Man Holds a Fish A

With gratitude

This book is dedicated to those who appear in it

Glenn Busch A

Man Holds a Fish

What I Have Seen

Glenn BuschA few years before she died, my mother told me the story of my beginning. I was conceived, she said, in the late afternoon, a still, bright sky over the field of long grass in which they lay, about them the sound of insects, above them the slow circling of seabirds on rising currents of warm air. Nine months later I was born dead. Or at least, without breath. A determined doctor by the name of Ballin worked hard to get me going.

What I know of those moments, what I understand of my life now and all that’s occurred in between, comes from fragments such as this. Multifarious bits and pieces, seen and heard along the way.

Our stories sustain us; give substance to our existence. Some tell of a moment, others of a lifetime and beyond. Listen carefully to the stories of others and they may tell us something of ourselves. The story of any person exists first in the mind of its teller, perpetually renewing itself as, like smoke in wind, it is constantly shaped and reshaped in the flux of daily life. Narratives constructed from various facts, memories and rumours are added to, subtracted from, come together and fall apart in a continuous reassembling of experience and imagination. The human mind is a place where fact meets fiction, where reality and fantasy mingle easily and endlessly with fabrication, half-truths and invention. As they say, looking at something is no guarantee you will actually see it.

Nevertheless, the telling of tales is a very human thing to engage in, and at the time my mother – a woman who never had a problem with the word ‘exaggeration’ –recounted her story, it was told so simply, so plainly, that I like to think it held a certain veracity. It was she who gave me my first books, passed on the first stories; the genesis of what became a lifetime interest. Though, perhaps as a reaction to her constant overembellishment, I became attracted to the unadorned and have tried to see what unfolds in front of me in a less complicated way.

The images I have made, the various stories I have collected over time, do not belong to me – they are owned by those who have been willing and kind enough to share them. I have simply put down, as best I could, what has been told or, in this case, shown to me.

My father, a more straightforward person, lies now in a grey plastic box placed between books on a shelf, close to where I write this. Physically, there is not much of him left. Hardly anything at all. Some of him, as it always does, remained at the crematorium. My family, those who could make the journey south from Auckland – the city in which he had lived much of his life, and where he died – brought with them what they were given.

Half of his remains now reside with the Īnangahua River, where he swam as a child. It lies close to Reefton, a small 1870s gold-rush town on the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand, from where he came. The rest they delivered to me in Christchurch, on the other side of the Southern Alps. Because of his love of flying, that last little bit of him was to be deposited on the field of an air-force base. A place where, towards the end of the Second World War, he had presented himself, lied about his age and was trained to be a fighter pilot. By the time I arrived, however, the airfield was being transformed into a housing estate and depositing what was left of him on somebody’s newly laid front lawn was not really an option. So, here he is, with me still.

I loved my father and thought him, in his own way, to be special. He worked harder than most people I know, coping, undaunted, with the hand he had been dealt. As a child, I watched him deal with the sort of things we must, from time to time, face up to. Perhaps the most important things I learnt from him – by osmosis really –was the idea that you can do anything you set your heart to; that we are closer to each other than we sometimes think; and that nobody is more important than anyone else.

Compared to his, mine has most certainly been the lucky generation. At least it has been for some, and so far my own luck has held. My father’s story begins with pain; unhappiness his childhood companion. Later, there were other disappointments through which he strove to make our childhood better than his own. Above it all his braveness shone. He was tall enough, and handsome in the way we thought

New Zealanders of that time should look. Straight-backed, strong-jawed, a flash in the eyes, well-muscled, a man unafraid of mortal things. A man to stand with any other, in friendship – or conflict. A man who, against the odds, taught his children to love.

His story, my mother’s story, most people’s stories, are destined to go on after the last of our remains have been dealt with. Not a straightforward narrative of course, nothing linear or sequential as it sometimes appears to be in life, but perhaps something closer to a mosaic, a collage of memories and pictures held most closely in the minds of those who know and love us. Over time it will doubtless change. Within our storytelling tradition it will be added to or subtracted from, until finally, at some point in the future, it will disappear altogether. I don’t call it history. History, as someone once said, is for heroes and despots. Stories are something else altogether.

Adulthood happened easily for me. My parents’ nomadic tendencies encouraged it. By the age of fourteen, I was selling my labour for money whenever I was in need of it, spending what I earned on whatever made me happy – or was perhaps required. Life, so it seemed in those early years, was one random step in front of the other until, one fortuitous afternoon in the autumn of 1971, something happened that caused a shift in possibilities.

Quite by chance, I found myself in a room full of the most extraordinary people, or rather, photographs of people. They had been made by a man named Gyula Halász, known to the world today as Brassaï, the name he derived from his Transylvanian birthplace. It would be true to say that the work I stood looking at for many hours that day astounded me; and even before leaving the room, I realised a transformation had taken place. Some sort of shift or movement in the way I thought about what I might do with my life.

‘Hey!’ he says. ‘Hey.’ Then more quietly says, ‘Over here.’ I turn my body and my camera towards the voice that comes from behind me. It is early morning in the Auckland fish markets. The smell of kingfish, mullet, snapper, sea creatures of many kinds, permeates the building. The fluorescent lights flicker and bounce off the water that flows everywhere, covering the floor, the walls, the tables and the workers themselves. In front of me now is a man with Stalin’s moustache but not his face. He wears a European cap over a shy, gentle expression. He has kind, shining eyes and holds a large fish. ‘Take a picture of this,’ he says, happy and a little bashful at the same time. I raise the camera to my eye and do as I am told.

Later, in a darkroom under a dull red light, I watch hopefully for that moment of magic as the image slowly emerges in its tray of developer. ‘Yes,’ I tell myself, feeling happy and surprised at the same time. In front of me is the first picture I have made that seems to say something all by itself; the story of that moment, shimmering in the liquid. A picture made of silver, light and shadow. Hinting at the future, suggesting the past. His, and perhaps mine also.

Today, apart from my family and friends, it has become that thing which is most important to me. Indeed, from that time on, I became a maker of images, a gatherer of stories. My work, as I think of it, has been to preserve the stories, or, in the case of the book in front of you, the images, of people I have met along the way. To put down what I have seen in the best way I could. In doing so, I have tried to be honest with those who have shared the experience with me. Mostly they are small stories, or perhaps part of a story; a view of possibilities that requires the viewer or reader to reach inside themselves for a beginning or an end.

Once, a long time ago and full of the naivety of youth, I thought this to be enough. Now, older and more aware of the complexity of life, I am less certain. What once seemed to be whole now seems more like, well, fragments. Fleeting moments held now for a time in tiny particles of silver or ink. What I have become more convinced of are the things my father taught me: the durability of the human spirit, and the true kindness of strangers.

1. Three women Christchurch

3. Waiter, Salvation Army hostel Sydney

3. Waiter, Salvation Army hostel Sydney

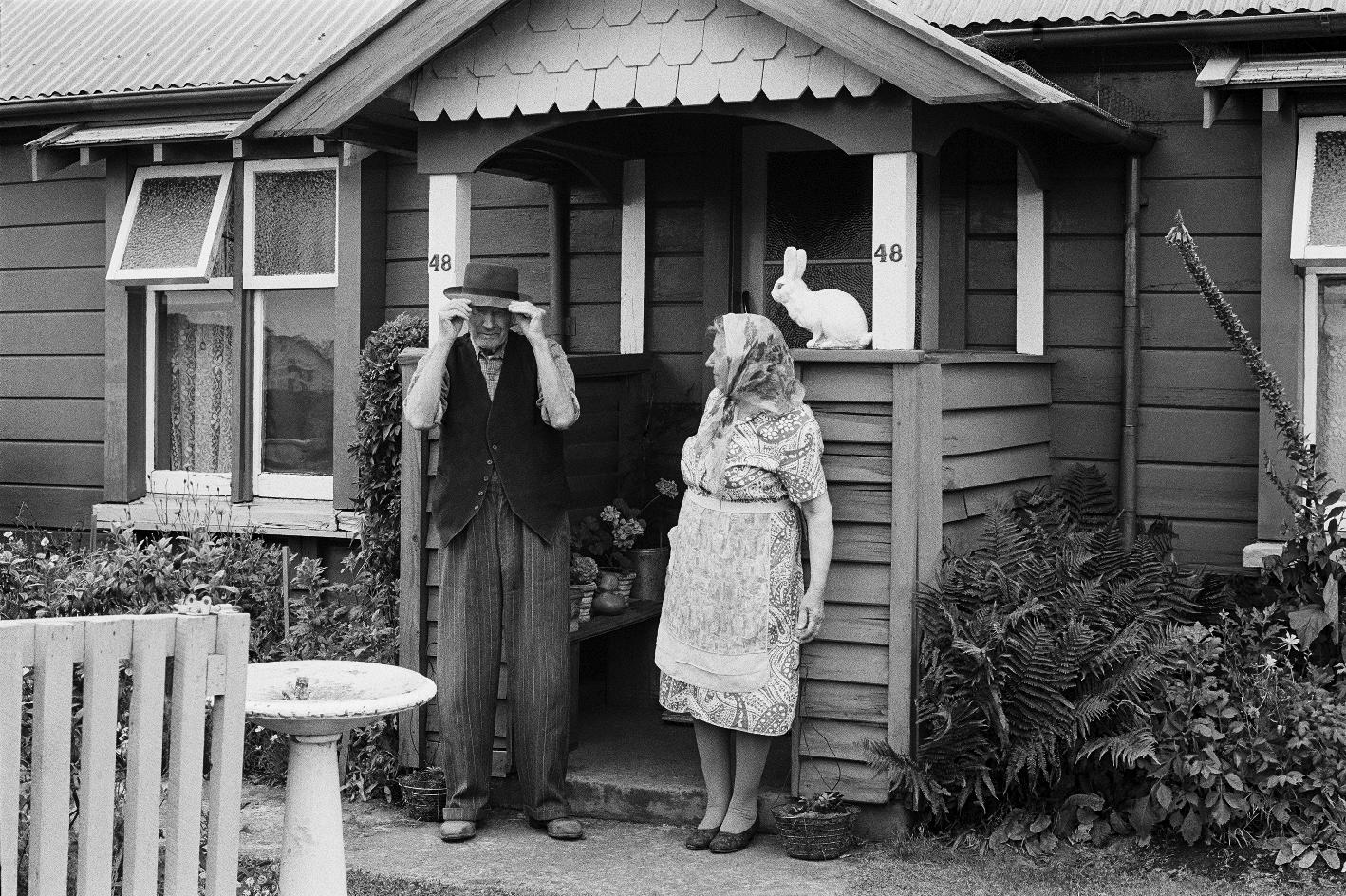

15. & 16. Couple with their white rabbit Christchurch

15. & 16. Couple with their white rabbit Christchurch

19. Woman with a wonderful hat

Auckland

19. Woman with a wonderful hat

Auckland

24. Woman in the sea, Whatipū Beach Auckland

24. Woman in the sea, Whatipū Beach Auckland

43. Boy with a broken arm, Cook Street Market Auckland

43. Boy with a broken arm, Cook Street Market Auckland

61. Man with a sledgehammer

Unknown location

62. Labourer, abattoir pig chain Christchurch

62. Labourer, abattoir pig chain Christchurch

About Glenn Busch

Glenn Busch, best known for his intimate, thought-provoking portraits and captivating social documentary work, was born in Auckland in 1948. He left school at 14 and spent his early years working as a manual labourer in many different places around Australia and New Zealand. His passion for photography began with the viewing of the work of the Hungarian photographer Brassaï and his understanding of the medium was helped through a chance meeting with John B Turner.

Throughout his career, Busch has focused on capturing the essence of daily life, often exploring themes of community, work and identity. His influential projects include Working Men, You Are My Darling Zita, The Man With No Arms and Other Stories, My Place and the ongoing Place In Time documentary project.

Busch has also contributed to New Zealand’s photographic education with his founding of the influential Auckland photography gallery, Snaps, and through his many years of teaching at the School of Fine Arts, University of Canterbury Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha.

A MAN HOLDS A FISH

RRP: $75

ISBN: 978-1-99-107201-6

PUBLISHED: August 2024

PAGE EXTENT: 168 pages

FORMAT: Hardback

SIZE: 330 x 280 mm

FOR MORE INFORMATION OR TO ORDER

https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/about/te-papa-press/contact-te-papa-press