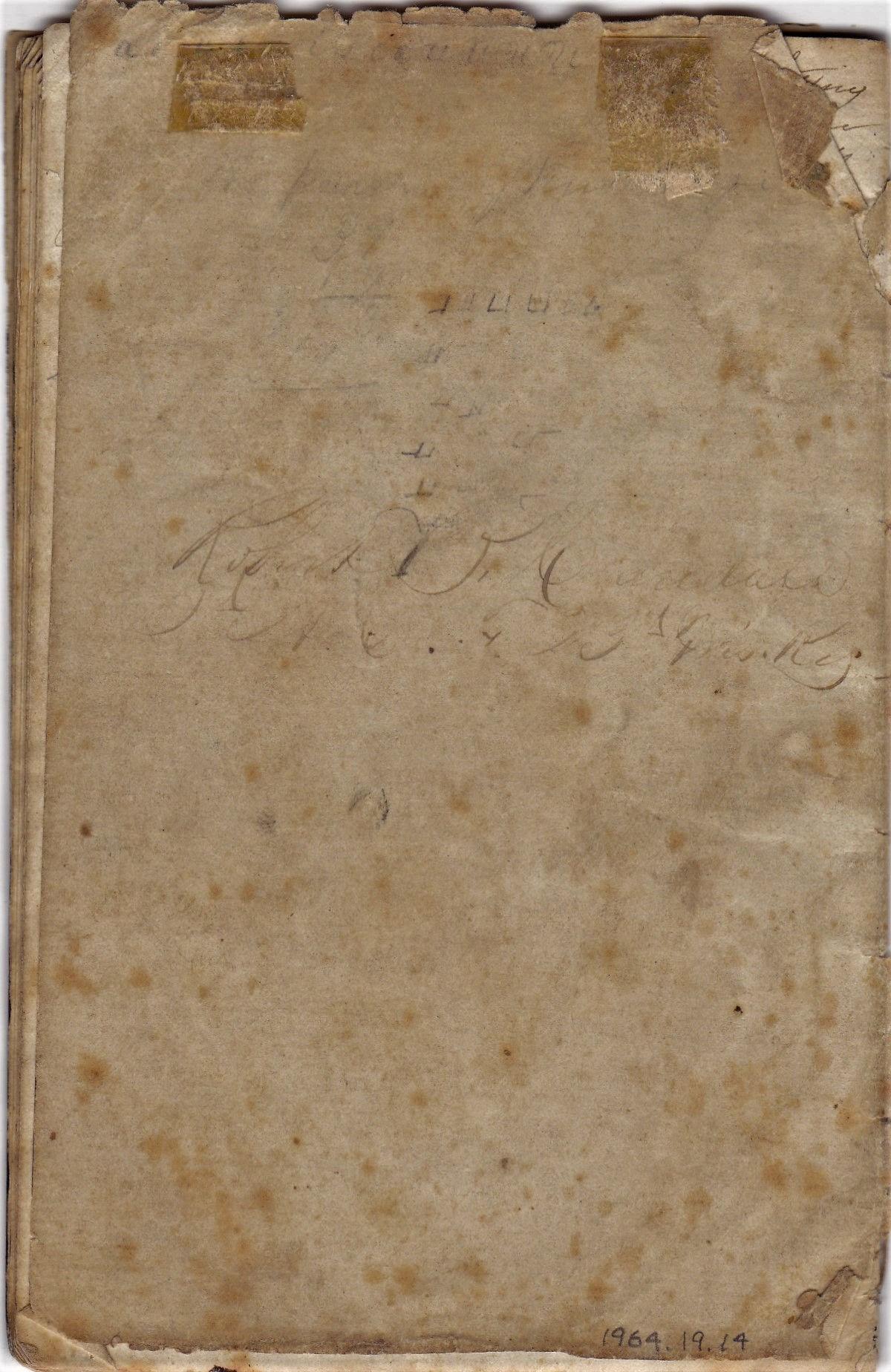

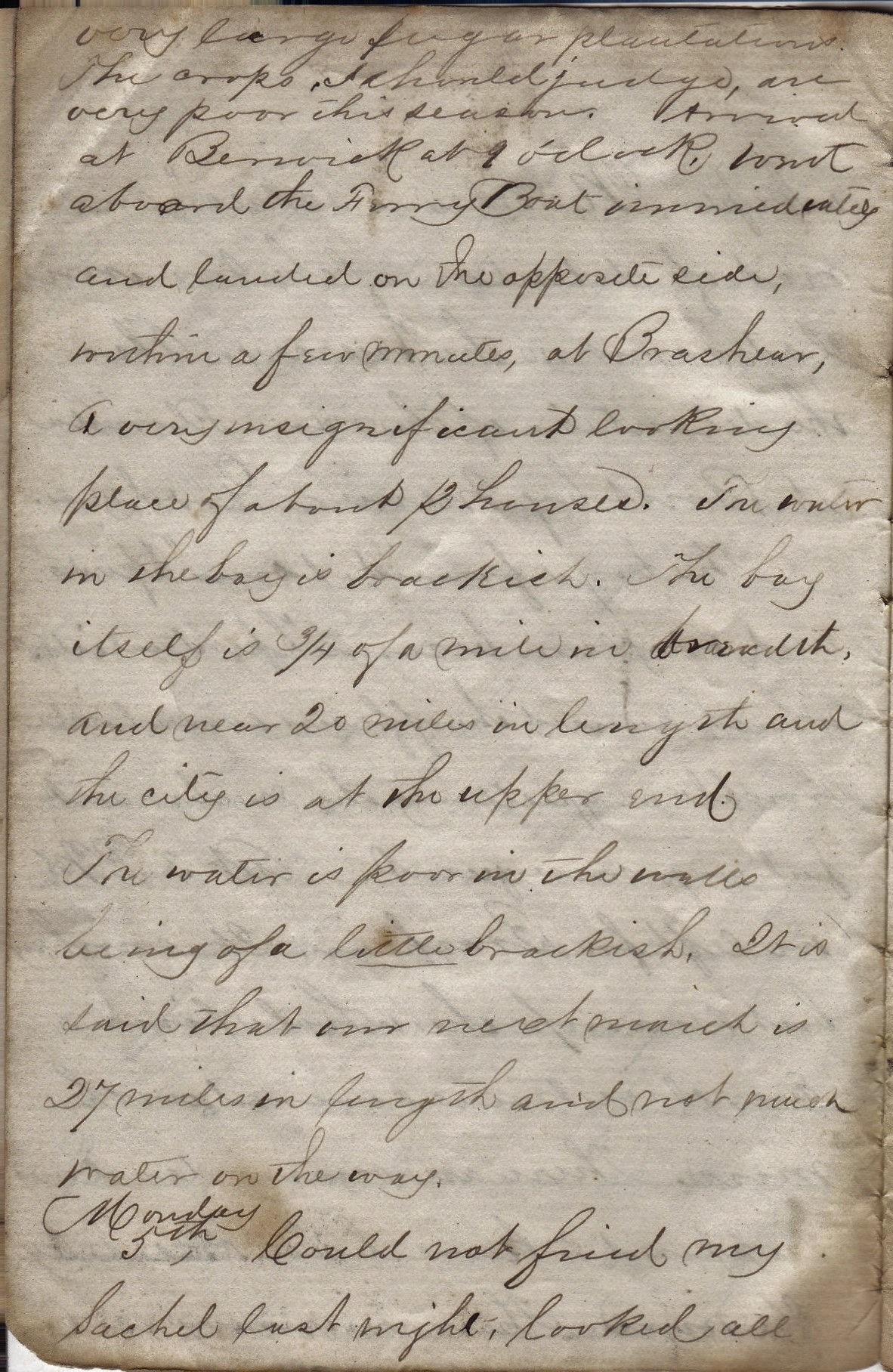

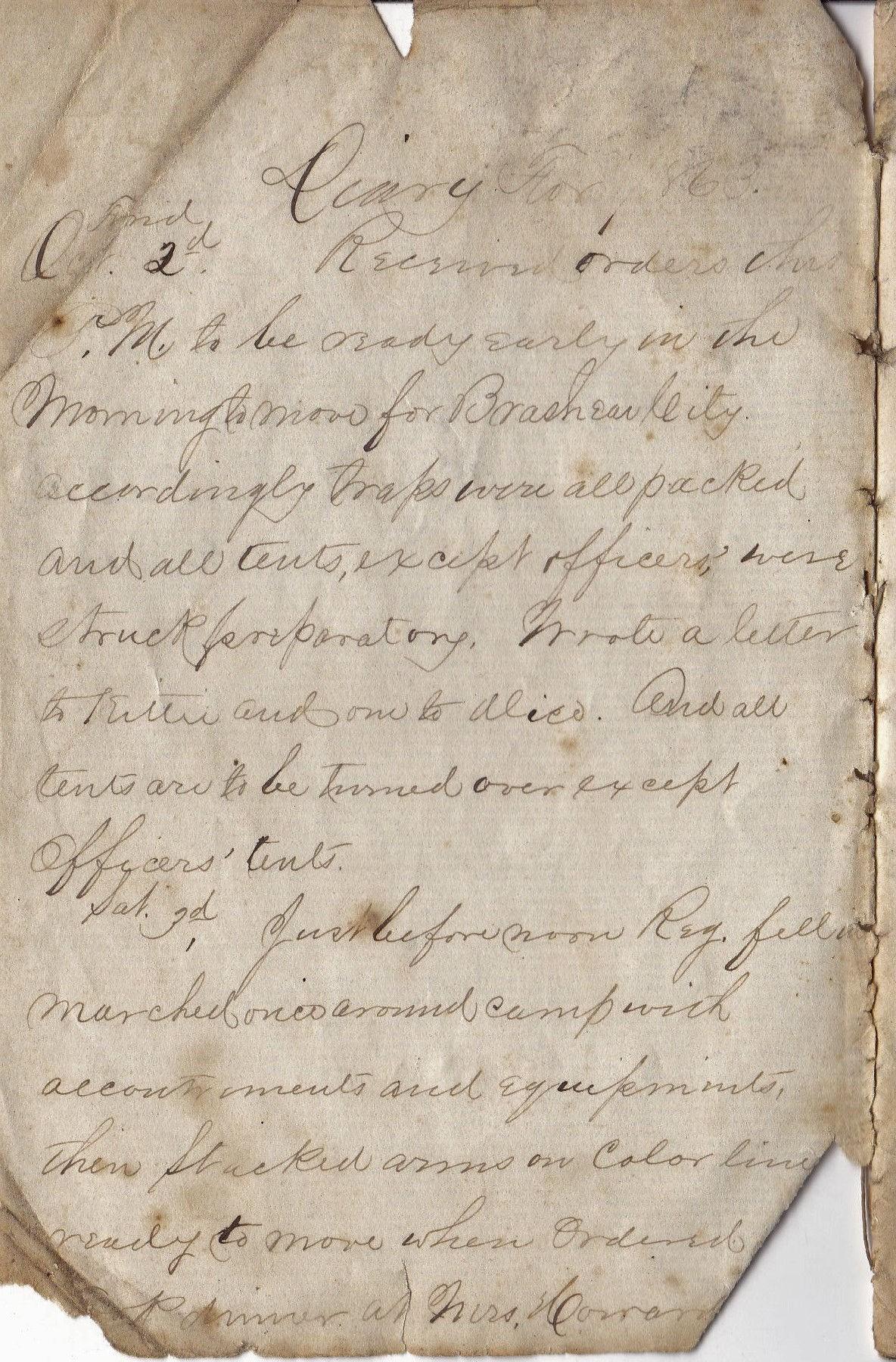

Robert Bruce Crandall Letters & Diary

1839—

1901

Civil War Wisconsin 23rd Infantry, Company F

1862

1865

1839—

1901

Civil War Wisconsin 23rd Infantry, Company F

1862

1865

Civil War Wisconsin 23rd Infantry, Company F

1862 1865

Researched and compiled from various sources by William C. Schuette

2021

© William C. Schuette

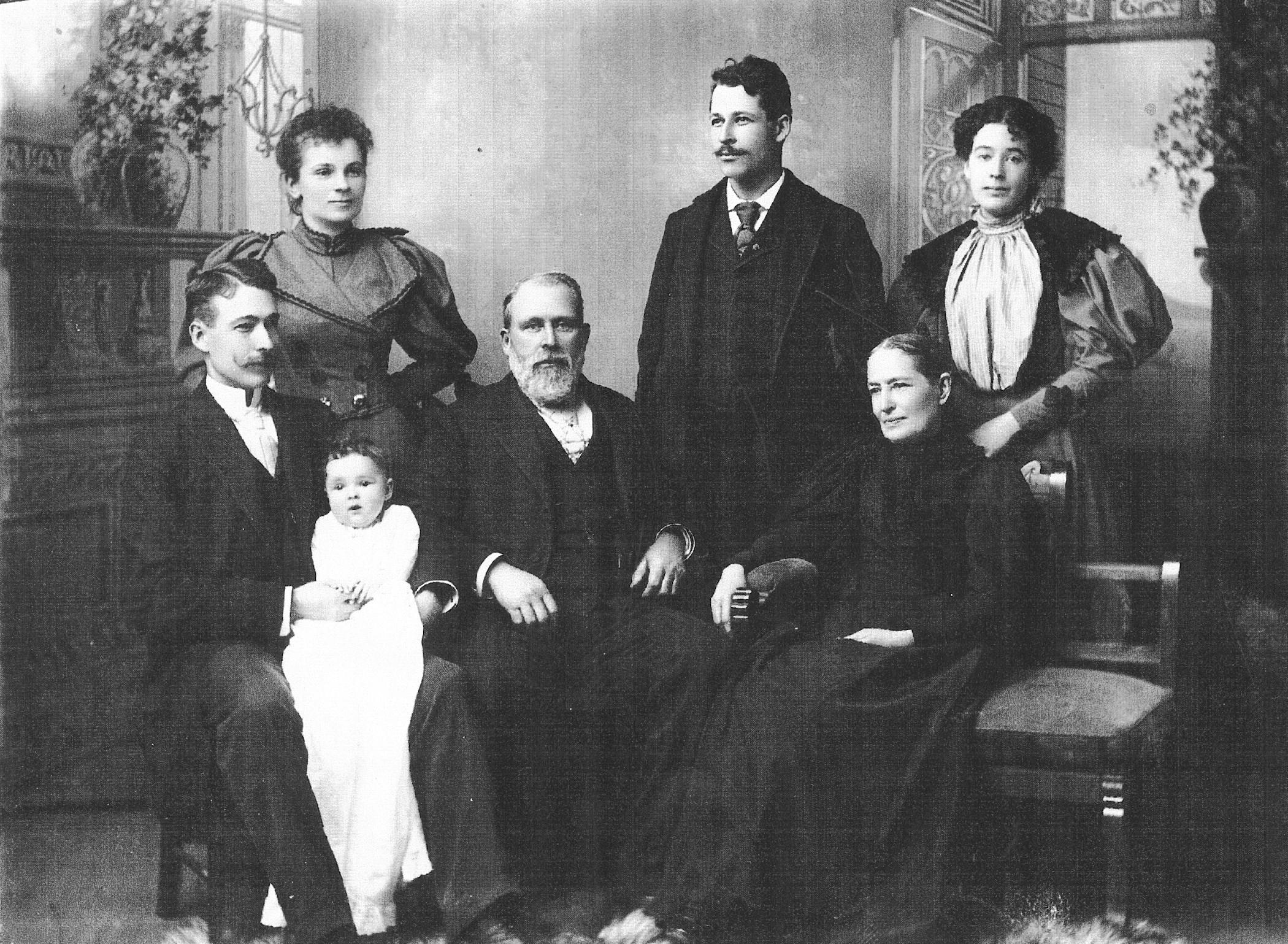

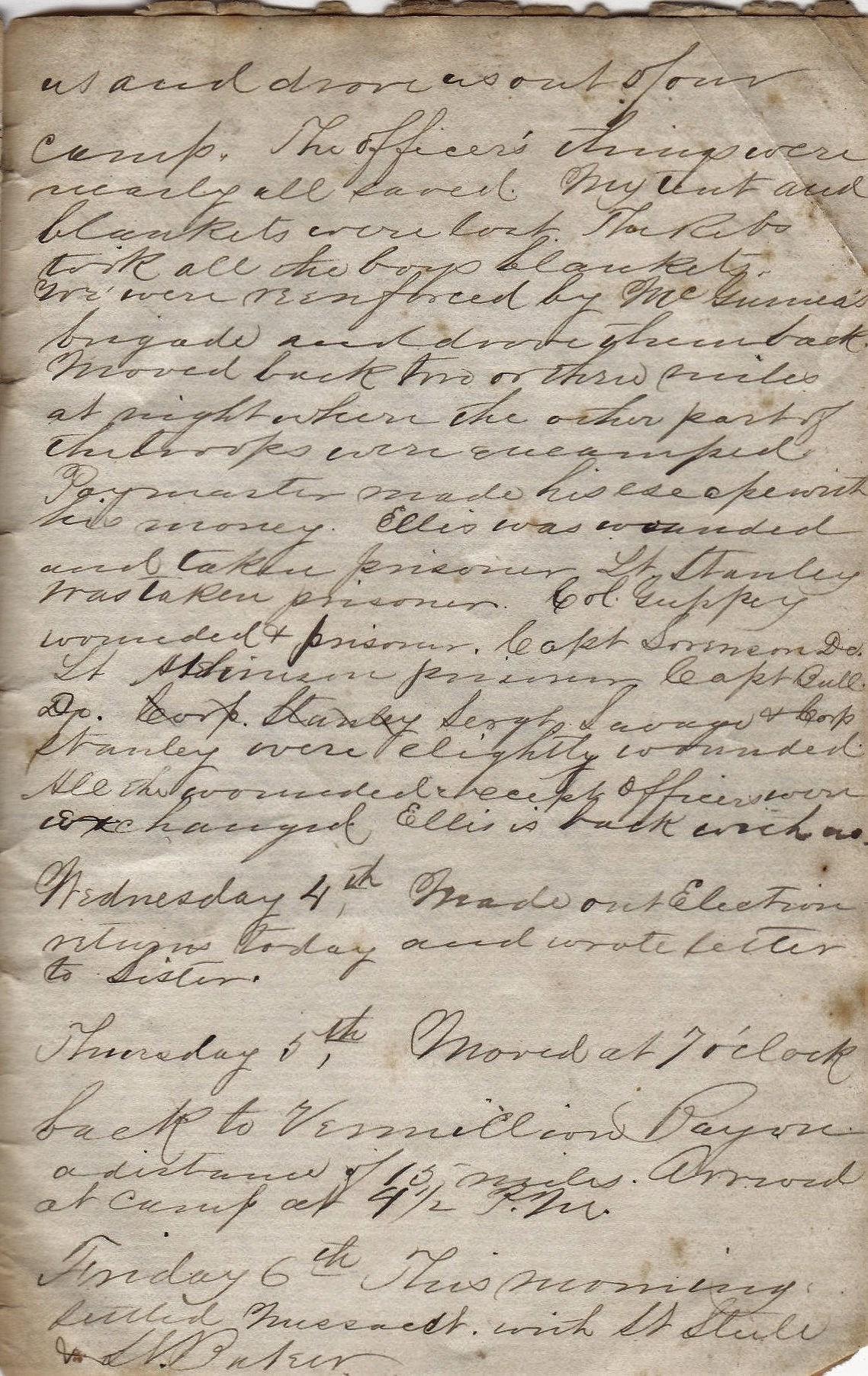

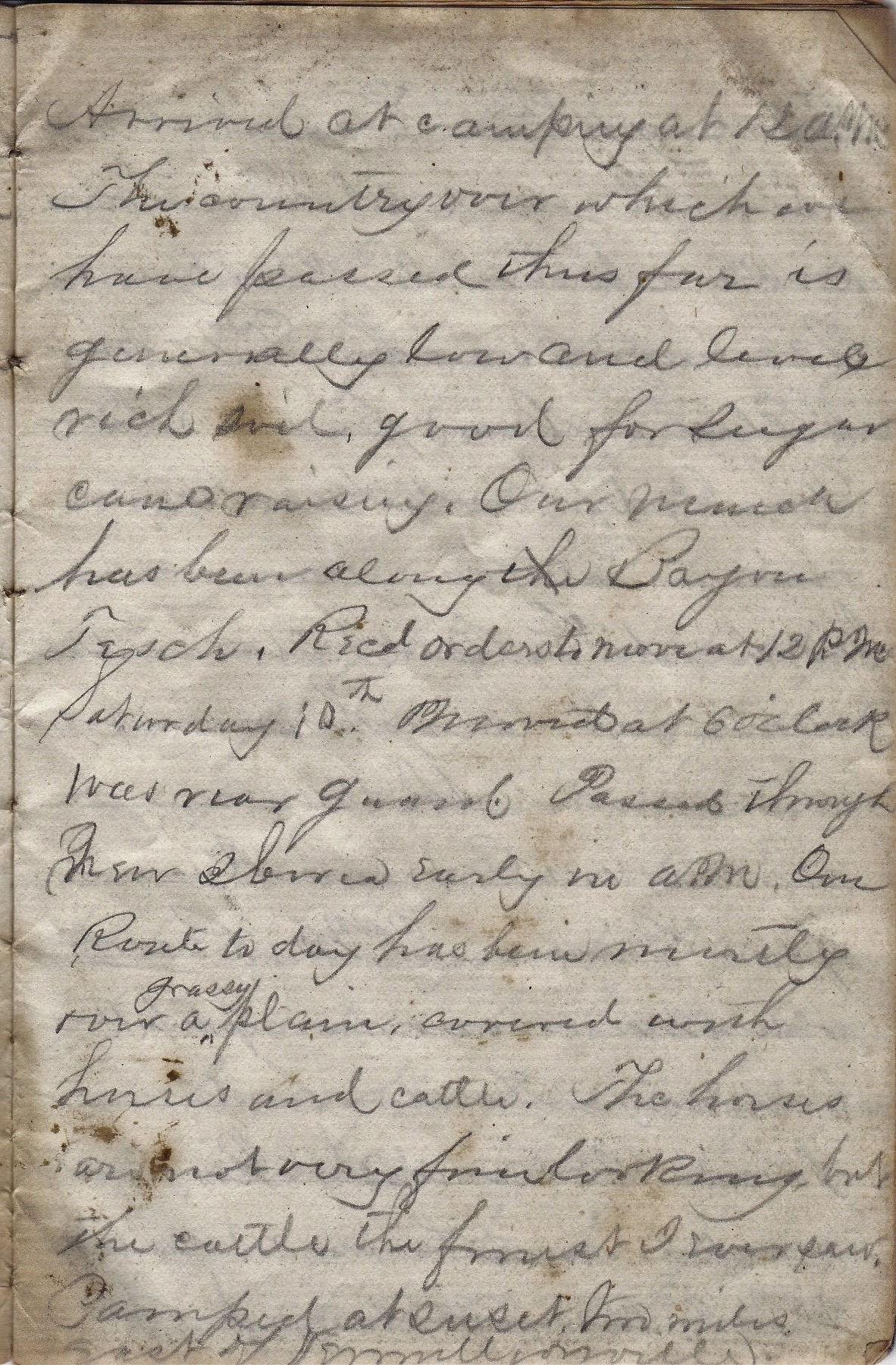

L-R: Day (David) Crandall (son) and wife and baby Day, R.B. Crandall, Morris Crandall (son),Alice Crandall (wife of R.B.)

Jessie Crandall (daughter)

taken in Olympia, WAca. 1898

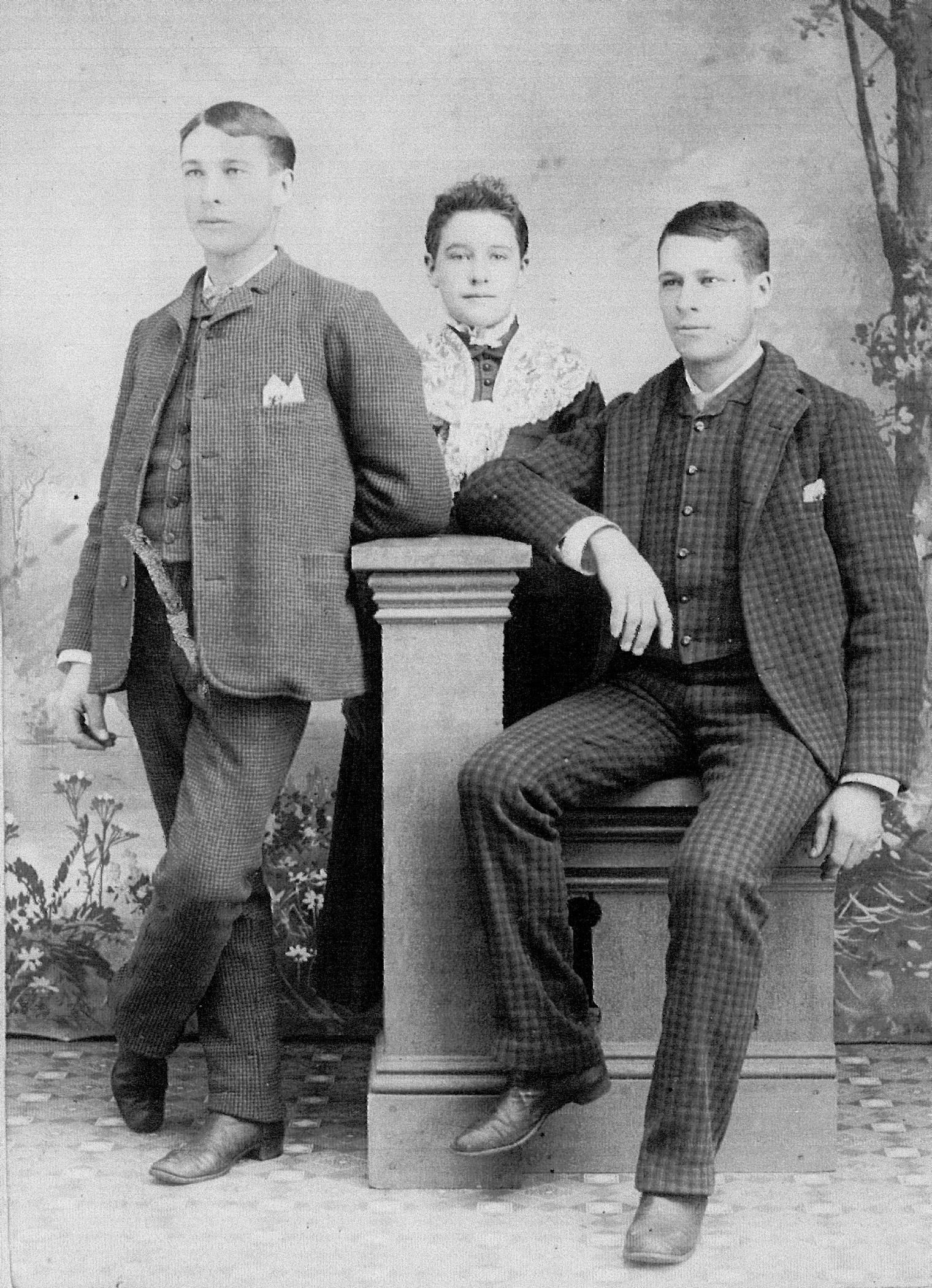

Photo Photo from the collection of Beverly Cabbage 2020L-R: Morris C. (Son of Robert &Alice), Jesse (Daughter of Robert &Alice), Day (David) E.

(Son of Robert &Alice)

Photo from the collection of Beverly Cabbage 2020

(Son of Robert &Alice)

