__Benzina___

t hanks to

team Benzina would like to thank: Ivar de Gier, Brian Ashley, Christine Smith, Pat Slinn, Richard Skelton, Joanna, Eve and Will. And - of course - all the contributors and advertisers. Sorry if we’ve forgotten anybody – your help and inspiration has been invaluable.

Front cover image Elise Waters

010 N

Words: Hans Jansens, Ian Gowanloch, Mark Williams, Ivar de Gier, Richard Varley, Gordon de la Mare, Alan Cathcart, Robert Smith, Rene Waters, Pat Slinn, Gary Inman, Howard Davies. Photos: Hans Jansen, Russ Murray, John Faulkner, Richard Varley, Paul Hart, A Herl, Kyoichi Nakamura, Robert Smith, Chipy Wood, Elise Waters, Pat Slinn, Vicki Smith. Brilliant effort, all of them, and much appreciated.

DO NOT PRINT THIS PAGE- USE AS GUIDE ONLY (ON INSIDE COVER)

BUT DO PRINT OPPOSITE PAGE!

Publisher & Editor Greg Pullen © 2012

www.teambenzina.co.uk

Chief photographic consultant Vicki Smith

www.ducati.net

Printed in the UK by Cambrian Printers Ltd

ISSN2043-0744

Lower Heath Ground, Easterton, Devizes SN10 4PX

Brakes photo right: Vicki Smith. More on the drum-braked MV Agusta F4 Special (below, right) on page 27, and on the Dondolino (bottom) on page 50

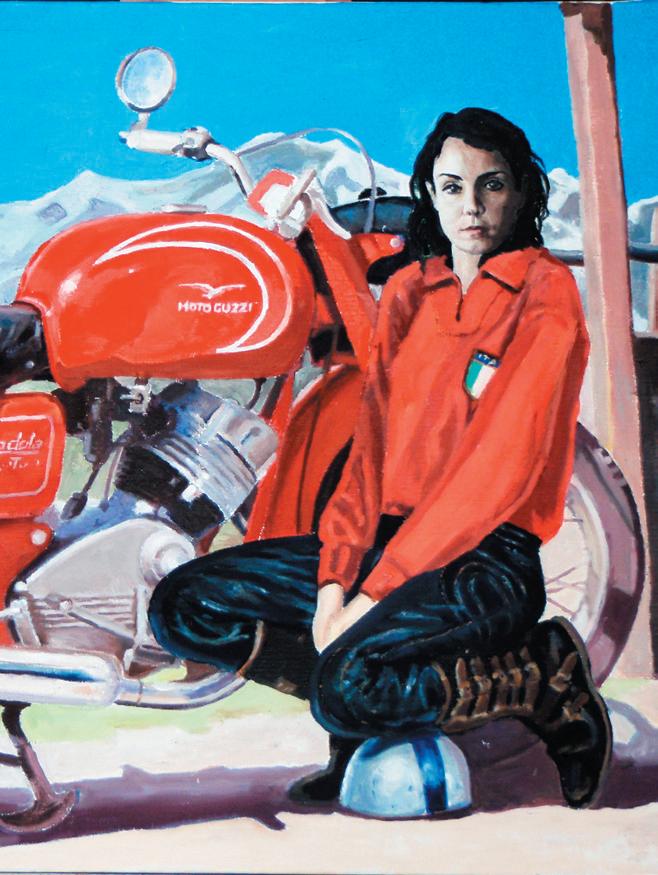

Veronica and TEL125 proving there’s more to motorcycling than motorcycles. One of these MVs gets a mention in the Fire Engine story later on, but blink and you’ll miss it.

Veronica and TEL125 proving there’s more to motorcycling than motorcycles. One of these MVs gets a mention in the Fire Engine story later on, but blink and you’ll miss it.

BIG ISSUE

Riding’s About More Than Just Motorcycles

Amotorcycle – especially an old, Italian motorcycle – needs a surprising amount of paraphernalia if it isn’t to become, at best, a museum piece or, at worst, a liability. A household’s less bike-centric members might even see an unused motorcycle as an asset worth selling off to fund something useful. Like a big TV, or even a nice little car. So the things and people who make motorcycling what it is, like riding gear, fuel stations, and engineers, are as important as your motorcycle, and are celebrated in this edition of benzina. People like the brilliant engineers Lino Tonti and Arturo Magni as well as Mr Dainese himself. The first thing most riders covert is a leather jacket, an item of clothing so iconic only motorcyclists and military pilots can legitimately wear one. So we’ve the thoughts of master artisan Lino Dainese on his life in leather, and how he felt compelled to make the motorcyclists’ lot a safer one after riding to England from his native Italy.

But first up is the sad demise of the small independent filling station, where you could not only get fuel but also gain access to advice, tools and even a workshop if things were going badly. It’s easy to forget that many of our roadside haunts, including the Ace Café and innumerable old-school dealerships, came with petrol pumps attached. Sadly those small old fuel stops are becoming just another sepia-tinted memory as petrol stations get bigger and more like supermarkets than anything connected to motoring. The traditional service station has gone the same way as the small motorcycle workshop-cumshowroom. They were bulldozed aside by big boys with moto-palaces built by marketing gurus to feel more like electrical retailers than the sort of oil-under-the-fingernails dealerships we grew up with. Yet while the giant hoardings

on the walls of these temples of desire might show motorcycles, sitting astride them are glamorous dudes and dudesses who look nothing like the sort of people usually seen on a bike. And now even these dealers of the Brave New World might prove to be temporary custodians of brand values as manufacturers dip their toes into the murky waters of selling online. Where will we ride to then?

Well, there are plenty of ideas in this issue – the final instalment of Richard Varley’s tour of Italian Cols, along with Pat Slinn’s memories of racing in Japan with fellow legends Steve Wynne, George Fogarty and Tony Rutter. Or if you like a more relaxed approach to travelling, Alan Cathcart uses an original Multistrada to explore the beauty of Puglia. And when you’ve supped your fill of Tarmac, the inimitable Mark William’s shares his thoughts on what Italian trial bikes really excel at – looking good in sunny piazzas, as it happens.

There are also the thoughts of Hans Jansens on the new Morini Rebello – yes, he’s seen the controversially styled new bike in the flesh – and Ian Gowanloch’s personal insight into how Audi’s takeover of Ducati fits into its history. Last but not least, Howard Davies of widecase.com offers advice on buying Ducati widecase singles. Which, as usual with fine Italian motorcycles, boils down to this; you should. So many motorcycles, so little time. Bags me the magnesium alloy beauty of the Moto Guzzi Dondolino on page 27.

Enjoy benzina #010

Greg

Photo: Russ MurrayPump It Up

A fond farewell to the humble filling station

An old filling station becomes a temporary (aka “pop-up”)Shrimpy’s restaurant overlooking the Thames prior to demolition and redevelopment in 2014

An old filling station becomes a temporary (aka “pop-up”)Shrimpy’s restaurant overlooking the Thames prior to demolition and redevelopment in 2014

Petrol, gas, benzina: call it what you will, but without fuel a motorcycle is just a collection of parts taking up garage space. For most of us getting fuel used to mean a visit to either a filling station (pretty much petrol for sale and nothing else) or a service station where (you guessed it) there was servicing and repair on offer as well as fuel.

Motorcyclists have an understandable interest in filling stations, with 100-150 mile being the typical range of most motorcycles compared to 300-plus for other road users. Judging by the photographs floating around the net, motorcyclists also seem to have an unhealthy interest in photographing their period bikes in front of rusting old pumps. And why not? It certainly accentuates any new paintwork or chrome.

I've fond memories of petrol stations, moonlighting at a handful during fifth and sixth form, partly explaining exam grades as well as how a school kid was running a motorcycle. Back then a pump jockey (as we liked to think of ourselves) would not only fill the tank while you sat in your nice, warm car, we'd be expected to check oil and battery fluids. There was commission to be earned by selling anything overand-above the petrol, and a friend already in the job was happy to explain how polite enquiries meant prizes. Like offering to check the oil as quickly as possible because the sooner you got that dipstick out, the lower the oil level would appear, with plenty of it still up in the head and galleries. Cringeworthy now, knowing what can happen to an overfilled engine, but back then all cars used a fair bit. Or so we told ourselves.

Agip station in Formia, on the west coast of Italy, with the mountains of the Parco Naturale dei Monti Auruncimore in the background. Fill up here and 80 miles further south is Naples and the gateway to the Amalfi coast, one of the most legendary roads in the world. Splendid in 1956 when this photograph was taken, but a bloated slow-worm of tourist busses today. Still worth travelling, though, and worth a 6am start-engines call. Photo: eni

It’s also amazing how much oil you could drain out of an apparently empty can if you left it upended overnight. Exactly enough for an oil change in a Honda 125 every six months, as it happens…

Next up was trying to convince folk to buy a new battery. In today's terms a battery cost around £150 so people were paranoid about checking them and making sure the lights weren’t left on. A generous offer to check tyre pressures might also lead to spotting illegally worn treads, and the sale of a pair of tyres. The only job that might have been begrudged was cleaning windscreens - no money to earn, and a real risk of waiting customers moving on to the next garage before we got to them.

