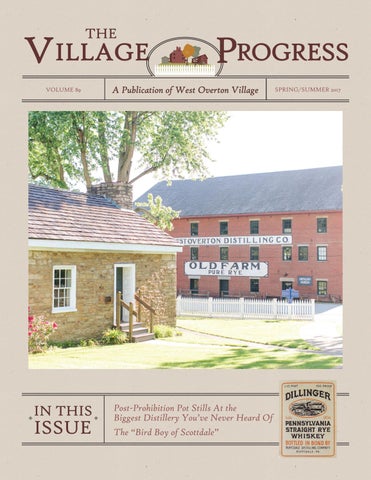

Village Progress

and our mission. For submission guidelines, please inquire at info@westovertonvillage.org or call 724-887-7910

FROM THE DIRECTOR’S DESK

The last year at West Overton Village & Museums has been full of promising developments. Our tour season is off to an amazing start, with our events and group tours seeing record breaking attendance.

We have great events on the horizon, which will continue to draw in new crowds. The 2nd Annual Blind Pig Party is coming soon in July, and The Whiskey Smash is back for another year in November. The Blind Pig Party will feature local brewers, great raffle prizes, and games! Last years’ party was a sold-out success, and we expect this year’s event to sell-out soon. Get your tickets now!

The 2017 May Mart & Makers’ Market continued to build on last year’s momentum, with a record high attendance of 2,000 people. The Makers’ Market, organized by Sonia & Matt Miller, is a great source for local businesses, and I’m pleased that West Overton has been able to provide the venue to showcase these artists and artisans.

Our historic buildings leased for private use have continued to draw in new businesses, and this year we’re delighted to see the addition of more artists and creatives. Our latest Village Renter Rustic Nostalgia has created a space for rustic farmhouse-inspired home décor. As we continue to update our grounds, we are happy to announce that two spaces are available to lease to potential shop owners.

Weddings continue to draw a broad audience to West Overton Village, thanks to our friends at Carson’s Premier Catering in Scottdale. Our historic space has long been a draw

for events rentals, and we are overjoyed to be a part of so many couples’ special day. Due in part to last year’s grant from the Laurel Highlands Visitors’ Bureau, the Overholt Room saw increased traffic from baby and bridal showers, business retreats, lectures, and many other events. We are glad to be a resource for both new audiences and our valued members. You too can become a member and support our mission!

The Distillery project is progressing more rapidly than ever before. We are renovating the space that will house distilling operations, and the equipment will be installed over the next few weeks. The distillery will be a unique way to help new audiences engage with the history of West Overton. We are excited to watch the process develop.

Speaking of drawing audiences, we’re seeing more group tours visiting the museum than ever before, and we are strategizing to ensure these numbers continue to increase in the coming years. With the hard work and dedication of our staff, board of directors and volunteers West Overton Village & Museums will grow to become a regional destination – a vision that I hope to see become a reality over the next few years.

Finally, I would like to offer my thanks and appreciation for our members and donors. Without your continued support, our institution could not grow the way it has over the past few years. Stop in and see us again soon, with your help our museum will continue to enrich and inspire our members and future generations.

~ Jessica Kadie-Barclay Chief Executive Officer

You Can Be a Part of Our History

To Support Us, Volunteer or Become a Member At: westovertonvillage.org/ support-membership/

BECOME A MEMBER!

Want to support West Overton? Become a Member! Membership support has far-reaching impact. From sustaining operations, funding preservation, and providing support for our programs, your membership dollars make a noticeable difference.

This year’s Blind Pig Party will kick off a fun initiative to encourage membership. Every new and renewing Homestead Level or higher member will receive a West Overton Village shot glass with a complimentary shot of Old Overholt whiskey to toast their support of our Museum.

Additionally, there are many benefits to being a West Overton member. Free admission to the museum and discounts at our gift shop are only the beginning! With several different levels, you’re sure to find a membership that best suits you. Starting in 2018 we will be adding a Corporate Level, for companies and businesses that would like to support the museum but do not necessarily need the individualized benefits of the other options. Teachers and Photographers also have the option of a separate membership tailored to the needs of their professions.

West Overton Village truly values its members and donors. Join the West Overton family and help us keep our history alive!

Second Annual Blind Pig Party | July 20, 7:00—9:00 p.m. Big Barn

Third Annual Whiskey Smash | November 18, 6:00—8:00 p.m. Distillery Museum and Overholt Room

Holiday Open House | December 2 Coming Soon ~ Details at westovertonvillage.org/events

MEET OUR STAFF!

Ashley Branthoover

Museum Guide Ashley Branthoover has been a regular presence over the past few years, and lately has expanded her role at our museum. Ashley started volunteering at West Overton over four years ago. As a volunteer, she first worked with our staff to revise and update our electronic catalog of archival materials and artifacts, and later she would volunteer as additional staff at our annual events. Starting in 2016, she began working as a museum guide for West Overton’s team.

At the same time, Ashley has been studying graphic design as an undergraduate. Since then, while continuing her work as a guide, her duties at West Overton have expanded to put her talents to use updating our graphics throughout the museum space (see below). Lastly, as of this year, we are using Ashley’s experience working with our collections in our latest project of digitizing and hosting online our collection of artifacts and archives—a benefit we will be extending to the public soon; keep watching for details! (see page 8 for a similar story). Please join us in thanking Ashley and all members of our team for their constant hard work and vision.

Top, from left: Mary Jane McFadden, Logan Holmes, Victoria Copenheaver, Bill Stone, Jessica Kadie-Barclay, Barry Whoric. Bottom, from left: Aleasha Monroe, Serena Pape, Gracen Kenney, Ashley Branthoover

his silent vigil over the

VILLAGE NEWS AND EVENTS

Rent Overholtthe Room

2017 May Mart & Makers’ Market

May Mart has been a constant feature at West Overton Village over the years, and like all things in the Village, we strive each year to make it better than before.

Traditionally organized and held by our Volunteer Garden Society, this year the event was expanded to be co-coordinated by our friends and neighbors at the Scottdale Historical Society.

year’s

Right: The event saw the grand opening of Rustic Nostalgia. See story below for more details!

This year featured for the second time the addition of the Makers’ Market, organized by Village renters and owners of Sonia’s Shabby Chic, an event that brings artisans and other vendors to the grounds.

Also, as detailed below, this year welcomed the grand opening of the Village’s latest renters, Rustic Nostalgia!

We would like to thank everyone involved in this event; we saw a record-breaking crowd of nearly 2,000 people on site. It was an amazing day! We hope to see you next time.

Welcome To New Village Shop: Rustic Nostalgia!

Rustic Nostalgia writes:

“Rustic Nostalgia is an antique boutique that has an array of pieces of the past and farmhouse inspired home décor. We restock our shelves with antiques weekly and are always out “pickin’” to provide for your love of vintage finds. In addition to antiques, we also specialize in handpainted barn wood signs for weddings and other events.

Our shop offers a number of unique small businesses that each have beautifully crafted items. We invite you to experience West Overton Village as we open our doors and celebrate our new location. Come visit us and celebrate this wonderful blessing as we welcome you into our shop.”

Find Rustic Nostalgia in West Overton Village on Frick Avenue. Their storefront, located in the historic “Worker House B,” will be open Thursday through Sunday from 12 to 5. Visit them online at facebook.com/rusticnostalgia.

Above: The Scottdale Historical Society hosted this

May Mart, an annual plant sale held in West Overton’s Overholt Room in the historic Distillery Museum.

eUp Next: 2017 Blind Pig Party

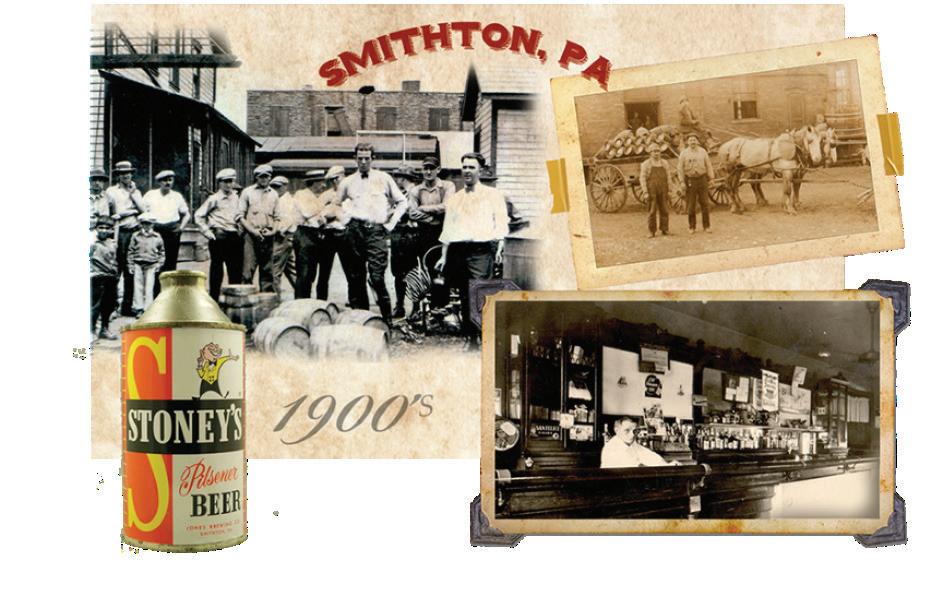

Our second Blind Pig Party is just around the corner! Last year’s event was a great success, and we want to celebrate again with you! This year, join us for drinks, food, and fun: beer from Penn Brewery and revived local favorite Stoney’s, a signature whiskey cocktail, and a full buffet dinner including roasted pig will be available. Local musician Mike Medved will be performing live, and fun games will be available for the evening.

The party will be held at our Big Barn on Thursday, July 20th from 7 to 9 p.m. There are a limited number of tickets available, so make sure you get yours soon. Admission includes four adult beverages and dinner, and you must be 21 or older to attend. Bring friends and family and enjoy a fun evening at West Overton! Tickets may be purchased at westovertonvillage.org/events/

Featured Cocktail: Old Overholt Sidecar

This year’s Blind Pig features the Old Overholt Sidecar, a variation of the Prohibition-era classic cocktail the Sidecar, a drink originally featuring a brandy base, is perfect to entertain large groups on a summer day. The drink, which can be mixed in advance and served shaken or over ice, is a refreshing combination of two parts Old Overholt rye whiskey, one part orange liqueur, one part fresh lemon juice, and one-half part simple syrup. See the instructions below to make a single serving.

Ingredients:

2 ounces rye whiskey

1 ounce orange liqueur

1 ounce lemon juice

½ ounce simple syrup

Directions:

Combine all ingredients in a cocktail shaker filled with ice. Shake for 20 seconds until evenly mixed and chilled. Strain the mixture into a cocktail glass. Garnish with a lemon or orange peel and enjoy.

2017 Blind Pig Features Historic Pennsylvania Breweries

After winning the deed in a 1907 poker game, William Benjamin “Stoney” Jones owned the Eureka Brewing Company of Smithton, Pennsylvania. After surviving Prohibition, surrounded by rumors of bootlegging, the brewery was renamed Jones Brewing Company. This rebrand also brought a name change to the beer. It was now officially named what people had been calling it for years: Stoney’s. 1936 brings the death of William “Stoney” Jones, and his son takes over the company. In 1988 Greg King, a fourth generation Jones, became the brewmaster after working for the company for 12 years. 1988 also brought new ownership by Gabby and Sandy Podlucky, who continued to run the brewery in the tradition of the Jones family. In 2017 the brewery brand found its way back into ownership of a Jones. Jon King, great grandson of “Stoney” Jones bought the brand in partnership with John LaCarte, and Greg King has returned as brewmaster. Stoney’s is more than a business, and will always be about family and tradition.

Image: stoneysbeer.com/wp/story

Penn Brewery tells the story of Pittsburgh’s European immigrants through its craft beer and homemade cuisine. Pittsburgh’s oldest and largest brewery, Penn is housed in the mid nineteenth-century landmark E&O Brewery building in the North Side’s Deutschtown neighborhood, which was settled by German immigrants. Penn Brewery began brewing craft beer in 1986, making them one of the earliest pioneers in the American craft movement. They started out brewing classic lagers and German beer styles, adhering to the strict quality standards of the 16th-century Bavarian Reinheitsgebot purity laws that limit ingredients to only water, barley, and hops. As they have expanded in recent years, Penn Brewery’s lineup now includes IPAs and other contemporary styles, like chocolate and pumpkin. They have stayed true to a promise of quality craftsmanship, brewing all of their beers by hand with toptier barley and hops.

For details about Stoney’s relaunch, see stoneysbeer.com/wp/

To see more about Penn Brewery, visit pennbrew.com

DIGITAL ARCHIVING

Preserving History For Future Generations

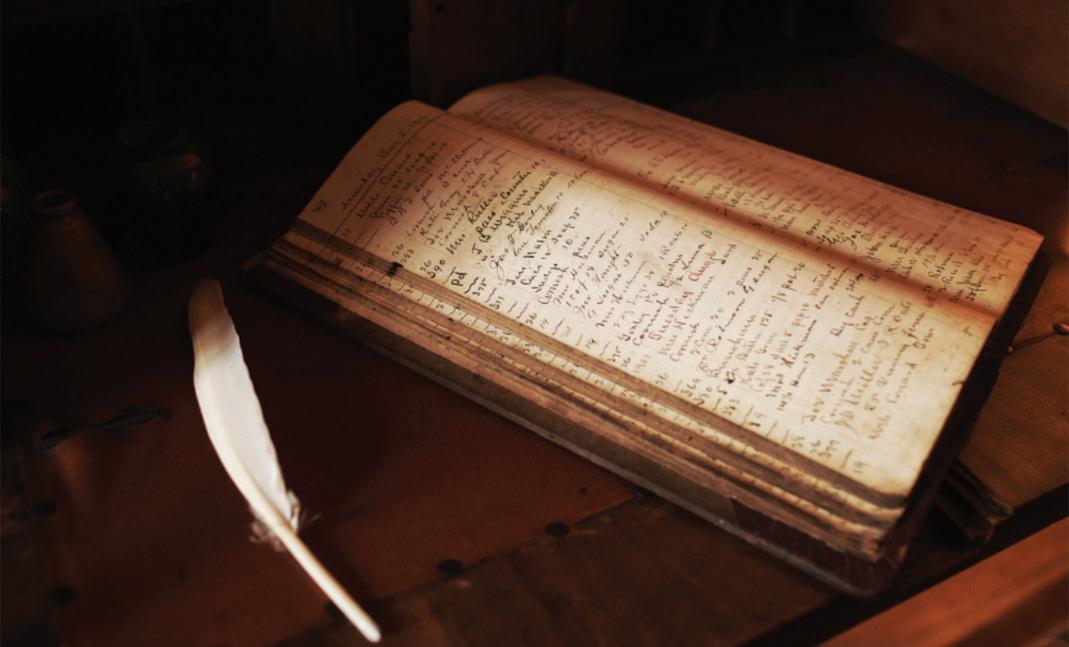

Since Helen Clay Frick founded the WestmorelandFayette Historical Society in 1928, we have been carefully conserving a collection of paper documents and artifacts for the use of future generations of researchers. In order to continue to be a resource for students, historians, and researchers, we have adapted to the methods by which researchers find and access documents and items for their works, and as curators of history, it is our responsibility to ensure that we remain a relevant resource for our community.

In this spirit, West Overton Village & Museums has begun the long process of digitizing our extensive collections to upload online for public access. The digitization effort is a joint endeavor between West Overton Village & Museums and the University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg’s History Department, Center for the Digital Text, and the Center for Applied Research (CFAR), including two Pitt-Greensburg history majors who are working as summer interns at West Overton to help digitize text and artifacts related to the museum’s Whiskey Collection. To set up the program we have hired as a seasonal consultant Rebecca Parker, a PittGreensburg graduate who has spent the last year as the Technical Assistant for the Center for the Digital Text and will be attending Loyola University of Chicago beginning in August 2017, where she will pursue a Master’s in Digital Humanities. Additionally, Dr. Pilar Herr, PhD, Assistant Professor of History at Pitt-Greensburg and Logan Holmes, Pitt-Greensburg graduate and current Museum Coordinator, are overseeing and coordinating the project.

