Cracking Design Codes

Understanding design codes as a tool for better urban development

Cracking Design Codes

Offices in Winchester & London adamarchitecture.com adamurbanism.com +44 (0) 1962 843 843

Published: November 2023

Editor: Nico Jackson

© ADAM Architecture 2023. Cover illustration by Evelina Dee-Shapland. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the Author.

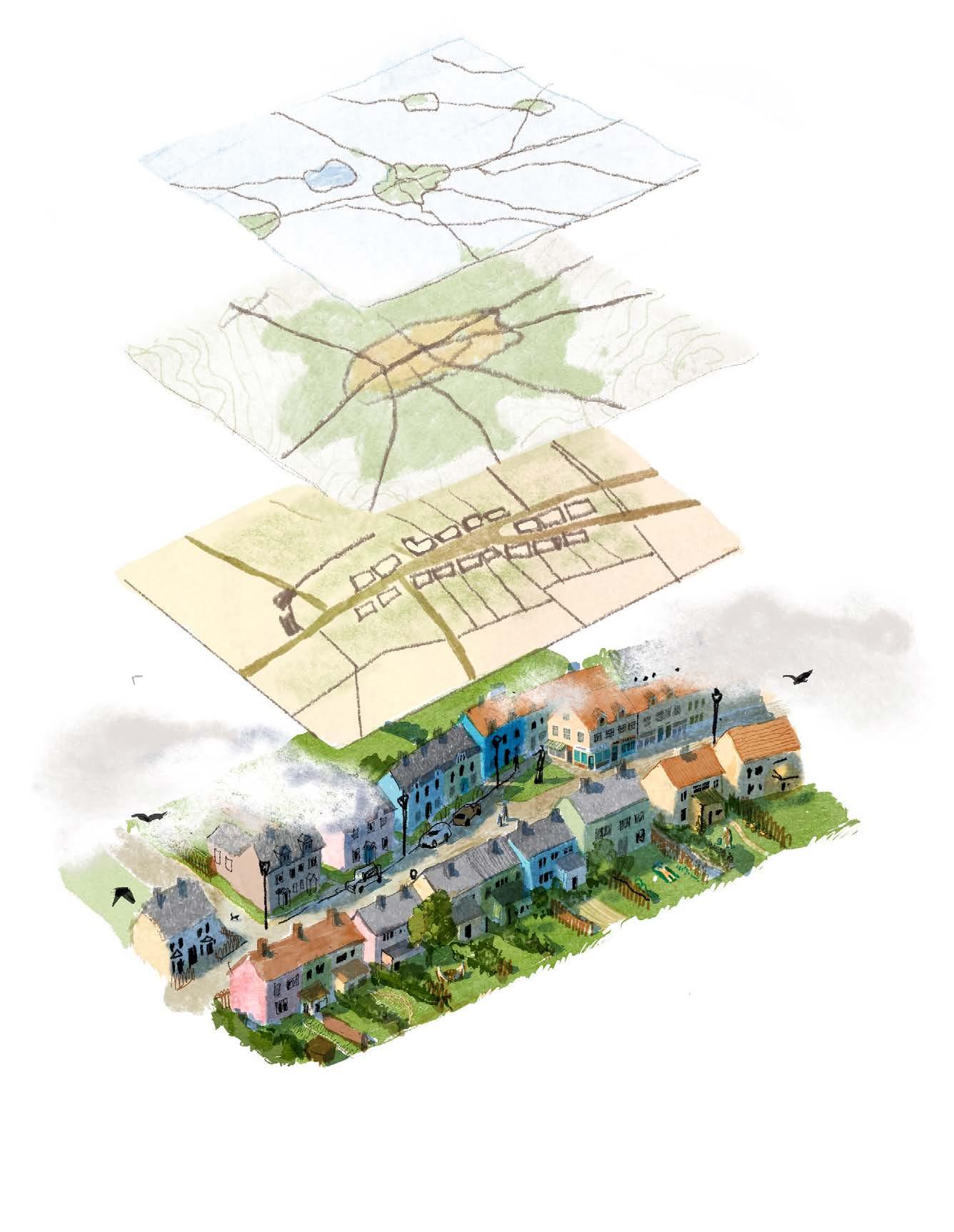

Conceptual aerial illustration of Shepton Mallet (1996). Credit: Chris Draper

Introduction

We first began writing urban design codes in 1996 with a residential project for The Duchy of Cornwall at Shepton Mallet, Somerset, followed by codes for similar developments at Midsomer Norton, Somerset and at Trowse, Norfolk. We have since accrued extensive experience in coding across the country and are unique in the way in which we write and administer a wide range of design codes, from the straightforward and contained, to the explicit and detailed. Our flexibility and range of coding allows us to be adaptable to the requirement of sites and clients’ priorities rather than adopting a dogmatic approach to a single methodology.

