Honi Soit operates and publishes on Gadigal land of the Eora nation. We work and produce this publication on stolen land where sovereignty was never ceded. The University of Sydney is a colonial institution. Honi Soit is a publication that prioritises the voices of those who challenge colonial rhetorics. We strive to continue its legacy as a radical left-wing newspaper providing students with a unique opportunity to express their diverse voices and counter the biases of mainstream media.

Hello! Welcome to the 2025 edition of Disabled Honi!

In This Edition...

Khanh’s Work on the Disco Space

Unwelcoming Borders

Welcoming Disability

Mask Up

Climate & Disability

Spina-bifida

Poetry

Indigenous Disability Studies

SRC Casework

Puzzles

Editors

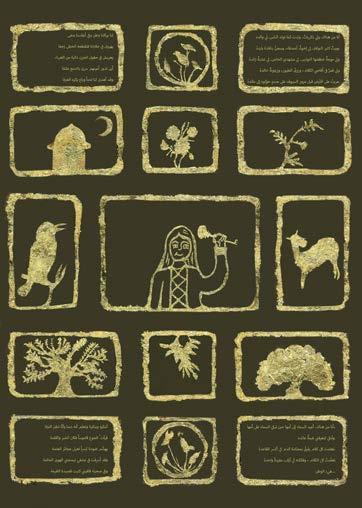

Our front cover by Dana Kafina (@biteapearl) is an artwork of our dear late friend Khanh Tran who put their heart, soul, and being into Honi Soit and DisCo. For your dedication to journalism, community, and disability justice – we dedicate this edition to you Khanh. We love you and miss you so much.

Many of us have found it hard going back to the Khanh Tran Room (previously known as the Disabilities Community Room) in Manning House. In the most nonchalant way, you would always be sitting there typing away on what was likely another erudite investigative piece all while maintaining a welcoming presence to whoever entered. We urge readers to read Carmeli’s beautiful piece on Khanh and their legacy on page 6.

The past year has been transformative for disability activism in Australia. Our community has shown up with unwavering solidarity for Palestine, recognising the intersectionality between disability justice and anti-colonial struggles. We’ve witnessed how disabled Palestinians face compounded barriers amongst the genocide, reminding us that disability justice must be global in its outlook.

We’ve celebrated the establishment of the USU Disability Inclusion Action Plan, promising to make student life accessible and inclusive. These consultations were important in ensuring lived experiences are central to policy development.

The significant assessment changes on the horizon embed Universal Design for Learning principles into assessment policy

Companion Piece, Dana Kafina Vale, Khanh.

Thank you to the Disabled Honi team for trusting me to make this artwork. I was a bit nervous, but I hope that it reflects the love all my comrades have. I see you all and adore you.

Khanh, thank you for every random info-dump you’ve given, thank you for every sweet treat or cosmetic, thank you for constantly exercising your free will and using it for joy (and Nintendo games in

Contributors

Purny Ahmed, Martha Barlow, Eko Bautista, Kayla Hill, Dana Kafina, Remy Lebreton, Gemma Lucy Smart, Grace Street, Vince Tafea, Tanish Tanjil, Lotte Weber, Victor Zhang

and design. We are actively involved in these consultations, advocating for flexibility, multiple means of engagement, and recognition of diverse learning styles; a significant shift from accommodations as an afterthought to accessibility as a foundational principle of education.

As we reflect on these developments, we’re reminded that disability activism is not just about fighting against barriers but also about imagining and creating more accessible futures: “Nothing about us without us.”

We thank all contributors, editors, and artists that made this edition possible. We hope you enjoy the product of the immense talent of the disabled community at USyd.

This one’s for you Khanh.

Ethnospace), for hyping me up when I felt insecure about my art, and for your incorrect takes about Boruto (I’m sorry, but the original Naruto remains superior), thank you for side-eyeing people with me at Palestine rallies when they randomly jumped at media opportunities.

What a privilege to have known you, however brief. Your memory is a blessing. Vale.

Purny Ahmed, Carmeli Argana, Martha Barlow, Eko Bautista, Pia Curran, Emilie GarciaDolnik, Kayla Hill, Mehnaaz Hossain, Remy Lebreton, Marc Paniza, Ellie Robertson, Mahima Singh, Gemma Lucy Smart, Jessica Louise Smith, Grace Street, Vince Tafea, Tanish Tanjil, Lilah Thurbon, Indiana Zezovski, Victor Zhang, William Winter

Martha Barlow, Dana Kafina, Remy Lebreton, Luke Mesterovic, Mahima Singh, Jo Staas, Grace Street, Vince Tafea, Tanish Tanjil

Crossley, Celina Di Veroli, Hamish Evans, Leanne Rook, Daniel Yu, and Sunny Shen.

advertising inquiries to publications.manager@src.usyd.edu.au.

9th April, 2025

Dearest gentle reader,

It is with the softest whisper — and the sharpest implications — that yours truly reports the quiet departure of Sir Antone Martinho-Truswell, steadfast Dean of St Paul’s College Graduate House. And as with all departures in polite society one must ask: is this merely the closing of a chapter… or the discreet erasure of a radical tale?

Since its founding in 2019, Graduate House was an anomaly — a bold, breathing challenge to tradition nestled within sandstone. While the main halls waltzed to the familiar rhythm of prestige and pedigree, this little house welcomed scholars of another kind: single mothers, First Nations students, disabled academics, international researchers, and those unacquainted with inherited privilege. Under Mr. Martinho-Truswell’s quiet leadership, it flourished — an academic sanctuary where purpose outweighed lineage, and scholarship was measured not in legacy, but in passion. For the first time in the university’s storied history, a residential college community dared to mirror society’s true diversity. Accessible fees, generous scholarships, and a culture of intellect over image made Graduate House not just rare, but revolutionary. Unlike grand gestures so often made for appearances, Mr. Martinho-Truswell led with quiet conviction, not performance.

But, dear reader, as we are well aware… progress is a fragile bloom. And those who fear its fragrance are rarely idle.

With Mr. Martinho-Truswell’s departure, no succession plan has been offered. Instead, Graduate House is to be absorbed into the broader college. Its independence — and its ideals — to be quietly folded into memory. The board, made up largely of gentlemen from more selective eras, seems to have chosen familiarity over vision. Was Graduate House ever truly cherished? Or was it simply tolerated — a convenient balm applied to ease the ache of the Broderick Review?

One cannot help but suspect the latter. After all, what brings in greater revenue: a house of scholars with purpose, or suites reserved for those whose surnames command donation forms?

As this remarkable community is dismantled, St Paul’s must ask itself what it is so readily discarding. Movements such as Burn the Colleges have called for the restructure of such institutions — perhaps it is not the colleges themselves that require cinder, but the dusty power structures that govern them.

Graduate House showed us what was possible. Its end reminds us how easily the future can be buried beneath the comfort of the past.

Yours most observantly, Lady

Thistledown

Contact Inclusion and Disability Services:

Register for Inclusion & Disability Services

Phone: +61 2 8627 8422

Email: disability.services@sydney.edu.au

Fax: +61 2 8627 8482

This publication was made possible by the Students’ Representative Council (SRC) and the Sydney University Postgraduate Repr esentative Association (SUPRA). Get in touch with us via email at:

SRC: disabilities.officers@src.usyd.edu.au

SUPRA: disability@supra.usyd.edu.au

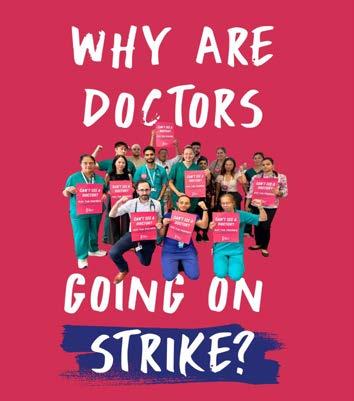

ASMOF Doctor’s Strikes

8th–10th of April

Check @asmofnsw

DisCo Honi Launch Thursday 10th of April at 6:00pm

Hermann’s Bar

International Student Collective Movie Night Friday 11th April at 7:00pm

Law Annex LT 101

Save Waterloo! Action

4 Public Housing Saturday 12th of April at 1:00pm Redfern Community Centre

No Pride in Detention PiP at Palm Sunday Sunday 13th of April at 2:00pm Belmore Park

Later in the year... Student Journalism Conference

15th–18th of August at USyd

More details coming soon!

Thousands of doctors across NSW will proceed with industrial action from Tuesday 8th April to Thursday 10th April. It is being led by members of The Doctors’ Union — Australian Salaried Medical Officers’ Federation (ASMOF) NSW. Public hospital staffing will be reduced to public holiday levels as multiple crises in the public health system reach breaking point.

The statewide action is a result of chronic understaffing, low pay compared to other Australian states, and unsafe working hours.

ASMOF President Dr Nicholas Spooner said the Minns Government has failed to take any action and walked away from award negotiations. Doctors have been left with no choice but to strike as their working conditions put themselves and patients at risk.

Hospitals will remain staffed to safe levels, with NSW hospitals operating under public holiday or

‘skeleton’ staffing over the three day strike, according to Spooner.

This is the first time in NSW that both junior and senior doctors from across departments have gone on strike. This is also the first time that doctors in NSW have taken industrial action since 1998.

ASMOF informed Honi that they are currently “overwhelmed by the level of support from ASMOF membership.” More than 30 hospitals across NSW are committing to industrial action, including regional areas such as the Riverina and North Coast.

Patient safety will not be compromised by the strike. Urgent priorities such as emergency departments and critical care units will remain fully staffed. Doctors will not undertake non-urgent duties.

In negotiations, the government has re-offered the same deal from June last year — a three per cent pay raise — despite looming threats

of industrial action. This did not assist in the attaining or retaining of more skilled staff specialists required in the NSW public health sector, according to Dr Spooner.

“We don’t want to strike. We want to care for our patients safely. However, we will not stand by while the NSW government allows the system to crumble. The system is not sustainable, and we cannot continue like this” says Dr Spooner.

“We call on Premier Minns to come to the table and provide the staffing, the conditions, and the respect that NSW doctors deserve. The future of our health system depends on it.”

Spooner says that doctors are leaving the state in significant numbers to work in other parts of Australia due to unsustainable working conditions in NSW.

“We are working dangerously long hours, including 16-hour back-toback shifts with barely any rest,

William Winter reports.

After over an hour of waiting for the doors of the Cullen Room in the Holme Building to open, the public session of the March University of Sydney Union (USU) Board Meeting began.

The first motion of the ex-camera session was to correct all previous minutes to ensure that the late Honi Soit editor Khanh Tran is referred to by the correct name.

The financial report followed. The USU was under-budget for this period, an anticipated loss due to the budgeting calendar being confirmed before 2025 semester dates were released. As it stands, the USU has a shortfall expected to be recouped by the April board meeting. Also expected by then is a final financial audit report for the 2023-2024 period.

We’ll give the USU credit for one thing: the Board is great at keeping us hooked. Who would’ve thought at the start of the year that we’d be eagerly anticipating the narrative resolution of USU Board financial

shortfalls?

Constable took his President’s report as read, touching on the staff town hall regarding incorporation. Honi will note that this public and ‘important’ town hall was not recorded for internal or external sharing. Constable then spoke to the results of the incorporation ‘member survey’ (read: push poll): “members are highly in favour… No individual proposal was below 75 per cent approval.”

We then come to open question time. Honi prepared quite a few questions for this segment of “What do they know? Do they know things? Let’s find out!”

Honi does not believe that the haste with which the Special General Meeting and constitutional changes are being adopted can accurately provide the chance for the USU community to assess the potential constitutional changes.

When asked about what form the USU will be pursuing

and often covering multiple roles due to chronic staff shortages.” Dr Spooner said.

The current conditions of chronic understaffing are unsafe for doctors and for patients.

“Many [doctors] are working 16hour back-to-back shifts with little rest, leading to exhaustion, burnout, and mistakes that put patients at risk.” says Dr Spooner.

“We urgently need safe working hours, including a guaranteed 10-hour break between shifts, to ensure fatigued doctors are not seeing patients.”

Read full article online.

for incorporation, Constable stressed that they will be seeking Incorporated Association.

Honi asked Constable: “Has the incorporation plan been formally endorsed by the Student Representative Councl (SRC), Sydney University Postgraduate Representative Association (SUPRA), and/or the University Executive?”

Constable replies: “Yes. The incorporation plan was endorsed to me by the President of SUPRA, the President of the SRC, and we have in principle support from key members of the University Executive… Joanne Wright has given her in principle support to the model, not just the incorporation plan.”

Honi has confirmed through a University of Sydney spokesperson that “Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Education) Professor Joanne Wright and Chief Governance Officer Michelle Stanhope gave preliminary feedback and general

in principle support for the USU’s proposed direction” for however “no formal constitution has been presented to the University for consideration at this stage.”

SUPRA President Vivian Bai: “I fully respect the decisions made by the USU Board on this matter. However, I would like to clarify that SUPRA Council has not yet had the opportunity to formally discuss or vote on the incorporation plan or the proposed structural changes.”

SRC President Angus Fisher: “I have not in my capacity as my SRC President officially endorsed a plan to incorporate. This is only possible if [the] Council votes to do so. Myself, as an individual, has noted I approved incorporation in principle.“

Honi will note here that the SRC formally voted to not endorse the USU incorporation at their council meeting this week.

Read full article online.

“Abortion Abolitionists” infiltrate campus with anti-women rhetoric, again

Emilie Garcia-Dolnik and Ellie Robertson report.

Disclaimer: Honi Soit does not support the inversion of the term “abolitionist”. These people are right-wing, pro-life extremists.

On Wednesday 2nd April, two men stood on campus with extremist anti-abortion signs, alongside aggressively pushing their antiwomen narratives to students walking past.

Self-titled “abortion abolitionists” held signs reading “Abolish Abortion to the Glory of God” and “Whatever happened to Human Rights?” for over two hours within Campus bounds. The same abolitionists were on campus late last year, where police removed them.

At 12:45pm, NSW police asked the men about their aims. The men then testified to their lack of accountability, loudly claiming “They approached us!” after baiting students into talking with them.

Honi understands that the socalled abolitionists did not seek permission to be on campus. One must wonder why USyd

management and security did not apply the Campus Access Policy (CAP) in this instance, provoking more significant questions about the policy’s selective application by USyd management.

In response to a request for comment, a University Spokesperson provided the following statement:

“Yesterday our protective service team requested council and police assistance...due to concerns about the potential impact of the group’s proximity to campus.

“We would have employed it if the group had moved onto campus as we’ve done previously, as they were not members of our community and did not have approval to gather here.”

Honi notes that at least one of the men was within campus bounds for a prolonged period before police interruption.

Martha Barlow, SRC Women’s Officer, as well as Lilah Thurbon, SRC Environmental Officer, were among those arguing with the two men. Martha said to Honi:

“WE’RE HERE, WE’RE QUEER, WE’RE NOT GOING TO DISAPPEAR!”

On Sunday 30th March, LGBTQIA+ rights group Pride in Protest (PiP) hosted a rally at Pride Square, Newtown to mark the International Transgender Day of Visibility (ITDOV). It was both a celebration and a call to action.

ITDOV held annually on 31st March, acknowledges the perseverance of trans joy and resistance throughout history. It raises awareness for the ongoing discrimination faced by genderdiverse people.

Recent Redbridge polling, has shown almost nine out of ten Australians are against major parties using transgender issues for political gain this election cycle. Protest co-chair and officer at the UNSW Queer Collective Alyss Cachia criticised the eagerness of the Coalition’s to “take up the culture war.”

“It’s disappointing to see the ‘Abortion Abolitionists’ back on campus, but with the current rise in Trumpian rhetoric and rightwing bigotry in the world, perhaps not surprising. It was heartening, at least, to see such a crowd amass to debate, call out and heckle them. When prodded on their beliefs, these people were quick to support abolishing no-fault divorce and openly tell us that women should just “close their legs”.

“They were then offended when we called them misogynists. They also do not believe in contraception or sex education or any measures that would actually make it easier to have children: a very clear indication that all they care about is controlling women’s bodies and criminalising vital healthcare. This kind of bigotry and violent rhetoric has absolutely no place on our campus, and we outright reject the right-wing Christian nationalism they were espousing. Safe, free and accessible abortion now!”

Honi posted a poll on social media regarding how the abolitionist’s presence on campus affects the student body. We received responses in 24 hours from 583

students out of 1,784 viewers where they expressed outrage at their presence on campus. This response is unsurprising to Honi It is interesting that, with this level of disdain and discomfort from the student body, the University did not kick them off sooner.

Read full article online.

If you or any of your loved ones have been affected by the issues mentioned in this article, please consider contacting the resources below:

NSW Sexual Violence Helpline – Provides 24/7 telephone and online crisis counselling for anyone in Australia who has experienced or is at risk of sexual assault, family or domestic violence and their nonoffending supporters. The service also has a free telephone interpreting service available upon request.

Safer Communities Office – Specialist staff experienced in providing an immediate response to people that have experienced sexual misconduct, domestic/family violence, bullying/harassment and issues relating to modern slavery.

Wirringa Baiya Aboriginal Women’s Service – Provides legal advice and sort for a range of issues, including domestic, sexual, and family violence, to Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander women, children and youth.

1800RESPECT – A service available 24/7 with counsellors that supports everyone impacted by domestic, family and sexual violence.

Greens candidate for Sydney Luc Velez cautioned against the new polling stoking “complacency” in queer politics at the election. Velez insisted that “we cannot let local representatives be silent on transphobia or hide behind excuses.” He cited the Queensland government’s decision to pause puberty blocker medications and the printing of anti-trans ads from Clive Palmer’s Trumpet of Patriot’s party.

Mish Pony, CEO of Scarlet Alliance, spoke of right-wing attempts to “take away [queer] rights and systematically erase us from existence.” This is nowhere clearer than in the United States. Eddie Stevenson, spokesperson from Community Action for Rainbow Rights, pointed out the irony that this is supposedly “the freest, most democratic, most liberated country in the world.”

The massive turnout of protestors marched from Pride Square to the University of Sydney. There, they defied the much-criticised Campus Access Policy that revoked students’ rights to protest on campus without prior approval from university management. National Tertiary Education Union flags flew in support.

The ultimate message of the day was one of joy. The transgender community is still far from the liberation they are fighting for, with restrictions on bodily autonomy, discrimination in healthcare discrimination and sport, and arbitrary detention at borders. Yet, there was a defiant happiness at the 30th March protest.

For Cachia, being transgender is an “amazing, unique experience.” She urged the crowd to “hold each other tightly” as the

Lifeline – 24/7 suicide prevention crisis support hotline for anyone experiencing a personal or mental health crisis.

LGBTQIA+ movement continues to build community and solidarity. Spokesperson ‘Miss Andry’ from the Sex Worker Action Collective NSW said that the rise of antitrans sentiments shows that “right-wingers fear our visibility. They fear the free, loving way that we live our lives, and how that might make others become more introspective and start caring for others in the same way that we do.”

At the conclusion of the event, the crowd was urged to continue the struggle for trans liberation beyond ITDOV and beyond the upcoming election. Grassroots organisations like PiP and the Trans Justice Project are seeking volunteers for community and local action groups.

Read full article online.

Inside Manning House, tucked away in a back corner on the first floor, stands the central hub for the vibrant disabilities student community at the University of Sydney. It’s got two zones: a smaller, quiet zone to accommodate students with sensory needs, and a larger space for socialising. From the panelled walls to the dimensions of the automated door, every design choice has been made with careful consideration to best accommodate students with disabilities.

The Disabilities Community Room (DCR) is to be renamed the Khanh Tran Room in honour of Khanh, SRC Disabilities and Carer Officer throughout 2022-2024 and former Honi Soit editor. When it came to disabilities advocacy, Khanh was a force to be reckoned with. Since starting at the University of Sydney in 2020, they were been involved in disabilities activism throughout their whole student life. There is no better proof of their fight for better access on campus than the USyd DCR.

Activists had been agitating for a dedicated disabilities space as early as 2017. Back then, former SRC Disabilities Officer Noa Zulman, Margot BeavonCollins, and Robin Eames saw an opportunity with the University of Sydney Union’s (USU) relocation of the Queerspace from the Holme building to Manning. When the move was completed in 2018, the USU expressed support for the room to be converted to a disabilities space. That support, however, was rescinded within the year, with the USU arguing that the space was needed for extra storage.

Carmeli Argana writes.

While there have been incremental movements since 2018, progress was largely stalled. Both the University and the USU had expressed their vague approval in developing the space, but a series of bureaucratic hurdles knocked back any attempts to advance the project. The COVID-19 campus shutdown throughout 2020-2021 also saw the University implement a funding freeze for approval of new Student Services and Amenities Fees (SSAF) applications. That included an application for $50,000 for the project, submitted by Sydney University Postgraduate Representative Association (SUPRA) Disabilities Officer Gemma Lucy Smart in 2021.

But things finally started moving along in the following year, with an Honi investigation published 24th April 2022 titled, ‘Such an exhausting process: The yearslong fight for a Disabilities Space on campus’. You can probably guess who authored it.

“Khanh’s article was really pivotal in adding pressure to the University, because it pointed out that USyd was the only Go8 university without a disabilities space,” Smart says.

As one of two student representatives on the University’s Disability Inclusion Action Plan (DIAP) Working Group, Smart recalls how they would constantly refer to Khanh’s article in meetings. The University’s pride worked to her advantage; the purse strings were loosened and the University decided that the quality of the final space should exceed that of the other Go8 members. When the SSAF funding freeze was lifted in 2022, the creation of a dedicated disabilities space skyrocketed to the top of the University’s priority list. And by the time the room was opened nearly two years later, the University had

invested well over the amount of Smart’s original SSAF application into student-led disabilities initiatives; approximately $200,000 according to people with knowledge of the matter.

Khanh’s article also made waves across USyd’s student unions. In the following Student Representative Council (SRC) and SUPRA meetings, councillors unanimously voted in favour of a motion to establish a disabilities space. The USU, which houses the autonomous collective spaces, also made it a priority. When former Board Director Alex Poirier took over the USU Disabilities Portfolio in July, he agreed to take an active role in the room’s development, seizing an opportunity in the planned renovations of Manning House to push the Board for inclusion of a disabilities space. Along with fellow Board Director Grace Wallman, they kickstarted the process for the USU’s own DIAP — the first of its kind for a student union in Australia.

“I went to Khanh when I was starting out with that role because they’d been around in the space for longer than I had, and just knew so much,” Poirier says. Khanh’s article was an important resource for the initial DIAP draft. After the draft was complete, Khanh came in and added suggestions that were more specific and actionable, Poirier adds.

To this day, the original draft is still covered in Khanh’s notes, blocks of pink annotations on an old Google doc.

Khanh continued to support the project throughout 2022, being part of discussions with Office Bearers during the process of securing a location. But they wanted to do more. In November that year, at the conclusion of their term as Honi editor, they ran for

the joint position of Disabilities Officers with Jacklyn Scanlan. They were both elected unopposed.

Disabilities Officer, Khanh went from being a student journalist who could only agitate for change from the outside, to having a seat at the table, with a Disabilities & Carer’s network and collective budget behind them.

During their first term as Officer, they were highly involved in the consultation process for the development of the room. They frequently liaised with various stakeholders across the SRC, USU and most importantly, the University’s infrastructure team, which was responsible for implementing the structural and architectural elements of the room’s renovation. Alongside Smart, they were relentless in keeping the project on track, chasing up the infrastructure team for updates during the process, largely via email correspondence at their prompting. As a former Honi editor, they had an edge in what they brought to discussions. They’d built up a wealth of institutional knowledge from their reporting to understand which pitfalls to avoid from previous officer bearers’ lobby attempts, and the best ways to apply pressure on the University. They were a prominent voice in discussions about the room’s policies as an autonomous space, its accessibility procedures, and its function and design.

In the present day, the walls are lined with acoustic panels to reduce noise and the carpet is a plain navy blue, avoiding bright colours that might affect students with sensory needs.

Powerpoints, light switches and temperature controls are located low on the walls to enable access for wheelchair users. Wheelchair users can also enter the space via the wide, automatic doors that swing open with swipe access. Inside the social zone is an acoustic booth fitted with adjustable lighting and an Australian electric and USB-C outlet. Printed instructions describe the booth as “an excellent place to study or take a break”. An iPhone-quality photo accompanying the instructions shows a picture of the booth taken by Khanh; their unmistakable silhouette — neatly trimmed hair and a pair of jorts — can be seen holding up a peace sign in the reflection of the glass door.

“The end product would not be what it is today without them,” says Grace Wallman, USU Board Director and former Disabilities Portfolio Holder. Along with the SRC and SUPRA office bearers, Khanh relentlessly pushed to ensure that students’ accessibility needs were considered by the University throughout the whole process, she adds.

Wallman took over from Poirier as Disabilities Portfolio Holder in mid-2023. At that point, the room’s renovation had been mostly completed. Wallman describes the care that Khanh took with the office bearers to ensure that feedback for the design proposals were heard; in particular platforming Smart’s feedback on carpet colours, lighting systems, powerpoint specifications. They were also a vocal member of the USU DIAP Development Committee that Wallman chaired, a committee established in 2023 as part of efforts to widen the scope of the DIAP development process.

By the end of the year, the room was ready for its final walkthrough. What had started out as the former ethnocultural space-turnedstorage room, had transformed into a state-of-the-art accessibility room, ready for use. That day, Khanh stood side by side with their fellow student representatives, taking in the fruit of their tireless labour. A room brimming with new possibilities for meetings, for social events, for hanging out with like-minded students. And ultimately, for something more. Something they had gravitated towards their whole life.

When Khanh and Scanlan were elected Disabilities Officers for 2023, they were faced with the impossible task of reviving a collective that had long struggled to engage students following the COVID shutdown. After all, what use was a room if there was no one to use it?

“One of our key priorities was making sure the collective could survive without us,” says Scanlan.

“We wanted people to get excited about the disabilities community and activism. We wanted fresh faces who were really excited about the collective to take over after us.”

Throughout their term, Khanh and Scanlan hosted meetings with guest speakers well-versed in disabilities advocacy, fought to save simple extensions, and held joint solidarity events with the other collectives. During 2023, they were able to double the size of the collective, according to Office Bearer reports submitted to Honi. But with only a handful of members, it wasn’t ready yet for a total change in leadership. When the SRC elections rolled around in November, Khanh decided to run for a second term with collective member and campaign veteran Victor Zhang.

“Having the Disabilities Room was a boon for the growth of the collective,” Zhang says. “For many disabled students, the Room is like a second home.”

Although the room was ready as early Semester 2, 2023, Khanh and other student representatives took their time to make it truly feel like a community space. Smart recalls of their several trips to Broadway together, buying medical supplies and fidget toys to furnish the room. Khanh even supplied lounges with weighted blankets, a tea station with an impressive collection, and snacks to stock the fridge.

“Khanh is synonymous with DCR because they made it feel like a homely place,” says Smart. “Once we had the room, they made it into the safe and welcoming space that it is.”

The Disabilities Community Room was officially launched on 19th April, 2024. The online feature image of the Honi article about the launch depicts Khanh and Poirier holding a craft store-bought red ribbon between them, while Wallman and Zhang are mid-snip with a pair of big, red scissors. (Once again, take a guess at who the article’s author was) By Zhang’s account, it was a successful event with student representatives, USU administrative staff who were involved with the room’s development, as well as members of the burgeoning Disabilities Collective (DisCo). They’d even invited the Director of Research and Policy for the Disability Royal Commission, Dr Shane Clifton, now the Director for USyd’s Centre for Disability Research and Policy (CDRP).

With securing a space for events no longer a logistical pain, DisCo began to take off. The DCR became the natural headquarters for all community events; teachins with guest speakers, campaign organising for upcoming rallies, casual study meet-ups during exam period. For the entirety of the academic year of 2024, DisCo had regular meetings every week, on par with some of the SRC’s bigger collectives. In September, the collective hosted a poetry night as part of the university-wide celebration of Disability Inclusion Week. Having built strong relationships with the University’s official DIAP Implementation

Group through their work on the DCR, Khanh was able to tap into University funding to fully cover expenses for the party.

When the SRC election season arrived in 2024, Khanh knew DisCo was strong enough to survive them. The fresh faces full of passion and excitement that they and Scanlan had hoped for had finally arrived. With full confidence, they handed over care of the collective to Remy Lebreton and Vince Tafea, SRC Disabilities Officers for 2025.

Tucked away in a back corner of Manning House, the Khanh Tran Room is the beating heart of the University of Sydney’s disabilities student community.

The Room is not yet in perfect shape; the automatic door occasionally malfunctions and locks people in, and student representatives are still pushing for the removal of swipe access as a barrier to entry. But much like the community it belongs to, it’s gone through one hell of a journey for the right to exist. Its very existence is an act of resistance, an act of triumph, an act of love.

Khanh Tran is one of the lucky few who truly spent their life doing what they loved — fighting for the oftenoverlooked communities they held close to their heart, in whatever small ways they could. But their contributions and their impact are far from small. Out of Khanh’s breadth of accomplishments as a disabilities activist, the Room is perhaps their greatest legacy.

Editor’s Note: Carmeli Argana is a former editor of Honi Soit. She edited alongside Khanh in 2022 on the team CAKE for Honi.

Gemma Lucy Smart welcomes the unwelcomed.

Australia has long positioned itself as a welcoming destination for international students and academics seeking worldclass education and career opportunities. However, beneath this welcoming façade lies a deeply discriminatory system that forces many international students and staff with disabilities to hide their conditions for fear of visa rejection or deportation.

At the heart of this is a contradiction within Australian Federal Law. While Australia’s Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA) aims to protect people with disabilities from discrimination, the Migration Act 1958 is specifically exempt from these protections. This means that Australia’s migration laws can — and do — openly discriminate against people with disabilities or health conditions.

All visa applicants must meet the Migration Health Requirement, which rejects applicants deemed likely to result in a “significant cost” to Australia’s healthcare or community services. Currently, this threshold is set at just $51,000 over ten years for permanent visas — a figure significantly below both Australia’s average per capita healthcare expenditure and comparable thresholds in countries like Canada and New Zealand.

For international students and academics with disabilities, this creates an impossible situation:

“It’s like we’re here for you [Australia] when you need us, but when the roles are reversed and we need you, it’s like, nope, sorry, you cost too much money, you go back to your own country,” explains Laura Currie in a BBC article, whose family faced deportation after their son was diagnosed with

cystic fibrosis.

Dr. Jan Gothard, an immigration law expert, notes that these policies create a culture of fear where international students and staff with disabilities feel forced to hide their conditions:

“People are afraid to disclose, afraid to seek help, afraid to access services they need to succeed academically or professionally.”

This creates a double bind for international students and academics with disabilities. Disclosing their disability might allow them to access University support services and reasonable accommodations. However, despite clear confidentiality policies and promises from the University, casual breaches of medical data privacy are all too common. There remains the fear that this same disclosure could potentially flag them for immigration authorities, risking their visa status or future visa applications.

For many, the fear of deportation outweighs the need for support. Students with conditions like ADHD, autism, depression, or physical disabilities often struggle through their studies without accessing disability support services that Australian citizens take for granted. Academic staff may hide their conditions from colleagues and administrators, working without accommodations they’re entitled to under Australian workplace law and the USyd Disability and Inclusion Access Plan.

The situation becomes even more problematic when we examine how Australia’s migration policy treats children with disabilities. Unlike ‘regular’ education or English as a Second Language programs,

which are considered community investments, ‘special education’ is categorised as a community cost in visa assessments.

This means an international academic whose child needs learning support is almost guaranteed to fail the health requirement, regardless of their skills or contributions to Australia. Since approximately half of all visa types have no waiver provisions for the health requirement, families are often simply rejected outright.

The human cost of these policies is immense. International students struggle through courses without needed accommodations, affecting their academic performance, mental health, and future prospects. Academic staff face career barriers and stress from hiding their conditions. Families are separated or forced to leave Australia altogether based on a family member’s disability.

The policy also prevents universities from benefiting from the diverse perspectives and talents of disabled staff and students who could contribute significantly to research, teaching, and campus life.

Civil society organisations like Welcoming Disability, led by Australian Lawyers for Human Rights and Down Syndrome Australia, are campaigning for urgent reform. They call for removing the Migration Act’s exemption from the Disability Discrimination Act, raising the cost threshold to reflect actual healthcare spending, and ending the practice of counting special education as a “community cost.”

The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability has specifically recommended reviewing the exemption in the DDA as it applies to the Migration Act

For Australian universities seeking to be truly global institutions,

addressing this issue is essential. The current system explicitly or implicitly forces international students and staff to choose between receiving support for their disabilities and maintaining their legal status in Australia - an impossible choice that no one should have to make.

As Australia competes globally for international talent, creating a more welcoming environment for people with disabilities would not only fulfill human rights obligations, but also enrich campus communities and attract diverse perspectives currently lost to discriminatory policies.

Until these reforms occur, international students and staff will continue to mask their disabilities, forgo needed support, and live in fear of a system that views them not as valuable contributors to Australian society, but merely as potential costs to be avoided.

Dedicated to the incredible activism of Nguyen Khanh Tran in this area, and their fearlessness in publicly identifying as a disabled international student.

This summer, all prospective beach days and lunch dates were cancelled once I tested positive for COVID-19. With my family overseas for their holiday, I was left to fend for myself in the toughest three weeks of my life. I spent every minute in immense discomfort, wishing I could sleep for more than twenty minutes at a time without waking up with violent coughs and a growing headache. Countless nurofen, tissue boxes, and cups of microwaved soup later, it was clear that this was not “just like the cold”. The impact of COVID on my body was palpable, and the lingering symptoms of Long COVID have not allowed any respite.

Two months on, I have tremendous fatigue, migraines, shortness of breath, body aches, and brain fog. I forget people’s names, I can’t stand for more than ten minutes at a time, and I am constantly aware of a dull pain throughout my body. On ‘good’ weeks, I can manage every second day out at uni for a few hours of class — that is, before inevitably crashing and taking a long nap to get me through the rest of the day. On ‘bad’ weeks, I spend all my time alternating only between my bed and different couches throughout the house, trying to ignore the discomfort in my body whilst also feeling overwhelmed with guilt and frustration at all the things I am unable to do that day. My life has literally been put on pause as the rest of the world goes on: I am now graduating

a year later than planned, I have not been at work for three months, I have had to involuntarily pull out of many projects, and I no longer have the energy to spend time with friends. My life has been completely uprooted.

Long COVID is a chronic condition in which people experience symptoms, sometimes for up to years, after the acute infection. Common symptoms include fatigue, chest pain, and brain fog, but you are also at risk of pulmonary and neurological complications. Furthermore, your immune system becomes permanently damaged by infection — not built up with immunity — meaning reinfection is extremely dangerous. 2022 research by the Australian National University found that 1 in 5 people who get COVID experience Long COVID. Being such a new condition with many ‘invisible’ symptoms, it is extremely under researched. Although much is unknown about Long COVID, we do know that anyone who gets COVID can develop Long COVID. It is a condition only diagnosed by a process of elimination, with no definitively known cure.

Five years on from the first lockdown, things have gone ‘back to normal’. Normal, meaning excess disability and death as everyone goes back to work. But is it really ‘normal’ for a preventable disease to rampantly disable and kill so much of the population? Such violence is taking place precisely because all measures that once responded to the urgency and seriousness of COVID have been axed: isolation is no longer legally required nor encouraged. Infrastructure like free, accessible PCR testing and Long COVID

DisCo Mask Bloc

Request N95 masks for yourself, your event, or your group - for free!

clinics have been shut down. Contact tracing is non-existent. Many workplaces — who do not offer sufficient paid sick leave — are demanding we come back into the office, and universities are bringing back stringent and compulsory in-person class attendance requirements for certain courses.

The state’s disregard of the risks and spread of COVID should not be surprising — the cost of previous safety measures on the economy was far greater than the cost of people’s lives. This is neoliberalism manifest, which we see elsewhere in healthcare: bulkbilling services have practically disappeared, hospitals have dangerous staff to patient ratios, there have been immense cuts to NDIS funding, trans healthcare is being denied to Queensland youth and in amerikkka/Turtle Island, and abortion access is increasingly fraught.

Disease is political. And a state-sanctioned pandemic is eugenics.

We must refuse to normalise mass disablement. We must refuse to be complicit in mass death. We cannot exist in the world acting as if disabled lives are disposable. The pandemic is not over. We ought to care for each other to prevent the spread of COVID, especially when the state refuses to intervene.

The best way to protect yourself (and others) from COVID and its complications is to not get COVID at all. Handwashing alone will not save you — it is time to start masking up again. You should reintroduce masking practices

in healthcare facilities, on public transport, at the supermarket, at concerts, and at protests. Consider even your lectures — how many times a week are you sitting in a packed room with hundreds of others for two hours? I can assure you that the slight inconvenience (or even embarrassment) of wearing a mask is much better than the inconvenience of becoming disabled with Long COVID.

It’s not just about yourself: with each precaution you choose not to take, you are telling disabled people that our livelihoods are not worth protecting.

Invest in N95s and KF94s. To save money in the long run, buy them in bulk through your households, workplaces, and organisations. The Disabilities Collective is launching a mask bloc which distributes masks to any individual or group at the University of Sydney who requests them — scan the QR code below.

You are not guaranteed good health, especially when you do nothing to prevent infection during a pandemic. Your carelessness about COVID will come at my (and your) peril.

I got my first period early, when I was 9 years old. It was long before any of my friends got theirs, and as a result took my mother and I by surprise. She had assured me that I wouldn’t start bleeding each month until I was older, 13 or 14 like she was.

The next two weeks were spent writhing with pain on the yellow tiles of my bathroom floor, disgusted by the thick blood that seemed to flow from me endlessly. My back ached sharply and constantly with pain that I sometimes felt so deeply it penetrated my chest. When I dragged myself out of bed, I was scared my legs would give out.

Lilah Thurbon discusses pain.

This is the first of many painful episodes I would later make sense of as endometriosis.

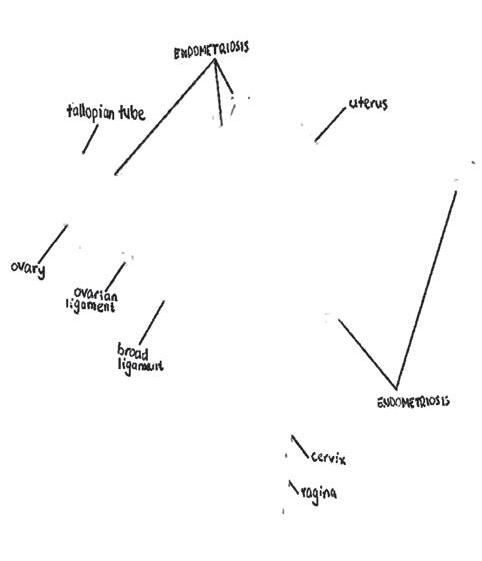

Endometriosis is a chronic condition in which tissue, similar to uterine lining, grows outside of the uterus. This causes lesions and scarring to form most commonly in the pelvic area. Still, there have also been documented cases of endometriosis found in the lungs, diaphragm, and in one extremely rare instance, the brain.

Well-known symptoms of endometriosis include chronic pelvic pain, heavy periods, bloating, pain with penetrative sex,and infertility. Endometriosis is also a very common disease, affecting approximately one in seven people with uteruses (and occasionally people without them too — endometriosis can recur even after a hysterectomy). Despite this, there is no known cause, no cure and no way to prevent it. The average time period between the onset of symptoms and receipt of diagnosis is six to eight years.

This is caused by structural medical misogyny, where women and gender minorities’ voices are dismissed by doctors and their pain minimised.

The gender research gap exacerbates this problem, with General Practitioners (GPs) and even gynaecologists often having outdated or incomplete knowledge about women’s health conditions. The only option for definitive diagnosis is a laparoscopic surgery, which is invasive and expensive. It’s not even curative — the endometriosis lesions they cut out will probably grow back. As a result, people often spend years in limbo, waiting on a diagnosis and trying to manage their symptoms with blunt instruments like the contraceptive pill.

The overreliance on hormonal birth control in the treatment of endometriosis is complicated.

Many women, including myself, rely on various forms of hormonal birth control to maintain a functional quality of life. I know that without my IUD, I would be frequently incapacitated by flare-ups.

I started taking hormonal birth control when I was 14. The preceding three years of heavy periods, each over a fortnight in duration, that left me anaemic, anxious, and frequently physically incapacitated from cramping and back pain. I was prescribed a combined oral contraceptive pill, Evelyn, with the promise of a lighter flow and reduced pain.

In the years that followed, I’ve switched pills once, had surgery for endometriosis twice, seen three gynecologists of varying quality and had a hormonal Mirena IUD inserted into my uterus. In desperation, I tried everything from diet changes to yoga and supplements, less because I believed they’d work, and more because I had run out of options.

Some alternative remedies helped manage symptoms or boost my overall health, but the most effective interventions were those backed by conventional medicine. Since my second surgery and IUD, I’ve been free from the disabling period pain that defined the decade before. I know this isn’t the end — many need ongoing surgeries as endometriosis returns. There’s no simple fix, but after years of being dismissed, receiving real treatment felt almost curative.

My first prescription for the pill was presented as a complete solution, even though I remained clearly symptomatic. When it stopped working and my pain worsened, I had to fight for further care. I was offered only opioid painkillers, to be used sparingly due to addiction risks — despite the fact my pain was chronic and constant.

This experience is disastrously common. Women and gender minorities are repeatedly and painfully failed by medical institutions.

Only recently has the government begun funding endometriosis research. The 2024 National Action Plan for Endometriosis revealed that two-thirds of women face healthcare discrimination. A promised $500 million in funding, largely thanks to pressure from Greens-led inquiries, is welcome, but overdue.

This recent spotlight on medical misogyny and the chronic under-resourcing of research into conditions affecting women and gender minorities is obviously a welcome departure from the previous status quo, where menstruation and period pain were taboos women were told to just get over. But increasing funding and visibility is only part of

the solution.

So much of medical misogyny is perpetrated by individual interactions with doctors and other medical professionals, and compounded by how our society fails to aptly grapple with gendered pain. Being labelled as ‘hysterical’ or a ‘drama queen’ by medical professionals deters women from seeking treatment that could alleviate their pain, drawing out diagnostic processes unnecessarily by years.

Even with a diagnosis, endometriosis remains misunderstood.

It’s often dismissed as a ‘bad period’ but its impact runs far deeper.

It isolates you not just from others, but from yourself. Many with chronic gynaecological pain don’t identify as disabled, even when their lives are deeply disrupted. For women and gender minorities, already alienated from their bodies by misogyny, chronic pain intensifies that disconnection.

As a cis woman, I often resent my anatomy for causing pain and for being a site of oppression. That tension makes it hard to name this as a disability, even when it clearly is.

Art by Mahima Singh

This isn’t a hopeful ending, but it’s honest: pain is personal and political. More research and treatment are vital, but without addressing structural misogyny, they’re not enough. We need to believe and listen to those who live with it.

Read full article online.

Tanish Tanjil is tired of waiting.

When the flood came, no one came for my grandmother.

She had broken her femur three years earlier and never walked again. Her leg had twisted into something uncooperative, rigid, untrusting. We made her a bed in the highest room of the house, which was not very high at all. We packed bags, not knowing if we would carry her or leave her behind. As the water climbed the steps in Bangladesh that year, my parents did not cry. They planned. The kind of planning you must do when the state has forgotten you.

This is what climate disaster looks like for disabled people: isolation, improvisation, abandonment.

In countries like Bangladesh and India, disability often means being confined to a bed in a shared room, on the second floor of an uncemented house, in a village no one can find on a map. It means your wheelchair rusts in the yard. It means you depend on your family for every movement, every meal.

Climate disaster does not just expose inequality. It manufactures it. Again and again, climate change becomes a pipeline into disability, and a trap for those already there.

The number of disabled people rises after every flood, every cyclone, every emergency that leaves behind injury and trauma. Climate change does not just impact disabled people. It creates disability. Extreme heat leads to heatstroke. Rising waters cause infection. Collapsing infrastructure causes physical injury. Displacement results in psychological trauma. Warmer temperatures accelerate the spread of diseases like dengue and cholera. Cyclones leave survivors with lasting Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Yet, most disaster response plans do not account for existing disabled people.

When disaster strikes, no one comes for you. Not the state. Not the neighbours. Sometimes not even your own family. So, you

stay. You drown. You are mourned quietly, if at all.

The United Nations says disabled people are two to four times more likely to die in natural disasters.

A 2020 study in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction found that most cyclone shelters in Barisal were inaccessible to those with mobility impairments. Evacuation drills often excluded people with disabilities altogether.

In Gaibandha district, 60 per cent of disabled residents had no access to early warning systems. Megaphones failed the deaf. Written warnings missed the blind. None of it reached those without formal education or assistive devices.

This is not a coincidence. It is a pattern.

I think about the disabled child who drowned in Hurricane Katrina because her family could not evacuate in time. About elderly residents abandoned in flooded care homes during Japan’s 2018 heatwave. About my own grandmother, whose life depended not on infrastructure, but on my parents’ impossible choice: to carry her, or to lose her.

But we do not talk about this.

We talk about carbon emissions and sea levels in abstract terms, as if the climate crisis isn’t right here, right now at our doorstep. We talk about vulnerable populations without asking who we made vulnerable in the first place. We praise the strength of communities after disaster hits, but we ignore the deep inequities that shape biopolitics; who lives, who dies, and who disappears from memory.

Climate change is not just a carbon crisis. It is a crisis of privilege.

Bangladesh makes up less than one percent of global emissions, yet we are on the frontline. Richer nations with the power to reduce emissions and invest in equitable adaptation are still debating whether to act; building walls instead of bridges, profiting from the fuel that floods us.

When Bangladesh drowns, because that is the fear that sits in my gut every time I look at satellite rainfall maps, I wonder who will care. Not about the economy. Not about the infrastructure. But

Art by Tanish Tanjil

about the people. The disabled grandmother who cannot climb stairs. The child who uses a wheelchair. The stroke survivor who cannot run.

But that’s not the whole story. Because disabled people are not just vulnerable. They are architects of survival.

If climate justice doesn’t centre disabled people, it’s not justice. It’s an illusion.

Across the Global South, disability-led climate initiatives are emerging. In Vanuatu, peerto-peer evacuation plans are designed around real bodies — not ideal ones. In the Philippines, grassroots groups are distributing inclusive emergency kits packed with medication logs, sensory tools, and visual guides. In Bangladesh, organisations like Access Bangladesh Foundation and the Centre for Disability in Development are training first responders and community members through DisabilityInclusive Disaster Risk Reduction (DiDRR) programs. These workshops simulate floods, evacuations, and sheltering from the perspective of people who are blind, wheelchair users, or neurodivergent. They ask the question no one else seems to: What if the most excluded person had to be the first to survive?

As disability activist Shamima Akter said in a recent workshop in

Shariatpur:

“We don’t want to be protected. We want to be included in the plan.”

If climate justice doesn’t centre disabled people, it’s not justice. It’s an illusion. Accessibility isn’t a ramp tacked onto a broken staircase. It must be the foundation. That means funding disability-led research. That means rewriting disaster protocols with disabled people at the drafting table. That means treating accessibility not as a favour, but as a right.

My grandmother survived that flood. But only because my parents chose to stay. That choice — between your mother’s life and your children’s — is one that no family should ever have to make. Yet, that’s the unspoken reality for millions. Climate disaster is not a great equaliser. It is a magnifier of all our failures — of inequality, of ableism, of systemic neglect.

We say “no one left behind” like it’s a promise. But right now, it’s a lie.

I’m writing this because I’m tired of this lie.

If you’re building climate policy, centre disabled people. If you’re funding disaster planning, fund disability-led groups. If you’re telling stories — tell ours. Loudly. Urgently. Before the next storm hits.

The water is rising again, and the stairs haven’t

moved.

According to Julie E. Maybee in her book Making and Unmaking Disability, the Middle Ages could be highly accommodating to disabled persons. Citing Metlzer, she quotes “[Labour was often tailored] according to individual (dis) abilities”, and all people were actively included in social and economic life. In stark contrast to our late stage capitalist world, the rise of oligarchic and far right movements in the USA and around the world marginalise people on the explicit basis of perceived productive capacity and the rejection of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA), with the disabled as clear first targets. So what changed from feudalism to capitalism to change these standards?

social model

Despite its relevance, disability justice is often an afterthought within broader social justice movements. However, no one is immune to disability. It can happen to anyone suddenly, at any point in life, yet is siloed to the realm of policy lobbying and liberal identity politics. Underneath this is the belief that disability is independent of social construction; located ontologically as a medical essence of the individual.

This could not be further from the truth. The social model explains disability as not an individual deficit, but rather a result of the systemic ways our society privileges particular kinds of accessibility and being, while marginalising others through inaccessible environments and discriminatory norms. But this leaves the question, why does society

privilege certain kinds of being?

Why is it that those whose bodies and minds are capable of the highest economic productivity with minimal accessibility requirements are located as the norm, and others as deviant? At its worst, we can see these logics, weaponised in biopolitical moralisations, reproduced in the structural violence of ableist healthcare policies or horrific events such as the Holocaust , dictating who lives and who dies.

The Marxist model adds to this framework an additional dimension of analysis — ‘The Economic’. It reframes these social structures and barriers as particular to capitalist economic structures and the exploitation it necessitates.

Capitalism is to blame.

Capitalism is a system of massdisablement. The exploitative conditions needed to perpetuate its cycle require able bodies, best suited to material needs of capital accumulation, with low social reproductive and welfare needs. It privileges certain forms of being based on how well they reflect this. Barriers of exclusion then become embedded within requirements stipulated for labour, and further within the disabling nature of the labour carried out. Its mode of production favours the kind of social organisation that incentivises disablement and ableism.

Viewing disability within the social model as merely representing those who fall outside structural normativity and accessibility can,

Remy Lebreton and Victor Zhang rage against the system.

therefore, be fairly misleading in a vacuum. This exclusion is not the result of neutral, random misfortune, but rather deliberate social and institutional choices. It is, in many cases, the clear byproduct of our broken system.

We need Revolution!

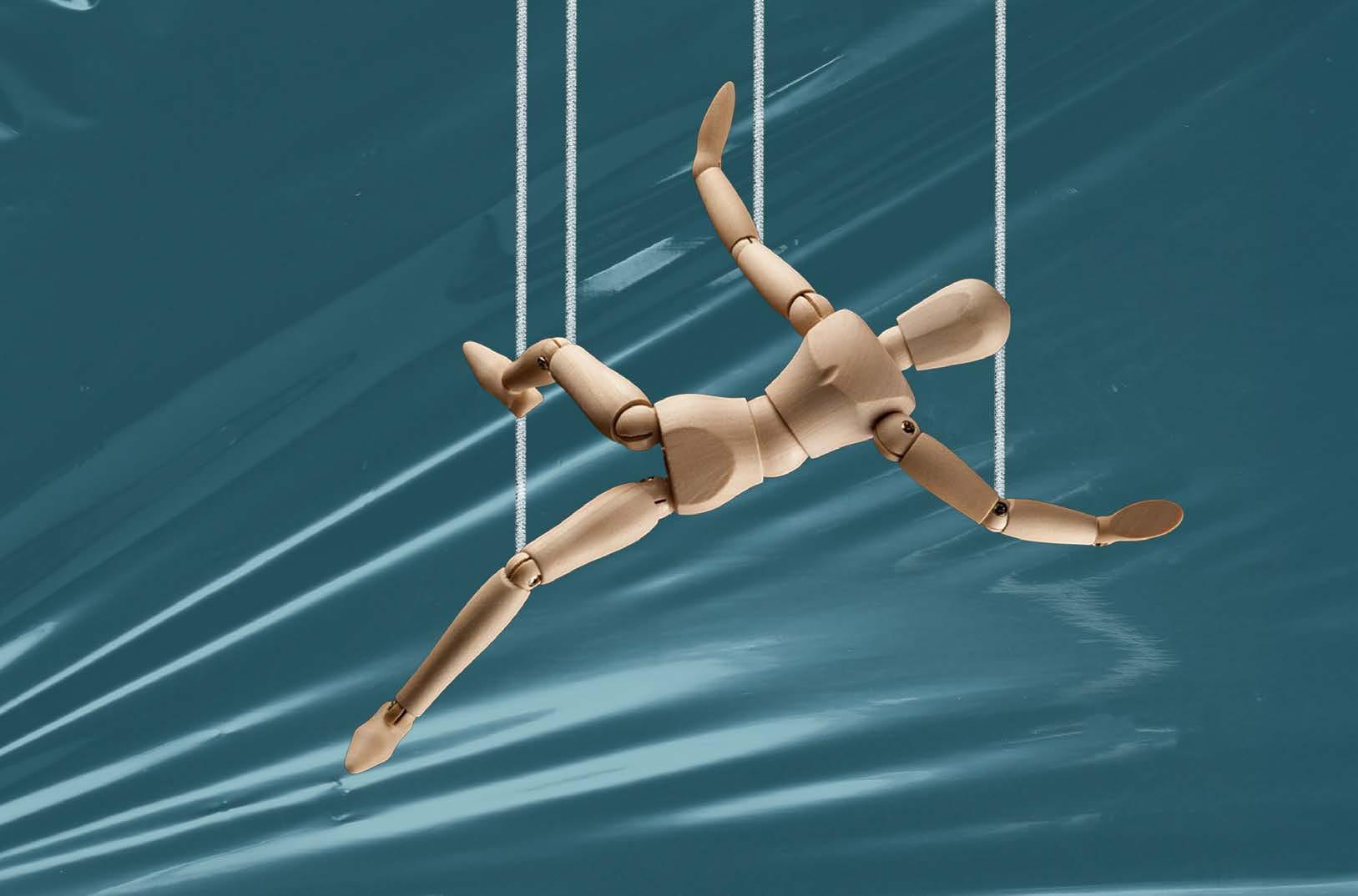

Marx himself identified the need for ever-increasing profit as inherent to capitalism. Without reinvesting profit into capital, the market economy inevitably withers. The tendency towards downward pressure on wages and employment to increase profits, ultimately reduces them. There is less money to be spent from wages earned, therefore less profit. Capitalism is functioning exactly as intended when it maximises profits in contrast to deteriorating conditions — as it squeezes blood from the stone at the expense of all other concerns, including disabled people, or anyone else’s wellbeing for that matter.

Alienation from the labour process, produced by this cycle, “destroys the integrity of the labouring body” according to David Harvey in his 2000 book Spaces of Hope. As workers are required to work harder, faster, and under worse conditions, they grind themselves down against the unforgiving and mechanistic system, extracting every last mote of productive capacity. No longer able to perform to normative standards, the system discards them. Disability then becomes a convenient excuse to fulfil the pressure towards unemployment required for the system to function, naturalised as a normal rate of unemployment.

Our house in Rizal was small but full. Four people lived within its walls: me, my Mama, my Lola (grandmother), and my Tita (aunt). But only one truly moved freely. My Mama was the axis around which our household revolved, a reality I failed to appreciate until much later.

From my earliest memories, my Mama’s day began before dawn. She would wake me for school, prepare my uniform, and ensure I had breakfast. But her morning had only just begun. Upon returning home, she would help my Lola out of bed, her curved spine making each movement

a careful negotiation. Then she would assist my Tita, whose limited mobility from childhood meningitis required patient attention.

Our sari-sari store provided our modest income. My Tita served as the shopkeeper while my Mama handled restocking, accounting, and inventory between cooking, cleaning, and attending to everyone’s needs. My uncle sent money to help support the household.

The hilly terrain of our neighborhood confined my Lola and Tita to our home. This barrier meant outings

The material and living conditions afforded to those in the productive classes of Marx’s time were abysmal, and these would frequently cause sickness and injury — even when such harms hadn’t already occurred on the factory floor. Whilst the average conditions in the Western world have improved significantly, do not be fooled. The disparity between the access to care services and healthy conditions between the top and bottom economic statuses in our society remains abysmal, not to mention the unimaginable suffering that the Global North imposes upon the Global South through expropriation.

Imperialism is of particular note to this, especially where colonial projects themselves function as mechanisms of genocide and mass disablement, as exemplified by Israel’s mass murder of Palestinians. Capitalism necessitates racism, sexism, queerphobia, and environmental destruction as they intersect with disability, in order to justify and excuse the conditions needed for its perpetuation and the escalation of its exploitation.

Capitalism cannot exist without exploitation. Its existence requires ‘othering’, and the sickening calculus of human capital. Policy and welfare can certainly ameliorate ableist conditions, but it will always inevitably manifest more when the profit motive demands.

Disability justice needs more than lobbying, it needs a revolution.

Marc Paniza unravels the invisible labour that shaped his childhood.

were rare, something I failed to consider when I complained about our lack of vacations.

I remember one summer clearly. My schoolmates shared stories about beach trips, and I came home full of demands. “Why can’t we go somewhere nice for once?” I whined. My Mama patiently explained the complexities: the logistics of transporting my Lola and Tita, the financial constraints. But her words passed through me unabsorbed.

It wasn’t until later that I realised: if I was itching to see beyond our walls,

how must my Lola and Tita have felt? My Lola passed away in 2013, having rarely left our home since 2008. When I visit beautiful places now, I often imagine my Lola’s reaction, what joy she might have felt seeing such sights.

The chamber pot or arinola sits in my memory, as a symbol of our daily adaptations. When friends visited and spotted it, their teasing was merciless. The shame led me to stop inviting friends over.

The humble doctor’s note. A magical beacon of hope for the disasterstricken student, who, on the day of their big exam finds themselves tragically struck down with a brief yet debilitating illness.

As per the University of Sydney’s special considerations policy, students who miss an assessment due to illness or misadventure have “no longer than three working days from the original assessment due date, the sitting date of the exam, the date of the missed class or missed placement” to submit their supporting documentation. This includes a Professional Practitioner Certificate, a medical certificate containing the same information, or a student declaration proving your exemption from a medical certificate in “extenuating circumstances.”

Sure, that may sound like a lot to achieve in three days, but we don’t want people faking sickness to get out of exams, do we? All in all, it sounds reasonable, right?

Well, not quite.

The doctor’s note works quite well if illness or misadventure lasts long enough that it’s not solved before you get a chance to see a doctor about it, but isn’t so debilitating that it prevents you from going to the doctor in the first place. Less fortunate are those of us with self-managed chronic conditions or disabilities which flare up unexpectedly — where consequences are infrequently serious enough to warrant going to the doctor, but serious enough that they may well cause you to miss an exam.

My Mama’s life as a caregiver began long before I was born. Her sister contracted meningitis during primary school, upending their family. Mounting medical costs forced the closure of my Lola’s restaurant. My Mama eventually abandoned her university studies due to financial constraints.

I’m type 1 diabetic, which at my age, level of independence and the level of subsidies on my medication and equipment means that most of the time, managing my diabetes is fairly easy and uneventful. But every now and then I have low blood sugars overnight and sleep through my glucose alarms, or I sleep at a weird angle that bends my cannula and I wake up to find I’ve not been receiving insulin all night. These things have simple fixes — sugar, insulin, and a bit of time — all of which I usually have on hand. This is the case for many chronic illnesses and disabilities. People experience flare ups of pain, bouts of depression or anxiety, episodes of fatigue things which to us are expected, manageable, and not warranting a doctor’s appointment, but temporarily prevent us from attending to our responsibilities. Even if I did want to go to the doctor, and I don’t mean this as a slight on the profession,

General Practitioners (GPs) tend to know very little about diabetes. Sure, they understand that my pancreas doesn’t produce insulin, but they know very little about the day to day management.

to understand how someone could need a wheelchair one day and not the next. Ambulatory wheelchair users face stigma and prejudice, often being accused of being lazy or faking it. Emblematic of a broader mindset, distrust of disabled people and our ability to judge and make decisions about our own needs is all too common — including when we need to go to the doctor.

Infantilisation when it comes to doctor’s notes is the tip of the iceberg. With a three day window, ‘just going to the doctor’ is easier said than done. For a start, it’s almost impossible to get an appointment within three days, especially with your regular doctor. This means calling around your local (or not so local) GPs, or sitting at a medical centre for hours on end, neither of which are particularly pleasant experiences when you’re sick. This problem has become even worse in recent years, with wait times for GPs steadily increasing, and bulk billing becoming an increasing rarity.

It’s hard for non-disabled people to understand the day-to-day experience of living with a disability. The fluctuations, the good days, bad days. We see this in the inane and repetitive discourse about ambulatory wheelchair users. Despite the fact that one-third of all wheelchair users have some level of mobility, people struggle

By the time I entered the picture, caregiving was the constant thread running through my Mama’s life. Every moment was dedicated to others’ needs: cooking, cleaning, assisting with mobility, managing medications, running the store, and raising me.

When my Lola passed away, my Mama moved to Australia. The irony wasn’t lost on me when her employment became aged care. She completed a certificate, joking that she hardly needed “a stupid certificate” for work she had been doing her entire life.

This leaves a space open for online telehealth doctors, who can promise you a sick note in 60 minutes for just $19.99! Yet for all the fears of people faking their illness, I don’t think these doctors investigate all that hard when you ask them for a sick note.

And to be honest, I don’t think faceto-face doctors investigate all that hard either when you ask for a sick note. At the end of the day, a doctor’s

I remember dismissing my Mama’s enthusiasm after her first professional manicure in Australia. Now I understand. These moments represented something she had rarely experienced, time dedicated solely to herself.

The household of my childhood was shaped by disability: our routines, our space, our finances, and my Mama’s life trajectory. She never framed her life as a sacrifice. They simply were the reality she navigated with grace.

Looking back, I see the constellation of accommodations that filled our home. What I once viewed as limitations, I now recognise as evidence of profound love. My Mama’s caregiving wasn’t just work; it was the expression of

note isn’t proof that you were sick; it’s proof that you went to the doctor and asked for a sick note.

Yet, in the face of all of this, the university made proposals last year to reduce the three day window to zero — so if we felt this was a lot to achieve in three days, you now have to get sick, get better enough to make it to the doctor, find an appointment (or sit in a medical centre for hours), attend your appointment then submit all your documentation in the space of one day.

This is a direct consequence of refusing to listen to and consult with actual disabled people. The issue lies in the fact that many of these decisions are being pushed through university management by people who have never had to make an emergency doctor’s appointment, and if they did, would have no trouble paying out of pocket.

Of course universities need some level of assessment and standardisation. Courses and accreditations would fall apart if there were no standards to hold students to. But if universities fail to make reasonable concessions to people with disabilities, they fail an enormous portion of their student body. This ultimately excludes disabled people from accessing higher education, and means we are doomed to continue perpetuating social structures which routinely discriminate against and exclude disabled people. This is not to pin the blame of systemic ableism entirely on the doctor’s note — but if we’re looking for somewhere to start, it sure is an option.

her deepest values.

The tragedy may be how invisible this work remains, how easily a child could grow up within it and still fail to truly see it. But perhaps that invisibility is also evidence of its success, care so seamlessly provided that it could be taken for granted.

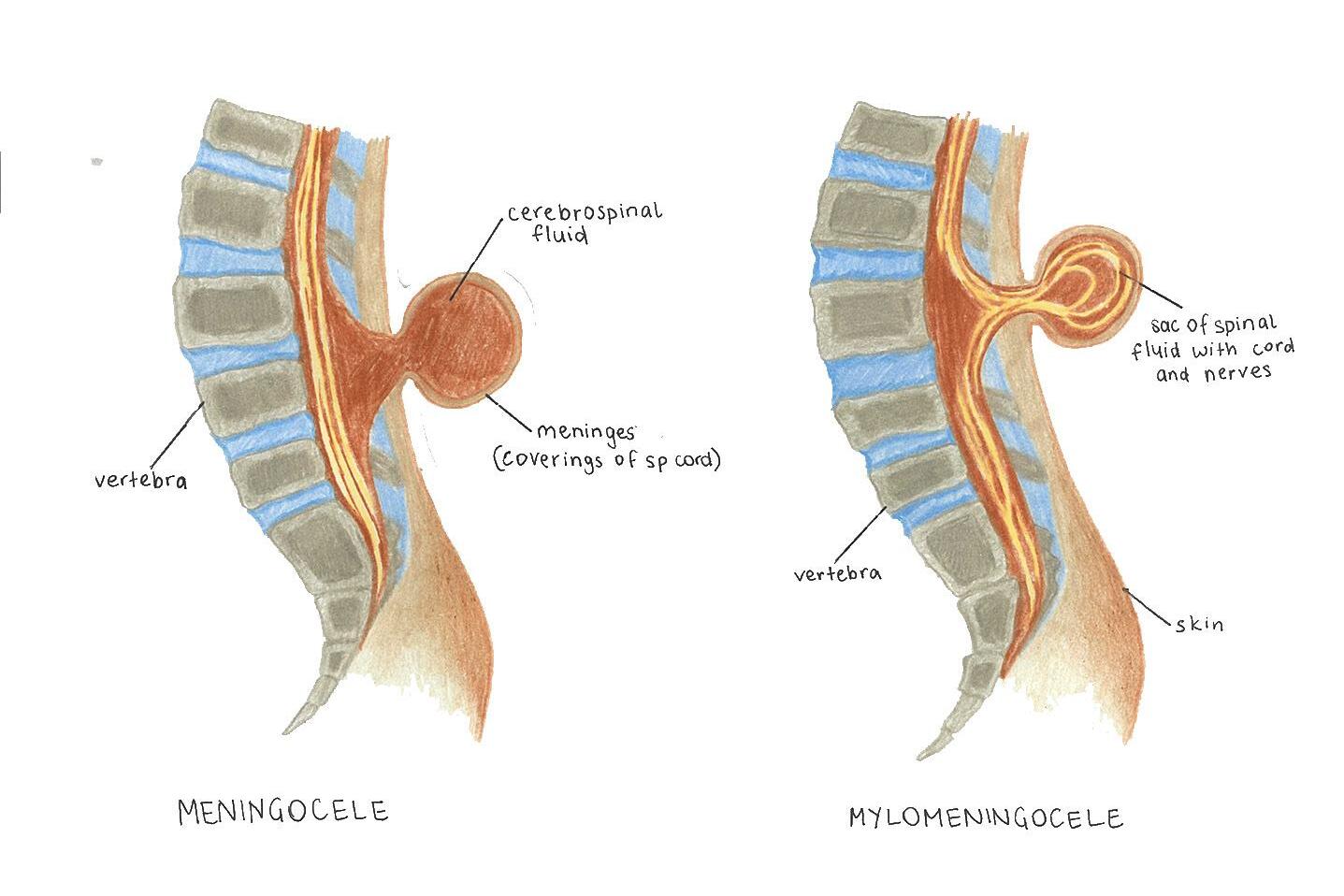

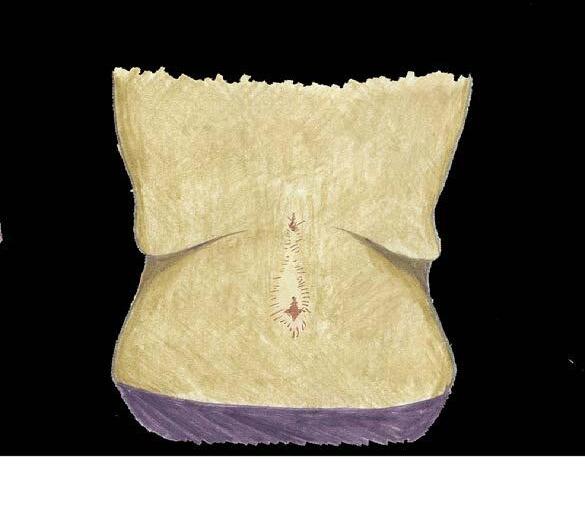

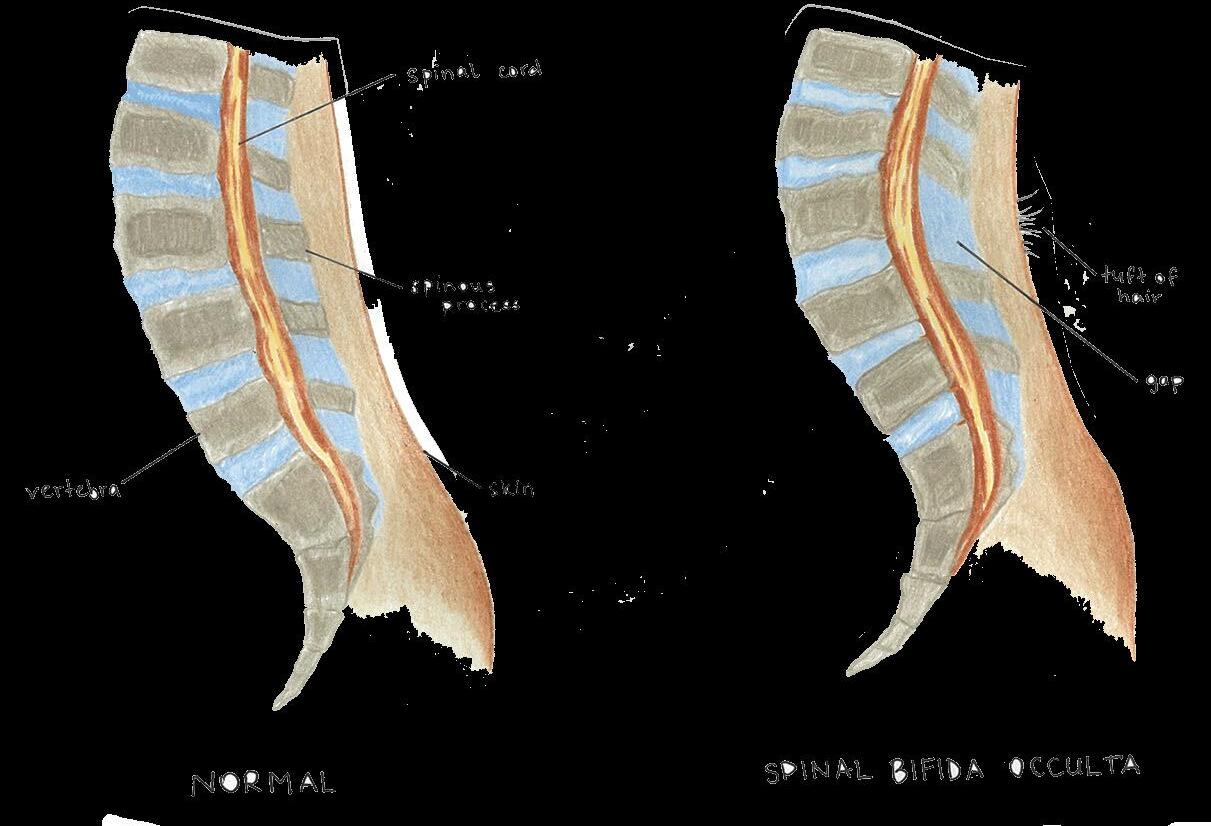

I was born with a congenital disease called ‘Spina Bifida’. My case was said to be rare — diastematomyelia — and although I have no recollection of what my parents went through, it is astounding that I am more able bodied than doctors expected I would be. Spina Bifida is a type of neural birth defect, where the spine and spinal cord do not close properly. It is thought that family history and not enough vitamin B-9 (folic acid) may cause Spina Bifida, however the cause is not exactly known. There are three main types of Spina Bifida:

1. Occulta — A small gap in the spine, and usually does not cause any disabilities.

2. Meningocele — A sac filled with spinal fluid comes out of the opening, and can cause minor disabilities.

3. Myelomeningocele — A sac filled with spinal fluid and part of the spinal cord comes out of the opening. This can cause moderate to severe disabilities, such as not being able to move the legs.

by

disabilities as well as chronic bladder and kidney infections. As first time parents, they still made the difficult decision to continue with the pregnancy. My first surgery was at two days old to close the opening in my back. The second surgery was at three years old to remove the bony spur. My parents were told that even if these surgeries were successful, there may be disabilities that I would develop later.

Growing up, I was slower than most kids. I had a huge scar on my back that I’ve since learnt to love. At around 11 years old, I wore a cast on my left leg. My condition

I was born with meningocele which is minor. However, I was diagnosed with diastematomyelia – which is an associated condition under meningocele. My spinal cord was split in half by a bony spur. It is difficult to determine the severity of this condition during prenatal diagnosis. My parents were told that I may need to use a wheelchair, develop hydrocephalus (a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid that can cause brain damage), develop tethered cord (that would prevent normal movement of the spinal cord), or have learning

resulted in some of the nerves in my left legs to be weaker. My foot and calf were smaller as the muscles atrophied, and I couldn’t stand on it properly. This large cast that I had to lug around in school meant that I had to wear ugly wide shoes and couldn’t cross my legs. Many people pointed out the way that I walk. I couldn’t help walking a little weird — my pelvis is tilted to accommodate my weaker leg. I often felt belittled, as teachers pitied me and I would sit on a chair unlike my peers on the floor. I would get stares and

ignorant questions about this plastic cast. Some would kick it like a toy. Every year the teacher would celebrate the student with the most remarkable attendance — reminding me that my attendance record was never 100 per cent as I would visit the Spina Bifida clinic for checkups for my casts, my back, and legs. I noticed that these experiences as a child meant that I didn’t fit in with the other kids.

How does my disability affect me today?

I am incredibly grateful for the support from The Children’s Hospital helping me through my developing years. It was rough to experience as a child, but due to the cast on my foot, I am now able to walk without any aides. I do have minor issues such as back pain and foot pain. I am thankful for the life I have today. It is a privilege to experience living. It’s wonderful that my body has adjusted to accommodate my shorter leg and has learnt to live amongst these ‘abnormal’ dimensions. It would raise more challenges if I required a wheelchair, but I know it would still be a privilege to experience living.