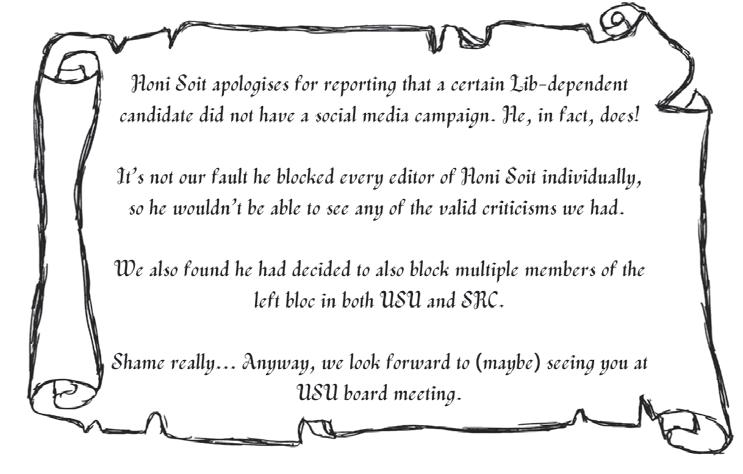

12, Semester 1, 2025

CONSPIRASOIT

The Conspiracy of Free Will

“Thank you Conspiracy!” Says Capitalism, as it survives another day

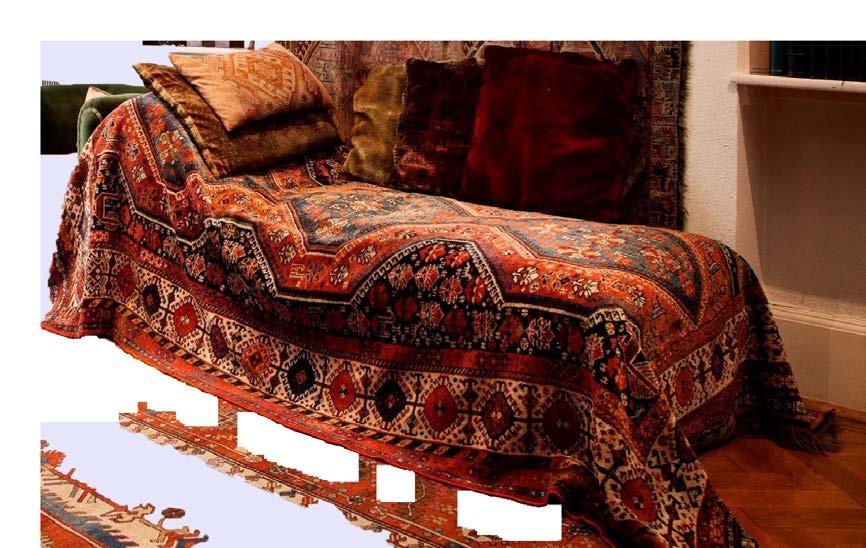

In Defence of Psychoanalysis

Honi Soit operates and publishes on Gadigal land of the Eora nation. We work and produce this publication on stolen land where sovereignty was never ceded. The University of Sydney is a colonial institution. Honi Soit is a publication that prioritises the voices of those who challenge colonial rhetorics. We strive to continue its legacy as a radical left-wing newspaper providing students with a unique opportunity to express their diverse voices and counter the biases of mainstream media.

Conspirasoit

Cranberry Juice

Renting for

Flying

Cult of Honi Free Will? In This Edition...

An alien child kidnapped me and forced me to write this edition.

Harold, the name of the alien, told me:

“Charlotte, Charlotte, you know that silly little student newspaper you write for? You must expose the perils of capitalism, and how conspiracies exist not to destroy it but to ensure its survival, feeding the illusion of control you humans seem to love so much.”

I looked at his opal eyes in shock. “What do you mean? Who are you? Can I see inside your UFO?”

“You’re too short for the UFO, sorry.” Harold said neutrally.

people have the most. On my planet we have a guy named Karl Marx, and he runs the joint with us.”

“Oh wow, a communist alien, who would’ve thought.” I said.

“What’s communism?

“Anyway, what’s your student newspaper called? Honi Soit? Perfect, you should call your edition Conspirasoit.”

“Oh my gosh, Harold, you’re so intelligent!”

While Harold let me go, I had to do what he said because my family weren’t too short for that UFO and now they’re being held hostage on it. Aw shucks.

the overstimulating nightmare of a place that conspires to destroy your soul. On page 15, you’ll read about Ramla Khalid’s suspicions on free will, and on page 17, you’ll discover Cassidy Turrell’s flat earther alter ego.

On the back page you will find Honi’s very own version of the famous ‘Rice Purity Test’. Please retake it as many times as you’d like — alien Harold was not pleased when Honi put this in.

I hope you enjoy reading Conspirasoit as much as I enjoyed putting it together with my incredible editorial team. As I say in my feature on page 6, learn to breathe together again, keep reading, and always question authority.

OMG my family just got thrown out of the UFO, thanks Harold!

Miss Flat Earther

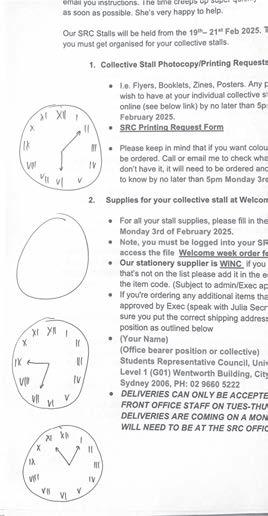

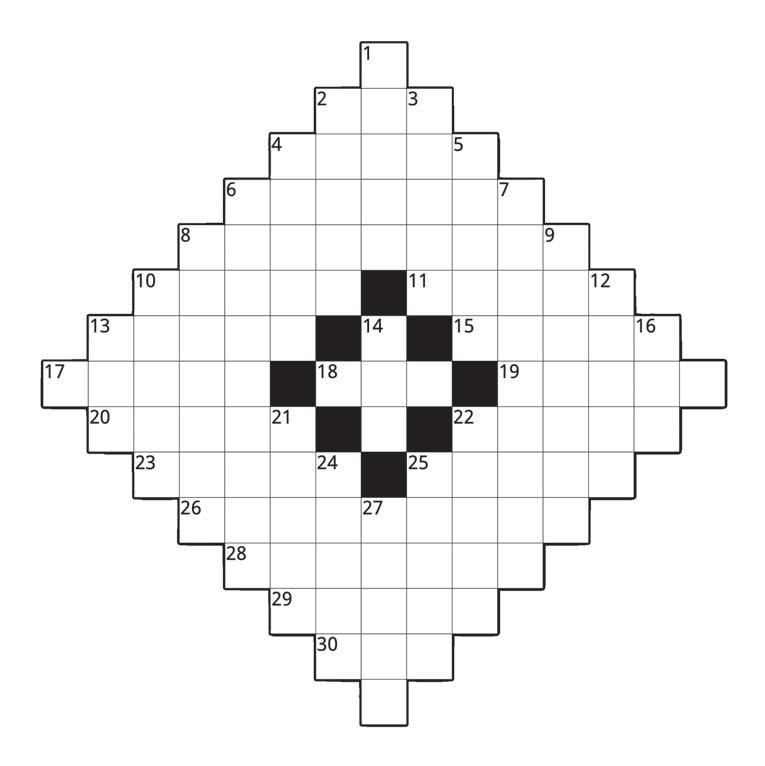

SRC Casework Puzzles

Editors

“Anyway, do you mind putting me on your front cover? I went human shopping the other day with my mother and I’m so interested in this system of yours, it’s so cool how very few

Within these pages, you’ll find Clara Tan’s Chemist Freakhouse on page 12, detailing

