Amplifying the Voices of Quilombola Communities Through Community-Based Tourism and Cultural Preservation in

Alcântara, Brazil

July 2025

Authored by:

Cat Diggs, Fabricio Martins, Russell Lin, and Dr. Ana Paula Pimentel Walker

Amplifying the Voices of Quilombola Communities Through Community-Based Tourism and Cultural Preservation in

July 2025

Authored by:

Cat Diggs, Fabricio Martins, Russell Lin, and Dr. Ana Paula Pimentel Walker

Capstone Studio Winter 2024

The University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning in collaboration with project partners, The Association of the Alcântara Ethnic Territory (ATEQUILA), The People Affected by the Alcântara Space Base Movement (MABE), The Alcântara Union of Rural Workers (STTR), The Alcântara Rural Women Workers Movement (MOMTRA)

Alcântara, Brazil & Ann Arbor, Michigan

Members of the 2024 Capstone Studio Team include:

Catherine “Cat” Diggs

Russell Lin sara faraj

The team was advised by Dr. Ana Paula Pimentel Walker, Ph.D., MURP, MA, J.D., and Urban and Regional Planning Ph.D Candidate Fabricio Martins For details about this project, please contact appiment@umich.edu

This report was placed into InDesign and edited by Anuska Singh, Russell Lin, and Cat Diggs

The 2024 Capstone Studio would like to thank our project partners - The Association of the Alcântara Ethnic Territory (ATEQUILA), The People Affected by the Alcântara Space Base Movement (MABE), The Alcântara Union of Rural Workers (STTR), and The Alcântara Rural Women Workers Movement (MOMTRA) – we could not have done this work without them. We are very grateful to the Quilombola community members and leaders who welcomed us during our visit to Alcântara in February and March of 2024.

A special thank you to Dorinete Serejo Morais, Danilo da Conceição Serejo Lopes, Davi Pereira Júnior, and Valdirene Ferreira Mendonça, for trusting us with this vital work and of the time, efforts, and collaboration they invested in making this project a reality.. We sincerely appreciate you and all of the Quilombola community members for your warm welcome during our fieldwork visit; for hosting us; cooking for us; for helping us coordinate site visits, photography workshops, oral history interviews; for sharing your insights about the diversity of the Quilombola experiences in Alcântara; and for being the most wonderful tour guides.

There is no doubt in our mind that this capstone experience will have contributed to making us into more well-rounded and equipped urban planning practitioners and advocates for a decolonial and just approach to planning our communities. We sincerely admire and stand in solidarity with the Quilombola leaders and community members we have had the honor to meet and work with. Their courage, determination, and commitment to your freedom as a people in the face of continued global and state violence are deeply inspiring. We are humbled to have been able to support the territorial struggles underway of the Quilombola peoples of Alcântara.

We also want to express our gratitude to Taubman College for providing us with an opportunity to participate in this incredible project. To our external advisors and reviewers on this project, Dr. Mieko Yoshihama, Ishan Pal Singh, Dr. Lesli Hoey, Dr. Scott Campbell, and Dr. María Arquero de Alarcón, who helped provide critical perspectives that propelled our project forward. A special thank you to our Graduate Student Instructor, Fabricio

Martins, for building needed capacity in our team of three students, especially as it relates to translating a portion of our deliverables into Brazilian Portuguese.

Last but not least, to our faculty advisor on this project, Professor Ana Paula Pimentel Walker, we want to say thank you. Thank you for creating an opportunity for us to partake in such a transformational experience. We would not have been able to complete this project without your expertise, collaboration, tireless interpretation efforts on the field, and most importantly, your dedication to making the world and the planning practice, which helps to shape it, more just. So again, we want to extend our sincerest thanks to you!

Organizations

Client-Partner

• ATEQUILA: The Association of the Ethnic Territory of Alcântara (Associação do Território Étnico de Alcântara) – was founded in 2007 and legally established in 2018. It also gets referred to as the Association of Maroon Communities’ Territories of Alcântara or the Association of the Alcântara Ethnic Territory. It represents 156 Quilombola communities in Alcântara.

• MABE: The organization of the People Affected by the Alcântara Space Base Movement (Movimento dos Atingidos pela Base Espacial de Alcântara) – was founded in 1999. It also gets referred to as the Movement of the Affected People by the Alcântara Space Center. It represents those Quilombola communities that have been displaced and those under the threat of displacement by the Brazilian Air Force due to the Space Center.

Other Collaborators

• Alcântara STTR: The Alcântara Rural Workers and Family Farmers Union (The Sindicato dos Trabalhadores Rurais e Agricultores e Agricultoras Familiares de Alcântara) – was founded in 1971 to defend Quilombola communities against displacement and human rights violations which ignited a social movement in the region.

• MOMTRA: The Alcântara Women Workers Movement (Movimento das Mulheres Trabalhadoras Rurais e Urbanas de Alcântara) – was founded in 1994. It also gets referred to as the Alcântara Working Women’s Movement. It works to center gender equality and women’s health in the struggle for territorial rights and identity in rural, and most recently, urban communities in Alcântara.

• The Ministry of Aeronautics in Brazil (Ministério da Aeronáutica: MaEr): It was established in 1942 to oversee aviation activities. Until 1999, the three commands (navy, airforce, and the military) were housed in independent ministries. Currently, they are an integral part of the Ministry of Defense.

• GICLA: Installation Group for the Alcântara Launch Center (Grupo de Implantação do Centro de Lançamento de Alcântara)

• UNDP: United Nations Development Program

• INFRAERO: The Brazilian Airport Infrastructure Company (Empresa Brasileira de Infraestrutura Aeroportuária)

• CPT/MA: Pastoral Land Commission of Maranhão state (Comissão Pastoral da Terra). It is an organ of the National Conference of Bishops of Brazil (CNBB) and born in 1975 to support rural workers.

• ITERMA: The Maranhão Institute for Colonization and Land (Instituto de Colonização e Terras do Maranhão)

• Palmares Cultural Foundation (Fundação Cultural Palmares) - It is housed within the Federal Ministry of Culture and issues the certificate of recognition based on the self-definition and self-identification presented by the Quilombola group along with the community’s general assembly minutes, the community’s historical account, and the certification application form.

• INCRA: The National Institute of Colonization and Land Reform (Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária) has many responsibilities, including the titling of Quilombo lands. ATEQUILA still awaits for the titling of its lands in Alcântara.

• ILO: International Labour Organization

• National Commission for the Sustainable Development of Traditional Communities: Included groups such as Indigenous Peoples, coconut breakers, Quilombolas, Fundo

de Pasto, Ribeirinhos, Benzedeiras, and others.

• IBAMA: Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recusos Naturais Renováveis)

• GSI: International Security Office

• OAS: Organization of American States

• CIDH: Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH). In 2001, Quilombola communities and allies pursued international human rights court within OAS to achieve legal protection and support in their case against the Brazilian government for violating their land rights. An assigned rapporteur from the OAS human rights commission identified 14 violations that occurred during the implementation of the Alcântara Launch Center in the 1980s.

• COHRE: Center for Housing Rights and Evictions

Locations

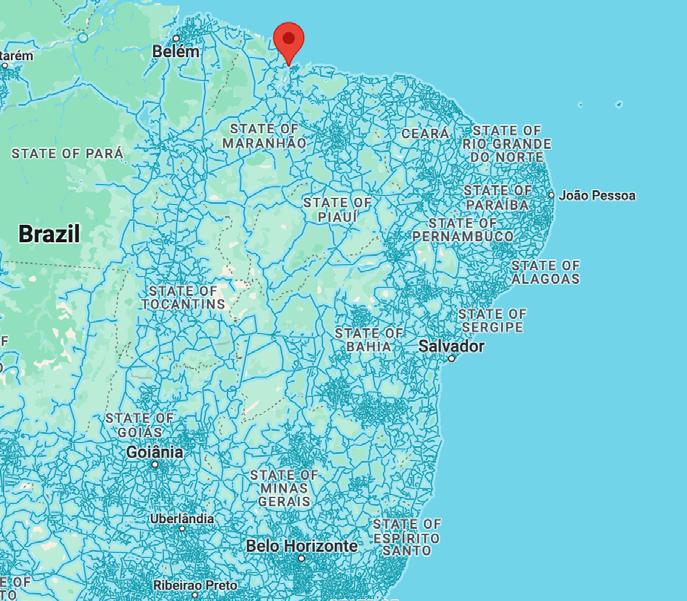

• Alcântara: Brazilian municipality in the state of Maranhão

• Maranhão: A state in the country of Brazil; located in the northeast region

• CLA: The Alcântara Launch Center (Centro de Lançamento de Alcântara)

• CLBI: The existing Barreira do Inferno Launch Center (Centro de Lançamento Barreira do Inferno)

• Alcântara contains three large Quilombola territories, including:

◦ ATEQUILA: The Ethnic Territory of Alcântara, which is affected by the Alcântara Space Launch Center and represents about 156 Quilombos

◦ Island of Cajual: An island that is located in São Marcos Bay near Alcântara. The island is an important Brazilian paleontological site, where fossils of animal species such as the Spinosaurus and the Sigilmassasaurus genus have been found, as well as plants such as conifers and ferns. Palmares Cultural Foundation certified it as a Quilombo in 2006. INCRA has published Relatório Técnico de Identificação e Delimitação (RTID), or Technical Identification and Delimitation Report. It awaits the collective title.

◦ Lands of Santa Teresa/Itamatatiua: The Lands of Santa Teresa are located in the lowlands of Maranhão state, mostly in the municipality of Alcântara, but also in the cities of in the municipalities of Bequimão and Peri Mirim. The lands also known as the Quilombo Territory of Itamatatiua, which are home to 40 Quilombola communities, belonged to Carmelite order since 1740. It was certified as a Quilombo by Palmares Cultural Foundation in 2006. INCRA has published Relatório Técnico de Identificação e Delimitação (RTID), or Technical Identification and Delimitation Report.

• PEB: The Brazilian Space Program (Programa Espacial Brasileiro)

• Bolsa Família: “A conditional cash transfer federal program “that contributes to the fight against poverty and inequality.”1

• TSA: Technology Safeguards Agreement, which refers to an agreement signed in 2019 by President Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump to authorize the Alcântara Launch Center (CLA).

• PNAE: The National Program of Space Activities (Programa Nacional de Atividades Espaciais)

• ATS: Agreement on Technology Safeguards

• ILO International Labor Organization Convention No. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples (C169): According to the ILO, C169 “represents a consensus reached by ILO tripartite constituents on the rights of indigenous and tribal peoples within the nation-states where they live and the responsibilities of governments to protect these rights.” 2 It was used to successfully secure an injunction against the Alcântara Launch Center (CLA) in 2006 that was preventing Quilombola communities from accessing land for food cultivation.3

• Transitional Constitutional Provisions Act of the 1988 Federal Constitution of Brazil: This section of the Brazilian Constitution

details measures to facilitate the country’s transition from a military dictatorship to a democracy.

• The Sarney Land Law: It was adopted in 1969 and addresses the use of state public lands in Maranhão state, which led to the privatization of land and to displaced families. Through this law, ethnic territories were deemed “vacant land” and therefore placed on the market for sale.

• PNPCT: National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Traditional Peoples and Communities, which was instituted by Decree 6040 in 2007.

• Unified Black Movement (Movimento Negro Unficado): The Movimento Negro Unificado (MNU, or Unified Black Movement), widely considered the most influential black organization in Brazil in the second half of the twentieth century, was founded in São Paulo in 1978 as the Movimento Unificado Contra Discriminacao Racial (United Movement Against Racial Discrimination, or MUCDR).4

• Quilombo(s); also quilombola communities

• Agrovila: The military-built communities that dozens of Quilombola communities were displaced to through the construction of the Alcântara Space Launch Center

• Babassu: A palm tree with edible palm fruits. Quilombola families produce

vegetable oil from the seeds of babassu palm, the middle laye mesocarp turns into flour production, and the husk produces charcoal. Other parts of the palm tree are also used in roofs and construction. Grown in Amazonian and other forests, it is a key commodity in the livelihood of many Quilombola communities.

• Women Babassu Coconut Breakers (Quebradeiras de Coco Babaçu): Women of the forest who usually gather and “break” coconut collectively. According to them: “We, the women of the Interstate Movement of Babassu Coconut Breakers (MIQCB), came together in 1990 to fight for our autonomy and quality of life and to protect the babassu forests where we live and work. We represent women Babassu Coconut Breakers from Pará, Maranhão, Tocantins and Piauí, and we seek to strengthen our identity as a traditional people and demand our right to land, territory and free access to the babassu plantations”.5

• Cassava flour: In Quilombola communities of Alcântara, making cassava flour is a traditional activity involving the processing of cassava roots into flour. This staple food item is prepared through a series of steps including peeling, soaking, chopping, grating, pressing, straining, sifting, oven-toasting, and fermenting, contributing to the community’s cultural and culinary heritage.

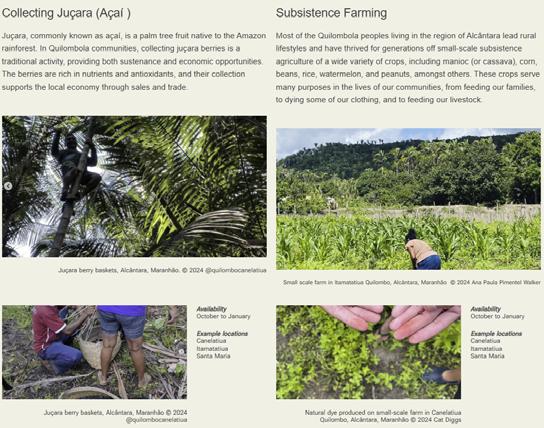

• Juçara: Juçara, commonly known as açaí, is a palm tree fruit native to the Amazon rainforest. In Quilombola communities, collecting juçara berries is a traditional activity, providing both sustenance

and economic opportunities. The berries are rich in nutrients and antioxidants, and their collection supports the local economy through sales and trade.

• Buriti weaving: A number of Quilombos in Alcântara, notably the Quilombo of Santa Maria, are known for handicraft work, specifically the ancient tradition

1. Rasella, D., Aquino, R., Santos, C. A., PaesSousa, R., & Barreto, M. L. (2013). Effect of a conditional cash transfer programme on childhood mortality: a nationwide analysis of Brazilian municipalities. The lancet, 382(9886), 57-64.

2. International Labour Office (2013), “Understanding the Indigenous and Tribal People Convention, 1989 (No. 169) : handbook for ILO Tripartite Constituents” ISBN: 978-92-2-126243-5 Available at: https://www.ilo.org/publications/ understanding-indigenous-and-tribalpeoples-convention

3. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality.

4. “Movimento Negro Unificado .” Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. Retrieved from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/ encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-andmaps/movimento-negro-unificado

5. Movimento Interstadual das Quebradeiras de Coco Babaçu. Available at https://www. miqcb.org/ Translated by the capstone team.

In 2022, Dr. Ana Paula Pimentel Walker, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, and Dr. Davi Pereira Júnior, a prominent leader within the quilombola movement and a professor at the Universidade Estadual do Maranhão (UEMA), met. We extend our sincere gratitude to Professor Bjorn Sletto from the University of Texas at Austin for facilitating this introduction.

During our conversations, we explored the potential for establishing a cultural exchange and engaged teaching initiative between the quilombola movements and organizations located in Alcântara, Maranhão, and a master’s program in urban and regional planning at the University of Michigan. The principal objective of this collaborative endeavor was to develop an international service-learning capstone studio. This initiative aims to equip University of Michigan students to exchange knowledge and provide meaningful service to grassroots organizations and labor unions in Alcântara, specifically the Association of the Alcântara Ethnic Territory (ATEQUILA) and the People Affected by the Alcântara Space Base Movement (MABE).

Professors Pimentel Walker and Pereira Júnior orchestrated both virtual and in-person meetings with various stakeholders from Alcântara to delineate the scope of the proposed coursework and the expected deliverables from the urban planning students. Key quilombola leaders and intellectuals—namely Dorinete Serejo Morais, Danilo da Conceição Serejo Lopes, and Valdirene Ferreira Mendonça—played an instrumental role in shaping the capstone project and informing the fieldwork methodology in accordance with the priorities identified by their organizations. Through field visits and extensive dialogue, we successfully established a mutually beneficial agreement regarding the project framework. This groundwork was pivotal for interested students to participate in the capstone project. Further details can be found in the subsequent pages.

We celebrate the enduring friendships that have developed throughout our journey toward racial justice. We express a heartfelt thank you to students Cat Diggs, Russell Lin, and sara faraj, along with the inspiring quilombola leaders, for their unwavering dedication and impactful contributions.

Sincerely,

Dr. Ana Paula Pimentel Walker and Dr. Davi Pereira Júnior

Ann Arbor, May 8, 2024

For centuries, the Quilombola communities in Alcântara have endured hardships from global and state violence and oppression –to which they have resisted and cultivated rich cultures and a shared sense of identity through collective ways of living. However, in the past few decades, the Brazilian state and international allies, such as the United States, have pursued renewed efforts to extract, displace, and exploit the Quilombola communities who call Alcântara home for the race to space. In the past few years, harmful patterns of the past have continued to materialize for the Quilombos in Alcântara through efforts to advance capitalist and international interests by expanding the Alcântara Launch Center (CLA)1,2,3.The CLA expansion, currently being mandated by the Brazilian government, would uproot 800 additional families, compounding the cultural

genocide and experienced by the Quilombos in Alcântara. On that occasion, the Brazilian state displaced 312 families. Notably, state recognition of Quilombola land rights started only after the fact in 1988, when Quilombo remnant communities received Constitutional recognition.4 Despite these hardships, the common threads and diverse mosaics that define Quilombola communities of Alcântara have persisted and been sustained through age-old subsistence practices, vibrant cultural festivals, collective territorial identities, and the common goal to protect and preserve the social and physical landscapes that make up the abundant Brazilian Amazon Forest that many Indigenous, Quilombola, and traditional communities have called home for centuries.5

To support the Quilombola struggle and bolster awareness of this struggle, the University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning Capstone Studio team (U-M Team), made up of students Catherine “Cat” Diggs, Russell Lin, and sara faraj, led by Dr. Ana Paula Pimentel Walker, embarked on an interactive and collaborative experience to co-develop a project with Quilombola clients, community partners, and community members. Our interactive capstone studio and coursework took place primarily during the Winter 2024 semester, with fieldwork in Brazil during February and March of 2024. This project would come to be called “Amplifying the Voices of Quilombola Communities through Community-Based Tourism and Cultural Preservation in Alcântara, Brazil”.

Our partners in this project — the Association of the Alcântara Ethnic Territory (ATEQUILA), the People Affected by the Alcântara Space Base Movement (MABE), the Alcântara Union of Rural Workers (STTR), and the Alcântara Rural Women Workers Movement (MOMTRA) — are essential actors in the Quilombos of Alcântara’s vital struggle for collectiveland title. Without their collaboration, our project would not have been possible.

Our goal and mission for this project was to develop diverse and sustainable deliverables that could serve as living documents and work to support our clients in their fight for self-determination and perpetual tenure security on their ethnic territories. The audience for this work is not only our client and partners – it is the international community that also supports the fight for sovereignty and a reparative path forward for social and environmental landscapes across the world.

With this work, we aim to shed light on the issues faced by Quilombola social movements in the Brazilian Amazon Forest and beyond to garner greater support for them. To do this work, we analyzed institutional and governance challenges of Quilombola peoples in Alcântara by prioritizing Quilombola scholarship to understand their historical and current struggles. Our efforts also included understanding the culture, norms, and history of our partners and the forces of urban planning that often shaped the challenging conditions in which they live to this day.

We specifically centered our project approach on decolonial planning methods that center equity, justice, and the voices of impacted communities, as opposed to Western,

paternalistic and top-down planning strategies. We also planned fieldwork engagements in Alcântara, Brazil to gather insights from Quilombola leaders and community members on the ground, to inform our recommendations. We hope they can be leveraged by community members, leaders, and teachers to build capacity and continue to catalyze this work in their own communities.

Our central goal for this project was to develop a community-based tourism (CBT) strategy that advances ethnic identity, social and environmental justice, and economic strength by employing qualitative research methods, such as case study research, a tailored literature review, informal conversations, asset-mapping, oral history interviews, and photographic research to understand and assess local perspectives on and conditions for CBT.

Qualitative methods have become an important aspect of good quality planning practice, and professional planning education has adapted to this reality.6 The communitybased tourism recommendations that we outlined for our partners in the CBT Manual that we prepared for this project also aim to celebrate the cultural diversity of Quilombola communities and to strengthen their economic and social autonomy. The CBT Manual has been published in two languages - English and Brazilian Portuguese - and will be distributed as a downloadable and printable PDF to Quilombola leadership in Alcântara.

The CBT Manual consists of a set of considerations that communities should take into account when brainstorming their grassroots-controlled tourism initiatives. The Manual takes into consideration community leaders’ goal to channel CBT efforts towards community development initiatives, with the purpose of raising funds to support community projects and capacity building.

In this context, tourism, fundraising, and advocacy are deeply interwoven. The CBT Manual is part of a CBT strategy that is anchored on communications and cultural preservation efforts, namely a website and virtual and in-person exhibits. A detailed guided map of key Quilombos and a calendar of their activities also have emerged from this project and are housed on the “Experience” web page of the website that we developed as part of the deliverables requested by our community partners. We describe the deliverables further below.

Quilombola community members led the creation of locally grounded data by participating in photovoice workshops designed to inform planning efforts through their own lived experiences and aspirations. Through this cilent-based project method, they engaged in collective reflection and fostered solidarity, aiming to drive social change by raising awareness from within the community. Participants from Canelatiua Quilombo, Itamatatiua Quilombo, and Alcântara took part in five workshops—two each in Canelatiua and Itamatatiua, and one in Alcântara—with a total of 32 community members involved. They captured and curated photographs that have been assembled into

an interactive ArcGIS StoryMap, highlighting narratives and perspectives that reflect their everyday realities. This StoryMap is featured on the “Celebrate” page of our project’s website, as detailed further below.

To support the ongoing use of photovoice, Quilombola leaders in Alcântara received a facilitator guide in Brazilian Portuguese and five point-and-shoot cameras, enabling them to continue documenting and sharing community stories on their own terms.

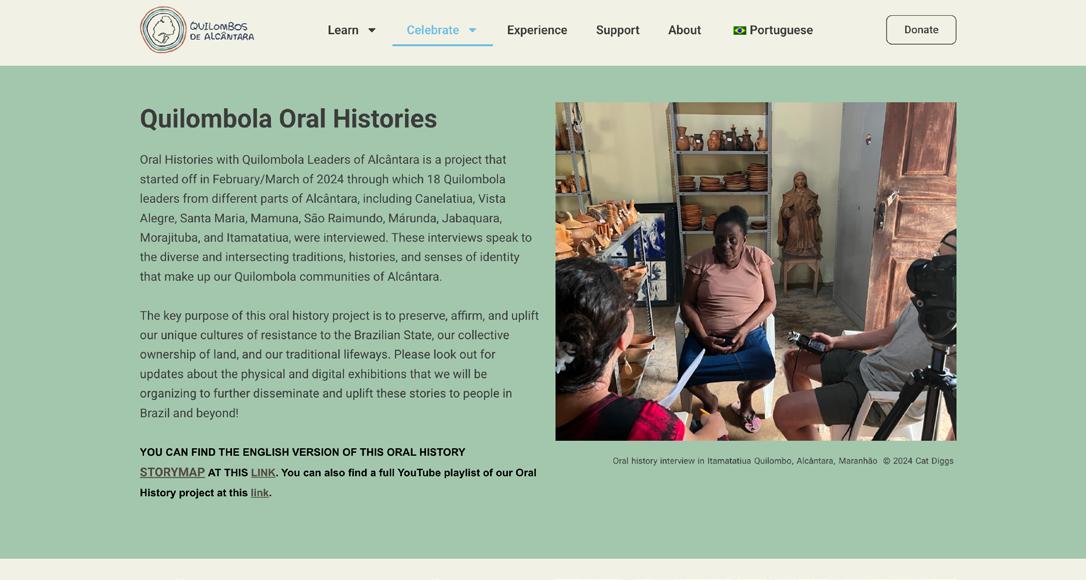

Through our “Oral Histories with Quilombola Leaders of Alcântara” project, we interviewed eighteen Quilombola leaders from different parts of Alcântara, including Canelatiua, Vista Alegre, Santa Maria, Mamuna, Márunda, São Raimundo, Itamatatiua, and Morajituba. These interviews spoke to the diverse and intersecting traditions, histories, and senses of identity that make up the Quilombola peoples of Alcântara. The key purpose of this oral

history project was to preserve, affirm, and uplift their unique cultures of resistance to the Brazilian State, their collective ownership of the land, and their traditional lifeways. This projects provides a platform for Quilombola leaders to speak to their ongoing struggle for land titling and the ever-present threat of displacement that their communities face whether it’d be because of the proposed expansion of the Alcântara Space Launch Center (CLA) on the coast, or because of private land grabs in more forested areas. Through our interview exchanges with the eighteen Quilombola leaders that we interviewed, we gained key insights on their perspectives on CBT and what they would be comfortable and proud to share with visitors coming to their territories. Their voices and insights have been included in the CBT Manual that we crafted.

The oral history videos that emerged from this project now live on an interactive map, built on the ArcGIS StoryMap platform, that features small summaries of each interview and a map that situates each interviewee geographically. This interactive content is embedded onto the “Celebrate” web page of the website we developed for this project, which we describe further below. Longer term, we hope that this project will turn into a traveling physical and digital exhibit in the Alcântara region and beyond! We have also provided our client partners with a bilingual (English and Brazilian Portuguese) Oral History facilitator guide that they can leverage to pursue and develop their own communitybased oral history projects in the future.

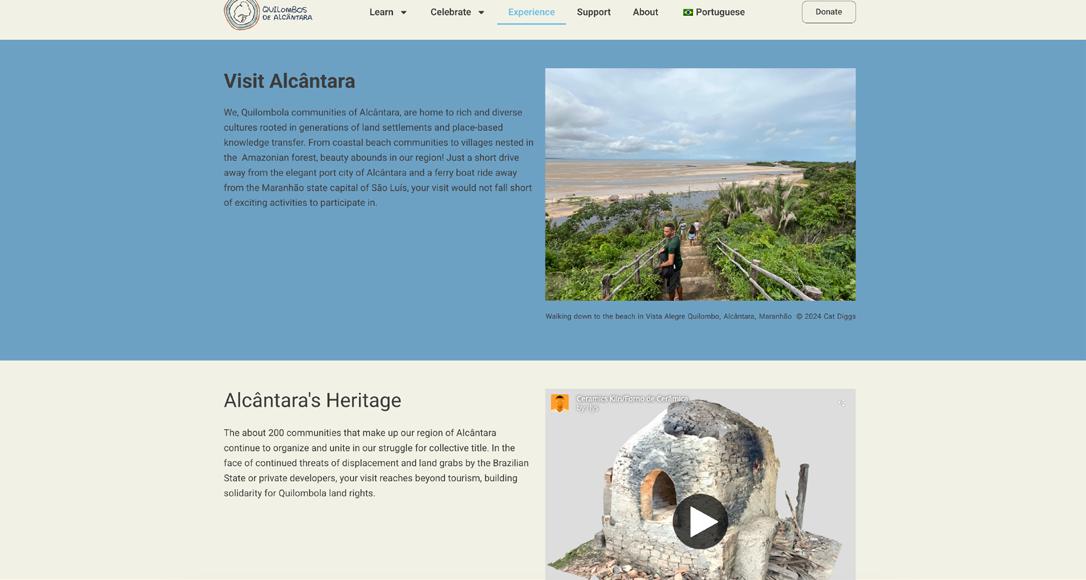

Finally, the website, titled Quilombos de Alcântara, which our client partners commissioned our team to develop, not only houses the aforementioned deliverables, but is also the digital face of the Quilombola communities and their social movements in Alcântara. In creating this information hub, our goal is to establish a platform that

our partners can maintain and populate with timely materials whenever they see fit. Structured into several main pages, the website is both informative and practical, offering a variety of content ranging from key historical events in the region and contemporary demographic details, to activities available for tourists visiting the Quilombola communities and various ways for website visitors to hear from (oral histories) and visualize (photographs) the stories of Quilombola leaders, youth, and community members.

We hope that through the varying assets that we have developed for the Quilombos of Alcântara they will be able to increase the domestic and global solidarity that their social movements need and deserve. With a recent and major ongoing land settlement process taking place under the current Lula administration, and with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights having found through their March 2025 decision that the Brazilian government was guilty of violating the human rights of Quilombo communities in Alcântara through the construction of the CLA in the 1980s, the Quilombos of Alcântara’s efforts serve as a model for other self-governing communities around the world. They make their voices heard and their movements seen and respected!

1. Brasilia. (2003, November 20). DECREE No 4,887, OF NOVEMBER 20, 2003. Presidency of the Republic - Civil House - Deputy Head of Legal Affairs. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/ decreto/2003/d4887.htm

2. McCoy, T., & Traiano, H. (2021, March 26). A story of slavery — and Space. The Washington Post. https:// www.washingtonpost.com/world/ interactive/2021/brazil-Alcântara-launchcenter-quilombo/

3. Pereira Júnior, D., & Prescod-Weinstein, C. (2024, February 20). Science shouldn’t come at the expense of black lives. Scientific American. https://www. scientificamerican.com/article/scienceshouldn-rsquo-t-come-at-the-expense-ofblack-lives/

4. Pereira Júnior, D., & Prescod-Weinstein, C. (2024, February 20). Science shouldn’t come at the expense of black lives. Scientific American. https://www. scientificamerican.com/article/scienceshouldn-rsquo-t-come-at-the-expense-ofblack-lives/

5. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258, 200. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas.

edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

6. Gaber, J. (2020). Qualitative Analysis for Planning & Policy: Beyond the Numbers. Second Edition. New York, NY: Routledge Press. https://doi. org/10.4324/9780429290190

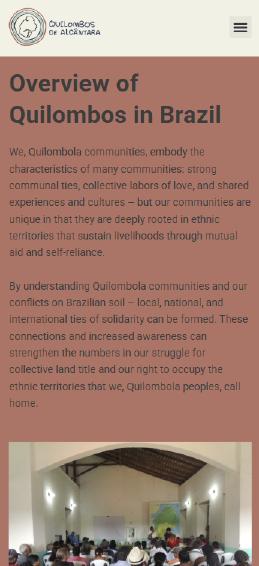

Quilombola communities of Brazil embody the characteristics of many communities: strong communal ties, collective labors of love, and shared experiences and cultures. However, Quilombola communities are unique in that they are deeply rooted in their ethnic territories that sustain livelihoods through mutual aid and self-reliance. Despite facing conflicts due to human rights violations and longstanding historical injustices such as colonization, slavery, and disinvestment, the Quilombola communities of Alcântara remain resilient as they continue to catalyze their social and political power to nourish and celebrate their cultural roots and heritage. By understanding

Quilombola communities and their conflicts on Brazilian soil, local, national, and international ties of solidarity can be formed. These connections and awareness can strengthen the numbers in the struggle for collective title and the right to belonging in ethnic territories that Quilombola people call home.

Our partners in this project —ATEQUILA, MABE, STTR, MOMTRA — are essential actors in the Quilombos of Alcântara’s vital struggle for collective land title.

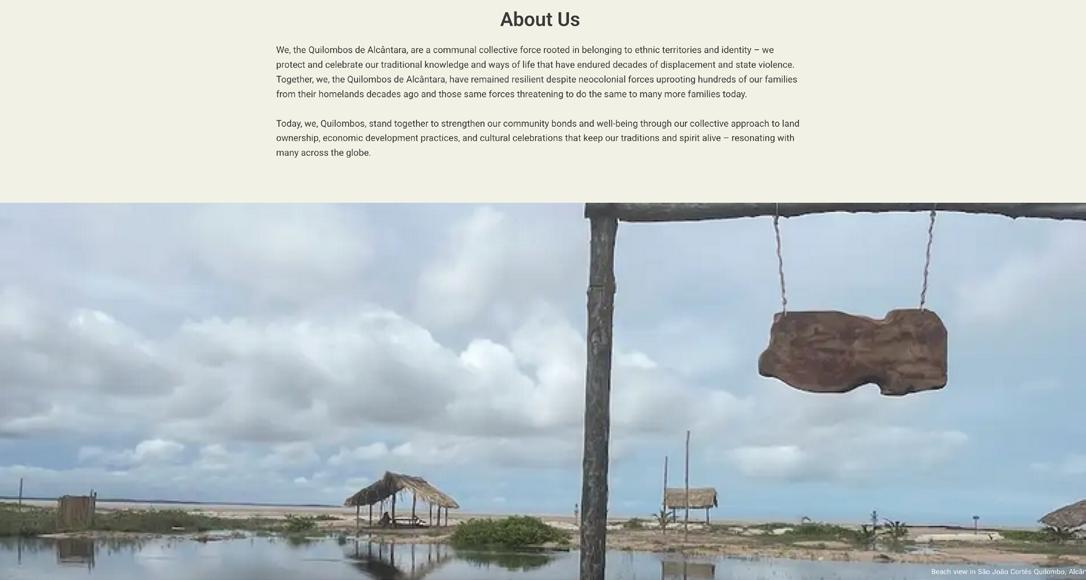

The Quilombos de Alcântara is a communal collective force rooted in belonging to ethnic territories and identity – they protect and celebrate their traditional knowledge and ways of life that have endured decades of displacement and state violence. Comprised of the Association of the Alcântara Ethnic Territory (ATEQUILA, Associação do Território Quilombola de Alcântara), the Movement of the People Affected by the Alcântara Space Base (MABE, O Movimento dos Atingidos pela Base Espacial de. Alcântara), the Alcântara Women Workers Movement (MOMTRA, Movimento das Mulheres Trabalhadoras Rurais e Urbanas de Alcântara), the Alcântara Union of Rural Workers and the Family Farmers (STTR, Sindicato dos Trabalhadores Rurais Agricultores e Agricultoras Familiares de Alcântara), and others – the Quilombos de Alcântara encompass and represent hundreds of community members in diverse Quilombos. These collective organizations

and movements, united in experience and history, thread their shared practices in the struggle for collective land titling, the fight against displacement from the Brazilian Alcântara Launch Center, and traditional ways of being that sustain culture and community health. Together, the Quilombos de Alcântara have remained resilient despite uprooting from their homeland fueled by neocolonial practices that once displaced hundreds of families and threaten many more today. Today, these collective Quilombos stand together to strengthen community bonds and well-being through ownership in collective economic development practices and cultural celebrations that keep the Quilombo tradition and spirit alive – resonating with many across the globe.

According to Dr. Davi Pereira Júnior, the Association of the Alcântara Ethnic Territory

(ATEQUILA) “is a collective construction by the communities and their representative social movements and a response to the signaling by the Brazilian state that it would comply with its constitutional obligations and international law.”1 The association, which officially formed in 2018 represents nearly 71% of the population in the municipality – encompassing nearly 156 Quilombola communities. In response to the need for political mobilization for collective titling and the securing of ethnic territories and belonging, ATEQUILA formalized to position itself as a legal association that could receive the collective land title and manage the territory following the recognition of Alcântara as an ethnic territory from the Palmares Cultural Foundation (FCP) in accordance with Decree 4.887/2003.2 Two organizations are responsible for recognition and titling: First, the Palmares Cultural Foundation, housed within the Federal Ministry of Culture, issues the certificate of recognition based on the self-definition and self-identification presented by the Quilombola group. From there, the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), positions the government as the agency responsible for titling quilombo lands. ATEQUILA still waits for the titling.3

Prior to Decree 4.887 of 2003, article 68 of the Transitory Constitutional Provisions Act (ADCT) of the 1988 Federal Constitution of Brazil stated for the first time in Brazilian constitutional history that “The remnants of quilombo communities that are occupying their lands are recognized as having definitive ownership, and the state must issue them

the respective titles.”4 Decree 4.887 of 2023 has been serving as the enabling instrument authorizing the administrative procedures that identify, recognize, and demarcate definitive lands occupied by remnants of Quilombo communities that are used to “guarantee their physical, social, economic and cultural reproduction.”5,6

ATEQUILA brought Quilombola community members together from the approximately 156 remaining Quilombola communities to discuss the legal pathways to receive the collective title in a way that could center belonging and identity. Today, ATEQUILA continues to work with other organizations and movements, such as STTR, MABE, and MOMTRA, to advance collective titling and protect networks of belonging from ethnic identity.7

Spanning well beyond its formal formation in 1992, the Alcântara Rural Women Workers Movement (MOMTRA) mobilized gender equality within the Quilombo community organizing strategy and fight for territory and identity. Specifically, MOMTRA arose to empower women in the sometimes

challenging and exclusive structure of the rural workers within STTR; women rural workers were not allowed to join the union until the early 1980s. Recognizing a greater need for women’s health services, preventative care, and promotion of self-care, MOMTRA also fosters the space and education for well-being and greater access to healthcare to improve the quality of life for women in Alcântara. Directly challenging the deeprooted patriarchal systems that many women rural workers face in the community and through state violence from the Alcântara Launch Center, MOMTRA collaborates with STTR, MABE, and other affiliates to bolster the fight for territorial rights through the lens of gender equality. Expanding beyond the bounds of assumed and often restrictive roles for women, MOMTRA affords an avenue for women in Quilombola communities to continue to participate in the struggle that has grown from the patriarchy.8 Recently MONTRA extended its activism to embrace the working women living in the urban center of Alcântara.

The organization People Affected by the Alcântara Space Base Movement (MABE), O Movimento dos Atingidos Pela Base Espacial de Alcântara formed in 1999 and was founded by Dorinete Serejo Morais to facilitate discussion around the social implications and harms the Alcântara Launch Center has caused for Quilombola community members. MABE is a social movement rooted in efforts to ensure the permeance of territory through identity awareness and the resistance of communities to land dispossession. MABE is a political movement that also aims to institutionalize Indigenous, traditional knowledge of community members through partnerships with STTR and other organizations and movements –further formalizing Quilombola collective identity, experience, and right to collective land ownership. The efforts of MABE and community members that belong have expanded the movement to the international stage, garnering support and solidarity in their collective struggles globally. Approximately 156 communities are a part of MABE, which holds the space for diverse perspectives and discussions of the territorial struggle in Alcântara, ultimately fostering a rich mosaic of political capital and collective power.9

The Sindicato dos Trabalhadores Rurais Agricultores e Agricultoras Familiares de Alcântara - MA (STTR) (Alcântara Rural Workers and Family Farmers Union) (STTR)11 – as founded in 1971 to defend the guarantee

of rights of workers. It also has a robust history of defending Quilombo territory in the face of displacement. Founded nearly a decade before over 62,000 hectares of land were seized from Quilombola communities by the government to build the Alcântara Launch Center, STTR was one of the principal organizations controlled and led by residents from impacted communities, harnessing the political capital and power of over 35 union delegates throughout the three Quilombola territories, including about 200 Quilombola communities.12The vast network of STTR spans many villages within Quilombola communities. It catalyzes the political and social capital of those on the ground to mobilize communities and strengthen their position, thus generating recognition from government agencies and legitimizing “invisible claims” and pressuring Brazilian officials to

comply with infra-constitutional treaties, such as Convention No. 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO), ratified in 2002 by the Brazilian government.13 Alcântara STTR continues to be an influential proponent for territorial and identity rights for Quilombola communities, defending their right to collective land titling before international bodies such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR).14, 15

The Quilombo is more than just a community that arose in the context of the struggles against colonialism, the transatlantic slave trade, and their legacies in Brazil. Quilombos are institutions that encompass social, territorial, cultural, political, symbolic, and economic ways of being that flourish outside capitalist regimes.16 Quilombola communities define the Quilombo, which often fosters a unique collective identity concerning territory and beyond through organizational structures and processes anchored on self-determination.

Quilombos are symbols of collective struggle and solidarity that cultivated the space for safety after exploitative labor.17 For Quilombo communities, collective ownership and shared use of land are integral to survival and identity. However, Quilombos have been threatened by Brazilian state operations and

international economic interests for decades, posing concerns about displacement from ethnic territories and the collective loss of identity for hundreds of Quilombo families.18, 19

During the violent oppression of slavery and colonization that saw its highest influx of enslaved Black people in Brazil in the 18th century, oppressors within the slave trade viewed Quilombola communities as a threat to colonial power.20 Quilombola communities were, and still are, a place “for reimagining and rebuilding the idea of community and identity itself” and reclaiming territory in the face of erasure and violence.21

This idea of collective resistance, community reimagining, and social rebuilding within the Quilombo is not unique to Brazil’s over 6,000 Quilombo communities, with approximately 217 Quilombos in Alcântara, Maranhão, divided into three territories: the Ethnic Territory of Alcântara, which was affected by the Alcântara Space Base; Cajual Island, and Santa Teresa, or Itamatatiua.22, 23 Formerly enslaved people throughout the Americas formed Quilombo-like communities to survive and combat the colonial growth machines driven by slavery that aimed to fragment social fabrics and ecosystems through capitalist systems of land and labor extraction.24

Today, Quilombola communities share a common struggle and identity in their experience as Afro-descending communities working to receive deserved recognition for their rights to collective land title and to sovereignty over their territories. However, their sustenance practices and traditional knowledge systems, which are deeply rooted in their unique territories and in their history of displacement and state violence, vary widely.25

For instance, the Quilombola communities in Alcântara form a vibrant social fabric that tells the story of the collective and individuals that make up the network. Although practices and traditions may vary from community to community, the 207 Quilombos of Alcântara cultivate a broad and intricate network of land-based skills and practices, from fishing

to agriculture and sustainable forest gathering to food processing and craft-making, such as Buriti palm weaving and ceramic artworks.26

From the earliest records of one of the first known Quilombos, the Quilombo dos Palmares that was home to over 30,000 inhabitants from 1597 to 1710, to the nearly 1.3 million people that self-identified as Quilombola in the 2022 Brazilian census –Quilombola communities persist through the ongoing hardships they face.27, 28 The 473,970 households with at least one Quilombola person in them spanned across 1,696 municipalities. Alcântara, Maranhão has one of the highest proportions of Quilombola peoples within its municipality as compared to that of other municipalities across the country. Out of its total population of 18,467, 84.60% of the population is Quilombola.29 These data from the first Brazilian census to capture Quilombola ethnicity highlights the robust and expansive pulse of the diverse Quilombola communities in Brazil – pointing to a collective power that covers nearly every corner of the country.

Quilombola communities are part of a vast and storied network of Afro-descending peoples who said no to being enslaved; who said no to empire and instead constructed a new sense of home and freedom in the lands that they were forcibly relocated to through the translatlantic slave trade. To quote Dr. Davi Pereira Júnior’s dissertation, “These institutions were present everywhere in the Americas where black slavery was instituted as a central component of colonial economic enterprises, and included Quilombos and Mocambos (Brazil), Garifunas (Honduras and Belize), Crueles (Nicaragua), Maroons (USA), Cumbes (Venezuela), Cimarrones (South America, Mexico and the Caribbean), Palenques and Raizales (Colombia), Bony (French Guiana) a Djuka (Suriname)”.30

These diverse territorial entities partook in the practice of marronage, or open resistance to slavery. In other words, Afro descendents would form their own settlements and governance systems in often remote areas of the lands they had been enslaved on, notably by escaping the grips of slavery or by staying back when plantation lords abandoned their lands during phases of economic downturn or after the abolishment of slavery. These Black settlements are often known for their communal land ownership practices and reciprocal relationships to land, which they live off of and traditionally occupy.31

They represent a form of cultural resistance and assertion of freedom in the face of deep-rooted institutional racism and systemic disinvestment in their respective territories. For instance, in their article, “Palenquero: The identity behind a language in Colombia”, Jpaquin Sarmieto explains that in “San Basilio de Palenque; a settlement established by runaway slaves from Cartagena”, its inhabitants formed a Spanish-based CreolePalenquero- to communicate with each other and define their sense of identity outside of the generations of oppression that had been imposed on them through slavery. To quote one of Sarmieto interviewees, John Jairo, “First I am Palenquero, then Colombian”.32

This same sense of pride to be part of these long histories of resistance to oppression and to be part of an ancestry of people who fought for their independence and sense of belonging on lands that they had been forcibly relocated to, resound across the African diaspora of the Americas, whether they be Maroons in Jamaica, urban or rural Black communities in America, or Quilombos in Brazil.

As argued by Dr. Davi Pereira Júnior in his dissertation, Quilombola communities were, and still are, a place “for reimagining and rebuilding the idea of community and identity itself” and reclaiming territory in the face of erasure and violence.33 Quilombola communities and other marooning communities across the diaspora continue to represent a threat to colonial power and capitalist labor and land extraction.

Finally, through their continued generational struggles to assert their human rights to belong and continue to occupy the lands they call home, marooning communities across the diaspora have come to be recognized by international human rights frameworks like the International Labor Organization Convention 169 for their inalienable right to traditionally occupy their lands. 34 Some of these communities, like the Quilombos, have obtained formal constitutional recognition in their countries. Despite these major legal wins and milestones, the struggle for their rights to live free of violence and colonial oppression continues!

1. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258, 183. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

2. Brasilia. (2003, November 20). DECREE No 4,887, OF NOVEMBER 20, 2003. Presidency of the Republic - Civil House - Deputy Head of Legal Affairs. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/ decreto/2003/d4887.htm

3. Portela Nunes, P.M. (2015). «Conflitos étnicos na Amazônia Brasileira: processos de construção identitária em comunidades quilombolas de Alcântara», Colombia Internacional, 84 | 2015, 161-185. Published May 1 of 2015, consulted May 8, 2024. URL: http://journals.openedition. org/colombiaint/12111

4. The 1988 Federal Constitution of Brazil, article 68 of the Transitory Constitutional Provisions Act (ADCT). https://www. planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/ constituicao.htm

5. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258.

Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

6. Brasilia. (2003, November 20). DECREE No 4,887, OF NOVEMBER 20, 2003. Presidency of the Republic - Civil House - Deputy Head of Legal Affairs. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/ decreto/2003/d4887.htm

7. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

8. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258, 176-180. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

9. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258, 170-175.

Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

10. Sindicato dos Trabalhadores rurais agricultores E agricultoras familiares de alcântara. Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social - INSS. (n.d.). https://www.gov. br/inss/pt-br/canais_atendimento/acts/ acordos-de-cooperacao-tecnica-acts-porestado/maranhao-ma/alcantara-ma/ sindicato-dos-trabalhadores-ruraisagricultores-e-agricultoras-familiares-dealcantara

11. STTR. (n.d.). POSSE DA NOVA DIRETORIA DO STTR DE ALCÂNTARA. STTR Comunidades. https://sttr.comunidades.net/

12. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

13. Serejo, D.. (2022). A Convenção n. 169 da OIT e a questão quiombola: elementos para debate. Coleção Caminhos, Justiça Global.

14. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the

Struggle for Territoriality, 14–258.

15. Vieira, C., & Santiago, B. X. dos S. (2023, October 9). The quilombola communities of Alcântara are bringing a historic case against Brazil to the inter-american court of human rights. EarthRights International. https://earthrights.org/ blog/the-quilombola-communities-ofAlcântara-are-bringing-a-historic-caseagainst-brazil-to-the-inter-american-courtof-human-rights/

16. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

17. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

18. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral

Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

19. McCoy, T., & Traiano, H. (2021, March 26). A story of slavery — and Space. The Washington Post. https:// www.washingtonpost.com/world/ interactive/2021/brazil-Alcântara-launchcenter-quilombo/

20. Silva, L. G. (2020). Palmares and Zumbi: Quilombo Resistance to Colonial Slavery. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. https://doi.org/10.1093/ acrefore/9780199366439.013.632

21. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258, 214. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

22. Pereira Júnior, D. (2020). Political Appropriation of Social Cartography in Defense of Quilombola Territories in Alcântara, Maranhão, Brazil. Sletto, B., Bryan, J., Wagner, A., & Hale, C. (Eds.). In Radical Cartographies: Participatory Mapmaking from Latin America (pp. 183-

202). University of Texas Press.

23. Fleischer, D. (2021, February 26). Making their own way: Brazil’s Quilombola Communities. Inter-American Foundation. https://www.iaf.gov/content/story/ making-their-own-way-brazils-quilombolacommunities/

24. Maria da Silva, G., & Souza, B. O. (2022). Quilombos in Brazil and the Americas: Black Resistance in Historical Perspective. Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy: A Triannual Journal of Agrarian South Network and CARES, 11(1), 112–133. https://doi. org/10.1177/22779760211072193

25. De Almeida Wagner, A. (2004). Terras tradicionalmente ocupadas: processos de territorialização e movimentos sociais. Revista brasileira de estudos urbanos e regionais, 6(1)Ç 9-9.

26. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 14–258. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas. edu/items/ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f2cafa831540c

27. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin].

UT campus repository. 14–258. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/items/ ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f-2cafa831540c

28. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). (2023, October 27).

Brasil Tem 1,3 milhão de quilombolas em 1.696 municípios: Agência de Notícias. https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/ agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/ noticias/37464-brasil-tem-1-3-milhao-dequilombolas-em-1-696-municipios

29. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). (2023, October 27).

Brasil Tem 1,3 milhão de quilombolas em 1.696 municípios: Agência de Notícias. https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/ agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/ noticias/37464-brasil-tem-1-3-milhao-dequilombolas-em-1-696-municipios

30. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas, Austin]. UT campus repository. 125. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/items/ ff775879-3730-412b-8a9f-2cafa831540c

31. Maroons and marronage. (n.d.). Obo. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/ display/document/obo-9780199730414/ obo-9780199730414-0229.xml

32. Udobang, W. (2016, December 2). Palenquero: The identity behind a language in Colombia. Al Jazeera. https://www.

aljazeera.com/features/2016/12/2/ palenquero-the-identity-behind-alanguage-in-colombia

33. Pereira Júnior, D. (2021). The Future of Alcântara Is Not (Just) Rocket Science : Quilombola Epistemologies and the Struggle for Territoriality. (Doctoral dissertation) University of Texas, Austin, 214.

34. The rights of Maroons in international human rights law. (2010b, April 28). Cultural Survival. https://www. culturalsurvival.org/publications/ cultural-survival-quarterly/rightsmaroons-international-human-rightslaw#:~:text=ILO%20169%20defines%20 tribal%20peoples,regulations.%22%20 The%20IACHR%20used%20the

The municipality of Alcântara is a biodiverse region situated on the edge of the Amazonian basin, renowned for its natural richness and historical significance. Split into two distinct ecoregions, namely the mangroves and the Tocantins/Pindaré moist forests, Alcântara’s ecosystems play a vital role in shaping land use practices, including farming and fishing.1

The North Atlantic coastline of Alcântara presents a complex blend of natural abundance and historical significance. While historically it has provided bountiful harvests from the sea and enabled trade through its bay, it has also served as the entry point for Europeans and enslaved people in the past, and more recently, the establishment of naval and space bases.

This ecoregion predominantly occupies a flat alluvial plain (flat or slightly sloping land surface) shaped by the Amazon River’s historical dynamics, with several rivers traversing its boundaries. The soil, mostly consisting of deeply weathered clay, is generally of poor quality.2 The dominant tree in this area is the açaí tree, whose fruits are widely used by locals.

The Amazon region features watercourses, often lengthy arms of rivers or channels, known as “igarapés.” These are relatively shallow and meander through the forest. Most igarapés resemble the dark waters of the Negro River, a significant tributary of the Amazon, carrying minimal sediment. Igarapés play a crucial role in supplying water to the region’s wildlife and plant life. Navigable by small boats and canoes, they serve as vital transportation and communication routes for inhabitants of the region.3 Moreover, streams serve as habitats for a wide variety of fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds, all of which rely on these waterways for their existence.

The farmland in Alcântara presents a dual narrative. While it sustains numerous communities with its rich fertility, not all areas are equally productive. The expansion of the space center and military bases has resulted in the displacement of hundreds of Quilombola communities, worsening the challenges of agricultural sustainability. Forced to adapt to new environments for crop cultivation, many struggle to thrive the way they did before being displaced.

According to a Terra de Direitos factsheet, titled “Quilombola titling: a historical debt of the Brazilian State” (2023), if the Brazilian government continues at its current pace of granting titles to Quilombola territories, it will take 2,188 years to “fully title the 1,802 processes currently open at the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform” (or Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária), also known as INCRA, the federal body responsible for Quilombola land regularization. By 2023, only 54 territories had been either partially or totally titled by INCRA since the property rights of traditional Quilombola people was formally recognized by the 1988 Federal Constitution. Of the 54 territories that have been granted title, 30 received a partial title, meaning that the title only applies to one area of the territory to which the filing

Quilombola community actually has full right to. The factsheet explains that, “The data does not include quilombola land regularization processes assigned to states and municipalities, or to communities that were not certified by the Palmares Foundation (FCP), a federallyfinanced body that promotes Afro-Brazilian culture, including certifying quilombola territories.”4

Many obstacles have been getting in the way of Quilombola communities obtaining rightful access to their collective land titles. For instance:

• the numerous stages to the land titling, notably certifying the territory, identifying and delineating it, recognizing it, declaring its social interest and finally, titling it, make it a long-drawn, unpredictable, and bureaucratic endeavor

• the varying levels of opposition by the Brazilian government to the titling process. While the Bolsonaro administration (20192022) only granted 6 partial titles during its 4 year administration, Dilma Roussef’s administration granted 14 during her first term as president.

• private land holding oligarchies and private land developers, who aim to acquire Quilombola land(s).

Furthermore, the generations of institutional racism rooted in Brazil’s colonial and slaveholding history, make land ownership structures between non-white and white inhabitants of Brazil inherently unequal.

The new Lula government, which was put in place in 2023, has taken important steps to demonstrate its commitment to Quilombola land regularization, including reinstating the Ministry of Racial Equality, which now

contains the Secretariat of Policies for Quilombolas, Traditional Peoples, and Communities of African Origins, Terreiro Peoples and Gypsies. It is run by the Quilombola and former member of National Commission for Black Rural Quilombola Communities (CONAQ) coordination board, Ronaldo Barros. There is still a strong push by CONAQ leadership and Quilombola communities on the ground to speed up the collective titling process.

3.3

FORTY YEARS OF RESISTANCE TO LAND DISPOSSESSION: A DEEPROOTED COLONIAL LEGACY

The region of Alcântara located in the Northeastern state of Maranhão, Brazil, which was formerly inhabited by the Tupinambás Peoples, has a history of European settler colonialism dating back to the 17th century. From a booming slave-run economy in the 18th century, to a declining plantation market

in the 19th century, Alcântara experienced Portuguese White flight in the late 19th century. This phenomenon led to the formation of multiple autonomous social groups, today known as Quilombos, who had been left behind by plantation lords.

Known for their land-based collectivist cultures and ways of life, the Quilombos of Alcântara lived removed from the intervention or support of the government until the 1970s when the Brazilian military started to lay claim to parts of the territory, thus displacing many Quilombola communities from their homes. In 1980, the Space Launch Center of Alcântara (CLA) was approved for construction in the region without prior consultation or consent from our local communities, leading in 1986 to its construction and to the forcible displacement of 32 of our Quilombola communities (more than 300 families), under the guise of a national security rhetoric. The CLA location was chosen due to the predictable weather, open ocean, and its 169 mile-distance from the equator - where the Earth rotates at a higher speed.5 These 502 displaced people were resettled to areas near the CLA called “Agrovilas” to live in military-built homes where growing their food and fishing became near-impossible. In response to these human rights violations, social movements began to form, all the while the 1988 Federal Constitution guaranteed the right of collective titles of Quilombo territories across the country. In 1989, the International Labor Organization Resolution 169 recognized the territorial rights of Indigenous and Tribal peoples, while in 2003 President Lula enacted Decree 4.88 of 2003 to establish procedures leading to the granting of the collective title.6 It is, however, not until 2020 that ILO acknowledged that the right of Quilombola communities to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent had been violated through the approval and construction of the CLA.

In 2020, the Brazilian government announced in a decree its plan to expand the CLA by over 30,000 acres, which could lead to the

displacement of over 2,100 peoples from communities in the regions, which have been founded hundreds of years ago by their escaped enslaved and freed ancestors.7, 8 A case at the Inter American Court of Human Rights concerning the human rights violations committed by the government on Quilombola Communities of Alcântara has been pending for a decision since 2023. The precedent-setting decision shall be taken in 2025.

Furthermore, in a historic decision on September of 2024, the Brazilian government and Quilombola entities have reached an agreement pertaining to the use of the Alcântara Space Base (CLA) and the protection of the rights of local communities, that is 152 remaining Quilombola communities in Alcântara, Maranhão, who have been directly impacted by the establishment CLA in the 1980s. The pact was announced on September 19th in Maranhão, alongside President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Its goal is to put an end to the 40 years of ongoing disputes between the Brazilian state (the Brazilian Air Force and the Ministry of Defense), who claimed the need to preserve land in Alcântara for the potential expansion of Brazil’s aerospace program and Quilombola communities of Alcântara, who have claimed historic ties to the land on which they depend for their subsistence and community health.9

Although the Alcântara Space Launch Center, or CLA, was initiated in 1986, a space agency in Brazil had been established years before during the country’s military dictatorship, which formally ended in 1985. Land clearance for the CLA began in 1980, six years before the construction of the facility, leading to a first wave of mass displacements among the Quilombola communities of Alcântara. Alcântara’s proximity to the equator and to the ocean makes it an ideal and cost-effective location for space launches10, both domestic and international, prompting the Brazilian government to develop numerous strategies for removing Quilombola communities from their land, rather than honoring their constitutional rights to traditionally occupy their territories.11

It’s crucial to note that the CLA wasn’t the sole reason for expelling the Quilombola from their ancestral lands; the Navy also played a role. According to a Quilombola leader interviewed in the context of our oral history project, the military also displaced the Quilombola to build villas for high-ranking military personnel.

Although the history of the Alcântara region far predates the arrival of Europeans settlers and the subsequent importation of enslaved peoples from Africa to the region, the history of Alcântara as it is today is largely shaped by the collapse of the plantation economy in the late 19th century, and the discovery inthe 1980’s of the ideal location for a Space Launch Center and renewed foreign interest for its use. The condensed timeline below shows several key events. For a full timeline please visit the website or this link.

• Grão-Pará and Maranhão General Trading Company was established. It was the first company to drastically influence the ethnic composition of the area because of its importation of enslaved African peoples to the region.

• The economic investment shifts, particularly the closure of major cotton and other commodity crop trading companies like Grão-Pará and Maranhão, played a pivotal role in Alcântara’s decline.

• This economic instability triggered a phenomenon of white flight, with plantation owners deserting their estates and infrastructure. Factors such as the dwindling domestic slave trade, mounting pressure against transatlantic slavery, and a shift in the economic axis further exacerbated Alcântara’s decline. Additionally, the proliferation of Quilombos across Brazilian territory and falling export prices on the international market added to the city’s woes, leading to a significant downturn in its fortunes.

• The collapse of large plantations led to the consolidation of autonomous social groups left behind by plantation lords. Within this context, multiple Quilombola communities were formed.

• The Ministry of Aeronautics receives 52,000 hectares of donated land from the State of Maranhão (via this letter) to build out the Space Launching Centre in Alcântara. This is the first step towards starting Brazil’s domestic space program.12

• The construction of the Space Launch Centre in Alcântara (CLA) was initiated, starting the process of evicting 32 Quilombo communities (or 320 families) in Alcântara, in the State of Maranhão.

• 520 people were resettled to areas near the CLA, which were called “Agrovilas”, where families were forced to live on 15 hectares of land, when national legislation had established a minimum rural allotment of 30 hectares. Moreover, the lands on which they were resettled were not conducive to subsistence farming and fishing.

• Residents of Alcântara resisted the possibility of only receiving small plots of land in their Agrovilas by barricading the road leading up to the CLA’s headquarters in Alcântara, when prominent members of the federal government visited the Space Launch Center.

• The Federal government signed a decree decreasing the rural land allocation from 35 to 15 hectares within the expropriation zone. This reduction failed to consider the social and ecological needs of Quilombola communities, leaving families in the Agrovilas with insufficient land to farm, fish, and subsist on.

• The Federal Constitution of Brazil was enacted, in which Article 68 of Transitory Dispositions guarantees the right to collective land titles to Quilombo territories. However, due to the discriminatory criteria that it imposes, it is nearly impossible to obtain the legal titles.

• A number of the affected communities supported by the Maranhão Society for Human Rights (SMDH), the NGO Global Centre of Justice, the Association of Black and rural Quilombo communities (ACONERUQ), the Federation of Agricultural Workers of Maranhão, and Global Exchange, presented a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE), presented an amicus curiae brief before the Inter-American Commission in support of this main petition.

• Quilombola communities in Alcântara filed a claim to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH) within the Organization of American States (OAS) on how the process of expropriation of their territories underway in Alcântara by the Brazilian state in the 1980s constituted human rights violations under the American Convention on Human Rights.

• The International Labour Organisation’s Resolution 169 prompted the Brazilian government to enact a decree regulating the right of collective property of the Quilombo communities, but left much to be desired in terms of the implementation of this decree.

• The Foreign Relations and Defence of the Senate Commission approved Decree no.393/03, which instituted the Technological Safeguarding Agreement between Brazil and Ukraine, authorizing the use of the CLA by the Ukrainian government. Both agreements are harmful to the development of national scientific and technological policies as they prohibit the transfer of technology from the USA and Ukraine to Brazil. The viability of both agreements will result in the forced displacement of over 1,000 Quilombola people to areas located far from the coast and already densely populated by other Quilombo communities.

• The VLC (Veículo Lançador de Satélites) Brazilian accident occurred on August 22, 2003, at the Alcântara Launch Center during preparations for the third VLS-1 rocket launch. A catastrophic explosion on the launch pad resulted in the destruction of the rocket and its payload, along with the tragic loss of 21 technicians and engineers. This incident marked a significant setback for Brazil’s space program, prompting a reassessment of safety protocols and technical practices while highlighting the inherent risks and complexities of rocketry.

• The Association of the Ethnic Territory of Alcântara (Associação do Território Étnico de Alcântara), also known as ATEQUILA, was founded, in order to obtain collective land titles for all Quilombos within Alcântara.

• Consultation workshops were conducted from August 24 to October 13, 2007 by the CLA, involving affected communities and their representative organizations, MABE, STTR, and others. The objective was to discuss the establishment of an associative mechanism to obtain collective land titles for the territory.

• The National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Traditional Peoples and Communities (PNPCT) was instituted by Decree 6040; recognising the collective land rights of Quilombola communities.

• The Technology Safeguards Agreement (TSA) was signed between Brazil and the USA to allow the CLA to launch American space crafts.

• STTR filed a complaint with the International Labor Organization (ILO) in April after the signing of the Technological Safeguards Agreement between Brazil and the United States due to its violation of Convention 169 and the right of Quilombos to Free, Prior and Informed Consent on their territories.

• The International Labor Organization (ILO) acknowledged the complaint lodged by STTR to represent Quilombola communities of Alcântara by asserting that the Technological Safeguards Agreement (AST) between Brazil and the United States breached the right to consultation outlined in Convention 169. The ILO stated its intention to take legal action against the Brazilian State for its failure to implement the Free, Prior and Informed Consent process mandated by ILO’s Convention 169.

• The Brazilian government, through Resolution 11, announced a plan to further expand the base by 30,000 acres, thus threatening to displace over 2,100 Quilombola peoples from their homelands.13

• In April 2023, after 40 years of disputes, the Brazilian state made a historic decision to acknowledge its international responsibility to honor the territorial rights of Quilombola communities in front of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and formally apologized to Quilombola communities of Alcântara for violating their rights as outlined in the American Convention of Human Rights.

• To take concrete actions to remedy these rights violations, the Brazilian government established the Interministerial Working Group to reconcile the interests of the Alcântara Space Center (CLA), while honoring the territorial rights of the Quilombo communities of Alcântara.

• Despite these efforts, relationships between Quilombo communities and authorities have grown more and more strained through 40 years of disputes. In January of 2024, Quilombola groups who had been invited to participate in consultations through the Interministerial Working Group withdrew from it because they did not consider that the process was leading to the titling of their lands.

• These groups demanded a meeting with Lula and expressed that the Brazilian Space Program had never released any technical studies that demonstrated the need to expand the CLA’s current land use from 8,700 to 21,300 hectares on Quilombola territory.

• In the end, the process was resumed outside of the Working Group to eventually reach an agreement, which is detailed below. 14

• In a historic decision on September of 2024, the Brazilian government and Quilombola entities have reached an agreement pertaining to the use of the Alcântara Space Base (CLA) and the protection of the rights of local communities, that is 152 remaining Quilombola communities in Alcântara, Maranhão, who have been directly impacted by the establishment CLA in the 1980s.

• The pact was announced on September 19th in Maranhão, alongside President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Its goal is to put an end to the 40 years of ongoing disputes between the Brazilian state (the Brazilian Air Force and the Ministry of Defense), who claimed the need to preserve land in Alcântara for the potential expansion of Brazil’s aerospace program and Quilombola communities of Alcântara, who have claimed historic ties to the land on which they depend for their subsistence and community health.

• Here are key components to this agreement:

1. The CLA will retain use of 9,200 hectares of land with no further challenges from Quilombola communities in the region.

2. The Military of Defense will no longer lay claim to 78,100 hectares of the land traditionally occupied by the Quilombos of Alcântara and will not challenge the Quilombos’ efforts to title their land through the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA).

3. Once the agreement is signed, INCRA will mandate the recognition and definition of Quilombola Territory of Alcântara, which covers the area of 78,105 hectares of land.

- From there, land regularization for Quilombola communities will be unlocked as it has been stalled for the past 16 years.

4. Lula will then sign a decree, which will declare the area to be of social interest for the purpose of land regularization

5. Within a one year period, INCRA will begin to title the identified territory.

6. A public company will also be created by the Brazilian government for the aerospace sector.

• The agreement will provide a foundation for the parties involved to seek counsel from international organizations to assess whether the dispute has been either fully or only partially addressed. In this context, Quilombolas of Alcântara await the soon-to-be rendered decision by the Inter-American Court on Human Rights regarding their recognition as a peoples through ILO 169.15

• In March of 2025, two years after Quilombola leaders of Alcântara brought the case to them, the IACHR rendered the following precedent-setting decision - “In the judgment notified today in the case Quilombola Communities of Alcântara v. Brazil, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) declared the State of Brazil internationally responsible for human rights violations against 171 Quilombola communities located in the municipality of Alcântara, Maranhão. The violations primarily concern their right to communal property, as well as other fundamental rights.”

ad for

The Alcântara Space Launch Center (CLA) is situated near the coast, and its construction has displaced numerous Quilombola communities along the coastline. According to Danilo Serejo, a Quilombola lawyer and author, the government’s failure to conduct an environmental impact assessment of the CLA has led them to completely overlook the negative impacts that the construction of the CLA has caused to the livelihoods of Quilombola communities whose forcible displacement to unfamiliar regions of Alcântara has threatened their food security, their ability to subsist off the land, and their sense of cultural identity.

The economic benefits promised by the CLA have not justified the social and environmental ecosystem destruction caused by its construction. In fact, 56 percent of the residents of Alcântara still live below the poverty line despite over 30 years since the center’s construction. President Bolsonaro’s rejection of G7 aid to protect Brazil’s sovereignty during the Amazonian fires in 2022 stands in stark contrast to his eagerness to hand over control of the CLA to the U.S. Some critics highlight provisions in the 2019 agreement between Trump and Bolsonaro that would grant the U.S. power to restrict access to the base and allow for the storage