven to my den ahead of schedule.

The sun, of course, returned. We packed up the picnic and walked back down to the house, popping our eclipse glasses on from time to time to check that the sun was still returning to its full

strength, but no longer in the thrall of a cosmic event that felt, for two minutes and 30 seconds, like the end of the world.

Earlier in May, I was off island with students when all of our Instagram accounts were suddenly flooded with spectacular photos of the aurora borealis. We’d been at Portland Stage, watching their spectacular production of Angels in America, but started to feel the FOMO (fear of missing out) regardless.

Determined not to miss it, we drove out of the city in search of a dark enough sky to catch our own light show.

A little way out of town at a trailhead, we could just see foggy streaks that, through a long-exposure photo, were revealed to be the Northern Lights. But we couldn’t believe there wasn’t more to the phenomenon, so we kept going until we found a soccer field.

The students ran out into the dewy grass and we chaperones followed, a little slower and more cautiously. The streaks were more prominent here, and a slight coloring could be detected that we didn’t see in town.

“It just looks like clouds,” one of them kept saying, disappointed at the

journal of an island kitchen

The baggage of being a vegetarian

Food identity comes with mixed blessings

BY SANDY OLIVER BY THE SUMMERof 1979, like many human beings around the globe and in times past, I ate relatively little meat. It wasn’t a matter of principle. I ate vegetables and grains largely for economic reasons, employed at a job qualifying me for food stamps for which I never applied. That summer I met the man who would be my husband of many years.

An ethical vegetarian, he’d been sickened by the experience of working in one of Belfast’s chicken processing plants before the industry moved south. The meal I cooked for our first date was all vegetables though I didn’t know he was a vegetarian. He was suitably impressed, entirely accidentally.

Being a vegetarian in the 1980s, though becoming more common, was still considered abnormal. We ate fish and dairy so our preferences could have been harder to accommodate.

In those days, vegetarian restaurants were scarce and most eateries offered no all-vegetable entrees; when eating out we’d order from the appetizer and salad menus.

Our favorite place to eat was a Lebanese restaurant with mezze. Mexican places offered a big spread of nachos and Indian restaurants served all-vegetable thali.

The Vegetarian Epicure and Mollie Katzen’s Moosewood Cookbook piloted me through lots of homemade meals in those pre-internet days. Once, a local newspaper having heard we were vegetarians, called me to ask what we ate at Thanksgiving, to which I replied “everything else,” since we could count on lots of side dishes plus dessert pie and not miss turkey so very much. Well, I missed turkey soup.

When we moved to a new town to caretake a small historical society, word got around about our vegetarianism. People meeting us for the first time used to say, “Oh, you are vegetarians, aren’t you?” Our reputation clearly preceded us.

I was sorry, though, to see how flummoxed a host could be with a vegetarian at the table. Our peers were more relaxed; some even cooked a few vegetarian mains as part of their weekly fare.

We’d say, “Please don’t fuss, we can eat just vegetables and salad,” but people strained to make sure there would be something we’d enjoy. My mother’s fallback was mac and cheese; my husband’s mother would say, “I don’t know what you fellas eat.” We’d say “anything except meat;” she’d often end up taking us out to eat.

Still, I was sadly aware that our choice skewed meals with others and as much as they might like us, entertaining us gave them pause.

difference between the in-camera and out of camera experience. I stood still, looking straight up. What had seemed like clouds suddenly writhed towards the very center of the sky, twisting and contorting unnaturally. The same feeling of dread and awe I’d experienced at totality crept back into my belly. I urged the rest of the group to do the same, and the complaints ceased as everyone absorbed the sight of the surge of solar energy dancing to its own rhythm. No photo had prepared me for the sensation. It feels arrogant to compare an eclipse and an aurora to a book release, but from what I’ve learned about my capacity for awe, there are some big emotions coming my way soon, unpredictable and a little frightening, but there for the purpose of opening and expanding my heart to the world.

Courtney Naliboff lives on North Haven where she teaches at the North Haven Community School and plays in the band Bait Bag. She may be contacted at Courtney.Naliboff@gmail.com.

We eventually moderated our stance, eating animal products, even raised pigs and chickens for food while continuing to cook favorite all-vegetable meals, though I think animal protein is overrated.