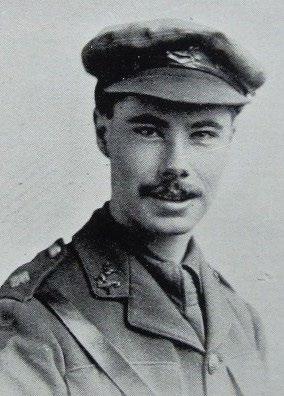

Charles Heron McDiarmid

Charles Heron McDiarmid was born on 18 September 1879 in the parish of Colvend in the stewartry of Kircudbright, eighteen miles east of Dumfries. He was the third of five children of John McDiarmid and his wife Mary Anne Jemima (nêe Hosack). John McDiarmid was originally from Dumfries but moved to Liverpool in about 1850 where he became a partner in the firm of J Aiken, Son & Co, ship brokers. In 1854 he married Margaret Affleck Robson, a surgeon’s daughter from Dumfries, but Margaret died childless in 1857 at the age of just 26. In 1861 John dissolved his partnership with J Aiken, Son & Co1 and entered into a new partnership with Thomas E Greenshields to form McDiarmid, Greenshields & Co, ship owners and brokers, with premises at 5 Seaton Buildings, 17 Water Street in Liverpool. In 1863 he married Janet Catherine Wahab, daughter of General Charles Wahab, Madras Army, and bought a large house at 5 Devonshire Road overlooking Princes Park in Liverpool. The couple had one surviving child, a boy called John (known as Ian) who was born in 1867. The 1871 Census shows the family living at 5 Devonshire Road with four servants.

Janet died in 1873 at the age of just 34. Two years later John married Mary Anne Jemima Hosack (known as Minnie), who, at 24 years of age, was 30 years his junior. Minnie was the daughter of James Hosack who, like John, was a wealthy Liverpool merchant originally from Kirkcudbrightshire. The couple’s first child, Evangeline Anna Catherine, was born in 1876, followed by Dora Hosack (1878) and Charles Heron (1879). The 1881 Census shows the family (less Ian who was at school in Scotland) living at 5 Devonshire Road. Minnie had two more children – Kenneth (born in 1881) and James Innes Aikin (1883) – and the 1891 Census shows the family still living at 5 Devonshire Road with no fewer than five servants. Eleven-year-old Charles was absent, having recently been enrolled at Mr A J Cripps’s Preparatory School in Bromborough.

In September 1894 Charles McDiarmid entered Sedbergh School in the Yorkshire Dales and became a member of Sedgwick House under Housemaster Bernard Wilson. He was followed by Kenneth in 1896 and James in 1897. Charles represented the school at cricket in 1897 and 1898 and was made a prefect.

In January 1898 Thomas Greenshields, John McDiarmid’s partner of 37 years, retired. James Milroy, who had joined the company in 1880, was taken into partnership2, and the business continued under the title of McDiarmid & Co3. By this time the company owned at least five ships.

The barque Criffel, built by Ritson & Co, Maryport, for McDiarmid, Greenshields & Co in

Charles left Sedbergh School in July 1898. In September 1899 John McDiarmid died at the age of 78 at his Scottish home at Auchenvhin in Dalbeattie, Kirkcudbrightshire4 John’s eldest son, Ian, who had been made a partner in his father’s business, had left the company in 18925 and died in 1897 at the age of just 30 As the oldest surviving son, and despite being barely 20 years old, Charles now joined James Milroy as a partner in the company.

Kenneth left Sedbergh School in 1900, and in the 1901 Census he is shown as a ship owner’s apprentice, visiting a retired naval officer and his family in Great Crosby. He later enrolled at the Royal Agricultural College in Cirencester and subsequently held an appointment in Burma with the Bombay Burma Trading Corporation6 James left school in 1901 and joined the army. He entered the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst as a Gentleman Cadet and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) in 19027

Charles appears to be missing from the 1901 Census, but the 1911 Census shows him as a 31year-old single man, boarding with the Linekar family at 14 Drummond Road in Hoylake. His occupation is given as steamship agent. By 1914 he had moved to 1 Valentia Road in Hoylake.

On the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914, James McDiarmid was a regular soldier serving as a Lieutenant with No 80 Company RGA in Singapore8 Kenneth, at home in Scotland whilst on leave from Burma, immediately applied for a commission in his local regiment, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB). On 4 September he was gazetted as a Second Lieutenant in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion9 and joined his unit at Portland in Dorset to begin officer training

Having lived and worked in Liverpool for most of his life, Charles decided to volunteer for the newlyformed King’s Liverpool City Battalion which would soon become better known as the Liverpool Pals. When recruiting began on 31 August, Charles enlisted as 15089 Private McDiarmid10 On his attestation form he is shown as 34 years and 330 days old, 5 feet 10½ inches tall with a 40-inch chest and 166 pounds in weight. He had a fair complexion, fair hair and light blue eyes. His occupation is given as shipping agent

Pals Battalions

On the outbreak of war Lord Kitchener was appointed Secretary of State for War. Kitchener believed that overwhelming manpower was the key to winning the war and he set about looking for ways to encourage men of all classes to join the army. General Sir Henry Rawlinson suggested that men would be more inclined to enlist in the army if they knew that they were going to serve alongside their friends and work colleagues. Rawlinson asked his friend, Robert White, to raise a battalion composed of men who worked in the City. White opened a recruiting office in Throgmorton Street and in the first two hours, 210 City workers joined the army. Within a week the Stockbrokers' Battalion, as it became known, had 1,600 men.

A few days later, Lord Derby decided to organise the formation of a battalion of men from Liverpool. Within two days 1,500 Liverpudlians had joined the new battalion. Speaking to these men Lord Derby said: “This should be a battalion of pals, a battalion in which friends from the same office will fight shoulder to shoulder for the honour of Britain and the credit of Liverpool.” Within the next few days three more battalions were raised in Liverpool.

When Kitchener heard about Derby's success in Liverpool he decided to encourage towns and villages all over Britain to organise recruitment campaigns based on the promise that the men could serve with friends, neighbours and workmates. These units were raised by local authorities, industrialists or committees of private citizens. By the end of September over twenty towns in Britain had formed Pals battalions. The larger towns and cities were able to form more than one battalion: Manchester and Tyneside had eight, Liverpool, Hull and Salford four, Birmingham and Glasgow three and several more were able to raise at least two battalions.

Pals battalions made up a significant proportion of Kitchener's army. From September 1914 to June 1916, 643 battalions were raised locally, compared with 351 raised through traditional recruitment methods. Many of these battalions suffered heavy casualties during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. The policy of drawing recruits from amongst a local population ensured that, when the Pals battalions suffered casualties, individual towns, villages, neighbourhoods and communities back in Britain were to suffer disproportionate losses. With the introduction of conscription in January 1916, further Pals battalions were not formed. Most Pals battalions had been decimated by the end of 1917 and were amalgamated into other battalions to regularise battalion strength.

The Liverpool Pals

Lord Derby’s idea was first put forward in the Liverpool press on 27 August 1914, suggesting that businessmen who might wish to join a battalion of pals, to serve their country together, might care to assemble at the headquarters of the 5th Battalion King’s Liverpool Regiment (KLR) at St Anne Street at 19.30 the following evening. Long before the appointed hour, St Anne Street was crowded with young men trying to get into the drill hall. It was obvious to Lord Derby even then that there were more than enough men present to form one battalion, and he sent a telegram to Lord Kitchener offering to raise a second battalion. All would-be recruits were invited to assemble at St George’s Hall on Lime Street the following Monday morning, 31 August, for attestation. By 10.00 a full battalion of 1,050 recruits had been accepted, and as they had all to be medically examined and processed into the army, it was decided that no more volunteers would be taken that day. All those waiting outside were told to return on Wednesday 2 September when the process would begin again.

Within a week, Lord Derby had over 3,000 recruits, enough in fact to raise three battalions of Pals. At this stage he decided to call a halt to the recruiting campaign, for the time being at least, and try to turn the 3,000 men he did have into some kind of military unit. In mid-October Lord Kitchener gave Derby permission to raise a fourth Pals battalion, to bring the men so far recruited up to Brigade strength. On 19 October Derby once again turned to the city’s press to call for recruits for his fourth battalion, and by 11 November this battalion was also full, the excess recruits being formed into two reserve Pals battalions.

The four main Pals battalions were officially titled the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Service Battalions of the KLR, although they were also designated the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th City Battalions As an ex-public schoolboy and businessman, Charles was considered to be officer material, and on 2 September 1914 he was commissioned as a Temporary Captain in the 18th (Service) Battalion KLR (2nd City)11 and assigned to No 4 Company.

With the problems of training and equipping over 3,000 men becoming apparent, the pressing need for uniforms exposed another issue, that of the cap badge the Pals would wear. The Pals were Service Battalions of the KLR, whose members had worn the insignia of the White Horse of Hanover since 1716. However, the unique quality of the Pals was that they had been raised in person by Lord Derby, and his crest – an eagle perched on a cradle containing a baby – was well known in Liverpool. Thus the idea began to take root that the Liverpool Pals should wear the Eagle and Child of the Derby family. The proposal was submitted to the War Office for approval, and on 14 October 1914 word was received from Buckingham Palace that this approval had been granted. Lord Derby presented each of the original recruits with a solid silver version of the badge as a memento. Some time later the other ranks in all four battalions were also issued with distinctive shoulder titles denoting the battalion to which they belonged.

Lord Derby decided to build a permanent camp for the Liverpool Pals in the grounds of his own home at Knowsley Park, but in the meantime accommodation would have to be found in the local area. The 17th Battalion were billeted in an old watch factory at Prescot, while the 18th Battalion were accommodated in tents at Hooton Park Racecourse on the Wirral. The men of the 19th Battalion, with no permanent home, lived in their own homes and drilled each day at Sefton Park. With no equipment available except for a handful of obsolete Lee-Metford rifles, the Pals’ initial training was limited to PT, drill and marching.

In early November the 19th Battalion moved into their new accommodation at Knowsley Park. Shortly afterwards the 20th Battalion was raised, and the men were quartered at the Tournament Hall in Knotty Ash and trained each day at Knowsley Park. On 3 December the 18th Battalion moved to

Knowsley Park, followed by the 20th Battalion on 29 January 1915. The 17th Battalion never actually moved into the new camp, as Prescot was only a couple of miles away from Knowsley Park and near enough for the men to march to each day. Thus by the end of January 1915 all four battalions were able to train together as a brigade.

While Charles was training with the Liverpool Pals, his two brothers were on their way to the Western Front. On 23 March 1915 Lieutenant Kenneth McDiarmid joined the 2nd KOSB, part of the 5th Division which was holding the line in the infamous Ypres Salient12. Ten days later, on 2 April, Captain James McDiarmid joined the 1st Brigade RGA as Adjutant13. His new unit was in the Vieille Chappelle sector, some twenty miles south of Ypres.

Three miles south-east of Ypres was a man-made spoil heap known as Hill 60. Although only 60 feet above sea level, in the otherwise flat landscape of Flanders it gave artillery observers an excellent view of the ground around Zillebeke and Ypres. It was therefore of great tactical significance and changed hand several times during the course of the war. The Germans first captured Hill 60 in December 1914. The British responded by digging four tunnels into the hill underneath known German positions. The end of each tunnel was packed with high explosives. By mid-April 1915 they were ready to attack.

The task was given to the 13th Brigade of the 5th Division. On the night of 16/17 April the 1st Royal West Kent Regiment and 2nd KOSB took over the trenches facing Hill 60. At 19.05 on 17 April the first two mines were blown, followed by the rest ten seconds later. Debris was flung 300 feet into the air and scattered for 300 yards in all directions. At 19.06 the Royal West Kents, with two companies of the KOSB in close support, went over the top. Most of the German garrison had been killed by the mines, and any survivors who were capable of resistance were bayoneted. Hill 60 was taken at a cost of only seven British casualties. The British began to consolidate, and by 01.30 a new fire trench had been dug on the hill as well as two communication trenches to connect it to the old front line At 03.30 the KOSB relieved the Royal West Kents in the new trench

The Germans were characteristically quick to recover, and at 04.00 on 18 April they launched a counter-attack. Under a tremendous artillery bombardment and constant attacks by hand grenades, the KOSB were forced back below the crest of the hill, where fierce hand-to-hand fighting went on all night. The KOSB held on grimly to their position until they were relieved by the 2nd Duke of Wellington’s Regiment at 11.30. Later that day the hill was retaken by the Dukes and 2nd KOYLI.

Casualties were heavy. The KOSB lost 3 officers and 38 men killed, 7 officers and 128 men wounded and 35 men missing. One of the dead officers was Lieutenant Kenneth McDiarmid. In a letter to Minnie, his Commanding Officer wrote14:

“He not only showed a splendid example of leadership, but of great heroism. Though wounded he refused to go away from the firing line, and, finally, when his platoon was very much reduced in numbers and the Germans were in consequence pressing on to the parapet, he leapt on to the parapet himself and met his end most valiantly fighting at close quarters. He was an officer whose brave deeds will never be forgotten in the regiment and whose charming personality made a great impression on me for the three short weeks I knew him.”

Had he lived, Kenneth’s gallantry might well have been rewarded with a Military Cross, but at the time only the Victoria Cross could be awarded posthumously. However, he was mentioned in despatches15 which must have afforded some consolation to his family.

Meanwhile, back in England, on 30 April the Liverpool Pals moved to Belton Park in Grantham to continue their training. Shortly after their arrival, the four Liverpool Pals battalions became the 89th Brigade, and, together with the Manchester and Oldham Pals of the 90th and 91st Brigades, formed the 30th Division. Manoeuvres at Harlaxton Park and trench digging at Willoughby Park began to familiarize the men with their anticipated roles in France. Route marches were extended to 28 miles in full kit and packs as the process of physical hardening was progressively increased. In early June each battalion received a batch of 80 Lee-Enfield rifles, and platoons took it in turns to practice live firing and bayonet techniques.

On 7 September the 30th Division moved to Larkhill on Salisbury Plain. The battalions received their full complement of Lee-Enfield rifles together with four machine guns, enabling the men to complete their final musketry course. Training continued for a further eight weeks and now included brigade and divisional exercises. In early November embarkation orders arrived and the Division was mobilised for service in France.

The Liverpool Pals sailed to Boulogne on 7 November 1915 After a night at a rest camp, they entrained for Pont Remy on the Somme and marched to billets in the surrounding villages The Pals remained in the area for nine days, by which time they had begun battle training in earnest. On 17 November they marched by stages to the Vignacourt area, north of Amiens, where they spent four weeks training in the latest weapons and methods of trench warfare, including bombing practice and respirator drills.

On 16 December the 89th Brigade began to move forward to what was the northern end of the Somme sector. Each battalion was assigned to a different part of the line where they were attached by companies to an experienced battalion for a week’s training in the trenches. The 18th Battalion went into the line at Hébuterne on 18 December, their companies being attached to battalions of five different infantry regiments. No 2 Company was attached to a battalion of the Ox & Bucks Light Infantry, and on the night of 20 December men from both battalions went out on a combined patrol

into No Man’s Land. They encountered a German patrol, and in the ensuing fire-fight 24620 Lance Corporal Reginald Rezin was killed, the first of the Liverpool Pals to be killed in action.

At about this time the BEF decided to intermix brigades from the newly-arrived New Army divisions with brigades from the regular divisions, and at the same time to exchange New Army battalions for regular battalions within each brigade. The idea was to “stiffen” the inexperienced Divisions by mixing in some regular army troops, although by now many of the pre-war regulars had gone and the regular battalions themselves were often largely composed of new recruits. Thus on 20 December the 91st Brigade was transferred from the 30th Division to the 7th Division, to be replaced by the 21st Brigade, and on Christmas Day the 18th KLR were transferred from the 89th Brigade to the 21st Brigade. The composition of the 30th Division at the end of 1915 was thus as follows:

21st Brigade

2nd Yorkshire Regiment

2nd Wiltshire Regiment

19th Manchester Regiment (4th City)

18th Liverpool Regiment (2nd City)

89th Brigade

17th Liverpool Regiment (1st City)

19th Liverpool Regiment (3rd City)

20th Liverpool Regiment (4th City)

2nd Bedfordshire Regiment

90th Brigade

16th Manchester Regiment (1st City)

17th Manchester Regiment (2nd City)

18th Manchester Regiment (3rd City)

2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers

In January 1916 the 30th Division moved south to Maricourt on the extreme right of the British held sector of the Western Front. The 21st Brigade was allotted a sector near Carnoy, and for the next two months the 18th KLR were in trench routine – a period in the front line, then in support, then in reserve, and a few days rest in billets – suffering regular casualties through shelling and sniping16 At 01.00 on 29 January the German artillery opened up a fierce bombardment on their front line trenches where No 3 Company held the line. At 02.00 this company came under attack by trench mortars and rifle grenades, and half an hour later their left flank was attacked by about 100 German infantry. The Pals responded with rifle fire and grenades, and after a fight lasting fifteen minutes the enemy withdrew. The Battalion lost 2 killed and 8 wounded, but at least the Pals had been “blooded”, and Captain Arthur Adam and 16709 Lance Corporal Alexander Cohen were decorated with the MC and DCM respectively for their part in the action, the Battalion’s first gallantry awards.

In March and April the battalions of the 30th Division worked on fatigues behind the lines, followed by brief periods of training and more fatigues. Since mid-February the Somme had been selected as the location for a major offensive, and with virtually no labour battalions available to Fourth Army, the material preparation for the offensive fell to the infantry. Thus the men were engaged in tasks such as laying railway tracks, widening and strengthening roads and burying cables.

In the first week of May the 21st Brigade returned to the front line around Maricourt, and for the next six weeks the 18th KLR alternated between duty in the trenches and rest in billets, losing a further 6 men killed and 23 wounded. The Battalion was relieved from the front line on 11 June, and the following day they moved to Fourdrinoy where the men were given intensive training in preparation for the offensive. Nearby to Fourdrinoy, at Briquemesnil, the whole of the Montauban area had been reproduced in great detail. A complete system of trenches had been constructed representing all the objectives to be attacked by each brigade. After eight days of continuous rehearsal here, the Battalion moved into billets at Etinehem. On 26 June they moved up to Bray where they began their final preparations for the assault. Finally, at 18.30 on the evening of 30 June, the 18th KLR marched to the assembly trenches and took up their positions for the “Big Push” – the Battle of the Somme.

The Battle

In January 1916 the commanders-in-chief of the French and British armies, Joffre and Haig, had reached agreement to mount a joint offensive on the Western Front in the coming summer. Although Haig had argued for an offensive in Flanders, the decision was taken to attack along a wide front at the point where the two armies met close to the Somme river. The choice could hardly have been worse; the chalk-based nature of the ground here had allowed the Germans to construct deep underground shelters, largely untouchable by artillery. North of the Somme river, the German lines ran along the higher ground, protected by dense concentrations of barbed wire and linked by heavily fortified villages and redoubts. The offensive would be led by the French and was scheduled for mid-August 1916.

On 21 February 1916, however, everything changed. The Germans launched a massive offensive further south against Verdun, and the French were forced to divert huge numbers of troops in the town’s defence. The fighting at Verdun ran from February to December and radically changed the priorities of the Somme offensive. From being in a supporting role, the British would now have to take the lead, although French forces would still be heavily involved. Furthermore, to relieve the pressure on Verdun, the British would have to attack six weeks earlier than originally planned. The new date for the start of the Somme offensive was 29 June 1916.

In essence, the plan involved a massive artillery bombardment of the German lines, followed by attacks from the British Fourth Army and the French Sixth Army across a broad front. The British Third Army would contribute a limited diversionary attack at the northern end of the main attack front. The major objective for the British was the town of Bapaume, while the French aimed for Peronne. If a breakthrough could be achieved, the Allied forces could then attack north into the German flank, and cavalry could surge through to exploit the gap.

On 24 June the British artillery opened a bombardment that was to continue until the morning of the attack. The bombardment was intended to destroy the German defences completely, but the shells failed to penetrate through to the underground shelters and left much of the barbed wire intact. Indications that things were not going quite to plan came around 28 June. Patrols sent out at night to examine the German defences found that the results of the bombardment were not as effective as expected. Because of this, and because of recent heavy rain, the barrage was extended for another two days, pushing back the attack date to 1 July.

Dawn broke over the Somme on 1 July 1916 with a final intensification of the week-old artillery bombardment, the British guns firing for an hour at a combined rate of 3,500 rounds per minute. In addition, between 07.20 and 07.30, ten explosive-filled mine works, dug beneath the German trenches, were detonated. The largest of the mines contained more than 60,000 lbs of ammonal explosive, and they literally lifted large sections of the German trenches into the air. Two minutes after the last mine detonated, the whistles blew and thousands of British and French infantry surged from their trenches into the attack.

The Somme attack plan broke down as follows. General Allenby’s Third Army was to make a diversionary attack in the far north of the battlefield around Gommecourt. Its purpose was to draw fire away from the main attack further south, made by General Rawlinson’s Fourth Army from just east of Serre to Maricourt. Waiting to exploit any British breakthrough was Lieutenant General Gough’s Reserve Army. The French Sixth and Tenth Armies, meanwhile, were to attack in the south below Maricourt.

Tens of thousands of Allied soldiers now climbed out of their trenches into No Man’s Land, in good visibility with no element of surprise – the blowing of the mines and the cessation of the bombardment told the Germans they were coming. German machine-gunners, who had emerged from their dugouts and quickly set up their weapons, and the largely untouched German artillery now delivered slaughter on an industrial scale. Entire battalions were almost wiped out within minutes. Those who managed to cross No Man’s Land often found themselves stuck against uncut barbed-wire, where they were picked off by accurate rifle fire.

In a devastating day of killing, the British sustained 57,470 casualties, of which 19,240 were fatalities. Nor was the loss for any great gain. British attacks in the north made no progress at all, while the furthest British penetrations made by Fourth Army were about a mile in depth at their greatest extent further south, taking the villages of Montauban and Mametz. In the far south, by contrast, the French armies actually exceeded most of their Day One objectives, being better supported by artillery and their infantry using more effective tactics of surprise and manoeuvre.

By the time night fell on 1 July 1916, the Somme battlefield was choked with British dead and wounded, the worst one-day loss in British history.

The Capture of Montauban, 1 July 1916

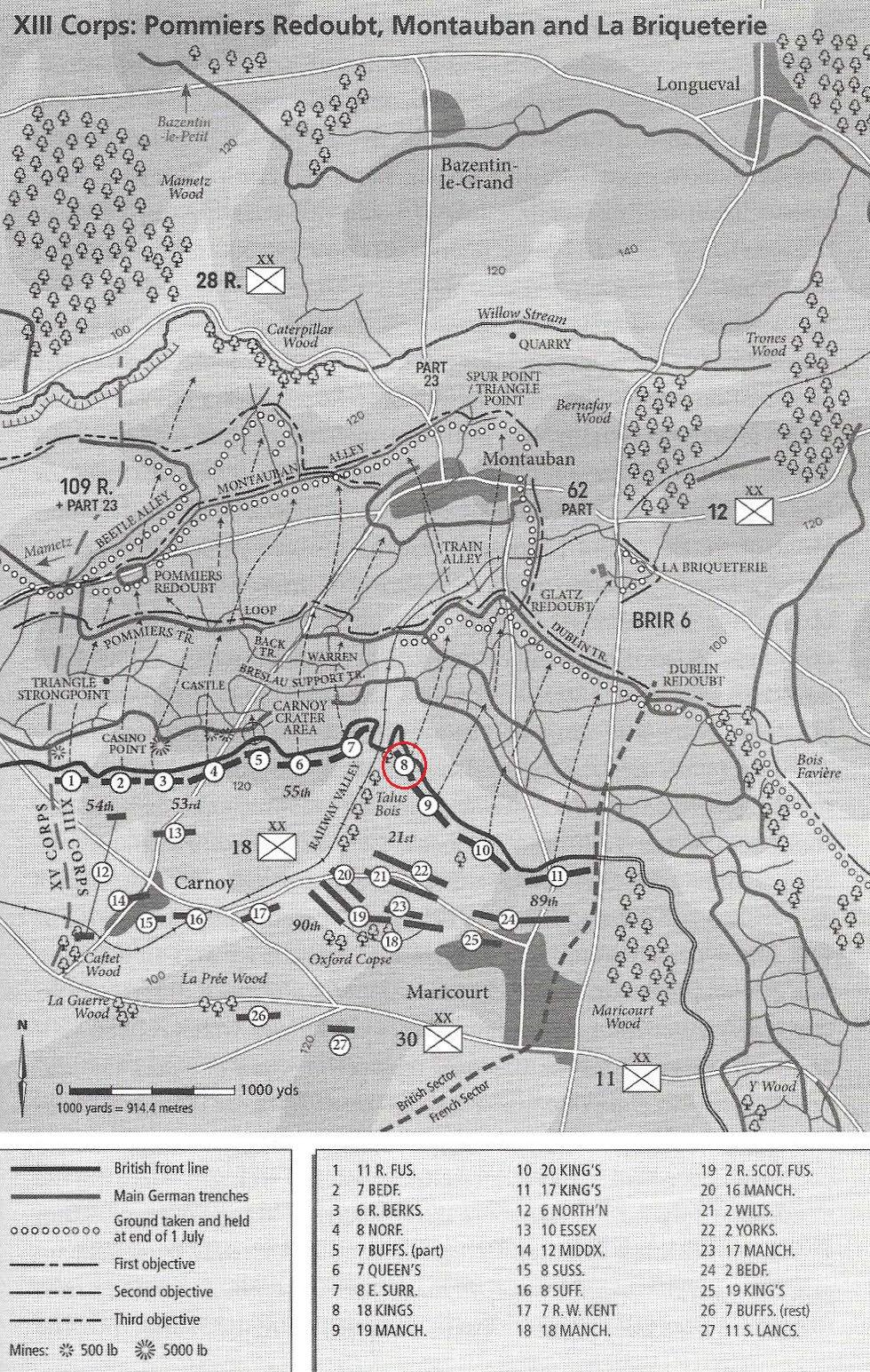

On 1 July 1916 the objective for the 18th and 30th Divisions of General Congreve’s XIII Corps was the village of Montauban. The 18th Division was to attack to the left, the 30th Division to the right, with the 9th Division in reserve. The 30th Division was tasked with securing their first objective between the Maricourt Ridge and Montauban by 08:28, and the plan was to achieve this with the 21st and 89th Brigades. Once the initial objectives were secured, the 90th Brigade would pass through and seize Montauban.

The attack had the benefit of excellent field observation, together with reconnaissance from the air by the RFC. The artillery bombardment had succeeded in destroying most of the German artillery and had also blown up the German artillery command post with a heavy shell. The wire had been well cut, and the French heavy artillery had destroyed many of the German’s deep dugouts – which

were not as good in this sector – by using high explosive, not shrapnel, shells. In addition, six Russian saps had been built into No Man's Land to cover the men's attack. All in all, the attack on Montauban was a good example of co-operation between the different arms of the Army.

The objective for the 21st Brigade was the German trenches on a front stretching about 1,000 yards to the left of the junction of Glatz Redoubt with Dublin Trench. The 18th KLR and 19th Manchesters, on the left and right respectively, were in the first wave of the assault, with the 2nd Green Howards in support and the 2nd Wiltshires in reserve. The 18th KLR were to attack from the assembly trenches to the east of Talus Boise, a jutting finger of woodland which pointed towards the German trenches below the south-eastern corner of Montauban. Their objectives were the German trenches and fortifications of Glatz Redoubt to a point where a railway track cut the road running from the southwest corner of the village. Glatz Redoubt, like all the fortified German positions, was a warren of trenches, saps and hedgerows which could hide machine gunners, riflemen and snipers. At this point in the line, No Man’s Land was about 300 yards wide.

The 18th KLR would attack in four waves. The first wave consisted of half of No 1 Company (Captain Charles Brockbank) and half of No 2 Company (Major Robert Cornish-Bowden). Likewise, the second wave mirrored the first, with the addition of a platoon of “moppers-up” from the 2nd Green Howards. No 4 Company (Captain Charles McDiarmid) formed the third wave and No 3 Company (Captain Arthur Adam MC) the fourth wave.

The British artillery had been pounding the German trenches for a week, but at 06.25 on 1 July a final intense bombardment started. At 07.22 the Stokes mortars of the 21st Brigade Trench Mortar Battery opened a hurricane bombardment on the German front line, known as Silesia Trench, from two Russian saps that had been dug into No Man’s Land. At 07.29, under cover of the barrage, the first wave climbed over the parapet and formed up in No Man’s Land At 07.30 the bombardment lifted off the German front line, the whistles blew and the first wave advanced towards the enemy lines, followed at 100-yard intervals by the second, third and fourth waves.

Because of the shellfire, the barbed wire in front of Silesia Trench had been obliterated, and the first wave had little difficulty in reaching what was left of the German front line before most of the defenders had got to the surface. Second Lieutenant Eric Fitzbrown was the first officer of the 18th KLR to reach Silesia Trench, and as he led his men forward over the enemy front line, the Germans were already retreating towards their support line and beyond. Fitzbrown emptied his revolver at them as they ran, and his men pressed on towards the support line. Here, the Pals came under machine gun fire from the high ground on the right until the gun was finally silenced. The support line was then systematically cleared by bombing parties, who killed or captured what remained of the defenders. Thirty prisoners were taken, but inevitably the Battalion had taken casualties as well.

By this time the Germans were beginning to recover from the effects of the shelling, especially in the rear and reserve line areas, and before the British artillery barrage moved forward onto the high ground just in front of Montauban, they began to bring machine guns out onto the trench parapets, which were well concealed by hedges. From here, they were able to pour a devastating fire onto the third and fourth waves of attacking Pals who were either still leaving the British front line or just crossing No Man’s Land. 17122 Private William Gregory was a member of XVI Platoon of Captain McDiarmid’s No 4 Company17:

“First of all you had to get up the fire step; the ladders were on the fire step, and our platoon commander, he’d just got half way up when he was shot through the head; he’d gone before we even got out of the trench! His name was [Second Lieutenant Gordon] Golds. I was one of four that eventually got to the German lines out of sixteen. It was machine gun fire that was hitting us, you could see the flash as it passed, and you knew that your friends had been hit. They were lying all over the place and some were screaming. It was awful, and I was only a kid of nineteen.”

Meanwhile, as the leading waves began to move forward towards the German reserve line, known as Alt Trench, and then on to Glatz Redoubt itself, they suddenly came under enfilading fire from the left. This was from a machine gun which the Germans had sited at a strongpoint in Alt Trench. The gun itself was protected by a party of snipers and bombers, who, hidden by a rough hedge, were dug into a position in Alt Trench at its junction with a communication trench known as Alt Alley. These bombers and snipers were themselves protected by rifle fire from another communication trench, Train Alley, which snaked back up the high ground and ran into Montauban itself. The machine gun fire was devastating, and it is likely that the majority of the Battalion’s casualties on the day were caused by this single gun. To make matters worse, the men, out in the open, could not move forward because the British barrage was still pounding the area around Glatz Redoubt.

Captain Adam now tried to lead his men forward to take the enemy position, but he was hit by sniper fire almost before he had left Silesia Support Trench. Nevertheless, he pressed on towards the hedge until he was hit again. More bombing parties then moved up, but they were also hit by sniper fire or stick grenades. Second Lieutenant George Herdman had his head blown apart by a grenade, whilst the tenacious Fitzbrown was shot through the head and also killed. Despite being seriously wounded, Adam now called up a party of bombers to reconnoitre the enemy’s position, but shortly afterwards he was hit and killed by a German grenade. The bombing party, led by Second Lieutenant Hugh Watkins, then pushed slowly forwards towards the hedge, and Watkins orders his best throwers to hurl Mills grenades at the German stronghold. Either by great skill or great luck, one of these grenades landed amongst the German bombers, killing two and scattering the rest. This allowed the bombing party to force their way up Alt Trench and Train Alley, shooting Germans in the hedges and bombing them in their dug outs. Once more, about thirty Germans were captured. With the machine gun crew killed or captured, the survivors of the Battalion were able to push forward towards the right flank and take the original objective, Glatz Redoubt, which fell at 08.35.

On the right of the 18th KLR, the 19th Manchesters had also fought their way into the Redoubt, and both battalions began the process of consolidating and re-entrenching their gains. The 89th Brigade had also achieved all their objectives At the same time, the 18th Division on the left and the French on the right had also successfully carried out the first phase of their attacks. The way to Montauban village, on the top of a slope 1,000 yards away, was open. It was time for the 90th Brigade to advance.

At 08.30 the 16th and 17th Manchesters, followed by the 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers, climbed out of their assembly trenches and moved forward. At first all went well. As the three battalions advanced in perfect order up the slope, a few German shells fell among them, but the ground had been so pulverised by the British bombardment that the explosions in the soft earth caused few casualties. But the attackers were now in an exposed position with both flanks wide open, for the French had decided to go no farther and the 18th Division was held up by strong opposition.

As the leading waves began arriving in Train Alley, a single German machine gun crew on the left of the 16th Manchesters opened fire. One of the Battalion’s Lewis gun teams engaged the post and silenced it, but not before it had caused heavy casualties to all three battalions. The machine gun fire had thrown the leading troops into confusion and the meticulous formation of the early advance was lost. Two separate crowds of men charged the village. The capture proved to be easy; the Germans holding a trench outside the village surrendered with hardly a fight. The village itself was in ruins; a French heavy mortar battery had been firing on it for a week. The only living thing to be seen in Montauban was a fox. With the village secured, the Manchesters pushed on to their final objective – a trench known as Montauban Alley – and this, too, was swiftly taken with more prisoners. The Germans counter-attacked the positions held by the 16th Manchesters almost as soon as they had occupied Montauban Alley, but they were repelled by Lewis gun and rifle fire, and within fifteen minutes all was quiet. By 11.00 all of the 30th Division’s final objectives had been taken

The survivors of the 18th KLR held the Glatz Redoubt until the evening of 2 July when they were relieved and moved back to their old assembly trenches on the eastern side of Talus Boise. On the following day, a roll call showed an effective strength of just 6 officers and 288 men.

The Cost

The 30th Division had achieved a great success. Together with the 18th Division, it had taken Montauban, the first village to fall in the Battle of the Somme. It had also suffered fewer casualties than the divisions to the north – a total of 3,001. Unfortunately, the Division’s success was largely wasted. Having taken Montauban, XIII Corps could have outflanked the German armies further north and achieved the breakthrough Haig had wanted. However, while Haig had planned for a

breakthrough, the commander of the Fourth Army, General Rawlinson, had preferred a “bite and hold” strategy. General Congreve, being a careful commander, followed Rawlinson and ordered his men to consolidate. The opportunity of 1 July was lost.

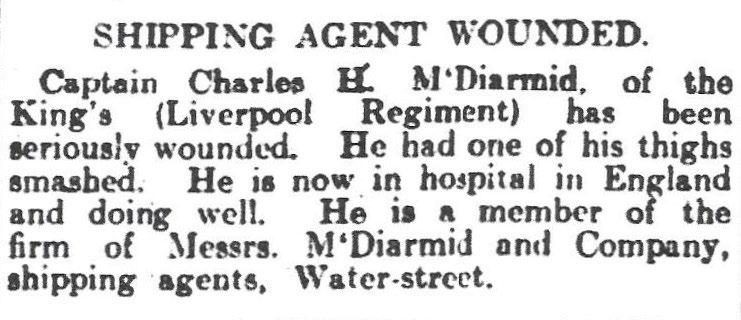

According to the 21st Brigade War Diary, the 18th KLR lost 7 officers and 162 men killed, 9 officers and 222 men wounded and 93 men missing on 1 July 1916 – a total of 493 casualties. Once all the missing men had been accounted for, the total number of fatalities was 7 officers and 164 men18 One of the wounded officers was Captain Charles McDiarmid. Charles was hit by a bullet which went through his right thigh and fractured his femur. His wound was serious, and had he been fighting in the northern sector of the Somme front, where the attack failed and the wounded were left stranded in No Man’s Land, he might well have died. However, the success of XIII Corps’s attack meant that the wounded could be recovered relatively quickly from the captured ground and moved swiftly along the casualty evacuation chain.

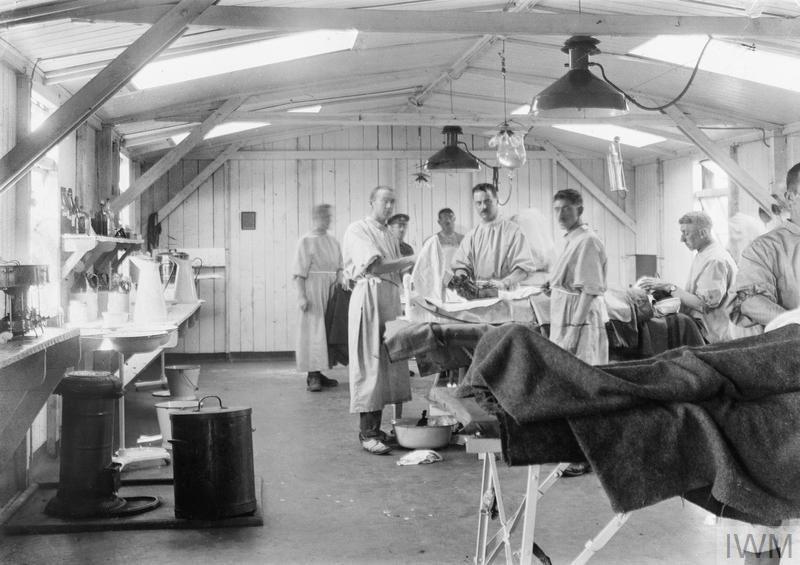

After being carried from the battlefield by stretcher bearers, Charles was taken by motor ambulance to the Main Dressing Station at Dive Copse, a large tented facility between Bray and Corbie, where he was assessed and triaged. His wound was cleaned and bandaged and splints were applied to his leg. He was also given an anti-tetanus serum and possibly morphine.19 He was then taken by motor ambulance to No 21 Casualty Clearing Station at Corbie where he was operated upon and a piece of metal removed from his thigh. From Corbie an ambulance train took him to the base hospital at Boulogne, and from there he was evacuated to England aboard a hospital ship.

In the Battalion War Diary, Charles McDiarmid was one of six officers mentioned as having “distinguished themselves for gallantry and devotion to duty” during the attack on 1 July 1916. Three of the six were subsequently decorated20, but alas there was no award for Charles.

Afterwards

Charles McDiarmid spent eighteen months in hospital, during which he underwent three operations. Two were sequestrectomies to remove fragments of dead bone that were the cause of infection, while the third was to insert new splints. He finally left hospital in January 1918, and on 19 February he relinquished his commission after being assessed as permanently unfit for further military service. Charles attended a Medical Board on 28 June 1918 which described his condition as follows:

“The right knee is completely ankylosed, and he had a discharging sinus at the back of the right thigh. Wears a splint. General health good. He is being admitted to Alderhey Military Hospital on Monday July 1st for further operative procedure by Sir Robert Jones. He has to walk with sticks and has difficulty getting about. He is not able to carry on any employment. His earning capacity is impaired by 80% for six months.”

A year later, on 21 July 1919, a second Medical Board concluded that his condition was much the same:

“GSW right thigh. Two scars, one of entrance and one of exit, which has not healed. Two operation wounds healed – probably a piece of dead bone which is keeping the wound of exit open. Shortening of leg 3 inches, due most probably to loss of bone from comminution. Stiffness due to long continued splinting. Unable to walk without the assistance of two sticks.”

On 8 March 1920 Charles presented himself for a medical assessment at a Pensions Board in Manchester. It concluded that there was little improvement in his condition since his last appearance before a Medical Board. He had a disability due to ankylosis of the knee and shortening of the leg. He also still had a discharging sinus. As regards ongoing treatment, he was able to change his dressings himself and was an outpatient at Alderhey Hospital as and when required. His injury was assessed as permanent and his degree of disability as 70%. A final Pensions Board assessment on 3 June 1920 came to the same conclusion. Charles was granted a wound pension of £50 per annum with effect from 1 July 191621.

After leaving hospital, Charles rented two rooms at 50 Stanley Road in Hoylake and returned to work as principal of McDiarmid & Co It appears that the company’s fleet of sailing ships had been sold before the First World War and it was now a shipping agency, acting on behalf of shipowners or charterers to manage all aspects of a vessel’s port call, including ship brokering, cargo handling, customs clearance, freight forwarding and documentation. The company also acted as secretary to various shipping conferences, including the Calcutta Steam Trade Conference and the Canadian Atlantic Freight Conference.

Charles was a keen golfer, and in 1920 he was made Captain of the Royal Liverpool Golf Club (RLGC) at Hoylake. Charles first joined the RLGC as a teenager in 1897 and became a Life Member under the purchasing scheme of 191122. Royal Liverpool was – and is – one of the most famous golf clubs in Britain. In Charles’s lifetime it hosted the Open Championship five times, and in the 96 years since it has done so a further eight times, most recently in 2023.

In the early spring of most years Charles sailed to Marseille and back, a trip that took two weeks, although whether this was for business or pleasure is not known. He arrived home from his last such trip on 9 March 1929, and three weeks later, on 29 March, he died suddenly at the age of just 49. His remains were taken to Scotland and buried five days later at Colvend, where he was born. In his will he left £35,391 to his mother Minnie and sister Evangeline (worth about £2.8 million in 2025).

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 4 April 1929

Postscript

The last surviving son of John McDiarmid was James. After serving in the front line with the 1st Brigade RGA for four months in 1915, James spent the rest of the war in various staff appointments as a Staff Captain and Brigade Major. He ended the war as a Major with the DSO23 and five mentions in despatches. After the war he continued to serve in the Royal Artillery, holding appointments at the Experimental Establishment at Shoeburyness and as OC Troops in Mauritius. He retired in 1930 and went to live in the family home at Auchenvhin in Dalbeattie, Kirkcudbrightshire

In the Second World War, Major James McDiarmid DSO (Retired) served on the staff of the Commander Orkney & Shetland Defences as Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General (DAQMG), responsible for all supply matters, from 28 September 1939 until the end of 194124

James never married and died at Auchenvhin in 196925. His sister Dora died in 1927 and Evangeline in 1962, both as spinsters. Thus ended the McDiarmid family line.

Notes

1 London Gazette, 2 July 1861.

2 Liverpool Echo, 9 March 1917.

3 London Gazette, 1 March 1898.

4 In his will he left £33,248 to Minnie (worth about £5.5 million in 2025). The other beneficiary was Morden Rigg, a cotton merchant who was married to Letitia Wahab, younger sister of John’s second wife Janet Wahab.

5 London Gazette, 6 January 1893.

6 De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour. The Bombay Burma Trading Corporation was formed in 1863 by the Wallace Brothers of Scotland. It was a leading producer of teak in Burma and Siam, as well as having interests in cotton, oil exploration and shipping.

7 London Gazette, 24 February 1903.

8 Monthly Army List, August 1914.

9 London Gazette, 3 September 1914.

10 The serial number block allocated to the first batch of recruits was 15000-16151. Charles was thus amongst the very first to volunteer for the new battalion.

11 London Gazette, 13 November 1914.

12 Battalion War Diary.

13 Brigade War Diary.

14 De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour.

15 London Gazette, 22 June 1915.

16 In the period 2 January to 3 March 1916, the Battalion lost 14 men killed and 48 wounded.

17 Quoted in Liverpool Pals

18 Soldiers Died in the Great War. More would die of their wounds in the coming days and weeks.

19 In the 24-hour period after Zero Hour, Dive Copse MDS processed a total of 106 officers and 1,150 other ranks, of which 97 officers and 727 other ranks were transferred to Casualty Clearing Stations.

20 Lieutenant Hugh Watkins received the MC (London Gazette, 25 August 1916), while Lieutenant Gerald Clayton and Second Lieutenant Ernest Stacey were mentioned in despatches (London Gazette, 4 January 1917).

21 Until 1920, officers’ pensions were administered by the War Office and the details recorded on their personal file. The minute sheets on Charles’s personal file show that his wound pension of £50 per annum was renewed on 1 July 1918, 1 July 1919 and 1 July 1920. After 1920, pensions were administered by the Ministry of Pensions (MOP) and Charles’s paperwork was transferred to MOP File OA 6286. Unfortunately, only the file index card survives which has no further details.

22 Life Membership was usually conferred upon a golf or administrative achievement. However, in 1911 100 members were offered the option of becoming a Life Member (and no longer paying fees) for a one-off payment of £100. The idea was to raise £10,000 for the purchase of the Links from Lord Sheffield who had previously owned it.

23 London Gazette, 1 January 1918.

24 Monthly Army List, January 1942.

25 His estate was valued at £205,734, worth about £3.6 million in 2025.

Acknowledgements, Sources & References

Ian Waters

Katy de la Rivière, Sedbergh School Archivist

Erin Shields – Royal Liverpool Golf Club Archivist

Imperial War Museum Photographic Archive

National Library of Scotland: Army Lists

Scotland’s People: National Records of Scotland: Statutory Births 861/31

Find a Grave: Memorial ID 256612211

Great War Forum

The Liverpool Pals Memorial Pages (liverpoolpals.com)

The National Archives:-

Captain Charles Heron McDiarmid’s Personal File (WO 339/66293)

War Diary of the 18th King’s Liverpool Regiment – Nov 1915-Jun 1918 (WO 95/2330/1)

War Diary of the 21st Brigade – Jan-Aug 1916 (WO 95/2327/1)

War Diary of the 2nd King’s Own Scottish Borderers – Aug 1914-Nov 1917 (WO 95/1552/2)

War Diary of the 1st Brigade Royal Garrison Artillery – Aug 1914-Oct 1916 (WO 95/208/2)

Ancestry:-

England & Wales and Scotland Censuses 1851-1921

England & Wales Birth, Marriage and Death Indices 1837-2007

England & Wales National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills & Administrations) 1858-1966

England & Scotland Cemetery Registers 1800-2024

Gore’s Directory of Liverpool

Kelly’s Directory of Liverpool

Soldiers Died in the Great War 1914-1919

De Ruvigny's Roll of Honour 1914-1919

British Army WW1 Medal Rolls Index Cards

British Army Service Medal & Award Rolls 1914-1920

UK and Ireland Incoming Passenger Lists 1878-1960

Newspapers:-

London Gazette

Liverpool Journal of Commerce

Liverpool Daily Post

Liverpool Echo

Liverpool Pals by Graham Maddocks (Leo Cooper 1991)

The History of the 89th Brigade 1914-1918 by Brigadier General F C Stanley (Liverpool 1919)

Zero Hour Z Day 1st July 1916 Volume II: XV Corps Operations between Mametz and Fricourt by Jonathan Porter (Jonathan Porter 2020)

The First Day on the Somme by Martin Middlebrook (Penguin 1984)

The First Day of the Somme by Andrew MacDonald (Harper Collins, Auckland 2016)

Slaughter on the Somme by John Grehan & Martin Mace (Pen & Sword 2013)