SOCIETY FOR EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY PRESENTS:

SEB GOTHENBURG 2017

3–6 JULY 2017

SWEDISH EXHIBITION AND CONFERENCE CENTRE

SEBIOLOGY.ORG #SEBAMM

SOCIETY FOR EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY PRESENTS:

SEB GOTHENBURG 2017

3–6 JULY 2017

SWEDISH EXHIBITION AND CONFERENCE CENTRE

SEBIOLOGY.ORG #SEBAMM

SESSION TOPICS WILL INCLUDE:

ANIMAL BIOLOGY

ECOTOXICOLOGY

• EFFECTS OF PHARMACEUTICALS ON WILDLIFE – BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN ECOTOXICOLOGY AND ECOLOGY

PHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS OF AQUATIC TOXICOLOGY

OSMOREGULATION AND ACIDIFICATION

• CHALLENGES IN THE ANTHROPOCENE:

ACID-BASE/ION REGULATION AND CALCIFICATION IN AQUATIC INVERTEBRATES

CLIMATE CHANGE AND AQUATIC LIFE:

EFFECTS OF MULTIPLE DRIVERS, FROM MOLECULES TO POPULATIONS

• INTERACTIONS BETWEEN

OSMOREGULATION AND ACID-BASE

BALANCE IN AQUATIC ORGANISMS

BIOMECHANICS, PERFORMANCE AND BEHAVIOUR

• THE OBLIGATION OF ACTIVITY – HOW DO ANIMALS GET FIT, AND WHAT TAKES THEM OVER THE HILL?

NATURALLY OCCURRING EXPERIMENTS: USING LIFE HISTORY EVENTS TO UNDERSTAND LOCOMOTOR PERFORMANCE

• CONSTRAINTS ON ADAPTATION AND PERFORMANCE: FROM INDIVIDUALS TO POPULATIONS

OTHER ANIMAL SESSIONS

INTEGRATIVE MODELLING APPROACHES TO THE FISH CARDIO-RESPIRATORY SYSTEM UNDER ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

– IS IT TIME FOR A FISH PHYSIOME INITIATIVE?

• BIOLOGICAL ADHESIVES: FROM BIOLOGY TO BIOMIMETICS OPEN BIOMECHANICS

• OPEN ANIMAL BIOLOGY

CROSS DISCIPLINARY –PLANT AND CELL BIOLOGY

CELL BIOLOGY

• PLANT CELL BIOLOGY

• CELL CYCLE AND THE CYTOSKELETON

MEMBRANES

• MEMBRANES

• LIFE AT THE INTERFACE: PLANT

MEMBRANE-PROTEIN DYNAMICS/ INTERACTIONS DURING ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

MODELLING GROWTH

CROP MODELS IMPROVEMENT WITH BIOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE: WHICH, WHY, AND HOW?

• MODELLING CELLS

• MOLECULAR CONTROL OF PLANT GROWTH DURING ABIOTIC STRESS PHOTOSYNTHETIC RESPONSE TO A CHANGING ENVIRONMENT – TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE ENERGY PRODUCTION

OTHER JOINT PLANT-CELL SESSIONS

• GENERAL PLANT AND CELL BIOLOGY

CELL BIOLOGY

• IMAGING PATHOGENESIS

• PALAEOGENOMICS AND ANCIENT DNA

PLANT BIOLOGY

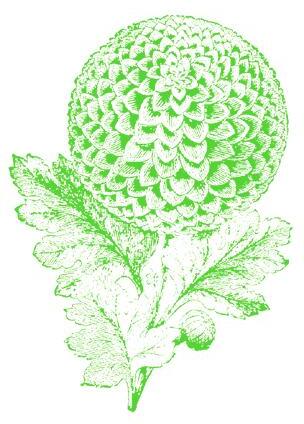

• CARNIVOROUS PLANTS – PHYSIOLOGY, ECOLOGY, AND EVOLUTION

• FROM GENOTYPE TO PHENOTYPE

SEB+

• EDUCATIONAL SESSIONS

• SCIENCE WITH IMPACT

• CAREERS DAY WORKSHOP FOR YOUNG RESEARCHERS

SOCIETY FOR EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY PRESENTS:

SEB GOTHENBURG 2017

3–6 JULY 2017

SWEDISH EXHIBITION AND CONFERENCE CENTRE

SEBIOLOGY.ORG #SEBAMM

SESSION TOPICS WILL INCLUDE:

ANIMAL BIOLOGY

ECOTOXICOLOGY

• EFFECTS OF PHARMACEUTICALS ON WILDLIFE – BRIDGING THE GAP

BETWEEN ECOTOXICOLOGY AND ECOLOGY

PHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS OF AQUATIC TOXICOLOGY

OSMOREGULATION AND ACIDIFICATION

• CHALLENGES IN THE ANTHROPOCENE:

ACID-BASE/ION REGULATION AND CALCIFICATION IN AQUATIC INVERTEBRATES

CLIMATE CHANGE AND AQUATIC LIFE:

EFFECTS OF MULTIPLE DRIVERS, FROM MOLECULES TO POPULATIONS

• INTERACTIONS BETWEEN

OSMOREGULATION AND ACID-BASE

BALANCE IN AQUATIC ORGANISMS

BIOMECHANICS, PERFORMANCE AND BEHAVIOUR

• THE OBLIGATION OF ACTIVITY – HOW DO ANIMALS GET FIT, AND WHAT TAKES THEM OVER THE HILL?

NATURALLY OCCURRING EXPERIMENTS: USING LIFE HISTORY EVENTS TO UNDERSTAND LOCOMOTOR PERFORMANCE

• CONSTRAINTS ON ADAPTATION AND PERFORMANCE: FROM INDIVIDUALS TO POPULATIONS

OTHER ANIMAL SESSIONS

INTEGRATIVE MODELLING APPROACHES TO THE FISH CARDIO-RESPIRATORY SYSTEM UNDER ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

– IS IT TIME FOR A FISH PHYSIOME INITIATIVE?

• BIOLOGICAL ADHESIVES: FROM BIOLOGY TO BIOMIMETICS OPEN BIOMECHANICS

• OPEN ANIMAL BIOLOGY

CROSS DISCIPLINARY –PLANT AND CELL BIOLOGY

CELL BIOLOGY

• PLANT CELL BIOLOGY

• CELL CYCLE AND THE CYTOSKELETON

MEMBRANES

• MEMBRANES

• LIFE AT THE INTERFACE: PLANT

MEMBRANE-PROTEIN DYNAMICS/ INTERACTIONS DURING ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

MODELLING GROWTH

CROP MODELS IMPROVEMENT WITH BIOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE: WHICH, WHY, AND HOW?

• MODELLING CELLS

• MOLECULAR CONTROL OF PLANT GROWTH DURING ABIOTIC STRESS PHOTOSYNTHETIC RESPONSE TO A CHANGING ENVIRONMENT – TOWARDS

SUSTAINABLE ENERGY PRODUCTION

OTHER JOINT PLANT-CELL SESSIONS

• GENERAL PLANT AND CELL BIOLOGY

• IMAGING PATHOGENESIS

• PALAEOGENOMICS AND ANCIENT DNA

• CARNIVOROUS PLANTS – PHYSIOLOGY, ECOLOGY, AND EVOLUTION

• FROM GENOTYPE TO PHENOTYPE

SEB+

• EDUCATIONAL SESSIONS

• SCIENCE WITH IMPACT

• CAREERS DAY WORKSHOP FOR YOUNG RESEARCHERS

T‘The future of universities’ – this UK event was sold out within hours of being publicised. Not surprising, given the uncertainty of Brexit and its impact on funding, students, researchers and the very nature of what a university is for. Change is the only unchanging certainty in life, but no one could have predicted how much the world would alter in just one year, and we haven’t even started yet; elections are coming up in many influential European countries and who knows what will happen in America?

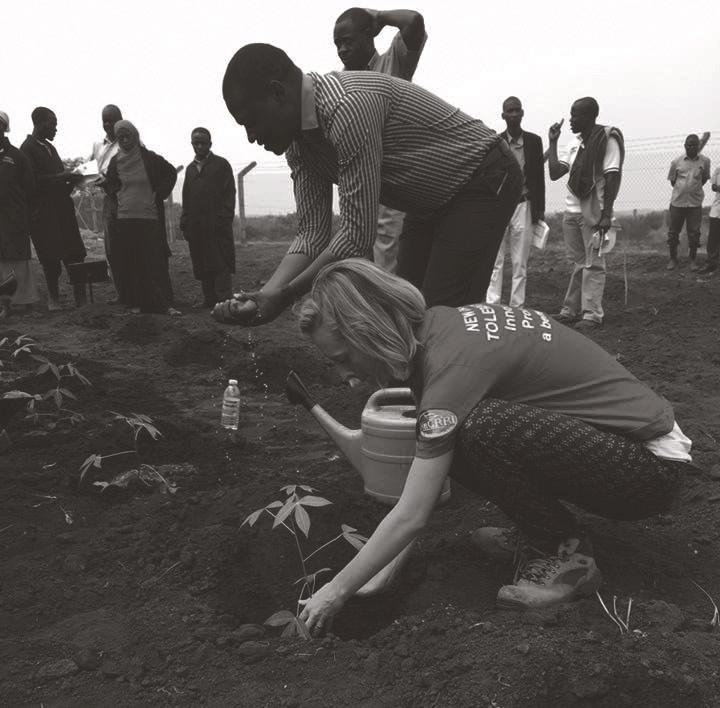

In this issue, our talented science writers report on ground-breaking genetic engineering techniques being employed by researchers to enhance crop yields and the photosynthetic power of plants – helping them to help us to adapt to our changing global environment. We may depend on these new technologies for our future sources of fuel or to feed people in drought-stricken areas of the world. In the midst of political turmoil, scientists will hopefully continue to receive vital funding to carry on their work in monitoring climate change and finding solutions to mitigate its effects.

www.biosciencecareers.org). I do this with the SEB and also in my spare time. It’s a far cry from my early days of doing research in the lab, where I was well away from my comfort zone, but where I learned that I really enjoy the company of scientists. They (generally) manage to combine mindful intelligence with having fun and I feel privileged to have spent the most-part of my career working amongst them – you guys – so thank you for that.

And on that note, I leave you with these words, written on the wall in Mother Teresa’s home for children in Calcutta:

People are often unreasonable, illogical and self-centred; Forgive them anyway.

If you are kind, people may accuse you of selfish, ulterior motives; Be kind anyway.

If you are successful, you will win some false friends and some true enemies; Succeed anyway.

If you are honest and frank, people may cheat you; Be honest and frank anyway.

Sadly, this is my last bulletin as President of SEB. Two years goes very fast so perhaps a moment of reflection is due.

I‘Keep calm and carry on’ is a motivational slogan from the Second World War and it’s a good mantra to hang on to right now. In situations where the political ‘powers that be’ are playing a game over which you have little or no control, carry on doing what you’re doing, and be prepared to stand firm on your beliefs and principles. At the personal level, you are talented individuals who still have influence over key aspects of your life: for example, what’s your USP? Knowing your own ‘Unique Selling Point’ and how to promote yourself as the ‘go-to person’ for your area of expertise (if I dare use that word) is a skill in itself nowadays, especially in this era of social media networking. It could be your specific bioscience knowledge, technical or teaching talents, personal attributes or even your connections which make you a valuable commodity in a particular employment sector. Unlike socio-economic and political influences, these are factors that are under your control, so why not think about focusing on them and developing yourself further. It will make you stronger and wiser.

For my part, I consider my strengths to be writing and advising – usually around career related issues (see my blog –

What you spend years building, someone could destroy overnight; Build anyway.

If you find serenity and happiness, they may be jealous; Be happy anyway.

The good you do today, people will often forget tomorrow; Do good anyway.

Give the world the best you have, and it may never be enough;

Give the world the best you’ve got anyway.

You see, in the final analysis, it is between you and your God; It was never between you and them anyway.

have really enjoyed my association with the SEB from as far back as 1983. On moving to Durham in 2000, I was encouraged by Martin Watson to join the Cell Section. In 2009 I was asked to take charge and instituted a phase of change in the Section, with more of a focus on interdisciplinary modes of working, adding physicists and mathematicians to the group. This has worked well and John Love continues to broaden the aspect of the Section whilst, at the same time, both the Animal and Plant sections continue to go from strength to strength. A period as Vice President and therefore chair of the Meetings Committee allowed me to introduce some of my own thoughts on the Annual Meeting. The Pecha Kucha continues to be attractive to poster presenters and I recall chairing the first session with Roger Leigh (a past President) showing how it should be done. Moving the Plenary Sessions to more amenable times was a success, and perhaps the most controversial decision was moving the conference dinner to the last night, which was prompted by the very poor attendance at the plenary session when the dinner was positioned on the penultimate night!

As Vice President and President, I have worked with excellent members of Council. In my first bulletin I said goodbye to some that I had worked with for several years and now

we have a relatively new team in place. They really are the unsung heroes of our Society bringing their advice and expertise to the table, ensuring that the Society is well governed so that we are an efficient, robust and sustainable Society for the future. As I step down from my role as Chair of Council in June, I will miss the fun, commitment and enthusiasm that I have observed throughout the SEB today. I look forward to continuing with the good friendships that I have made.

I WILL MISS THE FUN, COMMITMENT AND ENTHUSIASM THAT I HAVE OBSERVED THROUGHOUT THE SEB TODAY.

I note in my last two bulletins I appear to have discussed topics that I perhaps would only know a great deal about in my current role as Pro Vice Chancellor Science at Durham, discussing issues that perhaps affect our universities in the UK more that the Society itself. However, BREXIT does have an impact on all of us and the Supreme Court has voted that Parliament has to debate and vote before Article 50 can be triggered. I am not holding up any hopes that this will be reversed as of course the British people have spoken and it would be wrong for our MPs to vote otherwise. However, they have the opportunity to make amendments and hopefully senior university leaders can lobby for an appropriate position for science. The Prime Minister has said that there might be specific EU programmes in which we may want to participate, so I hold some hope. However, the EU position is that this would require free movement and I don’t believe this is on the table. My daughter is a chemical and nuclear engineer having graduated from Imperial College in 2015. Currently she is on the Nuclear Grads Training Scheme, so it was shock to her and the science community that on the 26th January the UK government confirmed that as part of the BREXIT arrangements we would be pulling out of the European Union’s nuclear agency EURATOM. This could endanger major collaborative projects in the EU particularly the world’s largest fusion experiment, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) in France. Let’s hope the UK government is more visionary with the Life Sciences!

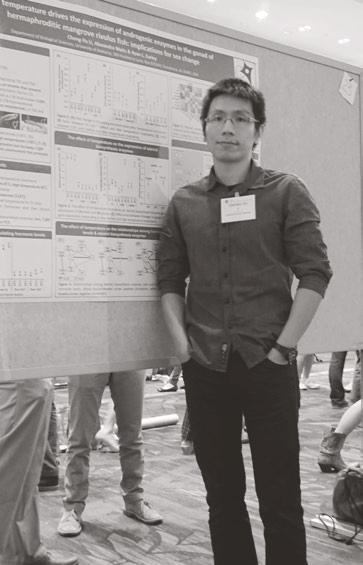

The SEB are preparing for a Scientific Smörgåsbord of experimental biology in Gothenburg on 3–6 July 2017 and there is still time for you to book your place for this exciting four-day conference.

We have some exceptional plenary lectures by Steve Perry (Bidder Lecture), Jonathan Lynch (Woolhouse Lecture) and Anthony Turner (Cell Plenary Lecture), which will set the tone for this year’s Annual Meeting.

Over the four days, our scientific programme will cover a wide range of topics of animal, cell and plant biology including ‘Photosynthetic response to a changing environment’, ‘Palaeogenomics and ancient DNA’, and ‘Constraints on adaptation and performance.’ Alongside a stimulating educational programme from the SEB+ section, there is a little something for everyone.

It isn’t all work and no play at the SEB Annual Meeting as there are lots of networking opportunities to meet with colleagues and share your research. If you are attending or planning to attend the Annual Meeting, there is still time to book your place at one of the following events.

We are pleased to announce that Åsa Nilsson Billme, an expert in diversity and inclusion strategies (Lectia), as the speaker for our Diversity Dinner on Tuesday 4 July. Åsa focuses on strategic operational, organisational and business development through D&I and is the founder and board member of the Diversity Charter Sweden. She has produced a number of tools and materials, training and workshops, traditional as well as e-learning and her experience ranges from advisory and consultant services to analysis and strategic planning, project management, training and implementation.

We look forward to seeing you there – you can sign up for the dinner when you register for the conference.

The SEB conference dinner will be held on Thursday 6 July at Kajskjul 8. Based in the old harbour of Gothenburg, this former 19th century warehouse provides a great setting by the sea. You will have the opportunity to enjoy a Swedish smörgåsbord, followed by entertainment to keep you dancing until the early hours, which is the perfect way to end your experience at the SEB Annual Meeting.

There are also a number of satellite meetings taking place either side of the Annual Meeting which may be of interest:

l Morphology meets Physiology: A tribute to Pierre Laurent, 30 June – 1 July 2017

l New breeding technologies in Plant Science

– Applications and implications in genome editing, 7–8 July 2017

l EMPHASIS: Plant phenotyping, 7 July 2017

More information on the Annual Meeting and satellite meetings can be found on www.sebiology.org/events.

From Sweden, to Italy, to Spain! After several site visits to numerous countries, the SEB would like to confirm the amazing locations for the 2018 and 2019 SEB Annual Meetings.

The 2018 Annual Meeting will be held in the beautiful city of Florence, Italy on 3–6 July 2018. The regional capital of Tuscany and home to Michelangelo’s David will capture you with its architecture and traditions of scientific research dating back to the Renaissance era. Come and ‘Get a pizza the action’ in Florence and save the dates in your diary.

In 2019, the Annual Meeting will be held in Seville, Spain on 2–5 July 2019. Famous for flamenco dancing, haciendas, tapas bars and orange trees, this city has a lot to offer in both culture and science which makes it a perfect location for the Annual Meeting.

Make sure you keep an eye out on social media and the SEB website for more information on the meetings. We look forward to seeing you there!

SOCIETY FOR EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY PRESENTS:

MORPHOLOGY MEETS PHYSIOLOGY: A TRIBUTE TO PIERRE LAURENT

30 JUNE – 1 JULY 2017

UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG, SWEDEN SEBIOLOGY.ORG #SEBGILLS

PLENARY SPEAKER:

· STEVE PERRY UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA, CANADA

INVITED SPEAKERS:

· MARTIN TRESGUERRES

SCRIPPS INSTITUTE OF OCEANOGRAPHY, UNITED STATES

· BOB SHADWICK

UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA

· GREG GOSS

UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA, CANADA

· JEHAN-HERVÉ LIGNOT

UNIVERSITY OF MONTPELLIER, FRANCE

· JUNYA HIROI

ST. MARIANNA UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF MEDICINE, JAPAN

· SCOTT KELLY

YORK UNIVERSITY, CANADA

· LAUREN CHAPMAN

MCGILL UNIVERSITY, CANADA

· COSIMA PORTEUS

UNIVERSITY OF EXETER, UK

· KATIE GILMOUR

UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA, CANADA

· DANIELLE MCDONALD

UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI, UNITED STATES

· COLIN BRAUNER

UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA

· DAVID MCKENZIE

CNRS, FRANCE

· GÖRAN NILSSON

UNIVERSITY OF OSLO, NORWAY

· JOHN FLENG STEFFENSEN

UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN, DENMARK

· MICHAEL WILKIE

WILFRID LAURIER UNIVERSITY, CANADA

· GUDRUN DE BOECK

UNIVERSITY OF ANTWERP, BELGIUM

ORGANISERS: SPONSORS:

· CHRIS WOOD UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA

· DAVID RANDALL UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA

· JONATHAN WILSON

WILFRID LAURIER UNIVERSITY, CANADA

· DANIELLE MCDONALD

UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI, UNITED STATES

· HAROLD BERGMAN

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING, UNITED STATES

· MARTIN GROSELL UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI, UNITED STATES

UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA

CANADIAN SOCIETY OF ZOOLOGISTS

ELECTRON MICROSCOPY SCIENCES

LAURIER RESEARCH

LAURIER INSTITUTE FOR WATER SCIENCE

LOLIGO SYSTEMS

MCMASTER UNIVERSITY

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING

Left Åsa Nilsson BillmeIn each issue of the member magazine we like to highlight some the fantastic achievements and research from our members. Here are some of the people we would like to congratulate this time round.

Former SEB President’s Medallist (2000), Professor Ottoline Leyser was made Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) for her services to plant science, science in society, and equality and diversity in science in the 2017 New Year’s Honours list. Professor Leyser, who is Director of the Sainsbury lab at Cambridge University, UK, was also the recipient of the FEBS: EMBO Women in Science Award, which recognises outstanding achievement by female researchers in the last five years. Professor Leyser received the award for her work on evolutionary, developmental and biochemical mechanisms that enable plants to respond and adapt to environmental changes. Her research led to the discovery of the mechanism of action of the plant hormone auxin and the identification of a second group of plant hormones known as strigolactones. She has formulated a model of how the two hormone systems interact to regulate plant development. Her current work aims to elucidate the mechanisms underlying this model. Professor Leyser has long championed women pursuing careers in science. Her book, Mothers in Science: 64 ways to have it all is a collection of stories of women who have successfully managed to pursue their academic careers in combination with motherhood and she continues to be an advocate for women in academia. Professor Leyser will receive her award at the FEBS 2017 Congress in September.

Reference: http://embo.org/news/pressreleases/2017/ottoline-leyser-honoured-withthe-2017-febs-embo-wis-award

Research by SEB Animal Section members

Drs Lewis Halsey (University of Roehampton, UK) and Susannah Thorpe (University of Birmingham, UK) has appeared on Discovery Channel Canada and a number of other media outlets. The main paper, published by the Royal Society, studied parkour athletes as a tractable model to better understand the movement energetics of large arboreal great apes. Researchers measured the impact of variation in morphology and locomotor behaviour on the rate of oxygen consumption (energy expenditure) of male parkour athletes as they repeatedly traversed an arboreal-like assault course. The course consisted of a range of generic gymnasium apparatus such as vaulting horses, raised blocks, high bars, wall bars and areas filled with loose foam blocks to emulate the range of mechanical conditions present along an arboreal pathway.

A multiple regression model showed that the athletes substantially improved the energetic efficiency of their movement around the course over repeated attempts, an analogy for the habitual routes taken by primates linking resources within their territory.

Furthermore, athletes with a larger arm-span and shorter legs were substantially more able to find energy savings around the course than their counterparts, whereas body mass was not influential. Thus the data suggest that, within a certain range, increase in body size is not detrimental to energy expenditure during arboreal locomotion. To find such strong associations within a single species with limited morphological range indicates the energetic benefits that can be accrued from minor morphological variation and is fundamental to understanding the processes through which morphology changed in hominoid evolution. Due to these results, Drs Halsey and Thorpe suggest that increased hominoid mass was an evolutionary tradeoff functionally linked to selection for a broad thorax and a long powerful arm-span to enhance reach and ensure the axial system could counter the demanding mechanical work of the forelimbs in 3D arboreal environments.

Furthermore, the findings show that large size must also have been functionally linked to the use of consistent branch-to-branch arboreal pathways in order to improve energetic efficiency through route refinement, and thus to enhanced intelligence permitting large ancestral apes to remember detailed pathway information over larger spatio-temporal scales.

See research footage and read the full article here: http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ content/12/11/20160608.figures-only

Dr Karen Polizzi, co-convenor of the SEB Synthetic Biology and the Physical Cell Group, was the principle laboratory supervisor of the winning team at iGEM Boston 2016. iGEM is an international synthetic biology competition which encourages teams of students to solve real world problems by building genetically engineered biological systems. Dr Polizzi’s team (Imperial College London, UK) beat out over 250 attendees from around the world to take the major prize. Their project, Ecolibrium, involved creating a genetic circuit that can control the relative growth rate of two populations in co-culture so that they will keep a desired ratio. The circuit, called GEAR (Genetically Engineered Artificial Ratios), consisted of three modules. The first was a communication module that allows the populations to estimate their own size and the size of the other population through quorum sensing. The second was a comparator module that uses RNA logic to compare the relative sizes of the two populations. The comparator module is connected to a growth control module that uses the balance of the two population sizes to control the expression of a phage protein that will slow the growth rate of the larger population, allowing the other population to catch up. The three modules were independently built, but in the future the team hope to be able to connect them into a working system.

Reference: http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/ newsandeventspggrp/imperialcollege/ newssummary/news_4-11-2016-11-1-47

Dr Cristobal Uauy (John Innes Centre, UK), Convenor of the SEB’s Crop Molecular Genetics Group, has led a collaboration with Rothamsted, Earlham Institute and UC Davis to create a resource which aides the study of gene functions in wheat. The group sequenced the protein coding regions of 2735 mutant lines and developed public databases including more than 10 million mutations. This collection of mutations is predicted to disrupt more than 90% of wheat genes. Researchers and breeders can search this database online and request seeds to study gene function or improve wheat varieties. It is hoped that this genetic tool will aide in combating the challenge of food security.

Reference: www.sciencedaily.com/ releases/2017/01/170116160534.htm

A recent study from the lab of Professor Steve Long (University of Illinois, USA) has found that lower leaves on the C4 crops corn and Miscanthus are less efficient at producing yield. The research, published in the Journal of Experimental Botany, compared the rates of photosynthesis in top and bottom leaves when placed in the same low light. It was found that when top and bottom leaves are placed in the same light, the lower canopy leaves showed lower rates of photosynthesis. Shaded corn leaves are 15% less efficient than top leaves and lower leaves are 30% less efficient than the top leaves of Miscanthus, a perennial bioenergy crop. Considering the crop as a whole, this loss of efficiency in lower leaves may cost farmers about 10% of potential yield. The next step for researchers is to find out why the loss in efficiency occurs and how it can be fixed to increase the yield in these, and potentially other, C4 crops.

Read the full article: ‘Loss of photosynthetic efficiency in the shade. An Achilles heel for the dense modern stands of our most productive C4 crops?’ FREE online at: https://academic. oup.com/jxb

Reference: www.sciencedaily.com/ releases/2017/01/170123125604.htm

Won an award or had your research in the news? We want to hear about it! Contact info@sebiology.org.

Opposite page

Ottoline Leyser

PHARMACEUTICALS

In a post-truth era, how do we communicate controversial science?

The Science with Impact event at the SEB Annual Meeting 2017 in Gothenburg will address this question, and discuss the good, the bad and the ugly of past approaches.

Arguably, one of the ugliest communication wars was fought over genetically modified organisms (GMOs), especially food crops. While some might still lick their wounds, the next generation of crops, bred through New Plant Breeding Technologies such as the Crispr/ Cas9 system, are already on our door step. But can these new crops be classified as GMOs? How they should be regulated is currently being discussed across the globe.

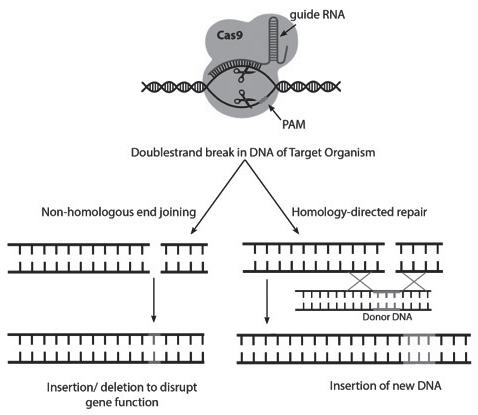

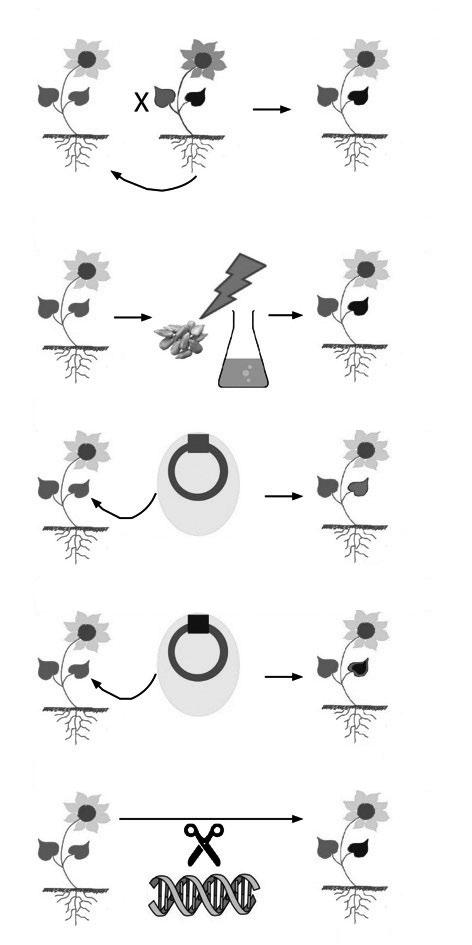

CRISPR/Cas9 is the new revolution in genetic engineering and many scientists are using it in their day-to-day research. CRISPR stands for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, and Cas9 is a CRISPRassociated nuclease. The system is often described as molecular scissors. It can be used to precisely target a certain position in a genome where it cuts the DNA and during subsequent repair, base pairs can be deleted, modified or inserted (see Graphic I). While a moratorium has been advocated for its use on the human germ line1 it is being applied to modify plants and fungi used in food. Only last year, a white button mushroom engineered with CRISPR/Cas9 to reduce browning was approved by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for commercial use and without it being subject to regulation2 . With the CRISPR/Cas9 system, a crop genome can be modified to breed beneficial traits. It can be used to introduce foreign DNA, rendering the resultant crop a GMO. If it is used to induce point-mutations, the resultant crop cannot be distinguished from a conventional breed, because the CRISPR/ Cas9 system is removed from the crop after it has done its job. The mutation could have

arisen spontaneously, or by other means of conventional breeding such as treatment with chemicals or radiation (see Graphic II). This is why scientists from China, USA and Germany have called to exempt so-called gene-edited crops from regulations that currently apply to GMOs3. The researchers argue that there is no scientific reason to distinguish between two mutated plants based on how the mutations were induced, i.e. either via conventional breeding or via gene-editing. Furthermore, using CRISPR/Cas9 to induce a mutation would lead to fewer unwanted effects in the genome than mutagenesis by chemicals or radiation.

Regulatory authorities across the globe now need to decide on how to legislate gene-edited crops and, more generally, New Plant Breeding Technologies (NPBT, see explainer). And time is running out. Already in 2015, six EU member states judged that a herbicide-tolerant oilseed canola that had been modified using an older gene-editing technique was not to be classed as GMO under EU law. The German Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety allowed the US firm Cibus, which created the crop, to go ahead with field trials.

At the time the EU commission asked these countries to halt their approval and wait for their legal interpretation of EU law. Will it be interpreted to state that any organism that was created using genetic modification techniques is a GMO, i.e. a process-based interpretation, or does it also allow for a product-based interpretation, i.e. that any organism containing foreign DNA is a GMO? The European Commission already instated an expert group on NPBTs in 2007, and although the Commission’s interpretation was announced for the end of 2015, then postponed to spring 2016, an official document has yet

FOR DETAILS ON OUR ‘NEW BREEDING TECHNOLOGIES IN PLANT SCIENCES’ SATELLITE MEETING (SEE PAGE 53)

to be released. Current events in France have pushed the ball even further afield: in October 2016, the French Government asked the European Court of Justice to rule whether NPBTs fall under EU law on GMOs and whether countries could ban these technologies 4 A ruling, and therefore a judgement of the EU Commission, cannot be expected before 2018.

ONLY LAST YEAR, A WHITE BUTTON MUSHROOM ENGINEERED WITH CRISPR/CAS9 TO REDUCE BROWNING WAS APPROVED BY THE US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE (USDA) FOR COMMERCIAL USE AND WITHOUT IT BEING SUBJECT TO REGULATION2.

l Site-directed nucleases (including zinc finger nuclease-1/2/3, TALENs, meganucleases and CRISPR systems)

l Oligonucleotide directed mutagenesis (ODM)

l Cisgenesis

l RNA-dependent DNA methylation (RdDM)

l Grafting (on GM rootstock)

l Reverse breeding

l Agro-infiltration (agro-infiltration sensu strict , agro-inoculation, floral dip)

GRAPHIC I. CRISPR/Cas9: how it works.

CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, and Cas for CRISPR associated. The Cas9 nuclease is guided to a specific target sequence in a genome by the guide RNA. It induces a DNA double-strand break for which it requires a short, conserved sequence called the protospacer-associated motif (PAM). The cut DNA is repaired by the cell’s repair system through non-homologous end joining. In this process, mutations can arise that disrupt gene function. If the introduction of a new DNA sequence is required, a donor-DNA is required for homology-directed repair.

Image credits:

Cornelia Eisenach and DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS), licensed under Creative Commons license.

Conventional Breed: Introgression Breeding

No GMO

multiple backcrosses

Conventional Breeding: Mutagenesis, Radiation or Chemicals

No GMO

Gene Modification: Transgenesis

Gene Modification: Cisgenesis

Gene Editing

GMO GMO GMO ?

Someone who did not want to wait so long is Stefan Jansson. Professor at the University of Umeå in Sweden, he demonstrated how scientists can communicate the risks and benefits of New Plant Breeding Technologies. In the tradition of self-experimentation, he cooked and ate what was probably the world’s first CRISPR lunch using gene-edited kale. Jansson is one of the organisers of a session on ‘New breeding technologies in the plant sciences’ at the SEB meeting in Gothenburg 2017. “We succeeded in convincing a Swedish authority to state that, according to their interpretation, the plants could not be considered genetically modified in accordance to EU regulations as they do not contain any ‘foreign DNA’,” he writes in a blog documenting the experiment5 . He grew the kale, which had been modified using the CRISPR/Cas9, in his own vegetable garden and when it came to harvest time, he invited the host of a Swedish radio station and cooked a CRISPR-kale pasta dish, the recipe of which can be found on his blog.

While in Europe the waiting game continues, the USA has recently taken a clearer stand. In January 2017, the USDA Animal and Plant Health Protection Service (Aphis) released documents which contain suggestions for new regulatory rules. Aphis advocates exempting crops produced by gene-editing from regulation but go even further: The authority also seems to want to exempt certain transgenic crops. Transgenic crops often contain sequences of plant pests such as the 35S promoter of the cauliflower mosaic virus or the left border sequence of Agrobacterium. But the authority states: “The experience has shown that the use of genetic material from plant pests has not resulted in the creation of plant pest risks in recipient organisms.” It did not refer to any systematic analysis of this experience, but the passage suggests that crops bred through Cisgenesis (see Graphic II) might no longer be regulated in the future.

could help to increase productivity without the use of herbicides and pesticides. It is up to scientists to communicate these benefits in engaging ways.

Cornelia Eisenach is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Zurich

1. http://www.nature.com/news/don-t-edit-the-humangerm-line-1.17111

2. http://www.nature.com/news/gene-edited-crisprmushroom-escapes-us-regulation-1.19754

3. http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/v48/n2/full/ng.3484. html

4. http://www.conseil-etat.fr/Actualites/Communiques/ Organismes-obtenus-par-mutagenese

5. https://www.blogg.umu.se/forskarbloggen/2016/09/ future-garden-plants-are-here-a-diary-from-the-firstcrispr-edited-plants-in-the-world/

HE GREW THE KALE, WHICH HAD BEEN MODIFIED USING THE CRISPR/CAS9, IN HIS OWN VEGETABLE GARDEN AND WHEN IT CAME TO HARVEST TIME, HE INVITED THE HOST OF A SWEDISH RADIO STATION AND COOKED A CRISPR-KALE PASTA DISH.

Left:

GRAPHIC II. Comparison between conventional breeding technical, ‘classic’ GMOs and breeding through gene-editing such as by CRISPR/Cas9.

Image Credit:

Cornelia Eisenach, adapted from Marchman et al. (2015) Feasibility of new breeding techniques for organic farming. Trends in Plant Science 20: 426–434

A ruling in the US is likely to impact on Europe, either politically or through import of potentially unclassified geneedited crops. Many organisations including those representing organic farmers are on the alert. Whether gene-editing results in changes that could be obtained through conventional breeding, or not, is not the crucial question. In the view of many organic farming organisations, manipulation of subcellular material is prohibited due to ethical considerations. So far, IFOAM, the European umbrella organisation of the organic movement, has called for NBPTs to be considered as GMOs, and its membership is expected to vote on the organic sector’s position in November 2017.

So, are traditional fault lines of past communication wars set to open again? NBPTs could have benefits for organic farming: geneedited crops that do not contain foreign DNA

Top:

The world’s first CRISPR lunch (probably).

Created by Stefan Jansson

In one way or another, most of our energy comes from the sun, captured by plants at the bottom of the chain. But as our populations rise, this puts increasing pressure on the photosynthetic capacity of our food and fuel crops. Researchers face the dual challenge of optimising photosynthesis to boost yields, whilst also equipping crops to cope with our changing climate.

During our Annual Meeting in Gothenburg in July 2017, strategies to achieve this will come under the spotlight in the session ‘Photosynthetic response to a changing environment – Towards sustainable energy production.’ Meanwhile, here is a taste of the exciting ideas that could revolutionise this most fundamental of processes for all life on earth.

Whilst light is essential to drive photosynthesis, too much of a good thing can also be a problem. Excess energy that can’t be used by the photosystems is transferred instead to other molecules – including oxygen – resulting in damaging high-energy oxygen radicals. To counter this, plants have developed a form of ‘reactive sunscreen’ known as nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ). This involves both the activity of the PSII subunit S (PsbS) protein and the interconversion of three carotenoid pigments in a process known as the xanthophyll cycle. When plants are exposed to sudden sunlight, this system is rapidly induced, damping down photosynthetic efficiency. But it takes much longer to reset the system – similar to how it takes our eyes time to adjust to the dimness of a dark room. This is a problem for crop plants that naturally experience fluctuating light levels, e.g. from passing clouds or shade from other leaves. “During this time the leaf is converting light that could be used in photosynthesis into heat, and as a result, this slow recovery could cost between 8 and 40% of potential carbon gain,” says Professor Steve Long (University of Illinois, USA and Lancaster University, UK). In a seminal paper1, published with colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, Steve has shown that targeting NPQ could be an effective strategy to boost stagnant crop yields. “We hypothesised that by accelerating the xanthophyll cycle and increasing PsbS, NPQ relaxation would be more rapid when leaves were transferred from high light to shade,” says Steve. “This was done by overexpressing three genes in transgenic tobacco

Right Chlorophyl fluorometer

sweet potato

Photo credit

Michael Martin, University of Georgia

plants and the results were startling. The transgenic plants were 14%–20% more productive in replicated field trials in terms of biomass accumulation than the control plants, with taller stalks and bigger, broader leaves. Because the NPQ process is the same in all crops, we see no reason why it should not produce similar increases in the major food crops.”

However, other mechanisms may also exist to dissipate excess light energy. Freezing conditions make plants particularly vulnerable to photo-damage – a problem deciduous trees avoid by simply shedding their leaves in autumn. But what about conifers that retain their needles throughout winter? “Conifers have clearly evolved efficient light-dissipation systems to survive boreal winters without irreversible damage – a trait we take for granted in our Christmas trees,” says Professor Stefan Jansson (Umeå University, Sweden), whose research so far suggests that spruce trees do not use the PsbS system to dissipate light energy.

“The PsbS system is very dynamic and requires a low lumenal pH, but in conifers, quenching is more static and the trees would have a problem to keep the lumenal pH low during the winter,” he says. So how do they manage it? At the Gothenburg meeting, Stefan hopes to shed some light on this in his talk ‘How can spruce needles be green in the winter?’ Stefan plans to present his first biochemical and ultrastructural studies, besides transcript profiling of overwintering spruce trees. “Ultimately, once we can suggest some mechanisms, we hope to confirm these by generating spruce trees with reduced capacity for these then seeing if they can survive the winter.” Potentially, understanding these mechanisms could suggest novel ways to protect photosynthesis in crops.

With pressure increasing on our dwindling fossil fuels, there is considerable interest in developing fuels that sustainably harness the power of photosynthesis. But conventional biofuel crops can divert land away from food production, and hence the ‘next generation’ of biofuels are focusing on engineering algae or cyanobacteria using synthetic biology approaches. Professor Eva-Mari Aro (University of Turku, Finland) explains her research on cyanobacteria: “Our goal is the

CONIFERS HAVE CLEARLY EVOLVED EFFICIENT LIGHT-DISSIPATION SYSTEMS TO SURVIVE BOREAL WINTERS WITHOUT IRREVERSIBLE DAMAGE – A TRAIT WE TAKE FOR GRANTED IN OUR CHRISTMAS TREES.

economically viable conversion of solar energy to chemicals and fuels using inexhaustible raw materials: sunlight, water and CO2 , rather than biomass which has a limited supply,” she says. Cyanobacteria are particularly suitable for a production chassis: their light harvesting and electron transfer processes are well known, they are genetically tractable and they have already been engineered to produce a number of useful fuels and chemicals2. Less is known, however, about the mechanisms they use for regulating photosynthesis as these appear to differ considerably from those in vascular plants. As Eva-Mari explains: “To dissipate excess electrons, algae, mosses, conifers and higher plants protect their photosystems using sophisticated regulatory mechanisms, including strict control of electron flow. But these systems are absent in cyanobacteria.” Instead, cyanobacteria rely on flavodiiron proteins that act as ‘electron valves’3. These function by using excess electrons to catalyse the photoreduction of oxygen to water. Indeed, so effective are flavodiiron proteins as electron scavengers that it is currently a mystery why they became lost in ‘higher plants’. At the Gothenburg meeting, Eva-Mari will be exploring this mystery during her talk ‘Maintenance of the photosynthetic apparatus in changing environments.’ “We believe that the evolution of photo-protective mechanisms was necessary for the transition of photosynthetic organisms from aquatic to terrestrial environments,” she says. But understanding the ancient flavodiiron pathway will be vital in order to optimize photosynthesis for the future. In artificially engineered cyanobacteria, strong electron sinks will be necessary to allow the ‘living factories’ to run at full capacity, as this avoids having to impose strict regulatory mechanisms to protect the photosystems.

Flavodiiron proteins could also help boost photosynthesis in terrestrial crops, as demonstrated by a study led by Kyoto University. Here, the flavodiiron genes FlvA and FlvB from the moss Physcomitrella patens were introduced into wild-type Arabidopsis. It was found that the flavodiiron proteins still acted as a strong electron sink and did not compete with normal cyclic electron flow. As such, the photosystems of the transgenic plants were more robust against fluctuating periods of high light intensity 4 . This suggests that despite flavodiiron proteins being lost in plant evolution, reintroducing them into crops could be a mechanism to protect them against photo-damage. It just goes to show that looking to the past can sometimes help to plan for the future…

Another strategy to optimise photosynthesis is to enhance the repair processes that renew components damaged by abiotic stresses such as cold, drought and heat. This is particularly relevant for the light harvesting complexes, which are responsible for the first stage of photosynthesis: harvesting energy from sunlight and transmitting this to the reaction centres. To prevent irreversible damage from over-excitation, these complexes have to be tightly regulated, being degraded in strong sunlight and assembled anew under low light conditions. “Despite the pigmentbinding proteins in light-harvesting complexes being among the most abundant membrane proteins on earth, their degrading protease remains unknown,” says biochemist Professor Christiane Funk (Umeå University, Sweden). At Gothenburg, Christiane will be presenting results from her studies on a promising protease family during her talk ‘Deg proteases – survival at abiotic stress’.” The Deg proteases (from Degradation of periplasmic proteins) are found in organisms from all kingdoms of life and in humans their roles include removing damaged cell components, tumour suppression and combating toxic protein aggregates that can cause neurodegeneration. Plants also possess Deg proteases; 16 Deg genes have been identified so far in Arabidopsis, with at least five located specifically in the chloroplast, making them prime candidates for photosynthetic repair. To investigate this, Christiane has been examining how deleting one or multiple Deg proteases affects growth

under various abiotic stress conditions in Arabidopsis and the cyanobacterium Synechocystis. “We compare the physiological phenotype, when they are grown under various abiotic stress conditions,” she says. Her results have already shown that Deg proteases can function in very specific ways: “We found that one of the three Deg proteases of Synechocystis 6803 is expressed in high amounts and is very active, while another one is activated only during abiotic stress like heat or high light,” says Christiane. Potentially, over-expressing stress-related Deg proteases could be a strategy to protect the photosynthetic machinery of crops from adverse conditions. But Christiane warns it might not be so straightforward: “Over-expression would remove malfunctioning proteins faster, but cells usually keep the number of proteases at exactly the right amount needed,” she says. “Overexpressing proteases might even cause additional stress as functional proteins may be attacked.” Her current work is investigating whether this would be the case by overexpressing Deg proteases in Synechocystis. Although under-explored until now, it seems likely that we will be hearing about the Deg proteases a lot more in the future…

To meet the demand for colourful fruit and vegetables all year round, much of the photosynthesis that produces our food takes place in controlled environments such as greenhouses and dedicated indoor ‘plant factories’. Whilst these minimize the impact of external stresses, they typically require supplemental light to achieve year-round crop production – which comes at a cost. “Lighting accounts for about 30% of the production cost in greenhouses and 50–60% of the costs in plant factories,” says Professor Marc van Iersel (University of Georgia). “To make this industry profitable and sustainable we need to look at how efficiently plants use the light they receive.”

To do this, Marc helped to develop a ‘biofeedback mechanism’, where the level of supplementary light is adjusted depending on how efficiently photosynthesis is operating in the plant. When a leaf absorbs a photon, the energy is either used in electron transport for

SO FAR, OUR FINDINGS SUGGEST THIS CAN RESULT IN ENERGY SAVINGS OF UP TO 60%.

YOU CAN REPLACE A SURPRISING AMOUNT OF AIR SPACE WITH SOLID TISSUE, AND SO ACHIEVE MORE PHOTOSYNTHESIS.

Photo credit: Amanda De Souza and Justin McGrath/ University of Illinois

photosynthesis, dissipated as heat or emitted as a lower energy photon (chlorophyll fluorescence). These three pathways are in competition, so that increased efficiency in one will cause a decreased yield for the other two. In the biofeedback system, a chlorophyll fluorometer attached to one of the plant’s leaves is connected to a central datalogger, which is also linked to the LED lights of the growth chamber. The datalogger uses readings from the fluorometer to calculate the quantum yield of photosystem II to derive a measure of photosynthetic efficiency. This is combined with the measured light level to give an estimate of the electron transport rate through photosystem II, which is compared to a pre-programmed target rate for optimal yield. “If the measured rate is lower than the target, the datalogger increases power to the lights, which increases the electron transport rate, and vice versa,” says Marc. Crucially, the system was tested successfully in three crops with very different light requirements: sweet potato (which requires high light), lettuce (which prefers moderate light) and pothos (an understory plant which needs deep shade). This demonstrates that the system could be used in the production of a wide range of food crops. However, it may be a while before biofeedback systems can be applied on a commercial scale. “We would first have to develop an affordable chlorophyll fluorometer that can scan entire canopies, rather than a small spot on a single leaf,” explains Marc. In the meantime, he has already developed another lighting system for greenhouses, using a controller that automatically adjusts the intensity of supplemental light depending on the amount of natural sunlight, ensuring that the crop always receives the right amount of light but no more. “So far, our findings suggest this can result in energy savings of up to 60%,” Marc concludes.

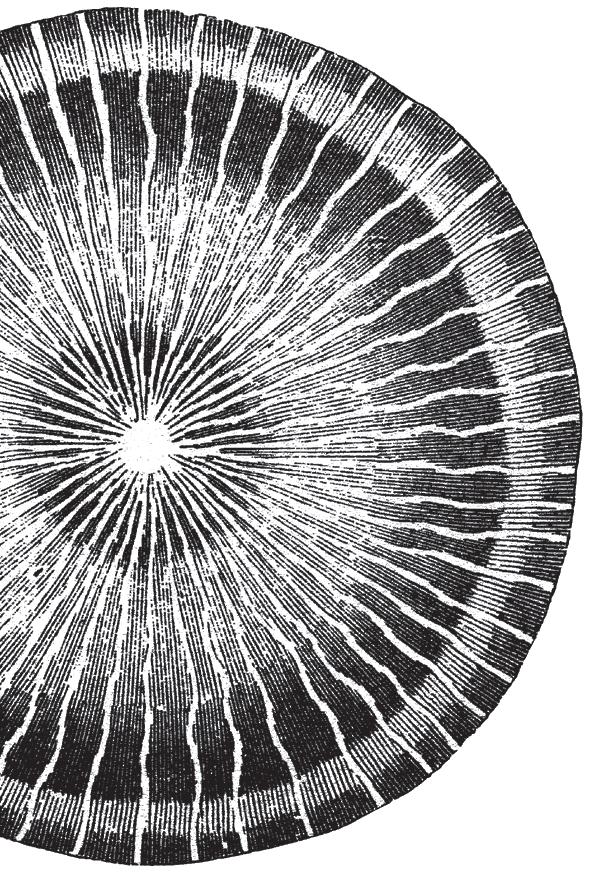

Most approaches to improving photosynthesis focus on the cells, but Professor Andrew Fleming (University of Sheffield, UK) believes that the spaces in between are just as important. Plant leaves show a distinct structure: the upper palisade layer is tightly packed with cells to facilitate light capture whilst the lower spongy mesophyll layer has a network of large air spaces to allow CO2 diffusion.

“Essentially, we have no idea how these layers develop,” says Andrew. “But we have found that by manipulating cell division and cell wall separation genes, we can indirectly

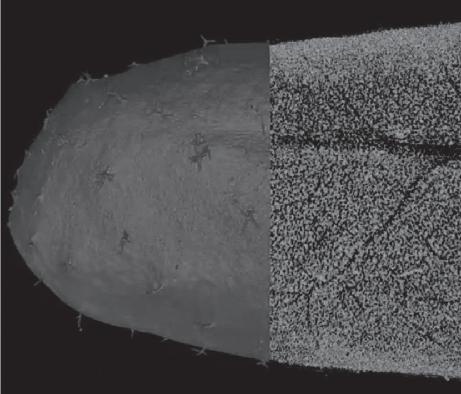

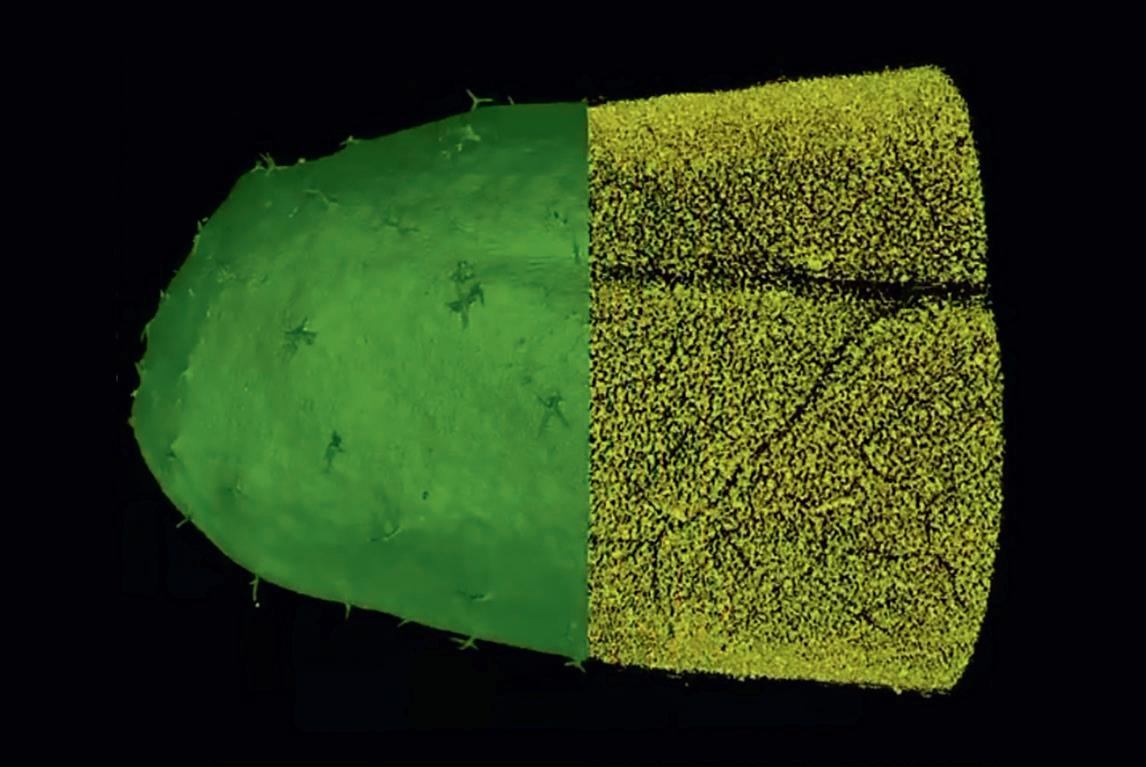

Above left

CT of Arabidopsis leaf, solid green leaf being stripped to reveal yellow airspace

Photo credit: Radek

Pajor, Nottingham University

Hounsfield CT

centre

alter the pattern of air spaces in the mesophyll.” Working with colleagues at the University of Nottingham, Andrew has been using micro-CT imaging (a 3D X-Ray technique) to quantify the distribution of air spaces in such Arabidopsis mutants. The plants are then tested with gas exchange analysis to determine how well photosynthesis is working. “We have found that, under controlled conditions, at least, there is a lot of flexibility in the system,” says Andrew. “You can replace a surprising amount of air space with solid tissue, and so achieve more photosynthesis.” So why haven’t plants evolved to naturally ‘fill in the gaps’ to boost photosynthesis? Andrew believes that one of the main factors is the additional cost in nitrogen and phosphorous that making additional cells would require.

More extreme mutations can even invert the actual patterning of air spaces between the layers. Normally, the density of air channels decreases from the mesophyll to the palisade layer, but one cell-cycle gene mutant showed a distinct peak of air channels in the palisade layer. Essentially, this allows more CO2 gas to reach the plastids where light capture takes place. “Compared to the wildtype, this mutant seems to photosynthesise particularly well indeed,” says Andrew. “This suggests that in the top palisade layer, the cells aren’t limited by rubisco or the amount of light but the concentration of CO2.” In his latest projects, Andrew hopes to explore whether similarly manipulating mesophyll architecture in rice and wheat also affects photosynthetic efficiency. “We are now working with engineers using gas and liquid diffusion modelling to investigate whether altering the pattern of air spaces changes the flux of gas within the leaf,” he says. “So far, altering mesophyll architecture has been an under-explored approach, but if it does prove to play a significant role in photosynthetic efficiency then, in theory, it could be improved.”

1. Kromdijk J, Głowacka K, Leonelli L, et al . (2016) Improving photosynthesis and crop productivity by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science 354, 857–861.

2. Aro EM (2016) From first generation biofuels to advanced solar biofuels. Ambio 45 Suppl 1, S24–S31.

3. AAllahverdiyeva Y, Mustila H, Ermakova M, et al . (2013) Flavodiiron proteins Flv1 and Flv3 enable cyanobacterial growth and photosynthesis under fluctuating light. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, 4111–4116.

4. Yamamoto H, Takahashi S, Badger MR et al (2016) Artificial remodelling of alternative electron flow by flavodiiron proteins in Arabidopsis. Nature Plants 2 16012.

Left Higher leaves on a cassava plant inadvertently rob lower leaves of their productivity due to photo protection, a process that protects leaves in full sun but inhibits photosynthesis in the shade. SEE PAGE 24 FOR FULL COLOUR IMAGEThese days we seem to have a ‘pill for every ill’ and most of us happily take them or administer them to pets without a second thought. But once released into the environment, these powerful drugs can start to have effects beyond their target consumers.

Unlike some forms of pollution, the issue of pharmaceutical waste has had a low profile up to now –hampered by the limited dialogue between ecologists and ecotoxicologists. At our Annual Meeting this year in Gothenburg, the symposium ‘Effects of pharmaceuticals on wildlife – bridging the gap between ecotoxicology and ecology’ will bring together researchers from traditionally unrelated fields to tackle this. By generating new theoretical knowledge and increasing the evidence base, we can start to make governments and the public aware of the impact our clinical waste is having on wildlife.

Toxic effects of pharmaceuticals on wildlife can pass largely unnoticed – until they cause a spectacular population crash. The sudden devastation in Gyps vultures in India certainly brought the issue to the public’s attention: between 1990 and 2007, their population fell by over 97%1 due to lethal ingestion of diclofenac, a non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug administered to cattle. The drug came into widespread use in 1994, after the Novartis patent on the active molecule ended. Suddenly millions of veterinary doses were being administered each year, including treatments to ease the suffering of dying cattle (due to their religious significance, cattle cannot be euthanized in India). Diclofenactainted cattle carcasses were thus the route by which many vultures were exposed to the drug. “Gyps vultures are particularly susceptible to diclofenac, as it causes necrosis of the kidney tubules and disrupts secretion of uric acid, the main component of birds’ urine,” says Rhys Green (University of Cambridge, UK), whose research helped establish the link between diclofenac use and vulture declines. “Most vultures die within two to three days of

exposure and post-mortem analyses typically show deposition of uric acid crystals in the majority of the tissues.”

Tragedies like these demonstrate the critical need for tighter controls on pharmaceuticals, yet governments and pharmaceutical companies are resistant to introducing changes. No government currently requires pharmaceutical companies to conduct environmental risk assessments for their products. In the case of the Gyps vultures, whilst veterinary use of diclofenac was outlawed in India, the drug is still approved for humans – meaning that it remains readily available to buy. Furthermore, the pro-drug aceclofenac is still available for veterinary use, despite the fact that it is rapidly metabolised to diclofenac in cattle2

Even when the effects aren’t lethal, pharmaceuticals can still have severe repercussions at the population or even ecosystem level. Aquatic species are particularly vulnerable as they are exposed to drug residues in urine and sewage from humans and treated livestock. Perhaps the most well known are the effects of estrogenic compounds, such as ethynylestradiol containing contraceptives. These alter the normal reproductive endocrine signalling pathways in fish, shutting down egg production in females and causing ovarian tissue to develop in males (known as ‘intersex’ fish). The molecular mechanisms driving this remain unclear, but it is thought that receptormediated estrogen-responsive pathways, as exemplified by abnormal secretion of the egg yolk protein vitellogenin in male fish, play a role. Nevertheless, the problem is clearly increasing: in key areas, such as the Potomoc River basin in the USA, up to 100% of sampled male smallmouth bass can be intersex 3 At the Gothenburg meeting, Deborah MacLatchy (Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada) will be

presenting her work on a curious fish that seems unusually resistant to estrogens: “The mummichog or Atlantic killifish ( Fundulus heteroclitus) is often the ‘last-standing’ fish in case studies of contaminated environments,” she explains. “They can withstand large extremes of temperature and salinity, and also conditions of low dissolved oxygen.”

Interestingly, whilst these fish share some responses to estrogens similar to that of other species, such as feminisation of developing fish, the adults are remarkably resistant to the drug’s effects on ceasing egg production, even at much greater concentrations. It’s currently a mystery why this is the case, and one which Deborah and her students are tackling: “It’s been like a mini-detective story!” she says.

“We are using an integrated approach linking mechanisms of action at the molecular and physiological levels to whole-organism and population-level outcomes.” So far, her studies have eliminated the possibility that estrogen uptake itself is reduced by the high-saline environments where killifish are found, compared to freshwater environments: “We now feel that a difference in the physiology of the ovarian tissue may be contributing to the exogenous estrogen resistance and we’re planning to present the findings in Sweden.”

The effects of pharmaceuticals are not limited to the physiological, as Kathryn Arnold (University of York) will demonstrate at Gothenburg during her talk ‘Sex, stress and food: Impacts of antidepressants in the

WE ARE USING AN INTEGRATED APPROACH LINKING MECHANISMS OF ACTION AT THE MOLECULAR AND PHYSIOLOGICAL LEVELS TO WHOLE-ORGANISM AND POPULATIONLEVEL OUTCOMES.

environment on birds.’ Although much of the work on pharmaceutical pollution has focused on aquatic organisms, birds are also vulnerable when they feed off contaminated invertebrates.

“Every bird watcher will tell you that sewage treatment plants are very good places to watch birds,” Kathryn says. “These tanks teem with maggots, earthworms and invertebrates that feed off pharmaceutical-tainted waste material, making them a reliable food source for wild birds, particularly in winter. We wanted to see the effects of the chemicals they are being exposed to,” says Kathryn. Antidepressants were a prime candidate: in England and Wales, roughly 50 million antidepressant prescriptions are written each year, and around 30% of these drugs pass through the human body completely unchanged. One of the most heavily prescribed, Prozac (also called fluoxetine), is even more active once metabolised.

Kathryn and her colleagues devised a study to mimic what happens when the birds obtain 50% of their daily food from sewage treatment plants. Wild-caught starlings were kept in outdoor aviaries and fed daily with a waxworm, some of which had been injected with the equivalent amount of Prozac to that estimated in worms from sewage plants.

After 16 weeks, the birds exposed to Prozac showed marked changes in behaviour, including a significant reduction in boldness and exploratory activity. More worryingly, the exposed birds also showed disrupted foraging activity. “Humans on fluoxetine often have appetite changes and the drug is even used to aid weight-loss,” says Kathryn. “We found analogous changes in the Prozac-exposed starlings.” In winter, birds follow a general foraging pattern where they have a hearty breakfast first thing to replenish energy reserves, then snack lightly throughout the

Right Mummichog group Photo credit: Bent Christensen Below left Juvenile whiterumped vulture Photo credit: Chris Bowden, RSPB

day to cover their energy needs, without becoming too heavy to escape predators. Then at twilight, another heavy meal helps them survive the long, cold night. Whilst the control group kept to this pattern, the Prozacexposed group did not show any peaks in feeding activity at the start and end of the day. “Under harsh conditions, this could impact whether these birds are able to survive the night,” says Kathryn. At Gothenburg, Kathryn will present her latest results, which indicate that antidepressants can also affect courtship behaviour. “Females in particular seem negatively affected by exposure to fluoxetine,” she says. “They become less interested in the opposite sex and we have evidence that males find females on Prozac less attractive.”

benzodiazepine binds to GABA-A receptors, changing their conformation to make them more receptive to the neuroinhibitory ligand GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid). As this receptor is present in all vertebrate species studied so far, it’s likely that these drugs act in the same way in fish, inducing anti-anxiety effects. “In some ways, the drug did what it is supposed to do – the salmon became less anxious and their fear of risk was removed,” says Tomas. “But in nature, if you are not scared, you had better be big, or you will end up dead!”

THIS GIVES VERY HIGH RESOLUTION DATA, AND TRACKS THE POSITION OF EACH FISH THREE TIMES A SECOND DOWN TO 10 CM ACCURACY, EVEN IN A LARGE LAKE.

Whilst lab experiments are useful for investigating drug mechanisms, “to get to the core of the ecological effect, we need to validate our findings in more complex realworld situations,” says Tomas Brodin (Umeå University, Sweden), who will describe this further in his talk ‘Ecological effects of pharmaceuticals in the environment – from lab experiments to field studies.’ His research on the behavioural effects of the sedative benzodiazepine on fish demonstrates all too clearly how conclusions made in the laboratory don’t always translate into the field. When young salmon were exposed to the drugs in a controlled indoor environment, their migration speed increased by approximately 50% – potentially a real benefit for survival of young salmon travelling downstream to reach the ocean. But when Tomas and his colleagues released tagged salmon into rivers and followed their progress, they found that the opposite was the case. “We discovered that the control fish actually survived much better than the benzodiazepine-exposed fish, which were eaten by predators such as pike,” says Tomas. “What appeared to be a real benefit in the lab was actually a big drawback in the field.” Tomas has also made use of acoustic telemetry to study the effects of benzodiazepine exposure on schools of wild perch. In this technique, the fish are fitted with unique electronic tags which emit sound waves into the surrounding water. “This gives very high resolution data, and tracks the position of each fish three times a second down to 10 cm accuracy, even in a large lake,” he says. “This means we can follow 200 fish at the same time, and see their relative positions to each other.” In this study, benzodiazepine caused these normally social fish to venture away from their conspecifics and instead spend more time in high-risk areas of the lake that contained predatory pike4. In humans,

Most pharmaceutical-related research focuses on animals, but evidence is emerging that they also affect plants, particularly during the crucial phase of early development. A study led by the European Centre for Environmental and Human Health at the University of Exeter Medical School and the Petroleum and Environmental Geochemistry Group at the University of Plymouth found that environmental exposure to non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) significantly affected root and shoot growth in lettuce and radish 5. Due to their pain-relieving effects, NSAIDs are prescribed widely for conditions such as arthritis, menstrual pains and migraines. These can enter the environment when they are excreted out of the body, or when surplus pills are disposed of at landfill. “We investigated a range of different common NSAIDs including ibuprofen, diclofenac and naproxen,” says Wiebke Schmidt (University of Exeter), who was involved in the study. “The results showed that NSAIDs can affect various parameters of plant development – including root and shoot development and water uptake.” Strikingly, different compounds had contrasting effects even when their chemical structures were very similar, suggesting that the presence of certain functional groups can be very significant. The addition of methylchlorine groups, for instance, was found to be associated with enhanced root length. The drugs also had drastically different effects depending on the crop species. Diclofenac sodium, for example, suppressed cotyledon opening in radish, but accelerated it in lettuce. Certain NSAIDs even appeared to affect the allocation of photosynthate, resulting in a smaller root: shoot ratio in the plant. “The long-term consequences of pharmaceutical pollution on agriculture and plants in the natural environment is not yet understood. However, as pharmaceutical usage increases, and therefore levels of these persistent compounds build in the environment, this remains a growing concern for the future of food security and sustainability,” Wiebke concludes.

WHEAT EXPERIMENTAL PLOTS AT JIC FIELD RESEARCH STATION. PAGE 09

LAKE TOSKTJARN. PAGE 27

CT OF ARABIDOPSIS LEAF, SOLID GREEN LEAF BEING STRIPPED TO REVEAL YELLOW AIRSPACE. PAGE 19

WHEAT EXPERIMENTAL PLOTS AT JIC FIELD RESEARCH STATION. PAGE 09

LAKE TOSKTJARN. PAGE 27

CT OF ARABIDOPSIS LEAF, SOLID GREEN LEAF BEING STRIPPED TO REVEAL YELLOW AIRSPACE. PAGE 19

HIGH

REAL-TIME pH MEASUREMENTS

SOFTWARE OPERATED AUTOMATED PROTOCOLS

BLOOD GAS

DIFFUSION CHAMBER

GAS MIXING SYSTEM

HEMOGLOBIN BINDING OF OXYGEN

PLATE RESPIROMETRY

This optical fluorescence oxygen system will measure individual respiration rates in tiny organisms like zebrafish embryos & larvae, rotifers, daphnia, mosquito, drosophila etc. inside 80-1700 μL gas tight glass chambers on a 24well microtiter plate footprint.

Despite this growing body of evidence, governments and pharmaceutical companies have so far been reluctant to take responsibility to do more to prevent drugs from entering the environment. “We already have the technology to remove at least 90% of pharmaceuticals from wastewater – the real problem is the cost,” says Tomas Brodin. However, there are some notable exceptions: in January 2016, new legislation was passed in Switzerland requiring wastewater treatment plants to implement an additional treatment process to remove micropollutants such as pharmaceutical residues. Many plants are now being equipped with ozone generators to allow ozone-oxidation of wastewater that can remove up to 80% of these harmful chemicals.

Another approach is to reduce the amounts of pharmaceuticals that get released into the environment. Kathryn Arnold is an advocate of ‘Green Pharmacy,’ where the environmental impact of drugs is taken into account during the decision-making process. “If there are two drugs that are equally effective and no difference in price, the one that is less environmentally harmful should be selected over the other,” she suggests. However, according to Lina Nikoleris (Lund University, Sweden), whose PhD examined the effects of 17α-ethinylestradiol contraceptives on fish, many practitioners are unaware of the environmental effects of the treatments they prescribe. “Most of the nurse midwives I interviewed during the course of my research were unaware that there are environmental issues with all of the hormonal contraceptives, believing that estrogen-free contraceptives, such as those based on progesterone, were environmental friendly,” she explains. “Relying on information from pharmaceutical companies, they also felt constrained because often only certain contraceptives are subsidised by the government, and these tend to be traditional hormonal contraceptives and not the new generation contraceptives which contain natural estrogen and the more easily broken down molecule progesterone.”

Of course, some of the burden rests with the public and the need to raise awareness of the continuing powerful effects of pharma drugs after they exit our own bodies. Tomas Brodin offers one suggestion, to take unused drugs back to the pharmacist for proper disposal to avoid them ending up in land-fill, and Deborah MacLatchy agrees: “Pharmaceuticals are amazing products of human ingenuity, and we need to apply that same ingenuity to ensure they don’t make it into the environment and cause more problems than they solve in medicine.”

KATHRYN ARNOLD IS AN ADVOCATE OF ‘GREEN PHARMACY’, WHERE THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF DRUGS IS TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT DURING THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS. ‘IF THERE ARE TWO DRUGS THAT ARE EQUALLY EFFECTIVE AND NO DIFFERENCE IN PRICE, THE ONE THAT IS LESS ENVIRONMENTALLY HARMFUL SHOULD BE SELECTED OVER THE OTHER,’ SHE SUGGESTS.

1. Prakash V, Green RE, Pain DJ, et al . (2007) Recent changes in populations of resident Gyps vultures in India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 104, 129–135.

2. Galligan TH, Taggart MA, Cuthbert RJ, et al. (2016) Metabolism of aceclofenac in cattle to vulture-killing diclofenac. Conservation Biology 30, 1122–1127.

3. Blazer VS, Iwanowicz LR, Iwanowicz DD, et al. (2007) Intersex (testicular oocytes) in smallmouth bass from the Potomac River and selected nearby drainages. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 19, 242–253.

4. Klaminder J, Hellström G, Fahlman J, et al. (2016) Druginduced behavioral changes: Using laboratory observations to predict field observations. Frontiers in Environmental Science 4, 81.

5. Schmidt W, Redshaw CH (2005) Evaluation of biological endpoints in crop plants after exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Implications for phytotoxicological assessment of novel contaminants. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 112, 212–222.

Rapid identification of lettuce seed germination mutants by bulked segregant analysis and whole genome sequencing.

Huo H, Henry IM, Coppoolse ER, VerhoefPost M, Schut JW, de Rooij H, Vogelaar A, Joosen RV, Woudenberg L, Comai L, Bradford KJ (2016)

The Plant Journal 88, 345–360

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ tpj.13267/abstract

Forward genetics has the potential to be highly useful for the identification of genes associated with specific phenotypes. Protocols can be devised to efficiently screen mutagenized populations for phenotypes of interest. However, subsequently identifying the specific gene(s) responsible for the selected phenotype(s) can be slow, laborious and expensive in crop plants with long generation times, large genomes and limited sequence data. Huo et al . describe a sophisticated genetic analysis in the identification of a gene for seed germination in an important crop ( Lactuca sativa) using allelic mutants that show enhanced germination under high temperatures. The authors used bulk segregant analysis by whole genome sequencing (BSA sequencing) of progeny obtained from crosses made between two allelic mutants to identify mutations in the ABA1 gene for both mutants. They also used traditional mapping to map the alleles to the same genomic region, complementing the mutant phenotype with a wild type copy of the gene and measuring ABA levels in the mutants. This genetic analysis allowed the authors to demonstrate that they had identified the causal mutations. Using the process described, Huo et al. claim that the time required to identify a causal locus can be at least halved, and also that it considerably reduces the amount of genomic sequencing required. As such this protocol will considerably increase the efficiency, and reduce the time and cost involved, in applying forward genetics in the identification of important traits relevant for industry.

Jim Ruddock, Managing Editor.ARGOS8 variants generated by CRISPR–Cas9 improve maize grain yield under field drought stress conditions.

Shi J, Gao H, Wang H, Lafitte HR, Archibald RL, Yang M, Hakimi SM, Mo H, Habben JE (2017)

Plant Biotechnology Journal 15, 207–216

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ pbi.12603/abstract

Rapid population growth coupled with limited resources and climate change calls for innovation to keep pace at a similarly rapid rate. In this article Shi et al . describe research into CRISPR–Cas9-enabled crop improvements aimed at expanding genetic variation to enhance maize breeding for drought tolerance. Maize ARGOS8 gene negatively regulates ethylene responses and when ectopically over-expressed improves maize tolerance to drought stresses. CRISPR–Cas plant breeding technology develops improved seeds by using native characteristics available within the target crop. Using HDR-swap and HDRinsertion, facilitated by CRISPR–Cas9 genomeediting technology, the authors modified the regulatory elements of the ARGOS8 gene in maize and generated new ARGOS8 alleles which had different expression patterns from the native allele. Field trials demonstrated an increase in grain yield under water-limited stress during flowering, and no decrease in yield under optimal water availability. This study is important because it demonstrates that single endogenous genes can be modified using CRISPR–Cas9 technology to produce novel allelic variants that have a significantly positive effect on a complex trait such as drought tolerance. The results are of broad interest to researchers in plant genome engineering, demonstrating a new and easy way to breed abiotic stress tolerance in key crops, revealing a means to enhance the productivity of maize, and ultimately helping to meet the increasing global demands of food security.

Jim Ruddock, Managing Editor.Effects of reduced carbonic anhydrase activity on CO2 assimilation rates in Setaria viridis: a transgenic analysis.

Osborn HL, Alonso-Cantabrana H, Sharwood RE, Covshoff S, Evans JR, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S ( 2017)

Journal of Experimental Botany 68, 299–310

https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw357

Loss of photosynthetic efficiency in the shade. An Achilles heel for the dense modern stands of our most productive C4 crops?

Pignon CP, Jaiswal D, McGrath JM, Long SP (2017)

Journal of Experimental Botany 68, 335–345

https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw456

Metabolite pools and carbon flow during C4 photosynthesis in maize: 13CO2 labeling kinetics and cell type fractionation.

Arrivault S, Obata T, Szecówka M, Mengin V, Guenther M, Hoehne M, Fernie AR, Stitt M (2017)

Journal of Experimental Botany 68, 283–298

https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw414

Fifty years after the discovery of C 4 metabolism the research field is resurgent, with the aim to introduce this pathway into C 3 rice. A JXB special issue celebrates both the discovery and recent achievements in elucidating the evolution and development of the C4 syndrome. Three papers reveal limitations to C4 photosynthesis under different environmental conditions. Osborn et al looked at carbonic anhydrase, which catalyses the hydration of atmospheric carbon dioxide for PEP carboxylase in the first step of the pathway. Using transgenic plants with reduced carbonic anhydrase activity, they found that at low intercellular CO2 partial pressure, as can occur under drought, mesophyll conductance may be a greater limitation even than activity of the enzyme. Water availability is just one of many potential limitations to plant growth, and these can be very different in agriculture. Pignon et al . found that shade from neighbouring plants is a significant issue in C4 crops whose progenitors were more limited by other factors. They suggest that targeting efficiency in CO2 assimilation under low light could be effective in increasing productivity. Limitations to C4 photosynthesis may suggest avenues for engineering, but as Arrivault et al . point out, better understanding of such a complex pathway is needed. They used mass

spectrometric measurements of 13CO2 labelling kinetics, gaining a better picture of carbon flow, concentration gradients of metabolites and the pathway’s flexibility. This approach revealed a small but significant flux to photorespiration that may increase under conditions where stomata close, such as drought.

Jonathan Ingram and Christine Raines, Senior Commissioning Editor and Editor-in -Chief.

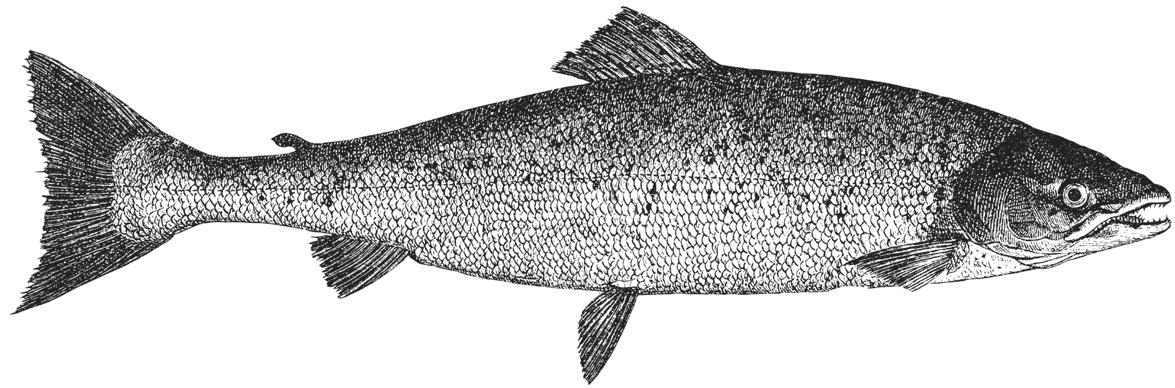

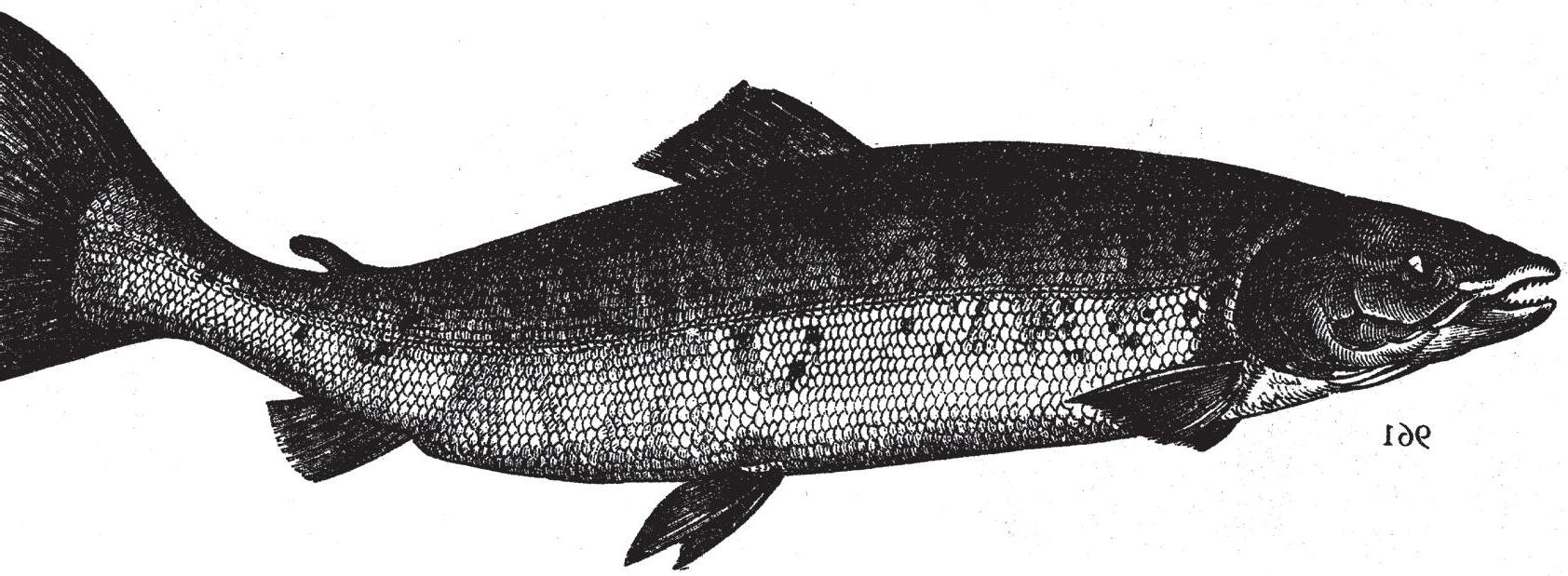

Unusual aerobic performance at high temperatures in juvenile Chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha.

Poletto JB, Cocherell DE, Baird SE, Nguyen TX, Cabrera-Stagno V, Farrell AP, Fangue NA (2017)

Conservation Physiology 5, cow067

https://doi:10.1093/conphys/cow067

To inform conservation measures for fishes and improve effective fish management, the impacts of key environmental variables such as temperature must be understood. As anthropogenic factors coupled with global climate change have altered water temperatures, research has increasingly focused on understanding the mechanistic links between temperature changes and declines in native fish populations. Physiological performance measures such as aerobic scope, or a metabolic index positively correlated with a fish’s ability to perform activities crucial to survival, can be used to assess plasticity in response to temperatures.

Poletto et al (2017) measured the aerobic scope of juvenile Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) acclimated to

one of two temperatures for several weeks (15 or 19°C), and exposed to a range of test temperatures (12 to 25°C). Across this wide range of test temperatures, both acclimation groups performed similarly and maintained aerobic scope up to 23°C, after which mortality occurred in some individuals. These results indicate that juvenile Chinook salmon exhibit a remarkable ability to maintain physiological stability through a broad range of water temperatures, and show a high degree of plasticity to cope with changing environmental conditions. Among salmonids, Chinook salmon inhabit the southern part of their range, and this ability might be a potential adaptation to cope with warmer water temperatures. The authors also suggest that the quantification of aerobic scope may be an important tool to incorporate into regional fish management, as variation in performance capabilities in other populations in the Oncorhynchus genus are consistent with local adaptation in aerobic scope.

Jamilynn Polpetto, Assistant professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln (current affiliation) .

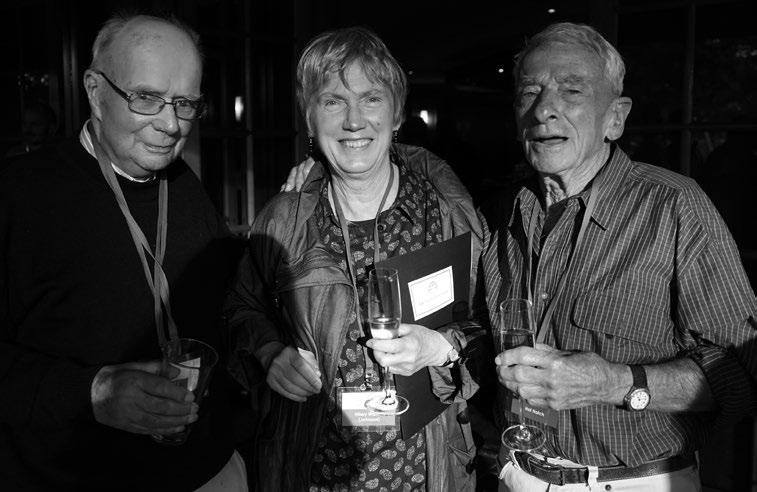

Left Pioneers of C4 photosynthesis Roger Slack (left), Hal Hatch (right) and Hilary Warren (centre, Hatch’s first PhD student) in 2016, 50 years after the first published characterization of the C4 photosynthetic pathway by Hatch and Slack.“It strikes me that being able to communicate complex scientific information in a clear way is similar to solving a puzzle,” says Catie Lichten, who works as a policy researcher for a not-for-profit policy research institute.