JANUS GATE AT THE 59TH VENICE BIENNALEPERSONAL ENCOUNTERS WITH KEY FIGURES IN AYMAN BAALBAKI’S LIFE: DR BASEL DALLOUL, ROSE ISSA, SALEH BARAKAT, NAYLA TAMRAZ, STEPHANE SISCO, SERWAN BARAN, SAID BAALBAKI, OUSSAMA GHANAMTHE ARTIST REFLECTS ON FRIENDS, FAMILY AND INFLUENCES # 58 BEING AYMAN BAALBAKI ARTS-STYLE-CULTURE FROM THE ARAB WORLD AND BEYOND SPRING 2022USD 20/EUR 18/AED 74

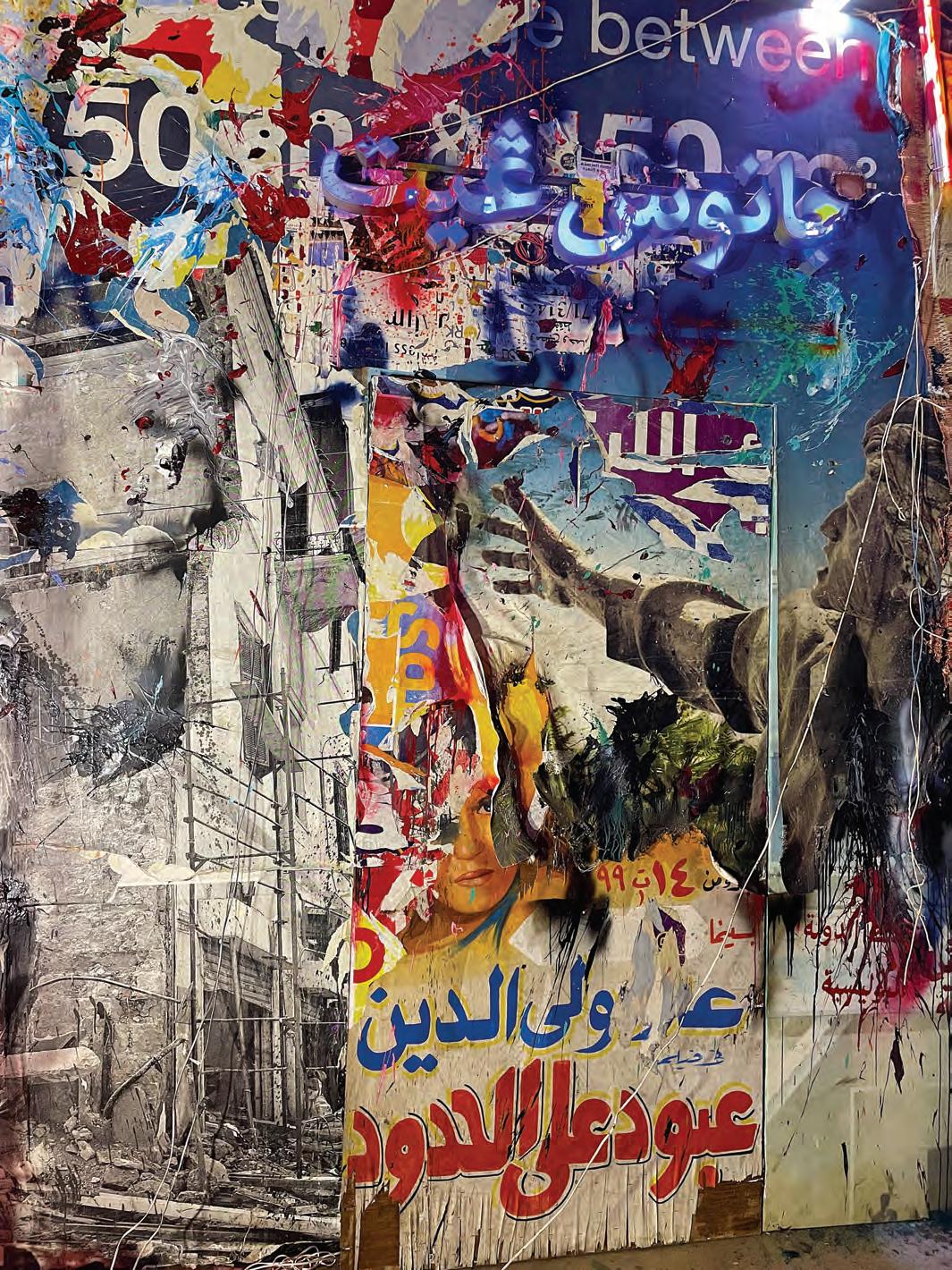

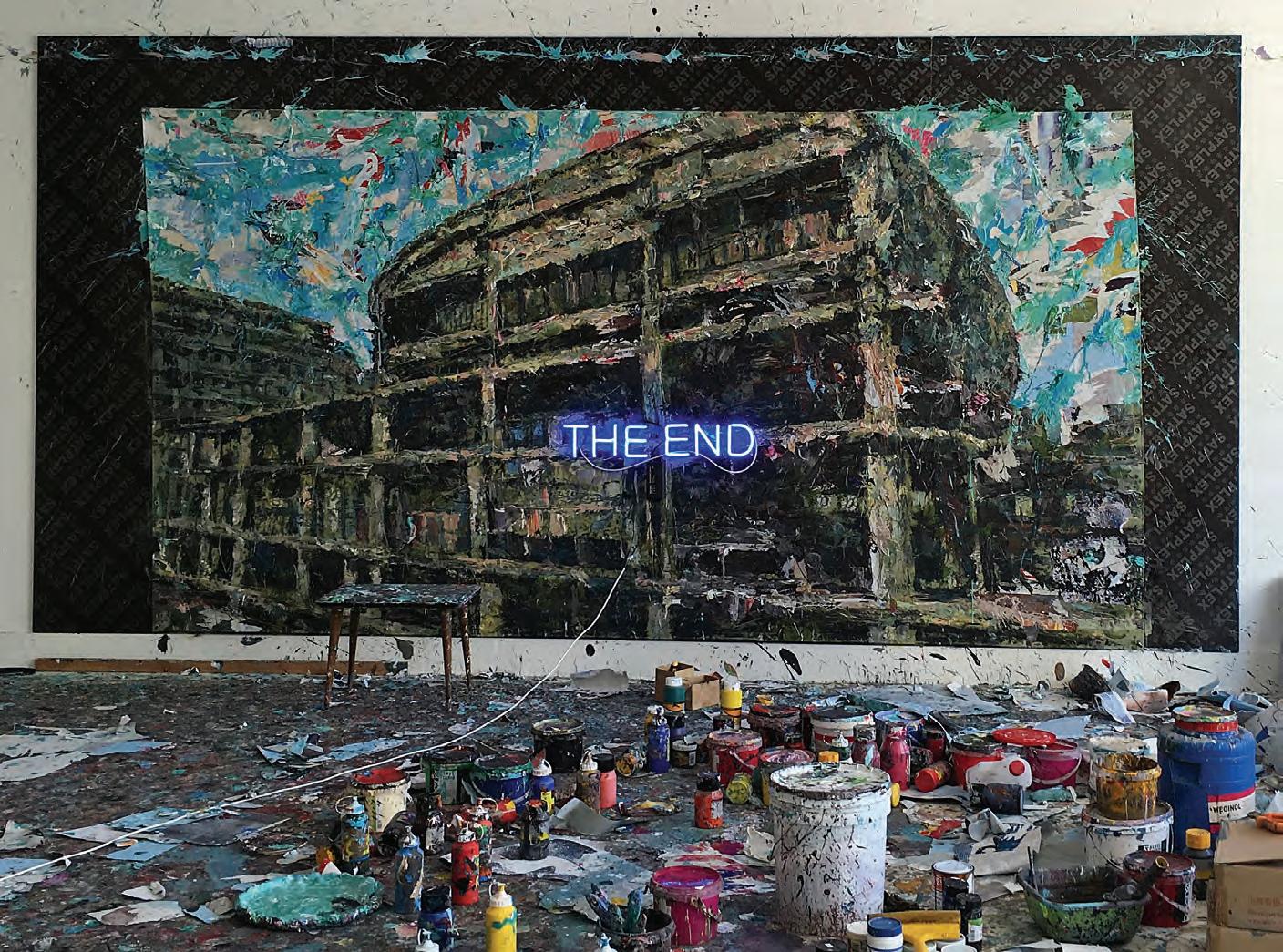

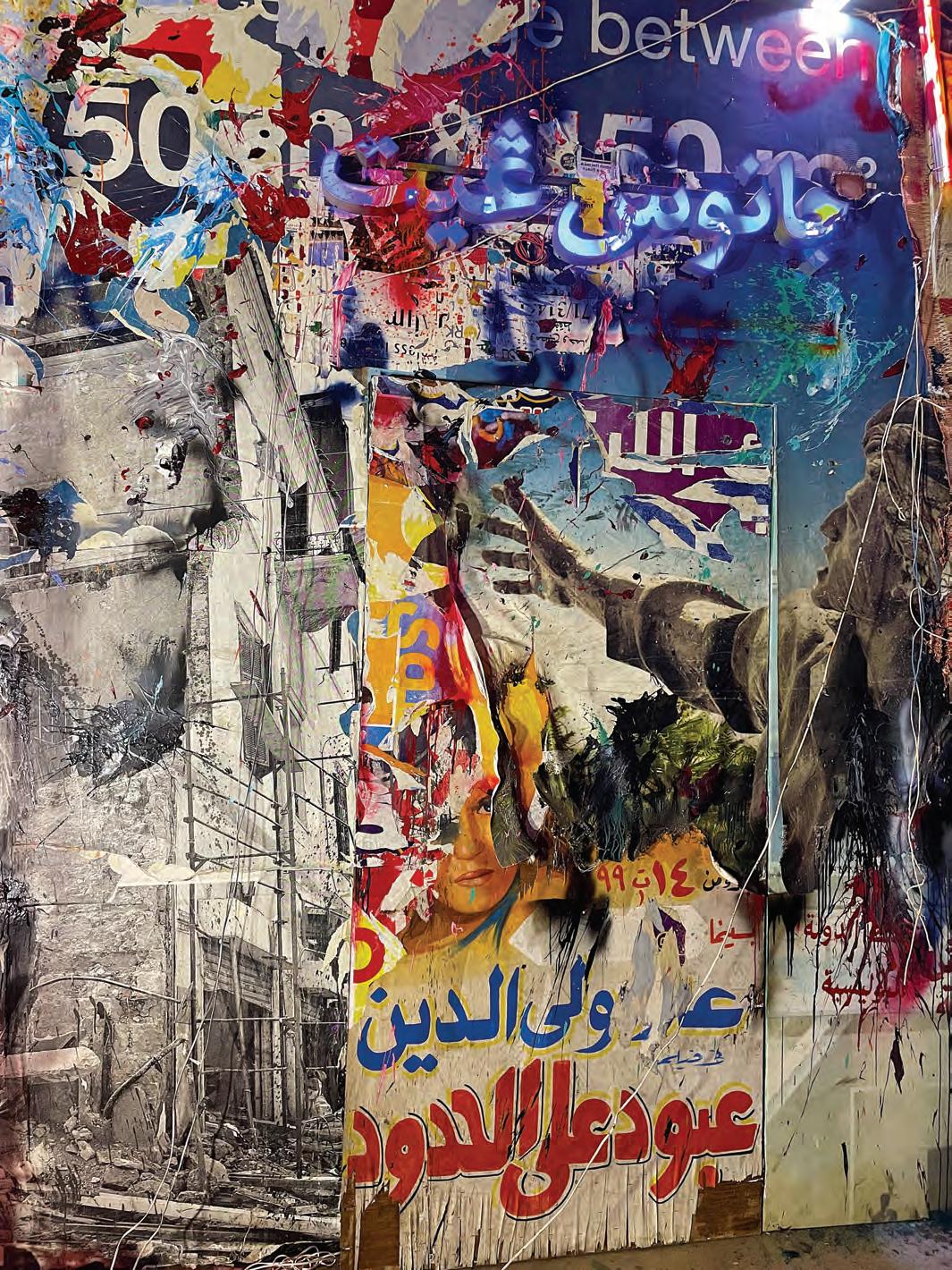

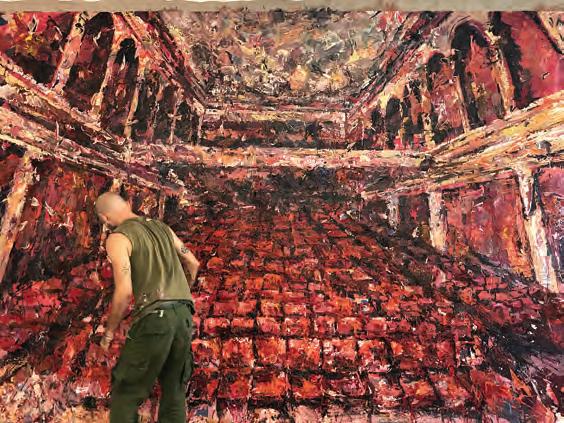

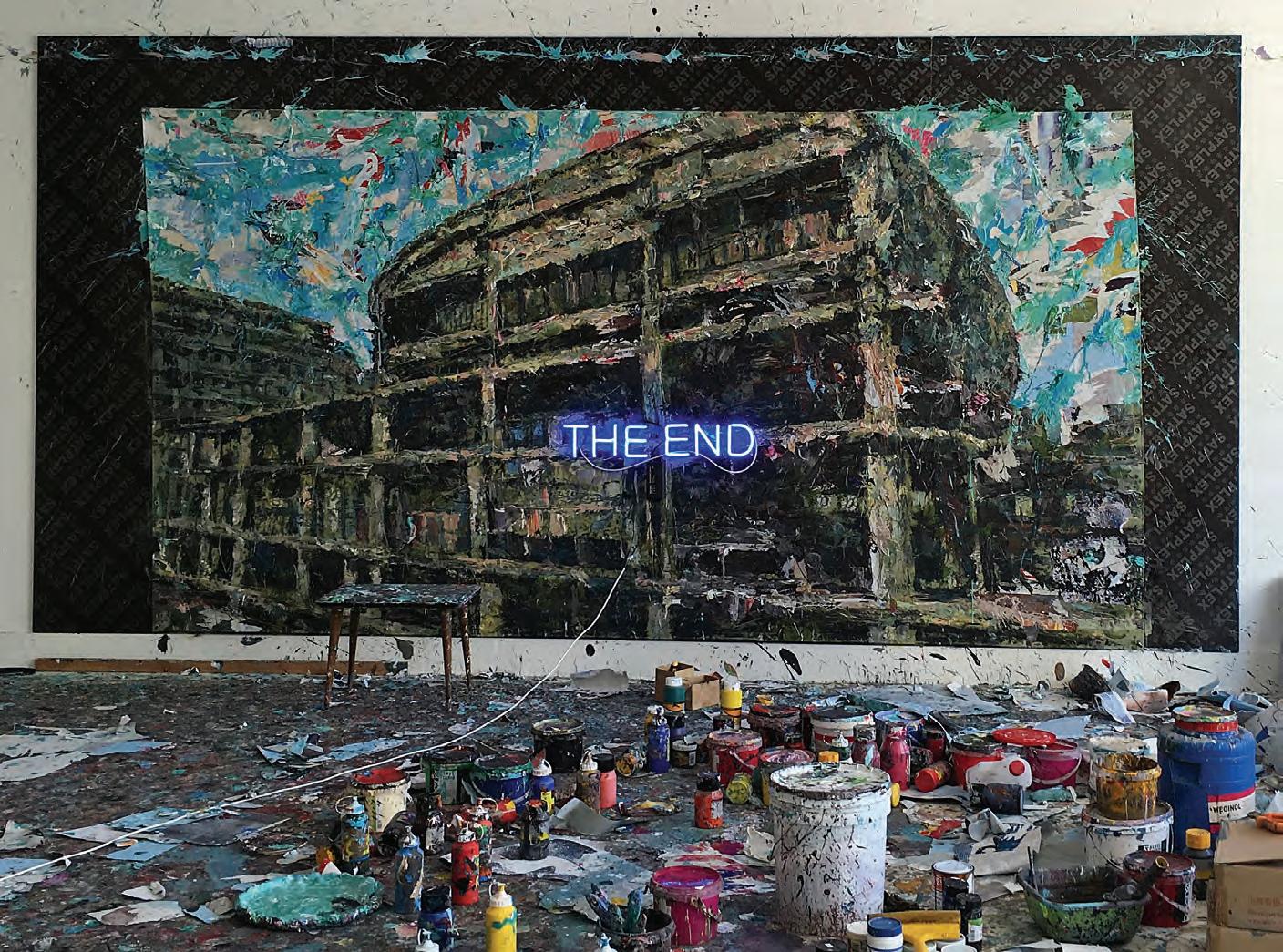

Ayman Baalbaki (1975), Lebanon Picadilly Theater, 2019

Acrylic on billboard laid on canvas 280x390 cm

Ayman Baalbaki (1975), Lebanon Picadilly Theater, 2019

Acrylic on billboard laid on canvas 280x390 cm

CONGRATULATIONS TO AYMAN BAALBAKI FOR REPRESENTING LEBANON IN THE VENICE BIENNALE 2022

MORE THAN 300 ARTISTS WITH OVER 4,000 ARTWORKS OFFERING DAILY THOROUGH RESEARCH CONTENT FROM THE EXTENSIVE COLLECTION OF THE DALLOUL ART FOUNDATION

SCAN THE QR CODE TO DISCOVER MORE OF AYMAN’S WORKS

DON’T FORGET TO SIGN UP TO RECEIVE OUR UPDATES

DAFBEIRUT.ORG

EDITOR’S LETTER

Welcome to Selections’ issue 58, a very special edition dedicated to Ayman Baalbaki who has been selected to represent Lebanon at the 59th Venice Biennale. Bringing a never-before-seen installation entitled Janus Gate, his work embedded with historical texture is represented at the Venetian Arsenal, a complex of former shipyards and armories clustered together in the city of Venice.

Throughout this issue we have invited key figures who have had a special relationship with the artist and his work. They have each written a personal piece about him. Founder of Dalloul art foundation and collector Basel Dalloul whose late father collected a large amount of his works. Basel developed a very close friendship to Ayman and documented a lot of his studio time.

Rose Issa, his first gallerist, who has exhibited him outside of Lebanon.

Saleh Barakat taking on his work at Agial gallery and was inspired by him to expand the size of his gallery in order to present Baalbaki’s larger works.

Art historian Nayla Tamraz, who has been following him closely for years and has written various essays, particularly through this latest period while he’s been working on Janus Gate.

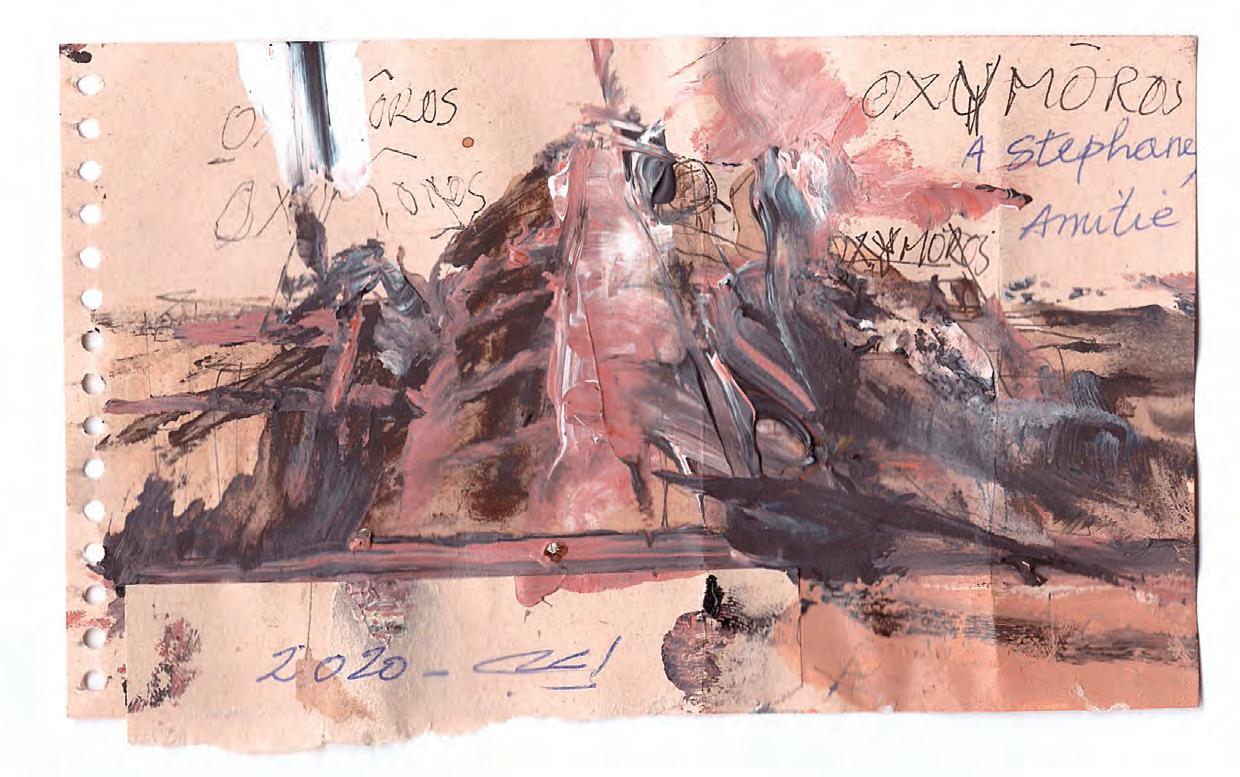

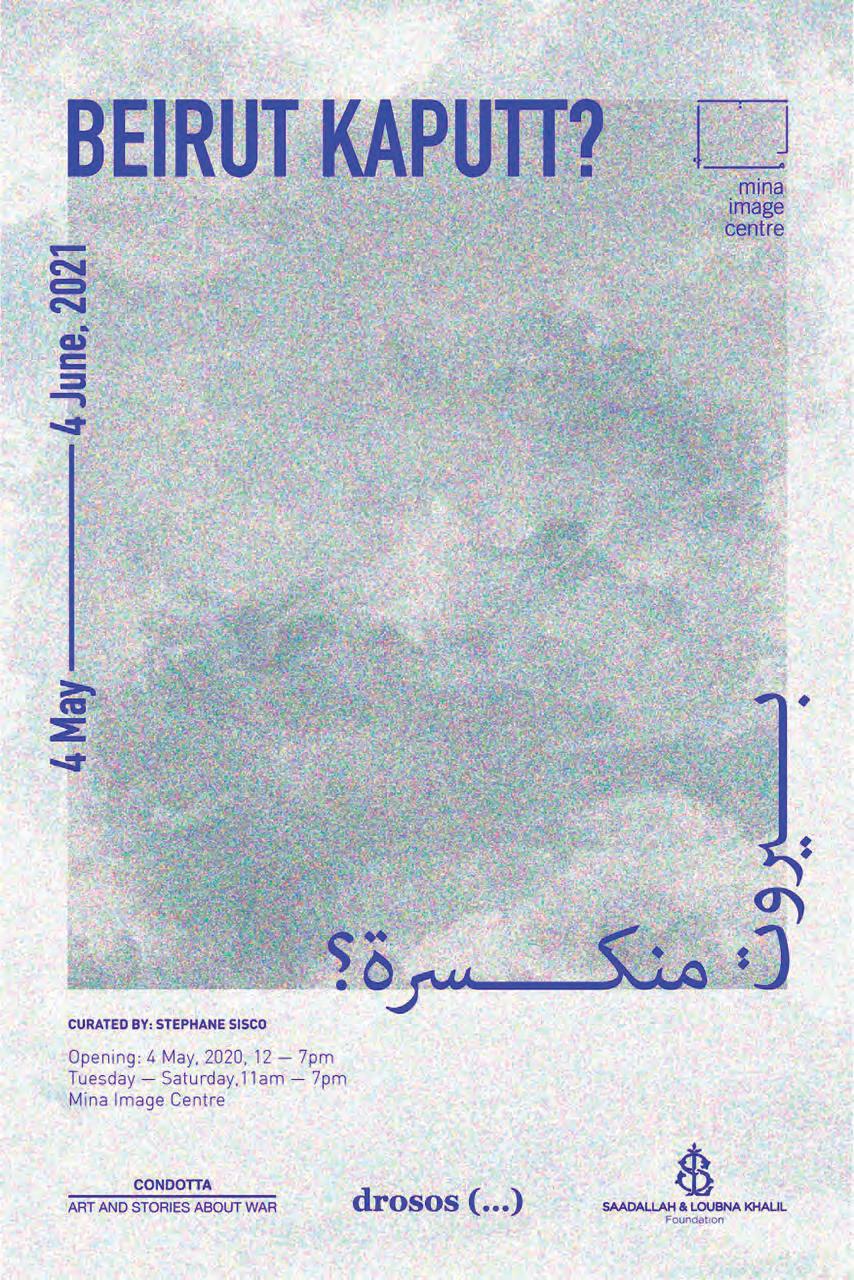

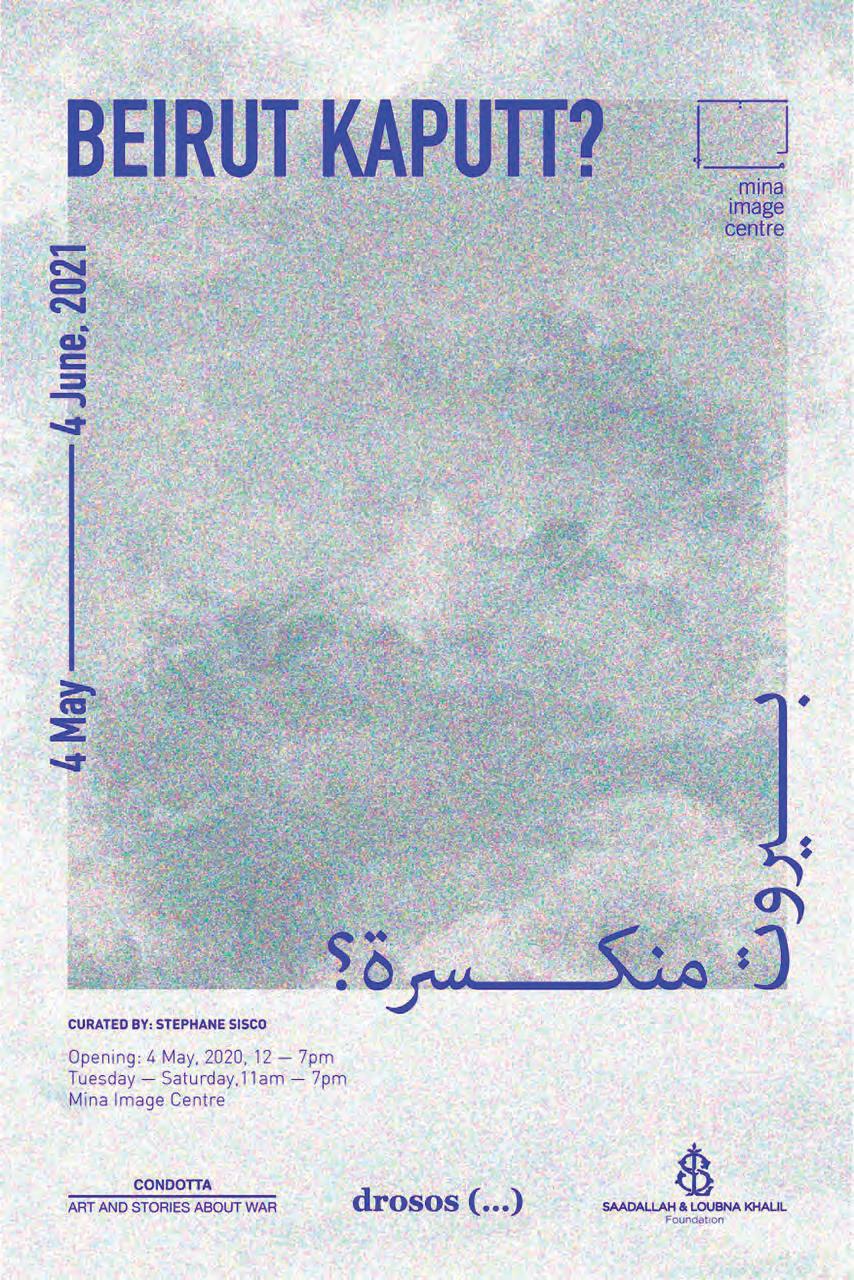

Curator Stephane Sisco bringing together a show entitled Beirut Kaputt! featuring Ayman who explained to him, through some of his first sketches, the concept of his latest work.

A personal friendship with artist Serwan Baran. Serwan writes about their story as contemporaries and their close relationship with artist Abed Katanani.

His brother, renowned artist Said Baalbaki, takes us through shared childhood stories.

Theatre director, Oussama Ghanam, counts their adventures and lengthy conversations.

Selections has also gotten up close and personal with Ayman to relate his personal anecdotes, intimate stories, his process and renowned achievements.

We hope you enjoy this issue as much as we did putting it together, and certainly hope to cross paths at the Venice biennale.

4

Liste Art Fair Basel 13 –19 June

Liste Art Fair Basel 2022

Liste Art Fair Basel

Liste Art Fair

Liste Art

Liste

Messe Basel, Hall 1.1

Entrance behind Art Unlimited

Maulbeerstrasse / corner Riehenring 113 4058 Basel

Main Partner since 1997

E. Gutzwiller & Cie, Banquiers, Basel

Liste Showtime Online, 13 wtimeO Liste –26 June 2022 liste.ch

BEING AYMAN BAALBAKI

10-19 Ayman Baalbaki’s Artistic Journey

20-34 Behind Janus Gate

36-57 Dr Basel Dalloul

An Encounter with Genius

58-69 Rose Issa

The Power of Talent

70-79 Saleh Barakat

No Compromise, No Limits

80-83 Nayla Tamraz

Revelations of an Extraordinary Mind

84-91 Stephane Sisco Brothers in Arms

92-97 Serwan Baran

Summer 2001, Summer 2022

98-100 Said Baalbaki

Beyond a Brotherly Bond

102-107 Oussama Ghanam

1 + 1 = 1

108-128 From Play to Slay

KEY FIGURES IN AYMAN BAALBAKI’S LIFE: DR BASEL DALLOUL, ROSE ISSA, SALEH BARAKAT, NAYLA TAMRAZ, STEPHANE SISCO, SERWAN BARAN, SAID BAALBAKI, OUSSAMA GHANAM THE ARTIST REFLECTS ON FRIENDS, FAMILY AND INFLUENCES # 58 BEING AYMAN BAALBAKI SPRING 2022 USD 20/EUR 18/AED 74 6

Spring – 2022

CONTENTS

Cover Photo by Marco Pinarelli

28.04 — 01.05.2022

&

Contemporary

by EASYFAIRS Follow us www.artbrussels.com Main partner

Tour

Taxis

Art Fair

Founder

Rima Nasser

Editor-in-Chief

Anastasia Nysten Designer

Maria Maalouf

Production Coordinator

Reem Bou Hussein

Contributors

Dr Basel Dalloul

Nayla Tamraz

Oussama Ghanam

Rose Issa

Said Baalbaki

Saleh Barakat

Seran Baran

Stephane Sisco

Selections Publishing House FZ LLC

Advertising & Distribution

Advertising & Editorial Inquiries

anastasia@selectionsarts.com

advertise@selectionsarts.com

selectionsarts.com

facebook.com/selectionsarts

instagram.com/selections.arts

Special thanks to

Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation DAF

Elie Khouri Art Foundation EKAF

ARTS-STYLE-CULTURE FROM THE ARAB WORLD AND BEYOND

MAGAZINE #58

8

10

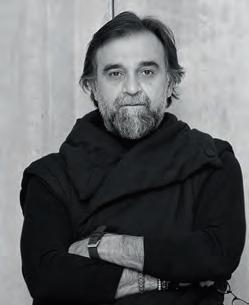

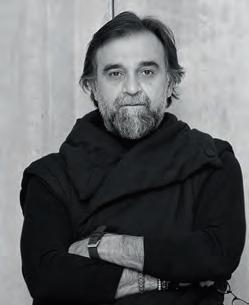

Photo by Marco Pinarelli

BEING AYMAN BAALBAKI

AYMAN BAABAKI, THE MAGNETIC ICON OF BEIRUT, STROKING HIS ARTISTIC INGENUITY BY HIS PRESENCE AND HIS WORK. HIS PERSONAL STYLE IS PRESENT IN THE VARIOUS MEDIUMS HE ENGAGES IN. HE IS ADVENTUROUS. HE RECONCILES THE PRECISE WITH THE CHAOTIC.

11

Written by Wafa Roz

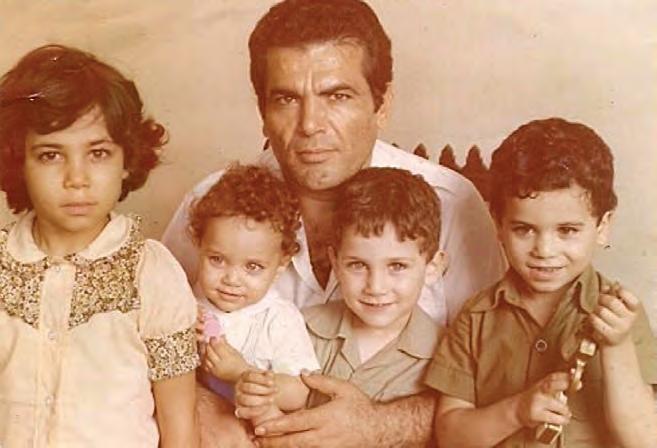

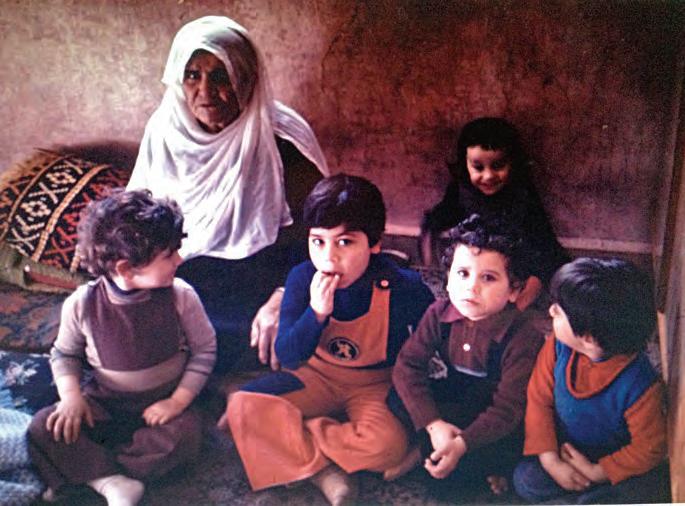

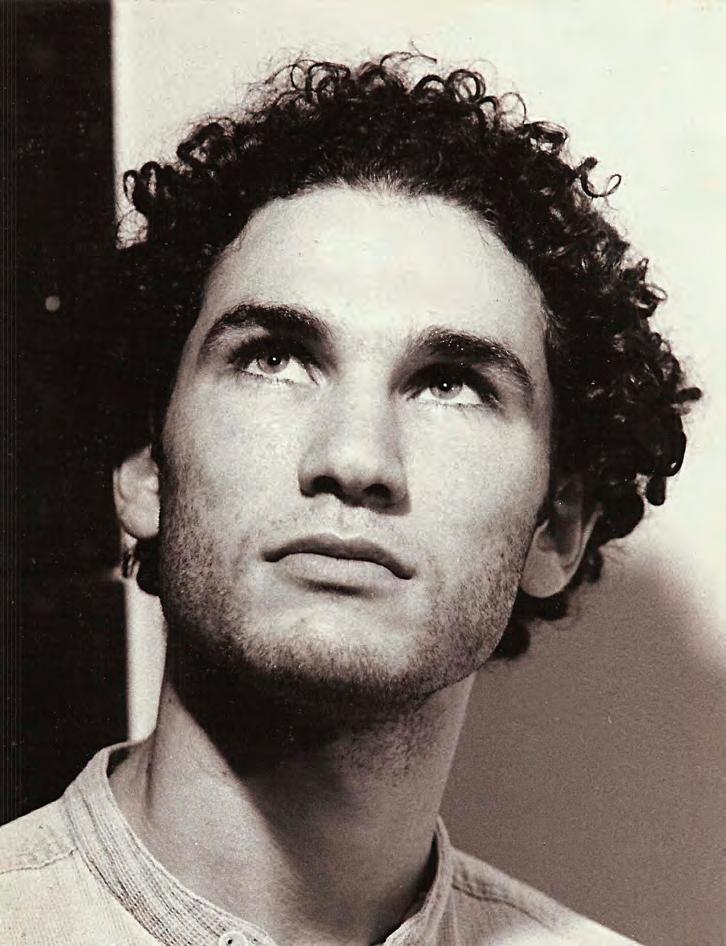

Ayman Baalbaki, a contemporary visual artist, was born in 1975 in Ras-el-Dekwaneh in Beirut, Lebanon. Originally from Adaisseh, a village in south Lebanon, his parents relocated to the Wadi Abu Jamil neighbourhood in central Beirut, where Ayman was raised. His father, Fawzi Baalbaki, and his uncle Abdelhamid Baalbaki (1940-2013) were both visual artists and educators. Also, Said, Ayman’s brother, and two of his cousins, Oussama and Hoda, are now established visual artists. Ayman finished his secondary education at the Ahlieh School in Wadi Abu Jamil in 1994[1] and then earned his diploma in fine arts from the Lebanese public University in Beirut in 1998. He did a one-year mandatory military service before moving to Paris in 2000. Ayman studied Art et Espace at the École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs (ENSAD) in Paris from 2000 to 2002 and completed his D.E.A in the art of images and contemporary art at Université Paris VIII from 2002-2003. In the summers of 2001 and 2002, Ayman attended the Ayloul Summer Academy in Amman, Jordan, a programme led by renowned SyrianGerman modernist Marwan Kassab Bachi (1934-2016), who later mentored Ayman.[2]

Baalbaki grew up during the Lebanese Civil War (19751990). As a young boy, he witnessed shelling, snipers, destruction, and the Israeli invasion of Beirut. Wadi Abu Jamil, previously known as the Jewish quarter, became a refugee haven for Kurds and Lebanese southerners fleeing the Israeli assaults. Baalbaki and his family stayed there for nearly two decades. In 1995, they moved to Haret Hreik in the southern suburbs of Beirut.[3] Sadly, Haret Hreik was razed to the ground during the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah July war, and the Baalbakis were displaced once again.

The memory of the Lebanese Civil War is a sensitive subject for many Lebanese. The war ended with the 1989 Ta’if Accord and the 1991 amnesty law that pardoned all political crimes before that date.[4] But, Baalbaki chooses to face the past or attend to a “devoir de mémoire,’’ as he puts it. A critical and imaginative artist, Baalbaki tackles the war’s painful events with cynicism, only to underscore the absurdity of war. Baalbaki’s body of work, including painting, installation, and sculpture, revolves around themes such as collective memory, loss, displacement, and identity. Rapidly, Baalbaki earned international acclaim for his staggering hyper-expressive paintings.

12

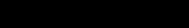

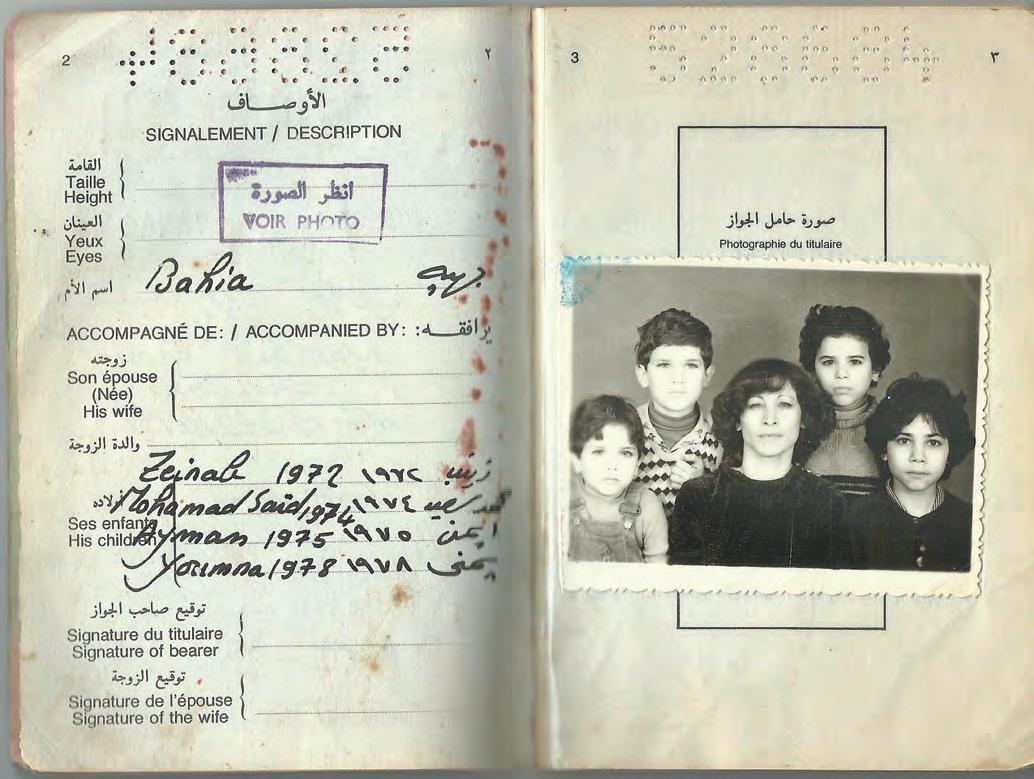

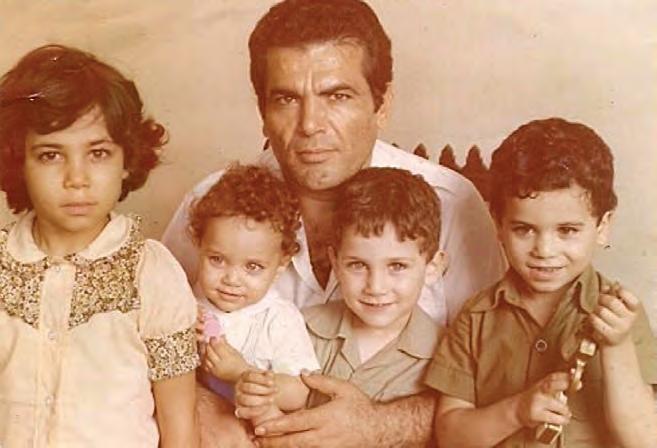

Opposite Page – Family passport used to travel to France. Bahia Baalbaki and her four children, Zeinab (b.1972), Mohamad Said (b.1974), Ayman (b.1975) and Youmna (b.1978).

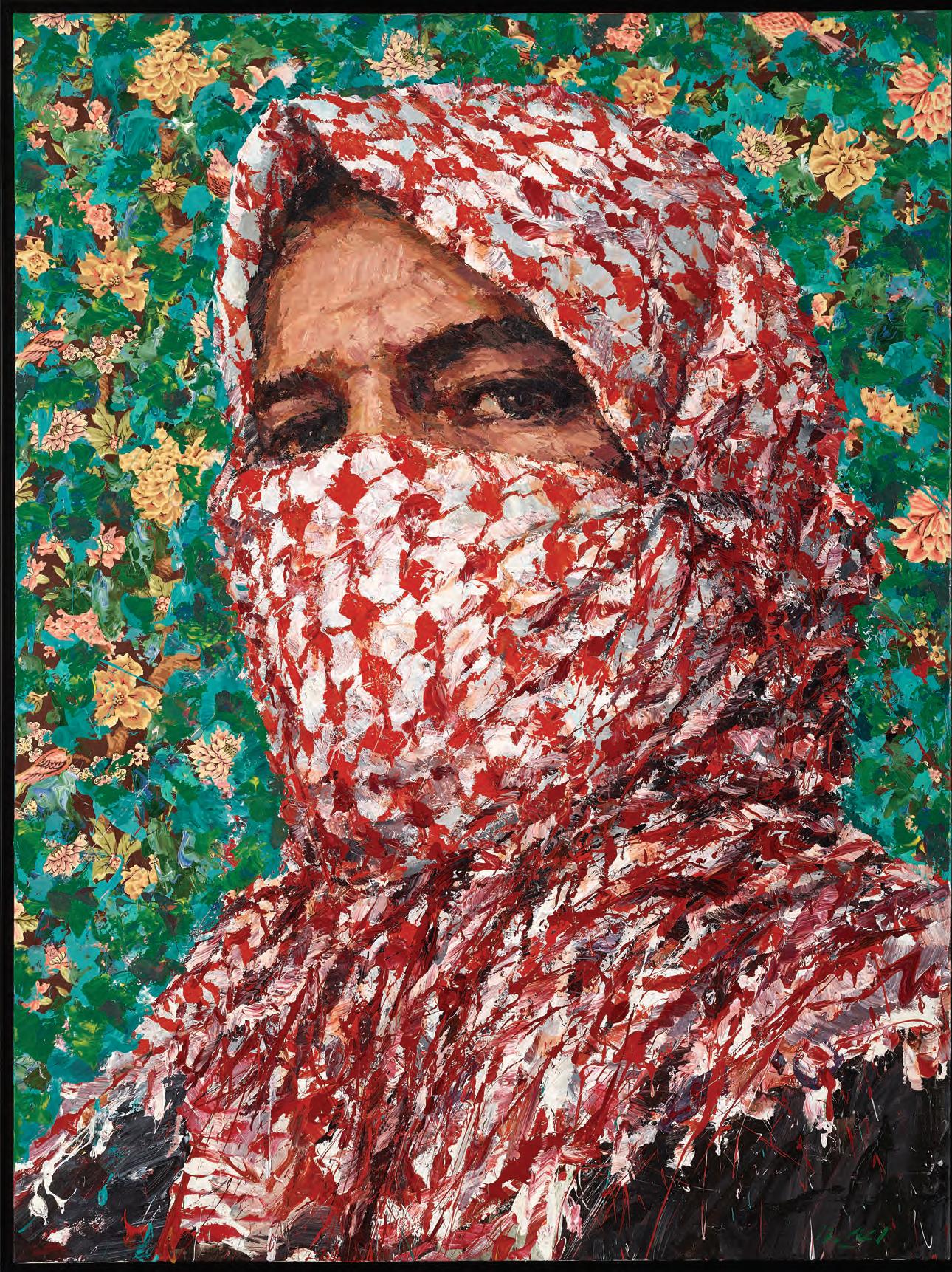

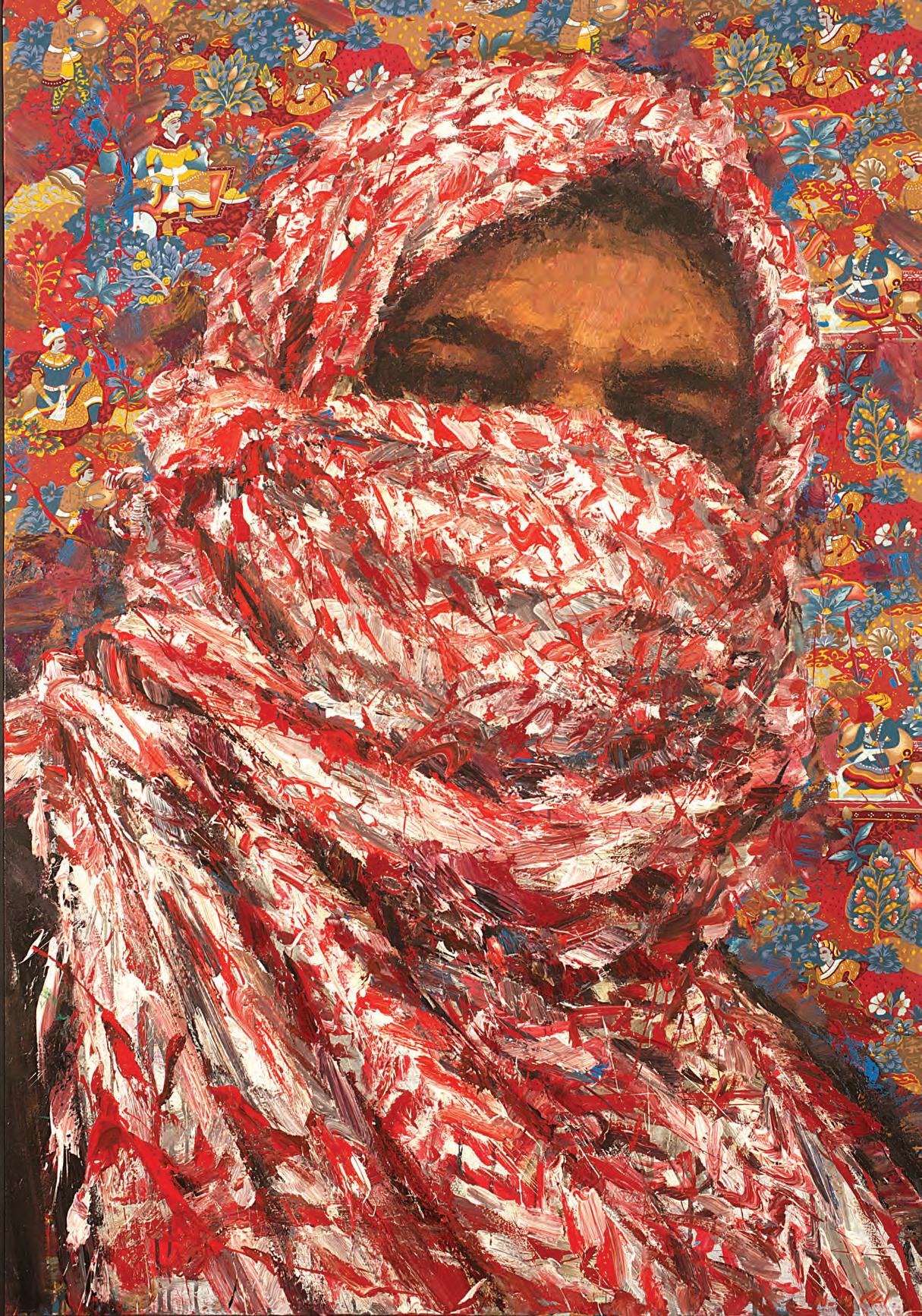

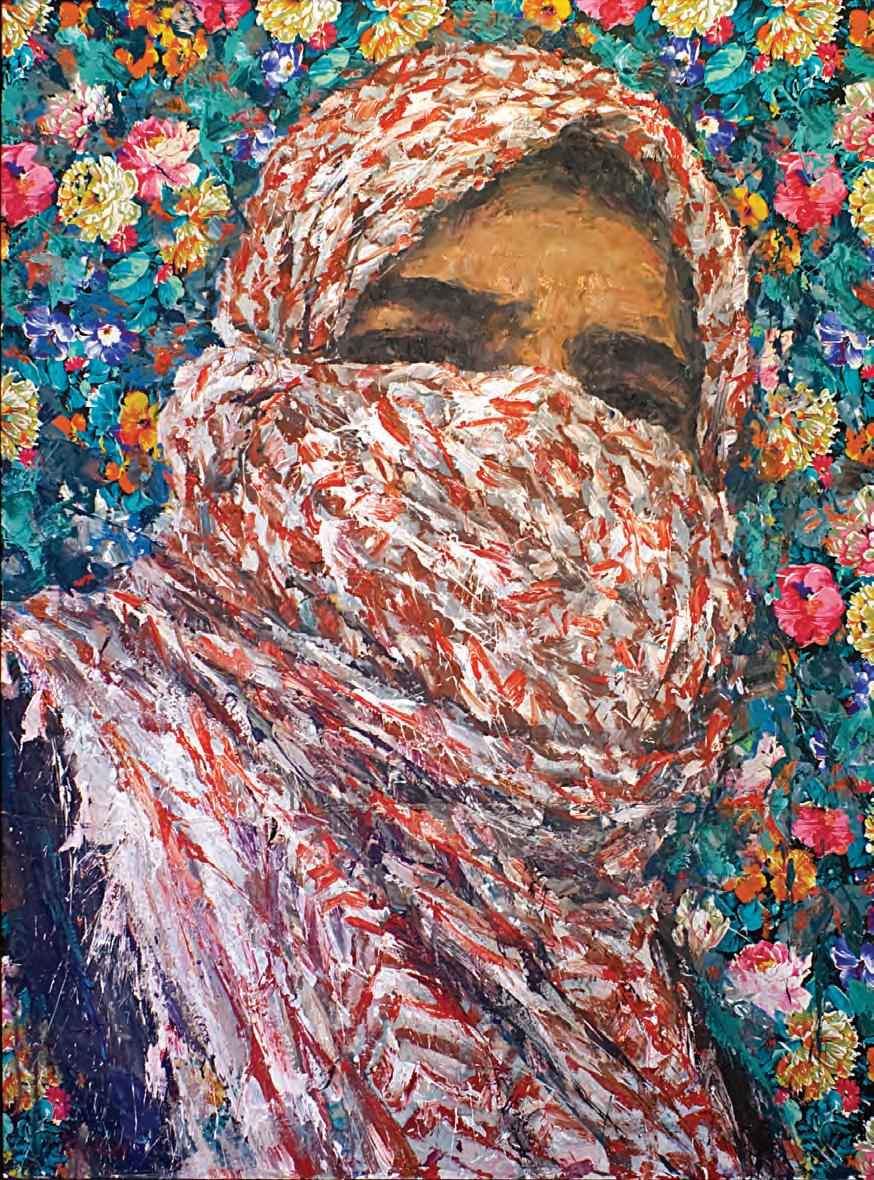

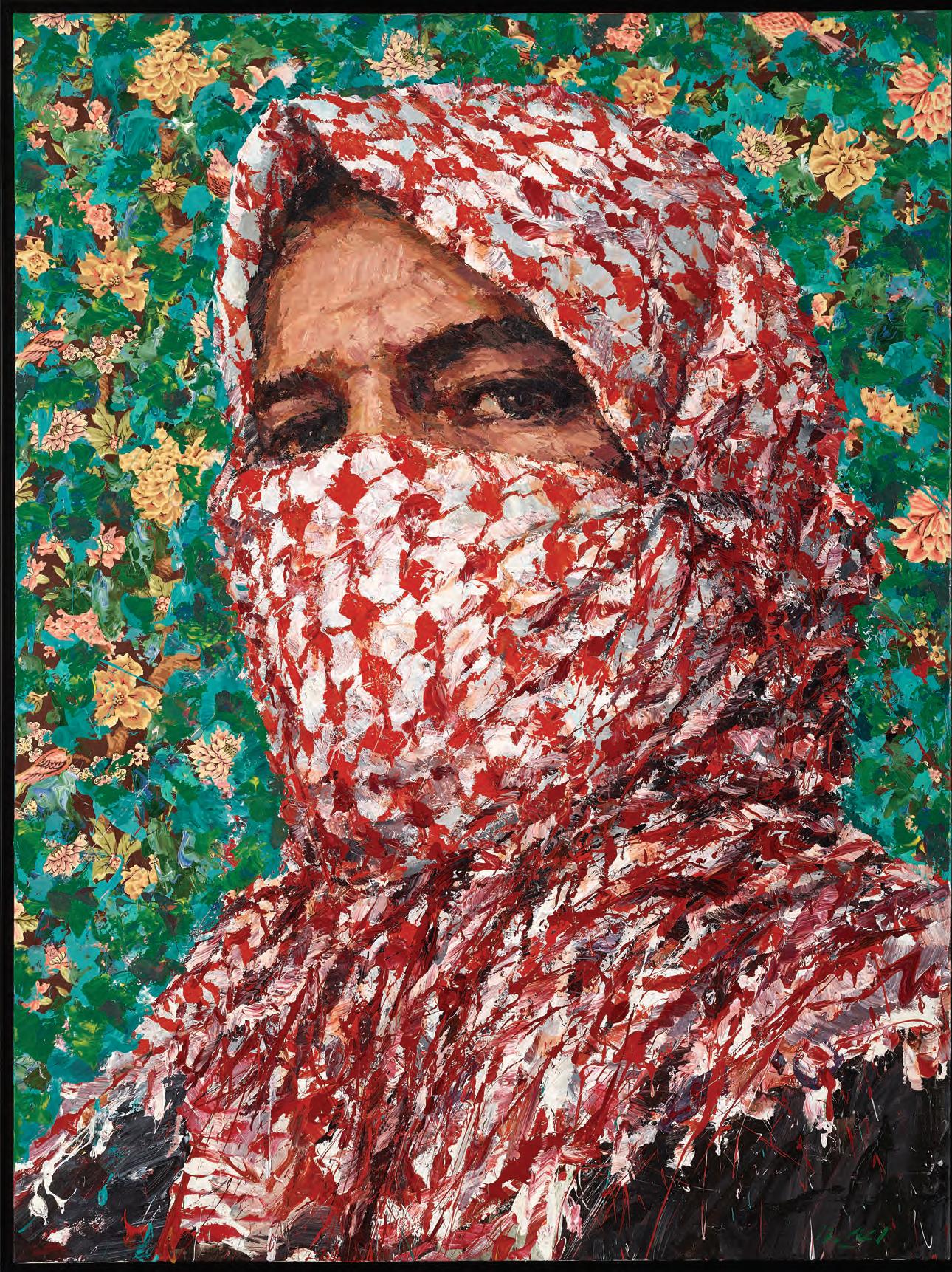

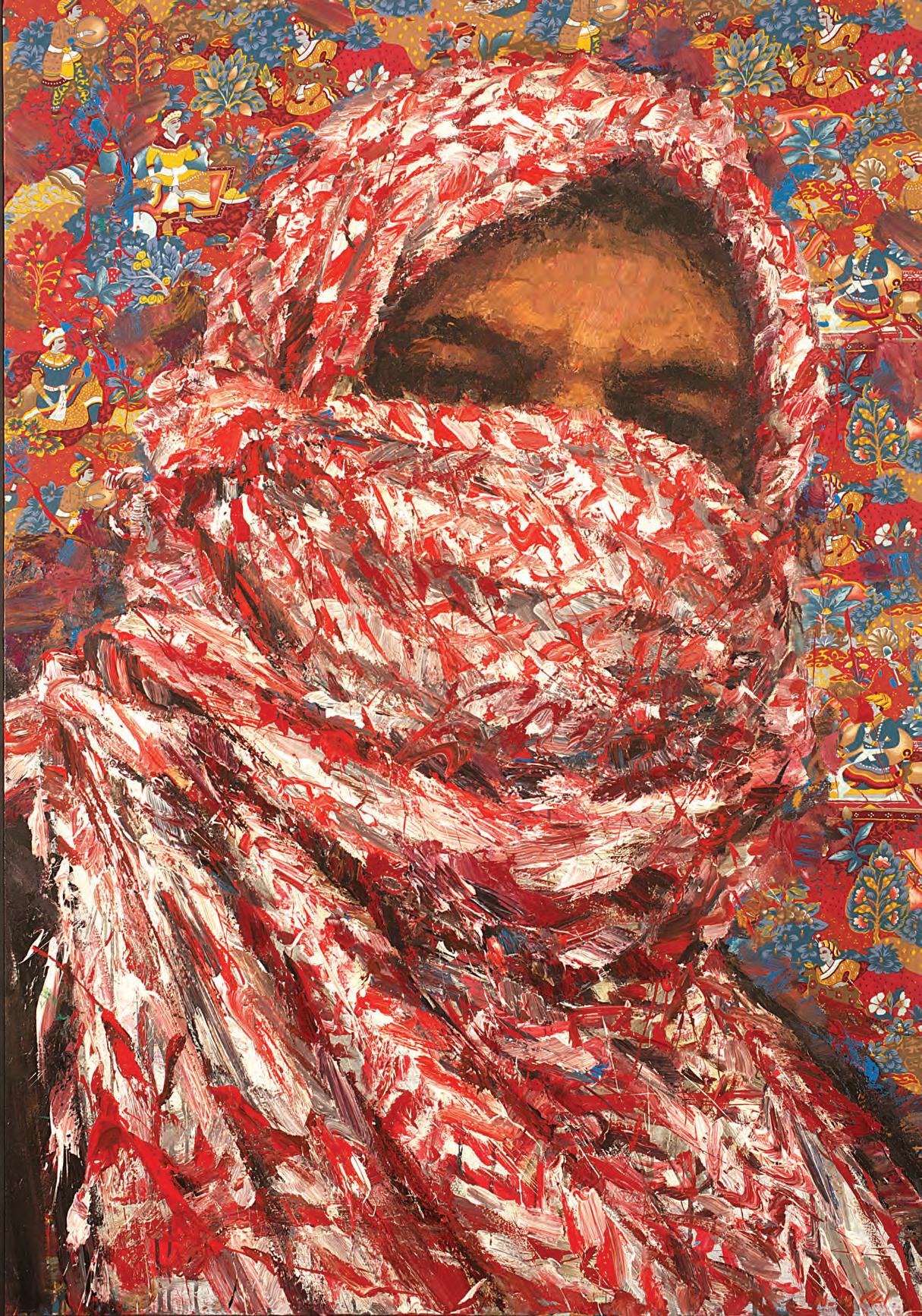

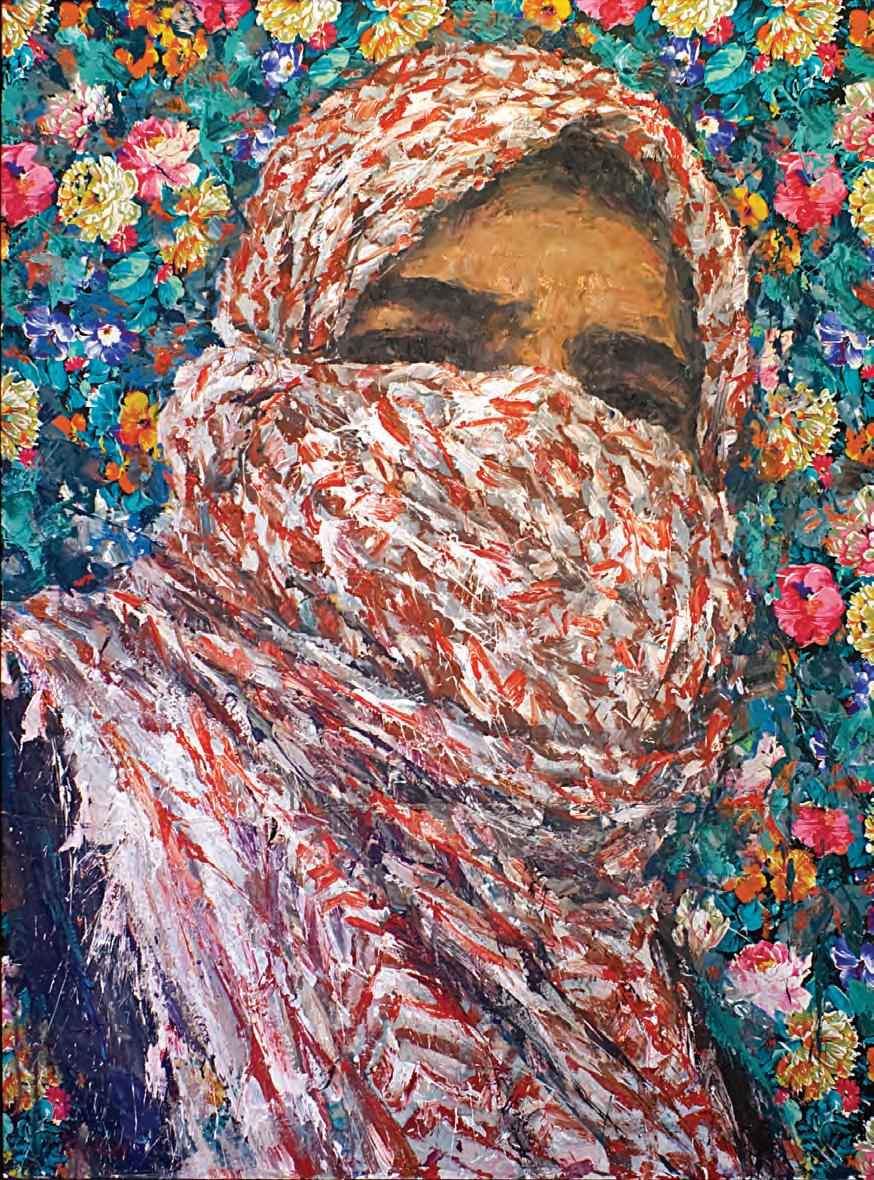

Baalbaki speaks of how he was inspired by the floral fabrics adopted in the ‘Kitschy ’outfits of the Lebanese southerners and Kurds who inhabited Wadi Abu Jamil. Baalbaki envisages these people “kept their once-left gardens and orchards in the floral fabric of their outfits.” The floral fabrics also reminded him of the clothes that people hung on their balconies on laundry lines, and which they had to leave behind during the 2006 July war.[7]

[1] Roz Wafa. Ayman Baalbaki Interview. Personal, May 16&19, 2020.

[2] Issa, Rose. “Biography .” Essay. In Ayman Baalbaki, Beirut Again and Again, 100. London: Beyond Art Production, 2011.

[3] Roz Wafa. Ayman Baalbaki Interview. Personal, May 16&19, 2020.

[4]“The Ta’if Accord that ended the war in 1989 failed to resolve or even address the core conflicts of the war, including the sectarian division of power in Lebanon,” “The Historiography and the Memory of the Lebanese Civil War.” Portail Sciences Po, October 25, 2011. https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violencewar-massacre-resistance/fr/document/historiography-and-memory-lebanese-civil-war.html.

[5] Roz Wafa. Ayman Baalbaki Interview. Personal, May 16&19, 2020.

[6] Tammouz Destruction & Loss,”. In Ayman Baalbaki, Beirut Again and Again, 47. London: Beyond Art Production, 2011.

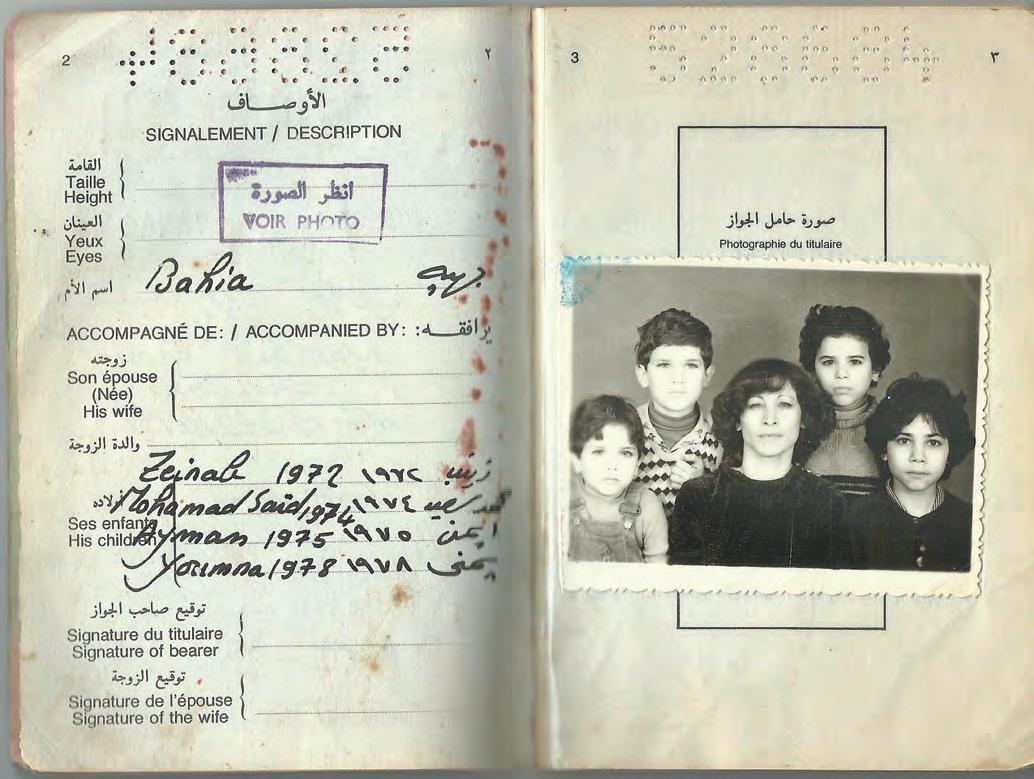

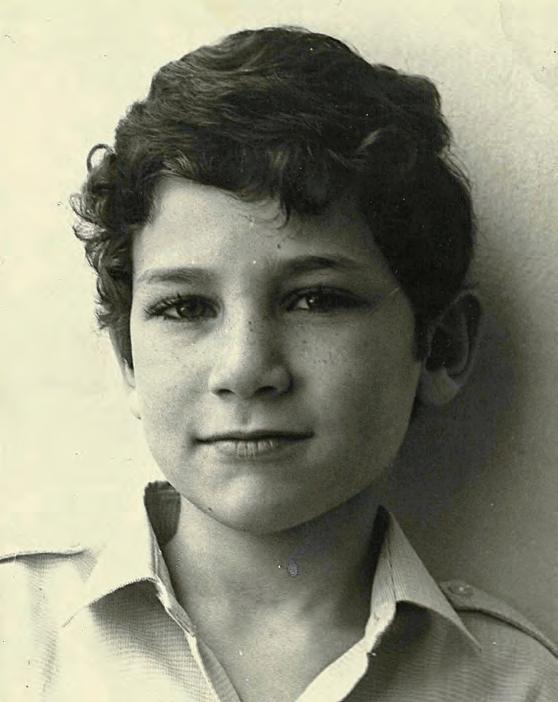

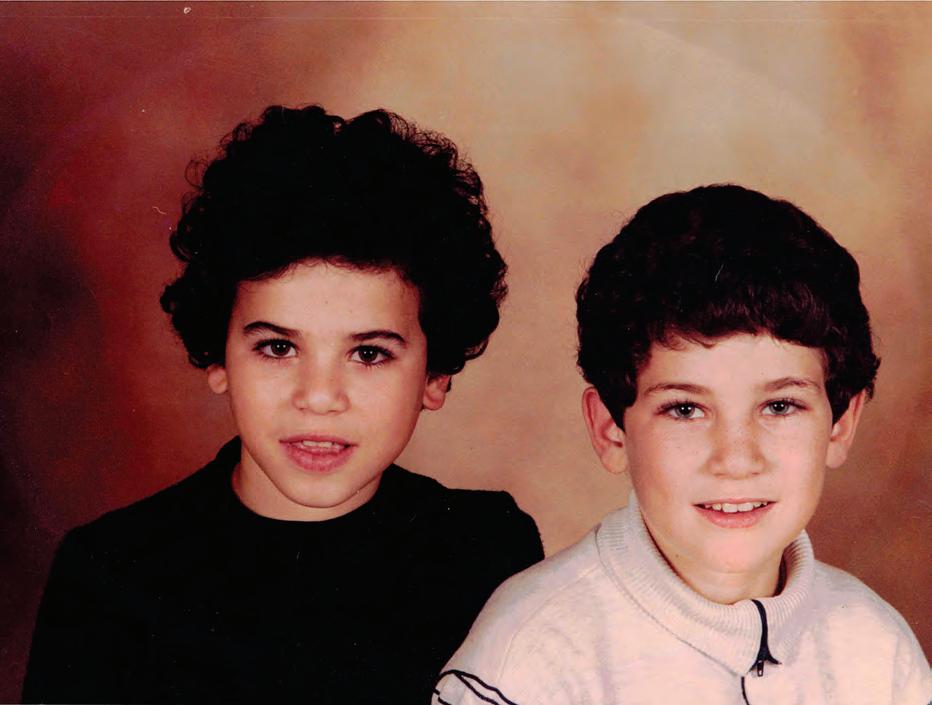

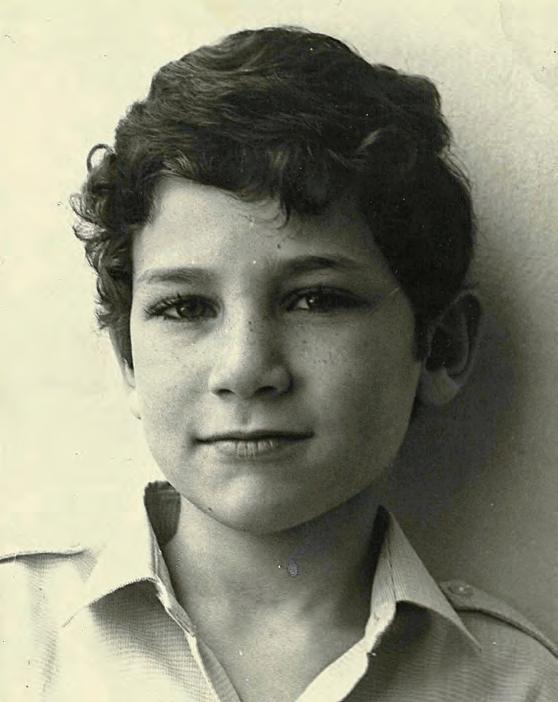

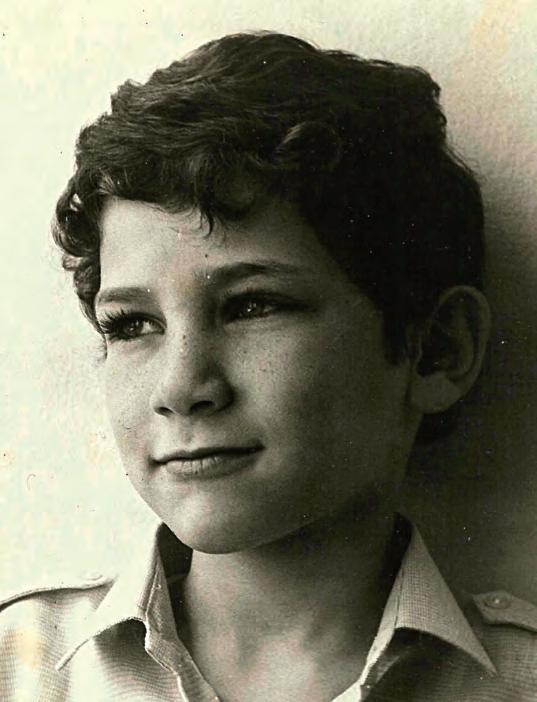

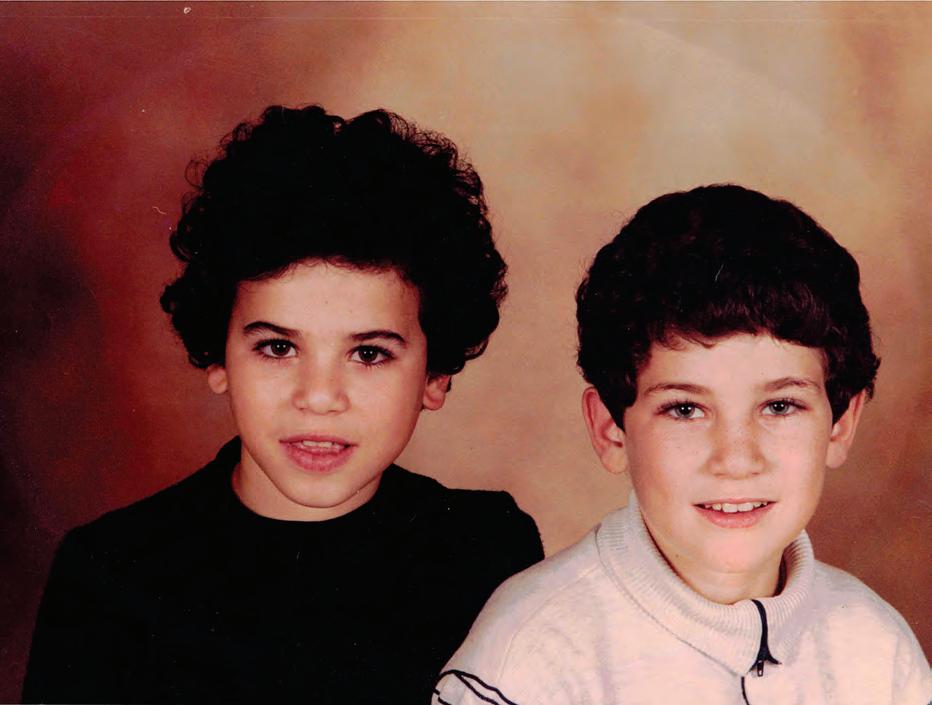

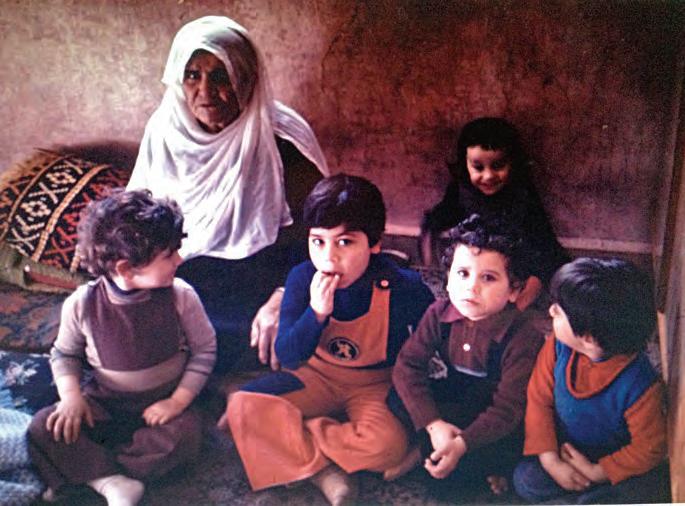

This page – Ayman Baalbaki aged 5 years old.

This page – Ayman Baalbaki aged 5 years old.

13

14

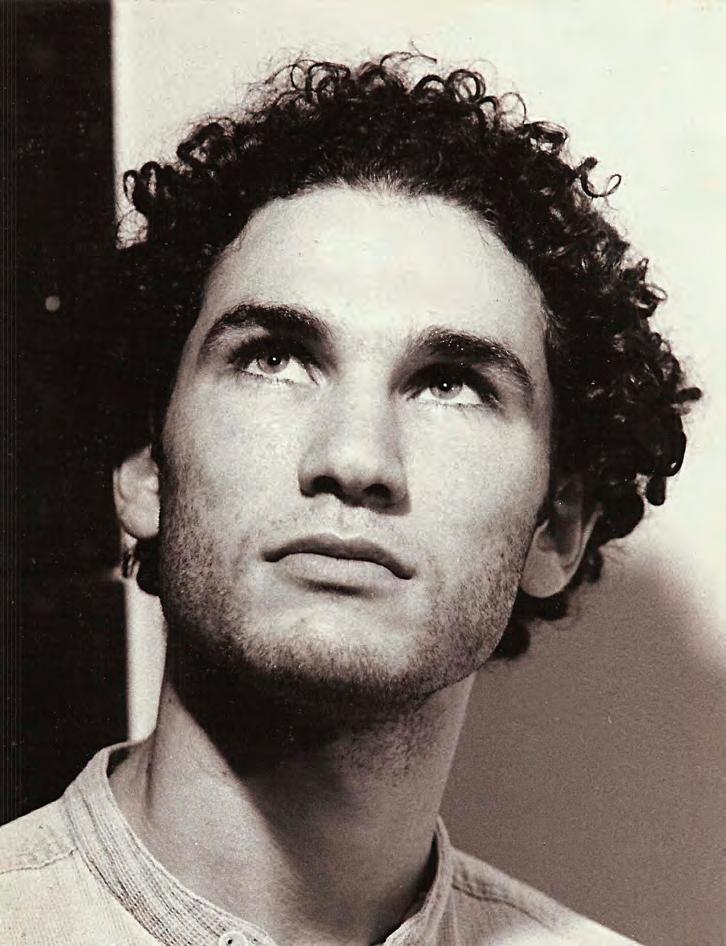

Ayman Baalbaki’s portrait by Gilbert Hage taken after winning first place at Empreintes, Joumana Rizk’s Maraya Art Gallery award in 1996.

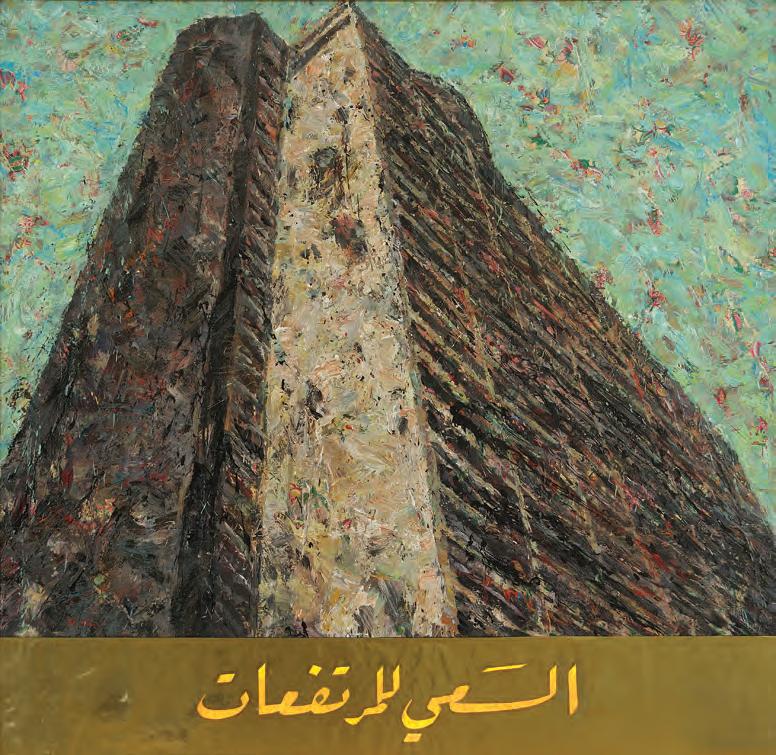

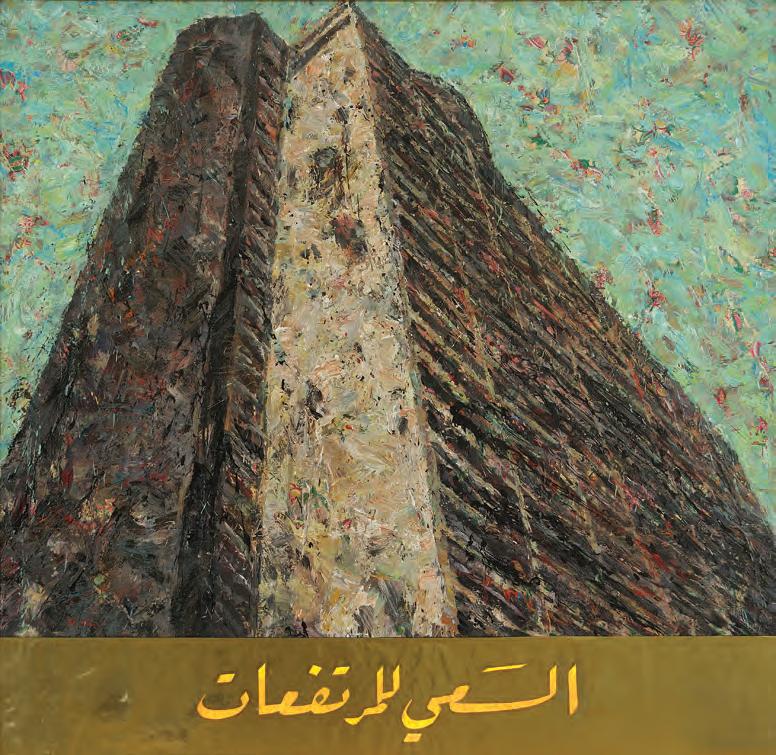

AS A COMMEMORATION, BAALBAKI PAINTS BEIRUT’S CIVIL WAR LANDMARKS –FAMOUS HOTELS AND HIGHRISE BUILDINGS THAT ARE NOW PEPPERED WITH SHRAPNEL AND BULLETS. BAALBAKI

PAINTED THE BURJ AL MURR TOWER, THE HOLIDAY INN HOTEL, THE ‘’BARAKAT SNIPER BUILDING’’ (RECENTLY TURNED INTO THE BEIT BEIRUT MUSEUM), AND ‘’THE EGG,” A NICKNAMED OLD MOVIE THEATRE. IN THESE PAINTINGS, HIS WORK TAKES ON A PERSONAL AND POLITICAL DIMENSION.

15

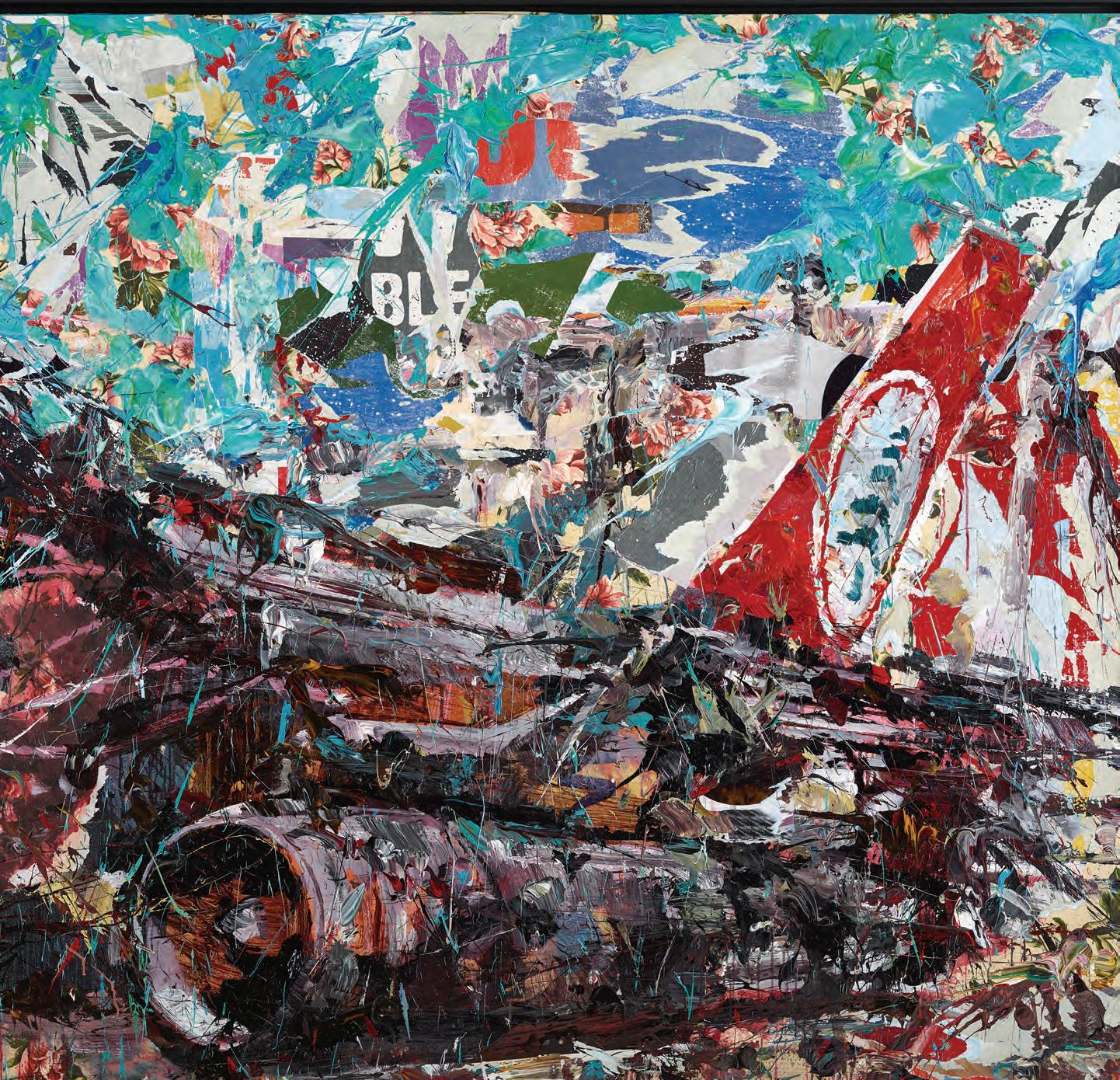

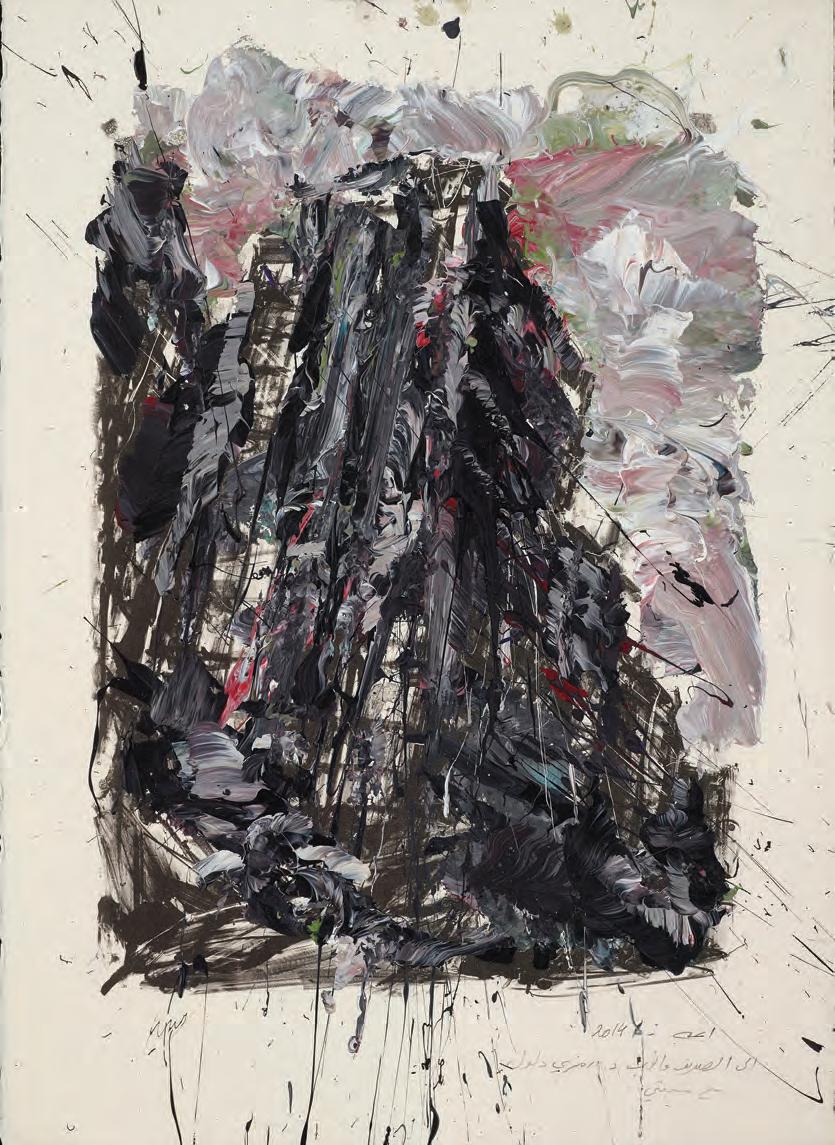

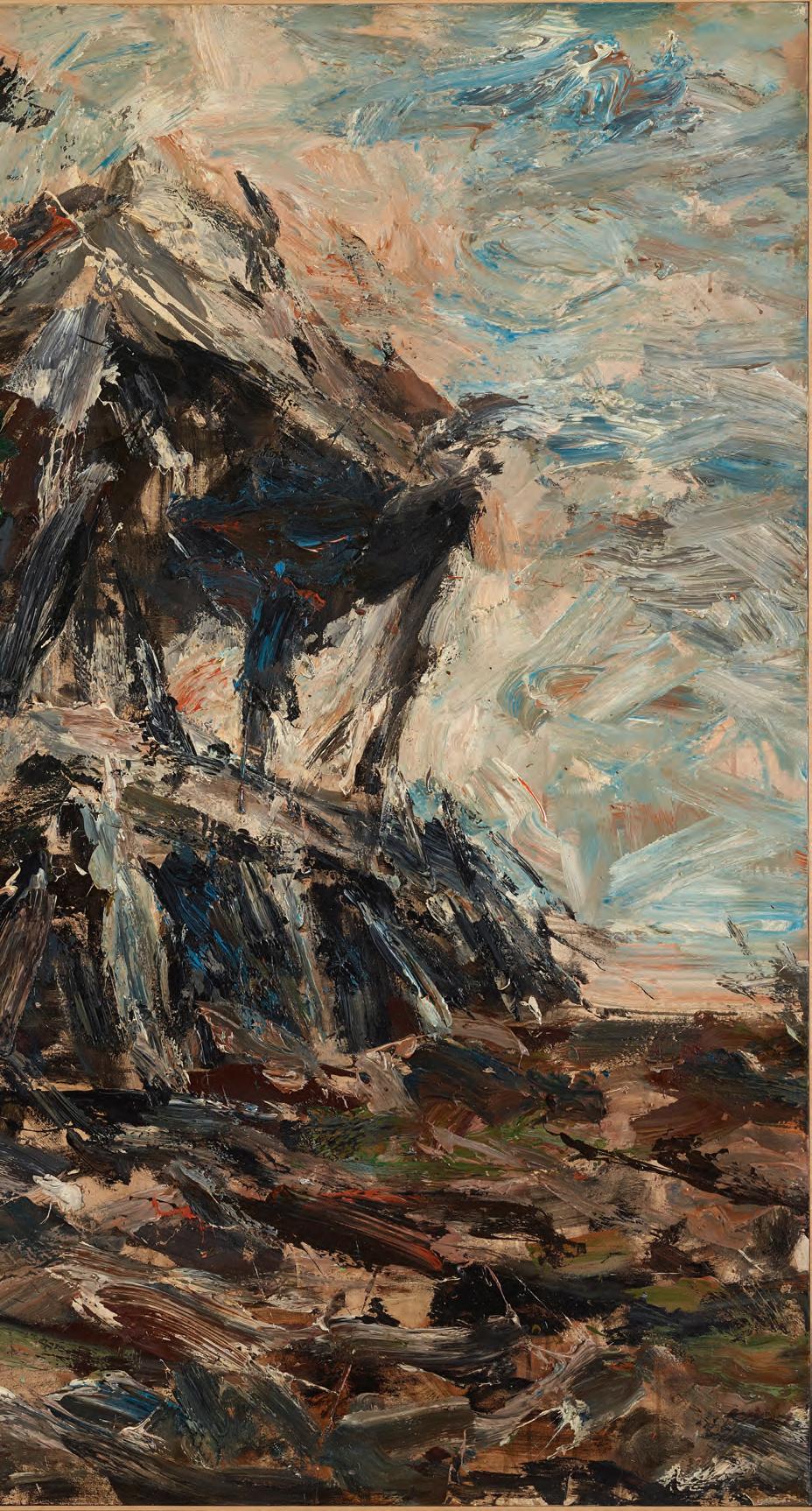

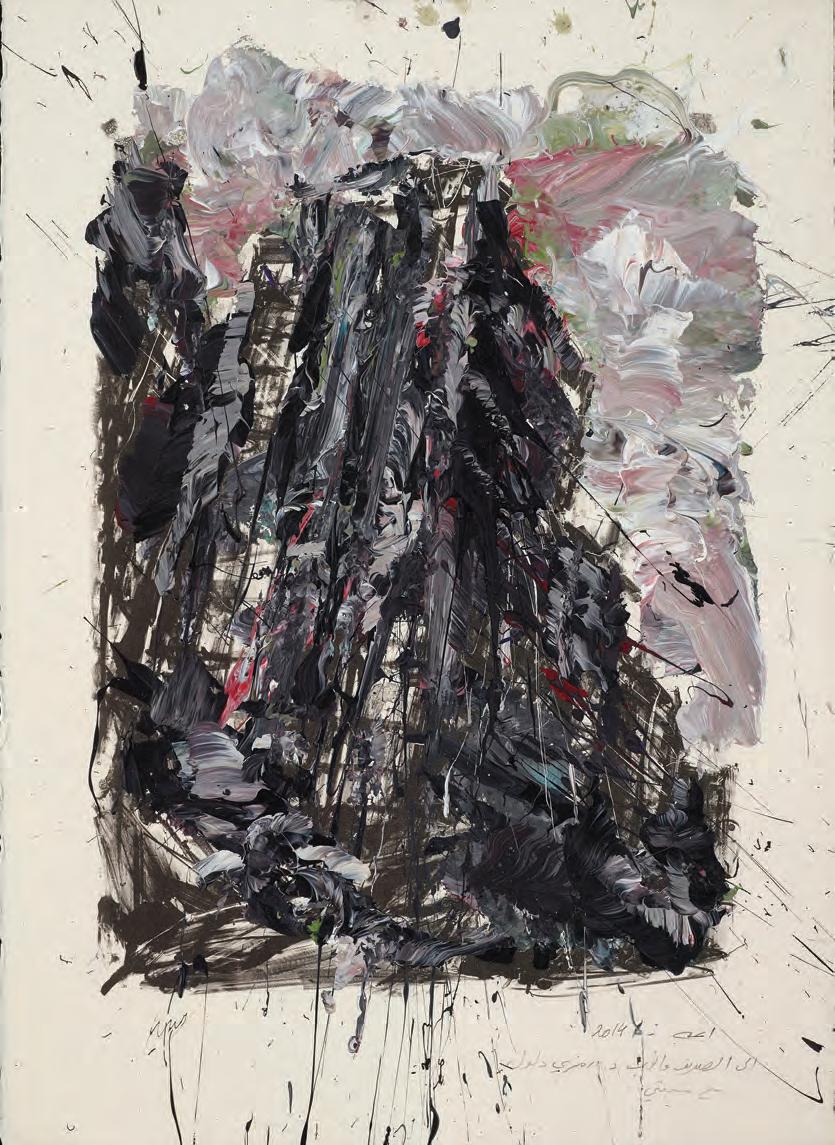

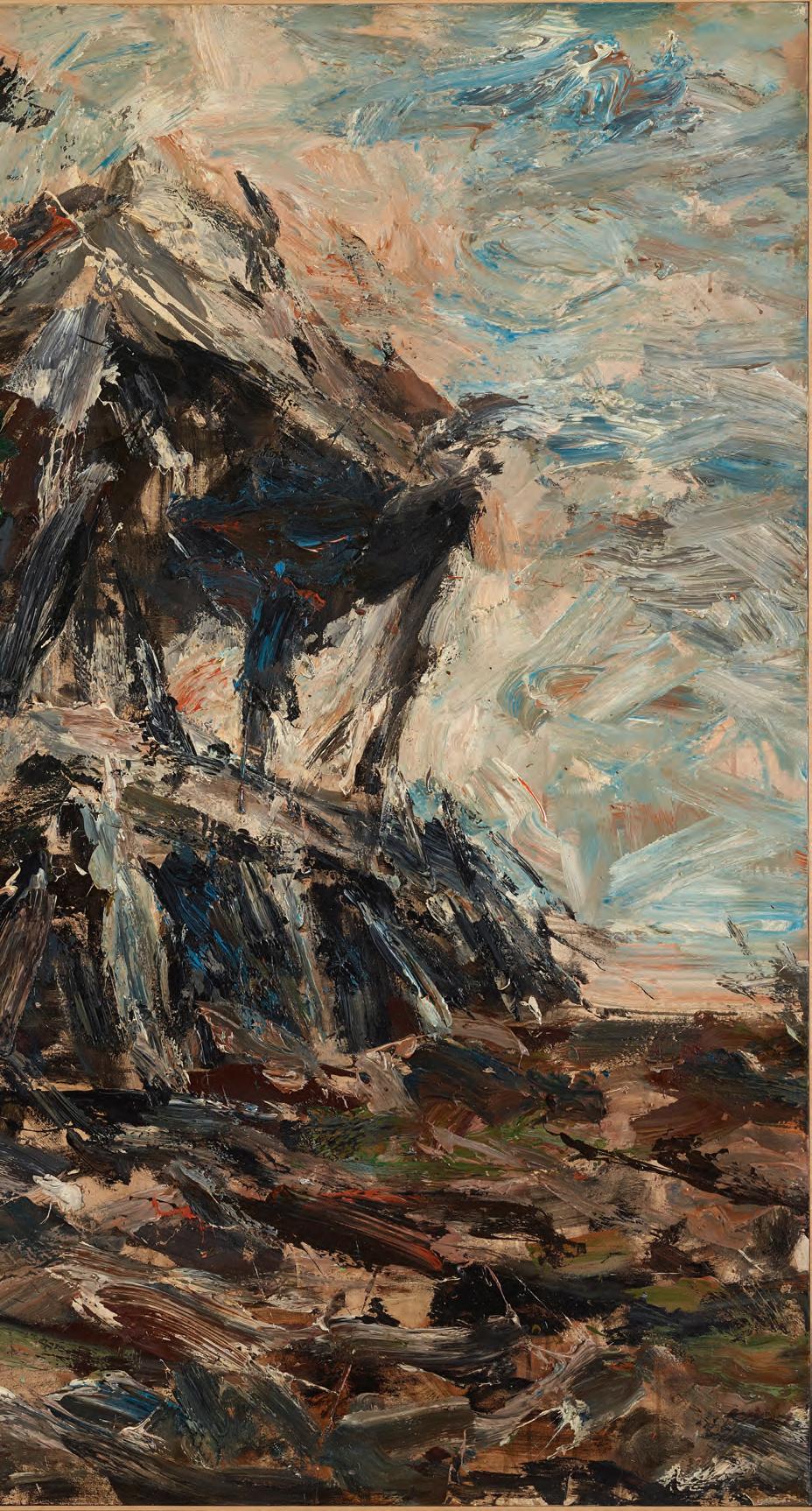

Baalbaki’s most alarming paintings are ones that depict havoc in the aftermath of war. These paintings belong to two ongoing series; one is Tammouz, which he started in 2007, as an elegy to the ravaged southern suburbs of Beirut, following the 2006 July war, and another, Contre-Jour, which he began in 2009.[5] Contre Jour is a play on words. It translates to Against Daylight in English, alluding to barbaric acts executed in broad daylight. Both series picture the destruction of individual architectural buildings in Beirut. In some of his paintings, Baalbaki depicts giant concrete bullet-riddled buildings in progressive collapse. Marked with despair and abandonment, most canvases amass crumbling ruins and debris. Baalbaki’s acrylics on canvas buildings usually occupy the centre of his canvas; black and grim like emblems of disaster. Baalbaki lightens the mood of his paintings with gaudy backgrounds toned in altered palettes of yellow, blue, green, or pink. At times, he mounts ready-made floral fabrics to the stretched canvas before he begins a piece.

Onto these flowery backdrops, Baalbaki applies paint in flat, thick, gestural brushstrokes, in an effort to re-enact modern warfare. Most paintings are untitled. Still, one is entitled Immeuble Yassine, 2010.[6] It features a ravaged building in Haret Hreik, where the Baalbakis once lived.

As a commemoration, Baalbaki paints Beirut’s civil war landmarks – famous hotels and high-rise buildings that are now peppered with shrapnel and bullets. Baalbaki painted the Burj al Murr tower, the Holiday Inn hotel, the ‘’Barakat sniper building’’ (recently turned into the Beit Beirut Museum), and ‘’the Egg,” a nicknamed old movie theatre. In these paintings, his work takes on a personal and political dimension. These buildings are located along the infamous “green line,” which once separated the militant factions of west Beirut from their rivals in east Beirut. The line was a footstep away from Wadi Abu Jamil.

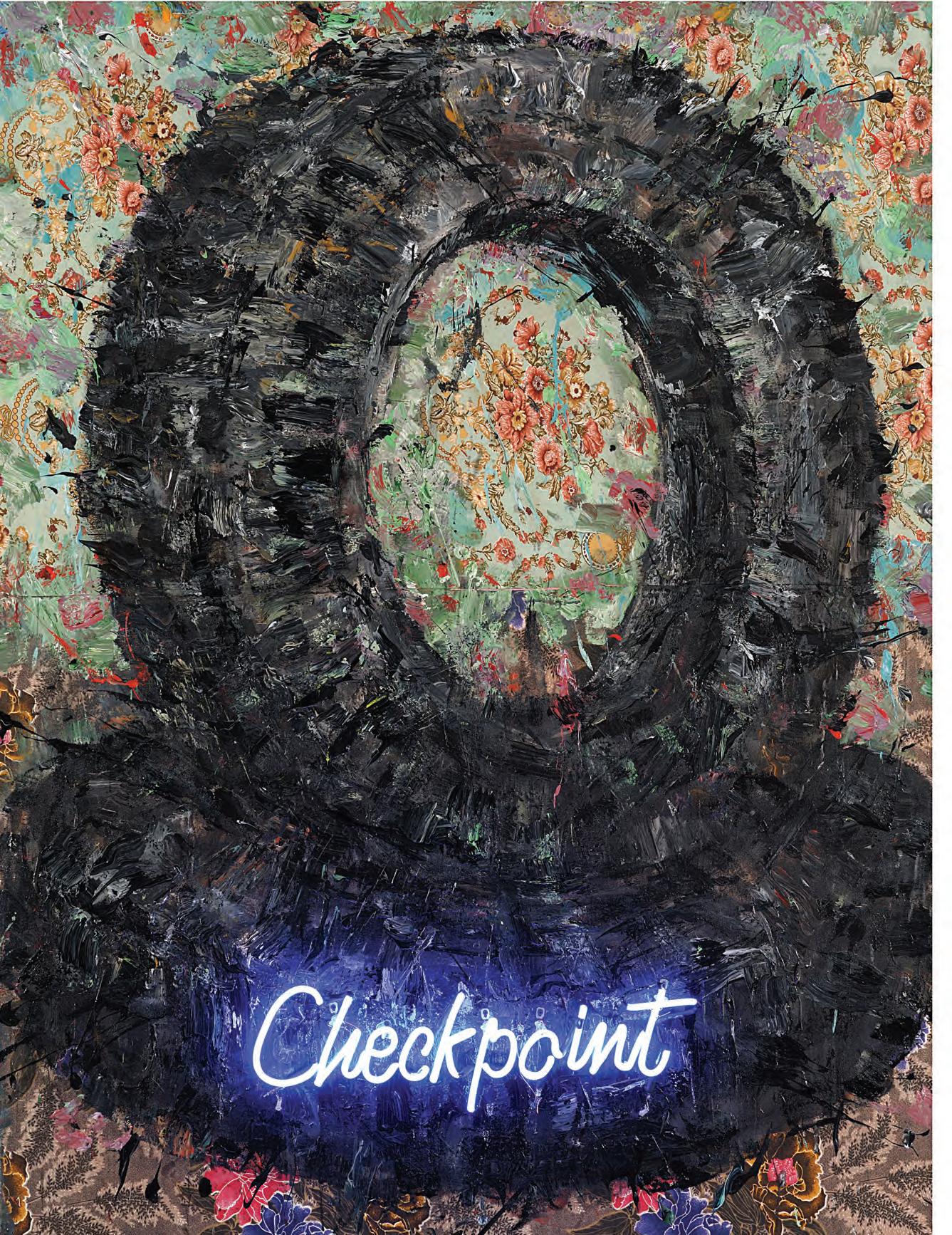

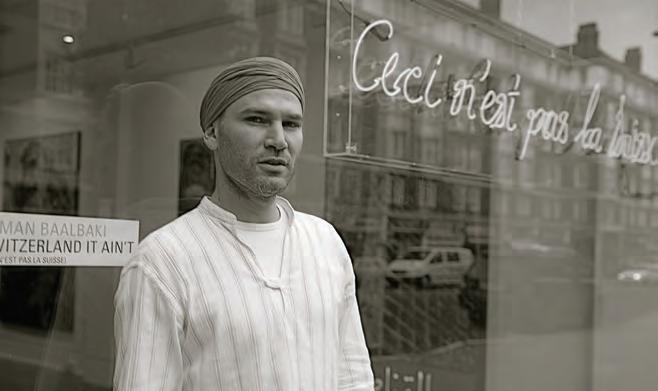

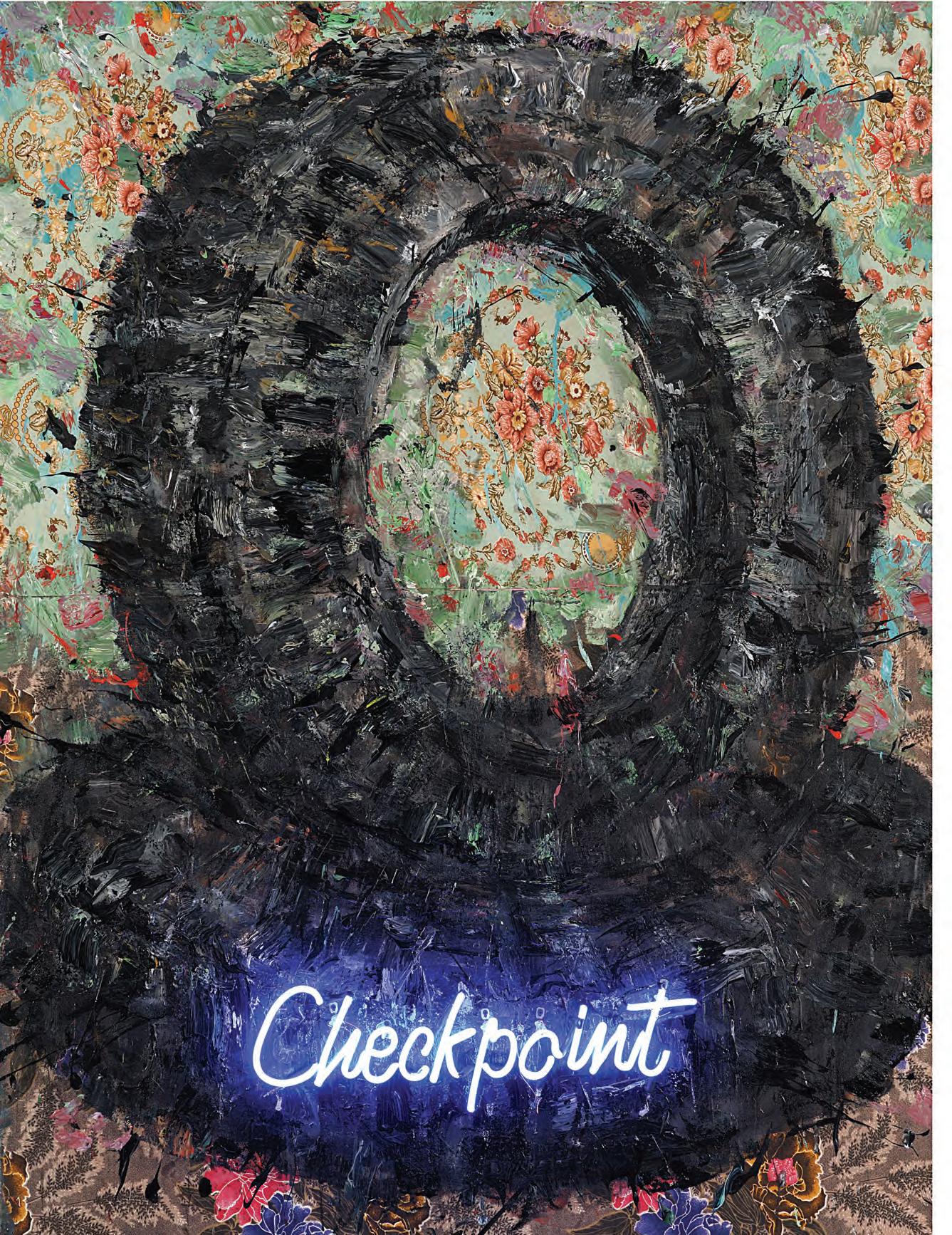

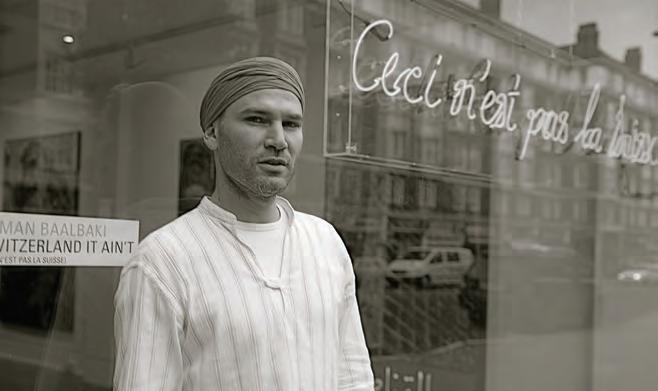

Baalbaki often incorporates text into his work, either in the form of metal stencil or neon light. For example, at the bottom of The Sniper,2009,[8] acrylic on fabric mounted on canvas painting, Baalbaki places a horizontal stencilled copper sheet that reads alqannas in Arabic, meaning sniper. Al-qannas is backlit in striking yellow, while the painting features the tall hulky building of the Holiday Inn hotel, which was a sniper’s nest during the war. The pop sign gives the painting a look of an Egyptian movie poster. Baalbaki’s Holiday Inn testifies to the transformation of a touristic haven, a place where movies were shot, to a fortress of war. Likewise, in 2009, during a solo show in London, Baalbaki displayed a blue neon light installation on the glass façade of the gallery’s entrance. It read “Ceci n’est pas la Suisse,” also the title of the show. His ‘pop art’ intervention resonates with Rene Magritte’s surreal image-word painting “Ceci n’est pas une pipe;” it mocks the fact that Lebanon was famously called “the Switzerland of the Middle East” before the war. Baalbaki said, “I wanted to incorporate in my work a textual aspect which is omnipresent in Arab culture.”[9]

[7] Roz Wafa. Ayman Baalbaki Interview. Personal, May 16&19, 2020.

[8] Issa, Rose. “Ayman Baalbaki in Conversation with Rose Issa.” Essay. In Ayman Baalbaki, Beirut Again and Again, 18. London: Beyond Art Production, 2011.

[9] “Breakfast at Baalbaki’s - Artbahrain.” Accessed May 21, 2020. http://artbahrain.org/wp2017/breakfast-at-baalbakis/.

[10] Fani, Michel. “Ayman Baalbaki: Searching f or Lebanon’s Soul.” Essay. In Ayman Baalbaki, Beirut Again, and Again, 25. London: Beyond Art Production, 2011.

[11] “ ‘Errance’ Displacement & Wandering .” Essay. In Ayman Baalbaki, Beirut Again, and Again, 76. London: Beyond Art Production, 2011.

[12] The Middle East,2014, mixed media painting is part of DAF collection.

[13] “Breakfast at Baalbaki’s - Artbahrain.” Accessed May 21, 2020. http://artbahrain.org/wp2017/breakfast-at-baalbakis/.

[14] One of the Al-Mulatham, acrylic on fabric laid on canvas, paintings dated 2013, (250x200cm) is part of DAF collection.

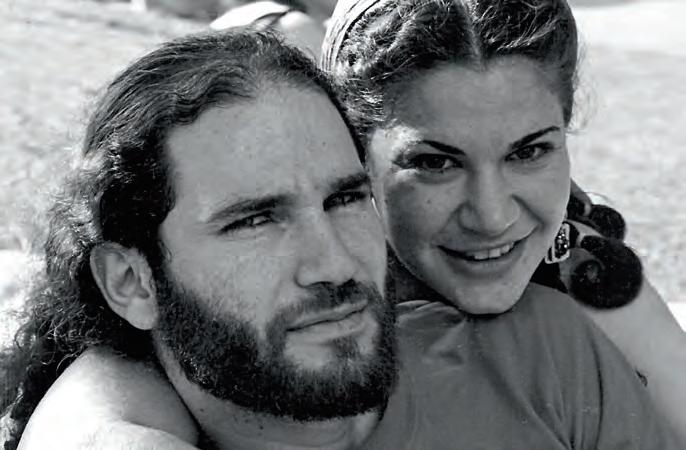

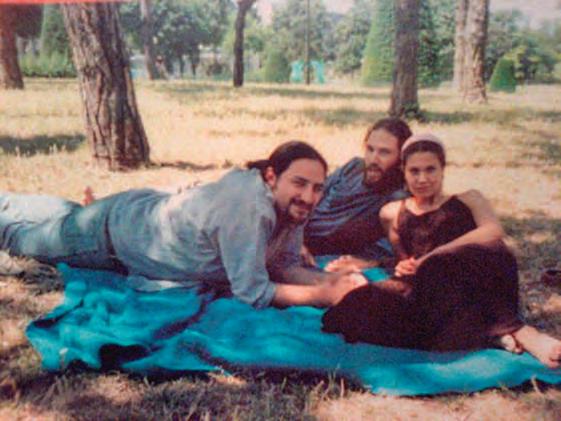

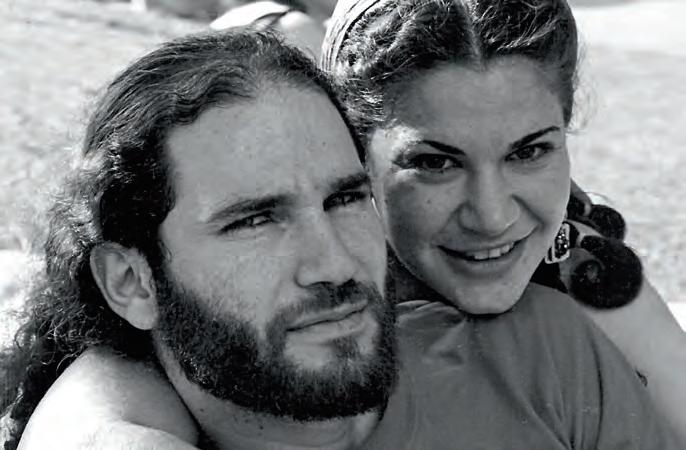

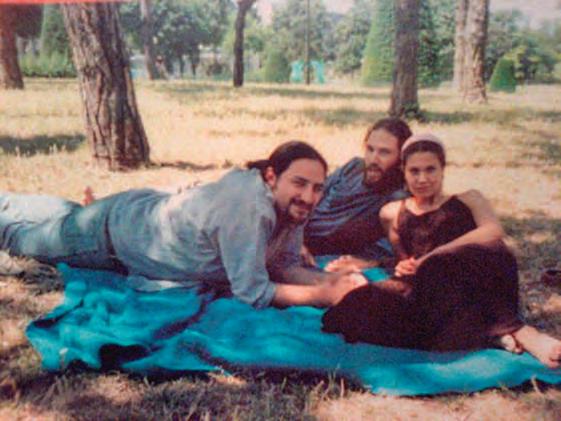

Ayman Baalbaki and Tagreed Darghouth in France, 2002-2003.

16

Baalbaki’s understanding of the significance of text in Arab culture goes back to his formative education years. His father was keen on teaching his children traditional Arabic poetry, specifically the pre-Islamic odes, alMu’allaqat. Besides learning the verses, Baalbaki gained insight from the thematic structure of the poems. Author Michel Fani was the first to relate Baalbaki’s art, contextually, to the thematic structure of al-Mu’allaqat. Fani explains, “three themes are at the heart of preIslamic poetry: a special relationship to space and place, wandering, and identity.” He then asks, “are they not exactly what guides Ayman Baalbaki’s brush and inspiration?”[10]

Indeed Baalbaki depicts displacement and wandering in a sequence of installations entitled Destination X, which he started as early as 2004. Drawing from Arte Povera, he deploys pre-used or cheap everyday objects. Destination X, 2010, for example, which was shown in Liverpool in 2010, comprises a worn-out red Fiat placed on a rotating platform with a neon light rim around it.[11] The car is loaded with household furniture and bedding

all tied up in a bundle on the roof of the vehicle: floral mattresses, pillows, bags, chairs, and plastic buckets. The bright colours and clumsy setup suggest frivolousness, even when the theme is not humorous at all. This play, in contrast between material and context, is also realised in Baalbaki’s 2013 Murano glass sculptures depicting car tires and X-shaped metal barriers as border checkpoints. In one of his most celebrated and controversial sequences of portraiture known as Al-Mulatham (the masked), Baalbaki experiments with the oftencontradictory themes of anonymity and visibility. Large-scale paintings, in acrylic on fabric laid on canvas, feature one gigantic bust view portrait of a fida’i (a freedom fighter) against a vibrant flowery background. [12] The head and face are obscured in a white and red chequered keffiyeh, and only the shadowed sharp eyes are spared. Though stunning in their animated patterns and bright colours, the portraits echo uncertainty and disillusionment. Baalbaki explains that these portraits “incarnate both hope and despair.” He also adds, “in every portrait, I seek to offer a different interpretation and a new way of reading.” [13] Curiously, author Michel

17

Ayman Baalbaki (center) with his brother Said (left) and sister Youmna (right)

Fani perceives Al-Mulatham as Baalbaki’s self-portrait in the guise of a fida’i. The word fida’i is usually associated with Palestinian freedom fighters. However, it generally translates to “the one who sacrifices himself” and is associated with Christ as saviour. Therefore, the fida’i can be anyone seeking redemption or salvation.

In Al-Mulatham, Baalbaki examines the keffiyeh as an iconographic symbol. The keffiyeh, a white square cotton scarf chequered in black or red, was initially used as a traditional headdress and soon evolved into a glorified symbol of the Palestinian resistance. In the west, it has become a symbol of Islamist extremists. However, for Baalbaki, Al-Mulatham is neither a glorified symbol nor a symbol of terror. Though Baalbaki’s keffiyeh is imposing, it is painted with frenzied red and white brush strokes. The fida’i holds no weapons and is drawn against a ‘kitschy’ background. Al-Mulatham is a complex and often misread masked hero.

What is most remarkable about Baalbaki is his signature expressionist style. This is best exemplified in one of his seminal mixed media on canvas paintings entitled The Middle East, 2014 measuring 207.5x407.5 cm.[14] Approaching the large-scale artwork, one is faced with

an explosion of paint in all directions - paint splashed, smeared, and dripping. The painting features the carcass of a wrecked Middle East Airlines aeroplane with the green cedar tree logo marked on its remaining red tail. At a closer look, the viewer discovers that cut-out prints and floral fabric lie underneath a thick stratum of a burgundy, grey, red and turquoise colour palette. This painting registers the bombing of the Beirut airport by Israeli forces in 1982; one more artwork dedicated to Lebanon’s eclipsed turbulent history.

“Most of the time, I don’t do preparatory studies,” says Baalbaki. “I start to paint spontaneously, and the painting takes over. It’s very violent,”[15] he adds. The artist draws inspiration from German Expressionism, NeoExpressionism, and Abstract Expressionism or Tachisme. Baalbaki applies paint in aggressive brushstrokes. At other times, he uses spray paint, or strikes masses of acrylic paint from a distance onto his canvas. He completes the desired picture in nearly one sitting. However, he revisits a painting several times before considering it done. This process sometimes takes him years.[16]

A free soul and an inspiring artist, Baalbaki currently lives and works in Beirut, Lebanon.

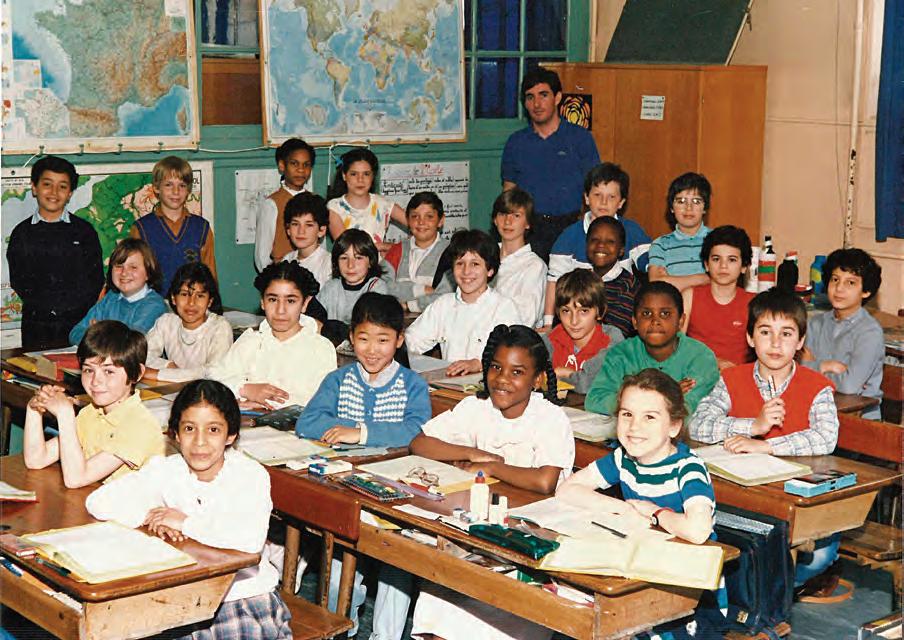

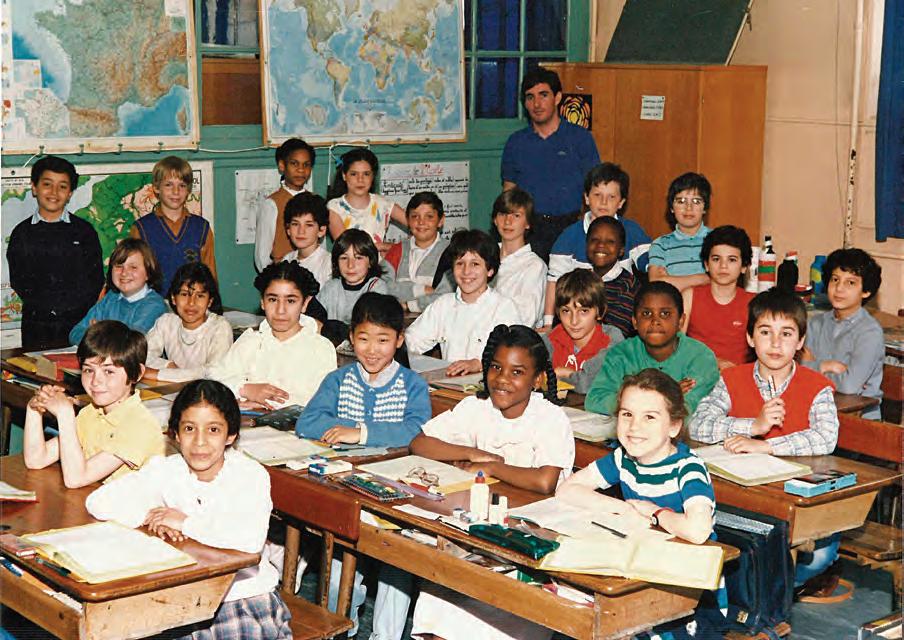

Ayman Baalbaki (wearing white, fourth student on the upper left) and Said Baalbaki (wearing red, third student from the upper right) at school in Gentilly, France, 1985-1986.

[15] Stoughton, India. “Ayman Baalbaki.” Executive Life, October 13, 2016. http://life.executive-magazine.com/art-culture/artists/ayman-baalbaki. [16] Roz Wafa. Ayman Baalbaki Interview. Personal, May 16 &19, 2020.

[15] Stoughton, India. “Ayman Baalbaki.” Executive Life, October 13, 2016. http://life.executive-magazine.com/art-culture/artists/ayman-baalbaki. [16] Roz Wafa. Ayman Baalbaki Interview. Personal, May 16 &19, 2020.

18

“I START TO PAINT SPONTANEOUSLY, AND THE PAINTING TAKES OVER. IT’S VERY VIOLENT,”HE ADDS. THE ARTIST DRAWS INSPIRATION FROM GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM, NEOEXPRESSIONISM, AND ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM OR TACHISME. BAALBAKI

SURELY APPLIES PAINT IN AGGRESSIVE BRUSHSTROKES.

“MOST OF THE TIME, I DON’T DO PREPARATORY STUDIES,” SAYS BAALBAKI.

19

Fawzi Baalbaki and his children Zeinab, Youmna, Said and Ayman (from left to right). Photo taken during Eid by Ayman Baalbaki’s uncle Abdelhamid Baalbaki.

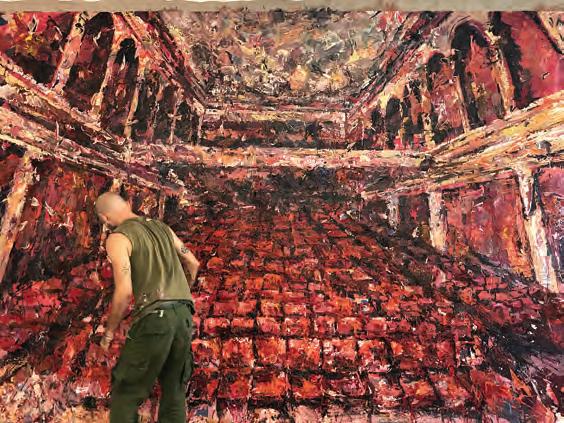

BEHIND JANUS GATE

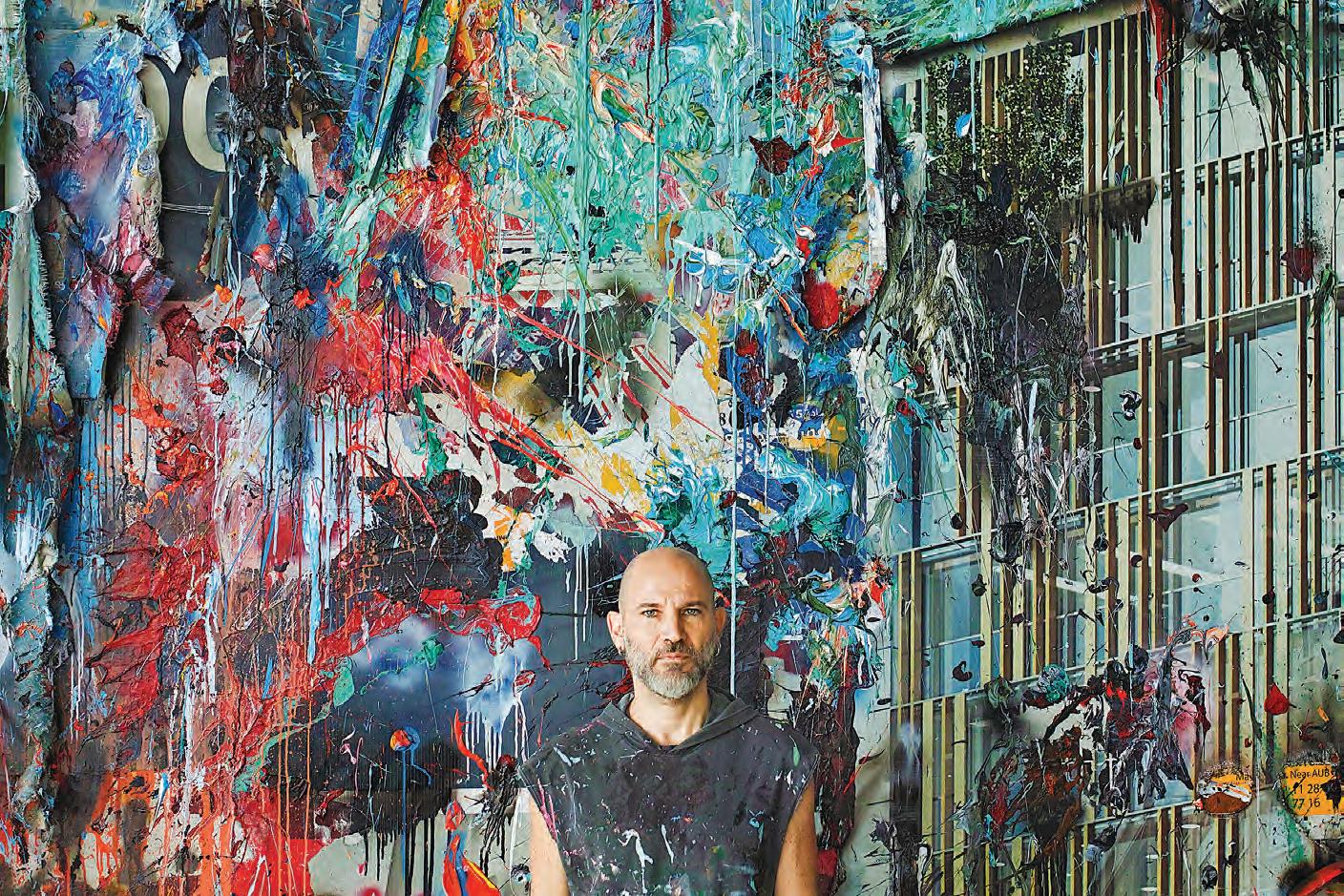

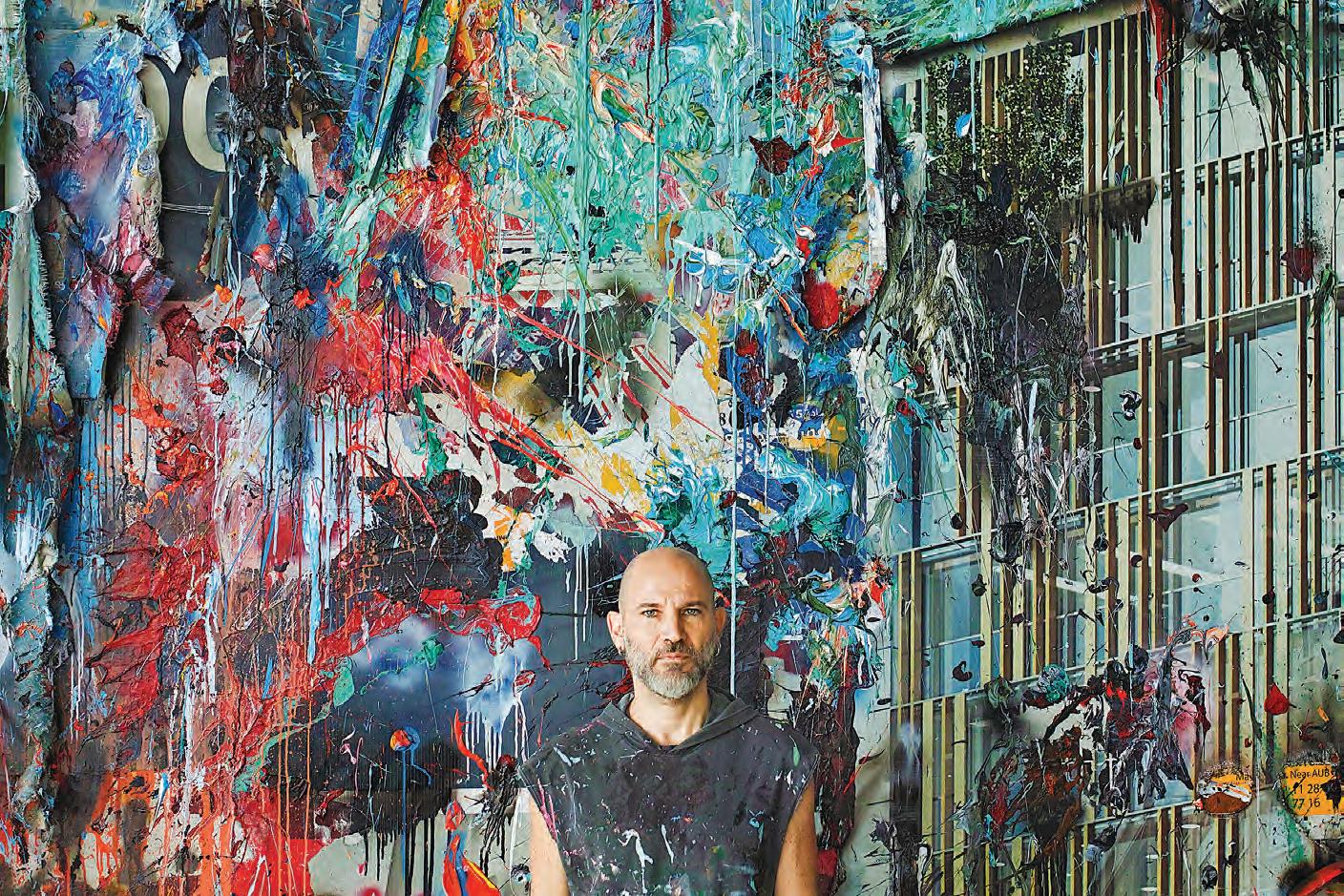

Ayman Baalbaki in front of his latest work, Janus Gate, 2022.

Photo by Marco Pinarelli.

Photo credit following images –

Marco Pinarelli

Ayman Baalbaki

Anas Ghaibeh

Anastasia Nysten

Basel Dalloul

Ayman Baalbaki in front of his latest work, Janus Gate, 2022.

Photo by Marco Pinarelli.

Photo credit following images –

Marco Pinarelli

Ayman Baalbaki

Anas Ghaibeh

Anastasia Nysten

Basel Dalloul

20

TITLED “JANUS GATE”,

AYMAN BAALBAKI’S WORK FOR THE LEBANESE PAVILION AT THE 59TH VENICE BIENNALE IS HIS MOST AMBITIOUS AND MONUMENTAL INSTALLATION TO DATE.

21

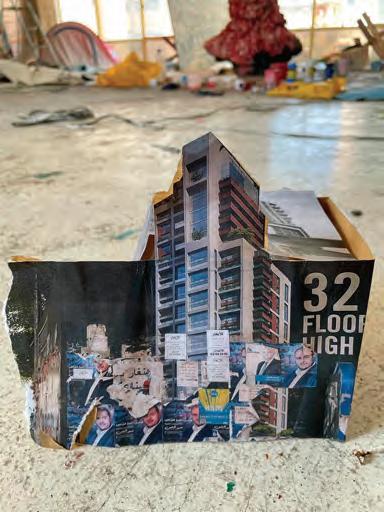

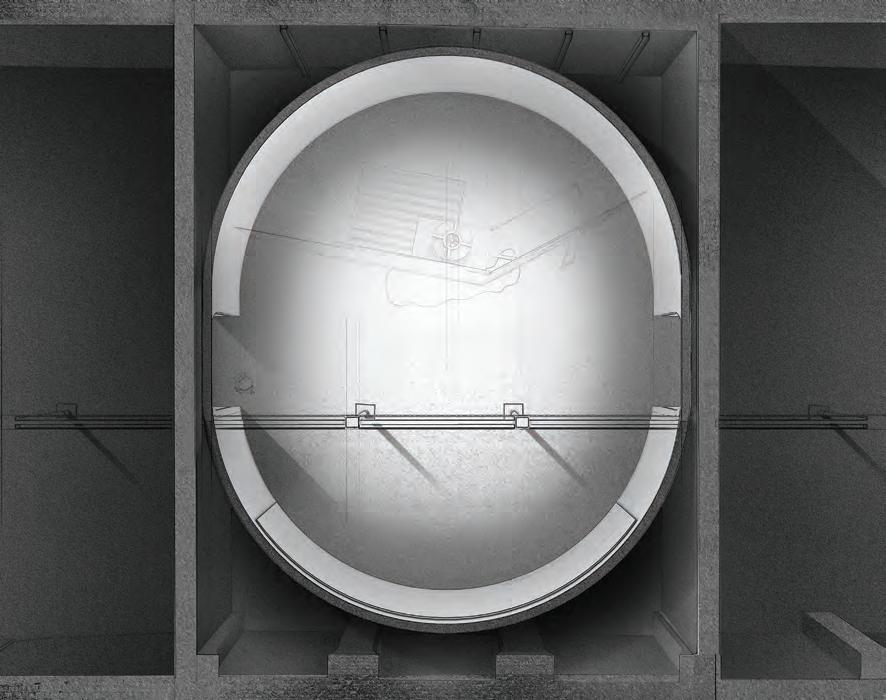

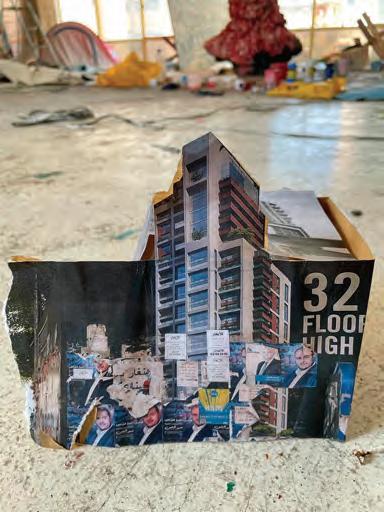

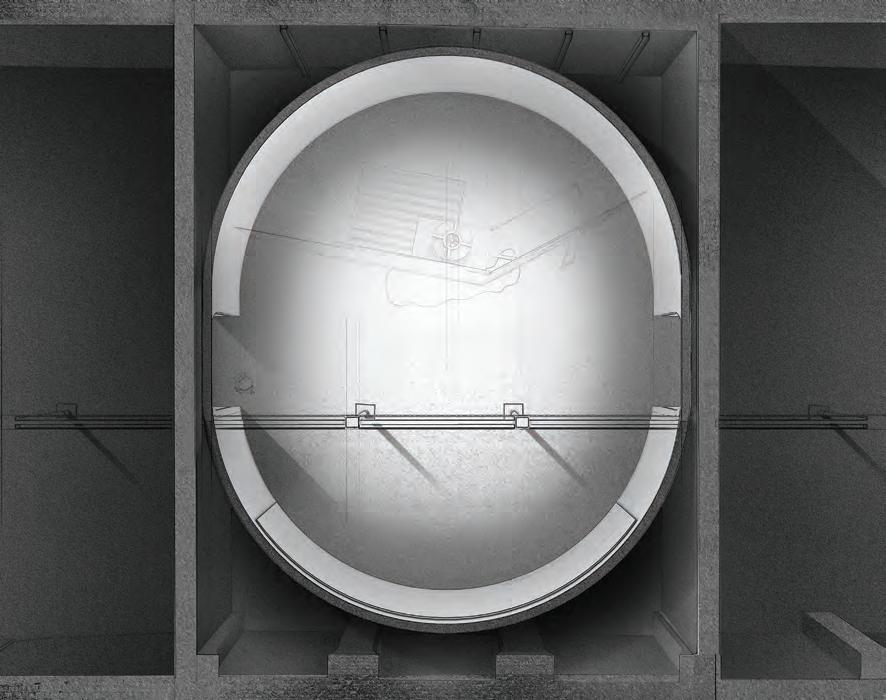

Mockup in cardboard of Ayman Baalbaki’s latest work, Janus Gate.

22

23

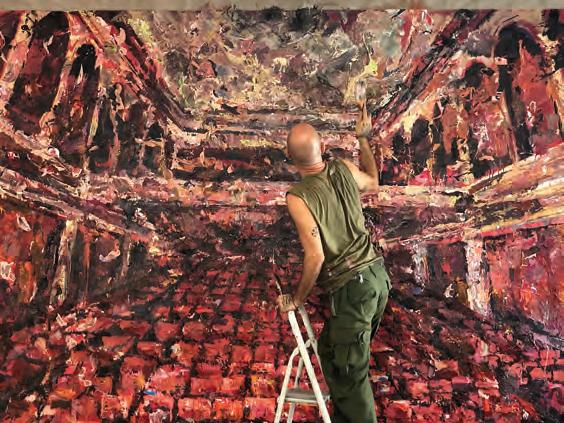

Ayman Baalbaki at work in his temporary studio by the Corniche in Beirut.

24

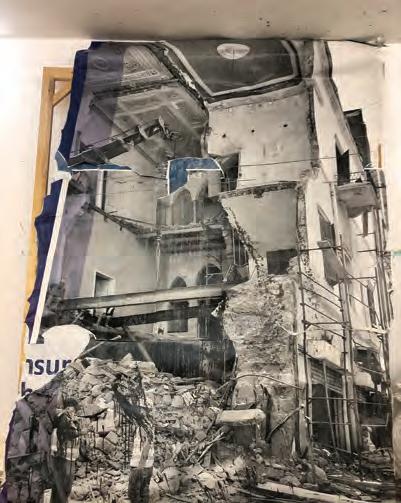

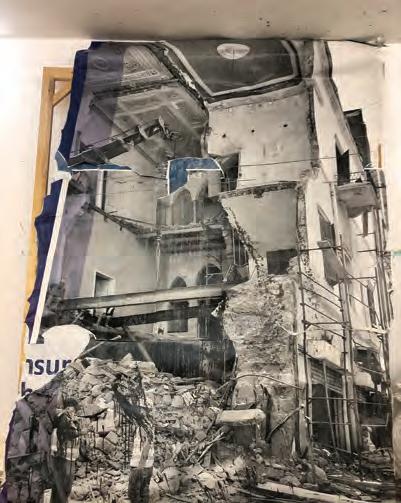

Ayman Baalbaki’s Janus Gate, work in progress.

25

26

Standing five metres high, the 3D structure allows you to pass from one space to the other, moving from an exterior plastered with utopian promises, much like the real estate construction facades that pepper Beirut, to an interior that resembles, in the artist’s words, “all the shantytowns and refugee camps in the world”.

The title “Janus Gate” plays on the duality of the Roman God Janus, who is often depicted with one face turned to the past and one to the future, symbolising both the beginning and the end of time. Janus is also closely associated with the role of gatekeeper, thus once again echoing the idea of boundaries, between life and death, war and peace. The door in Baalbaki’s installation evokes the expression “closing the gate of Janus,” which means to make peace. As Baalbaki has explained: “In my work, the gate is half-open, or half-closed. This ambiguity is similar to a game of heads or tails. This game, which is one of the oldest in the world, was played by the Romans with coins bearing the effigy of Janus. The option is thus presented, and the decision must be made!”

Baalbaki is one of two artists selected to create works for the Lebanese Pavilion, joining Danielle Arbid, who is presenting a video titled “Allô Chérie”, under the theme of “The World in the Image of Man”.

Nada Ghandour, curator of the Lebanese Pavilion, has described the project as an invitation to “a symbolic journey into the contemporary world through a theme, a city, and two artists… who maintain a political and aesthetic dialogue from a distance, by presenting artworks that are so far and yet so close.”

Both artists’ works naturally resound with echoes of the worst crisis to impact Lebanon in recent history, but also resonate with a global audience via their explorations of the “perpetual action of the human imagination on the reality of the world” or the increasingly heightened competition between the real and the

TITLE

GATE” PLAYS ON THE DUALITY OF THE ROMAN GOD JANUS, WHO IS OFTEN DEPICTED WITH ONE FACE TURNED TO THE PAST AND ONE TO THE FUTURE, SYMBOLISING BOTH THE BEGINNING AND THE END OF TIME. JANUS IS ALSO CLOSELY ASSOCIATED WITH THE ROLE OF GATEKEEPER, THUS ONCE AGAIN ECHOING THE IDEA OF BOUNDARIES, BETWEEN LIFE AND DEATH, WAR AND PEACE.

virtual. The olive green, for example, deliberately chosen by Baalbaki for his installation’s interior expresses the duality between war and peace, evoking the way that in wartime civilians are suddenly transformed into soldiers. Now, at one of the most prestigious international contemporary art events, at a pivotal moment in world history, Lebanon’s artists will take the spotlight with a resonance more chilling than could have been imagined, throwing down the gauntlet in an increasingly pressing battle of truth versus illusion and war versus peace.

THE

“JANUS

27

Ayman Baalbaki’s Janus Gate, work in progress.

28

29

Ayman Baalbaki’s Janus Gate, work in progress.

30

‘Le temps suspendu’ (work in progress), mixed media with resin, 2020

31

32

THE OLIVE GREEN, FOR EXAMPLE, DELIBERATELY CHOSEN BY BAALBAKI FOR HIS INSTALLATION’S INTERIOR EXPRESSES THE DUALITY BETWEEN WAR AND PEACE, EVOKING THE WAY THAT IN WARTIME CIVILIANS ARE SUDDENLY TRANSFORMED INTO SOLDIERS.

33

Aline Asmar from Amman, scenography of the Lebanese Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia © Culture in Architecture

34

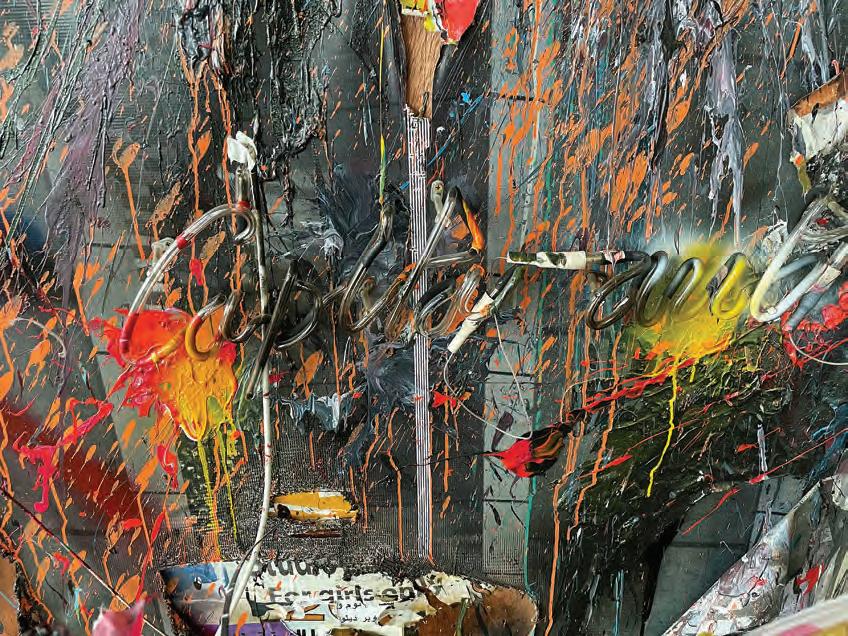

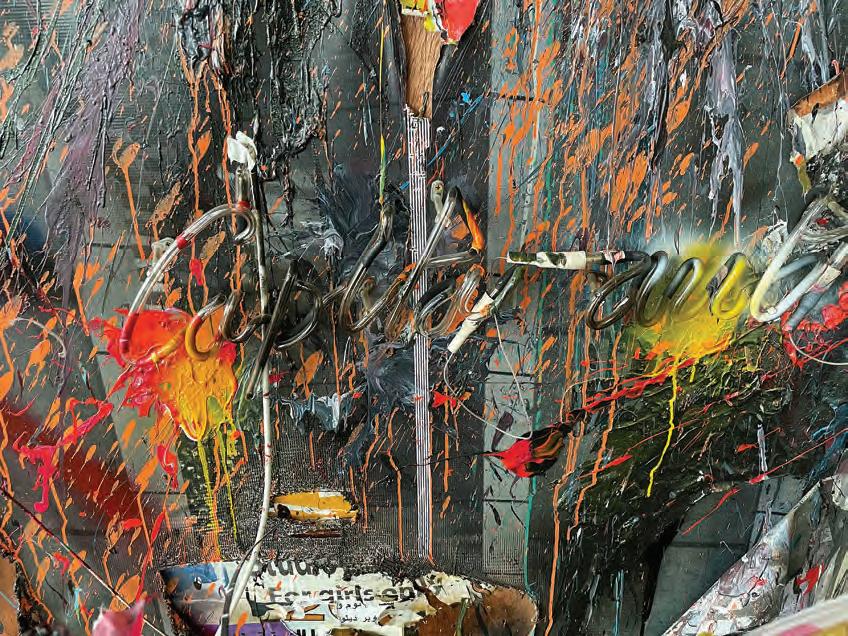

Front detail of Janus Gate.

Ayman Baalbaki, Janus Gate, 2021, mixed materials, details ©Ayman Baalbaki

A Focus on the French Scene: Natural Histories

Art & Environment

31 Project (Paris)

• 193 Gallery (Paris)

• 313 Art Project (Seoul, Paris)

• Gallery 1957 (Accra, London)*

• Galerie 8+4 (Paris)

• A&R Fleury (Paris) •

A2Z Art Gallery (Paris, Hong Kong)

• AD Galerie (Montpellier)

• Alzueta Gallery (Barcelona)

• Galerie Andres Thalmann (Zurich)

• Galerie Ariane C-Y (Paris)

• Art to Be Gallery (Lille)

• Galerie Arts d’Australie - Stéphane Jacob (Paris)

• Backslash (Paris)*

• Galerie Bacqueville (Lille, OostSouburg)

• Helene Bailly Gallery (Paris)

• Galerie Jacques Bailly (Paris)*

• Galerie Berès (Paris)

• Galerie Claude Bernard (Paris)

• Bernier / Eliades Gallery (Athens, Brussels)*

• Galerie Bessières (Chatou)

• Galerie Binome (Paris)

• Galerie Boulakia (London)

• Galerie Brame & Lorenceau (Paris)*

•

By Lara Sedbon (Paris)

• Galerie Chevalier (Paris)

• Galleria Continua (San Gimignano, Beijing, Boissy-le-Châtel, Havana, Rome, São Paulo, Paris)

• Danysz (Paris, Shanghai, London)

• Dilecta (Paris)

• Galeria Marc Domènech (Barcelona)

• Dumonteil Contemporary (Paris, Ivry-Sur-Seine, Shanghai)*

• Double V Gallery (Marseille, Paris)

• Gilles Drouault galerie/multiples (Paris)*

• Galerie Eric Dupont (Paris)

• Galerie Dutko (Paris)

•

Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire (Paris)

• Galerie Jean Fournier (Paris)

• felix frachon gallery (Brussels)*

• Freijo Gallery (Madrid)*

• Galerie Christophe Gaillard (Paris)*

• Galerie Claire Gastaud (Clermont-Ferrand, Paris)

• gb agency (Paris)*

• Galerie Louis Gendre (Chamalières)

• She BAM! Galerie Laetitia Gorsy (Leipzig)*

• Gowen (Geneva)*

• Galerie Alain Gutharc (Paris)

• H Gallery (Paris)

• H.A.N. Gallery (Seoul)*

• Galerie Max Hetzler (Berlin, Paris, London)*

• Galerie Ernst Hilger (Vienna)

• Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery (Berlin, London, Nevlunghavn, Schloss Goerne)*

• Galerie Hors-Cadre (Paris) • Galerie Houg (Paris)*

• Huberty & Breyne Gallery (Brussels, Paris) • Ibasho (Antwerp)*

• Galerie Catherine Issert (Saint-Paulde-Vence)*

• Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger (Paris, Lisbon)

• rodolphe janssen (Brussels)* • Galerie Kaléidoscope (Paris)* • Ketabi Projects (Paris) • Galerie Carole Kvasnevski (Paris)*

• Galerie La Forest Divonne (Paris, Brussels)

• Galerie La Ligne (Zurich)

• Galerie Lahumière (Paris)

• Alexis Lartigue Fine Art (Paris)

• Irène Laub Gallery (Brussels)* • Galerie Le Feuvre & Roze (Paris)

• Galerie Lelong & Co. (Paris) • Fabienne Levy (Lausanne)*

• Eric Linard Galerie (La Garde-Adhémar)*

• Galerie Françoise Livinec (Paris, Huelgoat)

• Loevenbruck (Paris)

• Loft Art Gallery (Casablanca)*

• Gallery M9 (Seoul)*

• Magnin-A (Paris)

• Galerie Marguo (Paris)

• Galerie Martel (Paris)

• Maruani Mercier (Brussels, Knokke, Zaventem)

• massimodecarlo (Milan, London, Hong Kong, Paris)

• Mayoral (Barcelona, Paris)

• Galerie Kamel Mennour (Paris, London)

• Galerie Marguerite Milin (Paris)

• Galerie Mitterrand (Paris)

• Galerie des Modernes (Paris)*

• Galerie Modulab (Metz)

• Galerie Lélia Mordoch (Paris, Miami)

• Galerie Eric Mouchet (Paris)*

• Galerie Najuma - Fabrice Miliani (Marseille)

• Galerie Nathalie Obadia (Paris, Brussels)

• Oniris.art (Rennes)* • Opera Gallery (Paris)

• Galerie Pact (Paris)

• Paris-B (Paris)

• Galerie Pauline Pavec (Paris)

• Rafael Pérez Hernando Gallery (Madrid)*

• Perrotin (Paris, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, Tokyo, Shanghai)

• Pigment Gallery (Barcelona, Paris)

• Galería Fernando Pradilla (Madrid)*

• Praz-Delavallade (Paris, Los Angeles)*

• Galerie Rabouan Moussion (Paris)

• La Galería Rebelde (Guatemala City, Los Angeles)

• Red Zone Arts (Frankfurt am Main)

• Galerie denise rené (Paris)*

• Galerie Véronique Rieffel (Abidjan)

• J. P. Ritsch-Fisch Galerie (Strasbourg)

• Galerie Romero Paprocki (Paris)*

• School Gallery Olivier Castaing (Paris)

• Eduardo Secci Contemporary (Florence, Milan)* • Septieme Gallery (Paris) • Galerie Sit Down (Paris)

• Galerie Slotine (Paris)

• Galerie Véronique Smagghe (Paris)

• Galerie Sono (Paris)*

• Michel Soskine Inc. (Madrid, New York)

• Galerie Pietro Spartà (Chagny)*

• Stems Gallery (Brussels)

• Richard Taittinger Gallery (New York)*

• Galerie Taménaga (Paris, Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto)

• Galerie Tanit (Beirut, Munich)

• Galerie Suzanne Tarasiève (Paris)

• Templon (Paris, Brussels)

• Galerie Traits Noirs (Paris)

• Galerie Patrice Trigano (Paris)

• Galerie Univer / Colette Colla (Paris)

• Galerie Vazieux (Paris)

• Galerie Anne de Villepoix (Paris)

• Galerie Wagner (Paris, Le TouquetParis-Plage)

• Galerie Olivier Waltman (Paris, Miami)

• Galerie Esther Woerdehoff (Paris, Geneva)

• Xippas (Brussels, Paris, Geneva, Montevideo, Punta del Este)*

07—10 2022 april

AN ENCOUNTER WITH GENIUS

BY DR BASEL DALLOUL

36

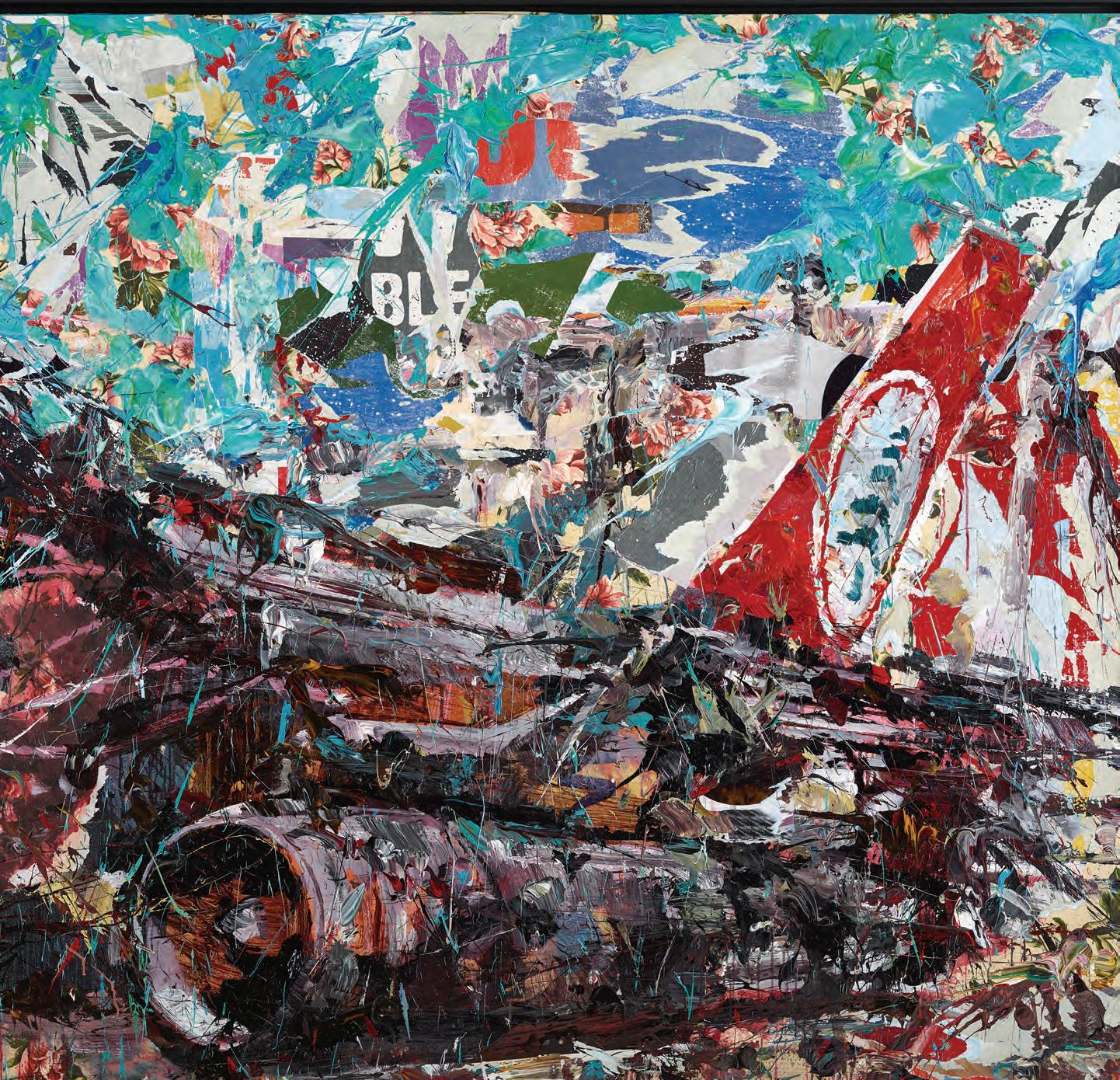

Ayman Baalbaki, The Middle East, 2014. Mixed media on canvas, 207.5 x 407.5 x 5.5 cm.

Dimension (Right): 200 x 150 cm.

Dimension (Left ): 200 x 250 cm. Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

37

DR BASEL DALLOUL

At the time my father was consolidating this particular family collection, in Beirut, from various residences we have around the world. On this occasion of our first encounter, my father had asked me to join him to meet this particularly talented, young Lebanese artist at his Hamra studio, which at the time, also served as his home.

I recall walking into this rather large room, with carefully placed neon lights along the length of the studio space. There were a couple of cosy seating areas, a bookshelf and loads of canvases standing against the walls. Towards the end of the room there were bottles of acrylic paint strewn all over the floor. Ayman, a rather handsome man with piercing blue eyes, was sporting an interesting teal turban on his head. My father dove into an intellectual conversation with Ayman while my curiosity took me around the room, looking at all these amazing

paintings of partially or completely destroyed iconic buildings from around Beirut. There was the Murr Tower, the iconic ‘Egg’ building, the Holiday Inn hotel, and several others. Ayman was also working on a series of Middle East Airlines planes, one of which my father had chosen; actually, it was the largest one in the series, as I recall, an asymmetric diptych, measuring 2 x 4 metres.

At the time, Ayman had completed a piece for my father from his “Al Mulatham” series, which depicted the Palestinian freedom fighter wearing a kafiyyah covering this androgynous looking person’s face. I remember hearing my father asking Ayman, prior to this commission, why the expression of his freedom fighters seemed downtrodden, as he had read the description in an article. My dad disagreed, and wrote Ayman a poem about the pride of the

Dr Basel Dalloul founded the Dalloul Art Foundation in 2017 to manage and promote his father’s (Dr. Ramzi Dalloul) vast collection of modern and contemporary Arab art. At over 4,000 pieces it is the largest collection of its kind in private hands. The collection includes but is not limited to paintings, photography, sculpture, video and mixed media art. Dalloul has had a passion for art since he was very young, inspired by his mother and father, both of whom are also passionate about art in all its forms.

I FIRST MET AYMAN BAALBAKI ABOUT A DECADE AGO, WHEN MY LATE FATHER ASKED ME TO TAKE OVER THE VAST FAMILY COLLECTION OF ART BY ARAB ARTISTS.

38

freedom fighters, holding their heads up high, fighting for the freedom of their occupied lands, and then asked Ayman to paint him one as described in the poem. The result was brilliant.

Because of the fatherly relationship that had developed between them, my father commissioned a couple of rather large pieces from Ayman: one was the Middle East Airliner destroyed on the tarmac at Beirut International Airport during an Israeli air, sea and land assault on June 18, 1982. The second piece my father was after was of the Tower of Babel. At the time, Ayman painted one for himself, and in his generous spirit, decided that my father shouldn’t wait, so he sold him his own piece, and because of his fondness for him, at a substantial discount I recall.

Ayman and I quickly developed a great friendship. I was still learning my way around our collection and Arab art in general. Although I had grown up with it all around us, my interest at the time was in Western art, particularly American modern, and pop, street, and outsider art. Ayman, coming from a family of artists, took me under his wing and taught me the ropes of art from the region. We both had keen intellectual minds, which worked well together; he was also a lot of fun to be around.

I met quite a few artists, critics, writers and art historians through my friend, all of whom I developed quick and deep friendships with. These relationships, and the knowledge I had accumulated from all of them at the beginning of my journey organising the family’s immense collection of Arab art, made what was a very steep learning curve in fact a breeze. I quickly learned the nuances of art from the Arab world and always had my dear friend and mentor to clarify areas I was a bit confused about. He was always generous with his time and quite patient with me. Once I had a good base after a few months of intense learning, I was ready to establish an institution whose mission was to introduce and inform audiences, both local and global, about art from the Arab world.

WAY AROUND OUR COLLECTION AND ARAB ART IN GENERAL. ALTHOUGH I HAD GROWN UP WITH IT ALL AROUND US, MY INTEREST

I founded the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, now known as DAF, and Ayman was a great guiding influence; he was very keen that the foundation become the reference for everything in terms of Arab art. He was very quick to point out that no such thing existed. Ayman was excited about the prospect of having a professional institution whose sole objective was to promote Arab art to the world through research, storytelling, and display. Our relationship became symbiotic. We were both in a position to guide and influence one another, in very positive and constructive ways.

Fast-forward a half-decade later and DAF had indeed become the reference institution for Arab art. The littleknown collection my late parents had put together over the span of a halfcentury went from obscurity to worldrenowned. Ayman Baalbaki always made sure I remained focused, and I did the same for him.

AYMAN AND I QUICKLY DEVELOPED A GREAT FRIENDSHIP. I WAS STILL LEARNING MY

AT THE TIME WAS IN WESTERN ART, PARTICULARLY AMERICAN MODERN, AND POP, STREET, AND OUTSIDER ART.

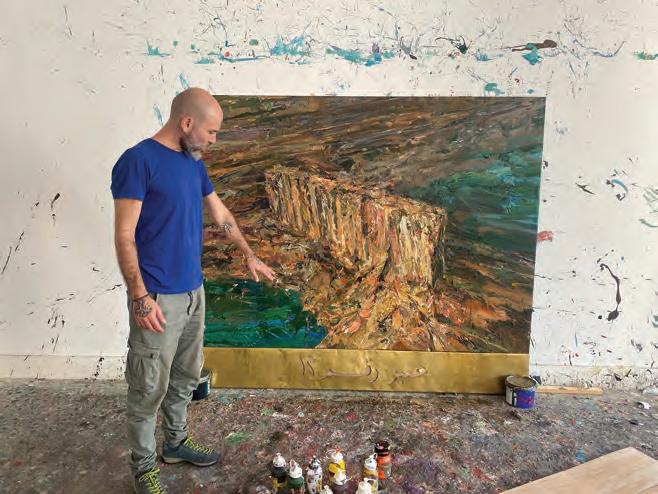

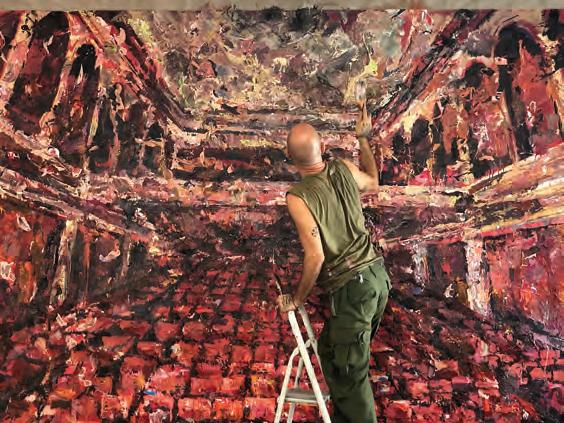

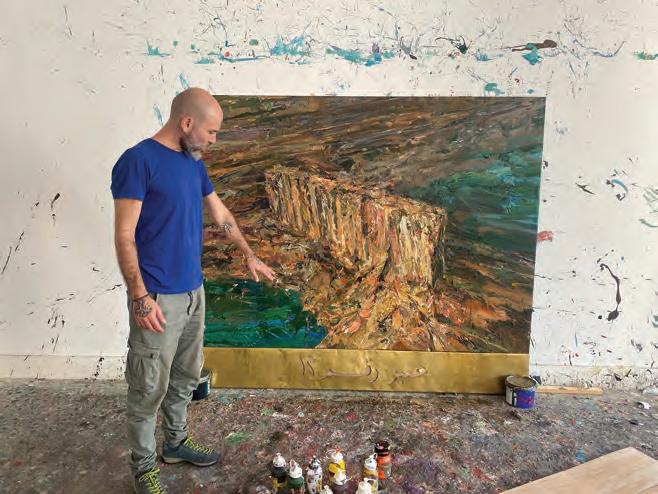

Upcoming pages –Ayman Baalbaki working on Picadilly Theatre (2019) in his studio in Furn El Chebbak.

Photos by Basel Dalloul.

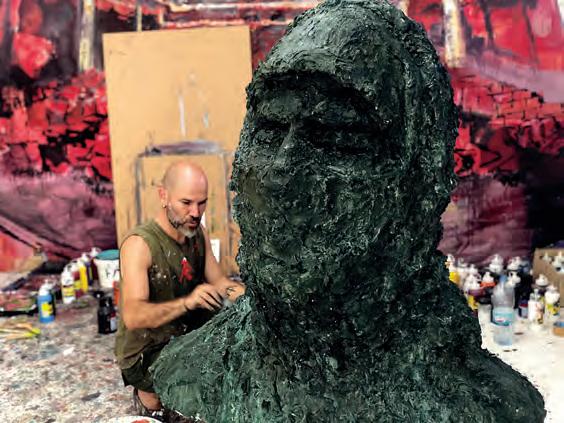

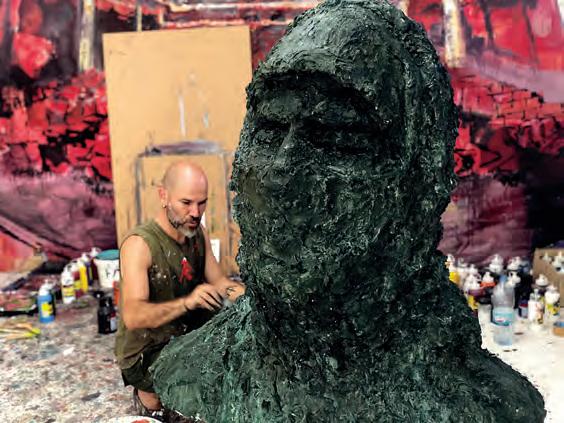

Ayman Baalbaki working on Al Mulatham bronze sculpture in his studio at Furn El Chebbak and the artisan’s atelier, 2019.

39

Photos by Basel Dalloul.

40

41

42

43

In late spring in 2019, Ayman had gone through a dry spell in art production, researching what he would do next. All of Ayman’s close friends were encouraging him to experiment with new techniques and get himself into a new groove. During this time, I remember calling Ayman to figure out what time he would be at his studio, so I could go and watch him work, which I often did. Ayman liked having good company around while he worked, especially during transitional times where he was trying out something new.

That day, he was with our dear friend, Serwan Baran, a rising star of an Iraqi artist who lives and works in Beirut. Ayman told me, “We’re going to play with clay.” Serwan was experienced with clay, but Ayman had never really worked with it or sculpted anything of significance before. I was happy that Ayman was trying out something new, so I encouraged him. That afternoon, Ayman sent me a picture of the bust he had sculpted out of the clay and I was stunned. It was a 3-D version of his “Al Mulatham,” which was identical in style and true to the image in the paintings. I was speechless. Ayman had never done anything like this before and yet on his first attempt at “playing” he had produced a masterpiece! This is the genius of Baalbaki at work, and I was happy to see him emerging from his dry period.

Making the bust wasn’t enough for Ayman. At the time, he was also experimenting with alternative materials, and wanted to enlarge the bust and cast it in resin, a material that quite intrigued him. I recall we first had to find a shop to 3-D scan the original bust, in order to enlarge the scan to the size Ayman had in mind. We then took that data-set to another shop to make a 3-D print of the enlarged version, cut out of Styrofoam. This rather large version was then taken to a casting shop to make the mould, which was then used to pour the resin into to make the final product, the larger than life 3-D “Al Mulatham”. Watching Ayman go through this process was like watching a kid in a toy store. He was lit up and focused and finally back in his element.

AYMAN TOLD ME, “WE’RE GOING TO PLAY WITH CLAY.” SERWAN WAS EXPERIENCED WITH CLAY, BUT AYMAN HAD NEVER REALLY WORKED WITH IT OR SCULPTED ANYTHING OF SIGNIFICANCE BEFORE. I WAS HAPPY THAT AYMAN WAS TRYING OUT SOMETHING NEW, SO I ENCOURAGED HIM.

Over the years, I had become very involved with my dear friend, Laure d’Hauteville, founder and director of the Beirut Art Fair. In 2019, for the landmark 10th Edition of the fair, Laure had asked me to convince Ayman to do something very special and gave him the prime spot at the entrance, to display the work he would create. We were only a couple of months away from the opening, so I quickly went to Ayman with the news. He had to come up with something big and fabulous, something that would stir the audiences coming to visit what was, sadly, in hindsight the last fair prior to Lebanon’s disastrous decline.

Ayman did not disappoint. He had always wanted to paint the legendary Piccadilly Theatre of Beirut, which had hosted some amazing shows by world-renowned and local performers. Sadly, it too saw its demise during Lebanon’s civil war and still stands abandoned. The work he envisioned was massive. At 3 x 4 metres, he began painting against the clock. Both

44

From left to right: Ayman Baalbaki, Serwan Baran and Basel Dalloul in Baalbaki’s studio.

45

Ayman Baalbaki, Untitled, 2018. Acrylic on paper, 74 x 105.5 cm. Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

This page – Ayman Baalbaki, Untitled, 2014. Acrylic on paper, 62 x 49 cm. Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki, Al Mulatham 2013. Acrylic on canvas and printed fabric, 250 x 200 cm. Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

47

49

Ayman Baalbaki, Untitled, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 201.5 x 252.5 x 4 cm. Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

our necks were on the line, so I made sure I visited my friend every day until he completed this monumental work.

Simultaneous to working on the painting, Ayman was also finishing up the largescale bust he had created. We both thought it would be nice to have the painting and the bust at the fair. The Piccadilly Theatre was epic, and definitely the star of the show. It was also the first major piece Ayman, the painter, had created, after a two-year dry spell. I, like everyone else, was mesmerised by the work. It was so good that you wanted to walk into it. The piece deserved to be at a major institution, but alas, it was sold at the fair to an important Swiss collector.

Fast forward to 2022; Ayman was selected to represent Lebanon at the prestigious Venice Biennale. He created a monumental work for the occasion, an installation approximately 5 x 11 metres called “Janus Gate”, which at the time I was writing this piece was already completed and crated. This subject is covered extensively in this special issue, so I’ll leave it alone for now, but I was also involved in this project with Ayman from day one to completion.

In January of this year, it came to my attention that the collector who had bought the iconic Piccadilly Theatre piece wanted to sell it. I figured it was time for this piece to come to its proper home at DAF. I reached out to the collector and negotiated a mutually acceptable price and, as I write this article, I am happy to announce the piece is now in the foundation’s custody.

While I could write a book about Ayman (and perhaps I may one day), I only have a limited number of words to describe him here, so I’m going to spend the rest of the time describing my dear friend. He is first and foremost a great intellectual mind, well-read and articulate. Ayman comes off as somewhat shy when he first meets someone, but quickly warms up once he’s comfortable. He is talented and in a class all of his own when it comes to his craft. Ayman is also one of the most polite and

generous people I know. I’ve personally spent hours watching him get into his groove, working his magic on canvas, carving metal and even moulding clay for the first time. To say Ayman is brilliant at his work, would be a big understatement.

For a decade now, Ayman has been and continues to be a part of my daily life. He is by far one of my dearest friends, and we are both confidants to one another and have developed a brotherly bond. During this time, I’ve consolidated my own knowledge of modern and contemporary Arab art and, thanks to Ayman, I myself have become somewhat of a force to reckon with in the art community from the region. So, I can comfortably say, while I’ve had the privilege of meeting hundreds of very talented artists from around the Arab world, none are as humble and talented as my dear friend Ayman Baalbaki.

I would also like to take this opportunity to thank two very special people in my life, my dearest friend Rima Nasser, the publisher of this magazine and her lovely daughter (my goddaughter as well), Anastasia Nysten, the editor in chief, for allowing me to write this piece in this very special edition of the Selections Magazine.

I am very proud that Ayman was chosen to represent Lebanon at the 2022 Venice Biennale, and I can’t wait to see what he does in the coming decades. Ayman, we all love you.

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki, Untitled, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 150 cm

From left to right: Ayman Baalbaki, Tagreed Darghouth and Dr Ramzi Dalloul in front of Baalbaki’s Al Mulatham (2013) at the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki, Untitled, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 150 cm

From left to right: Ayman Baalbaki, Tagreed Darghouth and Dr Ramzi Dalloul in front of Baalbaki’s Al Mulatham (2013) at the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

50

51

53

Ayman Baalbaki, Untitled, 2009. Mixed media on canvas, 150 x 200 cm. Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

54

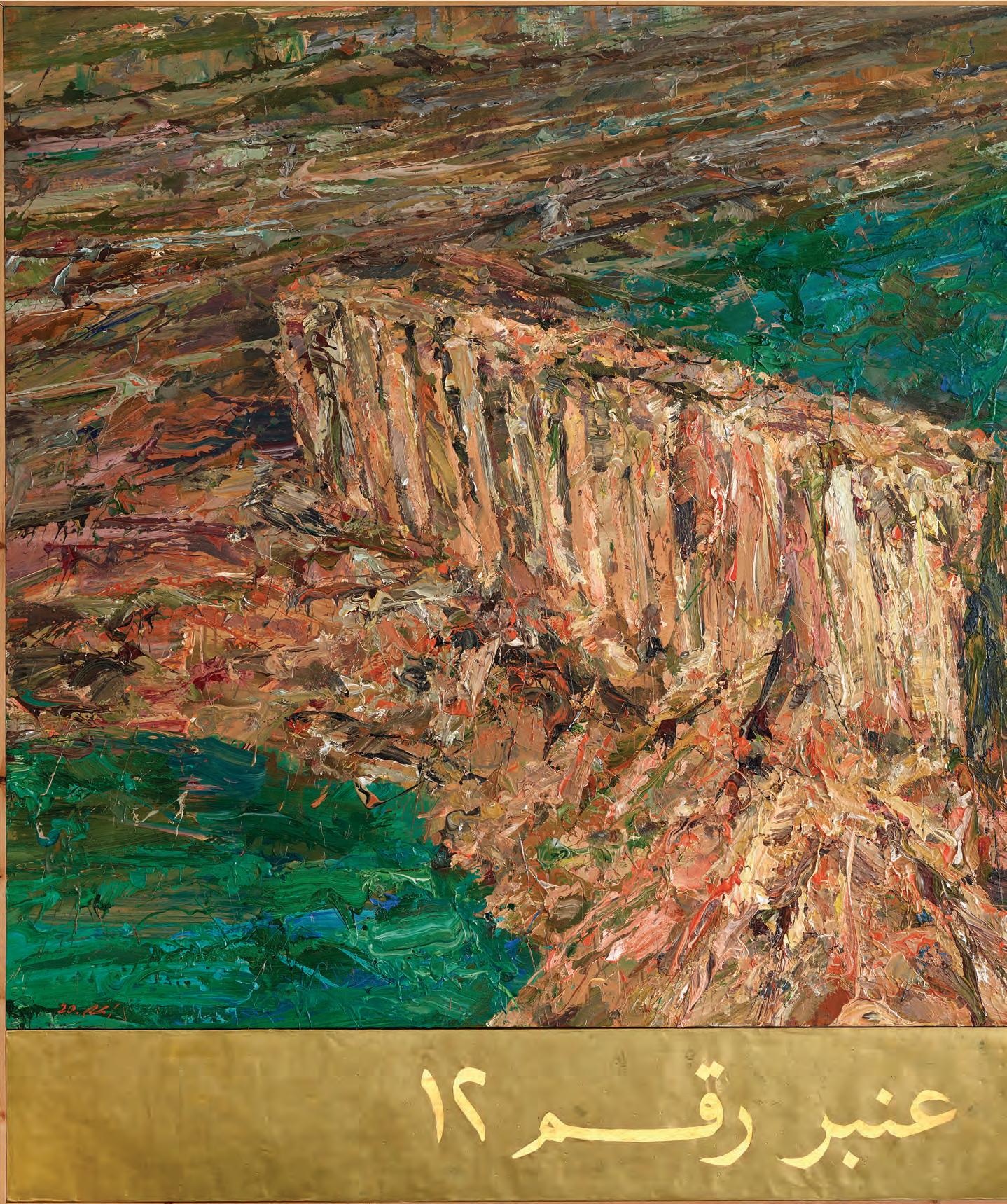

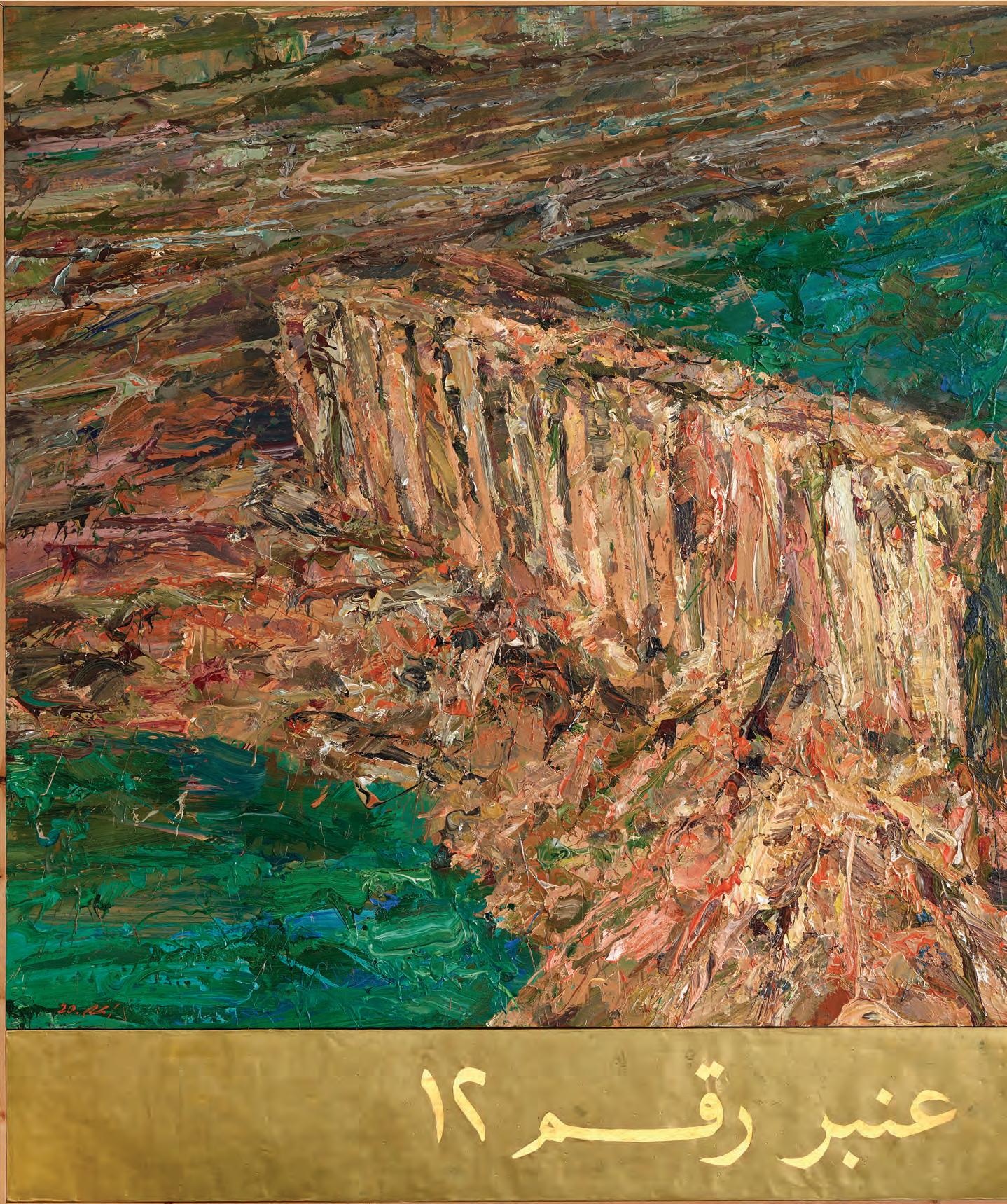

Ayman Baalbaki, working on Baalbaki’s Warehouse N°12 (2020) in his studio.

55

57

Ayman Baalbaki, Warehouse N°12, 2020. Mixed media and acrylic on canvas, 175 x 200 cm Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation

The Power of Talent

BY ROSE ISSA

Rose Issa is a curator, writer and producer who has championed visual art and film from the Middle East and North Africa in the UK for more than 30 years. She has lived in London since the 1980s showcasing upcoming and established artists, producing exhibitions with public and private institutions worldwide, and running a publishing programme.

Through curating numerous exhibitions and film festivals, she introduced Western audiences to many artists who have since become stars of the international scene, including: Ayman Baalbaki, Shadi Ghadirian, Monir Farmanfarmaian, Bahman Ghobadi, Hassan Hajjaj, Fathi Hassan, Farhad Moshiri, Abbas Kiarostami, Rashid Koraichi and Nja Mahdaoui among many more.

As well as holding exhibitions at Rose Issa Projects in London, she frequently co-curates exhibitions with international private and public institutions.

Rose also lends work to and advises on collections for public and private institutions and organisations around the world.

Rose was also a Jury member for the National Pavillions at the 50th Venice Biennale (2003) and sat on the Jury for the Arab British Centre (2013).

Since 2015, after the closure of the Rose Issa Projects space in London, she has been focusing mainly on copublishing.

ROSE ISSA

AS REGARDS THE ARTIST’S WORK, IT WAS LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT [1]. BOLD STRIKING PIECES, BURSTING WITH ENERGY, BRUSHSTROKES REFLECTING STRENGTH, DRAMA, BEAUTY AND BEWILDERMENT. THEN I MET THE MAN, AND LIKE EVERYONE ELSE WAS OVERWHELMED BY ALL THE QUALITIES YOU COULD HOPE TO FIND IN A YOUNG ARTIST.

58

Ayman Baalbaki with Rose Issa, ©Sueraya Shaheen.

Of course, he was then already 30, known by many: there was always a hint of jealousy or envy when people talked about him, but also love. Later, I too became jealous, in my case of his mother, for having given birth to such talented sons. I right away wanted to include his work in the different exhibitions I was preparing.

Ayman Baalbaki invariably wins over hearts and minds, even of those who have never seen his paintings. His genuine charm, his phenomenal artistic gifts, his generosity, his contained violence and calm – the latter occasionally tested – immediately impress. He is also one of the rare Arab artists who know their culture, language and history perfectly well.

Soon after we met and were making exhibition plans, I proposed he use my late parents’ flat as a workshop; but he was making money from his works and preferred to buy it outright. He partpaid me with paintings. Both he and his wife-to-be, the wonderfully talented Tagreed Darghouth, liked the flat, though in his case with reservations, as Tayouneh is far from Hamra, and he does not drive. But I wanted him to be distanced from bars, for his generosity was attracting a few parasites.

To meet him you had to go to Hamra, which was and remains his territory. You could always find him, if not in his studio, in a café or a bar, lending his bicycle to street kids who sometimes returned it to him the next day. Most of the time he was surrounded by singers, filmmakers, artists from Lebanon, Palestine, Syria or Iraq. This was a brotherhood of destinies, a common ground for artists from countries on the edge of precipice, reflecting despair, hope, terror and courage in the face of witnessed tragedies. For Beirut – from 2010 until the rape and the theft of the banks in 2020 –was their refuge and gathering point.

As art fairs, auction houses and galleries became bigger and smarter, museum projects came to the fore. While friends were hoping to build a museum of memory, housing reminders of our tragic contemporary history, Ayman’s paintings never ceased to record shared despair and destructions, images of fast-disappearing landmarks; so instead of a building we have the record of these artworks. The artist continued, in a distinctive and insistent way, to give collective trauma a space, and with it reclaim the values of historical truth.

At my project space in London we collaborated on three wonderful solo exhibitions and several group shows together. In 2009 came Ceci n’est pas la Suisse (before the 1975 war people used to call Lebanon ‘the Switzerland of the East’), a moving homage to his beloved Beirut. Two years later he continued his ceaseless exploration of his hometown’s history in Beirut Again and Again. [2]

59

Destination X installation shot at “Arabicity: Such a Near East” curated by Rose Issa at the Bluecoat Arts Centre, Liverpool, 2010.

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki, Al Mulatham, 2011. Acrylic on canvas, 185 x 129.5 cm. Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects.

This page – Ayman Baalbaki, Wake Up, 2012. Mixed media installation, 170 x 110 x 80 cm.

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki, Al Mulatham, 2011. Acrylic on canvas, 185 x 129.5 cm. Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects.

This page – Ayman Baalbaki, Wake Up, 2012. Mixed media installation, 170 x 110 x 80 cm.

61

Photograph: copyright of Andrew Youngson, Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects

Destination X, installation shot at “Arabicity” curated by Rose Issa at Beirut Exhibition Centre, 2010.

Two versions of the exhibition Arabicity [3] were prepared in Beirut and at Bluecoat Gallery in Liverpool, featuring his car installation Destination X. [4]

When I went to visit him in Liverpool just before the opening, it seemed that all the artist communities, workers, artisans and barmen of Liverpool knew him, yet he has never managed to learn much English. His translator became a friend. The truth is that he did not need language to communicate.

In the past 16 years, I have never gone to Beirut without first calling him. He gives me the pulse of the country, delights me with his new works, updates me on other artists’ projects, and continues to be my source, my energy, through the beauty he incarnates. He makes his city and his friends real.

[1] His first solo show at Agial Gallery, 2006, all works f rustratingly sold out. [2] This was followed by the first monograph of his work, Ayman Baalbaki: Beirut Again and Again, Beyond Arts and Rose Issa Projects, London, 2011.

[3]Arabicity, Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool, 2010.

[4] Also shown at Ourouba, an exhibition I curated at Beirut Exhibition Centre, 2010, with catalogue. The venue was dismantled by Solidere.

62

63

AYMAN BAALBAKI INVARIABLY WINS OVER HEARTS AND MINDS, EVEN OF THOSE

HAVE NEVER SEEN HIS PAINTINGS.

WHO

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki Checkpoint, 2009 Acrylic on fabric mounted on canvas 200 x 150 cm Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects.

Ayman Baalbaki, Czech Hedgehog, 2013. Acrylic on cardboard, 70 x 100 cm. Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects.

65

Portrait of Ayman Baalbaki by Sueraya Shaheen in front of Rose Issa Projects space showing Baalbaki’s exhibition “Ceci n’est pas la Suisse “ (Switzerland it Ain’t) on Kensington High Street in London.

66

Ayman Baalbaki, L’Armonial, 2011. Acrylic on canvas, 255 x 305 cm.Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects.

AT MY PROJECT SPACE IN LONDON

WE COLLABORATED ON THREE WONDERFUL SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND SEVERAL GROUP SHOWS TOGETHER. IN 2009 CAME CECI N’EST PAS LA SUISSE (BEFORE THE 1975 WAR PEOPLE USED TO CALL LEBANON ‘THE SWITZERLAND OF THE EAST’), A MOVING HOMAGE TO HIS BELOVED BEIRUT. TWO YEARS LATER HE CONTINUED HIS CEASELESS EXPLORATION OF HIS HOMETOWN’S HISTORY IN BEIRUT AGAIN AND AGAIN. TWO VERSIONS OF THE EXHIBITION ARABICITY WERE PREPARED IN BEIRUT AND AT BLUECOAT GALLERY IN LIVERPOOL, FEATURING HIS CAR INSTALLATION DESTINATION X.

67

68

Ayman Baalbaki, Al-Mulatham, 2010. Acrylic on fabric Laid on canvas, 200 x 150 cm. Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects.

69

Ayman Baalbaki, The ‘Sniper’, 2009. Acrylic on fabric laid on canvas, 210 x 125 cm. Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects.

Ayman Baalbaki, Fadae, 2005. Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 160 cm

Ayman Baalbaki, Fadae, 2005. Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 160 cm

No compromise, no limits

BY SALEH BARAKAT

Around 2001, when he was a young Lebanese University art graduate looking to do a PhD in art and 3D space in Paris, he showed me a series of works that I was immediately taken with. I told him that I would purchase them and sell them so he could finance his trip, as his parents weren’t able to do so at that point in time.

Our relationship grew slowly and organically over time. After two shows together, Ayman was one of the reasons why I wanted to have a big gallery, so that I could show his large works and give him the importance that he deserves. He and Nabil Nahas to a certain extent were the biggest drivers of my ambition for a larger space. Of course, the big gallery was meant to happen because Ayman had this enormous capacity to create mega paintings that were impossible to show in a

smaller gallery. We also needed the space and the dream of being able to create an installation rather than a painting exhibition, to give a complete effect.

It was a very friendly relationship from the beginning. It grew from somebody I had met as a young university student wanting to pursue his postgraduate studies to becoming more of a friend and, today, I still enjoy listening to his political ideas. His political engagement was apparent very early in his life. Born into a family of artists – his father and uncle are the wellknown modernists painters Fawzi and Abdelhamid Baalbaki – it seemed that his becoming an artist was just a matter of destiny and time. Since his professional career began, he never compromised on his ideas, on his multidisciplinary practice, or on his drive for perfection. Erudite and

Saleh Barakat is a Beirutbased gallerist who specialises in modern and contemporary art from the Arab world. He founded Agial Art Gallery (1991) and Saleh Barakat Gallery (2016) where he hosts an extensive program of exhibitions and events. He has also curated exhibitions elsewhere, including The Road to Peace (2009) at the Beirut Art Centre, retrospectives of Saloua Raouda Choucair (2013), Michel Basbous (2014) and Jean Boghossian (2015) at the Beirut Exhibition Centre, and he co-curated the first national pavilion for Lebanon at the 52nd Venice Biennale, as well as the itinerant exhibition Mediterranean Crossroads, in collaboration with Martina Corgnati and the Italian ministry of foreign affairs and Shafic Abboud (2013). He has lectured at Princeton University, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the British Museum and Christie’s Education in Dubai, and ne currently lectures in ALBA and USJ in Beirut. He served on the steering committee of the Arts Centre at the American University of Beirut, and on the founding committee of the Saradar Collection. He has been a board member of the National UNESCO since 2015 and currently serves on the advisory board of the School of Architecture and Design at the Lebanese American University. In 2006, he was nominated as a Yale World Fellow.

I FIRST MET AYMAN IN HIS STUDENT DAYS WHEN HE CAME TO THE GALLERY.

BEFORE HE EVEN GRADUATED AND BECAME A PROFESSIONAL PAINTER I USED TO SEE HIS PAINTINGS AND BUY SOME OF THEM.

71

SALEH BARAKAT

highly experimental, he continues to explore his fascination with the human condition. Although he is eight years younger than me, I have always enjoyed his acute, thorough and revelatory views on international politics and their relation to local and regional dilemmas. He expresses the essence of “glocality” as a citizen in tune with globalism while firmly rooted in his locality.

He achieved early success with his portraits featuring the kuffiyah, which evoked the eternal rebel in him. Later he went on to develop the “ruinform”, an icon of buildings in ruin, following the 2006 Israeli war on Lebanon. The total devastation of his childhood neighbourhood, including his family house, in the Beirut suburbs, instigated in him the desire to paint his people’s own “apocalypse”, as if cursed to live through one tragedy after another, in a Sisyphean cycle of destruction without end. When he later moved into sculpture, he remained unsatisfied for years until he achieved success with a body of sculptures where his touch seemed identical to his painterly brushstrokes, in spite of the difference in media. I have rarely encountered an artist whose practices of painting and sculpting are so perfectly intertwined.

He has recently found the fascinating capacity to transcend himself once again in his new artwork, “Janus Gate”. It is a monumental effort at bringing together his numerous multidisciplinary skills, showcasing his facets of painter, sculptor, installation artist and conceptual artist all in one piece and in the service of his political aims. I have watched this work develop over the course of two years from scratch. It began as an idea for an exhibition that we wanted to do in this gallery with laundry coming down from the high ceiling. It started in bits and pieces and then it became this proposal for the Venice Biennale, and it suddenly made sense. So, instead of doing one big exhibition of different pieces we did one big piece that became the exhibition.

OUR RELATIONSHIP GREW SLOWLY AND ORGANICALLY OVER TIME. AFTER TWO SHOWS TOGETHER, AYMAN WAS ONE OF THE REASONS WHY I WANTED TO HAVE A BIG GALLERY, SO THAT I COULD SHOW HIS LARGE WORKS AND GIVE HIM THE IMPORTANCE THAT HE DESERVES.

For me, Ayman is the artist who is the most engaged with his city, but he is also working on a human level, showing all the things that are happening in the world today, because Lebanon is an eccentric place, akin to a small laboratory where you can see, in an exaggerated way, what will happen everywhere else. The multimedia installation “Janus Gate” is a metaphor for our own world today, where we are living a schizophrenic existence between false promises and the bitter reality on all levels. It shows the failure of the political establishment that became a form of bureaucracy only feeding itself and no longer acting in the service of the citizen. The world is collapsing, the gap between rich and poor is widening, nature’s ecosystem is being abused, global warming is reaching its tipping point of no return; the planet is slowly turning into a total wreck, exactly like Ayman’s postapocalyptic structure. It’s never too late to be conscious of the necessity to close this metaphoric Gate of Janus, to reject the politics of wars, theft and greed, and work together to make our world a better one.

72

When this mega-installation will be displayed at the Lebanese pavilion in the Arsenale for the upcoming edition of the Venice Biennale, it will allow the international art public to discover anew th e “enfant terrible” of the Beirut art scene and his exceptional genius. I am one of those people who has infinite belief in the capacity of Ayman Baalbaki. Ayman is huge and monumental in what he can do but the country is not up to his level. We don’t have big institutions and usually you have to work according to the limitations of the country you are in, but this is not something I would push Ayman to do. I tell him to do whatever he dreams of doing and we will manage to adapt.

I feel privileged to have accompanied Ayman throughout the past 25 years and to have witnessed his evolution towards stardom. Beyond his artistic career, I have known Ayman the human being and the loyal friend. He has an unparalleled generosity towards his colleagues, especially in times of hardships, and is always present for unconditional yet subtle – and at times, tacit – support. As a handsome man, with a stylised dress code including a personalised turban, he impresses in his appearance as much as in his culture and stately wisdom. His friendship is beyond priceless.

73

Ayman Baalbaki Al Mulatham, 2019. Bronze, 57 x 50 x 28 cm. Edition of 3 + 2 artist proof

This page – Ayman Baalbaki, Untitled, 2019. Acrylic on carboard laid on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

This page – Ayman Baalbaki, Untitled, 2019. Acrylic on carboard laid on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

74

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki, Blowback invitation card

75

76

Ayman Baalbaki Installation shot, 2008.

Installation shot at Agial Gallery featuring from left to right:

The Embassy, 2016 Mixed media on canvas D. 120 cm

1559, 2016 Mixed media on laminate and neon D. 116 cm

Installation shot at Agial Gallery featuring from left to right:

The Embassy, 2016 Mixed media on canvas D. 120 cm

1559, 2016 Mixed media on laminate and neon D. 116 cm

77

The Embassy, 2016 Mixed media on canvas 250 x 400 cm

78

79

Works by Ayman Baalbaki at Agial Gallery

Revelations of an extraordinary mind

BY NAYLA TAMRAZ

I HAVE KNOWN AYMAN FOR SEVERAL YEARS. IT WAS 2004 OR 2005 WHEN WE MET. HE HAD JUST EXHIBITED THIS INCREDIBLE CAR, TOPPED WITH MATTRESSES AND BACKPACKS, AT THE BEIRUT THEATRE, REVEALING HIS PLAYFUL SIDE: AYMAN LIKES REALLY, ABOVE ALL, TO HAVE FUN WITH WHAT HE DOES.

Nayla Tamraz is a Lebanese writer, curator, researcher and professor of literature and art history at Saint Joseph University in Beirut where she has also been, from 2008 to 2017, the chair of the French Literature Department and where she created, in 2010, the MA program in art criticism and curatorial studies that she currently heads. She also organised several events including the symposium Littérature, Art et Monde Contemporain: Récits, Histoire, Mémoire (2014, USJ, Beirut). In parallel, she leads a career as an art critic and a curator. In this context, she cocurated the exhibition Le Secret (Espace Ygreg, Les Bons Voisins, 2017) in Paris and curated the exhibition Poetics, Politics, Places that took place in the Museum of Fine Arts of Tucumán in Argentina, in the frame of the International Biennale of Contemporary Art of South America (BienalSur, 2017). Her research is about the issues related to the comparative theory and aesthetics of literature and art in their historical context, which brings her to the topics of history, memory and narratives in literature and art in post-war Lebanon. Her current research explores the relationship between poetics and politics as well as the representations associated to the notion of territory.

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki, Babylon Tower, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 250 x 200 cm. Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

NAYLA TAMRAZ

Opposite page – Ayman Baalbaki, Babylon Tower, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 250 x 200 cm. Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

NAYLA TAMRAZ

80

Ayman Baalbaki, Quarter of beef, 2001. Acrylic and oil on wood, 26.5 x 20 cm.

Ayman Baalbaki, Quarter of beef, 2001. Acrylic and oil on wood, 26.5 x 20 cm.

He also painted at this time his mysterious Babel towers, deserted and hollowed out like the termite mounds he had seen during a trip to Africa. His rebellious and joker side, alongside his seriousness when it came to talking about painting, was interesting. Listening to him is always a pleasure. It was obvious that the act of painting, in Ayman’s work, was to become the subject of a narrative.

I then had the opportunity to write several texts for Ayman and, more recently, I also collaborated on the catalogue of the Lebanese pavilion of the 59th Venice Biennale by writing a text on his work. From being a writer on Ayman, I therefore became his historian, trying to bring order to this extraordinary nebula that is his work. Thus, I can say that I have never really stopped discovering and exploring this immense material, to the point of extracting elements that are sometimes unknown, but never trivial.

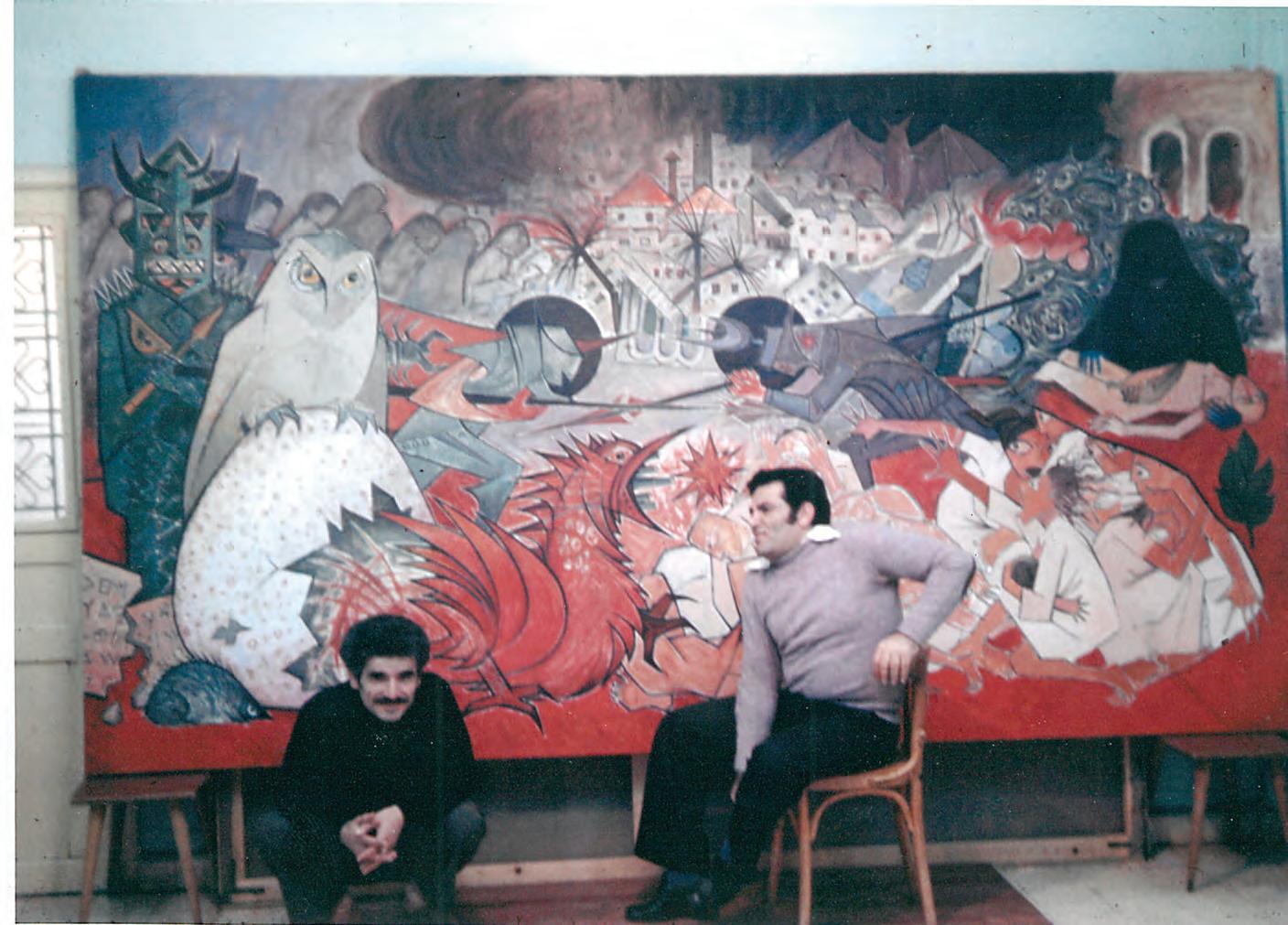

I would like to talk about Ayman Baalbaki by going back to a stage that clearly founded his life as an artist. Alongside his university education, in Lebanon and then in Paris, Ayman participated in the Summer Academy of Darat el Founoun in Jordan (2000-2001), held at the time by the painter Marwan Kassab Bachi. There, he had to deal with authentic questions: Why be an artist? What does it mean to be an artist? What forms an artist’s identity? Which tool, material and medium to choose? This step seems important to me, definitely because Ayman has never stopped asking himself these fundamental questions that continue to nourish him.

Also, under Marwan’s supervision, Ayman’s work developed into a dialogue with the pictorial tradition. With him he undertook the painting of his very well-known Sides of beef, as well as an astonishing work, little-known beyond a few insiders, of a series of crosses inspired both by the tortured crucifixions of the painter Antonio Saura and by the story of the mystical poet Al -Hallâj (about 857 –922), the founder of Sufism and who was himself crucified. Ayman Baalbaki, “the

painter of crosses” is one of the aspects of this artist that we obviously do not fully know, which also means that there is still a lot to say about him.

Now, if we take a step back to understand the relevance of Ayman Baalbaki’s proposals within the framework of contemporary artistic production on the Lebanese art scene, we need to place it in dialogue with the artistic experimentations of post-90s artists. These went more towards the practices of conceptual art with a specific discourse held on the post-war era. As an artist of this generation, Ayman offers a work inhabited by the same anxiety, but he nevertheless deviates from these practices by the very fact of his choice of painting, sometimes associated with a bygone modernity. Thus, painting for him is the place where this gap is considered, a place that blurs the codes and deconstructs the categories. It is therefore also the place where practices can be rethought.

83

Ayman Baalbaki Seeking The Heights, 2010. Acrylic on fabric laid on canvas, copper light box, 200 x 210cm.

Brothers in arms

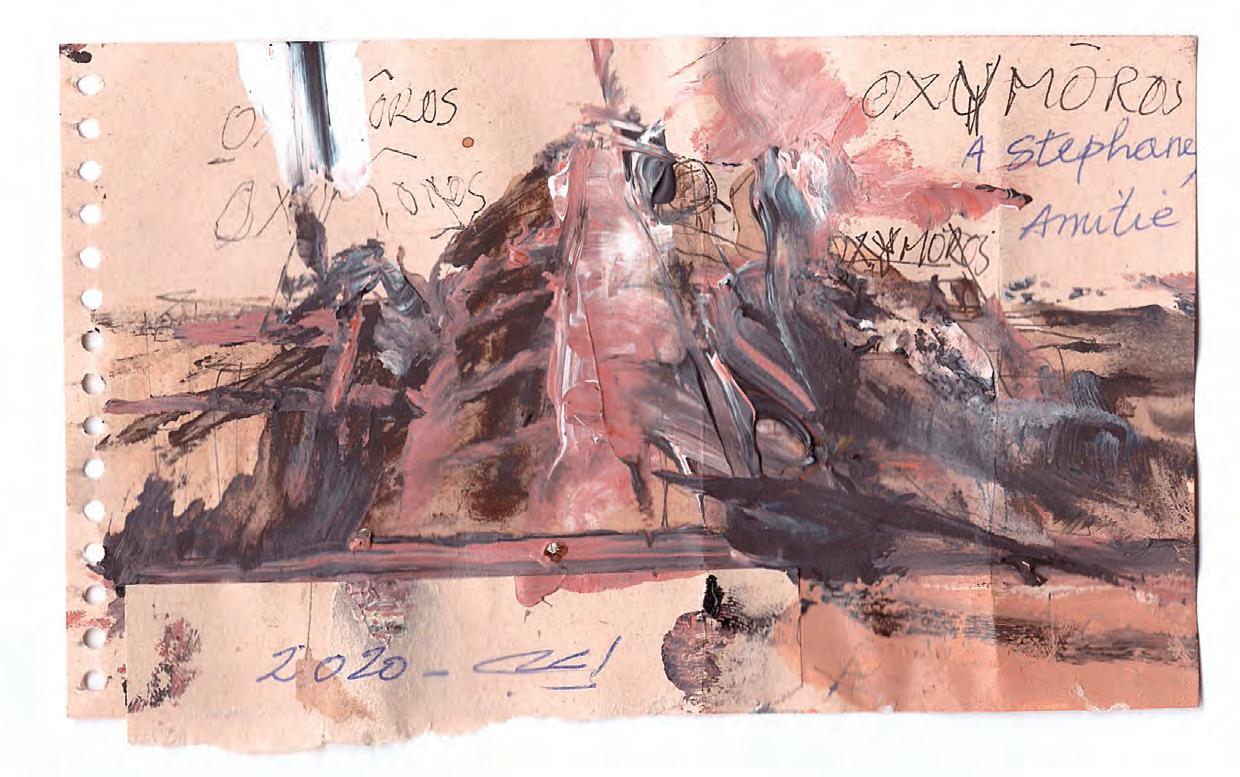

BY STEPHANE SISCO

BROTHERS IN ARMS. THAT IS WHAT WE ARE WITH AYMAN BAALBAKI. BECAUSE WE KNOW THAT THE REAL BATTLES, THE ONES AGAINST OUR OWN SELVES, ARE NOT FOUGHT DURING BUT RATHER AFTER THE WAR. SO, WE IMPOSE OBLIGATIONS ON OURSELVES BECAUSE WE CAN’T BEAR THE CONSTRAINTS THAT ANYONE ELSE WOULD WANT TO IMPOSE ON US.

Stephane Sisco, founder of the CONDOTTA FOUNDATION, spent all his life in theatres of war. He was the curator of Beirut Kaputt? in Beirut. His work is centred on the representation, narration and perception of war. He has been a crisis analyst starting on the field in Cambodia in 1988 and ending in The Democratic Republic of Congo in 2019. Anxious to transmit his first-hand experience of violence, he is also a great enthusiast of the arts and political philosophy and takes on the challenge of fighting ignorance through the subjectivity of talented artists. He does not live only in his memories but participates in the new war for attention.

STEPHANE SISCO

STEPHANE SISCO

84

Stephane Sisco discussing with the philosopher Slavoj Žižek

Ayman’s studio is both a physical place of work in progress that belongs purely to him, and also an imaginary space in which I find my own place to reflect - where I smoke in silence with him and smile at deceptively banal ideas that come to me about the political violence we have witnessed and which I know he will react to. Always surprising, always sideways, always elegantly.

It was here in his studio that our complicity was born, at the same time as the idea for “Beirut Kaputt?”. Because when confronted with the Beirut Port explosion, it’s as if we were obliged to follow “the effective truth of the thing” [la verità effettuale della cosa], rather than the image we carry of it.

Isn’t this Machiavellian injunction the only possible path for Art in war? In other words, isn’t the search for the effective truth of the thing through Art the only struggle to be waged against the impostors who provoke wars, and against all the impostors who live indecently from it without ever having actively fought?

When we are together, usually in Ayman’s studio, we often smile despite the seriousness and sincerity of the things we say, because we get along very well without really understanding each other. We talk about the same life without speaking the same language. We appreciate each other for having remained on the frontlines of our lives when we could have long since slipped away. In his studio, I distance myself from events and memories by looking at his work, and we regain the time confiscated by violence: he by painting, I by observing. And both of us commenting. Time and death and the search for lost time and the frantic quest to fight the race of time toward death through violence - this absurdity of pretending to bring finitude to an end through extreme brutality. All That Remains. The massacre of others’ time and the annihilation of others’ space through violence. All That Remains. This is what painting war is all about, and then taking the time to look at the traces, both visible and invisible, on the canvas.

85

Sketch by Ayman Baalbaki made in a coffee shop explaining ‘Janus Gate’ concept to Stephane Sisco, originally going to be called ‘Oxymoros’, 2020.

86

Ayman Baalbaki

Ayman Baalbaki

87

All that remains, 2014-2016. Acrylic on canvas, 250 x 600 cm.

Beirut Kaputt?, 2021

Beirut Kaputt?, 2021

88

Exhibition poster, curated by Stephane Sisco

In his studio, Ayman introduced me to other brothers: Serwan Baran and Abdul Rahman Katanani. And for my part in our communal heterotopia, I smuggled in Slavoj Zizek, from the time of the Yugoslav wars: “Welcome to the stinking Desert of the Real”.

For a better understanding of how this particular brotherhood of arms works, it began with a dialogue with Slavoj that never took place out of which the book, “Beirut Kaputt?” was made. Then, from a photo that Ayman took of some “Zizek in Leb” graffiti on a bank in Hamra, we decided with Slavoj that a real dialogue on the end of violence would finally take place between Slavoj and myself in front of “The End”, a painting by Ayman, at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. It is also a question, on this occasion, of discussing violence, its representation, the war, the war against oneself, the war of representations... between Ayman, Serwan, Abdul and myself - probably on a terrace overlooking the Mediterranean after Venice…

We try, therefore, to follow the effective truth of the thing by cobbling together activities among ourselves that would not exist without us. Why? Because we will be no more and no less than whatever we have contributed to.

And also, because to paint the war is to allow it to be seen - without giving lessons - in its absurd and fascinating brutality. And this is what makes all the difference between the luminous will of the artist and the dark submission to the degradation of profiteers and impostors.

Bien à toi, mon cher Ayman, en attendant de fermer les portes de Janus à Venise

Stills from a video montage of social media clips of the Beirut Port explosion by Florent Marcie

89

Ayman Baalbaki and Stephane Sisco unpacking ‘All That Remains’.

Ayman Baalbaki and Stephane Sisco unpacking ‘All That Remains’.

90

Stephane Sisco and Ayman Baalbaki looking at works.

‘Žižek in Leb’ painted on rolling steel door.

‘Žižek in Leb’ painted on rolling steel door.

91

Photo by Ayman Baalbaki

Summer 2001 Summer 2022

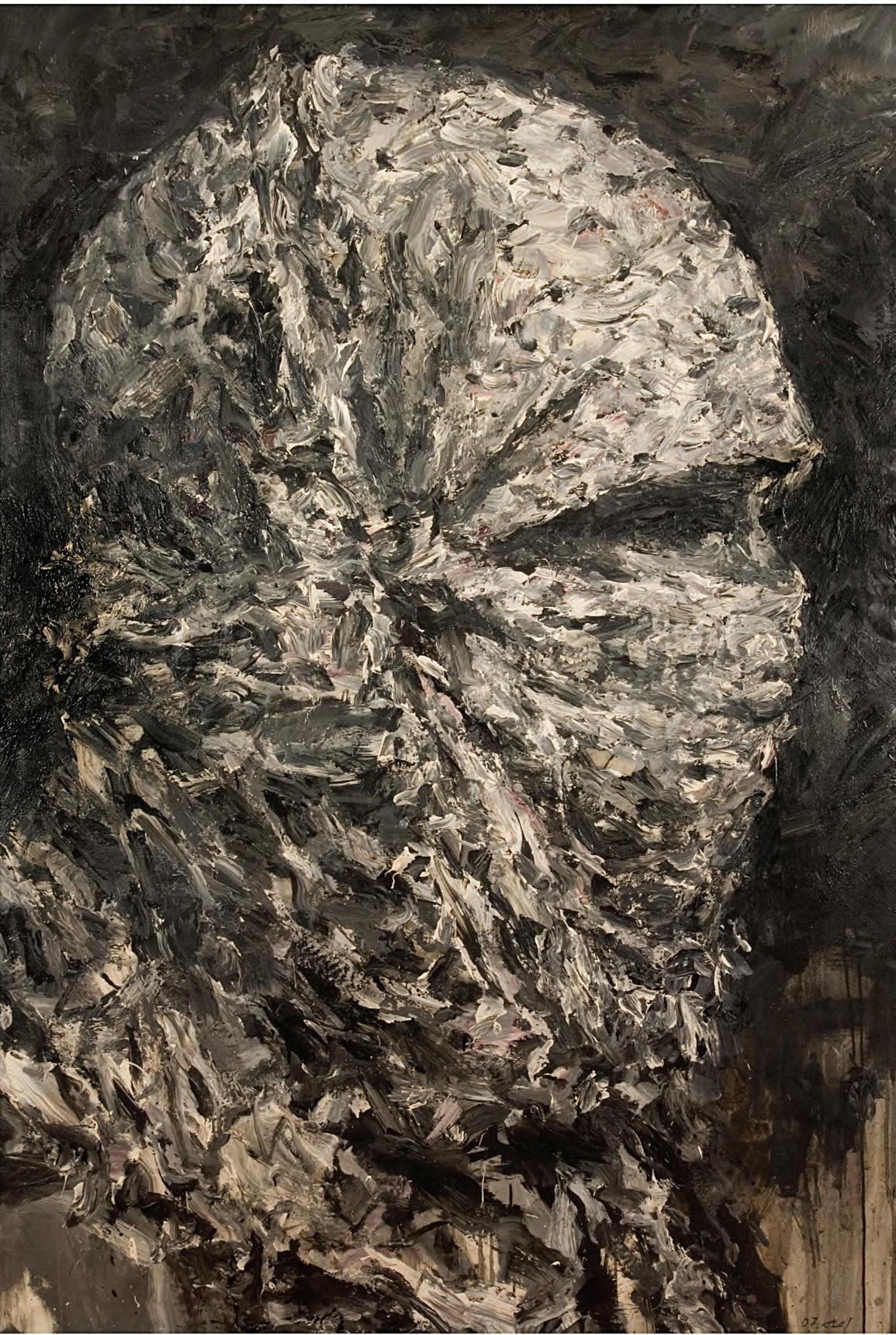

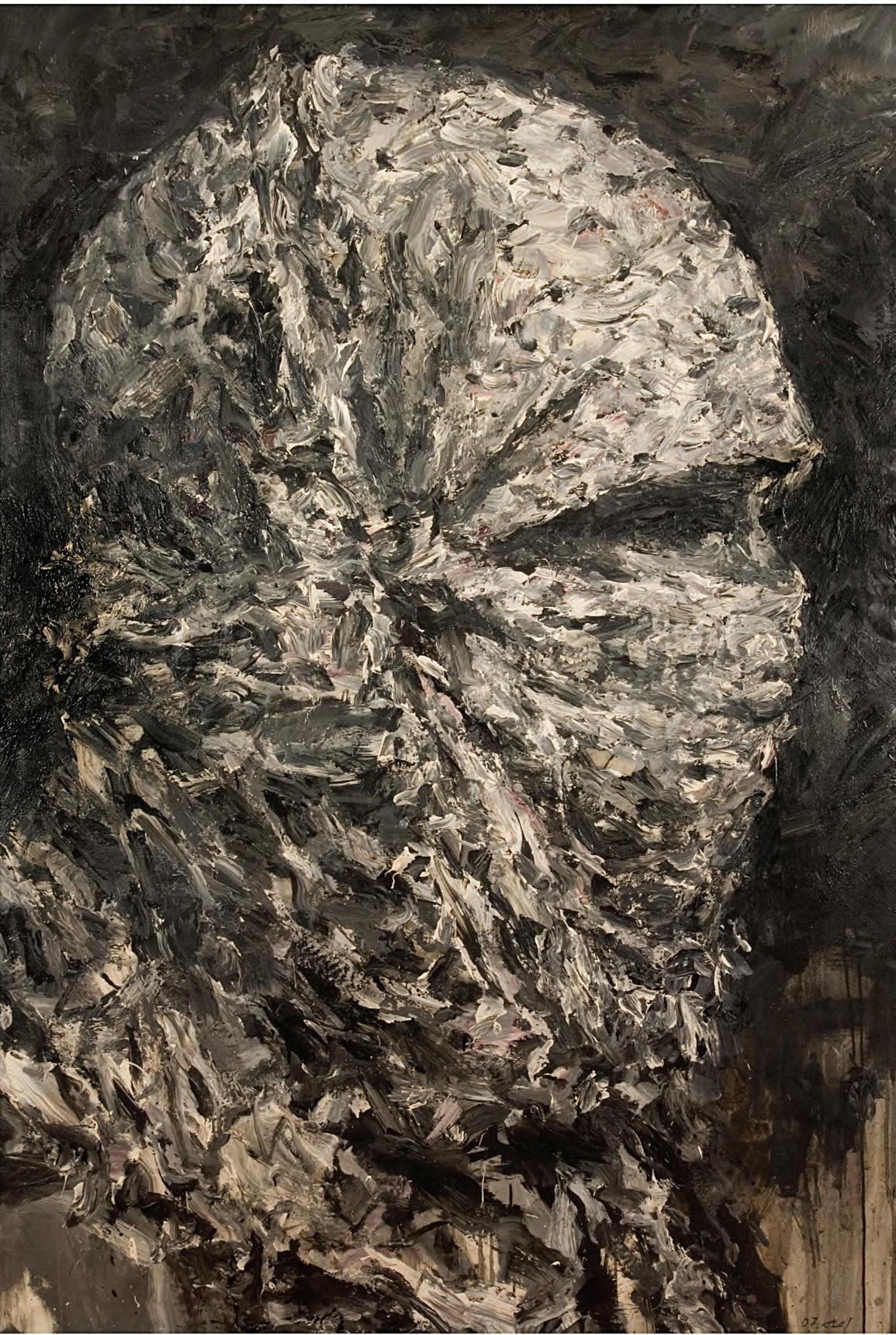

BY SERWAN BARAN

I met Ayman, the young man from Beirut, a head full of hair, civil war tragedy and religious conflicts. He was a quiet, well-educated person with a mature vision, carrying a great turbulence deep inside, revealed only when necessary. He was also a great listener, talking only when necessary. What connected us was the memory of the war and the “remnants” of people after it. He paints with high emotion and speed aiming for the spontaneity he discovers while catching the aesthetic moments of the act; he paints pieces of dead cows in the colours of fresh meat, the detached horse’s head in the colours of dark blood with highly expressive approaches.

Serwan Baran (b. Baghdad, 1968) is a Beirut-based Iraqi painter and sculptor. He received a bachelor’s degree of Fine Arts from the University of Babylon in Hillah, Iraq. In the 1990s, his work was shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Iraq. He was awarded a youth prize in Baghdad in 1990, and the first and second prizes of the Baghdad International Festival of Plastic Arts in 1994 and 1995, respectively. In 2001, he participated in the Ayloul Summer Academy, a residency program led by artist Marwan Kassab-Bachi at Darat al-Funun in Amman, Jordan. In 2003, he moved to Amman during the American invasion of Iraq. In 2013, he moved to Beirut, where he has since been living and working. He represented Iraq at the 58th International Venice Biennale in 2019 with the solo exhibition, Fatherland, curated by Tamara Chalabi and Paolo Colombo. Other solo shows include A Harsh Beauty at Saleh Barakat Gallery (2020); Indelible Memory at Gallery Misr, Egypt (2020); Canines at Agial Art Gallery, Beirut (2018); Living on the Edge at Nabad Art Gallery, Amman (2013); Elected at Matisse Art Gallery, Marrakech (2013); and Whispers at Orfali Art Gallery, Amman (2012), among others in Amman, Damascus, Tokyo, and the Dominican Republic. He has participated in group exhibitions at Saleh Barakat Gallery, Beirut (2018); The Mojo Gallery, Dubai (2015); Al-Markhiyya Gallery, Doha (2013). His work was featured in the Cairo Biennale, Cairo (1999, 2019); Al-Kharafi Biennial, Kuwait (2011); and the fourth Marrakech Biennale, Marakech (2012). Baran is a member of several artist associations in Iraq.

SERWAN BARAN

From left to right: Ayman Baalbaki and Serwan Baran.

Photo by Hady Sy.

SERWAN BARAN

From left to right: Ayman Baalbaki and Serwan Baran.

Photo by Hady Sy.

92

MY FIRST MEETING WITH AYMAN WAS IN SUMMER 2001 IN THE ATELIER IN AMMAN WITH THE CREATIVE MARWAN KASSAB-BACHI/ DARAT AL FUNUN-JORDAN.

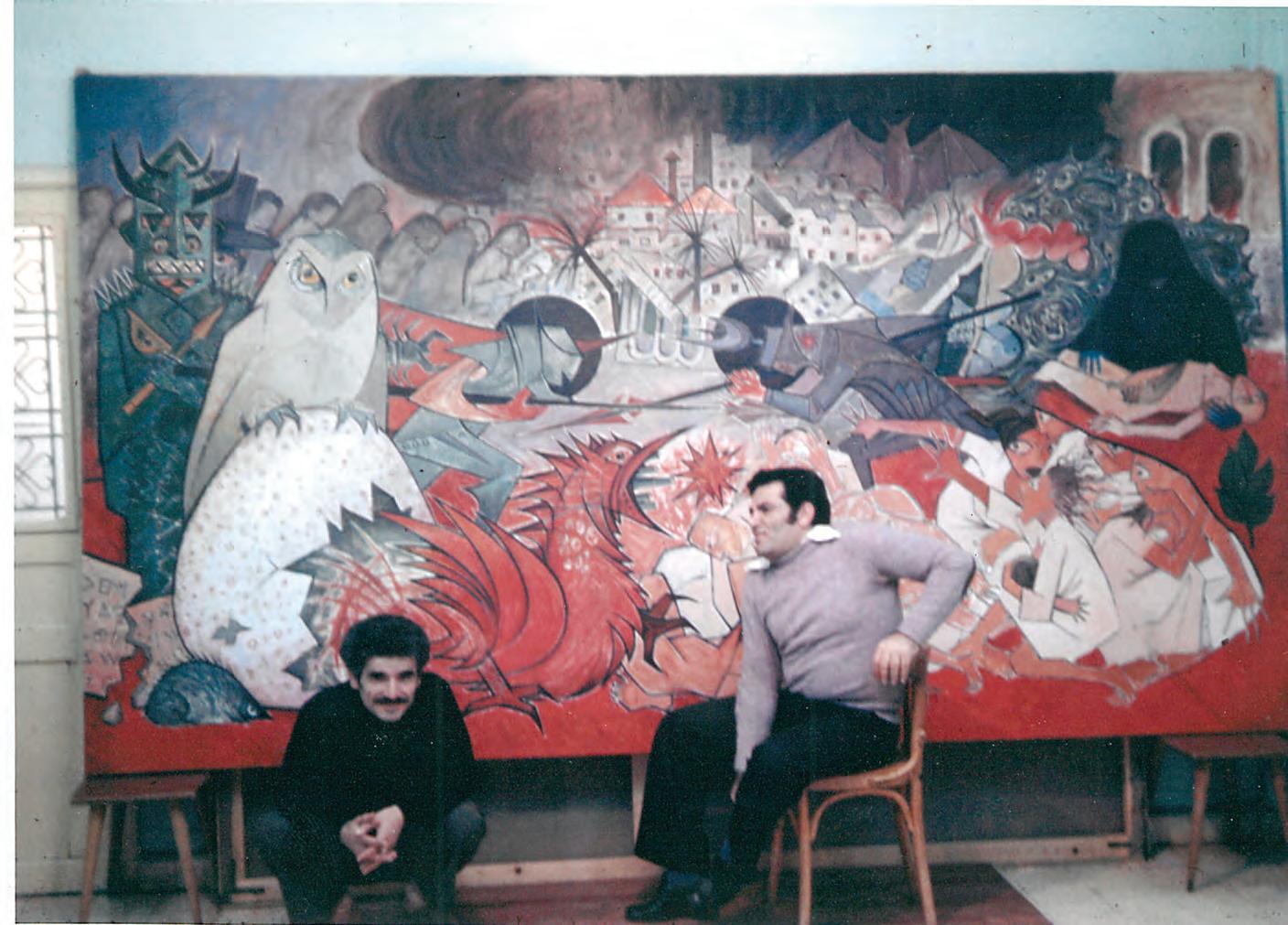

We were in an ongoing discussion with Professor Marwan and the other students, Said Baalbaki, Tagreed Darghouth, Samer Al-Kurdi, and a group of ambitious Palestinian youth, about freedom of thought and performance, focusing on staying away from embellishment and beautification of artistic work. I remember at the time asking him for my portrait before he leaves to Paris for his art studies. I also remember that Professor Marwan was very impressed with the portrait. He insisted on me keeping it, not giving it to anyone. I didn’t know why... As the days passed in the workshop, I enquired about it and he said: “Your important works should be kept for your history”.

I remember Ayman, at the time, using to cut off from the surrounding world whenever he painted, devouring the painting like a savage child, emptying all his creative energy until the work is finished. He enjoys speed and spontaneity in doing things, charged with high emotion, away from excessive decorations. His performance was fascinating, a bit fierce. We spent a good time painting and wandering the popular markets looking for colourful Iraqi traditional rugs, the rustic antique pieces he and Professor Marwan loved. He is extremely emotional, always seeking the history of the things he buys for very small amounts. We were living in a subsisting way, remembering the works of the great German Expressionists and post-war artists who left their mark on art history. Today, and for 21 years, we still criticize each other’s work, trusting each other’s vision through our daily pursuit of beauty and techniques. As the workshop was over, each of us traveled to a destination.

The meeting was in Beirut in 2008. Ayman has attended maturity, experience, and professionalism. It was my first visit to Beirut… After 4 years, Ayman was one of the first friends who encouraged me to stay and settle in Beirut. He and Tagreed Darghouth were the first to receive me. Ayman still has the same concern for 21 years. This anxiety and turmoil were reflected positively on his artistic work, leading him to be very careful with the decision to finish the work in order to be convincing to himself before the people around him. After 2012, we all worked as a group that ties us together in friendship and the memory of the workshop with Marwan; and most importantly, we all worked in the drawing field or present our works in a contemporary drawing style. The meetings were daily, starting with our morning breakfast and ending with a Beiruti evening. I watched Ayman closely, his choice of topics, returning to their historical or political reference, and destroying forms to rebuild them in his own way. The impact of the streets and the graffiti spreading in Beirut was his main obsession, always looking for protests painted on the walls, continually capturing the simplest traces of human action on the streets, collecting and reviving damaged posters and advertisements.

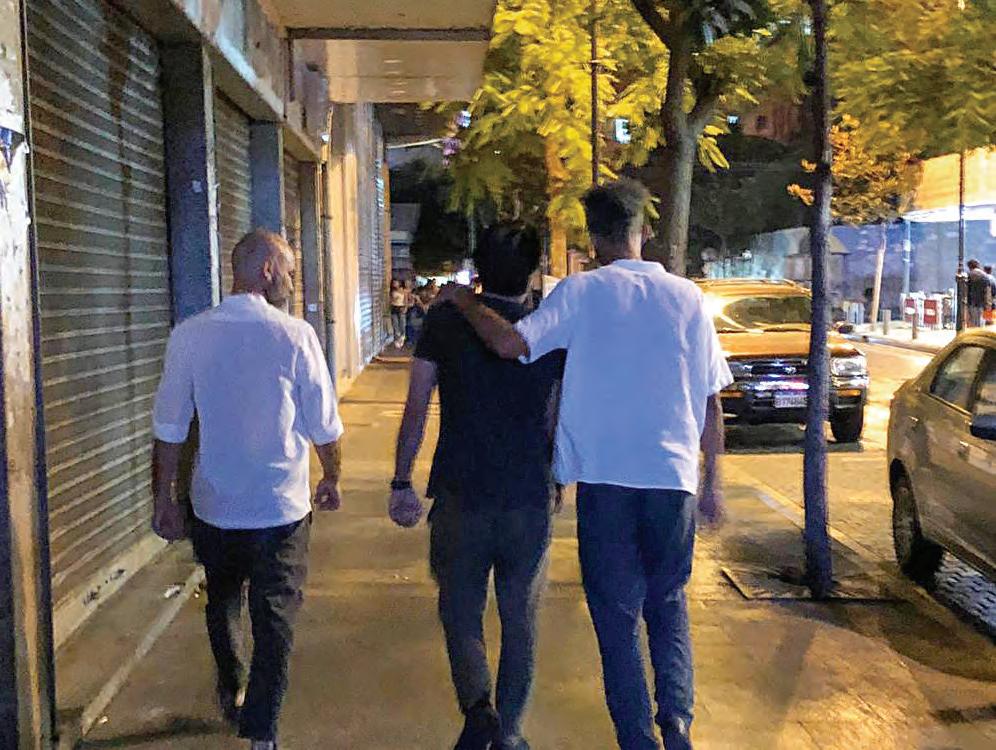

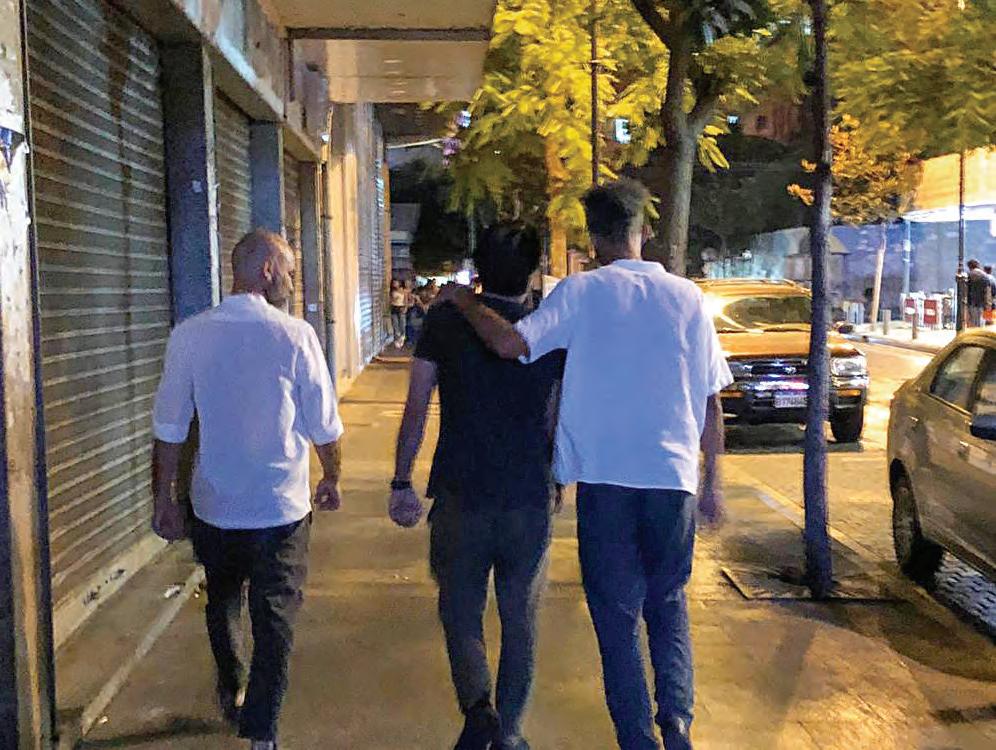

For 12 years in a row, we met daily with our creative friend, Abdul Rahman Katanani, reflecting on creating an artistic movement with no specific intention, only because we shared similar ideas about revolutionary serious art away from the decorative painting. We shared several projects, the most important were the Cairo Biennale and the Beirut projects in Venice Biennale 2019. We work together, we share opinions. Sometimes we disagree, other times we agree. We lived our ups and downs. I still remember Ayman’s face on the day of the Beirut explosion and the great pain it brought upon his city. We went out to Gemmayzeh that day to help and participate in cleaning up the city. We had memories in every part of the stricken city, but we were really positive about the power Beirut had to restore itself, with the help of its lovers.

Left to right, Ayman Baalbaki, Serwan Baran and Abdelrahman Katanani walking down Hamra street.

Left to right, Ayman Baalbaki, Serwan Baran and Abdelrahman Katanani walking down Hamra street.

TODAY, AND FOR 21 YEARS, WE STILL CRITICIZE EACH OTHER’S WORK, TRUSTING EACH OTHER’S VISION THROUGH OUR DAILY PURSUIT OF BEAUTY AND TECHNIQUES. AS THE WORKSHOP WAS OVER, EACH OF US TRAVELED TO A DESTINATION.

93

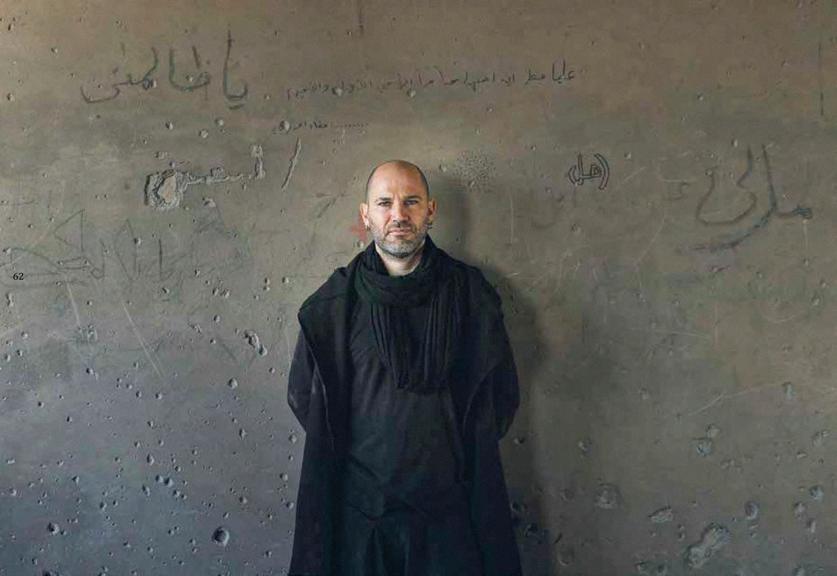

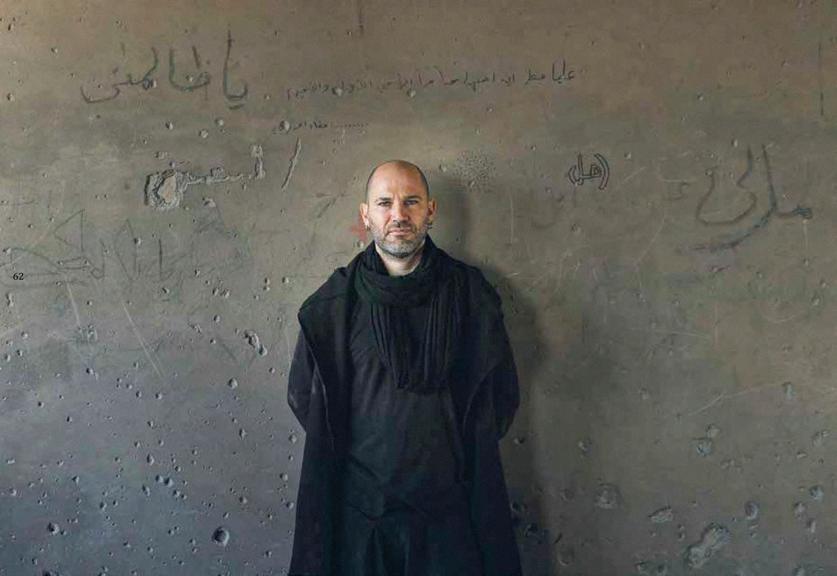

Portrait of Ayman Baalbaki

by Serwan Baran

by Serwan Baran