V E R T I C E S VERTICES

Career Journeys, Project, Insights and Inspirations

“When I left Penn State in 1965, I spent four years in the military and then my journey in architecture began. I didn’t know what to expect but I had abiding interests in “housing”, traditional architecture and urbanism with historic preservation thrown into the mix. I am blessed in that pursuit to this day.”

As an undergraduate I had the opportunity to study abroad for a semester at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, followed by a summer of travel throughout Europe. After serving a full four years in ROTC I was able to choose to go back to Europe, serving 3 years in Germany before a final tour of duty in Vietnam. My time in Europe exposed me to the magnificent and rich history of architecture. Traditional architecture and urbanism would later become the central theme of my work.

In 1974 I became a partner in the New York City “branch” of a small 10-person firm based in Baltimore. With hard economic times in 1997, I was unemployed before becoming the managing partner in another startup firm HAUS (Housing and Urban Services) PC. Our parent company assigned us a commission to design 5,000 units of housing in Tehran I asked a bunch of questions, and 5,000 units translated to a population of about 16,000 residents. So where were the schools – elementary to high schools? What about commercial space and so on. Our client eventually agreed the project was a new town and the design of Qanat Kosar was underway, and in 1978 we would win a design award for new town planning from Progressive Architecture Magazine

HAUS was just beginning, winning a second commission to design the National Iranian Oil Company’s headquarters – but the revolution in Iran in the fall of 1978 eventually toppled the Shah of Iran’s’ regime and forced the shutdown of HAUS.

On December 22, 1978 I found myself being interviewed for the position of Project Manager/Design Director for a new mixed-use project on 5th Avenue in New York – Manhattan. On January 2, 1979, I met Donald Trump – the project was Trump Tower. My team would eventually grow to 8, plus about 20 engineers across disciples including structural, mechanical, electrical, plumbing, curtain wall design and wind tunnel testing to name a few. 1979 was spent in preliminary design and zoning approvals because Trump Tower was one of the most complex applications of floor area bonuses in the New York City Zoning Code. What started out as an allowable floor area ratio of 15 (FAR – multiplied by the size of the site) grew to 38 through the application of bonus rules. Try explaining that to 28 different entities that had an opportunity to comment to the city during the review process. Eventually we won approval and fast tracked the construction drawings, so TT opened in 1983, shortly thereafter winning multiple design awards. So fun facts. The building is mixed use, a four-story atrium (one below the street), 14 floors of office space and 263 condominium apartments. The building is 58 stories, a number Donald didn’t like. He reasoned that a residential building is typically 10’ floor to floor, so where the apartment floors started would normally be the 30th floor. Counting up from there the building became 68 stories. That logic worked legally but try explaining that to the fire marshal. Also, when you visit the retail atrium you will only find one column thanks to city zoning staff, but that’s a whole other story.

My relationship with Donald earned me a partnership in the firm – Swanke Hayden Connell Architects. Eventually my thinking turned back to traditional architecture and urbanism resulting in the design of Americas Tower at 1166 Avenue of the Americas also in Manhattan. As it often happens junior partners in large firms (the Swanke staff grew to over 400 with offices in Washington, Chicago, Miami and London) often find their upward path blocked. In my case the senior partners except for Al Swanke were my age so I decided to pursue my dream and joined the housing industry.

Along with my accreditation in the Congress of New Urbanism (CNU), I became the Design Director and Town Architect for Bigelow Development in Aurora Illinois where we built a new town of 1,200 singlefamily units employing the principles of traditional architecture and urbanism. We were also working in Texas and Georgia when the housing bubble of 2008 burst and crippled the housing industry. My design group was the first to be laid off -but fate smiled on me yet again as I was able to fulfill a life long dream of teaching which was motivated by my desire to give back.

So, a 2-year tenure in the Judson University (in Elgin Illinois) Department of Architecture, teaching the 4th year design studio and acting as visiting (walk around) instructor and critic in the 5th year Masters Degree Studio. Guess what – I was teaching in the “traditional architecture and urbanism track”.

Adjunct Professors in 2009 were required to have a Master’s degree, but my 5-year B.Arch. didn’t count -- so I had to make another hard decision.

Now in 2025, I’m in St. Petersburg, Florida, a sole practitioner with an exclusive focus on residential design and remodeling. My work is across architectural styles, and I still get the occasional commission for a traditional home, but most of my clients prefer modern architecture.

The study abroad program and my thesis were the most impactful experiences during my time at Penn State. The Studio experience emphasized individual development and mentoring, not a prevailing design dogma, and was led by professors who were often practicing architects with clients, budgets and construction concerns. These factors combined with the small class size, long studio hours in relative campus isolation, camaraderie and variety of project assignments, including community development,

The required courses in Art and Architectural History as well as Studio Art, which educated me in the amazing history of the profession and encouraged personal creative thinking. (We briefly lost our accreditation in my second year because our curriculum was too heavy with science and engineering and short on art and architectural classes.)

The Study Abroad Program broadened my world view. Studying in the UK and traveling in Europe were life-changing experiences. The extended time abroad brought the history of architecture to life as demonstrated by the continued use of buildings changed and adapted over centuries.

I don’t know how I progressed from a C/D student to straight A’s Dean’s List by my 4th year, winning 1st prize with Jim Alexander and Barry Eiswerth from the Pennsylvania Society of Architects for our 5th year design thesis, and named a Distinguished Graduate. The support of Professor Lou Inserra (who was with us in the UK), and Professor Gregory Ain (Department Head in my 5th year) were instrumental. Their patience and positive encouragement are heartfelt to this day.

“While my current role is not the traditional architecture role, I find that I love what I do while still being in the realm of architecture. The skills I learned in architecture school such as time management, organization, being able to take constructive criticism, and hard work have all helped me in my journey to find a career that worked for me.”