Where has the requirement for design codes sprung from?

In the last decade a small number of activists have campaigned to bring beauty back into the heart of development policy. For many decades there have been individual campaigners such as Sir John Betjeman, and amenity societies such as SAVE Britain’s Heritage, who have campaigned to preserve much loved and architecturally significant buildings, but until more recently less attention has been paid to what is being built now. That is until the late Sir Roger Scruton and a small group of supporters, began to push for an urban environment that was more conventionally ‘beautiful’.

In 2018 Scruton began a project at the think tank Policy Exchange producing, with Jack Airey, Building More, Building Beautiful. The report included conclusive polling evidence that the majority of the public – from every age, income bracket and ethnicity – prefers traditional design and believes that newly built homes and properties

should be sympathetic to their surroundings. So why was so much new building flying in the face of such public preference? The conclusion of this, and previous reports, was that the local councils were controlling design. In addition, the high cost of land meant that people who were buying the homes couldn’t afford the additional cost of design and finally, that the planning system was weighted in favour of volume builders.

These arguments resulted in the government launching the Building Better Building Beautiful Commission, headed by Scruton. The lead researcher, Samuel Hughes, has continued with a newsletter called Place Matters The commission’s eventual report, Living with Beauty, argued for the public’s preferences to be considered and respected, and for individual communities to take control of aesthetics.

Cecil Square, Stamford, Lincolnshire

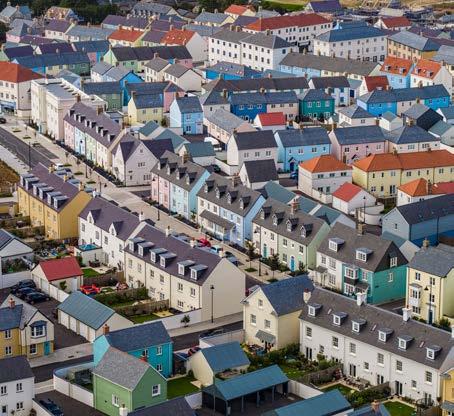

Nansledan, Newquay

The Office of Place was subsequently launched to support the development of design codes across England. It was formed with Nicholas Boys Smith who runs Create Streets, the not-for-profit pressure group that aims to create better public places and is supported by an advisory board.

The government’s National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) states that all local planning authorities should prepare their own design codes consistent with the principles set out in the National Design Guide and National Model Design Code (NMDC), and which reflect local character and design preferences.

The design codes produced by ADAM go far beyond what is set out in the National Model Design Code, and indeed often serve a much more focused purpose to help define specific places being created

At the end of 2022 a report by Policy Exchange advocated the creation of a new national school of urban design, backed by Michael Gove, appointed Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities in October 2022. In his foreword to the report, he acknowledged that although British architecture remained a ‘national coveted brand’, much of what is built in the UK is let down by the surrounding environment. ‘Places must be at the heart of levelling up but if places themselves have no heart and soul, then levelling up too will falter.’ He suggested that by improving urban planning, communities might be more likely to accept new buildings, particularly housing developments. The report states that the School of Place would ‘seek to wholeheartedly revive traditional architecture from the annals of obscurity to which contemporary architectural education has unfairly consigned it’ but would also offer a ‘broad range of other stylistic approaches’.

It is within this ever-changing political context that we continue to refine and extend our use of design codes, evolving the way we code as we continue our research and learn from our extensive experience in urban design.

Woodstock, Oxfordshire

What are design codes?

Design codes provide a set of parameters within which the developers and builders involved in a project can refine their contribution, allowing for a degree of freedom inside the overall framework. They are critical to maintaining consistency across a development.

Design codes can control the way a development is planned, or the way individual buildings are designed within a masterplan, or both. They can dictate a style or simply control specific features, such as materials and heights

The type of code that is deemed appropriate – whether they set factual limits or are just guidelines – will depend on the different developments, developers, and authorities.

While we have pioneered the use of non-stylistic design coding, we also produce detailed pattern book codes. The pattern books have a focus on local identity and visual assessment, describing urban form and character as well as architectural language. Each has their strengths and weaknesses, and we continue to evolve and improve our approach to coding using elements of each and lessons learned from each experience.

What unites our approach to all design coding is that it is vision-centred, place-specific, simple, objective, binding, offers a variable level of control, promotes the permanence of buildings, and offers flexibility. It also prioritises images over words, to aid clarity and understanding

There are various prescribed ‘codes’ which affect the design of buildings and spaces, such as the National Model Design Code (NMDC) published by the government in 2021, and the National Planning Policy Framework. Both are limited in their ability to serve their intended purpose. The design codes which ADAM Urbanism produces prescribe controls beyond the scope of normal planning policies or existing statutory regulation.

Design codes work alongside the production of a masterplan, serving as a prescriptive framework in which to implement the masterplan’s design principles.

Nansledan, Newquay

Key principles are established to ensure character, consistency and quality are established, measurable and maintained. The visual and written components of the code should build upon the collective design vision developed by the client, the developer and urban designer.

Design codes can range from a light touch approach to detailed control. They provide constraints, but also certainty and delivery expectation, for a future developer or designer, depending upon the type of code employed. Different types of code allow for different levels of choice and in certain circumstances the code can vary throughout a scheme. For example, in some developments it might be felt that codes are only needed to control key areas in the public realm, and a percentage of houses need not comply. While a masterplan establishes the broad spatial layout of a development, the design code delivers a more detailed resolution of design parameters, including urban form, materials, and architectural details

The design code ensures that the character of the architecture reflects the individual character of each street in terms of form,

massing, set-back, materials, architectural detailing and public realm materials, and properly integrated green infrastructure.

All codes should be written clearly and objectively, with room to evolve, encouraging a long-term approach to the development of a scheme. Imprecise, or advisory guidelines are open to interpretation and are less likely to achieve the desired outcomes for a client but read in conjunction with objective criteria their use can be effective

Woodstock, Oxfordshire

When are design codes used?

Design codes are most often used on larger scale masterplans, or where developments are built out over a long period of time. They help ensure consistency, particularly within the public realm across the site. However, they may also be used on smaller schemes, particularly in outline planning applications. On smaller sites, the landowner might also be looking to sell the site to a developer or housebuilder while wanting to control the quality of the development for legacy reasons and to reassure stakeholders and residents.

How are design codes implemented and enforced?

Poundbury, Dorset

• Design codes only work if they are effectively implemented within the context of a good masterplan; they don’t in and of themselves ensure good urban design.

Enforcement

and parallel legal frameworks are essential to the success of any design code.

• Design codes are typically enforced by the project owner and/or their agent but are sometimes adopted and enforced by an external agency such as a local authority. Without any legal status the codes will not be enforceable. This can be through Contractual Law or Planning Law. Giving the codes legal status ensures that the codes will be implemented and enshrining them in Planning Law ensures that the requirements will be maintained for the whole life of a project, from inception to completion.

• We encourage clients to identify the aims for their development and which areas need to be coded; they then establish the legal framework for enforcing the control of the code. Once these factors are in place, we create a bespoke code.

• ADAM design codes require little subjective interpretation, allowing for a simple ‘checklist’ method of evaluation, which ensures an uncomplicated review process and avoids subjective interpretation of style or aesthetics.

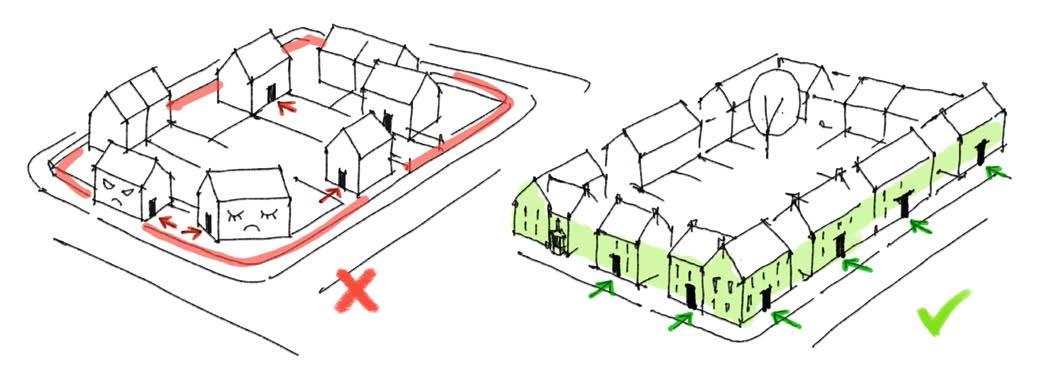

• ADAM design codes generally only seek to control those parts of the urban environment which face onto, or are visible from, the public realm – although all boundary treatments which border the public realm are controlled.

• Design codes should be able to be objectively administered.

I How are design codes implemented and enforced?

• To ensure ease of implementation visual codes are often more effective than written ones.

• Design codes need to be revised regularly to remain effective and workable or structured as a site wide code with more detailed area codes coming forward as development land is released or development progresses .

• The intention is that the National Model Design Code will encourage local authorities to be more effective at preparing and administering codes by others. However, codes administered by landowners and master developers (or their agents) who have a long-term interest in the land are likely to be more successful in terms of control and delivering a better place, because they can be more dogmatic and are not constrained by the test of ‘reasonableness’ which applies to planning.

• There are different types of controls used to implement design codes; more than one can be used on the same development.

• Local Development Orders (LDOs) set the parameters for detailed planning consent for the development. Authority is delegated to the landowner to administer the process. To date, Nansledan is the only scheme we have administered under this process and is the largest LDO awarded in the country.