The collection currently consists of WOV’s extensive whiskey-related texts and artifacts, including ledger books, receipts, labels, bottles, and other artifacts. This collection, known as the Whiskey Collection, will allow researchers to access materials related to the history of the whiskey industry that may otherwise have been inaccessible. After digitizing the Whiskey Collection and making it available online, West Overton plans to continue to digitize other collections within its archives. As our collections and archives cover countless items and topics in history, the process of digitization will be an ongoing effort. Over the next few years, we are excited to develop this opportunity to modernize our institution as well as become a resource for students to gain firsthand experience in one of the fastest growing fields for public historians.

As a small non-profit institution, we rely on the support of our friends and nearby resources to pursue projects that would otherwise not be achievable. In that spirit, Mount Pleasant Public Library collaborated with West Overton staff and interns to help bring the museum’s collections to the digital universe, now accessible by anyone with an internet connection.

The Westmoreland County Federated Library System (WCFLS) received a ScanPA grant to help digitize the state’s historical treasures and share them online at the PA Access website. Member libraries may use the equipment in their communities, and as a member library Mount Pleasant provided the ScanPA equipment on loan to West Overton staff and interns as a “trial run” to establish a precedent to extend the digitization process to Mount Pleasant Public Library in the fall. “This project will be a test run for the county’s ScanPA equipment, and we can learn from trial and error so the libraries can then hold community scanning events,” said Mary Kaufman, Mount Pleasant Library director.

By the end of 2017, we expect the Whiskey Collection to be available online for public use. As the project nears completion we will make this resource available through our website. Watch for details!

From Top:

West Overton Museum Guide Ashley Branthoover and University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg Intern Alex Fell.

Tinplate photographs show Elizabeth Overholt and John Wilson Frick, parents of Henry Clay Frick. West Overton Village & Museums Permanent Collection.

Fron Top:

Museum Coordinator Logan Holmes, Mt. Pleasant Public Library Director Mary Kaufman, and University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg Intern Serena Pape discuss West Overton’s cataloging system in artifacts storage.

Logan Holmes pulls documents from the archive room

Rebecca Parker, Serena Pape, Ashley Branthoover, and Alex Fell

Program Manager Rebecca Parker, left, and Serena Pape upload metadata to the Omeka server for researchers.

Images, unless otherwise noted, by Susan Isola, University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg Director of Media Relations.

THE “BIRD BOY OF SCOTTDALE”

Tom Zwierzelewski, Scottdale Historical Society

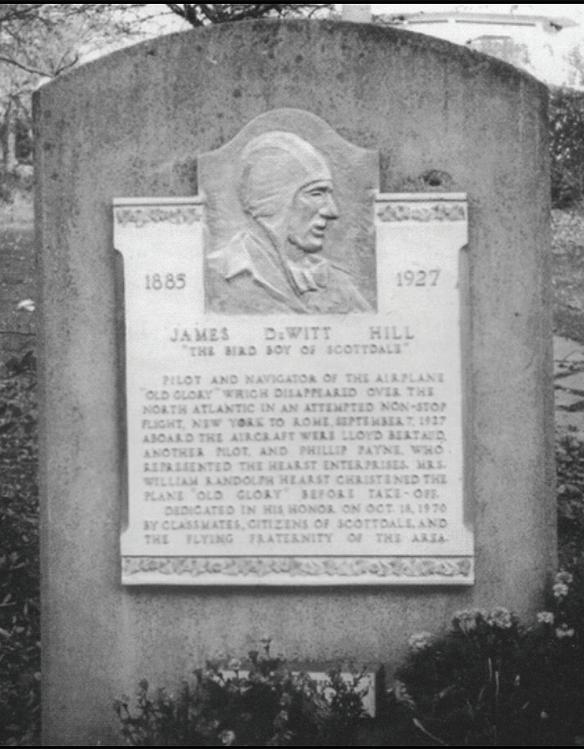

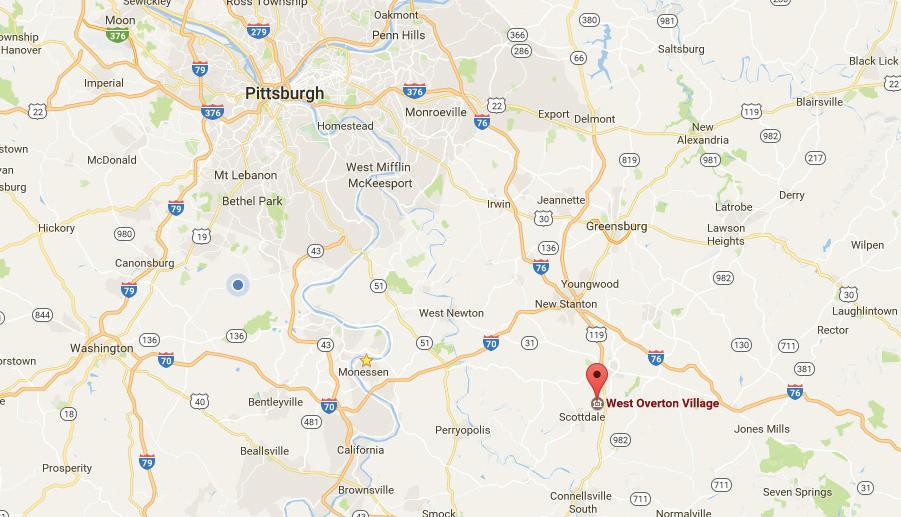

In Scottdale there is an unassuming monument dedicated to James Dewitt Hill “The Bird Boy of Scottdale”. It is located by the Gazebo near the corner of Pittsburgh and Spring Street. The Bird Boy of Scottdale is a story of aviation history.

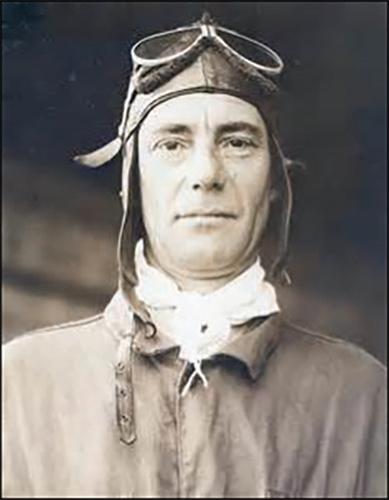

J. D. Hill was born March 2, 1882 in Scottdale. He was the fourth of five children to parents James Dewitt Hill Sr. and Mary Emma Long Hill. The young Hill was intrigued by the experiments of the Wright Brothers. Hill’s home was known as the Hill House and was located between Grove and Pearl St., where the Scottdale Manor is located today. At a young age, J.D. took his mother’s best tablecloth to parachute off the stable. When it failed, he convinced his younger brother Frank to try the stunt, ending with the same results. J.D. must have carried this failure with him, because he never parachuted again, no matter how damaged any plane was that he eventually flew. After high school , Hill went on to Lafayette College in Easton, Pa., studying mechanical engineering. His interest in airplanes and engineering continued, and he returned to Scottdale, working at the A. C. Overholt Garage for a short while. Hill designed a model plane that he suspended from the family clothesline. The concept was ahead of its time. Hill became more involved in flyin,g determined to learn it from the ground up. By 1915, Hill’s experience as a pilot and engineer landed him a job as an aviation instructor at the Thomas School in Ithaca, N.Y. In 1916 Hill was a civilian instructor for the Army until the end of World War I. In 1919 Hill was employed by Oregon-Washington-Idaho Airplane Co. where they demonstrated Curtiss aircraft with the goal to promote air travel, airports, and flying schools.

Forty-three-year-old J.D. Hill joined the Air Mail Service on July 1, 1924. He was first assigned to fly from Cleveland to Hazelhurst Field in New York and he was later assigned to Hadley Field, N.J.

On the New York to Cleveland run, pilots flew across the Allegheny Mountains, one of the most difficult flights, known as the Hell Stretch. The primitive planes and cockpit instrumentation offered little help in navigation. Hill was known for his cigar smoking to time his flight path. One day Hill took off from Cleveland to Hadley Field with a load of mail and a pocketful of cigars. Hill lit a cigar as he headed down the Cleveland runway, being told to expect clear weather ahead. That cigar lasted until Mercer, Pa. He then noticed his clock had stopped working. Hill said to himself, “Cleveland to Mercer, that’s 75 miles. I have 255 miles to go. Let’s see… 75 into 255 is 3 and 30 left over, so that’s 30/75s or two fifths. If I smoke three and two-fifths cigars I should be at Hadley Field.” As the plane soared above the clouds, Hill chain-smoked the four cigars he had taken out of his pocket. When two-fifths of the fourth cigar were gone, he descended from the clouds and there was a welcome sight: Hadley Field. J.D. was also the first pilot to complete a night flight for the Air Mail Service.

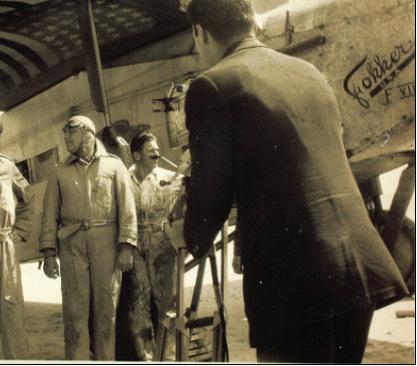

Charles Lindbergh, with the Spirit of St. Louis, completed the first trans-Atlantic flight from New York to Paris in May 1927. In the midst of this trans-Atlantic fever, a non-stop race to Rome

was sponsored by publisher William Randolph Hearst. J.D. Hill and Lloyd Bertaud contacted Giuseppe Bellanca to build a plane capable of making the flight. The timeline for the project was going to take more time than the team could allow. They made arrangements with Philip Payne of the Daily Mirror, a Hearst paper; in exchange for a plane, the Mirror could send Payne on the flight for publicity. Hearst offered Hill and Bertaud an F-VII-A Fokker monoplane. On July 30th the plane was christened “Old Glory,” but the weight of the plane delayed the flight. Old Glory was a colorful craft, with a gold cantilever wing and a steel silver fuselage. American flags were painted on the wings with the words “Old glory” beneath. But the plane was heavy, weighing 12,700 pounds fully fueled. The start of the flight was moved from Roosevelt field in New York to Old Orchard Beach, Maine, which offered a greater distance for takeoff.

On September 6, 1927, Old Glory made a successful takeoff; reports stated the plane was flying low as Hill piloted over Nova Scotia to Newfoundland. The last sighting came as the plane flew over the steamship California, 350 miles east of Cape Race, Newfoundland.

On Sept. 7th at 3:57am the plane radioed an SOS and six minutes later the steamship Transylvania received a second distress call. High seas, rain, and wind made the search next to impossible. Five days later the S.S. Kyle found the wreckage of Old Glory, but the bodies of J.D. Hill, Bertaud, and Payne were never recovered.

In October of 1927, A. G. Trimble, a childhood friend, suggested that a memorial be erected to honor James Dewitt Hill.

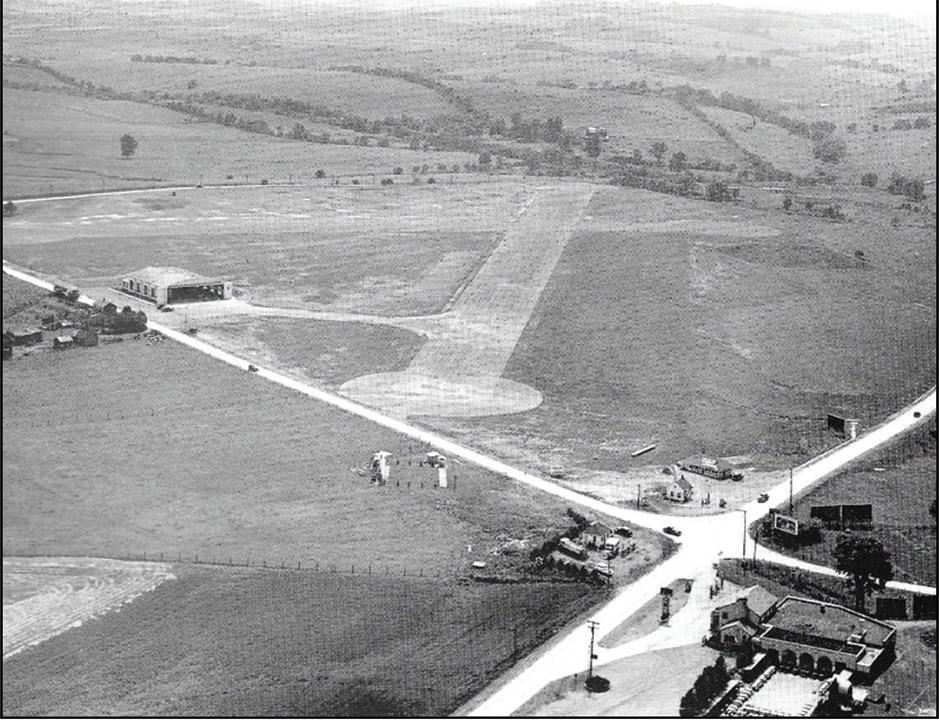

In 1928, another famous Scottdale pilot, Charlie Carroll, suggested that his Latrobe Longview airport be named for his mentor, J.D. Hill.

The J. D. Hill Airport was dedicated on June 2, 1928. The hangar (shown above) was built from repurposed materials from the Old

Meadow Mill south of Scottdale. The planes would taxi from the runway to the gas station shown on the corner of Lincoln Highway (U.S. Route 30). In time the airport was known as the Hill Airport, a name which most people believed it received because it was on top of a grade along the Lincoln Highway. After a decade the airport was known as the Latrobe Airport, and later the Arnold Palmer Airport. Forgotten are the names of the Old Glory crew as they slipped beneath the waters of the Atlantic into the pages of history.

On October 18, 1970 Hill’s childhood friend A.G. Trimble finally got his 43-year-old wish; a monument was placed along Pittsburgh Street honoring the Bird Boy of Scottdale. (image J. D. Hill dedication)

The memorial is more than a tribute to J. D. Hill. Buried in the base is a time capsule (image 1348) that included the dedication speech from his schoolboy friend A.G. Trimble, a flag that had flown over both the North and South Poles, and a list of the contributors for the memorial. Citizens, aviation representatives, old friends, and officials gathered by the gazebo in Scottdale to honor James Dewitt Hill the “Bird Boy of Scottdale.”

This story is reprinted with Permission from the Scottdale Historical Society. Find the Scottdale Historical Society and Loucks Homestead at scottdalehistoricalsociety.com or facebook.com/scottdalehs/

