COMMUNITY

University of Michigan

A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning

Agora Journal of Urban Planning and Design Volume 18: 2024

The Agora Journal of Urban Planning and Design in an annual, student-run, peer-reviewed publication of the University of Michigan’s A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning

A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning 2000 Bonisteel Boulevard, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2069 USA

www.agorajournal.squarespace.com

2331-2823

COPYRIGHT

Agora Volume 18 2024, the Regents of the University of Michigan

LISENSING

TYPE

PRINTING

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non CommercialShare Alike 40 International License

ATF Garamond Text, Neulis Neue, Zahrah, Lucida Sans, Georgia, Minion Pro

ULitho

Ann Arbor, Michigan

DISCLAIMER

The views and opinions expressed in this journal reflect only those of the individual authors and not those of the Agora Journal of Urban Planning and Design. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions. All figures are created by authors unless otherwise noted.

Previous Editions

AGORA

GROWTH

CHANGE

DETROIT

ENDURANCE AND ADAPTATION

CONNECTION

PUBLIC I PRIVATE

ALTERNATIVES

DIVISIONS

PROGRESSION

PERSPECTIVE

SEMBLANCE

TRANSFORMATIONS

CONVERGENCE

R/EVOLUTIONS

PARTICIPACTION REIMAGINE

A18 BOARD

EDITORS IN-CHIEF

Revati Thatte

Marisol Mendez

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Upasana Roy Lawson Schultz

SYMPOSIUM DIRECTORS

Vaidehi Shah sara faraj

BLOG AND WEBSITE MANAGER

Isabella Beshouri

Vanessa Lekaj

DEPUTY EDITORS IN-CHIEF

Calvin Blackburn

Rebecca Griswold

DEPUTY CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Allison Yu Elyse Cote

DEPUTY SYMPOSIUM DIRECTORS

Jessie Williams

Lauren Jenkins

FINANCE AND FUNDRAISING MANAGERS

John Morrow

Theodore Shapinsky

A18 STAFF

Andy Larsen Anuriti Singh Celine Shaji

Cleo Randall Kraig Sims Roy Khoury

Yuyang Ma LAYOUT EDITORS

Faculty Advisor’s Letter

DR. SCOTT CAMPBELL

It gives me great pleasure to welcome this year’s volume of Agora. In 2006, a small but ambitious team of master’s students went against the tide of skeptics and launched this journal, navigating from initial inspiration through volunteer recruitment, article solicitation, editing, fund-raising, and publication. This process has unfailingly persisted through heavy course loads, budget cuts, graduate student strikes, blizzards, campus protests, the crunch of winter semester capstone projects, and the Zoomlinked dark days of COVID.

One power of this student-led journal is to hear the voices of the next generation of planners, designers, and urbanists. Unencumbered by historical convention, these authors are freer to explore contemporary challenges beyond the confines of the classroom. They are not afraid to ask hard questions and point out injustices. The themes of these articles are richly varied, though a leitmotif is the unsettling, crisis-filled times we live in.

One author explores the historical burden of racial segregation, displacement, and foreclosure, all in the larger context of racial capitalism. Another author critiques the superficially sensible yet highly detrimental restrictions on where former felons can live in New York City, making homelessness an even greater risk. Yet another author explores community land ownership models

as a promising path towards affordability for manufactured housing. This analysis of structural inequality and marginalization extends into international contexts, including an article on the twin legacies of colonization and modernist architecture in Cameroon.

Sustainability and environmental justice also emerge as powerful themes. One team explores impending climate migration and the need to adapt architectural designs for displaced residents. Another critically examines the legacy of Detroit’s industrial history and the failure of environmental regulations and local planning to protect vulnerable populations. A third author takes on the persistent problem of the automobile’s dominance in Panaji, India, threatening environmental health and crowding out users of public spaces. A final article takes a different view of the city: a poetic narrative of the vibrant sidewalk life in Hanoi.

The faculty and staff offer our wholehearted congratulations to the authors and Agora staff, especially co-editors Revati Thatte and Marisol Mendez, for a job well done. We appreciate your tireless efforts to sustain and nurture this vital platform for new and brave voices for urban innovation and social change.

Scott Campbell Faculty co-adviser

(with Julie Steiff)

Editor’s Letter

REVATI, MARISOL, CALVIN AND REBECCA

Each edition of the Agora Journal of Urban Planning and Design acts as a time capsule that strives to capture the most pressing problems in urban planning. The essence of urban planning is to pursue and faithfully serve the public interest, meaning that while we reenvision our communities, we must also be aware of ideals and factors that endanger their safety and wellbeing. Additionally, in a time when misinformation threatens to upend society as we know it, the need for a strong sense of community becomes ever more urgent. As fundamental planning theories become more mainstream — think walkable neighborhoods with safer streets, climate action plans centered around environmental justice, and collective housing options accessible to all — the underlying question of what it means to build a future that works for everyone still lingers in the air.

Agora’s 18th installment, Community, aims to answer that question. Interpretations of “community” vary widely, as seen in our excellent selection of pieces this year. Student contributors from schools across the University of Michigan detail heritage and history that makes us who we are today. From the modes of transit that make discovering a new city possible to the vibrant street life that characterizes public spaces, our authors not only suggest improvements that can increase social cohesion, but also pay tribute to the natural human tendency to build

community. Students also delve into some of the more thorny and wicked problems of the past that impact communities of tomorrow, including long-standing public health crises and outdated criminal justice policies. Our hope is that this edition of Agora challenges traditional thinking and illuminates a path towards more accessible spaces for everyone.

The book you hold in your hands is a labor of love created by a community of planners, architects, and urban designers. This edition of Agora stands on the shoulders of 18 years of student-led scholarship, nurtured and nourished by the outstanding faculty and student body at Taubman College. We are immensely grateful to our student editorial board for the countless hours spent editing and designing the journal; to faculty and doctoral students who graciously shared their expertise and enhanced our selected pieces; and to our ever-so-supportive faculty advisers, Julie Steiff and Scott Campbell, for their guidance along the way.

We hope you enjoy Agora 18.

Marisol Mendez and Revati Thatte Editors-in-Chief

Calvin Blackburn and Rebecca Griswold Deputy Editors

Setting Up Sex Offenders for Failure: How the intersection of law and city planning exposes sex offenders to longer prison sentences

Trust and Deed: The Communal Ownership of Manufactured Housing

Bed-Stuy is Losing Blackness: A Case Study Exploration of Racial Capitalism, Gentrification, and Foreclosure.

Acknowledgements

The publication of Agora 18 was made possible by the Taubman Endowment Fund.

We would also like to thank the following individuals for their time and expertise in conducting peer reviews for Agora 18:

JONATHAN LEVINE

RICHARD NORTON

MORGAN FETT

LAUREN HOOD

MARÍA ARQUERO DE ALARCÓN

We would also like to give special thanks to our faculty advisors, Dr. Scott Campbell and Dr. Julie Steiff.

WEBSITE + BLOG @ agoragram

The Last Shall be First:

How Colonization Defines the Urban Fabric in Cameroon

PHILIPPE KAME

Master of Architecture

ABSTRACT

The colonial encounter between the indigenous populations of Cameroon and Europeans was a rocky one, fraught with unfairness and horrors that deeply impacted the lives of these populations and radically shifted the course of their histories. Cultural power, as the most conspicuous form of soft power,1 was heavily exploited by the colonial authorities in subjugating the indigenous populations. Their values, beliefs, and worldviews were all supplanted and dominated by European ideologies leading to an acculturation. This cultural genocide has had as many destructive effects as human genocides affecting the formation of modern African societies for years to come. While this essay is primarily focused on uncovering the formation of the urban environment in Cameroon, this research also offered an interesting account and clearer understanding of the urban African experiences under colonial domination. Before the 1980s, rural societies and agrarian studies were believed to offer a more authentic account of Africa than cities,2 as many believed cities were the result of Western machinations on the continent. The growing interest in the lives of Africans under colonial rule brought cities to life as nexus points for a better understanding of colonial rule. Such a research thesis might be problematic on its own but it offers the primary sources on which the author based their findings. Thus, starting with a brief history of colonialism in Cameroon, the paper proceeds with discussions of urban projects and architecture in the main city of Douala under German and French occupation. These discussions will offer a point of departure towards understanding the formation of the urban environment in Douala, before exposing the issues with these urban environments and attempting to trace their origins back to colonialism. This will present ways in which Cameroonians have tried to forge new paths for themselves while navigating their complex urban environments.

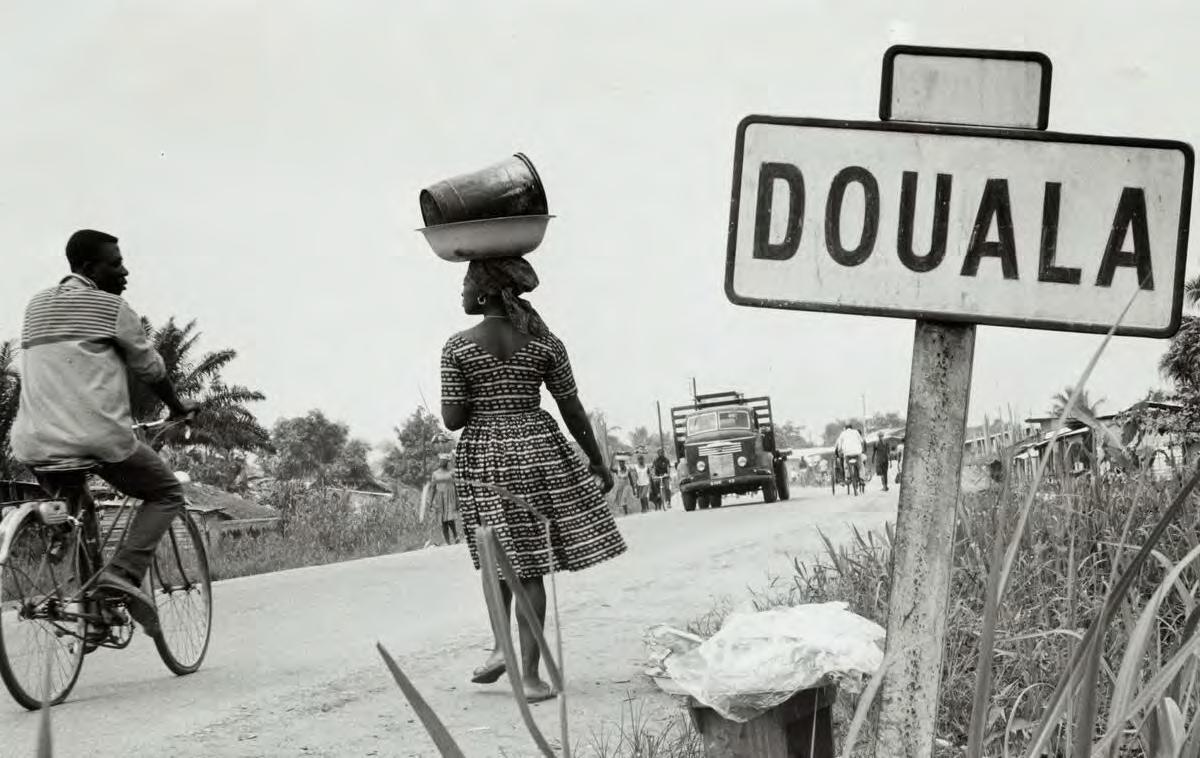

Figure 1. On the way to Douala.

Source: Photograph by John Taylor. International Mission Photography Archive, Ca.1860Ca.1960, Bibliothèque Du Défap, University of Southern California

INTRODUCTION

Cameroon can be seen as a unique case due to its colonial history. The country has witnessed the occupation of not one, but three different colonial powers: first Germany, then followed by Great Britain and France after World War I. The impact of these different forms of urbanization, logic, and administration made its cities quite heterogeneous.1 Moreover, it is important to note colonial rule was never full, but always partial and mixed in itself.2 Colonial rule was always rearranged and/ or distorted as it was implemented to adapt and better dominate. Yet in the face of global economic restructuring, particular economic arrangements, cultural inclinations, and forms of external engagement during the post-colonial period, African cities developed differences that made them singular.3

In Cameroon, the city of Douala offers the best account of the colonial history of the country. Its geographical location on the coast of Cameroon led it to be the first point of contact European adventurers had with the rest of the territory, making it the epicenter of all colonial enterprises in Cameroon, be it the European penetration, resistance movements to colonial occupation, and the struggles for independence. Therefore, through social, political, economic, and cultural changes induced by the colonial presence, relations have been forged between the indigenous populations of Douala and the Europeans. The city of Douala today retains much of its colonial footprint as we will see later.

Indeed, most of the urban planning of the city was a colonial invention still in existence. Goerg points out: “If it is obvious that colonization did not import the city in Africa,

Figure 2. “European Hospital.”

Source: International Mission Photography Archive, Ca.1860-Ca.1960, Bibliothèque Du Défap, University of Southern California.

it can, however, be stated that the majority of Africans access the city via the colonial city and that, in the long-term dynamics that mark the continent, the colonial period of the city is a highlight of urbanization.4” Furthermore, urban planning during the colonial era was the result of an architectural legacy.5 Thus, keeping in mind most of these artifacts are still standing today, Zourmba Ousmanou, a Ph.D. researcher at the Università degli Studi di Genova, poses the compelling question if it is worth referring to colonial architecture in Africa as a heritage site. If this architecture were erected in celebration of the former oppressor, to what extent can they become heritage sites? Can the remaining colonial built environment convey cultural or historical significance to the communities in whose territories they are located?

Archives of the German protectorate were destroyed during the First World War and, as such, the colonial-built environment remains the principal witness of a history that impacted the whole nation. Furthermore, as Zourmba Ousmaniu advances, these buildings symbolize collective memories. These structures are tangible traces of the country’s colonial past, and their heritage value must be separated from the ideological rejection of colonial systems. As such, if we are to retain colonialism as a useful concept to

grasp African urban histories, an appreciation is required of the different influences that were brought to bear on urban spaces.6 I wish to make it clear that I am not of that school of thought that claims colonialism brought with it some benefits to African societies—its horrors are too many to see any kind of advantages to it. However, the colonial encounter metamorphosed African societies to the point where its citizens could only learn to adapt and reappropriate their history.

URBANISM AND ARCHITECTURE UNDER GERMAN RULE

The German occupation of Douala, Cameroon translates to an impressive revamping of the landscape to create a “little Berlin” in Douala. Urbanization was heavily promoted by the Germans in an attempt to in the creation of modern European centers was only partially realized as World War I broke out, and the conquest of the Allied Forces in September 19147 ultimately led to the establishment of the French Mandate over Cameroon.

Just as urban planning provided the German colonial government an opportunity to extend its control through public infrastructure, architecture was another tool exploited to mark German presence in the region. It is important to note that in the case of architecture, most of it was experimentation.8 Because architecture was to stand as a symbol of colonial domination, most of the styles and methods in which buildings were constructed were directly imported from Europe. However, colonial authorities would soon realize European models were not necessarily adapted to the local climate and context and would, thus, embark on iterative processes.

Mindful to register their presence in the region in the long-term, Germans would switch their approach to building in Douala using imported

materials from Hamburg such as wood, brick, cement, sheet metal, and tile, just to name a few.9 Plans for administrative buildings were not produced locally, but from Berlin; yet, the historian Jacques Soulilou notes that German architecture from the colonial period, unlike other colonial powers, developed free from any direct design influences that can be explicitly linked to what was happening at the same time in Europe. As mentioned earlier, colonial architecture under the German protectorate was full of experimentation as they adapted imported styles from Europe and adapted them to the local climatic conditions. For example, the Doecker buildings in Cameroon can be seen as Art Deco through their formal qualities but adapted to the local climate through elevated substructures to prevent moisture penetration and double roofs for solar insulation.10

Some examples of other administrative buildings included the headquarters of the first government of colonial Cameroon, constructed similarly to most buildings of German royalty. The building rested on a base one meter high, the walls were laid in bricks, and the floors were made of imported metal planks. The ceilings were made of corrugated iron laid on metal joists and covered with a layer of cement. Finally, the roof was made of wood covered with tarred cardboard11 The main wing had eleven rooms.

