A Publication by

A Publication by

Since 1974, MacMag has stood as a testament to the creativity and innovation of students at the Mackintosh School of Architecture. Each edition captures the spirit of its time, showcasing exemplary work and thoughtprovoking discourse. As we present the 50th edition, we reflect on this rich legacy and the continuous evolution of architectural education and practice.

Our theme, ‘Legacy in Motion’ embodies the dynamic interplay between tradition and progress, honoring the foundations laid by our predecessors while embracing the transformative forces shaping our future.

In this milestone issue, we delve into the impact of emerging technologies, such as AI, on design thinking and problem-solving. Simultaneously, we highlight efforts to foster diversity and inclusion within architectural education, recognising that a multitude of perspectives enriches our collective work.

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the students who have contributed their work, reflecting the diverse talents and visions within our community. Their projects exemplify the innovative spirit and critical inquiry that define the Mackintosh School of Architecture.

We invite you to journey through MacMag 50, celebrating the legacy that has brought us here and the motion propelling us forward.

Foreword

School Photo

50 Years of Macmag

Transient Spaces

Stage 1

Co-Lab

Innovation & Lasting Impact

An Interview with Danny Campbell

Stage 2

Housing and Film

An Interview with Johnny Rodger

The Mack CAN! Pass The Hope In Solidarity

Stage 3

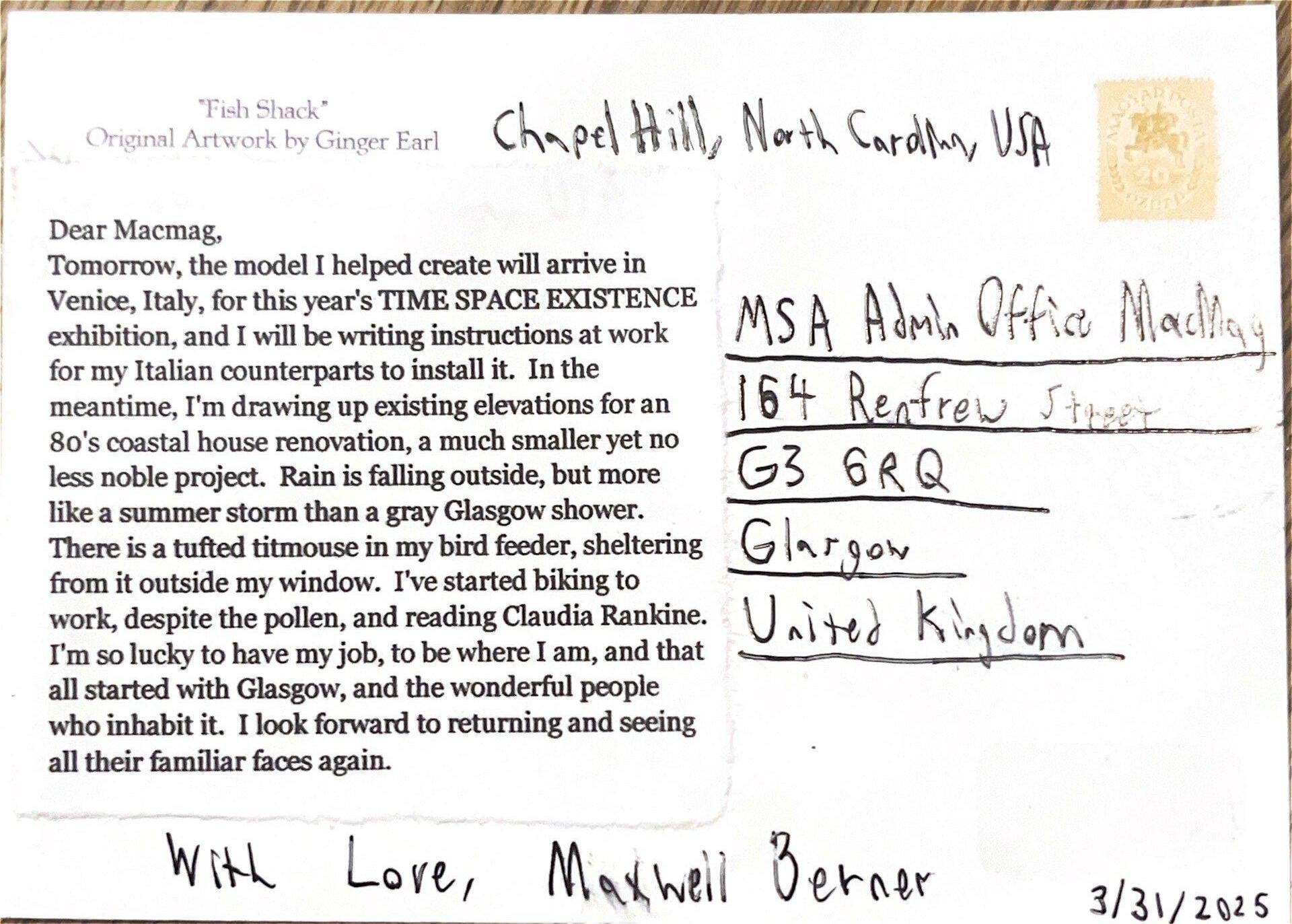

Postcards from Practice

Not All Legacies Are Made of Bricks and Mortar

An Interview with Grace Choi

Stage 4

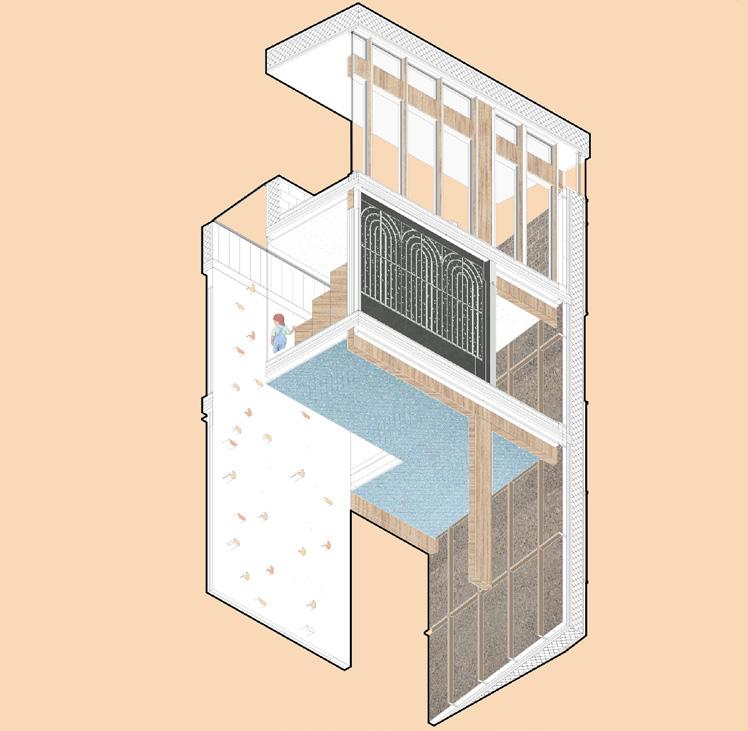

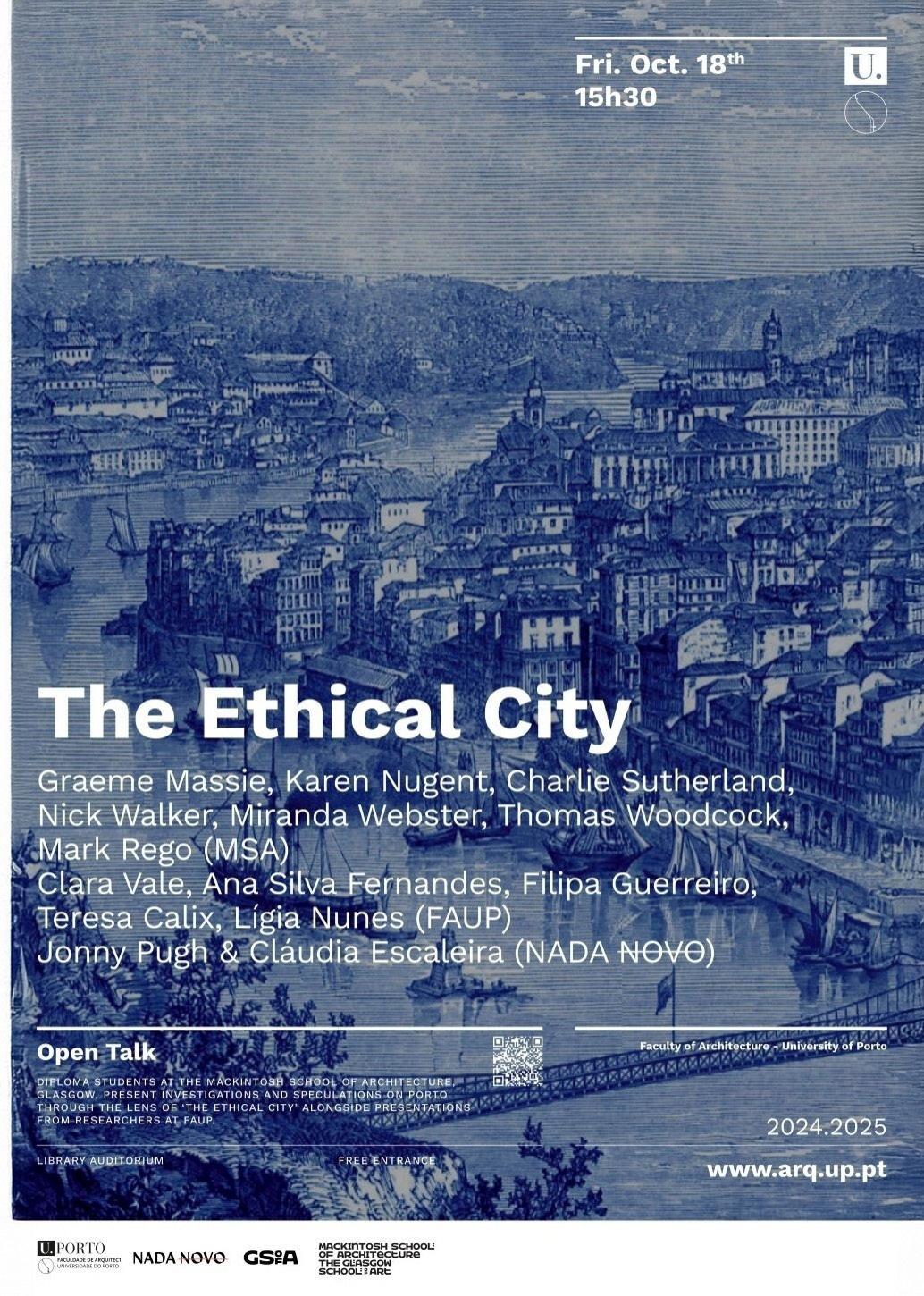

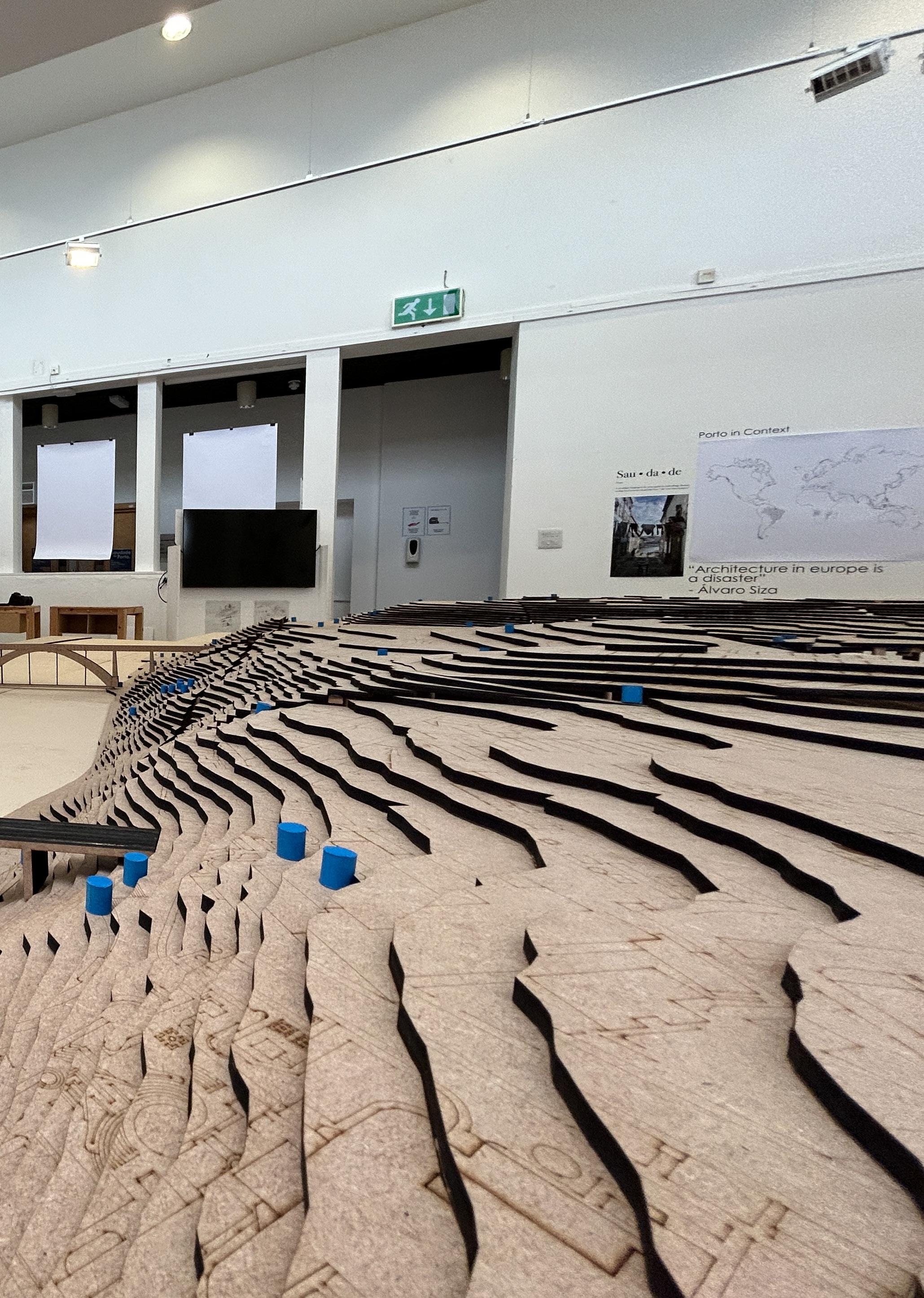

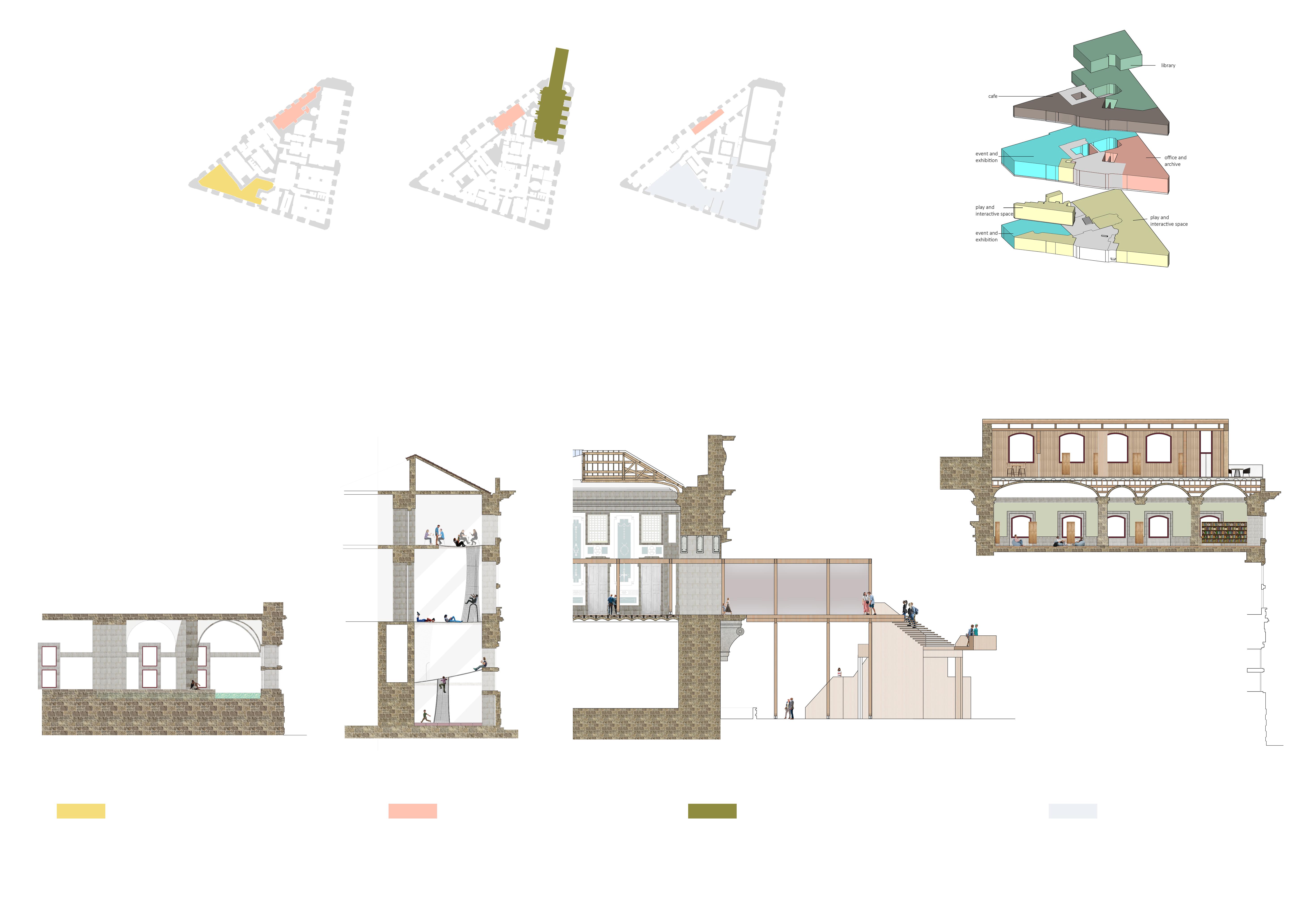

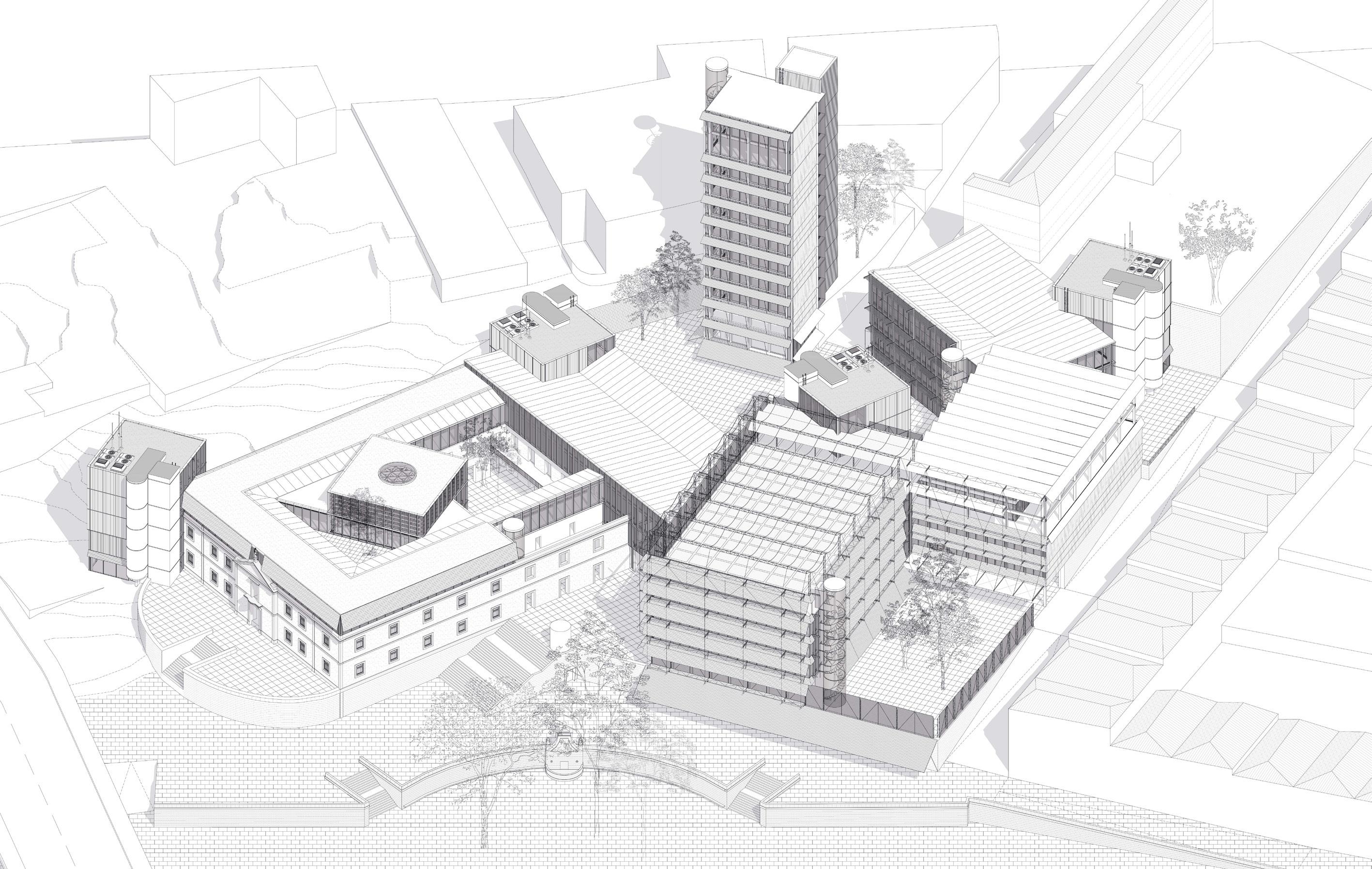

Porto Exhibition

Construct the Context

An Interview with Álvaro Siza

Stage 5

Revolutionising Architecture

An Interview with Amir Hossein Noori & Danny Campbell

E-R-AI Initiative at AFAD

An Interview with Juraj Blaško & Kristína G. Rypáková

Masters by Conversion Masters

Project

BY SALLY STEWART - HEAD OF SCHOOL

So MacMag turns 50, and continues to capture and document the work, preoccupations and challenges concerning its community, students and staff, graduates and wider profession.

As the theme the MacMag team have chosen suggests, legacy in motion, the Mackintosh School connects to its roots and traditions while never remaining in stasis. Although the fundamentals we teach about would be familiar to its first graduates, the world around us has changed, and is changing even while we think about how to respond to it.

Just as MacMag continues to evolve, so will MSA graduates. It’s that motion that keeps going.

Here’s to the next 50 years.

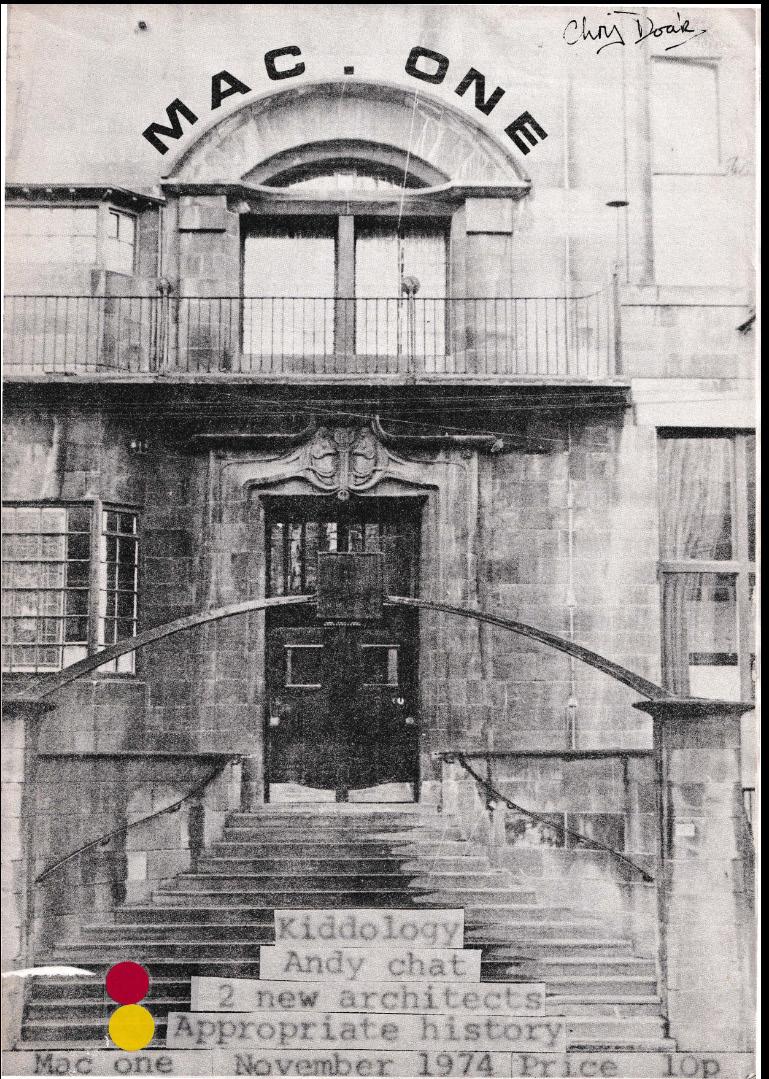

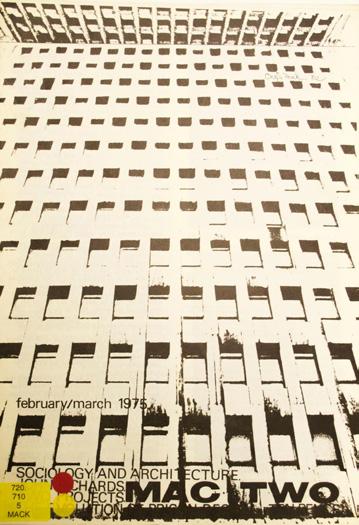

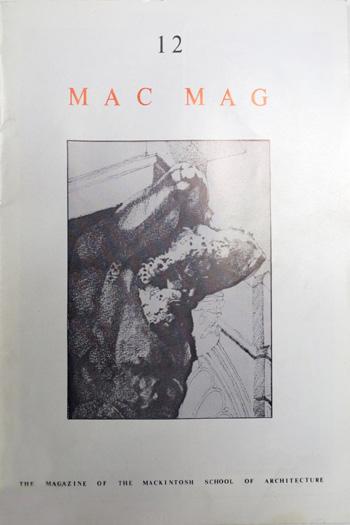

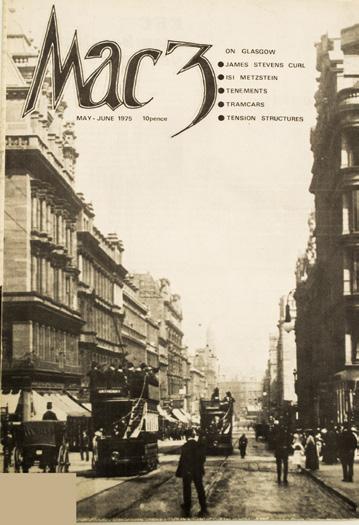

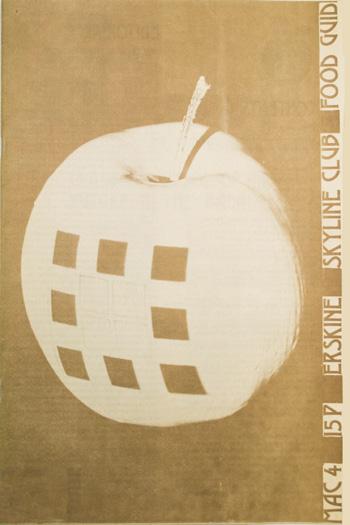

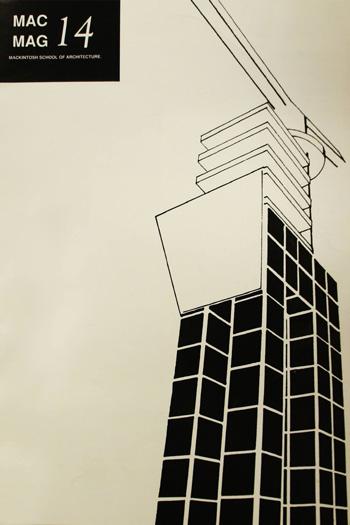

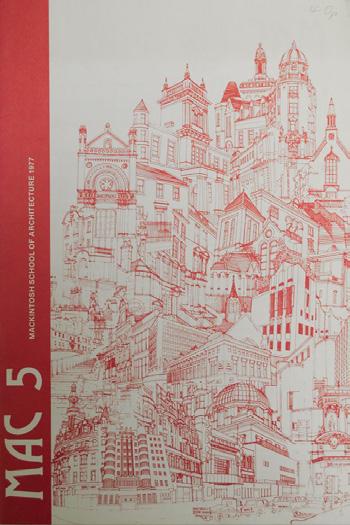

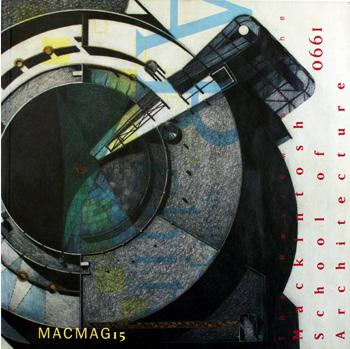

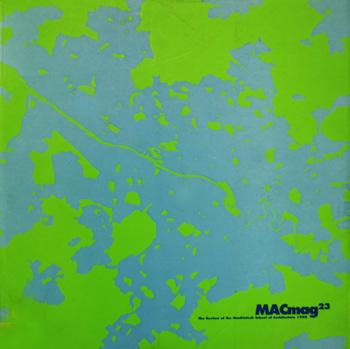

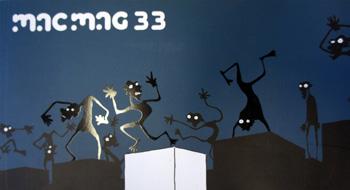

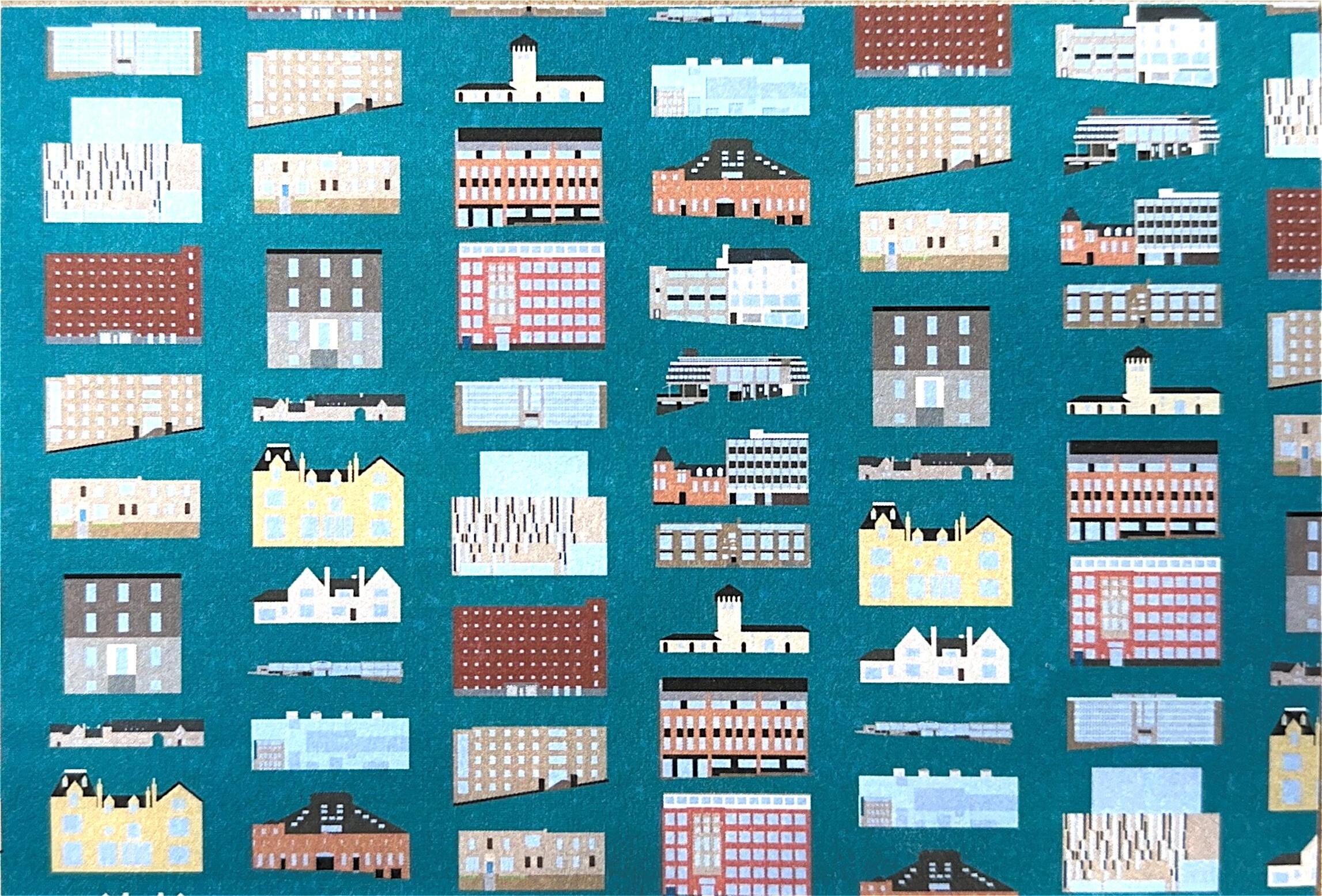

The MacMag came to be in 1974 with the publication of ‘Mac One’ by an editorial team of five – Mark Baines, Ian Bridges, Stuart Haden, Alison Harris and Nigel McKenzie. As editors of this milestone 50th edition, we thought it the perfect time to reflect back on the history of the MacMag, and its legacy.

Some of the original editors continued their work on the magazine up until the 5th issue. From here, it seems to be the beginning of an editorial team which changes yearly. An annual passing of the baton as it were.

The early issues regularly included articles, interviews, book reviews, letters, photography, poetry and a few exemplary examples of student work. Some of these have persisted more than others, with students now receiving a much wider showcase of their projects.

Along the way, new technology gave way to a new format. Computer Aided Design changed the way we draw and the way we present architecture. Hand drawings, while not abandoned entirely, gave way to digital renderings. Technical drawings which can now be scaled in seconds; images which can be transformed and cropped at will. As a result, the MacMag has shrunk (in size but not in content).

In 2014, a fire in the Mackintosh building destroyed the iconic library and took with it countless books and a collection of MacMags. That same year, there was an appeal launched to rebuild the collection – an appeal which architect and school alumnus Chris Doak answered, kindly donating a number of magazines from his personal collection to renew these archives. It is for this reason that many of the early issues, now digitised, bare his signature on the front cover.

In 2015, the editorial team curated an exhibition ‘Celebrating 40 Years of MacMag’ in The Lighthouse Gallery, Glasgow. The exhibition showcased all of the MacMag covers, side by side – a tradition which we have continued on in the following pages.

The Covid-19 pandemic rocked the world, and with it the academic calendar. In 2019/2020 coursework came to a standstill, lectures paused, and studios closed. Everyone’s education was affected by this, maybe none more so than our current Stage 4 students, who began their studies in a digital environment, stripped of the community and friendships usually built in the studio and halls of residence.

The MacMag was not unscathed either. Editors of MacMag 45 were unable to print and distribute the magazine in its usual form and so published the first wholly digital edition of MacMag. While this marked an extremely sad period for many, the issue raised an optimistic theme of ‘Proaction: how emerging architects are confronting the issues of today’s precarious world’ - a sentiment which is more important than ever in today’s precarious geopolitical and environmental climates.

For the past several years, the MacMag has been a dual publication of a physical and digital magazine. The digital issue takes the mag far beyond its original reach and the physical magazine is sold, as a fundraising activity, to staff, allumni, industry professionals, students and their proud family and friends!

We don’t know if the editors of the first magazine imagined it would have endured for 50 years and become a staple of the Mackintosh School of Architecture’s yearly calendar but we certainly hope that this legacy continues. And hope too, that in 50 years from now, some of our current students (hopefully retired after a long and fulfilling career in architecture) will be sitting down to read MacMag’s 100th Edition.

Since its inception, the Mackintosh School of Architecture’s ‘Friday Lecture Series’ has been a platform for architects, as well as related practitioners, to connect with and inspire students. The series seeks to delve into topics that extend beyond the boundaries of the set curriculum, enriching the overall educational experience in the process.

Traditionally, the first semester is curated by a member of staff. In this instance, Nick Walker, in conjunction with Missing in Architecture, curated the series under the theme ‘Research into Practice’. With the second semester however, the responsibility falls to students, this year, I took the helm.

Titled ‘Transient Spaces’, semester two of the Friday Lecture Series was an exploration into the role contemporary ephemeral architecture is playing in the preservation of club culture. A selection of four leading experts were invited to lead discussions illuminating the diverse facets of the theme:

Hugh Scott Moncrieff from CAKE, who began with a comprehensive overview of his practice’s work, before honing in on his experience working on Visionaire and Agnes, two temporary stages he designed for the London-based DIY culture and grassroots festival RALLY.

Matteo Ghidoni from Salottobuono, who began with a more holistic approach, detailing four ephemeral spaces he had designed for varying international events. He concluded with a final structure, Rotunda, which he created for the 2022 edition of Horst Arts and Music Festival.

Ben Hayes and Theo Games Petrohilos from unknown works, who gave a particularly exhaustive lecture, running through almost the entire process of their stage The Armadillo. From their initial concept sketches right through to the erection of the structure, they placed a particular focus on the acoustic research and development involved in the procedure too.

Oli Brenner from badweather, who spotlighted the wide variety of ephemeral projects he’s worked on. His

work is often featured at many contemporary forwardthinking festivals, including Horst Arts and Music and Waking Life, which hold art and architecture to a similar status as the musical component, which is frequently the primary focal point.

At its zenith, it was possible to find a 1,200-capacity club two doors down from another 1,000-plus-capacity club, in a town with a population of 50,000. Nowadays, the reality of this is much more dire. Since 2009, over two-thirds of clubs have disappeared globally. The number of nightclubs in Britain fell from 3,144 in 2005 to only 1,733 ten years later – a 45% drop.

In the struggle to prevent this however, one common thread amongst alternative and progressive spaces that are attempting to redefine the rulebook, is the incorporation of ephemeral architecture.

