DETROIT

Collective Ideologies Toward Planned Reciprocity & Just Futures

Collective Ideologies Toward Planned Reciprocity & Just Futures

University of Michigan, Taubman College, Master’s of Urban and Regional Planning Professional Capstone Project

Lawson Capri Schultz 2025

Detroit Interwoven Acknowledgements

This project is a reflection of the care, wisdom, and generosity that others have poured into me throughout this academic journey.

First and foremost, I extend my deepest gratitude to Ashley Atkinson, my client for this project and my mentor in all other contexts. I believe we both deeply share, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore so eloquently put it, a motivation “to learn how to interpret the world in order to change it... to contemplate and document the vibrant dialects of objective and subjective conditions that, if properly paid attention to, help reveal both opportunities for and impediments to human liberation” (Gilmore, 2022). Thank you for demonstrating what love for community looks like in action. When I doubted myself, your trust and support reminded me of my own capacity. Beyond the seedlings you plant at the farm, I hope this project stands as a testament to the successful growing season you have cultivated in me, through your patience, guidance, and no-pesticide approach to mentorship.

I am also profoundly grateful to the faculty in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning. A special thanks to Lauren Hood, my faculty advisor for this project. Taking your course at the University of Michigan on reparative planning was transformative. It introduced me to the incredible urban agriculture work happening in Detroit and provided a powerful framework for questioning ‘traditional’ planning paradigms.

Lastly, to my classmates, friends, and family, your presence has carried me to this graduation finish line. I am endlessly grateful for the community we have built together.

Cheers

Schultz 2025

Purpose

The

Hegemonic

Communal Amenities under Capitalism

Public Libraries

Public Parks

Traditional American Planning

Commodification of Housing

Distinct Land Uses

Sprawl

Ramifications on Detroit

The Predominance of Single-Family Housing

Vacancy

Land Ownership

Buen Vivir

Aloha ‘āina

Satoyama

Dugnad

Autogestión Afrofuturism

Guided by the question, what would it mean to plan from a place of love?, and inspired by Cornel West’s assertion that “justice is what love looks like in public,” this project was created for Keep Growing Detroit (KGD) as a resource aligned with the organization’s mission to build a food sovereign city. This report builds upon KGD’s focus on the principles of Biiskaabiiyang, Sankofa, and re-remember which emphasize connection to land and ancestral wisdom. Rooted in the unique context of Detroit, this report acknowledges the city’s vast potential and the ongoing justice-driven work of activists, farmers, and community members. It also seeks to contribute to broader discussions about the future of urban planning in the United States.

1

The report begins with a historical and sociological investigation of the disconnection between humans and nature in the United States, how this separation has been reinforced through urban planning, and the implications for Detroit. This section includes spatial analysis using GIS to illustrate these dynamics and examines communal spaces and resource-sharing practices that have persisted within capitalist and colonial paradigms.

Drawing on Angela Davis’s argument that “we will not be free to imagine other ways of addressing crime as long as we see the prison as a permanent fixture for dealing with all or most violations of the law,” and inspired by Simpson et al. (2020), who call for a system of care rooted in new imaginaries, this project aims not only to critique current systems but to highlight existing and possible alternatives. The report continues with an exploration of global ideologies and practices that offer different understandings of well-being and sustainability, with particular attention on collective worldviews with explicit notions of human-nature unity.

Finally, the report wraps up with a review of existing examples of nature-centered communities and urban spaces and a discussion of additional possibilities for action and implementation. These possibilites aim to reflect the collective ideologies discussed in an attempt to offer grounded visions for planning practices that center justice, relationality, and care.

1 “Biiskaabiiyang, a word from the Anishinaabe language that captures the essence of returning home after being away for an extended period, finding oneself transformed yet familiar; Sankofa, a concept from the Asante Twi language of the Akan people of Western Africa, which expresses the importance of reaching back into our past to retrieve essential wisdom and understanding; and to re-member, the English word of not just remembering, but actively putting back together what has been separated, reconstructing our connections with intention and purpose” (Keep Growing Detroit, 2024).

The next generation of planners must consider both short- and long-term actions that ensure the wellbeing of all members of our communities. This requires a departure from hegemonic planning practices in the U.S., which have too often perpetuated harm and neglected the vital roles that nature and community connection play in shaping thriving urban environments.

Research demonstrates that exposure to nature improves emotional wellbeing and reduces stress (Cox et al., 2017; Kabisch et al., 2017). Passive exposure, such as sitting or walking in a forested area and long term proximity to green and blue spaces (bodies of water), is linked to psychological health (Meidenbauer et al. 2020; Bratman et al., 2019). Cox et al. (2017) found that vegetation cover of 20% or higher and afternoon bird abundances were two factors “positively associated with a lower prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress.”

Active exposure to nature, such as participation in urban gardening, reduces stress, restores attention, and lowers depression (Grebitus, 2021; White, 2011; Beavers et al., 2022). Urban gardening specifically fosters community relationships, collaboration, and empowerment, which is linked to improved wellbeing and mental health (Golden, 2023; Audate et al., 2019; Langemeyer et al., 2021; Grebitus, 2021; Tornaghai, 2017; Colson-Fearon & Versey, 2022).

Green and blue spaces also provide physical health benefits. Walking through natural areas can improve memory performance (Bratman, 2015). In urban areas, green spaces promote physical activity (Kabisch et al., 2017).

L. Schultz

The Need for Nature & Community

Gardening increases vegetable consumption among adults and children, improving dietary quality and health (Carney et al., 2013; Al-Delaimy & Webb, 2017; Alaimo et al., 2023; Golden, 2023; Algert et al., 2016). Participation in school gardens encourages children to regularly consume fresh produce and try new foods (Brinkmeyer et al., 2023).

Within urban spaces, care for natural areas benefits people and nature. Maintaining vegetation cover provides cooling to reduce urban heat island effect and can improve air and water quality (Kabisch et al., 2017). Urban agriculture preventions erosion, boosts soil quality, creates habitats that supports diverse plant and animal life (especially pollinators), and contributes to circular waste management by remediating contaminated soils and promoting nutrient cycling (Newell et al., 2022; Seitz et al., 2022; Galhena et al., 2013; Matteson et al., 2008; Frankie et al., 2019; Bennett & Lovell, 2019; Beniston, 2012; Galhena et al., 2013; Pal, 2020). Rainwater harvesting and composting further reduce water and food waste (Parece, 2022). Urban agriculture increases knowledge and appreciation for environmental sustainability (Martin et al., 2016; Langemeyer et al., 2021).

As Beatley emphasizes in Biophilic Cities (2011), the importance of natural spaces extends far beyond their functional benefits. Beatley argues that nature is an essential part of urban life; he writes, “nature should not be an afterthought or viewed only in terms of the functional benefits” (p. 14). Instead, he advocates that “experiencing nature in cities is as much about hearing, smelling, and feeling as it is about seeing” (p. 36).

Research suggests that community connections are linked to wellbeing and mental health (Fowler Davis & Davies, 2025). Social ties are correlated with psychological wellbeing through direct causation and reducing the negative impact of stressors (Huppert et al., 2004; Kawachi, 2001). Kingsbury et al. (2020) identified that social cohesion “buffer[s] the effects of stressful life events” for children, specifically shown through reduced risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Community connections and interpersonal relationships are also unequivocally necessary for long-term physical-health, including reduced disease morbidities and mortality risk, emphasizing that people need each other to survive (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017; Holt-Lunstad, 2021).

A growing body of research demonstrates the significance of shared identity-based connections for marginalized populations. Emotional connectedness fostered within shared identity-based connections is also linked to improved mental health among Black people, transgender and nonbinary people, and Black LGBTQ people (Sherman et al., 2020; Watts & Thrasher, 2024). Reachers John & Castleden (2025) found that community connections within indigenous populations in Canada lead to increased engagement in healthcare and self-care, especially significant given that “colonization disrupted and sought to delegitimize Indigenous relationships, having devastating impacts on Indigenous health and contributing to persistent Indigenous health disparities”.

Community connection and cohesion are linked to civic engagement. While one study by Carbone &McMillin (2019) found that social cohesion is negatively associated with civic engagement, there is significant literature that suggests otherwise. Collins et al. (2014) found that “residents who reported higher levels of bonding social capital also reported higher levels of neighborhood collective efficacy.” Gearhart (2020) also suggests that social cohesion is linked to civic participation in the form of voting. In addition to civic engagement, community connectedness can also influence perceptions of environmental sustainability. Cope et al. (2022) report that community belonging is associated with people’s perceived relationship with nature and environmental sustainability. Moreover, Roger & Bragg (2012) contend that increased sense of place “can motivate people to engage in actions for sustainability.”

In the United States, a nation established by and for landowners, the separation between people and nature has been socially constructed and systematically reinforced to serve capitalist, colonial interests. The average American only spends about 5 percent of the day outside (Beatley, 2011). Human-nature dualism is the philosophical concept that humans and human culture is opposite and distinct from nature (Dussault, 2016). In the process of founding the United States, white Christians and Western ideology violently supplanted Indigenous peoples, and with them indigenous ideologies and culture, a process which embedded a “colonially defined matrix of lands” into the country’s political and economic systems (Kamelamela et al., 2022).

2

The disconnection between people and nature has been calcified through American institutions, politics, and culture (Beery et al., 2023; Everard, 2011). For example, during the 18th century in the United States, American painters produced romantic imagery of the American West. These works contributed to cultural imperialism and to the cultural invention of the “wilderness,” as a sublime humanless natural area of “wild unsettled lands of the frontier” (Miller, 2006; Cronon, 1996). Romanticization of the West as humanless wilderness also served as revisionist history, helping to eliminate the presence and history of Indigenous people and erase evidence of colonial violence (Miller, 2006).

In her analysis of Thomas Moran’s painting, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (1872, oil on canvas), Miller (2006) describes that the painting “resolved these painful historical realities in a wishful image of the peaceful transfer of ownership and sovereignty from the Native American to the white colonizer” (p. 105). Natural beauty was thus constructed as most valuable when devoid of people. At the end of the 19th century, this contributed to the national movement to establish federal national parks and wilderness eras. As the colonial state continued to violently remove Indigenous people from their homelands and forced them into reservations, the government began to establish formal measures to protect natural areas from development at the turn of the 20th century (Everard, 2011; Cronon, 1996; Miller, 2006).

2 Some researchers argue that Christianity contributes to the normalization of human-nature dualism in Western culture. While many religious belief systems subscribe to the idea of life after death, Elvey (2006) describes that Christian theology posits life after death, “beyond this world of earthly habitation… denies the interdependence of humans with nature”.

L. Schultz

2024). For instance, Kotsila et al. (2021) highlight the privatization of water for “its better management”.

While some coalitions continue to discuss and take action around regenerative, degrowth, and integrated human-nature relationships, since the 1970s, “neoliberal capitalist discourse has dominated global affairs” (Riedy, 2020; Tulloch & Neilson, 2024). Consequently, Turner et al. (2004) highlight that a majority of people around the world can be considered to be living in “biological poverty” in which people lack access to regular engagement and connection to natural systems, even those as simple as trees. Nature has become a resource reserved for wealthy Americans with “the creation or restoration of green amenities – parks, gardens, greenways” contributing to gentrification “in the context of neoliberal development paradigms” (Kotsila et al., 2021). Thus, neoliberal environmentalism has further entrenched American people’s disconnect with nature. Beery et al. (2023) distinguishes various forms of disconnection from nature, including ”disconnection due to ecological illiteracy and loss/lack of biocultural memory; and disconnection due to lack of knowledge of outdoor recreation behaviours and skills”.

Individualism, encompassing American fondness for “geographic mobility, access to land, and security of property rights,” is deeply ingrained in mainstream American culture (Bazzi et al., 2017). Sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset suggested that American culture specifically epitomises “liberal individualism”, which he dubbed “Americanism” (Grabb et al., 1999).

The word, individualism, was first coined in reference to American society. Kerber (1989) documented that French diplomat, Alexis de Tocqueville, “used “individualisme” to describe a social relationship that he took to be distinctive to American society” in 1832. Throughout the 19th century, individualism became culturally associated with westward expansion and the American frontier. While research does not support the notion that early Americans would expressly use the term individualism to self-describe, researched have argued that the American “frontier fostered a culture of rugged individualism,” by attracting “individualistic migrants, and then mak[ing] them more individualistic over time” (Bazzi et al., 2017). American individualism is not isolated to frontier times. Rather, data suggests individualism has continued to grow since the 1960s, built into the rise of the American suburb.

Despite the dominance of privatization and individualism in American planning practices, public libraries and parks stand out as enduring examples of communal infrastructure. These spaces offer services and embody values of shared access, collective care, and public investment in wellbeing.

Libraries are key place-based assets in our communities. The American Library Association estimates that there are more than 124,000 libraries across the United States today. While the majority of libraries are public school libraries (more than 80,000), there are also about 18,000 private school libraries and 17,000 public libraries (“Library Statistics,” 2025). The American public library was born around the same decade as the United States itself. The library established in 1790 in Franklin, Massachusetts is widely recognized by library historians as America’s first public library. New Hampshire later became the first state to establish a tax funded public library in 1833 and to pass legislation enabling libraries in 1849 (Abbott et al., 2015; Kevane & Sundstrom, 2014). Michigan was another state with legislation that incentivized building libraries due to provisions mandating township libraries within the Michigan state constitution (Kevane & Sundstrom, 2014).

By the 1870s, more and more states saw the rise of local public libraries, with smaller branches becoming popular in the 1890s. During the Progressive Era in the United States with growing political support for academics, the population of public libraries skyrocketed. Between 1891 and 1929, the number of public libraries in the United States grew dramatically, increasing tenfold from 565 to

Communal Amenities under Capitalism

Throughout American history, the uses and values associated with parks as public spaces have varied with early parks being viewed as tools for social reform and later as a space for recreation as an inherent benefit in of itself, with wider acceptance of leisure as an essential aspect of healthy life (Taylor, 1999). Parks have been employed to serve a variety of purposes, from promoting democratic ideals, fostering community connection and social awareness, boosting tourism, to supporting mental and physical wellbeing. Reflecting on the varied history of American parks can inform our imagination of parks for our current and future communities.

In the late 1800s, America’s early urban parks were produced as spaces for passive use to escape into pleasant nature, often incorporating lakes, meadows, and rolling hills (Cranz, 1982). In this same period, large cities began to slowly locate playgrounds in municipal parks, marking a shift toward progressivism park development. For example, a playground was added to Washington Park in Chicago in 1876. Twenty-five years later, in 1901, Chicago established formal legislation permitting playgrounds in municipal parks (Cranz, 1982). Around the turn of the century, playgrounds were officially integrated into New York City parks, moving away from the early “sand garden” playgrounds that could be found at schools in the 1880s (“History of Playgrounds,” n.d.).

From 1900 to 1930, progressivist park development was in full swing, emphasizing parks as instruments of social reform. Reform parks functioned as early urban revitalization efforts by replacing land uses such as garbage dumps, burial grounds, and overcrowded housing (Cranz, 1982). Recreational programming during this era was typically categorized into physical, social, aesthetic, and civic activities and included swimming, dancing, public meetings, concerts, and gardening (Cranz, 1982).

Detroit Interwoven Communal Amenities under Capitalism

One of the first documented instances of gardening in a public park took place in New York City in DeWitt Clinton Park in 1902, where children were assigned individual sections (Cranz, 1982). In the following decades, the New York Parks Department also attempted to pursue small-scale parks as part of a backyard parks movement. Cranz (1982) notes that while the “department formally incorporated the use of vacant lots in their programming” in 1915, the backyard parks movement was overshadowed by the City Beautiful Movement which gained more momentum and public attention (p. 84). Playgrounds also continued to grow in numbers around the country. In 1908, Manhattan had 11 playgrounds in public parks, and by 1915, Manhattan had 70 playgrounds with equipment (“History of Playgrounds,” n.d.).

8. Human Be-in (Source: Lonnie Robbins).

9. (Happening) Reading the News by Marta Minujín (Source: LibreTexts).

White flight and suburban sprawl in the 1960s led the American middle class to associate public parks with danger and avoid parks rather than seek them out. Remaining urban parks were “stripped of vegetation for easier maintenance and police surveillance” (Cranz, 1982, p. 153). Social resistance in the 1960s, built on progressivist era social and active programming, produced an additional array of creative and experimental programming in urban parks including:

• ‘Be-ins’

• ‘Chalk-ins’

• ‘Happenings’

• Concerts

• ‘Dancemobiles,’

• ‘Cinemobiles,’

• Fashion Shows

• Child-care services

• And a variety of festivals. However, in the 1970s, park use transitioned away from programming and “reverted to appreciation of park landscape itself” (Cranz, 1982, p. 143).

4 Be-ins, also called Human Be-ins, were “public gatherings—part music festivals, sometimes protests, often simply excuses for celebrations of life” prominent in hippie movement of the 1960s and 1970s. (Frommer, n.d.).

5 Happenings were live art performances that “combined elements of dance, theater, music, poetry, and visual art to blur the boundaries between life and art.” (Cain, 2016).

6 The Dancemobile was a program unique to New York City, “sponsored in part by the New York State Council on the Arts, as well as the New York City Administration of Recreation and Cultural Affairs” (Miller, 2024). A total of 15 shows occured across all five boroughs.

L. Schultz 2025

Detroit Interwoven Communal Amenities under Capitalism

In decades since, communities have continued to innovate with size and utility, such as with the creation of ‘pocket-parks’ and ‘adventure playgrounds. In some cities, urban parks remain in a point of tension with competing opinions of parks as valuable assets or financial drains.

Planning decisions have further embedded private property, land use distinctions, and patterns of sprawl in American society. These planning paradigms reinforce human-nature dualism and individualism as dominant ideologies and in turn perpetuate racial and socioeconomic injustice and ecological unsustainability.

Around the world, “there has been a progressive privatization of the land, and an associated transition of the benefits derived from land and landscapes from public goods into private property” (Everard, 2011, p.12). In the United States, private property is rooted in Enlightenment ideals that link individual freedom to land ownership, reinforced by Millian liberalism and a “preference for securing individual political autonomy through control of one’s property” (Norton et al., 2014). Inheritance laws and the reliance of local governments on property taxes further entrenched private ownership (Katz, 1977). Planning in the U.S. reflects a broader cultural resistance to collective land stewardship. Rather than fostering community, it pushes property owners toward economically productive uses.

7

Land and housing have been commodified through ownership. Land as fictitious capital and home ownership as real estate serve as wealth-producing financial assets (Soederberg, 2018). In addition to housing as a commodity, where housing has become a tool for capital accumulation, the housing market also serves as a force to ensure labor is reproduced. This is especially true through landlord and renter models, where housing becomes another site of exploitation (Soederberg, 2018). Since the 1960s, housing has been the largest expense for American households (Pattillo, 2013). Housing-as-political economy normalizes poverty as an industry through housing insecurity and neutralizes the need to ‘earn’ housing (Soederberg, 2018). Housing disparities are higher than during the American era of segregation, with white homeownership rates being 30% higher than Black homeownership rates in 2018 (“Coronavirus relief,” 2020).

A growing portion of global housing stock is owned by corporate finance, contributing to our global eviction and homelessness crisis (Barenstein et al., 2022). From 2008 to 2013 in the European Union, “4.1 million people were made homeless through evictions” (Soederberg, 2018). In addition to evictions and homelessness, millions of people live in insufficient quality rental housing. From 2020 to 2022 in Detroit, Michigan, the vast majority of eviction cases were filed against residents living in substandard housing.

7 Exerpt from Schultz (2024) “The need for communal housing schemes” (Unpublished).

People have modified land cover throughout all of human history (Black et al. 1998; Ellis, 2021). Munoz et al. (2014) identified that in the United States, “indigenous land-use practices created patches of distinct ecological conditions within a heterogeneous mosaic of ecosystem types,” formed through agriculture and woodland management. Today, the majority of ecosystems around the world have been transformed by human land use, with railroads, commercialized farming, and highways as the primary technologies driving intensive use and ecological changes (Ellis, 2021; Black et al. 1998). In addition to varying technologies, formal land use regulations have also molded the “suite of cultural practices” that form America’s “land use regime” (Ellis, 2021).

Zoning serves as the primary tool used to establish distinct land uses. Planners designed zoning regulations to organize cities, mitigate potential conflicts between land uses, and preserve property values. The first official land use regulations in the United States began well before the country was founded, with “rules for the enclosure of agricultural land and the management of riparian rights appearing as early as 1634” (Shertzer et al., 2022). Segregation ordinances also predated the comprehensive zoning practices America utilizes today. In 1910, Baltimore public officials passed the “West Ordinance,” instituting the country’s first municipal segregation ordinance (Shertzer et al., 2022).

In the following decade, early American city planners drew upon German zoning as a model for comprehensive zoning regulations (Silver, 2016). With growing pressures of dense urban housing and health challenges of industrialization, New York City adopted an ordinance in 1916 to manage land use, density, heights, and other design regulations (Shertzer et al., 2022; Silver, 2016). Zoning became an embedded practice in American land use management following the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act (SSZEA) of 1924 and the Ambler Realty v. Village of Euclid Supreme Court case in 1926. The SSZEA established a model law to guide states to enable zoning, and the Euclid Case cemented zoning as a constitutionally valid police power of local government justified by the governments’ role to protect community “health, safety, and welfare” (Silver, 2016). Despite such a goal and the economic theory that zoning reflects “current optimal use of land,” (Shertzer et al., 2022) urban planners and historians today widely recognize many adverse impacts patterns of restrictive zoning contributes to including

• persistent segregation (Rothwell & Massey, 2009; Goetz, 2021; Shertzer et al., 2022),

• racially disproportionate environmental health hazards (Maantay, 2002; Wilson et al., 2008), and

• low density development (Freemark, 2023).

L. Schultz

Rather than challenging inequality, land use planning has historically served to “consolidate a generalized sense of individual land ownership at the expense of the commons,” prioritizing private wealth and speculative value over community needs or ecological sustainability (Fawaz & Moumtaz, 2017). In regard to the widespread practice of ‘master’ planning, Fawaz and Moumtaz (2017) contend

“that more than wrestling to balance the rights of private property owners and the common good, planners ultimately contribute to the consolidation of a particular understanding of the landscape (as propertied), the prioritization of the exchange value of land or its role as a future asset at the expense of common uses (e.g. subsistence agriculture), and ultimately the consolidation of private individual interests at the expense of a possible shared imaginary.”

In the mid 1900s, cities in the United States saw high rates of white flight to suburbs leading to population loss and vacant properties. Cities therefore faced a reduction in the local tax base which they relied on for the majority of revenue. Despite relatively similar local government structures and capitalist development, planning patterns of post-industrial Canadian cities have departed from Rust Belt American cities, specifically with “very different levels of inner core land abandonment” (Hackworth, 2016). Although these outcomes cannot be attributed to a few singular causes, Hackworth (2016) contends that they arise from three primary factors:

• forced consolidation of municipalities,

• suburban growth restrictions, and

• differing spatial patterns of anti-Black racism.

In contrast to white flight and suburban sprawl that depleted the tax base of post-industrial American cities, Canada’s lower emphasis on local control allowed for regional restructuring to pass, which produced larger tax bases for their cities. In regard to different spatial patterns of anti-Black racism, Hackworth notes that there is no majority Black city in Canada, thus reducing the impact of racism on one concentrated area in particular.

Vacant land is now a common feature of American Rust Belt cities, “in total, there are 269 neighborhoods in 49 American Rust Belt cities that have lost more than 50% of their housing since 1970” (Hackworth, 2016). Vacant land and vacant buildings do not provide property taxes for local governments and lead to lower property values for adjacent parcels (Hackworth, 2016). Hackworth and Dantzler (2025) argue that a “market-growth paradigm” focused on selling abandoned land to increase the population of tax-paying residents, “is ineffective or even counterproductive in

L. Schultz 2025

Detroit Interwoven Ramifications on Detroit

severely disinvested urban areas.” Hackworth and Prentiss (2015) highlight that despite the recent increasing establishment of land banks as alternative land management networks, land banks similarly “emphasize tax-paying end users as the ideal policy outcome,” while collective models remain unpursued. Today, American cities are, “more racially isolated than they were even under the period of de jure racial segregation” (Hackworth, 2018).

Detroit experienced white flight, sprawl, urban renewal, and vacancy to an intense degree. Following the Detroit Riot of 1967, many people were quick to label Detroit as a city of abandonment, poverty, and decay (Thompson; 2013). While these patterns did lead to concentrated disinvestment, Detroit’s historic fabric is made up of a complex web of challenges, community action, remaining uncertainty, and possibility.

Planning institutions exacerbated racial inequity in Detroit. Black Bottom and the adjacent neighborhood Paradise Valley were predominantly Black neighborhoods in Detroit, Michigan demolished in the late 1950s to make way for federal highways (Rudelich, 2023). The Regional Planning Commission (RPC) merged with the Supervisors Inter-County Committee (SICC) in the 1960s, forming the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG). Batterman (2021) argues that “SEMCOG survived the 1970s only by vowing to defend local control and eschewing a role in resolving issues of racial segregation and inequality, while accommodating the prevailing pattern of sprawl and disinvestment.”

In the five year period from 2017 to 2023, census data reveals that Detroit’s population and the number of total housing units have both decreased. Based on GIS analysis of City data, building vacancy and unoccupied housing units have both decreased (Table 1).

L. Schultz

Table 1. Detroit Demographic Data 2017 & 2023 (Source: U.S. Census).

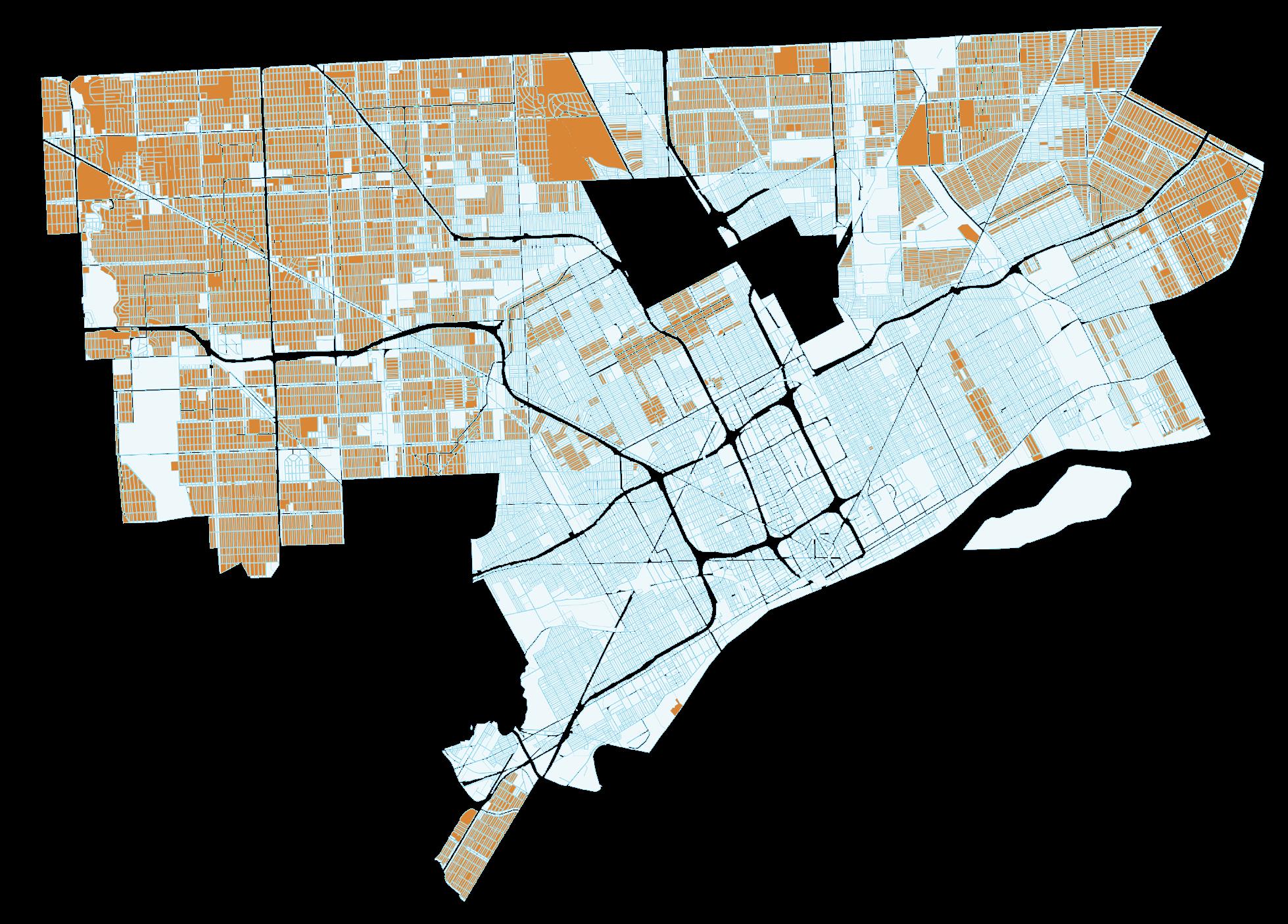

Today, about 67% of Detroit parcel area is zoned residential, 8% is zoned commercial, and 16% is zoned industrial. Mapping zoning across the city reveals that non-residential uses are concentrated together, rather than being equally distributed throughout neighborhoods. The median proportion of residential zoning of neighborhoods is much higher than the average at about 83% residential. Similarly, the median proportion of industrial zoning of neighborhoods is much lower than the

2. Detroit Zoning. average, at 0%, due to the large proportion of neighborhoods without any industrial zoning. Only some of the largest parks in the city are zoned as “Parks and Recreation,” while others are within areas zoned as “Single-Family Residential District” or other residential uses. For example, the Chandler Park neighborhood is zoned as completely residential despite having a 200 acre park.

TM, W1)

(B1, B3:B6, PCA, SD1, PC, MKT)

(SD2, SD4, SD5, B2)

12. Map of Single-Family Residential Zoning in Detroit.

In 2018, the American Community Survey reported that 67% of housing units in the United States were single-family dwellings (Neal et al., 2020). Census data reveals that in 2017 about 66.7% of housing units in Detroit were single-family, detatcheddwellings (see Table 3). From 2017 to 2023, the rate of detached single unit houses decreased, with attached single unit houses and buildings of 20 or more units increasing the most (Table 3).

Roughly 67% of Detroit parcel area zoned for single-use residential use. In comparison, Boston, Massachusetts and Milwaulkee, Wisconsin, cities with comparable populations, but different development patterns, have rates of single-family zoning at about 35% and 27% respectively (“Land Use,” 2010).

Table 3. Detroit Housing Data 2017 & 2023.

While Hackworth and Dantzler (2025) warn that “over-emphasis on spaces of depletion has tended to reinforce stereotypes of Black, Indigenous, and other communities of colour rather than leading to change,” it is notable to understand how market-based planning has shaped the Detroit we know today. In recent decades, high property assessments and subprime lending have been major contributors to perpetuating vacancy across racial lines. Between 2008 and 2019 about one-third of Detroit’s properties were foreclosed due to unpaid taxes (MacDonald, 2019). Gillis (2019) contends that tax foreclosures are a justice issue because “the use of streamlined property tax foreclosure laws to curb speculation and abandonment have few mechanisms in place to distinguish between poverty and irresponsible ownership, which has led to the displacement of low-income residents” (Gillis, 2019). Overall, these patterns have continued to contribute to the high rate of vacancy in Detroit.

Across the whole city, about 34% of all parcels do not have any buildings or structures (nearly 140,000 parcels). Accounting for the area, these parcels make up about 23% of the total parcel area in the city. The mean number of buildingless parcels (682) and mean total area of buildingles parcels (72 acres) per neighborhood are both higher than the medians (344 buildings, 37 acres) indicating that patterns of empty parcels are concentrated in some neighborhoods rather than distributed throughout.

L. Schultz

Detroit Interwoven Ramifications on Detroit

Belle Isle and the Brewster Homes neighborhoods are outliers on the low end with zero buildingless parcels. These findings are not surprising given that Belle Isle is one singular parcel, and Brewster Homes is the fifth smallest neighborhood of all 205 neighborhoods, and demonstrates a concentrated area of development. In contrast, the Douglass, Riverbend, McDougall-Hunt, State Fair, Greenfield Park neighborhoods are outliers with significant portions of their total area with buildingless parcels.

Out of the over 240,000 buildings in Detroit, nearly 3,500 buildings (about 1.5%) were registered as vacant in 2022. This is likely an underestimate of all vacant buildings, given that some may be vacant but unregistered. Twenty one of the 205 total neighborhoods had no vacant buildings. However, nine neighborhoods were outliers on the high end with building vacancy rates between 3.3% and 8%: Poletown East, Carbon Works, Eastern Market Core City, West Village, Milwaukee Junction, NW Goldberg, Greektown, and Gold Coast.

* Find names of Detroit neighborhoods in numbered list in the Appendix.

Land ownership has become a central issue in Detroit’s efforts to address vacancy. One key response to the city’s growing number of vacant properties has been the creation of the Detroit Land Bank Authority (DLBA) in 2010 (Rudelich, 2023). By 2020, the DLBA had become a major player in Detroit’s real estate landscape, owning 25% of the city’s properties, including around 22,000 homes (Rudelich, 2023). In 2024, the DBLA owned nearly 65,000 parcels (about 16% of total parcels in the city) making up nearly 10% of total parcel area. Despite the land bank’s significant presence, Detroit residents “struggle to gain long-term access to and ownership of land on which to farm” (Pothukuchi, 2017).

Compounding the land bank’s efforts is the issue of land speculation and vast ownership by wealthy individuals, which has contributed to the displacement of residents and the further privatization of public space. Land speculation is the practice of buying up low-cost land and holding it to sell at a land point for profit. Speculative buyers, often with little interest in the neighborhoods themselves, have acquired large swaths of land, contributing to rising property values and evictions. At least 20% of Detroit’s land is owned by property speculators (Hill, 2025).

High-profile investors such as the Ilitch family and Dan Gilbert have been associated with large-scale land purchases in the city (Aguilar, 2019). In addition, re-

L. Schultz

Detroit Interwoven Ramifications on Detroit

porting from 2013 highlights other, lesser-known individuals who have amassed substantial property holdings, including Michael G. Kelly (1,152 parcels), Matt M. Tatarian (1,003 parcels), and Manny Moroun (619 parcels) (Michigan Radio Newsroom, 2013). This concentration of land ownership among powerful actors reinforces Detroit’s long standing struggles with displacement and racialized spatial inequality. As Akers and Seymour (2018) observe, “the outcomes of displacement and dispossession in the complex chains of relations between finance, speculation, and the state do not land in an arbitrary manner, but are tethered to the past and present racial-spatial ordering of US cities.”

Analysis of park area per neighborhood in Detroit reveals that the city’s parks tend to be large, making up significant portions of the neighborhoods they are located in, leaving many neighborhoods without any designated park land at all. The City reports that there are more than 300 parks in Detroit, and that 29 miles of greenway are being developed (“Parks and Greenways, N.d). Additional GIS analysis of park area indicates that Detroit currently has about 10.5 sq mi of formal park space. Rouge Park (1.85 sq mi) and Belle Isle (1.53 sq mi) are the two largest parks.

In contrast, 59 of Detroit’s 205 neighborhoods do not have any park land. Schoolcraft Southfield, Bagley, and Conner Creek are the largest neighborhoods without any parks. Of these 59 neighborhoods, the neighborhoods of Russell Industrial, Waterworks Park, and Milwaukee Junction are primarily industrial with little land designated as residential. Similarly, the neighborhoods of State Fair, New Center, and Greektown do not have residentially zoned areas and are primarily commercially zoned.

In the face of an abundance of vacant land, urban agriculture in Detroit has emerged as a robust grassroots movement connecting people to nature and to one another and promoting justice and food sovereignty. The Garden Resource Program (founded in 2003) and Grown in Detroit (created in 2006) were two of the first major urban agriculture initiatives. Momentum continued with the establishment of D-Town Farm and the Detroit Black Food Security Network (now Sovereignty Network) in 2008 (Ignaczak, 2024). As Ignaczak (2024) notes, these initiatives were pivotal in mobilizing resources and community power to reimagine food systems in the city.

Community organizing led by the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network helped secure the establishment of the Detroit Food Policy Council, in 2009, with support from the City Council, institutionalizing community-led food planning. This momentum was further solidified with the founding of Keep Growing Detroit (KGD) in 2013, which reinforced urban agriculture as a critical tool for advancing food justice (Ignaczak, 2024). That same year, the city passed its urban agriculture

Detroit Interwoven Ramifications on Detroit

ordinance, legitimizing agriculture as an accessory land use and setting the stage for more intentional integration of growing spaces into city planning.

Detroit’s zoning regulations now distinguish between ‘urban gardens’ and ‘urban farms.’ Urban gardens, which may not exceed one acre, are primarily for non-commercial use and are permitted by right in most residential and business zones. Urban farms, which can exceed one acre and support commercial sales, have more permitted uses and are regulated differently. Where agriculture is designated a conditional use, farmers must apply for special land use approvals to demonstrate compliance and preparedness (City of Detroit Zoning Ordinance, n.d.).

The movement has continued to grow. On Juneteenth of 2020, the Black Farmer Land Fund, a coalition of three long-standing organizations: DBCFSN, Oakland Avenue Urban Farm, and Keep Growing Detroit, was born (“About Us,” 2022). Their mission centers on rebuilding intergenerational land ownership for Black farmers in the city. In 2023, the City of Detroit established an Urban Agriculture Division, which aims to align city resources with farmers’ needs. Tepfirah Rushdan was appointed as the first urban agriculture Director (Ignaczak, 2024), but has since become the Director of the Office of Sustainability.

L. Schultz

Figure 17. Detroit Zoning, Urban Agriculture.

Based on 2024 data from Keep Growing Detroit’s Garden Resource Program, there are 389.5 acres of gardens and farms currently supported across the city. While some neighborhoods like Brightmoor and Campau/Banglatown are standouts in garden density, 18 neighborhoods, including residentially-zoned areas like Grand River-St Marys and East Canfield, do not have GRP gardens (Fiture 20). Conversely, KGD’s efforts support nearly 25,000 Detroiters through programming like the Urban Roots Leadership Program, Summer Youth Apprenticeships, gardening classes, and events (Keep Growing Detroit, 2024).

Neighborhood-specific examples offer a closer look at the diversity of Detroit’s agricultural ecosystem. In the Farnsworth block, in 2011, a couple sparked cultivation of a farm with livestock, orchards, and bees across 11 city lots. Jackman (2015) states, “they’ve been able to add more agricultural energy to the core Weertz has provided”. The Oakland Avenue Urban Farm in the North End represents another expansive model (Figure 20). Operating on six acres spread across 30 lots since 2000, OAUF blends food production with arts, mentorship, and public space. Plans for site development include a commercial kitchen, artist residencies, and a community library (Pacheco, 2019).

In Jefferson Chalmers, Feedom Freedom Growers and Sancutary Farms foster urban agricultural practice grounded in sustainable and just principles. Founded in 2009 by Myrtle and Wayne Curtis, the Feedcom Freedom Growers combines agriculture, education, and art. Their work has expanded to multiple lots (Sysling, 2021). Sanctuary Farms, established in 2021, operates a garden, compost operation, and involvement in citywide collaborations like the Detroit Community Composting Collective Pilot and the Water Consortium. Sanctuary Farms hosted over two dozen events in 2024 (Sanctuary Farms, 2024).

Complementing resident action, the City implemented a new animal keeping ordinance on January 31, 2025, which permits residents to keep up to eight chickens or ducks and four beehives for personal use (Corey & Myers, 2025). Urban farms are allowed more birds and hives, scaled by acreage. The ordinance marks a step forward in supporting local food production within residential contexts (“Animal Husbandry,” 2025).

Despite this vibrant web of urban agriculture across the city, several barriers remain. Long-term land access and secure ownership continue to be critical challenges for growers. Costs associated with water access, and the complexity of navigating

city regulations are also concerns. Additionally, climate change introduces new uncertainties around growing conditions and infrastructure needs. These hurdles highlight the importance of sustained advocacy and policy reform to support Detroit’s community-led food system.

While ideologies rooted in human-nature dualism and individualism are dominant in American culture and planning paradigms, other worldviews offer alternative ways of understanding and organizing our relationships with the environment and one another. This section explores a range of global ideologies, largely rooted in ancestral and place-based knowledge. Philosophies and practices such as ubuntu, buen vivir, Hawaiian indigenous paradigms, and satoyama emphasize collectivism and the inseparability of people and nature. The principles of dugnad and autogestión center communal support and collective action. Further, afrofuturism highlights the importance of creativity in imagining alternative futures beyond the constraints of existing systems.

Ubuntu in Swazi, or botho in Sotho, is a social philosophy commonly translated as “humanness” (Holtzhausen, 2015; Nolte et al., 2019; Nxumalo, 2025). Originating from the Bantu indigenous South Africans, ubuntu stems from the Zulu phrase, “umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu,” meaning a person is a person through others (Nxumalo, 2025; Olusegun, 2023; Seneque et al. 2023). Ubuntu brings each individual into relation with the whole collective and with nature forming “deeply interconnected and deeply interdependent” relationships (Seneque et al. 2023; Olusegun, 2023). Like Biiskaabiiyang, an “Anishinaabe word that captures the essence of returning home after being away for an extended period, finding oneself transformed yet familiar” (KGD, 2024 annual report), Seneque et al. (2023) writes that “ubuntu already exists. The wisdom is already there—and we are just being activated again.” Both concepts speak to an innate human longing for connection, community, and relational belonging, one that can be reawakened through the conscious rejection of colonial practices.

In the American context, embracing alternative planning paradigms is a necessary step toward decolonization and the reactivation of ubuntu. To embody ubuntu is to move beyond individual self-interest, recognizing how our actions reverberate through our relationships with others and with the natural world (Olusegun, 2023).

The core principles of ubuntu are outlined differently by various scholars. Whereas Olusegun and Nolte et al. center sharing and solidarity in their description of embodying ubuntu, Seneque et al. developed a process made of five core principles: co-initiating, co-sensing, co-inspiring, co-creating, and co-evolving (Olusegun, 2023; Seneque et al. 2023). Similarly, Nxumalo (2025) outlines five fundamental principles within ubuntu philosophy: dignity, survival, solidarity, compassion, and respect.

L. Schultz

Naude warns that “ubuntu scholarships are still subject to the hegemony of the North.” Within this report indigenous language used to describe non-colonial philosophies have passed through several western passageways. In this case, the majority of scholarly literature is disseminated by universities in English and French.

Buen vivir is a theoretical concept, political ideology, and lived practice that is often translated to mean “living well” (Caria & Domínguez, 2016; Guardiola & García-Quero, 2014; Jimenez et al., 2022). The concept of buen vivir was “inspired by Andean Indigenous cosmologies— particularly from the Quechua and Aymara Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru” (Jimenez et al., 2022). This linguistically succinct phrase is associated with an abundance of meaning. A majority of researchers highlight harmony and

reciprocity with nature, respect for indigenous peoples, and collectivism as core principles for producing both material and spiritual wellbeing (Caria & Domínguez, 2016; Jimenez et al. 2022; Villalba-Eguiluz and Etxano, 2017; Guardiola & García-Quero, 2014; Richter, 2025; Bakal & Einbinder, 2024; Malo Larrea et al. 2024; Coral-Guerrero et al., 2021). Malo Larrea et al. (2024) record eight distinct sub principles: reciprocity, balance, harmony, creativity, serenity, ancestral knowledge, socio-political organization, and community work.

English Quichua/ Quechua/Kichwa

Reciprocity Randi-Randi

Balance Pakta Kawsay

Harmony Alli Kawsay

Creativity Wiñak Kawsay

Serenity Samay

Ancestral Knowledge Yachay

Socio-Political Organization Ushay

Buen vivir emphasizes a bio-centric perspective in which relationships between people and nature, or Pachamama (mother nature), is harmonious and reciprocal. For instance, harmony can be embodied through a “relationship of belonging rather than domination or exploitation,” therefore conserving ecosystems and biodiversity (Caria & Domínguez, 2016; Guardiola & García-Quero, 2014; Merino, 2016). Unlike Western culture that has socially constructed nature and humans as distinct, Andean indigenous philosophy

L. Schultz

Community Work Ruray; Maki-Maki

Table 4. Principles of Sumak Kawsay (Malo Larrea et al., 2024).

does not make this binary distinction and instead underscores a “total embeddedness of human beings within the natural environment,” (Jimenez et al. 2022) where “nature is ontologically indivisible and inseparable from human beings” (Coral-Guerrero et al., 2021).

In contrast to growth-oriented economies or sustainable development paradigms, communities embody buen vivir through collective practices (Richter, 2025). Collective practices in aggregate create communitarian or solidarity economies built upon, “redistributive justice, self-management, liberating culture, equity, sustainability, cooperation, and not-for-profit commitment to local communities” (Jimenez et al. 2022). Bakal & Einbinder (2024) emphasize the significance of buen virvir economic practices, remarking,

“GDP, as an indicator of the dominant model of development, must be dethroned and replaced by frameworks informed by the values, practices, and worldviews of local and Indigenous communities, many of whom are at the forefront of climate mitigation strategies that include environmental protection and sustainable food systems.”

Villalba-Eguiluz and Etxano (2017) articulate three diverging theoretical approaches within buen vivir that they label: indigenous, ecologist, and socialist-statist. They argue that the term buen vivir specifically applies to ecologist and socialist-statist frameworks, while buen convivir (to coexist well) and sumak kawsay, the Quichua translation, are used within the indigenous framework.

Others bring into question these related labels and terminology. While some researchers synonymize buen vivir and sumak kawsay, suggesting each phrase as translations of each other from different indigenous languages, Malo Larrea et al. (2024) argue that the two terms have distinct meanings. Malo Larrea et al. explain that buen vivir is a political construct, and sumak kawsay is “an ancestral cosmo-

Detroit Interwoven Collective Ideologies vision but is also a politically strategic concept” (Table 5).

In 2007, buen vivir emerged as a prominent political ideology in Ecuador. The left-wing party incorporated it in the country’s new constitution as a “foundational principle of the new state” (Caria & Domínguez, 2016). Buen vivir has also been utilized in Bolivian political contexts.

Table 5. Buen Vivir Translations (Guardiola & García-Quero, 2014; Merino, 2016; Richter, 2025; Bakal & Einbinder 2024).

Language Quichua/ Quechua/Kichwa

Spanish buen vivir

Quichua/ Quechua/Kichwa sumak kawsay

Aymara suma qamaña

Guaraní ñandareko

Mapuche küme mongen

Maya-Achí utziil kasleem

Ashuar shiir waras

English living well

L. Schultz 2025

Despite beginning as a “a critical political discourse of social and indigenous organisations against neoliberalism and extractivism” in both countries, buen vivir is now a contentious political concept (Jimenez et al., 2022). While buen vivir can serve as a “praxis of development, challenging problematic Western, liberal, and anthropocentric assumptions about power and socio-ecological systems” in contrast against Western worldviews (Jimenez et al. 2022), Caria & Domínguez (2016) argue that since achieving status as the dominant political ideology, it has been skewed for political gain and “has become contradictory and intolerant” with actual policies passed in Ecuador. Further, Villalba-Eguiluz & Etxano (2017) warn of ambiguity and unresolved contradictions.

One example of buen vivir in practice is the “Potato Park” in Peru. In 2000, Asociación ANDES, a Peruvian NGO, partnered with five indigenous communities (Chawaytire, Pampallaqta, Sacaca, Paru Paru, and Amaru) in Pisaq “to create an organisational structure in accordance with its customary laws, to steward its potato diversity, food producing habitats, waters, and biocultural resources” (Jimenez et al., 2022). The Potato Park consists of 9,200 hectares, or roughly 23,000 acres, of land fostering more than 1,400 varieties of native potatoes. In addition to communal land, the community also established a communal fund which redistributes 10% of annual earnings from tourism and restaurants among community members.

The Association of Committees of Community Production (ACPC) in Guatemala also connects buen vivir principles to their commitment to food sovereignty. The ACPC was founded in 2001 by community leaders from 22 local communities (Bakal & Einbinder, 2024). The association included about 450 families at the time of its establishment. Located in the Xesiguán watershed in the Maya-Achí territory of Guatemala, the ACPC aligns local food production with the role of revitalizing the deforestation watershed through a seed-saving cooperative and agroecological farming. The primary agroecological farming methods used include “micro-irrigation for dry-season farming, water catchments, enhancing vegetative cover through agroforestry, and increasing soil organic matter,” as well as community networks of “farmer-to-farmer extension, the development of new local markets, and locally produced organic bio-inputs” (Bakal & Einbinder, 2024).

Aloha ‘āina, meaning love the land, is one of many Hawaiian phrases that epitomizes the multitude of indigenous Hawaiian ethics based in reciprocity, placebased, intergenerational knowledge that guide Hawaiian philosophy and way of life (Kealiikanakaoleohaililani & Giardina, 2016). Indigenous Hawaiian worldview establishes an indivisible relationship between people and nature, animate and inanimate, through “conscious, subconscious, and unconscious” relationships (Kealiikanakaoleohaililani & Giardina, 2016). These relationships form the basis of an embodied sacredness ethic where daily actions are sacred exchanges consistently reinforcing the meaning and connections. In Hawaiian culture, ‘ohana, translating to family in English, also extends past Western understandings of family relationships to inherent connections to nature, “‘i’iwi bird, the taro plant, lightning, a particular shark guardian, or a particular rock formation.” Extending the Hawaiian meaning of family to also include community relationships and all elements of nature further illustrating the indivisibility of humans and nature.

Figure 25. Kō (Sugar Cane) (Source: Mark Yang).

Aloha ‘āina is embodied through mālama ‘āina. Mālama ‘āina, meaning care for land, is demonstrated through the integration of place-based knowledge embodied in culture and daily life such as resource management practices and plant names (Chin, 2011). Kealiikanakaoleohaililani & Giardina (2016) describe an “act of loving an entity must translate into caring for that entity, with care including protecting, tending, stewarding, and where needed restoring health and wellbeing.” Ahupua’a is an indigenous Hawaiian resource management system from the 15th century that is rooted in the physical features of the Hawaiian islands (Acorda, 2023; Meyer, 2014). Ahupua’a describes the practice of shared water usage and subdividing land made into balanced geographic zones (Jamero, 2024; “Ahupua’a System,” n.d.). The ahupua’a spans from the volcanic mountains to the ocean with interconnected forested upland and cultivated areas downland toward the ocean. The cultivated areas were made up of irrigated and rain-fed production spaces. Mountain rainfall flowing downstream was utilized for communal and personal gardens growing ‘uala (sweet potatoes), before the remainder continued downstream feeding into managed fishponds between the shores and open oceans. Niu (taro), ‘ulu (breadfruit), mai’a (bananas), and kō (sugar cane) were grown in rain-fed areas known as mala (“Ahupua’a System,” n.d.). Located in the ahupua‘a of Ha‘ena on the island of Kaua‘i, Limahuli Valley is one of the few remaining areas in Hawai‘i where both archaeological sites and the natural landscape have been preserved (Acorda, 2023).

In addition to ahupua’a, plant names also demonstrate the culture of land stewardship. Kagawa-Viviani et al. (2018) describe, indigenous Hawaiian plant names reflect “observational skills, farmer connections to place, often a delicious sense of humor and affirm the poetic beauty of Hawaiian language and the world of the kalo farmer.”

In Japan, the mosaic-like landscapes forming the boundary areas between the mountains and the towns are called satoyama. The term satoyama (sato meaning home village and yama meaning mountains) was originally used to specifically refer to shared land near rural residential communities that were managed by people for generations (Indrawan et al., 2014; Takeuchi et al., 2016). Rather than controlled gardening, management practices created generative encounters, “making appropriate disturbances” in the forested areas (Gan & Tsing, 2018). Foraging edible plants and mushrooms and gathering fallen plant matter to use as green manure for farming were common management practices. Until the 1950s, about 20% of land in Japan was considered satoyama (Indrawan et al., 2014; Gan & Tsing, 2018). Since then, Japan has experienced a dramatic reduction in common land (Indrawan et al., 2014).

Figure 26. Gokayama (Source: Mikiko Walker).

Since the 1990s, evolving population dynamics, market-driven shifts in agricultural practices, and a growing body of research and public awareness around biodiversity have contributed to expanded interpretations of satoyama (Ito & Sugiura, 2021; Sehra & MacMillan, 2021). Contemporary understandings now position satoyama

8 “Common land’. However, the term is generally used to describe a piece of land in either state or private ownership to which other people have certain traditional rights to use in specific ways, such as being allowed to graze their livestock or gather firework. This differs from ‘communal land,’ which generally refers to (mainly rural) spaces in the collective possession of a community” (Everard, 2011, p. 5).

not only as an forested spaces between mountains and residential areas but also as a cultural symbol reflecting a deep connection to nature and as a social-ecological system that embodies a “model of balancing between production and conservation” (Ito & Sugiura, 2021). Under this broader understandings, satoyama landscapes can encompass a variety of land uses including rice paddies, agricultural fields, bamboo forests, woodlands, grasslands, irrigation canals, reservoirs, and human settlements(Indrawan et al., 2014; Takeuchi et al., 2016; Ito & Sugiura, 2021). These land use patterns support diverse, interconnected habitats that offer ecosystem services to surrounding communities, such as improved air quality, pollination, and the prevention of soil erosion and flooding (Katoh at al., 2009; Takeuchi et al., 2016).

In addition to the general concept of volunteering that we are familiar with in the United States, Norwegian culture has a unique, specific volunteering tradition, called dugnad, that originates from the country’s historic farming communities as far back as the 14th century (Simon & Mobekk, 2019). As countries around the world became more industrialized in the 1800s, Norwegian family farms formed networks of agricultural co-operatives (Almås & Bye, 2020). Farmers normalized dependence on each other through voluntary and collective support. Outside of agriculture settings, a culture of dugnad continued throughout Norwegian society. Dugnad does not have a direct translation in any other language and is most commonly interpreted to mean face-to-face, unpaid work, with a defined start and end time, followed by a social gathering (Simon & Mobekk, 2019). In most cases, the social gathering is a community meal.

Simon & Mobekk (2019) share that following globalization, the meaning of dugnad has become broader and “people’s willingness to engage in voluntary collective work such as dugnad has declined.” While today, dugnad can be understood more broadly as collective volunteer work without necessarily implying face-to-face work in a specified time window, “the use of the term dugnad in such new areas of application coexists with the traditional use” (Simon & Mobekk, 2019).

The term autogestión, often translated into English as “self-management,” goes beyond self-reliance and entails collective capacities, democratic participation, and horizontal organization (Vieta, 2010). Emerging historically through socialist worker activism in both Europe and Latin America, autogestión developed as a resistance to state failures in securing social wellbeing (Vega, 2023). Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, autogestión has been closely linked with concepts of self-organization, self-governance, and autonomy. Marx, for instance, used it to describe the ways in which workers might subvert capitalist control by organizing themselves to collectively manage factory production (Yap, 2019). In this context, the idea of “economies of solidarity” emerges as an expression of autogestión; these economies emphasize equitable redistribution, shared responsibility for production, mutual aid, cooperativism, and democratic decision-making (Vieta, 2010). In practice, communities have forged creative modes of autogestión that lessen reliance on state structures and strengthen grassroots economic and local initiatives (Ortiz Torres, 2020).

However, while self-organization can serve as a liberatory force on both individual and collective levels, it is not inherently emancipatory. As Yap (2019) argues, it can also replicate and reinforce existing hierarchies and inequalities. For instance, urban gardens should not be romanticized as natural incubators of self-organization; rather, they are dynamic spaces that both shape and are shaped by broader social processes. In this light, autogestión, as a living and adaptive strategy of resistance, resilience, and self-determined possibility, must be practiced intentionally and critically.

Afrofuturism, coined by Mark Dery in the 1990s, is a framework of imagination and cultural aesthetic that has emerged as an assertion of Black humanity, culture, and creativity against the context of current and historical marginalization of Blackness and Black people (Capers, 2022). Afrofuturism is employed in diverse forms of art, literature, and other cultural expressions as speculative fiction that centers Blackness and creates “fantasy space where the Black voice exists outside of Eurocentric” (Cadle, 2022). Octavia Butler is one of the most well known authors of Afrofuturist literature. By centering Black characters in exploratory works of science fiction literature, Butler invited her readers “to imagine a better future and then work towards creating it” (“Remembering Afrofuturist,” n.d.).

Jones (2022) extends this point, positing that “afrofuturist feminist rhetoric helps us build inclusive futures that do not depend on the regurgitation of the present into the future.”

Expanding on ideologies rooted in community and ecological connection, frameworks such as green reparations and recommoning offer potential altnerative paradigmns with which to plan equitable and nature-integrated cities.

Green reparations connect ecological development with racial justice by acknowledging and addressing the historical harms of environmental exclusion and disinvestment in Black communities. As Coates (2014) outlines, discriminatory housing policies like redlining extracted generational wealth from Black families to benefit white communities. Green reparations seek to restore this loss not just economically but through intentional urban design. Unlike green gentrification, which can obscure painful histories with superficial beautification, green reparations emphasize restorative public spaces that make space for memory, healing, and continued presence (Draus, 2019).

In Baltimore, city agencies have begun integrating racial equity goals into urban nature strategies. The city’s Green Network Plan and revised Sustainability Plan demonstrate efforts to “co-opt urban nature as a site of critique” and counteract dominant spatial imaginaries rooted in whiteness and colonialism (Shcheglovitova & Pitas, 2023, p. 251). This approach reframes green development as a tool for justice, not just sustainability.

Recommoning is a strategy of reclaiming shared ownership and control over vital resources such as housing, land, and water. It has strong applicability to urban greening and food sovereignty efforts. One form of recommoning is the “remunicipalize” public goods, establishing collective governance over privatized or commodified systems. In Terrassa, Spain, water systems were returned to public hands, and a citizen observatory was established to ensure ongoing community oversight (Geagea et al., 2023). Similarly, cities like Naples have restructured their legal frameworks to define water as a public good, protected as a shared resource (Geagea et al., 2024).

When applied to land, recommoning is often employed to reimagining housing as a right rather than a commodity. Limited equity cooperatives (LECs) are one model where residents collectively own housing and limit resale profits to maintain affordability. Although this model restricts wealth accumulation, it offers significant benefits like affordability, community control, and housing stability (Barenstein, 2022). Detroit Interwoven Nature-Centered Community Models 38 L. Schultz 2025

Members purchase shares in a cooperative rather than owning individual properties, and earnings from selling those shares are capped, preserving affordability for future residents.

Community land trusts (CLTs) are another key recommoning model. CLTs treat land as a communal resource, often managed by nonprofit organizations that lease it to residents while ensuring affordability and stewardship. This model originated in the civil rights era when Black leaders, including Bob Swann, formed New Communities, Inc. as a response to systemic land loss (Davis, 2010). Today, CLTs continue to center resident governance and resist speculative real estate practices. Though they also limit wealth-building, CLTs prioritize long-term stability, democratic participation, and socially responsible development (Miller, 2015). Together, LECs and CLTs present established, community-led structures that support recommoning through land and housing justice.

These recommoning models can be directly adapted to manage urban green spaces and community agriculture by placing land under collective stewardship rather than market control. Community land trusts and cooperatives could ensure that gardens, parks, and farms remain accessible, affordable, and protected from displacement pressures. By treating access to nature and food as shared rights, cities can cultivate more resilient, just, and ecologically rooted communities.

Detroit Interwoven Nature-Centered Community Models

Located in the Porte de Clignancourt district of Paris, Jardin du Ruisseau was established by residents in 1998 to rehabilitate an abandoned railway site (“Les Jardins du Ruisseau,” 2021). Officially opened in 2004, the project now spans more than 3.5 acres and includes ecological education programs, biodiversity conservation initiatives, cultural events, and shared gardening spaces (Figure 30). It sits on land owned by SNCF-Réseau and is leased and supported by the City of Paris, reflecting a partnership between grassroots organizing and municipal governance. The space includes La Recyclerie, a cultural venue and DIY workshop housed in the old train station, offering community-led repair programs and pop-up markets (“Sommaire,” 2023).

Agripolis, also called Nature Urbaine, is located in Paris at Porte de Versailles. It is the largest urban rooftop farm in the world. Spanning 14,000 square meters, the farm grows more than 2,000 pounds of produce daily using aeroponic systems (Baldwin, 2019). Crops include around 30 varieties of fruits and vegetables, all grown without pesticides (Brady, 2020). This site supplies fresh produce for a bar and restaurant and hosts educational programs and corporate workshops.

40 L. Schultz 2025

Detroit Interwoven Nature-Centered Community Models

The Sweet Water Foundation (SWF) in Chicago offers an example of a multi-use community agricultural space. Known as The Commonwealth, this “regenerative neighborhood node” spans six city blocks and integrates a roughly 2 acre urban farm with repurposed homes, parks, greenhouses, arts spaces, and educational hubs (“The Commonwealth,” n.d.). SWF’s programs include Community Supported Agroecology, Wellness Wednesdays, and intergenerational educational events that invite residents to farm, create, and reflect together. SWF shares that they are guided by commitments to the principles of regeneration, ‘small is beautiful’, chaord, sankofa, the seventh generation principle, and ‘open source’.

The central question that emerges from this exploration is:

How can learnings from global examples, literature, and local action be meaningfully and actionably applied in Detroit to contribute to planned reciprocity and just futures?

Planned reciprocity requires that the City of Detroit’s planning and policies work in concert to foster long-term mutual benefit between residents and the environment. While Detroit has made notable progress, such as the 2013 urban agriculture ordinance and the recent animal keeping ordinance, there remains an urgent need to further align policy with the values, practices, and desires of Detroiters.

Superblocks for Shared Regenerative Land Use

• Pilot removing or limiting-use of roads to create pedestrian-first “superblocks” integrating community gardens, farms, parks, and play spaces.

• Adopt a framework that allows residents to close alleys for use as community gardens or gathering spaces.

Detroit’s expansive vacant land offers a unique opportunity for intentional, community-driven transformation. Exisiting examples of regenerative superblocks include plans in Barcelona to reclaim streets for pedestrians, green space, and social life, and the Vitória Régia Community Gardens in Brazil that reclaims undevelopable land for food production (Albuquerque, 2023) (Figure 32). In Barcelona, superblocks (or superilles) are made by combining nine pre-existing blocks by limiting the use of vehicles on the intersecting roads to create shared space (“Barcelona’s Superblocks,” 2023). Barcelona’s blocks are already built in a square grid system facilitating this union, but superblocks can be created from other block combinations as well (Figure 33).

Baltimore’s Alley Gating & Greening Ordinance enables residents to convert alleys into safe, green community spaces while improving neighborhood cohesion (Nathanson & Emmet, 2007). This model serves as a similar function as forming a superblock but at a much smaller scale which could be implemented more immediately as a case by case basis without needing to wait for visionary, large scale land use planning.

Ecosystem-Centered Development Regulations & Incentives

• Set minimum green infrastructure requirements for developments, accounting for surfaces like green roofs, permeable paving, and vertical greenery.

• Mandate green infrastrcuture, such as green roofs or bioswales, for large developments.

• Provide zoning bonuses, expedited permitting, water fee credits, or property tax abatements for developments that include urban agriculture.

In downtown Berlin, Germany, Biotope Area Factor (BAF) “can be established in landscape plans as an ordinance,” which considers surface permiability, vegetation cover, green roofing, and other factors (“BAF,” n.d.). Another example of an environmental focused development regulation is Toronto’s green roof policy. In 2009, the City of Toronto established a bylaw that requires green roofs on developments over 2,000 square meters ranging from 20–60% coverage (“City of Toronto,” n.d.).

Greening & Sovereignty Neighborhood Financing

• Support resident-led greening and urban farming through capital grants for restoration, land acquisition, and community engagement.

• Build on precedent of land returned to Indigenous communities, such as the recent return of land at Historic Fort Wayne to the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi (Barrett 2025).

Metro, “the metropolitan planning organization for the Oregon portion of the Portland metropolitan area,” operates the Nature in Neighborhood grant program (“Unified Planning,” 2024). Nature in Neighborhood grants are available for “tribal governments, public schools, non-profits, community-based organizations, local governments and special districts” to fund projects for land acquisition, ‘urban transformations’, restoration, and neighborhood livability (“Nature in Neighborhoods” n.d.).

Keep Growing Detroit (KGD) already facilitates a rich array of practices rooted in collective care, including tool-sharing programs, volunteering, dinners, and promoting land access for Black farmers. These efforts align strongly with the principles outlined in this report. Building on this foundation, and drawing from relevant literature and models, the following ideas are offered as possible ways to continue expanding the impact of KGD’s work:

KGD could explore hosting workshops or publishing guides on creating smell- and touch-focused gardens, specifically designed for people with visual impairments. Additionally, practical resources on how to design community gardens that are more accessible to individuals with low mobility or who use mobility aids could help ensure more residents can engage in these spaces. Given the mental and physical health benefits of spending time in nature, expanding the ways people can interact with gardens is especially relevant for neighborhoods with few or no nearby parks, such as Bagley, North Rosedale Park, East Piety Hill, West Village, and Campau/ Banglatown.

In addition to existing community-building events for Black Farmer Land Fund awardees, KGD might consider hosting events centered on shared identities and experiences, such as gatherings for Spanish-speaking farmers, LGBTQ+ POC farmers, and immigrant groups. These affinity spaces can offer a critical layer of emotional safety, affirmation, and joy in community agriculture.

KGD and its partners, including the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network and Oakland Avenue Urban Farm, have already taken bold steps toward food justice and land liberation. The creation of the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund in 2020 marked a pivotal moment in addressing land access and the racial wealth gap in the city. Inspired by that model, future efforts might include support for community land trusts, particularly in neighborhoods with high vacancy rates and low park access, such as Riverbend (45% vacant parcels, 3 parks), Penrose (38% vacant, 0 parks), Greenfield Park (37% vacant, 1 park), and Fox Creek (34% vacant, 0 parks).

Lastly, an ambitious adventure could include creating a urban agriculture festival, at a city-wide scale like Dally-in-the-Alley, or something smaller like a neighborhood parade, that celebrates local fresh produce, farmers, and chefs.

I aim to collaborate with communities as a planner and researcher to build collective capacity and help activate visions of sustainability, safety, joy, and liberation. I grew up in Newark, Delaware (Lenni Lenape ancestral land) and moved to Michigan to pursue a Master of Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor (ancestral and contemporary homeland of the Anishinaabeg, including the Three Fires Confederacy: the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples).

While in Michigan, I have had the opportunity and privilege to learn from and alongside many Detroiters. This project extends from my previous work with Keep Growing Detroit, where I served as a Brademas Fellow and summer intern in 2024, supporting their mission of achieving food sovereignty in every neighborhood in Detroit.

I approach this work with humility and a commitment to lifelong learning. I recognize that building just futures requires constant reflection, accountability, and a willingness to be transformed by the people and places we serve. As a white, non-Detroit resident, I acknowledge the limitations of my perspective. This report aims to serve as an introduction and offer examples, recognizing that it is critical to engage directly with Indigenous and local residents whenever possible.

Detroit Interwoven References