ENGAGING

JULIET FRASER

MO LAUDI

After the Second World War, all kinds of movements emerged in the arts, and therefore also in contemporary music. Past trauma and new awareness collided and generated diverse outcomes in the Cold War reality. Never-again war and a desire for a new free and tolerant future were the motives for often experimental art expressions that came to focus on political activism, engagement, communality and attention, to name a few social themes of that era. Composers such as Luigi Nono, Mauricio Kagel, Hans Werner Henze, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Louis Andriessen incorporated fierce political themes (often communist in nature) into their work.

After 1980, the most extroverted political themes disappeared next to the technical discourse of composition and new technological innovations. New music became a seemingly self-reflective and inaccessible academic art form to many people. The music itself became central, and less so the message or the audience. As always, European white men were the ones writing the manifestos. That being said, change was in the air and the world got introduced to female composers like Finnish Kaija Saariaho, and Russians such as Sofia Gubaidulina and Galina Ustvolskaja.

In the past ten to twenty years, art has become political again, but from a different angle. Due to the new media infocracy, the Western canon is no longer the standard for what is good and bad art, even if white men

are still strongly present in the making of decisions. The share of women and nonbinary artists on stages and behind the scenes is growing, and makers from continents other than Europe and the United States are making themselves heard. Diversity and inclusivity are themes that recur everywhere, whether we attend events in Reykjavik, Venice, Viitasaari, Donaueschingen or ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

Sounds Now emerged from a desire of nine European new music festivals and organisations to open up a new awareness of those who are behind the sounds we encounter today, whether in the orchestra pit, on stage or participating themselves. This can only be successful if we are also willing to change and question everything we thought was right, thus giving people a chance to speak of what they consider important. The expectations of creators, performers and audience are in transition, so we need to keep this dialogue going in order to remain relevant in this rapidly changing world.

In this publication with the theme “Engaging”, we are happy to give some of these concerns a platform with the help of some of the most interesting names in the field. Juliet Fraser is, in addition to being a fantastic singer, a great advocate for structural change. Mo Laudi is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. He is inspired by African knowledge systems, post-apartheid transnationalism, international and underground subcultures. In our Sounds Now project “Freedom to

Move”, with singer Sofia Jernberg as our artistic conscience, we give new voices and faces a stage. The most special and personal stories are included in this brochure.

Enjoy reading.

Johan Tallgren and Bert Palinckx

BY JULIET FRASER

What does it mean to be engaging? There is a sense of suspension, of breath or of time, and a tension — a crackle in the air, perhaps. As artists, we may engage in art-making for many different reasons: art for art’s sake, as a political statement, for the money, etc. We may be tempted to reduce these motivations to a sliding scale between the aesthetic and the functional, but a hand-thrown coffee cup reminds us that the extremes need not be at odds: all motivations are legitimate and often complexly overlapping. As audience members (I hesitate to use the word consumers), we may engage with art to be comforted, aroused, challenged or entertained. Again, to reduce the conversation to art vs distraction or the mediated vs the immediatised would be an unhelpful oversimplification. There are so many moving parts, from the intention through the process to the outcome (the art), to the context and the criticism and the crowd (all frames, of sorts). Engagement is full of contradictions, in a good way.

In performance, a musician seeks to engage their audience, to win their trust and hold their attention. Some performers have a charisma that does the heavy lifting; the material is secondary, elevated by the strength of the performing personality. Some are rather the vessel for compelling material, adopting a performance style that gets out of the way of the music. Others have dazzling skill; the material here is a showcase for technical virtuosity. The rare G.O.A.T.s have all three: skill, strong

material and huge charisma — think of Bowie, Billie Holiday or Beyoncé. For classical performers who specialise in interpreting others’ material, however, the question of how we engage you as listeners, to what we draw your attention, is more complicated.

It is only since I have started teaching that I have begun to understand how flexible a new-music singer must be. We must be chameleons, able to embody an extraordinary breadth of aesthetics: from the popinfused pseudo-sampling of Bernhard Lang to the expressionistic drama of Gérard Grisey, from the sensual ferocity of Rebecca Saunders to the controlled surface tension of Morton Feldman, each invites a different vocality and a different physicality on the concert platform. This is not the same as playing a character, as one might do in opera; it is a more subtle, more embodied relationship with the work’s sonic material and its aesthetics. And yet cultivating this embodied relationship between physicality and material seems to be an art that is not taught. Singers trained at conservatoire according to the traditional classical pedagogy tend to engage their voice only in one sort of sound (bel canto) and their body only in one mode of stagecraft (dramatic); as a result, when they encounter the pluralism of contemporary classical music, the effect is either liberating or overwhelming.

MATERIAL, MATERIAL, MATERIAL has become my mantra. Enquire of the material what sort of vocality and what style of physicality it requires. Engage some intelligence and some creativity in this area! Applying the (presumed) conventions of late nineteenth-century repertoire to all classical music for evermore creates a quite unnecessary flattening out of performance. Contexts differ, as do performers’ personalities, physicalities and aesthetic proclivities — far more fun for us to lean into these differences. Furthermore, the notion that we on stage have to work extra hard to ‘sell’ new music is nonsense: too often an overegged performance style gets in the way of the music. As the poet and psychoanalyst Nuar Alsadir explains:

The most direct way of connecting with others is to experience genuine feeling within yourself, so that your emotion, transmitted to others as beta elements, triggers their mirror neurons to fire. It is then that they will experience and process your emotion as though it had originated within their own bodies, that they will feel moved.1

A performance can offer an audience many forms of journey. It may strew crumbs along a path and we, as listeners, hungrily follow the trail; it may offer doorways into worlds and invite us to choose our own adventure. In his essay ‘Audience’, choreographer Jonathan Burrows describes the pleasure of ‘watching in a more wasteful way’, of retaining the distance of an observer that allows for ‘those brilliant shifts that stick in my head’.2 It is not necessary for a performance to become a spectacle in order to engage the audience’s attention — the understated, the oblique, the gentle are no less engaging than the vertiginous or the bombastic.

In contrast, the term ‘audience engagement’ barely concerns itself with any of these considerations. It is a speculative construct driven by twentyfirst-century capitalist anxieties — about growth, about success — and utterly divorced from the creative engagement in an art form. Performers now experience intense pressure from funding bodies, promoters and agents to worry about audience engagement: contracts regularly include clauses stipulating that a performer promotes the event on social media and funding evaluations measure ‘impact’ in quantitative rather than qualitative terms. Engagement, we are taught, is about numbers.

I don’t seek to sing the most notes, though. This sort of Trumpian metric would have me singing higher, faster, louder, BETTER than everyone else. No, engaging with my art form means, first and foremost, engaging my craft with my intellect and my emotion; my secondary aim is to

1 Nuar Alsadir, AnimalJoy (Fitzcarraldo, 2022), 41.

2 ‘Audience’ in Jonathan Burrows WritingDance (Varamo Press, 2022), 65-7.

engage my listeners, to move them or touch them or surprise them in some way. Measuring the first aim is entirely subjective and unscientific; measuring the second is similarly anecdotal and very patchy, and I like that. The audience is not a single entity: it is a group of individuals, all bringing different experiences and expectations to an occasion. Thinking strategically about how to engage ‘them’ seems like a fool’s errand. Just busy yourself with making magic.

Barthes famously complained that the grain of the voice was being polished out by the increasing ‘professionalisation’ of singing. As we see in competitions, from BBC Cardiff Singer of the World to The Voice, the audience responds to flare over flawlessness. Witnessing a body at work is a fascinating thing — the effort compels us to watch. As Alsadir writes,

Work that preserves the grain — the fluids and funk that flow through a living body — brings you back to a moment of cognition because, as Barthes puts it, “the symbolic ... is thrown immediately (without mediation) before us.” You feel the stuff in the singer’s voice, the finger that sticks through what was meant to be two-dimensional space. This “directness,” Sontag writes, “... entirely frees us from the itch to interpret.” We can feel (rapid motion of wings).3

Icarus ascends. The desire to engage with another sets up a moment of vulnerability — what happens if they do not take hold of the hand that we extend? A performance is always an act of discovery, for the performers and for the audience, of ourselves and of one another.

3 Alsadir AnimalJoy , 316.

The task at hand is the making of music. The task at hand shifts from day to day: I am engaged in an ongoing practice. In my daily practice, I begin by warming up my voice. I have my little routine of scales and exercises, but these days prefer to start with very long notes, calming the nervous system and thinking purely about vibrations and resonance. (I actively try not to engage the brain at this stage because it normally tells me that I should give up immediately.) I then open a score. This may or may not be something that I am due to perform, but it is a way of setting the singing body to work on a more precise task, and a task with some expressive intent. So, from here on I am engaging the brain, but the challenge is to hold in balance the left hemisphere of the brain (concerned with problem-solving and effective practice), the right hemisphere of the brain (injecting spontaneous creativity) and the body’s response to all that brain activity (producing the sound). Technique offers a consistency of craft that then allows the right hemisphere the space to play.

Calling all this a ‘creative’ practice somehow smooths away the corners that are so monotonous and so banal and, often, so uncreative. Most days I feel engaged more in a battle with myself than in a creative process. I don’t want to start, I don’t want to sing, I’m frightened of what it will sound like or feel like... I know I am not alone in this struggle, though voicing it remains something of a taboo.

Material is the alchemical ingredient precisely because it shifts the balance or the focus of the task. I am now engaged in a process of negotiation with an entity that is separate from me. Both sides reach towards an encounter. And it is the breadth and depth of material with which I can engage that keeps me singing: how many other genres offer a singer such a dressing-up box? A score rarely gives more than a hint of the transformation at hand. The magic moment comes when the material

begins to speak to me, to reveal ‘who’ it is and what it needs from me, how best to embody it. One hopes that this magic happens during private practice, that one has time to enjoy the process of channelling, but not all material is so forthcoming; sometimes it only reveals its needs during performance — thrilling, certainly, but also a little destabilising. Which is why premieres should be much less of a spectacle and, ideally, should not be recorded.4

We tend to talk about ‘a technique’ and about ‘a practice’ as if they are somehow fixed but, in reality, they are constantly shifting, accumulating new layers of knowledge in the body or mind, or shedding dusty remnants of long-forgotten ways of doing or thinking. If the material tends to be the focus of the day-to-day, far beneath lie the tectonic plates of one’s practice. This is the domain of The Existential Questions: Who am I? What am I doing? Does any of it matter? My tectonic plates seem to shift every seven or eight years, causing great upheaval, most of which is supposed to stay hidden from the public eye. The plates last shifted in 2022 and, as I continue to stumble through the long fog of uncertainty, a new perspective is slowly emerging. These shifts or crises, I now realise, are part and parcel of an unfolding practice. When the questions stop, it will be time to do something else.

Burrows proposes that ‘Practice is a doing which is not yet art.’5 I like this distinction between the quotidian doing and the mystical transubstantiation that turns the doing into art, but I am worried that I don’t know where the line is between the two, or who gets to judge. Does my practice only become art in front of an audience? Sometimes, yes,

4 A little rant emerged at this point but was extracted to become a separate essay outlining an alternative approach to recording new works: Juliet Fraser, ‘On the Record’, Substack, 27 June 2024, https://open.substack.com/pub/julietfraser/p/on-the-record?r=25b6q6&utm

5 ‘Practice’ in Burrows WritingDance , (Varamo Press, 2022), 28.

but not only, and not as a rule. The frame cannot make the art, surely... Neither can it be contingent upon success, whatever that means. For me, art is perhaps the doing of the practice that cannot be redone. I understand better now what I am trying to do with all this music. It is the irredeemability of a performance that I find liberating: there is no turning back, only pressing onward, upward, hoping for flight.

Art takes time. It is a cliché to curse the click-bait culture of our times but here’s where the struggle lies because questions take time, ambiguity takes time, change takes time. Music is all about time but where is our interrogation of form and pacing when we consider how we make and share this music? Anna Kornbluh, amongst others, situates us in an epoch of immediacy, in which the unceasing flow of images dominates the thickness of mediated encounters and, basically, we all lose our minds:

‘Immediacy impedes the public, conceptual, and reasoned mediations that are essential to limiting the devastations of deinstitutionalized society, privatization, and ecocide, and crucial for imagining different frames of value, meaning, representation, and collectivity.’6

In this age of the individual, we seem to be trying to dismantle the cult of the genius composer whilst erecting the cult of the composer-of-themoment. For all the talk of diversity, we still seem determined to celebrate only a handful of superstars. We should worry a little for the few men and the fewer women who are featured here, there and everywhere, blazingly and briefly in demand, as is the rule of immediacy’s game. Lord, deliver them from burnout. We clamour over the individual whilst speaking loftily of community: how do we resolve this contradiction?

6 Anna Kornbluh, Immediacyor,TheStyleofTooLateCapitalism (Verso, 2023), 18.

1. We slow down.

Pacing oneself is perhaps a luxury, but it should not remain the privilege of the few. As artists, we may yet have some work to do claiming the right to say “no”, or “not yet”, or “not like this”, for it takes courage to acknowledge one’s idiosyncratic creative metabolism and ensure that the industry respects it. Ted Gioia, in his viral Substack post entitled ‘The State of the Culture, 2024’, articulates something many of us have sensed when he explains the enormous pressure art is under today to conform to the bite-sized hits of the dopamine culture:

The fastest growing sector of the culture economy is distraction. Or call it scrolling or swiping or wasting time or whatever you want. But it’s not art or entertainment, just ceaseless activity. The key is that each stimulus only lasts a few seconds, and must be repeated. It’s a huge business, and will soon be larger than arts and entertainment combined. Everything is getting turned into TikTok — an aptly named platform for a business based on stimuli that must be repeated after only a few ticks of the clock. TikTok made a fortune with fast-paced scrolling video. And now Facebook — once a place to connect with family and friends — is imitating it. So long, Granny, hello Reels. Twitter has done the same. And, of course, Instagram, YouTube, and everybody else trying to get rich on social media. This is more than just the hot trend of 2024. It can last forever — because it’s based on body chemistry, not fashion or aesthetics[...] So you need to ditch that simple model of art versus entertainment. And even ‘distraction’ is just a stepping stone toward the real goal nowadays — which is addiction 7

7 Ted Gioia ‘The State of the Culture, 2024’, Substack, 18 February 2024: https://www. honest-broker.com/p/the-state-of-the-culture-2024.

In Gioia’s food chain, Art is swallowed up by Entertainment which is being swallowed up by Distraction which is being swallowed up by Addiction. I just wonder if Art can dart away, and escape the jaws of all the bigger fish. It may be under pressure from the Silicon Valley culture economy, but I am hopeful that there will always be an audience for art that does not participate in this fast-paced, insatiable economy. Perhaps this is the strength of new music: composition is a slow act, and the nature of our engagement — as performer or audience — is generally too much like hard work to be categorised as ‘entertaining’. Our resilience, ironically, could lie in our resolutely slow and focused processes.

2. We gather in new ways.

Historical collectivism within classical music has failed us. According to the dominant narrative, classical music is struggling against irrelevance, elitism, the perpetuation of inequality and literal, fiscal bankruptcy. How and with whom we gather can change this narrative, however: new models of collaboration are working to discredit the myth of the genius composer, from performer-composer co-creation to far greater discussion around collaborative consent; new models of curation are dismantling old hierarchies and rewriting the guest list; new models of environmental sustainability for our industry could quickly be implemented if we looked to those already developed in the theatre world8.

When we gather, we recalibrate ourselves as individuals within a community. I have a lot of time for discussions around artistic identity, but the current strain of narcissism that treats ‘my truth’ as academic insight and facilitates the desperate proliferation of identity-focused projects is a creative dead-end: as Kornbluh puts it, ‘Every I, lousy with

8 Theatre Green Book UK has just been released in its second edition: ‘News’, Theatre Green Book, accessed 26 June 2024, https://theatregreenbook.com/june-2024-second-edition-launch/. Where is classical music’s first edition?!

panache’9. This is not about woke or anti-woke — the culture wars can play out without us. It is possible to demonstrate solidarity without collapsing into tribalism, to build a community offering respite from the algorithms that exacerbate our insecurities about body, identity and status.

When we gather, we fortify ourselves. It is strategic to recognise that we cannot each fight all fights on all fronts. A contemporary, intersectional collectivism might assemble multiple battalions, united in a vision for change but with discrete targets. Marianna Ritchey, for example, wants to weaken the power of institutions:

The kind of anti-institutional orientation I wish we would develop is one that refuses to see institutions ... as the benevolent distributors of rights and freedoms that we might one day receive if we ask nicely enough. Instead, we should orient ourselves toward people, and toward constructing autonomous forms of musicking that don’t require institutional patronage.10

I take a softer view, seeing institutions and organisations as formed of people, many of whom are desperate to contribute to positive change, but Ritchey is right to challenge the conditions of institutional patronage and her ‘autonomous forms of musicking’ could pave the way for a radically different distribution of power and agency.

Meanwhile, organisations such as Black Administrators of Opera are engaged in the fight to expose and reform systems of racial inequity in opera. Their open letter, published in 2020 and building on Black Opera

9 Kornbluh, Immediacy , 54.

10 Marianna Ritchey, ‘A Critical Perspective on Diversity and Inclusion in US Classical Music Discourse’ in VoicesforChangeintheClassicalMusicProfession:NewIdeas forTacklingInequalitiesandExclusions , Eds. Anna Bull and Christina Scharff with Ass. Ed. Laudan Nooshin (Oxford University Press, 2023), 99.

Alliance’s A Pledge for Racial Equity and Systemic Change in Opera , called for ‘the necessary changes for greater equity in our field’ and presented a list of five actionable solutions. When asked in an interview why Black administrators had mobilised, Quodesia Johnson explained that ‘the industry needed to hear directly from its administrators because there is a habit of dismissing the artists who do not often see all of the moving pieces outside of what happens onstage.’11 Later she says,

It is very difficult to hoard power when you’re in community with someone because you start to share space, you start to be accountable, you start to witness the narratives of others, and you’re forever changed when that happens, when you connect on a human level.12

This example models so much: one organisation supporting another, administrators supporting artists, demands accompanied by solutions. Like the opera world, our new-music scene is international but comparatively small. I am engaged in my struggles and you are engaged in yours, but if we pay attention to how our respective struggles intersect, change might come a little sooner.

3. We engage thinkingly.

We cannot afford to be unthinking in how we engage in all of this. Many of the concerns around the implications of specific technologies on our specific cultural economy, such as streaming, social media and AI13 are

11 Antonio C. Cuyler, ‘(Un)Silencing Blacktivism in Opera: An Interview with Quodesia Johnson about the LettertotheOperaFieldfromBlackAdministators’ in Voices for ChangeintheClassicalMusicProfession , 257.

12 Ibid, 259.

13 Gioia is useful on this topic too, see https://www.honest-broker.com/p/how-the-music-business-can-tame-the.

double-edged swords, offering potential benefits as well as significant threats — this is what makes a quick-fix solution so elusive. Equally, the effort to bring our education, programming and funding models in line with twenty-first-century mores and render them fit to serve future generations requires sustained creative thought. Include artists in these efforts: please let them through the gates.

And engagement need not be a synonym for activism. You do you, babe; just do it with your eyes open. For it will require personal and collective intentionality to stem the tide of immediacy, distraction and general unthinking bullshit:

‘An economy that prizes the circulation of images, human capital entrepreneurs, and the datafication of everything into endless counting of the homogenized same realizes in plasma the mythic promise of the fluid screen. Narcissus’s mirror is industrially ordained.’14

I don’t want to think in terms of human capital and ‘content’15. I don’t want to participate in the datafication and the endless counting. I don’t understand why we, who are after all concerned with sound , are participating in the pointless circulation of images. Why is our industry so complicit in such unthinking gluttony? Where did all the questions go?!

14 Kornbluh Immediacy , 53.

15 Spotify CEO Daniel Ek recently caused a twitter storm when he began a post on X with these words: ‘Today, with the cost of creating content being close to zero, people can share an incredible amount of content.’ The kickback from artists was glorious. Daniel Ek (@eldsjal), X, 29 May 2024, https://x.com/eldsjal/status/1795871513293320204

Why are we doing things this way?

Why participate?

Why document?

Why digitise?

Why pirouette faddishly around the same few topics?

Why fetishise the premiere?

Why avoid the ambiguities?

Why so fearful?

Fear is a threat because it freezes our creativity; we cannot see the possibilities. Sound, to me, is thick with possibility. Our performances can be an invitation to engage in a world that prioritises ears over eyes, listening over speaking, questions over answers, togetherness over isolation, magic over the mundane. They can help us hold fast to slow process, rigour, care and real-life connectedness. Distraction is at the surface level but engagement effects some sort of shift within us. Even better, engagement is reciprocal: we shift and we are shifted. And eventually the tide turns.

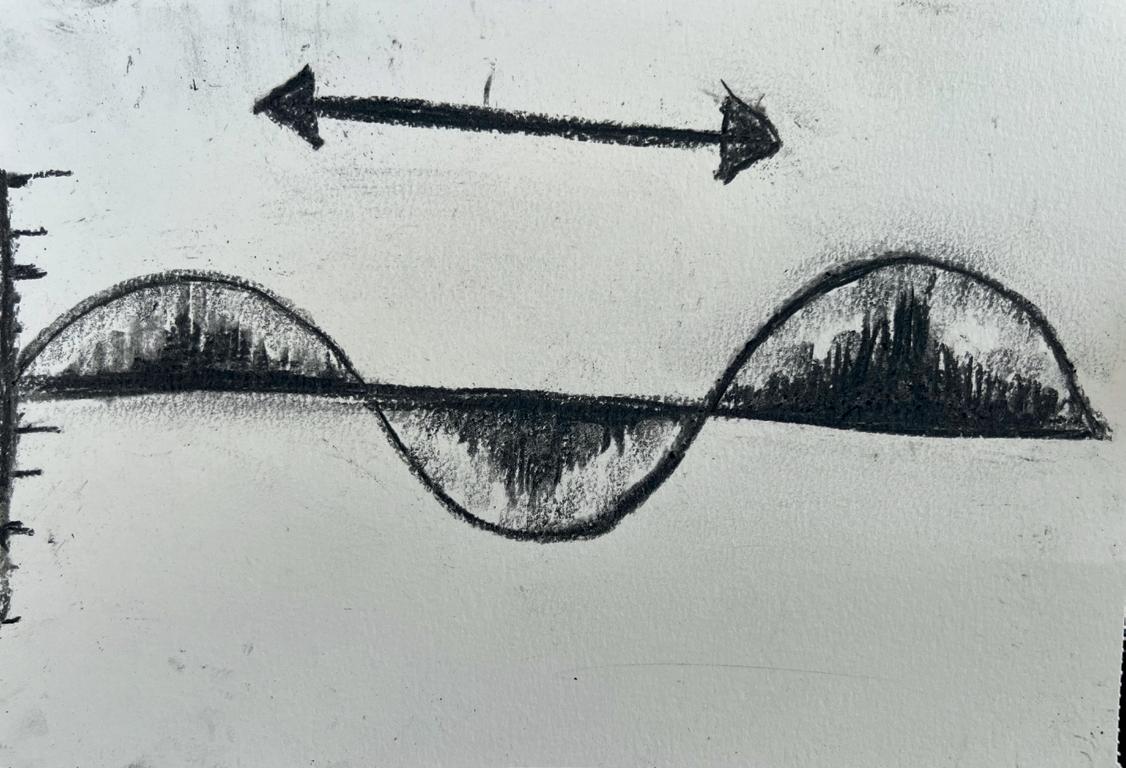

Sound is produced when an object vibrates, creating a pressure wave. This pressure wave causes particles in the surrounding medium to have vibrational motion. As the particles vibrate, they move nearby particles, transmitting the sound further through the medium. What is the role of the artist if it’s not to make the revolution irresistible, to make hearts and minds vibrate to a higher frequency. The DJ performs a curated, researched playlist transitioning bpm and harmonic tones, deconstructing a song, blending one song to another, to formulate a set that blurs the role of the musician vs that of the DJ as the role of the curator vs that of the artist. The vibrations set off by artists with their

activism can transform a gallery, a church, into a space of resistance as the audience creates a vibrational motion into their community.1

This essay, envisioned as a sonic lecture, aims to construct and imagine the contours of the Globalisto philosophy, articulating how it is intricately woven into practice from its very inception, through its foundational principles, theoretical frameworks, and practical applications. It explores the dynamic interplay of culture, identity, and resistance, invoking the critical cultural insights formulated like a poem, a song, a DJ-set, to reveal a philosophy that transcends boundaries and embraces the interconnectedness of our global existence. Sound has an unparalleled ability to transcend linguistic and cultural barriers. My sonic lectures are encounters for collective ‘deep listening’ (as coined by Pauline Oliveros) and sharing, during which emotions and ideas are evoked that resonate on a personal and universal level. These are moments when I share my sonic compositions combined with histories, stories of their making and rationale. When I begin my sonic lectures, I often start with a question: “Who can name the president(s) of Jamaica?” Typically, I’m met with silence. Then I pose a similar question, this time substituting “presidents” with “musicians.” Instantly, the room comes alive with enthusiasm and eager responses: Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Lee Scratch Perry… As we know, one good rap song is better than a thousand speeches. Music has a unique power to engage, connect and resonate with people in a way that few other mediums can. It transcends borders, barriers and speaks to our emotions, our experiences, and our shared humanity. While academic speeches and formal discourse have their place, sometimes they fail to capture the imagination and passion that

1 Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape, Globalisto.APhilosophyinFlux.ActsofImbizo in Mo Laudi and Alexandre Quoi (eds.), MAMC+, (Saint Etienne, les presses du réel, 2023), 15.

music effortlessly ignites. This phenomenon underscores how to reach people, to inspire and engage them, we must speak their language. For many, that language is music.

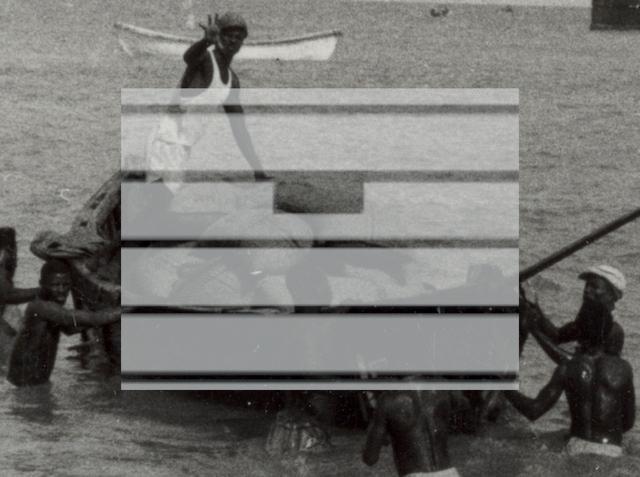

In an era increasingly characterised by fear, fear of the other, fear of being cancelled amidst deepening societal divisions, the role of art is more crucial than ever. As an artist deeply committed to the transformative power of sound, I frequently explore how our endeavours in exhibitionmaking, sound composition, and DJing can contribute to engaging in a more harmonious, equitable, and just society. In 2022, I included some of the 1950s, 60s and 70s African Drum magazines from the Sciences Po Bordeaux archive in the exhibition I curated in 2022, Globalisto: A PhilosophyinFluxat MAMC+ in Saint Etienne, as a way of indicating how popular culture can formulate and influence a thought process, thereby itself becoming a philosophy.

Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape, Preliminary sketch for the installation Rest-itution(Renaminga collection). Who owns the past owns the future , 2022, Multimedia installation: borrowing a 19th century figurine of a hunter from Benin (probably from the Kingdom of Dahomey or the city-state of Porto-Novo) from the MAMC+ collection, ceramic (Prototype to Protest II), sound composition, Globalisto, A Philosophy in Flux , MAMC+ Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, Saint-Etienne Métropole, France, 25 June-16 October 2022.

Curator Vanessa Desclaux, who was involved in the exhibition Michael Jackson: On The Wall at the Grand Palais in 2018, asked me “When did your work become critical?” I could not pinpoint a precise moment but growing up in apartheid made it hard to ignore the realities. I grew up in a culture that Ezekiel Mphahlele describes as “an urban culture out of the very conditions of insecurity, exile, and agony.”2 My upbringing was shaped by the harsh realities of city life, marked by constant uncertainty, displacement, and suffering. It was this environment that informed my artistic practice profoundly: reflections on global ubuntu, mindfulness, gender fluidity, spirituality, and a connection with nature, deconstructing the past and constructing new futures through economic and social justice, and encouraging dialogue and understanding.

2 Es’kia (Ezekiel) Mphahlele, “On Negritude In Literature” (1963)

The music of resistance was my lullaby, and as children, we play-danced the toyi-toyi, the Southern African dance used in political protests in South Africa. Toyi-toyi begins with spontaneous chants that might include political slogans or songs or the typical stomping of feet during protests. It was a common sight at rallies and marches. It was not only a tool for boosting the morale of the protesters but also a strategic method to intimidate the opposition. The sight and sound of a large group of people moving in unison, chanting and stomping their feet rhythmically, was a powerful psychological weapon that showcased the strength and unity of the movement.

Hush,Hush(ThulaThula) - Harry Belafonte & Miriam Makeba

The inception of Globalisto can be traced back to a confluence of critical theories and practices that challenge the Eurocentric hegemony. It’s a philosophy that finds its roots in the anti-colonial struggles, the civil rights movements, and the burgeoning demand for a post-nationalist perspective. Drawing on the exploration of Black radical aesthetics, Globalisto emerges as a framework that insists on the fluidity of identity and the permeability of cultural boundaries.

I created the Globalisto philosophy, drawing from African knowledge systems, postcolonial theory, and international subcultures. Globalisto envisions radical hospitality and a borderless existence where the global and local intertwine in complex and often violent ways. As I traveled the world, whether alone or with different music groups, one stark reality became evident: walls separated cultures and societies. Upon landing in a new country, our treatment varied dramatically based on our origins. Some of us passed through customs quickly, while others waited for hours. This repeated across nations, illustrating a pattern of systemic inequality. The disparity in the strength of passports saddened me profoundly. While some of my friends could travel freely, I had to plan

months in advance to obtain a visa. Even today, my mother, a choir leader, has to queue for months to be allowed to come and visit me. This led me to question the existence of borders and the artificial constraints placed on movement. Why must Africa exist within borders created by Europe? Why is it so easy for goods to traverse borders, yet so difficult for people?

Through Globalisto, we navigate the complexities of the old world to forge a new one. This philosophy is a call to action, advocating for hope and transformation. It challenges us to rethink our place in the world and our relationships with one another.

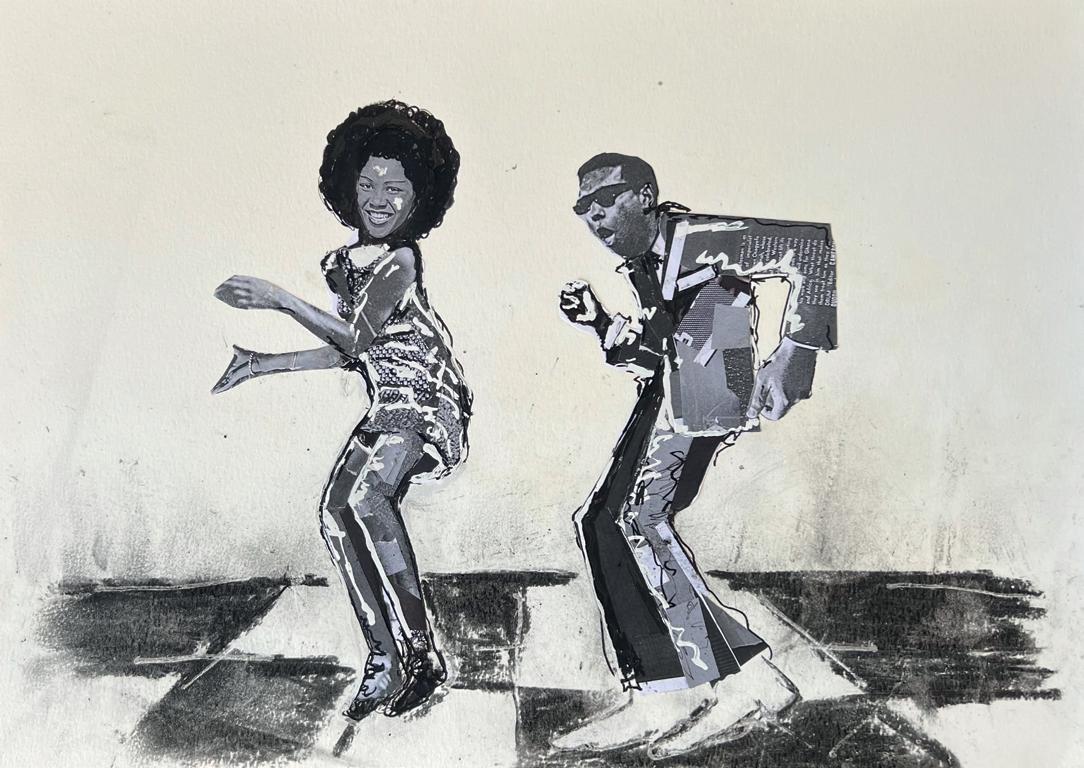

Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape, Vosho , 2023, ink and mixed media on paper. Courtesy of the artist.

In the early 2000s, I arrived in London with the hope of being embraced by the city. However, I quickly realised that I needed to create my own space, as there was a significant lack of awareness about the electronic

music scene in South Africa. This situation is hard to imagine today, with the log drum South African sound of Amapiano now viral on platforms like TikTok prompting thousands of dances. After DJing in various locations, I established the Joburg Project Club Night as a home away from home.

The Joburg Project was the only weekly residency in London offering South African house, Kwaito, Afro House, and Deep House. This event attracted attendees from all over England. Notably, some of the tracks we played began to gain recognition, such as TownshipFunk by Mujava which was signed to Warp Records two years later. This particular track had a substantial impact in the UK and influenced numerous UK funky British producers.

Upon relocating to Paris in 2008, I encountered a similar void; there were no venues dedicated to Afro-House or Kwaito at the time. Despite Paris being a generally open city, a certain form of segregation persisted. Individuals tended to limit themselves to specific areas, neighbourhoods, and particular styles of music, often resulting in a lack of exposure to diverse musical cultures. Cross-genre mixes were infrequent, as people preferred to adhere to a single style of music. One experience underscored this issue. While I was searching for a venue to organise a party, the owner inquired if the crowd would be mixed. Upon noticing my reaction, he attempted to backtrack, explaining that it was not about me personally, but rather that the neighbourhood became apprehensive upon seeing a crowd of black people. This incident highlighted a broader societal issue. If more white people attended coupé-décalé parties in the suburbs, we might witness the emergence of new musical styles, similar to the scene in London.

These experiences motivated me to persist in my efforts to create a safe, inclusive space for primarily South African electronic music, ensuring its recognition and appreciation within new cultural contexts. By doing

so, I aimed to bridge cultural gaps and promote a more diverse musical landscape. After some time, I established Globalisto as a club night at the Nouveau Casino, Chez Moune, Gaité Lyrique and Alimentation Générale. I established a record label, self-releasing 2 EPs in 2017 : Jozi Acid and Paris Afro House Club

Fela Kuti once said, “Music is a spiritual thing, you don’t play with music. If you play with music you will die young. You see, because when the higher forces give you the gift of music...musicianship, it must be well used for the gift of humanity.” DJing, rooted in communal celebration and cultural expression, is a powerful tool for fostering unity. By creating inclusive and dynamic musical experiences, DJs can bring people together, encouraging a sense of community, shared purpose and communion. In DJ sets, blending genres and styles from around the globe creates a sonic journey that reflects the diversity and richness of the human experience. This act of musical curation is, in itself, an embodiment of the Globalisto philosophy — celebrating our differences while highlighting our commonalities.

I composed Rebirth of Ubuntu (2017), akin to Por Cima (2017) featuring Flavia Coelho and the Calypso Queen remix of Calypso Rose (2016), to enact a profound traversal through the Black Atlantic, forging connections that defy the constraints of geographic and temporal boundaries. The sonic tapestry of Rebirth of Ubuntu unfolds through a meticulous orchestration of ceremonial Venda drums, spiritual rhythms from Ghana, and the pulsating heartbeat of a classic Chicago house 4/4 kick. This confluence of percussive elements, rooted in ancestral calls and ritualistic cadences, beckons listeners into an aural voyage that is both ancient and futurist, simultaneously invoking the earth’s primordial echoes and the urban expanse of contemporary house music. The snare, a resonant reminder of township music, dances in tandem with the vibrant strains of coupé-décalé, crafting a percussive dialogue that transcends continental divides. The synth, reminiscent of dark, morphing German techno, weaves in and out of the auditory field, creating a subaqueous sensation, a sonic baptism that culminates in the cathartic release of the chorus. The bass, a distant yet insistent presence, pulses with a rhythm that is almost hip-hop, anchoring the track in a lineage of Black musical innovation. In this polyphonic interplay, Rebirth of Ubuntu asserts a vision of a borderless world, a sonic utopia where the music itself is the vehicle of passage. The track echoes the diasporic connectivity and transatlantic reverberations that eloquently articulate its examination of Black performance and aesthetic practice. Here, the music becomes a site of encounter, where the listener is invited to traverse the liminal spaces between tradition and modernity, ritual and innovation.

It was this foundation in music-making, creating gatherings, and bringing people together that led to the invitation for me to curate an exhibition at Bonne Espérance in Paris in 2021. Nothing was known of my formative years as (street) artist. I titled the exhibition Salon Globalisto. The

exhibition, reminiscent of the Salon des Refusés, served as a home for conversation and dissent, showcasing diverse artists, materials and genres to create a rhythmic balance. Highlighting post-apartheid transitionalism, my aim was to foster a community space of resistance and healing, challenging the traumas of white supremacy and celebrating South African artists in Paris.

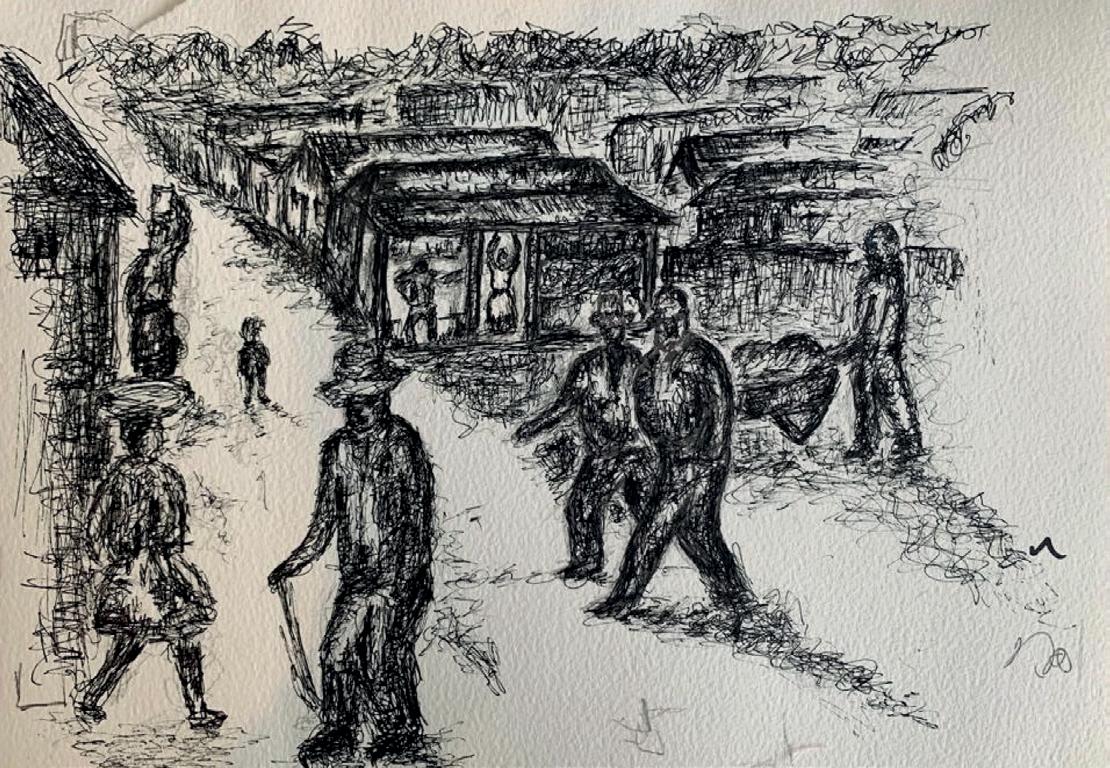

Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape, Street Scene , 2020, Ink on paper, 21 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

In Conversation with Gerard Sekoto was composed in 2021 as a sound installation within the sacred space of Notre Dame de Bonne Nouvelle, Paris. It unfolded as a sonic thread woven from the fibres of struggle, protest, and the ceaseless fight against the shackles of slavery. Sekoto’s 1959 recordings of Negro spirituals, under the imprint of La Voix de l’espérance, emerged as a historical counterpoint, a sonorous archive that gestured toward the persistent haunt of colonial and apartheid legacies. These spirituals, imbued with the weight of collective memory and resistance, were interlaced with contemporary compositions

that invoked Eastern meditative crystal sounds and the pulsating arpeggiators of techno music. This juxtaposition cultivated a radical auditory space — a convergence of sacred and profane, meditative and kinetic — that reconfigured the church as a site of radical hospitality, akin to the communal ethos of the nightclub.

Commissioned for the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2019, Motho ke Motho ka Batho (A Tribute to Mancoba) honours the life and work of Ernest Mancoba, a pioneering South African artist. This soundwork was part of the artist’s retrospective I Shall Dance in a Different Society curated by Alicia Knock. As the first solo show of a black African artist at the Centre Pompidou, this exhibition marked a significant milestone, reflecting both progress and the enduring need to shift narratives and change society. Mancoba’s message, which sought to unite the spiritual, material, and political dimensions of humanity for a better understanding and a more just world, deeply reverberates with my practice. I wove together the resonant voice of Mancoba, chanting mineworkers from Marikana, samples of Solomon Linda’s globally renowned song Mbube , the haunting resonance of Xhosa throat singing, the rhythmic intensity of drum playing and my own ambient compositions. The chants of surviving Marikana miners, recorded one year after the massacre in 2012, are coupled with my own recordings of the sounds of Winnie Mandela’s funeral in Soweto in 2018, to create a powerful narrative of resilience and resistance. By incorporating these elements, the work not only pays homage to Mancoba but also to the broader collective memory and ongoing struggles of South African people. “Motho ke Motho ka Batho,” a South African expression meaning “A person is a person because of other people,” reflects the ubuntu philosophy that Mancoba often referenced. This principle of interconnectedness and mutual respect is central to the installation, reinforcing the idea that our humanity is deeply entwined with our relationships with others, which is also the core of Globalisto philosophy. This project, along with other Globalisto

initiatives, continues to develop new engaging forms, taking the sonic to concrete dimensions and challenging invisibilities and exploitations.

Congo Square in D# Minor (2021) is a composition in which I explore the pan-African experience through sound. Invited by Sammy Baloji to engage with the historic preparatory research for his work Johari Brass Band and extensive music archives, I integrated these findings with my own archival materials. This synthesis enabled the construction of a soundscape that draws parallels between Congo and South Africa, traversing through New Orleans and France. The objective was to interrogate the shared pan-African experience of appropriation, the exploitation of natural resources, and the commodification of Black bodies.

The historical significance of Congo Square in New Orleans serves as a foundational narrative. Enslaved individuals were permitted to congregate and perform music in this space once a week. Following the French military’s departure to Haiti in the late 18th century, abandoned brass instruments were adopted by local communities, catalyzing the development of innovative and globally influential music styles. These styles incorporated complex syncopated drum patterns, lung-based rhythmics, grooves, and claps, which became essential elements of jazz.

My initial encounters with brass bands in South Africa, particularly within the Ga Molepo Church and the Zion Christian Church (ZCC), left a lasting impression. These bands performed with remarkable vigor and groove, blending religious celebrations with African traditions such as dinaka/ kiba, the traditional music of the Sotho people. This hybrid spirituality is reflected as well as references the Hip Hop and RnB samplings of brass bands from Historical Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), as exemplified by Beyoncé’s Coachella Homecoming performance.

CongoSquareinD#Minor amalgamates these multi-layered influences, emphasizing how enslaved individuals re-appropriated Western wind instruments, often constructed from metals extracted from African mines. Instruments such as trumpets, tubas, trombones, and French horns are mixed in a manner akin to a Gumbo dish, infused with African roots and the Black and Creole origins of jazz inspired by Congo Square. The composition includes samples from a jazz funeral — a New Orleans tradition involving second line street processions — alongside found recordings of the Congo River, funeral processions in South Africa, and scarification ceremonies in Congo. The call-and-response unison of the horns creates a trance-like atmosphere, capturing a sense of collective spirituality. The work also integrates excerpts from a lecture by Dr. Howard Nicholas, which discusses the economic dynamics that perpetuate Africa’s underdevelopment and the exploitation of raw materials by

wealthy countries without fair compensation. My accompanying playlist of 100 tracks aims to fuse the extensive history and contemporary relevance of brass bands worldwide, highlighting the interconnected influence of marching bands, African and European musical traditions, and performance practices on popular culture.

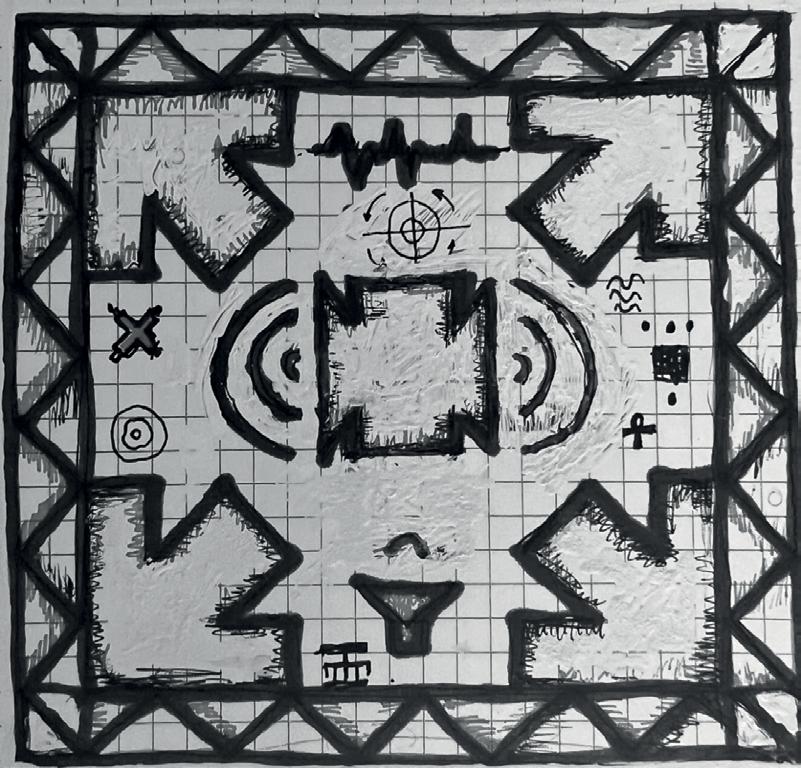

Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape, Preliminary sketch for the installation of Helfritz’Wunderkammer (TheEthnographicGazeandtheHistoryofCabinetsofCuriosities) , 2022. Courtesy of the artist

I was invited by Sandrine Colard to create a new sound and video installation for the exhibition UNDISCIPLINED at the Rautenstrauch-JoestMuseum – Cultures of the World in Köln. Titled Helfritz’ Wunderkammer (TheEthnographicGazeandtheHistoryofCabinetsofCuriosities) , this immersive installation comprised ten-channel TV monitors, a CCTV camera, scaffolding stand, five-channel surround sound, and a ten-minute sonic composition. The project was a response to the life and work of German composer, music ethnologist, and “explorer” photographer Hans

Helfritz (1902-1995), who donated approximately 80,000 photographs to RJM and his sound recordings to the Akademie der Künste der Welt in Berlin.

Drawing on my experience in Afro-Electronic music since the late 1990s, I prepared a multiscreen sonic sculpture inspired by Jamaican sound system speaker culture. The sound work included my original compositions in dialogue with Helfritz’s earlier work. The images were transposed into digital collages and NFTs, allowing for the re-mediation of part of this material to relay plural perspectives on Helfritz’s productions and to deconstruct the ethnographic gaze.

ofCabinetsofCuriosities) , 2022, video still. Courtesy of the artist

I became interested in the parallels between Helfritz’s practice and my own, particularly regarding the exploration of sound and the visual, as well as the connections between archiving, curating, and colonialism. The work is an experimentation with form; monitors create a sculptural

installation akin to a physical and digital wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosity. It critiques the subliminal violence often present in the art of curating, in collecting images, and in museums. The camera is considered a tool of power and surveillance, implying complicity.

The installation converses with the exhibition UNDISCIPLINED, revisiting the history of appropriation akin to hip-hop sampling, referencing undocumented eras clashing with underground subcultures. Sound, as the invisible artform, mirrors the often-invisible Black labour behind the imperial project. By re-contextualizing Helfritz’s work, I aimed to highlight the complexities of historical narratives and the ongoing impact of colonialism, creating a space for reflection and dialogue. The project exemplified the Globalisto philosophy by challenging dominant historical narratives and emphasizing the importance of interconnectedness and co-questioning the gaze.

In Berlin, I began to meditate on the notion of rest. This meditation was not just about the physical act of resting, but rather the musical notation of rest, the silence that punctuates sound, the intervals that give shape to music. The Rest Painting series began in 2022. The rest note in music, an interval of silence marked by symbols indicating the length of the pause, became a significant symbol. The particular note value indicates how long the silence should last. These paintings evoke the notion of rest as Saidiya Hartman describes it — the silence of the archive. Rest is an act of rebellion against the commodification of Black bodies and resources. These intervals are not empty; they are filled with the weight of what has been left unsaid, unseen, unheard. In our world, rest is radical.

In the archives I have researched, I have constantly been struck by how much is hidden, how much is kept silent. The silence of the archive is not

just about what is absent, but about what is deliberately left out, what is kept from view. The rest paintings are my response to this silence. They are my way of saying that rest is necessary, that silence is powerful, that we must reclaim these intervals for ourselves.

Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape, Rest-itution , 2023, Part of “The Rest Paintings” series, Acrylic, clay, coffee, charcoal, earth, found objects, on canvas, 22 x 28.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Rest, in this sense, is not just about taking a break. It is about resisting the commodification of our time, our bodies, our lives. It is about saying no to the demands for constant productivity and visibility. It is about carving out spaces where we can simply be, without the pressure to perform or produce. I aim to challenge the invisibilities and exploitations that are so pervasive in our world. By making rest visible, by giving shape to silence, I hope to create a space where we can pause, breathe, and reclaim our time, our bodies, ourselves.

Freedom to Move was set up by Sounds Now to research the relationship between freedom and the boundaries of musical genres within the contemporary classical music field; to stretch the field of contemporary music with unheard voices and music.

The human voice is the most personal, vulnerable instrument, as it is so connected to the body. Freedom to Move brings together different voices and provides a space where singers from different backgrounds can express themselves freely without any one voice dominating, or someone telling them what to do and how to do it. A space where they can work according to their own choices and creative process.

Freedom to Move took place In five different festivals/cities around Europe: November Music in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands; hcmf// in Huddersfield, UK; Wilde Westen in Kortrijk, Belgium; Borderline in Athens, Greece; and Ultima in Oslo, Norway. Five professional or trained singers (m/f/x) were invited to work for three days, with Sofia Jernberg (Sweden) serving as artistic coach. On the third day, there was a public presentation of the result. One or two instrumentalists, depending on the festival, would join. The singers were interviewed about their musical backgrounds and about experiencing freedom and boundaries in their musical and personal lives. In the following pages, you can read two of these interviews. And all of their stories, interwoven with the music they created during the workshop, can be heard by scanning the QR code below.

During the project, it became clearer than expected how much it meant for the vocalists to join a project like Freedom to Move. They valued connecting and working with other singers (who are also makers) outside their own circle, to share reflections on the creative process and to create new paths for collaboration. The space for and exchange of experiences as a minority was highly valued. Time spent with these minority questions and with the voice -- both the musical voice, but also the voice as an individual -- was deeply appreciated.

The singers created their own piece and also worked on an ensemble piece, with Sofia Jernberg driving the process. She helped the singers untie and unchain boundaries, and facilitated freedom with musical exercises, open scores and personal inspiration, enabling the singers to find their own way.

The workshop also gave the singers insight that as Europeans, working with contemporary music, they are able to collaborate with each other and explore minority questions in a hands-on way.

Sofia Jernberg, artistic coach and Geeske Coebergh, artistic producer

Music was in my life the moment I was born. My parents are very into the arts as people who like culture, who support culture, who feel that culture is a way of creating a civilization and not just a means of enjoying life, but substantially in the way we live. When I was five, my dad was co-founder with a group of people that started a cultural movement on Cyprus. This movement came from people that were forward-thinking at the time; most of them were visualizing a different world. They started poem nights, music festivals, and they started a choir. So everyone brought their children to this choir. I was one of the children. As I was only five years old, I couldn’t read. So I started repeating stuff and then slowly, gradually, I started reading scores before I started reading texts. A year later I started playing the piano, with a German teacher. I played the piano for ten years, and until I was 20 years old, I was in this choir. We traveled a lot. So for me, music was a means to meet with other people, to interact, to see places that normally I wouldn’t see.

Every Saturday we had our rehearsal. Every summer and winter, it was our journey. And I feel that it started as a way of me belonging to a group of people where I’m not being judged as an effeminate person. Because that was what was happening at school. At school I was singing as a gifted student, every time that we had something. I felt attacked for that. I felt excluded because I was singing at school. And at the same time at the choir, I felt that I belonged. At some point, I started writing my own

songs. So in school, every time we were graduating, we were singing one of my songs that I had written for the occasion.

It was strange: nobody told me you can study music. Everyone was like, you should be an actor. And I started acting. But music is always part of what I do. I speak music: I listen to music in the street, I like people’s voices. It’s a language that I speak. My family was very supportive. It was hard for a male child to play the piano and be in a choir. It was supposed to be girl stuff. It’s a very male-dominated island.

As a child I went to church with my grandmother. I listened to all these beautiful melodies from the Byzantine era. That blend of tradition, it speaks to my heart, although I’m not a religious person in terms of the church. I’m a religious person when it comes to cosmic energy. Sometimes in church, I could feel that cosmic energy existing and I was amazed. At home we were listening to classical or Greek folk music or popular music. Every summer, I was at my grandma’s with my cousin, and she was bringing the new CDs with all the pop music. So I am this amalgam of all of it. I am at a point in my life where I create my own music again, without guilt, after a long, very personal process. I decided that I will just go with this broad idea of what music.

My voice is lyrical. I’m a baritenor, so the possibilities of what can come my way are vast. At some point I lost the access to my voice, because it was bringing forward parts of my identity, parts of who I was, and parts of my identity that were almost criminalized in the society. So I pushed my voice downwards. And for many years during my theatrical studies in Greece and Paris, I was avoiding singing. I was avoiding creating music also. I was avoiding creating my own lyrics or music. I was writing poems. I was writing other stuff. So I was not present, or if I was present, I was there, but in the corner of the creation, not in the centre.

When I saw the call for Freedom to Move, I realised that it’s about singing, improvising. As the call is called Freedom to Move, I wanted to take it one step further. I felt like deciding that I have the freedom to move, even if it reveals parts of my identity that are scrutinised. I am at a point in my life where I feel confident and strong with the parts of my voice that reveal my personality as a whole and not as a certain tiny little box that the system wants me to be in. So “freedom to move” resonated a lot.

At the moment I am creating my own album. So the workshops are an opportunity to meet other people and do other stuff. I feel that Freedom to Move is a way for me to dive into waters that I haven’t so far. I’m not just a musician. I’m not just a singer. I’m a performer. What I bring to the table is my ability to be present. And what I realized from the interaction with Sofia is that you can be present in many ways. So it’s not a matter of a result, as a final piece; it’s first a matter of where this presence can take you, not where you decide to go with that presence. I needed that in my life at this point, this switch, this alternative, because it can be anything. It can go anywhere. I just was rehearsing a traditional song from Cyprus, which is written in both languages of the island, in Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot. I perform it in both languages, and I have performed it in the many million ways it can be performed.

Having the ability to give space to myself to be present, not knowing where this presence will take me, I think it’s a huge gift that is being given. Or that I give to myself. Or that we all gave to ourselves.

My musical background is mixed. I started classical singing lessons when I was eleven, so I come from a classical singing background, that’s the technique that I learnt. However at the same time, I grew up in London in social housing. Classical music was not the kind of music that I listened to at home; there I listened to electronic music and rap. My Dad loved Motown, pop trance and nineties electronic dance music and my Mom liked neo soul. So I come from a very varied musical background. I felt a kind of tension going to school and doing these classical singing lessons, and knowing that I had this voice. It was so different from where I grew up and what I knew from home and all the people around me.

When I left school, I became interested in electronic music and using digital software. And I had this feeling that maybe I would do something different than singing. So I followed a sound art and design course. But while I was making sound-based arty kind of pieces, I missed the traditional and wanted to combine the two different genres.

I went to Goldsmiths University and did my undergraduate in music in the traditional music pathway. And I forged all of those different things together. I was doing classical singing and composition, improvisation and sound art. That was when I learned that I could cross over these practices. I could use my voice with all of its technique and everything I’d

learned, and I could also use it in improvisation and live electronics, for example. I could do something different with it.

After my undergraduate degree, I took a year off, just making music. Then I did my Masters in music creative practice at Goldsmiths. During those two years, I really developed my work, which focuses on the voice and the body and their connection. The feminine voice – I am still exploring this as well.

When I first read about Freedom to Move , I definitely thought it sounded exactly like something that would be up my street. As a singer and an artist, I’m always trying to expand and develop my work. When I saw the announcement, I thought: this is so different for me, from what I’ve done recently. I’ve just done something very text-based and this workshop offered me the opportunity to think of my voice, or the voice, in a different way. The opportunity to explore something new and also work with other people – that sounded amazing. And also working with Sofia Jernberg: I’ve seen her work and it is very inspiring to me. For me, it was everything together that I want to do: experimenting more with the voice, with other people, and learning from someone who is really inspiring.

We did a lot of different improvisations and I liked that every time, we would change something and try it again, or try something different. It was also really interesting to work with the other voices. I had no idea what to expect. To meet everyone and to hear all of the different voice types. Also when you improvise with people, especially the first couple of times, you definitely hear people’s interests, the techniques that they like to go to or the vibe that they default to with an improvisation. It is interesting to hear that and it challenges you, because you’re thinking:

what’s mine? But then you all challenge each other to change as well, because you’re inspired by what someone else is doing.

It is so interesting just to improvise with people you’ve never met before. It’s funny that you go into a room and you haven’t even known the others for five minutes and you’re making crazy sounds together. It was a great experience to meet everyone and to just hear all the sounds that everyone was coming up with.

Soprano JULIET FRASER specialises in the gnarly edges of contemporary classical music. She maintains a busy schedule of international performances as a soloist, regularly performing with ensembles such as Musikfabrik, Klangforum Wien, Ensemble Modern and Quatuor Bozzini, and as a duo with pianist Mark Knoop. She is an active commissioner of new repertoire and has worked particularly closely with composers Laurence Crane, Pascale Criton, Frank Denyer, Cassandra Miller and Rebecca Saunders. Juliet is artistic director of the eavesdropping festival in London and programme director of VOICEBOX, a programme for advanced singers specialising in contemporary vocal performance. Juliet also enjoys writing words about being a performing artist. Essays have been commissioned by Sounds Now, Britten Pears Arts, MaerzMusik and the Fragility of Sounds lecture series, and published in Glissando , TEMPO and by Wolke. She self-publishes on Substack and her own website. In 2023 she was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Music by Southampton University.

www.julietfraser.co.uk

NTSHEPE TSEKERE BOPAPE (Mo Laudi) is a multidisciplinary artist, curator, and DJ-producer living and working between Johannesburg and Paris. He is the founder of the Globalisto philosophy, which emphasises global spiritual interconnectedness through art and music. As a Stellenbosch University research fellow, Bopape explores innovative artistic expressions and cultural dialogues. He has been invited to lecture at prestigious institutions such as Beaux-Arts Nantes in France and Brno University, sharing his expertise and insights on contemporary art practices. His dynamic career blends various creative disciplines, reflecting his commitment to fostering cross-cultural understanding and collaboration. Through his work, Mo Laudi continues to push boundaries and inspire new ways of thinking in the art world.

Sounds Now is a 5-year project presented by a consortium of 9 European music festivals and cultural institutions that disseminate contemporary music, experimental music and sound art.

In this project, we are concerned with the way in which the contemporary music and sound art worlds reproduce the same patterns of power and exclusion that are dominant at all levels of our societies, all the more so because these sectors are committed to promoting progressive agendas.

Sounds Now consequently aims to stimulate diversity within this professional field by reflecting and challenging current curatorial practices. Activities are directed at bringing new voices, perspectives and backgrounds into contemporary music festivals. Centering on three pillars of diversity — gender/gender identity, ethnic and socio-economic background — the project includes a range of actions such as labs for curators, curating courses, artistic productions, symposia and research. In this way, Sounds Now seeks to open up the possibility for different experiences, conditions and perspectives to be defining forces in shaping the sonic art that reaches audiences today.

www.sounds-now.eu

The Creative Europe programme is the European Commission’s framework programme for support to the cultural and audiovisual sectors. It aims to improve access to European culture and creative works, and to promote innovation and creativity.

The Culture Strand of Creative Europe helps cultural and creative organisations, such as those involved in the Sounds Now project, to operate transnationally. It provides financial support to activities with a European dimension that aim to strengthen the transnational creation and circulation of European works, developing transnational mobility, audience development (accessible and inclusive culture), innovation and capacity building, notably in digitisation, new business models, education and training.

The Sounds Now project gratefully acknowledges the support provided by Creative Europe in bringing artists and cultural operators the opportunity to foster artistic works and improve practices, thereby contributing to a strong and vibrant European music sector.

www.eacea.ec.europa.eu

© 2024, Sounds Now

All rights reserved

Published by Musica Impulse Centre

Design: Patty Kaes

Print: Haletra, Houthalen-Helchteren, Belgium

Distribution Musica Impulse Centre, Pelt, Belgium

ISBN 9789464667523

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner and writers.

ISBN 9789464667523