Ephemeral architecture can be defined as the design and creation of structures that are primarily classified by their temporality. Often built for festivals, exhibitions, fairs, or as stage sets for performances, these structures provide a specific function for a limited duration. Ephemeral architecture has the ability to transform public spaces, in turn making them more dynamic and adaptable.

Oli Brenner, from badweather, maintains that ephemeral architecture “offers a liberation from the constraints of traditional architecture”, its similarly comparable to the “grassroots club culture and utopian ideals of festivals that have emerged to subvert rigid social norms.” He further believes that “it presents an opportunity to rethink how space is conceived, challenging conventional structures and fostering new forms of interaction, engagement and programming.”

Karim Khelil, member of the Turner Prize-winning architecture collective Assemble Studio, believes “nothing lasts forever, even the death of club spaces.” As such, it poses the question: if ephemeral architecture is not the entire answer to saving club culture, what is, and what does this future hold?

In the face of a plethora of factors all combining to exert adverse pressure on club culture’s very survival, ephemeral architecture is but a small solution to a much wider problem. Ultimately, to see a complete preservation of club culture, much wider change at a cultural, societal, governmental and economic scale would need to happen.

However, simply because ephemeral architecture doesn’t present the complete solution, it doesn’t mean it can’t play a significant role in preserving – indeed enhancing in many ways – club culture today and into the future.

We’re living in an era of increasing political, economic and societal upheaval, points out Oli Brenner. “Dancefloors, whether in a club or festival setting, remain sanctuaries for escape, personal transformation and the fostering of community. These spaces offer a fleeting alternative reality where the pressures of the outside world fade into the background and are replaced by thumping bass, the rhythm of dancing bodies, and more recently, by spatial and architectural interventions that transport music lovers into entirely new worlds.”

“Change is really the only constant in our lives,” Brenner continues, “but the landscape of conventional architectural design is not set up to facilitate this. Buildings can take a number of years to design and construct, often by which time they are completed the values, aesthetic ideals and programmatic requirements behind the design process have quickly become outdated. Temporary architecture is much more about capturing and facilitating a moment, a single event in time, the event fades, but the memory remains”

The beliefs surrounding ephemeral architecture can be seen to be intrinsically linked to those beliefs surrounding club culture. It could be contended that the two are kindred spirits.

The incorporation of contemporary ephemeral architecture into the domain of club culture can be seen to be of significant merit. Whether it’s providing the flexibility and adaptability to allow spaces to change with societal trends, the social experimentation and inclusivity to cater and foster emerging or marginalised scenes, or the innovation and sustainability to push out the standardised boundaries, its positive impact is significant.

It could be argued that the current dilemma is simply a realignment with the “dance floor’s underlying utopianism,” argues Ed Gilliet in Resident Advisor. Ultimately, the same “cultural ennui and political inertia we’re experiencing today is what made dance music necessary and possible in the first place”, more than 60 years ago. Throughout history, he says, “the dance floor has consistently flourished during times of rupture and instability, and remains as vital as ever.”

As John Leo Gillen says in his book Temporary Pleasure: Nightclub Architecture, Design and Culture from the 1960s to Today, “the role of the nightclub is to embody and challenge the here and now – a place, a scene, a moment – and then to die and make way for the next.”

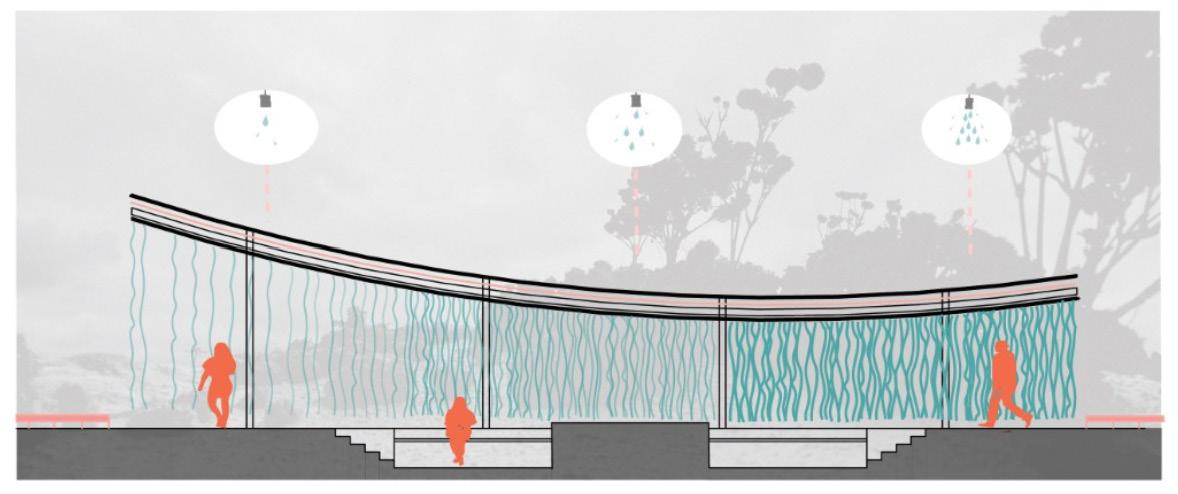

The experimental architecture, scenography and design collective badweather, designed Rainroom for the Horst Arts and Music Festival.

“We were asked to make an intervention for a space, which is a massive warehouse with a huge gaping roof light,” said Oli Brenner. “When we got there, the ceiling had fallen in, and this kind of organic garden had started to create in the middle of the space. So, we made a massive pond structure that mirrored the opening in the ceiling.”

Through this intervention, they transformed the dilapidated and underutilised warehouse, into a vibrant, spirited oasis. “A huge waterproof membrane was built with reclaimed railway sleepers, which I think cost one euro each, so a really economical way of building. And we also had all these tiles left over, so we incorporated them into the design as a means of reuse and not needing to buy extra material.”

As an integral part of the continuing renewal of the forsaken ASIAT military site (located just north of Brussels), this project transpired out of the pandemicinduced closure of clubs. Initially conceived to cater for socially distanced events over the pandemic, the space has gone on to evolve to host a plethora of occasions, including raucous club events.

The Armadillo, a stage designed by unknown works, was a self-initiated project, instigated primarily by their passion for sound. Initially unveiled at Trinity Buoy Wharf in celebration of the 2024 London Festival of Architecture, the stage was later deconstructed and reerected at Houghton Festival in Norfolk.

The stage, as unknown works explained in their lecture, “is the first external structure in the UK to be made using Eucalyptus timber.” They went on to add, “the material is a highly durable and water repellent alternative to typical spruce or cross-laminated timber.” The Armadillo takes the profile of stepped timber arches ascending in size, fabricated through 42 prefabricated CLT panels, and evolved through the use of new research into CLT construction and fabrication.

The structure has been optimised for natural acoustic amplification without producing sound feedback to performers. The angles of the timber panels project sound outwards, while slender gaps along the tessellating archways are lined with an opaque silicone membrane. The arches are inset with programmable lighting tracks, providing a dynamic multi-sensory arts experience.

For unknown works, “it was really important that [they] got the details right in regards to sustainability.” Festivals are some of the most carbon-intensive events, with “around 23,500 tons of waste generated annually across the UK music festival circuit.” Given this, it was key the project enabled easy repurposing and relocation through its design for “disassembly and reuse, minimising waste and maximising its lifespan.”

The aims of Stage 1 are threefold:

Stage Leader: James Tait Co-Pilot: Georgia Battye

• To train hands in new ways of architectural observation, representation, and exploration.

• To open minds to the challenges and possibilities of being an architect in our current times.

• To embed students in the studio culture of the Mackintosh School of Architecture and wider Glasgow School of Art.

To achieve this aim, Semester 1 focuses on equipping students with the good habits required to achieve high standards of architectural production, exploration, and enquiry. Semester 2 builds on this foundation allowing students to develop, play, and explore with increasing agency and autonomy as the year progresses. Through the course of the year we introduce students to:

• New ways of seeing architectural space.

• Various ways of representing architectural ideas and aims, through drawing, modelling, and verbal communication.

• The analysis and appraisal of precedents and case studies, with a particular focus on the vernacular

• Exploring the creation of architectural space, through its tectonic and atmospheric dimensions.

• Understanding place and space, through mapping and site investigation.

• Basic concepts around the reuse and adaption of buildings, particularly in response to the climate crisis

• Distilling and editing work to be clearly understood and appreciated by others.

• Working and collaborating with others within MSA and the wider GSA.

• Developing designs in detail, applying knowledge gained in Architectural Technology.

• Synthesising the knowledge, approaches, and skills gained throughout the year towards a climateresponsive, tectonically-engaged, culturally-aware final project.

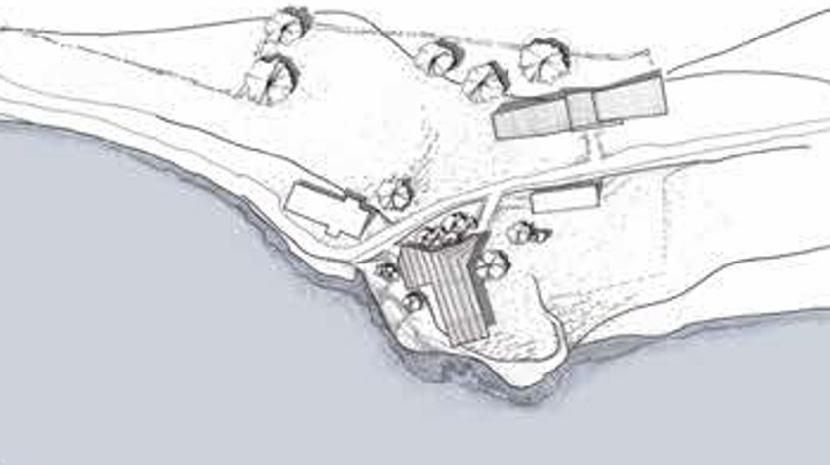

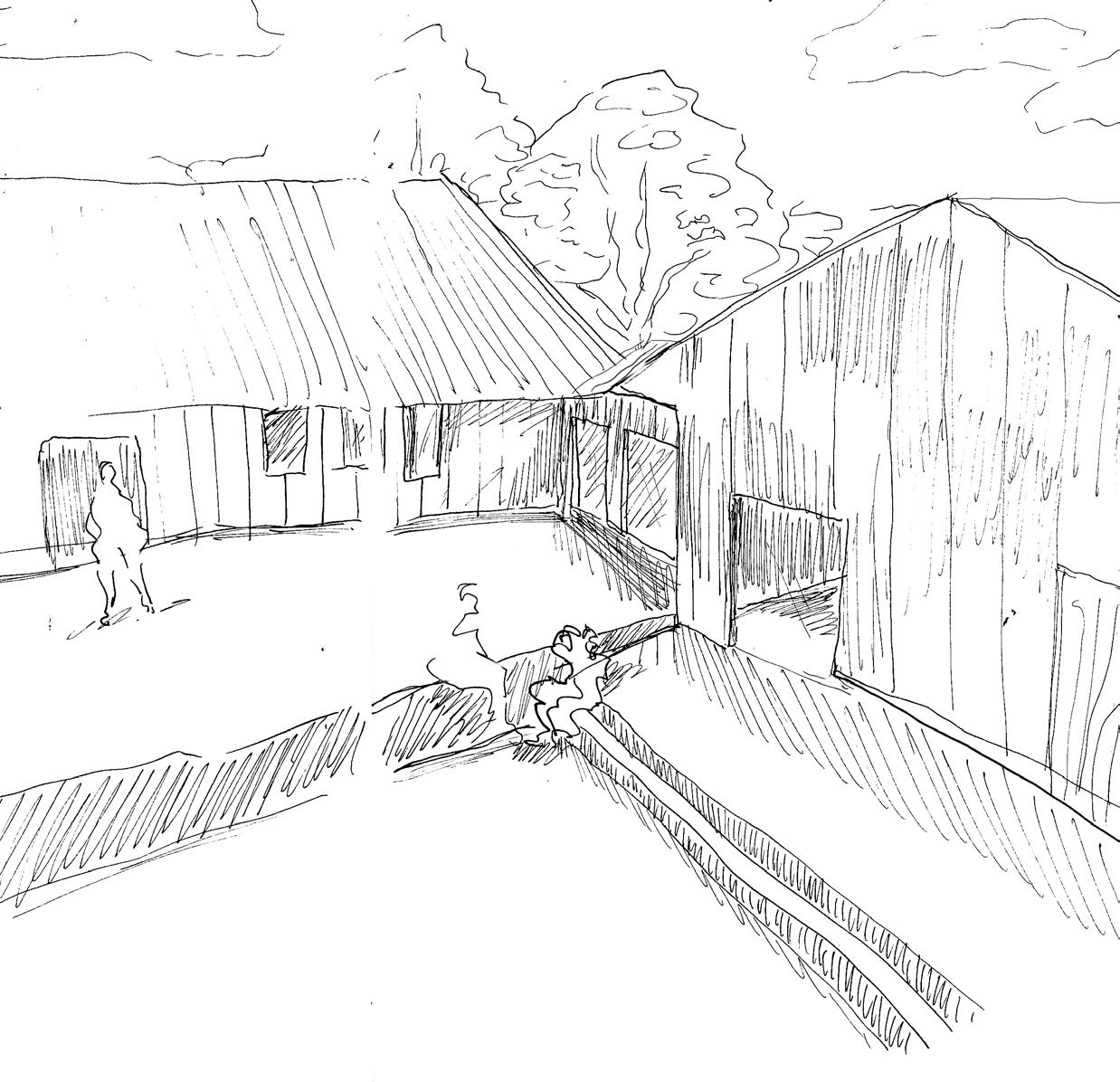

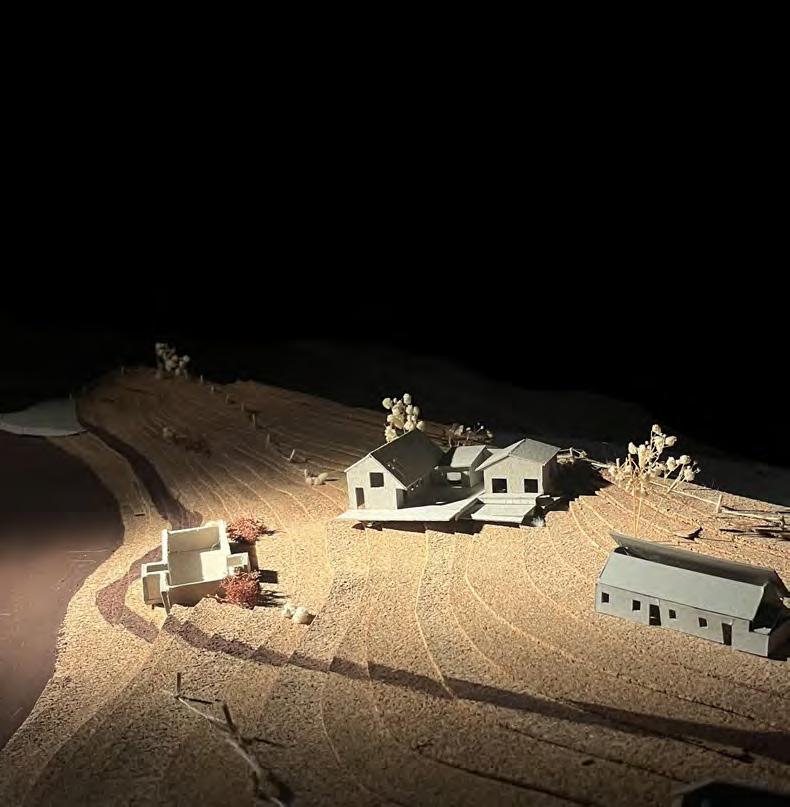

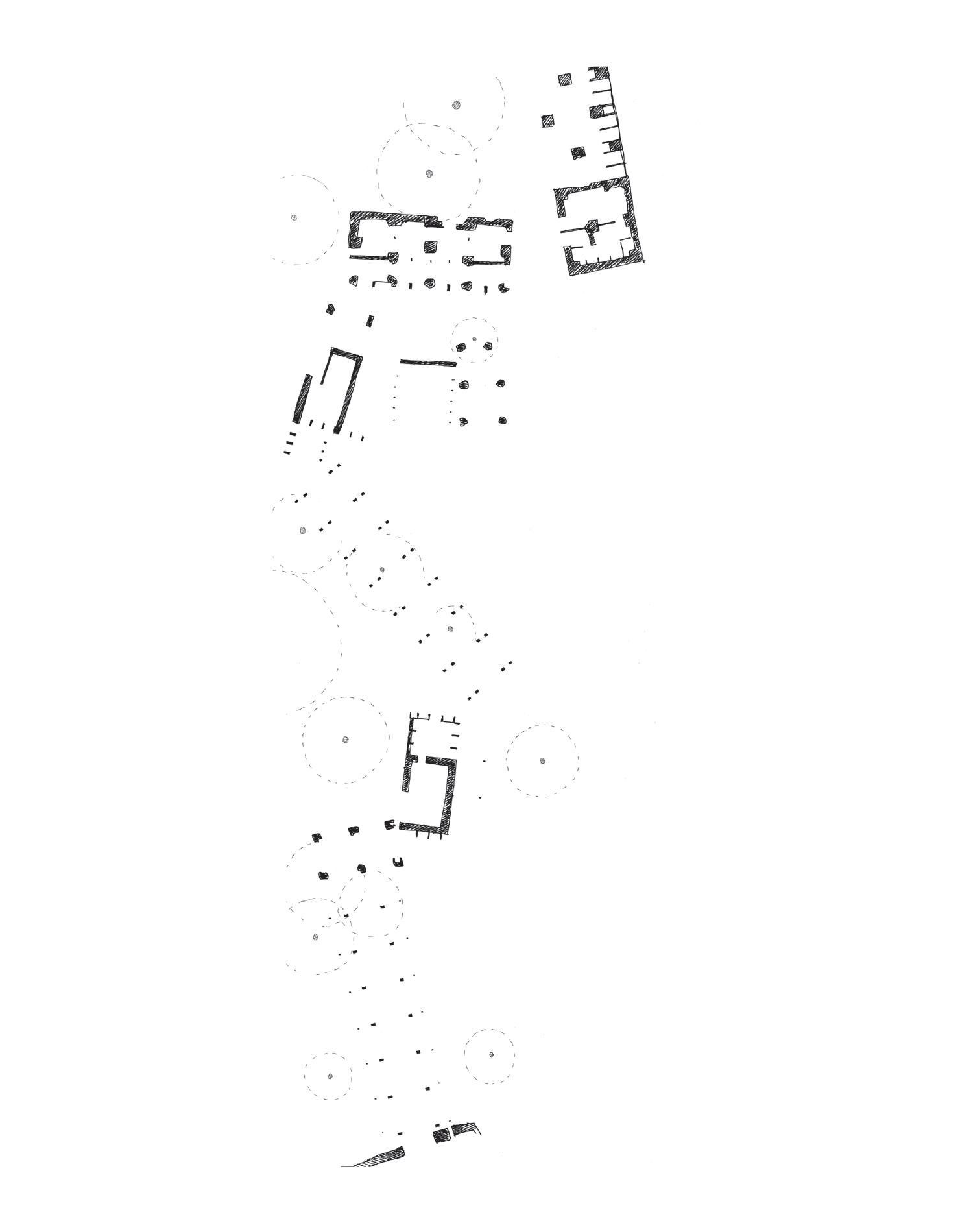

As part of a wider shift in the undergraduate years to engage with rural environments, the year has been embedded in the Isle of Skye. We organised a series of talks from local makers, artists, and architects forging new links between the school and the local community. Investigations of Struan Jetty (on the west coast of Skye) laid the foundation for two projects - an adaptive reuse of a listed stables building and the establishment of a community gathering hall - located on this same site. The study of place has been essential in allowing our students to test their analyses and ideas in-situ.

Ultimately, students by the end of this first year will become critically engaged, technically skilled, and independent free-thinkers ready to progress to the next stage of their architectural education.

“Forget the summer job in a bar at a nightclub - get a job on a building site. Pick up a dust covered, coffee stained drawing with tiny 6pt text on it and try build from it; Lift up and lay down the 20kg concrete blocks the architect has specified for four straight hours; try and usher a 10m high piece of glazing into place on a crowded construction site.”

Representing Space

Granary House

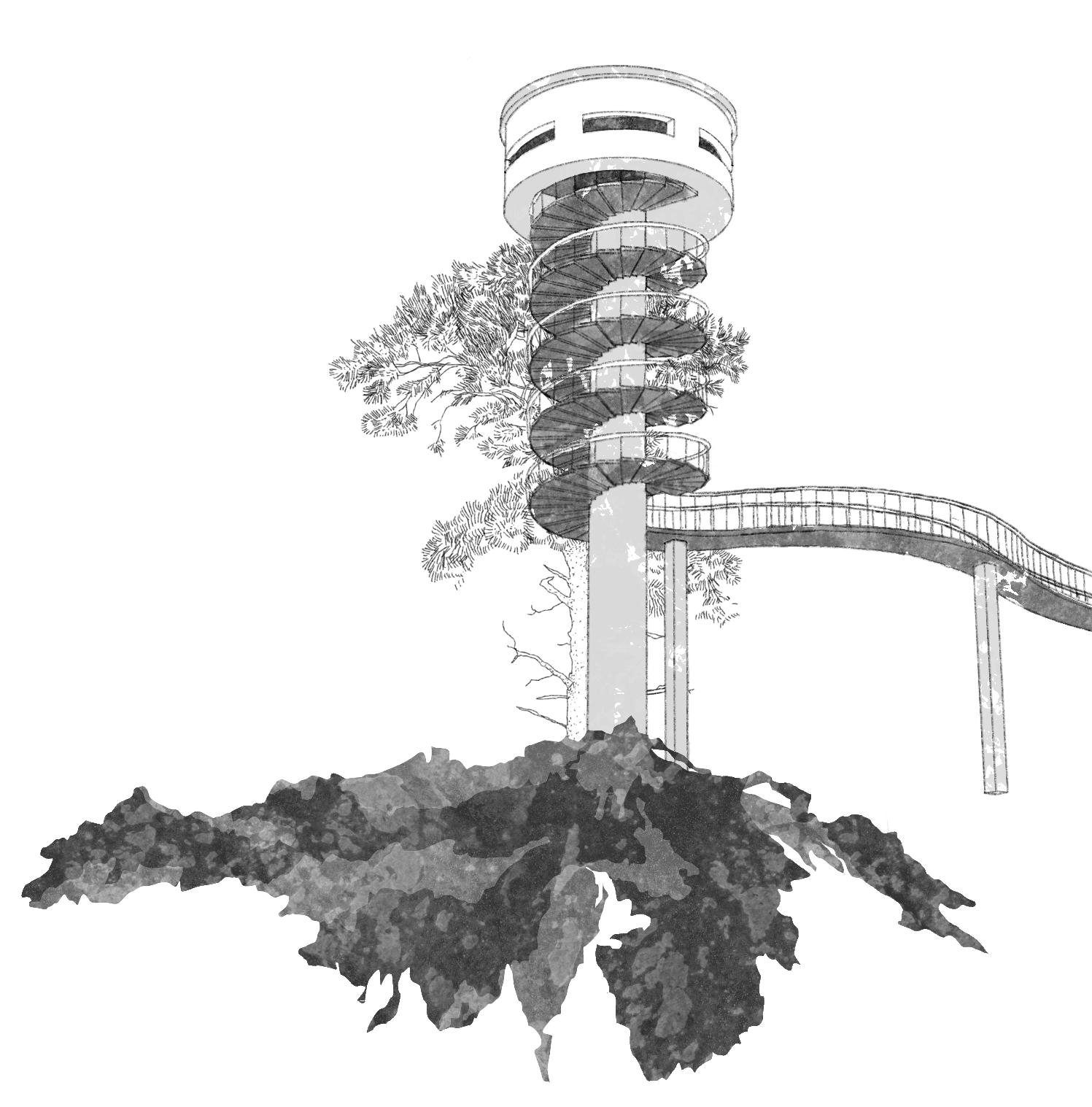

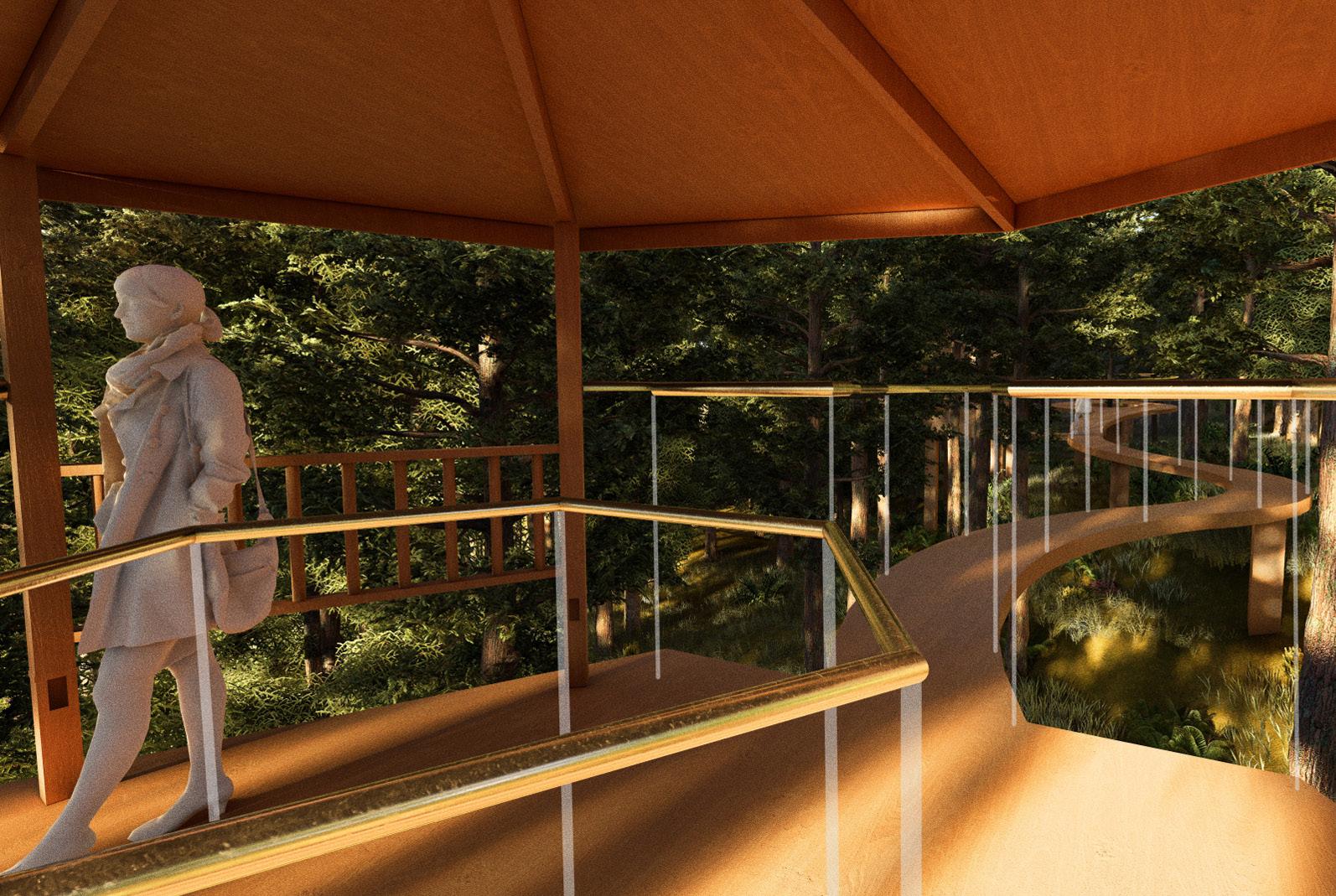

Skye Pavilion

Lost in Atmospheres

Experimental Modelling

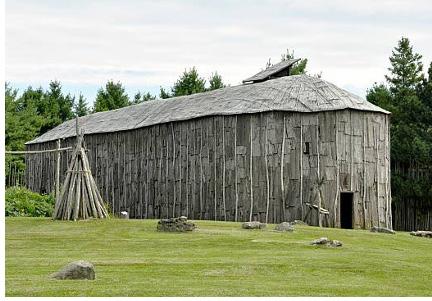

Cridhe nan Gleann – 'Heart of the Glens' Gathering Hall

A Showcase

Detail

Culture Hall

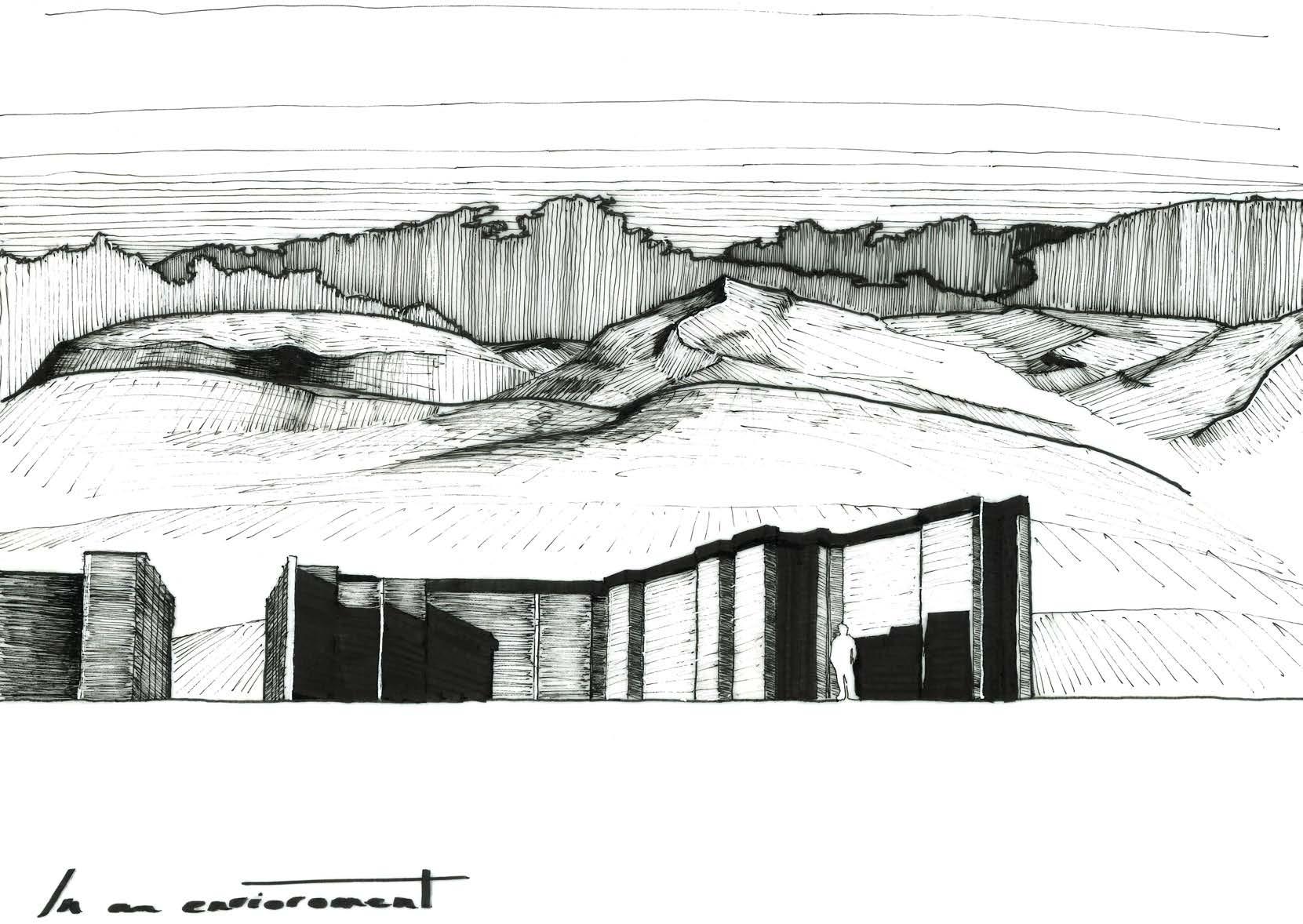

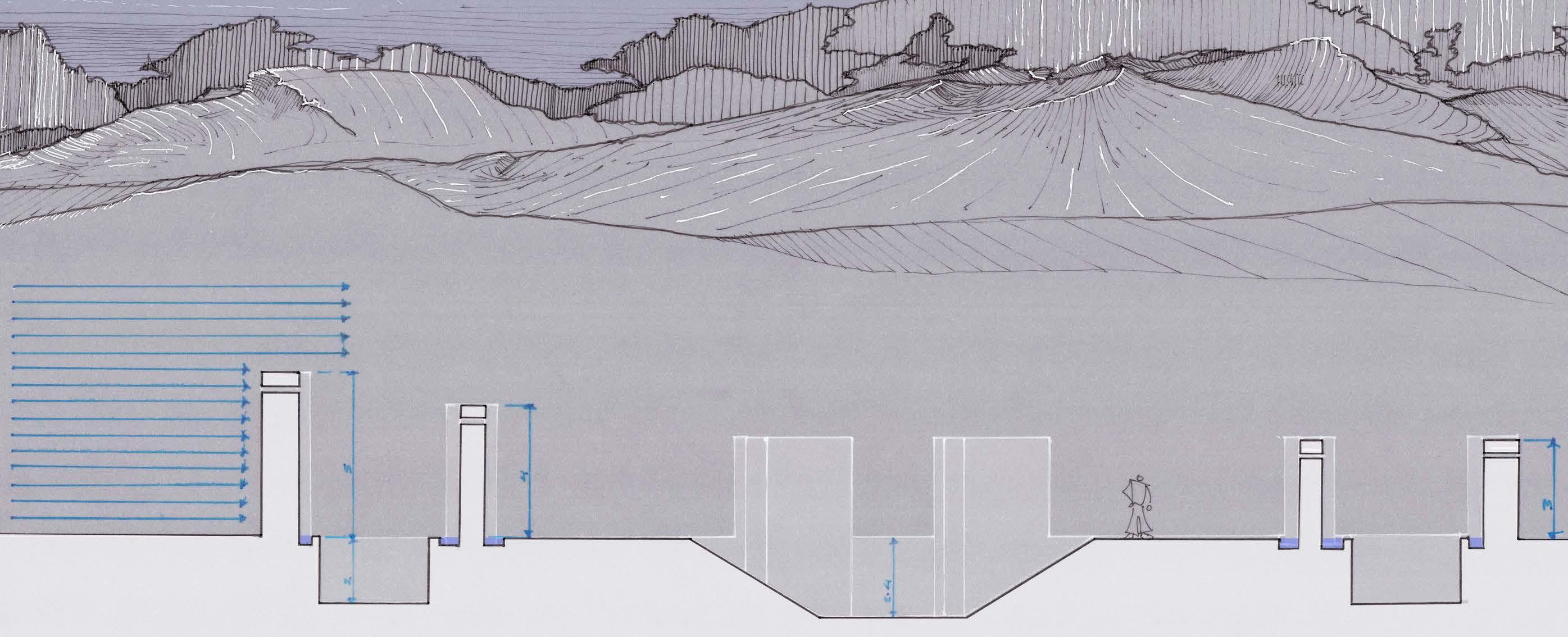

Designing with the Landscape by by by by by by by by by by

Katie Owen

Katie Owen

Tanisha Uddin

Hayden Young

Abigail McCulloch

Abigail McCulloch

Elodie Poumet

Morven Cavers

Enqian Huang

Isabella Smith

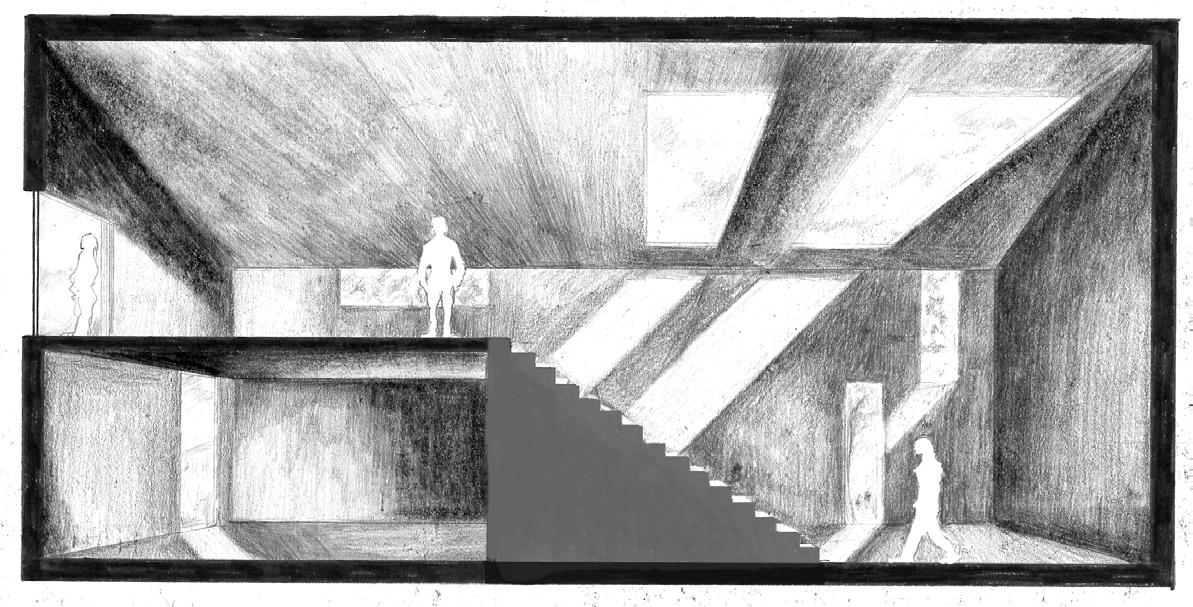

BY KATIE OWEN

A project about representing a space through orthographic projection. The first step taking with this project was measuring our body and using anthropometric to gather a sense of proportions the human body takes in architectural spaces. By taking a chosen space, surveying it, we began to an emotive image real tangible form.

Scale @ 1:50

BY KATIE OWEN

This project began by researching into vernacular architecture. My chosen typography was the granary house mainly the Granaries in Austrius. Key aspects when studying this project was that vernacular architecture is designed BY the poeple and OF the people.

