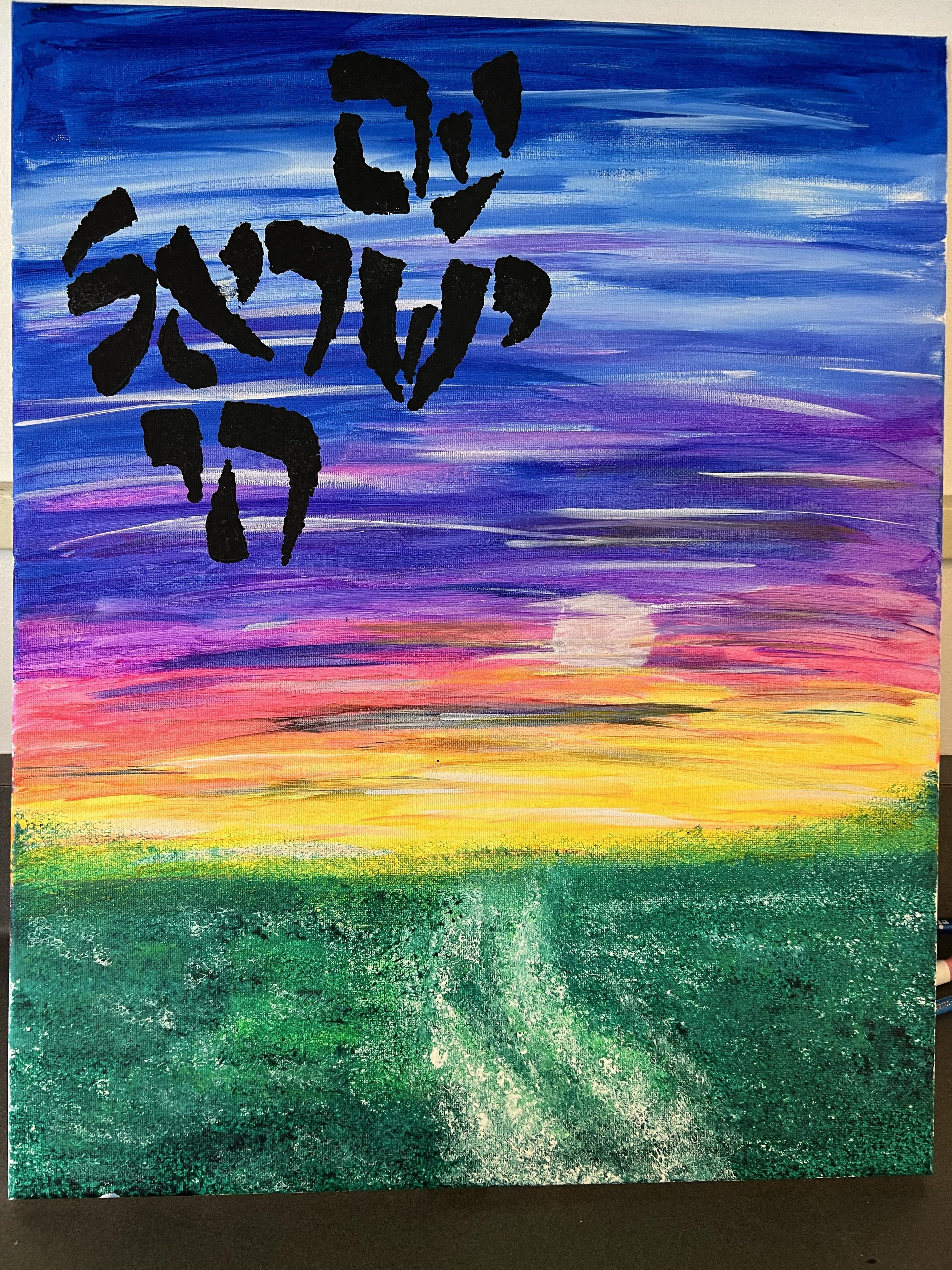

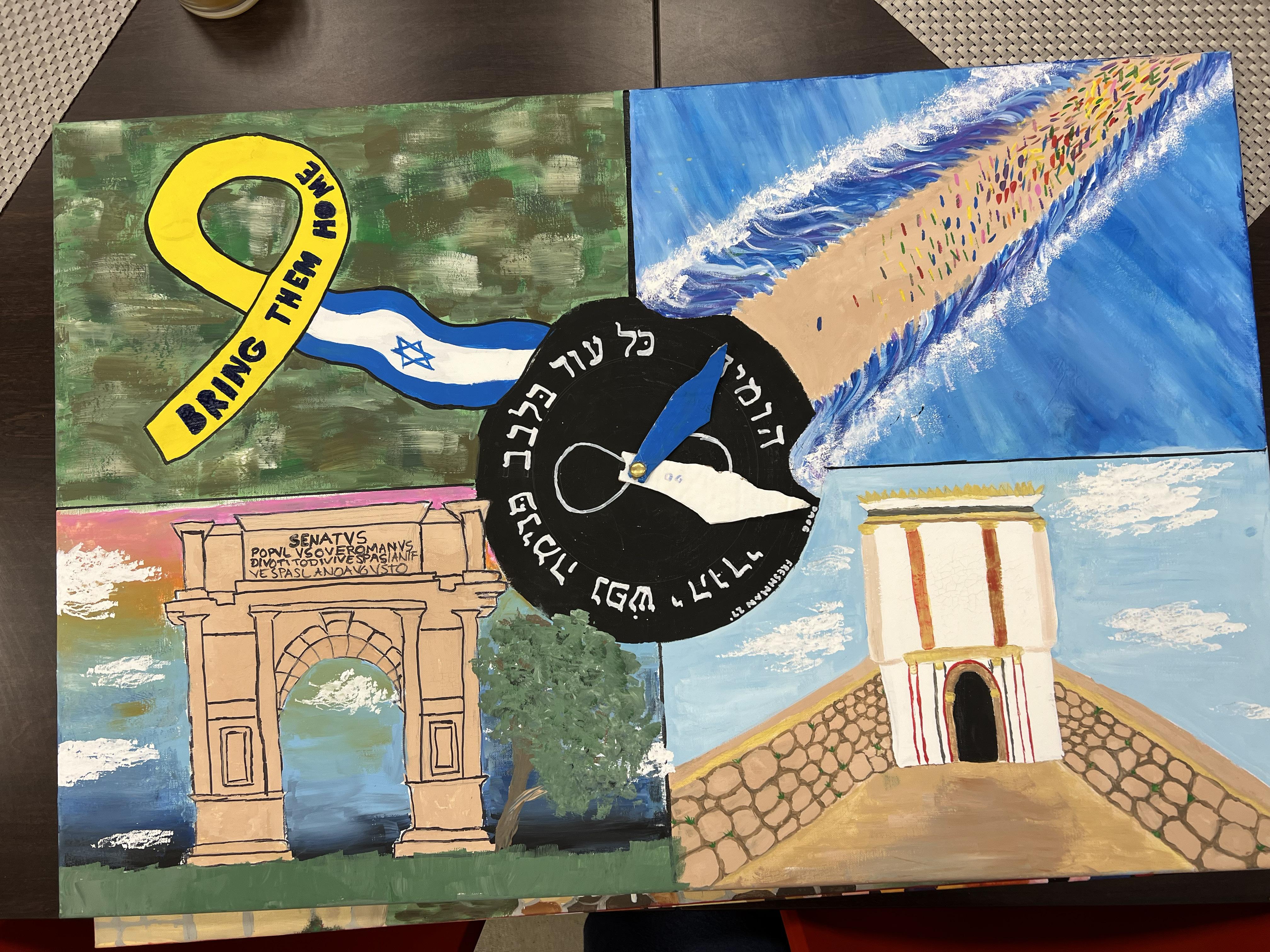

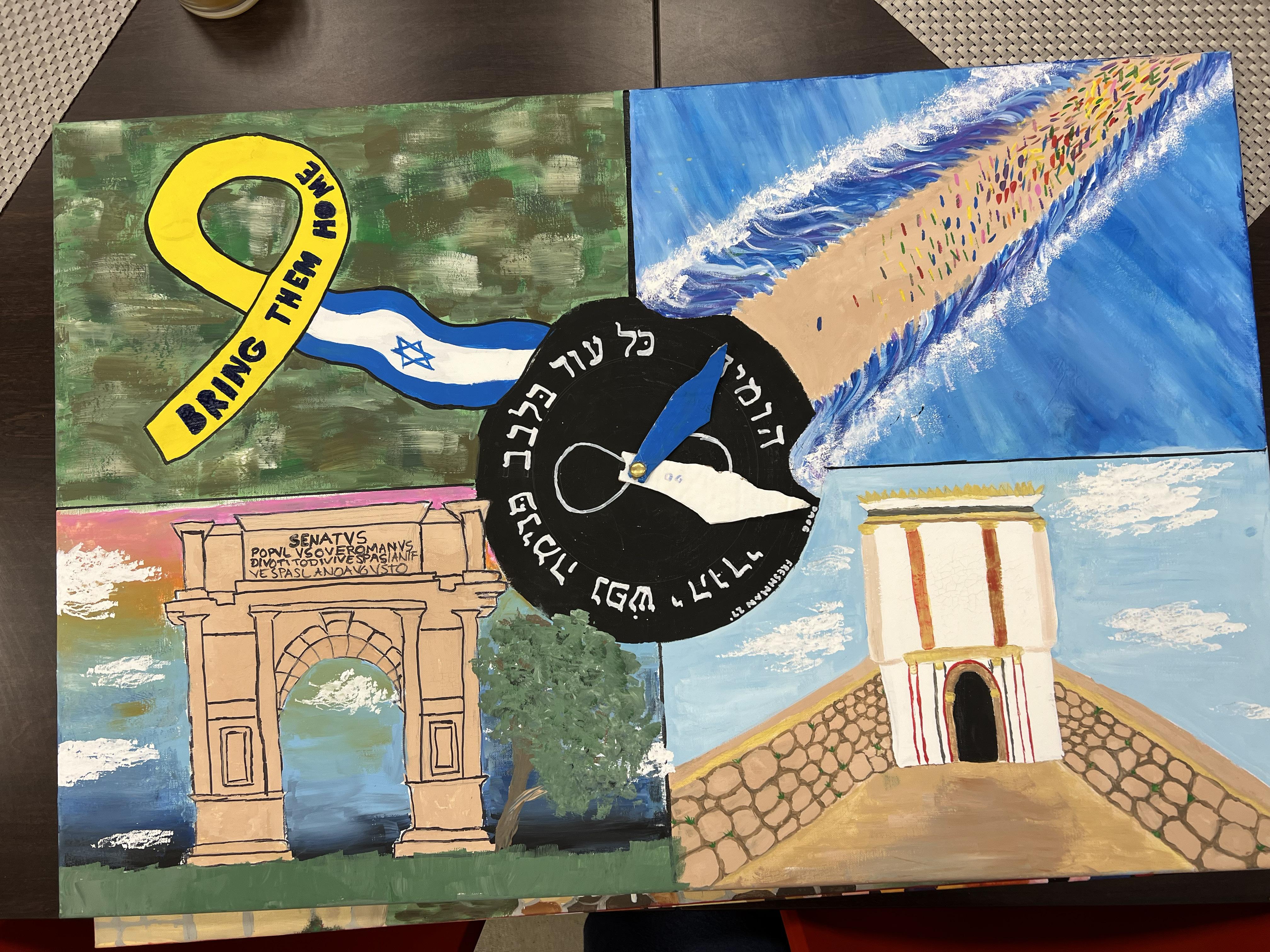

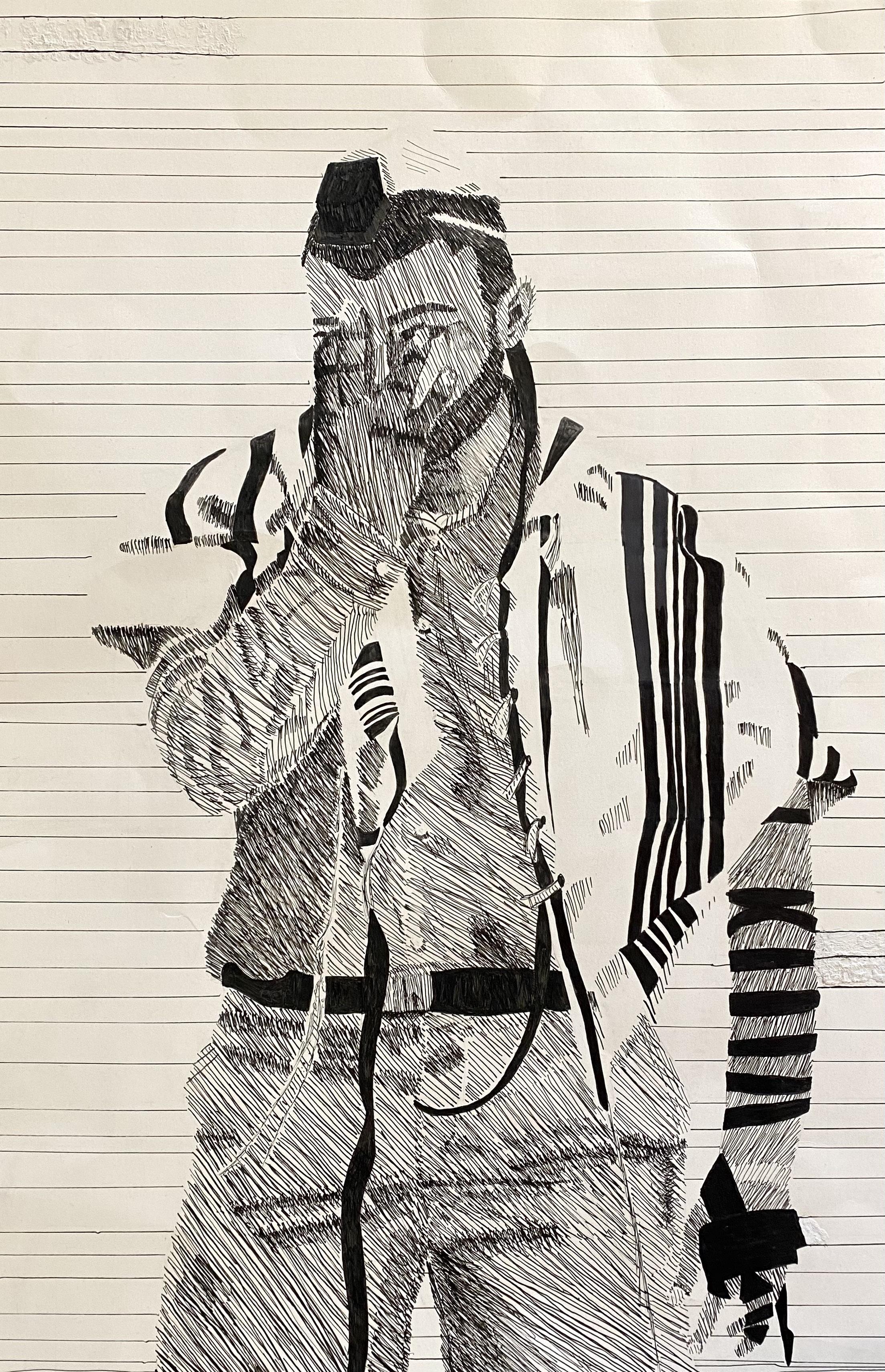

COVER ART BY AMALIA ZUCKER SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘24

COVER ART BY AMALIA ZUCKER SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘24

One of the most iconic elements of Pesach is the recounting of our salvation on Seder night. And yet, the way in which we do it is entirely unintuitive. If I were to ask you from which Torah text the Haggadah might borrow in order to retell the Pesach story, I imagine you would point to the story in Shemos - in other words, the actual Exodus story. ere’s no better source than the source itself! And yet, the Haggadah never quotes the story from Shemos. Instead, it quotes from the lens of… a farmer, many years later. Indeed, when - a er having arrived in Israel - the farmer would dedicate his new fruits to Hashem (hava’as bikkurim), he would accompany it with a . at declaration references our salvation from Egypt as the conduit to our eventual arrival to Israel. It is the psukim from that declaration that we read on Seder night. And the question is, why? Why not tell the story from a rst-hand account, instead of from the farmer’s second or third hand account?

I want to suggest an idea developed partly from my own exploration and from the fascinating insights of my teacher, Rabbi Fohrman: e goal of the Haggadah — and, for that matter, of Pesach — is actually not to simply retell the Exodus story. e goal is to see ourselves, today, as bene ciaries of Hashem’s love. To see ourselves as direct bene ciaries of Yetzias Mitzrayim of millennia ago and to express ongoing gratitude. Even more, Hashem’s love that we saw so explicitly during the Exodus continues — albeit in less overt forms — today. In other words, in retelling the miracle of the Exodus from Egypt, we also recognize the hand of God in our lives throughout the

at’s why we choose to retell it through the eyes of the farmer, someone who clearly and explicitly sees how he is a bene ciary of the Exodus, who sees his story as part of our national history. On seder night, the farmer is our teacher. So, yes — we’re meant to study the story, but toward the end of recognizing our spot in that gorgeous

What a tting description of our school, too. Every single member in every “generation” of Shalhevet sees him/herself as an integral part of our story. Each one helps to write it. In this edition of Orot Shalhevet, we celebrate the magni cent varied vibrance of that tapestry. Each unique voice - each student, faculty member, and alumnus - teaches us how to bring Hashem into our lives. Each one is a farmer, a teacher. with you and share the kedusha with others. It is my bracha that the varied and unique voices of our faculty, students, and alumni infuse our holidays with meaning, and the (beauti cation of the Torah within). As I always note, the teachers, students, and alumni are all the Orot (lights) that come together to form our dazzling Shalhevet ( ame).

TO THE FOLLOWING SUPPORTERS WHO HAVE GENEROUSLY SPONSORED THIS EDITION OF OROT SHALHEVET. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO THEM FOR HELPING TO PROMOTE THE SPREAD OF MEANINGFUL TORAH LEARNING AND SPIRITUAL GROWTH IN OUR COMMUNITY. PLEASE ENJOY THE TORAH YOU WILL FIND WITHIN IN THEIR MERIT. thank you

& AVI ASHKENAZI

SIMON & DALYA BACKER

IN MEMORY OF OUR SABBA, HARAV HAGAON DOVID BEN DOV YEHUDA Z'L,

IN HONOR OF HIS BIRTHDAY ROSH

CHODESH NISSAN

DEBBIE & MICHAEL BLOCK

IN HONOR OF RABBI DAVID AND GILA BLOCK. WE ARE SO PROUD OF YOU AND LOVE YOU!

DAHLIA & ELAN CARR

MAYA & NEIL COHEN

ELISA & BRADFORD DELSON

JENNIFER & YARON ELAD

IN MEMORY OF DR. AMITAI ETZIONI

MICHELLE FELLNER

DAVID FISHER

IN MEMORY OF LINDA CARO FISHER, BELOVED GRAN OF CAROLINE AND OLIVIA KBOUDI

CARA GROSSMAN & ZEV WAINBERG

DEDICATED BY THE WAINBERG FAMILY IN MEMORY OF THEIR BELOVED FATHER & ZAIDY, DR. MARK WAINBERG Z"L, ON HIS 7TH YAHRZEIT

MOLLY & SAEED JALALI

IN MEMORY OF MAYER BEN SHAUL SALAMA Z"L

BARBARA & JONATHAN POLLACK

DESI ROSENFIELD

IN HONOR OF MY SONS EDAN AND ITAI

SCHWARZBERG FAMILY

ALISA & ROY SHAKED

HONORING ALL THOSE NOT AT THE SEDER TABLE THIS YEAR, WE ARE THINKING OF YOU WITH LOVE AND STRENGTH

LIZIE & AVISHAI SHRAGA

FOR THE SAFETY OF THE IDF SOLDIERS AND THE SECURITY OF THE STATE OF ISRAEL.

#BRINGTHEMHOME

ADAM & TAALY SILBERSTEIN

LESLEE & ALEX SZTUDEN

RABBI GORMIN IS PART OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH FACULTY AT SHALHEVET, WHERE HE TEACHES TALMUD, JEWISH PHILOSOPHY, CHASSIDUT, AND TEFILA (PRAYER). WHEN NOT INSIDE THE HOLY WALLS OF SHALHEVET, RABBI GORMIN IS THE REGIONAL DIRECTOR OF WEST COAST NCSY. RABBI DEREK GORMIN STUDIED POLITICAL SCIENCE, MUSIC AND SOCIOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE, AND RECEIVED A CERTIFICATE OF INTERNATIONAL POLITICS FROM YONSEI UNIVERSITY IN SEOUL, KOREA. UPON GRADUATION, DEREK WAS BLESSED TO SPEND TIME DIVING INTO THE DEPTHS OF HIS JEWISH HERITAGE IN VARIOUS YESHIVOT IN JERUSALEM.

Sometimes it’s great to steal. Stealing a few moments from each day to enumerate the greatness that exists in Jewish heritage can be life-giving. From the “Great Synagogue” in Jerusalem to Gedolei Torah, our sages who serve as iron links in the chain of our heritage, the greatness is pervasive and inspiring. Greatness is part and parcel of the Jewish experience. e Hebrew word “gadol” is rich in meaning, capturing aspects of size, age, importance, authority, and more in our holy tongue. ere are several manifestations for each of these terms within Jewish law; how old need one be for the mitzvot of the Torah to be obligatory? How high can a Chanukah Menorah be placed? How large can a Kosher etrog be? We just met one of the Gedolei Yisrael (One of the great scholars of the Jewish people).

is brings us to the question at hand: Why is the Shabbos before Pesach called “Shabbos HaGadol ( e Great Shabbos)?” And perhaps more importantly, what does that have to do with me?

One reason Shabbos HaGadol is deemed "great" is due to its historical signi cance. On this Shabbos, the Jewish people took a lamb, the Egyptian deity, for the Passover sacri ce. is act demonstrated a major level of courage and foreshadowed their upcoming liberation from slavery, making this Shabbos truly great. Hence, Shabbos HaGadol. (Code of Jewish Law, Orach Chaim 430:1, Mishna Berurah 430:1). e Chasam Sofer writes that this day, the Shabbos of actively rejecting and targeting the Egyptian God, was when we, as a Jewish people, really grew up, a “Bar Mitzvah” of sorts. We took responsibility for our actions. is Shabbos is when we matured as a people, we became “gedolim” taking ownership of our destiny and triggering the ultimate redemption.

e name "Shabbos HaGadol" runs even further into the depths of our heritage, fusing Shabbos itself with the Exodus from Egypt. e famed Gerrer Rebbe, the Immrei Emes, suggests that before the Exodus, Shabbos primarily symbolized physical rest from the 39 melachos used for the building and maintenance of the Mishkan, creative labors akin to Hashem resting a er creation. Shabbos underwent a transformative shi post-Exodus, becoming a day inextricably linked to the memory of our liberation. As Friday night Kiddush emphasizes, Shabbos is now a "Zecher L’Yetzias Mitzrayim" – a remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt. e Torah underscores this connection, urging us to "remember that we were slaves in the land of Egypt, and Hashem... has commanded you to make the Shabbos day" (Devarim 5:14). Shabbos, it seems, was not fully realized until it bore witness to the Exodus from Egypt. With both creation and liberation shaping its essence, this particular Shabbos before Pesach was when Shabbos gained its fullest level of greatness, earning the title Shabbos HaGadol.

Shabbos HaGadol is all about maximizing the potential of Shabbos. Shabbos HaGadol o ers us an opportunity to recalibrate our Shabbos experience, ensuring it is maximally engaging and truly great for all members of our shared community. Here are ve tangible ideas to consider stealing from Pesach, to best upgrade and enhance your Shabbos experiences throughout the year:

Meticulous Preparation: Pesach brings with it our massive yearly To Do list, ensuring that our experience is both Kosher and meaningful. People half-jokingly refer to it as anxiety inducing condition called P4 (Post Purim Pesach Preparations). Translate this to our weekly Shabbos experience by preparing during the entire week in some form.

Shammai the Elder would spend all week eating in honor of Shabbos. When he saw a ne animal for purchase, he would say: “ is is in honor of Shabbos.” If he later found an even better one, he would eat the rst one and leave the better one for Shabbos (Beitza 16a). e entire week was a build up towards Shabbos. e world says, “an ounce of preparation is a pound of cure.” e Jews say, “If you don’t cook on Erev Shabbos, you won’t eat on Shabbos!”

Guests: A thematic pillar of Pesach is welcoming strangers. Looking towards the verse, “just as we were strangers in the land of Egypt…” We joyously, and hopefully honestly, call out “to all who are hungry come and eat, all who want to celebrate Pesach should come join us.” Guests are a great way to liven up your table, teach your children about the mitzvah of hachnasas orchim, welcoming guests, and meaningfully share experiences with others. With this in mind, consider what your Shabbos invite list looks like each week. Consider reaching out to “that family who goes to the other shul” or “that guy I see in minyan sometimes, but don’t really know him yet.” Shabbos is an incredible tool that unites our people, but only if we let it. In the words of R’ Shlomo Carlebach, “you can’t really keep Shabbos, until you share it with someone else.”

Tell the Story: A pillar mitzvah of the Seder is Sipur Yetzias Mitzrayim, a storytelling experience, recounting the narrative of our liberation. We can apply this idea of sharing narratives to incorporate an aspect of sharing blessings, positive points from the week, or highlights with your family and friends around the Shabbos table. Spend some time telling your story, including all of the blessings (in the words of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, nekudot tovot) that the Almighty provides.

Table to the nines: On Pesach, we bring out our nicest dishes, our ne china, and our best serving utensils. e table is o en set a day or two in advance and the anticipation builds towards the big moment of Seder Night. Consider exploring what our Shabbos tables looks like. Is the tablecloth beautiful? What type of silverware do we use? Don’t get me wrong, I am not saying we need to reinvest in ne china. Yes, and…If you choose to use disposable dishes, recognize that there is plastic throw away, and then there is PLASTIC THROW AWAY. Get the nicer ones, you know, the one with the design on it.

e Haggadah: On Pesach night, we follow the powerful script of our redemption from slavery to freedom. Very o en, lines in the Haggadah are assigned to speci c family members for emphasis, humor, or comfort. e literal seder (order) of the evening is established for us, verse and song. We all know which cousin will lovingly, cutely, and o en incorrectly sing the 4 questions. Let’s consider the script for our Shabbos meals in a similar way. Who says what when? How will we include all the family in the conversation? What are the topics of conversation? Which songs are we singing and who chooses them? Who is sharing a dvar Torah and why not have 3, 6, or 12? What is the climax of the experience? How do we end? Let’s have a seder, in the actual sense of the word. As an educator, dare I suggest formulating a meaningful, thought-provoking, engaging lesson plan for our Shabbos meals.

With these ideas in mind, sending wishes for a Kosher and joyous Pesach, launching into upgraded and glorious Shabbos experiences all year long!

RABBI ELI BRONER SERVES AS THE 9TH GRADE DEAN AND JUDAIC STUDIES TEACHER AT SHALHEVET, AS WELL AS YOUTH DIRECTOR OF BETH JACOB CONGREGATION. RABBI BRONER HAS BEEN A LEADER IN THE FIELD OF JEWISH EDUCATION FOR WELL OVER TWO DECADES, TEACHING ALL SUBJECTS OF JUDAIC STUDIES TO STUDENTS FROM FIRST TO TWELFTH GRADES. RABBI BORNER RECEIVED HIS BACHELORS OF RABBINICAL STUDIES FROM THE RABBINICAL COLLEGE OF AMERICA AND SEMICHA FROM YESHIVA COLLEGE IN SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA.

Picture this: Bnei Yisroel have been slaves for hundreds of years, they have endured all types of su ering, and they are hoping to be redeemed as their ancestors have promised them. Time and again, Pharaoh has reneged on his promise to let them go even in the face of nine plagues. Finally, Hashem tells Moshe to instruct them to prepare to leave, and the rst command he gives them is to keep a calendar based on the moon. He does not tell them to rst circumcise themselves, proclaim a state, or bake Matzot. Keeping a calendar would seem to have nothing to do with being redeemed or freedom.

Everything about Bnei Yisroel’s experience during the exile and its redemption has been carefully orchestrated from the moment G-d told Avraham that his children would be slaves in a land not their own. Every step and interaction has been scripted to form Bnei Yisroel into the nation they were to become and take their place as a light unto the other nations.

What, then, is the signi cance of establishing a Jewish calendar as the prerequisite of redemption? If it is being given as the rst mitzvah, it must have a particular signi cance for Bnei Yisroel and their process of redemption and becoming a nation. We know that there is a mitzvah to remember and recount the experience of the redemption from Mitzrayim every day; as such, there must also be a lesson on how to live our lives as a free nation from this mitzvah.

We can look at this from two perspectives. On one level, the mitzvah of Kiddush Hachodesh can be seen as a means of granting Bnei Yisroel freedom. On the second, setting a Jewish calendar and sanctifying time must be signi cant in terms of what it teaches about mitzvot in general, if this was given as the rst mitzvah to Bnei Yisroel. Both perspectives will also give us insight into how we can lead a life of meaning, purpose and freedom.

e Sforno explains the mitzvah of Rosh Chodesh and speci cally, the term “Lachem,” “for you” (Shemot 12:2), as follows. From now on, these months will be yours, to do with as you like. is stands in stark contrast to the years when you were enslaved, during which you had no control over your time or timetable at all. While you were enslaved, your days, hours, and even minutes were always at the beckoning call of your taskmasters.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks in his Hagada quotes Rabbi Avraham Pam who explained this in the following manner. e di erence between a slave and a free human being does not lie in how long or hard each one works. Free people o en work long hours doing arduous tasks. Rather, the di erence lies in who controls time. A slave works until he or she is allowed to stop. A free person decides when to begin and end. Control over time is the essential di erence between slavery and freedom. Control over the calendar gave the Israelites authority over time. e rst command to the Israelites was thus an essential prelude to freedom.

Rabbi Sacks explains that to be truly free, one must have control over one’s time. By observing a Jewish calendar, we have the opportunity to rebalance our lives daily, weekly, monthly, and throughout the year. By davening three times a day, we set our day up in a way that acknowledges Hashem’s involvement in our lives and allows us to set the agenda of the day. Shabbat enables us to focus on family and deep connections as well as on activities like learning and rest. And Rosh

Chodesh allows us to take stock of the month that passed, its highs and its lows, and make plans for the month to come. e Ramban on this mitzvah adds an additional dimension to this idea. e mitzvah given to Bnei Yisroel by Hashem establishes the month of Nissan as the beginning of months, marking the start of the Jewish calendar. is designation serves as a reminder of the miraculous Exodus from Egypt, as each month is counted from Nissan onward. e absence of individual names for the months in the Torah reinforces this commemoration, with months referred to simply by their numerical order. While Rosh Hashana is in Tishrei, the designation of Nissan as the rst month signi es its importance in the context of redemption. us, the commandment emphasizes the perpetual remembrance of the Exodus through the counting of months. is emphasizes the importance of using time and speci cally Rosh Chodesh to re ect on the gi of freedom granted to us when we le Egypt and make time holy and productive.

Sanctifying Time and its Importance as the First Mitzvah

Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, explains that time is the rst creation (see Sforno on 1:1); thus, the sancti cation of time is the rst mitzvah commanded to Israel. All of creation is dependent on the rst creation, which is time. Appreciating “time” therefore allows one to appreciate all creations. As such, even before space could be created, there was already a creation that was subject to change, i.e., time. Man himself experiences this every day when the day begins, and one then goes about lling it with activities. So by sanctifying Rosh Chodesh, we are injecting time with holiness, allowing us to ful ll its purpose of transforming the mundane into holiness.

Aside from the fact that time is the rst creation, we must also look at the rst mitzvah in terms of what it can teach us about mitzvot in general and what they are supposed to accomplish. e main point of performing mitzvot is to take the mundane and permeate it with holiness. is is the very essence of what we are doing by ful lling the mitzvah of Rosh Chodesh. We take an ordinary day, make it holy, and have it set in motion which days will be transformed from weekdays to holidays such as Pesach, Shavuot, and Sukkot.

A Jew’s primary service is to actualize the spiritual potential embedded within all creations. For example, one takes a piece of leather, turns it into a pair of Te llin, and then wears them to perform a mitzvah. e simple piece of leather is transformed into a holy object, forever changing it and ful lling its objective for existing. is is true of all creations, including time. us, by celebrating Rosh Chodesh, we reveal the very purpose of time, which is to sanctify it and ll it with productivity and holiness.

e Value of Time

e value of time is derived from both time itself and what you choose to do with it. Time is inherently valuable because it is nite and irreversible. It is a fundamental aspect of existence and the framework within which all events occur. Time's value lies in its scarcity and its role in shaping our experiences and lives.

