WEEK EIGHT, SEMESTER TWO, 2023

But What Have You Done for Us Lately?

Misogyny in Young Politics

FIRST PRINTED

Sydney

Anonymous Page 10 Iggy Boyd Page 12 Katarina Butler Page 14

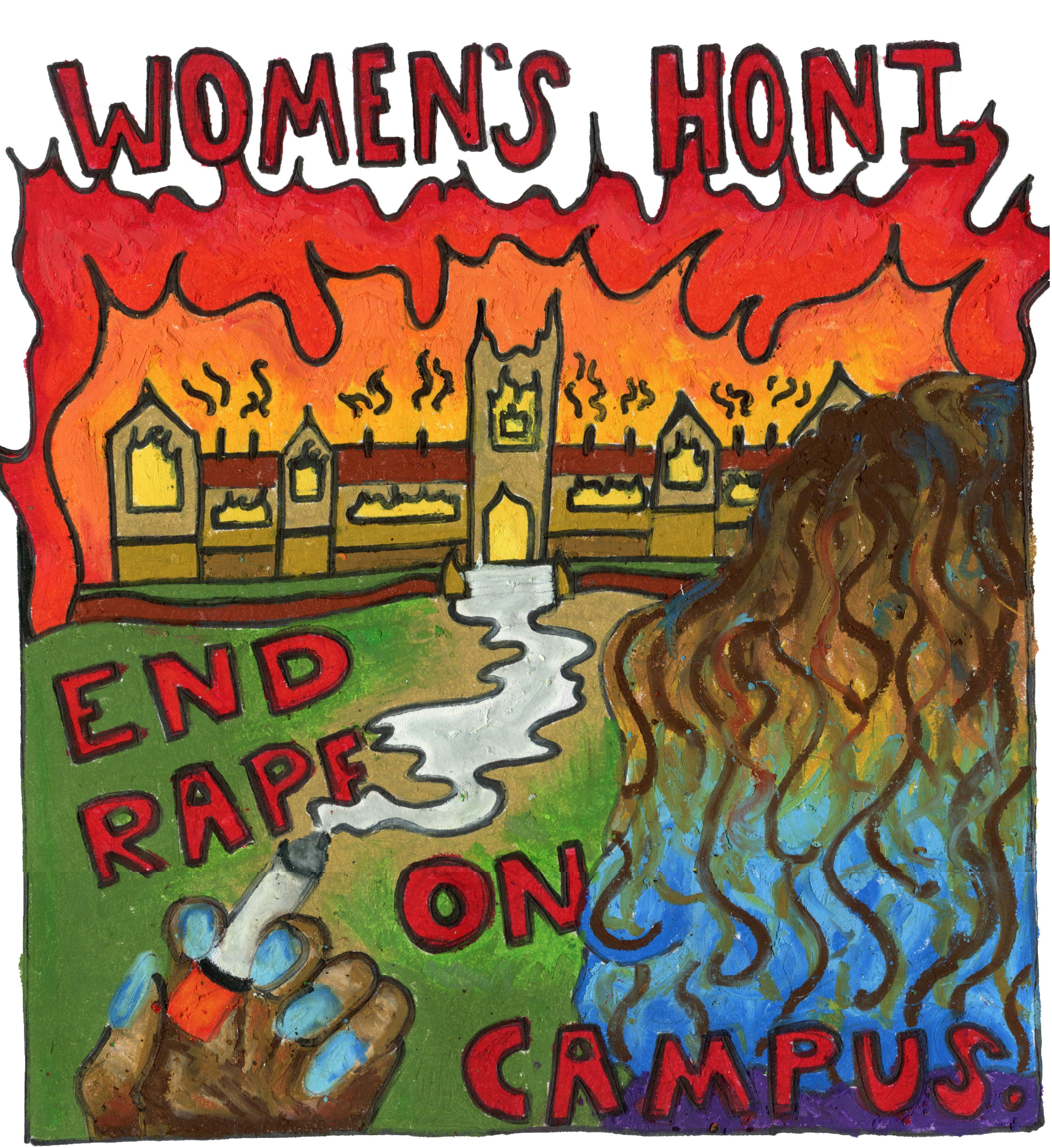

Sexual Violence at the University of

1929

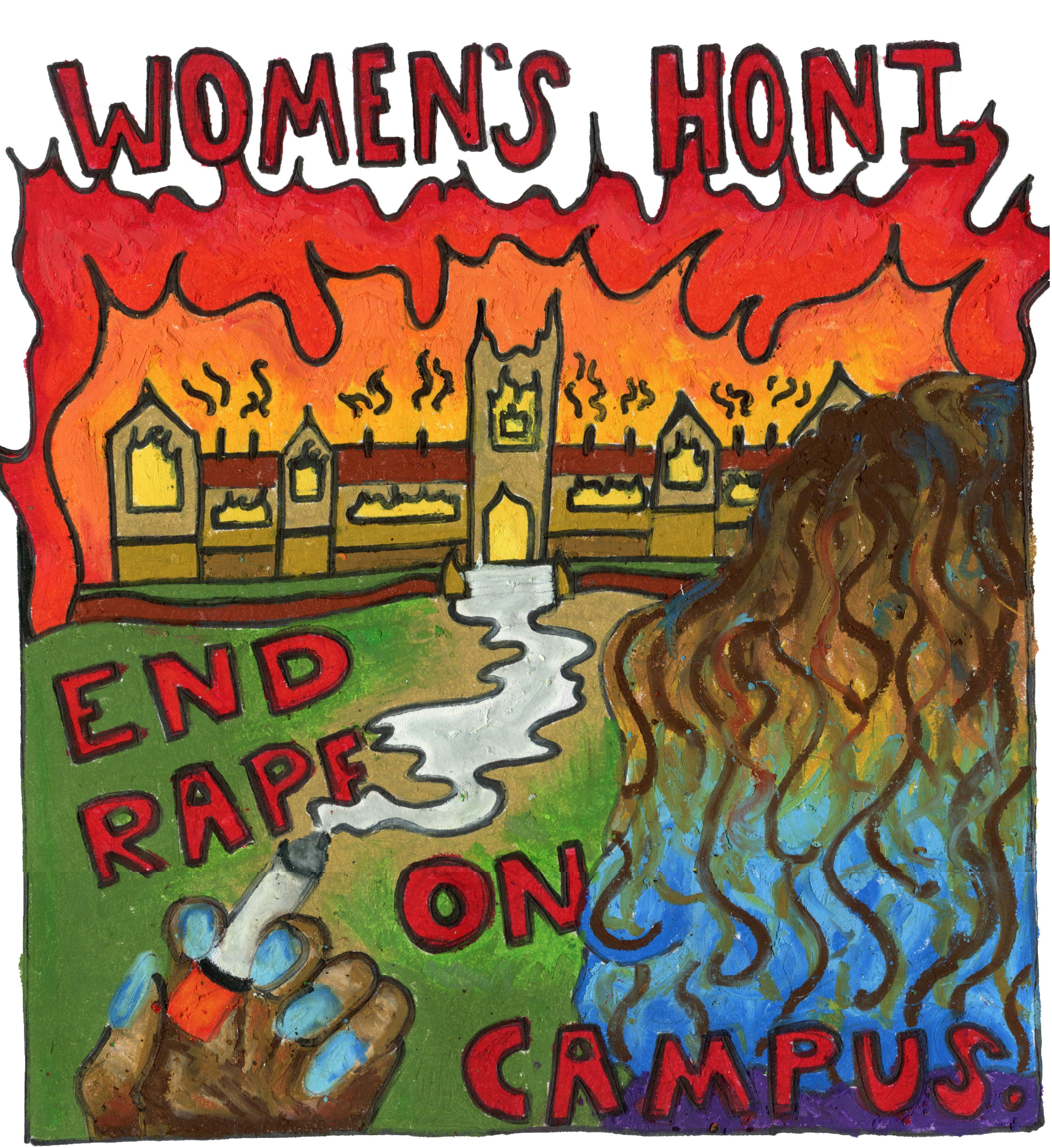

The University of Sydney Women’s Collective presents...

Women’s Honi was written, edited and published on the unceded land of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. Sovereignty was never ceded and the violent and genocidal process

of colonisation is an ongoing one. Black deaths in custody continue and the rate of Indigenous child removals has only risen since Kevin Rudd’s ‘apology’. The University of Sydney is a colonial institution; Management’s decisions to purchase even more land in Redfern and reject the NTEU’s call for First Nations hiring quotas over the last year demonstrate this very clearly.

It must be kept in the forefront of our minds that the Colonial project is one which is ongoing in

Editor-in-Chief

Iggy Boyd

Editors

Alev Saracoglu, Annabel Li, Bipasha Chakrobaty, Caitlin O’Keeffe-White, Eloise Aiken, Eloise Park, Esther Whitehead, Grace Porter, Grace Street, Jo Staas, Katarina Butler, Mariika Mehigan, Mehnaaz Hossain, Misbah Ansari, Simone Maddison, Veronica Lenard, Victoria Bitter, Zeina Khochaiche

Contributors

Annabel Li, Ellie Robertson, Eloise Aiken, Gracie Mitchell, Grace Street, Iggy Boyd, Jessica Sant, Juneau Choo, Katarina Butler, Mariika Mehigan, Simone Maddison, Victoria Bitter

this country and that by extension non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women still operate in socalled “Australia”. The horrors of the Colonial regime in this country affect Black and Indigenous Women of Colour in a manner far beyond that of non-Indigenous and nonBlack women. We pay our respects to elders past, present and emerging and extend our respects to all Aboriginal staff and students at the University.

Feminist justice requires that we

Acknowledgement of Country In this edition

hold Indigenous justice to be an imperative, to be non-negotiable and non-compromising. We must continue to fight for decolonisation. Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land.

Editorial

Hello, and thank you for taking the time to pick up this year’s copy of Women’s Honi. It has been the result of a painstaking effort on the behalf of the editorial team, whose names can be found on the left. I would like to say a huge thank you to all who contributed, made art and edited, your work and contributions make up the heart of this publication. This publication is the result of a collective effort in every way.

In making this publication, I hope we are able to maintain and advance discussions of feminism, anti-colonialism and anti-capitalism on campus and continue the proud history of the Women’s Collective into the future. From discussions of how women are treated in hospitality jobs, to misogyny within religious denominations, to the Matildas and the Labor Government on Women, we hope to provide a snapshot of current feminist discourse, and ideas within our Collective and the feminist movement writ large.

We have a feature on the Colleges, which also covers the recent history of national surveys and the need for more, and more oversight of sexual violence on University campuses. End Rape on Campus (EROC) and Fair Agenda have been laying the groundwork for years, and have run an excellent campaign

Where to Receive Support for & Report Sexual Violence

National Sexual Assault Counselling Service

1800 RESPECT Redfern Legal Centre

02 9698 7277 rlc.org.au/contact

Women’s Legal Service NSW

1800 801 501 Wisnsw.org.au

Inner City Legal Centre LGBTIQ+ specialist service

1800 244 481

Iclc.org.au

Australian Human Rights Commission

1300 656 419

Anti-Discrimination NSW

1800 670 812

Access the online form to submit disclosures and complaints of sexual violence on campus to the University with the following link, or with the QR code on the right: sydney.edu.au/about-us/vision-andvalues/making-a-safer-community-forall/report-sexual-misconduct/form. html

If you need an interpreter, call the free Translating and Interpreting

that they are not to be regarded as the opinions of the SRC unless specifically stated. The Council accepts

this newspaper, nor does it endorse any of the advertisements and insertions. Please

this year to demand an Independent Taskforce to hold universities to account for sexual violence. The fact that they have managed to push so hard and so effectively for this during such a frigid and opaque process as this year’s Higher Education Accord speaks for itself.

We believe these are important ideas to share, particularly as the campaign against misogyny and sexual violence so often falls to the wayside in activist movements, on and off campus. We have come together to create this publication as a Collective year after year because what women and nonbinary people write and believe about their rights and their history shouldn’t be ignored. It should be celebrated, studied, critiqued and developed upon for the good of our shared movement.

We hope that no matter where you are, whether on stolen Indigenous land in this country or abroad, you can find something within these pages that will inspire you, teach you something new and perhaps even inspire critique in this time of deep and intense change, when the world we live in nonetheless seems to remain still.

In love and solidarity,

Iggy Boyd

2023 Women’s Officer

Service (TIS) at 131 450 and they can contact these support services for you. Being a victim does not affect your visa status and should not affect your employment status.

Editorial 2

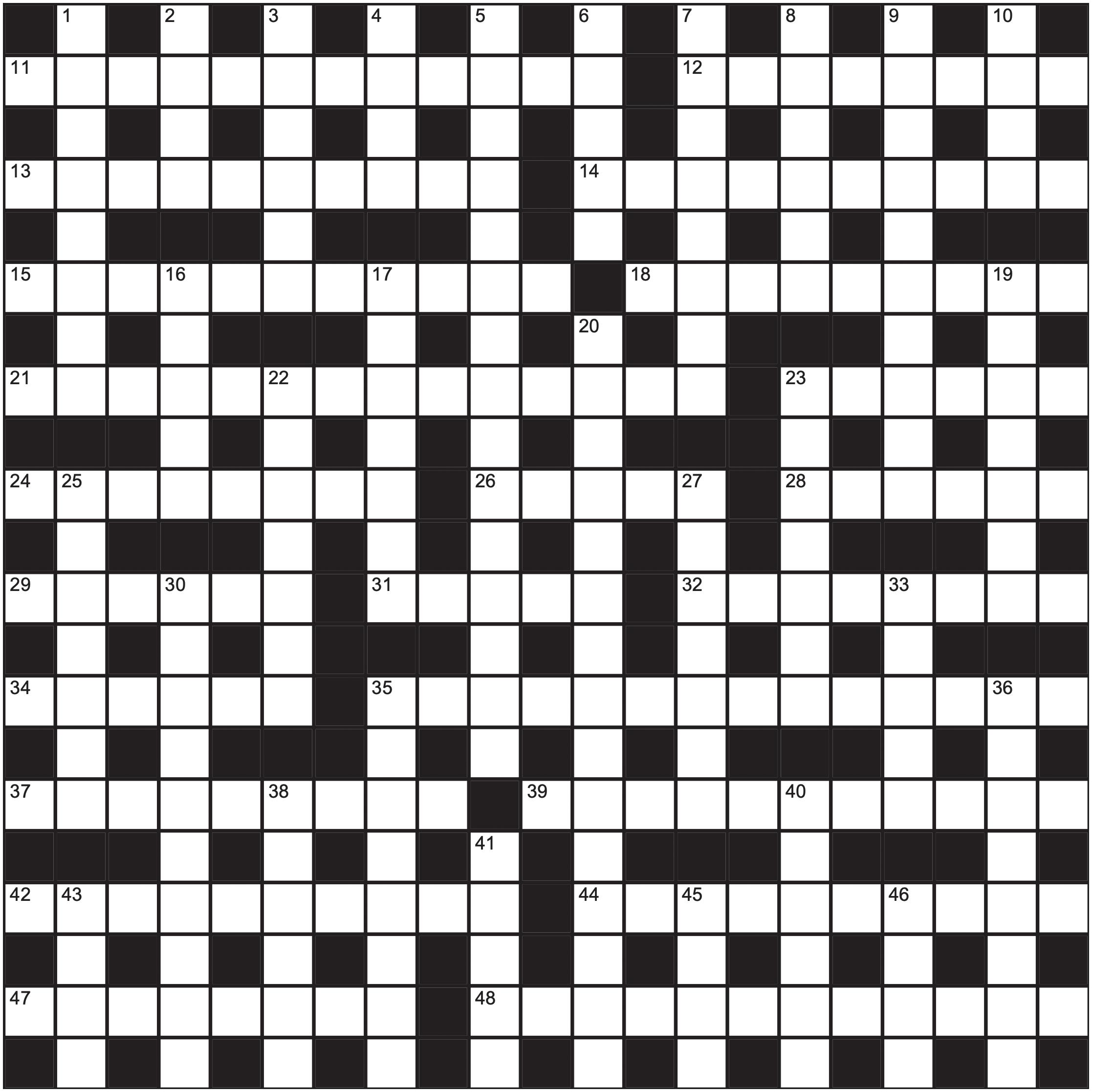

Artists Annabel Li, Emma Qi, Liset Campos Manrique, Margot Roberts, Tin Jen Kuo 4 6 8 10 12 16 19 20 21 22 23 Rural Lesbians Women in Bars Anglican Misogyny Misogyny in Young Politics Labor on Women The Colleges The Matildas SRC Reports Caseworkers Puzzles Comedy Jo Staas Front Cover ISSN: 2207-5593. This edition was published on Tuesday 19 September 2023. Disclaimer: Honi Soit is published by the Students’ Representative Council, University of Sydney, Level 1 Wentworth Building, City Road, University of Sydney NSW 2006. The SRC’s operation costs, space and administrative support are financed by the University of Sydney. Honi Soit is printed under the auspices of the SRC’s

(DSP): Gerard Buttigieg, Grace Porter, Jasper Arthur, Simone Maddison, Victor Zhang, Xueying Deng. All expressions are published on the basis

no responsibility for the accuracy of any of the opinions or information contained within

direct all advertising inquiries to publications.manager@src.usyd.edu.au.

Directors of Student Publications

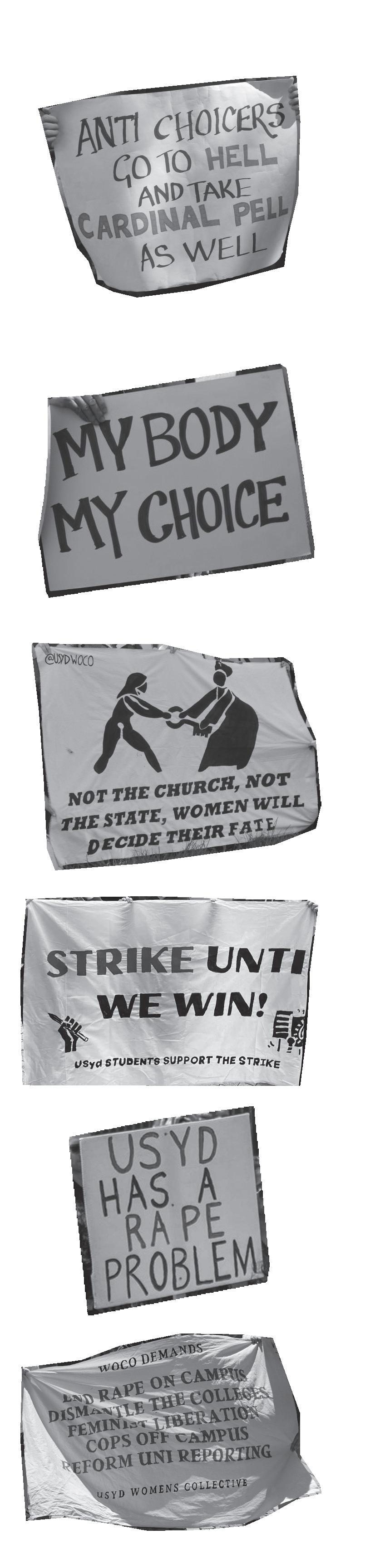

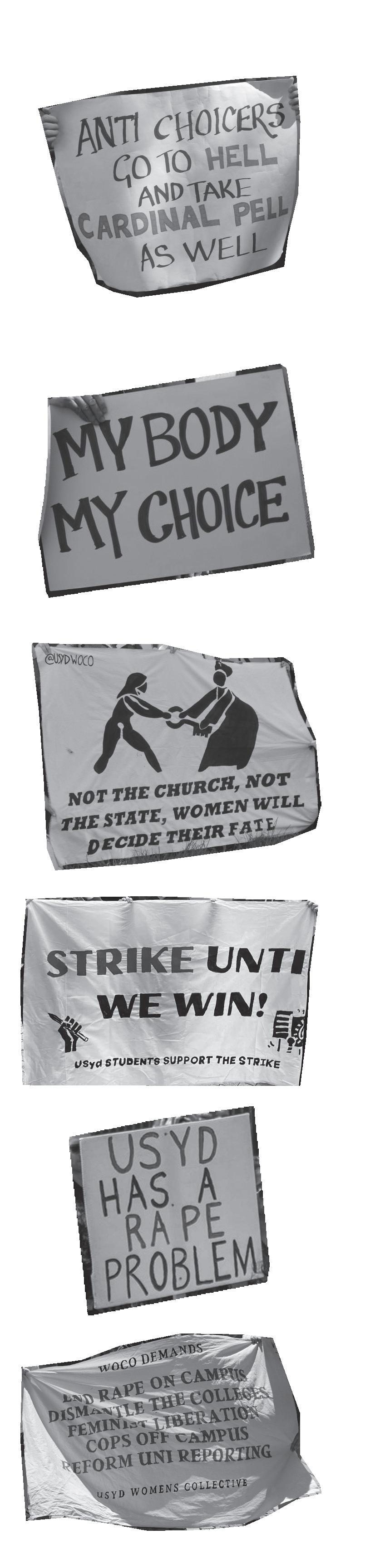

What is the Women’s Collective?

The University of Sydney Women’s Collective (WoCo) is an intersectional, feminist and activist organising group. We are active around issues of sexual violence on campus and abortion rights, particularly with regards to fighting misogyny and other bigotries on campus. We have existed for over 50 years and are continually fighting to improve the lives of students who are women and non-binary. We recognise the interconnected nature of all oppression in capitalist society and we strive to work with, and uplift the voices of, all persecuted identities, illustrating our shared struggles and our shared path to liberation. We are an inclusive and welcome space and we encourage all feminist students to get involved with our Collective.

WoCo meets and organises on the stolen land of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. We live in a settler-colonial state which perpetuates racial violence against the Indigenous people of this country. As such, we recognise we must centre Indigenous justice in our fight for feminist justice. As a Collective, we are deeply aligned with the First Nations struggle to decolonise the illegitimate settler-state of so-called ‘Australia.’

We fight to end rape on campus, for abolitionist feminism, for Indigenous sovereignty, for reproductive rights and abortion access, for safe housing and for an end to the Colleges. We are explicitly anti-capitalist, we understand the injustices central to the capitalist project and the individual capitalist “dream”, and we equally understand the interrelation between capitalism and patriarchy and of all those chains that bind oppressed people contained therein. Thus we wish for, and act in pursuit of, a world free of colonialism, of capitalism, of patriarchy, and of the overthrow of all oppressions that bear upon the women of the world.

We meet weekly to discuss activism, current events, feminist theory and other related topics. We also organise protests, forums on feminist politics, reading groups, social events, film screenings and more. To get involved, visit our Facebook, Instagram or Twitter, or send us an email!

Facebook: University of Sydney Women’s Collective

Twitter: @usydwoco

Instagram: @usydwoco

SRC Email: womens.officers@usyd.src.edu.au

Other Email: usydwomenscollective@gmail.com

The Coquette-to-Tradwife Pipeline

Trigger Warning: this article discusses topics including sexual violence, racialised violence, paedophilia and eating disorders.

She has liked to wear bows in her hair ever since she was a little girl. She liked pink, and then blue, but when she started listening to Lana Del Rey she realised she prefers purple. She wears her ballet flats, white and silky, to reflect the glow of the Vivienne Westwood pearls hanging around her neck. She lights iridescent candles to fall asleep, awoken only by a true love’s kiss on her glossy lips and the smell of burning lace. And so she is suspended on my screen, dripping with Chloe and alone in a sea of fresh flower petals.

class hyperfemininity.

When novelist Hannah Webster Foster labelled her semi-fictional protagonist Elizabeth Wharton as The Coquette in 1797, she associated this term with flirtation and the temptation of sexual fate. As a young woman, Wharton enjoyed “seducing” two potential suitors but would not commit to marrying either of them. Her death by the age of thirty-seven, in a roadside tavern after giving birth to a stillborn baby, was intended to provide a moral lesson for young women engaging in “sexually provocative” behaviours: that bad things will befall “fallen women.”

paedophilic connotations, the coquette aesthetic idolises pro-eating disorder content; ten years after Tumblr’s ban on pro-self-harm blogs, they remain inextricably connected and visible.

It is unsurprising then, that the coquette aesthetic is continuously linked to the recent phenomenon of “trad wives.”

When this vision of a young woman appeared on my TikTok feed earlier in the year, I was instantly struck by her composed and curated commitment to a new online trend. Cited by major fashion magazines like Vogue and Nylon as a “return” to more romantic and playful styles, this “coquette aesthetic” has overseen the rising popularity of heart-shaped necklaces, chiffon headbands and Brandy Melville. But these symbols are neither new nor benign fashion choices. The words in the title of this article are the exact search terms I found attached to “coquettecore” on Twitter, highlighting its racist, sexualised and misogynistic connotations. In its nostalgia for the styles of Victorianera dress and vintage Americana, this movement expresses a far more sinister resurgence of white, middle-

“Of course, the stigma and shame embedded in Wharton’s “coquette” has prompted many twenty-first century social media influencers to profess they have reclaimed this term as an emblem of femininity, sexuality and agency.”

For Kellen Beckett, it is a challenge to mainstream society’s association of “pretty things” with “being uncool”; for Duckie, this style “helps me connect to my inner child.” But coquettecore will never be truly emancipatory as long as it is founded upon structures designed to oppress and objectify women.

This brand of “girlish promiscuity” has become almost synonymous with a Lolita aesthetic. Recognisable through its use of childhood symbols like ruffles, frills and ribbons, the coquette aesthetic sexualises the innocence of young women. Beyond these obviously

Advocating for women to return to the home and “find fulfilment” in caring for their breadwinner husbands, the trad-wife movement capitalises off the same conservative values of “ideal femininity” as that of the coquette: docility, infantilization, a rejection of feminism and an adherence to heteronormative binaries. To be sure, the coquette’s sexualisation appears antithetical to the conservative family values enshrined in the tradwife. But upon closer inspection, both movements are guided by their purpose to degrade women. These two aesthetics therefore remain dependent on the rhetoric of what scholar Brenda R. Weber calls “toxic femininity”, restricting women’s behaviour to please the male gaze.

But coquettecore will never be truly emancipatory as long as it is founded upon structures designed to oppress and objectify women.

The coquette-to-tradwife pipeline is perhaps best articulated in the movements’ racialized and racist elements. Although researchers like

Eviane Leidig might argue that the proliferation of the #coquette and #tradwife hashtags on social media might pluralise the cultural diversity of content creators, both movements originate in and reproduce Whiteness. Coquettecore not only idealises white bodies and European brands contemporarily, but also trivialises physical symbols of colonial power like corsets as “fashion.” Furthermore, the trad-wife identity is often a dog-whistle to nationalist and white supremacist rhetoric; its purpose can be traced neatly as an answer to “The Woman Question” articulated by alt-right groups. Given these overlaps between race and gender, both movements’ iterations in the past and present must be articulated as intersectional issues committed to dismantling these power hierarchies in fashion and beyond.

It is only by removing our heartshaped sunglasses that we, as feminists, can begin to take the rise of such hyperfeminine and racialised popular movements seriously. Indicative of a burgeoning postfeminist culture that prioritises personal choice over radical reforms to structural inequality, coquettes and tradwives are neither novel nor ahistoric. This young woman, although immortalised in the TikTok algorithm, may still break free of this pipeline.

Art by Ting-Jen Kuo

The Myth of Marytyrdom: Women’s Involvement in the Jacobite Movement

A key challenge for feminist historians has been inserting women into histories which have excluded us. History has largely utilised sources produced in the public sphere: legal documents, public records, speeches, letters and correspondence. So how do we include women when they were largely unable to participate in this activity for much of human history? These challenges become increasingly evident as we venture further into the past, away from the identifiable ‘waves’ of feminism, and into a time when female education was an unimaginable concept.

Jacobitism was a Scottish independence movement in which the Jacobites fought for the restoration of the Catholic Stuart Monarchy to the British throne and opposed the Protestant Hanoverians. From the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries, the Jacobite Movement was a key threat to the British monarchy. It’s a history which has captured the cultural imagination: a key moment of national Scottish identity and a site of historical revisionism for England, or more recently, the selected subject matter for the popular book and television series, Outlander.

The Jacobites thrived in the underground because it was deeply treasonous, occurring at a time in which female literacy rates were modestly increasing, allowing women, albeit only the rich and powerful, unprecedented access to political circles. If one was caught engaging in Jacobite activities; from expressing sympathies, to outright contributions to the war effort, they would be subject to harsh punishments. As such the networks were pushed to the fringes, and the public sphere became dominated and surveilled by the English and a Jacobite visual

Analysis 4

Simone Maddison scrolls through the trad-wife aesthetic fawn bambi coquette Russian bimbo core Slavic girl aesthetic.

Mariika Mehigan talks to women forgotten in the archives

“No men, no meat, no machines”: The Forgotten History of Australian Radical Lesbian Separatism

The Women’s Liberation movement of the seventies has a somewhat confused place in our cultural memory. Instinctively, we might think of certain images: bra-burning, freelove hippies or dissatisfied suburban house-wives, perhaps recognisable figures such as Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, Simone de Beauvoir or Germaine Greer. Some think of its connection with other distinct yet interrelated progressive movements; anti-Vietnam, Gay Liberation, Civil Rights or environmentalism, or they may associate it with Gough Whitlam’s Prime Ministership. In current feminist circles this time may be considered the cause of some most insidious inheritances; biological essentialism, transphobia and the progenitor of ‘White’, ‘Liberal’ or ‘girlboss’ feminism. Notably, the narratives of today either choose to look at this time either to convey feminism’s successes or emphasise its failures.

Yet unsurprisingly this tendency erases the nuanced and wide tapestry of feminist thinking occuring at the time. The existence of Radical lesbian separatist communities in New South Wales is a history which complicates this binary distinction.

Throughout the seventies, there existed three woman-only regional communities in northern New South Wales which loosely followed the ethos of ‘No men, no meat, no machines’. These communities, named Amazon Acres, The Valley and Herland, were founded by feminists who splintered from urban-based feminist and queer collectives that proliferated in this time, who desired a place in which they could embody their politics in all aspects of their lives. The residents slept and ate communally, mainly practiced non-monogamy, spent their days farming only what they needed and made every major decision via

language emerged in order to keep the movement alive, thriving in the private. Men would have certain symbols carved onto their glassware or phrases like ‘Our Prince Is Brave, Our Cause Is Just’ sewed into their garters to keep their beliefs close to them. Women could have the same embroidered on one side of their fans, allowing them control who they hide their Jacobitism from and who they let in, subtly expressing their allegiances while avoiding the watchful eye of English authorities.

Coinciding with the rising literacy rates of upper-class women in Scotland, women were able to engage in the movement from afar. These women leveraged their wealth, networks and familial influence to contribute to the war effort, often in violent or duplicitous ways. Many sent money to

committee. Amazon Acres, the most well-known of these communities, was a one thousand acre property of uncleared bushland located near Wauchope that was purchased through donations from readers of feminist publications, such as the Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter, many of whom never lived on or visited the lands. The community had only about one hundred people in permanent residency at any one time, yet the land acted as a ‘community resource’, welcoming many visitors from all over Australia. These communities provided a place of refuge for queer women experiencing misogyny in Gay Liberation groups and homophobia in feminist circles. At these farms, women could reclaim the notion that the Australian bush was a site of “white masculine endeavour” and explore their identities without the threats of a patriarchal society, the toxic influences of capitalism and the taboos of homosexuality.

The politics these communities espoused are one of the most literal interpretations of the ‘personal is political’. Many residents saw each lifestyle decision as an unavoidably political one. Queer female relationships, in particular, were seen as an opportunity to dissolve socially prescribed sex roles and entirely embrace the notion of sisterhood. The “Radicalesbian Manifesto”, released in 1973, states “fucking with another woman just removes one more barrier in our minds, enables us to learn to love our woman-selves in another woman”.

In relation to nonmonogamy, the same paper reads; “we have to break down the sanctity of relationships… We believe that the primacy of genital sexuality, the idea that it is a consummation, is a male trick”. Some who subscribed to this thinking were largely unsympathetic to those in relationships with men. One claiming, “until all women are lesbians there will be no true political revolution… feminists who still sleep with the man are delivering their most vital energies to the oppressor”.

As such, many rules were established, yet few could agree on them. The “tyranny of the dissenter” plagued the communities. Some couples choose to remain monogamous while living on the farms, prompting criticism from others for being ‘exclusionary’. While the practice of non-monogmy for some proved complex and fulfilling, heartbreak became commonplace. Some desired to eat meat, remain in contact with male relatives or friends, bring their young male children to live with them, or farm using modern technology. All stances which caused

significant debate. A political lens of today exposes these contradictions even further. As the exploration female and queer identities were emphasised, considerations of race and class were largely ignored. Many would not have had the financial freedom to relocate or travel to the farm, making Amazon Acres a ‘community resource’ to those with expendable income. While occupants rejected the notion that the Australian bush was a site of “white masculine endeavour”, inclusionary of women, further acknowledgement of this as a colonial activity was never made. Nor was there an acknowledgement of their use of unceeded Indigenous land.

As the eighties progressed, the energy that these communities formerly had began to dwindle. Many became tired of the disagreements and the harshness of an Australian rural climate, eventually desiring autonomy and privacy, increasingly choosing to sleep and eat alone, enter into monogamous relationships or embark on careers which required relocation to urban centers. However, Amazon Acres in particular lives on, remaining in the ownership of the collective.

As we wrestle today with tackling many distinct yet interrelated injustices, it’s both deflating and encouraging to see how many were exploring these same questions some fifty years ago. As the notion of intersexuality we now have a more comprehensive vocabulary for marrying numerous schools of progressive thought, yet face many of the similar challenges that the residents of Amazon Acres, and other communities experienced. While few have an adequate answer to how we can ‘fix’ these issues, this history encourages us to take a more nuanced approach when we look to the past, being sure to acknowledge its failures, as well its successes.

Prince Charles and organised locations for him to stay in as he traversed Scotland in the lead up to battles. One woman, Anne Mackintosh, a member of the prominent Mackintosh Clan, defied her husband and his Hanoverian sympathies by mobilising her family’s power to raise men for the battle. Another named Lady Margaret Nairne, seventy six at the time of the second Rebellion in 1745, convinced many members of her family to involve themselves directly in the Rebellion. She hosted Prince Charles as he was travelling across Scotland and

ordered men to intercept impending attacks after receiving tips. Upon her daughter’s arrest, she wrote a letter pleading for clemency on the grounds that she was a “weak, insignificant woman”. Her daughter was known for her ruthless recruitment, threatening to burn down men’s family homes if they didn’t enlist and to execute dissenters.

These stories raise questions about how we understand and commemorate women’s history. This aspect of the Jacobite movement has been woefully

understudied in the historiography, as historians tend to prioritise the battles and their minutiae while skewing women’s involvement into a palatable story with commercial appeal. For many, when we discuss ‘Female Jacobitism’ we think of Flora MacDonald - a pious, beautiful and young martyr for the Jacobite cause. Yet this limiting narrative, once again shoehorning women into either ‘Damned Whores’ or ‘God’s Police’, homogenises the uncomfortable, complex and often distasteful human reality. Many of these ‘Damn Rebel Bitches’ were unlikeable; wealthy, manipulative and brutal women whose activity defied social conventions and contemporaneous standards of female behaviour and were, most importantly, painfully real.

Analysis 5

The existence of Radical lesbian separatist communities in New South Wales is a history which complicates this binary distinction.

Mariika Mehigan imagines a new (and old) community

Coinciding with the rising literacy rates of upper-class women in Scotland, women were able to engage in the movement from afar.

Re(creation)

Men whistle, grunt, leer. You reach over to collect a glass. You see them looking down. Do you want to be a woman? Do you want to be stared at? The men don’t get stared at. They breeze through – unnoticed. They can banter, be friends, and it’s never regarded as anything more. But for us, it’s never that. Every conversation is pervaded by this anticipation, expectation, hope that they could get more. Their eyes are heavy, their voices deep, their words slurring, they’re hungry.

The pub used to be the man’s place. Escaping you, at home. It still is. But it’s a mating place now. One doesn’t have to look further to see how gender operates in Australia. “It’s 2023,” he says. But that doesn’t mean things are better. The present supplies us with this assumption that things are better than “the past”. But in the pub, time flattens, we reach back into the past.

Eyes greedy, hands touching backs, standing taller. You don’t want to be here anymore. Do you like beer? Do you like seltzer? You’re not even sure what you like. Everything’s gendered. You hate it. Can you be feminine? Can you be masculine? What do your clothes say about you? If you wear a singlet, you’ll get more looks. If you wear a t-shirt and baggy pants and a carabiner, you’ll get more respect. Do we have to teach men how to be better? Do we have to spend our time and energy being uncomfortable for the scant future possibility we will feel better? You can’t help but feel apathetic.

You think, and think, and you can’t stop. That feeling they’ve taken away from you. And you’re crying now, at

work, embarrassed. And you’re crying all the way home. And when you close your eyes you see their eyes. Your body exists. Viewed from all angles. Can they see your nipples? Is your stomach showing? Does it look good? Do you look attractive? You want to be desired but you hate that desire. You know that women in plaits get more tips. Creepiness is profitable. You don’t know how to deal with this. Do you just accept? Or do you fight? You’re sick of feeling uncomfortable but do you make yourself feel uncomfortable? Is it your fault? Are you encouraging it? Facilitating your own objectification, infantilising yourself?

You’re exaggerating now. You go on about it too much. It’s the only thing you talk about apparently. That is, according to yourself. And when you talk about it with them, you search for their validation that these are actual issues. You can’t think of a lifeboat better than misandry. But you still need their confirmation that these are problems. That your discomfort, caused by them, is only valid once recognised by them. “What did they say to you?”, he asks. And you feel already dismissed, what can you say that will make him understand how it feels? So you exaggerate. Because you don’t know how else to make him understand.

Push it under, forget about it, ignore it. So you play the silly girl. You order your seltzer. When you carry the plates, and stack glasses, the casual comment “do you need help with that?” reminds you that you’re not okay. That you’ll never be okay. Everything is male territory, which makes you weak. You can’t carry anything. Every utterance

etches, scrawls, lining up boundaries. And you’re not one of them. You can’t trust them.

These things can’t stay down for too long. They don’t bubble up. They split and pierce you. They gurgle and foam. And you’re there crying outside work. And you’re there crying all the way home. Your body stings from where they touched you. And you can’t feel good now. It’s been taken away from you. He’s taken it away from you. He looked in shock. He said sorry. He called her sweetheart. He touched her lower back. He invited her to have a drink. You need someone to tell you that things are fucked up.

“It’s a masculine environment,” you say, trying to explain. “But there’s plenty of women around today,” he responds.

Don’t take up too much space. Don’t ask for too many things. Don’t make any errors. Don’t make too much noise. You can be judged for those things, you’re needy now. Don’t complain. Don’t say anything. Nothing will change. Nothing changes. You’re told we have to accept some level of discomfort to exist. But you don’t want to accept these things. Acceptance is aiding and abetting.

You’re not smiling enough. Your smile is painted, they paint it for you. They own your smile now. Your muscles are now theirs too, for crafting, for profiting from. Your body, clothes…it’s all theirs now. You want to shroud yourself in baggy clothes–covered, blanketed, unseen. But maybe that’s worse than being seen. If you aren’t recognised by the male

gaze, do you even exist? Are you really a woman? We are reducible to gender. Everything’s reducible to gender. But that’s so reductive.

When you reach down, you can only know that, at least one time, one of those men have thought about you crouched down. You can imagine what they are thinking. You wish you could turn my brain off. Gender is boring now. We talk about more interesting things. I’m going on again. I’m making a big deal again. I should shut up. Am I communicating this right? Is this good enough? Do you know what I mean?

Pubs make a small part of the world. And we can remake it. They make a world where ratios are analysed, where women are spiked, where women work the floor, and men work in the back of the house. Alcohol aggrandises people. Gives them the confidence to say that you’re pretty. They make a world that aids these behaviours in turn of a profit. A world where a woman can’t be at a bar alone. A world where women invite you in, as front of house, into their own oppression. A world where female managers aren’t respected. A world where spiking is an accepted danger and sexual assaults occur. And maybe we can remake this world? Right now there’s too much profit and not enough solidarity. It works for people. And it works for people not to think about it too.

But, we can make pubs better. With many people acting, at many different scales, through many different avenues, we can affect change. They don’t have to be the way they are. Don’t accept it – it shouldn’t matter what I wear to work tonight.

Magical Women: The Beauty of Femininity in Literature

History suggests that there lies a strange madness within the female experience. With Hippocrates suggesting the cause of hysteria was the movement of the uterus inside the body, he portrays the illusion that mania is exclusively an experience unique to women. By warping the binary between reason and fantasy, contemporary feminist fiction flips this notion on its head through the employment of magical realism, introducing a new vehicle through which androcentric society can be deconstructed, celebrating the intrinsic magic of femininity, however unsettling it may be.

Building off their foremothers such as Margaret Atwood, Angela

Carter, and Isabel Allende, many contemporary feminist authors use this specific brand of magical realism to explore the delusional, dreamlike landscapes long thought to be the mind of a woman. Congruent themes such as supernatural womanled cults, depictions of motherhood as miraculous, and deconstructing symbols long attributed to repressive expectations of womanhood are all common threads through which recent literary works have masterfully exposed the beauty that lies within and around the feminine experience, highlighting its otherworldly and disrupting complexities.

Perfectly portraying this concept, Canadian author Mona Awad has succeeded in telling tales through grotesque and satirical takes upon the

performance of beauty and chastity women have long been taught to uphold. Her 2019 novel Bunny follows a grad student, Samantha, as she is slowly seduced into the violently feminine cult of her university classmates, who all refer to each other as ‘Bunny’. As you travel deeper into the text, Samantha’s narration slowly distorts as she becomes as sweet and sickly as her fellow bunnies. It is a tale of women’s disruptive power, resentment towards the softened dispositions they are expected to maintain exploding into a magical terror unleashed upon others. Bunny and Awad’s other works use fantastical elements to facilitate her analysis of womanhood, subverting colonial and patriarchal desires of youthful innocence and subservience by exposing the horrors of the feminine. American writer, Carmen Maria

Machado, also utilises magical realism in her works. Her 2017 short story collection Her Body and Other Parties emulates womanhood through distorted depictions of queer love and motherhood that are paradoxically joyful and painful. Magical realism weaves through each story, deconstructing the arbitrary borders that define fact and fiction, patriarchal entrapment and feminine freedom. Throughout the collection, Machado questions whether magic and femininity are synonymous — is it not magical that wombs can form life? That our bodies can disfigure themselves into a myriad of roles? The collection’s second story, ‘Mothers’, examines this through its tale of the narrator, a single mother who is reminiscing upon the life her

Bars 6

Jessica Sant enchants the ideologies of femininity.

Victoria Bitter works at a pub.

watch this space

sure most bars have fire exits but they are no less dire or straight

sure no two bars are alike some bars do open mic and others poetry nights but they all have the same fate and are in the most dire of straits and surely this is the saddest one bar none

oh where have all the dyke bars retire where are the women in gay attire where the dynamo livewire and mitochondria that power houses whole families not nuclear and homes away from home entire and queer

oh birdcage is our last safe time i fear the bank safe as vaults from male desire on wednesdays though nights events and parties

are not brick and mortar bars but pyres of heaven locked out and down prior shine on junipero biconic and other meetings shinier than gala apples brighter than swarovski crystals and more glittery than disco balls mirroring flashes of paid event photography but

dream big bigger than liminal ritualised trances or social dancing rites in transition from sappho o clock to straight a m and gay happy hours to last call for queer beers woman wines vers vapes or switch cigs aim high higher than eventbrite tix big events bright dj lighting bigger nights out or even brighter dresses special makeup occasion hairstyles and accessories made for all tomorrows parties all next weeks festivities all futures celebs and all the worlds stages on dance floors lost for ages but found bi monthly and off happy hours to be missed waiting for our next performance lined up and dress coded come back

my dyke days gay nights and queer time in a lack of safe spaces lez places or homo homes where do dyke adjacent women and nb folk go after hours where are the l words before licensed opening and sapphics after closing time tell me

where are the femmes who inspire me and the mascs whom i admire where the fatales who plot conspire and know how to change a tyre

or gear and hold their wheel at ten and two steer and drive a manual car or bike here from lewisham wentworth point dulwich hill clyde botany marrickville petersham canterbury bankstown tuggerah rozelle summer hill eastwood anywhere but near they the ones who i aspire to be

where does sappho play the lyre where do girls play with fire where do sirens sing in choir and where do i inquire god please show me one dyke bar not another dive bar not another dine in bar not another dime a dozen bar not another dice roll or coin flip bar not another dike to rock climb or another dike barrier to hike but a dyke bar not far and on par with the best where a dyke walks into a bar with a carabiner or the bell jar and sees in the darkness a northern star its failures, as well its successes.

daughter may have had if her other mother had not left. The intrinsic magic of motherhood is celebrated in all its emotional complexities, the narrator admiring how “women can turn children into this world like breathing.” In this way, the magic in ‘Mothers’ is the mothers themselves, illustrated as fantastical, miraculous, and uniquely feminine.

Symbolism throughout Canadian writer, Camilla Grudova’s The Doll’s Alphabet takes on a distinctly womanly shape as she attacks the patriarchy at its roots, denouncing hegemonic ideals of women’s value in society through recurring magical motifs. Enchanted machines, factory work so hazardous only a woman can complete it, and dreamy and pretentious philosophy boyfriends form strange throughlines across The Doll’s Alphabet. Grudova explicitly

highlights the bonds between women in ‘Unstitching’, where “one afternoon, after finishing a cup of coffee in her living room, Greta discovered how to unstitch herself.” Greta’s male partner fears her new appearance after ‘unstitching’ herself, whilst her neighbour Maria only admires her; “Maria knew that she looked the same inside and could also unstitch herself, which she did, unashamed, in front of Greta.”

The act of ‘unstitching’ is never particularly explained. Still, in my mind, it encompasses stripping us bare, ridding ourselves of worldly values such as assets, wealth, and accomplishments, and instead, revealing the fundamental experiences that have shaped our identities the most. Whether it’s a moment we felt most scared, joyous, or insecure, I believe many of these experiences would be uniquely feminine, acting like an invisible string that ties us all together. At the end of this story,

there is an overwhelming sense of the coexistence of women in society and how our lives can so easily reflect someone else’s, a theme that continues throughout Grudova’s collection.

Machado, and Grudova are only a taster of the many contemporary feminist novelists who utilise magic to tell our stories, blurring the hostile barriers that continue to hold us back, and, in turn, celebrate

Literature

Juneau Choo

To the Sydney Anglican Diocese,

I left one of your Anglican churches in 2018, and it is undoubtedly the best decision I have ever made.

Before this is construed as a takedown of Christianity itself, I want to make clear that my issues lie specifically with the Sydney Anglican Diocese. I believe that faith and institutions can be separated, however, what I cannot stand by is the way that your institution weaponises emotions and existential fear in order to propagate a deeply misogynistic and homophobic agenda.

At twelve I fell in love with church and I quickly allowed it to become my world. I attended every event I could — youth group, Bible study, night church, youth camps. What I did not realise at the time, was how much of the teachings centred on the role of women and sexuality. I now see that the church I attended was obsessed with gender, and obsessed with sex.

I’m ashamed to say that I did not question when I was told that women should not preach in church, that in fact, they should not MC services, or lead Bible studies. Not only did I believe you, I began to shape my future around how I would serve as a woman in the church — creche or women’s ministry (teaching, but only to women, children and pre-teen boys). That’s it really. You taught me that as a woman I would be ‘saved through childbearing’, that I was a ‘helper to man’, and intended to ‘submit to my husband’.

The below are scans of notes I took in one of the many services I attended that focussed on how I, as a young girl, should dress so that I would not lead my brothers in Christ to ‘stumble’.

The below is a helpful diagram provided by the church that clearly shows what women are and aren’t allowed to do within the church.

You seemed surprised when research showed increased levels of domestic violence within the Anglican church compared to others. Yet you say that it has nothing to do with your teachings. I was thirteen when I wrote down what is pictured below, desperately trying to capture the words verbatim. It is unforgivable that that church taught that a wife should submit to a husband who doesn’t love her. You should feel deep shame for believing a brochure and a five-minute segment in a sermon is enough. I believe you blatantly perpetuate abuse by preaching the dangerous rhetoric of submission.

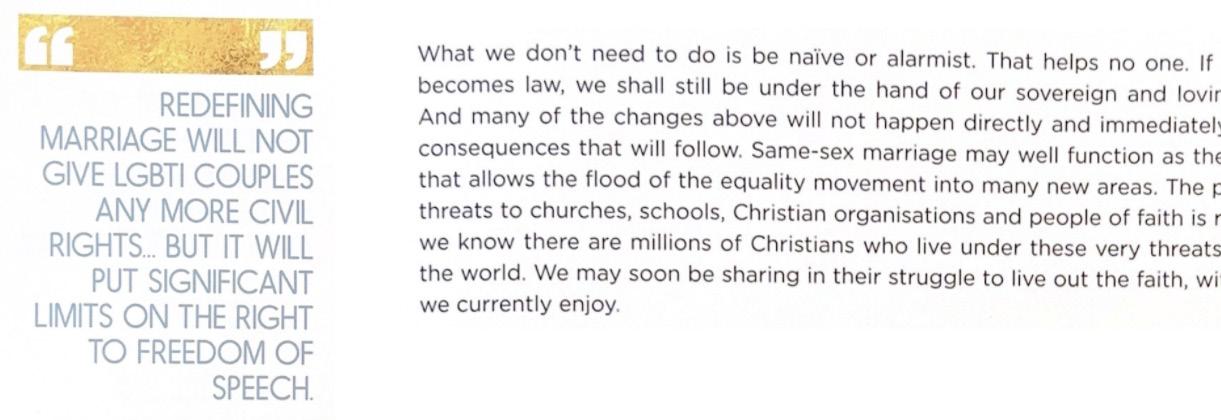

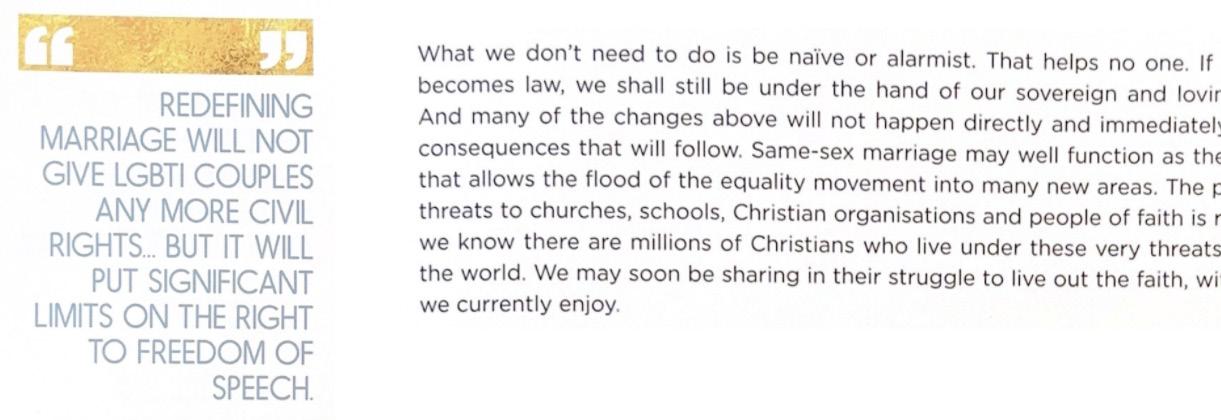

But it doesn’t stop with women. As a diocese you donated $1 million to the No campaign in the same sex marriage plebiscite in 2017. Whilst I was too young to vote, I sat through numerous services amongst hundreds of kids, hearing you explain why people who are ‘experiencing same sex attraction’ were simply giving in to sin, in the same way that others are inclined to lie, cheat or murder. Although, the church would refuse to use the term ‘gay’ as this would imply ‘a happy and accepting community’. Instead they used the more neutral label of ‘same-sex attracted’. They brought in a same-sex attracted preacher who brought his wife and kids, saying that as long as he didn’t act upon his same-sex desires, he would still be accepted into the kingdom of God. As a young girl figuring out her bisexuality, it was impossible not to internalise every single sermon, leaving me to reckon for years with a deep shame.

8

The below are excerpts from the Sydney Anglican brochure which was sent to all Sydney Anglican churches encouraging parishioners to vote No in the same-sex marriage vote.

Not only did you erase the broad spectrum of sexuality in your sermons, you addressed transgender identity in a way that essentially erased them. It is shameful that you would release a pamphlet on gender roles and reduce trans identity to a literal footnote.

You taught me to reject critical thinking. Whilst you would host ‘Big Question’ nights that would tackle sexuality, gender and evolution, your answer was always ‘God is good, trust His word’. I now realise how easily you weaponised these thought-terminating cliches. If we questioned too much, this was because we weren’t faithful Christians — and only faithful Christians go to heaven. By manipulating existential fears and fostering guilt, you are able to spread dangerous messages, exempting yourselves from criticisms because of your biassed interpretation of ‘God’s word’.

When I first left the church, I felt determined to do something, to change how you operated. But what is so heartbreaking, is that you will not change. You will continue to appoint men into positions of power who affirm your beliefs. You will argue that these beliefs are unchangeable even as you watch other Anglican Diocese become more inclusive and appoint female archbishops. I wish that you would listen to women like Julia Baird who have consistently advocated for change within your churches. Yet, you refuse to give up the chokehold you have, and it has resulted in a cycle that keeps women in creche and men at the lectern.

I have found freedom in leaving your church. And all I can hope is that others can do the same.

Sincerely,

Eloise Aiken

Eloise Aiken

9

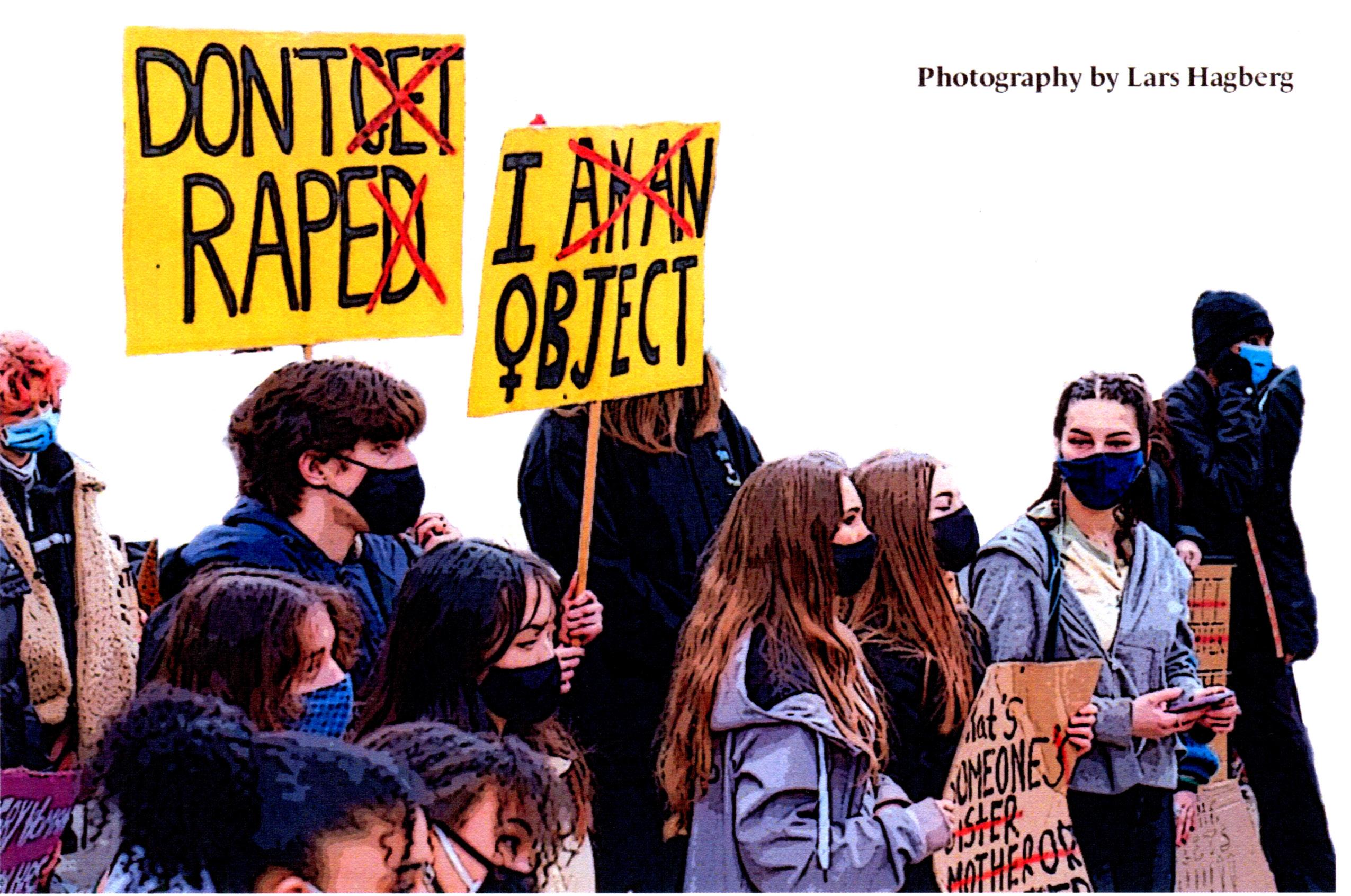

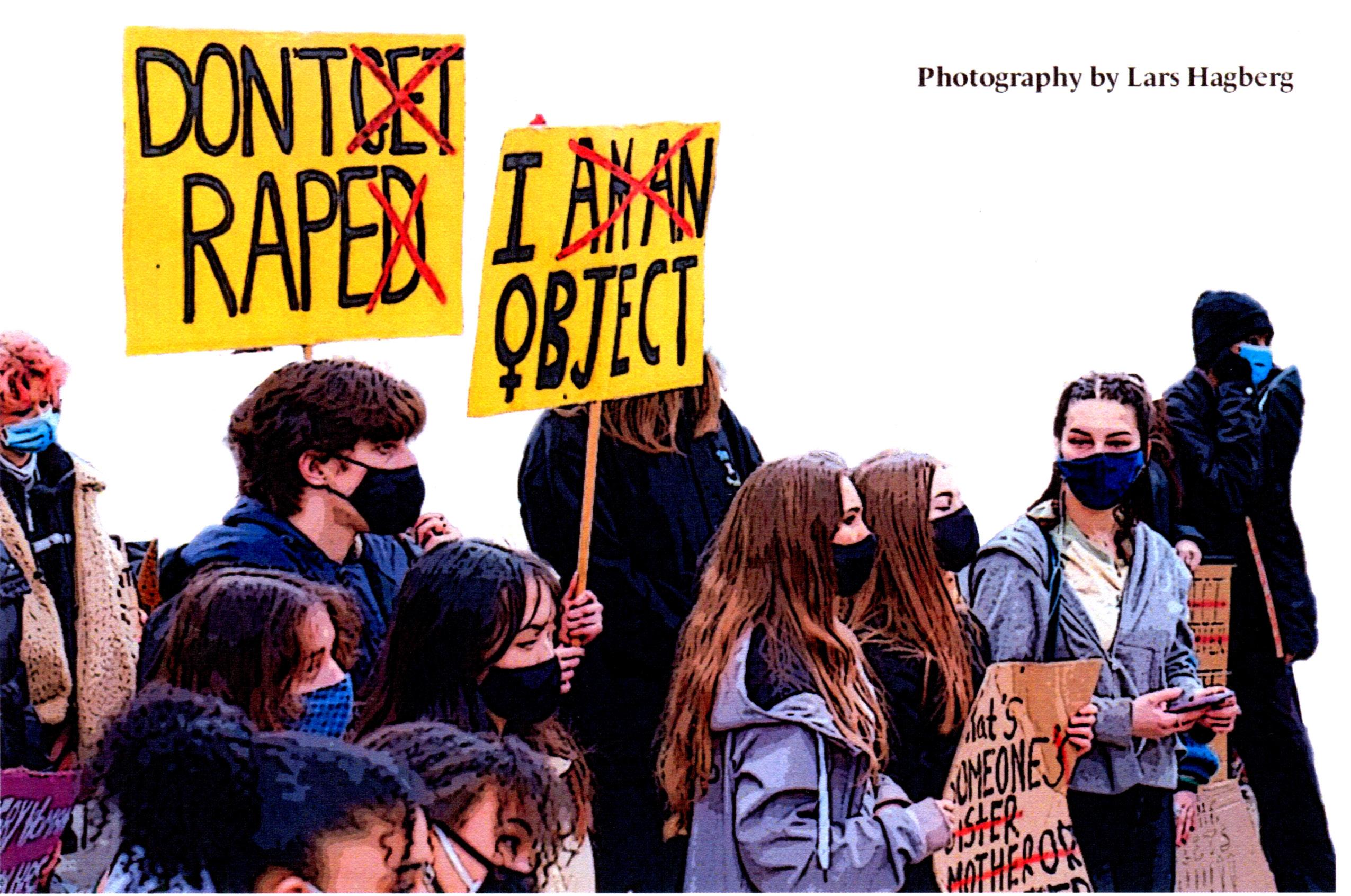

MISOGYNY IN YOUNG POLITICS

Trigger Warning: This article contains mentions of sexual harassment and assault.

This article was inspired by numerous conversations I’ve had with other women on this subject matter. I draw from both my own and their experiences collectively. I’ve come to realise that I lead two separate lives in student politics. The first one is of unflappable optimism and elation. One where we advocate and fight for a more equitable world that prioritises people over profit. Where we celebrate our victories and endlessly wheel and deal, hatching crazed schemes over drinks at the local pub.

But there lurks a second, shadow life. One that I and every woman in young politics experiences at some point. There is only one word for it: misogyny.

There is a misconception that these attitudes exist solely in the far-right, with their insistence on traditional gender roles and their unrelenting crusade to control women’s bodily autonomy. However, misogyny runs rampant in every political space like different strains of a virus. It can remain latent for a time before viciously attacking and infecting every crevice of our organisations, not just at the University of Sydney but also in youth politics more broadly. In every corner of young politics, every woman has lived this life and has a story all too familiar.

It is the grossly lewd comments made in social settings — for example, a male colleague implying that he’d ‘cream himself’ based on a woman’s choice of clothing.

It is the constant undermining of our contributions, our causes and campaigns, especially in regards to women centric issues like sexual violence and reproductive justice, consistently taking second priority to causes and initiatives led by men.

It is the imbalance of emotional labour where women often fall into the “maternal therapist” archetype. We take up the burden to watch out for the wellbeing of younger recruits as well as facilitating the often mentally taxing “debrief sessions” with other faction members.

Meanwhile, those same senior faction members – who are also woman-identifying – are often excluded from being involved in critical decision making processes. In other words, we are given the unglamorous responsibilities of this emotional labour without having any authority or say in the direction of the organisation.

It is the accusation that you’re in bed with your male colleague, with the implication you’re sleeping your way to the top, rather than your hard work and competency being acknowledged.

It is the flippant dismissal or outright rejection of sexual harassment and assault allegations. We are constantly and painfully reminded that men would rather back up their mates instead of holding them accountable.

This is all, for the most part, tacitly accepted. We lament and commiserate together over these instances. Yet I’m still to witness anyone calling out these behaviours as they happen.

Even worse, what these isolated instances produce is an insidious culture where women are not

respected as people, equal to our cis male counterparts. Our value as a sexual commodity takes priority over our value as a legitimate political operator, let alone as whole thinking and feeling person.

Subsequently, this leads to a tacit acceptance and widespread endorsement of intimidation, harassment, sexual assault and violence towards women. The horror stories I have heard, particularly where perpetrators and predators remain within political organisations, always give me chills.

The reporting process usually goes one of two ways. Either the reporting process becomes drawn out and arduous; since the burden of proof falls on the survivor, it becomes their responsibility to present and compile evidence. This onerous process often retraumatises and triggers survivors, leaving them in an exacerbated mental state. After all that, perpetrators still remain in these organisations with only a minor slap on the wrist at worst.

Or alternatively, the organisation in question has no formal reporting process because it was not designed with survivors’ needs in mind. As a result there is a lack of any proper mechanism to expel or discipline the perpetrator at all.

Beyond political factions and organisations, misogyny bleeds into the institutions we are elected to. The attitudes our student leaders display and accept then exacerbate sexism throughout our broader communities. How can we expect our institutions and our society to not be misogynist if our own internal spaces and political institutions remain persistently

affected by it?

Moreover, it pains me to admit but many of our leaders in these spheres will become the real leaders of ‘tomorrow’. Parliament is already notoriously an unsafe place for women, with the ABC reporting that one in three staffers experience sexual harassment as well as the allegations brought by Lydia Thorpe, Brittany Higgins and Karen Andrews to name a few. Again, this culture of tacit acceptance in adult politics pervades through Australian society on a macro level.

Misogynistic attitudes manifested in both discriminatory actions and actual violence towards women will likely continue to infect our political spheres at every level. Sometimes, in my more mentally fragile moments, I question the ethics of bringing other young women into these spaces when the risks are so staggeringly high. Am I doing the right thing by them or am I simply enabling an ongoing system of oppression?

However, like I said that at the start of this article, I am still an unflappable optimist. I fundamentally believe that together we can bring about a better world. If we are ever going to cure our political spaces from the virus of misogyny we must not look to men but to each other.

Yes, we often hail from differing parts of the political spectrum and we will always have those disagreements. This is more than acceptable, as healthy disagreement and discussions can strengthen our political organising. But aside from that, we need to foster a meaningful sense of solidarity with each other and back each other up in this context. Only we can understand and empathise with each others’ experiences; only we know our needs. Our community and the world at large will never improve for women, unless we as women push for change ourselves.

I could rant for so much longer about this topic, as I’m sure many others could. We play out endless alternate scenarios of ‘what ifs’, console each other, cry together and wish for better. But it is only together, in the midst of such systemic inequality, that we can be a stronger collective force than we are as lone individuals.

Perspective 10

This is all, for the most part, tacitly accepted. We lament and commiserate together over these instances. Yet I’m still to witness anyone calling out these behaviours as they happen.

Anonymous on the pervasiveness of sexism and rejection of women’s perspective in StuPol and beyond.

Trigger warning: This article contains mentions of sexual harrassment and assault.

“She’s going to be a heartbreaker when she’s older, isn’t she?” says the old man on the street, convincing himself that he’s just being nice.

“The boys only hit you because they like you!” says every mum on the playground while you’re crying after one of the boys slapped you across the face until it stung.

“Aw, you’re a little minx, aren’t you?” says my dad, presumably without really understanding the word ‘minx’ to its full extent.

It started early. It started earlier than we might have expected. It started when our eyes began sparkling, our hair began swaying. It continued when we started to walk; when we began to talk. It continued through our earliest school days and carried through to our preteen years. It showed on the streets; in our schools; on the bus; in bars and clubs; for many, it showed at home. But our knowledge of it grew with experience. We didn’t get taught this. We had to learn through trauma, through tales from the women around us, from the uncomfortable feeling when an old stranger is leering at us, and the whistle from a car full of boys.

In saying that, the discomfort and disgust didn’t come naturally. I used to be flattered when a group of much older boys would beep their car horns at me. I took it as a compliment. Finally, I’m the girl they think is pretty, I would think to myself at 12 years old when a group of 21-year-old boys drove past and wolf whistled at me. That gesture grew old very fast. When I saw it happen to my friend’s younger sister, I started feeling the discomfort. That’s when it hit me.

It wasn’t just in the streets. It happened in school. It happened when our socalled ‘protectors’ were supposed to be protecting. I was given a set number of points in high school like an object in a game show. All the girls were. The boys would run around the school, slapping girl’s behinds. With each slap, they gained the points that were attached to the girl. Whoever assaulted the greatest number of us won. None of us thought it was wrong until one teacher (Ms. Gardner, bless her) stood and spoke about the intent behind it. Even then, there was no assembly to address, and no punishment given regarding this dehumanising game.

Of course, this was just an early sign of sexual assault and harassment. This was just the warmup. Now most of the girls in my school have had experience and trauma by the age of 15 years old.

It got worse and more common as we grew older. I noticed it most when I got to university; living alone for the first time, trying to make new friends, trying to figure out who we are and living up to the casual hook-up culture that is so incredibly romanticised and sought after. I enjoyed the hook-up culture to begin with. It felt almost rebellious after living with my parents for so many years. Until I was unable to move under a man’s body weight and the overwhelming fear of being raped flooded my mind. This was only one of my experiences with this, and scarily enough, I am only one of millions. Hook up culture became something that gave me overarching issues with self-confidence, body image, self-worth and respect.

When I told my female friends, they were almost in tears. They had empathy. They knew how it felt to be frozen under a man; how it felt to be helpless. They told me “It wasn’t your fault” or they just hugged me with sheer care and love. Either way, I felt safe at last. I was able to take a break from being a female, and just be a person. Taking all this into consideration, one of my male friends was my rock in this scenario ... he was absolutely amazing. That wasn’t the case for all of them. The change of perspective of who my “good guy” friends were was astounding after I began speaking of the incident with them.

That is only my experience of being a girl turning into a woman, and this piece is a miniscule glance into the wider issue. The issue that continues to come up time and time again is the relationship between the education system and the sexualisation of women. In my experience, the school didn’t take any action to resolve or reform the issue regarding the mindset the boys in my area had about women. They simply glanced over the fact that every single girl in my year had been assaulted, or at the very least harassed. In addition to this, one of the 5 classes I had regarding sex education was a graphic movie of a girl being sex trafficked. Every girl in the room left crying. The boys had a good rest of their day.

of sexually violent offenders who have been residents in the past — using “in the past” very loosely.

Before becoming a co-ed college this year (2023), St Paul’s College has built up a reputation of being home to the toxic culture of masculinity in the privileged that still has many people talking. One of the major issues with the continuation of these cultures is that these generations of private school children are placed in an environment where disrespect towards women is accepted and encouraged. With respect to their current placement in societal hierarchies, these men are likely to go on further and become leaders, teachers and “respectable” citizens creating a continuing cycle of hostility and perpetuation of these values onto upcoming generations.

“What?! You have such bad taste in men.”

“That’s awful... but why did you let him come over when he was drunk?”

“I’m so sorry that happened to you. Maybe you should just take a break from men.”

Once again, the blame was taken from the man, and placed right back onto me. The reason I ended up there was because of my own doing; because I allowed a friend to stay at my place; because I have bad taste; because I go for the wrong men, or I go for too many men. It was never because what that man did was fundamentally wrong. Even after all this, I couldn’t bring myself to report him. I couldn’t ruin his life, even though he ruined so many aspects of mine, for the fear that I’d be accused of giving a false accusation.

The issue lies in the ways public and private schools handle these types of situations. In high school, there are too many stories of sexual harassment, rape and image-based sexual abuse to count. If we delve into private schools specifically, it is well known that the environment of these schools are based around a culture of peer pressure, sexualisation and patriarchal values. Though this has been going on for decades, it has only recently been talked about in the media. With an increase of people going against these institutions, more accusations and stories of sexual violence continues to show, some schools (specifically in Sydney) have taken to the media to address these accusations. While these efforts are a brilliant step forward in education, it breeds the question: what about past generations.

As we know, those who attend private school are predominantly from wealthy families, which tends to lead into higher education. The University of Sydney has elite residential colleges, which tends to cost over $700 a week. Looking into Usyd’s St Paul’s College (a previously allboys and brother school to the all-girls Women’s College), there has been a prominent history

The risk of this provides a stagnation in the progression of sexual education, leading to the risk of women growing up facing the same issues in the future. This indicates that action needs to be taken within schools and in the field of education as a whole. Some of the recent changes in education have been led by former and current students, not experts in the field of consent or sexual education.The cycle needs to be cut from an early age and should not be the job of only survivors. I believe that the first way to really begin the route to respect is by ensuring offenders are punished in a way that allows them to understand what they did wrong. The more passive schools are with their actions and discipline, the more sexual violence there will be. Young girls should not have to experience violence to learn that everyone should be taught not to commit these crimes.

Analysis 11

They just hugged me with sheer care and love. Either way, I felt safe at last. I was able to take a break from being a female, and just be a person.

I couldn’t ruin his life, even though he ruined so many aspects of mine, for the fear that I’d be accused of giving a false accusation.

Ellie Robertson abolishes shitty education.

But What Have You Done For Us Lately?

The State and Federal Governments On Women

In last year’s federal election, the Liberals suffered a reckoning at the hands of conservative-voting women, who migrated to voting for Teal Independents en masse. Since then, the Liberals have attempted to address the issue of being correctly perceived as a misogynistic party in their own eccentric way: denying, deflecting and vainly monologuing at all who will listen about ‘what the Liberal party can do for women’. The Liberals offer women nothing. But the Labor party are not wont to intervene on this issue, and now that they hold both the State and Federal Governments, what have they offered women and non-binary people?

Abortion

In 2019, the year of the passing of the Abortion Law Reform Act, the Labor Party made a promise. Tanya Plibersek, speaking as then-Shadow Minister for Women, indicated that Labor, if elected, would bring to Government a policy wherein public funding for hospitals would be tied to their willingness to provide abortion care. Since then, we have seen little change and even littler improvement in the accessibility of abortion in NSW; in March this year, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that only two hospitals in NSW provide abortion services, those being John Hunter Hospital in Newcastle and Wagga Wagga Base Hospital. It goes without saying that these are not accessible for people living in Sydney. Labor failed to win the election in 2019, and have since largely refused to comment on the topic of requiring public funding for hospitals to go towards abortion care.

One can produce a whole host of polls which demonstrate that greater funding for, and greater access to,

believed that “every public hospital delivering women’s health services should also provide abortions.” The public voting response to proposed laws around restricting, or allowing, abortions since the repeal of Roe v Wade in the United States demonstrates huge popular support for accessible abortion care. Considering all this, and considering that NSW Parliament already voted in favour of abortion care under a Liberal Government in 2019, why won’t the Labor Government commit to actually improving access to reproductive health care in NSW?

The Federal Senate Inquiry into Reproductive Health Care Access passed down its final report in May of this year. It goes to great lengths to note the difficulties the vast majority of people wishing to get an abortion will find when trying to access one which is safe, timely and affordable. Despite this, the Inquiry does not determine that it must be mandatory for public health funding recipients to provide abortion care; instead it simply recommends that there should be more money for abortion care. “It is outrageous that private hospitals receiving public funding denied healthcare to pregnant people in need,” said Greens Senator Larrissa Waters, the chair of the Inquiry. She followed by saying, “[w]e could not get consensus agreement through the Senate inquiry to require private hospitals to provide abortion care as a condition of receiving public funding.”

Public funding for hospitals in this country goes to both public and private hospitals; thus, public hospitals are also not required to provide abortion care in order to receive public funding. As long as ‘conscientious objections’ are a legitimate reason for hospitals to not provide abortion care, no change in this area will ever be achieved. Further, abortion cannot just be offered in cases where the life of the pregnant person, or the health of the foetus, is at risk. Non-fatal illnesses are treated every day at hospitals; abortion is healthcare and must be accessible in all instances. The State and Federal Governments across the country must actively choose to no longer embrace cowardice around providing full reproductive healthcare for all.

