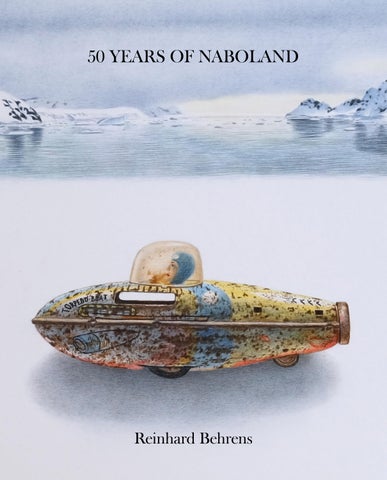

50 YEARS OF NABOLAND

Reinhard Behrens

Reinhard Behrens

by Christina Jansen

In this landmark retrospective, The Scottish Gallery is honoured to present 50 Years of Naboland – a celebration of the extraordinary imaginative journey undertaken by Reinhard Behrens.

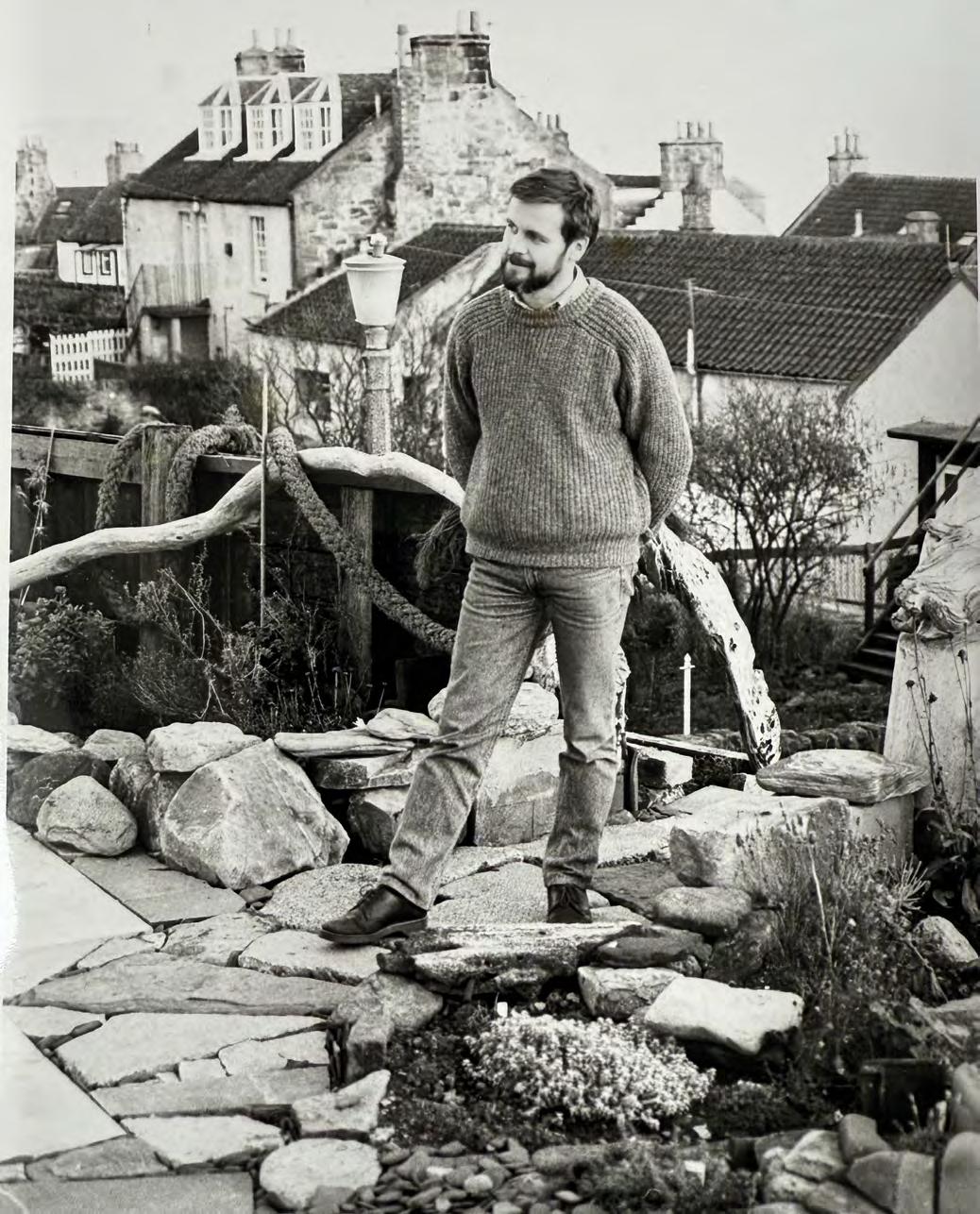

Behrens, originally from Hamburg, has lived and worked in Scotland since the late 1970s, developing his practice through a lifelong engagement with the landscape, seascape and history. His postgraduate studies at Edinburgh College of Art marked the beginning of a deeprooted connection to Scotland.

Since the mid-1970s, Behrens has quietly constructed one of the most idiosyncratic and enduring artistic universes in contemporary art. Rooted in personal mythology, archaeology, environmental reflection and a distinctive northern sensibility, Naboland is both a place and an idea: a parallel world glimpsed through the lens of play, memory and dream.

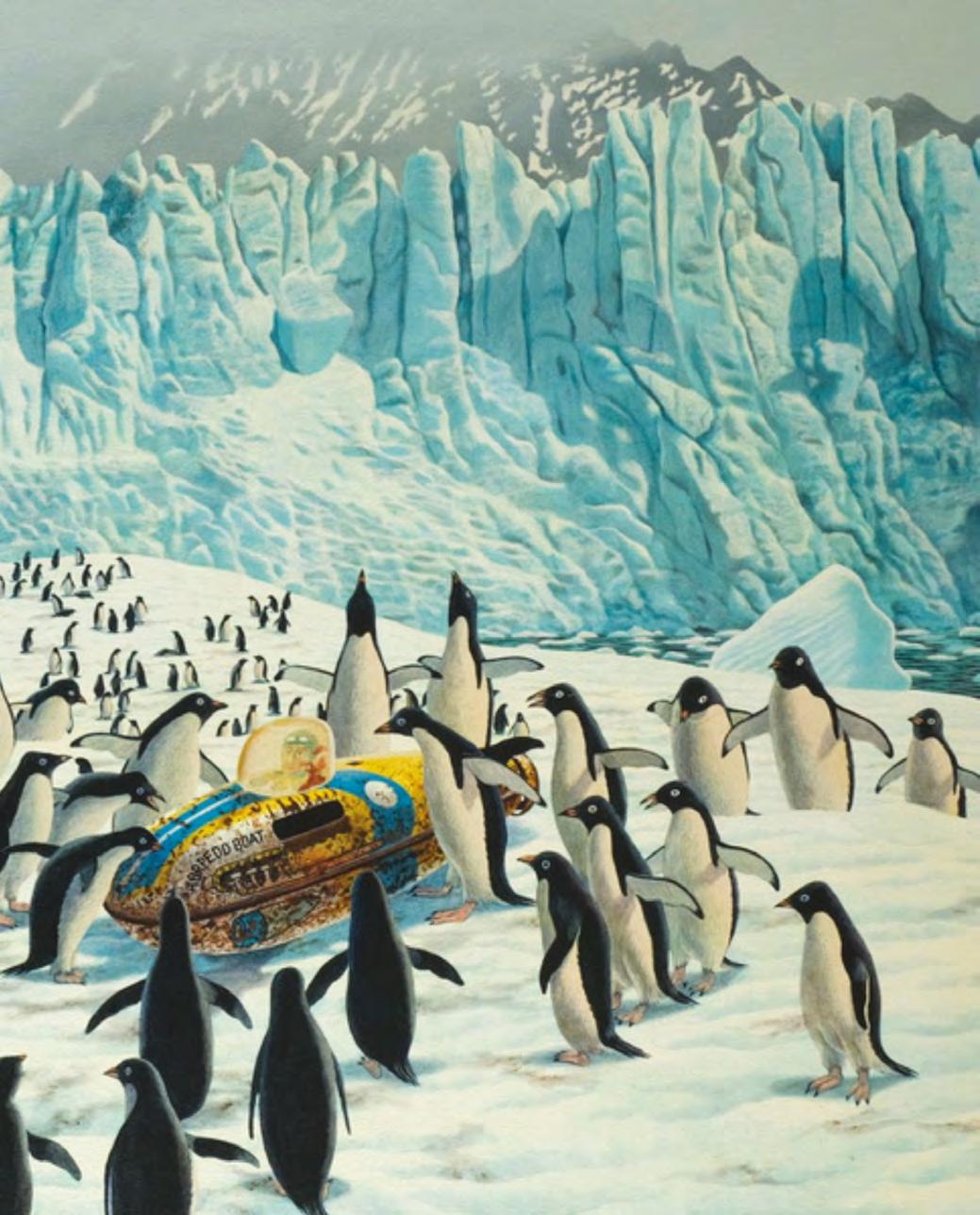

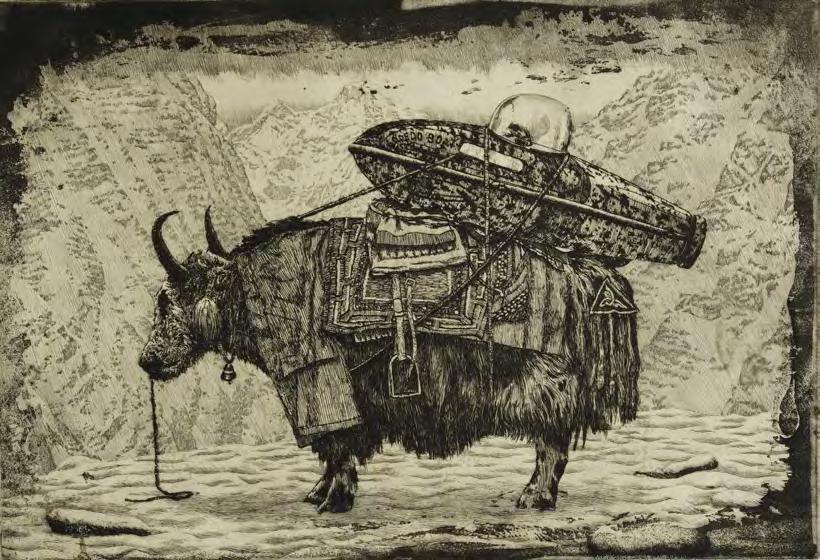

Behrens’s work resists easy classification. It is part expedition journal, part museum installation, part allegorical theatre. At the centre of his evolving vision stands a deceptively humble object – a brightly coloured toy submarine, discovered on a North Frisian Island in 1974. Since then, this modest vessel has become a recurring avatar in his practice: a symbol of human curiosity, displacement and naivety. It drifts through imagined polar landscapes, burrows into archaeological strata, and even interrupts canonical works of European art history with both humour and quiet poignancy.

50 Years of Naboland spans painting, etching, works on paper, installation, and animation. From his Arctic hut built from driftwood and domestic flotsam to drawings echoing the precise draughtsmanship of explorers and scientists, Behrens documents Naboland as if it were both fact and fiction – a place of poetic resonance rooted in tangible materials and personal experience.

Central to the Naboland concept is the notion of evidence, manufactured artefacts and displays that mimic museum practice, encouraging the viewer to suspend disbelief and enter into a space where the absurd coexists with the archaeological, the nostalgic with the environmental. While often whimsical in tone, Behrens’s work carries with it an increasingly urgent ecological message: Naboland is a meditation on our fragile relationship with the natural world, and the objects we leave behind.

As Naboland turns fifty, this significant body of work is perhaps more relevant than ever, a quietly defiant space of invention and resistance, where imagination itself becomes a form of preservation.

We invite you to enter Reinhard Behrens’s unique and enduring world, to become part of its evolving mythos, and perhaps, to find your own traces in its snow-covered ridges, miniature relics, and glinting, half-buried truths.

The Explorer’s Hut, 2023

by Reinhard Behrens

For a long time I have been fascinated by the notion of serendipity. I hope that the following text will give an illustration of how the chance findings of two elements provided the fuel for my artistic work that has lasted half a century, and shows no signs of running out any time soon. Those two findings turned out to be keys into a parallel world of found objects, real and imagined travels and the associations that are triggered in anybody who stumbles into this world.

Many of us know the thrill of strolling aimlessly along a beach enjoying the coming together of three elements that are in continuous dynamic relationship with each other. This amphibious environment in which waves reveal and hide in equal measure what is thrown ashore lets us witness for a brief moment tidal forces that have existed long before us and will continue long after we have gone. What could be intimidating gives most of us a sense of empowerment as we are close to forces

far greater than us that affirm our awareness of being alive. In this state of wave-induced dreaminess, many of us take to beachcombing and enjoy the surprises of shell fragments, coloured stones, feathers and, of course, in growing numbers mixed in with these, bits of plastic and man-made objects. Many of us will collect stones and shells in the hope that they will magically extend those holiday moments when we display them on shelves in our homes.

Sadly, those hopes are quickly eroded by the routines of our daily professional lives, and what was inspiring during a brief moment of relaxation is forgotten over the need to manage our daily affairs.

Unless you are an artist! Then you make those moments of inspiration your currency and nurture an open-mindedness towards the surprising and unexpected that becomes the essential mental prerequisite for your work.

I invite you to enjoy the fruits of my artistic foraging and follow me into a territory that needs no passport but a sense of wonder and the willingness to suspend disbelief for a little while.

Born in Hamburg in 1951, I grew up in postwar Germany. My father returned late from captivity in the Soviet Union, and my mother was a refugee from East Prussia. As an only child, and with no television, I created an inner world of drawing and enjoyed outdoor play with friends. While others acted out battles with stick guns, I was more interested in designing dens, often built in the ruins of bombed-out buildings.

Squinting into the sun, Hamburg, 1958

During this time, I was captivated by Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant illustrations and a book about a toy canoe journeying across Canada, an early sign of the artistic voyage ahead.

In 1968, I visited the Documenta exhibition in Kassel, which was curated around the theme of Individual Mythologies. I was deeply moved by Edward Kienholz’s claustrophobic The Beanery and Claes Oldenburg’s entertaining Mouse Museum. I also watched a documentary on the Netsilik Inuit, who lived in harmony with nature without producing waste.

The question of how an ever-increasing population can still live responsibly on this planet has remained a concern of mine, and it is a theme that appears, sometimes obliquely, in my work.

While studying art, I worked on exhibitions at Hamburg’s Kunstverein and was inspired by Peter Blake’s whimsical British sensibility and Nikolaus Lang’s forensic Spurensicherung (securing of traces) installations, where found objects from an abandoned Bavarian farm were neatly arranged in boxes.

1968 was also the year the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine animated film was released,

another example of British humour and hopefulness during a time of intense political unrest around the world.

In 1973, I travelled to Iceland. The wild volcanic landscape, with its elegant, nameless glacial meltwater streams, filled me with awe and made me aware of the fragile crust on which all our human activity takes place. At one remote abandoned farmhouse, still strewn with household objects and eerily intact, I discovered items including a catalogue of Icelandic farm equipment. Reykjavik also charmed me with a small museum, tightly packed with specimens and local artefacts.

Returning to Hamburg by plane, halfway through the flight, I looked down at a rugged, mountainous terrain with interlocking fjords and a green patchwork of fields that seemed to belong to a storybook. Gradually, I realised I was looking at Scotland!

In 1974, while beachcombing on a low-lying North Frisian Island, I spotted something different from the usual flotsam and jetsam. Colourful and glistening in the afternoon light, half buried in sand and seaweed, was a metal object in the shape of a toy submarine. I kept it as an unusual trophy, intending to draw it, as I had done with other found objects.

I imagined a little boy had played with the submarine too close to the ferry pier, only to

see it slip into the sea, lost forever. He could not have known what would become of his toy, and neither did I.

On closer inspection, the toy had small writing on its side: Made in China. Two halves of shaped metal formed the body. A yellowed, scratched plastic dome protected the rubber head of a young-looking pilot. When squeezed, the pilot’s face distorted, reminding me of photos in Eduardo Paolozzi’s sketchbooks, which showed how G-force twisted a test pilot’s expression into a grimace. Small patches of rust had eaten into the submarine’s printed colours, but the words TORPEDO BOAT remained clear.

In the following year, I spent three months in Turkey, working as an artist with the German Archaeological Institute. We were based in Bergama, ancient Pergamon, on the Aegean coast. After a guided tour in the midday heat, I was bedridden for days with sunstroke. Through a haze of fever, I saw a Turkish

newspaper someone had left by my bed. One article featured a map of the Dardanelles and a photograph of a damaged submarine beside a cargo ship’s bow. The only word I could read was the name of the cargo ship: NABOLAND.

In my feverish state, I remembered the toy submarine I had found the previous year and imagined it exploring this newly discovered territory. If I ever made it home, I resolved to devote my artistic life to filling this magical name with stories, both real and imagined. I would create “evidence” for Naboland, to make the case for its existence undeniable. At times, I even imagined that Naboland might become more widely known than my own name. But for that to happen, I would need something else, something that appeared years later.

In 1978, I applied for a scholarship to study abroad and visited Edinburgh College of Art, where the Principal, Sir Robin Philipson, welcomed me warmly. In 1979, I returned for a full year of postgraduate study.

Scotland’s landscapes, coastal paths, and ancient sites, especially on Orkney, deepened my connection to the themes I was exploring. I was struck by places like Skara Brae and the Brough of Gurness, where visitors could step into structures thousands of years old. My studio quickly filled with finds from the shore: skulls, feathers, stones, sandals, and the submarine. When a fellow student responded enthusiastically to the submarine, I knew Scotland was the right place for Naboland to flourish!

Joining the Edinburgh University

Mountaineering Club gave me a more intimate experience of Scotland’s wilderness. I imagined myself on a polar expedition, hiking misty ridges and pitching tents on snowy slopes.

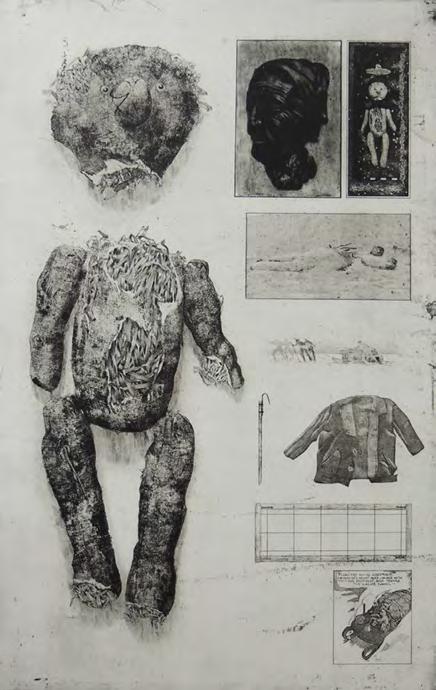

During a visit to Hamburg, I was beachcombing along the Elbe and discovered what I thought was a misshapen potato. On closer inspection, it was a teddy bear’s head, its fabric worn smooth and eyes of orange plastic. A few metres away lay the body. The bear, now stripped of fluff and ears, resembled a relic, like the mummified animals I had once seen in the Museum of Mankind in London.

This was another treasure for Naboland. Like the submarine, it had moved from innocent plaything to honoured artefact. I made an etching of it, titled Tollund Teddy, evoking the preserved iron-age Tollund Man found in a Danish bog.

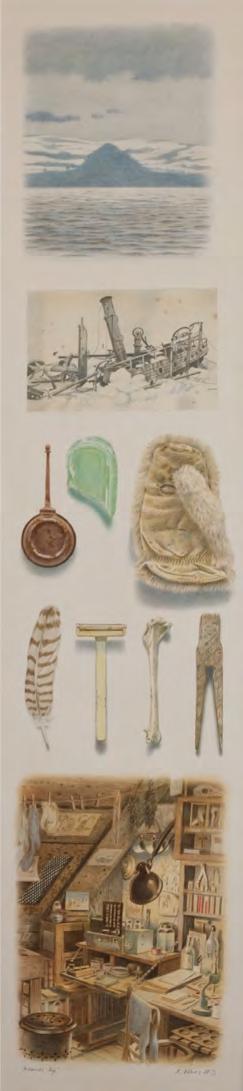

For my postgraduate show, I created etchings, mountain paintings, and installations that resembled archaeological sites. I received the Andrew Grant Travel Scholarship and extended my stay in Scotland. In a later exhibition, I built my first Arctic Hut from driftwood and found objects. It resembled a shelter from an explorer’s journey and became a recurring motif in my work.

At Edinburgh College of Art I also met Margaret Smyth, a fellow artist who later became my wife. Her friendship, encouragement and practical help became essential to Naboland’s evolution. Exhibitions followed in Glasgow, Orkney, Stirling, and Aberdeen. At An Lanntair in the Hebrides, locals said my hut resembled the abandoned summer shelters, or shielings, scattered across the land. That unintentional parallel affirmed Naboland’s authenticity. In later shows, the hut reappeared as a drifting raft on seas of salt.

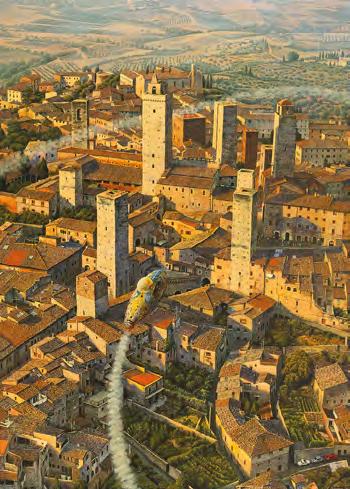

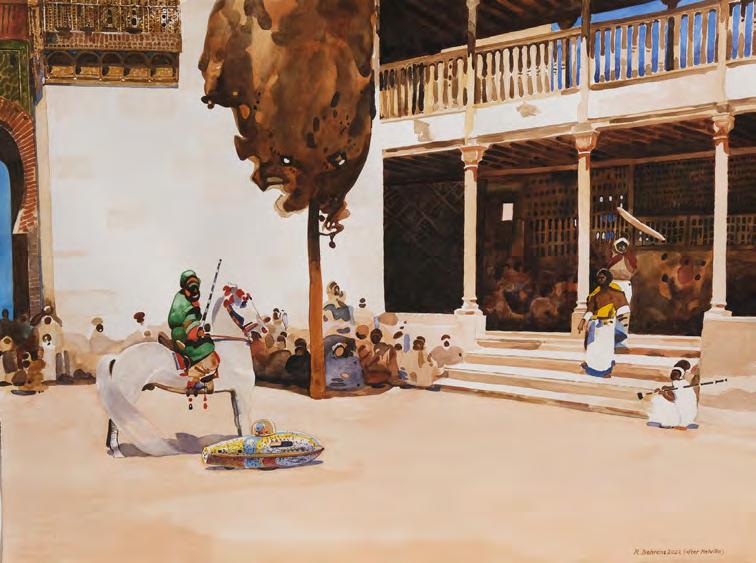

Sometimes the submarine slips into historical artworks: pulled by Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow, ducking cannon fire, floating through Venetian canals, or breaching a frozen loch in Arthur Melville’s watercolours. These interventions gently connect past and present, imagination and memory.

Pittenweem

Margaret and I settled in Pittenweem, Fife, in the 1980s. Our home and studios overlook the harbour and sea. We joined the town’s arts festival and began turning our home into a gallery every summer. We reimagine our rooms as part museum, part stage, and part studio.

A Canadian visitor once entered the hut installation and became overwhelmed with emotion. It had stirred a long-buried memory. Others bring gifts, like fragments of rigging, expedition notes, or old toys that echo the aesthetic of my displays.

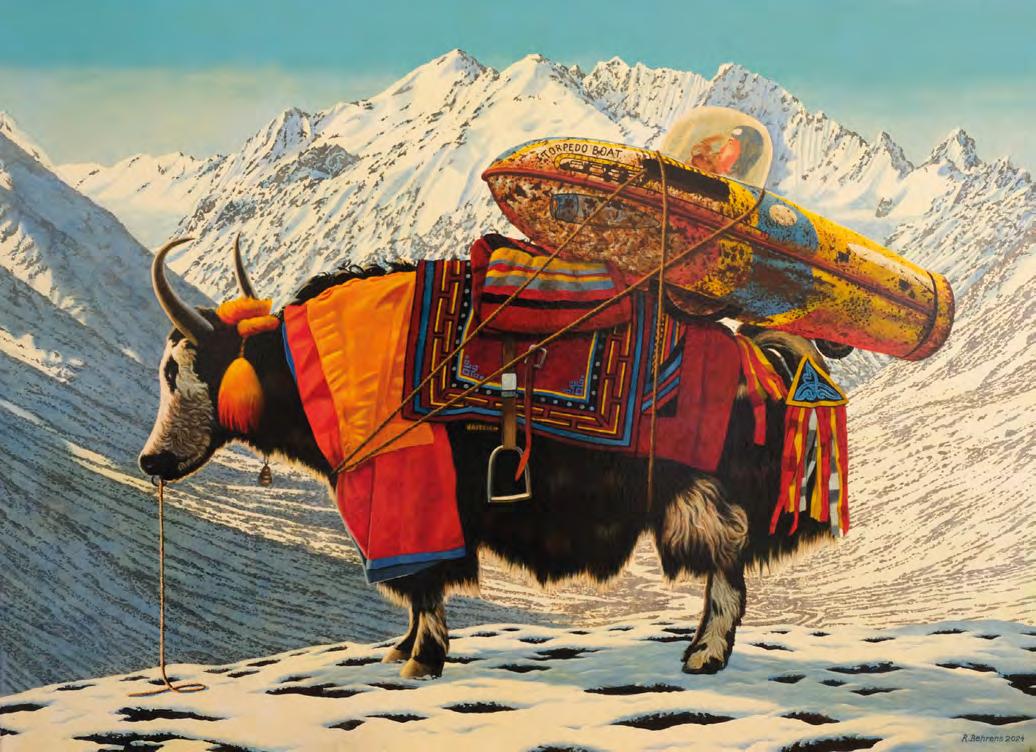

In 1990, we travelled to Nepal, trekking through forests and over snowy passes in the Annapurna range. My response became The Last Yeti, an installation in Dundee’s Natural History Museum. Visitors passed from taxidermy displays beneath the skeleton of the Tay Whale into my imagined Yeti Hall, complete with flickering electric candles and fictional artefacts. The work hinted at the loss of species and the vanishing edges of our known world.

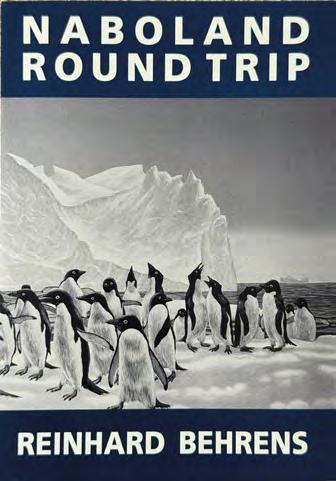

In 1996, the Naboland Round Trip Bus, a converted double-decker by the Arts in Fife, toured schools across Fife. That year, I also joined a Flemish art exchange and created a series tracing the submarine’s journey from Pittenweem to contemporary Ghent through stormy seas and surreal townscapes by Flemish painters of the past.

In 2001, we travelled to Tuscany with our daughter Kirstie. The submarine, ever faithful, surfaced in paintings like Touchdown in Tuscany and San Gimignano – Nowhere to Land. Later, in Venice, it appeared again in San Trovaso MOT and Just in Time, darting past clocktower statues that have rung the hour since 1499.

In 2007, two animation students at Duncan of Jordanstone proposed turning Naboland into a film. I built miniature sets, created stop-motion sequences, and worked with an original soundtrack.

One room in our house became a film set, the submarine interior, complete with wires, lights, and moving parts. The result was Naboland News, an ambitious attempt to animate the world I had imagined.

However, Naboland exists not only in my artworks but also in the minds of those who visit it and contribute their own associations. I happened to find the first two keys, the toy submarine and the name Naboland, but others are invited to add their own connections.

Naboland is not about escapism alone. It also offers space for reflection. The icy regions I once romanticised are now among the most endangered. Where I once depicted them as eternal, I now know they are vanishing.

My work may be inspired by travel, but its true fuel is imagination, which allows me to explore without increasing my carbon footprint.

Perhaps Naboland’s enduring appeal lies in its authenticity. It is a fictional world made from real places, objects, and memories, where storytelling and curiosity shape both artist and viewer. In Naboland time blurs and imagination holds dominion. The submarine is my silent observer, a visitor ignorant of its impact - sometimes welcome, often intrusive, a metaphor for us humans. Naboland exists not on any map, but in the interplay of imagination and material, where the ordinary becomes extraordinary, and the lost can be rediscovered through art.

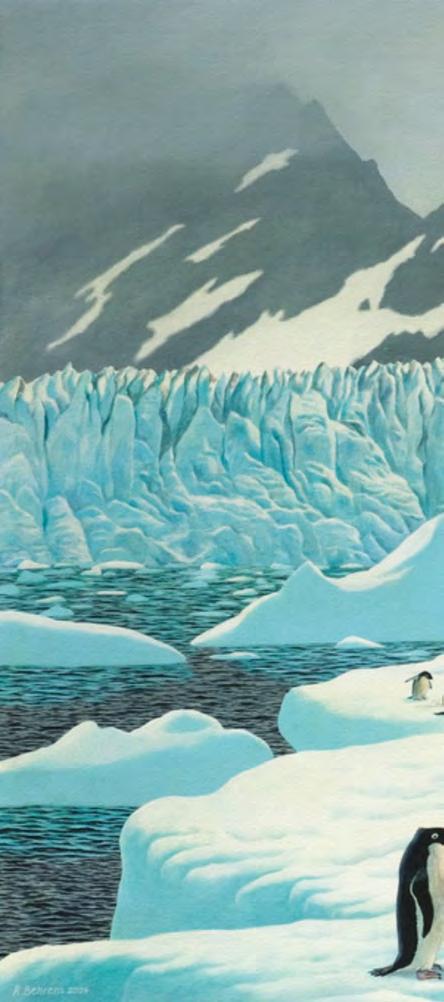

1. A Frosty Morning, 2024

2. Tourism, 2024

3. Arctic Apathy, 2022

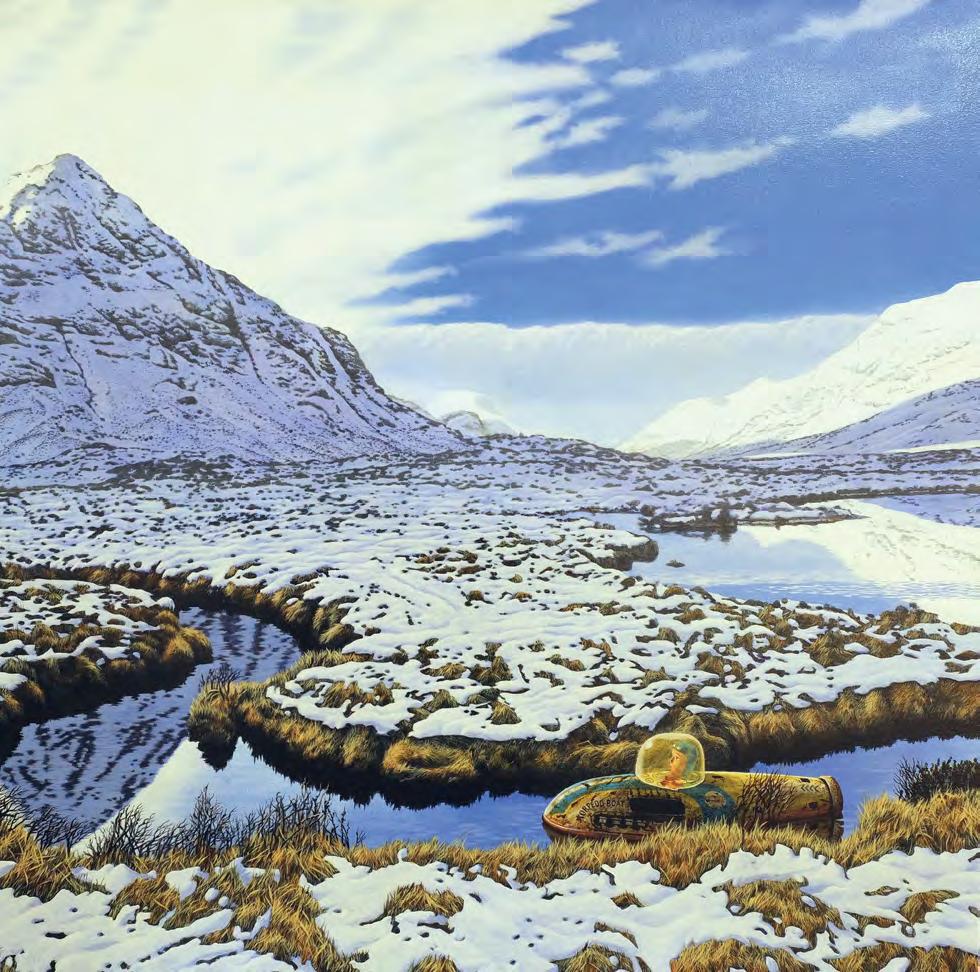

4. Sub Zero, 2023

5. Trip of a Lifetime, 2024

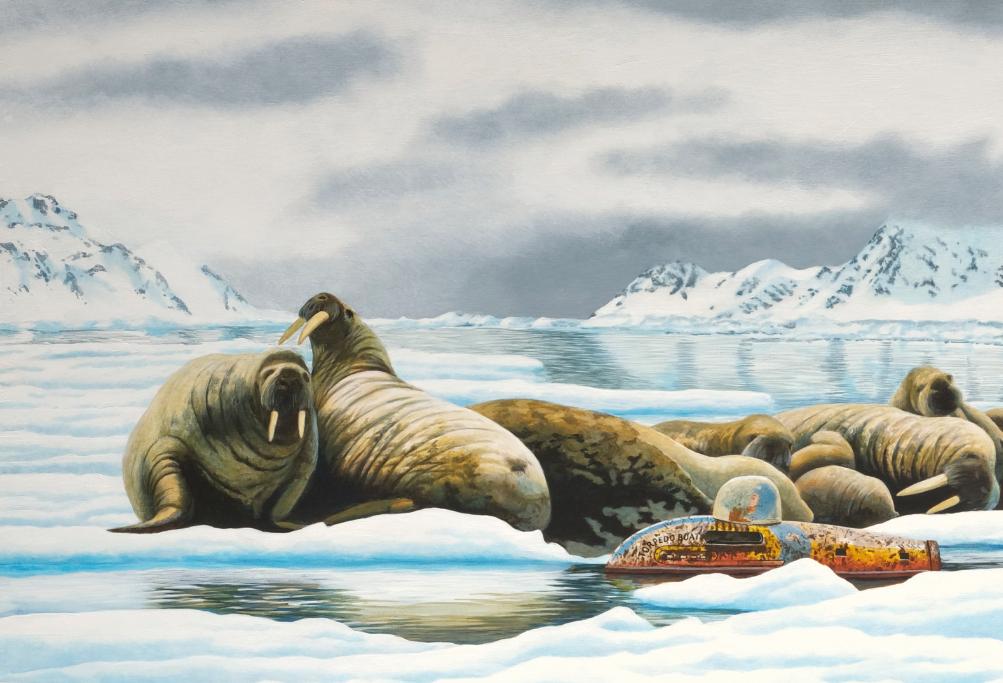

6. Arctic Awkwardness, 2020

7. Summer Snow, 2023

8. After the Blizzard, 2018

9. Off Season Visit, 2025

10. Stuck in Venice, 2025

11. Just in Time, 2025

12. San Trovaso MOT, 2025

13. Early Arrival, 2025

14. The Wrong Canal, 2025

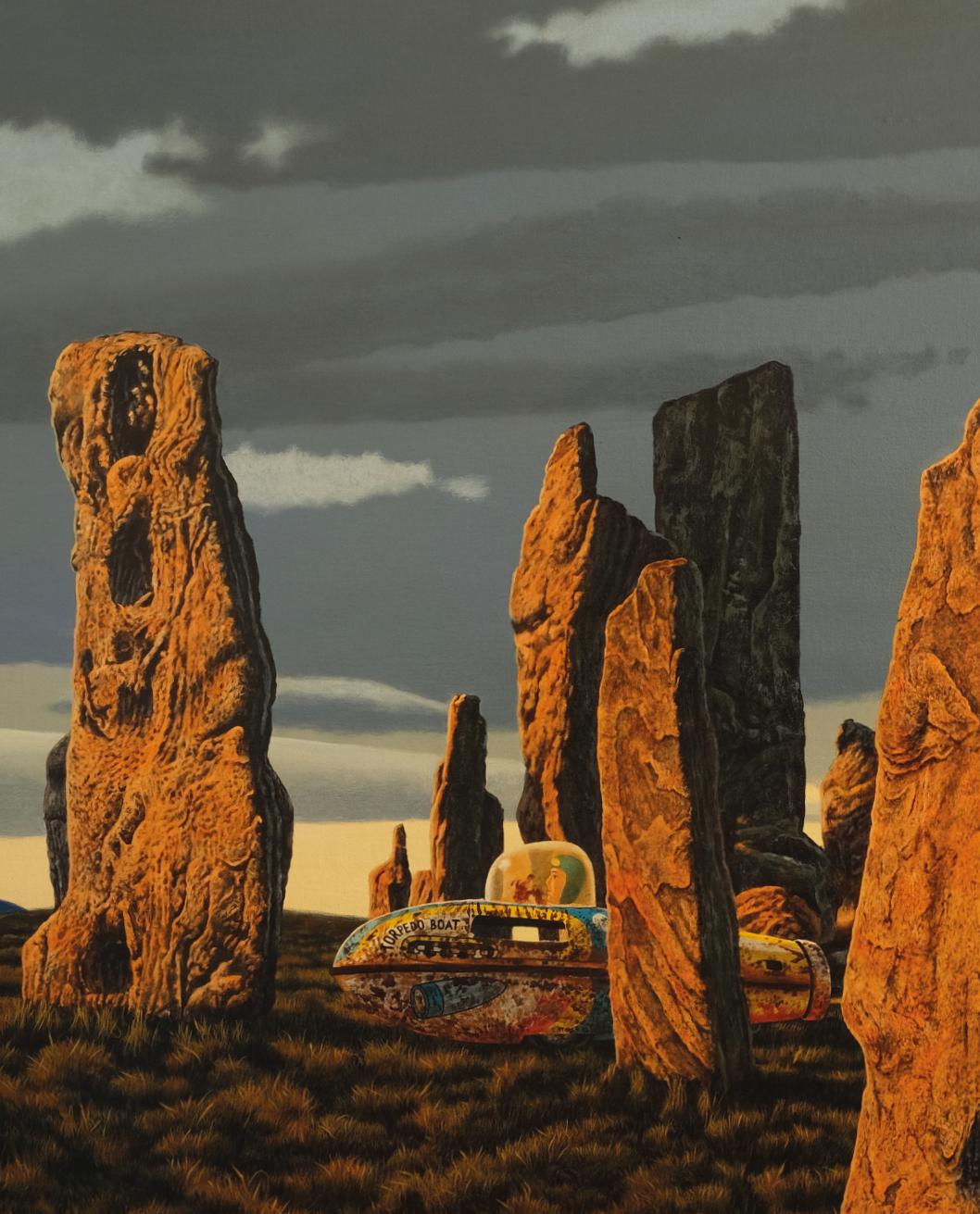

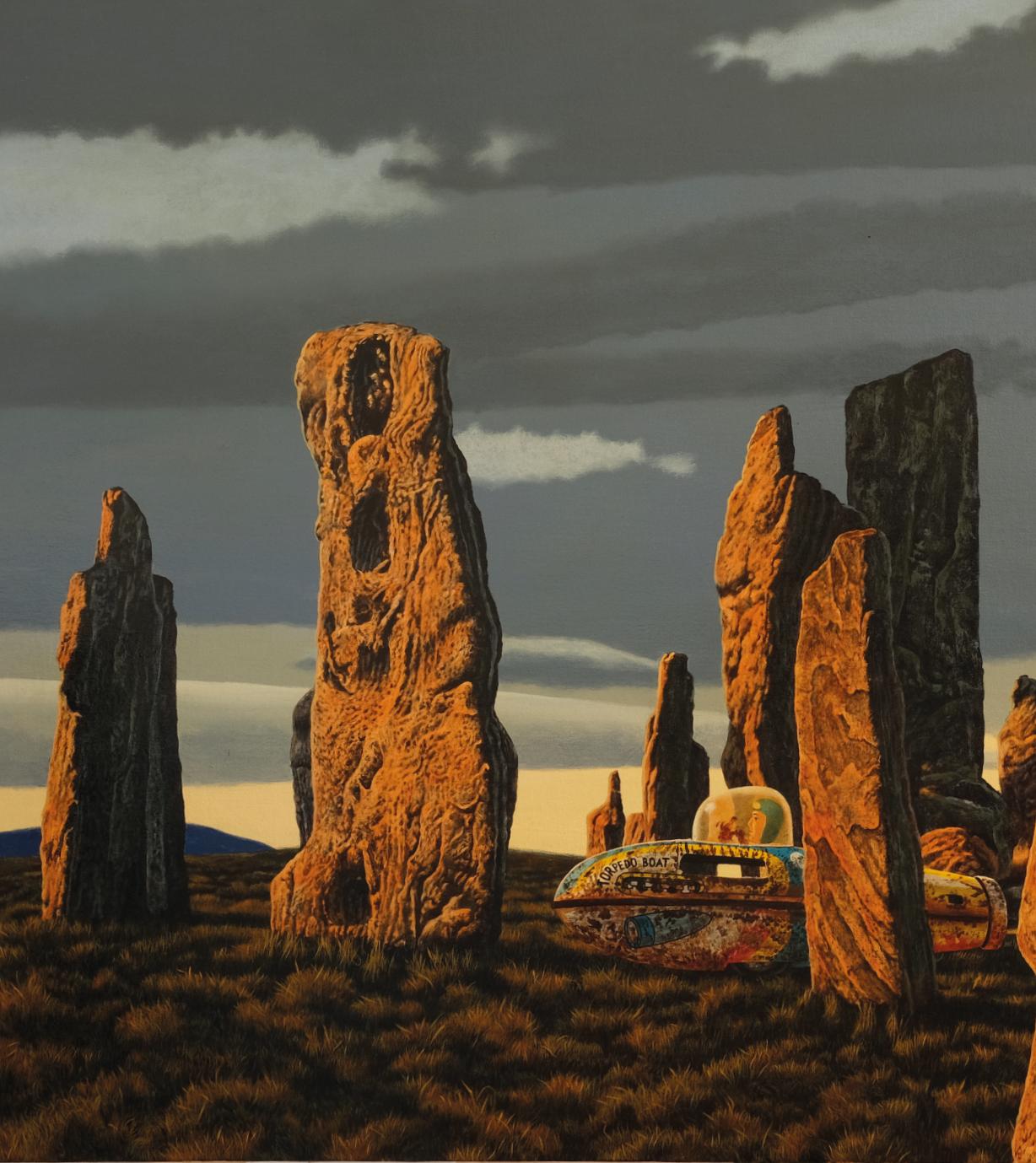

15. The Neolithic Trap, 2024

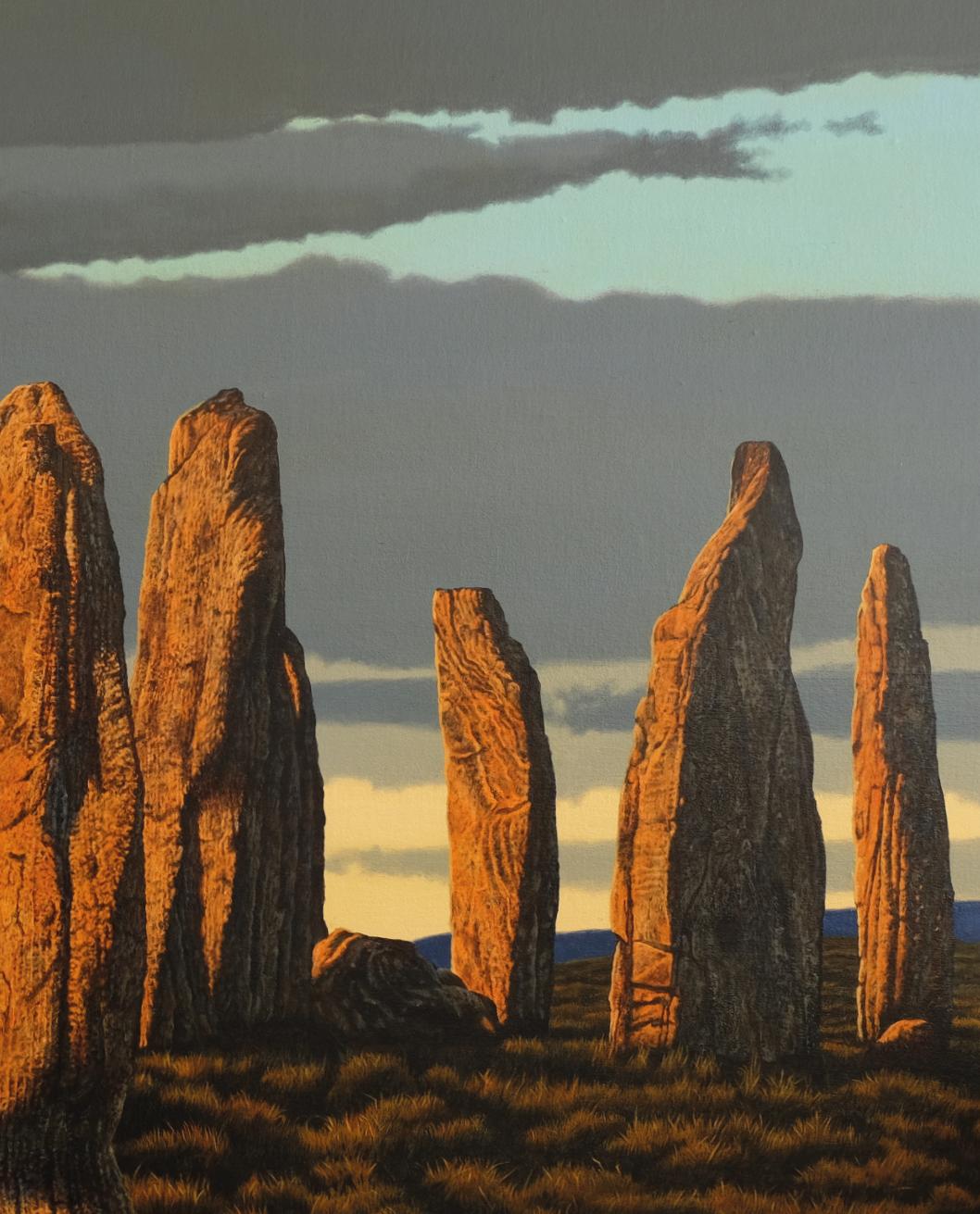

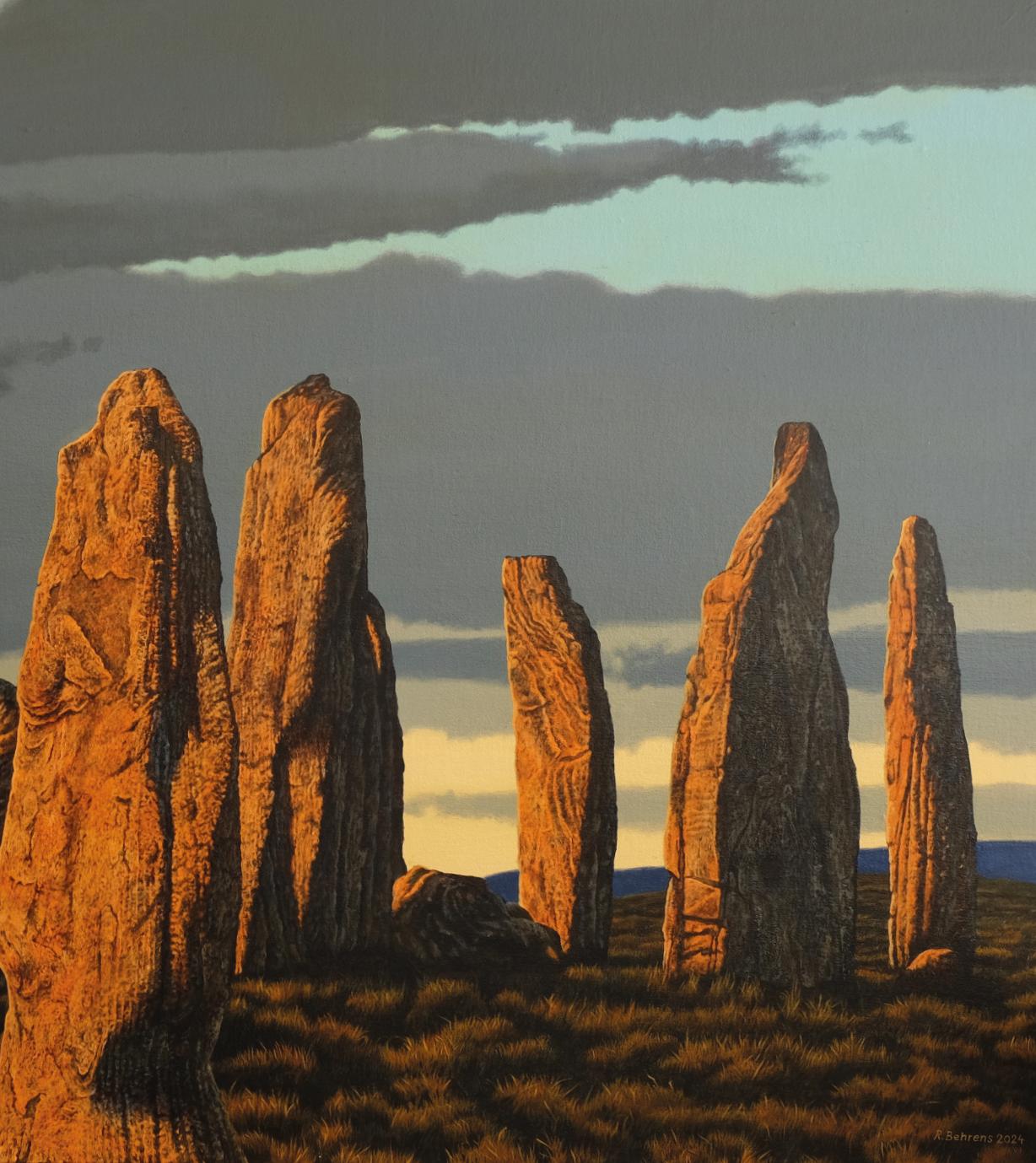

16. Calanais Sunset, 2024

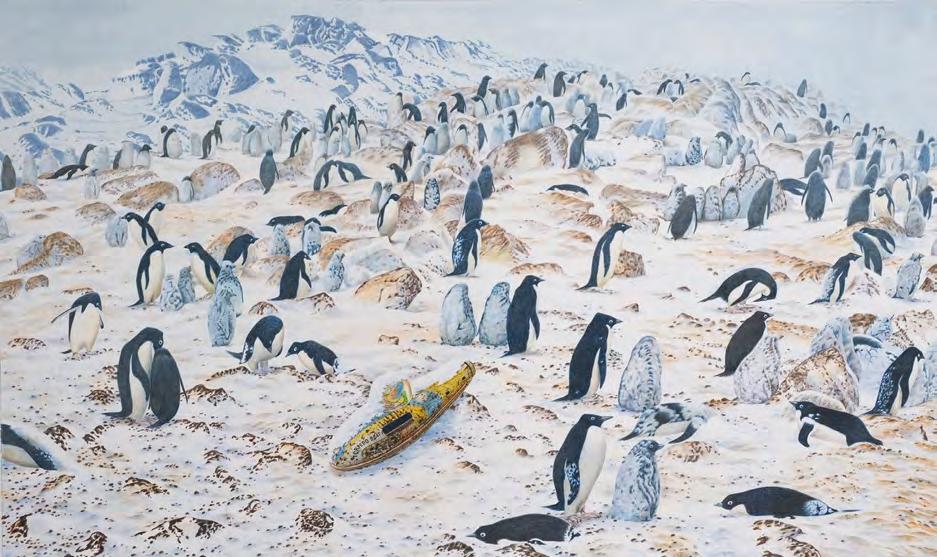

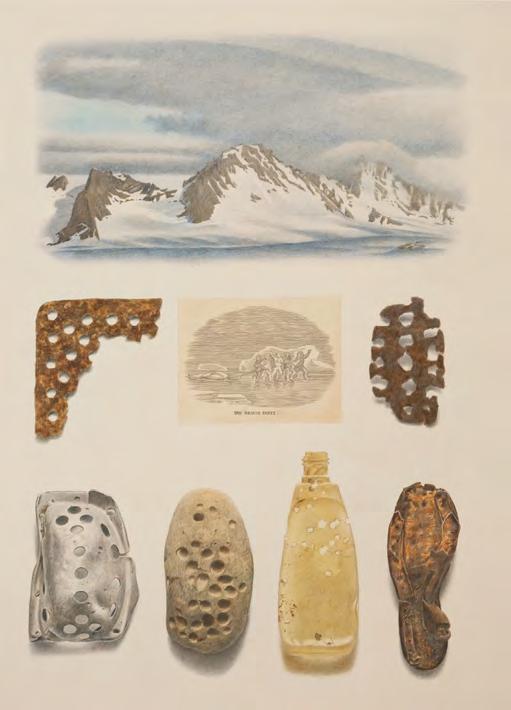

17. Antarctic Archive, 2021

18. Tollund Teddy, 1981

19. Callanish, 1984

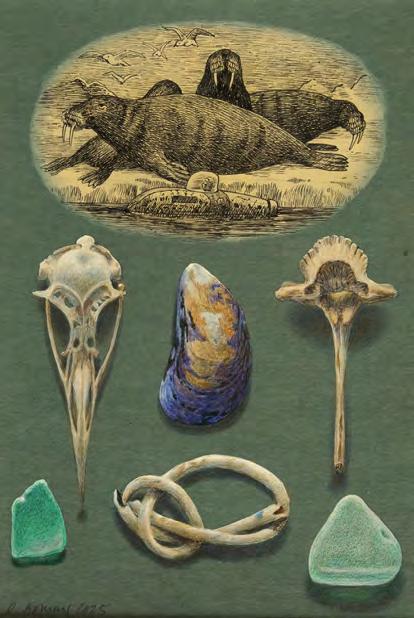

20. Walrus, 2025

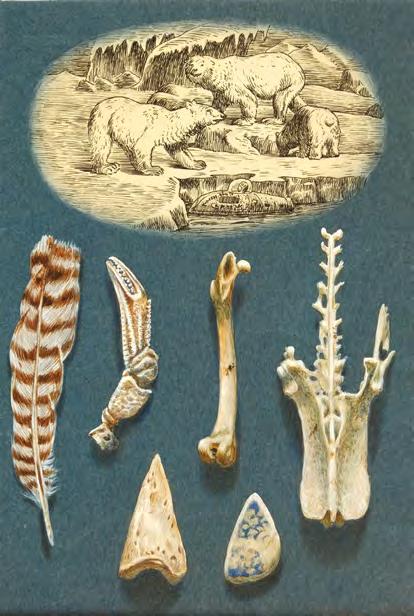

21. Polar Bears, 2025

22. Slow Progress, 2024

23. Breakthrough, 2025

24. The Rescue Party, 1999

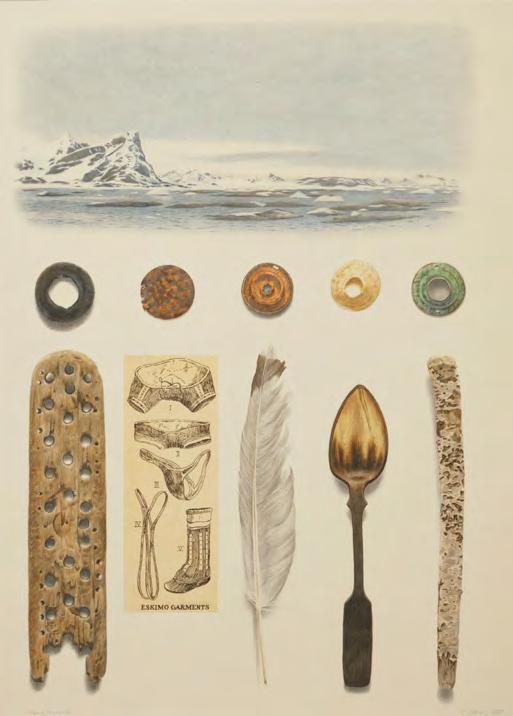

25. Eskimo Garments, 1999

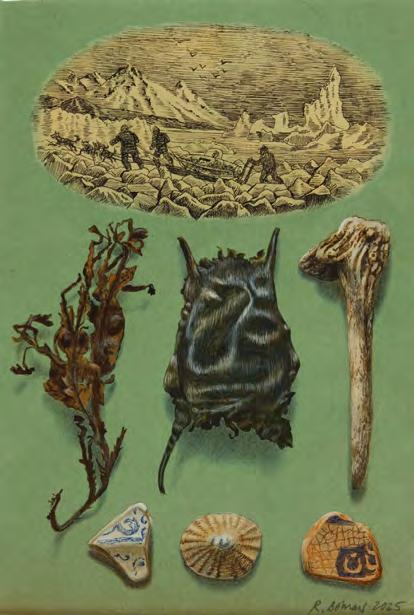

26. A Tricky Route, 2025

27. Antarctic Strip, 2013

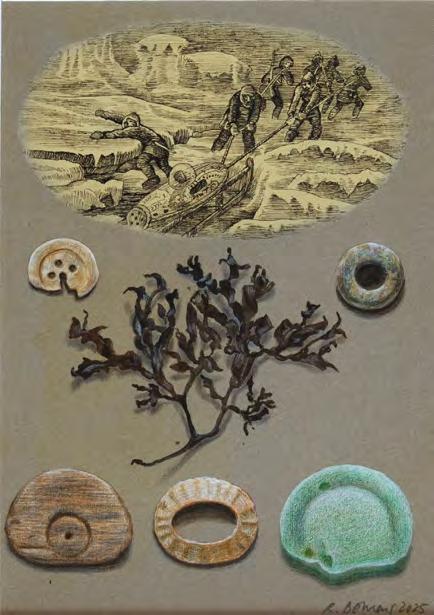

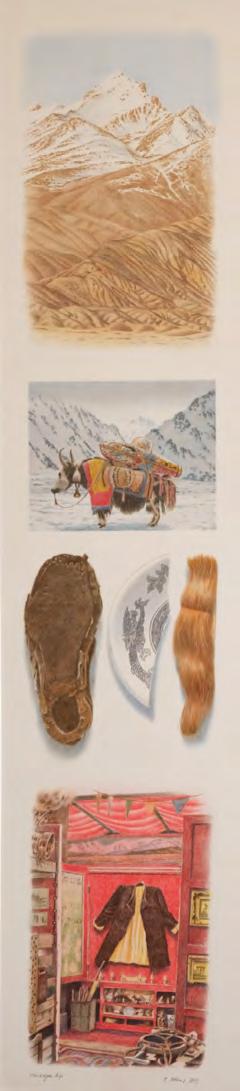

28. Inuit Collection, 2024

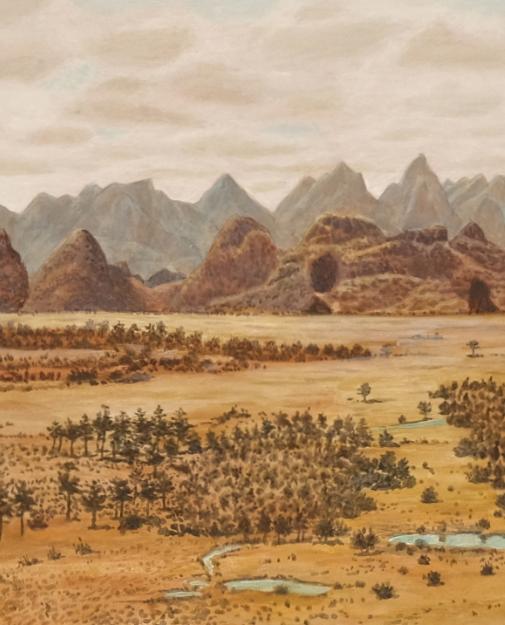

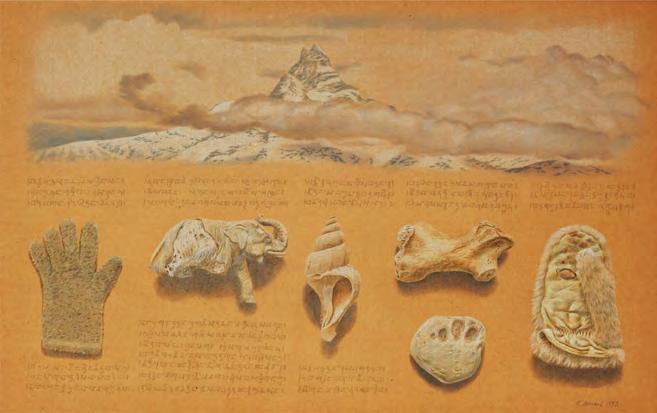

29. A Sudden Drought, 2019

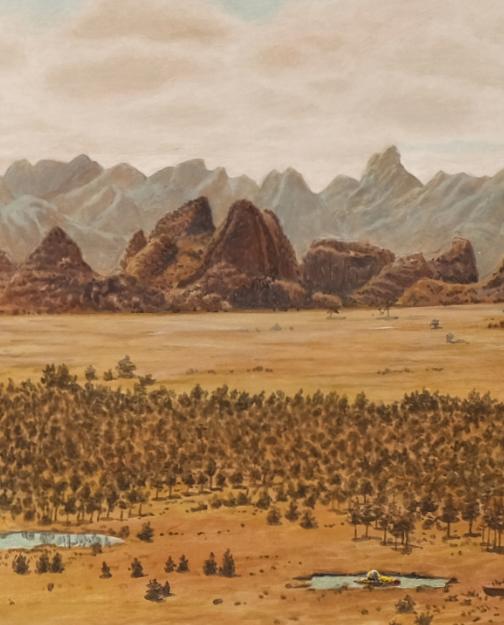

30. Himalayan Strip, 2013

31. Fishtail Mountain, Nepal, 1993

32. Rough Terrain, 2025

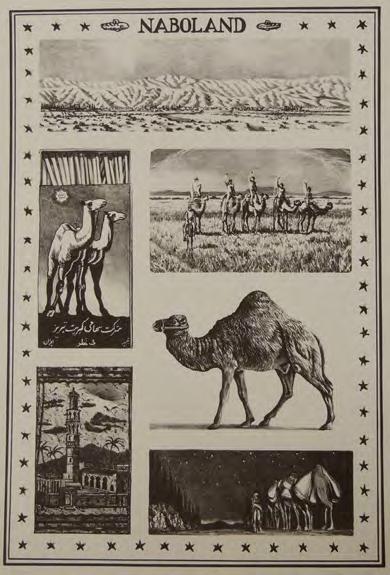

33. Naboland, 1977

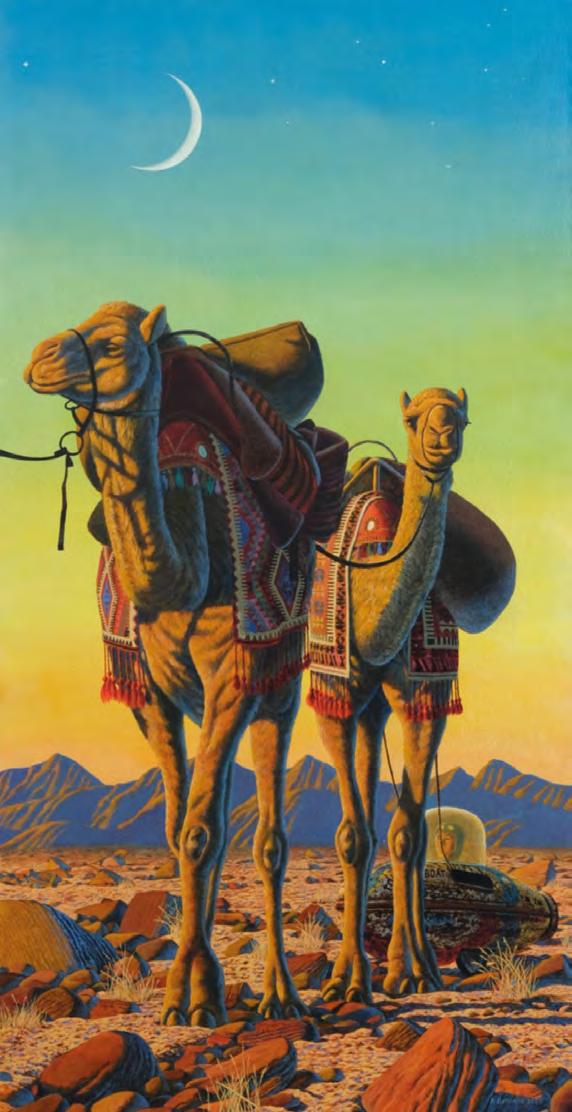

34. Waiting for Water, 2023

35. The Captured Spy (After Melville), 2022

36. Skating on Duddingston Loch (After Melville), 2022

37. A Welcome Lift, 2024

38. Shangri-La Express, 2021

39. Taxi to Tibet, 2024

40. Shangri-La Express, 2019

41. The Long Goodbye, 2025

Scotland’s landscapes, coastal paths, and ancient sites, especially on Orkney, deepened my connection to the themes I was exploring. I was struck by places like Skara Brae and the Brough of Gurness, where visitors could step into structures thousands of years old... I knew Scotland was the right place for Naboland to flourish!

15. The Neolithic Trap, 2024 acrylic and oil on board, 100 x 140 cm

17. Antarctic Archive, 2021 acrylic, watercolour and ink on paper, 76 x 93 cm

23. Breakthrough, 2025 ink and pencil on paper, 23 x 16 cm

1971 – 78 Hamburg College of Art

1979 – 80 German Academic Exchange Grant for Post Graduate Course in Drawing and Painting at Edinburgh College of Art

Solo Exhibitions

2025 The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

2023 Tatha Gallery, Newport-on-Tay

2021 Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

2008 Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

2006 Marishal Museum, University of Aberdeen; Bonhoga Gallery, Shetland

2005 Methil Heritage Centre, Fife

2004 Byre Theatre, St. Andrews

2000 Pittenweem Arts Festival (Invited Artist)

1999 Roger Billcliffe Gallery, Glasgow

1997 Kirkcaldy Museum and Gallery

1996 Arts in Fife Bus Tour; Campo Santo Chapel, Ghent; Crawford Arts Centre, St. Andrews; Galerie Claude André, Brussels

1993 St. Andrews Festival, University of St. Andrews; Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

1992 Galerie Gehring, Frankfurt; Aberdeen Art Gallery

1991 Barrack Street Museum, Dundee

1989 Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

1988 Seagate Gallery, Dundee; Pier Arts Centre, Stromness

1987 McLaurin Art Gallery, Ayr; Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

1986 An Lanntair, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis; Artspace Gallery, Aberdeen; Crawford Arts Centre, St. Andrews

1985 Smith Art Gallery and Museum, Stirling

1984 Glasgow School of Art; Printmaker’s Workshop, Edinburgh

1982 Edinburgh College of Art; Henderson’s Gallery, Edinburgh

Public Collections

Aberdeen Art Gallery

Art in Healthcare

BBC Scotland

Edinburgh City Arts Centre

Educational Institute of Scotland

Grampian Hospitals Art Trust

Historic Environment Scotland

Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery

Kirkcaldy Museum and Art Gallery

McManus Museum and Art Gallery, Dundee

Perth Museum and Art Gallery

Royal College of Physicians

University of St. Andrews

Published by The Scottish Gallery to coincide with the exhibition:

Reinhard Behrens

50 Years of Naboland 2 - 25 October 2025

Exhibition can be viewed online at: scottish-gallery.co.uk/naboland

ISBN: 978-1-917803-07-6

Designed and Produced by The Scottish Gallery

Printed by Pure Print

Front cover: Sub Zero, 2023, pencil and pastel on board, 38 x 100 cm (cat.4)

All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy or by any other means, without the permission of the copyright holders.

A Naboland Alphabet

A is for airborne, an arctic affair,

B is a box for a battered brown bear.

C is a clock that cannot count figures,

D is a desk for a diary, dumb diggers.

E is the earth through snow, etched in enamel,

F fur and a flask and a filigree camel.

G gives grey serge, grey print and grey sky,

H – here’s a hare-mould, hull, herbs hanging dry.

I am implements, inclement weather, and ink.

J just a journeyman, jugs in a sink.

K is for keys and kit, kindliness, knives,

L is for lantern, electric light, leathern archives.

M is for mushrooms made out of mops,

N is for nails bought in Naboland shops.

O is our open door, overland laps,

P printing and postcards, people perhaps.

Q is for quarto, the quest for quality,

R is the radio set, rubric, reality.

S is for scooter, skull, sandals and socks,

T is three toe prints trapped in the rocks.

U useful, unusual, the used and renewed,

V is valor-stove, very much valued.

W white wilderness, from window upwinds,

X marks the xenographer, mapping his finds.

Y is a yarn of the yester and yonder,

Z zeal in the zone of a zillion wonders.

Sally Evans, 1984