2022-2023 CANDLER CONCERT SERIES HELENE GRIMAUD, piano October 27, 2022 | 8 p.m. ´ `

This concert is presented by the Schwartz Center for Performing Arts. 404.727.5050 | schwartz.emory.edu | boxoffice@emory.edu

Audience Information

Please turn off all electronic devices.

Health and Safety

The Schwartz Center follows the Emory University Visitor Policy with additional protocols outlined at schwartz.emory.edu/faq.

Photographs and Recordings

Digital capture or recording of this concert is not permitted.

Ushers

The Schwartz Center welcomes a volunteer usher corps of approximately 60 members each year. Visit schwartz.emory.edu/volunteer or call 404.727.6640 for ushering opportunities.

Accessibility

The Schwartz Center is committed to providing performances and facilities accessible to all. Please direct accommodation requests to the Schwartz Center Box Office at 404.727.5050, or by email at boxoffice@emory.edu.

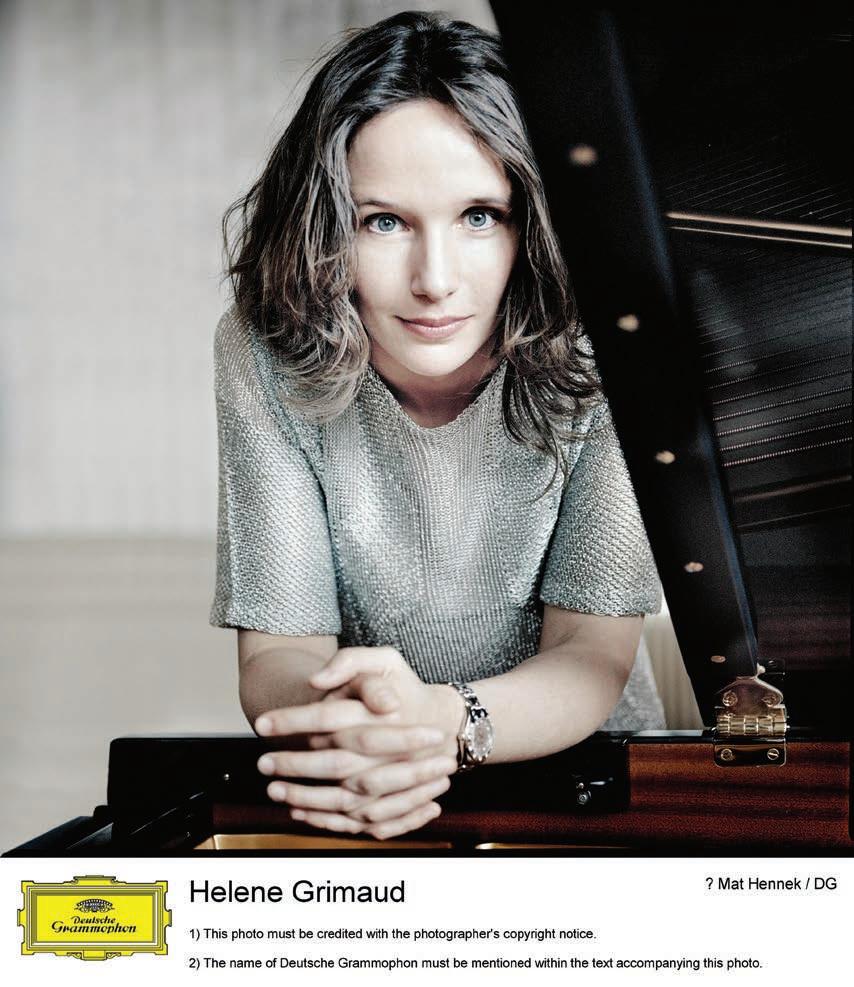

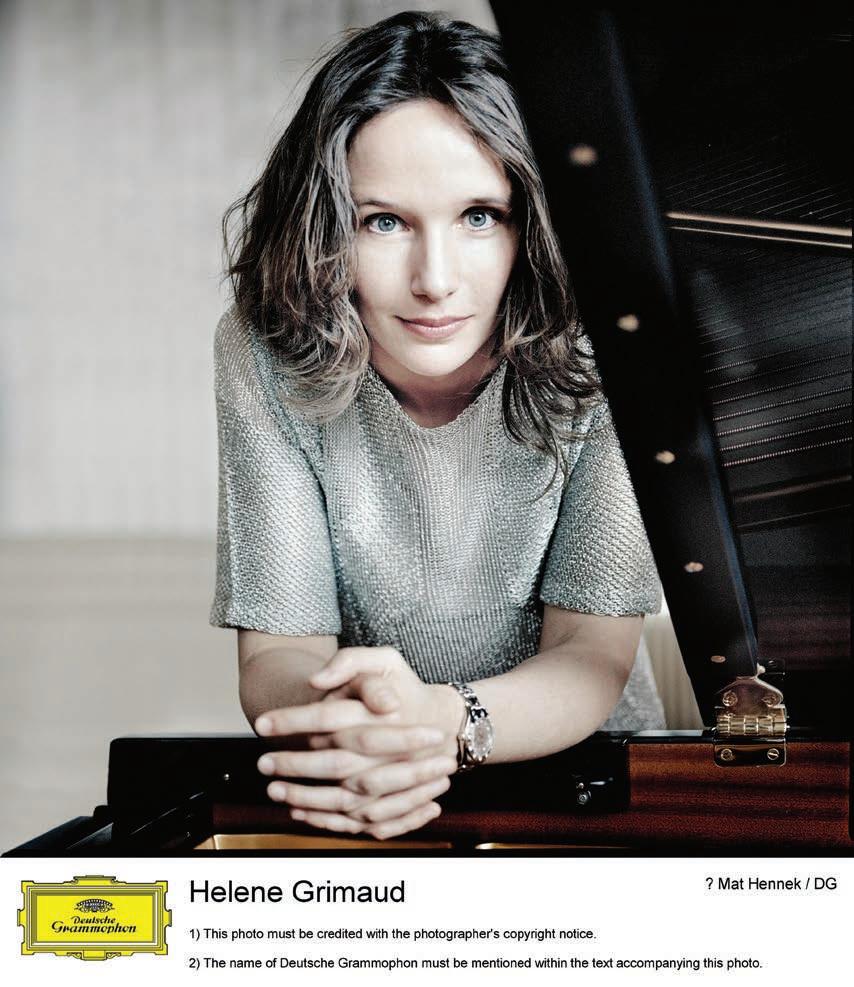

Design and Photography Credits

Front Cover and Interior Photos: Mat Hennek Cover Design: Nick Surbey | Program Design: Lisa Baron Back Cover Photo: Mark Teague

Acknowledgment

This season, the Schwartz Center is celebrating 20 years of world-class performances and wishes to gratefully acknowledge the generous ongoing support of Donna and Marvin Schwartz.

This program is made possible by a generous gift from the late Flora Glenn Candler, a friend and patron of music at Emory University.

CANDLER CONCERT SERIES

HÉLÈNE GRIMAUD, piano

Thursday, October 27, 2022, 8:00 p.m.

Emerson Concert Hall Schwartz Center for Performing Arts

2022–2023

Bagatelle I

Program

Valentin Silvestrov (b. 1937)

Arabesque No. 1 Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

Bagatelle II Silvestrov

Gnossienne No. 4 Erik Satie (1866–1925)

Nocturne in E Minor, op. 72, No. 1 (posth.)

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849)

Gnossienne No. 1 Satie

Danses de travers, No. 1, En y regardant à deux fois from Pièces froides II Satie

La plus que lente Debussy

Mazurka in A Minor, op. 17, No. 4 Chopin

Waltz in A Minor, op. 34, No. 2 Chopin Clair de lune from Suite bergamasque Debussy

Rêverie Debussy

Danses de travers, No. 2, Passer from Pièces froides II Satie

—Intermission—

Kreisleriana, op. 16

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

4

Program Notes

Valentin Silvestrov, Bagatelle I and Bagatelle II

Valentin Silvestrov was born in Kiev on September 30, 1937. He came to music relatively late, at age 15. He at first taught himself, and then, between 1955–1958, went to an evening music school while studying to become a civil engineer during the day. From 1958 to 1964, he studied composition and counterpoint with Boris Lyatoshinsky and Lev Revutsky at Kiev Conservatory. In 2022, Silvestrov fled from Ukraine to Berlin, Germany.

Between 2001 and 2005, Silvestrov worked with small forms and pure melodies, composing numerous cycles for various small instrumentations—including more than 260 cycles for piano solo. Silvestrov describes the short pieces as “bagatelles” in the center of which is the melody, and in which he tries to seize and halt the melodic moment, intonations, calls, and motifs that flash past, without imposing the burden of what is termed thematic elaboration.

During the political unrest in Ukraine, Silvestrov fought for his country with “musical means,” composing numerous choral works, including Prayer for Ukraine.

Claude Debussy, Arabesque No. 1, La plus que lente, Clair de lune, and Rêverie

Claude Debussy was born in France in 1862. Although his family did not have much money, he began studying piano at the Paris Conservatory at age 11. Debussy’s legacy is one of the major contributors of music to late 19th-century Impressionism. Impressionist music, like Monet’s artwork of the same period, evokes an overall mood or atmosphere rather than a specific emotion.

Written when Debussy was in his late 20s, the Arabesque No. 1 is part of a two-part set. Like the impressionistic music of the period, the piece focuses on color over form, alternating in the bass between two chords rather than in a V–I progression. The melody uses whole tone pentatonic scales, which makes the piece seem light and airy, with a lot of space between the notes.

In 1910, Debussy visited Budapest and was influenced by the Gypsy-style cafe ensembles he heard. Of one in particular he wrote, “In an ordinary, commonplace café, he gave one the impression of sitting in the depths of a forest; he arouses in the soul that characteristic feeling of melancholy in which we so seldom have an opportunity to indulge.” La plus que lente (slower than slow) evokes this impression of melancholy.

5

Around 1890, Debussy began working on Suite bergamasque, a piano suite in four movements: Prélude, Menuet, Clair de lune, and Passepied. Clair de lune (moonlight) was originally called Promenade sentimentale (sentimental walk), both from poems by symbolist poet Paul Verlaine. It was renamed shortly before publication in 1905. Debussy had previously set Clair de lune for voice and piano twice, along with 18 other Verlaine poems.

Rêverie was likely sometime between 1880 and 1884, at the beginning of Debussy’s career. The composer’s emerging voice is already clear and recognizable in Rêverie. The work is an exotic and dreamlike exploration of the textures and harmonies that Debussy would develop with even greater narrative drama in his later works.

Erik Satie, Gnossienne No. 4; Gnossienne No. 1; Pièces froides II, Danses de travers, En y regardant à deux fois and Passer

Erik Satie was an eccentric French avant-garde composer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He did not consider himself a musician, but a gymnopedist and measurer of sounds. He took lessons from a local organist as a child and attended the Paris Conservatory beginning in 1879. His piano playing was called worthless and he took many leaves of absence from it, finally receiving his diploma at age 40.

Satie began writing the Gnossiennes around 1890, and no one really knows what the word means. Some believe it is from the Greek gnosis, which means knowledge. They are written in free time without bar lines, over simple, repeating harmonies. En y regardant a deux fois (Give it a good look) and Passer (Go on) are from Pièces froides II, Danses travers (Crooked Dances), which—like the Gnossiennes—feature no bar lines or key signatures.

Frédéric Chopin, Nocturne in E Minor, op. 72, No. 1; Mazurka in A Minor, op. 17, No. 4; Waltz in A Minor, op. 34, No. 2

The nocturnes are Frédéric Chopin’s most intimate and personal utterances. Some are wistful, some reflective, some melancholy, some faintly troubled, and some serenely joyful. All are sensuously beautiful, suffused with elegance and deeply poetic impulses. During Chopin’s lifetime, they were his most popular pieces. Twenty-one survive, the first written when he was 17, the last three years before his death. As the title implies, they are suggestive—faintly or strongly as the case may be—of some aspect of dusk, evening, twilight, or the dark night and associated emotions.

6

Chopin wrote 50 mazurkas throughout his life, from deep melancholy to abandoned gaiety, with many moods between those extremes. A Chopin mazurka is not only a vehicle for emotional expressiveness, but also for musical ingenuity, including chromaticism, daring modulations, and striking harmonic coloration. In the all-important matter of rhythm, the authentic folk heritage of the three-quarter-time dances is conveyed by the strong accents that appear most frequently on the third beats of measures, sometimes on the second. And modal inflections, with their Slavic nature, add distinct color to these remarkably varied pieces.

The waltz developed in the last half of the 18th century out of country dances from Austria and southern Germany, and in the Romantic era was absorbed into the world of salon music. While it maintained its essential musical characteristics—triple meter with one chord to the bar—various nuances reflective of the Romantic spirit of the time were introduced. Chopin’s cultivation of the “sad waltz,” the waltz in a minor key, was one of these. Another was the amount of melodic content he saw fit to give to the left hand. His wistful, almost moping Waltz in A Minor, op. 34, No. 2, displays both of these qualities. It opens with a texture that sees the normal role of the hands reversed: it is the right hand playing the “oompah-pah” pattern while the left sings out a mournful melody in the cello range tinged with pathos. While the major mode does appear to provide a bit of sunshine from time to time, the mood remains nostalgic, with more than a hint of melancholy.

—Notes by Debra Joyal

Robert Schumann, Kreisleriana, op. 16

Violinist Johannes Kreisler represented, for Robert Schumann, the very essence of the new Romantic spirit in art. This eccentric, hypersensitive character from the fiction of E. T. A. Hoffmann was a cross between Nicolò Paganini and Dr. Who, an enigmatic, emotionally volatile figure committed to plumbing the depths of his creative soul.

Schumann’s tribute to this symbol of creativity in art, his Kreisleriana of 1838, is as wildly inventive and emotionally unstable as the artistic personality it describes. Each of the eight pieces that make up the work comprises contrasting sections that reflect the split in Schumann’s own creative personality, a bipolar duo of mood identities to which he selfconsciously gave the names Florestan and Eusebius.

Florestan, Schumann’s passionate, action-oriented side, opens the work Äußerst bewegt (extremely agitated) with a torrential outpouring of emotion that only halts when the introspective daydreamer Eusebius takes over with more tranquil lyrical musings. The pairing is reversed

7

in the following movement, Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch (very intimate and not too fast), which begins thoughtfully, but is twice interrupted by sections of a much more rambunctious character.

Schumann’s inventiveness in creating this series of mood-swing pieces is astonishing. Each is a psychologically compelling portrait of a distinct temperamental state, enriched and made whole by embracing its opposite.

Projecting these portraits is no easy task for the pianist as Schumann’s writing, especially in slower sections, often features a choir of four fully active voices with melodies as likely to rise up from the bass, or to emerge out of the middle of the keyboard, as to sing out from on top. Indeed, the smooth part-writing and polyphonic texture of many sections point to another prominent feature of Schumann’s writing: his great admiration for the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Schumann’s desire to give a Bachian solidity of structure to his writing is most evident not only in his four-voice harmonization textures but also in his use of close three-voice stretto in the fifth movement and fugato in the seventh, not to mention the many extended passages based on a single rhythmic pattern in the manner of a Bach prelude.

But most remarkable in this work is the sense of mystery and unease that it radiates as a result of the pervasive use of rhythmic displacement in the bass, where strong notes often fail to coincide with the strong beats of the bar, in imitation of the unregulated movement of tectonic plates of thought and feeling in the mind of the creative artist.

8

—Note by Donald G. Gíslason

“There is a sparkling life in Grimaud’s approach to the music, as her phrases breathe easily and she places even individual chords so precisely, they each seem to represent discrete thoughts.”

—New York Classical Review

Hélène Grimaud, piano

Renaissance woman Hélène Grimaud is not just a deeply passionate and committed musical artist whose pianistic accomplishments play a central role in her life. She is a woman with multiple talents that extend far beyond the instrument she plays with such poetic expression and peerless technical control. The French artist has established herself as a committed wildlife conservationist, a compassionate human rights activist, and a writer.

Grimaud was born in 1969 in Aix-en-Provence and began her piano studies at the local conservatory with Jacqueline Courtin before going on to work with Pierre Barbizet in Marseille. She was accepted into the Paris Conservatoire at just 13 and won first prize in piano performance a mere three years later. She continued to study with György Sándor and Leon Fleisher until, in 1987, she gave her well-received debut recital in Tokyo. That same year, renowned conductor Daniel Barenboim invited her to perform with the Orchestre de Paris: this marked the launch of Grimaud’s musical career, characterized ever since by concerts with most of the world’s major orchestras and many celebrated conductors.

Between her debut in 1995 with the Berliner Philharmoniker under Claudio Abbado and her first performance with the New York Philharmonic under Kurt Masur in 1999—just two of many notable musical milestones—Grimaud made a wholly different kind of debut: in upper New York State she established the Wolf Conservation Center. Her love for the endangered species was sparked by a chance encounter with a wolf in northern Florida; this led to her determination to open an environmental education center. “To be involved in direct conservation and being able to put animals back where they belong,” she says, “there’s just nothing more fulfilling.” But Grimaud’s engagement doesn’t end there—she is also a member of the organization Musicians for Human Rights, a worldwide network of musicians and people working in the field of music to promote a culture of human rights and social change.

For a number of years, she also found time to pursue a writing career, publishing three books that have appeared in various languages. Her first, Variations Sauvages, appeared in 2003. It was followed in 2005 by Leçons particulières, and in 2013 by Retour à Salem, both semiautobiographical novels.

9

It is, however, through her thoughtful and tenderly expressive musicmaking that Grimaud most deeply touches the emotions of audiences. Fortunately, they have been able to enjoy her concerts worldwide, thanks to the extensive tours she undertakes as a soloist and recitalist. A committed chamber musician, she has also performed at the most prestigious festivals and cultural events with a wide range of musical collaborators, including Sol Gabetta, Rolando Villazón, Jan Vogler, Truls Mørk, Clemens Hagen, Gidon Kremer, Gil Shaham, and the Capuçon brothers. Her prodigious contribution to and impact on the world of classical music were recognized by the French government when she was admitted into the Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur (France’s highest decoration) at the rank of Chevalier (Knight).

Grimaud has been an exclusive Deutsche Grammophon artist since 2002. Her recordings have been critically acclaimed and awarded numerous accolades, among them the Cannes Classical Recording of the Year, Choc du Monde de la musique, Diapason d’or, Grand Prix du disque, Record Academy Prize (Tokyo), Midem Classic Award, and the Echo Klassik Award.

Grimaud’s early recordings include Credo and Reflection (both of which feature a number of thematically linked works); a Chopin and Rachmaninov sonatas disc; a Bartók CD on which she plays the Third Piano Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra and Pierre Boulez; a Beethoven disc with the Staatskapelle Dresden and Vladimir Jurowski, which was chosen as one of history’s greatest classical music albums in the iTunes “Classical Essentials” series; a selection of Bach’s solo and concerto works, in which she directed the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen from the piano; and a DVD release of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra and Claudio Abbado. In 2010 Grimaud recorded the solo recital album Resonances, showcasing music by Mozart, Berg, Liszt, and Bartók. This was followed in 2011 by a disc featuring her readings of Mozart’s Piano Concertos Nos. 19 and 23 as well as a collaboration with singer Mojca Erdmann in the same composer’s Ch’io mi scordi di te? Her next release, Duo, recorded with cellist Sol Gabetta, won the 2013 Echo Klassik Award for “chamber recording of the year,” and her album of the two Brahms piano concertos, the first recorded with Andris Nelsons and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the second with Nelsons and the Vienna Philharmonic, appeared in September 2013.

This was followed by Water (January 2016), a live recording of performances from tears become . . . streams become . . ., the criticallyacclaimed large-scale immersive installation at New York’s Park Avenue

10

Armory created by Turner Prize–winning artist Douglas Gordon in collaboration with Grimaud. Water features works by nine composers: Berio, Takemitsu, Fauré, Ravel, Albéniz, Liszt, Janáček, Debussy, and Nitin Sawhney, who wrote seven short Water Transitions for the album as well as produced it. April 2017 then saw the release of Perspectives, a two-disc personal selection of highlights from her DG catalog, including two encores—Brahms’s Waltz in A-flat and Sgambati’s arrangement of Gluck’s Dance of the Blessed Spirits—previously unreleased on CD/via streaming.

Grimaud’s next album, Memory, was released in September 2018. Exploring music’s ability to bring the past back to life, it comprises a selection of evanescent miniatures by Chopin, Debussy, Satie, and Valentin Silvestrov which, in the pianist’s own words, “conjure atmospheres of fragile reflection, a mirage of what was—or what could have been.”

For her most recent recording, The Messenger, Grimaud created an intriguing dialogue between Silvestrov and Mozart. “I was always interested in couplings that were not predictable,” she explained, “because I feel as if certain pieces can shed a special light on to one another.” Together with the Camerata Salzburg, she recorded Mozart’s Piano Concerto K466 and Silvestrov’s Two Dialogues with Postscript, and The Messenger—1996, of which she also created a solo version. Mozart’s Fantasias K397 and K475 complete the program. The Messenger was released in October 2020.

Grimaud began the 2022–2023 season with a recital of her Memory recording in Santa Fe’s Lensic Performing Arts Center. In addition to this evening’s concert, her plans include performances of Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and Fabio Luisi (October), Vancouver Symphony Orchestra and Otto Tausk (November), and St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and Stephane Deneve (January); Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor with Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and Louis Langree (October); finishing the year with a recital at Carnegie Hall (December). The new year starts with her European tour with Camerata Salzburg in Ludwigshafen, Salzburg, and Turin (February). Followed by recitals in Vienna, Luxembourg, Munich, Berlin, and London (March–May), to name a few.

Grimaud is undoubtedly a multi-faceted artist. Her deep dedication to her musical career, both in performances and recordings, is reflected and reciprocally amplified by the scope and depth of her environmental, literary, and artistic interests.

11

20TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON

The foundation of the performing arts at Emory began with the vision and gifts of Flora Glenn Candler and came to full fruition in this exquisite venue with the support of Donna and Marvin Schwartz. The 2022–2023 season marks 20 years of world-class performances at the Schwartz Center for Performing Arts.