JOURNEYS

OF DISCOVERY

15 years of the ADAM Architecture travel scholarship

Dedicated to the memory of Sam Little (1991 – 2022)

OF DISCOVERY

15 years of the ADAM Architecture travel scholarship

Dedicated to the memory of Sam Little (1991 – 2022)

OUR THANKS TO THE EXTERNAL JUDGES

DAVID BIRCH

NOTED BRITISH CERAMICIST AND MANAGING DIRECTOR OF THE LONDON POTTERY CO LTD

ELEANOR DOUGHTY

FREELANCE JOURNALIST AND REGULAR CONTRIBUTOR TO COUNTRY LIFE, THE TIMES, DAILY TELEGRAPH AND THE I PAPER

PROFESSOR LORRAINE FARRELLY

HEAD OF ARCHITECTURE, UNIVERSITY OF READING

KATHRYN FINDLAY

PRINCIPAL DIRECTOR AT USHIDA FINDLAY ARCHITECTS

CHRIS FOGES

EDITOR OF ARCHITECTURE TODAY

MATT GASKIN

HEAD OF THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AT OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY

SIR PETER HALL

BARTLETT PROFESSOR OF PLANNING AND REGENERATION, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

MICHAEL HAMMOND

CO-FOUNDER AND CEO AT BUILT ENVIRONMENT MEDIA. EDITOR IN CHIEF AT WORLDARCHITECTURENEWS.COM UNTIL 2018

TIMOTHY SMITH

COURSE LEADER AT KINGSTON UNIVERSITY AND CO-PARTNER OF ARCHITECTS SMITH & TAYLOR

JONATHAN TAYLOR

UNDERGRADUATE DESIGN STUDIO TUTOR AT KINGSTON UNIVERSITY AND CO-PARTNER OF ARCHITECTS SMITH & TAYLOR

DR MARCEL VELLINGA

PROFESSOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY OF ARCHITECTURE AND DIRECTOR OF THE PLACE, CULTURE, AND IDENTITY RESEARCH GROUP IN THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY

PROFESSOR GEORGIA BUTINA WATSON

HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND RESEARCH TUTOR IN THE JOINT CENTRE FOR URBAN DESIGN AT OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY

Architects seek inspiration for their work from a wide range of sources, but for many the greatest inspiration will always come from travel.

I was fortunate on leaving school in 1991 to be awarded a scholarship with a friend to travel in Tuscany for two months. We proposed to travel the length of the River Arno, taking us from Pisa to Florence, then southwards towards Arezzo and finally north towards the source of the river on Mount Falterona. We set ourselves the task of drawing and painting the bridges over the river; the skills developed on that trip provided the foundations of my architectural career.

On becoming a director of ADAM Architecture in 2004, I suggested that we might set up a travel scholarship with the aim of inspiring students and encouraging architectural exploration. We launched the scholarship in 2005, and from the start we were impressed by the variety and high standards of applications that we received. As we are a practice specialising in traditional architecture and urbanism, it was always our intention that the scholarship would illustrate the breadth and depth of this field. We have never been disappointed; the applications each year have always included surprising and unexpected areas of study which still address our core interest in the continuity of tradition.

In recent years, it has become an annual routine to launch the travel scholarship at the beginning of the year, with most applicants choosing to travel during the summer holidays. We receive submissions from all over the world and aim to get these down to a shortlist of five or six candidates; generally we are looking for specific areas of study with a carefully considered itinerary and clear objectives. Interviews are held in our office and each year we have been joined by external judges whose insights have been invaluable.

In 2020, and having run our Travel Scholarship for 15 years, we looked back at the quality and quantity of amazing work which had been carried out by the scholars and thought that these deserved to be gathered together in a book. In this endeavour we have been helped immeasurably by Nicola Jackson who carried out the huge task of contacting our scholars, assembling and editing the material for publication and working with Sue Beaumont, Evelina Dee-Shapland and Jenn Holmes in our office to bring everything together.

We very much hope that this book will inspire those who read it, and that it will continue to promote the careers of our numerous scholars. Our final thanks go to our scholars for showing, in a wide variety of ways, the value of travel to us all.

George Saumarez SmithWorld

EDITED

These pages document so much more than travelogues from enthusiastic young architects. Of course, there are plenty of references to meals shared and enjoyed, train journeys taken, and friendships made along the way, but at the heart of each chapter is an architectural insight as fresh and revealing as anything you might read in a more conventional book on architecture.

From Italy to Israel and Cuba to China via numerous other countries across the globe, the travel scholars document their journeys with remarkable insight, offering us something new even when – in the case of the evolution of Italian villas or the romantic decay of Cuba, for example –the subject was apparently well known to us.

Rather like the subjects they chose to interrogate, the way in which the scholars went about documenting their findings varied enormously. Some were the length of a university thesis, with the erudition to match. Others consisted primarily of drawings and photographs, with extended captions alongside them. Collating them, and ensuring that they formed a coherent whole, seemed a daunting task, until we decided to celebrate their very different approaches, linking them only by the design of the page layouts.

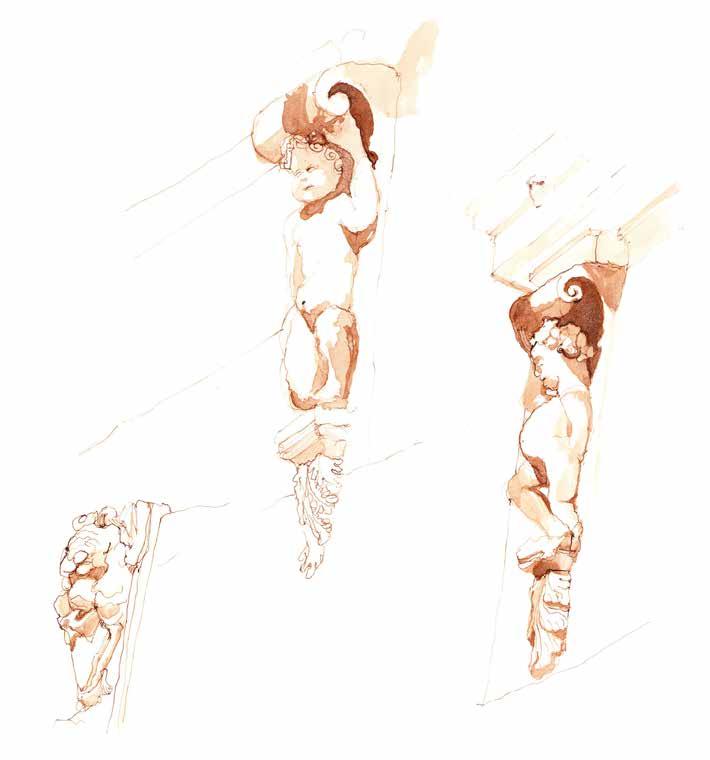

The enthusiasm with which these scholars approached their subjects, and the beauty of the measured drawings, watercolour sketches and photographs they used to illustrate their findings, meant that as I edited each one, they became my favourite; that is until I moved onto the next, and they began to jostle for my attention and affection. I am now as eager to visit the remarkable rockhewn churches of Ethiopia and the monumental stone masonry of ancient Japanese castles as I am to spend a long weekend exploring the streets of Valletta or seeking out an art deco garden. Chiara Hall’s research on the human figure in Sicily’s Baroque architecture revealed how much I had missed in one of the destinations already familiar to me. The poetry of her prose drew me in as much as the luminosity of her illustrations:

‘Some of the buildings host the most original and bizarre grotesques I had yet seen: startling bespectacled and blindfolded faces hold scorpions and rats between missing teeth; knowing faces tease and mock; seductive sirens (with scaly fish tails) distract; sweet cherubs embrace; imaginary musical notes emanate from musicians with flutes and guitars; and a lonely dark figure, with a wrinkled forehead and outstretched hands, supports a balcony.’

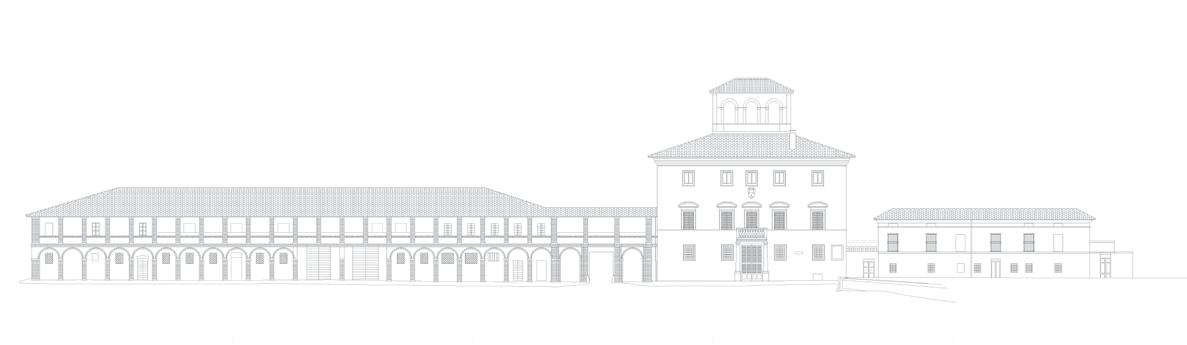

Chiara has gone on to work in the Heritage and Culture Team for Building Design Partnership (BDP). James Hills also travelled to Italy, to research ‘The Villa Suburbana and Dense Suburbs’. In 2020 he set up his own practice, Drawnwork, and is currently working on the design and construction of a garden building within the grounds of a Grade II listed 16th century country house, building upon his research.