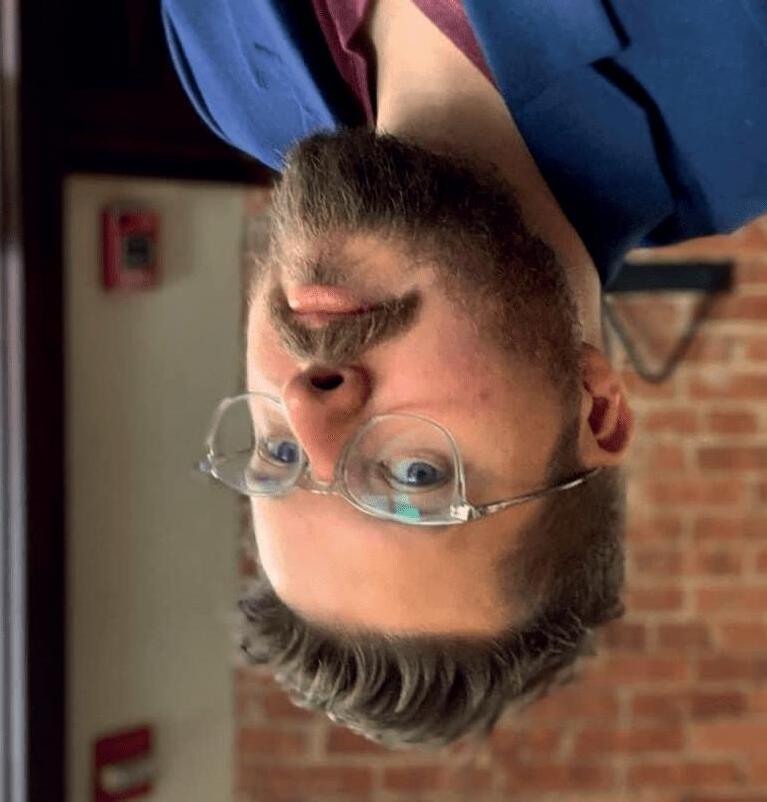

My journey as an architect didn’t quite pan out how I had envisioned when I was in architecture school at Penn State. After graduating in 2014, I moved to Denver where I worked at a small architecture firm mainly on multifamily projects. I became a licensed architect in 2016 and moved to what I thought was my dream firm working on high-end houses in the mountains. After spending a year there, however, I realized that maybe architecture wasn’t my best fit. Having always had a knack for technology, I transitioned to a medium sized firm in Denver working as a BIM manager for 3 years. While there, I worked with computer programming to create efficient workflows for the firm and I realized that this is what made me the happiest. I applied for a job at UpCodes which is a company that helps architects and contractors approach building codes in a more efficient manner. I initially started as a content manager, but after a few months, I was able to transition to a software engineering role using some of the skills I picked up as a BIM manager and through self-guided learning after work. While my current role is not the traditional architecture role, I find that I love what I do while still being in the realm of architecture. The skills I learned in architecture school such as time management, organization, being able to take constructive criticism, and hard work have all helped me in my journey to find a career that worked for me.

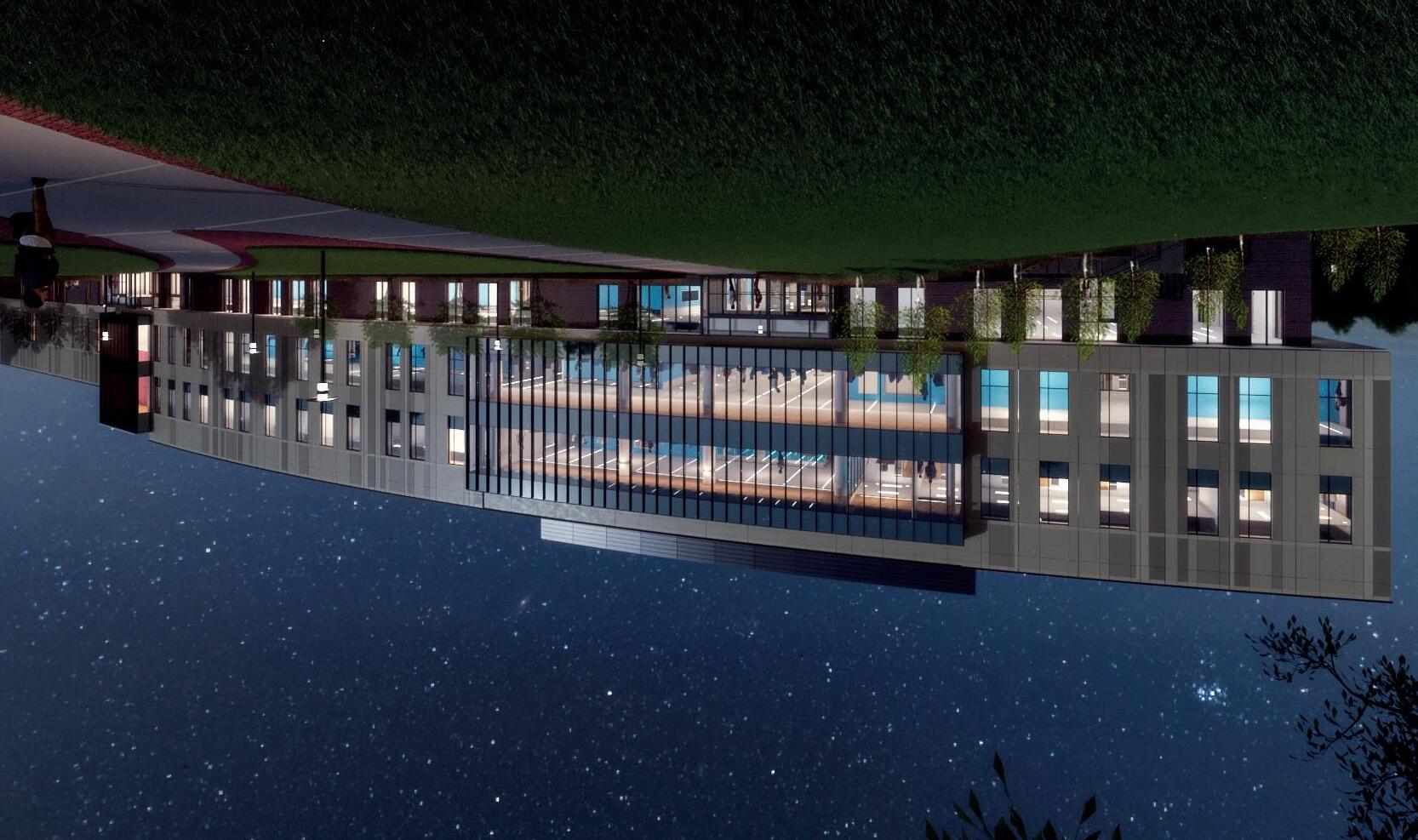

The Roth Living HQ project in Denver was a lot of fun to work on. I was able to work on this project through all of the design phases from Schematic Design to Construction Documents. It has a blend of office space with a show room on the ground floor with a portion of the building overhanging the entrance to the parking lot at the back. Typical to any architecture project, the building went through several iterations until we were able to land on a design the client loved while still being able to fit into the budget. We had to work closely with the structural engineers in particular to make sure that the building stayed true to the design but also worked structurally as needed. Overall, this was a fun project to design and implement as it posed several code, structural, and budget constraints that all had to come together for the final result.

I was always interested in technology and my experience at Penn State allowed me to continue to pursue that interest. I was able to take elective courses that taught me visual scripting and learn how computer code can be used to create bespoke designs. These classes were the foundation for the ultimate switch to my current career in software engineering. While architecture isn’t my career anymore, it was due to the classes available to me in the architecture program that I was able to find something I truly enjoyed.

“Surprisingly, I find myself most often reflecting back on the Art / Architectural History Courses from Penn State. At Disney we create places that are inspired from locations around the world and from different time periods. Having that knowledge of the past gives me a jump start on creating designs that feel authentic.”

I graduated from Penn State with my B.Arch degree in 2014. I received my diploma on a Saturday and two days later was headed to Orlando, FL for what I thought was only a summer internship at, “The Most Magical Place on Earth”. 10 years later, now with several projects under my belt, I am still in Florida, designing experiences that amaze and inspire. My initial internship was with the Facility Asset Management (FAM) team at Walt Disney World. As the name implies, this is the team responsible for maintaining the entirety of the Walt Disney World Resort. This includes all 4 Theme Parks, 2 Water Parks and 25 Resorts. My responsibilities in this role were similar to other architecture internships (as-built measurements, code compliance and CAD drawings). After my year long internship, I joined the show set team at Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI) Put simply, show set at WDI refers to all the scenery or built structures that

fall outside of a general contractor’s expertise. At first, I was a little worried about dropping the word architect / architecture from my title (I had just gone to school for 5 years so I could be licensed). But I quickly learned that many of the show set designers at WDI had architecture degrees. Our understanding of spatial relationships gives us an advantage over designers from other backgrounds. The skill sets I learned in school translated very well in this new role and I have always put a more architectural spin on my responsibilities. At the time, the company had just started to utilize Revit on large projects, evolving from the days of CAD. With my background, I was able to lead the team through coordination sessions with the architects and engineers.

After a few years of show set design, I switched to production design. On WDI projects, the Production Designer is responsible for the translation of a Creative

Director’s vision from sketch / written narrative into built environment. I have a lot of influence over the design of projects now, and believe that my architectural education allows me to make practical choices while not sacrificing the quality of the final product.

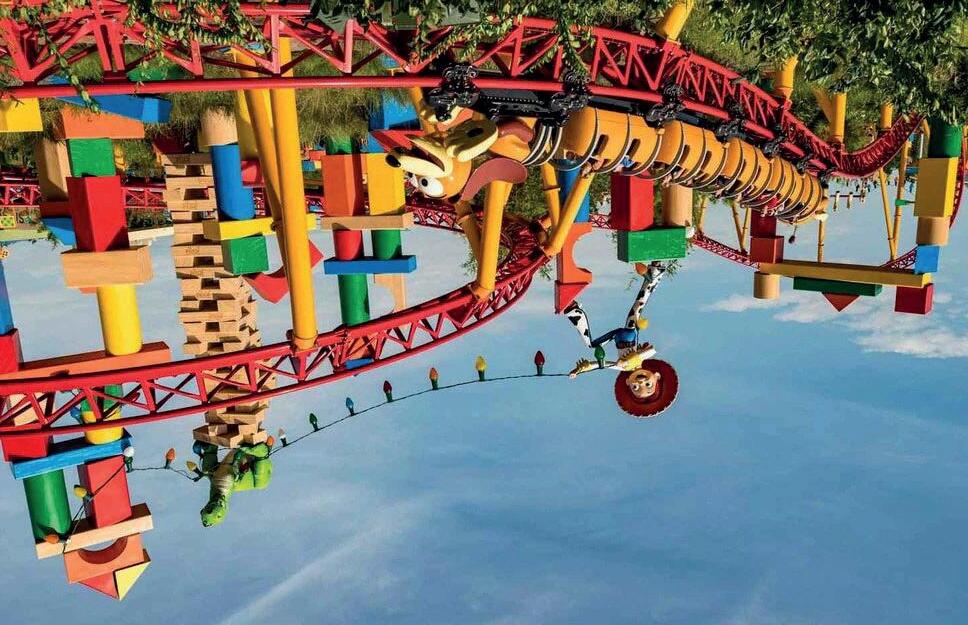

My first project with Walt Disney Imagineering was Toy Story Land (TSL) at Disney’s Hollywood Studios. I was on the project from very close to the beginning of the concept phase and was able to stay on through construction. I was responsible for the design of Slinky Dog Dash, the family coaster and then the execution of the whole land from a show set perspective. Never did I think I would literally be playing with blocks at work, but real toys became amazing tools as we developed the different scenes throughout the land. Although it appears simple, the coordination required between the ride engineer, structural engineer, and myself to ensure the safety of all guests was extensive. This project was also my first opportunity to see the power of BIM during the construction phase. The team was diligent about checking for clashes in the coordinated model and it allowed all our set installs to proceed without (lengthy and costly) interruptions.

When I first arrived at WDI, Sketchup was the program of choice. As projects became more complex, Revit was used for its coordination capabilities. Now, 3D rendering and previsualization has emerged as a powerful tool for our studios. Using Unreal and other gaming engines we can provide upper leadership in the company a virtual ride on our attractions very early in the process. Even with the new visualization tools, I still find 2D plans, sections, and elevations just as important for getting the feel of a space across to my Creative Directors.

Ten years after graduating, I still think back to my time in State College. Surprisingly, I find myself most often reflecting back on the Art / Architectural History Courses from Penn State. At Disney we create places that are inspired from locations around the world and from different time periods. Sometimes we are even given the chance to create whole new architectural styles. Having that knowledge of the past gives me a jump start on creating designs that feel authentic.

An architecture degree is the ultimate design degree. Exposure to structural engineering, MEP, graphic design, lighting design, and interior design, make architecture students the swiss army knife of designers. Just because something isn’t a building doesn’t mean it’s not architecture. My advice to students is to not limit themselves to the traditional architecture firm / route. Design roles are numerous in the job market. Use the skills from school to put your own spin on future opportunities

“Quality designs should contain a strong underlying concept, whether formal or conceptual. I want students to know that, in practice, it is possible to carry an idea all the way through from finish to end. However, it requires a client, team, and personal resolve to ensure a design is not watered down. ”

The Importance of a Strong Concept: Since graduating from Penn State in 2013, I have led a double life, simultaneously pursuing an academic and professional career. I have completed a master’s degree in real estate from Georgetown University and a Ph.D. in Urban Regional Planning and Design from the University of Maryland I have also published research in the field and taught over 20 courses at both George Washington University and UMD. Over the same time frame, I worked for my thesis advisor, James Wines, at Sculpture In The Environment (SITE) in New York City, then specialized in façade design at Pei Cobb, Freed and Partners. I briefly quit the profession, working as a construction contractor for a year, then worked as a designer, primarily on interiors at Skidmore Owings and Merrill, in Washington, D.C. A week before the COVID-19 pandemic, I made a career move to Michael Graves, and have been working on conceptual design for competitions, as well as urban design and planning. For the past few years, I have been the project lead for the United States Capitol Complex Master Plan, responsible for the 20-year planning vision for the U.S. Capitol Building, Congress, and the Supreme Court, among other entities.

Instead of featuring one project, I am sharing snippets from multiple projects that have been meaningful to me. Each project crosses numerous disciplines and scales, but design thinking and creative problem-solving are at the heart of each. Most importantly, each project has a strong central concept that guides the design trajectory. You know, the things we are all taught in the studio and try to keep in practice. The first project is the Century Plaza Towers; I worked on this project under Henry Cobb, FAIA. This project featured two residential towers directly behind Minoru Yamasaki’s Century Plaza Hotel. Henry’s approach to diagramming inspired me; he appeared to be less interested in existing tower precedents and more interested in finding inspiration in the geometrically precise diagrams of Borromini’s churches, St. Ivo, to be exact. We implemented a rigorous process to develop a stable design parti diagram, and once we did, the building would change in footprint, maybe 30 times, but the underlying parti would remain. The teaching of Jamie Cooper whose rigorous exploration of form helped prepare me to understand how to translate a basic idea into disciplined architectural form. The next project is a series of independently designed watches, including the gradient, pride, and pixelate watches. These watches won several design awards on an international stage, such as the Chicago Athenaeum’s GOOD Design Award. They were featured worldwide, including in the MoMA store and the Guggenheim. I started this journey while working for James Wines before designing and producing watches on my own, we produced a watch called the Terra-Time, inspired by topography models. The initial design was a great lesson

in applying a concept at a very small scale and keeping the essence of the idea. I later applied this same thinking while working on my own to the Pride Watch, where the symbol of the rainbow became both the focus of the idea and the device for communicating time. The rainbow would get broken, only to unify twice a day, at noon and midnight.

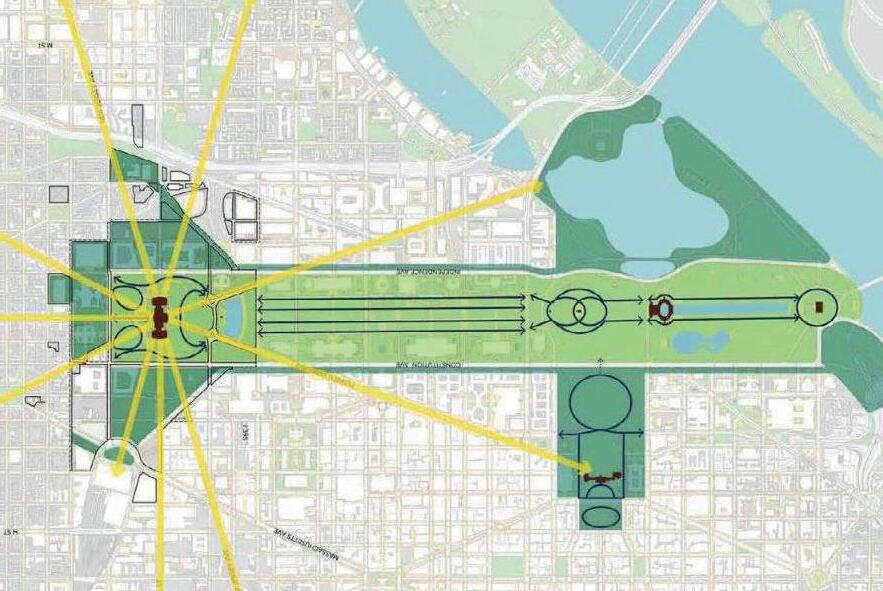

The final project is the Capitol Complex Master Plan. Serving as the leader of the planning and urban design team has been a privilege, and like the previously mentioned projects, the design parti is everything; in this instance, there are strong concepts already in place; in this instance, the party dates back 300 years. The L’Enfant plan generates strong principles to follow; the diagonals radiate from specific points in the city to form the street grid. The ultimate node may be at the Capitol Building itself. The McMillan plan and Frederick Law Olmsted’s concepts surrounding the Capitol also provide further conceptual direction. While this project is in its infancy, if I have learned anything from my previous experiences, these existing concepts should be significant.

To conclude, quality designs should contain a strong underlying concept, whether formal or conceptual. I want students to know that, in practice, it is possible to carry an idea all the way through from finish to end. However, it requires a client, team, and personal resolve to ensure a design is not watered down. It is much easier to throw your hands up and let the design become what it may be, but fight the good fight; it will pay off.

Alex Donahue, Ph.D., AIA, NCDIQ (B. Arch. ‘12, M. Arch. ‘13, PSU M.S. Real Estate ‘19, Georgetown Ph.D. ‘24 Univ. Maryland)

Senior Associate, Michael Graves

Adjunct Professorial Lecturer, Interior Design, Corcoran School of Arts, George Washington Univ.

During my time at Penn State, I had the privilege of studying under James Wines on four occasions: in first-year studio, his research seminar, my fifthyear thesis, and later as a member of my graduate research thesis committee. From the outset of my academic experience, I was struck by his unwavering commitment to both intellectual rigor and creative exploration. He maintained a low tolerance for mediocrity and consistently challenged me to treat each project as the most important undertaking of my career.

“I was lucky to gain many key skills and essential experience by participating in this project from concept through construction. Beyond instilling a love of design excellence and collaborative process, the PBT Annex also highlighted the need for quality cultural spaces that serve the community“

My mantra after graduating in 2014 was that I could go anywhere or do anything for at least a yeareffectively, go on an adventure and see where it led. I accepted a job at IKM, Inc., in Pittsburgh. The appeal of Pittsburgh and IKM was similar; both were in states of reinvention and transition, and I had the opportunity to be an active voice in the process. Unsuspecting as I was, I had no idea I’d fall in love with the contrasting richness of nature and industry in Pittsburgh and go on to build a life and family there over the subsequent eleven years.

At IKM, I obtained my license and learned how to be a well-rounded architect with a bevy of skills in design as well as project and client management. I had the opportunity to cultivate a diversity of interests beyond

traditional architecture as well - in design thinking, organizational psychology, and adaptive leadership.

A powerful project in the formative years of my career was the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Annex. As an emerging professional, I was lucky to gain many key skills and essential experience by participating in this project from concept through construction. Beyond instilling a love of design excellence and collaborative process, the PBT Annex also highlighted the need for quality cultural spaces that serve the community. These guiding ideas around the importance of community cultural spaces trace back most memorably to the Fourth Year comprehensive design studio with Lisa Iulo and Eric Sutherland. Over a semester, we created “A Center for New Media” located in

Harlem, NYC. My partner Chris Peterson and I worked to craft a design that embodied a philosophy of “harmony through contrast,” where the building inhabitants were united by shared experience. This concept is also evident in the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Annex - an industrial backdrop, grounded in concrete and steel, raises the dancers up as beacons above the city. Working with larger institutions such as Carnegie Mellon University West Virginia University Medicine, and UPMC provided a strong career foundation, even while my interest in community-based revitalization grew over time. I became a member of the National Organization of Minority Architects in 2019, and co-founded the Minority Architects of Pittsburgh Scholarship in 2020. Since our founding, we’ve provided over $50,000 across more than 70 awardees, and worked to connect students studying architecture with resources across the city. These scholarships give students and professionals a small financial lift when they need it, but more than that, they provide a community that is rooting for them to succeed.

The same drive that brought me to Pittsburgh - that desire to be part of something bigger than myself - motivated me to pivot my career in 2023 when I shifted from the larger-scale corporate architecture world to smallscale practice. Studio Volcy, where I currently serve as Project Manager, is a boutique design and development firm that works with missionfocused organizations to bring their projects to reality. We work with many community-based non-profits who require new facilities in order to sustain and expand their impact, often providing strategic planning insight as well as design.

The first project I worked on from concept through construction at Studio Volcy is the Urban Reach Center for the Urban Academy Charter School of Greater Pittsburgh. After purchasing a stately yet leaky old building in disrepair, Urban Academy brought on Studio Volcy and Tink+ Design to complete a wholesale renovation of the building interior and exterior. The end product is a luxurious and functional interior with an emphasis on bold, fresh colors and a dynamic palette of materials. The transformed building contains a library, accessible demonstration kitchen, a learning laboratory, and administration space and is an asset to the neighborhood.

It is rewarding work, and I value the opportunity to make a difference in this city that I love every day.

My time as a student at Penn State was a formative period in my life. One of the biggest habits I’ve tried to maintain from that time is keeping a sketchbook. Beginning in first year, Marcus Shaffer instilled the practice of sketching as recording. Although my practice has been at times inconsistent, being able to use drawing and writing as a way to design, ideate, and form snapshots of my life experiences has been a gift. Nowadays, in addition to using my sketchbook as part therapist, part travel journal, I use it to work through design details and future ceramic projects - replete with plans, sections, details, and glaze combinations. Pulling from the lens of Juan Ruescas’ Parti class, my goal is to craft a consistent signature design that is evident in all my creations - in both the built world and in functional pottery.

The word of advice I pass along most often is from Rebecca Henn“it’s never done, it’s just due.” This is true of so many things in life and has served me well! Rebecca also instructed us in how to write about architecture, and how to translate the sublime from the built experience to the written word. I am grateful for all I learned at Penn State, and feel fortunate that my architectural education formed a strong foundation for what has been, so far, a successful and satisfying career.

“My career today could not be further from what I think I may have envisioned back when I was a student ... my focus has shifted quite drastically into the urban realm, and the spaces that extend beyond the threshold of the building,”

Hello – my name is Jared Edgar McKnight, and I am a designer and researcher with over 13 years of professional experience. I am a Senior Associate and Designer at WRT, an interdisciplinary landscape architecture, planning, urban design, and architecture firm based in Philadelphia and San Francisco. I work across WRT’s offices and disciplines, and conduct research through WRT and the University of Southern California’s Landscape Justice Initiative. My work, and research, focus on projects that support both environmental and social resilience, through community engagement and design interventions that challenge the structures that isolate and exclude communities and ecosystems, with an empathic lens that considers those whose voices are not often heard, or designed for.

I graduated from Penn State in 2011 with my B.Arch with Honors, and a B.A. in International Studies, and my career today could not be further from what I think I may have envisioned back when I was a student. Since graduating, my focus has shifted quite drastically into the urban realm, and the spaces that extend beyond the threshold of the building, drawn by my desire to consider our landscapes and as the most public-facing venues to deploy our most

equitable impact as designers through community-driven, climate-responsive, and collaborative designs that employ research and engagement to advocate for new futures for public space. After Penn State, I pursued my M.Arch at the University of Pennsylvania and began working at WRT in Philadelphia in June 2012, where I continue to work today.

In 2019, I relocated to Los Angeles to pursue a Master of Landscape Architecture + Urbanism at the University of Southern California, and today I am based remote in Los Angeles and advancing a professional portfolio of work at WRT that is focused on parks and open space, and the design of resilient visions for front-line communities in the face of climate change.

My current projects include: the Liberty State Park Master Plan in Jersey City, NJ; the Cleveland Harbor Eastern Embayment Resilience Strategy (CHEERS) in Cleveland, OH; the Guy Park Manor Environmental Education + Resiliency Park in Amsterdam, NY; and other large-scale waterfront park spaces that carefully consider the role of nature-based solutions and landscape as resilient infrastructure for the communities they serve.

In addition to my current portfolio of professional work, I also continue my ongoing research and advocacy work on the Spatial Politics of Homelessness in Los Angeles, CA and Philadelphia, PA as part of a series of grant-funded research tracks focused on the criminalization of unhoused individuals in public space. I have been a guest lecturer at USC, a juror and design critique at Universities across the country, and presented at over 25 local, national and international conferences.

I purposefully did not share images of some of my current work, because it was the projects I was exposed to early on in my professional career that were the catalyst for my passion to return to school, and shift my practice to a focus on resiliency, landscape architecture and planning. I was very fortunate early in my career to gain exposure to the design and construction process on some large scale civic and cultural projects at WRT that expanded my views of the profession as an interconnected system of disciplines that rely on each other to achieve transformation and revitalization. Among those projects were: the Hoover-Mason Trestle at the SteelStacks Arts + Cultural Campus in Bethlehem, PA – an adaptive reuse project that designed a new public walkway and park on top of a former rail line that once imported the raw materials required for the steel-making process on site into a new cultural landscape, lined with signage and interactive experiences that told the story of Bethlehem Steel and this site; and the Oyama Yuen Harvest Walk in Oyama-Shi, Tochigi Prefecture, Japan - a bold project that revitalized this area from a parking lot to a car-free vibrant public realm, through the concept of “shopping in the park.” Each of these projects were instrumental in my early career in working with a collaborative and interdisciplinary team of consultants, and specifically in working in entirely exterior conditions that were part of the public realm.

Both of these projects tested my design abilities, taught me about materiality, detailing, accessibility, and the interconnected systems of design decisions that lead to meaningful transformations, but they also taught me about the importance of the narratives and stories that these projects would unearth for the people who experience them, and how to build on those stories to heighten the impact of the design. These projects solidified my desire to return to school so I could continue practicing with a focus on landscapes in our urban and natural environments, and working with communities in innovative new ways.

At Penn State, there were so many professors who were instrumental in shaping how I learned to approach design and continue to work to this day. A few professors stand out because of their style of teaching, and their eagerness to collaboratively guide my work in new directions. A few prominent names come to mind for the impact they have had on me on a personal level: Ute Poerschke for sharing the beauty of craft and detailing in her work and showcasing how a profession can span both academia and practice in extremely meaningful ways, Katsuhiko Muramoto for his endurance and support throughout my honors thesis and encouraging me to expand my work beyond the envelope of the building, Darla Lindberg for genuinely altering the chemistry of my brain through her graduate coursework and always offering a safe and reassuring space for inquiry and iteration, James Wines for being my first studio that encouraged us to embrace site systems in our work at an urban scale (with an incredible team of classmates: MOKS), and Scott Wing who was a steadfast voice of reason, mentor and advisor throughout my time at Penn State. Each of them selflessly and graciously imparted something that I continue to value and explore in my career today, and I extend an immense amount of gratitude to each of them for their influence.

“. . .an addition/renovation project of the High School would influence every student. . . This is not always widely accepted across projects, clients, or the public taxpayer, however, after seeing how well-designed architecture can impact, the community support was undeniable.”

My path has been linear in nature, starting full-time at KCBA as an Emerging Professional, becoming a licensed architect in 2017, named an Associate in 2021, and recently a Principal in 2025.

I have always had a foundation in making culture and later in academic passion. Working in both the Architectural Model Shop at Stuckeman and The Learning Factory as a Machine Shop Teaching Assistant. I was an Adjunct Professor at Thomas Jefferson University. In 2020 for the Architecture Comprehensive Studio and guest critic for the Penn State Graduate Architecture Program and recently completing the Advanced Academy Certificate Program to obtain Accredited Learning Environment Planner (ALEP) credential. points has changed. The evolving pace of technology has and will continue to affect the design process. However, at the core - a guiding concept will always be critical to a successful project.

Since I was 6 years old, I dreamed of becoming an Architect. At times, my career is exactly as I envisioned as a PSU Student, with design, critical thinking, and passion as drivers of my day. The differentiation for me is the focus of my architecture career in public buildings, both municipal and education. Growing up in Elementary and Secondary Schools that were 40+ years old and rigid in their programming, I never dreamed of wanting to work on education projects. However, the constantly changing nature of education and the challenge of creating high quality education environments has become a passion to improve for future generations.

The practice has remained the same in terms of design and document, but how we arrive at those

For the Altoona Area High School, KCBA led the planning and design for a wholesale reimagining, expansion, and modernization of this large-scale regional high school. The reconfigured 447,000 sq. ft. high school complex accommodates 2,400 students including 9th graders. Off the main entrance, and reflecting the community’s passion for music education, the Performing Arts cluster features rehearsal spaces and a 1,200-seat auditorium. Next, the Learning Commons houses a retractable seating area accessible on both the first and second floors

serving myriad purposes: flexible commons for break-out activities, forum for lectures and events, and audience seating for an adjacent black box theater linked via an operable partition. The STEM Commons offers a threestory volume with a second story cantilevered balcony accommodating experiments and demonstrations, directly connected to science, robotics, and engineering labs. Lastly, the Technology Commons hosts outdoor activities, linked to a math lab, CNC studio, materials lab, and wood shop. The community of Altoona needed an impactful educational project, and an addition/renovation project of the High School would influence every student graduating from Altoona Area School District. This is not always widely accepted across projects, clients, or the public taxpayer, however, after seeing how well-designed architecture can impact, the community support was undeniable. We believe that the impact learning environments have on academic success of students is undeniable.

Many of my professors had an impact on my career, but now, Ute Poerschke, as a practicing architect while also an academic, inspires me to continue to engage in academia while actively running a firm.

One example of the passion I experienced though Ute was during a third-year studio project for the Erie Maritime Museum to Study Wind Turbine integration into Buildings. The relentlessness to continually explore, dig into a building typology or program, and continuously learning and improve through the design process continues to this day.

“I encourage my students to be curious, ask many questions, and explore new tools/ procedures and career paths. The industry is constantly evolving, and the world needs more architects and designers of the built environment in whatever capacity or industry they are willing to serve.”

At PSU, one of my passions was haptic learning and learning spaces. These spaces helped me personally gain exposure into the field of architecture through woodworking, technical education, and AutoCAD classes in middle and high school. My 5th year thesis focused on learning pedagogies and an active learning campus for students grades 6-12 in Washington, D.C.

Naturally, when I entered the workforce I looked for professional practices that aligned with my interests. This allowed me to work for the firm Ayers Saint Gross where I spent 8 years designing active learning spaces like the Howard Community College - Mathematics and Athletics Complex (MAC), and student life communities like Whittle-Johnson and Pyon-Chen Residence Halls with 900+ beds and Yahentamitzi Dining Hall that feed 1000+ students a day. I also explored many other building typologies to become a well rounded designer. One of my more memorable projects was the Sagamore Whiskey Distillery. This three-building waterfront complex rich in Maryland rye whiskey-making history was the first project I took from concept sketches/ models to construction details/ construction administration. This project stretched me as both a designer, technical architect, and ambassador for the clients needs. It showcased how much I could learn and develop quickly by learning through doing. During that time I worked to complete my license exams and APX hours 3 years after graduation.

Post licensure I got heavily involved in the AIA National Young Architect Forum (YAF) and also cofounded the Baltimore Chapter of the National Organization of minority architects (Bmore NOMA) in 2018. I served as the Bmore NOMA communications director and then Parliamentarian. Within AIA I served as the Mid-Atlantic Young Architect Regional Director for MD, D.C., and DE. I also served as the Senior Editor

and then Communication Director/ Editor-in-Chief of CONNECTION YAF Publication, publishing 10+ Publications and 100+ Articles/ pieces advocating and elevating the voices of young architects. My time with both Bmore NOMA and YAF fostered the development of so many genuine relationships with peers in the industry that help guide me in my career. These same peers encouraged me to apply and win an AIA Young Architect Award in 2023.

In 2021 I began to explore alternate career paths in public service as a design manager for the Army Corp of Engineers working on the Defense Intelligence Agency HQ Annex. Currently, as a Senior Project manager for the General Service Administration in the Capital Region, I am actively managing ongoing design, renovation construction, and feasibility studies for both the Department of State and Department of Education headquarters in our nations capital.

I also have the privilege of adjuncting at Morgan State University teaching digital fabrication and design-build studios in an effort to help develop the next generation of haptic learners, thinkers, and designers. It’s exciting to see how we as designers translate our ideas to full-scale built works. Students have share with me how often they feel they are novices to the industry, and with 10 years in I still feel as if I am just beginning my career.

I encourage my students and all students to be curious, ask many questions, and explore new tools/ procedures and career paths. The industry is constantly evolving, and the world needs more architects and designers of the built environment in whatever capacity or industry they are willing to serve.

I often remember my impromptu conversations professors Marcus

Alexandra

in their own way encouraged me to develop my voice, and I remember taking those conversations to heart in my career.

“Be open to following a career path you may not have anticipated; it may lead you in a positive direction. If not, pivot or turn back, but remember any professional experience provides value towards figuring out where you want to be in your career.”

From the first, what do you want to be when you grow up question asked as a kid, my answer was always “architect.” I pursued that goal through school and achieving licensure, with most of my professional career spent at the Pittsburgh office of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, working primarily on large higher education new construction projects. While working on different project phases, I learned that I enjoyed construction administration and the project management side of practice.

I valued the life experience I gained from studying aboard in Rome and developed an interest in sustainability during school, which led me to pursue a master’s in environmental policy at University College Dublin. Unfortunately, the world changed in the middle of the program, and I found myself back home finishing my degree remotely during the Covid lockdown. After briefly resuming working for an architecture firm remotely--which I found difficult--I decided to apply for a position at Penn State as a coordinator for the university’s internal construction group.

Once at Penn State, I learned about my current role as a Project Manager with Office of Physical Plant’s Design & Construction division. We manage projects across campus, acting in an owner capacity by hiring design teams and contractors, managing the project budget and schedule, and working with user groups to renovate and expand facilities. I’ve managed projects ranging from full-scale building renovations, replacing the flagpoles on Old Main lawn, to repairing the water damage caused by a laser cutter fire (can’t say I was expecting that one!). I have the opportunity to work with people from design and construction backgrounds, but also researchers, students, and campus administrators. If you had asked me as a 10-year-old, or even at 19 or 25, if I expected to stop working as an architect, I would have said no. However, I enjoy being back on a college campus and working with many different people while taking a project from inception through closeout. Be open to following a career path you may not have anticipated; it may lead you in a positive direction. If not, pivot or turn back, but remember any professional

experience provides value towards figuring out where you want to be in your career.

The architectural project I’m most proud of is the High Meadow Studio at Fallingwater. To the north of Frank Llyod Wright’s Fallingwater, an educational facility hosts residencies and summer programs, including an expanded two-car garage into a studio and workshop. This small, lowbudget project embraced the core of BCJ’s ethos: nature of place and material. Through strategic design, material and color selection, daylighting, and natural cooling strategies, the project provided a balance of function and form. I’d attended one of the summer programs at Fallingwater in high school, and the opportunity to work on designing improvements to the facility I’d spent time in was a full-circle moment. Because of the project scale, small design team, and my past connection to the site, I felt ownership of the project, an opportunity that’s atypical early in a design career. If presented with a chance to work on a small project, even if it doesn’t seem very exciting, I’d encourage anyone early in their career to jump at the prospect.

Many of the professors at Penn State left lasting impressions from teaching the tactile importance of design by putting a pencil to paper, playing with a physical model, and working with materials; skills that were appreciated and further nurtured at BCJ. While working with Jawaid Haider on my thesis, I learned the importance of the history of a place and telling a story through architecture. Now that I’m no longer practicing as an architect, I appreciate the critical thinking and application of design theory for solving problems beyond ‘typical architecture’ that I learned from classes and side projects with Darla Lindberg. Since returning to the area, it’s been nice to reconnect with professors and attending lectures and events at Stuckeman.

“Any professional journey in architecture is shaped by three key elements: the type of work, the workplace culture, and the tangible benefits (or lack thereof) extended to employees. As architects, we are deeply passionate about our work—but that passion can sometimes blind us to the importance of the other two.”

From Studio Crits to Statewide Change: What I Wish I Knew Leaving Architecture School

The transition from academia to the professional world was, at first, profoundly disappointing. I hated my first few jobs and seriously considered changing careers altogether. I loved architecture school — I thrived on theoretical explorations, out-of-this-world conceptual challenges, and deep dives into how architecture shapes human experience. I was enthralled by the idea that space could impact people in powerful, intimate ways. So when I entered the profession and found the reality bland by comparison—and, frankly, financially underwhelming — I genuinely questioned whether I’d made a huge mistake.

For the first decade of my career, I wrestled with what it truly means to be an architect—never quite fitting the stereotype and constantly wondering whether that meant I didn’t belong, or if the practice itself needed to evolve.

In school, my professors often emphasized the value of diverse work experience. I took that to heart, making deliberate choices about each career move. To date, I’ve worked at five architectural firms and now serve in the public sector. Each role has helped refine—though not fully answer— that lingering question of what it means to be an architect. But the through line has been about alignment: aligning my values, passions, and personal life with the work I do.

In my experience, every architectural journey is shaped by three key elements: the type of work, the workplace

culture, and the tangible benefits—or lack thereof—extended to employees. As architects, we’re deeply passionate about our work, but that passion can sometimes blind us to the importance of the other two.

Early in my career, I found that some of the firms doing the most beautiful work also expected countless hours of unpaid, unrecognized labor—all underpinned by poor business practices. I loved the projects, but I also wanted a life outside of work. I was ready to go above and beyond, but I expected fair compensation and acknowledgment in return.

As a young woman, and often the only woman in the room, I had to learn to take up space—literally and figuratively—for people to take me seriously. “Fake it till you make it” wasn’t just a mantra; it was a survival tactic. Now, as a mother of four young children, I can say with certainty: architecture remains a challenging profession for many parents, especially mothers. And that needs to change.

I may not have a tidy answer to what it means to be an architect, but I know this: I want to be an agent of change. I want to shape the human experience and the built environment in positive, lasting ways. I want to help build a profession that is inclusive, equitable, and values not just the work we do, but the people who do it. Anchored in these values, my career has become everything I hoped it could be. Today, I serve as the Assistant Director of the Bureau of Real Estate within the Department of General Services for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. In this role, I’ve been

instrumental in developing and implementing the state’s Space Optimization and Utilization Initiative, a transformational effort to reduce leased space, consolidate and co-locate services, and invest in state-owned properties to create sustainable, modern, and flexible work environments.

The Space Optimization and Utilization Initiative represents everything I love about architecture: civic engagement, analytical conceptual thinking, and the relationship between people and place - all in service to the people of Pennsylvania. We collected and analyzed over 13 million square feet of office space across 40+ agencies to understand how our facilities were being used. We conducted site visits, stakeholder workshops, and policy reviews to understand not just the physical layout of space, but how it’s actually experienced and influenced by workflows, organizational culture, and employee needs.

Because space is personal—even in a professional context—change management became a cornerstone of our process. We weren’t just moving people; we were asking them to embrace a new way of working. We piloted many strategies in our own office first—boosting space density by 25% and capacity by 45%. More importantly, when skeptical customers toured the space, many walked out with a different perspective—buy-in born from experience, not just a pitch. One thing always emphasize about this initiative: it’s about more than just space—it’s about the research, analysis, collaboration, and leadership that make transformative environments possible.

Traditional architecture practice tells us success means seeing something tangible—bricks and mortar—but true impact takes many forms. This initiative may not fit the conventional image of an architect’s project, yet every step has drawn on the core of my architectural training, especially the focus on people and place.

Nothing hardens your shell quite like an architecture critique. Standing before a panel as they dissect your work builds a rare kind of confidence. That training taught me how to develop conviction in my ideas, anticipate criticism, and build resilience. It also taught me how to translate complex, technical concepts into language anyone can understand—an essential skill, especially when telling someone you’re changing their workspace after many years. Not every audience has welcomed me with open arms, but confidence, clarity, and empathy have helped turn tough conversations into collaborative ones.

I still don’t have a neat, label-ready answer for what it means to be an architect. But I know I’m one who leads with purpose, who believes in the transformative power of design, and who is committed to making this profession—and the spaces we shape—better for the people they serve.

For a long time, I felt like was navigating this field alone—so much so that I questioned whether I even belonged. A great mentor can be the difference between surviving and thriving in this field. At every step in my journey, I’ve been lucky to learn something meaningful from those around me. Today, I work alongside two brilliant women who challenge and inspire me in equal measure—proof of the power of collective intelligence and the growth that comes from having a community of colleagues who fill your gaps. Surround yourself with people who reflect the kind of professional—and person—you want to be. They matter more than you think. For those of you passionate about architecture but instead frustrated by your career path hang in there. Define your values. Set boundaries. Protect your life outside of work. Don’t settle for less than you’re worth. You have the power to make your career everything you want it to be.

“Lighting Design allows me to work on 20+ projects at once, mastering one aspect of the design while still having a huge impact. What I love most about this field is blending art and science and using light to shape how we feel and experience space...”

I graduated from the Penn State Architecture program in 2009, which was a difficult time to find a job. A few professors recommended we either move home, go to graduate school, or consider architecture adjacent career paths. The thought of continuing my education past Penn State or even exploring other fields hadn’t occurred to me, but the realities of the economic climate quickly set in. I interned the past two summers at Studio Daniel Libeskind and I knew I wanted to eventually end up back in New York City, work on exciting and inspiring projects, and design more for the human experience - something I felt was lacking in the projects I had been involved in while working at SDL.

After a bit of soul (and Google) searching, I discovered the career of lighting design and that

there was a Master’s degree program at Parsons in NYC. From some classes that touched on lighting at Penn State with Ute Poerschke, I realized that it’s a more complicated and technical field than I originally thought. It felt like the perfect fit and could build on the architectural foundation I had acquired during my undergraduate studies. Upon graduation from Parsons, I landed a job at Tillotson Design Associates and have since grown into a Principal role there. What I love most about this field is blending art and science and using light to shape how we feel and experience space. Often, the lighting for my projects strives to be something you hardly notice - seamlessly integrated into details and rendering architectural forms and materials in a way that feels like they were meant to be.

Lighting Design allows me to work on 20+ projects at once, mastering one aspect of the design while still having a huge impact. I’ve had the privilege of collaborating with renowned architects such as Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Gabellini Sheppard, Adjaye Associates, Field Operations, WORKac, BIG, SHoP, Kieran Timberlake, and Foster + Partners among many others, on projects that are both iconic and innovative.

The Shed in NYC with DS+R was one of the most challenging and rewarding projects I’ve worked on. It’s the kind of boundary-pushing project I dreamed of working on as an architecture student. As a lighting designer, it was intimidating and complex. The Shed is a dynamic cultural venue requiring high levels of flexibility, not only in performance programming but also in its physical structure, including a massive ETFE-clad shell that physically moves on wheels. The nighttime vision for the project was a diffuse, ambient glow emanating from the ETFE pillows, but upon further study the material was surprisingly transparent and extremely reflective. We chose to graze light up the diamond structural pattern to bounce light indirectly back onto the ETFE, which successfully limited views into the light fixtures and created a magical effect. It required countless on-site mockups with the design team to get right, and I even had to conquer my fear of heights and get into the lift myself to test fixtures.

My professors at Penn State helped shape my design sensibility and attention to detail that proved invaluable in my lighting career. Most notably, Darla Lindberg, my thesis advisor, taught me to constantly question the “why?” of a project. In lighting design, that translates to developing a strong concept from the beginning by targeting the problem that needs solved. Then, checking in consistently to ensure that concept holds true through time, value engineering, and difficult detailing.

“The engagement with the community and stakeholders in the design of public spaces continues to be one of the most rewarding aspects of the process for me.”

My journey to becoming an architect began at a very young age. As the son of a carpenter who designed and built the house I grew up in, I was constantly exposed to construction and the built environment, and later realized that these experiences would greatly influence my career path.

I never specifically thought about architecture as a career until my junior year of high school when I began applying to colleges. The “Selected Major” portion of the application became a process of elimination, trying determine where my interests and abilities would fit best, and it eventually became clear that architecture was the best fit.

Following graduation, I began working at SCHRADERGROUP in Philadelphia after meeting their team at the Stuckeman Career Fair. I was drawn not only by the high level of design they provided, but also by the collaborative process that the firm promotes. The engagement with the community and stakeholders in the design of public spaces continues to be one of the most rewarding aspects of the process for me. I was immediately immersed in a variety of K-12 & Public Safety projects at various phases of design, and this broad exposure was an invaluable way to start my career and laid the groundwork to achieve my licensure in 2018.

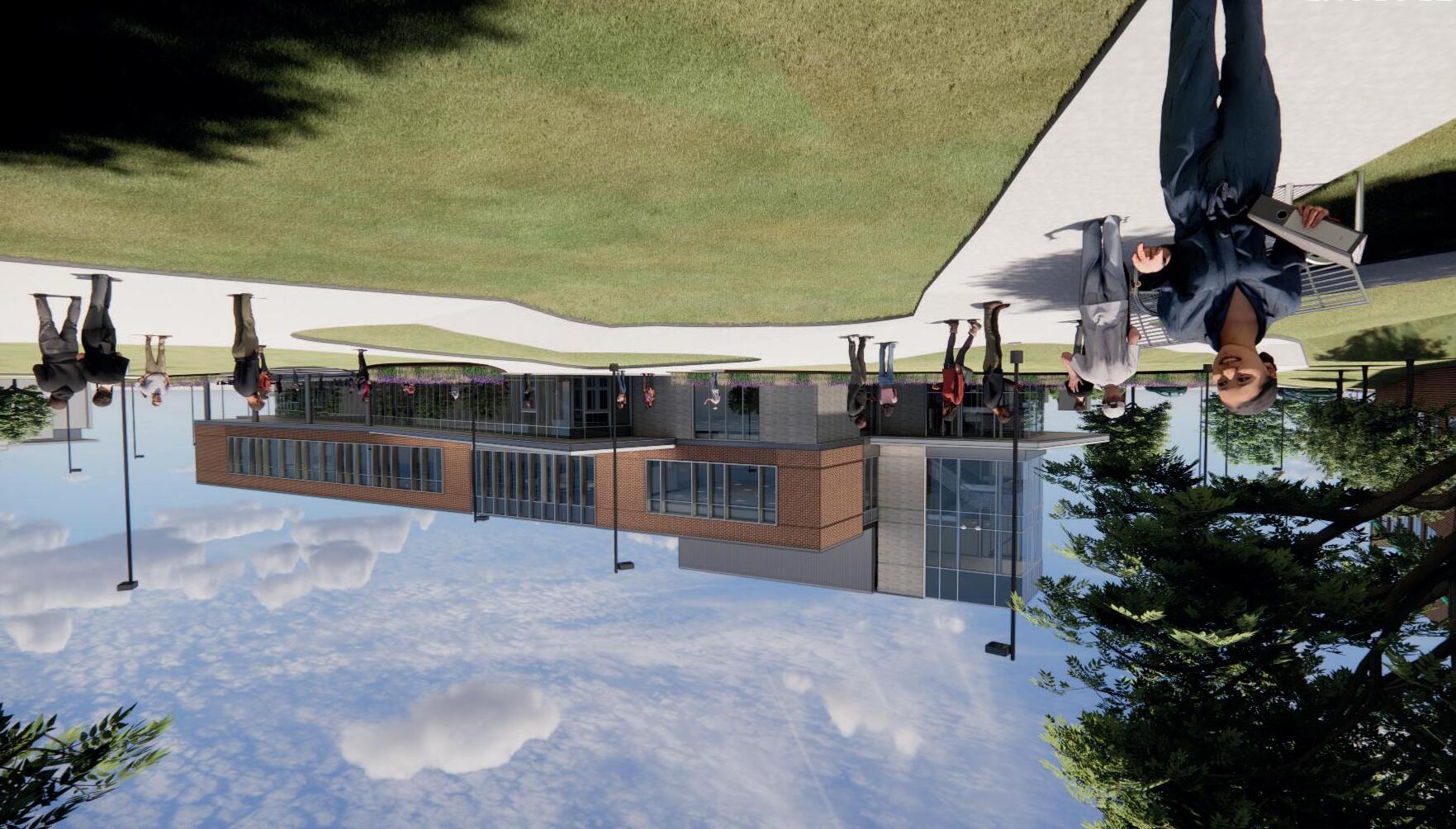

In my nearly 12 years at SG, I have been fortunate to have been involved in dozens of projects in a variety of markets, especially education. Most recently, I was fortunate to work as Project Manager on a 45k SF new construction classroom building for the PSU Harrisburg campus. It was incredibly rewarding to work with the OPP group through the design process to successfully deliver an engaging design that came in under budget. The project will begin construction soon and the entire team is excited to see the building come to life.

My 5 years at Penn State were incredibly rewarding and solidified my decision to pursue a career in architecture. My final semester in the BIM Studio was especially crucial in forming my path following graduation. The program, led by Bob Holland & Scott Wing, was a perfect distillation of the collaborative process of architecture and I’ll always be grateful for that experience and the preparation for my transition into the profession that it provided.

With this 5th issue of Vertices featuring early career alumni from the 2010s, we’ve now collected profiles of nearly 50 Penn State architecture alumni representing each graduating decade since the 1970’s (and even a few from the 60’s!).

Besides the individual career journeys and accomplishments, these profiles also collectively act as a 2020’s survey of the evolving practice of architecture. And we can see more early career alumni are branching out from the traditional practice of designing buildings (whether “on the boards” or rather “at the CAD workstation”).

The teaching and practice of architecture has expanded beyond expertise in building typologies, disciplines and development stages. Architectural careers are now pursued in the development of building technologies and systems, materials research, lighting and sound, biophilic environments, stage and set design, and even virtual environments.

Let’s choose to be encouraged by these new career roles and trajectories, even as the agentic and collaborative AI models are rapidly gaining ground in generic building design -- the AI models won’t be replacing human creativity, ingenuity and deep understanding of unique project objectives and integration of crossdiscipline endeavors any time soon.

Notwithstanding current attempts to label architecture as a non-professional degree -the knowledge and qualifications needed to support the legal responsibilities and licensure remain comparable to any other profession and as rigorous as ever. As we speed up the practice of designing and constructing the built environment with new tools, we can also increase our bandwidth and devote greater energy to innovating solutions to optimize each project and inspire new creations.

I will also be exploring the next act in my own career arc – moving on from the World Trade Center project. So I look forward to discussing my next role and continuing this platform for telling career stories of so many more Penn State alumni. We Are!

Carla Bonacci, FAIA, PP Vice-President, Architecture Alumni Group and Editor, Vertices