The Behrens Family

THE BEHRENS FAMILY

Reinhard Behrens

Margaret Smyth Behrens

Kirstie Behrens

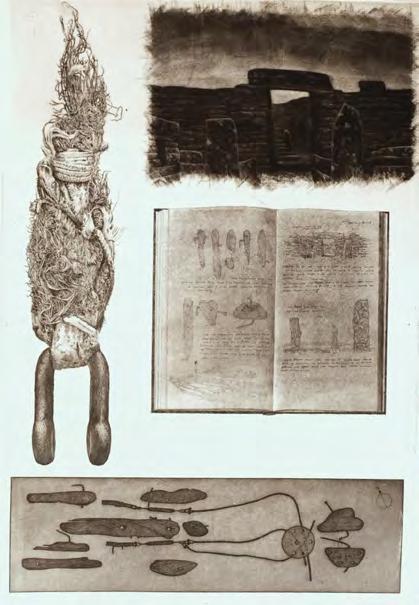

David Behrens

October 2025

The Behrens Family | A Creative Constellation

In celebration of 50 Years of Naboland by Reinhard Behrens, The Scottish Gallery is proud to present a rare and intimate portrait of a remarkable artistic family: The Behrens. This exhibition brings together the individual practices of Reinhard Behrens, Margaret Smyth, David Behrens, and Kirstie Behrens. Although each artist follows a distinct path, their work shares a deep-rooted commitment to imagination, craftsmanship, and the natural world.

For many, the Behrens family is best known as the crown jewel of the Pittenweem Arts Festival in Fife, where, each summer, they open their doors and welcome the public into their creative world. Their home becomes a living studio, exhibition space, and gathering place, offering a unique and generous insight into their working lives and the connections between them. This act of openness and hospitality reflects the spirit that underpins their work: a belief in creativity as something to be shared, explored, and enjoyed.

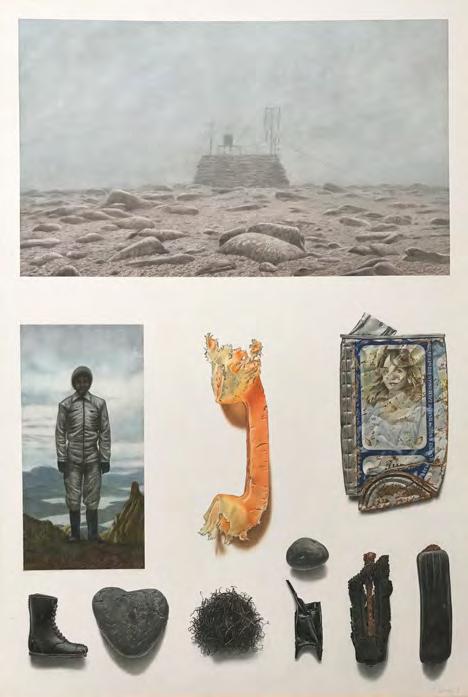

At the heart of this family constellation is Reinhard Behrens, who is the visionary creator of Naboland, the mysterious imagined world he has been exploring since 1975. With its submarines, strange coastlines, and dreamlike cartography, Naboland is both an artistic mythology and a lifelong journey of invention. Reinhard’s work invites us to consider travel, place, and the persistence of wonder. These themes ripple through the wider family’s practice in surprising and meaningful ways.

Margaret Smyth, painter and long-time artistic supporter with Reinhard, brings a quiet lyricism to her work. Her paintings, often rooted in nature and memory, offer a meditative counterpoint to the narrative drama of Naboland. Together, their artistic lives have formed a deeply generative

partnership that has nurtured creativity across generations.