Photo from the collection of Beverly Cabbage 2020

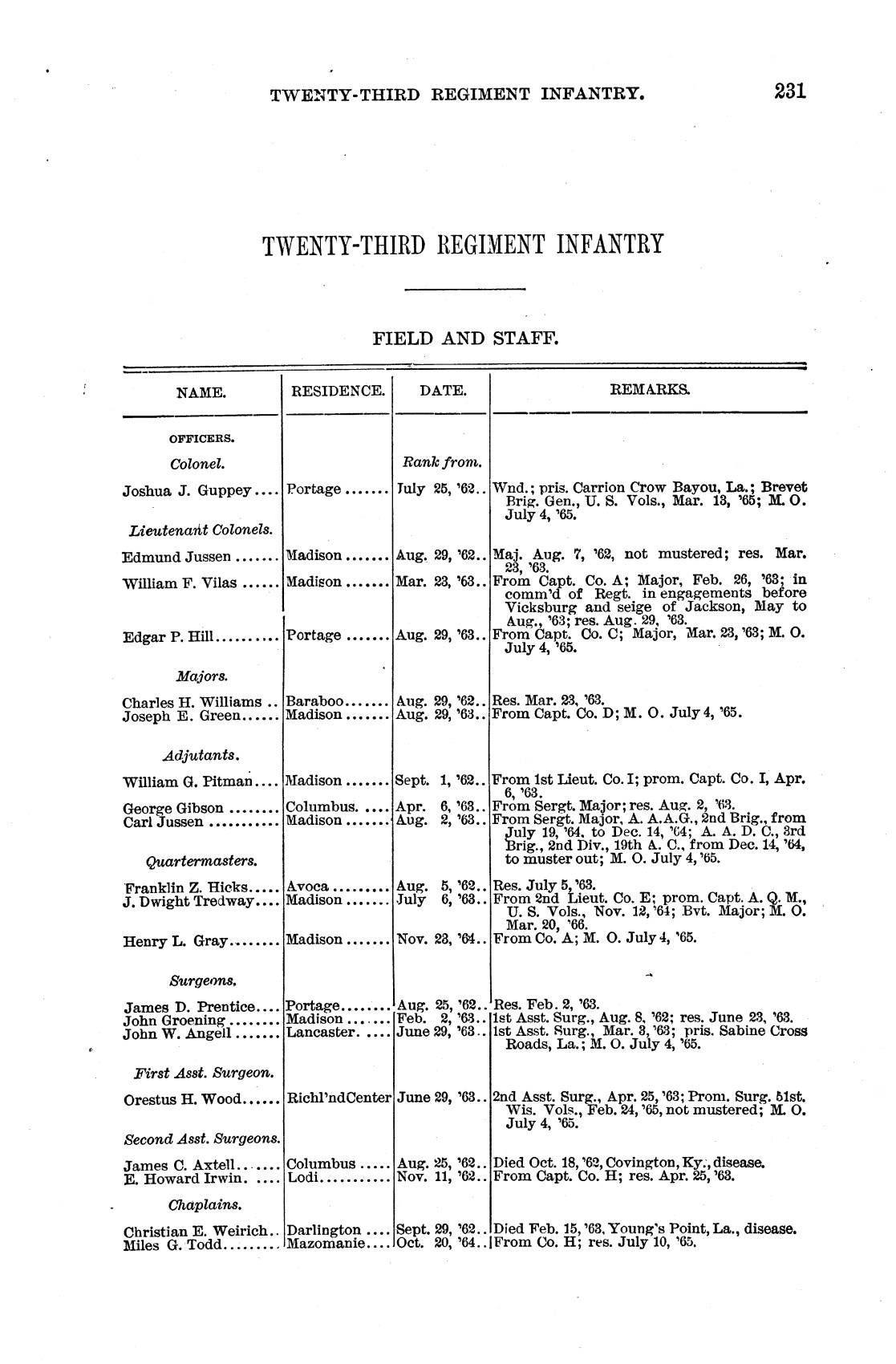

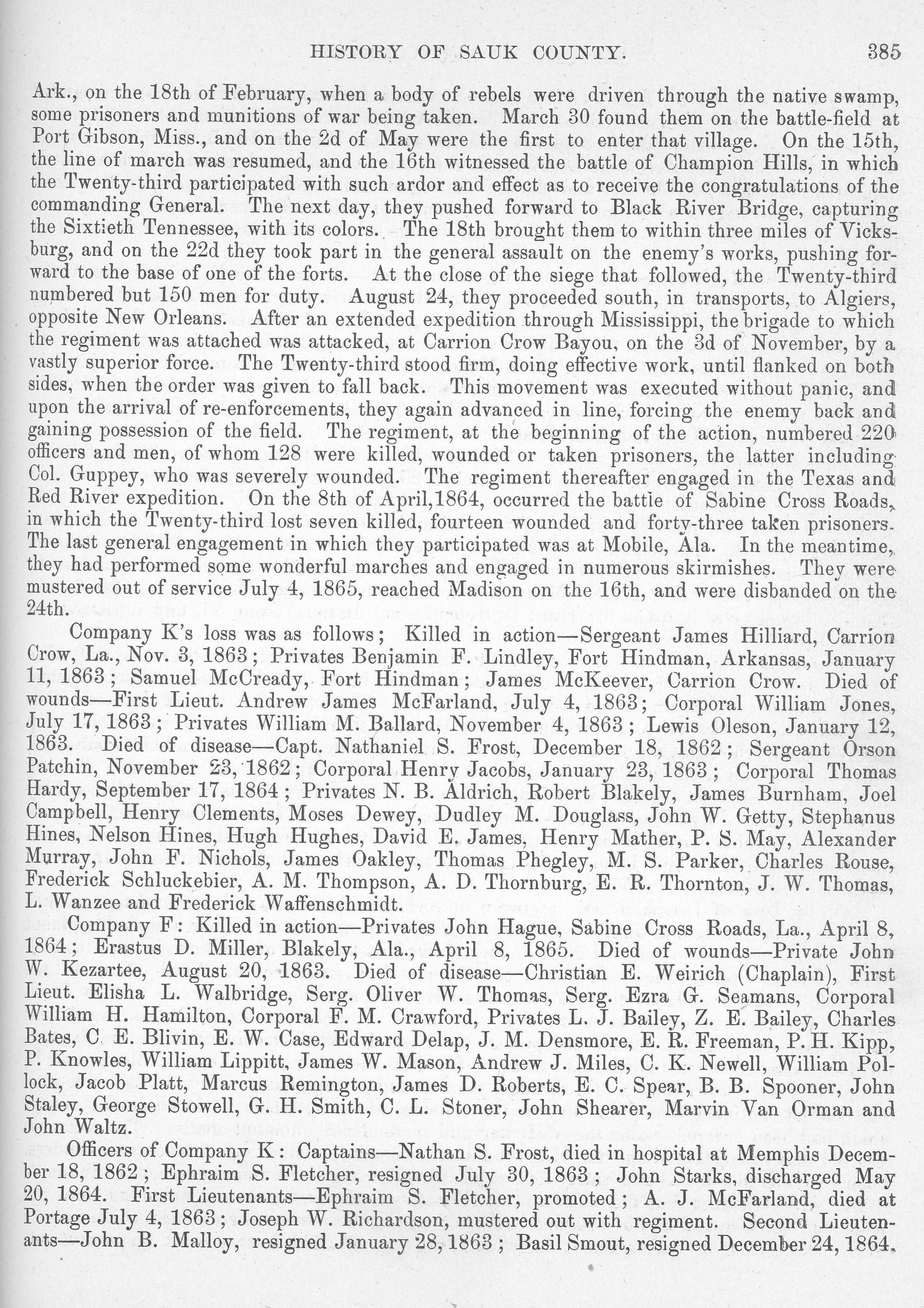

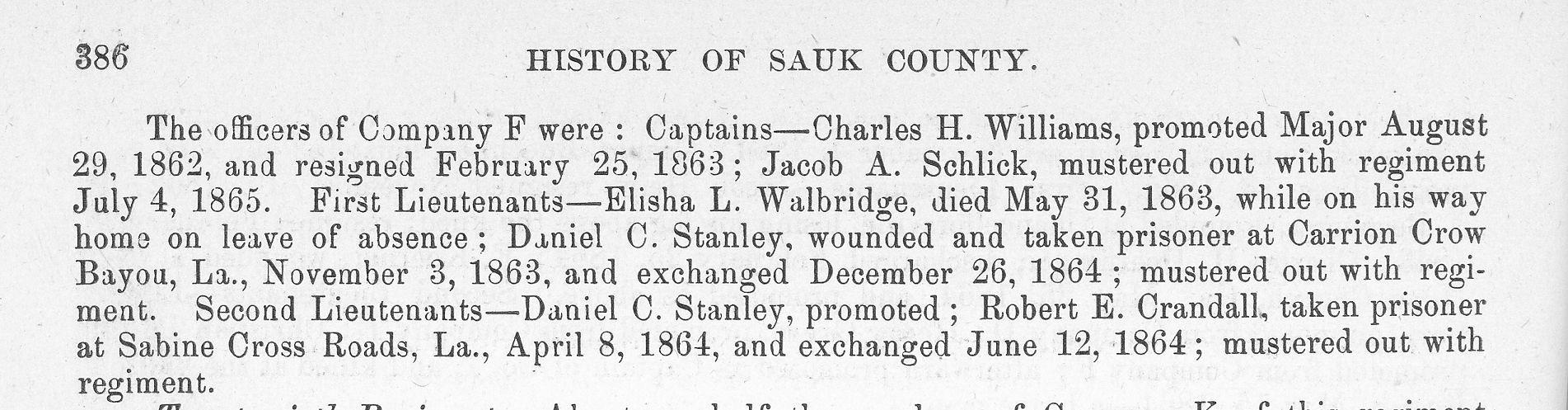

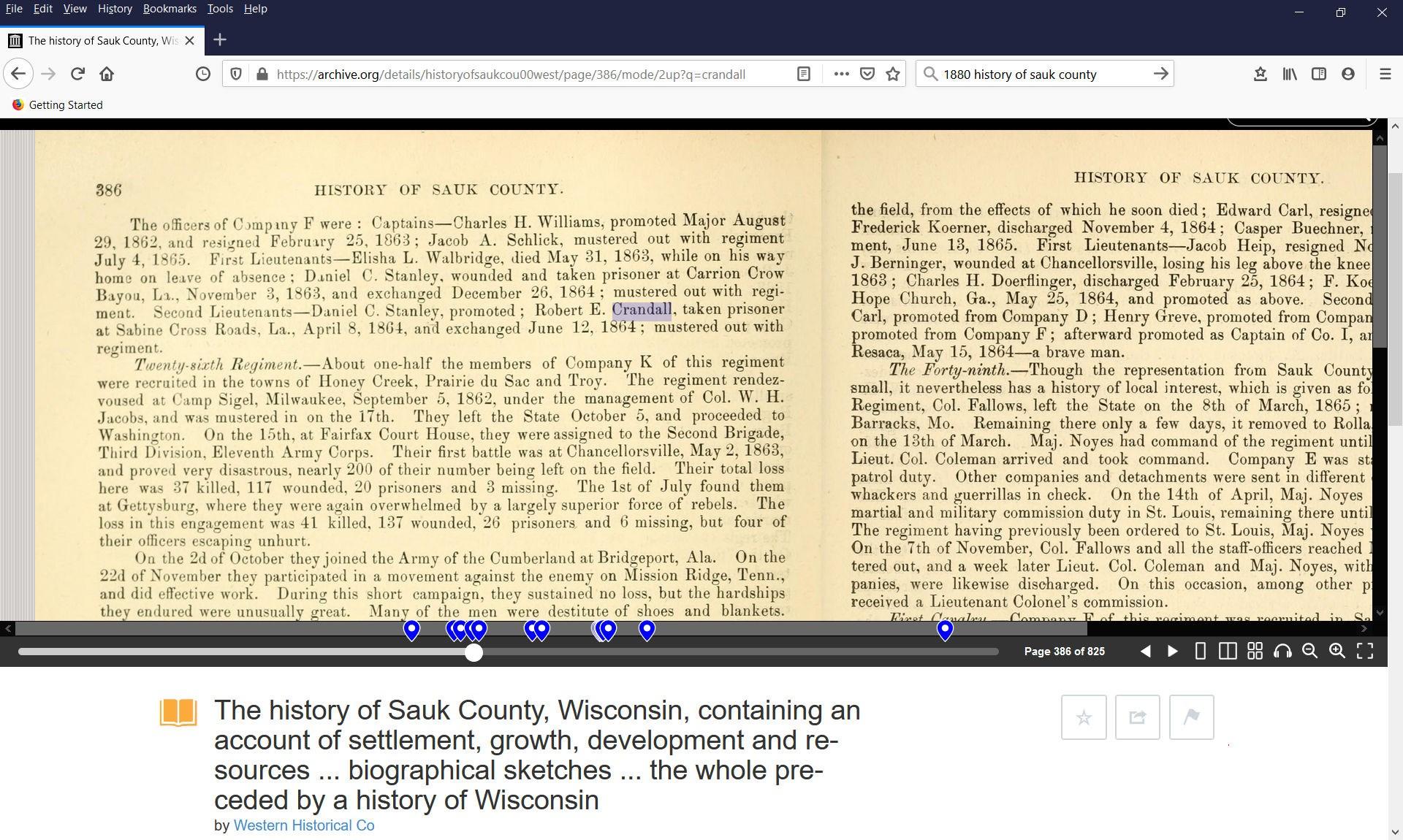

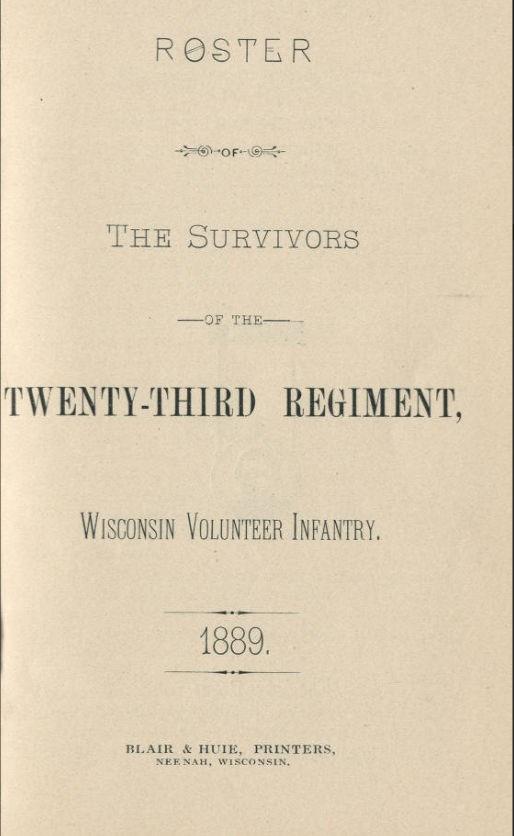

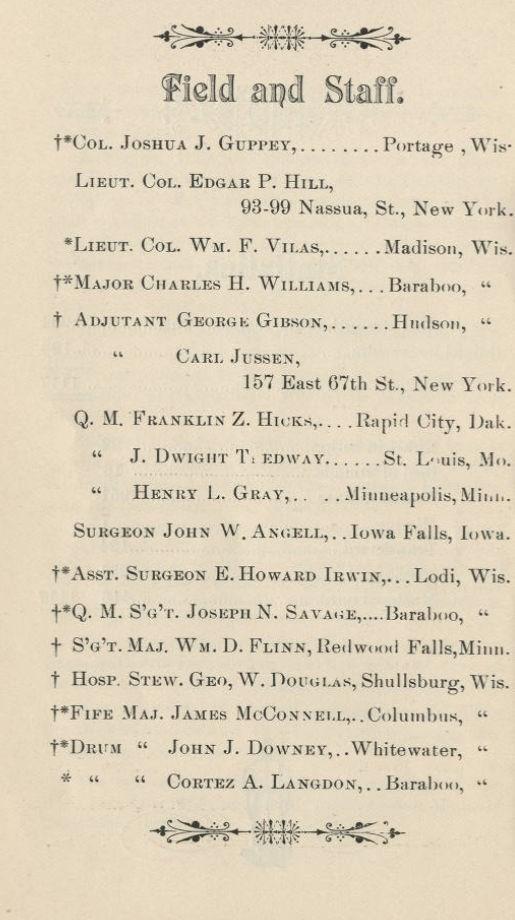

Twenty-third Infantry. Col., Joshua J. Guppey, Lieut.-Cols., Edmund Jussen William F. Vilas, Edgar P. Hill; Majs., Edmund Jussen, Charles H. Williams, William F. Vilas, Edgar P. Hill, Joseph E. Green.

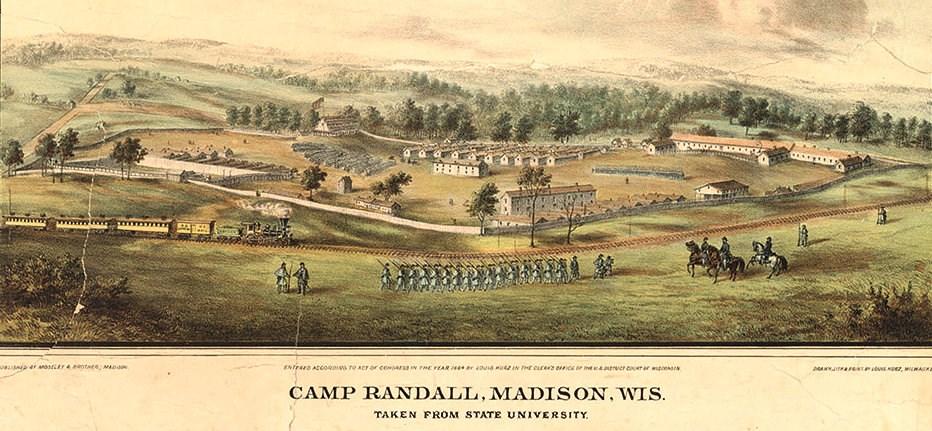

This regiment was organized at Camp Randall, Madison, in Aug., 1862, and left the state Sept. 15 for Cincinnati, whence it was ordered south to join the army before Vicksburg.

It was with Gen. Sherman in the assault on Chickasaw Bluffs and assisted in the reduction of Arkansas Post. The action of the regiment was the occasion of congratulatory orders from division and brigade commanders. It then proceeded to Young's point, La., near Vicksburg, where three-fourths of the men were stricken with virulent diseases because of adverse sanitary conditions.

The regiment was on scout and foraging work until April 30, 1863. It was brought into reserve at Port Gibson and entered the village the following day - the first Union troops to occupy it. It took the advance of the division at Champion's Hill, doing such effective work as to call forth compliments from the general commanding.

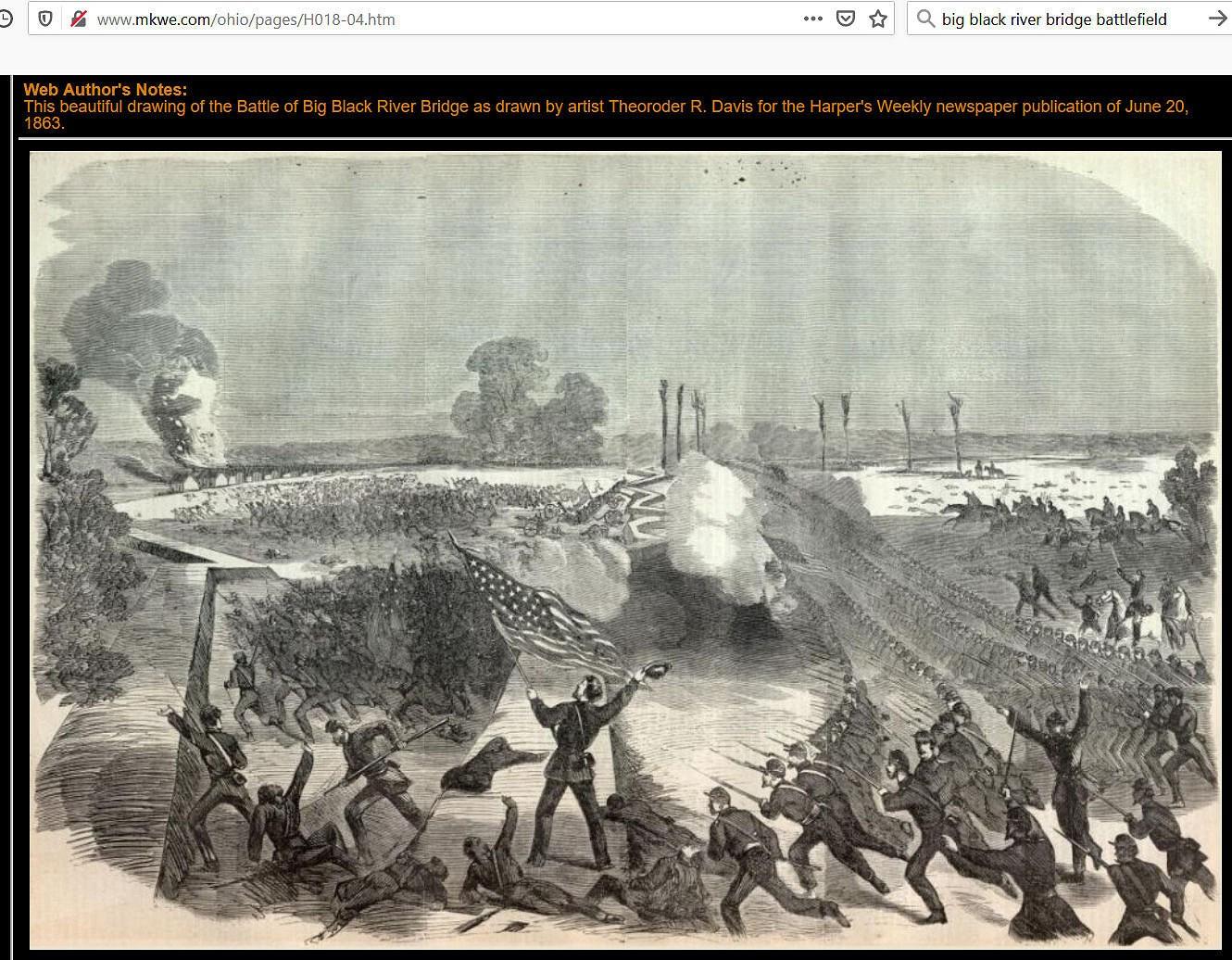

The following day it went into action at the Black River bridge, its brigade capturing the 60th Tenn. and carrying the enemy's works by assault. It reached Vicksburg on the 18th, and participated in the general assault on the 22nd, reaching the base of one of the forts under a heavy fire. It was on duty until the surrender, at which time losses had reduced its numbers

to 150 men who were fit for duty.

It participated in the attack on Jackson, and was constantly on duty until the evacuation of that point. It then joined the expedition through Louisiana, going as far as Barre's landing near Opelousas, which it occupied the entire summer.

The return march begun Nov. 1 and two days later a superior force attacked at Carrion Crow bayou, driving two regiments through the 23d's lines. Flanked on both sides, the regiment fell back, formed a new line when reinforced, drove the enemy back in turn and regained the lost ground, receiving for its gallantry the public thanks of the commanding general, though it lost 128 out of 220 engaged. It reached Brashear City, Dec. 13, and was ordered to Texas, where it remained until Feb. 22, 1864, when it returned to Louisiana. It was in the celebrated Red River expedition, was in the battle of Sabine CrossRoads, and the action at Cloutierville.

It was in camp at Baton Rouge from May 25 until July 8 and then proceeded to Algiers and Morganza where it remained until Aug. 18. It was transferred to the 3d brigade, 2nd division, 19th army corps, and was engaged in guard, post, garrison and reconnaissance duty until May 1, 1865.

It was then ordered to Mobile, where it was engaged in siege, patrol and picket duty, and short expeditions until July 4th, when it was mustered out.

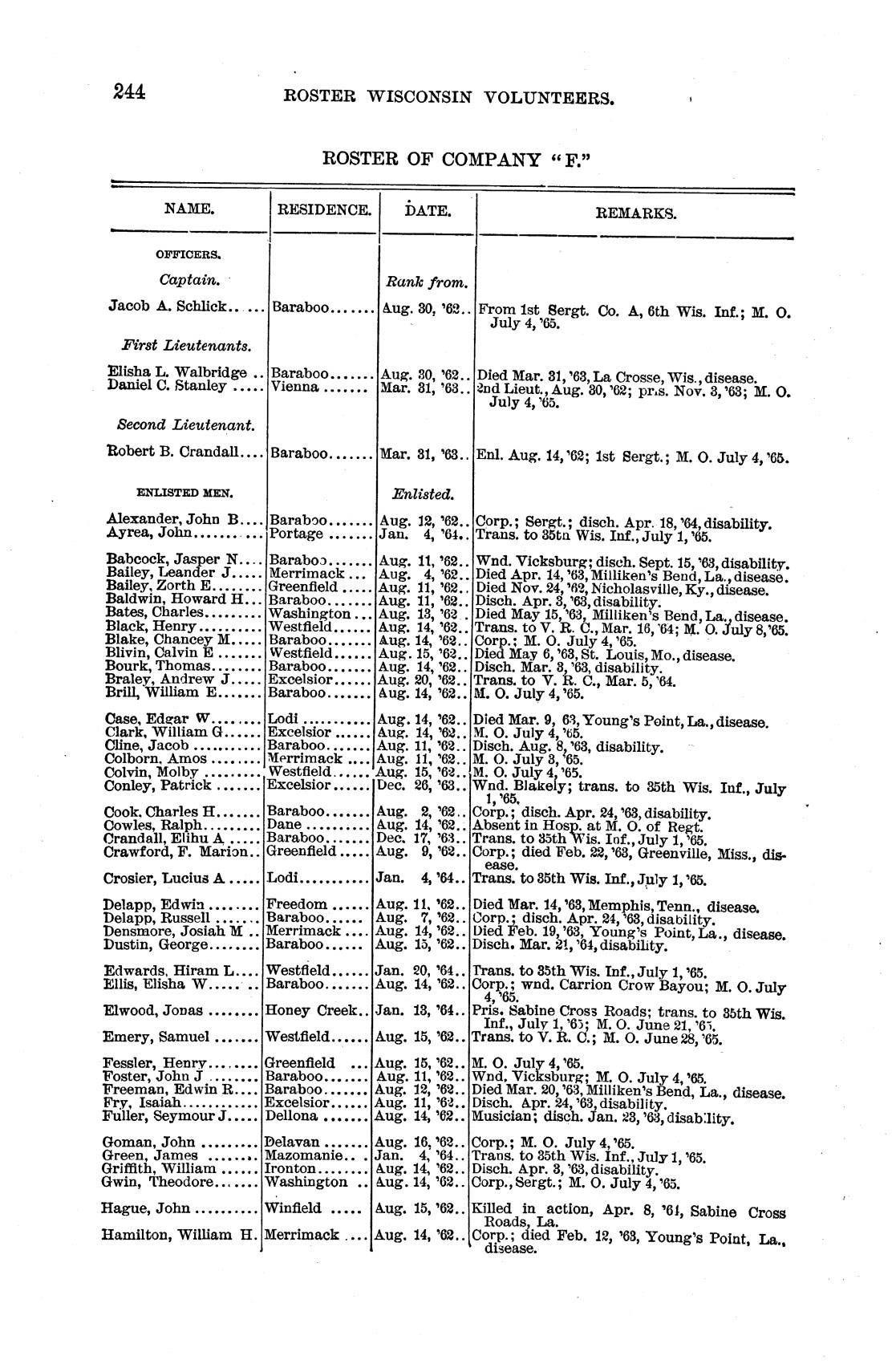

Wisconsin Genealogy Trails

Wisconsin Genealogy Trails

August 27, 1862---

Our Volunteers Gone In obedience to an order received last night, the Baraboo Rifle Company left this morning at 10 o’clock, for Madison. A large number of friends of the company assembled, to bid them Good-bye. Parting addresses were made by Judge Orton, Mrs. I. Codding, and Miss Mortimer, and on behalf of the company, by Robert B. Crandall.