Companion Piece, Oscar Lawrence

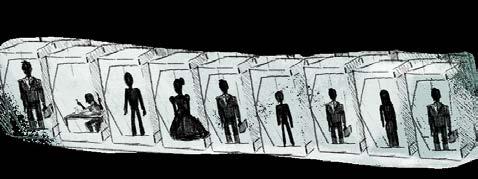

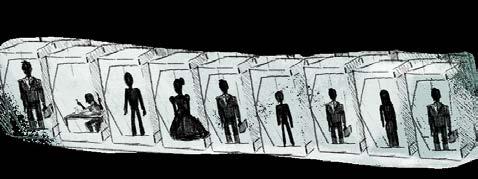

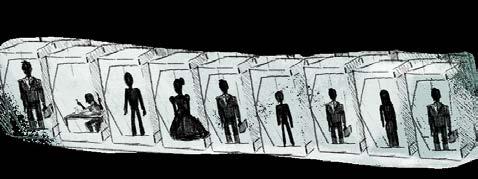

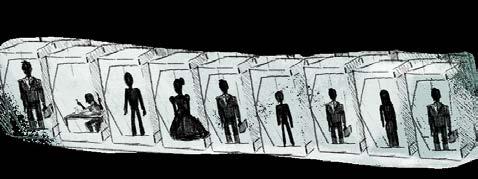

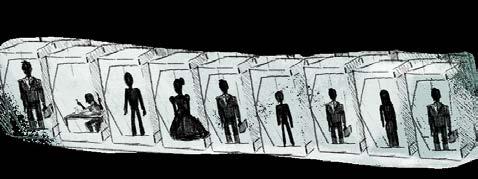

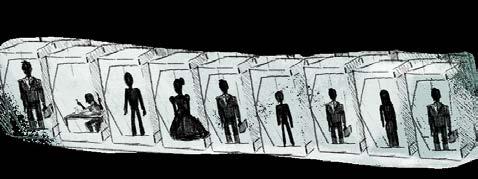

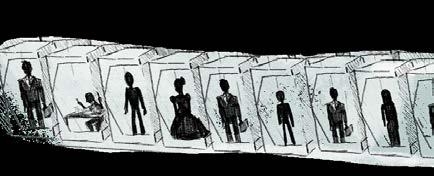

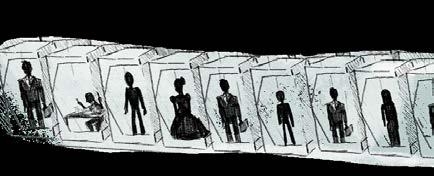

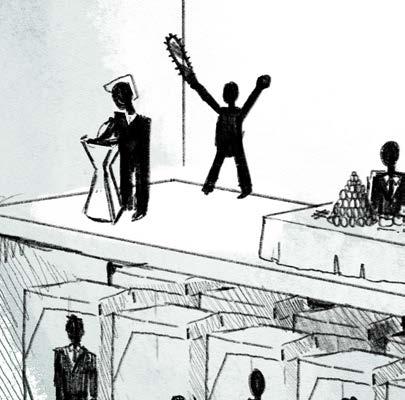

Charlotte Saker: I tasked Oscar with a very specific and detailed concept that I am so grateful he did justice. I wanted to depict the commodification of people: trapped in boxes on shelves, each shelf representing a different social class. The middle class is the most crowded, weighing down the shelf beneath it both literally and metaphorically. The idea is that no matter your class, everyone is boxed in, though some manage to escape, either because they’re wealthy enough to transcend the system, or because they’ve been left out of it altogether. The aliens introduce the conspiracy element, observing the scene as though selecting from a catalogue of humanity.

Purny Ahmed, Emilie Garcia-Dolnik, Mehnaaz Hossain, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Lotte Weber, William Winter, Victor Zhang

Front Cover

Oscar Lawrence

Oscar Lawrence: This art request had me stumped for a little bit if I’m being honest — the task of blending something so real and tangible like the class system, with the surreal nature of conspiracy theory, felt like trying to mix oil and water. I think my piece does reflect a middle ground between the two concepts, highlighting the absurdity of the existence of both. My piece exists as a sort of parody of the wellknown political caricature of the pyramid of the capitalist system, within which the working class (often represented towards the bottom of the pyramid) are forced into the Atlantean task of bearing the weight of the middle and upper classes on their back. This is reflected through

Love, Charlotte.

the toy store’s shelves, representing each class, with the boxes symbolising comfort (or, alternatively, entrapment) within the system that they live in.

I think it reflects a lot of current feelings towards class disparity and injustice, some may feel the need to use conspiracy as a form of escape from the inevitable reality of the system we live under. Alternatively, the idea that some higher power is subliminally controlling us seems, in a sense, comforting.

Gracie Allen, Sophie Bagster, Iris Brown, Ewan C, Avin Dabiri, Gian Ellis, Emilie Garcia-Dolnik, Ramla Khalid, Ting Jeng Kua, Grace Lagan, Angus McGregor, Mehnaaz Hossain, Kiah Nanavati, Marc Paniza, Amelia Raines, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Clara Tan, Faye Tang, Cassidy Turrell, Sebastien Tuzilovic, William Winter, Judy Zhang, Victor Zhang

Artists

Chloe Drougas, Deepika Jain, Oscar Lawrence, Ellie Robertson, Clara Tan, Lotte Weber, William Winter

inquiries

Dear Honey Letter to the Editor

Since I am penning this fundamentally in relation to the conflict between Israel and Palestine, let me make my position on this conflict clear at the outset. I am an undergraduate Arts student and a returning student having initially graduated in the 1970s.

I condemn the killing, torture, and oppression of any human being. As a student of history however, I can understand both actions and reactions. This does not equate with agreement. People cannot enjoy peace and co-exist in an atmosphere of hate or fear.

The meeting convened by the SRC on Wednesday, which considered motions in relation to Palestine, the definition of Antisemitism, the Campus Access Policy and the position of Usyd was conducted in a civil manner. Respect was shown to Jewish spokespeople who sincerely opposed the motions, and at no time could they be justified in claiming otherwise.

Instances of anti-semitism that they spoke about on campus cannot but be condemned and culprits should be expelled. But do our Jewish students also recognise that those Jews who differ on the conflict are castigated by their own? They are “self-hating Jews”, they are shunned in their own community, alienated within their families, and also subjected to violence by other Jews. Ask any of them who are brave enough to be outspoken – ask the Peter Slezaks. I have Jewish friends who can line up and outline how they have been treated by their own community and also threatened with violence. Provocateurs also abound –ask those who witnessed “journalists” from Murdoch’s press who descended on the Cairo Restaurant in Enmore.

So much of the current debate takes as its starting point October 2023. Why? Hamas’ actions then, can only be seen by anyone who claims objectivity and rational analysis as a reaction. A reaction to what? Ask this question. All of history is action and reaction. Let’s not be sidetracked by labels such as “terrorists,” after all, Menachem Begin, who led Israel as its sixth Prime Minister, was an Irgun self-proclaimed Zionist terrorist in the 1940s.

So does the story start with October 2023? Does it start with 1948? Does it start (as our Jewish students told us at the SRC meeting) with the Romans? These questions will need to be settled to everyone’s satisfaction but can they?

The way forward is simple in suggestion but complex in achievement. It is a situation where Jews and Muslims and Christians share the land and live alongside each other. But peace will never be achieved while illegal settlements are tolerated, and what is left for Palestinians are the scraps and while they see what were their ancestral homes before 1948, stolen and “developed” by others. This in my view, means that a two-state situation will always be tenuous. There has to be one secular democratic demilitarised state that respects the equality of all regardless of gender or religion or race.

Let me finally say that I was an undergraduate in the late 1960s and a veteran of the student movement when thousands marched down Broadway to join the Moratorium against national service of young men who were not yet of voting age. The Viet-Nam moratorium opposed the war of the industrial West against an impoverished people who sought nothing more than to determine their own future. The greatest military power on earth was defeated by people who in some cases shot down enemy helicopters with bows and arrows!

Usyd never suffered as a result of the freedom allowed on campus to protest then. The University thrived as a vital element of democratic freedom and critical thinking.

Mark Scott with your anti-protest Campus Access Policy take note. The definition of Anti-semitism issue is manipulating the university’s management.

Byron Comninos

Dear Honi,

I was the student who found love. Now I am in the process of three tragedies.

The first tragedy was the project ending. I knew that the enjoyable times of us being together would not last long, that there would be no more excuses for us to work through the night alone together ever again. So once the project was finished, the first tragedy occurred.

The second tragedy is when this subject is over. Already, I only see her at best twice a week, but with only a few weeks left of this semester, it will be over too. In this small time left, I got to know her a lot better than before, but this too will become irrelevant. As uni must go on, the second tragedy will come.

The third tragedy is still something unknown. Whether I confess and be rejected, or it be the last time I see her ever, there will be a third tragedy to my onesided fairytale. I truly am scared and depressed in anticipation for the end ofsomething that has been truly special, but as a servant of my own life, I must accept and move on. Even with tears coming straight from my heart, the third tragedy isinevitable.

To Her: I don’t think you will ever read this, but if you do, thank you for bringing joy back into my life again, no matter how brief. I really appreciate all of our time together. Live your life well, please.

With Pain But Immense Gratitude, “A student who found tragedy”

To the Student who found love,

WHAT’S ON?

Cut Ties with HUJ Rally

23rd of May, 12pm Outside F23

surgcore by surgFM 23rd of May, 7pm The Chippo Hotel

National Day of Protest: Cut Ties with Trump’s America

24th of May, 1pm Sydney Town Hall

SRC Vaccination Drive 27th of May, 9am

Let’s Talk Endometriosis Panel

28th of May, 1:30pm F23 Auditorium

You might have found tragedy, but I won’t call you the ‘student who found tragedy,’ because tragedy does not negate the love you have experienced over the last few weeks.

I respect your acceptance of the change (or as you call it, the tragedy) that is taking place in your life right now. It is a difficult thing to come to terms with, the loss of something that was so special.

That being said… Where is your solutions oriented mindset? Where is the devotion and dedication that was present in your first letter? You have a phone — get her Insta or her number. You don’t have an excuse for late night study sessions? But you are still studying, and so is she — plan an evening to just study your separate subjects together. Build a friendship, if not a romance. If this is so important to you, you will at the very least try.

Yes, you might be rejected. But like you said, that is still unknown. To not allow yourself even the chance of a friendship or something more is to limit yourself.

Don’t limit yourself.

With hope, Honey

Rumour Has It...

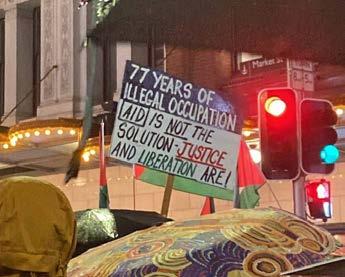

77 Years of Nakba: Thousands protest in Sydney against Israel’s Occupation

Sebastien Tuzilovic and Iris Brown report.

Thousands gathered in the rain on 15th May at Sydney Town Hall in protest on Nakba Day. This year marks 77 years since the Nakba, the initiation of the genocide with the first major displacement of Palestinian’s by Zionist settler colonialists. Between 750,000 and 1,000,000 Palestinians were driven from their homes, many murdered, many tortured and sexually assaulted. Al-Nakba, meaning “The Catastrophe” in Arabic, refers to the events of 1948, but for Palestinians the Nakba never ceased, and continues today.

Amal Naser of the Palestinian Action Group (PAG) began with an Acknowledgement of Country. Naser spoke of her family’s history and connection to the violence of 1948, emphasising that the violence and terror continues today.

Naser is the granddaughter of two Palestinian refugees who spoke to her of their witness to massacres where “no one was spared, not young, not old, not man, not woman”, where militias marched from house to house, expelling the Palestinians whose families had lived there for generations, where those seeking shelter were killed in the street.

Naser’s speech did not limit the understanding of the Nakba to a single historical event, instead explaining how it echoed throughout Palestinian history through the trauma suffered, and how the violence inflicted by Israel continues to this day. She stressed recent instances of war crimes such as the monitoring and limiting of calories entering Gaza, the bombing of food infrastructure, and the recent atrocities committed since October 7th. Her address ended with a recognition of the Australian Labor Party’s (ALP) complicity in this genocide through its inaction.

The first speaker, Fouad Charidi, was born in Al-Jalil, a village in Northern Palestine. He was just a boy when violent Zionist forces attacked, and was forced to leave his home. Charidi spoke at the rally; he has spoken at Nakba rallies in the past, sharing his story.

“If you open my heart, you will see Palestine,” he began. “It is our land, our sky, our dream which will never, never die”. He emphasised the ongoing nature of the Nakba, citing Israel’s continued ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian people and its recent manifestation last October. The current tragedy in Gaza is not the result of a war between two equal parties but a brutal occupation by Israel.

Charidi made reference to the many generations of his family that have lived in the land, stating “Jerusalem city was being built 2100 years before Moses was even born. We are not terrorists. We are peaceful people”. He noted that Palestinians have been robbed of their homeland, at the price of Israelis whose descendants are of other nationalities, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whose father was from Poland.

Damian Ridgwell of PAG, a co-chair of the rally also emphasised the ongoing nature of Israel’s relentless genocide since the Nakba. He talked of the 53,000 Palestinians killed since October 2023, and the support which the ALP provides Israel. This criticism specifically cited Penny Wong’s statements that Australia could not make determinations of Israel’s actions from afar. Damien stated that the Israeli Cabinet’s recent declaration is a clear sign that they wish to cary out genocide, deportations, and war crimes.

Renee Nayef, a Palestinian student from the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), described the Nakba as a “catastrophe upon a catastrophe”. She condemned Israel withholding food from Gaza, and assassination of journalists, particularly the murder of Hassan Eslaih and a twelve year old witness. The lack of international response, Renee said, was indicative to the fact that Palestinian lives do not matter to the world.

“We know that these murders are not the exception. They are the definition… Palestinian bodies are the foundation on which this occupation was created, and they are the foundation on which it continues to develop. And therefore there can be no other option but to fight for the end of the occupation in its entirety.”

At this point rain began to fall and umbrellas went up, many with Palestinian flags printed on them. The Greens representative of Newtown in the NSW Legislative Assembly, Jenny Leong’s acknowledgement of country focused on the shared history of settler colonialism and genocide in both Israel and Australia. Leong spoke to the Greens’ support for Palestine and the current inaction of the Labor government, pointing to the recent “hype” by conventional news media over the Greens loss of seats as nearsighted, as they attempted to brand it as an issue of dwindling Australian interest in Palestine. She stated that for the Greens, supporting Palestine was not an electoral decision, but rather a moral one. Previous speakers

had also highlighted that the Greens vote was at a historic high, and the Liberals, a party which heavily supported Palestine, lost by a historic margin. Like the other speakers, Leong stressed the continuing nature of the Nakba.

Students for Palestine member Yasmine Johnson stated the genocide in Palestine started with the blessing of all major powers, including America and Australia. “They drew the borderlines and declared their ongoing support for a state which led, as its first objective, the annihilation of Palestine…the major powers have sat and watched as over and over and over again, Israel has erased and redrawn those lines to create new brutal realities for Palestinians”.

Johnson read out extracts from a letter by Mahmoud Khalil, a legal resident of the United States and prominent figure in proPalestinian university demonstrations, who had been forbidden to see his the birth of his daughter by the United Stated Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“Why do faceless politicians have the power to strip human beings of their divine moments?” Johnson identified the root of the Palestinian suffering as a sick and twisted system that prioritises power and profit.

The march then began, past Town Hall and down through the city in the heavy rain. Musicians played Arabic music on the sidestreets, and protesters chanted and held aloft Palestinian and Lebanese flags. The protestors gathered where Pitt Street Mall meets Market Street to listen to the final address.

Dr Bushra Othman, a PalestinianAustralian and granddaughter of Palestinians who were murdered, and a doctor who had travelled to Gaza to aid at the Shuhada al-Aqsa Hospital, spoke about the attacks on healthcare workers and doctors, and of her colleagues who had been unable to help due to damage to their hospital. She emphasised the dire state of the hospitals in Gaza, stating that “all we can do is watch as patients die slowly before our very eyes”. She talked of her firsthand experience witnessing genocide. Her address concluded with reference to the martyred Palestinian dead.

“They’ve shown all of us how to wake up every single day and live with honour, dignity, and courage, they have sacrificed and paid the ultimate price. It’s time for us all to step up. Long live Palestine.”

USU Board Election Provisional Results Announced

The 2025 University of Sydney Union (USU) Board Election Results are in! This year, 12 candidates contested the election for six positions on the Board. Provisionally elected are Archie Wolifson (Independent), Sally Liu (Penta), Michelle Choy (Independent), Layla Wang (Independent), Annika Wang (Independent), and Noah Rancan (Liberal).

USU President Bryson Constable (Liberal) announced that over 5,400 members of the USU voted this year with the quota being 783 votes. While the quota is not significantly higher than the previous years which sat at 729 votes, the voter turnout was significantly higher. Voter turnout, while steadily increasing year on year, has still not reached pre-pandemic levels.

Undergraduate and Staff Fellows of Senate elected

Honi Soit reports.

After six months of vacancy, Ethan Floyd has been elected as undergraduate Fellow of the USyd Senate, the highest governing body of the university. Elected Senate Fellows serve two year terms. The 2024 election of the undergraduate Fellow was suspended following alleged ballot irregularities and a new election called for the position on 18th March, 2025. 3,848 students voted in this election.

The 2025 election of undergraduate Fellow of Senate also coincided with the election of three staff Fellows of Senate, with two fellows from and elected by academic staff members and one fellow from and elected by non-academic staff.

The two-year term of the staff Fellows begin on 1st June.

Elected by the academic staff are Professor Joel Negin and Professor Ben Saul. Negin is the Head of the Sydney School of Public Health. Saul, currently serving as one of the staff Fellows, is the Challis Chair of International Law at the Sydney Law School and the United Nations Special Rapporteur on counterterrorism and human rights.

Elected by the non-academic staff is Edwina Grose, Director of the Graduate Research School under the University’s Research Portfolio.

Charlotte Saker and Victor Zhang report.

Wolifson and Liu were elected over quota in count one. Wolifson received a primary vote of 901; Liu received 801 primary votes. Choy received the third highest primary vote and was elected in count eight. Both Layla Wang and Annika Wang were elected in count ten, each receiving a similar number of primary votes. Rancan was elected in count eleven.

Despite most candidates this year running

as independents, Honi has observed through preference deals that four of the six candidates elected, formed part of the left bloc.

In her report, USU Elections Returning Officer Simone Whetton described the campaigners’ “behaviour this year [as] the worst.” May the candidates cause more mischief on Board (within reason, of course).

Where is the outrage?: National protest against gender-based violence

Amelia Raines reports.

Content Warning: Mentions of violence and sexual assault against women.

Where is the outrage? Where is the media? Where is the USyd left? Where are the men?

On Saturday 10th May, national protests against gender-based violence took place, mourning the hundreds of women’s lives who have been stolen, and demanding government action after stagnant responses to the issue and unnerving silence on the campaign trail.

As of 9th May, 25 women have been killed in 2025, and 103 women were killed in 2024, according to Australian Femicide Watch.

Event organisers and community members remarked that various media outlets pulled out from covering the National Rally Against Violence to instead organise coverage for the newly

appointed Pope. It seems that this issue continues to recede to the bottom of the priority list of many, when it warrants unequivocal urgency. The crowd was passionate but not large enough, and predominantly comprised of women.

Organiser Jayda Khan opened the event with an Acknowledgement of Country. She commenced the speeches alongside organiser Amelia Grace Wilson-Wiliams.

“We don’t just gather as protesters. We gather as survivors.”

She remarked how the scourge of domestic violence went grossly unacknowledged by either candidate vying for Prime Minister: “We weren’t even a blip in the election. We’re here to say no more.”

She introduced feminist activist and Butterfly Foundation ambassador Mia Findlay.

“This is the third time I’ve spoken in Hyde Park”, she said. The last time she had spoken, in November 2024, protesters grieved the lives of 83 women killed that year. “In the few months since, 42 more women have been added to that tally.”

Prabha Nandagopal, a Human Rights and Discrimination Lawyer, remarked on the disproportionate reporting of women dying due to gender based violence, with deaths of women of colour continuing to be underreported in our communities.

The following speaker was Sarah Rosenberg, founder of With You We Can: a platform which assists survivors of sexual violence in navigating the justice system. She spoke to the continual failures of the criminal justice system to protect women. “Audrey Griffin’s murderer was known to police,” she said.

She spoke to the work of the Australian Law Reform

Commission Inquiry into Justice Responses toward Sexual Violence as a “step in the right direction”, with much more work needing to be done.

Wiradjuri woman and City of Sydney councillor Yvonne Weldon addressed the crowd and delivered a Welcome to Country.

She underscored the importance of a community approach: “Don’t stay silent and normalise the behaviours that cannot and should not be accepted.”

The rally concluded in solemnity, with organisers reading the names of the 103 women killed in 2024, and 25 women in 2025 as of 9th May. Attendees then observed one minute’s silence to pay respect to those who have been killed.

The National Rally Against Violence published six demands:

1. Investment in Primary prevention

2. Commitment to the

National Housing and Homelessness strategy

3. Mandate traumainformed training for first responders

4. Bail law reforms

5. Consent law reforms

6. Funding for Crisis Support services

It is incumbent on the whole community to show up against violence. Women will continue to show up and agitate until actual change is delivered — will men show up too?

If you or any of your loved ones have been affected by the issues mentioned, please consider contacting the resources below:

NSW Sexual Violence Helpline –1800 385 578

Wirringa Baiya Aboriginal Women’s Service – 1800 686 587 1800RESPECT – 1800 737 732

Read full article online.

“Every penny of our tuition fee becomes a missile fired at Palestinians”: Students vote against new definition of antisemitism at SGM

On 14th May, a Student General Meeting (SGM) was called to get student consensus on two topics: the new definition of antisemitism, and the University of Sydney’s ties to Israel.

Quorum was called at 5:20pm, with the meeting officially beginning at 5:28pm. The meeting was a formal vote on five motions:

1. Reject the new definition of antisemitism adopted by all Australian Universities

2. Endorsing the call for a single, secular, democratic state across all of historic Palestine

3. USyd completely revoke the anti-protest Campus Access Policy and commit to guaranteeing free speech and the right to protest.

4. USyd end its complicity in Israel’s apartheid regime and genocidal onslaught in Gaza

5. USyd SRC to financially and materially provide resources to support the campaigns supported in the previous motions.

Angus Dermody from Students Against War (SAW), speaking to the necessity of the SGM, said, “We are here because for the last year and a half Israel has… killed at least 50,000 people in Gaza, tens of thousands of those are children, tens of thousands are being starved to death.”

He referenced many ongoing ties between USyd and Israel, including exchange programs with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Technion, and Tel Aviv University; though he noted “We forced them to stop sending students to the Bezalel Art Academy in Israel.”

Dermody reinstated the aims of the meeting: “Cut ties with Israel, cut ties with Apartheid, cut ties with weapons companies.”

The first motion calling to reject the new definition of anti-semitism was moved by Bree, who spoke to the conflation of anti-semitism and anti-zionism as a tool used to “fearmonger Jewish students”. She reiterated the ongoing role of Jewish people in the fight against Zionism, and the separation between Judaism and Zionism itself. “Trying to smear proPalestinian protestors as anti-semitic is fighting the movement that is fighting for Jewish safety around the world.”

The first speaker against the motion spoke as a representative of the Australasian Union of Jewish Students (AUJS) and emphasised that they are elected by Jewish students from across different states. They stated that the movers of the motion at the SGM were uninterested in criticising Israeli policy but rather “interested in making Jews feel unsafe… interested in vilifying them”.

The second speaker in favour of the motion was Miriam, who spoke to the fact that this definition conflates any criticism of Israel’s actions as anti-semetic. The definition, the speaker argued, can and will be used to stop Palestinian solidarity on university campuses. She referred to UTS and UNSW as universities who have rejected the definition, and affirmed that “standing against injustice is not hate”.

The motion was then taken to a vote, and was carried unanimously.

The second motion was to endorse a single, secular, democratic state across historic Palestine.

The first speaker for the motion, Sophia, spoke about the importance of being involved in university action on Palestine and resisting complicity and complacence in genocide. “No one can be authentically human while preventing others from being so.”

The first speaker against the motion, the same speaker from AUJS, spoke in support of a two-state solution, saying “I completely agree… but I don’t see at all how one big state where everyone lives in Kumbaya, you know, everyone’s suddenly going to start loving each other, and no one’s going to kill each other anymore magically. I don’t see how that achieves self-determination for either people.”

The second speaker against the motion said “I would like for you to all look at how Hamas, a terrorist organisation, came into government in Gaza. This is just one simple example of a lack of factual information behind the things that we are voting on. You’re welcome to stand up and turn your backs on me, I won’t take it personally.” The crowd immediately stood up in unison and turned their backs on the speaker.

The motion was then taken to a vote, and was carried.

A procedural motion was moved by Dermody to move Motions 3, 4, and 5 en bloc and to wrap up the meeting with a rally at F23. The procedural carried.

The first speaker for the bloc was Jesper Duffy (QuAC). Duffy talked about the weaponisation of free speech and the use of the Campus Access Policy to censor students. “The university has told us

time and time again that this policy is for the psychosocial safety of everyone on campus, that we are allowed to dissent, but only quietly, so as not to offend the sensibilities of anyone who does not agree with us. They monitor the left-wing students on campus.”

The second speaker in favour was a First Nations student, who said “My people suffered massacres and genocidal ideology to the point where I can’t even look at my family tree two generations back because it’s gone… I came here hoping for a safe place from a really queerphobic, racist town in Queensland. And yet, what am I met with but racism, queerphobia… the threat over protesting. It is disgusting, it is sickening, and I will not stand for any of it.”

Fisher asked if speakers against the bloc would like to be given a ground reply. Seeing none, the reply was waived and the bloc was taken to a vote. The bloc was carried unanimously.

With all motions carried by an overwhelming majority, the SGM is called to a close. After the SGM, students went to rally at F23 to continue the protest.

Students held up banners that read ‘Free Palestine’, and ‘Anti-Zionism [does not equal] Anti-Semitism’. Crowded around F23, Vieve Carnsew closed the rally: “I’m going to end [the rally] with a chant that the University and Albanese have tried to ban us from chanting: From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free. From the sea to the river, Palestine will live forever.”

Read full coverage of the SGM & rally online.

Conspirare: “To breathe together”. The latin root is a poetic embodiment of harmonious human consciousness, and perhaps our oldest political act. Yet, drifting through centuries of upheaval and paranoia, conspiracy has been swept into the undercurrent of modern fear.

Conspiracy has curdled from communion into something more sinister.

Now a word defined by shadowy plots and secret cabals, conspiracy has taken root across every institution: from papal banking scandals to climate change denialism, to QAnon and election rigging. But beneath these headlines lies something stranger still. In the 21st century, conspiracy has transformed again, into the invisible lifeline of a system built on illusion: capitalism

Woah,it’s another essay on capitalism. Not.

Capitalism is often imagined as a machine: banks as gears, markets the engine, and governments the control panel. But beneath these mechanics, it runs on belief.

The belief is in endless growth, in merit as the measure of worth, and in markets as neutral arbiters of value. As The Limits of Neoliberalism, the market is not a spontaneous force but a “carefully constructed fiction”, one that has been elevated to the

legitimise inequality as deserved, exploitation as progress, and crisis as innovation. In an unstable world, these stories offer the illusion of order.

We seek stories to bring humanness to a greater sense of being. There is no such thing as time: we collectively decided thousands of years ago to experience life as a passage of years. Days, minutes, hours are constructions which weave together our experience of our plane of existence. Capitalism is the fable we choose to experience as a collective conscious. Without such a way of being, we exist in

socio-economic anarchy. Yet, capitalism begets a sense of naturalness which excuses its flaws and negates its purposeful conception.

As Naomi Klein explores in This Changes Everything, even environmental catastrophe is recast as market opportunity, disaster capitalism turning collapse into commodity. What we believe about capitalism is less about economics than about storytelling.

Conspiracy, then, is capitalism’s most seductive genre. It offers the comfort of control, the idea that there’s an author out there writing each chapter of the world, which is easier to accept than a system with no author, no centre, no exit. As Fredric Jameson famously put it, “conspiracy is the poor person’s cognitive mapping” a way of making sense of a system too abstract to grasp. It is easier to name a villain than to face the machine.

Like a conspiracy theory, capitalism explains harms such as inequality, climate collapse, and political inertia through a system that feels coordinated. There’s no mastermind, just structure where outcomes feel intentional, even when no one is in control.

Where conspiracies hide in shadow, capitalism hides in plain sight. Its genius is in naturalising itself so completely that this system is the only way of achieving ‘normal’.

At the intersection of capitalism and conspiracy is a peculiar kind of faith in explanation rather than truth. We crave stories to create order out of chaos, and while conspiracy gives us a puppeteer to blame, the real power lies in the strings. The quiet, structural forces we mistake for fate.

Much like capitalism follows the process of commodification, extraction, and alienation, conspiracy too follows a process. My favourite rendition of this is Subhendu Das’ eight-step model:

1. An activity begins, driven by organisational selfinterest.

2. It is designed to benefit business, not society.

3. It gains momentum and spreads.

4. People forget who started it and why.

5. It becomes mainstream, and dissenters are seen as foolish.

6. Society is brainwashed and cannot think otherwise.

7. The activity no longer advances humanity; it merely sustains business.

8. Negative effects emerge, but the system is too entrenched to stop without force.

Here, unethical behaviours become naturalised.

Capitalism doesn’t simply contain conspiracies: it is structured like one. Capitalists don’t meet in secret rooms, but follow a logic that is concealed by normalisation rather than abstraction.

At the core of Das’ eight-step conspiracy process is the revelation that systems designed for business interests gradually become so culturally embedded they seem natural. Think about the fast fashion industry, the Sheins and Temus of the world. Clothing is sold at prices so low they defy logic, because the real cost is offshored to underpaid workers, toxic dyes in rivers, and landfills of discarded stock.

People buy into the system because it is convenient and affordable. There is an inherent need for the existence of this ‘convenience model,’ since it is the only one many of us know. The goal is not to clothe individuals, but to sustain a business model. By the time consumers realise the environmental and human cost, the practice has already become a cultural habit. As Das notes, “You do not need a secret room for conspiracy. All you need is collective forgetfulness.”

This is how we maintain the paradox of fast fashion, this fatalistic assumption that the systems exist and are inevitable.

We can look at this phenomenon using physics. Das claims that profit violates the “sigma law” his term for the laws of conservation: “The amount of material and labor used for the product must be equal to the cost.” You must violate or cheat the sigma law to make profit. Profit is not value creation, but extraction disguised as growth: a systemic deception.

Hidden fees drain billions from consumers annually; both political parties are owned by the same capitalist interests, meaning “no matter who you elect, capitalism always wins”. Even democracy is part of capitalism’s conspiracy, an illusion of choice designed to mask an underlying lack of power.

Capitalism manufactures conspiracy theories to ensure its own survival. From celebrity culture to mass media, from consumerism to free market ideology, these stories atomise society, keep people “stupid, sick and isolated” and prevent collective revolt. “We know we are doing bad things, but we cannot escape,” Das writes. “Capitalism is pulling us down.”

Like politician Mark Fisher, who showed how capitalism absorbs dissent and turns rebellion into lifestyle, Das shows how conspiracy operates as a logic, not necessarily a secret. It is a system with no single villain, only incentives and illusions. Fisher called this capitalist realism: the belief that nothing else is possible. Das calls it organised crime against people and the land. I call it something else: the condition we live with, endured because stories help us survive the chaos.

Real conspiracies become invisible not because they are

hidden, but because they are routine. There is no mystery when it is all around us. This is how capitalism survives. Once the public forgets who started the system, why it exists, or how it profits, the process can sustain itself indefinitely. Look no further than the Vatican and its enactment of the capitalist order.

The Holy ConspiraSee

The Vatican — the Holy ConspiraSee if you will — is God’s symbol of divine order. On most days, the Holy Spirit floats around protecting the ancient fortress of earthly divinity, but in the 1980s, the Holy Spirit seemed to have disappeared for a little bit. See, the Vatican has housed one of the most complex financial conspiracies of the modern era. Behind its spiritual sanctity,the Vatican Bank, formally titled the Institute for the Works of Religion (IOR) became a hub of global laundering, Cold War funding, and capitalist ambition cloaked in the language of God.

The most infamous episode came with the collapse of Italian Bank, Banco Ambrosiano in the 1980’s, whose main shareholder was IOR. Its chairman, Roberto Calvi, dubbed “God’s Banker,” was found hanging beneath London’s Blackfriars Bridge. His death, ruled a murder, uncovered mafia links, offshore shell companies, and over one billion dollars in vanished funds. The Vatican denied responsibility, but later agreed to pay partial restitution for its “moral involvement.”

The IOR operated with little oversight. It was exempt from Italian law; its books were closed; its leaders answered only to the Pope. A 2025 Guardian report revealed that Pope Francis had inherited a “box of documents” from his predecessor, detailing the scandal in full: a symbolic passing of a systemic conspiracy from one papacy to the next.

According to Fortune, the Vatican Bank manages roughly $6 billion in assets, much of it tied to religious orders and charitable funds, and remains plagued by mismanagement. The Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project released that, despite Pope Francis’s efforts to restructure financial governance, the IOR still faces significant criticism for internal opacity and inadequate compliance.

The Pillar Catholic argues that merely treating Vatican corruption as a spiritual failing, rather than a financial and political system failure, risks enabling its continuity.

Looking at the human failings of those who claim to represent God on Earth; it’s clear the Church did not simply fall into scandal. It followed Das’ conspiracy process step by step: elite profit, public amnesia, institutional immunity. Its faith-based legitimacy became the perfect cover. In the same way we do not question the Church’s belief in the existence of God, we do not question the existence of the capitalist system that cloaks us like a hug. As Das puts it, “Capitalism is organised crime disguised as a system.” In the Vatican’s case, that disguise was moral sanctity.

They rigged my election!

Conspiracy also thrives in democratic systems, particularly through the narrative of election fraud. While there’s little evidence of large-scale rigging in countries like the U.S. or Australia, the belief in it is politically powerful. It is a belief built on tiny bricks of mini conspiracy. If we know that sabotage occurs on a small scale, it is easy, even comforting, to believe that larger actors can string together a larger narrative of malicious fraud, snatching autonomy from the hands of the voters. The creation of a larger, ‘plausible’ conspiracy of electoral deception mires our ability to see the broader construction of the capitalist system.

This netting of plausible electoral distrust transforms structural disillusionment, with inequality,

representation, or stagnant policy, into a personal grievance. When trust in journalism and science collapses, capitalism’s own chaos fills the void with conspiracy.

Right-wing media outlets such as Fox News and Sky News actively exploit this distrust. They don’t just reflect conspiracy narratives, they help build them.

PBS NewsHour has detailed how post-2020 election denialism spread via coordinated misinformation, boosted by algorithms and monetised outrage.

What’s striking is that the real conspiracy often doesn’t happen through ballot-stuffing or hacked machines, but through legal, systemic manipulation. In How to Rig an Election Cheeseman and Brian Klaas show how authoritarianleaning governments undermine democracy through more subtle means: gerrymandering, voter suppression, media capture, and weaponised bureaucracy. It’s about engineering outcomes before votes are even cast.

This logic extends beyond the U.S. to Australia. In the lead-up to the 2022 federal election, Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party spent more than $100 million on targeted ads that stoked distrust in both major parties, established vaccine policy, immigration policies framed as threats to “Australian values,” and the electoral process itself. Palmer’s campaign, though comically unsuccessful electorally, helped flood the information space with confusion and suspicion. Meanwhile, groups like Advance Australia have echoed the rhetoric of stolen elections and “woke elites” borrowing directly from the Trumpian American far-right playbook.

According to Monash Lens, Australian conspiracy movements have increasingly adopted QAnon-style language, reframing everything from public health to voting logistics as ‘elite sabotage’. Despite repeated factchecks from RMIT FactLab and the Australian Electoral Commission, myths about ballot harvesting, digital voter manipulation, or globalist interference continue to circulate.

