REAL WORLD CHANGES

The SEB Magazine is published biannually — Spring and Autumn (online) — by the Society for Experimental Biology and is distributed to all SEB members.

Advertising

Advertising in the SEB magazine is a great opportunity to reach a large community of biologists. For more details contact b.danois@sebiology.org

Design and artwork:

Robert Wood, Time Design Studio robertwood@timedesignstudio.co.uk

Contribute with an article!

Interested in writing an article for the SEB magazine? Get in touch: b.danois@sebiology.org

Deadline for copy: Issue: Spring 2026 Deadline: 1st March 2026

SEB Executive Team:

SEB Main Office

The Society for Experimental Biology County Main, A012/A013 Lancaster University, Bailrigg LA1 4YW, UK admin@sebiology.org

Chief Executive Officer

Pamela Mortimer (p.mortimer@sebiology.org)

Governance Officer

Sarah Ellerington (s.ellerington@sebiology.org)

Conference and Events Managers

Keji Aofiyebi (k.aofiyebi@sebiology.org)

Jennifer Symons (j.symons@sebiology.org)

Membership Manager

Jordy Turl (j.turl@sebiology.org)

Administrator Officer

Olubunmi Oduah (b.oduah@sebiology.org)

Membership & Administration Officer

Julius Kelly (j.kelly@sebiology.org)

Education, Outreach and Diversity Manager Dr Rebecca Ellerington (r.ellerington@sebiology.org)

Outreach Education and Diversity Intern

Gina Vong (intern@sebiology.org)

Communications Manager

Benjamin Danois (b.danois@sebiology.org)

SEB Honorary Officers:

President Gudrun De Boeck (gudrun.deboeck@uantwerpen.be)

Vice President

John Love (J.Love@exeter.ac.uk)

Treasurer Tracy Lawson (tlawson3@illinois.edu)

Publications Officer

Diana Santelia (diana.santelia@usys.ethz.ch)

Plant Section Chair

George Littlejohn (george.littlejohn@plymouth.ac.uk)

Cell Section Chair

Ross Sozzani (ross_sozzani@ncsu.edu)

Animal Section Chair

Felix Mark (Felix.Christopher.Mark@awi.de)

Outreach, Education and Diversity Trustee

Sheila Amici-Dargan (anzsld@bristol.ac.uk)

SEB Journal Editors:

Journal of Experimental Botany

John Lunn (Lunn@mpimp-golm.mpg.de)

The Plant Journal

Katherine Denby (katherine.denby@york.ac.uk

Plant Biotechnology Journal

Johnathan Napier (johnathan.napier@rothamsted.ac.uk)

Conservation Physiology

Andrea Fuller (Andrea.Fuller@wits.ac.za)

Plant Direct

Richard Haslam (richard.haslam@rothamsted.ac.uk)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the Editorial Board or the Society for Experimental Biology. The Society for Experimental Biology is a registered charity No. 273795

FEATURES SPOTLIGHT

In this Autumn 2025 issue of The Society for Experimental Biology magazine, we celebrate the theme “Real World Changes” which highlights research and initiatives that extend beyond the lab to make tangible impacts on society, the environment, and education. Across animal, plant, and cell biology, our members demonstrate how experimental research can influence the world around us.

FEATURES

In the animal kingdom, biology reaches far beyond laboratory experiments. Taking Animal Biology Beyond the Lab by Alex Evans (page 18) explores how research informs conservation, education, and innovation. One article follows tracking of endangered turtles to guide sustainable fishing practices, while another describes a handson outreach program introducing children to animal adaptations and natural selection. A third story showcases how bio-inspired design is helping tackle environmental challenges like microplastic pollution. These examples reveal how animal biology can make a real-world difference. Cell biology is demonstrating its impact on global challenges as well. Micro to Macro: Examining the Global Impact of Cell Biology by Alex Evans highlights research on sustainable agriculture, innovative use of AI to predict plant resilience, and creative approaches to teaching lab skills. These projects not only advance scientific knowledge but also foster inclusivity and inspire the next generation of STEM talent, showing that cell biology can affect society on multiple levels.(page22) Plant biology, meanwhile, is literally reaching for the stars. Sending Plants to Outer Space: Growing Life Beyond Earth by Caroline Wood on page 26 explores how plant research supports long-term human space exploration, including growing crops in microgravity and designing closed-loop systems for sustainable food production. Other projects investigate how plant systems can be optimized for extreme environments, offering insights that benefit both space missions and agriculture on Earth. Together, these stories illustrate the transformative potential of plant science.

REAL WORLD CHANGES

BY BENJAMIN DANOIS

MEMBERS HIGHLIGHTS

In this issue, we proudly showcase the achievements of our members. From conservation initiatives to innovative education programs, SEB members continually demonstrate creativity, dedication, and impact. Each contribution represents a shining star in the SEB constellation, inspiring peers and the public alike.(page XX)

SPOTLIGHT

This edition features exclusive interviews with Katherine Denby, Editor-in-Chief of the Plant Journal, and Andrea Fuller, Editor-in-Chief of Conservation Physiology. We also highlight two inspirational figures: Jeroen Aeles and Zineb Agourram. These conversations offer insights into leadership, research, and the future of experimental biology.

OUTREACH, EDUCATION AND DIVERSITY

Two-Eyed Seeing / Indigenous Science by Gina Vong (page 54 ) emphasizes integrating Indigenous knowledge with Western science to enhance ecological sustainability and community wellbeing.

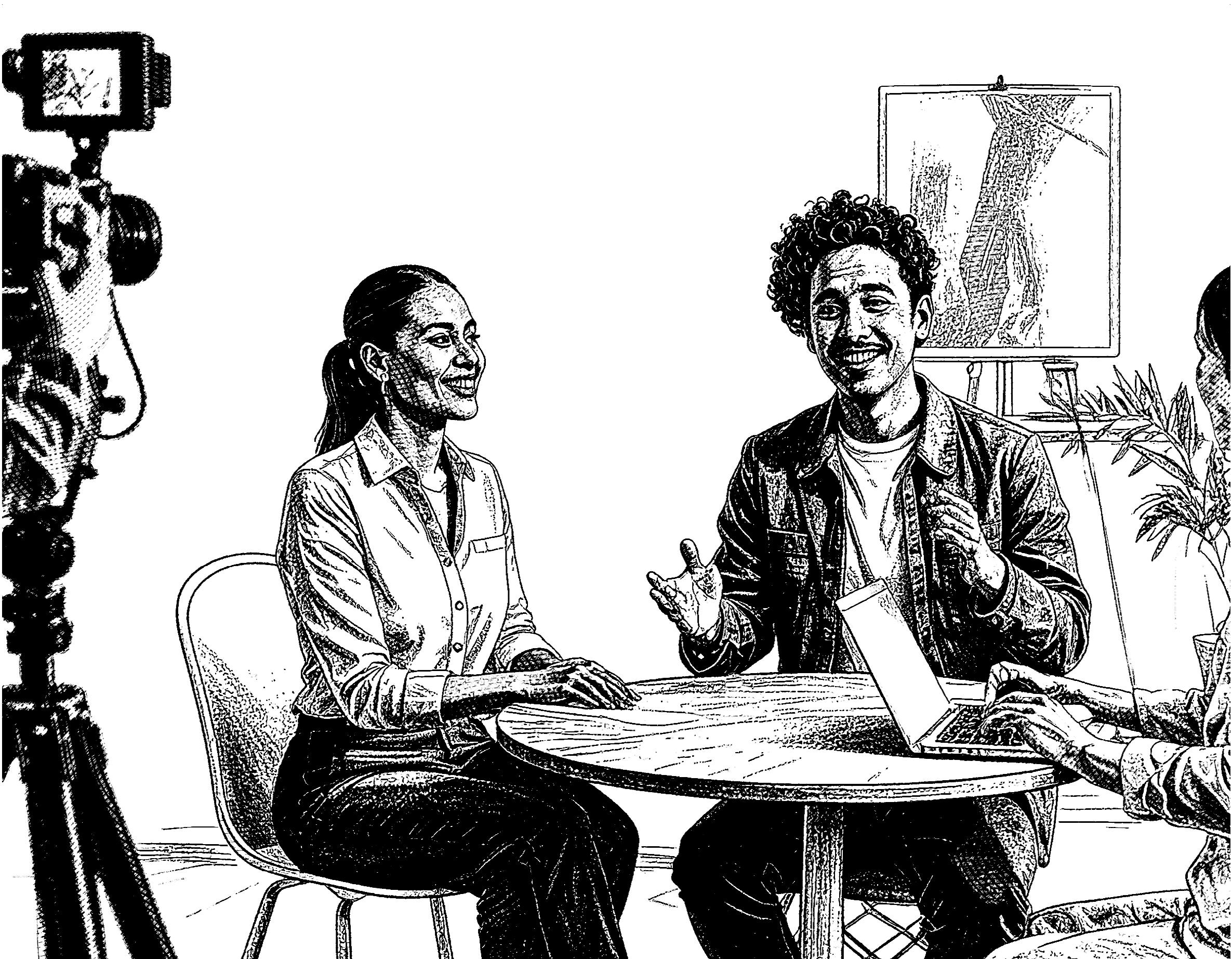

Becoming a Media Spokesperson by Caroline Wood (pages 48) offers guidance for biologists to engage with the media, build trust, and communicate clearly with the public.

In Starting a Science Blog, still written by Caroline Wood, (pages 50), the focus is on using blogs to share research, develop writing skills, and foster connections beyond academia.

Finally, How Experimental Biology Can Drive Ecosystem Recovery by Rebecca Ellerington demonstrates how experimental approaches in ecology inform restoration of resilient, biodiverse ecosystems and guide policy decisions. (page 52)

EVENTS

Looking ahead, the SEB Cell Symposium “EcoMito” will take place 19–20 February 2026 in We are excited to announce three major events taking place in 2026:

ECOMITO: BRIDGING CELLULAR PERFORMANCE TO ECOPHYSIOLOGY (ANIMAL SYMPOSIUM)

19–20 February 2026, Lyon, France

Bringing together researchers interested in linking mitochondrial, cellular, and whole-organism performance in ecological contexts.

AI IN BIOLOGY EDUCATION (OED SYMPOSIUM)

9–10 April 2026, Nottingham, UK (with hybrid participation available)

This symposium will explore how Artificial Intelligence can be integrated into biology education in inclusive, ethical, and practical ways. Featuring talks and interactive workshops, it will support educators and researchers in developing new pedagogical approaches.

SEB ANNUAL CONFERENCE FLORENCE 2026

7–9 July 2026, Florence, Italy

Join us for our annual conference focused on the theme of resilience, with sessions across Animal, Cell, Plant, and OED biology.

REMEMBRANCE OF STEVE LONG

We also take a moment to remember the life and contributions of Steve Long, a dedicated SEB member throughout his career. A note honoring his legacy, kindly written by Amanda Cavanagh, is included in this issue. (page 14)

PRESIDENT’S LETTER

PROFESSOR TRACY LAWSON

PRESIDENT, SOCIETY FOR EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY

The world around us is changing fast. The daily news about climate change, (mis)use of artificial intelligence, political instability, and threatening pandemics can be overwhelming and paralysing. We might feel helpless at times, but we are not. Your research matters and can influence Real World Changes .

In the words of Jane Goodall, a truly inspirational scientist, breaker of barriers, persevering and resilient when no one believed in her research, “I want to make sure that you all understand that each and every one of you has a role to play… your life does matter, and every single day you live, you make a difference in the world. And you get to choose the difference that you make.” For us, as experimental biologists, the difference that we make can be through a direct impact by helping to develop vaccines (where would we have been without preceding fundamental science leading to mRNA vaccines only a few years ago), breeding resilient crops, providing data for environmental protection guidelines, and truly understanding the needs and capacities of cells, plants, and animals to help the so much needed conservation and restoration of what is left… But it is also clear that we cannot, and do not need to, do this alone. Citizen science projects and communityled projects create a levering field to promote and use our knowledge. Education and outreach from ‘real scientists’ are needed more than ever in these days of fake news.

Also we, as the Society for Experimental Biology, cannot and do not want to do it alone. We want to involve our membership as much as possible, encouraging members to engage with all aspects of the Society. We always welcome feedback, and by engaging more through Special Interest Groups we want to create opportunities to strengthen our community links. So, don’t be surprised to find some emails from your Special Interest Groups in your inbox soon! One group that already let us know that they want to be more involved are the Early Career Researchers. A new Early Career Working Group will facilitate their participation and create opportunities to contribute to the future of the SEB, ensuring that their voices will be heard.

Of course, we can only do this if we hear from you! Thank you to all delegates who updated their contact details and joined our Special Interest Groups at our fantastic Annual Conference in Antwerp last July. You were wonderful!!! The ‘Room with a Zoo’ conference centre was buzzing with activity, inspiring talks and posters ignited bright ideas, and meaningful collaborations and new friendships were started during the many networking opportunities. I can’t wait for our next meeting in Florence! Can you? But you don’t have to wait that long. Check our website for other events: free webinars from our OED webinar series, from our SEB Career Building and from Conservation Physiology are posted . If you want to stand up for science, join a ‘Sense about Science’ workshop and learn how to engage with the media and increase your impact in our changing world.

And to finish with more of Jane Goodall’s words, “You have it in your power to make a difference. Don’t give up. There is a future for you. Do your best while you’re still on this beautiful Planet Earth that I look down upon from where I am now.”

Be the change you want to see.

I WANT TO MAKE SURE THAT YOU ALL UNDERSTAND THAT EACH AND EVERY ONE OF YOU HAS A ROLE TO PLAY… YOUR LIFE DOES MATTER, AND EVERY SINGLE DAY YOU LIVE, YOU MAKE A DIFFERENCE IN THE WORLD. AND YOU GET TO CHOOSE THE DIFFERENCE THAT YOU MAKE.

– JANE GOODAL –

Gudrun De Boeck President, Society for Experimental Biology

SEB NEWS

BY JULIUS KELLY

ANTWERP 2025

A HUGE THANK YOU...

Once again, over 100 years since its conception, the Society played host to yet another successful, informative, and social conference in the historic city of Antwerp, Belgium. From a host of guest speakers, workshops, breakout sessions, and special interest group gatherings to 100s of posters and numerous social activities, including the evening walk around the zoo, the conference shone.

We look forward to welcoming you to the 2026 Annual Conference to be held in Florence, Italy (7–9 July), a city renowned for its art, architecture, and culinary expertise. The theme of the 2026 Conference is ‘Resilience’.

SEB THANKS GINA VONG

It was a pleasure to have Gina, a PhD student who spent 3 months interning with the SEB and the Journal of Experimental Botany. During her stay, she contributed to Outreach, Education and Diversity, helping to write articles and educational resources, while gaining insight into the inner workings of a successful society. We thank her for her great work and wish her the best of luck with the rest of her PhD.

SEB SAFETY AND INCLUSIVITY

At the SEB, we are committed to fostering a safe, respectful, and inclusive community for all. The Society is proud to have a Code of Conduct that outlines the standards of behaviour we expect from anyone engaging with SEB, whether as a member, delegate, speaker, or supporter. This Code of Conduct supports the Society’s aim of maintaining a positive and welcoming space where all individuals feel valued and safe.

INTRODUCING THE NEW SEB TRUSTEE STRUCTURE FOR 2025 AND BEYOND

Earlier this year, members were invited to put forward nominations for the 2025 Trustee elections. As a result, we are pleased to confirm the upcoming appointments of two long-standing members of Council to new Trustee roles.

Professor Tracy Lawson, who was due to complete her term as SEB President in July 2025, has been appointed as Treasurer for a 4-year term starting from 8 July 2025.

In addition, the current SEB Treasurer Professor John Love, due to retire from that post in July 2027, will transition into a new role as Vice President (and subsequently President) for a combined 4-year term, also starting from 8 July 2025.

All of us at SEB thank Tracy and John for their continued service, and look forward to the next chapter of their leadership within the SEB.

PLANT ENVIRONMENTAL PHYSIOLOGY GROUP (PEPG) SYMPOSIUM, PORTUGAL 2025

The PEPG’s Field Techniques Workshop took place in September at Naturasolta – Quinta de São Pedro , Portugal. The symposium comprised +90 plant biologists coming together for a series of practical workshops, alongside presenting their work in the form of a poster. The symposium, a biannual event, included 14 established scientists as well as representatives from 10 scientific manufacturers.

JXB 75

2025 celebrated the 75th anniversary of the Journal of Experimental Botany and in this momentous spirit a scientific meeting was held in Edinburgh. The successful meeting attracted a varied range of attendees to share their science, socialize, enjoy the fruits of the city and look forward to the future.

MEMBER NEWS

In each issue of the member magazine, we like to highlight some of the fantastic achievements and research from our members. Here are some of the people we would like to congratulate this time around.

IARI DRUMMOND

University of Plymouth

The SEB would like to congratulate Ari Drummond (University of Plymouth) for the publication of two research papers this summer:

A sensory investment syndrome hypothesis: personality and predictability are linked to sensory capacity in the hermit crab Pagurus bernhardus (Proceedings of the Royal Society B, click here for more info)

Shifting attention: assessing antennular ‘gaze’ in the hermit crab Pagurus bernhardus (Animal Behaviour, click here for more info)

Ari’s first article received notable media attention, being featured by the BBC (click here for more info) and discussed during a live interview on BBC Radio Devon on 17 July 2025.

SARAH RAYMENT

Nottingham Trent University

The SEB would like to congratulate Sarah Rayment (Nottingham Trent University) on becoming the first Director of the Biosciences Scholarship Research Centre at her university (click here for more info).

She also received one of the prestigious ViceChancellor’s Awards for Excellence in Scholarship, announced in June and to be formally presented during the university’s winter graduation ceremony in December.

DOMINIC HILL

University of Reading

The SEB extends its congratulations to Dom Hill (University of Reading), who was recently honoured at the Potato Industry Awards. Dom’s achievement is especially noteworthy as he is actively seeking roles in science communication and postdoctoral research. We’re delighted to include a link below to the World Potato Congress Industry Awards for readers interested in learning more:

<click here for more info>

CHARLIE WOODROW

The SEB extends its congratulations to Charlie Woodrow on the launch of his new podcast series The Environmental Review, which explores environmental research and current issues in ecology and climate science. The series can be found on Spotify (click here for more info).

Charlie’s work has also attracted media attention and features field research conducted in the Swedish Arctic, including temperature experiments with bumblebees.

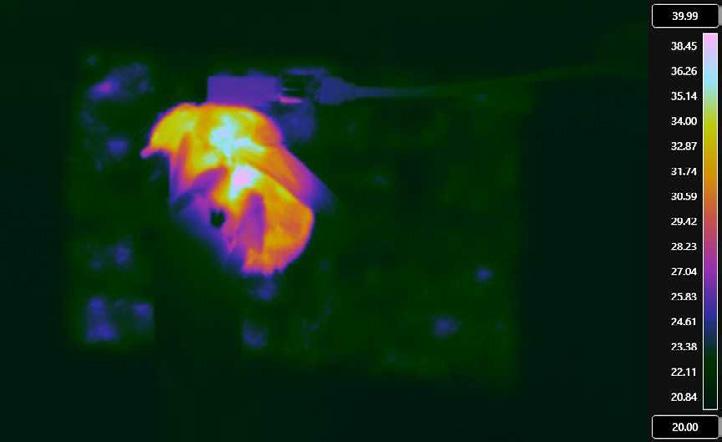

Thermal camera image of a buzzing bee with temperature scale in degrees Celsius.

PEPG FIELD TECHNIQUES WORKSHOP 2025 –SCIENCE, SKILLS, AND COMMUNITY IN LISBON

BY AMANADA CAVANAGH

The Plant Environmental Physiology Group (PEPG) gathered this September for its muchanticipated Field Techniques Workshop, hosted at Quinta de São Pedro, a long-running field research site just outside Lisbon. Nestled among olive groves and overlooking the Atlantic, this site has hosted the workshop since 2012 on a biennial basis (pandemic years notwithstanding). It once again provided the perfect backdrop for a week of technical training, collaborative science, and community building for nearly 100 participants from around the world.

SCIENCE AND SKILLS AT THE CORE

The week’s programme wove together lectures, practical sessions, and networking opportunities. The workshop is renowned for blending rigorous technical sessions with an open, collaborative spirit. Mornings were filled with expert-led lectures on everything from gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence to soil–root interactions, ecosystem fluxes, and remote sensing. A key feature of the workshop is the integration of manufacturing partners in the training program, which give participants the opportunity to explore cutting-edge tools, with our partners at METER, LICOR, Walz, Hansatech, Ocean Optics, and JB Hyperspectral providing demonstrations and guidance throughout the week. Afternoons shifted to practical sessions where participants tested instrumentation, explored data workflows, and learned directly from leaders in the field—bridging the gap between theory and practice. Of course, the participants themselves are making exciting discoveries in fields ranging from molecular physiology, phenomics and wholeplant physiology, with a focus on integrating methods across scales. Poster sessions provided a stage for early-career researchers to showcase this work, and it was particularly exciting to see many non-model species featured, demonstrating

the breadth and relevance of plant physiology in diverse real-world systems. Four outstanding presenters were recognised with poster prizes: Phoebe Dibbin-Dean (Trinity College Dublin), Nicola Walter (University of Nottingham), Emilio Villar Alegria (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin), and Joe Colbert (UIUC). Their work reflected the scientific breadth and creativity that PEPG workshops consistently foster.

A COMMUNITY THAT CONNECTS

PEPG is the longest running SIG in the plant section, and we celebrate our 50th anniversary this year. The workshop has always been about more than just techniques—it’s about building a community of plant physiologists. This year’s programme wove in plenty of opportunities for connection: a lively wine trail to connect early-career researchers and industrial partners, a competitive trivia night, a midweek surfing trip and Lisbon city explorations, and a relaxed final-night BBQ under clear Portuguese skies. These moments outside the lecture hall fostered friendships, collaborations, and the kind of candid conversations that carry into the lab and field long after the workshop ends.

What makes PEPG special is this blend of serious science and genuine community. Participants leave not only with new technical skills but also with a stronger sense of belonging in a field that thrives on collaboration. As one attendee put it: “You come for the training, but you leave with a network you can lean on for years to come.”

The 2025 workshop exemplified why this event remains a highlight of the SEB calendar and was a testament to the group’s mission: advancing plant environmental physiology through shared knowledge, hands-on learning, and inclusive community. For those who missed it, future workshops promise the same balance of rigorous science, practical skills, and the unmistakable PEPG spirit.

LOOKING AHEAD

The 2025 Field Techniques Workshop was supported by SEB Symposium funding. As PEPG approaches its 50th anniversary in 2026, members can look forward to more celebratory events and continued leadership in advancing plant environmental physiology.

STEPHEN P. LONG, FRS (1951–2025) A TRIBUTE FROM THE SOCIETY FOR EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY AND THE PLANT ENVIRONMENTAL PHYSIOLOGY GROUP (PEPG)

BY AMANADA CAVANAGH

If you’d ever met Steve Long, you probably remember a few things: he could likely out-pace you on a run, probably outwit you with a practical joke, and certainly talk your ear off about photosynthesis. Often, he could manage all three in the same day.

After studying Agricultural Botany at the University of Reading, Steve completed his PhD at the University of Leeds in 1976 under Harold Woolhouse, for whom the SEB’s Woolhouse Lecture in plant sciences is named (which Steve himself delivered in 2008).

Steve’s doctoral work explored the chilling tolerance of C4 plants, and though he eventually traded saltmarshes for agricultural fields, the curiosity that started there never faded. In 1975 Steve joined the University of Essex, where he spent almost a quarter of a century building one of the most respected groups in photosynthesis and environmental physiology. His earliest work focused on creating methods to study leaf-level photosynthesis and scale it to field models at a time when there were no commercial cuvettes and infrared gas analysers were noisy and temperamental. Colleagues recall this period as one requiring “equal parts perspiration and inspiration.” These experiences shaped Steve’s enduring philosophy: the best science arises from both rigorous measurement and inventive problem-solving.

This approach carried naturally into his engagement with the SEB’s Plant Environmental Physiology Group (PEPG). Steve became a key figure in SEB’s Plant Section, ensuring environmental physiology was recognised as a vital part of plant science. He was a consistent supporter of the PEPG Field Techniques Workshops, attending and presenting since the 1990s and every year since their revival in 2012. These workshops exemplified his belief

in hands-on training, mentorship, and building scientific community. In fact, Steve could often be found scouting rising research talent for his lab throughout the practical and social sessions of this very workshop.

In 1999, Steve moved to the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign, where he eventually became the Stanley O. Ikenberry Chair Professor of Plant Biology and Crop Sciences. He led a world-class program revolutionizing improving photosynthetic efficiency and crop improvement, mentoring a generation of scientists and driving research with global impact. Steve also shaped scientific

Steve Long and Steven Driever (WUR) preparing plants for measurements at the 2023 PEPG Field Techniques workshop.

publishing, serving as founding editor of Global Change Biology, GCB Bioenergy, and in Silico Plants, and was a long-serving section editor of Plant, Cell & Environment. Across his work, he combined scientific rigor with curiosity, humour, and generosity, whether in the field, or a postworkshop or seminar discussion.

Steve Long’s legacy is profound: through his research, mentorship, and unwavering support for the SEB community, he helped define what it means to study plants in their environment. His impact will be felt for generations, both in the research he produced and the people he inspired.

Above

Steve with PEPG members at the Field Course in 2023. Back (from L-R): Steve Long, Yazen Al-Salman, Steven Driever, Carl Bernacchi, Richard Webster, Howard Griffiths, Tracy Lawson, Andrew Leakey. Front: Caitlin Moore, Shellie Wall, Amanda Cavanagh, Liana Acevedo-Siaca, and Hannah Schneider.

WHY BECOME A CONVENOR?

SEBIOLOGY.ORG

SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS

• Influence the field: Organise symposia, workshops, and networking events that bring together leading scientists.

• Expand your professional network: Collaborate with experts, policymakers, and industry leaders.

• Enhance your leadership skills: Gain experience in managing scientific programs and steering research discussions.

• Boost your carreer: Demonstrating leadership within an international society

TAKING ANIMAL BIOLOGY BEYOND THE LAB

BY ALEX EVANS

Experimental biology helps us to explore the fundamentals of animal biology, but research isn’t conducted in a vacuum, and these scientific advances often have significant and practical applications in the realms of education, conservation, and policymaking. This is just a snapshot of the ways in which animal biology is currently impacting the wider world.

BIOLOGGERS AT LOGGERHEADS

Sea turtles are facing a growing number of threats to their survival, not least of which is the ongoing encroachment of human activity into their natural habitat, which carries with it a range of concerning hazards for vulnerable marine life. Thankfully, there are researchers out there who are providing important data-backed insights for practical wildlife conservation. “I’ve always been fascinated by turtles, and they’re really what first inspired my passion for marine biology and conservation,” says Amy Bowler, who recently completed her integrated masters in Biological Sciences at the University of Exeter. “I remember being struck by images in David Attenborough documentaries of turtles caught in fishing nets, which made me aware of the threats they face.”

It was during her time in Exeter that Amy took a module with Dr Lucy Hawkes that first sparked her interest in how technology and data could be used for effective wildlife conservation. “From there, I worked with her to develop my master’s project, where I combined turtle tracking data she had collected with fisheries data, to look at risks

of fishery bycatch on loggerhead turtles in Cabo Verde, which is home to the world’s third-largest loggerhead nesting colony,” she says.

Amy’s research was especially focused on the potential impacts of bycatch, which is the unintentional capture of non-target species while fishing. This can often result in injury, stress, and even deaths, all of which pose a serious threat to loggerhead populations. “Northwest Africa is a particular bycatch hotspot because it hosts the world’s third-largest nesting colony, while also experiencing intense and often unregulated fishing activity, and models indicate a risk of population declines if bycatch continues unchecked,” explains Amy. “Current solutions range from safer handling of incidentally caught turtles to gear modifications like turtle excluder devices, which let turtles escape from fishing nets, while area-based approaches, such as marine protected areas or seasonal closures, can also help reduce risk.”

However, these solutions often require accurate and reliable information to be effective, which isn’t always readily available. Addressing these important gaps in the data formed the basis of Amy’s

in Northwest Africa. “Twenty-six turtles were fitted with satellite transmitters to track their movements,” she explains. “I combined this with fishing effort data from Global Fishing Watch, which uses automated ship tracking data to create a global record of fishing activity.” By overlapping these datasets, Amy was able to quantify the amount of overlap between turtles and fisheries to examine the potential bycatch risk. Interestingly, the data not only looked horizontally across area, but also vertically across depth, adding a three-dimensional perspective of the aquatic dimensions involved. Finally, Amy drew conclusions from her calculations and reviewed current loggerhead conservation policies to consider just how effective existing measures are, and where management could be strengthened. Amy strongly believes that these results could have clear implications for fisheries management and hopes that they will be used accordingly. “I found that turtles and fisheries overlap extensively, both horizontally and vertically, with trawling emerging as the biggest risk,” she says. “I also identified key countries whose fishing activity coincides with turtle movements, showing where management action could make the most difference.”

The findings of this research help to demonstrate how the existing protections in place don’t always reflect the true risks of bycatch, and any enforcement of bycatch measures is currently limited,

making it even more important that research like Amy’s is integrated into management strategies. “My results suggest that solutions like gear modifications, such as turtle excluder devices, could be particularly effective,” she says. “It’s also important that any new management measures are adapted to the local socioeconomic context. This region is a global hotspot for loggerhead bycatch, which represents a major threat to the population. Addressing this issue is therefore critical to securing the long-term future of one of the world’s most significant loggerhead turtle populations.”

Considering next steps for this area of research, Amy knows that there is still work to be done, but that modern techniques are more than up to the task. “As technology develops, biologging and modelling approaches will continue to offer powerful tools for understanding turtle movements, and predicting when and where risks are highest,” she says. “Expanding these approaches across multiple species and regions could also provide a more complete picture and support coordinated conservation strategies.” Finally, Amy would like to acknowledge the team of researchers that collected the valuable turtle tracking data,1 and to add that her thesis research is currently being prepared for publication.

MY RESULTS SUGGEST THAT SOLUTIONS LIKE GEAR MODIFICATIONS, SUCH AS TURTLE EXCLUDER DEVICES, COULD BE PARTICULARLY EFFECTIVE

THE TRUE EXTENT OF BYCATCH RISK IS PROBABLY UNDERESTIMATED

SKULL SKILLS FOR KIDS

Modern academics in scientific fields have two primary responsibilities. Firstly, to contribute new and exciting knowledge to the wider scientific community. Secondly, to directly educate university scholars seeking to understand and build on this knowledge themselves. But who says this responsibility needs to start and end with university students? Why not spark that curiosity and thirst for knowledge in younger minds? These are questions that are certainly old news to two researchers in the UK who have been adapting their undergraduate practical workshops to inspire younger audiences. Dr Kelly Ross, a lecturer in the School of Biosciences at the University of Liverpool, UK, and her colleague Dr Michael Berenbrink, a senior lecturer at the

Kelly and Michael presenting their skulls at the Victoria Gallery and Museum, University of Liverpool.

credit: Kelly Ross.

Right:

Photo

University of Liverpool in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behaviour, are responsible for taking one of Michael’s university practical classes and unleashing it on the public. “My PhD supervisor, Michael, came up with the idea, as he already had this fantastic evolutionary biology undergraduate practical using mammalian skulls,” says Kelly.

The first time that Kelly and Michael began to deliver this workshop was around Halloween, and they dived head first into the theme ‘Spooky Science’ with their skull-filled workshop. “We even had some fairy lights inside the skulls and darkened the room, but this got a bit too scary for some of the younger kids and we left that bit out in later incarnations of the activity,” says Kelly. “It was a way of taking something we already do well at the university and making it accessible, exciting, and fun for a whole new audience.”

Kelly says that the driving force behind adapting a workshop focused on animal anatomy and identification skills was providing children an opportunity to engage with real scientists and real scientific techniques, without infantilizing their audience. “I think real-world science gives children that ‘wow’ moment, the chance to see and touch something tangible, and realize they’re learning the same science that older students do. It makes science feel alive and relevant to their own experiences,” she explains. “That kind of hands-on, inquiry-based learning helps build curiosity and critical thinking, and hopefully sparks an interest that could grow into a lifelong passion for STEM.” Rebuilding an undergraduate workshop for a completely different audience is no easy feat and came with its share of challenges for Kelly and Michael. “The biggest challenge was definitely translating university-level material into something that young children could engage with,” she explains. “It meant rethinking the tools, so instead of dichotomous keys, which are quite abstract, we made it much more playful. Children are given clues—like what the animal eats, what its footprints look like, or even what its poo looks like—and then they match those to the skulls. We also weave in storytelling and visuals, so it feels like a detective game rather than a classroom exercise.”

While it may have been a difficult task to get off the ground, this has been more than compensated for by the incredible opportunities it has provided for local young people. “We get to bring children into university spaces, let them meet real scientists, and create positive experiences of higher education early on,” says Kelly. “It’s also a great way for the university to build relationships with the community.” Kelly and Michael have also delivered this activity as a more widely accessible ‘Skull Detectives’ workshop outside of the Halloween season, which introduces children to a variety of skulls from mammalian species that may be encountered in the wild in the UK. “The activity subtly shows how their presence can be detected from their tracks and ‘droppings’, and what foods, and thereby

REAL-WORLD SCIENCE GIVES CHILDREN THAT ‘WOW’ MOMENT

environments, they depend on for their existences,” says Kelly. “This was used to raise awareness of shrinking habitats and the conservation of species, including reintroductions, such as that of beavers into England.” By demonstrating the difference in form and function between the teeth of carnivorous, herbivorous, and omnivorous species that aligned with their favoured diets, Kelly and Michael were able to educate the children on the core principles of adaptation and natural selection. To bring it all home, they also encourage the children to examine their own teeth and compare the similarities and differences they find with their mammalian cousins.

