photographers, who in theory operate under no such constraints, take their images in remarkably formulaic and purposeful ways: from family gatherings and birthday parties to holiday snaps and tourist sights. Look through any photographic archive and there are notably few photographs of people engaged in everyday activities such as brushing their teeth, washing the dishes, driving their car, sitting in an office. Photography is no ‘eye of God’, everywhere present despite the camera, in the form of the smartphone, now being so.

Museum photography collections do not stand outside history. Like photography itself, they can only represent or illustrate the past in limited ways, and this makes them contingent, idiosyncratic and partial. They are shaped by museum policy, staff interests, public perceptions and chance events. And some photographs, due to their perceived lack of public interest or value, rarely make it into museum collections at all. Public collections seldom acquire pornography, for example, despite it being a use to which photography has been put since its earliest days.6 Technical, medical and police photography are also largely absent.

For these reasons, New Zealand Photography Collected does not aim to tell a ‘complete’ history of photography in this country. It responds instead to a call by photo historian Geoffrey Batchen for histories about photography rather than of photography.7 Histories of photography tend to base themselves on the model of art history. A linear progression of styles, developed by a series of exemplary practitioners and images, is constructed, and artist status is imposed on many workaday photographers of the past. Such histories are abstract, concerned with images rather than physical photographs and how they are used and consumed in the real world. Histories about photography, on the other hand, deal with questions of production, reproduction, dissemination and collection. They consider not only how photographs operate in their time but also how they operate through time how their meanings change and multiply. This book is structured into chapters that reflect, broadly, why the photographs were made in the first place and some of the reasons they were then collected. It shows one way a history about photography can begin to look.

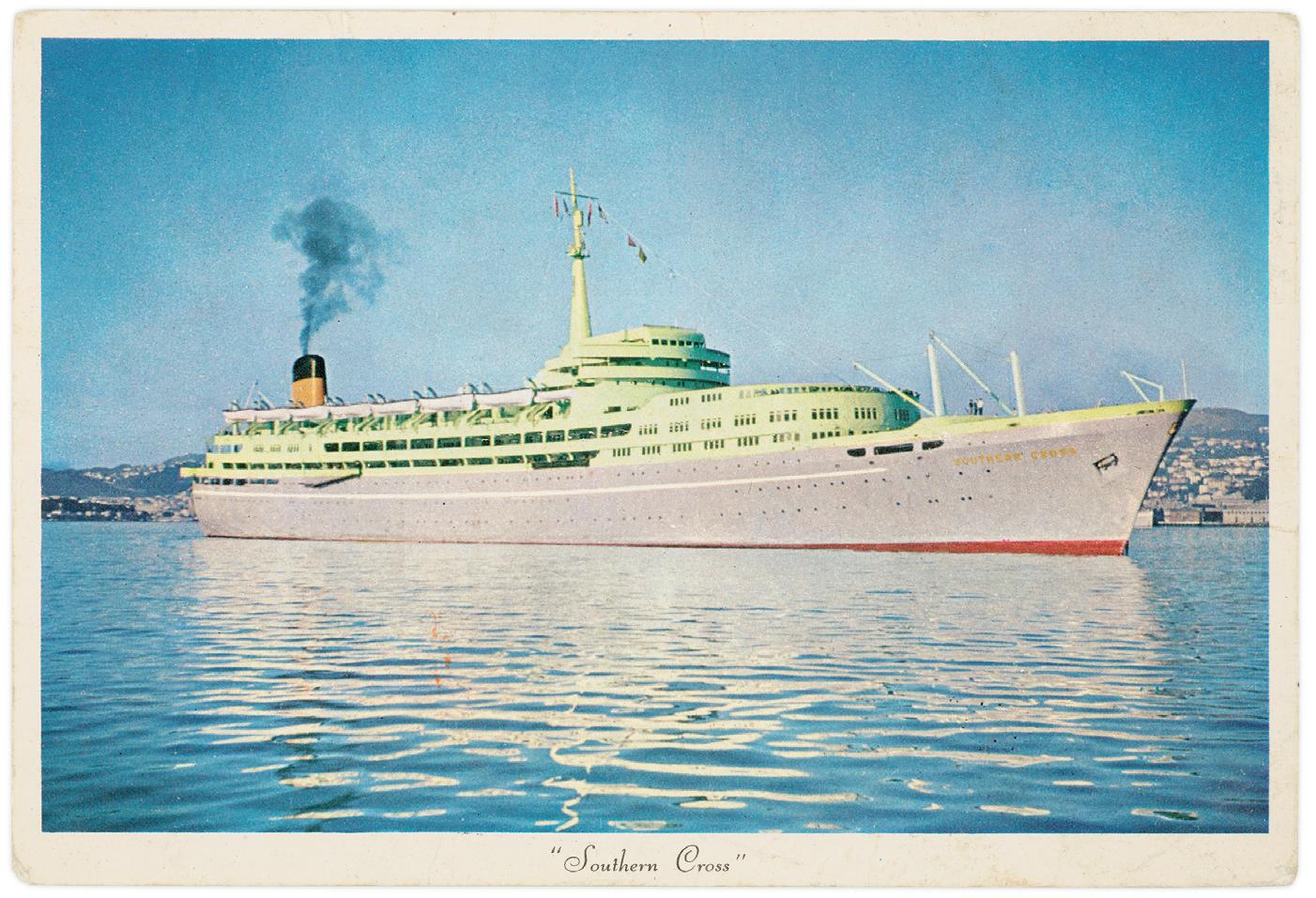

Left:

Unknown photographer

Southern Cross, Wellington, 1956

Postcard, offset lithograph, 92 × 142 mm

Private collection

Below:

Unknown photographer

Untitled, c.1910

Postcard, Woodburytype

Purchased 1996, PS.000448

Opposite:

Berry & Co

Mrs Robinshaw, c.1905

Gelatin glass negative, half plate

Purchased 1998 with New Zealand

Lottery Grants Board funds, B.044433

Algernon Gifford

Down Deep Cove, early morning, c.1895

Hand-coloured glass lantern slide, 80 × 80 mm

Gift of Mrs Murray, 1967, LS.005456

Oakley Studios or Crown Studios

New Plymouth High School Old Boys surf team, 1926

Gelatin glass negative, whole plate

FB Butler / Crown Studios Collection.

Gift of Frederick B Butler, 1972, C.003397

Chapter 1, ‘How we looked’, features studio portraits and snapshots of people. These are the photographs we take and accumulate of ourselves, our families and friends. Part of the motivation for taking such photographs is as a hedge against forgetting. Paradoxically, they are also easily forgotten. Once a person has passed from living memory, their photographs lose meaning, become mute. As family interest fades, such images often end up in a museum. Here in volume, and across many individuals and families patterns become clear. We see what sort of clothes people wore at a certain point in time, how they presented themselves in poses, the photographic techniques used, and what they did with the photographs. Where an individual might accumulate a composite family portrait from photographs, a museum assembles something approaching a national portrait, a catalogue of society. A coded set of private meanings is replaced by new, public readings.

Chapter 2, ‘Being there’, looks at the phenomenon of the ‘view’: from its origins in nineteenth-century landscape photography to its later expression in postcards and glossy publications. We consume these to bring what is remote close to hand: if we cannot easily visit Fiordland’s spectacular scenery, for example, we can experience it vicariously via book, magazine and website photographs; and if an event does not happen in our neighbourhood, we can see photographs of it in a newspaper or online. Photographs of such subjects operate the same way in a museum collection, but here the distance is not so much in space as in time. By collecting these photographs we can see how a place or event looked in the past. Unlike portraits in museum collections, most places and events are identified, and it is their specifics museums are more interested in than their general qualities.

Photographs of people, places and events combine in chapter 3, ‘Belonging and aspiring’. Here it is not any of these in isolation, but how they operate, often together, to help form social identities. We acquire and display group photographs of ourselves in clubs, sports teams and school classes, on tramping trips or at workplace functions that help define who we are. We also consume advertising images that propose who we could be, if only we drank the right soft drink, bought the right clothes or drove the right car. Again, by assembling such images in volume, and applying the perspective of time, such images lose their individual character and allow museums to reveal how we thought about ourselves at a collective level.

Museums do not simply collect photographs; they also create them. Chapter 4, ‘Pursuing knowledge’, presents a range of photographs originally taken for scientific, research or documentation purposes, which have gained new significance with the passage of time. In the case of the Dominion Museum, for example, the identities of two men pictured demonstrating tukutuku weaving in the 1923 photograph overleaf were incidental: the photograph was taken by a staff member as an ethnographic record, to document a technique. The men are in fact Te Rangihīroa (Peter Buck) and Āpirana Ngata two leaders of the 1920s renaissance in Māori culture who were both later knighted for their services to Māoridom. Today, we understand the photograph as documenting a significant moment in Māori development and for this reason approaching the status of taonga, or cultural treasure itself. Photographs like this suggest that the meaning of an image can change not only when it enters a collection but also during its time within the collection.

A contemporary photography movement emerged in Aotearoa in the late 1960s, and the National Art Gallery began collecting in this field in 1976. When the gallery merged with the National Museum to form Te Papa in 1992, Te Papa inherited this body of contemporary work examples of which appear in chapters 6 and 7.8 Chapter 5, ‘Conceiving a photographic art’, presents the historical backstory of the contemporary

George Crummer

Two women, c.1914

Gelatin glass negative, half plate

B.027758

George Crummer was born in New Zealand but lived in the Cook Islands from the early 1890s, where he married a Cook Island woman. He operated as a trader and photographer, and was also a bioscope

(cinema) operator for a time. He does not seem to have had a studio, as most of his portraits of locals are taken outdoors with improvised backgrounds. In this case, an assistant sits on top of a tivaevae quilt. His presence, the figure-ground pattern of the tivaevae, and the deterioration of the negative around its edges combine to create an inadvertent second image that competes with the portrait of the women.

Alfred Henderson

Wellington Physical Training School pupils.

Inscribed: Miss Sinclair, 1905–12

Gelatin glass negative, half plate

Purchased 1999 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds, B.079755

Double portraits of women posed closely together often appear in the photographic record. The sitters perhaps friends or sisters frequently wear the same clothes or have the same hairstyles, creating a doppelgänger impression. In this case,

there is an additional uncanny effect where the stripes on the outfits run together in the middle, suggesting a single dress covering melded bodies. The appearance is reinforced by the arm of the young woman at left doing double duty for both individuals in the centre. Visual ambiguities do not stop there: at right, in the background, the ornate frame of a mirror strangely fades away vertically. It is, of course, simply painted on the backdrop in a way designed to simulate our peripheral vision.

Unknown photographer

Bunny (Mary) Donachie (née Jones) ironing an egg, c.1954

Gelatin silver print, 212 × 155 mm

Gift of Colleen

Opposite: FR Lamb

Margery, Leo, Jeffrey comic, c.1960

Frame from stereo transparency pair, 11 × 12 mm

Purchased 2009, CT.058251

Just what sort of backyard comedy hijinks the people in this photograph are getting up to, or who they are, is unknown. Its most delightful characteristic, however, can’t be reproduced in the pages of a book. The photographer, FR Lamb, used a stereo camera to produce a pair of colour slides. Viewed through a View-Master’s binocular eyepiece, the twin images snap into super-real 3-D. The View-Master was introduced in 1939 and is still being manufactured today. While many of us would have been raised on commercially produced reels of cartoon characters and scenic wonders, Lamb’s stereo kit allowed him to make his own cardboard discs. He was probably one of only a few New Zealanders to do so.

Unknown photographer

Group sitting in a field, c.1917–20

Gelatin glass negative, half plate

Purchased 1991, A.009907

Amateur photographers have always enjoyed clowning around with the camera. This photograph has had its negative retouched so the three women, who are almost identically dressed (they could be sisters), sit quite intimately with two men who have been transformed into skeletons. Was this just a joke, or an act of revenge or spite? With no information on the photographer or the subjects we will probably never know. The retouching is crude, with black ink applied on the upper side of the glass negative, so it could be scraped off to reveal the two men. This would return us to the image made in the camera, but would irrevocably destroy its subsequent reworking, which is part of its historical meaning as well.

Ellis Dudgeon

Lake Hawea, c.1947

Hand-coloured gelatin silver print, coloured by Elaine Watson, 1962, 404 × 500 mm

Purchased 2023, O.051365

It is almost unknown for a hand-colourist to be identified on a photograph, but this one has a handwritten label on the back reading ‘Hand painted photograph by Elaine Watson, July 1962.’ This records that Watson hand-coloured it, not that she took it, for we know from a 1947 book in which it was reproduced in black and white that it was taken by Ellis Dudgeon, a photographer who ran a studio in Nelson from 1930 to 1970. Dudgeon’s scenic hand-coloured photographs were widely seen. Indeed, this image appears in colour on the cover of the upmarket magazine Mirror: New Zealand’s national home journal

in 1955. In that version, the colouring is quite different: there is much more yellow in the tī kouka (cabbage trees), there are red flowers on the bushes by the lakeside, and it is much brighter and sunnier throughout. It is a more upbeat, holiday image than Watson’s subdued and uniformly toned version, showing just how much interpretive room there was for colourists, who were rarely present when the photograph was taken.

Opposite:

National Publicity Studios

Mt Ngauruhoe National Park [sic], 1950s

Hand-coloured gelatin silver print, 376 × 300 mm Purchased 2011, O.037772

In 1924 the Department of Internal Affairs set up a Publicity Office to produce films, photographs

and printed material to promote the country to tourists and immigrants. At the end of the Second World War, the office split into the National Publicity Studios and the National Film Unit. National Publicity Studios (NPS) photographers travelled New Zealand looking for promotional images such as this hand-coloured mountain vista. Where Whites Aviation were taking photographs to sell as décor items, NPS were making their images to sell New Zealand. They typically focused on tourist attractions and aimed to present the country in the best light. There was apparently a list of guidelines for the photographers that included no photographs showing cars more than ten years old, no buildings with signs on them, and only depicting Māori who were ‘well dressed’ or wearing customary clothes.

Gordon H Burt Ltd

Display advertisements for ‘Petone’ Quality Goods, c.1928

Gelatin glass negative, whole plate

Purchased 1999 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds, C.019291

In an era when New Zealanders mostly wore clothes manufactured in this country, and much of this was woollen, places like Petone, Kaiapoi, Roslyn and Mosgiel were also synonymous with their woollen mills. These in turn became used as brand names by the manufacturers.

Even swimsuits were made of wool. Until synthetics came on the market, wool was a better choice than the revealing wet T-shirt effect cotton

could produce. However, wool tended to sag and cling to the body when wet in more revealing ways than today’s swimwear.

The model in these display cut-outs looks more like an airbrush painting than a photograph, but small details suggest there is a real person underneath all the retouching the way she grasps the rope, the clearly photographic nature of the wooden bollard on which she sits, the dimples around her knees, and the untidy nature of the towel or scarf she seems to be holding in her upstretched hand.

Spencer Digby studio

Wellington Cat Show, 10 June 1961

Roll film negative, 60 × 60 mm

Spencer Digby / Ronald D Woolf Collection.

Gift of Ronald Woolf, 1975, F.014897

Spencer Digby studio Persian cat, 1970

Roll film negative, 60 × 60 mm

Spencer Digby / Ronald D Woolf Collection.

Gift of Ronald Woolf, 1975, F.016389

Photographing cat shows was all part of the job for the Woolf family, who from 1960 ran the Wellington studio originally founded by Spencer Digby. Their negatives record large numbers of individual cats sitting in cages, but it is the photographs with people that are more interesting. They reveal not only how the competitions were social events, but also the relationships people had with their pets.

Opposite:

FR Lamb

Hay’s procession, Christchurch, 1956–57

Frame from stereo transparency pair, 11 × 12 mm

Purchased 2009, CT.058924

FR Lamb

Hay’s procession, Christchurch, 1956–57

Frame from stereo transparency pair, 11 × 12 mm

Purchased 2009, CT.058955

Christmas parades were begun by department stores in the 1930s as a way to announce the arrival of Santa Claus at their store. The parades became increasingly elaborate, with Santa accompanied by fairies, clowns and characters from nursery rhymes. Hay’s department store, a Christchurch institution for fifty years, began their parades in 1947. These were often photographed, though only rarely as stereo images for a View-Master disc like these shots.

Back in 1880, Pierre Janssen had outlined the sensitivity of photographic negatives to invisible parts of the spectrum, a sensitivity we now know extends from infrared to ultraviolet light, X-rays and gamma rays. Photography would go on to record other things we cannot see, from stopped motion and the bottom of inhospitably deep oceans to distant stars too faint for the naked eye.

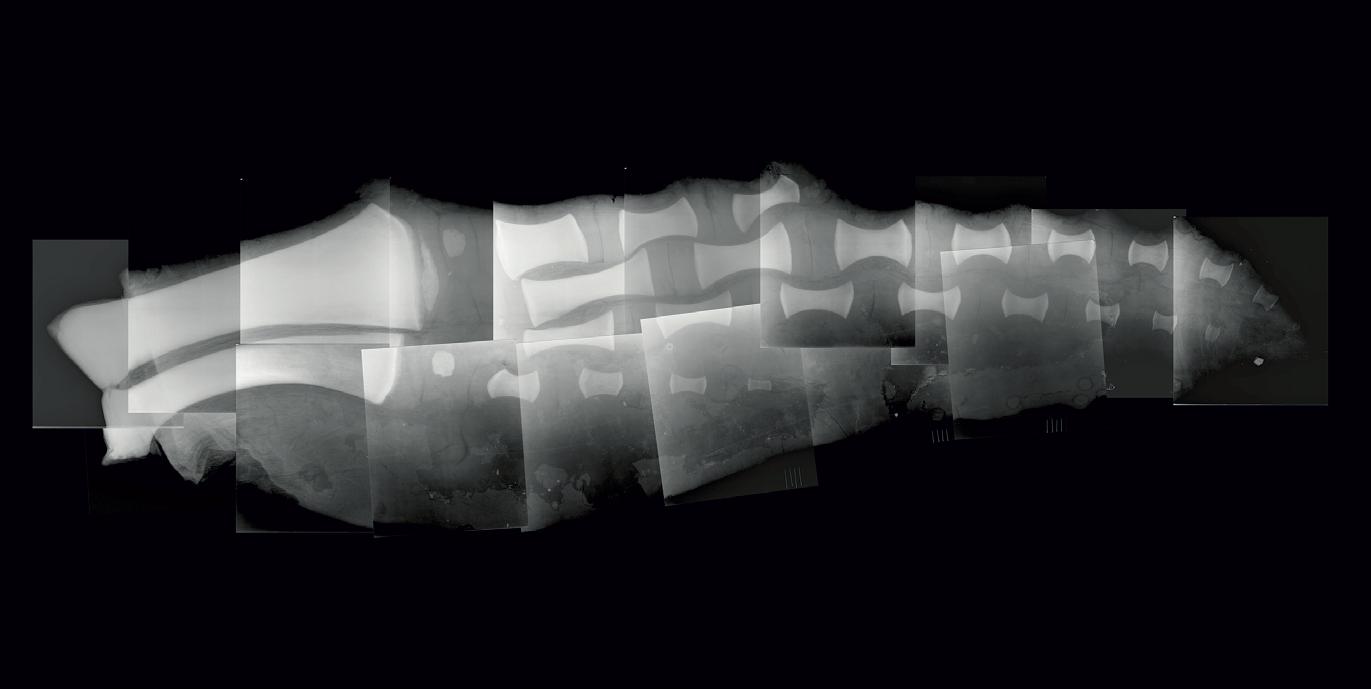

Museums continue to photograph specimens, but technology has transformed the practices Hamilton instituted over a century ago. X-rays reveal skeletal structure with no need for dissection; electron microscopy pictures tiny, ocean-dwelling snails with a previously unimaginable clarity; and digital processing techniques such as focus-stacking enable even minute objects to be photographed in full focus. The internet has allowed visual databases such as New Zealand Birds Online to be accessible by more than just the museum specialist, so anyone with an internet connection can identify a bird, plant or fish.

In the case of ethnology, the discipline itself has been upended. Māori have demanded the right to drive and direct museum scholarship on their culture; no longer are they the passive subjects of research. Where visual databases previously arranged taonga using the taxonomies of Western science, digital technology enables arrangement by tribal origin. Moreover, iwi are creating their own databases of taonga (treasures), drawn from museum collections all over the world.

As photographic techniques continue to improve, historical scientific photographs tend to lose usefulness, at least in terms of their original purpose. A photograph of a bird or plant made today is more helpful to the researcher than one made in 1900. It will be in colour, sharper, more likely to be of a live specimen (and, if so, closer) and its digital format will be easier to access and share. But period photographs have value nonetheless. Historic images of habitats, for example, show changes over time. Older photographs illuminate the twinned histories of photography and science, telling us about an era’s scientific ideas and the way in which photography was used in their pursuit. And lastly, they carry a period aesthetic that reflects prevailing technology, photographic and scientific conventions, intended uses, and attitudes towards subjects. Historical photographs made in the name of science are not the dated detritus of discarded ideas, but fascinating visual artefacts of their time.

Above:

Amy Kate Wilkinson Pigeon, Kapiti, c.1935

Hand-coloured lantern slide, 80 × 80 mm (support)

Left:

Raymond Coory, Anton van Helden and Pacific Radiology Ltd X-ray composite of a juvenile humpback whale flipper, 2007 Digital image, TIFF MA_I.357641

Above:

Jean-Claude Stahl

Buller’s albatrosses courting, Solander Island, 2003

Digital image, TIFF

MA_I.350067

Leon Perrie

Underside of Cyathea milnei fern frond showing reproductive structures, 2014

Digital image, JPEG

MA_I.360160

Above right:

Augustus Hamilton

Austral Islands carved canoe paddles, 1903–13

Gelatin glass negative, whole plate

MA_C.000403

James McDonald

Making hinaki nets [Nikora Toitupu and TauTamakehu at Hiruhārama], 1921

Gelatin glass negative, half plate MU000523/005/0331

Opposite:

James McDonald

Mat takapau made by Mrs Pokai [Whanganui River ethnological expedition, Koroniti], 1921

Gelatin glass negative, half plate MU000523/005/0715

In 1921, James McDonald accompanied ethnologists Elsdon Best and Johannes Andersen on a three-week expedition up the Whanganui River to document Māori traditions. They filmed, photographed and made wax-cylinder sound recordings. At first they were treated with suspicion, for the notebooks that Best and Anderson used made some people think they were tax collectors. But when Te Rangihīroa joined the expedition to record weaving and eel fishing techniques, and spoke on the marae at Koriniti, fears were allayed, for he was well known as the former second-incommand of the Pioneer (Maori) Battalion and for his work in improving Māori health. Anderson wrote that they ‘received the keys of the city’ and were treated with ‘royal hospitality’ from this point on.8 In photographing weaving for Te Rangihīroa, McDonald found that he ‘got interested in kit weaving & mat making’ himself.9

AM Macdonald

Road workers, c.1928

Gelatin silver print, 226 × 270 mm

Purchased 2009, O.031788

Arnold Morell Macdonald was an Invercargill barrister and solicitor and an early New Zealand pictorialist. As William Main has pointed out, the New Zealand climate was not so conducive to the misty, atmospheric effects so favoured by British pictorialists, but here Macdonald was able to take advantage of some humangenerated haze.6 He also captured a nice rhythm in the diagonal line of men advancing with shovels at different angles into the steam and bitumen vapour.

Opposite:

Isabel Walmsley

The edge of eternity, 1940s–50s

Gelatin silver print, 296 × 248 mm

Purchased 1996, O.000294

Isabel Walmsley’s mystically titled image is, perhaps appropriately, difficult to describe. It seems to depict a figure on a mountain top overlooking a vast, misty landscape below. There are strange things happening with the scale though. On close viewing, what looks like a large river may be a stream just metres away from the figure. And the cloud layer seen from above is too high to fit with the foreground, let

alone the sun or moon, or with what appears to be a mountain range with patches of snow seen side-on (rather than from above) on the left.

The construction may not make logical sense, but that was not Walmsley’s concern. The overall effect aligns with the pictorialist desire to avoid the mundane and literal in favour of the romantic and mysterious, and the title reflects her stated interest in mystical religions.

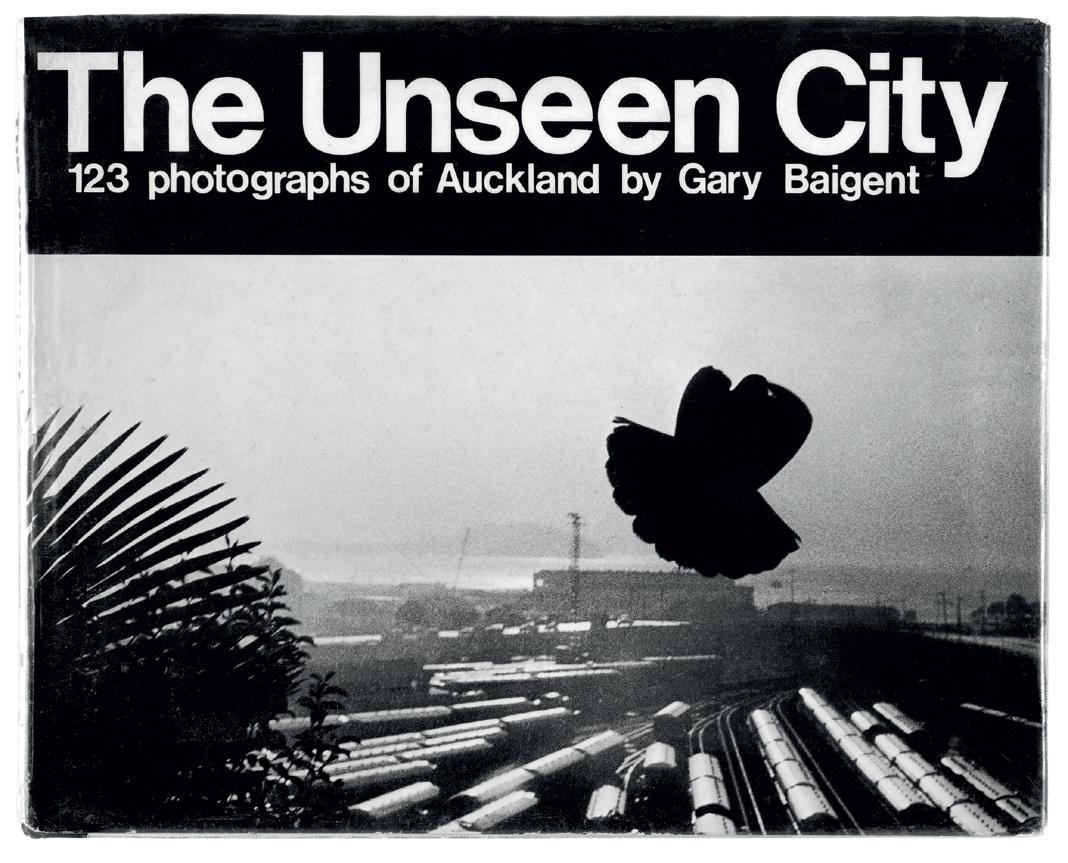

The predominant outlet for documentary photography has been publication its storytelling, serial nature suits the sequential experience of turning the pages of a book or magazine. Publications also serve the persuasive intent of much documentary work well, for their images can be more broadly disseminated and over a longer time than those seen in a one-off exhibition. New Zealand’s first documentary photography books appeared in the 1960s. In 1964, the Department of Education published Westra’s alternately celebrated and reviled booklet for schools, Washday at the Pa the story of a Māori family living in the country with no electricity or other modern amenities. Her second book, Maori (1967), was a far more substantial publication that took the journey from childhood to death as its thematic structure. Gary Baigent’s The Unseen City, the third significant documentary book of the decade, appeared in the same year as Maori and a year after Cleveland’s The Silent Land. In it, Baigent depicted what he saw as the ‘real’ Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland a gritty black-and-white world as it was on the street, in pubs, on construction sites and in student flats rather than hackneyed promotional shots in colour of happy families at leisure in the Domain, scenic views featuring the Auckland Harbour Bridge, or yacht races on the Waitematā Harbour. The book was, predictably, no great commercial success, but it nevertheless stands as a landmark. It appeared at a time when younger people were challenging societal norms and seeking alternative points of view on the world. By drawing on his own bohemian lifestyle, Baigent created a publication that represents the beginning of contemporary New Zealand photography as we know it today of photographers dealing with their immediate, personal experience of contemporary life.

In Pōneke, John Daley saw Baigent’s roughly shot and printed book and decided he could do better. He pounded the central-city streets after work on Friday nights and later extended his beat to Tāmaki Makaurau, using the camera to connect with a world that was a long way from his conservative, small-town upbringing. But Daley was not as lucky with publishers as Baigent; told there was no market for such a book, he was forced to shelve the idea for more than thirty years. When Big Smoke was finally published in 2004, part of its interest lay in the fact that his photographs had become historical evocations of an era now past.

If history wasn’t Daley’s original concern, it was certainly the domain of the photographer John B Turner, who helped Daley with layouts for his book in the 1960s. Turner was the Dominion Museum’s photographer from 1967 to 1970. His contact with the museum’s historical photography collection made him realise not only how little of the past had been recorded, but also how the same was true of the present. Turner embarked on a project to document the changing face of Johnsonville, the outer Te Whanganuia-Tara suburb where he lived. Far more importantly, however, he became a proselytiser for the value of recording contemporary history, communicating the lesson he had learned as a museum photographer to a generation or more of independent photographers.

Turner left the museum to become a lecturer in photography at the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts the only institution in the country then to offer tertiary study in photography. He was also a founding editor of the influential PhotoForum magazine, whose first issue was published in 1974. The two positions gave him a strong platform from which to promote documentary photography. In the second issue of the magazine, for example, he stated his case for a historical rationale to documentary. On the cover was a 1924 photograph by Leslie Adkin and a quote from internationally renowned French photographer Henri CartierBresson: ‘We photographers deal in things which are continually vanishing, and when they have vanished, there is no contrivance on earth which can make them come back again. We cannot develop and print a memory.’5 Inside, images by historical photographers James Bragge, Charles Spencer and Gordon Burt featured alongside the work of contemporary photographers John Fields and Paul Gilbert. In the 1990s, the PhotoForum organisation moved into publishing exhibition catalogues and books, and in 2008 launched the slim magazine MoMento. Today it supports a regular beat of personal photobooks. Throughout these transformations, documentary photography has remained a constant thread in PhotoForum’s publishing, a ‘do-it-ourselves’ response to commercial publishers’ lack of interest in the genre.

Above:

Danny Lyon

New arrivals from Corpus Christi, 1967

Gelatin silver print, 160 × 230 mm

Purchased 1990 with Ellen Eames Collection funds, O.003901

Opposite, clockwise from top:

Ans Westra

Ruatoria, 1963, from Washday at the Pa

Gelatin silver print, 198 × 186 mm

Purchased 1985 with New Zealand Lottery Board funds, O.003536

Gary Baigent

The Unseen City: 123 photographs of Auckland, 1968

Book, 279 × 217 × 22 mm

John Daley

Behind Civic Theatre, Auckland, 1969

Gelatin silver print, 182 × 268 mm

Gift of John Daley, 2012, O.038878

Turner also assembled a substantial library of international books on personal photography, which had been unobtainable in Aotearoa. Imported titles such as Danny Lyon’s Conversations with the Dead (1971), on prison life in Texas, and Bruce Davidson’s East 100th Street (1970), which took New York’s East Harlem as its subject, were shared freely with young photographers hungry for models of contemporary practice. Glenn Busch and Robin Morrison were two such photographers who were inspired by Turner’s library. Busch, for example, went on to produce his book Working Men (1984) on manual labour, and Robin Morrison published The South Island of New Zealand from the Road (1981). The enthusiasm for personal documentary that marked an entire generation of New Zealand photographers, from the late 1960s to the 1980s, owed much to Turner’s influence.

In the 1960s and 1970s, photographs and photographers were seen far less often than they are today. If asked why they were taking photographs of strangers in public places, most documentary photographers would have struggled to give an answer intelligible to a public not yet exposed to decades of documentary photography books and exhibitions. But if bystanders were puzzled, they were also tolerant. Today, with the potential for photographs to be circulated on the internet and security cameras everywhere, personal privacy is a more prominent issue. Any photographer working in public with professional-looking gear is now regarded with much greater suspicion than their historical counterparts.

Well before visual surveillance became a regular part of life, the idea that photographers were in a position of power over their subjects had

George Silk

Timber felling, King Country, 1947

Gelatin silver print, 277 × 267 mm

Purchased 2020, O.048713

The Family of Man is the most famous photography exhibition of all time. Mounted by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1955, it toured to thirtyseven countries and was seen by over ten million people. The exhibition never came to New Zealand, but we still had a part in the story among the 503 photographs was this one by New Zealand-born Life magazine photographer George Silk.

The exhibition design was akin to a trade fair, with the photographs flush-mounted and grouped in immersive, thematic environments rather than framed in linear art gallery wall hangs. Some were enlarged to huge scale, others were printed small. They were placed anywhere between floor level and ceiling height on the wall, or suspended on hanging screens. Silk’s image was displayed most radically of all mural-size, flat on the ceiling, so the viewer would be in the position of the photographer, looking up at the axe man.

John Pascoe

Trainee physical education teachers, March 1944

Gelatin silver print by Athol McCredie, 1985, 176 × 204 mm

Purchased 1985 with New Zealand Lottery Board funds, O.003512

Health and fitness were growing international preoccupations in the first half of the twentieth century, seen by many as the basis for a healthy society and nation. In 1937, the Physical Welfare and Recreation Branch of the Department of Internal Affairs was created to improve the fitness of New Zealanders by promoting sports and physical education. Physical fitness instructors

went out to community groups and ran keepfit classes for public servants at lunchtimes and in the early evening. When the Second World War broke out, the branch was particularly focused on improving the fitness of air force cadets and members of the home guard, police and Emergency Precautions Service.

John Pascoe was employed from 1941 to 1945 by the Department of Internal Affairs to photograph the war effort at home as well as government programmes such as this. His dramatic, low-angle perspective recalls German and Soviet images of similar fitness activities in the 1930s though for Pascoe, the influence may have come filtered through the pages of Life magazine in the work of photojournalists such as Margaret Bourke-White.

Richard Barraud

Untitled (Nick, Neil, Ross, Aly, 306 Tinakori Road) [Wellington], c.1965

Gelatin silver print, 254 × 378 mm

Purchased 2008, O.031406

Opposite:

Max Oettli

Dave’s birthday party, Auckland, 1972

Gelatin silver print, 165 × 237 mm

Gift of the photographer, 2020, O.048914

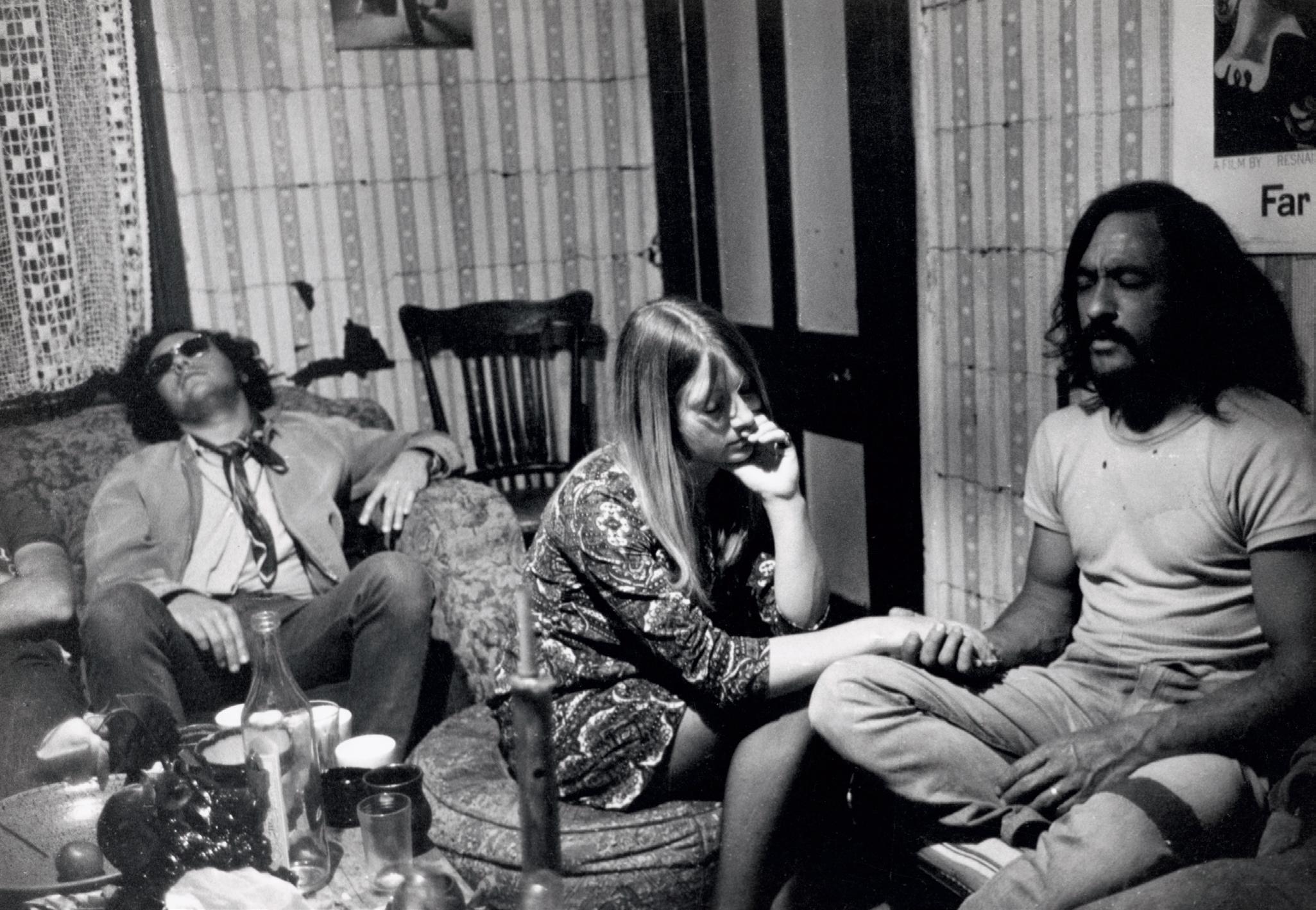

Gary Baigent

Party, Brighton Road, Parnell, Auckland, 1964

Gelatin silver print, 156 × 238 mm

Purchased 2006, O.030073

The sense that you are there, in the room, or faceto-face with the subjects, characterises some of the best documentary photographs. In Richard Barraud’s image we are so present we almost become the man at left, his raised arm our arm. We are in the mid-1960s and folk music is still cool though Bob Dylan’s first fully electric album, Highway 61, sits in the background and a painting by Ross Ritchie, an artist of the moment, is on the wall.

Max Oettli and Gary Baigent’s images were shot from further back but nevertheless share the same ring of truth, reminding us of parties we’ve probably all been to. Oettli describes arriving home late at night to Dave’s birthday party and shooting a couple of frames from the doorway: ‘The room would be filled with sweet smoke and presumably the Rolling Stones latest, Sticky Fingers, blasting out of a good stereo with massive speakers.’ Dave, on the sofa, was ‘pretty spaced out’ as usual, and Frances was, ‘I suspect, trying to tactfully hint to [her partner] Arthur that it’s getting onto sleepy time’.10

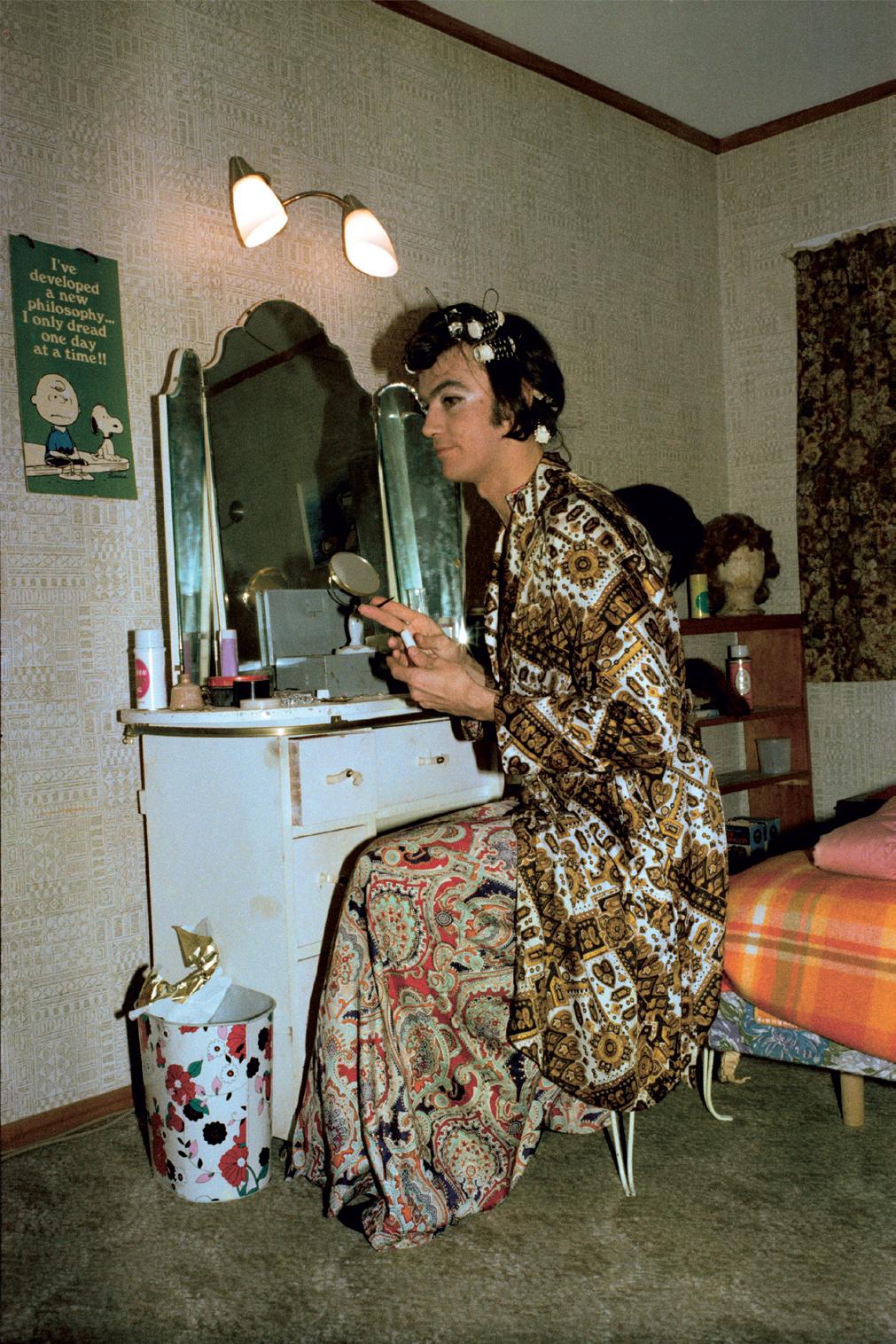

Fiona Clark

Geraldine at home, 1975

Inkjet print, printed 2002, 240 × 160 mm

Purchased 2016, O.043783

Fiona Clark

Ian/Geraldine at home, 1975

Inkjet print, printed c.2015, 243 × 162 mm

Purchased 2016, O.043430

Opposite:

Fiona Clark

Diana and Tiny Tina at Mojos, Auckland, 1975

Inkjet print, printed 2002, 242 × 163 mm

Purchased 2016, O.043781

Fiona Clark became involved in Auckland’s gay and transgender scene when she was studying photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts and working in coffee bars downtown. For Clark, the community where she ‘felt safe for the first time in my life’19 was the obvious choice of subject: ‘I didn’t see anything else to photograph There was no other option for me but to be true to who I was.’20

Clark took many of her photographs at Mojo’s, a club on the corner of Queen and Wakefield streets. For another young art student who visited, David Lyndon Brown, the performers at the club signified ‘bravery, dedication and defiance. They are men who have transformed themselves, recreated themselves, against all odds, into women. They have realised their own mythology.’21 Many of the people Clark photographed in the 1970s have since died, but where she could, she has photographed her subjects later in life: ‘As a photographer I think it’s so rich and beautiful. All the tragedy and joy are part of our culture, but it’s never seen that way, we don’t have a recognised visual history. It’s time it was celebrated.’22

David Cook

Maurice and Annie’s lounge, 1993, from the series ‘Jellicoe and Bledisloe’ Inkjet print, 483 × 599 mm

Purchased 2020, O.049117

Opposite:

David Cook

Plunket Terrace, 1993, from the series ‘Jellicoe and Bledisloe’ Inkjet print, 483 × 599 mm

Purchased 2020, O.049118

These photographs were taken when David Cook and his partner were raising a family in Hamilton East in the 1990s. It was a working-class suburb of state houses where, with few fences dividing one property from another, much of life was public people fixed cars in the front yard, children played in the street and some residents lived in converted garages. Cook made it his business to meet people and ask to photograph them.

In Maurice and Annie’s lounge, we see Labour opposition leader Mike Moore on the TV with a view through the window to the state houses his party had once built, and which were then

being sold off by a new government intent on a free-market economy. And two girls up a tree, photographed close with camera flash in the late afternoon light in a way that creates a heightened sense of reality.

Today the photographs have an historical quality a record of a community in a more innocent period before their neighbourhood was gentrified and designated a heritage zone.

If it sounds trite to say that we are surrounded by photographic imagery today, this is only because it is hard for us, collectively, to remember the situation in, say, 1960. It was half a lifetime before the internet; television had yet to be seen across the country; movies only screened at the theatre; and the front pages of daily newspapers consisted of classified advertisements. Photojournalism of significance was restricted to overseas magazines, and there were no photography books except those of the ‘beautiful New Zealand’ variety.

In the following decades, photographs became part of our everyday lives. It became increasingly difficult for photographers engaged in thinking carefully about how to use the camera to ignore the fact that whatever photographs they produced would exist amid a sea of other photographs. Rather than being read as original artistic expressions, they would be viewed as more or less already taken. As a result, much recent work has focused on photography itself as its subject matter. Yvonne Todd’s strangely ‘off’ portraits deal with the artifice of studio photography; Gavin Hipkins and Ava Seymour show what can happen when you combine seemingly incompatible images; Conor Clarke considers how we read photographs; and a whole school of photographers, including Laurence Aberhart, Mark Adams, Andrew Ross, Natalie Robertson and Chris Corson-Scott, use large-format film cameras in ways that draw on nineteenth-century practices.

In this environment, it is perhaps unsurprising that New Zealand photographers like Ben Cauchi, Joyce Campbell and Wayne Barrar have chosen to revive antique photographic processes. Their ambrotypes, daguerreotypes and platinum prints seem to seek refuge from present complexities by going back to a time when representing nature was an apparently direct and straightforward matter. They remind us of how photography was first experienced as a wondrous and mysterious medium causing us to think about it in a different way.

The adoption of obsolete processes and techniques is sometimes interpreted as a reaction against digital photography, for where the digital is ephemeral, virtual and multitudinous, these processes offer the permanence, materiality and uniqueness of the handmade. However, aside from a few notable exceptions, such as Lisa Reihana’s digital constructions, it is not as though there is a surfeit of fictional, computer-created work in contemporary photography. The reality is that most photographers using digital processes are using them much as they would analogue technology, or to heighten an effect created largely by analogue means such as Yvonne Todd’s use of subtle digital tweaking to enhance the hard-to-put-your-fingeron strangeness she achieves through pose and costume. Contemporary photographers may appreciate digital technology’s convenience and the greater control it offers over colour and tone but less to depart from the world than to reproduce it with greater fidelity. Digital technology has enabled large-scale prints to be made more cheaply; exhibition colour prints are now regularly on a scale that was only rarely seen in the 1970s or 1980s. Digital processes have also facilitated an explosion, internationally, in the number of photographic monographs due to the cost savings they have introduced to book production.

Books also include the photobook a term that came into use around the year 2000, and described the photographic equivalent of an artist’s book. It was often handmade, produced in small print runs, had little text and functioned as an artwork in itself, rather than as a book that reproduces photographs. Photobooks have boomed in recent years, becoming a field of practice in their own right. One explanation for this is that digital technologies make it cheap and easy for anyone to produce their own book. And like

Above:

Yuki Kihara

My Samoa girl, 2004–05

Chromogenic print, 805 × 605 mm

Gift of Yuki Kihara, 2009, O.033243

Opposite:

Sheryl Campbell

Droplet, 2020

Self-published photobook, 242 × 187 × 13 mm

Purchased 2023, RB001442

Lisa Reihana

Marakihau, 2001

Chromogenic print, 1990 × 1190 mm

Purchased 2002, O.026797

anachronistic photographic technologies, photobooks offer an alternative to the digital in the form of physical, crafted, personal objects much as vinyl records contrast with streaming. In these respects, photobooks seem like a shift back to the 1970s small-scale, intimate, handmade and sold through a cottage industry of distributors rather than bookshops or dealer galleries.

The real significance of photobooks, though, may be that they allow for the ordering of images. Photography has always been produced in volume (never more so than in the digital age), and gathered together in collections that are ordered in some way, as outlined at the beginning of this book. As photography writer and curator David Campany said, ‘ “Composition” is not confined to the rectangle of the viewfinder; it is also a matter of the composition of the set, series, suite, typology, archive, album, sequence, slideshow, story and so forth.’ 7 For contemporary photographers, exhibitions offer opportunities to order their work, but books go further by imposing a sequence, allowing a narrative to be built from apparently unrelated and meaningless single images. The whole can be greater than the sum of its parts, making the photobook an entirely new form of photographic expression.

In addition to the forces shaping contemporary New Zealand photography, which have come from within the medium over the last fifty years, there has been a huge growth in art-world infrastructure and support, though it is too early to assess its effects exactly. Contemporary photography has been substantially accepted into the art world, shown by dealer and public galleries, bought by public and private collectors, taught extensively in tertiary institutions, and accepted for awards, grants and artists’ residencies. Now seen as artists, many leading photographers hold teaching positions within academic institutions, and others have established careers that are as much outside this country courtesy of residencies, biennales and overseas dealers as within it. In all this, we see a diversity and volume of support and opportunity that did not exist half a century ago. There is a risk that due to desire for both novelty and spectacle on the one hand, and the security of a canon of star names on the other this infrastructure can become a closed, interlocking system. But the sheer quantity of work being produced and seen today promises that some photographers will evade the pressures of careerism and commercial success to teach us new things about the nature of the medium. Time will eventually expose the true shape of our present and reveal which photographs have lasting originality and meaning. The challenge, as always, for public collections is to try and divine this sooner rather than later.

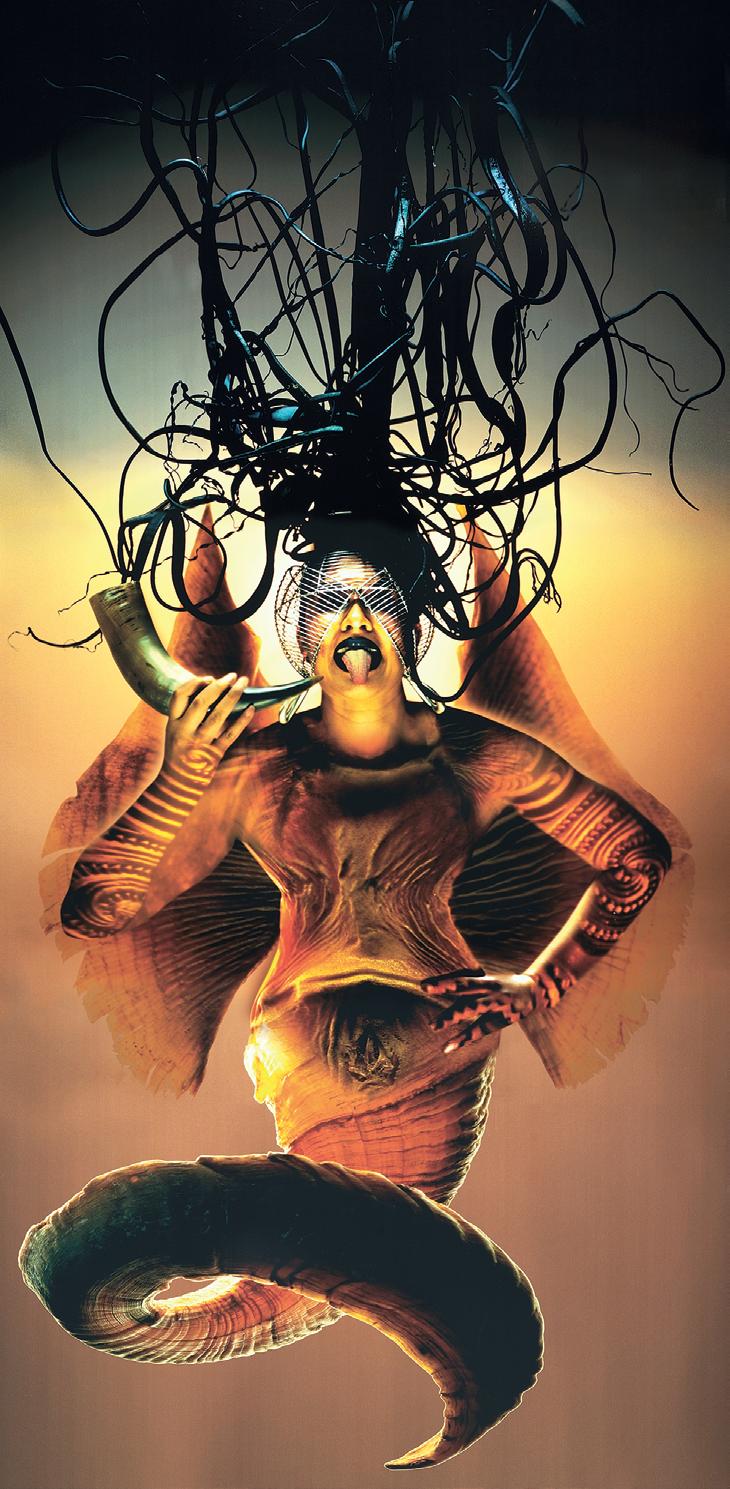

Tia Ranginui

The tangi of Rūaumoko, 2023

Inkjet print, 805 × 1200 mm

Purchased 2025, O.052215

In Māori narratives, Rūaumoko is the atua (deity) of earthquakes, volcanoes and seasons.

He was the youngest son of Ranginui and Papatūānuku, the sky father and earth mother. When the parents were forcibly pushed apart by Tāne, and Papa was turned face down, Rūaumoko remained with his mother still in her womb according to some stories, or at his mother’s breast in others. Rūaumoko was carried into the world below, and the earthquakes he causes are responsible for the changing seasons, releasing the heat or cold of Papa to the surface of the land and thence to the air.

The title The tangi of Rūaumoko, combined with the flames, may suggest Rūaumoko’s grief at the human despoilation and abuse of Papatūānuku, with his sorrow expressed in climate warming, caused by the heat he can generate. The woman spectacularly yet serenely on fire could be Papatūānuku, Rūaumoko in female form, or another atua altogether.

Laurence Aberhart

Laurence Aberhart (1949–) is known for his black and white images of Masonic lodges, churches, marae, cemeteries and war memorials. These subjects speak of the past: of memory, mortality and melancholy. He captures each on a large-format camera mounted on a tripod, which he then prints as a contact print the same size as his huge 8 × 10-inch negatives. This technique, complete with long exposures, follows nineteenth-century practice, creating a resonance between Aberhart’s process and his history-laden subjects. He has had a solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, in 2002; a survey at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, Australia, in 2005; and a major retrospective at City Gallery Wellington in 2007. The latter was accompanied by a substantial publication titled simply Aberhart. His more recent work, on First World War memorials in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, was published as ANZAC in 2014. Aberhart was made an Arts Foundation Foundation Te Tumu Toi Laureate in 2013.

Mark Adams

Born in Ōtautahi Christchurch, Mark Adams (1949–) graduated from Ilam School of Fine Arts, University of Canterbury in 1970, and has since developed a photographic practice focused on the people, land and histories of Aotearoa New Zealand. Adams’s body of work reflects a sustained engagement with postcolonial history and cultural practices, with subjects including Māori carving, Samoan tatau practice (published as Tatau in 2023 and earlier books in 2003 and 2010), and sites of historical significance, including those important to Ngāi Tahu (published as Land of Memories, 1993) and the landing places of Captain James Cook in the 1770s (published as Cook’s Sites: Revisiting history, 1999). In 2025, a survey exhibition of Adams’s work, Mark Adams: A survey | He kohinga whakaahua, was shown at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, accompanied by a substantial book with the same title.

Leslie Adkin

Leslie Adkin (1888–1964) was a gifted amateur scholar and polymath, publishing scientific papers in geology, exploring and mapping the Tararua Range, and researching the history of Māori occupation of the Horowhenua region all while running his farm at Taitoko Levin. He was also a passionate and prolific photographer, carrying a large, cumbersome camera on expeditions, and recording his social life in candid, ebullient images. Especially notable are the albums that celebrate his courtship, marriage and family life with Maud Herd. In 1946, Adkin moved to Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, where, in the later years of his life, he worked for the New Zealand Geological Survey for nine years. At his death he left a collection of 7000 negatives, as well as diaries, albums, manuscripts, drawings and Māori artefacts. The negatives and diaries are in Te Papa’s collection, and his albums are split between Te Papa and the Alexander Turnbull Library.

JW Allen

James (or Joseph) Weaver Allen (1821–1886) was a photographer operating in Ōtepoti Dunedin from

1866 to at least 1871. After initially working as a grocer, Allen was trained in photography by Dunedin-based William Meluish and became a prominent topographical photographer as well as embracing the trend for cartes-de-visite. Allen died in Melbourne.

American Photographic Company

The American Photographic Company was established by John McGarrigle in the late 1860s on the corner of Queen Street and Wellesley Street East in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. McGarrigle capitalised on the craze for cartes-de-visite, producing small, affordable albumen prints of Māori. His images usually show his subjects in close-up, looking directly at the camera or just to the side, and they are among the most immediate early photographic portraits of Māori. In 1876, fire destroyed much of McGarrigle’s studio, and two years later he sold his remaining glass negatives to another Auckland company, Hayes & Mandeno, who in turn sold them to Burton Brothers of Ōtepoti Dunedin. McGarrigle sailed for Australia, where he briefly managed a drapery store in New South Wales, but he eventually returned to Aotearoa New Zealand and resumed his occupation as a photographer. Why McGarrigle called his former studio American Photographic Company is unclear he had no known links to the Americas. The studio’s 116 surviving negatives are held by Te Papa.

Edith Amituanai

Edith Amituanai MNZM (1980–) was born in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland to Samoan parents. She has a Master of Fine Arts from Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland. Her early photography is characterised by scenes set in domestic spaces that frame the identities and interactions of her subjects. Amituanai has often turned her lens on her family and members of her West Auckland community to explore ideas of home and the interface between private and public space. In 2007, she was the inaugural recipient of the Marti Friedlander Photographic Award; in 2008, she became the first Pacific finalist of the prestigious Walters Prize for her exhibition Déjeuner, a series of photographs of professional rugby players living overseas and the family homes they left behind. In 2019, she had a survey exhibition at Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi that was accompanied by a substantial publication, Edith Amituanai: Double take

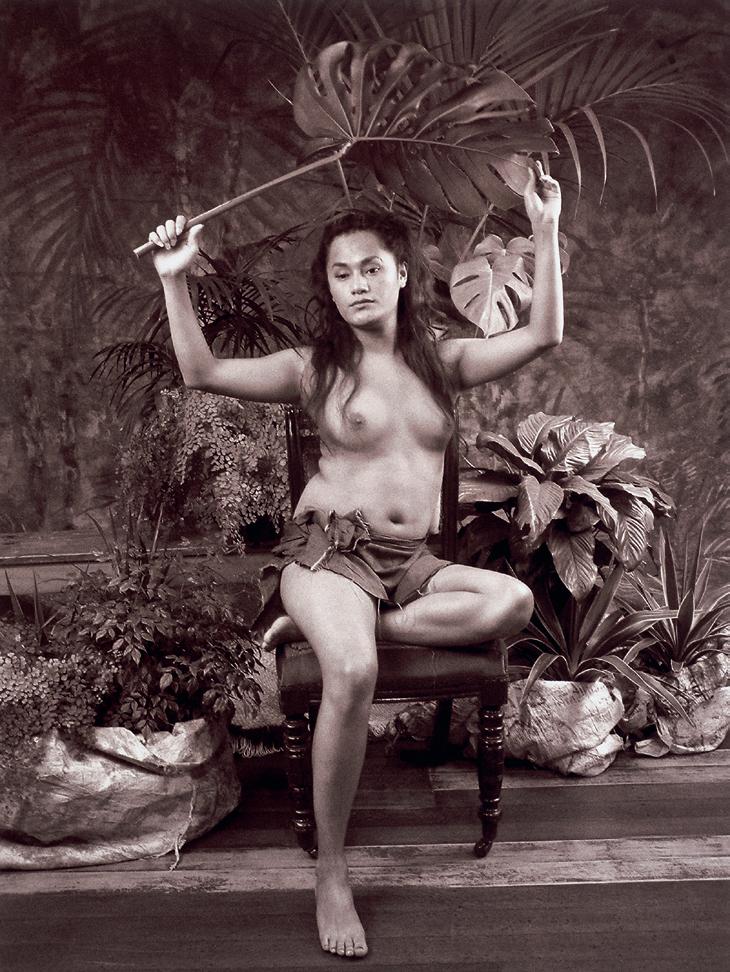

Thomas Andrew

Thomas Andrew (1855–1939) was born in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and operated a studio in Ahuriri Napier from c.1882 and then another in Tāmaki Makaurau. He visited Sāmoa on a tour of the Pacific aboard the schooner Southerly Buster in 1886–87 and took photographs in many other Pacific locations, including Niue, Nauru, and the Marshall, Caroline and Cook islands. In 1891, after his Tāmaki Makaurau studio burned down, he moved to Apia, Sāmoa where he became known for studio portraits and idyllic scenes of island life created for the tourist market. Andrew also documented significant historical events, including the volcanic eruption of Mount Matavanu, the funeral of writer Robert Louis Stevenson, and the Mau movement, which fought for Sāmoa’s political autonomy. His photographs were prized in Sāmoa

as a record of the local culture, and remain a valuable and fascinating resource today. Many of Andrew’s negatives have been lost, but surviving examples and many prints are held by Te Papa.

Gary Baigent

Gary Baigent (1941–) was born in Wakefield, Whakatū Nelson. He majored in painting at Ilam School of Fine Arts, University of Canterbury from 1960 to 1962. After graduating from Auckland Teachers’ Training College in 1963, he worked in a succession of jobs in timber yards, on the railways and wharves, and in woolstores and paper stores. At the same time, he worked on The Unseen City (1967), a book documenting Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland’s urban life, which marks a watershed moment in contemporary New Zealand photography. In 1973, he was selected for the seminal publication and exhibition, Auckland City Art Gallery’s Three New Zealand Photographers: Gary Baigent, Richard Collins, John Fields. Baigent has worked as a trainee television camera operator, a gardener, farm worker, commercial diver, freelance yachting journalist and an assistant editor at SeaSpray magazine. His work was included in the Te Papa Press book The New Photography: New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers (2019).

Frank Giles Barker

Frank Giles Barker (1891–1955) was an architectural and industrial photographer operating from 1920 to 1955. He had a succession of studios in Pōneke Wellington city before working from his home address in 1936. He was contracted by the city’s council throughout the 1920s and 1930s to document engineering and construction projects such as the Western Access Scheme, a twenty-year series of works to improve access to the western suburbs. Barker was also an accomplished scenic photographer who produced postcards of the Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington and Te Matau-a-Māui Hawke’s Bay districts.

Wayne Barrar

Wayne Barrar (1957–) was born in Ōtautahi Christchurch and completed a degree in science at Canterbury University. He then studied fine art at Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland, and design using photography at Wellington School of Design, Massey University. Barrar’s photographic practice draws on his scientific background, exploring the inter-relationship between nature and culture and human impacts on the landscape. His first major book on these themes was Shifting Nature (2001). In 2010, the exhibition Wayne Barrar: An expanding subterra, documented underground spaces that have been used as storage units, industrial parks, dwellings and tourism facilities. Torbay Tī Kōuka: A New Zealand tree in the English Riviera (2011) depicted the appropriation of the New Zealand cabbage tree, or tī kōuka, as the Torbay palm in South West England. His 2016 exhibition and publication, The Glass Archive, looked at the histories of creating, collecting and archiving microscope slides of diatom skeletons. Barrar is Honorary Research Fellow at Whiti o Rehua School of Art, Massey University, where he was formerly an associate professor.

Richard Barraud

Richard Barraud (1945–1988) was among a new wave of Aotearoa New Zealand photographers to use documentary as an expressive form. He studied photography and design at Wellington Poly-technic (now Massey University) from 1963 to 1966 and was, as a student, a prolific photographer, capturing the daily lives of his flatmates. A fully integrated observer of his subjects, his images from this time had a gritty immediacy far removed from the pictorial traditions of previous decades. Wellington Polytechnic School of Design tutor, William Main and American graphic designer David Graves, were influential, with their passions for photography and pop art respectively. Barraud died prematurely, and a posthumous exhibition, Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite: Richard Barraud, photography 1965–1975, was held at McNamara Gallery, Whanganui, in 2007. It showcased Barraud’s diverse practice that encompassed not just photography, but also painting, drawing, photomontage, collage and hand-lettering. Unfortunately, much of his work did not survive his bohemian and increasingly peripatetic life.

Janet Bayly

Janet Bayly (1955–) completed a Master of Fine Arts at Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1979 and has since enjoyed a career as a photographer, curator and museum director. In her photographic practice, Bayly has explored alternatives to conventional photography and been influenced by the moving image, painting and art history. Early in her career, she specialised in producing Polaroid SX-70 instant colour prints. Examples were included in the National Art Gallery’s 1982 touring exhibition and publication, Views/Exposures: 10 contemporary New Zealand photographers, and PhotoForum’s Six Women Photographers (1987). Bayly has been Director-Curator at Toi Mahara, the district gallery of the Kāpiti Coast, since 2006.

John Bell

John Bell (1846–1914) was born in Silton, Dorset. By 1881, he had a portrait studio in Frome, Somerset. In 1896, Bell advertised in the Western Gazette Almanac as a photographer with twenty-five years’ experience, with a new studio fitted with the best lighting, equipment and the ‘latest improvements’ in Hendford, near Yeovil, Somerset, for ‘the production of High-class Photography at Moderate Charges’. This was one of five of his branches. The others were in Shepton Mallet, Bath, Barry Docks and Trowbridge. Bell retired in 1911 and lived in Burnham-on-Sea until his death.

Berry & Co

Berry & Co was William Berry’s (1857–1949) photographic studio in Pōneke Wellington city. After working for the New Zealand Photographic Company for several years in the late nineteenth century, Berry acquired the company and established his first studio on Cuba Street in 1899. The following year, he commissioned the architect William Crichton to design a three-storey building to house his new photography studio and shop at 147 Cuba Street. The new premises opened in 1901, and here Berry took portraits of a wideranging clientele from bridal groups to First World

War servicemen. After Berry’s retirement in the mid1920s, the studio continued to operate under his name until late 1927. About 3200 surviving Berry negatives are held by Te Papa.

GW Bishop

George Wesley Bishop (c.1840–1887) arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand around 1863 and married in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in 1866. He was later in the Te Kauaeranga Thames area from around 1868 to 1879. His photographs of the Thames goldfields were exhibited in the Vienna World Exhibition of 1873, but today he is known for his images of Māori. Bishop sold his studio in 1876 and became a chemist, first in Te Kauaeranga and then in Tūranganui-a-Kiwa Gisborne in late 1879. His life ended in San Francisco when he was shot by his partner.

Peter Black

From the mid-1970s Peter Black (1948–) has consistently practised in the mode of a street photographer, operating in public places. He began working in black and white, concentrating on framing and (often absurd) juxtaposition, showing how the camera sees differently from the human eye. Since 2007, he has worked exclusively in digital colour while continuing to draw attention to the public environment we all inhabit but mostly prefer not to examine too closely. He had a solo exhibition at the National Art Gallery in 1982, with an associated publication, Peter Black: Fifty photographs, and another at City Gallery Wellington in 2003, Peter Black: Real fiction, again with a catalogue of the same title. His more recent books include I Loved You From the Moment I Saw You (2011), The Grass is Awfully Green (2013), Frozen (2015), The Shops (2016), and Motel Life (2021).

Rhondda Bosworth

Rhondda Bosworth (1944–) graduated from Ilam School of Fine Arts, University of Canterbury in 1973, and from Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1980. Bosworth was one of the cohort of photographers associated with PhotoForum, and she responded to the rise of feminism in the 1970s with work that depicted the female body, often with a subtext suggesting psychological tension. Her personal experience has been central to her work, which responds to ‘the hegemony of the male world view’. In a series of stark, black-and-white studies, she depicted her own face and figure in poetic and sometimes disturbing images, which allude to issues of gender, memory and identity. Later, she began to tear and cut photographs and reassemble the fragments. More recently, she has photographed family papers and photographs, including the crumpled and frayed poems her father carried as a soldier in the Second World War. Since 2010, Bosworth has moved to digital photography, learning new printing technologies and, after decades of working in black and white, experimenting with richly saturated colour.

James Bragge

James Bragge (1833–1908) was born in England and moved to South Africa in 1854, where he learned the techniques of photography. By the mid-1860s, he had

settled in Pōneke Wellington city and established his own business. Bragge specialised in images of Pōneke, often returning to a favoured spot over several years and documenting the city’s development. In the 1870s, he ventured further afield and travelled through the Wairarapa, taking photographs along the way. These images, which often document the clearing of land and the building of roads, bridges and settlements, were collected in an acclaimed album titled Wellington to the Wairarapa. In 1879, the Wellington City Council commissioned Bragge to produce twenty-five photographs of local scenes for the Sydney International Exhibition, and these won an award against international competition. Later in life, Bragge concentrated on portrait photography, working from his studio on Manners Street and his home on Adelaide Road. Te Papa holds Bragge’s 169 surviving negatives and a similar number of prints.

Brian Brake

Brian Brake OBE (1927–1988) took up photography as a boy and in 1945 moved to Pōneke Wellington city to work for the portrait photographer Spencer Digby. In 1948, he joined the National Film Unit where he specialised in mountain documentaries. Arriving in England in 1954, he initially struggled to find work, but a turning point came when he joined the Parisbased photo agency Magnum. Brake travelled the world on assignment for Magnum and made two significant trips to China in the 1950s. He spent three months in India in 1960, photographing ‘Monsoon’, the photo-essay that established his international reputation. In the same year, he photographed ‘New Zealand, Gift of the Sea’, for National Geographic magazine, and in 1963, he turned this photo-essay into a best-selling book of the same name. At the end of the decade, he returned to making documentary films, and in 1976, settled in Titirangi, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, to concentrate on photographing for book projects. Brian Brake’s archive of negatives, transparencies and prints is held by Te Papa.

Stella Brennan

Stella Brennan (1974–) is a writer and sculptor living in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Her practice is diverse, and she is known for her interrogation of digital media. She co-founded the Aotearoa Digital Arts Network in 2002 and was co-editor of the Aotearoa Digital Arts Reader anthology (2008). Brennan’s work has been exhibited in numerous international galleries and festivals, including the Biennale of Sydney and the Liverpool Biennial, and she was a finalist in the 2006 Walters Prize for her installation Wet Social Sculpture an operating spa pool installed in an art gallery into which visitors were invited to immerse themselves.

In 2023, City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi staged Stella Brennan: Ancestor technologies, a survey exhibition of Brennan’s practice. Included in this was Brennan’s photographic installation Thread between darkness and light, drawing from her family archive of 120-year-old, glass-plate negatives, which were printed on large silk banners. Her book of the same name was published by Rim Books in 2024.

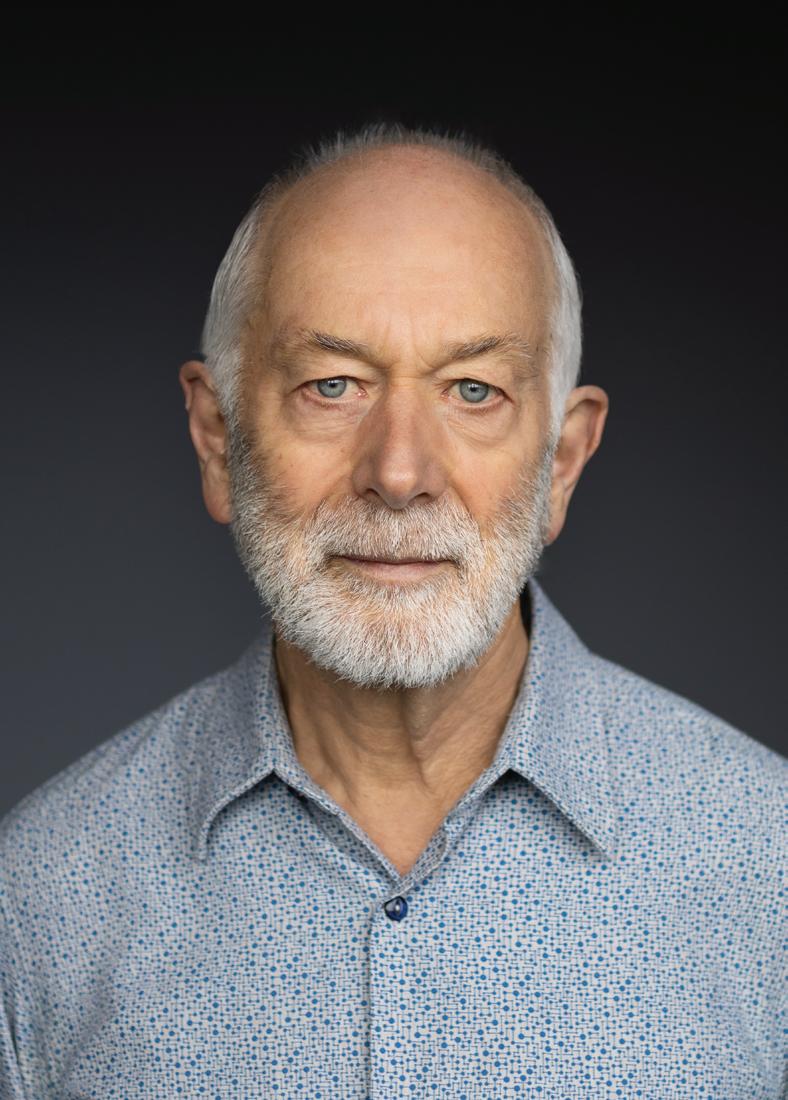

Athol McCredie is Curator of Photography at Te Papa. His familiarity with Te Papa’s photography collection began in the mid-1970s, when he worked as a photographic assistant at the National Museum. There, he printed many collection negatives in the darkroom, from the huge glass plates of James Bragge to 35 mm negatives taken by scientists on field trips. Inspired by these images, he co-curated a 1978 exhibition on Leslie Adkin. The success of the Adkin exhibition led to a role at the National Art Gallery as photography exhibitions researcher until 1981. From 1986–87, he was part-time visiting photography curator at the Gallery, where he worked on contemporary acquisitions and curated Politics and Photographs (1987) from the collection.

In 1993, after a period as a freelance researcher, curator, collection manager and photographer, he became art curator (and subsequently acting director) at the Manawatu Art Gallery (now part of Te Manawa). In 2001, he moved to Te Papa where he found the national museum and national art gallery photography collections combined, and with much historical material added. He has continued building this collection, concentrating particularly on twentieth-century and contemporary work.

His publications include The Tour: Photographs (1981), Witness to Change: Life in New Zealand; John Pascoe, Les Cleveland and Ans Westra (with Janet Bayly, 1985), Fields of Golden Daffodils (1991), Brian Brake: Lens on the world (editor, 2010), New Zealand Photography Collected first edition (2015), The New Photography: New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers (2019) and Leslie Adkin: Farmer photographer (2024). He has contributed chapters to several books, and written many short texts for Te Papa Press publications, from Icons Ngā Taonga (2004) and Art at Te Papa (2009) to Flora: Celebrating our botanical world (2023).

This book is built on the framework of the first edition and I would like to acknowledge everyone who made that version possible. Particular thanks are due to Claire Murdoch, Te Papa Press publisher, who gave the first edition the go-ahead; Te Papa Press editor Hannah Newport-Watson who steered it through all phases of production; Helen Curran, who edited the text; Jeremy Glyde, who prepared the digital files for printing; and designer Alan Deare, who took my rough layouts and turned them into a book.

For this current edition, I’d like to thank Te Papa Press for proposing a refresh of the 2015 first edition. I was more than happy to take up the opportunity to include new work including collection photographs that had not been scanned in 2015 or which have been added to the collection since that date.

Many hands are involved in making a book. It begins with research, and I would like to thank Kirstie Ross, Jean-Claude Stahl and Jennifer Twist for their assistance, and acknowledge the resources of the Alexander Turnbull Library as well as those of Te Papa, and most especially Papers Past. I am also indebted to Stephanie Gibson, Sean Mallon, Colin Miskelly, Lissa Mitchell, Phil Sirvid and Andrew Stewart for reading sections of the text and making suggestions for improvements.

In the selection and juxtaposition of images I was hugely aided by Lizzie Bisley’s sure eye. She was always a willing sounding board whenever I was weighing up options.

At the production stage, Jo Elliott of Te Papa Press ably managed the workflows, keeping on top of endless details. Olivia Nikkel and Olive Owens also provided assistance. Virginia Were edited the text and reworked my less well written passages with a sure hand. Yoan Jolly reviewed and adjusted all the scans, translating my vague requests for ‘more oomph’ or ‘less murk’ into appropriate technical adjustments. Alan Deare and Dave McDonald of Area Design took their original design and gave it a more contemporary look as well as devising some adventurous improvements on my layout suggestions. Indexer Brian O’Flaherty made the book more useful and proof reader Kate Stone helped make it error-free.

Special thanks are due to Victoria Munn and Emily Goldthorpe who researched and drafted the biographical statements on photographers; Courtney Johnston, for spending some of her precious time to write a useful foreword; and Haley Hakaraia, who ensured we had the support of iwi and hapū to include photographs of their tūpuna.

More broadly, I would like to note the efforts of pioneering New Zealand photo-historians Hardwicke Knight, William Main and John B Turner, whose work provides a foundation for all books such as this. A debt is also owed to those who have built, documented, cared for and promoted the Te Papa collection from which this book is drawn. Beginning in the 1900s, these include Augustus Hamilton, James McDonald, John T Salmon, Charles Hale, Frank O’Leary, John B Turner, Trevor Ulyatt, Michael Fitzgerald, Luit Bieringa, Warwick Wilson, Peter Ireland, Mark Strange, Eymard Bradley, Paul Thompson, Ross O’Rourke, Adrian Kingston, Lissa Mitchell and Anita Schrafft. Recognition is also due to those curators outside the photography field who have instigated or supported acquisition of some of the photographs used in this book. They include Sean Mallon, Stephanie Gibson, Hanahiva Rose, Megan Tamati-Quennell and Isaac Te Awa.

Lastly, of course, I would like to acknowledge all the photographers, without whom this book would not have been possible. Thank you to all who gave their permission for work to be included. And special thanks to Mark Adams, Peter Black, Rhondda Bosworth, Bruce Connew, Murray Cammick, David Cook, Michael Hall, Mary Macpherson, Max Oettli, Chris CorsonScott, Tia Ranginui, Clive Stone and Jane Zusters, who assisted in a variety of ways.

As with any project like this there is as much good work left out as included. Selection was often a painful process, and I would like to acknowledge the many photographers whose work I admire and respect, but for one reason or another, could not fit in. Museum collections are assembled for the very long haul, so there will always be opportunities to present this work in future exhibitions or publications.

New Zealand Photography Collected: 175 Years of Photography in Aotearoa

RRP: $90

ISBN: 978-1-99-107207-8

PUBLISHED: November 2025

PAGE EXTENT: 392 pages

FORMAT: Hardback

SIZE: 305 x 250 mm

FOR MORE INFORMATION OR TO ORDER https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/about/te-papa-press/contact-te-papa-press