SEEING

There is more than one way to access the written word. The contributors to this volume have kindly agreed to record themselves reading/ performing their own texts. You are invited to read their words in the pages ahead, but also to listen to them by scanning the QR codes at the bottom of the page.

We hope you will enjoy these pathways into the text, and the different perspectives they offer.

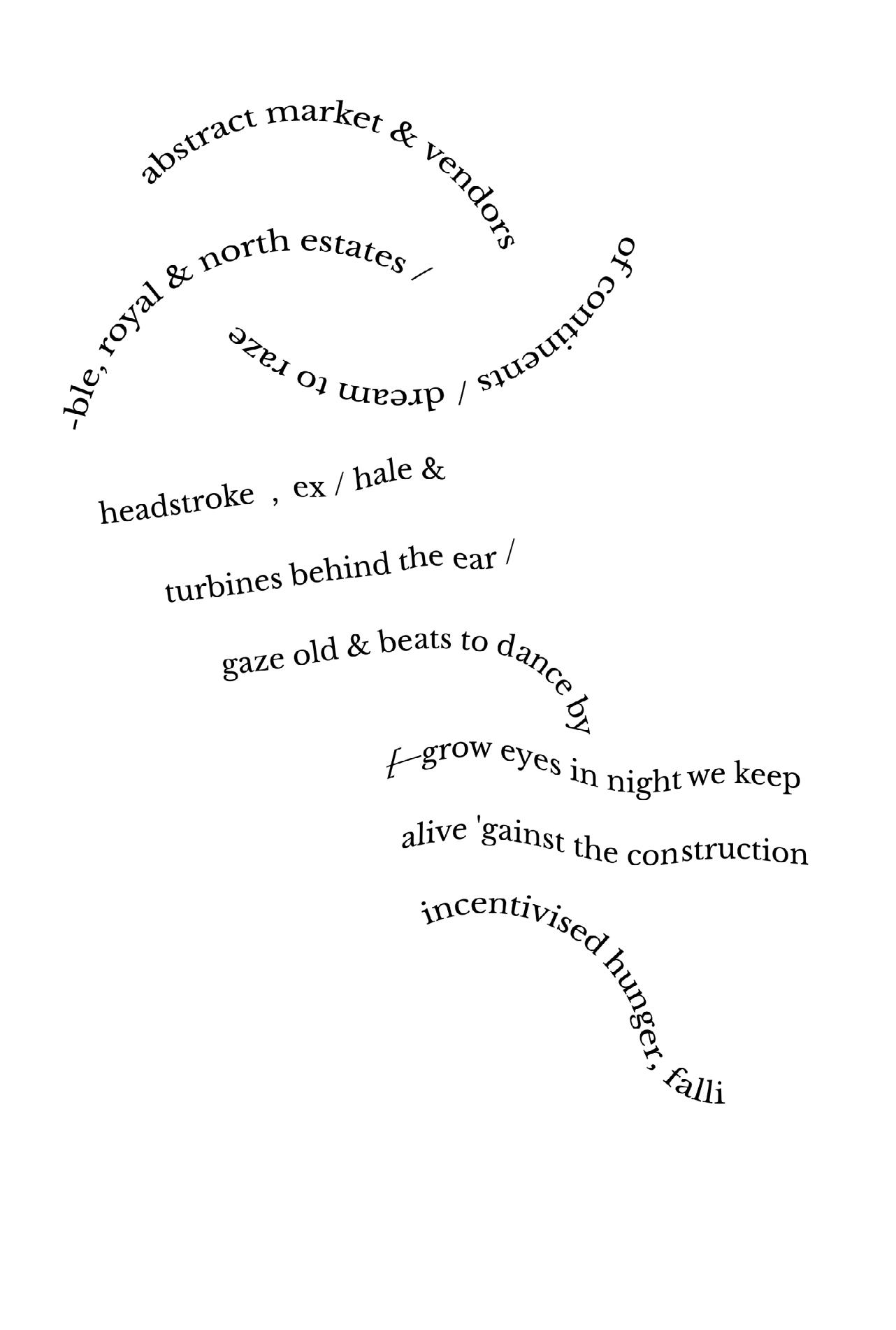

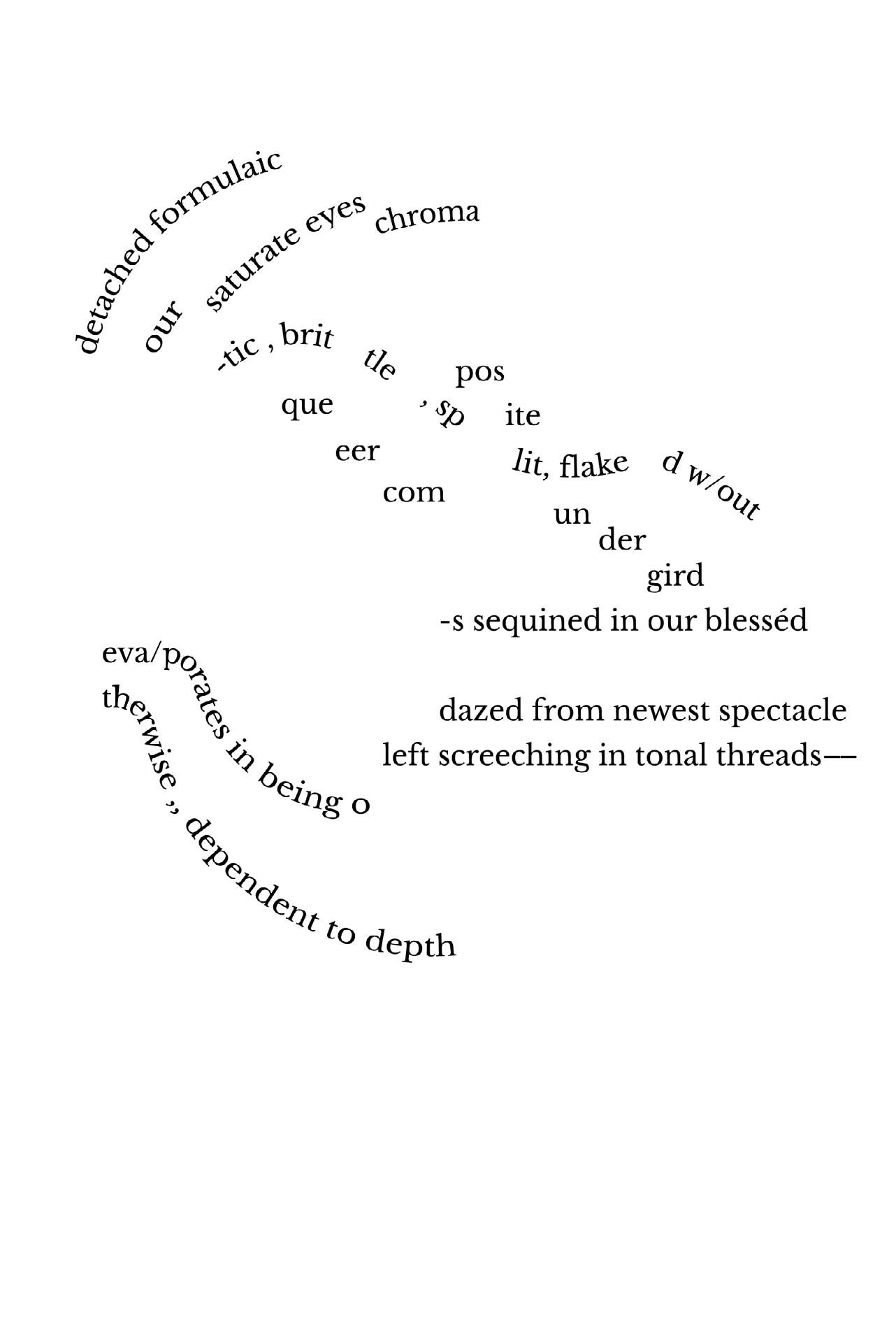

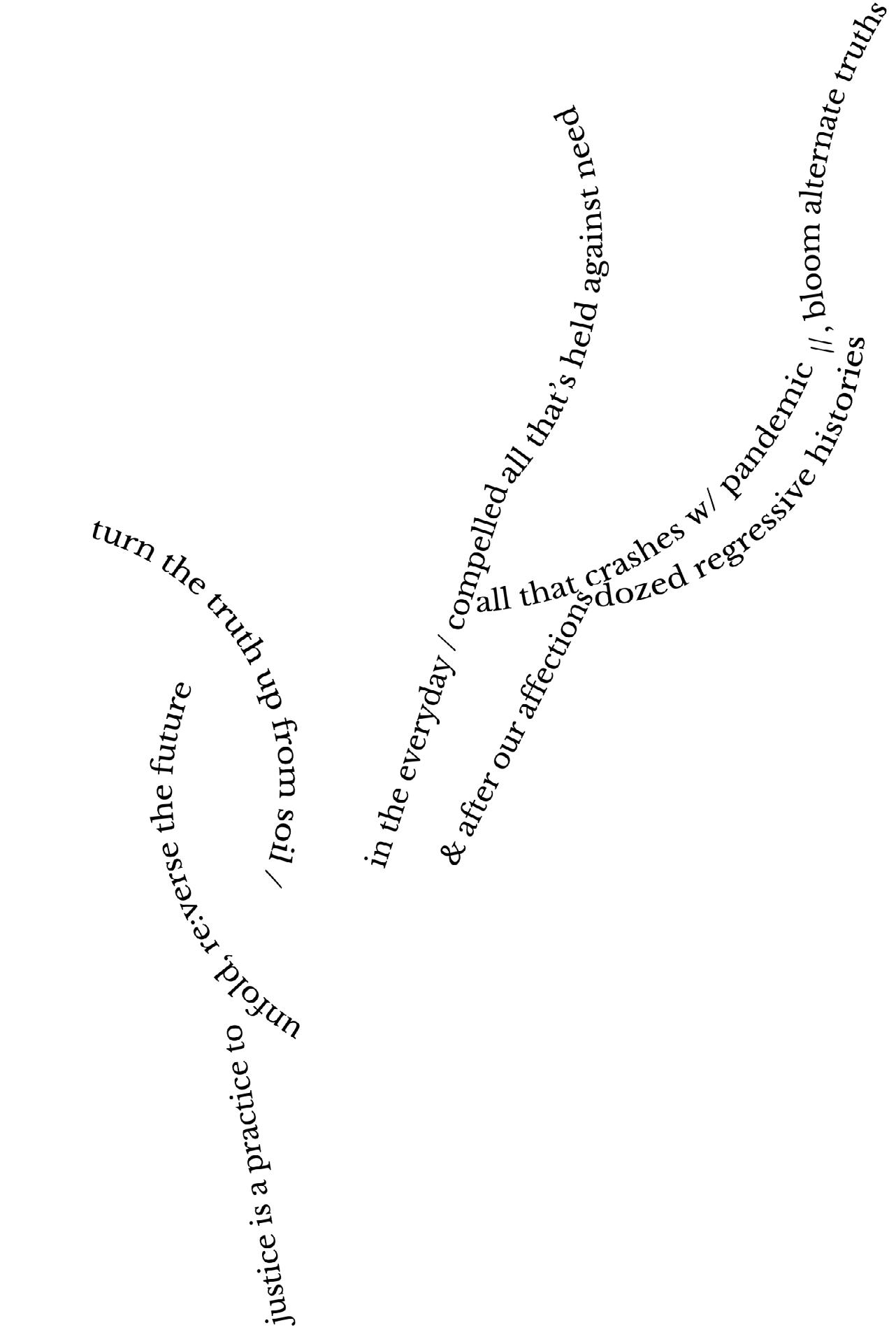

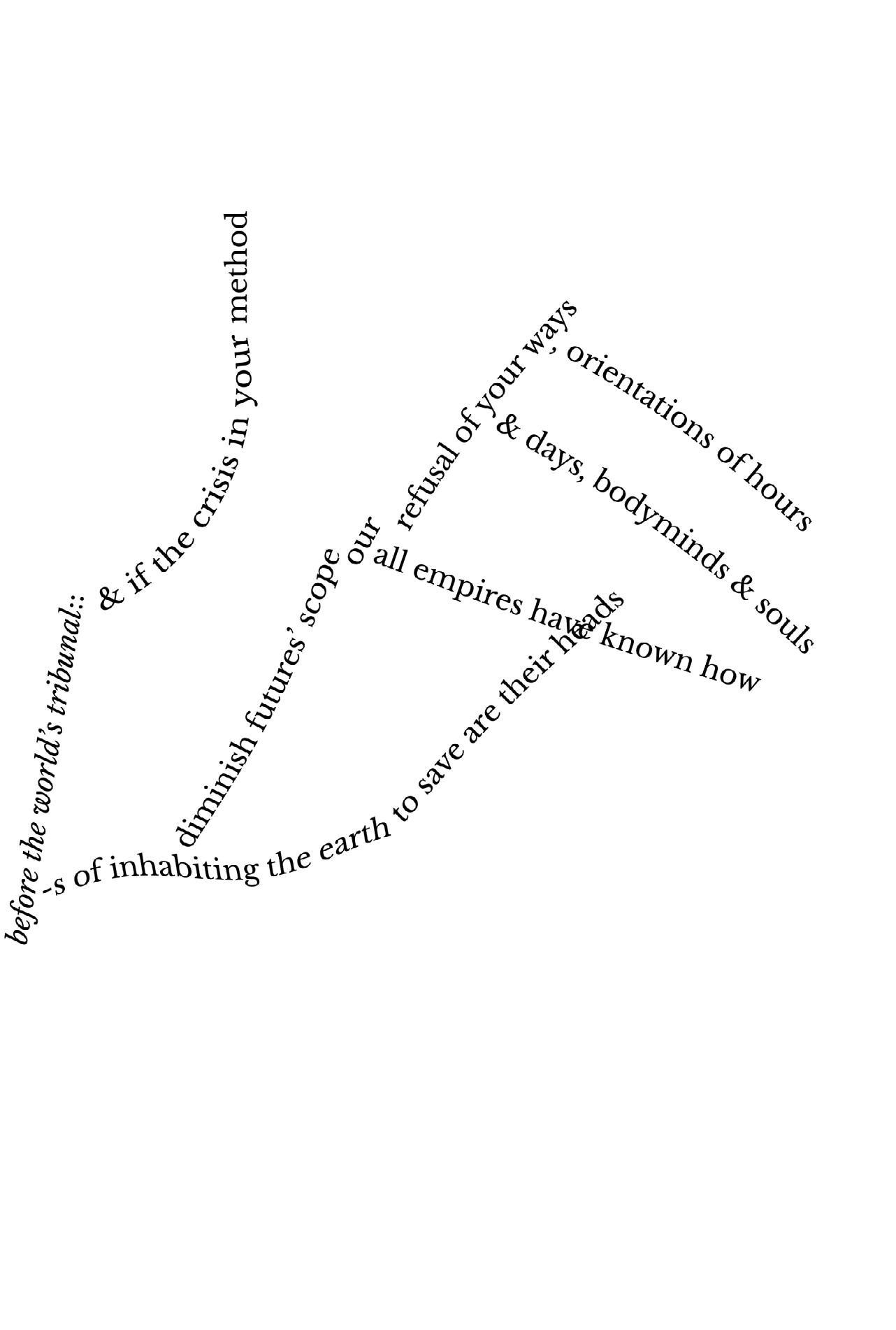

The poems of apparitions take the form of the ‘niner’, a nine line poem, typically in sequences of nine poems – more recently adopting a line of nine syllables, &/or other numerical orderings in the number of sounds or words related to nine. coined by contemporary poet Mendoza and adopted by various innovative writers, the niner is seemingly a sonnot, resembling a sonnet while radically departing from its conventions; a perverse sounding that adopts a seemingly masochistic musical containment. the nine syllable line itself a brash, punk (or post-punk) response to the metrics of anglophone verse. the form has allowed for experiment and study in dialect and accent, and their effect upon the language contained in a line of nine syllables or beats.1

apparitions – here represented in nine poems, but in full a sequence of eight-one poems in the nine – is a work forged through text and performance. in performance, poems are reordered, deconstructed on a twenty-seven or thirty-six second loop, where one-in-nine lines are recorded and layered atop each other. the selection of lines for recording (or cuts of nine syllables across different lines) is improvised; the lines placed wherever they are sounded in the loop cycle; and the reconstituted poem played out after each set of nine poems. the sonic

1 See Linus Slug, Type Specimen, London: Contraband Books, 2014; Mendoza & Peter Manson, Windsuckers & Onsetters, London & Munich: Materials, 2018; Mendoza & Peter Manson, Windsuckers & Onsetters, audio recording, 2018, online at https:// soundcloud.com/materials-materialien/sets/windsucker-onsetters (accessed 26 August 2022).

architecture of the work becomes spherical, rotating as new propositions of longitude, shifting the focus of gravity on the surface of the shape. these transformations are understood politically: firstly, knowing that the architectures of form – like the built environment in the Global North – are rarely built for the making of marginalised lives.2 Through experimentation, poetry can propose alternative grammars, syntaxes and transformed relations to space, operating at various levels of meaning and sense. Secondly, knowing that the sounding of speech & voice bears (traces of) struggle, in the face of violent, dematerialising economic and social conditions, compounded with the ‘organised abandonment’ of neoliberal governance during the coronavirus pandemic.3 These are poems of resistance, on the question of justice contra racial capitalism and state violence, emerging from politicised LGBTQIA communities and Black and brown communities.

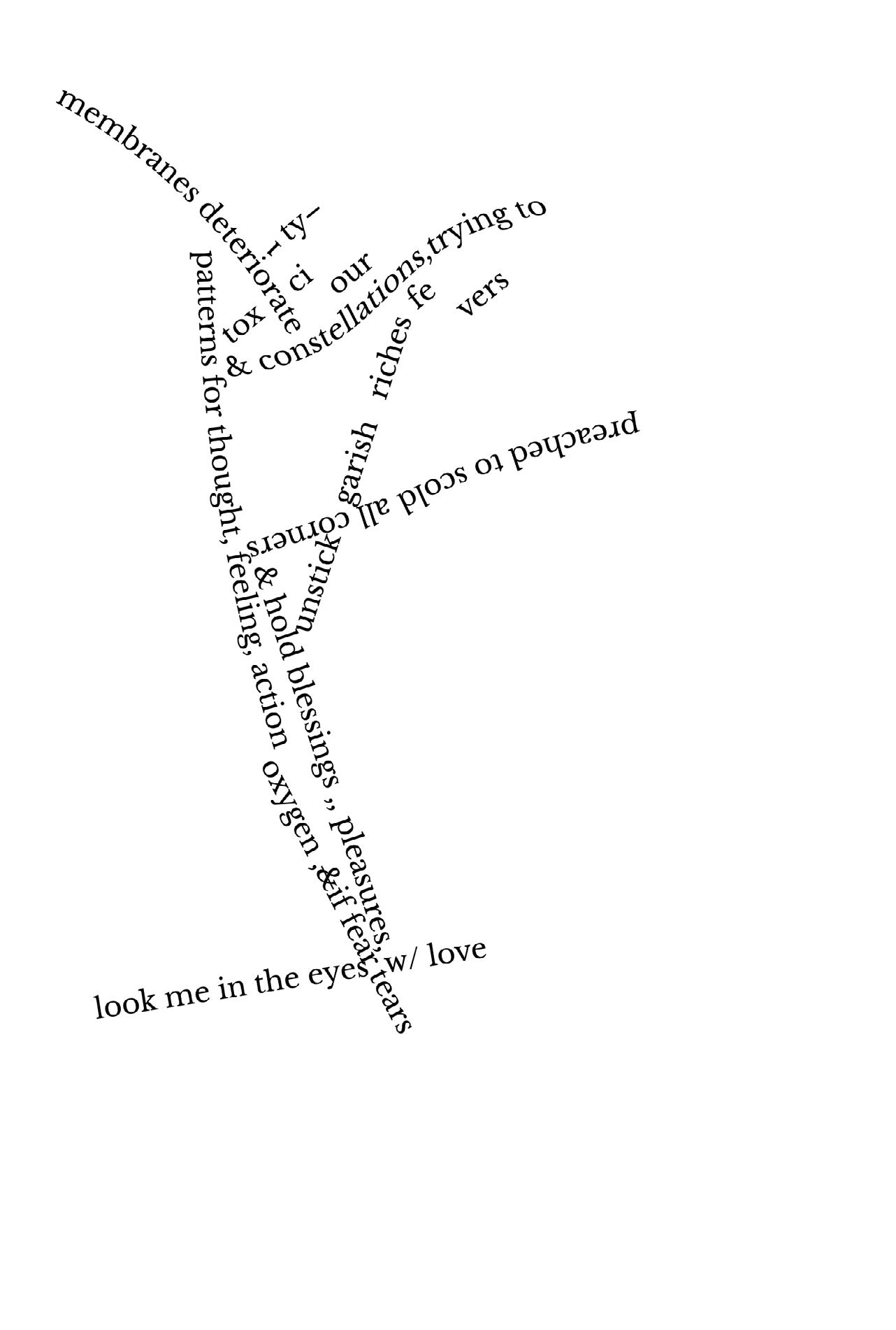

The poems presented in Seeing transcribe these energies – sonic, political – back into the visual field – with lines shifting, rotating and undulating through various mathematical degrees of the nine degrees of the nine. lines curve towards each other, reconfiguring the ordering, stanzas turning 180°, openings and closings of poems switching. they are visual propositions / a performance score towards a next iteration of the work. they disintegrate and de/compose, some into seemingly organic forms, reaching upwards and towards alternate truths.

2 This is an iteration of a question in the work of Lubaina Himid, ‘we live in buildings –do they fit us?’

3 As a term, ‘organised abandonment’, i.e., the strategic divestment of resources from certain groups of people, comes from Ruth Wilson Gilmore.

Thanks to Yasmine Dammak, Bissi and Zoé Devaux (Paradise City Festival)whosharedtheinterviewwithBissifromMissfittewithme.This interview was also part of Devaux’s thesis on queer feminist electronic nightlife.ThanksalsotoRuthTimmermansforherextensivefinalediting of this article.

On the club scene and at festivals, people still dance all too often to the beats of male DJs. Men still predominantly have the deciding vote here, but over the past decade, these spaces have discovered that female producers also exist. Somewhere in-between, LGBTQIA+ artists are also trying to gain a space on the same stage. Nevertheless, the live music industry is still mainly a heteronormative, male business. In reaction, various queer1 feminist collectives and initiatives have emerged in recent years, building their own ‘safe.r space’2 and working towards greater diversity, equality and inclusivity on the dance floor.

1 The terms queer and LGBTQIA+ have been used alternately here. This is based on the wording that the collectives and festivals themselves use. Here the term ‘queer’ is often used interchangeably with LGBTQIA+ as a general term.

2 A safer space is a place where people can fully and comfortably participate without fear of being harassed or discriminated against because of their biological sex, race/ ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, cultural background, religious affiliation, age, or physical or mental ability. Using the term ‘safe.r space’ reflects the fact that discrimination and harassment can occur even in spaces where norms, policies and procedures have been put in place to prevent such behaviour. No space can ever be 100% safe for all people because everyone’s requirements to feel safe are different, hence safe.r space.

It is indisputable that both female and queer artists get far less visibility than their male colleagues. Just as art galleries are still mainly the territory of white, cisgender men, the latter are often the directors and managers of concert venues and media outlets specialising in dance, such as radio stations and magazines. And these white, cisgendered men often seem to have a hard time seeing you if you are not a white, cisgendered man. There also appears to be little room for manoeuvre: despite the call for more diversity, job vacancies are often filled by people who are recognisable to leaders. Even queer events are mainly organised by straight men.

That makes it essential to continue calling artistic and business managers to account for the lack of diversity in their selections. The programming of festivals, concert venues, radio stations and editorial choices in printed media, and consequently the visibility they give artists, do not only give artists an income but also influence the way our entire society thinks about diversity. Visibility is important to inspire a new generation of artists, but it is also crucial to the acceptance of those who currently feel excluded from society. If you don’t give a platform today to the female or queer artists who have everything it takes to be a headliner tomorrow, how will they ever be able to grow into headline artists?

I’m standing in line for the Brussels nightclub C12. When my friends and I get to the entrance, a C12 employee asks whether we know about the club and the music they play there; we also hear about C12’s safety policy. ‘Don’t do anything without the other person’s permission. There is a helpdesk where you can alert us to any problems. If you see someone in need, help them. That way we all work together to keep things safe.’

C12 is one of Brussels’ more aware nightclubs. It is a club where the organisers have the courage to admit their mistakes.

However, they haven’t got this far without setbacks. In 2018, the German DJ Konstantin, who runs the techno label Giegling, was accused of verbal and physical sexual harassment by several women. Just that week, C12 had programmed a Giegling event with Konstantin as the main act. Clubbers at C12 complained about the poster, and the event was cancelled. C12 decided to present an entirely female line-up that evening instead.

Since then, C12 has tried to pamper its audience with a highly diverse offering. For example, drag performer Juriji Van de Klee organised her Benediction evenings there. One of the highlights was an evening with Honey Dijon, known as a trailblazer for the trans DJ community, at the turntables. The programming also reveals a certain awareness at C12 of the role that trans, LGBTQIA+ artists and women have played in the history of electronic music, a role that should not be underestimated. That does not prevent C12 from slipping up now and again, and neither does it silence criticism of the motivation for the diverse programming at what is, after all, a commercial club.

During my recent night out at C12, the line-up was entirely male. That was also reflected in the striking predominance of men in the audience. Looking around for a moment as I danced, I found myself entirely surrounded by men. Unfortunately, this is not the first time I have felt alone somewhere as a queer woman.

That stands in stark contrast to the diverse audience who came to dance at the ‘experimental ecosystem’ of Circle Park in Anderlecht two weeks earlier to the techno beats of a programme filled by three Brussels-based queer feminist collectives: Missfitte, Rebel and Not Your Techno. These

three collectives are all strong advocates in their own way for more diversity, equality and inclusion on the dance floor. The line-up consisted entirely of female and/or queer DJs, and the dance floor was bursting with people of colour, women, queers, non-binary and – incidentally –cisgender people.

Strikingly, the first ten metres of the dance floor were reserved for women and queers. ‘Women and queers to the front’ read the placards. In the toilets, there were reminders everywhere that the organisers aimed to create a safe.r space, including a telephone number where you could leave comments. There was also a staff member at the entrance explaining that this was a safe.r space. As Yasmine Dammak of Not Your Techno explains: ‘We feel that our biggest achievement thus far is creating a safe.r space. We have implemented this safe.r space in several party series, with the best being our party at Décoratelier in August 2021 and our recent edition with our fellows from Missfitte and Rebel collectives. The crowd was so diverse, loving, and respectful.’

The demographics of the electronic dance scene are totally different to the way they were in the early years. House music began in Chicago in the 1980s as an underground phenomenon played mainly by black DJs. The audience were very diverse as well: queers and women experienced these house parties as a safe space. During the 1990s and 2000s, the genre was picked up in Europe by a mainly white, male audience. The origins of the music in the black and queer community had been forgotten by then, and house, like all other dance music, was seen as entertainment for the white community. That has meant that new generations of visitors constantly have to be reminded of the history of electronic dance music.

Unfortunately, the reactions are not always positive. ‘Keep politics out of music’ is an intermittent rallying cry when attention is drawn to discrimination and harassment on the dance floor. But as the American DJ Umfang said during a debate on Techno Activism at the Polish festival Unsound in 2017: ‘Being a woman is a political act.’ Constantly demanding your own space and right to exist is something you have to do as a queer as well as a woman.

Although the black (gay) community played a major role in the emergence of electronic music, you still hardly find people of colour and/or with a different gender identity in positions where they can have a decisive voice in creating change. That is why, as a first step, promotors, artists and club owners – who build their organisation or brand on the basis of that culture, after all – should take a more robust attitude to diversity, equality and inclusion on the dance floor. Yasmine Dammak is ready with a few suggestions: ‘They can start with adapting their door policy, informing people at the entrance… Briefing their staff about their presence… Adapting and improving their communication skills to solve problems but certainly also to anticipate them.’ Many studies have since shown that a diverse audience offers the best guarantee for the preservation of values and the sustainable development of organisations. Or, as Dammak puts it: ‘We would also like to see changes in their recruitment pool. The more representation we have in the club scene, the safer we can feel, the more recognition we feel too.’

Year after year, the figures have been backing up the sorry state of diversity, equality and inclusivity on stage. The organisation female:pressure has been publishing its FACTS survey every two years since 2013. It

studies the proportions of male/female/non-binary performing artists at festivals. The figures for 2020-2021 show a slight increase in female and non-binary artists on stage to 27% (combined). In 2014, this figure was less than 10% at the electronic music festivals studied. These figures seem to be confirmed by the report published by the Walloon-Brussels organisation Scivias in June 2022. Scivias investigated the gender distribution at festivals in Wallonia and Brussels in the summer of 2022.

It came to the conclusion that of the 1255 solo artists counted, 78% could be associated with the male gender, 21% with the female gender and fewer than 0.5% identified themselves as non-binary. These staggering numbers are also confirmed by The Jaguar Foundation which released, in the summer of 2022, the ‘Progressing Gender Representation in UK Dance Music’ report, in which it explores the gender disparity in the UK electronic music scene.

If we only look at averages, however, we easily lose sight of the major differences and even outliers that do exist: whereas the Brussels-based Schiev is evenly distributed, the Dutch Dekmantel only has 24% female performers on its stage; Heroines of Sound in Berlin obviously has an almost 100% female and/or non-binary line-up.

While the statistics provide impetus to map the extent of the problem, Bissi from the Brussels collective Missfitte wonders: ‘Where do you stop? When the balance hits 50%? The feminist issue is bound up with many other struggles. This is only the tip of the iceberg. It’s hard enough to reach a balance here, while there are many other problems we haven’t even touched.’ It is true that none of these reports consider the other ‘intersections’ that the collectives mentioned above are trying to highlight. What about the visibility of LGBTQIA+ artists and people of colour? To what extent does geographical origin play a role in the programming? And is there space on stage for people with a disability?

Whereas the commercial clubs are often still miles away from the origins of the electronic dance scene, the fight for change and more diversity, equality and inclusion in society at large is a difficult one. That is why a new generation of queer feminist collectives have taken the initiative to create a nightlife especially for women, transgender people and gender nonconforming people in recent years. These collectives are not only found in Brussels, but all over the world: Burenhinder (Antwerp), Maricas (Barcelona), Mina (Lisbon), Oramics (Poland), Room4Resistance (Berlin), etc. Some collectives are more active and activist than others.

Missfitte, founded by Noemi Cano, started organising its first events in 2018. In November 2019, the collective organised a debate evening on queer culture and the club scene. There, the Brussels-based producer and DJ Sara Dziri explained the idea behind Not Your Techno, which had been founded half a year previously. That collective, which includes Yasmine Dammak, aims to develop into a community and platform that organises parties with diverse, upcoming talent on the electronic music scene ‘with a focus on female-identifying, queer and POC3 artists.’ Dammak: ‘We felt a need to bring some changes and improvements to the electronic music scene. The scene has been quite EU-centred, which was logical decades ago but is far from the reality nowadays. Belgium is becoming more diverse, and we need to implement this diversity in the electronic music scene too. We wanted to be part of this evolution and therefore started our own community.’

These collectives thus also work towards greater awareness among clubbers of the lack of diversity in (mainstream) clubs and the media. They do this both explicitly and implicitly: a casual visitor who knows 3 People of Colour

nothing about the organisation and its aims may notice that the night feels different. Very slowly, these collectives have also begun to impact mainstream club culture. Dammak: ‘More and more organisations are reaching out to talk and organise events with us, in which our expertise considering safe.r spaces and inclusivity is implemented.’

Besides the work of these collectives, a specialised festival circuit is also taking shape. These festivals are organised by people from the LGBTQIA+ community and appeal to the same community. This creates a platform for queer artists, mainly in the electronic underground. In turn, a safe.r space is emerging where everyone can be themselves, without intruders or subjection to a heteronormative gaze.

Whereas WHOLE | United Queer Festival has already been held four times, Body Movements, which had its second edition in the summer of 2022, is the first British queer and trans electronic music festival. Instead of having headline acts, the founders of Body Movements – event organiser Clayton Wright and DJ Saoirse, both members of the queer community – opted to work in partnership with queer collectives. That enabled them to create a diverse and authentic programme. More important still is that they want to reclaim queer events. After all, the British queer community is concerned to see many queer events in London being organised by companies run by heterosexuals.

Flesh Festival made its debut in 2022 as the first camping festival in London. It is the brainchild of Samantha Togni, an Italian living in London. For some time now, Togni has been creating venues that give a voice to all underrepresented and unrepresented groups in the music industry. In doing so, they pay attention to all genders, cultures and backgrounds that are still blatantly being ignored by the industry. As with Not Your Techno, the security team at their events is mainly female and queer. Dammak: ‘If we must provide the security team ourselves, the selection

will be based on the audience. We believe that the representation of the audience influences the choice of our security team, which is queer, female-identifying, POC, etc.’ At Flesh Festival, ninety per cent of the lineup are women, transgender people and non-binary artists with a wide spectrum of ethnicities.

The dance floor isn’t the only place where more diversity, equality and inclusion are needed. Radio stations and magazines are also in a sorry state.

In 2020, I spoke to a PR manager (name known to the editor), who is responsible for marketing a handful of Belgian and foreign acts. He told me that the music programming at the Flemish broadcasting service, the VRT, was mainly done by male teams. ‘At Radio 1,’ he added, ‘almost all of them are old men.’

That is not only the case for commercial and/or public broadcasters. The playlists of smaller radio stations (including internet radio) are also determined by a predominantly male team. Resident DJs are more often men than women. Recently however, something seems to be changing on the radio landscape. For example, the Irish Dublin Digital Radio states in its mission statement: ‘We aim to provide a platform for voices that would otherwise be underrepresented or excluded in contemporary discussions.’ Refuge Worldwide in Berlin claims that it mainly wants to profile itself as a gender-balanced radio station with attention to minorities.

If you look at the (online) radio community, the unique position of Radio Vacarme (French for ‘noise’), founded in 2021, is striking. This Brusselsbased web radio station, set up by Chloé Pinaud, Winona Andujar,

Delphine Tézé and Federica Grassi, broadcasting from Brasserie Illegaal, calls itself feminist and queer. Vacarme went online in February 2022 with an intense and diverse programme. It offers a safe.r space for artistic and cultural productions, debates on feminism, the LGBTQIA+ community and conversations about current social issues. Their selection of residents is also extremely diverse. With live shows, DJ sets, podcasts and talk radio, Radio Vacarme holds space for a highly diverse offering and audience.

In 2020, I set up my own online platform, Dissonant, after a career of more than twenty years as a journalist, curator and member of the editorial team at a music magazine. At that point, the magazine had two women in its core editorial team. It wasn’t always easy to find space for interesting, innovative female and queer artists in the magazine. A frequently heard comment – that I also regularly see cropping up elsewhere in the music scene, such as recently in an online debate on an all-male line-up at a punk festival – is that ‘it needs to be good, though’. Even in 2022, a double standard still applies, and gender stereotyping is ubiquitous in the music industry. What is more, this attitude is also typical of how knowledge about music is valued and transmitted within the music industry: anything outside the canon is not taken seriously. This approach can also be found in present-day music journalism.

Dissonant is a reaction to that frustration. Although the platform is still in search of a format as a place for journalism, it has been a monthly radio show on Radio Vacarme since February 2022. I aim for my Dissonant show to hold space for women, LGBTQIA+ people, non-binary and other gender nonconforming producers in electronic music. For the time being, Dissonant is unique in the Belgian radio landscape, but fortunately there are like-minded online initiatives elsewhere in the world. For example,

Feminatronic both creates a monthly playlist on Soundcloud and has a blog with a listening summary. Feminatronic expresses the intention ‘to celebrate the eclecticism of electronic artists who identify as female.’ Female Frequencies is a DJ crew and collective, but also a radio show on reboot.fm in Berlin, which plays music by female, trans and non-binary producers. In Britain, jacki-e is fighting gender inequality in electronic music with her show ‘Draw The Line’. Radio Kamikaze, operating out of London, broadcasted a series of exclusively LGBTQIA+ artists in May.

On the eve of Pride 2022, the AB in Brussel organised ‘Outrageous’, a festival evening deliberately aimed at queers, with only queer artists on stage. It was as though the concert promotors had only realised that evening that there was an audience thirsty for queer artists. “It’s a success. We were so worried no one would come”, I heard someone whisper to her partner. Other venues in Brussels have been aware that queers also want their own night for longer. Besides party concepts like Los Ninos, Gay Haze and Cat Club, Queer Future Club made its debut at the end of 2019 with a programme of its own, at Fformatt which has since closed down. This summer, Paradise City Festival offered stage space to Rebel and Not Your Techno, and C12 has invited the DJ and LGBTQIA+ advocate Eris Drew to perform in autumn 2022. One thing is striking. Most of these organisations and concert venues are still run by a small, very homogeneous group of men at present. Diversity, equality and inclusion still cannot be taken for granted, but Yasmine Dammak is optimistic: ‘We feel things are moving. There is a little evolution considering booking women and trying to balance line-ups, but we need more recognition and visibility in the scene. There is still a lot of work to do.’

It will be good!

(she/her, b. 1976) is a queer music enthusiast, journalist, curator and designer. In her writing practice — which grew from writing critiques to articles and essays — she experienced first-hand what it’s like to be a (queer) woman in the music field, as a spectator and as a professional. It didn’t stop her from growing as a journalist, though at some point she concluded she’d mainly written about white, male, straight artists. While her awareness grew, she formed her curatorial practice, where she immediately put her focus on LGBTQIA+, women and people of color first.

In 2020 she founded the website dissonant.nu with the goal to create a platform in support of women, non-binary and lgbtqia+ people in (primarily) the electronic music scene. In 2022, Dissonant also became a radio show.

NAT RAHA is a poet and activist-scholar, based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Nat is the author of three collections of poetry: ofsirens,body&faultlines (Boiler House Press, 2018), countersonnets (Contraband Books, 2013) and Octet (Veer Books, 2010). Recent anthologies featuring her work include 100 Queer Poems, We Want It All: An Anthology of RadicalTrans Poetics and ON CARE. Nat’s creative and critical writing has appeared on Poem-a-Day, and in South Atlantic Quarterly, Third Text, TSQ, Transgender Marxism (Pluto Press, 2021) and Wasafiri Magazine. Her work has appeared in recent exhibitions at Mimosa House London, yaby Madrid, and in 2021 she co-curated ‘Life Support: Forms of Care in Art and Activism’ Exhibition at Glasgow Women’s Library.

Nat holds a PhD from the University of Sussex and is co-authoring a book Trans Femme Futures: An Ethics for Transfeminist Worlds with Mijke van der Drift.

Seeing is believing, so they say.

But is that simple?

Is it not more accurate to say that we see what we already believe?

We have all looked at things, at situations, at people, and not seen them for what or who they are. Sometimes we see something completely different to what’s actually in front of us. And sometimes we don’t see anything at all: the object of our gaze is invisible, even when they are waving their hands and jumping up and down.

Seeing is an act of perception, involving the person who is doing the seeing. It draws upon everything that has shaped them up to that point, and cloaks the one being seen in these many invisible threads. That is why seeing is also an act of judgment. It’s true that taking in the whole picture is hard, perhaps even impossible. But deliberately or not, most often we dim our own vision, seeing only a fraction of what is actually there. We can be willfully blind.

And so, seeing is also an act of recognition. Of whom we are seeing, first of all. But also of ourselves, as we situate ourselves in relation to what we are looking at. How we see someone is a way in which we selfdetermine. Seeing is never neutral. It is a reciprocal act of recognition, a tug-of-war of acknowledgement and engagement between the one doing the seeing, and the one being seen.

Can we see further, more intensely, with a wider view? Can we be aware of what has shaped us, and actively see beyond these influences?

We all have flaws in our perception. By understanding them, we can become more aware of ourselves, our illusions, our (narrow) perspectives. And once we are aware, we can grow, expanding our ways of seeing, connecting with greater truth to those around us. For we are all different: that is what we have in common.

In this second volume of the Sounds Now annual publication series, we invite readers to come back to the texts over and over, with different ways of seeing. The texts are also voiced by both writers, bringing another perspective to the content. Scan the QR code and enjoy the richness of the written as well as the verbal word.

McKenzie and Esther UrsemSounds Now is a 5-year project presented by a consortium of 9 European music festivals and cultural institutions that disseminate contemporary music, experimental music and sound art.

In this project, we are concerned with the way in which the contemporary music and sound art worlds reproduce the same patterns of power and exclusion that are dominant at all levels of our societies, all the more so because these sectors are committed to promoting progressive agendas.

Sounds Now consequently aims to stimulate diversity within this professional field by reflecting and challenging current curatorial practices. Activities are directed at bringing new voices, perspectives and backgrounds into contemporary music festivals. Centering on three pillars of diversity — gender/gender identity, ethnic and socio-economic background — the project includes a range of actions such as labs for curators, mentorship programmes, artistic productions, symposia and research. In this way, Sounds Now seeks to open up the possibility for different experiences, conditions and perspectives to be defining forces in shaping the sonic art that reaches audiences today.

www.sounds-now.eu

The Creative Europe programme is the European Commission’s framework programme for support to the cultural and audiovisual sectors. It aims to improve access to European culture and creative works, and to promote innovation and creativity.

The Culture Strand of Creative Europe helps cultural and creative organisations, such as those involved in the Sounds Now project, to operate transnationally. It provides financial support to activities with a European dimension that aim to strengthen the transnational creation and circulation of European works, developing transnational mobility, audience development (accessible and inclusive culture), innovation and capacity building, notably in digitisation, new business models, education and training.

The Sounds Now project gratefully acknowledges the support provided by Creative Europe in bringing artists and cultural operators the opportunity to foster artistic works and improve practices, thereby contributing to a strong and vibrant European music sector.

www.eacea.ec.europa.eu

© 2022, Sounds Now

All rights reserved

Published by Musica Impulse Centre

Design: Patty Kaes

Print: Haletra, Houthalen-Helchteren, Belgium

Distribution: Musica Impulse Centre, Pelt, Belgium

ISBN 9789464667509

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner and writers.