Teshuva, repentance, is quite unusual. Most mitzvos can generally be divided into two categories: ose that are limited to a particular time (eg. Lulav, Shofar, creative activity on Shabbos), and those that are timeless (eg. fear of God, the prohibition of lashon harah). Indeed, this is the organizing principle that the Smak, R’ Yitzchak of Corbeil, uses to divide his comprehensive list of mitzvos. e problem is, teshuva seems to be neither. Or both. e Yamim Noraim season that begins with Elul and culminates with Hoshanah Rabbah is characterized by the mitzvah of teshuva. And yet, unlike other holiday-speci c mitzvos, teshuva is not limited to the Yamim Noraim. Yes, it’s a mitzvah to repent between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, but it’s also a mitzvah on February 4th. So, is teshuva during this season just a “duplicate” of what is a mitzvah throughout the year anyway?

Perhaps there are actually two di erent types of teshuva, and while they carry the same name, they are as di erent - to borrow language from Halachik Man - “as east is from west.” R’ Aharon Lichtenstein (Return and Renewal) suggests that throughout-the-year teshuva (what he calls “occasional teshuva”) is about xing that which is broken. It can be repentance for a single sinful act, a series of actions, or a general “spiritual collapse.” is teshuva is, by nature, myopic, immediate, symptomatic. But there’s another type of teshuva, not triggered by a particular sin or decline, but by the Yamim Noraim season. is teshuva is “not so much a treatment as a checkup” (p. 143), in which we tend to the whole self. We’re meant not to be reactive, but to proactively look inwards, to be re ective and introspective. To look at failings in their larger context and gure out how we can grow, improve, develop, recenter and reinvent ourselves. It’s meant to encompass the totality of our spiritual experience. at’s the mitzvah of this season.

Part of what makes Shalhevet unique is that our education is not just about facts and knowledge; we are constantly looking to grow, to become the best versions of ourselves. We focus not only on improving certain areas or developing particular skills, but on the whole student, on becoming good people, cultivating menschlechkeit, enhancing our relationship with Hashem. We try to channel R’ Yisrael Salanter’s charge that “All year round ought to be like Elul.” at holistic, growth-oriented teshuva approach permeates the Torah of our students, alumni, and faculty in this extraordinary volume.

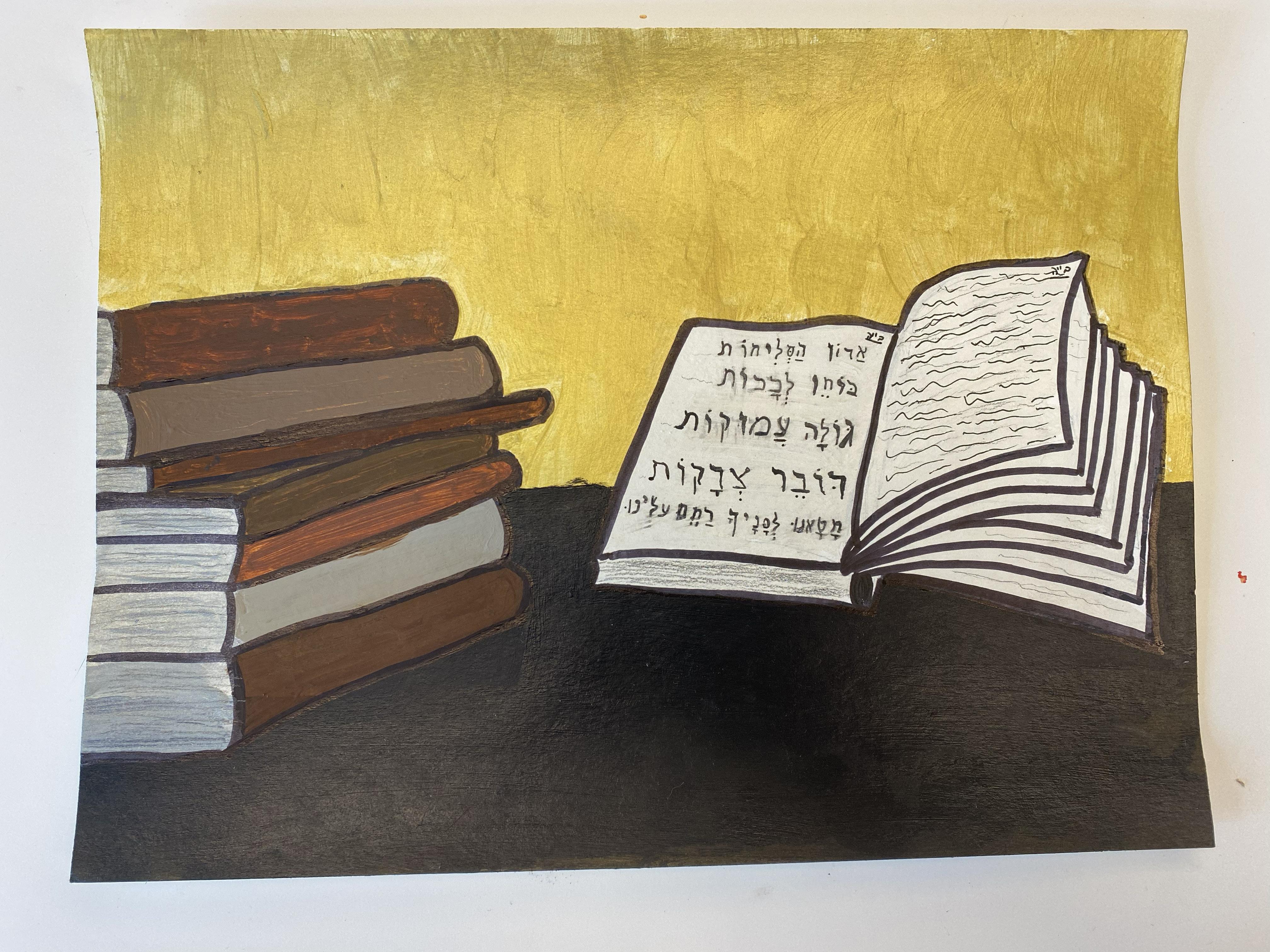

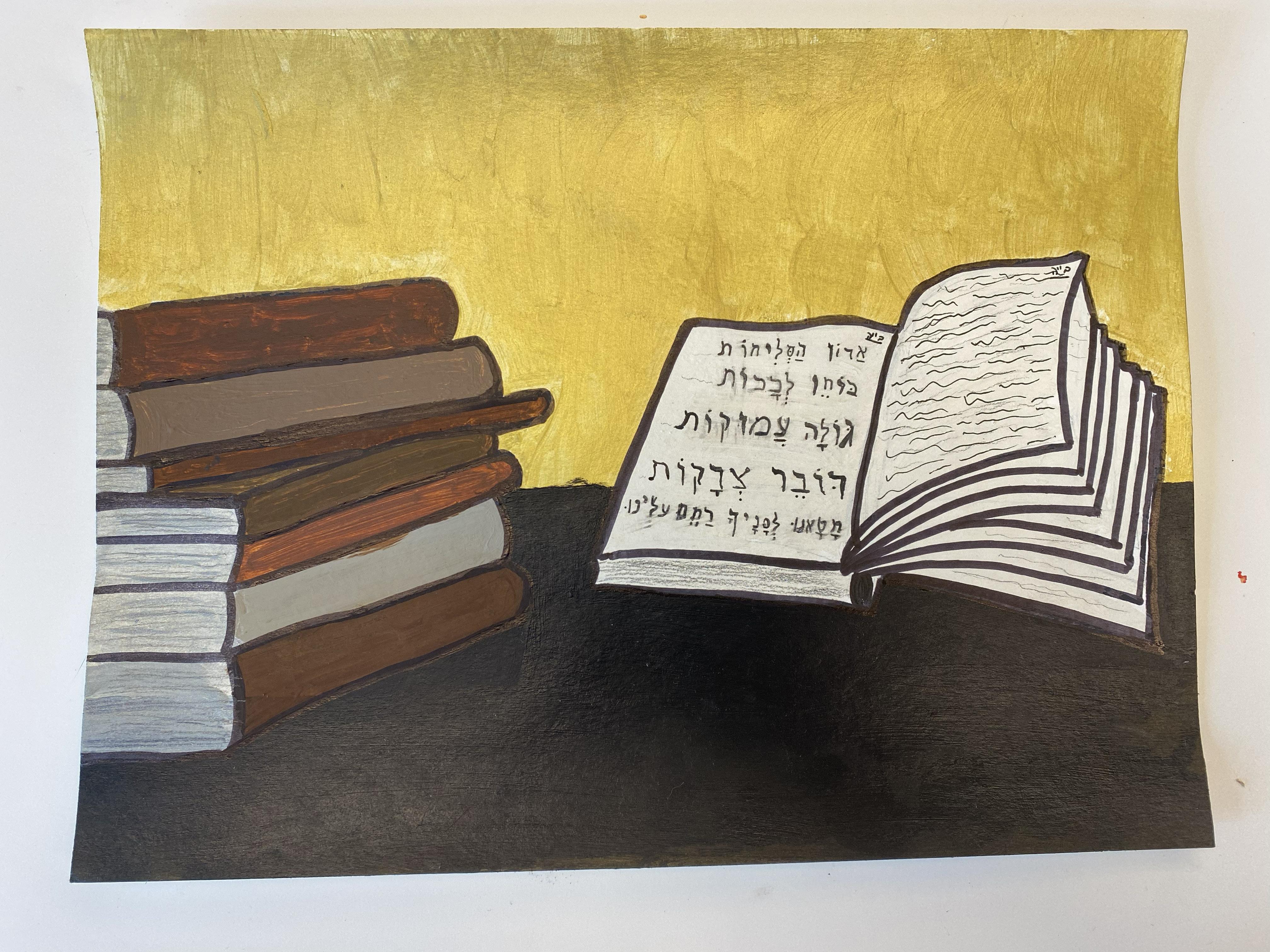

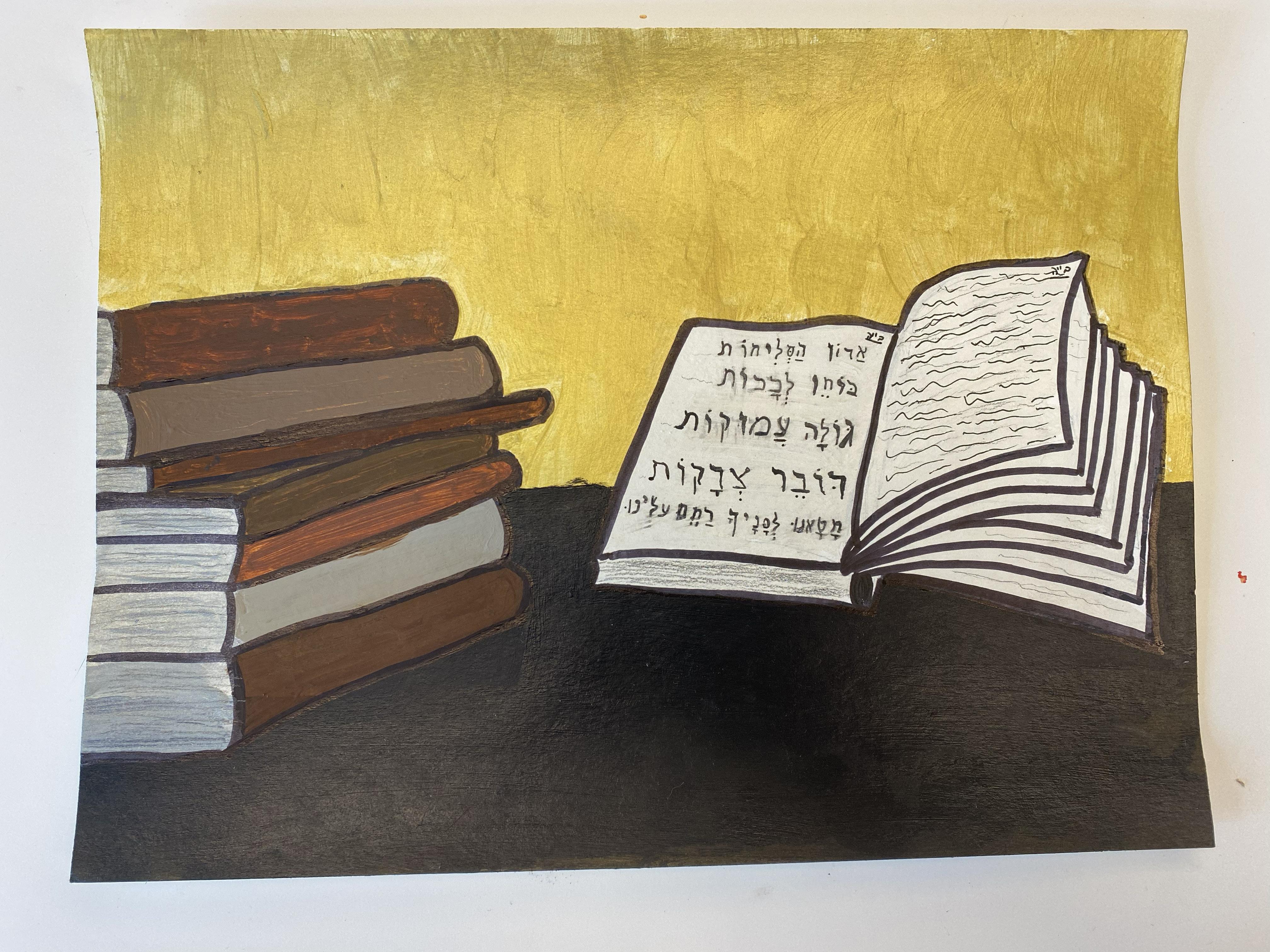

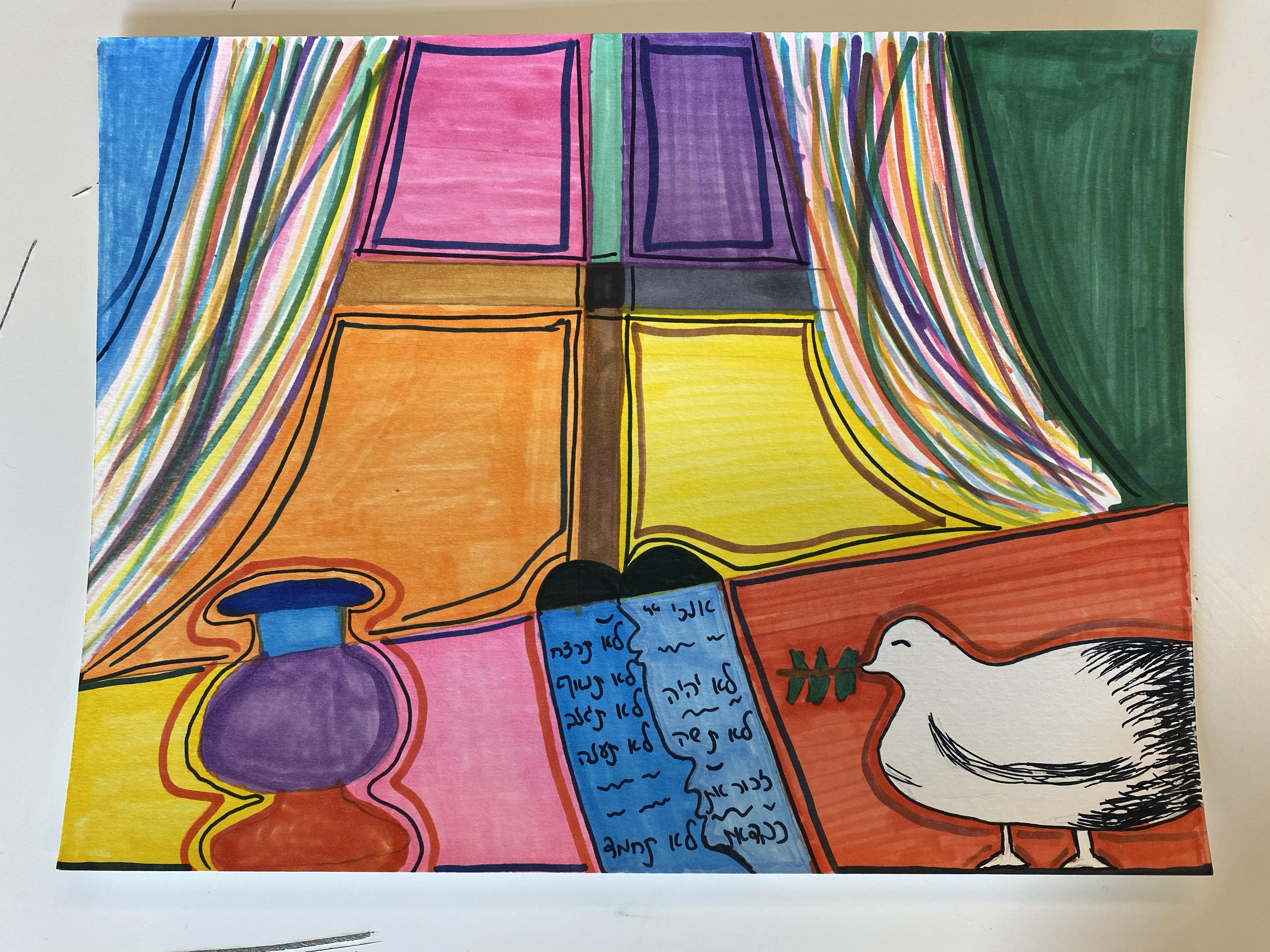

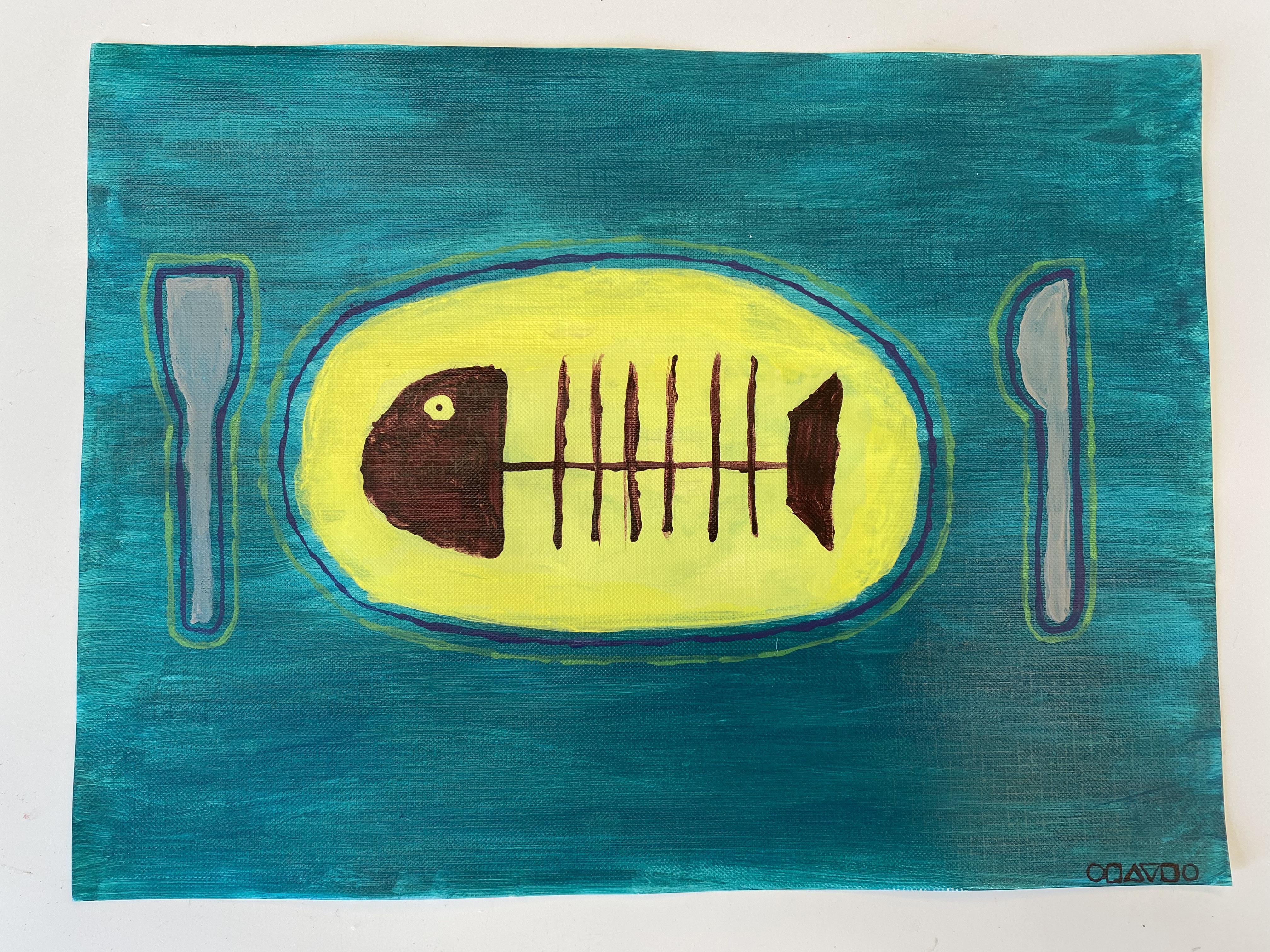

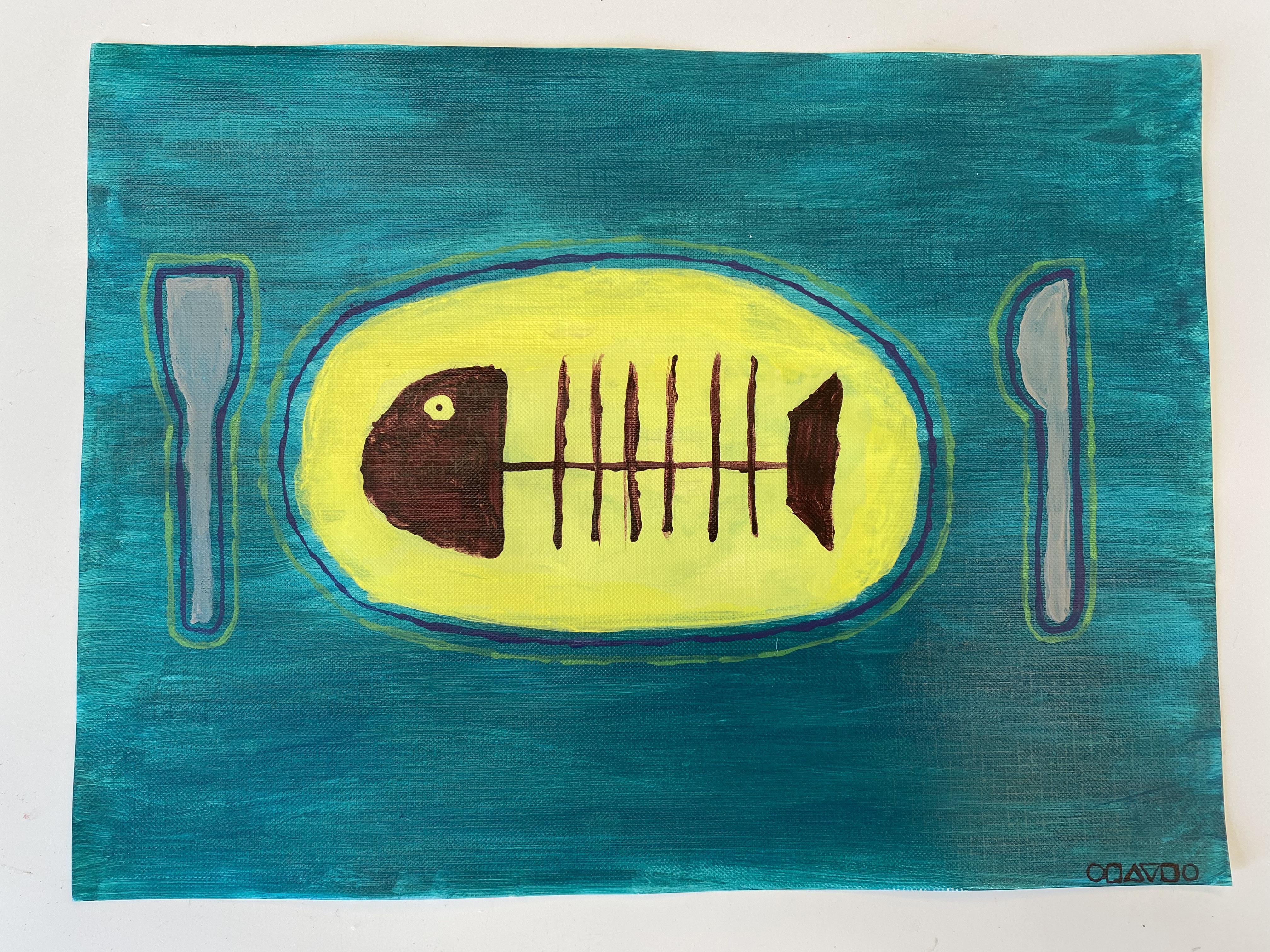

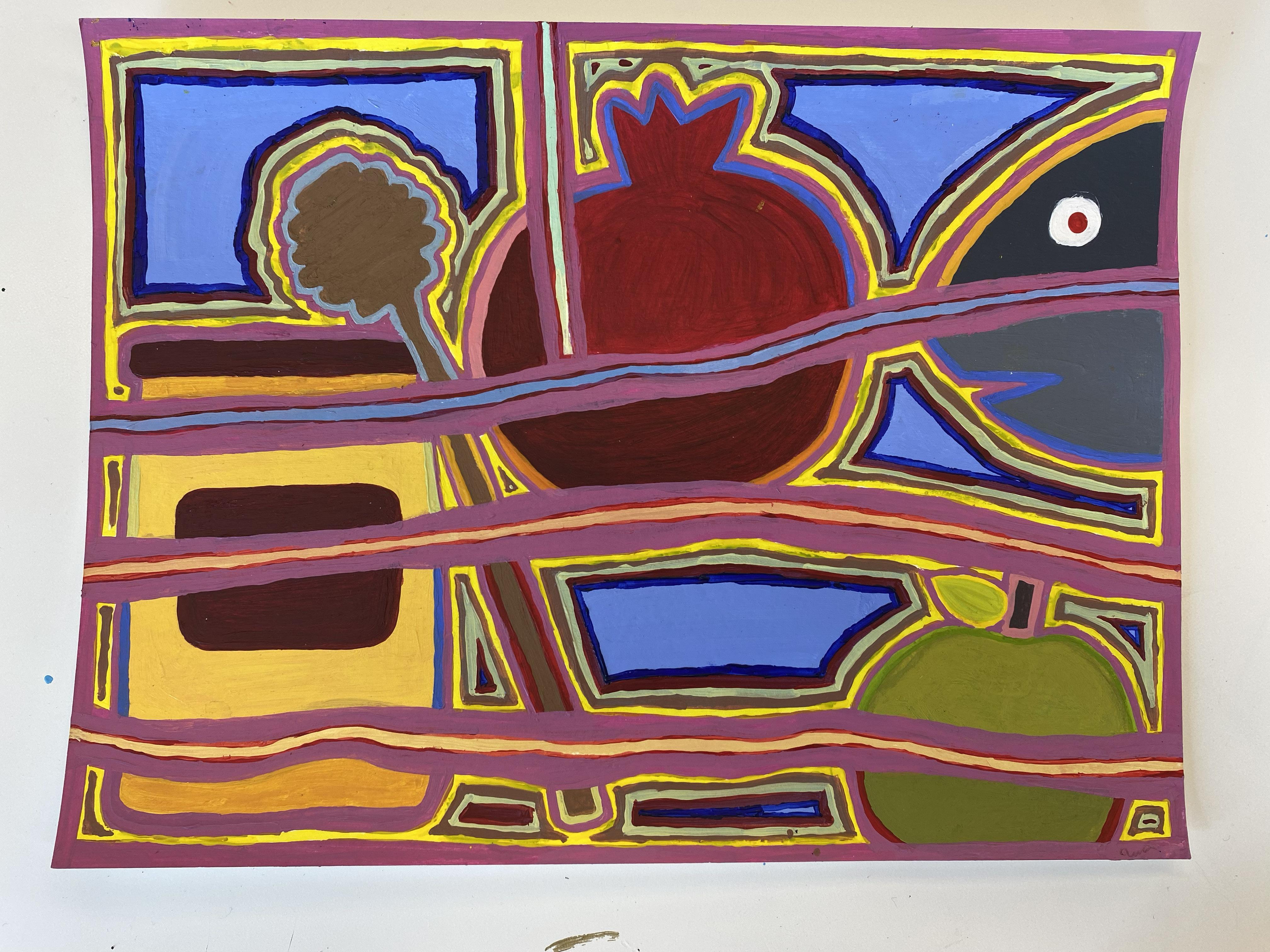

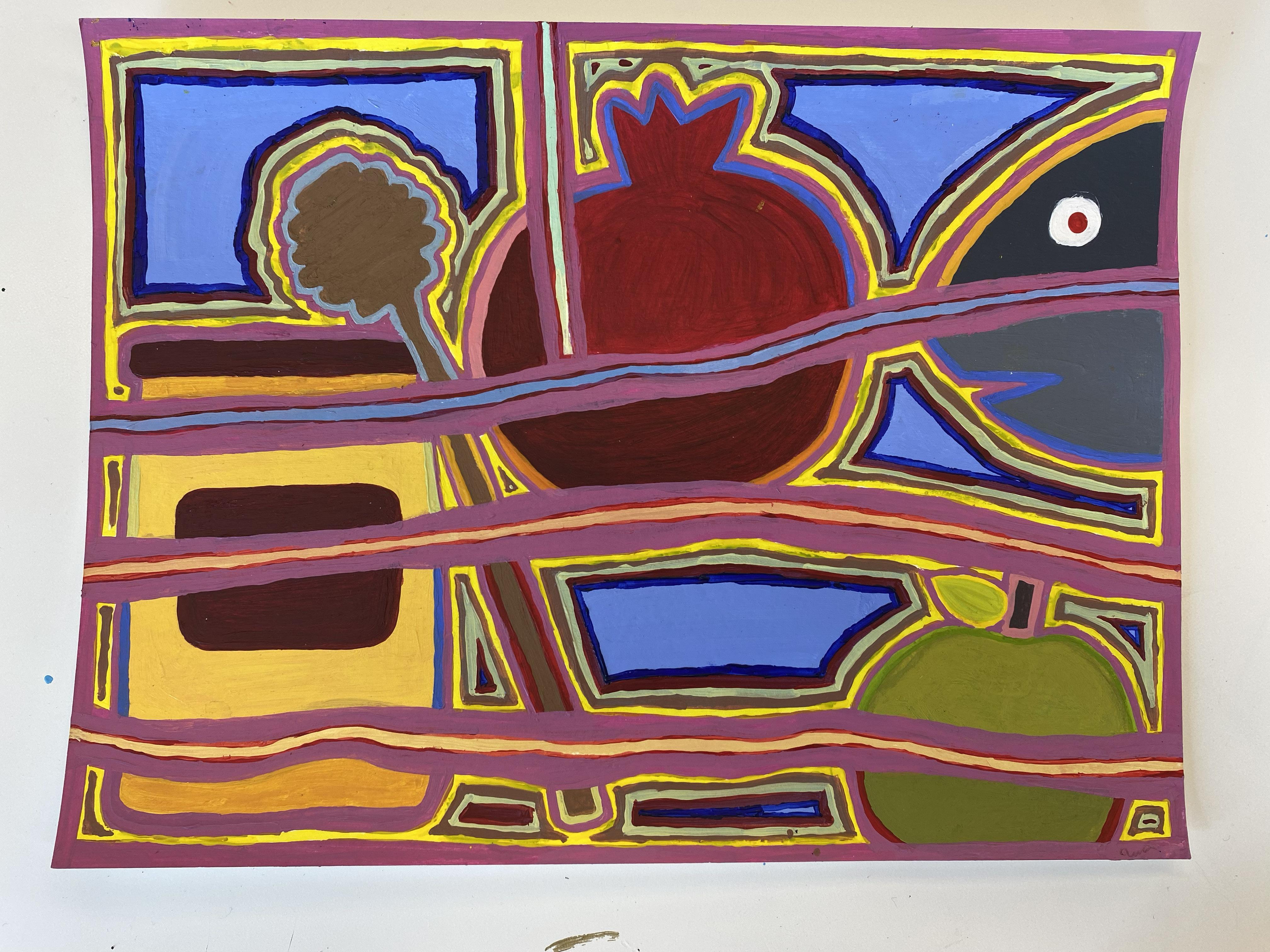

Wherever you are for the chagim, take Orot Shalhevet with you and share the kedusha with others. It is my bracha that the varied and unique voices of our faculty, students, and alumni infuse our holidays with meaning, and the stunning student and faculty artwork serves as hiddur mitzvah (beauti cation of the Torah within). As I always note, the teachers, students, and alumni are all the Orot (lights) that come together to form our dazzling Shalhevet ( ame).

Kesiva V’chasima Tova, Rabbi David Block

ALIZA KATZ

SUKKOT: THE JOURNEY INWARD

ARI

RABBI ELI BRONER

TEMPORARY STRUCTURES, ETERNAL FOUNDATIONS: THE SPIRITUAL LESSONS OF SUKKOT AND MARRIAGE

YAGIL

thank you

TO THE FOLLOWING SUPPORTERS WHO HAVE GENEROUSLY SPONSORED THIS EDITION OF OROT SHALHEVET. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO THEM FOR HELPING TO PROMOTE THE SPREAD OF MEANINGFUL TORAH LEARNING AND SPIRITUAL GROWTH IN OUR COMMUNITY. PLEASE ENJOY THE TORAH YOU WILL FIND WITHIN IN THEIR MERIT.

KAREN & AVI ASHKENAZI

DALYA & SIMON BACKER

GAIL KATZ & MAYER BICK

DAHLIA & ELAN CARR

MAYA & NEIL COHEN

ELISA & BRADFORD DELSON

JENNIFER & YARON ELAD

SHARON & ALAN GOMPERTS

MOLLY & SAEED JALALI

MALKA & JOSH KATZIN

STACY & RANON KENT

ORTAL & AMITAI KLYMAN

LISA & GARY LAINER

LERNER FAMILY

DESI ROSENFIELD

ROSETTE & BARRY SCHAPIRA

NAOMI & RABBI ARI SCHWARZBERG

TAALY & ADAM SILBERSTEIN

LESLEE & ALEX SZTUDEN

BRENDA & HAROLD WALT

SHANNON & JUSTIN WEISSMAN

RABBI GABE FALK IS THE DIRECTOR OF TORAT SHALHEVET AND A LIMUDEI KODESH TEACHER. HE LEARNED IN YESHIVAT HAR ETZION AND RECEIVED SEMICHA FROM YESHIVA UNIVERSITY. HE HOLDS A B.A. FROM COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, IS WORKING TOWARDS AN M.A. IN JEWISH HISTORY FROM REVEL, AND WAS A WEXNER GRADUATE FELLOW. BEFORE JOINING SHALHEVET, RABBI FALK SERVED AS THE ASSISTANT RABBI AT GREEN ROADS SYNAGOGUE AND TAUGHT AT FUCHS MIZRAHI SCHOOL IN CLEVELAND, OH.

In my own emotional map of the Days of Awe, Rosh Hashana is primarily characterized by fear and trepidation. Aptly named, the Days of Awe are days on which we – broken and awed human beings – stand in judgment before the in nite, omnipotent Master of the Universe. e trembling words of the angels in ‘U’netaneh Tokef’ loom large: ךיניעב

ןידב, “for they will surely not be exonerated in your eyes”.

But this is only one possible image of the Yamim Noraim. I’ve long been enamored by the descriptions of the Yamim Noraim prayers at Yeshivat Otniel. Reportedly, at Otniel, prayer is transformed into hours of euphoric singing and dancing. At Otniel and other Yeshivot in Israel, the Ashkenazi tradition of heavy-hearted petition is replaced by joyous celebration.

Of these two models of Yamim Noraim prayer, awe and trepidation on the one hand, and joy and jubilation on the other, which is more “correct”? As we stand before Hashem on these Yamim Noraim, how should we carry ourselves? What is the proper emotional experience?

A passage in Masechet Erechin seems to address this question directly. Noting that Rosh Hashana looks and feels a lot like the other holidays (melacha is prohibited and it is presented in the moadim section of the Torah), the Gemara makes the following suggestion: perhaps we should sing Hallel on Rosh Hashana! Hallel, of course, referred to by the Gemara simply as shira, or song, conveys our praise and gratitude to Hashem. e suggestion or hava amina is an important one; perhaps, contends the Gemara, Rosh Hashana should be celebrated, not feared

e Gemara rmly rejects this suggestion by presenting the famous image: God, the ultimate judge, sits with two ledgers before him: Sefer HaChaim and Sefer HaMetim - the book of life and the book of death. Given the gravity of this moment, asks the Gemara, do we dare sing [the Hallel]? Put di erently, song is usually an expression of gratitude precipitated by the culmination of an experience, such as the salvation from an enemy or a successful harvest. However, the “danger” of Rosh Hashana has not yet passed – the ledgers are still open, and our fate hangs in the balance. Surely, concludes the Gemara, the Yamim Noraim must be days of awe, not days of joy.

e Yerushalmi (Rosh Hashana 1:3), however, o ers a powerful and critical counterpoint. Usually, explains the Gemara, when one waits in anticipation of a judgment, one wears dark, mournful clothing. In contrast, says the Gemara, look at the mood of Bnei Yisrael on Rosh Hashana:

ey wear white, drape themselves in white, shave their beards; they eat and drink merrily, knowing that Hashem will perform miracles.

e image presented by the Yerushalmi is also familiar: we treat Rosh Hashana as a Yom Tov with all of the accouterments of the holiday experience. And why is this? For we know that Hashem will perform miracles. e dread of the anticipated judgment is replaced in the Yerushalmi by a level of presumptuous certainty - God is on our side,

tipping the scales of justice in our favor. And so, we allow ourselves to celebrate.

Two verses re ect these two modes. In the less famous verse, we are instructed: האריב ׳ה תא ודבע - serve God with awe (Tehillim 2:11). In the understandably more famous verse, the instruction is ipped;

(Tehillim 100:2). Two models of the service of Hashem, present throughout the year, reach a particularly acute point of tension during the Yamim Noraim.

Furthermore, these two models echo the metaphors used to depict Bnei Yisrael’s relationship to Hashem:

,םינבכ

םידבעכ. Is our relationship to Hashem familial with the intimacy of the father-son relationship, or is it the more formal, more distant relationship of a servant to their master? e na a minah (practical di erence), of course, is our question: are we lled with joy or dread as we stand in judgment?

Rav Avigdor Nebenzahl, storied Rav of Jerusalem’s old city, suggests a creative solution. Both emotions are present! ey re ect two di erent planes of our relationship with Hashem: individuals and community. As individuals, we stand before Hashem with trepidation – our lives truly hang in the balance and we plead for rachamim. However, the collective unit of Kneset Yisrael, the congregation of Israel, stands before the Ribono Shel Olam overwhelmed with joy. Hashem’s love for his people is unconditional, and we have certainty that our collective judgment will be a positive one.

My teacher, Rabbi Dr. J.J. Schacter, o ers a di erent approach that I believe speaks powerfully to both the human and the religious experience. Rabbi Schacter quotes two complementary statements of the Rambam. e Rambam, in classical style, bridges the gap between these two emotions. Addressing the question of Hallel on the Yamim Noraim, he writes:

But we do not recite Hallel on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur since they are days of fear and trepidation, not days of abundant joy.

ese are not days of abundant joy, suggests the Rambam. But surely, notes Rabbi Schacter, joy is a present and integral component of our experience. e joy and trepidation must be held together, they are two aspects of a shared experience. Life does not simply break down into experiences of joy or fear. e complexity of life dictates both - there is tremendous joy in our celebration of life, of family and most importantly, of the opportunity we have to live as Jews with mission, purpose and destiny. But we also stand before God with keen awareness of our existential fragility -and this lls us with trepidation.

In his commentary on the Mishna, the Rambam characterizes the “fear” of the Yamim Noraim as follows:

ey are days of service, of contrition, of fear from Hashem, and ight to take refuge with Him.

e awe and trepidation from God drives us to take comfort and refuge with Him. Our fear and our joy are manifestations of the same experience - a profound encounter with the Ribono Shel Olam.

e Gemara in Masechet Brachot o ers us a similar reconciliation of sorts between the two modes of religious expression. e verse in Tehillim states: הדערב וליגו. Rejoice with trembling. How, wonders the Gemara, can one rejoice with trembling? Surely these two emotions are incompatible!

Rav Ada Bar Matna says in the name of Raba: Where there is rejoicing, there too should be trembling. us, we are asked to hold both of these emotions together in our lives and in our Avodat Hashem. is has been a year of fear and trembling for Am Yisrael. But it has been a year of deep joy as well as we see how the Jewish people has united as one to counter our enemies. On these Yamim Noraim, we stand before Hashem holding the full complexity of the human experience together - and we ask Hashem for the expansive capacity in our hearts to do so:

- unify our hearts so that we may love and fear your name.

Let us dance with the unbridled joy of Yeshivat Otniel and pray with the trepidation of the angels as the day of judgment approaches, and may all of Am Yisrael be inscribed in the book of life, the םייחה רפס

ELIJAH STERN GRADUATED FROM SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL IN 2023. HE IS CURRENTLY LEARNING SHANA BET IN YESHIVAT HAKOTEL AND IS PLANNING ON DRAFTING INTO THE IDF IN MARCH.

e month of Tishrei may be the most jam-packed, roller coaster of a month in the entire Jewish calendar. In one month, we experience הרות תחמש ,תוכוס ,רופיכ

,הנשה שאר, and nally the Shabbat of order to fully encapsulate the signi cance of Tishrei speci cally this year, I want to focus on the last main event of the month: תישארב תשרפ.

e Torah says (אל:א תישארב) that once the creation of the world was completed on the sixth day, God saw all that He had created, and ״דאמ בוט הנהו״, “it was very good,” contrary to all the other days in which the creation is described as ״בוט הנה״, “it was good.” e question is why does the Torah add the word דאמ (very) at the end of creation? Wasn’t most of creation simply called בוט (good)?

e ן״במר quotes Onkelos on this pasuk who says that the addition of the word דאמ is to show that everything in the world has a speci c time and purpose, and even “the evil is necessary to uphold the good.” In other words: (this too is for the good). At times like these, a er a year of the lowest of lows, it can be really di cult to wrap our heads around the words הבוטל הז םג. However, I don’t think it is a coincidence that תישארב תשרפ in which we can learn the lesson of הבוטל הז םג from דאמ בוט, falls out this year the day a er הרות תחמש, the day on which we commemorate one year since לארשי םע experienced its biggest pogrom from the time of the Holocaust.

ונרופס gives another answer as to why the Torah adds the word דאמ a er the creation of the world is fully completed with the formation of humans. He says that nishing a project of many di erent parts is greater than the accomplishment of each part on its own. Once Hashem nished the creation of the whole world, he could nally call it part alone was only בוט

However, if it is true that the entire world is דאמ בוט, then why does most of the world seem to be Shouldn’t it all be good, or at least most of it? Why has our entire world seemingly been shi ed to a constant feeling of loss and pain?

I believe one answer to this question lies within Onkelos’ answer to the question about the words Onkelos, evil also has a place in the world. We cannot always understand why it has surfaced in such a terrible way at this time, but we should understand that this is all part of Hashem’s plan and order of the world.

Perhaps we can also o er another to this question based on ונרופס’s explanation. When ונרופס better when it is completed than the individual accomplishments themselves, we can learn from here how we, the Jewish people, should conduct ourselves in the face of tragedy. Each of us are great on our own, but the world will be a much better place when the Jewish people are united as one, and every person is putting in his or her תולדתשה as possible. Hashem chose the Jewish people as his nation, and it means that we have the ability to make the world just as great as Hashem describes it, דאמ בוט. But sometimes we need challenging situations to push ourselves to do so. Finally, I think it is fair to say that Tishrei is considered “ e Motivational Month.” We repent for all of our sins and come

up with many promises to God and resolutions to become better people, but we don’t always keep them or stay true to our goals the entire year. A great example of this is the gym. January is always the busiest month of the year at the gym with all the people who made “new year’s resolutions” to get in shape. However, a month or two later, once February and March roll around, the gym becomes a lot emptier than it was on January 1st because people do not always keep their word. A er a month of re ection, repentance, celebration, and renewal, it is crucial to remember that the Jewish people

RABBI ABRAHAM LIEBERMAN IS A MEMBER OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH FACULTY AT SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL. HE PREVIOUSLY SERVED AS THE HEAD OF SCHOOL AT YULA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL. RABBI LIEBERMAN LEARNED AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY AND RECIEVED SEMIKHA FROM EMEK HALAKHA IN BROOKLYN. HE RECIEVED HIS M.A. IN JEWISH HISTORY FROM THE BERNARD REVEL GRADUATE SCHOOL (YU), WHERE HE IS CURRENTLY WORKING TOWARDS HIS DOCTORATE.

One of the striking aspects of Rosh Hashanah is that Hallel, which is recited on other holidays, is not said. In fact, one can think of a number of reasons why Hallel should be recited.

e book of Nechemyah (8:1-12) narrates, regarding a convocation on Rosh Hashanah, of the people (the exiles from Bavel who returned to the Land of Israel) reacting with tears and sadness, a er hearing the Torah being read and explained. ey understood that their behavior was not up to standard. Ezra and Nechemyah respond to their situation:

Go, eat fat foods and drink sweet drinks and send portions to whoever has nothing prepared, for the day is holy to our Lord, and do not be sad, for the joy of the Lord is your strength. (8:10)

We are then told that the people followed the instructions:

en all the people went to eat and to drink and to send portions and to rejoice greatly, for they understood the words that they informed them of. (8:12)

Clearly, the text intimates that Rosh Hashanah is a day of joy when we would expect that Hallel should be said.

It is true that Rosh Hashanah is the Day of Judgement, and there were in fact some individuals, including some sages, who fasted on Rosh Hashanah. But the above verse is used as proof that one may not fast on Rosh Hashanah, and that is the nal decision of the Shulchan Aruch (O.H. 597:1):

We eat and drink and rejoice and do not fast on Rosh Hashanah.

e Gaon of Vilna (R. Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman, 1720-17970) quotes the above verse to teach that crying on Rosh Hashanah is also forbidden (Ma’aseh Rav, 207, though others disagree).

Another proof that Rosh Hashanah has the same status of the other holidays can be found in the laws of aveilut (mourning). If a person started sitting Shivah, even for a short time before a Chag, and the Chag falls out during the Shivah, it has the power to cancel the rest of the mourning period. In that context, the Shulchan Aruch rules:

. “Rosh Hashanah (and Yom Kippur) are considered like regular festivals, to cancel the remaining period of Shivah” (Yoreh Deah 399:6). Again, we see that Rosh Hashanah is of equivalent status to other days of Yom Tov. us, we would expect that Hallel should be said.

e Talmud Yerushalmi in Rosh Hashanah (1:3) states:

“Is there a people like this people? Usually in the world, a person who knows that he will stand trial

dresses in black, wears a black headdress, and lets his beard grow, since he does not know how his trial will end. But the Jewish People are not so, they wear white, wear a white headscarf, trim their beard, eat, and drink, and are happy. ey know that the Holy One, praise to Him, will perform wonders for them.

Again, we see that Rosh Hashanah is a day of rejoicing and we would expect that it should require the recital of Hallel. Furthermore, the Talmud in Masechet Rosh Hashanah (34a) interprets a verse from Psalms as referring to Rosh Hashanah:

“Sound the shofar at the New Moon, at the full moon [keseh] for our feast day” (Psalms 81:4). Which is the Festival on which the month, i.e., the moon, is covered [mitkaseh]? You must say that this is Rosh Hashanah [the only Festival that coincides with the new moon, which cannot be seen].

Invariably, here too Rosh Hashanah is viewed as a Festival and as such would require Hallel.

One halachic aspect of all Chagim is the Mitzvah of simchat yom tov, rejoicing on the holiday. Rosh Hashanah is included in this aspect, as one can see from the Rambam (Mishneh Torah, Yom Tov, 1:1, 6:16-17), Shulchan Aruch (O.H. 529), and from the verses in Nechemyah quoted above.

e Chatam Sofer (R. Moshe Schreiber, 1762-1839) in his Derashot (Derashot Chatam Sofer Ha-Shalem, Drash 15, p.191) writes: “Surely there is great joy on Rosh Hashanah, so one should [theoretically] recite Hallel, due to the fact that Hashem has given us the power to repent and eagerly waits for us to improve and to bless us with a good year.”

Given all the points made above, one can understand the question of the angels posed to Hashem. e Talmud in Rosh Hashanah (32b) relates the following:

Rabbi Abbahu said: e ministering angels said before the Holy One, Blessed be He: Master of the Universe, for what reason don’t the Jewish people recite songs of praise, i.e., Hallel, before You on Rosh Hashanah and on Yom Kippur? He said to them: Is it possible that while the King is sitting on the throne of judgment and the books of life and the books of death are open before Him, the Jewish people are reciting joyous songs of praise?

e same text of Rabbi Abbahu appears in Arakhin 10b as an answer to why Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is not listed among the days of the recitation of Hallel, since they both ts the requirements needed to say Hallel: a) Work is forbidden, and b) it is called a Festival.

is statement of Rabbi Abbahu is codi ed in the Shulchan Aruch (O.H. 584:1):

. “We do not recite Hallel on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.”

e Tosa sts commenting on the above statement (Arakhin 10b, s.v. amru) explain that while the Jewish People do not say Hallel on Rosh Hashanah, the angels in heaven continue singing and praising Hashem.

So clearly by all indications, Hallel should be said, yet the fact that humanity stands in judgement does not permit its recitation. Maimonides (1138-1204) in his Commentary to the Mishnah (Rosh Hashanah 4:7) explains further:

“…Since we do not recite Hallel neither on Rosh Hashanah nor on Yom Kippur, because they are days of prayer and submission before God and fear of Him and test before Him and repentance and supplication and request for pardon, and it is not appropriate in these conditions to be happy and to rejoice.”

In the Mishneh Torah (Hanukah 3:6), Maimonides clari es this point:

“Hallel is not recited on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, since they are days of repentance, awe, and fear, and are not days of extra celebration.”

is distinction regarding the extra celebration that is not to be displayed on Rosh Hashanah helps us understand another Halachah regarding Rosh Hashanah. In our Amidah on the rest of the Chagim, we add the words: , “Holidays to rejoice, Festivals and times of joy,” yet we are told in the Shulchan Aruch: (O.H. 582:8): “We do not recite (on Rosh Hashanah in our Amidah) the words: Holidays to rejoice, etc.” So while the concept of simchat Yom Tov, rejoicing on a Chag, includes Rosh Hashanah, overdoing it by stating that Rosh Hashanah is a holiday to rejoice would not be appropriate, and the same applies to Hallel. e main focus of Rosh Hashanah is the creation of the world, the kingship of Hashem, and judgement of humanity. It is not a time for extra celebration as we contemplate these heavy matters. As far as Hallel is concerned, we remain silent.

e well-known U’netaneh Tokef prayer was inspired by the words of Rabbi Abbahu, as we speak there about being inscribed for a good year. As it describes Hashem’s judgement of the World, we nd the following line:

. “A great shofar is sounded, and a silent, subtle voice is heard.” Rav Kook (R. Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, 1865-1935) in dealing with this passage writes (“Sparks of Light: Essays on the Weekly Torah Portions, Based on the Philosophy of Rav Kook,” pp.160-161) that the word הממד, silent, signi es deep understanding (like ןרהא םודיו when Aharon was silent, at the loss of his children).

It is an acceptance of the greatness of Hashem and His judgement of us that we stand in awe on Rosh Hashanah and do not recite Hallel. erefore, while the angels will sing even on Rosh Hashanah, we humans remain silent, and our only sound is the sound of the Shofar.

May we all merit a Shanah Tovah! RAFAEL KAHEN

is summer at camp, my eida (group) focused on the value of kesher, or connection. It was there that I learned that the idea of connection serves as a foundational virtue of the Jewish identity, with its presence embedded in our stories, values, and practices. Whether those connections be with oneself, within the community, or with Hashem, Judaism conveys that our moral and spiritual lives are intertwined with the relationships we foster. As we approach the High Holidays, particularly Rosh Hashana, we are called to remember and re ect on our actions over the past year. Similarly, we are reminded that God knows all of our deeds – both the positive and the negative that we have done throughout the year, as we mention in the section of Musaf on Rosh Hashana known as Zichronot (Remembrances). It is why we spend the holiday yearning for a spot in the Book of Life and why Rosh Hashana is also referred to as Yom Hazikaron Day of Remembrance. rough Rosh Hashana, we grapple with the overarching theme of connection to God, with ourselves, and the community, all in the context of the commandment to remember and re ect.

Naturally, because zikaron includes the idea that God knows of and remembers our actions, Rosh Hashana is also a holiday that reinforces the importance of evaluating our connection to Hashem, with all it encompasses. While we may be taught that God knows all throughout the year, it is on Rosh Hashanah that we are forced to acknowledge this supreme knowledge, something which, to me, produces anxiety surrounding what I did or didn’t do, in a religious context. ese anxieties, however, lead me to a stage of accountability that I also do not nd myself in throughout the rest of the year. To me, Rosh Hashana is a time of warning. Within our relationship with God, we are allowed to mess up – with that allowance contingent on doing teshuva and xing those wrongdoings. erefore, Rosh Hashana, because of the anxieties regarding God’s remembrance of our actions, forces us to look closely at our spiritual practices – showing us the areas where we must improve or where our connection to God may be weak. It is a holiday that, because of its correlation with God, pushes us to resolution, where we not only acknowledge our wrongdoings, but nd for ourselves a pathway of sorts that pushes us to a spiritual high.

Rosh Hashana is not only a time of religious re ection and improvement, but also a holiday that allows us to build our relationship with, and subsequent con dence in, ourselves. Because of the mandated re ection that occurs on Rosh Hashana, we are granted an opportunity to reimagine our own selves, and the morals we want to commit to. Rosh Hashana, however, is not simply a time of renewal and new year’s resolutions, but rather something stronger and, in a way, radical. We are not only given the chance, but the obligation, to assess who we were throughout the year and what we strive to become. rough mandated re ection and meditation, we are able to cra a positive connection with our own selves – as we become self-aware, acknowledge our attributes, navigate the ways we can improve, and learn to accept and care for ourselves, in ways that can carry themselves throughout the year.

Finally, the concept of remembrance is also one that manifests itself in the communal aspect of connection. God commands us to remember and re ect on what He has done for us, which we do in the Zichronot section of Musaf as well. And while that does apply to the individual, it is also ever present in the communal history of the Jewish people. It is a way for us to take a step back from meditation and self-re ection, and instead renew the lasting connections we make

with others. roughout Rosh Hashana, we see this represented through the blowing of the shofar. While the blasts,

DR. SHEILA KEITER IS A MEMBER OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH AND GNERAL STUDIES FACULTY AT SHALHEVET. SHE HAS A B.A. IN HISTORY FROM UCLA, A JD FROM HARVARD LAW SCHOOL, AND RECEIVED HER PHD IN JEWISH STUDIES FROM UCLA, WHERE SHE TAUGHT IN THE DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES.

Normally, if you wanted to learn from the Gemara about repentance and atonement, you would turn to masechet Rosh Hashanah or Yoma, which touch upon the two high holidays that mark the season of teshuva. However, repentance and atonement are not the sole province of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. ere are ample opportunities for self-evaluation, self-improvement, and atonement throughout the year. Any time is a good time. In that spirit, I want to examine a text from masechet Sukkah.

In a discussion regarding which types of mats can be used as proper schach for a sukkah, Reish Lakish cites an opinion from Rabbi Hiyya and his sons. But before doing so, he o ers an unusual tribute to them:

For Reish Lakish said: Here I am an atonement for Rabbi Hiyya and his sons. Because in the beginning, when the Torah was forgotten by Israel, Ezra went up from Bavel and established it. Once again it was forgotten. Hillel the Bavli went up and established it. Once again it was forgotten. Rabbi Hiyya and his sons went up and established it. (b. Sukkah 20a).

ere is nothing unusual about attributing an opinion to an earlier sage, but this extended history is another matter altogether. Clearly, Reish Lakish is trying to praise Rabbi Hiyya. He places him in the same ranks as Ezra and Hillel, sages who preserved the Torah at a time when it could have been lost. Ezra came to Eretz Yisrael in the h century BCE with other Jews returning from the Babylonian exile. Known as Ezra the Scribe, he was instrumental in establishing the centrality of the written Torah during the Second Temple period (Ezra 7:6). Hillel the Elder came to Eretz Yisrael in the rst century CE from Bavel at a time when the population had forgotten much of the teachings of the earlier sages, particularly those of Shemaya and Avtalion (b. Pesachim 66a). Hillel emerged as a leading sage by reestablishing that Torah.

RabbiHiyya, who lived in the second century CE, did share some qualities with these two illustrious sages. Like Ezra and Hillel, Rabbi Hiyya moved from Bavel to Eretz Yisrael. But that may be where the similarities end. While a brilliant Torah scholar, there is no historical evidence that Rabbi Hiyya or his sons did anything extraordinary to save the Torah from being forgotten. us, Reish Lakish’s introduction seems to serve as exaggerated praise.

Reish Lakish’s opening pronouncement that he serves as a kapparah, an atonement, for Rabbi Hiyya and his sons is curious. is too seems to be complimentary, a tribute to Rabbi Hiyya’s greatness. Yet, it almost undermines the praise that follows. If Reish Lakish is to serve as an atonement for Rabbi Hiyya, this implies that Rabbi Hiyya requires atonement in the rst place. Still, since no human is perfect, we can safely presume that Reish Lakish calculated that even Rabbi Hiyya could use some assistance in that department. us, Reish Lakish’s declaration seems to be one of devotion to a cherished teacher.

More bewildering, and more to the point of our discussion, is Reish Lakish’s assumption that it is even possible for him to serve as Rabbi Hiyya’s atonement. What makes Reish Lakish think he can do this? It seems fairly logical that a person can atone only for his own sins. You cannot assign an agent to atone on your behalf any more than you can have someone else lose weight or take your medication for you. e idea that a third person could achieve atonement for someone,

especially if that person is no longer living, smacks of indulgences, payments extracted by the pre-Reformation church to assure the heavenly salvation of a departed relative. Furthermore, even if such a thing were possible, it seems rather presumptuous of Reish Lakish to atly declare himself the kapparah for Rabbi Hiyya and his sons as if it were a done deal. One would think that only Hashem could decide such a thing.

As such, we may better understand Reish Lakish’s statement as an aspiration rather than a factual assertion. He is stating. “Let me be an atonement for Rabbi Hiyya and his sons.” e hope to be the kapparah for another person is an expression of love. He would love to be the atonement for any outstanding sins Rabbi Hiyya might have. is is the same impulse that people o en feel for a departed parent or loved one. We hope that our good acts can serve as a kapparah for them. We express this sentiment during Yizkor when we pledge to give tzedakah on behalf of our departed relatives in their merit. We hope this mitzvah will work to the bene t of their souls. e same feelings that extend to parents can extend to a teacher or rebbe. We want to do something to show our continued love and devotion. If and how this might function practically is the subject for a di erent discussion.

But we can also think of Reish Lakish’s statement in terms of collective atonement. It is not strictly true that only the individual can achieve atonement for herself. is may be true on a strictly individual level, but as a group, as a community, even as a nation, we also need kapparah. In many respects, Yom Kippur is all about collective atonement. e original Yom Kippur service in the Mishkan saw o erings designed to achieve atonement for all of Israel. e twin goats, one serving as a collective sin o ering, and one serving as the scapegoat that took the shared sins of Israel to Azazel, expiated communal guilt, not that of any particular individual (Lev 16).

Today, we preserve this sense of shared atonement in the Yom Kippur liturgy. Almost everything we say is in the plural. From Kol Nidrei to the nal Avinu Malkeinu of Neilah, we talk about “we,” “us,” and “our,” not, to quote the Beatles, “I Me Mine.” Even the most personal portions of the Yom Kippur prayers, the confessional vidui, is phrased in the plural. It is not “I was guilty, I betrayed, etc.,” but ונמשא, “We were guilty,” ונדגב, “We betrayed,” etc. ךינפל ונאטחש אטח לע, “For the sin we sinned before You.”

ARIEL MOHEBAN SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘24

RABBI YAGIL TSAIDI IS THE MASHGIACH RUCHANI, LIMDUEI KODESH TEACHER, AND DIRECTOR OF ISRAEL GUIDANCE AND SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL. RABBI TSAIDI GRADUATED FROM YESHIVA UNIVERSITY, RECEIVED SEMIKHA FROM RAV ZALMAN NECHEMIA GOLDBERG ZT"L, AND WAS A MAGGID SHIUR AT YESHIVAT MEVASERET TZION IN ISRAEL.

Every Rosh Chodesh Elul, I nd myself circling back to the idea of authenticity. is theme has been permeating within the Shalhevet walls for a few years now, so what better way to elaborate on it than through a devar Torah on the subject related to Yom Kippur?

Each year on the tenth of Tishrei, for twenty- ve hours, all a liated Jews are on the same page. While we all have our favorite holiday, Yom Kippur takes on a universal magnitude of its own. It asks us to reach deep inside and bring out our greatest self. Although re ecting and pushing ourselves to greater spiritual heights is quintessential to the months of Elul and Tishrei, I always nd myself looking for some direction. What is the truest and most authentic way to initiate this process?

My father, the real Rabbi Tsaidi, was an avid fan of nding inspiration from the Siddur/Machzor for the themes of each holiday. When dealing with the above question, he brought to light the following line from Kol Nidrei.

With the consent of the Almighty, and consent of this congregation, in a convocation of the heavenly court, and a convocation of the lower court (the court of man), we hereby grant permission to pray with transgressors.

What an interesting way to start the Yom Kippur Te lah. Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook, zt”l, asks the following question on this Te lah. If Yom Kippur is truly about perfecting and authenticating ourselves, then why would we surround ourselves with sinners? At least on the holiest day of the year, one would think that one should perhaps push oneself to daven speci cally among inspiring Jews, and at the very least not daven among sinners. Rav Tzvi Yehudah’s father, Rav Avraham Yitzchak Hakohen Kook, zt”l, strengthens the question by citing the following Gemara from Masechet Kritut

… at Rabbi Shimon Chasida says: Any fast that does not include the participation of some of the sinners of the Jewish people is not a fast, as the smell of galbanum is foul and yet the verse lists it with the ingredients of the incense.

e Gemara in Masechet Kritut goes even further than permitting one to daven with sinners only on Yom Kippur. According to Rabbi Shimon Chasida, any Ta’anit (fast) that does not include the participation of sinners does not even count as a proper fast. He supports this statement by referencing the Chelbanah, which was one of the worst smelling odors in the world, yet it was required in the ingredients for the incense that was used in the Kodesh Kodashim. We are le right where we started. Why in the Kodesh Kodashim, the holiest space in Jewish history, would we allow something that smells atrocious? is seems terribly disrespectful for a space of such a holy magnitude. More importantly, we turn back to our original question: Why on the holiest day of the year would we strongly advise davening among sinners?

My father explains that Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook zt”l interprets the line mentioned above from Kol Nidrei in a more homiletical fashion.1 In his opinion, this Te lah has a deeper meaning that relates not only to other sinners, but to each of us as well. Rav Kook writes in his Orot HaTeshuvah that when we prepare for the Yamim Noraim, we try to bring forth the best version of ourselves.

But Rav Kook claims that if you are only doing that, you have missed out on an essential part of Elul, Rosh Hashanah, and most importantly, Yom Kippur. Hashem does not want the best version of you, he wants the realest version of you! He doesn't want you to leave your sins at home, he wants you to bring those very sins with you to Te lah. When the Te lah says, “ - to daven with sinners,” it means the sins within you! You should not hide these sins from Hashem; rather, they should be at the forefront of your conversation with the Almighty. G-d wants zero holding back from us. If it’s happiness, anger, excitement, confusion, or any other emotion or feeling that one can think of, Hashem wants to hear it… all of it!

As the great Elie Wiesel once said, “...telling G-d how angry we are is a way of telling him that we love him.” e goal is not to hide like Adam, Chavah, or Yonah from Hashem. e goal is saying to G-d, “Hineini, here I am as I am.”

Rav Kook elaborates that Chelbanah, with its atrocious smell, was used in the Kodesh Kodashim as a sign to show us that G-d has great, but realistic, expectations of us. He knows that we all have certain attributes that if magni ed can make us feel or look like sinners. e Chelbanah on its own had a potent, putrid smell, but was used along with the other great smelling spices for the incense. Once it was mixed with the other spices, not only could one not smell the Chelbanah, but the incense together smelled incredible, and the Chelbanah contributed to that smell. So too, when we join our sins together with the mitzvot we have ful lled and our positive attributes, we thereby present our true selves to Hashem in a manner that is just as beautiful as the ketoret

ETAN LERNER '26 IS A MEMBER OF SHALHEVET'S BEIT MIDRASH TRACK (BMT). HE IS THE EDITOR OF NITZOTZEI TORAH, SHALHEVET'S STUDENT TORAH PUBLICATION, A MEMBER OF THE ROBOTICS TEAM AND HEAD OF THE PHILOSOPHY CLUB.

As Yom Kippur 5785 approaches, I’d like to take the opportunity to explore the fundamental elements of Te llah in general to enhance our understanding of the Yom Kippur liturgy in particular.

At the beginning of the fourth chapter of Tractate Berachot, known as Te llat HaShachar, the Gemara records a machloket between Rabbi Yosi bar Rabbi Chanina and Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi about the origin of Te lla. e former posits that Te lla stems from institutions of the patriarchs, while the latter argues that it is based on the Temple service. Rabbi Yosi bar Rabbi Chanina points to various pesukim in Bereshit describing actions of the patriarchs which can be interpreted as referring to davening, arguing that each of the three patriarchs instituted one of the three Te llot (Shacharit, Mincha, and Arvit, respectively). Rabbi Yehoshua, on the other hand, bases his argument on the synchronization of the timing of the prayer services with the daily Temple sacri ces. Concerning Arvit, he explains that although no sacri ces are o ered at night, the fats and limbs not consumed by the re could be burned all night.

While this is certainly a classic sugya, the Gemara does not o er a de nitive ruling as to which opinion is accepted. Furthermore, an additional element concerning this dispute is hard to understand: how could the origin of something as fundamental to our relationship with Hashem as Te llah be disputed, with extremely distinct possible resolutions?

While an answer to this crucial question is not found in the Gemara itself, the Rambam lays out a beautiful conceptual framework for the origin of Te llah in his Yad Hachazakah that can help us resolve the di culties. In the ninth chapter of Hilchot Melachim, the Rambam writes that Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov, among other contributions, instituted the daily prayers. is halacha makes it quite clear that the bottom line is that the Avot instituted the daily prayers. But does this mean that Shacharit, Mincha, and Maariv are not based on korbanot at all? As we will see, the Rambam elsewhere clearly indicates that the Te llot are also connected to korbanot

At the beginning of Hilchos Te lla, the Rambam provides an introduction to the background of Te llah. He explains that there is a biblical mitzvah to pray each day. is form of prayer, however, has no xed time or liturgy. Each person can pray in their own way, meaning some would pray multiple times every day in a more articulate manner and some only once a day in a simpler way. A er the Babylonian exile, languages became mixed together and the Beit Din of Ezra the scribe realized that they needed to create a “script” for our conversation with Hashem, a liturgy. ey therefore established daily prayers based on the sacri ces – the twice-daily korban tamid (daily o ering, of Shacharit and Mincha) and the Musa n (Musaf). e evening prayer, the Rambam writes, is not intrinsically obligatory, but the Jewish people have accepted it as obligatory upon themselves. Lastly, the Rambam mentions the Neilah prayer, traditionally said on fast days (now only Yom Kippur), which will be discussed soon. Additionally, in principle one also has the option to add an extra Shemoneh Esrei, modeled a er the korban nedava (free-will o ering), though today we do not generally add additional Te llot to the standard ones.

us, our Shemoneh Esrei consists of both elements; two expressions of our endeavor to engage with our Creator harmonize to form our daily prayer. How does this dynamic a ect the text of our Shemoneh Esrei?

Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, in Shiurim L’zecher Avi Mori (shiurim given in memory of his father, one of which deals with Nesiat Kapaim, the priestly blessing), cleverly demonstrates how this dualism is found in Shemoneh Esrei. He asks that

an apparent redundancy exists: why do we need both the bracha of Shema Koleinu and that of R’tzei, since in both we ask Hakadosh Baruch Hu to accept our prayers? e answer, the Rav writes, is obvious: Shema Koleinu is oriented towards our sicha (as the Rav describes it) with Hashem – the primal, de’orayta element of Te llah elucidated by the Rambam, while the bracha of R’tzei is oriented towards the Temple service and acceptance of our sacri ces – the Temple-oriented side of Te llah. Shema Koleinu urges Hashem to heed our requests and accept our prayers, while R’tzei asks Hashem to accept our korbanot. rough these two bakashot (requests), we can fully reveal the striking dualism found in our liturgy. Yom Kippur, more than any other day in our calendar, dramatically accentuates this dynamic between the two components of Te llah. One example of this relates to the prayer of Neila, which nowadays is only recited on Yom Kippur. e Talmud Yerushalmi (beginning of Ta’anit, ch.4) records a machloket between Rav and Rabbi Yochanan whether nei’lat she’arim (closing of the gates), to which the Te llah of Neila corresponds, refers to sha’arei heichal (the gates of the Beit Hamikdash) or sha’arei shamayim (the gates of Heaven itself). is machloket is important with respect to the proper zeman of Neila and whether Birkat Kohanim is performed during Neila (which are beyond the purview of this article), but it also outlines two fundamental approaches to Neila: does Neila exist as sicha, the ancient form of Te llah, which corresponds to sha’arei shamayim, or as a Beit Hamikdash-oriented service, as sha’arei heichal implies?

Zooming out, we see this tension throughout Yom Kippur as well. It seems, in fact, as if the entire day showcases this duality. For instance, in the liturgy we stress our relationship with Hashem and beg Him directly for forgiveness and for our needs. At the same time, we recite the Avodah section of Musaf based on the service of the Kohen Gadol on Yom Kippur. Historically, the Kohen Gadol acted on behalf of the rest of Bnei Yisrael in performing the critical Temple service of the day and thereby achieving atonement for the people. is took place long before the Te llot for the day were composed, as only during the times of the Gemara did our liturgy begin to take form.

We can even discern this tension in our descriptions of Hashem. Sometimes we call Him “Avinu” (our Father) and sometimes we refer to Him as “Malkeinu” (our King). us, our relationship with Hashem also varies accordingly, as sometimes we view ourselves as His sons, and sometimes He is our Master and we are His servants. roughout Yom Kippur, we mention both of these expressions of our relationship with Hashem, and they are intertwined in our Machzor.

MORAH ORTAL IS THE HEBREW DEPARTMENT CHAIR AT SHALHEVET. SHE HOLDS A BA IN LITERATURE AND EDUCATION FROM BAR ILAN UNIVERSITY, AN MA IN TEACHING HEBREW AS A SECOND LANGUAGE FROM MIDDLEBURY COLLEGE, AND IS CURRENTLY A DOCTORAL CANDIDATE IN MODERN LANGUAGES.

ALIZA KATZ '25 IS A MEMBER OF OUR BEIT MIDRASH TRACK (BMT), CO-CAPTAIN OF THE CROSS- COUNTRY TEAM, AND A WRITER FOR THE BOILING POINT.

During the time of the Beit HaMikdash, seventy bulls were sacri ced over the course of Sukkot, with the number decreasing each day from thirteen on the rst day to seven on the last, and then a single bull on Shemini Atzeret. Why does a holiday known as "zman simchatenu" (the time of our joy) involve a ritual that seems to represent a decline, especially when there is a principle in the Gemara of “ma’alin bakodesh” – we increase in matters of holiness?

is issue is highlighted in a well-known debate between Hillel and Shammai on how to light Hanukkah candles. Shammai argues that we should begin with eight candles and decrease each night, which “corresponds to the bulls [o ered] on the festival [of Sukkot].” But we do not hold like Shammai. On Hanukkah, unlike Sukkot, our practice is to increase the candles each night because Hillel argued that “we increase in matters of holiness” (Shabbat 21b). So, why do we decrease the bulls on Sukkot?

To begin answering our question, let’s rst consider a deeper connection between Hanukkah and Sukkot. Historically, the rst Hanukkah was actually a delayed celebration of Sukkot. A er reclaiming the Temple, the Maccabees wanted to celebrate the festival that had been missed during the war. In fact, much of the Gemara's discussion of Hanukkah halachot and minhagim references Sukkot practices. For example, “A Hanukkah lamp that one placed above twenty cubits is invalid, just like a sukkah [whose sechach is more than twenty cubits high]” (Shabbat 22a). is makes the contrast between decreasing bulls on Sukkot and increasing candles on Hanukkah even more deliberate.

e Gemara also introduces a parable that explains the single bull on Shemini Atzeret and also why the number of bulls decrease in general on Sukkot. e Gemara explains that the korbanot are similar to a king throwing a feast for all of his servants. Yet, “when the feast concluded, on the last day, he said to his most beloved servant: Prepare me a small feast so that I can derive pleasure from you alone” (Sukkah 55b). e bull o ered on Shemini Atzeret “corresponds to the singular nation, Israel,” who is similar to the most beloved servant in the parable, with whom the king wishes to spend time with alone. e decreasing number of bulls represents a transition from a broad, universal focus to a more intimate and personal connection with God.

is transition is brought into even sharper relief if we consider one of the reasons why seventy bulls in total are brought on Sukkot. e Talmud (Sukkah 55b) tells us that the seventy bulls represent the seventy nations of the world, and our o ering them as korbanot atones for the sins of the nations and promotes peace and unity.

As the holiday progresses, the focus narrows from the world at large to the Jewish people, culminating in Shemini Atzeret, a day of special closeness between God and Am Yisrael. e decreasing number of korbanot re ects a shi from quantity (the external, universal aspect) to quality (the internal, personal connection with God).

is contrast explains why Sukkot and Hanukkah di er. Sukkot moves from a broad, universal connection with God to a deeper, more intimate one, emphasizing that as we progress spiritually, the focus should shi from the external to the internal. Hanukkah, in contrast, highlights the importance of taking that inner spiritual strength and spreading it outward, increasing light and holiness in the world. e central mitzvah of Hanukkah, pirsumei nisa (publicizing the miracle), underscores this idea. Hanukkah starts with a personal, internal victory – rea rming the Jewish people’s spiritual identity a er overcoming a threat – and then extends outward to in uence the rest of the world.

SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘24

RABBI ARI SCHWARZBERG IS A LIMUDEI KODESH TEACHER AND THE 12TH GRADE DEAN AT SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL. RABBI SCHWARZBERG RECEIVED HIS SEMIKHA FROM YESHIVA UNIVERSITY AND HOLDS A MASTERS OF THEOLOGICAL STUDIES FROM HARVARD DIVINITY SCHOOL.

ere is a well-known question asked by R. Zerachia Halevi,1 one of the great Spanish rishonim, most commonly known as the Ba’al Hamaor. In his commentary on the Rif, he wonders why we recite the beracha of “הכוסב בשיל” (“to sit in the sukkah”) each time we have a meal in the sukkah, whereas on Pesach we only recite the beracha of “הצמ תליכא לע” (“on the eating of matzah”) during the Seder, but when we eat matzah during the rest of the chag, we recite the regular beracha of “ץראה

e assumption of this halachic question is, of course, that the mitzvot of eating in the sukkah and eating matzah for seven days are similar and should therefore share similar properties. Considering that both Sukkot and Pesach are 7 days with a דעומה לוח, and both the sukkah and matzah represent the central mitzvot of the holiday, it would seem appropriate that the two mitzvot would resemble one another.2

In addition to the Baal Hamaor’s question, we can note two other halachic distinctions between Sukkot and Pesach. e rst is that on Pesach the same ןברק was o ered in the שדקמה תיב each day, while on Sukkot each day had a di erent number of תונברק that were o ered on the altar (you may notice when davening Musaf on Sukkot that there is a di erent ןברק mentioned in הרשע הנומש each day). Secondly, the ארמג records that on Sukkot we recite the full Hallel throughout the chag, while on Pesach a full Hallel is only recited on the rst day(s), but ללה יצח (half-Hallel) is recited on the rest of the chag in which two paragraphs are omitted.

My teacher, Rav Michael Rosensweig, Rosh Yeshiva and Rosh Kollel at Yeshiva University, suggested that we can better appreciate these di erences by closely examining the presentation of Sukkot and Pesach in the Torah in גכ קרפ ארקיו רפס. ere, the Torah describes חספ as follows:

In the rst month, on the fourteenth day of the month, at twilight, there shall be a passover o ering to Hashem, and on the eenth day of that month Hashem’s Feast of Unleavened Bread. You shall eat unleavened bread for seven days. (Vayikra 23:4-5)

Although the Torah notes that Pesach is a seven-day holiday, the emphasis is clearly on the rst day. e 15th day is a גח and then, the Torah says, we should continue to eat matzah for seven days. is becomes all the more apparent when compared to the presentation of Sukkot about 30 pesukim later.

Say to the Israelite people: On the eenth day of this seventh month there shall be the Feast of Booths to Hashem, [to last] seven days.

Here, the entirety of Sukkot -- – is described as being 'הל, and no particular emphasis is given

1

2 e Baal Hamaor himself suggests a distinction that a person does not have to eat matzah a er the rst night of Pesach, but a person cannot go all of Sukkot without dwelling in a sukkah. erefore, the beracha on matzah is only recited on the rst night, while the beracha on dwelling in a sukkah is recited every day.

1 Rav Rosensweig also noted that the distinction between חספ and תוכוס is evident in the תוכרב recited a er the הרטפה on דעומה לוח תבש. Feel free to look in your siddur or machzor to nd and explain the di erent חסונ for each גח. See also Shulchan Aruch (490:9) & Mishna Berura (663:9).

RABBI ELI BRONER SERVES AS THE 9TH GRADE DEAN AND JUDAIC STUDIES TEACHER AT SHALHEVET, AS WELL AS YOUTH DIRECTOR OF BETH JACOB CONGREGATION. RABBI BRONER HAS BEEN A LEADER IN THE FIELD OF JEWISH EDUCATION FOR WELL OVER TWO DECADES, TEACHING ALL SUBJECTS OF JUDAIC STUDIES TO STUDENTS FROM FIRST TO TWELFTH GRADES. RABBI BORNER RECEIVED HIS BACHELORS OF RABBINICAL STUDIES FROM THE RABBINICAL COLLEGE OF AMERICA AND SEMICHA FROM YESHIVA COLLEGE IN SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA.

As we approach the holiday of Sukkot, a time when we leave our homes and dwell in temporary structures, we are given a profound opportunity to re ect on what truly constitutes a home, as well as the source of our sense of security and permanence. is re ection is especially relevant for me this year, as my daughter prepares to stand under the Chuppah, a similarly temporary structure, yet one that symbolizes the beginning of a lifelong journey.

e Sukkah: Feeling Hashem’s Embrace and Protective Presence

In his Chassidic teachings, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, o en emphasized the idea of the Sukkah as a space that transcends the physical, embodying divine protection. is idea is echoed in the Kabbalistic understanding of the Sukkah as a "shadow of faith" (Tzila D'Meheimnuta), a place where we are enveloped by Hashem’s presence, despite the fragility of the structure. Similarly, the Chuppah signi es not just the physical home the couple will build together, but the spiritual foundation of their marriage, one that is anchored in faith, love, and mutual respect.

When we enter the Sukkah, we are embraced by Hashem's presence, much like a child is held close by a parent. is embrace is not just a physical experience but a profound spiritual connection that o ers us strength and comfort.

e Sukkah, despite its temporary nature, becomes a place of enduring spiritual refuge. is idea parallels the Chuppah, where the couple begins their journey together, held within the divine embrace, which will sustain them throughout their lives. e Sukkah teaches us that our true security lies in this divine connection, not in the physical structures we inhabit.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, in his commentary on Parshat Emor, notes that true security does not come from the physical structures we build, but from the relationships and values we cultivate within them. Sukkot teaches us that while our homes and even our lives may feel impermanent, our connection to Hashem and to each other provides the ultimate security. is resonates with the message of the Chuppah, where the couple is not just entering a new stage of life, but committing to build a relationship that will withstand the tests of time and circumstance.

Everything Must Be Dedicated to Hashem

(ו:׳ג

e Torah commands, “For seven days you shall dwell in sukkos” (Vayikra 23:42). In de ning this mitzvah, our Sages state, “You must live in the Sukkah just as you live in your home” (Sukkah 28b). For the seven days of the holiday, all of our daily routines must be carried out in the Sukkah. As our Sages explain: “For all of these seven days, one should consider the Sukkah as one’s permanent dwelling, and one’s home as temporary.... A person should eat, drink, relax... and study in the Sukkah.”

Both the sukkah and the chuppah share the common trait of being temporary, almost fragile, yet they are steeped in deep

spiritual signi cance, representing the foundations of something enduring and unbreakable. e sukkah, with its walls that can sway in the wind, reminds us of the temporary nature of our physical lives, yet it also signi es trust in Hashem’s protection and helps us focus on what is important. e chuppah, open on all sides, represents the couple's new home that they will build together – open to guests, to the community, and to Hashem, who is an equal partner in their union.

A core message of Sukkot, as emphasized in Chassidic teachings, is that everything we do must be dedicated to Hashem. Just as we bring our daily lives into the sukkah – eating, sleeping, and rejoicing within its walls – we are reminded that every aspect of our existence should be infused with holiness and purpose. is dedication is also re ected in the marriage covenant under the Chuppah, where the couple dedicates their lives and their home to a life of Torah, mitzvot, and the service of Hashem.

In our broader lives, this lesson encourages us to infuse our daily activities with purpose and devotion. Whether in our work, our relationships, or our personal growth, we are called to create a space for the Divine in all we do.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson also teaches that the Sukkah is a space where we are not only protected, but also invited to experience a profound closeness with Hashem. is idea reinforces the concept of the Sukkah as a place where spirituality permeates everyday life, transforming the ordinary into the sacred. Similarly, the chuppah serves as the starting point for a marriage where Hashem is present in every aspect of the home.

is teaching reminds us that the sanctity of the Sukkah and Chuppah lies not in the physical structure, but in the divine presence that lls them. It is this presence that turns a house into a home and a temporary dwelling into a space of eternal signi cance.

e Sukkah as a Space for Individuals to be United

e Talmud (Sukkah 27b) teaches that the Sages interpret the verse “For seven days you shall dwell in sukkos” (Vayikra 23:42) to mean that it is tting for all of Israel to sit in one Sukkah. Although no Sukkah can physically contain the entire Jewish people, this vision emphasizes the profound unity that Sukkot symbolizes.

Rav Kook elaborates on this concept, explaining that the Sukkah represents a repaired state of harmony and mutual respect. e experience of dwelling in the Sukkah, which follows the spiritual renewal of Yom Kippur, allows the diverse sectors of the Jewish nation to come together in an atmosphere of increased harmony and understanding. is idea can also be applied to marriage, where two individuals create a uni ed home by making space for each other's needs and perspectives.

In our daily lives, this lesson extends to how we interact with others, reminding us to cultivate patience, empathy, and openness in our relationships. Just as the Sukkah invites everyone to enter, we too should be inclusive and accommodating in our dealings with others. Whether in personal relationships, at work, or within the community, making space for others’ thoughts, feelings, and needs is essential for fostering unity and peace.

Bringing Sukkot’s

e teachings of the Sukkah and Chuppah extend beyond the realms of marriage and family life. ese structures remind us all, regardless of our life stage, that our true security and stability is rooted in our spiritual lives, not in our physical surroundings. Sukkot encourages us to embrace the uncertainties of life with faith and trust in Hashem, knowing that it is our spiritual and emotional resilience that will see us through.

In our daily lives, we can incorporate these lessons by focusing on the values and relationships that truly matter. We can build our personal "sukkot" by creating environments that prioritize kindness, love, and faith over material wealth or physical strength. Whether at home, work, or in our communities, we can strive to foster spaces where the divine presence feels welcome, where relationships are nurtured, and where the impermanent is recognized as a pathway to the eternal.

Let this Sukkot inspire us to look beyond the temporary and fragile aspects of life, and to build our own lives on the solid foundations of faith, community, and divine connection.