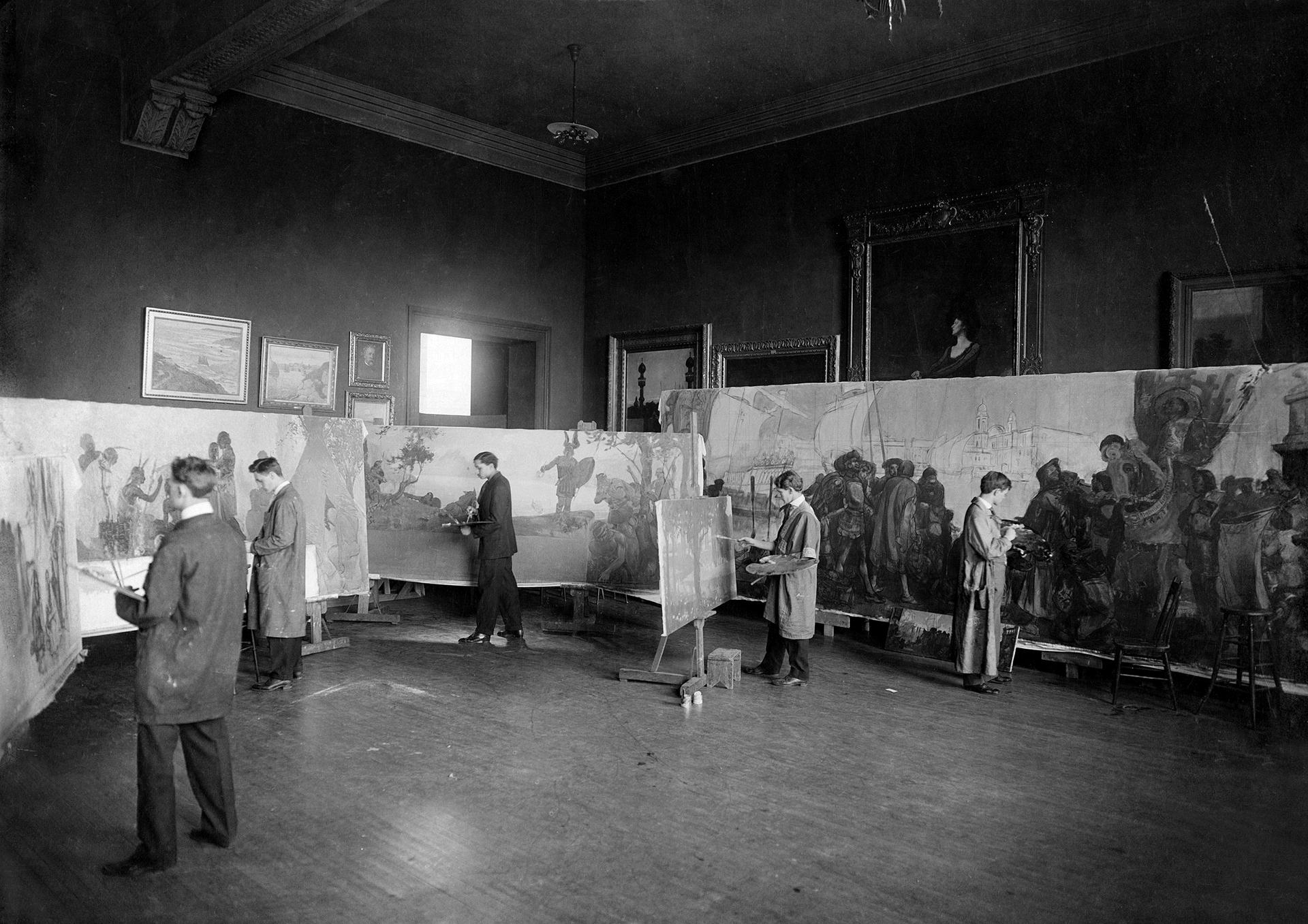

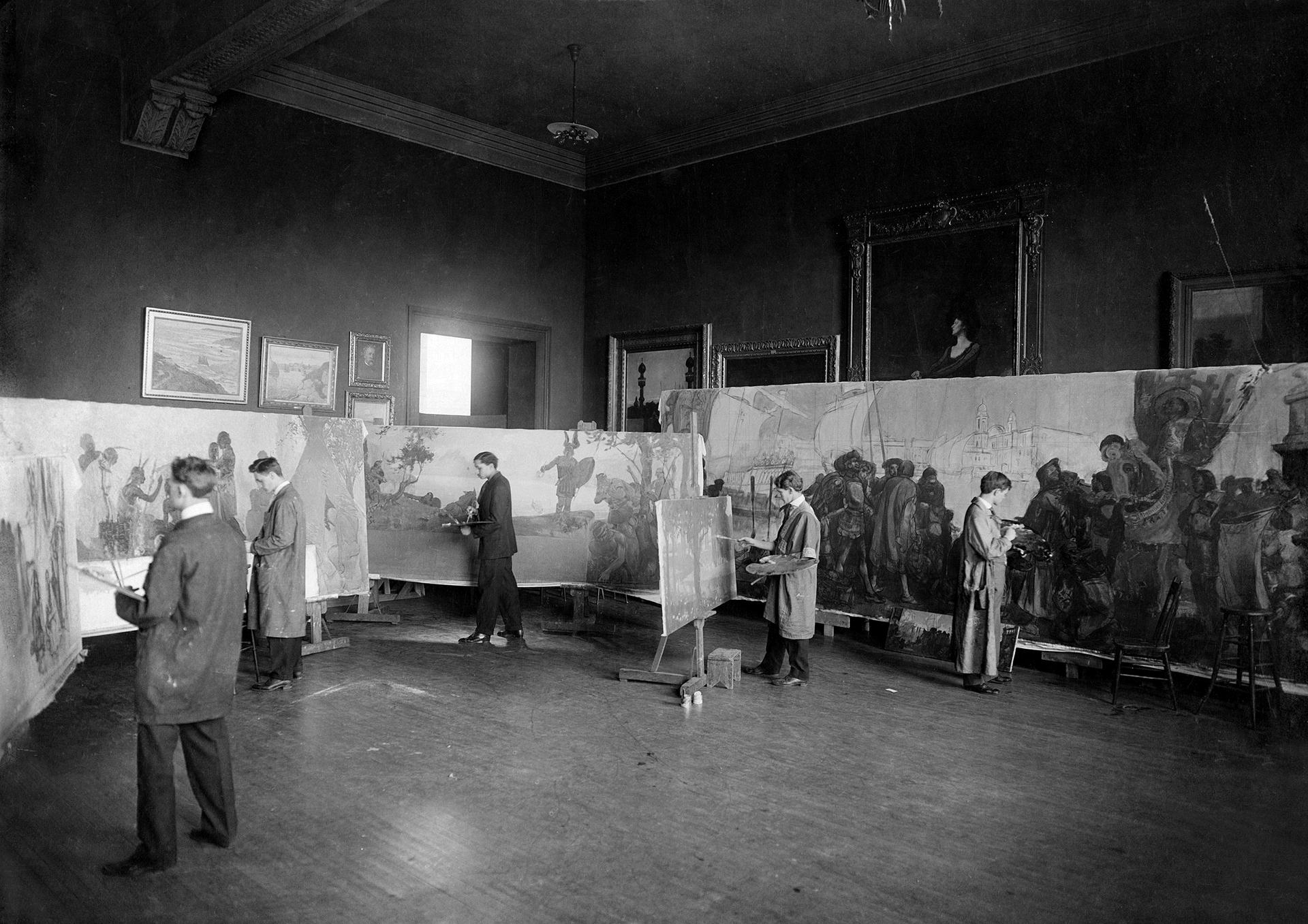

MASTER CLASS

Inside the Last American Museum School with SAIC Alumni

April 19- June 21, 2025

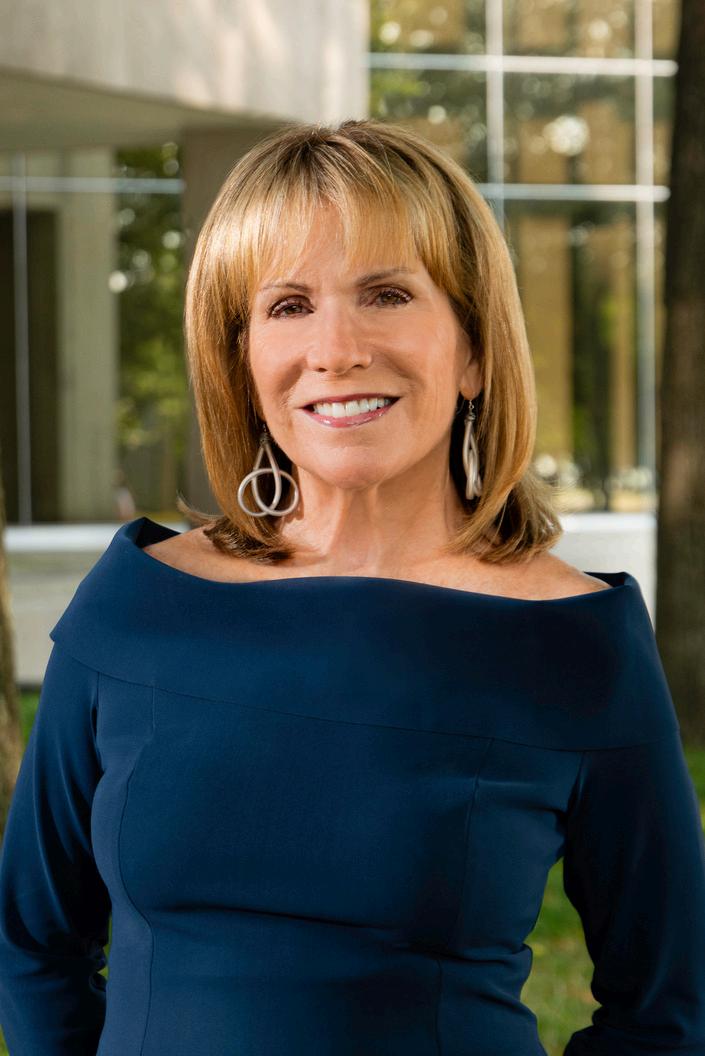

Co-Curated with Lisa Wainwright and Elissa Tenny

Essays by Lisa Wainwright and Michelle Grabner with contributed writing by:

Giovanni Aloi, Carol Becker, Ionit Behar, Silvia Beltrametti, Jeremy Biles, Steven Bridges, Romi Crawford, James Elkins, Eileen

Favorite, Brian Leahy, Margaret MacNamidhe, Matt Morris, Allison Peters Quinn, Daniel Ricardo Quiles, Patrick Lynn Rivers, Pia Singh, Francesca Wilcott, Mechtild Wildrich, David Raskin, Barbarita Polster and John Yau

Photography by Nathan Keay

Lindsay Adams MFA ‘25

Noelle Africh MFA ‘22

Luke Agada MFA ‘24

Alberto Aguilar MFA ‘01

Latifa Alajlan MFA ‘23

Cecilia Beaven MFA ‘19

Aviv Benn MFA ‘18

Samantha Bittman MFA ‘10

Elijah Burgher MFA ‘04

Robert Burnier MFA ‘16

Nik Cho BFA ‘22, MFA ‘24

Alex Bradley Cohen BFA ‘14

Jeane Cohen MFA ‘18

Paula Crown MFA ‘12

Chelsea Culprit BFA ‘07

Tavin Davis MFA ‘23

Dana DeGiulio MFA ’07

Austin Eddy BFA ‘10

Stephen Eichhorn BFA ‘06

Peter Fagundo MFA ‘02

Nicola Florimbi MFA ‘24

Howard Fonda MFA ‘01

Jae Ford MFA ‘16

Jonathan Gardner MFA ‘10

Magalie Guérin MFA ‘11

Antonia Gurkovksa MFA ‘11

Efrat Hakimi MFA ‘19

Andrew Holmquist BFA ‘08, MFA ‘14

Mika Horibuchi BFA ‘22

Patrick Dean Hubbell MFA ‘21

Steven Husby MFA ‘03

Omair Hussain BFA ‘18, MFA ‘25

G.D. Johnson MFA ‘25

James Kao MFA ‘06

Em Kettner MFA ‘14

Minami Kobayashi MFA ‘18

Meredith Kopelman Post-Bacc ‘20, MFA ‘22

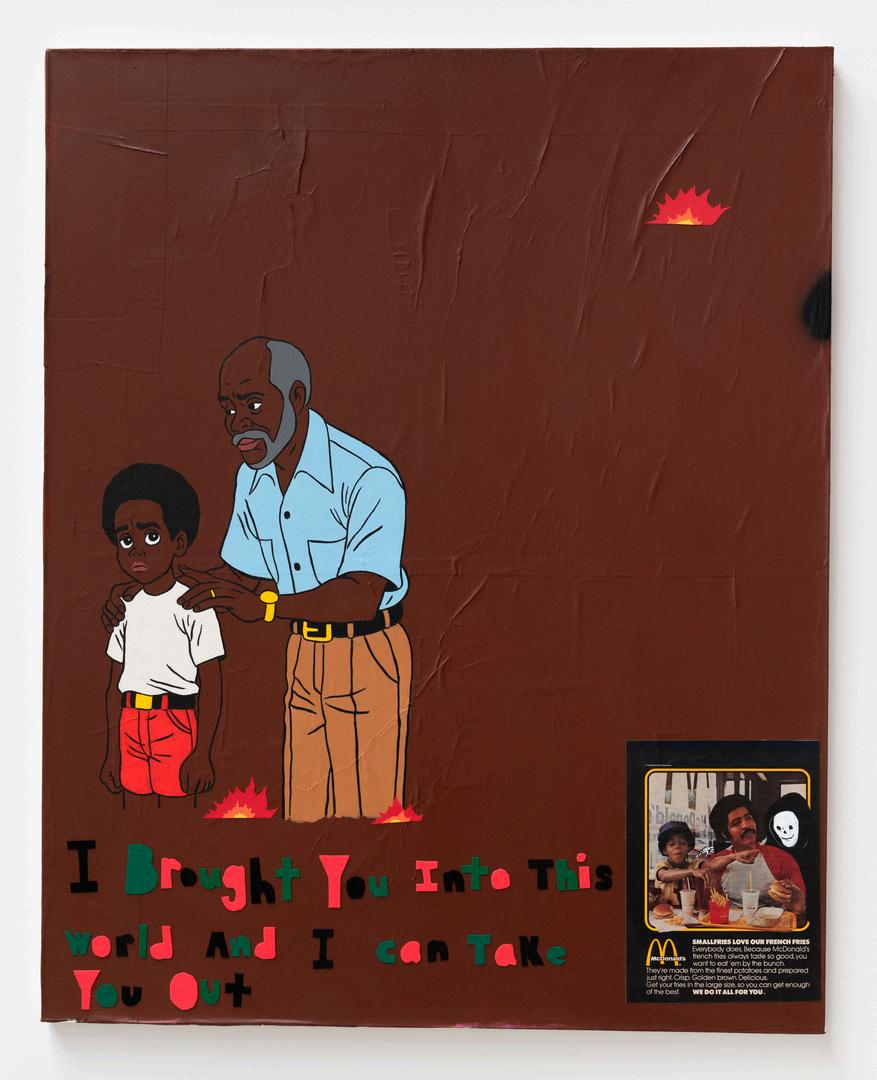

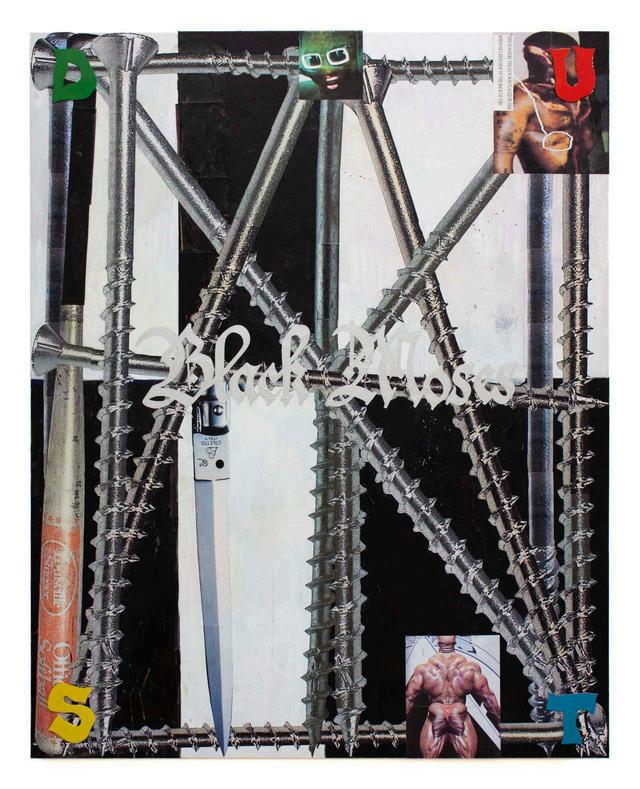

David Leggett MFA ‘20

Tony Lewis BFA ‘10, MFA ‘12

MJ Lounsberry MFA ‘23

Wangari Mathenge MFA ‘21

Kristoffer McAfee BFA ‘20

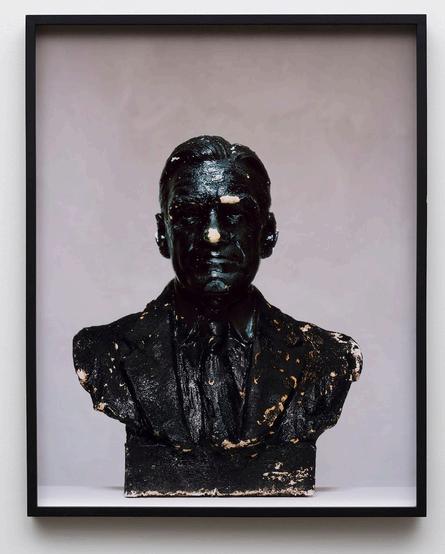

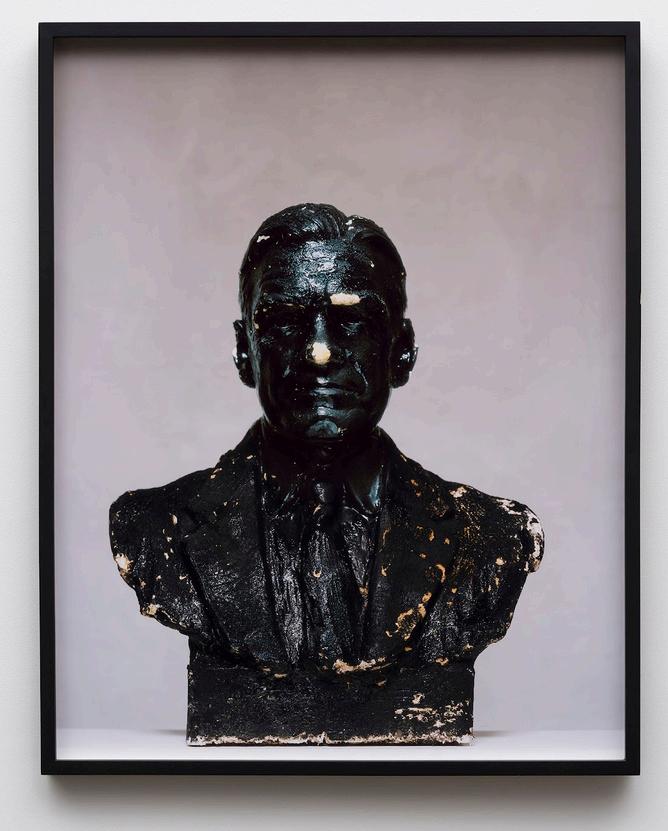

Rodney McMillian Post-Bacc ‘00

Isabella Mellado MFA ‘23

Emily Miller MFA ‘25

Jeffly Gabriela Molina MFA ‘16

Aliza Nisenbaum MFA ‘05

Angel Otero BFA ‘07, MFA ‘09

Ruth Poor MFA ‘22

Kaveri Raina MFA ‘16

Pedro Trueba Ramírez MFA ‘25

Autumn Ramsey BFA ‘05, MFA ‘13

Celeste Rapone MFA ‘13

Josh Reames MFA ‘12

Clare Rojas MFA ‘02

Sterling Ruby BFA ‘02

Charlotte Saylor MFA ‘25

Claire Sherman MFA ‘05

Sumakshi Singh MFA ‘03

Cameron Spratley MFA ‘21

Keer Tanchak MFA ‘03

Sebastian Thomas MFA ‘23

Alice Tippit MFA ‘13

Orkideh Torabi MFA ‘16

Cody Tumblin BFA ‘13

Omar Velázquez MFA ‘16

Jonathan Worcester MFA ‘24

Hiejin Yoo BFA ‘14, Post-Bacc ‘15

Molly Zuckerman-Hartung MFA ’07

Home Court Advantage

by Lisa Wainwright

“Power in art is not like that in a nation or in big business. A picture never changed the price of eggs. But a picture can change our dreams; and pictures may in time clarify our values. The power of artists is precisely the influence they wield over the fantasies of their public.”

Alan Kaprow, 1953

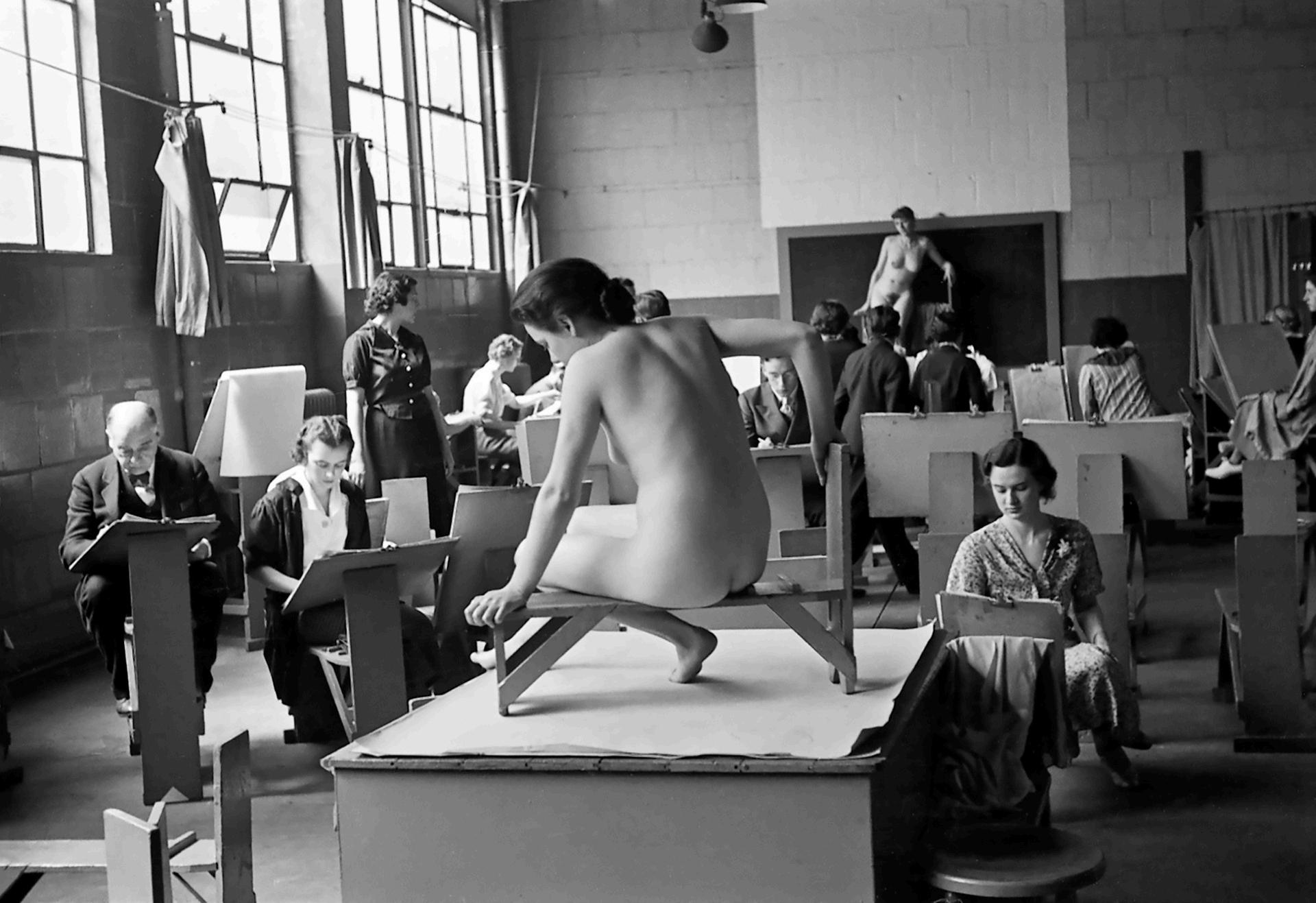

It is not commonly understood that the founding of the Art Institute of Chicago was hatched by a small band of resourceful artists in 1866. When 35 painters and sculptors met at the Reynold’s Block building on Dearborn and Madison streets to found the Chicago Academy of Design, their mandate was to create “ a free school of ‘life’ and ‘antique’ drawing and to run a gallery that

would sponsor literary, musical, and dramatic events.” Tragically, the Academy’s first building at Adams and State: its classrooms, galleries of paintings, and hundreds of plaster casts for copying, were destroyed by the infamous Chicago fire of 1871 But three years later, in 1874, the school was back up and running in different digs, and by 1879 with support from a new board of trustees, and a seemingly grander set of aspirations, the institution renamed itself the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. In 1882, the name was again changed to what we all fondly recognize as the Art Institute of Chicago. As programs

developed and the galleries grew, the school and the burgeoning museum were so intertwined that by the late 19th century into the early 20th, the first few Deans of the School simultaneously held positions as Directors of the Museum. And ever since this propitious beginning, the museum and the school have been linked by the shared civic vision emblazoned on our earliest logo, Artem Fovemus: “Let us encourage the Arts.” This founding legacy, the proposition that creating the new while dialoguing with the past, an idea initiated by artists, continues to inform all who study in our studio/museum spaces Master Class: Inside the Last American Museum School with SAIC Painting Alumni showcases the results of such an exceptional model of learning, of how rooting in the visual, material, and physical arena of a museum collection is to learn one ’ s practice from an array of eminent teachers across time and place

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago is the only remaining museum school in North America, where the proximity of making to great works of art is our pedagogical lodestar. The SAIC Painting and Drawing Department, in particular, thrives in this milieu, as the riches of world-class paintings are just down the hall from our studio classrooms This geography is our home court advantage, that our artists behold great works of art while studying their métier They know the playing field well The 69 artists in "Master Class" reveal many variations of contemporary painting expressions, but all are grounded in a remarkable history of art and art instruction that only a museum school affords

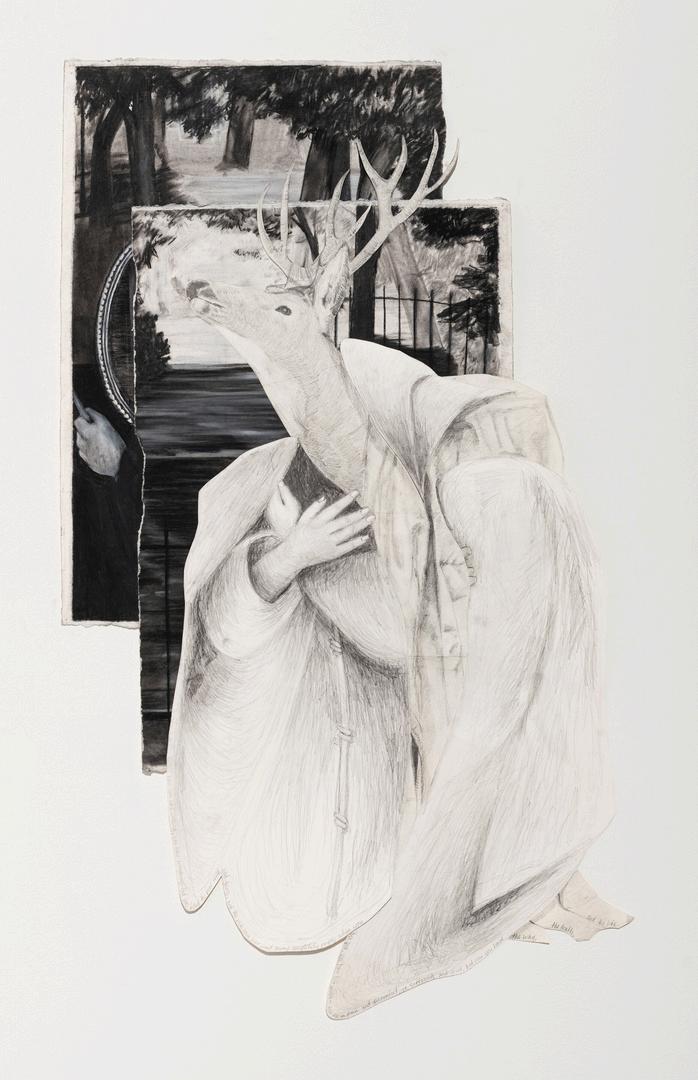

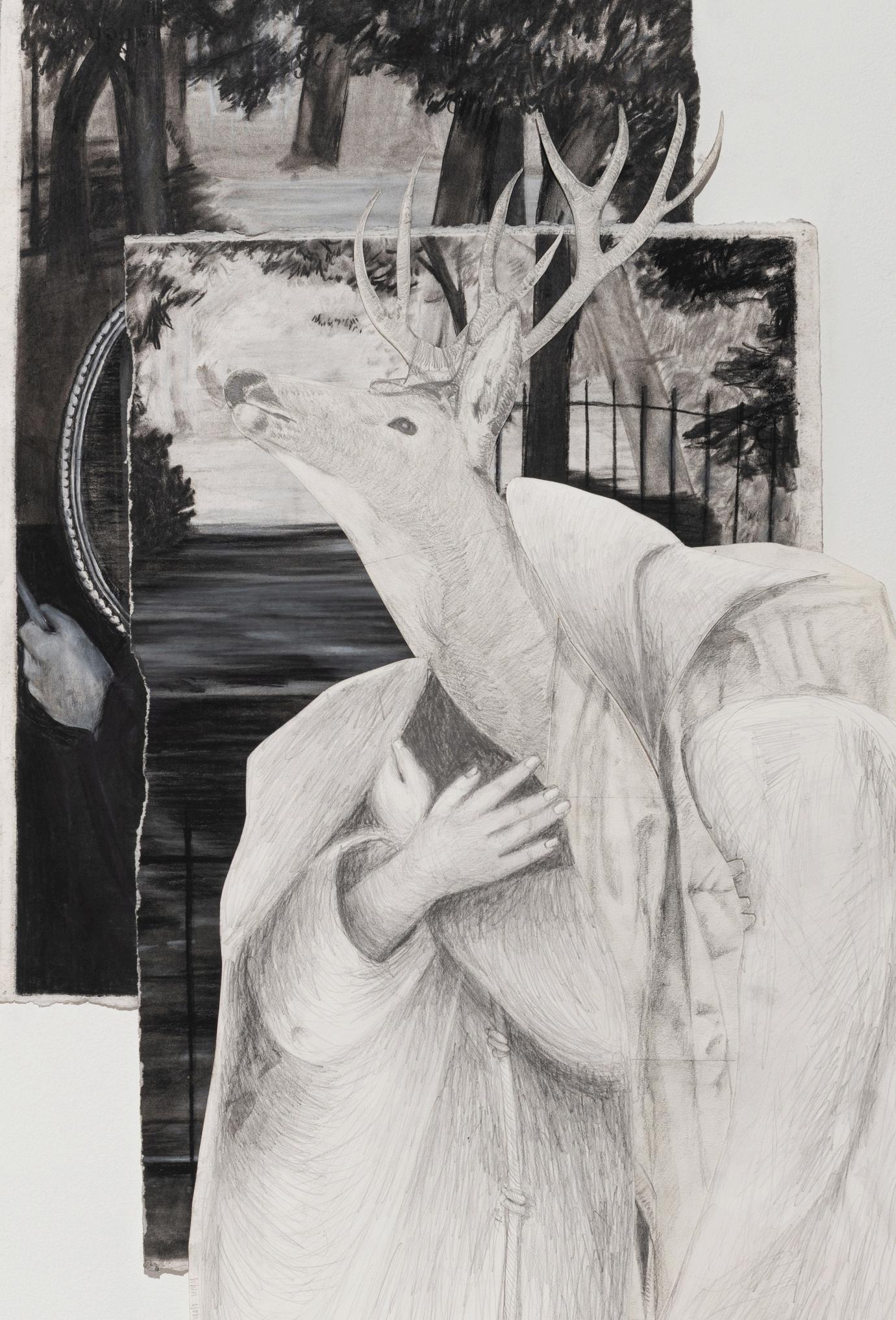

All the major genres of painting parade through Master Class with landscapes, still-lives, figurative works, and abstractions a testament to the inexorable examination of our human condition represented in the museum ’ s rich holdings. Slippages between genres are in evidence as well, for the show illustrates an admixture of styles and subjects that continue to reflect the nature of our pluralistic tendencies in contemporary art since the 1970s (if not before). And painting’s obsession with the interplay of representation and abstraction in the same field abounds. There’s both gestural and hard-edge abstraction here, expressive handling of paint, of the body and the gut, as well as exacting congregations of crisp shapes that offer up myriad formal plays. In the former, we seem to dip into aura, sentiment, or a turn towards authenticity in defiance of this age of digital numbing. This affect also describes some of the abundant figurative work in the show with almost half of the exhibition given over to figuration. The intensity of identity politics that captured the attention of the art world is still in play, albeit less formulaic Interiority, if not alienation, seems to drive these representations which makes more and more sense as the world drifts into terrifying socio-political terrain Similarly, Surrealism has a strong foothold here, as if the real is now so fractured by disinformation and untruths that fantasy becomes our only lingua franca Chicago is also home to important collections of Surrealist art and the museum is renowned for its key holdings in this area It is therefore no surprise that for those who studied in its galleries, the example of Surrealism, with its strange correspondences of motifs and ideas, seeped into these artists’ thinking and into the work.

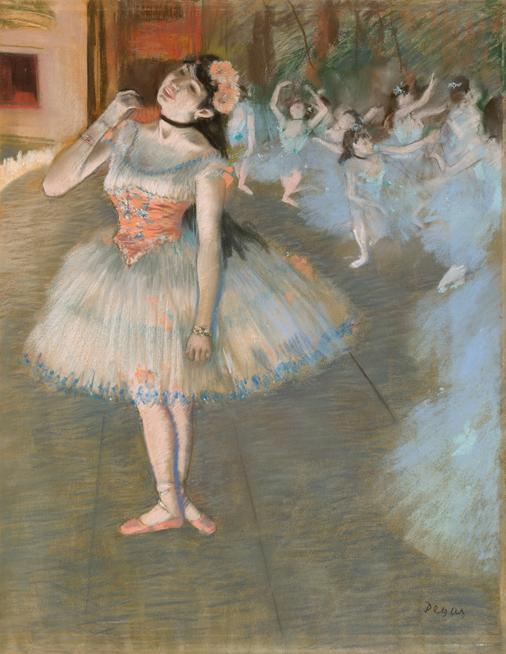

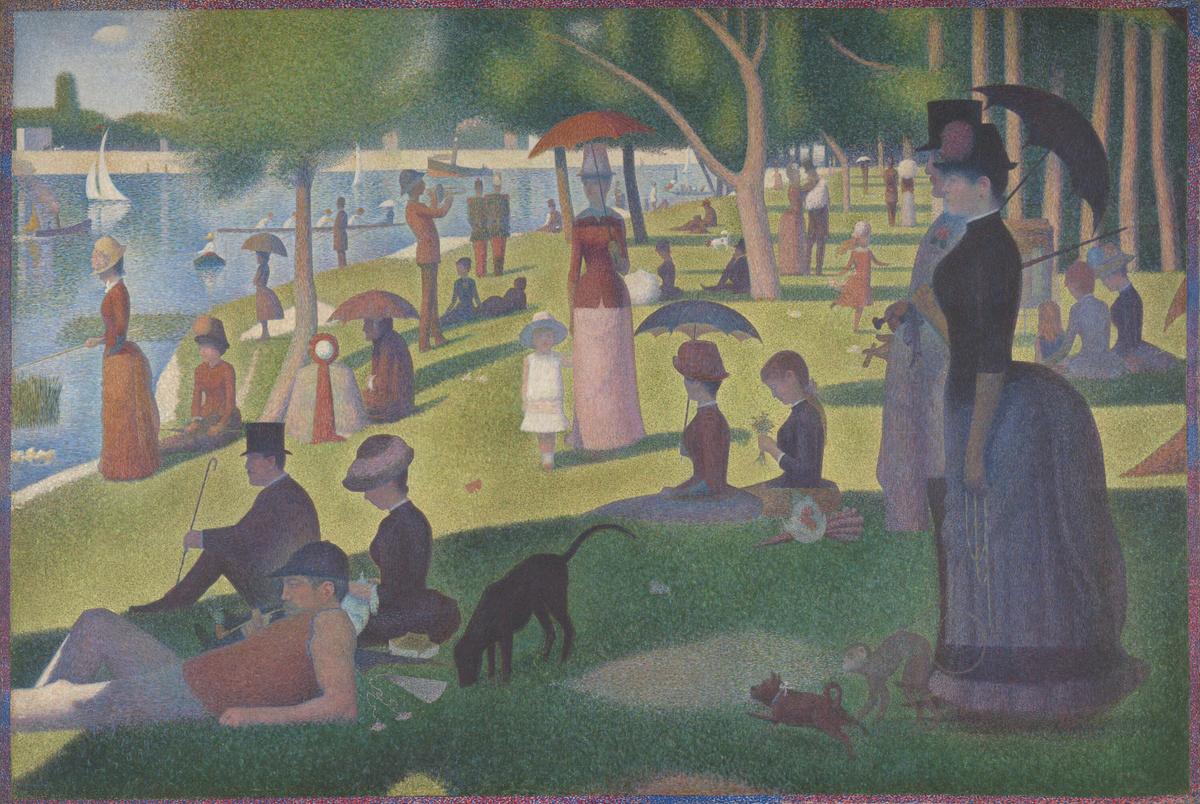

While the “ museum as muse ” is a longstanding paradigm for artists and a conceit Kynaston McShine entertained in his exhibition of the same name at MOMA in 1999, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s homecourt advantage is its ability to put this concept squarely at the center of its operations. As such, each of the artists in Master Class was asked to identify a work from the Art Institute collection that inspired, informed or has affinities with their work. In the artists’ selections, the OGs of modernism or their precursors dominate: Turner, Bonnard, Monet, Degas, Gauguin, Seurat, Matisse, Miro, and O’Keeffe appear (interestingly O’Keeffe for three artists) And there are the heavy hitters of the 1950s: Pollock, de Kooning, Mitchell, Katz, and Rauschenberg How curious that along with the de-centering of the canon in our recent efforts towards diversity, the avant-garde moves of these famous painters still beckon, even for the BIPOC artists in the show, many of whom chose canonical works Luke Agada’s Unstill Life (Elegy in Blue), 2025 tracks back to his selection of Arshille Gorky’s elegiac The Plow and the Song, 1946, another immigrant story, for Agada left Ethopia while Gorky fled Armenia Both convey unstable presences through biomorphic forms that slither into just the edge of being Omair Hussain’s

Hussain’s bold abstraction, Untitled, 2024, more commanding than would be indicated by its modest scale, curiously takes its cue from the palette of Jackson Pollock’s The Key of 1943. Pollock’s break with Renaissance perspective through a cubist, then surrealist detour speaks to Hussain’s perceptual plays, but Pollock’s content is emptied out here, a source of freedom, I imagine, Hussain thoroughly enjoys The Art Institute’s magnificent collection of Monet landscapes spoke to Lindsay Adams in her work, A thousand lights of sun, 2025, albeit Adams’s spaces often arise from musings on Black historical sites, rather than the sheer light and color afforded by Monet’s pleasant gardens; even so, both beautifully capture ephemeral traces of time Finally, the queer eye of Elijah Burgher’s Head of Orpheus, 2025 finds strange resonance in

operations, or that the museum institution itself has been a periodical turn-off for activist student-artists (let us recall that “Monsieur Matisse” was burned in effigy on the front steps of the museum in 1913), we have seen a return to the museum and to modernism, in particular, given the rapid stylistic advances of this period that forever changed painting and still informs makers today In our age of fulsome appropriation, imitation and copying, the museum remains a stalwart source.

So, if only we could hang Chelsea Culprit’s Devil's Garden Escalante, 2023 back in the museum ’ s gallery next to his choice of Paul Gauguin’s The Day of the Gods from 1894 Both deploy the water’s surface as an opportunity for indulging in decorative shapes and patterns, and the languid, nude figures signal the simmering eroticism in which both artists traffic But again, it is a symptom of this moment, that Gauguin, an artist who goes in and out of fashion in the academy given his objectification of non-Western women and, frankly, girls, is here recognized as an important source “Love the art, hate the artist,” seems to be a workable theme these days, and the Art Institute has such a huge collection of gorgeous Gauguins that his imprint on our painters has been and continues to be inevitable. Notwithstanding the idea that modernism emerged, in part, from a series of colonial

her choice of the small Edgar Degas’ The Star, 1879-1881, for I want to compare their performing bodies, their similarly gesturing limbs and cocked heads. In Culprit’s hands, there’s more aggressive contortion as if she seeks to expose the true manipulation of the female form by so many male artists before her. The fluttering, sweet, pastel scopophilia of Degas’s ballerinas gives

gives way to a stark feminist reprisal here. And while we are at it, let’s place Peter Fagundo’s Bone Machine, 2024 up in the museum too, next to his selection of Henri Matisse’s Bathers by a River, 1909–17. Fagundo’s commingling of tropes a grisaille rectangle of a soft-porn image inserted into the middle of a colorful abstraction serves up that postmodern gambit where pictorial dissonance echoes the delusional nature of our oversaturated semiosphere Matisse also situates bodies against abstracted grounds, with a similar atemporal effect, for one

of modernism’s subjects was a rapidly changing world. And why can’t we put Minami Kobayashi’s In a room on a high floor, 2024 next to Pierre Bonnard’s Earthly Paradise, 1916-20. It would be so easy on the eyes to move from Bonnard’s landscape of delicious hues and sensual shapes over to Kobayashi’s similar expanses of lovingly painted surfaces and bucolic charm Finally, Hopper’s iconic painting of The Nighthawks 1942 would be wonderfully renewed by hanging Wangari Mathenge’s Our Time, 2024 next to it Mathenge’s close-up of a resting figure rendered in the exact palette as Hopper’s, exudes the same elegiac loneliness that haunted those figures sitting quietly at the counter in Hopper’s night painting nearly 100 years before.

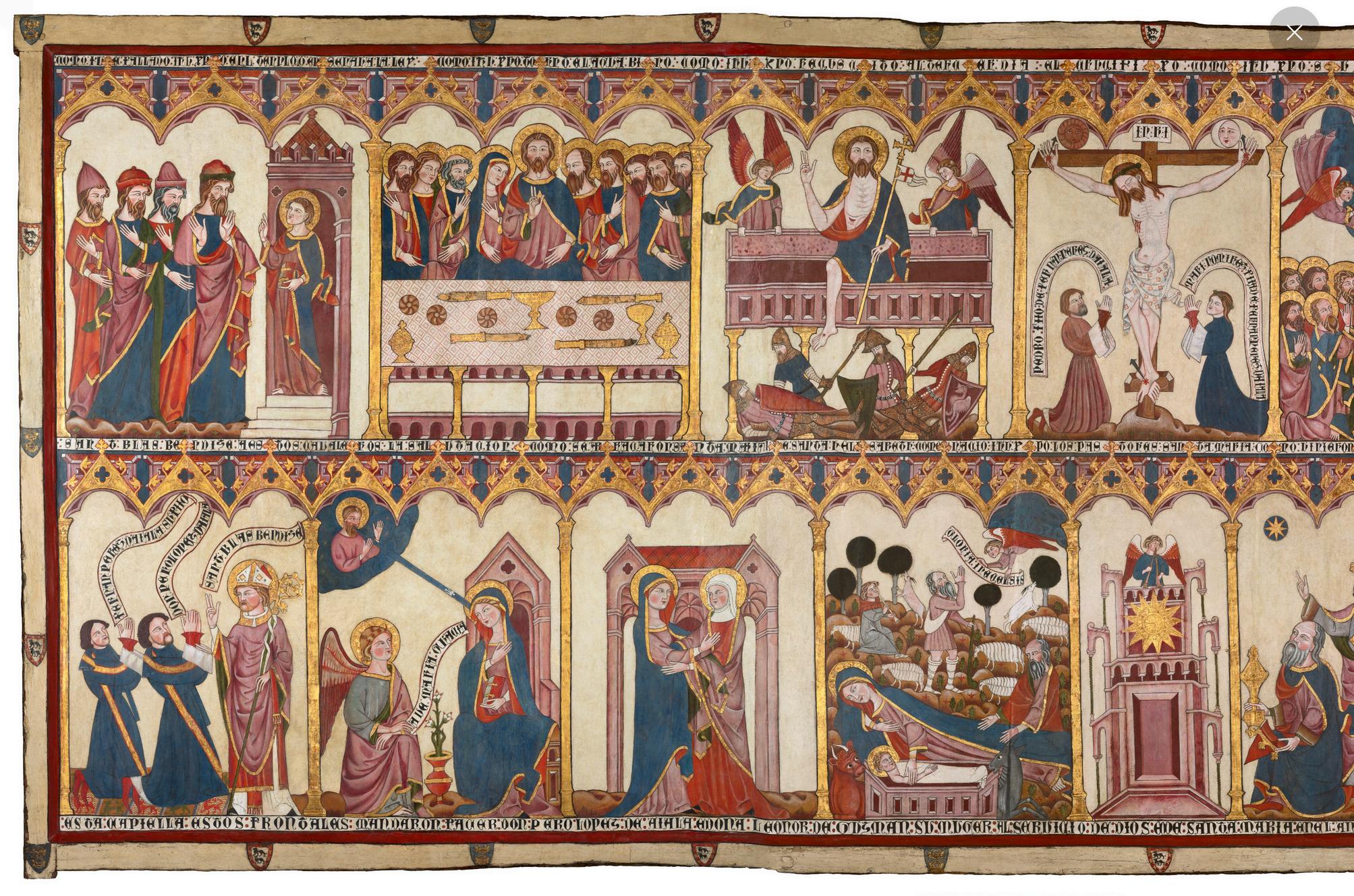

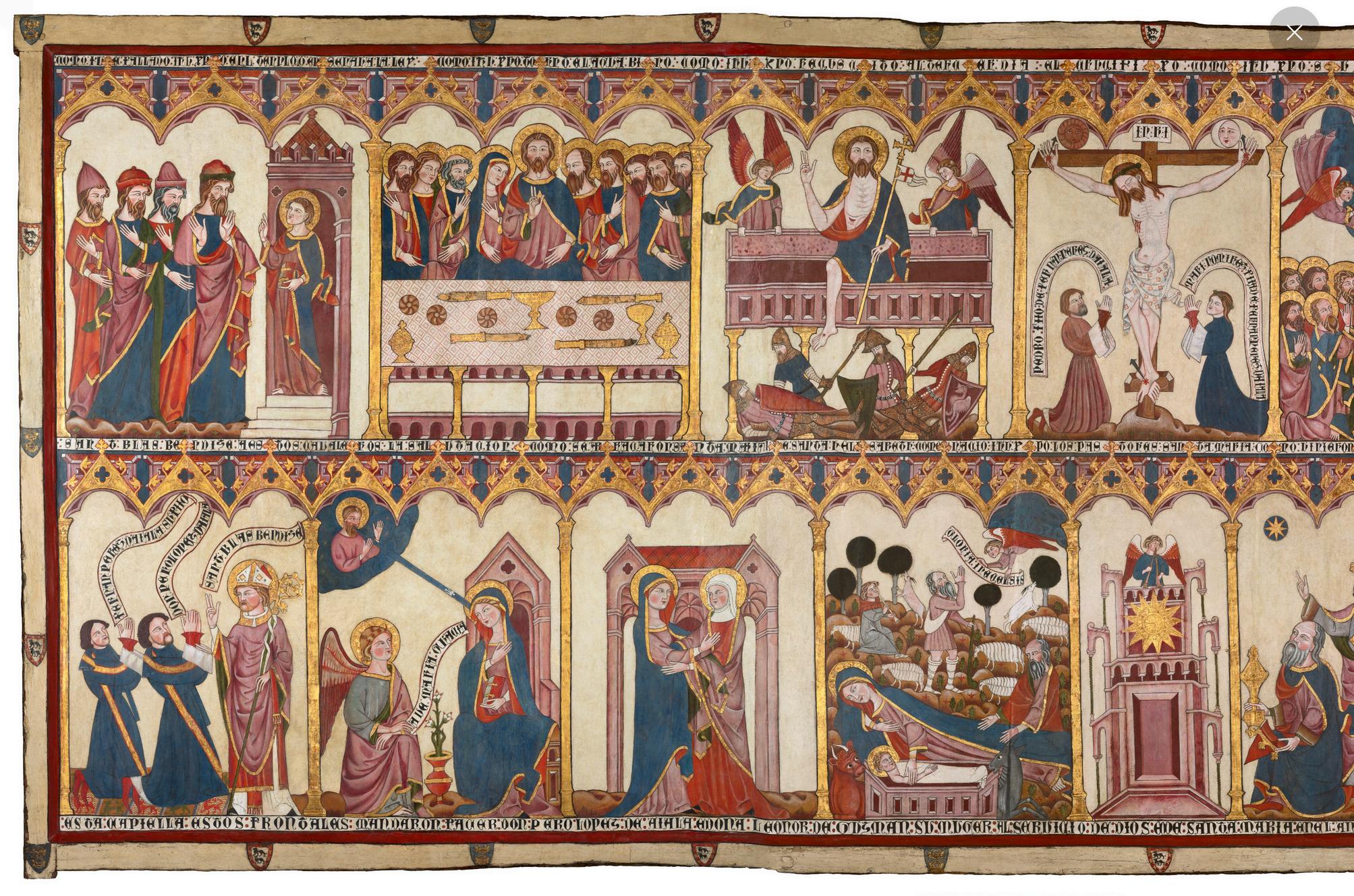

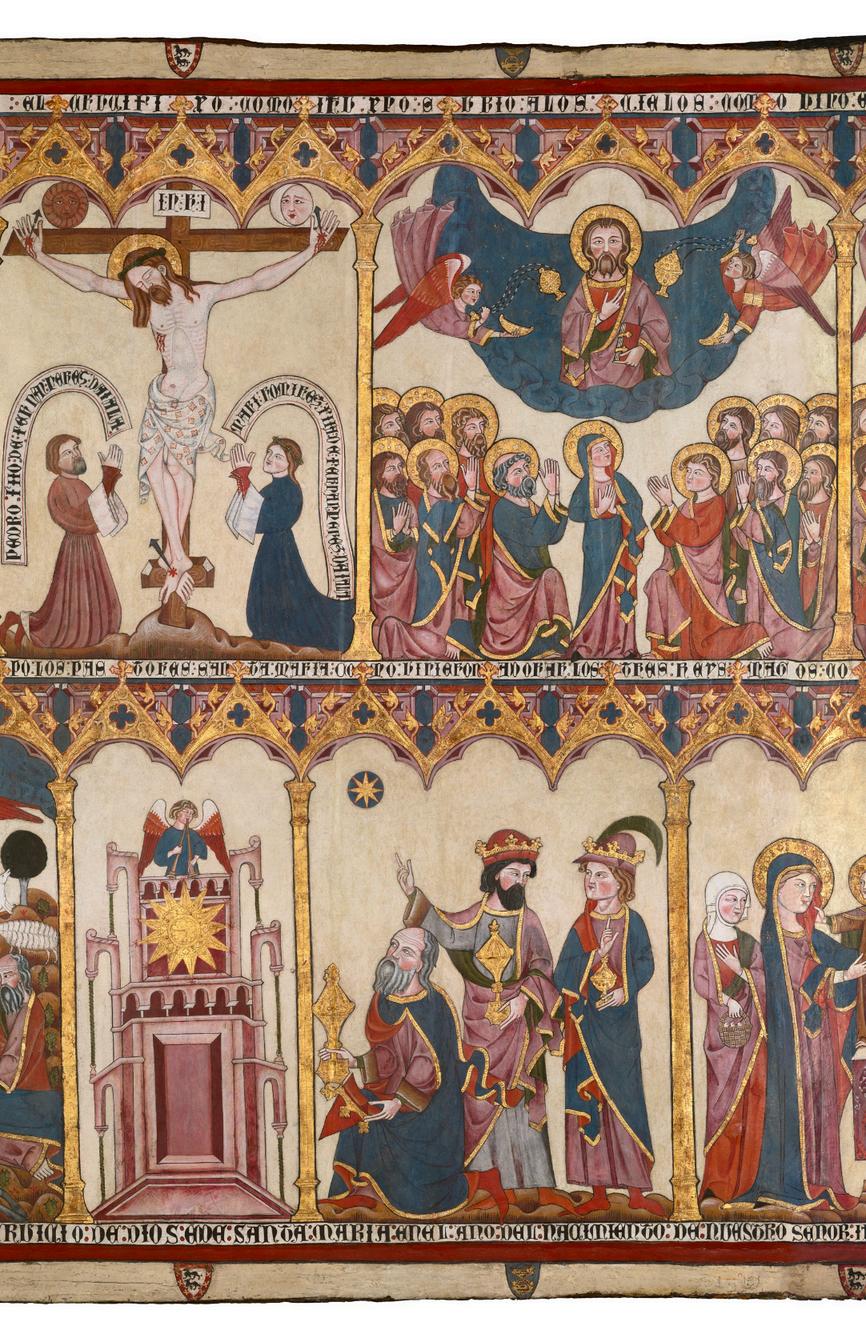

The ease at which the museum examples resurface in many of these artists’ works in Master Class says something about the power of the museum as a repository of sustaining sustaining knowledge Indeed, some of the chosen pairings by the artists are quite direct, as if the significance of the original bears repeating. Sebastian Thomas borrows the format of decorated medieval panels from the Art Institute’s Retable and Frontal of the Life of Christ and the Virgin, 1396 for his playfully heraldic piece, The Nocturne Knights II, 2024. Omar Velásquez lifts the iconic rock straight out of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Black Rock with Blue Sky and White Clouds, 1972 to rest amidst his rebus of surrealist motifs in Ocaso, 2024. Mika Horibuchi Curtain Drawn III, 2018 is a copy of Adriaen van der Spelt and Frans van Mieris’ Trompe-l’Oeil Still Life with a Flower Garland and a Curtain, 1658, only she isolates the mysterious curtain that had framed the original floral scene in a virtuosic display of illusionism. Howard Fonda’s rhythmically patterned surface is also a still-life composite of the Art Institute’s Ming dynasty vase (1368–1644), the Sorrowing Virgin (c 1490) painted by the workshop of Dieric Bouts, an 1864 seascape by Édouard Manet, and a striped, aubergine-colored bit of wallpaper (c 1915) by the Austrian designer Dagobert Peche together a kind of democratizing effort in the manner of André Malraux’s “ museum without walls ” And Patrick Dean Hubbell points to a Navajo rug from 1800–1890, in his deconstructed 6

Patrick Hubbell, Your Clarity Rises Above All Of My Faults, 2023

“Germantown Eye-Dazzler” Rug (detail) Made 1800 - 1890, Navajo (Diné) deconstructed exegesis on the value and circulation of traditional Diné crafts.

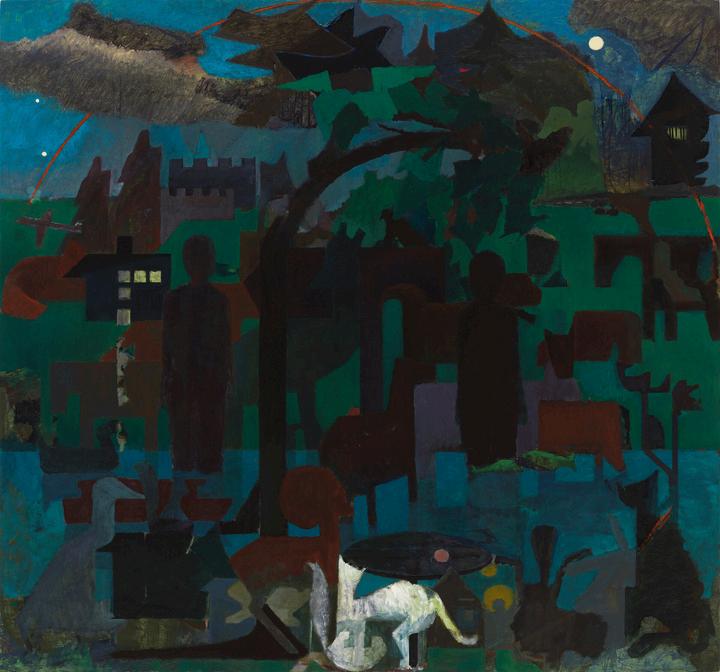

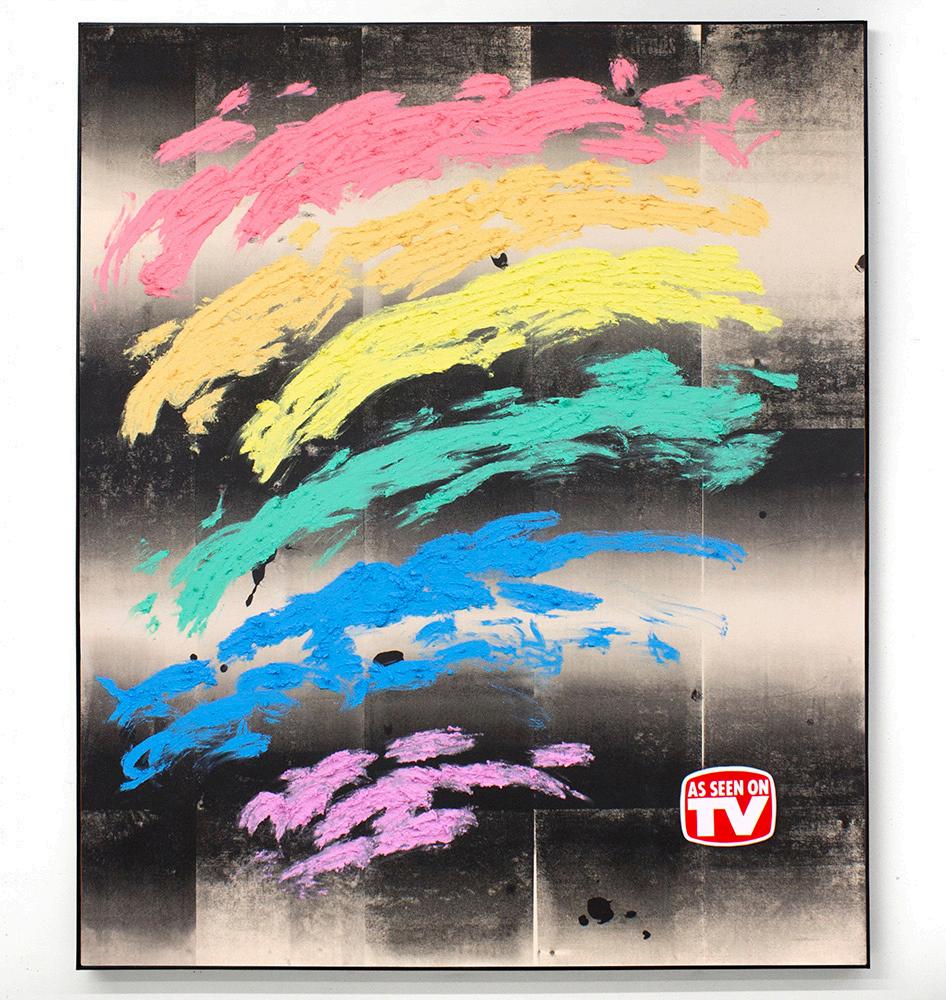

Still other selections by the artists in the exhibition are more unexpected, if not curiously weird Robert Burnier turned to the example of Matteo di Giovanni’s The Dream of Saint Jerome, 1476 with tempera giving way to painted aluminum in Burnier’s Matene Mi estos en Ordo, Mia Amiko (Ho Sinjoro), 2022 The autonomy of Burnier’s pure abstraction seems hardly adjacent to the Judeo-Christian undergirding of the Matteo di Giovanni But hey, all that pleated and folded drapery here, and throughout the history of painting, no doubt stimulated Burnier’s aesthetic maneuvers, not to mention the relatively new perspectival plays of the 1476 panel in its own time. Jeffly Molina’s figurative work (Feelings, 2023) might seem distinct from the pure abstraction of Agnes Martin (Untitled #12, 1977), and yet both share a profound still and quiet pathos. Similarly, Noelle Africh’s process-based Flood, 2024 juxtaposed with Luc Tuyman’s Angel, 1992, emphasizes Tuyman’s earthy marks and subdued palette, or is it the reverse? Tuyman’s ghostly angel is really incidental to the painting’s read, and while Africh, in contrast, leaves out images altogether, there is something numinous hovering inthe elusive variations of the surface of this painting. George Johnson’s awkwardly elegant composition, There is a buzzing/my foot feels strange, 2025 look back to the somewhat obscure American painter, Morris Kantor, whose work, Haunted House, 1930, is a melancholy scene of human despair, with the same masculine ennui that inhabits much of Johnson’s work And Josh Reames goes to Bruce Nauman as his museum pick, an interesting choice in that both Reames’ Under the Bright Light, 2022 and Nauman’s Clown Torture, 1987 are wry engagements with the pernicious power of the mass media’s manipulative control, today once again, dangerously relevant Reames’ choice of a video is also an example of the painters in the show who singled out non-paintings as their AIC selection Like Reames,

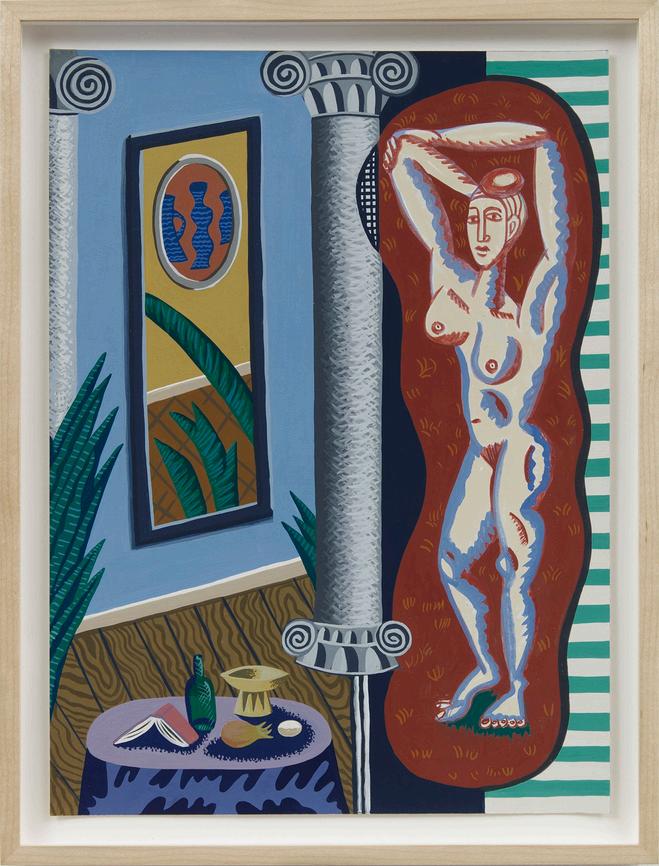

Cameron Spratley turned to David Hammons’ historic piece Phat Free, 1995-99, with its banging metal bucket kicked down a dark street, as a meditation for his own rendition of deliciously treacherous accoutrements in Dust2dusT, 2025. Interestingly, two of the six Latina women in the show, Isabella Mellado and Cecilia Beaven reached back to ancient Roman sculpture, as the weighty classicism of these objects grounded their otherwise wildly inventive forms Clare Rojas took her inspiration from a Ceremonial Knife (Tumi), 1100-1472 from Peru, whose sharp curvilinear shape and forceful mythic creature gets updated in her Protective Mother, 2022 And Efrat Hakimi’s array of collaged tokens in Protective Amulet against Miscarriage (1), 2021 finds formal resonance in her choice of a beautiful Moroccan textile, a man ’ s cape (Akhnif) from 182575, an item with a darker history as it was sometimes worn inside out to mark the wearer as Jewish.

Master Class positions the last 25 years of painting alumni in relation to the museum, and what emerges is a renewed commitment to a tenet of modernism that prized freedom above all else. The avant-garde, to which many of these 69 artists still clearly relate, boldly broke new ground, upsetting the status quo again and again to assert new means of making and by extension, thinking And all of it paralleled the relatively new political climate of democratic revolution When the artist Albert Oehlen proclaimed that artists “ are technicians of freedom,” at the School of the Art Institute’s 2015 commencement address, where the Director of the Museum at the time, Douglas Druick, was also receiving an honorary doctorate, he was speaking to artists in a museum school For to be free is to know one ’ s past, in order to reinvigorate one ’ s present.

There seems to be a return to medium specificity in this show, where facture, color and shape slow us down to the pleasure of pure painting again. Has painting returned to its roots in an attempt to counter the onslaught of so many pulsing digital screens? It does appear that the wonder of painting, its visceral, palpable materiality, its chromatic buzz and sensual luminosity holds our visual attention again despite the cacophony around us We live in what some have observed as an ‘atemporal’ moment, a collapsing of eras in an all-consuming internet space, a kind of perpetual present that seems to cannibalize all in a schizophrenic fashion But our museum school still continues to find a kind of historical mapping useful, even if it means productively disrupting some of the narrative The museum collection serves as a means of anchoring one ’ s practice to a system of shared traditions, whether in the form of thoughtful resistance or emphatic embrace, or an admixture of both. It does so not ironically, that postmodern stance, but as an ethic of heroic experimentation. The different frequencies of painting on offer in the Secrist | Beach show are all beautiful to behold and thoughtful to consider. They offer new perspectives on that which is familiar, subtly adjusting and modifying and making it fresh. These material propositions executed through the individual voices of artists remain a hallmark of a democratic society. We must never take for granted the freedom we enjoy to produce what we will, to make our independent claims through deliciously formal means, and for such aesthetic gestures to “influence the fantasies of the public,” as Allan Kaprow suggested many years ago.

7

FOOTNOTES

1

Allan Kaprow, “The Artist as a Man of the World,” Essays on Blurring of Art and Life, Jeff Kelley, ed (University of California Press) 53

2

Thomas C. Buechele and Nicholas C. Lowe, The Campus History Series: The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2017), 7

3

4

Thanks to Dr. Kevin Carney for the apt metaphor of a ‘home court advantage.’

Kynaston McShine, The Museum as Muse: Artists Reflect (Museum of Modern Art, 1999)

6

Nairobi artist, Michael Armitage’s deep interest in Gauguin speaks to the global allure of this artist

5 André Malraux, Museum without Walls (New York: Doubleday and Co , 1967)

See the seminal text: Frederic Jameson, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” The Anti-Aesthetic, Essays on Postmodern Culture, Hal Foster, ed (Seattle, Washington: Bay Press, 1983) 111-125

Work

by Michelle Grabner

“Actual work in a discipline requires one to recognize how much others know and one doesn’t, a loss in ego that brings a gain in skill.”

Jonathan Kramnick, Criticism & Truth, 2023

Master Class: Inside the Last American Museum School with SAIC Alumni for Chicago’s Secrist | Beach Gallery, is a luminous and rigorous teaching exhibition It foregrounds the enduring value of sustained engagement with art objects of close and iterative looking, of contemplative study, and of critical interrogation. It revels in deep formal and conceptual analysis, and in the gravitational pull of the aesthetic sphere.

The exhibition comprises a diverse array of contemporary works that traverse cultural histories, temporalities, geographies, and artistic sensibilities. While resolutely contemporary, Master Class is philosophically aligned with George Saunders’ 2021 volume A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, a hybrid of literary analysis and craft pedagogy centered on canonical short stories by Chekhov, Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Gogol. Saunders’ text, like the Master Class exhibition is a tribute to the recursive nature of creative work to close reading, revision, and the ethics of form. While Saunders’ insights are drawn from literature, his convictions resonate profoundly with this curatorial project

Engaging interrelationships between artwork and artwork, artist and influence, past and present, the exhibition delights in the generative frictions of influence, inspiration, paradigm, and critical criteria Sixty-nine contemporary artists all alumni of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Painting and Drawing Department selected a work from the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago as a tribute and a model in their own artistic development In placing new works in conversation with historic antecedents, the exhibition enacts a reverent yet vitalizing pedagogy, affirming SAIC and AIC sisterhood as a perpetually animated site of study and provocation.

Like Saunders’ approach to the short story, the exhibition Master Class insists on the ethical dimension of artistic practice. Saunders reminds us that every sentence must be earned, that writing is an act of ongoing revision, and that the relationship between writer and reader is one of profound and mutual investment. So too does this exhibition suggest that the act of looking of studying and re-studying is itself a form of dedication and a dialogue across time. We encounter

encounter works in the AIC in order to understand the physics of form. We are looking to see what we can steal. The artworks that we study at the AIC are the high bars from which to measure our own work. And while some historical works in the collection of the AIC are great in spite of certain flaws, we discover that many are great because of their flaws And we are often reminded in the presence of other work that we can’t know what our studio problems will be until we work our way into them and then, we can only work our way out

This exhibition reminds us that attachments to artwork is a galvanizing phenomenon Through repeated encounters looking, questioning, analyzing, quarreling the work becomes more than an object of study It becomes an object of tone, attitude, sensibility, ethos, and affect Such works may affirm or unsettle. They may surface the social, political, and economic frameworks within which art circulates. Or they may simply offer aesthetic pleasure. In entering into dialogue with the artwork from the AIC collection, artist confront its past, its institutional present, and its speculative future. The museum and its holdings are thresholds: sites of inquiry and curiosity, ethical engagement, and creative renewal.

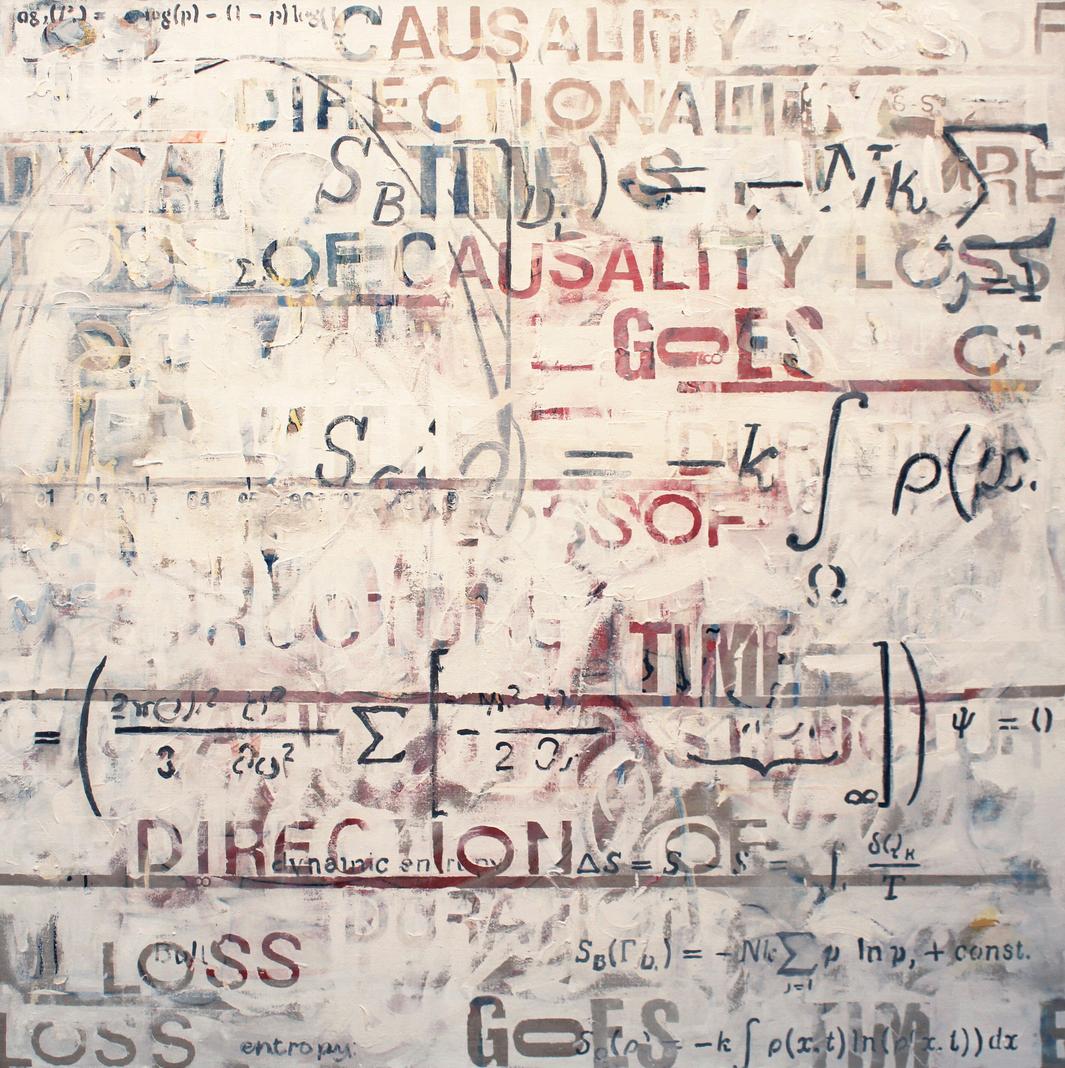

For example, the conceptual rigor and procedural systems at play in Jack Whitten’s Khee II (1978) reverberates in Jonathan Worcester’s studio practice and is reflected in this exhibition through Ogive (2024). Worcester’s field of meandering moiré patterns, palpable paint body, and inscrutable layering extends Whitten’s linear composition into a dynamic, architectural and fluid abstract motif While Sol LeWitt and Ellsworth Kelly’s works inform the foundational visual vocabularies of Samantha Bittman and Alberto Aguilar, it is the intellectual provocation of René Magritte’s The Tune and Also the Words (1964) that animates Paula Crown’s text-based painting Where Does Time Go? (2016) Rumination on mathematical equations, language systems, and painterly intonation, Crown’s painting entangles Magritte’s metaphysics with the direct experiences of a Jasper Johns’ painting

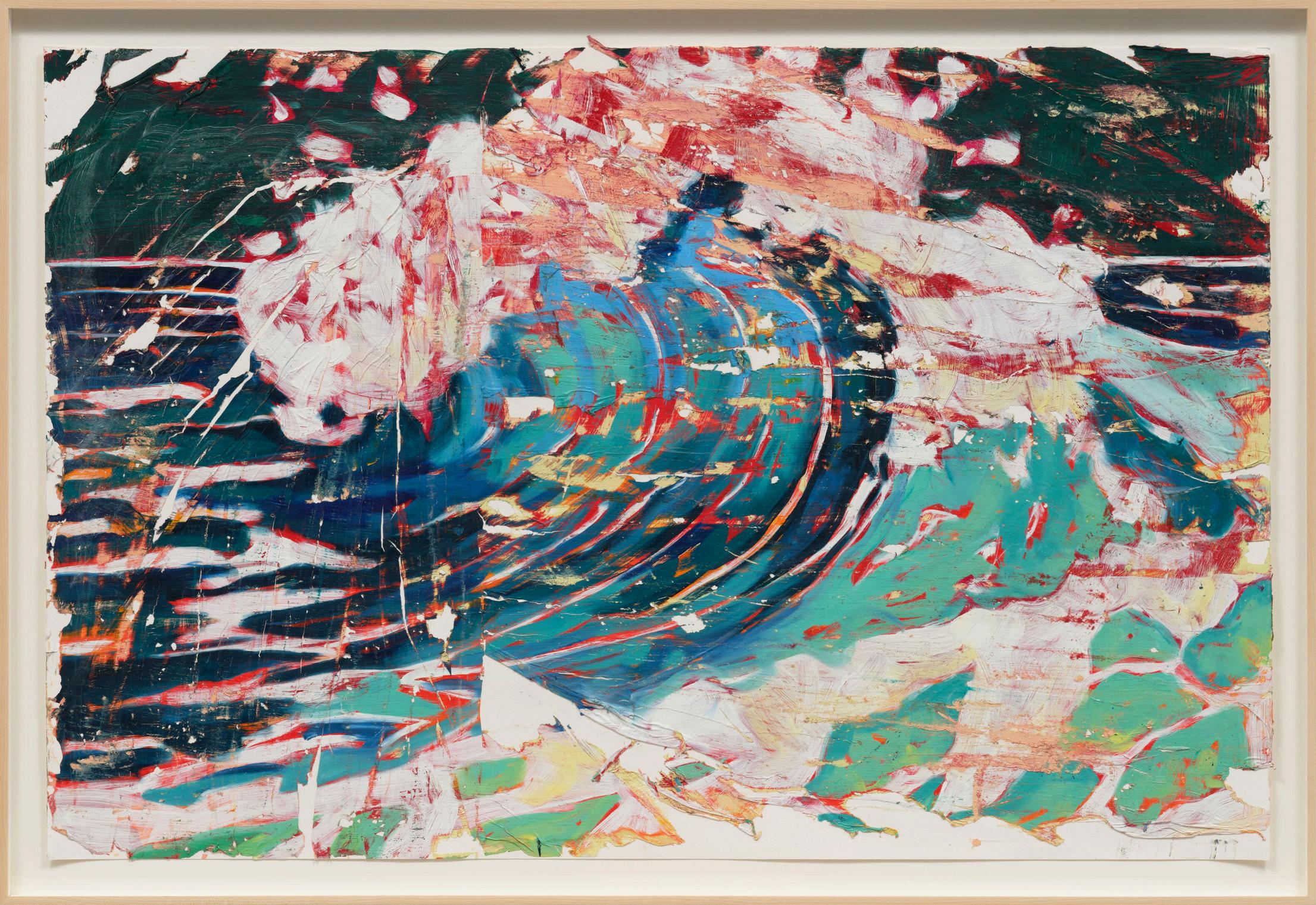

Perhaps not surprisingly, ardent, body-scaled gestural expression whether in Joan Mitchell’s much-cited City Landscape (1955) or Willem de Kooning’s seminal Excavation (1950) remain dominant touchstones for contemporary painters such as Latifa Alajlan, Jeane Cohen, and Angel Otero Meredith Kopelman’s Anything But (2024) similarly exemplifies excited brushwork, yet it is Fishing Boats with Hucksters Bargaining for Fish (1832–42) by J M W Turner that she scrutinizes and sources for turbulent, abstract energy within her seascapes

Genre paintings also abound in Master Class By bringing the viewer into thematic agreement, genre allows artists to anchor historical, stylistic, and narrative interpretations across painting’s known categories such as still life, portraiture, and landscape The codes that probe the sublime within these classifications find articulation in the contributions of Dana DeGiulio and Claire Sherman. Sherman’s Moss and Branches (2018) shares an uncanny luminosity with George Inness’s Afterglow (1893), while Man Ray’s moody, arcane Percolator (1917) informs DeGiulio’s painterly tactics. In DeGiulio’s still life, tussled dabs of paint choreograph a dispersion of cut white roses and contrasting green foliage. As in Man Ray’s work, it is the application of paint and directional brushwork not mere representational likeness that generates the allegorical potential. Representation also yields to color as an organizing principle in Tavin Davis’s numerous blue-sky landscapes, which channel the tonal abstraction of Georgia O’Keeffe’s The Black Place (1943).

Magalie Guérin’s Untitled (Gabriele) (2025) is neither a copy nor a study; rather, it is a muse on Gabriele Münter’s Still Life with Queen (1912) Guérin reworks Münter’s storybook arrangement through an array of contrasting of visual vocabulary that far outreach Münter’s expressionist lexicon Despite a textured surface, unrelenting color clashes, and the inclusion of super-flat graphic shapes, Guérin’s work still holds compositional equilibrium and retains the genre of “still life ” Conversely, Stephen Eichhorn’s Aloe Agave Aloe Bloom (2025) over-esteems the structural formalism of his benchmark, the photographer John Pfahl Eichhorn’s contribution instead distorts perspectival space through unnatural lateral symmetry and a digitally flattened visual field.

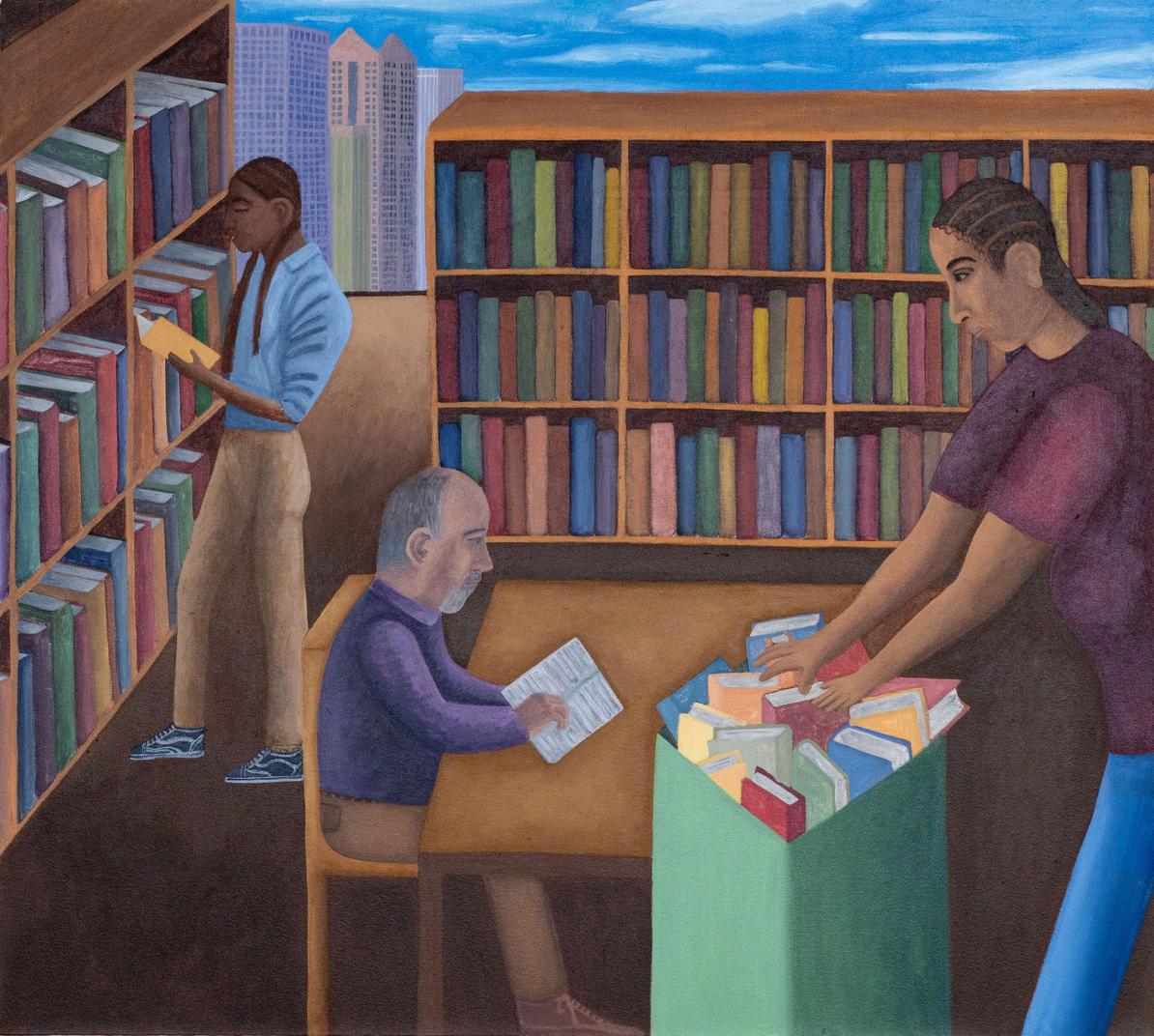

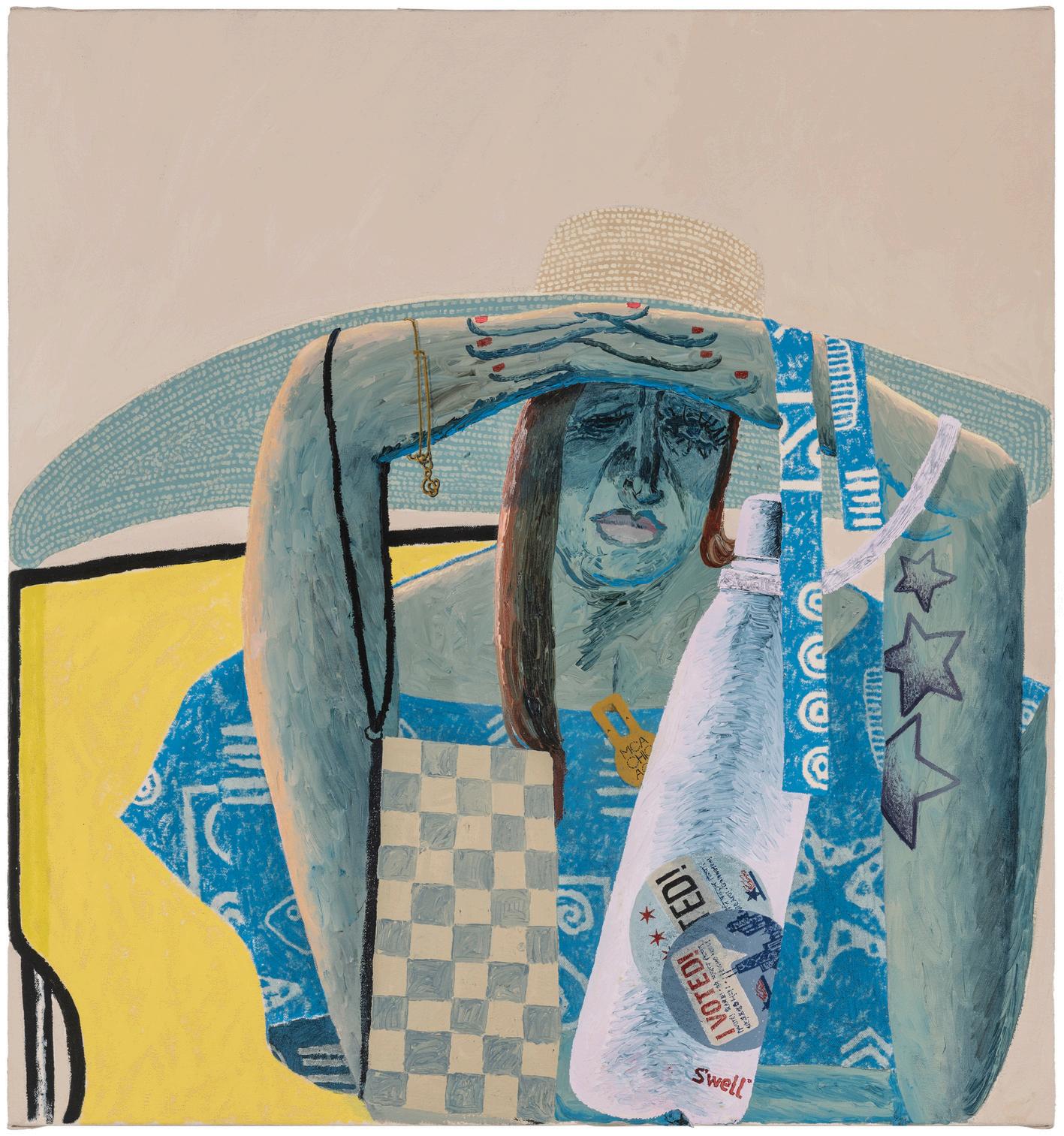

Given the Art Institute of Chicago’s rich holdings of Matisse and the enduring prominence of the figure in the contemporary cultural imagination it’s no surprise that Matisse’s linear contours echo in the works of Andrew Holmquist and MJ Lounsberry. Figurative works by Jim Nutt, Joan Miró, Tsuguharu Foujita, and Ivan Albright are also cited as impactful sources, suggesting that the abstracted body continues to reveal more than its academic counterparts. This is evident in Jonathan Gardner, Kaveri Raina, Autumn Ramsey, and Sterling Ruby works as they seek to convey humanistic qualities through the articulation of strange and unearthly bodies Nik Cho and Alex Bradley Cohen also deploy blocky, shape-driven nonrealistic depictions of the figure, but both of these artists ground their figures in social spaces Cho’s large-scale yet intimate depiction of men in a bar and Cohen’s vibrant library scene evoke familiar compositional painting contexts particularly David Hockney’s American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman) (1968) while Cohen also finds resonance in Jacob Lawrence’s The Wedding (1948)

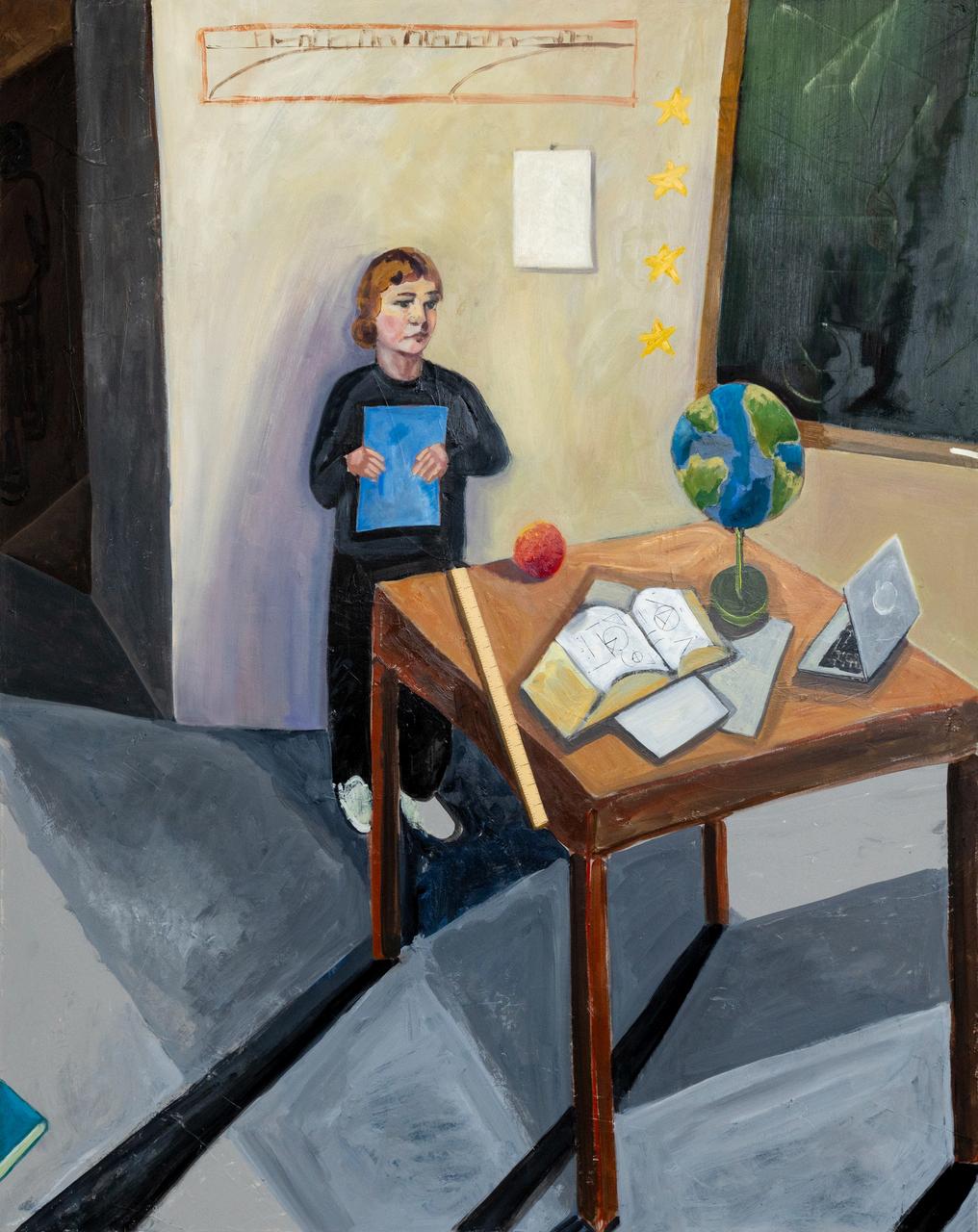

No study of AIC’s collection is complete without acknowledging the historical weight of its European Impressionists James Kao’s Starlight (2018) recognizes Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884–86) as its driving influence, while Keer Tanchak’s series of oil-on-aluminum paintings gestures toward the warm, atmospheric sensibility of Édouard Vuillard’s Landscape: Window Overlooking the Woods (1899). Nicola Florimbi is likewise drawn to the exceptionality of the commonplace. In Measure Up (2024), a daunted figure stands in a classroom surrounded by instruments of learning measuring stick, laptop, open books, globe capturing the psychology of doubt in the routing of learning Though not Impressionistic in style, Florimbi’s composition is deeply influenced by

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s The White Tablecloth (1731–32), a still life life of bread, wine, and meat rendered with a quiet dignity that seeds the Impressionist ethos.

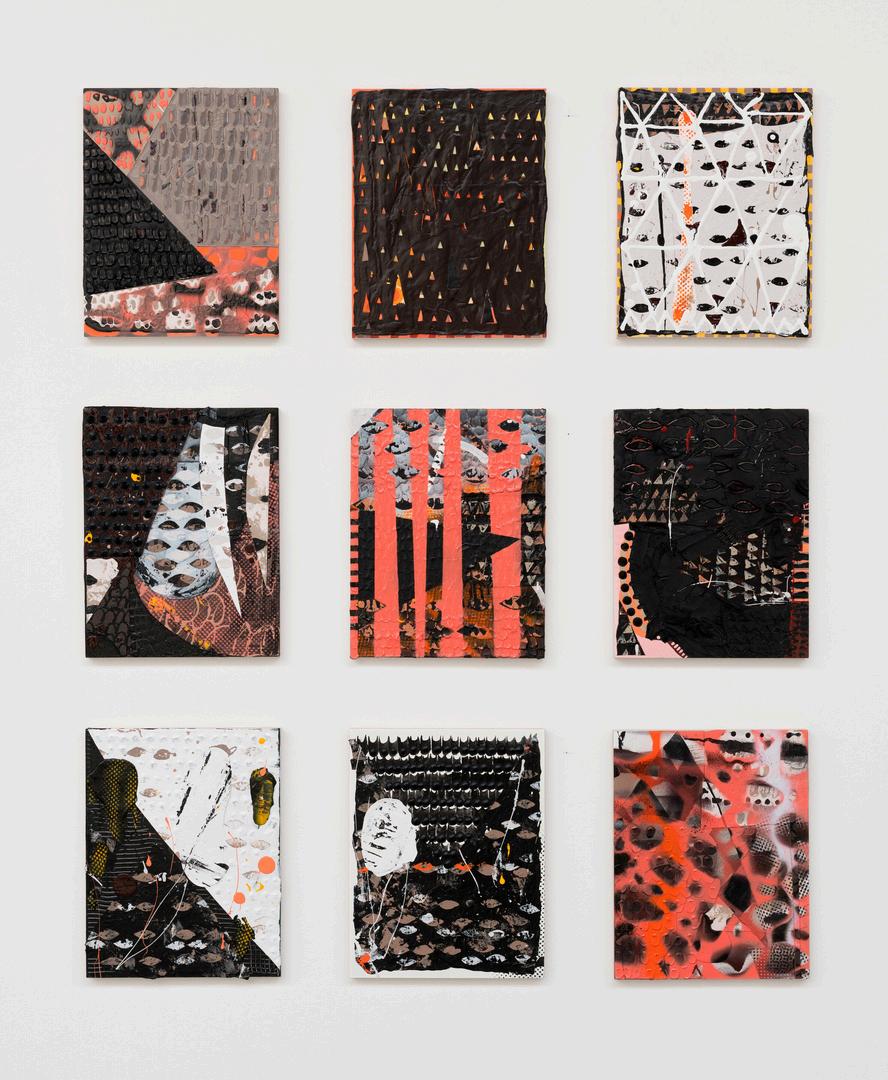

The irreverence of Neo-Dada is fully alive in Antonia Gurkovska’s abstract compositions from her Closed Circuit series (2024–25). Like Gurkovska, Charlotte Saylor explores this inheritance in Houseboat (2024), a folded and stained canvas textile embedded with found materials, including the artist’s own brushes Gurkovska explicitly references Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit (1955), while Saylor’s practice also embraces a gap between art and life

Simultaneously, Saylor draws on the vitality of surface and gesture found in Henri de ToulouseLautrec’s At the Circus: The Bareback Rider (1888), a rapid oil sketch on the vellum surface of a tambourine, where painting and the found object collide.

Formalism’s visual rhythms are embraced with perseverance and tenacity in works by Tony Lewis, Steven Husby, Austin Eddy, Alice Tippit, and Jae Ford. These artists perpetually investigate stabilities and disruptions, symmetry,

Saylor, Houseboat, 2024

asymmetry, dominant and residual structures reworking design tenants, prescribed orders, and value systems. Early modern abstraction in the AIC’s holdings, from Stuart Davis and

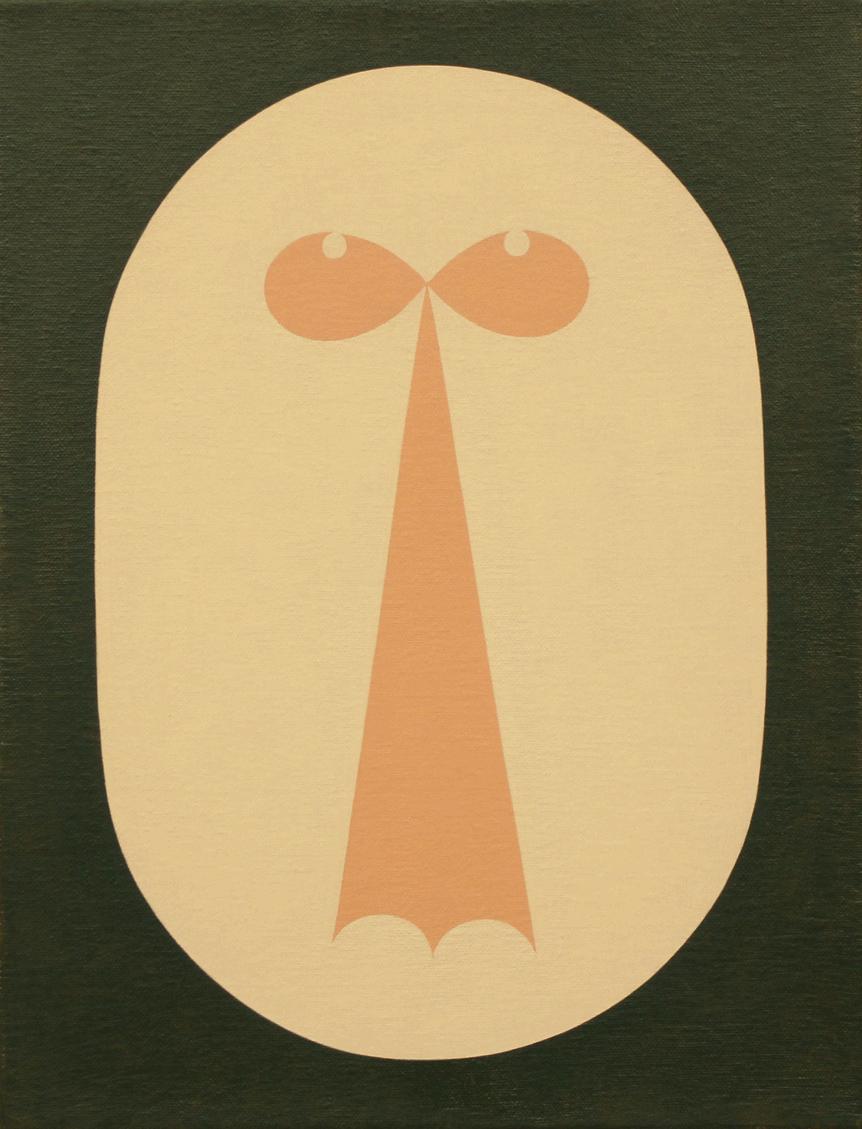

Georgia O’Keeffe to Minimalists like Frank Stella and John McCracken, offers formal and material vocabularies for artists to parse the temporal patterns embedded in social life, histories, and economies. While Alice Tippit’s Stone (2023) references Francis Picabia’s Untitled (Match-Woman 1) (1920), Tippit reorganizes Picabia’s portrait and its diagonal ground into a flat painting organized with perfect lateral symmetry Tippit’s Stone turns Picabia’s witty jab at portraiture into a universal sign that can circulate without origin or context. While Husby’s softly rendered acrylic shapes evoke architecture’s vertical predictability, Lewis’ dense clusters of graphite and colored pencil work probe messier entanglements each visualizing social metaphors: structure and faith for Husby, contamination and conflict for Lewis.

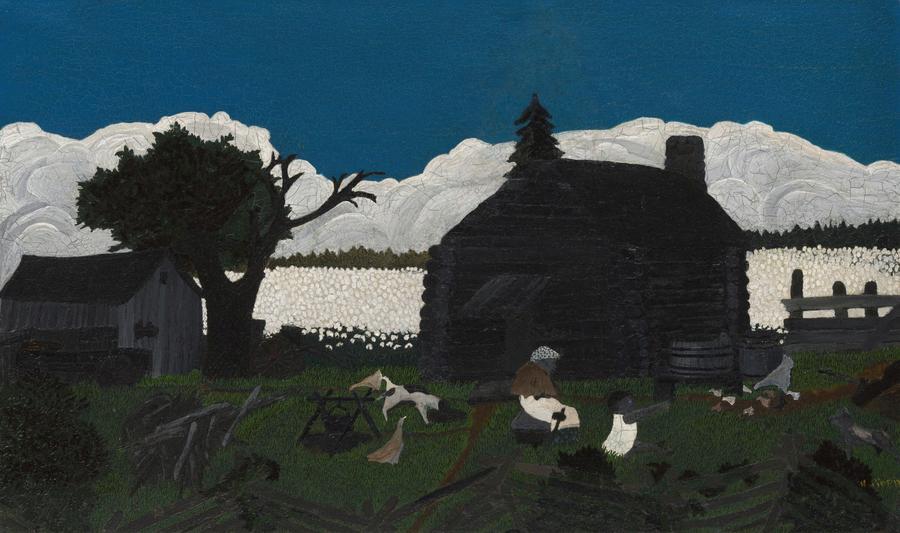

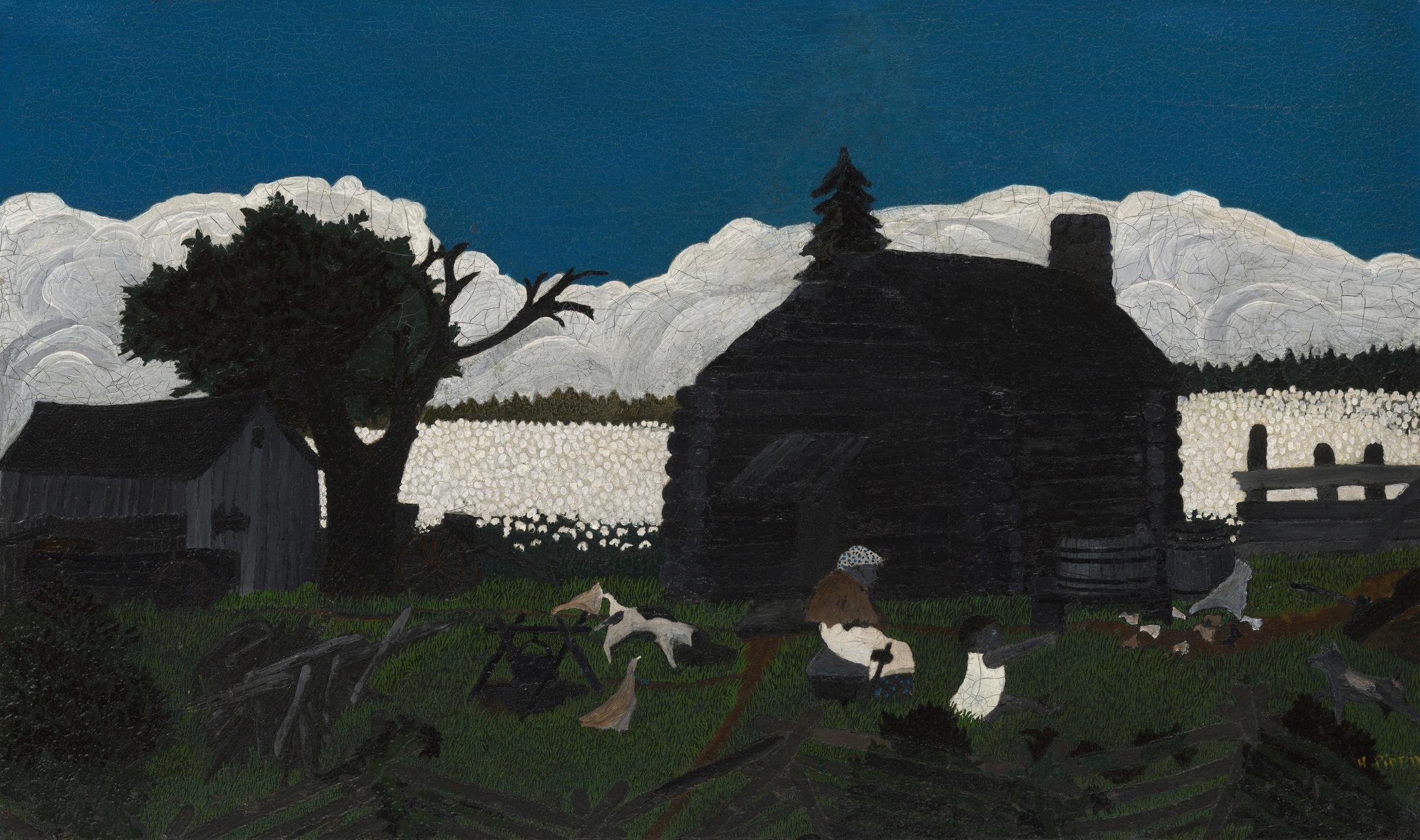

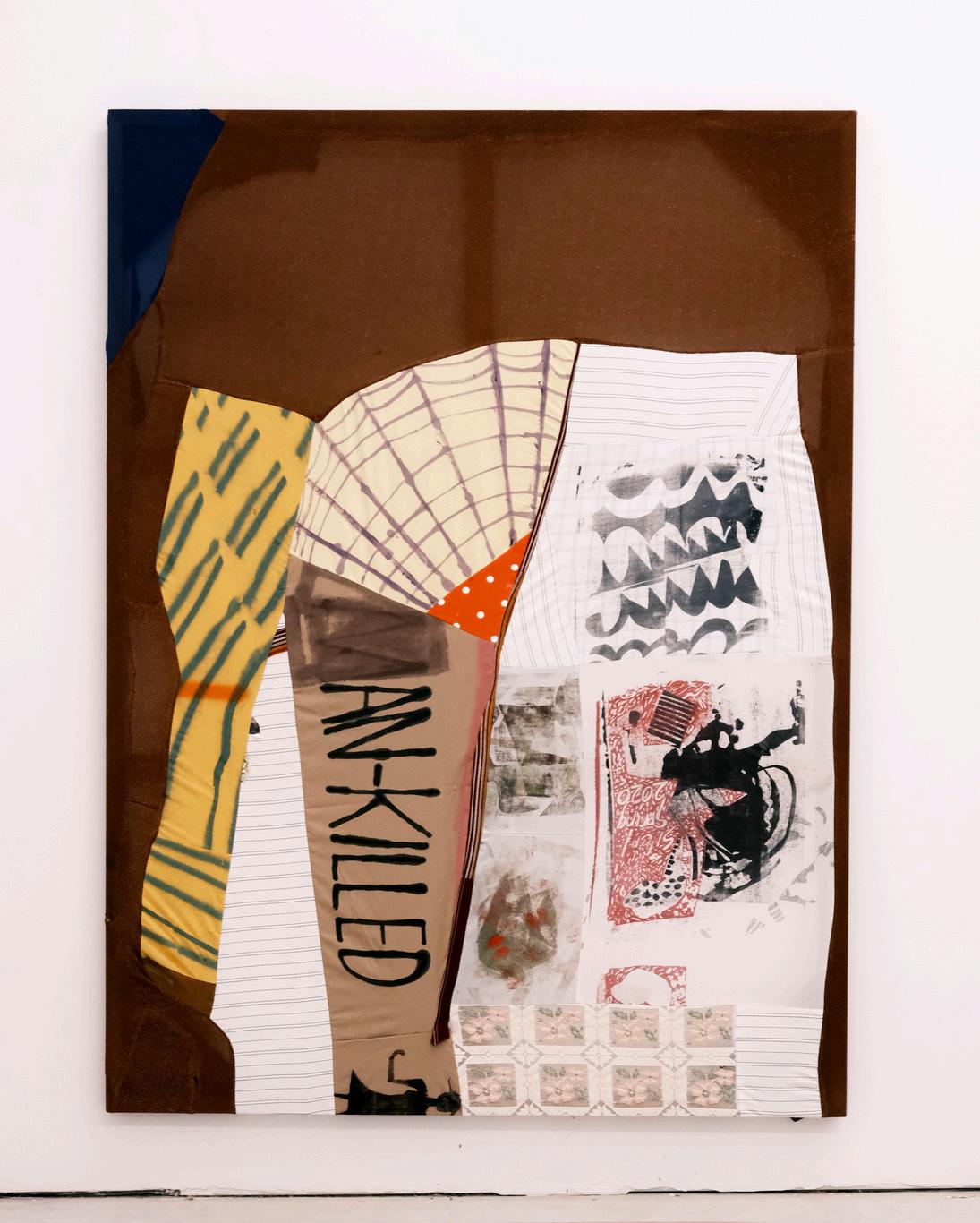

Less analogous but more politically explicit are works by Rodney McMillian, Kristoffer McAfee, David Leggett, and Molly Zuckerman-Hartung. While their work may not narrate endemic American histories like Horace Pippin’s Cabin in the Cotton (1931–37) or Kerry James Marshall’s Many Mansions (1994), they each share a commitment to revisiting historical injustices and the interrogation power Even Molly ZuckermanHartung’s reflexive One Lives Several Lifetimes in the Space if an Hour (2025) conflates notions of freedom with intervals of labor. While referencing Matisse’s Woman before an Aquarium (1921-23), a painting depicting a woman observing goldfish circulating in a fishbowl, Zuckerman-Hartung’s work, with its stitches, seams, and indirect printmaking processes cannot constrain the elasticity and subjective qualities of time.

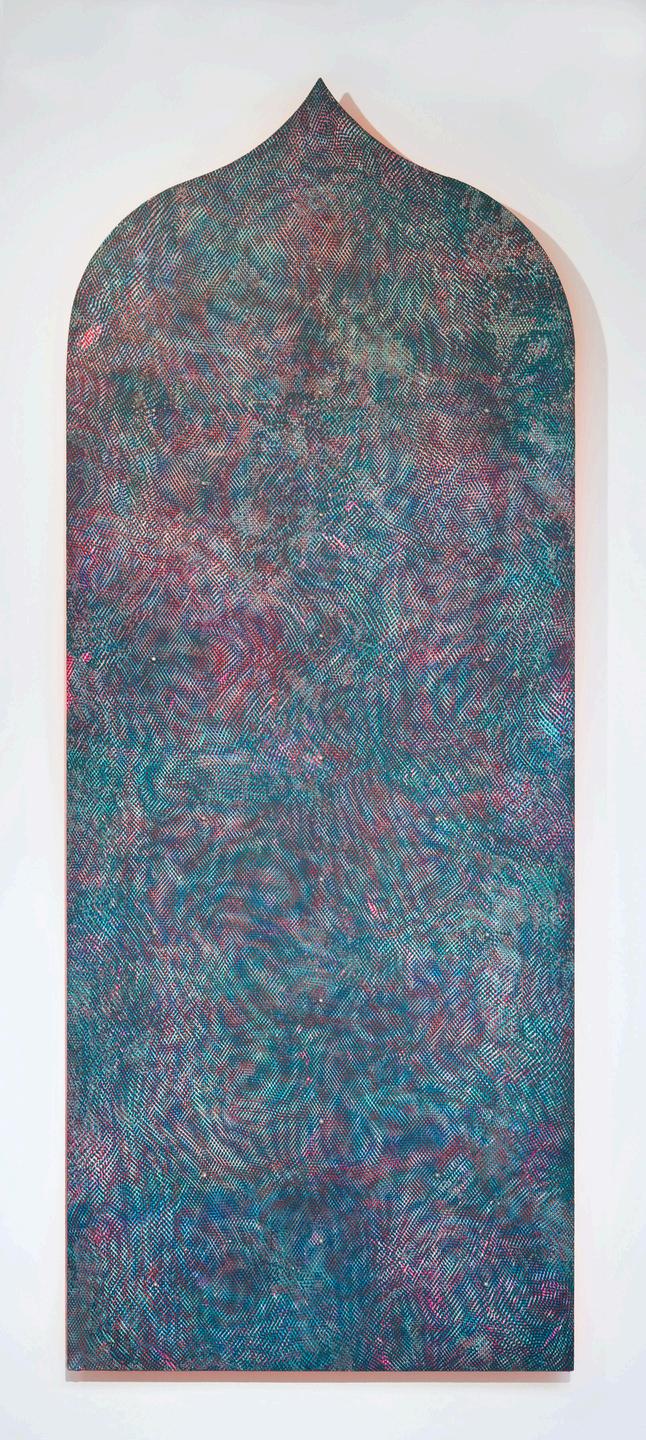

Many artists in the exhibition are drawn to specific specific works in the AIC’s collection not solely for formal or thematic alignment, but because they inspire deep attachments. These attachments may take the form of reverence, memory, admiration, or quiet devotion. For example, Sumakshi Singh acknowledges the contemplative arch

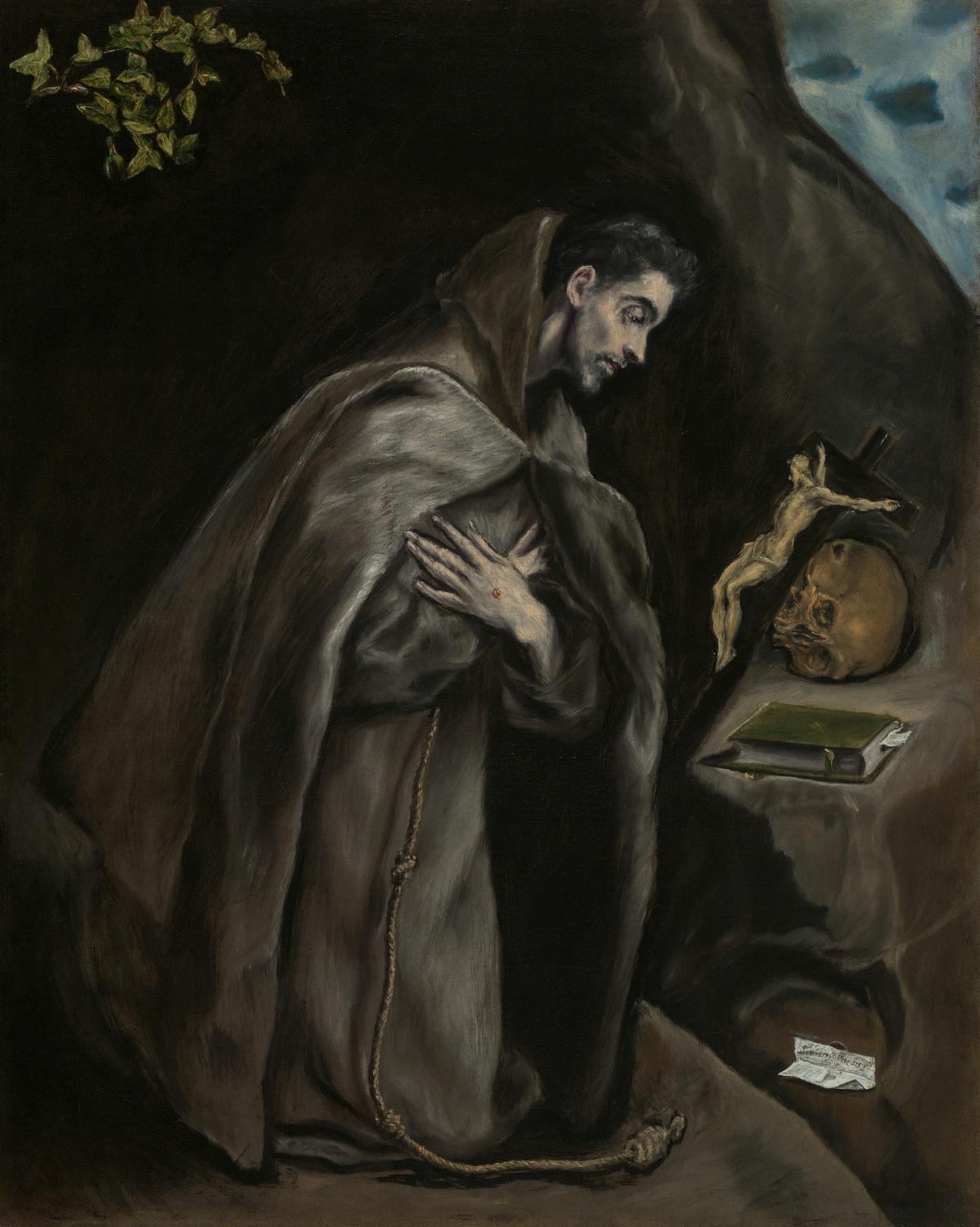

architecture of Tadao Ando’s 1992 gallery, a sacred space designed for reflection and aesthetic encounters. Em Kettner is moved by a pair of Coastal West African slippers (bata ileke, 1875–1925), Pedtro Trueba Ramírez by the Barcelona Chair for a canonical period in his move to Chicago, while Orkideh Torabi selects Katsushika Hokusai’s Self-portrait as a Fisherman (1835), and Cody Tumblin brings attention to Bob Thompson’s The Descension (1961) These references may not always map directly onto the artists’ formal practices, but they signal emotional kinships The same can be said for Aviv Benn’s selection of Charline von Heyl’s Interventionist Demonstration (Why-a-Duck?) (2013) or Celeste Rapone’s choice of Gertrude Abercrombie’s Selfportrait of My Sister (1941) While the connections between practice and referent may appear loose, they are rooted in sincere admiration Emily Miller is captivated by the surreal imagination of Remedios Varo’s Still Life Reviving (1963), while Hiejin Yoo engages Alex Katz’s iconic window motif, scaling it down to explore intimacy and containment. The psychological intensity of Aliza Nisenbaum’s subject in Marisol’s Nighttime Porch (2024) finds a spiritual counterpart in her chosen reference, Rufino Tamayo’s Woman with a Bird Cage (1941), just as Ruth Poor’s Francis (2020) echoes the devotional power of El Greco’s Saint Francis Kneeling in Meditation (1595–1600).

Saunders concludes A Swim in a Pond in the Rain with a story told to him by a student: “Robert Frost came to a college to give a reading. An earnest young poet stood up and asked a complex technical question about sonnet form, or something like that. Frost took a beat, then said, ‘ young man, don't worry: work ’” Saunders weighs in and says, “I love this advice It's exactly true to my experience We can decide only so much The big questions have to be answered by hours at the desk So much of the worrying we do is a way of avoiding work, which only delays the (workenabled) solution So don't worry work, and have faith that all answers will be found there ” In a footnote Saunders’ makes a correction to this student account by stating that, “A few years later, a frost scholar came up after an event and offered a gentle correction What Frost had actually said, (he said) was: ‘Young man, don't work: WORRY?’ Well, that's true, too (Maybe worry can be a form of work.) But if it’s true for you, I endorse that advice too. Go forth and don't work. WORRY.”

In the spirit of Saunders, and all who contributed to this exhibition, we are reminded that the work of others offers not only reference, but dialogue. These materials are not static artifacts they are active agents in our thinking and making. Engage them closely as they are among our most vital tools.

George Saunders, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain (Bloomsbury: New York, 2021) p 383

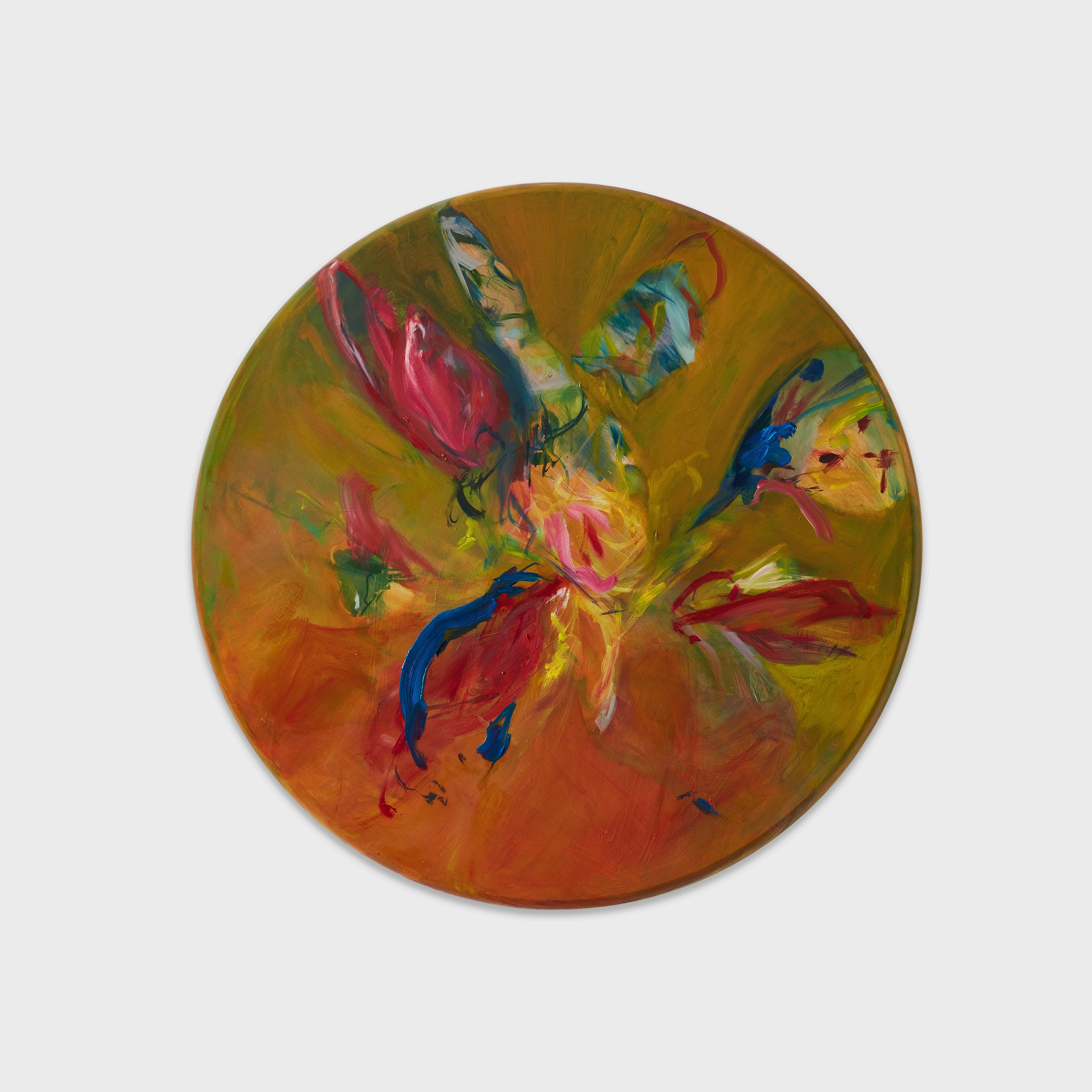

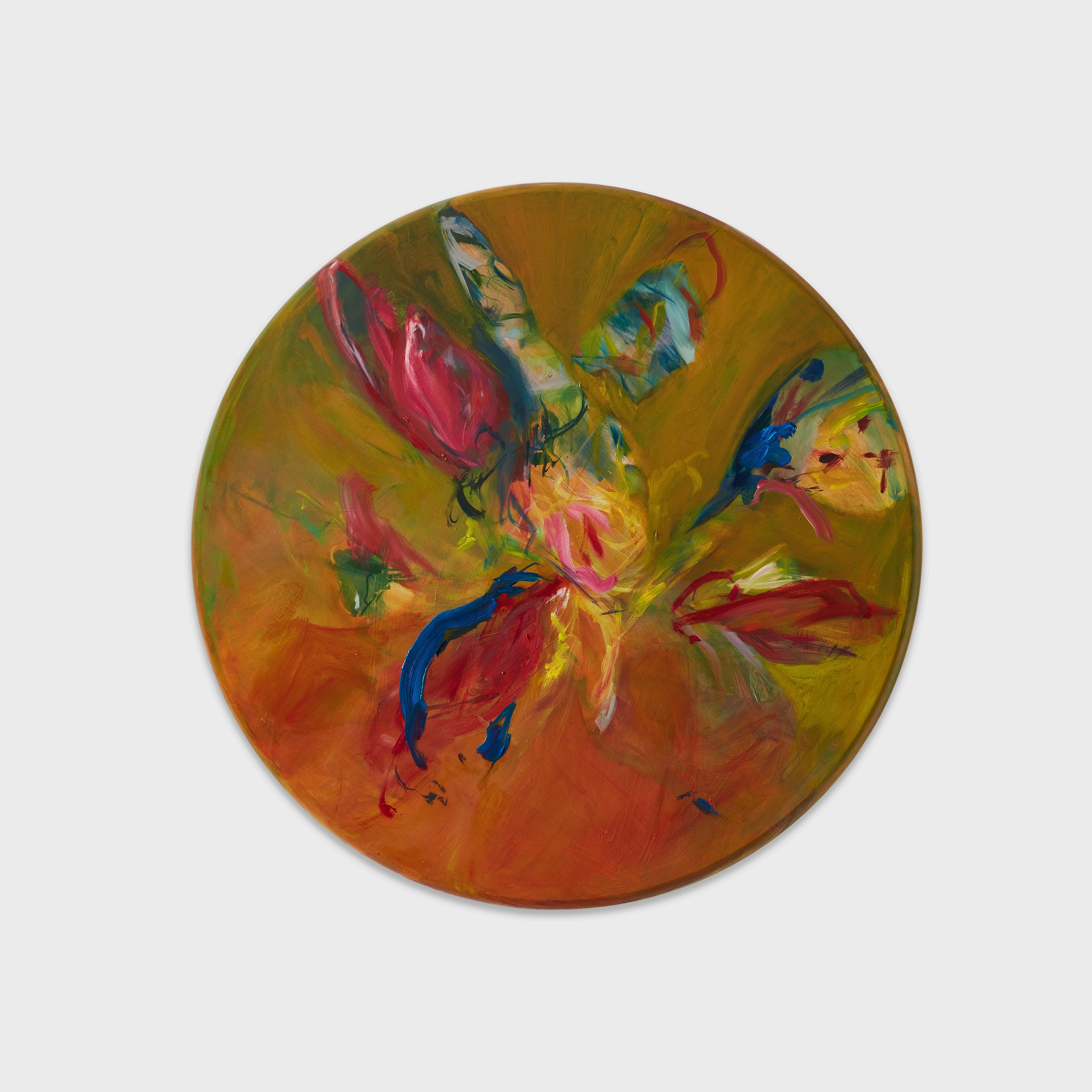

Lindsay Adams MFA ‘25

If it is possible to suggest flowers rather than represent them, that is how Lindsay Adams has painted A thousand lights of sun, 2025 There is some vestige of the traditional still-life, grounded in the implied horizontal of a table with shadowy hues of bluish grey beneath The upper background is vibrantly multicolored and expressive, reworked many times over by the artist Warm reds, ochres and streaks of light blue could denote an infinitude of flora reaching into deep space or something as inert as wallpaper Atop this color field, flashes of bright yellow, in the top half, and dark green, in the bottom, hint at petals shooting up or drooping forth Representation here takes its cues from the edgeless possibilities of the tondo format itself. The brushwork is free; pictorial space only just holds together.

For this exhibition, Adams’s selection from the Art Institute Collection is Claude Monet’s Irises, 1914-17, which, despite being twice the size, shares with A thousand lights of sun a delirious abundance of flowers painted in a manner halfway to outright abstraction, as well as an “allover” composition that fills the entirety of the frame. Monet did occasionally employ circular canvases, such as several entries in the iconic Nympheas (Water Lilies) series that date to 1908. In these, the curve of the tondo contrasts visibly with the many “horizons” implied by the water lilies as they recede into the distance This facilitates the Nympheas’ subversive deconstruction of landscape: reflections from the blue sky above produce an upside-down world that is in turn vivisected by the lilies, which remind us we are looking at the surface of the water detaching us from traditional perspective By Irises, we can no longer discern where the reflections end and the “real” flora begins, as the iridescent blues that perhaps correspond to the sky above extend well past any imaginable horizon into the foliage implied in the upper left half of the painting As Giverny was Monet’s experimentation sanctuary at the end of his career, Adams has spoken openly about her works corresponding to a safer, immersive Black space and time. The title quotes from a Langston Hughes poem:

“My hands!

My dark hands!

Break through the wall!

Find my dream!

Help me to shatter this darkness, To smash this night, To break this shadow Into a thousand lights of sun, Into a thousand whirling dreams Of sun!”

~ Daniel Ricardo Quiles

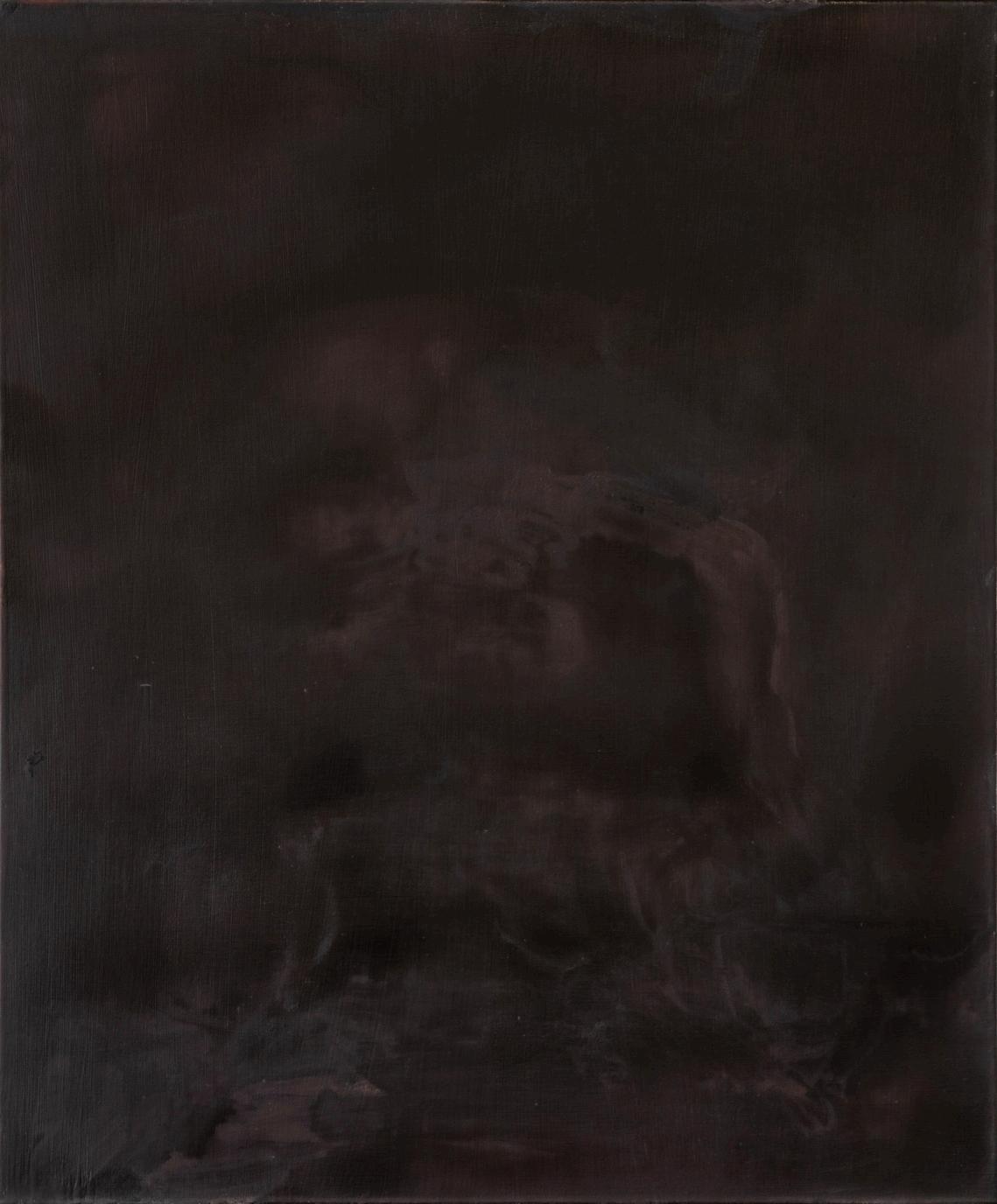

Noelle Africh

Africh’s paintings challenge our perception of what we sense and what we see, moving away from the idea of a single author imposing their will upon the material Subdued colors have seeped deep into the canvas, and the unstable components used by the artist pigment, calcium carbonate and animal glue (combined in a technique called distemper) grant the material its own agency. This resists simplistic definitions of abstraction or figuration, which is particularly striking in Flood from 2024, with its enormous depth of black and greenish colors. Despite their demanding presence, these works are fragile objects, subtly evoking their toxic predecessor (when lead was used instead of chalk), and are highly sensitive to temperature changes. Are we seeing figures, or is the material itself alive? How long will those works endure? There is a strange, even spiritual, quality to these pieces. This condition resonates with Luc Tuymans’ Angel from 1992, which also employs muted colors and ghostly presences. The seated angel’s face remains invisible perhaps only hinted at in shadow with wings that resemble stone, a harp in hands. What must have drawn Africh to this piece is Tuymans’ instinctive refusal to set boundaries between figuration and abstraction No light shines on or emanates from the angel; its meaning is elusive, and our gaze bounces back Are we the intended viewers, or are we merely witnessing a process initiated by the artists, but ultimately controlled by the materials themselves? In Africh’s and Tuymans’ works, appearance and disappearance seem governed by the painting, as if it decides what it will reveal This is both unsettling and captivating, drawing us deeper into an experience only the most skilled painters can accomplish

~ Mechtild Widrich

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Luc Tuymans, Angel, 1992

From left to right:

Not Yet, 2024

Distemper on linen over panel

12 x 9 inches

Worm in the Bud, 2024

Distemper on linen over panel

9 x 12 inches

Flood, 2024

Distemper on linen

23 5 x 19 inches

Sender, 2023

Distemper on panel

12 x 16 inches

Reliquary, 2023

Distemper on linen

20 x 14 inches

Hindsight, 2025

Distemper on linen over panel

20 x 16 inches

Loomer, 2023

Distemper on linen over panel

20 x 16 inches

Hindsight, 2025

Distemper on linen over panel

20 x 16 inches

Cruciform, 2024

Distemper on linen over panel

10 x 8 inches

Luke Agada

MFA ‘24

Broad ribbons painted in arresting colors stretch across Agada’s canvases. They loop into themselves or dwindle into tendrils. They’re not the only forms he paints: oblongs, ovals, and rounded-off rectangles appear too. I won’t call them biomorphic. This term doesn’t refer to color and has become a general descriptor of the kind of forms Agada paints. Alfred H. Barr, MoMA’s first director, introduced the word “biomorphic” into art history in 1936 The artists Barr had in mind were those who, like Gorky, were steeped in Surrealism’s heritage Acknowledging the unconscious; acknowledging memory that’s what Surrealist artists do A decade after Barr’s coinage, to paint The Plough and the Song, a nostalgic Gorky left his New York studio, returning in his memory to childhood, to Armenia, to the outdoors (farming’s yearly cycles of crops and harvesting) Agada’s Unstill Life: Elegy in Blue, however, stays indoors and attuned to color

That color is the blue the title promises. Where is it? Not in Unstill Life’ s upper third. Here, a warm, toffee brown (bounded in a large rectangle) dominates. Across it shoots a dark brown ribbon (it looks like a peacock’s feather). But the thick ivory band (the composition’s right-hand border) sends us back to that part of Unstill Life (its lower third) where we find the title’s color. A lightened-up ribbon of Prussian blue, slanted at an oblique angle, runs around an oval of dark brown the composition’s off-center focus.

All along, we discover, we ’ ve been exploring a room or more exactly, a “ room-space. ” The term is T.J. Clark’s, a British art historian drawn to oil paintings’ myriad effects. He coined “ roomspace ” in 2017 to describe the kind of interior that, he argues, became characteristic of the bourgeoisie and modernity For Unstill Life, I add to Clark’s identification of room-space a preference observed by the German critic Walter Benjamin among the same social class that fascinates Clark: the bourgeoisie of late 19th-century Paris Upholstery, lots of it, filled their room spaces Overstuffed, over-decorated, couches, armchairs, and cushions abounded They offer no “give ” Why not? Because they were defensive padding, Benjamin said, against what was outside To see such padding at work, look at the disgruntled youngster sprawled against icy turquoise seating American artist Mary Cassatt painted her (Little Girl in a Blue Armchair [1878]). In The Tea (1880), also by Cassatt, we see a couch used as a perch for two young women. To see what a room-space could provide, look again at Unstill Life’ s ribbon of blue.

The focus turns out to be a bed for a dog. The dog seems fast asleep: tiny curls of tan paint delineate closed eyelids. Creamy paint in Agada’s ribbons describe a long snout, elongated neck, shoulder, and just one descending front paw. Unlike the padding observed by Benjamin and depicted by Cassatt, this body makes a well in the cushion or mattress beneath. Agada does no more than evoke this: it’s where the ribbon of blue surrounding the dog deepens into shadow. That’s where the blue of the title is seen to give, is seen to welcome.

~ Margaret MacNamidhe

Selection from The Art Institute of Chicago collection: Arshile Gorky ,The Plow and the Song, 1946

Alberto Aguilar MFA ‘01

As a student and now faculty at SAIC, I have always found the museum to be a place of refuge. I have my favorite works and regulars I return to, but I'm more interested in making new discoveries As a resident artist at the museum in 2016, I created a video series titled "Formative Works," where I invited ten artists to take me to the piece that has most impacted their own practice I did this because I had become numb to the collection and desired to see it through new eyes

Through countless visits to the museum, I have been very aware of the work Red, Yellow, Blue, Black and White by Ellsworth Kelly. I could argue that it's not of particular influence to me, but that would be false since many things in the collection have subconsciously played a part in forming my artistic sensibility. Especially iconic works such as this. I really appreciate its simplicity, being made up of seven attached canvases painted in primary colors, black and white. In a way, it takes the ideas of Piet Mondrian even further by stripping painting of mark making altogether and minimizing certain decision-making aspects such as composition, thereby reducing elements of chance.

I was in Mexico City this past March and came across large sheets of colorful crepe paper which I used in a performance while there As this show approached I had the idea to hang sheets of this paper on the rafters of Secrist | Beach as a simple gesture that could also speak of my current location When I arrived at the papeleria on the final days of my trip to choose the colors for this installation, the work by Ellsworth Kelly came to mind I did a quick search and pulled up the image on my phone At that moment I decided I would mimic this painting This alleviated having to think about what colors to choose and allowed me to make a direct reference to a work in the museum Lately I have been thinking about the use of simple gestures to create maximal visual impact.

~ Alberto Aguilar

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Ellsworth Kelly, Red Yellow Blue White and Black II, 1953

on March 31, 2025,

Latifa Alajlan MFA ‘23

Latifa Alajlan and Joan Mitchell are both actively resisting normative perceptions of gestural abstraction Though working many decades apart, the color choices of these two SAIC graduates represent only the surface of their shared approach. At a much deeper level, both artists craft a balance between physical engagement and conceptual exploration, carefully expanding the boundaries of gestural abstraction to reflect their unique cultural influences and individual positionalities.

Alajlan’s What the Wind Left Behind -

ﺎﻣ provides powerful evidence that the observation of the world around us along with the labor of converting these observations into painting are not only inextricably linked to emotions, knowledge, and personal experience, but also cultural influences seeping into our consciousness. The all-over use of the canvas with bright acrylic colors dominated by warm yellow and orange, and ranging to light green and blue, is deceptive: patterns, notably one in black resembling an Islamic star, suggest a deeper connection between the artist’s vocabulary and her cultural heritage These symbols heighten the tension between spontaneous expression and cultural memory, inviting reflection on identity and place

Mitchell’s City Landscape (1955), with bright, expressive colors at the center of the canvas and enveloped by stone-grey rectangular forms, references the rapid changes of the post-war American urban landscapes. The “outside world” referenced in the title is interpreted intuitively, with the artist’s meticulous process resisting the dominant male narrative of Abstract Expressionism at the time. Both artists, through different cultural contexts, disrupt and expand the boundaries of abstraction, offering a fresh and deeply personal perspective.

Mechtild Widrich

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Joan Mitchell, City Landscape, 1955

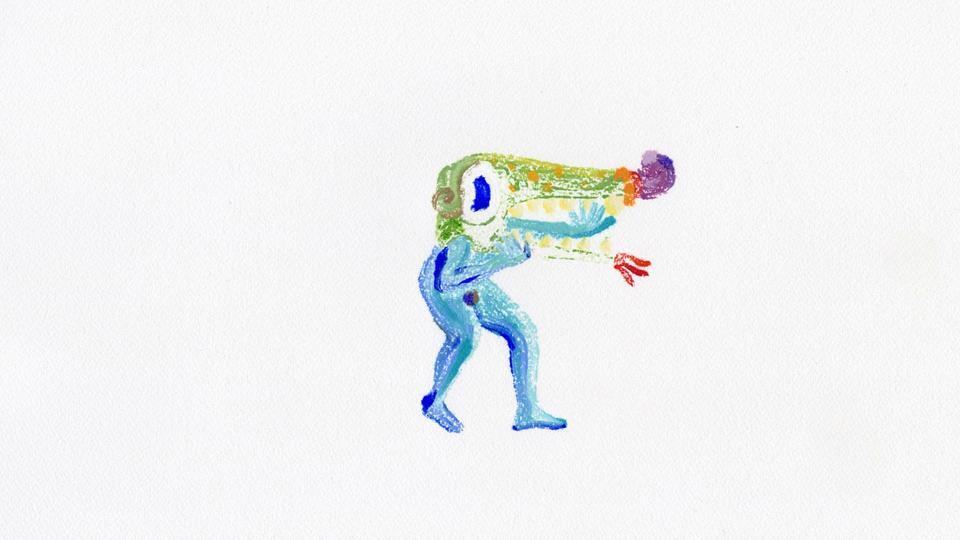

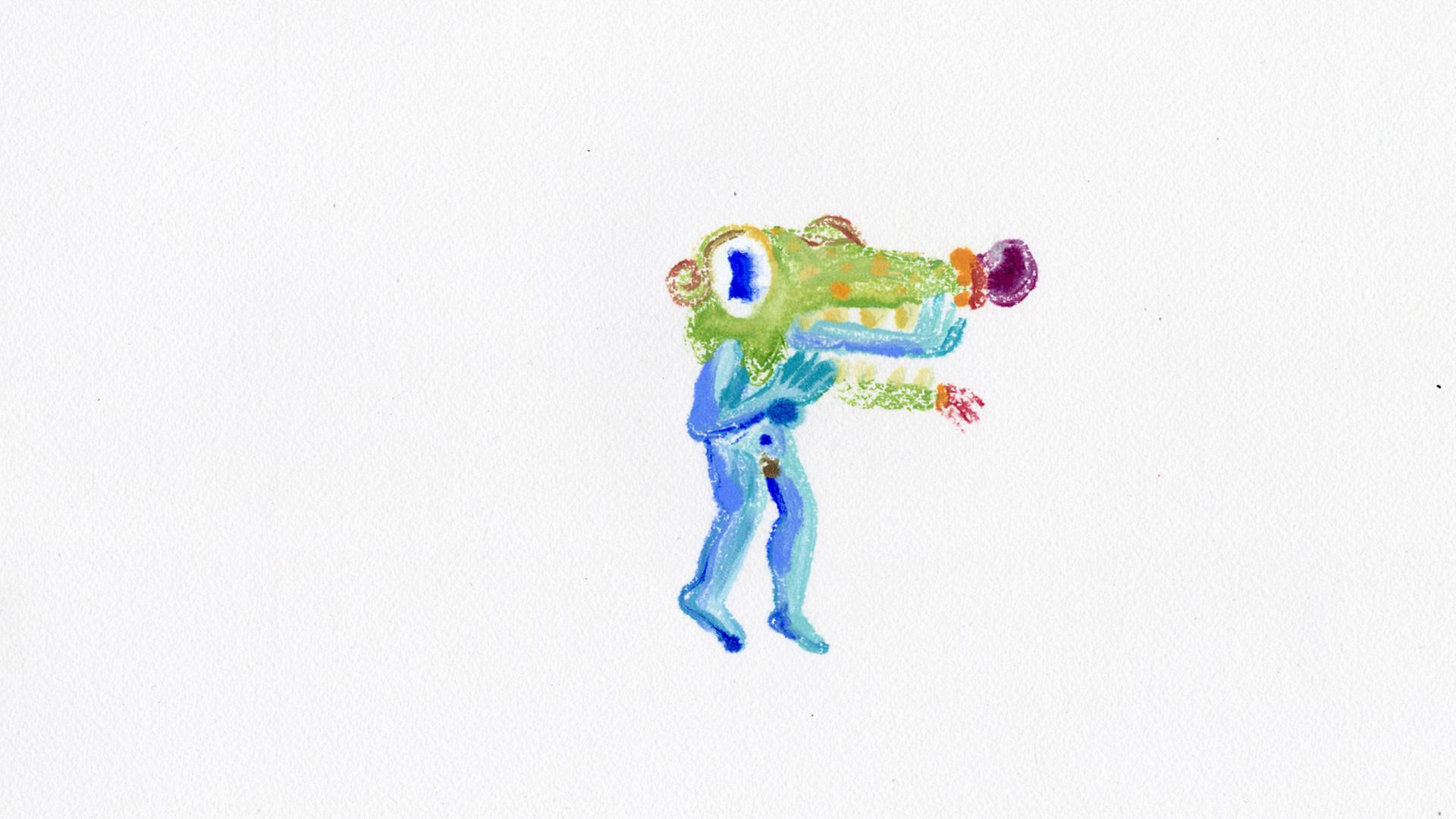

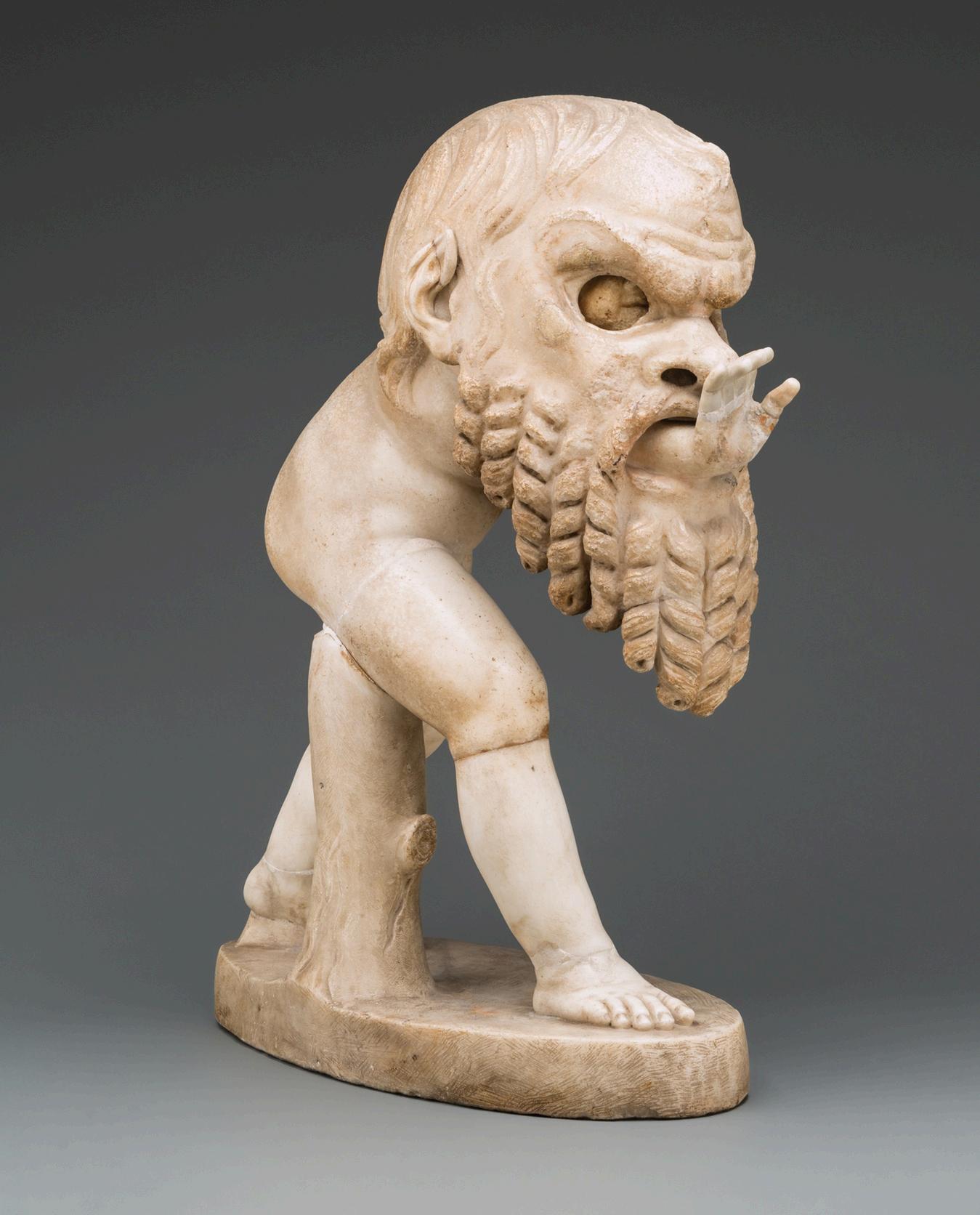

Cecilia Beaven MFA ‘19

Cecilia Beaven’s vibrant monotypes update a beloved sculpture in the collection of The Art Institute of Chicago. In Statue of a Young Satyr Wearing a Theater Mask of Silenos (1 CE–100 CE), a youthful arm reaches out of a gaping mouth. What has drawn this mischievous youth to the grotesque mask? We circle the marble, searching for clues. With his long, tendrilled beard, the mask of Silenos a companion of Dionysus, the god of wine and merriment wears life’s experiences on his furrowed brow We cannot know whether the young satyr is playing dress-up or if he finds himself entrapped within the old reveler’s guise

Born in Mexico City, six thousand miles from the marble’s origin, Beaven makes the ancient Roman sculpture her own In place of the young satyr posing as Silenos, Beaven has inserted a woman within the mask of Cipactli. An aquatic monster of Aztec mythology, Cipactli was an insatiable creature sacrificed by the gods and transformed into Earth, its green spine forming our mountain ranges. Like the young Roman satyr, the satyress plays with forces much greater than her, risking her innocence. In Beaven’s accompanying animation, the masked blue woman spins and spins, at once menacing and joyful. Even when viewed in the round, we are again left with more questions than answers.

Such creation stories lie at the heart of Beaven’s personal mythology. Across her multidisciplinary body of work, Beaven reveals what she calls “the fictional nature of the artist’s world.” Colorful humans costumed as imaginary animals inhabit her otherworldly landscapes. These hybrid forms reflect the artist’s diasporic identity, drawing from her experiences both in Mexico City and Chicago Like the Art Institute’s Statue of a Young Satyr Wearing a Theater Mask of Silenos, the connection between the inner and outer realms of Beaven’s creatures remains elusive Her masked figures underscore the ancient and enduring practice of identity performance After all, don’t we all wear a mask of some kind?

~ Francesca C Wilmott, PhD

Aviv Benn

MFA ‘18

Aviv Benn’s painting Glass Upon (2024) depicts a figure, multi-limbed and suspended between a moon and a sun, standing sentinel in tension between symbolism and abstraction The floating figure’s penetrating eye, which seems to be the source of its form’s vitality, serves as a focal point, with patterns emanating downward into ambiguous wing-like limbs Animated and restless, the creature engages with its surroundings as though negotiating its own place in an uncertain world. In this and other works by Benn, painterly scenes are populated with wideeyed figures confronting a volatile reality, offering a psychological reckoning through the interplay of vibrant patterns, shifting shapes, and bold colors.

This reckoning echoes, in a different register, the generative instability at the heart of Charline von Heyl’s approach. Her paintings construct meaning through contradiction juxtaposing disparate symbols, gestures, and references in ways that resist resolution. Rather than offering coherent narratives or fixed signs, von Heyl’s canvases stage collisions: between abstraction and figuration, language and image, intention and accident. This refusal to settle opens up an expansive visual field, where meaning is not located but continually reconfigured

In Benn’s work, that instability is transposed into an existential register Her figures emerge from the churn of symbolic forms not to clarify them, but to live within their fragility to make meaning amid disorientation If von Heyl’s compositions unsettle semiotic ground, Benn’s characters are shaped by that very ground’s volatility, their forms charged with the psychic labor of orientation in a world that refuses to hold still.

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Charline von Heyl, Interventionist Demonstration (Why-A-Duck?), 2013

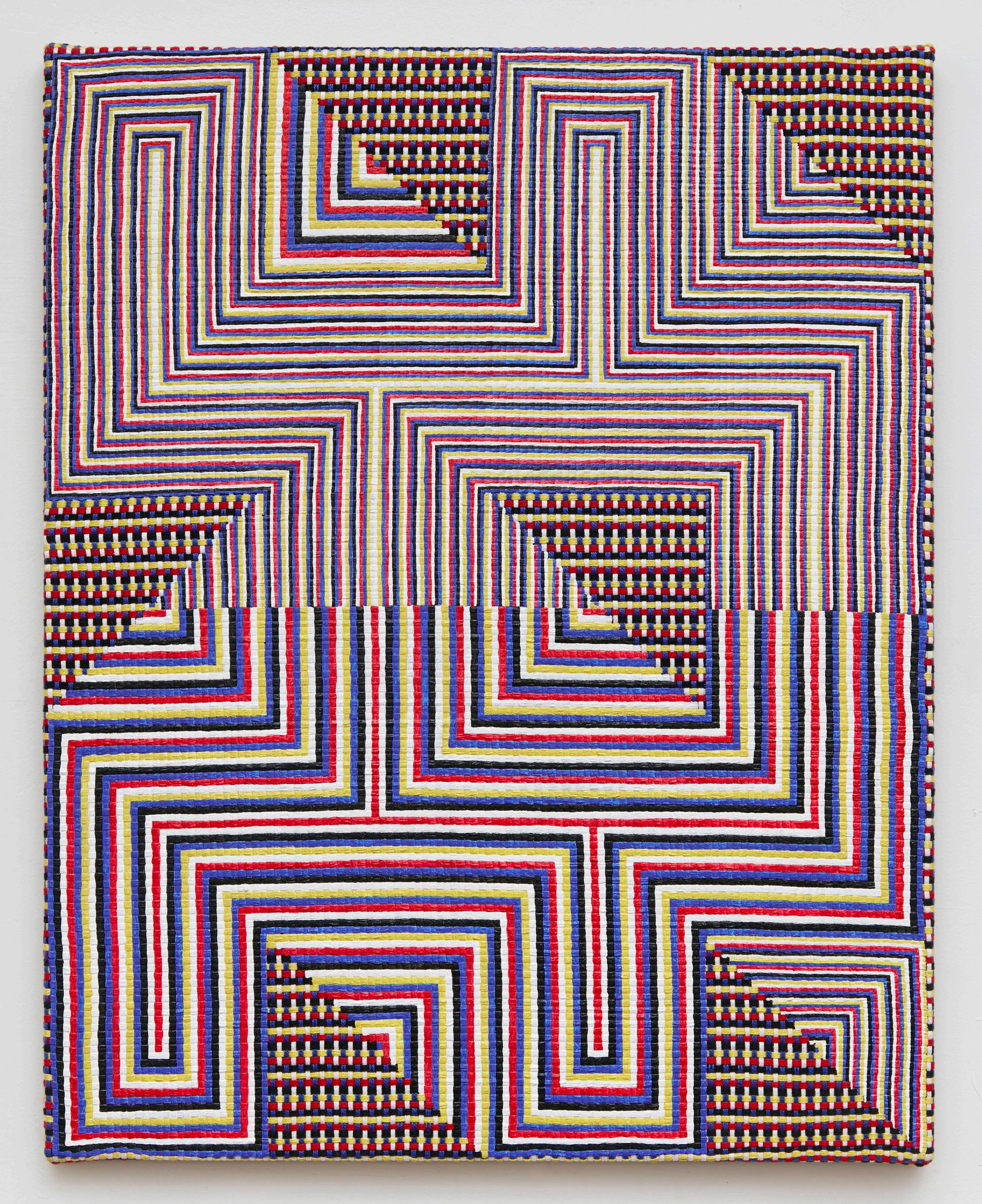

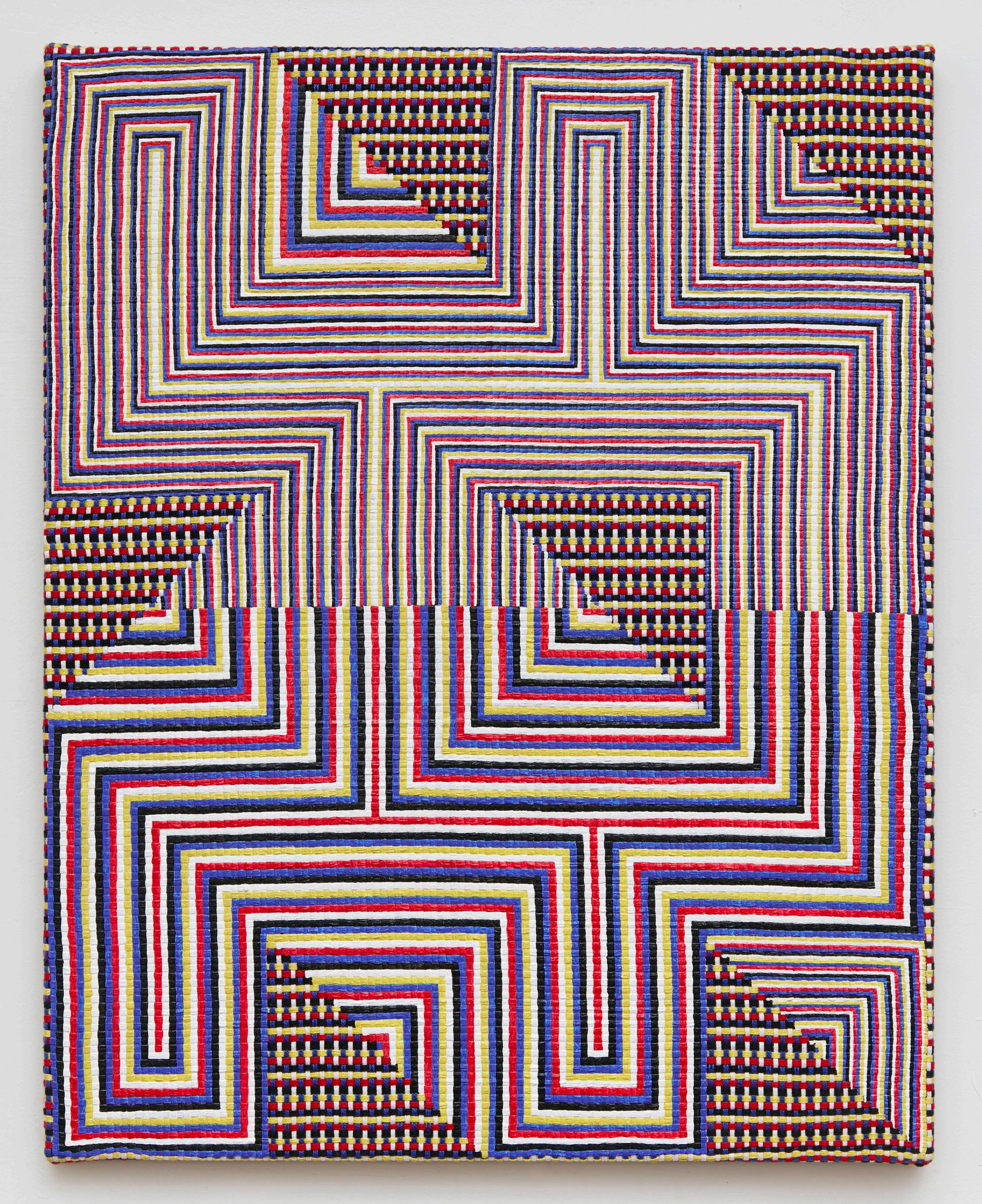

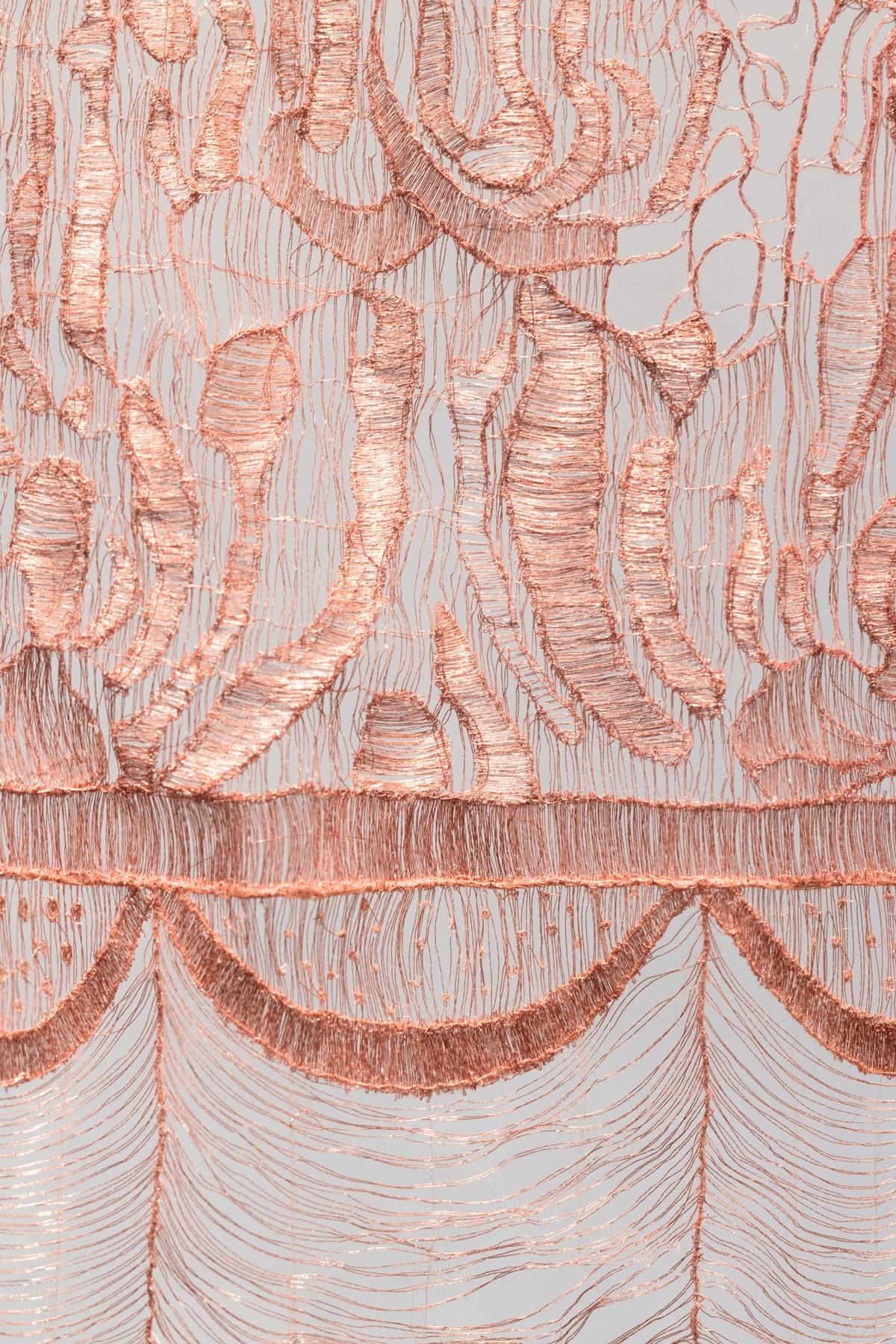

Samantha Bittman MFA ‘10

Samantha Bittman’s Untitled (2020) draws viewers into a mesmerizing interplay of precision and tactility. At first glance, the work’s geometric rigor symmetrical lines folding into tight labyrinths of color seems reminiscent of digital schematics or algorithmic patterns Yet, upon closer inspection, the illusion of mechanical perfection dissolves into something far more visceral Handwoven textile stretched taut over a wooden frame betray the labor-intensive process underpinning each rhythmic curve and acute angle The application of acrylic paint adds another layer of tension, masking portions of the woven surface while allowing glimpses of its fibrous texture to pulse beneath

Bittman masterfully juxtaposes the calculated language of geometry with the inherent materiality of weaving, setting up a dialectic exchange between the visual orderliness of form and the physical irregularities of craft.

This tension between the systematic and the sensuous finds a counterpoint in Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #118: 50 randomly placed points connected by straight lines (1971). LeWitt’s conceptual approach abstracts geometry to its purest terms: immaterial, cerebral, and transcendental. The drawing exists less as an object than as a set of instructions, realized anew with each installation. While both artists engage with grid logic and geometric seriality, Bittman’s work resists LeWitt’s near-immaterial idealism Instead, she anchors abstraction within the tangible, invoking the lineage of fiber arts and the embodied knowledge of handwork

~ Giovanni Aloi

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #118: 50 randomly placed points connected by straight lines, 1971

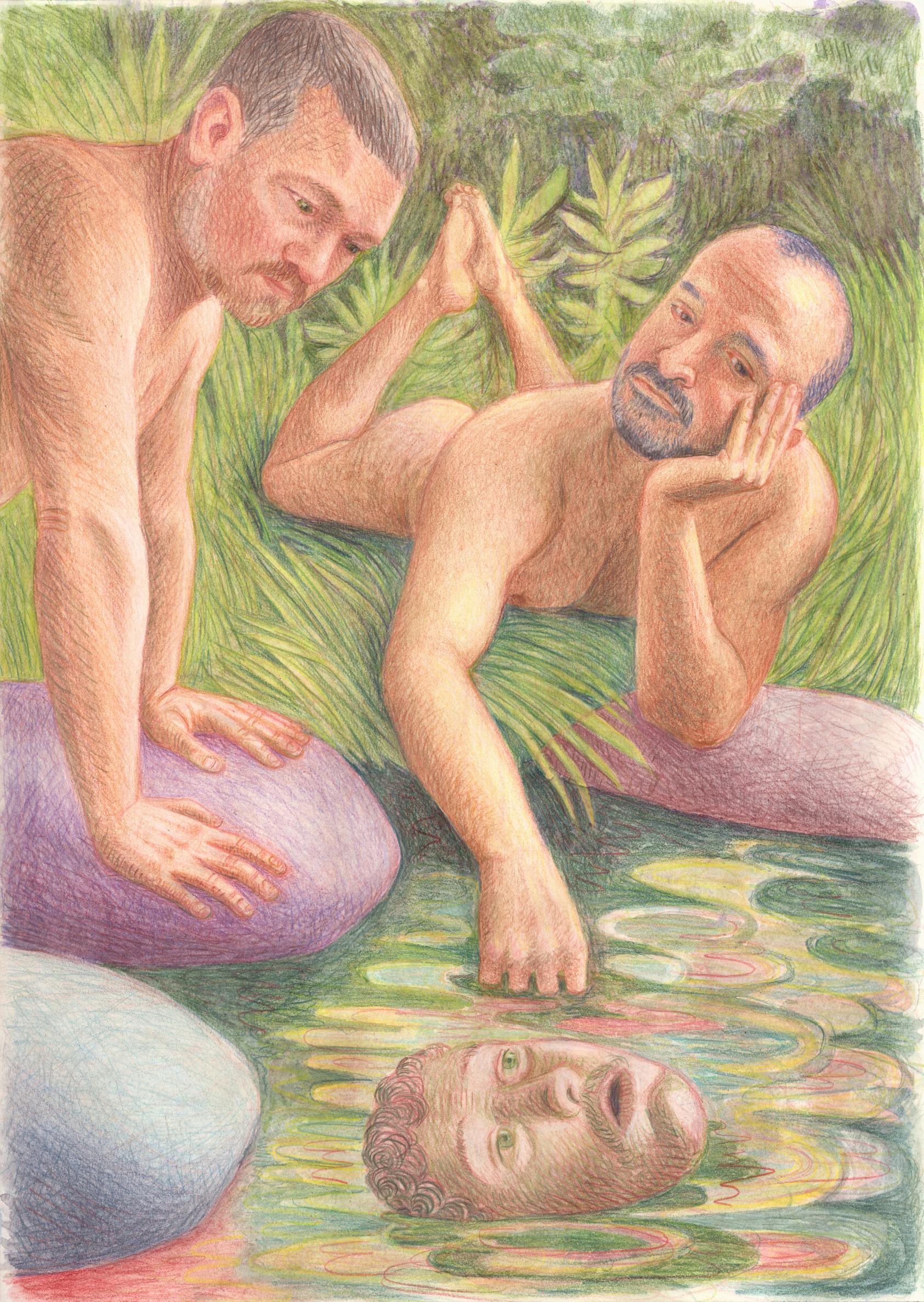

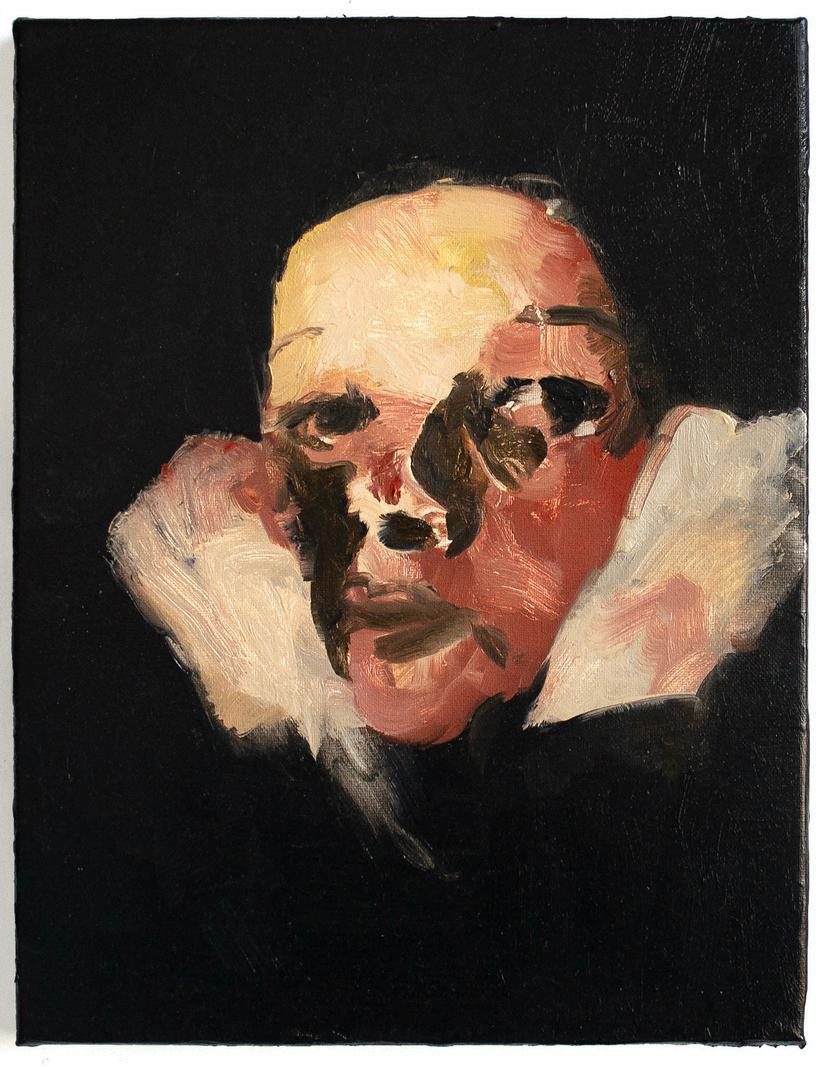

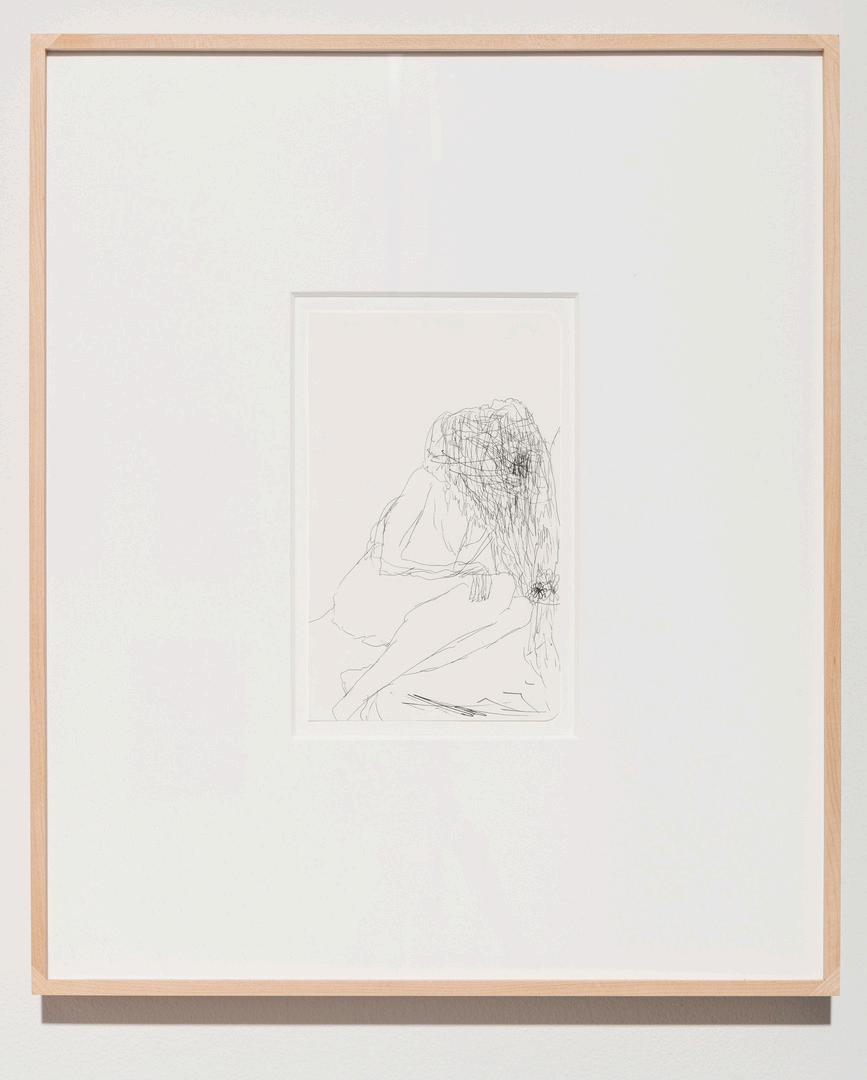

Elijah Burgher MFA ‘04

What is the relationship between decapitation and creativity? Elijah Burgher asks, pondering the myth of Orpheus, the poet, lover, and traverser of the underworld whose fate left him sundered. The juxtapositions contained in Elijah's question (decapitation/creation and thus destruction/formation, expiration/inspiration...) lend it the quality of a riddle. Head of Orpheus responds to that riddle. It's a subtly strange image: the drawing's balanced composition and the calm demeanor of the two nude figures the attentive artist and his languorous lover are in tension with an element of horror: a severed head borne by swirling waters. But it's not only Orpheus's head. It is, Elijah reveals, also the head of Hylas, of Kvasir, and of other mutilated figures, as well as of the artist himself Site of an intense syncretism, the head of Orpheus becomes something of an everyhead And this severed everyhead sings a seductive song from the midst of the silently whorling waters into which the artist's beloved dips his fingers, lost with his companion in a daydream, a folie à deux One may thus wonder: has the image of the severed head been conjured in reverie? Or has the singing head seduced the lovers, luring them to the waters of a dream? But it's not a matter of either/or: the lovers' shared daydream draws forth the severed head even as the head draws the lovers into a little shared madness The coincidence of an artist's inspiration and a poet's expiration resounds with another strange correlation: the linking of decapitation with the psychedelic waters of Paul Gauguin's Mahana no atua (Day of the God), where patches of color seem to shift like blobs in a lava lamp. In the mythic imaginary, water both kills and germinates, dissolving and giving rise to all forms. Water is death and water is life. Water anticipates forms and sustains creation, linking all things by disintegrating each thing. Gauguin's waters are a primordial fundament, a zone of indistinction, the depths of dream and the unconscious, a formless, fluxuous chaos, an amorous realm of fluidity and fusion in which everything comes and comes apart. Another name for this liquid is love, the universal solvent. Love cuts, love liquefies, love dissolves. To lose one's head in the swirling waters of love is to be seduced by the poet's song, inhaling the fermentatious breath of death in the act of conjuring images To draw is therefore to return to the fundament, to sunder oneself, becoming another So what is the relationship between decapitation and creativity? The riddle's solution is dissolution falling apart to come together in a dreamspace where to love is to lose one's head is to draw is to decapitate is to touch the waters of chaos from which all images emerge

~ Jeremy Biles

Robert Burnier

MFA ‘16

Matene Mi estos en Ordo, Mia Amiko (Ho Sinjoro), 2022, typifies a working method that Robert Burnier has perfected over the last decade: acrylic color contrasts organized on thin aluminum sheets that are intricately folded, rolled, and crumpled into three-dimensional shapes “Neither painting nor sculpture” or perhaps both painting and sculpture they stage intergenerational conversations with Ferreira Gullar’s “non-objects,” Donald Judd’s “specific objects,” and postwar canons of “expanded painting” that now include Black luminaries such as Alma Thomas, Sam Gilliam and Jack Whitten The work at hand implies a series of inward folds from the corners of a flat sheet painted creamy white such that it resembles paper, that material opposite of metal The folds proceed in a counterclockwise spiral, building the work’s thickness, until a final flap, the only one painted ochre, folds over itself.

Teasing out the yellow nested in such a warm off-white, the ochre helps, in Burnier’s words, to “expand the sensitivity of color” via pairing or relationship. The artist’s selection from the Art Institute, Matteo di Giovanni’s The Dream of Saint Jerome, 1476, also models such contrasts, if we can look past representation to apprehend form. Coral-colored squares comprising the floor in the foreground pop against the dark grey rectangles of the upper two-thirds of the painting, decorating its walled background and yielding a shallow overall space for the figures. Ochre functions as an accent, clashing in different hues, against the coral as the color of four of the figures’ boots. In Saint Jerome’s dream, he is lashed by a heavenly council for preferring Greek and Roman sources to the Christian Bible a curious admission of guilt that nonetheless celebrates the Italian Renaissance’s revival of pre-Christian culture Christ seated in judgment on the far left decenters the vanishing point to the fountain at Jerome’s right, a sign of the destabilizing tension between oppositional modes of belief and representation

Burnier’s title is Esperanto for “In the morning, I’ll be alright, my friend (oh Lord),” a line from Marvin Gaye’s song “Flyin’ High (in the Friendly Sky).” Gaye’s song is also dialectically fraught, oscillating between the misgivings and hope associated with addiction:

“In the morning, I’ll be alright, my friend

But soon, the night will bring the pains

The pain, awful pain”

Esperanto is itself the linguistic site of a failed universalist project, a language made up of all other languages, something like a false or failed synthesis Yet failures haunt us because their dreams were unfulfilled and as such, could someday return when the world is ready

~ Daniel R. Quiles

Nik Cho

BFA, MFA ‘24

Nik Cho dreamily renders spaces like bars and banks of bathroom urinals in hot, vibrant warmth played against breathy blues, wicked greens, and flushes of orchid violet Populating these scenes are couples or groups of svelte young men rendered like Yves Saint Laurent fashion plates, each one pulsing with hesitant yearning Checkers, stripes, flouncy drapes, and radiant red grids translate the libidinous narratives of paintings like Cho’s Be Yourself No Matter What They Say, 2024, into flashing arrays of seductive color, pattern, and mood lighting akin to the color drenched vignettes of Barry Jenkins’ 2016 film Moonlight. That David Hockney and specifically Hockney of the 1960s would serve as inspiration for Cho’s work is evident; in fact, the youthful nerd twink Hockney of the late sixties with a taste for color-clashing striped jumpers would fit in with Cho’s tender boys with hands on each other’s thighs.

While it should be noted that many of Hockney’s paintings in the 1960s, after his relocation to Los Angeles, depict naked men in showers (sometimes together) and in bright-and-sunny backyard pools, as well as the bare-assed slumberer in The Room Tarzana, 1967, and a portrait of Christopher Isherwood and his partner Don Bachardy, painted in 1968, the same year as the Institute’s Hockney, the comparably more staid and conservative portrait of renowned art collectors Fred and Marcia Weisman in Hockney’s American Collectors, 1968, nonetheless share some of the ontological propositions that accompany Hockney’s depictions of figures embedded in and continuous with the spaces where we observe them Synthesizing the effects of the wide use of photography on new understandings about painting, with the legacies of abstracted figures from Hopper, Vuillard, Milton Avery, Tamara de Lempicka, and Marsden Hartley Hockney gets to LA amid a swinging sixties reckoning around the inciting flashpoints of Gay Liberation (not to mention protests of the US’s military involvement in Asia in and around Vietnam and organized Civil Rights movements). Sixty years hence, Cho’s paintings proceed from the risks and courage that were called for in that time to imagine, constitute, and inhabit shared spaces of belonging and intimacy like those he depicts.

Matt Morris

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: David Hockney, American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman), 1968

Be Yourself No Matter What They Say, 2024

BFA ‘14

I’ve always loved The Wedding, a tiny yet luminous painting by Jacob Lawrence from 1948. Its presence in the darkened galleries of the American wing brings light and optimism to America's complicated past.

The Wedding is a small painting, yet its colors are bold and its light is luminous. Its figures are rhythmic, and delight in rhyme with their environment Its narrative and scale is accessible Yet it’s not a setting and situation one comes across accidentally, both in its form and presentation this moment is cared for by both the artist and everyone involved in this wedding

I’ve been shaped by Jacob Lawrence’s ability to narrate a scene with such economy His openness and generosity is depicted through his ability to construct and depict scenes of everyday life with such simplicity In my own painting, Library #1, I attempted to weave an image together to depict a moment in time, using color and shape in similar ways.

This is what I’ve yearned for as an artist, to make images that evoke a sense of belonging, specifically a sense of belonging across difference. Jacob Lawrence is painting the African American experience during the great migration and Harlem renaissance; I’m painting multicultural America with all its internal conflicts and all its attempts at tolerance and solidarity.

Like Jacob Lawrence’s The Wedding, I hope that Library #1 can be an invitation to experience a sense of belonging, if only for a moment in time.

~ Alex Bradley Cohen Alex Bradley Cohen

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Jacob Lawrence, The Wedding, 1948

Jeane Cohen MFA ‘18

Layers of vibrant pigment cascade across the canvas, eschewing the delicate containment traditionally associated with botanical depiction. Cohen’s Rose Garden (2022) channels the energy of gestural abstraction to deliver a visceral reimagining of floral subject matter, invoking a sense of vegetal becoming roses not as delicate, idealized beautiful forms, but as shifting, dynamic entities, imbued with an elemental vitality that exceeds their visual likeness The artist’s handling of paint rejects decorative prettiness, opting instead for eruptions of color and texture that push the boundaries between growth and decay, chaos and cohesion

This approach finds resonance in Joan Mitchell’s City Landscape (1955), a work whose sweeping, luminous gestures shaped the remit of mid-century abstraction. Like Mitchell, Cohen treats the canvas as a living field a space in which paint encapsulates force, movement, and memory. Cohen’s palette dense crimsons, smudged greens, ephemeral pinks suggests petals, stems, and soil, without ever slipping into overt figuration. Here and there, among the free brushwork, fragments of floral anatomy emerge and dissolve into an organic flow.

In Rose Garden, abstraction frees its vegetal subject from the shackles of western iconography: the roses are stripped of their ornamental veneer, reconstituted as processes of flux and transformation. Cohen’s work inherits Mitchell’s liberatory aesthetic language but extends it toward a deeper inquiry into the essence of the vegetal, where form dissolves into sensation, and the garden blooms outline an unruly, immersive dimension rather than an object to behold

~ Giovanni Aloi

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Joan Mitchell, City Landscape, 1955

Paula Crown MFA ‘12

Paula Crown confronts the days that lie between Not the first day That is the Word the first touch, first mark, first sign, the first “in the beginning ” Not the last That’s the hour no one knows, a whitewash when dreams return to dust

Her painting Where Does Time Go? (2016) features churning layers of words, equations, colors, and brush strokes, each demanding attention before sinking below. As soon as I noticed the word “time,” I looked past it – she formed the letters with a negative typeface outlined by choppy strokes of white acrylic paint. She left the linen weave exposed in some areas and filled others with eight flicks of black paint, two blue marks, a red heart, and four more patches of red that vary in thickness and tint. Yet even these human touches struggle to endure.

Crown focused on revealing the destructive force of entropy through mathematics and markmaking. The term “entropy” appears at least once in what seems to be her actual handwriting, the same cursive script she might use to send condolences to a friend. This intimate moment, however, doesn’t reveal more than the impersonal equations Each touch blends emotion with belief

Sure, there’s a bit of René Magritte’s paradoxical give-and-take in any painting that challenges communication or, really, in all art that explores the contradictions of meaning But Crown doesn’t share Magritte’s sense of nihilism After we spoke, she forwarded a poem by David Whyte that resonates with the lament of Where Does Time Go? “I want to know / if you are willing / to live, day by day / with the consequences of love / and the bitter / unwanted passion of your sure defeat.” Here, the holy fall to their knees.

~ David Raskin

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: René Magritte, The Tune and Also the Words, 1964

Where Does Time Go?, 2016

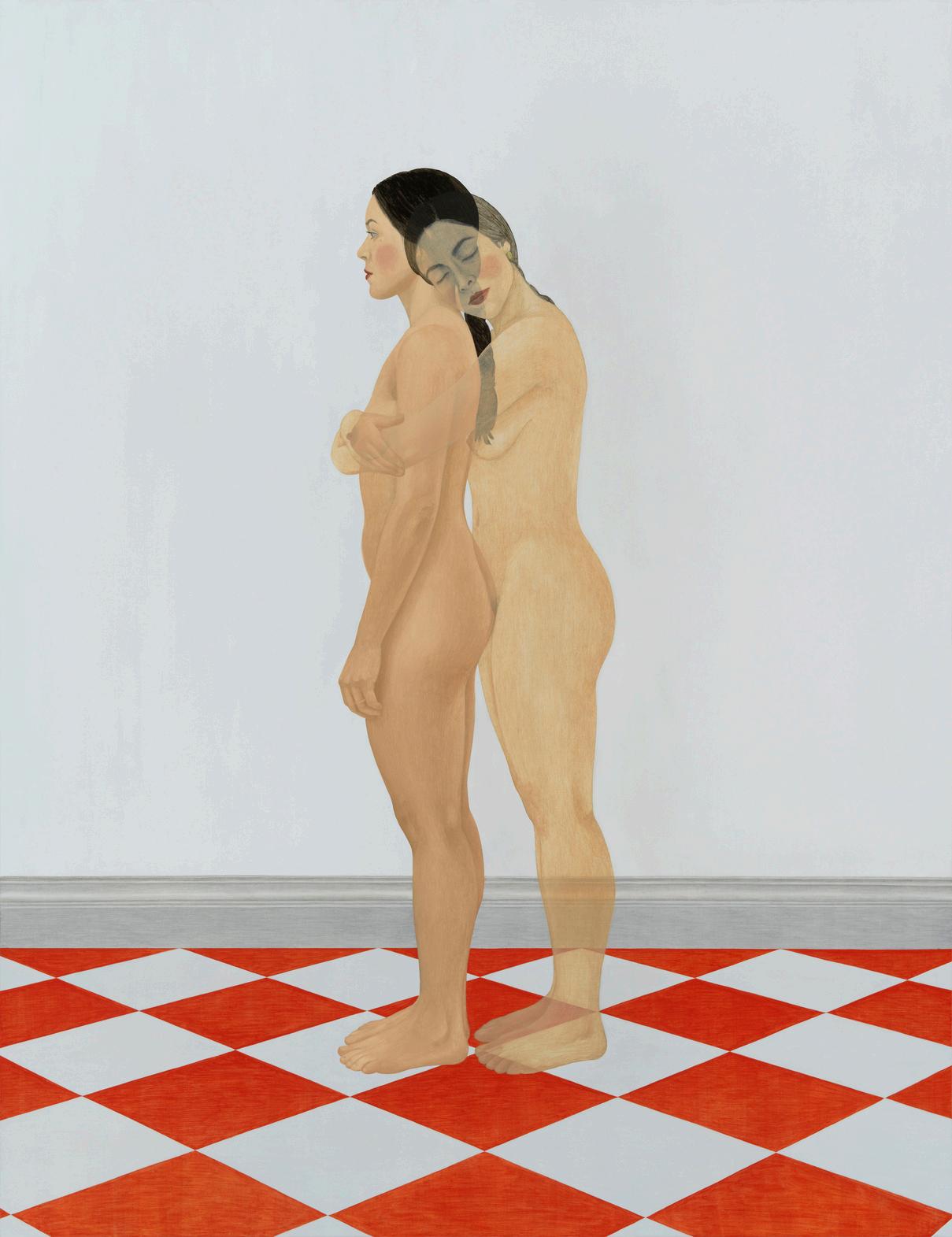

Chelsea Culprit

MFA ‘07

Bird’s-Eye View: Chelsea Culprit’s Devil’s Garden Escalante

Chelsea Culprit paints with an awareness of art history’s long shadow while simultaneously guiding us toward an experience of bodies as landscapes. Her work captures lived experience, emphasizing how each body contains a world how a body can become a monument, an archetype Inspired by the sandstone formations of Utah’s Devil's Garden, Devil’s Garden Escalante (2023) portrays dancers transformed into public monuments, imagined as geological formations

For over a decade, Culprit has explored representations of the dancer, the nude entertainer, the sex worker this recurring female figure allowing her work to evolve alongside her own experiences. Her figures have shifted from depicting particular dancers, as in Slow Monday (2014–2016), to becoming monolithic, standing in for others. “They’re like a feminist Mount Rushmore,” she explains of the figures in Devil’s Garden Escalante. Rather than being shaped by artificial adornments like plastic shoes, earrings, and synthetic hair, they emerge organically, built up over time like layers of sedimentary rock.

Having lived in Chicago for many years, Culprit considers the paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago to be her root influence particularly Edgar Degas’ The Star (1879/81), a work she returns to when reflecting on representation. “This is a man painting ballerinas but why?” she asks The painting raises questions: Who is looking at the dancer from this vantage point? Another ballerina? An instructor? A patron? Having trained in tap, jazz, and ballet herself, Culprit wonders whether she is the subject or the artist: “How do I represent myself if all the depictions of me are created by others?”

She approaches artists like Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Pablo Picasso with an initial appreciation for color, technique, and paint handling fully indulging in their visual pleasure But beyond that, she interrogates their deeper implications: What does this painting mean to me? Where do I situate myself within it? Their aesthetics are inseparable from the power dynamics and socio-political constructs that define bodies in space. These artistic choices are not neutral; they embody the structures that shape representation itself.

Ionit Behar

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Edgar Degas, The Star, 1879-1881

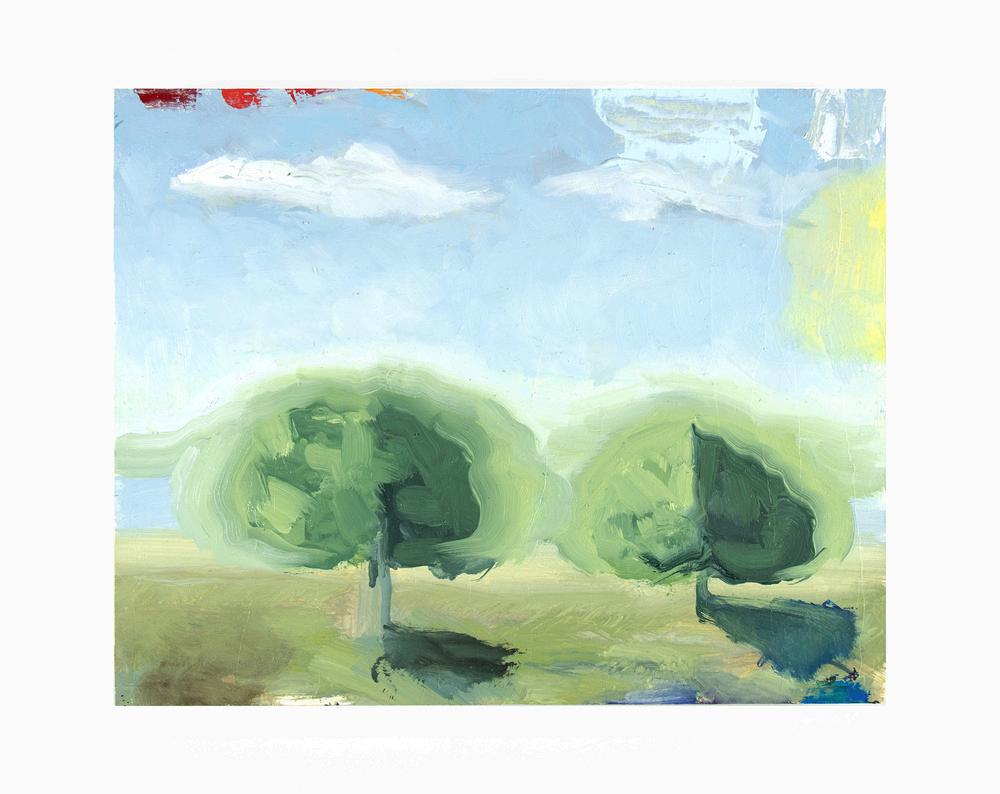

Tavin Davis MFA ‘23

A quiet, contemplative expanse, where soft pastel hues, thickly textured clouds, and vacant horizons evoke not only the vastness of physical landscapes but also the fragile architecture of solitude. Davis’s restrained brushwork underscores the precarious balance between isolation and introspection, drawing from a deeply personal relationship with the rural vastness of Montana. For Davis, the horizon operates as both boundary and threshold a liminal line imprisoning and preserving, an emptiness that paradoxically shelters the self The layered surfaces of his painting, built from oil and wax, become traces of endurance, marking time in the remote spaces he describes as simultaneously oppressive and sacred

This charged stillness finds an echo in Georgia O’Keeffe’s The Black Place (1943), a canvas encapsulating the vision of the barren New Mexican desert she adored O’Keeffe’s landscape, too, is devoid of human presence; her smooth, rolling forms border abstraction, speaking to the reductive clarity she sought in nature and in herself. For O’Keeffe, the desert was not merely scenery but a sanctuary an external mirror for internal solitude, an arena for self-reckoning and a shelter to retreat.

A trait that aligns the approaches of both artists might lie in their ability to transform the landscape into a terrain of the psyche, where vast emptiness becomes a conduit for reflection. In Davis’s painting, as in O’Keeffe’s, isolation is neither alienation nor loneliness but a heightened presence a solitary encounter that reaches into the depths of more than scientific archaeological registers, revealing a landscape as much of the soul as of the earth.

~ Giovanni Aloi

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Georgia O’ Keeffe, The Black Place, 1943

First row, left to right:

Day 68: Good Company, 2024

Day 83, Stone Cold, 2025

Day 71: Everything I've Ever Said, 2024

Second row:

Day 70: November's Actually Pretty Good, 2024

Day 67: The Painting Fell Into My Palette, 2024

Day 85: Care Free and Brain Dead, 2025

Third row:

Day 75: Bite Me (In Iridescent Blue), 2024

Day 49: Every Hour is Happy Hour, 2024

Day 74: Christmas, Texas, Alexander Beetle, 2024

Fourth row:

Day 53: Not Nature, Not Illustration, Not Picturing, Not Culture, Not Observation, Not Memory, Not Fiction, and Certainly Not Ironic, 2024

Day 64: The Worst October (Reflecting on the war in Gaza), 2024

Day 72: Visitor Center, 2024

Fifth row:

Day 73: The Big Rock Candy Mountains, 2024

Day 69: Laughing with a Stupid Face, 2024

Day 82: Behind the Sky, 2025

Dana DeGuilio MFA ‘07

“Lovely and ugly like a Tuesday morning”: On Dana DeGiulio’s paintings

Dana DeGiulio’s paintings engage with materiality in a way that feels deeply honest, unpretentious, and direct. They do not strive for grandiosity or self-importance but instead embody a kind of radical humility. Like an open system, these paintings are porous, responsive, and aware of their own limits. There is a kind of disembowelment at play, not in the sense of loss or destruction, but as an intentional refusal to be neatly packaged or resolved. The paintings hold space for doubt, embracing the messiness and unpredictability of material engagement. They are a deconstruction full of possibility, an undoing that carries with it a kind of optimism. In this space, painting is not about coherence but about presence and the physical existence of things This approach to painting rejects traditional notions of mastery; rather than trying to be something fixed or finished, DeGiulio’s work remains fluid Her paintings grapple with the scale of the individual in relation to larger structures “ no one makes anything alone,” DeGiulio explains

Man Ray’s Percolator (1917), housed in the Art Institute of Chicago’s collection, is what DeGiulio calls her “favorite painting ever. ” It is a small, enigmatic work that defies easy classification simultaneously ugly and beautiful, awkward yet eye-catching. For DeGiulio, its appeal lies in this contradiction, in its ability to hold opposing qualities in tension without resolving them. She describes it as being “lovely and ugly like Tuesday morning.” There’s a raw honesty to the comparison, a recognition that beauty isn’t always about polish or perfection but about something more lived-in, more real. Percolator, like DeGiulio’s paintings of roses, skulls, lemons, Judy Garland portraits, and more roses, don’t insist on significance or strive for grandeur; instead, they linger in the space of the everyday, embodying the strange, unglamorous poetics of ordinary but deeply felt experience.

~ Ionit Behar

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Man Ray, Percolator, 1917

Austin Eddy BFA ‘10

In Sky Above Clouds, O’Keeffe’s iconic skyscape, we see pastel orderly heavens, each cloud like a stepping stone to a shared vision. We recognize it. And yet, it’s better than anything we ’ ve actually seen from the window seat of an airplane. The wind effaces every cloud, changing it by the second, imperfect ovals But O’Keeffe has arrested that slow effacement, we are steady in her vision, we exhale The palette soothes with its serene blues, greys, whites, and pinks The hues of infant clothing, the pillowy softness

In Austin Eddy’s Full Moon, A Summer by the Sea, sea snakes wind through the moonlit sea, the opposite horizon from O’Keeffe’s lit sky And yet the pastels in both paintings reflect each other only Eddy’s mountain range hints at a darker essence. The pinkish halo around Eddy’s moon echoes O’Keeffe’s horizon line. The stony moon ’ s reflection becomes a pale peach in the sea. What’s below the surface in Eddy’s vision creates a full circle with what’s sky-high in O’Keeffe’s.

Maybe Georgia’s heaven is a careful symmetry of cumuli. Maybe Austin’s heaven undulates with seaweed and moonglow.

Eileen Favorite

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection: Georgia O’Keeffe, Sky Above Clouds IV, 1965

Stephen Eichhorn

BFA ‘06

In the aesthetic dissonance these images embody a lush, algorithmic bloom by Eichhorn and John Pfahl’s meticulous intervention on a weathered shed lies a shared meditation on the nature of seeing. Eichhorn’s floral construction, radiant against black, is an orchestration: botanical forms layered, spliced, and re-strung with a precise digital cadence. Lines slice horizontally through the garland, suggesting a latent rational system beneath the organic. Pfahl’s image, Shed with Blue Dotted-Lines, Penland, North Carolina from 1975, feels more reticent, yet no less deliberate. The blue dotted line punctuates the old doors like annotations, suggesting fields or trajectories, gently tampering with the supposed objectivity of the lens. In both works, there is a refusal to take the world at face value. Instead, what’s offered is a reconsideration of the photographic act as one of inscription, of undoing appearances to let artifice and order quietly emerge.

In both, the gesture is not about deception, but about attention Eichhorn and Pfahl do not impose upon the world; they enter into dialogue with it One through a digital baroque, the other through mark-making Their works remind us that an image is never passive It is constructed on intentional choices, cropping, framings, contiguities and interruptions

To see, then, is to intervene And in these subtle interferences floral, chromatic, linear we are drawn into the artists’ patient choreography: not of what is, but of what might be glimpsed when the eye lingers, when vision becomes an act of thought.

~ Giovanni Aloi

Selection from the Art Institute of Chicago collection:

John Pfahl, Shed with Blue Dotted-Lines, Penland, North Carolina, 1975

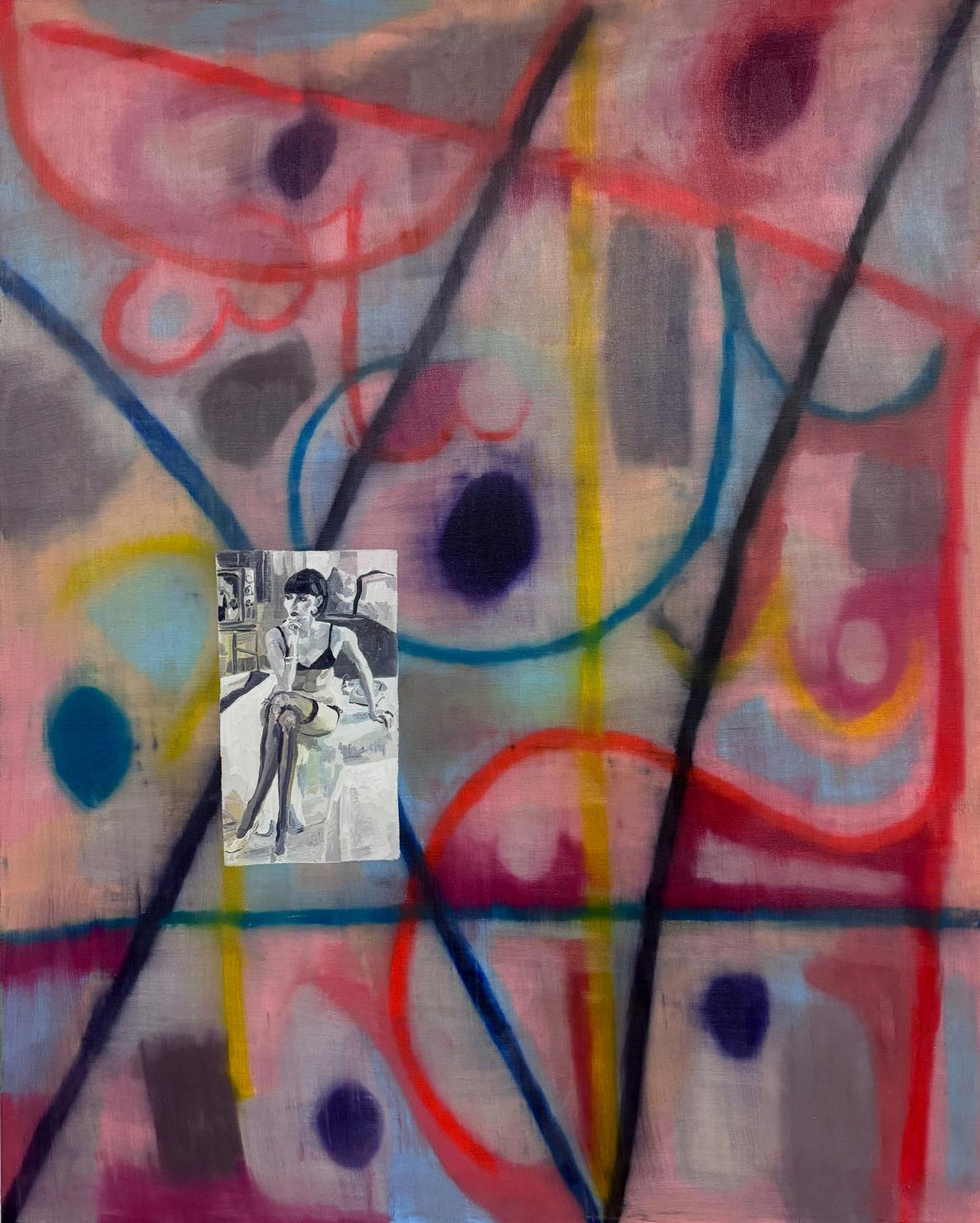

Peter

Fagundo MFA ‘02

In a 2024 interview, Peter Fagundo called painting a place to pose questions and take risks Fagundo engages Matisse’s Bathers by a River (1917) to question and redirect risk

Bathers, Fagundo’s interlocutor, was an unsettling shift for Matisse. In Bathers, Matisse sampled Cubism, and himself layering elements, over time, forcing viewers to look askew. Bathers, completed, differed from the original concept. Experts have concluded that Matisse reconfigured Bathers between 1909 and 1917 by overlaying rigid wide vertical breaks to parse canvas. One vertical column break, eventually black, was a blue river. This palimpsestic foundation undergirded the gradated transformation of a more conventional (i.e., safe) pastoral painting with five nude women into a more-Cubist painting with four nude female figures appearing stone-like. Matisse arrayed female figures, legibly abstracted, in the completed work within a thriving river landscape, with one woman being headless.

Inspired by Bathers, Fagundo’s Bone Machine (2024) also rests upon sampled layers Bone Machine, like Bathers, is parsed, but not with columns Instead, Fagundo’s piece has two curvilinear vertical lines referencing three pairs of curvilinear lines on the right side of Bathers Other more horizontal curvilinear lines intersect with these lines Within the spaces created by intersection are abstracted shapes sampling breasts in Bathers

Notable in Bone Machine is Fagundo’s inserted sample of Helmut Newton’s Viviane F, Hotel Volney (1972). The inset a painting of a photograph within a painting injects sex-gender into Bone Machine but without the risqué edge, making Newton a feminist bogeyman.