SPORTSMANSHIP CITIZENSHIP THROUGH

A Century of Citizenship Through Sportsmanship

3 Founding vision

World War I veterans came home with a dream of creating a program that would instill the values of citizenship, fitness, sportsmanship and discipline among young people. Future Hall of Famer Bob Feller was one of more than 10 million athletes who lived up to that vision.

14 A “code that’s not going to change”

No one is sure who initially drafted the Code of Sportsmanship, but its words have resonated for nearly a century, as guiding principles for players.

16 Survival during hard times

Americanism Division Director Dan Sowers raised funds and built relationships that pulled the program through the Great Depression.

21 War and growth

American Legion players left the diamond to serve in World War II, and the program flourished in the late 1940s, with help from the Ford Motor Co.

31 American Legion Ambassadors

Under the guidance of combat-wounded former pro player Lou Brissie, the program took its values on the road in a tour of Latin America.

35 The legacy of George W. Rulon Program coordinator for whom the American Legion Baseball Player of the Year is named left his mark across three decades.

55 Home base for the ALWS

Shelby, N.C., became the singular venue for the American Legion World Series in 2011, and attendance records have been continuously shattered since, with millions viewing the tournament on ESPN, and fueling the local economy.

70 “Different than any other baseball”

Over the last century, American Legion Baseball players have learned much more about the game, and life, than catching, throwing and hitting.

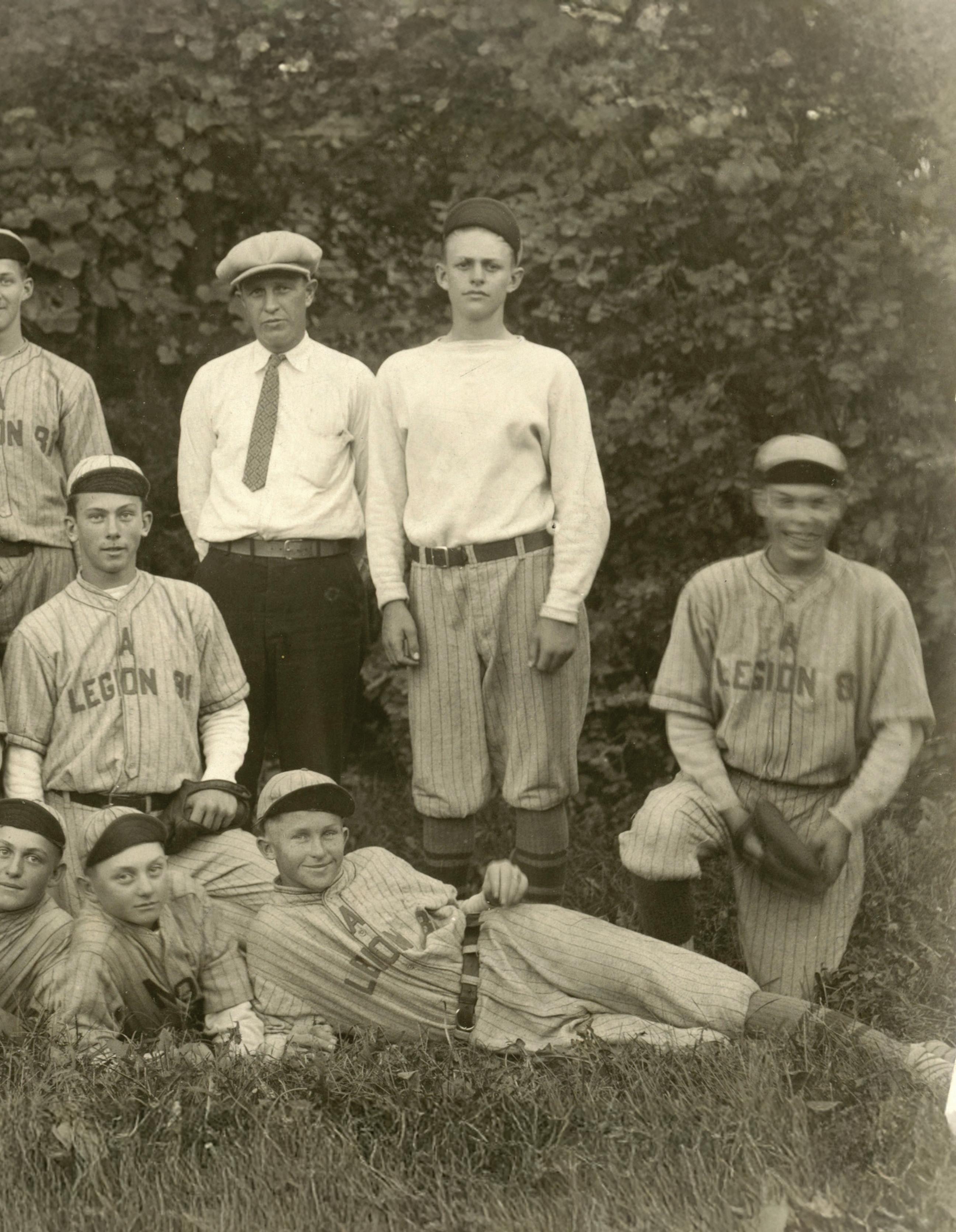

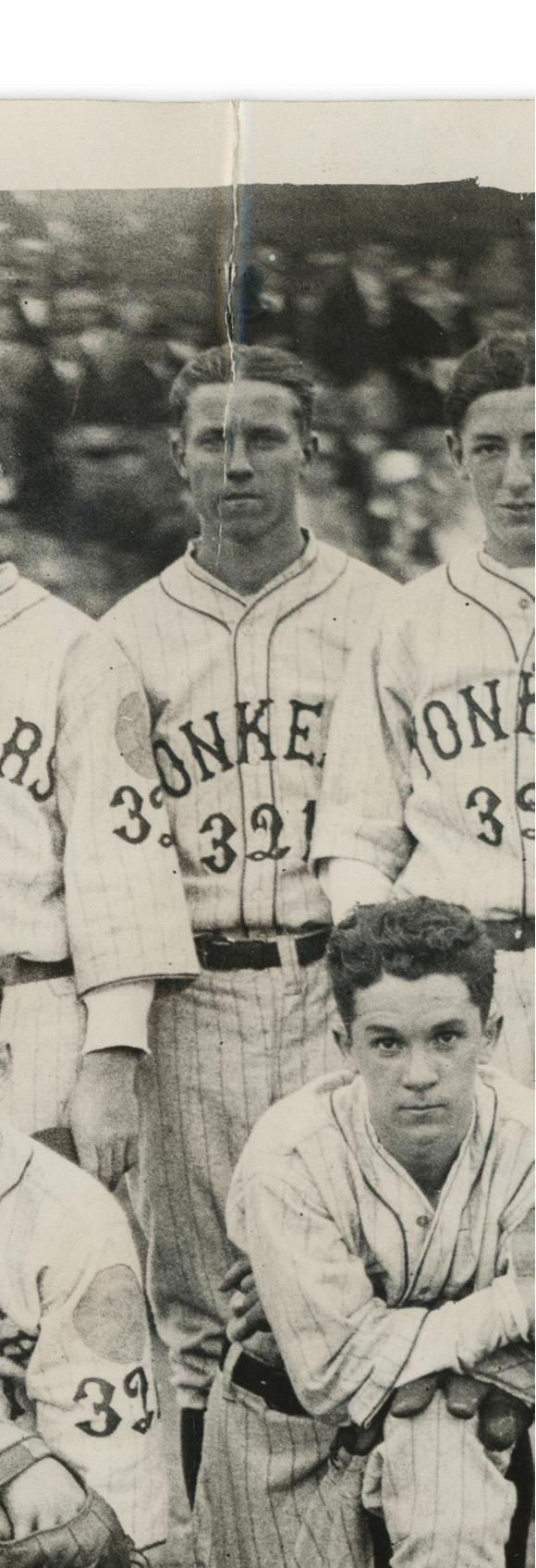

Top photo (opposite): One of the oldest known American Legion Junior Baseball team photos was taken in 1928 of the team sponsored by the all-women USS Jacob Jones District of Columbia Post 2, whose commander, Mabel F. Staub, appears in the center of the group.

Bottom photo (opposite): Dubuque County, Iowa, stands for the national anthem before game 7 of their American Legion World Series game against Idaho Falls, Idaho, at Keeter Stadium, Shelby, N.C., in 2021. Photo by Ben Mikesell

In

first

Founding vision of American Legion Baseball extends beyond the diamond

Bob Feller was a cow-milking, hay-baling farm boy who grew up near Van Meter, Iowa. When he wasn’t doing chores, he was throwing and catching with his dad behind the barn. At 12, the boy’s skills were so remarkable that his father believed he was ready for American Legion Baseball, among older players. No one could have known then the iconic fi gure Bob Feller would become, not only as an athlete but as a model of responsible citizenship.

Over the last century, more than 10 million young people have followed that model, learning to play “the right way” and respectfully serving as citizens, through American Legion Baseball.

Mentored by American Legion coaches who had fought in World War I, young Bob quickly understood that this kind of baseball was different. It was not simply about striking out opposing batt ers. He att ended ceremonies, parades and other community activities of The American Legion, inspired by his Legionnaire coach, Les Chance. He soaked it in.

“Mr. Chance was the rural mail carrier,” Feller later recalled. “He would chug up to our farm in his Model-T Ford and deposit the mail in our box. I can shut my eyes and see him now, a stocky man, just a litt le on the plump side, with a friendly grin. He had a fi ne sense of humor and laughed easily.

Whenever I think of American Legion ball, I think of Lester Chance. A World War I veteran, he organized and coached the American Legion team at Adel, Iowa. I still can hear his pleasant laugh. Whenever he rode up to our farm with the mail, Mr. Chance and Dad would talk baseball, and apparently, they did some talking about me.”

Feller started at third base in his fi rst year of Legion ball and moved to the pitcher’s mound the following season. The third year, he and some of his teammates transferred to a bigger team, sponsored by the Highland Park American Legion post in Des Moines, with the blessing of Mr. Chance. By age 15, Bob Feller was striking out 15 to 18 batt ers an outing, and he transferred to the Valley Junction post team in West Des Moines. There, an umpire, who also happened to be a scout for the Cleveland Indians of Major League Baseball, was astonished by the teen prodigy. Soon, representatives of the Indians were att ending his games.

At 17, he was a starting big-league pitcher for the Indians, taking the fi rst steps on a journey that would ultimately land him in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. But that is only part of Bob Feller’s story and the example he would set for the entire American Legion Baseball program, which turned 100 years old in 2025.

were one among four teams to play in the first

The whole concept of American Legion Baseball was borne of World War I and the experiences of those who served overseas among young people who were not especially fit, nor particularly literate, or knowledgeable about the reasons they had been called to arms. All of those conditions were reasons for The American Legion’s first generation to develop programs to strengthen the nation by mentoring youth.

“You remember it was only a few years ago we commenced hastily and earnestly to take stock of our boy power and manpower, because we realized in those days that it is the nation of physically fit men who would win the war,” John L. Griffith told delegates to The American Legion Department of South Dakota Convention on July 17, 1925. “We took stock and found approximately half of our boys were physically defective.”

Griffi th, an Army major in World War I who went on to serve as the fi rst commissioner of athletics in the Big 10 Conference, was invited by his friend and fellow veteran, Department

Commander Frank McCormick, to address Legionnaires in Milbank, S.D.

There and then, the seeds of American Legion Baseball were sown.

Griffith had led physical fitness training for troops during the war and believed there was more to the value of competitive sports than trophies and bragging rights. He told the South Dakota Legionnaires that organized athletics could not only correct physical fitness deficiencies of young men at the time, but The American Legion was extremely well-suited to prepare a new generation for war, if one should come, in other ways, as well.

“And if we do not have another war, at least they will be better citizens,” Griffith suggested.

The South Dakota Legionnaires drafted and passed a resolution to advance the concept up the chain. Four months later, at The American Legion National Convention in Omaha, Neb., the program was authorized as a nationwide initiative.

WHEREAS, Athletic competition conducted under proper direction are the best-

known means of teaching boys good sportsmanship, an essential of good citizenship, and in addition have genuine civic value; and

WHEREAS, A more physically fit citizenship can be obtained by extending the benefits of athletic training to the greatest possible number of boys and young men, a large percentage of whom are not receiving adequate training at present. Be it, therefore,

RESOLVED, That The American Legion, in seventh annual convention assembled, adopt the general policy of extending athletic competition to more boys in America, and that the organization promote and cooperate with other organizations in promoting athletic programs and in securing playgrounds and other facilities therefore; and, be it further

RESOLVED, That the National Americanism Commission be empowered to appoint a man to be designated as the national athletic director, to direct the general athletic program of The American Legion, of which junior baseball championships should be a part.

McCormick played in the first pro football championship

South Dakota American Legion Department Commander (192425) Frank McCormick’s love of athletics – and skill in sports –ran deep. The World War I veteran started as a wingback for the Akron Pros in the first American Professional Football Association championship game – predecessor of today’s Super Bowl –in 1920. The association was renamed the National Football League in 1922.

Prior to that – and prior to his wartime service – he was captain of the University of South Dakota football and baseball teams. He played football, basketball and baseball for four years at USD, starting in 1912.

While serving in the 337th Machine Gun Battalion of the 88th Army Division in the war, McCormick continued to compete on military football and baseball teams. He played pro baseball and football after discharge, landing a spot on the Pros, first as a guard and later as a wingback. That

team went on to beat Jim Thorpe’s Canton Bulldogs 7-0 on the way to the APFA championship, awarded on the basis of Akron’s leaguebest 8-0-3 record.

McCormick also coached at his alma mater, as well as the University of Illinois, and was athletic director at Columbus College in Sioux Falls, S.D., from 1922 to 1925.

He did all that prior to leading The American Legion of South Dakota and calling on his friend and fellow veteran, Big 10 Athletics Commissioner John L. Griffi th, who planted the seed that became American Legion Baseball at the 1925 department convention.

After his stint as department commander, McCormick went on to coach football and baseball at the University of Minnesota, where he later served as athletic director from 1931 to 1941 and from 1945 to 1950.

Over the next century, millions of young people from all walks of life and skill levels would learn teamwork, discipline, sportsmanship and citizenship from the veteran-run program. For many of those players, the game they loved would be hard-wired into their sense of Americanism.

Bob Feller was such an American Legion Baseball alum. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy two days after Pearl Harbor was att acked, leaving his professional baseball career and a lucrative contract (even with a deferment at his disposal because his father was terminally ill) to fi ght in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Serving his nation at that critical moment in history was a bigger responsibility to him than playing baseball.

He was assigned to the USS Alabama as a gun captain. By the time of his discharge on Aug. 22, 1945, he had six campaign ribbons and eight batt le stars.

“I think I had the war in a more realistic perspective than seamen who hadn’t grown up among Legionnaires,” Feller later wrote. “I knew it would be a long war, a bitter, bloody one. I wasn’t as impatient as many of my mates, and I didn’t gripe about the fact that it was cutt ing into the prime of my baseball career. I knew there was danger of death daily, but I

knew there was a job to do, a job that had to be done to keep our nation strong at the risk of grave personal sacrifices.”

Two days after his discharge from the Navy, Feller was back in uniform, once again for the Indians. He threw a complete game in his fi rst return start, striking out 12 in a 4-2 win over the eventual World Series champion Detroit Tigers.

His pro baseball career, divided into two parts – prewar and postwar – included eight Major League All-Star Game appearances and one World Series title. He was the American League wins leader six times and Major League strikeout leader seven. He threw three no-hitters as a pro, one before he went to war, and two others aft er he came home. The Sporting News in 1999 ranked him 36th among the 100 Greatest Baseball Players of all time.

In 1962, Feller was the fi rst former American Legion Baseball player enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. At the time, in the company of then-American Legion Baseball Program Coordinator George W. Rulon, Feller presciently said, “I may have been the fi rst Legion Baseball graduate in the Hall of Fame, but I won’t be the last.”

“The girl Babe Ruth”

The hard-hitting 13-year-old infi elder/pitcher/captain for Blanford, Ind., drew national media attention in 1928 not just because of a .571 batting average on a state American Legion Baseball championship team. The New York Times dubbed Margaret Gisolo “the girl Babe Ruth.”

The newspaper story appeared after the runners-up, Clinton Baptist, protested Blanford’s title on account of her gender.

The Legion consulted Major League Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis before ruling that nothing prevented Gisolo from playing American Legion Baseball. She went on to play in one regional tournament game, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. It was a season-ending loss.

Gisolo played throughout the 1930s on all-women traveling baseball teams, earned undergraduate and graduate degrees by 1942, and then, like so many of her male counterparts who had played American Legion Baseball, stepped into military service. She was a U.S. Navy WAVE during World War II, rising to lieutenant commander.

She continued in athletics throughout her life, teaching dance at Arizona State University and, in her 60s, competing in a senior tennis circuit. She played competitive tennis into her late 80s, was inducted into the Indiana State University Athletics Hall of Fame in 1996 and the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in 1998. She was 94 when she died on Oct. 20, 2009.

He specifically referenced catcher Yogi Berra, the New York Yankees great, who, like Feller, had walked away from professional baseball to serve his country in World War II. Among Berra’s secret missions was to soften the batt lefield for the Normandy invasion that ultimately liberated Europe from Nazi occupation on June 6, 1944. “I was on a rocket boat,” Berra explained to The American Legion Magazine in 1999. “I was on a twin-.50 machine gun, and I shot the rockets. We went in before the Army went in ... we stayed off about 400 yards from the beach and fi red the rockets in.”

Many other American Legion Baseball alums stepped off the field and into war theaters, including Boston Red Sox slugger Ted Williams, who played American Legion Baseball in San Diego in 1941, was the last Major Leaguer to bat over .400 in a season, and served both in World War II and the Korean War; 17-time All-Star pitcher Warren Spahn, a combat engineer who received a Purple Heart in the Batt le of the Bulge; 24-time All-

Star Stan Musial, who took 14 months out of his 22-year Major League career to serve in the U.S. Navy during World War II; Brooklyn Dodger Gil Hodges of Princeton, Ind., Post 25, who received the Bronze Star with Combat “V” for heroism under fi re while in the U.S. Marine Corps in the Pacific Theater of World War II; seven-time All Star Bob Lemon, who also served in the Navy during World War II; Eddie Matt hews, twotime Major League World Series champion, who served in the Navy during the Korean War; and Whitey Herzog, who was in the Army Corps of Engineers during the Korean War.

