26-28 June 2025

26-28 June 2025

Stirling

is in association with

Kindly supported by Eriadne & George Mackintosh, Claire & Anthony Tait and The Jones Family Charitable Trust

Hawick

is in association with

Thursday 26 June, 8pm Stirling Castle

Friday 27 June, 7.30pm Queen's Hall, Dunoon

Saturday 28 June, 7.30pm Hawick Town Hall

LARSSON Pastoral Suite, Op 19

MOZART Bassoon Concerto

Interval of 20 minutes

SCHUBERT Symphony No 6

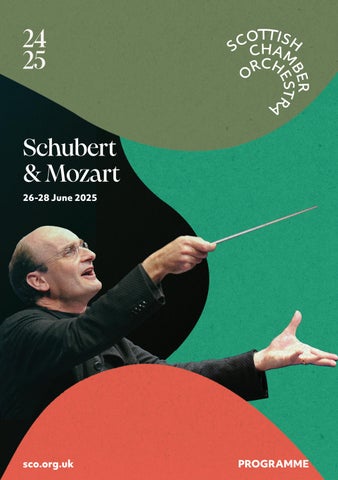

Andrew Manze Conductor

Cerys Ambrose-Evans Bassoon

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB

+44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

THANK YOU

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Creative Learning Fund

Sabine and Brian Thomson

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Second Violin Rachel Smith

J Douglas Home

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Ken Barker and Martha Vail Barker

Viola Brian Schiele

Christine Lessels

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

Sub-Principal Cello Su-a Lee

Ronald and Stella Bowie

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Productions Fund

Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher

Bill and Celia Carman

Anny and Bobby White

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Double Bass

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe

The Hedley Gordon Wright Charitable Trust

Sub-Principal Oboe Katherine Bryer

Ulrike and Mark Wilson

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

“A crack musical team at the top of its game.”

HM The King

Patron

Donald MacDonald CBE

Life President

Joanna Baker CBE

Chair

Gavin Reid LVO

Chief Executive

Maxim Emelyanychev

Principal Conductor

Andrew Manze

Principal Guest Conductor

Joseph Swensen

Conductor Emeritus

Gregory Batsleer

Chorus Director

Jay Capperauld

Associate Composer

Information correct at the time of going to print

First Violin

Eleanor Corr

Tijmen Huisingh

Kana Kawashima

Aisling O’Dea

Fiona Alexander

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Sarah Bevan Baker

Catherine James

Second Violin

Agata Daraškaitė

Rachel Spencer

Michelle Dierx

Rachel Smith

Stewart Webster

Rosario Hernandez

Viola

Max Mandel

Francesca Gilbert

Steve King

Elaine Koene

Cello

Amy Norrington

Su-a Lee

Donald Gillan

Kim Vaughan

Bass

Jamie Kenny

Margarida Castro

Flute

André Cebrián

Marta Gómez

Oboe

Carl Julius Lefebvre Hansen

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Maximiliano Martín

William Stafford

Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Alison Green

Horn

Kenneth Henderson

Jamie Shield

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Shaun Harrold

Timpani

Louise Lewis Goodwin

Peter Franks Principal Trumpet

LARSSON (1908-1986)

Pastoral Suite, Op 19 (1938)

Overture (Uvertyr): Adagio – Allegro

Romance (Romans): Adagio

Scherzo: Vivace

MOZART (1756-1791)

Bassoon Concerto in B-flat major, K 191/186e (1774)

Allegro

Andante ma adagio

Rondo: Tempo di menuetto

SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

Symphony No 6 in C major, D 589 (1817-18)

Adagio – Allegro

Andante

Scherzo: Presto

Allegro moderato

We may feel we’re relatively familiar with two of the composers in tonight’s concert. Franz Schubert and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart are iconic names, and those two figures represent a time and a place – Vienna (or at least Austria) in the late 18th and early 19th centuries – that seem to encapsulate the enduring pinnacles of classical music.

Tonight’s first composer, however, is likely to be far less familiar. But the inclusion of 20th-century Swedish composer LarsErik Larsson serves as a gentle prod or prick of the conscience, a reminder of just how much most of us still have to discover beyond Austria, Germany, Italy and France, in Sweden’s music specifically, and Nordic music more widely.

Larsson – who died as recently as 1986 – was almost certainly the most respected and most widely popular figure in 20th-century Swedish music, and a genuinely admired and cherished personality in his Swedish homeland. He was a prolific composer – of symphonies, concertos, chamber music, choral works and a huge number of scores for film and theatre – across an eclectic gamut of styles, from lush, rich Romanticism through to more ascerbic dissonance (no doubt influenced by his studies in Vienna with Alban Berg in the 1920s). But Larsson was also a deeply influential figure as a conductor, critic, teacher and radio producer. He worked as composer-in-residence, producer and conductor/bandleader at Swedish Radio between 1937 and 1954, creating music for many radio programmes, and devising new ways of integrating speech, music and broadcasting.

It was one of those new radio formats that provided the genesis for tonight’s first piece. In his day-to-day duties at Swedish Radio,

Larsson quickly struck up a friendship with Swedish poet Hjalmar Gullberg, who also happened to be the organisation’s head of drama. Thinking there must be better ways of presenting speech and music than simply plays and concerts, the two men devised a new format that they dubbed a ‘lyrical suite’, mixing poetry recitations with musical interludes. (Far more recently, BBC Radio 3’s Between the Ears series has attempted something similar, if more radical.)

Larsson and Gullberg’s first foray into the form came in an interpretation of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale in 1938. They followed that up with The Hours of the Day later the same year, for which Larsson wrote six short pieces to be heard alongside six poems by Swedish writers that considered particular moments in a day. The Hours of the Day was first broadcast on 11 October 1938, with Larsson himself conducting the Swedish Radio Entertainment Orchestra. He was clearly pleased with his musical

Larsson – who died as recently as 1986 – was almost certainly the most respected and most widely popular figure in 20thcentury Swedish music, and a genuinely admired and cherished personality in his Swedish homeland.

creations, extracting three of the original six short movements to form a stand-alone concert work, tonight’s Pastoral Suite

You might struggle, however, to link the Pastoral Suite’s movements directly to points in the day. There’s a certain sense of sunrise and new beginnings in the slow introduction of Larsson’s opening Overture, whose luminous, intertwining string lines surely doff their caps to similar ideas in Sibelius’ Sixth Symphony, completed about 15 years earlier. The pace swiftly quickens, however, for more rustic, bucolic music, with a few dissonant harmonies from the woodwind that disturb the sense of countryside idyll, and a bracing energy that dissipates at the movement’s quiet close.

The Suite’s passionate central Romance, scored for strings alone, is the work’s most popular section, and is often played as a stand-alone piece. Its restrained, hymnlike opening gives way to a more swaying, flowing central section, only to return with

greater passion towards the end. The closing Scherzo is full of infectious, open-air energy, and showcases the orchestra’s flautist as a soloist who returns again and again throughout the movement. It maintains its scampering movement throughout, even during its apparently slower central section.

We linked Mozart and Schubert, not unreasonably, to Vienna at the start of these notes, but the former was in fact still living in his birth city of Salzburg when he completed his Bassoon Concerto on 4 June 1774. Aged only 18, he was already an established, not to say prolific composer: he’d written several masses and other church music, a handful of short operas, numerous violin sonatas, no fewer than 25 symphonies, several serenades and divertimenti, and a clutch of string quartets (not to mention a whole catalogue of smaller works). Just the previous year, in fact, he’d gained his first employment, as a musician at the court of Hieronymus von Colloredo, Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg.

Aside from its specific date of composition, however, we don’t know a great deal about Mozart’s only surviving Bassoon Concerto. He’s thought to have written several others, though there’s no specific evidence, and the B flat major Concerto is the only survivor in its form. It’s been speculated, too, that he may have written the piece for the aristocratic amateur bassoonist Thaddäus Wolfgang von Dürnitz, a big fan of Mozart’s music, though the composer’s letters indicate that he only met von Dürnitz in 1775, the year after the Concerto’s completion. It’s probably more likely that he wrote the Concerto for one of the two bassoonists in the Salzburg court orchestra, Heinrich Schultz or Melchior Sandmayr.

What’s incontrovertible, however, is that the piece was authentically and specifically

conceived for the bassoon, since Mozart exploits the instrument’s sound world and personality so effectively in it. Indeed, it’s even been suggested that the piece was part of an attempt to revive the bassoon concerto as a popular form: though bassoon concertos had been well liked during the Baroque period (Antonio Vivaldi wrote no fewer than 39 of them, for example), their popularity had waned in later years. If that was his aim, Mozart might not quite have succeeded, but he nonetheless created what’s indisputably the bassoon repertoire’s best-loved and most frequently performed Concerto.

The first movement opens with a confident theme, complete with an urgent, repeatednote bassline, before a more graceful second melody takes over – though the pomp and swagger of the opening are quickly reestablished. The bassoon maintains the opening melody’s sense of nobility when it enters, but quickly embellishes and decorates the theme, with huge leaps and athletic figurations demonstrating the player’s virtuosic prowess.

There’s a gentle sense of flow to Mozart’s slower second movement, which shows off the bassoon’s lyrical, even vocal qualities in a tune that the composer would later transform into the much-loved aria ‘Porgi, amor’ in the opera The Marriage of Figaro. He closes with a gently tripping minuet dance that leaves its recurring theme to the orchestra (for the most part, at least), while the bassoon soloist supplies drama and decoration in intervening episodes.

From the 18-year-old Mozart, we turn to the 21-year-old Schubert for tonight’s final piece. And that’s a 21-year-old writing his Sixth Symphony, let’s not forget. Like Mozart, however, Schubert had started young (even

if he wasn’t quite as prolific): in terms of orchestral music alone, his First Symphony dates from 1813, when he was just 16, and he’d written a series of orchestral overtures from the age of 14. Perhaps that very youthfulness is one reason why Schubert’s early symphonies have traditionally been somewhat overlooked, even dismissed as mere juvenilia. Yes, there’s a lot of youthful enthusiasm, and a desire to impress with the latest styles and musical techniques. But there’s much to enjoy, too, in exploring the composer’s early orchestral passions, and in encountering his uncannily effective and memorable way with melody.

He wrote the Sixth Symphony between October 1817 and February 1818. And although it’s assumed that his early symphonies must have received amateur performances at the Vienna school where Schubert studied and later taught, none received a public performance during the composer’s lifetime. No 6, however,

If that was his aim, Mozart might not quite have succeeded, but he nonetheless created what’s indisputably the bassoon repertoire’s best-loved and most often performed Concerto.

came close. Schubert had been involved in planning a concert devoted to his own music, given by the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, which was scheduled for 14 December 1828. He’d first suggested his Symphony No 9 (the ‘Great’ C major), which he’d completed three years earlier, but the orchestra found it too taxing. As a rather simpler, shorter replacement, he offered No 6, which was duly premiered at the concert – a mere four weeks after Schubert’s untimely death on 19 November, at the age of just 31. It became the first of all Schubert’s symphonies to be publicly performed, and received a generally positive response. Critic Johann Baptist Schmiedel, for example, wrote: ‘New symphony in C Major by Franz Schubert (posthumous): a fine, diligently crafted work whose most appealing movements are the Scherzo and the Finale. One could perhaps criticise it for its overly opulent wind section, which makes the strings seem subordinate much of the time.’

To 21st-century ears more accustomed to brighter, more varied orchestral colours, it may simply seem as though Schubert is deftly exploiting the rich instrumental sounds in his ensemble. Those sounds are put to thrilling use in the first movement’s solemn, ceremonial opening, whose monumental chords and sweeping figures are surely a nod in the direction of Beethoven. When piping high woodwind kick off the movement’s main faster music, however, it’s more Haydn who’s the object of the young Schubert’s affections. A gentler, more graceful second main theme comes first from the woodwind, and after a stormy central development section, the movement ends in with grand, almost Rossinian operatic exuberance.

In his fascinating second movement, Schubert plays games with two contrasting musical ideas: a gentle melody with ticktocking accompaniment, and far louder, more boisterous music with dance-like energy to it. There is no going back once the

To 21st-century ears more accustomed to brighter, more varied orchestral colours, it may simply seem as though Schubert is deftly exploiting the rich instrumental sounds in his ensemble.

latter has got underway, and by the time the movement reaches its softly spoken conclusion, the two seemingly disparate ideas have effectively become one.

Schubert’s third movement marks the first time he included a playful scherzo in a symphony. But he clearly had a model: close your eyes, and you could almost mistake it for the scherzo from Beethoven’s First Symphony. A more rustic central section is punctuated by tolling bell-like sounds from strings, horn and lower woodwind, and the dashing opening music returns to propel the movement to its energetic close. Trumpets and timpani have made their presence felt throughout the Symphony – even in the slower, quieter second movement. But they come to the fore in the perky, light-footed march of the finale, which swerves into the sweetness of Italian opera later on, only for trumpet fanfares to ensure the Symphony ends in appropriately grand, ceremonial joy.

© David Kettle

Andrew Manze is widely celebrated as one of the most stimulating and inspirational conductors of his generation. His extensive and scholarly knowledge of the repertoire, together with his boundless energy and warmth, mark him out. He held the position of Chief Conductor of the NDR Radiophilharmonie in Hannover from 2014 until 2023. Since 2018, he has been Principal Guest Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. Last September he was appointed Principal Guest Conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra.

In great demand as a guest conductor across the globe, Manze has long-standing relationships with many leading orchestras, including the Royal Concertgebouworkest, the Munich Philharmonic, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Bamberg Symphoniker, Oslo Philharmonic, Finnish Radio, Mozarteum Orchester Salzburg, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, RSB Berlin, and the Dresden Philharmonic among others. In the 24/25 season, Manze will also make debuts with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, and return to the Hallé Orchestra, the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and the Salzburg Festival.

From 2006 to 2014, Manze was Principal Conductor and Artistic Director of the Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra. He was also Principal Guest Conductor of the Norwegian Radio Symphony Orchestra from 2008 to 2011, and held the title of Associate Guest Conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra for four seasons.

After reading Classics at Cambridge University, Manze studied the violin and rapidly became a leading specialist in the world of historical performance practice. He became Associate Director of the Academy of Ancient Music in 1996, and then Artistic Director of the English Concert from 2003 to 2007. As a violinist, Manze released an astonishing variety of recordings, many of them award-winning.

Manze is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, Visiting Professor at the Oslo Academy, and has contributed to new editions of sonatas and concerti by Bach and Mozart, published by Bärenreiter, Breitkopf and Härtel. He also teaches, writes about, and edits music, as well as broadcasting regularly on radio and television. In November 2011 Andrew Manze received the prestigious ‘Rolf Schock Prize’ in Stockholm.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Born in London, Cerys started playing the bassoon when she was 15, after first playing the double bass. She studied at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, learning with Miriam Gussek, Daniel Jemison, Helen Simons and Peter Whelan, and was awarded the Howarth-GSMD Bassoon prize in her first year. After participating in the Erasmus scheme in Amsterdam and graduating with first class honours, she continued her studies with Bram van Sambeek at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague.

Since moving back to the UK, Cerys has enjoyed a varied freelance career, performing with the RPO, LSO, Hallé, CBSO and The Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. She has been Principal Bassoon of the SCO since 2021/22.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is one of Scotland’s five National Performing Companies and has been a galvanizing force in Scotland’s music scene since its inception in 1974. The SCO believes that access to world-class music is not a luxury but something that everyone should have the opportunity to participate in, helping individuals and communities everywhere to thrive. Funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and a community of philanthropic supporters, the SCO has an international reputation for exceptional, idiomatic performances: from mainstream classical music to newly commissioned works, each year its wide-ranging programme of work is presented across the length and breadth of Scotland, overseas and increasingly online.

Equally at home on and off the concert stage, each one of the SCO’s highly talented and creative musicians and staff is passionate about transforming and enhancing lives through the power of music. The SCO’s Creative Learning programme engages people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse range of projects, concerts, participatory workshops and resources. The SCO’s current five-year Residency in Edinburgh’s Craigmillar builds on the area’s extraordinary history of Community Arts, connecting the local community with a national cultural resource.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. His tenure has recently been extended until 2028. The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. Their second recording together, of Mendelssohn symphonies, was released in 2023, with Schubert Symphonies Nos 5 and 8 following in 2024.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Principal Guest Conductor Andrew Manze, Pekka Kuusisto, François Leleux, Nicola Benedetti, Isabelle van Keulen, Anthony Marwood, Richard Egarr, Mark Wigglesworth, Lorenza Borrani and Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen.

The Orchestra’s current Associate Composer is Jay Capperauld. The SCO enjoys close relationships with numerous leading composers and has commissioned around 200 new works, including pieces by Sir James MacMillan, Anna Clyne, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly and the late Peter Maxwell Davies.

This summer, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra is bringing live music to 20 towns and villages across Scotland - from Golspie to Castle Douglas, Brechin to Kilmelford. Our Scottish Summer Tour celebrates the rich diversity of our musical heritage, featuring everything from timeless classics to a thrilling world premiere.

Your donation will help deepen our connections with local communities, showcase our exceptional musicians, and bring world-class performances to audiences who rarely have the opportunity to experience live orchestral music in their area.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Hannah on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk