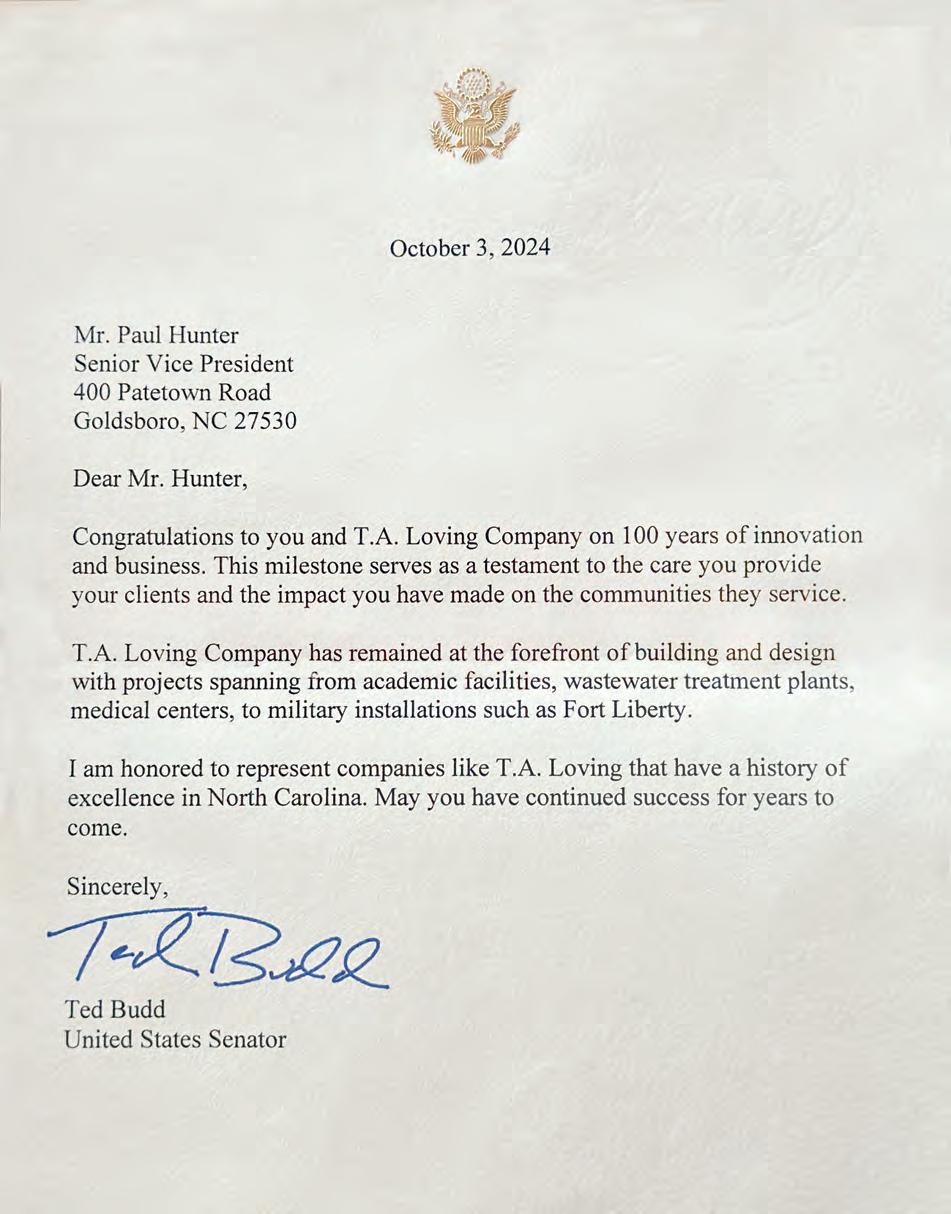

1925-2025

A CENTENNIAL SALUTE

1925-2025

A CENTENNIAL SALUTE

Centennial Celebration Book

1925 – 2025

400 Patetown Road, Goldsboro, NC 27530

919-734-8400

www.taloving.com

Sam Hunter, Chairman

Steve Bryan, Vice Chairman

Ty Edmondson, CEO

David Philyaw, President, Building Group

Charlie Fuller, President, Civil Infrastructure

Jason Hill, President, Conveyance Systems

David Philyaw and Paul Hunter, Centennial Book Committee

Book Design/Production: Sue Pace, Chapel Hill, N.C.

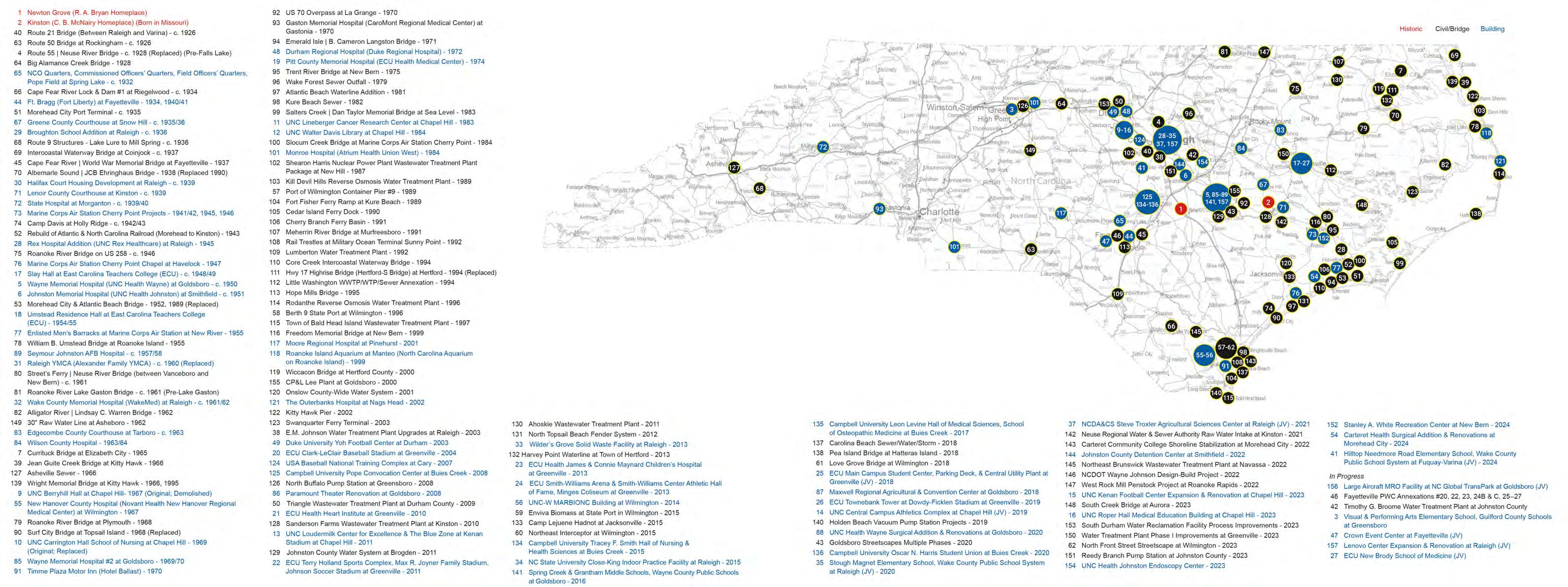

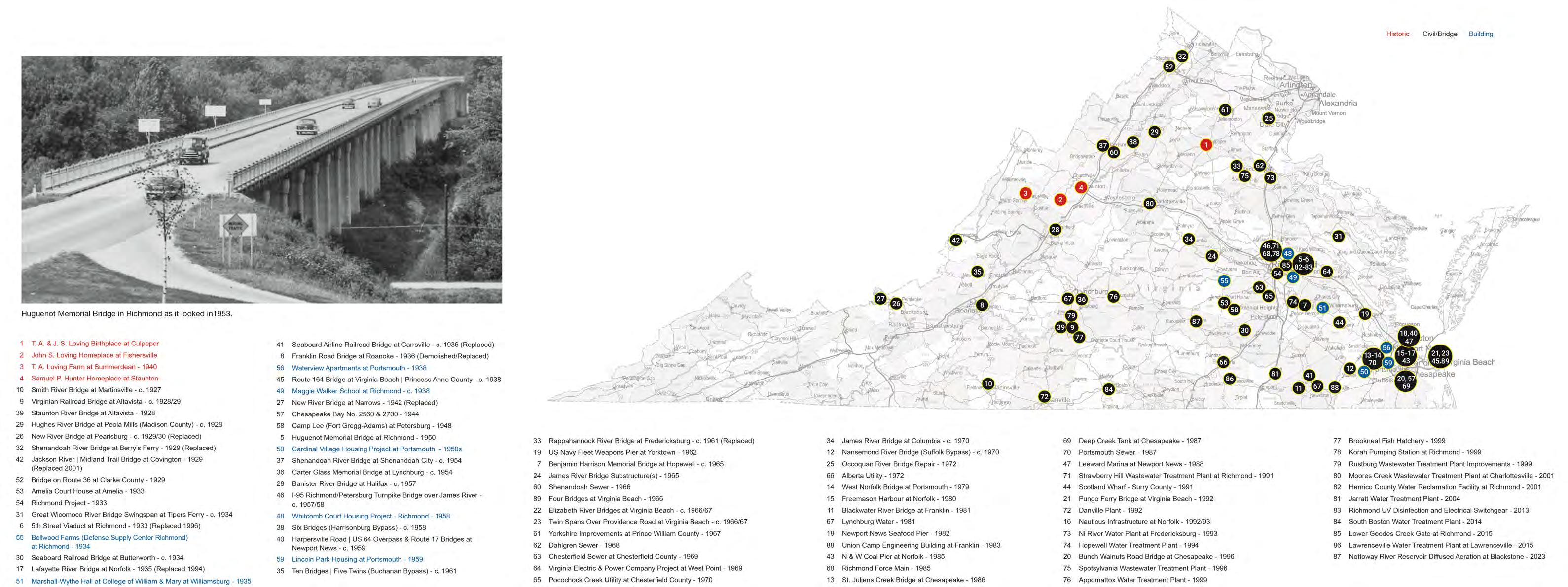

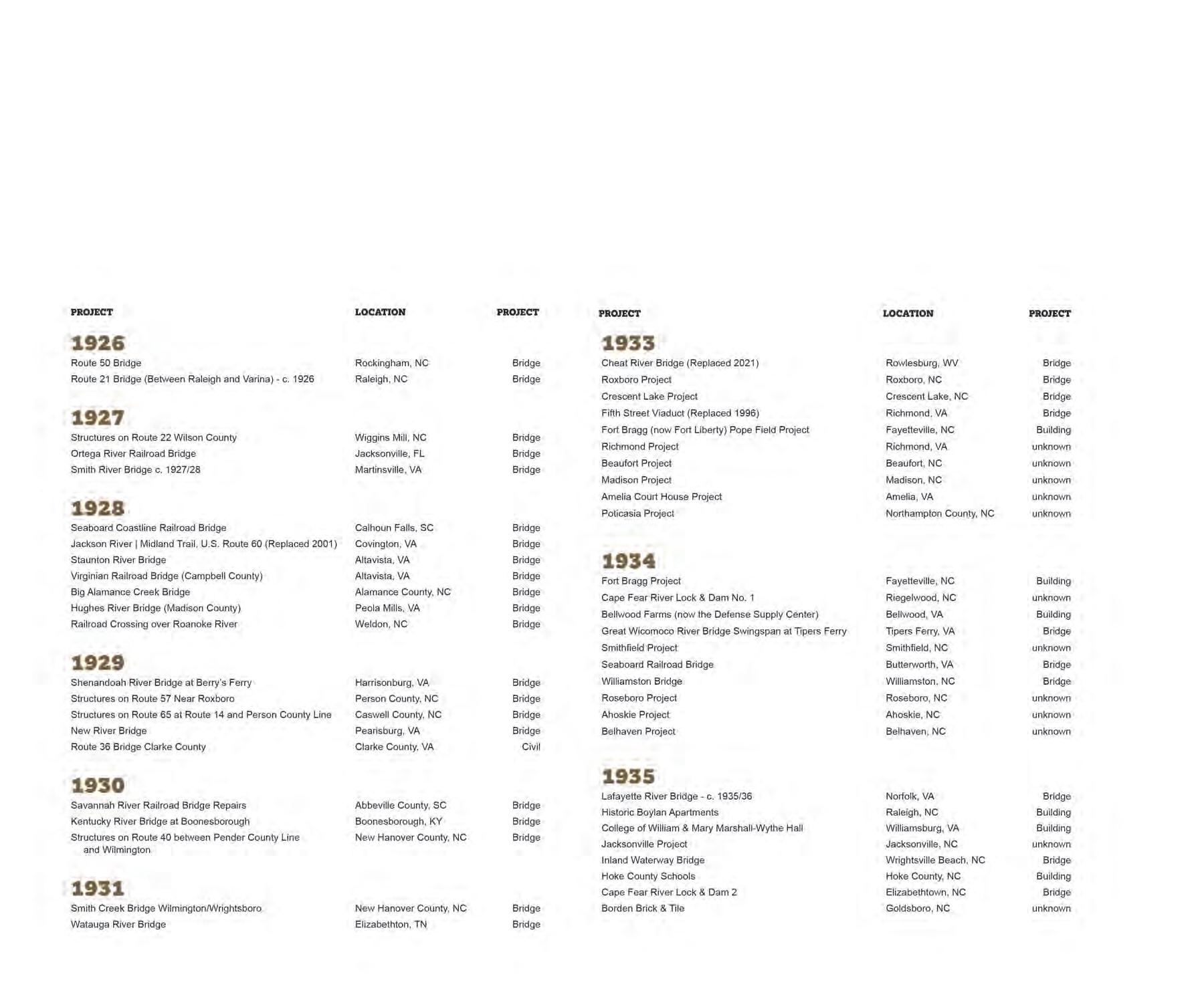

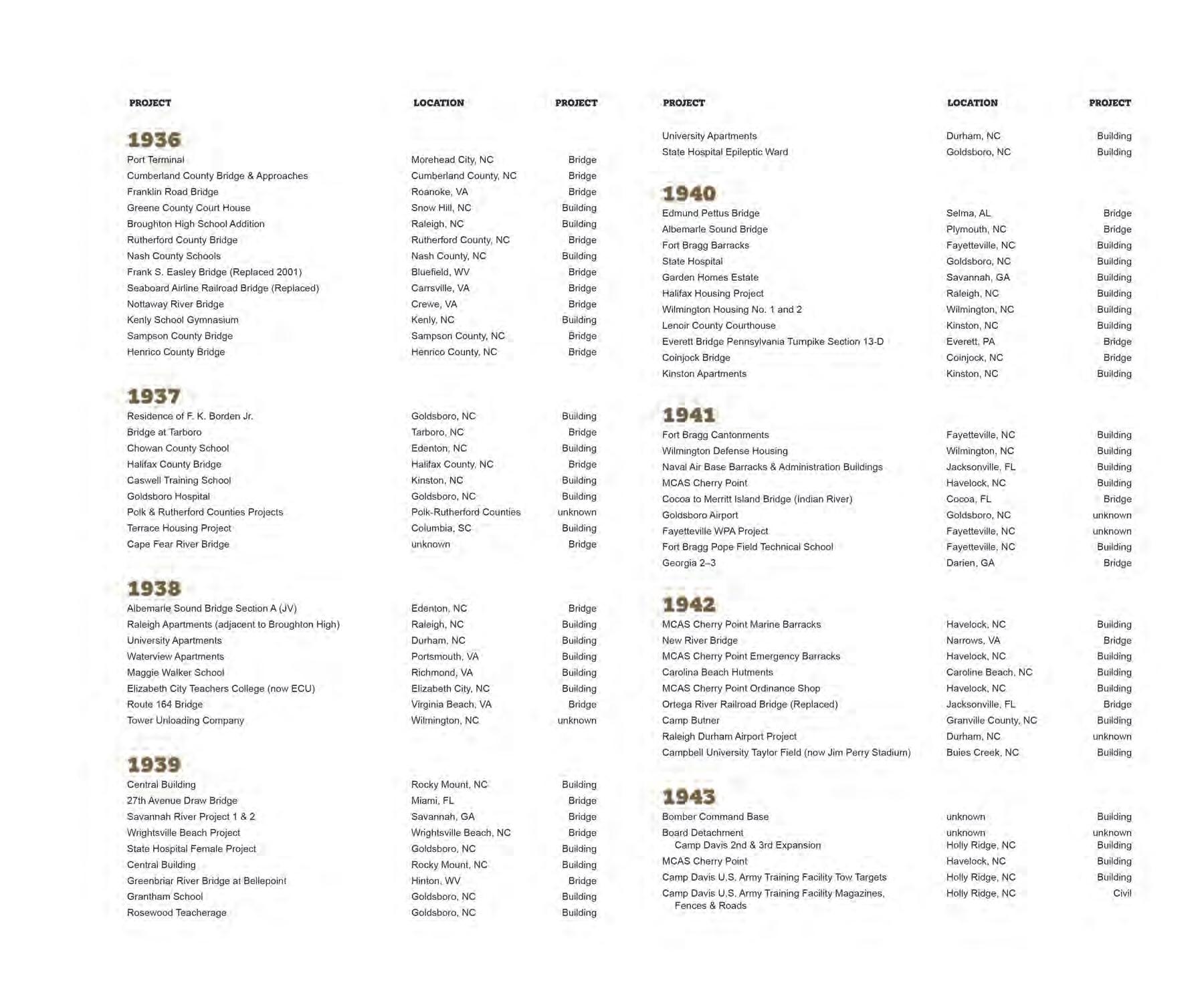

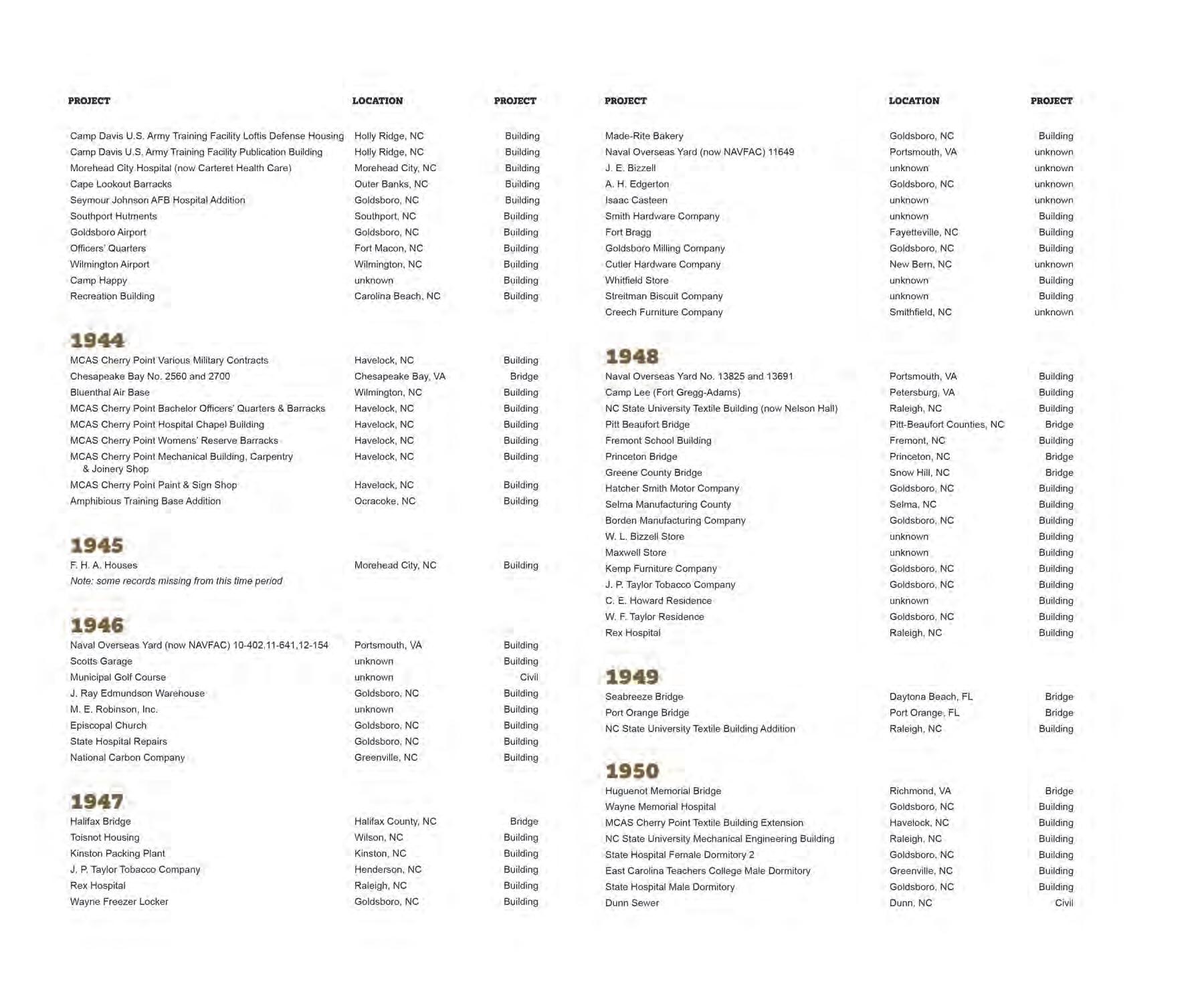

Maps & Projects Lists Production: Cat Bruvtan, Marketing Manager, T.A. Loving Co.

Photography / Acknowledgements

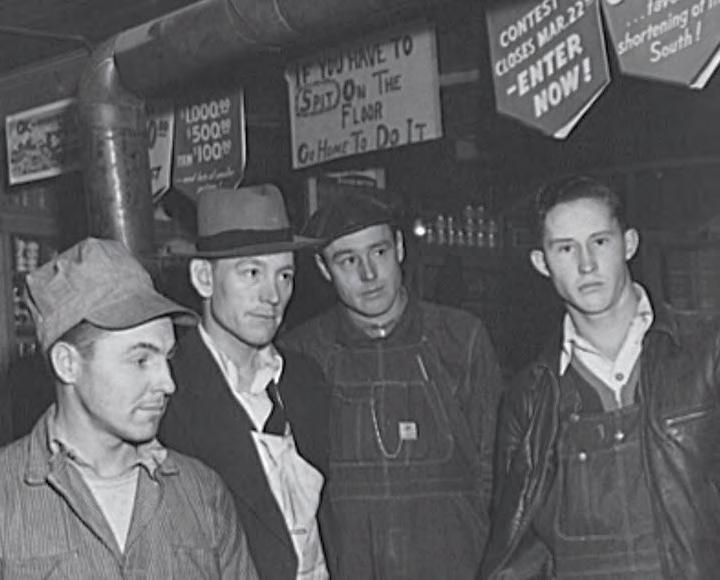

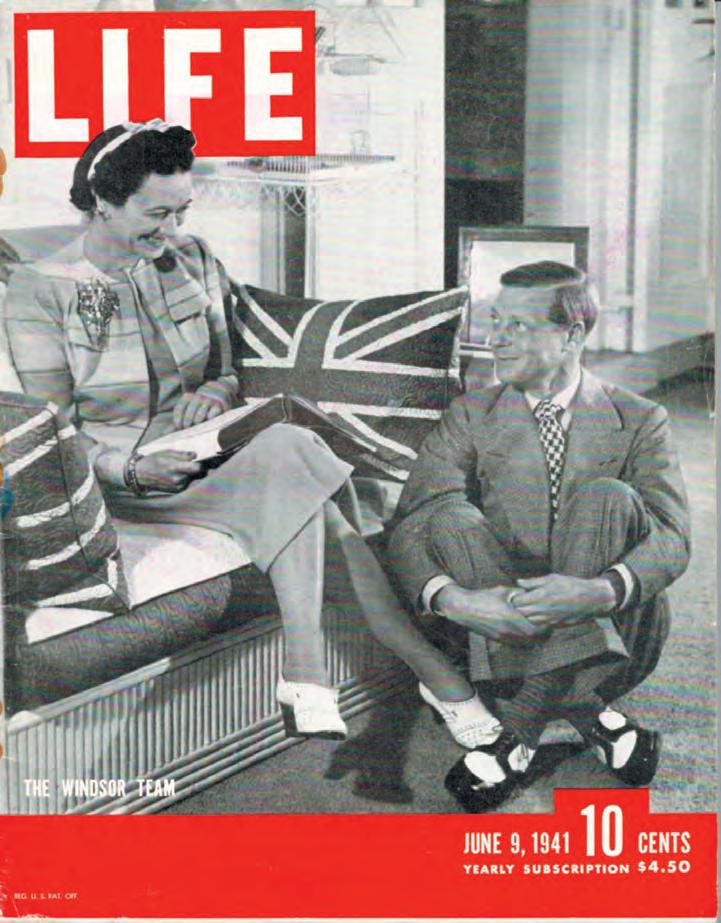

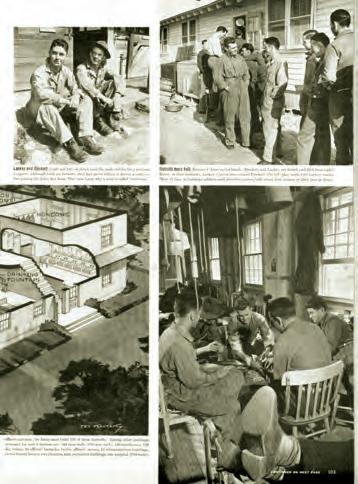

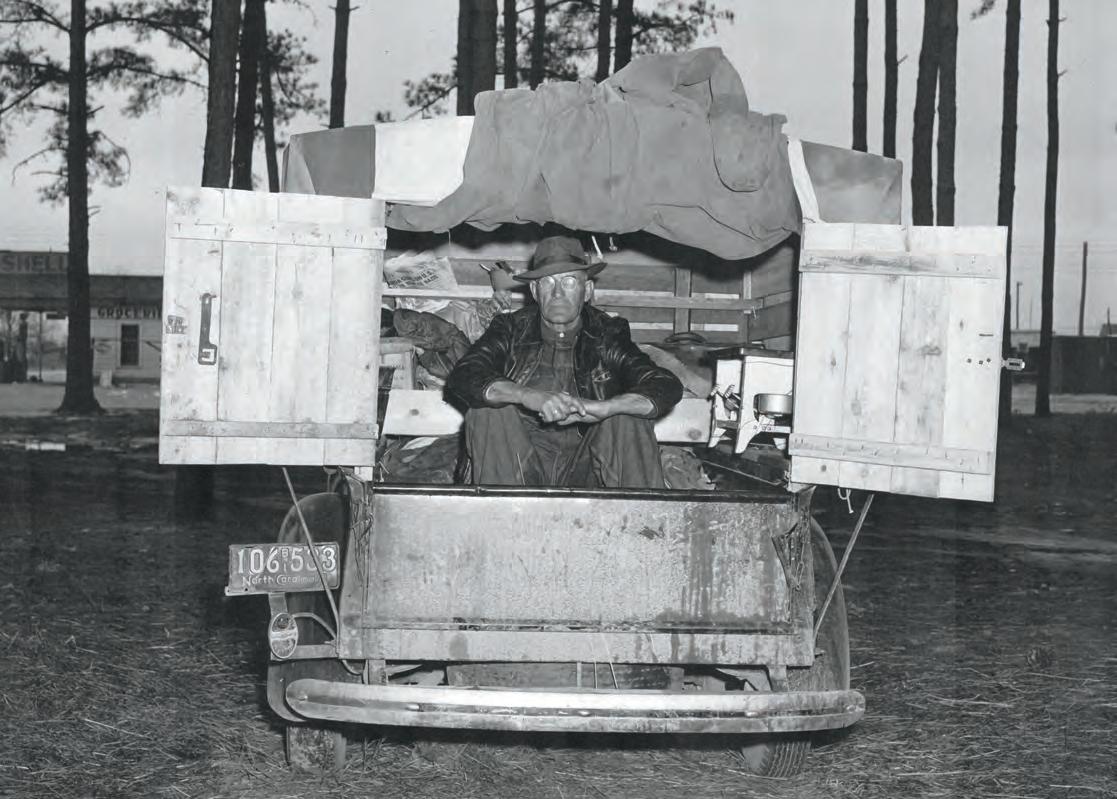

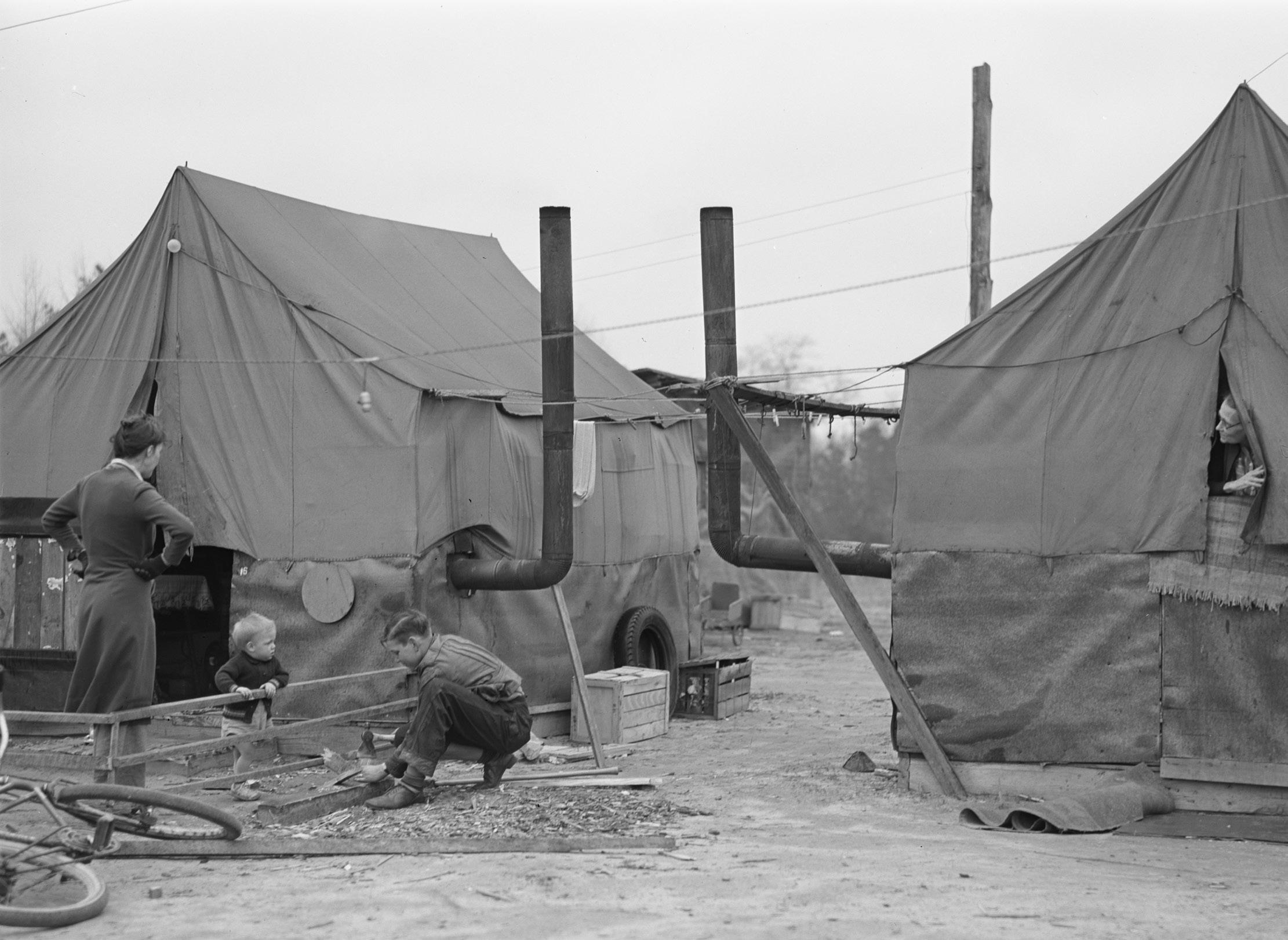

The majority of photographs and archival materials in this book have been cultivated over many years by the T.A. Loving staff. Additional sources include the Dawes Collection at Fort Liberty in Fayetteville, which provided many of the images in Chapter 5 on the company’s construction of what was originally known as Fort Bragg; David Cecelski and the Library of Congress for photos of Fort Bragg migrant workers on pages 94-95; and the libraries at area universities, including East Carolina, N.C. State and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for photos of company projects on their respective campuses.

Many thanks to T.A Loving staff members Jenni Auxier and Michele Carter for their assistance proof-reading and organizing company photo assets.

This centennial book is dedicated to the thousands of men and women who have proudly donned the T.A. Loving hat and spread across the Carolinas and beyond to construct an impressive resume of bridges, buildings and civil facilities.

“Remember to celebrate the milestones as you prepare for the road ahead.”

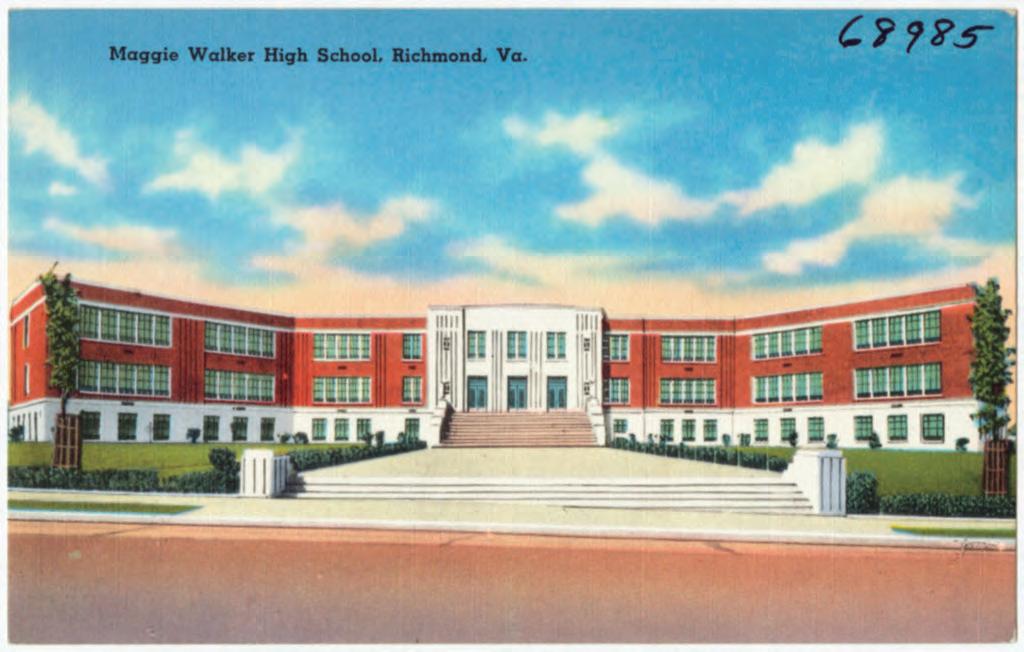

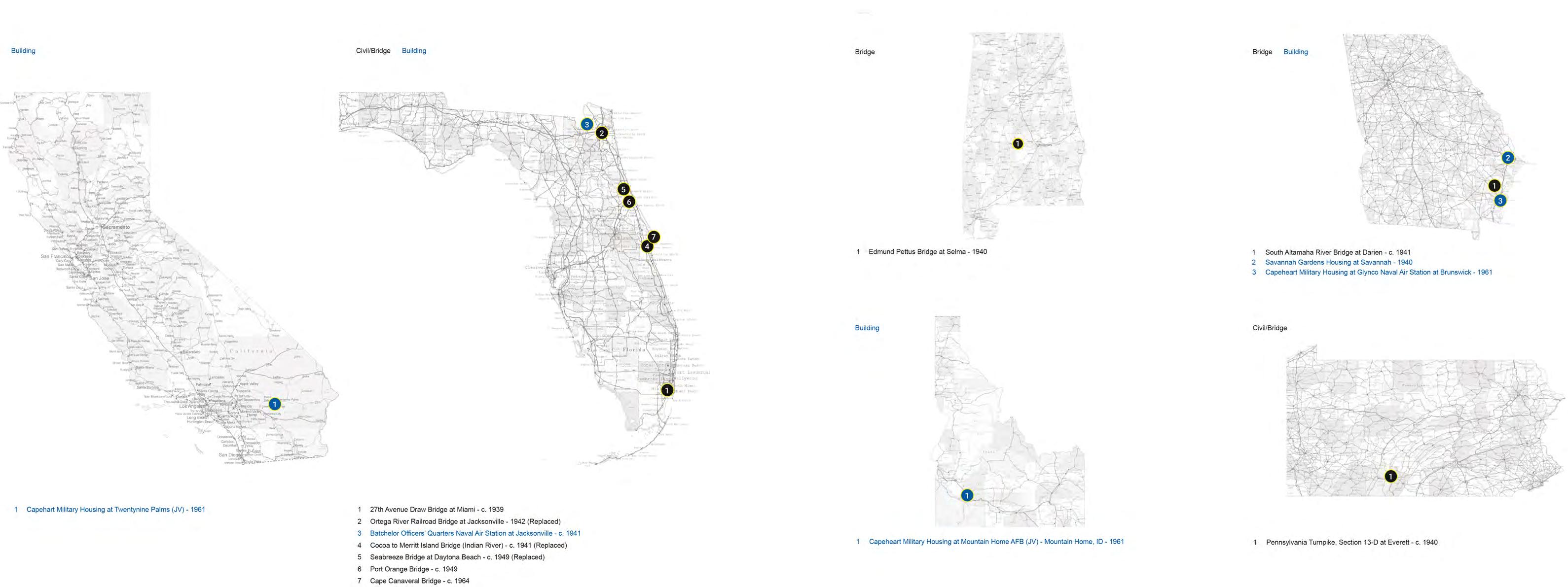

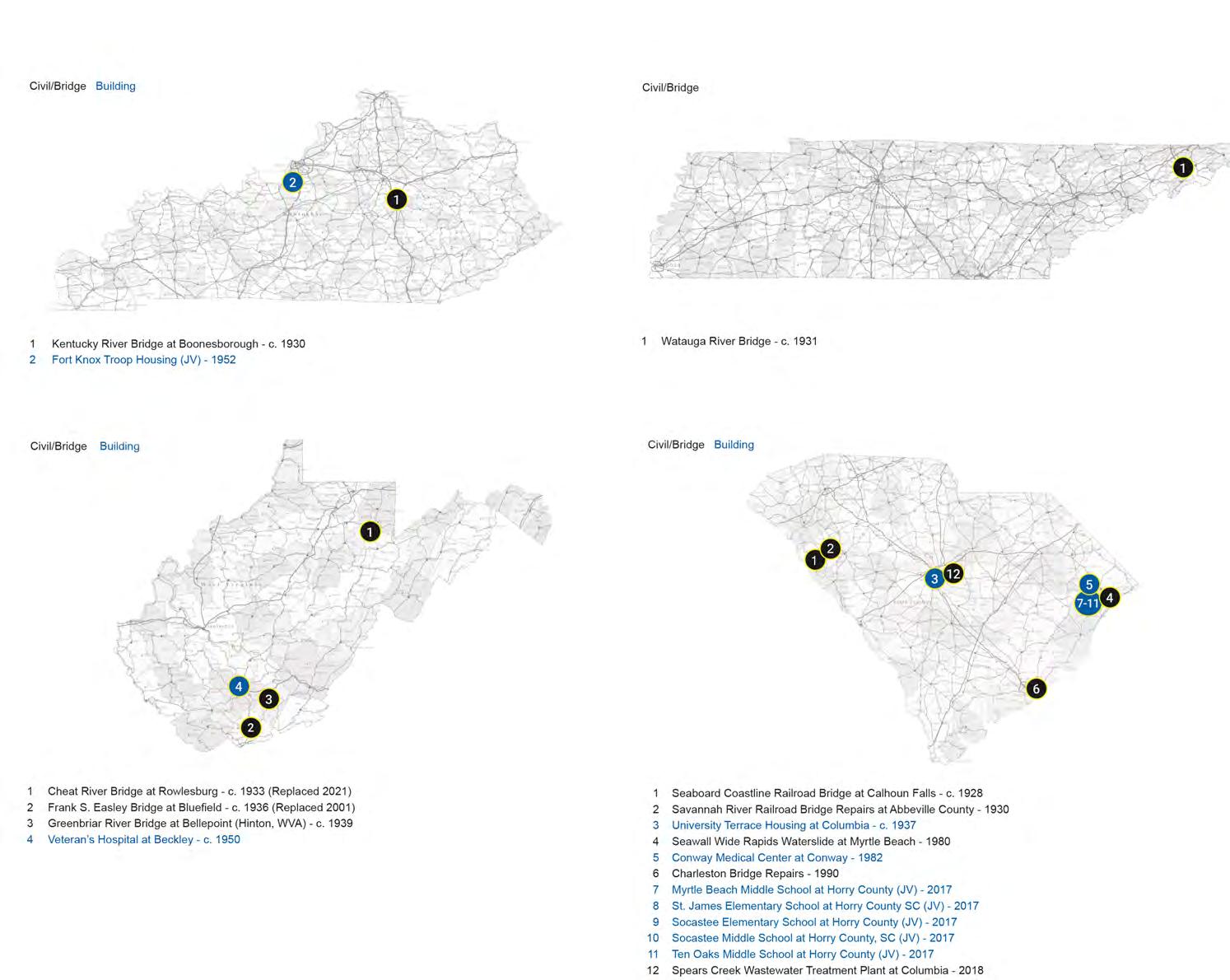

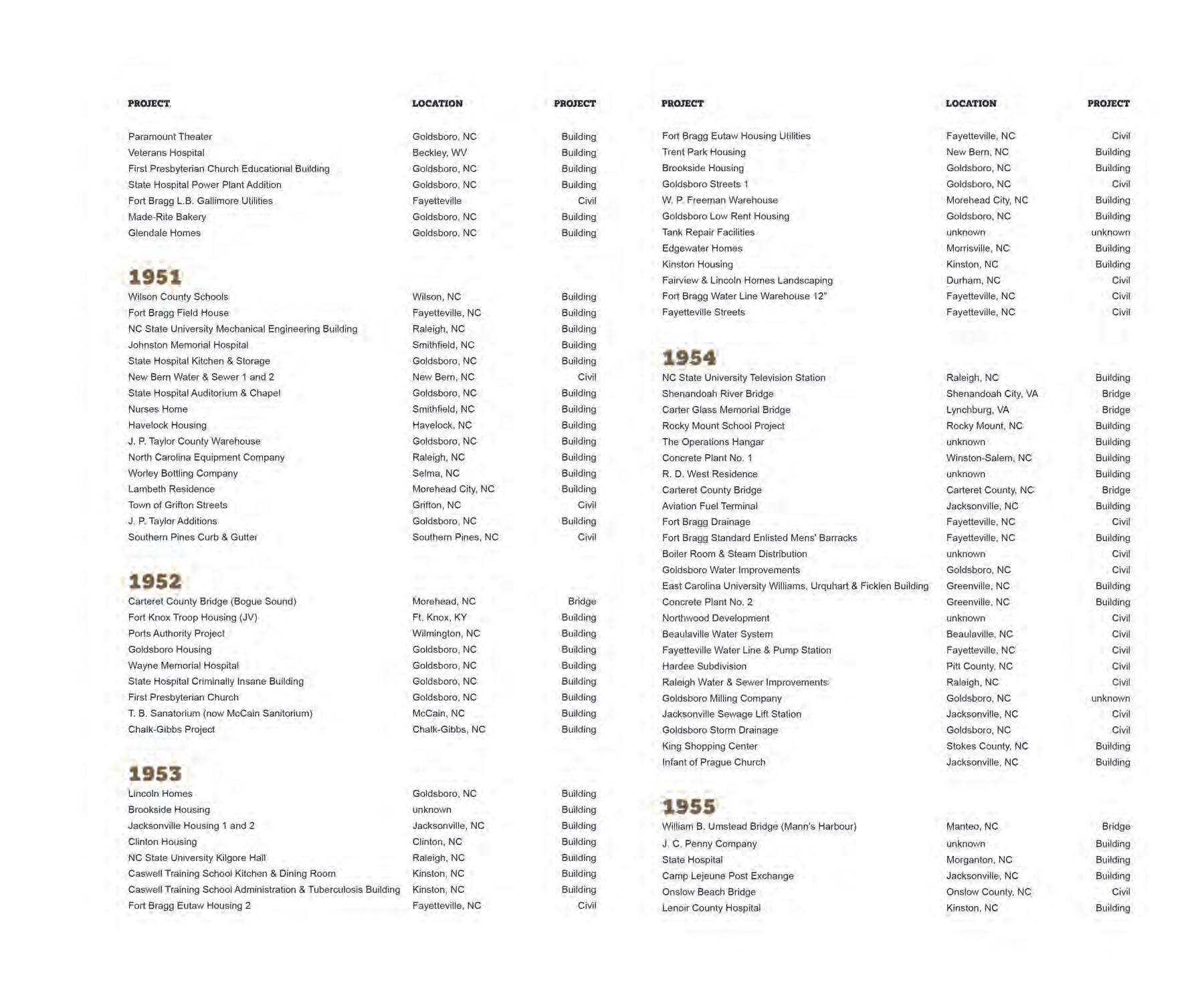

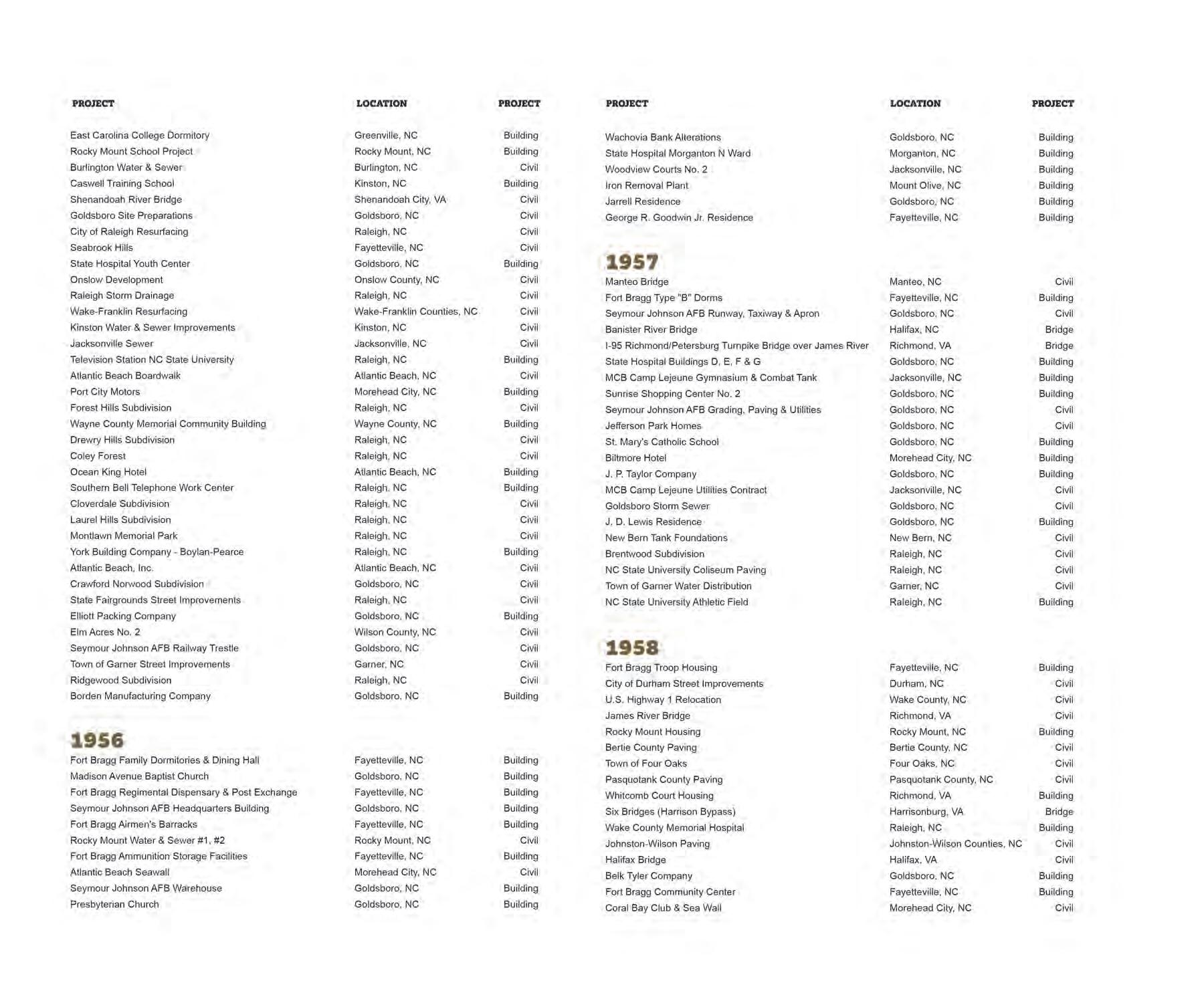

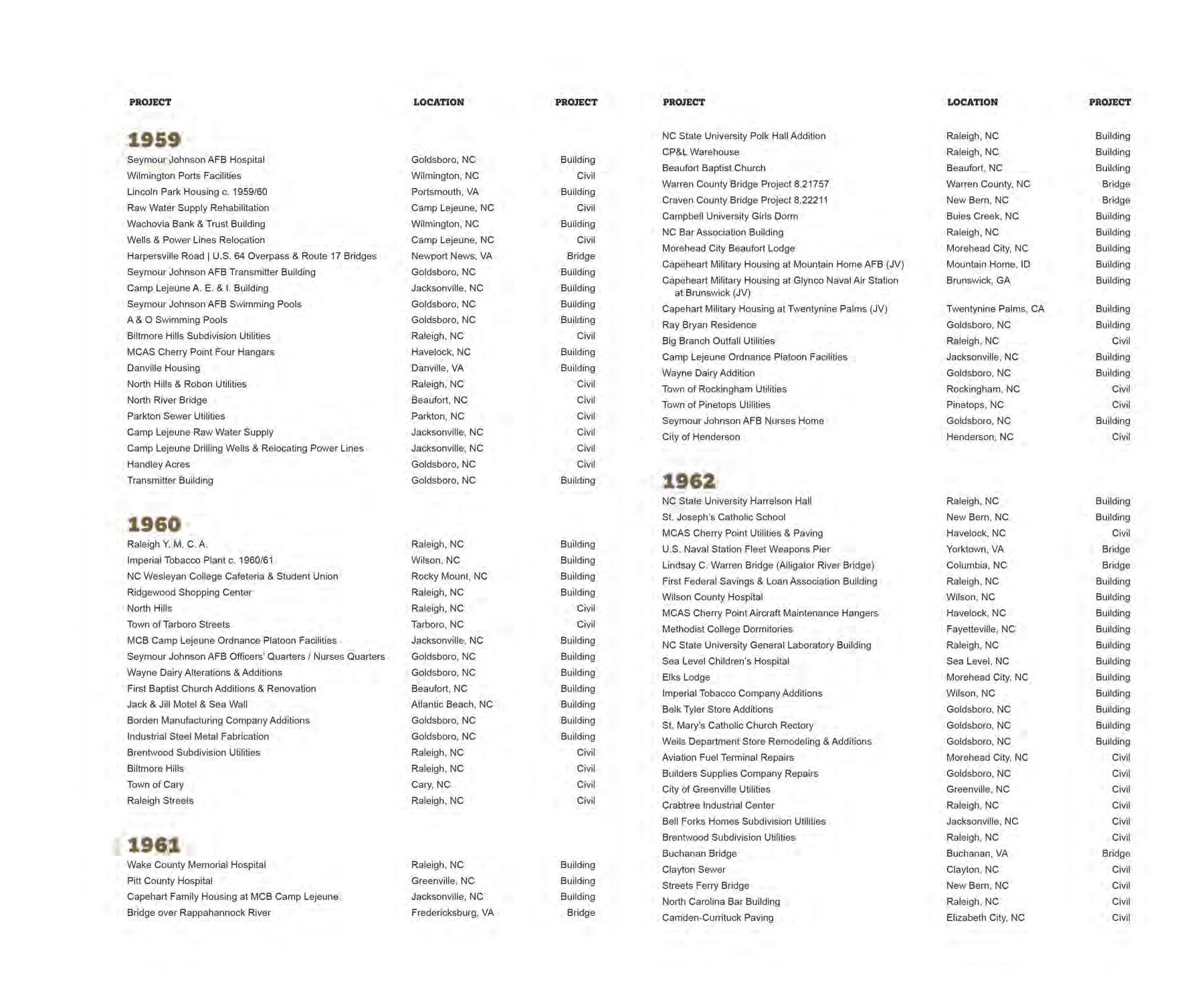

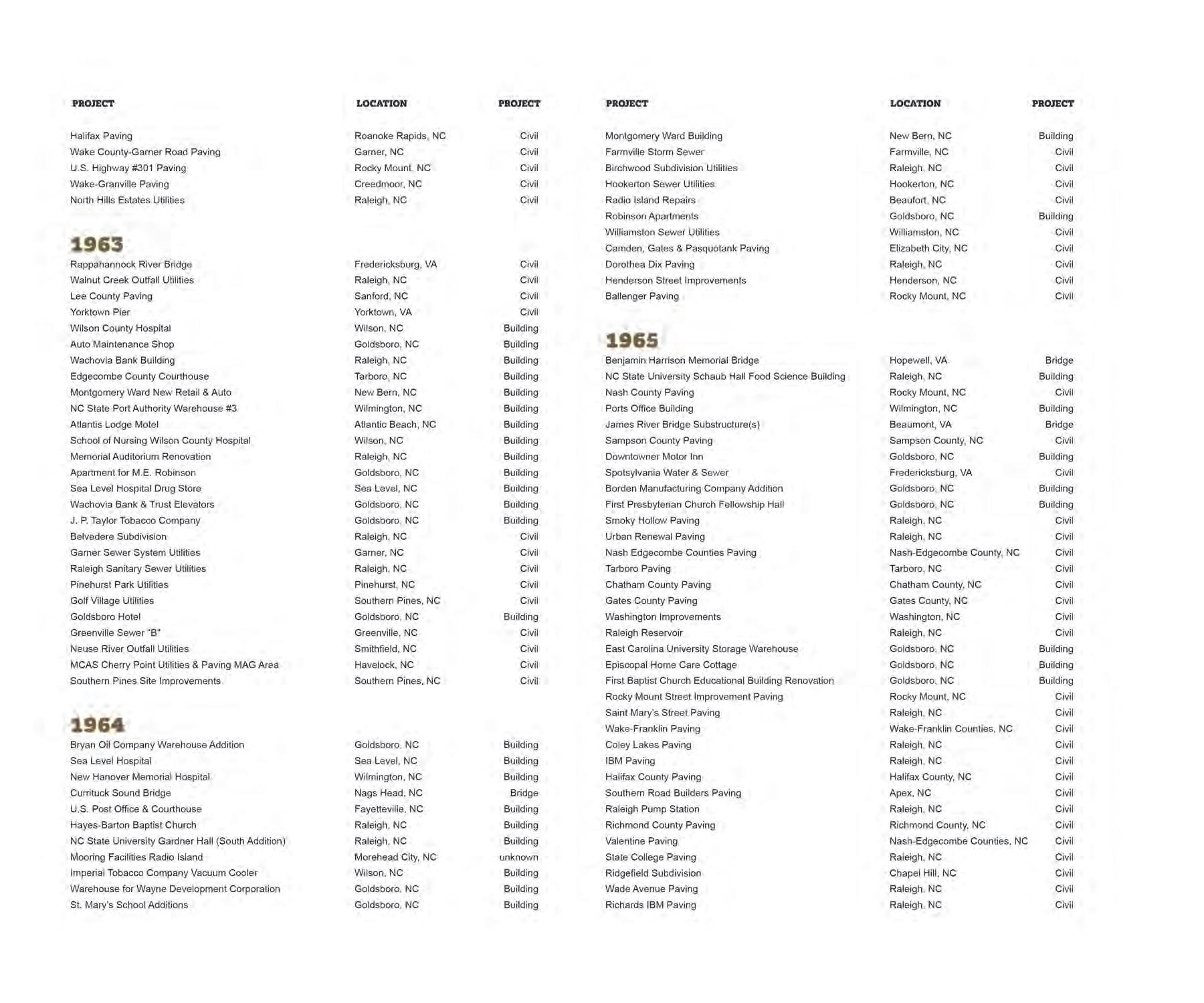

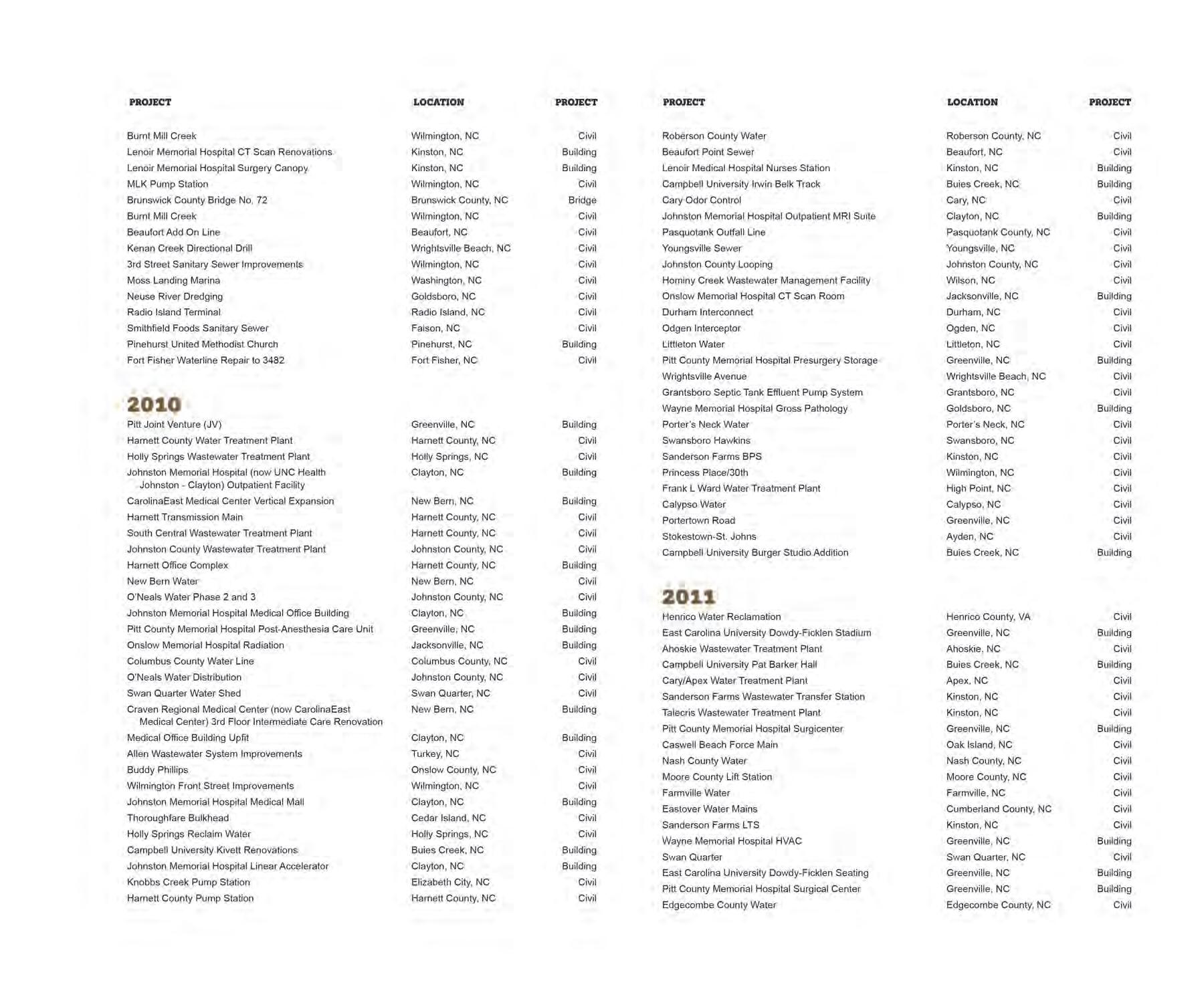

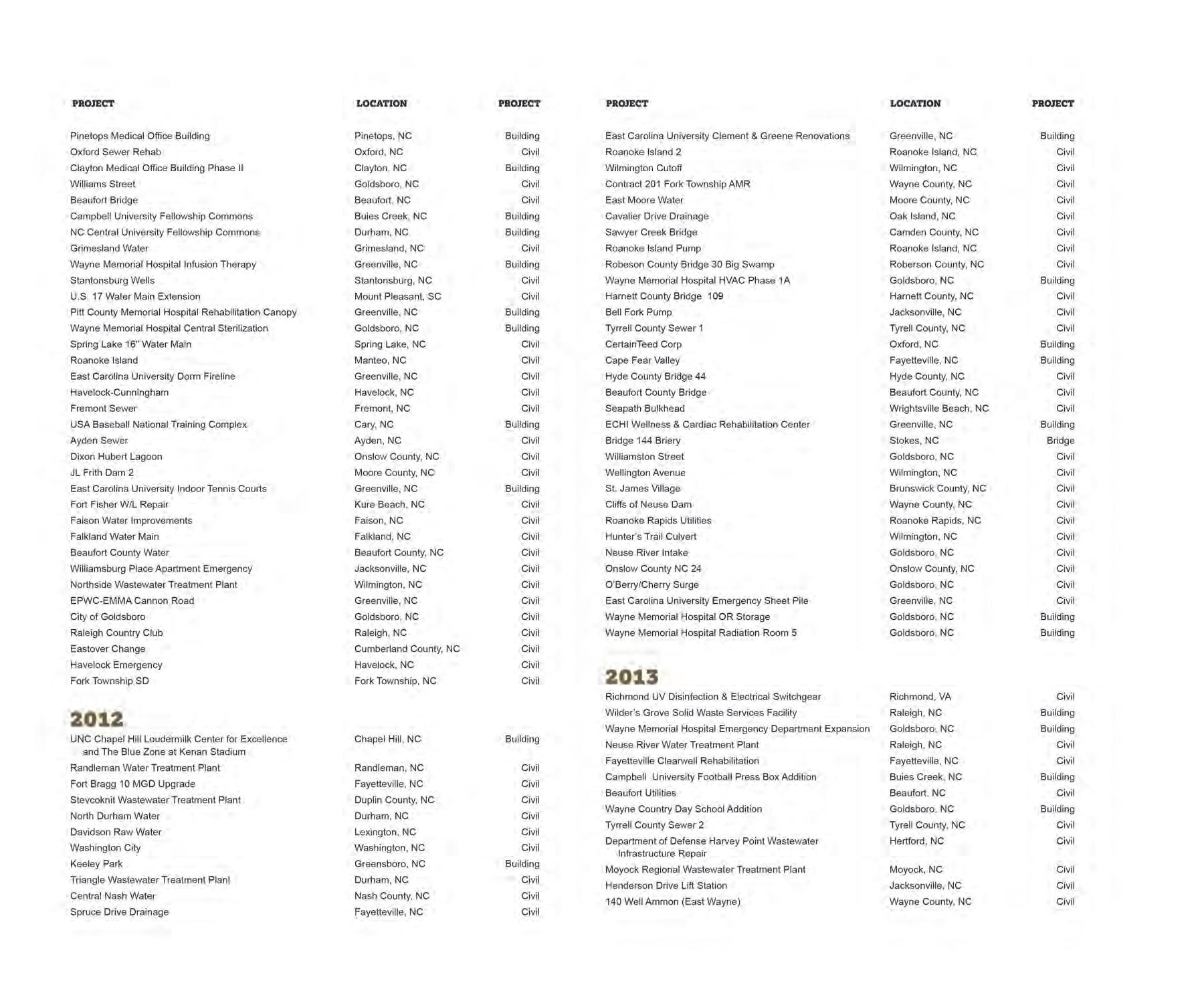

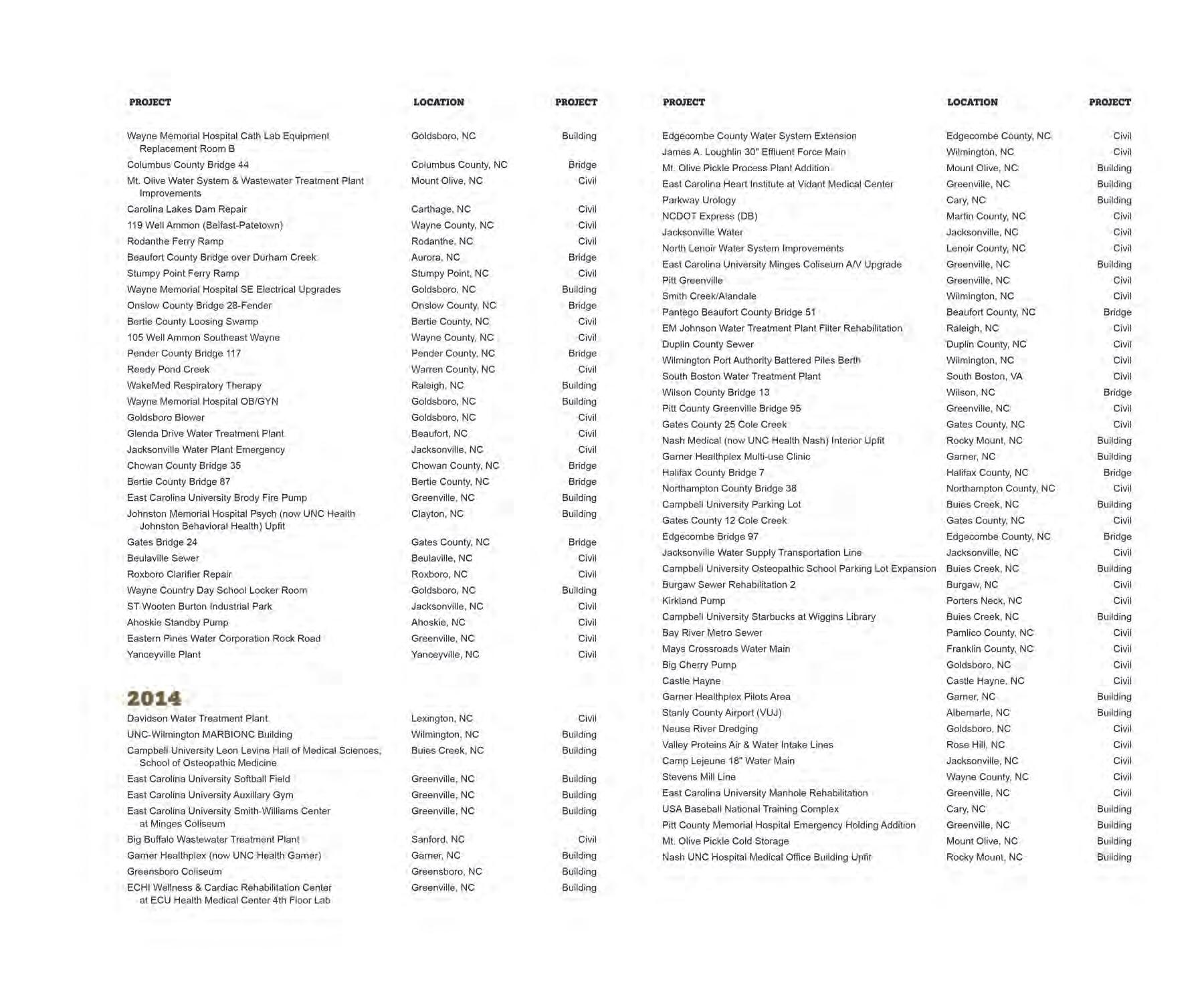

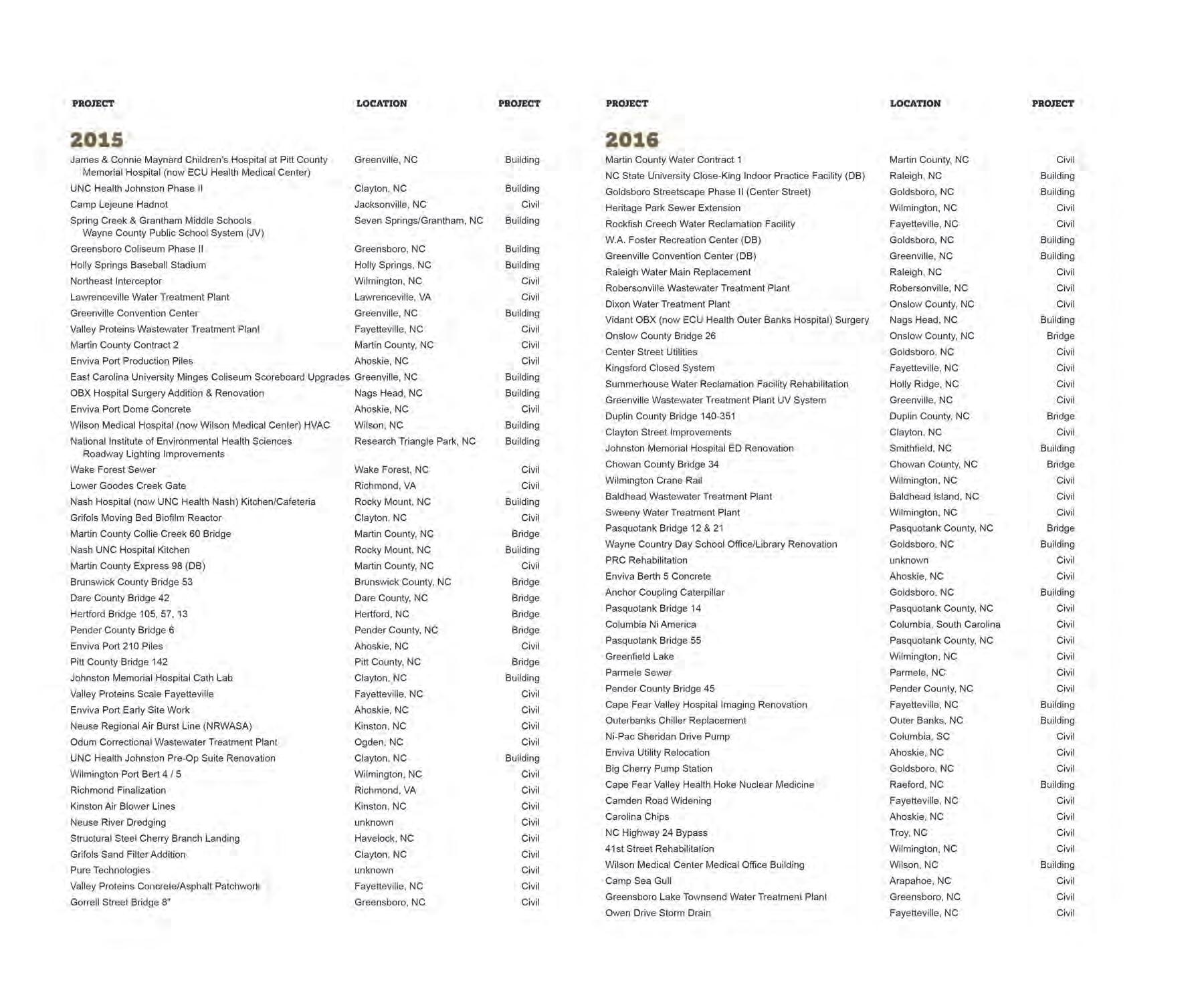

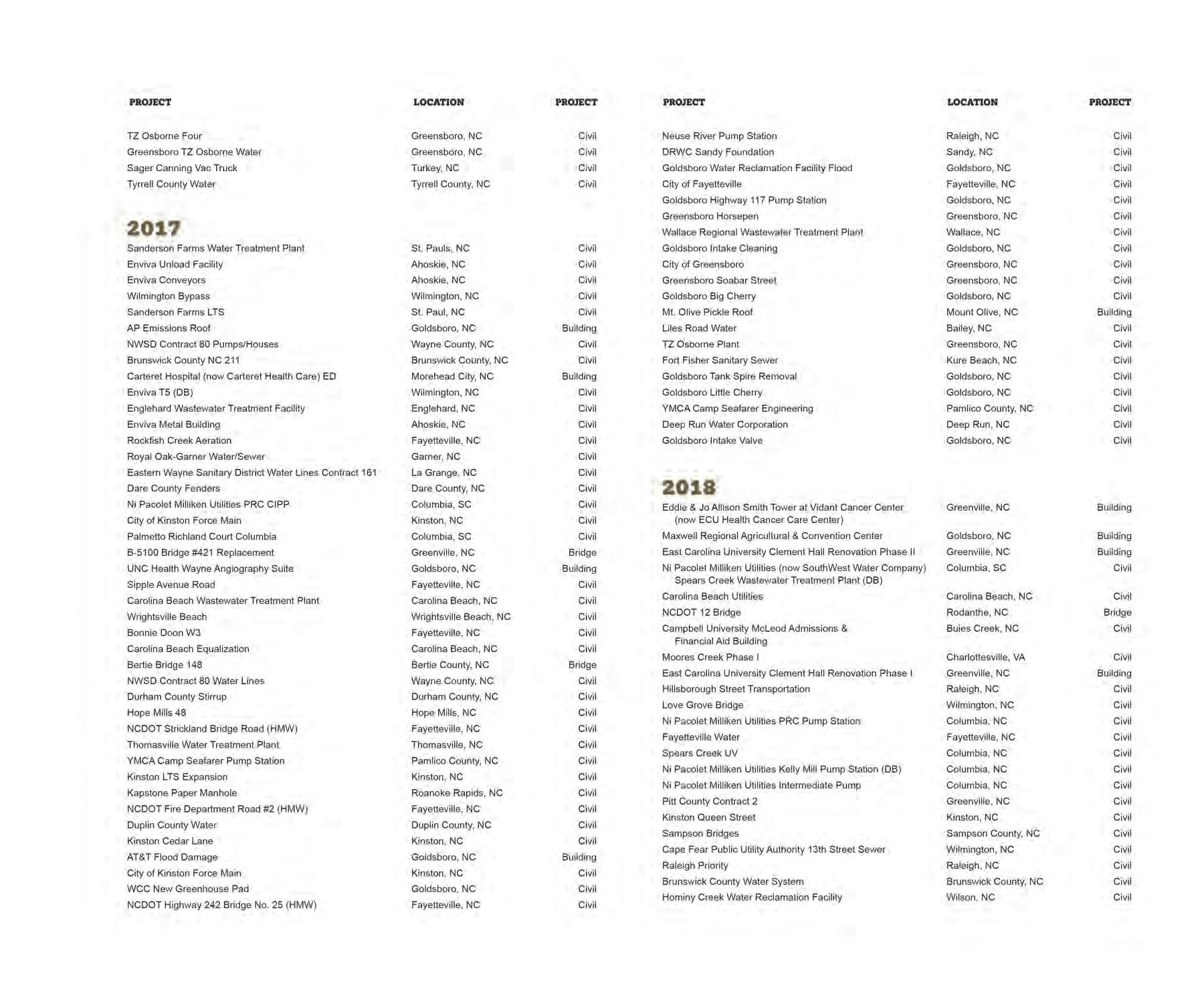

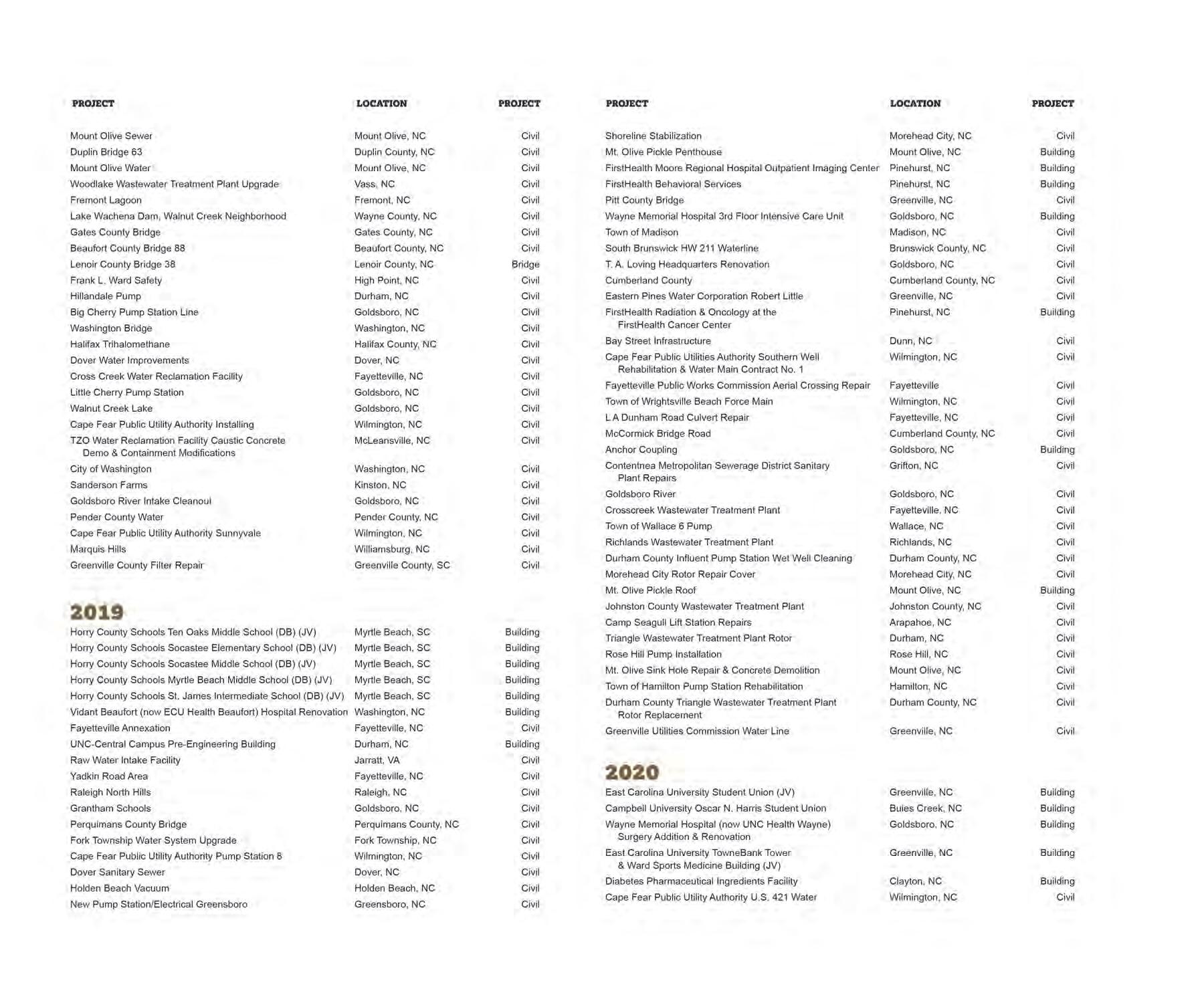

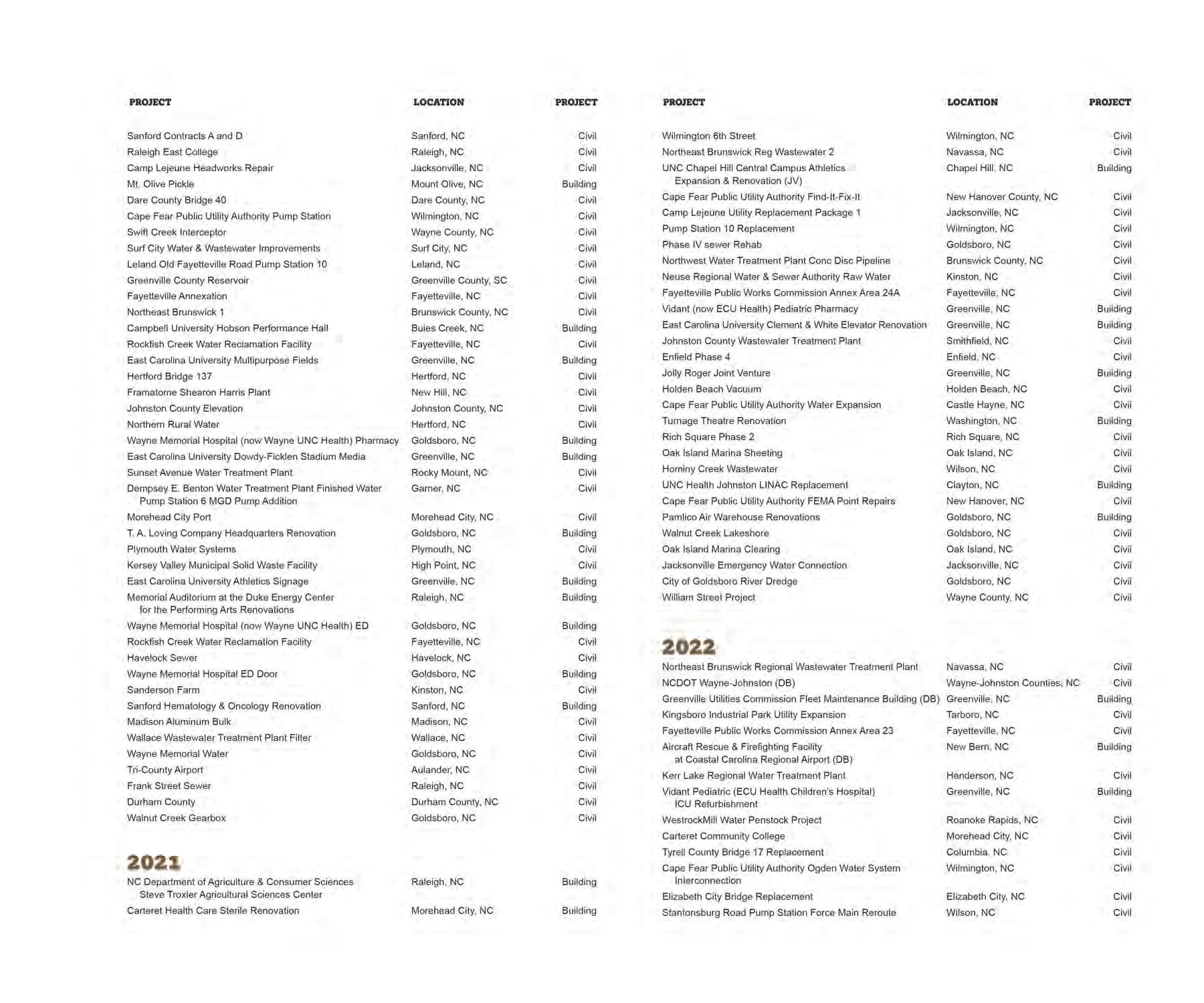

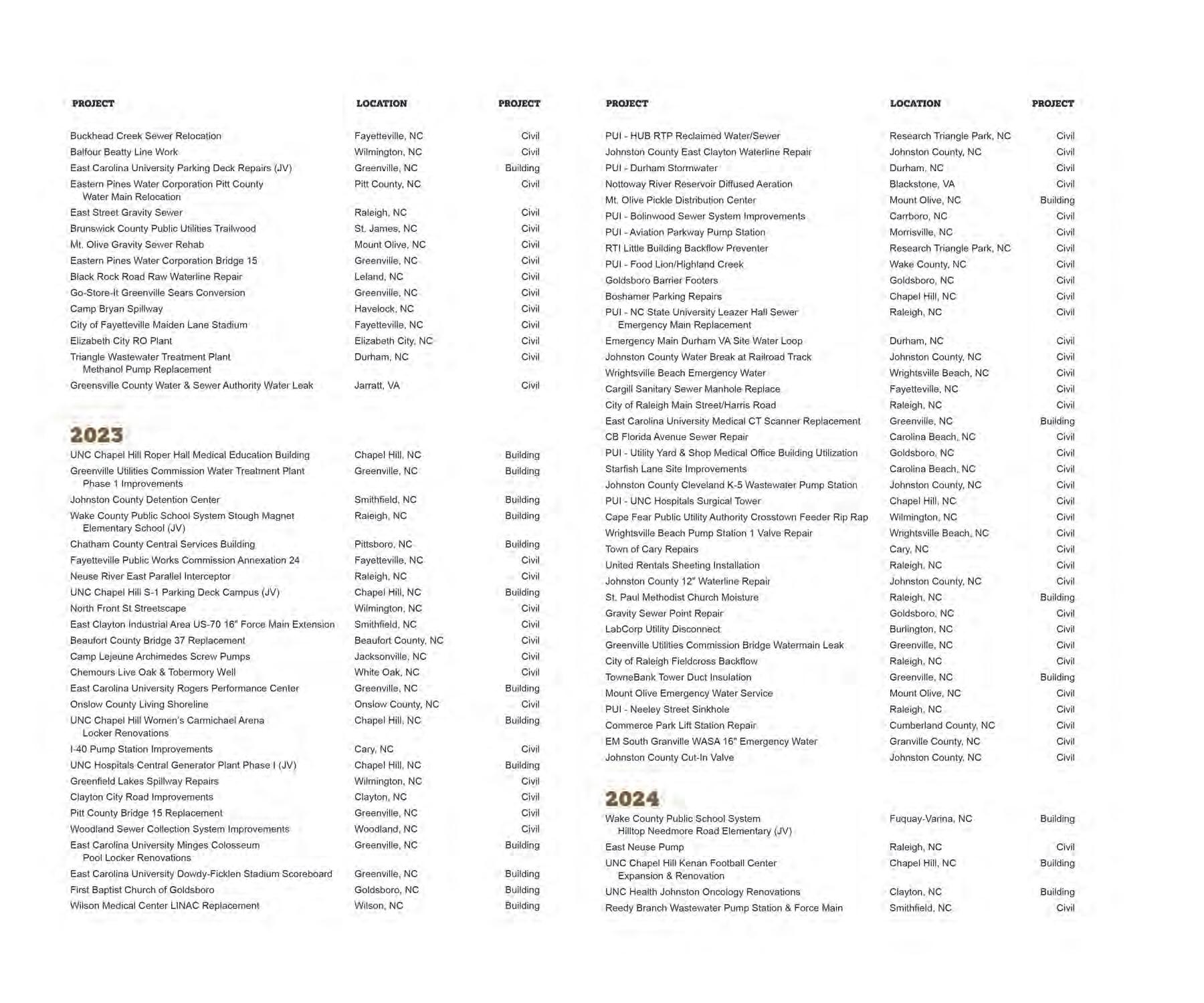

On these and the succeeding twelve pages are a vast array of the types of quality work T.A. Loving Company has produced since 1925.

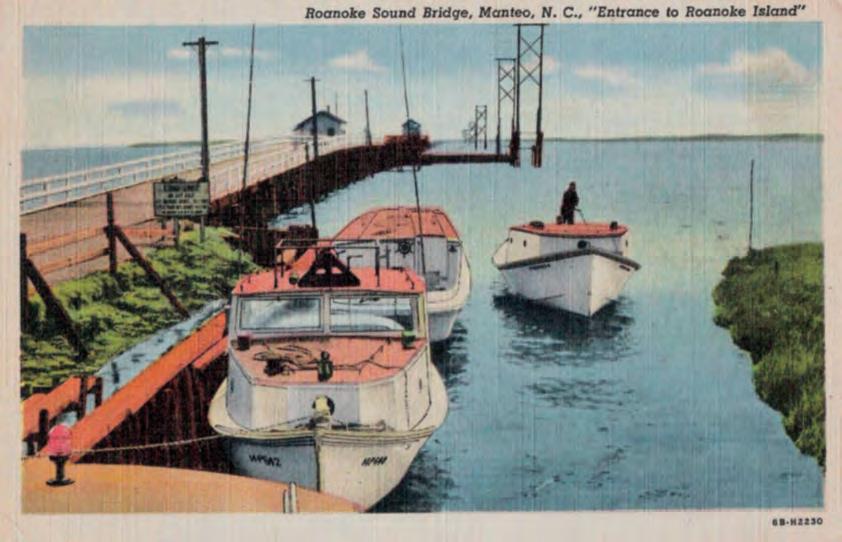

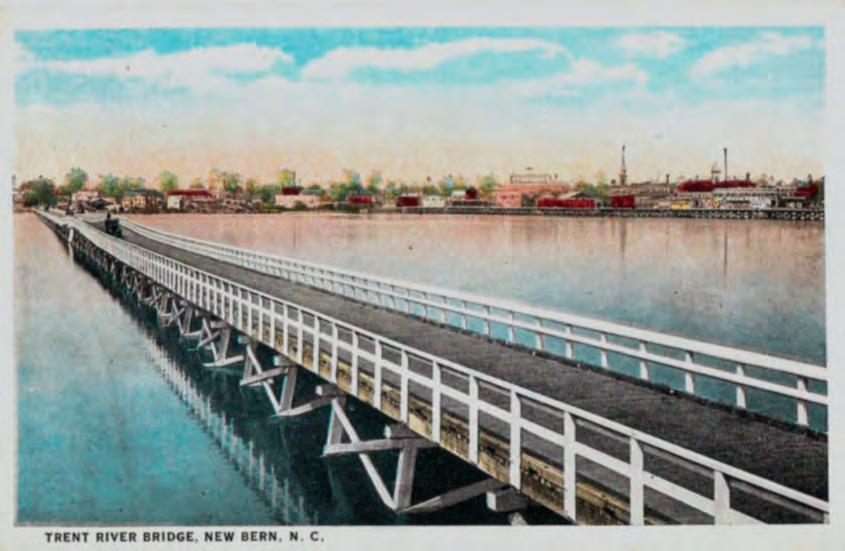

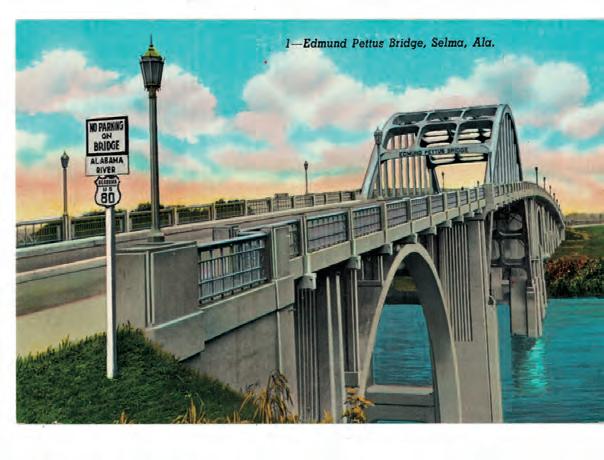

Bridges have spanned the many inlets of the Outer Banks and Intracoastal Waterway of North Carolina and crossed a river outside Selma, Alabama, a significant junction in the Civil Rights Movement.

and they will come.

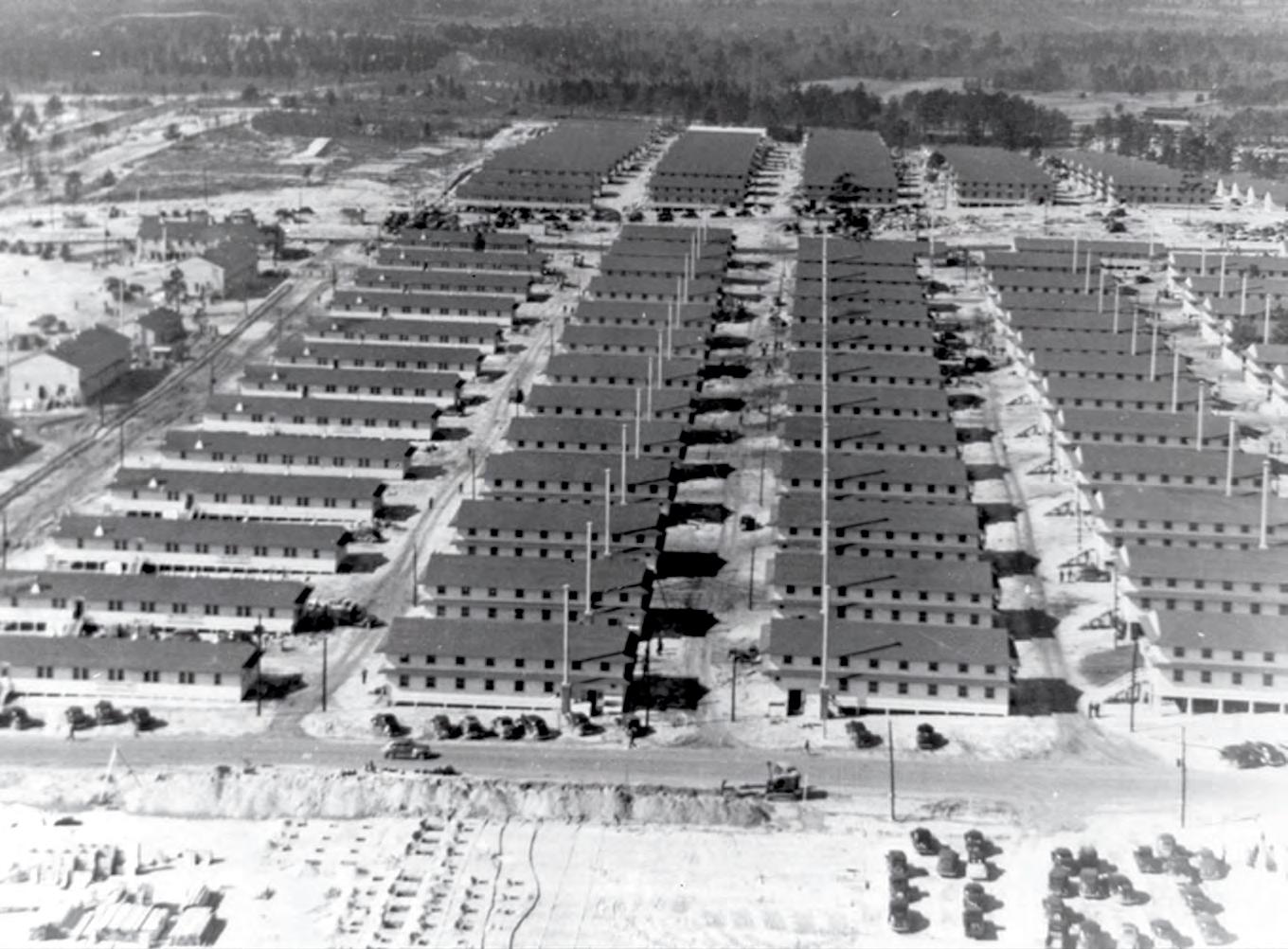

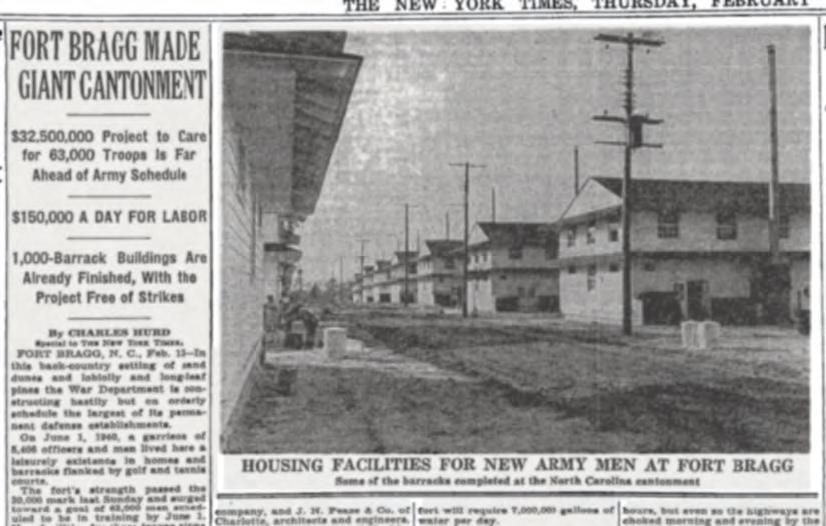

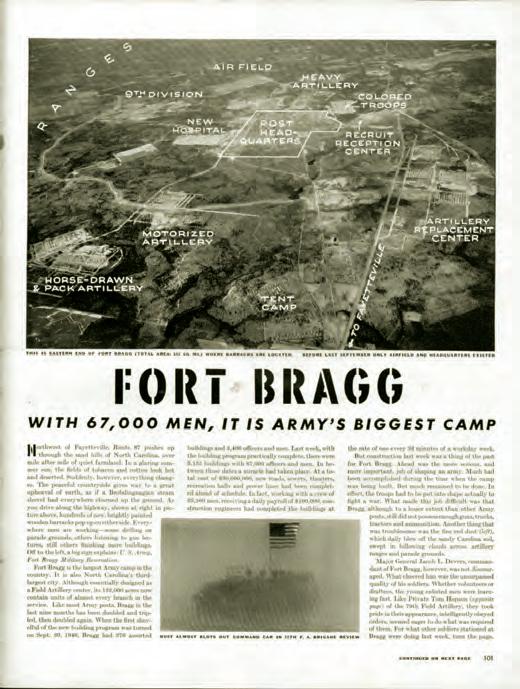

T.A. Loving Company had as many as 25,000 workers on the payroll in 1940 as it built Fort Bragg at breakneck speed as the United States prepared to enter World War II

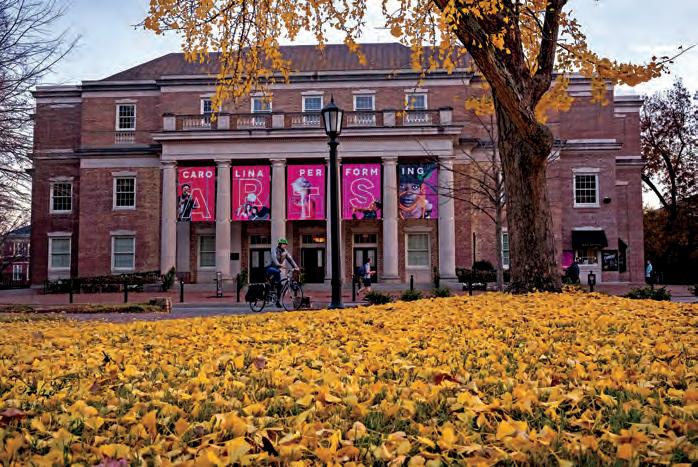

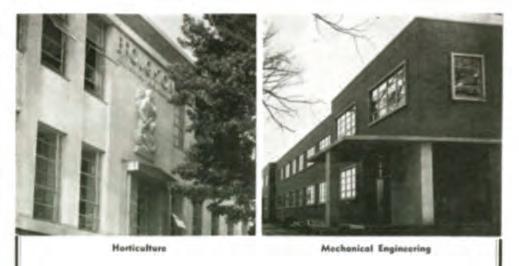

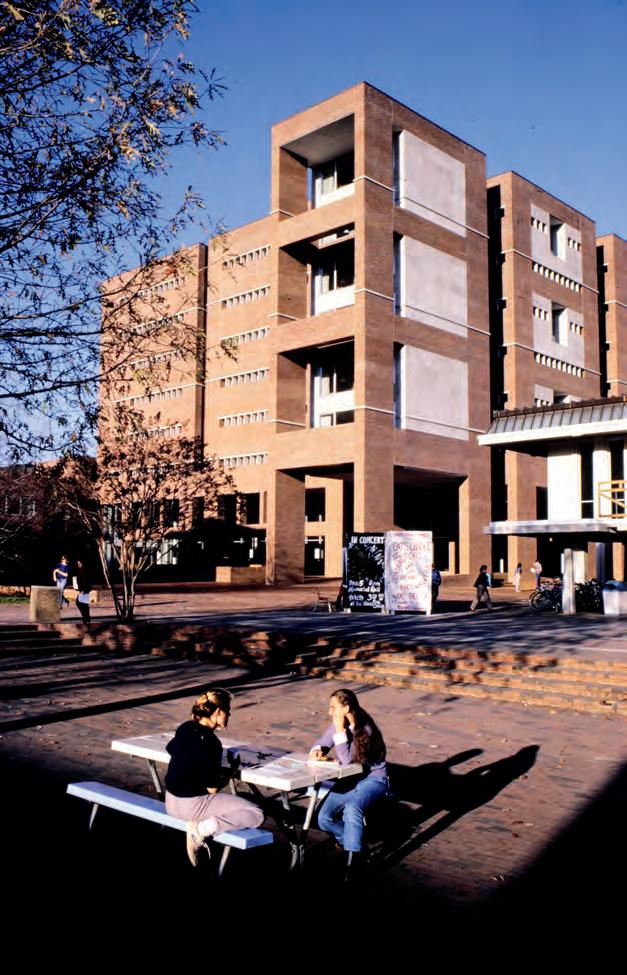

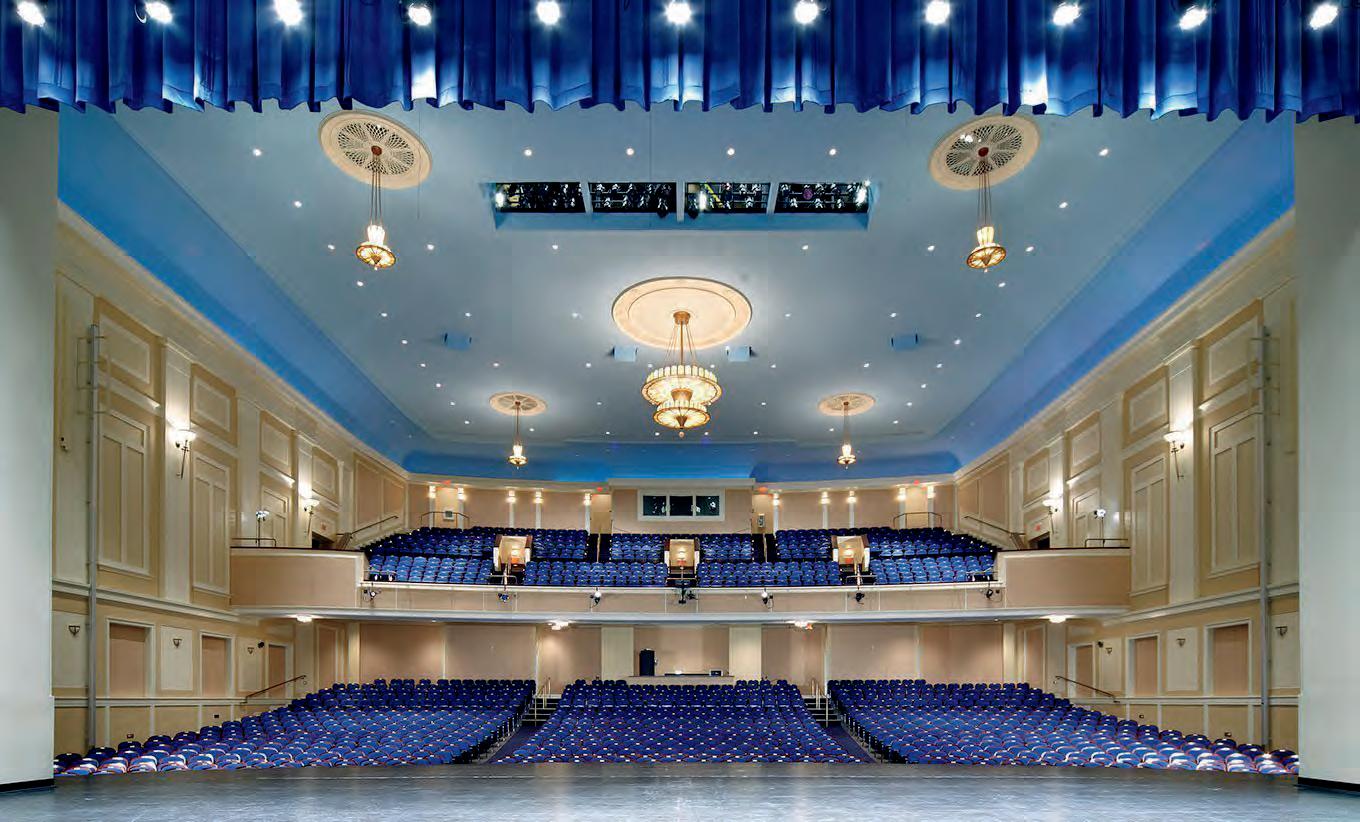

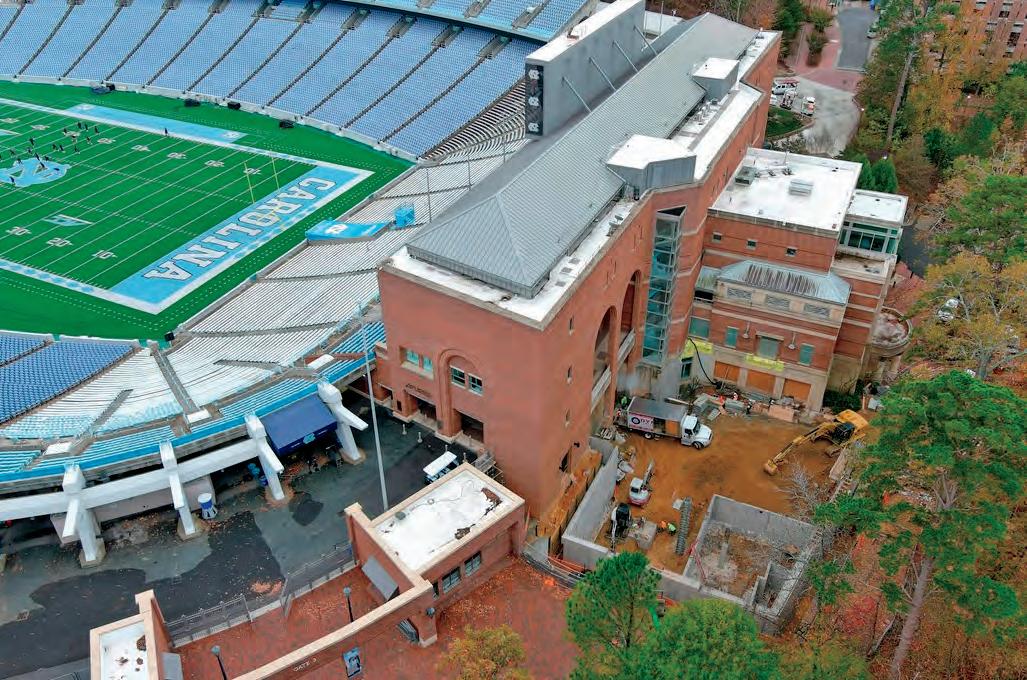

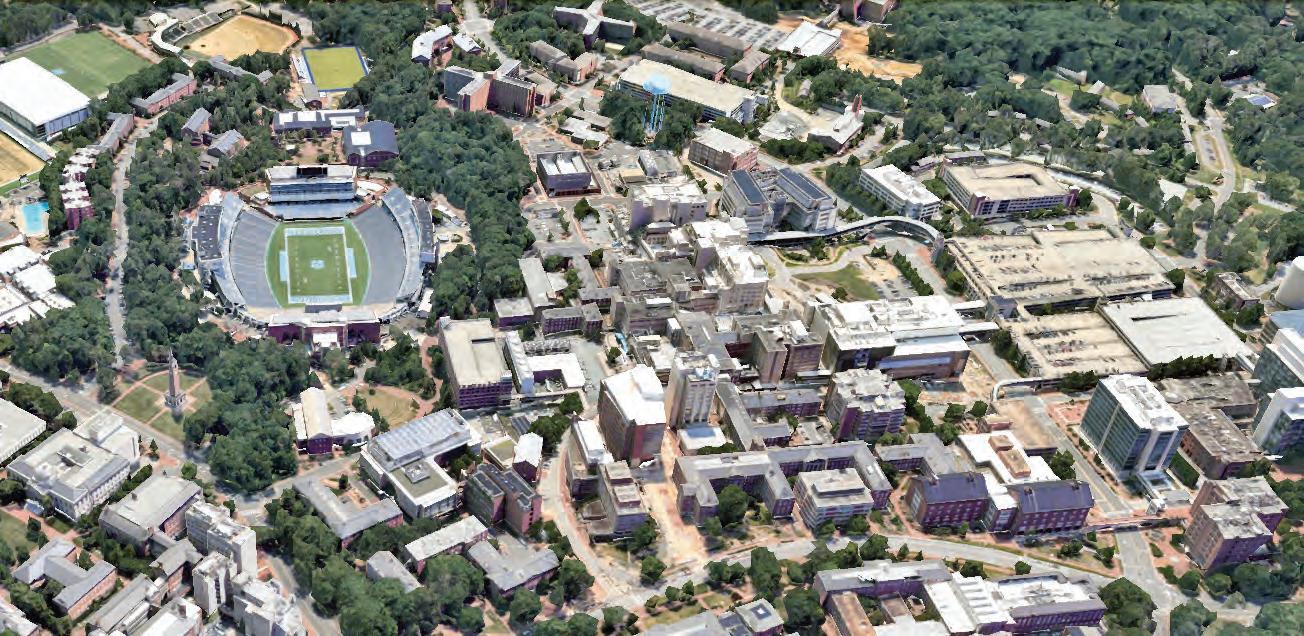

The company’s work graces most college campuses across Piedmont and Eastern North Carolina, including (L-R) approximately twenty projects at Campbell University, the Student Center at East Carolina, the Tri Towers dormitory complex at N.C. State and a total renovation of Memorial Hall at UNC.

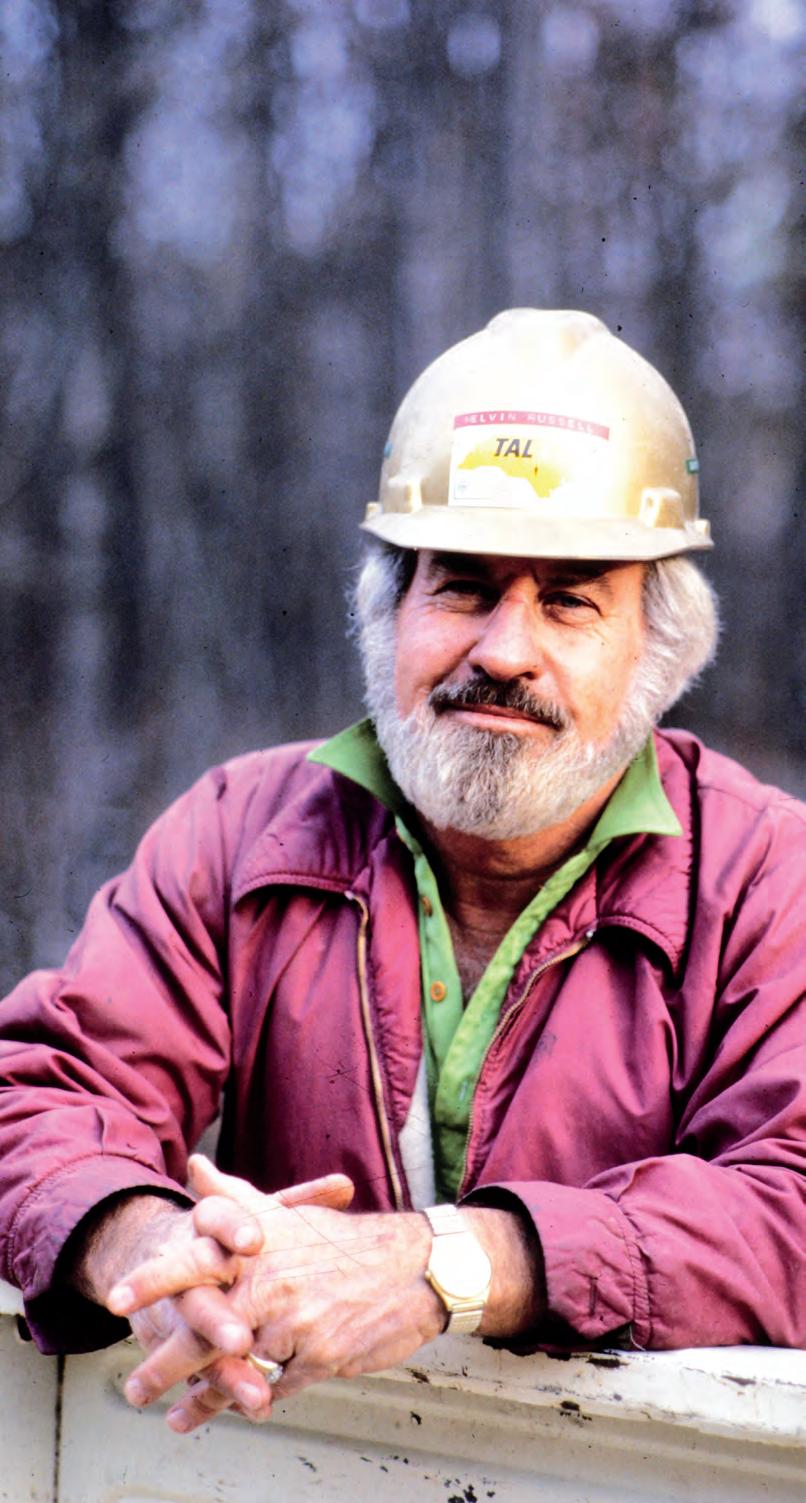

By Sam Hunter, Chairman

This volume is an attempt to acknowledge 100 years of T.A. Loving Company’s construction history and accomplishments. It is dedicated to the many employees and their families whose commitment has made our success possible.

As we have neared our centennial year, have reflected on my career and what drew me into construction in the first place. In hindsight, realize it was out of necessity. My father died when I was three, and being the only son in a farming family, I learned early to work hard, to help maintain horse-drawn farming equipment and to fix what broke. also learned that teamwork with other farmers was the only way to succeed.

Listening to my invalid Grandfather Hunter talk about his own bridge-building career and getting to know my future father-in-law, John Loving, bridge-builder extraordinaire, led me to choose engineering, not agriculture, as my major at Virginia Tech. My mother remarried and sold our farm, opening the door to a possible future in construction.

After college and marriage to my high school sweetheart Ann, attended graduate school and then served in the Navy Civil Engineer Corps in Norfolk and with the Seabees in Vietnam. Upon discharge from the Navy in 1971, I joined the Bridge Division of T.A. Loving, and my first project was to build a bridge over the Tar River in Greenville, N.C. Since that first assignment, my passion for construction and my pride in T.A. Loving Company’s accomplishments has only grown. As T.A. Loving turns 100, look back with pride at my own fifty-four years of employment here and at the leadership opportunities afforded me through those many years.

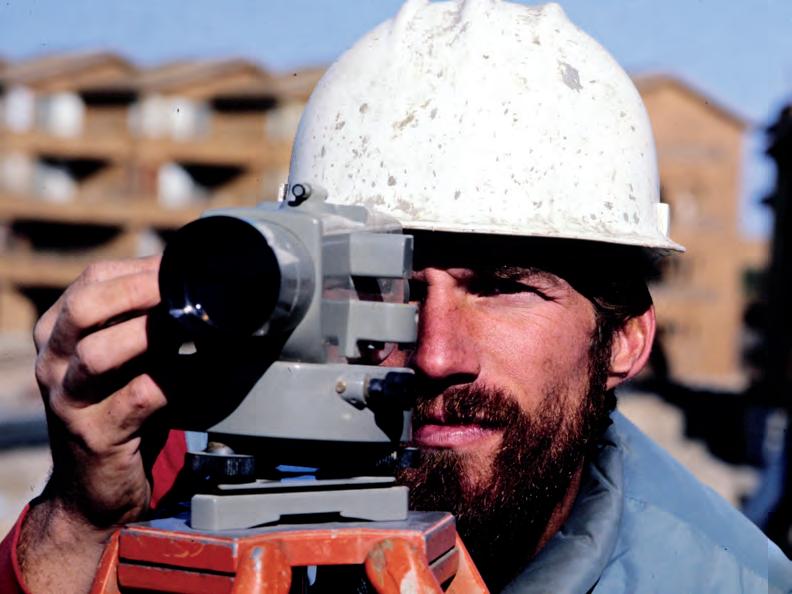

From 1925 to today, construction has moved from mules and steam engines to GPS guided equipment, from overalls and fedora hats to SMART protective apparel, from party-line phones requiring a switchboard operator to instant cell and satellite connections, from paper spread sheets to personal tablets, from hand-nailed structures with hand-mixed concrete to 3D printed and prefabricated buildings.

But time and modernization has not changed the culture of the company. T.A. Loving Co. remains faithful to its founder’s vision to provide meaningful and rewarding careers to generations of families. Commitment to excellence in construction has fostered such pride in our workforce that “Loving Life” is now our hashtag, joining the long time T.A. Loving plumb bob insignia. can retire with a grateful heart, knowing T.A. Loving’s future is in very capable hands.

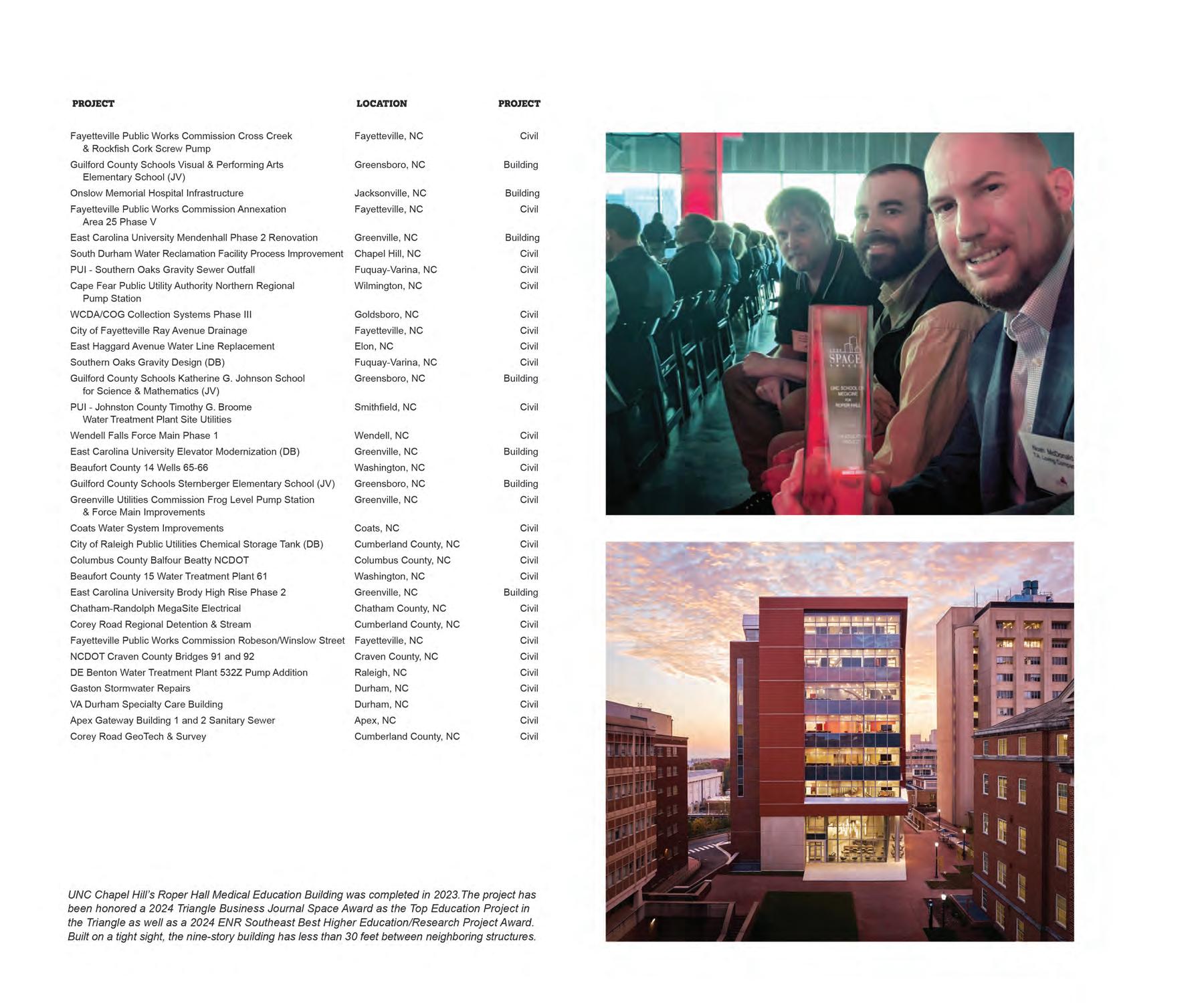

Company Chairman Sam Hunter applies his signature to a beam during construction of the Roper Hall on the UNC campus in 2022.

A wall in Ty Edmondson’s office is neatly adorned with six framed company logos dating back many decades. In two of them, the company name is presented as T.A. Loving, after the young man from Virginia who founded the company in 1925. In four of them, the feature lettering is some version of TALCO, an acronym the company used as its identifying mark for much of the late 1900s.

The thread running through each is the plumb bob—a weighted head narrowing to a point hanging from a piece of string. Historians believe the first plumb bob was likely used in Egyptian times and think the device played a major role in constructing the Pyramids, not to mention other uses in sailing and surveying the skies. They were also used by the ancient Greeks and Romans and remain the most effective and accurate tools for determining a vertical in construction.

“There’s a lot of symbolism with the plumb bob—straight and true and that’s how you build things,” says Edmondson, the company CEO. “Maybe it’s a little less that way now with all the technology. We have some younger guys come through here, point at it and say, ‘What’s that?’ I think it’s a great logo for our company.”

Adds Ann Loving Hunter, niece of the founder and wife of long-time company executive Sam Hunter: “The plumb bob says this company is going to do the job right. They’re not going to do it sloppily. You can trust them to do it the way it should be.”

It’s been that wa y for one century

building program. He established a sole proprietorship in his own name in 1925, and from this Goldsboro headquarters, the company has left its imprint across the southeast and beyond.

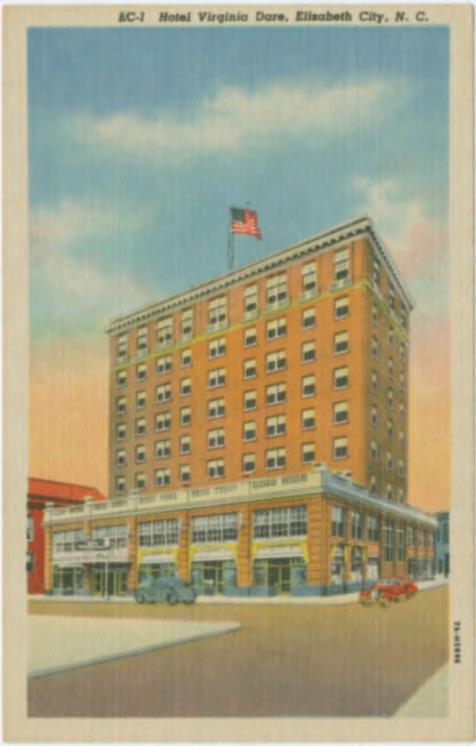

now with T.A. Loving Company. No one knows exactly how or why a young man ventured from the hills of Virginia south to Goldsboro in the mid-1920s, but it’s likely that T.A. Loving took his interest and acumen for construction to a town located at a key railroad juncture and assumed there might be work and opportunity. One of his first assignments was to help build a railroad overpass near Fremont for the state of North Carolina’s road

T.A. Loving Company built Fort Bragg at warp speed for the U.S. government in the early 1940s as America was bracing to enter World War II, having more than 25,000 employees on the payroll at one time and opening a new building every thirty-two minutes during the height of construction. It built the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, in 1940, a steel-througharch structure later named a National Historic Landmark as it was the site of a bloody conflict in 1965 when police attacked Civil Rights Movement demonstrators.

I t has erected multiple buildings at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, appropriately enough given the institution’s curriculum orientation toward engineering and architecture and the many company officials proudly hanging their N.C. State diplomas on their office walls. It built a classroom building at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill in 1970, then

returned half a century later, tore it down and in 2023 completed a new Medical Education Building on the same footprint— with the demolition actually costing more than the original construction.

It has left its thumbprint in health care across the Carolinas, building a surgical center for Wayne UNC Health Care just a mile and a half as the crow flies from its company headquarters in Goldsboro.

Brett Bond, a healthcare senior project manager and a T.A. Loving employee since his summer internships starting in 2006, supervised that surgical center in Goldsboro from 2015-16. In 2021, he watched his one-year-old son treated in that very facility for an ear infection.

“We came in through the door and into the lobby we’d built, into the triage room we’d built, into the E.R. we’d built and then back up the post-op room we’d built,” Bond says. “I saw every bit of it come together. It gave you quite a sense of pride to see the work you’d done be put to good use—and in my case, see your own son treated in that hospital.”

It has built bridges spanning the inlets, sounds and rivers of the Outer Banks and

the coastal areas of North Carolina from Manteo down to Morehead City.

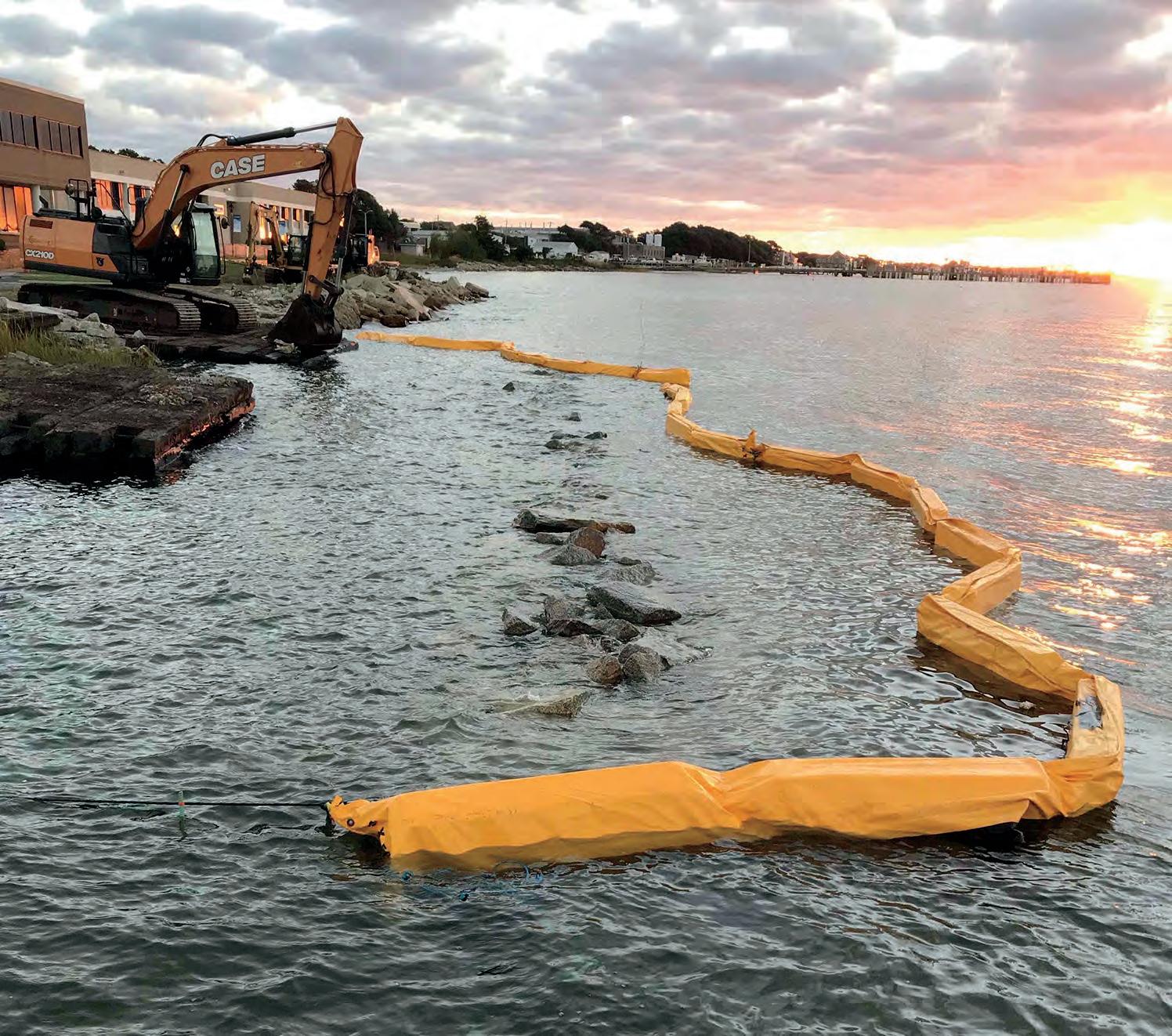

It has worked with hundreds of towns and municipalities on water distribution and sewage treatment facilities, from a wastewater treatment facility in Brunswick County to utility repairs and rehabilitation at Camp Lejeune.

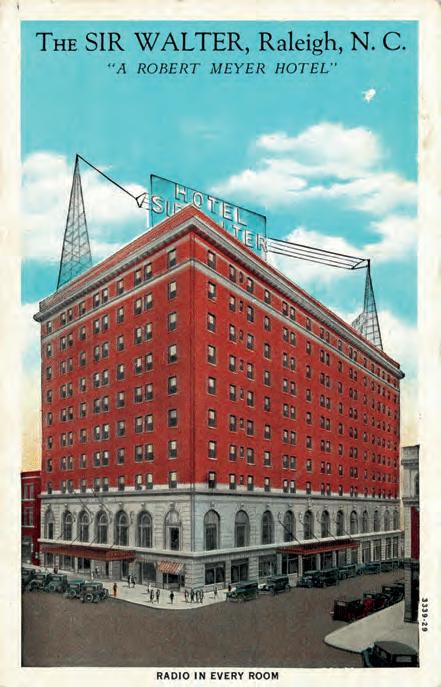

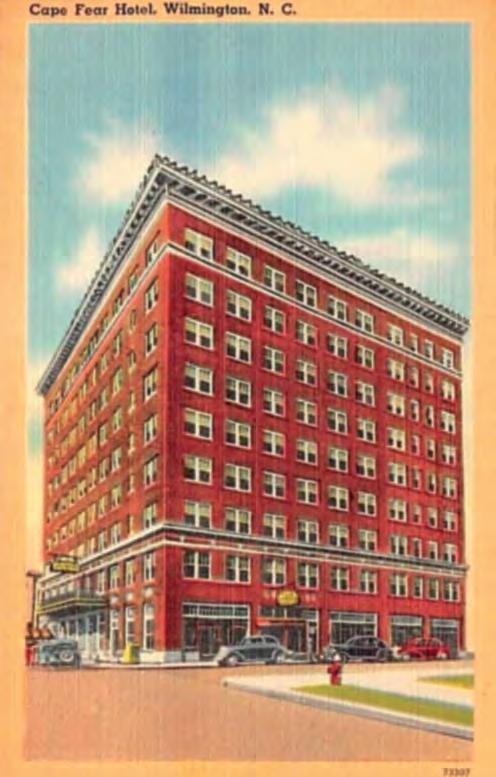

It has enhanced urban landscapes from Raleigh to the coast, appropriately enough given that Raymond Bryan Sr., the company president from 1947-69, was at the forefront of developing Raleigh’s Cameron Village, one of the nation’s first open-air shopping centers. What goes around comes around frequently in the company’s considerable vault of work. In 1960 it completed a sixstory building for Wachovia Bank and Trust Building on Front Street in Wilmington, one magazine story rhapsodizing over the $1 million price tag and a cutting-edge exterior surface treatment of sparkling quartz. That building was razed in 2008 and the lot sits vacant, just one block from T.A. Loving’s 2022 project of supervising a $3.5 million streetscaping overhaul. And at any juncture and any given moment in North Carolina and beyond,

you might very well see a T.A. Loving banner hanging on a ground-level fence or hoisted from a crane high above the hard hats and heavy machinery.

“One of the nice things about being in construction, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re in management or a laborer, is you can be driving around with a friend or family member and cross a bridge or pass by a building and say, ‘I helped build that.

I worked on that,’” says Sam Hunter, who joined T.A. Loving in 1971 and worked his way up to president and CEO in 1988. “You can see what you’ve done, and that is very satisfying and rewarding.”

Stephen Salter, who joined T.A. Loving in November 1993 and is the general superintendent/assistant vice president of the Bridge Group, remembers a meeting with an engineer at the N.C. Department of Transportation regional headquarters in Edenton and noticing a battery of television monitors showing traffic cameras at bridges in that area of northeast North Carolina. Salter counted six bridges or work sites built by T.A. Loving shown on the eight TV monitors.

“I cross bridges everywhere I go and

I say, ‘Well, I worked on this one and I worked on that one,’” Salter says. “When you’re driving eastern North Carolina, you won’t go many roads where you won’t have driven over a bridge that we’ve built. You head to the coast, you’re going to cross a T.A. Loving bridge.”

And there are the jobs you don’t see. It’s

one thing to build five K-12 schools around Myrtle Beach with dozens of cutting-edge energy conservation features as the company did in the early 2000s and yet another to lay nearly 45,000 feet of sewer, water and storm drain lines under the streets of Carolina Beach as it did in 2019.

“ Everyone associates T.A. Loving Company with our Building Division because it’s so visual, but if we don’t do the water and sewer, this world comes to a crashing halt,” says Paul Hunter, senior vice president and son of Ann and Sam Hunter. “Dad has said as long as I can remember the need for water and sewer will always be there. But that part of our work is buried. You never know it’s there.”

“My wife and I’d go by a wastewater treatment plant on the road driving somewhere and she’d say, ‘What’s that

smell?’” says Jerry Smith, who joined the company in 1967 and was senior vice president of the Utilities Group upon his retirement in 2015. “I’d say, ‘That’s the smell of money!’ That’s been an important area of work for this company for many, many years.”

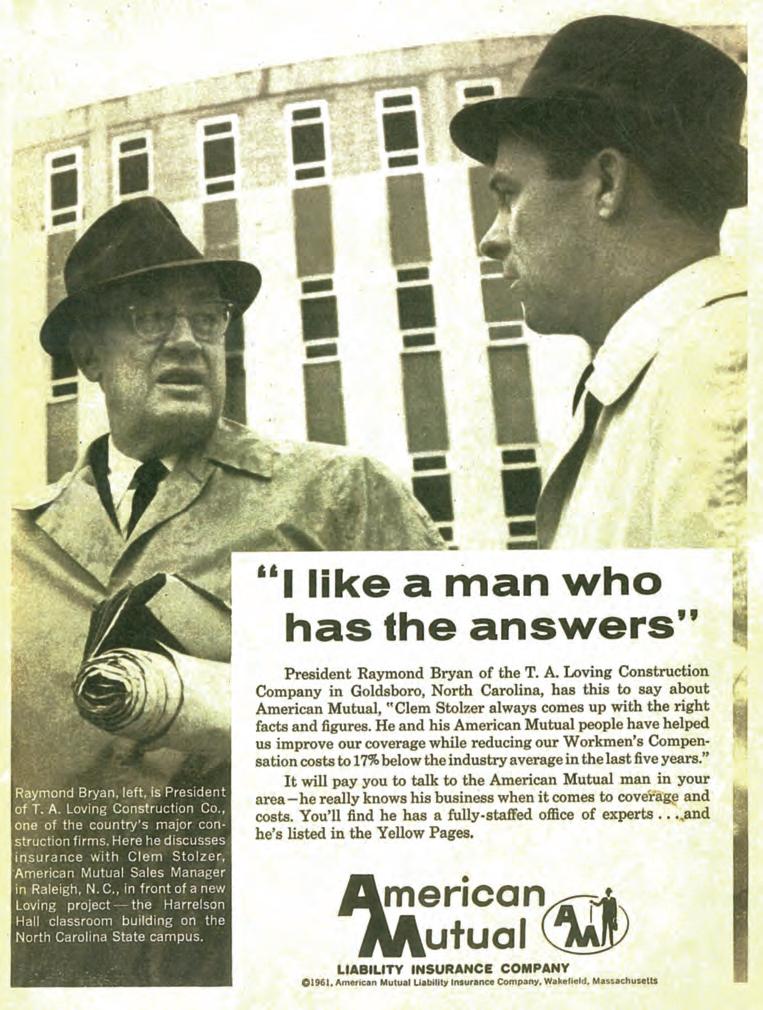

Along the wa y, the company has collected various awards, including the 2004 “Best General Contractor” by the construction trade association, Carolinas Associated General Contractors. “T.A. Loving makes you want to perform well for them,” noted one subcontractor in supporting Loving’s nomination that year. The company “has literally built itself into a small piece of American history,” noted a story in an N.C. State University publication about Raymond Bryan Sr. The Country Club of North Carolina in Pinehurst in the early 1960s was the first of a coming genre of golf course communities by offering a golf course, residences and a variety of recreational amenities within a gated community, and its founding members were among the movers and shakers in the North Carolina business community. That they would hire

T.A. Loving Company to handle the roads and sewer construction was a feather in the company’s hat. Company President Raymond Bryan Jr. joined the club and built a home along the sixteenth hole of the Dogwood Course that remains in the family today.

“They have an excellent reputation for this type of work, gained over a long period of years, and we know they will do the job as well or better than anyone else we could get,” James Poyner, a Raleigh attorney and founding partner of the club, said in a letter to the investor group in December 1962. “They are large enough to do the job quickly and are giving us a completion date of June 1.”

Engineering News-Record magazine in 1983 listed the company among the top 400 construction companies in the United States, and T.A. Loving appeared regularly beginning in the 1980s when Arthur Andersen & Co. and Business North Carolina magazine began publishing a list called The North Carolina 100 comprised of the state’s largest companies. T.A. Loving was included in the under $50 million sales category in 1986 and was still there in 2021 in

the $100 to $199 million sales category.

The Department of the Army Corps of Engineers presented the company with an Outstanding Service Evaluation in 1991 in a trestle replacement project on the Military Ocean Terminal at Sunny Point in Brunswick County.

“The efforts of your personnel resulted

in overcoming the challenges presented to us during Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm,” the contracting officer said in a letter to Sam Hunter.

“This company is very respected within the industry,” says Bob Ferguson, a senior vice president and decades-long veteran in the construction business. “T.A. Loving

does what it says it’s going to do. There’s not a lot of fanfare, not a lot of flash. We just keep doing what we’ve done for a century. That’s an honorable thing, and this is an honorable company.”

“If any of us are pitching a job, we don’t have to explain who T.A. Loving is,” adds Ty Edmondson. “They know who T.A. Loving is.”

Noah McDonald joined the company in 2007 and worked his way up to senior project manager and assistant vice-president.

“Sometimes I’ll tell someone I work in construction and they ask, ‘Who do you work for?’ I’ll say T.A. Loving, and people’s eyes get big and they say, ‘Wow, that’s a very respectable company, they’ve been around a long time,’” McDonald says. “The name certainly carries a lot of weight—certainly in North Carolina but beyond as well.”

Tony Robinson, a general superintendent in the Civil Infrastructure Plant Group, remembers going into a hardware store in Havelock one time and needing some supplies. T.A. Loving didn’t have an account there and he asked the store manager if he could set one up.

“The guy said not to worry about it,” Robinson says. “He knew T.A. Loving paid their creditors and said anything they had, I could take. That’s testimony to taking care of business and paying our bills. We don’t always make money on a job, but we try to give owners a good project.

“A hundred years is something to be proud of. You see a lot of construction companies not make it. You see some big

names out there that just faded out and went away.”

David Philyaw, who joined the company in 2004 and was Building Group president in 2023, was speaking to a group of East Carolina University students one time and was asked how big was the company and where does it work?

“Let me answer this way,” Philyaw said.

“There is a ninety-nine-percent chance you’ve either been in a building that we’ve built or been across a bridge that we built or drank water that came out of a pipe that we put in the ground. And not many companies can say that.”

the decade leading up to October 1929. The evolutionary arc of T.A. Loving Company mirrors that of many businesses and institutions in American history—it leaps out of the heady economic times of those rip-roaring 1920s; stumbles during The Great Depression but is nimble and resourceful enough to stay afloat while many of its competitors go under; gains its ballast and foothold during the postwar era of the late 1940s; and burnishes its core niches and explores new opportunities as they evolve over the ebbs and flows of the next half century into today.

They weren’t called “The Roaring Twenties” for nothing.

Many Americans used and owned automobiles, radios and telephones for the first time. North Carolinians prospered from the development of tobacco, textile and furniture operations. The first motion pictures were produced. Charles Lindberg crossed the Atlantic Ocean in an airplane. The stock market quadrupled in value over

“You’ve got to like construction and you’ve got to like to build things,” says Bob Ferguson, who grew up on a farm outside Concord. “You’ve got to like seeing people’s dreams become reality. And if those three things are part of your core values, if that’s a part of your nature, then T.A. Loving has been and remains today a great place to be.”

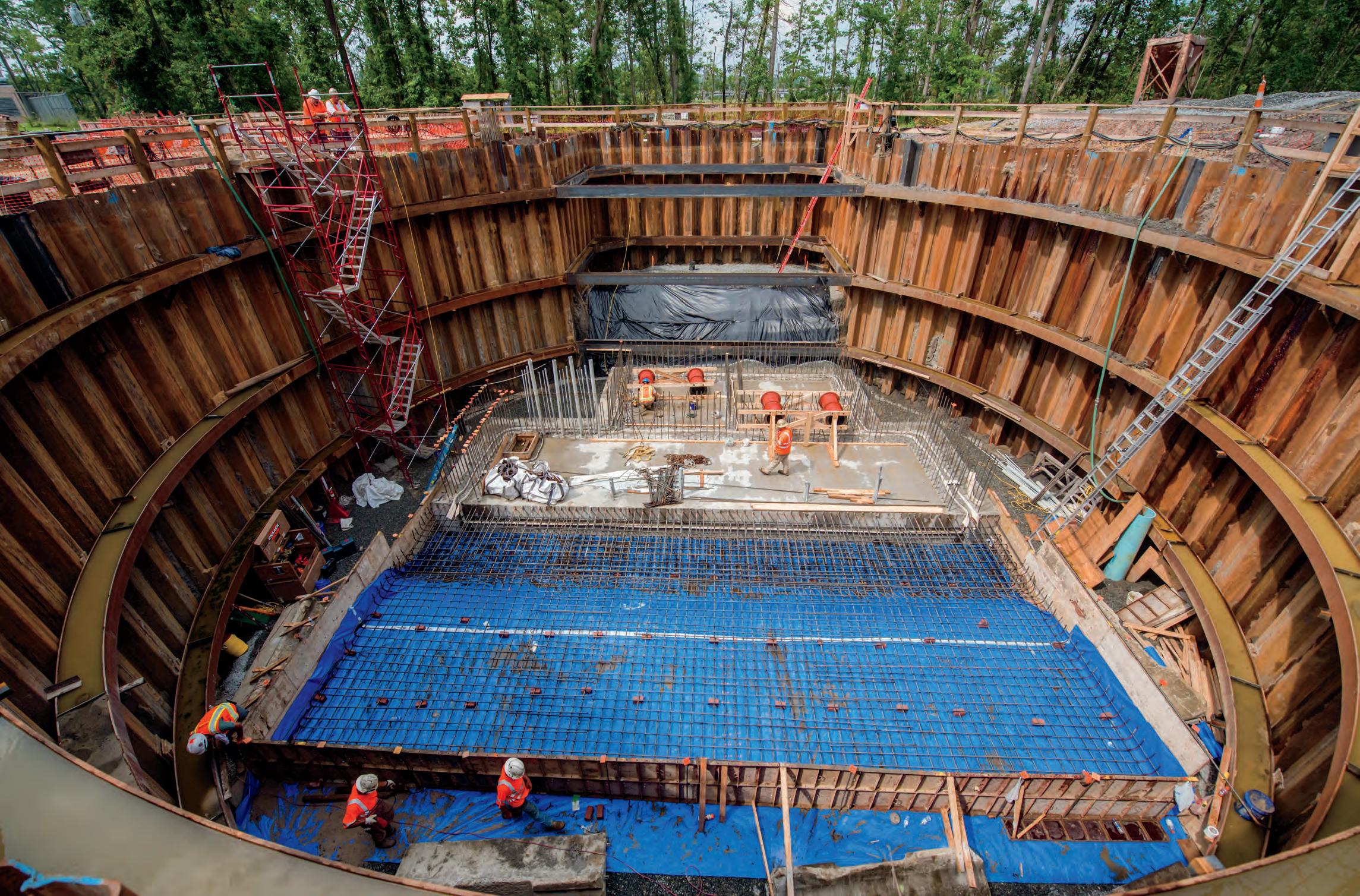

Ty Edmondson loves his work and the variety offered in working for a multifaceted construction firm because every day is different.

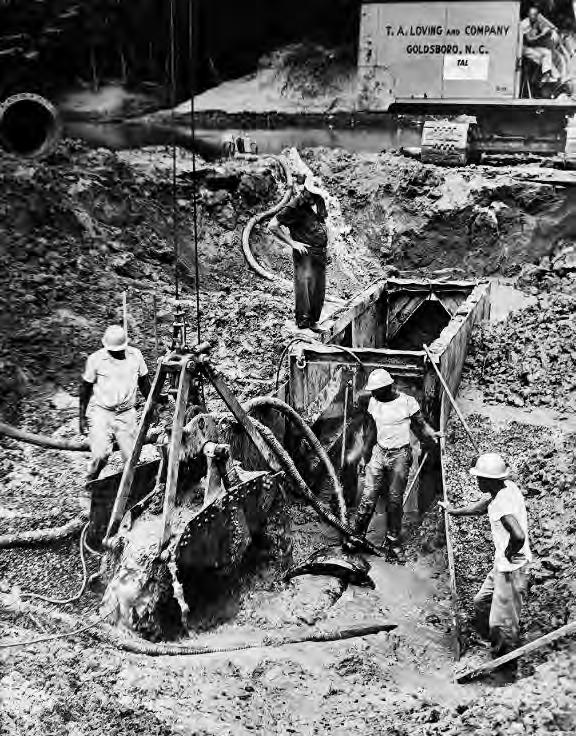

“It’s not like you show up at a factory

and we’re stamping out widgets today just like you did yesterday,” he says. “The thing about our business is we tend to go into the ground with a lot of our work, so there are all kinds of unknowns. You don’t know what to expect when you dig twenty feet for a sewer line or forty feet for a pump station. There are so many unknowns. What the soil conditions are and how wet it’s going to be are questions you have to answer every day.”

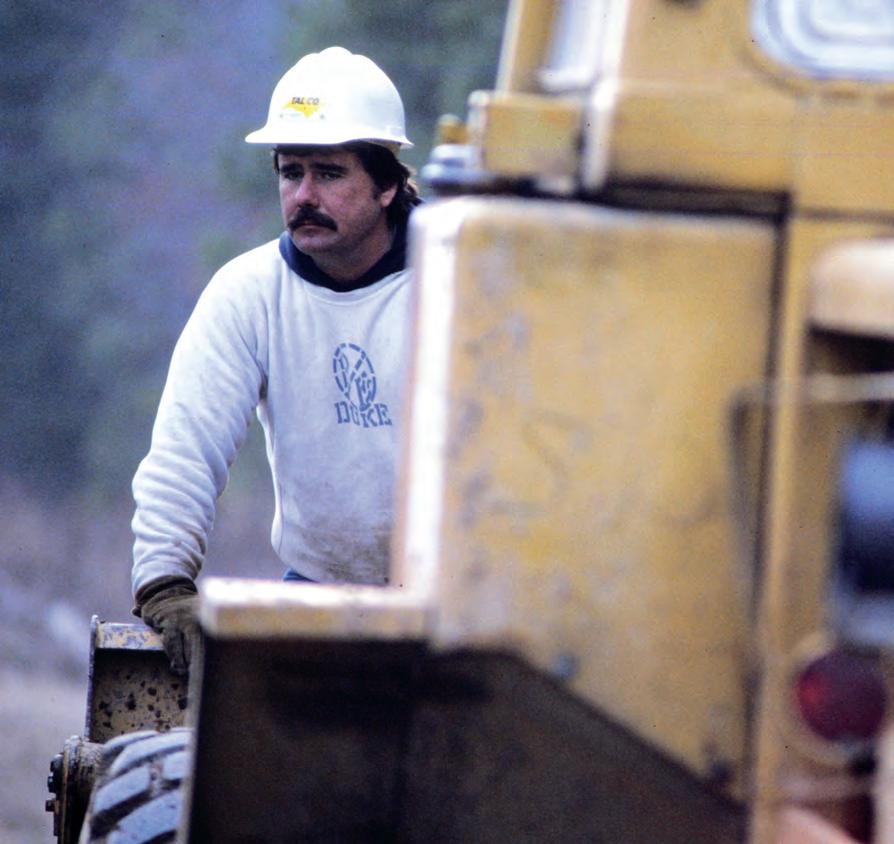

Times have certainly changed from the free-wheeling early days when there was little government regulation over construction safety. Paul Hunter remembers his baptism into the business in the early 1990s, working summers in college on a bridge project in Eastern North Carolina. Each morning he’d climb into a “man basket,” which allows workers to access areas they can’t get to from the ground or a ladder and are elevated and managed from a crane. One of the crane operators was named Lee Black; he was skilled at maneuvering the crane and had a playful sense of humor as well.

“Every morning he’d fly me up to the bridge cap and I’d do whatever work I had up there,” says Hunter, who worked as a foreman for seven years, then assistant

superintendent, superintendent, project manager and an estimator. “Then he would fly me up to the top of the boom and cut me free, basically letting me freefall two hundred feet all the way down to the water. Right when I was getting set to hit the water, he’d put the brakes on. I can tell you he did put my feet in the water many times over two summers.”

Hunter smiles and shakes his head.

“You’d probably go to jail if you got caught doing that now.”

Indeed, the safety element of the construction industry has evolved enormously over the last century. At one point on big jobs it was common practice for a contractor to include in its bid for the project the costs associated with a worker fatality.

“A hundred years ago, safety was not the first thing on everybody’s mind,” says David Philyaw. “It was about production and getting things done. Casualties were accepted to some degree. That doesn’t make it right, but that’s the way it was. It was dangerous work, and someone might get hurt or killed.”

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration Act of 1970 provided

employees and their representatives the right to file a complaint and request an OSHA inspection of their workplace if they believed there was a serious hazard or their employer was not following OSHA standards.

“At T.A. Loving, we implemented a safety policy before OSHA became the law,” Philyaw adds. “We were ahead of the curve.”

The p hysical challenge is part of the job as well. After all, you’re outside pushing, pulling, lifting and digging in every condition imaginable. Stephen Salter grew up in Sunbury, a small town in Gates County near the coast, and was an avid outdoorsman. The prospect of working around water was appealing when he joined T.A. Loving in November 1993, and his first day on the job was working at the Wright Memorial Bridge in Currituck County.

“I like to froze to death,” he says. “I grew up in the country and did a lot of hunting and a lot of fishing, and I always thought I was prepared for the weather. I remember being out there early in the morning and already being cold and I thought to myself, ‘This will never happen again. I’ll be prepared.’

T. A. LOVING COMPANY • 100 YEARS

work or no

is the

“The weather’s the hard part, dealing with the heat, dealing with the cold. It’s July and it’s a hundred degrees and ninetyfive percent humidity, that’s tough. Same thing in the winter. It’s February and the wind’s blowing twenty-five miles an hour and raining every thirty minutes. That’s a tough environment to be in. I remember one time having to break ice to get to a tugboat. But every job has its hardships. You just figure it out and work through it.”

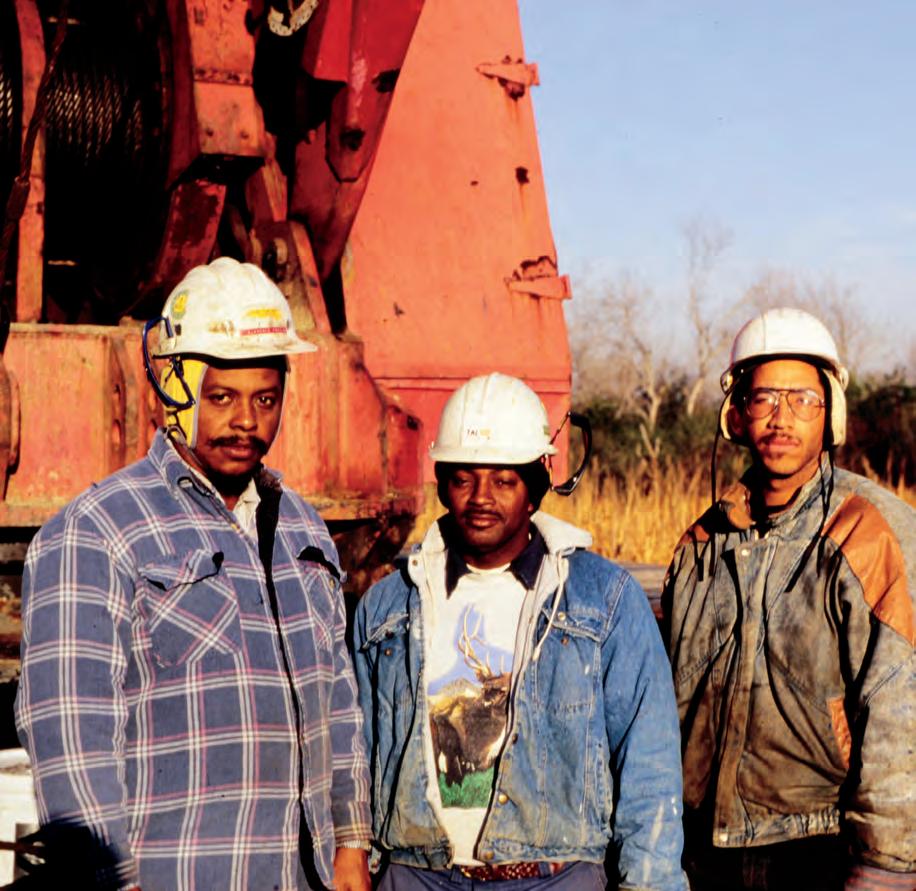

Tony, Edgar and Timmy Humphrey have worked collectively nearly 155 years for T.A. Loving Company, and the brothers have seen it and done it all. They have dodged alligators while replacing sewer lines in Wilmington. They have dug a tunnel by hand-shovel under a railroad track near Echo Farms outside Wilmington. They have crawled through a tunnel in Kinston and scraped out dirt two feet beyond a boring pipe, thrown the dirt on a wagon, wheeled it out by rope and repeated the process over and over.

“It’s hard to find people who really want to work hard now,” Edgar says. “They want the job but really don’t want to get out and sweat. Any construction work is

physical work. It can be hard, but it’s how you make it.”

Another of Paul Hunter’s early assignments as a part-time summer employee was in 1992 working in Wilson on the NovoPharm Pharmaceutical plant on top of a black rubber membrane roof of a 250,000 square-foot building.

“That broke me quickly working on a roof,” he says. “I worked the whole summer on that roof, and two days before I left, they cut the air conditioning system on. It was like forty degrees cooler instantly with the draft coming through the intake penthouses.”

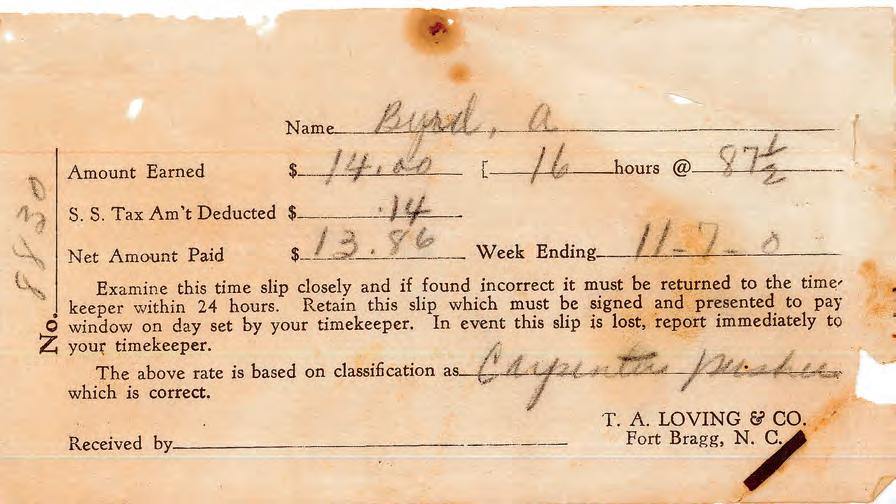

Technology has certainly evolved over a century. The company employed so many men building Fort Bragg in Fayetteville leading into World War II that banks couldn’t handle the payroll transactions and job administrators had to work with cases full of cash—necessitating aroundthe-clock security. Company archives include reams of yellowed paper with handwritten job estimates that in later years were produced on manual typewriters, then electric machines and later computers.

Jerry Smith proudly points to where he

used to have thick calluses on two fingers of his right hand.

“They use computers toda y, but we wrote our estimates and bids out longhand,” he says. “We submitted our bids manually. I enjoyed the excitement of putting something together—getting a set of plans and a spec book, reading it and going out and looking at the job, coming back and putting a bid together, hearing your name called at the bid opening, then doing the job and seeing it turn out well. There was excitement in preparing a bid, submitting it and waiting for the bid opening. You’d go there not knowing if you got it. There might be ten other people bidding on it. It was exciting to put two weeks of work in and then win the bid.

“Today it’s different because everything is done electronically. It’s high-tech to bid for a job. Most places won’t accept paperwork. You’ve got to email it to them or send it to them electronically.”

Ferguson observes the contrast in “older people in the business, me being one of them” to the newer generation contractor, engineer and architect. “We could take a blueprint and see the building

evolve mentally,” Ferguson says. “We could see pictures in our head. We could close our eyes and actually see what it was supposed to look like. Over time, I would be interviewing people to work for me and they didn’t seem to be able to do that.”

The advent in the early 2000s of BIM (Building Information Modeling) has changed the industry everywhere. BIM is a term that has become ubiquitous in the design and construction fields as it integrates multi-disciplinary data to create detailed digital representations that are managed in an open cloud platform for real-time collaboration.

“Today people can cut slices through the building, they can cut them in half, they can look at 3D pictures of it, they can roll it and turn it and look at it from the foundations in the ground to up on the roof to where the equipment is placed,” Ferguson says. “It has just been a fascinating evolution to watch.”

Jason Arnold, senior vice president for field operations, views it as a compliment that Procore, a Carpinteria, Californiabased software company, has used input from T.A. Loving officials in developing

its industry standard platform that allows construction executives to manage every aspect of a job from one application.

“We’ve got a ten-year relationship with them and they consult with us on best practices,” Arnold says. “They use our guys in the field to help develop software for the global construction industry. That speaks volumes to have a partner like that who recognizes our company as a formidable contractor.”

keeps them moving and keeps them paid.”

“One time, jobs were slack, so they had us cleaning up the office yard until something else came along,” adds Timmy Humphrey. “They try to keep you on and not lay people off.”

Jerry Smith remembers the company Christmas dinner in 2021, looking around the room and marveling at all the years and decades represented at the gathering.

Certainly the singular thread that has run through T.A. Loving Company from its inception is a culture of nurturing employees, giving them structure and opportunity and developing a close-knit, family atmosphere.

“Taking care of your people has been the biggest asset,” Stephen Salter says. “You know your check is coming. T.A. Loving has done a good job over the years keeping people working. A lot of companies will lay someone off when a job is finished, and it might be a while until the next one. T.A. Loving finds things for people to do and

“I was with the company forty-eight years, and there were people there who’d been there fifty or more,” Smith says. “The company wouldn’t have lasted so long if not for the people. I feel lucky being one of them, and that’s why I keep coming back here.”

Noah McDonald has a grandmother whose second husband was the son of a T.A. Loving employee dating back to the Fort Bragg project days in the early 1940s. His mother and aunt were going through some old boxes of memorabilia handed down through the family and found four old pay stubs made out to Arthur Byrd.

One stub showed Byrd earning $32.29 gross for 31.5 hours at $1.0205 per hour.

With thirty-two cents deducted for Social Security, he took home $31.97 for his work

“I feel like I ha ve relationships with people at T.A. Loving. That is different from an employee-employer arrangement All the really big companies have employeeemployer arrangements It’s not that way at T.A. Loving.”

That attitude manifests itself in everyday personnel decisions. Paul Hunter in early 2022 discussed a worker he’d hired the previous week.

as a “carpenter’s pusher.”

“I couldn’t believe that,” McDonald says. “Here I’m a T.A. Loving employee today and in our family are these pay stubs from the 1940s. That’s a pretty neat piece of history.”

Ferguson retired from the construction industry in 2016 but came back in 2019 and joined T.A. Loving. After a career spent with a handful of firms with national and even international reach, it would take a special opportunity to lure him back.

“T.A Loving is really in the people business, and if you take care of your people, your people will take care of you,” he says.

“And that’s what is attractive about T.A. Loving. We call it the construction business, but we’re really in the people business. It’s about growing and developing and nurturing people. And if growing and developing and nurturing people is rewarding to you personally and you like to build things, it’s one of the best places there is to be. And that’s really what it’s all about.

“I truly believe that guy can be a good laborer if that’s what he wants to do, but I also believe he has the chance to run the company one day,” Hunter says. “Nobody is holding anybody back around here, and I want to see people grow and be successful. It’s important to provide an environment for people to grow.”

Jason Arnold remembers from his job interview in 2006 that “culture is a big deal” with the company and in his early forties in 2022 had enough experience and clout he viewed his job partly as a mentor to younger employees coming along.

“Everyone is focused on grooming the next generation of builders,” Arnold says. “We’ve got a lot of really sharp, young talent and I just want to make sure that we

let them know that they can be plugged in wherever they want to be plugged in and I’m a conduit to help them.”

“By and large, my time and Ty’s time is spent making sure our people are in good shape and enjoying what they are doing,” David Philyaw says. “We help them resolve problems when they need it, but mostly our job is to empower everyone to make good decisions and run a project like it’s your business.”

Adds Edmondson, “We want every person here to be the best they can be. If you are a laborer and that’s what you aspire to, we want you to be the best laborer in the company. If you want to move up through the ranks, that opportunity is there. We have a strong entrepreneurial culture here. If you want to pursue a particular type of job or a particular type of market, if you come up with a plan that makes sense, we’ll support you. That’s powerful in an organization where people have that freedom.”

Madison Bryan Everett, daughter of company Vice Chairman Steve Bryan, joined the company in 2017 and directs the Bryan Foundation’s community outreach efforts. She remembers doing her homework as a

schoolgirl at the front reception station.

“I alwa ys felt comfortable hanging around the office,” she says. “People tell me all the time, ‘I remember when you were little and came around the office.’ I guess I’m all grown up now. But the family feeling is still strong. You see fathers and sons and grandsons having worked here. I love that aspect of T.A. Loving.”

established niches and the ability to pivot into an array of jobs, large and small. And it has an abiding culture of being a good place to work.

So you’ve made it safely to the milestone of one hundred years. One century. What’s next?

That’s a question that looms in the minds of company executives on a daily basis.

“I’ve had people ask me, ‘Well, what is the company going to do?’” David Philyaw says. “Are they going to get to a hundred and that will be enough? Absolutely not. Nobody believes that’s enough. I want T.A. Loving to be here another 100 years, and I know Sam and Ty and Steve and everybody wants the same thing.”

Many factors bode well for the company’s future. It’s positioned in a state with a healthy economic climate. It has well-

“Your history is a guide,” Edmondson says. “Our history is very rich. It shows you how you got this far. But you can’t get complacent. We want to maintain that opportunity for everyone to be able to excel. This company is a shining star, a North Star, if you will. It takes effort and work and continual improvement to maintain that culture. It’s more than a revenue goal. We want to be a good place for good people to work.”

Being nimble helps. T.A. Loving has the personnel to handle many projects inhouse but can easily draw from a network of subcontractors depending on the job.

Paul Hunter notes the Civil Infrastructure Group has the expertise and manpower to “self-perform” any project.

“We’re proud of that,” he says. “If our subcontractors were to fail or something was to go wrong, we’ve got guys who can step in and do just about anything.”

Philyaw adds: “We are self-performing, so we have our own labor and equipment. We’re

unicorns that way. Most of the companies we compete against don’t do any self-performing work. Very few companies can mobilize the kind of equipment like we can.”

Hunter notes that thousands of towns laid their first water and sewer systems in the first half of the twentieth century and many will be circling back for help.

“That’s hundred-year-old stuff and it’s not going to last much longer,” he says.

“That applies across the country. I think that’s a great opportunity. We’ve done a lot of storm repair over the years, particularly from all the hurricanes of the 1990s and

early 2000s. We know what it’s like when you don’t have water.”

T.A. Loving in 2022 maintained three offices—its headquarters in Goldsboro and satellite offices in Raleigh and Wilmington.

And there is a lot to monitor as the economic development dominoes were falling at a rapid and eye-popping pace across the Piedmont area and Eastern North Carolina in 2021 and into 2022.

Fujifilm/Diosynth Biotechnologies announced in March 2021 it would invest $2 billion and create 725 jobs with a cell culture manufacturing facility in Holly Springs.

Apple announced in August 2021 it would spend $552 million to establish a campus in Research Triangle Park and create at least three thousand jobs.

Toyota Motors in December revealed plans for a $1.29 billion automotive battery manufacturing plant in the town of Liberty as part of its Greensboro-Randoph “mega site.”

Boom Supersonic released its vision in January 2022 to build supersonic airliners at a plant it would build at Piedmont Triad International Airport outside of Greensboro as part of a $500 million investment.

A nd Amgen, one of the world’s leading biotechnology companies, broke ground in March 2022 on a $550 million manufacturing facility in Holly Springs.

“Think of it—Apple is coming to the Research Triangle. That’s a tremendous win,” Ferguson says. “North Carolina has the labor. We have the transportation. And we have a wonderful climate. We have four seasons, and none of them are harsh. North Carolina is a great place to live. T.A. Loving Company is well-positioned to take advantage of it.”

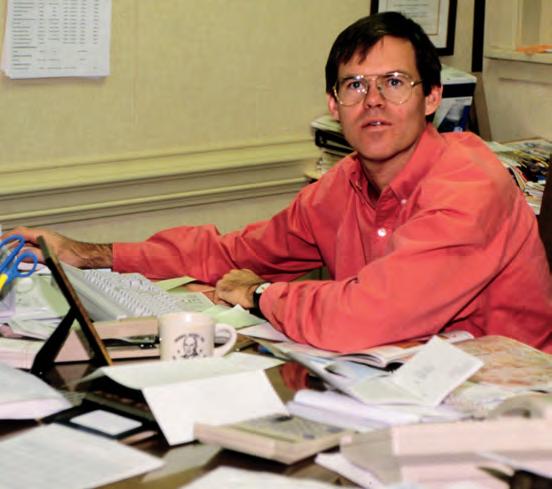

Ferguson sits in his Raleigh office in

March 2022, knowing in several years he’ll help appoint someone to take that spot.

“ The people are the most important thing because the clients buy the people,” he says. “Your clients buy the people because the people provide the service. And so I think the organic growth comes from them finding those people. The internal makeup of the person who sits in this chair is important—a T.A. Loving kind of person.”

With $200 million in revenues in the fiscal year 2022, T.A. Loving Company has the girth to accommodate a large range of jobs. But it’s not so big that it has to worry about managing more people and infrastructure than it can handle by going around the world competing for work. Philyaw sometimes refers to T.A. Loving as being a “boutique company.”

“That rings true,” Jason Arnold says. “We can go build a small job for Chatham County and it means something for both parties, or we can put the next hundred million dollar student center on a college campus and that

stands up on a national level.”

Ferguson adds: “This company is in a nice place where they are. They are a lot bigger than the smaller band of contractors and they are a lot smaller than the guys that are doing the five hundred million and the billion dollar jobs. They fall in this middle band, and there’s a good bit of room in that middle band.”

T.A. Loving Company, its leaders and employees will continue into their second century building bridges, repairing water mains at 2 a.m. and melding the latest construction management technology with age-old techniques, a plumb bob at the ready. “It’s a great day to be in construction,” says Ty Edmondson.

“A lot of times people lose sight of the work we do and how critical it is and the opportunities there,” Ty Edmondson says.

“That phrase is an optimistic way to look at what we do and the many challenges we have every year.”

It was appropriate that in July 2023,

ninety-eight years after the company’s launch, that brothers T.A. and John Loving would be inducted as Legacy Members into the Carolinas Associated General Contractors Hall of Fame during ceremonies at the Grove Park Inn in Asheville. They joined fellow company officials Raymond Bryan Sr. and Sam Hunter, who had been inducted earlier (Hunter in 2017 and Bryan in 2020).

“ I wish my father and uncle T.A. could have known that their work would be so respected and acknowledged by this remarkable gathering,” Ann Hunter said in accepting the awards. “They would be so proud to know that T.A. Loving Company for almost a century has provided employment for so many generations of families, where brothers, fathers, sons and daughters have found meaningful, rewarding careers. A sense of family persists even today.”

Added Paul Hunter: “They left a lasting mark across our great state as well as this country.”

The town of Culpeper, Virginia, was chartered in 1759 and named for Lord Thomas Culpeper, the Colonial governor from the 1680s, and described in an early document as occupying “a high and pleasant situation” amidst rolling hills and rivers to the northern and southern boundaries, roughly equidistant from Richmond to the south and Washington to the northeast. A young George Washington was commissioned as county surveyor and laid out a twenty-seven acre courthouse village complex with a jail, stocks, gallows and accessory buildings.

The town was a hot spot during both the American Revolution and the Civil War.

A group of residents organized themselves into the Culpeper Minutemen Battalion and rallied under a flag depicting a snake with thirteen rattles and the motto “Liberty or Death—Don’t Tread on Me.” Nearly a century later, the town’s strategic railroad location made it a significant supply station for Confederate and Union troops, and there were more than one hundred battles and skirmishes in the area.

Thomas Loving came to Virginia from England in 1635 with a party of sixty immigrants, and eventually some of his descendants settled in Culpeper, among them the family of Joseph Baker Loving and his wife, Lula Shadrach Loving. Joseph graduated from Richmond College and was an itinerant teacher and traveled on horseback around the Virginia countryside to visit one-room schoolhouses, and Lula was a music and piano teacher. They had six children, with Taylor Abbitt the second oldest being born in 1899 and John Shadrach the next to youngest following in 1907.

The thread that connects the Loving brothers to Goldsboro and T.A. Loving

Company a century later is Ann Loving Hunter, the daughter of John and the wife of Sam Hunter, a career-long T.A. Loving employee who was named president and CEO in 1990. “My grandfather being a school teacher, education was certainly emphasized in the home,” she says. “I know that T.A. did go to the University of Virginia for a short time and had mediocre grades and did not finish, he did not graduate. But T.A. just had this capacity to get organized, to get people to work and get things to happen and make things work out. He was a natural businessman.

“Now, my Daddy was very smart. He excelled in math and physics, and Latin, of all things. Daddy was next to the youngest, and both parents died while he was in high school. There was no money for him to go to college. So he never had the opportunity to further his education.”

But this team of brothers—T.A. with the ability “to get things done” and John with an innate feel for math and science—would combine over the years to build one of the South’s foremost construction firms.

In later years, a newspaper noted T.A.’s early experiences around Culpeper building

a barn and bridges, and Ann remembers him building a house for his sister. The 1910 census listed T.A. as a “laborer” on his family’s farm, and at nineteen he listed “farming” as his occupation on his World War I draft registration card.

“Taylor, when a boy in his early teens, built a barn on his father’s farm and as a young man was employed by the county of Culpeper to build bridges over some of the many open streams which cross the county roads,” the newspaper noted.

T.A. worked his way south from Culpeper by building houses and barns, and he was twenty-six when he ventured to Goldsboro and went to work with a local contractor who was constructing bridges, apparently his first assignment to work on a bridge across the railroad tracks between Pikeville and Fremont.

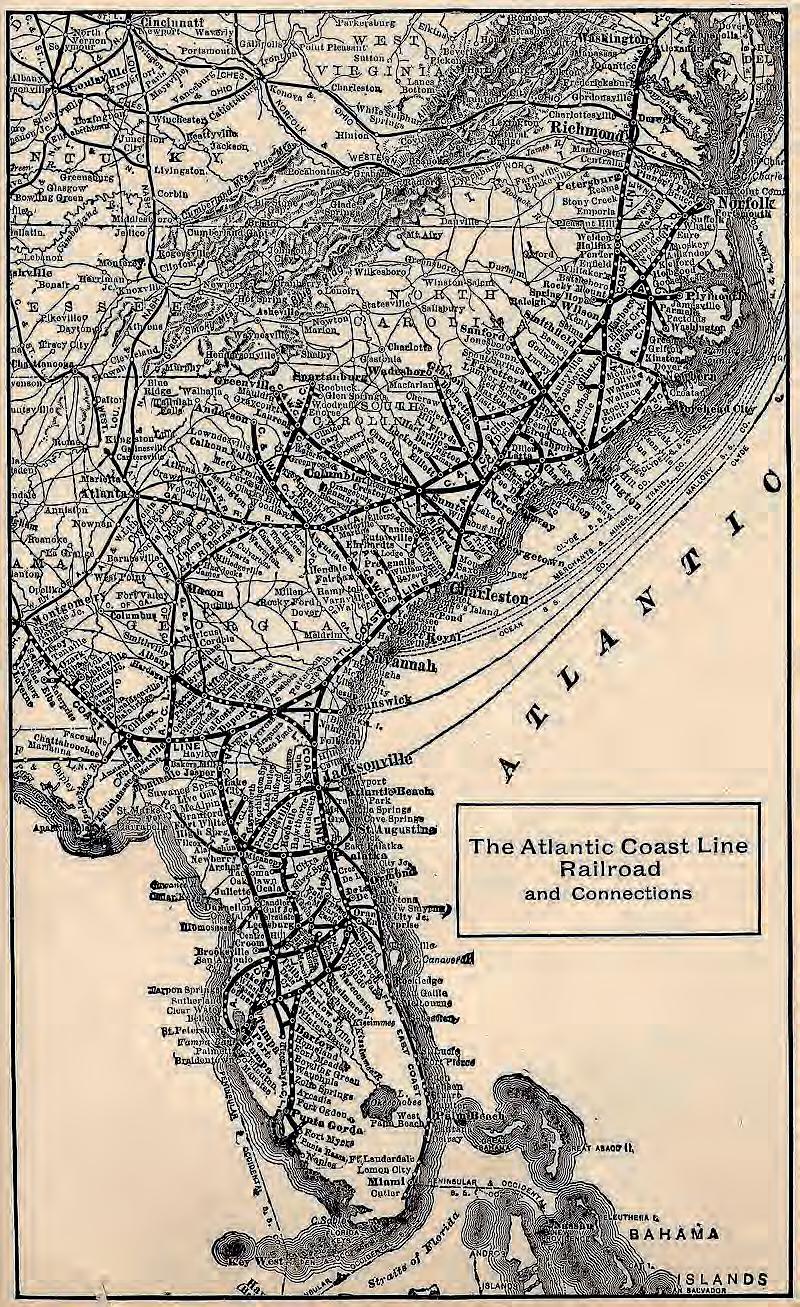

The town that would become Goldsboro was originally called Goldsborough and named after Major Matthew T. Goldsborough, an assistant chief engineer for the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad that was completed in the early 1840s. Goldsboro was incorporated in 1847, and the town grew around the intersection of the railroad and

New Bern Road. There was opportunity for an enterprising young construction worker, and Loving took his initial venture into the town and established his own company in 1925 as a sole proprietorship. He hired his nineteen-year-old brother as his chief associate.

The infant compan y’s niche was underlined in June 1926 when it won a bid for a bridge in Rockingham County.

The North Carolina Highway Commission entertained bids on fifteen projects, most of them road work, with the biggest job going to Nello Teer Company of Durham for $125,000 for fourteen miles of highway between Windsor and the Chowan Bridge in Bertie County. There was one bridge project, and T.A. Loving got the job—$36,000 for what was projected to be a ninety-five day project.

“From his first bridge job, he went on to another, then another,” said an early 1940s early newspaper story. “Assistants were added, an office opened and in the course of a few years the business was booming.”

Another early job came in April 1928 when the company secured a contract to repair a bridge for the Seaboard Air Line

Railroad across the Savannah River just west of Calhoun Falls, South Carolina. The bridge was the first permanent railroad crossing of the Savannah River north of Augusta and played a critical role in the shipment of granite from the newly founded granite industry in the town of Elberton, Georgia, just to the west. The Seaboard railroad was originally built in 1890 and modified in 1909. T.A. Loving Company’s work included adding one concrete pier, raising two granite piers to the 1909 track level and setting a pair of eighty-nine foot plate girders.

The company was retained by the Richmond Bridge Corporation in February 1933 for a modern iteration of an 1890 viaduct structure known as the Fifth Street Viaduct in Richmond. The bridge consisted of seven double-span rigid frames and crossed a stream known as Bacon’s Quarter Branch and connected downtown Richmond to some burgeoning residential areas. Work began in mid-May with more than one hundred skilled and unskilled workers and was completed in December. The job site was the scene of some late-night hijinks in June when a car laden with jugs of

whiskey was attempting to elude the police force. The driver, his lights extinguished, didn’t realize that the original bridge was no longer operable, attempted to drive over it and just missed plunging 150 feet to a certain death; he was saved by the fact that his axles dragged on wooden cross beams before he could tumble over.

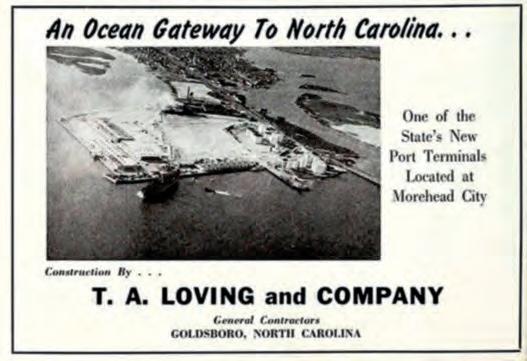

The company benefited from the Works Progress Administration during the depths of The Depression in the 1930s. The State magazine noted in October 1935 that WPA allotments for North Carolina had reached $2 million and would provide work for some 50,000 individuals. One of those was for construction of port terminals in Morehead City. T.A. Loving’s bid of $375,000 secured the job. “The new port will bring additional prosperity to North Carolina,” the magazine noted.

An article in a Culpeper newspaper in January 1935 was headlined, “Local Boy Makes Good,” and goes on to detail new construction at William & Mary College in Williamsburg and that the job, which included administration and faculty offices and classrooms, was being managed by Loving’s company.

“The fact that a Culpeper boy is handling this important construction work is a source of interest to his many friends in this town,” the story said.

T.A. and John married sisters, T.A. wedding Allene Crews and John taking Frances Crews as his bride. T.A. had just built a nice house for him and Allene in Goldsboro when she died of cancer in 1933 at the age of twenty-six.

“I remember T.A. being big and tall,” Ann says. “He was bald with little round glasses. He was very outgoing, he had a booming voice and he laughed a lot. He always had on a white shirt.

“Daddy always looked rumpled because he was working all the time. His hat was always bent, and he had on overalls and he just looked like he came off the job site. He always looked like he needed a haircut. But as he grew older, he became very precise about looking nice. He was probably sixtyfive when he organized a high school class reunion, and they took a group photo. He was the best-dressed and the most handsome one in the picture. He was healthy because he was physically active in the construction business all his life.

“He never aspired to work from an office. He wanted to be out on the job, where his crane operators, pile drivers, tugboat operators and laborers were among his treasured friends.”

The y oung company had to survive The Great Depression, and simply doing so beckoned well for the niche it had created and the company’s leadership. Ann remembers her father telling the story of going to West Virginia to build a bridge in the early 1930s and making a $3,000 profit.

“That money kept the company going,” she says. “As Daddy told it, they were about to go bust.”

It took guile and sweat and persuasion to survive those times. The company was building a culvert in the mountains west of Asheville during the early 1930s.

“They were out in the country with no hotel, no restaurants or boarding houses,” remembers Giles Trimble, a longtime employee who was John Loving’s righthand man and senior vice president and Bridge Division manager. “They found a country home—some called it a ‘poor house’—nearby with available rooms. T.A. talked the management into allowing his

people to live there as room-and-boarders.”

Halfway through the project, a salesman from Virginia Steel arrived to collect payment for a long-overdue bill for a shipment of steel. Loving told him all payments from the state so far had been used for salaries and other materials and that he had no money. He had to press the salesman to convince his boss to send yet another railcar of steel to allow them to finish the job. The bill was eventually paid in full.

“The salesman later said that the hardest day in his life was going into the president’s office of Virginia Steel and requesting permission to ship the final railcar of steel,” Trimble said.

Other companies weren’t so fortunate, and the demise of one building contractor in Goldsboro would prove fortuitous for T.A. Loving Company. William P. Rose was an architect and contractor, erecting numerous courthouses, hospitals and schools across Central and Eastern North Carolina in the early 1900s. But in 1930 and ‘31, he suffered substantial losses, and the town took a hit with the closing of Peoples Bank of Goldsboro, of which he was a director.

Raymond A. Bryan was born in Newton

Grove in 1899 and studied engineering at N.C. State University for two years in the late 1910s before entering the workforce with W.P. Rose Construction. He was thirtytwo years old in 1931 when Rose’s company went into receivership and Bryan lost his job. Bryan and Loving lived across from one another on Pine Street in Goldsboro, so it’s likely that them being neighbors prompted Loving to suggest that Bryan come to work for him.

“I was seven or eight years old in the late thirties when T.A. Loving’s house was being built,” Raymond Bryan Jr. remembered years later. “I ran a little drink stand and had a captive audience right across the street selling drinks to all the workmen.” Bryan was an ideal fit for Lo ving’s business and within four years worked his way up to being named general manager of the building division.

While T .A. lived and worked in Goldsboro, he maintained his Virginia roots by owning and operating a cattle farm in Swoope, Virginia, about thirty-five miles west of Charlottesville. John liked what he saw in T.A.’s farm and bought a farm himself in Fishersville, about ten

miles toward Charlottesville from Swoope.

John and Frances got married in 1942, and in March 1944 the couple gave birth to Ann, the first of three children. John’s allegiance to his life in Virginia would

become established early.

“Daddy was happy farming, raising cattle, riding horses, planting, harvesting, keeping bees, and for a time, he gave up working for T.A.,” Ann says. “He did one bridge project in New York for another company. He stayed at home with my mom and me. But then T.A. talked him into coming back to build bridges.”

John traveled around the South—to Selma, Alabama, to build the Edmund Pettus Bridge and to Daytona, Florida, to supervise the Seabreeze Bridge and Port Orange Bridge.

“Until I started the first grade, we were all over the place,” Ann says. “It was fun to me. I liked moving around and I liked riding the train to Florida. It was great. But then my sister came and I think Mama was pregnant with her third child, and they decided they were going to settle down back in Virginia. We went back to the farmhouse and that was home from then on.”

From 1925 to 1932, the compan y focused on bridge, highway and heavy construction. In 1932, it expanded into monumental, industrial, educational and housing construction of all types, according

to an early brochure, with operations in the Carolinas, West Virginia, Virginia, Alabama, Georgia and Florida. An early newspaper advertisement said, “For the big jobs, T.A. Loving and Company often get the bid.”

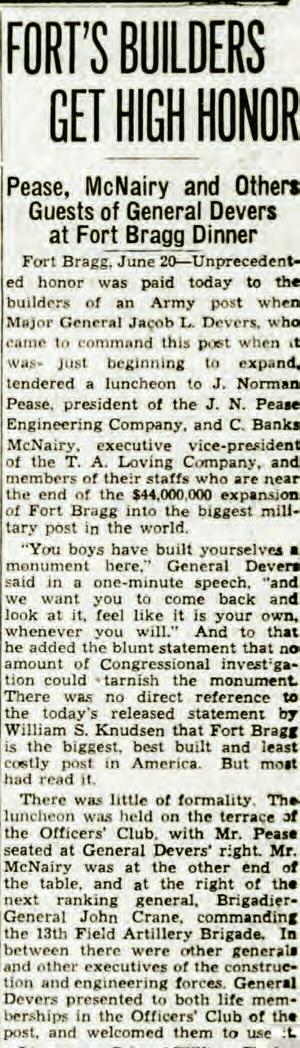

Charles Banks McNairy Jr. was another W.P. Rose Construction Co. employee who lost his job in 1931 and came to work for T.A. Loving. McNairy graduated from Kinston High, went on to the University of North Carolina and proved his mettle in the 1930s so much with Loving that he was tabbed in 1940 to be the wartime project manager for huge multi-million dollar military installations at Fort Bragg and Cherry Point.

His son, C. Banks McNairy III, joined the company in early 1948 and worked on jobs across the spectrum over forty-five years, eventually making vice president.

The business structure changed in 1937 as the company survived the bleak economic times and started to grow. It changed from a sole proprietorship into a corporation on Nov. 12, 1937, with T.A. Loving the president (owning 2,247 of 2,500 shares of stock), Bryan secretary/treasurer (183 shares) and McNairy vice president/assistant

secretary (seventy shares). John Loving was elected as a director and vice president on Nov. 24, effective the first day of 1938, and received seventy shares of stock as well. But he remained in Fishersville and set up an office for his headquarters.

“At one point, T.A. talked to Daddy about running the company,” Ann says.

“Daddy told him no, that he didn’t want to move to Goldsboro. He wanted to live in Virginia and wanted to keep building bridges. He considered Virginia home and quite honestly he was somewhere building a bridge all the time. He would just come to Goldsboro for stockholder meetings or company meetings.”

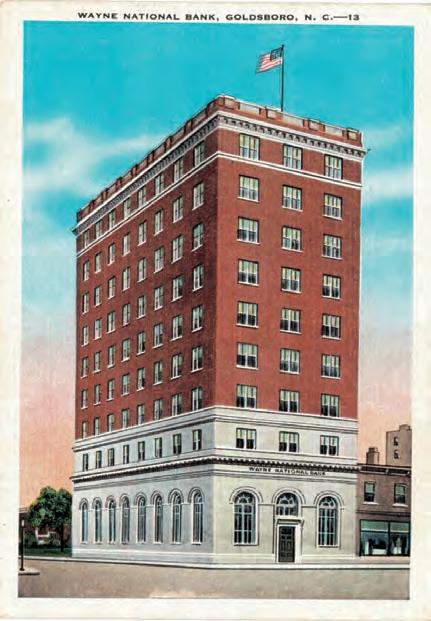

From 1931 to 1981, the company was headquartered in the Wayne National Bank Building, a nine-story structure that opened in 1924 at the corner of Walnut and James Streets in Goldsboro (it was later owned by Wachovia Bank). Hazel Allred Harmon followed Raymond Bryan from working for W.P. Rose Construction to T.A. Loving in 1931 and worked for the company for more than half a century.

“When we started out, there were three offices,” Hazel said in a 1983 interview. “Mr.

Bryan and Mr. Loving shared an office, two estimators shared another office, and I was the secretary/receptionist/bookkeeper with my office in between.”

By the mid-1950s, the company was occupying more than one half of the seventh floor, and it grew over time to take over the entire seventh floor and eventually moved onto the eighth floor as well. When the company went from typing payroll checks and processing handwritten payroll cards into the computer age, an elevator was constructed to get a National Cash Register Company mainframe computer up to the seventh floor. The company remained downtown until moving into its own headquarters on Patetown Road in April 1982.

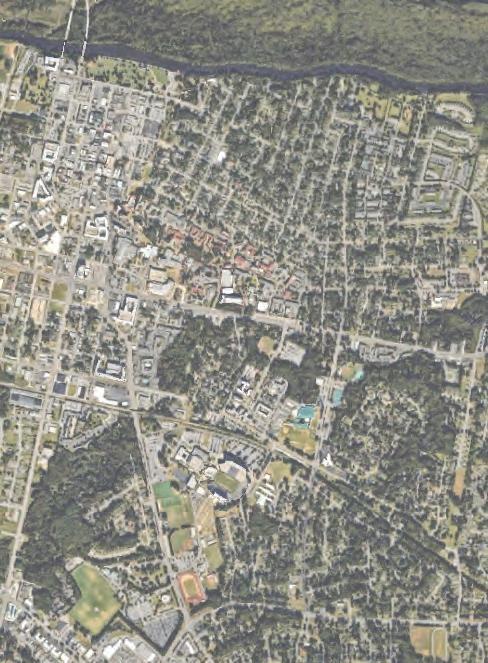

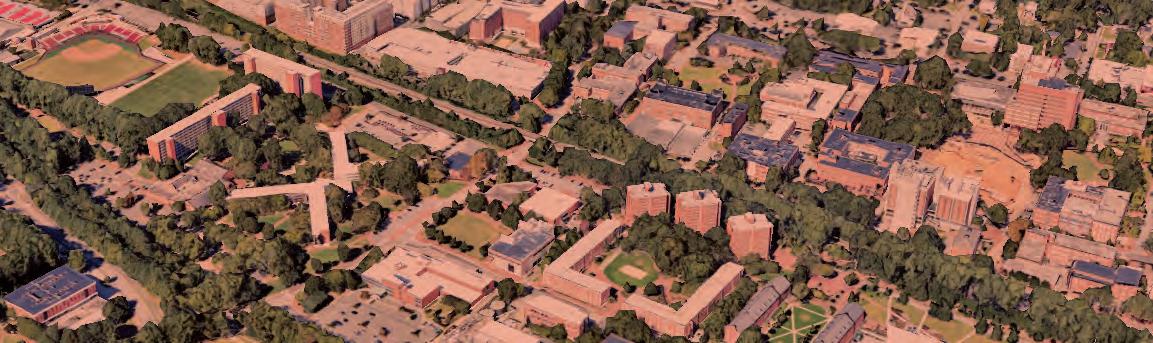

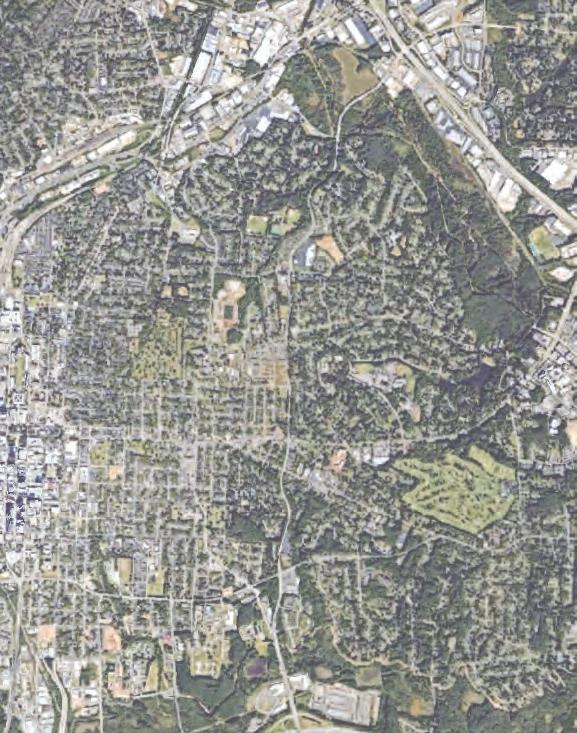

T.A. Loving Company first had a physical presence in Raleigh in the 1960s on Wolfpack Lane just northeast of downtown when it acquired a paving contactor named F.D. Cline Company. It maintained that office until the 1980s, when it sold the property. The company also maintained a satellite office on Airport Boulevard in Research Triangle Park in the early 2000s, primarily to service some major projects at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

The company’s business in the Triangle region continued to expand as the 2000s evolved, and in April 2019 the company opened an office on Glenwood Avenue in Raleigh. The new operation would serve as a hub for the company’s expanding portfolio of work throughout the Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill business, education and health care communities.

“Our ties to the Triangle have been strong for our entire company history spanning more than ninety years,” CEO Sam Hunter said upon the Raleigh office opening. “We take pride in producing quality construction projects that have become some of the area’s most recognizable landmarks—from the 1962 construction of Harrelson Hall at N.C. State to the Fayetteville Street renovation to the recently completed indoor football practice facility and soccer/lacrosse stadium at UNC. Our partnerships here are important to our business, and the new office allows us to better serve the daily needs of the Triangle market.”

There were more than 25,000 people on the payroll at one time during the early 1940s when the company was hired to build what was basically an entire city

for the United States military— barracks, roads, theaters, fire stations, hospitals and bridges at Fort Bragg in Fayetteville at a cost of $38 million. Other work included $585,772 on Albemarle Sound Bridge at Plymouth and $818,000 Garden Homes Estate in Savannah. The company also completed a $1.9 million defense housing project in Wilmington and $767,500 for administration buildings and barracks at naval air station in Jacksonville, Florida.

“Work was the great hobby of this builder, yet he carried his sense of humor and his pleasant personality into his most strenuous efforts,” the book North Carolina Roads and Their Builders noted of T.A. “Cross words had no part in his organization.”

Arthur Allred was typical of the kind of loyalty and longevity the company engendered. He started with T.A. Loving Company in 1932 driving a dump truck and mostly hauling gravel from sand pits near Fort Bragg. He made thirty-five cents a day. He served in the Army during World War II and then returned to Goldsboro and would work fifty-two years total for the company.

Not only was he a good employee, but he served the purpose of having the same blood

second wife, was elected to the board. The Building, Utility and Equipment Divisions were run out of Goldsboro, the Paving Division in Raleigh (it was sold in 1968) and Bridge Division in Fishersville.

Arthur Allred, W.E. Smith Jr., George Goodwin and Giles Trimble were among employees joining the company in the mid1900s and having served the company their entire careers.

type as T.A., who for much of his adult life suffered from an autoimmune disorder.

“My blood matched perfectly with his,”

Allred said. “We didn’t even have to put the blood in a bottle, we’d just go direct because our blood matched so perfectly. After the war, T.A. was in Miami and needed a transfusion.

Raymond said for me and my wife to get on the train and go down there. We drove his car back so he could ride the train.”

John was called “Captain John” by his workers and likewise had a devoted following.

“He was the nicest man you would ever meet

in a lifetime,” said Pete Jarrell, a long-time company employee. “He was a prince. He looked after his jobs. He went to his jobs. He saw what his men were doing.”

T.A. suffered from pernicious anemia and died at the young age of forty-seven in 1947, succumbing at University Hospital in Charlottesville following “several years of declining health,” according to a news report. When Loving died, Bryan was elected president in September 1947, John Loving was appointed vice president and McNairy secretary/treasurer. Ruth Loving, T.A.’s

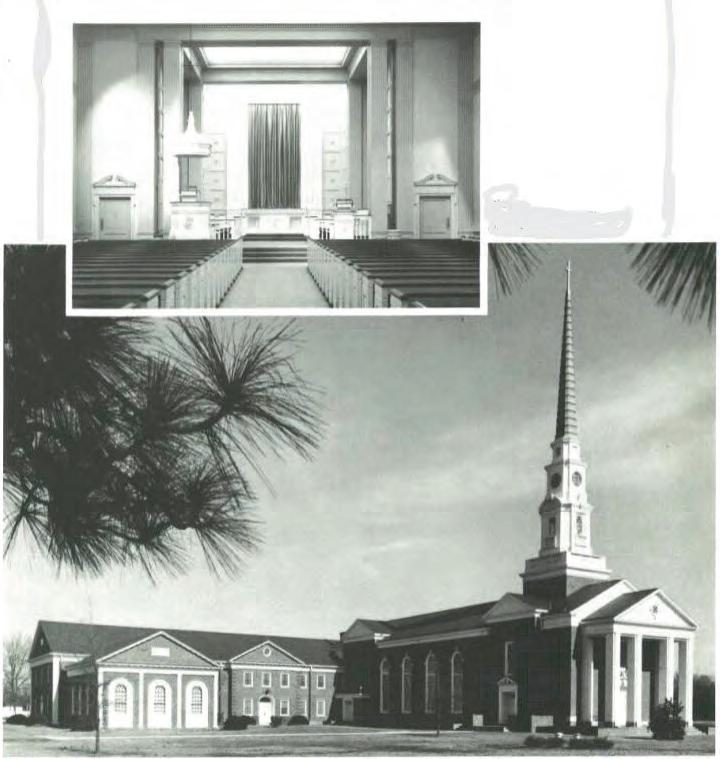

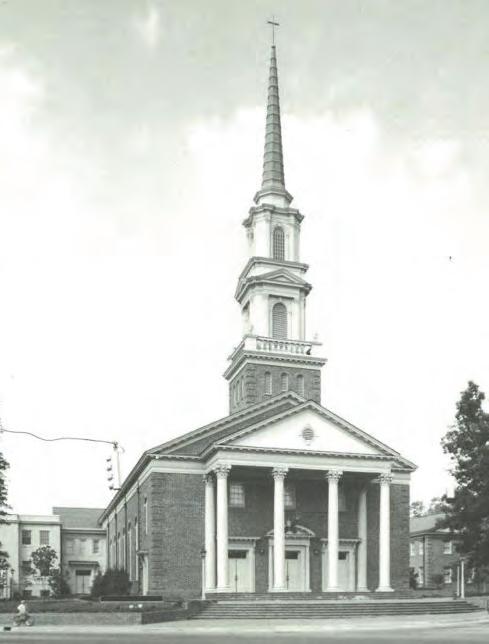

John Loving continued building bridges across the Carolinas, Virginia and beyond until settling into retirement in the 1980s. He and Frances continued to live in Fishersville, and one of his favorite projects in retirement was supervising the construction of an educational building at Tinkling Spring Presbyterian Church. Loving had served as an elder at the church, and when his wife died, he paid for a new pipe organ for the church sanctuary in her memory. Loving died in 1993 at the age of eighty-six.

“Every Sunday growing up we’d go to church,” Ann Hunter says. “Then we’d go out to lunch. It was his way of thanking Mama for all her hard work. Then he’d go pack his suitcase and head back out to build a bridge.”

T. A. LOVING COMPANY • 100 YEARS

T. A. LOVING COMPANY • 100 YEARS

The T.A. Loving Company name was adorned on equipment that traveled the state and the southeast. At left, workers in the mid-1900s are working on a wastewater treatment plant at the Neuse River Crossing near Goldsboro. The company’s more recent efforts to serve its hometown (opposite) are shown with an aerial view of the Center Street Improvement project in 2015.

Steve Bryan was about seven years old when he and his brother Ray “Buddy” Bryan III were playing in an upstairs bedroom in the family’s vacation house on Evans Street in Morehead City, just a block from Bogue Sound and a mile away from Atlantic Beach. They had fun watching from the window as tugboats flowed up and down the Intercoastal Waterway and passed through the drawbridge, and they’d use the crank mechanism on the window to mimic the opening and closing of the drawbridge.

One day they asked their grandfather, Raymond Bryan Sr., if they could walk down and get a closer look. Raymond was president of T.A Loving Company, which built the bridge in 1953 to replace the original bridge that opened in 1928.

“We walked down and my granddad introduced himself to the D.O.T. bridge guy and told him he worked for T.A. Loving, and he built that bridge,” Steve says. “‘These boys would like to hang out and watch you open the bridge,’ he said. So we went up those steps on that drawbridge and the man hit some buttons and the sirens went off and the gates went down. It was the coolest thing ever. I remember it like it was yesterday.”

The Bryan family heritage is full of stories like that, with four generations on the company payroll from Ray Sr. joining T.A. Loving in 1931 through today, with Steve in 2023 serving as vice chairman and his daughter Madison Bryan Everett joining the company in 2017 and working in several areas, most recently in corporate outreach and as Bryan Foundation associate.

“It’s hard to believe we’ve been around for a century,” Steve says. “I’ve heard the restaurant and construction businesses have

the highest failure rates. You see restaurants come and go. And if you’ve got a pick-up truck and a tool box, you can call yourself a contractor.”

“What has stood out to me is the overall sense of humbleness and generosity from my great grandfather, grandfather and father,” Madison adds. “I think that’s really special. What’s important to me is continuing that service to the community and the region that the Bryan family and T.A. Loving Company are known for.”

The Bryan family story begins in Newton Grove, a small town twenty miles southwest of Goldsboro originally chartered in 1879. James William and Irene Bryan both were school teachers and ran a farm, and their seven children born in the late 1800s were imbued with several core qualities that would serve them well.

“The children grew up with the advantage of having intellectual parents in a setting that demanded hard work tilling the soil before the advent of mechanization,” the Goldsboro News-Argus said upon the passing of Raymond Sr. in November 1982.

Raymond Sr. was born in 1899 and attended N.C. State University for two years

before going to work for W.P. Rose Company in Goldsboro in 1924. He lost his job during the early days of The Great Depression but quickly latched on with T.A. Loving, beginning as an estimator and in 1935 being named general manager of the Building Division with a salary of $250 a month, plus one-third of the profits from the division.

Though he lived in Goldsboro and worked out of the T.A. Loving headquarters, his reach extended to Raleigh in one direction and to the coast of North Carolina in the other.

James “Willie” York grew up as the son of a building contractor in Raleigh in the early 1900s and was building houses prior to World War II, but when the war began, the government restricted building materials for nonessential purposes and York closed his business. Bryan hired him to work for T.A. Loving, and in January 1942, Bryan sent York to Jacksonville to work as an expeditor on the expansion of the Marine Air Base at Cherry Point. Two years later, York supervised the construction of hundreds of small homes for servicemen in Jacksonville and in the process met Ed Richards of American Housing Company

and his architect, a transplanted Norwegian named Leif Valand. They were on the cutting edge of the prefabricated home building business, and York bought building kits from Richards and did extensive work in Morehead City.

After the war, York returned to Raleigh and resumed his home building business with Bryan as his partner, and they embarked on a project that would have a far-reaching impact on the evolution of the city. Bryan and York envisioned a mixed-use community modeled after Kansas City’s Country Club Plaza on 158 acres of former plantation land west of downtown. Valand provided the architectural plans in an “open-air shopping mall” concept that included sixtyfive retail stores, 112 offices, 466 apartment units and a hundred single-family homes. It was called Cameron Village and opened in 1949. It was Raleigh’s first master-planned community employing vertical integration where design, construction and property management were handled by an integrated vortex of ownership and management. Cameron Village Inc. was owned fortyfive percent by York, forty-five percent by Bryan and ten percent by James Poyner, a

The plumb bob has been a part of T.A. Loving Company’s corporate logo from the start. But what has changed over the years is the usage of “T.A. Loving” and “TALCO.”

For at least the first half century of its existence, company collateral, signage and advertising used the name of the man who founded the company in 1925, Taylor Abbitt Loving. But a company brochure from the 1980s had begun referring to the company as TALCO, and a booklet published in 2000 to commemorate its seventy-fifth anniversary featured a logo with the plumb bob graphic separating TAL in boldface and CO in a lighter face.

The company in 2002 decided to move away from TALCO and revamped its logo.

“In the quest to maximize name recognition, we decided that the use of the name ‘Loving’ was going to be more beneficial in helping the marketplace recognize and remember T.A. Loving Company when they saw our logo,” company marketing executive Mark Moeller said in a corporate newsletter story. “Unfortunately, the use of TALCO as our logo did not accomplish that and may have even created some confusion.”

The company’s current logo with the plumb bob separating TA and Loving was introduced in the summer of 2016. It was time for a fresh look and to differentiate the company from several other similar looking marks in the construction industry.

Raleigh attorney and York’s brother-in-law.

After York and his wife divorced in 1960, Cameron Village was sold to Connecticut General Life Insurance and subsequently leased back to York. One of the buildings in Cameron Village was named for Bryan, and Bryan Street is an appendage of Wade Avenue “inside the beltline” not far away.

Bryan’s association with Valand extended to T.A. Loving Company supervising Valanddesigned office buildings in Raleigh for Cameron-Brown Company and First Union Bank on Six Forks Road; the Central YMCA on Hillsborough Street; the W.T. Grant Department Store in Goldsboro; and Holly Hill Mall in Burlington.

Bryan’s summer home in Morehead City and connections with the “Crystal Coast” area that includes the elongated strip of beaches from Atlantic Beach west to Emerald Isle positioned him to be among the founders of a new club in Atlantic Beach called the Coral Bay Club. It opened in June 1958 and was built by T.A. Loving Company, and the ranch-style clubhouse was designed by Valand. The board of directors read like a Who’s Who of business and social circles in the central and eastern

parts of North Carolina, including Mrs. Eddie Cameron of Durham, James Poyner of Raleigh, J.S. Ficklen Jr. of Greenville, Robert M. Hanes of Winston-Salem and Willie York of Raleigh.

“The Coral Bay Club spells easy, but luxurious summertime living,” said a passage in Our State magazine. “Guests who have been everywhere say quite frankly there is no place like it on the coast. There is an air of a big family house party—daytime, night time.”

The club remains a vibrant and viable operation today situated 1.5 miles from the Atlantic Beach Bridge toward Pine Knoll Shores. Steve Bryan has been using the club all of his life.

“It’s been a part of our family in the summer for as long as I can remember,” he says. “It was a place for dining and dancing. They had bands every Saturday back in the old days. I remember Les Brown and his Band of Renown was a regular. The club is doing well. I hear they have a waiting list now.”

Beyond running T.A. Loving Company, Raymond Bryan’s reach for doing good extended across the state of North Carolina.

He sat on the boards of Wachovia Bank, Carolina Power & Light Co., Atlantic and East Carolina Railway and Durham Life Insurance. He was an investor also in the North Hills Shopping Center in Raleigh and Cameron-Brown Company, a leading mortgage and financial services firm. Bryan contributed time and resources to numerous charitable and church endeavors and in 1975 received the N.C. Citizens Association Distinguished Citizen Award.

The Goldsboro News-Argus upon his death in November 1982 said, “He was a remarkable member of one of North Carolina’s most remarkable families.”

“He was a man of uncommon goodness,” said E. Leon Smith, pastor of First Baptist Church of Goldsboro in delivering the eulogy. “He was a builder of buildings and bridges, but more importantly, he was a builder of people. He gave freely of his time and resources for the lifting of the quality of human life and for the common good. In his quiet and unassuming manner laced with wisdom, he helped to guide his church, institutions of learning and numerous benevolent charities through this state.”

One contractor at his funeral observed,

Those that loved Ray knew him as a man of passion, music and fun, a lover of practical jokes and an admirer of all things beautiful.

“In a field that is as competitive as the contracting business, I know of no other person who was so universally admired.”

Bryan’s last notable achievement was leading his siblings into underwriting the $250,000 cost of a new library for their hometown of Newton Grove. The 2,900-square foot library was dedicated and opened in December 1982, just a month after Bryan’s passing. Wilmington-based architect Leslie N. Boney Jr., a long-time associate and services vendor of Bryan and T.A. Loving Company, delivered the dedication address and noted that his firm had designed the Walter Davis Library at the University of North Carolina that was under construction and being contracted by T.A. Loving and, at 436,000 square feet over eight stories, was considered one of the

largest university libraries in the nation.

“Mr. Bryan wrote to me and said that I had designed the largest library in the world, now would I design the smallest in the world?” said Boney, who then reflected over his years of working for Raymond Bryan and the influence Bryan’s parents had educating youngsters in Sampson County.

“Their work lives on in those who cannot be named or numbered,” Boney said. “I recognize that few, if any, families in Eastern North Carolina have had the influence and made the impact that Mr. and Mrs. Bryan and their children have.”

Where Raymond was low-key and softspoken, Ray Jr. was more outgoing. Ray Jr. was born in 1931 and was an only child. He grew up in Goldsboro, earned an Eagle Scout badge and played football for

Goldsboro High. He attended N.C. State and studied construction, graduating in 1953, and spent summers in college working for T.A. Loving in Daytona Beach on the Seabreeze and Port Orange Bridges. He served two years in the U.S. Army in Korea, then married Jo Ann Collier in 1955 and went to work for T.A. Loving. He became president in 1969 and managed the company for nineteen years, assuming the office of chairman in February 1988 with Sam Hunter taking over as president. He worked for years as an estimator then as project manager on various jobs on the N.C. State campus. His key lieutenants included Giles Trimble with the Bridge Division, Bob Loving running the Utility Division and D.C. Rouse in charge of the Building Division. The company also had a Paving Division that it sold to REA Construction in 1968.

Like his father, Ray Jr. was a master at tending to business, various philanthropic endeavors and supporting the educational and athletic communities at N.C. State (T.A. Loving Co. built the Wendell Murphy Football Center and the Carter-Finley Stadium expansion in the early 2000s as well

as the Park Alumni Center on the Centennial Campus). Bryan also carved time out for a wide variety of recreational interests; was a good golfer and a member of the Country Club of North Carolina in Pinehurst, an avid outdoorsman, a talented photographer and also loved to play the drums.

“Those that loved Ray knew him as a man of passion, music and fun, a lover of practical jokes and an admirer of all things beautiful,” read the eulogy following his death in March 2016. “Ray enjoyed getting along with people from all walks of life as he marched to the beat of his own drums.”

“My grandfather was modest, and while very successful in many ventures, it never changed him at all,” Steve Bryan says. “He treated everyone the same. When he spoke, people listened as he had something to say. My father was an only child, and while he was like his father in most ways, he was somewhat more outgoing.”

Steve graduated from N.C. State in 1982 with a degree in engineering and went to work for the company, but he didn’t want to come straight back to Goldsboro and asked to be sent elsewhere. He worked on the Union Memorial Hospital project in Monroe, then

moved back to Raleigh and commuted to Chapel Hill every day to work on a job at UNC Hospital complex. He worked four ten-hour shifts Monday through Thursday, then came to Goldsboro to help his father with the family’s other interests.

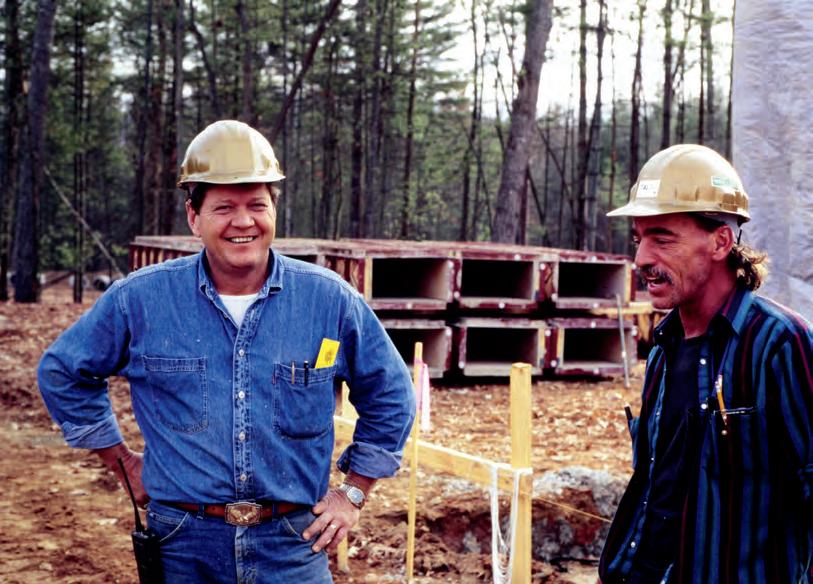

Like many others before and after him in the T.A. Loving family, the thrill of watching a project evolve from blueprint to ribbon-cutting captured Steve Bryan from the beginning.

“You start out with nothing, and it progresses, and the average person walking down the street doesn’t have a clue how that building is standing up, but the worker does,” he says. “He sees the footings, the steel, and the concrete. He sees the whole thing, and he can walk by and tell his grandkids and say, ‘Hey, see that building right there? I had something to do with it.’”

The first bridges known to mankind were likely no more than tree trunks or flat stone slabs laid over river banks. The principle of arched construction, in which shaped stones are fitted together and held up by the pressure of the blocks upon one another, was a huge development, and Roman engineers in the first century BCE were spanning rivers and gorges with arched structures..

Materials beyond stone and wood were introduced to bridge building in the 17th and 18th centuries when steam power evolved and new bridges made of iron were introduced. The 19th century saw the construction of more bridges than in previous centuries put together due to the rapid spread of railways and the need to build bridges to pass over or under obstacles. In time, steel and reinforced concrete made it quicker and cheaper to build longer and stronger bridges.

The geography of the state of North Carolina would lend itself particularly well as fertile ground for an entrepreneur in the bridge construction business like Taylor Abbitt Loving.

The Coastal Plain encompasses the two largest landlocked sounds in the United States—the Albemarle Sound and Pamlico Sound—and major rivers flowing from inland to the coast include the Albemarle, Pamlico, Neuse, New and Cape Fear. Hundreds of appendages to these major rivers with names including the words “swamp” and “branch” and “canal” and “creek” attest to the many challenges facing travelers getting from one side to another. And then there’s the matter of some three hundred miles of barrier

islands stretching from Corolla at the north to Ocean Isle at the south; accessing those lands require a ferry or bridge.

Bridge building in North Carolina in the early 1900s was certainly a good place to be.

“It was a difficult and bold undertaking with the machinery and engineering methods available in those days, but the skill with which it was wrought has met the test of time and has carried burdens of traffic such as few men in those days could ever imagine would pass that way,” read a 1963 We The People of North Carolina magazine article about one of T.A. Loving Company’s early bridge projects, a span over the Roanoke River in the town of Weldon.

There were also opportunities outside the state. One of T.A. Loving’s most notable endeavors was the construction of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. The bridge was 1,248 feet long and crossed the Alabama River just south of town. A 240-foot steel arch in the middle of the bridge provided the support. The bridge was named for Pettus, a former Confederate general and Democratic U.S. Senator, and replaced an old “horse and buggy” truss bridge built in 1884. It was thought when

it opened to be the “finest bridge between Savannah and San Diego,” according to one newspaper missive, and T.A.’s brother, John, was in charge of the project with key supervisors John Wall and Alfred Womble.

The work started in 1938, and the bridge was dedicated on May 24, 1940.

“It was quite a project to have been built back in the ‘40s by a little contractor in Goldsboro,” says Sam Hunter, son-in-law of John Loving.

“ Its grandeur will stand as an outstanding emblem of foresight and the progressive spirit of the people of the state and county,” Judge Watkins Vaughan said at the dedication.

Little did Vaughan know what kind of “progressive spirit” would come to bear on this particular bridge a quarter of a century after it opened.

On March 7, 1965, some six hundred black citizens frustrated they had been denied the right to vote—this a century after the end of the Civil War and a time when the racial legacies of slavery and Reconstruction lingered throughout the South—gathered peacefully in downtown Selma with a plan to walk fifty-four miles