These beliefs persist because they offer a comforting narrative. The danger is that when real electoral threats of corporate influence, political advertising loopholes, or fake news arise, they’re harder to address in a landscape clouded by manufactured paranoia. The myth of rigging becomes a tool not of revolution, but of reaction. And capitalism remains untouched, protected by the fog.

The world’s on fire

Perhaps no conspiracy better captures capitalism’s evasive genius than the one surrounding climate change. Denial is no longer fringe, it’s a coordinated survival strategy. For decades, fossil fuel giants like ExxonMobil funded misinformation campaigns, not to disprove climate science, but to delay regulation and buy time.

These campaigns planted just enough doubt to paralyse political will. Right-wing media reframed climate action as a threat to personal freedom and national identity. Climate change became a culture war. The science, too complex or too confronting, was replaced by digestible narratives: the electric car as saviour, the metal straw as rebellion, the “woke elite” as villain.

As Berkeley News notes, “Scientific papers are hard to understand… you’re more likely to believe someone you trust in your community.” In the climate space, this often means influencers, YouTubers, or TikTok creators repeating

misinformation dressed up as relatable content. Not because they’re malicious (sometimes), but because capitalism rewards engagement, and nothing engages like conspiracy.

Meanwhile, capitalism rebrands the crisis as opportunity. Enter green capitalism: the idea that we can consume our way out of collapse. Corporations sell sustainability while continuing to extract. Take Shell PLC; the oil giant sponsors climate conferences and advertises net-zero goals, even as it expands fossil fuel projects and lobbies against reform. Its ads turn public relations into moral cover. The story looks green, so no one asks about the emissions.

Coca-Cola, regularly named one of the world’s worst plastic polluters, markets its bottles as recycled and pledges to recover every one it sells. Yet it continues to produce billions of single-use plastics, most of which will never be recycled. The branding promises a circular economy; the reality is landfill.

These aren’t just hypocrisies, they are stories crafted to redirect scrutiny while business continues as usual. There is no denial, but misdirection.

So keep monetising, narrativising, and redirecting the destruction. Critique is welcome too, as long as it never demands real change. As Mark Fisher writes, “Far from undermining capitalist realism, this gestural anticapitalism actually reinforces it”.

The ultimate conspiracy isn’t that climate change isn’t real. It’s that capitalism wants you to believe you’re solving it, just don’t ask the wrong questions.

When I looked up the origin of “conspiracy” and that smug AI box told me it meant “to breathe together”, I couldn’t stop thinking about how time distorts everything; meaning, values, and of course, capitalism. Once a beacon of freedom and individuality, it now turns life into a commodity. Maybe we’ll get that ‘sustainable capitalism’ everyone keeps promising. Or maybe we just have to move forward with the freedom we have as best we can.

If stories have kept capitalism alive, maybe alternative ones can infect it.

Art by Oscar Lawrence.

On Art and Bearing Witness: Ahmed and Sakr on the Nightmare Sequence

“They try to silence us, but Palestine is everywhere, it’s even in the silence.”

— Lucia Sorbera

On 7th May, there was an invitation to participate in collective witness-bearing at the University of Sydney. Lucia Sorbera, chair of the Discipline of Arabic Language and Culture, as well as Professor of History, Michael McDonnell, hosted a panel on The Nightmare Sequence in conversation with Safdar Ahmed and Omar Sakr. The Nightmare Sequence is a collection of poems and artworks that bears witness to violent injustices; it is a testament to truth, a refusal to succumb to an erasable digital and cultural memory as well as the continued attempts to dehumanise Palestinians, and a collaboration that is committed to detailing the necessity of continued decolonisation across transnational bounds. It is a work that documents the insidious span of the Western empire beyond Palestine, alongside the cruel impacts of such: the collective grief, the destruction of an ideal of common humanity, and the dislocation of communities across the globe. It is truly devastating and a necessary read that ensures the violence of the Zionist entity and its Western allies will never be forgotten. Reading The Nightmare Sequence is a powerful punch to the gut, and it has never been more urgent to engage with works that continue to bear witness to violence mercilessly inflicted, on a scale never before seen in human history, against an innocent population.

Ahmed has emblazoned many of his artworks with the stamp ‘Genocide Culture’ as a term that both explicitly refuses the narrative of 7th October 2023 that decontextualises over 75 years of Israeli occupation, and holds to account Australian and broader Western continued complicity in the colonisation of the so-called Middle East. One jarring image in the book, imprinted with the term, references the Sufafend Massacre. In 1918, occupying Australian, New Zealander and Scottish soldiers committed a massacre against the citizens of the Palestinian village Sarafand Al-Amar, killing between

40 and 137 civilians. Speaking to the term, Ahmed said: “On one hand, it’s bad enough to see a genocide on our phones in such an unprecedented way, often by people filming [the horrors of] their own deaths. It’s shocking and horrifying. But, as an artist, a deeper horror came from feeling the inertia of our leaders and our media to tell the truth. The indifference in Australia’s political and media [landscapes].”

Contextualising the work, Sorbera noted the tradition of poetry across the Arab world, particularly elegies to commemorate the prophet Mohammed, and located the book as following “[the] footsteps of this long tradition.” In response, Sakr commented on the role of the Arab poet to lament and the value of cultural resonance beyond borders. He said that “[The Nightmare Sequence] is a continuation of my work, not an aberration”, that continues to discuss the violence reaped by the Western empire on Arab lands. Sorbera then probed the utility of art in the face of genocide, to which Ahmed responded that art constitutes “[an] informal counter discourse to the way Palestinians are commonly framed, [that is] through a dehumanising lens.” He notes that alongside horrifying images of genocide, there persist such powerful images of compassion. Directly referencing Hind Rajab, Ahmed said that “millions of people are sharing these [humanising] images, which is an important re-interpretation. Many of my pictures were in the spirit of those images.”

This too has manifest political implications in the domestic Australian context, as Ahmed noted the collapse of “every institution in our society due to the silencing of what is happening.” He directly referenced Antoinette Lattouf as an accomplished journalist unjustly penalised over support for Palestine. Ahmed further said that “the [media] cowardice is appalling because what is [the job of the media] if not to talk about [genocide]. If you can’t connect inequality here to the more global context of colonisation, genocide, and apartheid in Palestine, then what worth is it? Art has some help in opposing that. I’m sick of light installations that say fuck-all about this historical moment.”

Emilie Garcia-Dolnik writes.

To the same question, Sakr spoke to his own craft, bringing the question to the broader global context, where “poets are imprisoned around the world. In the global south, they are among the first to be imprisoned. One reason is because of the immediacy and reach to the masses, [as well as being] easily memorisable, aimed at the power of dictators and the ruling class.” To the audience he said that “all of us have a responsibility. We are using art in this way because we are artists. Whatever you do, use your leverage.” Sakr had his own poetry workshops cancelled last year following a Zionist smear campaign. Speaking about the experience, he said that “safety was the context for the cancellation of my workshops. It’s frightening to be gaslit every single day, by authorities using authoritative language. One day they will pretend that they weren’t saying these things, but we can prove it.”

In this realm of the imaginative future, Sakr and Ahmed expressed a cautious hope. Sakr was quick to acknowledge “we still have Nazis. A significant proportion of the population is celebrating [genocide]. [We can be] deliriously hopeful”. He continued, “The entire [human rights] framework has been pushed to a point of crisis. Race is being the thing that has cracked it open… We need decolonisation. This genocide cannot be forgotten. We have to fight from here.” He reminded the audience that “student resistance for Vietnam was not quick. It happened over several years.” Ahmed also urged the necessity of activist collaboration, and the marriage of scholarship and academic grounding in literature with activism to all students in the room. If nothing else, heed these words and let them spur you to act.

Sakr and Ahmed have crafted an incredible book that is truly horrifying and necessary. It is a potent reminder of the power we all possess to counter violence and dehumanisation through the act of bearing witness and acting in solidarity. All proceeds from book sales go to Palestinian charities. Honi urges all readers to support The Nightmare Sequence or donate directly.

The Death of Reason: How QAnon Reveals Our Post-Truth Reality

When philosopher Jürgen Habermas conceptualised the public sphere, he envisioned a space where citizens engage in rational discourse to reach consensus about social and political truths. This ideal rested on the assumption that participants would evaluate evidence, recognise logical arguments, and modify their positions accordingly. Today, that foundational premise lies in ruins. The rise of QAnon, a conspiracy theory claiming a secret war between Donald Trump and a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles, represents not merely a fringe belief system, but the collapse of this shared epistemological framework.

The QAnon phenomenon reveals a profound truth: the rational citizen, the cornerstone of democratic theory, has always been more mythological than real. The discourse process isn’t simply a disagreement about facts, but constitutes competing realities operating with fundamentally incompatible methods for

determining truth itself. The movement’s rapid growth from obscure 4chan posts in 2017 to a political force that helped fuel the Capitol insurrection demonstrates the fragility of the rational public sphere in an era where algorithmic media has replaced traditional information gatekeepers.

Within just three years, Q’s cryptic messages spread from anonymous message boards to mainstream platforms, finding receptive audiences among religious communities, suburban parents, and eventually elected officials. This wasn’t mere viral spread but a systemwide failure of our information ecosystem, where social media platforms optimised for engagement amplified the most emotionally resonant claims while factchecking remained isolated in increasingly distrusted legacy media.

We comfort ourselves with the belief that humans are fundamentally rational creatures — that given the same evidence,

reasonable people will reach similar conclusions. QAnon demolishes this comforting fiction. Most disturbing about QAnon isn’t that its adherents reject facts, but that they believe they are the true rational actors, the ones who’ve ‘done their research’. This self-perception as researchers is contradicted by their methodological approach, which relies heavily on confirmation bias rather than falsifiability, and their rejection of expert consensus in favour of anonymous, unverified sources.

They’ve developed elaborate methodologies to decode “Q drops”, the cryptic messages posted by the anonymous figure known as “Q” on platforms like 4chan and later 8chan/8kun. These drops, often written in an intentionally vague and ambiguous style, contain what followers believe are coded intelligence revelations about government operations and coming events. The very first Q post from 28 October 2017 on 4chan’s /pol/

board exemplifies this pattern. It alluded to an imminent extradition of Hillary Clinton, claimed her passport would be flagged, and predicted riots and people fleeing the country. Despite none of these events materialising, followers didn’t abandon their belief in Q. Instead, they reinterpreted the message in ways that preserved Q’s credibility, shifting timelines or claiming these actions were happening secretly. QAnon adherents spend countless hours analysing these posts, looking for patterns, timestamps, and connections to Trump’s tweets or public statements, creating complex systems of pattern recognition that mimic academic research. They call themselves ‘digital soldiers’ engaged in ‘information warfare’, assembling what they see as evidence into a cohesive worldview.

This isn’t mere ignorance. It’s an alternative epistemology, a competing framework for determining what counts as truth. The QAnon phenomenon shows how

Why UTIs Are Every Woman’s Worst Nightmare

Kiah Nanavati wants a solution better than craberry juice.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are often relegated to the sidelines of medical discourse, treated as minor, routine, and easily fixable. Unfortunately, for millions of women, this couldn’t be further from the truth. UTIs are one of the most common bacterial infections worldwide, disproportionately affecting women due to their anatomy, and their recurrence rate means many women live in fear of their next episode. Questions of dread flow through their mind: ‘When will it happen?’ and ‘How bad will it be?’ Behind the clinical terminology and cursory treatment lies a world of discomfort, disruption, and emotional exhaustion — one that is too often invisible.

An Epidemic Hiding in Plain Sight

Statistics show that over 50 per cent of women will experience a UTI at least once in their lifetime, with nearly a third suffering a recurrent infection. The numbers alone should be enough to raise alarm, but UTIs remain under-discussed and under-researched in broader medical conversations. Why? Because they are seen as commonplace: a “women’s issue” that is uncomfortable but ultimately harmless. This perception is not only inaccurate, it’s dangerous.

The consequences of untreated or mismanaged UTIs can be severe.

What starts as a burning sensation during urination or an urgent need to pee can escalate to a kidney infection (pyelonephritis), or in extreme cases with the worsening of symptoms, sepsis — a potentially fatal immune response.

The delay in appropriate care, often due to diagnostic oversights or lack of awareness, contributes significantly to these outcomes.

The Biology of Inequality

One of the reasons UTIs are so prevalent in women is simple biology. Women have shorter urethras than men, making it easier for bacteria (typically E. coli) to travel from the urethral opening to the bladder. Additionally, hormonal changes, particularly during menopause or pregnancy, can influence the balance of vaginal flora, further increasing susceptibility. Yet this biological vulnerability is often used to normalise infection rather than prompt better prevention and care.

What’s more troubling is the cycle that recurrent UTIs create. Women who experience one are significantly more likely to experience others, and each recurrence brings with it not just physical discomfort but mounting emotional strain and anxiety. The dread of another infection can alter behaviours, from how one engages in intimacy to how frequently one uses public restrooms, subtly but significantly eroding quality of life.

Misinformation and Medical Neglect

Women who present with UTI symptoms are frequently met with outdated advice: drink more cranberry juice, wipe from front to back, urinate after sex. While these tips may have some credibility, they often serve as band-aid solutions rather than comprehensive medical responses. Worse, some women report being dismissed by healthcare professionals, particularly when infections recur, or when tests return inconclusive results.

Antibiotic resistance has also complicated treatment. UTIs are bacterial and therefore antibiotics are the frontline response. However, overprescription, or inadequate dosing, has led to increased resistance, making some infections harder to treat. This not only prolongs pain but also increases the risk of complications. Furthermore, patients are often left in the dark about why infections recur or how to prevent them beyond general hygiene.

The lack of funding for women’s urinary health research further compounds the issue. UTIs are often categorised under general urological conditions, with limited distinction made for gender-specific impacts. Consequently, innovations in diagnostics, treatment, and prevention lag behind, leaving many women reliant on the same therapeutic tools that their mothers used decades ago.

The Emotional Toll

While the physical symptoms of UTIs are well-known — pain, burning, urgency — the emotional and psychological impact is vastly under-acknowledged. Women with recurrent UTIs often describe feeling embarrassed, ashamed, or isolated. The unpredictable nature of infections can interrupt daily routines, strain intimate relationships, and cause significant mental stress. For those who endure repeated medical visits, tests, and misdiagnoses, feelings of helplessness can deepen.

This “silent agony” is what makes UTIs more than a health inconvenience. It’s a recurring threat to autonomy, confidence, and emotional well-being. Many women living with recurrent UTIs report feeling trapped by their bodies, with the fear of unpredictable infection recurrence impacting daily life. This anxiety is often intensified by a broader sense of dismissal from healthcare systems and society at large.

Calling for Change

What’s needed is not just better treatment, but a cultural and medical shift in how we perceive, and prioritise UTIs.

Healthcare providers must be trained to take symptoms seriously, especially when dealing with recurring cases. Faster diagnostic tools, personalised care plans, and alternative therapies to antibiotics must be developed and made accessible.

But systemic change also starts with public awareness. Just as endometriosis, PCOS, and menopause have recently entered mainstream health discourse, so too must UTIs be part of an honest conversation about women’s health. Normalising the discussion can break down stigma and lead to more compassionate, informed care.

Women deserve to live without fear of an infection that society has minimised for too long.

By shining a light on the hidden burdens of UTIs, we can empower women to demand better: from their bodies, their doctors, and their healthcare systems.

the very concept of rationality has become weaponised. Both sides of our political divide now claim the mantle of rationality while dismissing opponents as irrational, emotionally driven, or ‘triggered’. Mutual dismissal makes genuine dialogue impossible, instead pushing people deeper into informational echo chambers where their beliefs go unchallenged, further fragmenting the Habermasian public sphere.

For decades, trusted institutions like the media, academia, and science served as arbiters of shared reality. These gatekeepers are now crumbling under sustained attack from multiple directions: economic pressures that prioritise clicks over truth, political efforts to undermine institutional credibility, and technological platforms that flatten distinctions between experts and amateurs. The result is an epistemological vacuum where conspiracy theories can flourish.

‘Do your own research’, a QAnon rallying cry, sounds reasonable enough. In practice, it means rejecting traditional knowledge authorities in favour of YouTube videos, anonymous imageboards, and social media echo chambers. When institutional trust collapses, the vacuum is filled by those who speak with absolute certainty, offering simple explanations for complex problems.

QAnon flipped traditional epistemology on its head: rather than evidence leading to conclusions, followers start with the conclusion (the cabal exists, Trump is fighting it) and work backward to find supporting evidence. Any contradicting information is dismissed as disinformation, part of the conspiracy itself. As Q cryptically puts it: Disinformation is necessary. This self-sealing quality makes QAnon nearly impossible to refute for those already inside its reality tunnel.

Our information ecosystem further exacerbates these tendencies, designed not for truth but for engagement. Platforms like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter don’t optimise for accuracy — they optimise for emotional response. The algorithms that govern these spaces don’t distinguish between true and false rather amplifying content that triggers strong reactions. Content that makes us feel righteous anger, moral superiority, or existential fear spreads faster than nuanced analysis or uncomfortable truths.

QAnon exploits this perfectly. Their narratives tap into: fear of child exploitation, distrust of elites, and hope for justice. Each new Q ‘drop’ functions as a cliffhanger, keeping followers perpetually engaged as they await the next revelation. By casting followers as heroes uncovering hidden truths, QAnon provides meaning and community to those who feel alienated by mainstream society.

The uncomfortable reality is that QAnon reveals the fundamental flaws in how we conceive of human rationality. We are not primarily logical creatures who occasionally succumb to emotion. We are emotional creatures who occasionally use logic to justify what we already believe.

