CLAIRE HARMAN

All Sorts of Lives

Katherine Mansfield and the Art of Risking Everything

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Vintage in 2024 First published in hardback by Chatto & Windus in 2023

Copyright © Claire Harman 2023

Claire Harman has asserted herright to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

penguin.co.uk/vintage

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781529918342

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Isabel Schmidt

Contents Introduction 1 1. How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped 15 2. e Tiredness of Rosabel 39 3. e Child-Who-Was-Tired 61 4. e Daughters of the Late Colonel 83 5. An Indiscreet Journey 107 6. Bliss 131 7. Je ne parle pas français 159 8. Prelude 181 9. e Garden Party 209 10. e Fly 235 Acknowledgements 259 List of illustrations 263 Bibliography 265 Notes 269 Index 289

Introduction

When Katherine Mans eld died, on a freezing January night in 1923, it seemed as sudden as a light being switched o . Running up stairs triggered a violent consumptive cough, ‘a great gush of blood poured from her mouth’, and within minutes she was dead. She was only thirty-four years old. She had always lived in a headlong manner, and to the casual

1

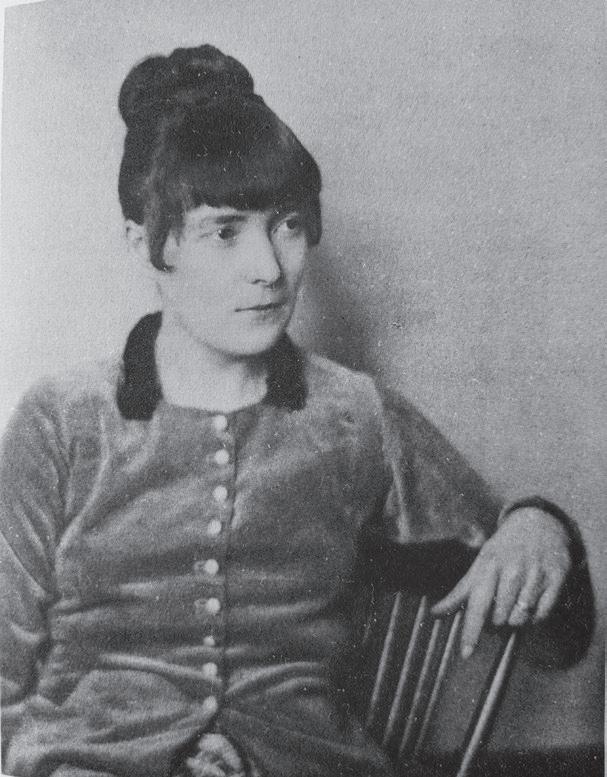

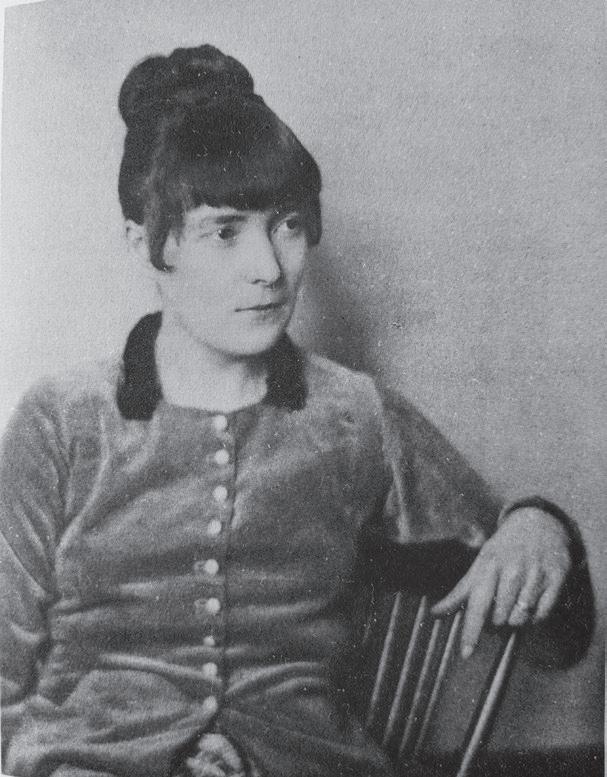

Katherine Mans eld, 1917.

observer her short life might have appeared di use and chaotic, with its many love a airs, its reckless adventures, pregnancies, feverish friendships and hatreds, and going ‘every sort of hog since she was 17’, as Virginia Woolf noted with interest. at is how she found herself in ight from a one-day marriage in 1909, working as an extra in the lm industry in 1913, stuck in a Zeppelin raid in Paris in 1915, and frequently hard up and on the move. ‘She lived like someone on the run,’ the critic Lorna Sage has said, but in Mans eld’s case it was on the run to something rather than away from it. ‘Work,’ Mans eld wrote emphatically in her journal in 1919. ‘Shall I be able to express, one day, my love of work – my desire to be a better writer, my longing to take greater pains. And the passion I feel. It takes the place of religion – it is my religion – of people – I create my people - of “life” – it is Life.’ Few writers of her generation had such dedication to their art and such focus on it, and few demanded so much of themselves; in her last year, by which time she had published three collections and written over one hundred short stories, Mans eld still felt she had only just got into her stride. ‘Do other artists feel as I do,’ she wondered, ‘the driving necessity – the crying need? . . . To write something that will be worthy of that rising moon, that pale light. To be “simple” enough.’

As we reach the centenary of this singular writer’s death, it seems a good time to take a fresh look at her life and her achievements side by side, through the form she did so much to revolutionise: the short story. She died before literary modernism had been labelled or de ned, but was at the heart of it along with Virginia Woolf, D. H. Lawrence, James Joyce and T. S. Eliot (all of whom she knew and had strong opinions about),

All Sorts of Lives 2

and she pioneered ‘fragmented’ narratives ahead of them all, looking for ways to foreground ‘the so-called small things’ that interested her so much. ough she was an outsider, on the margins of both English society and every artistic group she ever had contact with, she came to relish that position, and gravitated naturally towards the most marginalised ctional form. Working entirely on her own, she opened up a whole new range of possibilities in short ction, showing life in intimate snapshots, asking questions instead of proposing answers, and summoning up complete lifetimes in just a few strokes of the pen. Indeed, apart from Chekhov, it’s hard to think of any single writer who contributed more to the sophistication of the short-story form in the twentieth century, reading and borrowing from other literatures, adapting techniques from avant-garde painting, music and new media such as the cinematograph, trying all the time to nd a suitably expressive vessel for her questing modern consciousness.

One has these ‘glimpses’, before which all that one ever has written (what has one written) all (yes, all) that one has ever read, pales . . . e waves, as I drove home this afternoon - and the high foam, how it was suspended in the air before it fell . . . What is it that happens in that moment of suspension? It is timeless. In that moment (what do I mean) the whole life of the soul is contained.

Mans eld’s impact wasn’t felt very strongly at rst, partly because no sort of ‘Mag.-story writer’ (as Wyndham Lewis described her dismissively) was ever considered to be as signicant as a novelist or poet. In the year of her death, Raymond

Introduction 3

Mortimer found the posthumously published stories disappointing and wondered if her artistic reputation would ‘ever stand higher than it does at present’, while the quality of what was being put in front of the public divided fans and critics alike. Mans eld, a meticulous, fastidious person, had instructed her husband John Middleton Murry to destroy all her un nished works and personal writing and ‘leave no sign’; ‘He will understand that I desire to leave as few traces of my camping ground as possible,’ she wrote in her will. What happened was just the opposite. Murry, such an ambivalent partner in life, became Mans eld’s most devoted and single-minded promoter in the years after her death, publishing collections of stories both nished and fragmentary, letters, journals, notebooks; so much material, in fact, and of such a revealing nature, that he was accused, even by friends, of ‘boiling Katherine’s bones to make soup’. Her reputation su ered something of a diminishment as a result; all those drafts, notes and scrapbooks made it impossible to ignore how seriously Mans eld had taken her art, but at the time, Murry’s claims for it seemed in ated. Her irregular and short life, devoted as it was to an irregular and short form, didn’t t at all well with the dominant idea of pantheon literature, on a large scale, with heroic resonances.

Revival of interest in feminist writers in the 1970s and 80s, and the appearance of two landmark biographies of Mans eld, by Claire Tomalin and the New Zealand scholar Antony Alpers, changed the received image of her for a generation of readers, and in the decades since then a steadily increasing amount of scholarship and editorial work, including the full editing of Mans eld’s letters, journals, notebooks, poems and criticism,

All Sorts of Lives 4

has revealed the range and depth of her mind, her subtlety, craft and penetration. She is now acknowledged as the pre-eminent practitioner of the form she concentrated on so exclusively, and the roster of her writer-admirers is stellar – among them, Elizabeth Bowen, William Trevor, Rebecca West, Katherine Anne Porter, A. E. Coppard, Angela Carter, Willa Cather, Ali Smith. V. S. Pritchett paid warm tribute to ‘her economy, the boldness of her comic gift, her speed, her dramatic changes of the point of interest, her power to dissolve and reassemble a character and situation by a few lines, or to excite by an image’, and Alice Munro, who has in our own century brought the form to a point of perfection that Mans eld would have marvelled at, has said she ‘just clung ’ to the older writer’s example. ey have all responded to the extraordinary freshness of Mans eld’s vision but also her technical boldness, the risk-taking mentality that made her, as Kirsty Gunn has said, ‘the creator of a narrative form so familiar to us that we barely think of it as one at all’.

What readers (as opposed to writers) might value most in her writing is her incredible ability to recreate semblances of life. She quite deliberately aimed to perfect this skill after the death in the Great War of her brother Leslie, as a way of resuscitating her memories of him and ‘all the remembered places’: ‘I shall tell everything, even of how the laundry basket squeaked.’ e stories she wrote in this mode – ‘Prelude’, ‘At the Bay’, ‘ e Garden Party’ – are her very best, full of sights, sounds, objects and scents so vividly recalled from her New Zealand childhood that they have a solidity and substance quite apart from the story, and seem to exist on their own. ese were marvellous feats of memory; she could also perform acts of pure imagination with almost

Introduction 5

hallucinatory power, as in this scene evoked for her friend Samuel Koteliansky:

Sometimes when I am awake here, very early in the morning, I hear, far down on the road below, the market carts going by. And at the sound I live through this getting up before dawn, the blue light in the window – the cold solemn look of the people – the woman opening the door and going for sticks, the smell of smoke – the feather of smoke rising from their chimney. I hear the man as he slaps the little horse and leads it into the clattering yard. And the fowls are still asleep – big balls of feather. But the early morning air and hush . . . And after the man and wife have driven away some little children scurry out of bed across the oor and nd a piece of bread and get back into the warm bed and divide it. But this is all the surface. Hundreds of things happen down to minute, minute details. But it is all so full of beauty – and you know the voices of people before sunrise – how di erent they are? I lie here, thinking of these things and hearing those little carts . . .

A single overheard sound triggers in her imagination a sense of all the life around it, and her letter scatters its seed in the mind of the reader, making those scurrying children, roosting chickens – even the wisps of smoke – something akin to a memory of one’s own. It’s truly a kind of magic. And then there is the quality of her ‘noticings’, to use the word coined by another avid Mans eld fan, Philip Larkin, and her

All Sorts of Lives 6

unquenchable appetite for experience, of any kind. ‘It’s . . . true that life never bores me,’ she told Bertrand Russell in 1917:

It is such strange delight to observe people and to try to understand them, to walk over the mountains and into the valleys of the world, and elds and road [sic ] and to move on rivers and seas, to arrive late at night in strange cities or to come into little harbours just at pink dawn when it’s cold with a high wind blowing somewhere up in the air, to push through the heavy door into little cafés and to watch the pattern people make among tables & bottles and glasses, to watch women when they are o their guard, and to get them to talk then, to smell owers and leaves and fruit and grass – all this – and all this is nothing – for there is so much more.

You didn’t need any special conditions; ‘To be alive and to be a “writer” is enough,’ as she said, with those interesting quotation marks around the word ‘writer’. ‘Sitting at my table just now I saw one person turning to another, smiling, putting out his hand – speaking – and suddenly I clenched my st & brought it down on the table and called out – there is nothing like it’. Illness heightened her desire to extract the most out of every moment of life and also in uenced the form and style of her work. Much of what she wrote in the years after the diagnosis of her tuberculosis in 1918 was done at great speed; there were also signi cant periods of inability to work at all, fraught with frustration and alarm. e quality of what she did write was uneven (though considerably less so than one might anticipate, given the awful conditions), and she was seldom (if ever) fully satis ed

Introduction 7

with what she had achieved, but there was always that ‘longing to take greater pains’. Her world narrowed rapidly; from being a bright young thing turning heads in the Café Royal one year, she became an invalid ‘crawling about the room like an old woman’ the next, as Virginia Woolf was alarmed to see. By 1920, when she was still only thirty-one years old, she was living the restricted and lonely life of an invalid; ‘nearly all my days are spent in bed or if not in bed on a little sofa . . . I cant walk about or go out.’ ‘ is is reality,’ she wrote bitterly to Murry, ‘bed, medecine [sic ] bottle, medecine glass marked with tea and table spoons, guaiacol tablets, balimanate of zinc.’

Illness also changed her idea of whom she was addressing, both in her published work and in the massively larger arena of her personal writing, the diaries, notebooks and letters that lled so much of her time in the last years. ‘I have tried to make it as familiar to “you” as it is to me,’ she wrote to her friend Dorothy Brett when she was composing her great story ‘At the Bay’. ‘You know the marigolds? You know those pools in the rocks, you know the mousetrap on the wash house window sill?’ Putting ‘you’ in quotation marks is a salute to all her future readers, precious company for the isolated, sick and disappointed woman waiting in a series of rented villas in the South of France for a miracle to happen. Murry, far away in England, couldn’t satisfy her craving for talk, for letters, for help to probe her fears and troubled emotions, or to share her ‘noticings’. So, more and more, these things went into the notebooks. ‘Come my unseen, my unknown, let us talk together,’ she wrote at the beginning of one in 1921.

She understood how powerful a medium it could be for her – she even thought of writing a ‘minute notebook’ speci cally for

All Sorts of Lives 8

publication (partly anticipating the twenty- rst-century practice of auto ction), but perhaps decided that the way to maintain the right tone was in privacy. ‘What must one do? ere is no question of what Jack calls passing beyond it: this is false. One must submit. Do not resist. Take it. Be overwhelmed. Accept it fully – make it part of Life. Everything in Life that we really accept undergoes a change. So su ering must become Love. is is the mystery.’ e irony is that without Murry’s outing of her wishes, this key aspect of her writing, and of her personality, would not have survived, showing her both at her most vulnerable and most strong and informing so profoundly the masterly stories that she wrote in these same bleak nal years. Without the one form of truth-telling, there might not have been the other.

Risk! Risk anything! Care no more for the opinions of others, for those voices. Do the hardest thing on earth for you. Act for yourself. Face the truth.

*

Why does the short-story form appeal to readers, and why has there been a marked resurgence of it in this century? Is it to do with changes in the way texts are composed and published? Attention span? Hardware, even? Perhaps the availability in so many people’s pockets of access to limitless texts has helped create a better appreciation of neat, brief ction and a search for the best practitioners. For it’s certainly not just entertainment that the great short-story writers provide, but in nite food for thought, asking the biggest questions in the smallest spaces, producing myriad variations on the human comedy and the

Introduction 9

peculiarities of human nature in what George Saunders has called ‘fastidiously constructed scale models of the world’. It’s a demanding form; it gives a writer nowhere to hide, for everything in a short story has to have earned its place, even if what you’re reading looks eeting and insubstantial – perhaps especially then. Shortness is the least important thing about it and ‘story’ itself less important than other qualities such as intensity and insight, which Mans eld deftly demonstrates can perhaps be more easily recognised than de ned:

I am written in prose. I am a great deal shorter than a novel; I may be only one page long, but, on the other hand, there is no reason why I should not be thirty. I have a special quality – a something, a something, which is immediately, perfectly, recognizable. It belongs to me; it is of my essence. In fact I am often given away in the rst sentence. I seem almost to stand or fall by it. It is to me what the rst phrase of the song is to the singer. ose who know me feel: ‘Yes, that is it.’ And they are from that moment prepared for what is to follow . . . What am I?

A bit of a riddle, then, but one we don’t have to solve so much as enjoy.

Such a brilliant writer might not, you could say, need much commentary or explanation. e stories (and the letters and the journals) can be trusted to do their own work, exert their own forms of eloquence. But the enraptured reader in me also wants to talk about these e ects, savour them and praise the writer. I think she would approve, since she started the conversation

All Sorts of Lives 10

herself and was always delighted with a response. Writing back to a fan in 1922 who seemed to have ‘seen what I was trying to express’, she thanked her for it heartily: ‘It is a joy to write stories but nothing like the joy of knowing one has not written in vain.’

So, in this book I’m going to look at ten of Katherine Manseld’s stories – one or two of them not very well known, some world-famous – and read them in connection with her life. I’ve chosen not a ‘top ten’ but a group representing aspects of her evolution and achievement. How do they work? Where do they come from? And what was she striving for?

Katherine Mans eld was not a saint, she was not even a kind person; she was formidable. Her hatreds were as powerful as her loves – possibly more so – and she was often deliberately evasive, using her considerable powers of self-mastery to de ect attention, as Angela Carter concluded, ‘from a core of mystery she wished to keep to herself; perhaps the mystery was her creativity’. ere’s volatility in her work; stark realism in some stories and mawkishness in others; hit-and-miss results when she adopts an accent or any sort of pose, hurry as well as ight. But she knows this, she embraces it; and expresses it with brilliant clarity:

True to oneself! Which self? Which of my many – well, really, thats what it looks like coming to – hundreds of selves. For what with complexes and suppressions and reactions and vibrations and re ections – there are moments when I feel I am nothing but the small clerk of some hotel without a proprietor who has all his work cut out to enter the names and hand the keys to the wilful guests.

11

Introduction

e writer Frank O’Connor said something surprising about the short story – that it is perhaps uniquely able to grapple with the human condition of loneliness. I’ve found this a very resonant remark in the period of forced isolation and spiritual entrenchment which we’ve recently been living through. People have always read for consolation, and for company, but it has become clearer than ever in the past couple of years how important to all of us literature is, maintaining essential connections between one person and another, the living and the dead.

Katherine Mans eld is the perfect companion in these circumstances. She never moralised, but strove to open our eyes to the beauty, sadness and sheer weirdness of everyday life and see more of ‘the detail of life, the life of life’. Towards the end, when she was facing an appalling physical and existential crisis, her own stratagems had to be rethought and revolutionised, but her seeking spirit and her belief in the power of words never dimmed. ‘I mean to make Life wonderful if I can . . . that’s what writing means to me – to enrich – to give.’

I’d like to show that she still has extraordinary power to make us see di erently, to teach us how to notice things, and that her ction can o er precious sources of comfort, delight and surprise to a whole new generation of readers. She was certainly ahead of her time, and is in some ways still ahead of ours, waiting to be recognised and responded to afresh. Literature was never, for Katherine Mans eld, merely decorative or the means to an end, but vitally – viscerally – important, and involved a lifelong commitment: ‘I want, by understanding myself, to understand others,’ she wrote, ‘to try all sorts of lives – one is so very small – but that is the satisfaction of writing.’ e satisfaction of reading, too.

All Sorts of Lives 12

Note about the text

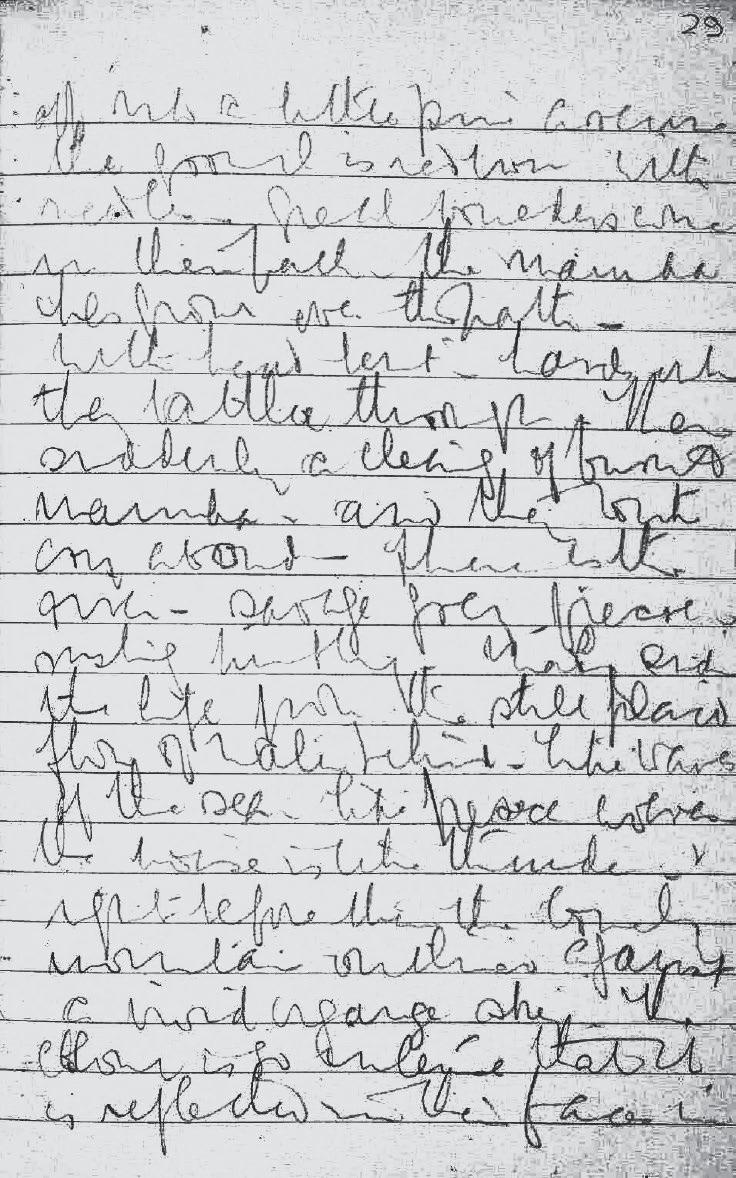

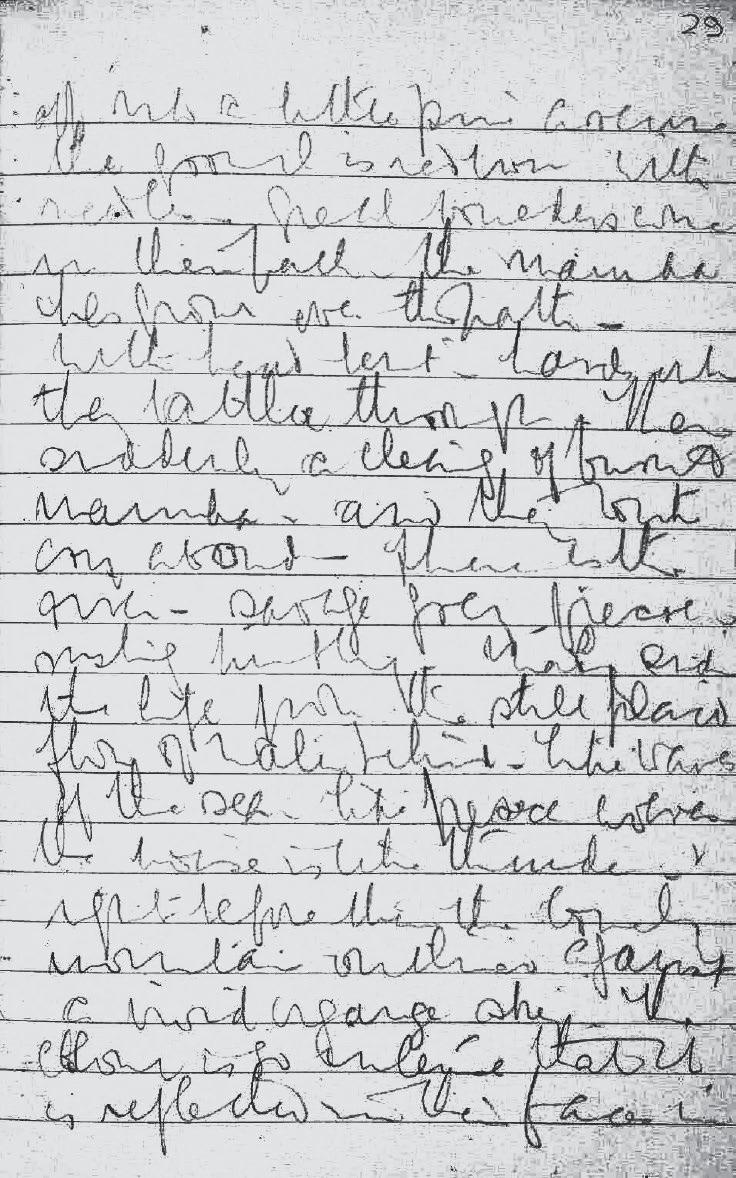

Katherine Mans eld’s handwriting at speed was frightful, ‘often so impenetrable that one cannot always be sure of the spelling of a word’, as Margaret Scott, the heroic editor who rst transcribed Mans eld’s complete notebooks for publication, has said. Here is an example of what Scott and other scholars have had to grapple with, a page from Katherine’s Urewera journal:

13

Introduction

( e rst lines read ‘o into a little pine avenue – the ground is red brown with needles. Great boulders come in their path’.) ‘In her early notebooks [Mans eld] was scribbling so fast that the only form of punctuation she used was a dash . . . quicker to make than a backward-turning comma or a stationary full stop’, Scott explains, but adds that there are some manuscripts ‘in which she simply scribbled non-stop without any breaks or pauses’.

is breakneck tendency means that although Mans eld was a stickler for certain forms of correctness in her published works, the punctuation in her private letters, notebooks and journals is minimal. And terrible. Early editors corrected it silently; more recently it has been painstakingly restored to its full original slovenliness. e reader should therefore bear in mind that the apparent errors in extracts from those sources used in this book are as the author wrote them.

Katherine Mans eld used many names, and many spellings of them. I make use of four variants, ‘Katherine’, ‘Mans eld’, ‘Kass’ and ‘Kathleen’, when and where their di erent in ections seem most appropriate.

All Sorts of Lives 14

How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped

e Story

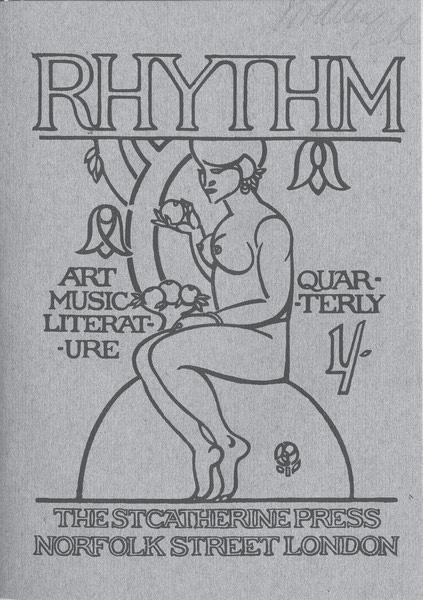

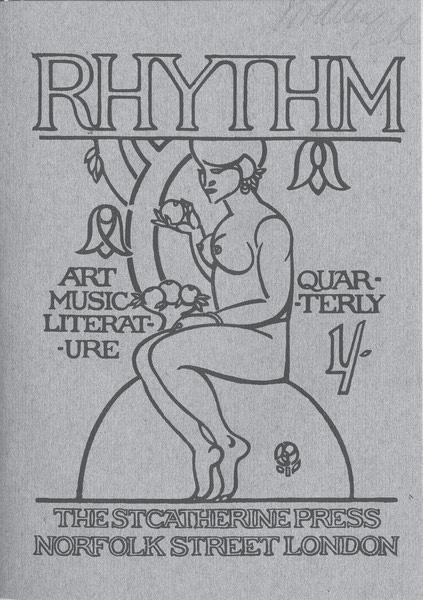

Katherine Mans eld started to contribute regularly to the avantgarde monthly, Rhythm, in 1912, soon after its young editor, John Middleton Murry, met and fell in love with her. Her rst book of short stories, In a German Pension, had just been

15 1

published and was causing a stir; she was also well known as a contributor to e New Age, a political weekly that frequently featured George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells, two titans of contemporary literature. Rhythm was the latest, youngest and edgiest addition to a vibrant little-magazine scene and had an ultra-modern ‘primitivist’ aesthetic, with woodcuts by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Georges Banks, blocky typeface and thick laid paper. It soon became Murry and Mans eld’s joint venture, with a recognisable stable of writers and artists, including Frank Harris, the Paris-based Fauvist J. D. Fergusson and a young Spanish artist called Pablo Picasso. Mans eld’s new work was showcased (poems as well as ction); she also wrote editorials and supplied a lot of the book reviews, under the initials ‘KM ’.

What wasn’t clear to readers of Rhythm was quite how much else of the magazine had been written by her: the poems of an exciting new Russian poet, ‘Boris Petrovsky’, for instance, or the naive stories of another previously unknown author, ‘Lili Heron’. Pseudonyms and aliases had been a long-standing – one might say essential – part of Katherine Mans eld’s advance on literary life, expressive of her playfulness and evasiveness and also a way of hedging her bets; would she succeed as a novelist or poet, a writer for adults or children? She had already gone through many permutations of her real name in private, and was to publish under a number of others, including Julian Mark, Matilda Berry and Elizabeth Stanley; ‘within me I contain multitudes!’ as her admired Walt Whitman declared. And it was ‘Lili Heron’ whose story appeared in Rhythm ’s September 1912 issue.

‘How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped’ relies heavily on

All Sorts of Lives 16

withholding all sorts of information. e location is exotic but not speci ed; the protagonist is guileless yet unreliable; the plot develops but isn’t in any ordinary sense resolved. We are told the story entirely from the point of view of Pearl, a child about three years old, who has been left to look after herself while her mother is busy working. Quite what Mother does (it sounds as if she is a laundress) or what kind of home their ‘House of Boxes’ is remains unclear, but Pearl is swinging on a gate when she is approached by two women in brightly coloured dresses, who between them are carrying a big basket of ferns. ey seem pleased to hear that the child’s mother is busy, and ask if Pearl would like to come along with them. ‘ “We got beautiful things to show you,” whispered one.’ As they get further from home and Pearl begins to tire of walking, the women are described for the rst time as ‘dark’, but it still isn’t clear what their motives are, and at no point is the little girl frightened of them.

In the log house where the women take her, there are a lot of other people like them, who are amused by Pearl; ‘they crowded close and some of them ran a nger through Pearl’s yellow curls, very gently, and one of them, a young one, lifted all Pearl’s hair and kissed the back of her little white neck’. One of the men rolls an enormous peach towards her and they all laugh when she asks if she can eat it. is is clearly nothing like home; there are treats and jokes and no one reprimands her for spilling juice all down her clothes. ‘“ at doesn’t matter at all,” said the woman.’ e only jarring detail (reported but not interpreted by Pearl) is when a man, of unspeci ed colour, comes into the room ‘with a long whip in his hand. He shouted something. ey all

How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped 17

got up, shouting, laughing, wrapping themselves up in rugs and blankets and feather mats.’

From the log house they travel on in carts to the sea, to a village where ‘all the people were fat and laughing, with little naked babies holding on to them or rolling about in the gardens like puppies’. Seen through Pearl’s eyes, the experience is more thrilling than frightening, and the comforts of a close and tactile society very welcome to one who has obviously been brought up in various kinds of want. e word ‘Maori’ is never mentioned, but it doesn’t need to be – this is a generic Other – and any sinister possibilities of the kidnap are never exposed or fully explored, for ‘a lot of little men in blue’ – an embodiment of racial panic and impending vengeance – come running across the sand to retrieve the white child, blowing whistles and shouting. ey know, or think they know, something about the situation that has been withheld from us readers, but when Pearl screams at the sight of her rescuers, we sense immediately that something is wrong.

It’s certainly a strangely disquieting piece, very short (only about 1,000 words in all), slight by comparison with Mans eld’s later work, and of an unsubtle kind of simplicity, not least because the naive language needed to sound plausibly like that of a three-year-old is limiting and produces a crude and cartoonish view of the dark people’s di erence. It has the air of an experiment, or fragment of something bigger, and there is a draft from 1906–7 in Mans eld’s notebooks also featuring a child called Pearl Button (and other drafts with a protagonist called simply ‘the little girl’), which suggests Mans eld had plans to write something longer in the same mode or about the same

All Sorts of Lives 18

child. She would have had trouble keeping this voice going for the length of a novel, though – if that is indeed what she was intending. So many fragments in her notebooks weave in and out of similar material, changing the names of characters (sometimes mid-fragment), that it’s hard to tell.

But the cleverness of the story, and the thing Mans eld learned to exploit more e ectively later, is in the manipulation of the point of view. In ‘Pearl Button’ she is using what is (now) called ‘free indirect discourse’ or a ‘close third person’ voice, that is, writing as if the narrator is passing on a character’s experiences and thoughts, but not judging them. Or not appearing to judge them, for of course there’s always space between the author and the narrator in which to plant doubts and ironies; that’s what the space is for. So Pearl’s eventful day with strangers is reported as almost entirely delightful because that is how she experiences it – a release from boredom and neglect, nice food, smiling adults, an abductress who is ‘warm as a cat’ and a rapturous rst experience of the sea. If the word ‘kidnapped’ wasn’t in the title, the reader would hardly be concerned at all. e reader might even be slightly bored. But that one word changes everything.

I think Mans eld knew she was on to something important to her own craft here, and wanted to preserve it, even if not under her own name. All her most innovative later stories, such as ‘ e Aloe’, ‘Prelude’ and ‘At the Bay’, explore the close third person to brilliant e ect, moving from one point of view to another in interconnecting but discrete episodes. ey also all feature children whose thoughts and actions are given equal weight with the adults’, never sentimentalised or moralised. We ‘share space’, as it were, with a multiplicity of characters in turn and feel really

How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped 19

close to them – for the duration of their part of the narrative. en the camera moves on.

You can see why Mans eld chose to publish this story under a pseudonym, though; its fairy-story feel is quite inconsistent with her other contributions to Rhythm, which included a remarkable realist piece called ‘ e Woman at the Store’ and a character study of a down-and-out, ‘Ole Underwood’, both set rmly and explicitly in New Zealand, Mans eld’s home. It also staved o criticism of Rhythm for publishing too much of her, and ‘Lili Heron’ does seem to have done the trick, for ‘How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped’ wasn’t identi ed as a work by Katherine Mans eld until it was included in a posthumous collection. Until then, it sat there in plain sight, on Rhythm ’s stylish pages, a symbol of her restless imagination and her delight in playfulness.

A symbol too, perhaps, of divided loyalties, for anyone today reading this story about an alluring but never-quite-reachable Otherness will be struck by how closely it speaks to some intensely preoccupying themes in Mans eld’s own life. Two nations, two races, two sexes; where does she belong, and could the answer be almost too hard to face? Pearl’s kidnap is a disaster only when it is over, and she has to go back to her own people. Katherine Mans eld left her native country for good in 1908 and in some senses was never at home anywhere again; in 1919, seven years after publishing ‘Pearl Button’, she felt doomed to be the eternal outsider:

I am the little colonial walking in the London garden patch – allowed to look, perhaps, but not to linger . . . a

All Sorts of Lives 20

stranger – an alien . . . nothing but a little girl sitting on the Tinakori hills & dreaming.

What had brought her to feel like this?

e Life

e Beauchamp family at Las Palmas in 1903, en route for London. KM is back left.

In March 1903, the party disembarking from the SS Niwaru in the port of London must have seemed the very picture of an entitled bourgeois clan; father, mother, aunt, uncle, four daughters and one little boy in a sailor suit, a canary in a cage, dozens of suitcases and hat boxes, book boxes, a cello and even a clavichord; the Beauchamps had taken the whole passenger accommodation

21

How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped