ALSO IN THIS SERIES

Native Birds of Aotearoa

Native Plants of Aotearoa

Native Insects of Aotearoa

Native Shells of Aotearoa

Native Fishes of Aotearoa

Native Birds of Aotearoa

Native Plants of Aotearoa

Native Insects of Aotearoa

Native Shells of Aotearoa

Native Fishes of Aotearoa

Phil Sirvid

Spiders are members of the phylum Arthropoda along with insects, crustaceans and several other groups of animals with an exoskeleton made mostly of a hard material called chitin. Spiders (order Araneae) are a part of the class Arachnida, a group that encompasses the eight-legged arthropods. Within the order Araneae there are two suborders: the Mesothele, considered to be a sister group to other spiders and with ancestral traits such as body segmentation; and the Opistothele, which contains the great majority of spider species. Mesothele are absent from Aotearoa. Opistothele is further divided into the infraorders Mygalomorphae and Araneomorphae.

Mygalomorphs are the quintessentially hairy tarantula-like spiders. Aotearoa lacks tarantulas (family Therephosidae), but other kinds of mygalomorphs including banded tunnelwebs (Hexathelidae) and trapdoor spiders (Idiopidae) are present. Mygalomorphs are characterised by the presence of four book lung openings, and fangs that are oriented down the midline when at rest. This requires the spider to rear up to deploy its fangs, as they are tucked under the body.

Most spiders belong to the infraorder Araneomorphae. These spiders have a single pair of book lungs at most, and their fangs are oriented across the body; bites therefore don’t require a change of body position. An exception to the typical araneomorph body plan is the family Gradungulidae (e.g. Sorensen’s spider, page 33). They are still considered araneomorphs but have two pairs of book lungs like mygalomorphs.

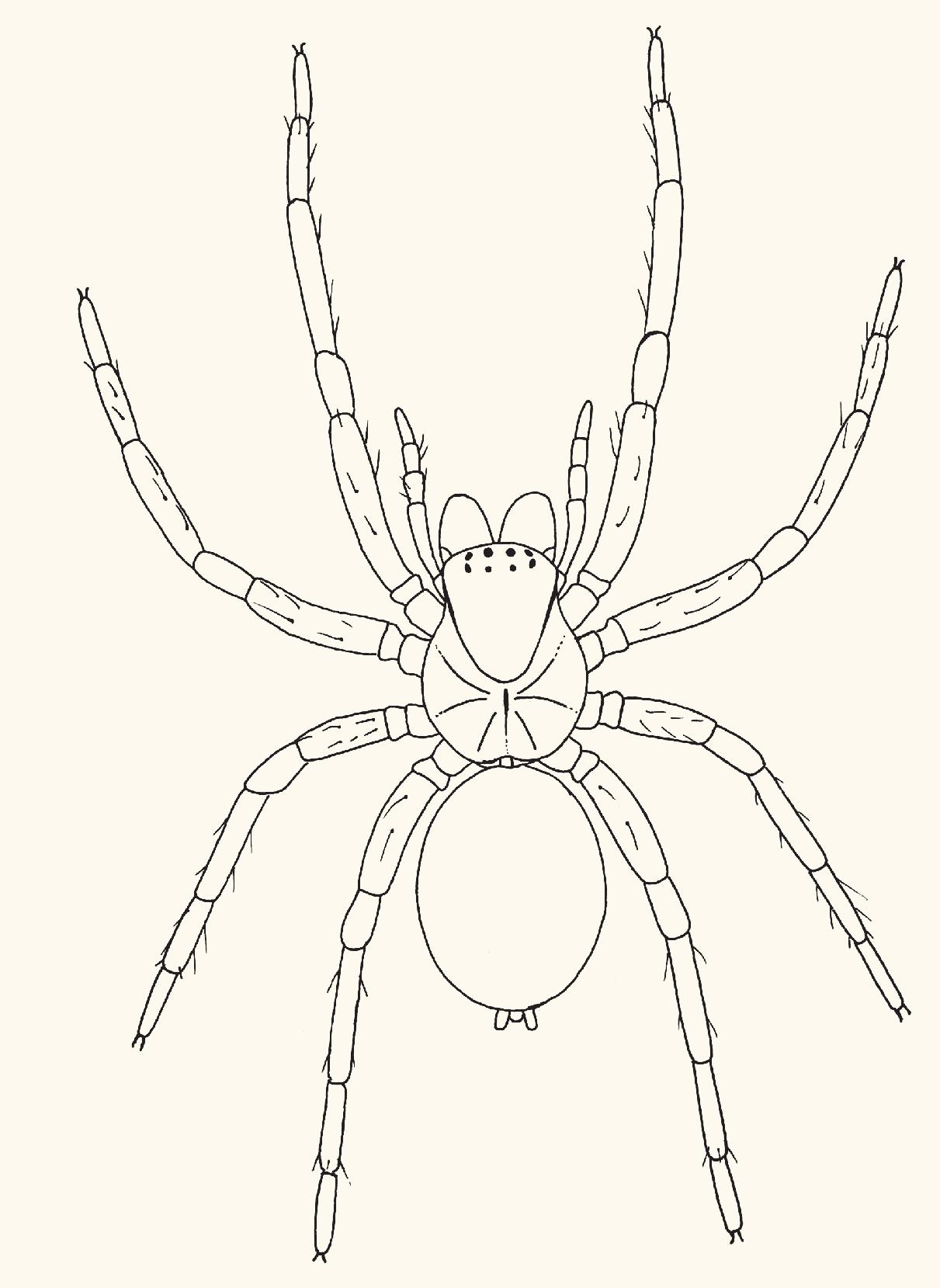

Spiders and other arachnids all have 12 appendages. Famously, eight of these are legs. However, arachnids also have a pair of chelicerae and a pair of pedipalps. The chelicerae are front and centre on the body of the spider. In spiders, a chelicera consists of a basal segment (or paturon) that carries the fang. The chelicerae are flanked by the pedipalps. Except in adult male spiders, pedipalps resemble small legs but lack the metatarsal segment. In mature males, the furthermost segment of the pedipalp develops into the

Femur Coxa Trochanter

Cephalic region

Thoracic region

Cephalothorax

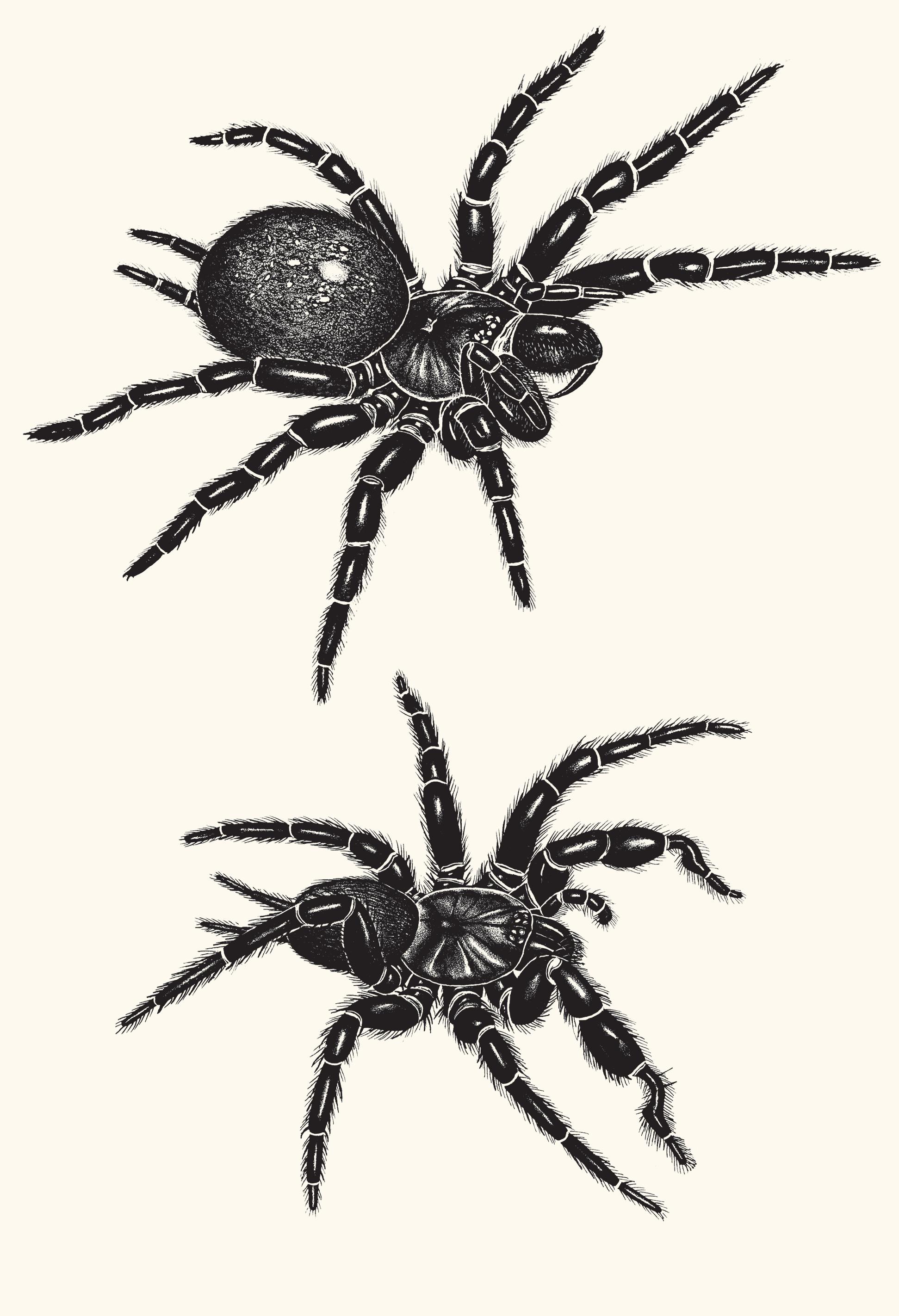

Porrhothele antipodiana

One of the first spiders to be collected from Aotearoa, this species was described by French scientist Charles Walckenaer in 1837. Black tunnelweb spiders belong to the family Porrhothelidae, which is unique to Aotearoa. They were also a source of inspiration for the design of Shelob in the movie adaptation of JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

Description: These spiders are large, with females (above) sometimes exceeding 30mm in length. Porrhothele antipodiana is black except for a brick-red or toffee-coloured carapace. Males (below) are smaller and their first legs each have a thick, spine-covered tibial segment followed by a hook-like metatarsus. Porrhothele is one of three mygalomorph genera where two spinnerets extend well beyond the rear of the body. Both Porrhothele and Stanwellia (page 31) have four spinnerets but Stanwellia has a mottled abdominal pattern, while Hexathele (page 25) has six spinnerets.

Habitat and distribution: Porrhothele antipodiana is widely distributed across Aotearoa, including main Rēkohu Chatham Island, where it is thought to have been accidentally introduced. Other species have much narrower ranges; for example, P. quadrigyna is found only in Northland. These spiders make loose, tubular webs with a wide area of silk at the entrance, typically constructed in natural crevices such as hollows in trees, or under logs and stones, ideally in humid conditions. Although commonly forest dwellers, P. antipodiana can survive quite well in woodpiles, gardens and under houses.

Biology: Black tunnelwebs are reportedly New Zealand’s largest spiders by weight. They grab prey that stray too close to their tunnel entrances, most commonly beetles and other ground-dwelling arthropods, although they may also attack more challenging prey such as garden snails (Cornu aspersum). Males are often seen in spring seeking females to mate with. If courting is successful, the male clasps the female, who becomes passive. His modified front legs allow him to position her for mating.

Status in Aotearoa: Endemic

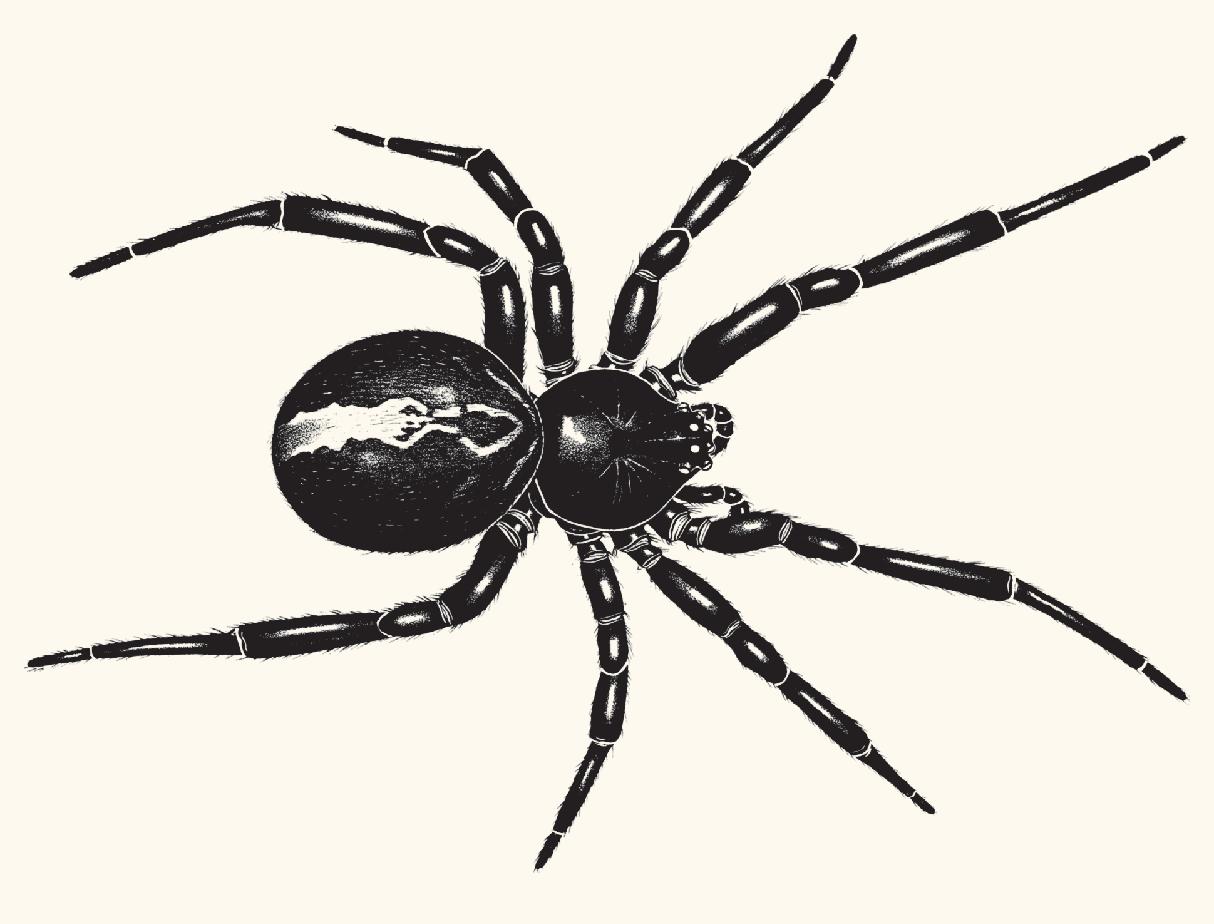

Spelungula cavernicola

At up to 15cm across, this is the largest spider species by leg span in Aotearoa. The scientific name of Spelungula cavernicola reflects its preference for cave habitat. It is also one of only two spider species protected under Schedule 7 of The Wildlife Act 1953.

Description: Females can reach a body length of around 20mm, although the total leg span is around 15cm. Males are smaller. The cephalothorax is reddish brown and the legs are banded in shades of brown. The abdomen is pale brown with some grey-black patches on the dorsal surface. This species also has the gradungulid features noted for Gradungula sorenseni (page 33).

Habitat and distribution: This species is known from a few cave systems in the Whakatū Nelson, Te Tai-o-Aorere Tasman and Te Tai Poutini West Coast regions, particularly around Ōpārara and Tākaka.

Biology: The Nelson cave spider has only rarely been seen outside its usual cave habitat, on misty humid nights, but it is not known how well it can survive there. Attempts to rear it in captivity have yet to succeed. It has extremely long legs, a feature seen in many cave arthropods, where constant darkness means that touch is more important than sight. Their main prey is cave wētā. If a spider senses one, either through vibrations in the air or in the cave surface, it will attempt to grab the wētā and drop on a strand of dragline silk. Cave wētā normally escape threats by jumping, but this method deprives them of a surface to push off from. In late spring, egg sacs begin to appear. These are large and teardropshaped and are suspended from cave ceilings by a strand of silk.

Status in Aotearoa: Endemic. Because of their limited habitat and unusual nature, the Nelson cave spider is absolutely protected under The Wildlife Act. It is an offence to harm these spiders or to collect them without authorisation from the Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai.

Celaenia spp.

As the common name suggests, some of these spiders resemble bird droppings, making them look unappetising to predators. Despite being part of the orbweaver family Araneidae, they have an uncharacteristic approach when it comes to silk and prey capture.

Description: Females range from 3 to 7mm long with males about half the female’s size. They have broad abdomens, so look wider than than they do long. The abdomen is typically humped and often has several projections and protuberances, more pronounced in females. Colouring is often a mix of dirty white and shades of brown. Together, colour and body form can give a passable impression of bird droppings, although some also look rather skull-like, giving rise to the other common name of death’s head spider.

Habitat and distribution. This genus is found throughout Te Ika-a-Māui North Island. It is less common on Te Waipounamu South Island but is known from as far south as Ōtepoti Dunedin. They are usually found on bark and foliage and are sometimes seen in gardens.

Biology: Despite being officially classified as orbweaver spiders because they share some anatomical features with other members of that family, these spiders do not construct a snare to catch prey. Instead, they hang suspended from a thread, waiting for moths to fly up to them and then grabbing them and biting them. As the moths are male, it is assumed that the spiders are somehow mimicking the pheromones of female moths to attract them. Moths are too large for younger Celaenia, so instead they mimic the pheromones of much smaller flies and attract those instead. Egg sacs are about 5mm in diameter and look like brown balls with stalks, although size and surface texture can vary between species. As females often produce a cluster of egg sacs, they can look like a bunch of tiny leathery grapes.

Status in Aotearoa: Celaenia has several endemic species. There are also several endemic Australian species and several species native to both countries.

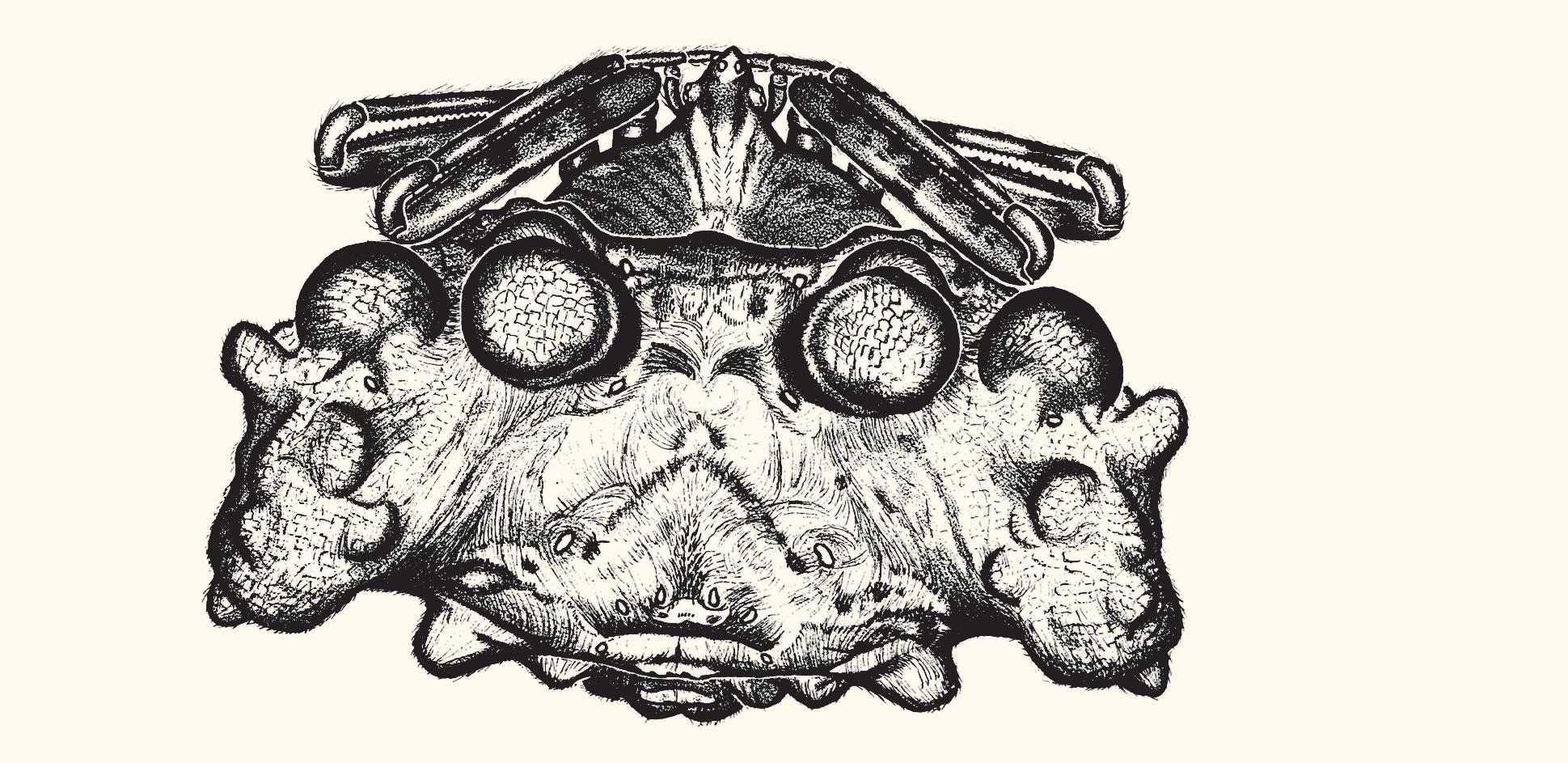

Plectophanes spp.

These spiders have an unusual carapace shape that allows them to use their eyes like a periscope.

Description: Females reach up to 12mm; males are about three-quarters of this size. The most distinctive feature of the genus is the form of the carapace around the eye area. Viewed from above, this appears as a narrow projection pushed out from the front of the carapace and in advance of the chelicerae. All eight eyes are positioned on this projection. Although eyes on projections or protuberances can be found in other spiders, such modifications are confined to males – in Plectophanes it is found in both sexes. The carapace is typically dark brown and the legs are often banded. The abdominal colouring is frequently a mix of dark brown and paler brown or whitish patterning.

Habitat and distribution: Members of this genus have been recorded from Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland to Rakiura Stewart Island. With the exception of P. frontalis, known from Taranaki to Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington and Wairarapa, most species have narrow geographical ranges. Periscope spiders hide in holes in trees by day. This makes them difficult to find, and it is possible that species distributions are more extensive than they appear.

Biology: The common name of periscope spider is apt. These spiders are nocturnal and by day shelter in disused insect holes in trees, often in twigs and branches. At night, they move to the entrance. Except for the eye projection, the spider remains concealed in the hole, peering out in periscope-fashion (see detail). When prey is sighted, the spider rushes out to grab it before returning to its retreat to feed. Unlike Ariadna (page 37), a genus also known to utilise old insect holes for their retreats, periscope spiders don’t use silken trip lines to warn of approaching prey; instead they appear to rely on sight as their primary means of detection.

Status in Aotearoa: Endemic

Latrodectus katipo

This species has a Māori name that translates as ‘night stinger’, in reference to the unpleasant bite that could be experienced when sleeping among the dunes where these spiders live.

Description: Females reach about 8mm long. They are black, with a prominent red stripe on the rear of the abdomen and a red hourglassshaped marking on the underside. From Taranaki northwards, katipō lack the red markings. Males are much smaller, with abdomens marked with a black-and-white checkerboard pattern. These spiders may be mistaken for the Australian redback (Latrodectus hasselti) and the false katipō (Steatoda capensis). However, the redback is larger and has longer legs and the false katipō has a much finer red stripe.

Habitat and distribution: This spider formerly enjoyed a wide range across the coastal dune systems of Te Ika-a-Māui North Island. On Te Waipounamu South Island, it was found along the east coast and the northern half of the west coast. It prefers living among native coastal dune grasses, but has lost a lot of habitat due to changes in land use and to colonisation by exotic dune plants. It can be locally abundant, but the range is far more fragmented than it once was.

Biology: Katipō is a member of the genus Latrodectus, more commonly called widow spiders, which is infamous for being venomous to humans. Fortunately, the katipō is the smallest member and its bite delivers a proportionately smaller dose of venom that is unlikely to be fatal, though it will be painful. As arachnologist Robert Jackson noted, ‘You won’t die, you’ll just feel like you will.’ Hospitals carry antivenom. As katipō face several threats to their survival, having not only lost habitat but also facing competition and direct predation from other species (including the false katipō), they are now fully protected under The Wildlife Act. The Australian redback has established in Central Otago and is spreading. Genetic evidence shows that the two species can interbreed and there is thus a potential to lose katipō populations through hybridisation.

Status in Aotearoa: Endemic

Like true scorpions, which are not found in Aotearoa, false scorpions have a pair of pincer-tipped pedipalps, but they lack the scorpion’s stinging tail. They also have the remarkable habit of exploiting larger animals for transport.

Description: Most specimens are 5mm long or less. The body is flat, but its shape is variable. Teardrop-shaped and ovoid forms are common; in the latter, the profile may be slender or broad depending on the species. The carapace takes the form of a flattened plate that is often divided across the body, while the abdomen is segmented. Both the chelicerae and the much larger pedipalps are pincer-tipped.

Habitat and distribution: False scorpions are found in most terrestrial environments, and as such occur throughout most of Aotearoa. They are particularly common in forest leaf litter and in soil near the surface.

Biology: These are predatory animals. While they lack the scorpion’s stinger, many false scorpions have venom glands in their pedipalps that are employed when seizing prey. The chelicerae of false scorpions also have silk glands. Silk is used to construct shelters, which are used for a variety of purposes including moulting and rearing young. Females keep their eggs and the first nymph stage attached to their bodies, secreting a nourishing ‘milk’ to their young. False scorpions use their pincers for more than prey capture. They can be used to clamp onto the legs or antennae of larger insects, using the insect as transport, a behaviour called phoresy. They often make use of flying insects (and sometimes bats), alighting after the insect lands. If you find a false scorpion indoors, chances are this is how it got there.

Status in Aotearoa: Although there are several introduced species, the vast majority are endemic.

Many thanks to Kane Fluery and Tūhura Otago Museum for generously sharing Barry Weston’s timeless illustrations with us. Thanks to Nadine Dupérré for providing her wonderful illustrations, and special thanks to Yoan Jolly for designing the tick image on page 112 and for preparing the illustrations for publication. Thanks to Cor Vink, Allen Heath and Gozalo Giribet for peer review and to the team at Te Papa Press for managing the project.

Many thanks to Tim Denee for the cover and series design, Sarah Elworthy for the typesetting, Teresa McIntyre for the copy edit, and Emily Goldthorpe and Olive Owens for proofreading.

Unless noted below, all illustrations by Barry Weston © Tūhura Otago Museum, Dunedin. Originally published in ‘The Spiders of New Zealand’, vols 1–6, Otago Museum Bulletin, Otago Museum, Dunedin, 1967–88, and New Zealand Spiders: An Introduction, Collins, Auckland, 1973, they have been modified for publication.

Pages 44, 46, 48, 50 (lower image), 52, 66, 72 (lower image), 82, 92 by Nadine Dupérré, modified for publication.

Page 112 by Yoan Jolly © Te Papa.

Bold page numbers refer to species and genera descriptions.

A

Amaurobioides spp. 83

Arachnura feredayi 13, 59

Ariadna spp. 37, 41, 97

B

Banded tunnelweb spider 10, 25

Bird-dropping spiders 63

Black tunnelweb spider 23, 25

Black-headed flax jumping spider 79

C

Cambridgea spp. 73

Cantuaria spp. 15, 27, 29, 31

Celaenia spp. 63

Chickenwire web spiders 53

Clubiona spp. 87

Comb-tailed spiders 19, 99

Common square-ended crab spider 13, 75, 77

Cribellate orbweaver spider 55

Cycloctenus spp. 93, 95

Cyclosa trilobata 61

D

Desis marina 71, 83

Diaea spp. 43, 77

Dolomedes aquaticus 67 dondalei 67 minor 65, 67

F

False scorpions 8, 9, 115

Flower spiders 17, 43, 77

GGarden orbweb spider 57

Giant goblin spiders 13, 39

Gnaphosidae (family) 89

Golden-brown jumping spider 81

Gradungula sorenseni 33, 35

Green dictynid spiders 101

H

Hahniidae (family) 99

Hard ticks 113

Hexathele hochstetteri 23, 25,31

Hutton’s spider 51

Huttonia palpimanoides 51

I

Intertidal spider 71

Ixodidae (family) 113

K

Katipō spider 9, 17, 19, 109

L

Laniatores (suborder) 119

Large brown vagrant spider 91

Latrodectus katipo 9, 17, 109

Leafcurling sac spiders 87, 89

Linyphiidae (family) 111

Long-legged harvesters 119, 121

Lycosidae (family) 13, 69, 91

Lynx spider 105

M

Malkaridae (family) 45, 47

Mecysmaucheniidae (family) 47, 49

Migas spp. 29

TE PAPA TE TAIAO NATURE SERIES: NATIVE SPIDERS OF AOTEAROA

RRP:$27.00

ISBN: 978-1-99-107211-5

PUBLISHED: October2025

PAGEEXTENT:136 pages

FORMAT: Hardback

SIZE:184x125mm

FOR MOREINFORMATION OR TO ORDER

https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/about/te-papa-press/contact-te-papapress