Because here's the thing - there were around 500 cars for every petrol station 30 or 40 years ago, compared to nearly 4,000 today. Every other village seemed to have a filling station and a mile from where we hold our tea-and-cakes meetings was a thatched cottage with a petrol pump in the front garden. A little further afield, hidden down a country lane, is Wayside Garage; home to the much-missed Ollie Bridewell and his brother Tommy, who still wrings the neck of a big Beemer in British Superbikes on his weekends off. Because Tommy, like his late brother and their father and grandfather before them, run a tiny village service station, which used to mean putting down the spanners or dragging themselves from underneath a car to fill the tank of a waiting local. These days Tommy and his Dad will still fix your car or motorcycle, but the fuel pumps have long gone. Along with the few remaining locals, these days everybody queues at the big national (and international) chains selling fuel at pennies-per-litre less than any independent retailer could hope to do. So a way of life has gone and for motorcyclists in unknown territory there’s the constant gamble on the distance to the next filling station when passing a forecourt cluttered with cars, barbeque charcoal, soggy newspapers and tacky gifts for forgetful sons and husbands. If you do decide to stop and top-up you have to serve yourself, then queue behind someone doing the weekly shop, before you can finally pay. Assuming the cashier doesn’t insist on you taking off your helmet first (which means taking your gloves off) while the woman in the queue behind you tuts theatrically. It’s the same story at supermarkets (especially those self-service tills) and online shopping - we do all the work, and the chap who used to serve you has long gone. Along with his shop, the post office, library and everything else that made a small town tick. I'm sure there was at least as much delivery work back then too, because most shops would deliver, and of course stock had to get to them first.

This is why, fuel aside, everything's cheaper now in real terms than it was 60 years ago. But that also means far fewer semiskilled jobs are available. Some you win, some you lose. Or rather, some win, some lose. Along with small shops, pubs and village tea rooms, the independent filling station is all but extinct. Some of the buildings were fabulous, many from the great age of Art Deco, but few get reused. People have tried turning them into museums or themed restaurants, but the real money’s in knocking them down and building houses. So that’s what happens. Although a few became small, independent, motorcycle dealers they’ve all but gone now, usurped by the huge, corporately branded, homogenous showrooms. But even they might next to disappear as somewhere to ride out to: Ducati and others have had success with selling limited edition motorcycles via websites, and now the resurrected Moto Morini factory has decided you’ll only be able to buy their motorcycles online. The claim is they’ll be delivered through dealers who will undertake servicing and warranty work, but unless Morini expect the bikes to be desperately unreliable it’s surely naïve to expect a dealer to survive on servicing and warranty work alone. Just as there’s no money to be made in selling petrol unless you’re also selling coffee, sandwiches… everything, in fact, except service. At least the folk who ride old motorcycles know how to check things like the oil level. Other people might be in for a bit of a shock. B

(The gentle art of doing nothing)*

Il dolce far niente

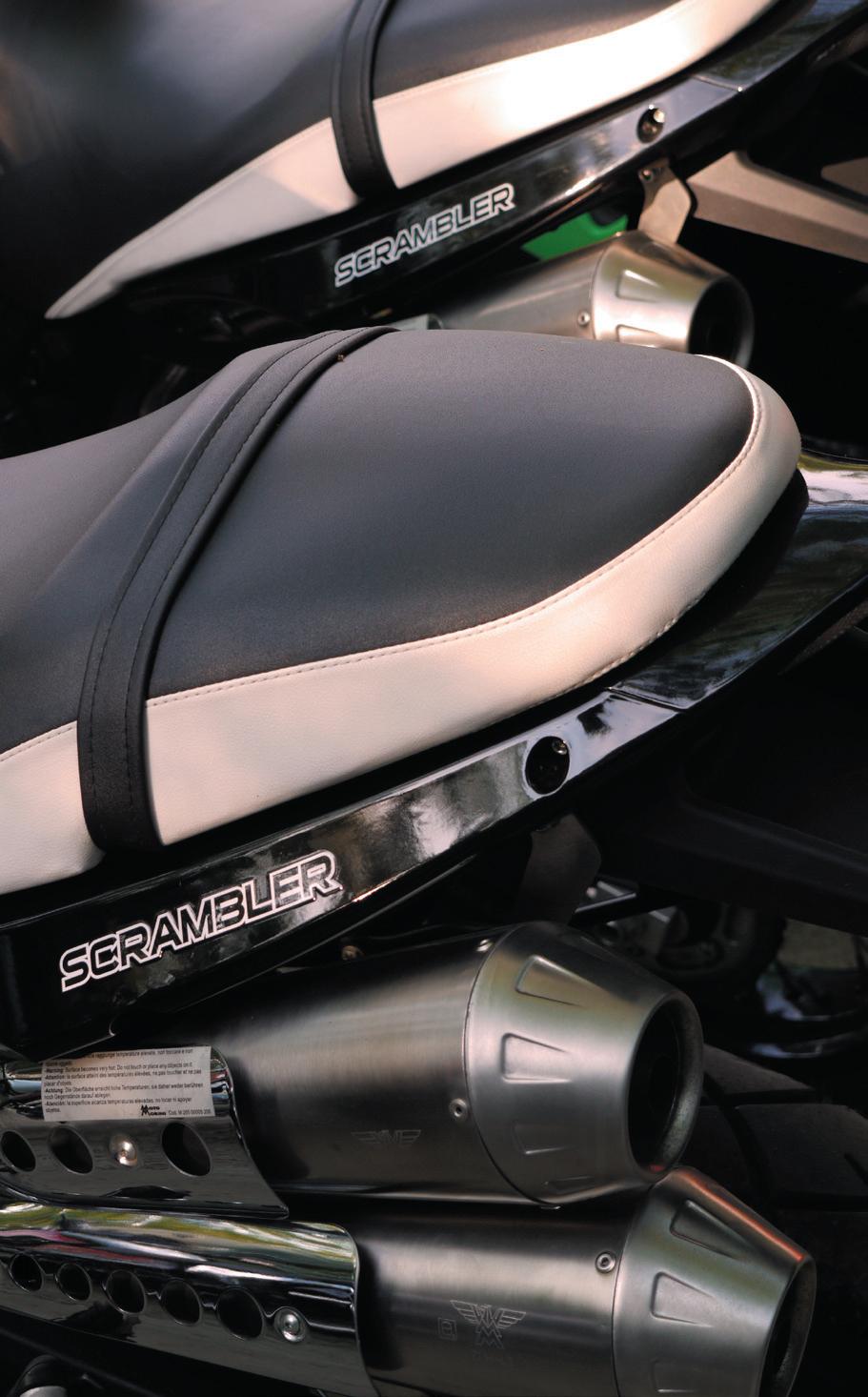

* Colloquially - “Sweet Fanny Adams” wouldn’t translate literally, either. photos, clockwise from right: “Desert Storm” Granpasso; new Morini owners unveil new Rebello - is the chap on the left wearing a wig?; seat extends at the push of a button - same idea as a 1970s MV750; DIY dohc conversion to a 175; 125cc two-stroke, the first post-war Morini; Mauro shows off his restored Tresette

Words and photos: Hans Jansens

One of the good things about riding an Italian bike is that you actually have the country of origin around the corner. Well, you do if you live in the Netherlands. And even better, riding an Italian motorcycle to Italy is so much more enjoyable than just watching and having feelings for the wheeled wonders to come out of that country. So the perfect reason for going to Italy would be to travel down to an Italian motorcycle meeting to relax with friends and then, when the day’s riding is done, enjoying good food and wines.

The ride down south from the Netherlands is always an enjoyable one. You can skip the Dutch flatlands and the dull highways by moving into the Ardennes as quickly as possible, but from there on the party gets going. The Ardennes in Belgium, and particularly in Luxemburg, are beautiful and once in France you have the choice of riding the country roads towards Verdun or moving into the Vosges and the famous Schwarzwald (Black Forest) of Germany. Twisties galore, and some of the best riding in the world. For this trip I chose to ride from Verdun to Besancon and on into the Jura mountains. From here the Alps are only a stone's throw away, and once they’ve been crossed it's just a hundred kilometres or so to Morano sul Po in Piedmonte. This small village and the surrounding valley might be famous to most of the world for growing fabulous risotto rice, but for some of us it’s better known for hosting an annual Morini meeting. Or Moriniday as they call it. 2012 was the twenty-third event. We meet on the banks of the river Po, in the same old sports camp used by presidente Fulvio Surbone and his friends from the village for this years gathering. Luckily there’s a cool breeze blowing across the river because otherwise the mosquitoes would fly in from the surrounding rice fields and eat us all alive.

Arriving on Friday afternoon and chatting to people, as Morinis come and go –well, mainly come - it is already getting busy. People from nearby villages nearby come over to see what's going on and to enjoy the open-air kitchen serving local specialties alongside wines from the surrounding hills. Everything a Morini rider could need is here and within easy reach.

A new Morini is born!

In the evening one corner was dedicated to a newborn Morini: the Rebello Giubileo. This is the latest derivate of the 1200cc series, first seen in 2005, and the first new design from the latest owners of the Moto Morini name. Although the new firm is registered in Milan under the banner of Eagle Bike, the bikes are still to be built in Bologna. Naturally the showing of the Rebello nuovo generated plenty of discussion: will this model be the saviour of the famous marque? Is it smart to sell it only via the internet? And do we actually like it? Well.... as far as the last question is concerned, I haven't heard from anyone who actually did like it. Apart from a 1200cc engine that we already know and love (and the front forks) not much positive comment came from the Morini fans. And to be frank, even in the flesh, it's not very pretty. Too bad. Even so, they claim to have sold 600 over the internet and are being assembled this autumn. (Morini have now stopped taking orders, saying the Rebello’s entire 2012 production run is sold out- Ed)

The good news is that other 1200 models are also being produced again so existing owners can order parts and new owners can be welcomed to the Morini fan club. The Granpasso was also shown in a new colourscheme, labelled 'Desert Storm'. An awkward name, perhaps, but it does looks good.

On Saturday the rally really gets going. The weather is perfect, and at one point the whole site is home to over a hundred Morinis, of all ages and models: at least one of every example – even the rarest production modelsseems to be present. Lots of people gather for lunch, as always in Italy the main meal of the day, and combined with good wine it makes everything seem even more enjoyable than it already is. Then there’s an afternoon tour through the surrounding hills (After a big Italian lunch with wine? Very Italian – Ed). Instead of one, long, slow line crawling across the mountains, speeds get serious, and a girl on a 3½ Sport almost misses a sharp uphill bend. Fortunately she keeps the shiny side up. And looking back, the large Morini-snake crossing the mountain roads is a beautiful sight.

photos, clockwise from right: Valentini bikes on parade; no expense spared restaurant facilities; late sixties 250 Rebello; lusting after an original fifties Rebello 175 racer - just a shame photos don’t do sound; apparently abandoned 500 racer, with fabulously scuffed tyres; pert Scrambler bums. You can see more of Hans’ writing and photos at www.impaginator.nl

Along with the expected classics, this year brought a large turnout of the bikes from the past six years, like the Granpasso and Corsaro. And then there were the beautifully prepared classic racebikes. One was simply lifted from a van, leaned against a tent pole and left there. Where the owner went no one knows. And then a crowd gathered as an original 1950s Rebello is fired up. Brilliant events within an event.

There’s also a line-up of Valentini specials attracting plenty of spectators. Valentini was a seventies tuner from Prato who made kits for the 350cc models consisting of bodywork, two-into-one exhaust systems, rearsets and more. Nowadays they are considered classics in their own right and the bodywork has actually been put back into production. Valentini was also the tuner for the Moto Morini Camels that were entered in the Paris-Dakar and other rallies.

As quickly as people had appeared, they disappeared as evening approached. A small group remained for dinner and the party afterwards with a lottery - and a real Italian disco band!

On Sunday morning Franco Lambertini (the genius behind all Morini’s V-twins, interviewed in benzina #4) showed up with some great anecdotes and was happily answering questions. Unfortunately one his answers confirmed he isn’t working with the new owners of Morini. Perhaps his best story was about the high speed test runs with the first 3½ Sports on an autostrada near Bologna. At first, holding a stopwatch, everybody was pretty amazed at how fast the bike was, and thought there must have been a mistake in timing the bike. When a second run confirmed the high top speed the guy responsible for marketing decided to raise the proposed list price by some hundreds of lire!

Anyway, after pranzo it's bye-bye and ‘till next time. Let's hope the weather is the same next year, because the atmosphere, food and wines will certainly be as good as they always are.

Tomorrow Calling

this is what morini are staking their future on - the Rebello 1200 Giubileo. Giubileo means Jubilee, as in 75 years of Moto Morini. This gets pointed out everywhere from the logo on the seat to the small sticker on the headlight (left). Apparently sold out for 2012, even at a list price of 13,900 euros (around £11k), the 130bhp/198Kg (wet, apart from fuel) bruiser comes across as a tweaked Scrambler which is no bad thing. But, just months after Morini’s relaunch, the Scrambler is being offered at a 2,000 euro discount from its original price to now retail at just 7,900 eurosbarely more than £6,000, which is less than either the Guzzi V7 Stone or Ducati Monster 696 that offer around half the Scrambler’s 128bhp. The Scrambler might also look better than the Rebello, which is unfortunate when you discover Rebello means “Beautiful King.”

One way or another, the Rebello is Morini’s future. On the next page Ian Gowanloch, who almost certainly has more old Ducatis than anyone else on the planet (and will happily sell you spares for yours via his Italsparesducati listings on ebay.au), contemplates Ducati’s future - and past - under changing ownerships.

HAPPY FARM IAN GOWANLOCH

Back to the future

Afew months ago Ducati Meccanica was bought by the Volkswagen Group and placed under the management control of the Audi team. What does it mean? A fair bit I think, but first a bit of history. Ducati didn't begin the post Second World War period in good shape; their factory at Borgo Panigale had been completely destroyed by a very accurate bombing raid on the 12th of October, 1944 and to thwart the occupying army, tools, machines and people had been hidden all through Bologna and surrounding districts. There was total disarray.

Much of what Ducati had made before the war had no market afterwards. There was no money to buy high end electrical, electronic and photographic goods. Italy had been bombed, if not back to the stone age, then certainly a sizeable step towards it. The idea to produce the Cucciolo engine was inspired. Italians needed cheap transport that could dodge the bomb craters in the roads. It also well suited Ducati's understanding of precision engineering.

However, by the end of 1948 the Ducati works was bankrupt. Even though the Ducati brothers were proud that they had not assisted the Nazi war effort in any way, they received no compensation or assistance of any kind to help rebuild their factories. Their inability to repay the debts they incurred in financing the work themselves was their undoing. Ducati passed into state control and a third of a century of management-led highs and lows ensued. In March 1949 the factory was actually shut down for two weeks while state appointed managers argued that no more money should be invested in keeping the operation going.

Remarkably, almost from the beginning, the new engineering department at Ducati had a life all of its own. The unique Dr. Taglioni arrived in 1955 and immediately set about being very different. From around that time until the arrival of the Americans in the mid '90s an undercurrent of corruption spread through the factory. Bribes were demanded of suppliers in order that their components might be used on the production line. The suppliers hated it.

By 1970 the Italian motorcycle industry was in crisis. Small manufacturers were disappearing everywhere as more young people chose small cars rather than motorcycles as their preferred form of transport. Ducati's production numbers were very small and their prices quite high. What to do? Make a large capacity road bike, something they were not familiar with. Somewhere in Dr T's mind the concept was already well developed. The principles had already been proven with a 500 GP bike. The 750 GT was in production in a very short period of time and its derivatives are now widely regarded as being among the most desirable bikes of the era.

All through the '70s, factory policy vacillated between

being pro and anti racing as various managers came and went. The bikes were obviously competitive. Despite a lack of continuous development, and the fact last minute decision making often led to ridiculously short preparation times, they often won. The mid 70s saw a disaster of a different kind. The transition from the 750 range to the 860s didn't go well. The styling was a disaster and the bikes had had little development mechanically. They were rejected by the market. At the same time the factory invested probably more than it could afford to in bringing parallel twins into production. They were almost bullet proof mechanically, but only almost. And they were also rejected by the market. The lack of sales at that time almost sent the factory broke. Again.

In 1980 the VM group, the state owned organisation at that time in control of Ducati, pondered whether the firm should be allowed to continue making motorcycles at all. Ducati's range of small diesel engines was successful but the motorcycle side of the business produced only a few thousand bikes a year and didn't make a profit. But a bright spark in VM's management recognised the name had a following and decided to implement some quality control to add to that image. Change in the factory proved difficult: well, impossible actually.

Within a few years Ducati Meccanica was for sale. A few parties showed interest and Cagiva somehow ended up with the prize. That was 1984, and almost immediately Cagiva‘s management announced the Ducati name would no longer be used and that the factory would produce engines for use in motorcycles branded Cagiva. Two things happened to change their minds. There was a massive outcry from aficionados world wide and Cagiva Alazzurras, particularly the 350, sat in showrooms, ignored by uninterested potential customers.

Almost immediately after the takeover, there was a clash of cultures between Cagiva managers and the workers in Bologna. Problems caused by a lack of managerial control, and a lack of understanding and respect on both sides, never went away. The water cooled, fuel injected, four valve per cylinder engines that were to catapult Ducati into the future underwent a difficult. By the early '90s, Cagiva had seriously run out of money. Component manufacturers eventually stopped supplying because they were not being paid for their products. Incomplete bikes filled the factory's warehouses. The American TPG investment group saw the possibility of investing money in management and production machinery to improve quality, productivity and profits. They understood well the business of money, but seemed to have little grasp of the business of motorcycles. This new clash of cultures was enormous and at times even comical. A feature of that time was the firm's inability to make a model that had wide market appeal over a prolonged period.

The last few years have been the most stable ever. Impressively modern quality control has been introduced at the factory but the company has still been a bit directionally vague in terms of model design.

In brief, there has been 66 years of chaos. Add in brilliance and despair and artistic creativity and near disaster. In many ways it has been a peculiarly Italian thing. Chaos is the byproduct of creativity; creativity the illegitimate child of chaos.

A short distance across the plain from Borgo Panigale is the small town of Sant'Agata Bolognese where you will find the Lamborghini factory. The people from Audi took control of Lambo a few years ago. In that brief period sales have doubled and the cars have become something that people actually want to own rather than just lust after. Germans and Italians are very different people. As a generalisation I don't think Germans are as innately creative as Italians. They work at their products and designs, patiently perfecting them, honing their rough edges. For Italians creativity is more immediate, explosive even. And the end result is quite different.

The people from Audi left the Italians at Lamborghini doing what they do best and added what they do best to the mix.I expect more of the same at Ducati. Should be interesting times ahead. B

Fair comment?

Laverda owners’ club stalwart John Faulkner has no truck with anyone who criticises the Laverda 250 Chott - these are his and, although he’s also got some of Breganze’s big four-strokes, he passed on these photos with the note that read “The best model built by Moto Laverda - the 250 Chott. Do not listen to anyone who may foolishly try to deny this fact - they are obviously deranged.” But he will admit leaving them standing for long periods of time can lead to a nasty surprise at the magnesium alloy crankcases/crankshaft interface. John certainly wouldn’t advise leave your Chott out in the snow...

OutRunning Of Road

Mark Williams

Mild In The Country

Little gives me more pleasure, or at least little that I can write about in a family magazine such as this, than leafing through the back issues of Benzina that Mr Editor Pullen kindly gave me before we arm-wrestled over terms and conditions of my employment. But observing the mouth-watering array of Italian machinery so stylishly presented in said pages, I cannot help but notice that not much of it is of the knobbly-tyred variety. And that, my friends, is a source of great dismay… although not surprise, because brilliant though they may be at all other forms of bikery, in the last 40 years the Italians haven’t really built a decent trailbike.

They have tried, I know, they have tried, but by any objective measure – admittedly a measure I’m generally a stranger to – what it comes down to is a catalogue of despair. And just before you choke into your Peroni, take a look at this:

Anything with a V-twin engine and knobbly tyres: Try picking it up after you’ve dropped it in the gloop… always assuming you got it as far as the gloop in the first place. And in the case of Cagiva’s Elefant, not a happy choice of name.

Aprilia Pegaso: Nice looking bike, but too heavy and too limited in the suspension department for real-world mudpluggery plus, as it’s Rotax-powered, it isn’t entirely Italian.

Beta Enduro: Well as I mentioned last time, the 125cc ‘stroker of mid-70s provenance was a willing little fellow and also nice and light, but the forks were apparently made out of chrome-plated lead. Okay, the more recent Beta Alps were better specc’d, but essentially they were trials bikes with bigger tanks and seats… and Suzuki engines.

Morini Camel: Again, the name says it all. And a trailbike with a left hand kickstart? Oh puhleeeease!

SWM: Now you’re talking, at least as far as competition machinery was concerned, but to make them viable against the then state-of-the-art Japanese enduro and moto-x machines, their engines were frighteningly peaky, and of course being Rotaxes, not Italian at all. And when packaged as trailbikes, they weren’t much milder and cost too much.

I think that’s probably enough for now, and I bet that those of you with long enough teeth, or who’ve spent far too long looking at yellowing copies of The MotorCycle, will be shouting about the wee capacity

Gileras, Ducatis, Morinis and even Parilla ‘Regolaritas’ that acquitted themselves so well in the International Six Day Trials of the 1950s and early ‘60s. And you would be right to do so. But (a) they weren’t in any way available for domestic consumption, and (b) were ridden by latterday gods who could run up mountains carrying a motorcycle in each hand, rebuild their engines in 30 seconds flat, and pull out a spare one hidden under a bush when all else failed, which it usually did.

Mind you, looking at the pics in Mick Walker’s sadly long out-of-print ISDT – The Olympics of Motorcycling, it’s hard not to foster a deep spiritual yearning for such punky-looking bikes, especially the Gileras with their gorgeous red and white tank graphics – see how superficial I am? – and one does wonder, well I do anyway, why the remaining Italian manufacturers haven’t replicated that look in the same way that Guzzi is now doing with some of its roadsters? But back in the days when I was a serious trailbiker and even a not-so serious enduroist, there was next to nothing available that was Italian and worthy of the name, with the possible exception of Laverda’s 250cc Chott.

Introduced in 1976, on paper the Chott was quite a tasty prospect. It had a relatively powerful (26bhp) engine boasting lightweight magnesium cases, a dry clutch and its chassis, whilst old-school in terms of suspension, featured a fully enclosed chaincase (c/f MZ and others) and did its job well enough. And of course being Italian, with its gold painted engine and fashionably chiseled tank, it looked the biz. But owing to much tut-tutting from the bean counters at Breganze, it lacked the direct oil injection sported by its lowlier and much cheaper competitors from further east, and unless you were a serious competition rider in those days, mixing up petroil was a messy and unnecessary business. And as a competition bike, the Chott just didn’t cut it because it wasn’t powerful enough and its awfully notchy gearbox lacked the slick action and the right ratios to render riding a five or six hour enduro a tolerable exercise. Plus, it had a troublesome Dell Orto carb and an underslung ‘zorst which issued a seductive invitation to rocks and stumps, namely “Come and abuse me.”

Which brings me, as it must, to the Ducati singles that by now my reader may well also be fuming about. Yes, the ohc 4-strokes built by the Bolognese during the 1960s and ‘70s were in many respects well suited to the dual-purpose indignity us oldsters call trailriding, especially the 350cc SCR version. They were lighter and mightier than the horrid old pushrod motors BSA/ Triumph were still sticking in what they optimistically marketed to off-road adventurers (and which in some cases were actually called ‘Adventurers’), and revved like the clappers but with good spread of torque. However whilst they, too, had their kickstart levers on the wrong and awkward side, at least they usually did start, even when hot, which is more than could be said for the Brit bikes.

Ducati dutifully packaged these delightful although electrically challenged motors in ‘street scrambler’ mode, but forgot to add wheels that were big enough to successfully negotiate the ruts and rocks that lay far from the madding crowds posing around on ‘em outside the local pizzeria. And their forks weren’t really long or progressively damped enough, either. All of which probably betrays the true purpose of Italian trailbikes back in the glory days: they were made for looking good on, not for going good on, so that all-in-all, if you did want to do anything much more than pretending that you rode them in anger off tarmac, you had to spend a lot of time and money making that possible. Commodities that most of us mudpluggers just didn’t have, then or indeed, now. B

This ISDT Gold Medal winning factory Lodola Regolarità sits in the Guzzi museum. “Regularity” (regolarità) events were popular in Italy during the 1960s, typically 2,000km events to test off road ability. Like the Motogiro, using such events to prove the capabilities of small capacity bikes was brilliant marketing. So Guzzi took the 235cc ohv Lodola and converted it for regolarità use, which happily made it competitive in international six-day trials (ISDTs). Having abandoned the 175 Lodola’s overhead cam (which complicated decokes) when relaunching the bike as a 235cc GT (like La Cicciolina), for ISDTs Guzzi retrofitted the ohc head and some works bikes also got 247cc and a 5 gears. Running alongside Stornellos the Guzzi team ran away with the “Silver Vase” at the 1963 ISDT in Czechoslovakia.

La Cicciolina PART III

No easel and oils on Richard’s Lodola - just Castrol Valvemaster and the bare necessities opposite, top: Lodola Regolaritas in action, imagined with the help of a computer rather than Richard’s talents. Such stuff as dreams are made of

So it was. As usual La Cicc started first kick and we were to say farewell to the hotel staff. Girls who waved nicely, smiled wistfully, blew kisses and watched us leave whilst secretly of the conviction that most of us were insane. My fantasy was that Miss Forza Italiana would somehow miraculously appear on a large Harley Davidson and say she was going our way, could she tag along? She was definitely an H-D girl (1200 Sportster Black, I imagine) with a neatly tailored snakeskin jacket. But no. Surely there’s an ‘app.’ that can make these things happen? I obviously have the wrong kind of mobile phone.

Our next hotel was to be the Hotel Savoia at the head of the Pordoi Pass. Gordon and I persuaded Dave to ride straight to the hotel and try to get some rest as he was clearly suffering. We would ride together towards Trento where Dave would turn north to head directly for Pordoi. But for some reason Dave missed the left turn at San Michele towards Pordoi and followed us towards Trento. As we approached the town, I led us off the trunk route. Gordon followed and to my astonishment Dave carried on. My last sighting was of him proceeding onto a flyover above our heads, neck craned over that wretched

GPS screen, which had caused nothing but trouble from the word go. He obviously hadn’t seen us turn off. There was nothing we could do. La Cicc. certainly couldn’t catch him now so we followed our planned route in the direction of Borso Valsugana. Our first objective was the Passo di Vezzena at an altitude of a mere 1,402 metres (4,600 feet). We then doubled back to the SS47 and continued past Borso and turned north through through Castelnuovo and Telve to the Passo Manghen, an altogether more impressive pass at 2,047 metres (6,715 feet). There is no level area at the top; it crosses a knife edge but the views are still worth stopping for. We also had to take photos and there, waiting for us was the Reliant Topless 3 x 2 of George and Celia. Gordon had to struggle to put the V-Strom on its sidestand on the knife-edge pass with no flat bit, with help from George and myself.

The trouble is that after a while I find I’m not quite sure what is level and I don’t trust sidestands entirely. Gordon seemed to have the same problem, I think, as I helped him find the ground with his high side boot. There are few more terrifying feelings than the moment when you come to a standstill and put your foot down where you think there should be solid ground and there’s nothing . You get this sudden sensation that there’s an eight foot drop where you were going to put your foot; it’s a

physical sensation, your brain starts to manufacture the perception that you are on the edge of a precipice, complete with all the body reactions. Yet it’s just an inch or two more than you expected.

Often, when descending to a hairpin turn I feel as though I have become momentarily disoriented and no longer have a precise feel for gravity, as though I could be a couple of degrees out either way. I think I’d have to spend a lot more time in the mountains to eliminate this feeling. What is certain is that on the really fast descenders, the German and Austrian riders, obviously have no such problem. They have a different kind of perceptual problem; an illusion of invincibility which affects self-preservation. They never seem to consider the possibility of an unforeseeable event around the next corner. We did hear of the odd bike crash in which bits of bike were strewn across the road but the riders were all okay. Also noticeable was the way in which they kept re-passing us. We would often see the same riders again and again. My medals of honor go to the girls riding pillion on these bikes; they really are clinging on for dear life!

La Cicc went on and on, up and down hills, engine spinning at impossible speeds, brakes squeaking and still doing ninety miles to the gallon. I know this because Gordon kept all sorts of data in his precious notebook, including how much fuel we were all buying. He also kept a detailed record of where we’d been, which I did not. I knew I was probably going to regret this negligence later, but right then I was living for the moment.

La Cicc’s back brake is considerably more use than the front, which squealed so horribly I avoided using it, except in emergencies, such as when I had to stop. I was developing a style of alpine riding which avoided the use of brakes at all wherever possible. The gearbox took a beating instead. Modern bikes, with their ABS equipped, four pot caliper disc brakes (which never fade) live on the front brake. If in doubt,

grab a handful of front brake. The rear brake is generally only used at very low speeds, maybe when filtering through traffic. Modern bikes are higher, heavier and under deceleration, usually caused by braking, weight shifts forward so that in the back brake can have no useful purpose and is best forgotten, unless of course, you have to hold the bike facing up a steep hill, when the dynamics are reversed and front brake use can cause embarrassment. Interestingly, the new fashion for longer, lower bikes with a low centre of gravity and rotation, 'cruisers' as they are called, are in a dynamic sense a step back towards older machines like the Lodola.

We dropped down through Cavalese and climbed the Passo di Lavaze (1,808m – 5,931 feet) which unlike Manghen, has a saddle shape with a lake and hotels. We had stopped to take photographs and relax when a man in a Lancia drew abreast of us. He was clearly interested in La Cicc. and asked if I would be going to Mandello for the ninetieth anniversary celebrations the following week. 'Unfortunately not,' I replied. 'Pity. You have come such a long way. You have ridden from England?'

He shook his head, in what I took to be awe, when I replied in the affirmative. 'I used to manage a hotel in Mandello del Lario,' he said, wistfully. The woman in the passenger seat, who I took to be his daughter, patted his arm as if comforting a child. I have noticed how La Cicc has this ability to remind the older generation of happy memories from the past. When passing through towns like Bolzano or Merano, people walking along the pavement would point at La Cicc and wave, telling whoever was with them, often a child, that it was a Lodola. The entrance to one petrol station was blocked by a coach whose driver and guide wanted to speak to me about the bike. Gordon said I was becoming a serial attention seeker but it was gratifying to stir people's memories and indeed their spirits. Italians have a great

passion for their machines whether Ferraris, Ducatis or Moto Guzzis and these are household names. They think of them the same way as we regard the Supermarine Spitfire; with love and reverence. The design and manufacture of their creations is a matter of industrial pride which is written through each and every machine like the writing in a stick of rock. I was in Mandello a couple of years ago and they still speak of the Moto Guzzi factory rowing eight which went to England in 1948 as the Italian national eight and won gold medals in the Olympic Games. Where else but in Italy would you find a motorcycle factory built beside an alpine lake?

We continued to the Costalunga Pass (1,752 metres –5,750 feet) and on towards Canazei where after a very sharp left, we began the twenty eight turns of the Pordoi Pass (2,239 metres – 7,346 feet). La Cicc had to work hard ‘against the collar’ with all eleven horses straining; accelerating hard in first, snatching second and then the bike would momentarily leap forward as the energy stored in the heavy flywheel was released, then I would wind it on to the next tornante, look at the descending road above - nothing coming the other way so I would swing out onto the ‘wrong’ side of the road and aim for the apex of the corner while keeping the power on. The next corner would come up all too soon, maybe a left hander with a car approaching the bend from the opposite direction while being overtaken by two BMW GS’s. Staying high to the outside of the bend and dropping to first gear, I would give her full throttle until she was ready for second again. And so on, like this, for twenty eight turns until at last we burst onto the broad saddle of the col to snatch third gear then fourth, accelerating through the town towards the Albergo Savoia.

Dave was fast asleep when we arrived. This time he had felt no disturbance in the force, which was worrying as, previously, I had believed that Dave never slept!

The head of the Passo Pordoi is a saddle shaped col and looming over it, like an ancient citadel close by to the north, are the jagged crags of Sassolungo (9,670 feet) and Sassopiatto while to the south is the peak of Belvedere. The road continues to Arabba in the East and it is, at Pordoi, the highest surfaced road in the Dolomites. The car park at the hotel was home to the usual suspects, George and Celia in the Rialto, several Morgan Plus 4s of different ages, several Mazdas, three recent BMW bikes, Gordon’s Suzuki, Dave’s Yamaha, Aaron’s Porsche and, of course, La Cicc. A footpath used by many walkers descended to the carpark from the Belvedere direction and one could sense the obvious delight of the walkers, many from Germany and Austria, whose eyes lit up at the sight of so many unusual vehicles. They wanted to know from whence we had come; and why? And where were we going? Some spent a lot of time looking at the Morgans, having never seen so many in one location or, perhaps, never having seen one before. What was certain was that they had never seen a Reliant 3 X 2 before either, and at least two Germans showed they had a sense of humour after all by exploding with laughter. 'Ah, Grosse Brittanien,' said one older hiker, seeing the GB plate on La, 'Have you ridden from England?' 'Yes,' I replied. 'All the way?' @Yes, why not?' Of course, I was being a little provocative; my backside tells me why not every time I get off the bike. 'How far?' 'Twelve hundred miles. Nineteen hundred kilometres, I suppose.' He shoom his head incredulously. 'You have to ride back?' 'Yes. I'm afraid so.' 'Amazing. Good luck.'

The thing about La Cicc. is she looks like a toy beside the giant modern BMWs and even as I look at her, it’s hard to believe that we have come so far. How our horizons and our expectations have changed and yet I have not been noticeably disadvantaged by choosing to come on what one member of the group termed 'a totally inappropriate machine'. Another had immediately retorted: 'No, on the

contrary, highly appropriate.' La Cicc was always at the centre of controversy, and rarely ignored.

Alan and Pam were having a run of bad luck with their Morgan Plus 8. It had been lovingly restored, with no expense spared, over an extended number of years and it looked beautiful. When the bonnet was opened along its centre hinge, a V8 was revealed in an engine bay which was cleaner than most hospital operating theatres but something in the electrical system, maybe the engine cooling fan, was cooking alternators. And there was a problem that left them at the foot of an alpine pass with hardly any brakes left; had the fluid boiled? The next morning at Pellizano they had donned overalls (the 'they’ will not have escaped you), bled the brakes and changed the oil while I fiddled with La Cicc’s carburettor, but they were unable to get anything done about the electrical problem and had resorted to switching the cooling fan off, ergo, no mountain passes. They had managed to get up to Pordoi by keeping the heater on at full blast in a losing race to keep the temperature down. They would spend a few days climbing the local peaks on foot, such as the Sassolungo. On reflection, I suspect that we were not the only casualties and, indeed, more problems were to befall La Cicc.

Before dinner Lufkin kindly bought me a spritzer. 'Are you sure old boy? Do they know what a spritzer is?' 'Como se dice in Italiano ‘spritzer’,” I asked the barmaid. 'Spritzer,' she said, expressionlessly. 'I’ll have one too,' said Bubbles. 'Anche per la.' 'Va bene. E Lei,' she indicated Lufkin. 'Una birra per favore.' 'I say,' said Lufkin, 'You speak the lingo?' 'Only a bit,” I replied, feeling as though I’d stepped back into the bygone age of the Woosters.

Having little in common with Lufkin and Bubbles, I nonetheless felt obliged to entertain them. Lufkin had already complained bitterly about German motorcyclists, saying that he found their behaviour so unacceptable that he almost felt like driving into them, so I thought I would redress the balance and tell him the story of Aaron’s positive experience in the tunnel a few days ago. When I got to the part where the German’s fist entered the Mercedes by way of the foolishly open driver’s window, they both recoiled in horror. Lufkin’s head seemed to shrink into his knitted tank top and Bubbles took a step back at this story of ‘beastliness’ on the cols. So much for social interaction. They soon found someone else to harangue, having first scanned the room for any German bikers who might have found their way in.

We sat at dinner, enjoying a panoramic view of the pass while the temperature dropped very quickly, and as it approached the dew point, banks of cloud began to form, obscuring the valleys below. I had heard there was a shrine to a local climbing hero in a hotel about two hundred metres away so Gordon and I decided to take a look after the meal. In the lobby of the hotel was a glass case containing a beautifully restored 1939 Moto Guzzi 250 - an Airone, I think, which had belonged to Tita Piaz, the 'Devil of the Dolomites', celebrated alpinist, author and sometime politician who, during the Fascist dictatorship, had spent some time in prison, presumably because of his opposition to Mussolini. Ironically, Moto Guzzi was also Mussolini’s personal choice of motorcycle for duties of State.

The Airone looked to be about the same size as a Lodola and had many features in common. The Lodola was in fact Carlo Guzzi’s last design (1955), so it was bound to have things like upside down forks and the carburettor looked very similar with its separate float chamber. Gordon considered ways of liberating the bike from its glass case; maybe replacing it with the V-Strom. We’d obviously had a bit too much to drink so we wove our way back through the mist, past a bar with thumping music, carousing bikers and cigarette smoke.

Attending the tour gets you a sticker - and incredible memories. Event is open to motorcycles, plus open top 3-wheelers and cars. Not sure that excuses the chopped Reliant opposite.

The next morning we were having breakfast at seven thirty as usual. A possible six passes lay ahead but exhaustion was beginning to set in. Dave’s face had swollen up and despite his denials, he was clearly not one hundred percent. For myself, I had missed so many passes that I was probably only in the running for the Tour de Cols equivalent of the Wooden Spoon, especially having missed a whole day on Tuesday.

We took it easy and did the Passo di Valles (2,033 metres –6,670 feet) and the Passo Fedaia (2,057 metres – 6,750 feet). My new interest was blasting through tunnels and galleries, making as much noise as possible. I noticed that La Cicc’s cylinder head was becoming covered with oil, leaking most probably from a rocker cover fastener which had stripped its thread when being reassembled at Pellizano; this is as close I’m going to get to an admission of guilt! Occasionally some oil would find its way onto the blued exhaust pipe and instantly vaporise with that unmistakable aroma. On a fifty two year old bike, threads in aluminium are going to wear out. It looked a lot worse than it was but I was concerned about oil loss; I couldn’t tell how much she was using.

Somehow or other Gordon and Dave missed that turn in Canazei and I found myself climbing to Pordoi without them. I went back to the hotel, showered and changed, expecting them to appear at any minute. Time for a capuccino. I haven’t mentioned coffee and we’ve been in Italy for a week. Coffee has been part of my life since I saw 'The Ipcress File’ back in the 1960s. Harry Palmer’s gritty character, played by a young Michael Caine, was somehow given another dimension by his requirement for real coffee while everyone else in Britain had only just discovered instant, that stuff that came in a glass jar, resembled volcanic ash and tasted like gravy browning. The coffee grinding and percolation is a shorthand in the film for seduction and sex and leads to Harry’s conquest. The implied sexiness of coffee and lovingly making real coffee didn’t escape a young lad who was looking for ways of impressing women. The first thing I did when I left home was buy a coffee grinder and an espresso maker. Now I’m all grown up I have a Pavoni espresso machine which looks like a chrome plated piece of Victorian railway equipment. The whole process of making coffee has become as important as drinking it; a complicated social ritual.

Even today, for all the talk of barristas and the huge coffee chains, the English seem for the most part to have missed the

point once again. They think it’s a beverage, like a quick cup of char to keep them going while they carry on working; like when the gas engineer arrives six hours later than arranged, to repair the boiler. 'Would you like a cup of tea?' I ask. 'You got any coffee?' 'Expresso? Cappuccino?' He probably thinks I’m being sarcastic but he doesn’t want to take a chance that I’m serious. 'Haven’t you got Nescafe?' 'No, sorry,' 'Oh, I’ll have tea then.' 'Earl Grey or Yorkshire Breakfast Tea? I’ve also got some Lapsang Suchong.' Six hours late indeed!

In Italy, excellent coffee is the rule rather than the exception and we were quite happy to sit on the hotel terrace under the gaze of Sassolungo, chat and drink coffee and eat cake all afternoon, but after about twenty minutes Gordon hurtled into the car park looking seriously harassed. 'Dave’s been knocked off his bike,' he reported anxiously as he struggled to leap from the V-Strom in one unrehearsed balletic move that would have tested Dame Margot Fonteyn in her day. We hardly had time to absorb this information when down the road, his voice shifted several octaves by the Doppler Effect, but heard clearly over the roar of his Yamaha, came Dave. The Devil of the Dolomites had returned. He entered the car park at high speed, not once checking his GPS. One instinctively knew it was serious! His bike bike wasn’t much damaged and the car driver in question had been dealt with by some German motorcyclists and the Carabinieri, in that order, but he was understandably angry and shaken up. He had finally become the victim of some of the careless driving that Lufkin had noted the day before.

The standard of driving in both France and Italy is poor. I hate to say this because I enjoy driving in both countries but I know a few people who don’t. Some American acquaintances, members of a Moto Guzzi Club in Seattle, emailed me on their return to the ‘States. They said they had never been so terrified in their lives and there was no way they were coming back to Europe. I had a more sanguine view; one had to enter into the lunacy of it in order to survive. The incident with Dave and others I had witnessed recently began to plant seeds of doubt in my mind. Yes, driving and riding in Europe are more dangerous than at home, especially when the roads are crowded. Generally the roads are less busy and there’s room for everyone but, when the numbers increase then behaviour seems to deteriorate and individuals become far more dangerous. I recalled that on the road from Sondrio to Pellizano, large trans-European trucks had missed me by inches in their haste to get past, clearly breaking every speed limit and not slowing for built up areas. I wondered what the road accident statistics were like; Ed put me in the picture. He lives for six months of the year in France and clearly loves the country. Appalling, he said.

Saturday would be the last day of the event for La Cicc as I had already decided to leave a day early. I had to cover eighteen hundred kilometres between Sunday morning and Wednesday afternoon.

My average speed was likely to be around fifty kilometres per hour and I couldn't use autoroutes, so I’d got nineteen hours of riding plus stops for coffee, say twenty two hours over three and a half days and that was without any holdups or breakdowns. If I left on Monday the stats would be worse. I needed to be within striking distance of Le Havre by Tuesday night to be on the dock in Le Havre by two thirty on Wednesday afternoon. 'If I go now,' I said to Dave and Gordon, as I topped up the oil tank with half a litre of SAE 40,'You will be free to travel faster. You can use the Autoroutes and we’ll probably all arrive at the ferry terminal at around the same time. A pursuit race and the competitor with the biggest handicap leaves first.'

My first objective was to find a quick way into Switzerland and early Sunday afternoon found me drawn towards the Stelvio Pass from the direction of Trafoi. I don’t know if this way was any worse than any other approach but when I was maybe half way up, the remaining relentless turns became visible for the first time. From memory there are thirty seven turns but perhaps just ten from the top, La Cicc began misfiring badly and losing power. I did a quick U-turn and headed back towards Trafoi. My bid to take a shortcut to Davos Platz had been foiled.

I stopped half way down and took a track off the hairpin down to the Berghotel Franzenhohe where people sat, somewhat incongruously at tables along a terrace which faced the pass as it ascended, turn by turn, above them. All I wanted was to sit down and regroup; to look at my maps and find another route to Switzerland. I ordered a cappuccino and the waitress returned moments later as I spread my map over the table. She had noticed the bike and seemed quite chatty. 'German?' 'No, English,' I replied, 'And you?' 'Polish,' she said with a grin. 'Ah,' no wonder your English is so good.'

It soon became obvious that the only way was to go back past Trafoi and then turn north for Austria then west into eastern Switzerland. As I was leaving a hotel guest stopped by the bike. 'A real bike,' he said, “Even down to the oil leaks.' He was right. La Cicc was looking the worse for wear and oil had now spread over the front of the engine and formed

into brown tar on the exhaust pipe. I checked the oil level for good measure, not that I had any more to put in. The leak from the rocker cover was obviously getting worse but at least she still started first kick. I trickled off towards Trafoi and Spondig, where I turned left towards Venosta and Austria. At Sluderno I saw a sign for Switzerland, off to the left. Next time I’m there, I will take that road as I now realise it would have taken me to Zernez and Davos. No longer trusting my instincts I stopped and got the maps out whilst absentmindedly leaving the ignition on. When I realised what I had done, and this was only after several minutes, I tried to start the bike without success and a growing feeling of foreboding. La Cicc always starts first kick. Was I going to be stuck in Sluderno? No, as it happened, because after a few minutes of recovery the bike started and I took the road for Austria following the north side of the Alp towards Susch and then Davos. At the Austrian border a group of Austrian motorcyclists stopped and took photos of La Cicc. Near Davos we turned and headed for Landquart. I had memorised the the route and the towns came up without any nasty surprises until I arrived at Sass, about twelve kilometres from Landquart. There was a nice little restaurant and hotel, The Aquasana, so I pulled up on the hard standing outside. On a Sunday afternoon in this part of Switzerland in September, everything is pretty quiet. I arranged with the landlady for a room right up under the eaves of this Swiss chalet and took a much needed shower. I had an excellent meal of Schweinsteak in a hot chilli sauce with Rosti, preceded by a spritz and followed by fruit and an assortment of cheeses. Her husband cooked it and after I had finished he asked me to come outside to look at what was in his garage. As the door swung up, a dark blue Triumph Vitesse convertible was revealed. What he wanted was a GB plate like the one on La Cicc., could I get one for him? No problem I said, he was to consider it done. Overnight it rained heavily but, snug under those eaves, I slept soundly; better than I had for a week.

At breakfast I was joined by a Dutch couple who had arrived overnight on a Triumph Rocket 3, which dwarfed La Cicc, having ten times her engine capacity. The proprietor of the inn had covered La Cicc. with a plastic sheet at some time during the night, to protect her from the rain. The bill all in, when converted from Swiss Francs was 65 Euros or £56 for bed, breakfast and evening meal in a really comfortable, traditional Swiss Inn run by friendly people. It had stopped raining and I set off with the intention of reaching Besancon by early evening. As things turned out, that was not to be.

As I entered the tunnel after waiting at the roadworks, the bike began to misfire badly and it became touch and go as to whether I could coax her to the end of what turned out to be quite a long tunnel. These tunnels are the last place any motorcyclist wants to break down. There is usually a footpath but this is invariably protected by a high kerb with a heavily ogee curved edge, not something one could ride up or even lift a bike over. I was lucky and somehow she kept running until we were out into the daylight. We drifted downhill to silence and after a kilometre or so, we were on the outskirts of Landquart and came across Grisoni Racing’s Ducati Dealership, where I rolled to a halt on the forecourt. This turned out to be the end of La Cicciolina’s journey as, try as we might, we could not get her to start again. This time it was not a fuelling issue, but an electrical fault which would not be solved until several weeks later, at home in England. I knew it was either a battery or a coil problem but by the time I had tried my best to fix her without success, I had run out of time to meet the boat on Wednesday. AXA Recovery quickly assessed the situation and arranged for the bike to be shipped home while I was provided with a hire car - but that is another story. Suffice to say, if you are ever lost in the one way road system in Le Havre, don’t panic; just get off your bike or out of your car and walk to your destination. Then go back and do it in the vehicle! It will save you hours of frustration.

epilogue

Dave and Gordon caught up with me in Le Havre and together we travelled back to England.

La Cicciolina arrived home on a trailer, less than a week later and in perfect condition, which was a pleasant surprise and thanks in part to Grisoni Ducati who looked after her for me until she was picked up. Since then I have decoked her and had the stripped thread helicoiled. A new ignition coil has been fitted and she now looks none the worse for wear. I took the front wheel and brake assembly to SRM Engineering near Aberystwyth where they skimmed and trued the hub and brake shoes. I checked the charging system and all of its components and found no faults apart from one of the pinch bolts tensioning the dynamo drive belt had stripped its thread but, even as I write this I am thinking that in 1959, no motorcycle manufacturer in the world could have foreseen that one day their product would be expected to have its lights on at all times, day or night. I wonder?

As for her mechanical performance, there was no problem at all. The bike just kept going through rain or sunshine without a hiccup. The issue with the carburettor was, with hindsight and

la cicciolina’s* Vital Statistics (oddly similar to a lodola Gran Turismo) OHV 235cc: 11 bhp @ 6000rpm: 264lbs/120Kg price in GB (1960): £219 19s 10d including tax.

*la cicciolina was a slim young blonde of hungarian decent who became a porn star and then an Italian mp you can’t make this stuff up...

page 46 of the Owner’s Manual, preventable. The various oil leaks were minor and mostly down to my not taking enough trouble over assembly, although I hadn’t thought this at the time. Over the two thousand hard miles she used or lost less than a litre of oil.

What had I learned? Well, you can go all over Europe on an old bike without coming to much harm. You will be welcomed almost everywhere and most people are only too pleased to help. There is still romance in having a motorcycling adventure as long as you don’t overplan the trip. You don’t need to worry overmuch about what can go wrong and a degree of uncertainty only makes it more fun. I carried everything I needed in a single twenty litre bag and I still had two tee shirts that I hadn’t worn when I got home. The most important thing in the Alps is to have a machine which is light and manageable and to take a battery charger!

Whilst driving along the Swiss motorway between Wollerau and Zurich in the rental car, I was passed by a slim young woman on a very large, black Harley Davidson. She was wearing a snakeskin jacket and as she disappeared into the distance, from time to time a woof and warble of the vee-twin carried back to me. Finally, she was gone. B

DONDOLINO

th E lodola Wa S th E f I nal motorcycl E d ESIG n E d By carlo GU zz I , and th E maG n I f I c E nt dondol I no m IG ht hav E BEE n th E BES t. th IS IS th E S tory of ho W h IS 1920 prototyp E E volv E d I nto th E f I n ES t GE ntl E man’S rac E r a chap co U ld BU y I n 1946

Words: Greg Photos: Greg Paul Hart Vespamore Phtography

Hard to believe these images are recent, but the period atmosphere’s no accident. Paul Hart (vespamore. com) radically develops out-of-date film to produce something closer to art than digital junkies manage.

Dondolino

As a young engineer, Carlo Guzzi obsessed about motorcycles, but rather differently from the way we might today. Not for him dreams of long rides on challenging roads, but rather the hands-on experience of unravelling the broken dreams of other riders in his workshops on the shore of Lake Como. The Guzzi family had a holiday home nearby, in what was to become Mandello del Lario, and the Moto Guzzi HQ that stands there today is the oldest motorcycle factory in the world.

As a young Carlo dismantled failed engines this quiet, introverted, man fantasised about building a motorcycle that would be reliable, fast, and manageable by a rider of even Carlo’s modest stature. He disapproved of manual hand pumps that required a rider to provide a motor with its oil, when a moment’s inattention could seize an engine, especially if the rider was concentrating on another matter – racing, for example. Surely, Carlo thought, an engine could drive a pump? And the exposed chain which transferred a crankshaft’s power to the gearbox was dirty, dangerous and prone to breaking. An enclosed gear was the obvious solution for Carlo Guzzi, yet it took decades for other engine designers to see that he was right. But Carlo was more than an engine designer. He could see that designing an engine that could fit into a bicycle-style frame was never going to create a motorcycle as fine as one where the engine and cycle parts were designed from the start to work as a single machine. These are obvious ideas today, but in the years before the First World War, they amounted to radical thinking.

The prototype that Carlo finally built in 1920 survives as the first exhibit seen by visitors to Moto Guzzi’s museum. Despite a compression ratio of 3.5:1, necessitated by the poor quality of the fuel available, the motorcycle could achieve almost 100kp/h (62mph). On Italian roads in 1920 that was quite fast enough, especially since Carlo Guzzi had eschewed the received wisdom of building the largest capacity motorcycle possible. The world’s largest motorcycle manufacturers were American, with Indian and Harley-Davidson the market leaders. America’s wide open spaces led to long-distance record breaking and purpose-built racing venues which demanded horsepower and the ability to hold an engine flat out for long distances, but on Europe’s tight and twisting roads safe handling and low weight were at least as valuable as outright power, especially on the gravel-strewn tracks that passed for public highways. Europeans also expected to see their chosen marque succeed in racing and in 1920s Europe that meant competing on public roads which, although ostensibly closed to traffic during races, still resembled pretty much exactly the sort of environment road riders faced.

Indian had some success with their V-twins at the two great road races of the era, the Isle of Man TT and the Milano-Tarnto, but that didn’t stop them building a vertical 500cc single for racing just like the British bikes that went so well at the TT. The other reason that Indian took a sudden shine to building smaller, lighter, cheaper motorcycles was that big, expensive ones were beginning to be marginalised by the world’s growing economic woes and the arrival of mass produced cars. In the 1920s a single cylinder engine of between 350 and 500cc looked like a smart bet if you wanted to race and sell motorcycles.

Carlo’s 499cc engine was very oversquare, exceptional at the time, with an 82mm stroke pushing through an 88mm bore. Yet the most obvious difference from other singles was the cylinder lying horizontally in the frame, keeping weight low and making the most of the cooling airflow, as well as allowing his brother Giuseppe to design an especially low-slung frame. Carlo’s insistence on gear primary drive also required the crankshaft to run backwards compared to other engines of the time. Given that a gearbox must spin in the same direction as the rear wheel of a motorcycle, driving the gearbox by a chain from the crankshaft requires that it also spins in the same direction. Guzzi’s gear primary drive meant the crankshaft had to rotate in the opposite direction but even this

small detail was turned to an advantage by his designing the big end to throw oil up to lubricate the top wall of the cylinder. This attention to cooling and lubrication was one of the principal reasons the Guzzi “flat” singles (as they came to be know) became famous for their reliability and longevity.

The three-speed, hand-change gearbox was built in unit with the crankcases, which also enclosed the clutch. To keep the crankcases as compact as possible, another feature of Guzzi singles which debuted on the prototype was a huge external flywheel. This pressed steel disc was quickly nicknamed the “bacon slicer” and these big flywheels remained a feature of the flat singles right up until their final incarnation as the Nuovo Falcone in 1976, although by then at least it had a metal cover.

Guzzi’s backers might have been impressed by the prototype, but they realised it needed developing into a motorcycle that would be economical to produce and own, as well as reliable in use. So the 4-valve alloy head was replaced by an unusual 2-valve arrangement in cast iron which featured an inlet sidevalve almost facing an overhead exhaust valve. The idea of combining an overhead valve with a sidevalve was not unique, but everyone else who adopted the idea placed the inlet valve above the piston and the exhaust valve to the side. The reasoning was simple: the inlet charge gains

most from the easier route into the cylinder since, unlike exhaust gases, it is not propelled by the force of combustion. But Carlo Guzzi was more concerned with keeping the exhaust valve in the cooling airflow, since this is the hottest part of a four-stroke engine and a part prone to failing. So his engine had the exhaust valve above the piston and the inlet valve to the side, and anyway the horizontal single could not really have a carburettor in front of its cylinder head.

Constrained by an inlet sidevalve fed by the Amac one inch carburettor, and despite raising the compression ratio to 4:1, the revised engine gave 8bhp. Dimensions, notably bore, stoke and capacity, were largely unchanged from the prototype, as was the chassis. The production-ready motorcycle was called the Moto Guzzi Normale (“Standard Guzzi Motorcycle”) and weighing in at a modest 130kg (286lbs) it could achieve 85km/h (53mph). But perhaps the most striking thing about this new motorcycle was how different it looked to everything else on the market, as if to emphasise that Moto Guzzi was a new company that would tread its own path regardless of fashion or received wisdom. Certainly painting the motorcycle a rather drab green-brown seemed perverse, but then building a factory in a small fishing village rather than following the herd south to Milan was just the start of Moto Guzzi’s reputation for doing things its own way.

In 1934 Moto Guzzi launched the 500V which in layout and appearance seemed like a marginally improved Normale. In fact the 500V was a complete redesign that brought in a true overhead valve cylinder head and a four-speed foot change gearbox. Power was 18bhp, so things were getting better, just not very quickly. The S and GTS versions of the new engine retained the old inlet-over-exhaust cylinder heads that limited them to 13bhp: even so, they outsold the ohv 500V (and the rear-suspended version of the V, the GTV) by two-to-one. It might seem astonishing so little progress was made in thirteen years, but there’s a clue in the fact the S/GTS survived until war broke out. These were hard times, with global recession, and expansionist policies, that meant the Italian public sector, including the police and military, were about the only people buying motorcycles. Even Mussolini had a Moto Guzzi, after all.

The other reason road bike design was progressing slowly was that racing motorcycles were going down a completely separate development path. In the early 1920s a pair of young Italian engineers, Carlo Gianni and Piero Remor, built a 490cc four cylinder engine which made 28bhp and immediately out-powered Moto Guzzi’s own four-valve, single cylinder, factory racer. By 1928 this four was developing 34bhp, and it would ultimately evolve into the dominant Gilera and MV Agusta four-cylinder racers. Carlo Guzzi was rightly convinced high revving multi-cylinder engines were the future, and he felt his single cylinder racers would be unable to compete, so he designed three- and four-cylinder engines that proved little other than that power without handling meant nothing. Carlo was also mistaken about how quickly the singles would be outpaced, and how long it would take to balance the power of multi-cylinder engines by mastering the mysteries of motorcycle chassis design.

There were also those in motorcycling who had spotted that as racing cars had become more divorced from their road-going counterparts, a lot fewer got sold. While racing success might persuade buyers to step into a particular

manufacturers’ showroom, it was better for business if some of those buyers would actually pay for their own racing machines. Especially when those old fashioned races for gentlemen competitors could attract over a hundred entries, rather than the dozen or so that were becoming worryingly typical at the more famous races.

Race organisers spotted this before the factories, and took to creating what we would now call production racing, although initially this amounted to insisting entries had lights and a stand. But Moto Guzzi were quick to realise that between their prosaic exhaust-over-inlet roadbikes and exotic fourvalve racers there was room for an over-the-counter production racer to sell to those gentlemen racers. The first of these had an overhead valve engine like the 500V, initially christened the Nuova C (for Corsa - “new racer”), and it won the 500cc class on its debut at the 1938 Circuito del Lario. By the time the production racer went on sale the moniker had become GTCL (Gran Turismo Corsa Leggera – colloquially “lightweight racing GT”) and for 1939 it became the Condor. This production model was also much improved over the Nuova C and a world away from the mainstream 500S/GTS. Cast iron heads and barrels were replaced with aluminium alloy, and crankcases were magnesium alloy. Just as importantly the Condor shared the 500V’s four-speed gearbox and with a foot shift, rather than the earlier hand-change, mere mortals might be able to race it. With a 7:1 compression and a monstrous for the time 32mm Dell’Orto carburettor even the customer bikes had a claimed 28bhp.

The Condor’s final flourish was a chassis that owed more to Moto Guzzi’s supercharged 250cc factory racer than any road bike. Magnesium alloy brakes and aluminium rims kept weight down to just 140kg (barely more than 300lbs) even in full road trim. Here was a motorcycle that could beat the supercharged Gilera four on the track, win the 1940 MilanoTaranto, and yet was also flexible enough to be used as a police motorcycle. The only real challenge came from the new Gilera Saturno in 1940, but then racing came to an abrupt end

as war burned through Europe. Just 69 Condors had been built when Moto Guzzi ended production and switched to building products more attuned to the needs of a country caught up in a bloody conflict.

Eventually the gentle beauty of peace returned and the people of Europe were treated to a very different way of life, free from pre-war regimes. Talk was of rebuilding and rationing, of making do and mending, of compromises and community. To these ends there was also an immediate ban on supercharged racing motorcycles, reflecting the reality of lower quality fuel. Carlo Guzzi stopped worrying about Gilera’s supercharged four-cylinder racer and started worrying about their 500cc single instead. Carlo set to developing the Condor into a Gilera Saturno beater. This was to be dubbed the Dondolino (“rocking chair”), some say reflecting the slightly suspect handling even though it seems odd that Moto Guzzi would abandon their habit of naming motorcycles after birds and switch to using less-than flattering nicknames. So there are those who wonder if the Dondolino name was simply reflecting Norton’s labelling of their racing frames as “Featherbed”. Whatever the reason, Moto Guzzi had a distinct advantage in the shape of Italy’s youngest and brightest graduate engineer, who had joined them in 1936, the brilliant Giuliano Cesare Carcano. From 1947 he would run the Moto Guzzi racing department and become most famous as the designer of Moto Guzzi’s V8 Grand Prix racer. But first things first.

The post-war economic climate ruled out a major redesign, so instead the 1946 Dondolino amounted to a much-improved Condor featuring a number of magnificent detail changes. The obvious visual difference is the aerodynamic rear mudguard which replaced the Condor’s more conventional fitment, yet so many Condors were upgraded by adding Dondolino components that it is far from a certain guide. Perhaps the most telling sign of Carcano’s attention to detail is the beautiful magnesium alloy 260mm front brake, with internal levers to gain a tiny aerodynamic advantage. Every little helps isn’t just an advertising strapline. Carcano’s famed obsession with saving weight is highly evident on the Dondolino with, as on the Condor, crankcases among the many components cast from magnesium alloy. In passing, it’s worth noting that

although magnesium alloy is often called Elektron, that name is a trademark of the German company that developed magnesium alloys for aircraft use in WWI. They didn’t make parts for Moto Guzzi.