The response to these adapted animal biology workshops has been overwhelmingly positive, with the project even winning an outreach award from the Institute of Integrative Biology. “Children consistently rated the activity very highly, and teachers told us how much their students enjoyed it,” says Kelly. “We’ve run the session multiple times at the University of Liverpool, as well as at the Liverpool World Museum’s ‘Meet the Scientist’ day in support of the university’s wider goals of promoting access and participation in science.”

FISHY FILTRATION

There are few words in the modern English language that are as universally despised as “microplastics”. Whether created intentionally, or as the byproduct from a gradual breakdown of larger plastics, microplastics represent an ever-growing threat to marine life across the globe with potentially catastrophic knock-on consequences for humanity. Thankfully, Dr Leandra Hamann, a postdoctoral

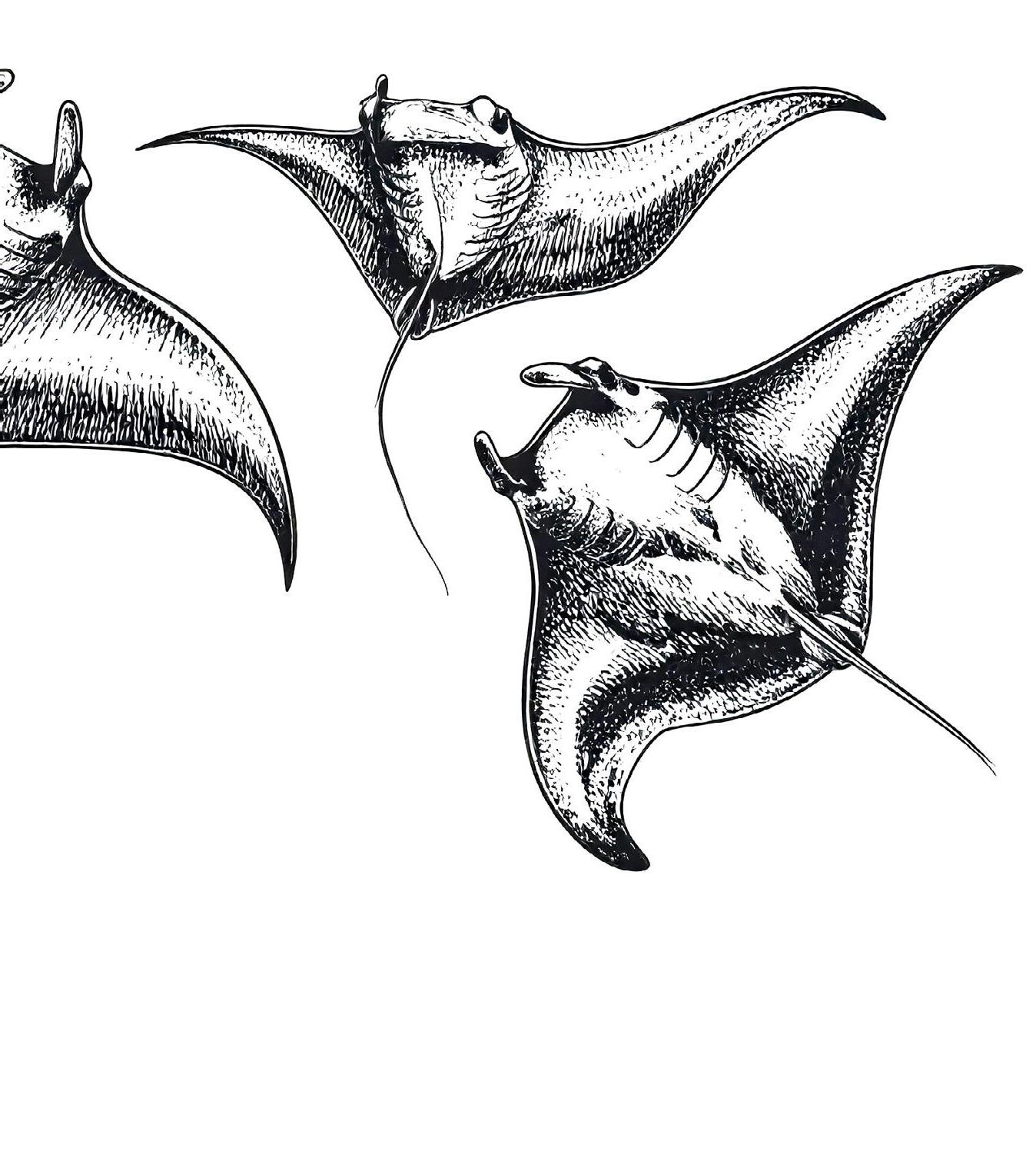

Top Roght: The filtration system inside the mouth of an Atlantic mackerel.

Photo credit: Leandra Hamann.

THE FILTER ELEMENT MIMICS THE MORPHOLOGY OF THE GILL ARCH SYSTEM THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE WAS DEFINITELY TRANSLATING UNIVERSITYLEVEL MATERIAL INTO SOMETHING THAT YOUNG CHILDREN COULD ENGAGE WITH

Right: Leandra investigating the filter mechanisms of manta rays.

Photo credit: Leandra Hamann.

Left: The filter elements tested by Leandra.

Photo credit: Leandra Hamann.

researcher at the University of Bonn, Germany, has been working towards a natural engineering solution to this wholly unnatural problem. “I was always fascinated by the idea of mimicking biological principles to improve engineered systems,” she says. “The proof of concept already exists in nature and you just have to transfer it, which sounds simple, but it is much more complex and difficult than that.”

The reason that microplastics are such a major issue is that they are physically persistent and accumulate easily in marine environments. During this time, they can be ingested by various organisms; they then steadily build up in tissues and organs, and eventually get passed on up through the food chain to larger and larger predators. “The effects on the organisms very much depend on the type of animal and the type of microplastics,” says Leandra. “For example, mussels retain microplastics through filter-feeding and they can then be found in various organs where they can have adverse health effects. Unfortunately, many organisms have not been studied for the health effects posed by microplastics yet, so there is ongoing research to fully estimate the long-term risks.”

One of the major sources of marine microplastics from Europe are fibres released from washing machines into the sewer system and out into

the oceans. The challenge that Leandra set for herself was to identify and implement a bioinspired filter that would help to reduce the quantity of microplastic fibre emission from such washing machines. “My research contributed to understanding animal biology and helping to develop new products and processes,” she says. “I was working on the problem of microplastic pollution and started thinking about using filterfeeders as biological models to develop new filters and reduce microplastic emissions.”

It is important to understand that the mechanisms that filter-feeders employ in the wild are surprisingly diverse, and finding the best fit for this project was not an easy task. “There are over 35 different particle separation mechanisms in filter-feeders and I needed to pick one that was suitable to design a washing machine filter,” says Leandra. “I briefly looked at the mucus filtration in sea squirts, and the depth filtration in flamingos, but then settled with the cross-flow filtration in ram-feeding fishes.”

For 2 years, Leandra studied different fish species to gain a deep understanding of their filter-feeding

mechanisms, before being able to translate it into a simplified 3D-printed model capable of being fitted to a washing machine.

The product of Leandra’s experimentation is a functional prototype for a fish-inspired filter, which consists of a filter element and the housing fitted around it. “The filter element mimics the morphology of the gill arch system in the fish mouth,” she explains. “For example, it has a similar mesh size, a similar tapered geometry, and a similar angle of attack.” The physical properties of the filter element provided Leandra with just the right conditions to maximize filtration, while the housing helped direct and control the flow of water in and out of the filter, even including two valves that mimic the periodic cleaning and swallowing mechanisms of the fish. “In laboratory experiments, we found that the fish filter has a retention efficiency of 97.5% for standardized microplastics fibres, which is as good as conventional filter designs,” she says. “However, the fish filter has the great advantage of collecting the fibres outside the filter element and housing through the specialized cleaning mechanism; therefore, clogging is delayed, and it is much easier to remove and deposit the collected microplastics.”

As for future development of these fish-inspired filters, Leandra sees two paths ahead. Firstly, more research to aid in developing and improving the mechanics of the filter-feeding system, or even comparative investigations into other biological models for the filters. Secondly, examining the practicalities of translating these bio-filters into a mass-producible filter that could be implemented in all washing machines to significantly reduce microplastic release. “The filter still needs to be improved and optimized to fit technical requirements,” says Leandra. “But I am not an engineer or product designer, so I really hope that a company will pick up the idea and develop it further into a finished product.”

References: 1 Lucy A Hawkes, Annette C Broderick, Michael S Coyne, Matthew H Godfrey, Luis-Felipe Lopez-Jurado, Pedro LopezSuarez, Sonia Elsy Merino, Nuria Varo-Cruz, and Brendan J Godley.

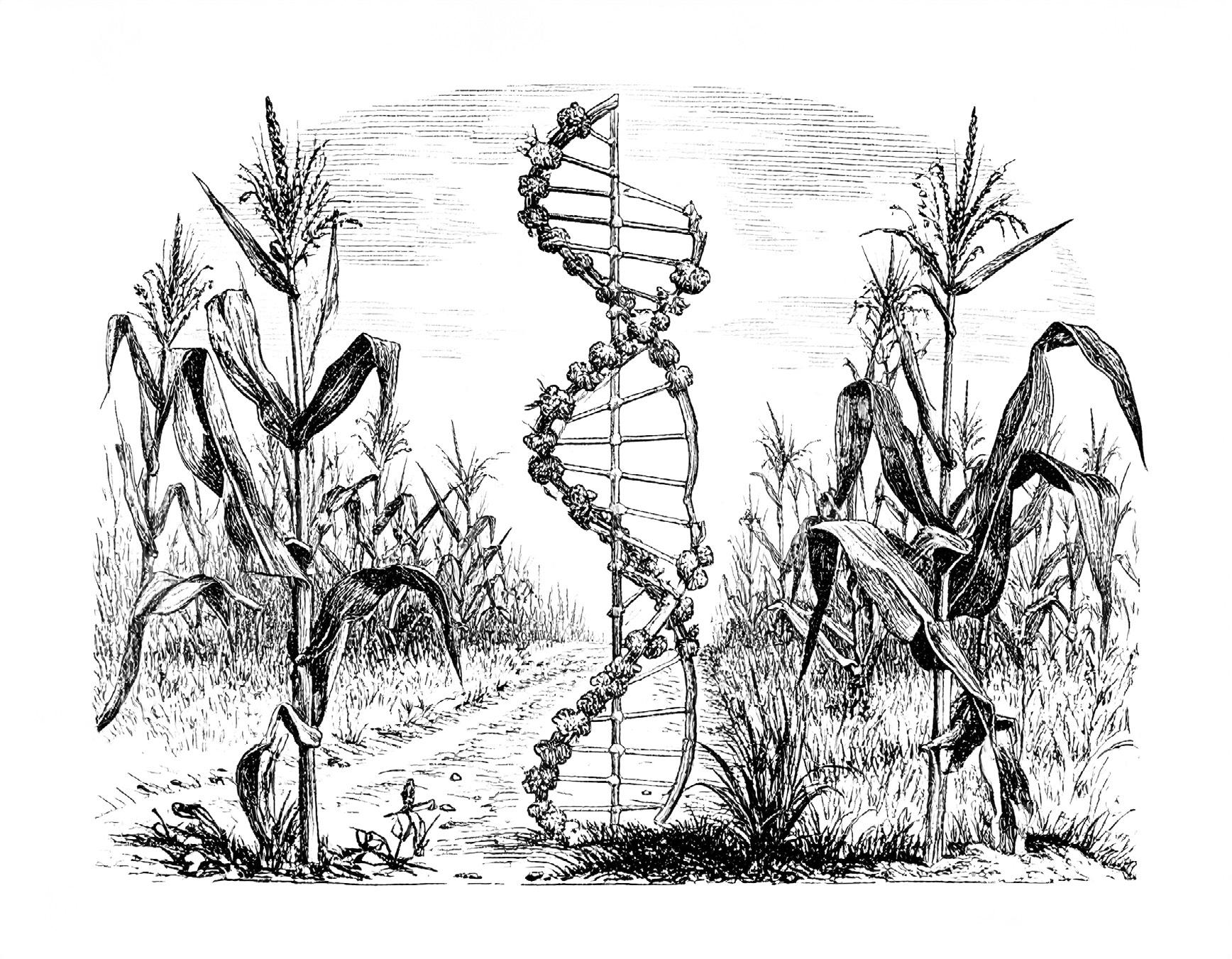

MICRO TO MACRO: EXAMINING THE GLOBAL IMPACT OF CELL BIOLOGY

COULD PLANTS BE THE NEW PESTICIDES?

BY ALEX EVANS

Many world-changing discoveries began under a microscope, before radically altering the way that we live our lives. Let’s take a look at examples of projects by SEB Members that have taken their research out of the lab and into the “real world”.

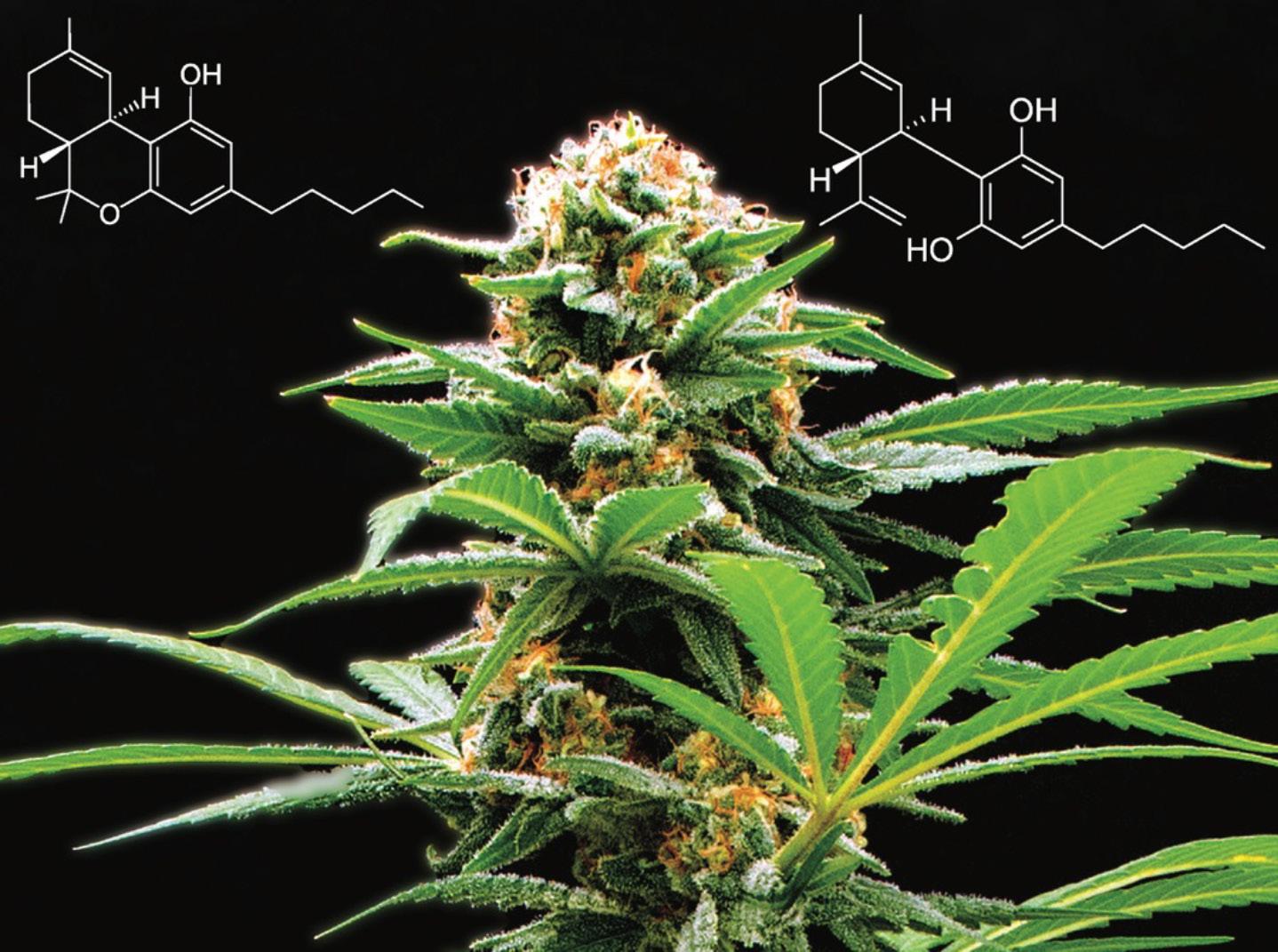

Food security is an ever-growing global concern, drawing attention from plant and cell researchers all around the world… but what does it take to go from lab-based fundamental research to practical application on an industrial scale? Dr Søren Bak, Professor at the Faculty of Science’s Department of Plant and Molecular Biology at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, has been studying plant defence compounds for 25 years and, more recently, has been looking to transfer his findings into tangible products for these global agricultural issues. “For the last couple of years, I’ve had a real interest in how we can translate this into something that can be useful in society,” he says. “We’ve stumbled around some molecules that we now think have potential to be part of a solution.”

Søren’s research has primarily focused on the pesticidal properties of saponins, a diverse group of toxic compounds found in many plant tissues. Saponins have been used throughout human history for their biological properties, with more recent uses including cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and as adjuvants in vaccine development. Søren is most interested in their use as a pesticide because they act in ways that differentiate them from other synthetic agents. “Many insecticides target the muscle or nerve function, but these target membrane structures,” he explains. “There is a lot of variety between the compounds as some are very highly active, and some are completely inactive. It can be hard when talking to potential investors because they don’t understand that there are thousands of different saponin structures with different biological functions.”

Some of Søren’s recent work has demonstrated that these compounds possess positive properties that other synthetic pesticides do not. “We now have the first papers coming out showing that they actually bind to soil and there are bacteria that will break them down,” he says. “The main problem

with the synthetic pesticides is that they sort of just rush through the soil structures and end up where we don’t want them, so that we’re pretty happy about.” As an example of the protective power of saponins, Søren explains how they have used extracts from Barbaria vulgaris, painted them onto some leaves while leaving others bare, and then exposed them to a common pest species. “We added diamondback moth larvae, which is a major pest in agriculture and crucifers,” he says. “Those that were treated with the extracts are not eaten, but the other ones that are not treated, they are eaten.”

This is a critical time for developing natural plant compounds into practical applications, since the EU (European Union) is committing to reducing its reliance on synthetic pesticides by 2030, adding to the drive to research alternative solutions. But as Søren explains, conducting the fundamental research is one thing; acquiring funding to take that research to the next stage is entirely different. “My main problem is decoding how we create funding for moving a project that is a basic science project into innovation,” he says. “There’s this valley of death between having the basic science working and then finding somebody that will put real money into it.”

One major barrier that Søren is up against is EU regulation 1107, which regulates plant-derived defence compounds the same way it regulates synthetic pesticides. “That’s not what is happening in Brazil, in the USA, and many other countries,” he explains. “In the EU, there is a conservative view that these are like synthetic compounds, even though they are derived from nature.” Søren would like for these natural plant compounds to be reclassified as ‘low-risk substances’ that have a proven safety and a low environmental impact, and face fewer restrictions on their deployment, but this goal may still be a while away. “There’ve been a lot of disappointments, but I find it very

Right:

The core team at MetaboHUB-Bordeaux Metabolome in the Fruit Biology and Pathology laboratory (Rémy Cordazzo, Chemical Engineer; Pierre Pétriacq, Head of Bordeaux Metabolome; Claudia Rouveyrol, Technician). Photo credit: Sarah Rayment.

WE ARE LOOKING AT CREATING A SHARED LANGUAGE

Søren’s current solution is the BioPlanPro project, where he is exploring the wider world of innovation and legal barriers that might delay the implementation of naturally occurring plant defence compounds into agriculture. “We are looking at creating a shared language, a common understanding that can bridge these barriers,” he says. Even deciding on something as seemingly simple as a name for these compounds needs to be explored and discussed with the correct stakeholders to minimise the risks of a cultural backlash, like the negative response that genetically modified organisms (GMO s) received across Europe in previous years. “We’re interviewing a lot of different stakeholders, advisors, farmers, consumers, interest organisations, and EU regulatory bodies,” he says. “We are trying to extract who thinks what, who says what, and where the important overlaps are.”

While the journey so far has been difficult, Søren believes that this project is an important step forwards in reducing our reliance on synthetic pesticides and moving towards more natural solutions. “My motto is to learn from nature and work with nature, and that’s what we want to do here,” he says. “We want to purify compounds that exist in nature and then use them as they were supposed to be used, to allow plants to defend themselves against insect pests and fungal pests.”

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN THE WORLD OF OMICS

It should come as no surprise that artificial intelligence (AI) is officially here to stay. What was once science fiction has rapidly become a household name, as well as a powerful tool for the advancement of biological research. However, with great power comes great responsibility, and many

MY MOTTO IS TO LEARN FROM NATURE AND WORK WITH NATURE

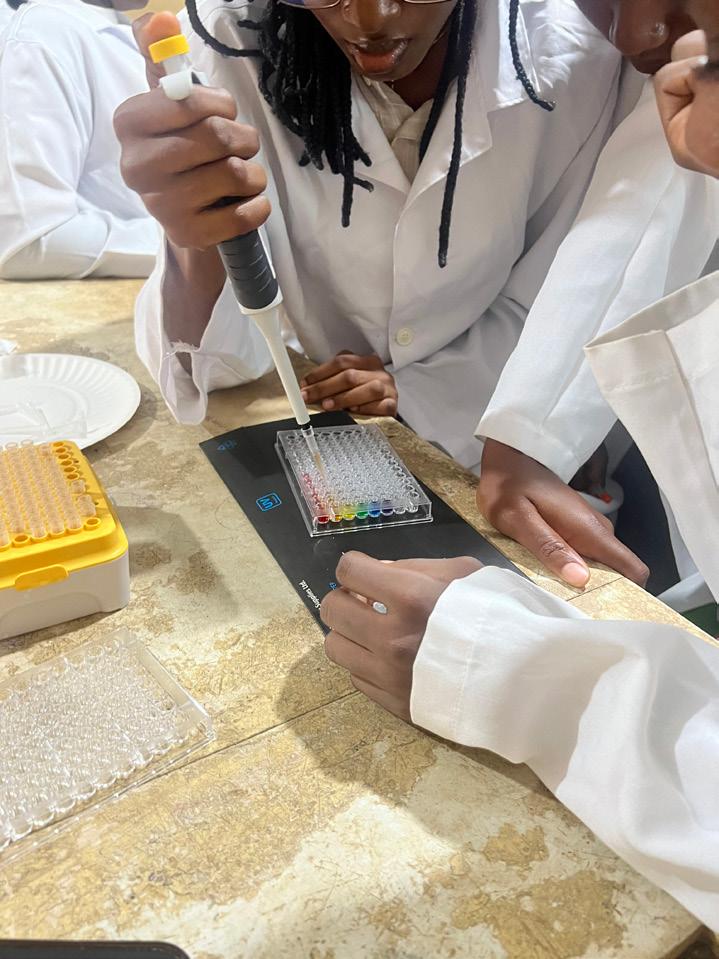

Left Page: Sarah’s colleague Dr Bunmi Omorotionmwan with participating students at the University of Benin, Nigeria.

Photo credit: Sarah Rayment.

scientists are calling for these tools to be treated with respect to ensure that they’re being used both effectively and ethically in the name of science. “AI has made remarkable breakthroughs in the analysis of complex, multiscale, and heterogeneous datasets,” says Dr Pierre Pétriacq, an Associate Professor in plant physiology at the University of Bordeaux, France, and director of MetaboHUB-Bordeaux Metabolome facility. “Naturally, I began using AI to process omics datasets in order to extract as much relevant information from them as possible.”

The advent of accessible AI has brought many benefits to the world of cell biology research, allowing for new discoveries and rapid advances in our learning that may have previously been beyond our reach. “AI and machine learning offer powerful means to decode the complexity of biological systems,” says Pierre. “At the cellular and molecular level, they enable us to integrate and interpret high-dimensional omics data, predict phenotypic outcomes from molecular profiles, identify key biomarkers and regulatory pathways, and accelerate hypothesis generation and experimental design.”

While many of AI’s advantages are broadly applicable across experimental biology, some areas of research benefit even more than others, as Pierre explains. “These tools are especially valuable in metabolomics, where the data are often noisy, heterogeneous, and deeply interconnected with phenotype,” he says. “Machine learning helps us move beyond descriptive analysis towards predictive and mechanistic understanding.” However, despite the relatively sudden ease at which AI and machine learning have become integrated into our society, these systems are still in constant development and can be prone to mistakes, which, in the context of high-impact biological research, could have catastrophic consequences. “One major challenge is the integration of diverse omics datasets in a way that preserves biological meaning and interpretability,” explains Pierre. “This is crucial for translating AI-driven insights into actionable strategies in agriculture and conservation, including enhancing crop resilience through omics-informed breeding or informing agroecological transitions with predictive models of plant–environment interactions.”

Pierre also makes the case that AI can be a useful tool in helping to support data-driven policymaking around critical topics such as biodiversity, sustainable farming, and ecosystem services, but that in order to do so, the right guidance frameworks and collaborations need to be agreed upon first. “To truly harness the potential of AI in research and innovation, we need to adopt FAIR-compliant1 data practices, encourage interdisciplinary collaboration, and ensure our models are transparent and explainable,” he says. “We’re making real progress towards interoperable data ecosystems, but strategic effort and shared commitment are still needed to close the gap.”

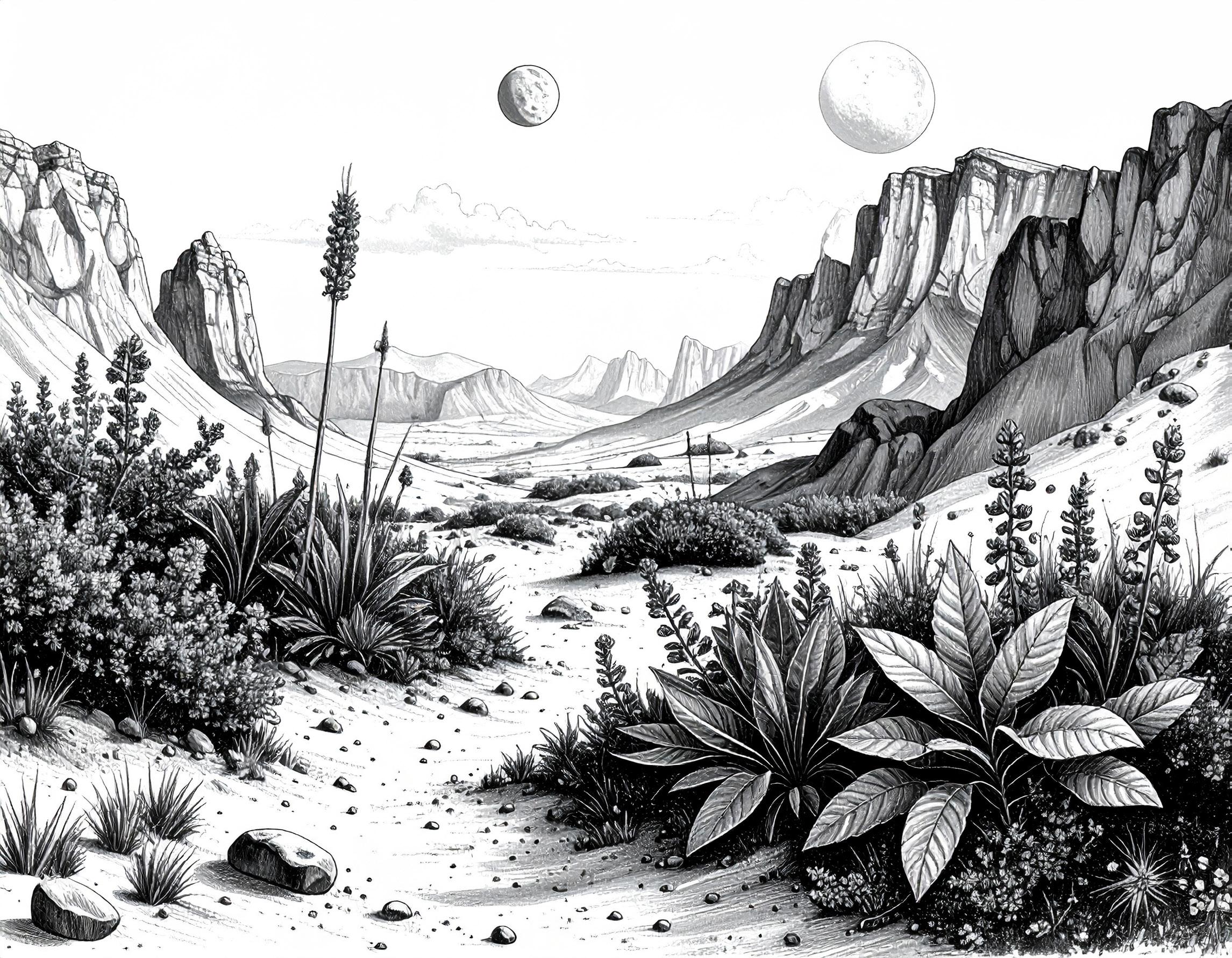

In practicality, these AI tools are typically developed using large training sets and make use of machine learning algorithms to identify patterns in data, and to make predictions or observations that may be hidden to the human eye. Here are a few recent examples of where AI has been used to impact the world of omics research. “For example, in the Atacama Desert, metabolomics-based machine learning has revealed a core set of metabolites linked to extreme climate resilience across diverse plant species,” says Pierre. “Notably, recent studies have extended this insight beyond leaf and soil metabolomes to include the soil microbiome, offering a multilayered understanding of plant adaptation to harsh environments.”

“Additionally, in a recent submitted study, we show that plant–fungal interactions can be predicted from leaf chemistry and even spectral reflectance data,” says Pierre. “This opens up exciting possibilities for non-invasive monitoring of biotic interactions, ecosystem health using remote sensing, and metabolomic signatures across multispecies experimental design.”

complexity,” he says. “As we move forwards, it’s essential to foster collaboration between biologists, data scientists, and policymakers; only then can we ensure that AI serves both scientific discovery and societal good.”

THE GOAL IS TO BUILD ROBUST, TRANSPARENT TOOLS THAT CAN GUIDE REAL-WORLD DECISIONS

So, what does the future hold for AI in the omics research space? Pierre believes that integrating multiple omics into unified predictive models could be a game changer, if done correctly. “This will require advanced data fusion techniques, scalable and interpretable machine learning algorithms, and FAIR data infrastructures and semantic annotation,” he says. “We also need to address challenges like data labelling, model generalisation, and ethical considerations around AI use in biology.”

“Ultimately, the goal is to build robust, transparent tools that can guide real-world decisions in agriculture, conservation, and beyond,” he says. “These advances not only enable us to pursue more ambitious projects involving large numbers of observations and conditions, but they also promise to reduce analytical costs. This shift could be transformative, helping to democratise omics sciences—especially metabolomics, which remains costly—and making them more accessible to breeders, farmers, and other stakeholders.”

Finally, Pierre is keen to remind people that AI is not only a computational tool for modern problem-solving but may also revolutionize the way that scientists operate from now on. “It’s a catalyst for rethinking how we approach biological

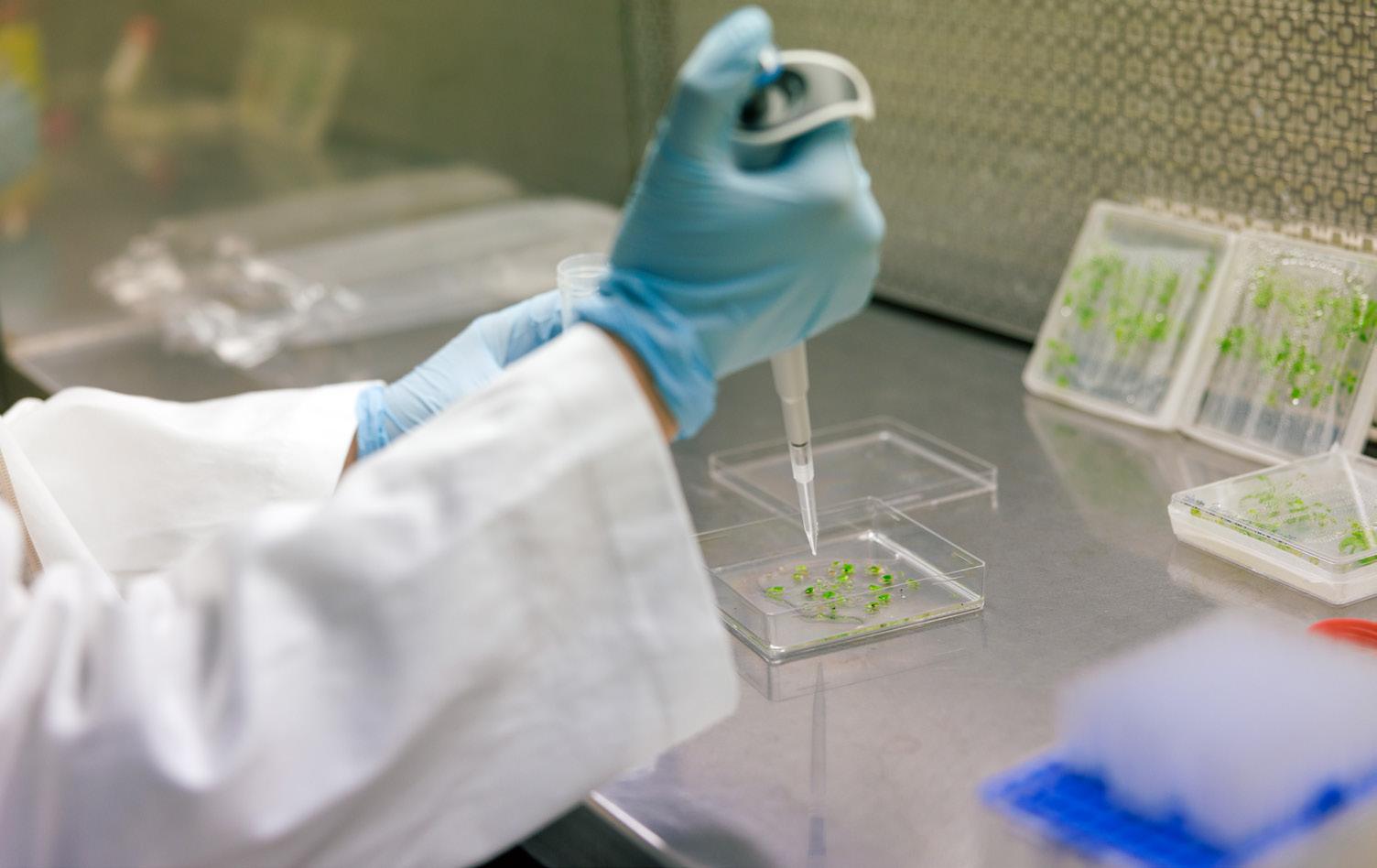

PIPETTES TO PIXELS

Laboratory skills can be learned in many ways, whether that’s through practical workshops, books, or videos; but creativity can capture the mind in ways that other methods simply cannot. Along with a few colleagues, Dr Sarah Rayment, a senior lecturer in molecular sciences and the Centre Director for the Bioscience Scholarship Research Centre at Nottingham Trent University (NTU), has developed a creative challenge for students that transforms fundamental cell biology lab skills into an artist’s arsenal. “I have a long-standing interest in creativity in biology education as well as practical education,” says Sarah. “As part of my teaching, I work with integrated masters students to create multimedia as part of an assessment. My determination to build creativity into our curriculum was fuelled when one of these students said that science education ‘drums creativity out of you’.”

The idea for these creative lab-based competitions first emerged out of necessity due to teaching restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. “We created a ‘bioskills kit’ that students could use at home to do experiments and practice their skills,” says Sarah. “We used microscopy competitions to engage students and build some community when they couldn’t be physically together. As students returned to campus, my colleague Jody Winter evolved the bioskills activities to include the pixel art challenge.”

The actual rules of the pixel art challenge are surprisingly simple, which is exactly what enables the students to get so creative. “Pipetting accuracy

and creating serial dilutions are the focus for the pixel art activity,” says Sarah. First, the students create serial dilutions of food dyes and use these as their ‘colour palette’. They then use 96-well plates to create an image with each well acting as one pixel. “We give students a chance to map out their image using a paper image of a 96-well plate if they want to,” says Sarah. “It is a really straightforward process and makes learning these skills a lot more fun.”

On the surface, art challenges may not seem like an obvious link to the development of biology skills, but precision pipetting and setting up serial dilutions are important tricks of the trade for budding biologists, and creative methods can often be the most engaging way to learn. “Given how fundamental these skills are for many areas of biology, the activities can be contextualised for the specific student group and the experience of the academic,” says Sarah. “For example, if showing students how these skills fitted into my career, I would likely talk to them about how they are involved in projects where I have undertaken making genetic libraries, and investigated signal transduction mechanisms and gene expression.”

To test out their workshop, the team at NTU2 recruited life science students at the University of Benin, Nigeria. “This came about as one of my colleagues, Bunmi Omorotionmwan, studied at this university and we realised that with her experience of the resources available at the university, the provision of equipment and expertise would enable undergraduates to develop their skills even if laboratory facilities were limited,” she says. As well as developing key bioscience skills, the team at NTU were keen to capitalise on this opportunity to explore the students’ awareness and understanding of jobs in science. “For this group

ONE OF THESE STUDENTS SAID THAT SCIENCE EDUCATION ‘DRUMS CREATIVITY OUT OF YOU’

of students, careers were focused on public health diagnostics, which can cross multiple disciplines including cell biology, microbiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, and histopathology,” says Sarah.

The positive impact of this project on the students taking part has demonstrated the importance of injecting elements of fun and imagination into skills workshops, and also shows just how truly transferable some of these skills can be. “For the students that undertook the sessions, the immediate impact was an increase in their confidence in performing these lab skills,” says Sarah. “Importantly for us, 80% of these students said that they were more likely to consider a career with a practical element, which would have individual benefits, as well as for the country in the longer term.”

Having left the equipment and resources with the staff at the university in Nigeria, Sarah and her team hope that the university staff will be able to continue the practice, and that the impact of this initiative will have a long legacy. “We hope to go back to the university to talk to the staff there about the wider impact of the initiative,” she adds. The future of this project appears to be bright, with Sarah currently in the process of running a similar project in her local community, as well as upskilling school staff to deliver the activity with loanable resources in their own classrooms. Additionally, Sarah is especially keen in expanding this project for one demographic in particular. “I have a longterm interest in women in STEM and would like to focus on supporting women to develop these skills in areas where their opportunities may be more limited,” she says. “I will be looking to work with our international office to find international partners to work with, though would be open to hearing from SEB members too!”

Left Page Top:

Students at the University of Benin participating in the pipetting pixel art challenge.

Photo credit: Sarah Rayment.

Below:

Examples of the pixel art produced by the students.

Photo credit: Sarah Rayment.

I HAVE A LONG-TERM INTEREST IN WOMEN IN STEM AND WOULD LIKE TO FOCUS ON SUPPORTING WOMEN TO DEVELOP THESE SKILLS IN AREAS WHERE THEIR OPPORTUNITIES MAY BE MORE LIMITED

References:

1. FAIR stands for the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability of data.

2. The full team included Dr Sarah Rayment, Dr Bunmi Omorotionmwan, Dr Jody Winter, Dr Karin Garrie, and Jess Fountain.

SENDING PLANTS TO OUTER SPACE

BY CAROLINE WOOD

The world is firmly in the grip of a second space race. Countries across the world are scrambling to exploit extraterrestrial resources, establish permanent footholds on the Moon and Mars, and secure strategic dominance in satellite communications. But outer space remains a hostile, challenging environment, and plant science will play a crucial role if we are to move from fleeting visitors there to longer-term residents. Caroline Wood meets researchers working to help uncover how plants could grow, thrive, and sustain human life beyond Earth.

DUCKWEED: A TINY PLANT WITH BIG

POTENTIAL

“Space travel is the ultimate exercise in selfsufficiency and sustainability: you are stuck with only the things you took,” says Professor of Plant Synthetic Biology Jenny Mortimer (University of Adelaide). “On top of this, you have an extremely challenging environment: harsh radiation, and micro- or altered gravity. But using synthetic biology, we can engineer plants that thrive, not just survive; crops that are compact, more efficient at using carbon and nutrients, and able to produce not just food, but also materials and medicines.”

Professor Mortimer’s research focuses on engineering plant cell metabolism, particularly glycosylation, to develop crops for sustainable industries on Earth, and off it. In recent years, she has applied these skills towards designing plants to support astronauts on long-term space missions as part of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Plants for Space.1 “A key research focus for the Centre is to develop nutritionally complete, zero-waste plants optimized for controlled environments and vertical farming,”2 she says. A particularly promising candidate is a family of aquatic plants, the duckweeds (Lemnaceae), already consumed by various cultures in parts of Southeast Asia, for instance in curries and soups.

“Duckweeds include some of the fastest-growing plants on Earth—capable of doubling their

SPACE TRAVEL IS THE ULTIMATE EXERCISE IN SELFSUFFICIENCY AND SUSTAINABILITY: YOU ARE STUCK WITH ONLY THE THINGS YOU TOOK.

biomass in just a couple of days3—and they are tiny, among the smallest flowering plants on the planet,” Professor Mortimer adds. “They are also easy to grow in water and packed with protein, which makes them a very efficient food source. From a synthetic biology perspective, their small size and fast growth make them an exciting proposition for iterative engineering designs. Our projects include improving nutrition (e.g. increasing omega-3 fatty acids) and producing biomaterials (such as bioplastics). However, we first need to develop a synthetic biology toolbox to allow us to iteratively develop an on-demand production platform.”

However, Professor Mortimer is also exploring how to take other plant species to space. She is part of a team selected to develop a plant growth unit for NASA ’s Artemis III mission, which aims to land humans on the Moon in 2027. The Lunar Effects on Agricultural Flora (LEAF) payload is designed to germinate and grow three species (Arabidopsis thaliana, duckweed Wolffia spp. , and Brassica rapa) of plants on the lunar surface, while recording and transmitting information about their growth using sensors and cameras. “Excitingly, a set of these plants will be chemically fixed, and then those samples returned to earth for molecular analysis; a first for humanity,” says Professor Mortimer. “However, there are many challenges to overcome first, from ensuring that the plants germinate and grow after their launch, to making sure we have sufficient biomass for all the analyses on the return samples.”

Even if the seeds don’t germinate or survive, that result will still be incredibly valuable, she adds. “It would tell us about the limits of plant biology under long-term spaceflight and lunar conditions, and help refine future designs. In any case, our goal is that this work will inspire breakthroughs in indoor agriculture on Earth, contributing to more resilient and localized food production and biomanufacturing.”

EXCITINGLY, A SET OF PLANTS GROWN ON THE LUNAR SURFACE WILL BE CHEMICALLY FIXED, AND THEN THOSE SAMPLES RETURNED TO EARTH FOR MOLECULAR ANALYSIS; A FIRST FOR HUMANITY.

Top Left: Toe studies. Photo credit: Kin Pan Chung.

Above

Professor Jenny Mortimer standing next to the payload of the MAPHEUS15 campaign rocket in Esrange, Sweden, which flew a Wolffia experiment in collaboration with DLRs Jens Hauslage. Photo credit: Jenny Mortimer.

DECODING PLANT STRESS RESPONSES IN SPACE

But if plants are to ever provide food and other resources for long-duration space missions, it is critical that we better understand the stresses spaceflight imposes on them. However, performing experiments to answer this is challenging: access to spaceflight is rare and researchers typically can’t make as many physical observations as they would on Earth.

One answer, according to Professor Simon Gilroy (University of Wisconsin–Madison), is transcriptomic profiling, where plants grown during spaceflight are frozen, brought back to Earth, and analysed using RNA seq uencing to measure patterns of gene expression. Such studies generate immense amounts of data, but in isolation their usefulness is limited. In the early 2010s, Professor Gilroy and colleagues unified these in the first comparative transcriptomic database for spaceflight: the Test Of Arabidopsis Space Transcriptome (TOAST) database.4

“As spaceflight experiments are rare, combining

insights from as many as possible is imperative to gain the most insight from the data we do have,” Professor Gilroy says. “TOAST was a database that made between-experiment comparisons very easy. Cross-referencing the design factors within an experiment allows similar study designs to be selected, enabling the strongest multiexperiment comparisons as well as figuring out whether one particular element is having a major effect on the results. This kind of integrated analysis adds a lot of value to each rare spaceflight experiment.”