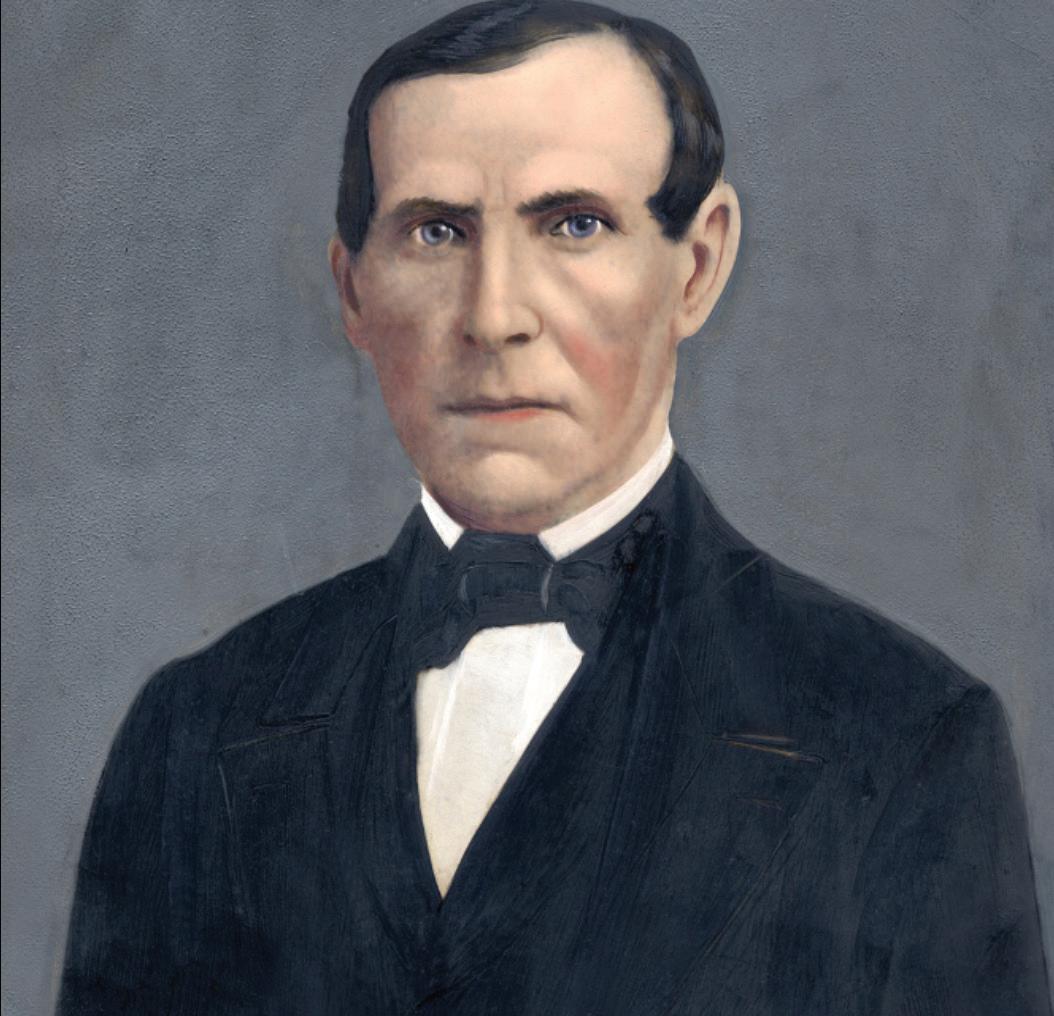

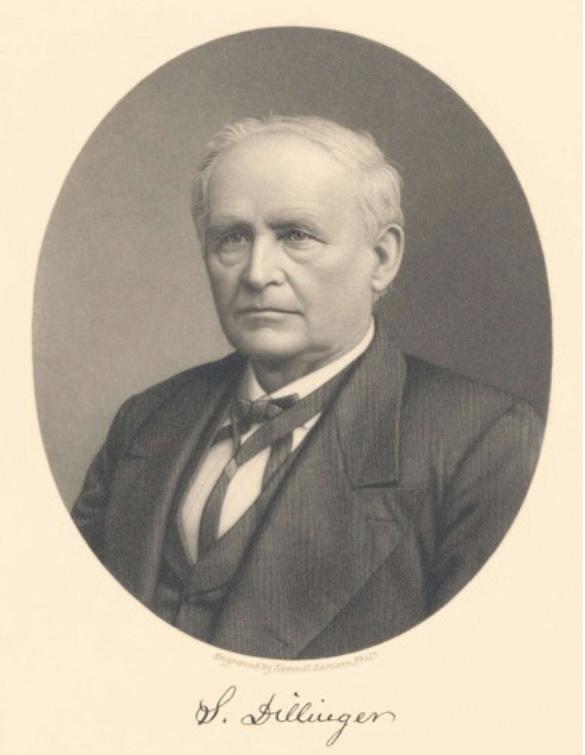

PROFILES IN WEST OVERTON HISTORY: HENRY O. OVERHOLT

Son of Martin Beidler Overholt and nephew to Abraham Beidler Overholt, the founder of the Overholt whiskey empire, Henry O. Overholt was born and raised on his father’s farm adjacent to West Overton.

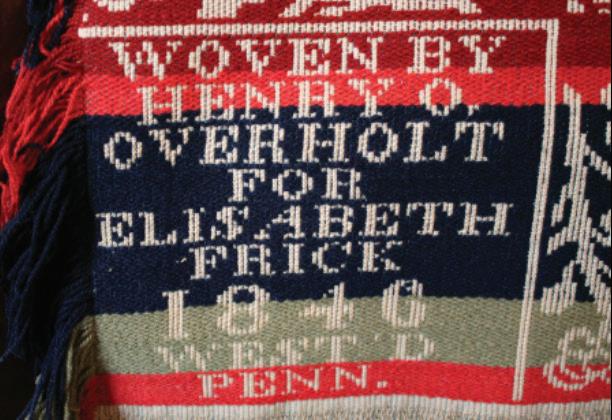

In the first half of the 18th century, many of the men of the Overholt family were engaged in the highly skilled craft of weaving to supplement their agricultural pursuits. While Abraham Overholt himself first toiled as a weaver in the village’s early years, in 1810, Abraham, now in his mid-twenties, had moved on to establish West Overton’s first distillery, which would eventually become a nationally recognized label. By the 1840s, Henry O. Overholt became the Master Weaver at West Overton Village. Henry’s use of the Jacquard Loom, a French invention by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1804, allowed the weaver to produce intricately patterned coverlets at a higher speed than was achievable in the village’s early history. Henry Overholt produced over 800 coverlets during his career, which by 1850 he sold for $3.00 to $4.50 each. Henry’s fine workmanship and bold patterns kept his coverlets in demand, and he wove his name and sometimes the name of the customer into many of the coverlets he made.

Henry married Elizabeth Bechtel (1819-1887) ca. 1839, and with her had eight children. His managerial involvement with the distilleries began to dominate his life between 1859 and 1868, and subsequently his weaving pursuits came to a halt. In 1868 Henry sold his interest in the Broad Ford distillery to his cousin, A.O. Tintsman, and relocated to Chairiton, Missouri, where he pursued farming until his death in 1880 at the age of 67.

To learn more: Anderson, Clarita A. American Coverlets and Their Weavers: Coverlets from the Collection of Foster and Muriel McCarl: Including a Dictionary of More Than 700 Coverlet Weavers. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2002.

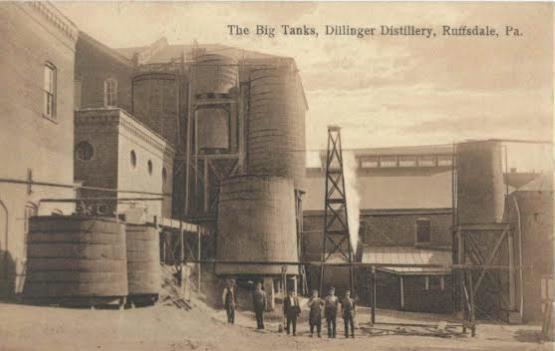

POST-PROHIBITION POT STILLS AT THE BIGGEST DISTILLERY YOU’VE NEVER HEARD OF

By Sam Komlenic

Tucked into a hollow in the Laurel Highlands of southwestern Pennsylvania stands a decaying distillery, closed decades ago, a late-day survivor of the hundreds that once dotted the landscape here in the cradle of American rye whiskey production.

Inside its cold brick walls, though, remain clues to spark the imagination of anyone interested in the history of American distilling. In fact, this remote enterprise has become a post-Prohibition distilling enigma.

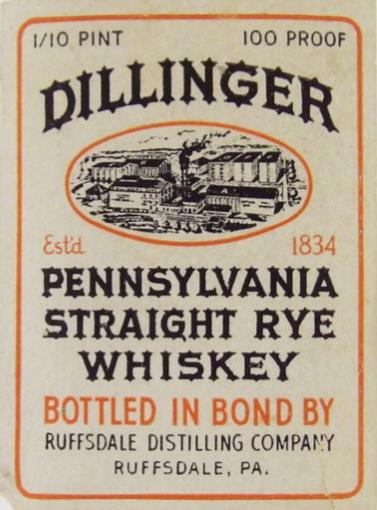

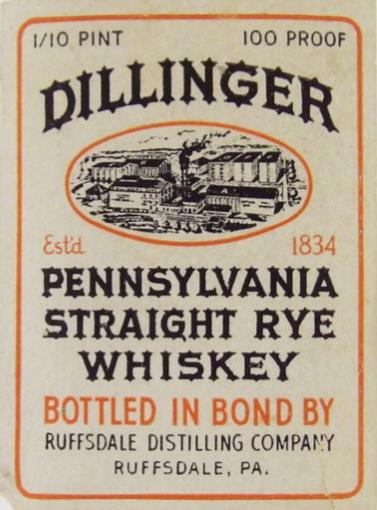

Pennsylvania was once home to some of the oldest and longest-lived names in the whiskey business— names like Overholt, Schenley, and Gibson, all known for their legendary Monongahela rye. Prior to the rise of Kentucky bourbon, rye whiskey from this winding river valley dominated the trade, gaining international notroriety. One name that rarely makes this list of notables despite its reputation, success, and longevity belonged to Samuel Dillinger, a backwoods farmer who transformed himself into a frontier industrialist.

Dillinger (pronounced with a hard “G”…Dilling-grr), a Mennonite of German descent, was born in Westmoreland County in 1810. He first honed his distilling skills as a young man at the stillhouse of Martin Stauffer on Jacob’s Creek, East Huntingdon Township, a tributary of the Youghiogeny River, and hence the Monongahela. Dillinger’s solo enterprise, started by 1834, began differently than most distilleries on the frontier.

In that era, the gristmill was usually constructed first, to serve the community’s needs; a distillery would have been built later to process excess grain. Dillinger started with a small still on his farm in 1834 and built a dedicated distillery building there, at nearby Bethany, in 1852. His gristmill wasn’t added until later, but in thus rolling terrain, the primary grain being grown, processed, and distilled throughout the region was rye.

Rye whiskey was big business west of the Allegheny Mountains, where it served not only as a social lubricant, but also as a high-demand export and the currency of choice on the frontier. “In many parts of the country [Western Pa.],” wrote one observer, “you could scarcely get out of sight of the smoke of a stillhouse.” Whiskey stills were of such value that entire farms were known to have been traded for substantial ones. The intense early demand for stills west of the Alleghenies has fueled speculation that their manufacture at the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers may have been the genesis of the metal trades in Pittsburgh, laying the foundation for its later dominance in iron and steel.

Dillinger’s West Bethany distillery was essentially a one-man operation, run entirely by hand, converting local grain into easily transported and more-marketable whiskey. As demand for his product increased, a new distillery and gristmill, a frame structure measuring 50 by 95 feet, replaced the first in 1856. It now employed 15 hands and produced 3,000 barrels of whiskey annually, valued at about $60 each.

The stills involved were “pot stills,” vessels that were filled with the liquid portion of a fermented grain mixture, tightly closed, and set to a slow simmer. The vapor produced eventually wound its way through a spiral copper tube immersed in cool water, a process that condensed the vapor into a refined, consumable liquid: rye-based ethanol. When the process was complete, the stills were opened, cleaned, and readied for the next batch. Early on, the whiskey was sold without aging, a clear distillate of rye grain. Later, as the advantages of barrel aging became known, distillers began to erect warehouses to store the whiskey until it attained some of the color and flavor of the charred oak barrel.

Boucher, John, History of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania (New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1906).

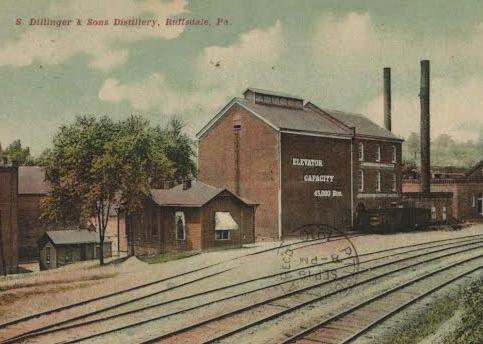

The West Bethany enterprise prospered for decades, so much so that when it was destroyed by fire in 1881, Dillinger had the resources to rebuild as a substantially larger operation. At the age of 72, he built his last distillery at Bethany Station (now Ruffs Dale), which provided the advantages of railroad access and was barely a mile from the original distillery site. A 3 ½-story brick building, equipped with a modern column still, was the backbone of a complex that included a 45,000-bushel grain elevator; boiler house; cooper (barrel-making) shops; and two connected brick warehouses on stone foundations, four stories tall with earthen floors and slate roofs, steam-heated in colder months to accelerate the aging process. Those warehouses still stand.

The column still utilized emerging technology that allowed whiskey to be distilled continuously through a multi-story copper cylinder without shutting down the still for cleaning or changing over to a new batch of mash. Fermented mash, including the grain solids, entered at the top and cascaded down across horizontal perforated plates; steam was forced in from the bottom, and the resulting vapor rose through the plates, freeing the alcohol from the mash, escaping at a point on the still that determined the strength of the spirit. This permitted substantially greater production of whiskey and streamlined the distilling process.

It was by this time that Dillinger brought his sons Samuel and Daniel into the trade, and the company became known as S. Dillinger & Sons. Dillinger rye whiskey became known throughout Pennsylvania, New York, Maryland, and well into the Midwest. The renown of the firm, however, rested not only on the quality of its product, but equally on the reputation of its founder.

Samuel Dillinger built his name as a wagoner on the National Highway, now U.S. Route 40, during the early years of the 19th century, transporting goods in a large covered wagon pulled by a team of six horses between Pittsburgh and Baltimore. Much of each load headed east to port was, quite possibly, Monongahela rye whiskey. This early form of freight transport proved financially rewarding and established a business-to-business network with merchants and tavern-keepers that would pay dividends later on. His savings were invested in property that later became known as the “home farm” at West Bethany, and Dillinger eventually engaged in the business of agriculture. It was during this time that he began to pursue the distilling trade, which added substantial value to his crops. He married Sarah Loucks, whose dedication, devotion, and work ethic have been noted as essential components of their success in life, and together they raised a family of nine children. Being a man of limited formal education, Dillinger worked tirelessly for a free school system.

Eventually, he owned over 600 acres underlain with bituminous coal, and became a pioneer of converting that coal into coke to fuel the iron furnaces at Pittsburgh and beyond. He also successfully invested in a short-line railroad, the South West Pennsylvania, to transport his coke to market. Yet, ever the farmer, in later years he continued to raise cattle at the distillery where they were fed on the spent mash.

A man of talent, vision, and determination, Sam Dillinger was held in high regard by his peers. Known as an employer who treated his workers and associates with fairness and compassion, he was wellrespected during an era when the business world was dominated by the “robber barons.”

When Dillinger died in 1889, his enterprise continued to be run by his heirs until the enactment of Prohibition. By 1906, the plant was capable of mashing 500 bushels of grain daily, producing 50 barrels of rye whiskey. Warehouse capacity increased to six buildings and more than 55,000 barrels, until S. Dillinger & Sons was second in production in the county only to the massive John Gibson’s Son & Co. at Gibsonton Mills, just up the Monongahela River from present-day Charleroi.

As with every manufacturer of alcohol (and Westmoreland County had plenty), Prohibition closed Dillinger’s doors in 1920, though the warehouses still held thousands of barrels of whiskey that could no longer be sold, except as “medicinal whiskey,” by prescription only.

By 1921 the company’s name had changed to the Ruffsdale (all one word by now) Distilling Company. It had been purchased by the Rosenbloom family, liquor dealers in Braddock, Pa. prior to Prohibition, and quite probably former customers of Dillinger. Like the Bronfmans and Rosenstiels of Seagram and Schenley fame, the Rosenblooms saw the potential of the repeal of Prohibition early on, investing in a distilling enterprise when few would have taken that risk. Under their hand, the distillery was outfitted to meet the demands of the 20th century, yet eventually would again pursue distilling in traditional pot stills.

Around the time of Repeal, during the early 1930s, a new building was erected to house a modern distillery behind the existing grain elevator. It stood four stories tall and contained a copper column

Atlas of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, 1867

still, plus a doubler and rectifying column (both intended to refine the base spirit), all fed by a new fermenting house. For whatever reason though, perhaps the feel for tradition they inherited from the Dillingers, the Rosenblooms were not satisfied with just this state-ofthe-art facility. Once this phase was complete, the most fascinating part of the ongoing expansion project began—the deliberate resumption of distilling in large-scale copper pot stills, the only know instance where a post-Prohibition distillery was specifically constructed for this purpose in the entire country.

Conventional wisdom says that Prohibition silenced America’s commercial pot stills forever. All whiskey after Repeal is thought to have been produced by the more efficient column stills that had overtaken the industry by the late 1800s. By 1919, few American distilleries had kept their old pot stills intact, and even fewer were still making whiskey in them. Prohibition was thought to have been the final nail in their collective coffin.

Not quite, it would seem.

In Ruffs Dale, directly behind the original Dillinger & Sons distillery and adjacent to the new building, rose a truly unique American distillery. This structure housed two huge copper pot stills. The primary still was used for the first distillation, using the wash (liquid) from the fermenting grain mash and had a capacity of 4,032 gallons, capable of four charges (fills) per day, while the secondary still (used to further refine and concentrate the spirit from the first still) held 3,784 gallons and could be charged twice per day. The fermented wash for the primary still came from a dedicated mash tun (a large wooden tank) that supplied a smaller fermenting house, totally separate from the main distillery. Both concave-bottomed stills stood about 18 feet high from the production floor. Their horizontal lyne (output) arms led to high-output “shell-and-tube” condensers.

Westmoreland History

Prepared by the Westmoreland County Historical Society

The Westmoreland County Historical Society is an educational organization dedicated to acquiring and managing resources related to the history of Westmoreland County and using these resources to encourage a diverse audience to make connections to the past, develop an understanding of the present, and provide direction for the future.

Visit Westmoreland County Historical Society: at westmorelandhistory.org or facebook.com/westmorelandhistory

Though interconnected to potentially increase their versatility, both the column and pot distilleries operated independently, and thus the company could produce nearly any style of whiskey or spirits desired. The fire brick-lined furnaces for those pot stills remain intact today, framed by tile walls and a bank of windows in that now-empty stillhouse.

Once this second phase was complete, the old distillery in front of it was demolished, replaced by a bank of four new grain silos. Finally, the old grain elevator was dismantled and an office annex took its place. The entire operation had been replaced and enlarged on the spot, with little or no interruption in production. Now there stood a completely new and quite different distillery than either of those that came before it.

Increased capacity for continuous distilling provided the potential to make large quantities of alcohol, allowing greater production of some products, including industrial alcohol to aid the allies’ efforts during World War II. Elsewhere in the plant, though, traditional craft distilling was taking place in coal-fired copper pot stills, but it remains unclear what their exact output might have been.

These were substantial stills, in a distillery whose primary product was rye, located in the heart of rye whiskey country; but some evidence indicates that the Rosenblooms saw potential in domestically distilled “Scotch whisky.” According to a 1948 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette detailing the sale of the facility, “It also has a complete unit for the manufacture of Scotch whisky, said to be the only one of its kind in the United States.”

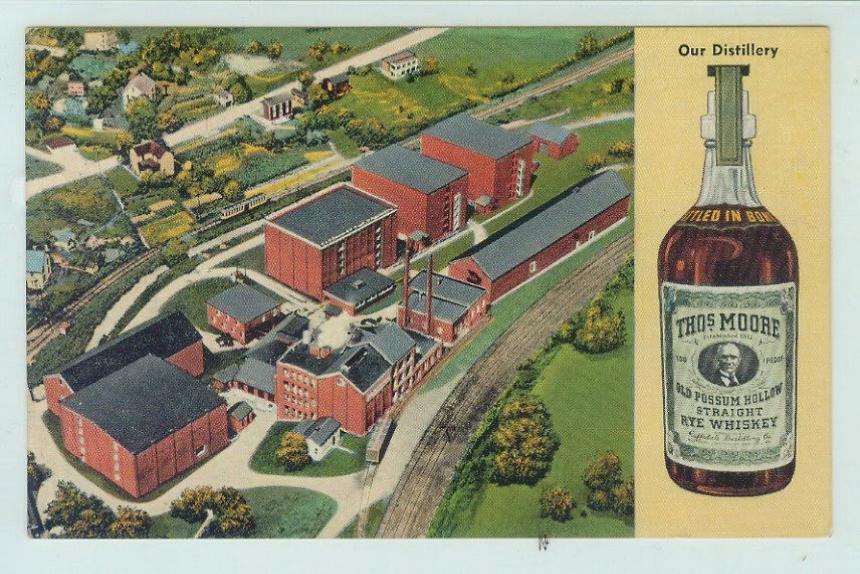

Could they also have been used for the production of traditional Pennsylvania rye whiskey? Well, maybe. One clue lies in a 1938 Pennsylvania State Liquor Store price list: Thos. Moore Old Possum Hollow Rye (a former McKeesport-distilled rye that became their flagship brand after Repeal) was by far the most expensive straight whiskey available, selling for 50 percent more than the average rye or bourbon on the list. The limitations of pot distilling could have demanded and justified that substantial premium.

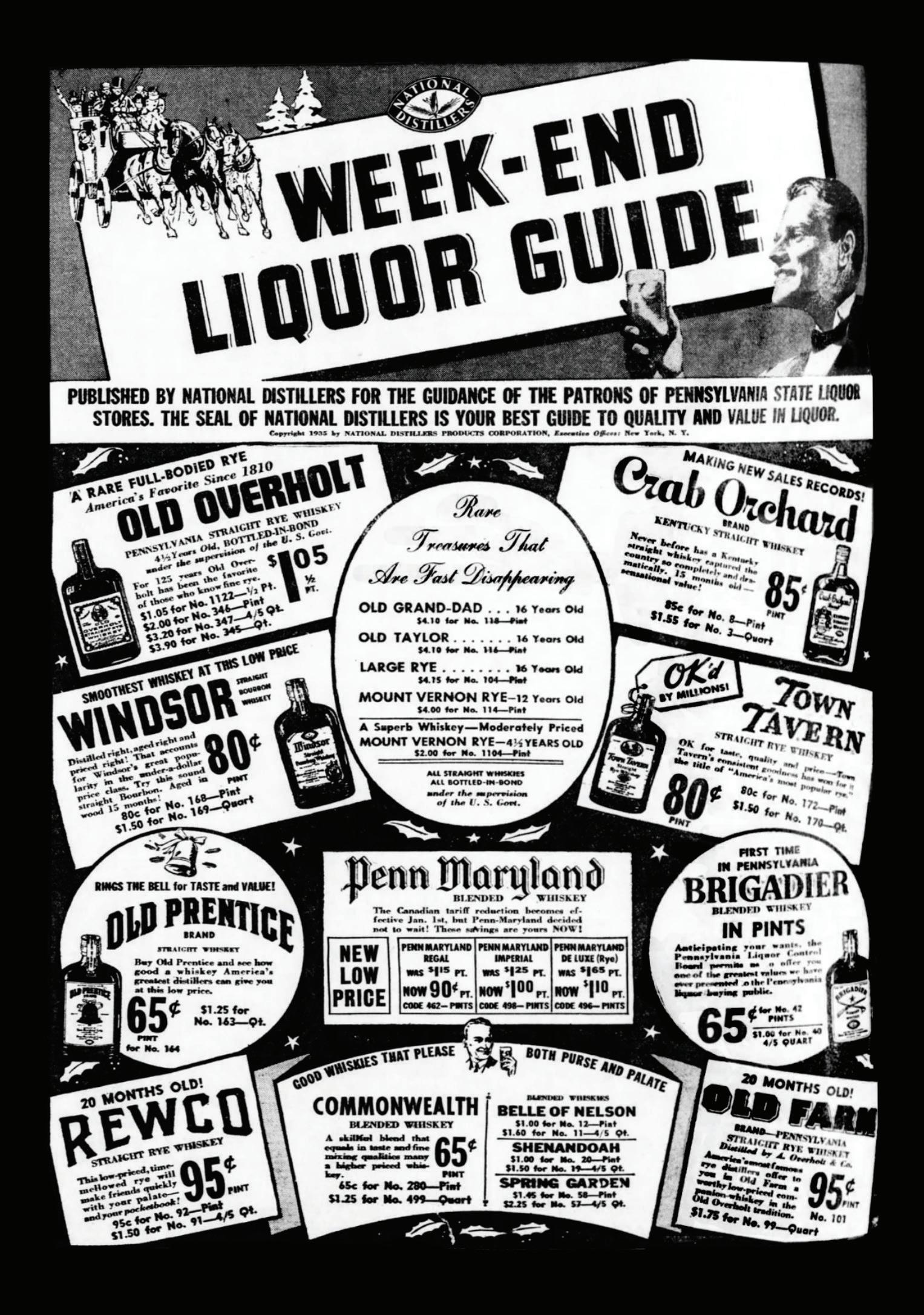

Pittsburgh Post Gazette, December 13, 1935. Digital Editing by Ashley Branthoover.

By the outbreak of the war, the company changed hands again, becoming Dillinger Distilleries, Inc. The pot stills, however, could have continued to operate until at least 1946, when the company’s Federal Registry of Stills lists both as being registered “for use,” with their purpose as “distilling whiskey or spirits.”

During this era the dynamics of the distilling business began to change, and Dillinger made a dizzying array of products in an effort to maintain market share—rye, bourbon, and corn whiskeys; blended whiskey; spirit whiskey; gin; and possibly whiskey liqueurs, while also contract-bottling private label whiskeys and imported rum. Though there are many artifacts (labels, bottles, ads, etc.) related to these various products, there are none known for any Ruffs Dale-distilled brands of faux-Scotch whisky.

By 1948, when the distillery was sold yet again, regular production had ceased at Ruffs Dale. In the 1950s, the property was acquired by the Seagram empire and renamed the Huntingdon Creek Corporation. Seagram used the Dillinger warehouses and those of the former Overholt distillery at nearby Broad Ford, Fayette County, to age whiskey from these and other area distilleries until the late ‘60s. In yet another strange twist, it was under their direction that the Dillinger stills would be restarted, one last time.

In December of 1956 or ‘57, workers were brought in from Kentucky and took nearly four months to prepare the maze of equipment for operation. Fortunately, the boilers were already in use to heat the whiskey-laden warehouses. Once started, the distillery was run for about two months, then went cold for good.

According to Art Smith, a warehouseman with Huntingdon Creek, the workers were told that it was done to retain the company’s distilling permits. The men, however, felt that Seagram was trying to replicate the Dillinger flavor profile, which by then had become part of some Seagram blends. Regardless, legal distilling had ceased forever, not only in Ruffs Dale, but in all of Westmoreland County. The copper equipment throughout, including those unique pot stills, was eventually cut apart and sold for scrap.

Little could Sam Dillinger have known how long his enterprise would endure, nor that its legacy would be as the last pioneer American distillery to run pot stills while the rest of the industry moved farther away from that long-established practice.

Samuel and Sarah Dillinger’s graves remain in the Alverton Mennonite Cemetery a few miles away. The Mennonites affix great significance to the obelisk, and this hillside holds many impressive examples, some as tall as 15 feet. The Dillinger plot is marked by a magnificent 30-foot granite obelisk on a base nine feet wide, which was reported to have required a team of 16 horses to haul up to the site. The obelisk is inscribed, “Erected to the memories of an honest man and constant friend; a devoted wife and loving mother.”

Now, in the 21st century, that monument represents not only the respect afforded the couple by their family and community, but also the tradition of the craft hewed to by Samuel Dillinger and his successors, long after every other American distiller had moved on.

A Note from the Author, 2017:

Modern-day craft distilling has seen the rebirth of pot distilling, though in the vast majority of instances these pots are a hybrid of both pot stills and column stills, keeping the post-Prohibition Dillinger pot stills the enigma I first found them to be.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Westmoreland County Historical Society.

References:

Beers, S.N. and D.G. Atlas of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, (Philadelphia: A. Pomeroy, 1867).

Boucher, John N. History of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, vol. 2 (New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1906).

Kyff, Robert S. “Whiskey Rebellion.” American History, 2, no. 3 (1994): 36.

Manufactories and Manufacturers of Pennsylvania of the Nineteenth Century (Philadelphia: Galaxy Publishing, 1875).

“Pittsburgh Buy Distillery,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 18, 1948.

Rust Engineering Co. et al. Original blueprints of the Dillinger Distilling Co. Pittsburgh, 1946-54 (Authors’ collection)

Sanborn’s Surveys of the Whiskey Warehouses of Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, New Jersey, and New York (New York: Sanborn-Perris Map Co, Limited, 1894).

alverton.info/id2.htm

HISTORIC COCKTAILS: THREE-MILE LIMIT

By Logan Holmes, Museum Coordinator

During Prohibition, the United States was legally all but a dry nation, and to adapt to the new restrictions on intoxicating beverages, a new global market emerged to ship spirits to the still-thirsty country. Buffalo and Detroit became the primary avenues for smuggling Canadian rye whisky to its dry neighbor to the south, shipping lines into Florida and the East Coast were centers for smuggling Cuban rum, while vermouth, champagne, brandy, and bitter liqueurs found their way to New York City to accommodate a taste for cocktails. While the U.S. Coast Guard maintained an active fleet for regulating rum-running, maritime law permitted governing bodies to operate only within three miles of the coast—a line extended to twelve miles by an act of Congress in 1924. Along this line, small ships evading the Coast Guard lined up to transfer illicit alcohol to smugglers; ships often hosted extravagant drinking parties and were known to support gambling, prostitution, and other illegal activities.

Much like the Scofflaw cocktail, featured in the Fall/ Winter 2016 issue of The Village Progress, the Three-Mile Limit cocktail appeared in bars as a means for bartenders

Historic Cocktail: Three-Mile Limit

Ingredients:

1 ounce white rum

½ ounce brandy

½ ounce rye whiskey

½ ounce grenadine

½ ounce freshly squeezed lemon juice

Directions:

Combine all ingredients in a cocktail shaker filled with ice. Shake for 20 seconds until evenly mixed and chilled. Strain the mixture into a cocktail glass. Garnish with a lemon twist and enjoy.

to openly mock Prohibition. The cocktail honors many of the liquors often associated with bootlegging during Prohibition: rye whisky, which made its way to American markets from Canada; rum, through Florida ports from Cuba; and French brandy. This cocktail is a fairly strong drink, and is best enjoyed sipped slowly. The rum and fruity notes from the grenadine and lemon juice make this drink well-suited for a hot day, and are accented very well with a pre-chilled cocktail glass.

To Learn More...

Ted Haigh, Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails: From the Alamagoozlum to the Zombie 100 Rediscovered Recipes and the Stories Behind Them. London: Quarry Books, 2009.

Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2011.

Timothy Olewniczak, “Giggle Water on the Mighty Niagara: Rum-Runners, Homebrewers, and the Changing Social Fabric of Drinking Culture During Alcohol Prohibition in Buffalo, N.Y., 1920-1933.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of MidAtlantic Studies, 78, no. 1 (2011).

MEMBER RECOGNITION

Special Thanks To Our 2017 Top-Level Members

Special thanks to all of our members who joined or renewed at the top membership levels as Village, Distillery, and Homestead members.

VILLAGE MEMBERS ($300)

Jack Davis; Duraloy Technologies, Inc.; Robert Ferguson, Jr.; Jay, Ann, and Maggie Frick; Mary Beth & Bob Klein; Tim & Linda Lewandowski; Steve Mascioli; Penn Line; Paul Stevens; Robert Tallerico; Christine Williams

DISTILLERY MEMBERS ($150)

Maynard and Jan Brubacher; Tim Carson; Diane Figg, Donald & Paula Johnson; Rick Rega; Gretchen Robinson; Marty Savanick; Vincent Schiavoni; Uber Co.

HOMESTEAD MEMBERS ($75)

Arnold and Shirley Babura; Childs Frick Burden; I. Townsend Burden III; Robert & Sara Ann Burton; Susan Endersbe; Elizabeth Fausold; Howard E. and Roxanne Markle; Levi & Gloria Miller; Jill Mott; Philip N. Overholt; Kurtiss & Bonnie Raygor; Kelly Skovira; George Smouse; Nancy Stoner; Carol & David Tullio; Dale & Paula Walker; George Woods; Frank A. Zabrosky

Old Farm Pennsylvania Straight Rye Ad, Pittsburgh Press, September 15, 1838

WEST OVERTON VILLAGE & MUSEUMS

WEST OVERTON STAFF

Jessica Kadie-Barclay: Chief Executive Officer

Friday & Saturday

10 a.m. to 3 p.m. June—September Thursday—Monday 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Group tours available by appointment year-round.

Admission to West Overton Village includes a docent-guided tour of the Distillery Museum located on the first floor of our 1858 historic distillery building, the main level of the 1838 Overholt Homestead, the Summer Kitchen, and the circa 1803 Springhouse, the birthplace of industrialist Henry Clay Frick.

Aleasha Monroe: Office Coordinator

Victoria Copenheaver: Development Coordinator

Logan Holmes: Museum Coordinator

Bill Stone: Building/Grounds

Devin Cole: Museum Liaison

Ashley Branthoover, Alex Fell, Gracen Kenney, Serena Pape: Museum Guide

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Richard Rega: Chair

Vincent Macsia: Vice Chair

Barry Whoric: Treasurer

Dr. Pilar Herr: Secretary

Patrick Bochy

John Faith

Lynn Kendrish

Sam Komlenic

Mary Jane McFadden

Margaret A. Pederson

Marty Savanick

Society

On behalf of the board, staff, wedding guests, and museum visitors, we thank our Garden Society volunteers for working diligently to make our grounds forever beautiful.

Jan Brubacher

Kristan DiBiase

John Faith

Mary Kaufman