The residential facility for the Colonial Governor-General, built in 1901, was a reproduction of the Schloss, a vintage German stately mansion that featured 72 bedrooms.12 Such a structure, in addition to the German police headquarters (Polizeitruppe Kamerun),13 built in 1889, is still standing strong today and serves administrative purposes to the local government. It is also important to note that the diffusion of architectural models takes place in a very restricted population group. As Soulilou explains: “European aristocracy or notable Duala, without forgetting the

numerous religious congregations which show proof of an astonishing uniformity. The vast majority of the Duala people living in the periphery continue to build as their ancestors did, except that there appear roofs covered with corrugated iron (German influence) and that new constraints related to urban development plans have also made their appearance.14”

URBANISM AND ARCHITECTURE UNDER THE FRENCH PROTECTORATE

Just like the Germans, architecture and urban planning for the French represented an opportunity to terrorize the natives and, thus, better dominate them. As such, these projects represented a visible expression of Western concepts of beauty and order. The imposing size of some of these constructions served the main purpose of domination and intimidation by virtue of their direct reference to the inordinate power and resourcefulness of their builders. Germany’s loss during World War I led to the distribution of its former colonies among the Allied powers; Cameroon was placed under the mandated control of France and Britain as a result. For France, the immediate reflex was to erase all traces of German presence in the territory, both intangible and physical. They quickly realized, however, that this might not be the ideal course of action and decided to retain some of Germany’s physical presence in Douala and Yaoundé and build upon them, often changing and redesigning them to suit a French hegemony. France’s infrastructural endeavor in Cameroon could also be seen as experimental as a result, and on the other hand, was more functionalist rather than aesthetics.

The period after the war is marked by a phase that aimed at restarting infrastructural projects left by the Germans, such as the port of Douala, which in 1927 was equipped with

a four-berth dock.15 A 1700m long maritime boulevard was also constructed, which later on would stimulate the establishment of trading houses.16 Concurrently, the French administration engaged in the development of a whole administrative apparatus, like the Germans before them, which included varied sectors like health, law, transportation, and commerce.

Earlier, we talked about the division of the urban space in Douala into two halves comprising a “European city” and an “African city.” Such an urban scheme would also be taken over by the French and developed even further. We see the apparition of “Cités” such as “la Cité des Douanes” in Akwa and la “Cité Chardy” at Bassa for railway executives in 1951.17 These Cité are mostly characterized by an agglomeration of tall buildings, most of which serve social housing purposes, the first of which has been erected on the edge of the cliff of the Joss Plateau. The urban division goes further, and we see the appearance of five zones: A, B, and C partitioning the city of Douala into housing and commercial zones.18

Zone A corresponds to housing and commerce all at once. Geographwically, Zone A is part of the European city on the edge of the Wouri River. Neighborhoods, such as Bali, founded in 1929 are attached to the zone, as well as part of Akwa, founded in 1938.19 In Zone A, the part of Akwa attached to it is its main commercial section, while neighborhoods such as Bali and Bonapriso are residential and Bonanjo administrative, all of which are for and by immigrants from Europe. This progressive expansion of the European city eventually pushed the natives further inland and up north.20

Zone B only serves housing purposes, as well as small commerce by the natives (what the French call “artisanat” (or craft in English). We thus move away from the center and further up north into the African city in

neighborhoods such as Deido and New Bell, as well as on the other side of the river in Bonaberi.21 Infrastructure in this zone mainly served the natives but had to go through authorization by the French authorities beforehand and follow European construction standards.

On the other hand, Zone C is defined as “traditional construction” and cannot be identified by any specific name.22 Geographically, however, it stretches from the extreme borders of the central zone at certain locations to the limit between the city and the rural area. No regulations governed this area and the kind of constructions that could be found follow traditional methods and aesthetics.

Although the architecture under the French mandate remained experimental and functionality was the principal concern, the landscape in Douala became more akin to the history of modern architecture in Europe. By this, I essentially mean architectural forms that appeared in the landscape could be attached to specific European styles, unlike the Germans. This could suggest an unwillingness by the French to develop a completely new architectural language as they tried to import a culture as is.23

Another difference in the architectural landscape under the French mandate is the appearance of large texts on the façade of public buildings. Some spelled “Chamber of Commerce,” “Courthouse,” or even “Native Hospital.” Soulilou reports this new architectural marquee is in line with the part didactic mission of the colonists under the requirement of the League of Nations to presumably prepare the natives for independence24

Ornamentation is featured predominantly in this architecture; art deco style aesthetics mixed with ornaments inspired by the

vegetation appear above the openings on the ground floors; 1930s style balustrades with square or cylindrical balusters would become a noticeable design feature at the windows and along the terraces that border the cliff.25 Additionally, a system of large openings arranged all around the building that allows for free circulation of air becomes predominant. Facades are imposed with repetitive rectangular modules, which the balustrades come to underline. The interior

“THE COLONIAL BUILT ENVIRONMENT TODAY

The interest of the French and German administrations to inscribe their presence in Cameroon over a long period led to considerable investment in architectural and urban projects, giving rise to quality constructions that lasted decades beyond their occupation.26 Moreover, their continuous

The interior distribution includes a vestibule located in the octagonal or square projection, followed by a living-dining room, generally separated from the first room by a low wall. On either side of this central space, doors open giving access to the bedrooms and the bathroom. The kitchen is relegated outside. This plan resumes, after all, the provision traditional, as noted above.”

of these constructions is also worth noting. Soulilou explains: The evolution of architecture in Europe corresponds to the architectural landscape change under the French mandate; hence, in 1955, villas akin to the international style started making their appearance in the neighborhoods of Zone A, such as Bonandjo.36

use by the Cameroonian governments post-independence made them resistant to the vestiges of their time. As AbdouMaliq Simone, Fellow at the Urban Institute of the University of Sheffield, effectively puts it, they are futuristic buildings built with a sharp approach.

Many of these vestiges are still standing today: for example, the Palace of the Prince Manga Ndumbe and the Tsekenis building have been reconfigured into entertainment and administrative spaces, respectively. The German Colonial Bridge, while no longer in use, nevertheless remains a landmark in the nation marking the collective memories as the country’s first bridge constructed in 1902 – it remains a popular tourist attraction in the city of Buea today. Administrative buildings, such as the Chancellor’s Schloss today, have been reconfigured into the governor’s house in Buea, while the stately National Museum of Cameroon in Yaounde previously served as a residence to the French governor in the 1930s.

Colonial urban planning schemes can still be identified today in the city of Douala, notably in its division into zones. Zone A, for example, still serves residential and commercial purposes, and mainly houses European

4.

A fourth zone has been added over time, Zone D, reserved for factories as Douala expanded its manufacturing capacity. These colonial urban schemes have had a deep impact on how the cities of Douala and Yaoundé have attempted to redefine themselves following independence. Nationalism brought a willingness to break free from any form of influence from previous colonial powers, yet the government of Ahidjo, the nation’s first president, just like the French colonial administration seemed to have mostly built upon what was already present. The division of the city of Douala along class and even racial lines today, akin to gentrification in Western countries, traces its origins to the colonial period. Nevertheless, it is commonly argued that African states performed reasonably well in the first decade following their independence.27

Pagoda” because of its architecture. Source: Rives Coloniales: Architectures, De Saint-Louis a Douala Edited by Jacques Soulilou

immigrants today—the neighborhoods of Bonandjo and Bonapriso are still termed as European cities as a result. Moreover, a division can be observed between Zone A and Zone C and B (which mainly houses middleand lower-class citizens of the city). While this division becomes blurry with time, this segregation of sorts happening in the city today can be traced back to colonialism.

The attempt of these states to transform national, political, and administrative apparatuses that were ill-suited for modernization expedited their development. Budgets were pushed beyond their limits to address the costs needed for physical and social infrastructure as well as to configure viable social contracts to provide frameworks for social cohesion, even if they

were to be temporary.28 This, unfortunately, led to an erosion of the political capacities of these societies leading to the imposition of regimes that establish enclaves of fiscal administrative capacity distanced from real engagements with either local social processes or institutions. As is particularly the case for Cameroon, many African states no longer make the symbolic efforts to demonstrate concern for the welfare of their

Figure 5. Tropical Modernism as seen in the Hall of Douala.

Source: International Mission Photography Archive, Ca.1860-Ca.1960, Bibliothèque Du Défap, University of Southern California.

populations, and discourses surrounding participatory governance have largely become performances deployed to attract the interests of donors (international lenders such as the IMF, or World Bank mainly).29 This leads to the phenomenon of “laissez faire” where the urban fabric of the city is dictated by its citizen.30

The city of Douala has witnessed impressive growth over the years since its founding. Before World War II, the city reached a population count of 40,000 inhabitants, a number that decreased during the war, then rose again after 1947 to 60,000 inhabitants.31 The city reached a milestone in 1954 and had a population of over 100,000. 7 years later, this number almost doubled, while the European population in the city also experienced a steady rise in parallel. This growth can partly be attributed to the Autonomous Port of Douala which reached a capacity of 1 million The city reached a milestone in 1954 and had

a population of over 100,000. 7 years later, this number almost doubled, while the European population in the city also experienced a steady rise in parallel. This growth can partly be attributed to the Autonomous Port of Douala which reached a capacity of 1 million tons by 1960 and has acted as a demographic attractor throughout the city’s history. The 1970s marked a decade characterized by major housing projects through the central government that promoted social housing and in part funded by the World Bank.34 Various state agencies were, thus, created to this effect to support planned housing areas and the restructuring of neighborhoods such as the Société Immobilière du Cameroun (SIC) in 1952, alongside the Crédit Foncier du Cameroun (CFC) in 1977 and the Mission d’Aménagement et d’Équipement des Terrains Urbains et Ruraux (MAETUR) in 1980.34

This continuous growth attributed Douala (the economic capital of Cameroon) and Yaounde (its capital city) to the roles as poles of complex financial centers at the national and international levels. The urbanization rate in Douala reached 52% in 2010, and the city itself housed 21.3% of the total population and 43.7% of the urban population.35 Eventually, with such fast-increasing urbanization, social infrastructures, accommodations as well as environmental settlements became overwhelmed with environmental degradation as a result. Despite this promising investment in public infrastructure by the new government, the rapid urbanization of the cities of Douala and Yaounde led to a crisis in the management of their urban spaces. Elvis Kah observes that most urban actors in the country are not town planners nor landscapers and the decision-makers have no basic training in the field of town planning. Indeed, if urban planning became formally established in Western countries in the 1930s.36then its application in new urban landscapes might require time to understand how these new cities function. These “urban

planners” in reality were politicians whose decisions went to satisfy politics rather than technical aspects.37 This leads to cities that do not follow specific logic and grow without preconceived plans, master development, and landscape planning. Bessengue represents one of Douala’s quarters where the struggle for remaking urban life has been most marked and often confusing.38 Bessengue is one of the city’s largest market areas, yet most of the markets in the cities of Yaounde and Douala in Cameroon exist with no pre-conceived plans, they are considered areas of insecurity, urban decay, insalubrity, and urban disorder that reflect urban poverty.39

Therefore, as Daniel Immerwhar—Professor of History at Northwestern University and author of The Politics of Architecture and Urbanism in Postcolonial Lagos— explains in the case of Lagos, Douala’s similarly rapidly urbanizing yet low-capital aspect can rightfully be assumed to be a continuation of colonial economic patterns. Such a continuation has also been encouraged by new world economic and political orders in which many African cities were thrown immediately after independence, as they were required to rapidly “modernize,” but not on their terms, but following Western standards and ideals of modernity. Many scholars, such as Immerwhar and AbdouMaliq Simone, have noticed the informal economies that have gained prominence over the years and characterized many African cities such as Douala resulting from rapid urbanization and lack of clear economic infrastructure. Contemporary Douala emerged from the relations of federated but autonomous towns.40 that were only nominally subsumed within the colonial and postcolonial logic of urban development.41 A phenomenon arises whereby the Cameroonian youth, in particular, can perform certain kinds of circulations; intersecting territories (towns) as means of substantiating local places.42 These urban residents are concerned about what kinds of games, languages, sightlines, etc can be

put in play to anticipate new alignments of social initiatives and resources.34 This show of resiliency and ability to strategically engage new forms of urban regulation primarily elaborated elsewhere leads to a kind of urban elasticity, as AbdouMaliq puts it, that provides a multiplicity of ways in and out, while at the same time, leaving cities either excessively fluid or sedentary. Thus, these “informal” economies lead to processes of ‘‘normative’’ urbanization as such activities themselves act as a platform for the creation of a very different kind of sustainable urban configuration for Cameroonian citizens. These informal economies represent how Cameroonians have attempted to negotiate with colonial cities opposed to them on their terms.

ENDNOTES

1. Simone, AbdouMaliq. For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

2. Schler, Lynn. 2002. “The Strangers of New Bell: Immigration, Community and Public Space in Colonial Douala, Cameroon, 1914–1960.” PhD diss., Stanford University.

3. Simone, AbdouMaliq. For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

4. Ibid

5. Ousmanou, Zara. “Meanings and Significance of Colonial Architecture in Douala, Cameroon.” Southampton: W I T Press, 2019.

6. Ibid

7. Ibid Schler, Lynn. 2002. “The Strangers of New Bell: Immigration, Community and Public Space in Colonial Douala, Cameroon, 1914–1960.” PhD diss., Stanford University.

8. Ibid Ousmanou, Zara. “Meanings and Significance of Colonial Architecture in Douala, Cameroon.” Southampton: W I T Press, 2019..

9. Ibid Mark, Peter. “Books -- Rives Coloniales: Architectures, De Saint-Louis a Douala Edited by Jacques Soulilou.” African Arts 28, no. 2 (Spring 1995): 18

10. Osayimwese, Ithohan. “The Colonial Origins of Modernist Prefabrication.” In Colonialism and Modern Architecture in Germany, 187-210, 225-241. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017.

11. Mark, Peter. 1995. “Books -- Rives Coloniales: Architectures, De Saint-Louis a Douala Edited by Jacques Soulilou.” African Arts 28 (2) (Spring): 18

12. Njoh, Ambe J., and Liora Bigon. “Germany and the deployment of urban planning to create, reinforce and maintain power in colonial Cameroon.” Habitat International 49 (2015): 10-20

13. Ousmanou, Zara. “Meanings and Significance of Colonial Architecture in Douala, Cameroon.” Southampton: W I T Press, 2019..

14. Simone, AbdouMaliq. “The Last Shall Be First: African Urbanities and the Larger Urban World.” In Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age, edited by Andreas Huyssen, 2008.

15. Ibid

16. Mark, Peter. “Books -- Rives Coloniales: Architectures, De Saint-Louis a Douala Edited by Jacques Soulilou.” African Arts 28, no. 2 (Spring 1995): 18

17. Ibid 18. Ibid

19. Ibid

20. Ibid

21. Ibid

22. Ibid

23. Njoh, Ambe J., and Liora Bigon. “Germany and the deployment of urban planning to create, reinforce and maintain power in colonial Cameroon.” Habitat International 49 (2015): 10-20

24. Mark, Peter. “Books -- Rives Coloniales: Architectures, De Saint-Louis a Douala Edited by Jacques Soulilou.” African Arts 28, no. 2 (Spring 1995): 18

25. Ibid

26. Simone, AbdouMaliq. “The Last Shall Be First: African Urbanities and the Larger Urban World.” In Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age, edited by Andreas Huyssen, 2008.

27. Simone, AbdouMaliq. “The Last Shall Be First: African Urbanities and the Larger Urban World.” In Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age, edited by Andreas Huyssen, 2008.

28. Simone, AbdouMaliq. “The Last Shall Be First: African Urbanities and the Larger Urban World.” In Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age, edited by Andreas Huyssen, 2008.

29. Simone, AbdouMaliq. “The Last Shall Be

First: African Urbanities and the Larger Urban World.” In Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age, edited by Andreas Huyssen, 2008.

30. Simone, AbdouMaliq. “The Last Shall Be First: African Urbanities and the Larger Urban World.” In Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age, edited by Andreas Huyssen, 2008.

31. Simone, AbdouMaliq. “The Last Shall Be First: African Urbanities and the Larger Urban World.” In Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age, edited by Andreas Huyssen, 2008.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Philippe Kame is an artist, designer, and fabricator currently pursuing a Master of Architecture degree at Taubman College. Originally from Douala, Cameroon, Philippe’s research and scholarship focuses on decoloniality and the restoration of indigenous African cultures. He is the founder of Culture Lens, a platform that aims at preserving and disseminating the traditional craft and art of Cameroon.

Setting Up Sex Offenders for Failure

How the intersection of law and city planning exposes sex offenders to longer prison sentences

MYLES ZHANG

PhD Candidate in Architecture

ABSTRACT

Our nation’s laws for sex offenders, although designed to protect the public, often have the opposite effect: increasing the chance sex offenders will be re-arrested and re-convicted for new crimes. The core of the problem is not that public safety rules, like Megan’s Law, are too weak. The problem is that these laws are written too strongly and too powerfully that they have the reverse effect: increasing the chances that sex offenders will commit new crimes. There are many problems with sex offender laws: too weak in areas they should be stronger; too strong in areas where they should be more flexible. But today I will examine just one aspect of the sex offender registry (the home address requirement) and how it affects one place (New York City). This analysis of New York City points to concrete and better ways to protect public safety than the current system: ways that reforming Megan’s Law will increase public safety.

New York’s policy requires indefinite incarceration for some indigent people judged to be sex offenders. The within-1,000-feet-of-a-school ban makes residency [...] practically impossible in New York City, where the city’s density guarantees close proximity to schools. R ather t han t ailor its policy to t he geography of New York City or provide shelter options for this group, New York has chosen to imprison people who cannot afford compliant housing past both their conditional release d ate and the expiration of their maximum sentences.

Courts, law enforcement agencies, and scholars all have acknowledged that residency restrictions do not reduce recidivism and may actually increase the risk of reoffending.”

Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor objects to sex offender registration requirements in case of Ortiz v. Breslin, February 22, 2022.1

In August 2020, as the pandemic ripped across prisons and homeless shelters, New York State struggled to find temporary accommodation for inmates being released from prison. In response, the state started renting temporary accommodation in hotels across the city, many left vacant by the pandemic-related temporary decline in tourism. A few inmates—some of them sex offenders—were placed at a hotel in the Upper West Side near Central Park, one of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods. State law requires sex offenders on parole to live 1,000 feet from the nearest school, but their hotel was just 500 feet from the playground of P.S. 87. In response, The New York Post blasted six of the offenders’ photos across the internet, along with descriptions of their offenses. One neighborhood mom told reporters at the playground of elementary school P.S. 87: “Look, we’re a progressive-minded community, and we tend to be sympathetic to the homeless. [….] But with sex offenders, [we] draw the line.”2

Our nation’s residency laws for sex offenders on parole struggle to balance two conflicting public safety needs: On the one hand, restrictions on residency and employment

keep offenders away from children. On the other hand, these same restrictions limit offenders’ successful rehabilitation as productive members of society. In a nation that has the world’s largest prison population, people incarcerated for all crimes have trouble finding housing after serving their sentences. Inmate re-entry is made even more challenging through the web of laws that restrict their ability to serve on a jury, vote, drive a car, own a home, and travel freely. In turn, housing and job insecurity are usually linked to increased risks of homelessness, mental health issues, and therefore greater chances that new crimes will be committed. In its own way, restricting former prisoners to the spatial margins of our society weakens rather than strengthens the goal of public safety.3

Sex offender laws, like Megan’s Law, are too weak in areas where they should be stronger: They need to better differentiate between violent and nonviolent offenders, and to create a meaningfully scaled parole system that surveils the offender in proportion to the offense. This will require reducing state supervision and parole requirements for sex

offenders deemed non-violent and at low risk of reoffending. Additionally, sex offender laws are too stringent in areas where they should be more flexible: Restrictions on where offenders can live increase the risk that many will become homeless, will need to turn to public welfare, or will be reincarcerated as a result of crimes committed due to housing insecurity. Examining one aspect of the sex offender registry (the home address requirement) in the context of one place (New York City) will aid in identifying the impacts on individuals leaving incarceration. This analysis of the urban form and city plan of New York City points to concrete and better ways to protect public safety than the current system: ways that reforming Megan’s Law will increase public safety.

1. DID THE CRIME, DID THE TIME... BUT STILL DOING TIME?

Jory Smith was supposed to be free. It was August 2020. He had finished his five-year sentence as a sex offender at the Marcy Correctional Facility, a medium-security prison in Upstate New York. But there was one condition for release: He had to give a new home address that met all the state’s requirements. But, because of the web of residency restrictions placed on offenders during parole, no landlord could accept his application and no place met all the requirements. Three years later—three years beyond the date his prison sentence ended— he was still in prison.4 Angel Ortiz was similarly kept locked up for two years longer than the planned date of his release, prompting a lawsuit before the U.S. Supreme Court and Justice Sotomayor. The case claimed that imprisonment beyond the date of planned release violated the constitutional rights of due process and amounted to “cruel and unusual” punishment. As Sotomayor clarified, “New York’s residential prohibition, as applied to New York City, raises serious constitutional

concerns.” She specifically singled out flawed residency requirements that make it impossible for sex offenders to find housing in dense urban areas, as well as a series of no fewer than a dozen studies indicating that residency restrictions had no effect on reducing crimes against children.5

Approximately eight percent of sex offenders are kept locked in prison after the end of their prison sentences because they are required to find housing as a precondition of release, but fail to secure housing due to severe restrictions on where they can live.6 Residency and job requirements are two of the biggest reasons many offenders are locked up for longer than their initial sentence. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (updated in 1995, commonly referred to as Megan’s Law) is a federal law that requires each state to create a public database of sex offenders.7 Their names, birth dates, ages, photos, convictions, home addresses, and all manner of other personal information are public information. The goal of this statute is to inform the public—particularly teachers and concerned parents—of any sex offenders in their neighborhood and to help them identify these people to keep their children away from them. The results are cataloged in a database for every state, including New York State.8 Other commercial websites have further synthesized state data into interactive maps of sex offenders in New York City and other American cities.9

Megan’s Law, a federal statute, only required offenders to give their home addresses and other personal details for purposes of publication. The New York state-level Sex Offender Registration Act (SORA), implemented in 1995, additionally barred offenders on parole from living within 1,000 feet of a school or place that children frequent. This law is mirrored in similar language and residency requirements in most other states. For most released inmates (convicted of all

kinds of crimes), the parole period lasts one to four years and rarely more than five years.10 During this time, they must register their address with law enforcement and must check in regularly with a parole officer. However, for sex offenders, the length of time they spend under supervision is longer.11 For level one sex offenders considered at “low” risk of reoffense, the registration period—during which they must share name and home address—is 20 years. For level two offenders at “moderate” risk and level three offenders deemed to have a “high” risk of reoffense, registration with permanent residency restrictions is in place for life. The specific type of crime does not determine the category of whether an offender is deemed to be level one, two, or three, nor does the judge determine this at time of conviction. Instead, a governor-appointed board of examiners determines the risk level, with career-altering and life-altering results depending on the board’s ruling.12

In addition to spatial restrictions, when reviewing applications, landlords and job recruiters can reject an applicant because of their criminal record. For non-violent offenders at low risk of reoffense, making their personal information public likely harms them more and exposes them to employment discrimination than reasonably benefits public safety. For instance, many jobs have zero interaction with minors, such as Amazon warehouse, auto assembly line, construction, finance, and bank teller positions. They are precisely the kinds of jobs where a criminal record as a sex offender is irrelevant to their ability to perform the job. Sex offender laws reason that even after release, offenders pose a continued risk to society and require continued monitoring. For usually more violent level two and three offenders, parole boards might justify their continued supervision and continued, likely lifelong, suspension of certain rights to privacy. But for non-violent level one offenders with low to non-existent recidivism, the case is strong that

posting their details to the registry will expose them to employment discrimination.13

In New York State alone, since the 1990s, dozens of separate amendments to SORA have added additional restrictions and reporting requirements beyond the requirements of Megan’s Law.14 Other more severe amendments have been proposed but failed. One bill proposed doubling parole from 10 to 20 years; another proposed registration for life for all offenders, regardless of the original crime. Another proposed restricting all level three sex offenders from coming within 1,000 feet of a school bus stop.15 Some proposals are unlikely to become reality, but they reflect the degrees of residential exclusion that lawmakers are willing to promote, despite limited studies following up on these laws to measure their effectiveness.

