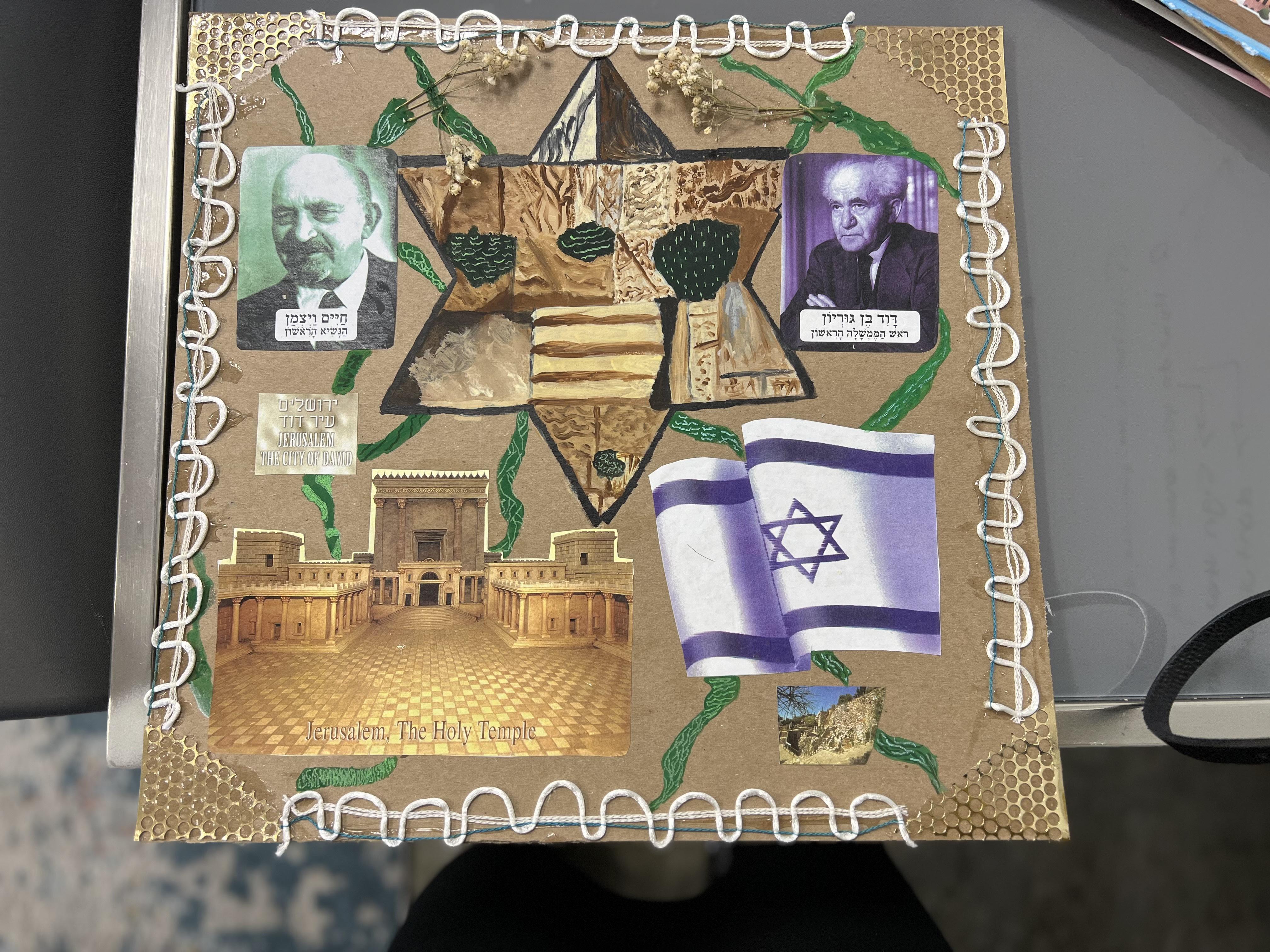

COVER ART BY BEATRICE GREEN

SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘26

COVER ART BY BEATRICE GREEN

SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘26

One of the most popular elements of the Pesach Seder is “Dayeinu.” And yet, it’s one of the most puzzling, too. If God had only done X, but had not done Y, dayeinu - it would have been enough. It’s a beautiful sentiment, but is it really true? For example: “If God had given us Egypt’s money but had not split the sea,” would it really have been enough? On the contrary, we would not be around to sing Dayeinu, regardless of how much cash we had in our accounts. Similarly, it seems unlikely that it would have been su cient “if God had taken us through the sea but didn’t close the sea upon the Egyptians” - the chase would have continued. Would it really have been enough “if God had drowned our enemies in the sea and had not supplied our needs in the desert for forty years”? Would salvation have mattered if we starved to death days later? Would it really have been enough “if God brought us to Mount Sinai but did not give us the Torah” - which, we assume, was

e Maharal o ers a simple yet stunning approach. ere’s a concept in the realm of biological systems and metaphysical philosophy called “irreducible complexity,” which posits that certain organisms or systems are intricately complex in their makeup, but would not function without every one of its parts. If there are 100 parts, it won’t function with only 99 - not even at 99% of its capacity. It will cease to function entirely until all 100 parts are there. As my rebbe, R’ Fohrman, suggests, the story of Yetzias Mitzrayim is irreducibly complex. e elements that were required to get us to the Promised Land were many. Says the Maharal, like a set of stairs, each one on its own would not have been enough in that it would not have accomplished the end goal of getting us to Israel to live with Hashem. But each step was necessary. And, only once we’re there - only once we arrive at the end - are we poised to look back and appreciate each of the intricate steps that it took for us to get there. “Dayeinu” doesn’t mean that each step on its own would have su ced; it means that each is enough to warrant gratitude. A er having told the story, a er seeing how Hashem ful lled the Divine promise, we can appreciate its irreducible complexity. We recognize that each part is necessary and deserves gratitude. Without just one, we wouldn’t be

And what a beautiful description of our school. Each individual voice - each student, faculty member, and alumnus - is remarkable, special, unique. Each one is “dayeinu.” But we’re also irreducibly complex; we are who we

with you and share the kedusha with others. It is my bracha that the varied and unique voices of our faculty, students, and alumni infuse our holidays with meaning, and the (beauti cation of the Torah within). As I always note, the teachers, students, and alumni are all the Orot (lights) that come together to form our dazzling Shalhevet ( ame).

RABBI DAVID STEIN AWE

3 5 DR. SHEILA TULLER KEITER SAVING FACE: PESACH AND THE USES OF POWER

9 ELLIOT SERURE MORE

thank you

TO

KAREN & AVI ASHKENAZI

DEBBIE & MICHAEL BLOCK

IN MEMORY OF OUR FATHERS DR. ALVIN SCHIFF AND MR. JACK BLOCK, AND IN HONOR OF OUR SON AND DAUGHTER IN LAW RABBI DAVID AND GILA BLOCK

DAHLIA & ELAN CARR

HADAR & MICAH COHEN

MAYA & NEIL COHEN

ELISA & BRADFORD DELSON

NAOMI & ABRAHAM DRUCKER IN MEMORY OF NAOMI’S MOTHER, DIANE RUCKENSTEIN

YVETTE & ERIC EDIDIN

RONIT & JACK EDRY

SHARI & JEFF FISHMAN

SHANA & MORDECHAI FISHMAN

SHARON & ALAN GOMPERTS

MOLLY & SAEED JALALI

MICKEY & HAIM KAHTAN

GAIL KATZ & MAYER BICK

MALKA & JOSH KATZIN

15 RABBI ABRAHAM LIEBERMAN

THE TEN PLAGUES

17 ETHAN FIALKOV

TEFILLAT VATIKIN: WHERE SCIENCE AND TORAH COALESCE

21 ISABELLA SZTUDEN

MOSHE & THE SNEH: THE VALUE OF TURNING ASIDE

23 MS. ARIELLA ETSHALOM

LOOKING UP TO LEADERS

25 CHAIM COHEN

BRINGING THE RAMBAM AND RAV SOLOVEITCHIK TO OUR SEDER

SIMONE & JASON KBOUDI

STACY & RANON KENT

DANIELLE & DR. STEVEN KUPFERMAN

TAMAR MESZAROS-SILBERSTEIN & DAVID SILBERSTEIN

ARIELLA MOSS PETERSEIL & NACHUM PETERSEIL IN MEMORY OF MY EMA, ROSALYN MOSS

םולשה הילע, WHO WILL HAVE HER FIRST YAHRZEIT ON YOM HAZIKARON

SUSAN & BENJAMIN NACHIMSON

DESI ROSENFIELD

JAY & SARA SANDERS

DR. ROBIN SCHAFFRAN & RONNIE EISEN

ROSETTE & BARRY SCHAPIRA

MICHAEL MAZAR & MICHAL SCHARLIN

NAOMI & RABBI ARI SCHWARZBERG

SERURE FAMILY

DRS. TAALY & ADAM SILBERSTEIN

MICHELE & DAVID SILVER

LAURA WASSERMAN & MICHAEL STEUER

LESLEE & ALEX SZTUDEN

TESSEL FAMILY

THE FOLLOWING SUPPORTERS WHO HAVE GENEROUSLY SPONSORED THIS EDITION OF OROT SHALHEVET. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO THEM FOR HELPING TO PROMOTE THE SPREAD OF MEANINGFUL TORAH LEARNING AND SPIRITUAL GROWTH IN OUR COMMUNITY. PLEASE ENJOY THE TORAH YOU WILL FIND WITHIN IN THEIR MERIT.

RABBI DAVID STEIN IS THE JUDAICS STUDIES PRINCIPAL AT SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL AND IS THE CO-FOUNDER OF THE LAHAV CURRICULUM PROJECT. DAVID ATTENDED YESHIVA COLLEGE AND RIETS FOR HIS UNDERGRADUATE AND SEMIKHA STUDIES, AND ALSO RECEIVED HIS MASTER’S DEGREE IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING FROM COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY. HE COMPLETED HIS MASTER'S DEGREE IN TEACHING AT AMERICAN JEWISH UNIVERSITY’S GRADUATE CENTER FOR JEWISH EDUCATION AS A WEXNER FELLOW/DAVIDSON SCHOLAR, AND IS CURRENTLY WORKING ON HIS DOCTORATE IN JEWISH EDUCATION AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY.

Parshat Bo presents the nal act of the story of Bnei Yisrael’s redemption, the seminal event that we commemorate each year on Pesach. Strikingly, as the climax of the story of the makkot approaches, Hakadosh Baruch Hu explains the point of the whole story:

רשא יתתא תאו םירצמב יתללעתה רשא תא ךנב ןבו ךנב ינזאב רפסת ןעמלו :וברקב הלא יתתא יתש ןעמל”

ינא יכ םתעדיו םב יתמש

“So that I can put these signs of Mine in his midst; and so that you may relate in the ears of your son and your son’s son that I made a mockery of Egypt and My signs that I placed among them – that you may know that I am Hashem” (Shemot 10:1-2)

e purpose here – of the repeated makkot and of the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart, now made possible only by God himself – is to “show My signs before him.” It is, in a word, to inspire. It is expressly designed to instill within the entire Jewish people – who see and experience it with their own eyes – the power and omnipotence of Hashem. It is, quite simply, so that “you may know that I am the Lord.”

Our parshanim here also explain the goal here in the same manner. As the Ramban puts it, this is being done to demonstrate Hashem’s power to future generations.

“ישעמ חכ םיאבה תורודל לארשי לכו התא רפסתש ידכו יתרובג תא םירצמ

“So that Egypt should recognize my strength and so that you and all of Israel should relate the power of My actions to future generations.”

e Ohr HaChayim takes this even further, writing that the purpose here is as follows: ".חצנל

תותואה קזחל"

“To strengthen the signs, which are the primary basis of faith, within the heart of the people Israel, so that it should be instilled within them and not ever forgotten.”

is display, in other words, is nothing short of a foundational learning experience in which the Jewish people are taught to believe in Hashem and in His greatness.

Yet, there is a complication to this educational approach as well, as pointed out by Aviva Gottlieb Zornberg in her “Re ections on Exodus”:

“Signs are rather amboyant concessions, theatrical demonstrations of power…. To resort to marvels and transformations is a descent to a more super cial mode of communication.”

Zornberg points to the repeated instances when the Torah describes things as being done before or seen by “the eyes of the people,” as in the following pasuk in Parshat Shemot:

“And Moshe performed the signs before the people’s eyes, and the people believed and heard…” (Shemot 4:30-31)

Similarly – perhaps especially – the very last words of the Torah provide a nal tribute to the importance of this educational style, describing Moshe as the one uniquely capable of performing signs and wonders “ לארשי לכ יניעל”, “before the eyes of all of Israel.”

Zornberg cautions that despite the importance of clearly demonstrating Hashem’s power, this phrase “introduces the nuance of the illusory, the too-immaculate facade.” She points to Rashi on Bereishit (42:24) who writes that when Yosef imprisoned Shimon ״םהיניעל״, “before the brothers’ eyes,” it was simply a show to intimidate the brothers; once they le , he released Shimon and gave him food and drink.

Signs and wonders, then, are certainly a potent demonstration of Hashem’s power. ey instill fear and inspire faith. Yet, they also conceal some of the deeper complexities of an authentic experience. ey bring to mind, lehavdil, the Great and Powerful Oz, or perhaps Queen Gertrude’s observation that “the lady doth protest too much.” And therein lies the educational challenge, for me at least. ere is no question that power inspires and that, as educators, our primary job is to inspire, nurture, and facilitate faith. And there is no doubt that the greatest teacher who ever was –Moshe Rabbeinu himself – relied on this pedagogical approach in his own leadership of Bnei Yisrael. At the same time, though, what is lost in this stance? Moshe himself, of course, harbored great doubts, asked di cult questions, and grappled with tremendous uncertainty. He argued with Hashem, challenged him repeatedly, and even tried stepping down from his own leadership role over the Jewish people (see Shemot 32:32 and Bamidbar 11:14). Yet, as we know from the end of Parshat Ki Tissa (Shemot 34:33-35), he literally and physically had to mask much of his own personal encounter with Hashem from Bnei Yisrael. In a sense, while Moshe cultivated an unparalleled ability to inspire his people, at the same time this may have come at the expense of his ability to authentically relate to them.

I was blessed to experience from my rebbe, Rav Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l (Rav Soloveitchik’s son-in-law), an approach that, for me, directly addressed this educational dilemma. He emphasized the beauty of acknowledging that “nothing is lacquered.” He refused to resort to simplicity in his relationship with Hashem and his Torah study and stood for so many as a model of nuance, integrity, and authenticity in Avodat Hashem. And, of course, he balanced this with the majesty of his presence and the power of Torah that he tried to convey. Like so many others, I was deeply and profoundly inspired by his ability to avoid the performative, to pull back the curtain to reveal true authenticity – while also projecting the wonder of the encounter with Hakadosh Baruch Hu. Sitting in shiur with Rav Lichtenstein was an awe-inspiring (and fear inducing!) experience – yet he balanced this with the ability to authentically grapple with complex moral, philosophical, and personal questions. As a teacher, I can now attest that this is no easy educational task, and I o en wonder - as I’m sure Moshe did as well - how best to balance the signs and wonders with the nuance and complexity for those we are entrusted to teach and inspire.

As we celebrate the holiday of freedom and redemption at the Pesach seder, perhaps the challenge for each of us is to walk this line as well. We recount and rejoice at the signs, awe, and inspiration of our people’s story, but also recognize the hardship, slavery, and continued challenges that face our world and community. Perhaps our Pesach celebration, then, is ultimately about an educational experience that can balance authenticity and inspiration b’chol dor vador - in each and every generation.

DR. SHEILA KEITER IS A MEMBER OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH FACULTY AT SHALHEVET. SHE HAS A B.A. IN HISTORY FROM UCLA, A JD FROM HARVARD LAW SCHOOL, AND RECEIVED HER PHD IN JEWISH STUDIES FROM UCLA, WHERE SHE TAUGHT IN THE DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES.

e story of Israel’s slavery and planned redemption from Egypt sets the stage for a grand battle between the advanced civilization of Egypt and the God of Israel, the Source and Master of all creation. Over the course of the ten plagues and the splitting of the sea, God asserts His mastery over nature, the gods of Egypt, and over the might of the Egyptian kingdom. Egypt never stood a chance. Why does Hashem wage this war against Egypt? ere are multiple reasons, including practical, theological, and political motivations. I wish to focus on one: God’s response to the abuses of human power.

ere is an odd moment a er the ninth plague, the plague of darkness, in which Pharaoh loses his patience following Moshe’s insistence that he allow all of Israel to leave to worship Hashem.

“And Pharaoh said to him: Go from before me; watch yourself; do not see my face again, for on the day you see my face, you will die” (Ex. 10:28).

e message is clear: e next time I see you, I will kill you. However, the syntax is unusual. One would typically phrase such a sentiment this way: Make sure I never see your face again, because the day I see your face, you will die. But Pharaoh reverses the pronouns: You will die if you see my face.

To confound matters further, Pharaoh’s words sound remarkably similar to words that Hashem will use later in speaking with Moshe. A er the sin of the Golden Calf, Moshe successfully pleads for forgiveness on behalf of Israel and then asks to see God’s glory. Hashem does not fully grant Moshe’s request.

“And He said: you cannot see My face, for a human may not see Me and live” (Ex. 33:20).

Once again, the pronouns evince a concern that your seeing My face will result in your death. is time, however, those pronouns make more sense. No corporeal human being, not even Moshe, can fully experience the Divine without surrendering his bodily existence. e experience would be too overwhelming.

Perhaps Pharaoh’s odd phrasing tries to capture this message. In ancient Egyptian theology, the pharaoh was also a god. Pharaoh may be using this language to assert his divinity, implying that Moshe and Aharon’s renewed appearance before him will result in their immediate deaths. It should not surprise us that Pharaoh coopts the language of God. He, too, is a god, or so he thinks.

What is most telling, however, is not that Pharaoh and Hashem use similar language, but how they use it. Pharaoh uses the language of not seeing his face as a threat. He seeks to control Moshe and Aharon with a show of power – if you see my face you will die.

Interestingly, we see Yosef exert power with a similar use of this language. When Yosef sends his brothers back to Canaan to fetch Binyamin, he warns them not to return without their youngest brother. As Yehudah explains to Yaakov:

“And if you don’t send [him], we will not go down [to Egypt], because the man said to us: You will not see my face without your brother with you” (Gen. 43:5).

Once again, it is you who will not see my face. In this case, Yosef uses this language to exert power over his brothers. His grand scheme requires they return with Binyamin, and the language he uses threatens them with unwanted consequences should they fail to do so. Yosef, as second in command to Pharaoh, exerts tremendous power over others, including control over all access to food during the prolonged famine. Even if Yosef was not considered divine, he stood as a representative of the pharaoh, who was. His language re ects this.

e human use of this language of “seeing my face” stands in stark contrast to the way in which Hashem utilizes it. When God tells Moshe that he cannot see His face, there is no implicit threat, no attempt to exert control. Rather, Hashem seeks to protect Moshe. Moshe literally cannot see God’s face (however we want to understand that) and live. erefore, Hashem must modify Moshe’s request in order to protect him. Hashem possesses in nite power, but unlike humans, He uses His power to protect, not to threaten and control.

is distinction o ers insight into one of the key functions of yetziat Mitzraim. Hashem did not take us out of Egypt solely for our own bene t. Certainly, the exodus constituted the basis for our covenantal relationship with God, which extends to this very day. However, Hashem also sought to revolutionize civilization for the bene t of all humanity. Egypt was the center of the civilized world and the greatest power of the greater region Yet it was a strati ed society that relied on militarism and slavery to exert control over the masses for the bene t of the pharaoh and the priestly class. e rest of humanity was disposable.

When Hashem wages war on Egypt, He is striking a blow against the old world order, one of oppression, exploitation, and callous disregard for human life. In its place, God seeks to create an ideal society steeped in kindness, protection of the vulnerable, and reverence for the value of every human being. ese are the values of the Torah that He will bestow upon Israel. But before He can do that, He needs to disrupt the previous regime. Hashem upends the power of the pharaohs, power used to dominate and abuse the powerless, replacing it with a moral code that demands protection of the powerless.

e Pesach Seder is sensitive to this distinction. We celebrate our freedom, but our freedom carries with it certain responsibilities. We must share our bounty with those less fortunate, as mentioned at the beginning of Maggid.

יתיי ךירצד לכ ,לכייו יתיי ןיפכד לכ

"All who are hungry, let them come and eat; all who are in need, let them come and make Pesach.”

We must educate our children to carry on these values, as explained in the middle of Maggid.

יתאצב יל 'ה השע הז רובעב רמאל אוהה םויב ךנבל תדגהו :רמאנש

“As it is said: ‘And you will tell your son on that day, saying: Because of this that Hashem did for me when I le Egypt.’”

And we owe the Omnipotent our praise for using His power to liberate us into His service, as noted at the conclusion of Maggid.

ונלו וניתובאל

" erefore, we are obligated to thank, praise, pay tribute, glorify, exalt, honor, bless, extol, and acclaim the One who performed all of these miracles for our fathers and for us.”

In addition, we must be ever mindful that power must be used to protect and never for its own sake. For true power comes from the Source of all power to Whom we owe everything. If we can remember that, perhaps, in a certain sense, we can see the face of God a er all.

ough the culinary juxtaposition of hamantaschens and matza pizzas may disguise it, Purim and Pesach are far more related than many realize. e two holidays occur within just a few weeks of each other and, when compared, shed light on one another.

e literary parallels between Purim’s and Pesach’s foundational stories indicate a connection between the holidays. In both stories, the Jewish people face adversity in the diaspora: genocide in Persia and slavery in Egypt. Subsequently, a protagonist, Esther in the Purim story and Moshe in the Pesach narrative, courageously risks their life to save their nation against a distinct antagonist, Haman and Pharaoh, respectively. Moreover, key events in the story of Purim transpire on Pesach. When Esther decreed a three-day fast for the Jews of Shushan, the last day of the fast fell on the rst day of Pesach. ough fasting is not allowed on holidays, especially on Pesach, which has a rmative mitzvot relating to eating and drinking, some opinions in Chazal explain that it was allowed on Purim because the fate of the Jewish people was at stake (see Pirkei D’rabbi Eliezer, 50).

e Talmud, too, addresses the correlation between these two holidays. In Masechet Megillah (6b), the Gemara discusses whether Purim should take place in Adar Aleph or Adar Bet during a leap year, when there are two months of Adar. Rabbi Eliezer argues that Purim should occur during the earliest opportunity, since we do not postpone doing a mitzvah. Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, however, maintains that it should be celebrated in Adar Bet because it is best to have Purim closer to Pesach to juxtapose and bridge together the two redemptions. Additionally, Rashi (Taanit 29a) states that the mitzvah to amplify one's happiness in Adar stems from the miracles of Pesach as well as those of Purim. ere is, however, one stark di erence between the two. In the story of Purim, Mordechai and Esther are the main characters of the redemption story. Surprisingly, Hashem’s name is not even mentioned once in the Megillah. In contrast, Hashem directly frees the Israelites from Egypt by manifesting ten awe-inspiring plagues. In fact, there is such a strong focus on Hashem's role in Yetziat Mitzrayim that Moshe is not even mentioned once in the Haggadah.

One could argue that with respect to Hashem’s role in the redemption as well, the two stories are similar. Despite the absence of His name in the story, Hashem orchestrates the miracle of the story of Esther to the same extent as that of Pesach, just in a more obscure manner. We do not see Hashem’s hand openly in the salvation, but in reality, Hashem guides the entire narrative from beginning to end. e idea of Nahafoch hu, which is at the core of the holiday of Purim, bolsters this perspective. e symmetrical reversal in the Purim story re ects an omniscient perfection of which only Hashem could be capable. Although Esther and Mordechai did what they could to take matters into their own hands, G-d was, in a manner beyond human conception, responsible for the miracle.

Perhaps we can also suggest an additional approach. I believe that Purim and Pesach re ect two ways in which we can react to hardship. Purim’s emphasis on human agency and Pesach’s focus on divine intervention re ect two sides of the same coin. When faced with tragedy, we can take a Purim approach, getting our hands dirty and attempting to change

ELLIOT SERURE, '23, IS A MEMBER OF OUR BEIT MIDRASH PROGRAM (BMP). HE WILL BE ATTENDING YESHIVAT ORAYTA BEFORE ATTENDING PRINCETON UNIVERSITY.our situation. However, we can also take a Pesach approach of relying solely on Hashem, such as by saying Tehillim and praying to Him. O en, the best approach is to employ both responses at the same time. When combined together, these two approaches of faith in God and human courage help us create a better world. May we merit to celebrate the holidays of Purim and Pesach with joy and appreciation for both types of redemptions.

Shir Hashirim, translated as Song of Songs, is a climactic and poetic work included in the 24-piece puzzle we call Tanach. e story, written by Shlomo Hamelech, displays the gripping yet exhilarating tale of two lovers who portray an incomparable sense of devotion while chasing a er one another. According to Ashkenazic custom, Shabbat Chol Hamoed Pesach was the day chosen for reading this story publicly. is seems incredibly odd – a graphic love story that is entirely unrelated to Pesach is read on the holiday representing salvation, freedom, and a new beginning for the Jewish people. What could be the reason for this unlikely placement, and on a more profound level, what is the story truly trying to convey about our history?

e simplest answer to these questions, suggested by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks z”l, is that both Yetzi’at Mitzrayim and Shir Hashirim are love stories between God and the Jewish people in which our faith and devotion to God are established.

Rabbi Sacks explains this in the following manner: “It is a love story – troubled and tense, to be sure… at is the theme of the Song of Songs...God chose Israel because Israel was willing to follow Him into the desert, leaving Egypt and all its glory behind for the insecurity of freedom, relying instead on the security of faith.” To Rabbi Sacks, the two stories are perfectly intertwined through the theme of love shared by both.

Although Rabbi Sacks’ answer is intriguing, there are more eye-opening answers to this intricate question. Rashi rejects the idea that Shir Hashirim is a love story between the Jews and God and instead describes it as a story of reunion following separation. e two main characters form an intense bond that links them together even when they are apart. So too, the Jewish people remain strongly connected and committed to God despite the countless exiles we have expe rienced. Rashi’s message is timeless; commitment and responsibility are lessons learned from both Shir Hashirim and Yetziat Mitzrayim, teaching the Jewish people that despite challenges and separation, our story is one of togetherness and de ance.

e Ibn Ezra furthers Rashi’s approach by suggesting that Shir Hashirim represents the history of the Jewish people (Introduction to Shir Hashirim and commentary to 8:12). It begins with the story of Avraham Avinu and concludes with a vision of the Messianic Era. is explanation alone, however, does not justify the need for reading it publicly on Pesach.

Rav Moshe Taragin of Yeshivat Har Etzion provides additional references and parallels elsewhere in Tanach to certain verses in Shir Hashirim. For example, Shir Hashirim states, “,יתיער ךיתימד הערפ יבכרב יתססל” “I have compared you, O my love, to a steed in Pharaoh’s chariots.” Chazal suggest that this comparison articulates a connection to Kriyat Yam Suf (splitting of the Red Sea) when Pharaoh arrived at the sea with his chariots. A few pesukim later, the text states, “,םיתורב ונטיהר םיזרא וניתב תורק” “ e beams of our houses are cedars, and our panels are cypresses.” According to R. Taragin, this seemingly describes the material B’nei Yisrael used to build various homes for God.

e Ibn Ezra, taken in consonance with the ideas of Rashi, R. Sacks, and R.Taragin, can provide us with an enlightening explanation about the purpose of Shir Hashirim. Indeed, Shir Hashirim is a love story between two people, but it is

OLIVIA FISHMAN, '23, AND TALIA SCHAPIRA, '23, ARE BOTH MEMBERS OF OUR BEIT MIDRASH PROGRAM (BMP). TALIA WILL BE LEARNING AT MIDRESHET HAROVA NEXT YEAR. OLIVIA WILL BE LEARNING AT MIDRESHET LINDENBAUM NEXT YEAR BEFORE ATTENDING WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS.also so much more. It is a metaphor for our history, the countless exiles we’ve survived, and what it means to be a member of Am Yisrael. Just as the Ra’aya (the woman) tirelessly searches for the Dod (her companion) and unites with him a er much e ort, so too, the Jewish people continue to search for God in a godless world in hopes of reuniting. Shir Hashirim encapsulates the underlying theme of Pesach, emphasizing the idea that despite our tumultuous past, the relationship between God and B’nei Yisrael remains mutually eternal. Yetziat Mitzrayim was the rst exile we emerged from, and Shir Hashirim outlines all our tales of survival throughout history until today. Reading Shir Hashirim on

RAV YITZCHAK ESTHALOM IS THE ROSH BEIT MIDRASH AT SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL. RAV ETSHALOM CONTINUES TO DIRECT THE TANACH MASTERS PROGRAM AT YULA BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL, GIVES SHIURIM THROUGHOUT THE CITY, IS A REGULAR CONTRIBUTOR TO YESHIVAT HAR ETZION'S VIRTUAL BEIT MIDRASH , AND IS A PUBLISHED AUTHOR ON TANAKH METHODOLOGY AND RABBINIC LITERATURE. HE ATTENDED YESHIVAT KEREM B'YAVNE, RABBI ISAAC ELHANAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, AND YESHIVAT HAR ETZION BEFORE RECEIVING SEMICHA FROM THE CHIEF RABBINATE OF YERUSHALAYIM.

e four cups of wine that we raise and drink at the Seder are among the more well-known practices of the evening. e rst Mishnah in the nal chapter of Pesahim mandates that the communal charity fund is obligated to ensure that the poorest person should be given no less than four cups of wine for the evening. What is behind this rabbinic enactment? Why wine? And why four cups?

e Jerusalem Talmud (Pesahim 10:1) poses this question and provides four answers (how poetic), each attributed to a di erent sage or, in the last case, the collegium. e rst answer, by far the most popular among both classic Mefarshim as well as in the folk consciousness, is that the four cups correspond to the four words that God instructed Moses to promise the people: ...יתחקלו ...יתלאגו ...יתלצהו ...יתאצוהו (I will take you out… I will save you… I will redeem you take you unto Me.) (Exodus 6:6-7). e second explanation is that the cups correspond to the four times that the phrase הערפ סוכ (Pharaoh’s goblet) appears in the interaction between the chief steward and Joseph while they were in prison (Gen. 40). e third, without referencing any verses, associates the four cups with the “four evil empires.” e “four empires” is a Midrashic trope built on a vision at the end of the book of Daniel (ch. 11), identifying four oppressive kingdoms to whom the Jewish people have been subjugated. e nal opinion is that these cups represent the four cups of bitter punishment that God will, at the end of history, force the nations that oppressed His people to drink – and, corresponding to those, four cups of consolation which he will present to us.

What are we to make of these suggestions? Don’t the rabbis know why the practice was instituted? Shouldn’t there be just one explanation?

To answer this question, we need to explore the di erence between a “reason” and an “explanation.” Any rabbinic enactment is generated for one reason – yet, once that enactment is in place, especially in the context of the Seder, the ultimate teaching experience, we provide multiple explanations to add meaning and texture to the practice and to use that practice to teach further. e many explanations for the karpas, for breaking the Matza and hiding it, for leaning –all speak to this phenomenon. Each of these practices is grounded in an original reason. In some cases, we no longer know that reason, and healthy, spirited debate is generated to try to identify it. Yet, explanations abound and there is no reason to think that the sages proposing their various explanations are in disagreement. Rather, each is providing an additional perspective, which helps us deepen and broaden what we experience while engaging in that custom.

Why are there four cups? e reason seems straightforward: ere are four di erent stages in the Seder, each of which requires a Shirah – song of praise to God. As the Talmud (BT Arakhin 10a) teaches, shirah must be said over wine. erefore, each of these stages – Kiddush, Haggadah (speci cally the blessing of redemption which is at the end of Maggid), Birkat haMazon and Hallel requires a cup as each is experienced as a shirah on this magical evening.

But what are we to make of the four explanations?

I’d like to propose that each one is suggesting a unique perspective on the experience of the Seder.

e rst opinion (the four phrases of redemption) is most straightforward – the evening is about celebrating the Exodus from Egypt, the ful llment of those four promises.

e second opinion deepens our thinking about the event we are reliving. It is not enough to celebrate the redemption; we must also cogitate about the reason we ended up in Egypt in the rst place. To that, we turn to the story of Joseph, a young man sold by his own brothers. We are o en the authors of our own oppression - and the Joseph story ought to be a cautionary tale.

e third opinion takes note of the fact that the Seder is not just about one historic event but about an eternal cycle. As we sing in v’hi she’amdah – “not only one tried to destroy us, but in every generation they try to destroy us and the Holy

RACHEL BLUMOFE SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘24

RACHEL BLUMOFE SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘24

RABBI ABRAHAM LIEBERMAN IS A MEMBER OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH FACULTY AT SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL. HE PREVIOUSLY SERVED AS THE HEAD OF SCHOOL AT YULA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL. RABBI LIEBERMAN LEARNED AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY AND RECIEVED SEMIKHA FROM EMEK HALAKHA IN BROOKLYN. HE RECIEVED HIS M.A. IN JEWISH HISTORY FROM THE BERNARD REVEL GRADUATE SCHOOL (YU), WHERE HE IS CURRENTLY WORKING TOWARDS HIS DOCTORATE.

eser makkot (ten plagues) in our Torah literature. ey are central to the foundation of our faith and to our remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt (zechirat yetziat Mitzrayim). ey also play a role at the Seder, where they are each speci ed by name. e Haggadah even states that the plagues continued at the sea, with some Sages claiming that the Egyptians were struck with up to two hundred and y plagues.

Clearly, the intended purpose of the plagues was multi-layered, ranging from the idea of Hashem manifesting His total control over nature and humanity, to the educational lessons of faith, to the approach of the Ralbag (Rabbi Levi ben Gershon, 1288-1344) that they instilled within the Jewish People the belief necessary for receiving the Torah. e Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270) writes that the plagues contain a triple lesson of faith: a) Hashem is the Creator of the universe, b) His powers are limitless, c) His החגשה (Providence) extends over the entire world. ese lessons were directed both at the Jewish People and at Pharaoh and the Egyptians, as Hashem employed the plagues to combat the ideology of the Egyptian theological system that involved many deities and the worship of Pharaoh as a divine being. ese cataclysmic events changed the course of human history on so many levels.

e number ten in reference to the plagues, although it does not appear in the Torah, has also given rise to deeper analysis and an additional array of questions. Why were ten plagues necessary? Could not Hashem have carried out the Exodus in a di erent manner, in which ten di erent plagues were not needed? Is there an order to these ten? And if indeed there had to be ten, can we nd connections to other concepts within Judaism that are also connected to the number ten? In fact, the Kabbalists link the ten plagues to the ten se rot (ten mystical emanations), others have found connections to the Aseret Hadibrot (Ten Commandments), and yet other commentators suggest parallels between the ten plagues and the ten tests of Avraham.

e commentaries address these questions in a variety of di erent ways. Don Yitzchak Abarbanel (1437-1508) in his Haggadah (Zevach Pesach) examines the ten plagues from two perspectives. In his rst notion, Abarbanel divides the plagues into the ancient division of the four elements of nature, namely: earth, water, air, and re. e rst ve are executed through the usage of water and earth, while the second set of ve are carried out by manipulation of air and re. Hashem’s demonstration of total control over the forces of nature thus prove His Hashgachah (Providence) over the entire world. In his second notion, the Abarbanel views the plagues as retribution and midah k’neged midah (measure for measure), showing how each plague serves as a punishment for what the Egyptians had done to the Jewish people during their slavery.

Rabbi Eliezer Ashkenazi (1512-1585) in his commentary to the Haggadah (Ma’asei Hashem) connects the ten plagues to the following Mishna in Pirkei Avot (5:1):

With ten utterances the world was created. And what does this teach, for surely it could have been created with one utterance? But this was so in order to punish the wicked who destroy the world that was created with ten utterances, and to give a good reward to the righteous who maintain the world that was created with ten utterances.

is Mishna points out that Hashem created the world through the usage of from the root “vayomer,” “and He said,” which is mentioned in the narrative of creation over and over concerning each of the items created. In the ten makkot, we nd a step by step “undoing of creation,” as each plague refers back to creation.

e Netziv (Rabbi Na ali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, 1816-1893) in his commentary to the Haggadah (Imrei Shefer) combines the two notions of the Abarbanel into one. He rst writes that Hashem’s providence is evident from His punishment of the Egyptians measure by measure. He then explains that initially, the Egyptians might have believed that Moshe Rabbeinu, through his knowledge of magic and sorcery, was the cause of the plagues, but slowly they began to realize that a higher power was behind it. In fact, the Netziv explains that the reason the Sages quoted in the Haggadah increased the number of plagues was because di erent punishments were meted out to the Egyptians individually, each one according to his actions.

e Maharal (Rabbi Yehuda Lowe ben Betzalel, 1520-1609) wrote an entire book about the Exodus from Egypt entitled Gevurot Hashem ( e Powers of Hashem) comprised of seventy-two chapters. In chapter y-seven, he deals in detail with the number ten and explains that the ten plagues were brought upon the Egyptians with rising levels of intensity. is order allowed Pharaoh an opportunity to repent, demonstrating that Hashem was only about vengeance and retribution. Philo of Alexandria (25 BCE-50 CE) takes a similar approach, writing that the rst few plagues were more like nuisances, and they became more severe only when Pharaoh kept on refusing and “hardening his heart.” is is also evident from the fact that warnings were attached to some of the plagues and that the plagues did not come in rapid succession but were drawn out. As the Mishnah (Eduyot Ch. 2:10) teaches, the plagues were stretched out over the span of an entire year.

In contrast to the explanations above, Rabbi Yaakov Meidan (Rosh Yeshiva, Har Etzion) suggests that the number ten was not set in stone; it was only a result of Pharaoh’s decisions, as the plagues could have stopped a er the third or fourth one. While the makkot brought destruction to the Egyptian economy and certainly were perceived as signi cant inconveniences, human casualties did not occur until Pharaoh continued to resist, at which point Hashem brought the tenth one, makkat bechorot (the plague of the rstborn). In other words, the rst nine plagues could be seen as plagues that exhibited Hashem’s Midat Ha-Rachamim, His attribute of mercy. Only in the end did justice) prevail.

Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner (1906-1980) suggests in his writings ( as a midpoint of sorts, connecting Creation, through the ten utterances ( culminating in the Ten Commandments. Each one of these stages is achieved through a di erent pattern power of language. Creation was begot by Maamarot (sayings) the world, there was no one to hear his sayings. In each step of Creation, Hashem hid behind the forces of nature. In the ten plagues, Hashem revealed Himself step by step as the Master of nature. is is connected to the power of (telling), where in order to tell the story of the redemption, someone asks a question that is then answered, as we do on Pesach night, relating the story of the Exodus to our children. is then climaxes into and the rest listen, as occurred in the Ten Commandments. Hashem thus transitions from the hidden stage of Creation to slowly revealing Himself through the unraveling of the ten plagues, to fully revealing and identifying Himself at Sinai as the G-d that took us out of Egypt.

As we sit down at the Seder this year and again retell the events of our rst redemption, may we merit to witness the nal redemption in our day. Chag Sameach to all!

1 All of the scienti c information presented in this article can be found at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5299389/, https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3001571#sec003, https://hubermanlab.com/sleep-toolkit-tools-for-optimizing-sleep-and-sleep-wake-timing/, and https://hubermanlab.com/toolkit-for-sleep/.

analogous to the language used in the studies – low-angle sun – to describe the properties that indicate sunset.

In the continuation of the same sugya, Rebbi Yosei ben Elyakim and Rebbi El’a enumerate two positive consequences of reciting the Shemoneh Esrei immediately a er the beracha of “ga’al Yisrael,” discussing redemption, known as semichat geulah l’te llah. Tosafos explains that these two consequences – “ ולוכ םויה לכ קוזנ וניא” (he will not be harmed all day) and “אמוי הילוכ הימופמ אכוח קיספ אלו” (a smile does not leave his face all day) – are bestowed speci cally upon those who observe semichat geulah l’e llah when davening Shacharis at sunrise like the vasikin. Scienti cally speaking, “not being harmed” likely refers to the neuroprotective e ects of proper circadian synchronization, and “smiling all day” could be an allusion to the sunlight-induced increase in dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, all of which contribute to a happier day.

To ensure vasikin Jews fully bene t from the morning sunlight during indoor prayers, the Shulchan Aruch (O.C. 90:4) prescribes speci c requirements for every synagogue: " ןדגנכ ללפתהל ידכ םילשורי דגנכ תונולח וא םיחתפ חותפל ךירצ" - “It is necessary to open doorways or windows facing Jerusalem, so as to pray opposite them.” is arrangement and positioning of the doors or windows towards Yerushalayim (situated west of the center of Judaism during that time, Bavel) enables the photosensitive retinal ganglion cells to obtain su cient exposure to the eastern Netz sunrays - through re ection - without the damage of direct sunlight. During Mincha, when direct exposure to the sun's weak rays is desirable, the same construction enables the westward setting sun to be positioned in front of those praying.

As the Zohar Hakadosh beautifully depicts and as these sources demonstrate, nature, and by extension, science, are merely manifestations of the words of the Torah Kedosha. It therefore becomes apparent that adherence to the rules of the Torah, the instruction manual to life, enables individuals to live in harmony with nature in the most optimal manner. Paradoxically, a Halachic Jew not only ensures the optimization and development of his or her spiritual self, but also represents the paradigm of physical health and well-being.

Armed with this knowledge of the scienti c practicality of our halachot, let us approach Pesach with a fresh perspective, embracing the sometimes peculiar customs and obligations with a newfound admiration. As we immerse ourselves in the spirituality of anything from Bedikat Chametz to drinking the four cups of wine, let us not neglect or overlook the potential physical bene ts that underlie our halachot. Let us enthusiastically acknowledge and appreciate Hashem’s handiwork in creating a universe governed by the laws of our Torah!

On a recent trip to Poland, I was introduced to the philosophy of the Kotzker Rebbe, who strove to nd the emet in the world and preached the importance of self-analysis. During a re ective activity near the Kotzker’s kever, we were told to look in a mirror and ask ourselves the following question:

What de nes who we are: our thoughts or our actions?

Much of the Jewish tradition suggests that actions reign supreme. Upon accepting the Torah at Har Sinai, the Jewish people eagerly exclaimed the phrase that has become imprinted into our memory and identity: “Na’aseh V'Nishma – we will do and we will listen.” Here, Na’aseh (taking action) is listed rst and expressed as the priority, which makes it one of the rst de ning characteristics of our national entity.

However, this elemental phrase, the banner of our Jewish identity, contains many more layers. e Gemara (Kiddushin 40b), in looking to clarify our primary responsibility as Jews, asks the following question:

“ is question was asked of them [the Elders]: Is study greater or is action greater? Rabbi Tarfon answered and said: Action is greater. Rabbi Akiva answered and said: Study is greater. Everyone answered and said: Study is greater, as study leads to action.”

At rst glance, it seems as though the Talmud o ers an answer that is contradictory to our previous understanding of Na’aseh V’nishma. According to this statement, the consensus of the Sages was that study is greater than action.

But a closer look reveals that the Gemara’s statement is meant to reframe and deepen our interpretation of the word Na’aseh. We cannot simply take action for the sake of being “doers.” Rather, we must begin by engaging in intensive study and thereby broaden our understanding of the world and the Torah for the ultimate purpose of informing how we ought to act. Blind action is not what is desired. Rather, Judaism demands action arising from the depths of understanding.

e Gemara’s enigmatic answer that study is greater because it leads to action paradoxically places action as the superior component in our lives – because we study so that we may act. Action imbued with deep understanding of what is needed is the ultimate goal according to the Gemara.

e well-known episode of the Sneh, the precursor of the entire story of yetziat Mitzrayim, encapsulates this concept as well. As Moshe herds the sheep of his father-in-law, Yitro, he happens upon a thorn bush engulfed in ames. He then exclaims:

“I must turn aside to look at this marvelous sight; why does the bush not burn up?” (Shemot 3:3)

ISABELLA SZTUDEN GRADUATED FROM SHALHEVET IN 2022. SHE IS CURRENTLY LEARNING AT MIDRESHET HAROVA IN THE OLD CITY AND WILL BE GOING TO BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY NEXT YEAR.e next pasuk repeats the rst phrase used in the previous quote.

“When Hashem saw that he had turned aside to look, God called to him out of the bush…”

Why do the pesukim use the phrase “turn aside” twice (אנ הרסא and תוארל רס יכ)? e Torah could have simply written only, “Let me see this great spectacle,” and “Hashem saw that he looked.” Why include the word הרסא (turn) at all?

One explanation I learned about the placement of the bush provides insight into this textual peculiarity. According to this explanation, the Sneh was planted amidst an area of the desert where many passersby would see it. Positioning the Sneh in such a populated location was intentional; it gave everyone the opportunity to stop and take a look. Yet Moshe Rabbeinu was the only one to take heed of the phenomenon, which is why the pasuk explicitly points out that he “turned aside.”

is incident occurred approximately sixty years a er Moshe ed Egypt and had already integrated himself into Midianite culture. Suddenly, though, Moshe notices the burning Sneh and decides to turn aside to examine it more carefully. He sees a bush that does not allow itself to be consumed by the re and he remembers Bnei Yisrael, who refuse to perish despite the years of genocide and slavery designed to exterminate them.

On that day, Moshe stood at the very intersection of his Talmud and Ma’aseh, between acquiring a deep understanding of his environment – the acknowledgment of Jewish su ering – and choosing to become the people’s liberator. Moshe’s cry of “I must turn aside” serves as the beginning of his transformation into the leader of the Jewish people. e Sneh taught him that he could no longer ignore the plight of his people, and following Hashem’s insistence that he was the right person for the job, Moshe agrees to take on the role of Bnei Yisrael’s savior. In light of this idea, perhaps the ground Moshe stood upon was not inherently holy (see Shemot 3:5), but became sancti ed once Moshe came to this vital epiphany.

In fact, Judaism has di ering notions of sanctity: one designated by God Himself, and one initiated by human beings. is contrast is illustrated in the distinction between the nature of Shabbat and Yomim Tovim. In Bereshit, the Torah tells us that Shabbat is immutably sacred because God Himself blessed the seventh day (ותא שדקיו יעיבשה םוי תא םיקלא ךרביו). However, when it comes to Yom Tov, humans (particularly the Sanhedrin) have the power and requirement to consecrate the day, because they determine the proper time to begin the celebration. Having the ability to create sanctity can be empowering, and as displayed by Moshe, we can create Kedusha by undergoing the process of perceiving and understanding, then creating goodness and xing injustices.

Any of us can become more like Moshe if we start to investigate our surroundings and begin to turn aside. Nowadays, this can mean inviting someone over who might feel excluded or giving a thoughtful compliment when you notice something positive about someone. It is only then that we can lay the foundations for change, ful ll our obligation as members of the Jewish people, and create our own sanctity.

May we all merit to be as re ective and upstanding as Moshe. Chag Sameach!

MS. ARIELLA ETSHALOM IS PROUD TO BE PART OF THE JUDAIC STUDIES FACULTY AT SHALHEVET, SERVING AS THE SHOELET U’MEISHIVA OF THE BEIT MIDRASH TRACK. AFTER RECEIVING HER B.A. AT STERN COLLEGE, SHE SPENT A YEAR TEACHING IN SAR HIGH SCHOOL'S BEIT MIDRASH FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM. ALONG WITH TEACHING AT SHALHEVET, SHE IS CURRENTLY WORKING TOWARDS HER MASTER'S IN BIBLICAL AND TALMUDIC INTERPRETATION AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY'S GRADUATE PROGRAM FOR ADVANCED TALMUDIC STUDIES (GPATS) AND WORKING AS AN ADVISOR COORDINATOR FOR MIDWEST NCSY.

Role models and mentors are in uential by creating a framework that motivates their proteges to follow in their footsteps and hopefully take their legacy further. ese individuals are o en viewed in one of two extreme ways; they are either glori ed or humanized. Both methods are extremely useful in following the leadership of a role model gure, but each also comes with a cost.

Glorifying is about raising the esteem of a mentor to an exceedingly high level. e followers know they will never reach the level of their leader, but they are pushed to try as hard as they can to reach a level even remotely close to the leader. e disadvantage is that sometimes this creates an imposter-syndrome complex that leads the followers to give up entirely and no longer view the model as a person they could ever realistically become.

Humanizing the leader works in the exact opposite way. It allows the followers to view the leader as a real person, with aws and fears just like them. is creates a more realistic view of how that person reached the standing that the followers aim to reach as well. e downside to this way of approaching a leader is that it can generate disrespect and disdain when the leader errs or conduct themselves in a manner that the followers disagree with, causing the followers to no longer look up to the leader. As with anything, nding the right balance between these two extreme approaches to viewing leaders will help develop the right level of respect without creating too high a standard for the followers.

We commonly struggle with this balance when looking at the characters in the Tanach. With most characters in the Torah, major moments in their lives are depicted in the text that highlight signi cant aws or paint them as angelic so we do not even feel we can learn anything of substance from them. Because of this, we need to ll in some of the details using mefarshim and hints in the text that help give us a broader idea of these leaders and how we can learn from them.

Moshe is a prime example of such a character. His story as a leader begins with him being told by Hashem at the burning bush that he will bring the people out of Egypt. And for us, that already makes him unrelatable. He is a human being who is being told by the Master of the world that he will do amazing things. He has the best support to push forward and speak to Pharaoh about letting the Jews go. Yet, in this exact story he does something that brings him back down to earth; he expresses his fear of becoming the leader of the Jewish people because of his speech impediment and refuses a direct request from Hashem. He says:

“Moshe said to Hashem, Please my Master, I am not a man of words, not yesterday and not the day before, not since You have spoken to me, for I am heavy of mouth and heavy of tongue.” (Shemot 4:10)

What exactly is this impediment, and how does Hashem’s solution of Aharon serving as his spokesperson calm Moshe down?

paints this as a physical aw that resulted from a test Moshe underwent when he was growing up in the palace1. is approach highlights the practical nature of Moshe’s concern. Moshe does not mention any fear he may have of accepting the leadership role Hashem requests of him and focuses mainly on the question of how he will communicate e ectively to Pharaoh and the Jewish people.

A second approach is that Moshe was simply nervous about serving in this role of leader, just like any of us would feel before stepping into a new role. Although he has the support of Hashem, he is still a human being who occasionally gets nervous. is paints Moshe in a more relatable light, which helps us learn more from his actions and how he handled the situation. Hashem tells him that although he may have a fear of public speaking, Aharon will assist him for a short time and then he can continue on his own2. When viewed from this perspective, we can learn much more from the story about how even the greatest leader of the Jews started o with a bit of help.

Whether Moshe needed practical help in communicating Hashem’s message to Pharaoh and the Jewish people or emotional help to alleviate his nerves about this new role, we learn about the importance of asking for help when we need it. By humanizing Moshe, we understand that as long as we are realistic about our level and capabilities and what we still need help with, we too can become leaders.

Pesach is a time when we remember the Exodus of the Jewish people from slavery in Egypt. It is a time when we retell the story of our liberation and re ect on its meaning and signi cance in our lives today. As we delve into the complexities of the story at the Seder, we can turn to two great Jewish scholars, the Rambam and Rav Soloveitchik, for insights and guidance.

One question that arises when re ecting on the Exodus is why God chose to free the Jewish people from slavery through a series of plagues, rather than simply granting their freedom. e Rambam addresses this question in Moreh Nevuchim, explaining that the plagues were not just a means of freeing the Jewish people, but were also a demonstration of God's power and a way of undermining the false beliefs of the Egyptians. By showing His power through the plagues, God was able to reveal the truth of monotheism and bring about a spiritual awakening among the Egyptians. As for the Jews, this whole experience was designed not only to liberate them physically but also to liberate them mentally and teach them about the importance of serving God.

Another question that arises when re ecting on the Exodus is why God allowed the Jewish people to su er in slavery for so long before freeing them. Rav Soloveitchik addresses this question in his essay "Redemption, Prayer, and Talmud Torah," explaining that the experience of slavery was necessary in order for the Jewish people to fully appreciate the gi of freedom. By experiencing the depths of despair and oppression for such a lengthy period, the Jewish people were able to fully appreciate the gi of liberation and recognize the hand of God in their redemption.

Both the Rambam and Rav Soloveitchik teach us how the Exodus story is not just a simple narrative of freedom from slavery, but a complex and multifaceted story that reveals the power and wisdom of God. e plagues were not just a means of freeing the Jewish people, but a demonstration of God's power and a way of revealing the truth of monotheism. e experience of slavery was not just a tragedy, but a necessary step in the process of redemption and spiritual growth.

As we retell the story this Pesach, let us remember the teachings of the Rambam and Rav Soloveitchik and re ect on the deeper meaning and signi cance of the story. For the Rambam, we should strive for spiritual freedom, breaking free from negative habits and self-imposed limitations that prevent us from ful lling our potential. For Rav Soloveichik, we must remember that just as our ancestors were redeemed from slavery, we too can experience personal redemption in our own lives. It is our duty to appreciate these personal redemptions as well through teshuvah and strengthening our relationship with God. e story of Pesach serves as a reminder of God's power and the potential for redemption in our own lives. May this Pesach be a time of physical and spiritual awakening and growth for us all.

CHAIM COHEN, '24, IS A JUNIOR AT SHALHEVET. HE IS THE VICE CHAIR OF SAC, CAPTAIN OF THE FLAG FOOTBALL TEAM, AND ON VARSITY BASKETBALL.