ISBN 979-8-218-17194-0

2 RECORDINGS OF THE SYMPOSIUM TALKS AVAILABLE AT: www.watch.psu.edu/stuckeman/design-consequences

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Alexandra Staub

CONFERENCE SPEAKERS

STATE LOOKS, BLACK DESIRE(S), HOUSING SCHEMES

Ife Salema Vanable

BUILDING SPATIAL JUSTICE: IN TWO ACTS

Rayne Laborde ON SISTERED DESIGN

Lily Song + Euneika Rogers-Sipp

ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION 1

THE RACIALIZATION OF SPACE AND THE SPATIALIZATION OF RACE

Antwi Akom

WHO COLLECTS THE DATA? A TALE OF THREE MAPS

Catherine D’Ignazio + Lauren F. Klein

DESIGNING LEGAL FUTURES

Andrea M. Matwyshyn

ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION 2

3

4 8 14 48 74 94 108 128 150 164

INTRODUCTION

“We are going to have to have people as committed to doing the right thing, to inclusiveness, as we have in the past to exclusiveness.”

Whitney M. Young Jr., addressing the American Instutute of Architects Annual Convention in Portland, Oregon, June 1968

Architecture and related disciplines rarely take into account racism and social equity, yet the built environment serves as a backdrop to both. Segregation, unequal access to infrastructure and opportunities, and an economic system that allows private interests to be disguised as public interest have fostered systemic inequalities that, even when recognized by the profession, seem removed from the problems architects are trained to address. This symposium will explore how, starting with their formal education, architects and designers in related disciplines can gain a better understanding of how our built environment helps shape society’s inequalities, how our decisions have consequences, and how we, as design professionals, can help bring about better social equity.

Architects and those in related disciplines are trained to seek solutions to problems that are largely defined through client values and demands. Additional stakeholders, such as users or community members, are rarely consulted directly. This has

4

resulted in architecture’s success being measured internally (through positive reviews by other architects or critics) or through the prestige or economic opportunities projects create for the client.

Increasingly, successful design hinges on technological advances that integrate technology into both the design process and its outcomes. Such advances are seen as a form of progress that allows for novel designs while attaining cost and labor savings and opportunities for new functionality. Yet the singular focus on technological advancement ignores social concerns, including the effects of opaque and biased algorithms used in decision-making, surveillance overreach and privacy breaches, and unintended consequences of the technology itself or its accessibility.

that ignore, and often work against, social equity. This has been especially prevalent in an economic system that encourages zero-sum thinking, where improving social equity is seen as cutting into a company’s potential profits. Consumption, rates-on return, and market advantages drive innovation, often to the detriment of social justice concerns.

In both situations – architectural design used primarily to enhance the designer’s and client’s prestige, and technology in design that focuses on creative novelty or cost savings – criteria for successful design have equated “success” with factors

Social equity extends to how design problems themselves are framed: What biases are inherent in the questions asked, what stakeholders are affected, and what are the extended consequences of proposed solutions? A few examples can illustrate the problem. Increased reliance on technology in the built environment benefits wealthier segments of the population with access to the newest products, smart devices, good internet, and credit that allows for online payments. Communities of color are disproportionately left out of the technology equation, leading to an acceleration of economic inequity.

The COVID pandemic illustrates further problems with how we are framing our

5

built-environment questions. Before COVID-19, shifts in housing, office work, retail patterns, and recreation were already designed to serve more privileged communities, often driven by a search for comfort in the face of climate change or environmental hazards. Already segregated communities of color, by contrast, systematically experienced cultural de-valuation, exposure to environmental hazards, and a dearth of infrastructure including adequate housing, healthcare, transportation, and food. Current concerns for viral pathogens have accelerated social and spatial trends that have privileged wealthy communities. White-collar workers shape social and spatial networks to meet their needs, discounting the needs faced by communities of color, who are more often employed in low-income, front-line service sectors.

to better understand underrepresented voices is an important first step. Learning to design for social sustainability is a necessary goal. In their work, the contributors to this symposium explore how to reshape our design agendas for more inclusivity and social equity.

The Design Consequences symposium allowed speakers to present their work or thinking on a topic related to social equity. Each panel was followed by a roundtable, where speakers discussed methods to bring social equity thinking into the professional curriculum.

How can architects and other shapers of future systems and spaces design for social equity and social sustainability?

Change must begin through reframing our design problems. Breaking down social and cultural value assumptions

In the first panel, speakers discussed means by which we can design for a more just society. This panel proposed methods to increase awareness of how injustice is generated and perpetuated, and examined both policy and built-environment solutions toward needed social change.

The ensuing roundtable explored how these questions should be addressed in the classroom: How can architectural and design programs innovate to help

6

students learn to design for inclusivity? How can we best bring ethical practices into the field of architecture and design? How can students transitioning into the workplace continue the quest for more inclusive design? How can we design the built environment to foster social equity?

The talks recorded online and in this catalog will hopefully provide readers in design fields with ideas for their own work. I would like to thank the speakers for the wealth of thoughts they have shared and the openness of the ensuing discussions. Inclusiveness takes commitment, and this is something we can all chose to do.

In the second set of talks, speakers examined how to better understand and predict consequences of technology on equity in the built environment, as well as their approach to integrating ethics in the field of technology and design. How can technology be designed to improve lives, how can such improvement become more equitable, and how can we better measure success in these endeavors?

Alexandra Staub State College, PA, October 2021

The ensuing roundtable explored the questions: How can we ensure that the technology we develop and use benefits all members of society? How can we avoid unintended technology consequences? How can we design technology for more inclusivity and social equity?

7

CONFERENCE SPEAKERS

Antwi Akom is a data scientist, health technologist, and community informatics research methodologist. He is a professor and founding director of the Social Innovation and Universal Opportunity Lab, a joint research lab between the University of California at San Francisco and San Francisco State Unviersity in the only College of Ethnic Studies in the United States. He is the co-founder of IC, the Institute for Sustainable, Economic, Educational, and Environmental Design. He has an extensive background in building collaborative, community-facing technology projects, and new models of urban innovation that help cities become smarter, more equitable, just, and sustainable. He is also the co-founder of Streetwyze, a mobile, mapping, and SMS platform that was founded to give underrepresented and underserved communities a voice in co-designing the product, places, and spaces that impact their everyday lives .

Key areas of his research include social determinants of health, health information technologies, health literacy, GIS, people sensing, food security, big data, community based participatory action research, and interdisciplinary research; collaboration and mentoring of junior faculty and trainees on race, pace, place, and waste. He has been a White House Opportunity Project Innovation Fellow, and is involved in multiple National Institute of Health grants and is actively engaged in mentoring of doctoral students, post-doctoral scholars and junior faculty.

Tessa Cruz is the director of engagement and design at Streetwyze. She has many years of experience in community engagement facilitation, community-based research, and geospatial data collection.

8

Catherine D’Ignazio is an assistant professor of urban science and planning at MIT. She is also director of the Data + Feminism Lab, which uses data and computational methods to work towards gender and racial equity, particularly as they relate to space and place. D’Ignazio is a scholar, artist/designer, and hacker mama who focuses on feminist technology, data literacy, and civic engagement. With Rahul Bhargava, she built the platform Databasic.io, a suite of tools and activities to introduce newcomers to data science. Her 2020 book from MIT Press, Data Feminism, co-authored with Lauren F. Klein, charts a course for more ethical and empowering data science practices. Her research at the intersection of technology, design, and social justice has been published in Science & Engineering Ethics, the Journal of Community Informatics, and the proceedings of Human Factors in Computing Systems (ACM SIGCHI) and Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (ACM CSCW). Her art and design projects have won awards and been exhibited at the Venice Biennial and the ICA Boston.

Lauren Klein is an associate professor in the Departments of English and Quantitative Theory and Methods at Emory University, where she also directs the Digital Humanities Lab. Before moving to Emory, she taught in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech. Klein works at the intersection of digital humanities, data science, and early American literature, with a research focus on issues of gender and race. She has designed platforms for exploring the contents of historical newspapers, modeled the invisible labor of women abolitionists, and recreated forgotten visualization schemes with fabric and addressable LEDs. In 2017, she was named one of the “rising stars in digital humanities” by Inside Higher Ed. She is the author of An Archive of Taste: Race and Eating in the Early United States (University of Minnesota Press, 2020) and, with Catherine D’Ignazio, Data Feminism (MIT Press, 2020). With Matthew K. Gold, she edits Debates in the Digital Humanities, a hybrid print-digital publication stream that explores debates in the field as they emerge. Her current project, Data by Design: An Interactive History of Data Visualization, 1786-1900, was recently funded by an National Endowment for the Humanities-Mellon Fellowship for Digital Publication.

9

Rayne Laborde is the associate director of cityLAB at UCLA, a design research center concentrating on urban spatial justice. Laborde is an architect, urban planner, and interdisciplinary researcher whose work combines community collaboration and planning methods with design practice that prioritizes public engagement while raising questions of agency and spatial justice. Her career began in human rights, including judicial advising to the United Nations and partnerships with the Kofi Annan Foundation through the International Center for Transitional Justice. A recipient of numerous grants and awards, she has contributed to, designed, and curated exhibitions across the world, including installations at the 2014 Venice Biennale and installations for the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Melbourne, and the UCLA Perloff Hall gallery.

Andrea M. Matwyshyn is founding director of the Policy Innovation Lab of Tomorrow (PILOT) Lab and a professor of law and engineering at Penn State. She is an academic and author whose work focuses on technology, information policy, and law, particularly information security, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence and machine learning, consumer privacy, intellectual property, health technology, and technology workforce pipeline policy. Previously, she was a professor of law and computer science at Northeastern University where she served as co-director of the Center for Law Innovation and Creativity. She is a faculty affiliate at the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School and a senior fellow of the Cyber Statecraft Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. Matwyshyn has worked in both the public and private sectors. In 2014, she served as the senior policy advisor academic in residence at the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. She has testified in Congress on issues of information security regulation, and she maintains ongoing policy engagements. Prior to becoming an academic, she was a corporate attorney in private practice, focusing on technology transactions.

10

Euneika Rogers-Sipp is a creative researcher at the Destination Design School of Agricultural Estates in Atlanta. Working at the intersection of conceptual and material practice, she develops projects that deal with the natural environment’s role in culture, examining the significance of mainstream industrial production in developed countries and local production in developing countries. Her current work explores the social and philosophical dimensions of reparation ecology, the curious intersections of the humane and inhumane, and art as a means of engagement, education, critique, and healing. Rogers-Sipp, under the name Ndg Bunting, facilitates, globally, curriculum design, workshops, and ritual spaces that address ecological crises.

Lily Song is an urban planner and activist-scholar. She is an assistant professor of race and social justice in the built environment at Northeastern University, jointly appointed between the School of Architecture and the School of Public Policy and Urban Planning. Her research and scholarship focus on the relations between urban infrastructure and redevelopment initiatives, socio-spatial inequality, and race, class, and gender politics in American cities and other decolonizing contexts. Her work both analyzes and informs infrastructure-based mobilizations and experiments that center the experiences and insights of historically marginalized groups as bases for reparative planning and design. Song was previously a lecturer in urban planning and design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), where she was founding coordinator of Harvard CoDesign, a GSD initiative to strengthen links between design pedagogy, research, practice, and activism. She holds a doctorate in urban and regional planning from MIT, a master’s deree urban and regional planning from the University of California, Los Angeles, and a bachelor’s degree in ethnic studies from the University of California, Berkeley.

11

Alexandra Staub is a professor of architecture at Penn State and an affiliate faculty member of Penn State’s Rock Ethics Institute. Her research focuses on how our built environment shapes, and is shaped by, our understanding of culture. This interest leads her to examine not just what we build, but also how we get there: design processes and their social implications, the economic, ecological, and social sustainability of architecture and urban systems, interpretations of private and public spaces, architectural ethics understood as questions of power and empowerment, and how social class, race, ethnicity, and gender shape our expectations for the use of space. She has presented and published her work extensively including the books Conflicted Identities: Housing and the Politics of Cultural Representation, published by Routledge in 2015, and The Routledge Companion to Modernity, Space and Gender, published in 2018. She is currently working on a book titled Architecture and the Search for Social Sustainability

Daniel Susser, a philosopher by training, works at the intersection of technology, ethics, and policy. His research aims to highlight normative issues in the design, development, and use of digital technologies, and to clarify conceptual issues that stand in the way of addressing them through law and other forms of governance. Specifically, much of his work has focused on questions about privacy, online influence, and the ethics of automation. Daniel is the Haile Family Early Career Professor and assistant professor in the College of Information Sciences and Technology, research associate in the Rock Ethics Institute, and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Philosophy at Penn State

12

Ife Salema Vanable directs i/van/able, an architectural workshop and think tank located in the Bronx. She is a practitioner, theorist, and architectural historian and is the inaugural KPF Visiting Scholar at the Yale University School of Architecture. She is also a doctoral candidate in architectural history and theory at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP), where she examines high-rise, high-density, residential towers erected in New York under the 1955 “Limited-Profit Housing Companies Law,” known as Mitchell-Lama, in an effort to expand the scope and range of histories and theories of multi-family urban housing and complicate narratives of public private partnership for its development. She has taught at the Yale School of Architecture, Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at The Cooper Union, and Columbia GSAPP. She has received numerous awards and fellowships, including a History and Theory Prize from Princeton University, a Columbia University Buell Center Fellowship, and the New York State Council on the Arts Grant.

13

STATE LOOKS, BLACK DESIRE(S), HOUSING SCHEMES

Ife Salema Vanable

Ph.D. Candidate in Architectural History and Theory

Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

Not long ago, during the final review presentations of a second-year architecture design studio I was co-teaching, at a time when such amazing and, at times, troubling performative spectacles were occurring as had been the only way, in-person, a particularly prominent member of the faculty stood beside me looking simultaneously uninterested and somewhat tickled. Smiling in a self-amused way, this member of the faculty leaned over and said, “He’s too good looking,” at least the second time this observation had been gleefully uttered to me by this professor. “Stop saying that,” I contended. As if scripted, one of my co-instructors passed by and asserted, “Let’s move on quickly with this one.” An urging directed at me in my role as designated keeper of time. To which I flatly stated, “They all get the same time.”

A Black male student, a year older than most others in his class — having taken a year off to travel, study, and work beyond, outside of, and perhaps against the academy — stirred these sentiments unbeknownst to him. Sitting on a stool as opposed to the customary and ritualized standing done before one’s work when laid bare to such scrutiny, such review, a scene of subjection, if I may extend an analytical frame offered by Saidiya Hartman: this student fielded inquiry with calm, fortitude, and an outward lack of self-consciousness, presenting by way of a voice marked by a smooth depth in a slow taking-his-time cadence; his ongoing performance, the mundane drama of his showing, was likely irksome to those unfamiliar with and made uncomfortable by such displays of firm self-possession from a young person, from a student,

15

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

racialized as Black, though not in the way anyone would actually openly admit. “He’s just too good looking.” A Black male reviewer was awed by the display, smiling in what Ralph Ellison might have concurred was “the Negro sense.” “Fear me for I am God,” was what he felt this student emoted in such a most obvious and matter of fact way.

I think about this often: this student, his mode of thinking, making, and doing, thoughtful and full, beautifully considered, imperfect, longing, resistant, although, honestly seeking support and guidance, almost always performative, his command, his audacity, and this set of reactions to his physical corporeal

presence, captively invoking a range of racial tropes, evinced ongoing modes of objectification, the thingified nature of Blackness (a la Bill Brown) and its simultaneous what Sylvia Wynter might call invisiblizing, its denial, and rejection; the flattening, erasure, and eviction from the category of legitimate student that often attends blackness in this context.

Fred Moten describes in his exploration, In the Break: The Aestetics of the Black Radical Tradition, that “Between looking and being looked at, spectacle and spectator-ship, enjoyment and being enjoyed, lies and moves the economy of what Hartman calls hypervisibility.” (Figure 1)

16

Figure 1: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

This hypervisibility is a condition of being seen, the excessive degree to which something, in this case notably Blackness, has attracted general attention, prominence, in this case superficially — literally at surface level — the level of skin, outward appearance, looks, embedded in what Hortense Spillers might suggest is a “bizarre axiological ground,” a strange site valuation and desire or desirability (Figure 2).

This student’s Blackness would typically render him useful, valuable to the marketing efforts of a particular school of architecture wanting to demonstrate, and even quantify, its diversity. What are the ethics, though, of his so-called inclusion to this sphere where he may be so violently, superficially regarded? How might inclusiveness connote not a bringing into, or providing access to rarified spaces of critique and evaluation, but instead, the active production of more capacious sites of study, a more hospitable opening up to a range of subjects, disciplinary and transdisciplinary dispositions, alignments, and subjectivities that instigate more bold and banal confrontation with a range of modes of being and knowing in spaces, sites, forms, uses, not commonly regard-

17 Ife Salema Vanable

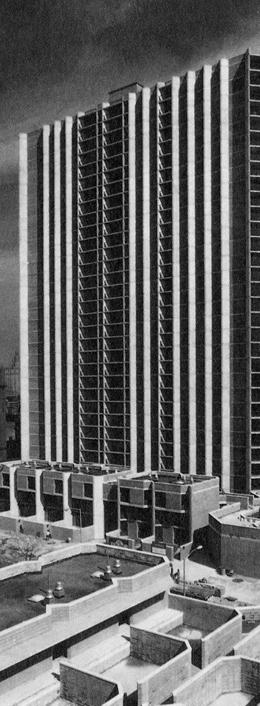

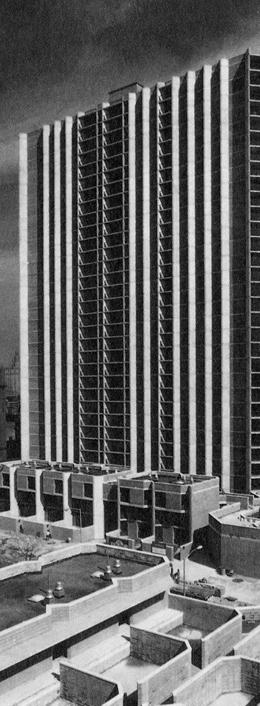

Figure 2: Harlem River Park Towers. Photo by Davis Brody Bond

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

ed as legitimate sites or territories of architectural inquiry, analysis, or design, where unauthorized epistemologies are sought after.

In this context, today, I will focus on orality, to sonic gesture (of which my own performance with you here today is part), on tales, tall tales, on their telling, (reconfiguring, or perhaps attending to what could be understood as a more current state in “historical movement [that has passed] from the priority of sonic gesture to the hegemony of visual formulation.” (Figure 3) I will focus on tall buildings, the sky, and the land, on Black folks out in the street, and at home, on my emerging dissertation project “Tall Tales: State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes.”

A project that seeks to operate at a critical intersection of historical analysis, theoretical speculation, and a close reading of language and rhetoric as a way to interrogate how modes of architectural production are operative parts of the same project that has historically, and continues to mutate, to produce varying ideas about racial difference. These alignments, not merely material, but arguably also constitute a discursive system, an aesthetic and sociotechnical mode of operation that orders the world in particular ways. Specifically, my interrogation of New York, 1970s, high-rise residential towers developed under the scheme known as Mitchell-Lama, affords a compelling and essential course of study due to the hybridity of scheme for housing (the result of pub-

18

Figure 3: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

lic-private partnering, not public housing, but not market rate), the simultaneous ambiguity and specificity with which the terms of its production have been managed (terms including “middle-income,” “family,” “household”), and the ways that its objects aesthetically deviate from and challenge expectations for how subjects racialized as Black are to be physically and materially housed, but also imagined as living in and dwelling.

I am curious about how housing, as a field of study and practice, praxis, and theoria, is often relegated to acts and discourse related to social justice and not also understood as a legitimate speculative and imaginative domain of action and thought, consciously willing to defy prevailing no-

tions of type, taste, and form. Where, as Ruha Benjamin has noted, “Imagination is a contested field of action…most people are forced to live inside someone else’s imagination.” (Figure 4) I wrestle with this “living inside,” inside someone else’s imagination, someone else’s imaginings of one’s place and the contours of that living, and also with living and learning otherwise; and as such have been studying modes of Black subjectivity and dwelling in tall buildings, the performance of domesticity and respectability, and the politics, aesthetics, and materiality of the making of home; the hope, desire, contentment, and aberration of housing.

As concerned with orality, this work seeks the relation of the oral to the written mark, “the convergence of meaning and visuality—[as sites] of both excess and lack,” to the archival. Work that is in many ways about what Ann Stoler puts forth in her 2009 text, Along the Archival Grain, “the force of writing and the feel of documents..., about commitments

19 Ife Salema Vanable

Figure 4: Harlem River Park Towers. Photo by Davis Brody Bond

Figure 5: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

to paper, and the political and personal work that such inscriptions perform.” (Figure 5) By confronting archival documents, the aim is to interrogate the ways in which architectural objects may have been culturally, socially, aesthetically, formally, or otherwise received over time, interpreted or evaluated and the biases, assumptions, and inventions that have shaped those operations.

As Saidiya Hartman has articulated, this embrace of documents is not to suggest any fidelity to truth or authority of the document, but is an attempt to consider what may be done with official, archived documents, given the limits, lies, omissions, and fabrications (Figure 6).

Attentive to legal rhetoric put to paper in legislative acts and the ways in which persons are figured in texts as targets and architectural artifacts marketed and rendered desirable though real-estate advertising, among other schemes and devices, this work deals with categories enacted by state and municipal authorities and their

20

Figure 6: The Jeffersons sitcom (1975-85).

enumeration; particularly attending to the oscillations, uncertainties, assumptions, and fabrications about what constituted “middle-income,” and the work of both gesturing to and eliding reference to racial categorizations. This work pursues architecture in the glut of bureaucratic documents that depict the daily work of city government. In so doing, this work mines those records teasing out predetermined parameters for how architectural developments meant to house were financed, developed, geographically situated across the urban domain, and designed, before any architect was commissioned; recognizing a kind of shadow architect therein. Pushed to outsize heights in the name of public benefit, simultaneously bold and unnerving, with aesthetics championed by the state, this work fundamentally seeks the often invisibilized (and often Black and Brown) residents, and their varied sanctioned, unauthorized, ingenious, pleasurable, sensuous, and, especially, quotidian domesticities and modes of dwelling.

With this, I aim to share questions I have posed simultaneously considering aesthetics, wanting, and the provision of accommodations and the relationships of these to modes of architectural production, practice, and pedagogy. This offering ponders the desirability of proximity to varying conceptions of Blackness (and Black students), alongside ongoing acts of its objectification, othering, and effacement, and asks how architectural thought within the academy, and as a physical,

material praxis, might be endowed with greater depth, nuance, specificity, radical, and even seemingly banal imagination.

I am deeply committed to interrogating how more imaginative, critical, and hospitable modes of shared study may be fostered, particularly in architectural pedagogy and those related fields that seek to reckon with and speculate on the built domain.

I have many more questions than I have any remedies or prescriptions. As an emerging theorist and architectural historian, I am meditating and speculating on the systems, desires, values, etc. that have made it (seemingly) necessary for a symposium on “design consequences” in the first place. In the context of this symposium, I am asking precisely what is meant by “social equity?” How are design consequences measured? Is this an evaluation of the past, present, or future? Who is the “our” being referred to? Who exactly needs to take responsibility for their ideas? Why is the study of “housing” deemed a “valuable framework through which to understand the issues of [so-called] social equity more generally?”

In terms of “designing for a just society,” my questions are less about how to bring discussions of racial justice and social equity into the classroom and more about how racial categorizations have been constructed and have been structurally operative and have transformed over time; how

21

Ife Salema Vanable

resources have been both hoarded and rendered inaccessible. Ultimately, perhaps I have some approaches and am truly interested in how to cultivate ways of thinking (and designing) with greater depth and nuance, that avoid flattening and rehearsing particular narratives.

As an emerging scholar being trained as a doctoral degree candidate in the history and theory of architecture, I have no interest in reconstructing the past “as it really was.” (Figure 7) The past “as it really was” is an illusory territory. Instead, my interests are fervently aligned with engaging architecture as a product of culture; a sociopolitical, sociocultural, and sociospatial artifact constructed as a result of historical processes that continue to resonate in the present moment and endure into the future. As such, architectural objects — buildings, spaces, urban territories — operate at both a wholly undeniable material level, as well as at the level of the immaterial — an ethical, behavioral, affective mode of operation.

Both the material and affective modes of operation of architectural artifacts maintain

an ongoing and continually transforming aesthetics and attendant politics. In this way, works of architecture that particularly intervene in urban domains populated by people of color, or more specifically inhabited by Black bodies, are regarded as what philosopher Jacques Rancière would refer to as “aesthetics acts, as configurations of experience that create new modes of sense perception and produce novel forms of political subjectivity.”

(Figure 8)

At the confluence of the law, legal rhetoric, public policy, and the development and construction of high-rise residential towers in New York City from 1955-1975 (perhaps a sort of pre-history or back story to the neoliberal project), space exists for interrogating how these objects and their financial, political, aesthetically-designed framing, sought to instantiate motives for constructing a sort of urban “middle-

22

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

Figure 7: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 8: Scene from Mandigo (1975 film).

classness” (or “dress up” a population regarded as undesirable and pathological in an architecture that would make them “respectable”), rooted in conceptions of race, geography, and finance. In my work, these hybrid objects, publicly funded and incentivized, though privately developed and managed architectural artifacts are regarded as “racial formations,” “historically situated projects in which human bodies and social structures are represented and organized.” (Figure 9) According to sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant, from whom I borrow this analytical tool:

A racial project is simultaneously an interpretation, representation, or explanation of racial dynamics, and an effort to reorganize and redistribute resources along particular racial lines.

Racial projects connect what race means in a particular discursive practice and the ways in which both social structures and everyday experiences are racially organized, based upon that meaning. (Figure 10) Asking such questions as to how these objects came into being, under what

circumstances, out of what body of legal, cultural, financial and social mores, directly engages what Luisa Passerini described as the “raw material of oral history.” In this manner, “the raw material of oral history consists not just in factual statements, but is pre-eminently an expression and representation of culture, and therefore includes not only literal narrations but also the dimensions of memory, ideology and subconscious desires.” (Figure 11)

Likewise, the raw material of oral history also, importantly, includes the dimensions of projection; that which is intimate and internal, as well as that which is thrown forth, outward, externalized.

Projection can be understood as a technique of self-preservation, a defensive act. Freud asserted that this “defensive projection” was an act of paranoia. The purpose of paranoia is thus to fend off an idea that is incompatible with the ego, by projecting its substance into the external world. The transposition is effected very simply. It

23 Ife Salema Vanable

Figure 9: Title image from The Jeffersons (sitcom 1975-85)

Figure 10: Scene from King Kong (1933 film)

is a question of an abuse of a psychical mechanism which is commonly employed in normal life: transposition or projection (Figure 12).

Transposition or projection as paranoid, thus defensive, protective, and preservationist, is also constructive; at once building up the self while simultaneously fashioning an external other. And while this defensive act may be upheld as the unconscious work an individual mind, I would suggest that this defensive act of self-preservation also operates at the level of society, at the level of collective imaginar[ies]. Paranoid projection at the level of society or nations undergirds racial formations, precisely those “historically situated projects in which human bodies and social structures are represented and organized.” (Figure 13) At the level of society, this form of projection operates to determine the ways in which nations work to define belonging, access, rights, and citizenship, while they concurrently construct and disseminate their own image and mythologize their own tenuous and embattled sovereignty (Figure 14); systematically casting

24

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

Figure 12: Title image from Good Times (sitcom 1974-79)

Figure 11: Co-op City, Bronx.

off or throwing forth that which is deemed incompatible with its sense of identity.

Identifying architecture as a cultural artifact, this work joins architectural historical and theoretical analysis with analyses of society and ideology. Racial projects engage the inequalities that racial regimes produce. As representational frameworks, the work of culture (through the various forms of media this work confronts), including real-estate brochures that announced the benefits of these works and solicited Black families, involves discursive practices that make sense of racial difference in the everyday, infiltrating and constructing the contours of seemingly

banal modes of black (urban and middle-income/middle-class) domesticity.

As Paula Chakravartty and Denise Ferreira da Silva assert, “houses are unsettling hybrid structures.” (Figure 15) The house as a juridical-economic-moral entity has even greater material (as asset), political (as dominion), and symbolic (as shelter) authority when agglomerated as highrise, high-density, multi-family housing for urban Black bodies (Figure 16). Schemes deployed in service of this system condition experience, delimit fields of action, and partition knowledge, becoming things with which to think and act. Mitchell-Lama housing as a State fabricated and

25 Ife

Salema Vanable

Figure 13: 1970s Harlem.

Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 14: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 15: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

authorized, and municipally elaborated scheme for housing black bodies in the urban domain embody these processes, making power relations explicit with logics not always merely reducible to that of capital (or profit). “Tall Tales: State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes” exits at this critical nexus, where imaginative invention interacts with and complicates literal meaning and where blackness (and to some extent the state and city) is a constantly reworked, redefined, and reconstituted frontier.