The approach has since been incorporated into the comparison tools built into NASA’s GeneLab data repository, and in data exploration environments.5 Data for these include NASA’s Open Science Data Archive, datasets reported in the literature, and even unpublished data provided freely by “the very sharing and supportive spaceflight community.” The result is rich depositories that enable researchers to mine for core, common biological responses to microgravity that could help inform countermeasures for adverse effects; for instance, improved growth hardware, cultivar selection, or gene editing.

“Because thousands of transcriptomic experiments have been performed on Earth, covering the effects of hundreds of different stresses, we can match patterns of gene expression in spaceflight with known molecular fingerprints of terrestrial responses,” says Professor Gilroy. “In effect, we

can ask what did a plant ‘experience’ in space, e.g. did it behave when growing in space similarly to a plant in a flooded environment on Earth, even though it isn’t actually being flooded in space?”

So far, it is clear that core spaceflight responses in plants include a reaction to oxidative stress and alterations in plant defence systems.6 “Another interesting change we have found during spaceflight is a shift in how the plant cell walls are laid down,” adds Professor Gilroy. “Much like astronauts lose bone and muscle mass as they no longer fight against gravity, the rigid celluloserich walls around plant cells are shifted in the weightless environment.”7–9 These changes could have far-reaching effects, including alterations in how well the plant can fend off pathogens, and how nutritious and digestible space-grown crops would be for astronauts.

“Having these data enables us to identify the critical questions we need to focus on if we are ever to use plants as part of the life-support systems that sustain astronauts,” adds Professor Gilroy. “The next steps will be to use techniques that monitor other plant components, such as metabolites and mineral composition, to build a much richer view of what is happening to plants in space. There is also huge potential for using artificial intelligence to mine these data in very sophisticated ways, such as mapping responses down to individual cell types.”

WE HAVE LEARNT A LOT ABOUT HOW STOMATA IMPACT CROP PERFORMANCE, BUT OFTEN AT SMALLER SCALES—LEAF-LEVEL OR WHOLE PLANT, FOR EXAMPLE—AND TYPICALLY THE TRANSITION FROM TRANSFORMATIONAL TO REAL-WORLD APPLICATIONS IS LACKING,’ SAYS CASPAR.

FROM FISH WASTE TO MARTIAN HARVESTS

Perhaps the most celebrated instance of plant science on screen is when astronaut Matt Damon in The Martian survives being stranded on Mars by growing potatoes using his own faeces as fertilizer. It illustrates a key challenge with cultivating crops on the Moon or Mars: with the surface devoid of organic matter and beneficial microbes, colonists would need to bring their own supplies of nutrients. But for the long-term, ultimately we need selfsustaining systems, and aquaponics could be the solution.

“Aquaponics is based on the principle of sustainability and the circular economy, in other words using waste as an integral part of the production system,” says Professor Benz Kotzen (University of Greenwich). The method combines growing plants with farming fish, which provide the organic nutrients. Fish excrete ammonia, which microbes (naturally present in the water) convert first to nitrite and then to nitrate. “Additional plant nutrients, such as phosphorous and potassium, can be readily

BESIDES PROVIDING FOOD ALMOST IMMEDIATELY, AQUAPONIC SYSTEMS CAN ALSO FACILITATE THE TRANSITION TO GROWING LAND-BASED CROPS

extracted from the fish faeces, which are removed as the water is filtered,” adds Professor Kotzen. “If done using anaerobic digestion, this has the benefit of producing methane gas, which can be used for cooking or heating.”

Leafy greens and salad crops in particular thrive on the nitrate-rich water, providing “a welcome relief from space-food diets” for human astronauts, whilst also filtering and cleaning the water for the fish, which in turn provide a welcome source of protein. Tilapia, a hardy, vegetarian fish, is an ideal candidate because it can survive on plant-based feeds (including algae, soy, and duckweed) that can themselves be cultivated within the system.

“Besides providing food almost immediately, aquaponic systems can also facilitate the transition to growing land-based crops,” says Professor Kotzen. “Any plant offcuts and inedible fish material can be composted and added to the planetary surface, in indoor controlled environmental chambers, to begin the soil-forming process.”

It sounds an elegant solution, but does it work in practice? To find out, Professor Kotzen and his colleagues compared the performance of crops grown either in horticultural soil with water, or in mineral composites simulating the Martian surface with the addition of aquaponic effluents.10 The range of crops tested was selected to provide a nutritious and diverse diet for human colonists: potatoes, tomatoes, dwarf French beans, carrots, lettuce, spring onion, chives, and basil.

Although the crops grown in the control soil generated higher yields, most of the ‘Martian’ crops produced a reasonable harvest. Significantly, in most cases, the plants that were grown with the addition of aquaponic effluents were much greener than those grown in the horticultural soil, indicating that the nutrient supply was more than adequate. “Unlike in soil, where nutrients are gradually depleted, the aquaponic water delivered a steady stream of nitrate with every watering,” says Professor Kotzen. “However, the plants grown in the Martian analogue and simulant soils germinated and developed more slowly. No doubt, this was due to the horticultural soil already containing the nutrients and microbes needed for the seeds to grow, whereas in the Martian soils these needed to be accumulated to sufficient quantities for comparative growth.”

But the benefits of aquaponics systems do not just apply to space missions. “Since aquaponics is very water-efficient, it could make a significant difference in areas affected by climate change and unreliable rainfall, such as Sub-Saharan Africa,” adds Professor Kotzen. And because aquaponic plants can be grown vertically, they could also be a space-efficient strategy to produce more food in urban areas. “There is no reason why we can’t set these systems up in hotels, restaurants, supermarkets, schools, and even prisons.”

of soil/simulant substrates from left to right: left, horticultural soil (organic content); middle, Mars analogue regolith substrate using the Chicago Botanical Gardens mix with materials from the UK; right, Mars regolith simulant derived from minerals from the USA and supplied by the Martian Garden company, which supplies simulants for research purposes.

credit: Benz

AQUAPONICS IS BASED ON THE PRINCIPLE OF SUSTAINABILITY AND THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY, IN OTHER WORDS USING WASTE AS AN INTEGRAL PART OF THE PRODUCTION SYSTEM.

Left

Photo

Photo

Kotzen.

Basil plants grown in Mars simulant regolith and without any organic material and fertilizers except for fish water

Photo credit: Benz Kotzen.

MOON-RICE: MINIATURIZING A STAPLE FOR OUTER SPACE

Nevertheless, even with nutrient-rich aquaponic effluents, it would take considerable time to terraform Martian soils so they could sustain land-based staples that would provide the bulk of astronauts’ calories. At the SEB’s 2025 Annual Conference in Antwerp, delegates had the chance to learn about an exciting new project exploring a different approach: highly miniaturized crops suitable for indoor growing.

“An ideal space crop would be compatible with space-efficient indoor vertical farming systems, very productive, and resistant to space stressors, such as high UV light exposure,” says Professor Stefania De Pascale (University of Naples Federico II). She is one of the principal investigators of the Moon-Rice project,11 a collaboration between the Italian Space Agency, the University of Milan, the University of Rome Sapienza, and the University of Naples Federico II. “We have set ourselves the challenge of shrinking rice down to the ‘superdwarf’ level—around 50 centimetres high—while still giving high yields.”

Rice, one of the major sources of calories for humans on Earth, has an attractive nutritional profile; its starch granules are small and easily digestible, it is gluten free, and it provides fibre, proteins, vitamin B, iron, and manganese. Furthermore, it can be readily cultivated using soilless methods, such as hydroponics.

But shrinking it down to the micro level creates challenges, as co-PI Dr Marta Del Bianco (Italian Space Agency) explains: “Dwarf varieties often come from the manipulation of the plant hormone gibberellin, but this can create problems for seed germination and productivity. Tackling this will require a holistic approach combining crop physiology, molecular biology, rice genetics, and space crop production expertise.”

To start with, rice lines carrying genes for the ideal characteristics of a space crop will be selected from a collection of CRISPR -Cas9 rice mutants. “These lines will be characterized for their agronomic traits, both in controlled environments on Earth and under simulated space conditions, including adaptability to hydroponic growth, stress resistance, yield, grain quality, waste biomass production, and metabolomic/nutritional seed profiles,” says Professor Vittoria Brambilla (University of Milan). “For instance, since meat production will be too inefficient for space habitats, we are investigating how to enrich the protein content by increasing the ratio of protein-rich embryo to starch.” Targeted genetic improvements will also be applied to modify crop architecture and physiology, including to increase the number of culms, enhance the number and size of productive panicles, shorten the crop cycle, and optimize yield and adaptability to space conditions.

Rice plants with different forms of dwarfism that the Moon-Rice project is investigating. Photo credit: Greta Bertegnon.

The candidate lines will then be tested under simulated space conditions, and subsequently in real space environments, to determine whether their agronomic characteristics are maintained in such a unique context. A particular concern is how the rice plants will cope with microgravity. “The perception of gravity in the root tips and nodes of the stem is critical for plant growth and architecture,” says Dr Bianco. “Since doing real microgravity experiments in space is expensive and impractical, we simulate microgravity on Earth by continually rotating the plant so that the plant is pulled equally in all directions by gravity.”

Even if the Moon-Rice project does not ultimately succeed in developing a rice variety that meets all the ideal criteria, the research team are confident that the project will deliver invaluable new knowledge, both for space cultivation and for developing more resilient crops on Earth. “Expanding our knowledge of plant cultivation

WE HAVE SET OURSELVES THE CHALLENGE OF SHRINKING RICE DOWN TO THE ‘SUPER-DWARF’ LEVEL— AROUND 50 CENTIMETRES HIGH—WHILE STILL GIVING HIGH YIELDS.

Left:

Rice cultivar characterization under controlled environmental conditions at the Crop Research for Space Laboratory, Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Naples Federico II.

Photo credit: Antonio Pannico.

in extreme environments will help address the global need for food, especially in inhospitable regions of Earth,” says Professor Raffaele Dello Ioio (Sapienza University of Rome). “A crop robust enough for space environments could also be suitable for the Arctic and Antarctic poles, in deserts, or in places with limited indoor space.”

As these examples show that successfully sending plants into outer space will require innovation across all areas of plant science. It certainly is an exciting time to be an experimental biologist!

References:

1. https://plants4space.com/

2. Gill AR, Miller TK, Wijeweera S, et al. 2025. Turbocharging fundamental science translation through controlled environment agriculture. Trends in Plant Science, DOI: 10.1016/j.tplants.2025.08.014.

3. Ofoedu CE, Bozkurt H, Mortimer, JC 2025. Towards sustainable food security: exploring the potential of duckweed (Lemnaceae) in diversifying food systems. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 161, 105073. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tifs.2025.105073

4. Barker R, Lombardino J, Rasmussen K, et al. 2020. Test of Arabidopsis space transcriptome: a discovery environment to explore multiple plant biology spaceflight experiments. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 147. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00147

5. Barker R, Kruse CPS, Johnson C, et al. 2023. Meta-analysis of the space flight and microgravity response of the Arabidopsis plant transcriptome. NPJ Microgravity, 9(1), 21. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41526-023-00247-6