WELL TRAVELLED

LOSE YOURSELF IN TASMANIA’S WILD WEST Head off the beaten track to discover the 'real' Tasmania. WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHY MARJ OSBORNE THERE ARE MANY TALES to be told of Tasmania’s Wild West. They are stories of ancient peoples whose voices echo displacement and loss, stories of men who would find a way or make a way, of rivers that refused to be tamed, a terrain that took no prisoners and a forest that promised to return. THE WALL We could think of no better introduction to the Wild West than The Wall. Located in Tasmania’s Central Highlands at Derwent Bridge, 85km from Queenstown, The Wall in the Wilderness is a 3 metre high and 100 metre long relief sculpture, mostly in Huon pine. It is the lifelong work of sculptor Greg Duncan, who began his carving in 2005. The Wall beautifully represents the history of the region, the piners who came to log forest, the miners who came to mine ore, and the wildlife that is now either rare or extinct. The detail in this rare piece of art is stunning, showing veins in the hands of workers, hardship chiselled into the faces of women who battled

82 covemagazine.com.au

– Issue 91

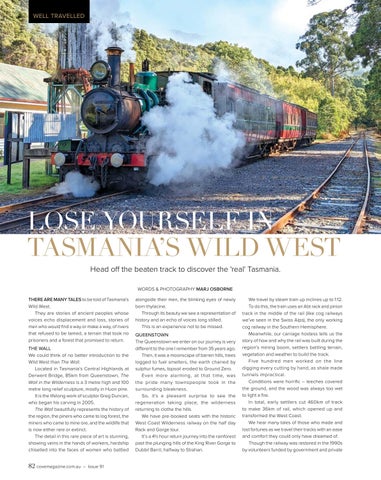

alongside their men, the blinking eyes of newly born thylacine. Through its beauty we see a representation of history and an echo of voices long stilled. This is an experience not to be missed. QUEENSTOWN The Queenstown we enter on our journey is very different to the one I remember from 35 years ago. Then, it was a moonscape of barren hills, trees logged to fuel smelters, the earth charred by sulphur fumes, topsoil eroded to Ground Zero. Even more alarming, at that time, was the pride many townspeople took in the surrounding bleakness. So, it’s a pleasant surprise to see the regeneration taking place, the wilderness returning to clothe the hills. We have pre-booked seats with the historic West Coast Wilderness railway on the half day Rack and Gorge tour. It’s a 4½ hour return journey into the rainforest past the plunging hills of the King River Gorge to Dubbil Barril, halfway to Strahan.

We travel by steam train up inclines up to 1:12. To do this, the train uses an Abt rack and pinion track in the middle of the rail (like cog railways we’ve seen in the Swiss Alps), the only working cog railway in the Southern Hemisphere. Meanwhile, our carriage hostess tells us the story of how and why the rail was built during the region’s mining boom, settlers battling terrain, vegetation and weather to build the track. Five hundred men worked on the line digging every cutting by hand, as shale made tunnels impractical. Conditions were horrific – leeches covered the ground, and the wood was always too wet to light a fire. In total, early settlers cut 460km of track to make 36km of rail, which opened up and transformed the West Coast. We hear many tales of those who made and lost fortunes as we travel their tracks with an ease and comfort they could only have dreamed of. Though the railway was restored in the 1990s by volunteers funded by government and private