ANNE LINDBERG

Of all colors

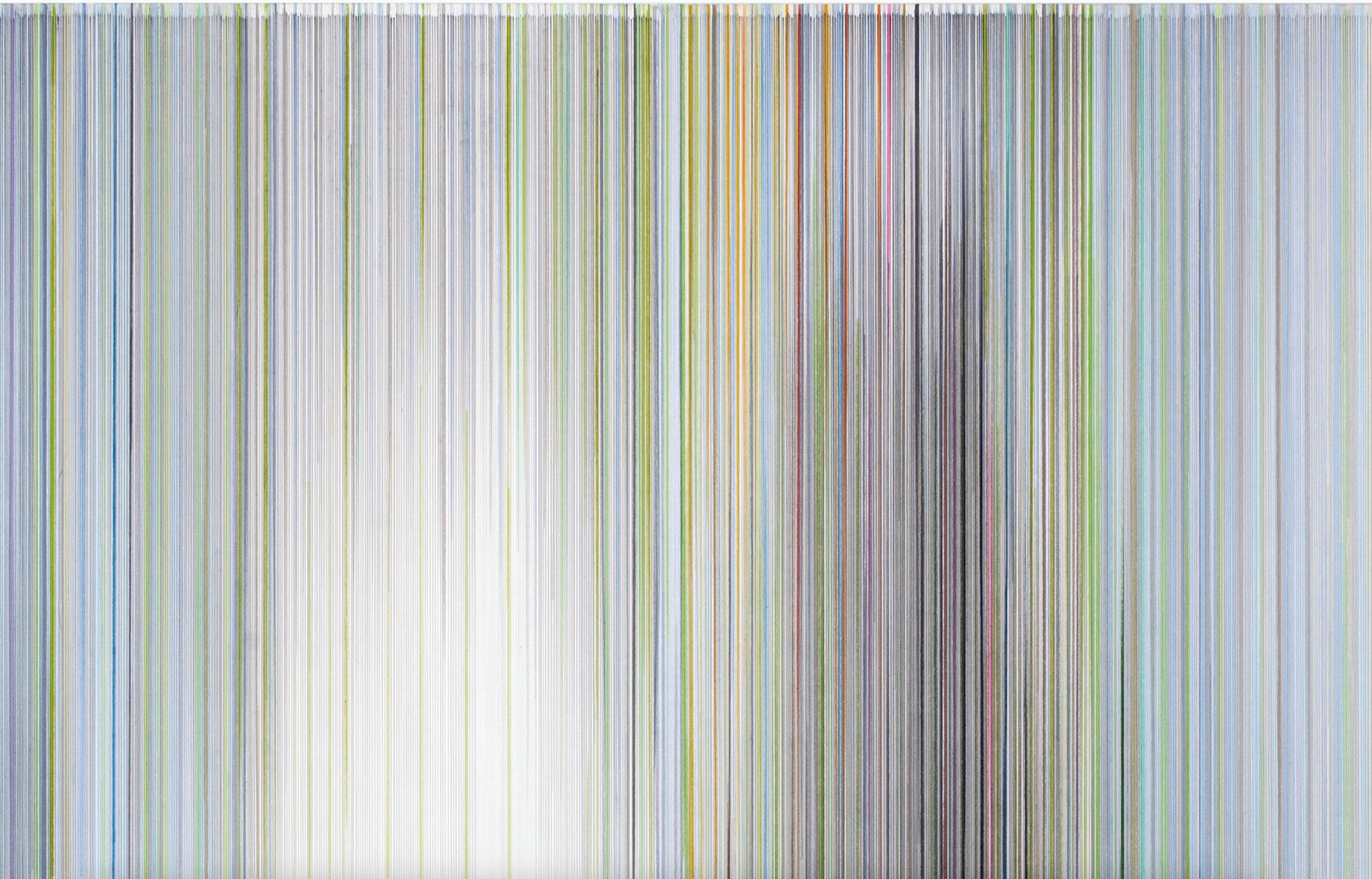

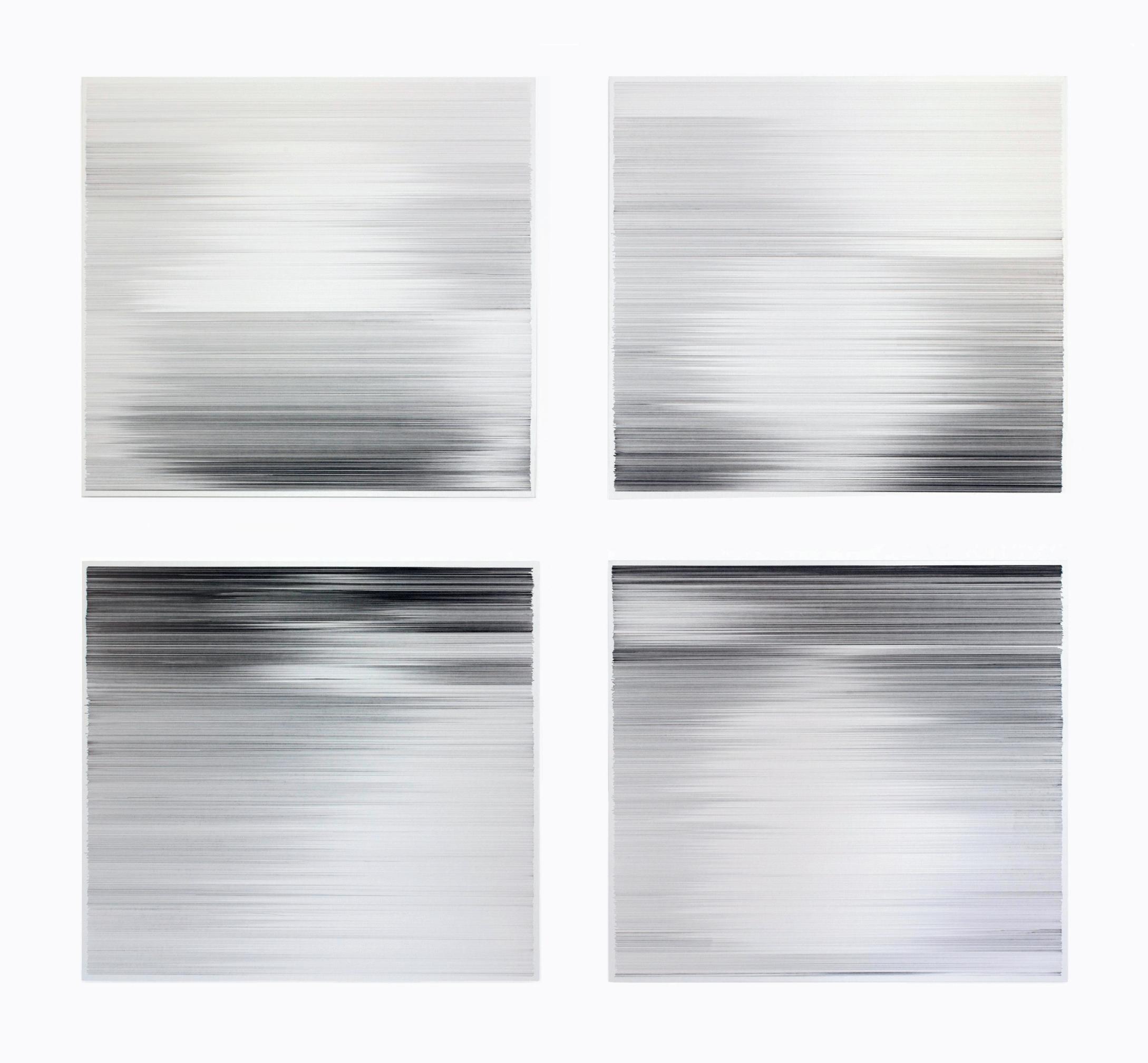

Cover image: altostratus (detail), 2024

all colors

ANNE LINDBERG Of

September 20 - November 16, 2024

Essay by Julie Lasky

Photographs by Nathan Keay

For Of all colors, Anne Lindberg created a sweeping horizontal sculpture made with thousands of lengths of fine cotton thread pulled taut from wall to wall under the gallery’s bow truss skylights. With a gap at the artist’s eye level, the form deepens in dark blue hues and gradually fades to almost imperceptible shades of white. Flashes of hot color appear to float within the gradient of blue. In addition to the installation, 13 new drawings made with graphite and colored pencil on mat board pick up elements compositionally and chromatically from within the thread installation. Ranging in scale and number of panels, Lindberg’s drawings explore the infinite and luminous possibilities of hue. Intermittent bold bands of contrasting color shifts imply a layered space while referencing changes in light that come with time of day, viewpoint and atmosphere.

Lindberg has long activated architecture with her siteresponsive thread installations. Her work is first experienced by the body, with intellect and perceptual analysis following. For Lindberg, space is a vital material, and just as important and rich with possibilities as thread, paper and pencils. Creating her architecturally scaled sculptures with thread is akin to working in the air, with the air and of the air to build a constantly changing experience. As she “stitches” the architecture, the airborne mass of delicate threads become filters for chromatic light, striking a voluminous pose with visceral results.

Stringing the Blues

by Julie Lasky

It is of course the sky. It is the sky’s pale deep endlessness, sometimes so intense at noon the brightness flakes like a fresco. Then at dusk, it is the way the color sinks among us, not like dew but settling dust or poisonous exhaust from all the life burned up while we were busy being other than ourselves. William Gass, On Being Blue

For decades, the Army Corps of Engineers has struggled to rationalize the Mississippi River, imposing rigor on the wayward, watery stripe as if it were a child with an attention disorder.

That is no way to treat a river, Anne Lindberg believes. In Iowa, where the artist was born and spent her childhood, the Mississippi forms the state’s bellied eastern boundary. “The river wants to meander, it wants to move, and we keep channeling it into this straight line, which doesn't make sense,” she says. “Controlling nature has had dire consequences.”

In 2022, she produced a 25-foot wide composition of eleven panels covered in shimmering pencil lines that seemed to float behind rigid ribbons of color. That work, ask the river what it carries, was introduced at the Figge Art Museum, in Davenport, Iowa, blocks from the Mississippi River. Blown apart and fragmented on the wall directly opposite it was a poem, “think like the river,” written by Ginny Threefoot, a poet who grew up in New Orleans, at the Mississippi’s terminus. Between this pair of expressions, each of which was developed in response to the other, stretched Lindberg’s sculpture breathe the river breath, an aerial hank of blue and yellow threads flaunting improvisatory streaks of aqua and green.

In Of all colors, Lindberg’s latest solo exhibition at SECRIST | BEACH, ask the river what it carries is back and surrounded this time by fellow subversives. Each work features the artist’s well-mannered linearity, the orderly precision of pencil strokes on paper, or in one powerful example, taut cotton threads suspended in parallel between walls. But as much as Lindberg’s art evokes order, it celebrates fluidity. Here, the primary engine is the color blue and color’s conjoined partner, light.

In unattainable hue, the 55-foot-long chromatic thread work that is the show’s centerpiece, a palette dominated by cobalt presents a snaky, protean counterpoint to engineered rigidity. As one passes the sculpture under the beautiful new gallery’s huge skylights, color as processed by the constrained eye and the chimerical brain turns the warp of Lindberg’s anchored threads into a dazzling wobble. Horizontal blue bands provoke inescapable ideas of ocean and sky, but then the color slips the bonds of convention and takes the mind over rapids.

What is that streak of blood red doing in Lindberg’s horizon? That furrow of Kelly green? The concept of an “unattainable hue” is attributed to Yves Klein, but it also relates to the idea of “impossible” or “forbidden” colors, a physiological quirk that produces colors in the mind that do not exist in the physical world. The eye confronts but is incapable of combining juxtaposed pairs of mutually hostile red-green or yellowblue and yields a private, subjective compromise. We believe we are in lockstep with fellow perceivers, envisioning a spectrum that can be measured in angstroms, but as with all questions concerning color, there is no telling how individual or collective our experiences are. Is my plum your plum? It is unlikely that we could agree on the exact color associated with the word “plum,” much less on whether that patch of purple is identical to us all.

Slippery color, slippery words, this hazy state is where Lindberg lives artistically, the visual and verbal being two sides of the same coin (or two walls of the same museum). Of all colors alludes to a quote from On Being Blue, A Philosophical Enquiry, written in 1976 by the novelist and essayist William Gass. Lindberg could have selected any number of fragments from that free-flowing meditation for her show title, but she picked a suspenseful bit of business: an introductory clause that offers, beyond its comma, to narrow the visible spectrum to a band of insight.

This is what the quote says in full:

Of the colors, blue and green have the greatest emotional range. Sad reds and melancholy yellows are difficult to turn up. Among the ancient elements, blue occurs everywhere: in ice and water, in the flame as purely as in the flower, overhead and inside caves, covering fruit and oozing out of clay. Although green enlivens the earth and mixes in the ocean, and we find it, copperish, in fire; green air, green skies, are rare. Gray and brown are widely distributed, but there are no joyful swatches of either, or any of exuberant black, sullen pink, or acquiescent orange. Blue is therefore most suitable as the color of interior life. Whether slick light sharp high bright thin quick sour new and cool or low deep sweet thick dark soft slow smooth heavy old and warm: blue moves easily among them all, and all profoundly qualify our states of feeling.

Gass’s thickly clustered adjectives signal the materiality he grants not just to the concept of blue but to language itself. In his description, language shimmers with the fluctuating interplay of words and referents, with memories and emotions. “A random set of meanings has softly gathered around the word the way lint collects…,” he writes in On Being Blue. “We cover our concepts, like fish, with clouds of net.”

This is what the river carries. Unstable color, which is inseparable from luminous meaning skittering off intentions and understandings. Twice (with lint and netting) Gass describes the haphazard construction of sense in terms of loosely assembled fabric, one an aimless refuse, the other an airy weaving. Is there a better example than clothmaking of humankind’s attempts to control the river-wild forces of nature?

Lindberg began her career diagramming weave structures in West African textiles as an intern at the Smithsonian Institution, and it seems no accident that the foundation of her work — those neat parallels — is that of a weaver warping a loom. “No English word has clean edges,” Joseph Conrad complained about the fuzziness of his adopted language. Lindberg’s art starts with clean edges, but these quickly dissolve. Her lines

thicken as her steady pencil proceeds over its long, guided course (“I’m breaking all the rules that architects are taught,” she says. “They’re taught to spin the pencil to keep it sharp”). Or they vanish into a spectral splash of white like features in an overexposed photo. Or they produce a visual buzz from the eye’s effort to take in the unseeable.

In Wallace Stevens’s poem “The Man with the Blue Guitar,” one of many literary works that Gass sews into his crazy quilt of references, blue is the creative medium in which the poem’s subject is immersed, fingers poised above the strings of the imagination (they are guitar strings, not cotton threads, but the parallel is compelling).

And the color, the overcast blue

Of the air, in which the blue guitar

Is a form, described but difficult, And I am merely a shadow hunched

Above the arrowy, still strings, The maker of a thing yet to be made;

Stevens is evoking Picasso’s The Old Guitarist. The musician is an avatar of the poet contorted within his creative sphere, blue a color not of open horizons but imprisonment in the self. Stevens has changed the color of Picasso’s resolutely brown guitar as its music waits to be actualized in the auditor’s experience, “a thing yet to be made.”

The color like a thought that grows Out of a mood, the tragic robe

Of the actor, half his gesture, half His speech, the dress of his meaning, silk

Sodden with his melancholy words, The weather of his stage, himself.

Far from lamenting, that meaning seeps, seemingly unbidden, out of personal experience as does the voice in these lines, Lindberg returns blue to the color of possibility and celebrates the relinquishment of control. She is energized by the vagueness of borders whereby we pass confidently from one state to another, from blue to yellow, from solid to liquid, from day to night without knowing exactly when we crossed the line.

“We all have some sort of internal understanding of what is day and what is night,” she says. “If you take a walk at twilight, there's this point at which you say, ‘Oh, I think I need to turn back because it's dark now,’” even if that critical degree of darkness doesn’t seem quantifiable. The difference is understood in profoundly imprecise ways. “I have a dear friend whose mother called the shadows at that time ‘the velvets,’” Lindberg recalls. “She said, ‘The velvets are rising.’”

Julie Lasky is a journalist, editor, and critic best known for her writings on design. She has been the deputy editor of The New York Times’s weekly Home section, the editor-in-chief of I.D. and Interiors magazines, and the managing editor of Print Magazine. She contributes to The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Architectural Digest, Elle Decor, Travel & Leisure, and other publications. She teaches in the graduate industrial design program at Parsons School of Design.

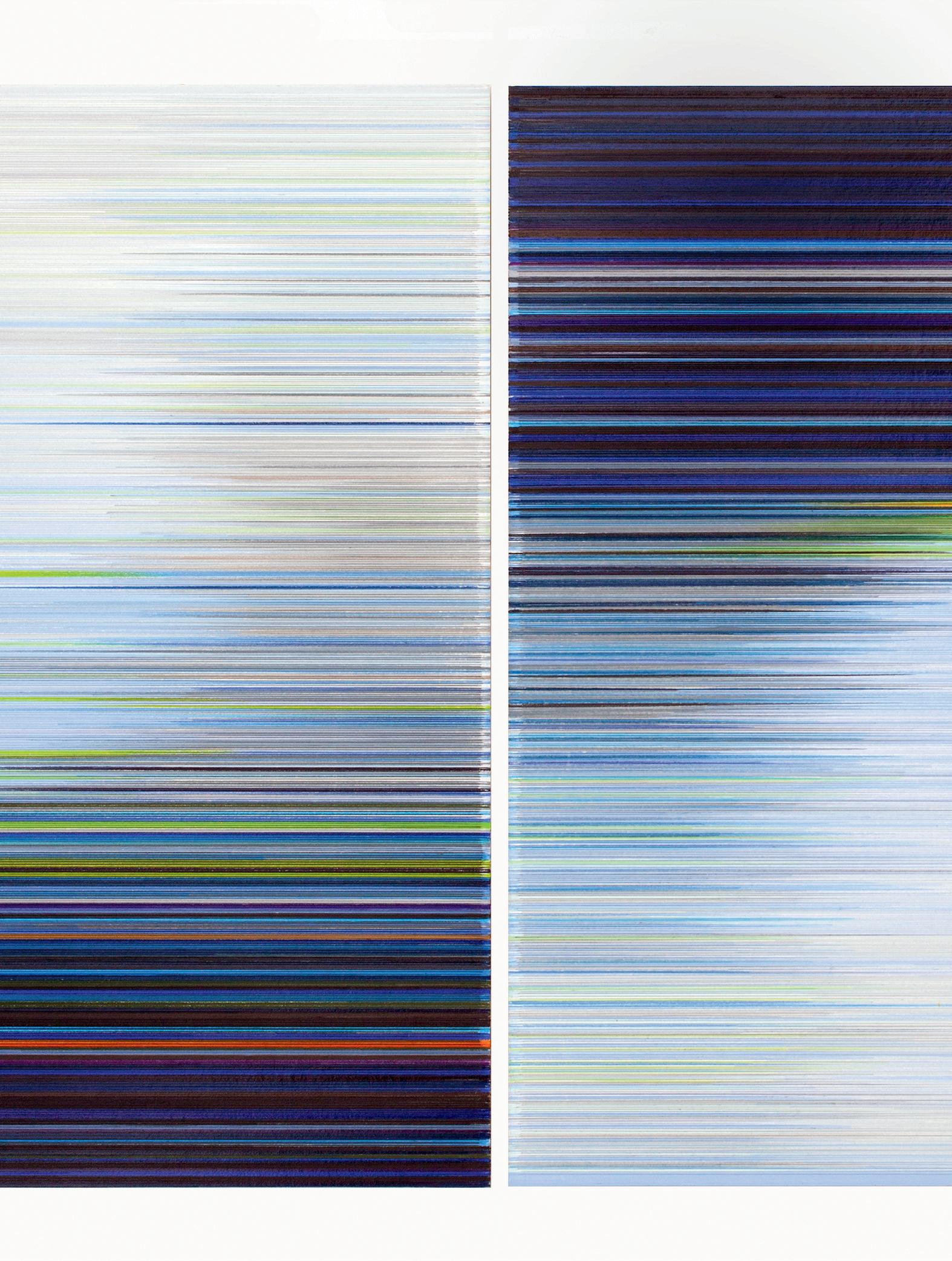

moving, one after another, 2023

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

50 x 70 inches

(title from opening paragraph of The Waves by Virginia Woolf (1931))

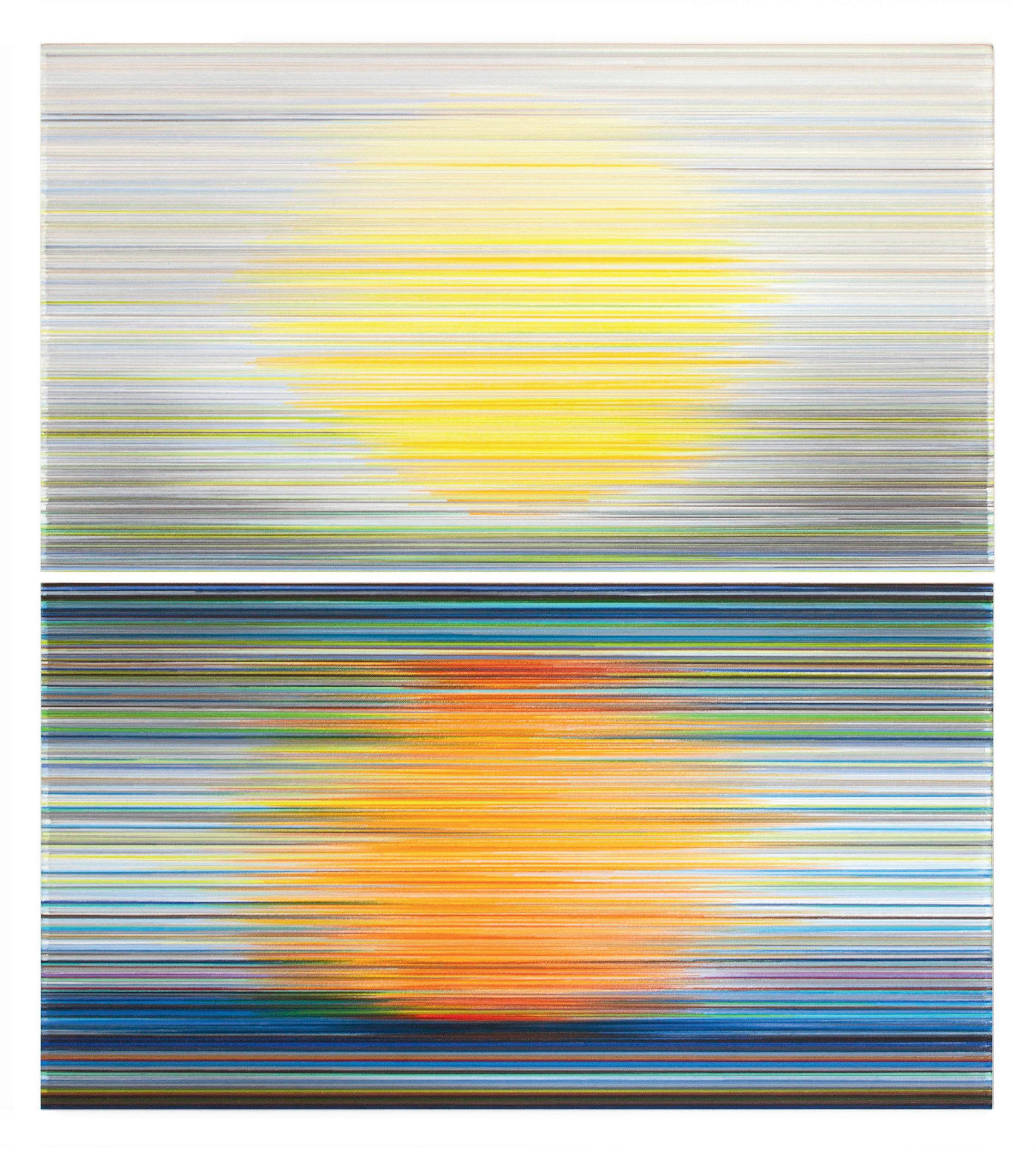

two suns, 2023

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

40.5 x 36 inches (two panels)

forbidden color, 2023

59 x 104 inches

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

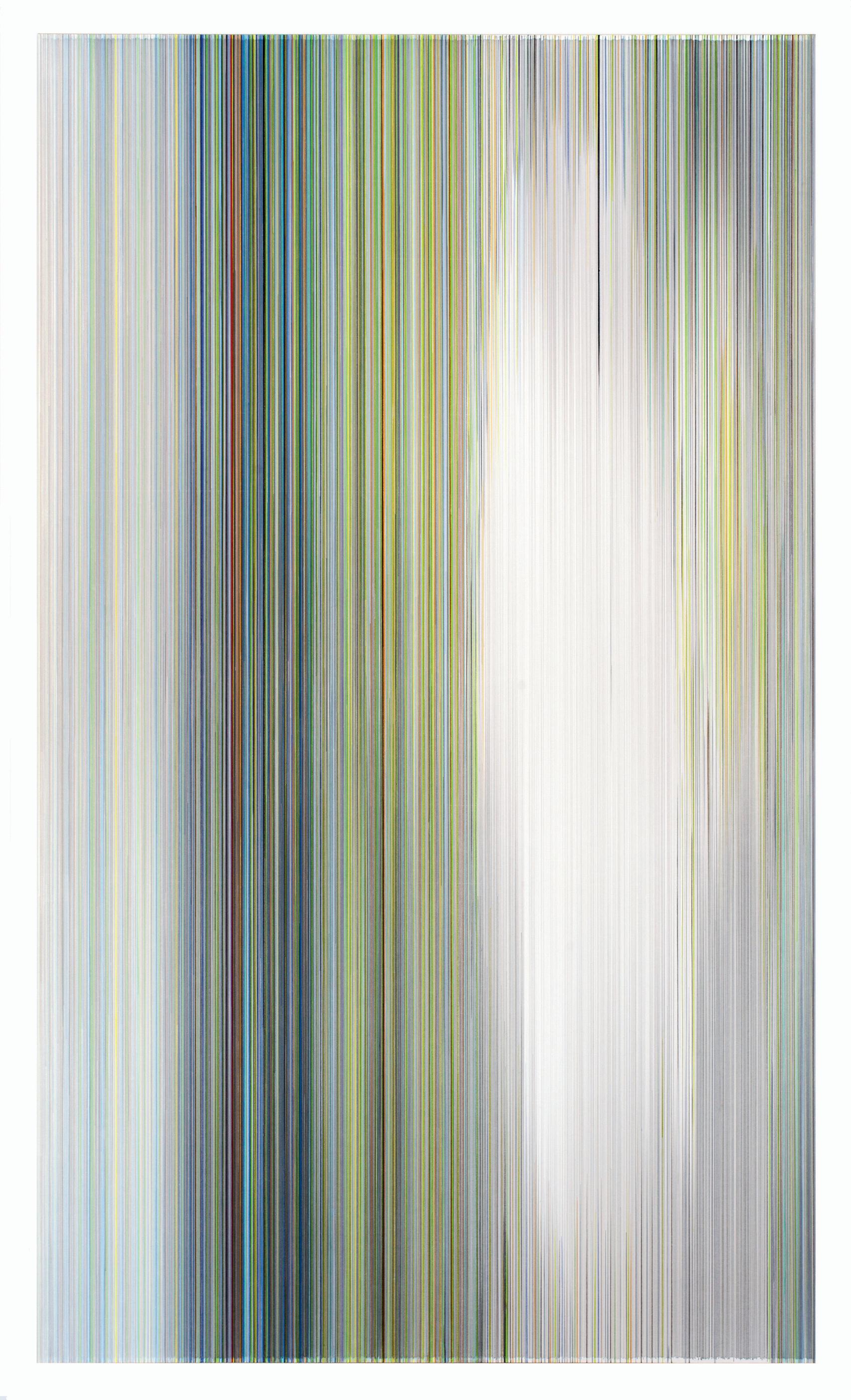

inseparable, 2023

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board 104 x 59 inches

altostratus, 2024

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board 45 x 96 inches (two panels)

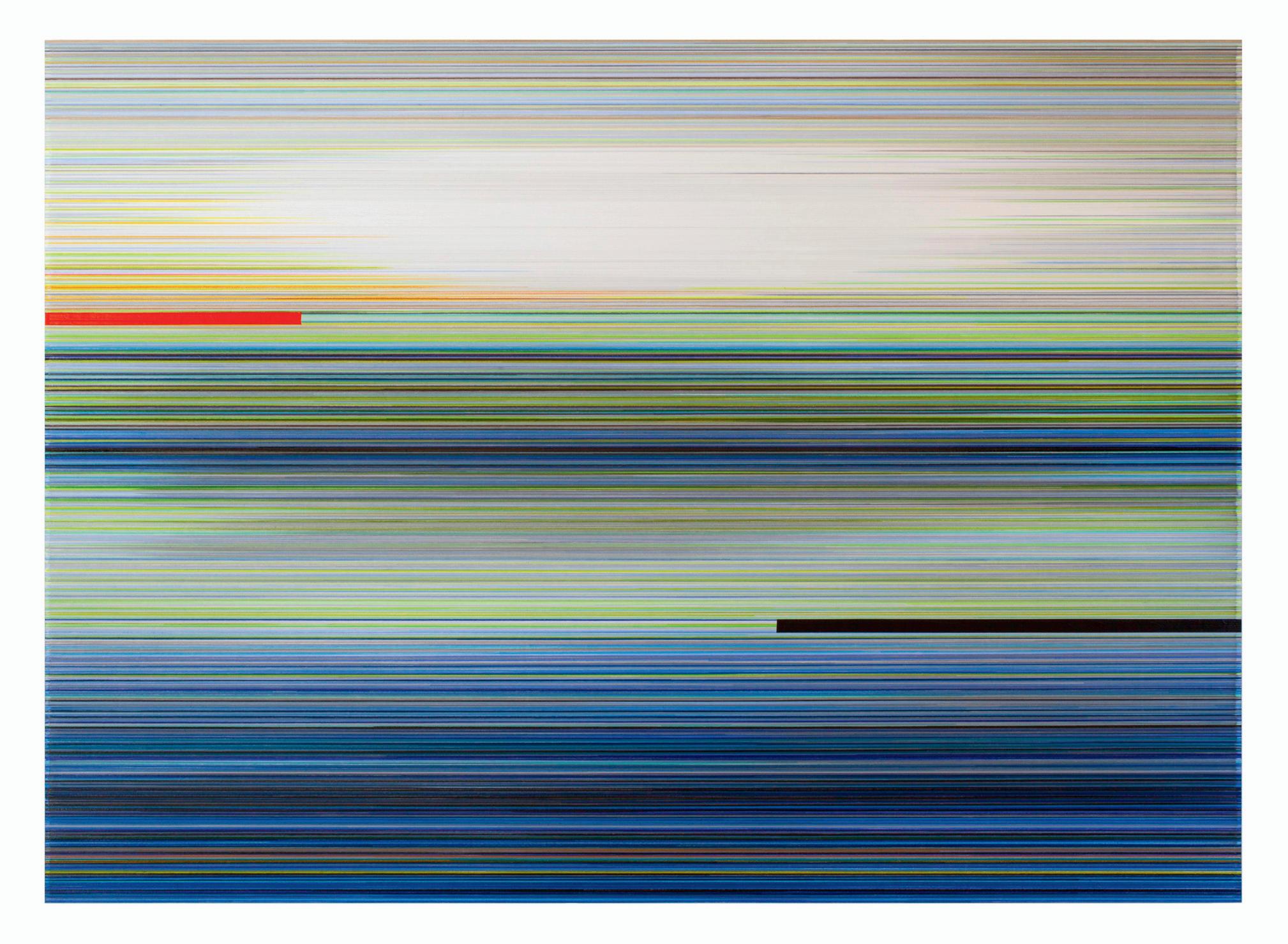

reveal, 2023

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

50 x 60 inches

reflect, 2024

56.5

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

x 30 inches (two panels)

unattainable hue, 2024

cotton thread and staples

44 x 564 x 117 inches

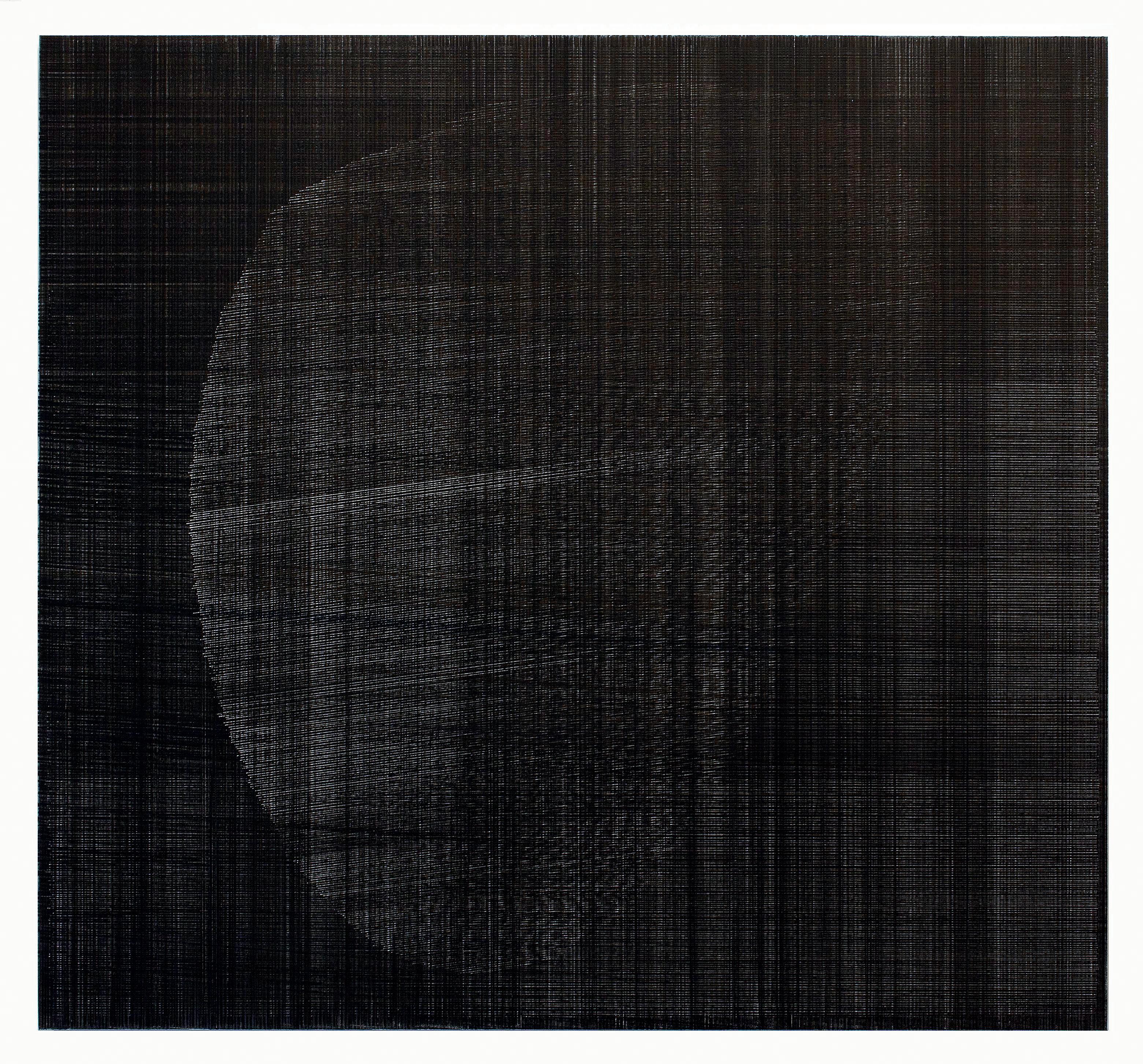

two moons, 2024

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

40.5 x 36 inches (two panels)

cloud cover, 2023

20 x 36 inches

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

crazy day, 2023

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

44.5 x 36 inches (two panels)

takes longer, 2024

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

70 x 50 inches

passing, 2024

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board 24 x 79 inches (three panels)

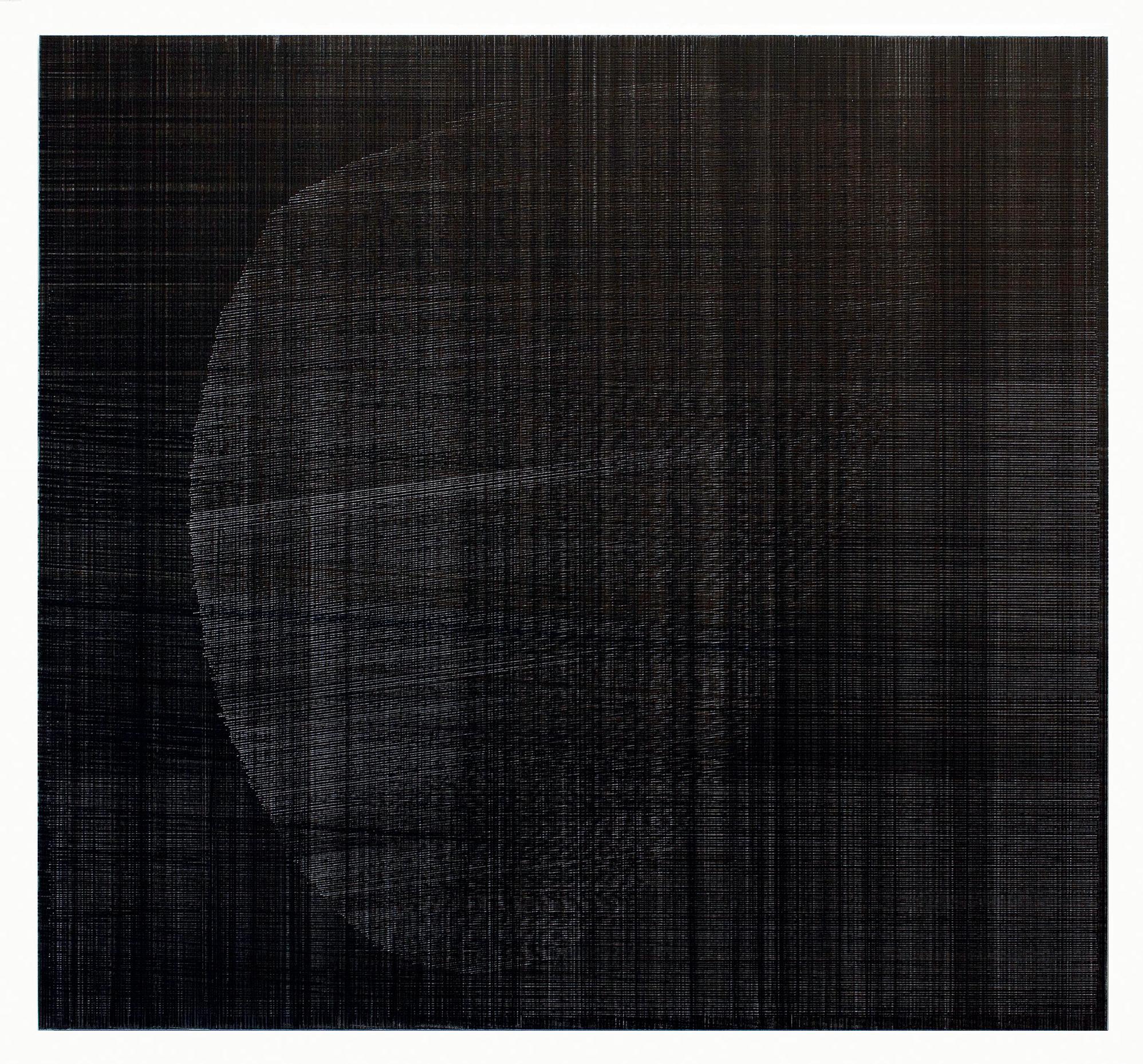

apparition eclipse, 2022

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board 104 x 59 inches

shadow light, 2024

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board 24 x 26 inches

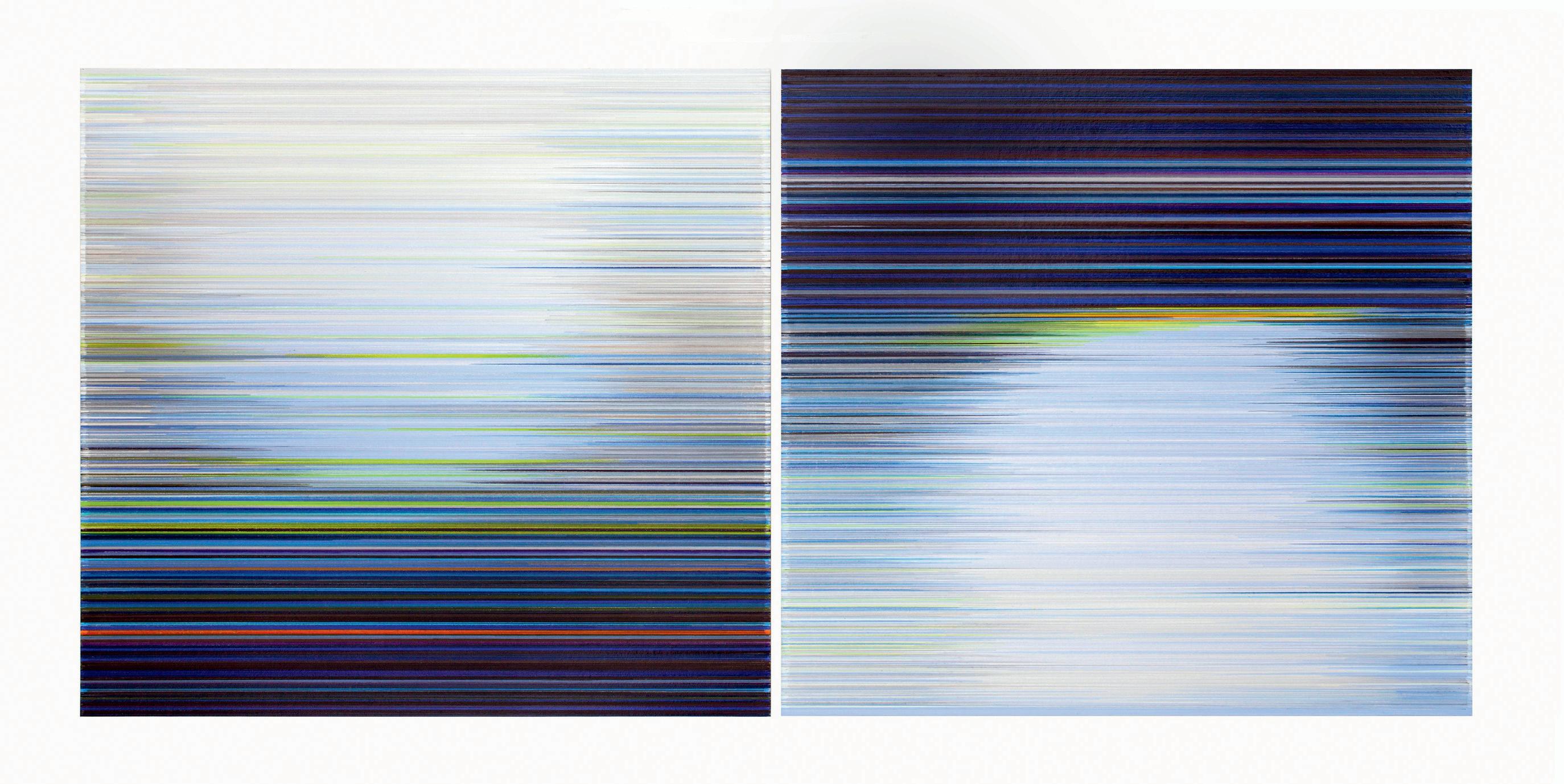

indistinguishable, 2023

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board

52 x 56 inches (four panels)

ask the river what it carries, 2022

Graphite and colored pencil on mat board 9 x 25 feet / 108 x 300 inches (eleven panels)

(title from poem by Ginny Threefoot)

Anne Lindberg makes immersive installations and drawings that tap a non-verbal physiological landscape of body and space, provoking emotional, visceral and perceptual responses. Her work generates fundamental questions about time, causality and sequence as it speaks to the vicissitudes of human experience.

Her recent exhibitions include Hangar Y (Paris), Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, The Textile Museum at George Washington University Museums, Everson Museum of Art, Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, Figge Art Museum, Museum of Arts and Design,, John Michael Kohler Art Center, Manitoga / The Russel Wright Design Center, Josee Bienvenu Gallery, University of Minnesota Regis Center for the Arts,

Her work has also been in solo and group exhibitions at such places as The Drawing Center, New York; Tegnerforbundet, Norway; SESC Bom Retiro, Sao Paulo; Mattress Factory; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Arts and Design, New York; Contemporary Art Museum of Raleigh; U.S. Embassy Yangon Myanmar; Atlanta Contemporary Art Center; Bemis Center for Contemporary Art; Akron Art Museum; Cranbrook Art Museum; Atlanta Contemporary Art Center; Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati; Laumeier Sculpture Park; The Warehouse Dallas; Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna; and the Omi International Art Center

Lindberg’s first monograph was released in late 2022 by Durer Editions (Dublin, Ireland).

Lindberg is recipient of awards including a 2011 Painters & Sculptors

Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant, Charlotte Street Foundation Fellowship, two ArtsKC Fund Inspiration Grants, Lighton International Artists Exchange grant, Art Omi International Artists Residency, American Institute of Architects Allied Arts and Crafts award, and Mid-America National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship. She holds a BFA from Miami University and an MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art. Her studio is in Ancramdale, New York.

Selections from the Artist’s Library

Anni Albers, Nicholas Fox Weber, Manual Cirauqui and T’ ai Smith, Anni Albers: On Weaving - new expanded edition, (Princeton University Press, 2017)

Anne Carson, Float, (McClelland & Stewart, 2016)

Durga Chew-Bose, Bruce Hainley and Olivia Laing, Agnes Martin: The Distillation of Color, (Pace Publishing, 2021)

William Gass, On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry, (David R. Godine, 1975)

Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal and Sue Scott, Mothers of Invention: Feminist Roots in Contemporary Art, (Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, 2024)

Alice Oswald and Paul Keegan, eds., Gigantic Cinema: A Weather Anthology, (W.W. Norton & Company, 2021)

Alice Oswald, Falling Awake, (W.W. Norton & Company, 2016)

Richard Powers, Overstory, (W.W. Norton & Company, 2018)

Michael Rossi, The Republic of Color: Science, Perception and the Making of Modern America, (University of Chicago Press, 2019)

Terry Tempest Williams, Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place, (Vintage, 1992)