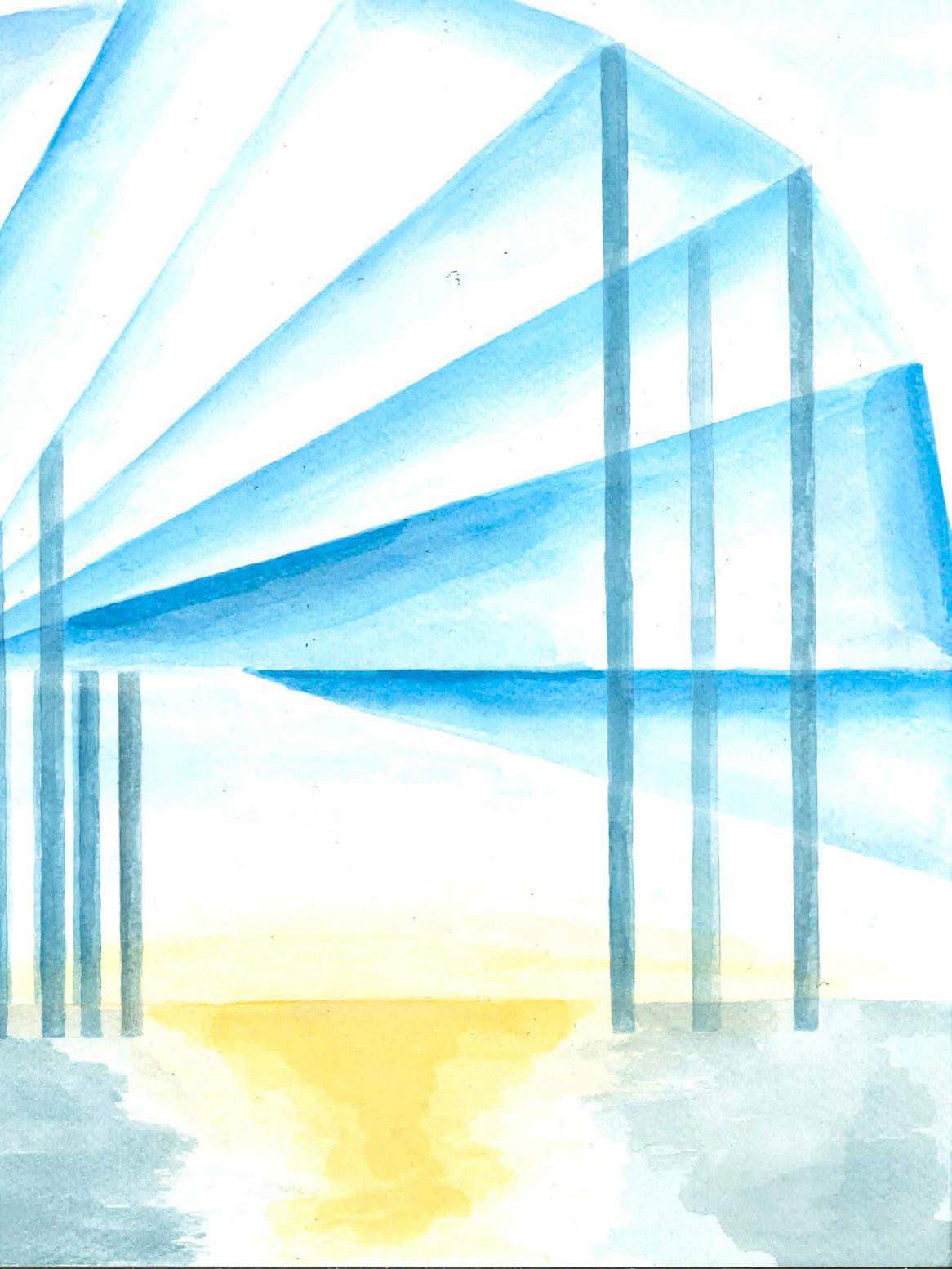

In this project, we were asked to create quick sketch models from offcuts to then adapt into a building for the Isle of Skye. The offcut model I chose had a quite striking and imposing form, and I didn’t want to sacrifice this in the process of adapting it, so I designed a pavilion. The open walls and square-frame roof are intended to create a balance in sheltering from nature and highlighting it. The orientation redirects wind to make the pavilion into a seclusion of sorts – contrastingly quieter than its surroundings, encouraging the user to appreciate the strength of the environment. The skylights are intended to mimic paintings; each unique and constantly changing.

BY HAYDEN YOUNG

For the third project of the semester, we were told to design a new space through its “tectonic and atmospheric dimensions”.

I was inspired by architect Peter Zumthor’s book ‘Atmospheres’ in which he spoke about, “the freedom of movement”. This concept inspired me, and I began to work on a design in which the user is encouraged to wander and stroll through and get lost in.

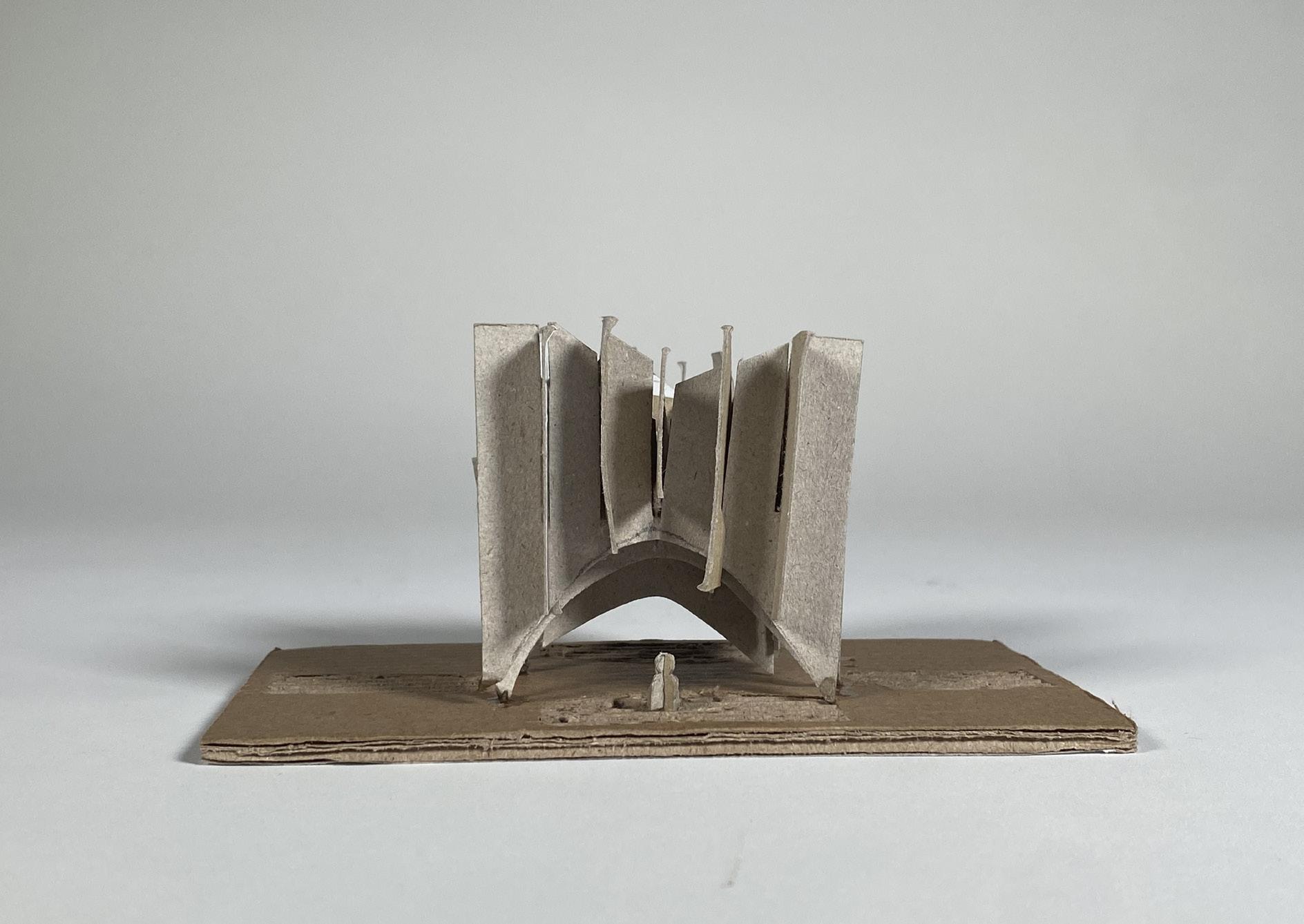

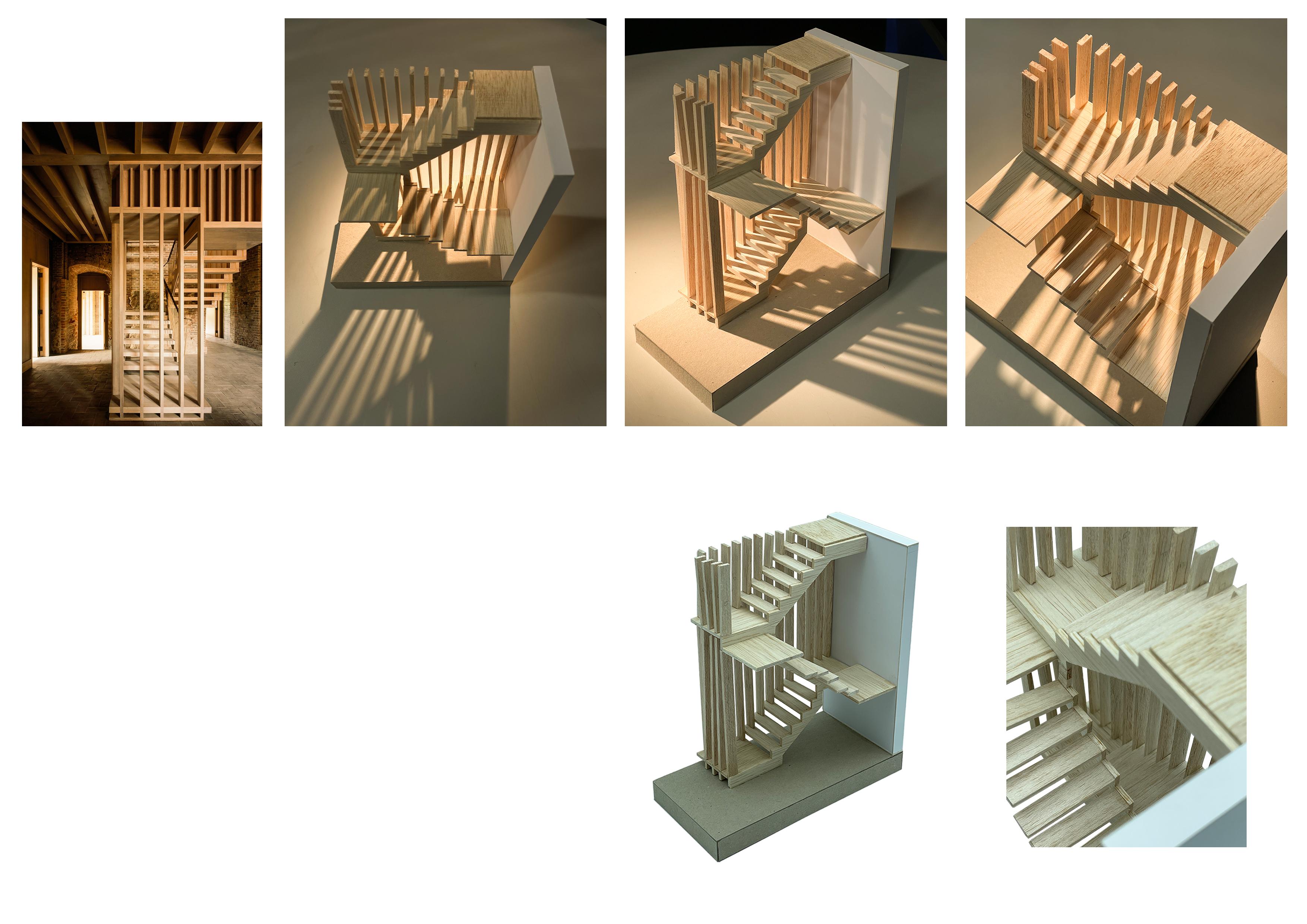

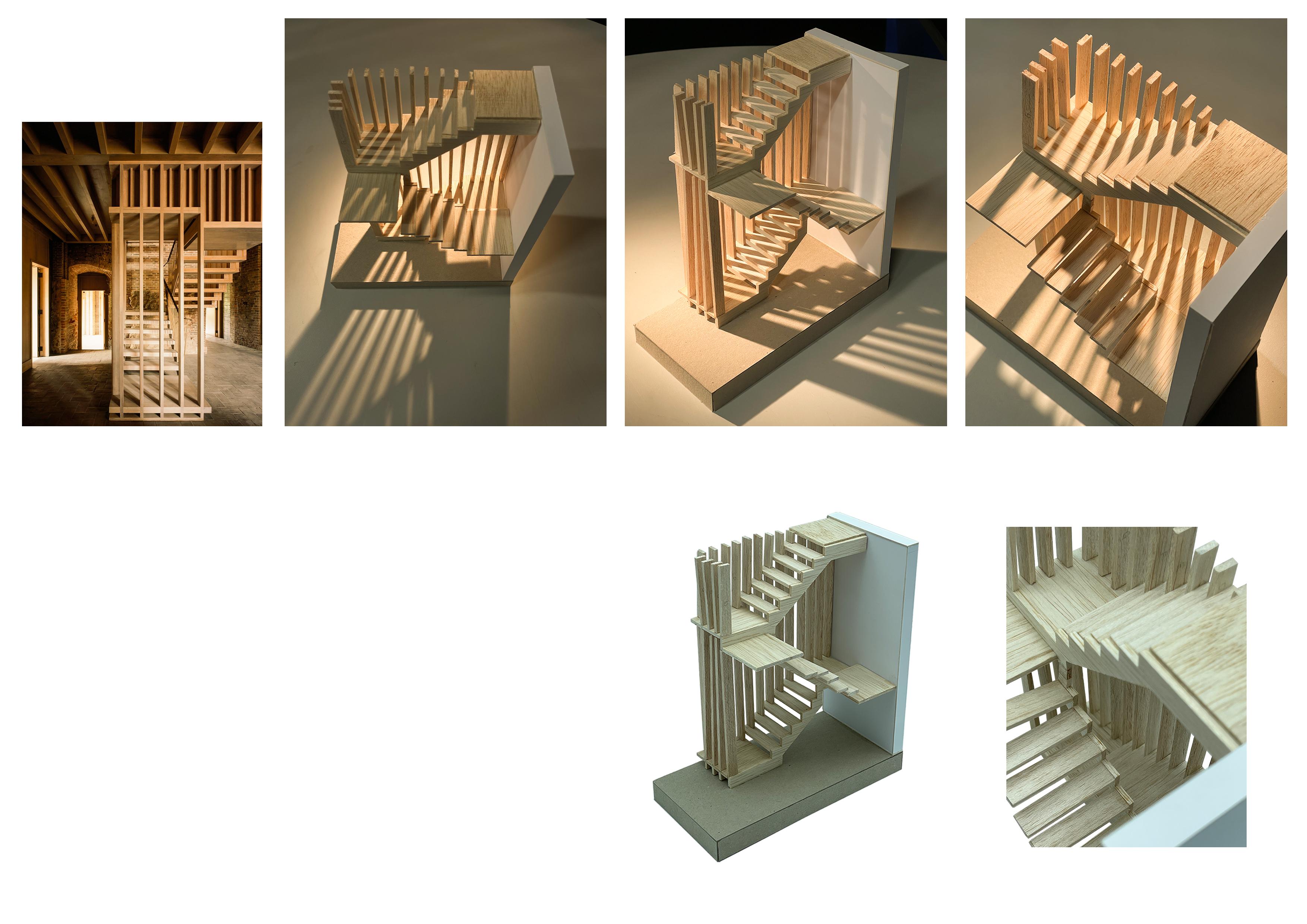

BY ABIGAIL MCCULLOCH

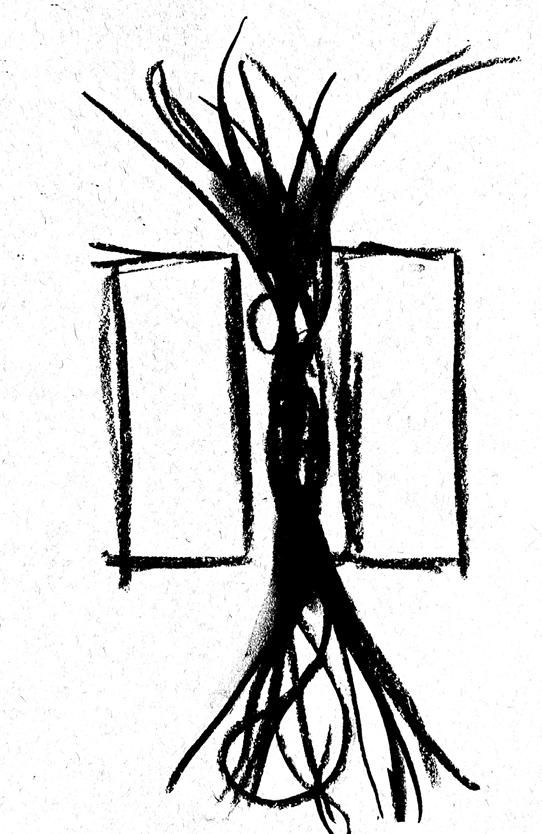

‘Explore the creation of architectural space through it’s tectonic and atmoshpheric dimensions’. We were given the task of developing a diverse range of experimental tectonic models which gave us a deeper understanding to the science and art of how a building is constructed, how it is made from constituent parts. When I was creating different structures, I found myself experimenting with triangular forms, types of domes and spiral forms inspired by Tomoko Fuse.

Proceeding further into this project we then had to evolve one chosen experimental model. Doing this we had to modify elements of the model itself considering its scale, access, and light. This made me understand and observe the atmosphere that our structure gives to others. Considering this I decided to develop my model that focused on a spiral type of form as I believed it was most impactful to interpret as it was so abstract and complex.

I have chosen for my structure to have a particularly large scale as I find large structures can inspire a sense of wonder, significance, and importance. It being greater in size also creates an environment where people feel more at ease and unrestricted.

When urban planning, access influences whether a space feels open and inclusive or restrictive and alienating. I simplified my design, so the spiral structure became slightly shorter as I was adding more timber columns to act as a defensive mechanism from the wind. Apart from this my structure is very open to create a sense of freedom and to create a sense of autonomy.

Architecture is not just about its structural form; it also engages our senses, influencing how a space makes us feel. Light is an aspect we consider in our designs as we use it to guide emotions, enhance experiences and define the character of a space. Adding more timber columns also had a great impact on how light hits off the structure, this helped me successfully achieve a surreal atmosphere.

BY ABIGAIL MCCULLOCH

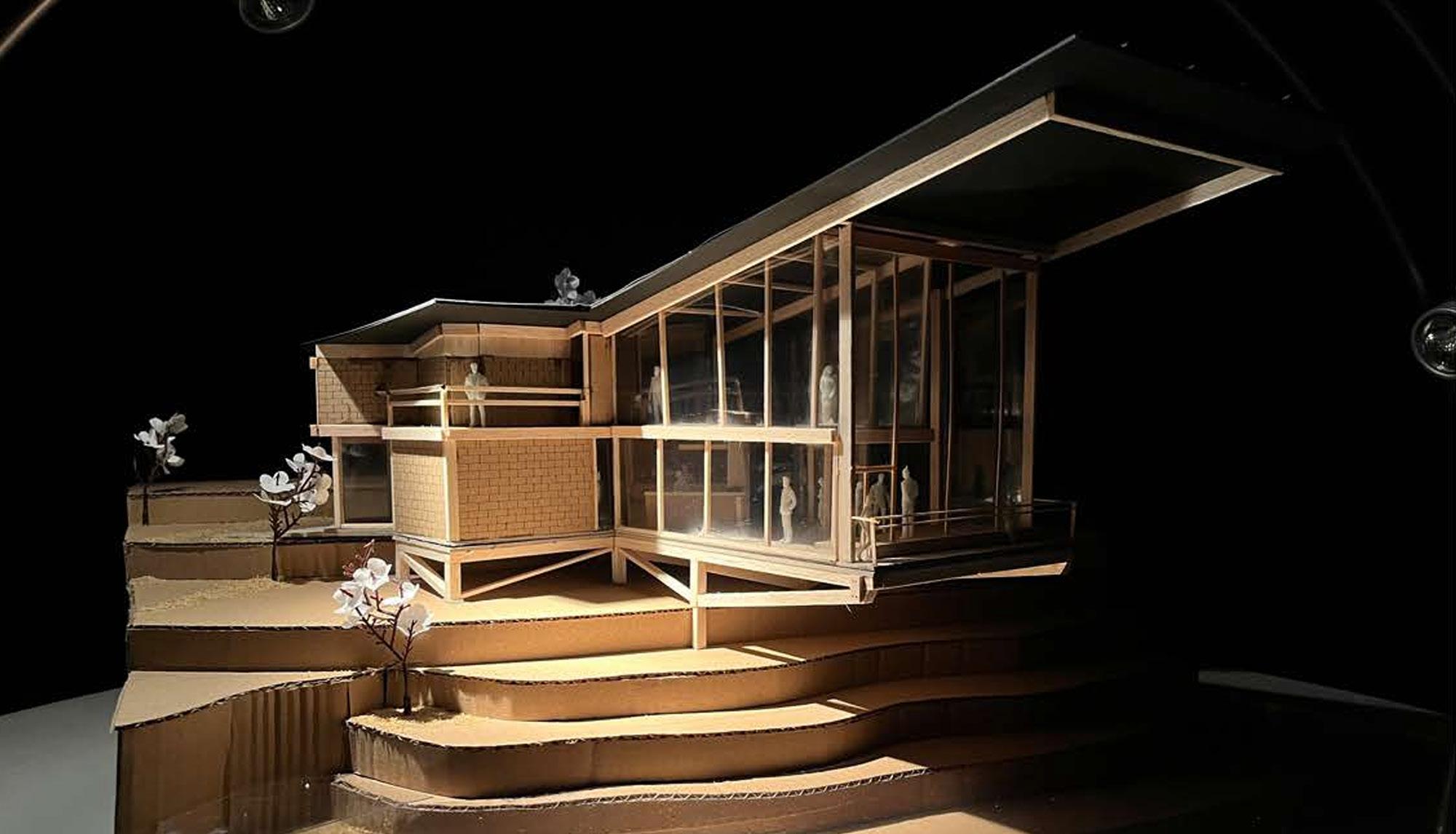

I have designed a Gathering Hall on the Struan Jetty site on the Isle of Skye—an area with strong ties to fishing and community. The challenge is to bring together locals and visitors in a single space that responds to the landscape, heritage, and ecology of the area, thinking critically about how our building will sit in the natural environment, how it’s accessed, and how it reflects the unique identity of the place.

My design outcome focuses on creating a structure that sits gently in the Skye landscape, drawing from vernacular building forms and locally sourced materials like timber. The Gathering Hall opens toward the loch, using large openings and a simple roof profile to frame views and bring the outdoors in.

The primary space serves as a communal hearth— flexible, warm, and welcoming—while the adjoining maker’s space is more intimate, encouraging skillsharing and creative exchange rooted in tradition.

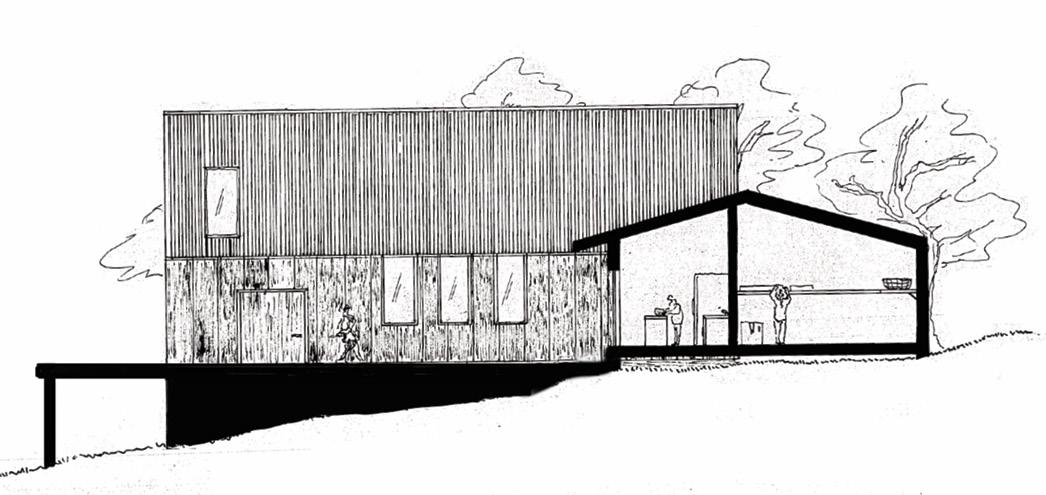

BY ELODIE POUMET

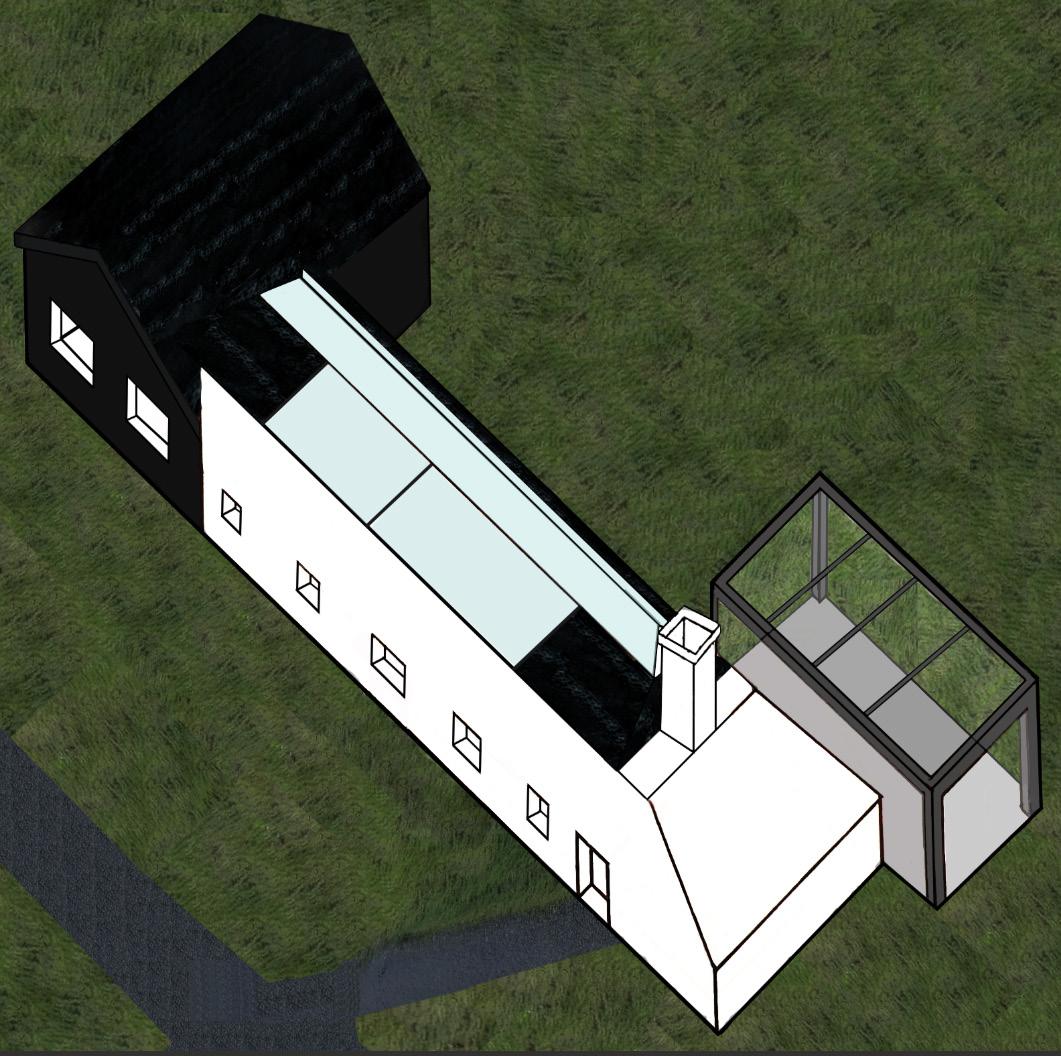

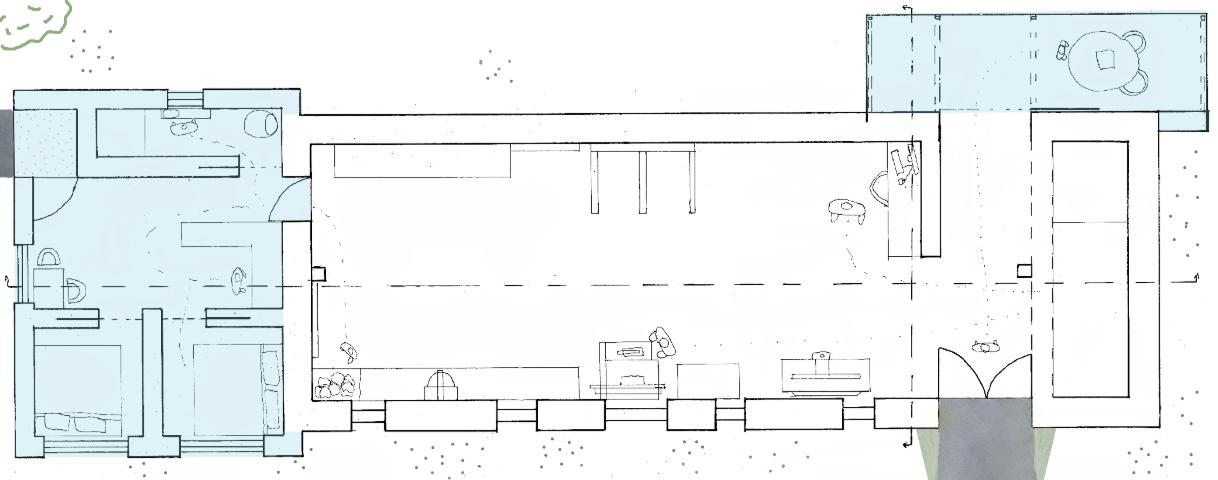

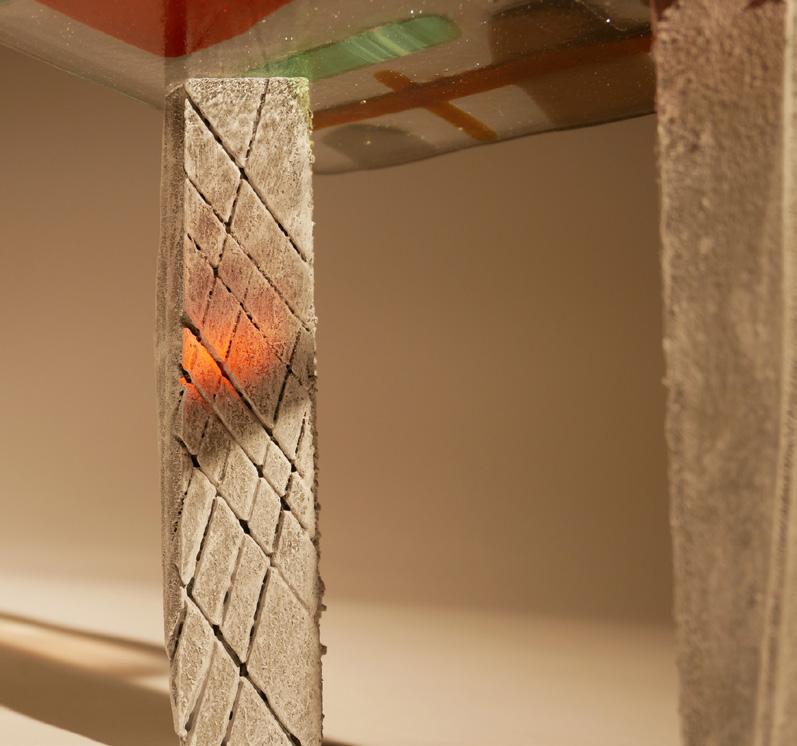

My work is a mix of multiple projects taking place on the site of Struan Jetty on the Isle of Skye. As our brief was to use a stable (or what is left of it) for it to become more than a simple workshop as it is composed of a living area. I decided to play with light and how it affects materials and textures. Throughout the day, the sunlight is going to reveal the building to reach the showcase room at the end of the day. I wanted to reproduce the process of the creation made by the artist inside that workshop through the building in itself. In order to be sustainable, I used materials that were already on the site as they are locally sourced. The living area is thought as an opaque mass made of stone and slate. To have a perfect balance of light and for it to be semi-opaque, I combined the former materials with glass. As the showcase room is thought to be transparent to reproduce the reveal process, it is a glass room with both steel and glass beams for the structure.

BY MORVEN CAVERS

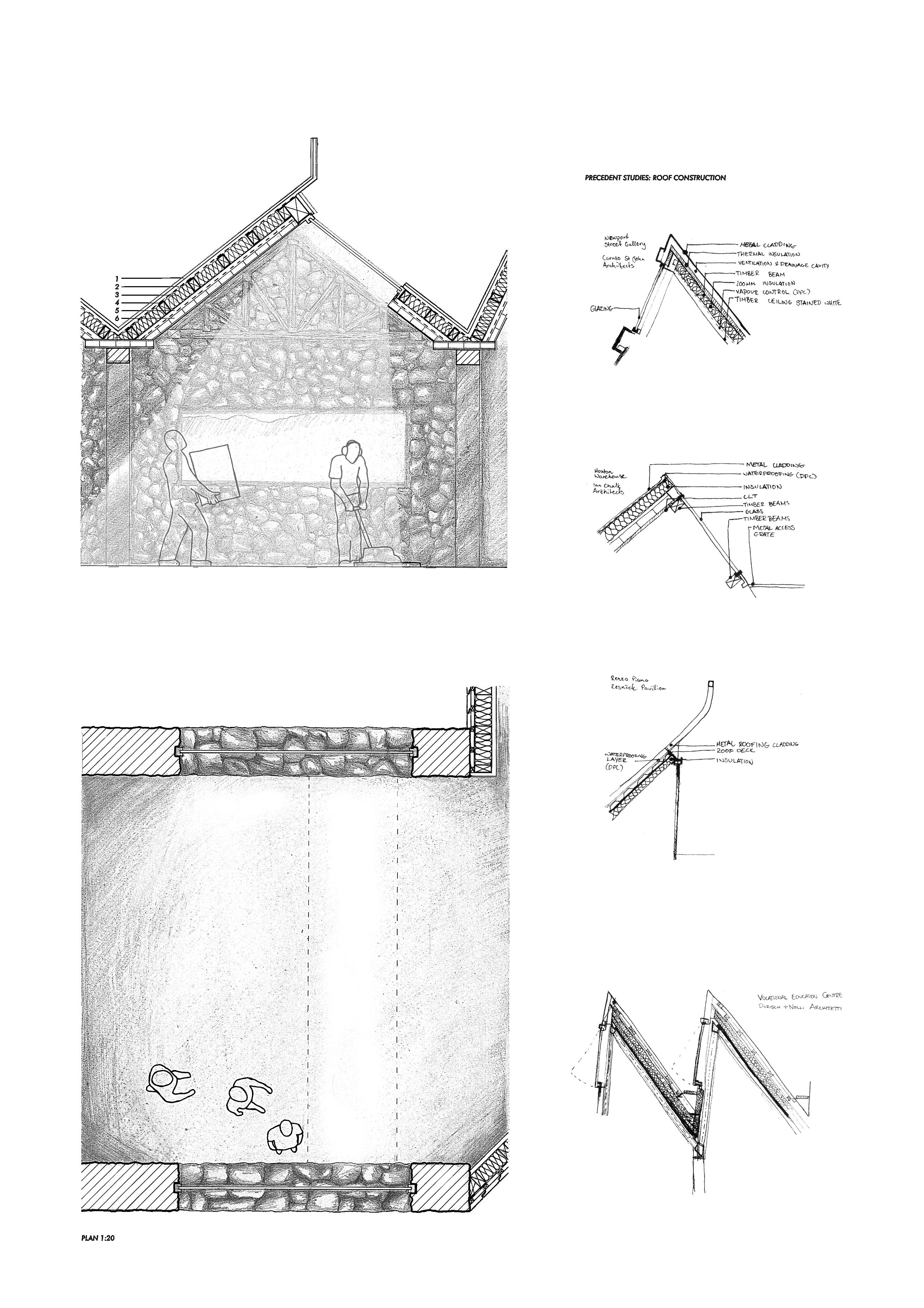

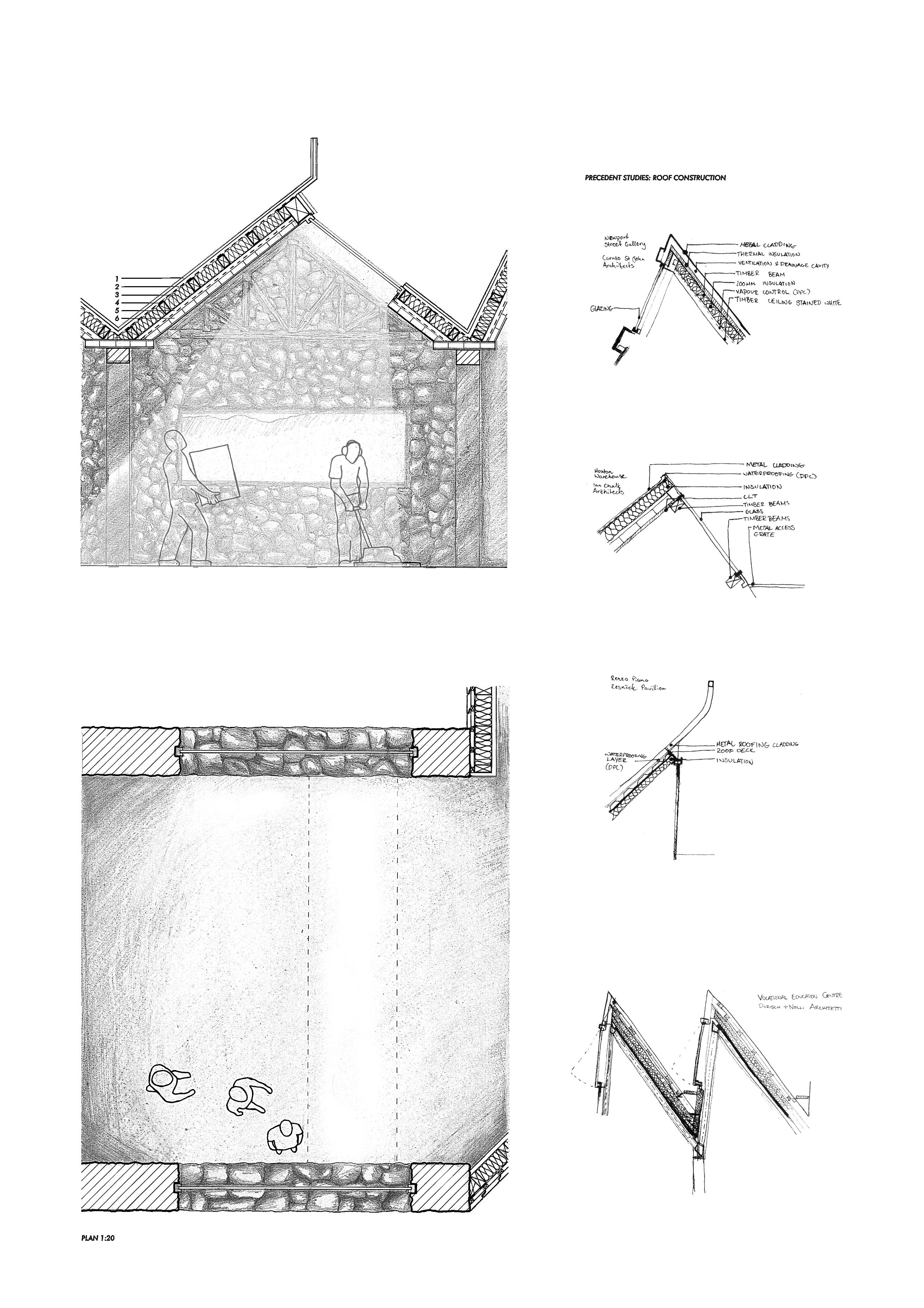

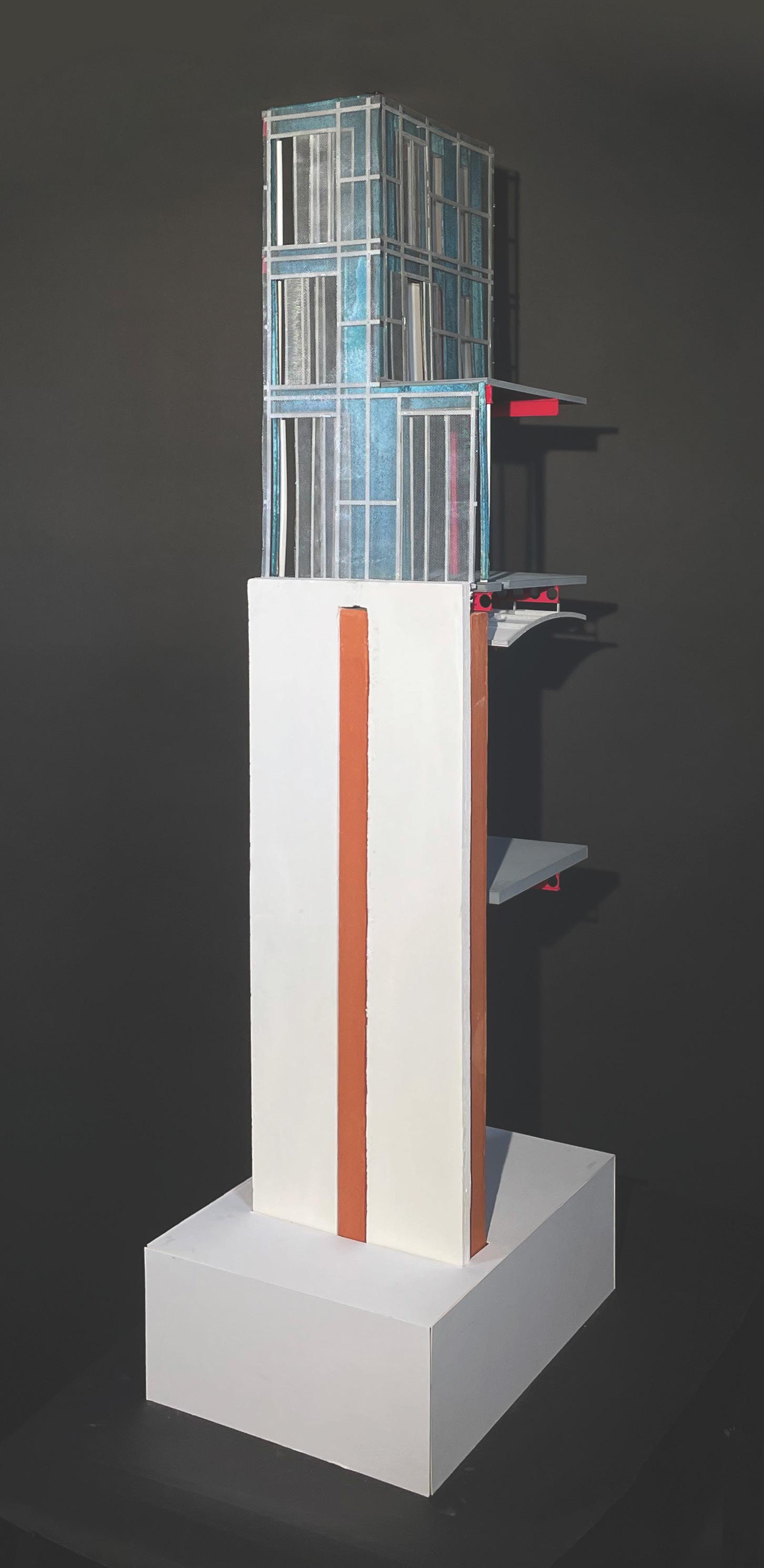

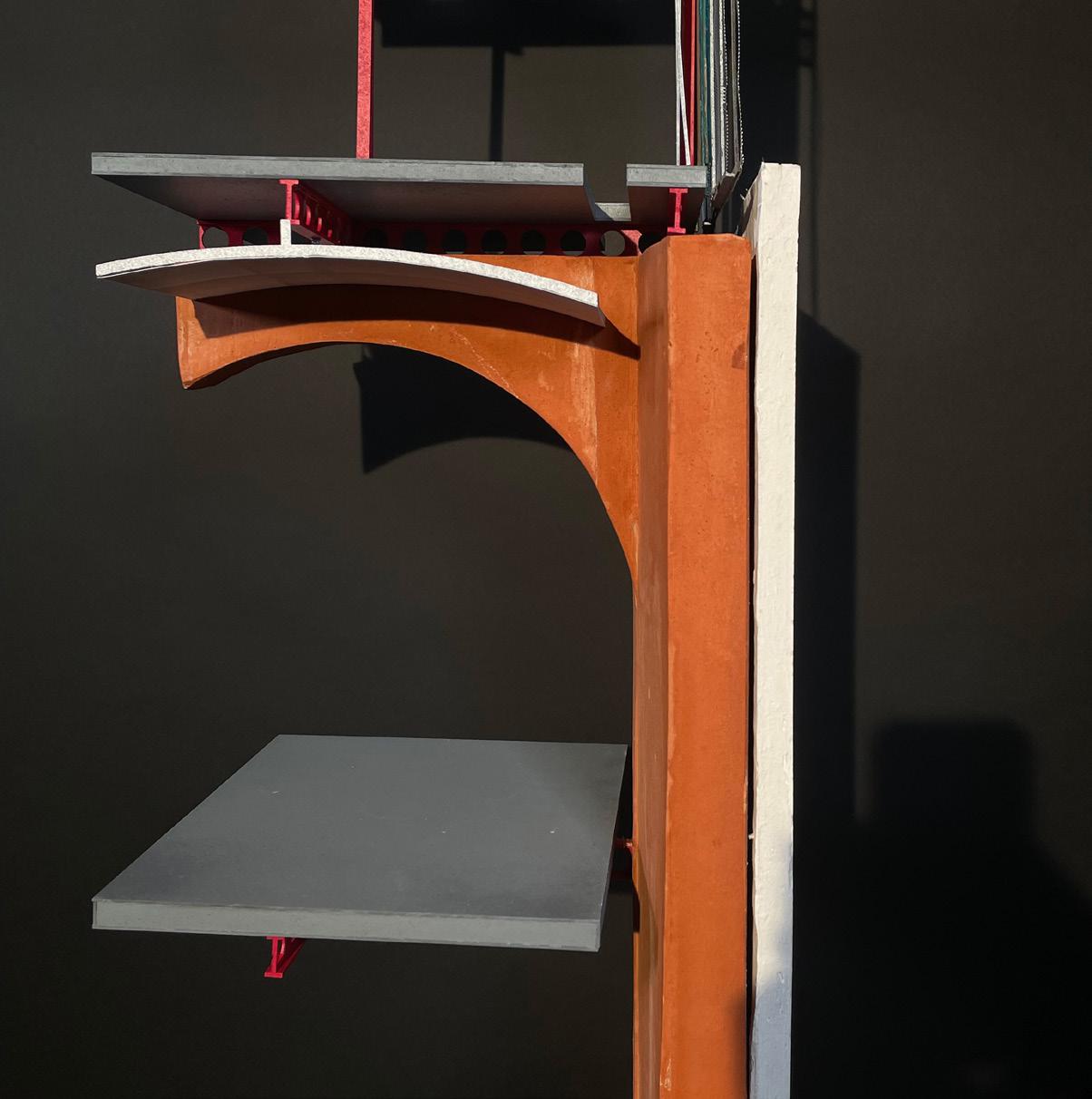

For our project P5B_DETAIL we learned about and analysed the inner workings of multilayer construction in a building’s structure and applied our studies to our own building designs. Through an active learning process this project effectively taught me the basics of multilayer construction.

BY ENQIAN HUANG

The project site is located on the Isle of Skye, which is close to the water, with a large area of outdoor scenery, and can provide a gathering and exhibition space. Through the distribution of space and roads, it maintains a strong connection with the surrounding buildings. The building consists of two floors, the main function of the ground floor is the gathering space, kitchen, and toilet, and the main function of the first floor is the exhibition space and conference room. The interior space adopts an open design.

In this project, I designed a building that can provide gathering and exhibition functions in combination with the local culture, the environment of the location and the specific requirements of the customer. My idea is to create a relatively open free space by combining scenes, and reduce the cutting of space on the basis of ensuring functionality. I try to use my design to express the meaning of the party hall to me personally. I think the party does not have to be in a specific space. I hope that

through the design and connection of all spaces, the entire building can also be part of the party. Therefore, a radial design technique is used. After entering the building, visitors can easily and conveniently go to various areas of the building, making the crowd more mobile in this space. The building structure is a combination of wood structure and stone bricks, and transparent glass can strengthen the connection between the interior and the interior of the building.

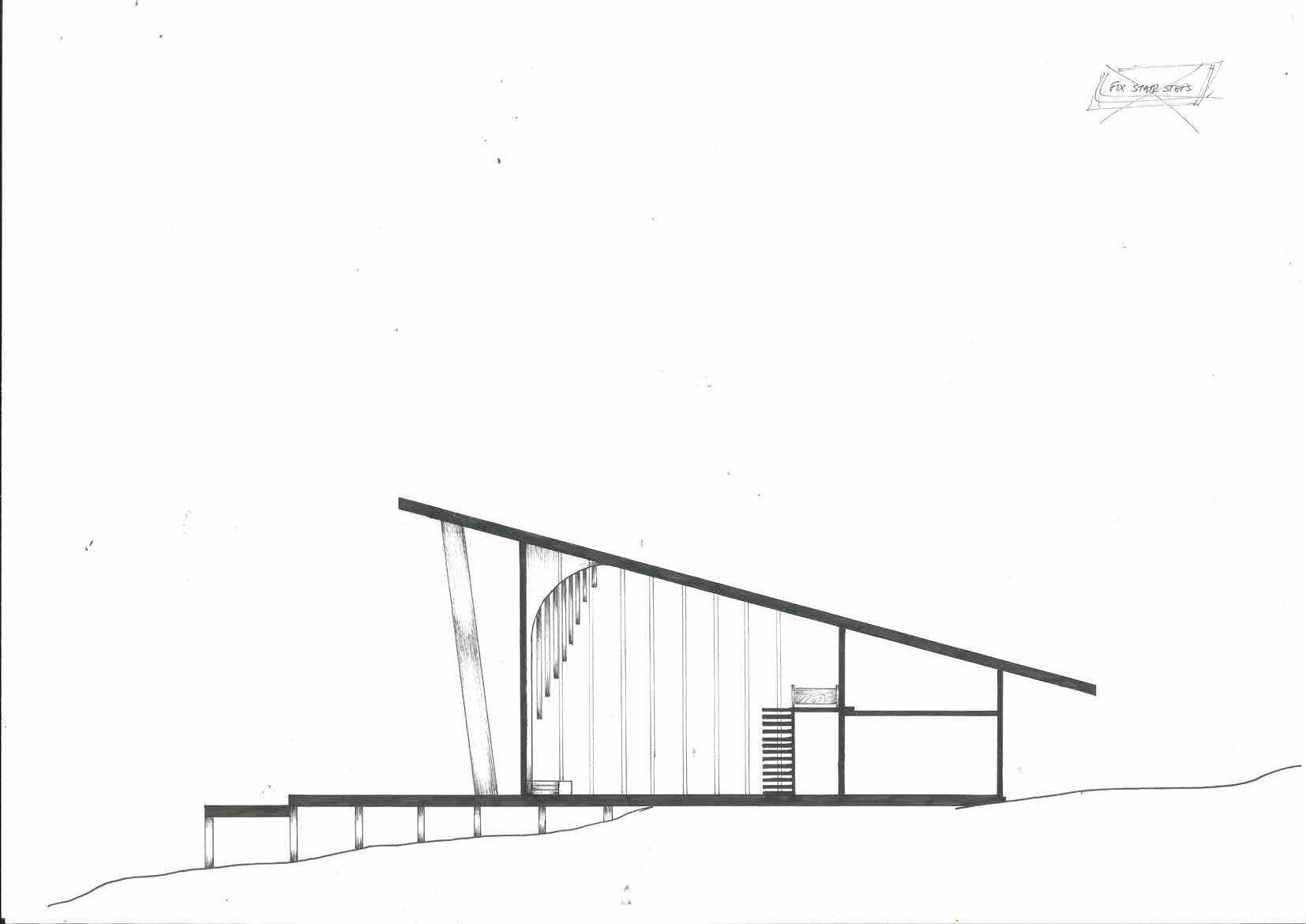

The brief for this project asks for a gathering space for the locals of Skye and also a gallery space for the chosen maker from the previous project. It requires an adaptive and reusable space for several types of community gathering events. The project also asks to consider the way the building intervenes with the landscape and how the weather will affect its design. My design utilises outdoor space alongside indoor space to create an effective gathering environment. The decking interacts with the sites topography as the steps leading up to it are dependant of the slope of the site. The building stands on stilts as this causes least amount of damage to the existing terrain. The gathering hall consists of carefully selected openings to create evocative lighting inside the space and to show off the sites best views. The doors of the gathering hall can slide open to allow easy access to the outdoor decking. The orientation of the building means that the outdoor area is sheltered from the wind coming from the South-West and that the best views and peak sunlight from the South enters the gathering hall.

Introducing Stage 1 students to sustainable creative practice, Co-Lab is designed to bring together students from across the schools and programmes of GSA to foster community and enable them to explore their potential as emergent creative practitioners through research, studio-based making, and collaborative encounters.

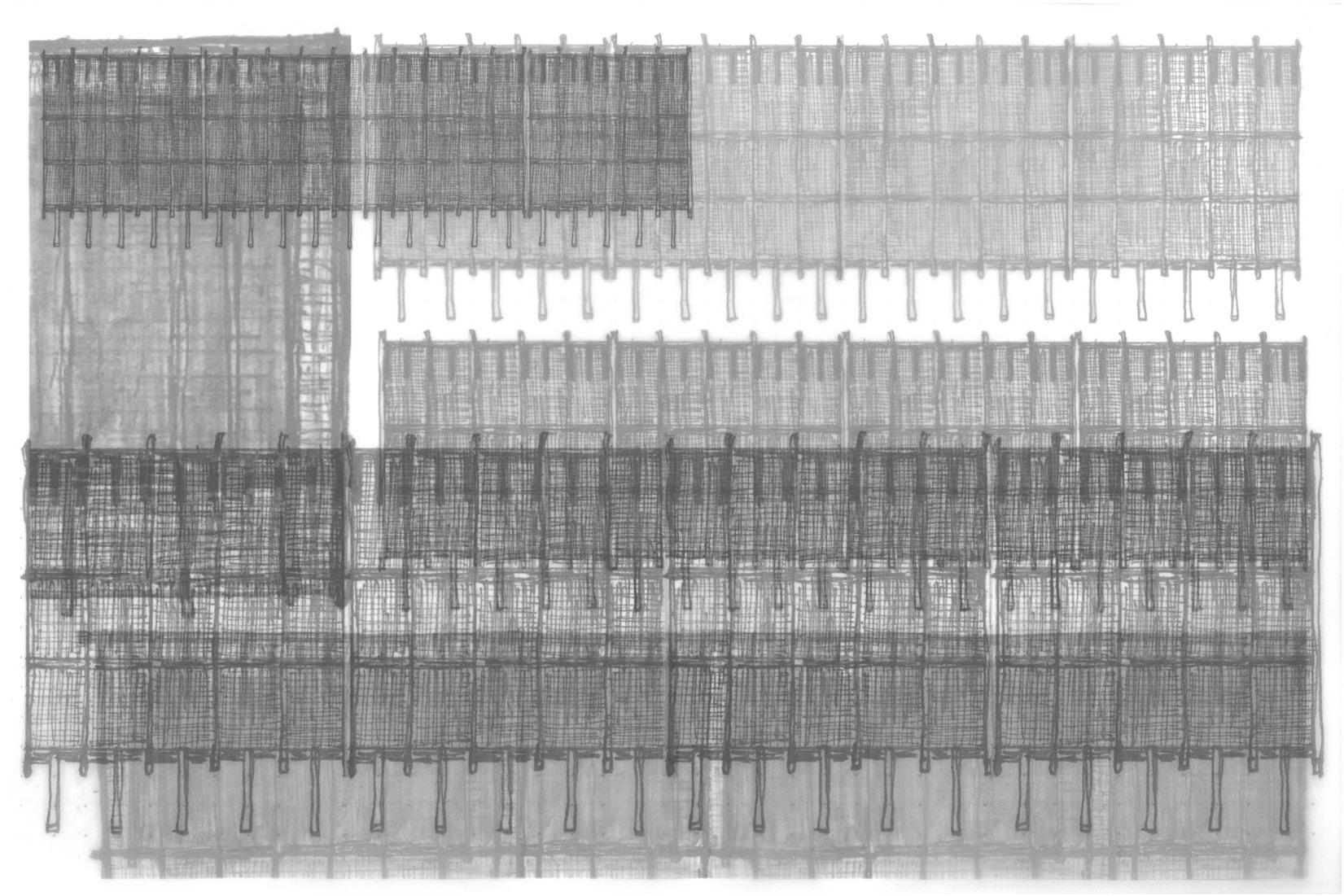

Co-Lab invited students to consider the meaning of ‘Bricolage’ through their chosen discipline and to develop a series of works in response to this. In an architectural context, the concept of Bricolage applies to cities, themselves layered constructs of connections, histories, and infrastructures that shape our daily experiences. Students explored this by observing a “Liminal Land” within the city: a vacant or derelict space in a state of transition. Through observation of this land, students considered its potential as a site of collaborative, creative work, establishing diverse lines of enquiry which allowed them to develop a collaborative conceptual response to their ‘Liminal Lands’ site. The work explores this in a range of themes and media, ultimately acting as a lens through which students consider the city as bricolage; the sustainable nature of their creative practice; and resourceful and conscientious ways of creating work in response to a particular place.

BY TANYA NESTEROVA

The Co-Lab project was our creative response to a derelict piece of land in Govan, Glasgow. We carefully examined the site, exploring its “unofficial” uses. Owned but neglected by the council, the area is home to rats and pigeons that linger near the old dovecot. Occasional dog walkers or nearby workers pass by, yet don’t feel a connection to the land. “Anything would be better than this” remarked one of the workshop owners, expressing a lack of empowerment to make a change.

It was particularly interesting for me how the journey there impacts the perception of the place. Following Chris Leslie’s advice during the mid-project reviews, I decided to re-visit Govan, taking a route through the Clyde Tunnel and returning via the new bridge. The contrast was striking. The suffocating experience of walking through the Clyde Tunnel felt symbolic of the deprivation Govan has endured over the past 60 years. In contrast, the new bridge represents hope—a path toward a brighter future and positive change. For now, these two routes coexist, offering different ways to access and experience this transforming district.

The act of walking itself became a meaningful experience. Observing the footprints on the walls of the Clyde Tunnel, the distant rails (which I traced in red and added to the tapestry), and the desire paths on the site led me into a reflective contemplation of time, movement, perspective, and change. Ultimately, walking itself can bring change. With each step, you carve a path— one foot in front of the other. And the experience of this process matters.

As AI transforms architecture, Danny Campbell, founder of HOKO Architects, is redefining its role in residential design. By integrating AI, vR, and AR, he’s pushing boundaries while keeping clients at the center. In this conversation, he shares insights on AI’s challenges, sustainability, and the future of architecture.

Can you tell us a bit about your journey—what inspired you to start HOKO, and how did AI become a key part of your practice?

My journey started like many architects - I wanted to be creative and design meaningful spaces, But when I entered the profession, I quickly realised that traditional practice was slow, inefficient, and often frustrating for both architects and clients. That’s what led me to start HOKO.

We set out to make architecture more accessible, particularly for homeowners, by streamlining the design process. AI became a key part of that mission when we realised how much of our work - analysing regulations, assessing feasibility, and even generating concepts - could be enhanced through automation. The goal was never to replace architects but to free them up for more creative, high-value work.

What unique challenges did you face when integrating AI into your work?

One of the biggest challenges was overcoming skepticism within the industry. Many architects view AI as a threat rather than a tool, so there’s been resistance to adopting new technology.

Another challenge was training our AI systemsarchitecture is highly contextual, and regulations vary, so AI needs to be able to process and apply complex, site-specific information accurately.

When did you realise AI could be a powerful tool within residential architecture?

Most people assume AI belongs in large-scale projects - skyscrapers and masterplans. But the reality is that AI is just as useful in residential projects. Homeowners have to navigate planning regulations, budgets, and

construction logistics, which can be overwhelming. AI allows us to automate parts of that process, ensuring more efficient project timelines and better-informed design decisions.

How exactly is HOKO using AI within its practice?

We’ve developed AI tools that analyse planning policies, read and assess drawings, and check designs against building regulations in real time. This drastically reduces the back-and-forth with planning authorities and helps us deliver more accurate designs, faster.

We also use AI-driven generative design, which allows us to explore multiple variations of a project instantly, helping clients visualise options they might not have considered otherwise.

In your opinion, how can AI be used to honor tradition while pushing creative boundaries?

AI doesn’t have to replace traditional design - it can enhance it. If anything, AI can help us study historical precedents, analyse proportions and materials, and integrate traditional techniques in a way that’s more informed.

It allows architects to focus on craftsmanship and the human experience, rather than spending endless hours on technical constraints.

There’s a big push toward sustainability in architecture. Given AI’s high energy consumption, how does it fit into a net-zero project?

It’s a fair point - AI does require energy, but so does inefficient design and construction waste. AI can help optimise building materials, and model energy performance more accurately. If a client is focused on net-zero, we use AI to ensure smarter decision-making, minimising waste and improving efficiency at every stage of the project.

How is AI changing the role of an architect? Is it just a tool to speed up processes, or does it actively contribute to design?

AI is absolutely redefining the role of an architect. It’s not just about automating tedious tasks - it’s changing how we approach design altogether. AI can suggest design solutions, analyse spatial relationships, and even predict how users will interact with a space. It’s a collaborative process where AI provides insights, and the architect makes the creative and strategic decisions.

AI is absolutely redefining the role of an architect. It’s not just about automating tedious tasks - it’s changing how we approach design altogether.

Your practice also integrates VR/AR—how are these technologies used in the design process?

We use VR and AR to bring projects to life before they’re built. Clients can step into a virtual version of their home, experience different layouts, and give real-time feedback. This not only helps clients make better decisions but also reduces costly changes during construction. It’s a game-changer for residential architecture, where every detail matters to homeowners.

Are there any risks or challenges that come with using AI in architecture? What should students interested in AI watch out for?

The biggest risk is over-reliance on AI. It’s a tool, not a replacement for human judgment. AI can suggest solutions, but it doesn’t understand emotion, culture, or the nuances of lived experience (at least not yet). Students need to be critical thinkers and understand how to balance technology with human-centered design.

Another challenge is the ethical use of AI. Data privacy, bias in AI models, and transparency are all issues that need to be addressed as technology advances.

If you could fast-forward 50 years, what impact would you like your work to have on the industry?

I’d love to see architecture become more accessible and efficient. Right now, the traditional model makes it hard for people to access good design. If AI and other technologies can help architects work smarter, lower costs, and improve the client experience, that’s a legacy worth leaving.

I also hope craftsmanship and high-quality construction make a comeback. AI can optimise the design process, but at the end of the day, architecture is about building spaces that feel good to live in.

What advice would you give to students and recent graduates about staying adaptable in a changing industry?

Stay curious and be open to learning. The industry is evolving fast, and the architects who succeed will be the ones who embrace technology while still valuing creativity and human connection. AI and automation will handle a lot of the technical work - so focus on the skills that make you irreplaceable: problem-solving, communication and innovative thinking.

Do you think students should be actively learning AI tools, and how can they start integrating AI into their studies?

Yes, absolutely. AI isn’t going anywhere, and understanding how to use it effectively will give you a huge advantage. Start by experimenting with generative design software and most importantly, stay informed about how AI is being used across the industry.

The best architects of the future will be the ones who can blend AI with creativity, sustainability, and humancentered design.

Danny Campbell’s work at HOKO Design is a testament to how innovation and tradition can move forward together. As AI continues to transform the industry, his approach proves that technology isn’t about replacing architects - it’s about empowering them to design smarter, more accessible, and more sustainable spaces. In a world where architecture is constantly evolving, Campbell’s vision ensures that the next generation of designers will continue to push boundaries while honoring the foundations of great design.

‘Stay curious and be open to learning. The industry is evolving fast, and the architects who succeed will be the ones who embrace technology while still valuing creativity and human connection.’

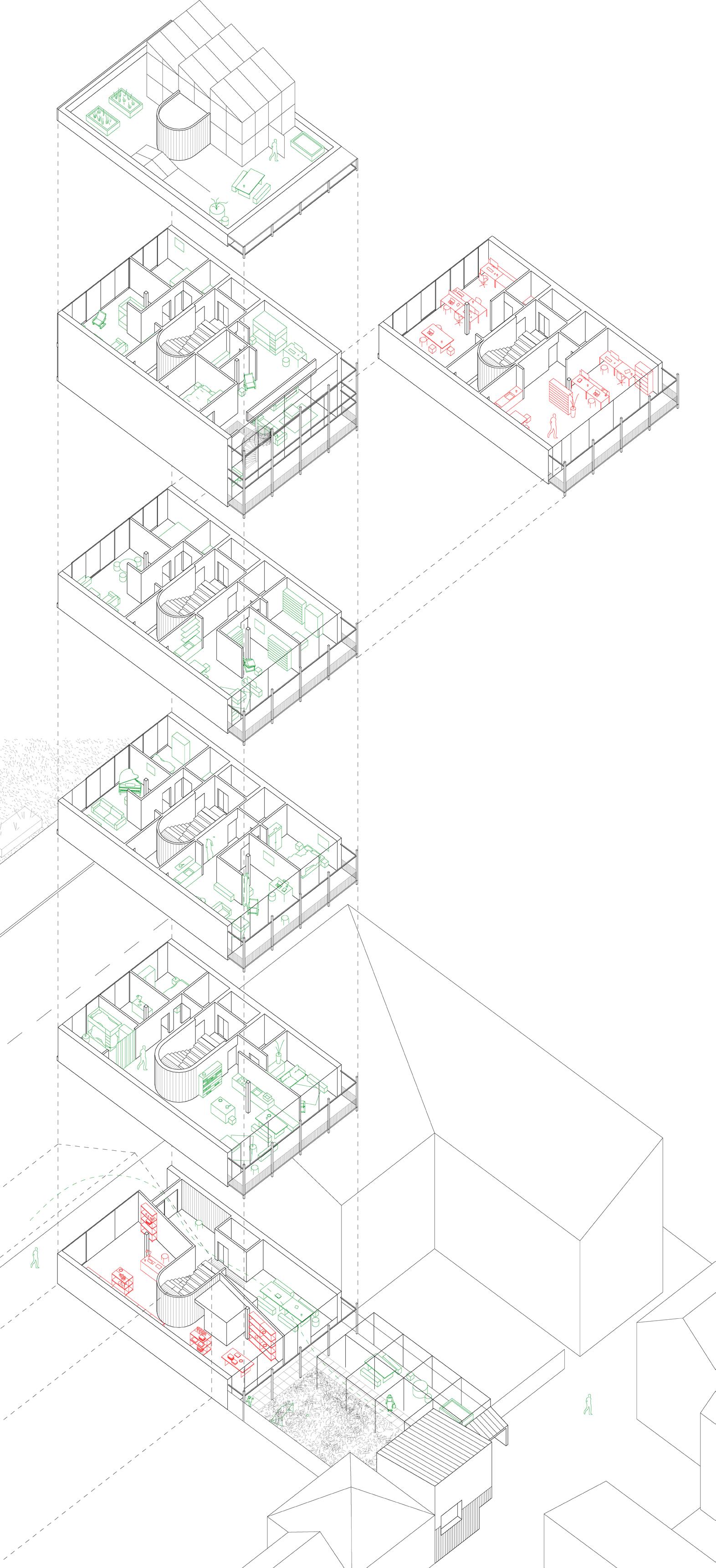

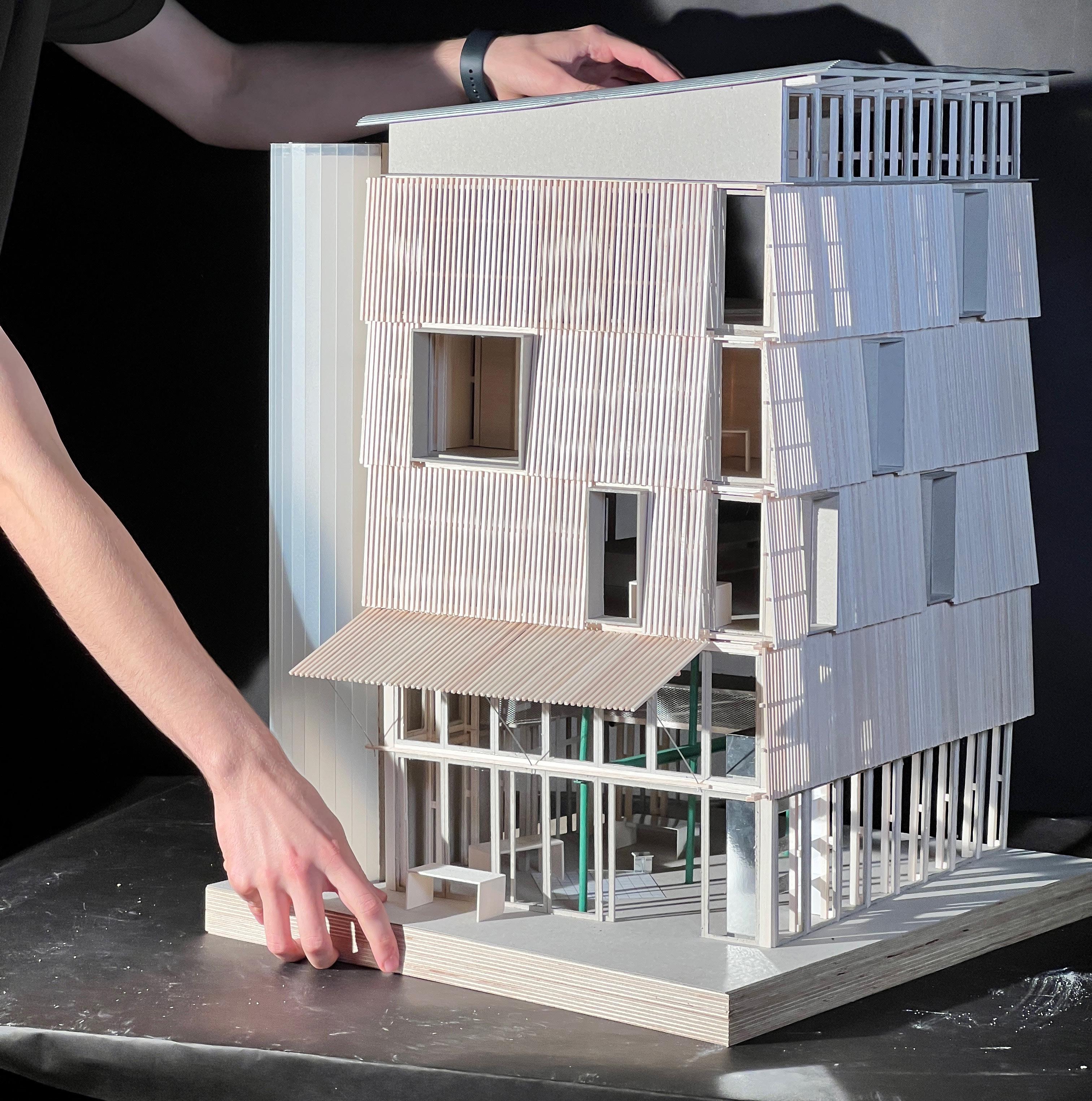

Stage Leader: Kathy Li Co-Pilot: India Czulowska-Burns

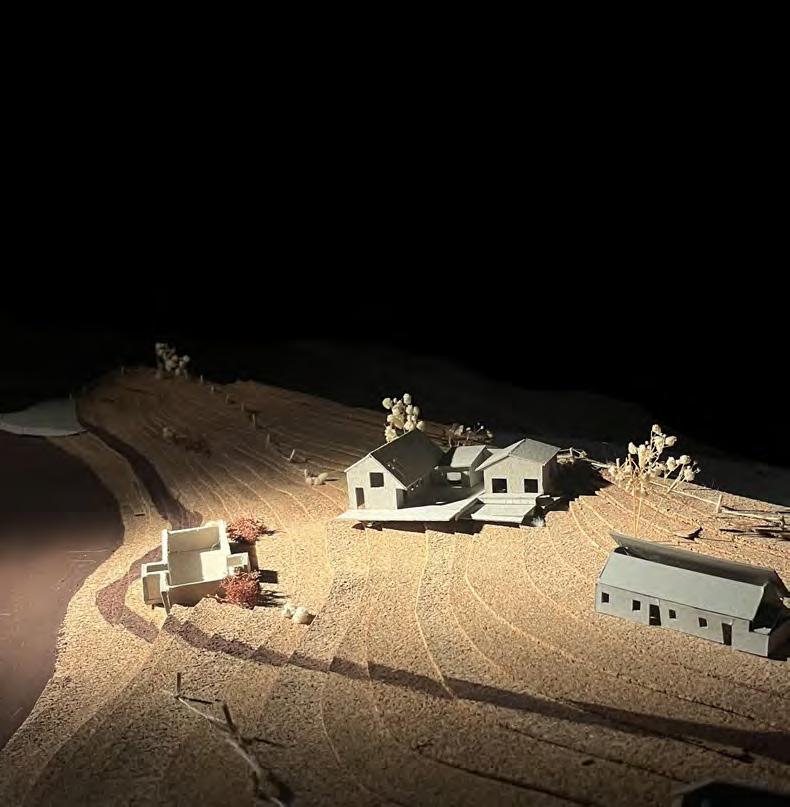

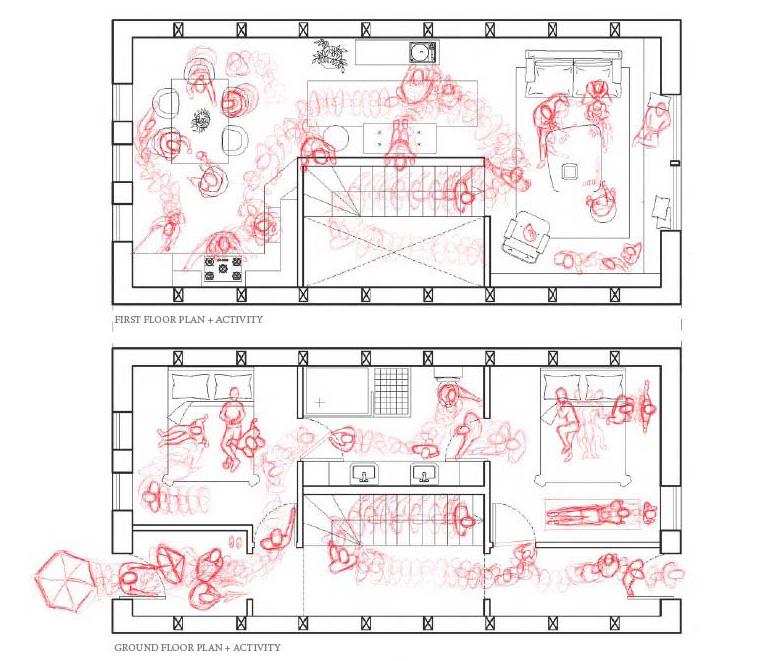

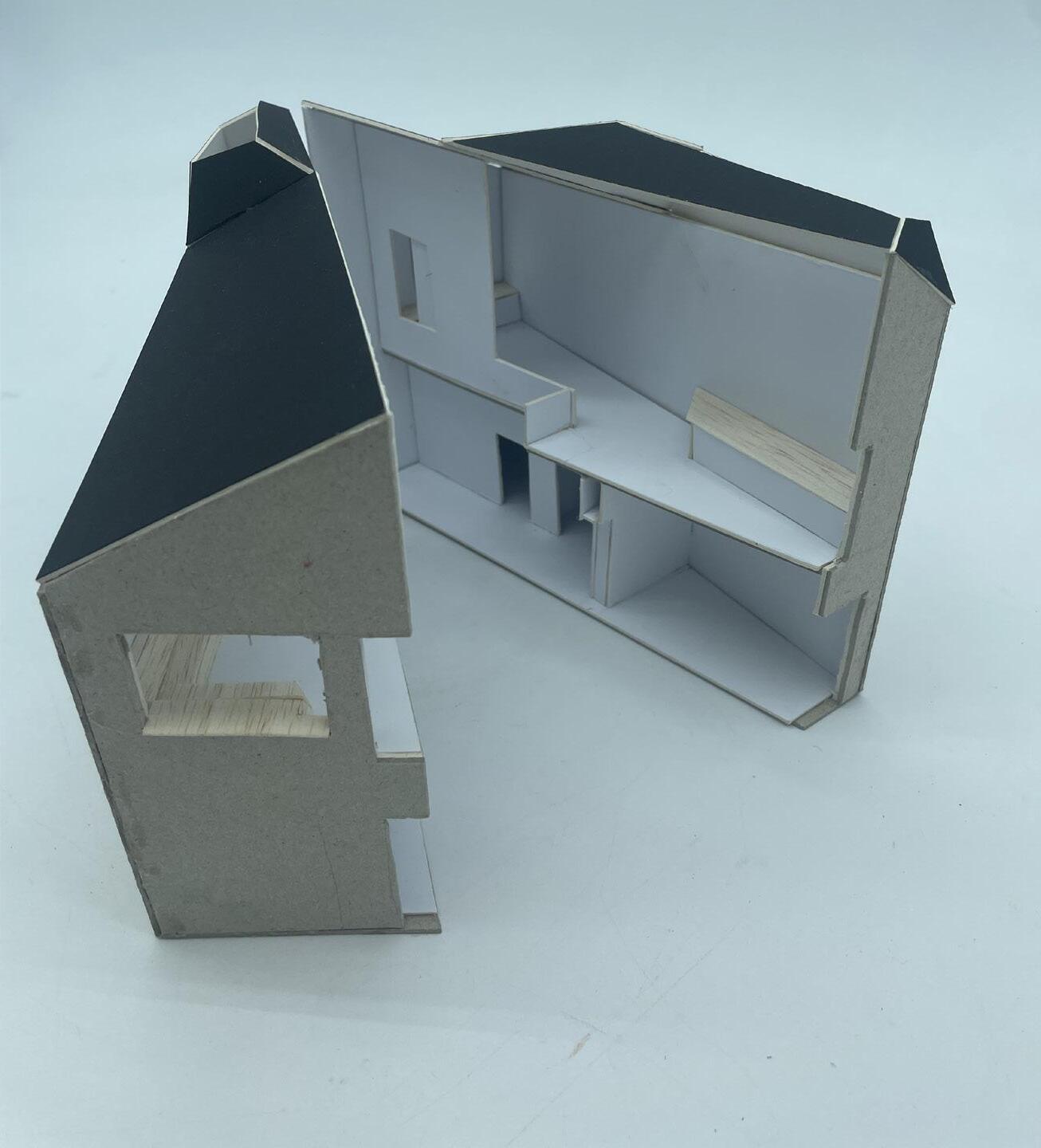

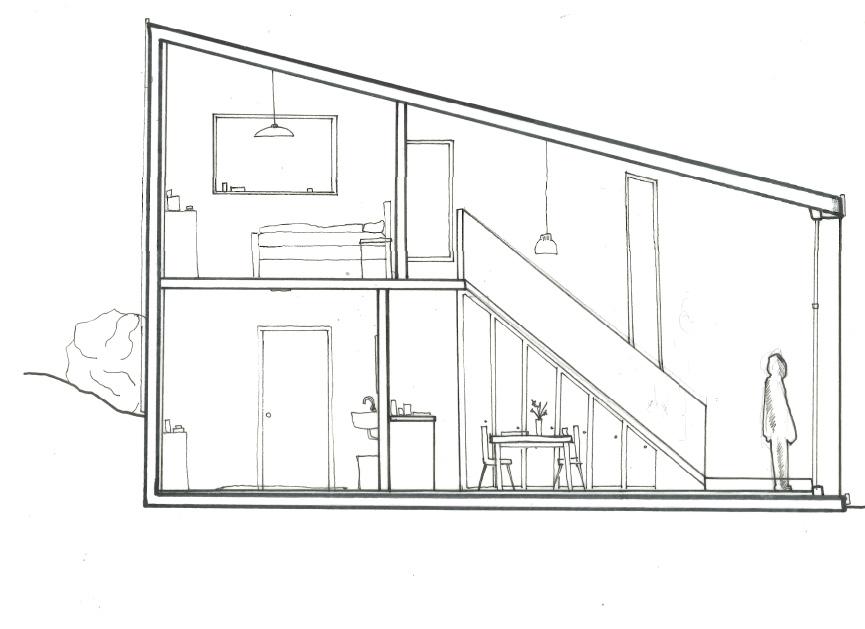

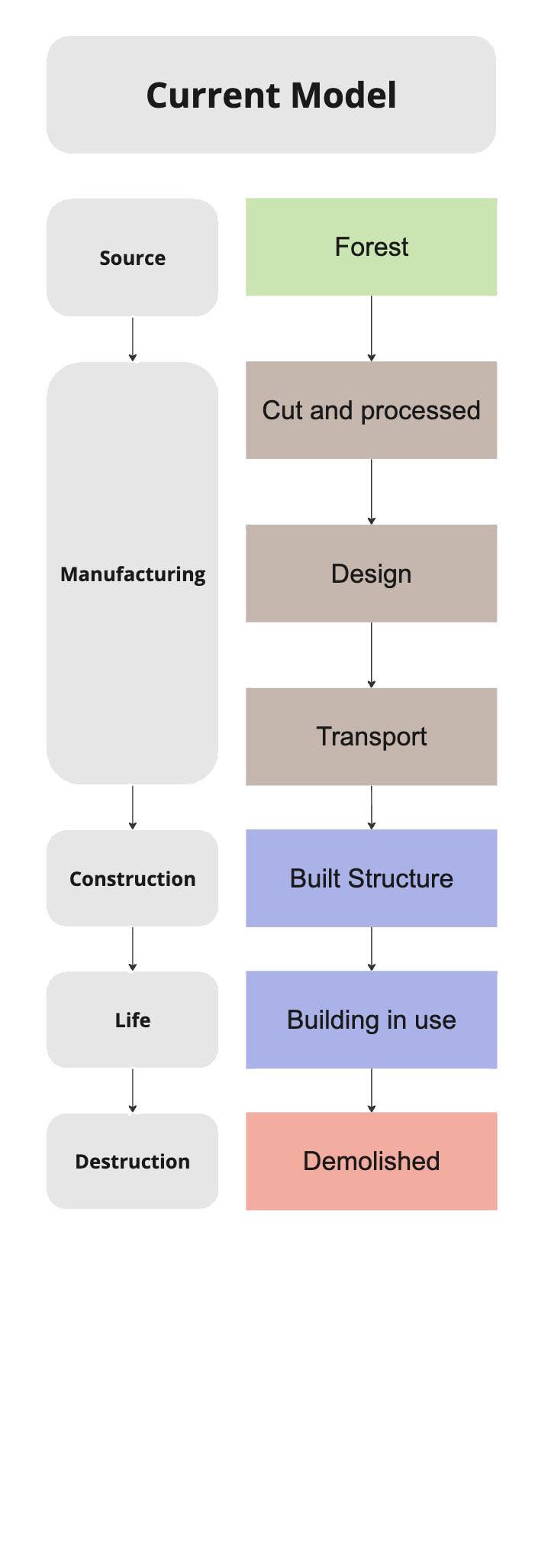

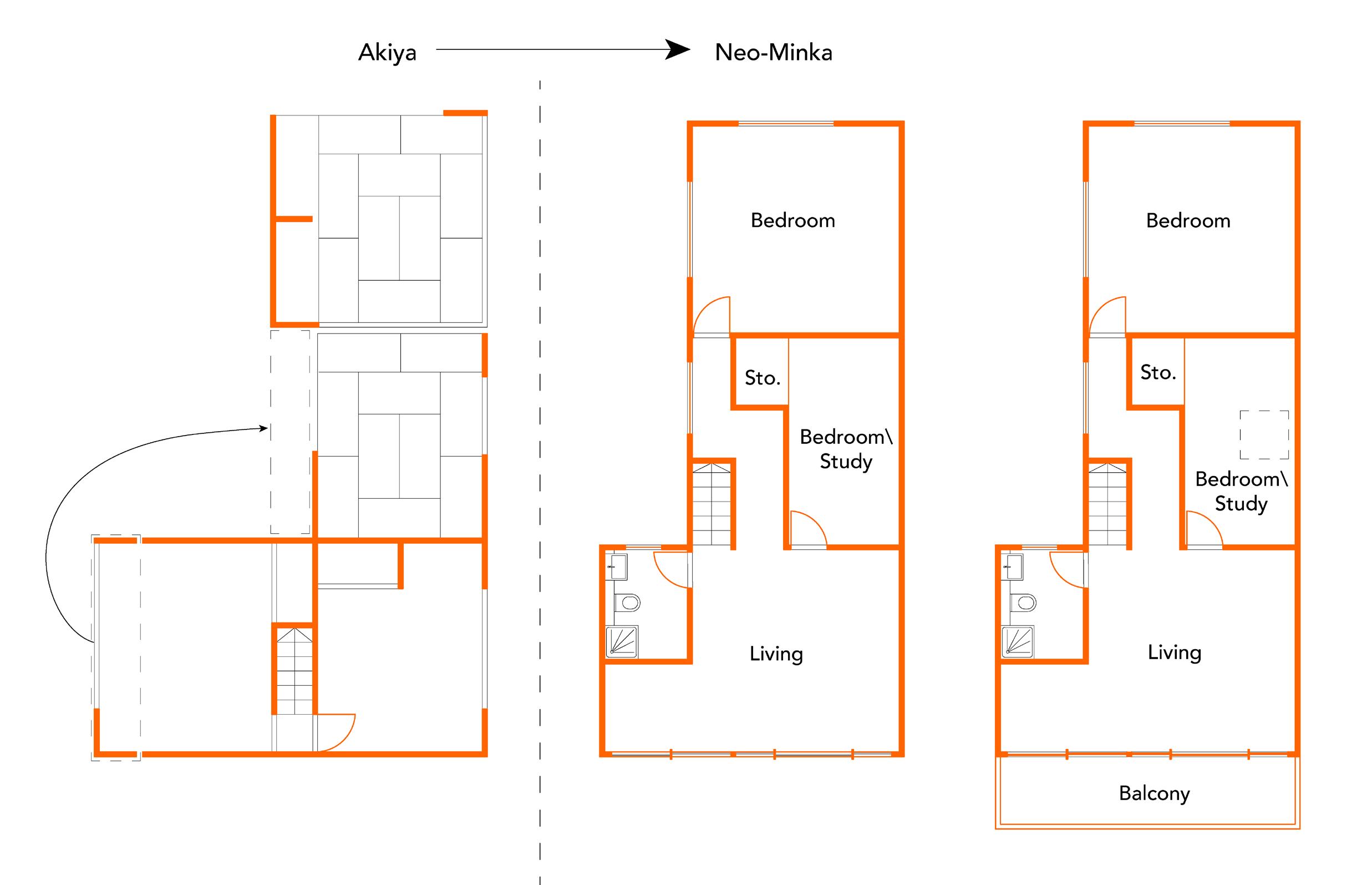

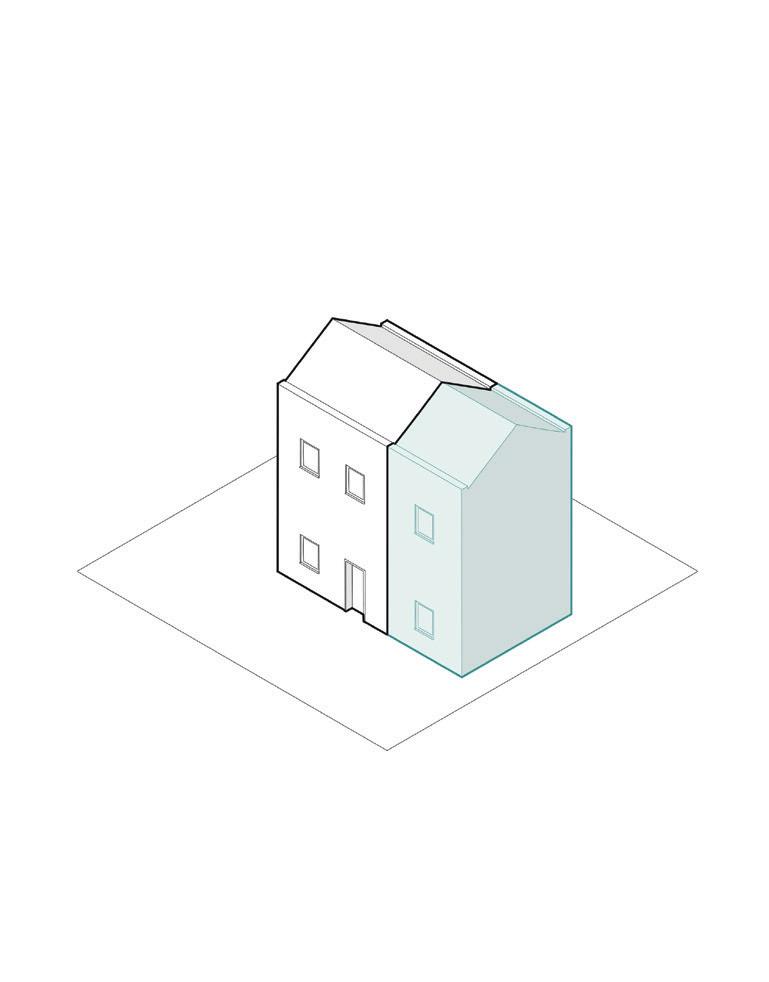

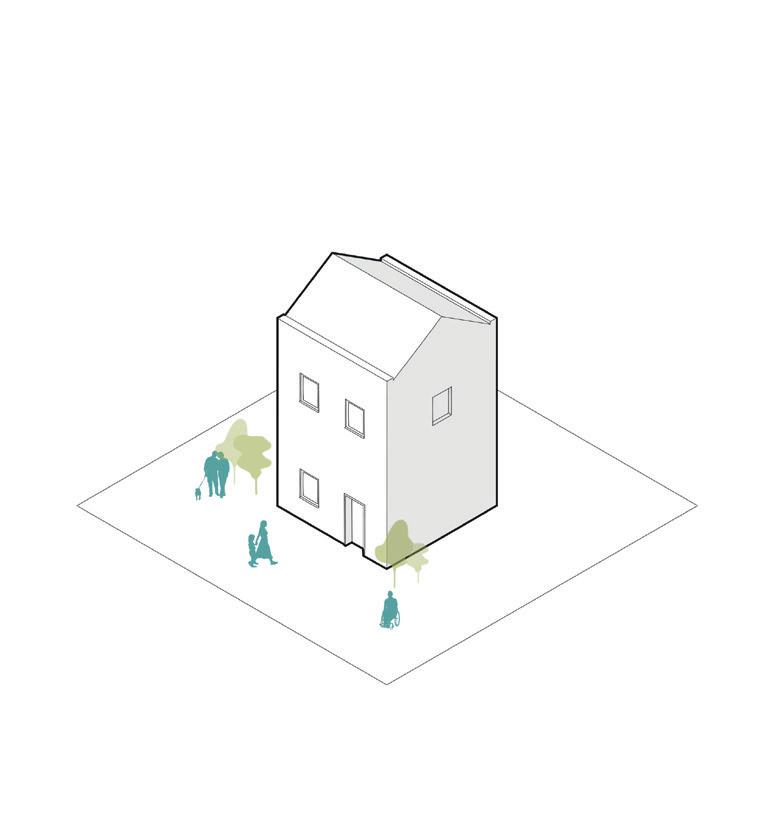

The theme explored in Semester 1 was housing for rural communities. Under the collective banner of ‘The Idea of a Home’ we returned again to Forres for our explorations. Articulated in four nested inter-relatable projects, we started at scales investigating buildability at 1:1 and ended at townscale of 1:200 to propose ideas of liveability. During our study trip we followed timber from forest, to sawmill, to construction and made many friends along the way. Students initially worked in groups for mutual support and were encouraged to research, test their ideas in discussion with their peers and staff, uncovering many aspects and issues of housing design encountered by society and architectural practice.

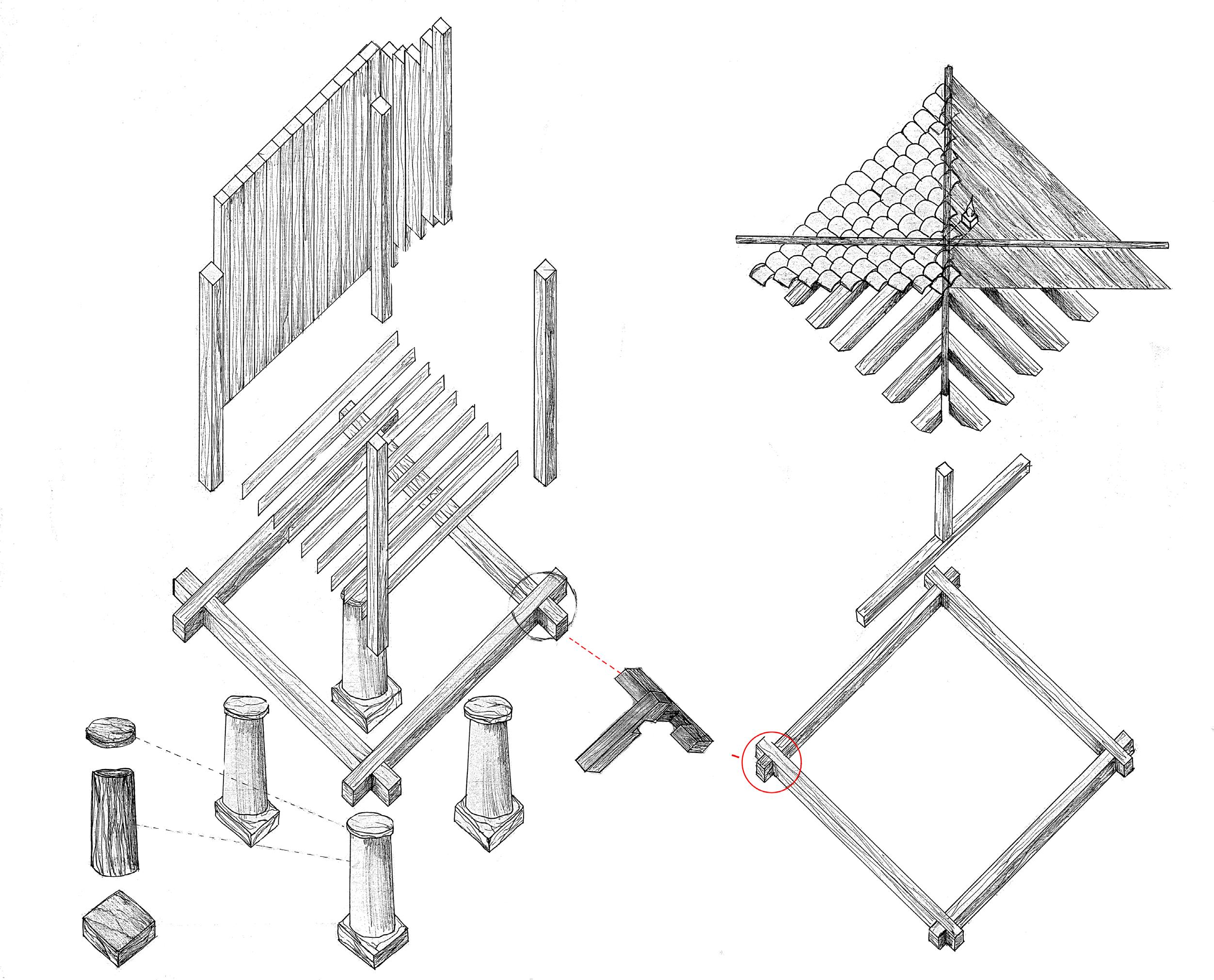

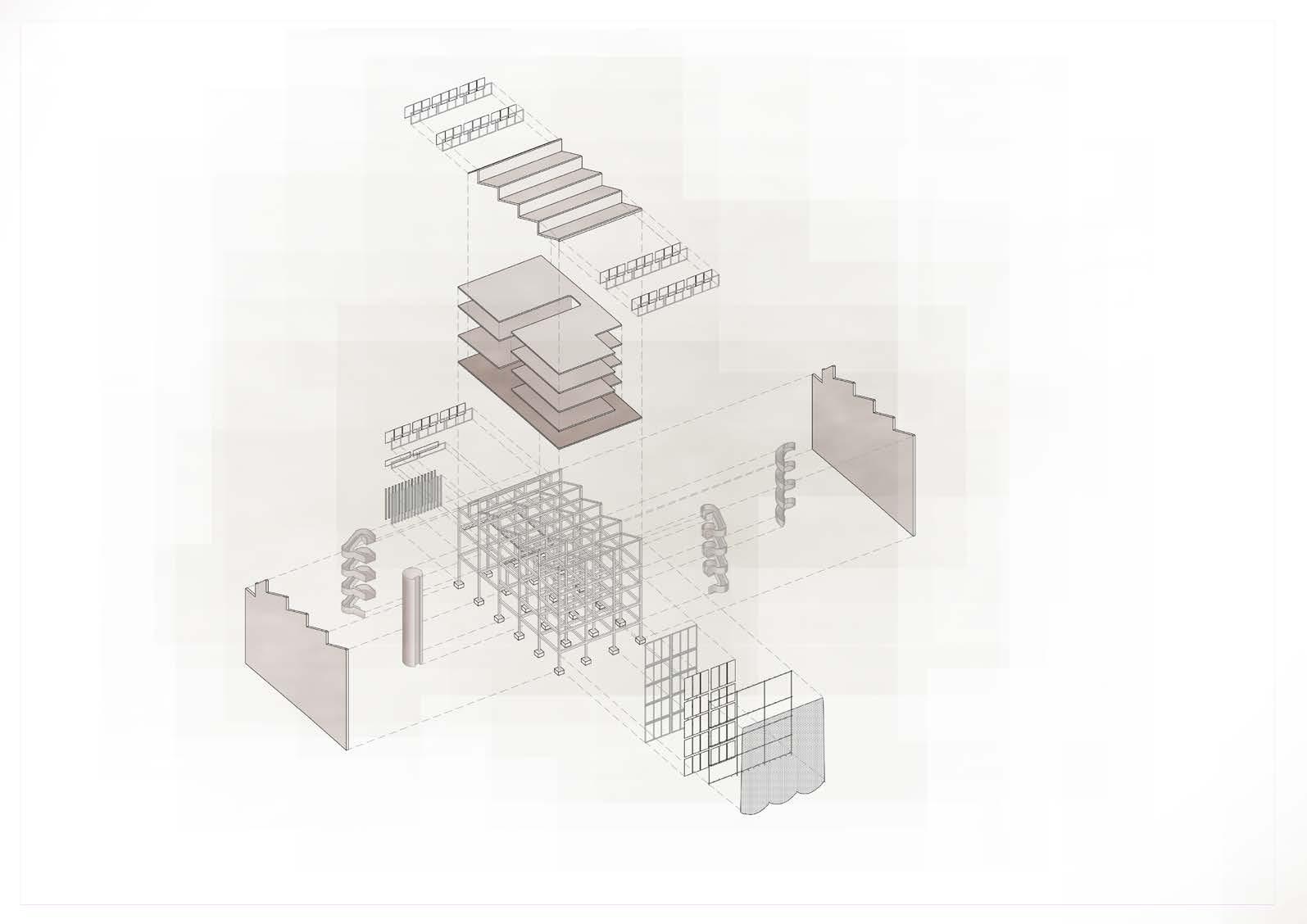

MAKE (Project 1): Students initially worked in groups to research by precedent, possible ways of making housing from timber, thinking specifically how timber is jointed at 1:1 and the possibilities of timber portals & frames.

SPACE (Project 2): Taking a standard ‘unit’ of 5mx10mx8m and working at 1:50 & 1:100, students developed design proposals for a singular house module, testing their ideas through design lenses of light, space, volume and delight.

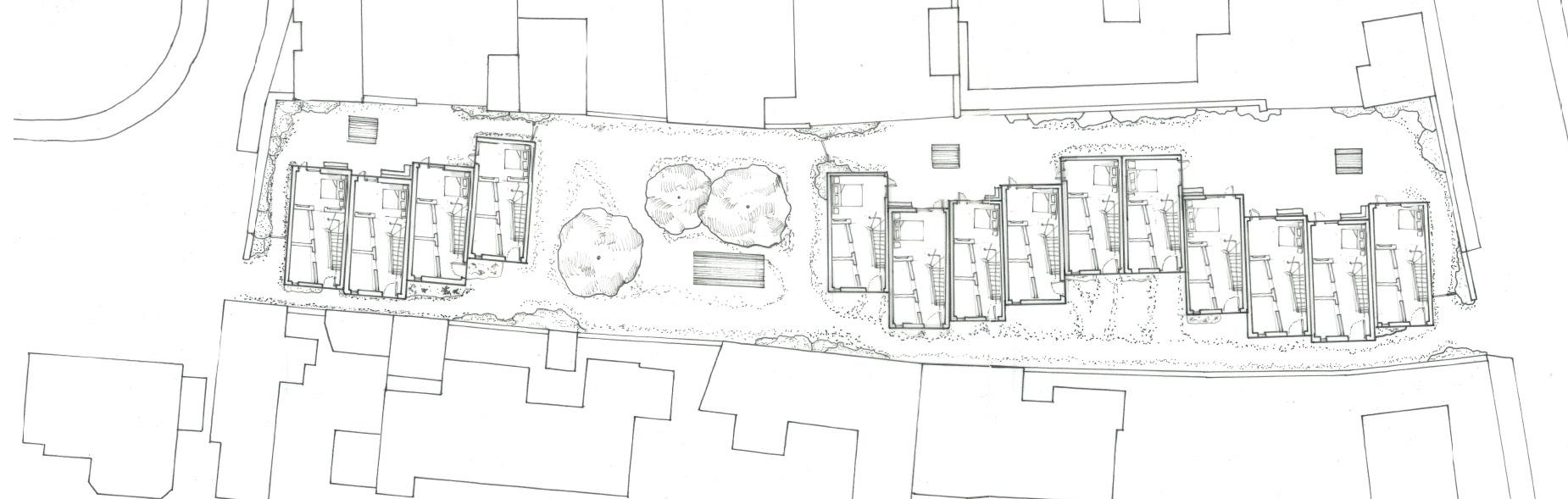

ROW (Project 3): Students were asked to repeat and adapt their units to create a row of 10-15 houses. Contextual information gathered during the study trip to Forres helped test initial ideas.

PLACE (Project 4): Back in Glasgow students developed their row housing designs, expanding their ideas to create social neighbourhoods.

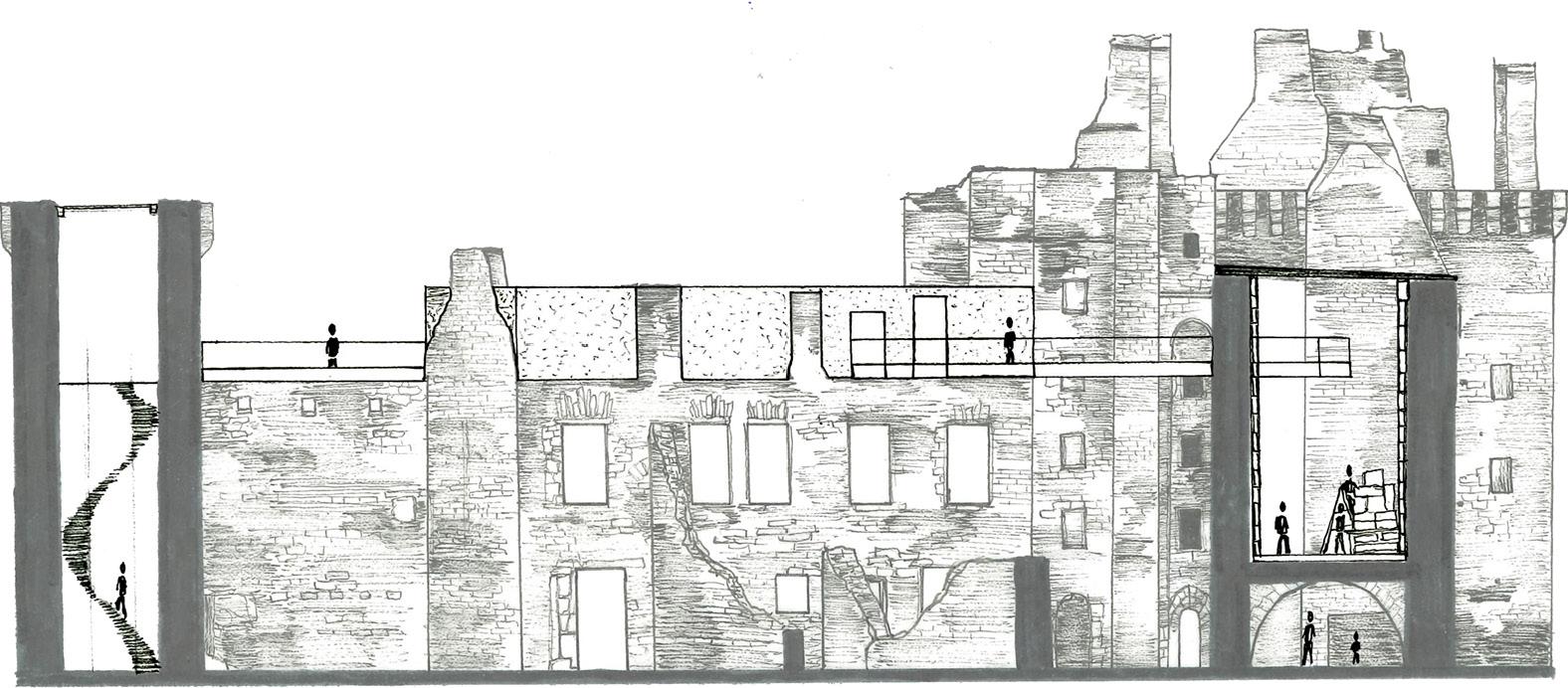

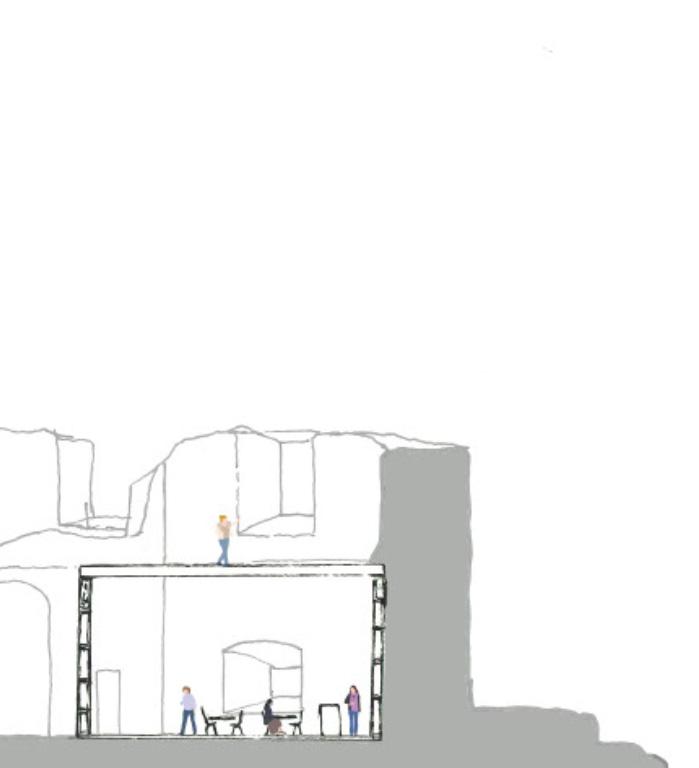

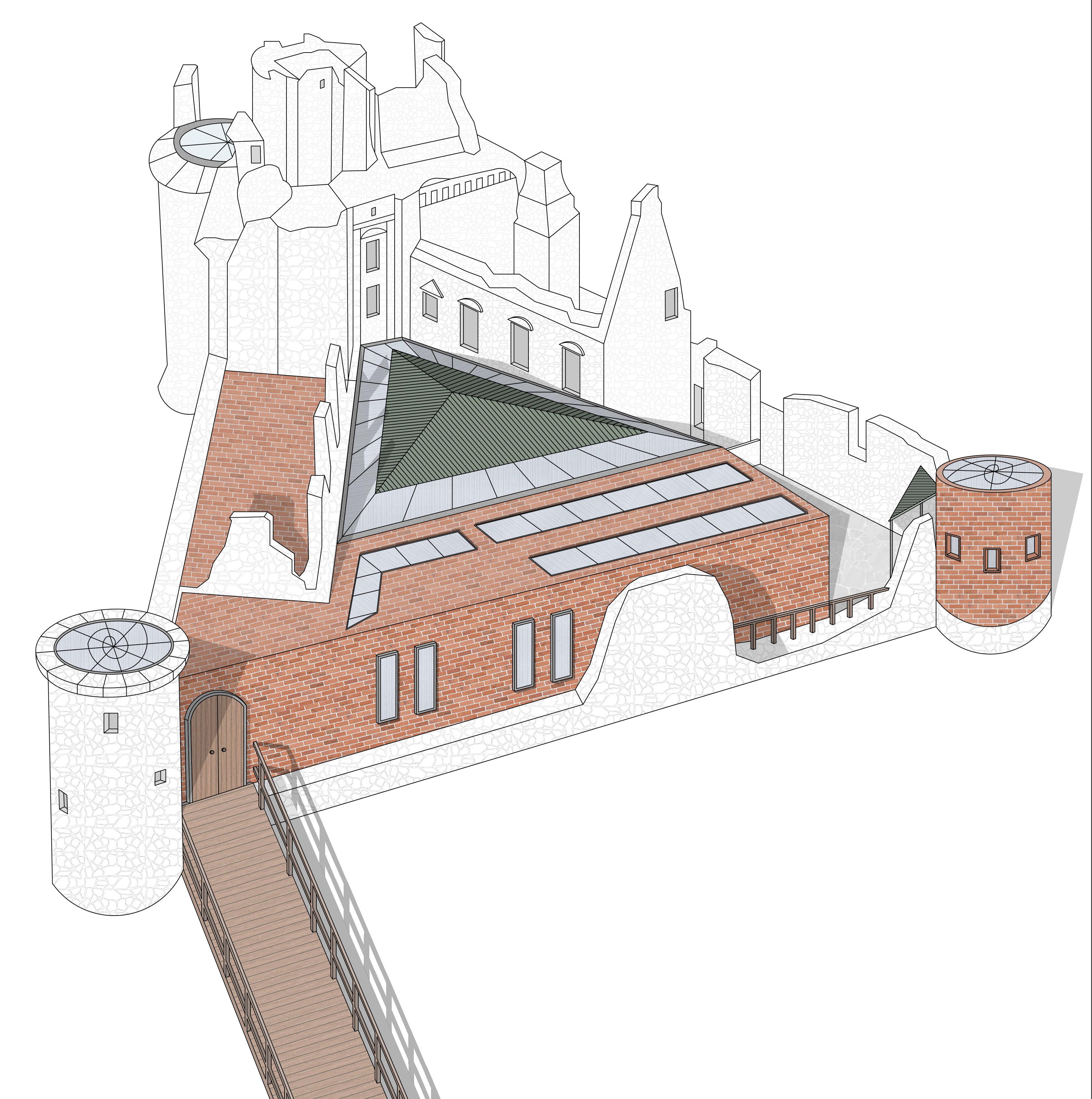

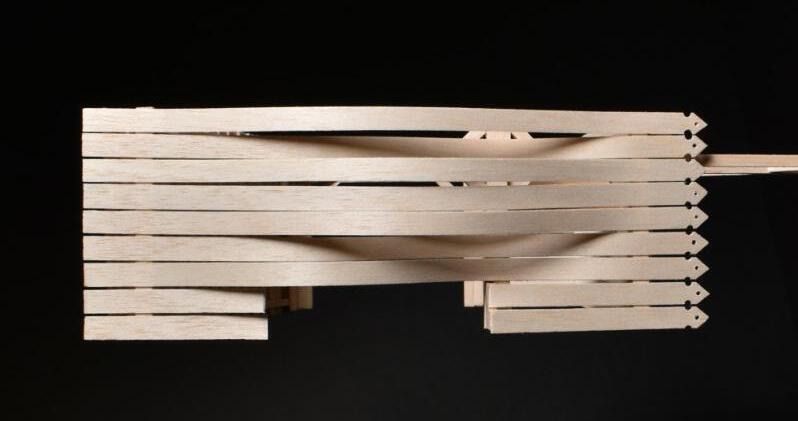

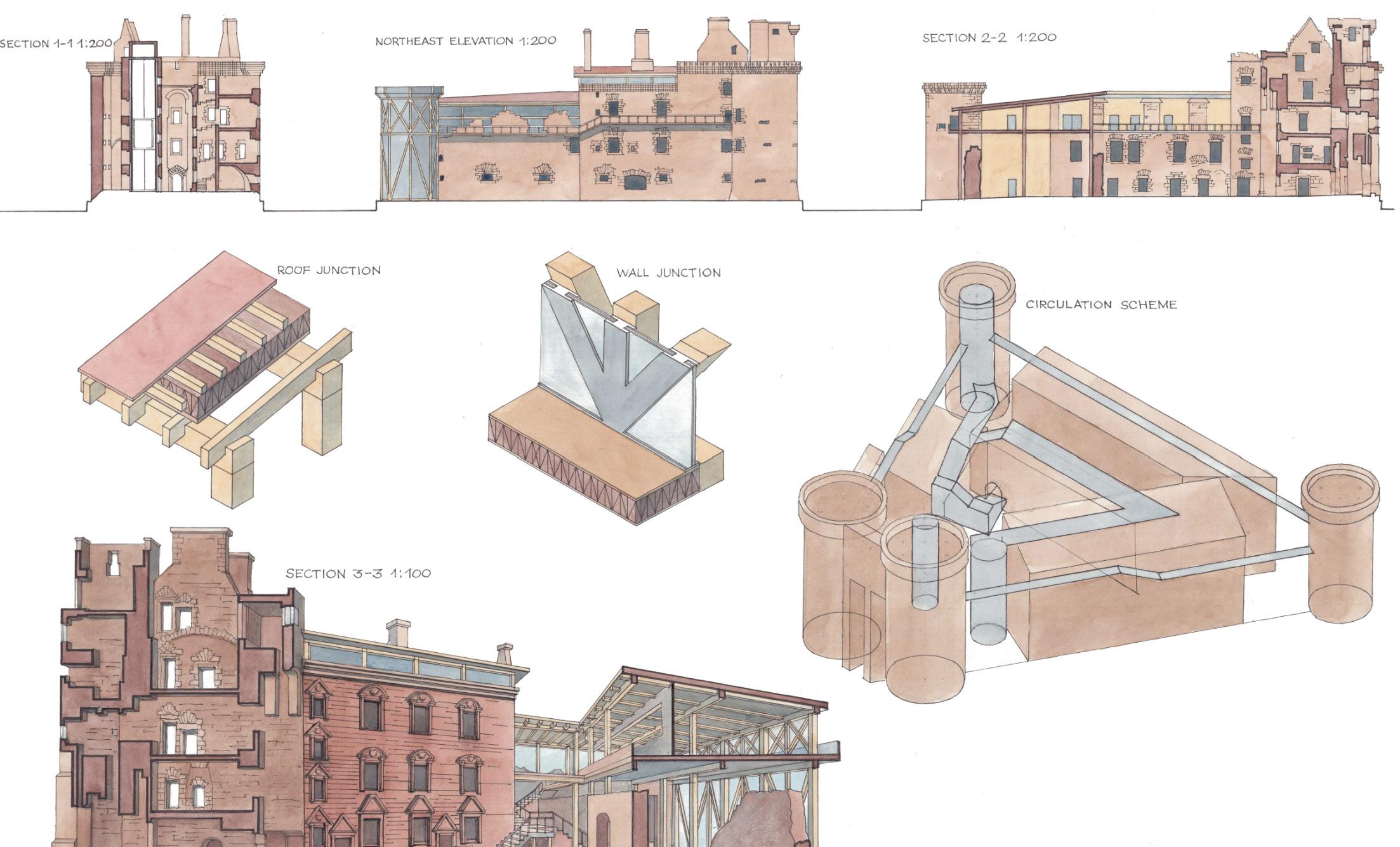

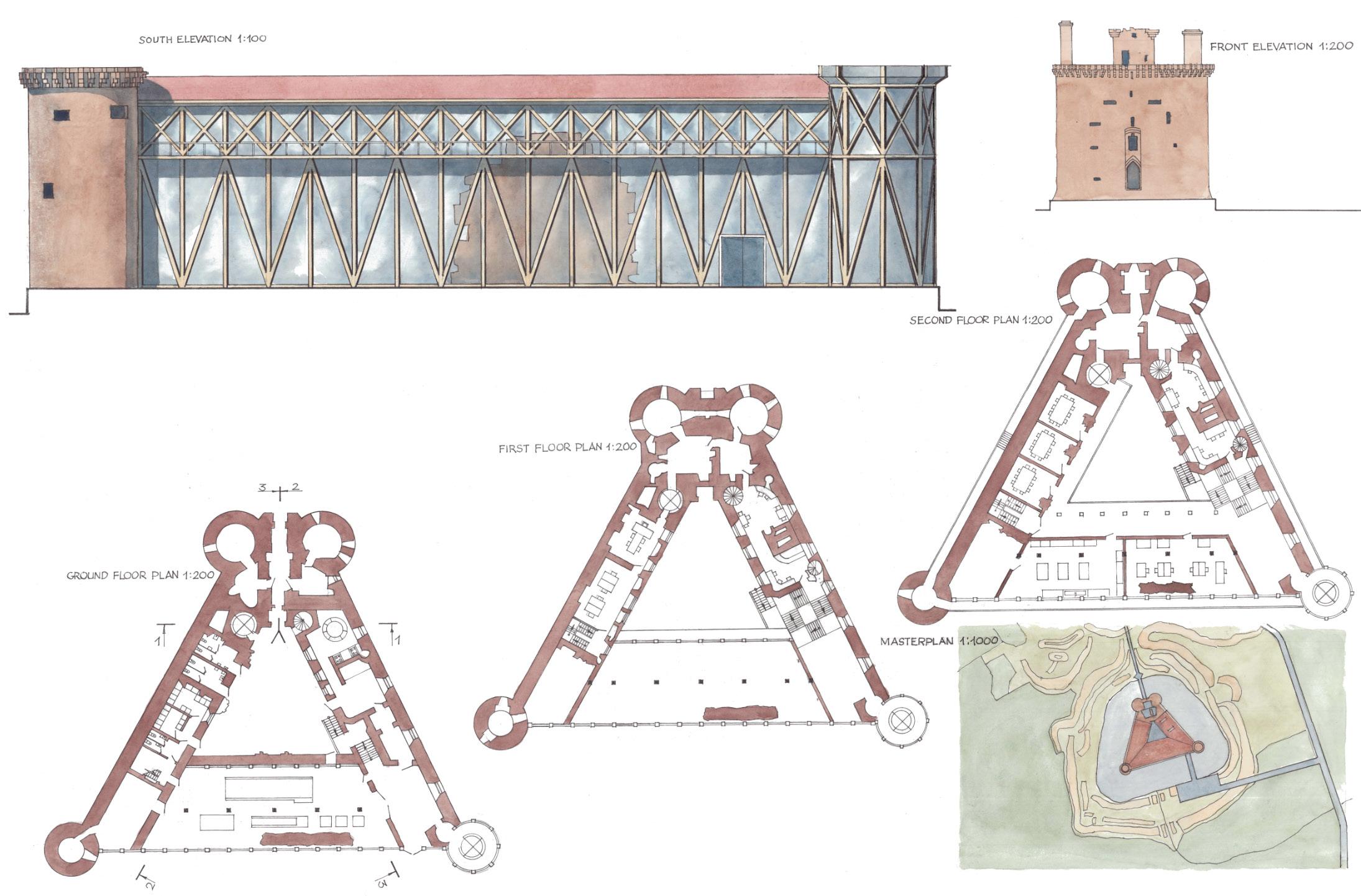

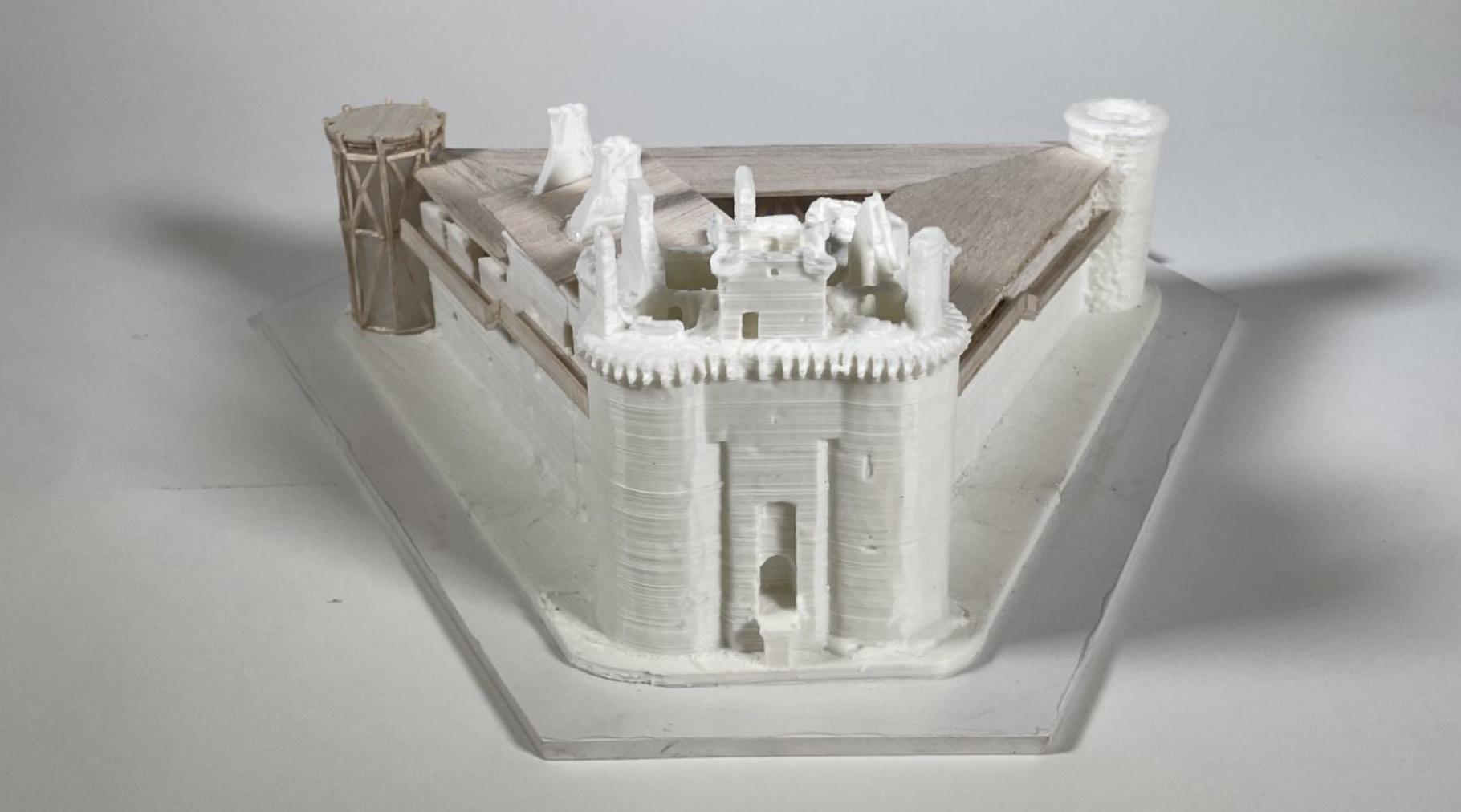

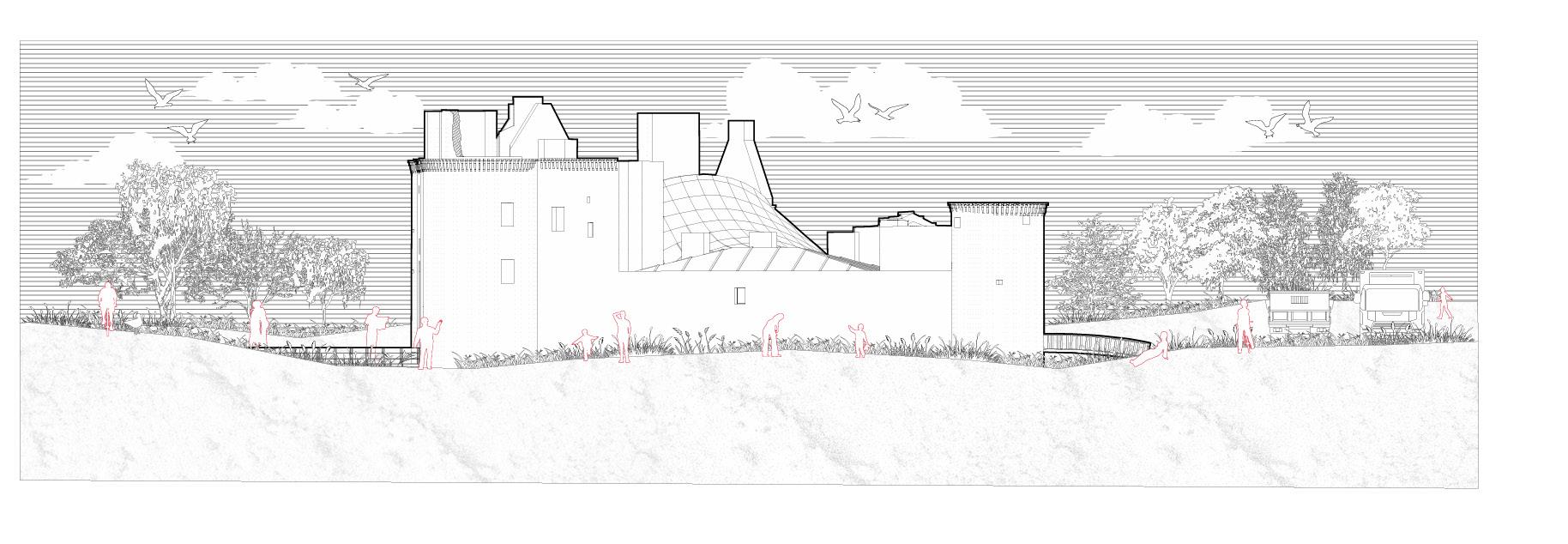

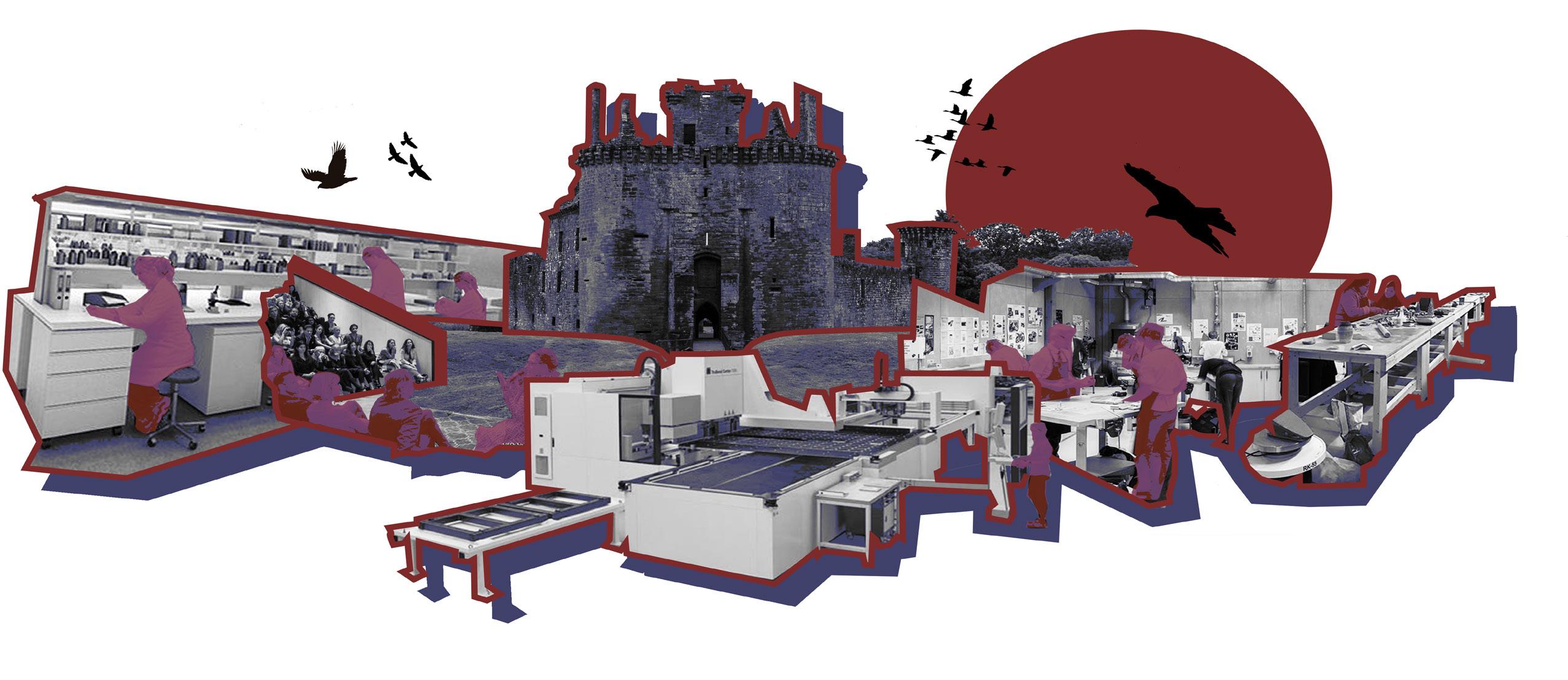

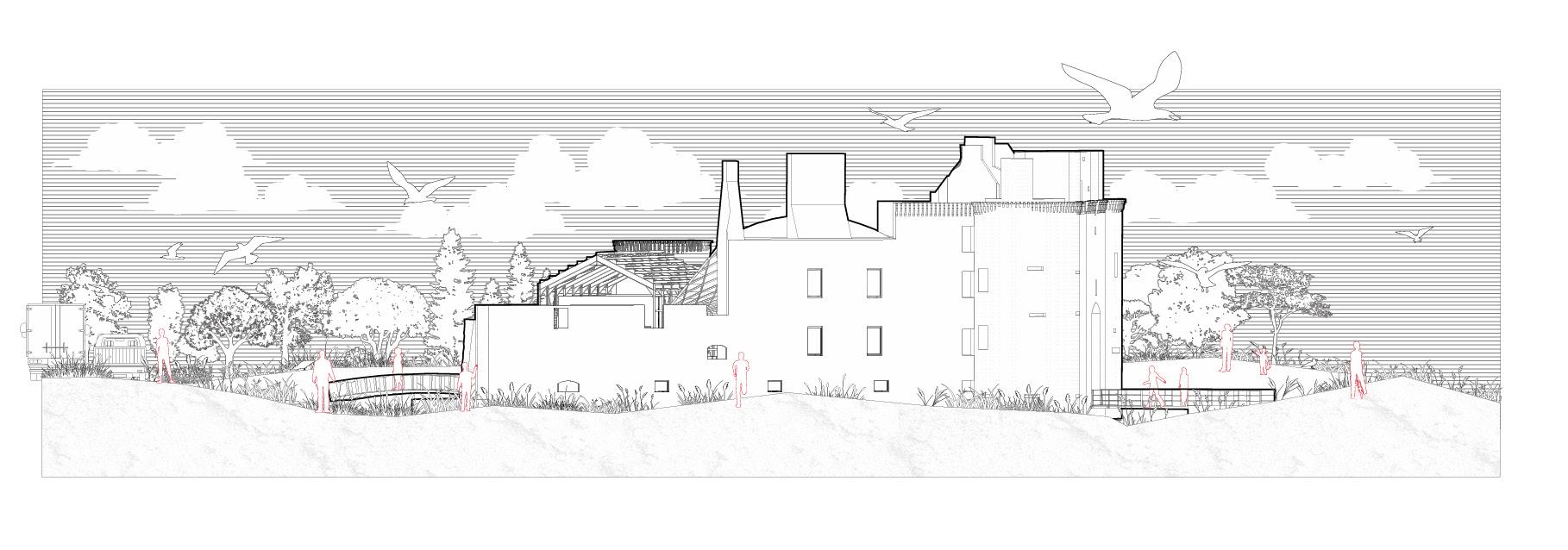

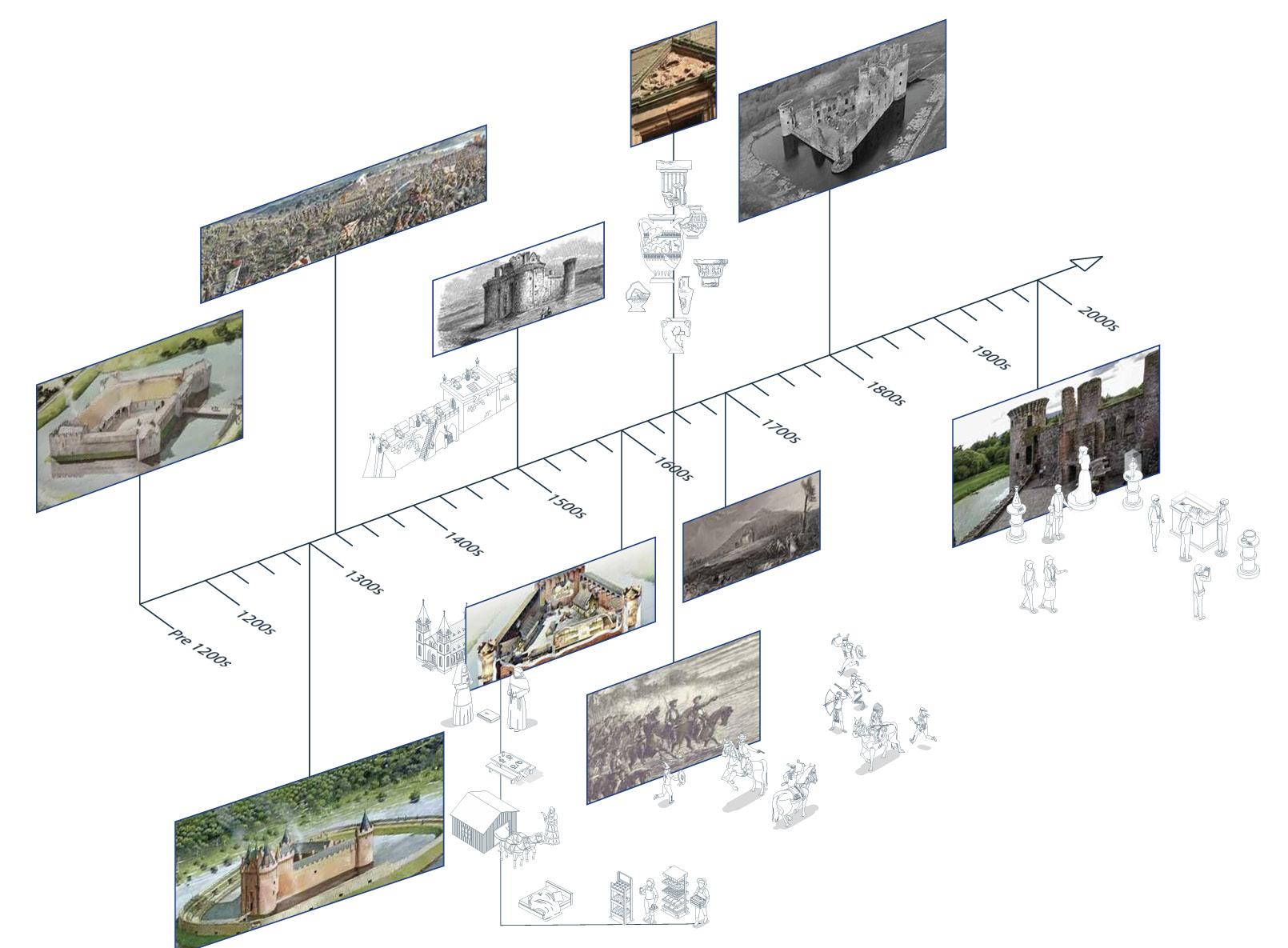

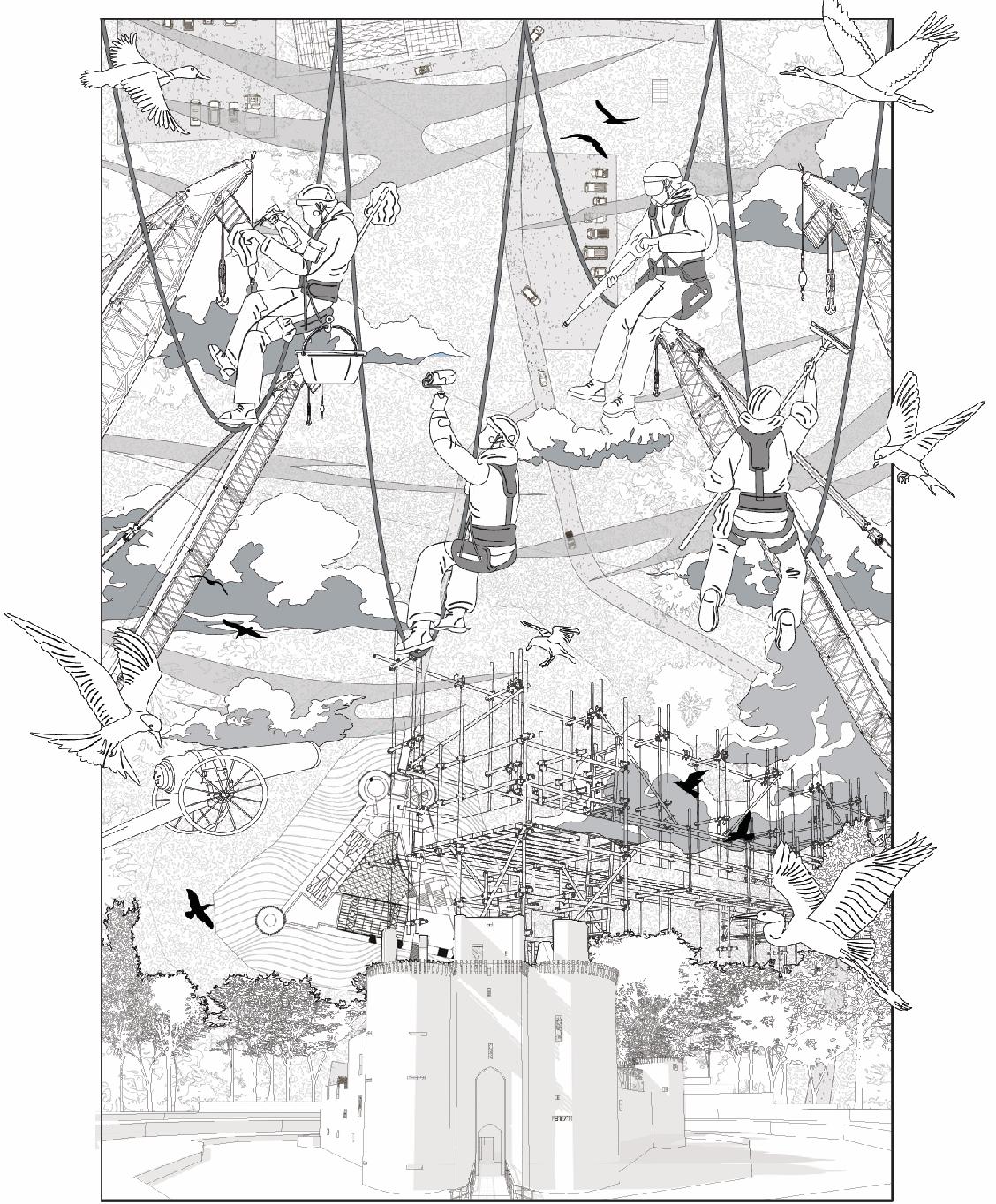

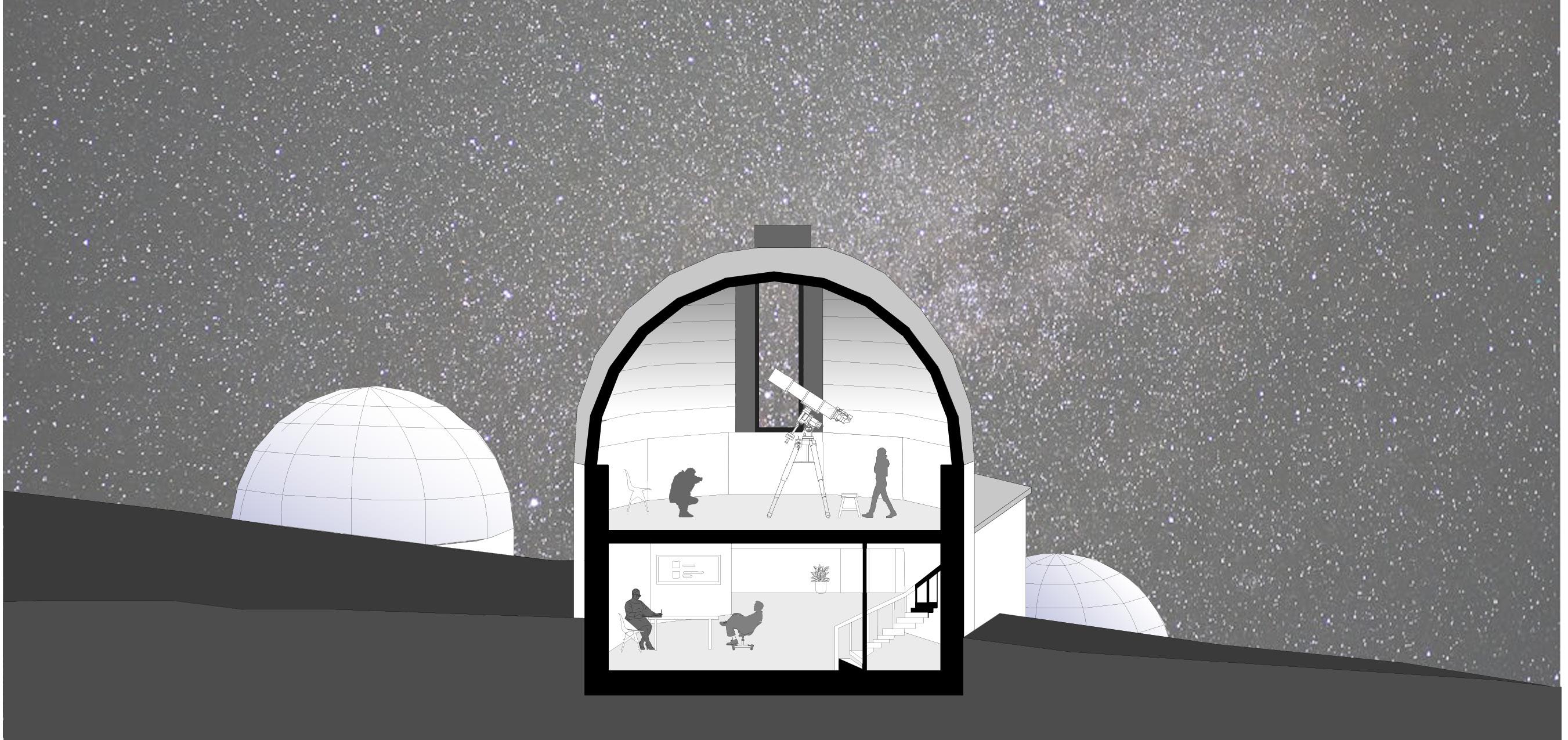

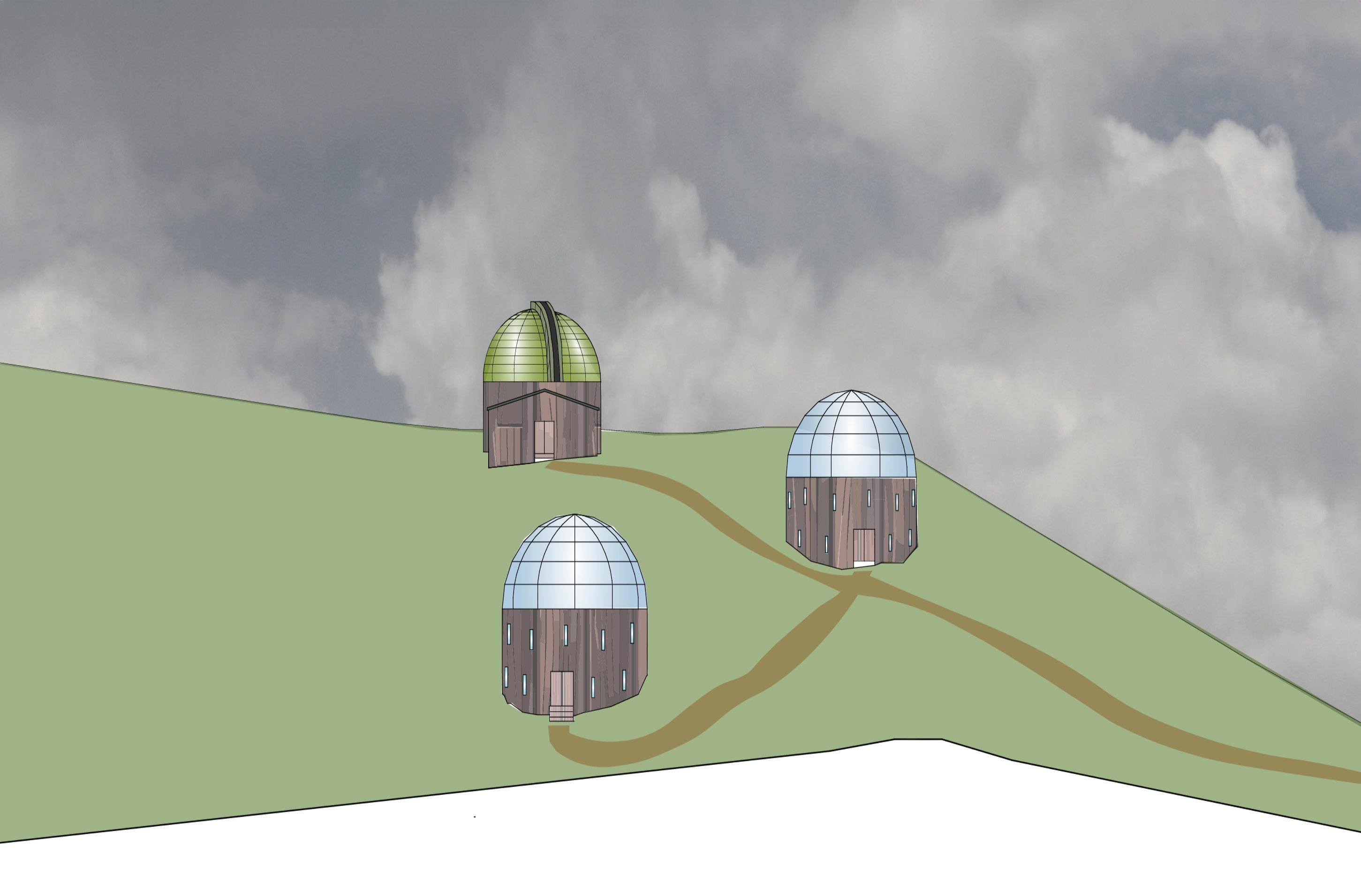

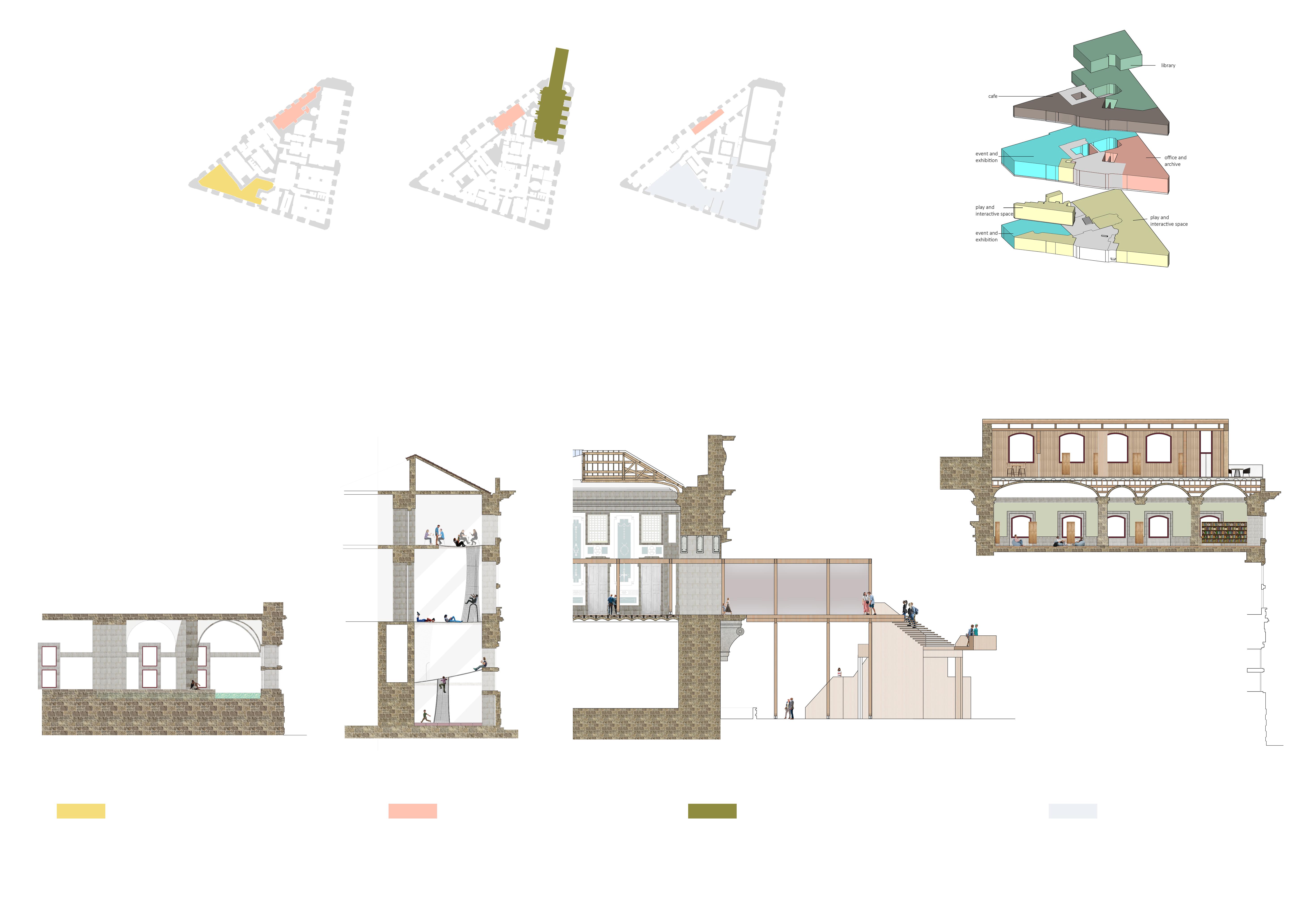

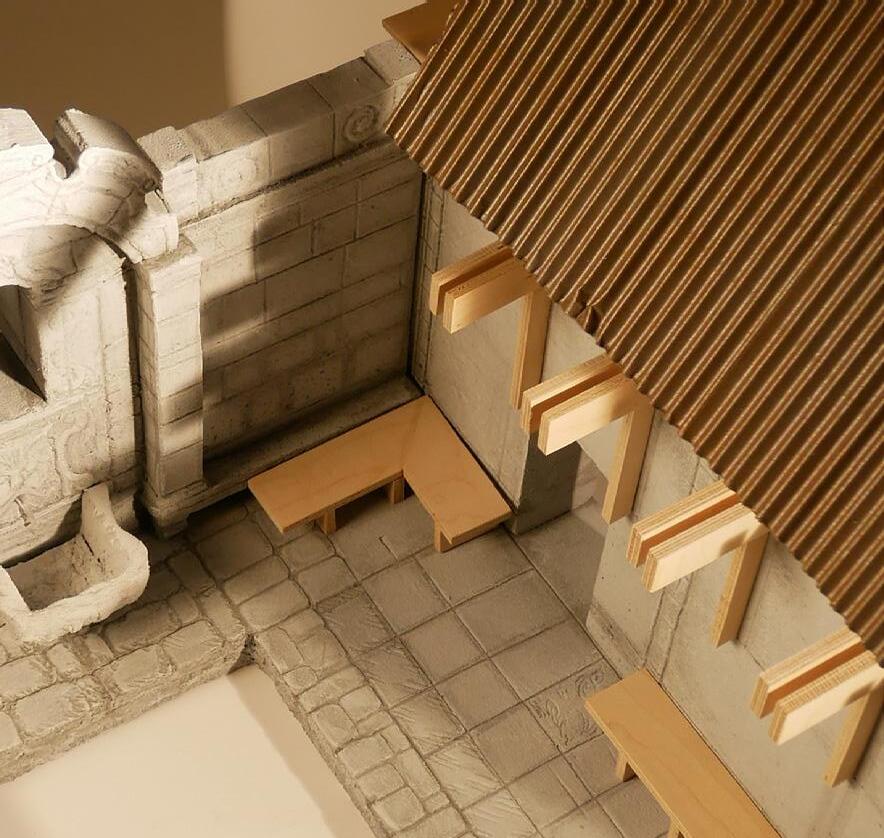

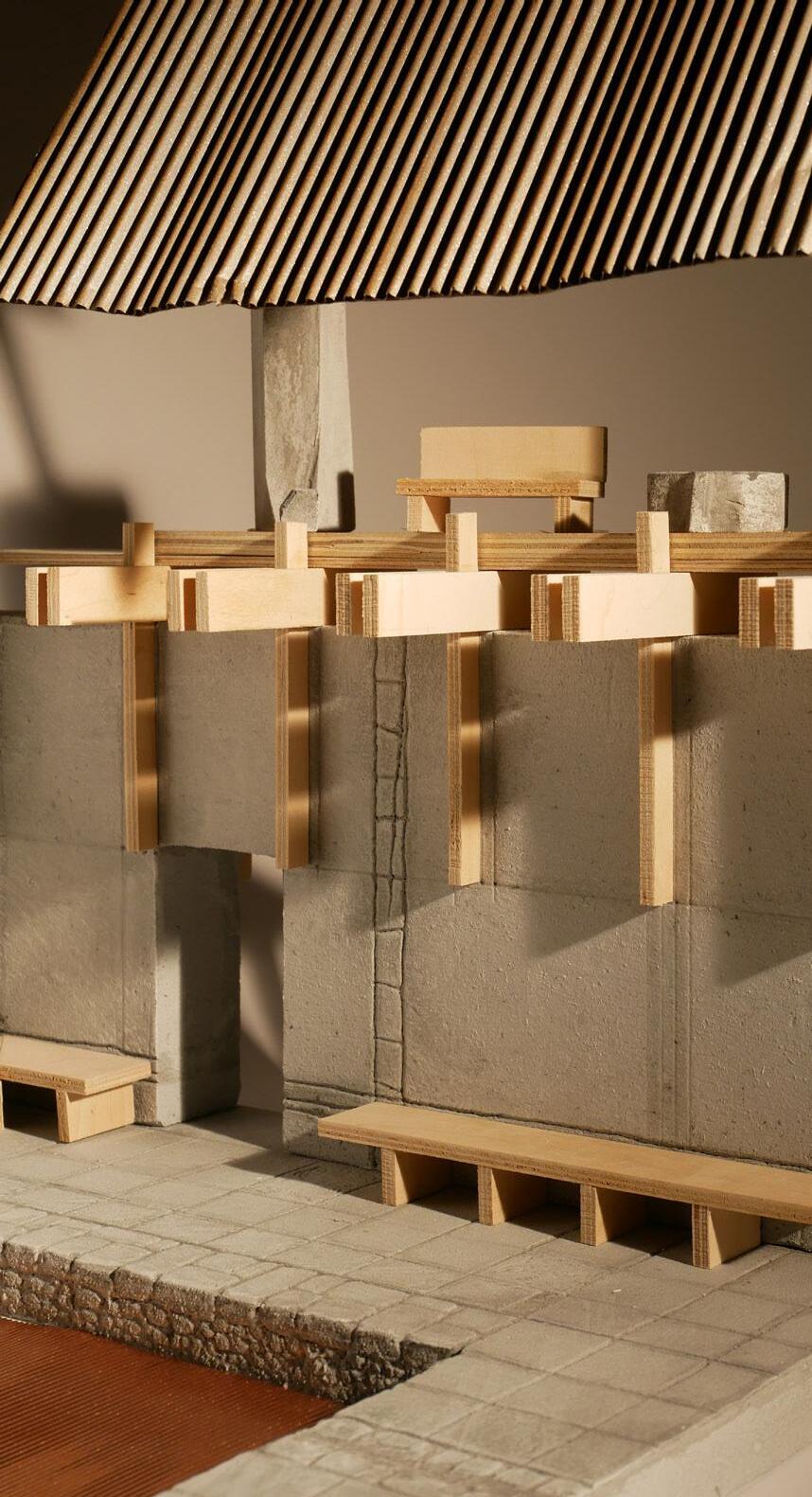

CONSTRUCTION HUB (Project 5): Semester 2 was dedicated to the adaptive re-use of the historic monument, Caerlaverock Castle in Dumfries. This unique setting provided an opportunity for students to be bold in their ideas and more self-directed in their investigations. In direct response to the shortage of relevant construction skills in our industry, the project was set as ‘competition’ to insert a new construction ‘school’ into part of the castle ruins. An ethical and professional component in the brief addressed decarbonisation in design, requiring application of low carbon, low impact design principles. Whilst the project is entirely theoretical, students we able to grasp basic strategies in adaption and re-use older buildings, whilst still considering lines of enquiry into functionalism, poetics, aesthetics, time and memory. We very much encouraged everyone to make time for experimentation in both analogue and digital formats, which included our first collective foray into the use of generative AI in architectural design.