The figure of the Black, throughout the diaspora, and especially in what is referred to as the United States of America, and Blackness by extension in this national, state apparatus, can be understood as a projection, an image, a fiction deployed to shore up the nation against reproach; the very “avoidance of self-reproach via the externalization of cause or blame.” (Figure 17) And while the category and notion of whiteness, as embedded in the narrative of the nation, is equally fictionalized and co-constructed, the “incalculably differentiated thing [is] the fetish character of Blackness and its open secret.” (Figure 18) Blackness, as such, is both magical and ordinary, rehearsed, constantly re-presented and practiced, embodied and structural, illusory, and haptic, rendered common at both the level of the individual and the

26

Figure 16: Waterside Plaza, New York. Photo by Davis Brody Bond

collective social body. As Fred Moten scholar and poet asserts:

Blackness is the name that has been assigned to difference in common, the animaterial inscription of common differentiation, which improvises through the distinction between logical structure and physical embodiment. Physical embodiment is not this or that skin color or bodily shape but haptic graph. Logical structure is not this or that determined or determinate discursive frame but common informality. (Figure 19)

My work exploring this complex body of high-rise residential towers, sponsored

27 Ife

Salema Vanable

Figure 17: 1970s Harlem.

Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 18: Cadman Towers, New York, 1973.

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

by well-crafted legal andfinancial maneuvers, is invested in the divergent tales of Black life, the “general gathering of dispersal,” (Figure 20) these buildings host. As racial projects, these buildings are simultaneously abstractions and wholly real. These projects are deliberately engaged, “not because of [their] centrality or authenticity but rather, because of [their] specific enactment of the marginality and minority that is the central and authentic feature of Blackness understood as a general, generative principle of differentiation.” (Figure 21) In this way, my work is particularly invested in an exploration of the “relationship between subjectivity and objects,” (Figure 22); in this case the object of the high-rise residential tower, as a large scale agglomeration, consisting of individual objects, apartments, and a mass of overwhelmingly Black bodies.

28

Figure 20: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 19: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

The high-rise residential tower at the macro level and the life lived within the individual unit, the individual apartment, constitute the territory wherein notions of Black domesticity are both projected and performed, as well as conceptions of respectability and where the legislation of dwelling is enacted. These objects act as, “a politically salient meeting ground of public authority and personal intimacy,” (Figure 23) whose tales can be told through the specific form of discourse identified as such by Alessandro Portelli as oral history.

Oral history has the potential to directly engage this territory of projection, where Blackness is the site of that which is thrown forth, cast as divergent from the social mores, behaviors, customs, and

ways of being that have been imagined as constitutive of the core of the national and state identity. This paranoid work of social and/or state projection delimits where and how individuals contained therein are categorized, located, and expected to interact with objects both in the physical, material world and in the social, cultural imaginary. This is a decidedly collective domain — expressly political, highly aesthetic, and particularly intimate

29 Ife

Salema Vanable

Figure 21: Schomburg Plaza, New York.

Figure 22: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 23: Demolition of the Trans-Manhattan Expressway, 1960.

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

— involving the relationship of parts to a perceived or imagined whole. It involves what philosopher Jacques Rancière refers to as a “distribution of the sensible:”

A distribution of the sensible establishes at one and the same time something common that is shared and exclusive parts. This apportionment of parts and positions is based on a distribution of spaces, times, and forms of activity that determines the very manner in which something in common lends itself to participation and in

30

Figure 24: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 25: Still image from Good Times (sitcom 1975-79).

what way various individuals have a part in this distribution. (Figure 24)

This distribution of the sensible, as a “system of self-evident facts of sense perception,” (Figure 25) invokes those faculties by which the body perceives and understands its relation to the external world and ultimately stores and remembers that information, namely memory. By establishing what is common, as well as exclusive parts, the distribution of the sensible operates at the level of society and at the level of lived individual, affective, material experience and betrays modes of consensus at work and the proliferation of commo sense. And while the seminal work in the field of oral history of Luisa Passerini and that of Allessandro Portelli are different on many levels, I recognize a particular correspondence at work between the two in their respective references to “consensus” and “common sense,” as well as in Anna Green’s interrogation of “collective memory.” As I work to unearth the historical processes at play surrounding the conceptualization and physical intervention of the body of architectural objects I have chosen to study, I have sought out the methods and theories of oral history alongside Black

studies and architectural historical and theoretical analysis to afford a means by which to directly engage those who dwell within these objects.

Oral history is defined by Anna Green as “the collection and analysis of autobiographical memory.” (Figure 26) While Green suggests that research into autobiographical memory often found itself “relegated to the sidelines by the scholarly community’s burgeoning interest in the social or cultural memory of the group,” (Figure 27) my approach is less interested in establishing a binary opposition between social or cultural memory and autobiographical memory and is instead interested in the ways in which the individual, autobiographical tale is mediated by collective remembrance. Citing historical sociologist Jeffry Olick, Green presents two facets of collective memory theory. Accordingly, collective memory may be either:

“...the lowest common denominator or normal distribution of what individuals in a collectivity remember, or…’the collective memory’ as a ‘social fact sui generis,’ a

31 Ife Salema Vanable

Figure 27: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 26: Lionel Hampton Houses, New York.

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

The work of oral history gets at how one comes into knowing how to be. There is a performative quality that foremost interests me, in both how — through what types of language, references, associations, etc. — tales are told and how personal, intimate life has been lived in a particular historical time and space, as constructed in

32

Figure 28: Tilden Towers Senior Center, undated pamphlet. matter of collective representations that are the properties of the ‘collective unconscious’ which is itself ontologically distinct from any aggregate of individual consciousness.” (Figure 28)

or by those tales — through what types of behaviors, rituals, corporeal, bodily events are described, distorted, or omitted. My interest is in both form and content. (Figure 29)

Anna Green concludes her interrogation of the use of the conceptual term “collective memory,” with the assertion that some would argue there is “much leeway in what one can claim to be,”(Figure 30) that “there is surely an element of conscious personal selection among the potential relationships and networks available in modern, multicultural cities.” (Figure 31) By contrast, this work seeks to complicate and undermine the supposition that the machinations of the wider society have fundamentally changed. The “creative autonomy” that Green — by way of her analysis and exaltation of the work of anthropologist Daniel Miller — argues is permitted individuals to a much greater degree in the “modern state,” ignores impositions and boundaries delineated by racial formations and their attendant politics. And while I disagree with Green’s analysis of the availability of choice, this work whole-heartedly agrees that “we must keep space for the resistant, curious, rebellious, thoughtful, purposeful human subject,” (Figure 32) the subject racialized as Black, especially the dissenting Black scholar has always and already made space, bent space, reworked space. (Figure 33)

A very distinct order and authority attends securing and maintaining housing, particu-

33 Ife Salema Vanable

Figure 29: Still image from Empire (1965 film).

Figure 30: View of the Washington Bridge Apartments and Extension Complex, New York (undated photo).

Figure 31: Nagle House advertisement, undated pamphlet.

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

larly under impoverished circumstances. Residents who interact with the well-established order and authority of this system, enact a certain dwelling ideology, reluctantly accepting the imposed order and authority, but with little protest. It is a form of “consensus, in the form of acquiescence to the established order and authority,” (Figure 34) as Luisa Passerini asserts that is part of what I seek to tease out through oral history interviews. My work directly engages the “material component of consensus” (Figure 35) in that the towers I pursue as my objects of study are actually providing housing, they afford residence. How individual subjects confront, accept, dwell in, resist, and enjoy, are pleased by the tensions, imposed restrictions, and forms of surveillance and regulation that come with these residences is what I seek to deploy oral history to confront.

