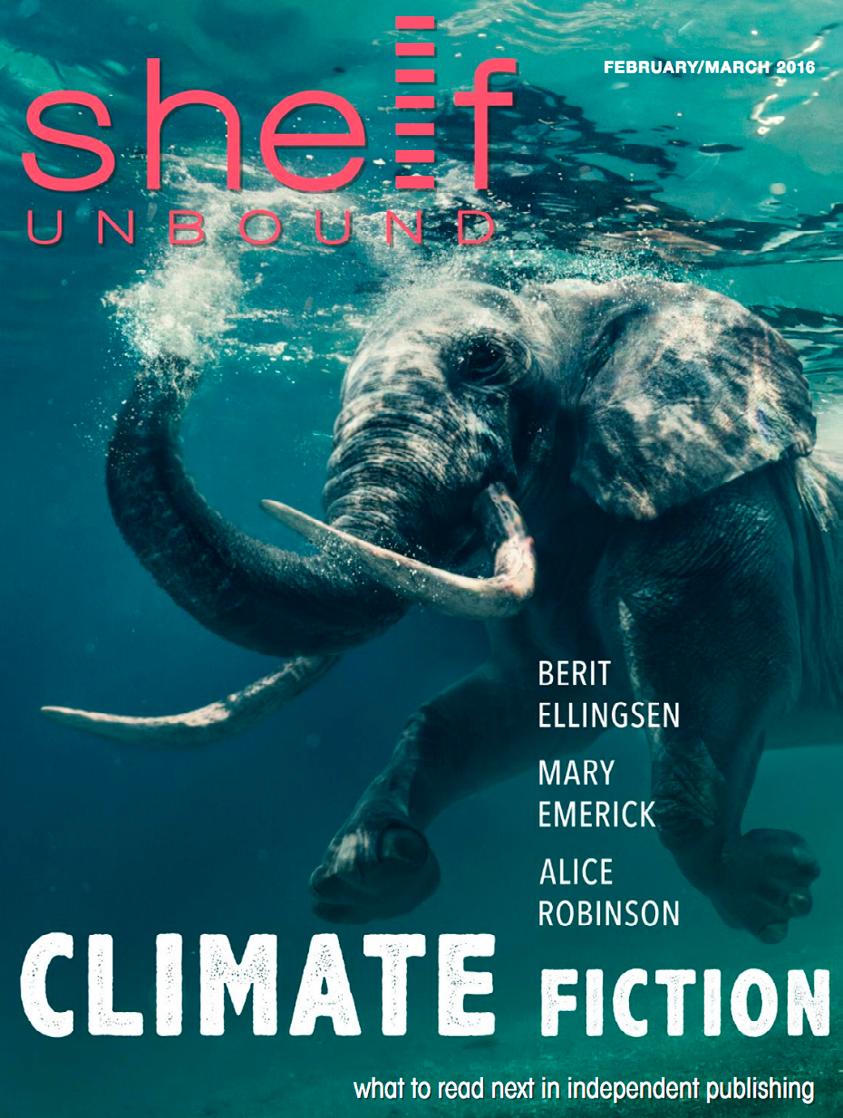

STORIES THAT CONNECT US:

INDIE FICTION FROM ACROSS THE GLOBE

FEATURING: GLOBAL VOICES IN INDIE PUBLISHING: AUTHORS WHO BREAK BOUNDARIES

EDITOR’S SELECTIONS: MUSTREADS FROM AROUND THE WORLD

WHAT TO READ NEXT IN INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING

OUR STORY

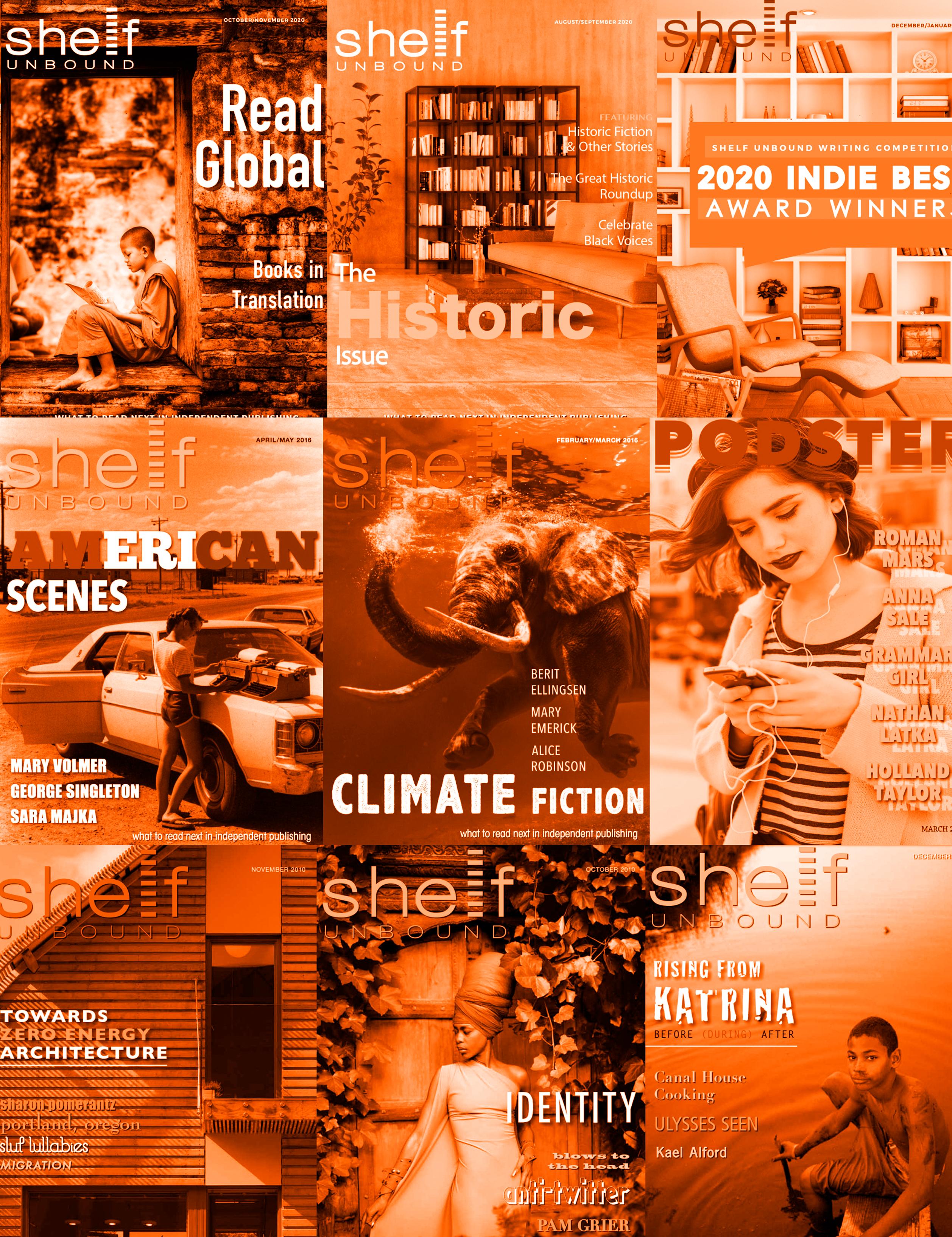

SHELF UNBOUND MAGAZINE

All we wanted was a really good magazine. About books. That was full of the really great stuff. So we made it. And we really like it. And we hope you do, too. Because we’re just getting started.

Shelf Unbound Staff.

PRESIDENT, EDITOR IN CHIEF

Sarah Kloth

PARTNER, PUBLISHER

Debra Pandak

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Corinna Kloth

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

Christina Consolino

Michele Mathews

V. Jolene Miller

Chrissy Brown

Corinna Kloth

FINANCE MANAGER

Jane Miller

For Advertising Inquiries: e-mail sarah@shelfmediagroup.com

For editorial inquiries: e-mail media@shelfmediagroup.com

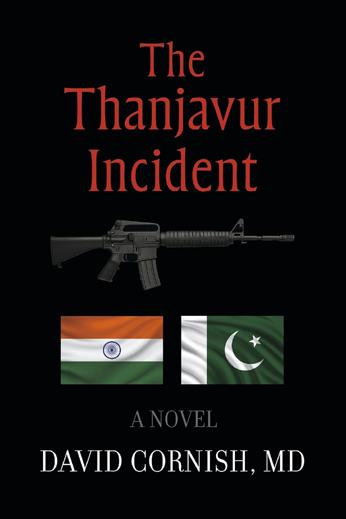

THE THANJAVUR INCIDENT

Commander Aarav Cheran—a renowned nuclear physicist and Indian Naval analyst—is thrust into a crisis that no war game ever imagined. As two nuclear nations edge toward catastrophe, Aarav must navigate a fractured landscape of political power plays, military brinkmanship, and catastrophic technological failure. The fate of millions may rest on his ability to outmaneuver forces poised to plunge the world into chaos.

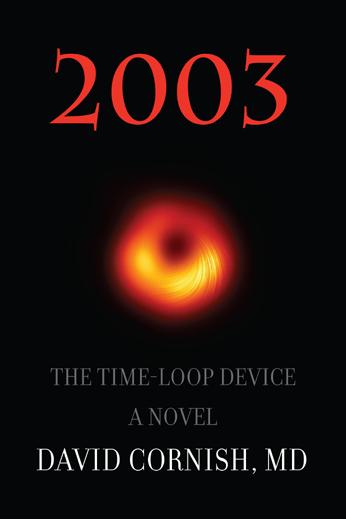

Nolan Emerson, PhD, is a brilliant young theoretical and experimental physicist who is a professor at the University of Geneva, and the lead scientist at the CERN particle accelerator. He is a leader in the areas of general relativity and quantum mechanics. Dr. Emerson devises an experiment so radical and revolutionary that it seeks to unlock the astounding, complex, and mysterious secrets of Einstein’s space-time. Ultimately, his work challenges the fundamental notions of consciousness and of the concept of reality itself.

1918: THE GREAT PANDEMIC

Major Edward Nobel’s mission, as a physician, is to help protect American troops from infectious ailments during the First World War. However, his unique vantage point in Boston allows him to detect an emerging influenza strain that is an unprecedented global threat. Eventually, the 1918 influenza pandemic killed up to 100 million people, and became the worst natural disaster in human history.

1877: A NORTHERN PHYSICIAN IN SOUTHERN UNGOVERNED SPACES

Colonel Charles Noble is a US Civil War veteran, and an Army surgeon reservist. Extreme violence in the former Confederacy, in anticipation of a national election, has caused President Grant to send additional federal troops to the Southern states. Terrorists are determined to counter Noble’s good intentions, as they threaten the civil rights, and the very lives, of all who oppose them.

1980: THE EMERGENCE OF HIV

Dr. Arthur Noble is a brilliant first-year medical resident in San Francisco. Noble encounters a strange new ailment that seemingly appears out of nowhere, and delivers its victims a most horrible merciless death. Dr. Noble struggles to find answers to the medical mystery, even as many researchers and society refuse to believe that it is a serious public health hazard, or that it even exists.