“Make the most of your time here in MSA and Glasgow. Try absolutely everything and especially get out of the studio more for a wider look at life, it will add so much more to your development as an architect - go to Friday lectures, Architecture Fringe events, exhibitions in the Reid gallery, use all the workshop facilities, apply for the exchange programme, become familiar with all the software available to you, try the RIAS mentoring scheme, get along to interesting events posted around GSA, see the GSA Degree Shows, visit the library more, go on study trips, enjoy sharing your studio space, use the maker spaces, visit GSA archives and collections, attend SEDA and ACAN events, regularly go for lunch or a drink in the vic bar (thankfully now re-opened), see what’s on at Civic House, visit all the Glasgow galleries and music venues, try some RIAS events and talks, get out to the beautiful Scottish countryside, explore Glasgow to places you’ve never been...of course there’s plenty more to add to this list but you’ll miss it when you’ve gone.”

Earthen Thresholds

Rural Housing

New Future Construction Hub

Row Housing in Forres

New Future at Caerlaverock Castle

A Living Ruin

Castle of the Three - A New Construction Hub

The Light Within Caerlaverock Castle by by by by by by by by by

Bora Akturk

Haaris Leung

Sebastien Rancourt

Alice Kemsley

Phoebe Wells

Mabel Sangster

Tomasz Sawczuk

Pavlo Bilyk

Tiffany Haung

BY BORA AKTURK

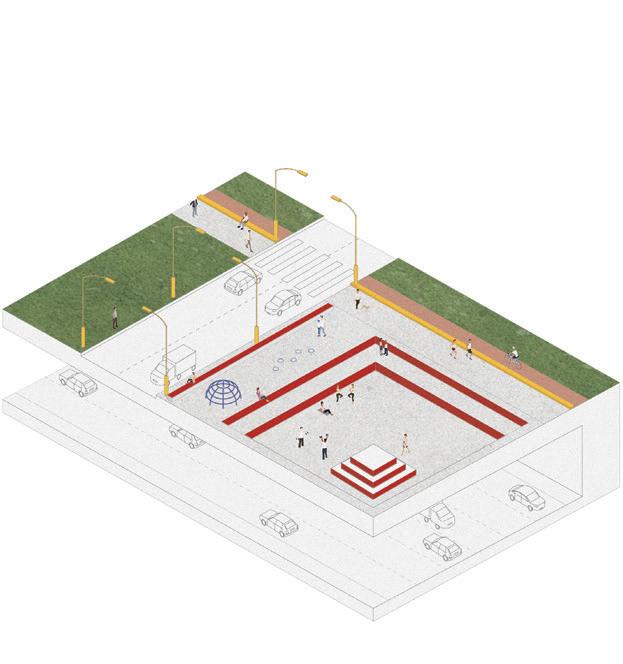

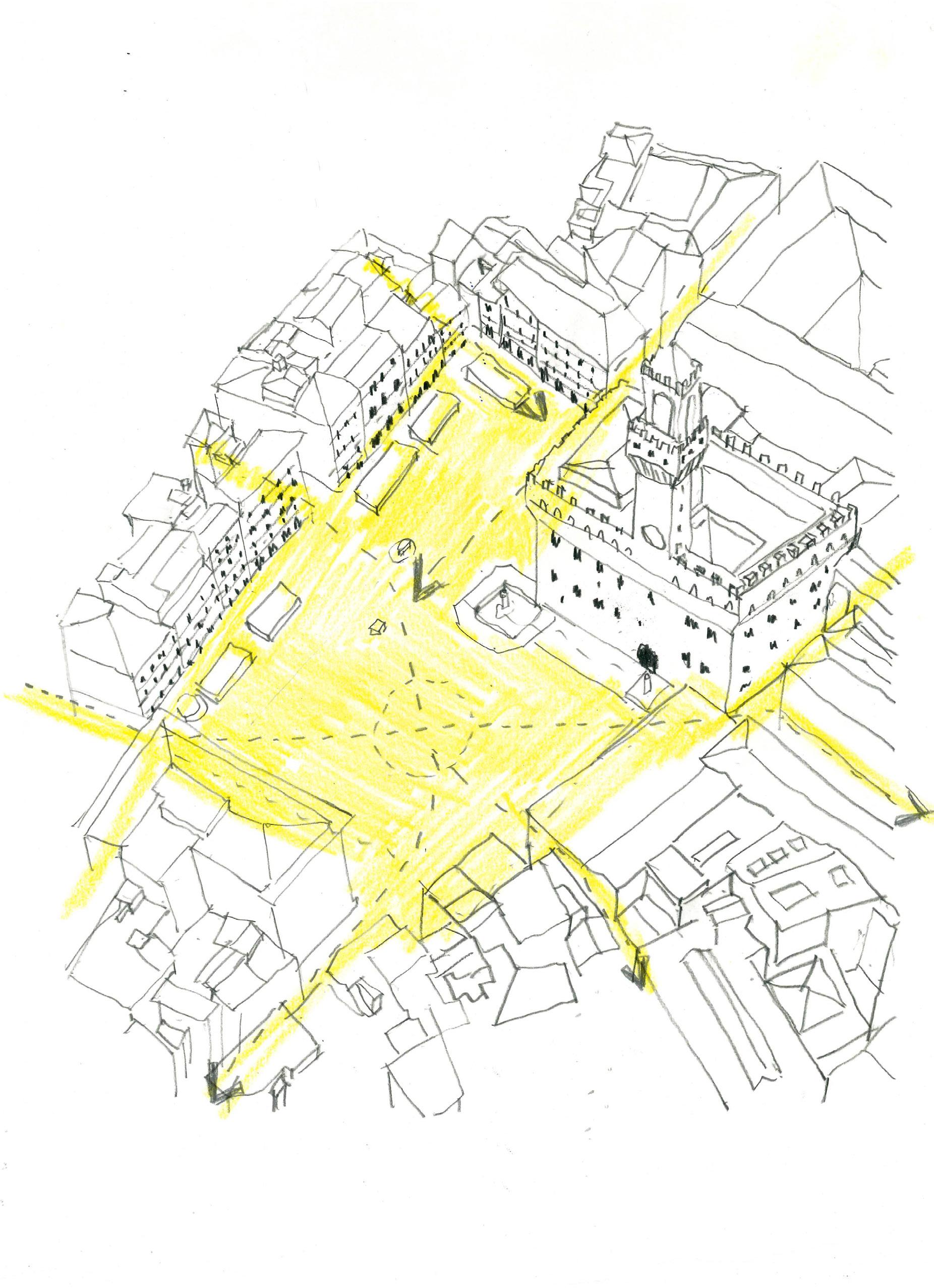

We were assigned a project to create a proposal for row housing on a car park in Forres. My proposal centred around experimenting with the contrast between public and private, through views, lighting and thresholds.

The site was located next to St Lawrence parish church and Singapore House, just off the high street that acts as the spine of the town. The former car park used to be a public garden until the late 19th century. My proposal attempted to bring the space back to the community while also creating a well defined set of row housing that integrated well with the new public throughways, without feeling intrusive.

The housing is aligned with the long end of the site to create two new paths, and is stepped to produce rhythms that draw people in by expanding and contracting. Included also are gaps that allow access from front to back, private dug-in fenced gardens for each unit, ramps, and steps that act also as seating.

To achieve this, I offset the closeness of the public and private spaces by creating a secluded introspective interior to the homes. The units themselves are intentionally closed and dark, with only specific views being given to the inhabitant as well as lighting through

cavities without views, while the site has many great views, it does not serve them but instead the occupant.

To psychologically distinguish the inhabitant upon entering the threshold the rammed earth walls are 1-metre thick and give a separation from the outside. The bedroom is also on the lower floor to create a protected bunker.

BY HAARIS LEUNG

The rural housing project tasked us to design a row housing scheme with specific dimensions. This project challenged our creativity and our ability to adapt our designs to the rural context and housing needs.

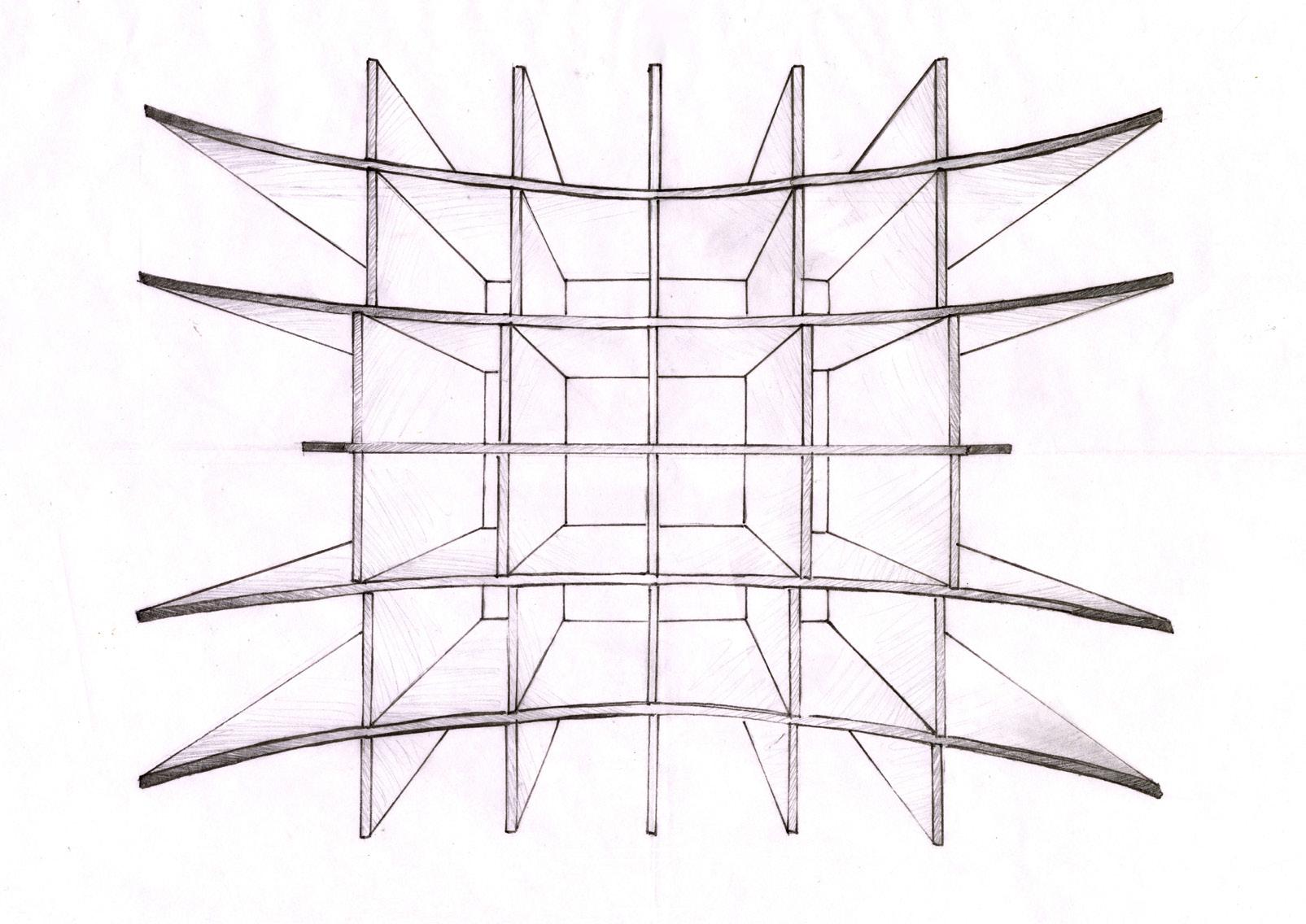

Curious to draw influence beyond conventional architectural precedents, my response to the brief drew inspiration from mathematics and wave functions. I began to explore the function of the sine wave and how that can translate into the form of a curved timber pitched roof structure. This initial design direction led me to arrange the interior with aspects of symmetry and flipped interior living.

Upon receiving our site—Forres, a rural town in Inverness—I conducted research into its landscape,

vernacular architecture, and existing row housing typologies. I drew inspiration from the region’s traditional pitched roofs, churches, and communal garden spaces, integrating these elements into my design to create a scheme that felt both contemporary and contextually rooted.

Circulation within the space was carefully considered to maximise functionality and fluidity. The arrangement promotes natural movement through the home, with open-plan first floor living areas encouraging interaction while maintaining a sense of privacy on the ground floor bedrooms. The curved roof structure not only informs the aesthetic but also guides the spatial flow, creating a seamless transition between living areas and enhancing the overall experience of movement within the home.

BY SEBASTIEN RANCOURT

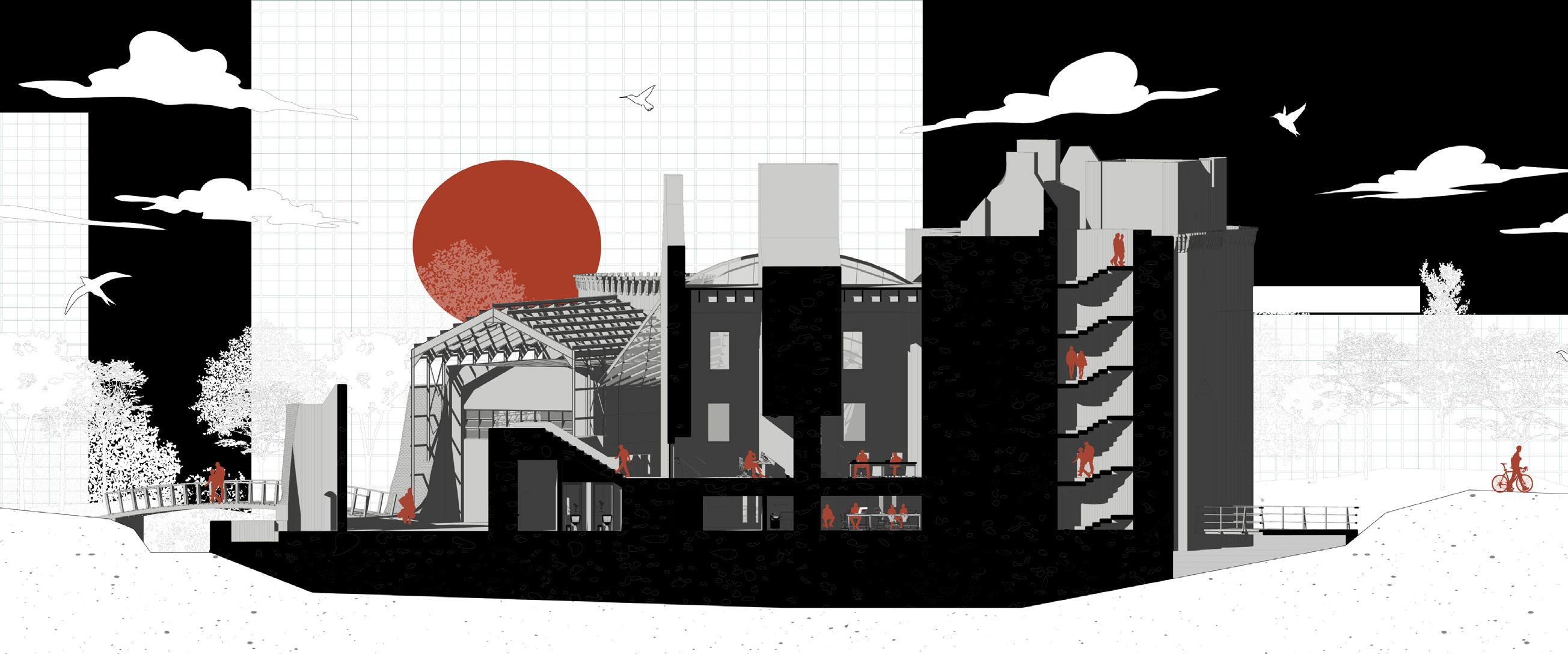

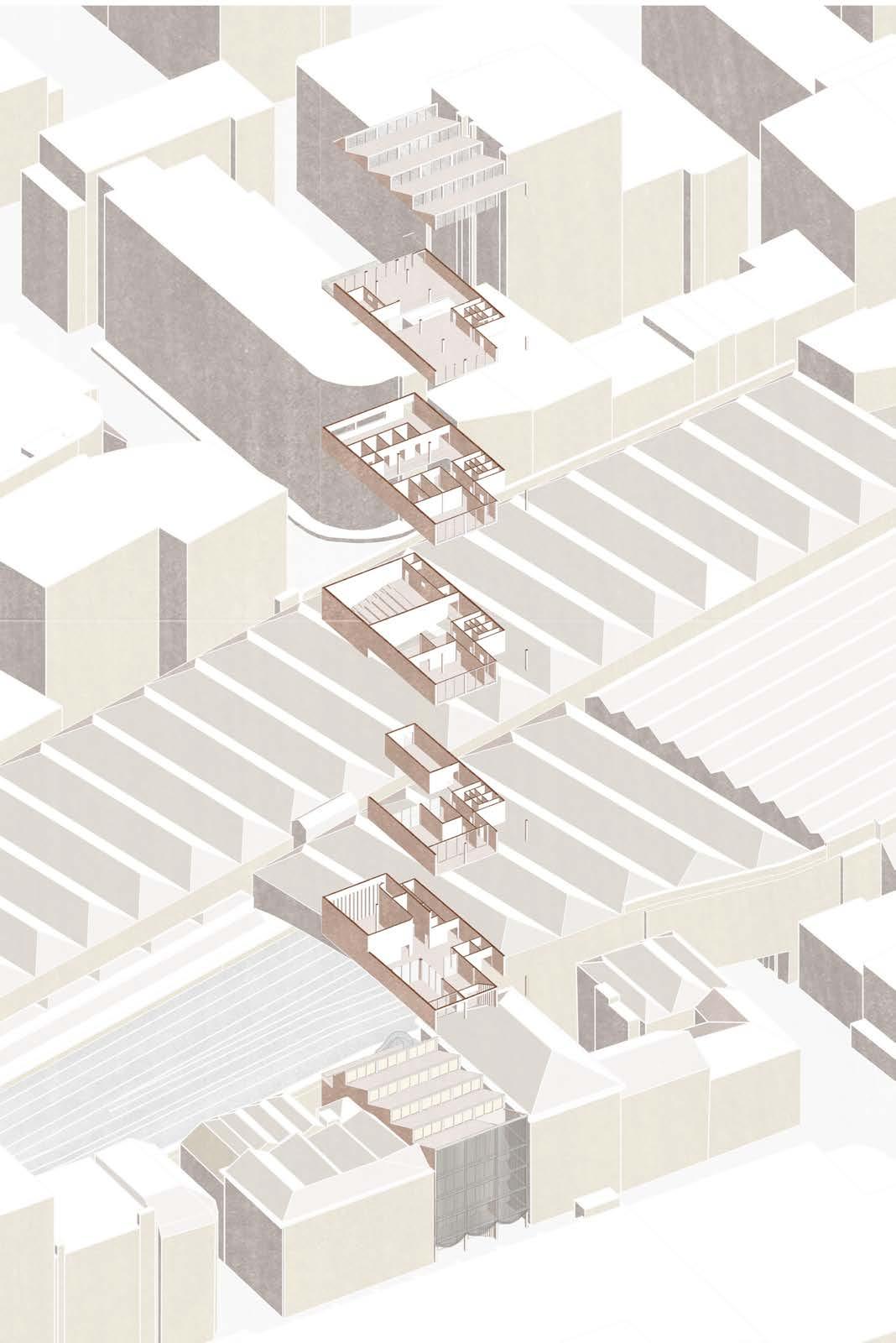

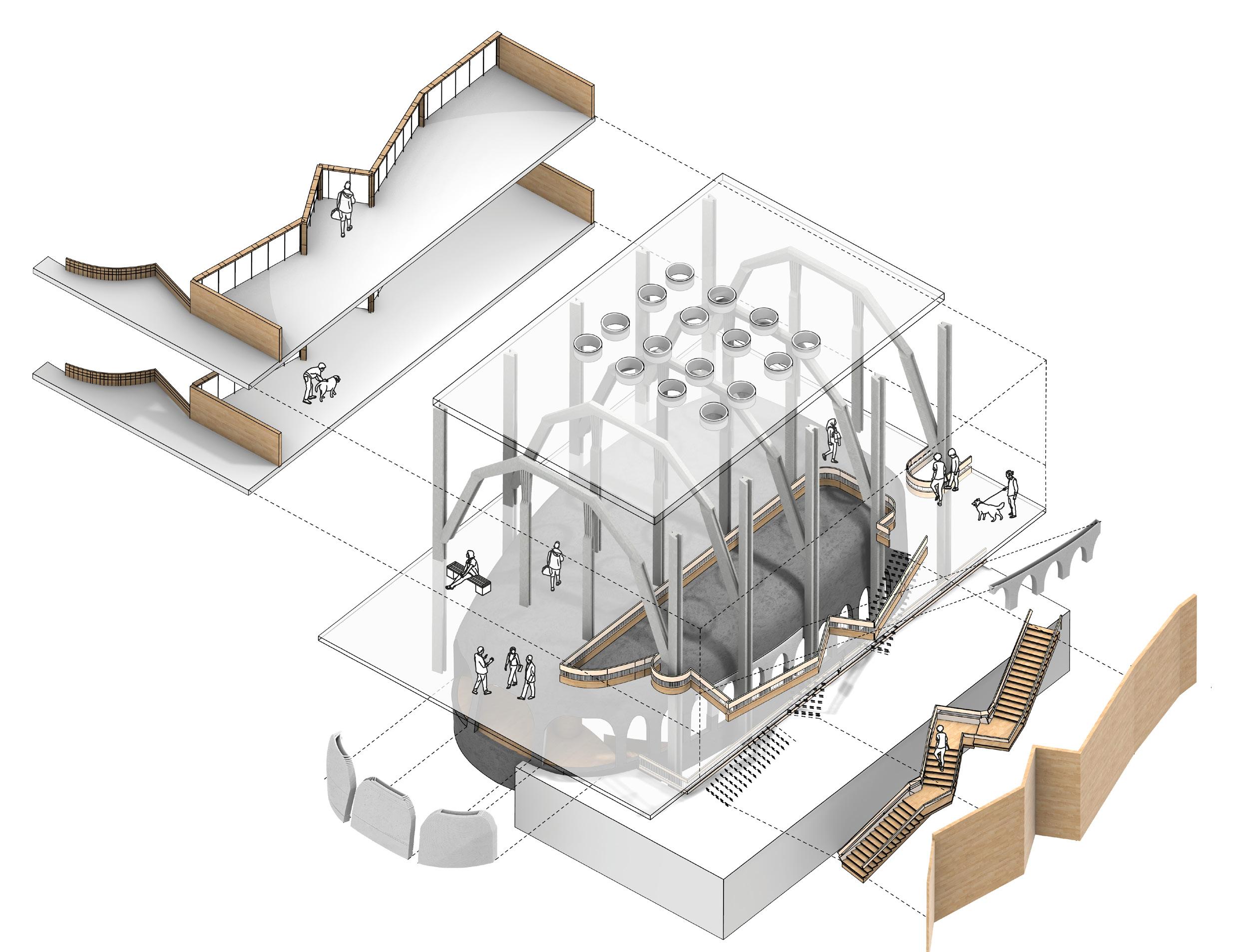

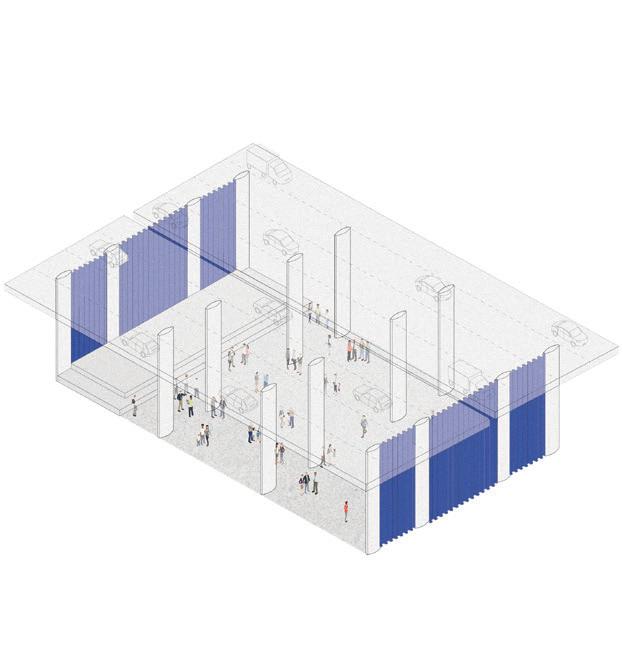

The project aims to encapsulate the concept of renovation through creating a ‘permanent scaffolding’ that inserts into the existing structure. Placing its visitors into an architectural narrative of construction serves to bring them into the process of development, reminding them the necessity of future change, in preserving our history whilst designing for the future. The lightweight steel scaffold structure facilitates this, whereby inhabitants are able to see all parts of the castle regardless of their position, whilst it simultaneously acts as a barrier to the existing material, treating the castle as an artifact.

BY ALICE KEMSLEY

This project was based in the small rural town of Forres in the highlands of Scotland. We were tasked with exploring the concept of conviviality through creating a set of row housing in one of two given sites in Forres.

For my design I focused on fostering connections between neighbours, harnessing natural light from above, and respecting the architectural and urban fabric of the town. By carefully integrating these elements, the project aims to create homes that feel both intimate and open, private yet connectedenhancing the lived experience within a historical and evolving context.

This project captured a specific moment in Forres, aiming to explore the idea that architecture is not static; it moves, adapts, and continues to shape communities long after the drawings are complete. I hoped that with time a community would grow in this space, and over time, continue to change at the pace of the world around it.

BY PHOEBE WELLS

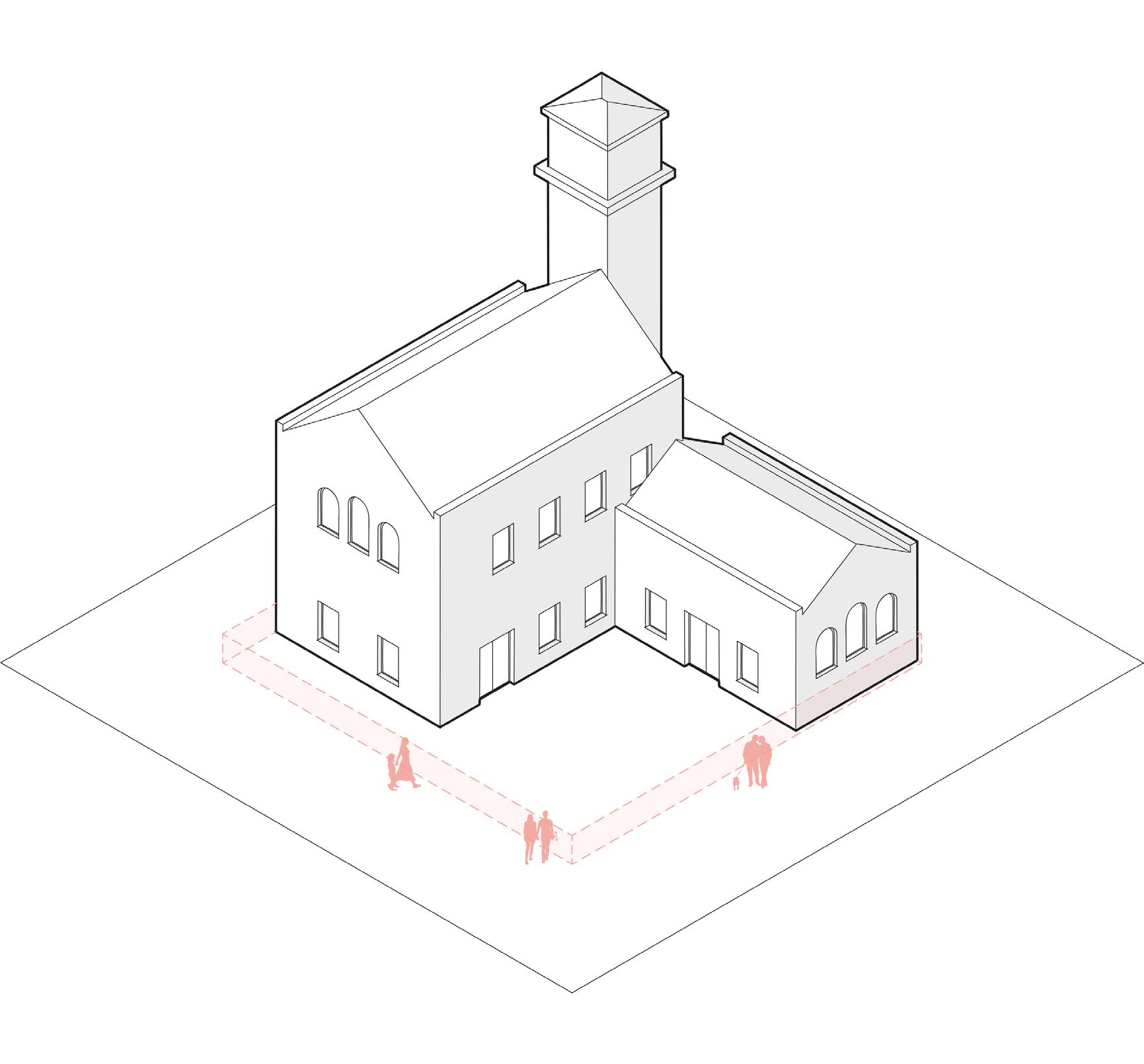

Caerlaverock Castle, a historic monument situated at the edge of a forest overlooking the coast near Dumfries, is entering a new phase in its long and complex history. Following over a century marked by conflict and now dormancy, the site is now being repositioned to serve a renewed purpose: a centre for innovative education with New Future Construction School. This new direction involves a strategic transformation of the castle’s existing spaces. Considered architectural interventions of hempcrete cassettes will enhance the visitor experience while preserving the historical integrity of the structure, with carbon neutrality at the centre of design. These updates aim to facilitate deeper, more meaningful encounters with the site’s heritage, as well as providing opportunities for innovative learning.

The project places a strong emphasis on public

interaction with the construction school. By creating a raised pathway to guide experience, visitors will ascend inside the infamous Murdoch’s Tower before walking, as many did before, along the historical ramparts entering the construction school at a height to observe the workshops. The walkway then crosses the courtyard, creating a new closeup experience of the stunning renaissance façade, leading down an existing spiral staircase to ground floor. These initiatives are designed to stimulate public interest and encourage dialogue around both the new construction school and the castle’s rich history.

Ultimately, this repositioning seeks to establish Caerlaverock not only as a preserved historical site, but solidify its new role as an exciting and evolving cultural resource—one that symbolises and demonstrates a sustainable future.

BY MABEL SANGSTER

This project envisions the adaptive re-use of Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, as a Rural Hub for the New Future Network. A social enterprise dedicated to tackling decarbonisation in the built environment. Located within the castle, the Hub will occupy a third of the footprint, leaving the rest of the space open for public exploration. Prioritising climate-conscious strategies - the project focuses on retrofitting with recycled materials, revitalising the site while supporting the transition to a net-zero future. The Hub will serve as a space for education, skills training and research - empowering both the local community and construction workforce to thrive. With a focus on accessibility, inclusivity and flexibility - it will foster public engagement in decarbonisation, architectural conservation and low-impact design. By creating a seamless connection between the castle and the Hub, the design encourages a journey of discovery where heritage and innovation converge into a sustainable future.

Line of Enquiry and Strategic Approach:

• Working within the boundaries of the ruin through use of insertion and building on top the existing, preserving the castle.

• Harmonising the old and new by paying homage to the castle through materiality and responding to historic features.

• Route of discovery, designing with intent of a path and journey to explore the space.

• Using low carbon and recycled materialsretrofitting and an efficient building envelope.

• Reconstructing the southern bridge of the castle to create accessibility for pedestrians and materials.

Set within the unique triangular plan of Caerlaverock Castle, near Dumfries, this project introduces a timberfocused construction workshop which was designed to engage three senses: sight, hearing, and touch. Timber, a renewable and sustainable material, takes centre stage— not only as structure, but as craft. This hub celebrates traditional timber techniques, aiming to train artisans in both structural and decorative work, reviving a once widespread but now largely forgotten skill.

The intervention restores the ruined western tower and encloses the inner court, reinforcing the castle’s original triangular shape. Visually, timber creates a warm contrast to the castle’s red sandstone, and its intricate detailing enhances the experience of wandering through the space. On top of the restored tower, a wind-powered multi-tone lyre plays violin-like notes, responding to changes in the wind. Touch is considered through material textures: the smoothness of timber offers a sensory counterpoint to the coarse stone.

Accessibility was also a key concern. With a ramp, accessible pathways, and two new lifts, visitors with mobility challenges can finally navigate both the interior and exterior of the castle comfortably making this castle a place to be enjoyed by everyone.”

BY TOMASZ SAWCZUK

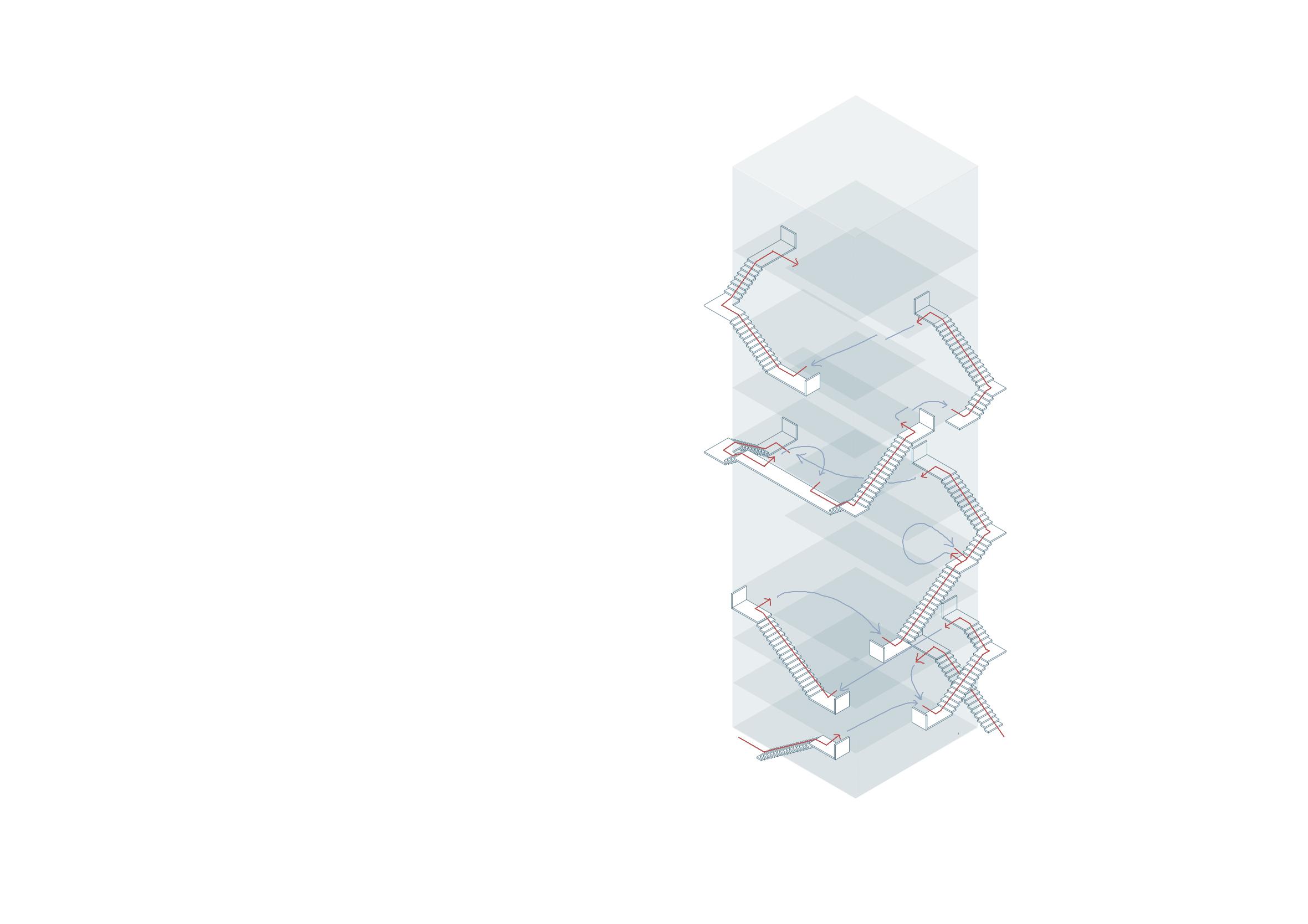

BY PAVLO BILYK

Since we are already building a new building in the ruins, I decided that why not reorganise the whole castle space by rethinking its purpose. So I moved the rooms from the Visitor Centre into the castle and combined them with the School of New Technology. This allowed the ruins to be put to good use, creating a single organism that does not distort the visitor experience.