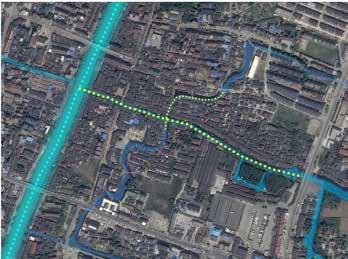

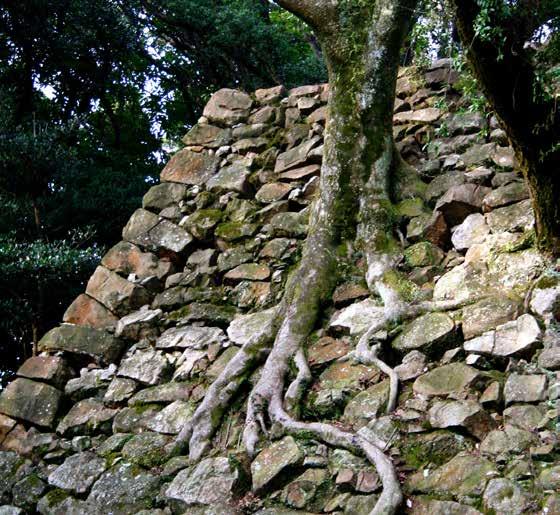

It is a measure of the success of the travel scholarship programme that some of the research visits resulted in design projects, and others have gone on to influence scholars’ careers. Evan Oxland has continued to pursue his fascination with stone, following his investigation of the Japanese castles, and now works as an architectural conservator and stonemason in Ontario, Canada. Nick Thompson’s visit to Valletta has had a strong impact on his practice both as a town planner and stone carver. Jingwen Zhao’s travels in China exposed the cultural differences between the public nature of Western towns and their public spaces, and the more introverted spaces of the Chinese water towns with their internal courtyards. She drew on what she had learned from her travels in a project for a museum that formed a part of her university thesis. Abigail Benouaich’s study of the Jewish ghetto in Rome resulted in an as-yet-unrealised design project for a new Jewish Cultural Centre. It was designed after extensive research, and discussions with the centre’s head. Tarn Philipp has returned to Ethiopia every year since 2014 to conduct significant research on new rock-hewn churches.

Perhaps the most surprising and glamorous consequence of any of the research projects was the invitation issued to Paige Johnson by Baz Luhrmann, to consult on his 2013

film The Great Gatsby. Her research on the search for the art deco landscape was also published in Apollo magazine. Most recently, Amanda Iglesias has thrown new light on the ecclesiastical work of Inger and Johannes Exner, which is almost unknown outside Denmark. She is now working for Robert A.M. Stern Architects in New York where she applies her ‘[sharpened]… design instincts, historical knowledge, and fluency with mid-century architectural forms’, which she says is a consequence of her research.

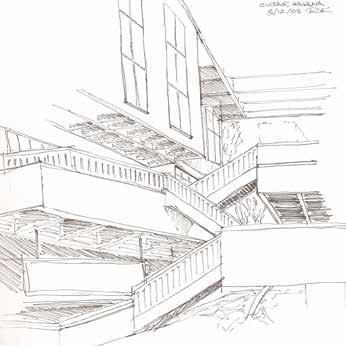

Of course, the most direct result of a travel scholarship affecting the trajectory of a career must be Robbie Kerr’s visit to Cuba. He was awarded the scholarship while working for the practice during his degree course at Edinburgh University. He joined the practice in 2010, before going on to become ADAM Architecture’s youngest director in 2016. He is still drawing on his research today, currently developing plans for new Cuban work, in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Old Havana.

Abigail Benouaich was awarded the 2014 ADAM Architecture Travel Scholarship. A British Israeli, born in Jerusalem, Abigail had studied the Ghetto of Rome for some years and was keen to continue her field research in Jerusalem and Rome, to explore the history connecting the two communities and their architecture.

Abigail’s love for architectural history, coupled with an eye for artistic abstraction, inspired her concept to explore the architectural transformation of the Modern Jewish Quarter of Rome, where she examined in detail the critical period of architectural transformation that operated on the urban landscape of the former Jewish Ghetto as part of a revolutionary and contemporary vision of Jewish regeneration in Rome.

This research project contains a selection of Abigail’s limitededition artwork and photography and concludes with her design project for the Jewish Centre of Culture which dramatises the achievements of the surviving Roman Jewish Culture.

Abigail has worked as an architect in Glasgow, London and Tel Aviv, and now lives in Sweden, where she has been studying for a Masters in Architectural Lighting Design at KTH in Stockholm.

All images, unless otherwise credited, are by the author.

The Ghetto of Rome offers an extraordinary vivacity, abundance of stratification, and layering of history that has influenced numerous relationships between the daily life of its Jewish inhabitants, its architecture and connection to the city of Rome, further distinguished by apparent contradictions and difficulties occurring over a 2,000-year history of conflict between the Jewish and Roman communities. In this context, the Jewish Ghetto presents a highly relevant case study of the topographical and architectural transformation that has occurred during the 19th century era of emancipation and its relative impact on the modern-day community of the Jewish Quarter.

For three centuries under Papal Rome (1555-1870), a walled ghetto was constructed in the Rione Sant’Angelo to separate the city’s Jews from the rest of the population. The intention of ghettoisation was to ‘expedite conversion and cultural dissolution’ but the outcome of the ghetto in fact had the opposite effect; the population established a ‘sub-culture’ or ‘micro-culture’ that ensured continuity.1

This study examines the conditions of the Jewish Ghetto prior to the Risorgimento regime in 1870, and the patterns of inhabitation and Jewish worship that evolved during the three centuries of confinement within the ghetto enclosure. Following the introduction of Architectural Emancipation in the mid-19th century, and the construction of the Great Synagogue as the ‘speaking symbol’ of emancipated Jewry, my research delineates the dichotomy between the role of the monumental Synagogue as a symbol of liberation under the Roman Republic and its fragility as the “new temple” during a period of Jewish decline.

To undertake my research, I travelled from Jerusalem to Rome to explore the origins of Rome’s ghettoized Jewish Colony. I document the rise and fall of the ghetto in the early 19th century and conversion of the centuries-old space of Jewish life into a topographical tabula rasa upon which the modern quarter and Great Synagogue appear as a ‘visible sign’ of Jewish Emancipation.

My research culminates with a critical analysis of the Great Synagogue, constructed in 1910, during a critical period of architectural transformation for the Third Rome, where a bold effect of erasure and re-inscription operated on the urban landscape of the Ghetto as part of a revolutionary and contemporary vision of Jewish regeneration.

4

I was born in Jerusalem and lived there as a child in the 1980s. We left in the early 1990s, moving first to northern England and then to Scotland. Fifteen years passed before I returned to the city to conduct this research, and yet I still think of Jerusalem as home. Not home in the sense of a place where I conduct my daily life or constantly return to, but home because it defines who I truly am, whether I like it or not.

The diversity and richness of Jerusalem, both in terms of its emotional and spiritual energy, make it a fascinating experience to an outsider. Four thousand years of intense political and religious wrangling are impossible to hide; traditions that overlap and interact in unpredictable ways, creating an urban context and patterns of living that belong to specific groups but also belong to everybody else. 2

The complexity and vibrancy of Jerusalem stems both from its location as a meeting point between Europe, Asia and Africa and the incredible depth of its history. It has been conquered, destroyed and rebuilt time and time again, with every layer of its earth revealing a different piece of the past. At its core is the Old City, a maze of narrow alleyways and historic architecture that characterise its four quarters – Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Armenian. While it has often been the focus of stories of division and conflict among people of different religions, they are united in their reverence for this holy ground. Indeed, there are few places in the world to match its significance.

Yet Jerusalem has never been a great metropolis. It has never had temples that can parallel those of Luxor, or grandiose public buildings as magnificent as those in Rome. It has always been a rather small and crowded city, built from the stone of its surrounding hills.

The energy of Jerusalem is introspective. It is born out of an interplay between the peoples that have been coming and going for millennia. It is not through anything material but through faith, learning and devotion that Jerusalem has gained its importance throughout history.3

When King David founded it as his capital in around 1,000 BC, it was, as it is now, a collection of rugged hills with little vegetation or water. The first of two temples was built on the Temple Mount, signifying the core of Jewish prayer and piety, until the Romans first appeared in Jerusalem in 63 BC, to instigate the most significant event in Jewish history, which is where our story begins.

The Romans – following hot on the heels of the Hellenistic influence – first appeared in Jerusalem in 63BC, and then gradually asserted their authority against Jewish resistance, which culminated in a failed revolt in 70AD, when the second, and last, Temple was destroyed. This event is painfully etched in Jewish history as the onset of a slow process of decline that would not end until the advent of Zionism. The Oxford historian Professor Simon Schama described the war with the Romans in these terms:

[T]he Jewish Roman war anticipated with such poetic excitement in the war scroll became grim, bloody reality in 70AD. An immense rebellion against Roman rule broke out in Galilee and Judea. A maelstrom of violence that required the weight of three legions under the command of General Vespasian and his son Titus to crush it, before moving on to Jerusalem where fanatic Zealots instigated a reign of terror to deter any talk of surrender...The spirit of the surrenders finally crumbled. The city walls were breached. The temple established as the exclusive focus of Jewish prayer and piety went up in smoke and flames. The Roman legions prized the massive masonry blocks from the top of the Temple Mount and sent them crashing onto the fine limestone pavement below.4

Alongside the slow development of the nascent religion, the Roman-Jewish conflict continued to simmer, and came to a head in another revolt in 132AD, after which Jews were banned from the city, bar one day a year, for many centuries. The city was renamed Aelia Capitolina, and with the Christianisation of the Byzantine Empire it was adorned with Christian churches, and became a veritable Christian city, devoid of any Jewish presence.

Back in Rome, a triumphant procession lead by Vespasian exhibited the spoils of Jerusalem in promiscuous heaps; but conspicuous of all stood out those captured in the Temple of Jerusalem. The destruction of Jerusalem was the making of the Vespasian family, The Flavians. Vespasian was declared Emperor of Rome, and Jewish loot and slaves provided the cash and the muscle for the building of the Colosseum.

For the following 14 centuries, a Roman Jewish colony was established in the Trastevere region of Rome.

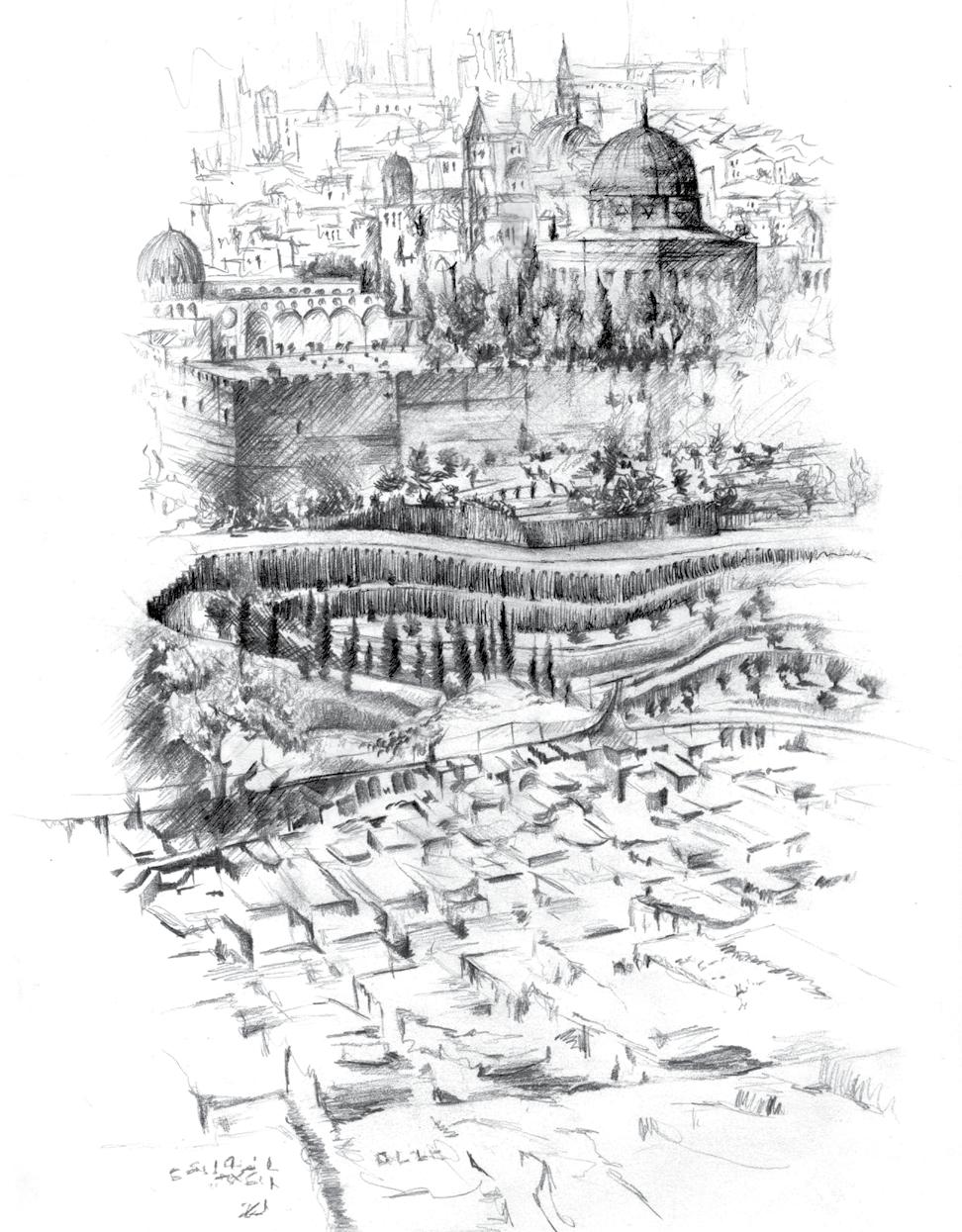

6 ‘ STONE ON STONE’. THE EXPERIMENTAL COLLAGE CAPTURES THE STRATIFICATION OF THE OLD CITY, WITH EVERY LAYER OF THE EARTH REVEALING A DIFFERENT PIECE OF THE PAST

7 THE SIEGE OF JERUSALEM BY ROMAN LEGIONS LEAD BY VESPASIAN ENDED WITH THE SACKING OF THE CITY AND THE DESTRUCTION OF HEROD’S SECOND TEMPLE

8 THE STONES FROM THE WESTERN WALL OF THE TEMPLE MOUNT WERE THROWN ONTO THE STREET BY ROMAN SOLDIERS

9 ON THE ARCH OF TITUS, THE SCULPTED FRIEZE DESCRIBES THE ROMANS MAKING OFF WITH THE LOOT FROM HEROD’S TEMPLE INCLUDING THE GIANT MENORAH

10 THE DESTRUCTION OF JERUSALEM WAS THE MAKING OF THE VESPASIAN FAMILY, THE FLAVIANS. JEWISH LOOT AND SLAVES PROVIDED THE CASH AND THE MUSCLE FOR THE BUILDING OF THE COLOSSEUM

11 DESCENT FROM THE ANCIENT FORTRESS OF MASADA LOCATED ON A PLATEAU IN THE JUDEAN DESERT OVERLOOKING THE DEAD SEA

12 THE SIEGE OF MASADA BY THE ROMAN TROOPS TOWARDS THE END OF THE JEWISH–ROMAN WAR ENDED IN THE MASS SUICIDE OF THE 960 JEWISH REBELS AND THEIR FAMILIES HIDING THERE

Under imperial policy, the Jews were forbidden from all legal employment. It became illegal to open any synagogues and they were ultimately forbidden from assembling in public at all. The Christian Empire was pushing the Jews into the shadows.

That was until 1555, when the Empire found a new way to isolate the Jews. The colony was forced to live in a small district of just a few residential blocks on the opposite side of the River Tiber. The gates were locked at night and a new word was born – the ghetto. Today, the word ‘ghetto’ is synonymous with poverty, racism and families in distress – all of which were true of Rome; the world’s first ghetto.

For three centuries under Papal Rome, a walled ghetto was constructed in the rione (neighbourhood) Sant’Angelo to separate the city’s Jews from the rest of the population. In the form of a rectangular trapezoid, the ghetto contained two main streets running parallel to the Tiber and several small streets and alleys that together occupied a seven-acre enclosure. The site, as the most insalubrious of the city thanks in part to the ravages of the river, was designated as the Jewish Ghetto. The space was densely populated, and extraordinary measures had followed population growth: additional storeys perched atop row houses with annex constructions protruding from negative rooftop spaces, blocking the light from reaching the already dank and narrow streets.5

During the ghetto period, space limitations, combined with the expanding needs of the growing population, had forced the Jews of Rome to construct a greater number of more concentrated storeys above the existing dwellings. The ghetto buildings could be easily distinguished by their smaller, more numerous rows of windows. In Rome’s ghetto, this difference was only visible in the upper storeys. Such buildings gave the impression of having been crushed by a great weight from above. The story of the ghetto was clear: ‘the Jews were collapsing under the weight of oppression’. The visiting historian Ferdinand Gregorovius described the ghetto area in these terms:

[D]irectly ahead are the ghetto houses in a row, tower-like masses of bizarre design...The rows ascend from the river’s edge, and its dismal billows wash against the walls...When

I first visited, the Tiber had overflowed its banks and its yellow flood streamed through the Fiumara, the lowest of the ghetto streets, the foundations of whose houses serve as a quay to hold the river in its course. The flood reached as far up as the Porticus of Octavia, and water covered the lower rooms of the houses at the bottom. What a melancholy spectacle to see the wretched Jews’ quarter sunk in the dreary inundation of the Tiber! Each year Israel in Rome has to undergo a new Deluge, and like Noah’s Ark the ghetto is tossed on the waves with man and beast. When the Tiber goes into flood the misery is multiplied. Those who live beneath take refuge in the upper floors which are intolerably crowded and tainted by pestilential atmosphere. 6

Shops lined the streets of the ghetto, together with a religious school, a rabbinical college, and five small synagogues in a single edifice called the Piazza delle Cinque Scole. During the three centuries of confinement, the heart of Jewish life centred around the Cinque Scole, where buildings tended to be small, introspective places of worship and study in which the Jews gathered to pray, but also to meet socially and to conduct the business of the community.7 By papal law, the Jews were forbidden to have more than one synagogue, but despite this the Cinque Scole building housed five shuls (synagogues) each established according to varying origins and traditions.

The Cinque Scole building was considered the ‘heart’ of the ghetto as it stood in front of the boundary walls that divided the Jews from the outside world, in the Monte de Cenci area. The only visible decorative element was a semi-circular fountain, which interrupted the overhanging presence of the wall.8 Despite the dreary

conditions of the ghetto, members of the community enriched the building’s undecorated interior with gifts and contributions from their European origins. Professor Simon Schama describes the Cinque Scole shuls:

[I]n the midst of the ghetto, there were some places where you could feel the sigh of relief that was Jewish Rome. The place, where for all the condescension, one could actually make a Jewish life. The shuls speak of the deep pathos of longing for Jewish beauty... Jews never considered it an obligation to construct rich buildings or ornamentation, because they always knew they would have to pick up the suitcase and leave them behind. And yet, you want to believe that

13 HIST ORIC MAP OF THE JEWISH GHETTO (1555) INDICATING THE WALLED ENCLOSURE AND FIVE ENTRANCE GATES

14 THE SITE OF THE FORMER JEWISH GHETTO IS LOCATED ON THE BANKS OF THE TIBER IN THE RIONE SANT’ANGELO DISTRICT. THE TIBERINA ISLAND SEPARATES THE DISTRICT ON THE EAST BANK FROM THE TRASTEVERE REGION ON THE WEST BANK

15 THE LIMITED EDITION MIXED-MEDIA PRINT, ‘URBAN DECAY’ CAPTURES THE STRATIFICATION OF THE URBAN FABRIC WHICH HAS INFLUENCED COMPLEX THRESHOLDS OF EXTERNAL INHABITATION

in the place you have just come to where you have been allowed to prosper or perhaps for a few generations at least be safe, honour your religion by making something beautiful. The whole place reconciles the idea of refuge with beauty.9

Under the Papal regime, the ghettoisation of the Jews was intended to ‘expedite conversion and cultural dissolution’. The outcome of the ghetto in fact had the opposite effect. The Jewish community developed a subculture, or ‘micro culture’, that ensured continuity. The Cinque Scole’s back-of-house places of worship and remarkably effective legal network of rabbinic notaries, together gave the Jews

the illusion that they, rather than the papal vicar, were running their own affairs.

The ghetto operated under papal control until the unification of Rome with Italy in 1870. Then 315 years after Pope Paul IV ordered the locals Jew into the ghetto, the city of Rome ordered them out.

The Risorgimento 1870 – 1910

Rome was declared the capital of the Third Italy in 1870, and city officials began to worry about the appearance of the Jewish Ghetto. Major public works were announced after centuries of neglect, as part of an urban strategy known as the Risorgimento, connoting an urban renewal and ‘return to health’. The Risorgimento of the ghetto was deemed indispensable before any other urban initiative with the objective ‘to demolish thoroughly… erasing a source of epidemics and a disgrace to the Capital’.10

Following a disastrous flood in December 1870, which brought the King of Italy for the first time to this new capital, the provisional city administration named an 11-member commission of architects and engineers, to formulate proposals for the ‘expansion and embellishment of the city’ with particular reference to the disposition of the River Tiber banks where the ghetto was to be demolished, the land elevated and embankments built to accommodate the modern Jewish Quarter.11 The regime was considered to be one of the most ambitious urban projects of the Third Rome.

In relation to the ghetto, the risorgimento served a shared cause. Alongside urban renewal, the term also evoked a

moral and cultural renewal consistent with the ideology of Emancipation, where it served to justify liberation and equal rights on the grounds that Jews would naturally regenerate themselves once they achieved parity with other citizens.

Several architectural works in the Jewish Quarter, including the construction of the Great Synagogue of Rome, sought to make this meaning explicit and strengthen the initiative of Jewish Emancipation as a pioneer of the movement ‘out of the ghetto’.

In the eyes of the city’s new leaders, the Jewish Ghetto bore witness to the temporal power of popes. The Third Rome could hardly allow such a telling vestige of the old order to remain as it contradicted the image of a regenerated Italy. The risorgimento of the ghetto, in contrast, offered a symbolic as well as a practical cure not only for the Jewish Quarter but also for the city and the nation. A correspondent for the Corriere Israelitico would describe the moment, in the 2,000-year history of Jewish Rome, as a ‘critical period of transformation’.12

Demolition of the Jewish neighbourhood began in 1888 and continued until the first years of the 20th Century. During this time, the displaced population of the ghetto –refugees of the Risorgimento Policy – did not have priority over their relocation. The 4,000 inhabitants who were being evicted were referred to new residential developments on the boards, between Porta Pinciana and Porta Salaria.

Two official efforts supported by the Roman council were, in the end, only of symbolic value. Neither were specifically geared towards the victims of the ghetto’s

18 HIST ORIC MAP OF ROME’S RISORGIMENTO TOWNPLANNING BY SAINT JUST OF 1908-1909

19 THE HISTORIC GRID OF THE FORMER GHETTO PRIOR TO DEMOLITION IN THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY

20 THE MODERN JEWISH QUARTER AS IT EXISTS TODAY, WHERE THE CLEARANCE OF LAND MADE WAY FOR GRANDIOSE URBAN PROJECTS INCLUDING TREE-LINED EMBANKMENTS ALONG THE TIBER RIVER KNOWN TODAY AS TRASTEVERE

pick. Since 1867, a Relocation Committee dedicated to the providing of ‘houses for the poor class’ developed some very limited low-rent housing. The council, perhaps bearing a guilty conscience, supported its work through the cession of free land, some 25,050 square metres on the Esquiline sold to Senator Rossi, who built upon it, at his own cost and over a period of three years, a number of low-cost houses, mostly for single Jewish families.13

Meanwhile, the clearance of the ghetto land made way for the grandiose urban projects of the Third Rome –building tree-lined embankments along the River Tiber and ample streets lined with decorative Umbertine

buildings. The last of the ghetto buildings to fall was the Cinque Scole Shuls to fund the construction of the Great Synagogue of Rome. Laudiadio Fano’s Modernist Chronicle describes this phase of transformation:

[T]he operation was performed quickly in an attempt to alleviate the community’s suffering. The demolition of the Ghetto and the decentralization of its inhabitants may have constituted a necessary transition, but the community was fragmenting...The last small shuls, in whose place the Synagogue is to be built, has finally been demolished...That old prison that always swarmed with noisy people is now a pile of rubble. How many events, how many memories are concealed beneath those stones?

The displacement of Jewish space was treated as one of the most significant events of the day. The Great Synagogue had risen ‘above the ruins of the ancient ghetto’ to refashion Jewish identity in Rome. The razing of the cinque scole shuls had converted the centuries-old space of Jewish life into a topographical tabula rasa upon which the Great Synagogue appeared as a visible sign of liberation. As contemporaries were well aware, a bold effect of erasure and re-inscription had operated on the urban landscape of the ancient ghetto.14

The Great Synagogue c.1910

[T]he Great Synagogue of Rome stands majestically on the banks of the Tiber near the Marcellus Theatre and across from the Tiberina Island. Inaugurated in 1910, it is a centralplan domed building with massive and compact forms. Its eclectic style combines Roman, Greek, Babylonian, and

Egyptian elements, the latter two appearing in the decorative details, mouldings, and column capitals. A square-shouldered structure crowned by a brilliant aluminium cupola, the building communicates stability, permanence, and strength. With a lateral facade facing the river and the principal facade rising above the small square, it cuts the figure of a modern fortress and its fiefdom.14

a ‘memory vessel’ between monuments it evokes and the one they built. The entry stood out amongst the 26 in that is eschewed the “Eastern” styles dominating Italian Synagogue architecture at the time.

Costa and Armanni assumed that ‘the synagogue should recall the place and architecture of Palestine at the time of the Temple. Because no monument of the period had survived, it was deemed favourable to adopt the style of the historical period in which the religious system had originated’.14 Finally, they argued that the building should harmonise with the rest of the city and thus required a more classical style.

A design competition for the Great Synagogue was announced in 1889, welcoming 26 design entries. The second prize design went to Attilio Muggia for a twin-towered, four-storey building with striped masonry that distinguished it from the other church styles. It would echo the temple of Jerusalem, and thus be indissolubly associated with the many locations in which the Jews has resided following the destruction of the second Temple.

The winning entry however, designed by Costa and Armanni Architects, evoked a different meaning. Reflecting the Temple era, the design intended to create

Along with the synagogue of Florence (c.1882), the principal reference for Costa and Armanni’s design was the main synagogue of Paris on the Rue de la Victoire (c.1874). The latter in many respects is more impressive than the Great Synagogue of Rome. Yet to an onlooker moving about either capital, the Parisian synagogue, whose facade is largely obscured on a narrow street, hardly makes a greater statement about the new and equal space of the modern Jew than its very visible 150foot counterpart on the River Tiber.14

Nor could an onlooker easily ascertain that the new building stood in the place – indeed in the emptied space –of the ancient ghetto.

Emancipated Jewry in Rome dating from the mid-19th century sought to substitute the role of the ghetto’s Cinque Scole shuls for the Great Synagogue of Rome –a bold architectural statement of liberation. The Piazza della Cinque Scole however, was a Jewish space like many in Western Europe that developed as a survival

mechanism during ghettoisation to retain Jewish tradition and collective memory following the dispersion of the community.

In contrast to the hidden world of the Cinque Scole, where the ‘back-of-house’ places of worship were modest and often so discreet as to be unrecognisable from the outside, the Great Synagogue of Rome was an imposing structure of a grandeur deemed to be exotic by the standards of the day. As bearer of the movement ‘out of the ghetto’ the Great Synagogue transformed real and symbolic space, rising from the ghetto’s ruins to signify the new place of worship for the emancipated Jew. The architecture of emancipation boldly announced that Jews were equal members of society, enjoying the same rights and freedoms as the majority whilst maintaining a distinctive religious faith.14

The Great Synagogue of Rome was perceived as a turning point in solidifying the history and identity of its community. As the new symbolic place of worship, however, did the Great Synagogue fall victim to its own success? In contrast to the modest shuls of the Cinque Scole, one could assert that the synagogue’s very monumentality created an inner void, a poor substitute for the communal and religious life it replaced. You could argue that the original intent of the synagogue was not accomplished but did in fact neglect Jewish life and further distance the Roman Jews from their ghetto origins.

The risorgimento of the ghetto was not referred to as ‘new times’ for the Jews of Rome but ‘new temples’. The destruction of the Cinque Scole placed significance on

the substitution of the Great Synagogue as the ‘new place of worship’ appearing as the ‘visible sign of the ready and the complete forgetting of past offences’.14

All monumental synagogues of this era shared this historical and ethical cause, but the role of the Great Synagogue of Rome as a ‘vessel of memory’ for the Jewish people was of more significance in the city of Rome than any other. As the seat of both the Catholic Church and the Roman Empire, the city had played a unique role in Jewish history.

The construction of the Great Synagogue of Rome further coincided with a sharp decline in Jewish religious life and intellectual culture specific to this late 19th century period. Combatants for Jewish renewal seized the opportunity to emphasise the decline that accompanied liberation and the poor direction provided by Jewish leaders responsible for the synagogue and for the Judaism it represented. In the context of the Jewish Ghetto, and in the shadow of the Catholic Church, the ghetto produced a rival narrative to a foundation-story of the Church and this constituted one of the highest priorities of emancipated Jewry in Rome and the agenda of the Great Synagogue.14

The contradiction between the Great Synagogue boldly symbolising liberation under the Roman Republic against its fragility as the ‘new temple’ during a period of Jewish decline, may imply that the Synagogue’s role as a ‘vessel of memory’ was in fact responsible for further severing the traditional process of worship that had evolved over many centuries in the former ghetto.

As such, does the Roman-Jewish Quarter still require a community space that reaffirms this diminished connection? What would be a suitable transformation of Jewish space in Rome as a means of reconciling the community with their long, recorded past and recent journey out of the ghetto?

The construction of the Great Synagogue was perceived as a turning point in the history and identity of the community.15 And yet, there was a strong argument to promote a more authentic form of Jewish identity in the Modern Quarter through insertion of a new community Jewish space.

The very issue of reviving Jewish collective memory in the Modern Quarter first came to the forefront in the 1970s, following World War Two, Fascism and liquidation of the ghetto in October 1943, when a new urban and cultural initiative was established by the Community of Rome. 16

A programme was established in 1975 by Bice Migliau, founder of the Jewish Community of Rome, to promote religious, educational and cultural initiatives in the Modern Quarter through the construction of a Rabbinical Court, nursery, primary and secondary schools, and a Jewish Library adjacent to the Great Synagogue. Over the course of the last 40 years, the Modern Jewish Quarter has developed a thriving Jewish/Roman community, and has fast become an epicentre for religious, cultural and community activity.

However, despite the Modern Quarter’s steep social and economic growth, a conceptual design opportunity for a new Jewish Centre of Culture was identified as part of an urban initiative established in 2014 by Micol Temin, head of the current cultural centre, with the objective ‘to

relocate the Jewish Centre of Culture to an alternative and more adequate location in the Modern Quarter’ on the basis of high accommodation costs and increasing spatial demands.

Allocation of an appropriate site for the Jewish Centre of Culture relocation strategy called for a thorough understanding of the ‘remains of ghetto life’ in the modern-day quarter, based on the assumption that the new building would exhibit a meaningful reflection on the Jewish Roman history of the former ghetto.

At the end of the 1980s, Rome’s Municipality began urban restoration of the Ghetto of Rome, with both unfinished demolitions and archaeological areas yet to reveal different pieces of the ghetto’s history. Excavations of the Piazza Delle Cinque Scole revealed that the Scole building was not anchored to the ground, but loosely founded over Roman ruins of various manufacture and importance. The last stratigraphy revealed that the shuls once rested on very well-conserved building constructions, most likely of the Trajan period.17

Today, the only remaining feature of the Cinque Scole is the historic fountain which was relocated to the new square following reconstruction of the Modern Jewish Quarter. All the surrounding buildings of the square were demolished apart from one semi-deconstructed building located on the border between Piazza delle Cinque Scole and Via del Portico d’Ottavia.

Research revealed that the building once lay adjacent to the boundary walls that separated the ghetto from the outside world. As one of the few ghetto buildings to remain, it was originally used as residential premises facing onto the former site of the Cinque Scole fountain. Then after the period of active construction in the early 20th century with the demolition of the ghetto, construction work stopped for ten years and the building adjacent to the Maria del Pianto church was left half demolished. Full demolition of the building was never completed and it is now under council ownership, functioning as a Jewish Information Point to serve the community.

The Jewish Centre of Culture project site is favourably situated at the heart of the remaining Ghetto heritage in the Modern Quarter. The site can form a gateway to the commercial activity along Via del Portico d’Ottavia, and also provide an alternative use for the Piazza delle Cinque Scole to raise the profile of the square, in sensitive recognition of its historic significance as the centre of Jewish life in the ancient ghetto.

In a dramatic texture of vertical elements, my proposed design for the Jewish Centre of Culture articulates a strong dialogue between historical authenticity and modernity by freely borrowing ancient Roman Jewish motifs and contemporising them in a way that is not blindly imitative. The triple-banded entrance arch is an allusion to the brickwork of the Marcellus Theatre, with each building forming the primary gateways to the Modern Quarter, and thus engages the entirety of the ghetto site in a continuous dialogue while each asserting a character all their own. The brickwork is precise, rhythmic, and beautifully scaled to evoke a sense of refinement only conceivable in a modern project.

Yet, there is something fundamentally timeless about the simplicity of the structure and its clear invocation of the Roman precedent. Form and material belong neither to the present nor to history, allowing the design to straddle the gap between the two in a manner uniquely befitting the modern-day Jewish Quarter.

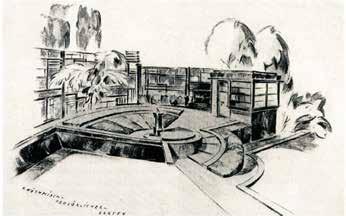

The central library space appeals to history in another way still, appropriating the enduring power of architectural ruin. Heavy structural columns that seem capable of supporting a weighty roof are capped instead by a light, glassy covering, creating an interior condition that feels entirely connected to the outside world, and exposes the hovering clock tower of the Santa Maria del Pianto church. As a result, the space is unburdened by the oppressive weightiness of a traditional roof and the immersive experience within the former ghetto site feels all the more authentic.

Following an era in which the architectural commissions of the Modern Jewish Quarter represented opportunities for government officials to pursue political agendas with

little sensitivity for the ghetto life the new buildings intended to displace, this proposal is refreshingly selfaware of its purpose as a new Jewish space connecting to the city’s ancient past. The architecture serves not to promote itself, but to dramatise the achievements of the surviving Roman Jewish culture without overshadowing them. It is a negotiation of the ancient and the modern, the inventive and the referential, and a sensitive rethinking of the library typology through thoughtful contextualisation.

The project was designed after extensive research, and discussions with the centre’s head. It was received very favourably but didn’t move beyond the initial concept phase. As far as I am aware, the development of a new Jewish Cultural Centre has not yet come to fruition.

1. Stow, Kenneth. Theatre of Acculturation – The Roman Ghetto in the sixteenth century. University of Washington Press, 2010.

2. Tamimi, Sami. Jerusalem. Random House, 2012.

3. I bid.

4. Schama, Simon. The Story of the Jews. Vintage, 2014.

5. L erner, Scott L. “Narrating over the ghetto of Rome”; article is a revised lecture given at the Center for European Studies on Visual Representation and Cultural Critique, Harvard University, 2005.

6. Gregorovius, Ferdinand. “The Ghetto and the Jews of Rome”. Schocken Books Inc, U.S, 1996.

7. L erner, Scott L. Op. cit.

8. Luca, Fiorentino. The Ghetto Reveals Rome. Gangemi; Bilingual edition, 2005.

9. Schama, Simon. Op. cit.

10. L erner, Scott L. Op. cit.

11. Kostof, Spiro. The Third Rome 1870 – 1950: Traffic and Glory. Exhibition Catalogue, March 28 1973 – March 8 1974, USA Berkley, University Art Museum, 1973.

12. L erner, Scott L. Op. cit.

13. Kostof, Spiro. Op. cit.

14. L erner, Scott L. Op. cit.

15. L erner, Scott L. “The Narrating Architecture of Emancipation”; article based on research for the Frederick Sheldon Fellowship, a visiting scholarship at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, Harvard University, 2006.

16. Inter view by Bice Migliau: Salvatore Fornari on the development of Jewish culture in Rome during the 1970s to the 1980s. Our mission was to recover within the Roman Jewish Community a different reality; to promote a process of Jewish identification – to reach a level of visibility, knowledge and interaction worthy of a large community in the Capital City. This was by no means an easy challenge.

Silvia Haia Antonucci. Un amore Capitale. Salvatore Fornari e Roma, Esedra editrice, Padova, 2014.

17. Luca, Fiorentino. Op. cit.

CUBAN ARCHITECTURE: DEVELOPMENT, DECAY AND OPPORTUNITY

CUBA

Robbie Kerr worked with ADAM Architecture during his degree course at Edinburgh University, winning a place on our Travel Scholarship before joining the practice in 2010 and becoming the company’s youngest director in 2016 at the age of 29.

The idea for this project was conceived during a trip to Cuba in August 2007. The scholarship made it possible for him to return the following year, travelling from the western isthmus to the eastern extreme, from the gritty suburbs of Marianao to the crumbling masterpieces of Central Havana.

The intention of the report was to unpick the perceived notion of ‘romantic decay’ in Cuba, identifying the political, economic and cultural factors that have helped shape the island’s architecture.

Robbie has experience leading designs for major private residences and public buildings as well as conservation and restoration projects. More than a decade later he is still drawing on his research, currently developing plans for new Cuban work, in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Old Havana.

What is published here are Robbie’s observations from his travels in 2008. Of course, much has changed in Cuba since, including the death of Castro, the restoration of ties with the EU, Russia, China and the US, and the devastating hurricanes of 2008 and 2012.

All images, unless otherwise credited, are by the author.

Cuba’s architecture has decayed idiosyncratically for over half a century. Isolationist politics and shortage of funds, while negative in many ways, have had the positive effect of protecting the island from urban developments that have disfigured much of Latin America, while also protecting the fascinating balance of Spanish, French and American influences which have helped to shape the urban landscape. Its geographical location exposes the island to severe environmental conditions. Hurricanes and lashing rain are not uncommon and have engendered self-reliance and adaptability.

The popular romantic view of the current architectural decay is the result of changes in economic, political and environmental conditions sustained over 500 years.

Sun and salsa, communism and Castro have dominated travellers’ perceptions of Cuba. The unintentional marketing of Cuba’s brand of ‘romantic decay’, the opulent decaying remnants of the past intermingled with tarnished present glory, combine successfully with the mystique that surrounds Fidel Castro. The positive effect is that it has preserved so many of the styles that have accumulated across the island creating today’s paradox of a capitalist veneer in a socialist country. The 18th century palaces and soaring Art Deco edifices peel within an otherwise socialist backdrop.

Physical deterioration can be seen in the solares (tenement blocks occupied by Afro-Cuban workers) or cuartería (dilapidated rooming houses) that now exist in large

parts of Old or Central Havana. Poor standards of living, hunger and improvised lives are far from what might be perceived as ‘romantic’. Despite financial difficulties, Cubans have developed a sense of pride in their dwellings and made alterations with incredible ingenuity. Ruthless subdivision to accommodate the shortage of shelter has seen porticoes altered to form new bedrooms. Four storey solares were once colonial mansions; patios and zaguán (halls) now open onto a multitude of different dwellings and a new architecture has been formed from these historical developments.

The present restoration of parts of Old Havana by the City of Historians office led by Eusebio Leal, has seen fantastic work completed and yet the contrast with the larger stock of dilapidated buildings can be jarring, and result in the new buildings having a Disney-like quality.

Tourism has radically altered the island’s appearance since the 1930s. The capitalist lens through which most visitors

witness the country has heightened their attention to the aesthetic degradation. This has resulted in a misconstrued perception about the extent and explanation for Cuba’s decay. Politics and economics shape a country; even so there are other more subtle influences at work, including the changing cultural currents and the steady environmental battering of the island.

The years of Spanish colonial rule between 1492 and 1898 produced an architectural and stylistic metamorphosis that has formed the basis of subsequent styles in Cuba.

Columbus arrived in Cuba in 1492. The earliest buildings, the airy rectangular bohíos, were palm roofed structures with openings to allow ventilation. These early settlements were made up of circular caney with the bohío arranged around a batey (piazza), the central cacique being the focus of communal activity. Many of these bohíos

can still be found in rural settings as basic abodes, some reinvented as beach houses.

The Spaniard Diego Velázquez was sent to colonise the island arriving at Baracoa in 1511. The settlers established what became known as the seven original settlements. The sporadic attacks by aborigines held back development of these cities and forced Velázquez to move his capital to the more fertile and geographically strategic deep bay of Santiago de Cuba.

Slaves from Andalusia were imported to work in the mines and to help build fortifications for the seven settlements. The expansion in the number of slaves changed Cuba forever and put increasing pressure on housing within the city walls, forcing vertical expansion. Early developments were seen in the cuarto esquinero (corner room), and the casa almacén (warehouse/store) began its final stages of metamorphosis by the end of the 18th century. A mezzanine level was introduced within the ground floor for slave quarters and offices, allowing merchants to sell their goods from below their own living quarters on the first and second floors.

The wars in Europe led to ransacking by French corsairs of Baracoa, Cuba’s oldest city, in 1546, and Havana, which was burnt to the ground in 1555. In the second half of the 16th century Philip II of Spain left a lasting mark on Havana. The Castillo de la Real Fuerza was commissioned

SOLARES

2 TENEMENT BLOCK 3 EXAMPLE OF THE MASSING HOUSING CARRIED OUT BY 'MICROBRIGADES' IN THE 1970S 4 A RURAL BOHIO NEAR BARACOAin 1561, projecting the Spanish power in the New World and beginning the defences for Havana Bay. Havana became the island’s capital in 1607, with dramatic results for the once prosperous Santiago de Cuba.

The island’s economy improved with the introduction of larger scale production of sugar cane and tobacco. This gave rise to the architecture that dominated the rural landscape for the next three centuries.

The British continued to harass the ports and harbours of Cuba into the 18th century. Their presence was short lived, but the changes made during Britain’s short occupancy had lasting impact; trade was officially opened up for the first time and foreign commerce poured in. The basis for American economic ties were laid.

The brief sojourn by the British stirred Spain, once again, into reforms, developing Plaza de Armas into the first civil square in 1773. The porticoes, which later became commonplace across the country, were introduced for the first time, offering respite from the glaring sun. The first roads outside Havana’s city walls were laid out, including Paseo del Prado. Buildings that defined the Cuban Baroque style were commissioned: the Palacio del Segundo Cabo and the Palacio de los Capitanes Generales are the finest examples of Cuban Baroque, characterised by sober linear designs and simple façades with NeoClassical cubic proportions that are also evident in the equally splendid Havana Cathedral.

In 1791 the impact of the slaves’ rebellion in Saint Domingue, Haiti, heralded a major cultural moment in Cuban history. The influx of French landowners and workers brought with them the culture, architecture, 6

agricultural expertise and experience of foreign trade to drive Cuba forward, transforming Cuba from a country of small towns to one of large, semi-industrial sugar and coffee plantations, using huge numbers of slaves.

The French ideology manifested itself in the agriculture of the cafetales (coffee plantations) around Santiago de Cuba and in the architecture of Cienfuegos. The NeoClassical style, subsequently developed and distorted over the ensuing years, was introduced by Etienne Sulpice. Plans were made for the expansion of the capital beyond its city walls. New calzadas were planned and built in the Neo-Classical style following existing routes such as the Zanja Real. The stylistic developments of colonnades offered protection for merchants selling their wares from below their casa almacén creating a distinct streetscape.

The 19th century was the most prosperous in Cuba’s history. The decentralisation between Spain and Cuba began and some of the most important urban and architectural changes occurred, with the building of new jails and courts, social improvements such as a sewage system, as well as new markets, theatres, promenades and gardens. The Cuban Count of Villanueva carried out a set of parallel plans of public works that included the introduction of the railroad in 1837. In ordering the construction of the Fountain of Nobel Havana he put his own stamp on the vistas of Havana.

The early colonial houses were mainly earth and mud constructions overlaid with plaster, but stone was used more widely in the 17th century. Insecurity during the first 300 years led to houses focusing inwards on the patio space allowing greater ventilation and light to penetrate the houses. The traditions of the mudéjar (the Moorish style of architecture which was prevalent due to significant immigration from Andalusia) began to be adapted for the local conditions. Roofs developed externally with the characteristic tejaroz, a terracotta cornice with Moorish traditions and internally with the timber techos de alfarjes, ornately carved timber roof beams. Some of the finest mudéjar examples can be found at Casa de Diego Velázquez in Santiago de Cuba. Its influence also spread with the development of the balcony that began to appear on façades as these insecurities faded – well illustrated in the Casa de Francisco de Basaba in Vieja (1728 / 1841).

Ornamentation was limited to doors and windows which became progressively larger and by the 19th century often extended from floor to ceiling. This was in turn reflected in the increasing height of rooms, adapting further to climatic necessities. The zaguán had been evolving from the late 17th century, getting wider to allow for the developments in transport. It was first seen in Casa Obra Pía. The barrotes and persiennes, the grills and louvres on windows and doors developed to adapt to current stylistic trends and the increased need for security. With this came further developments of the deep, rich chiaroscuro decoration around doors and windows, the contrast of the simple flat walls further emphasising this decoration. The mediopuntos began as timber fanlights above doors and

windows to aid ventilation. As the centuries progressed these were adapted to incorporate coloured glass.

Ideas of independence grew throughout the 19th century resulting in the Wars of Independence and large-scale destruction to provincial cities. The destruction of the ingenios (sugar mills), haciendas and any property that aided the Spanish economy left Cuba at one of its lowest economic ebbs. In Bayamo, patriotic citizens chose to burn their city to the ground rather than let it be retaken by the Spanish.

Despite America’s view of Cuba as generally unruly and lazy, the island was still viewed as desirable by its powerful neighbour. American presence had been slowly growing, with increasingly American characteristics in town planning. In 1898 the USS Maine exploded and sank while anchored in Havana harbour, with the loss of 258 American soldiers giving the US an excuse to declare war on Spain. Within a few weeks American intervention

had achieved the decoupling from Spain for which the Cubans had been fighting for 30 years. The countryside lay in ruins, the economy in tatters. The Spanish Colony had become an American Neo-colony.

American intervention and the birth of the Cuban Republic

Cuba was tied to its near neighbours for the next 56 years. The US ‘liberation’ of the island only strengthened social divisions, reflected in the architecture which included sprawling suburbanisation. The Americans developed urban real estate, but at a cost to the rural communities, which became the workshops and warehouses for the foreign power.

Work on the famous Malecón in Havana began in 1901, now a monument to ‘romantic decay’ but so nearly wrecked in the 1950s plans.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, Cuba saw the rise of Art Nouveau, and later Art Deco. The geometric designs were often simplified from their European counterparts. In the 1940s those Spaniards that remained tried to reassert their presence, building refined and elegant buildings that harked back to their former glories in the areas of the old city walls, as seen in the Asociación de Dependientes del Comercio. However, following the collapse of the economy at the end of World War I their influence finally waned. The government also used this interlude of prosperity to construct monuments within the existing built fabric; the impressive Neo-Classical

Capitolio – inspired by its counterpart in Washington and adapted by Cuban architects – adorns the Parque Central in Havana. The new Presidential Palace was constructed in an Eclectic style and decorated by Tiffany’s of New York.

The 20th century witnessed the highest volume of building in Cuba’s history, and with it the remains of the Spanish colony were left behind and forgotten. Old Havana fell into disrepair. The Vedado district (now the city’s central business district) began to develop; a 100-square-metre grid of 400 blocks to the area west of Central Havana fitting into the older urban fabric of calzadas (avenues). With 16-metre wide roads and parterres this is seen as some of the best colonial planning. The broad grid allowed the random insertion of single

houses in an eclectic variety of styles, as land was bought and developed thus avoiding the destructive process that was happening in parts of the historic centre.

Little was done to help the housing stock of the poor. The solares inhabited by the poor received only minimal aid to repair the decaying structures around them.

During the American occupation (1898-1902) much needed improvements were made to the built environment. Railways and roads were extended and companies like the Hershey Company did much to improve the infrastructure around its investments. Tiles and cement were introduced and had a detrimental effect on the stylistic consistency achieved by the Spanish.

The economic crisis of 1920 saw sugar prices slump, however by World War II Cuba was once again enjoying a construction boom. Grand state projects were used to occupy large quantities of unemployed; the Capitolio and the construction of the Carraterra Central (Central Highway) were two such examples. In November 1939, elections were held for the Assembly and the Constitution of 1940 was subsequently introduced. Its progressive social-democratic content contained for the first time articles on urban planning and construction on a local and regional scale and gave provision for low cost housing and industry.

However, as in 1910, public commissions once again missed the neediest. The quantity and quality of the low-income housing progressively got worse. Vedado’s boom began to slow and speculation developed on land

west of the Almendares River in the area that is now Miramar. Much like Vista Alegre in Santiago de Cuba, Miramar developed a Neo-Classical style interspersed with some modern additions. These areas were set back further from the roads than in Vedado allowing more green space. However, these developments encouraged the sprawl of single-family residents, straining the city’s transport routes and diluting the polycentric nature of both cities. These houses often lacked the quality of those constructed 100 years before and many were stylistically transplanted from Europe or America, built mainly by American contractors. Vedado was developing a more complex social structure as the poor moved into low quality buildings hidden behind mass-produced concrete capitals and ornamentation.

American architects bullied fashion and by the 1930s the influence of a ‘universal style’ such as the Hotel National by McKim, Mead & White was replacing more sensitive American developments. These included the regional classicism of Bertram Goodhue’s Santísima Trinidad Episcopal church, and sensitively designed Art Deco buildings such as the Bacardi Building, which exemplified the high quality of construction that was being achieved in many buildings at the time.

The homogeneity of the streetscape continued to decline and the demand for private property overtook communal developments. The architectural language of distinct areas began to change; the colonial houses that had slowly evolved were left to rot whilst, infilling around them, the government commissioned Modern and Art Deco buildings in the historic core. The insertion of an American-style financial centre within the confines of the old city further damaged this fabric.

Insensitive developments continued through the 1950s.

The Santo Domingo Convent was replaced by a banal office development and a car park was built below the formerly splendid Plaza Vieja. Cubans increasingly believed that the American city was the paradigm of progress. Little regard was being given to the surrounding environment. There were efforts to improve the conditions in the city; under French landscape architect Jean-Claude Nicolas Forestier the Havana Extension and Embellishment project (1926-1928) was proposed, including connecting the city with a series of ‘diagonals and rounds’ using tree lined avenues and parks to improve the ecology, but land speculation made development difficult and little was realised.

The final years of the Republic brought new levels of corruption and decadence, under the influence of dictator Fulgencio Batista and the American mafia. Monumentality in planning and construction reflected International Modernist influences.

Batista was at the forefront of Cuban politics for 25 years before his eventual downfall during Fidel Castro’s revolution. Batista’s ongoing suppression saw the closure of those bodies that challenged him. Arquitectos Unidos, a Cuban architectural practice and forum for debate, was closed in 1955.

The mob leader Meyer Lansky lived by the motto ‘too much is never enough’. The Hotel Havana Riviera with its staircase leading to nowhere and its opulent decoration is but one example of the decadence that the mafia encouraged. Tourism increased leaving an indelible print on Cuba’s architecture. New modernist cinemas, hotels and offices along La Rampa exemplify the range in quality of designs and construction. The intrusion of nondescript hotels along the white sands of Varadero destroyed the tranquillity of the timber and local stone summer residences. Large decadent casinos were introduced. By the 1950s corruption was entrenched amongst developers, often bypassing architects who merely signed the necessary documents.

During the 1950s the International style and the efforts to simplify the ideas of Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright began to develop. Modernism took over and the new graduates of the University of Havana, including

Ricardo Porro, were encouraged to reject links to history, infamously burning Vignola’s books.

Leading world figures visited, built and advised across the country. Walter Gropius visited in 1945; Richard Neutra built amongst other projects Casa Schulthess and Mies van der Rohe had drawings on the board for the Bacardi Headquarters in Santiago de Cuba when the revolution swept Cuba and altered the architectural language once again. A property act was passed which allowed developers to ignore the laws that had given Vedado much of its coherence and allowed a series of high-rises to spring up indiscriminately. The 35 storeys of La Focsa, the Havana Hilton and the Retiro Odontológico towered high above the Havana skyline, but with little coherence.

The progression of modern styles had increasingly ignored the essential ‘three P’ details of patios, porticos and persiennes that so successfully adapted buildings to the adverse climate. The architectural image of Colonial Cuba was developing into a complex mix of styles, often losing Cuban identity.

During this time there was a movement to rediscover Cubanidad – the essence of Cuba. The Creole culture, first introduced with slave imports, had had little influence on the built environment. However, the concept of ‘Creolisation’ was beginning to be explored in the early 20th century. The three P’s exemplified adaptation to the individual nature of the island but machismo and guajiro (sensuality) were also important factors.

Ricardo Porro, although a supporter of modernism, viewed much of Vedado’s developments as ‘cocacolonialismo’

and sought a more regionalist architectural legacy, an ‘Arquitectura Criolla’ as a way of halting the aesthetic deterioration which resulted from the confusion of styles. At the same time there were experimental projects which considered the nature of Cubanidad alongside Modernist ideology and created much of the richness of 1950s architecture. Eugenio Batista at Casa Falla Bonet made reference to colonial precedents, rendering them in a modern context. Frank Martinéz at Casa Pérez Farfante referenced Le Corbusier, incorporating louvres and glass into the reinforced concrete structure on pilotis, to create a soaring central space encouraging cross ventilation. The organic influence of Frank Lloyd Wright was seen in Porro’s Casa Villegas; a more personal expression was developed later in his work on the Escuelas Nacionales de Arte (National Schools of Art).

In the 1950s masterplans were proposed to develop and update Havana. The construction of the tunnel linking El Morro to Vieja in 1958 opened up access to undeveloped land to the east. Land speculation increased and with it uncertainty. The so-called Pilot plan put forward by José Luis Sert, President of The International Congress of Modern Architecture, only increased the detrimental effects of this speculation. Proposals included creating an artificial island across the Malecón housing casinos and hotels which would have only fuelled further land speculation and driven elevated rents higher. Sert’s design was a prosaic distortion of Le Corbusier’s Cité des Affaires in Buenos Aires proposing that the only way to stave off decay in the area was to return focus to the riverfront with an artificial island and five skyscrapers. Other proposals were to transform the historic core of Vieja that would

have clashed with the traditional framework. Once again it was the energy injected by the arrival of the revolution that halted Sert’s plans.

By the end of the Republic, Cuba, and Havana in particular, displayed huge disparity and contradictions. The older building stock had lapsed into a poor state of repair which contributed as much to the present notion of decay as the following 50 years of socialism. Suburbanisation and sprawl continued without the mandate of a masterplan. Peri-urban standards declined and shanties that sprung up were prone to flooding, had poor access and were near to noxious facilities. Meanwhile the Malecón and Quinta Avenida in Miramar became wealthy attractive enclaves leaving Vieja and Centro to deteriorate. The urban/rural divide between centre and

periphery had steadily widened during the Republic and was one of the first tasks for the socialist government to address. The economic ties to the Americans had reached disproportionate levels. The dependence on a single crop had long since passed a sustainable level and would continue to cripple the economy for another 40 years. The American presence had had a greater effect on the island’s architecture than anything else in the previous 400 years. Nonetheless, there was evidence of successful integration of new International Modernist ideas with Cuban nuances.

The arrival of the revolution halted the uncontrolled American developments and injected new enthusiasm and a utopian vision. One of the architects for the National

Schools of Arts (the Schools), Ricardo Porro, described the situation saying, ‘I was in love with the revolution and it was this emotional response that prompted a new direction in my architecture.’

The architecture of the Schools represents the best of Cuba’s revolutionary architecture. The search for Cubanidad that had started during the Republic was given new validity. Porro was able to realise his two architectural ideals; that it should have social merit and embody Cuban tradition.

The architects of the Schools design, a collaboration between Roberto Gottardi, Vittorio Garatti and Porro, shared a common aim to reflect the history, politics and reformation of architecture – the essence Cuban architects strove for when seeking Cubanidad. Education

was at the heart of socialist revolutionary fervour and the surviving young generation of architects rose to the challenge. The revolution forced the emigration of a generation of prospering architects that was to have farreaching implications.

From 1961, the architects had to find alternative materials owing to the lack of reinforced concrete that had driven the architecture of the Republic; brick and tiles were chosen. The choice of bóveda catalana (Catalan vault construction) meant that the versatility of form so important to these architects could be realised. The architects explored the ideas of Cubanidad in a rich diversity of forms abandoning the strict rigours of history yet retaining the essential lessons learnt in design adaptation.

Porro’s Modern Dance School, conceived in the ‘romantic’ stage of the revolution in the early 1960s realises the emotional expression of national identity. His Plastic Arts School explored the multicultural heritage of a hybrid Cuban baroque and the more matriarchal African culture, thus a village type plan uses the sensual forms of domes and fountains, developing the idea of patio spaces and cross ventilation. The School of Ballet, by Vittorio Garatti, addressed more obvious historical precedents in a modern setting; the brick persiennes and high mediopuntos characteristic of Colonial construction in Trinidad allowed the flow of air and dappled light to filter in.

country. Without a clear programme, or directors for certain buildings, progress was slow. They have remained in the same unfinished state since their inauguration in July 1965. The ensuing decay, a result of its abandonment and underuse, encapsulates further the ‘romantic decay’ of Cuba. The ‘Tikal of Cuba’, ruins of past glories, memorials to the passions invoked by the revolution, stands in the wilds of the once opulent Country Club. The Music School and School of Modern Dance are still functional, and children walk across the long grass between them, but the remaining three Schools are hidden among the vegetation that now covers these exciting designs.

The revolution ended land speculation and with it the damaging profiteering and disruptive developments; rents were reduced and more concrete prefabricated housing was proposed for the working classes. The results have blighted outskirts of major cities and rural settlements created after the revolution. The strengthening of relations with the USSR saw a domination of techniques and ideas similar to that which the US had had only 10 years earlier. Nikita Khrushchev encouraged Cuba to develop mass production and standardisation in the second half of the 1960s and into the 1970s. The prefabrication movement in Cuba received its major kick-start in the wake of the destructive Hurricane Flora in 1963 when the USSR gave Santiago de Cuba a ‘Gran Panel’ prefabrication plant.

The Schools conception was far from smooth; the October Crisis in 1962 and the ensuing embargo made construction harder as labour was diverted to defend the

The government undertook many of these new housing projects using the existing labour force which was organised into microbrigades of 33 people. These people would come from the same workplace, would be supplied with materials from the government and be supervised

by a project leader from the Ministry of Construction who dictated locations for developments. Lack of skills, due to the exodus of trained architects, and poor craft construction meant that the final quality often fell far below expected levels. After completion the houses were distributed by and to the worker collective based on labour, social merits and needs.

130,000 of these houses were completed in Alamar as part of The Development of Social and Agricultural Buildings (DESA). Other such examples include the developments of José Martí district in Santiago de Cuba, San Agustín in Havana and the houses of rural settlements such as Arroyo Blanco in Sancti Spíritus province. The projects exemplify the functional decay expressed by Alvaro Siza. All are symptomatic of bad planning; units are arranged without reference to the landscape or the wider built environment. There is no firm architectural concept and a lack of correct detailing; as a result there are areas of high humidity, thermal bridging and material deterioration. The individual blocks have no relation to those around them, are badly proportioned, insulated and sealed to the corrosive elements. Many have taken on Colonial house elements, but a lack of understanding of the original principles has seen unsuitable distortions. The intended green spaces have deteriorated into a ‘no-man’s land’. Services have been located in isolated buildings with few social spaces. These settlements have become ‘bedroom communities’ due to the lack of industry that could have transformed these conceptually good ideas into civic centres. The final results are far removed from the potential of what effective socialism could have produced.

The Schools and the Alamar housing show the ability of the revolution to produce some of the best and worst developments of Cuban architecture. Whilst both strengthen the notion of ‘romantic decay’ in different ways - the Schools adds to the romance of a lost past and Alamar strengthens the notions of perceived hardships -the resulting decay was the result of, in the case of the Schools, unstable developments within a complex socialist environment particular to the time and, in the case of the housing, of the poor realisation of a foreign induced scheme.

The distinctions between each period of Cuba’s architectural history can be directly linked to the energy that was injected into the island at the intersection between each era. By 1868, before the Wars of Independence, Cuba was prosperously placed with a rich and homogeneous development of Cuban Baroque and locally adapted Neo-Classicism. During the Republic, distancing from historical precedents saw the introduction of a variety of new types and styles of building that have strongly contributed to the ‘romantic decay’ seen today. As the Republic developed and Cuba became increasingly tied to the US, the island’s development began to lose the sense of Cubanidad; a tendency mirrored in other Modernist developments around the world. The political struggles of the revolution gave Cuba a pride in its independence and the early developments of The Schools saw the resulting exuberance displayed.

What would Havana have looked like today had it not been for the intervention of the revolution? There would have been an influx of international architectural work. The balance engendered by the search for Cubanidad would have languished. It is possible that much of the cultural heritage would have been lost, and that continued development would have led to ‘Miamization’ creating yet another American-influenced shoreline development such as San Juan in Puerto Rico.

Sert’s ‘Pilot Plan’ would have had huge implications. Without the revolution the scale of Havana would have been almost double the present size as development bypassed provincial towns. There would have been strips

of modernist glass-wrapped structures, high rise luxury hotels and steel towers. The suburban sprawl that had begun at the start of the century would have continued. Polarisation between the rich developments of malls, large supermarkets and private schools on the one hand and the poor shanties along the side of highways would have been exacerbated. Sert’s plans for Vieja would have radically altered its shape and function; the Malecón would have lost its unity and distinct identity.

Cuba stands on a new threshold. Its institutions will have to be prepared for the new consumer society that will surely emerge as the tension of the last 50 years is released. A vital part of the transition will be the degree to which the essence of Cubanidad that has enchanted the tourist and architect alike for the last 100 years is retained. Efforts are being made to establish zoning laws and to realise the value of the built heritage which must be retained despite the need for more accommodation.

The Office of the City Historian has been working hard with UNESCO. Universities in America and workshops and charrettes in Cuba have all been seeking methods to avoid the potential pitfalls of the 1950s ‘Pilot Plan’ and those errors realised by Eastern European socialist states after 1989. The transition to a socialist variant of capitalism has begun and already the dangers have become apparent. However, there is an opportunity for developers to use the negative dilapidation and material shortages that have arrested past constructions to positive effects; the development of the bicycle culture and the shortage of cars and the highly educated workforce developed by the Socialist government could set Havana on the path towards becoming a major green city.

SICILY