IN THIS ISSUE

FEATURES

20 Translation Nation: 10 Indie Presses Bringing the World to Your Bookshelf By Sarah Kloth

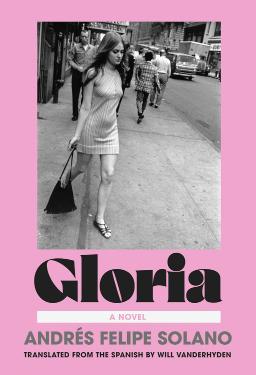

34 Interview with Will Vanderhyden, Translator of Gloria by Andrés Felipe Solano By Michele Mathews

40 New Release Roundup: Translated Edition By Corinna Kloth

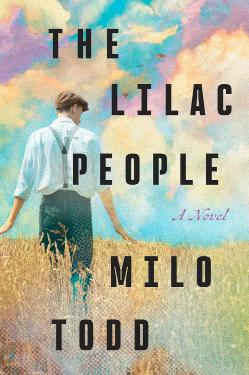

57 Interview: Milo Todd, The Lilac People By Corinna Kloth

66 Shorter Is Stronger: The Rise of Novellas & Short Fiction in Translation By Sarah Kloth

86 Interview: Sarah Aziza, The Hollow Half By Corinna Kloth

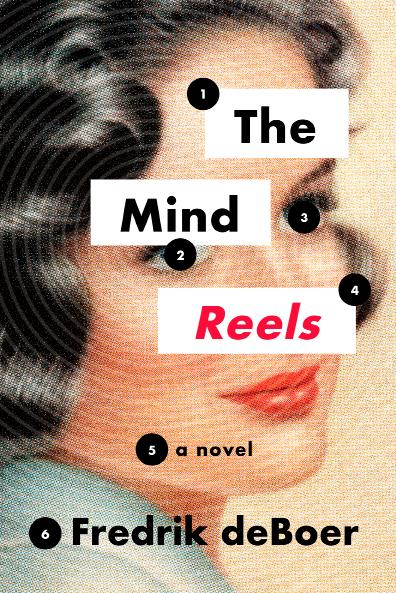

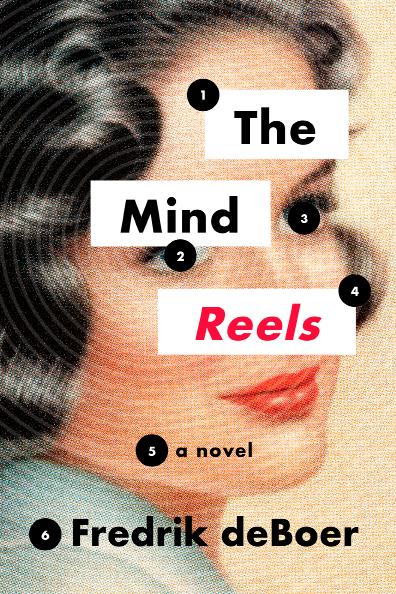

102 Interview: Fredrik DeBoer, The Mind Reels By Sarah Kloth

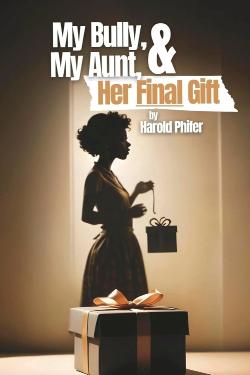

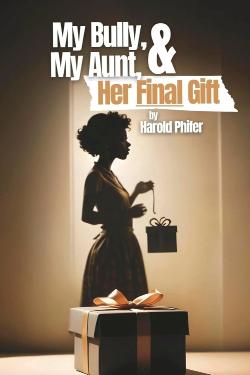

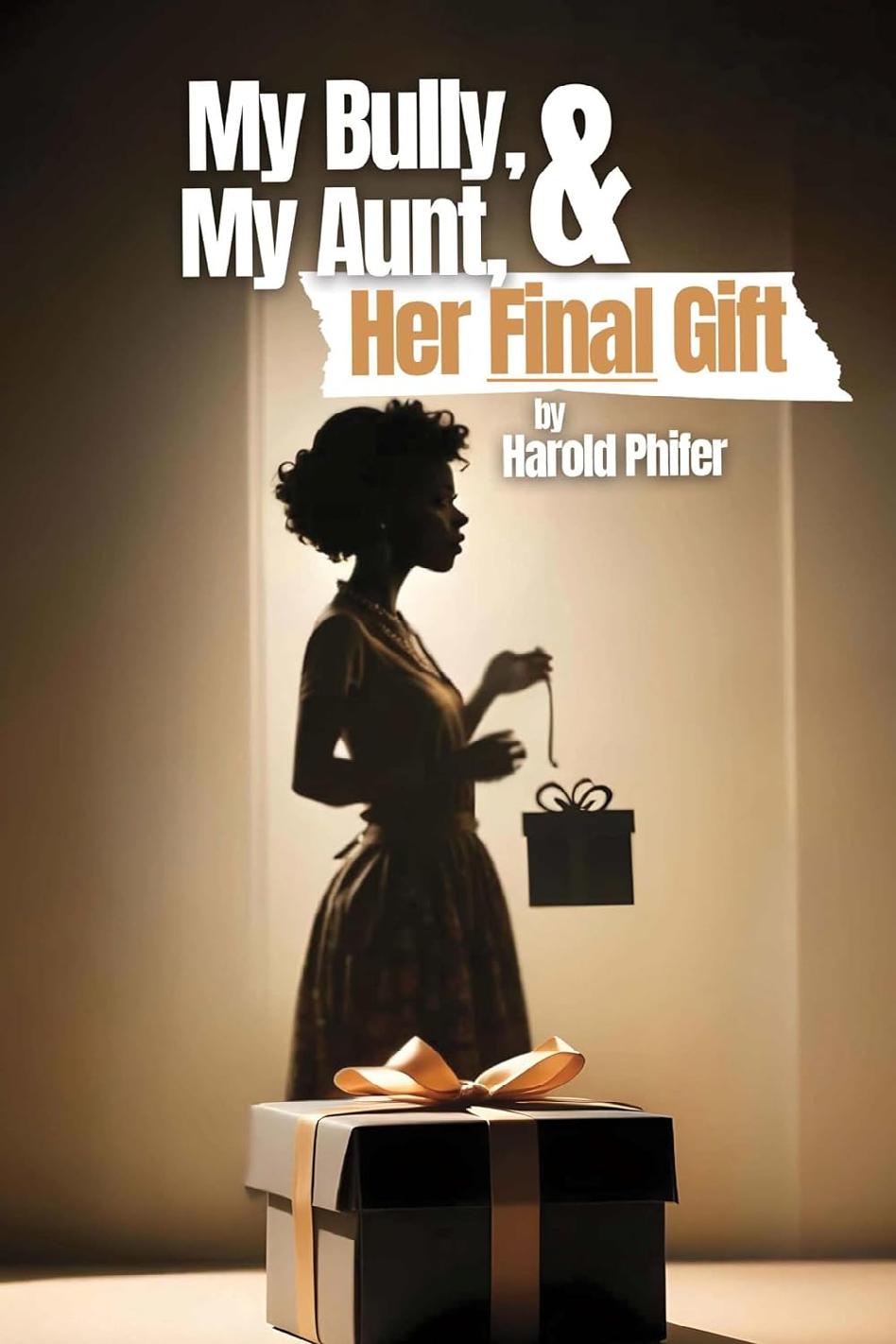

112 Interview: Harold Phifer, Author of My Bully, My Aunt, & Her Final Gift By Sarah Kloth

BY SARAH KLOTH, PUBLISHER

In prep for this issue, I finally picked up The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa, a novel that’s been sitting on my shelf for a while. It’s a powerful piece of translated fiction from Japan that explores a world where memories are slowly erased, and the characters fight to hold on to what’s disappearing. The more I read, the more I realized how much we rely on our memories to shape who we are—and how easily they can fade away.

What struck me most was how Ogawa’s novel captured something so deeply human: the way we hold onto the stories of our lives, even when the world around us changes. It’s a story of loss, yes, but also of resilience—of people trying to preserve the parts of themselves that are most important. And the fact that this novel made its way

Global Voices.

from Japan to readers across the globe reminded me how stories can cross borders and languages, and still find a place in our hearts.

That’s what makes this issue of Global Voices so special. It’s not just about the books or the authors; it’s about the journey these stories take as they travel from one culture to another, creating new connections with every reader they encounter. As you turn these pages, you’ll find stories from across the world—many of them translated— that offer a glimpse into lives, struggles, and joys that may be different from your own, but are still familiar in the most human way.

I hope these global voices in this issue resonate with you, leaving you with something that stays with you long after you’ve finished reading.

Enjoy the issue!

Gerry's latest potboiler even involves the White House—can you believe it? If you haven't joined the author's bandwagon yet, check out what reviewers have been saying about him.

"A great piece of literary work featuring well-crafted stories, focused scenes, and unpredictable endings.” - Kim Calderon, The Book Commentary

"He has a well-furnished mind, with an ingenuity dedicated to making readers laugh.” - Joe Kilgore, U.S. Review

"The Ladies from Long Island is one of the year’s best thrillers." - BestThrillers.com

Don't Miss These Other Bestsellers by Gerry Burke

Explore his other gripping novels that have captivated readers everywhere.

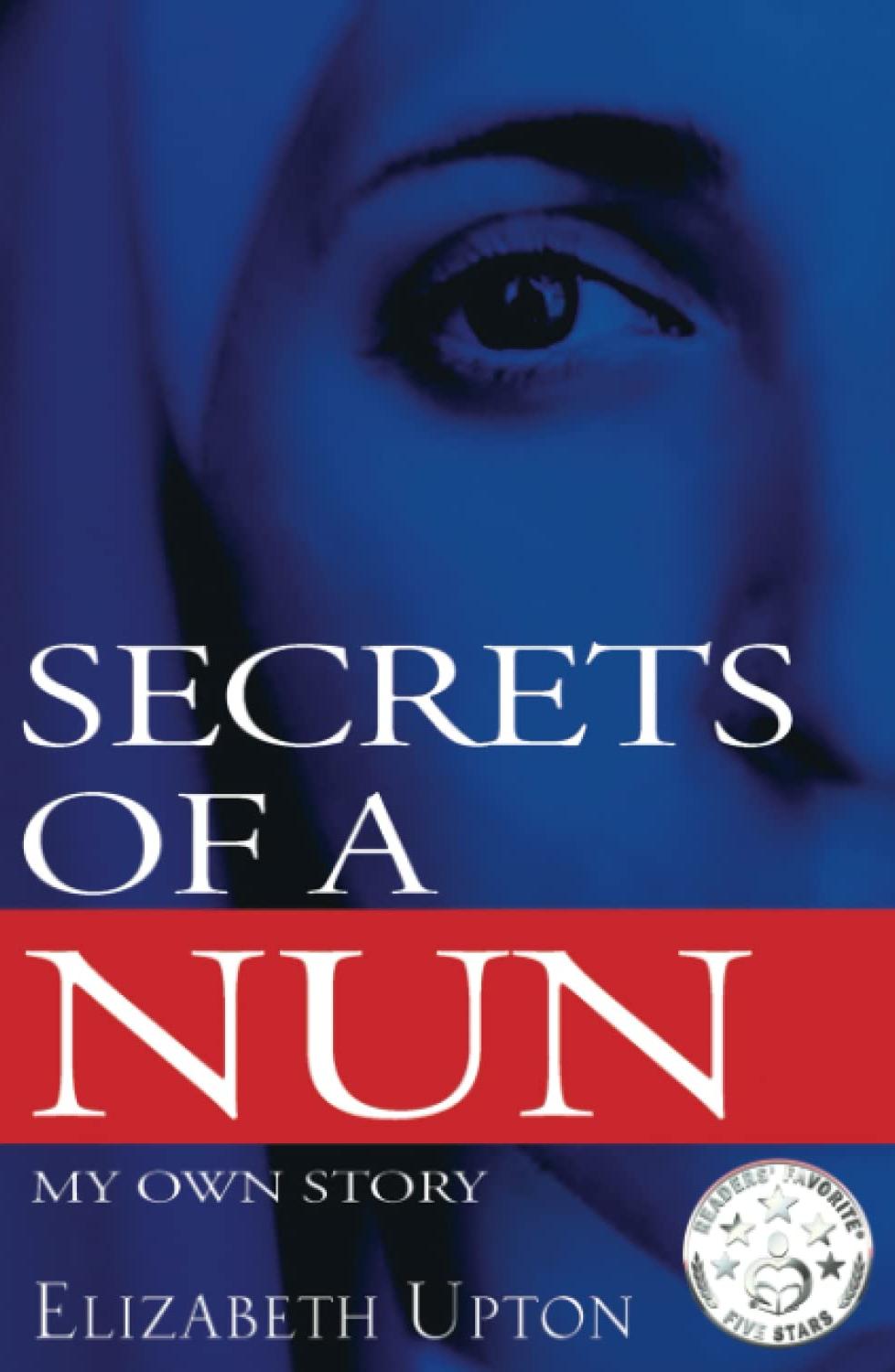

SECRETS OF A NUN

A 40-Year Journey to Self-Discovery Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the First Edition Publication Secrets of a Nun is a revealing, uncompromisingly honest, and deeply moving memoir that explores the soul of a former nun.

A true story of desire, courage, and faith in finding her authentic self.

After leaving behind her dreams of Olympic glory, Elizabeth entered the convent at the age of 15, where she spent 21 years struggling with celibacy, devotion, and self-identity. This memoir is a testament to her resilience and her journey to reclaim her life and her truth.

“A story of remarkable courage and spiritual awakening — a memoir of profound honesty.”

— Reader’s Favorite

NOW AVAILABLE IN PAPERBACK, EBOOK, AND AUDIOBOOK FORMATS

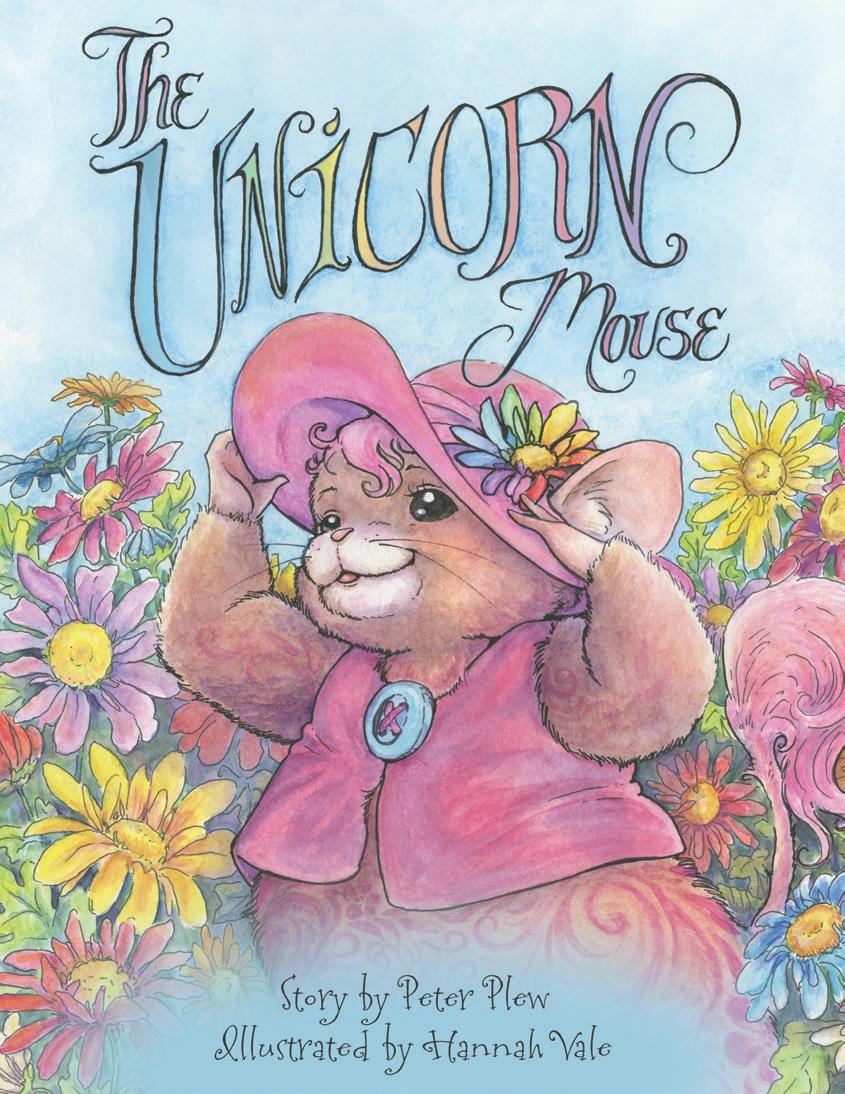

The Unicorn Mouse wasn’t like other mice. She had pink paisley fur and a furry fluffy tail. Most special of all, she had her unicorn horn. When she was little, she kept the horn hidden under her pink hat. But as her horn grows, the Unicorn Mouse knows one day she will have to share her secret with her entire kingdom.

Will she have the strength to be who she is, no matter what other mice might say? Could her unicorn horn change the hearts of everyone forever? Will you stand with her?

A story filled with the power of love, friendship, and self-discovery, The Unicorn Mouse is a new fairy tale for children and adults to treasure.

Visit TheUnicornMouse.com for more info!

Peter Plew is a Midwestern author and musician living with his family in Wisconsin, where he loves the muse of all four seasons. Peter attended the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music and studied English and Creative Writing at Marquette University. His quest in writing is to take the reader on a journey of the heart into fantasy worlds where self-discovery, healing, and positive imagery win the day! The Unicorn Mouse is Peter’s first book in the series with illustrator Hannah Vale.

“The Unicorn Mouse draws in readers with colorful illustrations and an enduring message that we are all different, yet just the same. This new classic is a tender tale of kindness and love for ourselves and others.”

—Karen Condit, author of Turtle on the Track and Turkey in the Tunnel

“Join the Unicorn Mouse on her journey to joy, love, and self-acceptance!”

—Amy Sazama, author of Fleetwood Dreams: Climbing a Mountain After a Landslide

“Unicorn Mouse shares a lovely message of self acceptance and the courage to be different. It is beautifully illustrated and told on an appropriate level for young children. It encourages kindness and the virtues of friendship and the importance of self love. It is a great story for young readers learning about the power that their words can have on others.”

—Mary

Beth Turchick, author of My Butterfly Garden with Grandma

“A bright and uplifting story that conveys an important message. The art and text combine to create an immersive, fantastic, yet realistic world for young readers!”

—Sean Michael Malone, author of The ABCs of Battle

INDIE IN THE NEWS

Top News in Independent Publishing

The indie publishing world is buzzing with exciting updates! From rising indie publishers expanding into new territories to indie authors making their mark with major book deals, the landscape is evolving faster than ever.

Here’s a roundup of the latest and greatest happenings in the world of independent publishing:

Indie Publishers Launch Collaborative Translation Initiatives

Independent publishers are joining forces to create collaborative translation initiatives aimed at expanding the reach of global literature. New partnerships between presses in Europe, Asia, and Latin America are facilitating

the translation of lesser-known works, making them accessible to wider audiences. This movement not only enriches the literary landscape but also strengthens the cross-cultural exchange between authors and readers worldwide.

Indie Publishers Champion Translated Works

Independent publishers are increasingly focusing on acquiring and publishing translated works, recognizing the value of diverse narratives. Imprints like Deep Vellum Publishing and Transit Books are leading the charge, offering readers access to international literature that might otherwise remain inaccessible. These publishers are not only expanding their catalogs but also fostering a deeper understanding of different cultures through literature.

Literary Festivals Spotlight

Translated Fiction

Events such as the "Translated By, Bristol" festival are celebrating the art of translation and the richness of global literature. Cofounded by author and translator Polly Barton, the festival features discussions with International Booker Prize-nominated translators and showcases works from underrepresented languages and regions, including Cameroon, Slovakia, and Latin America. This initiative underscores the growing interest in translated fiction and the importance of making diverse literary voices heard.

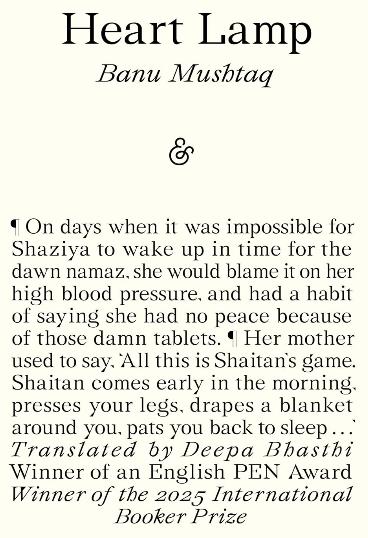

Awards Recognize

Excellence in Translation

The 2025 International Booker Prize highlighted the significance of translated works, with Banu Mushtaq's Heart Lamp, translated from Kannada by Deepa Bhasthi, winning the prestigious award. This marks the first time a shortstory collection and a Kannada translation have received this

honor, emphasizing the increasing recognition of Indian literature in the global literary community.

Independent Publishers Drive Change

A recent study by the University of Exeter reveals that independent publishers are transforming the sector, with the "Big Five" increasingly being sidelined in favor of smaller presses. This shift is particularly evident in the longlists for prestigious international literature prizes, where independent publishers are gaining prominence for their diverse and innovative offerings.

Wrapping Up

The independent publishing sector is experiencing a renaissance, with translated fiction playing a pivotal role in broadening literary horizons. Through their commitment to diverse voices and innovative storytelling, independent publishers are reshaping the literary landscape and ensuring that global narratives find their place in the English-speaking world.

Finalist: Next Generation Indie Book Awards

A Town on the Brink. A Janitor with a Past. A Reckoning Begins.

“A gripping, action-packed ride. Fans of Deliverance and The Godfather will love it.”

- Kirkus Reviews

The Philadelphia mob wants Twin River. But standing in their way is Gene Brooks—a Vietnam veteran, a high school janitor, and a man with nothing to lose. When the town’s darkest history begins to repeat itself— kidnappings, murders, and a school hostage crisis—justice can’t wait for the law.

A relentless thriller in the tradition of Dirty Harry, First Blood, and Death Wish, Twin River is a bloody salute to vigilante justice.

“This grisly thriller will sink its teeth right in you.”

- Kirkus Reviews

“Twin River II is ideal for those who prefer a dose of reflection and depth of character along with swiftly moving action and lurid confrontations” - Clarion Review

“Thrilling, action-packed, and captivating—leaves you eager for the next installment.” - Readers’ Favorite

His name is Palladin— as in pallbearer.

Wesley Palladin was raised to be a killer. Trained by his father and hardened by the Philadelphia mob, he perfected his deadly craft. But when a contract goes wrong, he vanishes— reappearing in Twin River as a quiet security guard.

Then he meets Matt Henry, a violent teen on the brink of destruction. As Matt battles extreme bullying, a brutal juvenile institution, and a dark hunger for revenge, Palladin becomes his mentor. But in a town plagued by kidnappings, human trafficking, and unchecked brutality, redemption comes at a deadly cost.

The Saga of Twin River Continues… and the Stakes Have Never Been Deadlier.

“Readers who love classic gritty crime novels like The Godfather will love Twin River III.” – Pacific Book Review

Twin River III: A Death at One Thousand Steps

When Twin River students Heather Wainwright and Alice Byrd are abducted into a twisted underground video ring, they have no idea of the horror awaiting them. Meanwhile, a violent confrontation brews as mobsters, mercenaries, and vigilantes collide at the sinister Happy Hollow Hunt Club, a fortress guarded by electrified fences, ruthless enforcers, and monstrous wild hogs.

Vietnam veteran Gene Brooks and young Matt Henry refuse to let evil reign in their town. With a team of unlikely heroes, they take the fight to the mob in a battle of grit, survival, and vengeance— culminating in a heart-stopping showdown at the historic One Thousand Steps.

“The latest visit to Twin River becomes an exhilarating exercise in sustained, multipronged tension” - Kirkus Reviews

“Intense, sinister, and thrilling, Michael Fields has finished the Twin River Series with a powerful ending” - Readers’ Favorite

Twin River IV: C U When U Get There

The final book in the Twin River series, C U When U Get There, delivers an explosive conclusion filled with terror, survival, and vengeance.

Resurrected in Death Valley, Cain Towers embraces his brutal nature. With his ruthless uncle Abel, he returns to Twin River, Pennsylvania, seeking revenge against Vietnam veteran Gene Brooks and the town that betrayed him. But their deadly path collides with three vulnerable teens— Stanley Banks, Niles Wilson, and Amber Crawford—who must fight to survive.

Inspired by real-life crimes, Fields delivers a relentless, pulse-pounding thriller. From the scorching desert to a town on edge, Twin River IV is an electrifying finale that will leave readers breathless.

“What you read in her collection of articles is what happens when a Black journalist does not compromise their identity to do their job.”

- Sonya Green, journalistpected Journalist, essays by Reagan Jackson

Through this collection of essays, author and activist Reagan Jackson, chronicles her journey into the world of journalism. Art, cinema, social justice, feminism, Black reparations, health & reproductive rights, dance, education—while Jackson’s subjects range far and wide, her writing brings an intimacy & immediacy to all.

“Emotions roar off the pages, pure, raw, and bristling. Long, meandering sentences lead the way, doubling back, bounding forward, and experimenting with language. Conversations run without punctuation or tags; different consciousnesses bleed together.”

- Elaine Chiew, Forward Reviews

Three Alarm Fire is a collection that presses into the most important concerns of our time. With a diverse set of characters and experiences, Juan Carlos Reyes’s debut fiction collection examines the range of grief and healing we navigate as Americans. Reyes explores themes of immigration, identity, family legacy, sexuality, trauma, and what belonging means, as well as the cultural tensions between us that can be downright explosive.

“A heartfelt story that took me back to the ‘inbetween’ chapter of my own life—an experience many other readers will relate to as well. I was sorry to see my time end with Joann and her crew.” - Maggie Carr, Co-founder, Elliott Bay Book Company, Seattle

At The Sylvan, a small Seattle luxury hotel, Joann finds herself caught between late-night confessions, love affairs, and friendships while trying to figure out her future. As the 90s roll on, a deepening connection with a teammate forces Joann to confront the bittersweet adventure of growing up, all while navigating the quirky, electric world of the hotel’s swing shift.

VIEW MORE TITLES AT HINTON PUBLISHING

My Bully, My Aunt, & Her Final Gift

Harold Phifer

Discover Resilience in the Face of an Unlikely Relationship

In My Bully, My Aunt, and Her Final Gift, Hal confronts the bittersweet memories of his childhood, shaped by his aunt’s unpredictable and often cruel influence. As he plans her memorial—a gathering no one seems eager to attend—Hal is pulled back into a world of twisted philosophies and emotional turbulence.

But amid the chaos, he discovers unexpected lessons that lead to healing, self-discovery, and redemption. Through laugh-out-loud moments and heartfelt revelations, this memoir reveals how even the darkest

Translation Nation:

10 Indie Presses Bringing the World to Your Bookshelf

BY CORINNA KLOTH

Translated fiction opens doors to voices, landscapes, and storytelling traditions that might otherwise remain out of reach. While the giants of publishing occasionally spotlight works in translation, it’s the small presses that consistently take risks, nurture new literary bridges, and expand what we can access in English. From the bold experiments of Deep Vellum to the elegant global catalog of Europa Editions, the mission-driven catalog of Open Letter, and the vibrant storytelling of Charco Press, these publishers are at the heart of a cultural exchange that feels both urgent and timeless. Here, we spotlight four presses and a standout title from each—books that remind us why translation matters.

1. Deep Vellum

(Dallas, TX)

Founded in 2013, Deep Vellum has become the largest U.S. publisher devoted to literary translation, operating several imprints like Phoneme Media, A Strange Object, and La Reunion. Its catalog spans over 1,000 titles from more than 60 languages and 75 countries— often emphasizing social justice and cultural diversity in fiction, poetry, and narrative nonfiction. The press has won major awards such as the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation and Big Other Book Award in Fiction, and its founder was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by France in 2024.

STANDOUT TITLE:

Solenoid by Mircea Cărtărescu (translator Sean Cotter), a mind-bending, philosophical novel set in communist Bucharest that received the €100,000 Dublin Literary Award in 2024, praised for its lyrical inventiveness and existential depth.

2. Europa Editions (New

York, USA)

Established in 2005, Europa Editions rapidly gained global recognition by launching high-impact literary international titles— most famously Elena Ferrante’s The Days of Abandonment and the Neapolitan series, which became global phenomena. Their editorial ethos blends literary elegance with broader accessibility. Europa consistently brings best-selling, acclaimed authors from Europe, Latin America, and beyond to English-language readers.

STANDOUT TITLE:

The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante ( translator Ann Goldstein)—an emotionally seismic novel that established both Ferrante’s career and Europa’s reputation on the international stage.

3. Open Letter Books (Rochester,

NY)

Since 2007, Open Letter has focused on a tightly curated annual list (around ten titles), prioritizing literary risk-takers and works of high artistic merit. In March 2025, it joined Deep Vellum officially to strengthen its distribution and reach. Open Letter is especially known for publishing prize-nominated and award-winning fiction in translation.

STANDOUT TITLE:

Melvill by Rodrigo Fresán (transl. Willanderhyden), which won the 2024 Republic of Consciousness Prize, representing the press’s commitment to experimental, boundary-crossing narratives.

4. Charco Press (Edinburgh,

UK)

Founded in 2016, Charco Press has quickly established itself as a vital publisher of contemporary Latin American fiction in English translation. With a sharp focus on bringing bold, socially engaged narratives to anglophone readers, Charco has introduced a range of innovative voices—from debut novelists to prizewinners—often from underrepresented countries and regions. The press has garnered multiple accolades, including International Booker Prize shortlistings and the Republic of Consciousness Prize, and was named Scotland’s Small Press of the Year in both 2021 and 2023.

STANDOUT TITLE:

Of Cattle and Men by Ana Paula Maia (transl. Zoë Perry). This stark, powerful novella centers on a slaughterhouse inspector navigating cycles of violence, labor, and masculinity in rural Brazil.

5. Archipelago Books (Brooklyn, NY)

Archipelago is a nonprofit press founded in 2003, devoted to bringing both contemporary and classic world literature in translation to English-language readers. They publish a beautifully curated list of fiction, poetry, and essays from a wide range of countries and languages—often championing pioneering or overlooked translations. Their editions are known for striking design and literary rigor, and their roster includes authors like Elias Khoury, Julio Cortázar, Mircea Cărtărescu, and Karl Ove Knausgaard.

STANDOUT TITLE:

Eastbound by Maylis de Kerangal (transl. Jessica Moore). Originally published in French in 2012 and translated by Archipelago in 2023, this novel follows a young Russian conscript attempting to desert across the Trans - Siberian railway.

6. New Vessel Press (New York, USA)

Founded in 2012, New Vessel Press focuses primarily on literary fiction and narrative nonfiction in translation. Their selections span global voices, with particular attention to writers exploring themes of memory, identity, and social justice. The press positions itself at the intersection of literary and intellectual inquiry, and its books often receive award recognition and deep critical reflection. The editorial ethos values translation as a form of creative collaboration.

STANDOUT TITLE:

The Words That Remain by Stênio Gardel (transl. Bruna Dantas Lobato). This debut novel offers an intimate, socially engaged portrayal of poverty and literacy in Brazil. Its translational nuance and emotional clarity earned it the 2023 National Book Award for Translated Literature.

7.

Istros Books (London,

UK)

Since its founding in 2011, Istros has specialized in literature from Southeast Europe and the Balkans—regions often sidelined in anglophone publishing. They spotlight writers from countries including Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, and Montenegro, publishing fiction and nonfiction with cultural specificity and literary resonance. Istros has introduced numerous authors to English-speaking audiences, often ranking as the premier Balkan-focused press in translation.

STANDOUT TITLE:

Doppelgänger by Daša Drndić (transl. Celia Hawkesworth & S.D. Curtis). A dense and haunting meditation on history, identity, and atrocity, this Croatian novel weaves documentary fragments, letters, and narrative to evoke the psychic weight of war-torn memory. It remains one of Istros’ most lauded releases.

8. Les Fugitives (London,

UK)

A boutique press dedicated to francophone women writers, Les Fugitives often publishes short, genre-bending works that defy conventional categories. Essays, memoirs, and literary hybrids are brought into English with care and poetic attention. The press is known for thematic coherence, feminist insight, and thoughtful translation—often spotlighting voices from Côte d’Ivoire to France who have not been previously published in English.

STANDOUT TITLE:

Suite for Barbara Loden by Nathalie Léger (transl. Natasha Lehrer & Cécile Menon). A lyrical and layered meditation on the actress-filmmaker Barbara Loden, this book interweaves film theory, biography, and personal reflection. Praised for its originality and emotional depth, it won the Scott Moncrieff Prize.

9. Two Lines Press (Oakland,

CA)

Two Lines specializes in literary fiction and nonfiction in translation from Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. The press champions culturally specific voices, often tackling themes of tradition, resistance, and desire within their regional contexts. While they have a relatively small list, their editorial focus favors urgency, representation, and craftsmanship—especially from queer and women writers as part of their Calico series and beyond

STANDOUT TITLE:

Lake Like a Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (transl. Natascha Bruce). A collection of nine powerful short stories from Malaysian writer Ho Sok Fong, this volume illuminates the emotional and social lives of women grappling with tradition, identity, and intimacy.

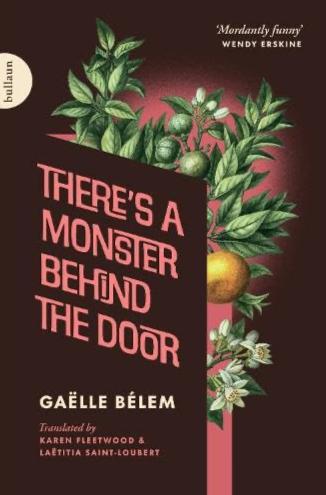

10. Bullaun Press (Dublin, Ireland)

Founded in 2021 by Bridget Farrell, Bullaun Press is dedicated to literary translation—particularly politically engaged and formally dynamic works from francophone authors and beyond. Its name draws from Irish folklore (bullán stones with hollow reverence), signaling a small press rooted in place yet oriented outwardly toward global conversation. Despite its youth, Bullaun has already earned major recognition in the UK–Irish small-press scene.

STANDOUT TITLE:

There’s a Monster Behind the Door by Gaëlle Bélem (transl. Karen Fleetwood & Laëtitia Saint-Loubert). A debut picaresque satire set in 1980s Réunion Island, this novel blends dark humor, postcolonial critique, and familial drama. It won the 2025 Republic of Consciousness Prize.

Small presses remind us that some of the most powerful literary exchanges don’t come from the mainstream, but from dedicated publishers working on the margins with vision and heart. By championing translated fiction, these presses make room for voices that challenge assumptions, celebrate difference, and connect readers across borders. Every book on their lists carries not only the story of its author, but the cultural context and history of the place it comes from—transformed yet preserved through the art of translation.

For readers, supporting these publishers is more than adding a great book to the shelf. It’s an act of participation in a global conversation. Each purchase, each recommendation, each moment spent inside a translated novel helps sustain the ecosystem that allows new stories to reach us. Translators, editors, and small press teams work tirelessly, often with limited resources, to ensure that these books don’t just exist but thrive in a crowded publishing landscape. Their work is a reminder that literature isn’t just entertainment; it’s a bridge.

As you explore the standout titles from Deep Vellum, Europa Editions, Open Letter, and Charco Press, consider them an invitation. An invitation to step into unfamiliar worlds, to listen to voices shaped by different languages and lived experiences, and to recognize the common threads that connect us all. The more we read across borders, the more we see that literature is not bound by geography—it’s a universal language of its own.

S T AGR

BOO K S T ARGA M

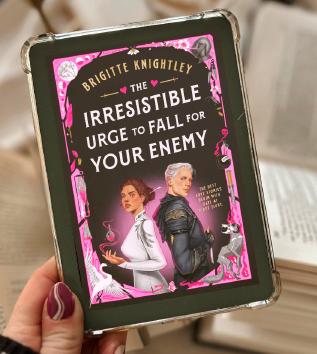

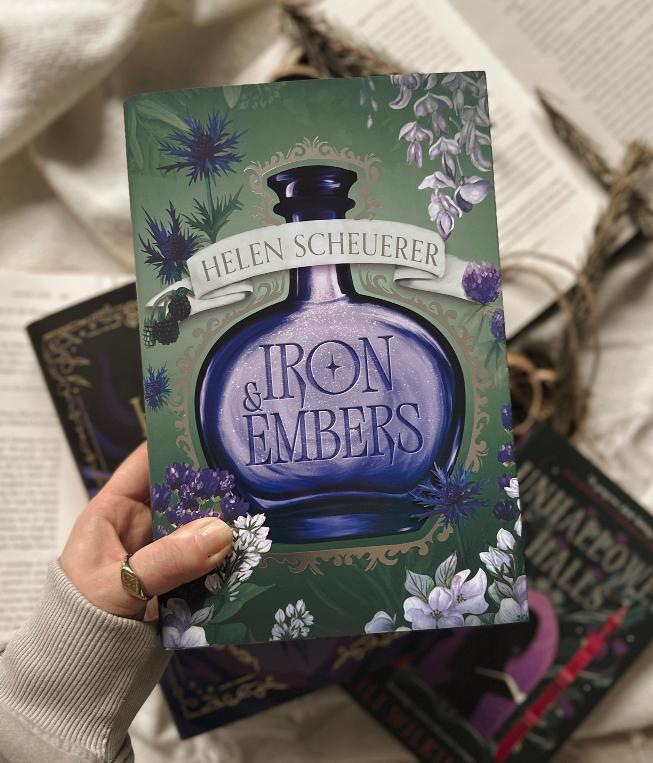

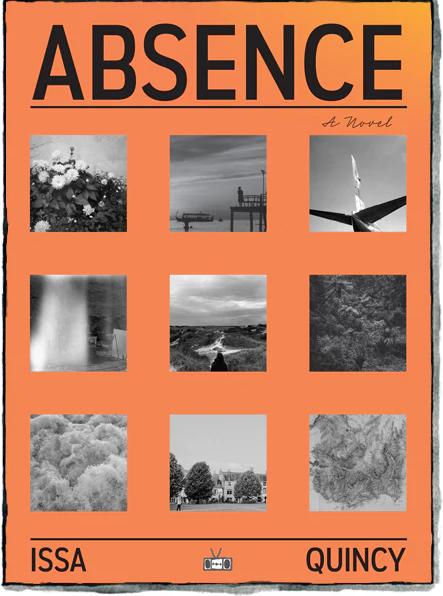

BOOKSTAGRAM

Each issue we feature a new bookstagrammer highlighting some of their amazing work.

@EverythingSophieReads

TELL US A LITTLE ABOUT YOU.

Sophie: I’m a year old bookstagrammer from Northern Ireland! I live with my partner, our two Siberian Forest cats, Arlo and Fiadh, as well as our Cocker Spaniel puppy, Fen. I work in IT and spend my evenings walking the dog, reading and I’ve recently discovered that I love to bake!

TELL US A LITTLE ABOUT YOUR BOOKSTAGRAM ACCOUNT AND HOW IT GOT STARTED.

Sophie: I’ve always loved reading but took a big break after finishing my MA in English Literature and started my bookstagram when I started to get back into it a couple of years back. I’ve met so many amazing people and had conversations with new friends from all over the world thanks to our love of fictional worlds!

WHO IS YOUR FAVORITE INDIE/SMALL PRESS AUTHOR AND WHY?

Sophie: Callie Hart! I read her self-published novel Quicksilver before it was picked up and traditionally published and I LOVED IT!

ALLTIME FAVORITE INDIE BOOK?

Sophie: Ice Planet Barbarians by Ruby Dixon! This series is so much fun and spicy, as well as tackling some really tough issues. I’ve enjoyed pretty much everything this author has written.

NAME: SOPHIE

FAVORITE GENRE: IT’S A MIX-UP OF HISTORICAL FICTION, THRILLERS, FANTASY AND SCI-FI.

BOOKS READ PER YEAR: USUALLY AT LEAST 100 - I TRY TO BEAT MY PREVIOUS YEARS GOAL! THIS YEAR I’M AIMING FOR 120.

FAVORITE BOOK: MY FAVOURITE BOOK OF ALLTIME IS PROJECT HAIL MARY BY ANDY WEIR - I REREAD IT EVERY YEAR!

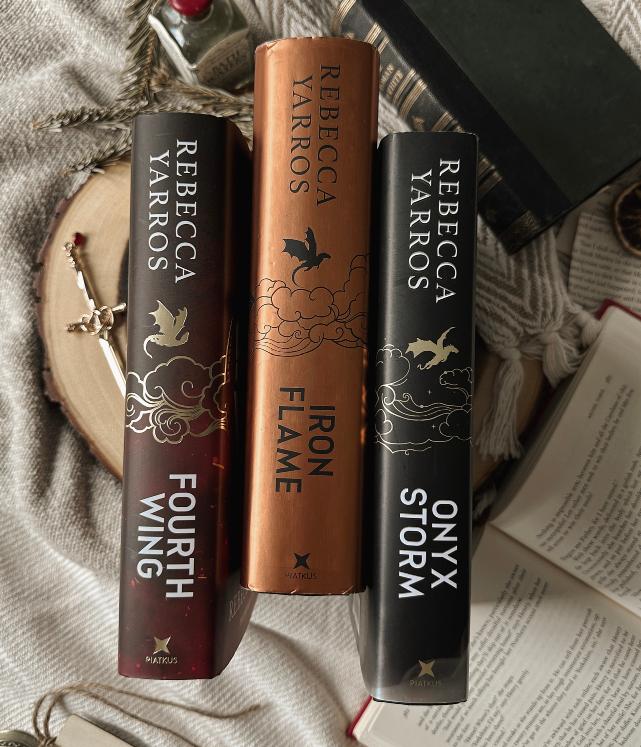

TELL US A BIT ABOUT WHY THE BOOKSTAGRAM COMMUNITY IS IMPORTANT TO YOU.

Sophie: Reading has always been something i’ve enjoyed, especially as a child. I can totally fall into fictional worlds and forget about any worries or stress I might have/be feeling that day. It’s the ultimate escapism! As far as bookstagram goes, it’s been so much fun chatting with other readers about the books we love (or didn’t enjoy!) and the buzz around big publishing dates (Onyx Storm By Rebecca Yarros for example) is just the best! I feel part of a really positive community and I love getting book recommedations too!

@EVERYTHINGSOPHIEREADS

SEE MORE BOOK ADVENTURES ON INSTAGRAM

Interview with Will Vanderhyden. Translator

of Gloria by Andrés

Felipe Solano

BY MICHELE MATHEWS

Andrés Felipe Solano’s Gloria is a layered, intimate novel brought into English by longtime collaborator and translator Will Vanderhyden. In this interview, Vanderhyden shares what drew him to the book, the challenges of capturing its unique perspective, and what he hopes readers will take away.

What initially drew you to Gloria, and how did you come to translate this particular novel?

WV: I’ve known Andrés Felipe Solano and have been a big fan of his work for more than a decade. Over the years I’ve translated samples of several of his books, which his agent would subsequently pitch to different publishers, hoping to find a home for his work in English. Gloria is his most recent novel, and so, like with his previous books, I translated a sample that his agent sent to publishers in the U.S. and U.K. And Dan López, a great editor at Counterpoint Press, ended up acquiring the rights, and he contracted me to do the translation.

What drew me to Gloria and to all of Andres’s work is his unique sensibility as a writer: he has an elegant and understated style, where not a word is wasted and everything is layered with meaning; a journalist’s eye for descriptive detail and an uncanny sense of pacing that allow him to efficiently construct character, mood, and atmosphere; and an interest in crafting intricate narrative structures that refract the specific and

personal into the timeless and universal. This sensibility is present throughout Andrés’s work, but I think Gloria is its most distilled and accomplished expression to date.

What were some of the biggest linguistic or stylistic challenges you encountered in translating Gloria?

WV: Getting the narrative perspective to feel right was one of the bigger challenges. The story is told in a close third-person, from the perspective of Gloria’s son, self-reflectively using a day in his mother’s life as a prism to try to understand her by turning her into a character and telling her story.

Andrés makes inhabiting that perspective seem effortless, zooming in and zooming out, jumping around in time, moving fluidly from Gloria’s interiority to subtle details that evoke her particular time and place in history to meta comments on aspects of the story he’s constructing as he’s constructing it. And he does all of this in a way that’s both intensely grounded and mysterious—there’s no hand-holding, no superfluous exposition.

It’s a lot to balance, but getting it right was fundamental to making the book work, so I spent a lot of time thinking about that POV and did my best—over the course of multiple revisions—to make it come alive in English.

Were there any particular passages or moments in the book that were especially rewarding—or maddening—to translate?

WV: Nothing that was especially maddening. There were many rewarding moments— beautiful lines, insights, impressive narrative maneuvers—but without context, without over-explaining or spoiling elements of the story, it’s hard to be specific.

I guess I can say that I really love the beginning, how, within a few pages, Andrés is able to evoke Gloria’s tumultuous inner life and the heightened tension of the day when we meet her, to ground us in a particular time and place, and to introduce the narrative conceit of the POV mentioned previously.

Here’s the opening passage:

“Getting that feeling dialed in in English was very rewarding and gave me a strong sense for how to spproach the rest of the book.”

“She has never smoked and may never light up a cigarette, but today, which I decide to imagine bright and bustling,

she should, she should take advantage of her boyfriend being late to slowly inhale the smoke, aware of how her lipstick is leaving a mark on the filter, the nervous pressure of her lips giving it a slightly oval shape. Inside that silvery blue cloud of smoke, the wait is less agonizing, more bearable, as they say of certain afflictions, because that’s what it is, a disquiet she discovered upon waking that morning, earlier than usual, when the light slipped softly in through her room’s window and she couldn’t yet hear animals knocking over bottles on that street corner in Queens. When she first opened her eyes, she’d even felt hopeful, reentering the world without fear. It usually takes her a little while to come to terms with what it is to be alive and awake, a few minutes to tentatively break the waters of sleep, but today is different, because today is a day that should last forever—that is, if Tigre ever bothers to show up.”

Getting that feeling dialed in in English was very rewarding and gave me a strong sense for how to approach the rest of the book.

How

do you approach preserving an author’s voice,

especially one as distinctive as Solano’s while still creating a fluid reading experience in English?

WV: When I’m translating, I think a lot about trying to make the feeling I get when I read the text that I’m writing in English mimic the feeling I get when I read the Spanish text, to use the tools of English and whatever skills I have as a writer to create an analogous experience that’s ultimately subjective, but that I hope will play on other readers’ nerve endings the way it plays on mine.

So, for me, it’s less about preserving the author’s voice and more about finding a way to recreate my own version of it. My process generally involves, in early drafts, following my intuition and letting myself make the choices that feel right in the moment, and then going back and putting the text through a pretty intense process of revision. And it’s usually through that process that I’m able to hone in on and fine-tune my English version of the author’s voice.

What was your working relationship like with Andrés

Felipe Solano during the translation process?

WV: Like I said, I’ve known Andrés for a long time and we’ve worked together on multiple projects, so we have a very comfortable and affable working

relationship. Typically, the process involves me getting to a place where I’m pretty happy with the translation and then turning it over to Andrés with a list of questions. He goes through the text and answers my questions and offers edits where appropriate. His English is quite good and he’s a translator himself, so we have a lot of trust in and respect for each other, which makes the process easy and fun and enlightening.

Gloria is known for its layered, introspective, and at times disorienting narrative. How did you balance clarity with fidelity to that complexity in English?

WV: I think this gets back to what I was saying about the POV. And so I guess I’ll refer back to that previous answer and just add that getting the POV to feel right is how I was able to strike the balance you mention in my translation. And the way I was able to get the POV to feel right was through revision.

How do you deal with ambiguity in the original text— do you try to clarify or preserve it?

WV: If something is ambiguous in the original text, I generally try to preserve that ambiguity. I try not to introduce ambiguity that isn’t there in the original, if I can avoid it. But generally, I trust that readers are smart and that ambiguity is part of what makes fiction great.

Do you see yourself more as an interpreter, a co-creator, or something else entirely when translating fiction?

WV: I don’t really buy into one particular metaphor for what I’m doing when I’m translating fiction. I think they’re all useful and inadequate in different ways. As I’ve said, for me, translating is about trying to recreate the feeling that I have while reading the Spanish when I read my English version. This is necessarily a subjective experience, and I can only hope that what feels right to me resonates with Englishlanguage readers.

HOW DO YOU NAVIGATE THE LINE BETWEEN STAYING TRUE TO THE ORIGINAL AND ENSURING THE TRANSLATED VERSION READS SMOOTHLY TO AN ENGLISH-SPEAKING AUDIENCE?

WV: Every translation is different and makes different demands of the translator and finding that balance you mention is always key, but I think, for me, again, the answer here is revision. For me, there’s usually a moment in the process of revision (sometimes it comes quickly and other times it’s more hard won), where things start falling into place and really clicking and the text starts to come alive in English. For me, it’s the most gratifying and creatively stimulating aspect of being

a translator and probably the reason why I do it.

Are there particular things you hope readers take away from this translation?

WV: I hope that all the things I’ve mentioned about Andres’s style and sensibility come across in the translation and that readers enjoy the book and find it beautiful and moving and deep.

How do you choose which books to translate? What do you look for in a project?

WV: Generally, I look to translate books that I love to read and want to write. So, I follow my tastes as a reader and my interests as a writer. Of course, this “job” is always a hustle, so, when presented with an opportunity that might not seem a natural fit at first blush, usually I’m grateful for the opportunity and happy to take a stab at it anyway.

Are you currently working on translating any other works by Solano—or other authors you’re excited about?

WV: I’m not currently translating anything by Andrés, but I know he has a new project he’s working on, which I can’t wait to check out whenever he’s finished.

I just finished translating a book by Rodrigo Fresán called Mantra, and I’m

in the middle of translating Fernando Arumburu’s El niño. This is the sixth novel of Fresán’s I’ve translated and the first of Arumburu’s. I’m pretty excited about both books and authors.

Through Will Vanderhyden’s translation, Gloria becomes not just a story of one woman’s life, but a testament to the delicate, intricate art of carrying a writer’s vision across languages. Vanderhyden’s deep respect for Andrés Felipe Solano’s sensibility— his precision, atmosphere, and layered

narrative—shines in his thoughtful approach to voice, perspective, and ambiguity. As Gloria reaches new readers in English, the novel invites us into its richly intimate world, while also reminding us of the translator’s quiet but essential role: bridging distances so that literature may resonate universally.

Centered around a real-life, historic concert at Madison Square Garden, this wide-ranging and nostalgic novel spans two continents and five decades as it charts the interlaced lives of a mother and son in New York City.

It is a bright spring Saturday: April 11, 1970. The famous Argentine singer Sandro is about to become the first Latin American to perform at Madison Square Garden, and Gloria will be one of the lucky attendees at what will be a legendary concert. At just twenty years old, the young woman walks through the electric streets of New York City full of hope and possibility. The disturbing images she recently encountered at her job at a photographic laboratory, the trauma of a father who was murdered when she was a child, and even the long-term prospects of her relationship with Tigre, her irascible boyfriend, are problems for another day. This day should be perfect and should last forever. Which it will, in surprising and unexpected ways.

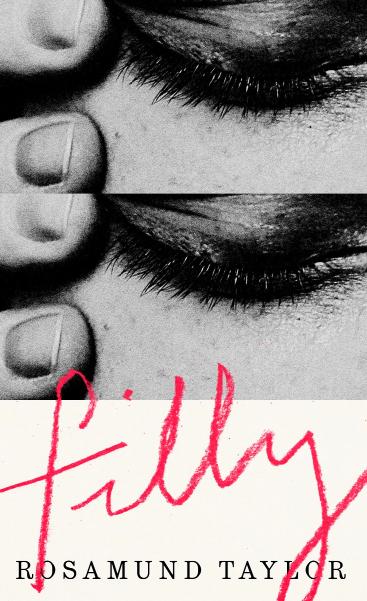

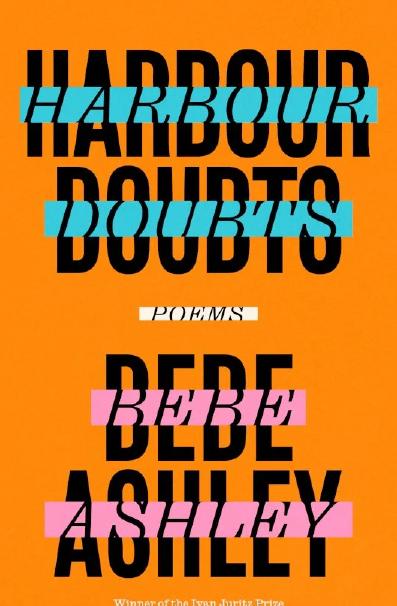

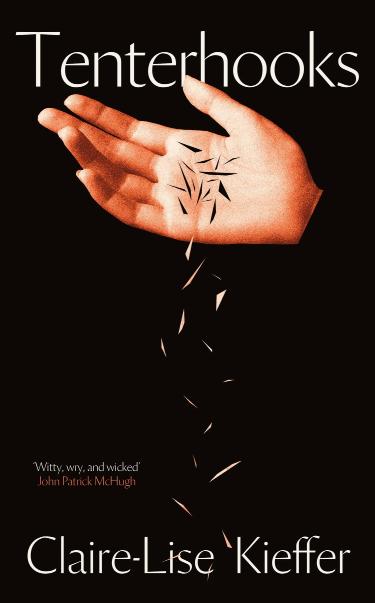

New Release Roundup: Fall 2025.

A Compilation of Translated Literature.

BY CORINNA KLOTH

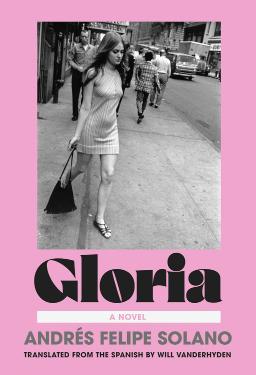

VI KHI NAO & LILY HOANG

Vi Khi Nào is the author of many books and is known for her work spanning poetry, fiction, theatre, film, and interdisciplinary collaborations, most recently The Italy Letters (Melville House) and The Six Tones of Water, coauthored with Sun Yung Shin (Ricochet). Lily Hoang is the author of five books, including A Bestiary (finalist for a PEN USA Nonfiction Book Award) and Changing (recipient of a PEN Open Books Award).

TIMBER & LUA

Timber & Lụa exists in duality as both original, innovative collaboration between Lily Hoàng and Vi Khi Nào and their primarily selftranslations of said work. Comprised of ten short experimental stories, Timber & Lụa is written in three different languages: Vietlish, Vietnamese, and English. Similar to Samuel Beckett and Vladimir Nabokov, who translated their own work (from English to French and from Russian to English, respectively), Hoàng and Nào extend that makeshift “tradition” by hybridizing their translation to graft the genetic material of one language (English) and the genetic material of another language (Vietnamese) to produce a new literary diasporic genre. From love story to the speculative to fairy tale, these ten stories accentuate Hoàng and Nào’s dynamic, eccentric range. Timber & Lụa coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of the Fall of Saigon (1975–2025), as a diasporic literary contribution and commemorative celebration.

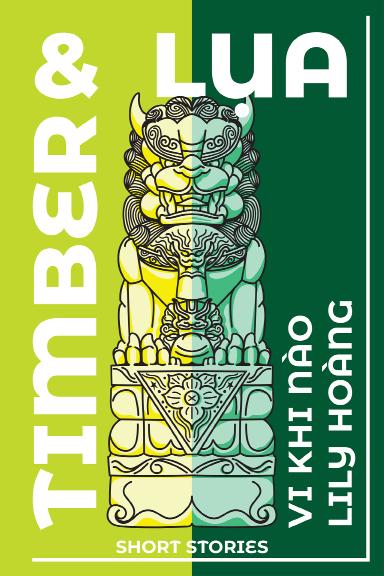

MY HEAVENLY FAVORITE

TRANSLATED BY MICHELE HUTCHISON

A confession, a lament, a mad gush of grief and obsession, My Heavenly Favorite is the remarkable and chilling successor to Lucas Rijneveld’s international sensation, The Discomfort of Evening. It tells the story of a veterinarian who visits a farm in the Dutch countryside where he becomes enraptured by his “Favorite”—the farmer’s daughter. She hovers on the precipice of adolescence, and longs to have a boy’s body. The veterinarian seems to be a tantalizing possible path out from the constrictions of her conservative rural life.

Narrated after the veterinarian has been punished for his crimes, Rijneveld’s audacious, profane novel is powered by the paradoxical beauty of its prose, which holds the reader fast to the page. Rijneveld refracts the contours of the Lolita story with a kind of perverse glee, taking the reader into otherwise unimaginable spaces. An unflinching depiction of abjection and a pointed excavation of taboos and social norms, My Heavenly Favorite “confirms Rijneveld’s singular, deeply discomforting talent” (Financial Times UK).

LUCAS RIJNEVELD

Lucas Rijneveld grew up in a Reformed farming family in North Brabant before moving to Utrecht. He is the author of The Discomfort of Evening, which was the first Dutch book to win the International Booker Prize, as well as three poetry collections.

DANTE ALIGHIERI

Mary Jo Bang has published eight poetry collections, including A Doll for Throwing and Elegy, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award, and new translations of Dante’s Inferno and Purgatorio. She teaches at Washington University in Saint Louis.

PARADISO

TRANSLATED BY MARY JO BANG

Mary Jo Bang’s translation of Paradiso completes her groundbreaking new version of Dante’s masterpiece, begun with Inferno and continued with Purgatorio. In Paradiso, Dante has been purified by his climb up the seven terraces of Mount Purgatory, and now, led by the luminous Beatrice, he begins his ascent through the nine celestial spheres of heaven toward the Empyrean, the mind of God. Along the way, we meet the souls of the blessed—those at various proximities to God, but all existing within the bliss of heaven’s perfect order. Philosophically rich, spiritually resonant, Paradiso is a reckoning with justice and morality from a time of ethical questioning and political division much like our own.

I GAVE YOU EYES AND YOU LOOKED TOWARDS DARKNESS

TRANSLATED BY MARA FAYE LETHEM

Dawn is breaking over the Guilleries, a rugged mountain range in Catalonia frequented by wolf hunters, brigands, deserters, race-car drivers, ghosts, and demons. In a remote farmhouse called Mas Clavell, an impossibly old woman lies on her deathbed. Family and caretakers drift in and out. Meanwhile, all the women who have lived and died in that house are waiting for her to join them. They are preparing to throw her a party. As day turns to night, four hundred years’ worth of stories unspool, and the house reverberates with raucous laughter, pungent feasts, and piercing cries of pleasure and pain. It all begins with Joana, Mas Clavell’s matriarch, who once longed for a husband—“a full man,” perhaps even “an heir with a patch of land and a roof over his head.” She summoned the devil to fulfill her wish and struck a deal: a man in exchange for her soul. But when, on her wedding day, Joana discovered that her husband was missing a toe (eaten by wolves), she exploited a loophole in her agreement, heedless of what consequences might follow.

IRENE SOLA

Irene Solà is a writer and visual artist. She is the author of the novels The Dams, When I Sing, Mountains Dance, and I Gave You Eyes and You Looked Toward Darkness, and Beast, a poetry collection.

ELISA LEVI

Elisa Levi is the author of a poetry collection and two novels. She specialized in playwriting at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Her short stories have been anthologized, and she has translated several books from English to Spanish.

THAT’S ALL I KNOW TRANSLATED BY CHRISTINA MACSWEENEY

Nineteen-year-old Little Lea lives in a rural town where life ends at the edge of the forest.

When a stranger loses his dog on the first day after the end of the world, Little Lea warns him not to follow it into the forest, that people who enter never come out. Over a shared joint, she tells him about the burning in her gut, winding a tale of loss, desire, and conspiracies.

Little Lea sees the world through backcountry eyes that distrust the outsiders who come but who also get to leave. When she isn’t working at her mother’s grocery store, she cares for her empty-headed younger sister, Nora, who only cries when she’s in pain. Meanwhile, her friend Catalina does nothing but cry. Little Lea wants Javier to love her, and she doesn’t want Marco, who leaves weed and his best potatoes on her doorstep. As the town prepares for their end-of-the-world festival, she faces her intensifying desire to leave, that burning that unsettles her life—she wants to be useful somewhere else, even if it means being unloved, unwanted, unable to return. That’s all she knows.disillusionment, and a clear-eyed examination of the passions that rule our lives and make history.

THE BOOK OF HOMES

TRANSLATED BY ELIZABETH HARRIS

The Book of Homes is the story of a man and his friendships, his upbringing, his discovery of sex and poetry, his detachment from a self-destructive family, and his liberation from the furniture that has followed him through 20 years of moves. His story jumps from home to home, upstairs to downstairs, each home a piece of the puzzle of his life. In its extraordinary, ambitious architecture, this novel brings to light all the stories hidden in the silence of domestic spaces.

ANDREA BAJANI

Andrea Bajani was born in Rome in 1975. He is the author of many award-winning novels, including, in English translation, If You Kept A Record of Sins (Archipelago, 2021) and Every Promise (Maclehose Press, 2013). He is currently a writer in residence at Rice University in Houston, Texas.

LEIF HOGHUAG

Giulio Mozzi has published twenty-six books—as fiction writer, poet, and editor. He is primarily known for his story collections, especially This Is the Garden, which won the Premio Mondello. “The Apprentice” (included in this collection) appears in an anthology of the top Italian stories of the twentieth century. He has even created an imaginary artist, Carlo Dalcielo, whose work has appeared in public exhibitions and books, like Dalkey Archive Press’s Best European Fiction 2010.

THE CALF

TRANSLATED BY DAVID M. SMITH

On violence, crime, guilt and atonement. We meet our narrator in an underground office where he sharpens pencils, shreds paper, makes coffee for the other employees and thinks over and over about a late night that he has been trying to forget for a long time. In between the meaningless work, he manages to scratch down some names and phrases, and conjures up a dream from 1980s Hadeland. In this saga, Hadeland is a shadow home where spooks, ghosts, angels and robot-like creatures are just as natural as animals and flesh and blood humans. But what happened that late summer night? What is it that the narrator has tried to forget? And who is this Calf, who was “killed to death”? Our narrator takes readers in circles through different events, times and places; a whirlwind in which the calf and other characters are like prisoners in a tornado from Dante’s Inferno.

THE INVISIBLE YEARS

TRANSLATED BY LILY MEYER

Andrea and Julián haven’t seen one another in twenty-one years—not since that tragic, fateful night their senior year of high school that marked their group of friends forever. A shocking phone call brings the two together again in Houston, where they begin to unravel the truth of that year, picking open long scabbed-over wounds from their upper-class adolescence in 1990s Bolivia and the scandal that ripped them apart.

A writer unhappy in his career and his marriage, Julián has been novelizing the past for his next book, trying to make meaning out of the events that changed the course of their lives forever. “I’d thought that writing about that time would free me, relieve the burden of the invisible years,” he writes, “but often it seems that it’s done the reverse.”

Juxtaposing the naïve invincibility of adolescence with the grasping uncertainties of adulthood, The Invisible Years deftly weaves a coming-of-age tale that leaves the reader hanging on every word, even as they know how the cards fall in the end.

RODRIGO HASBUN

Rodrigo Hasbún is a Bolivian writer and screenwriter. He is the author of eight works of fiction and nonfiction, including the novel Affections (Simon & Schuster), which received an English PEN Award and has been translated into twelve languages. Named one of Granta’s Best Young Spanish-Language Novelists in 2010, Hasbún’s short stories have appeared in Granta, McSweeney’s, Zoetrope: All-Story, Words Without Borders, and elsewhere. He lives and works in Houston.

YE HUI

Ye Hui is an acclaimed Chinese metaphysical poet who lives in Nanjing. His poems in Dong Li’s English translation have appeared or are forthcoming in 128 Lit, The Arkansas International, Asymptote, Bennington Review, Blackbird, Cincinnati Review, Circumference, Copihue Poetry, Guernica, Kenyon Review, Lana Turner, Nashville Review, POETRY, Poetry Northwest, and Zocálo Public Square.

THE RUINS TRANSLATED BY DONG

LI

Here’s a witch poet walking backward into the future. There’s an architect dispelling illusions and inviting us into communal living. The poems collected in The Ruins rise from a primordial wisdom that resists the quarrels of the marketplace, that keeps company under a leaky authoritarian roof and rubs off its burn, that carves out its own impossible freedom. In Dong Li’s luminous translation of Ye’s first fulllength collection, each poem braids myth and mystery, inviting the reader into a liminal space where “echoes of the ancient, the imagined, and the ‘now’ sound off each other” on the page (The Cincinnati Review).

(TH)INGS AND (TH)OUGHTS

TRANSLATED BY ELINA ALTER

From a rising star of Russian literature, a collection of short stories that straddles the line between delight and horror.

Twisting the art of the fairytale into something entirely her own, Alla Gorbunova’s (Th)ings and (Th)oughts is an endlessly inventive collection of thematically-linked short prose. Divided by subject—romance, philosophy, fate—the stories in this collection turn a magical lens to bitter realities.

ALLA GORBUNOVA

Alla Gorbunova was born in Leningrad in 1985 and studied philosophy at St. Petersburg State University. She is a poet and the author of several books of prose. Her book, It’s the End of the World, My Love, became Russia’s most discussed literary publication in 2020 and received The New Literature Prize 2020.

LEYLA ERBIL

One of the most influential Turkish writers of the 20th century, Leylâ Erbil was an innovative literary stylist who tackled issues at the heart of what it means to be human, in mind and body. Erbil ventured where few writers dared to tread, turning her lens to the tides of social norms and the shaping of identities, focusing intently on emotional conflict, and plumbing the depths of history and psyche.

WHAT REMAINS

TRANSLATED BY ALEV ERSAN, MARK DAVID WYERS, AND AMY MARIE SPANGLER

An experimental collection of “proems” from poet and author Leylâ Erbil, the first Turkish woman to ever be nominated for the Nobel.

These poems recount the history and present of the Turkish state, from the Byzantine Empire through the twentieth-century Turkey of Erbil’s experience. Now available for the first time in translation, What Remains is a fearless, deeply felt collection from one of the most influential Turkish writers in recent history.

THE ANIMAL ON THE ROCK

TRANSLATED BY LIZZIE DAVIS AND KEVIN GERRY DUNN

After the death of her mother, Irma decides to take a plane and hole up on a faraway beach. Through the course of her grief, the protagonist’s body, her instincts, and her perception, begin to experience a transformation as unexpected as it is natural. The skin over her joints become thick and scaly, her eyes take on a yellow gleam, and she spends more and more time bathing in the hot sun.

In these pages, Tarazona manages to address the perennial literary theme of metamorphosis, without relying on simple fantasy or didactic symbolism. More than a fable or a supernatural diversion, The Animal on the Rock is a profoundly biological and introspective novel with universal resonances.

DANIELA TARAZONA

Daniela Tarazona (Mexico City, 1975) is the author of Divided Island, winner of the prestigious Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize and published by Deep Vellum in 2024. In 2012, she published the novel El beso de la liebre (Alfaguara), which was shortlisted for the Las Américas Prize in 2013. In 2020, the book Clarice Lispector: La mirada en el jardín (Lumen) was published, co-written by Tarazona and Nuria Mel. Her work has been translated into English and French. She has been a fellow of Mexico’s Young Artists program and is currently a member of the FONCA fund’s National Network of Artists.

PACO CERDA

Paco Cerdà is a journalist and writer. He is the author of multiple award-winning books. The Pawn is the first book of his to be translated into English.

THE PAWN

TRANSLATED BYKEVIN BERRY DUNN

In this gripping historical saga, award-winning Spanish writer Paco Cerdà explores early Cold War anxieties through the lens of a famous chess match.

Stockholm, 1962. Spain’s first chess grandmaster, Arturito Pomar, faces off against eighteen-yearold American prodigy Bobby Fischer in a match that will become the stuff of legend, not so much for how it ends but for what it symbolizes. Shuttling back and forth across decades between the United States, Spain, the Soviet Union, and beyond, The Pawn tracks the careers of the two chess masters, expertly examining the geopolitical anxieties that pervaded the 1960s and went on to shape these men’s lives.propulsive, even more compelling.

WHAT GOOD DOES IT DO FOR A PERSON TO WAKE UP ONE MORNING THIS SIDE OF THE NEW MILLENIUM

TRANSLATED BY RANDI WARD

The rhetorical title of this collection posits the crisis that is underway. Simonsen asks: as a species among species, all composed of the matter of the universe, how has our compulsion to classify everything hierarchically estranged us from ourselves, each other, and Earth’s ecosystems? Simonsen challenges our anthropocentric pursuit of knowledge, exploring humankind’s relationship with itself as an element of the natural world. What good does it do for a person to wake up one morning this side of the new millennium follows the struggles of its narrator as he reckons with intensifying estrangement from his fellow organisms, gradually turning to the greater kinship of matter to find continuity, connection, and solace.

KIM SIMONSEN

Kim Simonsen is a Faroese writer and publisher. He is the author of seven books, as well as numerous essays and academic articles. In 2014, Simonsen won the Faroe Islands’ National Book Award for his poetry collection What good does it do for a person to wake up one morning this side of the new millennium. His newest poetry collection was nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 2024.

GISELA HEFFES

Gisela Heffes is a Professor of Latin American Literature and Culture at Johns Hopkins University as well as a writer, ecocritic, and public intellectual with a particular focus on literature, media, and the environment in Latin America. She is the author of several novels, including Ischia (Deep Vellum, 2023). She currently resides in Silver Spring, Maryland.

CROCODILES AT NIGHT

TRANSLATED BY GRADY C. WRAY

Although the outcome of Crocodiles at Night does not remain a surprise beyond the first paragraph, it expands outwards in philosophical, heartfelt reverberations true to Heffes’s style. Crocodiles at Night explores familial ties, memories and images of places that are no longer the same, the vagaries of the medical system, and social critique in this unfeigned, excruciating view of death and how it affects all who experience it.

INTERVIEW

Interview with Milo Todd

Author of The Lilac People

BY CORINNA KLOTH

Set against the vibrant cabarets of Weimar Berlin and the shadow of Nazi and Allied persecution, The Lilac People explores queer joy, survival, and resilience through the story of Bertie, a trans man whose fragile freedom is shattered by war. In this conversation, author MT discusses the forgotten histories that sparked the novel, the balance of love and survival on the page, and the enduring relevance of queer resistance across generations.

THE LILAC PEOPLE TRANSPORTS READERS TO BERLIN’S THRIVING QUEER UNDERGROUND DURING THE WEIMAR ERA, THEN THRUSTS US INTO A POST-LIBERATION WORLD WHERE SURVIVAL IS STILL FAR FROM GUARANTEED. FOR READERS UNFAMILIAR WITH YOUR BOOK, CAN YOU SHARE WHAT DREW YOU TO TELL BERTIE’S STORY—A TRANS MAN WHO FINDS JOY AND SAFETY IN 1920S BERLIN, ONLY TO SEE IT SHATTERED BY NAZI RULE AND LATER COMPLICATED BY ALLIED OCCUPATION? WHAT WAS THE SPARK THAT SET THIS STORY IN MOTION FOR YOU?

MT: The spark was a piece of

information I came across on social media around 2016. It stated that when the Allied forces liberated the camps, they let everyone go except the queer and trans people, who they then sent to jail to start their sentences for being queer and/or trans. I looked this up to make sure it was true, and that became the multi-year research project that turned into The Lilac People. I realized that there was important information about the German queer community not just after WWII, but before Hitler’s rise to power, as well. I knew I wanted to show both ends of that timeline, and I felt the most effective way to juxtapose them was through the eyes of one character.

YOUR NOVEL PULLS FROM REAL QUEER HISTORY, FROM THE ELDORADO CLUB’S CABARET SCENE TO THE EARLY INSTITUTE OF SEXUAL SCIENCE, AND THE BRUTAL REALITY OF QUEER PERSECUTION UNDER BOTH NAZIS AND ALLIED FORCES. WHAT RESEARCH MOST CHANGED HOW YOU SAW THIS ERA, AND HOW DID YOU DECIDE WHAT FACTUAL DETAILS TO WEAVE DIRECTLY INTO THE FICTIONAL NARRATIVE OF BERTIE, SOFIE,

AND KARL?

MT: My knowledge on queer history for this particular time and place was sparse before I started researching it for this book. So I guess I could say that virtually everything I learned changed how I saw the era. I never realized there was such a vibrant queer community at the time, and how it was the capital in the colonized world for queer rights, progress, culture, gender-affirming care, etc. But I was equally surprised to learn how there was so much persecution not only by the Nazis, but by the Allied forces thereafter.

I’m someone that tries to go by facts first. I don’t truly start mapping out the plot until I feel I’ve found as much historical information as I can. Then I try to create a plot around the most important pieces. It’s impossible to balance 100% historical accuracy with a fully engaging fictionalized plot, though, so there were a select handful of times where I had to make historical changes for the sake of the story. I tried to avoid making changes whenever I could, but when I had to, I made sure to note them in the back of the book. It’s important to me for readers to understand what was real and what was changed.

AT ITS HEART, THE LILAC PEOPLE IS NOT JUST A WAR STORY, BUT A LOVE STORY ABOUT BERTIE AND SOFIE BUILDING A FRAGILE LIFE TOGETHER WHILE HIDING THEIR TRUTHS. HOW DID YOU NAVIGATE THE TENSION BETWEEN ROMANCE AND SURVIVAL—BETWEEN WRITING TENDER MOMENTS OF LOVE AND THE CONSTANT THREAT OF BETRAYAL OR CAPTURE?

MT: People’s eyes may start to glaze over as I try to explain this, but here we go. I’m a hardcore planner to the point that I not only map out every scene before I begin writing, but also put together different kinds of charts and graphs. One of them is a line graph where I map the intensity of each scene. If a scene is high in tension, it goes up higher on the graph. If it’s low in tension, it goes lower on the graph. I also include a second line on the same graph, again with highs and lows, but this time with positivity or negativity. The more upbeat a scene, the higher I place the scene on the graph. The more depressing a scene, the lower I place it on the graph.

ABOUT THE BOOKS

Looking at those two lines, especially together, helps me visualize where the story may need some work or rearranging. For example, if I have several scenes in a row that are high up on the chart, that may mean there’s too much intensity going on for too long, and it’ll likely wear out my reader. Or if several scenes in a row are low on the chart, that may mean there’s too much depressing stuff without giving the reader a break, and so I should add in something lighter or more endearing. And then there’s the whole business of how the two lines intersect with each other per scene, and you end up with various combinations of intensity and positivity/negativity that I get an odd enjoyment out of juggling.

ONE OF THE BOOK’S MOST STARTLING TURNS COMES AFTER THE WAR, WHEN “LIBERATION” IS NOT THE FREEDOM MANY IMAGINED, ESPECIALLY FOR QUEER PEOPLE. THE ARRIVAL OF KARL, A YOUNG TRANS PRISONER FREED FROM DACHAU, TRIGGERS NEW DANGERS UNDER ALLIED FORCES. WHY WAS IT IMPORTANT FOR YOU TO EXPLORE THIS LESSERKNOWN HISTORY OF POST-

WAR OPPRESSION,

AND HOW DO YOU HOPE IT RESHAPES READERS’ UNDERSTANDING OF THIS PERIOD?

MT: Once I learned about this history, I couldn’t let it go. I’d wake up in the middle of the night thinking about it. Out of all the trans history I’ve researched over the years, this spoke particularly deeply to me. Despite all the attempts at erasure in all its ways, plenty of documentation had managed to survive through the sheer will of the community.

I wanted to write this book in honor of all these folks, nameless or otherwise, having survived the war or not. They were all equally important, and I felt the best way I could honor them was to get this history into the mainstream the best I could. So much of what this community did benefitted the rest of the trans community right up to the present day. I wanted to show my thanks by doing my part to make sure they were no longer forgotten. That’s ultimately what I hope readers get from this period: remembrance for these people. That, and the realization that what we think we know of history likely isn’t the whole story. Plenty of history gets coopted, erased, washed,

etc., but is nonetheless presented as the (whole) truth. I hope The Lilac People opens people’s eyes.

YOUR TITLE NODS TO DAS LILA LIED, AN EARLY 20TH-CENTURY GERMAN ANTHEM FOR SEXUAL MINORITIES. HOW DID THIS PIECE OF MUSIC INFLUENCE THE TONE OR SPIRIT OF YOUR BOOK? DO YOU SEE BERTIE AND SOFIE’S STORY AS A LYRICAL ACT OF DEFIANCE?

MT: The interesting thing about planning is no matter how much I map out my plots, they’ll always surprise me. The song wasn’t originally intended to play such a major part in the book, but rather was put in for flavor as the first known queer anthem. But as I wrote the rough draft, it took on a life of its own. Bertie, Sofie, and Karl all got into it, and I let them take the wheel. By the time I started the second draft, I wove in the song with more intention, using it as symbolism for defiance, joy, community, found family, etc. It ended up thematically doing heavy lifting for the entire story. I can’t imagine the book without it anymore.

THE BOOK MOVES BETWEEN THE ELECTRIC, VIBRANT ENERGY OF PRE-WAR BERLIN AND THE HUSHED, PERILOUS QUIET OF LIFE IN HIDING. AS A WRITER, HOW DID YOU BUILD THESE CONTRASTING WORLDS? DID YOU WRITE ONE TIMELINE FIRST OR WEAVE THEM TOGETHER AS YOU WENT?

MT: I mapped the timelines out separately to make sure they each made sense on their own, then wove them together in ways that best worked with the book’s pacing and the divulging of information. Charting things out, such as with the line graph I mentioned earlier, was particularly helpful.

In some ways, though, the juxtaposition of the two worlds wrote themselves, purely by historical accuracy. For example, the 1932/3 timeline mostly takes place in the winter, while the 1945 timeline mostly takes place in the spring. While the seasons are arguably opposites of their timelines—the happy stuff is taking place in the winter and the sad stuff is taking place in the spring—they’re indeed opposite of each other, and so

I went with this irony and played up the feel of each season to further the feeling of difference.

Once I started writing the actual rough draft, though, I wrote the scenes one after the other in the order I intended the reader to read them. This approach helped me with flow between timelines, instead of writing each timeline separately and then trying to splice them together.

ABOUT THE BOOKS

YOUR CHARACTERS GRAPPLE NOT JUST WITH EXTERNAL PERSECUTION BUT WITH INTERNALIZED FEAR, SURVIVOR’S GUILT, AND THE BURDEN OF SECRETS. WHAT WAS THE MOST EMOTIONALLY DIFFICULT SCENE FOR YOU TO WRITE, AND HOW DID YOU KEEP THE STORY AUTHENTIC WITHOUT OVERWHELMING THE READER WITH DESPAIR?

MT: Hands down, the most difficult chapter for me was what I refer to as “Karl’s Monologue.” (If you know, you know.) It’s a short chapter of maybe—I don’t know—all of four pages, but it was rough. The research for that part alone took me maybe a full year of hunting, due to the heavy amount of destroyed documentation and evidence.

Then when it came to writing the chapter, finding the balance between authenticity and readability was particularly tough. On the one hand, I wanted to truly honor what these people went through by presenting it without flinching. On the other hand, if nobody read the book because of this, exactly how was I helping honor these folks? I can get the story out there, but I also need folks to actually read it.

Since the subject matter of this chapter was particularly traumatizing, I decided to pull back on it. I didn’t lie or sugarcoat anything, but I also didn’t get graphic. Plenty of details and additional information didn’t make it in because I realized the gist was more impactful, forcing the reader’s imagination to fill in the blanks. I did, however, do something deliberately mean: I removed all white space. White space gives a reader’s brain a moment to breathe, break away, and process what’s on the page. But since the people who actually endured these things didn’t get a break or relief, I decided my reader wouldn’t either. I also presented the information in a halting way, in short sentences since that’s how Karl is speaking these things as he disassociates. This worked well

because it not only is part of Karl’s personality, but also forces readers to pay particularly close attention. You can’t look away, you can’t take a break, you’re locked in.

So definitely “Karl’s Monologue.” The research was the hardest, the subject matter was the most exhausting, and the writing and editing were particularly meticulous. I was so glad when I never had to look at it again.

THOUGH SET NEARLY A CENTURY AGO, THE LILAC PEOPLE FEELS ALARMINGLY RELEVANT IN TODAY’S CLIMATE OF RISING ANTITRANS RHETORIC AND ATTACKS ON QUEER RIGHTS. HOW DO YOU HOPE READERS CONNECT BERTIE’S STORY TO CURRENT EVENTS? WERE THERE MODERN ECHOES YOU FELT COMPELLED TO UNDERLINE— OR DID THEY SURFACE NATURALLY AS YOU WROTE?

MT: The Lilac People was never meant to be timely. Back when my publisher chose my release date, we didn’t know the world it’d debut into. But that said, there’s certainly plenty

of overlap between the time period of my book and our current era. But believe it or not, those overlaps wrote themselves. I simply presented the book in its organic time and place. Any overlaps are simply our modern era’s doing.

Even though I was researching and writing this book essentially in step with the Trump era, and I often saw parallels, I deliberately didn’t write toward that fact. I wanted to present the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany in their natural forms, not only for their own sake, but also because I worried trying to deliberately reflect our current times would, well, come off like I was trying to reflect our current times. And then the book would’ve risked coming off preachy, inauthentic, and other things that went against the purpose of me writing The Lilac People. So I left well enough alone and let history itself do the talking.

All that said, plenty of readers have (understandably) been concerned about our modern times since reading The Lilac People. In response to that, I’ve recorded a free, online course called “Modern United States vs Nazi

Germany: A Comparison Guide for Wellbeing.” It’s a deep dive and more information than you could imagine, but it’s everything I collected over the years. I sincerely believe knowledge is power, so I felt the best thing to do was share what I have with the world.

(Spoiler: We’re doing way better than Nazi Germany ever did. It’s not all sunshine and butterflies in the US right now, and people have gotten hurt and will continue to get hurt, but we’ll never get to the point Nazi Germany did. If you don’t believe me, go listen to my course. We have a lot of work ahead of us, and hopefully this course helps people understand where to direct their energy for resistance.)

MANY

QUEER AND TRANS STORIES FROM THIS ERA WERE ERASED FROM HISTORY. QUESTION: WHAT RESPONSIBILITY DID YOU FEEL IN GIVING VOICE TO THESE LIVES? WAS THERE A MOMENT WHERE YOU THOUGHT, “THIS STORY MUST BE TOLD, EVEN IF IT UNSETTLES PEOPLE”?

MT: I had a strong drive to give voice to these lives as soon as I learned given information. And the more information I learned, the stronger

that drive became. It was less about responsibility and more about anger. I was so angry on behalf of these folks; not just with what they endured, which would’ve been bad enough; and not even just that the Nazis tried to destroy all evidence of their crimes thereafter, which also would’ve been bad enough; but then self-described heroes such as the United States deliberately followed in the Nazis’ footsteps for cruelty toward these communities. My communities. I knew I couldn’t, and wouldn’t, play a role in continuing that coverup and silence.

But I also knew that the US population of today isn’t the same as the US population of then. Even if our government hasn’t improved much, plenty of folks in the US are open to hearing more about queer and trans identities, and I was optimistic that readers would take interest in The Lilac People.

But back to anger. I can be spiteful sometimes, and I let it shine during this whole process. Whenever I wanted to give up because of the amount of work and overwhelm this project created, I’d think about these folks, what they’d gone through, and how they’d been silenced. And then I’d get right back to

it. This was the most difficult book I’ve ever written, but they’re the ones who carried me through it.

FOR SOMEONE WHO’S NEVER HEARD OF THE LILAC PEOPLE BEFORE PICKING UP THIS INTERVIEW, WHAT DO YOU HOPE THEY FEEL OR UNDERSTAND AFTER READING BERTIE, SOFIE, AND KARL’S STORY? IF THEY REMEMBER JUST ONE IMAGE OR EMOTION FROM THE NOVEL, WHAT SHOULD IT BE?

MT: Aside from new knowledge on a particular time and place of trans history, I hope what stays with folks the most is the final imagery—which

I obviously can’t say much about here—as well as the party scenes. I hope people take away from this the fact that the trans community has had plenty of joy in the past, but also that we can endure quite a bit. Community is vital in times like these—whether Nazi Germany or the modern US or elsewhere—and it’s what will see us through. Support each other, honor each other, and do the best you can. This isn’t the first time we’ve gone through something like this. And in a way, that means we’re never enduring difficulty alone.

As my unintentional tagline has since become: The ghosts of history are watching, kissing our foreheads.

A moving and deeply humane story about a trans man who must relinquish the freedoms of prewar Berlin to survive first the Nazis then the Allies, all while protecting the ones he loves

In 1932 Berlin, a trans man named Bertie and his friends spend carefree nights at the Eldorado Club, the epicenter of Berlin’s thriving queer community. An employee of the renowned Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld at the Institute of Sexual Science, Bertie works to improve queer rights in Germany and beyond. But everything changes when Hitler rises to power. The Institute is raided, the Eldorado is shuttered, and queer people are rounded up. Bertie barely escapes with his girlfriend, Sofie, to a nearby farm. There they take on the identities of an elderly couple and live for more than a decade in isolation.

Shorter Is Stronger: The Rise of Novellas

and Short Fiction in Translation

BY SARAH KLOTH

In a literary landscape where time feels perpetually short and attention is constantly divided, the novella and short story have reemerged not as lesser forms, but as powerhouses of storytelling. In the world of translated literature, shorter works are not just gaining traction, they are shaping the future.

Why Shorter Works Travel Well

For decades, the economics of translation have been daunting. Long novels mean higher costs: more pages to translate, more risk for publishers, more shelf space to justify. Independent presses, ever the risk takers, are increasingly finding that brevity is both sustainable and compelling. A 120-page novella is not only cheaper to translate, it is also easier for readers to take a chance on.

Editors point out that shorter projects allow them to introduce new voices from around the globe without betting an entire season’s list on a single title. A smaller investment can mean greater freedom to take chances on innovative storytelling, experimental structures, and debut authors. That spirit of discovery is what keeps translation alive, and shorter forms are helping carry it forward.

The Reader’s Advantage

On the reader side, shorter works resonate with a cultural moment where time is scarce. Novellas and short fiction collections meet the needs of readers who want intensity without the sprawl. A well-cut novella offers a sharp burst, a single evening’s read that lingers far longer than its page count suggests. For many, the short form offers a complete world

IF YOU LIKED THIS... READ THAT!