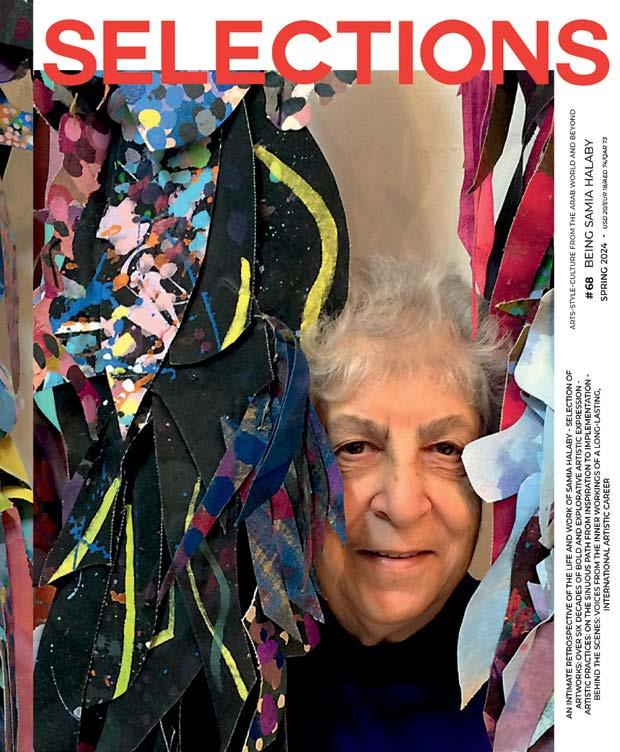

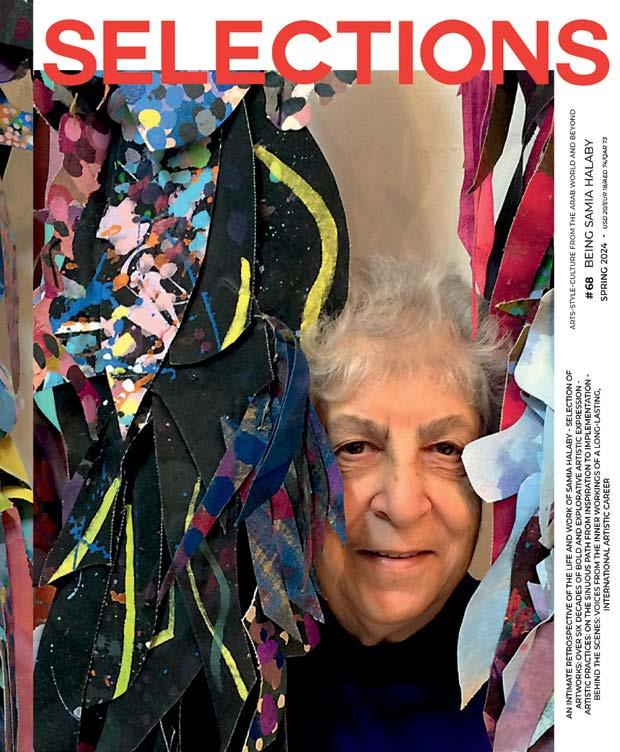

# 68 BEING SAMIA HALABY ARTSSTYLECULTURE FROM THE ARAB WORLD AND BEYOND

ARTISTIC

BEHIND THE SCENES:

INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC CAREER SPRING 2024USD 20 / EUR 18 / AED 74 / QAR 73

AN INTIMATE RETROSPECTIVE OF THE LIFE AND WORK OF SAMIA HALABYSELECTION OF ARTWORKS: OVER SIX DECADES OF BOLD AND EXPLORATIVE ARTISTIC EXPRESSION -

PRACTICES: ON THE SINUOUS PATH FROM INSPIRATION TO IMPLEMENTATION

VOICES FROM THE INNER WORKINGS OF A LONGLASTING,

In the ever-evolving world of contemporary art, there are certain luminaries who not only create stunning works but also embody resilience, passion, and a relentless pursuit of artistic expression. Among these luminaries stands Samia Halaby, a Palestinian-American artist whose dynamic energy and prolific creativity have captured the attention of the global art community.

In this issue of Selections, we are honoured to collaborate with Samia Halaby, whose recent journey through the art world has been nothing short of remarkable. Despite facing challenges, including the cancellation of a significant exhibition at the Indiana University, Samia’s dedication to her art remains unwavering.

roughout this year, she has traversed the globe, participating in shows and receiving well-deserved recognition for her groundbreaking work. Even as we worked on this issue, we found ourselves chasing after her, catching glimpses of her brilliance amidst the bustling energy of the Venice Biennale.

Samia’s art transcends boundaries, both geographical and cultural. rough her vibrant colours, bold strokes, and evocative compositions, she invites viewers to contemplate issues of identity, belonging, and social justice. Her work serves as a powerful reminder of the transformative potential of art to inspire dialogue, provoke thought, and foster empathy across borders.

As we celebrate Samia Halaby’s contributions to the art world, let us also recognise the significance of her journey as a Palestinian American artist navigating complex terrain. In a world marked by division and discord, Samia’s art serves as a bridge, connecting diverse communities and fostering understanding amidst differences.

We extend our heartfelt appreciation to Samia Halaby for gracing the pages of Selections with her remarkable talent and indomitable spirit, and congratulate her on the recent special mention extended to her by the Jury of the 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia.

EDITOR’S LETTER

6

Accidental Portrait of the Artist as the Evening’s Timeless HONOREE, Yasmina Nysten, Mixed media oil and acrylic on canvas, 100x120 cm.

Accidental Portrait of the Artist as the Evening’s Timeless HONOREE, Yasmina Nysten, Mixed media oil and acrylic on canvas, 100x120 cm.

30 – 51 Chapter I: An Intimate Retrospective of the Life and Work of Samia Halaby

30 – 31 Introduction

32 – 35 Early life

36 – 45 My Education

46 – 51 Apple Seeds - Being Some of the Landmarks of My Memory as a Palestinian

52 – 83 Chapter II: Selection of Artworks: Over Six Decades of Bold and Explorative Artistic Expression

52 – 53 Introduction

54 – 55 Early Painting Reminiscences of Palestine

56 – 57 Student Years

58 – 59 The Geometric Still Life

60 – 61 From Still Life to Graph Paper

62 – 63 Helixes and Cycloids

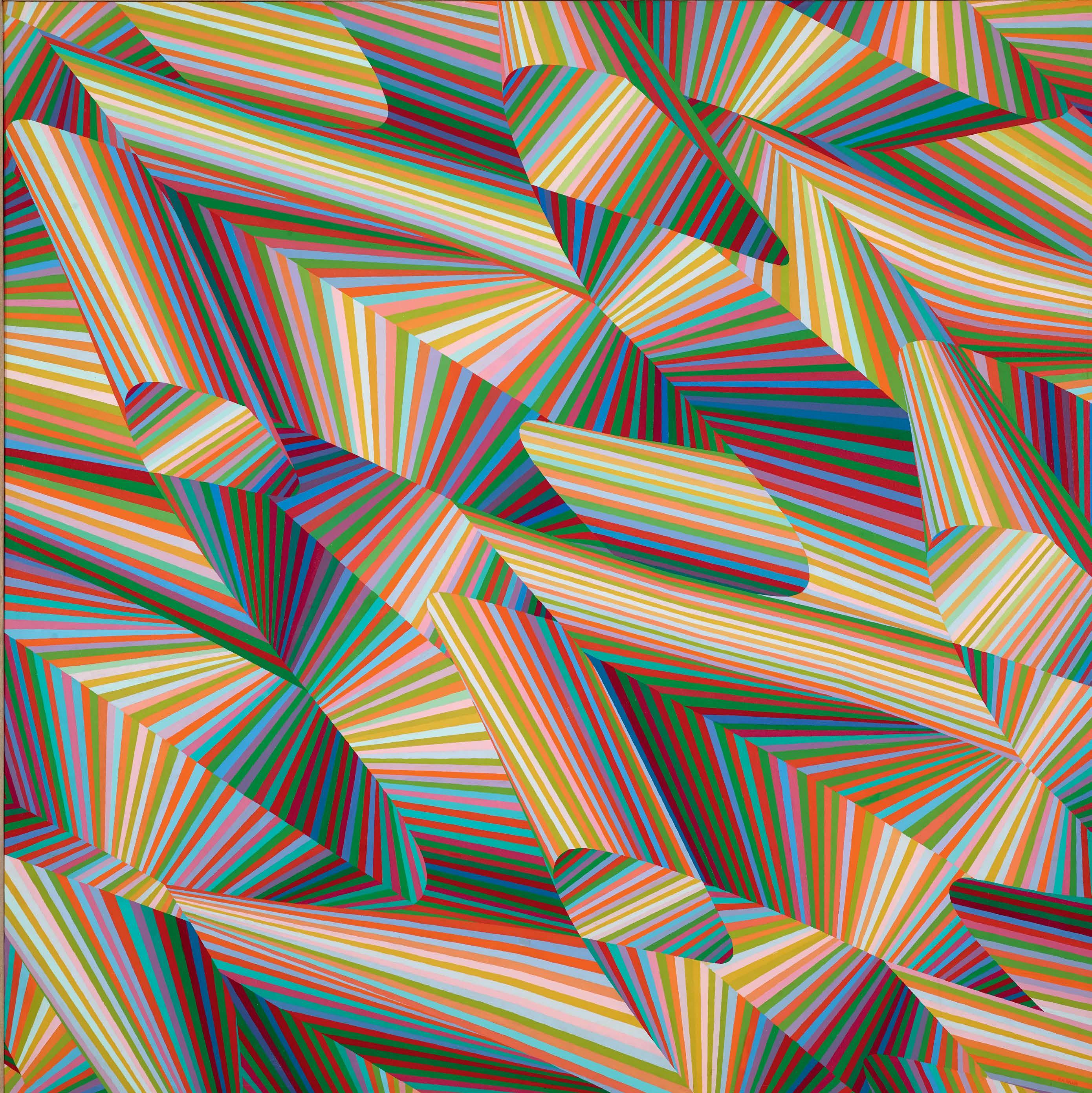

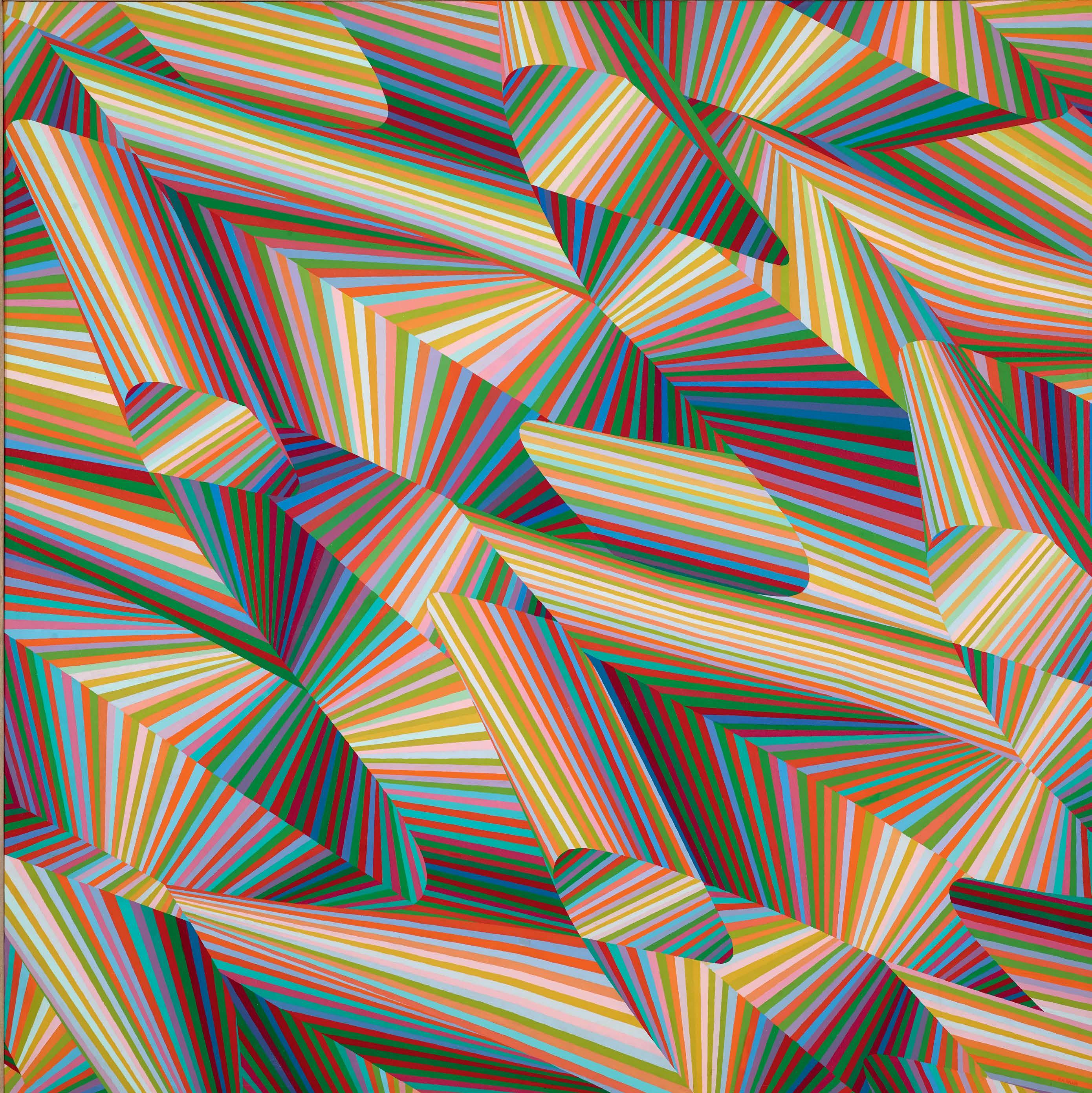

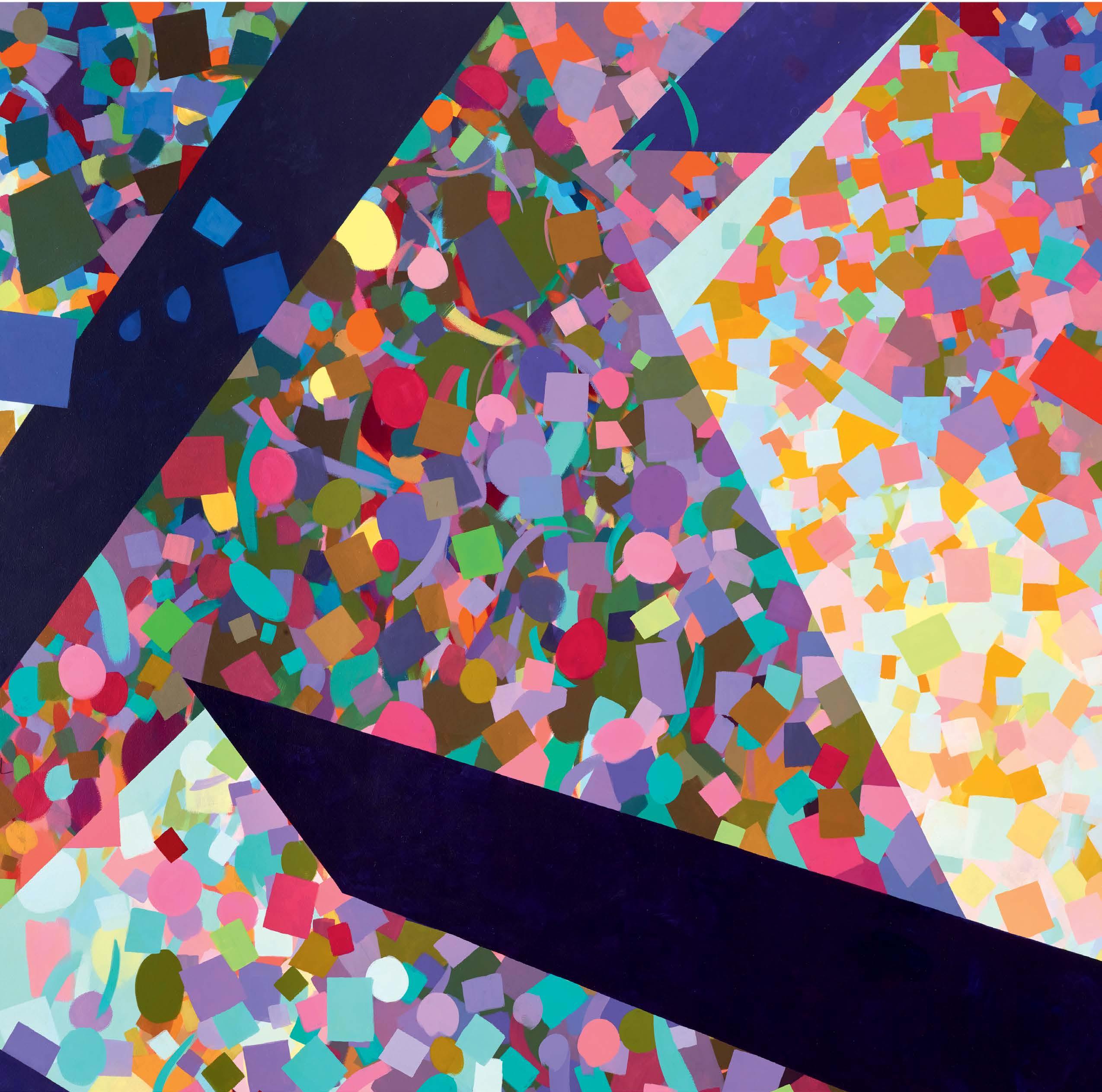

64 – 65 Diagonal Flight

66 – 67 Dome of the Rock and Arabic Art

68 – 69 Autumn Leaves and City Blocks

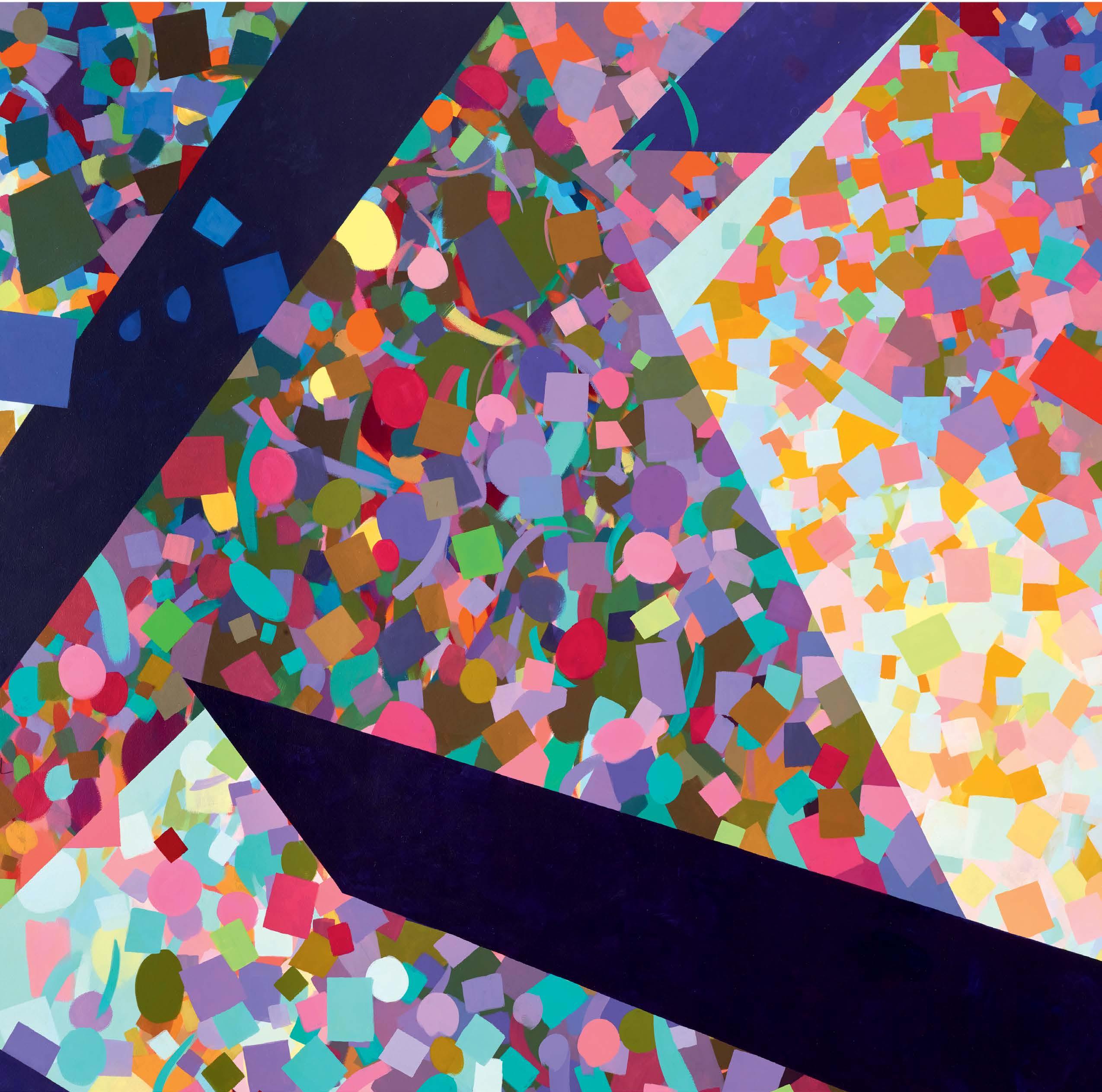

70 – 71 Growing Shape

72 – 77 Kinetic Painting and the Computer

78 – 79 Painterly Abstraction

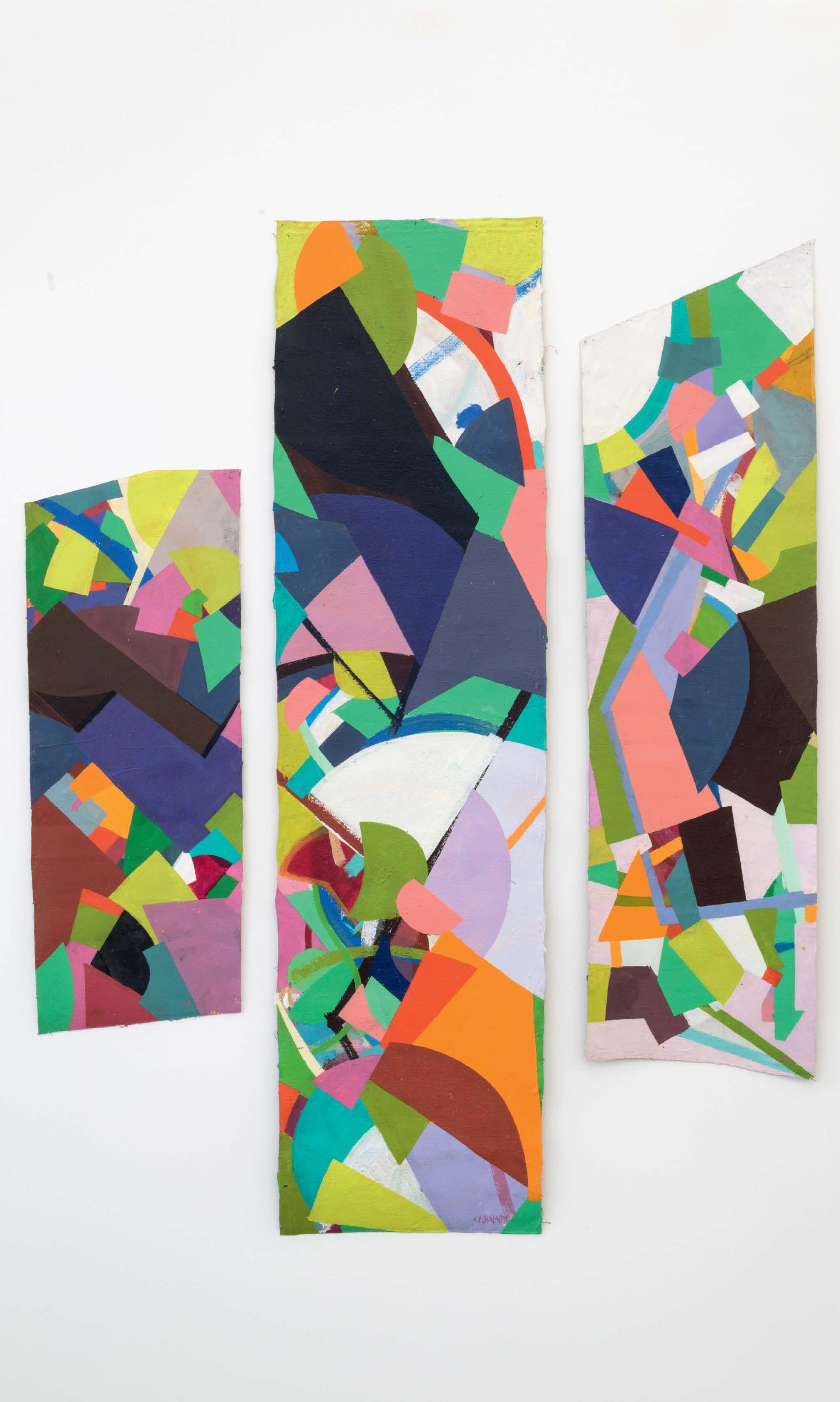

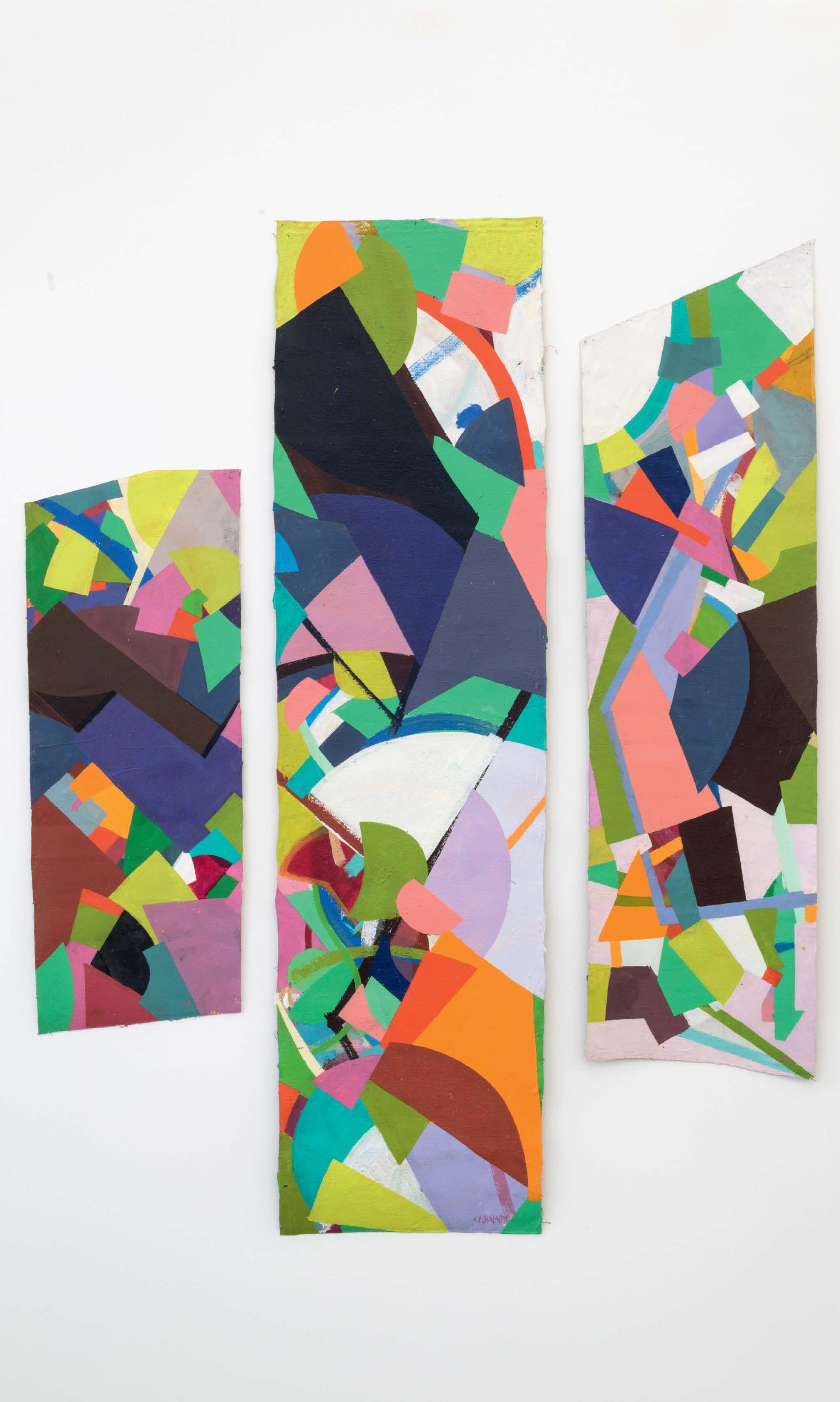

80 – 81 Free from the Frame and Back

82 – 83 Fusion: Time Space Motion

84 – 109 Chapter III: Artistic Practices: On the Sinuous Path from Inspiration to Implementation

84 – 85 Introduction

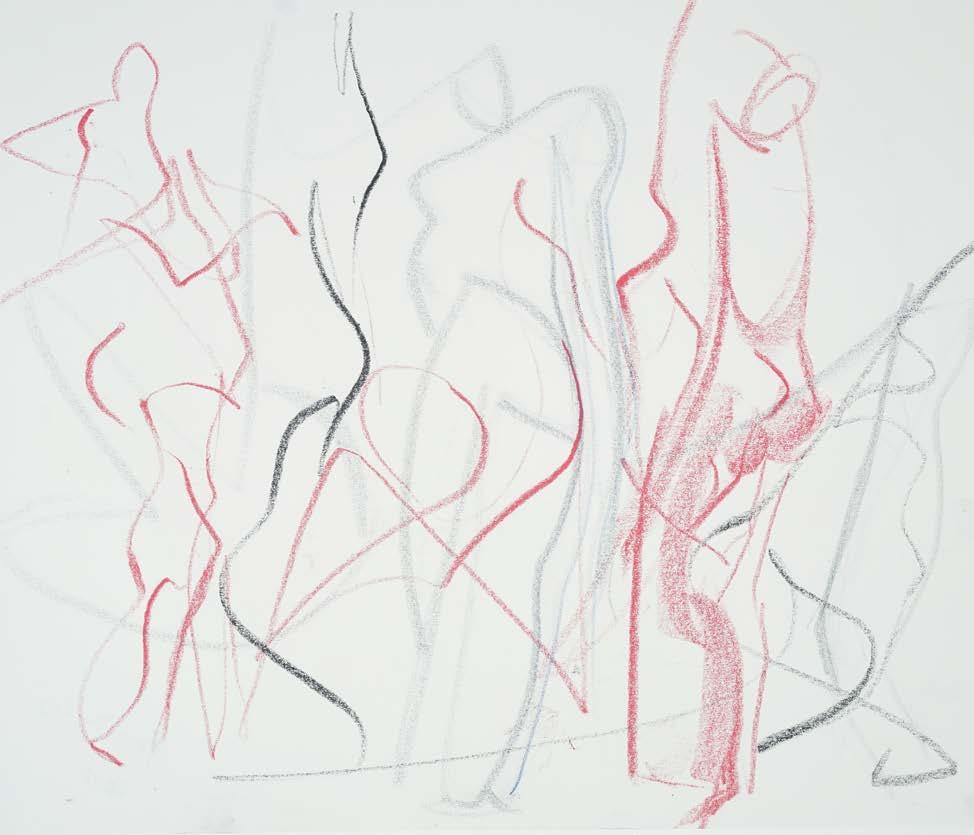

86 – 87 Autumn Leaves

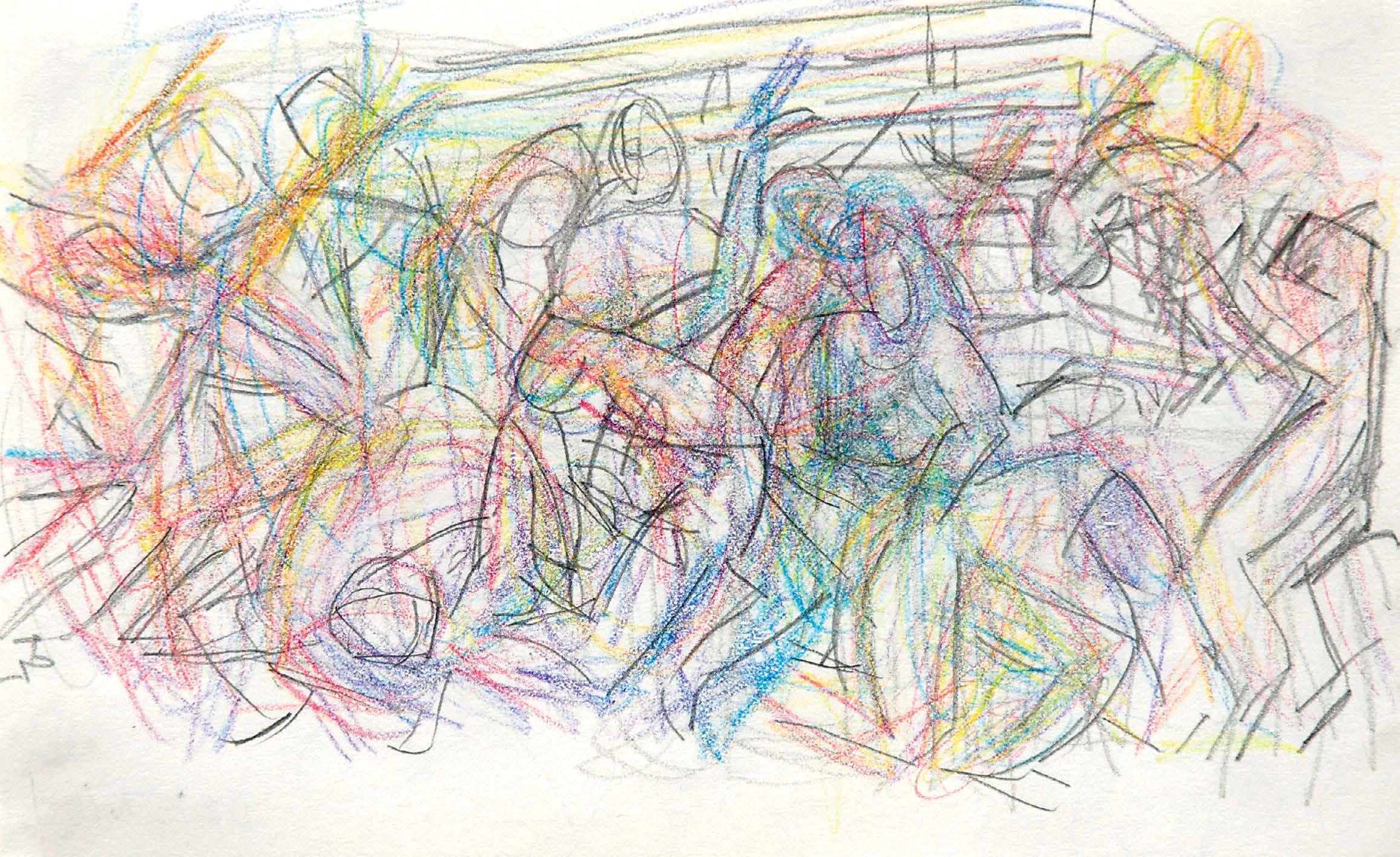

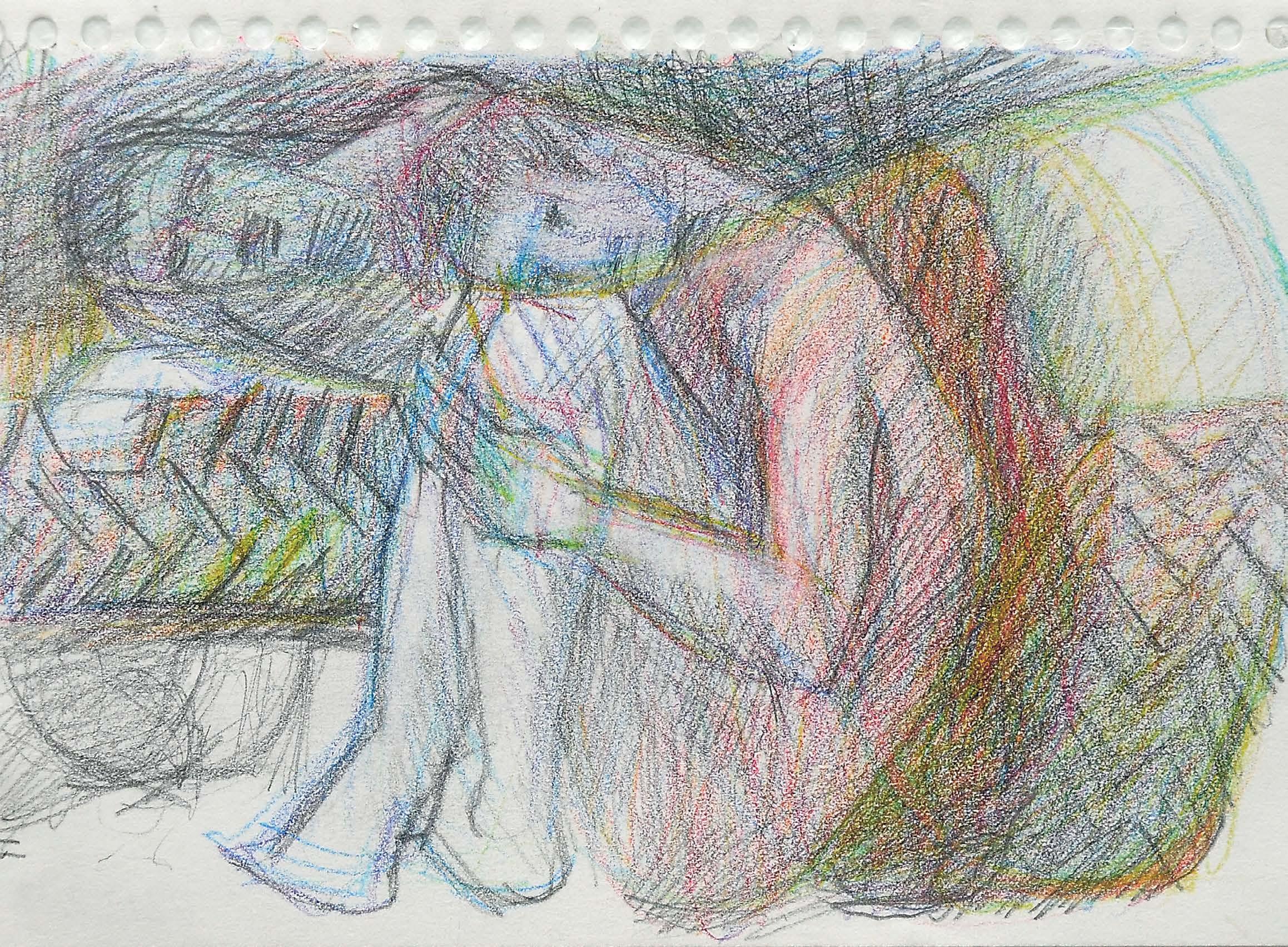

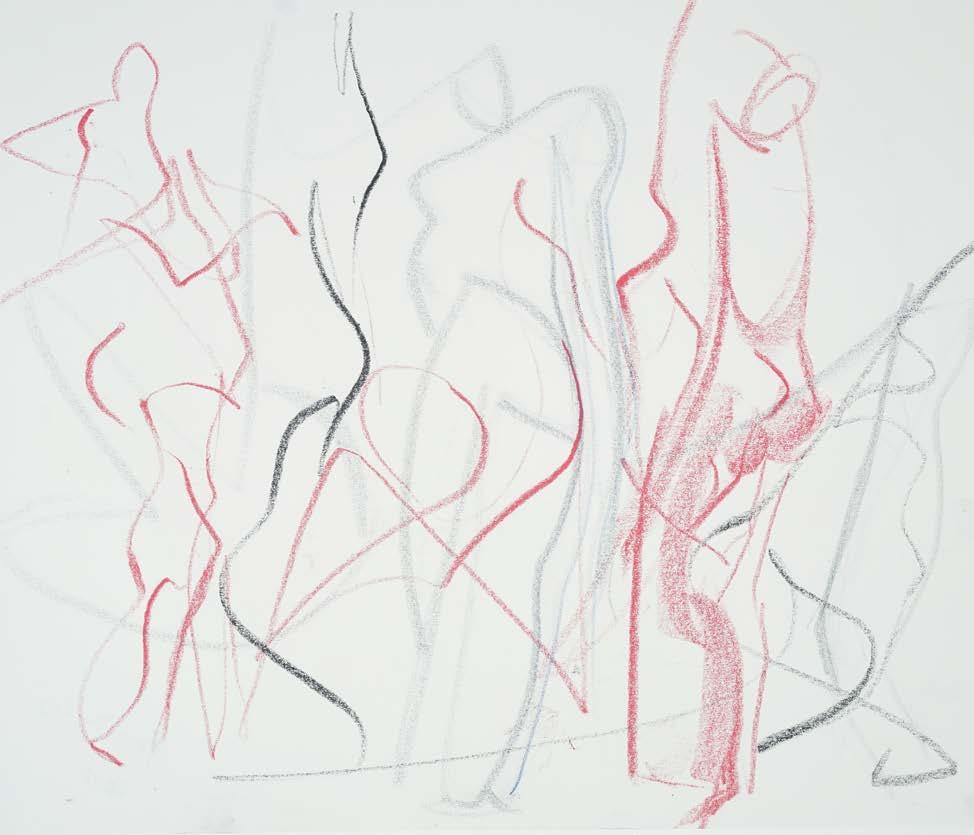

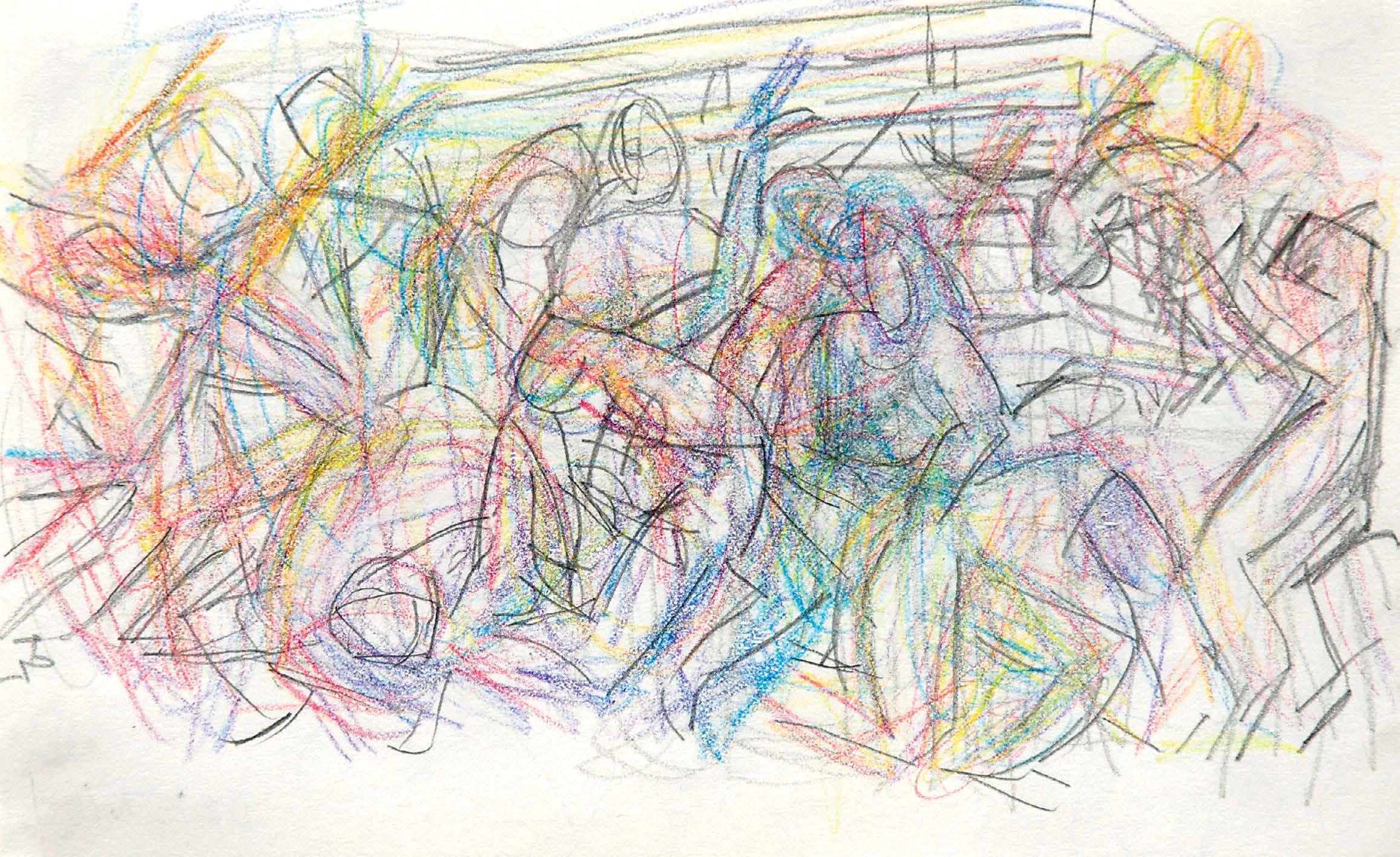

88 – 91 Dance on Canal

92 – 93 Interacting with Earth

94 – 95 Jabberwocky

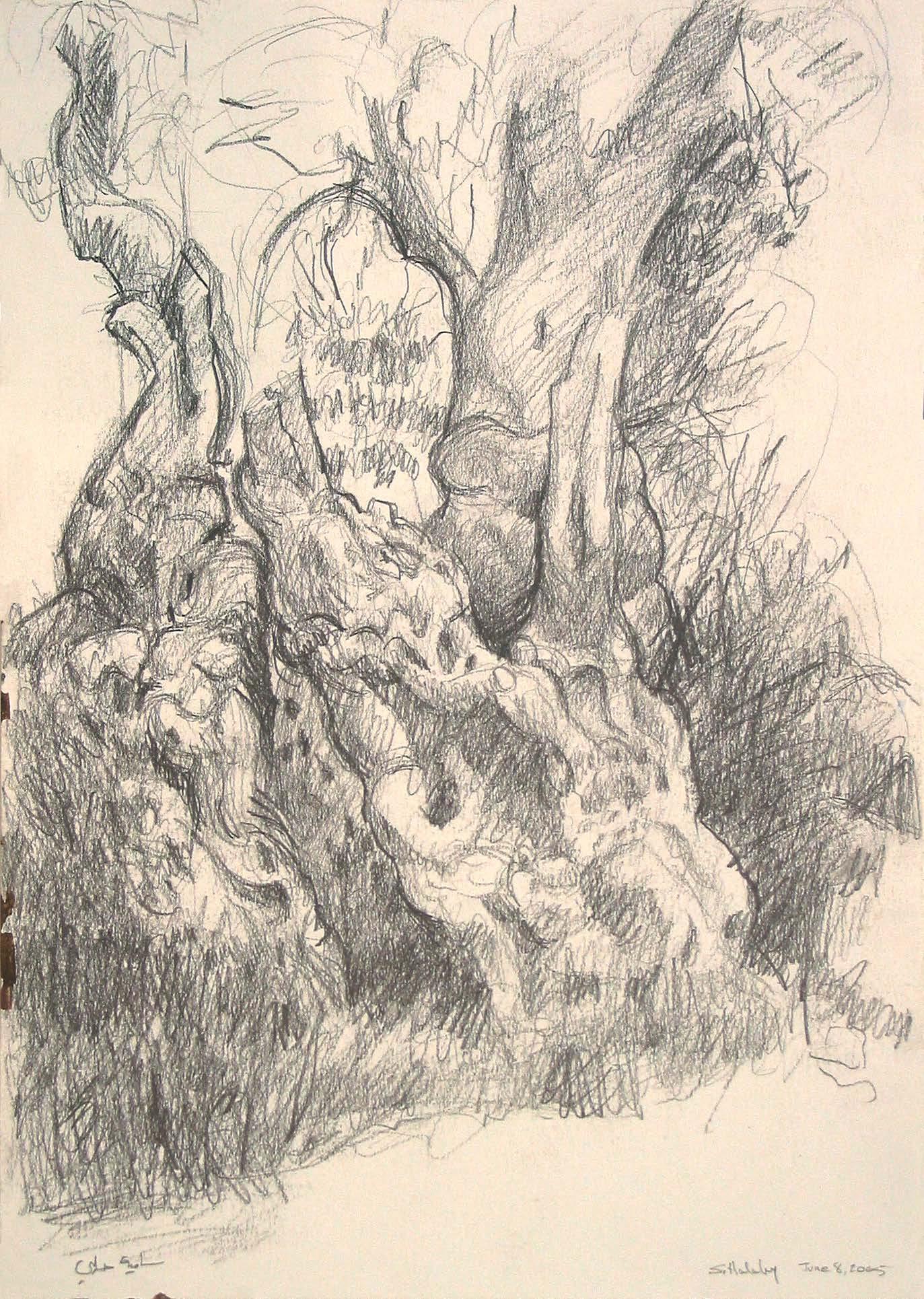

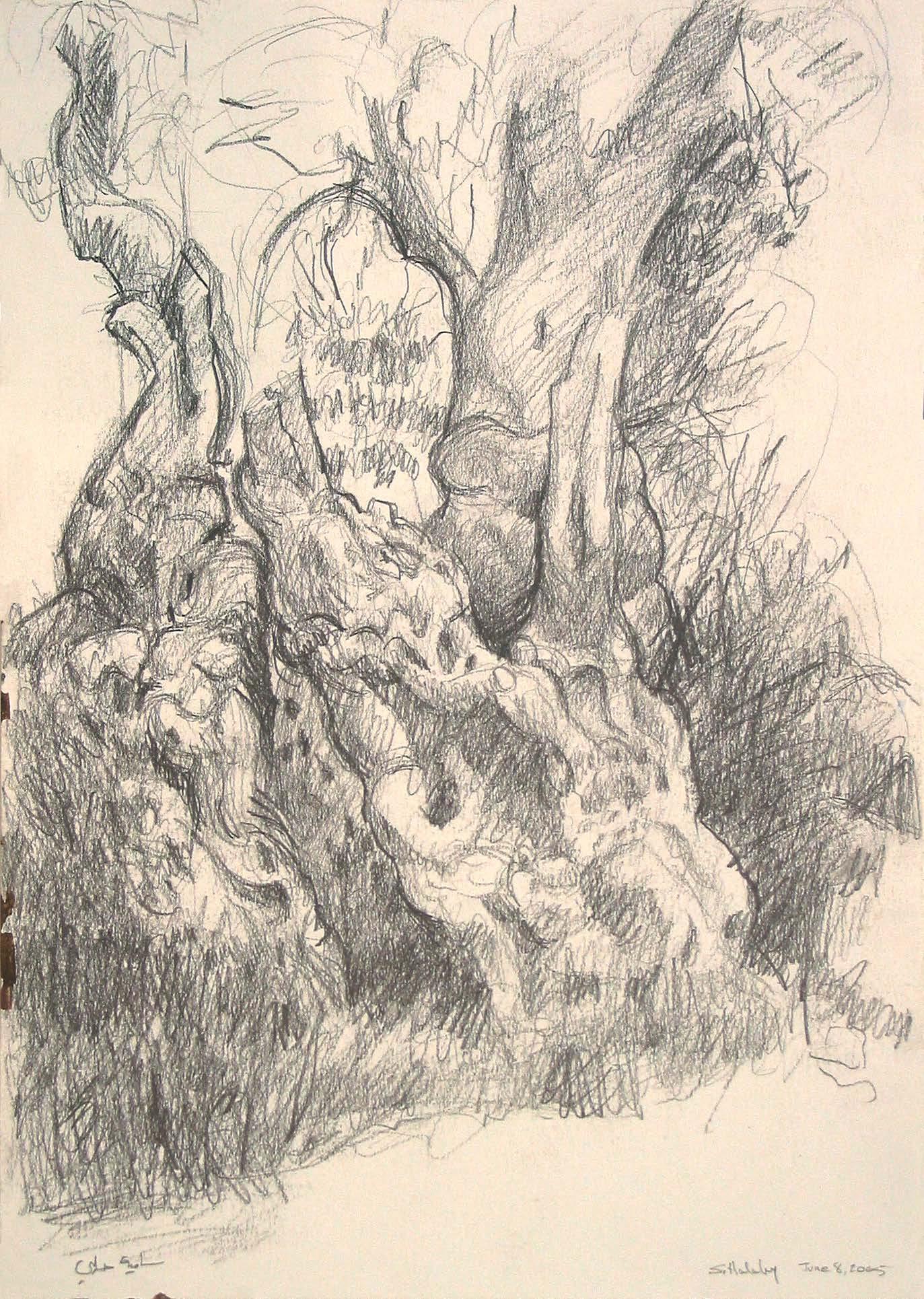

96 – 99 Olives of Palestine

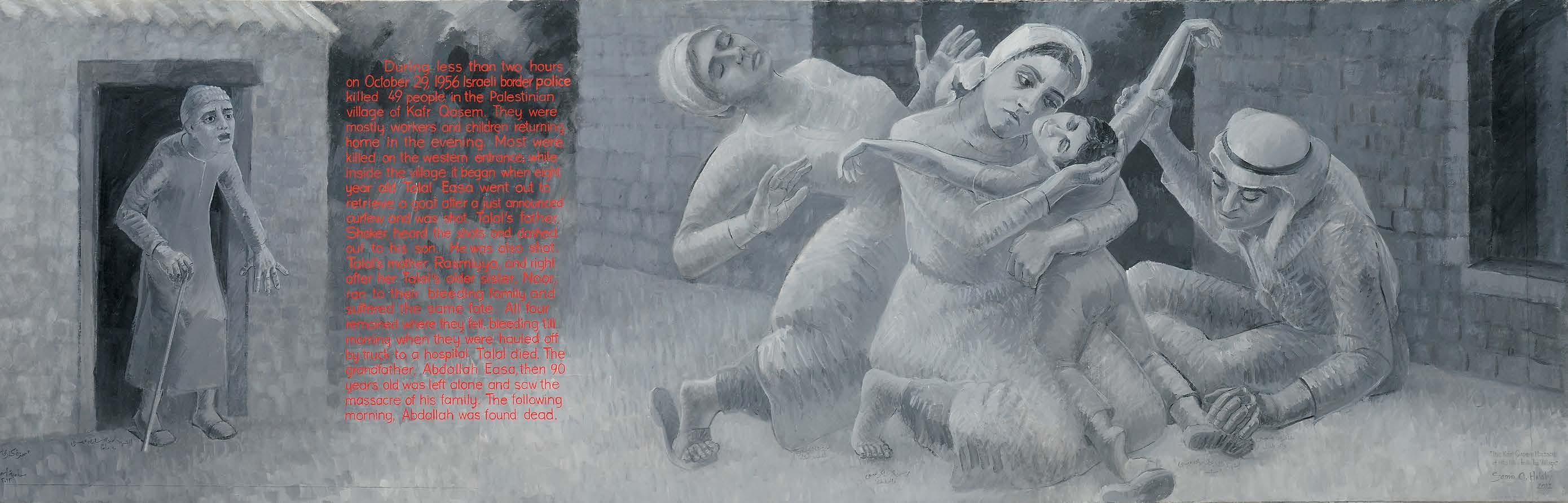

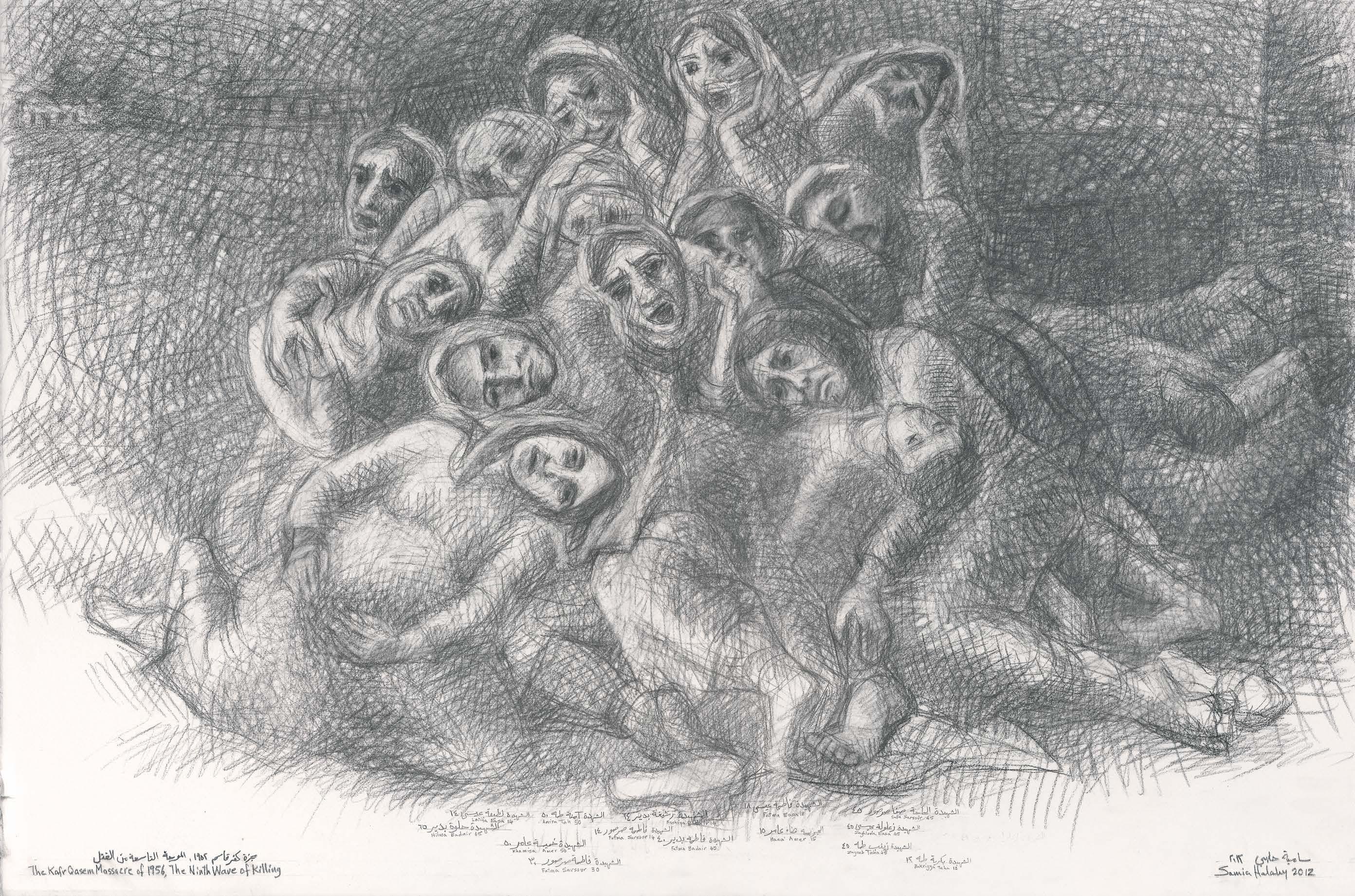

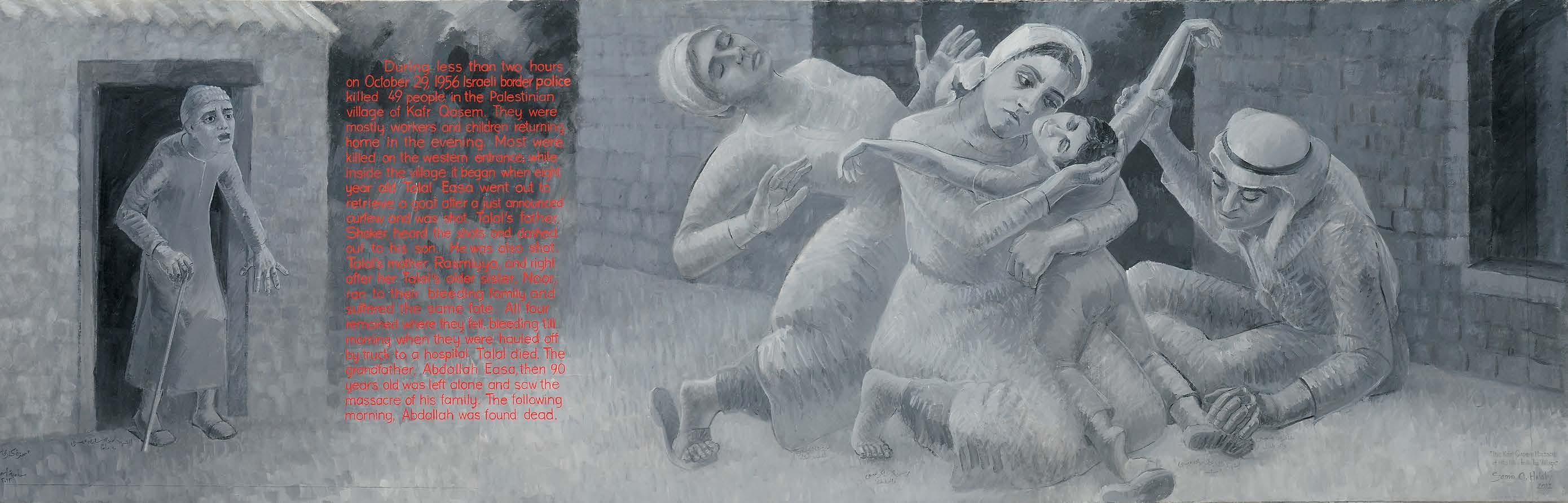

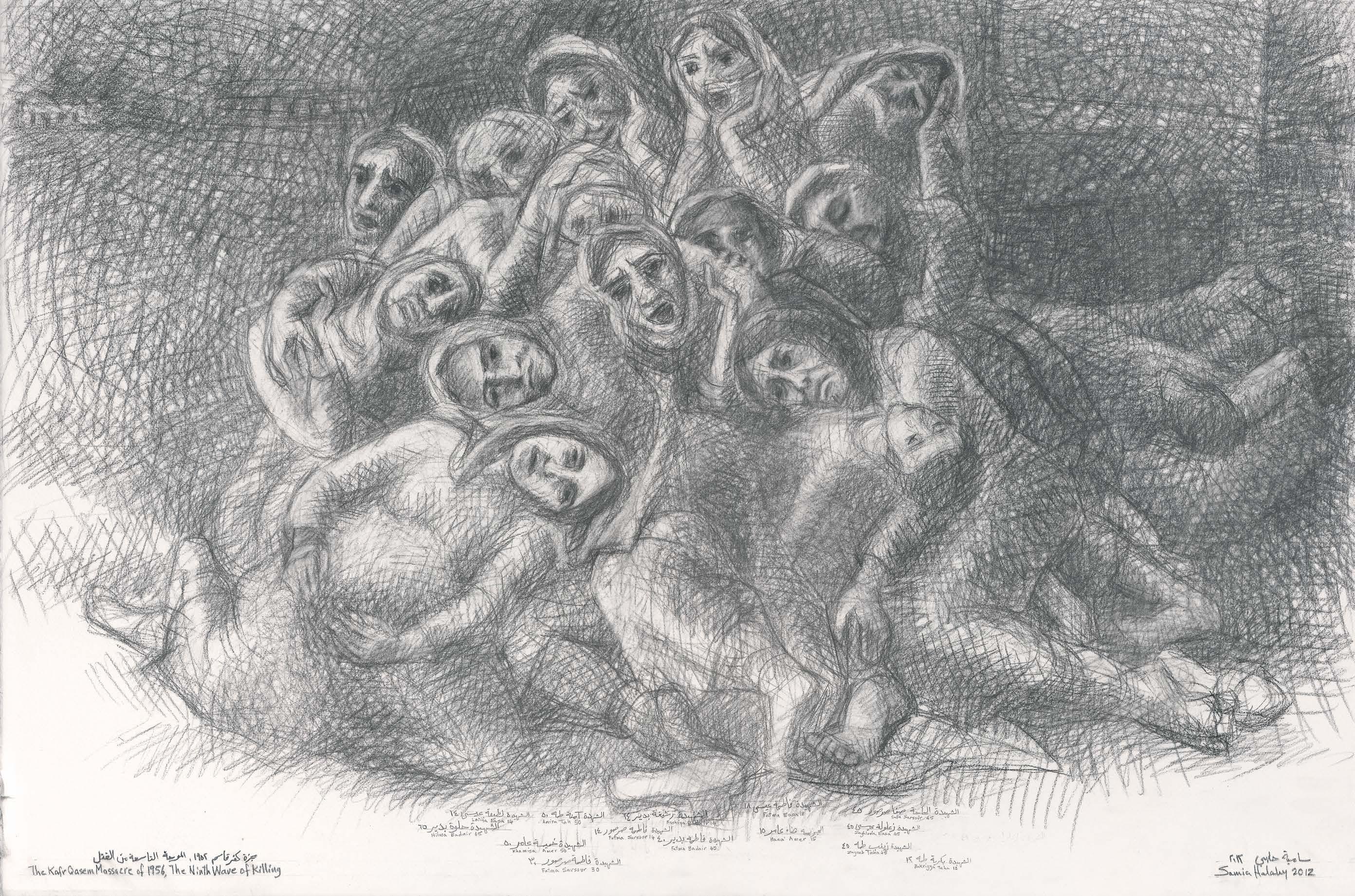

100 – 105 The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956

106 – 107 Hanging Sculpture Floating Paintings

108 – 109 The Art of Painting Invades My Clothes

110 – 111 Chapter IV: Behind the Scenes: Voices from the Inner Workings of a Long-Lasting, International Artistic Career

110 – 111 Introduction

112 – 121 Artistic Patronage and Commissioned Works: Dr. Basel Dalloul Carries on a Legacy of Kinship with Influential Work

122 – 127 Borderless Art: Andrée SfeirSemler Advances Artistic Prowess in Step with a Universal Zeitgeist

128 – 133 Ayyam Gallery: The GameChanger in a Career Faced with Obstacles

134 – 135 The Samia A. Halaby Foundation: Empowering Palestinian Communities

Through a Legacy of Art

136 Global Solidarity: The Ode to Black Liberation that Earned a Special Mention at the Venice Biennale

CONTENTS COVER

YORK, 2019.

PORTRAIT BY NIDA SINOKROT, TRIBECA, NEW

8

Orario [Opening Hours] 20.04 — 30.09 h. 11 — 19 1.10 — 24.11 h. 10 — 18 Chiuso il lunedì [Closed on Mondays] #BiennaleArte2024 labiennale.org Compra qui il tuo biglie o Buy your ticket Info +39 041 5218 828 promozione@labiennale.org

Founder

Rima Nasser

Editor-in-Chief

Anastasia Nysten

Designer

Maria Maalouf

Project Manager

Yasmina Hammoud

Guest Editor

Nadia Michel

Editorial and Advertising Inquiries

Anastasia Nysten anastasia@selectionsarts.com selectionsarts.com facebook.com/selectionsarts instagram.com/selections_arts

#68 ARTS-STYLE-CULTURE FROM THE ARAB WORLD AND BEYOND

10

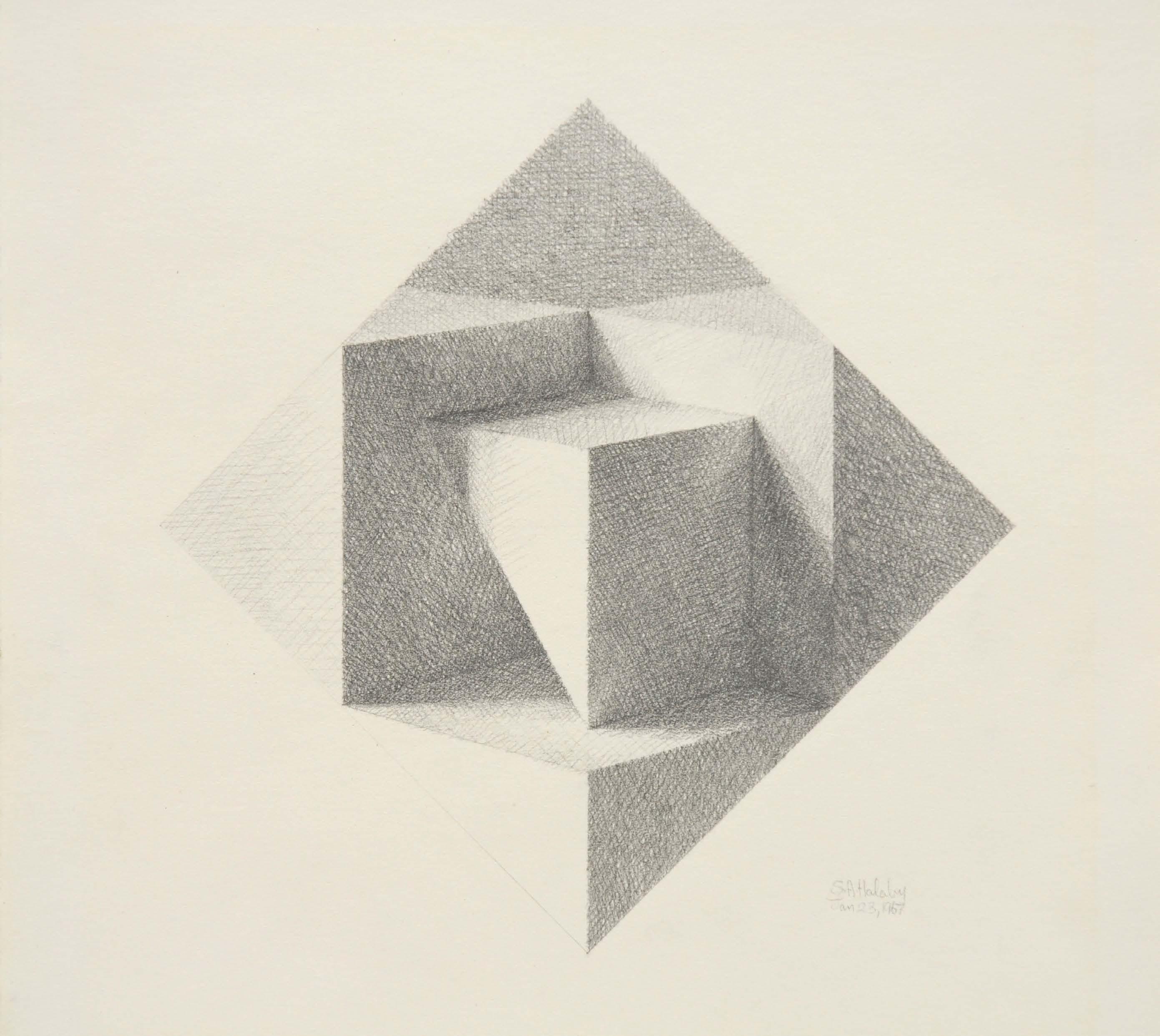

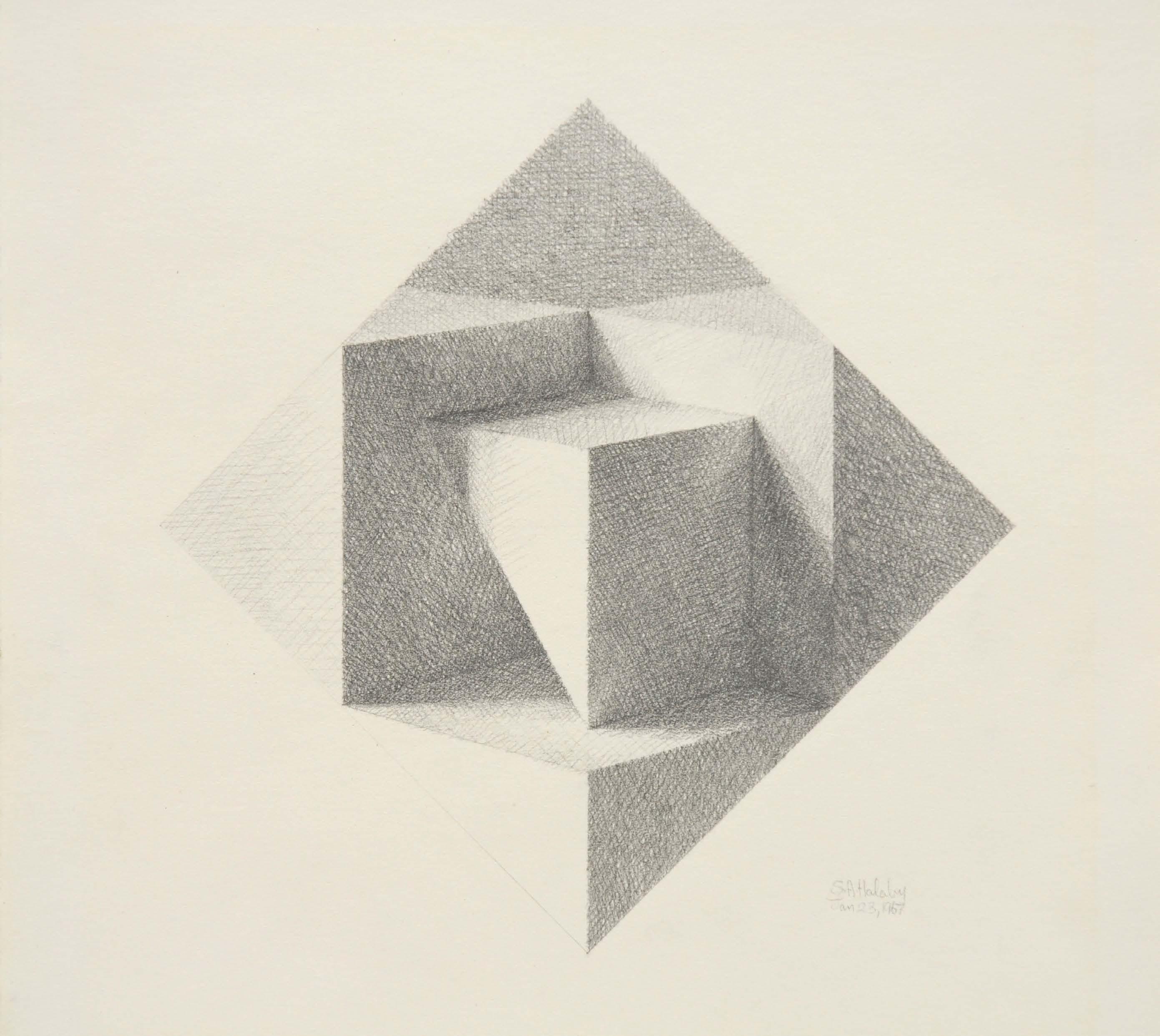

Diamond Cube in Cube, 1967, pencil on paper, 15 x 11 in (38 x 28 cm).

Diamond Cube in Cube, 1967, pencil on paper, 15 x 11 in (38 x 28 cm).

12

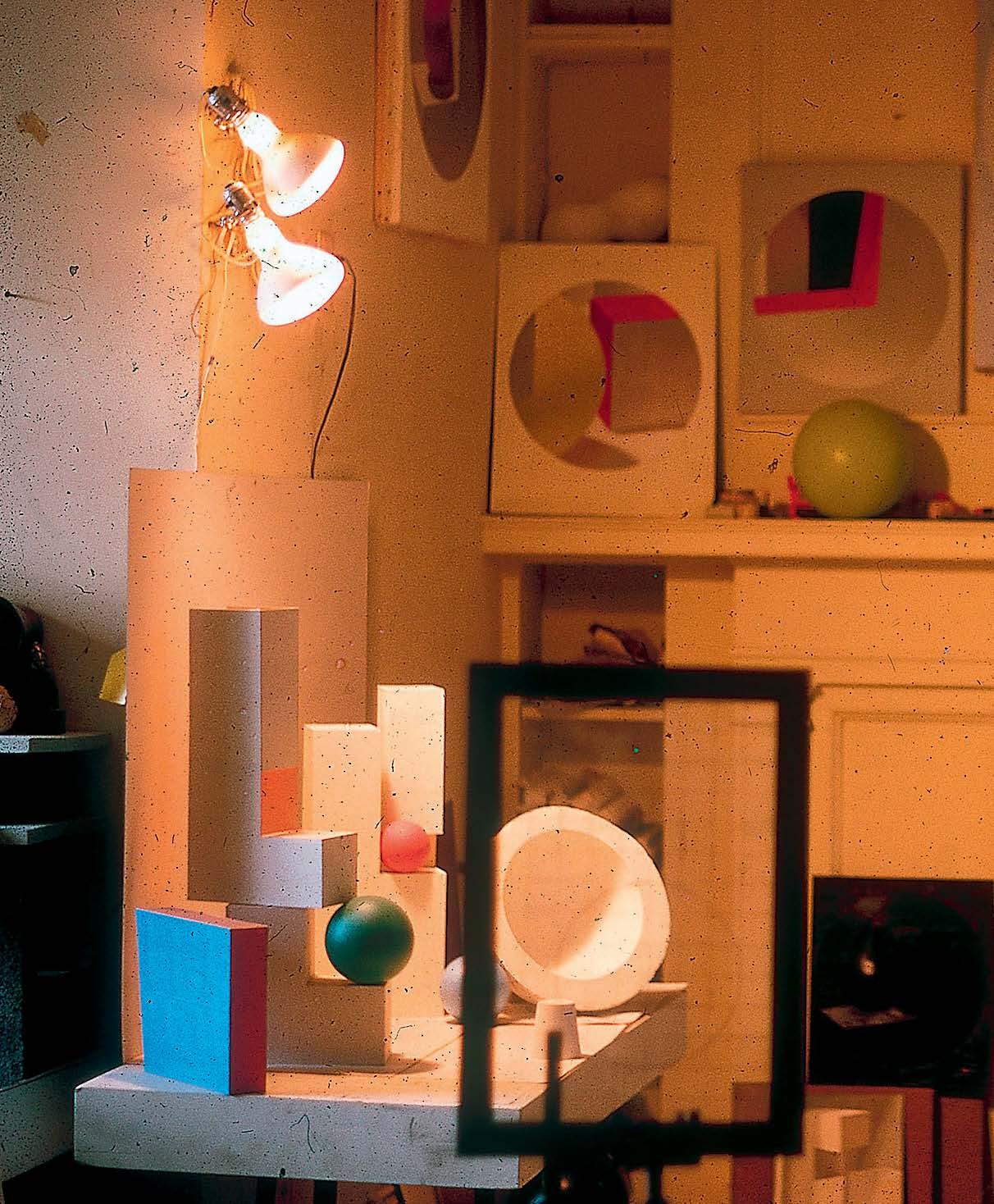

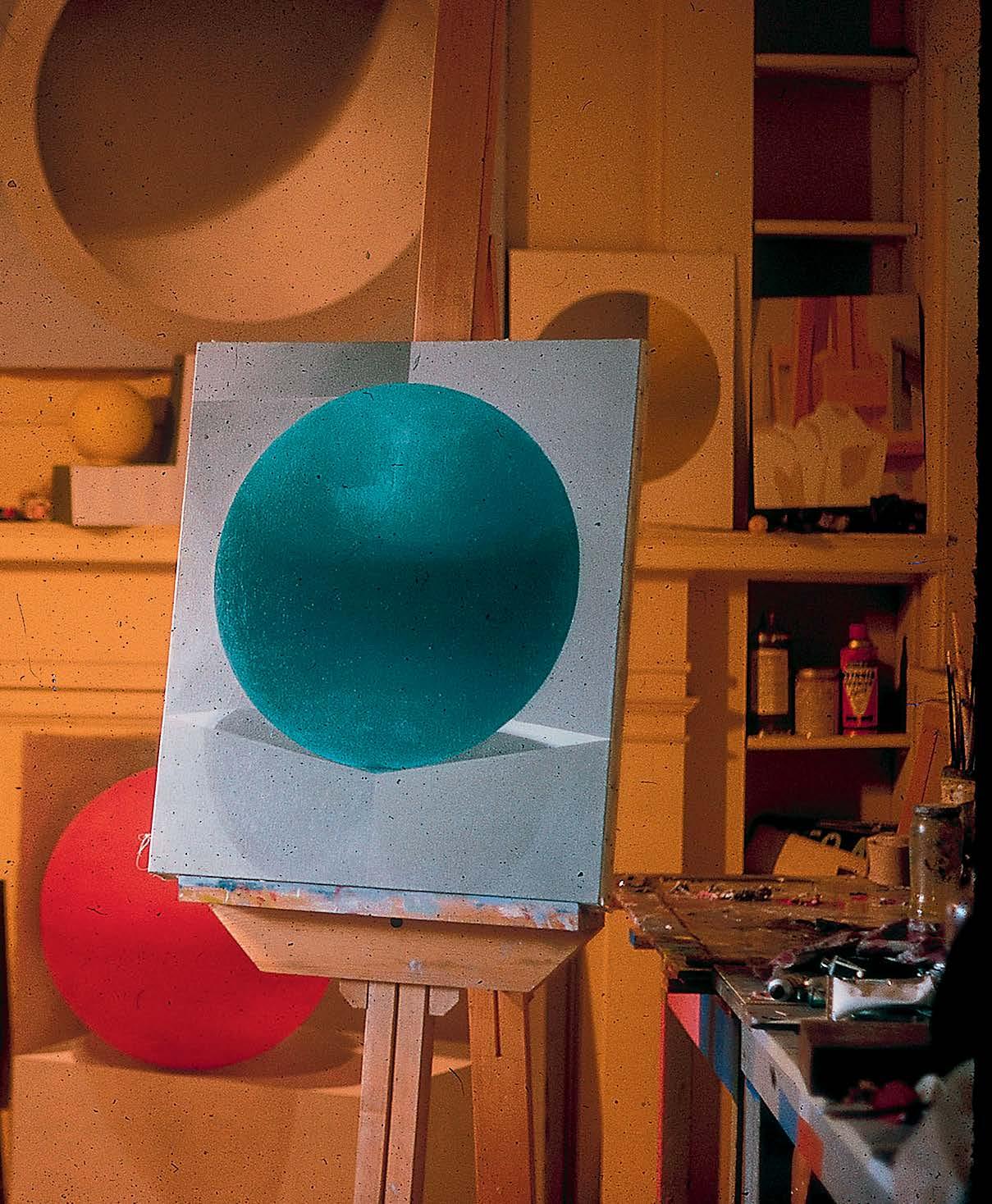

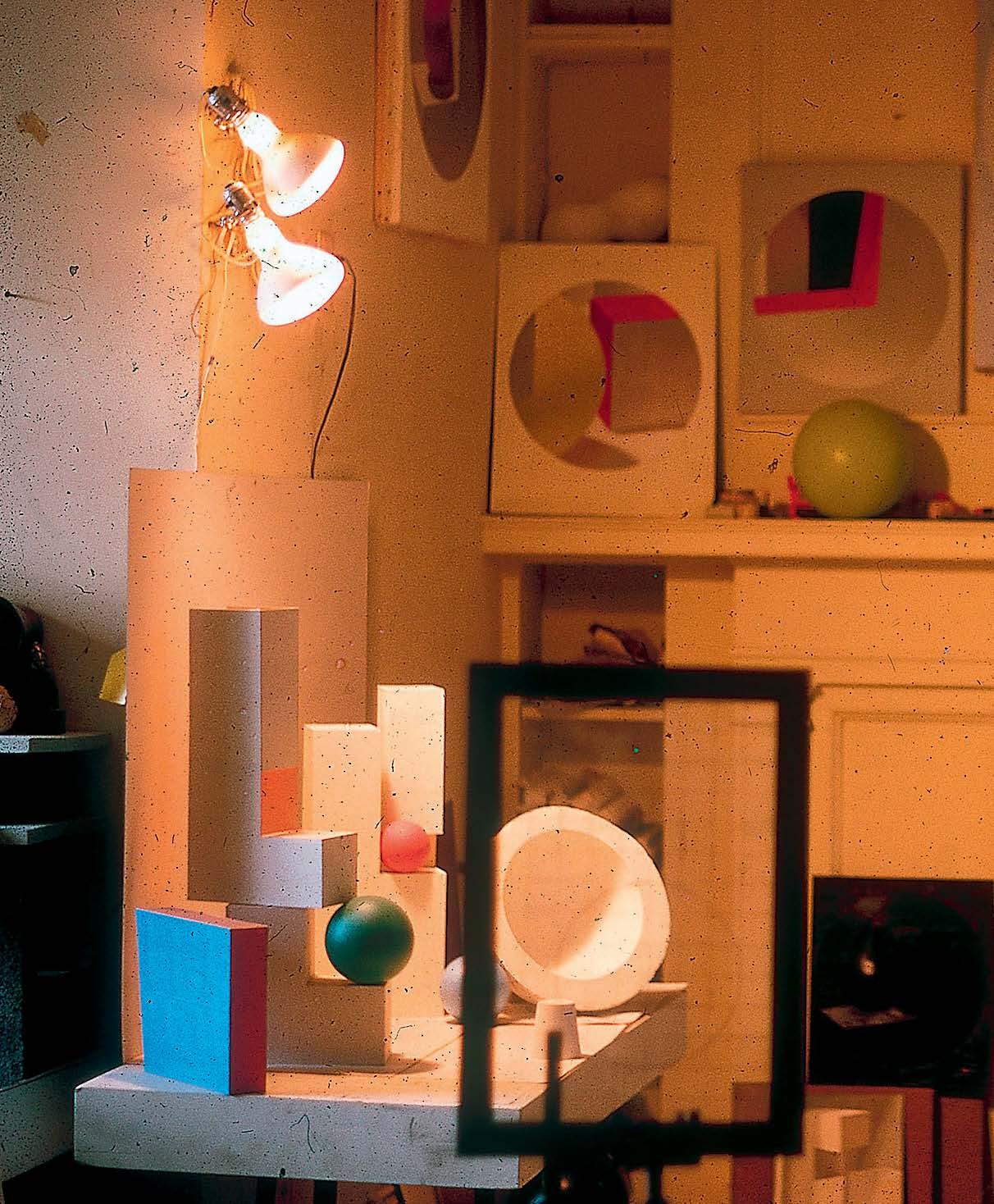

Kansas City Studio, 1966.

14

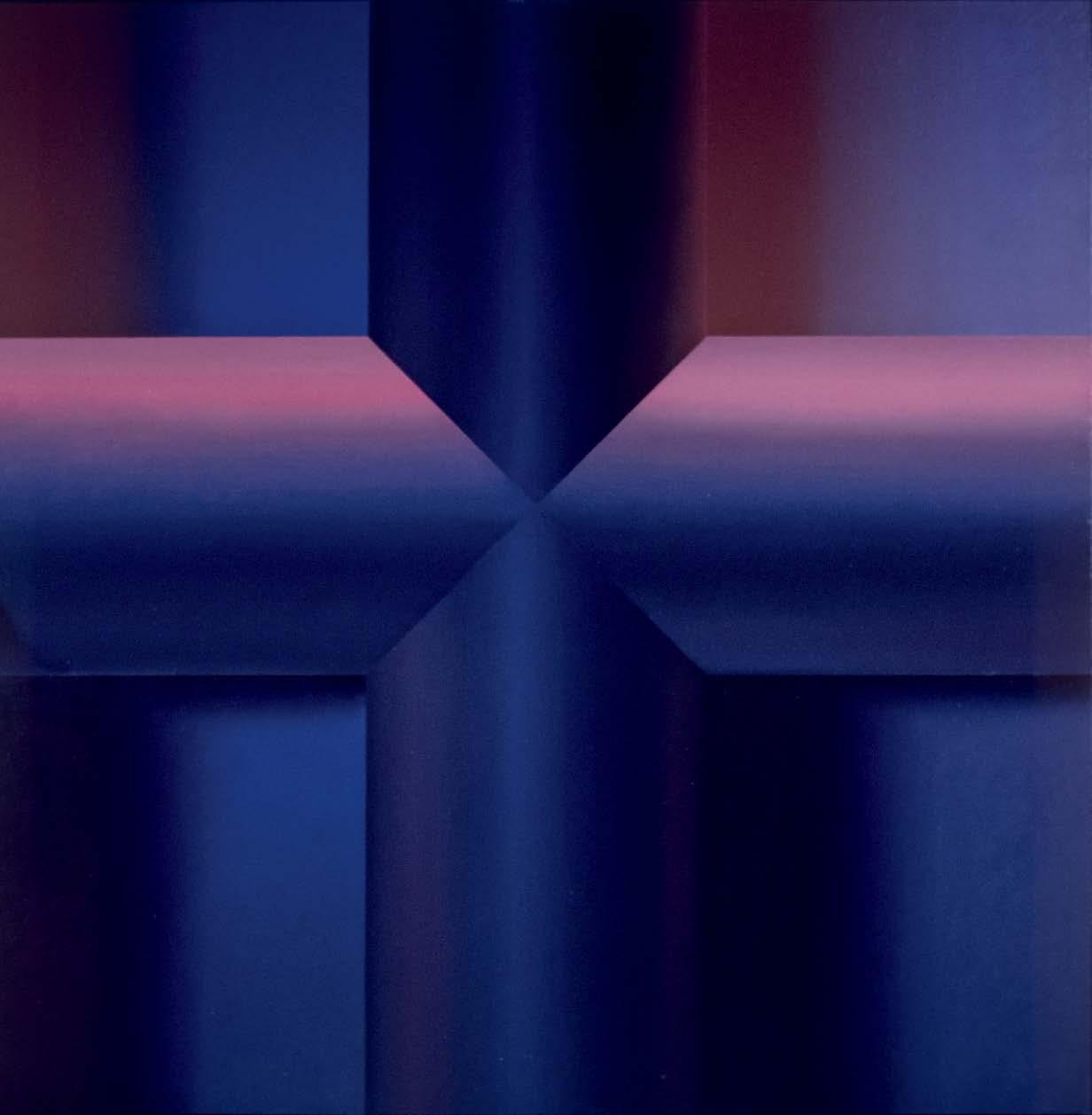

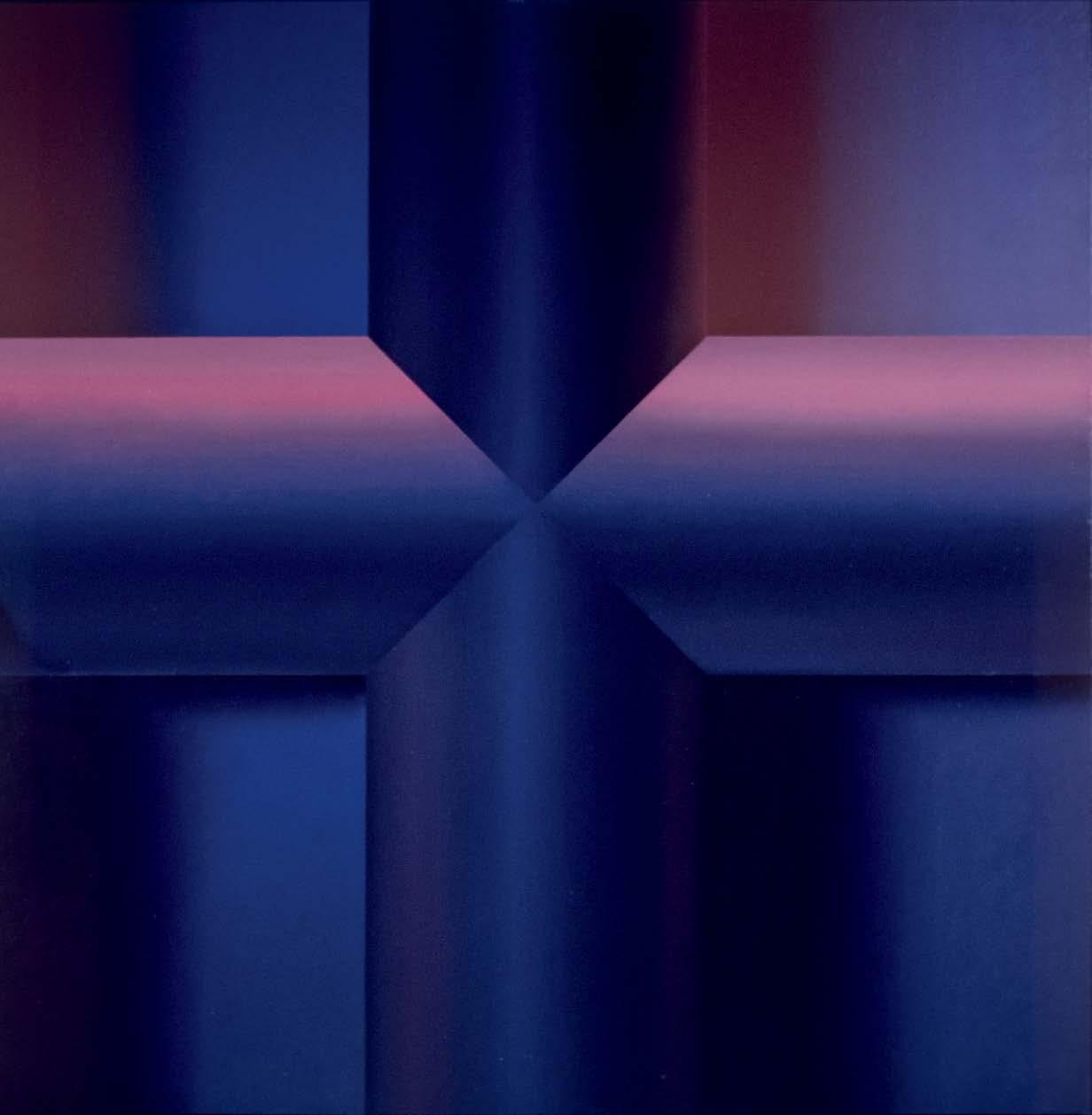

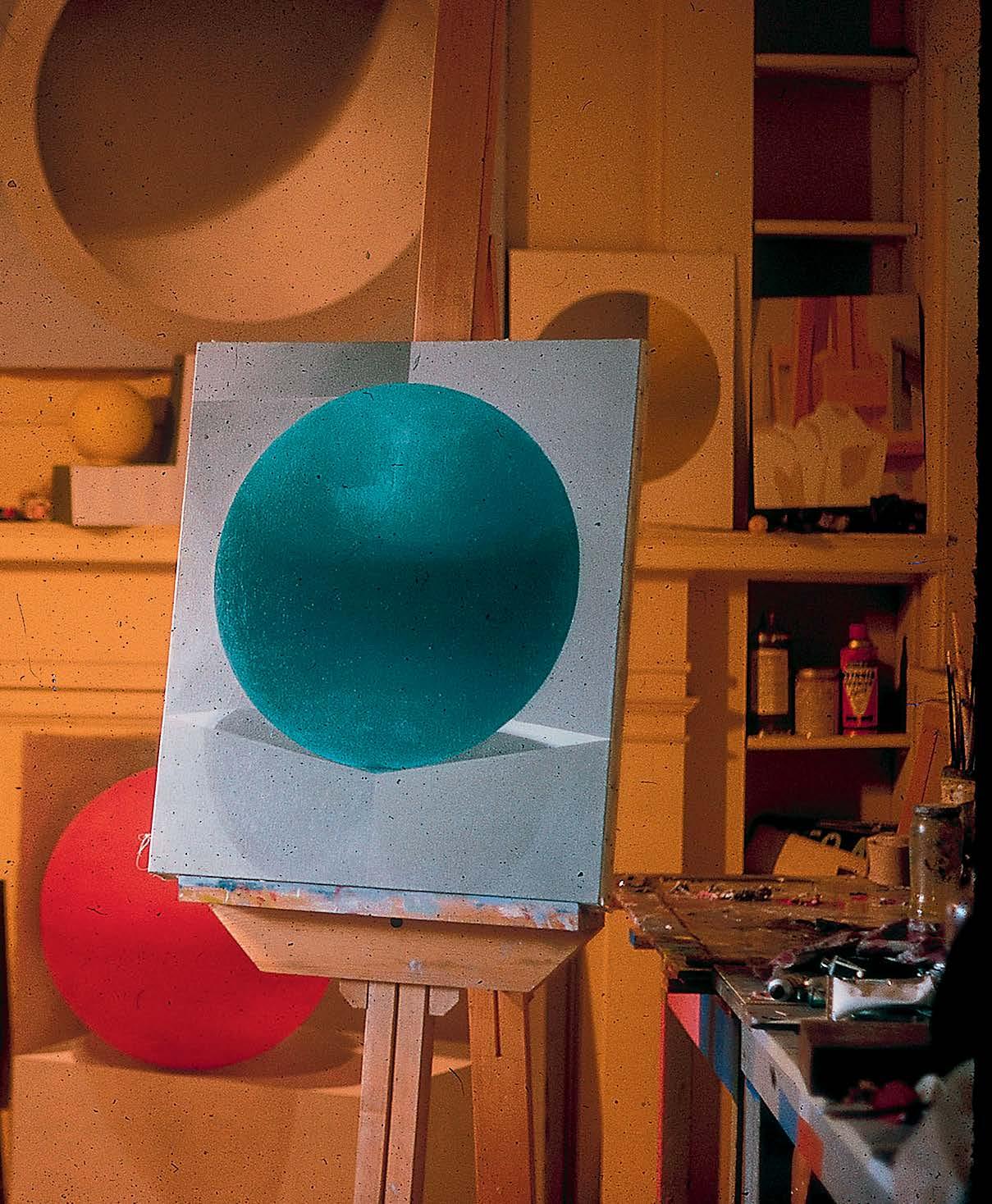

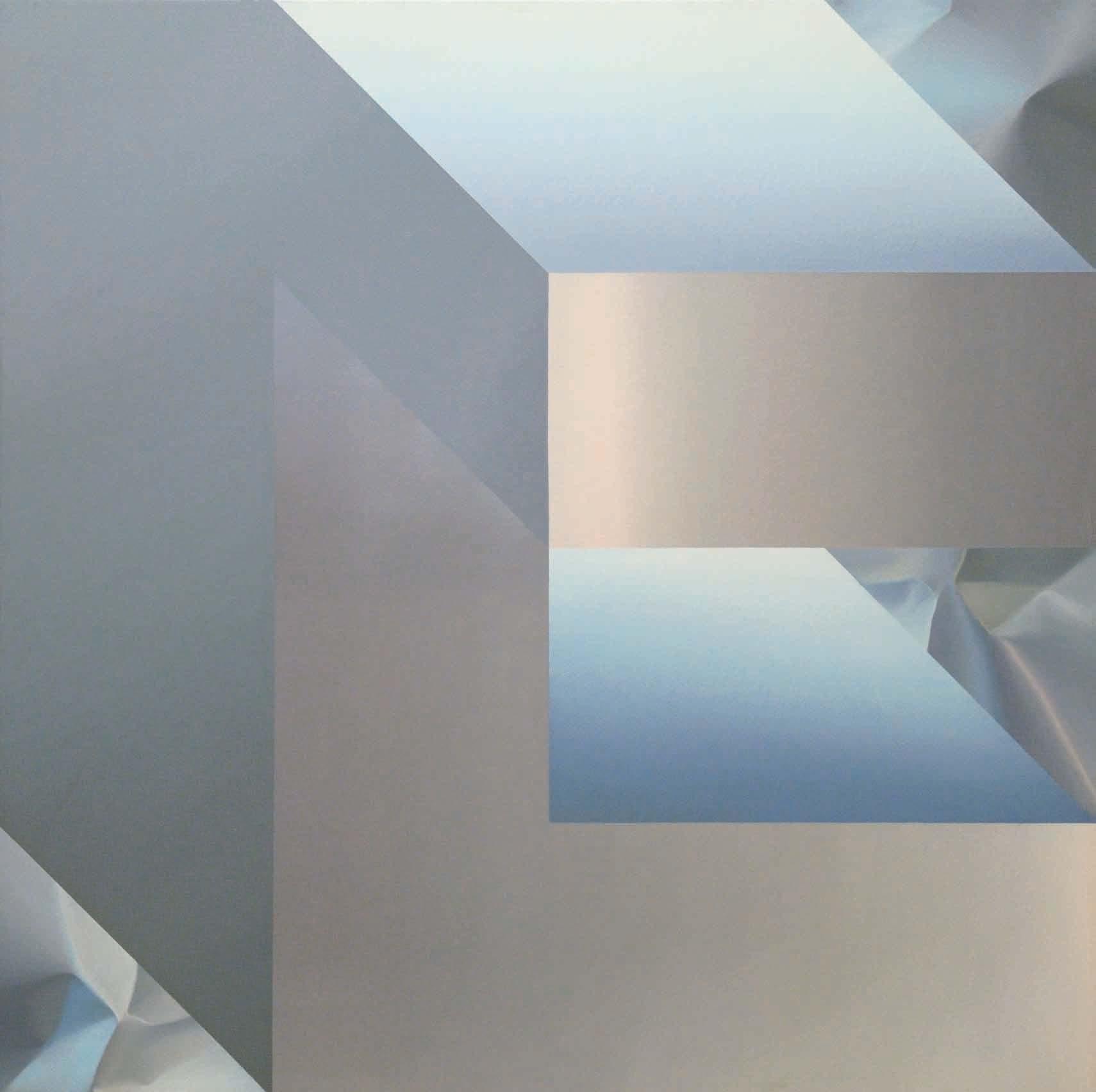

(This page) Blue Window Sphere, 1966, oil on canvas, 37 x 37 in (94 x 94 cm).

(Opposite) Kansas City Studio, 1966.

(This page) Blue Window Sphere, 1966, oil on canvas, 37 x 37 in (94 x 94 cm).

(Opposite) Kansas City Studio, 1966.

16

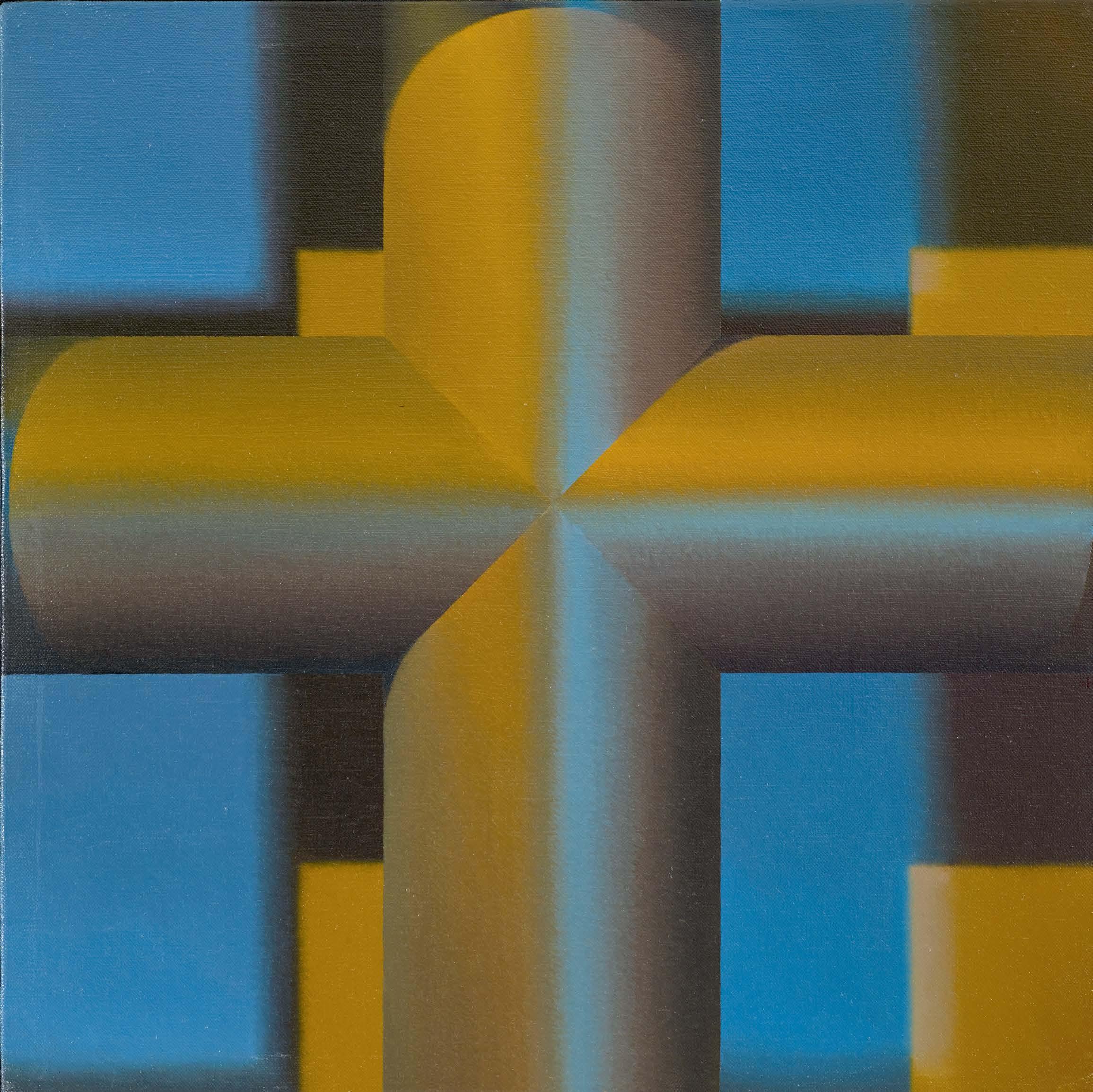

Dexter Michigan studio with Black and White, 1969.

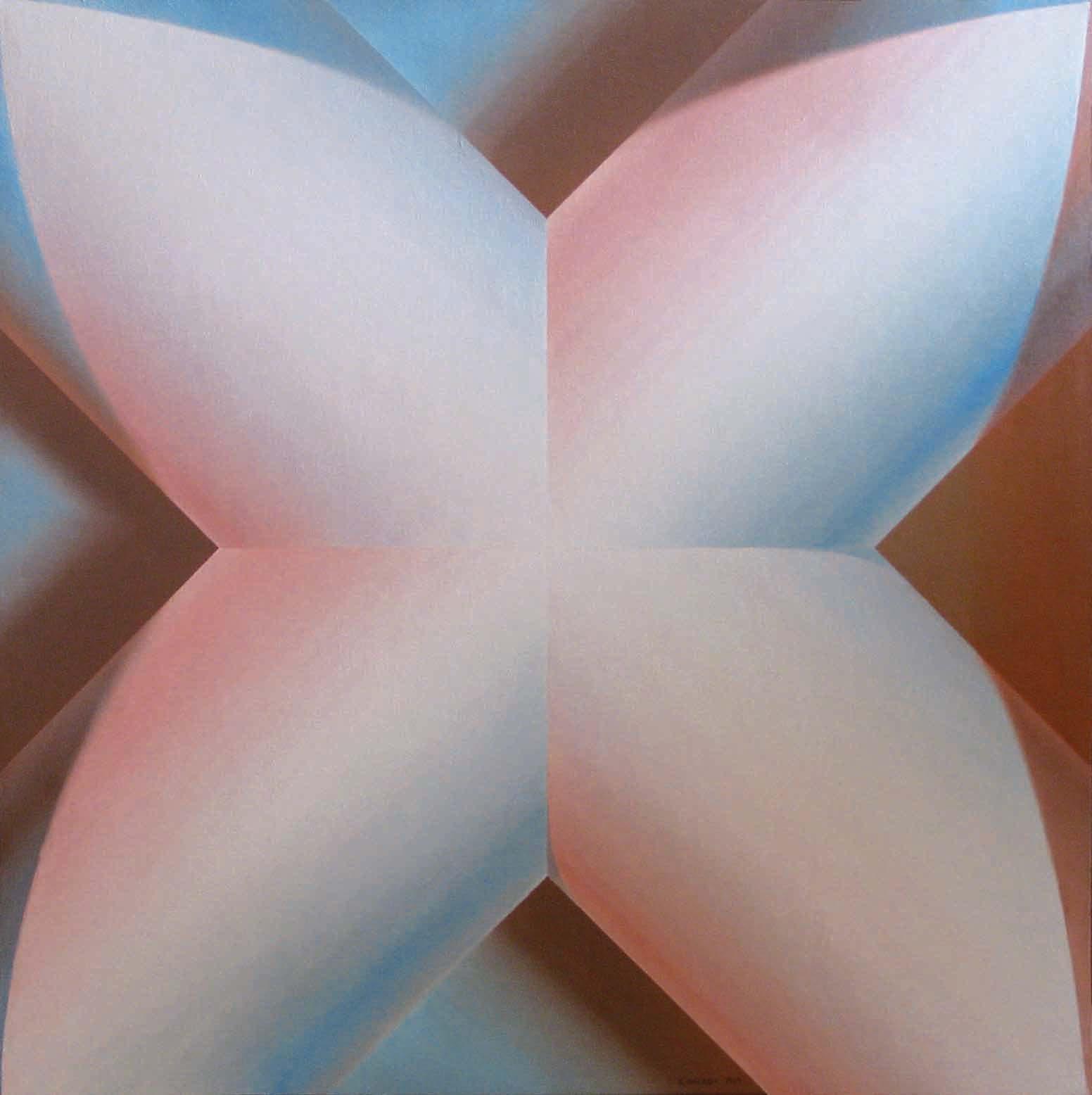

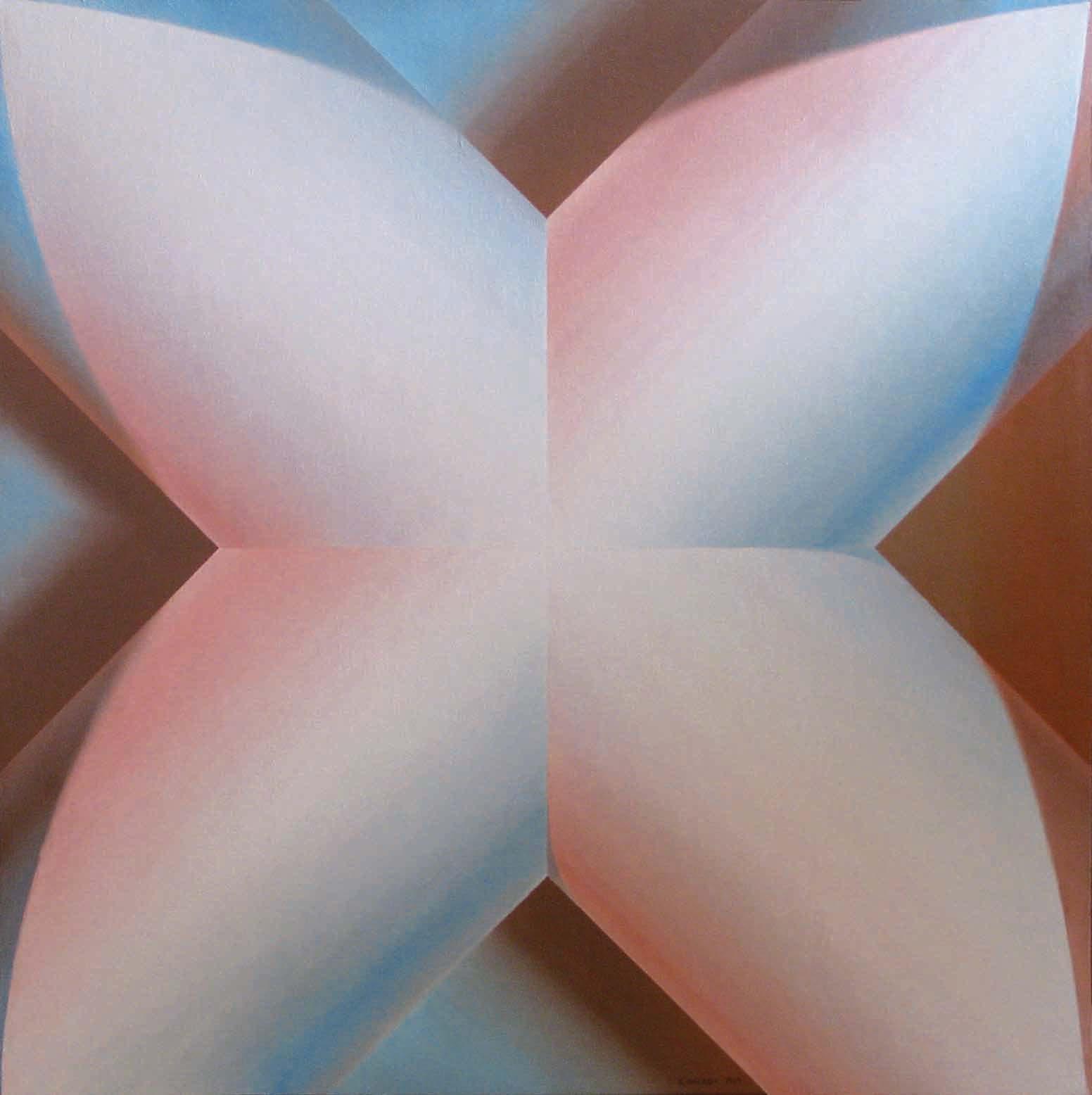

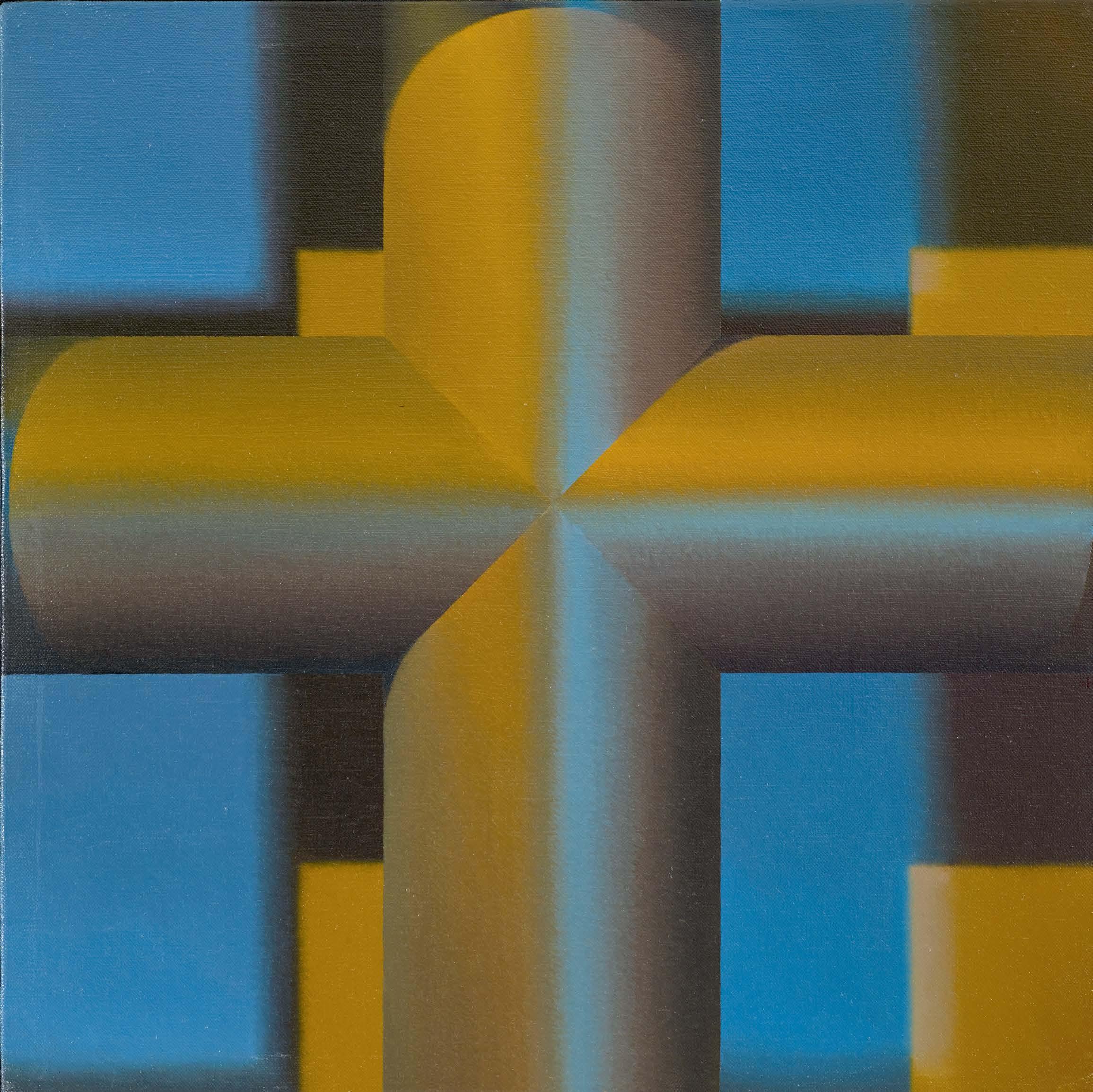

Sixth Cross, Diagonal Cross, 1969, oil on canvas, 35 x 35 in (89 x 89 cm).

Sixth Cross, Diagonal Cross, 1969, oil on canvas, 35 x 35 in (89 x 89 cm).

18

Portrait, New Haven, Connecticut, 1975.

Fire 1975, oil on canvas, 30 x 42 in (76 x 107 cm).

Fire 1975, oil on canvas, 30 x 42 in (76 x 107 cm).

20

Portrait, Tribeca, New York, 1976.

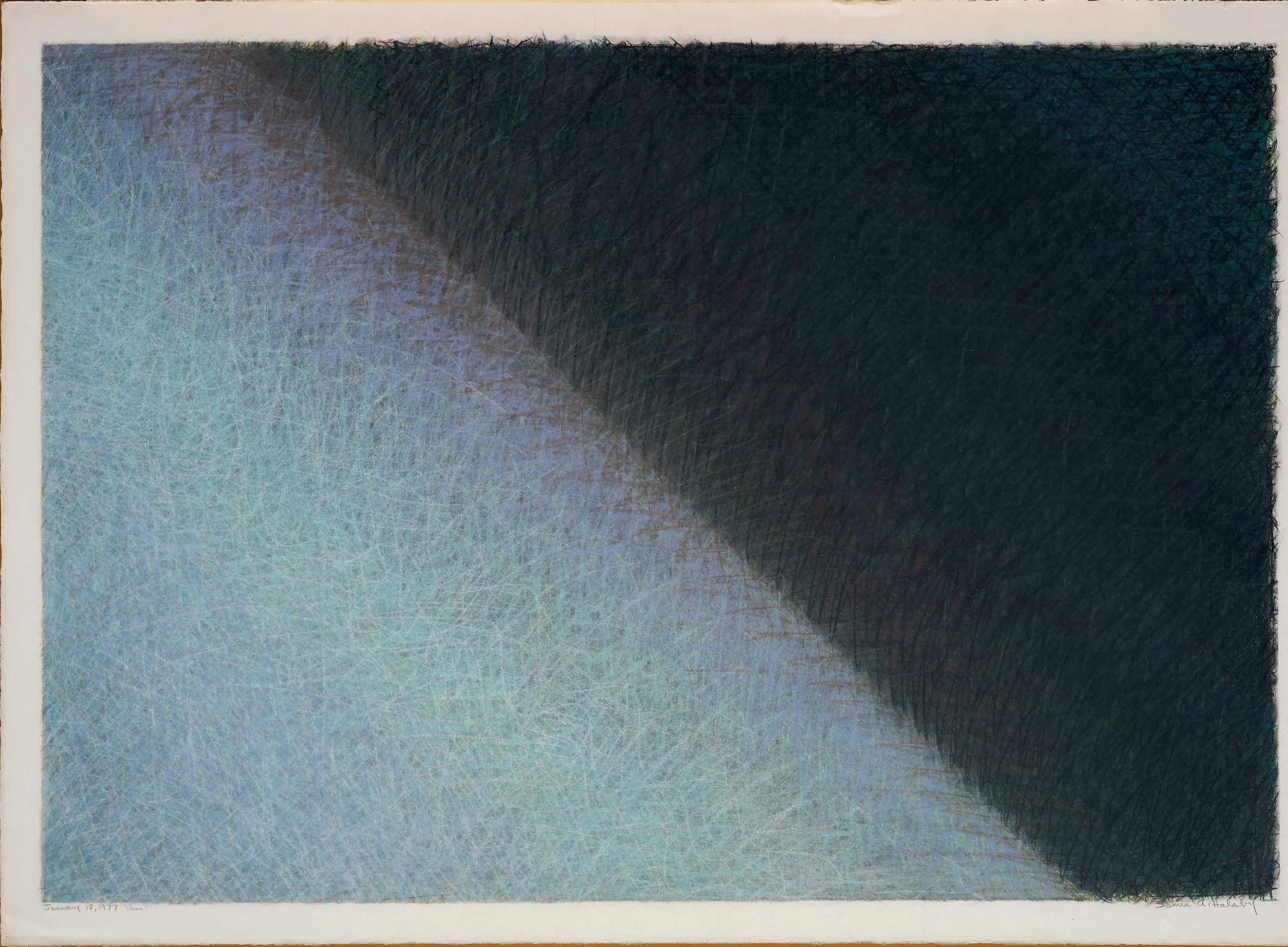

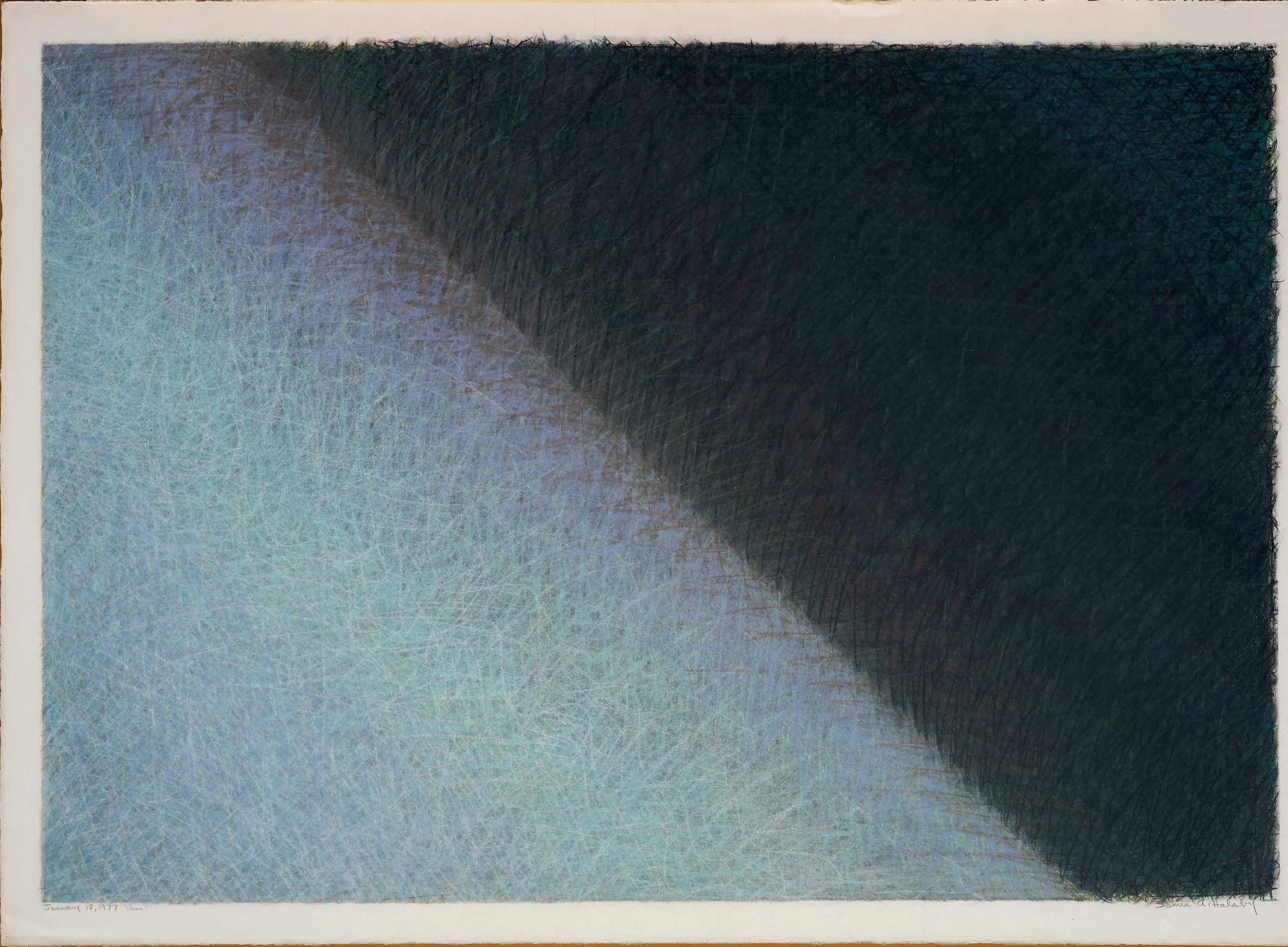

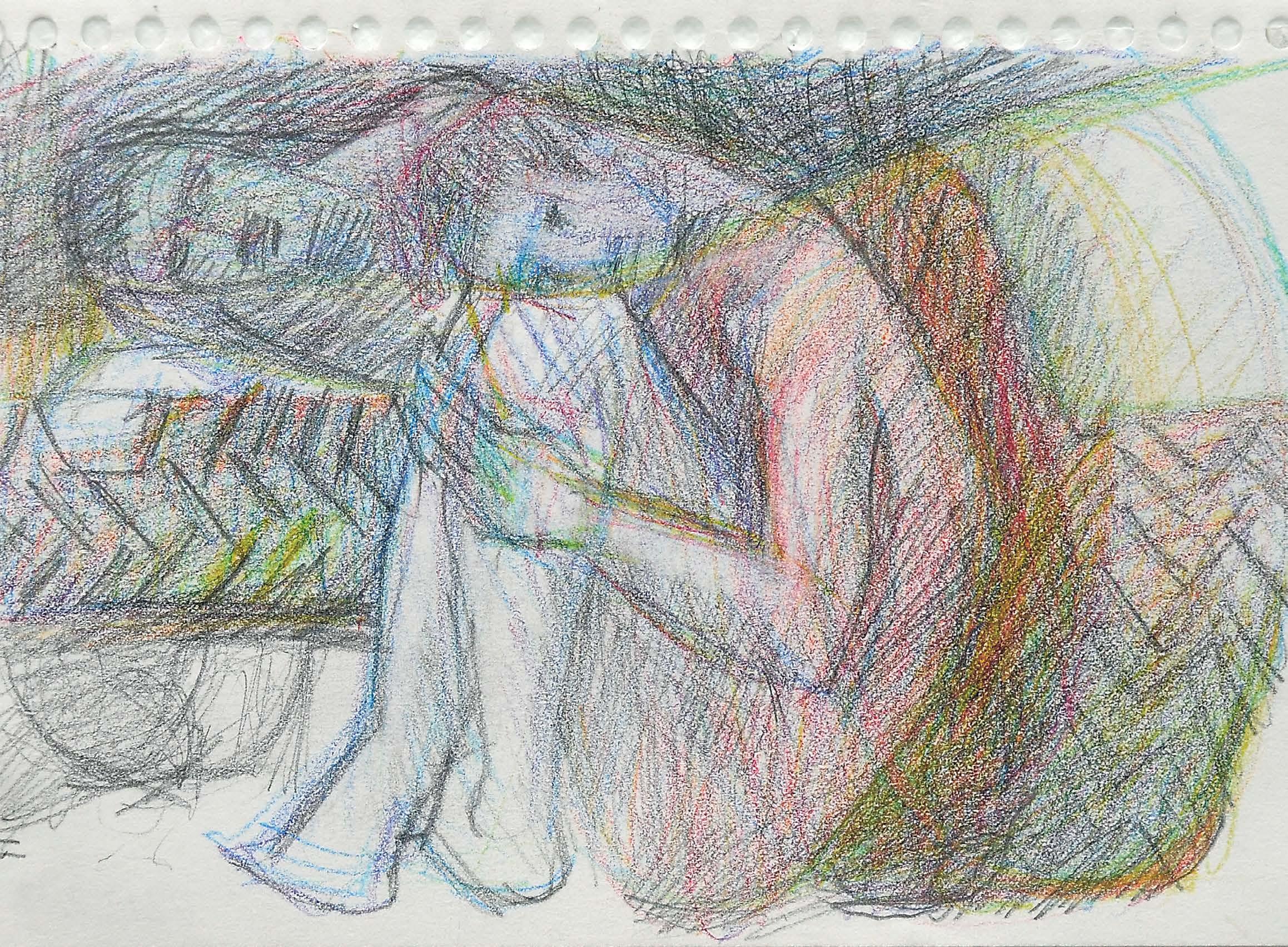

Ocean, 1977, wax crayons

22 1/4 x 30 in (56.5 x 76 cm).

Ocean, 1977, wax crayons

22 1/4 x 30 in (56.5 x 76 cm).

(Above) Studio, Tribeca, New York, 2007.

(Above) Studio, Tribeca, New York, 2007.

22

(Opposite) Three Mothers and 3 Exotic Birds Under an Olive Tree, Women of Palestine series, 20052009, acrylic on canvas, 85 x 72 in (216 x 183 cm).

24

Studio, Tribeca, New York, 2009.

26

Studio, Tribeca, New York, 2013.

28

Portrait, Tribeca, New York, 2013.

30

Portrait by Nida Sinokrot, Tribeca, New York, 2019.

Portrait by Nida Sinokrot, Tribeca, New York, 2019.

01

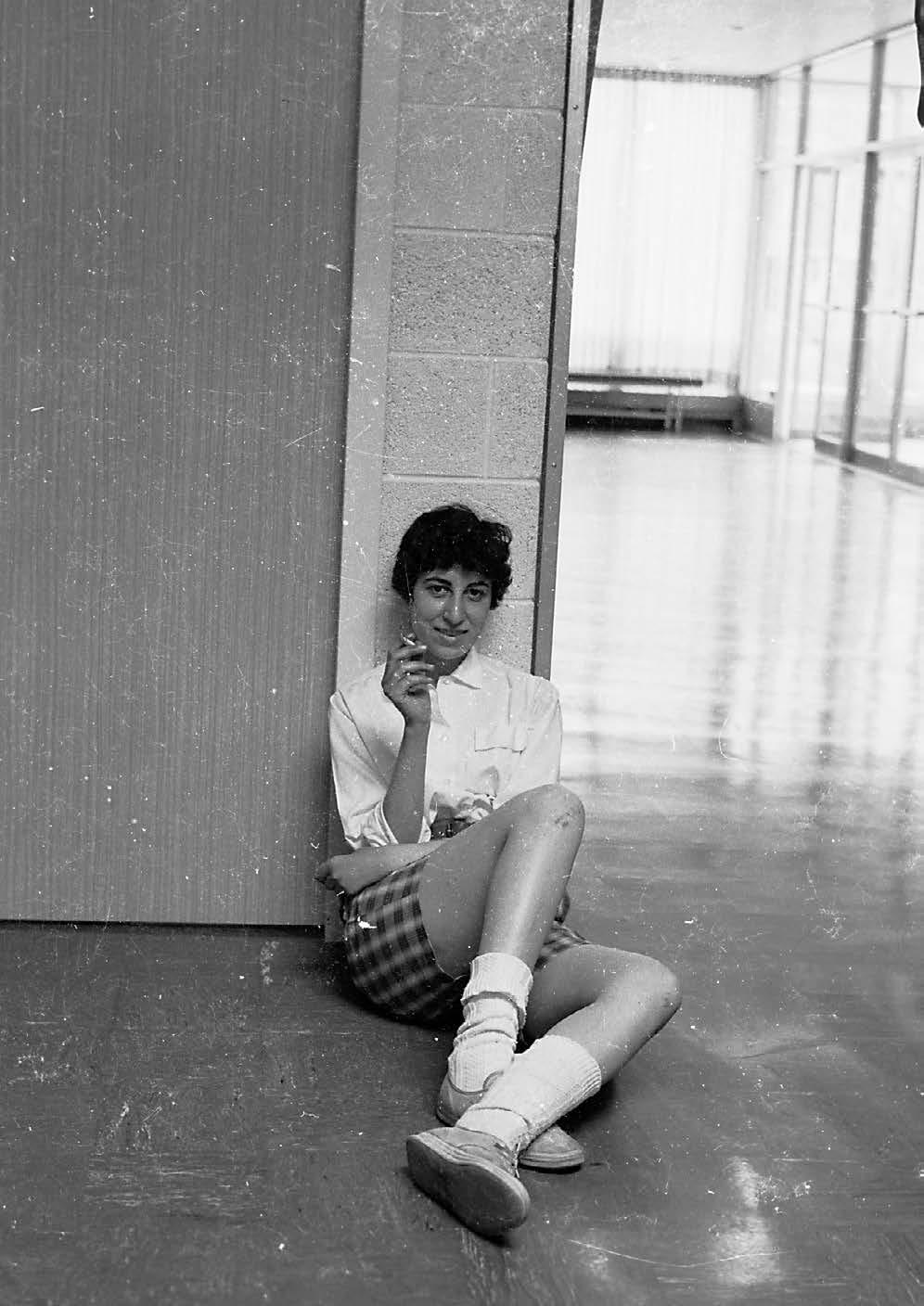

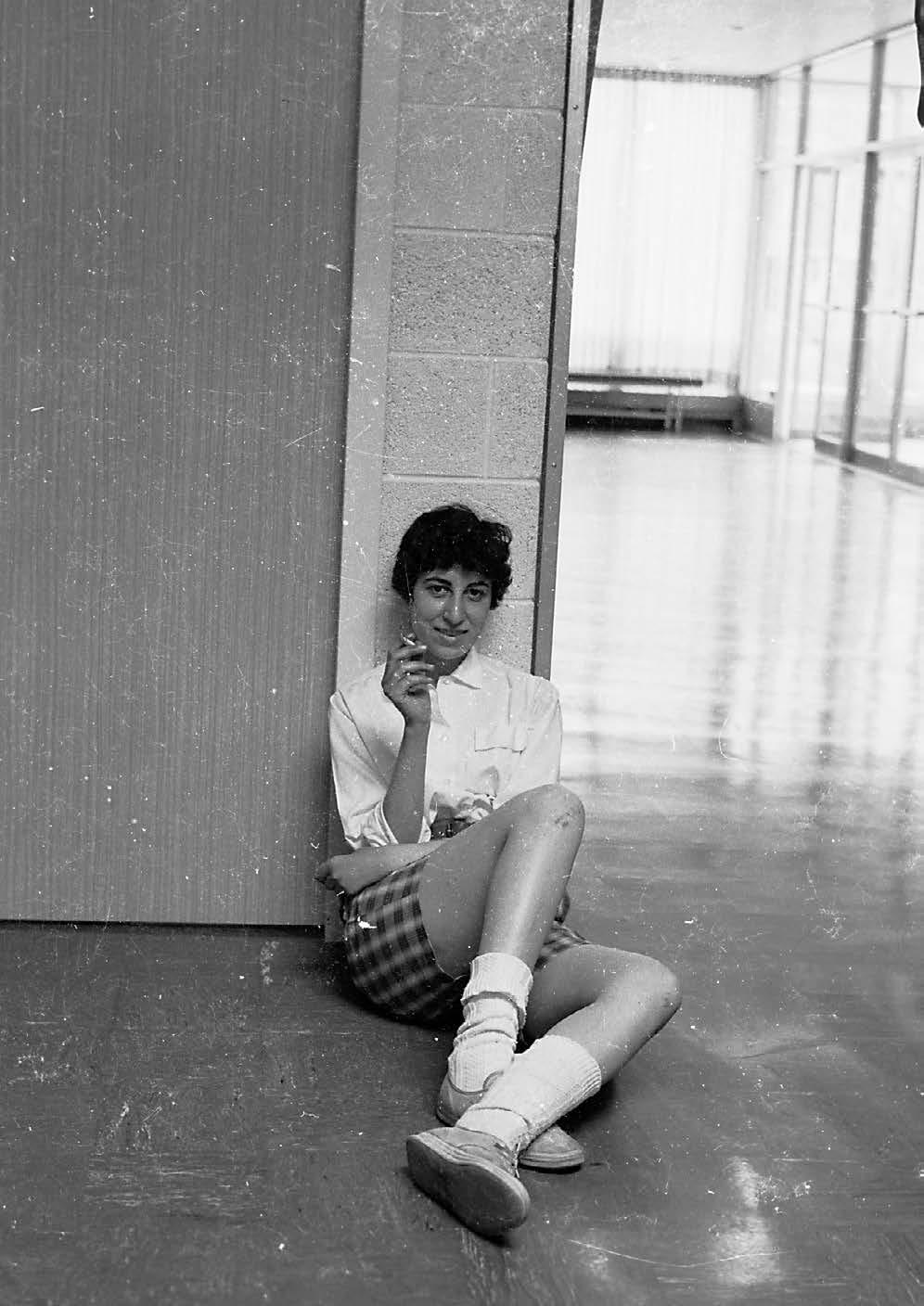

Samia Halaby at the student studio, Indiana University, 1963.

Samia Halaby at the student studio, Indiana University, 1963.

AN INTIMATE RETROSPECTIVE OF THE LIFE AND WORK OF SAMIA HALABY

Samia Halaby is not merely an artist but a beacon of creativity and activism within the Arab art world. Born in Jerusalem in 1936, her journey from Palestine to global recognition as a artist is as remarkable as it is inspiring. Halaby’s work transcends boundaries, blending traditional Middle Eastern motifs with modernist techniques, reflecting the complexities of identity and resistance.

Within the Arab art world, Halaby holds a significant place as one of the foremost abstract painters. Her bold and vibrant compositions have earned her international acclaim, challenging stereotypes and reshaping perceptions of Arab art. rough her dynamic use of colour and form, she invites viewers to explore themes of displacement, memory, and resilience.

Yet, New York City-based Halaby’s contributions extend beyond the canvas. roughout her career, she has been a vocal advocate for the Palestinian cause, using her art and position as a college professor as platforms for social and political commentary. Her activism is deeply rooted in her own experiences

growing up in Palestine amidst conflict and upheaval. Her art expresses an enduring spirit of resistance and hope in the face of adversity.

In an effort to preserve Halaby’s unique voice and narrative, we are privileged to share her memoirs of her childhood in Palestine. While editing for clarity and coherence, we have aimed to leave her words largely untouched, allowing readers to immerse themselves in her vivid recollections and personal reflections. rough her memoirs, Halaby offers a rare glimpse into the rich tapestry of Palestinian life and culture, capturing the essence of a land and people yearning for freedom and justice.

rough Halaby’s words, we are reminded of the power of art to unite people in the pursuit of a more just and compassionate world. Her story is not just one of personal success, but an example of the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity. By exploring her work, we discover a rich tapestry that combines aesthetics, philosophy, artistic technique and deeply engrained political views.

01

EARLY LIFE

(Left) Samia Halaby, approximately nine years old, Palestine, 1946.

(Right) Samia Halaby at a picknick in the mountains, Lebanon, 1950 or 1951.

I was born in Jerusalem, Palestine, on December 12, 1936. My mother told me that the hour of my arrival was 7:00 or 7:30 p.m. but I am not sure which she said. My mother’s name was Foutounie Abdelnour Atallah and she embodied that gentleness of spirit that typified Jerusalmite families. Our strong, typically, Arab family ties led to very wonderful memories for me of my grandmother, Maryam Zachariyya Atallah, and her husband Abdelnour Atallah. My father, Asaad Saba Halaby, on the other hand, was a strong-willed excitable Jerusalemite. His Mother was Wasile Amar and his father, Saba Jiryes Halaby, who as a lowincome Jerusalemite, had underone the pain that famine of the early 20th century that was artificially created by Britain and America. Saba Halaby died at an early age leaving my father orphaned, bereft of his

three older brothers, and at the head of the family at the age of twelve. He took on the responsibility, regretful of having to abandon his education, but sufficiently determined to fulfill his weighty new responsibility and thus arrived at adulthood a proud self-made man. To him my mother was a true lady and an encyclopedia of knowledge. She was educated at the Friends School in Ramallah and thirsted for education and pursued knowledge all her life. He wished I were like her and always called me ‘stubborn. When he said it in Arabic it had softer edges and kinder colours. When he said it in English it sounded hard. I am in deep admiration of their lives and victories and deeply saddened by the pain imposed on them by British colonialism, American imperialism, and Zionist and Israeli oppression and terrorism.

But my true heroin in my childhood was Maryam Atallah, my maternal grandmother, who in her wisdom entrusted me with family secrets and who, in my childhood, treated me as one who might be told what only adults should hear. She clearly expressed her will and was obeyed. On weekend visits driving up from Yafa to her home in Jerusalem,

34

she would tell my parents that my two older brothers were overshadowing me and thus she would keep me with her till the following weekend. I basked in the special attention of her household. I sat on a small stool resting my head next to her knees as she sat in the imposing stuffed leather chair, and heard her words. Her respect for my future adulthood has always been a source of wonder and strength. I often stood at the balcony of our home in Yafa, the famous port city where we lived, and yearned for her visits and dreamt of being like her. I think she knew that she was handing me a great gift and I still keep her words to myself.

I was sent to a British school called Tabitha Mission School. As an adult, I recognise in the name and my memories that it was a typical colonial project to brainwash children of the colonies to be loyal to the coloniser. But my school friends were irreverent, and we often giggled together at the British teachers’ arrogance and silliness and what we considered to be their ridiculous behaviour, their lack of love, their harshness, and strictures. The most ignorant of their English traits was their thirst for sunshine, which they

(Right) Left to right: Fouad (brother), Nahida (sister), Samia Halaby, Asaad Saba (father), Foutounie Abdelnour Atallah (mother), 1951.

(Left) Samia Halaby top centre, Maryam Atalla (Samia Halaby’s maternal grandmother) lower centre, Nahida Halaby (Samia Halaby’s sister) lower right, Nawal Halaby (Samia Halaby’s cousin)lower left, Beirut, 1950.

expressed by taking the class out to the playground to sit unmoving under the hot sun, which always gave me a headache. We had a prayer session each day and we stood row after row as words were delivered. I do not remember any of them but do remember giggling with my friends and being punished.

Being at a British school meant that my training in the Arabic language suffered. I regret this loss which continued to grow as imperialism and Zionism followed colonialism and disrupted our lives.

I am the third among four siblings: Sami, Fouad, myself, and Nahida, in descending order of age. Until this day we are close, reuniting annually. During Covid times in our eighth decade of life, we met weekly with pleasure on Zoom calls. Since Covid, the younger of

my two brothers, Fouad, has passed away and I recognise clearly the present season of my life.

In 1948 we were exiled by Zionist aggression aided by the British and America. After a brief residency in the mountain villages of Lebanon, my family and I lived in Beirut for a little over three years. Beirut was lovely at the time and I was young, healthy, and protected by my parents. But my memories are full of my parents’ generation’s troubled hearts, with all the painful tearing of family and social relations that were imposed on us. From adjoining rooms at home in our new small apartment, I could hear the ebbing urgency in the rumble of male voices as the men gathered, trying to comprehend the loss of Palestine. Great pain accumulated slowly in my heart and for years after political discussion caused me anxiety. Decades later, I realise that that the ebbing rumble of male voices was a profound lamentation, and sympathy replaced

anxiety. The women on the other hand had an emotionally easier task: they took action, supporting the flood of homeless refugees pouring in from the Galilee.

In Beirut, my school again was British, the British Syrian Training College, and again it was clearly the coloniser’s brainwashing machine. At this older age my school friends, of course all girls at an all-girls school, were more assertively politicised and decidedly more aggressive. We all understood that the teachers were them not us. We never took our complaints against each other to them. We settled our disagreements secretly among ourselves. Once,another student and I had a strong disagreement and a move from words to action was needed. We all hid in a weed grown abandoned playground of the school that we could secretly reach through the window of one classroom. Out we all went and the

36

two combatants, me and my friend, went at it till I tore her uniform which ended the fight as she became very worried about the potential problems it would cause. Someone ran and brought a needle and thread, my anger turned to solidarity, and I carefully stitched her torn uniform back together. By the time I had finished sewing her uniform the school bell had long had long since rung, and only the two of us were left. All the other girls had rapidly sneaked back in. The two of us had no way to get back in as class was in session. But we rang back in unseen as we knew none of the students would betray us.

I remember days of revolt where we collectively made normal school functioning impossible. I yearn for those little victories of childhood and hope to experience such exhilaration at the liberation of the international working class accompanied by the liberation of Palestine from the horror of the unbelievable abomination of history, Israel, that was started by British colonialism and utilised by US Imperialism.

In 1951, my parents decided that it was safer for their children to move to America. I was against it but did not, at the age of 14, think of ways of asserting or even describing my views. But it was understood that I did not want to go to America.

So, in 1951, at the age of fourteen, I found myself at an American high school where I began to experience the unpleasantness of patronising attitudes in some of my teachers and their occasional hostility when I outperformed my schoolmates. My father had moved us to Cincinnati, Ohio, and arranged for my sister and I to attend North College Hill High School. It was considered friendly, not so ‘fast,’ and more appropriate to our naiveté. After graduation, I attended the University of Cincinnati and in 1959 earned a Bachelor of Science degree. For this I underwent a five-year coop program that allowed students to study and work and that allowed me to earn my way through undergraduate school. I continued to find ways to support my education; while my home life was supported by my parents. As a graduate student, I first earned an MA degree from Michigan State

University in East Lansing followed by an MFA from Indiana University in Bloomington.

It was clear in our family that we will all pursue higher education. Years into adulthood when all four of us had embarked on our professional paths, my father would sometimes express his pain at having missed his own education because of the death of his father. Occasionally, he would be miffed about our arguments. But I had another role model for my education, other than Palestinian Arab tradition and my own mother’s learning. I had read as a young teenager about Andalusia and Arab scholarship and yearned to be something like it.

I YEARN FOR THOSE LITTLE VICTORIES OF CHILDHOOD AND HOPE TO EXPERIENCE SUCH EXHILARATION AT THE LIBERATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WORKING

CLASS

ACCOMPANIED

BY THE LIBERATION OF PALESTINE FROM THE HORROR OF THE UNBELIEVABLE ABOMINATION OF HISTORY, ISRAEL, THAT WAS STARTED BY BRITISH COLONIALISM AND UTILISED BY US IMPERIALISM.

(Left) Samia Halaby, The Caryatid porch of the Erechtheion, Athens, 1951.

(Right) Samia Halaby with her paternal aunt Sultanie Halaby, 1948.

38 MY EDUCATION

The University of Cincinnati, college of applied art, 1954-1959, Bachelor of Science in Design.

Life with my fellow students at the University of Cincinnati was pleasant and friendly. My immigrant status was recognised by some in friendly ways whence a nickname was given me by one friend, of Salmon Halibut. But the time was not completely free of unpleasant events revealing ignorant attitudes towards Palestinians. I was baffled that telling my still very fresh memories of experiencing exile elicited vacant stares or hostile reactions. As I adjusted to college life in the Midwest of America, the best social activities with fellow students were our interest in both the Ohio river front and the Art Museum in Mt Adams, where we often visited and chatted in envy of those who studied art there. We were aware and regretted the absence of any galleries in our city whose advocates boasted that ‘Greater Cincinnati’ had one million residents.

My education in the Midwest was excellent by no one’s intention or design. The different Universities I attended and the changing professorial staff somehow all converged on my own life’s timeline to create what in hindsight I consider to be an excellent art education – given that it was a Western art education and not one that took the rest of the world into cognisance. My professors at the University of Cincinnati were very interesting individuals and the fare was unexpectedly admixed. There were those who admired the Bauhaus movement and wanted to impress upon us principles they implied had originated there, such as that materials should be appropriate to intended use and that form should follow function. There were those who sought to be very scientific and their attitude manifested in our education regarding colour. Colour was presented in two different ways. One art teacher taught us some principles of colour matching but did us the more important service of giving us an understanding of the Munsell colour system. The other part was sending us to the physics department to study the physics of light and the physiology of the eye. I was impressed by our physics professor and thought of him as a great performer of magical demonstrations of the principles he taught. And although our textbook was supplemental, I read it several times over during that year and several times again after I graduated -- “An Introduction to Colour” by Ralph M. Evans.

Yet another current of thought among the young professors at the University of Cincinnati was social resistance, injected into us by admirers of the social realists and political justice painters such as Ben Shahn, Phillip Evergood, Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and other resistance artists of the Industrial Union movement. And finally, in my favourite class, drawing and painting, there was an old professor who had studied in Parisian academies and insisted on teaching us, one precise step at a time, the principles of chiaroscuro and perspective, and the proportions of the human figure. We spent a full year making crosshatch drawings of plaster casts. Then came the flesh and blood model to be drawn in charcoal only, no colour, and finally in our final year we were ready and permitted to touch brush and watercolour to paper using colour, of course. And since my major at the time was design, I underwent two rigorous years of drafting and executed perspective drawings with T-square, triangles, compasses, and ink pens. I took a drafting course for two years which taught me completely the details of the perspective theory in detail, including all the fixes it encompassed to correct for the fact that it really is not a comprehensive representation of what our one eye sees (the other eye had to be closed) when stationary.

I was not inclined to object to education, nor in fact were any of my schoolmates. We took it all in like birds in a nest with beaks wide open. It was the mid 1950s and, although a stranger to the land, I could tell that it was the post-depression era so everyone was grateful to have work and was worried they would lose their jobs. The students were generally serious about learning what was so dearly paid for by their parents.

Michigan State University, East Lansing, 1959-1960, Master of Art in Painting

At Michigan State University, I began to meet some of the minor stars of American contemporary art. Jackson Pollock’s brother Charles Pollock, a very gentle being, was teaching there and many visiting artists from New York arrived to give us a taste of a far-away exotic world. There was Boris Margo (19021995) whose teaching was vacuous and he passed through my education quietly leaving only the scent

(Top left) Samia Halaby, first months in graduate studio, Michigan State University, East Lansing, 1959.

(Top right) Samia Halaby at Michigan State University, East Lansing, 1960.

(Below) Samia Halaby paintings, Michigan State University MA show, 1960.

(Top left) Samia Halaby, first months in graduate studio, Michigan State University, East Lansing, 1959.

(Top right) Samia Halaby at Michigan State University, East Lansing, 1960.

(Below) Samia Halaby paintings, Michigan State University MA show, 1960.

(Top left) Samia Halaby in front of her painting, Michigan State University MA show, 1960.

(Top right) Landscape of a Barn and Broken Carriage, 1959 or 1960, o.c. oil on masonite, 24 x 35 ¾ in (61 x 91 cm).

(Below) Samia Halaby paintings, Indiana University, MFA Graduate show, 1963.

(Opposite) Fire, 1960, o.c., 33.5 x 44 in (85 x 112 cm).

40

of strange ambiances. The work of visiting artists often baffled me for seeming to be more about appearances and stylistic territory than to visual exploration. Now in hindsight, I recognise the carving out of a brand, a look that would identify an artist’s work but in my youth I only saw skeletons and remains. I attributed such painting to the private insanities of the older generation. I did not then know of the demands of ‘success’ and the commercial galleries, nor of the inordinate negative influence they could exert. What led me to make art was foreign to the success-oriented commercial gallery world that I eventually had to confront.

It was ‘macho’ time in the art world that year I spent at Michigan State University in East Lansing and male supremacy in the arts began to replace the more egalitarian student fellowship that I experienced in Cincinnati. Hypnotism with psycho analysis derived from the Surrealism movement of the 1930’s combined with the macho attitude, what might be thought of as the ‘truck-driver become artist’ syndrome, created art criticism focused on phallic symbols. A young art student could be totally demolished and embarrassed when some professor or fellow student suddenly pointed to some vague convergence of shapes and called out ‘aha, a phallic symbol.’ Educators began to posture and the attitude of serious learning at the University of Cincinnati was slowly replaced by teaching via proclamations.

But there were also memorable professors at Michigan State University who had no professional reputation but were good teachers who paid attention to us individually. One such was a professor whose family name was Hendricks, and I think that I never knew his first name. I remember him coming to class afterhours and finding me freely exploring curved lines,

and him telling me how important they were. In later years I would remember the significance of what I was doing back then.

Special among the lesser-known teachers at Michigan State University was a truly old professor by the name of John D. Martelli (1903-1979) who taught stone lithography. To persuade us of how fine and detailed stone lithography could be. He showed us decorative lacy frames used in advertising that he made to earn money. He enjoyed telling us how once he planned how to catch red-handed someone who stole his designs. He had laid a trap so that when the unsuspecting thief was accused and claimed innocence, he, de Martelli, would pull out an enlarging glass and insist the client take a careful look. At that point it would be revealed that the entire delicate lacework was executed using his signature so small that it was invisible to the naked eye, with John D. Martelli, repeated over and over. He enjoyed telling the story laughing profusely to my enduring admiration.

Indiana University, Bloomington, 1961-1963, Master of Fine Art

After a year of working as a hack designer in Cincinnati, I did two years of study at Indiana University in order to earn a degree that would allow me to teach at the University level. At Indiana University, the painting star then was James McGarrell whose work embodied the self-portraiture of affluent middle class-ness and homes full of material objects. I had embraced an idea that I wanted to be an abstract painter and no way was I inclined to imitate my teachers of the time. But still, I did hear them all out and learnt. James McGarrell used to tell me that New York rejected him and so he jumped over it to get to the European market. That impressed me and as I think about it now in my ninth decade of life, I see that I too had to jump over New York, not to the European market but to the Arab market, and then a small step into the world.

What was special about Indiana University was the presence and friendly fellowship of both practising artists and art historians in the same department and the magnificent interaction that took place from sharing hallways and neighbouring offices and studios. I was spellbound by art history and I was fortunate in attending classes by two very responsible and exciting lecturers. I would think to myself what a luxury it was to sit in a classroom and hear their narratives. I would quickly make a sketch in my notebook of the slides they showed, write the names, dates, and some of their ideas. Albert Elsen and Jack Wasserman were their names and they were outstanding lecturers. I heard every word and noted

every time Elsen postured in the light of the slide projector. I felt myself fortunate to be served up such lectures and that it was a rare and fleeting luxury. I felt truly grateful that I had the time and opportunity on a regular weekly schedule to sit in relative comfort listening to well organised lectures. They each had a reserved-shelf for their classes in the library and I can safely say that I looked at each picture and considered the ideas of the lectures and my own thoughts of aesthetic development, geography, and form; but I mostly found the reading unattractive.

Artistic Thought

As I try to push back into memory, it seems that I yearned to be an abstract painter from the very beginning. But what beginning is there? I am a part of the continuum of the cultural growth of mankind. I enter a river flowing at unpredictable and changing speed even reversing at times. I remember daring to do a small abstract painting in colours on cardboard sometime during my undergraduate education. In delicious isolation in the basement of our new house on Teakwood Ave in Cincinnati and still a teenager who grew up in Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Beirut, I dared myself to do so and broke the surface tension of belief. There it is, I thought, a small abstract painting, and then I forgot it as I returned to the demands of my education. It was in that same basement earlier, sometime in my teenage years, that I had requested and got permission to use a small room in the basement for my studio. What would have been a small up high window typical of Midwestern homes was not glazed and allowed no light. I noted that it looked more like a shoot that could become open. I concluded that this little studio, my very first, had once been a coal room in an old brick home. But I filled it with my tables and treasures and did some artwork there.

While still in high school, perhaps a year after arriving in the US, feeling very bored and not knowing what to do, my mother reminded me that I loved painting and suggested that I do some. I took up watercolours and available paper, set up a basket of fruit and spent the afternoon quietly absorbed. It was my first painting done after emerging from childhood and conscious of it being under my own responsibility without direction or advice. The abstraction done some few years later was the first abstraction that I did for myself. These two innocent, unremarkable paintings were the speed at which I veered into the fast moving river of the culture of picture making. It was the sixth decade of the twentieth century and only fifty years after the Soviet revolution and the birth of abstraction,

that in later years I came to envy so much. That short span of time was several times the number of my teenage years. Now, a bit over a century after the Soviet revolution, I have carefully studied that history and have come to envy those forward-looking artists who lived at the time of the revolution and experienced the huge power of its inspirations.

During my graduate education my aesthetic thoughts began to flow, a kind of secret life of visual ideas. At first, I did paintings, prints, and drawings of simplified, geometricised images aggregated in frontal compositions describing familiar scenes, many of which included a female form seen from the back as though I was looking at myself as a young female who was looking into a world she remembers. Often there was a palm tree and a house. It was the palm tree that I drew endlessly in my childhood. I often drew it on the foggy window of the Rover my father drove us in as we commuted weekly between Yafa and Jerusalem to visit grandparents and cousins. Later during my graduate year at Michigan State University, I began to want to do abstract painting but did not know how to study abstraction or how to think about it. At that time, I loved Paul Klee and that helped a little. But his paintings were too similar in spirit to my first innocent attempts and that is probably why I liked him and thus they did not help me develop the next steps. Eventually, I managed to transform some of those initial geometricised ideas that I began with into a kind of textural impressionism and a few of them formed my graduation show at Michigan State University in 1960. Their subjects were shadowy figures and landscapes.

During my first year as graduate student at Indiana University, in trying to be abstract, I made paintings of my environment and tried to camouflage the parts into abstract imagery. As I look back, it interests me that in many of them the subject was scenes in the kitchen and if figures were present, Often one of them would be me. It seems that again, as in my first works, I had substantial focus on asserting that I existed; and since family life took place around the table at mealtime, the kitchen was often the background theatre. In due time my love of art history began to guide me and encourage me to consciously adopt influences from

42

the abstract and revolutionary art of the 20th century. By my last year at Indiana University as a graduate student I experienced a breakthrough. I remember it as one of many which happened to me subsequently many times. Suddenly my hands and my intuitions knew what to paint in ways that converted conscious rumination into quiet, unquestioning certainty.

The result of my breakthrough was flat colour paintings and I did many of them. I began to see that they were abstractions based on visual experiences of surfaces in our surroundings. In them shape, size, space, and colour were all relative. They were the paintings of my MFA exhibition at the Indiana University Gallery in 1963. Thus, my graduate student paintings, over a period of four years, all put together in chronological order, seemed to first say that I exist in the world and therefore I will paint my understanding of it. The paintings poured out profusely once I started painting my understanding of something in the world outside of my life. The aimlessness of confusion that pushes artists into mysticism evaporated in the bright light of reality.

I took my MFA graduation show perhaps more seriously than the school expected me to. I was given an appointment to meet my examiners, the painting and printmaking faculty, who would decide if I were to fail or not. It was generally understood to be the final formality to earning a degree. I took my savings and went downtown to an upscale department store and bought a suit for the occasion, one which I wore on the long plane ride to Honolulu to start my first teaching position in 1964 at the University of Hawaii Manoa, on the Island of Oahu.

(Above) Hades, 1962, o.c., 50 x 32 in (127 x 81 cm).

(Below) Fern Silence, 1963, o.c., 24.5 x 31 in.

(Top Left) Samia Halaby arriving in Honolulu, 1963.

(Below) Trees and Shadows, 1962. Oil on masonite, approx 20 x 35 in (133 x 89 cm).

(Top right) Samia Halaby in her studio as a graduate student at Indiana University, 1963.

(Opposite) Totems, July 1961, o.c., 44 x 33 ½ in (113 x 77.5 cm).

44

, 1963,

20

(Below) Untitled

o.c.,

1/2 x 24 in (52 x 61 cm).

(Below) Untitled

o.c.,

1/2 x 24 in (52 x 61 cm).

46

(Opposite) Cubist Garden, April 1963, o.c., 14 ½ x 10 ¼ in (35.5 x 26 cm).

APPLE SEEDS

BEING SOME OF THE LANDMARKS OF MY MEMORY AS A PALESTINIAN

48

Assad Saba Halaby & Foutounie Abdelnour

Atallah (Samia Halaby’s parents), Beirut, 1949- 50.

DEDICATED TO MY POWERFUL ROLEMODEL MARYAM ZAKHARIYYA ATALLAH AND TO HER DAUGHTER, MY BRIGHT MOTHER, FOUTOUNIE ABDELNOUR ATALLAH, AND TO MY STUBBORN FATHER ASSAD SABA HALABY

I am their daughter and daughter of the amazing city of al-Quds (Jerusalem) and its tenacious ancient history, my heritage, centuries upon centuries of tradition. This special city of my birth is now being destroyed, its real population is mostly in exile. What remains is being daily tortured before the eyes of the world. But I, like most of my fellow Palestinians, know without doubt that we will return to rebuild Palestine and that our Israeli oppressors and their partners will have an appropriate end.

I embark on the effort to organise my memories because it seems that our thoughts and experiences are forbidden. Yet it must be heard as one of the true voices of our time. I feel happy to remember my family. And to myself first of all, I apologise for this English that I have come to be confined in, sentenced thus by history and dirty politics. I know that it is one of the injuries of exile, of the great tragedy of the Palestinian Nakba orchestrated by the evil empire – Israel and its US bourgeois masters.

A Hempen Sack of Raisins

Just before the First World War, as my father Assad Saba Halaby told me, there was deep hunger in Jerusalem – a serious famine. He was not yet nine years old and his father, to alleviate the pressure, apprenticed him to a merchant who eventually took him to a house in Amman. Finding his new home cold and cruel, he ran away and searched for a trader returning to Jerusalem. He finally found one who allowed him to walk behind the donkeys

for the long walk back to Jerusalem and allowed him to camp with them at night; but warned there would be no food.

At night, feeling some sympathy for him, the trader would give him a sack from the donkeys’ load to lay his head on. The child that my father was then could not sleep tortured by hunger and the smell of raisins inside the hempen sack. Then as my old father continued the story, his wrinkled face lit up with great pleasure, “with my little finger, I slowly, quietly dug a tiny unnoticeable hole in the sack and each night I quietly ate one little raisin at a time till I fell asleep.”

Bread of Life

His mother contracted typhoid, which meant that the Turkish administration of Palestine would haul her off to the wilderness, to a soldier guarded quarantine. Nothing was provided, only the wilderness. That is what my father told me, and he told me that his father would bundle up some food and water in a square cloth cross-tied and my father, being small and agile, would sneak through the lines of the Turkish soldiers. In this way he saved his mother from certain death.

Taxi

A couple of Americans, one a businessman and the other a professor, approached Assad, Halaby, my father, in Jerusalem and they cut a deal. It was the early 1920s and the two Americans wanted to go to Tehran. They promised to buy a car and give it to Assad if he would drive them to Tehran. Knowing that there were bad roads and not many gas stations, my father arranged to have extra gas tanks welded to the sides of the car.

Once in Tehran, the Americans asked to be driven to the Soviet Union. After questioning them at the border, the Soviet authorities told them that as their worker, Assad Halaby would be allowed entry, and as an intellectual, the professor would also be allowed in, but that the American businessman was not welcome. The professor entered, while my father drove the lone businessman back to Jerusalem. My father told me that that is how he became a taxi service. He was the first to offer public transportation in Gaza and was flooded with passengers. To accommodate as many as possible and to keep them safe, he would tie a rope around the car for the many standing on the jump-boards that ran along the sides of the old fashioned cars.

STOLEN SUGAR

FOOD BASICS WERE PURCHASED IN LARGE QUANTITIES. A LARGE HEMPEN SACK OF SUGAR CUBES WAS TUCKED IN THE CLOSET OF THE LONG CORRIDOR. OF COURSE, MY OLDER BROTHERS, SAMI AND FOUAD, ALWAYS INITIATED MISCHIEF AND DAY AFTER DAY THEY DUG A HOLE IN THE TOP OF THE BAG AND SEEING IT ALL, I BEGAN ENJOYING SUGAR CUBES AS WELL. MOTHER TOLD OUR FATHER AND HE STOOD US IN A CIRCLE AND FOUAD BLAMED ME AND I BLAMED SAMI AND SAMI BLAMED FOUAD AND ROUND AND ROUND WE WENT POINTING FINGERS. SAYING THAT WE WERE ALL GUILTY, MY FATHER PUNISHED US ALL; BUT I DO NOT REMEMBER THE PUNISHMENT ONLY THE CIRCLE OF POINTING FINGERS. EVEN NOW IT MAKES ME LAUGH WITH GREAT PLEASURE

50

Keeping Warm

My father would recall his youth when needing to remind us, his offspring whom he educated to the max, that we can be deft even in limited circumstances. Living poor in the city of Jerusalem undergoing that famine purposely created by the British and the Americans during the years of the First World War, he would put his pants under his mattress so that they would be well ironed by morning; then he would place a layer of newspapers between the blankets to keep himself warm.

Visual Pleasures and Dreams

Memories of my first years of life in Yafa are all pictorial. I remember my toddler’s bed with wooden slats in which I lay silently awake intently watching those tiny, strange flies of the Palestinian plains as they zipped around each other in a group in the centre of the room. How their motion defined a spherical space in the very centre of the room fascinated me endlessly and etched itself in my memory.One dream gave me great pleasure, a whole line-up of small, delightful creatures would march on an imaginary ledge as high as the door from the top of which they emerged.

Words had Colours

Words provoked colourful images and often with a metallic tinge. As time went by, these images faded. Occasionally, I would miss them then I would revive them by focusing on repeating the names I remembered. But they and their beauty are a faded memory. There only remains a few skeletons. I remember my name to have looked like a symbol of railroad tracks, two long parallel horizontal lines with many short verticals crossing them and all in dark metallic red. I remember the image that would get in my head when my mother would remark that my hands were chapped. I would see rough, splintered, dry, beige, wooden laundry pins formed like hands. I remember the shape and colour my sister Nahida’s name created; it was like a biomorphic shape, very pale silver with a golden glow. My brother, Fouad, is still that green copper and Sami a golden red. Sounds still have colour but there is no necessity to cultivate the sensation. Maybe there will be a future time where this tendency called synesthesia might be the basis of a word picture language of great usefulness.

Radio Samia and Nahida

As per the social norm during the mid-1940s, everyday my father came home from work to eat lunch and take a nap. After lunch, my sister and I would be confined to play in the antechamber of the apartment with closed doors all round while the remainder of the household proceeded quietly with their activities. We would be told to be quiet and only whisper and we would heed; but we would forget, and slowly our voices would rise. I remember my father as being stern but after his nap passing us on his way back to work, he would good naturedly say that radio Samia and Nahida had volume that rose slowly to great heights.

Bas-Relief in Mud

My brothers and cousin, the boys Sami, Fouad, and Munir played a game of territory in the mud. I wish that I could remember the logic of it. But the visual pleasure of it, the brown of the wet soil, the sliced shapes made by the catapulted knife, the consequent reforming of shapes all make up a beautiful, intensely pleasurable memory of a bas-relief in motion. First, they flooded the flowerbed with water. Then they marked out a rectangle by carving a deep channel in the mud. After marking out territories, they took turns flipping a penknife into the mud. It would somersault and land blade down. According to some principle, they then won a piece of the opponent’s territory and could therefore reshape the fields in the mud.

Once, I left them to their mud games and I went to the pink and red roses on the climbing bushes. I put my nose in the middle of one and took and inhaled deeply. An army of little black beetles emerged to sober my enchantment.

Munir

When Munir came to visit my two brothers, a team for mischief makers resulted. Their boisterous joy filled all spaces of the home. One day, they appointed me, their little sister, as guard and sat me on the lower steps to the rooftop laundry room as they played secret sex games. I sat obediently as they occasionally ran up and down the steps or quietly disappeared upstairs. When our father came home, it was time for payback. He lined us up on a table beginning with the biggest and down to the smallest, me. He made us take off our shoes and socks and extend our bare feet out towards him. He would not spank us anywhere else lest he injure our self-image. Ruler in hand he gave each bare foot a proper slap. When my turn came, they were very gentle slaps. I almost giggled but my father was very serious at that moment and so I swallowed my giggle.

Sultanie

She sat behind her crowded desk at her office. From the side, I watched highly focused as she used a blade to sharpen a pencil to perfection. We were the family of her brother visiting her office and I was a child that she delighted to entertain. Maybe she knew that the shape of each slice was a sculptural stroke upon my visual conscience?

SPECIAL TREATS SOMETIMES, I REMAINED WITH MY GRANDMOTHER BETWEEN WEEKLY VISITS UP THE MOUNTAINS TO JERUSALEM FROM THE PLAINS OF YAFA. IT SEEMED THEN THAT SHE, MARYAM ATALLAH, WAS TAKING ME TO HERSELF, TO HER HOME. SHE WOULD TELL MY PARENTS THAT I WAS OVERSHADOWED BY MY TWO OLDER BROTHERS AND THAT MY RIGHTS WERE BEING ABUSED. I DID NOT OBJECT. IN THE MORNING A SPECIAL TREAT WOULD AWAIT ME AT THE BREAKFAST TABLE - THE SKIN FORMED ON BOILED MILK COOLING MIXED WITH HONEY. SHE, MY GRANDMOTHER, HAD A BIG LEATHER CHAIR AND BEHIND HER WERE THREE ARCHED WINDOWS IN THE HEAVY STONE CONSTRUCTION. THEY WERE GRACED WITH HER

52

AMAZING CROCHET AND NEEDLE WORK. I SAT ON A TINY STOOL ADJACENT TO HER KNEES OVER WHICH I JUST BARELY COULD LOOK UP AT HER GENTLE FACE AND RICH WHITE HAIR FIXED IN A BUN. WHO WAS THIS GREAT WOMAN THAT I TRUSTED AND LOVED. SHE TALKED AND TOLD ME DETAILS OF HER LIFE THAT EVEN AS A FIVE-YEAR- OLD I KNEW WERE ENTRUSTED TO ME AND NOT TO BE REPEATED. WAS SHE RUMINATING ENTICED BY MY SILENCE? OR DID SHE INTEND TO GIVE ME WORDS THAT WERE FIT CONVERSATION BETWEEN ADULTS. I KEEP HER IMPORTANT CONFIDENCE TO MYSELF. I AM STILL AMAZED AT THE TREASURES I RECEIVED.

02

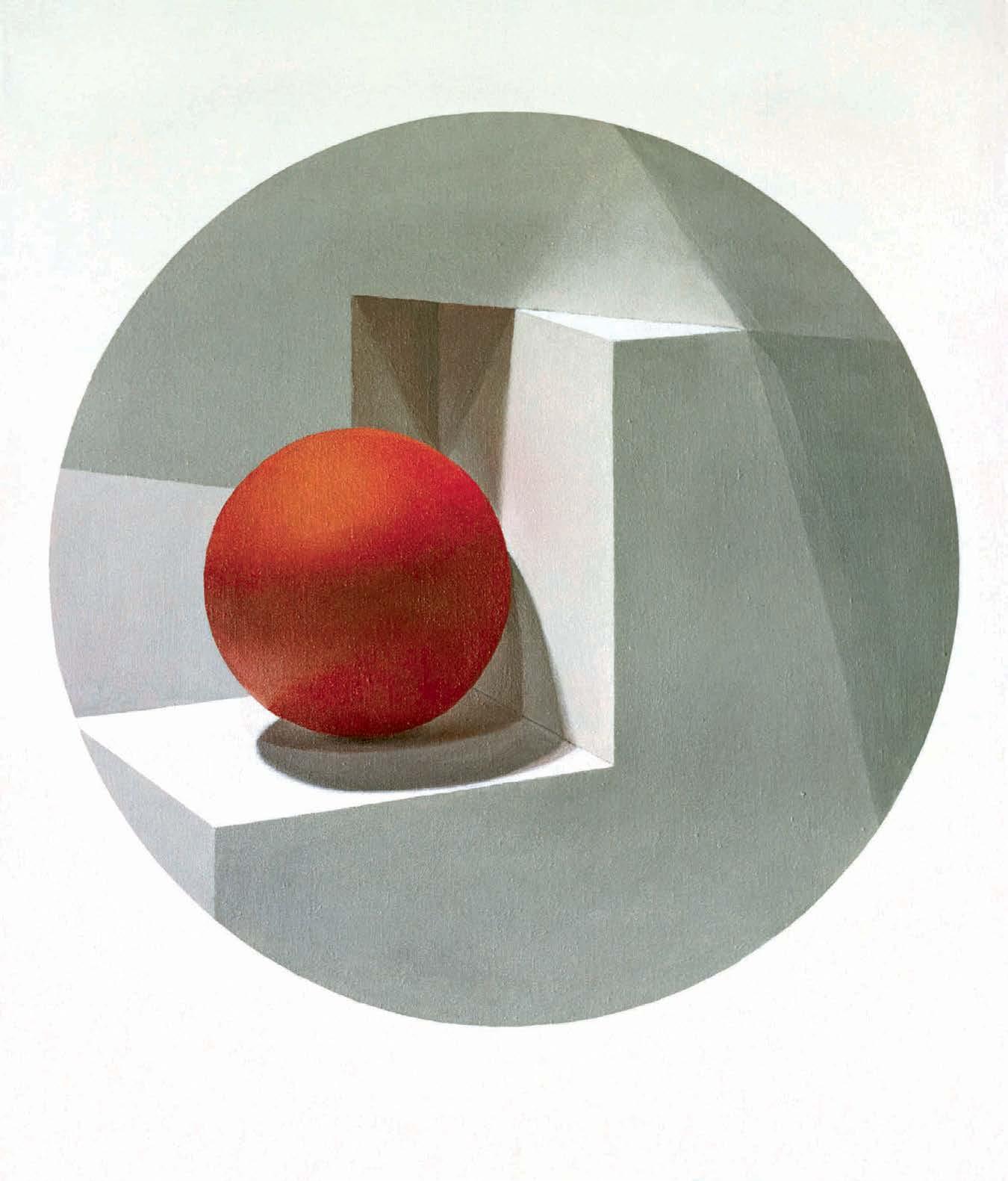

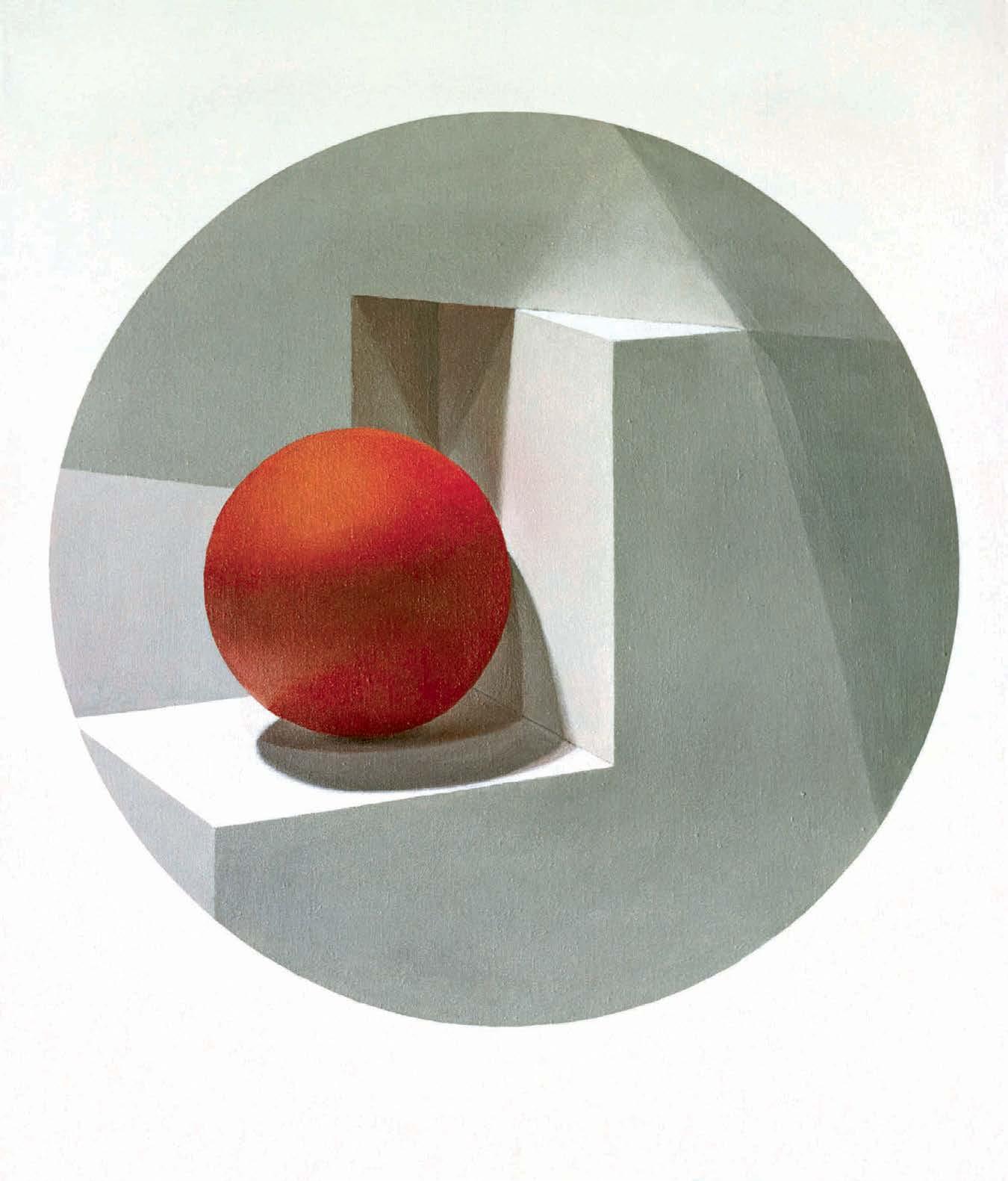

Orange Box, 1966, o.c., 22 3/8 x 26 in (57 x 66 cm).

Orange Box, 1966, o.c., 22 3/8 x 26 in (57 x 66 cm).

SELECTION OF ARTWORKS: OVER SIX DECADES OF BOLD AND EXPLORATIVE

ARTISTIC EXPRESSION

Halaby’s artistic evolution reflects a decades-long commitment to creativity and innovation. Her early exposure to the visual richness of Palestinian art laid the groundwork for a career marked by exploration and experimentation. Her journey took a transformative turn when she pursued her art education in the American Midwest during the 1950s, immersing herself in the shifting cultural landscape of the United States.

Inspired by the geometric abstraction and vibrant colours of Palestinian visual arts, Halaby’s earliest work was rooted in her identity. Abstraction, in its purest form, became her language, devoid of the influences of Western art theory and movements. However, as she delved deeper into her artistic practice, Halaby’s technique began to evolve, influenced initially by the meticulous detail and luminous colours of Dutch painting.

Her embrace of abstraction quickly expanded with an almost scientific approach, incorporating technological tools into her creative process. is intersection of art and technology allowed her to push the boundaries of traditional mediums, creating dynamic compositions that challenged the status quo.

roughout her career spanning over six decades, Halaby remained steadfast in her commitment to forging her own path, eschewing the gaze of professors and critics to explore her unique artistic vision. Her style, characterised by bold colours, intricate patterns, and geometric forms, defies easy categorisation, embodying a fusion of influences and ideas.

What follows offers readers a highly detailed, scholarly perspective on her artistic journey, inviting them to delve into the thought process behind each brushstroke and composition. As she recounts her experiences and reflections, she provides invaluable insights into the complexities of the creative process and the enduring power of artistic expression. Halaby’s artistic journey is a reflection of broader social, economic and technological changes and the transformative potential of art in a rapidly changing world, and also, the world’s transformative effect on the evolving practice of art.

(Opposite)

EARLY PAINTING REMINISCENCES OF PALESTINE

I hardly know that person whom I was during my late teenage years when my aesthetic thoughts began to gain conscious presence even while I was always scribbling on the covers of my notebooks or in the margins of my school books or on any available paper. Beginning in my childhood, gifts of crayons, chalks, and paint sets from family members tell me something of how I was seen and therefore of who I was. Once I took up the making of paintings during my undergraduate years, I found that my work of the time bears a strong imprint of Palestinian visual arts. Red Gate White Moon, 1960, fulfils exactly what four decades later I learnt while interviewing the artists of the Intifada. I was using images abstractly, I was not shading light to dark, and I was not even remotely interested in projection and perspective. Notions of western style depth were not even a small breeze in the air. The paintings, nevertheless, partook of abstraction and the relativity of space. Sometimes ignorance is wisdom. But it is dangerous to be ignorant as the minute you learn one little thing, confusion can send creative intuition into long-term hiding.

Red Gate White Moon, 1960, oil on hardboard, 32 x 23 3/4 in (81 x 60 cm).

57

STUDENT YEARS 58

(Opposite top) The Apron of Gorky’s Mother, 1963, o.c., 32 5/8 x 42 in (83 x 106.5 cm).

(Right) Largest Blue Green, July 1963, o.c., 56 ½ x 43 in (143.5 x 109 cm).

(Above) City (Al Quds), 1960, o.c., 39 x 44 1/4 in (99 x 112.5 cm).

(Opposite top) The Apron of Gorky’s Mother, 1963, o.c., 32 5/8 x 42 in (83 x 106.5 cm).

(Right) Largest Blue Green, July 1963, o.c., 56 ½ x 43 in (143.5 x 109 cm).

(Above) City (Al Quds), 1960, o.c., 39 x 44 1/4 in (99 x 112.5 cm).

I attended two different universities in the Midwest. I earned a Master of Art degree from Michigan State University and a Master of Fine Arts degree from Indiana University. In both cases, I started by exploring, feeling uncertain but continuously working. In both cases, after extended effort it would seem like the conscious part of my thinking would become disengaged and an intuitive part of me would take over silently and I would paint with assurance. It would be as though I had stumbled into a visual language that had far horizons and I would paint what later would look like a related series. Abstraction was on my mind and I sought it naively using images but camouflaging it through visual manipulation.

City, 1960, was one of the earliest paintings that was done at Michigan State University where I spent one year. It recalls Palestinian tradition in loyalty to 20th century abstraction as it contains hints of the city of my birth, Jerusalem. Soon after, I developed a way of creating texture on the surface of the oil painting over which I dry-brushed shadowy figurations using broad graduations of colour and light. At Indiana University, two years later, a similar process occurred as had at Michigan State University, I had arrived at a true abstraction no longer relying on ideas of camouflaged imagery. Largest Blue Green, 1963, and The Apron of Gorky’s Mother, 1963, belong to a series that I created late during my two years at Indiana University. I had arrived at a visual syntax of areas of flat colours that recalled flat surfaces and boundaries in our environment. My affinity to abstraction had finally asserted itself.

THE GEOMETRIC STILL LIFE

60

A few years after graduation, I began to wonder why I was always asking if this or that professor would like what I did. I decided that it was time to clean the house of my education and start something of my own completely. I wanted that something to be a beginning that would be expandable to a lifetime endeavour. After perhaps six months of intense testing of possible styles, I decided that I am going about my exploration the wrong way. If painting is about the world, then I should begin by painting ordinary things in my environment. A further idea occurred to me, that I would deliberately examine every detail of the act of looking, seeing and interpreting.

Finally, on inspiration from details of pristine Dutch painting, I began to build geometric still life objects and began to paint them. And as I became deeply absorbed in the making and painting, intuition took over the driver’s seat once again and all questioning and agonising over what to paint disappeared. The first works were brightly coloured spheres among white boxes based on the original inspiration from Dutch painting, the admiration of a fresh fruit on a brown windowsill in a Petrus Christus painting. To

build on this I crafted an idea that is called visual conjugation. The first mature results were paintings of spheres and of variations based on my notion of visual conjugation. After painting the sphere whole, I would begin slicing it in perfect geometric ways, and I would execute it in a variety of methods. I would take it from drawing to painting to bas-relief and back to drawing the bas relief. Once the treatise on spheres was complete, I performed a similar treatment of a variety of other geometric volumes. And I thought that visual conjugation would take many years and would keep growing. I felt that I had found the beginning of a thread of aesthetic thinking that would keep growing for many years, perhaps a lifetime.

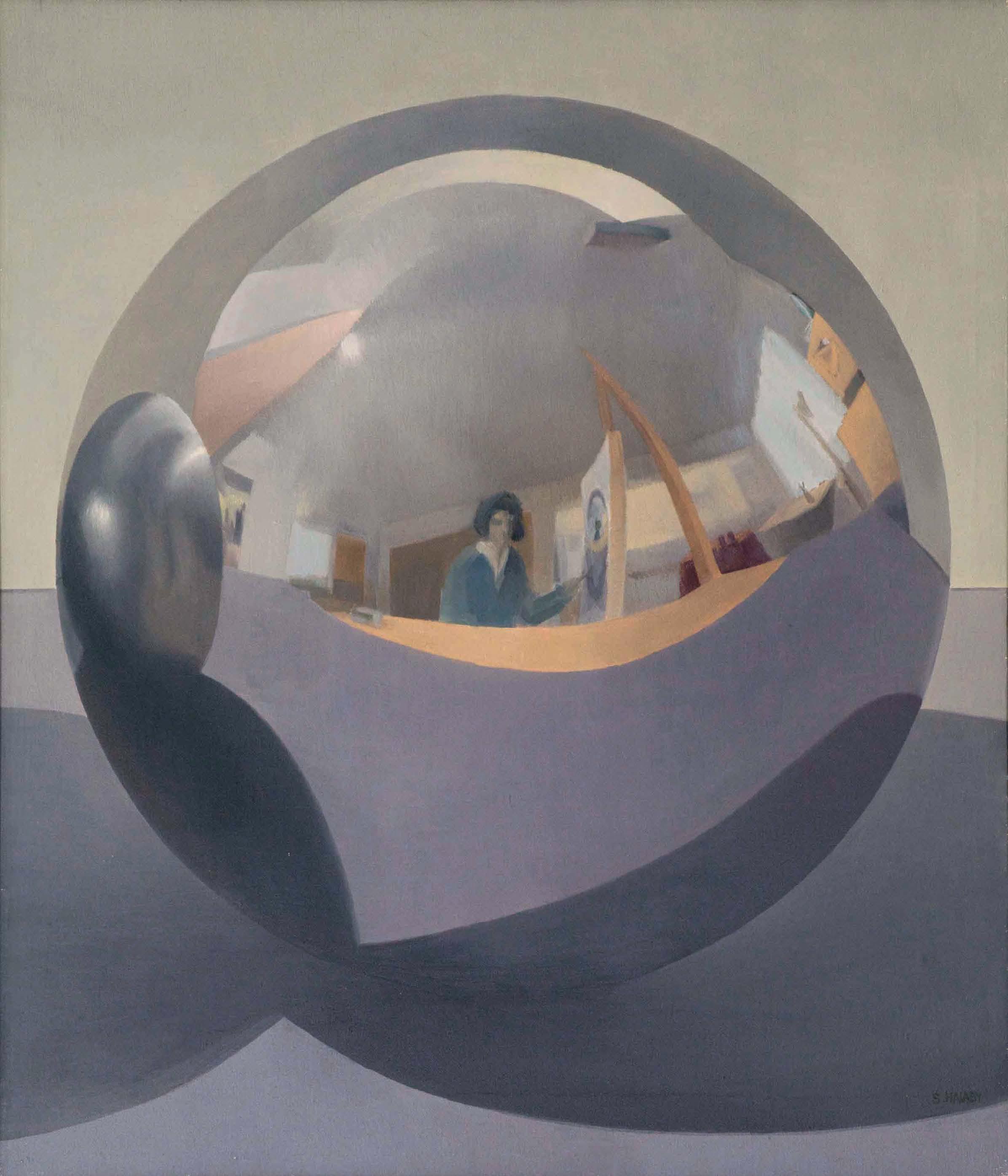

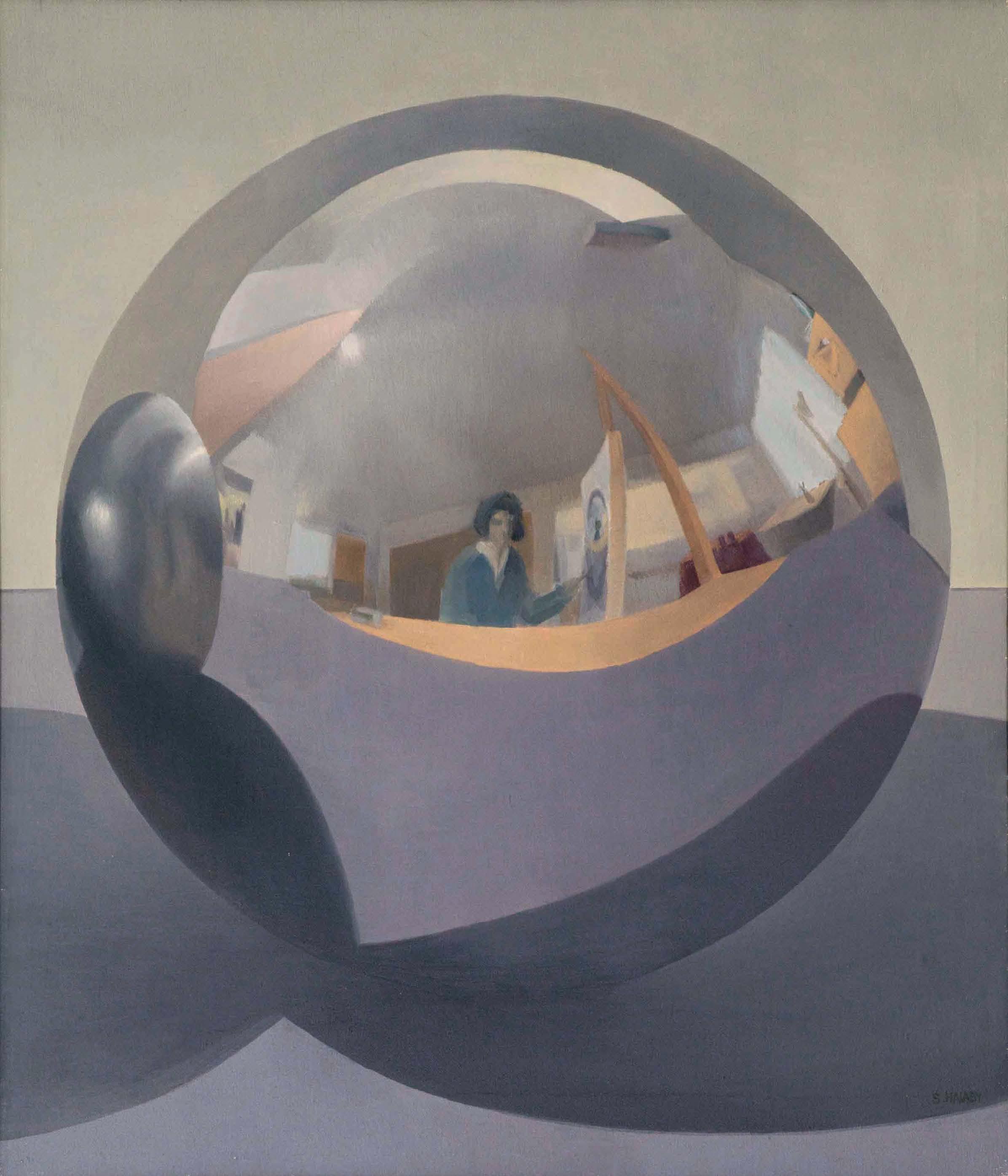

Mirror Sphere, 1968, was part of the treatise on spheres. By using a metal sphere, a huge ball-bearing someone gave me, the result was a reproduction of me sitting in my apartment in Ann Arbor, Michigan, painting the sphere. Part of the treatise on cylinders, Two Vertical Cylinders, 1968, were arranged using geometric proportions carefully crafted to relate to the perimeter of the painting.

(Opposite) Mirror Sphere, 1968, o.c., 26 x 22 ½ in (66 x 57 cm).

(Left) Two Vertical Cylinders, 1968, o.c., 21 x 21 in (53.5 x 53.5 cm).

(Opposite) Mirror Sphere, 1968, o.c., 26 x 22 ½ in (66 x 57 cm).

(Left) Two Vertical Cylinders, 1968, o.c., 21 x 21 in (53.5 x 53.5 cm).

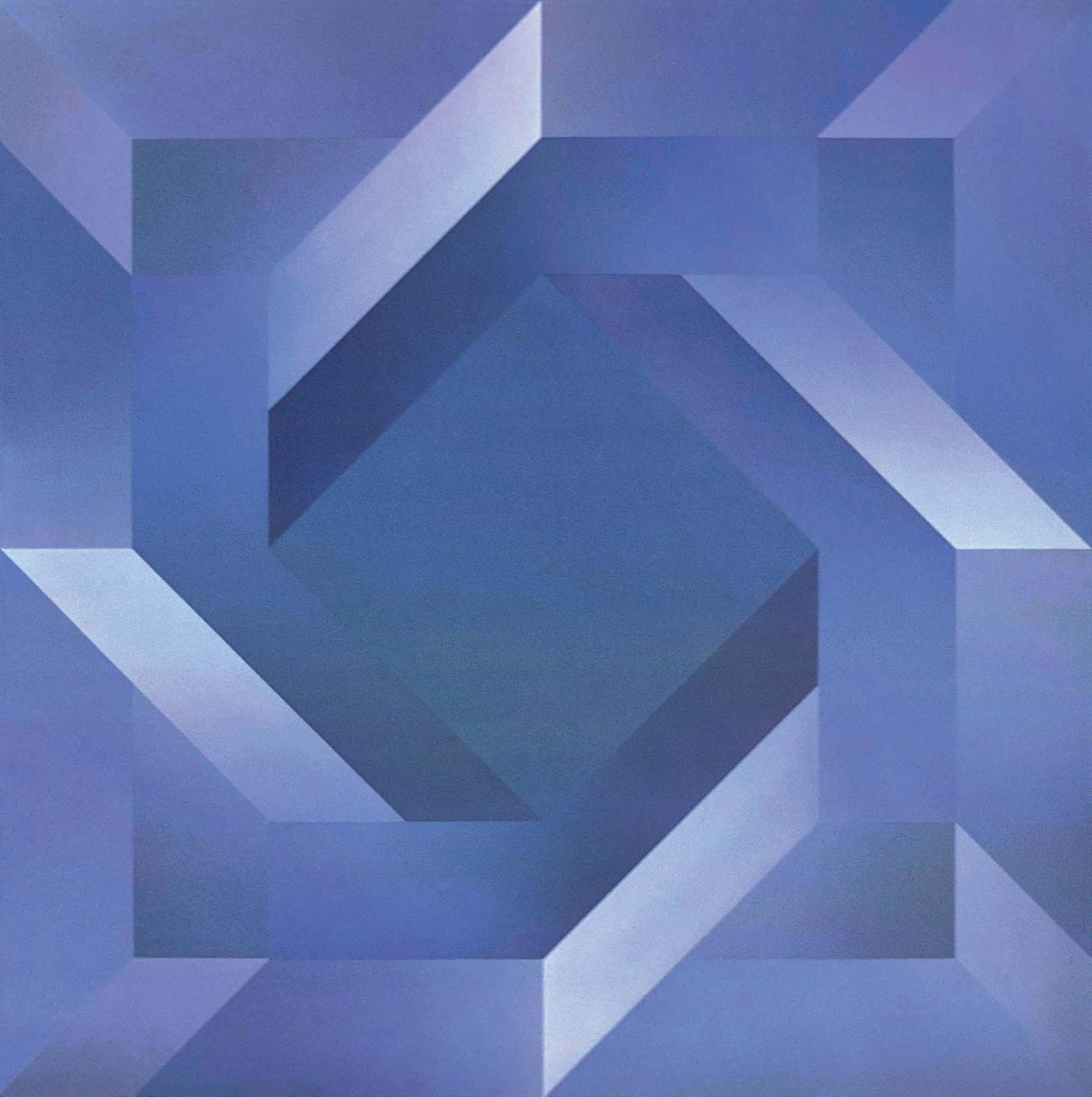

FROM STILL LIFE TO GRAPH PAPER

(Below) Fourth Spiral, 1970, o.c., 48 x 48 in (122 x 122 cm).

(Opposite) White Spiral, 1970, o.c., 66 x 66 in (167.5 x 167.5 cm).

(Below) Fourth Spiral, 1970, o.c., 48 x 48 in (122 x 122 cm).

(Opposite) White Spiral, 1970, o.c., 66 x 66 in (167.5 x 167.5 cm).

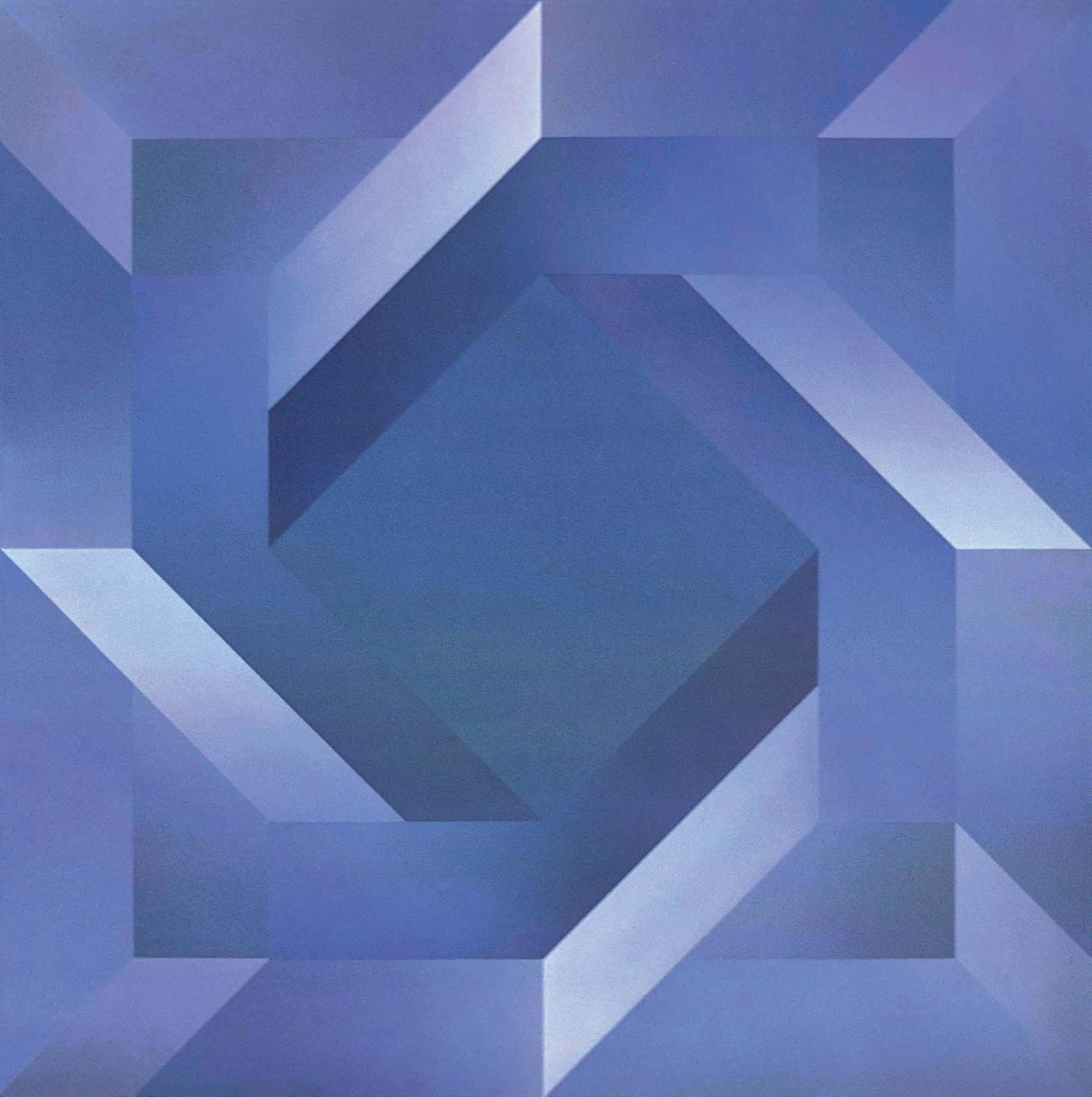

62

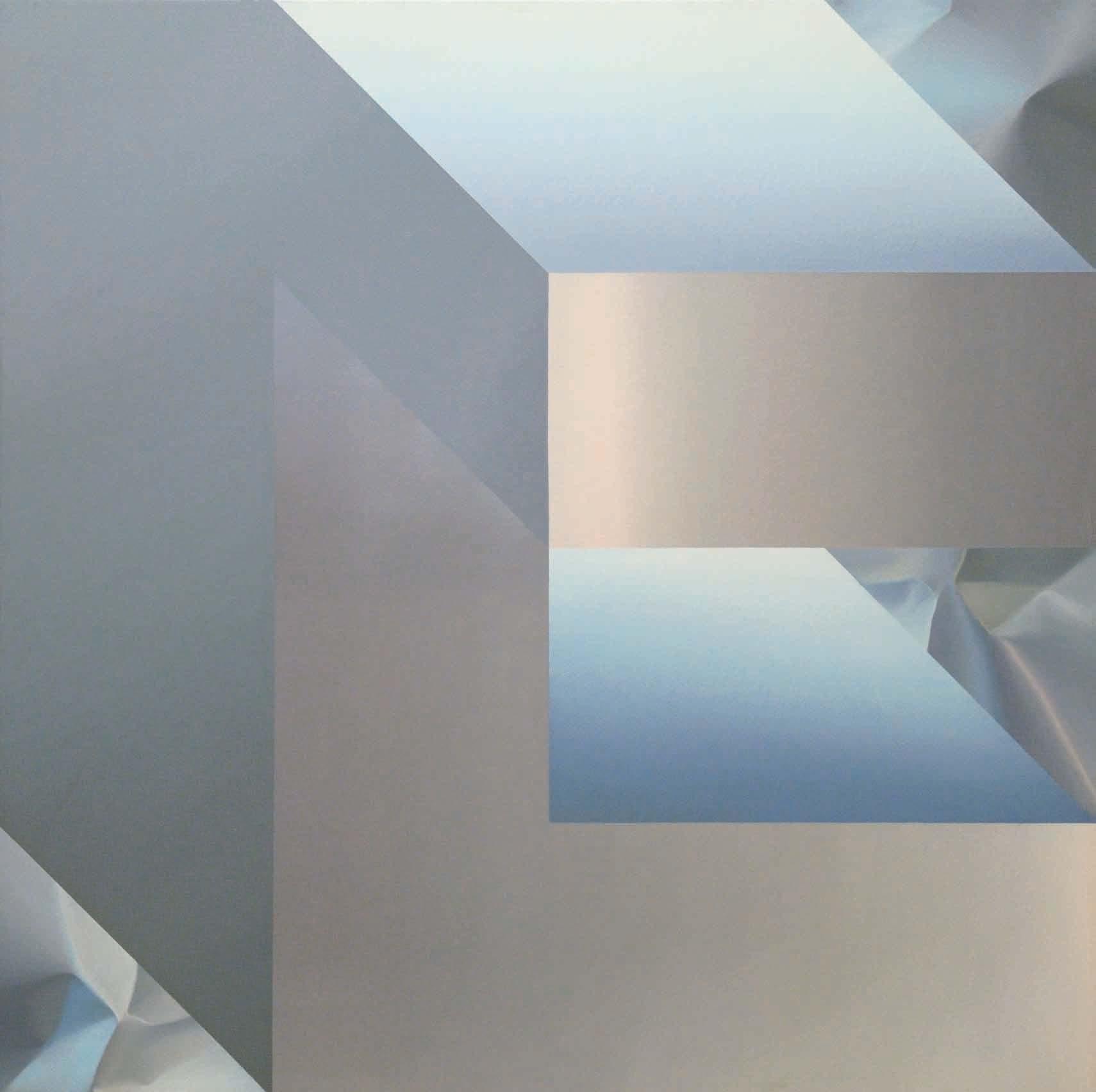

Arriving at those imagined many-years-into-thefuture that I expected back then with my idea of ‘visual conjugation’, I began departing the world of still life objects and adapting to the world of discovering shape and volume on graph paper. The first efforts in this brief period of my work were rectilinear utilising isometric projection. Because they were invented volumes on graph paper, a measure of irrationality entered my work as a challenge to the logic of perspective. Isometric projection on graph paper allowed me to create illusions of volume that could not exist. That is, the volumes looked persuasive in the drawing but could not be built. Furthermore, I was not shading

the objects as though they were illuminated by a single light source nor was I exploiting reflected light and casting shadows to create the illusion of roundness. I simply shaded areas from light to dark disregarding genuine chiaroscuro. It was a step away from direct observation of still life objects and an unconscious return to my early fascination with abstraction.

White Spiral, 1970 is one of the first of these. In the negative spaces of the twisted rectilinear volume, I created a background that is the illusion of tinfoil. Fourth Spiral, 1970, uses the graph paper volumes in rotational symmetry inspired by Arabic art.

HELIXES AND CYCLOIDS

(Below) Aluminum and Steel, 1971, o.c., 66 x 66 in (167.5 x 167.5 cm).

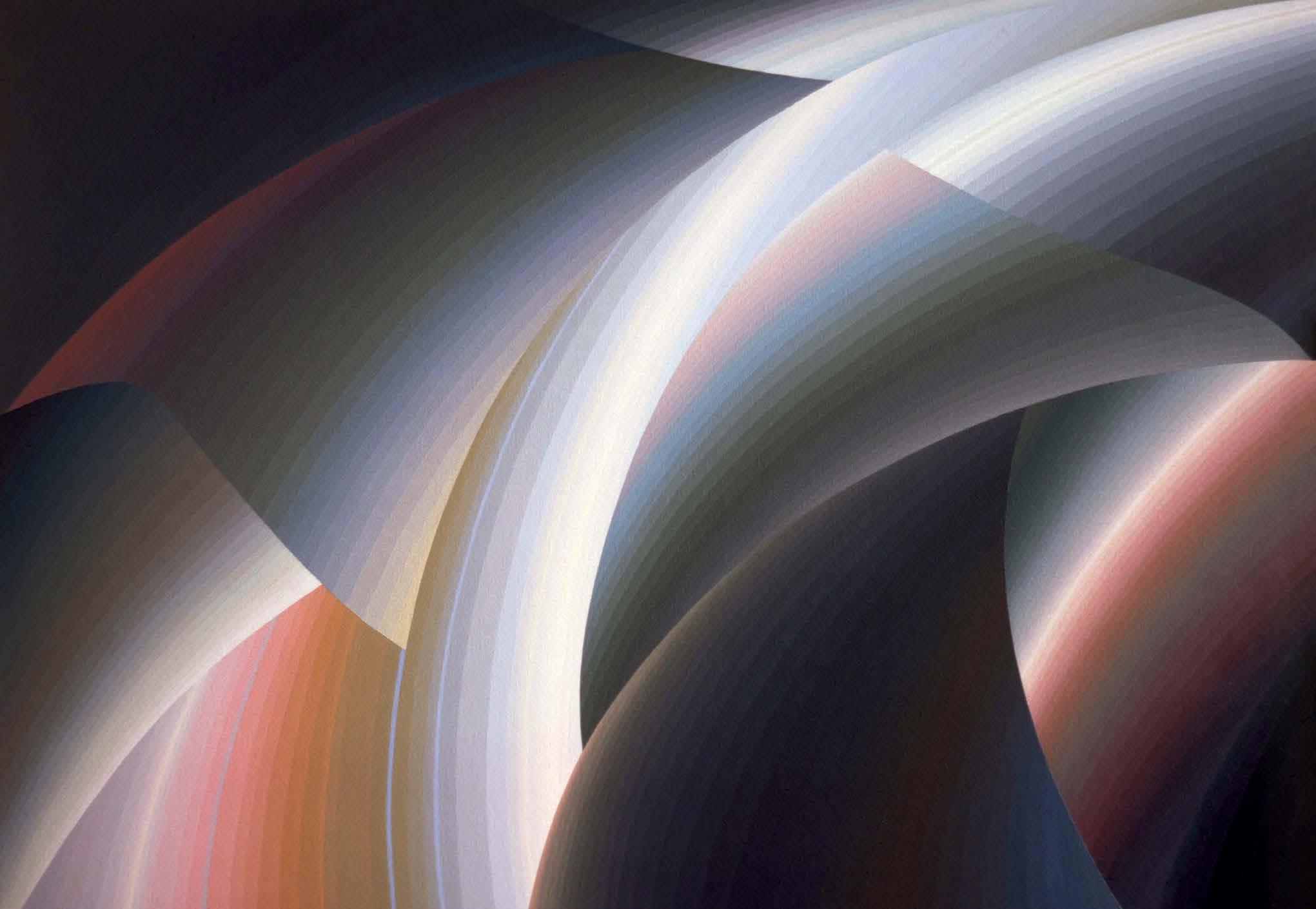

(Opposite) Mediterranean, 1974, 48 x 66 in (122 x 167.5 cm).

64

In downtown Cincinnati where I spent my first years in the US and where I went to college and where my parents lived, a school friend and I discovered an old building that was five stories high and full to the brim with dusty old books and magazines.The owner let us wander freely and most often we were the only clients. I found a section on old perspective and engineering books as well as books on the art of building heating vents. I purchased a good amount based on their fascinating illustrations. These books in combination with my new love of graph paper led me to the fascination of plotting curves. The helix became my new passion and I decided to plot it on a cone rather than a cylinder. I plotted two conical helices, one on a small cone inside a large cone that had also received a helix. I joined the two helixes running down their cones by projecting a surface between them. My old books said that it was a helicoid.

My foray into helixes and graph paper led to many plottings overlaid over one another. I would then select a part that looked to be a good painting. I would then paint the areas using shading not chiaroscuro. Though the shapes in the painting were filled with shading, I had taken the decision that I would not

permit overlap nor a negative and positive division of the space. Each area would compete to be in the front.

After my fascination with the helix began to wane, I tried cycloid curves, but in effect the fascination had run its course, and I was ready to move forward. But there was something else in the Helix series, something that I had remembered from my education about light and reflectivity. This was the challenge of using shading to make illusions of metallic surfaces. Shiny metals have always held fascination for us humans. The fact that they were the only materials that were selective in their highlights gave them a unique presence in the world of things we see. Being selective means that they did not reflect all the rights they received evenly. As an example, gold is the only material the highlights of which are yellow. A shiny plastic surface would have highlights that are white.

The illusion of bent metallic surfaces in the helix series gave them a unique attraction. In the case of Aluminums and Steel, 1971, the shading of the areas of the painting were imitations of a steel or aluminium sheet of metal that I had in the studio. Thus, by imitating a bent metallic surface, I was reflecting the room around me, a throwback to the painting Mirror Sphere, 1968.

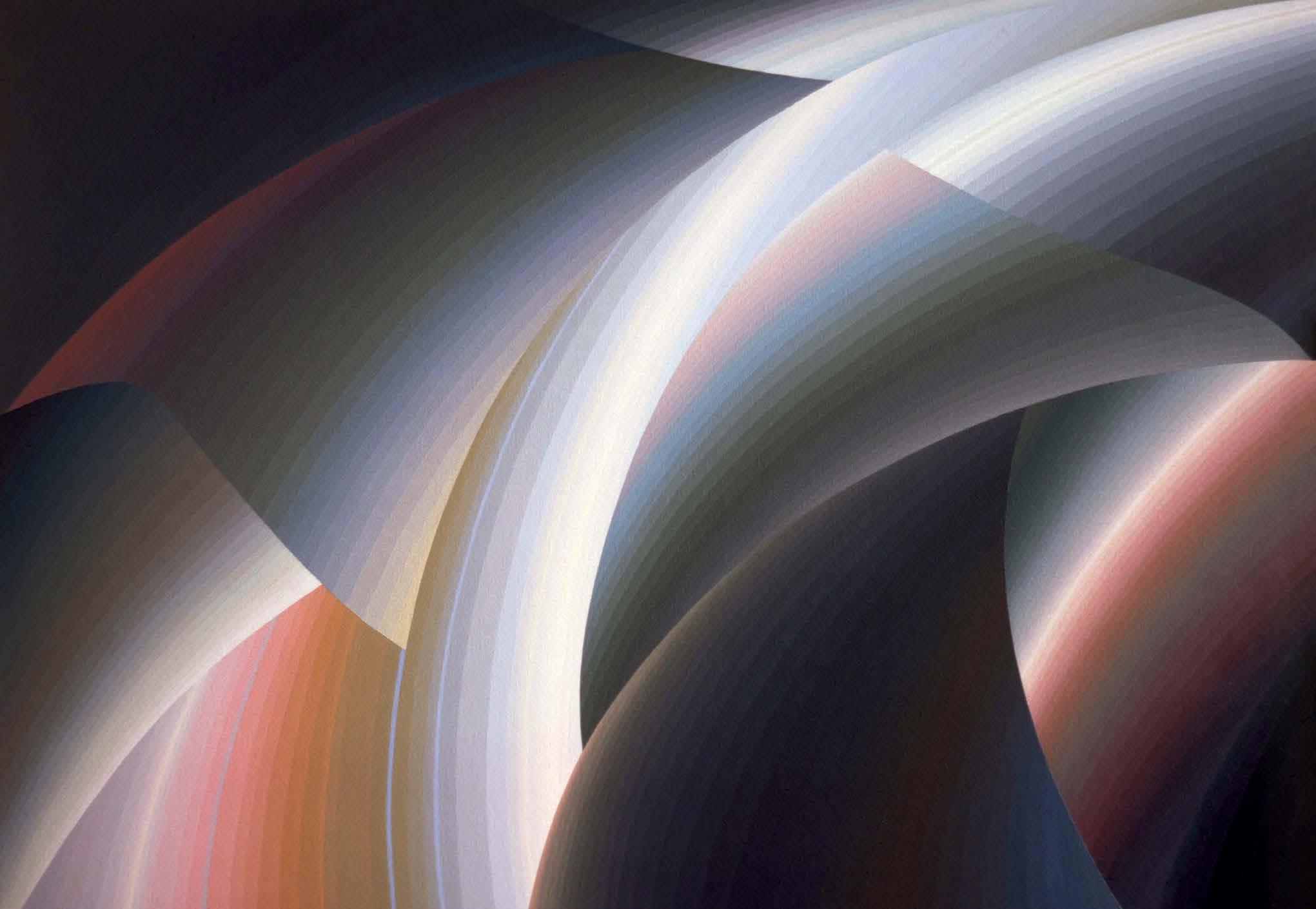

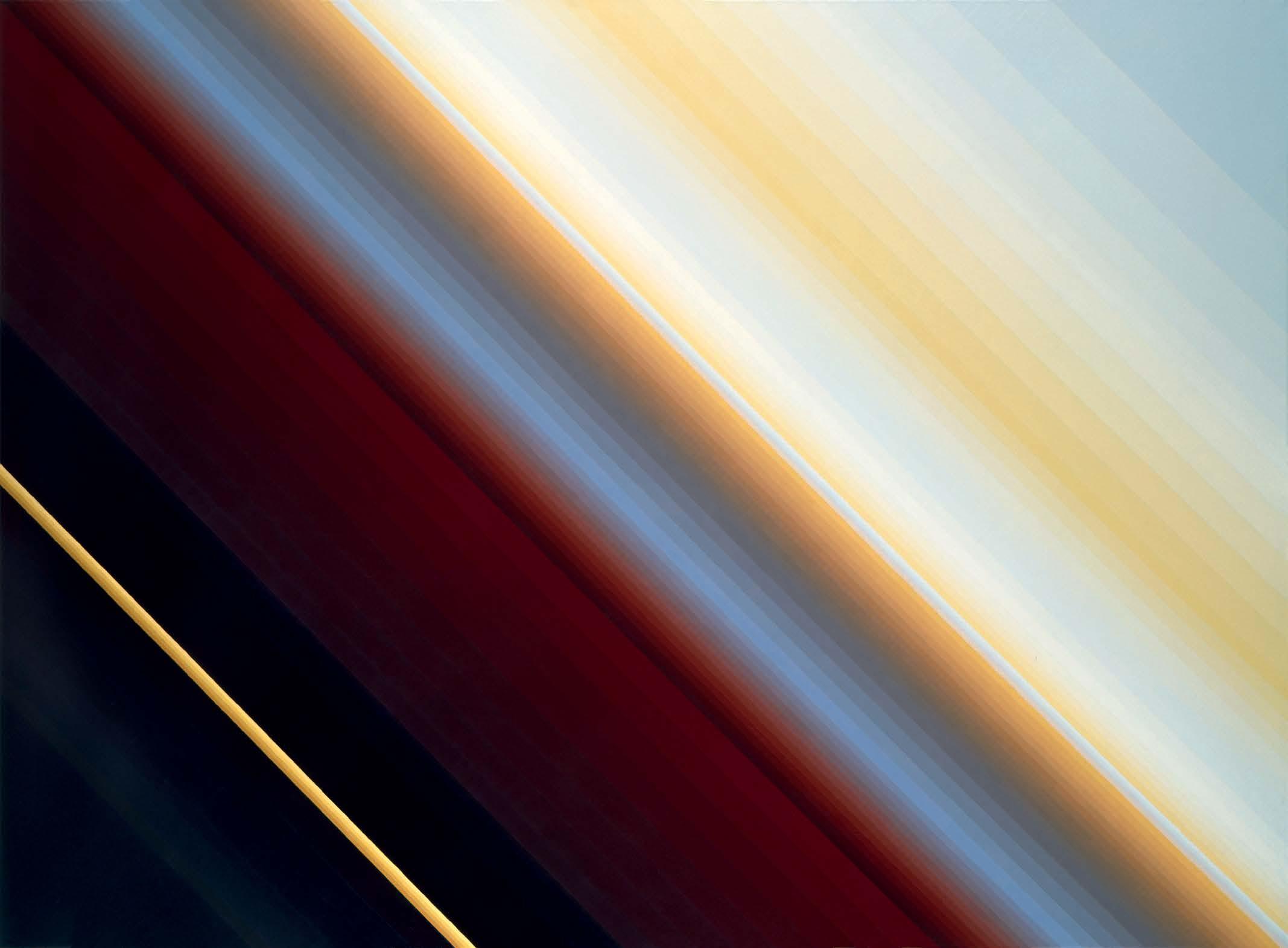

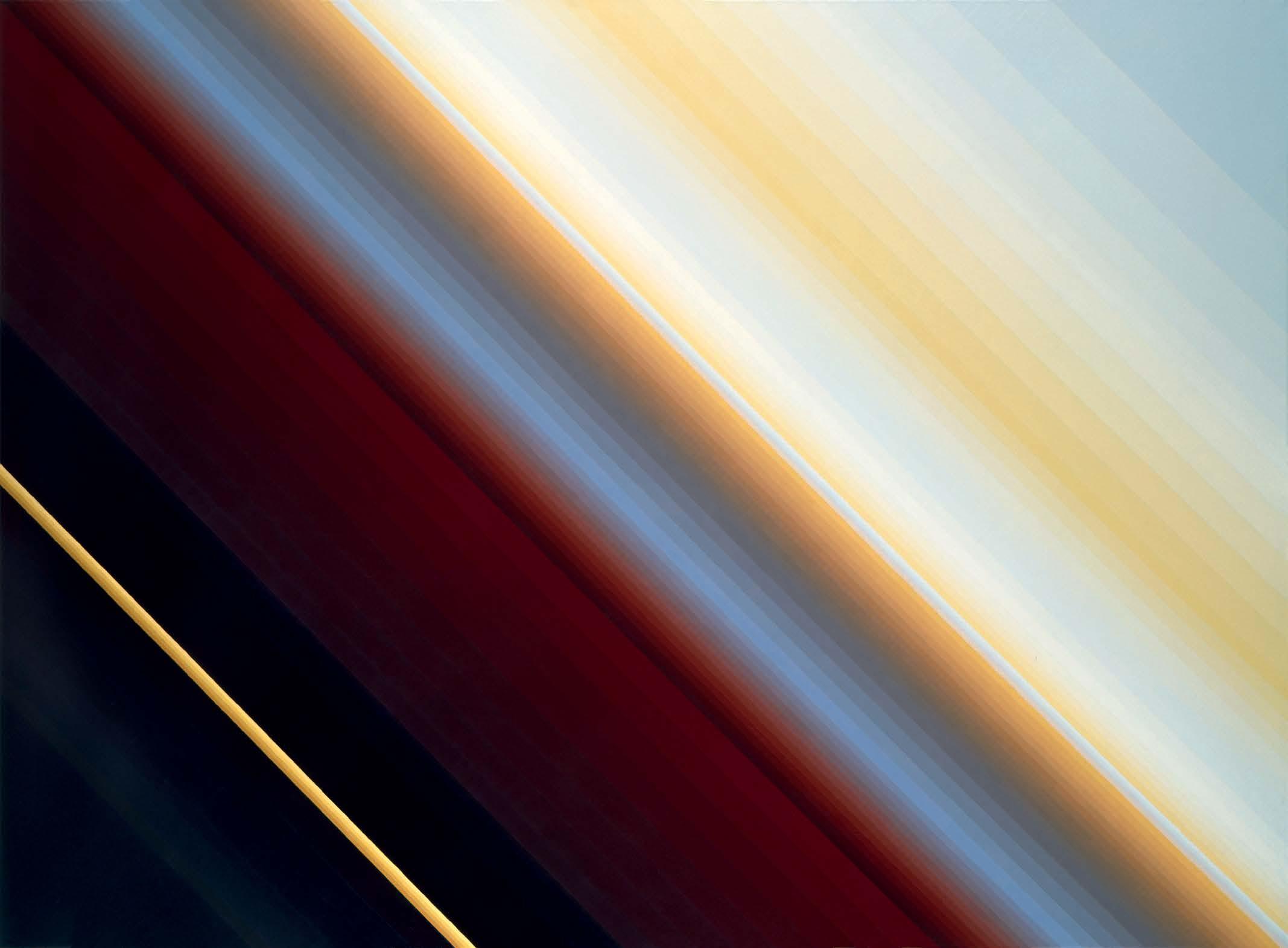

(Opposite) Saturn, 1977, o.c., 66 x 90 in (7.5 x 228.5).

(Below) Copper and Brass, 1976, o.c., 30 x 42 in (76 x 107 cm).

DIAGONAL FLIGHT

By 1977, the series of paintings based on plotting curves inspired a question. I had been shading not by pushing colours into each other but rather by breaking the surface into stripes based on the implied structure. I was applying narrow bands of colour one after the other in graduated light and colour, that is gradually changing both the level of light and colour in each consecutive stripe. This fascination with metal and how to shade took me back to explorations during the Geometric Still Life series. I asked, would we see a round cylinder if we shaded it perfectly but did not allow the top and bottom ellipses to appear in the painting? In pedestrian description: if a pipe ran from one end of the painting to the other and we saw no circular joints on it, would we see it as cylindrical volume? The result was facinating in that we did not see it as perfectly cylindrical but also its actual size became relative as there was nothing else in the painting to indicate relative measure. The space of the Diagonal Flight series could be infinitely large or small. By challenging and exploiting perspective, I had

ambled backwards into abstraction. Now I had experience and knowledge and began to think of space in ways that transcends the finiteness of a geometric still life.

I always remember my love of the sea by the side of which I grew up in Yafa and Beirut, my sense of freedom in standing at the edge of the water looking at the blue waters of the Mediterranean and moving my eyes to the sky and knowing that no one owned that expanse, that it was free space for me to fly in. So now, I had to select a direction for the diagonal that I was using. I saw a group of children playing at being aeroplanes flying in the sky and took note of how they zoomed about arms spread horizontally like wings, voices singing engine sounds. When they turned, they banked diagonally imagining themselves aeroplanes, they mostly favoured their right arm. It was these children playing that guided my choice of direction hoping my viewers would feel like flying into the space of a painting arms spread like wings.

67

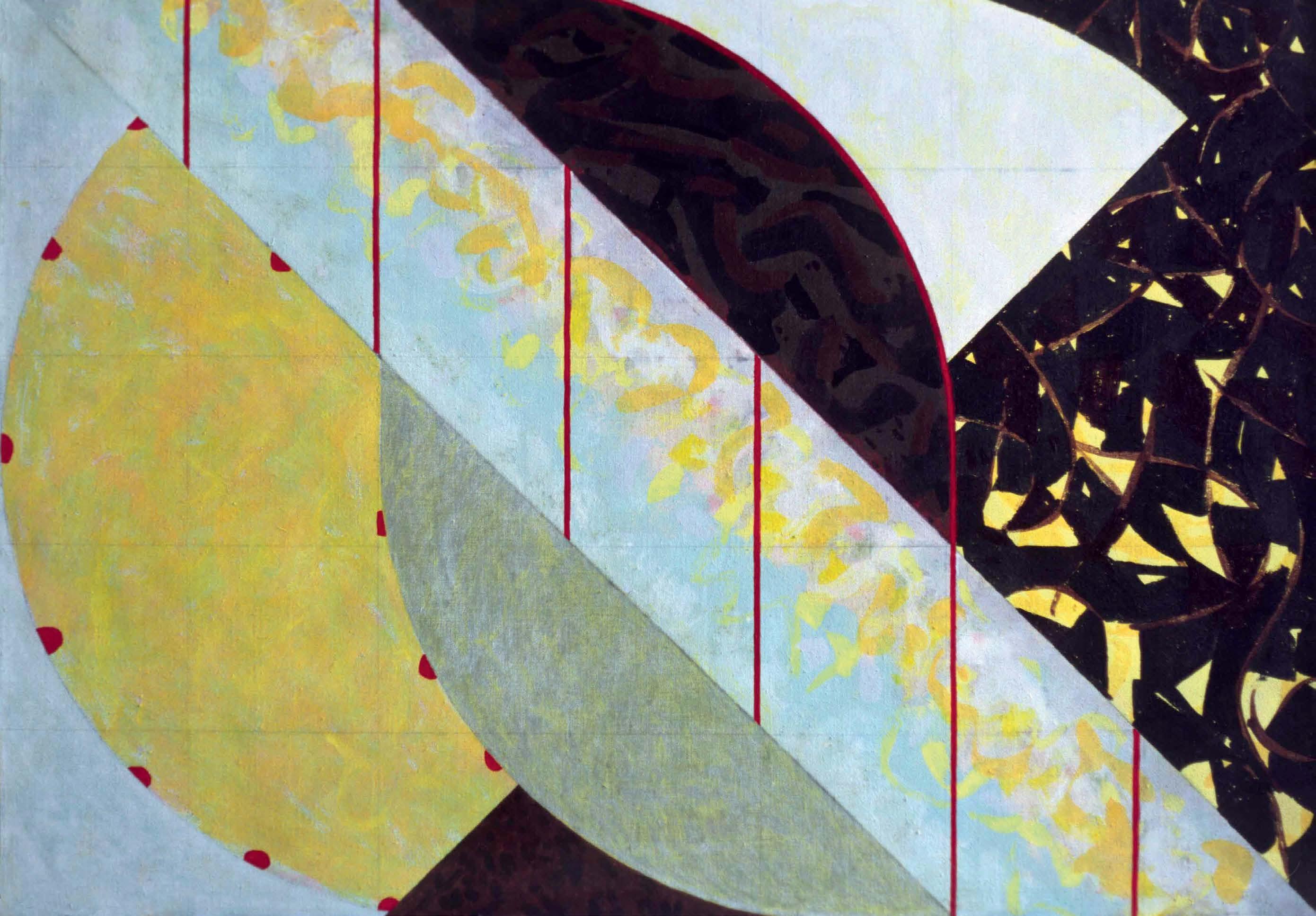

DOME OF THE ROCK AND ARABIC ART

68

One or Two Pink, 1980, o.c., 48 x 66 in (122 x 167.5 cm).

The Diagonal Flight series seemed so perfect, such a glorious conclusion from a 15 year-long exploration into how we see that took me from careful illusions of concrete objects to relativity of space and depth. I had stumbled into abstraction backward it now seems to me though in practice it was an earnest exploration that moved forward. My first dry period ensued, and I did not really know what to do with my determination to extend an original idea for a lifetime. I wandered here and there with some hints of time and motion beginning to appear in my work. The Diagonal Flight series always seemed about unapproachable high speed. Finally, the logic of abstraction in historic Arabic art, the art of the mosques and Palaces of the Feudalist age of the Arabs penetrated my aesthetic consciousness and I returned to my admiration of the inlaid marble panels of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem that I had seen in 1966. Thus in 1980, after a year of confusion, assurance returned when I decided that I would adopt the compositional principles of mediaeval Arabic panels of inlaid marble, wood,

stained glass, or stone. I decided to allow the rectangle to give birth to every shape in the painting. The rectangle of the painting, its frame, was no longer a window through which I would look at the world but rather a panel that received ideas gleamed with our eyes and processed in our thoughts.

In One or Two Pink, 1980, there remains some shading from previous periods, but shapes were now being filled by textures to imitate the way different patterns of marble met to define a boundary without a line between them. Electric Bulbs, 1981, follows an earlier practice in the series where circles were used in place of squares. Each of the two circles filled a square that would be defined by the sort side of the rectangle; while the diagonal cylinder was created by casting fourty-five degree lines across the surface from two corners of the rectangle.

Electric Bulbs, 1981, a.c., 35 x 44 in (89 x 112 cm).

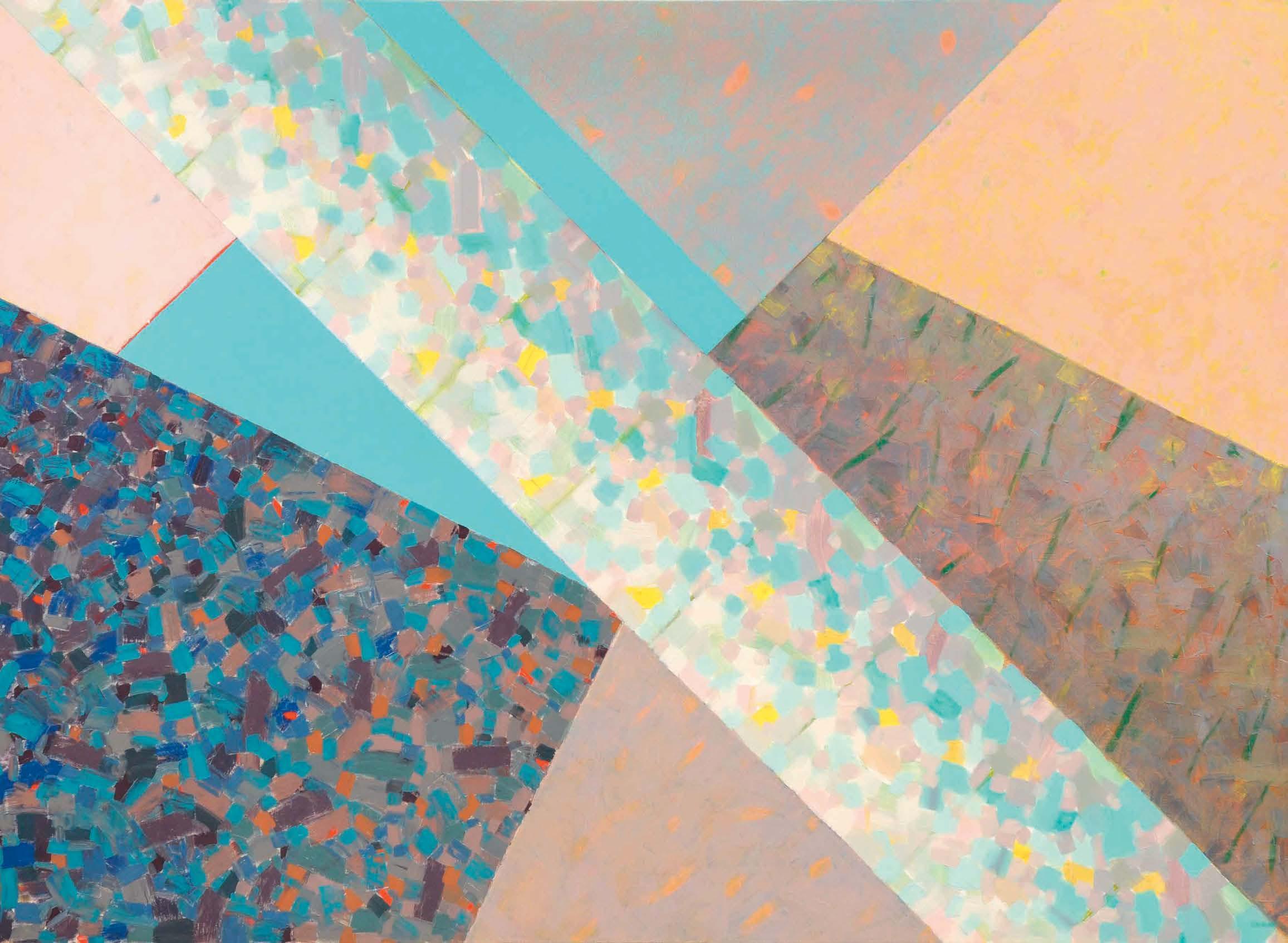

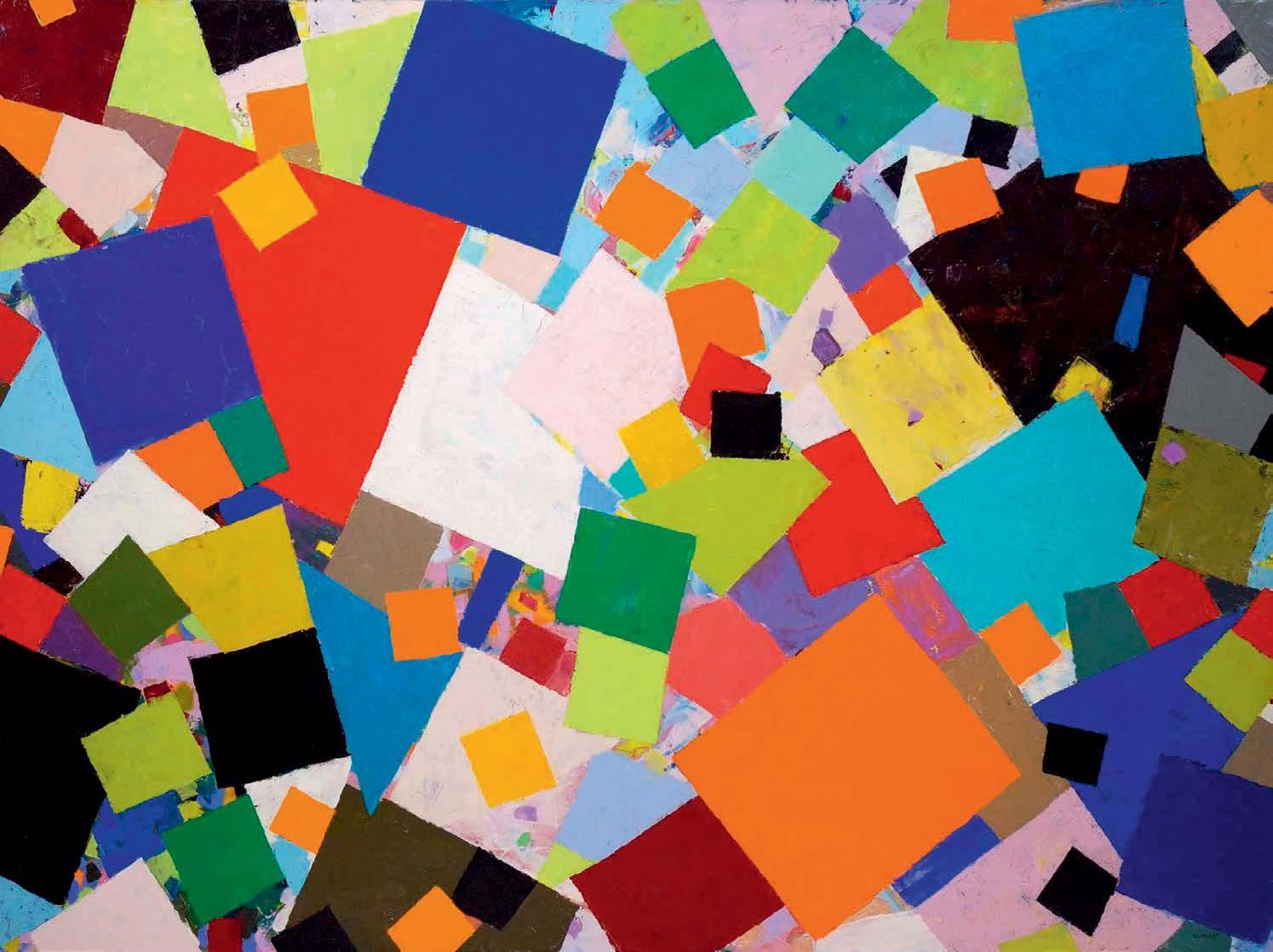

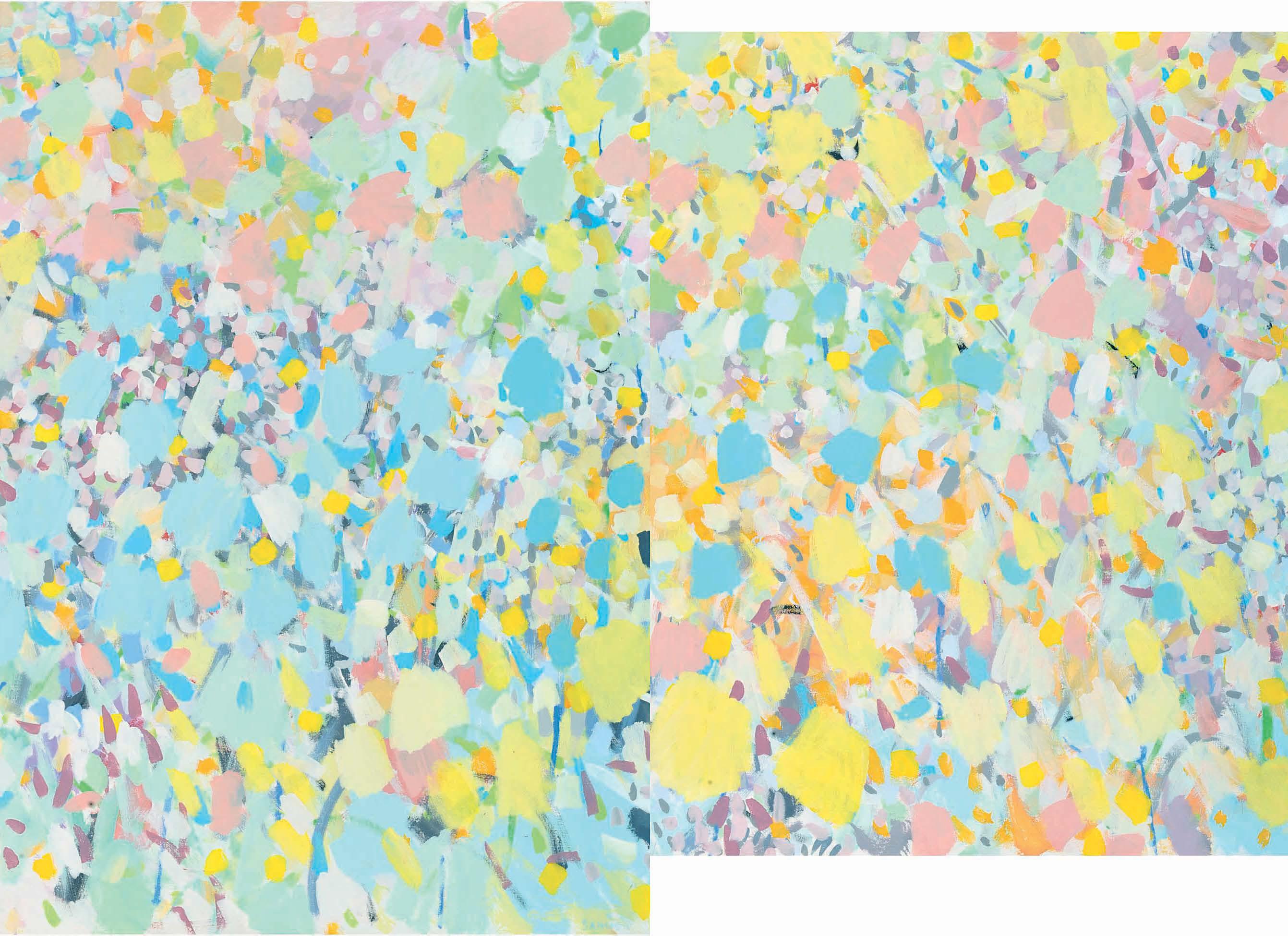

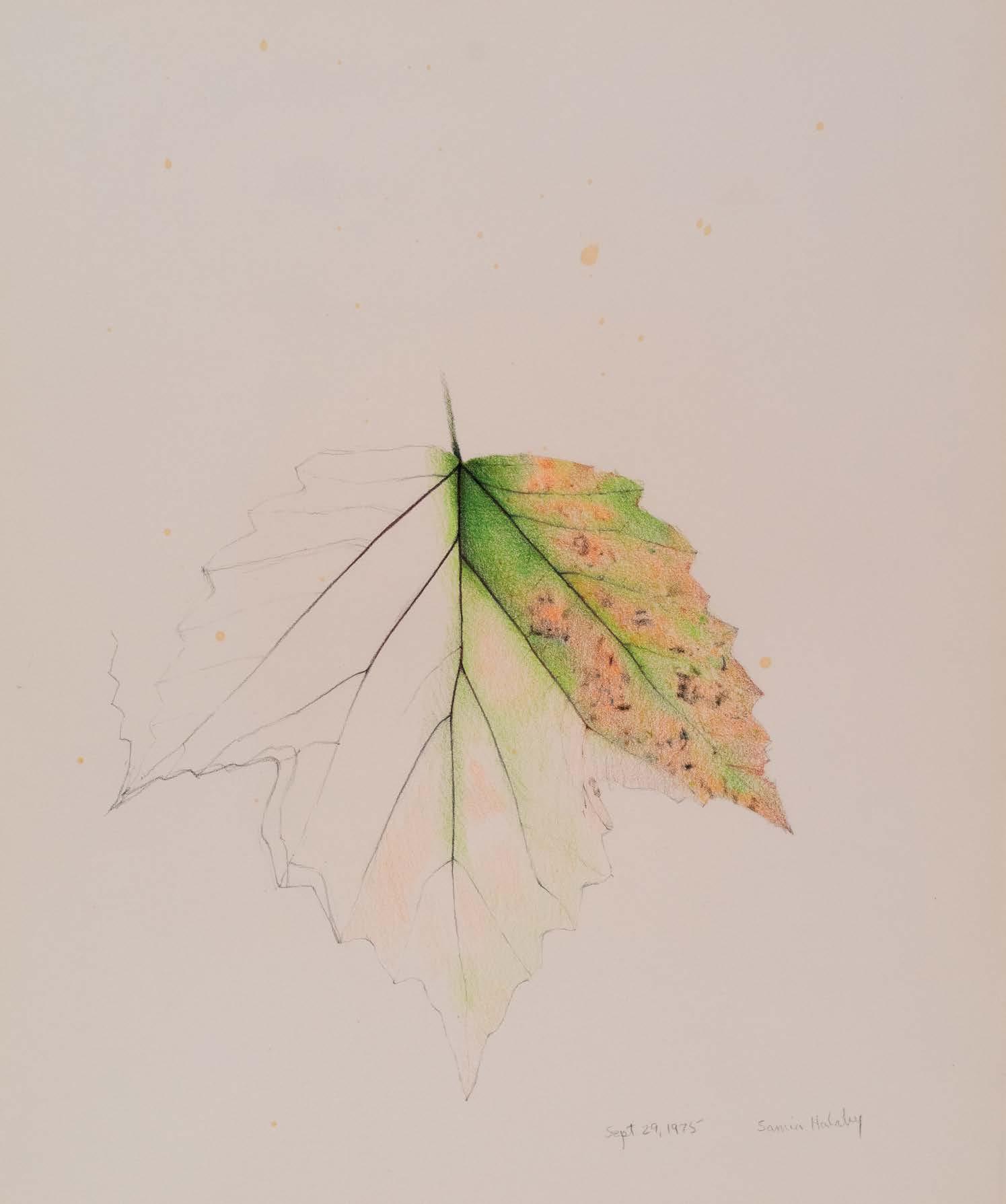

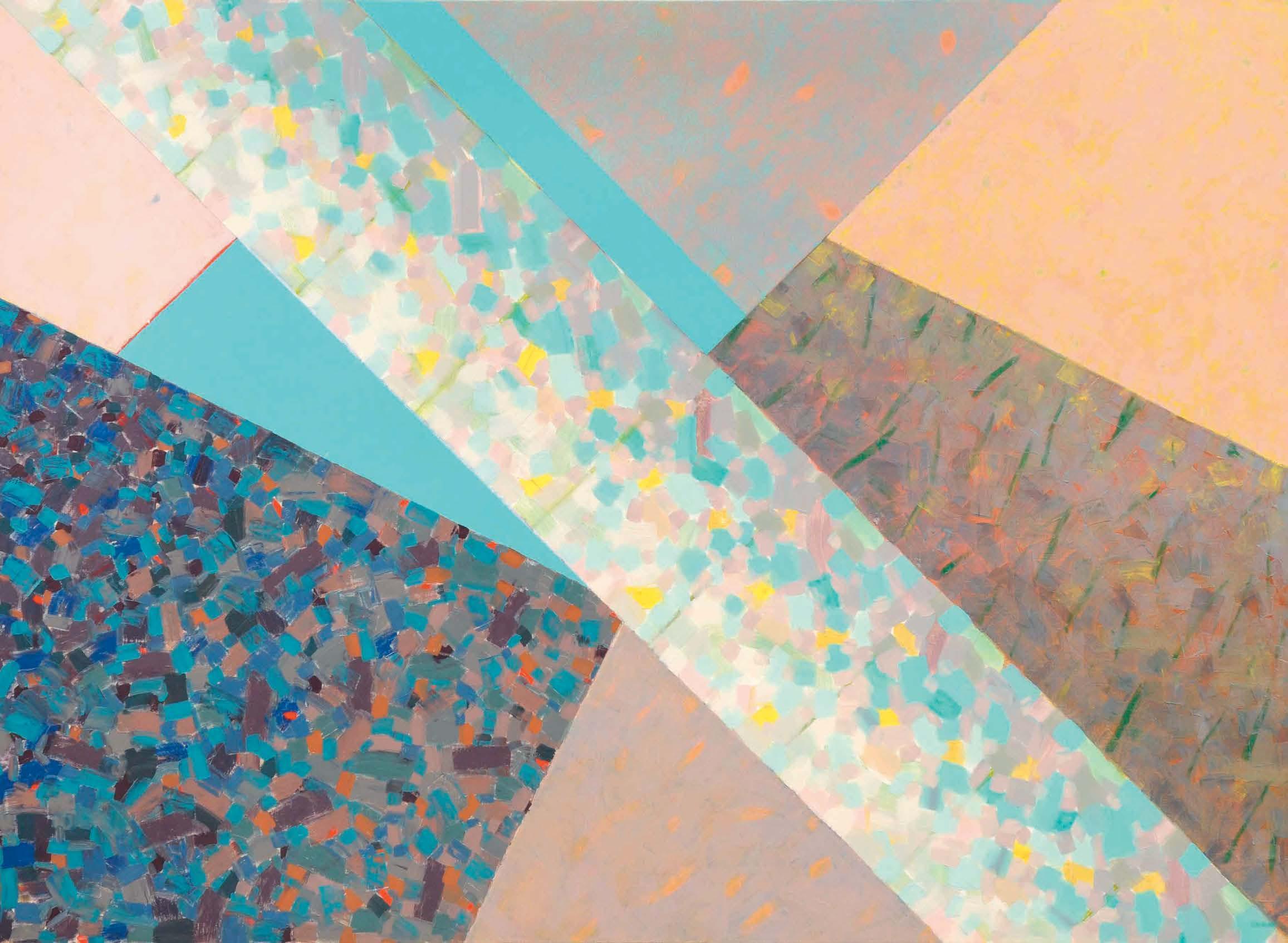

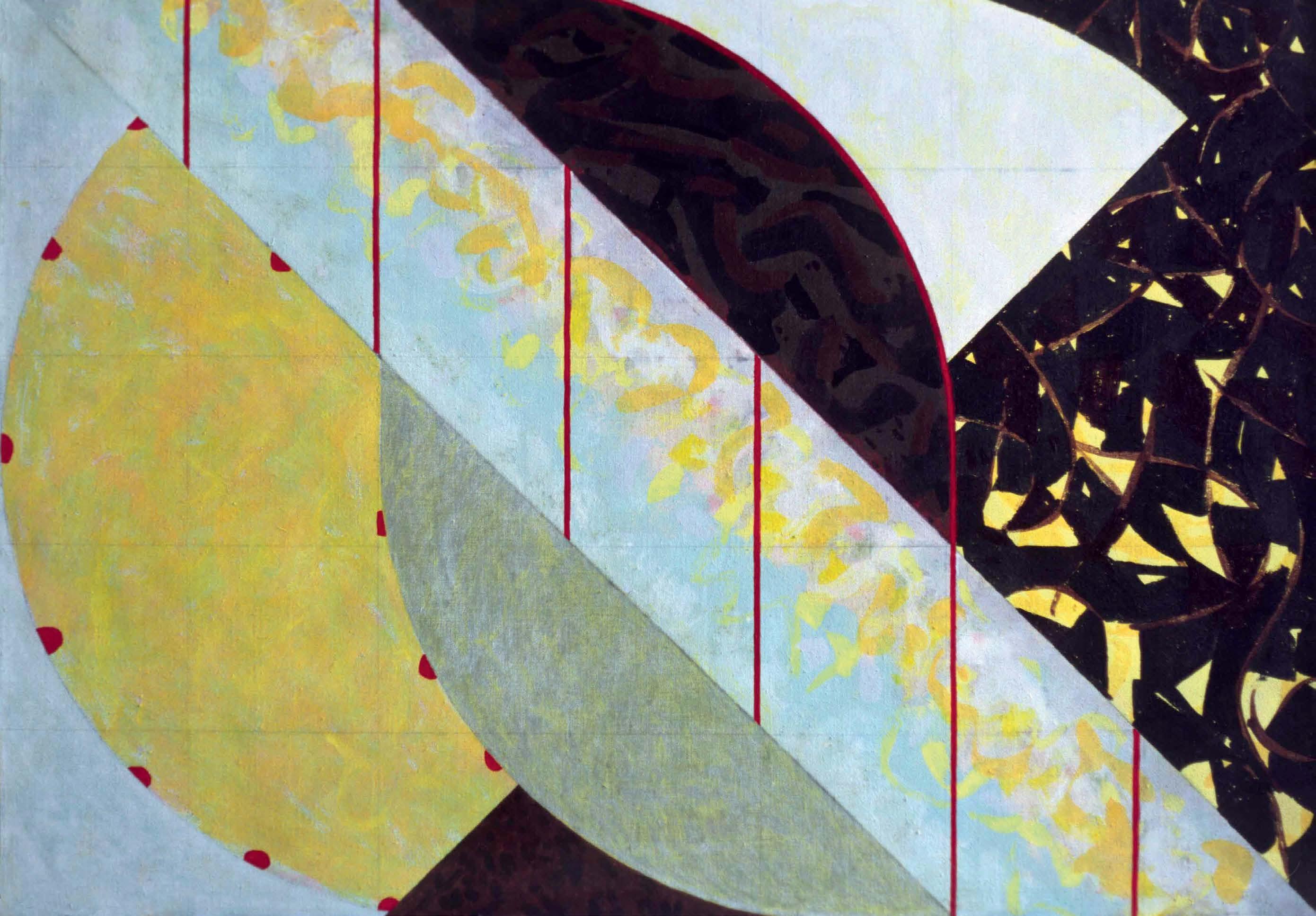

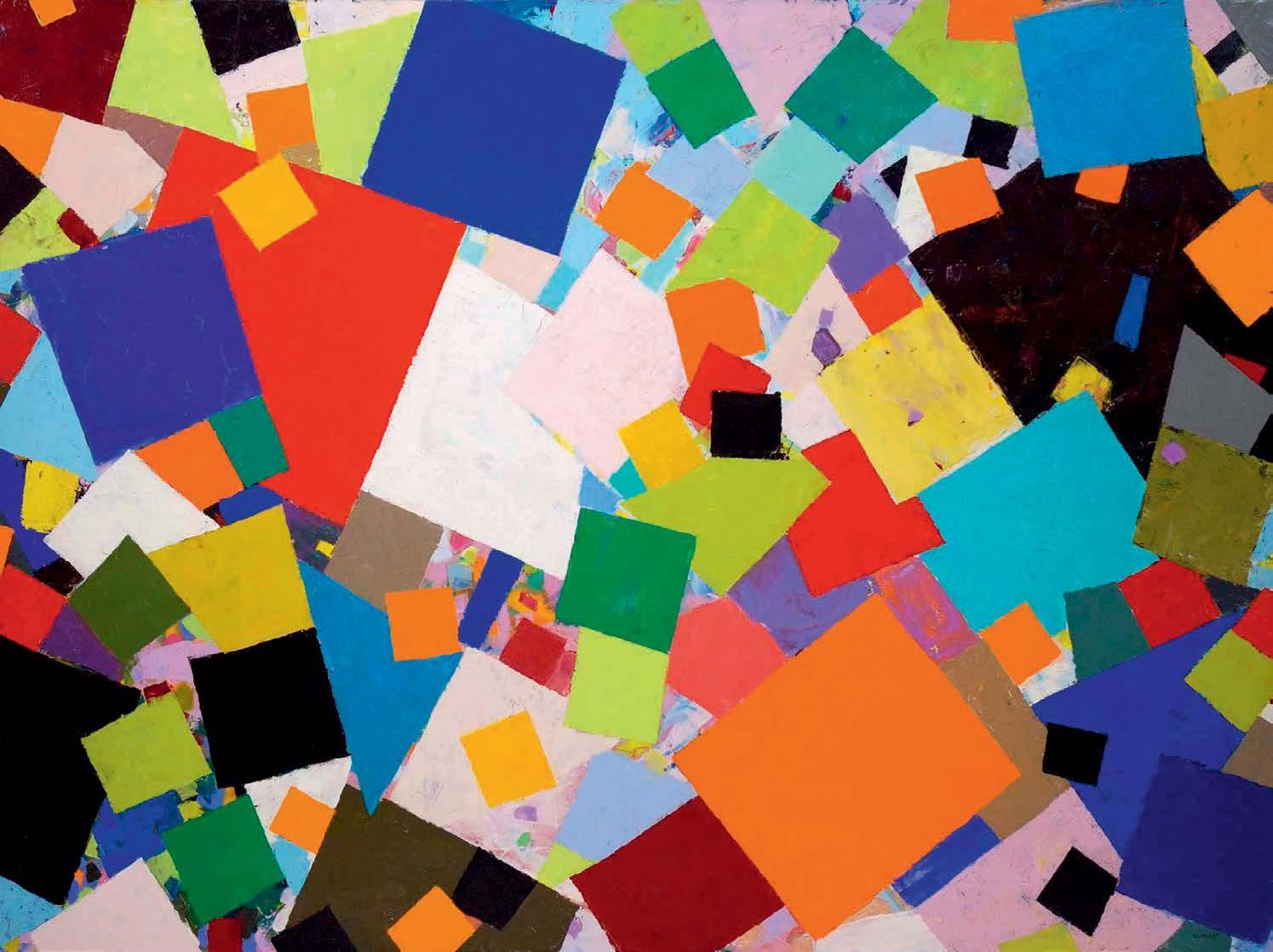

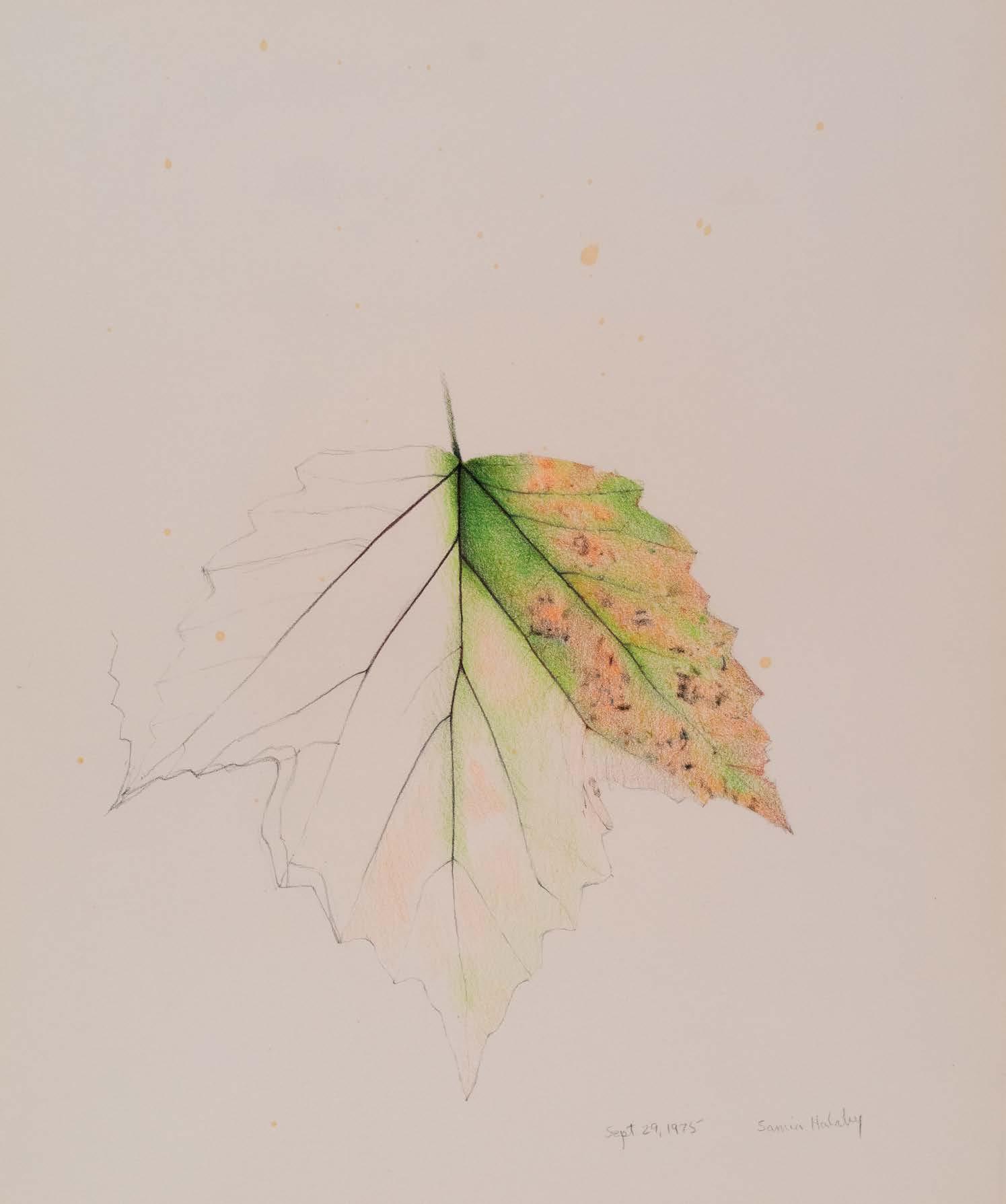

AUTUMN LEAVES AND CITY BLOCKS

In 1975, while still living in New Haven, I found myself enchanted by Autumn leaves and did an extensive study of them. The combination of fascination and extensive effort capturing their visual message formed a substantial part of my aesthetic understanding. The scope and intensity of the study, processing and sifting through important insights, and how they interconnected with later insights, finally asserted themselves during the early 1980s. Painting is the top feeder in the ecology of my aesthetic thought, the lion that demands the greatest effort on all levels of practice. Abstraction was now clearly my direction and with absolute clarity I gave up both shading and perspective. I was on my way to something completely contemporary and completely related to nature. Something that imitated nature and reality but not in the ways of the Renaissance. At the time, I had not yet said to myself that I was painting the world as I see it while moving in it; and that the idea of painting the world from a frozen point of view was left out of my abstraction definitively.

Another attribute of my new abstraction was the understanding that many different things in nature possess similar visual syntax and abide by similar principles of growth. I was discovering the relationship between how leaves grow and how veins spread through them as they expanded to how a city grows. Cells in a maple leaf resembled the blocks and lots in maps and farmlands. I worked out many of these new ideas in One Yard Past the Shingle Factory, 1982, and continued the exploration in Fan Tail, 1982. One Yard Past the Shingle Factory was a tip-of-the-hat to Marcel Duchamp in cognisance of the New York critic whose claim to fame is saying that Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912, was like an explosion in a shingle factory.

Fan Tail, 1982, was the actual arena where the individual brush marks that had been limited to single areas in the Dome of the Rock series, began to fly free of their boundaries and activate the entire surface. But this idea remained dormant and came to full fruition in the following period, the Growing Shape series.

Down West Broadway in the Evening, 1983, is the quintessential example of the Autumn Leaves and City Blocks series. It was inspired by my walking down West Broadway inTribeca, my neighbourhood, in the evening when suddenly the traffic lights down the avenue all turned red at the same time. The brown atmosphere of the building and the bright red of the lights created sensations some of which I captured in this painting.

70

(Opposite) One Yard Past the Shingle Factory, 1982, o.c., 66 x 90 in (1675 x 228.5 cm).

(Above) Down West Broadway in the Evening, 1983, oil on canvas, 65 x 75 in (165 x 190.5 cm).

(Right) Fan Tail, 1982, o.c., 60 x 60 in (152 x 152 cm).

(Opposite) One Yard Past the Shingle Factory, 1982, o.c., 66 x 90 in (1675 x 228.5 cm).

(Above) Down West Broadway in the Evening, 1983, oil on canvas, 65 x 75 in (165 x 190.5 cm).

(Right) Fan Tail, 1982, o.c., 60 x 60 in (152 x 152 cm).

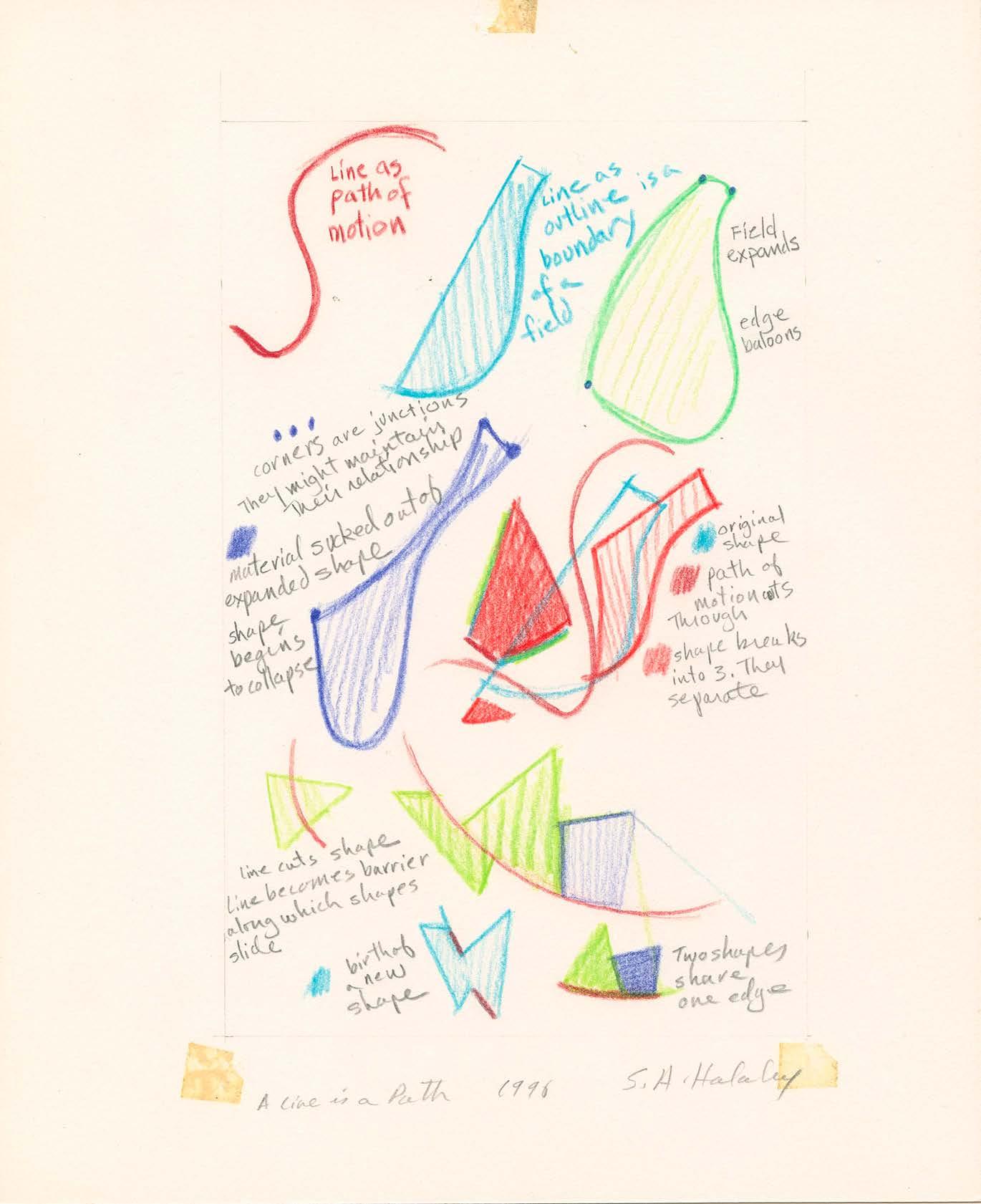

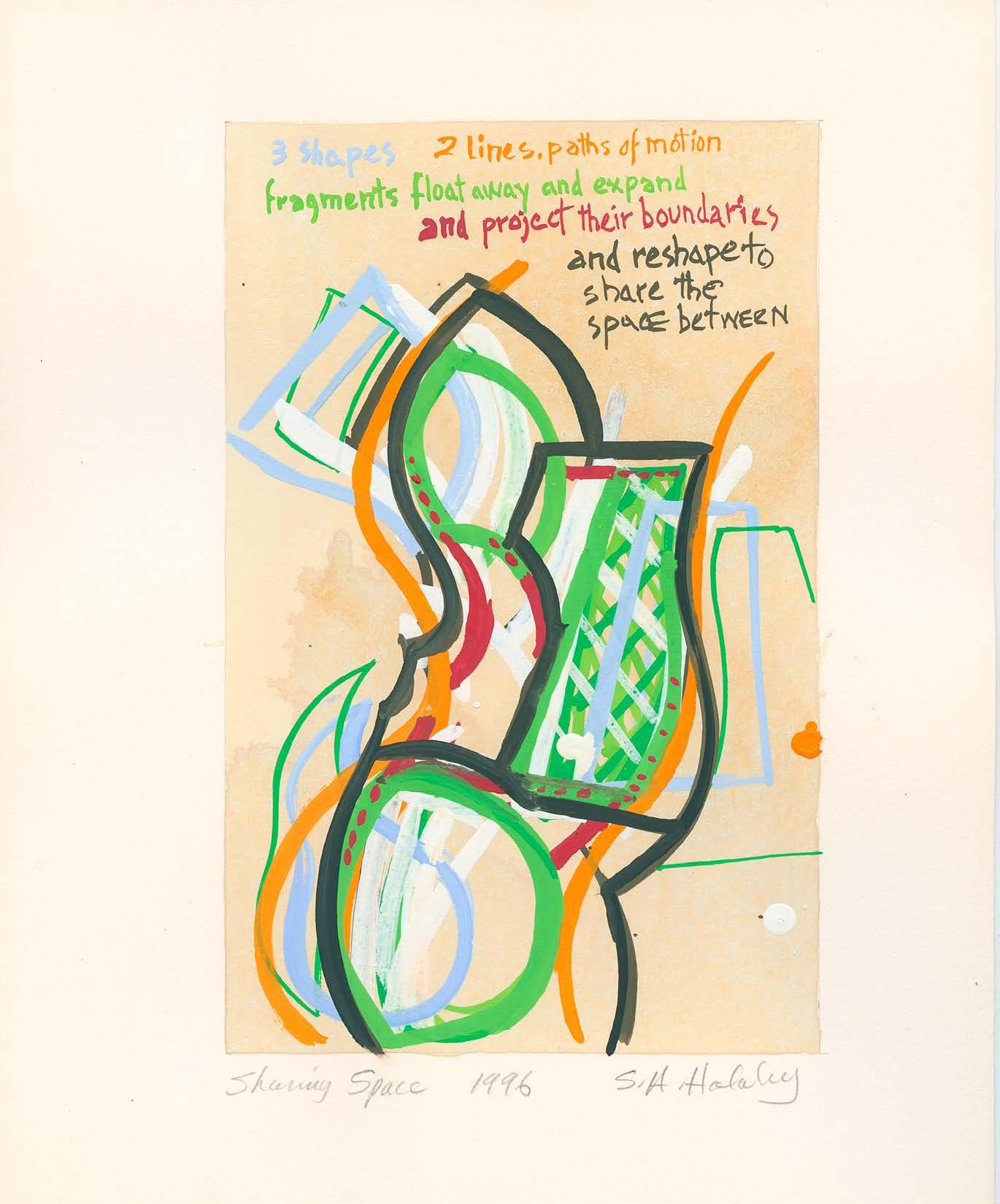

GROWING SHAPE

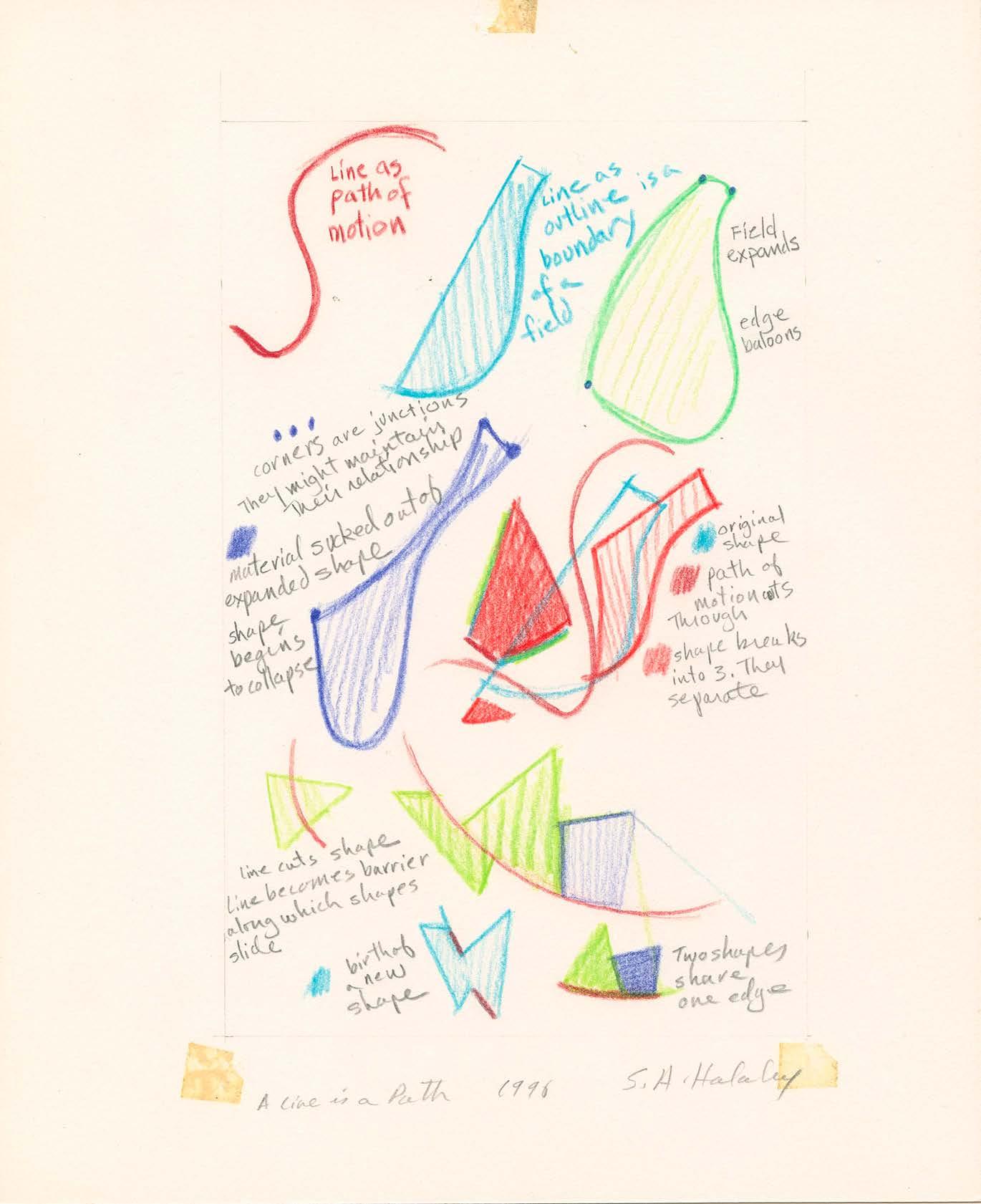

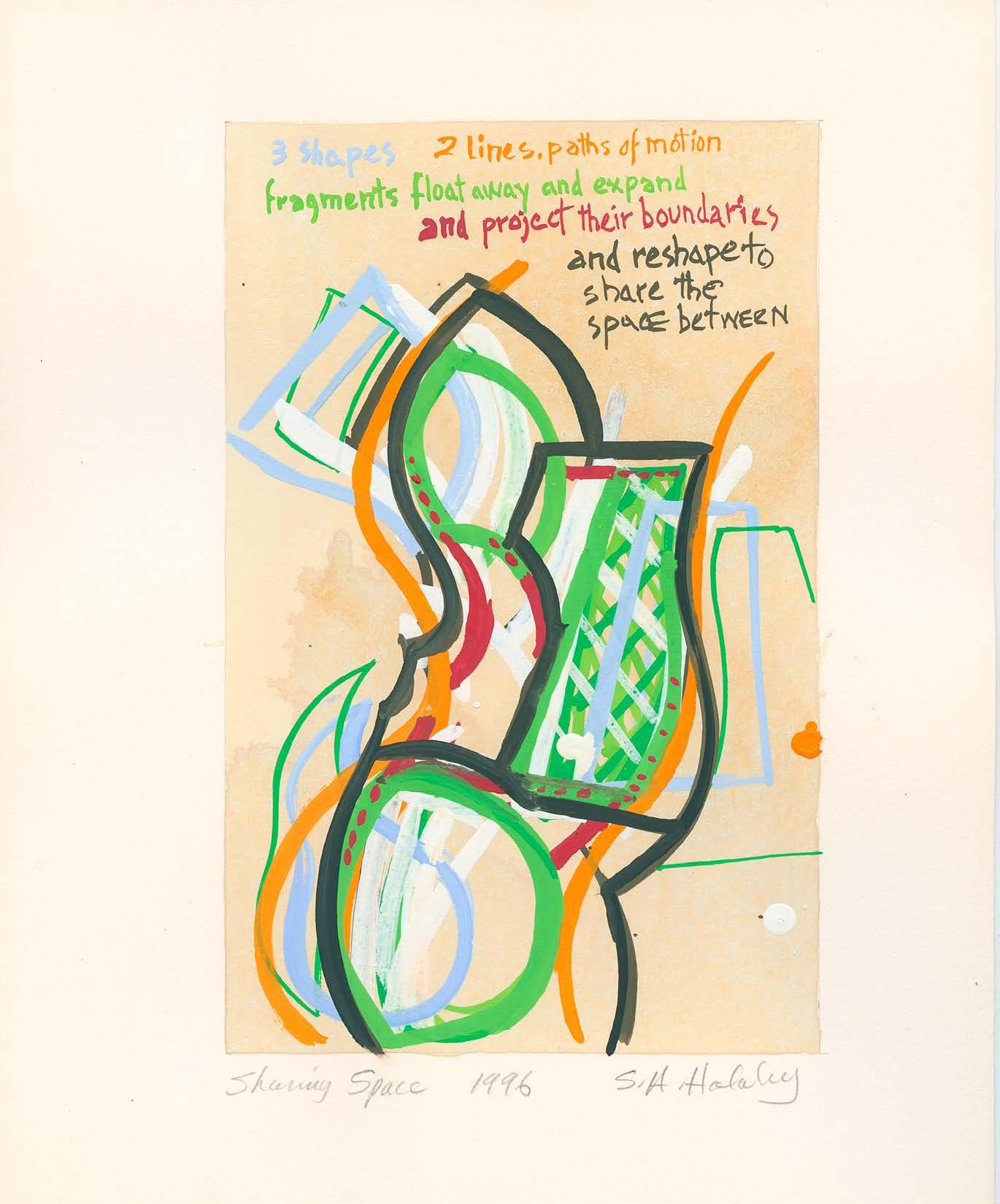

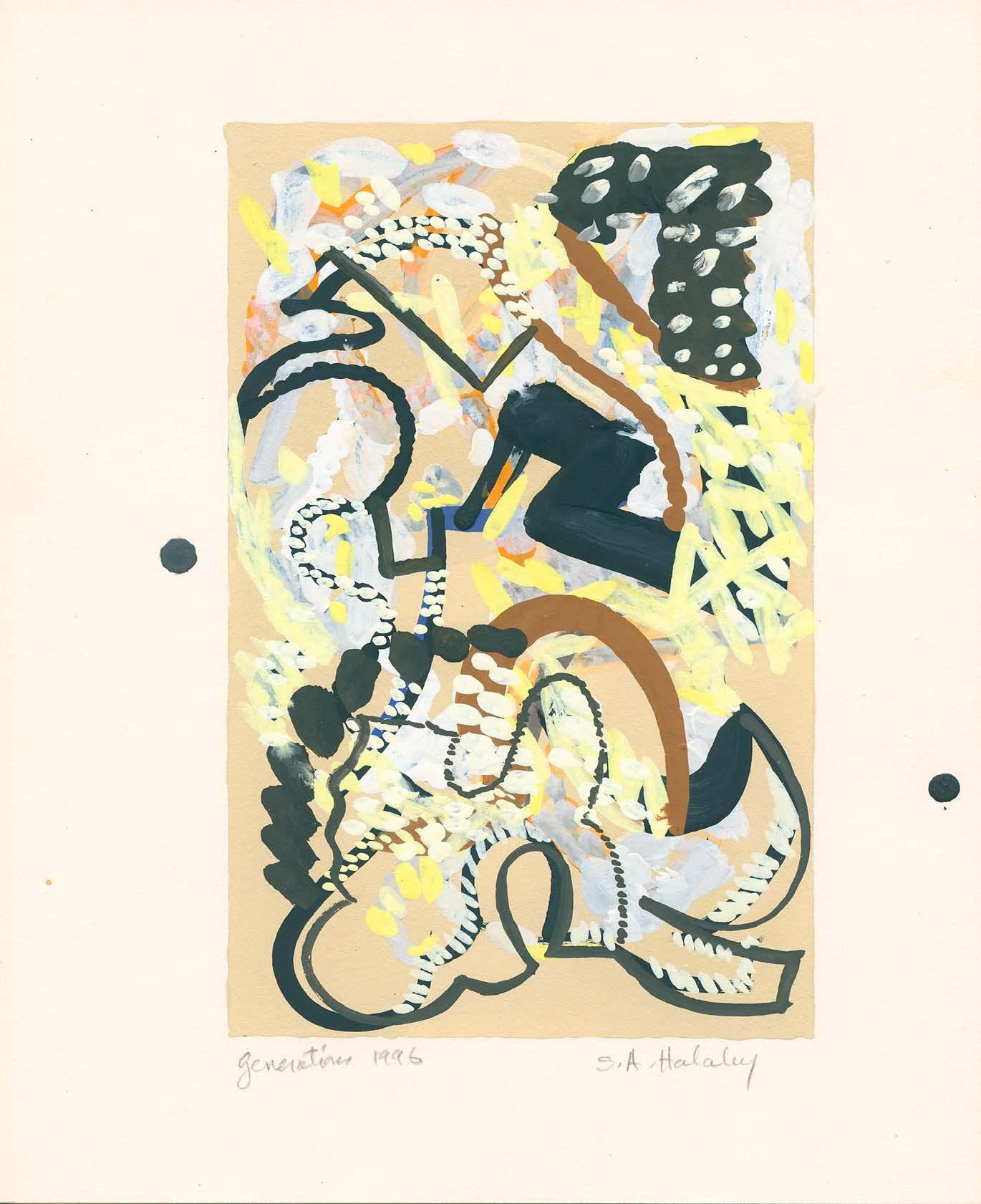

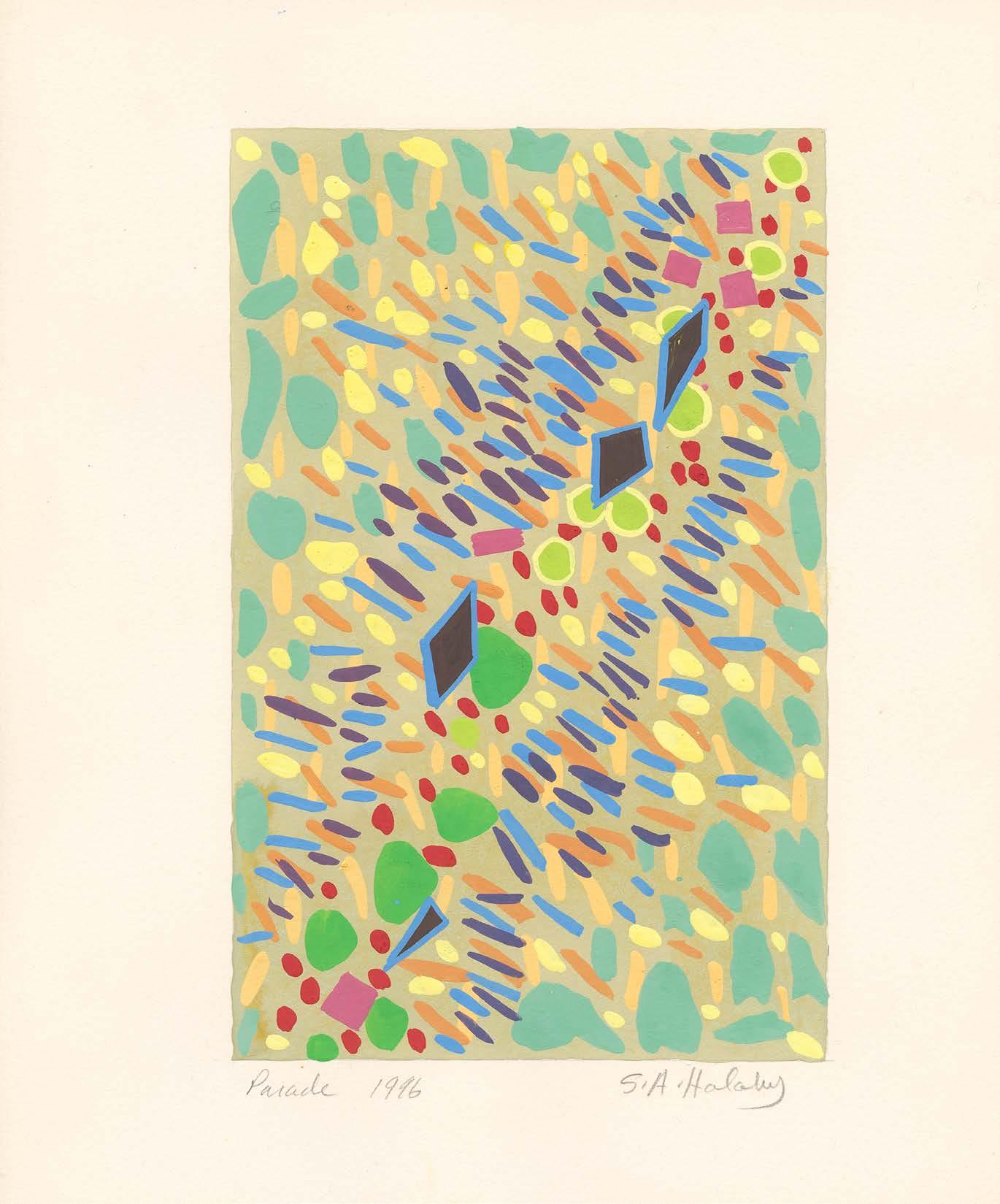

The Growing Shape series in my work emerged from the previous engagement with discovering principles in nature that could be translated into the process in making paintings. It was the early realisation of the idea of making a painting grow as a leaf grows. In One for Pollock and Tomlin, 1996, I was recognising my debt to Abstract Expressionism by indicating the names of two artists of the movement that I admired. Those are Jackson Pollock and Bradley Walker Tomlin. In this painting the idea of line acting like a path of motion dividing a field was uppermost as it was in the painting Rufus, 1986. Paths of motion might be rivers, or paths animals make, or the scary ones that humans make like super-highways to chop up the farmlands.

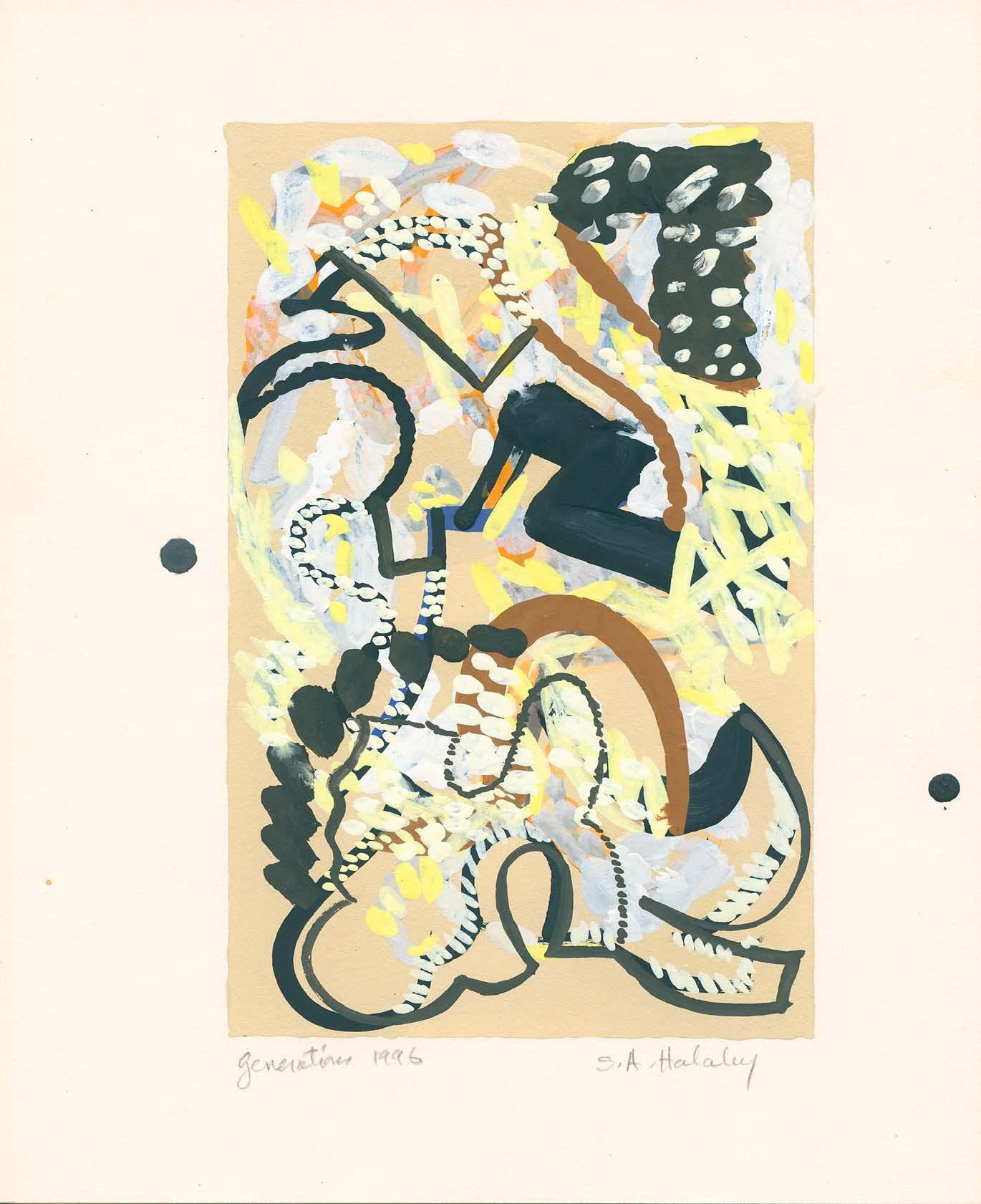

(Opposite, clockwise) A Line is a Path, A Shape is a Field II, 1996, gouache and crayon on paper, 8.25 x 5 on 11 x 8.5 in (on 28 x 21.5 cm).

Generations, 1996, gouache on paper, 8.25 x 5 on 11 x 8 ½ in (on 28 x 21.5 cm).

Sharing Space, 1996, gouache on paper, 11 x 8.5 in (on 28 x 21.5 cm).

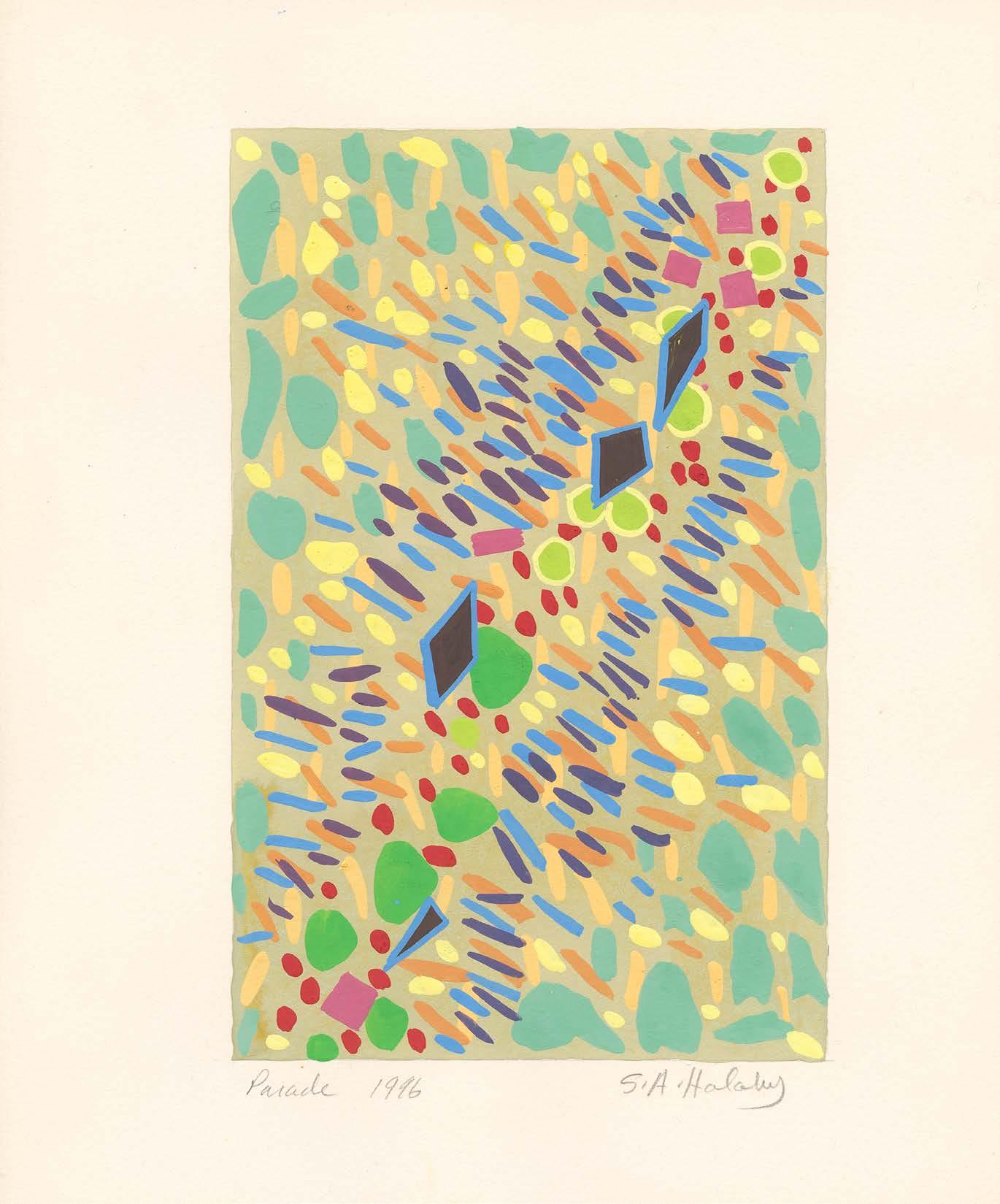

The Parade, 1996, gouache on paper, 8.25 x 5 on 11 x 8.5 in (on 28 x 21.5 cm).

(Above) One for Pollock and Tomlin, 1986, a.c., 36 x 67 in (91 x 170 cm).

73

KINETIC PAINTING AND THE COMPUTER

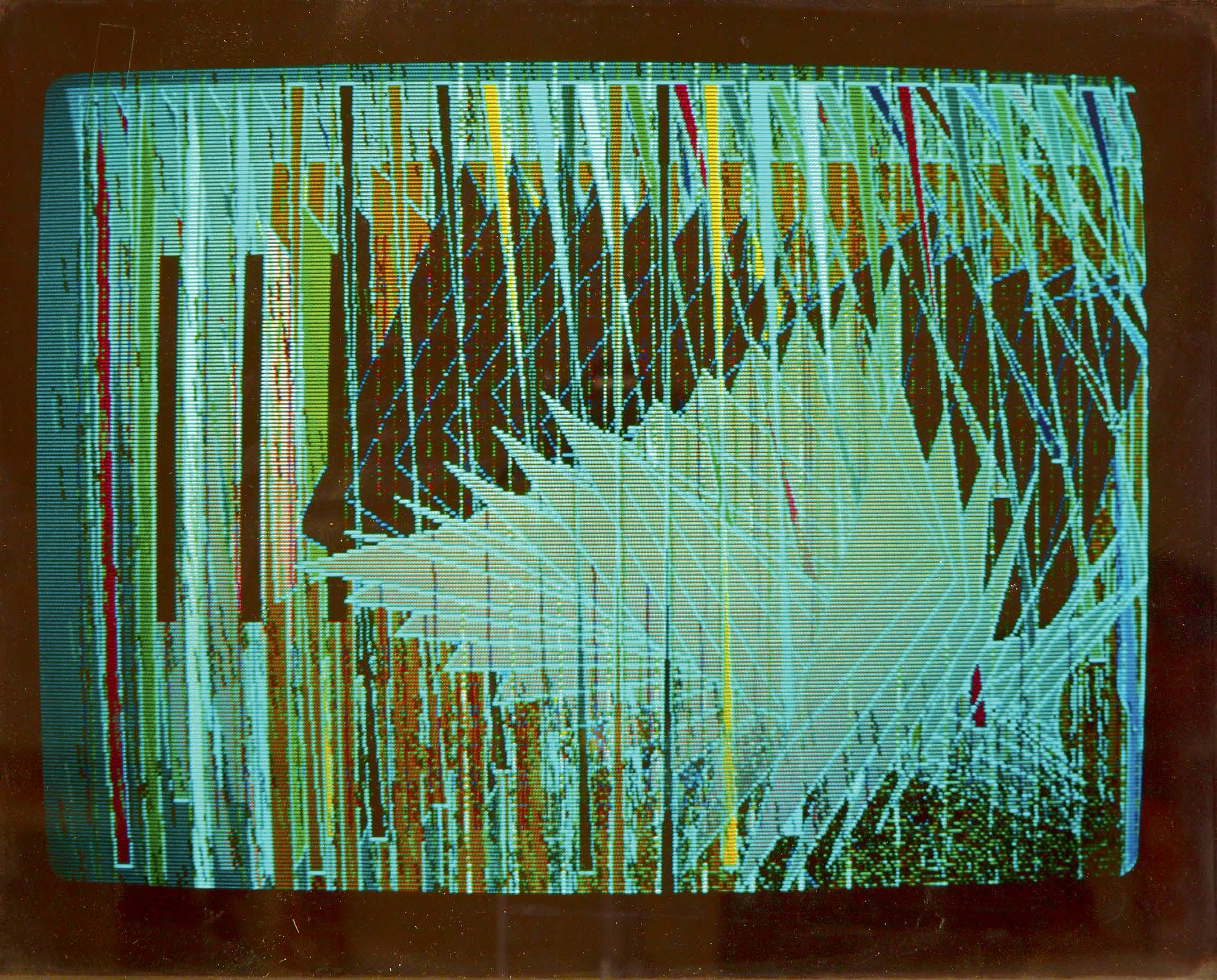

At the beginning, I used the programming language called BASIC which was relatively easy to learn. As my work developed, I began using the C programming language. ere is a difference in my work between the two. C being more structured led to my making more smoothly organised, more thoughtful kinetic paintings. While those kinetic paintings programmed in BASIC had the charm of being created while I was excited and amazed at the power of the technology.

74

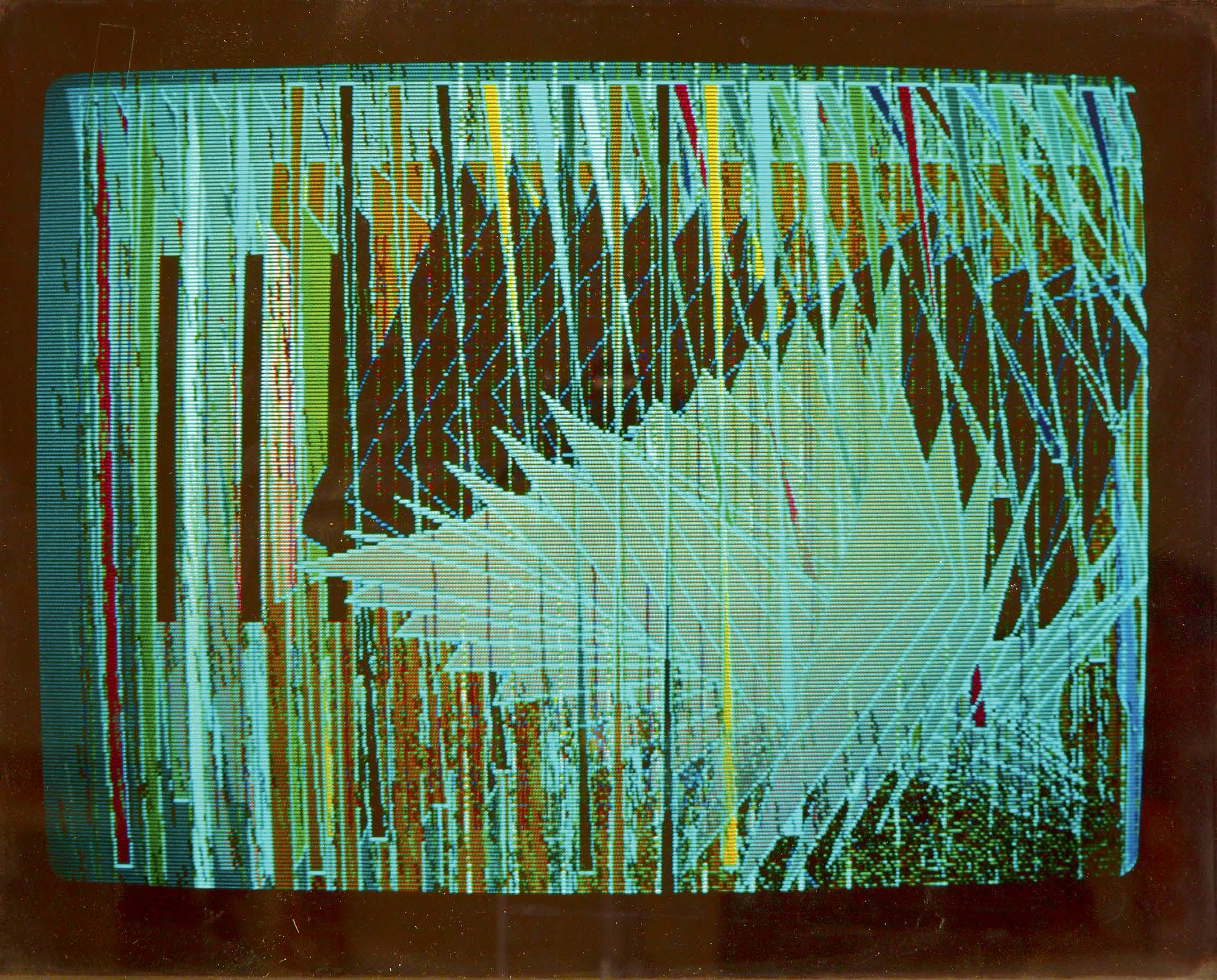

(Above) Central Park, 1986, digital film, 640 x 480.

(Opposite) Bird Dog, 1987, digital film, 640 x 480.

KINETIC PAINTING AND THE COMPUTER

is photograph shows the historic first exhibition of my computer programs on the Amiga 1000. e context was my one-artist show at Tossan-Tossan Gallery in January of 1988, in New York. To the left on a table is my Amiga 1000 running several of the kinetic paintings that I programmed in 1986 and 1987. To the right of the Amiga 1000 is a television running a video recorded from the Amiga. On the left are two oil paintings hanging on the wall. is view reflects what was going on in my aesthetic life. Oil painting and digital programming of computer films were growing simultaneously together like an adult and child.

(Above) Programming the Amiga, 1987.

(Right) Installation View of the 1988 One-Artist Show at Tossan-Tossan Gallery in New York.

A black and white photo of me sitting at the table that I built to house my Amiga in my studio. I worked on programming and painting in the same space at the same time. At first my programs seemed to reflect earlier aesthetic thought. With practice, I began to allow programming to affect the aesthetic process and thus began to think of things that could only be done through programming and algorithmic planning. Although experience with computing enlightened my practice, it was not a sketching method for painting on canvas. Painting, using pigment on canvas, continues to grow within the mature aesthetic sphere that I had created.

76

e Amiga Screen has a unique texture that when enlarged looks like a beaded image. But showing the work on the original screen only serves historical recreation. I believe the artwork itself is embedded in the original thinking. Just as the screen of the Amiga 1000 filled my field of vision when I was programming, it is fitting that in public

spaces it should be shown in a size that fills the viewer’s field of vision using the most advanced technology. I used to think that the Amiga itself became the art when running one of my programs. But I had a change of heart as I experienced the Amiga kinetic paintings exhibited in public on monumental LED screens.

Photograph of Bird Dog on the Original Amiga Sreen, 1990.

KINETIC PAINTING AND THE COMPUTER

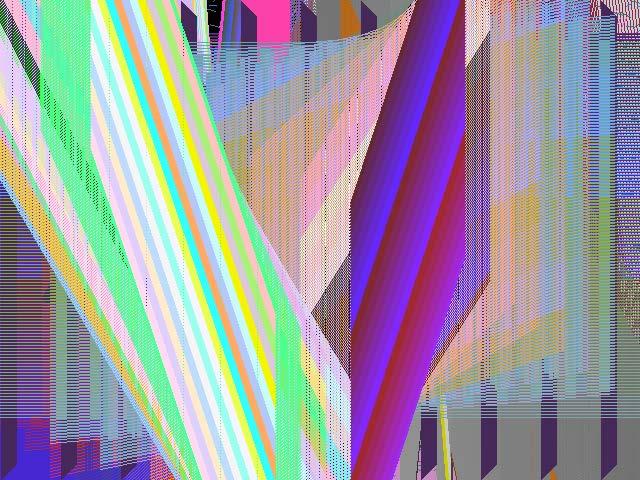

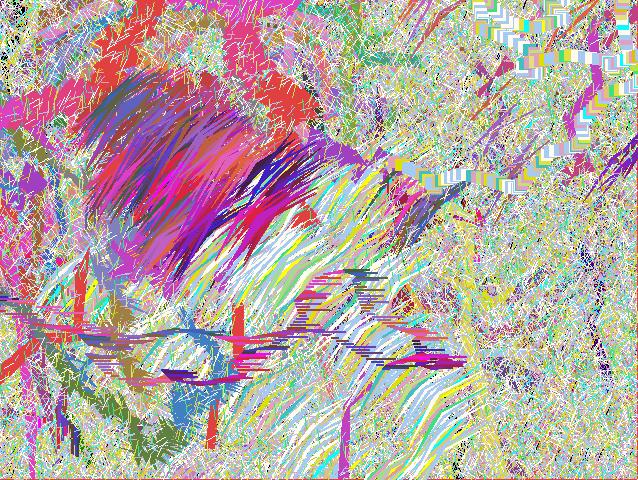

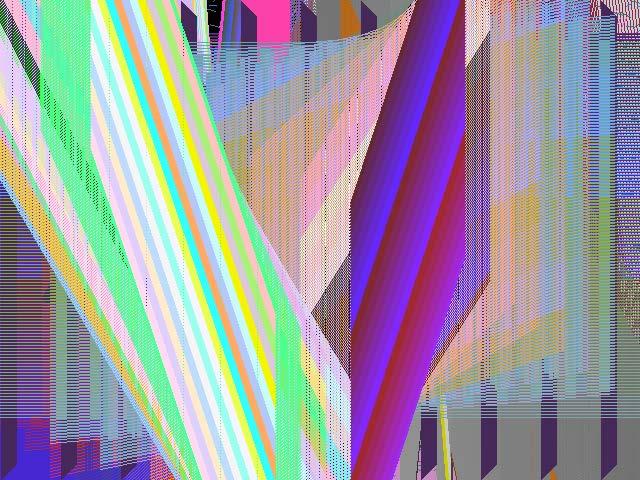

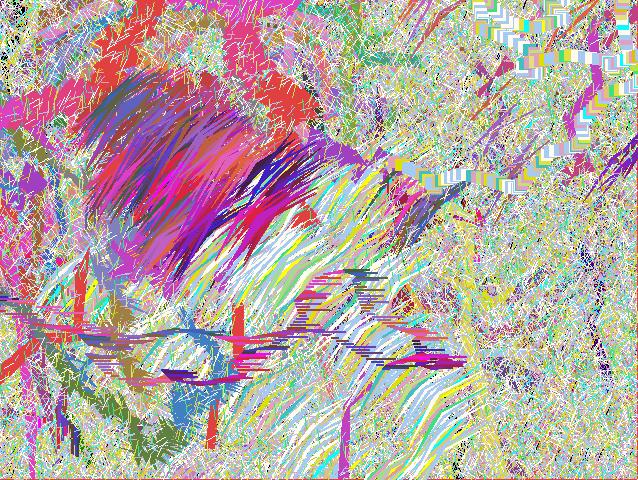

e following are created as single digital images using the Kinetic Painting Program, an App I programmed during the early 1990s. During the late 1980s having seen electronic musicians jamming on stage after the conference days at the Small Computers in the Arts Network in Philadelphia, I began to yearn to jam abstract images in motion with musicians. I converted the computer’s keyboard into an abstract painting piano where each key press creates visual material or short moving images. I called it the Kinetic Painting Program. I could use it to create unique single images by playing the keyboard until a painting that I really like developed on the screen. I would then save it as a file (a bitmap) and give it a title. Of course, I could use the program to jam with musicians in performance. I made recordings of my collaborations with musicians. During the 1990s and 2000s, I performed mostly with Kevin Nathaniel and his group and we called ourselves the Kinetic Painting Group.

(Opposite above) Video recording of performance by Samia Halaby and Kevin Nathaniel at Abu Dhabi Art, November 22, 2023.

(Opposite right) Photograph of Samia Halaby and Kevin Nathaniel on first visiting the great instillation of the artworks Yafa and City at Manar Public Art Project in Abu Dhabi.

(Left top) Brass Women 2, 1994, digital image made using the Kinetic Painting program, 640 x 480.

(Left) City 2, 2006, digital image made using the Kinetic Painting program, 640 x 480.

(Below) Branching 15, 2009, digital image made using the Kinetic Painting program, 640 x 480.

78

A live collaboration of jamming image and sound between me and Kevin Nathaniel. While I played my Kinetic Painting Program, Kevin used a variety of percussion instruments. e process of our work has always been to practise ideas but never to nail them down. en we always perform impromptu, a kind of traditional jamming as in jazz, or traditional irtijal as in Arabic performance.

Photographs dating from November 21, 2023, on the beach at night in Abu Dhabi enjoying the amazing billboard sized installation on a 16 x 24 foot LED screen installed as part of the Manar Abu Dhabi Public Art Project accompanying Abu Dhabi art. e screen is composed of ninety-six smaller LED screens each measuring 2 x 2 feet, so organised as to create a perfect 6:4 ratio of the original artwork produced on a PC dating from the early 1990. On first finding the installation having just arrived in Abu Dhabi, Kevin and I began to dance and invited the attending staff to join us and they did.

80

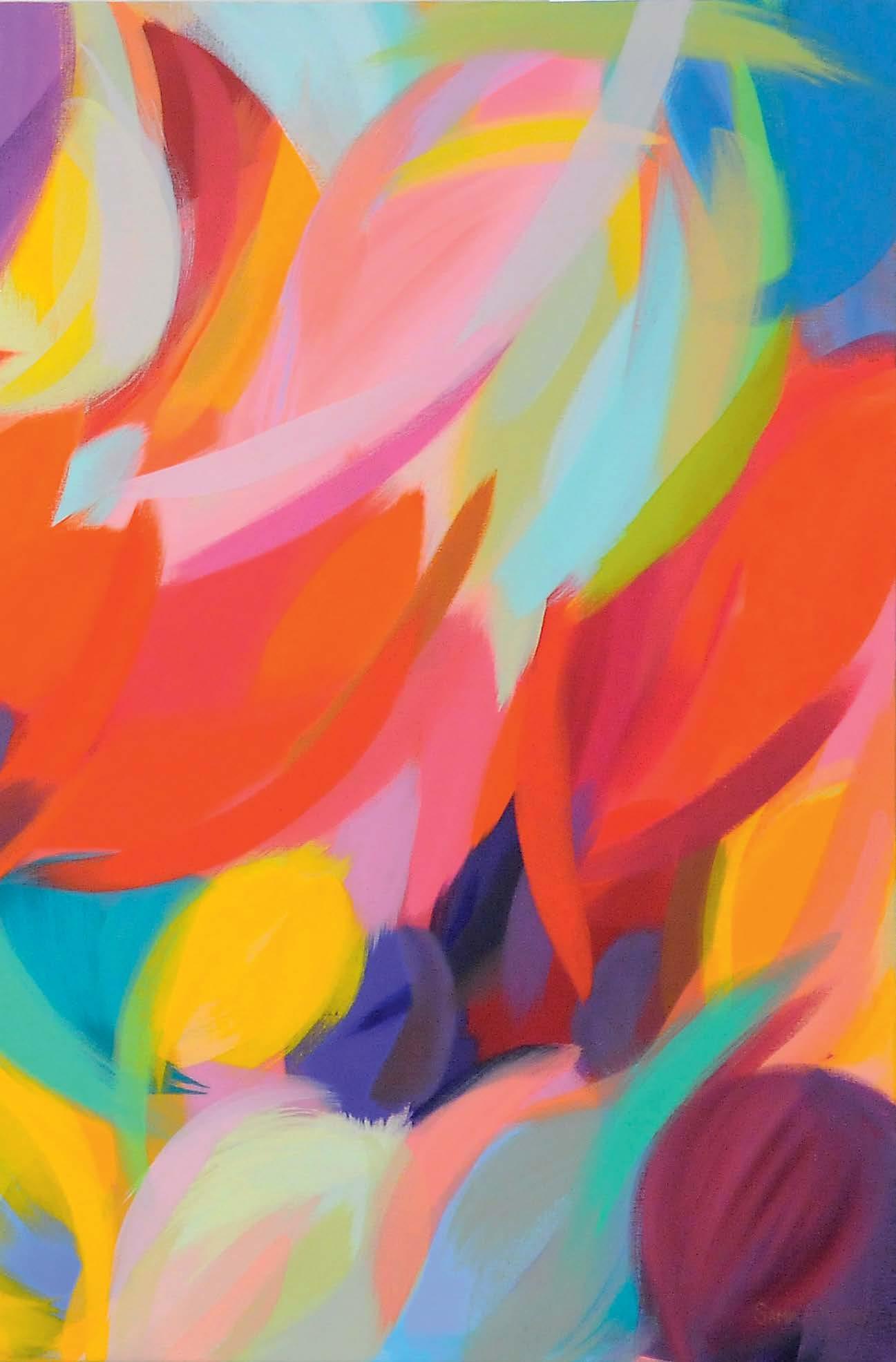

PAINTERLY ABSTRACTION

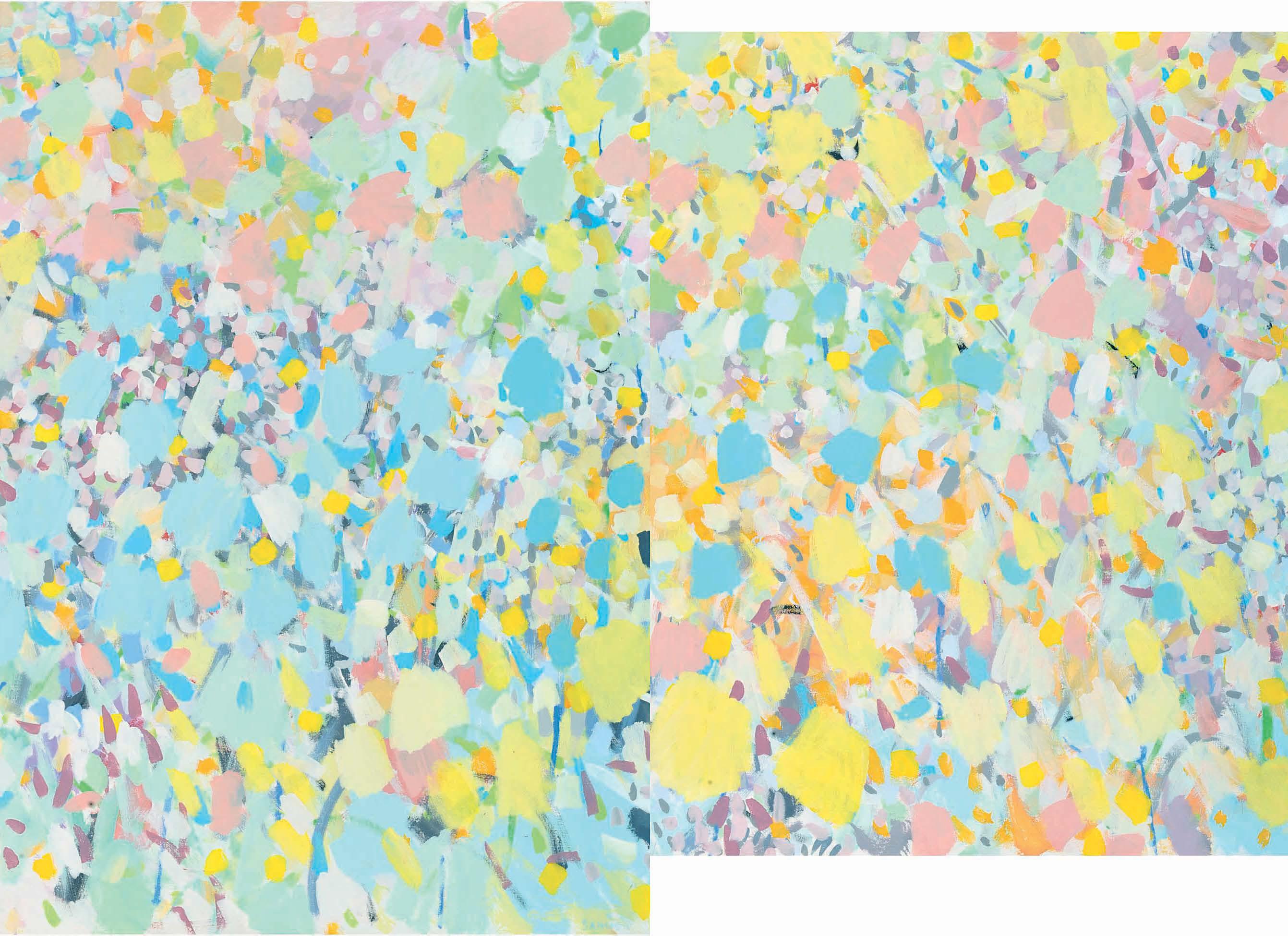

My aesthetic path kept expanding with growing understanding of how time in both 20th century abstraction and mediaeval Arabic art had combined to teach me how to extract ideas from nature that become processes to make a painting grow as nature does. e richness of the world world we see had led me to begin examining something else about seeing and that was the strategies we use to examine our surroundings as we move. How the focussing of our eyes jumps from one location to another found its way into my paintings as I began to lay down brush marks distributed according to a sequence we might use in looking as we move. Several sets distinguished by their colours became something the viewer could unpack as as she or he looked at a painting of what on the surface seemed a multiple of coloured spots. Morning Rain, 1997, was the first mature piece in the Painterly Abstraction series.

e difficulty in making these paintings work was the immediate association one made with a landscape that painterly colours implied. Any dark clump became a bush or a tree. Any horizontal sequence became a horizon line. is meant that as soon as three-dimensional illusions appeared, the relativity of space was cancelled and with it abstraction. My reaction was always dismay. I recognised the failures immediately and strove hard to overcome them. Now, after the struggle I went through with painterly abstraction, I know completely the fact that seeing is an educated process.

Morning Rain, 1997, a.c., 52 x 118 in (132 x 278.5 cm).

Morning Rain, 1997, a.c., 52 x 118 in (132 x 278.5 cm).

FREE FROM THE FRAME AND BACK

82

All along the way since the very beginning, I questioned the meaning of the picture plane in painting. at being the surface and perimeter of the painting and how they affect the visual material they hold. ey form the boundary between the content of the painting and the world outside it. I loved studying the many ways that historical periods have used these boundaries and I love exploring and pushing the boundaries myself. us came the period of liberating my painting completely from the rectangle and removing the wooden stretcher completely.

I began to paint on pieces of canvas, cutting them into shapes and stitching them together. In my mind was how beautiful each leaf of a tree was and how the whole tree was made up of thousands of leaves. I thought to make art not only free of the stretcher but also one that combined multiple beautiful things to form one large work. Palestine from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, 2003, is the unquestioned queen of this period in my work. I imagine it to be a representation of the geography of Palestine beginning on the right we see the Mediterranean plains and the plethora of their vegetation, then moving to the middle to the mountains of Jerusalem and Birzeit arriving at night to see the olive, fig, almond, trees as well as the mountains with their striations of rocks and the stepped mountain sides carefully cultivated by our solid Palestinian villagers. en as we move further leftwards, we enter the desert on our way to the Dead Sea. It is a trip that I have taken often.

Palestine from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, 2003, acrylic on paper and canvas soft bas-relief, 9 x 15 feet, 275 x 457 cm).

FUSION: TIME SPACE MOTION

84

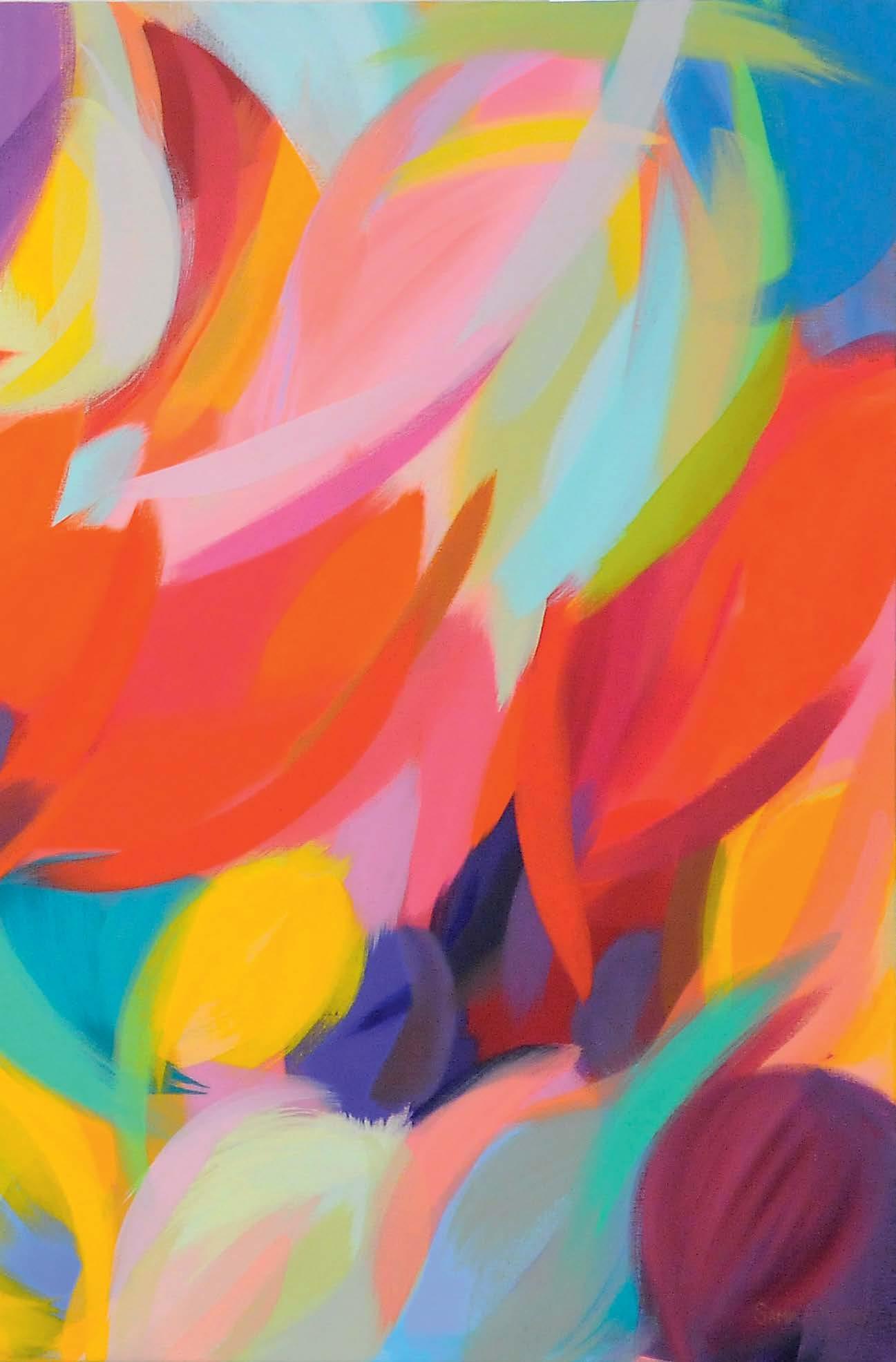

Damascus, 2010, a.c., 36 x 75 in (91.5 x 190 cm).

e most mature period of my many decades of thinking was given a strong push from the support of Khaled Samawi and Ayyam Gallery that accepted me into their fold in 2008. As my work began to sell for the first time in my life, I began to make more work on canvas than on paper. I have always been productive and had focused on paper because it was easier to store. ere was a time when I challenged myself to only allow paintings to exist if I were willing to give up a window to keep them. As more of my thoughts found realisation in larger, more serious works on canvas, my aesthetic cogitation sped forward and I began to think about the world the way I paint. Space,time and movement became inseparable, that is they became one attribute. reatening any one of them destroyed the whole world of reality.

Damascus, 2010, was a homage to the great city and the beauty and colour that I found there. I made many photographs of the markets and the city and often combined pairs of them into one photomontage. is painting does not represent any one thing in Damascus, it is more reminiscent of how flowers grow and how seeds mature. But as abstraction deals with the general, one might say that Damascus became for me a gateway to amazing beauty in its neighbourhoods and markets and helped release and bring to flower many of my ideas and observations of nature.

8603

Seventh Leaf Study, Autumn Leaf series, gouache on paper, 7 x 6 in on 13 ½ x 10 ½ in.