All went on to enshrinement in Cooperstown. Vietnam War Medal of Honor recipient James McCloughan of South Haven, Mich., spoke of character, mentorship, family, behavior and wartime service when he addressed teams assembled at American Legion Post 155 in Kings Mountain, N.C., prior to the 2018 American Legion World Series in nearby Shelby.

“I urge you to remember what my father told

me … do your best. And you know what? If you do your best, when you look in the mirror at night, you can say you did it for another day, and you did it well. Remember the many people you represent back home. If you think about that, you’ll always do the right thing. You’ll always perform and behave the way you should.”

On July 31, 2017, McCloughan – who, after Vietnam, had gone on to coach the same American Legion Baseball team he played for as a teenager – received the Medal of Honor from President Donald Trump in the White House. Forty-eight years earlier, McCloughan had been surrounded by enemy Viet Cong forces at Nui Yon Hill, was wounded by shrapnel, refused evacuation and rushed through a storm of bullets to save the lives of no fewer than 10 other soldiers.

The day after he spoke to the players in 2018, McCloughan sang the national anthem and threw out the fi rst pitch to kick off the 91st American Legion World Series in Shelby, the tournament’s home venue since 2011.

A few tips from Bob Feller

(The American Legion Magazine, 1963)

Having been involved in virtually every facet of the Legion baseball program, may I offer a few tips to make it a more enjoyable, worthwhile experience?

TO THE PLAYERS

• Know the rules. Read and study as many books as you can on fundamentals.

• Concentrate on one position, but be prepared to play another when necessary.

• Work on your playing weaknesses, rather than on your strong points.

• If you’re a pitcher, cover your arm at least to the elbow on warm days and down to the wrist on cool days. Warm up for 10 minutes on a cool day; fi ve or six minutes on a warm one. Make sure you concentrate on fast balls and master control before experimenting with curves.

• Get plenty of sleep and eat the proper foods. (When I was a boy, my dad said, “Bob, do me a favor. Don’t use alcohol or tobacco until you’re 21.” I promised him I wouldn’t. I still don’t smoke and rarely touch alcohol, and then only in its mildest form.

• Pull for your teammates, especially when you’re sitting on the bench.

TO THE PARENTS

• Obtain your doctor’s approval should there be any question about your boy’s participation because of physical or emotional considerations.

• Be on hand to see his games. This is more important than making a cash donation to the league.

• Root for your son; it will help build his confidence. Never sharply criticize his play, especially in front of others.

• Try to play catch and pepper informally with him and other youngsters in the neighborhood.

• Most of all, always remember that baseball is a game, not a life-and-death matter.

TO THE COACHES

• Be patient with your players and never raise your voice to them. Remember that errors are as much a part of the game as the bat and the ball.

• Treat all the boys exactly alike. Never cater to a star or you will be doing him an injustice as well as yourself.

• Try to get to know each boy personally, and his parents and home background.

• Whenever possible, give your substitutes a chance to play.

LEGION BASEBALL

HALL OF FAMERS - The early years

Among the 89 former American Legion players inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, here is a selection from the early years. For a complete list of American Legion Baseball Hall of Famers, visit legion.org/baseball

1962 - Adel/Des Moines, Iowa Known as the “heater from Van Meter,” Feller is believed to have thrown 105 mph fastballs and, at age 8, could already unleash curveballs. He played American Legion Baseball at an early age and starred for the Cleveland Indians before leaving his pro contract to serve in the Navy during World War II; he returned to the mound after the war and produced one of the greatest Major League Baseball careers in history. He continued to support American Legion Baseball throughout his life.

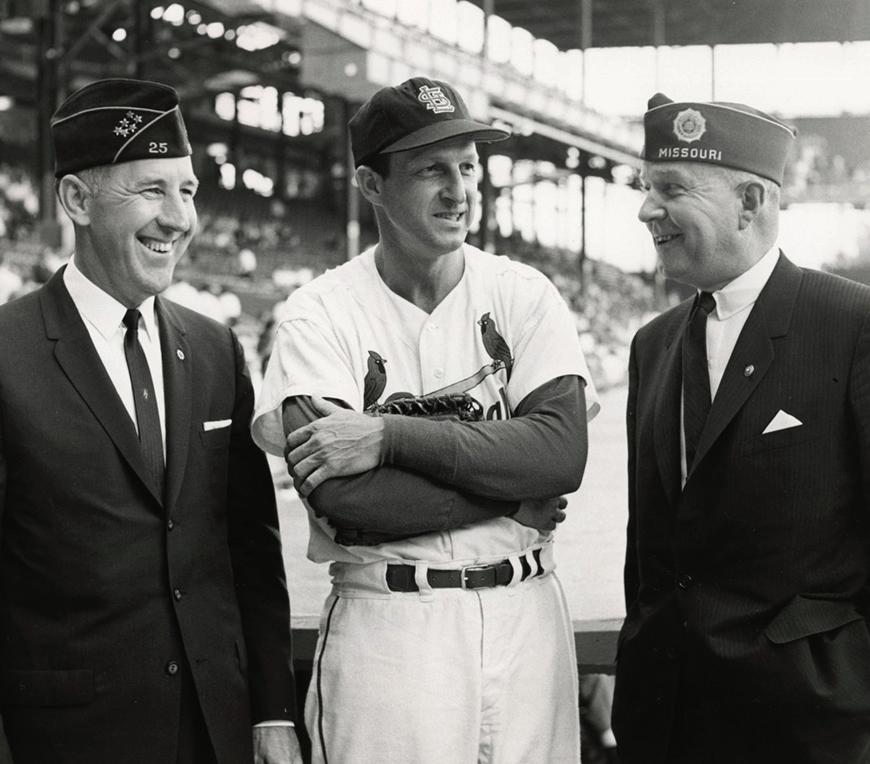

Stan Musial

1969 - Donora, Pa. A first-ballot Hall of Famer, the slugger appeared in a record 24 All-Star games and was the American Legion Baseball Graduate of the Year in 1961.

Ted

Williams

1966 - San Diego, Calif. Regarded as one of the greatest hitters of all time, World War II and Korean War fighter pilot Williams played American Legion Baseball in San Diego and was the American Legion Baseball Graduate of the Year in 1960. During his war-interrupted pro career, he was a 19-time All-Star whose overall batting average was .344.

Yogi Berra

1972 - Post 245, St. Louis, Mo. Berra won 10 World Series titles as a player, more than any other in Major League Baseball history, and was a three-time American League MVP and 18-time All-Star. Born Lawrence Peter Berra, he received the nickname “Yogi” during his American Legion Baseball days, after attending a movie that had a short piece on India. A friend, Jack Maguire, noticed a resemblance between Berra and the “yogi,” who practiced yoga, on the screen.

Warren Spahn

1973 - Buffalo, N.Y. The 1963 American Legion Baseball Graduate of the Year, Spahn set a record for wins by a lefthanded pitcher, finishing his 21-year career with 363 victories. In 1957, Spahn won the Cy Young Award and led the Milwaukee Braves to a World Series championship.

Pee Wee Reese

1984 - Louisville, Ky. A two-time World Series champion and 10-time All-Star, Reese is also famous for his support of teammate Jackie Robinson, the first Black player in the Major League’s modern era.

Bob Lemon

1976 - Long Beach, Calif. Thirty years after his pitching helped the Cleveland Indians win the 1948 World Series, Lemon stepped in as manager of the New York Yankees and led them to the 1978 championship. The 1978 title came after Lemon was fired by the Chicago White Sox earlier in the season.

Bobby Doerr

1986 - Post 162, Los Angeles A nine-time All-Star with the Boston Red Sox, Doerr posted six seasons of 100-plus RBIs. He finished his career with 2,042 hits and 1,247 RBIs, as well as 223 home runs.

A code “that’s not going to change”

The need for an American Legion Code of Sportsmanship was fi rst discussed in 1925, the same year the program was born. It is unclear who wrote it, or precisely when, but it summed up the ways in which American Legion Baseball would differ from other youth sports programs.

In 1928, The American Legion’s Americanism Commission submitted a report to the 10th National Convention, in San Antonio, Texas, that explained the connection between good sportsmanship, good citizenship and

American Legion Baseball. “The big purpose of the junior baseball program is not merely to get the boys into the national game,” the report stated. “It is to teach them concrete Americanism through the playing of the game.” The report lined out guiding principles:

Good sportsmanship: “The principles of good sportsmanship are closely related to the principles of good citizenship and that by teaching a boy to be a good sportsman in his youth, we will make a better American of him in his adult life.”

Respect for law: “Without rules, which we call laws, life would be just a meaningless chaos and anarchy in which no one would get anywhere. A respect for law is one of the chief things which every boy should get out of the junior baseball program.”

Fair play: “Nothing in life is worthwhile winning unless it is won on the square.”

Loyalty: “A boy who has learned this in his boyhood will be loyal to his family, to his associates and to his country when he reaches manhood.”

Teamwork: “He must learn to play for the success of his team and not his individual glorification ... Teamwork is merely another name for cooperation, and ability to cooperate is necessary to every good citizen.”

Gameness: “Not to quit fi ghting until the last out is made.”

Democracy: “The game, played under the Legion program, brings together boys from the families in all positions in life, from the poor homes down by the railroad yards and from fi ne homes on the boulevards. These boys playing together come to

recognize each other for what each is worth in himself and not for what position his family may hold in the community … Th is is true democracy. Carried over into adult life, it will constitute one of the basic att ributes of good citizenship.”

The commission then shared American Legion Baseball’s Code of Sportsmanship, words that have endured for over a century: I will keep the rules, Keep faith with my teammates, Keep my temper, Keep myself fit, Keep a stout heart in defeat,

Keep pride under in victory, Keep a sound soul, a clean mind, And a healthy body.

National American Legion Baseball Committee Chairman Gary Stone of Missouri, who coached future Major League All-Star Albert Pujols when he played in the program, expected nothing less of his athletes than to live up to that code, regardless of their skill level or anything else.

“We are still teaching the same things,” Stone says. “You always have sportsmanship, citizenship and working together for a goal, and that’s not going to change.”

Survival during hard times

Only twice between 1926 and 2025 was there no American Legion Baseball World Series. Those years were 1927, a budget decision, and 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. In both years, however, many American Legion Baseball teams competed at the local and state levels. The American Legion made its pilgrimage to France to commemorate the 10-year anniversary of U.S. entry into World War I in 1927,

and fi nancial support for baseball was not forthcoming. The cost of the national program’s fi rst year – in which Yonkers, N.Y., defeated Pocatello, Idaho, 23-6 in Philadelphia before a crowd of an estimated 3,000 for the fi rst American Legion World Series title – also had exceeded budget, and the future looked bleak.

New staff leadership in The American Legion soon changed the forecast. An aff able World War I veteran named

Dan Sowers, bespectacled and over 325 pounds, was hired as the organization’s Americanism director and soon was able to secure a $50,000-a-year commitment from Major League Baseball club owners to resume the national program in 1928. Th at commitment also included a gold pocket watch for each player on the championship team, plus transportation and tickets to the Major League World Series. American Legion Baseball champions would

"Father of American Legion Junior Baseball"

Dan Sowers, born May 8, 1895, in Pocohantas, Va., enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1917 and was attached to the Press Censorship Division of the General Staff of the American Expeditionary Forces, where his fellow soldiers referred to him as “the largest body of troops in the AEF.”

Having practiced law in Kentucky

continue to be rewarded with a trip to the World Series over the century.

Sowers regularly met with club presidents and Major League Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to report on the program that would soon serve as a massive feeder system for pro ball. Early on, Sowers thanked the big-league teams for their support, not just for the money, but for reasons etched into the program’s founding vision. “I doubt if the activity

and Washington D.C., he was an upbeat communicator and devoted member of The American Legion, serving as staff director for the Americanism Division and on the national Americanism Commission until 1950. He died Nov. 28, 1955, after a long illness, having spent much of the Depression years raising funds to keep American Legion Baseball alive.

First World Series ball

The American Legion’s Emil Blackmore Museum in Indianapolis has among its artifacts one of the original baseballs used in the first American Legion World Series, in 1926.

has put an extra penny in the cash box of any ball club,” Sowers once reported. “It has put in the record of American history an outstanding, unselfi sh, and generous contribution toward the building of character in those youngsters who are steadily marching on to manhood to take over the reins of the aff airs of this country in the future.”

MLB grants continued annually until 1933 when the grim reality of the Great Depression took its toll. Major League Baseball funding disappeared for two years, and that sent Sowers back on the fundraising trail.

He called upon his fellow World War I veteran, past American Legion Department of Illinois Commander and future U.S. Navy Secretary Frank Knox, publisher of the Chicago Daily News. Knox committed $5,000 for American Legion Baseball and challenged other newspaper publishers in the country to match or beat it. Five others met the challenge. Sporting goods companies like Spalding and Wilson also contributed. It was enough, barely, to keep American Legion Baseball alive in the Depression. By 1935, as the program was drawing bigger and bigger crowds to games around the country, Major League Baseball was back on board, with a

A cartoon in the American Legion Monthly back when the baseball program was getting underway expressed the enthusiasm of young people who needed the game.

lowered annual grant of $20,000.

In 1936, a decade removed from its paltry turnout in Philadelphia for the fi rst American Legion World Series, the series in Spartanburg, S.C., drew an estimated 60,000 spectators to the stands, an attendance record that would not be broken until 2011.

“Baseball in general, and American Legion ball in particular, not only survived but expanded in the years of the Great Depression,” historian William E. Akin wrote in “American Legion Baseball: A History, 19242020” (published in 2022). “After all, there was litt le else for kids and young men to do.”

Akin noted that it was 1933 when the fi rst American Legion Baseball alum made it onto a Major League roster. Pitcher John Salveson of Long Beach, Calif., did not win a game for the New York Giants that year, but he did record the fi rst base hit in the big leagues by a former Legion player.

The following year, fi ve former American Legion players were on Major League teams. In the decades to come, over half of pro baseball and All-Star Game rosters would be composed of young men who had learned the game, as well as its values, on Legion diamonds across the land.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis, commissioner of Major League Baseball during the program’s infancy, was a big fan and supporter of grants to assist it in the lean years. A baseball autographed by Landis is housed in The American Legion’s Emil A. Blackmore Museum collection.

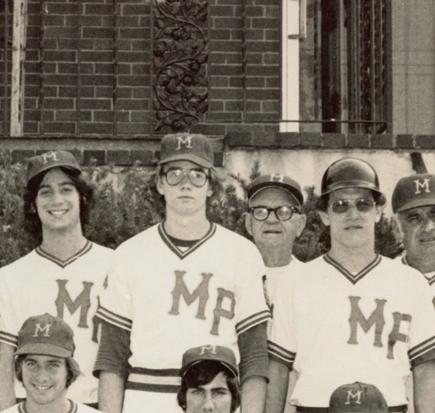

American Legion National Commander L. Eldon James (1965-1966) helps his son Donnie in Aberdeen, S.D., shoulder an enormous bat specially designed for the 40th anniversary of Legion Baseball. The bat is on display at American Legion National Headquarters.

“We called him Bunny”

“The story has taken on a Rosa Parks kind of status here in Springfield,” author Richard Andersen wrote in a letter to American Legion National Adjutant Daniel S. Wheeler in October 2014.

The “story” had occurred 80 years earlier, at a time of racial segregation and tension in many southern states. The Springfield, Mass., Post 21 team had advanced to the sectional American Legion Baseball tournament in Gastonia, N.C. There, one of the Massachusetts players, star pitcher/outfielder Ernest “Bunny” Taliaferro, was not welcome.

He was a beloved teammate. He was also Black and because of his race was denied a room in the same hotel as the rest of the squad. At the first practice, an estimated 2,000 men surrounded the field and shouted slurs, threatening him and his teammates, then reportedly began throwing bottles, cans and half-eaten hot dogs at Bunny. Word was going around that two other tournament teams would not take the same field as Taliaferro. Local officials said they could not guarantee team safety if he were to play.

That evening, Coach Babe Steere called a team meeting. He gave the boys two choices. Play in the tournament without Bunny, or pack up and go home, suspending a season full of hope for an American Legion World Series berth. Second baseman Tony King, the team captain, spoke up.

“Bunny is a member of this team. If he doesn’t play, neither do I.”

The team voted unanimously to return to Springfield. When they arrived at the train station, Aug. 23, 1934, the players and coaches were greeted by a crowd of more than 1,000 fans applauding the decision to stick together.

In 2003, a stone monument was installed at Forest Park, where Post 21 had played its games:

Brothers All Are We

It was an act of loyalty and love for their friend and brother which sent a message that bigotry has no place in the game of baseball or in the game of life; a message proclaimed by a band of 16-year-old kids a generation before the barrier of racial prejudice of major league baseball was torn down with the recruitment of another black, Jackie Robinson.

Andersen’s books “A Home Run for Bunny” and “We Called Him Bunny” were published in 2013 and 2014.

Following that, letters between Springfield, Gastonia and The American Legion acknowledged with regret the moment from a different time and welcomed “an opportunity to heal old wounds and start a new promise,” as Andersen stated in his letter to American Legion National Headquarters.

Wheeler made the point in his reply that “American Legion Baseball has taught hundreds of thousands of young Americans the importance of sportsmanship, good health and active citizenship. The program is also a promoter of equality, making teammates out of young athletes regardless of their

income levels, social standings or the color of their skin.”

Gastonia Mayor John D. Bridgeman wrote to Springfield Mayor Domenic J. Sarno in 2014 that, “What happened in 1934 is certainly a sad chapter in our city’s history” and that Gastonia – which elected its first Black mayor in 1976 –had evolved greatly since that time. Still, he wrote, “On behalf of the citizens of the City of Gastonia, I would like to express our deepest regret for the treatment experienced by the American Legion New England champion baseball team from your fair city in 1934, particularly Mr. Bunny Taliaferro.”

That summer, Gastonia sent a team to play a goodwill game in Springfield. The following summer, Springfield sent two teams to play in Gastonia.

On Aug. 23, 2014, Tony King – last surviving player of the Post 21 team –was honored at age 96 at the Soldiers Home in Holyoke, Mass., on the 80th anniversary of the team’s decision. After Mayor Sarno proclaimed it “Tony King Day,” the former team captain told the Springfield Daily Republican: “This is a wonderful gesture. I only wish all of my teammates could be here with me.”

War and growth

As former American Legion Baseball players were shipping out to fi ght in World War II, the program marched on in the early 1940s and blossomed as the decade unfolded.

During the war, the nation was rationing fuel, rubber, metal, shoes, food and other items. Transportation became difficult, and American Legion Baseball team numbers declined. The program, however, continued to operate with ongoing support from Major League Baseball. The American Legion World Series would be played in communities large and small, from Miles City, Mont., to Los Angeles, Calif., throughout the 1940s. Cincinnati, a legendary baseball city, produced three national champions in that decade, including the fi rst of fi ve titles claimed by Robert Bentley Post 50 over the years, the most of any team in the program’s fi rst century. Oakland, Calif., Post 337 won back-to-back crowns in 1949 and 1950, both in Omaha, Neb., and was the fi rst team to take consecutive titles.

Cincinnati Legion teams qualified for the World Series 14 times between 1944 and 1988, but Omaha is the city that produced the highest number of tournament appearances – 19 – between 1939 and 2022, including one title.

The national NBC radio quiz show “Play Ball” aired in 1946, featuring Major League players answering questions from announcers and real pro umpires about the rules and lore of the game. Pee Wee Reese, who played Legion ball in his hometown of Louisville, Ky., and went on to become a 10-time Major League All-Star shortstop, told of how the youth program brought players together “from different schools and every corner of town. There was no favoritism shown by American Legion Junior Baseball coaches, as to race, creed or color. Every boy is given a chance to learn baseball. They learn it through the heart of playing the game with a real spirit of cooperation.”

In 1946, with some 800,000 American Legion Baseball players taking the field, the Ford Motor Co. infused the program with a $500,000 sponsorship and established a 5,000-dealership team-support network across the nation. In 1947, Ford commissioned New York Yankees legend Babe Ruth to travel the country to promote the program. In August of that year, Ruth attended the American Legion World Series in Los Angeles and presented the championship trophy to the Post 50 team from Cincinnati, along with a Spalding baseball that he had autographed.

The “Sultan of Swat” continued to promote American Legion Baseball

in his fi nal years (he died on Aug. 16, 1948) and in 1949 was posthumously awarded the Legion’s highest honor – the Distinguished Service Medal.

“Babe Ruth meant many things to his country,” American Legion Past National Commander James F. O’Neil told the 31st National Convention at the award presentation. “He gave us lessons in fair play that were felt far beyond the field of sports. He served as our ambassador of good will and brought to many people their fi rst real understanding of our way of life.”

Th at year, the number of American Legion Baseball teams hit a previously unprecedented high of 15,912,

and the number of players exceeded 1 million nationwide. Among them was shortstop Ray Herrera of Bill Erwin Post 337 in Oakland, Calif., who received the inaugural American Legion Baseball Player of the Year Award in the fi rst of back-to-back championship seasons. His teammate, catcher J.W. Porter, took Player of the Year honors the following season, a remarkable accomplishment for both athletes in that one of their teammates was Frank Robinson, who would go on to become a 14-time Major League All-Star, fi rst-ballot Hall of Famer and the fi rst Black manager in the bigs.

Awards with meaning

The Howard P. Savage Jr. Trophy, in honor of The American Legion’s 1926-27 national commander, was established in 1928, awarded to the Legion department that produces that year’s American Legion World Series champion.

The player with the highest batting average in American Legion World Series play began receiving the Louisville Slugger Award in 1945; it was renamed The American Legion Baseball Slugger Trophy in 2013.

The American Legion Baseball “Big Stick” Award has been presented since 1972 to the player with the most total bases, as determined by the official scorers of the respective regional tournaments and the American Legion World Series.

The Ford C. Frick Trophy, in honor of the third Major League Baseball commissioner (1951-1965), was established in May 1952, to be presented to the runner-up team in the American Legion World Series.

Catcher Sherm Lollar of the Chicago White Sox received the first known American Legion Baseball Graduate of the Year award in 1958; the American Legion National Executive Committee made it an official award in 1968.

The American Legion’s National Executive Committee approved the James F. Daniel Jr. Memorial Sportsmanship Award in 1965 in honor of the longtime Americanism Commission chairman, “to the American Legion Baseball player participating in the World Series who

best represents the principles of good sportsmanship emphasized by the program, as determined by a designated selection committee.”

The Jack Williams Memorial Leadership Award , first presented in 1968 to honor the longtime Department of North Dakota adjutant who always stressed the importance of adult mentorship of youth, is awarded to the manager and coach of the national championship team.

The Dr. Irvin “Click” Cowger Memorial RBI Award was authorized by National Executive Committee resolution May 5-6, 1971, in memory of the highly decorated World War I veteran and longtime American Legion Department of Kansas adjutant, to the player who drives in the most runs in national competition.

The Commissioner of Baseball Trophy was authorized Oct. 20-21, 1971, by national resolution to be awarded to the American Legion Baseball World Series Champions.

The Bob Feller American Legion Pitching Award was authorized and first presented in 1978, in honor of the Cleveland Indians Hall of Famer who grew up playing American Legion Baseball, for the player who throws the most strikeouts in national regional and World Series competition.

On May 15, 1986, The American Legion Baseball Player of the Year Award was renamed the George W. Rulon Baseball Player of the Year, in honor of the program’s longtime coordinator.

“I think I am who I am today because of the standards of the American Legion program. It sets the right standards for how you should act when you’re out on the baseball field. It’s an important part of my career, both for baseball and off the field.”

Arizona Diamondbacks relief pitcher Paul Sewald , 2024 American Legion Baseball Graduate of the Year, who helped lead Las Vegas Post 76 to a record 75 wins and the 2008 American Legion World Series title; that year, he received the James F. Daniel Jr. Memorial Sportsmanship Award, presented annually to an ALWS participant who best embodies the principles of good sportsmanship.

AMERICAN LEGION BASEBALL HALL OF FAMERS - Post War era

Here is a small selection of former American Legion Baseball players enshrined in the Hall of Fame since the 1980s. For a complete list, visit legion.org/baseball

Bob Gibson

1981 - Omaha, Neb. Gibson was the World Series Most Valuable Player in each of the St. Louis Cardinals’ two titles during his tenure. The nine-time All-Star added two Cy Young Awards to his resume. He is a member of the MLB All-Century team and was inducted into the Hall of Fame on his first ballot.

Whitey Herzog

2010 - New Athens, Ill. After eight seasons as a player for four different teams, Herzog was a scout, manager, coach, general manager and farm-system director in the pros and led the St. Louis Cardinals, as manager, to the 1982 World Series title.

Sparky Anderson

2000 - Post 715, Los Angeles. A member of the 1951 American Legion World Series championship team, Anderson spent just one season playing in the Major Leagues but would go on to win 2,194 games as a manager with the Cincinnati Reds and Detroit Tigers. He led “The Big Red Machine” to consecutive World Series titles in 1975-76 and added a third championship with Detroit in 1984.

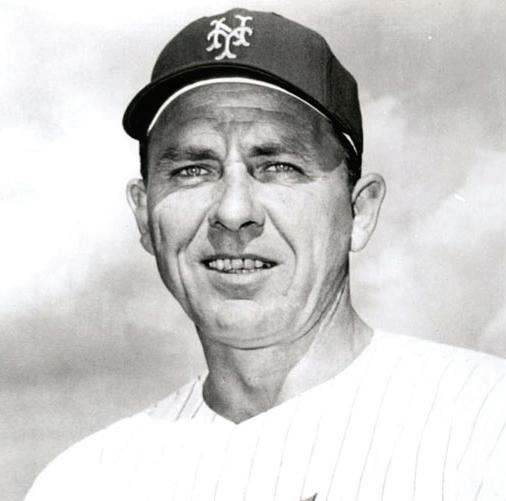

Gil Hodges

2022 - Post 25, Princeton, Ind. An eight-time All-Star and three-time World Series champion as a player and manager, Hodges made his Major League debut at age 19 for the Brooklyn Dodgers before joining the Marine Corps and serving in World War II, where he received a Bronze Star as a combat anti-aircraft gunner in the Pacific Theater. He played 18 years in the majors and managed the 1969 “Miracle Mets.”

Cody Walsh, a player from the 2024 American Legion World Series champions from Post 70 in Troy, Ala., gives tips to local youth on how to throw the ball.

Legion Baseball values mirrored in Play Ball program

American Legion World Series champions have made an annual tradition of participating in Play Ball clinics and events throughout the country since 2017, in conjunction with Major League Baseball and USA Baseball.

Since then, American Legion players and coaches have helped young people – from Mount Rushmore to Shelby, N.C. – learn fundamentals, healthy competition and how to have a good time outdoors.

“It’s important because little kids need someone to look up to, learn new things about the game, and it’s a good time,” said Cody Walsh, a player on the Troy, Ala., Post 70 team that won the 2024

American Legion World Series. He and his teammates, along with former Major Leaguers and Olympians, volunteered at a Play Ball clinic in Inglewood, Calif., on Oct. 26, 2024.

Coach Ross Hixon of the Troy team –guests at Game 2 of the 2024 Major League World Series – said the Play Ball program exemplifies what American Legion Baseball is all about, especially in the way it helps build community.

“Playing together is one thing; I don’t know if any of these kids know each other at all, but they’ll get out here and play and, you know, catch a ground ball and throw to first, just the teamwork side of it,” he said. “Not only playing the

game but helping out. They can’t do the event without volunteers, so teamwork’s probably the biggest thing. And then commitment just to come out here and be up early … and have fun while you’re doing it.”

“I’ve been walking around watching the boys interacting with the younger kids,” League City, Texas, Post 554 Coach Ronnie Oliver said after his players volunteered in Dallas in 2023, the year they won the American Legion World Series.

“It’s something for them to give back to the community and letting them work with kids younger than them and having that knowledge to pass on. It’s great, I love it. Enjoying everything I’m seeing in there.”

Stars of Major League Baseball, all former American Legion players, were put on the spot in a 1946 NBC radio series called “Play Ball.” The program promoted American Legion Baseball and captivated fans as the players answered questions from Major League umpires and others. Recordings of those broadcasts are archived and can be heard on The American Legion national website at legion.org/baseball/centennial

“School would let out, and immediately we would go on a fi ve-, six-state tour in our air-conditioned bus. Not only did we have our local Legion post behind us, but everybody else in town, too. A good team would come into town, and we’d draw 4,000 to 5,000 people.”

- Billings, Mont., Royals Post 4 American Legion Baseball star Dave McNally, who played on two teams that reached The American Legion World Series, including one that played in the championship in 1960. That year, McNally once struck out 27 batters in a single game on his way to an 18-1 record. Later, as a Baltimore Oriole, he became the only Major League Baseball pitcher to hit a grand-slam home run in a World Series game; the bat and ball he used are enshrined at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

Championship razor for Sparky Anderson

On Sept. 8, 1951, Crenshaw Post 751 of Los Angeles came back from an early deficit to an 11-7 win over White Plains, N.Y. Post 135 for the American Legion World Series title. The team was led by hard-hitting third baseman Billy Consolo and shortstop George Lee “Sparky” Anderson, who would go on to play in the majors and later manage the Cincinnati Reds to Major League World Series championships in 1975 and 1976, and the Detroit Tigers to a title in 1984.

A two-time American League Manager of the Year, Anderson was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000.

His team’s American Legion World Series victory came in Detroit’s Briggs Stadium, where he would go on to manage the Tigers from 1979 to 1995.

Following Crenshaw’s hard-won title in 1951, according to William E. Akin’s “A History of American Legion Baseball: 1924 – 2020,” the seventh California team to win an American Legion World Series paraded through Los Angeles winding up at Clampett’s automobile dealership on Figueroa Street. The owner himself gave each player an electric razor and a team jacket.

ABOVE: The American Legion Ambassadors board a plane in Miami, beginning the first leg of a Latin American tour sponsored by Pan American World Airways.

LEFT: The Legion team lines up to pledge allegiance to the flag before playing a goodwill game against a team from Panama.

American Legion Ambassadors

Leland Victor “Lou” Brissie gave American Legion Baseball a dose of star power in the 1950s. As a teenager, Brissie was pitching in a South Carolina textile league when he fi rst caught the att ention of legendary Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack. Brissie, a devout Christian, instead went to Presbyterian College until he enlisted in the Army in 1942.

As a corporal in the 88th Infantry Division, Brissie fought through Italy until, on Dec. 2, 1944, a German artillery shell shattered his leg into 30 pieces. He crawled through mud to take cover as the barrage continued. The leg became infected, and medics said it would need to be amputated, or he would likely die. Brissie told them no. More than 20 operations later, he came home with a Purple Heart, a Bronze Star, and his wounded leg in a metal brace. Mack remembered him and gave him a chance. After a 25-win year in minor league ball, Brissie was called up to start for the A’s. He went

on to go 16-11 in 1949 and made the MLB All-Star team. He continued playing, in his leg brace, for the A’s and later the Cleveland Indians as a teammate of Bob Feller, until his retirement in 1953.

The following year, Brissie was commissioner of American Legion Baseball.

The number of teams continued to grow – to more than 23,000 in 1957 –on Brissie’s watch. Funding, however, was not keeping up.

Pan American World Airways stepped up in 1956 and sponsored a Latin America tour of the “American Legion Ambassadors,” a 16-player team from arou nd the country whose athletes were selected on the basis of scholarship, leadership, citizenship and playing ability. Leaving from Miami for a schedule that included 19 games, multiple exhibition clinics and visits to countries including El Salvador, Panama, Colombia, Puerto Rico and Cuba, the team received a telegram from U.S. President Dwight

A shattered leg from combat in World War II did not stop Lou Brissie from returning to the sport he loved after discharge. He pitched in the minor leagues for a stint before Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack called him up. He later pitched for the Cleveland Indians.

In 1954, following his retirement from Major League play, Brissie came to work at American Legion National Headquarters as commissioner of the American Legion Baseball program.

D. Eisenhower:

“To the young men on The American Legion baseball team and to their coaches as they begin their goodwill tour of South America I send greetings. As representatives of the American people, I know you will enjoy the hospitality of the countries you visit and you will exhibit the highest standards of American sportsmanship both on and off the playing fi eld. In so doing you will serve your country well in the cause of international peace and understanding. Congratulations and best wishes for a great adventure.”

The Ambassadors toured schools, embassies, palaces, government offices, military installations, American Legion posts and historic sites. One game was aired live over Armed Forces Radio throughout the Canal Zone. In the end, the players fulfi lled the wishes of the president , according to a March 1957 article in The American Legion Magazine

“If there was any doubt that this good will mission had done its job, it was soon dispelled,” wrote the magazine’s associate editor, Irving Herschbein. “Letters and citations from officials of the countries visited, from Americans living and working there, and from the U.S. State Department, all praised the conduct of the team and the wonderful impression the Ambassadors had made.”

In 1958, Brissie appeared on an American Legion video as part of its “Back to God” movement during that decade. “The contribution this pro-

gram has made to our nation cannot be measured, like the distance from home plate to fi rst base, but it is real,” Brissie told a crowd gathered at American Legion National Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “It exists just as surely as the God we serve.”

He spoke of teamwork, sportsmanship, fair play and respect for “the rights and dignity” of others, lessons he believed represented the enduring value of American Legion Baseball. “When that citizen of tomorrow takes his position in the aff airs of our nation, he will have the moral and spiritual

LEFT: Opening game ceremonies prior to the team’s first game in Cartagena, Colombia.

about jungle warfare, and snakes, at the training center in Fort Davis.

LEFT: Dr. Alfred J. Suraci, team physician, leads a workout prior to the first clinic in San Salvador.

strength needed to meet the challenges America will face. We could ask for no fi ner tribute to American Legion Junior Baseball. We could serve no greater cause.”

As team numbers and participants grew through the 1950s, the cost of the national program mounted, and discussions began about possibly playing the American Legion World Series at a permanent site, like the College Baseball World Series in Omaha, Neb., or the Litt le League World Series in Williamsport, Pa. Nearly 50 years later, that idea would come to fruition.

Rare footage online

See a 20-minute video titled “Ambassadors at Bat,” produced in 1956, that captures the entire American Legion Ambassadors’ Latin American tour, made by The American Legion National Headquarters and sponsored by PanAmerican World Airways. This and other historical videos of American Legion Baseball are online at:

www.legion.org/baseball/centennial

“Legion Baseball teaches the philosophy of sports, of competition, and that’s the critical thing, much more than winning or losing.”

Chuck Lindstrom, 1953 American Legion Baseball Player of the Year, remembering his time playing for Winnetka, Ill., Post 10, which propelled him to college and professional baseball, including one Major League appearance, and a 23-year career as a coach

The Legacy of George W. Rulon

Wounded in combat while serving in the Army’s 1st Infantry Division during World War II, George W. Rulon of Fargo, N.D., came home with two Purple Hearts, a Silver Star and a Bronze Star. After earning a college degree, he soon went to work for The American Legion’s Department of North Dakota. He had been an American Legion Baseball player as a teen, and a sportswriter for a time, but his fi rst job for the veterans organization had nothing to do with athletics. He was a service officer, helping veterans with their disability benefits and health care and, later, as assistant adjutant for the department. At Post 2 in Fargo, he ran the bingo game, raised funds for the March of Dimes and served in the color guard.

In 1958, Rulon was hired at American Legion National Headquarters and worked in membership until 1961 when he took the reins of American Legion Baseball. His title was “program coordinator,” the term “commissioner” having been scutt led after Lou

Brissie’s tenure.

The next year, Rulon was in Cooperstown, accompanying Bob Feller at his induction ceremony into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

“As I stood there awaiting the induction proceedings, (George Rulon’s) presence suddenly sent me back to those wonderful days in American Legion ball,” Feller wrote in 1963. “The same things happened to me many times in the majors. Often, I pitched before stands crowded with Legionnaires who were attending American Legion conventions in Chicago, New York, Washington, Philadelphia –almost every city in The American League circuit. I’d see the Legion caps all around and immediately I’d fi nd myself thinking back to the days when men wearing those same caps were building my baseball foundations.”

At that time, Feller was 44 and leading the American Legion Baseball division of the Cleveland Baseball Federation. He traveled from ballfield to ballfield – 120 American Legion teams in the city at that time – and occasion-

George W. Rulon (left) shares a moment with 1961 National Baseball Hall of Fame inductee

Max George Carey (center) and Richard R. Roniger (right), 1960 American Legion Baseball Player of the Year, during the annual Hall of Fame Baseball Game in Cooperstown, N.Y., July 24, 1961. American Legion Photo

President Lyndon B. Johnson used this pen, now kept at American Legion National Headquarters, to sign a resolution proclaiming Aug. 31 - Sept. 6, 1965, as “American Legion Baseball Week,” in honor of the program’s 40th anniversary. U.S. Sen. Karl Mundt, R-S.D., the resolution’s author; South Dakota Gov. Niles Bow; and Major League legend Ted Williams were among the dignitaries at the Aug. 30 banquet in Aberdeen, S.D., to kick off the American Legion World Series there. Mundt told about 1,000 in attendance that the program was “an opportunity to participate, through baseball, in better understanding of citizenship.” Photo by Jennifer Blohm

ally even pitched batt ing practice. “I treat the boys as big leaguers, mixing curves with fast balls – well, a 44-year-old Feller fast ball. If the boys get a kick out of this, the feeling is mutual … All of them will be better citizens because of their American Legion Baseball experiences.”

In Rulon’s quarter-century as program coordinator, the name American Legion Junior Baseball was shortened to American Legion Baseball. The age limit for players was raised to 19, thus allowing 18-year-old college freshmen to participate. The commitment from Major League Baseball had increased over the years to $75,000 annually. American Legion Baseball celebrated its 50th season by returning to its birth state for the World Series in Rapid City, S.D., in 1975.

Stadiums in communities like Boyertown, Pa., and Fargo, N.D., were built or rebuilt specifically for American Legion play. Rulon had always contended that the World Series is best – and best attended – when it is played in a smaller community, rather than a big city. And a fledgling cable television network, ESPN, recorded its fi rst broadcast of the American Legion World Series in 1979.

Rulon retired from The American Legion on Jan. 1, 1987, and died two years later.

During his tenure, the World War II combat veteran got to know one future Hall of Famer who, like Bob Feller, embodied the program’s founding vision. “The 1964 American Legion World Series should have been called the ‘Rollie Fingers Series,’” William E. Akin, wrote in “American Legion Baseball: A History, 1924 –2020.” Dominating on the mound and at the plate, the lanky, 6-foot-4 Upland, Calif., Post 73, pitcher/outfielder threw two wins in the tournament, captured the Louisville Slugger Award for highest series batt ing average (.450) and after a regular season posting a 0.67 earned run average, was named American Legion Baseball’s Player of the Year. He soon signed a contract with the Kansas City Royals and in the early 1970s helped lead the Oakland A’s to three championships. In 1981, Fingers won the Cy Young Award and was the American League’s MVP, the only player to

be named most valuable in Legion and Major League ball.

When Fingers personally accepted his American Legion Baseball MVP award in 1965, George W. Rulon made the arrangements and accompanied the California teen who was presented the award by none other than Bob Feller. “George was always smiling and nice to talk with on the phone,” Fingers told Th e American Legion Magazine in 2019 aft er he, himself, had made presentation of the Legion award an annual tradition at the Hall of Fame. “Everything about George was professional. The guy loved Legion baseball like no one else.”

Like so many American Legion Baseball alums – including Cincinnati Hall of Famer Johnny Bench; his teammates Ken Griffey Sr. and Pete Rose; legendary pitcher Tom Seaver; New York Yankees manager Joe Torre; and Rick Monday of the Kansas City Royals/Athletics, Chi-

LEFT: Rollie Fingers of Upland, Calif., Post 73 dominated the 1964 American Legion World Series, earning Player of the Year honors. American Legion Photo

BELOW: Fingers shares a moment admiring the championship ring of Will Smith, George W. Rulon American Legion Player of the Year for 2016, at Doubleday Field in Cooperstown, N.Y. Photo by Vi Nguyen

cago Cubs and Los Angeles Dodgers – Fingers made time for military service during his professional playing days, in the U.S. Army Reserve from 1966 to 1972.

In 2019, the year of The American Legion’s centennial, Fingers, Feller, Bench and D-Day veteran Yogi Berra were among those named to a fan-voted American Legion All-Centennial Team. Fans voted for Torre, who received the prestigious American Legion James V. Day “Good Guy” Award in 2015, as manager.

In 1986, the American Legion National Executive Committ ee passed a resolution to rename the American Legion Baseball Player of the Year trophy in honor of Rulon, who was known for his funny stories about the program through the years and always wore the same mustard-colored shoes to the World Series for good luck against rainouts. One reward for receiving Player of the Year honors

is an all-expenses-paid trip to Cooperstown, N.Y., for the Hall of Fame Classic on Memorial Day weekend, the centerpiece of which is a seven-inning exhibition game featuring former MLB stars who are enshrined.

The award’s stated criteria: “integrity, mental att itude, cooperation, citizenship, sportsmanship, scholastic aptitude and general good conduct.”

When Will Smith of American Legion World Series champion Texarkana, Ark., Post 58, received the George W. Rulon Player of the Year Award in 2016 from Fingers and then-American Legion Americanism Chairman Richard Anderson, he summed up his moment in Cooperstown this way:

“Baseball is a lot more than just hitt ing and fielding. Being involved in American Legion Baseball has taught me a lot of things, like to respect the game, to respect small things and to respect the culture. I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else.”

Puerto Rico power

Ed Kimmel’s home run over the centerfield fence was the key to Valley View (Pennsylvania) Post 575’s clinching state tournament game against Wyalusing, Pa., in 1960.

One of the most successful American Legion Baseball programs of the 1970s did not come from the continental United States. The Department of Puerto Rico took fi ve straight regional championships and back-to-back American Legion World Series crowns by Rio Piedras Post 146 in 1973 and 1974. Puerto Rico teams qualified for the ALWS 10 times between 1969 and 2024, with one more championship, in 1984, taken by Guaynabo Post 134.

Among the greats who came up through American Legion Baseball in Puerto Rico was Ivan Rodriguez, 13-time Gold Glove catcher for seven MLB teams, inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2017. He played Legion ball in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico. Another Hall of Famer, 12-time MLB All Star Roberto Alomar, played for Post Salinas in Puerto Rico’s American Legion program.

John P. “Jake” Comer was elected national commander., 1987-88.

The homer that inspired a commander named Comer

A special honor was in store for the first player to hit a home run in the 1975 American Legion World Series, in recognition of the program’s 50th year. The ball would be retrieved and sent to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

On the first pitch in his first at-bat, second baseman David Perdios of West Quincy, Mass., parked it.

Not only did the ball go to the hall, that moment launched a half-century of love of the program for John P. “Jake” Comer, who was commander of The American Legion’s Department of Massachusetts that year and had arranged travel to the series in Rapid City, S.D., for 55 parents and supporters of the

Morrisette Post 294 team.

“My love of baseball came about because of that world series,” Comer explained. “I was never much into baseball before that. I got excited about American Legion Baseball from that point on. Then I started going to all the ballgames back home and going to the regional tournaments.”

A Korean War veteran who joined The American Legion in 1962 and went on to serve as national commander in 1987 and 1988, Comer is joined by American Legion Finance Commission Chairman Gaither Keener of North Carolina on the American Legion World Series, Inc., board of directors.

Comer has not missed a series since

Shelby, N.C., became home for the event. Game after game, he can be found in the stands, carefully keeping his own scorebook, checking the stats of each player and enjoying the hospitality – which for many years included a haircut at the same barber in Shelby.

“He’s a member of the Legion,” Comer said in 2016. “He’s part of this program. When I walk into his barber shop, he says, ‘Hi Jake.’ That, to me, is why we have to support Shelby as they support us. It’s just great for our program.”

After his historic home run, Perdios went on to coach the West Quincy Legion team and at Milton College. “He was Mr. Baseball for a long time,” Comer said.

“Back in the day, you got one trophy, and that was MVP for the team that won it all. You didn’t get a trophy for showing up to practice. You got put on the bench if you didn’t show up. I learned from American Legion Baseball and my coaches, that you’ve got to work hard for it. It’s not going to be given to you.”

Hall of Fame relief pitcher Lee Smith of the Chicago Cubs, who played American Legion Baseball in rural Louisiana (only after his farm chores were done); he explained in 2019 that he remained close friends with his Legion coach, James Morgan, who was 87 at the time

What service meant to Johnny Bench

Hall of Fame Cincinnati Reds catcher Johnny Bench was presented with the James V. Day Good Guy Award at the 2016 American Legion National Convention. His career as a player after American Legion Baseball for Post 24 in Anadarko, Okla., is legendary. In 1973, two years before he helped lead the Reds to back-to-back Major League World Series titles, he was named the American Legion Graduate of the Year. His patriotism and commitment to service, however, are less known.

John Raughter of The American Legion Media & Communications Division interviewed Bench before a national convention luncheon where members learned there was more to the two-time National League MVP than his time behind the plate.

On his military connections: My dad actually served two hitches in the war – World War II. He was in North Africa

and Italy. I enlisted in ‘66 in the Army Reserve for six years. Did my basic training at Fort Knox and my combat support training at Fort Dix. I was a fi eld wireman and made several summer camps – Watertown, N.Y., Camp A.P. Hill and Fort Sill, Okla.

On fitting Army Reserve drills around a pro playing career: The team didn’t have a choice, really. I did my weekends. They made me a cook. And I would get over there at 4:30 in the morning, and I would prepare the meals and as soon as lunch was served at 11:30, they released me, so I could actually get to the ballpark and play games that afternoon. I was an E-4 when I got out. I graduated first in my class in combat-support training. I enjoyed the military. I did my basic training, I got out right in the middle of spring (baseball) training after they started. So I was in good shape, probably the best shape of my career. I was still in the minor

leagues. I came up in `67. (MLB player) Bernie Carbo and I were together. I think he was the No. 1 draft choice in ‘65. We did what you had to do. That was the obligation, and you fulfilled your obligation as a good American.

On the influence American Legion Baseball had on him: It was huge. We had organized baseball in Binger, Okla. My dad started that team, but when I got to be 14, in order to move up, we certainly didn’t have the size of the city in order to support an American Legion team, so I had to go to Anadarko. That team in Anadarko actually had a couple of kids sign in the Major Leagues, so there was a lot of attention due to the quality of players that were on that particular team, and it was sort of a hotbed for players in those days.

On his support for veterans after baseball: I co-hosted an event with Doug Flynn (former MLB player) –

Hope for the Warriors … for seven or eight years. I also do USA Cares down in Louisville, Ky. We raised a little over $500,000. Almost all of that goes to mortgages, to groceries, to gas to supplement the needs of the families. We know that 22 veterans commit suicide every day; 19 are Vietnam veterans. I’m sort of the honorary chairman of Save a Soldier, kind of like an AA meeting where they meet up and talk to each other about their lives.

My dad came back (from war) and his dreams were dashed. He wanted to be a catcher in the major leagues, and so he wanted one of his sons to be a catcher.

On traveling with Bob Hope to support U.S. troops. I went to Vietnam with trepidation with how I would be received. I was healthy and in the Major

Leagues. It was phenomenal. They just welcomed me with open arms and of course, Bob, for what he does for the morale of the troops and everything else. We were in and out of Vietnam three times. I went to Desert Storm in 1990. We went to West Point, Anchorage … we went around the world.

On the reason he created the Johnny Bench Scholarship Fund: I didn’t go to college. I had some scholastic scholarships. I was valedictorian. I had athletic scholarships in baseball and basketball. My dream was to play baseball, so when I was drafted, I signed … but I didn’t get to go to college. I think it was important; I think education was the most important thing. So that was the one thing when I retired that I wanted to start was a scholarship fund.

The Barth tradition

Joe Barth Sr. started the Brooklawn, N.J., Post 72 American Legion Baseball team in 1952. In his 61 years as skipper, he led the team to 26 state championships and two American Legion World Series titles.

The tradition of success became a dynasty in the 21st century. His sons, both former players who grew up around American Legion Baseball, coached Post 72, with their dad always at their sides as team manager. One of those sons – Dennis, who was born at the same time his father was coaching in an American Legion World Series – led Brooklawn to fi ve straight championship tournament berths between 2011 and 2015 and won titles in 2013 and 2014.

Joe Barth Sr., Joe Barth Jr. and Dennis Barth are all past recipients of the Jack Williams Memorial Leadership Award as the top American Legion managers and coaches of the year.

A Woodland Hills, Calif., American Legion infielder makes a tag on a Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, baserunner in the 1989 World Series title game. Woodland Hills would go on to win it all that year, completing a 39-7 season. American Legion photo

Bowie Kuhn on “intangible values”

Modern baseball had turned 100. American Legion Baseball was celebrating its 50th anniversary. At the time, 83% of big-league rosters were comprised of former American Legion players. Major League Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, a member of American Legion Post 342 in Freeport, N.Y., who later received the Legion’s most prestigious award, the Distinguished Service Medal, wrote these words in an October 1975 article for The American Legion Magazine:

For most Americans, the impact of the game has run much deeper than its entertainment value. Everyone instinctively sees in baseball a game modeled after what is important in life itself. The evidence of that runs deep. It has always been so widely recognized that nobody raised the slightest question when nationwide American Legion Baseball for youngsters was fi rst proposed at the South Dakota state convention in Milbank, S.D., in 1925.

The idea wasn’t put forward simply to get youngsters to play a game. There was unanimous agreement that while baseball would help in physical training and “get kids off the

streets” it would also be a school for all sorts of intangible values in the game of life, such as “citizenship,” “teamwork,” “integrity,” etc.

Nobody ever said that about shooting pool or playing tag.

But, of course, the degree of teamwork and self-discipline in baseball when nine men have to be ready (without a fraction of a second delay) to coordinate themselves in one explosive blending of their different skills and responsibilities; each man being where he has to be or backing up another; ignoring the possibility of injury to execute the play; always alert to the total, changing situation; and all the time heeding managers and coaches and readapting in an instant if a teammate misplays – all this is the superlative parallel in sports to the highest ideal of humans working together in life …

… But more important, on Legion diamonds across the country, these young men are learning not only the skills of baseball, but the valuable lessons of sportsmanship, self-discipline, teamwork, courage and integrity which will make them better American citizens.

“When you play Legion ball, you are playing with people who care about you. There are friends who you have played with and friends who you have played against. It’s just more structured, and the competition, I feel, is a lot better. It was one of the best opportunities I’ve had.”

Braden Shipley, pitcher, Medford, Ore., who led Post 15 to the 2009 American Legion World Series and was selected by the Arizona Diamondbacks in the 2013 Major League Baseball draft

Rick Monday’s great play

The Chicago Cubs were in Los Angeles for a game against the Dodgers on April 25, 1976, when two protesters – a father and son – ran onto the field and attempted to light a U.S. flag on fire. The wind blew out the first match. A second match was struck.

But before it could catch the flag on fire, Chicago centerfielder Rick Monday, who had played American Legion Baseball in California for Santa Monica Bay Cities Post 123 as a teenager, sprinted to the scene, gabbed the flag and rushed it to safety. The protesters were hauled off by security.

The crowd rose, locked arms and

began singing “God bless America.” The scoreboard flashed the words “RICK MONDAY, YOU MADE A GREAT PLAY.” ESPN later called it one of the 100 greatest plays in the history of baseball.

“Whatever their protest was about, what they were attempting to do to the flag was wrong for a lot of reasons,” Monday later told the media. “Not only does it desecrate the flag, it desecrates the effort and the lives that have been laid down to protect those rights and freedoms for all of us.”

If anyone was a lock that year for American Legion Baseball Graduate of the Year, an award presented to a

former Legion player on the basis of “character, leadership, playing abilities and community service,” it was Monday, who spent 19 seasons in the big leagues and served six years in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserves, actively drilling for half a year annually before spring training between 1966 and 1971.

In 2006, Monday testified before Congress with The American Legion and the Citizens Flag Alliance, in support of a constitutional amendment to protect the U.S. flag from deliberate acts of desecration. At the hearing, he brought along the flag he had saved, which he has kept throughout his life.

Dave Winfield on the right way to play

At a time when the reputation of the sport was reeling in America, under the cloud of steroid abuse, disinterest in the inner cities and lack of access to playing fields, former St. Paul, Minn., American Legion Baseball star Dave Winfield wrote what he called “a check-up and a prescription for our national pastime.” The New York Yankees Hall of Famer authored “Dropping the Ball” and promoted his “Baseball United” concept to restore faith in the game.

In an October 2007 interview with The American Legion Magazine, Winfield said, among other things:

The game I love is hurting. There is a disconnect in the game. Under that disconnect, there are three Cs. One is competition. One is cost. And one is continuity. This is why I titled the book “Dropping the Ball.” Baseball, for a long time, was passed from father to son, generation to generation, seamlessly. It didn’t cost anything. Now Parks and Recs don’t have budgets to support baseball, and other sports have come into that vacuum. When I grew up, baseball was huge – the primary sport in America.

Now, this isn’t the case. People didn’t think the Super Bowl would succeed. People didn’t aspire to be an NBA player. College sports were nowhere near as large as today. There were no such things as video games, and kids in America could go outside and play for hours at a time unsupervised. Society has changed. A lot of places today don’t even have baseball teams that are of primary importance or competitive, especially at public schools. So, America is looking at two separate but unequal paths to playing baseball. If you grew up in an urban area with an under-funded Parks and Recreation department, you have little chance of playing good baseball.

I offer suggestions … It may be the strength of an American Legion program or a Parks and Recs department. It may be the strength of a small businessman or a large corporation saying we are going to establish an area where we have fields designated for youth baseball, at each level, with consistency of coaching, moving to the next level.

The public is conflicted about the

top players. People are conflicted about, “Should I support them? Should I like them? Do I want my kids to be like them?” That’s the image people have of baseball and our top players. When we look back 10 years from now, we will look at 1996 to 2006 as an era that’s suspect. Some argue that the drugs weren’t illegal in the sport at the time. I say, “Hey, the drugs were illegal in America. If you were transporting, selling or using them, you can go to jail. So. they were illegal. That’s not a defense.”

(American Legion Baseball) was a very positive experience for me. It was a proud time for our community, too, because we had some pretty good teams and gained some recognition. It was just part of the youth baseball experience that brought our community close together – the families, the kids, the experiences of growing up. It was valuable. I had good coaching, and we had good teams. The American Legion tournaments contributed to me getting college scholarships and being drafted by Major League Baseball.

Rules to promote player health and safety

American Legion Baseball made a significant move to protect the arms of young pitchers in the mid 2010s.

The Pitch Smart initiative – advanced by USA Baseball and Major League Baseball – called on all American Legion teams to adopt and adhere to guidelines to educate parents, players and coaches to prevent long-term injuries. The philosophy of the initiative was adopted by The American Legion, which has a seat on the USA Baseball Board of Directors, and soon became fully compliant with pitch-count restrictions and rest requirements to prevent overuse of arms, which can end player careers before they even get started.

Approved in 2017 and adopted in 2018, the rule change reduced the daily maximum of pitches from 120 to 105. Pitcher rest requirements were adopted for American Legion play, including:

1-30 pitches: 0 days

31-45 pitches: 1 day

46-60 pitches: 2 days