The company had been warned to hold themselves in readiness to go into camp at short notice; but it

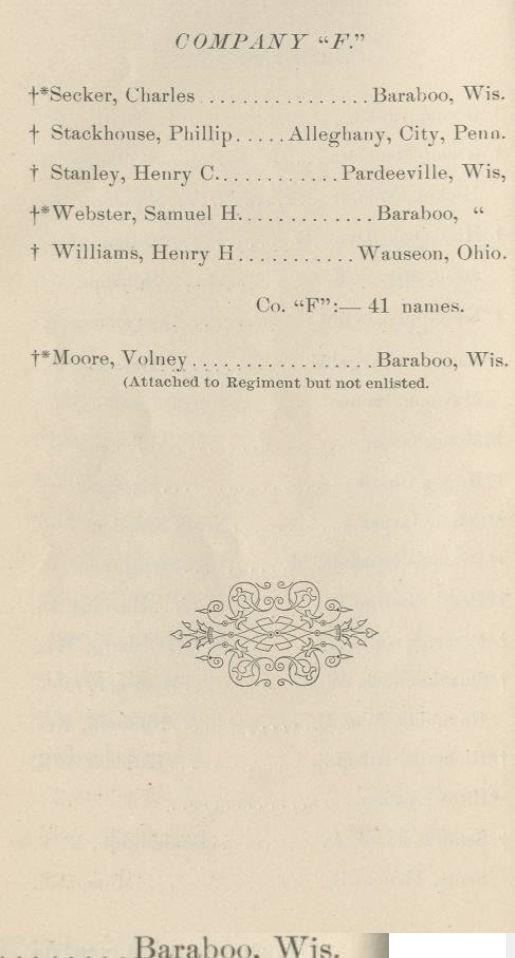

Captain CHARLES H. WILLIAMS

Lieutenants J.A. SCHLICK, E.L. WALBRIDGE

Malby Colvin Amos Colborn

John J. Hinds

Lucius Crozier

George B. Pearl George Dustin

Calvin P. Bliven

John H. Fulle

E.G. Seamans Edwin R Freeman

Hiram Snell James T. Gorgas

Beeman B. Spooner

Israel Greeney

Samuel Emery D.W. Hitchcock

Theodore Gwin Wm. H. Hamilton

Chauncey M. Blake James Hogeboom

Samuel H. Webster Charles Klumpp

George Van Orman Peter H. Kipp

Jesse Morley

Robert B. Crandall

Edward N. Narsch

Elisha W. Ellis

Joseph N. Savage Jr.

John W. Kezerta

William Lippitt

Charles Moore

James W. Mason

Homer D. Newell

Argalus Langdon C. Newell

William E. Brill

Jasper Odell

Charles F. Cooke B.B. Palmer

Edward Kingsbury

George A. Paddock

LJ. Bailey Jacob Platt

Samuel Maxham

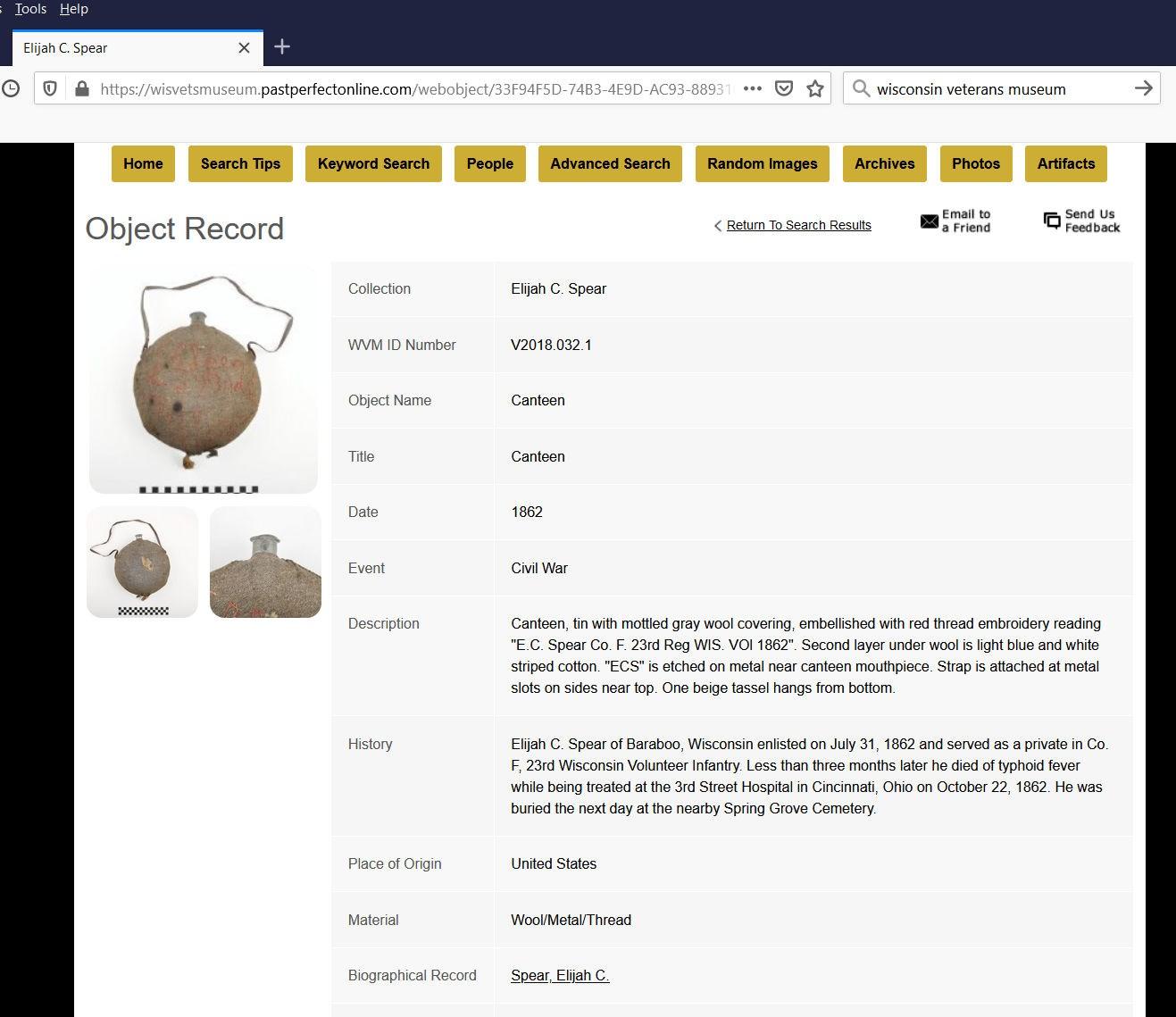

Elijah C. Spear

William Quackenbush

James D. Roberts

Russell Delp Adam Richart

Zephaniah Palmer

Byron W. Pruyn

Zoeth E. Bailey

Cortez A. Langdon

Amasa Ritter

Marcus Remington

George Smith

Philip Stackhouse

H.H. Baldwin William L. Spooner

was hard to part with them so suddenly, notwithstanding. God bless them!

August 27, 1862

BARABOO RIFLES

The following are the names of our brave boys who compose the company formed here for the Twenty-third Regiment. A better company, in any respect, has never been raised in Wisconsin.

Baraboo RepublicJasper N. Babcock

Thomas B. Scott

John J. Foster

Abraham Lezert

George Stowell

Jeremiah Sullivan

Philos O. Stutton

Charles Secker

Daniel C. Stanley John Staley

Henry H. Johnson

Henry A. Morrill

Marvin Van Orman

Elisha H. Catlin

Orsamus W. Stutton

William Sproul

Charles L. Stoner

John Sheaser

F. Marion Crawford Calvin Traver

Henry C. Stanley

W.A. Slade

Andrew J. Miles

Henry Fessler

J.M. Densmore, Jr.

George Moog

William H. Hogeboom

Andrew J. Braley

William Simon

John Goman

Marvin E. Jopp

Jacob Cline

Henry Ketchum

E.W. Case

Ralph Cowles

J.H. Rhodes

John B. Alexander

Charles Bates

Henry Black

Thomas Bourk

William J. Clark

John E. Camp

Charles A. Thomas

Oliver W. Thomas

Jacob Vandenberg

Henry H. Williams

Henry Weller

Andrew A. Wescott

Marvin Wiggins

Joseph Waddell

John Waltz

George W. Waddell

W.W. Pollock

Thomas F. Holden

E.B. Reynolds

John Kenworthy

William Griffith

Ira J. Hall

John Hagon

Joseph Fisher

Smith Z. Deveraux

Jason Shaw

Peter Knowles

Isaiah Fry

September 3, 1862

To Leave Soon By a letter received this morning, we learn that the 23d Regiment is under orders to leave as soon as they can possibly be got ready, which will probably be before the end of the week. The Sauk Co. Guards took to Madison 125 men, and as no company is allowed more than 98 men, quite a number, aside from those thrown out through disability, must be transferred to some other company. A braver set of men never stood in line than Capt. SCHLICK and his gallant fellows.

Promotions Capt. C.H. WILLIAMS, of the Sauk Co. Guards, has been promoted to the rank of Major of the 23rd Regiment. Lieut. SCHLICK, succeeds him as Captain. E.L. Walbridge becomes 1st Lieutenant, and DANIEL C. STANLEY succeeds Lieut. WALBRIDGE as 2d Lieutenant.

These are worthy promotion(s), and will gratify the many friends of the company. Since the leading officers are not all to be taken from the ranks of regiments in the service, which seems to us to have the true policy, we do not see how the present corps of officers could be bettered.

Baraboo Republic

nent corner; it was generally remarkable that the second company did the finest marching. At 8 o’clock we were served with coffee, bread and cheese, and at 9, “fall in!” then away for Toledo. The most of [the men] enjoyed a good night’s sleep. We reached Toledo at 7 A.M. Tuesday, had an hour for breakfast and to run around, then off again for Columbus. We were troubled with but a single runner this day. His box of cigars being confiscated instanter, the boys were so jubilant, the Colonel called us the musical company. By the way, the Col. paid us a high compliment before leaving Madison. On Sunday, many members of other companies being in the guard house, the Colonel visited them, and giving them a severe reprimand, wound up by saying that Co. F. had not had a single man in the guard house yet, and he would point them to it as an example.

September 24, 1862---

From the 23rd Regiment

Camp Guppy, Near Covington, KY. Sept. 18, 1862.

Editors Republic: Yesterday, at twenty minutes past four o’clock, we stepped upon the “old Kentucky shore.” Last Monday morning we left Madison at 9 ½ A.M. The boys were very lively that day, and commenced trying their hand at confiscation, by appropriating to their own use the contents of baskets and boxes passed through the cars by those extortionary boy peddlers, or runners; they soon learned to avoid our cars, which met the approval of our officers, for they said we were far better off without the trash than with it.

The people on the road were very enthusiastic. It being “washing-day,” the ladies would run out and seize anything the most convenient, from a pocket handkerchief to a table cloth, and wave it till we were out of sight.

We arrived at Chicago at 6 o’clock P.M., and paraded through the principle streets for two hours. Co. F received loud applause upon turning every promi-

This afternoon we passed through a good fruit country. It was amusing to hear the exclamations of the boys at the rich sight of the apple and peach trees bending beneath their heavy weight of fruit. “Stop the iron horse, till we fill our pockets!” was one of the many. But at some of the larger stations we had opportunities for gratification of our taste, and to enjoy at the seme time the liberality of the citizens, who brought baskets full of fruit, and distributed among us.

We reached Columbus at 8 ½ P.M., had a very good supper, and a little exercise, and started for Cincinnati at 10. Sunrise this Wednesday morning found us 8 miles from the city. The morning was pleasant, and the scenery along the Ohio river is beautiful indeed, at this season of the year. Arriving at the depot, we marched up to Fifth street market, where we ate the best meal that we have had since leaving home. The regiment was then dismissed till dinner. The boys enjoyed themselves hugely in seeing and eating.

After dinner we received our haversacks and canteens, and after two hours more of recreation were formed into rank and took up the line of march for the scene of active operations. We crossed the river on a pontoon bridge, and marched back five miles to the line of defense. The evening was very warm, and the road very dusty, so that our progress was slow, night overtaking us before we reached our camping ground, which is on the top of one of these high Kentucky hills. Camp fires were visible for miles around. Dusty and fatigued, we laid ourselves down to rest

and the road very dusty, so that our progress was slow, night overtaking us before we reached our camping ground, which is on the top of one of these high Kentucky hills. Camp fires were visible for miles around. Dusty and fatigued, we laid ourselves down to rest without supper. We had just begun to realize camp life proper; our few days’ stay in Madison was mere play; but I heard no grumbling.

This morning we breakfasted on not the best of fare, it having been brought from Madison and marched back to the Ohio river, a few miles above Cincinnati. Water is very scarce back from the river it having to be hauled to camp by dray. We have been exceedingly fortunate in getting so good a ground.

When the Colonel called on the General commanding, this morning, to get our position, the General asked him where he was from. On being told, the General said, “Yours was the regiment that marched through the city yesterday, I believe? You will cam on the river, sir.”

The Major just told me that we should not remain here long. The21st and 24th Wis. by whose side we camped last night, left to-day for Lexington. We are camped in a nice peach orchard, minus the peaches, of course. Received our cartridges this morning.

Our friends will please direct their letters to Cincinnati, Ohio.

October 1, 1862

D. Baraboo RepublicFrom the 23rd Regiment: CAMP BATES, Ky, Sept. 25, 1862

Messrs. Editors. Do you like letter reading? We received our first mail yesterday. Anxiously each one awaited the calling of his name by the Captain, who held the package of letters. Many were disappointed, and turned waay saying, “why do they not write?” No one who has not been some distance from home, can realize the blessings of letter writing the pleasing sensation that cheers the soul on breaking a letter from loved ones. More especially do we realize this fact during the first few months of absence. Therefore we hope our friends will write us often, thus cheering us on in the great work upon which we have entered.

Our company has been favored with good health since we left Madison, having but one man in the

hospital. The position of our camp is a very desirable one, occupying as it does the extreme left of the line of defense overlooking a large extent of country on both sides of the Ohio river, and easily accessible to excellent water. The line of defense is said to be fifteen miles in length, guarding the cities of Cincinnati, Covington and Newport, and upon which have been at one time upward of 100,000 men. The number is now decreasing daily, being drawn off to reinforce the army at Louisville.

Our food is now good and plentiful, but before the departments of camp were thoroughly arranged, it was poor indeed. Here, as in Madison, we have been remembered by friends. Mrs. T. Thomas, who is now in Cincinnati, sent us the other day several boxes of nice peaches and other delicacies, and promised us more in a few days. If Sauk County has one man that has been more active than others in devising and meeting means for the suppression of this rebellion, that man is T. Thomas, Esq., and the unassuming manner in which he has done it, reflects upon him the greater credit. The effectual working of your branch of the Sanitary Commission is due to his energy, he having earnestly recommended it several months ago; which Commission we believe to be one of the most important institutions connected with the war.

How many thousand soldiers who have so nobly fought in the late battles in Virginia and Maryland, are today asking the blessings of Heaven to res down on the women of the North, for their labor to provide the thousand articles of use and comfort, to relieve their sufferings from sickness and wounds.

“Woman! Blest partner of our joys and woes!

E’en in the darkest hour of earthly ill, Untarnished yet, thy fond affection glows, Throbs with each pulse, and beats with every thrill!

Angel of comfort to the failing soul.”

How many sad and mournful countenances there must have been in Sauk County on the reception of the news of the disaster to the Sixth Regiment! But while fathers and mothers now mourn the loss of their brave sons, who perishing in this fearful storm, they may look forward to the time when ragings shall have ceased, and the sun of Freedom,

Righteousness and Prosperity shall beam forth upon a purified nation, and the faithful historian shall have recorded the names of the nation’s heroes, and proudly point to the name among them of him whom God permitted them to raise up to defend their country in its hour of peril.

I intended to speak of Proclamation of the President, and its reception by our regiment, but my letter is already full.

We have not received our tents yet, consequently have the full benefit of the cool, refreshing night air.

D. Baraboo RepublicNovember 12, 1862---

From the 23rd Regiment.

CAMP PRICE, (Near Nicholsville) Ky. November 5, 1862

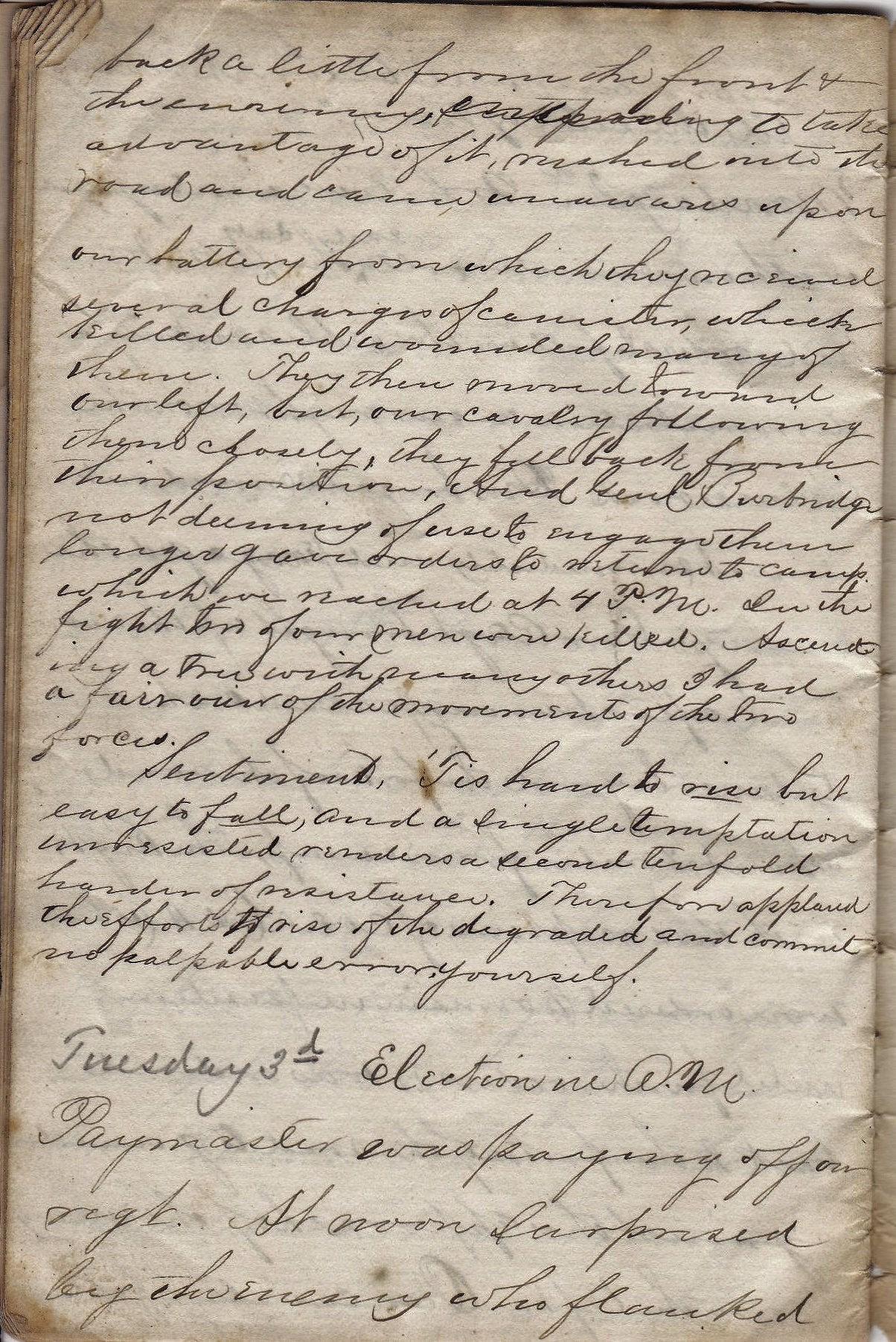

ELECTION.

I send you the result of the election, as I have been able to gather it this morning, giving only the votes for the leading candidates for each office, and the vote of the reg’t.

sword and bayonet are the two great levers that move the machinery of our Nation’s destiny. If these be worked with hands prompted by hearts resolved on raising the Nation to the highest standard of true greatness, they will success.

We mourn the loss of one of our kindest boys. Mr. Spear was born in Racine, Wis. and was twentyone years of age. He was the first member enlisted in our company, and the first ready to perform its duties. We never heard him complain, always cheerful, obedient and obliging. He sustained a high moral and religious character, always avoiding the many vices that attend a camp life. His history is well known by your citizens it need not be repeated. He died in Cincinnati, 3rd Street hospital, Oct. 22d, of typhoid Fever.

D. BarabooRepublic

December 31, 1862

From the 23d Regiment.

The following private letter, written by a member of the 23rd Regiment, will give some information of the whereabouts of “our boys.”

Company F polled 75 votes. There was no excitement. We voted, then immediately prepared for two grand reviews, which came off between the hours of 10 and 11:30 A.M. and 2 and 4 P.M. what an illustration of the workings of the principles of a fee government. Men can step up to the polls, and deposit a vote for their representatives in State and National councils, who have pledged themselves to support the free institutions of this loved country, then, turning away, shoulder the rifle and enter the ranks to battle the traitors, who would tramp those institutions into the sesspool (sic.) of despotism. The ballot box,

We last night received orders to cook three days rations of provisions, and to be in readiness to go on board the transports on short notice. Will probably go on board to night or early to-morrow morning. Our destination is Vicksburg. We go to Helena the first day, to somebody’s landing the second, and to Mulligan’s Bend, about 10 or 15 miles above the city next. Gen. W.T. Sherman is in command. I do not know how many troops belong to this command, which is called the Right Wing of the army of Tennessee. We are in the 1st Brigade, Gen. Burbridge, 1st Division, Gen. A.J. Smith. There will be at least 20,000 men from this point, and perhaps 30,000; besides there is a large force at Helena.

In 1861, to mail a 1/2 ounce letter up to 3,000 miles would have cost 3 cents. That’s about 80 cents today.

March 18, 1863

‘Twould amuse you to hear us boys, while partaking of our frugal meal, discuss the various nice dishes gotten up by our mothers at home. Pies, cakes, jellies, puddings, stews, &c., are fully dispatched by words and wishes, when we wind up by saying, “Well, what is the use of talking, being in, bear it.”

Our company was in the expedition up the river from the 14th to the 26th [1863] ult. The object of this expedition was to disperse guerilla bands that have been planting batteries along the river, thus annoying our transports. I did not go with the company, but the officers say that they did not accomplish much, and had a pretty tough time of it.

Two Regiments of this brigade, the 23rd Wis. and _____, Col. Guppy, commanding, have orders for a similar expedition to-morrow morning, with ten days rations. Baraboo Republic

August 6, 1863

23rd Regiment – We learn that Lieut. John Starks, of Company I, was severely wounded; also Jasper N. Babcock and J.J. Foster of Company F.

January 4, 1865

From the 23d Regiment

HELENA, Ark. Dec. 26th, 1864

Ed. Republic Sir: Through the medium of your columns, and in behalf of Company F, we desire to return our sincere thanks to the friends of the Company in Baraboo and vicinity, for their kindness and liberality in contributing so generously to our comfort.

The box of good things which was sent to us arrived here last Saturday, the 24th, when it was opened, and every thing found to be in tip-top order. Preparations were immediately made for cooking that portion of the edibles that was not already prepared for the table, and a committee appointed to arrange the tables, and to distribute the viands. Having no table cloths, we used newspapers, which were found to answer all practical purposes. After the usual bustle, and hurrying here, there, and everywhere, were there was nothing to do, (however there were no dishes broken, as our dishes are all clean tin) we at last got everything prepared when Capt. Schlick and Lieuts Stanley and Crandall

joined us, and Company F all sat down to a repast fit for a king. The boys all did ample justice to the delicacies and substantials, and a right merry Christmas we had. Many were the expressions of gratitude to the donors, made by the men who have seen so many hardships, and known so little of the comforts of home for the last two years. We assure you that such marked attention and respect is most highly appreciated by us, rough “sons of Mars.” It is very pleasant for us to know, that we have the sympathy and support of our friends at home, and hereafter as heretofore, it will always be our highest aim to merit the confidence and respect of those who have so nobly sacrificed their own interests upon the altar of Union and Liberty, Truth and Freedom, by willingly parting with their husbands, brothers, and sons, that they might go and battle with the traitors who would destroy our Government.

We all look forward to the time when peace shall be restored to our beloved country with emotions of pleasure, but we want it to be a permanent peace, or none. We love our country just as dearly now, as we did two years ago last August, when one fine morning, we bade you farewell, and started “for the wars.” No one of us then knew but that friendly grasp of the hand would be the last; and to many it was, for many of our bravest boys are slumbering in the silent tomb. But their memory is enshrined in the hearts of their comrades as well as in the hearts of the “loved ones at home.” Hoping that we shall partake of our next Christmas dinner at home, and in the society of our friends, we once “More beg you to accept our thanks for past favors, and believe us to be, as ever, true to our country, &c. T.G. Baraboo Republic

August 23, 1865

[Excerpt] For Superintendent of Public Instruction, Lt. R.B. Crandall, of Baraboo was nominated. Lt. C. has but recently returned with the veteran 23d, in which regiment he had risen from the ranks to the grade of an officer. He is recommended by those who best know him as well qualified for the position.

August 30, 1865

[Excerpt] Republican-Union Nominations. For Superintendent……R.B. Crandall

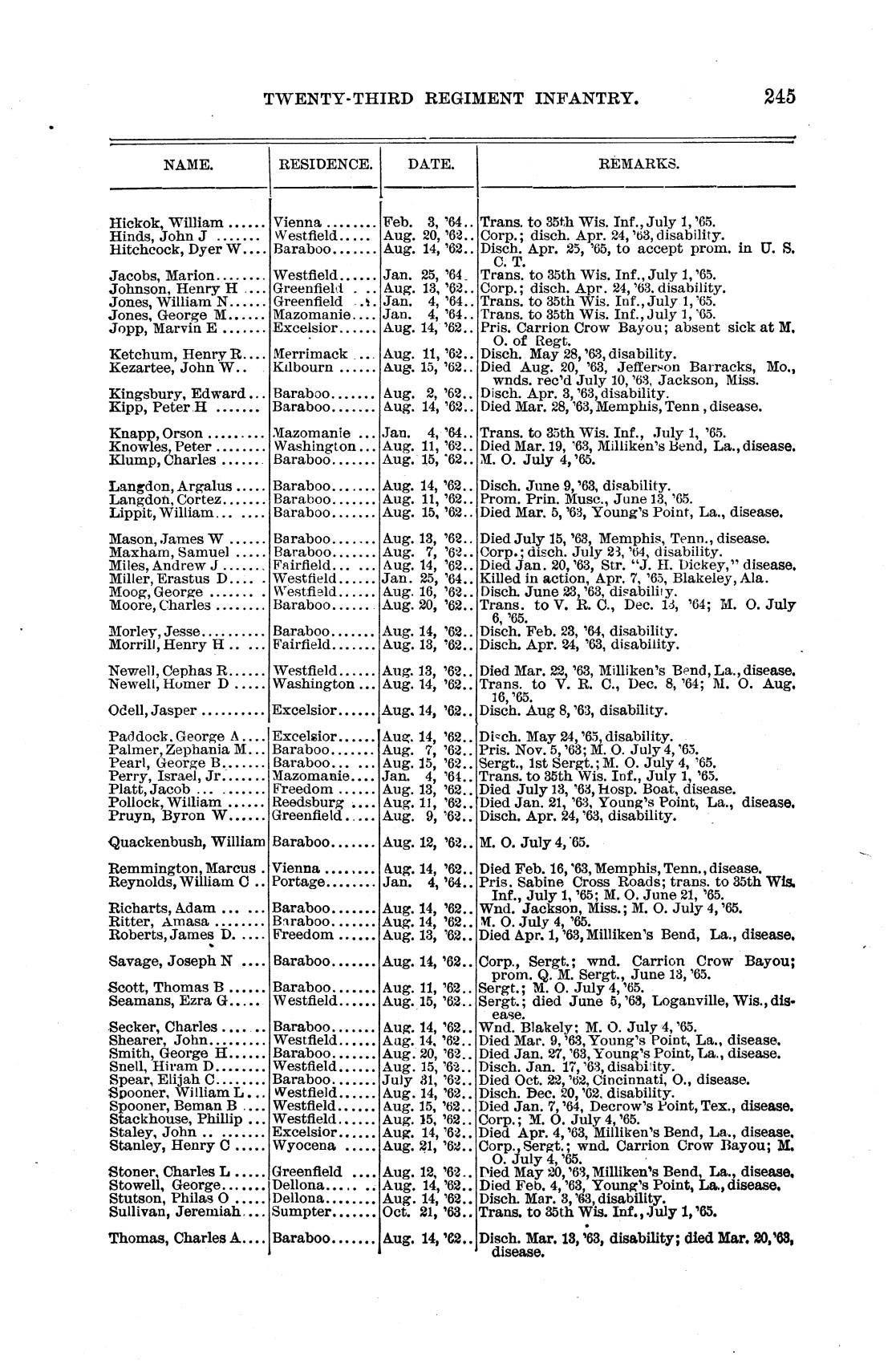

This type of recruiting poster would have been seen all across the North at the beginning of the Civil War.

The $302 being offered to new recruits is equivalent to $9,000. in today’s purchasing power. The average salary for a laborer in 1861 would have been $306 for a 60 hour work week.

Lieutenants were second in command of infantry and cavalry companies and artillery batteries. Infantry lieutenants assisted the company captain in their positions behind the line of battle by guiding the troops in their movements and firing. Robert B. Crandall was a Second Lieutenant.

The salary of a Second Lieutenant during the Civil War, was $105.50, which would be equivalent to $3,105 in purchasing power today.

In some early battles soldiers often shot people from their own side. Uniforms at the beginning of the Civil War, however, showed greater variety than would be true later in the conflict. Many men wore whatever they brought from home. Eventually, the uniforms became more standard with the Union army wearing navy colored uniforms and the Confederates wearing grey. The Union uniform consisted of a dark blue wool coat with light blue trousers and a dark cap called a forage cap.

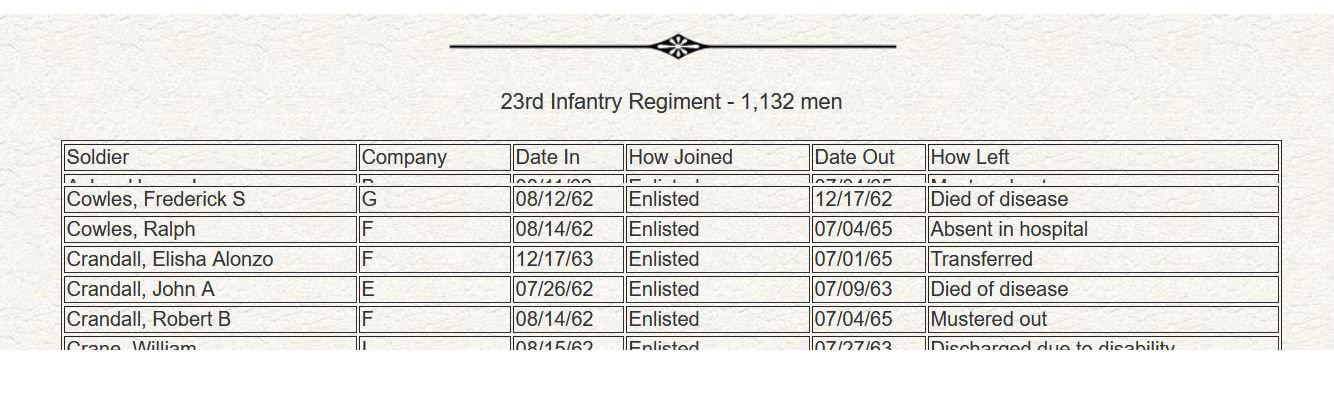

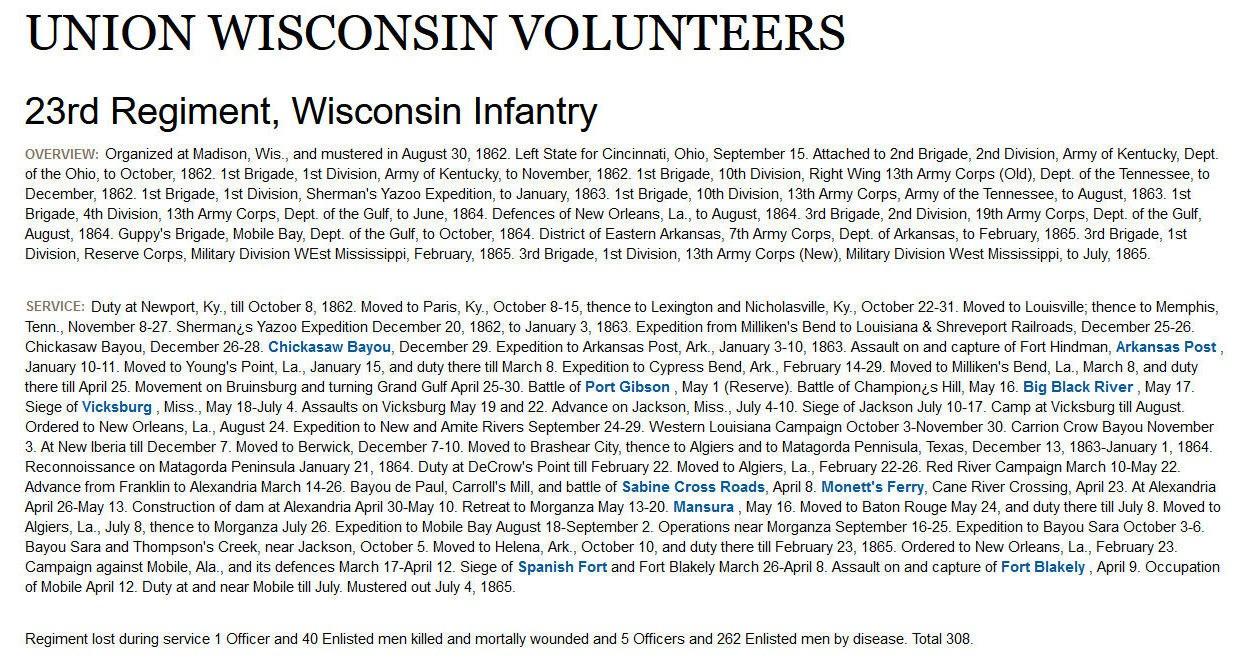

Overview:

Organized at Madison, Wis., and mustered in August 30, 1862. Left State for Cincinnati, Ohio, September 15. Attached to 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, Army of Kentucky, Dept. of the Ohio, to October, 1862. 1st Brigade, 1st Division, Army of Kentucky, to November, 1862. 1st Brigade, 10th Division, Right Wing 13th Army Corps (Old), Dept. of the Tennessee, to December, 1862. 1st Brigade, 1st Division, Sherman's Yazoo Expedition, to January, 1863. 1st Brigade, 10th Division, 13th Army Corps, Army of the Tennessee, to August, 1863. 1st Brigade, 4th Division, 13th Army Corps, Dept. of the Gulf, to June, 1864. Defenses of New Orleans, La., to August, 1864. 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, 19th Army Corps, Dept. of the Gulf, August, 1864. Guppy's Brigade, Mobile Bay, Dept. of the Gulf, to October, 1864. District of Eastern Arkansas, 7th Army Corps, Dept. of Arkansas, to February, 1865. 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, Reserve Corps, Military Division West Mississippi, February, 1865. 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, 13th Army Corps (New), Military Division West Mississippi, to July, 1865.

Service:

Duty at Newport, Ky., till October 8, 1862. Moved to Paris, Ky., October 8-15, thence to Lexington and Nicholasville, Ky., October 2231. Moved to Louisville; thence to Memphis, Tenn., November 8-27. Sherman’s Yazoo Expedition December 20, 1862, to January 3, 1863. Expedition from Milliken's Bend to Louisiana & Shreveport Railroads, December 2526. Chickasaw Bayou, December 26-28. Chickasaw Bayou, December 29. Expedition to Arkansas Post, Ark., January 3-10, 1863. Assault on and capture of Fort Hindman, Arkansas Post , January 10-11. Moved to Young's Point, La., January 15, and duty there till March 8. Expedition to Cypress Bend, Ark., February 14 -29. Moved to Milliken's Bend, La., March 8, and duty there till April 25. Movement on Bruinsburg and turning Grand Gulf April 25-30. Battle of Port Gibson , May 1 (Reserve). Battle

of Champion’s Hill, May 16. Big Black River , May 17. Siege of Vicksburg , Miss., May 18July 4. Assaults on Vicksburg May 19 and 22. Advance on Jackson, Miss., July 4-10. Siege of Jackson July 10-17. Camp at Vicksburg till August. Ordered to New Orleans, La., August 24. Expedition to New and Amite Rivers September 24-29. Western Louisiana Campaign October 3-November 30. Carrion Crow Bayou November 3. At New Iberia till December 7. Moved to Berwick, December 7-10. Moved to Brashear City, thence to Algiers and to Matagorda Peninsula, Texas, December 13, 1863January 1, 1864. Reconnaissance on Matagorda Peninsula January 21, 1864. Duty at DeCrow's Point till February 22. Moved to Algiers, La., February 22-26. Red River Campaign March 10-May 22. Advance from Franklin to Alexandria March 14-26. Bayou de Paul, Carroll's Mill, and battle of Sabine Cross Roads, April 8. Monett's Ferry, Cane River Crossing, April 23. At Alexandria April 26-May 13. Construction of dam at Alexandria April 30-May 10. Retreat to Morganza May 13-20. Mansura , May 16. Moved to Baton Rouge May 24, and duty there till July 8. Moved to Algiers, La., July 8, thence to Morganza July 26. Expedition to Mobile Bay August 18-September 2. Operations near Morganza September 16-25. Expedition to Bayou Sara October 3-6. Bayou Sara and Thompson's Creek, near Jackson, October 5. Moved to Helena, Ark., October 10, and duty there till February 23, 1865. Ordered to New Orleans, La., February 23. Campaign against Mobile, Ala., and its defenses March 17-April 12. Siege of Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely March 26-April 8. Assault on and capture of Fort Blakely , April 9. Occupation of Mobile April 12. Duty at and near Mobile till July. Mustered out July 4, 1865.

Regiment lost during service 1 Officer and 40 Enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 5 Officers and 262 Enlisted men by disease. Total 308.

• Organized at Madison, Wis., and mustered in August 30, 1862.

• Left State for Cincinnati, Ohio, September 15.

• Attached to 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, Army of Kentucky, Dept. of the Ohio, to October, 1862.

• 1st Brigade, 1st Division, Army of Kentucky, to November, 1862.

• 1st Brigade. 10th Division, Right Wing 13th Army Corps (Old), Dept. of the Tennessee, to December, 1862.

• 1st Brigade, 1st Division, Sherman's Yazoo Expedition, to January, 1863.

• 1st Brigade, 10th Division, 13th Army Corps, Army of the Tennessee, to August, 1863.

• 1st Brigade, 4th Division, 13th Army Corps, Dept. of the Gulf, to June, 1864.

• Defences of New Orleans, La., to August, 1864.

• 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, 19th Army Corps, Dept. of the Gulf, August, 1864.

• Guppy's Brigade, Mobile Bay, Dept. of the Gulf, to October, 1864.

• District of Eastern Arkansas, 7th Army Corps, Dept. of Arkansas, to February, 1865.

• 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, Reserve Corps, Military Division West Mississippi, February, 1865.

• 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, 13th Army Corps (New), Military Division West Mississippi, to July, 1865

• Duty at Newport, Ky., till October 8, 1862.

• Moved to Paris, Ky., October 8-15, thence to Lexington and Nicholasville, Ky., October 22-31.

• Moved to Louisville, thence to Memphis, Tenn., November 8-27.

• Sherman's Yazoo Expedition December 20, 1862, to January 3, 1863.

• Expedition from Milliken's Bend to Louisiana & Shreveport Railroad December 25-26.

• Chickasaw Bayou December 26-28.

• Chickasaw Bluff December 29.

• Expedition to Arkansas Post, Ark., January 3-10, 1863.

• Assault on and capture of Fort Hindman, Arkansas Post, January 10-11.

• Moved to Young's Point, La., January 15, and duty there till March 8.

• Expedition to Cypress Bend, Ark., February 14-29.

• Moved to Milliken's Bend, La., March 8, and duty there till April 25.

• Movement on Bruinsburg and turning Grand Gulf April 25-30.

• Battle of Port Gibson May 1 (Reserve).

• Battle of Champion's Hill May 16.

• Big Black River May 17.

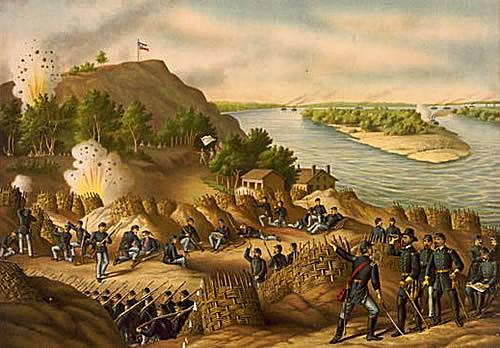

• Siege of Vicksburg, Miss., May 18-July 4.

• Assaults on Vicksburg May 19 and 22. Advance on Jackson, Miss., July 4-10.

• Siege of Jackson July 10-17.

• Camp at Vicksburg till August.

• Ordered to New Orleans, La., August 24.

• Expedition to New and Amite Rivers September 24-29.

• Western Louisiana Campaign October 3-November 30.

• Carrion Crow Bayou November 3.

• At New Iberia till December 7.

• Moved to Berwick December 7-10.

• Moved to Brashear City, thence to Algiers and to Matagorda Peninsula, Texas, December 13, 1863January 1, 1864.

• Reconnaissance on Matagorda Peninsula January 21, 1864.

• Duty at DeCrow's Point till February 22.

• Moved to Algiers, La., February 22-26.

• Red River Campaign March 10-May 22.

• Advance from Franklin to Alexandria March 14-26.

• Bayou de Paul, Carroll's Mill, and battle of Sabine Cross Roads April 8.

• Monett's Ferry, Cane River Crossing, April 23.

• At Alexandria April 26-May 13.

• Construction of dam at Alexandria April 30-May 10.

• Retreat to Morganza May 13-20.

• Mansura May 16.

• Moved to Baton Rouge May 24, and duty there till July 8.

• Moved to Algiers, La., July 8, thence to Morganza July 26.

• Expedition to Mobile Bay August 18-September 2.

• Operations near Morganza September 16-25.

• Expedition to Bayou Sara October 3-6.

• Bayou Sara and Thompson's Creek, near Jackson, October 5.

• Moved to Helena, Ark., October 10, and duty there till February 23, 1865.

• Ordered to New Orleans, La., February 23.

• Campaign against Mobile, Ala., and its defences March 17-April 12.

• Siege of Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely March 26-April 8.

• Assault on and capture of Fort Blakely April 9.

• Occupation of Mobile April 12.

• Duty at and near Mobile till July. Mustered out July 4, 1865.

Regiment lost during service 1 Officer and 40 Enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 5 Officers and 262 Enlisted men by disease. Total 308.

All information on this document is from Dyer's reference

The Battle of Mansfield, also known as the Battle of Sabine Crossroads, on April 8, 1864 in Louisiana formed part of the Red River Campaign during the American Civil War, when Union forces were attempting to occupy the Louisiana state capital, Shreveport.

The Confederate commander, Major General Richard Taylor, chose Mansfield as the place where he would make his stand against the advancing Union army under General Nathaniel Banks. Taylor concentrated his forces at Sabine Crossroads, knowing that reinforcements were nearby. Banks prepared for a fight, though his own army was not fully assembled either. Both sides were reinforced by stages throughout the day. After a brief resistance, the Union army was routed by the Confederates, consisting mainly of units from Louisiana and Texas, reportedly strengthened by hundreds of men breaking parole.

Prelude

During the second half of March 1864, a combined force from the Union Army of the Gulf and navy led by Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, supported by Admiral David Porter's fleet of gunboats, ascended the Red River with the goal of defeating the Confederate forces in Louisiana and capturing Shreveport. By April 1 Union forces had occupied Grand Ecore and Natchitoches. While the accompanying gunboat fleet with a portion of the infantry continued up the river, the main force followed the road inland toward Mansfield, where Banks knew his opponent was concentrating.

Major General Richard Taylor, in command of the Confederate forces in Louisiana, had retreated up the Red River in order to connect with reinforcements from Texas and Arkansas. Taylor selected a clearing a few miles south of Mansfield as the spot where he would take a stand against the Union forces. Sending his cavalry to harass the Union vanguard as it approached, Taylor called his infantry divisions forward.

The morning of April 8 found Banks's army stretched out along a single road through the woods between Natchitoches and Mansfield. When the cavalry at the front of the column found the Confederates taking a strong position along the edge of a clearing, they stopped and called for infantry support. Riding to the front, Banks decided that he would fight Taylor at that spot, and he ordered all his infantry to hurry up the road. It became a race to see which side could bring its forces to the front first.

Confederate

At the start of the battle, Taylor had approximately 9,000 troops consisting of Brigadier General Alfred Mouton's Louisiana/Texas infantry division, Major General John G. Walker's Texas infantry division, Brigadier General Thomas Green's Texas cavalry division, and Colonel William Vincent's Louisiana cavalry brigade.[4] He had also called on the 5,000 men in the divisions of Brigadier General Thomas J. Churchill and Brigadier General Mosby M. Parsons that had been encamped near Keachi, between Mansfield and Shreveport. These troops arrived late in the afternoon, after the battle had commenced.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that there were additional Louisiana men in the ranks. This included paroled soldiers from units that had surrendered at Vicksburg. Historian Gary Joiner claimed that “there may have been from several hundred to several thousand of them. The Confederate Governor of Louisiana, Henry Watkins Allen, had organized two battalions of the state guard and brought them to Taylor's aid, yet the documentary record is unclear as to what role they played in the battle. Joseph Blessington, a soldier in Walker's division, wrote that, “The Louisiana militia, under command of Governor Allen, was held in reserve, in case of an emergency.” In addition, Blessington wrote that, from the surrounding communities, “old men shouldered their muskets and came to our assistance”.

At the start of the battle, the Union forces consisted of a cavalry division commanded by Brigadier General Albert L. Lee, consisting of approximately 3,500 men, and the 4th Division of the XIII Corps, commanded by Colonel William J. Landram, consisting of approximately 2,500 men. During the battle, the 3rd Division of the XIII Corps, commanded by General Robert A. Cameron, arrived with approximately 1,500 men. The battle ended when the pursuing Confederates met the 1st Division of the XIX Corps, commanded by Brigadier

General William H. Emory, with approximately 5,000 men, including the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry, the only regiment from the Keystone State to fight in the Union's 1864 Red River Campaign.[9] Thomas E. G. Ransom commanded the XIII Corps during the engagement, while the XIX Corps was commanded by William B. Franklin.

During the morning, Taylor positioned Mouton's division on the east side of the clearing. Walker's division arrived in the afternoon and formed on Mouton's right. As Green's cavalry fell back from the advancing Union forces, two brigades moved to Mouton's flank and the third to Walker's flank. The Arkansas division arrived around 3:30 pm but was sent to watch a road to the east. The Missouri division did not arrive until around 6:00 pm, after the battle was fought.

At around noon, the Union cavalry division, supported by one infantry brigade of Landram's division, was deployed across a small hill at the south end of the clearing. Shortly thereafter the other brigade of Landram's division arrived. Cameron's division was on its way, but would not get there until the battle had already begun. For about two hours the two sides faced each other across the clearing as Banks waited for more of his troops to arrive and Taylor arranged his men. At that point, Taylor enjoyed a numerical advantage over Banks. At about 4:00 pm, the Confederates surged forward. On the east side of the road, Mouton was killed, while several of his regimental commanders were hit as well and the charge of his division was repulsed. However, west of the road, Walker's Texas division wrapped around the Union position, folding it in on itself. Ransom was wounded trying to rally his men and was carried from the field; hundreds of Union troops were captured and the rest retreated in a panic. As the first Union line collapsed, Cameron's division was arriving to form a second line but it too was pushed back by the charging Confederates, with Franklin wounded as well but remaining on the field in command. For several miles the Confederates pursued the retreating Union troops until they encountered a third line formed by Emory's division. The Confederates launched several charges on the Union line but were repulsed, while nightfall ended the battle.

The Union forces had suffered 113 killed, 581 wounded, and 1,541 captured as well as the loss of 20 cannons, 156 wagons, and a thousand horses and mules, killed or captured. More than half of the Union casualties were from four regiments – 77th Illinois, 130th Illinois, 19th Regiment Kentucky Volunteer Infantry and 48th Ohio. Most of the Union casualties occurred in the XIII Corps, while the XIX Corps lost few men.

Kirby Smith reported that Confederate loss was “about 1,000 killed and wounded” at Mansfield, but precise details of Confederate losses were not recorded. Some of the wounded, perhaps thirty, were taken to Minden for treatment. Those who died of wounds there were interred without markers in the historic Minden Cemetery. They were finally recognized with markers erected on March 25, 2008. The local town of Keachi converted its women's college into a hospital and morgue on its second floor. One hundred soldiers' remains are marked nearby in Keachi's Confederate Cemetery, maintained by the local Sons of Confederate Veterans and Daughters of the Confederacy.

After the Union troops retreated, they fought Confederates again on April 9 at the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

From Wikipedia

- Organized on Aug 30 1862 at Camp Randall, Madison, WI

- Enlistment term: 3 years

- Mustered out on Jul 4 1865 at Mobile, AL

Available statistics for total numbers of men listed as:

- Enlisted or commissioned: 1134

- Drafted: 1

- Killed or died of wounds (Officers): 1

- Killed or died of wounds (Enlisted men): 40

- Died of disease (Officers): 5

- Died of disease (Enlisted men): 262

- Prisoner of war: 75

- Died while prisoner of war: 1

- Disabled: 181

- Missing: 3

- Deserted: 3

- Discharged: 95

- Mustered out: 401

- Transferred out: 145

Twenty-third Infantry WISCONSIN

Twenty-third Infantry. Col., Joshua J. Guppey, Lieut.-Cols., Edmund Jussen William F. Vilas, Edgar P. Hill; Majs., Edmund Jussen, Charles H. Williams, William F. Vilas, Edgar P. Hill, Joseph E. Green.

This regiment was organized at Camp Randall, Madison, in Aug., 1862, and left the state Sept. 15 for Cincinnati, whence it was ordered south to join the army before Vicksburg.

It was with Gen. Sherman in the assault on Chickasaw Bluffs and assisted in the reduction of Arkansas Post. The action of the regiment was the occasion of congratulatory orders from division and brigade commanders. It then proceeded to Young's point, La., near Vicksburg, where three-fourths of the men were stricken with virulent diseases because of adverse sanitary conditions.

The regiment was on scout and foraging work until April 30, 1863. It was brought into reserve at Port Gibson and entered the village the following day - the first Union troops to occupy it. It took the advance of the division at Champion's Hill, doing such effective work as to call forth compliments from the general commanding.

The following day it went into action at the Black River bridge, its brigade capturing the 60th Tenn. and carrying the enemy's works by assault. It reached Vicksburg on the 18th, and participated in the general assault on the 22nd, reaching the base of one of the forts under a heavy fire. It was on duty until the surrender, at which time losses had reduced its numbers to 150 men who were fit for duty.

It participated in the attack on Jackson, and was constantly on duty until the evacuation of that point. It then joined the expedition through Louisiana, going as far as Barre's landing near Opelousas, which it occupied the entire summer.

The return march begun Nov. 1 and two days later a superior force attacked at Carrion Crow bayou, driving two regiments through the 23d's lines. Flanked on both sides, the regiment fell back, formed a new line when reinforced, drove the enemy back in turn and regained the lost ground, receiving for its gallantry the public thanks of the commanding general, though it lost 128 out of 220 engaged.

It reached Brashear City, Dec. 13, and was ordered to Texas, where it remained until Feb. 22, 1864, when it returned to Louisiana. It was in the celebrated Red River expedition, was in the battle of Sabine Cross-Roads, and the action at Cloutierville.

It was in camp at Baton Rouge from May 25 until July 8 and then proceeded to Algiers and Morganza where it remained until Aug. 18. It was transferred to the 3d brigade, 2nd division, 19th army corps, and was engaged in guard, post, garrison and reconnaissance duty until May 1, 1865.

It was then ordered to Mobile, where it was engaged in siege, patrol and picket duty, and short expeditions until July 4th, when it was mustered out.

Its original strength was 994. Gain by recruits, 123; total, 1,117. Loss by death, 289; missing, 1; desertion 6; transfer, 124; discharge, 281; mustered out, 416.

Source: The Union Army, vol. 4, p. 59

Report of Col. Joshua J. Guppey, Twenty-third Wisconsin Infantry, including operations to May 22.

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of the part taken by this regiment in the battles that have taken place since the army landed in the State of Mississippi:

On May 1 last, the regiment, after marching the entire night preceding, was formed as a part of the reserve in the battle of Port Gibson. In the forenoon, by order of Gen. Burbridge, it supported Foster's Wisconsin battery and Sheldon's brigade, Gen. Osterhaus' division, in several advances. In the afternoon it rejoined the brigade and took the advance on the right of the line.

Later in the day it was deployed as skirmishers, drove the enemy from the woods toward Port Gibson, took 20 prisoners, and destroyed a large quantity of small-arms.

On the morning of May 2, the regiment was in line of battle at 2 a.m., and at daylight took the advance toward Port Gibson, having the honor of being the first regiment which entered the city, and which gave the first cheer for our national flag, raised over it by Gen. Burbridge. During the day the regiment did duty as provost guard.

On May 16, the regiment was engaged in the battle of Midway Hill. In the evening five companies were deployed as skirmishers, and afterward two companies were added to them. They did most efficient service in driving the enemy's skirmishers and gaining knowledge of his position. Capts. Greene and Bull, who each commanded parties, displayed excellent conduct and judgment, and are entitled to great credit for their skill and bravery. Two companies of the enemy's skirmishers were literally cut to pieces, if the account of prisoners afterward taken may be believed.

In the afternoon the regiment was placed in reserve and did little, except make an advance under a heavy fire from the enemy's artillery, to support the Eighty-third Ohio and Sixty-seventh Indiana. I believe the advance was made in a manner which met the approval of the general commanding.

On May 17, the regiment took part in the battle of Black River Bridge, and constituted the reserve, when the Sixtieth Tennessee Regiment surrendered to the brigade; three hundred and sixty stand of arms captured, the destruction of which was assigned to this regiment, and they were accordingly destroyed under my supervision.

HDQRS. TWENTY-THIRD REGIMENT WISCONSIN VOLS., Near Vicksburg, Miss., May 25, 1863.I have little to say of the affairs which took place under the walls of the forts near this city on the 20th and 22d instant. Whatever name may be given to them, they were, in reality, nothing more than reconnaissance's in force, and should be so regarded.

On the 20th, my whole regiment was deployed as skirmishers, and did their duty most gallantly. Lieut. A. J. McFarlane was wounded severely while leading his men against the enemy, who were concealed in the fallen timber in front of one of their forts. Later in the day Lieutenant Bull was wounded.

On the 22d, the brigade aided in shutting up a large number of the enemy in one of their forts so closely that they could neither discharge their cannon nor their small-arms. Here Lieutenant Starks was wounded, and Sergeants [Judson A.] Lewis, Company C, and [Daniel] Eder, Company D, were killed. Our gallant soldiers seemed determined to get inside the fort by some means. Not being able to scale its walls, they tried to dig them down, and not succeeding in this, they hailed with cheers the cannon which had been ordered up, and two of the companies of my regiment (B and E) dragged it up the hill to the walls of the fort, where it was most vigorously served. It was too late in the day, however, to accomplish the desired result. Heavy reenforcements poured in to aid the enemy, and all that we could do was, with the aid of a covering brigade, to retire in good order. The fire of musketry was the hottest that I have ever seen, and the bravery of our soldiers under it is beyond all praise.

All of my officers behaved with distinguished gallantry. Lieut.-Col. Vilas and Maj. Hill proved themselves to be brave and skillful leaders, and handled the men entrusted to their charge with much skill.

Being in command of the reserve, my work principally consisted in guarding against attempts of the enemy to turn our right flank, several of which were made, and all of which failed.

Our total killed, wounded, and missing in these engagements were:

Very respectfully, your obedient servant, J. J. GUPPEY, Col., Commanding.

Lieut. R. CONOVER, Acting Assistant Adjutant-Gen.

Source: Official Records CHAP. XXXVI.] BATTLE OF CHAMPION'S HILL, MISS. PAGE 38-37 [Series I. Vol. 24. Part II, Reports. Serial No. 37.]

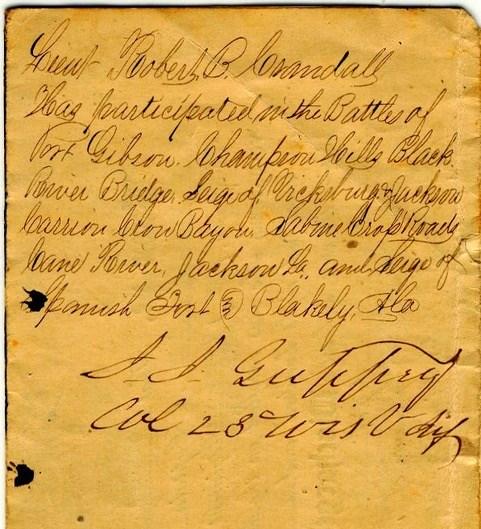

From the collection of Beverly Cabbage

October 2020

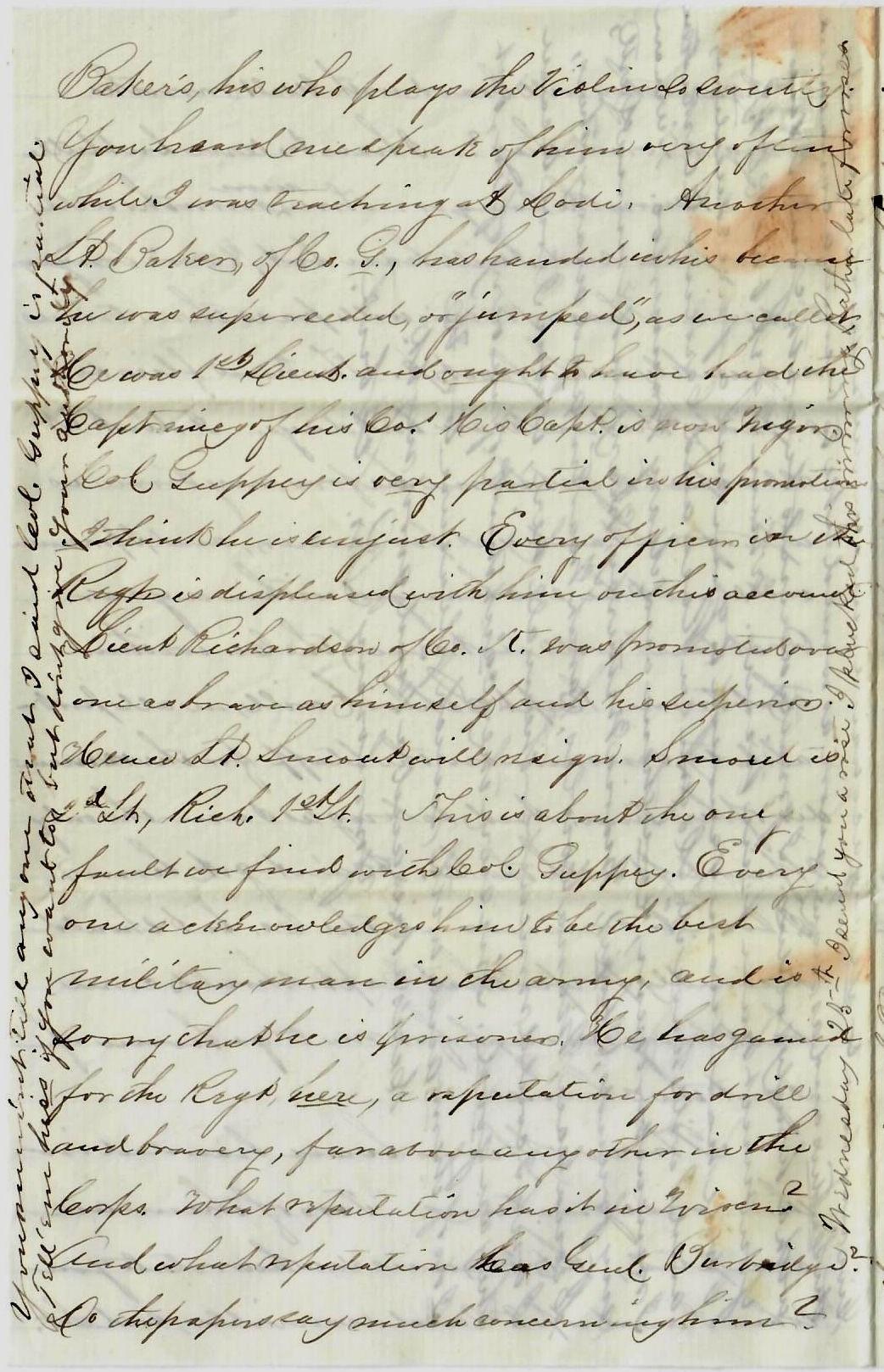

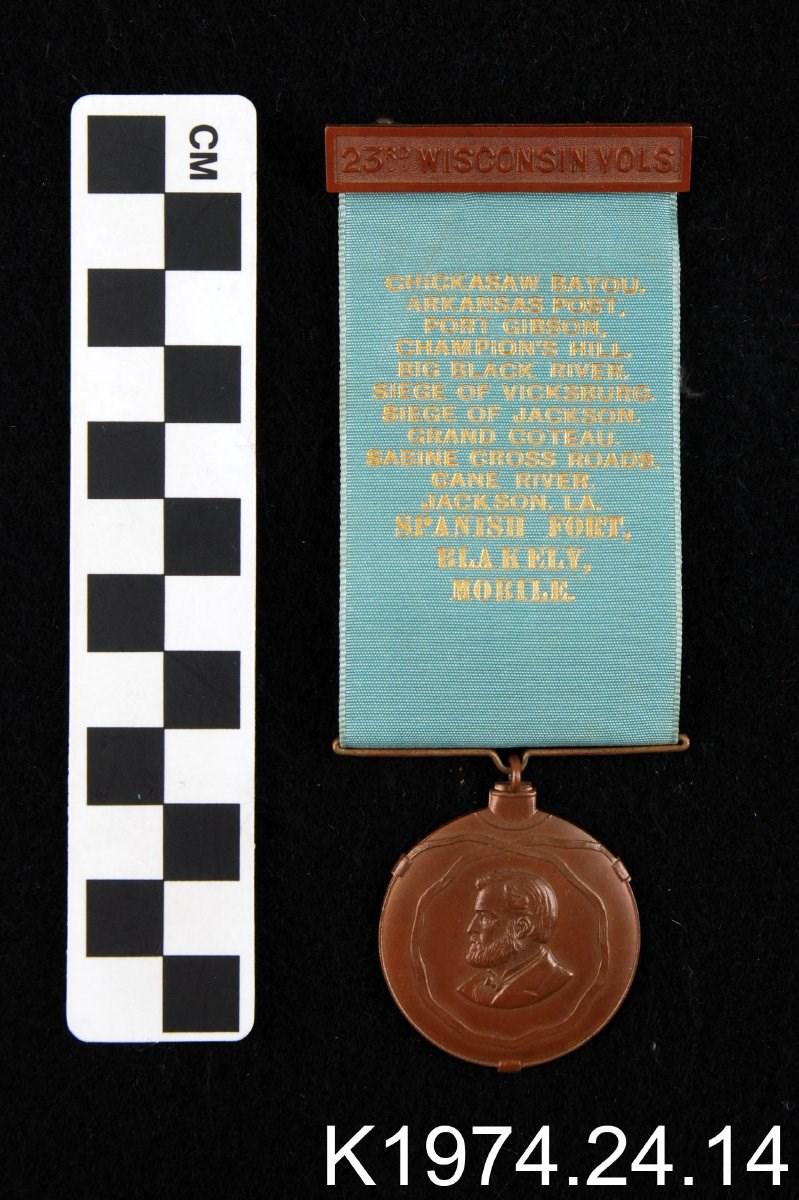

Lieut. Robert B. Crandall has participated in the Battles of Port Gibson, Champion Hills, Black River Bridge, Seige (sic) of Vicksburg & Jackson, Carrion Crow Bayou, Sabine Cross Roads, Cane River, Jackson, La, and Seige (sic) of Spanish Fort & Blakely, Ala. J.J. Guppey, Col 23 Wis Volit.

Col. Guppey was commissioned an officer in the Union Army in 1861 and was assigned to the 10th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. In 1862, he was promoted to Colonel and assumed command of the 23rd Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment at Camp Randall. The regiment, with Guppey in command, later took part in the Battle of Fort Hindman and the Battle of Champion Hill. Guppey later contracted malaria and suffered a wound in battle that incapacitated him for a time. Afterwards, he took part in the Red River Campaign. In 1865, he participated in the Battle of Fort Blakely. Guppey was mustered out of the volunteers on July 4, 1865. On January 13, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Guppey for appointment to the grade of brevet brigadier general of volunteers to rank from March 13, 1865, and the United States Senate confirmed the appointment on March 12, 1866. After the war, Guppey was active in the Wisconsin Army National Guard until retiring in 1893.

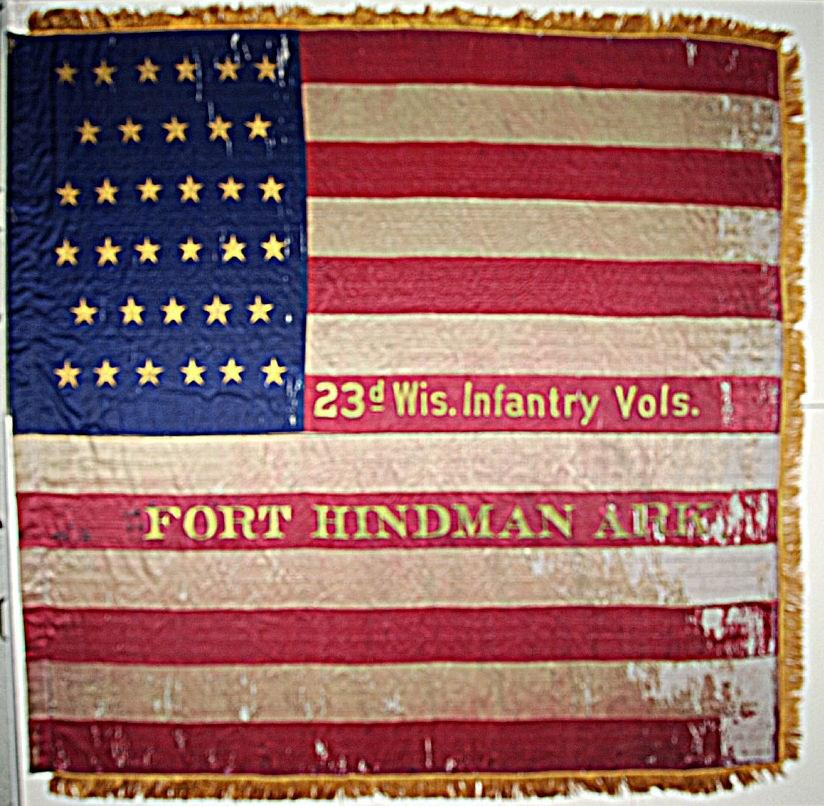

From the collection of the Wisconsin Veterans Museum

Many corps, divisions, brigades, regiments, and even individual companies carried unique flags, many of them designed and sewn by women "back home" who presented the unit with the flag. In a number of cases, the state seal of a regiment would be embroidered or painted onto a flag. A unit that performed well in a battle might get permission to add the name of that battle on its flag, and veteran units might have a halfdozen or more battle names on their banners.

The Battle of Arkansas Post, also known as Battle of Fort Hindman, was fought from January 9 until 11, 1863, near the mouth of the Arkansas at Arkansas Post, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. Although a Union victory, it did not move them any closer to Vicksburg

The Confederate States Army constructed a large, four-sided earthwork fortification near Arkansas Post, on a bluff 25 feet above the north side of the river, forty-five miles downriver from Pine Bluff, to protect the Arkansas River and prevent Union Army passage to Little Rock. The fort commanded a mile view up and downriver. It was a base for disrupting shipping on the Mississippi River. The fort was named Fort Hindman in honor of General Thomas C. Hindman of Arkansas. It was manned by approximately 5,000 men, primarily Texas cavalry, dismounted and redeployed as infantry, and Arkansas infantry, in three brigades under Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Churchill. By the winter of 1862–63, disease and their life at the end of a tenuous supply chain had left the garrison at Fort Hindman in a poor state.

Union Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand was an ambitious politician and had permission from President Abraham Lincoln to launch a corps-sized offensive against Vicksburg from Memphis, Tennessee, hoping for military glory (and subsequent political gain). This plan was at odds with those of Army of the Tennessee commander, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. McClernand ordered Grant's subordinate, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, to join the troops of his corps with McClernand's, calling the two corps the Army of the Mississippi, approximately 33,000 men. On January 4, he launched a combined army-navy movement on Arkansas Post, rather than Vicksburg, as he had told Lincoln (and did not bother to inform Grant or the general in chief, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck).

January 9

Union boats began landing troops near at Notrebe's Plantation, 3 miles below Arkansas Post in the evening of January 9. The troops started up river towards Fort Hindman and Sherman's corps overran the Confederate trenches. The enemy retreated to the protection of the fort, anchored on the east by the Arkansas River, and adjacent rifle-pits running west across the neck of land. By 11:00 am the following morning the remainder of the Union army had gone ashore. Churchill was stunned by the overwhelming size of the Union force and immediately requested reinforcements from his superior, Theophilus H. Holmes. Holmes advised Churchill to “... hold out till help arrived or until all dead.”

On January 10 the Union army moved upriver to fully invest the Confederate garrison. Two brigades from Peter J. Osterhaus' division of George W. Morgan's corps were detached from the main movement of the army. Colonel Daniel W. Lindsey's brigade was put ashore on the riverbank opposite the fort and Colonel John F. De Courcey's brigade was held in reserve near the initial landing site. Morgan advanced Osterhaus (accompanying his remaining brigade) along the levee of the river followed by his remaining division under Andrew J. Smith. Sherman followed with David Stuart's division along the river and sent his other division under Frederick Steele inland to find a flanking route, but failed due to swampy land and impassable roads.[3] The advance of Morgan's column overran the first line of Confederate trenches manned largely by dismounted Texas cavalry.

As McClernand's soldiers moved against the fort, Porter's gunboats; Baron DeKalb, Louisville, and Cincinnati, moved against the fort. The Navy pounded the fort at a range of 400 yards. The Union tinclad Rattler moved in too close, ran aground and took heavy fire at point blank range from the fort. After several hours the Naval bombardment had inflicted heavy losses to the Confederate artillery. Meanwhile, McClernand sent an army lieutenant up a tree to observe if Morgan and Sherman's troops were in place. The lieutenant reported they were in place and ready to assault, but Sherman's troops were still moving into position through muddy swamps. By the time the Navy's attack concluded it was too dark for the infantry to assault although some skirmishing had taken place.

On the morning of January 11 McClernand's forces were deployed in an arc facing Fort Hindman and its riflepits. Running West to East were the divisions of Steele, Stuart, Smith with Osterhaus anchored on the Arkansas River. Churchill's defenses were manned by Colonel James Deshler's brigade on the left and Colonel Robert Garland's brigade on the right. McClernand's infantry attacked around 1:00pm and made little progress at first. At the same time Porter's gunboats moved in to attack aided by Colonel Lindsey's brigade across the river. Within an hour the fort's east face was reduced to rubble and its artillery silenced. Steele's attack on the west was led by the brigades of Brig. Gens. Charles E. Hovey and John M. Thayer with Francis P. Blair, Jr. in reserve. To the east Stuart supported with the brigades of Colonels Giles Smith and Thomas Kilby Smith against the rifle pits of Deshler's Arkansas and Texas soldiers. In the center A.J. Smith spearheaded his attack with Brig. Gen. Stephen G. Burbridge's brigade supported by Colonel William J. Landram. Burbridge's men became embroiled in small arms fight which caused more than 1/3 of all Union casualties. Osterhaus advanced against the fort with Colonel Lionel A. Sheldon's single brigade.

At 4:30pm McClernand was planning to order one massive assault against the defenders when white flags of surrender began to appear. The battle ended with some confusion. Porter's gunboats picked up infantry from Lindsey's brigade and ferried them across the river who climbed into the crumbling remains of Fort Hindman. Porter personally accepted the surrender of Colonel John Dunnington who was in charge of the fort's artillery. General Steele entered the rifle-pits under a flag of truce to discuss surrender with Colonel Deshler. As the two conferred, Deshler noticed Steele's men continually moving closer and demanded they be ordered to stop or he'd open fire again. General Sherman arrived on the scene to personally seek out Churchill. However, Sherman stood by as Churchill and Colonel Garland became involved in an argument over surrendering. Garland claimed he had been ordered to surrender while Churchill denied giving such an order. Colonel Deshler rode up from his front and declared to the group he had not surrendered at all and insisted on renewing the fight. Sherman ended the argument by pointing out the Union forces had all but occupied the Confederate's works. Some Union soldiers had even begun disarming the Confederates. One final scene took place as a Union staff officer rode into the fort and demanded the Navy vacate, so A.J. Smith's infantry could take possession. However, the fort had already been surrendered to Porter. Colonel Dunnington, who had a background in the Navy, conceded a small satisfaction at being able to surrender to a fellow Naval officer instead of the infantry.

The defeat at Arkansas Post cost the Confederacy fully one-fourth of its deployed force in Arkansas, the largest surrender of Rebel troops west of the Mississippi River prior to the final capitulation of the Confederates in 1865. Union forces suffered 1,061 casualties, with 134 killed; Confederate 4,900, almost all by surrender. Although Union losses were high and the victory did not contribute to the capture of Vicksburg, it did eliminate one more impediment to Union shipping on the Mississippi. Grant was furious at McClernand's diversion from his overall campaign strategy, ordered him back to the Mississippi, disbanded the Army of the Mississippi, and assumed personal command of the Vicksburg Campaign.

“Glorious! Glorious! My star is ever in the ascendant. Now, on to Little Rock.” John A. McClernand responding to the victory

That Grant removed McClernand for this reason is a contested point. In his Memoirs (Loc 5013), Gen. W.T. Sherman said that no word was received from Grant until after the battle. On the 13th - when the army rendezvoused at the mouth of the Arkansas River after destroying the fort - McClernand showed Sherman the letter in which Grant disapproved of the plan. Sherman notes that Grant's letter was written before the outcome of the battle was known: “When informed of this, and of the promptness with which it had been executed, he could not but approve.”

The Battle of Port Gibson was fought near Port Gibson, Mississippi, on May 1, 1863, between Union and Confederate forces during the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. The Union Army was led by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and was victorious.

Grant launched his campaign against Vicksburg, Mississippi, in the spring of 1863, starting his army south from Milliken's Bend on the west side of the Mississippi River. He intended to storm Grand Gulf, while his subordinate Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman deceived the main army in Vicksburg by feigning an assault on the Yazoo Bluffs. Grant would then detach the XIII Corps to Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks at Port Hudson, Louisiana, while Sherman hurried to join Grant and James B. McPherson for an inland move against the railroad. The Union fleet, however, failed to silence the Confederate batteries at Grand Gulf. Grant then sailed farther south and began crossing at Bruinsburg, Mississippi, on April 30. Sherman's feint against the Yazoo Bluffs the Battle of Snyder's Bluff was a complete success, and only a single Confederate brigade was detached south.

The only Confederate cavalry in the area, Wirt Adams's regiment, had been ordered away to pursue Grierson's raiders, and Maj. Gen. John S. Bowen performed a reconnaissance in force to determine Grant's intentions. Bowen moved south from Grand Gulf with Green's Brigade and took up a position astride the Rodney road just southwest of Port Gibson near Magnolia Church. A single brigade of reinforcements from Vicksburg under Brig. Gen. Edward D. Tracy arrived later and was posted across the Bruinsburg Road two miles north of Green's position. Baldwin's Brigade arrived later and was positioned in support of Green's Brigade. Onehundred-foot-tall (30 m) hills separated by nearly vertical ravines choked with canebrakes and underbrush rendered Bowen's position tenable, despite the overwhelming Union force heading his way.

The absence of any Confederate cavalry would have a major impact on the campaign. If Bowen had known that Grant's men were landing at Bruinsburg and not Rodney, he would have taken a position on the bluffs above Bruinsburg, denying Grant's army a bridgehead into the area. Federal efforts to push rapidly inland were slowed because Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand had forgotten to issue rations to the men. Despite the resulting delay, however, the Army of the Tennessee moved onto the river bluffs unopposed and pushed rapidly towards Port Gibson. Shortly after midnight on May 1, advanced elements of the 14th Division under Brig. Gen. Eugene A. Carr engaged Confederate pickets near the Shaifer House. Sporadic skirmishing and artillery fire continued until 3 a.m. Wary of Tracy's Brigade to the north, McClernand posted Brig. Gen. Peter J. Osterhaus's 9th Division facing that direction. Having developed each other's positions, the opposing forces sat down and waited for daylight.

General Carr scouted the ground before him and realized that a frontal assault through the canebrakes would be fruitless. He devised a turning movement in which one brigade would move slowly forward through the canebrake, while the second brigade would descend into the Widow's Creek bottoms and strike for the Confederates' left flank. Brig. Gen. Alvin P. Hovey's 12th Division arrived and surged forward just as Carr's men were storming the Confederate position. Both flanks were turned, and Green's men broke and ran. McClernand stopped to reorganize, then launched into a series of grandiose speeches until Grant pointed out that the Confederates had simply withdrawn to a more defendable position. Reinforced by Brig. Gen. A. J. Smith's 10th Division and Stevenson's Brigade of McPherson's XVII Corp, McClernand resumed the pursuit. With 20,000 men crowded into a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) front, McClernand's plan appeared to be to force his way past the Confederate line. A flanking assault by Col. Francis Cockrell's Missourians crumpled the Federal right flank and gave McClernand pause. Sundown found the two sides settling into a stalemate along a broad front on the Rodney Road several miles from Port Gibson.

On the Bruinsburg Road front, Osterhaus had been content to pressure Tracy's command with federal sharpshooters and artillery, occasionally launching an unsupported regiment against the Confederate line. Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson showed up late in the afternoon with John E. Smith's brigade. Donning a cloak to disguise his rank, he reviewed the front lines and quickly devised a turning movement that would render untenable the entire Confederate right flank. Twenty minutes after the troops had been staged for the assault, the Confederates were retreating into the Bayou Pierre bottoms, having left behind several hundred prisoners. The road to his rear now threatened, Bowen commenced retreating through Port Gibson to the north shore of Bayou Pierre.

On May 2, Grant quickly maneuvered Bowen out of position by sending McPherson to cross the Bayou Pierre at a ford several miles upstream. Struck with the realization that McPherson could cut him off from the bridge over the Big Black River, Bowen ordered the formidable defenses at Grand Gulf abandoned, the magazine exploded, and the heavy artillery destroyed. Union gunboats, investigating the nature of the explosion, arrived and took Grand Gulf without a shot. Grant understood the nature of the explosion and rode to Grand Gulf with a small escort, enjoying his first bath in weeks, and celebrating the capture of what would become his central supply depot as he moved inland. As he relaxed, he caught up on correspondence, including a message from Banks that he was nowhere near Port Hudson. Grant's plan to detach McClernand to Banks would have to wait.

Too late to do anything more than affirm Bowen's decision, Maj. Gen. William W. Loring arrived and took command. Heavy rear-guard activity took place as the Confederates scrambled to remove their force across the narrow bridge. Advanced elements of the XVII Corps arrived in time to save the bridge from destruction. The ragtag army that had fought so well at Port Gibson would not rest until they had entered the Warrenton fortifications nearly ten miles away. Here they began improving the fortifications along the roads to Vicksburg, expecting that Grant would be close behind. Grant, however, would have other plans; the roads on the west bank of the Big Black River were open all the way to the Mississippi state capital and the critical rail link to Vicksburg. Against this target, Grant poised his army to strike.

The Battle of Jackson, fought on May 14, 1863, in Jackson, Mississippi, was part of the Vicksburg Campaign in the American Civil War. Union commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee defeated elements of the Confederate Department of the West, commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston, seizing the city, cutting supply lines, and opening the path to the west and the Siege of Vicksburg.

On May 9, Gen. Johnston received a dispatch from the Confederate Secretary of War directing him to “proceed at once to Mississippi and take chief command of the forces in the field.” As he arrived in Jackson on May 13, from Middle Tennessee, he learned that two army corps from the Union Army of the Tennessee the XV, under Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, and the XVII, under Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson were advancing on Jackson, intending to cut the city and the railroads off from Vicksburg, Mississippi which was a major port on the Mississippi River. These corps, under the overall command of Grant, had crossed the Mississippi River south of Vicksburg and driven northeast toward Jackson. The railroad connections were to be cut to isolate the Vicksburg garrison. And if the Confederate troops in Jackson were defeated, they would be unable to threaten Grant's flank or rear during his eventual assault on Vicksburg.

Johnston consulted with the local commander, Brig. Gen. John Gregg, and learned that only about 6,000 troops were available to defend the town. Johnston ordered the evacuation of Jackson, but Gregg was to defend Jackson until the evacuation was completed. By 10 a.m., both Union army corps were near Jackson and had engaged the enemy. Rain, Confederate resistance, and poor defenses prevented heavy fighting until around 11 a.m., when Union forces attacked in numbers and slowly but surely pushed the enemy back. In mid-afternoon, Johnston informed Gregg that the evacuation was complete and that he should disengage and follow.[1]

Soon after, Union troops entered Jackson and had a celebration in the Bowman House, hosted by Grant, who had been traveling with Sherman's corps. They then burned part of the town and cut the railroad connections with Vicksburg. Johnston's evacuation of Jackson was premature because he could, by late on May 14, have had 11,000 troops at his disposal and by the morning of May 15, another 4,000. The fall of the former Mississippi state capital was a blow to Confederate morale.

General Sherman appointed Brig. Gen. Joseph A. Mower to the position of military governor of Jackson and ordered him to destroy all facilities that could benefit the war effort. With the discovery of a large supply of rum, it was impossible for Mower's Brigade to keep order among the mass of soldiers and camp followers, and many acts of pillage took place. Grant left Jackson on the afternoon of May 15 and proceeded to Clinton, Mississippi. On the morning of May 16 he sent orders for Sherman to move out of Jackson as soon as the destruction was complete. Sherman marched almost immediately, clearing the city by 10 a.m.. By nightfall on May 16, Sherman's corps reached Bolton, Mississippi, and the Confederacy had reoccupied what remained of Jackson. Jackson had been destroyed as a transportation center and the war industries were crushed. But more importantly the Confederate concentration of men and materials aimed at saving Vicksburg were scattered. Sherman would later lead an expedition against Jackson following the fall of Vicksburg to clear Johnston's relief force from the area.

The Battle of Champion Hill of May 16, 1863, was the pivotal battle in the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Union Army commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confederate States Army under Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton and defeated it twenty miles to the east of Vicksburg, Mississippi, leading inevitably to the Siege of Vicksburg and surrender. The battle is also known as Baker's Creek

Following the Union occupation of Jackson, Mississippi, on May 14, both Confederate and Federal forces made plans for future operations. General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding all Confederate forces in Mississippi, retreated with most of his army up the Canton Road. However, he ordered Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, commanding three divisions totaling about 23,000 men, to leave Edwards Station and attack the Federals at Clinton. Pemberton and his generals felt that Johnston's plan was likely to result in disaster and decided instead to attack the Union supply trains moving from Grand Gulf to Raymond. On May 16, however, Pemberton received another message from Johnston repeating his former orders. Pemberton had already started after the supply trains and was on the Raymond-Edwards Road, with his rear at a crossroads one-third mile south of the crest of Champion Hill. When he obediently ordered a countermarch, his rear, including his supply wagons, had become the vanguard of his attack.

Around 7 am on May 16, Union forces engaged the Confederates and the Battle of Champion Hill began. Pemberton's force formed into a three-mile (5 km)-long defensive line that ran southwest to northeast along a crest of a ridge overlooking Jackson Creek. Grant wrote in his Personal Memoirs, “... where Pemberton had chosen his position to receive us, whether taken by accident or design, was well selected. It is one of the highest points in that section, and commanded all the ground in the range.”

Pemberton was unaware that one of the three Union columns was moving along the Jackson Road against his unprotected left flank on Champion Hill. Pemberton posted Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Lee's Alabama brigade on Champion Hill where they could watch for a Union column reported moving on the crossroads. Lee soon spotted the Union troops and they in turn saw him. If the enemy force was not stopped, it would cut the Confederates off from their Vicksburg base. Pemberton was warned of the Union movement and sent troops to defend his left flank. Union forces at the Champion House moved into action and their artillery began firing.

When Grant arrived at Champion Hill at about 10:00 a.m., he ordered an attack to begin. John A. McClernand's corps attacked on the left and James B. McPherson's on the right. William T. Sherman's corps was well behind the others, departing from Jackson. By 11:30 a.m., the Union forces had reached the Confederate's main line. At 1:00 p.m., they took the crest, the troops from Carter L. Stevenson's division retiring in disorder. McPherson's corps swept forward, capturing the crossroads and closing the Jackson Road escape route. The division of John S. Bowen counterattacked in support of Stevenson, pushing the Federals back beyond the Champion Hill crest before their surge was halted. However, they were too few to hold the position. Pemberton directed William W. Loring to send forces from the southern area of the line, where they were only lightly engaged with McClernand's ineffective attack, to reinforce the Hill. However, Loring refused to budge, citing a strong Union presence to his front.

Grant now counterattacked, committing his forces that had just arrived from Clinton by way of Bolton. Pemberton's men could not resist this assault, and he ordered his men to use the one escape route still open, the Raymond Road crossing of Bakers Creek. By now, Loring had decided to obey Pemberton's order and was marching toward the fighting by a circuitous route that kept them out of action. Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman's brigade formed the rearguard and held at all costs, including the death of Tilghman, killed by artillery fire. Late in the afternoon, Grant's troops seized the Bakers Creek Bridge, and by midnight they had occupied Edwards. The Confederates fell back to a defensive position at the Big Black River in front of Vicksburg. The Battle of Big Black River Bridge the next day would be the final chance for Pemberton to escape.

Champion Hill was a bloody and decisive Union victory. In his Personal Memoirs, Grant observed, “While a battle is raging, one can see his enemy mowed down by the thousand, or the ten thousand, with great composure; but after the battle these scenes are distressing, and one is naturally disposed to alleviate the sufferings of an enemy as a friend.”

Grant criticized the lack of fighting spirit of McClernand, a rival for Union Army leadership, because he had not killed or captured Pemberton's entire force. McClernand's casualties were low on the Union left flank (south); McPherson's on the right constituted the bulk of the Union losses, about 2,500. The Confederates suffered about 3,800 casualties. According to diarist William Eddington, so many Confederate horses had been killed, Union soldiers could not easily approach the abandoned batteries; after the Battle of Big Black River Bridge, Union horses were sent back to recover them. The Confederates' effective loss included most of Loring's division, which had marched off on its own to join Joseph E. Johnston in Jackson.

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of the part taken by this regiment in the battles that have taken place since the army landed in the State of Mississippi [only portions related to the Battle of Champion Hill are included by the editor]:

On May 16, the regiment was engaged in the battle of Midway Hill. In the evening five companies were deployed as skirmishers, and afterward two companies were added to them. They did most efficient service in driving the enemy's skirmishers and gaining knowledge of his position. Captains Greene and Bull, who each commanded parties, displayed excellent conduct and judgment, and are entitled to great credit for their skill and bravery. Two companies of the enemy's skirmishers were literally cut to pieces, if the account of prisoners afterward taken may be believed.

In the afternoon the regiment was placed in reserve and did little, except make an advance under a heavy fire from the enemy's artillery, to support the Eighty-third Ohio and Sixty-seventh Indiana. I believe the advance was made in a manner which met the approval of the general commanding. On May 17, the regiment took part in the battle of Black River Bridge, and constituted the reserve, when the Sixtieth Tennessee Regiment surrendered to the brigade; three hundred and sixty stand of arms captured, the destruction of which was assigned to this regiment, and they were accordingly destroyed under my supervision.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

J. J. GUPPEY, Colonel, Commanding.The Battle of Big Black River Bridge was fought on May 17, 1863, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. After a Union army commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant defeated Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton's Confederate army at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, Pemberton ordered Brigadier General John S. Bowen to hold a rear guard at the crossing of the Big Black River to buy time for the Confederate army to regroup. Union troops commanded by Major General John McClernand pursued the Confederates, and encountered Bowen's rear guard. A Union charge quickly broke the Confederate position, and during the retreat and river crossing, a rout ensued.

Many Confederate soldiers were captured, and 18 Confederate cannons were taken by the Union troops. The retreating Confederates burned both the railroad bridge over the Big Black River, as well as a steamboat that had been serving as a bridge. The surviving Confederate soldiers entered the fortifications at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and the Siege of Vicksburg began the next day.

On the night of the 16th, after the defeat at Champion Hill, Pemberton formed a line at the crossing of the Big Black River in order to buy time for his army. For this rear guard, Pemberton selected the Missouri troops of Bowen's division, Brigadier General John C. Vaughn's Tennessee brigade, and the 4th Mississippi Infantry Regiment.This force numbered about 5,000 men. The left of the Confederate line was held by Brigadier General Martin E. Green's brigade of Bowen's division, Vaughn's brigade held the center, Bowen's other brigade, commanded by Colonel Francis M. Cockrell, was positioned on the Confederate right, and the 4th Mississippi was placed between Cockrell and Vaughn. Vaughn's brigade was composed of inexperienced conscripts, and Bowen's division had seen heavy fighting at Champion Hill. The Confederate line was supported by Wade's Missouri Battery, Landis' Missouri Battery, and Guibor's Missouri Battery.A railroad ran through the Confederate position, and the river could be crossed either over the railroad bridge or over a steamboat that had been positioned crossways across the river, creating a makeshift bridge.