I am fascinated, and have been for some time, with the fantastic modes of operation of the seemingly banal and contradictory. I fully accept and relish the “tension between individual reality and general [historical] process…” (Figure 36) And while the high-rise residential towers I pursue are objects that have emerged from particular sociopolitical, sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts — equally constructed under the law,

34

Figure 32: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

through certain development and financing schemes and are aesthetically determined in very specific ways — these highrise towers are also products of a specific cultural imaginary. I refer to this domain in a manner that Alessandro Portelli might agree with, as “Tall Tales;” sits enmeshed in fabrication, lies, tales, attended by deceit and fakery, always already operating on multiple registers. The specific dialogic nature of oral history is an essential tool for my work, particularly because it is equally fraught with its own contradictions and tensions. “The expression oral history therefore contains an ambivalence…: it refers to both to what the historians hear (the oral sources) and to what the

historians say or write.” (Figure 37) What I hear is significant, however what I write is supremely important to me.

Architectural histories of housing perpetuate narratives that align Blackness with dispossession or totally ignore it and unconsciously universalize whiteness, while simultaneously working diligently to ignore architecture’s role in the development and implementation of racial projects. Revolving around categoriza-

35 Ife Salema Vanable

Figure 33: Tilden Towers, Bronx, New York (undated photo.

Figure 34: Confucius Plaza Apartments, New York (undated photo).

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

tions of form and type, architectural histories of housing have in many instances neglected how deeply connected seemingly mundane configurations of domesticity have been tied to and been generated as a result of the constitution of racial categories and the perpetuation of a moralizing mission. As such, modernist “towers in a park,” when not narrated in terms of universal access to light and air, have alternatively been and remain a continuously vilified trope when taking into account any discussion of race. These narratives often render Black residents victims of architecture, for whom the high-rise residential tower as type is deemed inappropriate, damaging, and damning. As the story goes, Black bodies, particularly Black families with children, and the housing they have been relegated to are deemed pathological. Black poverty is overwhelmingly used to explain the overrepresentation of black folks in sub-standard housing and their presence aligned with the perpetual decay of urban domains.

For all its seemingly progressive intent, the Mitchell-Lama housing program (and the accompanying body of large-scale, urban architectural artifacts) could be read as a bellwether for the fate of Black Americans within an increasingly privatized and global-

36

Figure 35: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

Salema Vanable

ized economy; one version of a back story to the neoliberal moment (Figure 38). What some scholars may refer to as the rise and fall of a failed experiment in postwar largescale, middle-income housing, my dissertation finds striking the endurance and mutability of the program across time and media — as legislative rhetoric, financial scheme, marketed object, aesthetic entity, architecture, cultural artifact, and host of physically lived, domestic realities; infiltrating and working on the social, cultural imagination. While the last project enacted under the legislation was certified for occupancy in the late 1970s (as the city of New York was facing serious financial decline), this work recognizes its ongoing productivity in the realm of myth-making, spinning tales, promoting an image of benevolent government intervention, that in fact mask a particularly mundane maintenance of racial hierarchy and subjugation; where Blackness is constantly veiled and simultaneously centered.

Jack Halberstam, in this opening essay to Fred Moten’s and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, writes in “The Wild Beyond: With and for the Undercommons” that: “In the essay that many people already know best from this volume, ‘The University and the Undercommons,’ Moten and Harney come closest to explaining their mission. [A stance with which I feel methodologically aligned]. Refusing to be for or against the university and in fact marking the critical academic as the player who holds the ‘for

37

Ife

Figure 36: Independence Plaza, New York.

Figure 38: Knickerbocker Plaza, New York.

Figure 37: Still image from Independence Day (1994 Film).

and against’ logic in place, Moten and Harney lead us to the ‘Undercommons of the Enlightenment’ where subversive intellectuals engage both the university and fugitivity: ‘where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still Black, still strong.’ The subversive intellectual, we learn, is unprofessional, uncollegial, passionate, and disloyal. The subversive intellectual is neither trying to extend the university nor change the university, the subversive intellectual is not toiling in misery and from this place of misery articulating a ‘general antagonism.’ In fact, the subversive intellectual enjoys the ride and wants it to be faster and wilder; she does not want a room of his or her own, she wants to be in the world, in the world with others and making the world anew.” (Figure 39)

38

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

Figure 40: 1970s Harlem. Photo by Jack Garofalo

Figure 39: University Village Towers, New York (undated photo).

DISCUSSION

Alexandra Staub: Thank you very much, Ife. That was a remarkable essay. You’ve interwoven so many themes into a mosaic of cultural phenomena. I’d like to circle around to some of your topics. You talked about racial categorization and oral history as a means of accessing individual subjectivities. At the same time, society at large objectifies the people you interview. You tie that in with the idea of architecture as an artifact and as a product of culture. The people and the architecture are both a construct of culture, and you’re delving into the ways in which the two intersect.

Many of your stunning images are from pop culture of the 1970s. Considering the U.S. housing history after World War II and through the 1970s, this was a time during which white families increasingly moved into suburbs and Black families were relegated to high-rise housing in the cities. I was wondering if you could comment as to your choice of using the 1970s as a point of analysis?

Ife Vanable: The 1970s are an important periodization for my work as an architectural historian. New York State’s 1955 Limited Profit Housing Companies Law, known as Mitchell-La-

39 Ife

Salema Vanable

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

ma, did not initially produce the number of housing units hoped for in the 1950s and 1960s. And, in many ways, the Mitchell-Lama housing program was conceptualized and enacted as a deviation from New York City public housing authority projects — architecturally, socially, and financially. With the private, though publicly subsidized, development of low-moderate and middle-income housing, the housing program produced architectural objects and simultaneously defined the contours of a desirable middle- income Black resident. Without access to wealth or income to sustainably enter into market-rate housing, as the law was written, this desired and envisioned resident would nonetheless be recognized as different in terms of finances, status, family composition, and values from an imagined more low-income public housing tenant. Many of the images I shared reflect how this imaginary was also constructed in popular culture. [The Jeffersons, Good Times]

a notion that is often attributed to the “tower in the park” ideal, touted as seeking that sought universal access to light and air. This led to urban policy schemes that benefitted developers of middle-income housing.

With these architectural and financial ideals and incentives, in the late 1960s, developers in New York began to produce ever-taller housing. In other parts of the country, high-rise residential towers were being demolished, yet New York was going ahead with production. The largest number of high-rise residential towers came into being in New York between about 1968 and 1975. This was the time when New York was on the brink of financial and material decline, and the Bronx was assumed to be burning. At this time, in 1970s New York, something else is happening that often is untold [Paris Match]. For me, that becomes the very fertile ground from which the tales I unearth emerge.

In 1961, a set of revised zoning resolutions in New York City provided benefits and bonuses to developers for open space, following

Alexandra Staub: What you’re describing — the idea of putting families into a certain type of housing and encouraging them to become middle-class or to remain

40

Ife Salema Vanable

middle-class and not take on perceived characteristics of poor families — sounds like social engineering. Was that what was taking place in New York City?

Ife Vanable: In New York, the Mitchell-Lama housing scheme contributed to the making of the city itself. Designed in very robust ways, by architects like Paul Rudolph and I.M. Pei, or well-known mid-sized firms, such as Davis Brody and Associates, as well as firms like Bond Ryder before Max Bond joined Davis Brody, Mitchell-Lama housing is still quite desirable. The apartments are large and were affordable. Though affordibiity was not a term used at the time, there was much more emphasis on tenant income. I would say the city was not necessarily interested in transforming families as much as it was in maintaining its own status by keeping families who supported the city. People deemed “essential” during the COVID pandemic, for example, those who work for municipal agencies and authorities – post office workers, bus and train drivers, nurses, or home care aids – would have been classified as Mitchell-Lama tenants.

In many ways, Mitchell-Lama housing can be understood as a form of catchment, a way to keep bodies in the city. These were folks who could have potentially moved elsewhere, those who once had a home and decided to do away with having to shovel snow, or the responsibilities of maintaining a home, or folks who loved the view from the 28th floor high-rise apartment unit. While recognizing these developments as a form of catchment, simultaneously my work recognizes desires to live in ways not always aligned with prevailing narratives of a single-family home as the most desirable object. I’m so interested in how these objects and the program operates on both these levels.

Alexandra Staub: New York during the late 1960s and early 1970s was experiencing many difficulties and social disruptions. How do the towers figure in?

Ife Vanable: Some of the projects in Mitchell-Lama took fifteen years to build. An example is Waterside Plaza, which was the only development east of the FDR Drive and is constructed on invented land

41

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Scheme: Discussion consisting of pilings. Developers were very committed to moving forward with these projects. In the course that I’m currently teaching, we talked about the sense of distance from the ground and the notion of danger associated with being in a high-residential tower. Some students told me that their families moved out of high-rise buildings due to fear of being unable to escape during a fire or not wanting their children to run up and down the stairs and play in the elevators — all things that I actually did growing up because I lived on the 28th floor in one of these buildings. Distance from the ground is simultaneously desirable and also a means to capture bodies. The street has been seen as a site of disturbance and chaos. The tower begins to create a very palpable and real, physical, material distance from the street. There is an idea that housing, containment in towers, provides a sort of stable distance from the street. A notion of the stable family persists after

Daniel Moynihan’s 1965 report [titled The Negro Family, the Case for National Action], in which the Negro family is analyzed as unstable and pathological. These towers do emerge in this moment as part of a narrative toward stabilizing a seemingly “unresting” urban population at the level of the street. This construct between the street and the sky is something that I’m constantly thinking about and looking at.

Alexandra Staub: A fascinating thought. From an architectural viewpoint, the tower has to be very stable because there’s the structure to consider. The engineer is involved from day one. Metaphorical and physical stability overlap here.

I was wondering if you could speak a bit more about racial categorization. You mentioned that Black people and Black families were seen as pathological, but on the other hand, everything that you’ve said about the tower sounds very positive. Where is the overlap for you?

Ife Vanable: I obviously do not align my-

42

self with Moynihan’s thinking of the Black family as pathological — a framing based on the perceived lack of a male figure, and the ensuing critique of a matriarchal structure. Hortense Spillers writes that if you look at the Black family, you can find a father, that there is not merely instability, but otherwise familial compositions that might not be registered or valued in the same way. Value questions are prominent. I resist the narratives that urban housing in the form of high-rise residential towers is inherently problematic, or that a spatial concentration or even segregation of Black bodies is inherently bad.

space, the idea of the terminal bedroom, the separation of uses, and the categorizations of domestic space. It’s one of the first things you learn to do when you draw floor plans of domestic spaces — you call out where the living room is, where the bedroom is, where the bathroom is — ongoing processes of demarcating. These ideas of social structures inherent in dwelling are also implicated in racial categorization.

In many ways, Mitchell-Lama was an integrationist project. The initial idea was that if you take families of moderate income and put them next to people who are more middle income, there would be a growth in values and behaviors. But I really resist perceiving the towers as a problem. I even question where and how the problem is described, and the tendency of architecture to operate in terms of problems and solutions. Robin Evans writes about the production of domestic

Alexandra Staub: It sounds as if you are emphasizing the value of particular and specific cultures that you find in the housing you’re studying. In your oral history project, I assume you’re interviewing residents of the towers?

Ife Vanable: Yes, current and former resident activists, tenants, and organizers.

Alexandra Staub: As a final question: you mentioned COVID at one point. I’m just wondering if what you are unearthing in your own research has some implications for what you see happening today?

Ife Vanable: I get this question a lot

43 Ife

Salema Vanable

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

when I talk about this work. I do historical analysis and research, but am also engaged in a theoretical project framing questions around media and documents. As I’m analyzing oral histories, talking to people, I’m also looking at how these projects are represented in media, and how they’ve been understood and received across time. My aim has been to see how we pose questions, how we assert certain schemes of value, how we talk about things as being good or bad, and how we ask questions about where those designations come from. I’m aiming for a methodological transformation that I hope to integrate pedagogically. We need to examine the way that we can move through the work pedagogically and in practice with greater attention to nuance. We need to ask questions about things that are seemingly cemented, and we need to take those things apart with greater depth and specificity.

Alexandra Staub: One of the underlying premises of this symposium is that we do need to explore alternative ways of generating knowledge, asking questions, and finding answers. I would like to thank you very much for your fascinating talk and for this discussion.

44

45 Ife Salema Vanable

State Looks, Black Desire(s), Housing Schemes

BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS [INCLUDING BOOK CHAPTERS]

Ernest, John, ed. The Oxford Handbook of The African American Slave Narrative. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Evans, Robin. Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays. London: Architectural Association, 2003.

Adams, Timothy Dow. Telling Lies in Modern American Autobiography. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Bloom, Nicholas Dagen and Mathen Gordon Lasner, eds. Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies That Transformed a City. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Brilliant, Eleanor L. Urban Development Corporation: Private Interests and Public Authority. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1975.

Brooks, Daphne A. Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850-1910. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Browder, Laura. Slippery Characters: Ethnic Impersonators and American Identities. Chapel Hill and Lodon: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Brown, Carolyn S. The Tall Tale in American Folklore and Literature. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Brown, Wendy. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty. Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books 2010.

Brown, William Wells. The Escape; or, a Leap for Freedom: A Drama in Five Acts. Boston: R. F. Wallcut, 1858.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex.” New York & London: Routledge, 1993.

da Silva, Denise Ferreira. Toward a Global Idea of Race. Borderlines. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Ellison, Ralph, and Albert Murray, Johan Callahan, ed. Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray. New York: The Modern Library, 2000.

Fields, Karen E. and Barbara J. Fields. Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life. London and New York: Verso, 2014.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

Frazier, E. Franklin. The Negro Family in the United States. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1939.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Gikandi, Simon. Slavery and the Culture of Taste. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Green, Anna. “Can Memory Be Collective?” In The Oxford Handbook of Oral History, edited by Donald Ritchie, 96-111. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Hackworth, Jason. The Neoliberal City: Governance, Ideology, and Development in American Urbanism. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and representation. Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992.

Hurston, Zora Neal. Mules and Men. London: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1935.

Jenkins, Candice M. Private Lives, Proper Relations: Regulating Black Intimacy. Minneapolis and London: University of Minneapolis Press, 2007.

Marable, Manning. Race, Reform and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945-1982 (The Contemporary United States). Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1984.

46

McKittrick, Katherine, ed. Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Durham, NC & London: Duke University Press, 2005.

Mignolo, Walter D. The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010.

Moynihan, Daniel Patrick. The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Policy, Planning and Research, March 1965.

Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. New York and London: Routledge, 1994.

Passerini, Luisa. Autobiography of a Generation. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for Wesleyan University Press, 1996.

Portelli, Alessandro. “Oral History as Genre,” in The Battle of Valle Guila: Oral History and the Art of Dialogue. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

Rainwater, Lee and William L. Yancey. The Moynihan Report and the Politics of Controversy: A Trans-action Social Science and Public Policy Report. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1967.

Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, eds., Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988, 271-313.

Stern, Robert A.M., David Fishman, and Thomas Mellins. New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. New York: The Monacelli Press, 1997.

Willmann, John B. The Department of Housing and Urban Development. New York, Washington and London: Frederick A. Praeger, Publishers, 1968.

Young, Kevin. The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness. Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2012. Articles and Reports.

Kaplan, Samuel. “Bridging the Gap from Rhetoric to Reality: The New York State Urban Development Corporation.” Architectural Forum (November 1969): 70-73.

Marriott, David. “Inventions of Existence: Sylvia Wynter, Frantz Fanon, Sociogeny, and ‘the Damned.’” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 11, no. 3 (2011): 45-89.

Passerini, Luisa. ‘Work Ideology and Consensus Under Italian Fascism,’ History Workshop Journal, no.8 (1979): 84.

Saldahna, Arun. “Reontologizing Race: The Machinic Geography of the Phenotype.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Vol. 24 (2006): 9-24.

Scott, David. “The Re-enchantment of Humanism: An Interview with Sylvia Wynter.” Small Axe 8 (September 2000): 119-207.

Thompson, Jr. William C., Comptroller. “Affordable No More: New York City’s Looming Crisis in Mitchell-Lama and Limited Dividend Housing.” City of New York: Office of the Comptroller, Office of Policy Management, February 2014.

Vale, Lawrence J. and Yonah Freemark. “From Public Housing to Public-Private Housing.” Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 78, No. 4 (2012): 379-402.

Wynter, Sylvia. “The Ceremony Must Be Found: After Humanism.” Boundary II 12, No. 3 and No. 13, No. 1 (Fall 1984): 19-70.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/ Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation - An Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Fall 1993): 257-337.

47

Ife Salema Vanable

BUILDING SPATIAL JUSTICE: IN TWO ACTS

Rayne Laborde Associate Director of cityLAB UCLA

Rayne Laborde Associate Director of cityLAB UCLA

ABSTRACT

Building Spatial Justice: In Two Acts highlights a small portion of the recent work of cityLAB as related to Design Consequences. cityLAB is a design research center housed within UCLA Architecture and Urban Design. As a group of architects, designers, urban planners, researchers, and theorists, we explore the challenges facing our contemporary cities, and particularly our home, Los Angeles. As part of a public education institution, our mission involves community partnerships, mentorships, and developing new methodologies for embedded research. For us, this happens in three parts:

1. through cityLAB as a whole;

2. through our partner the Urban Humanities Initiative, which is an interdisciplinary, year-long graduate certificate program for students in architecture, urban planning, and the humanities;

3. through our field office dedicated to long-term partnerships in the Westlake/MacArthur Park neighborhood of LA.

49

PREFACE: DESIGN AS LEVER

When it comes to studying and acting within our city, “Design is our Lever.” In thorny issues at the intersection of policy, capitalist market forces, and racism (which are intrinsically linked), of land use and accessibility and connectivity, we see design research as an opportunity both to highlight the complexity of the issues at play and to showcase alternative possibilities. Solutions, and good design, require interdisciplinary work at all scales but for us, the project of design research is a catalyst for larger-scale change. Ways of seeing, then, are incredibly important. Design research has the capacity to get everything and everyone on the page, to explore connections less easily seen, to tease out hidden narratives, and to piece it all back together anew. It is true that design and architecture have very real limits. Seeing design as a lever recognizes the ways in which architecture, aesthetics, and urbanism are abused as tools of power, oppression, intimidation, and displacement. We see the consequences across our cities. This leveraging also maximizes our ability to use design as a tool of communication, or even an act of translation, between different disciplines, groups, and interests. Our actions foreground the ability of design to suggest, excite, delight, and provoke radical possibility in the everyday.

ACT 1: DESIGN EVOLVING POLICY

as endless suburbia may be lacking in complexity, but it is not entirely incorrect: half a million lots in our city are zoned for single-family use, the most restrictive zoning type. This suburban ideal is, in many ways, an economic dilemma cloaked in the wrapper of a design consequence. It’s the marketing of and subsequent desire for the single-family home as the American dream, that perfect image of the standalone house bordered back and front with perfectly maintained lawns. It’s the attached garage and white picket fence — a contained and private world filled with all the appliances, trinkets, and finishings that attract home as a vessel of consumer culture demanded. Even in a city short on land and water, the image of this as “home” remains powerful. As an economic investment bolstered by a housing crisis driven by anti-development sentiment, the symbolic and fiscal power of the single-family home has only grown. And yet, it forms an antithesis to the sustainable and humanistic density we need.

Until five years ago, local planning departments exercised full control over the density (or lack thereof) on these lots, almost always limiting construction to the traditional home. Secondary houses on the same lot — what we refer to as backyard homes or accessory dwelling units (ADUs) — were costly, allowed only in select areas, and only through a long and drawn out discretionary process. Restrictions were so profound that between 2003 and 2010, only eleven ADUs were permitted in Los

50

Building Spatial Justice: In Two Acts

The familiar imaginary of Los Angeles

Angeles. This is not to say that ADUs did not exist in the city; in fact, design, land use, and socioeconomic consequences in the neighborhood of Pacoima converged to normalize this typology. Pacoima is in the northeast San Fernando Valley. Of its 100,000 residents, 85% are Latino, one-third are under 18, and nearly 20% live below the poverty level, with a median

household income of $49,000.1 As in the rest of the region, high real estate prices and population pressures have led to a shortage of affordable housing.

Though Pacoima is zoned R1 (single-family residential) and 80% of its housing units are detached homes, the lived reality of neighborhood residents tells a different story of density and alternative models. One in five residents live in shadow

51

Rayne Laborde

Figure 1: CityLAB, Large Lot Design Concept, 2008.

housing: garages, rented rooms, and illegal units. These illegal units are especially prevalent in the peculiar lot type unique to Pacoima. The neighborhood has over 1,000 extra-long single-family lots that yield 10,000 square feet of surface area, nearly twice the size of the average LA residential lot. As of 2016, 95% of these extra-long lots had illegal units constructed in the backyard. Born out of necessity yet popularized through effectiveness, Pacoima residents were modelling a different future for suburbia:

a more sustainable yet equally communal way of life that was particularly impactful for intergenerational households.

Pacoima’s accessory dwelling units were unpermitted; they could lead to steep fines or demolition, and they decreased property value rather than building equity. Together with the neighborhood group Pacoima Beautiful, cityLAB sought to imagine a future in which these illegal second units could instead be an equity-building asset as well as a safe, dignified way to provide

52

Building Spatial Justice: In Two Acts

Figure 2: cityLAB, Neighborhood Analysis, 2010.

denser housing without fundamentally altering neighborhood character or straining the existing infrastructure of a fragile neighborhood. Resisting gentrification was a priority, as was affordability. This meant validating, legalizing, and proliferating the ADU across multiple typologies and regions through a streamlined approval and construction process. As either an attached or detached structure, ADUs can support intergenerational families, provide affordable rentals for students or older adults, and reorganize underutilized yard space – or even provide new surfaces for thickened occupation.