However, the value of time is also heavily in uenced by what you choose to do with it. Time becomes meaningful when it is used purposefully and productively. Engaging in activities that align with your goals, passions, and values can make time feel more valuable because it contributes to personal growth, ful llment, and happiness.

So, while time itself is inherently valuable due to its nite nature, the true signi cance of time is o en realized through the actions, experiences, and relationships that it facilitates. Life is not just about the passage of time, but also about how e ectively and meaningfully you use it.

As we embark on yet another season of redemption, it is incumbent upon us to make sure that we enable the lessons of the rst Rosh Chodesh to in uence the way we view and use time. It is not something we should take for granted, and we must remember that it is what makes us free of the slavery and the mundane. Let us remember that Hashem has gi ed us the power to make time our own.

Here are some practical suggestions for how to maximize your time and use it properly.

Daily Re ection: Set aside a few moments each day for re ection and introspection. Whether it's through writing a journal, meditation, or simply quiet contemplation, taking time to assess one's thoughts, actions, and goals can foster

personal growth and spiritual development.

Shabbat: Dedicate time to make Shabbat a central feature of the week. is can include attending Te lla, enjoying festive meals, engaging in Torah study or discussions, and creating a sacred space for rest and rejuvenation.

Rosh Chodesh: Take time to re ect on the past month and assess how you have spent your time. Set personal objectives or goals for the month ahead.

How will you sanctify your time?

KIANA SURPIN SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘25

KIANA SURPIN SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘25

MARTZI HIRSCH '26 IS IN SHALHEVET'S ADVANCED GEMARA SHIUR (AGS). HE IS THE COMMUNITY EDITOR OF THE BOILING POINT, AND ON THE BASKETBALL TEAM.

Shir HaShirim, one of the ve Megillot in Tanakh which we read on Pesach, is a series of romantic poems and songs that celebrate the beauty of the love between a man and woman. Traditionally interpreted as a Mashal (metaphor) for the relationship between Hashem and Bnei Yisrael, which was manifested through the Pesach story and Yetziyat Mitzrayim, the Megilla can be viewed as an illustration of the Mitzvah of Ahavat Hashem (loving Hashem).

e Rambam clearly takes this approach that Shir Hashirim is designed to show us how to love Hashem. As he explains in his Mishneh Torah (Hilchot Teshuva 10:3): “A lovesick person's thoughts are never diverted from the love of that woman. He is always obsessed with her; when he sits down, when he gets up, when he eats and drinks. With an even greater love, the love for God should be implanted in the hearts of those who love Him and are obsessed with Him at all times, as we are commanded (Devarim 6:5): ‘[Love God...] with all your heart and with all your soul.’ is concept was implied by Shlomo (Shir HaShirim 2:5) when he stated, as a metaphor: ‘I am lovesick.’ Indeed, the totality of the Song of Songs is a parable describing this love.”

As the Rambam notes, the Torah in Sefer Devarim (6:5) already commands us to love Hashem to the greatest extent that we humanly can.

You shall love Hashem your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might.

But how can one attain such a deep relationship with Hashem as portrayed in the Torah, Shir Hashirim, and the Rambam? And how are we expected to do so simply because we are commanded to? Can Hashem really command us to feel a certain way or simply have an emotion?

To answer this question, let us examine some other mitzvot in the Torah that also appear to focus on inculcating certain emotions. Similar to the Mitzvah of Ahavat Hashem, the Torah in Parshat Kedoshim (19:17) commands us not to hate our neighbor.

You shall not hate your fellow in your heart. Reprove your fellow, and you will not incur guilt on their account.

Here too, it seems that we are being commanded to feel a certain way. But the Ramban interprets the Pasuk as a commandment not to harbor hatred within one’s heart, but instead encouraging one to outwardly rebuke their neighbor if they harbor negative feelings. According to this understanding, the Torah is not commanding us not to hate, but rather to confront our feelings and deal with them in a practical manner.

In the very next Pasuk, we are given the Mitzvah of Ve’ahavta LeRe’acha Kamocha, which Rabbi Akiva called the “fundamental principle of the Torah,” and is the rst of three times we are commanded to love in the Torah.

You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against members of your people. Love your fellow [Israelite] as yourself: I am Hashem.

Here too, the question arises, how can one be commanded to feel an emotion? e Ramban adheres to the same logic as in his commentary on the previous Pasuk, stating that the commandment to love one’s neighbor as he loves himself should not be taken as a direct order to love another as they naturally love themselves. Rather, the Ramban holds that this is a commandment which involves acting in a manner that exhibits love to others, similar to how one wishes good things for himself.

Later in Parshat Kedoshim (20:34), the Torah again lists a mitzvah to love, this time focusing on a convert.

You will treat the convert who dwells with you just like any other citizen: You will love him like yourself; for you were strangers in the land of Egypt: I am the Eternal, your Almighty.

e 13th century commentator Chizkuni elucidates this Pasuk as well as directing us to treat a convert the way we would want to be treated. e Pasuk simply takes Ve’Ahavta LeRe’acha Kamocha a step further, saying that we should treat a Ger speci cally the way we would want to be treated, as we too were once Gerim in Eretz Mitzrayim.

us, the generalization that we are supposed to take away from and is that these are not Mitzvot which command us to feel a particular emotion, but instead to perform an action. In the Gemara (Yoma 86a), Abaye suggests that the Mitzvah to love Hashem can be ful lled by performing Mitzvot which will subsequently lead to others loving Him. e Gemara reiterates that when people see how wonderful it is to do Hashem’s Mitzvot, people will love Hashem.

Following this logic of the Ramban and the Gemara, we can explain that the Mitzvah of Ahavat Hashem as well is not an obligation to feel a certain way, but a guide to direct us on a path of Mitzvot and thereby nurture a deeper connection with Hashem, one of Ahava. As Rashi explains (Devarim 6:5), doing Mitzvot out of Ahava (love) is far greater than doing them out of Yirah (fear). Ahavat Hashem is the culmination of a life lled with the pursuit of Mitzvot.

Although the Pshat of the Mitzvah of Ahavat Hashem is the manifestation of our love for Hashem through the performance of Mitzvot, when looking at this Mitzvah through the eyes of Shir HaShirim, it seems that the Megillah takes the Mitzvah a step further, and describes it not as an obligation, but as an experience, which the Rambam so seamlessly describes. e commandment to love Hashem transcends a mere adherence to Mitzvot and fosters a genuine and personal relationship with Hashem, an experience that varies from each person to person but ultimately leads to a deeper connection and understanding of Hashem one way or another. It o ers us a more ambitious understanding of a person’s relationship with Hashem. Although Ahavat Hashem begins with the actions and responsibilities of mitzvot, a life of mitzvot can lead to a relationship with Hashem that is illustrated in Shir Hashirim. On Pesach, we have the opportunity to re ect on the history and miraculous beginnings of the Jewish people, and it is my hope that we can all use this chag as an opportunity to develop a greater sense of Ahavat Hashem.

DR. SHEILA KEITER IS A MEMBER OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH FACULTY AT SHALHEVET. SHE HAS A B.A. IN HISTORY FROM UCLA, A JD FROM HARVARD LAW SCHOOL, AND RECEIVED HER PHD IN JEWISH STUDIES FROM UCLA, WHERE SHE TAUGHT IN THE DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES.

Pesach is a holiday where minhagim take center stage. Some minhagim represent the traditions of particular historic communities, while others may be unique to given families. e Pesach seder, while seemingly rigid in its structure, is surprisingly exible in its ability to absorb variation. But are all Pesach minhagim equally valid? e Mishnah addresses this question in masechet Pesachim, where it examines varying practices surrounding Pesach and its ritual celebration.

In a place where they customarily eat roasted meat on the nights of Pesach, we can eat [roast meat]; in a place where they customarily do not eat it, we do not eat it (m. Pesachim 4:4).

e menu for seder night seems an odd subject for a formal minhag, but this particular dish, roasted meat, comes with historic and halakhic signi cance. e korban pesach, the special sacri ce brought the day before Pesach, consisted of a lamb or goat-kid roasted whole with its entrails alongside it. A er the destruction of the Beit Hamikdash and the cessation of the korban pesach, the appropriateness of eating roasted meat on Pesach night became problematic.1 On one hand, eating roasted meat could commemorate the defunct korban pesach. On the other, doing so might appear like we are still sacri cing the korban pesach in the absence of the Temple, something strictly forbidden.

e Gemara turns to an especially problematic minhag emerging years later in Rome:

Rabbi Yossi said: Todos, the man of Rome, directed the people of Rome to eat goat-kids with their entrails on the nights of Pesach. ey [the rabbis] sent [a message] to him: If you were not Todos, we would have decreed excommunication on you, because you have caused Israel to eat sancti ed food outside [Jerusalem] (b. Pesachim 53a).

Todos (not to be confused with the American band Toto or Baum’s ctional terrier) seems to have pushed the minhag of eating roasted meat to its limits. By having the Jews of Rome roast goats along with their innards, he seems to be reenacting the korban pesach. is minhag troubles the rabbis because it comes so close to actually bringing the sacri ce outside of Jerusalem, a clear halakhic no-no (See Rambam, Hilkhot Ma’aseh Hakorbanot 10:5).

Yet, the rabbis let it slide. Why? e Gemara attributes this rabbinic leniency to Todos and his reputation. Just who was Todos, and why was he able to avoid rabbinic censure? e very next amud of the Gemara asks whether Todos was an important man or just a powerful one. e Gemara answers by telling us that Todos taught Torah and supported Torah scholars (b. Pesachim 53b).

e Gemara is keen to establish that Todos is righteous because it does not seem that way on the surface. In addition to the questionable minhag he establishes, his name is not Jewish, Todos being the Greek equivalent of eodore. Todos is also identi ed as a man of Rome, the most exilic of all places, since it was the Romans who destroyed the Beit Hamikdash.

With this in mind, let us examine the Gemara’s description of what Todos actually taught:

1 Today, the predominant practice is not to eat roasted meat at the Seder. See the Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 476:1. e zero’a shank bone sits on the Seder plate in commemoration of the korban pesach.

Todos the man of Rome also explained this: What did Hananyah, Mishael, and Azariah see that they delivered [themselves] in sancti cation of God’s name to the ery furnace? ey raised a kal v’chomer argument for themselves from the frogs: As with the frogs, which are not commanded regarding sanctifying God’s name, it is written of them, “And they will come [and go up] in your house [etc.] and in your ovens, and in your kneading troughs” – when are kneading troughs found near an oven? Say it is when the oven is hot – we, who are commanded regarding sanctifying God’s name, all the more so! (b. Pesachim 53b).

Todos is seeking to explain why Hananyah, Mishael, and Azariah, Jewish heroes from Sefer Daniel, were willing to sacri ce their lives rather than commit idolatry. Keeping with our Pesach theme, Todos makes a comparison to the plague of frogs. e frogs swarmed homes, lling ovens and kneading bowls, even if the ovens were heated. A hot oven spells certain froggy death, yet in they went. Todos suggests Hananyah, Mishael, and Azariah took inspiration from those frogs, seeing it as their duty to die in sancti cation of God’s name rather than commit the cardinal sin of idolatry.

Whether Hananyah, Mishael, and Azariah truly considered frogs in their moment of truth is less important to us than Todos’ interest in these three would-be-martyrs. Hananyah, Mishael, and Azariah lived in Bavel during the Babylonian exile. Todos, living in exile in Rome a er the Roman destruction of the Beit Hamikdash, must have felt a kinship with these gures. In the very heart of Bavel, Hananyah, Mishael, and Azariah were willing to retain their faith in the de ance of King Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian emperor who destroyed the rst Beit Hamikdash. Todos views them as models for his own attitudes toward the Roman empire, destroyer of the second beit hamikdash.

When Todos directs his community to prepare roasted goat-kid alongside its entrails, he is doing more than ritually reenacting the korban Pesach, which would be halakhically problematic. Rather, Todos is asking the Jewish community of Rome to engage in an act of religious de ance against the Roman Empire. e message of this reenactment in the very heart of the Roman capital is clear: You may have destroyed our Temple, but you cannot destroy Judaism. e Jewish people will live on and worship the God of Israel no matter what. For this reason, the rabbis can excuse Todos.

is demonstrative act is reminiscent of another part of the Pesach narrative. In preparation for the nal plague, God commands Israel to place the blood of the paschal lamb on the doorposts of their homes. An omniscient God does not need visual markers to protect Israel from the tenth plague. Rather, the sign is for Israel. e blood constitutes an act of de ance against Egypt, a public sacri ce of the sheep they worshipped. It further served to strengthen Israelite identity and resolve. Israel had to nd the con dence to publicly identify themselves as God’s people, to commit to His service. ose of us living in exile today face a similar situation. ere are many advising we hide our Judaism to avoid sparking antisemitism, as if such hatred were our fault. But we can look to Todos and the Jews of Rome, to Hananyah, Mishael, and Azariah in Bavel, and even to the Israelite slaves trepidatiously awaiting God’s judgment on that long night in Egypt. e Jewish people exist to be Jews, to sanctify and glorify God’s name to the world. As the Haggadah tells us: “For this reason we are obligated to thank, to praise, to glorify, to exalt, to venerate, to bless, to elevate, and to extol the One Who did all of these miracles for our fathers and for us.” May He continue to do so. Pesach kasher v’sameach.

ASHER DAUER GRADUATED FROM SHALHEVET IN 2019. AFTER HIGH SCHOOL, HE LEARNED AT YESHIVAT TORAT SHRAGA BEFORE ATTENDING YESHIVA UNIVERSITY'S SY SYMS HONORS PROGRAM. ASHER IS GRADUATING IN MAY AND WILL BE WORKING IN INVESTMENT BANKING ANALYST AT HOULIHAN LOKEY.

e Hagaddah, which recounts the Jewish exodus from Egypt, re ects the journey from slavery to freedom. At various Seder tables I’ve attended over the years, I have o en noticed that some variation of the following question o en arises: While acknowledging the miraculous victory over the Egyptians and our subsequent freedom as an event worth celebrating, wouldn't it have been preferable for the Jewish people to have never entered Egypt and experienced enslavement in the rst place? To answer this question, let us turn back to the Torah’s rst reference to yetziat mitzrayim, found in a much earlier dialogue between God and Avraham (then called “Avram”).

God tells Avram, 1 (I am the Lord, Who brought you forth from Ur Kasdim, to give you this land to inherit it), a declaration resembling many others in the Torah with the substitution of “Ur Kasdim” for the more ubiquitous “Eretz Mitzrayim.” Avram immediately responds, (O Lord God, how will I know that I will inherit it?), and few pesukim later, God informs Avram of the impending Egyptian slavery and redemption a few generations later.

Several questions can be asked on this conversation, most notably regarding Avram’s response and how it connects to yetziat mitzrayim. Rashi provides two explanations for what Avram may have meant: a request for a tangible sign that the inheritance of the land would really occur – a seemingly bizarre and uncharacteristic lapse in Avram’s faith, or an inquiry about what merit of the Jews would ensure the promise’s ful llment. Some rabbis have employed Rashi’s rst explanation to answer the initial question about the purpose of our slavery, arguing that the slavery was administered as a punishment for Avram’s distrust.2

I would like to entertain a di erent approach – linking Rashi’s second explanation with our descent and redemption from Egypt – that I heard from one of my YU rebbeim, Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin. Ur Kasdim was the place where, according to a famous midrash in Bereishit Rabbah, Avram symbolically jumped into a ery furnace to protest idol worship and survived. In telling Avram that he would take him from Ur Kasdim and give him and his descendants the promised land, God was implicitly rewarding him for his glorious act of vindication. Avram then inquired what would justify our eventual deliverance, not out of skepticism, but in order to receive an assurance that the land of Israel would be given to both the lo y champions of God’s name and to his more modest descendants.

Up until this point in the Torah, chosenness had been reserved exclusively for the ery furnace people, the awe-inspiring leaders who defended God’s name with grandeur, such as Avram himself. Avram therefore wanted to ensure that the merit of the land of Israel would extend to the less conspicuous, non- ery-furnace Jews as well. To ful ll Avram’s request, we needed to transform ourselves from a divided family o en bifurcated into good guys and bad guys (Yitzchak and Yishmael, Yaakov and Eisav, etc.) to a uni ed nation. God thus noti es Avram of the eventual slavery and explains to him that the experience was not designed to serve as a punishment. Rather, it was a necessary means to building this national

1 Bereishit 15:7

2 See also Nedarim 32a where this approach is suggested.

identity by jointly experiencing the tribulation and liberation. is idea illuminates the practice of celebrating the Seder with diverse extended relatives, spanning various observance levels, denominations, and personalities. By retelling the story of yetzyiat mitzrayim, we commemorate the culmination of our quest for a national identity, celebrating Jewish peoplehood as a uni ed family.

SHEVY GOMPERTS

SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘26

SHEVY GOMPERTS

SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘26

RAMI MELMED '24 IS A MEMBER OF SHALHEVET'S BEIT MIDRASH TRACK (BMT). HE IS THE AGENDA CHAIR, CAPTAIN OF THE BOY'S TENNIS TEAM, AND FOUNDER OF THE RIF - SHALHEVET'S BAND. AFTER GRADUATING, RAMI WILL BE ATTENDING YESHIVAT MA'ALE GILBOA FOLLOWED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY.

e Haggadah, which tells the story of the Jews’ redemption from Egypt, famously minimizes mention of Moshe, the central character in the redemption story. Notably, the Haggadah begins with the story of the Israelites’ descent into Egypt, yet it also fails to mention the most central character in that story, namely Yosef. According to the Abarbanel, everything which happened in Egypt was the fault of Yosef’s brothers, as they ultimately were responsible for selling him into slavery and setting o the chain of events which eventually brought the Israelite clan to Egypt. He supports this idea with a textual connection between the brothers’ casting Yosef into the pit, (“and they cast him into the pit”, Bereshit 37:24), and Pharaoh ordering the Jewish babies to be cast into the Nile, (“every male-born child should be cast into the river”, Shemot 1:22). If, according to the Abarbanel, the entire descent to Egypt and the subsequent redemption of the Jews from Egypt only occurred because of this story of Yosef, shouldn’t he have at least been mentioned in the Haggadah?

To address this, Rav Yitzchak Mirsky summarizes several “hints” to Yosef throughout the seder in his Haggadah Hegyonei Halacha, one of which is through karpas. Unlike the Rambam, who holds that any vegetable can be used for dipping prior to the meal, the Maharil requires a speci c vegetable, referred to as “karpas,” to be used. Rabeinu Manoach says that the word “karpas” (ספרכ) itself is a hint to the םיספ תנותכ (i.e., the word ספרכ includes the word ספ, or stripe), the coat of striped colors that Ya’akov gave to Yosef and which the brothers dipped into the goat blood a er selling Yosef. is is alluded to by the dipping of the Karpas at the Seder before the meal. Interestingly, there is a custom in many Yemenite communities to dip the karpas into the charoset, which the Talmud Yerushalmi (Pesachim 10:3) says is reminiscent of blood, much like the dipping of Yosef’s coat into blood. Rabbi Elchanan Wasserman adds further context, fortifying the notion that the dipping of the םיספ תנותכ has had historical rami cations. He writes that lies are o en built on kernels of truth, and blood libels throughout Jewish history may have had their origins in the brothers dipping Yosef’s coat into blood. It is also noteworthy that blood libels have historically been connected with Pesach and matzah.

Although the rst dipping may represent the Israelites having gone down to Egypt as a result of Yosef being sold by his brothers, the second time we “dip” at the Seder can be symbolically connected to yet another “dipping.” e second dipping of the Marror in the Charoset occurs a er we have completed Magid, told the story, and described the redemption of the Jews. is time, the dipping is reminiscent of the redemption from Egypt. Rabbi Eliezer Ashkenazi compares this second dipping a er Maggid to the dipping of the hyssop into the blood from the Korban Pesach:

“And you shall dip it into the blood in the vessel and apply it to the doorposts” – symbolizing the actual moment of redemption from Egypt.

us, the double-dipping which we sing about in Mah Nishtanah represents both the descent to Egypt through the brother’s selling of Yosef (i.e., dipping the coat into the goat blood) and the redemption from Egypt with the Korban Pesach (i.e., dipping into the blood and painting the doorposts).

Another allusion to Yosef and his being sold at the seder may perhaps relate to the rule that the Korban Pesach must be eaten in a group. One could suggest that one reason we must eat the Korban Pesach with a community of people is to demonstrate our being inclusive of other Jews, to “correct” the hatred of Yosef’s brothers.

Nevertheless, despite these potential allusions to Yosef within the Haggadah, he is still not mentioned outright. Yet Moshe, too, is not mentioned as a major gure in the story. One famous reason for this is to diminish the emphasis given to human agency and remind ourselves that redemption is ultimately in the hands of God. We can similarly suggest the same reasoning for Yosef being omitted from the Haggadah as well. Just as God was responsible for the Jews’ redemption, God was also responsible for their exile.

RABBI ABRAHAM LIEBERMAN IS A MEMBER OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH FACULTY AT SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL. HE PREVIOUSLY SERVED AS THE HEAD OF SCHOOL AT YULA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL. RABBI LIEBERMAN LEARNED AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY AND RECIEVED SEMIKHA FROM EMEK HALAKHA IN BROOKLYN. HE RECIEVED HIS M.A. IN JEWISH HISTORY FROM THE BERNARD REVEL GRADUATE SCHOOL (YU), WHERE HE IS CURRENTLY WORKING TOWARDS HIS DOCTORATE.

e Etrog makes its rst appearance on Sukkot as one of the Four Species, the Arba Minim. On Tu B’Shvat, it appears again as one of the foods used to celebrate Chag Ha-Ilanot, and in many communities a special prayer is recited on Tu B’Shvat to merit a perfect Etrog for the upcoming Sukkot holiday. We have also seen its appearance on Rosh Ha-Shanah as one of the Simanim.1 It is sometimes used on Yom Kippur as one of the items smelled to make the fasting easier.2 In addition, it is related to Shavuot, as will be shown below, which leads one to wonder: Does the Etrog also make an appearance on Pesach? Let’s see!

ere are many foods we consume specially on Pesach; one of them is the Haroset. e origin of the Haroset is in the Mishnah (Pesachim 10:3), where it is mentioned as a dip (into which the Marror should be immersed). e Mishnah does not supply a reason for this ritual or even tell us the ingredients used to make the Haroset. e Talmud in explaining the reason (Pesachim 116a) states:

Rabbi Levi says: It is in remembrance of the apple. And Rabbi Yochanan says: e Haroset is in remembrance of the mortar (used by the Jews for their slave labor in Egypt). Abaye says: erefore, (to ful ll both opinions), one must prepare it tart and one must prepare it thick. One must prepare it tart in remembrance of the apple, and one must prepare it thick in remembrance of the mortar.

e commentaries point out that Rabbi Levi (bar Sisi, 1st generation Amora in Eretz Israel) is referring to the Pasuk in Shir Ha-Shirim (which is read on Pesach) that states: “Under the apple tree I awakened you” (Song of Songs 8:5), which is an allusion to the Jewish people leaving Egypt (Sefer Ha’orah, compiled by the students of Rashi, #87) or to the Jewish women who birthed their children in Egypt under apple trees (Rashbam, Pesachim 116a, s.v. Zecher l’tapuach, citing Sotah 11b; see also Shemot Rabbah1:12). e opinion of Rabbi Yochanan (2nd generation Amora in Eretz Israel) opinion is clear, that it is a reminder of the clay bricks the Jewish People used in their construction work. Abaye (4th generation Amora in Babylonia) o ers a suggestion of how to reconcile both opinions.

In the Yerushalmi (10:3, 37d), we nd a third reason:

“Rabbi Joshua ben Levi said, it has to be thick. His words imply that it is a remembrance of the mortar. ere are Tannaim who state, it has to be so ; their words imply that it is a remembrance of the blood.”

e blood is understood to be a reminder of the blood of the Korban Pesach that was placed on the doorposts in Egypt (Shemot 12:7,13). Tosafot (Pesachim 116a, s.v. tzarich) cite the above Yerushalmi and add that red wine and vinegar should therefore be used to moisten the Haroset mixture and so en it, making it useable as a dip. ey then quote a

1 See Orot Shalhevet, Tishrei 2023, pp.19-21.

2 Although some recommend refraining from smelling besamim or the like on Yom Kippur, most authorities permit. See Mishnah Berurah (612:18) and Peninei Halachah (https://ph.yhb.org.il/plus/15-07-01/).

Geonic responsum (no longer extant) that teaches that the Haroset should be made from fruits mentioned in Shir Ha-Shirim because those fruits represent the Jewish People. ey name: 1. Apples 2. Pomegranates 3. Dates 4. Figs 5. Nuts 6. Almonds. All six of these are mentioned in di erent pesukim in Shir Ha-Shirim.

e Rama (Rabbi Moshe Isserles, 1530-1572, O.H. 473:5) cites the above opinion of Tosafot, and this has become the standard Ashkenazi custom in most communities. While in most of our communities today the Haroset is sweet, the older customs use the apple to add tartness to it (Rashi and Rashbam, Pesachim 116a) or add vinegar (Rambam, Hilchot Chametz Umatza 7:11). Rabbeinu Manoah (end of the 13th century-start of the 14th century), in his commentary to the Rambam, speci es that the apples should be sour and that the vinegar should be derived from strong wine. is point is made by other authorities as well.

e Etrog is not mentioned explicitly in any of these sources. However, some later authorities do entertain the possibility that the Etrog should also be used. Rabbi Henoch Henich Teitelbaum (1884-1943), known as the Admor of Sasow-Kretzki, author of She’eilot Uteshuvot Yad Hanoch (Halachic responsa) was asked (siman 8) whether he had stated that one should use an Etrog as an ingredient in Haroset. In his answer, he quotes some of the above opinions and adds that the Talmud (Shabbat 88a) compares the Jewish People at the time of Matan Torah to a tapuach because the apple fruit is visible before its leaves; similarly, the Jewish People said “na’aseh,” we will do, before “v’nishma,” and we will listen. Rabeinu Tam (1100-1171) explains (s.v. piryo kodem) that the tapuach mentioned in the above Talmudic statement in fact refers to an Etrog (see also Tosafot, Ta’anit 29b, s.v. shel tapuchim; this reference would also connect the Etrog to Shavuot). Rabbi Teitelbaum then quotes a Midrash (Vayikra Rabbah, ch.30( stating that the Jewish People are compared to an Etrog. erefore, he suggests that if one can use an Etrog as an ingredient in Haroset, in particular the very one used on Sukkot, he should do so, due to the rule of, אתירחא הוצמ הב דבעתיל ,אדח הוצמ היב דבעתיאד ליאוה once an item was already used for one mitzvah, one should use it again for another mitzvah (Shabbat 117b).

Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik (1903-1993), quoted by Rabbi Yechiel Michel Shurkin (Harerei Kedem vol.2, 102:3), addresses this exact question and quotes many of the above sources, in particular the last one, that identi es the tapuach with the Etrog. Rav Soloveitchik concludes that one should place an Etrog into the Haroset, in particular, in light of what

ETAN LERNER '26 IS A MEMBER OF SHALHEVET'S BEIT MIDRASH SHIUR (AGS). HE IS THE EDITOR OF NITZOTZEI TORAH, SHALHEVET'S STUDENT TORAH PUBLICATION, A MEMBER OF THE ROBOTICS TEAM AND HEAD OF THE PHILOSOPHY CLUB.

In his Mishneh Torah, the Rambam brings an unusual source for the mitzvah of retelling the story of the Exodus on Pesach. He writes the following:

It is a positive commandment of the Torah to tell of the miracles and wonders wrought for our ancestors in Egypt on the night of the eenth of Nisan, as [Shemot 13:3] states: "Remember this day, on which you le Egypt," just as [Shemot 20:8] states: "Remember the Sabbath day." (Rambam, Hilchot Chameitz Umatza 7:1)

ere are two main questions stemming from Rambam’s words. First, he quotes an odd pasuk to explain why we are commanded to tell the story of Pesach, “zachor et hayom hazeh.” Most Rishonim use the pasuk “vehigadeta lebincha” (Shemot 13:8) as the source for the mitzvah of the seder, at which we recount the miracles of Pesach. Why would the Rambam use this pasuk instead of “vehigadeta lebincha - and you shall teach your children?”

Even more peculiar in this Halacha is the connection Rambam creates between Pesach and Shabbat. Why did he feel that such a comparison was necessary in order to explain the Seder, and what do Pesach and Shabbat have in common?

e rst parallel of signi cance lies within the Aseret Hadibrot, which appear in parshiot Yitro and Vaetchanan, with slight (but crucial) variations. When we are commanded in the fourth dibbur to keep Shabbat in Parshat Yitro, the Torah explains that the source of this Mitzvah is Hashem’s creation of the world in six days and cessation of work on the seventh day. is is the most common explanation used, but in Parshat Vaetchanan, a di erent reason is given for keeping Shabbat: yetziat Mitzrayim.

In his commentary on the fourth dibbur, Ramban (Devarim 5:15) quotes Rambam’s Moreh Nevuchim (2:31), which explains why yetziat Mitzrayim is also a reason for Shabbat. Rambam writes that as slaves in Egypt, we did not have the ability to rest. Yetziat Mitzrayim and our freedom from slavery gave us the opportunity to rest each week, and Hashem therefore tells us to observe Shabbat to remember this, as well as creation.

ere remains one striking comparison, speci cally between the two quoted pesukim, which potentially explains why the Rambam quoted this pasuk. Both pesukim contain the word zachor, remember. Ostensibly, this word does not have any particular signi cance; it is quite common, appearing almost 200 times throughout the Torah. But when remembering that the common source for the Seder is vehigadeta, the word zachor used in this context takes on tremendous signi cance.

Perhaps the parallel of zachor used by the Rambam in citing these pesukim tells us that the mechanism for remembering both days is similar or connected. Instead of lahagid, to tell, the purpose of the Seder is lehazkir, to remember, and so too, the purpose of Shabbat is also lehazkir. What is this common practice of remembrance, and are there any similarities between the days themselves and how they are practiced? Answering this question will also allow us to understand the purpose of zikaron in the entire Torah.

Rambam paskins that the practical mechanisms through which zikaron is carried out on Shabbat are Havdalah and Kiddush. In Hilchot Shabbat (29:1), Rambam quotes this pasuk as the source of the deorayta Mitzvah to make a verbal declaration when Shabbat begins (Kiddush) and when it ends (Havdalah). By quoting this pasuk of zachor, Rambam maintains that Kiddush and Havdalah are, rather than separate commandments, intrinsic parts of Shabbat, and de ne what it means to commemorate Shabbat. While these rituals both include wine, reciting them on wine is only a derabanan enactment. e purpose of both Havdalah and Kiddush is to create a hevdel, separation, bein kodesh lechol, between sancti ed (Shabbat) and mundane (the weekday). Essentially, the purpose of these two declarations, and therefore zachor, is to recognize the uniqueness of Shabbat.

How can this be applied to Pesach? e entire Pesach Seder communicates the same message. For instance, the purpose of the four questions is to provide a clear distinction between Pesach and other nights. By singing Mah Nishtana, we demonstrate the signi cance of Pesach.

But beyond Mah Nishtana, Pesach has more unique qualities. Pesach also represents the time in which Hashem was closest to Bnei Yisrael. Never before in the history of humanity has Hashem played such an active role in people’s lives, bringing Pharaoh, one of the most powerful individuals in history, to his knees and in icting mighty plagues upon the Egyptian people. A er showing the Egyptians His all-powerful dominion over the heavens and the earth, Hashem delivers Bnei Yisrael, the chosen people, out of Egypt, beyad chazakkah uvizroa netuyah, with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. No other day in the calendar is a greater testimony to divine providence than Pesach.

As Rambam has brilliantly demonstrated, the word zachor means more than remembering. Zachor means to recognize the signi cance of a particular day. To do so, we separate it from other days through mechanisms such as Kiddush, Havdalah, and Mah Nishtana. According to Rambam, the purpose of the Seder is to recognize and tell of the unmatched miracles and wonders that occurred on Pesach.

Zachor has one more unique quality. Zachor reminds us that just as certain days in our Jewish calendar are di erent, so are we. We are a mamlechet kohanim vegoi kadosh, a holy nation chosen by Hashem to bring light into this world. Zachor

MAITAL HILLER GRADUATE FROM SHALHEVET IN 2020. AFTER HIGH SCHOOL, MAITAL LEARNED AT MIDRESHET HAROVA AND IS NOW A PSYCHOLOGY MAJOR ON THE PRE-HEALTH TRACK AT NYU.

In the teachings of Pirkei Avot, Ben Zoma says, “Who is wise? One who learns from everyone” (4:1). is simple yet profound statement resonates at our Seder table, reminding us that wisdom is not reserved exclusively for scholars, but is accessible to anyone who pursues it with openness and curiosity. e essence of Pesach is not con ned to the pages of the Haggadah, but rather is kept alive in the stories we share, the questions we ask, and the traditions we pass on.

e Gemara in Pesachim (116a) expands on this theme of inquiry and learning, illustrating the inclusive nature of the Seder. “ e Sages taught: If his son is wise and knows how to inquire, his son asks him. And if he is not wise, his wife asks him. And if even his wife is not capable of asking or if he has no wife, he asks himself. And even if two Torah scholars who know the halakhot of Passover are sitting together, they ask each other.” is Gemara teaches us the signi cance of questions, not just for the sake of answers, but as a fundamental expression of our engagement with the story of our liberation. e Seder invites everyone, regardless of their level of knowledge or understanding, to participate in the dialogue that has de ned our people for generations. In this manner, it uniquely honors the act of questioning as a foundational element of our faith, o ering a path to a deeper comprehension and connection.

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger brings these ideas into contemporary focus, highlighting the existential value of questioning within our spiritual and communal lives. He teaches that the act of asking questions, especially in a world that o en values quick answers and super cial understanding, is what keeps our tradition vibrant and alive. Questions create a "vacuum for wisdom to ll," propelling us forward in our search for meaning. Rabbi Weinberger's insight remind us that our engagement with the Pesach story, with its themes of freedom, redemption, and divine providence, demand a willingness to ask, to wonder, and to seek.

We also nd the importance of instilling a culture of questioning emphasized twice in Parshat Bo in connection to Yetziat Mitzrayim.

“And when your children ask you, ‘What do you mean by this rite?’ you shall say, ‘It is the passover sacri ce to God, who passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt when smiting the Egyptians, but saved our houses’” (12:26-27).

“And when, in time to come, a child of yours asks you, saying, ‘What does this mean?’ you shall reply, ‘It was with a mighty hand that God brought us out from Egypt, the house of bondage’” (13:14).

ese pesukim highlight the centrality of questions in transmitting our heritage, particularly as it relates to the exodus. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks brings this idea full circle by emphasizing the Torah's unique approach to education and inquiry.

He says that unlike traditions that prioritize blind obedience, Judaism celebrates the intellectual and spiritual growth that comes from questioning. rough the example of the four children in the Haggadah (some of which are derived from the pesukim above) as well, we see that everyone, regardless of their ability to understand or inquire, is valued and has a role in the ongoing dialogue of Jewish life.

As we sit at our Seder tables, let us embrace the role of both student and teacher, recognizing that wisdom comes from a humble heart that is open to learning from everyone. Let us ask questions, not just to ll the silence, but to deepen our understanding and to strengthen our bonds with one another. Let us learn from everyone at our table and ensure that

RABBI GABE FALK IS THE DIRECTOR OF TORAT SHALHEVET AND A LIMUDEI KODESH TEACHER. HE LEARNED IN YESHIVAT HAR ETZION AND RECEIVED SEMICHA FROM YESHIVA UNIVERSITY. HE HOLDS A B.A. FROM COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, IS WORKING TOWARDS AN M.A. IN JEWISH HISTORY FROM REVEL, AND WAS A WEXNER GRADUATE FELLOW. BEFORE JOINING SHALHEVET, RABBI FALK SERVED AS THE ASSISTANT RABBI AT GREEN ROADS SYNAGOGUE AND TAUGHT AT FUCHS MIZRAHI SCHOOL IN CLEVELAND, OH.

Questions lie at the very heart of the Seder night. From the הנתשנ המ to the inquiries of the Four Sons, questions are the catalyst for our discussions, the frame for our storytelling on seder night. ese questions are rooted in the pesukim, which — while Bnei Yisrael are still in Mitzrayim — predict the questions that their future children will ask:

"

On the surface, these questions seem educational—they are a useful and engaging springboard by which we tell our story. But the educational approach does not fully explain the centrality of the question-and-answer dynamic. e Shulchan Aruch tells us that if one does not have children, a husband and wife should ask the הנתשנ המ to one another, and if a person nds themselves alone for the seder, they should ask the questions to themselves! We stick to the question-and-answer format even when there is seemingly no educational value.

In Pachad Yitzchak (Pesach, 17), Rav Yitzchak Hutner explains that the questions-and-answers form of inquiry re ects the form in which geula - redemption - appears in the world. In Jewish history, Geula necessarily follows galut, freedom follows hardship – but it is not clear why Am Yisrael must endure the hardship of slavery before experiencing freedom. Rav Hutner leverages the question-and-answer format to shed light on this question.

Questions stem from uncertainty—we ask questions when we are faced with events that we do not understand. Answers, he counters, alleviate the anxiety of that uncertain moment and create a new experience of resolution and comfort. We would not appreciate the joy of the answer without rst experiencing the uncertainty of the question. e joy one experiences when resolving an open question far surpasses the joy of knowing something from the start.

Geula occurs in much the same way. Pesach is about the experience of contrasts — from shibud to geula, from darkness to light, from su ering to great joy. e contrast enables us to fully appreciate the resolution — our geula. For Rav Hutner, the medium of the Seder night – questions and answers – powerfully illustrates its essential message.

e Ba’alei Chassidut take this idea one step further. In his work Sod Yesharim, Rav Gershon Chanoch Henoch Leiner (the 3rd Rebbe from Izhbitz-Radin) argues that the secret to understanding geula lies not in the answer to the question, or the question-answer format, but in the act of questioning itself.

At the root of every question lies a degree of chutzpah. Questioning indicates our willingness to challenge the status quo and a belief in the possibility for change. When a child reaches the all-too-familiar, cute-but-annoying age when they ask “why” about everything they encounter, they are actually doing something rather profound. As a child encounters the world for the rst time, they are challenging us to reconsider all of the things we have taken for granted and the assumptions that we have accepted as fact. ere is a brazenness to the child’s questioning: Why do things need to be the way they are? Can’t the world be di erent? Rav Leiner believes that these questions are a rst and crucial step in creating change in the world.

e questions we ask on Pesach identify the changes in our seder — הנתשנ המ, Why have things changed? When things begin to change, our ability to ask questions is heightened — we begin to question all of the things we took for granted. On the one hand, the child is bothered by the new experiences of seder night, but on the other hand, he is equally

bothered by the mundane routine of the previous night’s dinner — why do we take our normal routines for granted, the child asks! e chutzpah of our children challenges us to embrace change. ese questions highlight the changes that are happening in the world and push us to embrace those changes as the beginnings of hitchadshut, innovation and creation.

To reach geula, Rav Leiner writes, we must internalize this chutzpah and question our status quo: Does the world need to be the way it is today? Can it be more perfect? What do we need to do to move in that direction? A very similar sentiment echoes across Rav Kook’s messianic writings. In a widely controversial stance, Rav Kook believed deeply that the chutzpah of the secular kibbutznik Zionists was a major catalyst in the redemption of Am Yisrael.

e notion of תושדחתה, renewal stands at the core of the Pesach seder. We tell a story that begins with slavery and ends in freedom, and we thus re-a rm our belief in hitchadshut. It is no coincidence that Pesach takes place in Chodesh HaAviv, the time of year when “the rains are over and gone, the blossoms have appeared in the land…and the sound of the turtledove is heard in our land.” (Shir HaShirim 2:11-12).

is theme comes to the fore at the very end of Maggid, when we nish the story of Yetziat Mitzrayim and begin Hallel. We introduce the Hallel with a telling line:

השדח הריש וינפל רמאנו, and we should say before Him a new song.

Why, speci cally, do we call this Hallel a השדח הריש? What does this phrase refer to?

At the end of the Birkot Keriat Shema in Shacharit, we proclaim: םילואג וחבש השדח הריש, those who have been redeemed (Bnei Yisrael) sang a shira chadasha (Az Yashir). Bnei Yisrael experienced the transformative nature of geula: something new has transpired in the world, they have just moved from darkness to light, from bondage to freedom. When they, in turn, give ללה to Hashem — the דימת םוי לכב ובוטב שדחמ, their shira necessarily re ects that. On seder night, when we have reexperienced the journey of Yetziat Mitzrayim and re-a rmed our belief in hitchadshut, we too are moved to sing a shira chadasha to Hashem. is year especially, as we answer (or ask) the Mah Nishtana, we should note the powerful way in which questions attune us to the winds of change, to the possibility for hitchadshut, and to the Jewish people’s undying belief in geula. May Am Yisrael merit to move from the uncertainty of our questions to the unbridled joy of the Divine answers.

ELISHAI KHOOBIAN '24 IS A MEMBER OF SHALHEVET'S BEIT MIDRASH TRACK (BMT). HE IS THE BUSINESS DIRECTOR FOR THE BOILING POINT, A BUSINESS CLUB BOARD MEMBER, ON MOCK TRIAL, AND A MEMBER OF THE TENNIS TEAM.

Dayenu is a poem made of 15 stanzas, which we sing every year during Magid at the Pesach seder. Each stanza introduces one miracle or gi that Hashem gave us when leaving Mitzrayim and in the desert, and then says that even if another additional one had not been given, “Dayenu,” it would have been enough. e poem is a beautiful way of showing our appreciation to Hashem for each gi He bestowed upon us.

If He had given us their wealth, and had not split the sea for us, it would have been enough!

Dayenu means “it would have been enough,” implying that each miracle alone would have been su cient, and we did not need the next one.

However, if one examines all 15 stanzas, there are a couple lines that stand out. roughout the story of the Jews in the desert, we see them complaining about being stuck by the sea, not having food or water, not being able to enter Israel, and most of all, that Hashem brought them out of Mitzrayim just to die in the desert – they are constantly complaining. Now, 2000 years later, we sit like kings in our comfortable chairs and say that if God just took us out of Egypt and did not perform any other miracle, including Kriyat Yam Suf, Matan Torah, Shabbat, or helping us enter Israel, it would have been enough.

Upon looking through the passage of “Dayenu,” one should be very bothered. How could an Orthodox Jew sit at their Pesach table and say that we would have been ne without ever receiving the Torah or the land of Israel? Without both, who knows where the Jewish nation would be today or even exist? How could a Jew even write such words and how could the authors of our Haggadah approve of them? Just leaving Egypt would not have been even close to enough.

e Abarbanel gives a simple explanation to the problem, explaining that the song of Dayenu is followed by Hallel shortly therea er. Dayenu does not mean “that would have been enough” and that the other gi s were truly unnecessary. Rather, Dayenu actually means, it would have been enough for us to praise God.

If He had provided for our needs in the desert for forty years, and not fed us manna - it would have been enough (for us to say thank you)!

e Abarbanel thus adds on to the translation of the word, “Dayenu,” giving it more meaning. When we say “it would have been enough,” we mean that even one miracle would have been su cient reason to say Hallel and show our appreciation. It is a way of emphasizing our true gratitude for each singular miracle that took place.

Rabbi Hillel Goldberg o ers an additional, eye-opening solution. We read in the Hagadah the following:

In every generation each person is obligated to imagine themselves as if they were taken out of Mitzraim.

e whole point of the seder is to commemorate and essentially relive our exodus from Egypt and the miracles that took place at that time. Every year at the beginning of the seder, we start o by singing “ונייה םידבע”, “We were slaves” – not our ancestors or forefathers, but “we.”

When singing Dayenu, we are supposed to imagine that each of those miracles just took place in front of our eyes. Looking at it this way, we can understand that since each moment was so miraculous and insane, the Jewish people did not worry about any future moment. Rabbi Goldberg gives an example of a newly-wedded couple. When they are under the chuppa getting married, they are not thinking about how their retirement will look. ey are so happy with their newly formed relationship that future steps do not even enter their minds.

So imagine you were a slave your whole life, and then you witness 10 super-natural miracles and are freed along with your whole family. On your way out, your previous owners change their mind, and you are now stuck in between a sea and returning to slavery. All hope is lost. And suddenly, the sea splits, creating a dry path for you to go into. at moment is so overwhelming and abbergasting that no future moment could even enter your consciousness. At that moment, the sea splitting was genuinely enough!

When singing Dayenu, we have the obligation to imagine that each miracle took place in front of our eyes. If Hashem just gave you the Torah, which was one of the most signi cant moments in human history, you would understand that no one was thinking at that time about going into Israel – at that moment, it would have been enough. If Hashem fed us everyday with the magical food, Manna, we would be so satis ed that we would not think about Shabbat – at that moment, it would have been enough.

While this is a beautiful explanation for most of the stanzas, there is still one that should bother the reader.

If He had brought us before Mount Sinai and did not give us the Torah, it would have been enough.

If Hashem just took us all the way to Har Sinai and did not give us the Torah – in no context would that ever have been enough. e whole point of leaving Egypt was for that moment at Har Sinai. Judaism is reliant on the Torah, and the whole point of leaving Egypt was to receive the Torah, so why would that have been enough?

e Ben Ish Chai says that when the Jews went to Har Sinai, Hashem could have simply given them 613 laws and that would be it. It could have been like the Rambam’s Mishneh Torah. However, He did not just give us a list of what we can and cannot do; He gave us the Torah, which is a blueprint to live our daily lives, with stories and context that we can connect to today. So that line really means: If Hashem took us to Har Sinai (and just gave us a list of do and don’t commandments) and did not give us the holy Torah we have today, Dayenu.

RAV YITZCHAK ESTHALOM IS THE ROSH BEIT MIDRASH AT SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL. RAV ETSHALOM CONTINUES TO DIRECT THE TANACH MASTERS PROGRAM AT YULA BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL, GIVES SHIURIM THROUGHOUT THE CITY, IS A REGULAR CONTRIBUTOR TO YESHIVAT HAR ETZION'S VIRTUAL BEIT MIDRASH , AND IS A PUBLISHED AUTHOR ON TANAKH METHODOLOGY AND RABBINIC LITERATURE. HE ATTENDED YESHIVAT KEREM B'YAVNE, RABBI ISAAC ELHANAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, AND YESHIVAT HAR ETZION BEFORE RECEIVING SEMICHA FROM THE CHIEF RABBINATE OF YERUSHALAYIM.

Just before beginning the "question-answer" format of the Seder, we raise the Matzah and make a series of three short statements in Aramaic (the vernacular at the time of the composition of the Hagadah). ese include, in order, a declaration identifying the “bread of a iction”, an invitation to anyone who is hungry to join us and partake of our Korban Pesach, and a prayer that next year, unlike now, we will be in Eretz Yisra’el as noblemen.

ere are several classic questions that are asked about "Ha Lahma 'Anya":

Why is the paragraph in Aramaic?

How could we reasonably be inviting someone into our house to join us in eating the Korban? - At that late hour? No one may partake of a Pesach o ering without having joined a Havurah in advance (no later than the slaughtering of the Pesach that a ernoon)!

Why is the prayer at the end presented in a doubled form - here/Israel, slaves/noblemen? Why not combine the two?

What is the purpose of this paragraph? is enigmatic series of three lines seems to have no glue that holds it together, nor an obvious reason for its inclusion at this point of the evening.

e ultimate goal of the evening is to give thanks to God for the Exodus, as we discussed in last year’s article. e key word which turns the story-telling into singing, “Le khakh,” e ectively argues that since God redeemed us and since we are reliving that experience, it is incumbent upon us to extol, praise and sing to God. e vehicle for that Shirah is "Hallel"; since this is an evening of Hallel, it is prudent for us to examine the “Hallel experience”.

In an unusual twist, we can gain insight into the meaning of Hallel by identifying the one holiday when it is not recited, Purim. e Gemara (Megillah 14b) provides three answers as to why Hallel is not said on Purim:

2. A B C 1. 3. 4.

e Megillah is the Hallel

Hallel is not recited for a miracle which took place outside of the Land of Israel.

Hallel is guided by the opening line: "Give thanks, you servants of God" (Psalms 113:1), the implication being that we are only servants of God, and no longer servants of Pharaoh. Even a er the miraculous salvation in Shushan, we were still subjects of Ahashverosh.

We must sadly admit that much of the goal of Yetziat Mitzrayim has not yet been realized. Even those components which were "real" for a time are not currently part of our reality. ere is no Beit haMikdash, we continue to be scattered throughout the world and at this critical time in our history, we are operating in survival-mode rather than having the luxury to ful ll our destiny as teachers and inspiration for the world.

We come to a Seder with only one side of the Exodus experience – poverty and oppression; nobility and freedom are still part of an unrealized future and a nostalgic past. ere are two roles for the Matzah – as an independent Mitzvah commemorating the refugee experience, and as an auxiliary to the regal Pesach o ering. e only one which we can honestly point to tonight is the "Lahma ‘Anya" – like our ancestors in Egypt, we are “pre-Geulah”.

Now we can understand the paragraph. Before beginning our “fantasy” trip through Jewish history (one symptom of which is the conversation around the table, which we call “Maggid” - in Hebrew), we declare that we are celebrating a "poor" Seder – and we pray that next year, we should be able to do it "the right way".

We make this declaration in the vernacular, as it is the last point of "exile-reality" during the evening.

We ironically invite people in to share our "Pesach", reminding ourselves that the Pesach is missing from the table while pointing to the sad situation that we could reasonably have fellow Jews who are hungry and need a place to have their Seder – hardly nobility!

We then point to the two factors making our Hallel incomplete – we are "here" (even those in Eretz Yisra'el say this because the rest of us are not yet home) and we are "slaves" (under foreign rule); these two features get in the way of a complete and proper Hallel.

At this point, we pour the second cup, signifying the redemption which we will reenact - and, God willing, live to experience in "real time".

e story of the splitting of Yam Suf is an extremely popular one that plays a large role in the Pesach holiday, and we even mention it every day in our Shacharit prayers in Az Yashir. It seems from the Torah in Parshat Beshalach (14:21) that the splitting of the sea was initiated when Moshe held out his sta :

“ en Moshe held out his arm over the sea…and turned the sea into dry ground, the sea was split.”

However, the Midrash (Mekhilta DeRabbi Yishmael) has a di erent approach about what actually happened: “When the tribes were standing at the sea, each of them said: I will not go down rst into the sea.” e Midrash then relates that “Because they stood and deliberated, Nachshon, son of Aminadav (nasi of shevet Yehudah), leaped into the sea.” According to the Midrash, Nachshon entered Yam Suf until the water was at his throat, believing that Hashem was with him. Nachshon then prayed to Hashem saying, “Save me, O Hashem, for the waters have reached my soul.” us, according to the Midrash, Nachshon’s Emunah in Hashem was the catalyst for Hashem to save the Jewish people. e Midrash even says, [Mekhilta DeRabbi Yishmael,] “My loved ones are drowning in the sea, and the sea is raging, and the foe is pursuing, and you stand and wax long in prayer?”

e Midrash’s answer as to the catalyst for the parting of Yam Suf is Emunah combined with human initiative. Emunah and human initiative are both heavily demonstrated by Nachshon because when all the tribes refused to jump into Yam Suf, Nachshon had no fear of taking human initiative because he had Emunah in Hashem. His Emunah was so immense that he was even willing to die for Hashem, and that is what saved the Jewish people. Without Nachshon’s Emunah, he would not have taken human initiative to the point of death.

In our lives, it is important to compare ourselves to Nachshon and strive to develop both our faith and the ability to take human initiative. Faith is a powerful part of life, as it provides inspiration to yourself and others, and it allows you to enter a challenge with your head up because you know you will succeed. Along with faith, human initiative is also a powerful element for success because through our e orts, we thereby acknowledge that not everything is easy and handed to us on a silver platter. Sometimes, we have to work harder and go the extra mile to achieve success. May we all merit to achieve the success and salvation of Nachshon ben Aminadav in our own lives.

EYTAN BENSTVI '26 IS SOPHOMORE IN SHALHEVET'S ADANCED GEMARA SHIUR (AGS).

ARI EISEN SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘27

ARI EISEN SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘27

ELIANA WAINBERG '24 IS A MEMBER OF SHALHEVET'S BEIT MIDRASH TRACK (BMT). SHE IS THE CHIEF LAYOUT EDITOR FOR THE BOILING POINT, HEAD OF THE YEARBOOK COMMITTEE, AND A MEMBER OF THE VOLLEYBALL AND FLAG FOOTBALL TEAMS. NEXT YEAR SHE WILL BE LEARNING AT MIDRESHET HAROVA IN THE OLD CITY.

We recite Hallel to praise God's miracles and His redemption of the Jews from crisis on days that a) are called a Moed (holiday), and b) a miracle occurred. We recite the full Hallel on Shavuot, Chanukah, Sukkot, Shemini Atzeret, Simchat Torah and the rst two days of Pesach, but we recite only half-Hallel on the rest of Pesach. Why do we only say the full Hallel on the rst day of Pesach, two if in chutz la’aretz, whereas on Sukkot we say the full Hallel on all days?

A simple answer to this question can be found in the Gemara Arakhin (10a-b): Why this di erence that on Sukkot we complete [literally: say] Hallel on all the days, and on Pesach we do not say on all the days? e days of Sukkot are di erentiated from one another regarding the sacri ces due on them, while the days of Pesach are not di erentiated from one another regarding their sacri ces. [ e number of bulls to be sacri ced on Sukkot was lessened from day to day, while on Pesach, the number stayed the same.]