Understanding this isn’t about excusing dangerous conspiracy thinking. It’s about recognising that addressing our posttruth crisis requires more than simply providing ‘facts’ to the ‘misinformed’. It requires rebuilding systems of shared reality and trusted information, a project that may define the coming decades of our democracy. The real question isn’t why some people believe in QAnon, but whether any of us can truly claim to be the rational citizens that we imagine ourselves to be.

“You go to the places you don’t want to go to”: Inside the rental crisis facing older Australians

Grace Lagan reports on the experiences of Australia’s older renters.

Rob* calls me just after his latest rental inspection, which has thankfully gone well. “The [property manager] was actually decent, they didn’t pick on having some laundry on the couch or whatever.”

He’s seen the full gamut of landlords and realtors over the years. Now in his late forties, Rob has been renting since he was 19. While he’s worked on and off, the disability pension has been his major source of income since he left home. Rob is currently living in a major regional centre in Victoria. He will be renting until he gets off a social housing waitlist, which, in his estimation, may take seven to ten years.

The other option is to purchase a home using the money he stands to inherit upon the death of his ageing father. “Sadly, it is [factored into my lifeplanning]. I don’t want it to be. That’s the only way I’ll ever get out of renting.”

“The current rental market is awful”, said Jamie from South Australia. “I am self-employed with a low income, so I expect that I will be renting for the rest of my life.”

While the major parties spruik policies to support younger Australians into home ownership, Rob and Jamie are part of a growing cohort of older renters forced to compete in an increasingly expensive private rental market that often doesn’t cater for their needs.

Renters over 60 now make up around 12 per cent of the Tenants’ Union of NSW’s advice and advocacy caseload. That’s “almost a doubling” on the figures six years ago, according to Tenants’ Union CEO Leo Patterson Ross. He notes the upward trend has been observed across housing providers and advocacy bodies, including homelessness services. “They’re also seeing similar increases in [the number of] older people who are struggling because they have been renting”.

Reporting on the housing crisis tends to focus on the plight of millennials and Gen Zers, locked out of home ownership by the invidious interaction between rising dwelling prices and paltry wage growth. Implicit in these accounts is the treatment of home ownership as the best — or as economists would say, optimal — mode of accommodation. We tend to take this assumption for granted but like many national myths, the ‘Australian Dream’ of home ownership is not so much founded on collective aspiration as it is on a set of specific and entrenched policy settings.

This phenomenon has been recognised since at least the mid-1980s, when public policy academic Francis Castles published his influential history of the Australian welfare state, The Working Class and Welfare. In Castles’ account, Australia’s historically robust industrial relations system and redistributive wage regulation allowed for the development of a “wage-earner welfare state”. Under this system, most people had high enough incomes to buy their own homes early in their working careers and pay them off by retirement. This meant that welfare benefits like the Age Pension were set at lower levels, because they arguably didn’t need to account for accommodation costs.

You don’t need an economics degree to recognise that times have changed since then. Trade union membership has dropped precipitously, wage growth has slowed, and rates of home ownership have declined from their post-war peak. What hasn’t changed is the assumption that welfare benefits

don’t need to cover accommodation costs, despite research from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute showing that if rates of outright home ownership declined, Australia’s pensioners would be some of the poorest in the OECD.

There are significant individual, systemic, and fiscal consequences for our nation’s reliance on private homeownership — consequences that older renters are already beginning to experience.

Married Brisbane couple Katie and Adam both owned homes in previous relationships which they sold in their respective separations.

“If we owned our own place it would be bliss”, Katie said. “[It would be] a place to grow old and raise our grandchildren together and it hurts me that I have to rent”.

The couple are now considering moving to Bangkok to escape the expense of the Brisbane housing market. Unable to save for a deposit while also paying rent, Katie is also worried that they won’t be able to retire if they stay, given they “haven’t had superannuation [their] whole lives.”

Patterson Ross also notes the particular difficulty faced by renters who haven’t earned superannuation over their entire working careers. “They haven’t had as much time to build up a large pool,” he said. “Particularly for older women, we see people who might have almost no super and so they really are reliant on the Age Pension, which is, I think, recognised as not adequate, particularly for renters.”

Reliance on income support payments also limits renters’ choices of where to move. “When you’re renting on Centrelink, you go to the places you don’t want to go”, Rob said. “You go to places where the crime rate is high, or where you’re hours from the major cities.”

It can also complicate applying for private rentals. Rob notes that most lease applications will only ask if the individual is employed or unemployed, requiring him to extensively explain his source of income. “A lot of landlords will look at someone with a pension and go, ‘no’.” This is despite the fact that, as he argues, his income under the disability pension is effectively “guaranteed”.

Of course, not all benefits are created equal, and older renters may be left in the lurch if they are forced to suddenly rely on a lower rate of payment.

Rob’s elderly mother is also a renter, living in South Australia with Rob’s stepdad — we’ll call them Anne and Michael. The pair are able to afford a rental property for just the two of them because Michael receives the Veteran Payment, a benefit paid at a higher rate than all other income support payments bar ABSTUDY.

Rob worries about what will happen to Anne when Michael dies. “When he passes, she will have to get a roommate. That’s depressing.”

While moving out with flat mates might be a rite of passage for younger renters, older renters are understandably more averse. “There are young people on job seeker who really wouldn’t like to be in a sharehouse, but there’s a broader number of young people who are more comfortable,” notes Patterson Ross. “It sort of feels more normal, whereas for an older person, it can feel more confronting and uncomfortable.”

“I don’t want to have to share someone’s house at this age, I don’t want to have to do housemate things”, said Rob. However, with rental prices on the rise, sharing is beginning to become a necessity for some older renters. While currently living alone, Jamie has previously “shared accommodation with different people four times”. Katie and Adam have “no choice but to have a boarder”.

Older renters are also likely to face more difficulty moving. “Health and mobility issues [narrow] the suitable rental buildings available,” said Jamie. “The stress and physical efforts involved with frequent moving from 12-month and other short-term leases is also more difficult.”

Patterson Ross also notes that older rents may have “more ties to a particular community or location that are harder to replicate”. This can lead to difficulty accessing “medical assistance, but also social supports as people’s mobility and different aspects of their health decline.”

“We’ve seen this particularly in relation to public housing or social housing relocations, but also in the private rental market as well. Someone with Alzheimer’s will really struggle to change location. When [they] have to move home, it’s really disruptive to their ability to continue to live independently.”

As both Rob and Patterson Ross acknowledge, older generations aren’t the only demographic struggling in Australia’s private rental markets. “The worst combination [for renting] is to be someone young and on low income”, Rob argues. I am struck by his empathy for younger renters, in spite of the generational wars we’re constantly told are raging.

When asked about whether they believed the newly re-elected Labor government would take action to fix the housing crisis, none of the renters were completely convinced substantive change would be realised.

“I am hopeful something will be done. They’ve promised more public housing and the first homebuyers scheme looks to have promise.” Rob said, but he worried that builders and developers would be able to exploit smaller-scale, demand-side reforms to “jack the prices up.”

Jamie and Katie both considered the prevalence of investment property holdings among politicians on both sides of the aisle to be a barrier to substantive political change.

“I doubt that any significant changes will be made to help renters, especially given that they have already backed off of overhauling negative gearing and capital gains tax,” Jamie said.

In a call back to the Castles thesis, Patterson Ross suggests the problem could be solved by ending Australia’s fixation with home ownership.

“If we made renting better and made it more attractive, it would actually ease the pressure on owner occupation. I think at the core we need to make sure that renting is a viable option for people for their whole lives, because it is”, he said. “There are a number of reasons and situations where people aren’t going to be able to buy, That doesn’t mean they shouldn’t have some stability, some dignity in their homes”.

* The names of some interviewees have been changed to preserve their anonymity

Euro-blind

It’s that time of year again. The sea of flags illuminated by bright lights, the slightly dated Europop bangers with bizarre staging, and of course the wind machines, are all back once again for another year of Eurovision. Eurovision is a lot of fun, and it claims to be an apolitical competition but, as we know, claiming to be apolitical is in itself a very political stance. In an international opinionbased competition like Eurovision, it is impossible for it not to be.

Eurovision by nature projects the values of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and by extension the European Union (EU); thus, political entries which promote these values are often overlooked and not policed. Songs campaigning against war, such as Hungary’s 2015 entry ‘Wars For Nothing’ and 2020 Polish entry ‘Empires’ in support of climate action, sing about heavily politicised topics. However, they align with the goals and values of the EBU and the EU hence they are let off the hook.

This is most clearly expressed through the competition’s inclusivity, especially of the LGBTQI+ community. As early as 1961, gay man Jean-Claude Pascal won for Luxembourg. The most successful song in the competition’s history belongs to intersex competitor Salvador Sobral. Drag Queens Conchita Wurst and Verka Serduchka, Bicons Loreen (singer of Euphoria and Tattoo), as well as Duncan Laurence (singer of Arcade) and largely queer band, Måneskin are all examples of queer competitors who have won or come second in Eurovision, and have received global recognition from the competition. Last year queer artist Nemo won with a song about their

Red-Haired Phantasies: