Puffin books

Other titles by Struan Murray

ORPHANS OF THE TIDE SERIES

Orphans of the Tide

Shipwreck Island

Eternity Engine

Other titles by Struan Murray

ORPHANS OF THE TIDE SERIES

Orphans of the Tide

Shipwreck Island

Eternity Engine

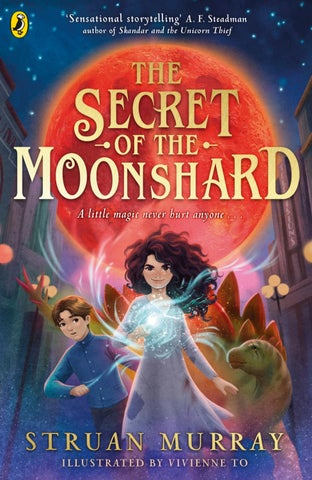

ILLUSTRATIONS BY VIVIENNE TO

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Puffin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

www.penguin.co.uk

www.puffin.co.uk

www.ladybird.co.uk

First published 2024 001

Text copyright © Struan Murray, 2024 Illustrations copyright © Vivienne To, 2024

The moral right of the author and illustrator has been asserted

Set in 12/17 pt Bembo Book MT Std Typeset by Jouve ( UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All correspondence to:

Puffin Books

Penguin Random House Children’s One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7 b W

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

It was a cold morning among the clouds, and Mr Honeywinkle had only minutes to live.

Floating in the sky was a marble building as big as a mountain, propellors sprouting from it like metal sunflowers. Its roof was flat with a trapdoor at one edge, and if you had pressed your ear to it that morning you’d have heard the muffled thunder of footsteps, then brutal war cries, then a name, hurled like a curse:

‘Domino! ’

Sparrows scattered as the trapdoor slammed open and a girl burst out, a sack on her back and a crazed glint in her eye. She had a mane of black hair, wore a tattered grey dress, and was particularly tall for her age. She shivered as

the wind wrapped around her, staring upward. The moon hung red in the sky, like a dollop of molten lava.

Fresh shouts swept up from below, howling for her head on a stake. The girl smiled and ran across the rooftop, swinging the sack down to her side. Overhead the moon had changed colour: from red to a deep emerald green.

Again the trapdoor banged open, and up came a pack of children, bleary-eyed, pyjama-clad, bristling with hate and rage. Their leader was an angelic girl with apple cheeks and golden locks, who looked ready to commit a murder.

‘Give him back to me, Domino!’ she cried, above the wind and the propellors.

Domino’s heart pounded with the force of a sledgehammer, pumping blood as hot as fire. She approached the edge of the roof.

And dangled the sack over the side.

‘Don’t you dare!’ Claudette screamed, taking a step closer.

Domino lowered the sack an inch. ‘Say you’re sorry.’

Claudette’s eyes narrowed, and the other children ground their teeth and cracked their knuckles. Domino counted ten explosive heartbeats, then lowered the sack another inch.

‘I’m sorry!’ Claudette shrieked.

‘For what?’

She turned up her nose. ‘For . . . not being nice to you.’ ‘And?’

‘What else is there?’

‘I want details.’

Claudette rolled her eyes. ‘I don’t know! For throwing your clothes in the sea. For putting those ants in your bed. For . . . for writing you those letters where I pretended to be your dead parents.’

The other children giggled. ‘Don’t laugh, idiots!’ Claudette spat.

Domino waggled the sack. ‘Now say you’ll never be cruel to me again. Say you’ll treat me nice, and stop making fun of me for being sick and poor and everything else.’

‘Yes, fine, I’ll stop doing all of it. Just give me back Mr Honeywinkle!’

Domino looked down at the sack swaying gently in the wind. Through pink streaks of cloud she saw the sea, and beyond that a city that stretched towards the horizon: a whole country of twisting streets. Her breath caught as the sun flared, revealing colourful doll’s-house buildings and, between them, roving figures smaller than sand grains. It was a city she thought about every moment of the day, a city that haunted her dreams. A city she’d never been to.

‘Fine.’ She stepped away from the edge. ‘Here you go.’ Claudette squealed in relief, striding towards Domino with her head held high, reaching out her hand with the confidence of someone who always gets her way.

‘You mean it?’ said Domino. ‘You promise?’

Claudette smiled – a kindly, tender smile. ‘Of course.’

Domino handed over the sack, and Claudette clutched it adoringly to her chest. She took a deep, satisfied breath, then slapped Domino hard across the face.

Domino fell to her knees, ear ringing, cheek burning hot. Claudette’s smile soured to a sneer, the other children rubbing their hands in malicious expectation.

‘You think I’m going to treat you nicely, after this? You think I’m ever going to stop, when you are such an evil, penniless spider?’

Domino held her hand to her cheek, staggering away from the others, who giggled as they spied the tears leaking between her fingers. Claudette tugged irritably at the string holding the sack shut. ‘You can’t even tie a knot right!’

Domino sniffed, now halfway back to the trapdoor. From her sleeve she retrieved a little box, which rattled as she opened it. She rubbed the last of the tears from her cheeks. There was no need to make any more.

At last, Claudette undid the knot. ‘What’s . . . what is this?’

She upturned the sack, and clumps of chicken feathers fell out.

‘What’s going on?’ Claudette said, her voice tight. ‘Where . . . where is Mr Honeywinkle?’

There was a scrape, and the fizz of a new flame. The others all turned, and found Domino holding up a lit match.

Claudette’s face paled. ‘What are you doing?’

‘I didn’t steal Mr Honeywinkle just now,’ said Domino. ‘I only pretended to so you’d follow me up here. I stole him an hour ago, while you were all asleep.’

She pointed to another sack tucked behind the trapdoor, which they’d all run past in their hurry. The sack was upside down, and poking from the bottom was a short string.

Claudette’s lip trembled. ‘What . . . what’s that?’

‘I gave you the chance to say sorry. This is your fault.’

Domino whipped off the sack with a flourish, and there he was: Mr Honeywinkle, button eyes and green bow tie, a little tuft of stuffing bursting from one ear. He was strapped to a bright red rocket.

‘No,’ Claudette whimpered. ‘No, please! I take it all back, I’ll – no, Domino, don’t!’

Domino had already lit the firework. She retreated to a safe distance, and Claudette squealed and ran towards her teddy bear. But it was too late – with a shrieking whoosh, the firework shot into the air, taking the bear with it. There was a spray of stuffing as Mr Honeywinkle’s leg brushed a propellor, but the rest of him kept going – higher, higher – thundering up towards the moon. Domino felt a warm, happy glow in her heart as the firework exploded, filling the sky with little shards of silver light, and little shards of Mr Honeywinkle.

Claudette dropped to her knees with a scream that split

the air, the other children blinking in shock as stuffing fell about them like snow. Her work finished, Domino snuck back towards the trapdoor.

‘What’s that ?’ said a boy.

Domino turned in confusion. Claudette’s face was buried in her hands, but the others were gaping at the sky.

The trails of firework smoke had been washed away by the wind. The moon was red again, but there was something glowing orange, getting larger with each second. It flared so bright that Domino had to cover her eyes.

‘Get downstairs!’ the others yelled, bundling up a weeping Claudette and rushing for the trapdoor. But Domino kept staring, wondering what the light in the sky could be. It only occurred to her too late that she should have been running for shelter as well.

There was a deafening crack then a spray of sandstone that became a dark biting cloud that smothered the roof. For a moment Domino couldn’t see, coughing up mouthfuls of dust. Then the cloud cleared, and she took a wary step forward, gazing in wonder and fear.

It had carved a crater in the rooftop, and it sat at the centre, glowing red. Like a dollop of molten lava.

A piece of the moon.

Domino stood frozen. The piece of the moon was barely larger than she was, but the longer she stared, the larger it seemed to become, growing like a sunrise until the rest of the rooftop vanished from her mind.

It looked to be made from red glass, and she could see something inside it, swirling restlessly, its shape always changing before Domino could decide what it was. She had the strangest sensation that it contained a part of her somehow, like a shifting collection of her own dreams.

The trapdoor opened and a huge man emerged. He saw Domino, saw the moon piece, then shrieked in horror, scooping her up and fleeing down the stairs.

‘Wait!’ she yelled. ‘What’s it doing there?’

‘Shut up,’ Garballous growled, tossing her inside a cupboard of yellowed bedsheets. The door slammed, the

lock clicked, and she was left in the dark, the memory of the moon fragment burning through her thoughts like a hot coal.

It could have been five minutes or thirty before the door opened again. Garballous took Domino’s face in one hand, inspecting it closely, then grunted and dragged her along the corridor, steering her through a doorway.

‘Sit.’

Garballous’s office was a narrow room of a hundred shelves and a thousand glass jars. Inside the jars, dead things floated: a mouse here, a human ear there. The preserving liquid gave the room a sickly green light that danced across Garballous’s bloated face, making him look like an angry reptile.

‘All they could find was the head,’ he grumbled, sitting down behind his desk. ‘I’ve just been speaking to poor Claudette – look !’ He pointed to a puddle beneath Domino’s chair. ‘Her tears still haven’t dried. She says you did it.’

‘Was that actually a piece of the moon, sir?’

‘Yes. It happens sometimes. Put it from your mind – you’re safe now. Or should I say you’re in terrible danger, if you don’t tell me the truth.’

‘Claudette’s a filthy liar, sir.’

‘She’s neither filthy nor a liar, which is more than I can say for you! When was that dress last washed?’ He eyed one suspiciously blood-red stain, then glared at her. ‘So

why’d you do it? Revenge, obviously. And attention, oh yes. You crave attention: good or bad.’

‘Why would a piece of the moon fall?’

‘I said put it from your mind!’ Garballous pulled a comb from his desk and tugged it through his little moustache. He was a large, bitter man who disliked everything except dreaming up punishments for Domino. He was the closest thing she had to a friend.

‘I asked around –’ he waggled a scrap of paper – ‘and apparently Claudette was calling you all sorts of nasty things yesterday. I wrote some down.’ He cleared his throat and began to read. ‘ “Brainless, talentless, poor. Terrible at maths. Belongs in the sewers.” ’

Domino dug her fingernails into her knees. ‘I never heard her say that last one.’

‘No, I added that myself.’ He placed the paper on his desk. ‘Not Claudette’s best work, but I can see why such words might get under your skin.’

‘They didn’t get under my skin.’

Garballous rolled his eyes. ‘Might I remind you that last week you swapped poor Humphrey Burt’s toothpaste with his rash cream because he called you sickly? He’s still refusing to brush his teeth, you know, and – I saw that! I saw that smile, Domino. Don’t think I didn’t see that!’

‘Nuh-uh, I didn’t smile, sir.’ The corners of her lips twitched again.

‘To think of all the things I’d rather be doing than keeping an eye on you. I am a Science Baron of great renown, Domino – I invented the automobile, the television!’

‘You’re right, sir. Someone as brainy as you shouldn’t be wasting his time punishing stupid girls like me. You should let me go so you can get on with your brilliant work.’

Garballous rolled his eyes. ‘That trick might work on the other Science Barons, but I am well practised in dealing with manipulative, ungrateful, unwashed –’

‘I am grateful.’

‘Well, you’ve a funny way of showing it! We feed you, clothe you, educate you, and still you see fit to torment the other children. Claudette wants to go home now, you realize? She says she hates it here.’

‘She loves it here! Everyone’s afraid of her, or worships her. She’s a bully, she needed taking down a pig or two.’

‘Aha! And I suppose you were the one to do it? And it’s “peg”, not “pig”, you potato-brained child. You admit it then?’

Domino batted her eyelashes. ‘I heard a rumour that you’re the cleverest of all the Science Barons. I bet it’s true, sir.’

Garballous slapped one hand on the desk, accidentally bouncing a clay sculpture of his own face nearer to the edge. It was a flattering portrayal of his doughy cheeks and button nose that he’d made on his annual day off.

‘Mr Honeywinkle was dear to Claudette’s heart. A first birthday present from her parents. She loved him, not that you could understand such a concept. Called him her “guardian angel”.’

Domino bit her lip, trying not to smile again. ‘Well, maybe she should be happy, sir? Her angel finally got to fly.’

‘That is it !’ Garballous pounded his fist so hard on the desk that the clay face wobbled halfway off the edge. ‘Enough, Domino. Enough.’

‘If you want me to stop doing things like this in future –’

He sprang forward. ‘Was that a confession?’

‘I said things like this in future. Let me go down to the city, sir. For an afternoon. Then I promise to always behave.’

He drummed his fingers irritably on the desk.

‘I’ll come straight back, sir. I’ll have to come back.’

‘You’ll die before you come back.’

‘You don’t know that for sure. The magic –’

‘Do you think this is a negotiation? You are not allowed to leave. You cannot leave, and – until we find a cure – you will never leave.’

He glared at Domino, and she glared back, until the force of his gaze made her blink. She noticed the jangle of metal at Garballous’s belt: thirteen keys, her path to anywhere in the Scientarium Celestis, including straight out of it. But where could she go? How long would she last down in the city? The others were right – she was sick,

and could never leave. She was trapped here, a thousand feet in the sky with fifty Science Barons and three hundred children, and every one of them hated her.

A hot rage itched all over Domino’s body, and she nudged the clay sculpture of Garballous’s face. It toppled to the ground, smashing to a million pieces.

Garballous blinked down at his ruined face. He lifted the sheet of paper from his desk. ‘Slow-witted, friendless, badly dressed. Belongs in the sewers.’

‘Claudette said my parents despised me!’ Domino yelled. ‘She said that’s why they sent me here.’

‘Well, that’s not true. You’re here because of your condition. Your parents didn’t despise you.’

‘I know that!’ Domino struggled to keep her voice steady. ‘It still hurts.’

‘Not that they were upstanding citizens, either. Trying to rob that bank – what did they think was going to happen? They’re lucky their stolen automobile went over that bridge: imagine if they’d lived to discover what a nasty, hate-filled creature you are?’

‘You’ve told me all this before.’ Domino stood up. ‘Shut up!’

‘Would you rather we simply end our experiments? Stop searching for a cure?’

‘Yeah.’ Domino slumped back into her chair. ‘Then I can leave and be done with the whole horrible lot of you. I want to see the world.’

Garballous gave a weary sigh. ‘The world will kill you, Domino. Now listen – I have a deal for you. A Science Baron has returned to the Scientarium after years conducting research abroad. He’s in need of an assistant, and, despite my many warnings, he has requested you.’

‘ Me? Everyone here hates me. Why would he want my help?’

‘I asked him the same thing, repeatedly. Apparently he wants to keep his work a secret, and given that you can’t leave the Scientarium, and have no friends to tell secrets to, you’re the best fit.’

Domino blinked. Secrets were among her favourite things. She knew, for example, that Baron Barcelina liked to sing lullabies to her lab rats when she thought nobody was listening, and that Emily Pence kept a photograph of Claudette that she threw darts at.

‘What’s he like, this Science Baron?’ said Domino, imagining a wrinkled, warty old man. Most Science Barons were warty old men. The rest were warty old women.

‘It doesn’t matter what he’s like.’

‘Is he young and handsome, sir?’

‘He’s been generous enough to take you on as his responsibility – which means you’re no longer my responsibility.’ Garballous ran a pudgy hand through his hair, taking several strands with it. ‘But here’s the catch: you’re only allowed to work with him so long as you behave. I mean it, Domino – your best behaviour. No more

mud-filled chocolate cakes, no more locking boys inside spider-infested rooms. Not even a drawing pin on someone’s chair. You can start by returning that crystal pendant of Baron Tussock’s you stole from his classroom.’

‘What? But that wasn’t me ! This is a terrible deal. Why would I want to help some ugly old man with his stupid experiments?’

‘He’s young and handsome.’

‘I agree to this deal.’

Garballous seemed to deflate with relief. ‘Good. Hold out your arm.’

Domino rolled up her sleeve, stretched out her palm, and spat on it. Garballous’s eyes bulged. ‘What are you doing, horrible child?’

‘This is how you seal a deal, sir,’ she said authoritatively.

Garballous pulled a small glass tube from his desk drawer, with a needle at one end and a handle at the other. ‘I’m not shaking your hand – I’m taking your blood. It’s been a week since your last leeching. Hold still.’

Domino winced as the needle went into her arm. ‘Haven’t you got enough by now?’ she said, kicking the desk impatiently. The tube filled deep red.

‘Blood doesn’t keep fresh long – we need a regular supply if we’re to find you a cure.’ Garballous held the tube to the light, pursing his lips in satisfaction. ‘And remember: no misbehaving, whatever the other children do. Now go, get to class.’

Domino shuffled to the door, afraid she’d just agreed to a bad deal. Oh well, she supposed, if this new Science Baron proved to be boring, she could always break it. She reached for the door handle when a thought occurred to her. ‘Sir . . . you screamed when you saw that piece of the moon.’

Garballous picked up a book from his desk, appearing to read it. The book was upside down.

‘The moon is magical,’ said Domino. ‘So that piece must have been full of magic. How come it didn’t hurt me?’

He turned a page aggressively. ‘I got you away quickly enough. You were lucky – if it had landed any closer, you’d probably be dead.’

‘But you screamed, sir. Why were you so frightened?’

Garballous put down the book, watching her for a long moment. ‘Because you were in danger. Because not everyone here hates you, Domino.’

A little smile crept across her lips. Garballous stood up, and she felt that he was about to say something nice.

‘Now get out of my sight.’

By the time Domino had been old enough to want friends, she’d realized she had none.

No matter how hard she’d tried, the children of the Scientarium Celestis had never accepted her as one of their own. Their problem with Domino, so far as she could tell, was that she had a disease and, worse, no money. She was a poor, sick girl whose parents hadn’t even paid for her to be there like the rest of them.

‘Why isn’t she in a cage with the other experiments?’ Claudette was fond of saying, her eyes flicking down the breakfast table to make sure Domino had heard. ‘What if her sickness is contagious?’

When Domino was two hours old, her mother and father had carried her from the hospital to their home, closer to the centre of the city where magic was strongest.

They were just minutes from their front door, eager to start their new life as parents, when Domino turned purple and stopped breathing.

Back in the hospital the doctors had revived her, and declared it was simply bad luck. After all, magic did try to kill people sometimes. So her parents had carried her home again, only for a strong wind to blow in from the direction of the Moonshard, and for Domino to stop breathing again. Baffled, the doctors handed her to the Science Barons, who conducted tests, and were delighted by what they found.

Domino was allergic to magic.

Her condition was completely new: no one had ever had it before. ‘You should count yourself lucky,’ Garballous once told her. ‘Without this illness, you’d have no redeeming qualities whatsoever.’

This had earned him three flies in his soup that night, which had earned Domino three weeks’ detention.

Domino had lived in the Scientarium since she was eight hours old: a complex problem waiting to be solved. The Science Barons loved solving complex problems, even if it meant improving Domino’s life.

‘An academic study of great importance,’ she’d heard one of them say. ‘An intolerable nuisance,’ she’d heard from another. They loved Domino for her disease, and hated her for everything else. But in Domino’s opinion there was nothing good about her illness. It was the reason she was

stuck up here, friendless, alone, and in a constant battle with the other children.

‘You make it worse by fighting back,’ Garballous had told her for the hundredth hundredth time, and Domino wished she could take the words and jam them down his flabby throat. ‘Every time you pull one of your pranks, they just attack you all over again. End this cycle. Be good.’

‘I tried being good. They were just as mean.’

For years, she’d worried that the children might go too far – might try to hurt her – until one day Jenna Colvin had tripped her in the chemistry corridor and she’d fallen down a flight of stairs, breaking her arm along the way. Jenna had owned up to it proudly, like she’d expected a medal, but instead was locked in the dungeons, where even Domino had never been sent, and left for a week with nothing but water. She’d come out pale and silent, and Domino hadn’t had the heart to put glue in her shoes like she’d planned.

‘Wow,’ Edmund Evans had said, seeing the state Jenna was in. ‘She looks worse than Domino.’

That night Edmund Evans needed four boys to help him out of his shoes. The other children, meanwhile, had learned an important lesson: it was fine to hurt Domino’s feelings, just not the rest of her.

‘You’re not allowed to die until after we’ve cured you,’ Garballous had explained. ‘It would be a great setback for science.’

Domino sighed as she stomped along the corridor to class. She’d been excited about blowing up Mr Honeywinkle ever since coming up with the idea yesterday. But now it was done she had nothing to look forward to. And however interesting this new Science Baron might be, he was still a Science Baron.

She opened the door, expecting to be shouted at for being late, but found a busy classroom alive with chatter.

‘Silence!’ yelled Baron Barcelina. ‘I’ve told you already – pieces of the moon do fall sometimes. But this piece has already been safely disposed of.’

‘Miss!’ yelled Susan Glover. ‘Is it true the new Baron’s a famous explorer? Oh . . . it’s her.’

The class fell silent as they glared at Domino; thirty disapproving frowns, thirty sneering mouths.

‘Domino,’ hissed Baron Barcelina, as if a Domino was a species of ugly beetle that had crawled into her classroom. Barcelina was a tall, thin Science Baron whose clothes had been burned and torn by a thousand failed experiments, stitched up so often she resembled a scarecrow. ‘You’ve been with Baron Garballous, I assume. Sit.’

Domino dawdled along the aisle, feeling the outraged stares of her classmates. She wedged herself in to her chair: she had long skinny legs, the cause of her height, and could barely fold them beneath the desk. Barcelina swept towards the chalkboard, and Domino met the gaze of the girl in front.

Claudette was no longer wearing her red uniform. She was dressed in black, a veil over her face, dried tears tracing her cheeks like glistening snail trail. She watched Domino with pure hatred.

‘Twenty seconds and I’ve already lost your attention, Domino!’ Barcelina snapped. ‘A new record.’

‘I was listening, miss!’ Domino lied.

Barcelina hit her cane against the board, where reptilian skeletons were drawn in chalk. ‘Then tell me: how did the thunder lizards go extinct?’

Domino breathed in relief. It was a mark of how little respect Barcelina had for her intelligence that she would ask such a simple question. ‘Magic. When the Moonshard fell thousands of years ago –’

‘Millions of years,’ Barcelina corrected her.

‘Right, millions. Well, the moon is magic, and the piece that fell was so big it let out tons of magic when it smashed into the world, and the thunder lizards all died.’

Barcelina’s lip curled in disappointment. ‘Yes, the Moonshard poisoned the world with magic, destroying the thunder lizards.’ She straightened proudly. ‘But science brought them back again. With the destruction of Dark Lord Surphantile two centuries ago, the Age of Wizards was ended. Since then, science has guided us away from magic and ignorance, from tyranny and – What is it, Domino?’

Domino lowered her hand. ‘Is it true there’s still wizards living in the city, miss? In secret?’

The others hissed in disgust, as if Domino was holding a dead bat.

‘I’ll hear no talk of wizards in my class, Domino.’ Barcelina’s voice crackled with threat.

‘Miss!’ called Henry Turnbull. ‘If a piece of the moon fell on the roof, does that mean we’re going to die like the thunder lizards did?’

Barcelina rubbed at her temples. ‘No, foolish child. The Moonshard is massive, gigantic . Now can we please –’

There was a shrill, inhuman cry, and a greenish cloud drifted through from Barcelina’s laboratory. She tutted, pulling on thick protective gloves. ‘I have to check on an experiment – nobody move an inch.’

‘No, no, no,’ Domino whispered, as Barcelina vanished through the door. Sixty eyes flicked in her direction.

‘You’re going to get it now, Domino,’ said Henry Turnbull.

‘You’ll regret what you did,’ said Susan Glover.

‘Is it true your father was just a chimney sweep?’ said Timothy Ruddle.

‘Quiet,’ hissed Claudette. She rose from her desk, leaning in so close that Domino choked on her perfume. ‘I wonder . . .’ She looked Domino up and down. ‘What’s the most precious thing in your sad little life? How can I make you understand what it felt like?’

‘Claudette, I’m sorry about Mr Honeywinkle.’ Domino swallowed as the others circled her desk, grinning like hyenas. ‘Why don’t we just call it even?’

‘You’re always fondling your hair. I don’t know why – I’ve seen tidier bird’s nests. A bird could die in there and you wouldn’t find it for weeks.’ Claudette smiled. ‘But you love it, so that’s what I’ll take from you.’

Susan Glover presented Claudette with a pair of sharp scissors, and Domino leapt to her feet, banging her knees on the desk. ‘No, wait! I have a bear of my own. Mrs, uh . . . Mrs Chubbykins! I’ll go get her, and you can behead her, set fire to her!’

Henry Turnbull grabbed Domino’s arm and wrestled her on to the desk. She twisted her head to look up, and found Claudette towering over her.

‘Any last words as a person with hair?’

Domino considered pleading, begging for mercy, then something vicious squirmed in her chest. ‘I’m glad I did it,’ she spat. ‘Mr Honeywinkle deserved what happened to him, and so did you. You’re a bully; you make the world a worse place. I’d blow up a thousand bears just to teach you a lesson.’

The children shoved her hard against the desk. Icy fingers gripped her neck. Claudette hissed in her ear: ‘This . . . is for Mr Honeywinkle.’

Domino heard a deafening snip.

Aclump of black hair fell by Domino’s cheek. She waited for the next snip.

But it never came. The others were silent. Domino looked about for an explanation, and found him standing by the door.

He was both young and handsome and more besides. His eyes were bright and blue and flicked from one student to the next, pausing on the scissors hovering by Domino’s hair, the tears on her cheeks. He looked nothing like the sunken-eyed, sun-deprived Science Barons, their clothes ill-fitting and stained with ink and soup. He was tanned, dressed sharply in a black coat with a red cape hanging over one shoulder. He had a small smile on his lips, and Domino got the impression he wore it always.

‘Where is Baron Barcelina?’

‘She had to attend to an experiment,’ said Claudette, in a faraway voice. Even she seemed stunned by the man’s appearance.

He glanced at a golden pocket watch. ‘It’s a shame for you to miss out on valuable teaching. Why don’t I take over?’ He strode to the front of the classroom, sitting in Barcelina’s chair. From his coat he removed a rosepatterned teacup that he filled with tea from a silver flask. He sipped contentedly while the class watched, frozen in confusion.

‘You, with the scissors. Come here, please.’ Claudette scoffed. ‘I only take orders from Science Barons.’

The man took another sip. ‘Well then, you’d best do as I say, hadn’t you?’

Whispers fluttered eagerly between desks. ‘That’s him!’ ‘The new Baron!’ ‘The explorer!’

Claudette stalked to the front of the classroom.

‘How is your knowledge of chemistry?’ the man asked.

‘The best in class – the best in all the Scientarium.’ Claudette threw a glare at the others, who nodded hurriedly in agreement.

Wow, the man mouthed. ‘That is impressive.’ He scanned the shelves of dusty bottles behind him. ‘Tell me – what happens when you mix Mornius’s Reagent with Solution of Philipina?’

Claudette gave a haughty sniff. ‘It creates a colourless liquid and a light cloud of harmless pink smoke.’

‘Are you sure?’

Claudette’s lip curled. ‘Of course I’m sure.’

The man nodded, then suddenly came alive, slamming down his teacup and plucking two bottles from the shelves: one of red liquid, the other yellow. ‘Here we are.’ He handed her the bottles, then placed an empty beaker on the desk. ‘Why don’t you give the class a demonstration?’

Claudette hesitated, then popped the cork from the yellow bottle and emptied it into the beaker. She unstoppered the red one and went to pour that in too.

‘Now that I think of it,’ the man said lightly, ‘I was under the impression that if you added Mornius’s Reagent to Solution of Philipina, it created a violent, deadly explosion. Why, a single drop would produce a blast big enough to catch you in it, and me too, unless I step back to about –’ he moved away from the desk – ‘here. But of course I’m sure you know better. You are the best in class, after all.’ He smiled at her warmly.

Claudette looked at the bottle in her hand, then down at the beaker. ‘You’re wrong.’

‘Yes, I’m sure I am. Go on then, pour.’

Domino watched in fascination as Claudette’s fingers trembled.

‘You’re . . . you’re just trying to confuse me, aren’t you?’

His smile widened. ‘Why would I do a thing like that?’

Claudette tilted the bottle, and the red liquid trickled along the neck. Her legs were trembling now too. A single droplet reached the end, curling over the lip of the bottle. The entire class seemed to have stopped breathing.

Claudette squeaked and put the bottle on the desk.

‘What’s wrong?’ said the man.

She fixed her hair, readjusted her sleeves. ‘I’ve changed my mind,’ she muttered.

‘I’m sorry?’ He leaned forward. ‘I didn’t catch that. Did you say that you might be wrong?’

‘I said I’ve changed my mind,’ Claudette hissed through gritted teeth. Her face had turned red.

The man picked up his teacup. His smile had vanished, his expression as cold as a statue’s. ‘Then please take your seat, Claudette.’

She opened her mouth to say something, then shut it with a snap. She shuffled back to her seat, and the class watched her critically, like a sheep now sat where a wolf had been before. The man took another sip of tea, and Domino watched him in silent awe.

‘Baron Magnus,’ said Barcelina, appearing from her laboratory. There was a slimy handprint on her coat. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘Educating,’ he said, pocketing his cup and flask, then bowing to Barcelina. ‘Good day, everyone.’ He opened the door, and Domino’s heart sank to see him leave.

Then he paused, and turned back. His eyes met hers. ‘Domino, might I have a word?’

Her heart felt full of helium. ‘Any word you like!’ she said, cringing as she heard herself. She leapt from her seat, deftly avoiding the legs thrust out to trip her.

She caught up with Baron Magnus as he was striding down the corridor. ‘You were just tricking Claudette,’ she said eagerly. ‘Those chemicals don’t really explode when they’re mixed, do they, sir?’

‘No.’

Domino grinned. She felt certain she’d encountered a master of her own craft, and it was suddenly very important she impress him. ‘They weren’t actually going to cut my hair off, you know. It was just a game. Everyone here really likes me – I’ve got hundreds of friends. And no enemies at all. Is it true you’re an explorer, sir? I don’t know much about the world outside Abzalaymon. Do they have thunder lizards there?’

‘Not many. Most thunder lizards are down in the city.’

‘I’ve never been down to the city. Not that I care, you know? Garballous says I can have a television one day, if I behave. So I can always see thunder lizards on that.’

‘Do you not normally behave?’

‘No, I always behave, sir.’

Magnus looked down at her, a twinkle of mischief in his eye. ‘I heard a rumour about a firework and a teddy bear. Mr Honeywinkle, I think his name was?’

‘Did you know a piece of the moon hit the roof earlier, sir?’ Domino said hastily. ‘I was up there playing with my friends, and smash! There it was. Garballous said I’m your new assistant. I think you’ve made a good choice, sir. I’m very well behaved.’

A boy appeared at her side. ‘Hey, Domino, stolen anything lately?’

She shoved the boy down a side corridor, but he scurried right back. He had neatly combed black hair and large, darting eyes, and wore the blue jacket of a servant. ‘Don’t get your grubby paws on my nice uniform, you little thief.’

‘And who’s this?’ asked Magnus.

‘He’s no one,’ said Domino. ‘I’ve never met him in my life.’

‘My name is Calvin,’ said the boy. His shoulders were bunched up to his ears, his hands rubbing together like he was plotting some terrible revenge. ‘Look at this.’ He held out a golden bracelet for Domino’s inspection. ‘Fancy, isn’t it? There’s a man in the city who’ll buy it for thirty moons.’

‘He works in the Zoological Laboratories, sir, clearing up animal droppings,’ Domino told Magnus. ‘It’s the job he was born for.’

‘Are you two friends?’ asked Magnus.

‘No,’ they both said defiantly.

‘He started working here three months ago,’ said

Domino. ‘Right around the time valuable things began mysteriously vanishing from all over the Scientarium. Suspicious, isn’t it, sir? And somehow I’m the one who always gets the blame.’ She pointed at the golden bracelet. ‘Isn’t that Baron Gorma’s?’

Calvin hid his smile. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. Anyway, you’re the thief – you stole that rare scorpion while I was feeding the iguanas. Lost a day’s pay for that, you know.’

‘Scorpy was helping me play a trick on –’ Domino clamped her mouth shut. ‘I mean, go away,’ she hissed. But Calvin followed them down the stairs, studying Magnus carefully.

‘Who are you?’

‘He’s a Science Baron,’ said Domino, and Calvin snorted.

‘Yeah right. He doesn’t dress like one at all, and his back’s not bent from leaning over a desk his whole life, and –’ Magnus pulled out the medallion that all Science Barons wore: a sun with an hourglass inside it. Calvin’s eyes widened in horror. He shoved the golden bracelet round Domino’s wrist. ‘That’s hers. I’ve never seen it before – she must have stolen it.’ He thrust out his hand. ‘Calvin Morvenpike, pleased to meet you.’

Domino batted his hand aside. ‘Listen, the Baron and I are doing important research – I’m his new assistant.’

‘Assistant? Are you sure, sir? Her attention span’s worse than my three-year-old sister’s. I’d be much better, and I’d charge a lot less.’

‘I’m doing it for free.’

‘Did she mention she has no friends? There’s something not right about her, sir. Listen, how about four moons a day, and I’ll even polish that medallion for you?’

They passed an open cupboard. Domino shoved Calvin inside, threw the bracelet in after him, then slammed the door shut.

‘I’m not sure that will hold him for long,’ said Magnus, with the hint of a smile.

‘It’ll take him a few seconds to find the handle in the dark. So, um . . . why’d you come back here, sir? I think exploring sounds much more fun than being trapped in the sky with a bunch of old fossils.’

Magnus laughed, a warm, musical sound. ‘Well, I thought it would be a good idea to check what the fossils – I mean Science Barons – have been up to. I’m still young by their standards; they don’t trust me with their secrets. And there’s one secret they’re very guarded about.’

‘What’s that, sir?’

‘You.’

Domino stopped dead, wondering which of her secrets he meant. Did they somehow know that she’d been the one to shave off Bernard Hoskins’ eyebrows?

Magnus glanced up and down the corridor. There was nobody in sight. ‘I was talking to Baron Garballous,’ he whispered. ‘He mentioned they’ve been taking your blood. Why would they be doing that, Domino?’

‘Oh, that’s hardly a secret. They’re trying to cure me, sir. I’m allergic to magic.’

‘And tell me, do Science Barons usually do things to help people, unless there’s something in it for them?’

‘I guess not. But what else would they need my blood for?’

‘Well . . . I’m not sure.’ He checked his watch. ‘Follow me – there’s something I think you’ll want to see.’

He led her out on to a balcony, into the bitter wind. Below, Domino could make out the shadow of the Scientarium cast upon the ocean – a bulky lump with a sharp spire sticking out from the bottom of it, like the world’s largest, ugliest ice-cream cone. Domino had never seen what the building looked like with her own eyes, only in grainy photos. But she knew that the ancient, floating castle of the Dark Lord Surphantile grew out of the base of it; or, rather, that the Scientarium had been built on top of the castle, after it had been flipped upside down.

Domino shuffled closer to the balcony edge. Below was the entrance landing, where people came and went from the Scientarium using a pair of gondolas. A huddle of Science Barons had gathered there, breath steamy in the

cold, their skin sickly and sallow from too many years and too little sunlight. Some had brought their inventions along to tinker with while they waited, others books to scribble in. Science Barons were not fond of talking to one another.

Garballous was there too, wearing a wide-brimmed hat as large as an umbrella. He was chatting with another group, old like the Science Barons, but much more extravagantly dressed in trailing tailcoats and creamy gowns, their faces crimson from wine and laughter.

‘Um, thanks and all for bringing me here,’ said Domino. ‘But I see plenty old people all the time.’

Magnus shook his head. ‘Look.’

Rising through the clouds was a large red gondola, squeaking towards the landing on wire cables, rocking gently to a stop. Domino gripped the balcony railing as two servants rushed towards its doors.

‘What’s inside it?’

Magnus smiled. ‘You said you wanted to see a thunder lizard.’

Domino jumped as a deep-throated roar rumbled from inside the gondola. Rumbled through the railing, through the marble beneath her feet. Rumbled through her bones.

‘No, I don’t believe it.’ She swooned, giddy with happiness. ‘A thunder lizard, here! But won’t it eat all those old people? It will, won’t it, sir? Maybe just a few of them?’

More servants rolled a giant steel container right up to the gondola, hiding its doors from view.

‘No,’ Domino moaned. ‘I can’t see!’ She leaned over the balcony, trying to glimpse the gap between the container and the gondola. The container’s door was lifted, and Domino found herself unable to breathe. Nothing happened. She stamped her foot impatiently.

Then, something greenish-brown rippled in the gloom. A shimmer of scales. The servants closed the door and wheeled the container inside the Scientarium.

‘I saw it! A bit of it, anyway.’

She looked happily at Magnus, but he was distracted, watching the gathering below.

‘Um, sir?’

Magnus started out of his thoughts. ‘I’m sorry, Domino, I thought you’d get to see the whole lizard.’

‘Who are those fancy people?’

‘The Steel Barons,’ he said disdainfully. ‘They own the factories down in Abzalaymon, where tens of thousands toil day and night. Together with the Science Barons, they run the city. Terronimous has brought them here for an important meeting at three, in the Digestion Room.’

‘To talk about what?’

‘Well, what unusual thing has happened in the last few hours?’

‘That falling piece of moon? But Garballous told me that wasn’t unusual.’

Magnus tapped the railing thoughtfully. ‘Then Garballous lied. There hasn’t been a recorded fall in centuries. Something is going on up here, and I intend to find out what.’

‘Can’t you just go to the meeting, sir?’

‘I’m not important enough. And if they caught me spying on them I’d be stripped of my title, or worse.’

Domino leapt eagerly. ‘But I could spy on them! I’m the best at spying, really – you’ll be so impressed.’

‘You? No. Absolutely not.’

‘But it doesn’t matter if I’m caught. I get caught misbehaving all the time – I mean, uh . . . no, that’s not what I meant to say, sir.’

The bell rang shrilly, and Magnus grimaced. ‘I’m supposed to give a class now.’ He bowed and swept inside, then peeped his head back round the door frame. ‘A pleasure to meet you, Domino. I look forward to us working together.’

He was gone before Domino could even manage a goodbye. She rushed in after him, but found the corridor empty.

‘Don’t go spying on that meeting,’ hissed a voice by her ear. Domino lashed out in surprise, punching Calvin in the face. ‘Hey!’ he yelped, back pressed flat to the wall, eyes watering.

‘You were listening? You little sneak!’

‘He just wants to know for himself what’s going on,’

said Calvin, rubbing his nose. ‘That’s why he asked you to go.’

‘He told me not to go.’

Calvin rolled his eyes. ‘That’s because if he’s spent more than thirty seconds with you he knows the best way to get you to do something is to tell you not to do it. I use the same trick all the time on my sisters.’

‘You don’t know anything about me,’ Domino snapped, squaring up to him. He was of a pleasing height: shorter than she was.

‘Yes I do. I watch you all the time.’ He covered his mouth. ‘I mean, um, you know, the same way I’d watch an automobile accident. Anyway, I’m an expert on human behaviour. I’m going to be a detective one day.’

Domino snorted. ‘You can’t be a detective! What sort of detective steals things all the time?’

‘You learn a lot about people when you steal from them. Now listen, don’t go to that meeting. You heard that man – these are the most powerful people in Abzalaymon. In the world, probably. Think what they’ll do if they catch you listening in on their biggest secrets!’

‘They won’t do a thing.’ Domino straightened up importantly. ‘They need my blood.’

‘So it’s true,’ said Calvin, his eyes widening. ‘They do take your blood. Because of your weird magic allergy? Well, maybe they can’t hurt you, but they can still

lock you in a prison forever. Just . . . don’t spy on the meeting, okay?’

Domino sighed. ‘Okay, I won’t go. You happy?’

‘Extremely,’ said Calvin, before running off along the corridor.

Four hours later, Domino went to spy on the meeting.

Domino had spent most of her life learning how to explore the Scientarium unnoticed. Her favourite routes were the ventilation shafts, filled with families of rats, the descendants of lab experiments Domino had set free years before. Despite what Claudette said, Domino did not have conversations with them, though she often recruited them for her pranks, like the time three white rats were found in the senior boys’ dormitory, with the numbers 1, 2 and 4 inked on their sides. The boys had been driven to hysterics trying to catch them, and had lost many nights’ sleep searching for the missing rat number three.

There was no rat number three.

So at the end of geology class, Domino followed the march of students towards maths, before ducking down a servants’ staircase and through the kitchens, crawling

unnoticed beneath the tables, across soup-splotched tiles, and into a tiny room known only to her and the servants. The floor was strewn with flower petals and melted candle stubs, the walls pocked with dozens of cubbyholes filled with clay figurines. There was a smiling toad with many arms, a fierce black tiger, and a woman with the head of a deer. A servant was kneeling in front of them. ‘Get out of here, girl!’ she hissed.

‘Don’t worry, your secret’s safe with me!’ said Domino.

Spirit worship was illegal, an ancient tradition that the Science Barons despised. ‘A lot of superstitious nonsense,’ she’d heard Barcelina say. ‘Poor people are foolish – as if imaginary beings will make their lives any better.’

Down another staircase she emerged beside the Digestion Room: a favourite napping spot for Science Barons who’d had too much custard for pudding. It was a small, woodpanelled room, hung with paintings of grouchy Science Barons who looked like they had experiments they’d rather be doing. Squashy sofas ringed the room, and a long table sat in the middle, surrounded by high-backed, uncomfortable-looking chairs. To one side was a large drinks cabinet that even Garballous wouldn’t open until evening – it would be perfect for hiding in. Domino crouched low to the floorboards and, holding her breath, crept across the room and opened the cabinet. Calvin tumbled out on to the floor.

‘What are you doing here!’