• National Model Design Code provides detailed guidance on the production of design codes, guides, and policies to promote successful design.

What are the different types of design code?

A Street and Placemaking Code

A design code which prescribes the urban form of buildings and spaces without prescribing architectural detail. Typically, parameters such as heights, the degree of enclosure, building setback and materials, are prescribed, along with more detailed prescription of the design of streets, open spaces, and boundary treatments. An example of this code is St Martin’s Park, Stamford.

Extract from Street Design Character Statement for Nansledan Phase 10A

Extract from Street Design Character Statement for St. Martins Park, Stamford, showing neighbourhood green

A Pattern Book

An objective analysis of the existing urban and architectural character of an area. Whilst a pattern book on its own would not necessarily be considered a design code, it can be extended to provide coding criteria for new buildings, based on the existing townscape and architectural precedents illustrated. It is a useful tool for public engagement. At Nansledan, Newquay, it was part of a suite of coding documents which under the Local Development Orders (LDO) process was simplified into the design manual, of which the pattern book is an appendix. Castle Howard and Sandringham are the only two examples where we have used a pattern book without a design code. For the Leconfield Estate in Petworth, we are using a pattern book with a design code (page 34).

An Architectural Design Code

A design code which prescribes the design of detailed architectural elements such as doors, windows, walls, roofs, and other key details. This type of code is typically combined, or used in conjunction with, a street and placemaking code. This code was used, for example, at St Martin’s Park, Stamford. Accompanying the St Martin's Park street and placemaking code is a separate building code. Typically, these are combined as a single design code. Land at the Green, Theale is a simple example of the more typical combined code; Oakley Vale, Corby is a more complex example; and Fairham, Nottingham is an example where a sitewide code is used in conjunction with a phase code.

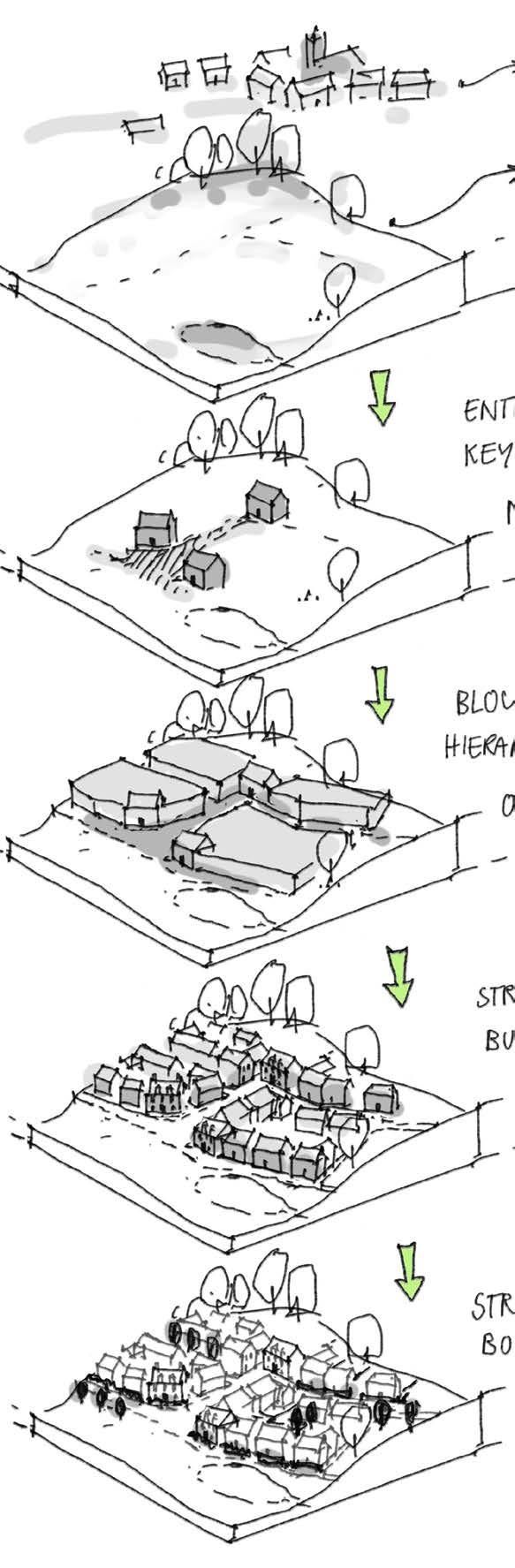

Preliminary sketches of Fairham Pastures, Clifton, Nottingham

Sandringham House, Norfolk

What are the benefits of design codes?

Shepton Mallet

• They provide enhanced economic value that better design, and a stronger sense of place and local identity, can deliver. On phased developments codes help to give certainty to developers of the quality of developments on adjacent sites and confidence in value, as well as the benefits listed below.

• They provide a clear vision, tailored to local needs and economic and social benefits.

I What are the benefits of design codes?

Design codes improve design quality, tying down ‘must have’ design parameters and ensuring consistency, which is particularly important in controlling the interface where phases are being sold to multiple developers. This helps achieve a coherent urban form.

• They help to bring key stakeholders together early in the process leading to smoother working relationships and to a better understanding of expectations and constraints from the start.

• In June 2022 Matthew Carmona, Professor of Planning and Urban Design at University College London, wrote that ‘design codes have gained a new status in the English planning system and their use looks set to grow and grow. Like any tool, there will be good design codes and bad ones and just having a code in place is no guarantee that design quality will be delivered. They need to be well conceived, carefully crafted and consistently executed to achieve that, and all these things take time, skills, and resources to secure. However, when done well, as other research has shown, they do have the potential to deliver superior design outcomes.’ Testing design codes in England – 21 lessons.’ Matthew Carmona (matthew-carmona.com)

• In our opinion, design codes controlled by the landowner or master developers are most likely to deliver successful places. When in the sole control of the local authority, delivery and monitoring can be inconsistent, which is problematic given that planning operates on precedent, so if a code is broken once, it loses validity for the remainder of the project’s duration.

Bar chart to show that although dwellings within developments with a design code have a higher production cost, the sales value is significantly higher.

• Above all, design codes help to ensure the creation of beautiful places that people want to live and work in, as well as giving greater certainty to those using them. In the best-case scenario, the use of design codes can speed up the planning process and save costs.

‘Like any tool, there will be good design codes and bad ones and just having a code in place is no guarantee that design quality will be delivered. They need to be well conceived, carefully crafted and consistently executed to achieve that, and all these things take time, skills, and resources to secure. However, when done well, as other research has shown, they do have the potential to deliver superior design outcomes’

- Matthew Carmona, Professor of Planning and Urban Design at University College London

ADAM Urbanism projects in the United Kingdom

Over the years we have continued to learn about the benefits of design codes, and how best to write them to suit individual clients and briefs. Codes do not necessarily lead to good design but

through our ongoing experience working with codes and the largest volume housebuilders we are refining our approach to coding to aid this shortcoming.

Western

Berewood,

St

Wilton

Nansledan Newquay, Cornwall

Poundbury, Dorset

Waterlooville, Hampshire

Sandringham, Norfolk

Fairham, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire

Martin’s Park, Stamford, Lincolnshire

Harbour, Edinburgh Granton Harbour, Edinburgh

Trowse Newton, Norfolk

Duke’s Rise, Shepton Mallet, Somerset

Thicket Mead, Midsomer Norton, Somerset

Welborne, Fareham, Hampshire

Tregunnel Hill, Cornwall

Wellesley, Aldershot, Hampshire

Leconfield Estate, Petworth Bohunt Park, Liphook, Hampshire Pond Farm, Burghfield Common, Berkshire Whitfield, Dover

Land at the Green, Theale, Berkshire Oakley Vale, Corby, Northamptonshire

Park, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire

Castle Howard Estate, York

Park View, Woodstock, Oxfordshire

Luzborough, Romsey, Hampshire

ADAM Urbanism case studies in the UK

Nansledan, Newquay

The design coding at Nansledan is developed from the pattern book of local architectural typologies

The design coding at Nansledan has been developed from the pattern book which identifies the forms and characteristics of successful urban and architectural typologies within Newquay and cohesive settlements nearby. It suggests how urban patterns may be extended into new areas and thereby reinforce the best of the existing with the new. Reflecting local identity and provenance is a key requirement of the design code and by encouraging the use of local materials and resources in traditional forms of construction it seeks to create a genuinely sustainable development.

The concept for this significant urban extension has been developed with the benefit of extensive public consultation, which will be on-going throughout the life of the project. The aspiration of the Duchy of Cornwall, which will retain a long-term interest in the site, is to create an exemplary, dense, mixed use, sustainable extension that is distinctively Cornish in character

and closely tailored to the needs of the local community. It will also act as a catalyst to diversify and strengthen the local economy.

A consortium of developers has been forged with three privately owned, regional housebuilders to help ensure that the best long-term value is achieved for the development. Local supply chains were established at the outset to help ensure that the economic growth that is being generated by the development is enjoyed by the surrounding area, with local materials and resources used wherever possible to benefit the local economy and to ensure that the character reflects the local identity.

Facilities include a district centre and multiple local centres, a primary school, GP surgery, care homes, and significant green infrastructure. The project began on site in the summer of 2013, with successive phases of around 100 units per year brought forward over a 40-year period.

Client: The Duchy of Cornwall, CG Fry, Morrish Homes and Wainhomes

Role: Masterplanner, co-ordinating architect, design architect for some buildings; author of pattern book, prescriptive architectural design code and street character code

Working with: WSP, AWP, Parsons Brinkerhoff, Camco, Fabrik and The Prince’s Foundation, Purl Design, Yiangou Architects, Francis Roberts Architects and Alan Leather Associates

Site: 218.4 ha

Scheme: 4,000 homes plus commercial space and amenities

Status: Started onsite in 2013

Awards: National Urban Design Award 2021; AJ Architecture Award Highly Commended 2021; RIBA South-West Region Award 2021, Civic Trust Regional Finalist Award 2021, British Homes Awards 2020

Duke’s Rise Shepton Mallet

The first design code was written by ADAM in 1996 for this new neighbourhood in Somerset

This new urban neighbourhood is situated close to the existing town centre of Shepton Mallet. It was developed according to traditional urban design principles and has the character of a selfcontained village. Terraced houses constructed with traditional materials that harmonise with the local vernacular predominate. The scheme has proved a considerable commercial success, with properties maintaining a premium value on account of the quality of the design.

The code aims to create a distinctive selfcontained community that fits with the larger community of Shepton Mallet. A high standard of design will protect the future value of the land.

The code is based on an analysis of the existing settlement, ensuring the requirements deliver a similar character and quality of local traditional settlements, whilst providing modern services and standards.

The guidance defines the spatial and formal qualities that the scheme is to exhibit without prescribing design solutions. Descriptions of details, such as the form of appropriate traditional windows, is quite detailed and specific.

A relatively small number of design requirements establish the qualities that will be exhibited in every part of the scheme. These define the palette of materials and their use and specific details that are to be incorporated. This ensures a consistency of approach is maintained throughout the whole development.

‘Model Design Standards’ show how the qualities expressed in the design guidelines can be achieved, providing explicit information. They are not binding but express what the landowner would like to see in the design.

Client: The Duchy of Cornwall and the Vagg family

Developer: Bloor Homes

Role: Masterplanner, co-ordinating architect, design architect & author of building code

Working with: Tetlow King and other architects

Site: 17 ha

Scheme: 550 houses and apartments

Status: Completed in 2011

“[Field Farm], with its traditional architectural and landscaping approach, creates a strong sense of place. The development provides variety and interest through the use of well detailed architectural features and a range of high-quality materials”

- CABE South West Housing Audit, 2007

St Martin’s Park, Stamford

Building detail control is ensured through an architectural design code, an effective tool in combination with the adopted street and placemaking code

An architectural design code prescribes the design of detailed architectural elements such as doors, windows, walls, roofs, and other key details. Accompanying the St Martin’s Park street and placemaking code is a separate building code. These can also be combined as a single design code.

The St Martin’s Park site comprises land occupied by the former Cummins factory and an adjacent area with extant permission for business use, owned in part by South Kesteven District Council (SKDC) and Burghley Land Ltd. The site is bounded by the railway line to the north and is opposite the registered park and gardens of Burghley House in Stamford, Lincolnshire.

SKDC and Burghley Land Ltd’s aim is to provide a high quality, mixed-use development that will enhance the approach to Stamford from the east and preserve the setting of Burghley House and its grounds, with a development that is of Stamford. A key aspiration is to support local economic growth and replace the number of jobs lost from the site at its closure as well as tailoring a development to local housing need and retirement living.

Client: South Kesteven District Council and Burghley Land Ltd.

Role: Masterplanner, .authors of prescriptive street & placemaking design code

Site area: 14.7 ha

Scheme: 190 homes, 150 retirement living homes and 10,000m2 of commercial space

Status: Outline application including street and placemaking code approved Feb 2022 (submitted Nov 2020)

concept for frontage character along the edge of Burghley park

Early

masterplan - showing how the site can be developed in accordance with the street and placemaking code

a

A key space in the commercial areas of the site

Illustration of proposed commercial unit at a key entrance to the site

Section through

key green space forming the new approach to Stamford from the east

Illustrative

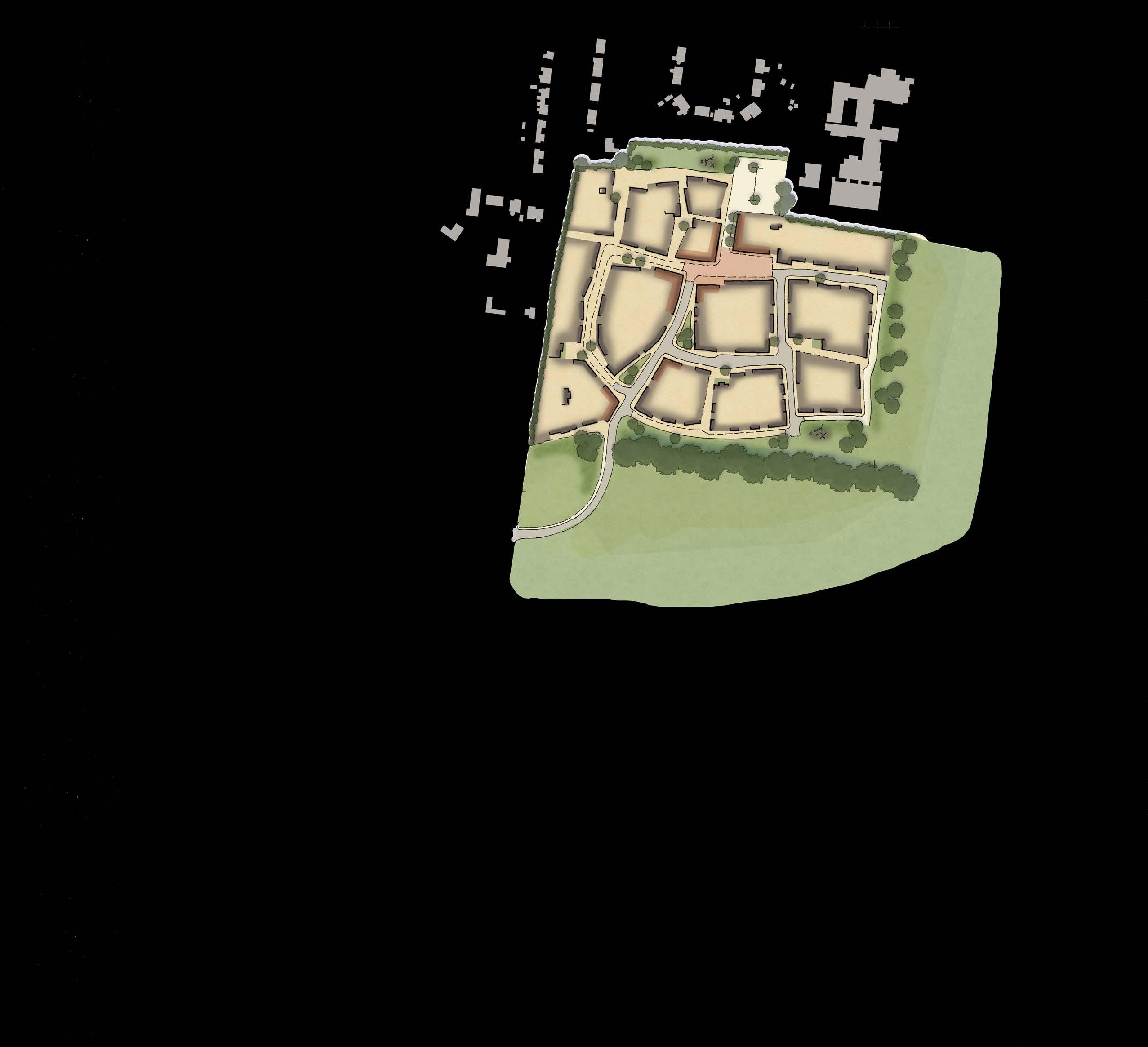

Fairham, Nottingham

A sitewide code is used in conjunction with a phase code for this new sustainable district

Fairham will be a new sustainable district for Nottingham that will respect the local character and the landscape while having its own special identity. It will be a complete community with a variety of homes of all sizes and tenancies as well as places to work, shop, relax and play. There will be a school, community buildings, parks and playing fields. It will be a place for healthy living, the countryside will be close to all areas of the development, and the district’s centre will be landscaped sympathetically, to provide a continuation of the countryside. While most everyday needs will be within easy walking and cycling distance, Fairham will also be well-connected by public transport to the city of Nottingham and by road to major highways.

Each part of Fairham will have its own individual identity which will come together to create a harmonious and coherent new district. Traffic will

be controlled, and the priority will be for the safety and convenience of pedestrians and cyclists. The landscape will be comprehensively designed, and the buildings will be carefully controlled to make sure that the quality of the place comes through from the largest space to the smallest detail. Energy conservation achieved with a whole-life environment, the reduction of vehicular movement and building construction will inform all aspects of the development. Lessons will be learnt as it grows, and beneficial technical advances will be incorporated as they become available. Objective design codes, authored by ADAM Architecture, are used to ensure the development is built in line with the local area, ensure quality, coherence across the site, and adherence to the high levels of design and quality.

Fairham will set a high standard for all future development nationally.

Client: CWC / Homes England

Role: Masterplanner of record, architect, and author of design code

Working with: Landscape Architect FIRA

Site: 89 ha

Scheme: 3,000 dwellings, employment, a local centre, and community use

Status: Under construction

Site Wide Design Code

Supplementary Documents:

Fairham Centre

Driftmoor

Upper & Lower Brecks

Hearts Lee (east & west)

Fairham Business Park

Pond Farm, Theale

A building manual was used here, alongside both a design and community code, and a design code

The ambition of Englefield Estate is for a fresh approach that will build on the Estate’s local legacy of delivering homes for the local community. The Estate wishes to bring about development in which it can take pride, helping to build community and create a new and lasting legacy. Of primary concern is how to create a more effective synergy between the urban and rural, creating new places that people will choose to live in, to work and to visit, while responding to the overwhelming need to promote sustainable living and shape a brighter future.

The building manual is designed to evolve over time and adapt depending upon the needs of different parts of the estate. Initially it is intended for the Theale site. A range of guidance is outlined for land on the edge of Theale, adjacent

to the AONB and opposite the entrance to the Estate. The guiding documents are subject to review and adaptable to emerging ideas and technologies. The purpose of the manual is to control the design across the whole site to ensure consistent development quality and a coherent visual character. It provides overall guidance in relation to the public realm and buildings across the site. It also sets out the underlying philosophy and aspirations for the site and prescriptive requirements to ensure that the vision is delivered successfully. It provides a limited palette of materials and defines elevational types and elements; it does not control the style of individual buildings. It protects the public facing aspects of the architecture.

Artist's perspective illustration

masterplan

Client: The Englefield Estate

Role: Masterplan and design code

Working with: Lockhart Garratt landscaping

Site: Burghfield 4.2 ha, 100 homes

Theale 7.2 ha, 105 homes

Status: Ongoing

Artist's persepctive illustration

Site boundary

Proposed trees (indicative locations)

Retained trees

Proposed orchard

Trees to be removed

Indicative location of proposed SUD’s feature(s)

Open space

Proposed residential houses

Proposed flat over garage

Parking/carport/outbuildings

Play area

Illustrative

Leconfield Estate, Petworth

A pattern book identifies key features to consider for any future development

This pattern book was commissioned to identify local building traditions, styles and placemaking principles that can inspire any new future development at Petworth. The Leconfield Estates is a private, traditional, agricultural landed estate in the ownership of Lord Egremont and his family. It is centred around Petworth House and includes many properties in the town, and most of the land that surrounds it.

The core of Petworth is an attractive market town with a range of independent shops and facilities. The pattern book is intended to act as a rich resource of details for the design of urban

spaces and buildings. It provides a broad historic background to Petworth’s development over the centuries, identifying some of the key patterns of urban character and form. It is followed by an analysis of building typologies, studying the scale and proportions of the various building types. Building details and materials are also documented and common threads identified. Each section of the pattern book concludes with a summary of findings, recapped in overall conclusions which identifies the key features that would be desirable to take forward in any new development in Petworth.

Artist’s perpsective of Petworth street vernacular.

Client: Leconfield Estate

Role: Vision for estate land to the south of Petworth, and design guidance for up to 100 homes. Assist in the appointment of a development partner. Delivery of a pattern book, design requirements and design code

Working with: Savills

Site: Petworth South

Status: Ongoing

Illustrative masterplan

Artist’s perpsective of Petworth town hall.

Park View, Woodstock

The architectural design code employed here has resulted in a buoyant housing market

The 16.7 hectare site at Park View lies immediately to the south-east of Woodstock near to the World Heritage Site of Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire. It will be a natural extension and new quarter to the existing historic town. It is within walking and cycling distance of the town centre with a wide range of local services and amenities.

The masterplan provides for up to 300 new homes, where 200 homes had previously been refused planning permission. Fifty per cent are affordable homes, which consistently sell for above the local market rate on account of their desirability. Homes are sold off plan, predominantly to local people,

despite other sites stalling on account of high interest rates and economic uncertainty.

The retail units are set around a neighbourhood square, with potential for education facilities and public open space. The development includes affordable homes interspersed within the mix of one- and two-bed apartments, two-bed and three-bed terrace and semi-detached houses, as well as larger three-, four-, and five-bed family homes. The design code draws on the characteristics of Woodstock and surrounding villages and sets out the architectural form and the use of materials for the whole site.

The design code draws on the characteristics of Woodstock and surrounding villages

Client: Vanbrugh Unit Trust; PYE Homes

Role: Masterplan and architectural design code

Working with: Terrence O’Rourke and Fabrik landscape architects

Site: 16.7 hectares

Scheme: 300 new homes plus commercial

Status: 2018 with projected completion 2025

With thanks to...

ADAM Architecture would like to thank all those we’ve worked with over the years on a huge range of coding, including

Abbots Ripton Estate

Apley Estate

Ashfield Estate

Badminton Estate

Broadlands Estate

Burghley House Preservation Trust

Castle Howard Estate

CG Fry

Colman Estate

CWC Group

Duchy of Cornwall

Englefield Estate

Forth Property Developments Ltd

Grainger plc

Great Oakley Farm Ltd

Green Village Investments Ltd

Homes England

Inland Homes

Leconfield Estate

Morrish Homes

Pye Homes

Sandringham Estate

Vanbrugh Unit Trust (Blenheim Palace)

Wainhomes