On our first visit to the castle we were only able to see less than half of the ruins, it was important for me to give future visitors a feel for the whole atmosphere of the castle, which is why I started looking for ways to solve this problem. In my search I paid attention to such buildings as Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoie and the Reichstag building reconstructed by Norman Foster. In their projects they used the idea of a promenade, which allowed people to experience not only the pragmatic use of their buildings,

but also gave people the opportunity to enjoy a full walk around the building, seeing all the architectural merits of these structures. That’s why I rebuilt the main stairwells, added lifts and made the promenade platforms that are inside the building and around the perimeter of the building just on the outside.

BY TIFFANY HUANG

This project is to repurpose Caerlaverock Castle to a construction hub, mainly for researching materials and hosting workshops. A lightweight steel frame will support new additions without harming the old stone walls. Many of the walls will be built from K-Briq, a brick made from 90% recycled materials, helping to cut carbon emissions. The castle’s open courtyard, often soaked by wind and rain is proposed to be covered with

as a “living lab.” Students, builders, and researchers can test green building methods, study and try out new materials in real conditions. There will be workshops in the courtyard where is located in the centre of the castle, originally opened. By combining Caerlaverock’s rich past with smart, sustainable design, this project will protect the ruins and turn them into a leading example of eco-friendly construction. Future architects, engineers,

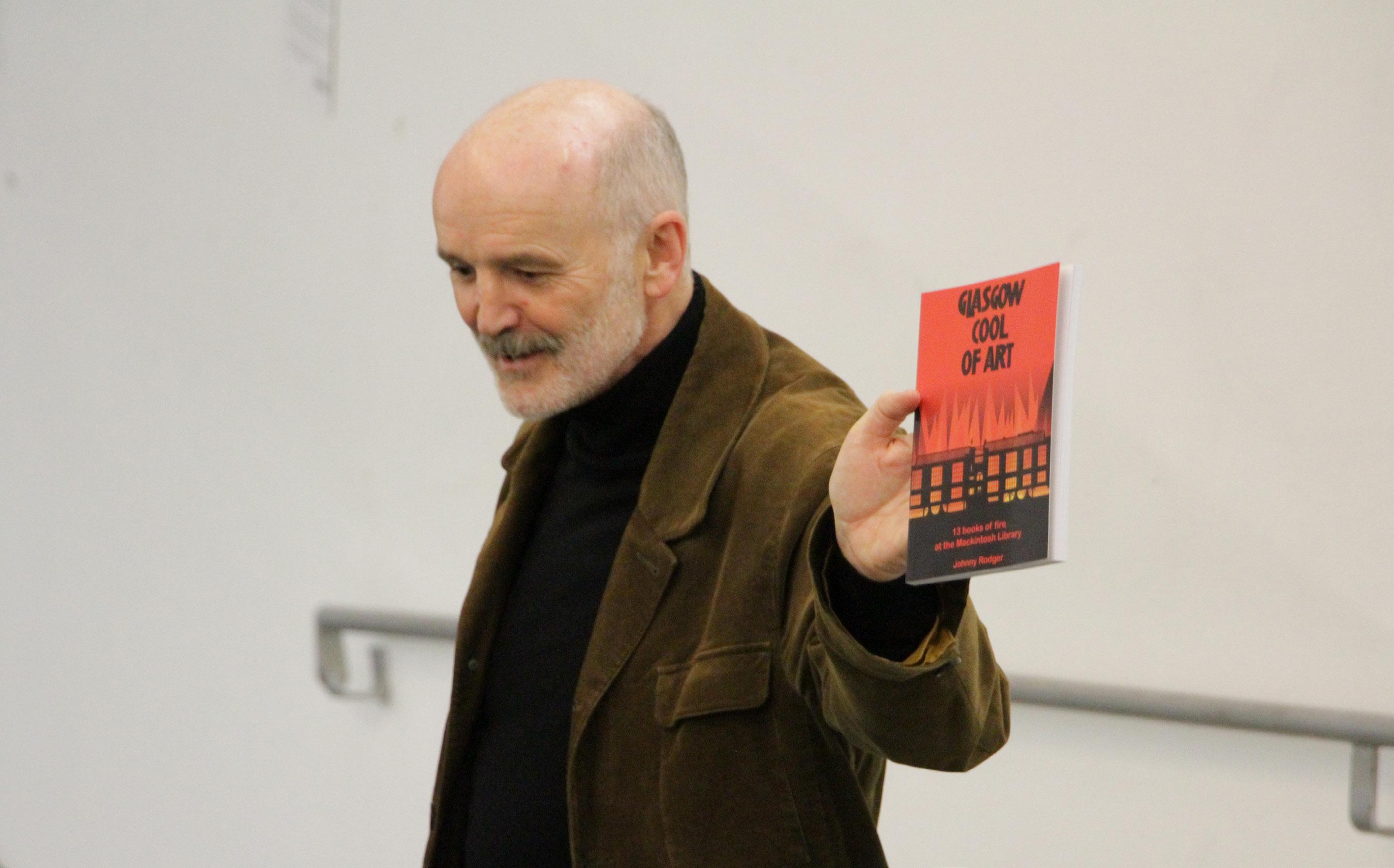

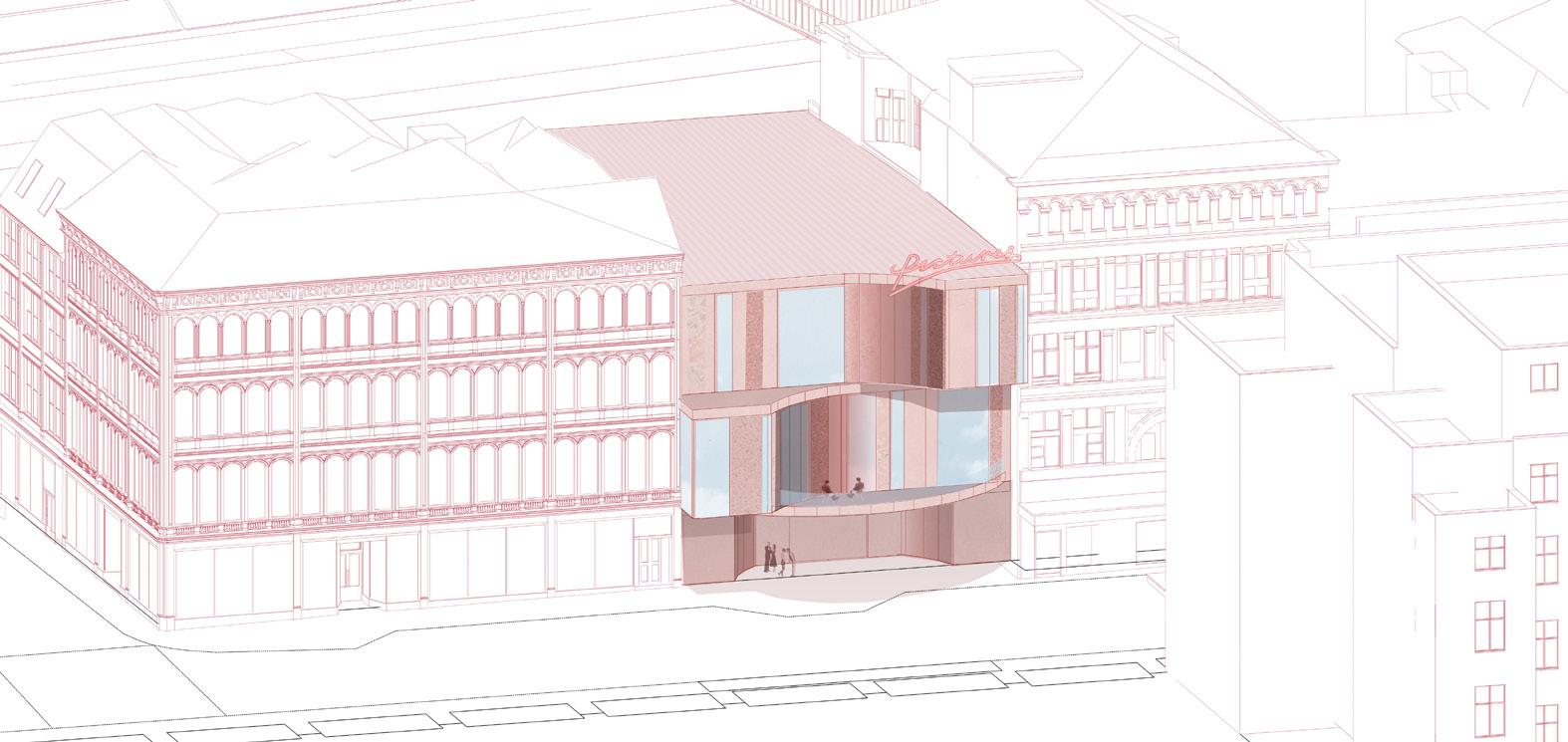

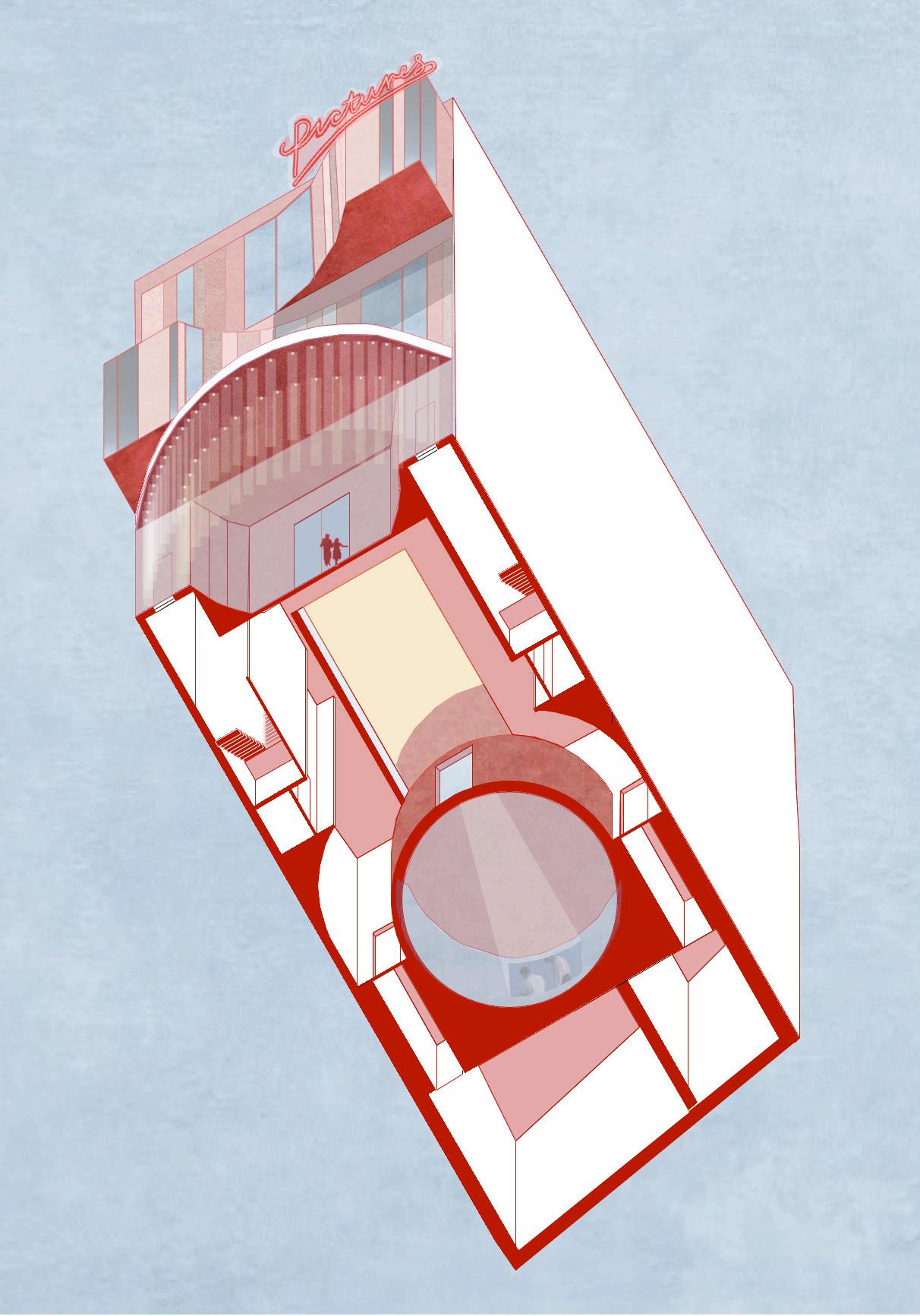

Following the launch of his latest book ‘The Housing Film’, we were joined by MSA Professor, Johnny Rodger for a chat about all things housing and film. The book launch took place on 25th November 2024 and included a screening of Chris Leslie film ‘Lights Out’ and a selection of student films produced during the Housing and Film elective course.

Tell us a bit about the elective course ‘Housing and Film’.

It started quite a while ago, I’d been teaching housing for a long while. And noticed at one point there’s lots of wee 5 and 10 minute films about housing. So over the first couple of years I thought, show that wee film and show that one, then I started to realise, actually, there is a thing, I mean it’s nobody’s ever called it before but ‘The Housing Film’ (the name of the book) and I thought, well, there’s actually just thousands of these, for any kind of issue that you want to talk about in terms of housing, that is important in the understanding of housing issues. And the films are various different types, so when I say housing film, I don’t mean it’s one particular type of film. There are many types of films that deal with housing issues, whether it be a documentary or a drama, a feature film, a drama-documentary, it was all different kinds of films. I would say, they’re all housing films because they’ve all got housing in there somewhere, as a major part of what the film is about. Then I thought, well why don’t we just make the class about housing and film.

It seems to be getting more and more difficult every year just to get students to read things. And there’s no way of ensuring that this happens, and so where do you go? But it seemed to me that film was, to a certain extent, a way around this because you know, maybe it’s true many of the texts can be dry and to do with figures and histories and years and all this. One thing was that the films can bring alive certain issues. You know, it shows people in the situation. I’m not saying it replaces the books - it doesn’t, but it brings the dryness of the material in the books to life. So maybe it makes it then easier to read the books - [it’s] a supplement that might, fire you up for it.

From the creation of the course, did you always intend to write a book on the same topic?

No, I didn’t intend to do that until about two years ago. It just gradually developed. And I think this an important human lesson because many people think that research works like that - you think “what will I write a book about? I think I’ll write a book about [this topic]”. And you go ahead and do that, you start from scratch writing about something, discovering about it and reading about it. And then you’ve got new thoughts about it that you want to give to the world, because you’ve become so scholarly, adept in it. That’s not the way it works in my opinion - in my experience you do a wee thing and then you discover something. You’re taking lots of little steps. You don’t even know you’re learning things. You’re learning things through your teaching, through your scholarly work, through your own reading, through your own experiences, through students engaging with you and you engaging with them and then suddenly you realise you’ve got a whole body of knowledge that has worked out through this.

Can you recommend a few films which you feel are representative of the housing film?

I would say, the classic is the 1935 film ‘Housing Problems’. Which for me is a great film and it raises so many issues about housing - about what housing means in a big modern city, about slum living and conditions, about how film can expose this and say things about this, and about class. Class relations, class apartheid. All these sorts of things are right there and it’s and also about gender. Maybe because the home had been seen (especially in the Industrial age), for right or wrong reasons, in many ways, as women’s domain. So, gender is right there from the beginning as well, and especially in that film because there was a woman, Ruby Grierson, the sister of John Grierson, who invented the documentary and this [film] was made by his team of documentarians. Ruby Grierson invented the vox populi process of interviewing people to camera. She was she was the first ever person to do that. So, she invented this technique, and she was a major part of creating this film, because that’s what’s really important, you get working class people speaking to camera about the way they live, which was really innovatory at the time, in 1935. And yet on the titles in the film, her name doesn’t appear.

So, there’s all sorts of issues as you can see from that, about gender and gender equality. It’s a brilliant film to start off with, and I think that it’s the first ever film that’s specifically and uniquely about housing. There’s lots of other films, going right back to the Lumiere Brothers in the 19th century, where they show the original knocking down of a house and that becomes a big feature in housing films about knocking down slums - it becomes a trope as it were. So that’s a documentary. But they’re not all documentaries.

One other really important film is ‘Cathy Come Home’, which is about homelessness. It’s a dramadocumentary made as a play for BBC, in 1966 by Ken Loach. It’s amazing, it’s harrowing, it’s terrible. It shows the reality of something as though it were a documentary, but yet it’s not. It allows you to question the border all the time in how it uses fact and fictionbecause it cites facts throughout, and it’s a narrative voice citing facts, but also has a dramatic narrative from the characters. Most of the people in the film are not actually actors. So you’re saying “Is it fact or is it fiction?”. Even the two main characters in it weren’t actually actors. They became actors after making that film and they became part of the campaign with ‘Shelter’. It had massive effect on society. 12 million people watched it on TV. So, it’s a massively influential film, and rightly so. I think it’s a great film in itself, but it’s a great housing film as well.

Our theme for this years magazine is ‘Legacy in Motion’, which muses on the idea that legacy changes over time. Do you think that we watch these films with a more critical eye given the benefit of hindsight?

I would say so, yes, definitely. Especially now because as we all know, we’ve (Western Society, possibly world society) shifted from being a literally orientated society where all sorts of things are learned about, carried on, and legacy goes on to different generations through writing and through books. That’s changing and has changed massively and it’s really through images now. Which is interesting and important, especially in an art school, because images are our stock and trade. There’s this whole idea that the image is right there, centre of culture now.

Some people, like Baudrillard, the French postmodern philosopher, back 30 years ago he was already saying this. Saying in the sense that this is a coming home for European Society because formerly, before the literariness, it was a culture of images. And it’s an interesting way to look at, obviously it’s much different from the way it was in early Christian Europe, it’s not the same type of static image and we have moving images. We have film, digital images, it’s different photographic images rather than painted ones. But nonetheless, I think we’ve become a society, where the

legacy, what we know of previous ages, we understand them through the image now. It doesn’t mean we’ve abandoned books but the image is much more accessible now and everybody, every day looks at images and understands things through images with not such a heavy dependence on literature. So I think that’s also another reason why it’s important to do this class and also to get students doing work in making films because it’s like we understand the legacy of housing through the images of housing and through film of housing. I think that’s absolutely important to see. And that idea of ‘Legacy and Motion’, well, that’s what we have with looking at the films of housing. It’s what makes it human. That’s what brings it alive. That legacy is in film, it is in motion, it’s moving and alive.

And that idea of ‘Legacy and Motion’, well, that’s what we have with looking at the films of housing. It’s what makes it human. That’s what brings it alive. That legacy is in film, it is in motion, it’s moving and alive.

Are there any recent housing films which you think will be reviewed and discussed in a similar way, 50 years from now?

I think some of the ones that will stand up most are films being made by artists because they’re made as a work of art, as well as something that documents. And of course, art does document stuff because it gives us this legacy of something (if it represents something). And so, for that reason, I would say, Steve Mcqueen’s ‘Grenfell’.

Steve McQueen is a massively important political artist and filmmaker. He made this film about the disaster of the fire at Grenfell and what it means politically. It’s very different from these other films. It’s very short, there’s sound on it but there’s no narrative. It’s just looking, just the image. And so you see this legacy, of a kind of organisation of housing that had all sorts of prejudices involved, and how these people suffered, and yet you see and understand it just through looking. He flies in, in a helicopter - just flies round the building again and again, and you watch it on the handheld camera. It’s really powerful and it really gets to the heart of that legacy in motion. It’s a great work of art and it will definitely be something that people will go back and look at in many years to come because it stands as a work of art. And as a work of art it also documents some really terrible and momentous happening, that hopefully will mean

things are learned from it, and there’s big changes in housing, and in the culture of housing, and the culture of the way we live in and organise our cities.

One discussion point raised in the book is the source of funding for the housing films. How should knowing that information impact your interpretation of a film?

Of course that’s important to us right from the start, but everyone is a lot more orientated towards the visual and critical about the visual. We learn how to criticise the visual - [to] understand the significance. Understand and read properly what the image means and what it’s saying to us, What is the significance of how it was formed? Who formed it? Who paid for it? Why it was made? What its intentions are; how it makes us feel; why it makes us feel that way. So, all these questions about its significance. And we’re all a lot better about that now because of this visual culture that we’re living in. So, if you’re asking about funding a film that’s part of that discussion and it’s to understand why. How has it been enabled, and why would somebody enable it? And I think that’s part of what the course and the book is, I would hope contributes towards the towards the building up of that visual culture and that critical take on the image and its legacy.

What is the importance is of depicting tenants as having agency versus passively waiting for change to happen?

Quite often you get, get architects, councillors, politicians, you get film makers, all coming from these professional classes talking about what’s going to be made, and what they’re going to do, and how they’re going to build these big schemes for the working class. And I guess that’s just the way society was organised then and it’s also to do with film technology as well, because film technology was so expensive and in the hands of the few. And of course, that’s the controlling few - be that BBC or big local authorities. So, working class people didn’t have access to very expensive technology. It wasn’t being used by them, it was being used to portray them. People speaking about them. Maybe some people do that a lot better than others, but it’s kind of problematic in terms of there’s a whole class of people who are depending for their welfareon the portrayal of their welfare, their understanding of their welfare and the and the promotion of a change in improving their welfare - on another class of people who are going to come to them with an expensive medium which they can’t afford and use it to portray them, that

doesn’t mean it’s always going to be bad results, but you can see why it might be problematic. If you watch these films, you’re kind of astonished how you’re invited to feel like you’re part of the same class - that’s implicit in the way it’s presented by the by the often middle-class, received pronunciation English voice (often presenter). And you’re kind of expected to feel you are on their side and they’re showing these people as something other.

But ultimately over the past, say 20-30 years [with] that technology becoming more available, people can make their own films. You can make a film with your phone. So, you start to get people speaking in their own voice about their own set of problems, about housing, which becomes a lot more interesting in terms of democratic presentation and understanding of people’s problems through their own voice. You’re already seeing [this in] some early films like in ‘Cathy Come Home’, for example, which is poly-vocal. I think that’s a that’s a really good change, and maybe it wouldn’t have been possible without the technology.

At your book launch, you screened the Chris Leslie film ‘Lights Out’, which touches on the demolition of high-rise flats in Scotland. What role does the housing film play in preserving the memory of a building, particularly when these buildings are being demolished and the land redeveloped?

Like we’ve mentioned the legacy is going to be largely through the visual technology, be it video, be it photography, we depend on that rather than through literary aspects of history. These buildings that you mentioned are very good example of that because they had a kind of sculptural profile on the East End [of Glasgow] because of the tiers of balconies that went around, they were really sculptural, and they stood there as a kind of landmark. And so, for them not to be there really changes things. Interestingly, while that film by Chris obviously details the ultimate downfall and disappointment, all the social changes and how people felt about these buildings. What it really documents well, is it shows these views of the building that are just amazing, so as a legacy, I think that’s really important.

The Mackintosh Climate Action Network (The Mack CAN) was founded in September 2024 as a student-led initiative to improve the conversation around climate literacy at the Mackintosh School of Architecture. What was once a pipedream has turned into a promising movement, supported by educators and industry alike. It has since grown to include a small group of kindred spirits looking to further their knowledge and take charge of their learning.

The climate crisis is the defining challenge of this generation. As architects, we hold tremendous leverage to challenge the status quo regarding the use of carbon-intensive materials and the inclination towards projects that prioritise profit over liveability. The current built environment industry contributes to both ecological and social decline. Climate literacy must be a core competency moving forward. This skill extends beyond mere proficiency in carbon calculations and towards having a critical understanding of materials, performance metrics, cost, politics, and the discussions behind implementing innovative materials and practices. Climate-literate architects must be able to assess the legitimacy of sustainability claims and navigate an industry saturated with over-promises and misleading jargon. Legacy ignorance and disregard for occupant health can no longer be permitted. The climate crisis presents an opportunity for architects to radically shift their thinking and methods.

Despite massive changes in the pedagogy of architectural education, we feel there is insufficient support in cultivating a critical and analytical mindset, understanding material life cycles, best practices, and the broader systemic challenges of sustainable construction. Students are taught to run environmental simulations but lack the know-how to incorporate them into the design process. Much of the research on sustainability is difficult to access and often buried in lengthy journals, paywalled reports, or convoluted online sources. Students must sift through mountains of information with limited support in navigating the metrics and discussions. The disconnect between theory and

practical application leaves sustainability as an abstract concept rather than an essential design philosophy.

Most crucially, the Mackintosh does not maintain a material inventory, meaning students rarely interact with the materials they specify. Without direct engagement, their ability to make informed choices remains unsubstantiated.

Since our inception, The MackCAN has acquired tangible resources to support our viewpoint. We have established the Natural Materials Library (located beside the MASS bar). This library features a the Mack CAN!

How can we rethink design responsibility?

growing collection of sustainable materials, including hemp, straw, timber, and cork. Accompanying documentation has been compiled to allow students to make faster and more accurate material choices for their projects.

In addition, we have compiled various case studies of well-executed buildings that have successfully incorporated natural materials or achieved a high standard of occupancy comfort. We have also created a comprehensive list of quick links, enabling students to browse relevant authorities and organisations in specialisations such as timber, mining, and recycling. We have built strong partnerships with sustainability organisations such as ACAN, STUCAN, GIA, RIAS, and SEDA, ensuring that students of the Mack contribute to the discourse on climate education at a national level.

While we have made significant progress, there is still so much that we wish to accomplish. Beyond expanding the Materials Library and resource lists, we aim to organise workshops, lectures, and possibly round-table discussions on sustainability topics. At a national level, we intend to continue our outreach efforts with ACAN and STUCAN, encouraging other architecture schools to establish similar initiatives. Additionally, we plan to consolidate more research on sustainability and best practices into an open-source resource list, which will be available to students and practitioners alike. However, our most ambitious goal is further to grow the community within the Mackintosh School of Architecture, strengthening discussions across different year groups and potentially funding some of our research.

The climate crisis is not a distant problem—it requires our commitment now. Architecture has the power to elevate communities, industries, and ecology. The MackCAN exists to challenge, educate, and equip students with the tools to shape a more sustainable future. Do you want to be part of it?

We invite you to join the conversation, challenge the status quo, and take ownership of your education. If you want to support our efforts or learn more, don’t hesitate to reach out.

Email: themackcan@gmail.com

Instagram: @themackcan

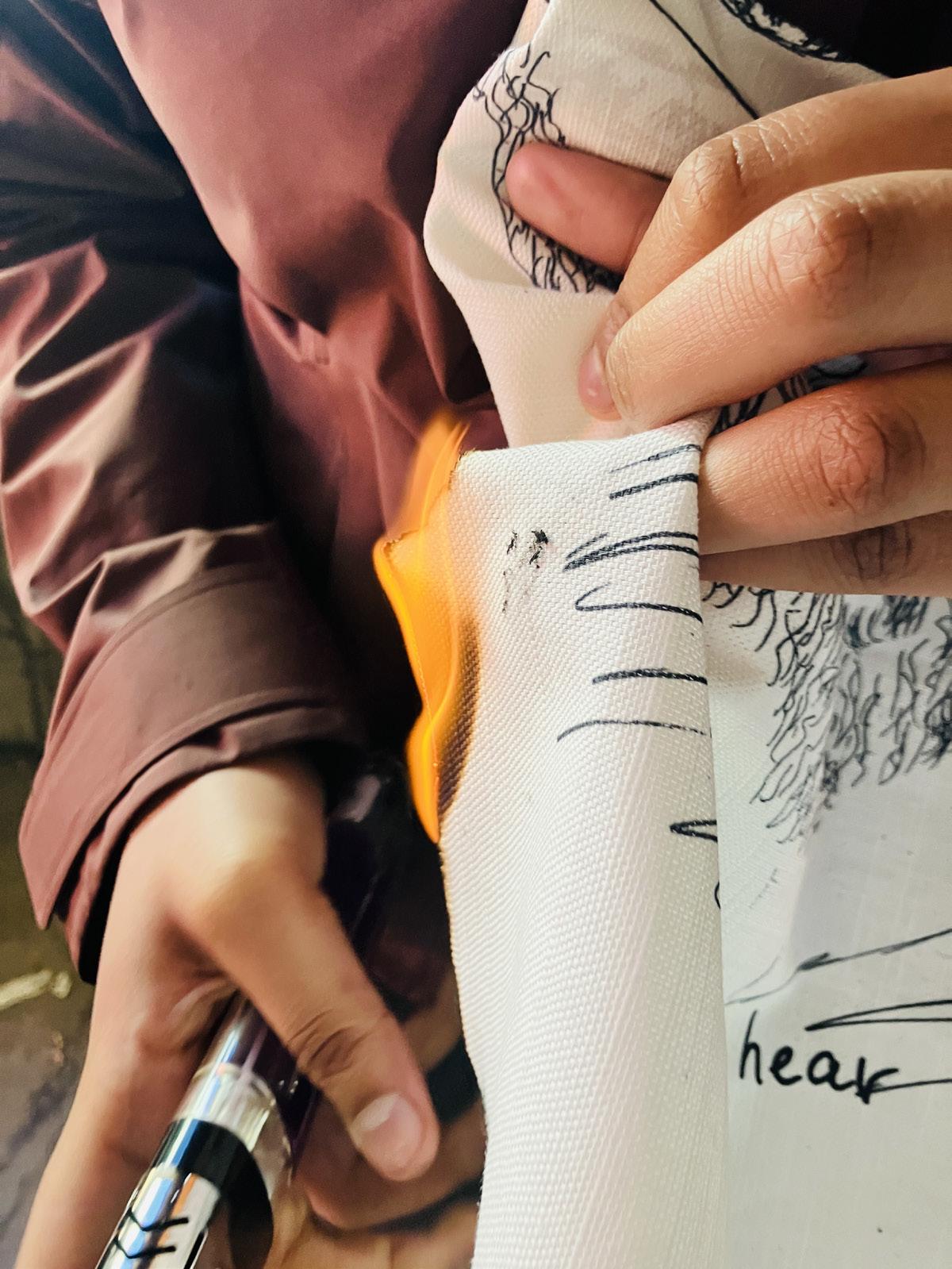

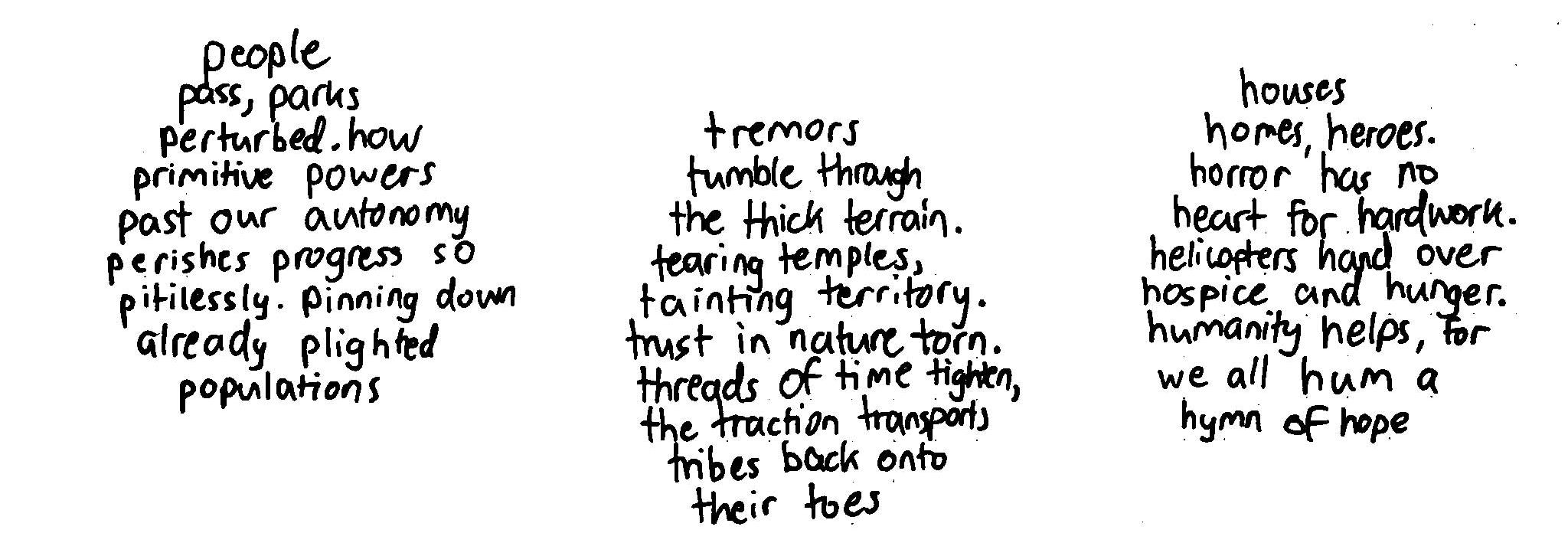

Pass The Hope (PTH Glasgow) is a studentled art campaign standing in solidarity with Myanmar, following the devastating earthquake on March 28, 2025. Inspired by the traditional Burmese toy Pyit Taing Htaung, a symbol of resilience that rises with every fall, students are invited to create and contribute art to ‘Pass The Hope’ to millions of people affected, to remind them the world has not forgotten them in difficult times of recovery.

On March 28, 2025, a 7.7-magnitude earthquake struck near Mandalay, causing widespread damage across central Myanmar. More than 3,700 people died, thousands injured, and many homes, schools, and hospitals were destroyed. The earthquake struck at a time when the country was already grappling with a severe humanitarian crisis, with over 3 million people displaced and nearly 20 million in urgent need of assistance. Communities are struggling with limited access to clean water, electricity, and medical care. There is a lot of ongoing support to the earthquake victims, but there is still a lot required in years to come, not just in the immediate aid and reconstruction, but in recovery and healing of the community.

When the Disaster Emergency Committee (DEC) reached out to help us start a fundraising campaign for the victims in Myanmar, we knew we had to take action. Our team quickly came together, with Nichole, Dolly, and Nicky motivated to bring the campaign to life. We recognized the urgency, the reach, and the responsibility of this collective effort, and its power to make a difference. Nichole K (she/her) from GSA Mackintosh School of Architecture, led the creative vision of the campaign with the generous help and support by the incredible network across GSA departments. She worked closely with Cole Hailstones (they/them), from GSA School of Innovation and Technology, to deliver the visuals of the video campaign, graphics and identity of PTH Glasgow. They are the first GSA student to Pass The Hope to Myanmar, and we would like to express our gratitude to them for their compassion and care in this campaign.

Pyit Taing Htaung ( ), is a traditional Burmese papier-mâché toy which stands upright no matter how much you toss it. The Burmese meaning of its name literally translates to “toss it, and it stands back up every time” - a phrase we felt perfectly captures the resilience of the people of Myanmar. We drew inspiration from this toy for two key reasons: its cultural significance as a symbol of strength and its physical roots, which is handmade from scraps and rubble, and commonly sold in the Anyar region (one of the hardest hit by the earthquake). Its shape also resembles an Easter egg, making our Easter weekend launch more relatable to audiences here in Scotland.

On April 17th, we hosted a launch event at the Vic Cafe and Bar, where we gathered to unveil our campaign video and officially launch our social media initiative. This occasion was meaningful, as we welcomed representatives from the Scottish media, including the Glasgow Times, along with the talented musician and former Glasgow School of Art student, Steven Lindsay whose generous contribution of the evocative track, “Nothing Will Ever Be The Same Again”, reflects deeply with the struggles and resilience of the people of Myanmar as they navigate the ongoing disaster. Our attendees came together to create beautiful artworks inspired by the Pyit Taing Htaung toy, all while savoring the warmth of traditional Burmese tea. It was truly a heartwarming afternoon filled with creativity, connection, and shared joy.

Pass The Hope is steadily growing, what began as a heartfelt idea has turned into a wider moment of solidarity. With the creative support of our artist friends and collaborators, Burmese diaspora and the general public, we’re turning grief into art, and art into connection. Through our Instagram page, we invite everyone to take part in Passing The Hope. Create any form of art inspired by the Pyit Taing Htaung toybe it crochet, animation, sculpture, poetry, whichever you express yourself best with. We have also started to establish connections with student communities across Scotland that are interested in hosting their own PTH events.

The initial emergency may have faded from global headlines, but for those affected by the earthquake in Myanmar, the road to recovery is only just beginning. Rebuilding lives takes time, resources, and something even more powerful - empathy. We know that our art cannot rebuild homes. But it can rebuild spirits. It can remind children of joy, help families feel less forgotten, and bring small but vital moments of strength. Healing is not just about food and shelter, it’s also about the little things: toys, safe spaces, creative outlets, and a sense that the world still cares.

We’re here for the long run. We hope you are too.

Be Part of the Hope, and Pass The Hope.

From wherever you are in the world, to Myanmar.

Email: pthglasgow@gmail.com Instagram: @pth.glasgow

Our first entry, by a close friend, Tom. Passing The Hope all the way from Poland with beautiful poetry to stay hopeful - the essence of Pass The Hope.