Equality Bill

Since government policy towards Women includes all women, Sydney MP Alex Greenwich’s proposed Equality Bill must be

Iggy Boyd asks the hard questions.

relevant to this discussion. The Equality Bill was introduced on the 24th of August, largely seeking to update portions of the Anti-Discrimination Act (ADA), particularly with regards to banning conversion therapy and enshrining self-identification for gender identity on state documents. The ADA changes include removing exemptions which allow private education institutions to discriminate against students and employees in certain cases, and limiting situations in which religious organisations can use discriminatory hiring practices to only roles relevant to religious practice. Legal protections are also proposed to be extended to those who are bisexual, asexual, non-binary and have ‘variations of sex characteristics’, and sex workers. There is a peculiarity to the sex worker part; it would be illegal to discriminate against sex workers as a population, but not against the act of sex work. Nonetheless, positive legislative change for sex workers is an excellent inclusion and is the result of many years of activism and demands from sex workers themselves.

Beyond this, The Equality Bill seeks to legislate the capacity for those 16 and above to consent to medical and/or dental treatment. This is particularly of importance to young people seeking gender affirmative care, although those under the age of 16 still need a counsellor to sign off on any treatment. It would also remove the requirement to undergo surgical procedures which change sex characteristics in order to alter state records of your sex.

On the problematic side, it would establish a lawful criteria for discrimination against transgender people in sport from the age of 12 onwards. It also fails to include legislation around outlawing medically unnecessary procedures on intersex children.

The State Labor Government has indicated it will not support this bill; it seems they intend to put it through the State Law Commission first. This would take a long time and seems tantamount to a delaying tactic; it also fits with NSW Labor’s strategy throughout their time in office, which is to commission a review first and act at an unspecified date much later, or never. Queer activist organisations such as Pride in Protest have expressed their desire for the bill to be passed immediately, with amendments to strengthen it, and have demanded further protections for sex workers,

Government 12

intersex people and queer people generally to follow. There are concerns that Labor may wish to include religious exemptions for conversion therapy bans, which would undermine the purpose of the legislation.

University Sexual Violence Taskforce

For much of this year, End Rape on Campus (EROC) and Fair Agenda have been running a campaign for a Federal Taskforce to oversee, and combat, sexual violence on University Campuses. On Thursday the 14th of September, a report was tabled from the Inquiry into Consent Laws led by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee. A crossparty committee, its recommendations included the following:

• That a third National Survey on Sexual Violence on campus be conducted, including students from age 17. This would be the second National Student Safety Survey.

• That the Commonwealth Government commissions an independent review of TEQSA’s (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency) response to sexual violence on University Campuses.

• That the Commonwealth Government immediately implements an independent

taskforce with strong powers to oversee Universities’ policies and practices around sexual violence, and to respond to sexual violence on campus and in student residences.

The recommendations were unanimous, despite Liberal Senator Paul Scarr chairing and three of the six overall members being in the Liberal Party. As these are simply recommendations, we must wait to see whether they are taken up by the Albanese Government. Nonetheless, to not take on these recommendations would be a very active decision by the Federal Labor Government to ignore this issue. In the meantime we may be cautiously optimistic that real oversight of sexual violence on campus across the country could be a reality sooner rather than later.

Further recommendations from the Consent Laws Inquiry include:

• For the Commonwealth Government to ‘assess’ the success of ‘pilot projects for specialised and trauma-informed legal services’ and fund them further if they are assessed as successful.

• For the Attorney-General’s Department to developed a ‘National Sexual Violence Bench Book’, specifically addressing rape myths, for ‘judicial officers’ to respond better to sexual

violence

• Furthering the inclusion, and consistent assessment, of affirmative consent laws across the country.

Beyond the positive recommendations around sexual violence on campus, the Inquiry provides relatively little as to addressing sexual violence in broader society.

This is only a brief summary of the issues concerning women that have been broached by Parliament and the Labor Party this year, as discussion of the new updates for the ‘National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032, and discussion of Labor’s largely hostile approach to union campaigns in feminised industries like nursing and midwifery, are beyond the scope of this article. Nonetheless we see, as we have seen time and time again, that governments of any stripe will overlook the concerns of women and non-binary people until they are forced, by public pressure and popular movements, to act. Feminist activists must understand this, and understand that Government approaches the concerns of Indigenous people, workers, migrants and more in the same manner. Feminist activists understand well the

Chinese Foot Binding

struggle of fighting for one’s rights when people across identity barriers don’t seem to care; this is all the more impetus for feminists to engage in and support all movements for liberation, to illuminate all areas of society with feminist politics and to demand feminist justice until none can feign ignorance as to its need.

Art by Emma Qi

“The violent mutilation of the feet eliminates boundaries between human and beast, organic and inorganic. It sweeps away barriers that usually divide mortals: wealth, age, sex, and so on. Violence renders the feet sacred. Naked, they become taboo for men. Women guard them as if guarding their lives. It also gives them the power for healing and cursing. All the tears and pus, all the decay and broken bones are hidden under the elaborate adornment of the shoes, which are never taken off, not even in bed. Yet violence is traceable everywhere: the odor of dead flesh seeping through the bandages, the tiny appendages that barely support the frail body.”

Wang Ping, Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China. 2000.

Government 13

Because it is my name!

I recently found myself at a reunion of my Catholic girl’s high school. It is a long story as to how I ended up there but suffice to say, it was a fun afternoon. There in the hall of my old high school sat women from the class of ’64 laughing about their geography teacher; young mums cradling their two-year-olds as the latter cried through speeches; and myself, biting into a delicious homemade scone. Amongst the laughter of recollections and cries of infants, not to mention the taste of raspberry jam, I couldn’t help but notice my fellow alumnus’ name tags.

Daly (née Hall).

Chan (née Doyle).

Joseph (née Allan).

The prevailing presence of ‘née’ stood out. As a young, inner west woman of the 21st century, the term ‘née’ is not a common occurrence for me to see when reading a name tag. Sure, some of my friends’ mums had the same surname as their husbands and both of my grandmas and many of my aunties changed their surnames after marriage. So, it was not new for me. Nevertheless, the dominance of ‘née’ started to bug me. And I realised why when a fellow ex-student started to make a speech. It was a speech about recollections from her time at the school, how things had changed yet stayed the same. We all listened with interest.

Yet, it wasn’t until this speaker revealed her maiden name – her ‘née’ name – that the other ex-students in that school hall remembered exactly who she was, who her sisters were, and who her parents were, the latter being a familiar presence in the school’s P&C during the 1980s. It became crystal clear to me then, like never before, that a woman’s surname – indeed, anyone’s surname – forms our identity. Our surnames give us recognition within a community, similarity with our siblings, and a connection to our sense of self. John Proctor’s famous proclamation in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible epitomises this: “Because it is my name! Because I cannot have another in my life!” Yet, many women do have ‘another’ surname in their lives.

Changing one’s name after marriage has only been a custom for women of Anglo cultures since the Enlightenment. Contrary to popular belief, before the mid 18th-century, many women held independent surnames from their husbands. Women’s surnames could have epitomised a key personal characteristic or trait, an occupation, or status in the community. However, the onset of the Enlightenment saw the definition of ‘citizenship’ change remarkably, particularly in England. As scholar Deborah Anthony notes, a woman changing her name after marriage in the English context was “employed to reinforce a patriarchal regime which deceptively claimed that the natural order… [and] supported the current male-oriented surname system in its creation of new systems of rights and identity”.

Indeed, ideas of citizenship became strongly tied around imperialism, industrialisation, and property. Married women in Anglo cultures now became “Mrs. Their-Husband’s-Surname” while their children “Child Husband’s-Surname.” Moreover, most young girls grew up with their father’s surname before being expected to take their husband’s surname once they were married; marriage was the expectation for young women of the Victorian era. Combined, these name changes reflected the property laws of this time. Indeed, it wasn’t until the end of the 19th-century until women in England, for example, did not have to relinquish their property and rights over their children after marriage.

Until the 1970s in Anglo cultures and some Asian cultures, it was bizarre if women did not change their name after marriage. Catalysed by the onset of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the 1970s, many women started to question the patriarchal nature of name changing, starting a trend in keeping one’s original name even if they married. This mirrored the naming customs in several other cultures and religions globally. For example, it is custom for Muslim women and women from South Korea to keep their surnames after marriage; in Greece, France, Italy, and The Netherlands, laws were put in place in the 1970s that forbid women from changing their surname after marriage; and in Spanish-speaking countries, as my Argentinian friend explained to me, it is custom for women to keep their surname after marriage. This consists of two surnames — one name from their mother and one from their father.

Yet, name changing upon marriage remains popular even in the 21st-century, particularly in the Anglosphere. A national survey carried out in Britain in 2016 found that 89% of women who participated had changed their surnames after marriage. What is even more striking is that 75% of the youngest age group who participated in this survey – 18-34-year-olds – changed their surnames after marriage. In a similar survey conducted in the United States, it was found that 70% of female participants took their husband’s name after marriage.

I am not saying that women shouldn’t change their surnames when married; it is important that women have agency to make their own decisions. Many women interviewed in the above surveys discussed that sharing a name with their husband meant that they felt more connected to their

children; in many Anglo families, it is assumed that children will take their father’s surname, and while double-barrelled names are not uncommon, they are still not the norm in many communities. Moreover, women might want to change their surname to distance themselves from abusive relatives or purely to enjoy the freedom of having a name change. Cultural traditions – and expectations – also play a role. However, it is important to discuss that if women change their surnames, we risk the chance of being erased, of being lost to history. Indeed, changing one’s name becomes particularly important in the study of women’s history. When researching this idea, I came across an article in The Guardian about the female artist, Isabel Rawsthorne. A promising creative in London’s visual art scene of the 1940s and 50s, Rawsthorne held three different surnames in her lifetime because of marriage. Rawsthorne made art using her three different surnames at different stages of her career, meaning that much of her work remains unaccounted for. As Carol Jacobi noted: “When Rawsthorne died no one connected her to the artist known as Isabel Lambert, who had created so many designs during the Festival of Britain, nor to the bohemian muse Isabel Delmer, and certainly not to the promising artist Isabel Nicholas, who had exhibited in London in the 1930s.”

While scholars are beginning to put Rawsthorne’s artwork together under one classification, this case study nevertheless highlights how changing a surname after marriage makes it difficult to trace the history of women.

Ultimately, I do appreciate that today, many women still want to change their surnames after marriage and that is okay. It is vital to acknowledge that in Australia today, many women have the freedom of choice to change our surnames – and keep our surnames – if we so desire. After all, what’s in a name? Well, perhaps more than we think. In my socialist-feminist mind, name changing remains a symbol of the patriarchal system that we still live under; keeping your original surname is a form of resistance. If people ever question this, I will just quote John Proctor: “Because it is my name! Because I can never have another in my life!”

Our surnames give us recognition within a community, similarity with our siblings, and a connection to our sense of self.

It is important to discuss that if women change their surnames, we risk the chance of being erased, of being lost to history.

Grace Mitchell will never have another name in her life.

The Idol - Girlbossing, gaslighting, and gatekeeping our contemporary culture of normalised sexual violence

Trigger warning: Discussion of sexual and racial violence.