YEOL EUM SON PLAYS MOZART

SCO.ORG.UK PROGRAMME

15

Dec

– 16

2022

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079. Season 2022/23 YEOL EUM SON PLAYS MOZART Andrew Manze Yeol Eum Son Thursday 15 December, 7.30pm Usher Hall, Edinburgh Friday 16 December, 7.30pm City Halls, Glasgow Bacewicz Concerto for String Orchestra Mozart Piano Concerto No 27 in B flat, K595 Interval of 20 minutes Dvořák Symphony No 7 in D minor Andrew Manze Conductor Yeol Eum Son Piano

The SCO is extremely grateful to the Scottish Government and to the City of Edinburgh Council for their continued support. We are also indebted to our Business Partners, all of the charitable trusts, foundations and lottery funders who support our projects, and to the very many individuals who are kind enough to give us financial support and who enable us to do so much. Each and every donation makes a difference and we truly appreciate it.

Core Funder

Benefactor Local Authority Creative Learning Partner

You FUNDING PARTNERS

Thank

Su-a Lee

Sub-Principal Cello

Business Partners

Key Funders

Delivered by

Delivered by

Thank You

SCO DONORS

Diamond

Lucinda and Hew Bruce-Gardyne Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

James and Felicity Ivory

Christine Lessels

Clair and Vincent Ryan Alan and Sue Warner

Platinum

Eric G Anderson

David Caldwell in memory of Ann Tom and Alison Cunningham

John and Jane Griffiths

Judith and David Halkerston

J Douglas Home Audrey Hopkins

David and Elizabeth Hudson Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson Dr Daniel Lamont Chris and Gill Masters Duncan and Una McGhie Anne-Marie McQueen James F Muirhead

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Elaine Ross

Hilary E Ross

George Rubienski

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Tom and Natalie Usher

Anny and Bobby White Finlay and Lynn Williamson

Ruth Woodburn

Gold

Lord Matthew Clarke James and Caroline Denison-Pender Andrew and Kirsty Desson David and Sheila Ferrier Chris and Claire Fletcher James Friend

Iain Gow Ian Hutton

David Kerr

Gordon Kirk

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley Mike and Karen Mair Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer Gavin McEwan Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown Alan Moat

John and Liz Murphy Alison and Stephen Rawles Andrew Robinson Ian S Swanson

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley Anne Usher

Catherine Wilson Neil and Philippa Woodcock G M Wright

Bruce and Lynda Wyer

Silver

Roy Alexander

Joseph I Anderson

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Dr Peter Armit

William Armstrong Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Michael and Jane Boyle Mary Brady

Elizabeth Brittin

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Lord and Lady Cullen of Whitekirk Adam and Lesley Cumming Jo and Christine Danbolt

Dr Wilma Dickson

James Dunbar-Nasmith Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer Sheila Ferguson

Dr James W E Forrester Dr William Fortescue

Jeanette Gilchrist

David Gilmour

Dr David Grant Margaret Green Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane Ronnie and Ann Hanna Ruth Hannah Robin Harding Roderick Hart Norman Hazelton Ron and Evelynne Hill Clephane Hume Tim and Anna Ingold David and Pamela Jenkins Catherine Johnstone Julie and Julian Keanie Marty Kehoe Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar Dr and Mrs Ian Laing Janey and Barrie Lambie Graham and Elma Leisk Geoff Lewis Dorothy A Lunt Vincent Macaulay Joan MacDonald Isobel and Alan MacGillivary Jo-Anna Marshall

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan Gavin McCrone Michael McGarvie Brian Miller James and Helen Moir Alistair Montgomerie Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling Andrew Murchison Hugh and Gillian Nimmo David and Tanya Parker Hilary and Bruce Patrick Maggie Peatfield John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter Alastair Reid Fiona Reith Olivia Robinson Catherine Steel Ian Szymanski Michael and Jane Boyle Douglas and Sandra Tweddle Margaretha Walker James Wastle C S Weir Bill Welsh Roderick Wylie

We believe the thrill of live orchestral music should be accessible to everyone, so we aim to keep the price of concert tickets as fair as possible. However, even if a performance were completely sold out, we would not cover the presentation costs.

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous. We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially, whether that is regularly or on an ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference and we are truly grateful.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or mary.clayton@sco.org.uk

Thank You PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR'S CIRCLE

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle is made up of individuals who share the SCO’s vision to bring the joy of music to as many people as possible. These individuals are a special part of our musical family, and their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike. We would like to extend our grateful thanks to them for playing such a key part in the future of the SCO.

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang Kenneth and Martha Barker

Creative Learning Fund David and Maria Cumming

Annual Fund James and Patricia Cook Dr Caroline N Hahn Hedley G Wright

CHAIR SPONSORS

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer Anne McFarlane

Viola Steve King Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham The Thomas Family

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman Cello Eric de Wit Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan Anne and Matthew Richards Productions Fund The Usher Family

International Touring Fund Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Principal Second Violin Marcus Barcham Stevens Jo and Alison Elliot

Principal Flute André Cebrián Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin Geoff and Mary Ball

–––––

Our Musicians YOUR ORCHESTRA

First Violin

Maia Cabeza

Alessandro Ruisi

Amanda Smith Kana Kawashima Aisling O’Dea Siún Milne

Fiona Alexander Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Cheryl Crockett Lorna McLaren

Second Violin

Gordon Bragg Rachel Spencer Wen Wang

Rachel Smith Niamh Lyons Carole Howat

Josie Robertson Eve Kennedy Viola Max Mandel

Zoe Matthews

Brian Schiele

Kathryn Jourdan Liam Brolly Rebecca Wexler

Cello

Philip Higham

Su-a Lee

Donald Gillan Eric de Wit Niamh Molloy Christoff Fourie

Bass

Nikita Naumov

Will Duerden

Sophie Butler Kirsty Matheson

Flute

André Cebrián Alba Vinti

Oboe Robin Williams Katherine Bryer

Information correct at the time of going to print

Horn

Roger Montgomery

Jamie Shield

Lauren Reeve-Rawlings

Harry Johnstone

Fergus Kerr

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Simon Bird

Trombone

Duncan Wilson

Clarinet Maximiliano Martín William Stafford Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans Gillian Horn

André Cebrián Principal Flute

Nigel Cox Andy Fawbert

Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

WHAT YOU ARE ABOUT TO HEAR

Bacewicz (1909-1969)

Concerto for String Orchestra (1948) Allegro Andante Vivo Mozart (1756-1791)

Piano Concerto No 27 in B flat, K595 (1791)

Allegro Larghetto Allegro Dvořák (1841-1904) Symphony No 7 in D minor (1885)

Allegro maestoso Poco adagio Scherzo. Vivace Finale. Allegro

A rousing concerto for strings from a composer who deserves far more attention; an apparently valedictory piano concerto; and a symphony that set out to put its country’s music on the map. There’s no shortage of contrasts between the works in tonight’s diverse programme, but the three pieces nonetheless share a sense of bounding confidence and enthusiasm, even if those qualities are conveyed through very different music.

Grażyna Bacewicz, composer of tonight’s opening piece, was one of Poland’s most respected composers in the early part of the 20th century, as well as a celebrated violinist – somewhat overlooked, as so many women composers have shamefully been, although today there’s ever increasing interest in her distinctive, sometimes idiosyncratic music. It blends a wit and clarity that she no doubt picked up during her studies in Paris – where she learnt composition with Nadia Boulanger and violin with Carl Flesch – with an earthier, more folk-like idiom that lends her works a rougher, sometimes more uncompromising edge. Bacewicz proved adept at navigating the restlessly shifting restrictions of Poland’s political landscape, too, adapting her style as Polish music was steered away from supposedly bourgeois modernism and towards a folksier style that would appeal to the broader masses, and managing to satisfy political demands without compromising her own, gently acerbic language.

Indeed, her Concerto for String Orchestra – written in 1948, just as Bacewicz was adapting to the demands of the recently established socialist system in Poland – sits at just that intersection in her music. Though

rather than embracing her country’s folk music, it looks back directly to the music of Bach, Corelli, Vivaldi and others, celebrating a bracing Baroque musical style while injecting it with distinctly 20th-century flavours.

Bacewicz’s compatriot and fellow composer Witold Lutosławski called the piece ‘probably the highlight of that “no-nonsense” period in Grażyna’s oeuvre, which encyclopaedias simplistically refer to as “neoclassical”.’ ‘Nononsense’ seems like an apt way of summing up the Concerto’s clarity, brevity and unerring sense of direction. No wonder it was such a success at its 1950 premiere – given by the Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Grzegorz Fitelberg, at the General Meeting of the Polish Composers’ Union – and went on to become the composer’s most popular piece in her native country. Following its US premiere two years later, critic Milton

Berliner wrote in the Washington Daily News: ‘There was nothing feminine about Miss Bacewicz’s piece. It was vigorous, even virile, with a pulsing, throbbing rhythm and bold thematic material.’ We might wince at his gendered characterisation 70 years later, but in terms of the music, you can see what he was getting at.

The Concerto’s bold, purposeful first movement opens with a striding theme that seems determined to escape the note to which it’s anchored, and after a short, hushed transition that introduces the violinist and cellist as soloists, its second main theme is even more rhythmic, punctuated by aggressive pizzicatos. Bacewicz combines and recombines her various elements in ever more complex and witty ways across the rest of the movement, always with a strong sense of purpose. Her atmospheric second movement sets a meandering melodic

It blends a wit and clarity that she no doubt picked up during her studies in Paris – where she learnt composition with Nadia Boulanger and violin with Carl Flesch

Grażyna Bacewicz

idea – first heard on a solo cello – against shimmering, heavily perfumed harmonies from the rest of the strings, which she subdivides into a rich, thick texture of up to 13 separate lines at one point. Bacewicz’s final movement is exuberant and strongly rhythmic, with switchback cross-rhythms and sudden harmonic twists. Its folk-like recurring theme, first heard high in the violins, ultimately drives the Concerto to its resolute conclusion.

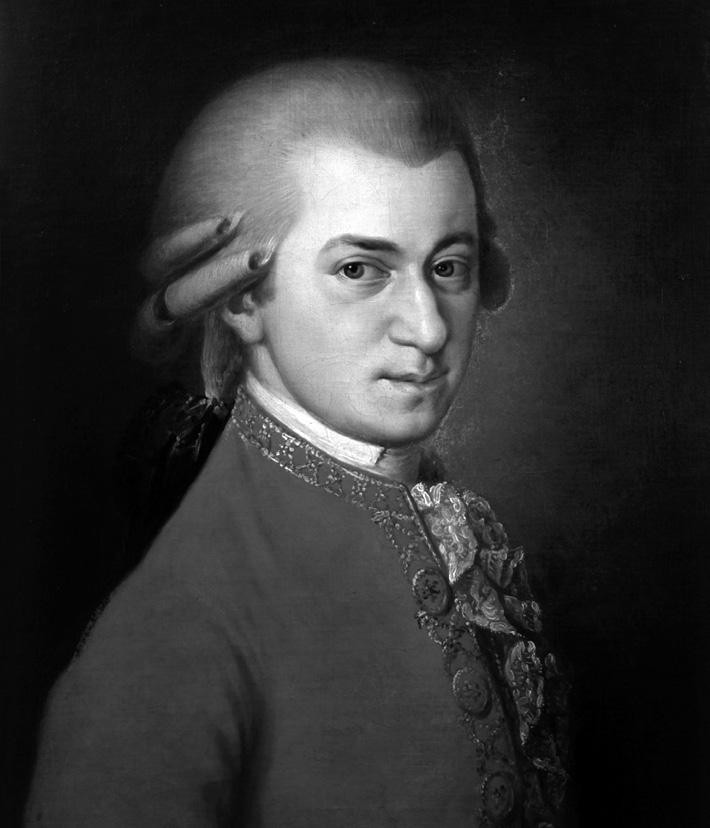

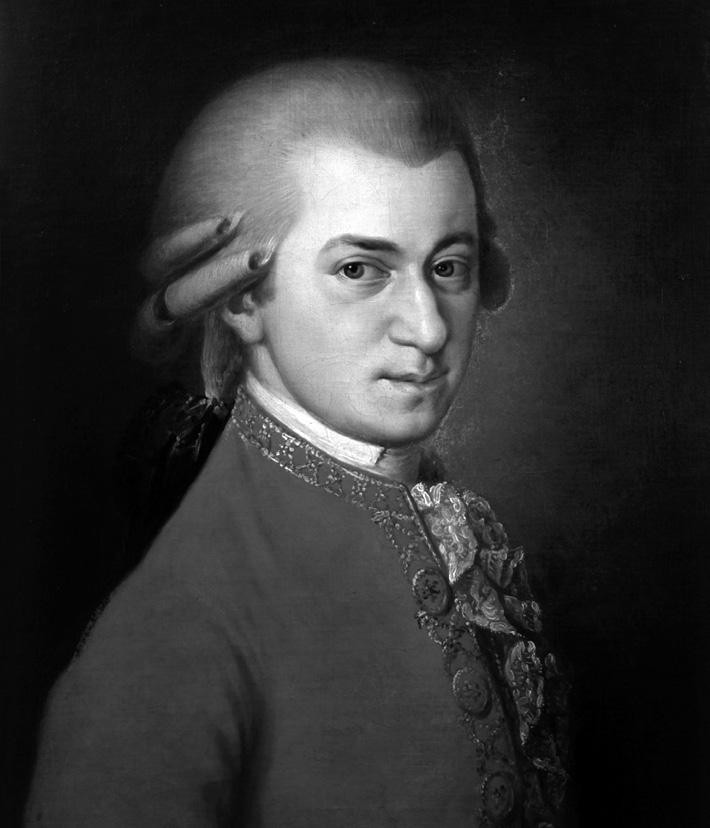

From a 20th-century composer looking backwards to an 18th-century composer looking – well, very possibly at least –forwards. It’s tempting to view No 27 as Mozart’s final piano concerto, which, of course, it is. But it was nothing of the sort while Mozart was composing it. As with his final trio of symphonies – Nos 39, 40 and 41, composed in quick succession and often romantically described as his farewell to the

form – any sense of valediction or summation in the Concerto comes from our own perspective, more than two centuries later, rather than from Mozart’s own writing desk.

Indeed, though scholars are divided, it’s entirely possible that he began the Concerto as far back as 1788. He didn’t complete it until January 1791, however, and gave the premiere himself on 4 March that year at a private benefit concert in Vienna for the clarinettist Joseph Beer. It would prove his final public appearance as a pianist: nine months later, Mozart was dead. But despite complaining of a few headaches and toothache in the spring of that year, Mozart hardly foresaw that the year 1791 would be his last.

It’s well known that Mozart’s final years were a time of financial and personal insecurity. He was no longer quite the darling of

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

But despite complaining of a few headaches and toothache in the spring of that year, Mozart hardly foresaw that the year 1791 would be his last.

Viennese audiences that he’d been in the early 1780s, and the disposable cash of wellto-do Viennese supporters was thinner on the ground after the Habsburgs had declared war on the Ottoman Empire in 1788. He was understandably concerned, too, about his wife Constanze’s stubbornly poor health. But 1791 proved a year of breathtaking creativity, in which Mozart produced two operatic masterpieces – La clemenza di Tito and The Magic Flute – as well as a string quintet, the Clarinet Concerto, the choral Ave verum corpus and the unfinished Requiem.

It’s understandable, however, that some discern a certain wistful sadness, even a quietly nagging pain, in the Piano Concerto No 27’s somewhat subdued intimacy. Even the first movement’s opening theme – the first of no fewer than four that Mozart crams into the orchestra’s introduction – has a certain plaintive introspection in its floating lyricism, though the pianist gently jollifies it with ornaments when they take it up later. Even the solo cadenza (Mozart’s own) towards the end of the movement seems pensive rather than particularly flashy.

The piano is left alone to open Mozart’s song-like second movement, and the music’s limpid simplicity isn’t without its passing storm clouds, even in the movement’s brighter central section. The bouncing rondo finale shares its main theme with the song ‘Sehnsucht nach dem Frühling’ (or ‘Yearning for Spring’) that he wrote around the same time, itself implying a certain melancholy amid the movement’s bounding energy, though its contrasting episodes more overtly show off the soloist’s agility.

It may seem justified, then, to sense a certain autumnal poignancy to the Concerto. But it’s more poignant, perhaps, to notice the piece’s

renewed sense of quietly spoken clarity, balance and confidence, qualities shared by the other works Mozart composed in his final year. They may indicate the beginning of an entirely new phase of creativity from the composer – which, of course, we’ll never experience.

We jump ahead just less than a century for tonight’s final piece. Despite its relatively humble origins, by the end of the 19th century, the symphony had become something of a cultural battleground for central European composers. On one side were those Germans and Austrians who saw the form’s abstract, rigorously structured arguments as evidence of musical superiority. On the other were composers working away from the centres of musical power – like Antonín Dvořák – who argued that they were equally capable of such profundity, though perhaps using different means.

Johannes Brahms – himself a composer of three mighty symphonies by the time Dvořák’s Seventh was premiered – had already stirred things up in recommending the young Bohemian composer to his German publisher Simrock in 1875. Dvořák was determined to prove himself as a sophisticated symphonic composer rather than simply a peddler of the popular Slavonic Dances that had made his reputation (and, furthermore, respectfully requested that Simrock use his Bohemian name Antonín rather than the Germanicised Anton on his published scores).

Dvořák had aimed to make his mark as a serious symphonist with his Sixth, following his friend Brahms’s advice to design it around conventional Germanic models. Nonetheless, it was quietly dropped from its intended premiere by the Vienna

Philharmonic in 1880, though it was so successful at its London premiere from the Royal Philharmonic Society four years later that the Society immediately commissioned another one. Dvořák launched into work in December 1884. ‘Just now,’ he wrote to a friend that month, ‘a new symphony (for London) occupies me, and wherever I go I think of nothing but my work, which must be capable of stirring the world, and God grant me that it will!’ He completed his Seventh Symphony in March 1885, with a determination that his new work would put Czech music on the map in front of an influential international audience. Premiered in London in April 1885, it was an immediate success, and remains for many Dvořák’s greatest symphony, eclipsing even the better-known ‘New World’. At its Vienna premiere two years later, where it mattered most to Dvořák, it received a predictably cooler reception.

No 7 is indeed the most tautly argued of Dvořák’s symphonies, though it blends a distinctly Bohemian lyricism with its strongly focused drama. The first movement’s gruff, dramatic opening sets the tone for what’s to come, though the main theme’s eruption across the full orchestra is followed by a far more flowing, lyrical contrasting melody for flutes and clarinets. The slow second movement’s hymn-like opening music hardly prepares the listener for its later turbulent outbursts, while the dancing third movement contrasts a stomping Czech furiant dance in the violins with a graceful Viennese waltz as accompaniment in the cellos and bassoons. Dvořák opens his finale with an ominous melody full of pungent Slavic inflections, before a march-like theme propels the Symphony to its roof-raising, unexpectedly optimistic conclusion.

© David Kettle

Antonín Leopold Dvořák

© David Kettle

Antonín Leopold Dvořák

Premiered in London in April 1885, it was an immediate success, and remains for many Dvořák’s greatest symphony, eclipsing even the better-known ‘New World’.

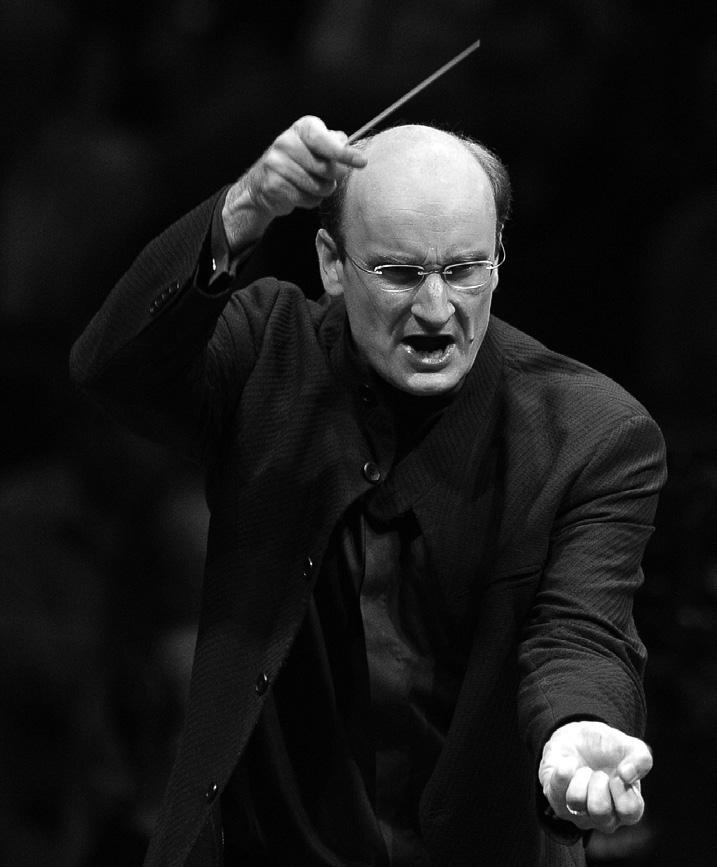

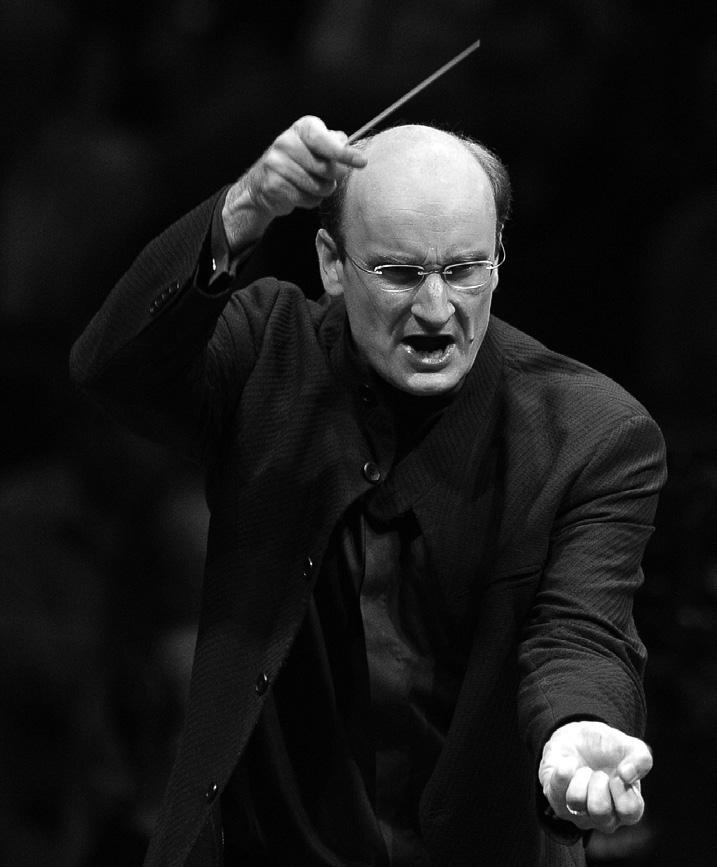

Conductor ANDREW MANZE

Andrew Manze is widely celebrated as one of the most stimulating and inspirational conductors of his generation. His extensive and scholarly knowledge of the repertoire, together with his boundless energy and warmth, mark him out. He has been Chief Conductor of the NDR Radiophilharmonie, Hannover, since September 2014 and his contract has been extended until summer 2023. Since 2018, he has been Principal Guest Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.

Following highly successful tours to China in 2016 and 2019, the 22/23 season sees the NDR Radiophilharmonie return to Japan for a busy touring schedule. Manze and the orchestra have embarked on a major series of award-winning recordings for Pentatone, focused on the works of Mendelssohn and Mozart. The first recording in the Mendelssohn series won the Preis der Deutschen Schallplatten Kritik. Manze has also recorded a cycle of the complete Vaughan Williams symphonies with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra for Onyx Classics to critical acclaim.

In great demand as a guest conductor across the globe, Manze has long-standing relationships with leading orchestras that include the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Camerata Salzburg, Royal Concertgebouworkest, and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. He is also a regular guest at the Mostly Mozart Festival in New York City. In the 22/23 season Manze makes his operatic debut with the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, conducting performances of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas alongside Schoenberg’s Erwartung, in collaboration with artistic director Serge Dorny. Other highlights of the 22/23 season include engagements with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, the Dresden Philharmonic, Atlanta Symphony and the Minnesota Orchestra, and conducting performances with the WDR Symphony as part of the Klavierfest Ruhr.

Manze is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, Visiting Professor at the Oslo Academy, and has contributed to new editions of sonatas and concerti by Bach and Mozart, published by Bärenreiter, Breitkopf and Härtel. He also teaches, writes about, and edits music, as well as broadcasting regularly on radio and television. In November 2011 Andrew Manze received the prestigious ‘Rolf Schock Prize’ in Stockholm.

Piano YEOL EUM SON

Poetic elegance, an innate feeling for expressive nuance and the power to project bold dramatic contrasts are among the arresting attributes of Yeol Eum Son’s pianism. Her refined artistry rises from breathtaking technical control and a profound empathy for the emotional temper of the works within her strikingly wide repertoire. She is driven above all by her natural curiosity to explore a multitude of musical genres and styles and the desire to reveal what she describes as the “pure essence” of everything she performs.

In high demand as recitalist, concerto soloist and chamber musician, Yeol Eum has won critical plaudits for the profound insights and intelligence of her interpretations. Her development as an all-round artist has gained from collaborations with conductors as diverse as Lorin Maazel, Dmitri Kitajenko, Valery Gergiev, Andrew Manze, Jaime Martín, Jun Märkl, Roberto González-Monjas, Jonathon Heyward, Ryan Bancroft, Pablo Gonzalez, Pietari Inkinen, Joana Carneiro, Gergely Madaras and Omer Meir Welber.

She has likewise discovered fresh creative perspectives since her appointment in 2018 as Artistic Director of Music in PyeongChang and as a regular chamber music partner with, among others, the violinist Svetlin Roussev and the Modigliani Quartet.

Yeol Eum Son’s 2022-23 schedule includes a succession of debut performances with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra (Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No 2), the NDR Radiophilharmonie (Beethoven and Rachmaninov concertos), the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No 1), the Orquesta Sinfónica del Principado de Asturias (Szymanowski’s Symphony No 4), Musikkollegium Winterthur (Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major), the Scottish Chamber Orchestra (Mozart’s Piano Concerto in B-flat Major K.595), and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra (Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No 2). She will close her season with the world premiere of a new work by the Swedish composer Albert Schnelzer in recital at the Helsingborg Piano Festival.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

WE BUILD RELATIONSHIPS THAT LAST GENERATIONS.

Generations of our clients have trusted us to help build and preserve their wealth.

For over 250 years, they have relied on our expert experience to help make sense of a changing world. During that time we’ve earned an enviable reputation for a truly personal approach to managing wealth.

For those with over £250,000 to invest we o er a dedicated investment manager, with a cost structure and level of service, that generates exceptional client loyalty.

Find out more about investing with us today: Murray Clark at our Edinburgh o ce on 0131 221 8500, Gordon Ferguson at our Glasgow o ce on 0141 222 4000 or visit www.quiltercheviot.com

INVESTING FOR GENERATIONS

Investors should remember that the value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up and that past performance is no guarantee of future returns. You may not recover what you invest. Quilter Cheviot and Quilter Cheviot Investment Management are trading names of Quilter Cheviot Limited. Quilter Cheviot Limited is registered in England with number 01923571, registered o ce at Senator House, 85 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4AB. Quilter Cheviot Limited is a member of the London Stock Exchange and authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority.

BE PART OF OUR FUTURE

A warm welcome to everyone who has recently joined our family of donors, and a big thank you to everyone who is helping to secure our future.

Monthly or annual contributions from our donors make a real difference to the SCO’s ability to budget and plan ahead with more confidence. In these extraordinarily challenging times, your support is more valuable than ever.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or email mary.clayton@sco.org.uk.

The SCO is a charity registered in Scotland No SC015039.

SCO.ORG.UK/SUPPORT-US

Delivered by

Delivered by

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

© David Kettle

Antonín Leopold Dvořák

© David Kettle

Antonín Leopold Dvořák