SCHOOL

ere’s no question that the most prominent mitzvah of this time of year is teshuva, repentance. And yet, quite puzzlingly, the Rambam (both in the Mishneh Torah and in his Sefer HaMitvos) seems not to count teshuva as a mitzvah at all. For example, writes the Rambam: “

when one repents and returns from sin, one must confess before God” (Hil’ Teshuva 1:1). It sounds as though teshuva is entirely optional - only that once one chooses to opt in, the proper way to do so is with vidui, confession. But how can that be? Are we really comfortable suggesting that teshuva itself is optional?

e Ramban, in his Derasha L’Rosh Hashanah, o ers a profoundly important insight into the nature of sin and return. When a person sins, he writes, “אטחה

,” the violation of God’s will technically lasts only for the instant of the sin itself. And yet, “

” if one remains in that state of rebellion without returning in teshuva, then every moment a erward is an ongoing act of de ance (Chavel ed., p. 249). e sin is no longer a single misstep in the past; it becomes a constant, active reality until one “interrupts” it with teshuva.

e Ramban’s fascinating suggestion is that teshuva is not simply an opportunity for repair but the very mechanism that halts the spiritual momentum of the sins themselves. Perhaps akin to Newton’s First Law of Motion, the spiritual energy of a sin continues forward until acted upon by an unbalanced force. Simply stopping the act of sinning is not enough to decelerate the uncontrolled freefall into metaphysical oblivion. Teshuva is that unbalanced force.

Based on this Ramban, R’ Michael Rosensweig suggests that there are actually two dimensions of teshuva. e rst is simply ending the state of “mered” that began with the sin. at sort of teshuva is not an independent mitzvah but stems from the very lav (negative command, sin) that was violated. But, it’s not enough to simply stop sinning. e second element of teshuva, the independent mitzvah of teshuva, “begins where omed b’mirdo ends” (p. 10). Neutralizing the sin is step one; only then can one take “a much more ambitious step with regard to one’s relationship with Hashem.” at is the mitzvah. And that begins with vidui, admitting the distance we created so that we can begin to rebuild. at second step of teshuva gets to the very core of Shalhevet’s ethos. We’re never satis ed with simply checking boxes or learning Torah in isolated moments. Instead, we’re always striving to grow, to build and nurture authentic relationships with our Creator. We try to learn and live Torah, always. And that journey towards transcendence is contagious. Perhaps the clearest evidence is found right here in this volume: More students and alumni than ever reached out to volunteer Divrei Torah for this special edition.

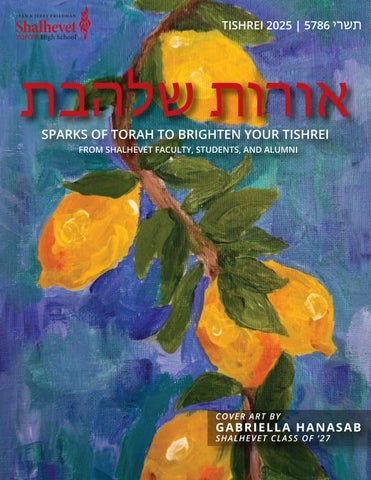

Wherever you are for the chagim, take Orot Shalhevet with you and share that kedusha with others. It is my bracha that the voices and insights of our community infuse your holidays with meaning and joy, and that the beautiful artwork within serves as a hiddur mitzvah, enhancing the Torah we live by. Our students, faculty, and alumni are the Orot that form our dazzling Shalhevet.

Kesiva

V’chasima Tova, Rabbi David Block

BETWEEN

TISHREI

PESACH

SELICHOT

HASHEM,

POWER TO THE PEOPLE: SIMCHAT TORAH AND THE DANCING OF THE HAKKAFOT

thank you

TO THE FOLLOWING SUPPORTERS WHO HAVE GENEROUSLY SPONSORED THIS EDITION OF OROT SHALHEVET. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO THEM FOR HELPING TO PROMOTE THE SPREAD OF MEANINGFUL TORAH LEARNING AND SPIRITUAL GROWTH IN OUR COMMUNITY. PLEASE ENJOY THE TORAH YOU WILL FIND WITHIN IN THEIR MERIT.

KAREN & AVI ASHKENAZI

BICK-KATZ FAMILY

ELISA & BRAD DELSON

ORIT & KEVIN EDELMAN

DRS. JENNIFER & YARON ELAD

MIRYAM HELLER

MALKA & JOSH KATZIN

SIMONE & JASON KBOUDI

LISA & GARY LAINER

DEENA & DAN MESSINGER

TAMAR MESZAROS & DAVID SILBERSTEIN

NAOMI & R' ARI SCHWARZBERG

DRS. ALEXANDRA & JOSHUA SHERMAN

ADAM & DR. TAALY SILBERSTEIN

JENNIFER & MARK SMITH

LESLEE & ALEX SZTUDEN

MINDY & MARK TREITEL

BRENDA & HAROLD WALT

JUSTIN & SHANNON WEISSMAN

TEHILAH & R' ARIK WOLLHEIM

DR. JONATHAN RAVANSHENAS IS THE DEAN OF STUDENT LIFE AT SHALHEVET, OVERSEEING EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION AND STUDENT ACTIVITIES. HE HOLDS AN UNDERGRADUATE DEGREE IN APPLIED CHILD DEVELOPMENT FROM UCLA AND A DOCTORAL DEGREE AND MBA FROM USC, SPECIALIZING IN EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY AND CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT. ADDITIONALLY, JONATHAN IS THE YOUTH DIRECTOR AT THE WESTSIDE SHUL AND CO-DIRECTOR OF MJ SPORTS CAMP, AN INCLUSIVE ATHLETICS PROGRAM FOR LA YOUTH AGES 3-12, DURING THE SUMMERS.

e roar of the crowd is still far o . e stadium lights haven’t yet ooded the eld. But in the locker room, the team is already preparing...stretching, strategizing, focusing on their strengths, and confronting their weaknesses. Every movement is deliberate, every word purposeful. ey know that when they step onto the eld, there will be no time le to prepare.

Selichot is our locker room. It is the quiet but urgent preparation before the Yamim Nora’im, the Days of Awe. It does not merely “get us ready.” It sharpens us, resets us, and aligns us before the great shofar sounds and, more importantly, before we stand on the grand stage of our meeting with the Ribbono Shel Olam, the King in the eld.

For Sephardic Jews, this preparation begins on Rosh Chodesh Elul, a full forty days before Yom Kippur, mirroring the forty days Moshe Rabbeinu spent on Har Sinai pleading for forgiveness a er the sin of the Golden Calf. For Ashkenazi Jews, Selichot begins later, in the days leading up to Rosh Hashanah. ough the calendars di er, the goal is identical: to awaken the soul from its spiritual slumber and enter the Yamim Nora’im already turned toward Hashem. e starting lines may not be the same, but the nish line is shared.

e Ben Ish Hai, in explaining the signi cance of Rosh Chodesh Elul, points to this moment when Moshe was called to ascend the mountain on Rosh Chodesh Elul:

ey wear white, drape themselves in white, shave their beards; they eat and drink merrily, knowing that Hashem will perform miracles.

“And Hashem said to Moshe: Carve for yourself two tablets of stone like the rst ones… And Moshe ascended Har Sinai… and he was there with Hashem for forty days and forty nights…”

(Shemot 34:1–4, 28)

Just as Moshe climbed higher each day, we too ascend, not in body, but in soul. For Sephardim, each day of Elul is another step up the mountain; for Ashkenazim, the climb is shorter but steeper, with an intense burst of focus before Rosh Hashanah. Di erent routes, same summit: preparing for the moment we stand before the King.

And yet, Selichot is not only about preparation. It is also about repairing the relationship and getting as close to the King as possible.

“Open for Me, My sister, My beloved, My dove, My perfect one.” (Shir HaShirim 5:2)

e Midrash explains that this refers to Hashem calling us during Elul. He is not distant or angry. He’s at the door. He’s knocking. But if we’re asleep, spiritually numb, we won’t hear it. at’s why the Sephardic Selichot opens not with comfort, but with confrontation:

“Human being, what are you doing asleep? Rise and cry out in supplication!”

Selichot is a spiritual siren. Not to induce fear — but to wake us from passivity. Rav Eliyahu Dessler writes that the greatest spiritual threat is הרגל — habit. Not rebellion – just routine. e danger is not that we stop believing — it’s that we stop feeling.

e Rambam echoes this urgency in Hilchot Teshuvah:

“Awake, sleepers, from your slumber! Arise, you who are in a trance! Examine your deeds and return in teshuvah!” (Rambam, Hilchot Teshuvah 3:4)

Selichot helps us do exactly that — not once, but for Sephardim, for every single day of Elul. It is built on repetition. Rav Chaim Friedlander explains: transformation comes not through one dramatic moment, but through consistent spiritual rhythm. Each morning in the Sephardic text of Selichot, we repeat, again and again:

“Forgive us, pardon us, atone for us.”

Ultimately, these words are not just lines in a siddur. ey become truths we’ve internalized and live by. Selichot is how we train our hearts to feel again. We then invoke the irteen Attributes of Mercy — the most powerful formula of divine compassion:

“Hashem, Hashem, G-d, compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abundant in kindness and truth… who forgives iniquity, transgression, and sin…” (Shemot 34:6–7)

e Gemara (Rosh Hashanah 17b) teaches that Hashem told Moshe: “Whenever the Jewish people sin, let them recite these words, and I will forgive them.” ese are not mere attributes, they are a promise.

Rav Shalom Messas zt”l, the Moroccan Chief Rabbi of Yerushalayim, once wrote that Selichot is a love song sung through tears. A broken heart is the holiest o ering — as David HaMelech declares:

“ e sacri ces of God are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, You will not despise.” (Tehillim 51:19)

What matters is not a perfect voice, but a present one. Not awless notes (although we Sephardim try), but honest cries. Selichot transforms us not through learning, but through longing. It prepares us for Rosh Hashanah not by telling us who we are — but by inviting us to become someone greater. It’s not about arriving pure. It’s about returning real.

Whether our Selichot span the full month of Elul or begin in the nal stretch before Rosh Hashanah, the essence is the same: to walk into the Yamim Nora’im awake, honest, and ready to return. And so, each morning, whether Sephardic or Ashkenazi, as the children of Hashem, we step into the “locker room” of the soul, going over the playbook of our lives, strengthening our spiritual muscles, and aligning our hearts. Because soon, the “championship game” arrives. e days when the stakes are eternal, when we stand before the King in judgment. If we have prepared well, with humility, longing, and hope, we will walk onto that eld ready to win the only victory that matters: closeness to Hashem.

ROSE ASH '26 IS IN THE BEIT MIDRASH TRACK AT SHALHEVET. SHE IS A MEMBER OF MODEL UN, MOCK TRIAL, AND CROSS-COUNTRY TEAMS.

On the rst day of Nissan, the day that Hashem informed the Jewish People that they would be imminently freed from bondage in Egypt and become a nation, they received a very interesting mitzvah: “ is month shall mark for you the beginning of the months; it shall be the rst of the months of the year for you” (Shemot 12:2). At rst glance, this reference to the month of Nissan sounds like the rst mention in the Torah of the commandment to celebrate Rosh Hashanah. ere is just one problem with this theory: the day of the Hebrew calendar that we celebrate as Rosh Hashanah occurs in Tishrei. But if this verse implies that Rosh Hashanah should take place in Nissan, why do we celebrate it in Tishrei?

At the very beginning of Tractate Rosh Hashanah (2a), we learn that there are actually four Rosh Hashanahs that take place over the course of the Jewish calendar. e rst Rosh Hashanah occurs on the rst of Nissan, dedicated to tracking the start of a Jewish king’s reign, as well as the beginning of the cycle of holidays for the year. e second is in Elul, marking the new year for animal tithes. e third Rosh Hashanah falls in Tishrei and is for counting classic calendar years and keeping track of Shmita and Yovel. Finally, the fourth new year—which takes place in Shevat—is the new year for trees. While the o cial Rosh Hashanah that we celebrate as our new year in Tishrei is the third one, Nissan seems like a close runner-up for the title.

e primary reason to assume that Rosh Hashanah should take place in Nissan is because God told us so – the Jews were directly informed that the month of their liberation, Nissan, would serve as the “Rosh” of their “Chodashim.” e nation complied, counting Nissan as the rst month of their year, the next month the second, and so on. is le Tishrei as the seventh month on the calendar. In Vayikra, we see what looks like a reference to the celebration of Rosh Hashanah—a day of rest during which we blow shofar. is event is held on the rst day of the seventh month. Naturally, it is confusing that we should recognize the beginning of the Jewish calendar over halfway into the year.

In the Gemara Rosh Hashanah (10b), Rabbi Eliezer states that the creation of the world took place in the month of Tishrei. is could explain why Rosh Hashanah is observed in Tishrei, as in his opinion, Rosh Hashanah commemorates the creation of the world. is is supported by the fact that in the Rosh Hashanah davening, we say “HaYom Harat Olam,” “today the world was created.” Perhaps this is supported by the pasuk that refers to Rosh Hashanah as "

", a holy day of complete rest, a commemoration with loud blasts. e reference to a “commemoration” may refer to remembering the creation of the world on its anniversary, the rst of Tishrei.

According to this understanding, why does it seem like we have two Rosh Hashanahs throughout the year? Perhaps because we actually do. In Tishrei, when God created the rst human beings, he introduced them as the rst individuals. Adam and Chava were God’s initial independent thinking, acting, and mistake-making creations. ey had the capacity to make their own choices and be uniquely their own selves, even if they were not always the best versions of themselves. Our Rosh Hashanah in Tishrei is devoted to improvement and introspection for each of us as individuals and our personal connection to Hashem. Over the course of the chag and the days that follow, we devote ourselves to repentance,

apologizing for our sins, and asking forgiveness. Casting away our mistakes from the previous year, we seek to renew ourselves – pure and fresh for the upcoming year. We develop our relationship with Hashem through private conversation and putting e ort into bettering our own character.

By contrast, the Rosh Hashanah of Nissan serves as the Rosh Hashanah for our nation. e miracle that occurred in Nissan was not the freeing of each individual Jew from the hands of the Egyptians. Rather, it was our debut as the Jewish nation, as God’s nation. Ramban (Shemot 12:1) comments that the reason we refer to Nissan as the rst month is not because it is the rst month of our calendar year, but because it is our nation's rst month of redemption. When the Torah refers to Nissan as the “Rosh Chodashim,” it is reminding us of the day that we were reborn and our national life as the Jewish nation began. Rosh Hashanah of Nissan, then, seeks to remind us of the signi cance of our relationship with God as a people.

In the end, the Torah gives us two beginnings, not one: Tishrei, the Rosh Hashanah of the individual, and Nissan, the Rosh Hashanah of the nation. Together, they capture the duality of Jewish life — that we serve Hashem both as individuals striving for personal growth, and as a collective people redeemed together. Embracing both dimensions allows us to deepen our relationship with God on every level.

ELIANA WAINBERG GRADUATED FROM SHALHEVET IN 2024. SHE SPENT A YEAR IN ISRAEL AT MIDRESHET HAROVA AND WILL BE ATTENDING THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND.

As we approach the month of Tishrei, we are invited into a period of re ection and preparation. is season begins with Selichot, prayers asking for forgiveness. e word “החילס” translates to “sorry” in modern Hebrew. But what does Selichot really mean? Does it make sense that we would say “sorry” to Hashem?

In everyday life, we tend to apologize for two reasons:

For others – Saying sorry is a way to show the other person that you are taking responsibility for your actions and admitting your guilt.

For ourselves – We have to look at ourselves and realize what we have done wrong and express our regret. But when it comes to Hashem, the rst reason seems to fall away. Hashem does not get o ended or hurt. He doesn’t need our validation. He already knows what’s in our hearts, our motives, and even our regrets, before we put them into words. In fact, the Rambam (Hilchot Teshuvah 2:2) describes Hashem as “He who knows the hidden who will testify concerning him that he will never return to this sin again.”

Hashem already knows our thoughts and intentions, so there is no need to inform Him that we take responsibility for our actions. Hashem also does not have feelings like humans have feelings and is not emotionally reactive in the human sense. erefore, He does not need us to admit our guilt.

erefore, reciting Selichot and saying sorry to Hashem must be for the second reason – a vehicle for introspection and developing awareness of our actions. It is not about wanting Hashem to forgive us, but rather about forgiving ourselves and deciding to do better.

During Elul, we re ect on where we went wrong during the past year. During Tishrei, we improve and plan how to be better in the future. Rosh Hashanah is the start to working on ourselves. In addition to Selichot, the custom to blow the shofar every morning of Elul serves as another daily reminder to work on ourselves. e Rambam explains a possible reason for this in Hilchot Teshuvah (3:4):

Wake up you sleepy ones from your sleep and you who slumber, arise. Inspect your deeds, repent, remember your Creator.

What is the signi cance of using a shofar, a ram’s horn, speci cally?

e rst mention of a shofar is in the story of the Akeida. Avraham is nally given a son who can continue his legacy, but then Hashem commands him to give up that very son. With no excuses and no pushback, Avraham is ready to do just that. Just as he is about to sacri ce Yitzchak, an angel stops him and a ram appears on the mountain. is ram becomes the substitute o ering for Yitzchak. When we blow the shofar, we are reminded of Avraham's total dedication to Hashem. Proper Teshuva requires that type of commitment and courage, realizing we made a mistake and trusting that Hashem knows what is truly right for us. 1. 2.

Selichot and the shofar remind us that we need to prepare to make ourselves a better future. We are reminding ourselves what it means to live with intention and values.

In Shir HaShirim Rabbah (5:2), Hashem says to Bnei Yisrael:

My children, open for Me one opening of repentance like the eye of the needle, and I will open for you openings that wagons and carriages enter through it.

As we transition from daily Selichot into Tishrei, let’s not let these prayers become routine. ey o er a chance to live with greater awareness, to take responsibility, and to improve ourselves. All it takes is one honest step, and Hashem will meet us with endless compassion.

SHAPIRO SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘25

ALIZA KATZ GRADUATED SHALHEVET IN 2025. SHE WILL BE LEARNING AT MIDRESHET LINDENBAUM IN YERUSHALAYIM AND THEN WILL GO TO HARVARD UNIVERSITY.

Every year, in the days leading up to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur — and again on Yom Kippur itself — we say Selichot, formal prayers asking for forgiveness and repentance. e central feature of the Selichot is the Yud Gimmel Middot, Hashem’s 13 Attributes of Mercy, which we recite numerous times. e Yud Gimmel Middot are clearly an important part of the teshuva process. As Rabbi Yehuda teaches in Masechet Rosh Hashana (17b), “A covenant was made with the thirteen attributes that they will not return empty-handed.” In other words, Hashem promises us: if you invoke these attributes, I will forgive you. e most widely accepted version of the 13 attributes is as follows:

Hashem (Compassionate)

Hashem (Compassionate)

E- l (Mighty in compassion)

Rachum (Merciful)

Ve’chanun (Gracious)

Erech apayim (Slow to anger)

Rav chesed (Abundant in kindness)

Emet (Truthful)

Notzer chesed la’ala m (Preserver of kindness for thousands)

Noseh avon (Forgiver of iniquity)

Pesha (Forgiver of willful sin)

Chata’ah (Forgiver of error)

Nakeh (Who cleanses).

e rst question that arises is why "Hashem" is listed twice? Why would that be two separate attributes? e Gemara in Rosh Hashanah answers that “Hashem, Hashem” means “I am Hashem before a person sins, and I am Hashem a er a person sins and repents.” Tosafot, quoting Rabbeinu Tam, explains further that the two names represent two separate attributes: God's mercy before sin, and God's mercy a er sin.

What does it mean for God to show mercy before someone sins? e Rosh o ers two explanations. First, sometimes a person needs mercy even for just intending to sin. For example, in the case of idol worship, even thinking about sinning is considered problematic. So the rst "Hashem" refers to God's mercy toward someone who has not acted yet, but whose intent already puts them in dangerous territory. Even then, God shows compassion. e second explanation of the Rosh is that God’s mercy before sinning refers to the idea of ba’asher hu sham—that God judges a person “as they are now,” regardless of whether they may sin in the future. In Bereishit, when Hagar and Yishmael are stranded in the desert and Yishmael cries out, the Torah says:

“And God heard the voice of the lad… for God heard the voice of the lad where he was.” (Bereshit 21:17)

Rashi, citing the Midrash, explains that the angels argued against saving Yishmael, knowing his descendants would one day harm Bnai Yisrael. But Hashem responded, “I will judge him according to his present deeds.”

God’s mercy, then, isn’t based on what a person will become—but on who they are in the moment. Even if God knows a person will sin one day, that future does not cancel out the present. Mercy is given based on the present.

e Or HaChaim in his commentary on Parashat Ki Tisa adds two more explanations. First, he argues that even if someone never sins, they still need God’s mercy—simply to exist and enjoy the world. He writes that “a person is in need of God's mercy even before he has committed a sin… if he does not have the merit… to [justify] his deriving pleasure from the world… God will bestow it upon him with mercy.”

According to this view, life itself is a gi , independent of merit. Just because someone hasn't done something wrong doesn’t mean they have done enough mitzvot to deserve everything they have been given. So even someone who hasn’t yet sinned still receives life and blessing purely through Hashem’s mercy.

e Or HaChaim’s second explanation is that God’s mercy a er sin is equal to the mercy shown before sin. He explains that “when God bestows goodness to a person in His mercy, then even if he sins, His goodness will not be lessened at all… erefore He spoke of mercy before the sin, in order to equate it with the mercy to be bestowed a er the sin.” In this view, the rst “Hashem” is not so much an attribute in itself, but a setup—a baseline of mercy, to emphasize that the second “Hashem,” the mercy a er sin, remains unchanged. God is, of course, compassionate when we’re innocent, but He remains compassionate even when we aren’t.

We have seen that there are many explanations for what mercy “before sin” means. But taken together, they point to one idea: whether we are righteous or sinful, deserving or undeserving, Hashem governs the world with mercy. We invoke these attributes again and again throughout Elul and Tishrei not only to ask for forgiveness, but also to remind ourselves of the kind of world we live in—one where Hashem grants us mercy before we sin, and continues to be merciful even a er we fall short.

DR. SHEILA KEITER IS A MEMBER OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH AND GENERAL STUDIES FACULTY AT SHALHEVET. SHE HAS A B.A. IN HISTORY FROM UCLA, A JD FROM HARVARD LAW SCHOOL, AND RECEIVED HER PHD IN JEWISH STUDIES FROM UCLA, WHERE SHE TAUGHT IN THE DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES.

From H.G. Wells to Dr. Who, time travel has been a prominent feature of science ction. While it may be great fun to contemplate traveling back in time, its physical and logical conundrums leave time travel ultimately untenable. e Talmud, on the other hand, o ers a much more practical time travel alternative. Masechet Yoma serves as a time capsule, preserving the inner workings of the Beit Hamikdash during the Second Temple period for anyone who wants to open up the Mishnah and travel there virtually.

Visiting the era of Bayit Sheni, we nd the Yom Kippur of that era was profoundly di erent from that of contemporary times. Our Yom Kippur centers on prayer, contemplation, and introspection. While we pray together as a community, we tend to focus mostly on the individual’s personal atonement. Yom Kippur in the Beit Hamikdash, however, was marked by a series of sacri cial and symbolic rituals designed to seek atonement for the entire nation. Even though the Yom Kippur rituals have changed dramatically over time, the Temple avodah can still inform our attitudes toward the present-day Yom Kippur service and can o er greater depth to our experience.

e rst mishnah in Yoma tells us that seven days prior to Yom Kippur, they would sequester the cohen gadol in one of the chambers of the Beit Hamikdash to prepare him for the big day (m. Yoma 1:1). ere are multiple explanations for this sequestration, but its primary purpose seems to have been to protect the cohen gadol from becoming ritually impure and, thus, un t for service. e cohen gadol was the star of the show on Yom Kippur. He was tasked with performing all of the major services personally. e spiritual fate of the entire nation rested in his hands. erefore, the cohen gadol’s sequestration also served as an opportunity to educate and prepare him for everything he needed to do that day. But sequestration could also have provided the cohen gadol with time to embrace the proper frame of mind given the solemnity of the day.

e gemara on that mishnah in Yoma draws an interesting parallel between the sequestration of the cohen gadol and Moshe rabbeinu’s entering the cloud when he went up Har Sinai to receive the Torah. Did Moshe’s time in the cloud serve as a period of sequestration before Moshe could commune more directly with Hashem? e gemara (Yoma 4b) further complicates this discussion by comparing two seemingly mutually exclusive texts:

“And Moshe could not come to the Tent of Meeting because the cloud was dwelling upon it…” (Ex 40:35).

“And Moshe entered inside the cloud and went up to the mountain…” (Ex 24:18).

If the cloud prevented Moshe from entering the Ohel Moed, how could he waltz right into it on Har Sinai?

Two opinions are pro ered. e rst argues that Moshe was able to enter the cloud on Har Sinai because Hashem grabbed him and pulled him into it. Normally, the cloud is not penetrable, but Hashem can forcibly transcend those limitations at His will. e second opinion states that Moshe’s experience was more akin to that of Israel’s entering the sea, that Hashem paved a path for Moshe the way He created a path for Israel to cross Yam Suf (Yoma 4b). e fact that

the gemara does not resolve this debate one way or the other suggests that the two opinions represent two di erent broader approaches to connecting with God. Does Hashem as the Omnipotent Creator require awe and deferential distance, one which we can transcend only at His mercy, or does Hashem invite connection by creating easy access?

is debate parallels the debate regarding why the cohen gadol was sequestered before Yom Kippur. Was the cohen gadol separated and prepared in an attempt to ll him with the requisite dread needed to face the Shekhinah, or was sequestration needed simply to ensure the cohen gadol’s state of purity so he could attend to the Yom Kippur services with enthusiasm? When the cohen gadol entered the Holy of Holies, was he crossing a barrier that normally cannot be transcended, like Moshe being pulled into the cloud? Or was this merely part of the Yom Kippur avodah, and something to be approached with joy, like the crossing of the sea?

ese two approaches aptly nd parallels with two contemporary approaches to Yom Kippur itself. Yom Kippur can be a day of dread. I refer not to the dread of fasting and the long day of sitting and standing in shul, although I o en hear people, especially teenagers, voice that dread. Rather, I mean the dread that comes with seeking atonement. Yom Kippur is a day when we face our King and Judge. We must ask ourselves, will Hashem forgive me? Do I deserve to be forgiven? Can others forgive me? Can I forgive myself? Do I deserve another chance? ese are heavy questions that are integral to the repentance process. Yom Kippur calls us to do some important and di cult self-work. Yom Kippur is yom ha-din, the day of judgment, and it demands seriousness and fear.

At the same time, Yom Kippur o ers a unique annual opportunity to spend the day in spiritual commune with Hashem. We have no work, no meals to prepare, no other responsibilities to distract us from basking in God’s presence. It is a day when we embrace our Father and Beloved. Yom Kippur can be a day of tremendous joy, of unparalleled spiritual highs, of love and rapture with the Divine.

e fact that the gemara does not resolve the machloket regarding how Moshe could enter the cloud suggests that we do not need to resolve the tension between these two approaches to Yom Kippur either. Truth be told, both are part and parcel of Yom Kippur. ere are times during the day when we nd ourselves begging Hashem for the opportunity to do things better. At other times, we nd ourselves soaring to spiritual heights.

Fear and dread on the one hand, and love and rapture on the other, not only coexist but serve one another. In order to improve our relationship with Hashem, we must be honest about our failings. At the same time, true repentance requires the type of open honesty that comes from love and trust. As we peel back the layers of our own shortcomings, we feel closer to Hashem. And as we draw closer, we feel the assurance of His love that allows us to fully confess and bare our

NOAM LERNER '28 IS A SOPHOMORE AT SHALHEVET. HE IS IN THE ADVANCED GEMARA SHIUR AND A MEMBER OF THE ROBOTICS, MOCK TRIAL, AND CROSS COUNTRY TEAMS. HE IS ALSO A CONTRIBUTOR TO NITZOTZEI TORAH, SHALHEVET'S STUDENT TORAH PUBLICATION.

Every year before Yom Kippur, each of us must make amends to God for our sins and also ask forgiveness from our friends for the times that we have wronged them. According to the Rambam in his Mishneh Torah, we must enact a four-step process to achieve forgiveness:

e sinner must verbally confess his mistake to God (as well as to the person who was wronged, for sins of an interpersonal nature). is is true even if he also brings a Korban to atone for his sins (in the time of the Beit Hamikdash).

One must feel genuine remorse about what one did wrong. is is true both for mitzvot bein adam l’Makom (sins between a person and God) and mitzvot bein adam l’chavero (between one person and another).

One must abandon the sin committed.

One must commit to act di erently in the future.

is process is one which is especially pertinent to Yom Kippur, which, according to the Midrash, was the day of atonement for Chet Ha’egel. Following the worship of the golden calf, Moshe davened for forgiveness for Bnei Yisrael, and they received atonement. e problem is that, as we have seen, the only way to atone for your actions is by following the process described above. Why, then, were Bnei Yisrael forgiven if they never asked for forgiveness from God themselves, and only Moshe requested forgiveness?

To understand how Bnei Yisrael repented, we must rst understand what they were repenting for. Rashi explains that the sin of Chet Ha’egel involved avodah zarah, adultery, and murder. On the other hand, the Ramban says that their original intent was to replace Moshe a er he did not return, and later, that turned into a desire for idol worship for some of the nation, and for others, active practice of avodah zarah. e Ramban adds that Moshe killed everyone who practiced avodah zarah openly, but he also prayed for atonement for the people. But this point of the Ramban is di cult to understand, since either it contradicts the way we are supposed to ask for forgiveness from Hashem, or there was no sin in the rst place and nothing to apologize for, which cannot be, since Moshe does ask forgiveness from God. e same di culty exists according to Rashi, that Bnei Yisrael never verbally apologized to God themselves.

e only two characters of the story who repent are Aaron and Moshe. Aaron and Moshe are commonly depicted as having two di erent personalities. Moshe is a prophet who is almost incapable of sinning, he is very close to Hashem, and he even merits a glance of Hashem’s “back.” In contrast, Aaron is rarely granted the privilege of talking to God, and here he seems to be instrumental in causing Bnei Yisrael's sin. But he is also considered a person of the people, he constantly tries to help them get along, and he represents them in some ways. According to Ramban, this is precisely why the people made the calf – it was meant as a replacement for Moshe, a symbol of his role as a distant and exalted leader. Aaron, who was closer to the people, tries to delay or redirect this desire, though he ended up enabling their mistake. Later, when Aaron apologized, he did so as someone who understood the people’s intent and spoke from within their position. In contrast, Moshe apologized more as a messenger – he had not sinned and was asking forgiveness on behalf of others who had not themselves apologized.

Even so, how could Aaron’s request for forgiveness work for everyone else? e answer is that this was not only a collection of individual sins but also a collective, national sin. ose who personally practiced avodah zarah were punished with death, but the nation as a whole still bore responsibility for allowing the sin to take place and for not preventing it. Since the transgression was carried by Am Yisrael as a collective, Aaron, as the voice of the nation, was able to repent on behalf of all.

GAVI KATRIKH IS A SOPHOMORE AT SHALHEVET. HE IS A MEMBER OF SHALHEVET'S BEIT MIDRASH TRACK (BMT). HE IS ON THE ROBOTICS AND MOCK TRIAL TEAMS AND IS A WRITER FOR THE BOILING POINT.

In the last Mishnah in Masechet Yoma (8:9), Rabbi Akiva makes a striking comparison:

Rabbi Akiva said: How praiseworthy are you, Israel, before Whom you are puri ed, and Who puri es you! Your Father in Heaven! As it says: “And I shall sprinkle upon you purifying waters and you will be puri ed.” And it says: “ e mikvah of Israel is Hashem” ( e word 'mikvah' in the context of the passuk means hope; however, Rabbi Akiva homiletically interprets the word as referring to a mikvah, as in a ritual bath). Just as a mikvah puri es the impure, so too, Hashem puri es Israel.

Rabbi Akiva equates a sinful state with ritual impurity, tumah, and being cleansed of that sinful state with ritual purity, taharah. ere are two ways that a person is cleansed of tumah. For most types of tumah, taharah requires immersion in a mikvah. For the more severe form of tumah (e.g., tumat met, contact with a dead body), taharah requires hazaah (sprinkling) with the waters of the parah adumah (red heifer). us, there are two ways of achieving taharah, and Rabbi Akiva’s teaching includes both, using two distinct pesukim. is would appear to indicate a distinction between the two types of teshuvah. However, the di erences between the two require understanding.

ere are two signi cant distinctions between the ways of achieving taharah, and thus, two distinctive paths to teshuvah that I would like to highlight. e rst relates to the volition of the person. Mikvah requires the initiative of an impure person to go to the mikvah to purify themselves, which they must do themselves. In contrast, the second type of teshuvah “hazaah teshuvah,” works di erently. As the Torah says (Bamidbar 19:19), אמטה

, “And the pure [person] shall sprinkle [the purifying waters] on the impure [person].” us, hazaah works only if one sprinkles the waters on another, and not if one sprinkles it on themselves.

e purpose of rabbinically instituted fast days, as well as other personal and communal fasts, is to inspire internal re ection and bring about teshuvah. e Rambam states this explicitly with regard to fast days (Hil. Taaniyot 1:2):

, “and this matter is one of the ways of teshuvah.” is would seem to refer to mikvah teshuvah where we must actively initiate and move ourselves along the path of repentance. e fast of Yom Kippur, on the other hand, is the only one whose obligation is d’orayta, from the Torah. Yom Kippur is a hazaah type of teshuvah, where Hashem comes to assist and aid us in doing teshuvah, as the Torah states:

“For on this day He shall e ect atonement for you to cleanse you. Before the Lord, you shall be cleansed from all your sins.”

Notably, the di erence between the Ha arah of Yom Kippur and that of a regular taanit tzibur re ect this idea as well. Both from Yeshayahu, the Ha arah on a taanit tzibur starts with the words, “

”, “seek Hashem wherever he may be found;” while the Ha arah for Yom Kippur begins with Hashem saying,

of My people!” ese verses show a clear discrepancy between rabbinic communal fasts and Yom Kippur. e Ha arah for a taanit tzibbur begins with an exclamation to make an e ort to seek out Hashem in times of need, while the Ha arah for Yom Kippur begins with Hashem saying to assist Bnei Yisrael, typical of “hazaah teshuvah.”

e second distinction between the two types of achieving taharah is in regard to what they deal with. e ritual of zerikah is inherently related to death. We take the blood of a slaughtered red heifer and use it to purify a person who came in contact with a corpse. Mikvah, on the other hand, symbolizes rebirth and renewal. A person in the mikvah curls up into a fetal position and reemerges from the water, as if exiting the womb. A convert leaves the mikvah, reborn as a new person, as a Jew.

ese two distinctions between the two types of teshuvah pose a very interesting conclusion: Death = Hazaah, and Hazaah = Yom Kippur; in other words, Yom Kippur is symbolically equated with death. Many of the practices that we have on Yom Kippur seem to re ect this idea. e ve main prohibitions of the day (refraining from eating, drinking, washing, anointing, leather shoes, and marital relations) are each designed to remove a person from worldly pleasures. Strikingly, it has become an Ashkenazic minhag to adorn oneself in a kittel, the same garment in which a person is buried a er death. Why, then, on Yom Kippur, o entimes referred to as the holiest day of the year, does Hashem want to make us experience death?

Once a year, Hashem presents us with a day in which we experience death itself to demonstrate a profound lesson. Death is not an end, it’s a beginning. Temporarily confronting and experiencing death allows us to gain a new outlook on life. Chazal teach us that there were no days more joyous for Klal Yisrael than Yom Kippur and Tu B’Av. Why? Because on Yom Kippur, we are given a chance for a fresh start, a chance to renew our lives. ere is no greater happiness than knowing

RABBI GABE FALK IS THE DIRECTOR OF TORAT SHALHEVET AND A LIMUDEI KODESH TEACHER. HE LEARNED IN YESHIVAT HAR ETZION AND RECEIVED SEMICHA FROM YESHIVA UNIVERSITY. HE HOLDS A B.A. FROM COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, IS WORKING TOWARDS AN M.A. IN JEWISH HISTORY FROM REVEL, AND WAS A WEXNER GRADUATE FELLOW. BEFORE JOINING SHALHEVET, RABBI FALK SERVED AS THE ASSISTANT RABBI AT GREEN ROADS SYNAGOGUE AND TAUGHT AT FUCHS MIZRAHI SCHOOL IN CLEVELAND, OH.

ere’s an endearing adage about Jewish holidays which de nes them all with the following formula: they hated us; they tried to kill us; we won; let’s eat. is maps on to almost all of the chagim – at least the excessive amount of food. Even fasting on Tisha B’av can be understood in this manner: the destruction of the Beit Mikdash is the inverse of “we won,” ergo - we do not eat.

However, the signi cance of Yom Kippur and the prohibitions of the day are far less clear. e ve innuyim (prohibited actions) – eating and drinking, washing, anointment, donning leather shoes, and marital intimacy – characterize the experience of Yom Kippur but are o en presented without a clear telos.

e starting point for this exploration is the curious verb which the Torah uses to formulate the mitzva of fasting:

, commonly translated as “you shall a ict your souls.” is translation would make our understanding of this mitzva somewhat clearer. As the Abarbanel explains (Vayikra 16:29), our souls are lled with regret for our mistakes and actions over the course of this year. By a icting our souls, we seek to cleanse our neshamot through su ering.

However, thinking of the ve innuyim as a ictions fails to capture the םוי לש ומוציע, the essence of Yom Kippur. To begin with, as the Abarbanel himself points out, there is another critical aspect of the day which is diametrically opposed to, and fundamentally incompatible with, a iction. In the very same passuk which presents the mitzva of innuy, the Torah also describes Yom Kippur as a ןותבש תבש, or in Rabbi Michael Rosensweig’s language, “the quintessential Shabbat.” Shabbos, of course, is a day of גנוע, pleasure, allowing the body to rest by abstaining from physical labor. While the Abarbanel seeks to resolve this tension, the question is far stronger than the answer. Ideally, we will uncover one underlying essence of Yom Kippur which can bind both יוניע and ןותבש תבש together.

e Gemara in Masechet Yoma is equally quick to curtail the “a iction” paradigm. If יוניע is in fact a form of a iction, why would we not try to go beyond the letter of the law, like we do in other cases, by nding other forms of a iction? Perhaps, suggests the Gemara in its hava amina (initial assumption), we should spend the duration of Yom Kippur sitting in extreme heat or frigid cold? is suggestion is quickly rejected. Yom Kippur then, must not be about abject su ering.

A second approach, championed by the Rambam in the Moreh Nevuchim, understands the םייוניע to be about abstinence and asceticism. In this framing, Yom Kippur asks us to elevate ourselves and achieve angelic transcendence by abstaining from physical pleasure. e goal is not to su er, but rather to champion the spiritual needs of our neshamot over the physical needs and desires of our earthly bodies.

is approach of יוניע as abstinence certainly resonates better with a contemporary audience. It also feels more consistent with much of the Machzor’s liturgy. Yom Kippur davening, while serious, is o en upbeat and contains moments of unbridled, ecstatic joy. But even if we adopt this understanding, there is still one unresolved question: how can we reconcile the two dimensions of our passuk: what common theme binds the ascetism of יוניע with the pleasure of תבש?

e Kli Yakar (Rabbi Shlomo Ephraim of Luntschitz, 16th cent. Prague) is sharply attuned to this question and suggests a remarkable and original approach to the ultimate telos of the םייוניע. His idea contains a few key stages. He begins by noting that we o en divide our sins into two categories – וריבחל

, interpersonal mistakes, and םוקמל םדא ןיב, infractions between man and God. is, suggests the Kli Yakar, is misleading – we do not live in two separate planes!

However, in order to obtain true atonement from Hakadosh Baruch Hu, the Jewish people must approach Him with one united front. e kapara of Yom Kippur, explains the Kli Yakar, is contingent on Am Yisrael healing the ssures which divide us. is, of course, is beautifully captured by the descriptions of the Avodah, the Temple service, on Yom Kippur. One Kohen Gadol o ers one ריעש on behalf of one nation – and then, רפכי להקה םע לכ לע, Hashem will atone for the entire nation.

e con dence that we have on Yom Kippur that רפכמ םוי לש ומוציע, forgiveness is guaranteed by the day itself, is predicated on Am Yisrael forming an םלש בבלב

– one united whole, ful lling Hashem’s will with a complete and undivided heart.

If this is true, then the spiritual work of Yom Kippur now emerges in clear focus. Our task on Yom Kippur is to heal our interpersonal divisions and to divorce ourselves from the human pursuits which engender division. is work is ful lled on two planes: יוניע and תובש.

e הכאלמ רוסיא of תבש instructs us to cease our labor and to rest from the acquisitional, entrepreneurial pursuits which animate a free-market society but inevitably create friction between us. Shabbat asks us to step back from the worldly pursuits which divide us and remember the powerful fraternity and nationhood which bonds us together before the Creator of the world. Yom Kippur, as ןותבש תבש, has the same goal: we step back from our worldly pursuits so that we can approach Hashem as one united םע.

But while this may be su cient on Shabbat, on Yom Kippur, this falls short. While refraining from labor might suppress the תינוציח העונת, a person’s external expression of competition, on Yom Kippur we are attuned to the תימינפ העונת –the emotional, psychological longings and desires which drive our physical actions. is, explains the Kli Yakar, is the purpose of the mitzva of יוניע on Yom Kippur. By abstaining from the physical pleasures, we seek to quiet those inner impulses and reorient ourselves toward unity with our fellow Jews and closeness with Hashem.

ere is a striking yet easily overlooked line at the conclusion of the Avodah section in the Yom Kippur te llah. In thanking Hashem for the gi of Yom Kippur, the Machzor characterizes the essence of this day with the following words:

A day on which it is forbidden to eat, a day on which it is forbidden to drink, a day on which it is forbidden to wash, a day on which it is forbidden to apply ointments, a day on which it is forbidden to engage in marital relations, a day on which it is forbidden to wear leather shoes. A day for restoring love and brotherhood, a day of abandoning envy and strife, a day which You will forgive all our iniquities.

e Machzor, echoing the words of the Kli Yakar, presents a profound vision of Yom Kippur. e true purpose of the ve innuyim is not to bring about su ering, but to redirect us away from the envy and strife that so o en shape our human lives. Instead, they call on us to renew our commitment to strengthening the bonds of bein adam lechavero through ahava and re’ut. Only then can we come before Hashem as an agudah achat—a united people—worthy of national kapparah and a year of beracha for Am Yisrael.

Every Yom Kippur, we read the book of Yonah as the Ha arah for Minchah. Interestingly, although Yonah is a prophet, he certainly does not appear to be someone whom we, as people striving to serve God and ful ll His mitzvot, should view as a role model. e traits exhibited by Yonah seem to demonstrate the opposite of this goal. Yonah rst attempts to escape from his mission given by God to rebuke the people of Nineveh by boarding a ship to sail elsewhere. Later, he does go to Nineveh and successfully inspires them to repent.

Following the completion of his mission, Yonah goes east of the city, builds himself a God makes a kikayon (usually interpreted as a large tree) to grow over Yonah. e next morning, God sends a worm to devour the tree. When Yonah sees this, he begs for death at the realization that the great shade he once had. However, the sukkah was presumably still standing. So why was Yonah saddened a er the removal of the kikayon if he could still take shade in the sukkah?

Logically, the sukkah must have at least provided for Yonah’s basic need of cover from the sun. It would be unreasonable to think that Yonah would build a sukkah that could not cover him su ciently from the burning hot sun. However, since the kikayon made Yonah extremely happy, it can be assumed that perhaps the that the sukkah could not, as a tree o en does provide more shade than a covered structure like a think of the kikayon as a greatly improved version of the sukkah that God graciously granted to Yonah. We can also view the sukkah as a product of Yonah’s work alone, yet it only provides for his basic needs under the sun.

For these reasons, it is sensible for Yonah to grieve at the destruction of his great tree. Yet one must realize it is not kikayon, but God’s kikayon. Yonah did not toil at all for that kikayon, yet he worked for his and thought into this sukkah, a sukkah he forgot about as soon as something better came along. Hashem gave Yonah the kikayon out of kindness, but just as Hashem gives, He also takes away. As it says in Job: " and Hashem takes.” We can learn from this that we should especially value things that we make ourselves through our own e ort. In addition, we should appreciate everything else that we are given as well, but we should also realize that it all comes from Hashem, and He can take it away at any time.

ese ideas are exempli ed on Yom Kippur, the day Hashem forbids us from taking pleasure in many of our physical activities, such as eating, bathing, and wearing shoes. But despite our a iction on this day, we do not complain. is is one reason why we read the book of Yonah on Yom Kippur. e book of Yonah teaches that God “strips” you of everything you love, your “kikayon,” so that you can realize just how great your

1 Job 1:21

ALYSSA PORTNOY

SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘26

SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘26

SHALHEVET CLASS OF ‘26

MAX MESSINGER GRADUATED SHALHEVET IN 2024. HE IS CURRENTLY STUDYING AT YESHIVAT HAR ETZION IN ALON SHVUT FOR HIS SHANA BET AND THEN WILL ATTEND UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND.

Sukkot! What a holiday! Meals outside in a booth, waving the arba minim, Hallel galore – oh, and it even has a bonus “Chag ha’Asif.” Right? Not quite.

e Torah introduces the holiday we know as “Sukkot” in two places in Sefer Shemot. e rst is among the many laws of Parshat Mishpatim (23:14–16), where God gives a list of three holidays which Bnei Yisrael are to celebrate “for Me”: ree times a year you shall celebrate for Me: keep the Festival of Matzot, seven days you shall eat matzot as I have commanded you at the set time in the spring month, for then you went out of Egypt, and they shall not appear before me empty-handed; and the Festival of the Harvest, the rst-fruits of your labors that you sow in the eld; and the Festival of Gathering, at the end of the year, when you gather from the eld all that you have labored.

We are given scarcely any information about the festivals in this passage. If we focus on Sukkot speci cally, not much is explained about this “Festival of Gathering.” It seems like the Torah is describing something we were planning on doing anyway, namely, gathering our crops. e Ramban points out that the Torah speaks in “העידי ןושל,” i.e., we are already aware of the events being spoken about – the agricultural process. We are somehow meant to turn our regular farming into a celebration of God. Great – but the Torah gives no details on what that means in practice. e second mention, in Parshat Ki Tisa (Shemot 34:18, 22–23), is a shortened but otherwise nearly word-for-word repeat of our list in Mishpatim. It is clear that there is some sort of religious value being ascribed to the agricultural cycle – but we still don’t know what’s so special about this “Chag ha’Asif,” nor do we know when to celebrate it beyond “at the end of the year.” It’s not until Parshat Emor, when we are presented with a list of all the holidays, that matters begin to clear up and more details are given (Vayikra 23:33–44). Going in order of the year, the Torah follows Yom haKippurim with Chag haSukkot, a seven-day holiday with a “mikra kodesh” (in our language, a Yom Tov) at the beginning, with a bonus Yom Tov of ” (essentially “stopping”) at the end. It is on the 15th day of the seventh month (Tishrei), and there is an extra sacri ce – but no mention of any Chag ha’Asif (yet).

e next few verses read like a conclusion to the entire list of holidays, with what appears to be a concluding verse: “these ” (just as the whole unit began back in 23:4), and that they are in addition to Shabbat and Rosh Chodesh. e section could end there – but then comes the word “ךא” (“but”), notated with a pazer trop (a high note of cantillation) to make sure we’re paying attention. A er having lulled us into thinking that we’ve successfully listed all the holidays, the Torah reintroduces the 15th day of the seventh month as a seven-day holiday with a bonus day at the end, only this time, it is described as “when you gather [םכפסאב] the grain of the land,” and we get two new mitzvot: taking the four species and rejoicing.

Now that we’ve gured out Chag ha’Asif, we should be done, but the Torah fakes us out once more with another pretend conclusion, apparently summing up this seven-day (plus one) period that we’ve now described twice:

You shall celebrate it for seven days as a festival for HaShem; you shall celebrate it as an everlasting law for generations in the seventh month. And yet immediately a erward there is another mitzvah given to perform on this seven-day period!

You shall sit in booths for seven days, every citizen in Israel shall sit in booths, so that they know for all generations that I housed the Israelites in booths when I took them out of Egypt; I am HaShem your God.

Rav Yoel Bin-Nun points out that this section’s structure is chiastic, that is, it mirrors itself:

Description of Chag haSukkot (23:34–36)

Description of Chag ha’Asif (39)

Special mitzvot for Chag ha’Asif (40)

Special mitzvah for Chag haSukkot (42–43)

Okay, so we’ve distinguished between the two holidays. Now what? As my teacher Rav Menachem Leibtag likes to say, is it a coincidence that Chag haSukkot falls out on Chag ha’Asif? Likely not. Rather, he explains, the gathering season is the perfect time for the mitzvah of living in the Sukkah. Remember the reason the Torah gave for it – so that we should remember the experience of outdoor living conditions we underwent in the desert in order to understand others’ plight. Being in the desert was a training of sorts for how to live as a nation once we reach Israel. Right a er we’ve gathered the grain, when food is aplenty and business is booming, it’s easy to feel like we don’t need God. We have everything we need! e chiddush of these holidays is to turn that abundance into thanksgiving to God (Chag ha’Asif) and to remember what it was like when life wasn’t so plentiful (Chag haSukkot), in the hope that by doing so, we’ll have better national behavior. Let’s add one more layer to this saga and return, for a moment, to Sefer Shemot. e second description of the regalim in Ki Tisa is nearly identical to the rst. Why does the Torah feel the need to repeat itself? We’re in the context of immediately post–golden calf. Moshe has negotiated a new contract (or covenant) on behalf of Bnei Yisrael, a er which God gives several warnings against idol worship and entering covenants with false gods. A er the warnings come a number of positive commandments, starting with Pesach and eventually continuing with Chag Shavuot and Chag ha’Asif. Rav Yosef Bekhor Shor draws a nice parallel between the chagim and the sin of the golden calf: while previously, the people associated with an idol “רחמ ׳הל גח” (“a festival for HaShem [through the calf] tomorrow”), these are the real chagim for HaShem.

Many other parshanim, however, highlight something quite fundamental to this new agreement between God and the people: don’t do avodah zarah, but do observe the holidays.1 Of all the mitzvot to mention at the beginning of the agreement, perhaps Chag ha’Asif is included at the core of our relationship with God as it represents a responsibility to act with chesed and to represent His values. Just as He housed us in booths when we sojourned, it is upon us to help others in their own wilderness. Sometimes it takes the mitzvah of Sukkah to remind ourselves of that.

Chag akh same’ach!

1 e Netziv (34:22) suggests that something about the nature of the holiday has changed post-לגע

SOPHIE KATZ '26 IS IN THE BEIT MIDRASH TRACK (BMT) AT SHALHEVET. SHE IS THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF THE BOILING POINT, ON THE AGENDA COMMITTEE, AND WRITES FOR NITZOTZEI TORAH.

In Vayikra 23, the perek known as םידעומה תשרפ, Hashem instructs Moshe to relay to Bnai Yisrael the details of all the festivals on the Jewish calendar. ese pesukim thus lay the foundations for the two seven-day biblical chagim: Pesach and Sukkot.

Both in the pesukim and – to a certain extent – in practice, these two holidays follow similar external models. With regard to Pesach, the Torah states:

“And on the eenth day of this month [the rst] it will be a Festival of Matzah to Hashem, seven days you shall eat Matzot” (Vayikra 23:6)

Concerning Sukkot, the Torah later states:

“On the eenth day of the seventh month it will be a Festival of Sukkot/booths for seven days to Hashem” (Vayikra 23:34)

e Torah uses similar structure to describe these two festivals. ey are also similar in that they are both seven days long with distinct, perhaps even unusual, rituals and objects used over the course of those days.

But Rabbi Michael Rosensweig notes that aside from these similarities, these twin holidays have separate, distinct theological purposes. Moreover, the temporal focus of these chagim di ers dramatically from one another, suggesting a distinct cadence and approach to best observe each in its own right.

ough structured similarly, the pesukim quoted above already hint at this di erence in focus. e language of “'הל

השמחבו,” emphasizes that the rst day of Pesach speci cally is classi ed as a chag for Hashem, mentioning the “ ולכאת תוצמ םימי

In contrast, the pesukim emphasize “הל

” almost as an a erthought to the chag to add to the simcha

,” that all seven days of Sukkot are considered a chag for Hashem.

Let us examine a few other di erences between Pesach and Sukkot that further illustrate this idea. One of the starkest di erences between them is the recitation of Hallel. On Pesach, we say full Hallel only on the rst two days (or just the rst day if you’re in לארשי ץרא), and half Hallel on the other ve days. On Sukkot, we recite full Hallel all seven days (plus on Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah).

e pattern of the korbanot for each chag follows a similar distinction. e korbanot for Pesach are the same each day, meaning the number of o erings each day of Pesach mimics the number o ered on the rst day. Sukkot, on the other hand, has a di erent number of korbanot brought each day, indicating the importance of each individual day.

One nal example of this idea comes from the brachot we say following the ha arah read on Shabbat Chol Hamoed. On Shabbat Chol Hamoed Pesach, the nal bracha concludes with just “ תבשה שדקמ.” On Sukkot, however, the bracha concludes “םינמזהו

” (according to Ashkenazic custom).

Each day of Sukkot has its own intrinsic, independent value, while the days following the rst days of Pesach function more like Sheva Brachot. Every day of Sukkot carries an equal weight to that of the rst, perhaps suggesting an imperative for us to work a little bit more to bring השודק to all the days, just as we would for the rst two.

RABBI ABRAHAM LIEBERMAN IS A MEMBER OF THE LIMUDEI KODESH FACULTY AT SHALHEVET HIGH SCHOOL. HE PREVIOUSLY SERVED AS THE HEAD OF SCHOOL AT YULA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL. RABBI LIEBERMAN LEARNED AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY AND RECIEVED SEMIKHA FROM EMEK HALAKHA IN BROOKLYN. HE RECIEVED HIS M.A. IN JEWISH HISTORY FROM THE BERNARD REVEL GRADUATE SCHOOL (YU), WHERE HE IS CURRENTLY WORKING TOWARDS HIS DOCTORATE.

Simchat Torah, celebrated at the end of Sukkot, is one of the most intriguing chagim. ough it follows Shmini Atzeret, it is not considered its second day but has its own identity. In Israel it coincides with Shmini Atzeret, while in the Diaspora it developed into a distinct celebration with diverse minhagim. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, while discussing the attempt of the Rambam to forbid the custom of standing during the reading of the Aseret Hadibrot (Ten Commandments) to show that every part of Torah is equally important, writes: “So despite strong attempts by the Sages, in the time of the Mishnah, Gemara, and later in the age of Maimonides, to ban any custom that gave special dignity to the Ten Commandments, whether as prayer or as biblical reading, Jews kept nding ways of doing so. ey brought it back into daily prayer by saying it privately and outside the mandatory service, and they continued to stand while it was being read from the Torah despite Maimonides’ ruling that they should not. ‘Leave Israel alone,’ said Hillel (Pesachim 66a-b), “for even if they are not prophets, they are still the children of prophets.” Ordinary Jews had a passion for the Ten Commandments. ey were the distilled essence of Judaism. ey were heard directly by the people from the mouth of God Himself. ey were the basis of the covenant they made with God at Mount Sinai, calling on them to become a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Covenant and Conversation, “ e Custom at Refused to Die,” Yitro, 5772).

How does all this relate to Simchat Totah and the dancing of the Hakkafot? Let me explain.

e Mishnah (Beitzah 36b) states: " ןידקרמ

" “One may not clap his hands together, nor clap his hand on the thigh, nor dance.” In other words, on Shabbat and Yom Tov, dancing is forbidden. e Talmud (ibid.) explains that this rabbinic decree was enacted due to fear that one may repair or construct a musical instrument. is is the accepted Halacha according to the Rambam (Laws of Shabbat 23:5) and many other Rishonim (e.g., Rif, Rosh). Rabbi Yosef Caro (1488-1575) in the Shulchan Aruch, both in the laws of Shabbat (O.H. 339:3) and in the laws of Yom Tov (O.H. 524:1), agrees with this opinion, forbidding dancing on Yom Tov and on Shabbat.

We are all familiar with the special sanctity of a Sefer Torah, הרות רפס תשודק, which also leads to many halachic restrictions (see Shulchan Aruch, Y.D. 282). We stand up the second we see it, we cover it up when it is not being read, we don’t turn our backs to it, it cannot be moved from place to place without a special reason, some Poskim even require ten people to walk with it while being moved to another location, and we refrain from touching the parchment. In addition to these, there are also many other practices that all demonstrate our respect and reverence for a Sefer Torah. It becomes quite apparent, then, that dancing on Simchat Torah during Hakkafot while holding a Sefer Torah should pose multiple Halachic problems, both with respect to dancing on Yom Tov and due to the apparent violation of the sanctity of the Sefer Torah. Why would this be allowed?

is question is strengthened by a suggestion of Rav Soloveitchik concerning the reason that Ashkenazim read the Torah on Simchat Torah night following the dancing. Rav Soloveitchik stated that one possible reason for this practice, which has no source in the Talmud, is to teach the lesson that a Sefer Torah cannot just be taken out of the Ark without a reason; it must be used for learning or reading. Even dancing with it for Kavod Ha-Torah does not su ce. Although we do not read from all of the Sifrei Torah removed from the ark for dancing, one has to be read from to demonstrate this point.

Indeed, many communities had the practice of using each Torah either to roll to the next day’s reading, to be checked for mistakes, or for reading from it verses that speak about blessing (pesukei beracha) – showing that it had a clear purpose, because simply dancing with the Torah does not su ce (Avraham Yaari, Toldot Chag Simchat Torah, p. 352).

Rav Yosef Qa h (Kapach, 1917-2000), one of the great Yemenite Poskim, strongly opposed the contemporary custom of dancing wildly with the Torah (Commentary to the Mishneh Torah, Shabbat 23:5): “I want to comment on the horrible custom that has developed in our community on Simchat Torah, when people dance… they also take hold of a Sefer Torah, and they li up and down as if it is a regular object! I remember Sages and Elders of the Yemenite Community, who approached holding a Sefer Torah with fear, trembling, and reverence and dancing a short speci c dance, keeping in mind the sanctity of the shul, taking two or three steps and bending their knees, and that was all. ey understood the rabbinic prohibition of dancing on Yom Tov and kept to it.” He further criticized the introduction of alcohol, food, and handing the Torah to children, lamenting that the true honor of Simchat Torah was being diminished.

e earliest reference to dancing on Simchat Torah comes from Rav Hai Gaon (939–1038). In a responsum (Teshuvot Ha-Geonim, Shaarei Teshuva 314) he wrote that although dancing on Yom Tov is technically a rabbinic prohibition, on this day the custom developed to allow it — but only out of Kavod HaTorah. Notably, Rav Hai does not mention holding a Sefer Torah while dancing. His position is quoted by the Maharik (Rabbi Yosef Colon, 1420–1480, Shoresh 9). Rabbi Yitzchak Ibn Ghayyat (Spain, 1038–1080) likewise cites and accepts Rav Hai’s view.

By contrast, early Ashkenazi Poskim, such as Ravyah (Rabbi Eliezer ben Yoel Ha-Levy, 1140-1225 in Vol. 3, Siman 795, p.485) and Rabbi Yitzchak ben Moshe of Vienna (1200-1270, in his Ohr Zarua, end of Laws of Yom Tov), retain the original rabbinic prohibition of dancing on Yom Tov on Simchat Torah as well, without any exception. is is also the opinion of many other Rishonim.

Nevertheless, the current custom in most places is to have seven Hakkafot of dancing with the Sifrei Torah. is practice began in the sixteenth century with Rabbi Yitzchak Luria (the Ari Ha-Kadosh, 1534-1572) in Safed, and spread widely through the writings of his student, Rabbi Chaim Vital (1542-1620) (Avraham Yaari, Toldot Chag Simchat Torah, pp. 259-318).

e Talmud (Beitzah 30a) already anticipated this tension. It records that although the Sages forbade clapping and dancing on Yom Tov, people nevertheless did so:

Rava bar Rav Hanin said to Abaye: We learned in a Mishna (Betzah 36b): e Rabbis decreed that one may not clap, nor strike a hand on his thigh, nor dance on a Festival, lest he come to repair musical instruments. But nowadays we see that people do so, and yet we do not say anything to them.

e Rabbis therefore applied the principle:

Leave the Jews alone; it is better that they be unwitting sinners and not be intentional sinners. Here, too, with regard to clapping and dancing, leave the Jews alone; it is better that they be unwitting sinners and not be intentional sinners.

Tosfot (Beitzah 30a, s.v. tenan) adds another leniency: “But for us it is permitted (to dance, etc.), because in their days (when this prohibition was issued) they knew how to make musical instruments; therefore the prohibition was applicable. But for us, as we are not experts at musical instruments, there is no reason for the prohibition.”

e Rema (Rabbi Moshe Isserles, 1520-1572), who always reports the Ashkenazi tradition, quotes the following points in his commentary to the Tur (ךוראה השמ יכרד, O.H. 339): a) the opinion of the above Tosfot, b) the opinion of Maharik, mentioned earlier, and c) the Talmud mentioned above that it is better that they be unwitting sinners and not be intentional sinners. Yet in his comments in Shulchan Aruch (O.H. 339:3), the Rema only quotes the Talmud (ibid.) and the opinion of Tosfot, and concludes: “And therefore this might be the reason why people today are lenient regarding dancing.”

e Mishnah Brurah (Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan, 1838-1933) in the Laws of Shabbat (O.H. 339:8) writes: “On Simchat Torah one is permitted to dance, as we recite praises of the Torah because of Kavod Ha-Torah, but not for any other

occasion, even for a Mitzvah.”

Stepping back, the picture is clear: While technically forbidden, dancing persisted because of the mitzvah of simcha and the Jewish people’s instinctive need to celebrate with song and movement. Halachic authorities found room to permit it — and on Simchat Torah, the day of completing the Torah, this joy became not only tolerated but sancti ed. Simchat Torah, then is unique. As we conclude nearly a month of chagim, this nal day celebrates the completion of the Torah reading cycle. Yet we do not stop; we immediately begin again, dancing in circles to show the endless love between the people and the Torah. As Rav Soloveitchik explains (“Hakafot-Moving in a Circles,” Man of Faith in the Modern World, pp. 150-160), the circle itself embodies this bond – never-ending, ever-renewing. is is beautifully illustrated by a vignette told by Sivan Rahav-Meir (Days are Coming, A Journey through the Jewish Year, pp.42-43) about Professor Nechama Leibowitz, when her students asked how she could devote so many hours to learning and teaching Torah. She responded, “ is is not about learning something new. It is about reading a love letter.

ISAAC MESSINGER IS A JUNIOR AT SHALHEVET. HE IS IN THE ADVANCED GEMARA SHIUR AND A MEMBER OF MODEL CONGRESS.

Every year on Simchat Torah, the same scene repeats itself: circles of people, young and old, singing and dancing with Torah scrolls in their arms. For a moment, the shul becomes less like a place for prayer and study and more like a celebration hall. No one is sitting and learning or davening; no one is giving a shiur. And yet, it is one of the holiest nights of the year. What is the signi cance of the fact that we mark the completion and beginning of the Torah not by studying, but by dancing?

I believe that Hakafot, the act of dancing in circles around the bimah, o ers a profound message. While Torah learning is o en linear, moving from one pasuk or daf to the next, hakafot are circular. ere is no clear start or nish; the joy loops endlessly, just like our relationship with Torah. On Simchat Torah, we don’t just celebrate nishing a book, we celebrate that Torah has no end. As soon as we reach the last word in Devarim, we immediately return to Bereshit. e cycle begins again, because Torah is not a project we complete; it’s a rhythm we live in.

In fact, hakafot are not just a modern custom; they have deep roots in our tradition. ey are taken from the ancient custom of aravah in which the Kohanim would encircle the altar in the Beit Hamikdash. e Mishna (Sukkah 4:5) describes that the Kohanim encircled the altar once a day during Sukkot, and on the last day, they increased to seven times. In the absence of the Beit HaMikdash, the Torah becomes our center, and the bimah becomes the mizbeach. We still want to ful ll the idea of hakafot, but we need our own way of relating to it, so we encircle what is most important to us: the Torah.

Although the custom of encircling the altar may be the source of today’s custom of hakafot on Simchat Torah, our hakafot also have their own meaning: they are intended to help us increase our level of simcha. e Baal Shem Tov was once asked, “Why is it that Chassidim burst into song and dance at the slightest nudge, without cause?” He answered that when Jews are inspired by a melody or feel the moment is one to dance, it doesn’t matter that to others it might seem crazy – to them it makes sense. On Simchat Torah, we are so enthralled by the Torah that our gut reaction is to sing and dance. e verse in Tehillim (100:2) states that we should serve God with joy - "החמשב ׳ה תא ודבע". On Simchat Torah, we take this teaching to the next level.

For me, the most meaningful part of hakafot is that it gives me a sense of happiness in connecting to God and the Torah. e day allows me to feel proud to be a Jew. I also feel it is important not just to learn, but also to dance. Simchat Torah is a day where all Jews, whatever their background, can come together and rejoice around the Torah. May we all merit to celebrate Simchat Torah this year with these powerful feelings of joy and pride in our Jewish heritage.

ARIEH ELAD IS A SENIOR AT SHALHEVET. HE IS A MEMBER OF SHALHEVET'S BEIT MIDRASH TRACK (BMT). HE IS THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF THE HAWK'S NEST AND CAPTAIN OF THE MODEL CONGRESS AND BASEBALL TEAMS.

As we celebrate Simchat Torah this year, ו״פשת, the celebration itself remains unchanged, yet the reality in which we experience it has been transformed. On this day, the Jewish world completes the Torah, from Bereshit through Devarim, and in the same breath, we begin anew. e hakafot of Simchat Torah remind us to rejoice in both endings and beginnings. But as we internalize its timeless rejoicing, we are again faced with a profound paradox calling for un ltered joy that stands in stark contrast to the weight of our collective broken hearts during the anniversary of the October 7th attacks, the dark shadow of unrelenting war, and (at the time of this writing) 50 hostages still held captive in Gaza.

It is important to note that Simchat Torah is, in fact, undeniably layered every year: as we conclude our annual cycle of Torah reading with Parshat V’zot HaBracha, we read of how B’nei Yisrael are faced with the trauma of Moshe Rabbeinu’s death coupled with the joy of entering Eretz Yisrael. Moshe is buried by Hashem, and the site of his grave is unknown. But B’nei Yisrael persevere through their grief, and Moshe’s chain of transmission remains unbroken. We then begin again, cycling back to the story of creation in Parshat Bereishit. In our times, we are faced with a trauma that not only persists, but evokes imagery from the darkest chapters of our history. e global Jewish consciousness is now shaped by two years of trauma as families are continually upended, our brave chayalim defend Medinat Yisrael, and the plight of the hostages persists.

Our communal disposition toward Simchat Torah has become marked by an emotional dissonance and gives rise to a tension we all carry: How do we uphold the imperative of rejoicing with our beautiful Torah amid this chronic state of grief? Is it inappropriate to act happy at this time? Is our dancing a mark of irreverence toward the souls who su er and parents who weep? Are we supposed to temper our joy or simply not dance?

In a piece published on October 18th, 1973, Rabbi Norman Lamm ל״ז, the former president of Yeshiva University, explores the di culty of nding joy on Simchat Torah only two weeks a er the devastating Yom Kippur War. He starts with the question: What is Simcha? Rambam tells us rst what it is not; it must never be תוללוהו תולכס, frivolity and levity. Rather, true Jewish joy must contribute to לכה

, it must be a form of service to the Creator of all that exists.

Rabbi Lamm discerned four speci c strands in this complex emotion, Simcha. First, Jewish joy is a sign of faith, not as a response to circumstances, but as our declaration to the existence of G-d as the Source of all. ךיקלא ׳ה ינפל החמשו means that we are to be joyous "before the Lord your G-d," meaning that our joy is our way of declaring that He runs the world. e second strand is ןוחטב, con dence in Hashem that He will help us even when outcomes may be uncertain. e third strand is a recognition of the complexities and ambiguities of life, and that there is no sorrow without המחנ, consolation, and no joy without sadness. And lastly, the fourth strand is Simcha as a form of de ance that can win over evil. ese four strands I interpret as the ingredients of Jewish resilience in the face of balancing the dilemma of joy and grief. We must believe, we must trust, we must feel, and we must have courage.

Rabbi Lamm also quotes ז:א

, which states:

“Nittai the Arbelite used to say: keep a distance from an evil neighbor, do not become attached to the wicked, and do not abandon faith in [divine] retribution.”

Rabbi Lamm’s message is clear: in times of crisis, we must not let despair harden us. We are commanded not to erase our pain, nor ignore evil, but to stand rm and insist on hope—to bless, to embrace life, to maintain faith in redemption even when it feels impossibly far away.

A similar message can be derived from the Tose a (Sotah 15:5), which teaches that according to Rabbi Yishmael, it would be appropriate not to eat meat or drink wine following the destruction of the Beit Hamikdash. However, in practice we do not do so because ןהב

- a court does not decree (restrictions) on the community that they cannot uphold. Despite the destruction of our most holy location, the greatest catastrophe to be talked about for millennia to come, life and its practices must continue. Joy and pleasure outweigh the e ects of disaster.

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, founding chief rabbi of Efrat, writes likewise about Simchat Torah and V’Zot HaBracha:

“We celebrate the Torah even as we read of Moses’ death because, for us, Moses never died; his grave is unmarked because through the words of the Torah that he communicated to us, he lives on. Moses, in essence, resides in his inner message, and the Torah by which we live and from which we study is his eternal legacy. It is this Torah over which we rejoice on Simchat Torah.”

Every year, it is customary among Ashkenazim to have a “Kol HaNe’arim” aliyah, when even the youngest children come up to the bimah to be part of the aliyah. During the aliyah, it is customary for everyone to recite the following pasuk together:

“ e Messenger who has redeemed me from all harm—Bless the lads. In them may my name be recalled, And the names of my fathers Abraham and Isaac, and may they be teeming multitudes upon the earth.”

Kol HaNe’arim is a joyful moment, meant to amplify the themes of renewal and continuity of the holiday. e םירענ stand under a tallit as if wed to Hashem and the Jewish people; Moshe Rabbeinu’s Torah legacy is ensured, surrounded by the community. But even this beautiful and symbolic ritual of Simchat Torah feels di erent this year, with the hostages that remain in Gaza. Although they are not children, they are still Am Yisrael’s sons and daughters, and we want nothing more than to ensure their protection and give them our blessing. Our joy is tempered by their absence and their continued su ering. And yet, just as Simchat Torah is the continuation of Moshe Rabbeinu’s legacy following his death, Kol HaNe’arim can give us hope that the blessings that we bestow will be heard and protect our captive sons and daughters as well.

is year, the deeper meaning of Simchat Torah is more poignant than ever. e beauty of endings and beginnings lies in the sacred imperative of renewal, a chance to bring hope and purpose into the new year. As we re ect on our collective trauma, the teachings of Torah and the strength drawn from faith guide us on how to acknowledge darkness without extinguishing our light. And in this moment, the Torah o ers us the words to begin again. When we dance, we are declaring that Am Yisrael endures, רקשי