However, New York’s state-level laws are less strict than those of other states. In Florida, sex offenders cannot go to playgrounds, public parks, shopping malls, and – in effect – any place where there might be any number of children. Florida’s registry laws are the strictest in the nation.16 In other states, entire prison psychiatric hospitals have been built to involuntarily detain inmates for months and years beyond the end of their prison sentence.17 The largest of these facilities is the Coalinga State Hospital in California, where up to 1,286 inmates can be detained after their sentences. A quarter reside at the Coalinga hospital because a court and/or doctor has determined they have a mental health disorder that requires constant supervision. The remaining three-fourths are there either as “sexually violent predators,” or because they have not yet met the state’s housing and employment prerequisites to leave prison.18 Most inmates cannot find housing even after finishing treatment, attending therapy, and committing to chemical castration for life – as both requirements of the treatment program and as ways to convince hospital

administrators they are no longer a risk. Other inmates reject participating in the treatment program altogether because even if they successfully complete it, they will not find a job and housing on the outside.19

2. HOW MUCH ARE SEX OFFENDERS ON THE REGISTRY AN ACTUAL RISK TO PUBLIC SAFETY?

What is the recidivism rate among the population formerly incarcerated for all crimes? There are few national studies about the recidivism rate among offenders; one of the most comprehensive is dated 1994, the same year Megan’s Law was implemented.20 This 1994 study had a sample size of 300,000 people from 15 states, convicted for all types of crimes — 67.5 percent of individuals released from prison were rearrested within three years of release. Of this sample, 51.8 percent returned to prison. However, there are many reasons they return to prison. About half of those who return to prison (25.4 percent of those released) do so because they have committed a new crime. The other half of those who return to prison (26.4 percent of those released) return for a nonviolent and technical violation of their parole.21 These types of violations include failing a drug test, missing an appointment with a parole officer, failing to register a change of address, driving without a license, and other questionable reasons to re-incarcerate people. The data also reveals that released prisoners with the lowest rearrest rates were those in prison for homicide (40.7%), rape (46.0%), driving under the influence (51.5%), and sexual crimes not including rape (41.4%).22

What is the recidivism rate among sex offenders? Another 1994 study of approximately 10,000 sex offenders revealed that 3.5 percent were re-convicted for a sex crime within three years—approximately 1

in 25 people.23 Of this same sample size, 24 percent were reconvicted for a crime of any kind during the follow-up period, or about one in four people.24 In comparison, released prisoners with the highest rearrest rates are those originally convicted of robbery (70.2%), burglary (74.0%), larceny (74.6%), motor vehicle theft, (78.8%), having or selling stolen property (77.4%), and having, selling, or using illegal weapons (70.2%). This refutes the claim that sex offenders will inevitably re-offend and must therefore be monitored for life; 3.5 percent is a uniquely low recidivism rate. Both 1994 studies of sex offenders and all released offenders capture a snapshot of the low recidivism rate before Megan’s Law was introduced. If measured by the data on recidivism, Megan’s Law in 1995 and New York’s SORA in 1995 were introduced in a period of low recidivism among sex offenders, despite public assertions at the time that recidivism was rising and that sex offenders would inevitably and unavoidably re-offend.25

The strongest argument in favor of Megan’s Law and SORA is that they provide public information on people who have committed crimes, and who are therefore perceived as likely to commit more crimes in the future. However, if the measured recidivism rate of sex offenders is used to justify the registration requirement, by that logic, other crimes with higher recidivism rates should mandate registration on a public registry. If those convicted for other violent crimes with a higher rate of re-offense are not made to live out the rest of their lives on a public registry, then the utility of the sex offender registry becomes questionable in light of the lower recidivism rate.26

Megan’s Law and a sweep of other “tough on crime” policies emerged during the 1990s War on Drugs and War on Crime amid growing (but largely unfounded) fears of unremorseful juvenile “superpredators.”

Prominent sociologists and criminologists like

John DiLulio claimed a growing population of “superpredators” could murder, rape, and abuse victims without remorse.27 Cases like the 1989 Central Park Five jogger case28 and the 1992 L.A. Riots29 focused national attention on a group of offenders that represented a statistical minority, leading to policy solutions such as the 1995 “three strikes law” in California. Similar to Megan’s Law, the “three strikes law” was driven by media reports of serial offenders; California lawmakers believed that only the harsh sentence of life in prison would be an effective deterrent. Similar to Megan’s Law which provided blanket punishments to violent and non-violent

offenders alike, the “three strikes law” did not distinguish between minor and major felonies, meaning that a three-time serial kidnapper would receive the same life-in-prison sentence as the serial thief caught for stealing from the convenience store. At the same time, the 1990s rise of a “meth epidemic” on urban streets fed into the nationwide perception that highly visible (but statistically minor) events of urban disorder like the 1992 L.A. Riots required sweeping new laws.30 Somewhere between fact and fiction, between a time of declining crime rates and rising media reporting on crimes, these policies emerged amid public pressure for politicians to do something, to do

Figure 1. The area in red represents spaces where sex offenders on parole are restricted from living, a 1,000-foot radius from any school.37

Source: “New York State’s Residency Requirements,” Myles Zhang Digital Portfolio, November 9, 2023

Note: Explore as interactive map at https://www.myleszhang.org/2023/11/09/pedophilia-and-public-space/.

Figure 2. A 1,000-foot radius drawn around the locations of schools in Midtown Manhattan. Sex offenders can live in the non-red areas, which tend to be non-residential areas closer to factories, highways, and sources of pollution.

anything. Thus, fears of an imagined minority of superpredators drove policies that, while written with these predators in mind, affected all classes of offenders and society at large. This resulted in both prison overcrowding and larger-than-predicted prison populations in a carceral state that is now the world’s largest.31

3. HOW MUCH DO RESIDENCY REQUIREMENTS RESTRICT HOUSING OPTIONS IN NEW YORK CITY?

The 1,000-foot residency restrictions in New York state law are more actionable in suburban areas than in urban areas. The law thus significantly restricts housing choices for sex offenders in urban areas. NYC Open Data indicates that there are 1,700 public school

facilities in the city, while the census estimates that there are 3,644,000 housing units in the city.32 Downloading the point locations of schools and drawing the 1,000-foot radius around each removes upwards of 95 percent of units from the market. Figure 1 shows the radius around each school and identifies the housing stock where offenders on parole are barred from living. This leaves the areas between red circles as the only places where they can lawfully live in New York City: fewer than 100,000 units. The actual map is likely even more restrictive than is shown below because the database of school locations does not include private schools and daycares.33

When considering the apartment vacancy rate in New York City is just three percent, the actual number of units available at any one time is likely fewer than 3,000. When

considering that half of New York City apartments rent for more than $1,800 per month, the actual number of eligible units at any one time falls to just several hundred. For a city with millions of housing units to exclude offenders from all but several hundred units available to rent at any given time speaks to the serious challenges of societal reintegration.34

The Urban Institute states, additionally, that 90 percent of landlords check for previous evictions, credit history, and criminal background when making their decisions.35 The combination of state laws (that restrict where offenders can live) and private choices from landlords (who can choose their tenants) result in a uniquely difficult housing market for released offenders. The housing shortage is the result of public policies and private choices. In a society that stigmatizes all former inmates—sex offenders and non-

offenders alike—finding housing becomes a uniquely difficult challenge. In its own way, housing insecurity can become a self-fulfilling prophecy for re-offense: People are more likely to be arrested for crimes like loitering, trespassing, and petty theft when experiencing housing insecurity and homelessness. Stigmatizing sex offenders to the degree they become homeless therefore increases the chances they will be rearrested.36

The exact unemployment rate among sex offenders is unclear, but an estimated 60 percent of sex offenders remain unemployed three to five years after leaving prison.38 Data on median income for sex offenders after release is not available, but the jobs they are more likely to hold pay minimum wage with limited benefits. At $16 an hour in 2024, New York City’s minimum wage works out to an annual income of $32,000 a year before taxes.39

Source: Google Maps

Figure 4. As a comparison, assume the metal block M on the University of Michigan Diag were a single building measuring ten feet square to a side. The exclusion zone would cover almost all of Central Campus. Counting the building perimeter of Central Campus as a single school zone, the exclusion zone would cover most of Downtown Ann Arbor.

Source: Google Maps

This would be well within the minimum income threshold required to be eligible for public housing — however, the New York City Housing Authority states on its rental application FAQ, “A lifetime registration [as a sex offender] results in a lifetime ban from public housing.”40

4. WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Current policy means that offenders released from prison have limited options. It would aid offenders in rehabilitation and return to society if current laws were reformed in at least these four ways:

First, reduce the residency requirement from 1,000 feet to 500 feet, or to an amount proportional to population density, in urban

areas. New York state law has historically struggled to balance the needs of low-density rural residents Upstate with the needs of mid-density suburban residents on Long Island and the needs of high-density urban residents in New York City. The 1,000-foot requirement is largely – and reasonably –written with rural and suburban communities in mind. Drawing a 1,000-foot radius around a suburban or rural school excludes offenders from a small number of houses near schools, due to the lower density of the community. For Upstate New York, the 1,000-foot radius excludes an estimated 19 housing units over an area one-ninth of a square mile in size.41 Therefore, there are likely to be fewer neighbors within a 1,000-foot radius of a given property in the suburbs. This suburban form also has high homeownership rates, creating a relatively fixed and less transient community where neighbors watch neighbors. While the

homeownership rate in New York City is just 33 percent, the homeownership rate is 70 percent in the rest of New York State (not counting the city) and 63 percent nationally.42

By contrast, drawing the identical 1,000-foot radius around any New York City property excludes about 1,400 units on average.43 Applying the 1,000-foot radius to Manhattan’s population density of 75,000 people per square mile excludes a still higher 4,300 housing units.44 Given the already highly transient population of New York City renters, the frequently used public transit network, and the millions of commuters passing through urban areas, the public safety benefits of excluding sex offenders from living within a 1,000-foot radius are debatable. For example, knowing from a public database that a sex offender lives five blocks away is of limited public benefit when there are some 10,000 neighbors or 10,000 possible suspects within 1,000 feet. In this way, the harm of this restriction in reducing housing options for offenders is likely much greater than the public benefit of this restriction.

Thousands of prisoners remain behind bars after serving their sentences, for the simple reason that they cannot find housing that meets parole residency restrictions. This is a burden on public funds and is of questionable benefit to public safety. There is no study or estimate of how much the state spends annually on keeping these offenders behind bars. But, for reference, the annual cost of operating the Coalinga State Hospital—effectively a “shadow prison”—was $298 million in 2019, or $218,000 per inmate. A good portion of Coalinga inmates have been involuntarily committed because of an incurable mental illness, but three-fourths are sex offenders unable to find housing and a job on the outside, which is a precondition of their release. In a society where sex offenders have some of the lowest rearrest rates of any group, Coalinga operates a very expensive

form of preventative detention. California’s five prison hospitals like Coalinga cost more to operate annually than the entire budget for all other prisons in the state.45 The per-inmate cost is particularly expensive due to a ratio of approximately one staff member to every inmate, permanent living facilities (including a bedroom and en suite bathroom provided to each inmate), and a range of efforts to make their involuntary commitment feel more like a hospital than a prison. They are not in a prison, by the legal definition; however, they are in a hospital with barred windows, in a rural location in the Central Valley surrounded by barbed wire.46

Second, instead of cost-prohibitive prisons and prison hospitals for sex offenders, there might be more effective and cheaper—but largely untried—programs that allow sex offenders on parole to live in supervised conditions with their parents, relatives, or other legal guardians. Inmates released to their families have lower rates of rearrest, higher rates of employment, and lower rates of homelessness.47 Under the current arrangement, however, if the parents and relatives live less than 1,000 feet from a school, then the offender cannot live with them, even if these relatives have a spare bedroom and will legally vouch that the offender will not be a public safety threat. This was the crux of the issue presented to Justice Sotomayor: Offender Angel Ortiz had already served his sentence, was eligible for release, and had offers from his mother and sister to live with them, but he was unable to because their home was too close to a school. Innovative legislation could be written that makes these family members the legal guarantors of the sex offender and held legally responsible if the offender under their care commits a new crime at the nearest public school.

Third, give parole officers more discretion and freedom to choose where offenders can live. The blanket 1,000-foot requirement

excludes from the housing supply many units that are otherwise entirely safe for offenders to live in. For instance, say that an apartment is 200 feet from a school, but is separated by a river or six-lane highway that requires a half-mile walk to get around. By strict legal interpretation of the law, this apartment is off-limits. But any parole officer and social worker given discretion and the power to interpret laws would approve the offender to live here. Giving more room to these state employees will allow them to interpret the law based on the wealth of factors shaping the built environment. The built environment is more complex than the law alone can legislate and describe in 1,000 feet. Well-written laws are flexible enough that they empower administrators and expert social workers to use their best judgment.

Lastly, we need new, updated, and reformed laws in line with the pace of technological change. In a world that is transitioning from the physical and urban to the digital and virtual, data-driven reforms to Megan’s Law are needed. Megan’s Law and the residency restrictions on sex offenders were largely written in a pre-internet age when the only way to commit crimes was through spatial proximity to victims. Therefore, a law presenting a spatial limit on residence near schools made the most sense for separating offenders from children. Today, there is a virtual world that is not bounded by space; the opportunity for offenders to contact victims extends beyond a physical limit of 1,000 feet and into the virtual world. This points to the need for continued restrictions on how sex offenders use the internet, and a shift in policing resources away from physical and towards digital spaces. Megan’s Law was written for a world without the internet. The proposed reforms are less about leniency toward sex offenders and more about creating more effective restrictions that are driven by data instead of superstition.

Additionally, in a system where inmates are released to society but in which their housing options are limited to certain neighborhoods with a lack of proximity to public schools, the result is the spatial concentration of risk in those neighborhoods—specifically low-income neighborhoods, which are also more likely to have a majority of minority populations. In the current system, majority-Black neighborhoods, which tend to have less spatial mobility and fewer school options, are already more likely to have lower rents compatible with what sex offenders can afford. Spatial racism constitutes the effect of intersecting inequalities in the built environment, where the same risks are concentrated and reconcentrated in neighborhoods that are least able to offer resistance.48 The New York Post complains about sex offenders living on the wealthy Upper West Side and quotes upperclass mothers to support their complaints. Low-income residents and residents in majority-immigrant neighborhoods might also have opposition to living near sex offenders, but rarely are their opinions given the time and visual real estate on the pages of The New York Post

Moral outrages and moral panics at avoidable crimes often motivate overdue legal reforms. Megan’s Law has the valid, noble intention of providing information to protect children from danger. Seven-year-old Megan Kanka was murdered by an offender living next door, with a criminal history unknown to his neighbors. The fortunate reality is that superpredators are exceptionally rare. The concept originated largely from the 1990s public misperception of rising crime rates. The resulting fears motivated multiple public policy reforms, including the 1,000-foot requirement. This realization points to the need for flexibility in punishment: a set of data-driven laws that recognize the large majority of people who become safe and productive members of society after release, with set-asides that allow the judge to impose harsher

sentences on the truly evil. The problem is when highly publicized media reporting on sensational crimes by a few leads to the public perception that freak criminal incidents are commonplace and require a stronger and more punitive police response than is merited.

Activist calls since George Floyd to “defund the police and prisons” suggest that funds now spent on incarceration would be better invested in communities and communitybased health and counseling programs that aid victims of both sex crimes and domestic abuse. There is currently no direct mechanism to take surplus funds from prison budgets and allocate those funds to victim compensation. However, the conversation about the most appropriate allocation of funds starts by chipping away at the cost of running prisons through clemency programs and reforming broken residency restrictions that are not backed by the data on recidivism.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to dissertation advisers Dan O’Flaherty for his research on homelessness and Mary Gallagher for her advice on case law. This essay was originally written for Heather Ann Thompson’s fall 2023 PhD seminar on The American Carceral State. Most of all, thank you to editor Jessie Williams for her patient and insightful line edits.

ENDNOTES

1. Angel Ortiz v. Dennis Breslin, Superintendent, Queensboro Correctional Facility, et al. on Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of New York, 142 S. Ct. 914, 23-29 (2022), https://www.supremecourt.gov/orders/ courtorders/022222zor_bq7d.pdf.

2. Nolan Hicks, Jennifer Gould, and Laura Italiano, “NYC ‘illegally’ placed pedophiles near Upper West Side playground,” New York Post,

August 7, 2020,

https://nypost.com/2020/08/07/nyc-illegallyhousing-pedophiles-near-upper-west-sideplayground/.

3. Stephanie Robbins, “Homelessness among Sex Offenders: A Case for Restricted Sex Offender Registration and Notification,” Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review 20, 2010.

4. Colin Kalmbacher, “Sotomayor Says ‘Courts Must Step In’ to Protect Constitutional Rights, Urges N.Y. to End Policy of ‘Indefinite Incarceration’ for Sex Offenders Who Served Their Time,” Law & Crime, February 22, 2022

https://lawandcrime.com/supreme-court/ sotomayor-says-courts-must-step-in-to-protectconstitutional-rights-urges-n-y-to-end-policyof-indefinite-incarceration-for-sex-offenderswho-served-their-time/.

5. Angel Ortiz v. Dennis Breslin, Superintendent, Queensboro Correctional Facility, et al. on Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of New York, 142 S. Ct. 914, 23-29 (2022), https://www.supremecourt.gov/orders/ courtorders/022222zor_bq7d.pdf.

6. Chris Gelardi, “They Were Supposed to Be Free. Why Are They Locked Up? New York has kept hundreds of people convicted of sex offenses in prison long past their release dates,” New York Focus: Who Runs New York?, October 17, 2023, https://nysfocus. com/2023/10/17/sex-offender-sara-prisonparole-new-york.

7. Megan’s Law, Pub.L. 104-145, 110 Stat. 1345 (1995).

8. “Sex Offender Registry, New York State Division of Criminal Justices Services, https://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/ SomsSUBDirectory/search_index.jsp.

9. “Registered sex offenders in New York, New York [database],” City-Data.com, https://www. city-data.com/so/so-New-York-New-York.html.

10. Sex Offender Registration Act, 1995 N.Y. ALS 192, § 168-1 (2019), https://www.criminaljustice.

ny.gov/nsor/claws.htm#a.

11. Dean G. Skelos, “Strengthening Megan’s Law,” N.Y. State Senate Newsroom, 2006, https://www. nysenate.gov/newsroom/articles/dean-g-skelos/ strengthening-megans-law.

12. What determines the risk assessment as level one, two, or three?

It is less the crime that determines the risk assessment and more the behavior of the individual during the time they are in custody. Two individuals could both be convicted of the identical sex crime, but one would get a level one designation on release and the other a level three, if during the time he was in prison, the latter was poorly behaved and exhibited traits indicating mental illness. The law does not specifically define what behavior amounts to a “sexually violent predator” but instead leaves this choice up to the discretion of the parole board.

13. “Time to Work: Managing the Employment of Sex Offenders Under Community Supervision,” U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Justice Programs, Center for Sex Offender Management, January 2002, https://www. govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-J-PURLgpo105645/pdf/GOVPUB-J-PURL-gpo105645.pdf.

14. “Nowhere To Go: New York’s Housing Policy for Individuals on the Sex Offender Registry and Recommendations For Change,” The Fortune Society: Building Poeple, Not Prisons, May 2019, https://fortunesociety.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/05/NowhereToGo.pdf.

15. N.Y. State Senate Codes Committee, “Prohibits certain sex offenders from entering a school bus or within one thousand feet of a school bus stop,” Senate Bill S5433, 202324 Legislative Session, referred to Codes Committee January 3, 2023, https://www. nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S5433.

16. Jill S. Levenson and Leo P. Cotter, “The Impact of Sex Offender Residence Restrictions: 1,000 Feet From Danger or One Step From Absurd?” International Journal

of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 49:2, 2005, 168-178, https://doi. org/10.1177/0306624X04271304.

17. David Feige (director), Rebecca Richman Cohen (producer), and Adam Pogoff (coproducer), Untouchable, released 2016, 1 hour, 45 minutes, http://www.untouchablefilm.com/ about-the-film/.

18. “Department of State Hospitals – Coalinga,” California Department of State Hospitals, November 7, 2016, https://www.dsh.ca.gov/ Coalinga/.

19. Louis Theroux (writer) and Emma Cooper (director), Law and Disorder Series, Season 1, Episode 3, “A Place for Paedophiles,” aired 19 April 2009, British Broadcasting Corporation, https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6baa33.

20. Patrick A. Langan and David J. Levin, “Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994” Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, June 2002, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/rpr94. pdf.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Roger Przybylski (author) and Luis C.deBaca (editor), “Chapter 5: Adult Sex Offender Recidivism,” in Sex Offender Management Assessment and Planning Initiative, (Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, 2015), https://smart.ojp.gov/somapi/chapter-5adult-sex-offender-recidivism.

25. Hal Arkowitz and Scott O. Lilienfeld, “Once a Sex Offender, Always a Sex Offender? Maybe not: The popular perception of incurable sex criminals may be quite off the mark,” Scientific American, April 1, 2008, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ misunderstood-crimes/.

26. Patrick A. Langan and David J. Levin, “Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994” Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, June 2002, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/rpr94.

pdf.

27. John DiLulio, “The Coming of the SuperPredators,” Washington Examiner, November 27, 1995, https://www.washingtonexaminer. com/?p=1558817.

28. The Central Park jogger case was a highprofile criminal case. The night-time assault and rape of Trisha Meili in Central Park led to the wrongful conviction of six teenagers. In a case of racial profiling and media storm, the case fed into public perceptions of New York City’s perceived lawlessness and criminal behavior by superpredator teenagers. Over the next 20 years, all those wrongfully convicted were exonerated based on new evidence and admissions by prosecutors to wrongful conviction. The case, in its time, symbolized the struggles and public hysteria motivating the 1990s War on Crime.

29. The 1992 Los Angeles Riots (also known as the Los Angeles Uprising) were a series of riots and civil unrest in Los Angeles County in April and May of 1992. The acquittal of four police officers for the wrongful arrest and beating of Rodney King caused mass public anger. The response was widespread looting and arson, resulting in 63 deaths and thousands of injuries. The event symbolized, for its time, both racial tension and public perceptions that urban disorder required both a powerful police presence and new “tough on crime” laws.

30. Matthew D. Lassiter, “Introduction,” in The Suburban Crisis: White America and the War on Drugs (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023).

31. Ibid.

32. Department of Education, “School Point Locations,” NYC Open Data, April 24, 2019, https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Education/ School-Point-Locations/jfju-ynrr/about_data.

33. “Nowhere To Go: New York’s Housing Policy for Individuals on the Sex Offender Registry and Recommendations For Change,” The

Fortune Society: Building Poeple, Not Prisons, May 2019, https://fortunesociety.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/05/NowhereToGo.pdf.

34. Vacancy rate and median rent for New York City in 2023 were calculated from the U.S. Census, as pulled from the database Social Explorer and analyzed in QGIS. Assuming a vacancy rate of three percent, then three percent of 100,000 units is 3,000.

35. Abby Boshart, “How Tenant Screening Services Disproportionately Exclude Renters of Color from Housing,” Housing Matters: An Urban Institute Initiative, December 21, 2022,

https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/howtenant-screening-services-disproportionatelyexclude-renters-color-housing.

36. Brendan O’Flaherty, “How to Think about Housing Markets,” in Making Room: The Economics of Homelessness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996), pp. 96-127.

37. Explore as interactive map: “New York State’s Residency Requirements,” Myles Zhang Digital Portfolio, November 9, 2023, https:// www.myleszhang.org/2023/11/09/pedophiliaand-public-space/.

38. James L. Johnson, “Sex Offenders on Federal Community Supervision: Factors that Influence Revocation,” Federal Probation: a journal of correctional philosophy and practice, 70:1, June 2006, https://www.uscourts. gov/federal-probation-journal/2006/06/sexoffenders-federal-community-supervisionfactors-influence.

39. “New York’s Minimum Wage Overview,” New York State: Department of Labor, as of January 1, 2024, https://dol.ny.gov/minimum-wage-0.