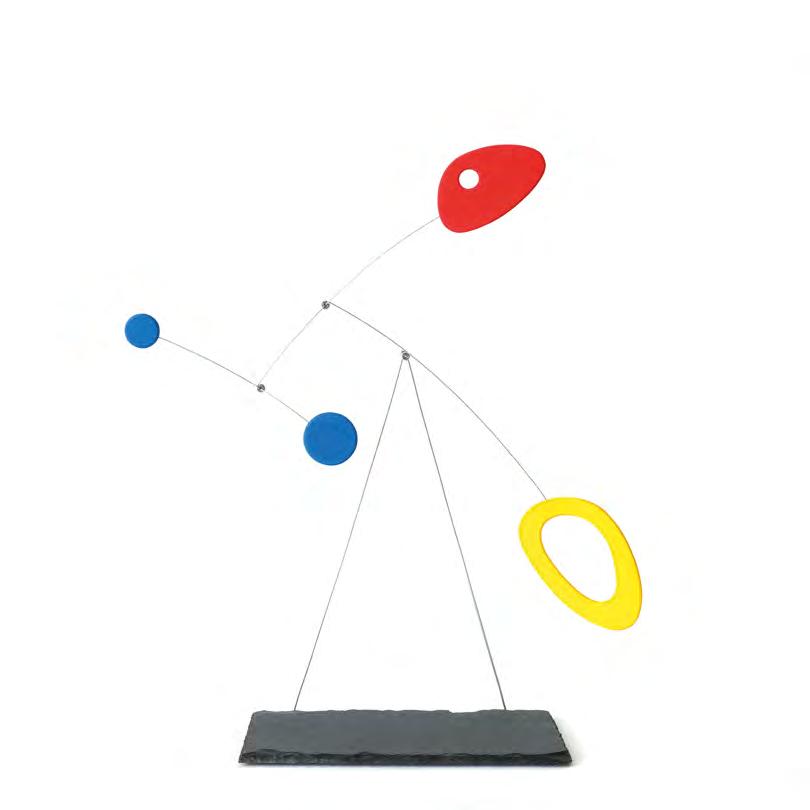

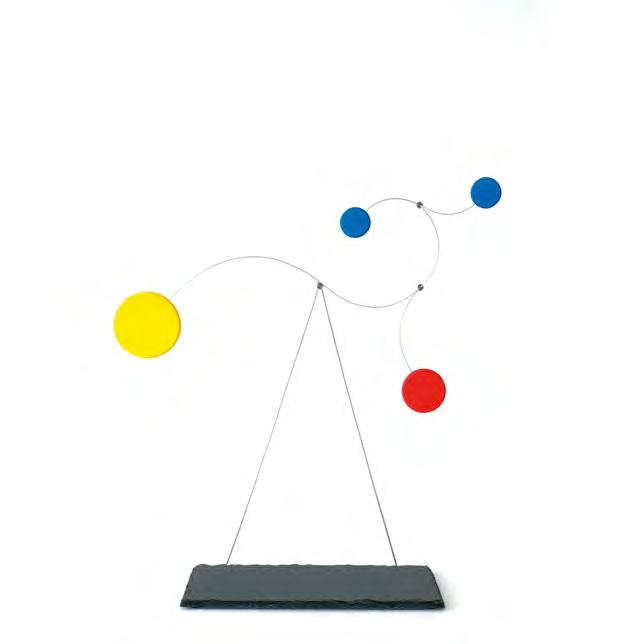

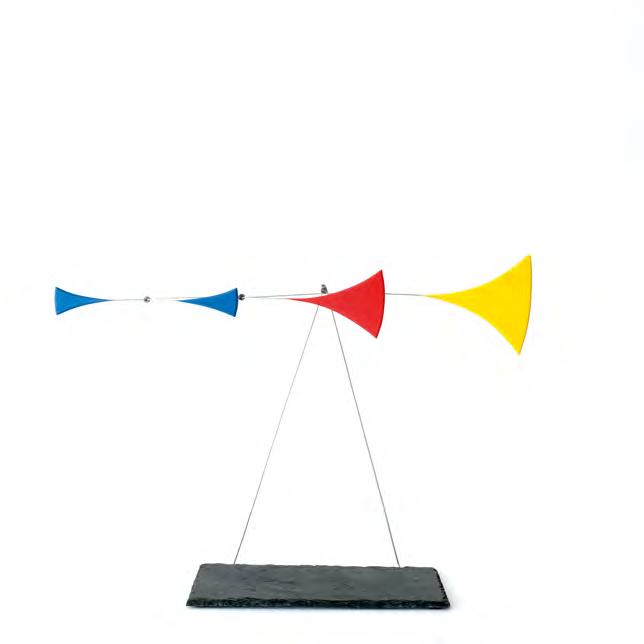

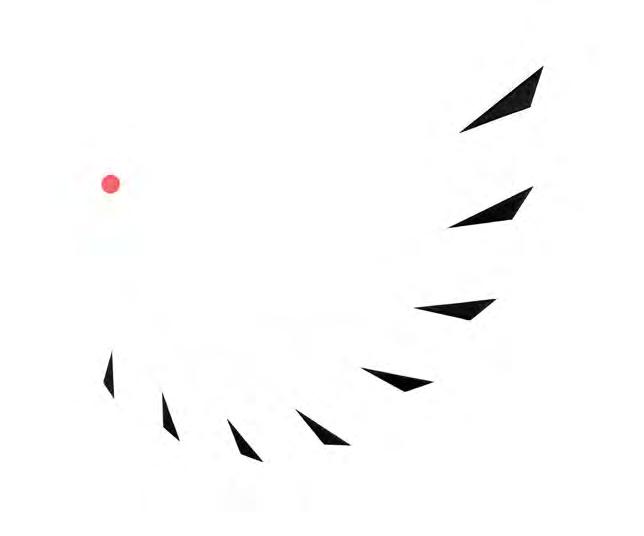

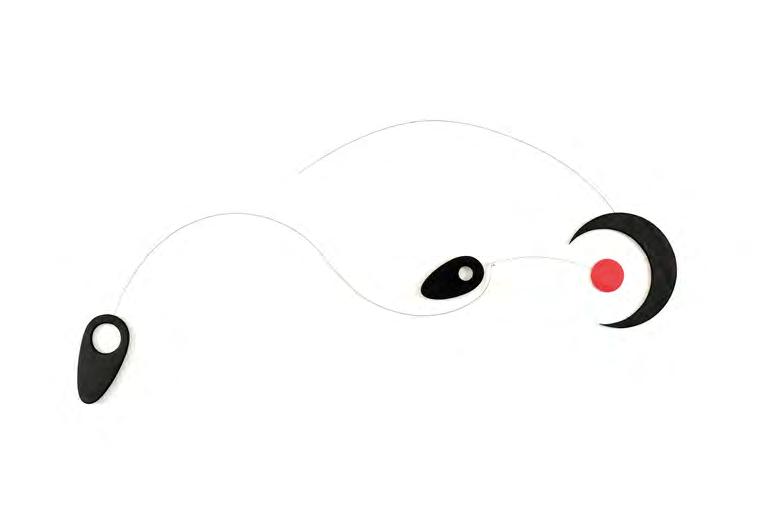

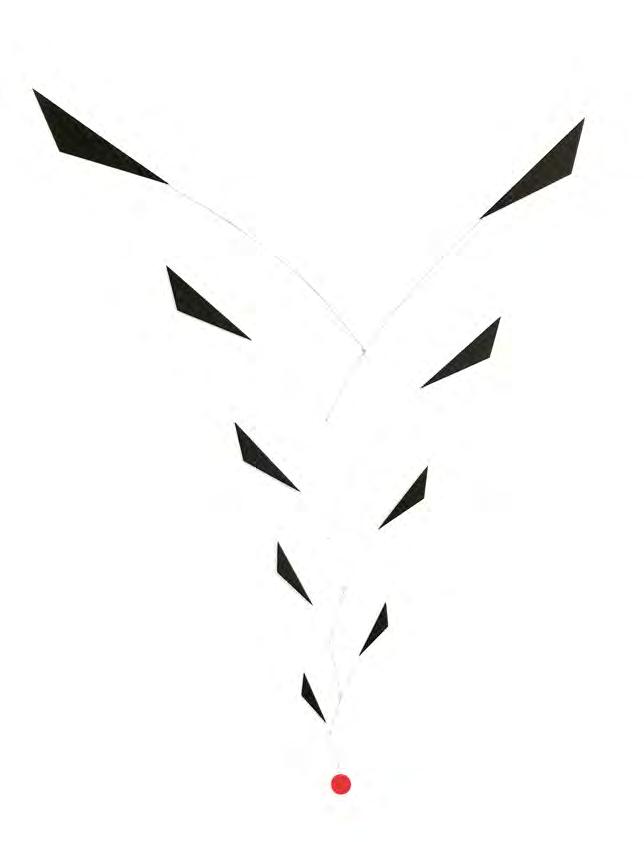

Their son, David Behrens is a trained musician and he blends music, sculpture, and movement in his kinetic automata and mobiles. David’s background in the arts is music and is currently an emerging composer and film scorer. David channels a playful intelligence into his artistic practice, with each mobile or automata animated by a sense of narrative and mechanical poetry. While David’s art shares his father’s sense of invention, his speaks with a distinct voice shaped by sound, rhythm, and cinematic vision.

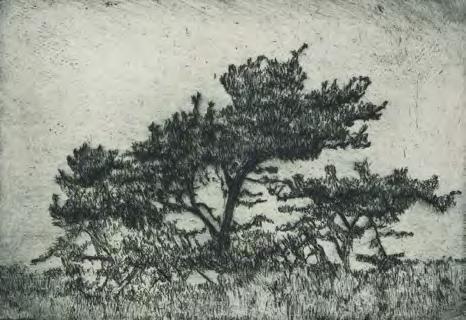

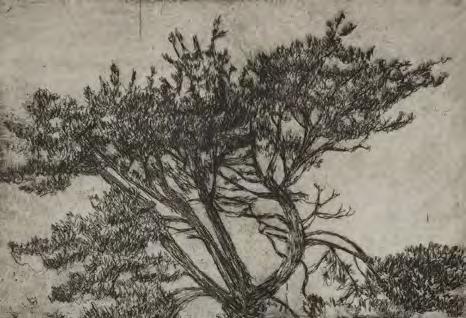

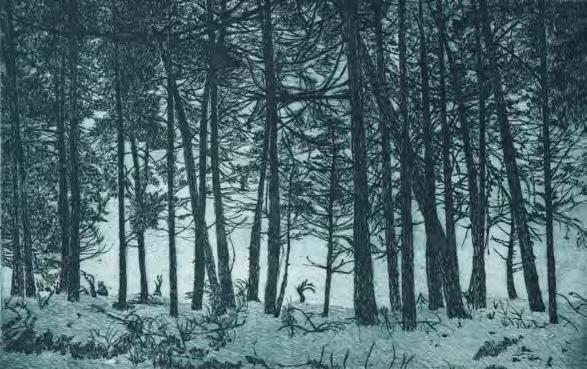

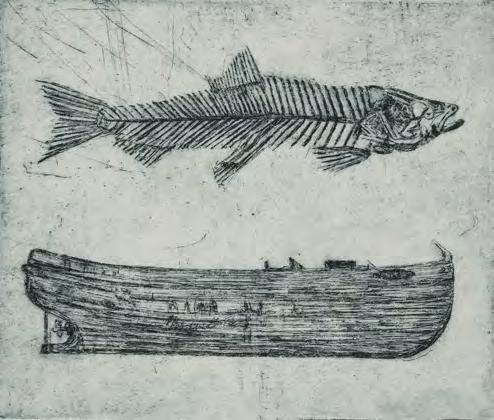

Kirstie Behrens, an accomplished printmaker, specialises in etching and drawing. A graduate of Duncan of Jordanstone, Dundee, her practice is grounded in careful observation and process, with a particular sensitivity to mark-making and material. Her work reflects her mother’s quietude and her father’s precision, offering a contemplative and refined perspective on the world.

Each artist in the Behrens family works independently, yet their shared values, imagination, integrity, and curiosity, create an invisible thread between them. This exhibition is not only a tribute to Reinhard’s milestone, but also an invitation to explore the connections between these four artists. The Gallery will be transformed by one family to reveal a unique lineage of creativity that is deeply personal, richly varied, and profoundly inspiring. I would like to thank the Behrens for their generosity of spirit, and for welcoming me into their home and shared studios. The personal access they granted has been a special and enriching experience.

Christina Jansen

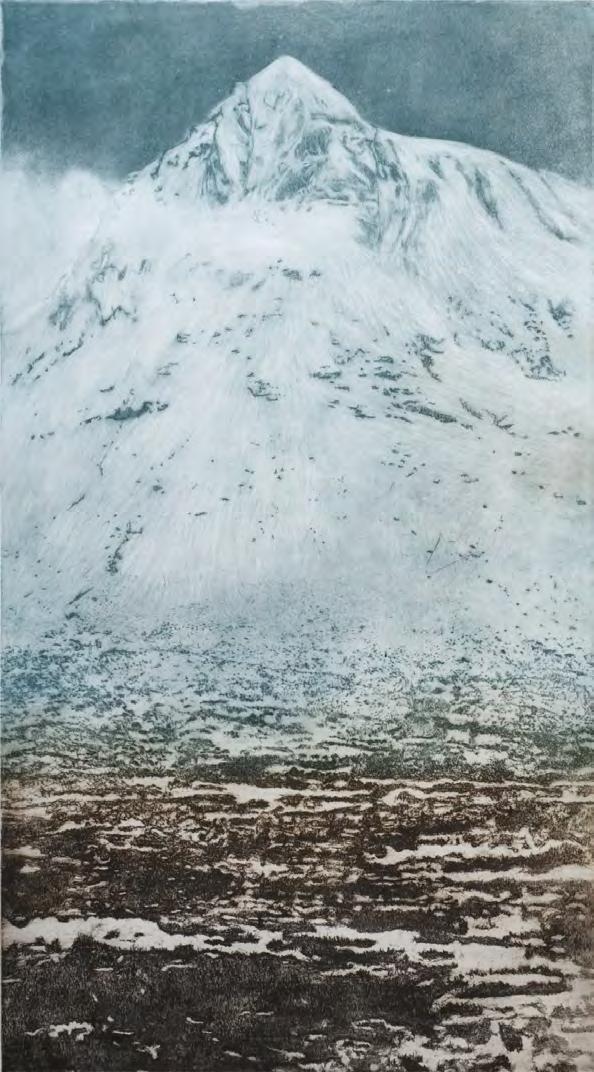

Kirstie Behrens, Buachaille Etive Mor II (cat.58)

The Deck at Pittenweem

Reinhard Behrens

The Behrens Family by Reinhard

Art has never been something separate from my life. It has been the constant thread running through it. For more than fifty years, I have explored the parallel world of Naboland, that has materialised in drawings, paintings, prints and installations. Alongside me, Margaret has followed her own artistic path with dedication and a quiet intensity. Ever since we met, art was part of the conversation, part of how we understood the world, and part of how we understood each other.

When we started our family, art remained at the centre of our lives. It was not something we had to make time for around work and home; it was the work and the home. Our children, Kirstie and David, were born into a house where making things, noticing things, and talking about them was simply the way life worked.

Margaret and I have never set out to turn our home into a kind of art school, but looking back, that is what it became. Not in a formal or structured way, but in the constant presence of materials, tools, works in progress, and ideas. The studio table might hold dinner one moment and drawings and brushes the next. There were always conversations about a painting’s composition, the line of a drawing, or how light falls on an object. Our children absorbed that atmosphere naturally.

Of course, raising a family and sustaining two serious art practices was not always straightforward. There were times when deadlines, exhibitions, and family needs collided. But because we both understood the demands

Behrens

of the work, we were able to support each other through the busy times. This instinctive shared understanding of the creative process, the need for concentration, the frustration when something was not working, and the joy when it suddenly did, meant we never needed to explain ourselves.

Kirstie and David have each found their own voices. Kirstie works with a sensitivity to texture and surface that feels both intuitive and deeply considered. David is drawn to movement, mechanics, and storytelling through automata and film. Their work is entirely their own, but I can see echoes of what they grew up with: the value of craft, the patience to experiment, and the willingness to follow an idea wherever it leads.

My own work on Naboland has always been highly personal, but it has never existed in isolation from family life. In fact, the playfulness, curiosity, and inventiveness that children bring to the world have often reminded me of the spirit I try to keep alive in my own practice.

When we are all in the same exhibition, as we are for The Behrens Family, I am struck by how different we are as artists and how connected. We do not share a single style, but we share an approach: the belief that art is worth the time, the patience, and the struggle it takes. There is a certain honesty and directness that runs through all our work, and I think that comes from living in an environment where making things was never treated as a hobby or a luxury, but as an essential part of living.

Reinhard Behrens, 2025

Naboland Hut interior (detail)

I am proud that we have been able to sustain our own practices while also raising a family. I am proud that Kirstie and David have grown into artists who are independent in their thinking, yet still part of the conversation. I am grateful to Margaret for the years of mutual support and shared purpose. And I am grateful for the fact that our home, sometimes chaotic but always full of life, has given us all the space to become the artists we wanted to be.

This exhibition is not the end of anything. It is simply another moment in a long, ongoing exchange that began decades ago and will, I hope, continue for many years to come. For me, it is a chance to see our work side by side, to notice the threads that connect us, and to reflect on the ways a life in art can be both deeply individual and entirely shared.

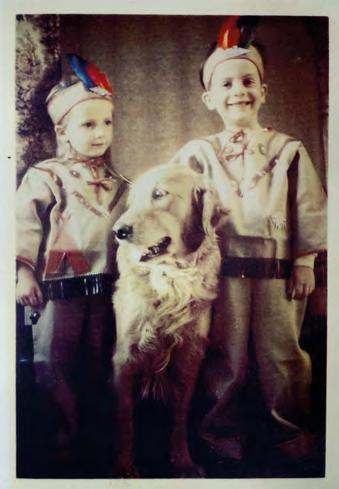

Design for wedding invitation, 1986 Guest of honour at wedding reception, 1986 39 years later in Pittenweem

1. Marooned on the Ice-floe, 1987 etching, aquatint and mezzotint, 49 x 69 cm

The House at Boreraig after Reinhard Behrens

I’ll not go to the house at Boreraig. I’ve no desire to watch the stones resign their gradual geometry; and there’s no comfort for me in the song of the rowan, as it empties the old seasons from its frame.

Instead, I’ll wear these tokens fixed to my conscience like dead stoats on a fence:

1 a riddled copper bowl which bleeds in the late rain;

2 a twist of barbed wire clogged with oily fleece;

3 an eroded bread knife;

4 a curl of bootsole, smoothed by a child’s foot; and 5 by the twisted lock of the broken door of the tumbled wall of the burned house of Boreraig; a key, infinitesimally turning in its hidden grave.

John Glenday

2. Boreraig, Skye, 1986 etching and aquatint, 50 x 33 cm

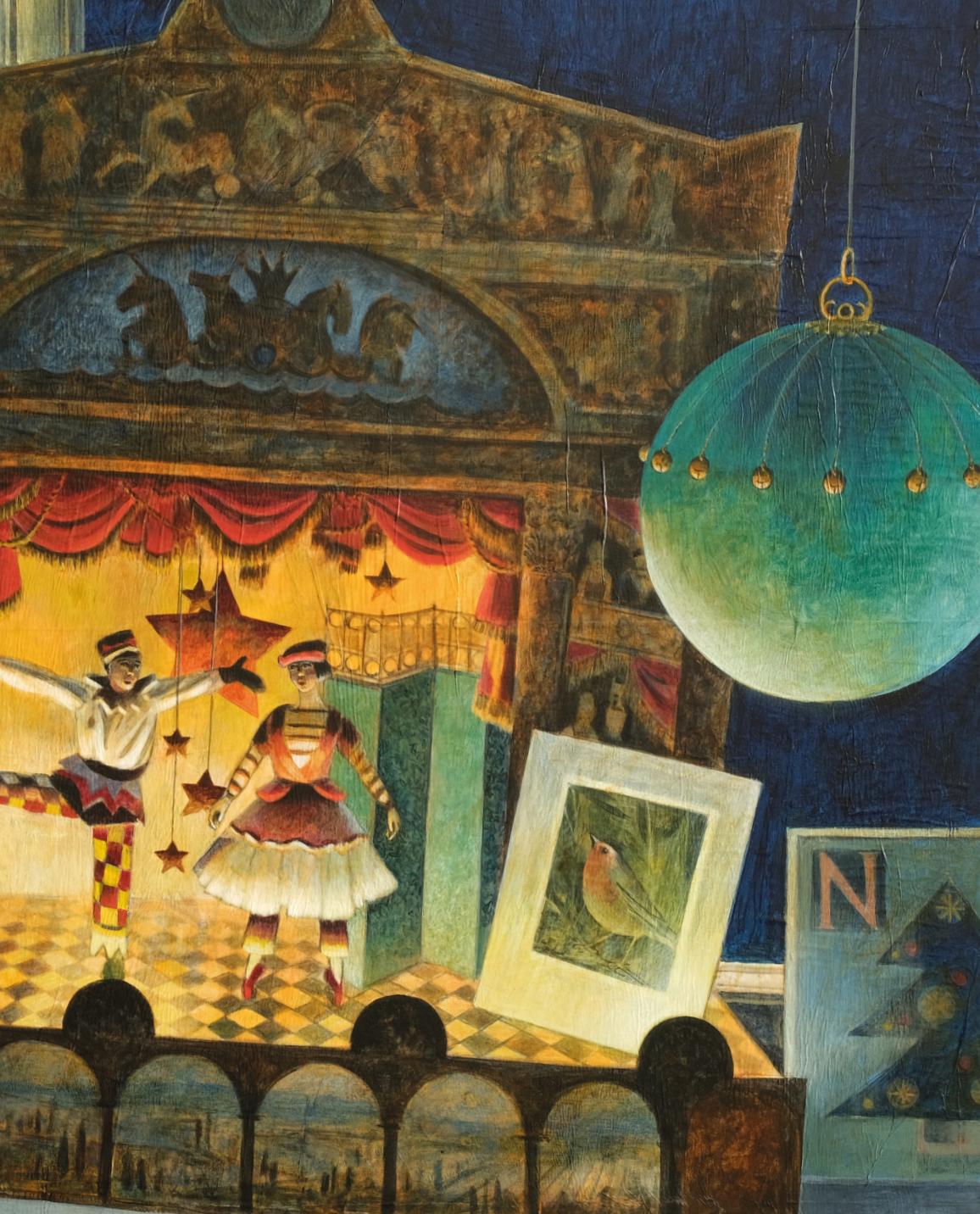

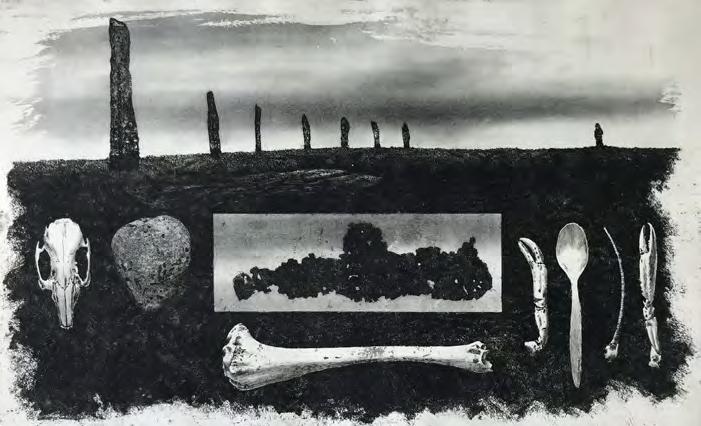

3. The Neolithic Trap, 2024 acrylic and oil on board, 100 x 140 cm

4. Brodgar, 1986 etching and aquatint 30 x 49 cm

5. Orkney Totem, 1980 etching, aquatint and mezzotint, 50 x 33 cm

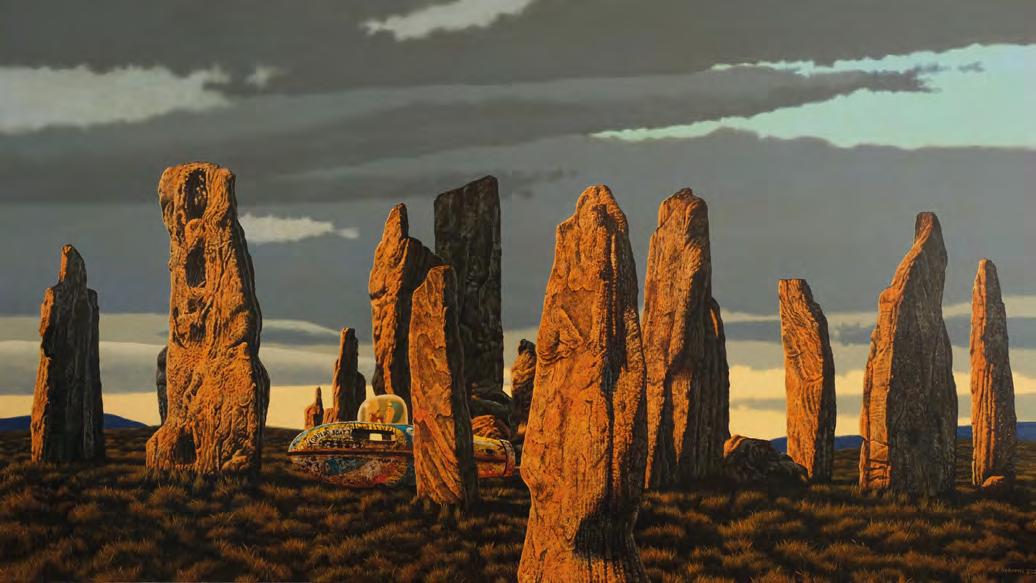

6. Calanais Sunset, 2024 acrylic and oil on board, 100 x 180 cm

7. Cairngorm, 1980 pencil on board, 67 x 45 cm

8. Inuit Valentine, 1989 pastel and pencil on board, 50 x 80 cm

9. Summer Snow, 2023 etching, drypoint and pencil, 49 x 83 cm

10. Trip of a Lifetime, 2024 acrylic and oil on board, 115 x 170 cm

Margaret Behrens

Painted Stages by

Margaret Smyth Behrens

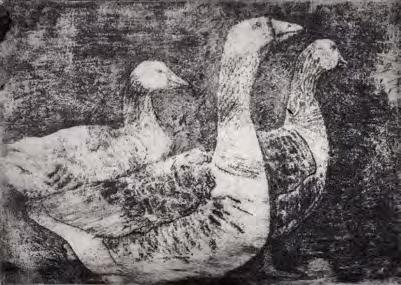

I was born and grew up in the Renfrewshire countryside in a house full of books, paintings and animals. It was a large, old, house with outbuildings, set within a couple of acres of wilderness garden and field, surrounded by rolling hills. From the top of the hill, Ben Lomond was visible, and looking south you could see the peaks of Arran. In early summer, what might have been called a lawn became a mass of blue speedwell and daisies. The geese grazed the grass closely but left the flowers untouched. I made many drawings and paintings of the geese. They were a favourite subject, but the entire environment, with its varied and eccentric menagerie, offered endless inspiration. We had everything from the usual cats and dogs to a parrot, chinchillas, a goat, two bush babies, a polecat, a solitary duck (who believed he was human, having been

hatched separately from the others), and many more. All waifs and strays were welcome, and I was probably the envy of many school friends. There were frequent excursions to nearby woods to make charcoal studies of trees or oil sketches on board. I also enjoyed making small gouache studies of corners of rooms in the house, likely influenced at the time by Vuillard.

The paintings in the house were mainly my grandfather’s, James Smyth, who had been a lecturer in the School of Design at Edinburgh College of Art. His paintings included still life and landscapes from across Scotland and his travels in Europe, along with sketchbooks. As a student travelling in Italy, I enjoyed trying to identify the locations of the paintings I had grown up with. There were also sketchbooks by my grandmother, Peggie Crocket, along with large design studies from her time at Edinburgh College of Art. After art college, she spent several months studying in Paris, visiting the Louvre and working from the Cluny Museum collections. She exhibited occasionally at the SSWA and other venues; however, most of her creativity found its way into clothing and furnishings, shaped by the Arts and Crafts movement. There are drawings of my father as a child, and later she sketched me and my brother, and there were always hand-drawn birthday and Christmas cards. This tradition was continued by my father. He inherited their artistic talents but turned to science, becoming a professor of marine biology and an early, influential voice in environmental education. His large library was full of beautifully illustrated books on flora and fauna. One of my favourites was Audubon’s Birds of America.

My brother left to study the MA course in Fine Art and I followed two years later studying Drawing and Painting. I thoroughly enjoyed my time at Edinburgh College of Art. I was a student

Margaret and brother, 1967

Edinburgh College of Art Diploma Examination 1912

Peggie Crocket second from left, James Smyth far right

Winter garden, Pittenweem

at the art college in the early 80s (1979-1983) and was also a post graduate student in 1984. I think we were among the last generations to benefit from a more formal structure, with allocated days for life drawing and life painting, head studies, anatomy, composition, and printmaking. David Michie, Elizabeth Blackadder and John Houston were all still on the staff. I remember Jimmy Cumming stating that a good painter should always be able to look at any colour and know how to mix it and this has stayed with me and has influenced my own approach to teaching.

In the 1990s, I received a letter from Diana Philipson. She wrote to tell me that David Michie had suggested that I was to be a recipient of one of her husband’s, Sir Robin Philipson’s easels. Reinhard and I visited her at her home, where she showed us the easel she had in mind. It was a large double easel, and she felt it was suitable for us both. The easel now lives in the bottom studio of our fisherman’s house in Pittenweem and is still used by both of us. Its engineering allows for complex positioning of canvases. The splattered paint and traces of white lead are a tangible link to its past and the many works that were created on it.

History repeated itself when, like my grandparents, Reinhard and I met at Edinburgh College of Art. We got married in 1986 and moved to Pittenweem in 1987 as I was teaching in the art department at St Leonards School in St Andrews. I very much enjoyed teaching and it was a very happy time putting down roots in Pittenweem, being inspired artistically by the new surroundings and thriving on the challenges and exchanges of ideas that teaching brings. From the beginning, the village was a friendly, welcoming community with strong connections to art. Joyce Laing, the renowned art therapist, lived nearby, and even closer was the granddaughter of the Glasgow painter John McGhie. Our garden looks up to his former studio. Our house faces south with a wide panoramic view, stretching from the

Pentland Hills and Edinburgh across the Lothian coast to the Isle of May and the mouth of the Firth of Forth. We often see dolphins passing and recently even a pod of orcas. With the Bass Rock nearby, diving gannets are a regular sight, and the sound of seals singing at night creates an atmosphere that is quite magical. This east coast light, along with the wide horizons, offers far more sunshine than the west coast. While I sometimes miss the hills and rugged coastline of the west, I do not miss the drizzle or the midges! We bought the house not long after spending time in Norway, and we were inspired by the compact and creative interiors of Bergen’s old houses. That influence shaped how we approached our own interiors, with playful and unconventional storage solutions. One example was a high bed built on a plan chest, with a false ceiling above used for painting storage. It was essentially a four-poster bed with only one post and a view of the sea.

As the family has grown, the use of rooms has evolved. With four artists working in the house, flexibility and compromise are key. Room usage often depends on who has the most pressing deadline. That said, we generally enjoy working under the same roof with none of us ever safe from a critique of ongoing work! We also feel lucky to be part of such a supportive local community.

We have taken part in the Pittenweem Arts Festival for nearly 40 years, and during this time, we have opened the studios to the public. It takes place over 10 days in early August. Like our family, the festival has changed and grown, but the blend of excitement and exhaustion remains familiar. Preparing feels like getting ready for a degree show. Studios are cleared, walls are painted, and artworks are hung and labelled. Unlike art college, these rooms are also living spaces, so clearing them is a bigger task. Furniture moves up a level, along with boxed artwork, props, and materials. Sometimes you have to walk sideways just to get through a room. No matter

how well we plan, it is always a last-minute rush. Now and again, we find a box during the year filled with a sock, half-eaten biscuits, a charger, a pencil sharpener, items gathered hastily before opening the doors. To anyone else, it would seem entirely bizarre. The days are full of moments. The cats usually retreat to the garden, though one might sneak into Reinhard’s installation and curl up on the bunk bed, like a miniature lynx. There is a strange intimacy to it all.

From an early age, David turned the kitchen table into a workshop. With balsa wood and wire in hand, he built replacements for sold pieces, working in full view of passersby like a craftsman in a shop window. More than once, after a long and tiring day, we have sat down for dinner only to hear voices. Visitors have let themselves in and are still exploring Reinhard’s installation.

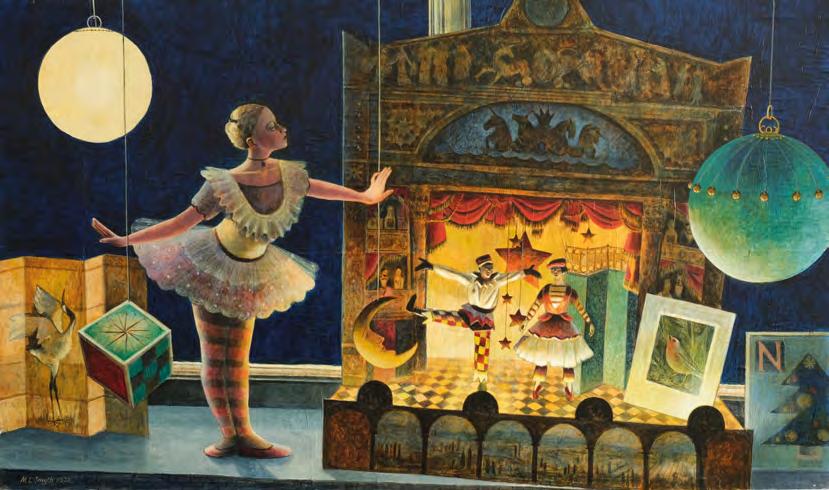

Over the years small paintings and sketches of

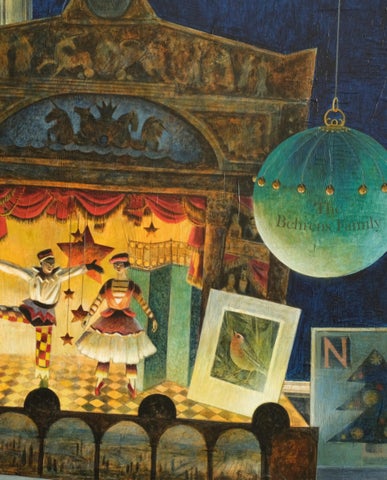

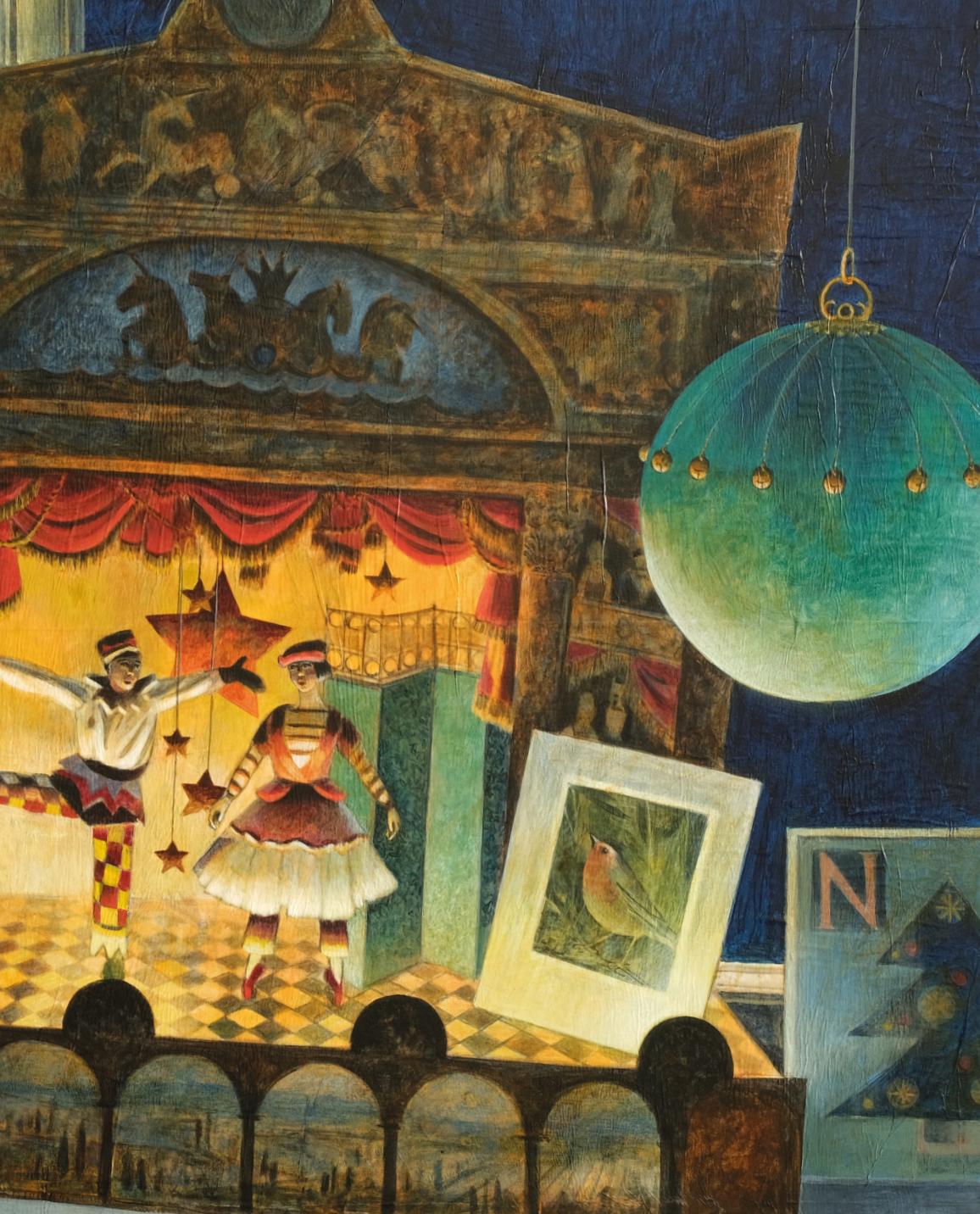

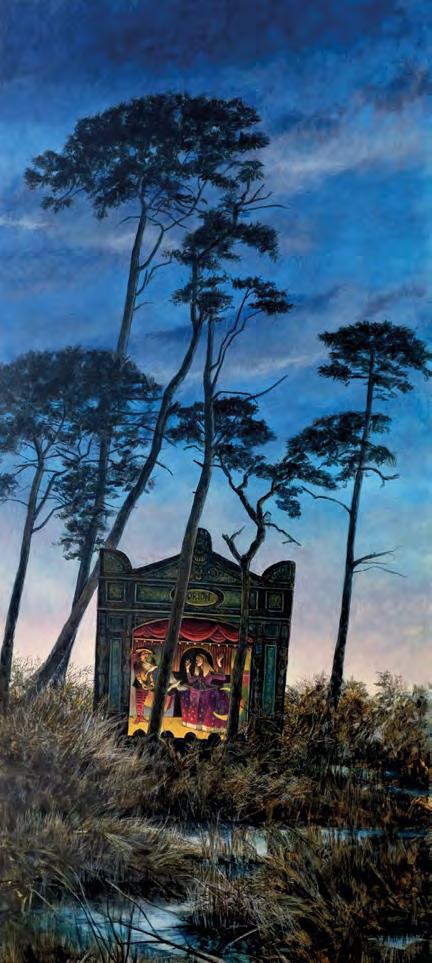

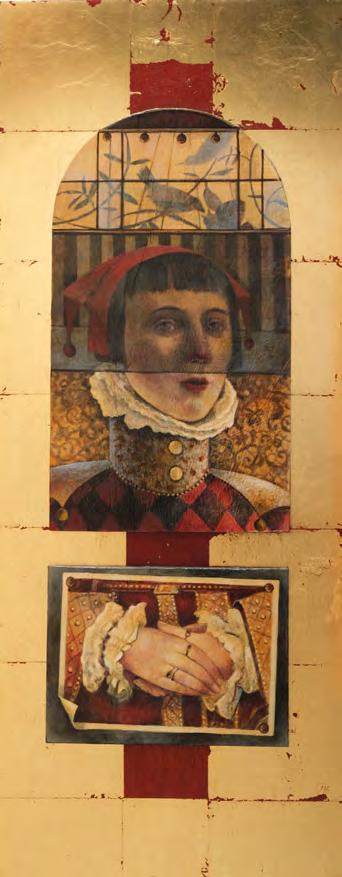

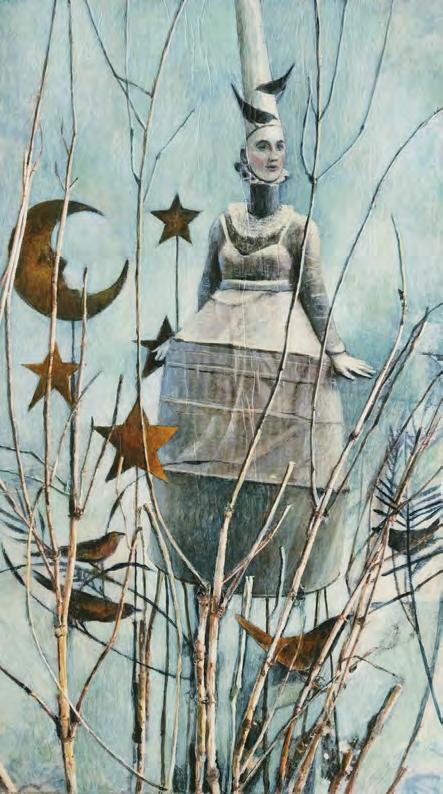

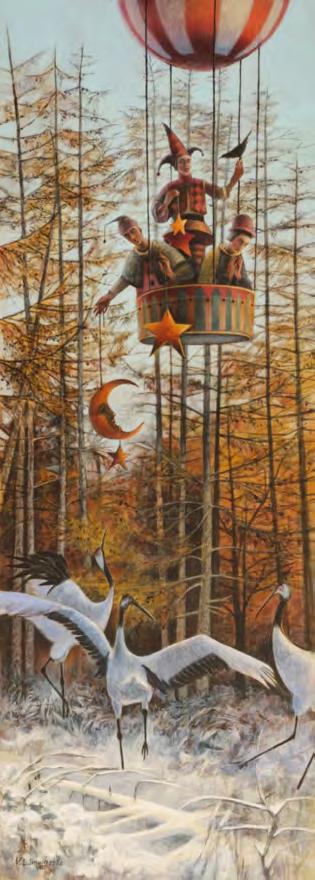

the children occasionally found their way into larger paintings of mine. They are not always recognisable, but sometimes one of them might have been asked to hold a balloon, a snow globe, or a flute. Some elements in my paintings are real, some are imagined, and some are a blend of both. There is a large cast of characters who shift roles between paintings. Among them is Coppélia, whom I found in a leaflet dropped on the floor during the festival. It advertised upcoming performances in Ross-on-Wye. I liked the expression on the dancer’s face. Her costume and scale have changed many times, but something of that first impression remains. The white figure was inspired by a street performer from Copenhagen I saw in Edinburgh. I changed the face but kept the white hooped skirt and gloves. The seaman and mermaids came from a book, possibly images from a fairground ride. These characters do not have specific personalities, though the seaman always seems slightly wistful. In recent years, landscape has become more dominant, and I enjoy placing small, intimate scenes within a theatre, circus tent or hot air balloon against more expansive natural surroundings. There is no fixed narrative. It is open to interpretation.

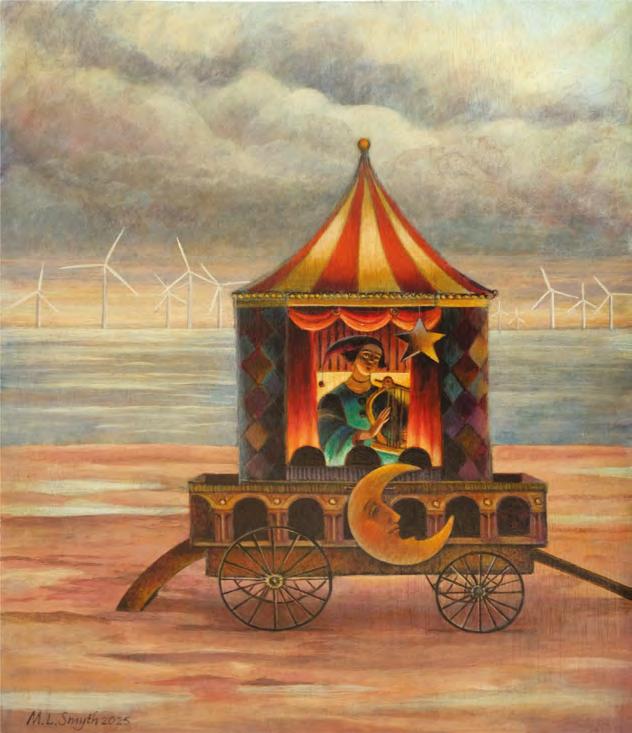

Recently, I have been composing scenes of musicians in carriages travelling along the beach, with wind turbines offshore. The performers could be from Renaissance paintings, but the turbines root the work in the present. I feel conflicted about them. I recognise their necessity but regret the loss of wild landscape. Offshore, I also worry about their proximity to bird colonies like the gannets on the Bass Rock. At the same time, I find them fascinating. Their movement has a kind of mechanical choreography, as their arms rotate to embrace the wind.

Reinhard and I feel privileged to live and work in such a beautiful part of Scotland and to be able to share this with Kirstie and with David when he’s not in London.

Portraits of Kirstie and David Behrens by Margaret Behrens

Margaret Behrens, 2024

11. Dawn Chorus, 2024 acrylic on board, 136 x 61 cm

12. After the Storm, 2023 acrylic on board, 87 x 116 cm

13. Coppélia’s Christmas, 2022 mixed media on board, 72 x 122 cm

14. On Tour, Finale, 2025 acrylic on board, 51 x 40 cm

15. On Tour, Cello Suite, 2025 acrylic on board, 51 x 40 cm

16. On Tour, Matinée, 2025 acrylic on board, 51 x 40 cm

17. On Tour, Birdsong, 2025 acrylic on board, 51 x 40 cm

18. Portrait with Birds, 2024 mixed media on board, 92 x 37 cm

19. Winter Fairy, 2023 mixed media on board, 40 x 23 cm

20. Arrival, 2025

acrylic on board, 110 x 40 cm

21. Sanctuary, 2024 acrylic on board, 133 x 59 cm

22. Reflection, 2024 acrylic on board, 40 x 29 cm

23. Winter Visitors, 2024 acrylic on board, 83 x 120 cm

Kirstie Behrens

Etched Landscape by

Kirstie Behrens

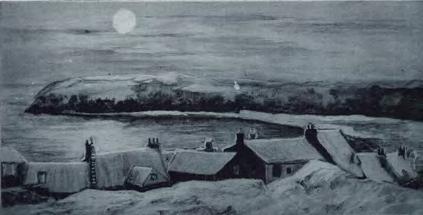

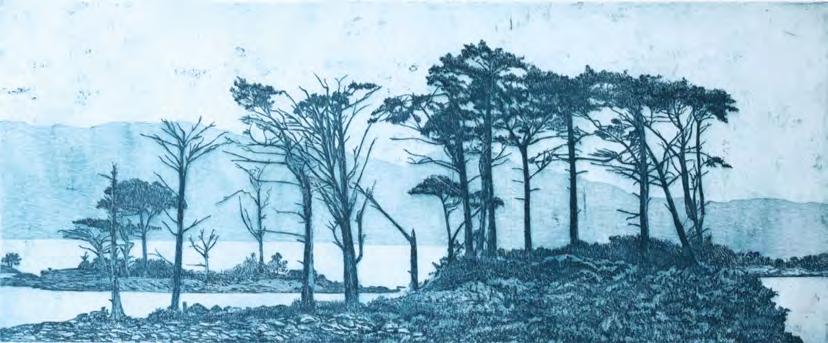

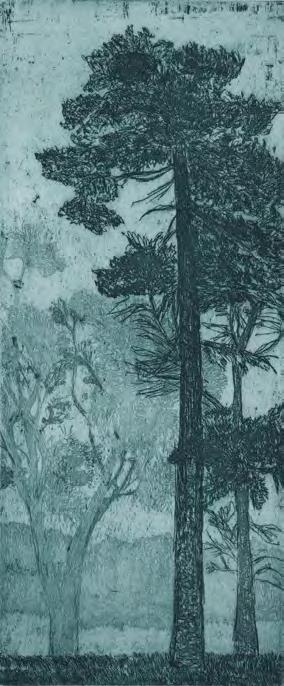

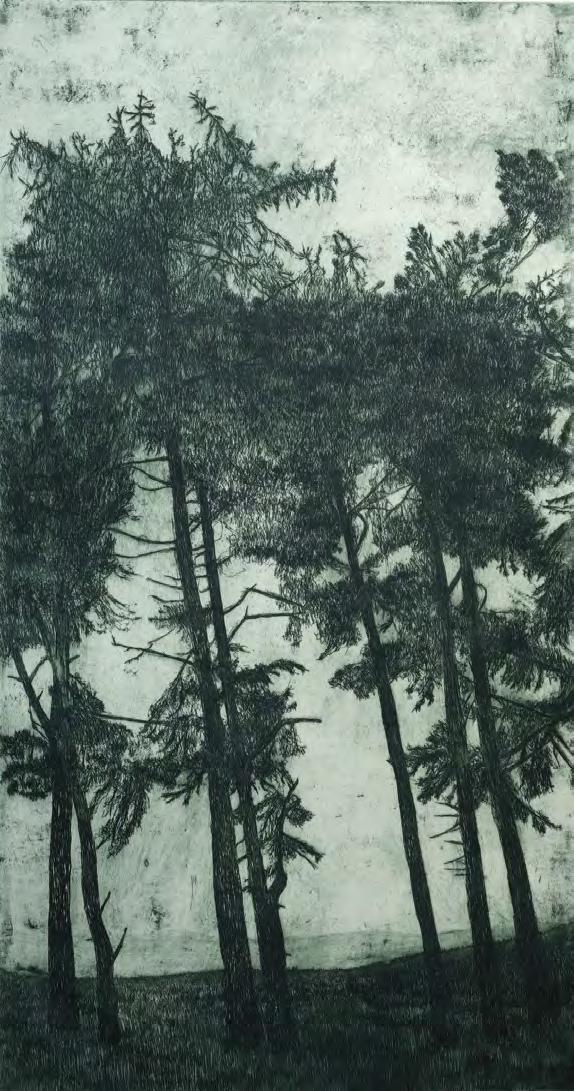

Etched Landscape is about the environment, more specifically, the meeting points between land and water. This includes coastlines, lochs, the peat bogs of Glencoe, the Angus hills, and the Cairngorms.

In March 2020, I travelled to Glencoe after a late, heavy snowfall. The trees were blanketed in white, and Rannoch Moor was transformed. Buachaille Etive Mòr stood almost entirely snow-covered, apart from the dark rock patterns peeking through. I’d prepared several large etching plates and used part of the lockdown period to work on one of them. In October 2020, during a lull in COVID restrictions, I took my first proof of Buachaille Etive Mòr and hiked up to the Lost Valley, where I left the etching under rocks. I had hoped to return a few months later to retrieve it and see what time and weather had done, but I didn’t make it back until last September, four years later. By then, only a few tiny fragments remained.

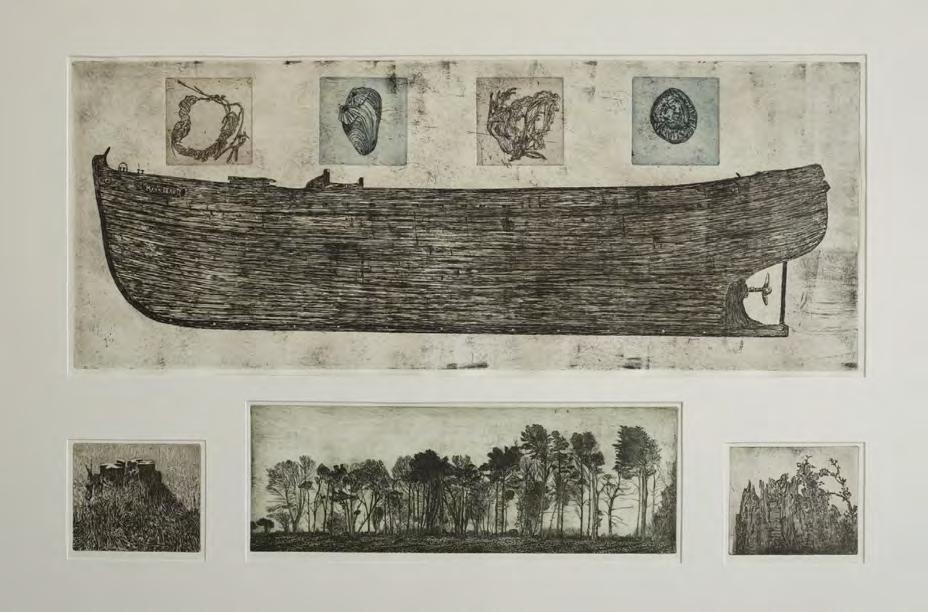

I’m currently Artist in Residence for the Manx Beauty project - a community initiative focused on rebuilding the historic fishing boat Manx Beauty, built in Cellardyke in 1937. As part of this, I’ve been working on four vertical compositions featuring sections of the coastline around Cellardyke in Fife near to where I live, and a larger etching of trees that run parallel to the water further along the coast. I’ve also included in this exhibition a series of small tree etchings from Yellowcraigs, across the water near North Berwick. The trees feel significant, Manx Beauty was made from wood, and these coastal zones would have been familiar to her during her fishing years.

Ten years ago, I first visited the Summer Isles, exploring the landscape around Achiltibuie. I returned recently, staying in a cabin in Assynt right on the beach, surrounded by dramatic mountains. I spent time making quick studies of the shifting landscape and sea under changing weather and light, similar to drawings I’ve done in Cellardyke around the harbour, looking out at views the Manx Beauty would have known well. I was struck by the fact that, although Assynt and Cellardyke are far apart, it’s the same water that connects them, and the Isle of Man too. I like thinking about water as something that links people and places, rather than separates them.

I love being in nature through all the seasons, but I particularly enjoy drawing trees in winter, when the structure of the branches and twigs is visible, and so are the negative spaces between them. The form of the tree is clearer without the softening of leaves and undergrowth.

Revisiting familiar places like the coastal path that runs past my home in Pittenweem at different times of year awakens all the senses: touch, sight, smell, and sound. You can’t see the wind itself, but you notice it in the way the trees move, feel it on your face, and hear it around you. On a visit to Skye, I built a wind harp and carried it up to the Old Man of Storr to capture the sound of the wind.

I love walking along the beach, looking at timewashed rocks and noticing how the land has been shaped by the rhythm of the sea over millennia. I often get absorbed in the tiny details of what’s just been washed up by the latest tide.

Kirstie Behrens, 2005

A portrait of Kirstie Behrens by Margaret Behrens Pittenweem in the snow

ETCHING

I started studying printmaking when I was seventeen and I was drawn to etching because I love to draw. I continued practicing etching through my time at art college and began to experiment a little more with colour. More recently, I’ve been combining etching with a mixed media approach, and I plan to explore this further.

I begin the process of printmaking by doing a drawing or painted sketch on location, supported by photographs. This combination is useful when I start to draw the image onto the metal plate. I enjoy the process of incising my lines into the hard ground of the etching plate, then waiting patiently as the copper sulphate acid reacts with the metal. Inking up the plate can take up to half

an hour, it takes longer if I use multiple colours or work with two plates. Since each plate is inked by hand, no two prints are ever the same. From the first mark to the initial proof, it can take about a month to complete all the stages, depending on the size of the plate. It’s always exciting to roll the plate through the press and lift the print to reveal the mirror image.

Sometimes I work on time-based projects where the elements themselves create marks - traces of the passage of time. I might leave an early proof of a print outdoors near the subject, allowing the environment to leave its own marks in dialogue with mine. I’ve buried prints in riverbeds, left them beneath trees, and submerged them under the sea through several tides. I often feel that these additional marks enrich the image and make it truly unique.

Kirstie Behrens at the etching plate

24. Winter Ram II polymer etching, 27 x 40 cm

25. Geese drypoint, 27 x 39.5 cm

26. Cellardyke Shore I, date etching and aquatint, 106 x 40 cm

27. Oban Ram polymer etching, 18 x 27 cm

28. Surprise II polymer etching, 39 x 26 cm

29. Hen IV drypoint, 39.5 x 27 cm

30. West Shore, Pittenweem drypoint, 27 x 39.5 cm

31. Sheep polymer etching, 40 x 27 cm

32.

Afternoon Light etching, 39.5 x 27 cm

33. St Andrews Pines II etching, 67.5 x 35.5 cm

34. Yellowcraigs Dusk etching, 20 x 27 cm

35. Yellowcraigs II etching and drypoint, 20 x 27 cm

36. Yellowcraigs Noon etching, 20 x 27 cm

37. Glenshee Winter II etching and drypoint, 39 x 53 cm

38. St. Michaels Treestump etching, 20 x 27 cm

39. Templeton Trees II etching, 62 x 35 cm

40. Glenshee Trees, Green etching and drypoint, 39 x 27 cm

41. Forgan Tree Stump etching, 91 x 53 cm

42. Winter Trees etching, 17 x 48 cm

43. Fish Skeleton - Manx Beauty etching, 20 x 24 cm

44. Manx Beauty - The Passage of Time etching and drypoint, 60 x 95 cm

45. Largo Pines etching, 59 x 96 cm

46. Summer Isles etching and drypoint, 29 x 78 cm

47. Loch Assynt etching, 107 x 65 cm

48. Achnahaird Dusk etching and aquatint, 67 x 26 cm

49. Achnahaird Dawn etching and aquatint, 67 x 26 cm

50. Achnahaird Noon etching and aquatint, 67 x 26 cm

51.

52.

53.

St. Michaels Pines II, Blue etching, 105 x 39 cm

St. Michaels Pines I etching, 105 x 39 cm

Scots Pine, Dusk etching, 39 x 27 cm

54. Glen Doll Pines etching, 107 x 65 cm

55. Winterwood II etching, 106 x 63 cm

56. Winterwood I etching, 107 x 60 cm

57. Windswept Trees etching and drypoint, 36 x 78 cm

58. Buachaille Etive Mor II etching and aquatint, 100 x 60 cm

59. Buachaille Etive Mor etching and aquatint, 106 x 61 cm

60. Cairngorm II, Blue etching and drypoint, 105 x 39 cm

61. Cairngorm I, Blue etching and drypoint, 105 x 39 cm

62. Glencoe I, Blue etching and drypoint, 105 x 39 cm

63. Glendoll I, Blue etching and drypoint, 105 x 39 cm

64. Glendoll II, Blue etching and drypoint, 105 x 39 cm

David Behrens

Musical Threads

by David Behrens

The novelty of growing up in a household of artists wasn’t something I truly appreciated until I started visiting friends’ houses and realised that they, in fact, didn’t have a bathroom full of mounting card and etching inks, or a kitchen where finding a tube of acrylic paint was easier than finding a bottle of ketchup. Strangely, the idea of hundreds of people wandering through our house each year for the Pittenweem Arts Festival was always quite exciting to me. Even before following in my sister Kirstie’s footsteps by selling some very early artwork at a stall, I was in charge of decanting box wine for various members of the public. It was an endeavour I pursued with such zeal that, to this day, I still associate the aroma of white wine with the buzz of preview nights. Now, in my mid-twenties and based in London, I reflect on this upbringing with ever-growing appreciation.

Spending my childhood immersed in my father’s imaginative world of Naboland took this sense of novelty to new heights. Some of my earliest memories involve ‘helping’ him assemble his travelling raft installation or mixing a disproportionately large quantity of plaster to build a prop for one of his ever-evolving animation projects. The iconic toy submarine was a constant source of inspiration if I was ever at a loss for birthday present ideas. I’ve lost count of how many versions I attempted to recreate across a variety of mediums. From balsa wood to baking, its familiar outline is embedded in many of my earliest artistic efforts.

In terms of my own practice, another early memory is of taking apart one of my favourite

toys, a mechanical pen, in order to understand how it worked. Needless to say, I had mastered the art of disassembly before that of reassembly, and the pen never returned to working order! Despite this, my fascination with anything mechanical outweighed all other interests. So, when visiting galleries where my parents were exhibiting, I naturally gravitated toward anything kinetic. This is a behaviour I’ll admit I still have to this day. While my early years were spent making maritime themed automata, I distinctly remember encountering the work of George Wyllie at his commemorative exhibition in 2012 and discovering the beauty of his more abstract kinetic spires. Around the same time, I also came across the work of Alexander Calder and his mobiles. Both artists awakened me to the idea that kinetic art need not be literal. And while I still enjoy the charm of representational automata, there’s a sleekness and purity to these abstract approaches that resonates more clearly with my love of kinetic art.

Alongside my visual practice, I was lucky enough to begin piano lessons at the age of seven. Though they initially felt like a chore, I gradually grew to appreciate music, going on to learn the saxophone and guitar during school, and eventually enjoying the process of writing music. The first significant union of art and music for me came at the end of my school years, when I created an installation of abstract mobiles accompanied by an atmospheric piano track. I loved how the relationship between the two mediums created something greater than the sum of its parts. Since then, I’ve nurtured this relationship each year at the Pittenweem

David Behrens, 2025

Arts Festival, where I write a selection of music to accompany my visual work on display.

After completing a degree at the Reid School of Music at Edinburgh College of Art in 2020, I’ve been fortunate to work on a range of music and art projects in diverse locations, including a school in The Gambia and a refugee camp in Greece. These experiences offered a refreshingly direct example of how artistic practice can have a meaningful impact beyond the expectations of the visual arts or music. From 2020 to 2024, I worked for the Fife-based East Neuk Festival, an annual music festival that also embraces the wider arts and engages local communities through large scale interdisciplinary projects.

Currently, I am undertaking a two-year master’s degree in composing for film at the National Film and Television School. The parameters of form, structure and composition exist across film, music and visual art. This exhibition, The Behrens Family, brings those ideas together. I have created a body of kinetic work that incorporates both visual and musical themes, a series of abstract visualisations of musical phenomena. The short Fundamentals series offers a playful experimentation with the building blocks of these parameters, while the other sculptures present a more distilled interpretation of the same principles in a subtler manner.

David’s early automata David, 2011

65. Fundamentals I balsa wood, wire and acrylic, 58 x 56 x 14 cm

66. Fundamentals II

balsa wood, wire and acrylic, 56 x 52 x 14 cm

67. Fundamentals III

balsa wood, wire and acrylic, 56 x 52 x 14 cm

68. Composition I balsa wood, wire and acrylic, 35 x 35 x 5 cm

69. Cadence balsa wood, wire and acrylic, 95 x 105 x 0.5 cm

70. Counterpoint

balsa wood, wire and acrylic, 60 x 140 x 0.5 cm

71. Pedal Note balsa wood, wire and acrylic, 150 x 118 x 0.5 cm

Reinhard Behrens (b.1951) PPSSA, RSW, RGI

Education

1971 – 78 Hamburg College of Art

1979 – 80 German Academic Exchange Grant for Post Graduate Course in Drawing and Painting at Edinburgh College of Art

Solo Exhibitions

2025 The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

2023 Tatha Gallery, Newport-on-Tay

2021 Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

2008 Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

2006 Marishal Museum, University of Aberdeen; Bonhoga Gallery, Shetland

2005 Methil Heritage Centre, Fife

2004 Byre Theatre, St. Andrews

2000 Pittenweem Arts Festival (Invited Artist)

1999 Roger Billcliffe Gallery, Glasgow

1997 Kirkcaldy Museum and Gallery

1996 Arts in Fife Bus Tour; Campo Santo Chapel, Ghent; Crawford Arts Centre, St. Andrews; Galerie

Claude André, Brussels

1993 St. Andrews Festival, University of St. Andrews; Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

1992 Galerie Gehring, Frankfurt; Aberdeen Art Gallery

1991 Barrack Street Museum, Dundee

1989 Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

1988 Seagate Gallery, Dundee; Pier Arts Centre, Stromness

1987 McLaurin Art Gallery, Ayr; Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

1986 An Lanntair, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis; Artspace Gallery, Aberdeen; Crawford Arts Centre, St. Andrews

1985 Smith Art Gallery and Museum, Stirling

1984 Glasgow School of Art; Printmaker’s Workshop, Edinburgh

1982 Edinburgh College of Art; Henderson’s Gallery, Edinburgh

Public Collections

Aberdeen Art Gallery

Art in Healthcare

BBC Scotland

Edinburgh City Arts Centre

Educational Institute of Scotland

Grampian Hospitals Art Trust

Historic Environment Scotland

Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery

Kirkcaldy Museum and Art Gallery

McManus Museum and Art Gallery, Dundee

Perth Museum and Art Gallery

Royal College of Physicians

University of St. Andrews

Margaret Smyth Behrens (b.1961)

RSW, SSA

Education

1979 – 83 Edinburgh Collge of Art

1983 – 84 Post Graduate Scholarship, Edinburgh College of Art

Teaching

1985 – 1991 Art Teacher at St Leonards School, St Andrews

1994 – 1997 Life Drawing Tutor, Crawford Arts Centre, University of St Andrews

2012 – 2024 Art Teacher at St Leonards School, St Andrews

Solo Exhibitions

2018 Bohun Gallery, Henley-on-Thames

2011 Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

2003 The Scottish Arts Club, Edinburgh

1996 Galerie Claude Andre, Brussels

1995 Courtyard Gallery, Crail

1994 Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

1994 Tweeddale Museum, Peebles

1992 Crawford Arts Centre, St Andrews

Since 1987 Pittenweem Arts Festival

1987 Maclean Art Gallery, Greenock

1986 Gladstone’s Land, Edinburgh

1985 Triangle Gallery, Edinburgh

Awards

2022 The W Gordonsmith and Mrs Jay Gordons, RSW

2002 The Scottish Arts Club Prize, RSA

1991 John Murray Thomson Award, RSA

Public Collections

Edinburgh University Fife House, Glenrothes

Kirstie Behrens (b.1991)

Kirstie Behrens is an award-winning artist and printmaker, based in Pittenweem in Fife. She graduated from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design in 2019 and in 2021 she won the Roy Wood Prize for Printmaking, the Art in Healthcare Award and the W Gordon Smith & Jay Gordon Smith Award from the Royal Scottish Academy. Kirstie practice revolves around time-based projects where natural elements are actively incorporated as tools in her practice, creating marks which leave traces of evidence of the passage of time. Traditional etching is a printmaking technique that involves using acid to bite into a metal plate (usually copper, zinc, or steel) to create an image. Using a sharp etching needle or other pointed tool, Behrens then draws directly onto the surface of the plate, exposing the metal beneath the ground. The lines and marks will later be etched into the plate. Traditional etching allows for a wide range of mark-making and tonal effects, making it a versatile and expressive medium for artists. While the process can be time-consuming and requires careful handling of hazardous materials, it offers unique opportunities for artistic experimentation and exploration. Trees are central to Kirstie printmaking practice. She often depicts trees in landscapes, or as standalone subjects, or as part of more complex compositions which feel more like intimate portraits. Her etched trees can evoke a range of emotions, from the isolated, serene beauty of nature to reflections on the passage of time and the cycle of life.

Education

2015 – 19 Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design Awards

2022 An Talla Solais Award, RSA

2021 W Gordon Smith and Jay Gordonsmith Award, RSA

2021 Art in Healthcare Award, RSA

2021 Roy Wood Prize for printmaking, RSA

2019 Graduate Exhibition Award Angus Alive

2014 Art in Healthcare Award, RSA

Since August 2021 Kirstie Behrens has been Artist in Residence for the Manx Beauty Project, Cellardyke, which is a community initiative to restore the fishing boat Manx Beauty

David Behrens (b.1998)

Born in Dundee in 1998, David Behrens is a versatile composer, performer, and educator with a strong commitment to both professional practice and community engagement. A First-Class graduate in Music from the University of Edinburgh, he was awarded the Andrew Grant Prize for Recital and published research on live performance programming. He is currently pursuing an MA in Composing for Film and Television at the National Film and Television School in London. Alongside his academic achievements, David has built a rich portfolio of work as a composer, performer, and teacher, writing scores for film, theatre, and choral commissions, while regularly exhibiting at major Scottish arts festivals. His dedication to community arts has seen him lead projects from The Gambia to Greece, creating original productions with children and adults in diverse settings, including refugee camps and schools. With experience spanning festival production, gallery work, and instrumental teaching, David continues to bridge creative practice with meaningful social impact.

Education

2025 – National Film and Television School, London

2016 – 20 University of Edinburgh

Awards

2020 Andrew Grant Prize for Recital, University of Edinburgh

Published by The Scottish Gallery to coincide with the exhibition:

The Behrens Family 2 - 25 October 2025

Exhibition can be viewed online at: scottish-gallery.co.uk/behrensfamily

ISBN: 978-1-917803-08-3

Designed and Produced by The Scottish Gallery Photography courtesy of the Behrens family archive and Christina Jansen Printed by Pure Print

Front cover: Margaret Behrens, Coppélia’s Christmas, 2022 mixed media on board, 72 x 122 cm (cat.13)

All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy or by any other means, without the permission of the copyright holders.