Sammy Vincent Doublet

Tutor: Dr Stamatis Zografos

Bartlett School ofArchitecture, UCL History and Theory ofArchitecture Dissertation

February 2024

Word Count: 5195

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices:

Metal Detectorists Challenging Dominant Discourses from the heritage industry through alternative archives and methods

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

Figure 1: Avoided Object, 1995 - Cornelia Parker, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens

Table of Contents Introduction 5 01 - Hanging artefacts on the ‘washing line’ - establishing the metal detecting forum as a community archive 9 13 02 - What is the heritage institution? Challenging license and intellectual property through archontic production 03 - How to use the forum as a model for heritage discourse 04 - Towards a participatory and inclusive heritage 11 Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices 18 Appendix - Conversations with Ed Wilson, Environment Agency 20 23 Bibliography

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

Introduction 4

Figure 2: Miscellaneous brooches, coins and buckles from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and various artefacts posted on the ‘Finds Identification’ subforum on metaldetectingforum.co.uk

INTRODUCTION

Cornelia Parker’s installation in the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens is a hanging assembly of objects, scavenged together by the artist with a metal detector. A collection of metal objects that - had they not been assembled in such a way - would not have been given any attention. Metal Detecting in the subsoil, much like archaeology, is a practice that sits on a mountain of discarded, unseen treasures.

What does heritage mean, now?

Who has the right to decide what cultural objects form part of a heritage canon?

Does heritage need to be ‘done’ differently?

Issues of selective tradition and who owns the past have been debated often, but not so specifically within the relationship between metal detectorists and archaeologists - two different bodies that walk the same landscapes in the hope of ‘revealing the unknown from the soil’1. This essay aims to understand how heritage can evolve to current contexts by looking through the lense of the metal detectorist in archival practice.

Commodifying Culture?

The term ‘heritage professional’ is used as a blanket term for those working to protect heritage - archivists, librarians, but - namely in this context - archaeologists. Making heritage a ‘profession’ suggests that the past is profitable - it can be sold or commodified. Commodifying cultural heritage has long-debated ethical implications - who owns the past and who decides what is valuable to cultural memory? To commodify is to create a product that has value and can be exchanged - suggesting a form of knowledge exchange where the object gets manipulated or reappropriated.

Within archaeology - the study of history through landscape excavation and object retrieval - this question becomes who decides what is ‘treasure’. Because artefacts are treated as ‘Portable Antiquities’, they can be removed from contexts and curated within display boxes of museums and heritage institutions - forming part of a selective archive used by curators to form a heritage canon.

A portable culture implies the risk that in the wrong hands, the antiquity gets sold off to the highest bidder, removing it from its inherent historical and landscape contexts before its cultural value can be assessedraising concerns about culture as commodity and its destruction of a shared cultural memory.

This leads to the notion of heritage and cultural protection. Archaeologists legitimise their selective archiving by framing it as a form of cultural protection‘a lot of what we defend as ‘our heritage’ is in fact ‘my heritage’, though many private owners choose to justify their private ownership by denying it’2. Custodianship over archaeological heritage is tied to notions of ownership - who owns the license or copyright over an artefact generally tends to supervise public exposure to the past.

Those that select the archive have the power to shape what is maintained in cultural memory.

The Metal Detectorist

This is where metal detectorists come in.

Metal Detecting, practiced by over 20,000 people within the UK, involves using a magnetic-coiled instrument to detect the presence of metal in the subsoil. As a hobby that directly deals with objects from the past within a landscape context, it has similarities in practice to archaeology. Distinctions, however, can be made between the two groups about their motivations for researching and digging, what they consider ‘heritage’ and what they choose to do with that artefact. The Portable Antiquities Scheme was set up alongside the Treasure Act 1996, and is a digital archive that documents all of the archaeological finds made and reported by the general public (mostly metal detectorists). The process encourages detectorists to report their finds to a ‘Finds Liaison Officer’, who is usually within the local authority of the detecting permission. They will then record the object and assess whether it has value on the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) database. The object then gets returned to the finder. This tends to be quite a long, bureaucratic process, with detectorists and land-owners alike becoming impatient. The exchange of knowledge from the hands of the hobbyist to the professional can feel like the amateur is letting go of their prize - removing their agency in contributing to shared cultural memory.

5 Introduction Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

1Edward Wilson, video call to author, November 10, 2023

2 Uzzell, D.L. (1992) Heritage interpretation. London: Belhaven, 17

Introduction Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices 6

Figure 3: A still from the BBC comedy series ‘Detectorists’, showing a saxon burial that is frustratingly undiscovered by the protagonists Lance and Andy. Metal detecting has long been viewed in a negative light, but the value of detectorists to heritage has been highlighted through television shows and articles that have popularised the hobby in contemporary times.

Despite the PAS being a successful catalyst for detectorists’ contributions to archaeological record, this essay will argue that the digital archive is not neutral, and it does create a heritage canon. The selective tradition of the archive, this essay argues, must manifest into an open source, deregulated repository of resources that frees up interactions with heritage and history.

The metal detecting community have forever been cast negatively as ‘looters’ of sensitive archaeological landscapes - as such, this essay argues that digital space is one of the only spaces the community of metal detectorists can truly claim as their own. This essay is concerned with archives, and extends this concept to the online forum as a case study and dominant conduit for community within the hobby, arguably a deregulated archive-repository of research that democratises heritage practice.

Academic Context

Studying archives and their biases is nothing new. The Algerian-French philosopher Jacques Derrida talks about the selective tradition in archival practice, about the creators of the archive as ‘archons’ and how these powerful beings command what is to be preserved - he call this process the ‘archontic power’3. This implies that culture and history are canonised, creating a selective shared memory.

This essay challenges canons and the discourses that archives generate. These themes are pivotal to the media professor Abigail De Kosnik’s philosophy in Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom, which is used as a springboard for this essay’s challenge to biased selective tradition within the heritage industry.

What this essay aims to do differently is propose the metal detecting hobby as a community-based approach to archaeological record. It confronts the idea of the traditional archive as a place for forgetting and exclusivity, and instead explores the online metal detecting forum as a digital repository of resources - a participatory medium where users contribute to an evolving heritage, rather than consume a biased canon with no hope of contribution.

The research question is, therefore, Cultural artefacts have always been preserved for the public by archaeologists in traditional memory institutions, but how can digital community archives - like metal detecting forums - provide a framework to increase the importance of heritage in public consciousness?

Dissertation Structure

The essay will introduce the concept of the metal detecting forum as a community archive, discussing how this digital platform is infrastructured to enable open cultural discussion. The ‘openness’ of these discussion channels will be elaborated on as the essay tries to unpick the concept of licensing, ownership and custodianship over the past in relation to these kinds of open source archive and will analyse archaeologists’ efforts to expand community engagement with heritage. The essay will then try to use the digital forum as a framework to understand how to better engage publics with the past.

The metal detecting forum, this essay argues, is an archive that allows hobbyists to combine archaeological tools, such as LiDAR data, with their own experiences of landscape and treasure. This idea has similarities to contemporary composition theory, emphasised in Stacey Waite’s Cultivating the Scavenger, an essay which advocates for the benefits of combining both academic and narrative-based writing. The detectorist ‘scavenges’ for treasure, and combines this phenomenology of ‘field-walking’ in the landscape with scavenged or re-appropriated archaeological methods. This essay will honour the detectorists by appropriating a ‘scavenger methodology’ within its composition.

Each chapter and each argument has manifested from the scavenging-together of academic writing and messy, narrative-based forum threads. The opportunity will be taken to juxtapose the architecture of the forum threads with academic writings on composition, archival practice, and copyright, helping to convey the opportunities that the metal detecting forum brings to contemporary heritage practice.

This essay aims to set up a dialogue about a participatory, inclusive heritage through an analysis of authorship, copyright and open-access archives in the metal detecting community.

7 Introduction Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

3Derrida, Jacques., and Eric. Prenowitz. ArchiveFever:AFreudianImpression/JacquesDerrida;TranslatedbyEricPrenowitz.Chicago ; University of Chicago Press, 1996, 3

Hanging artefacts on ‘the washing line’ Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices A B C

8

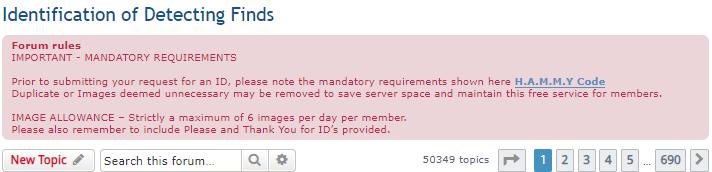

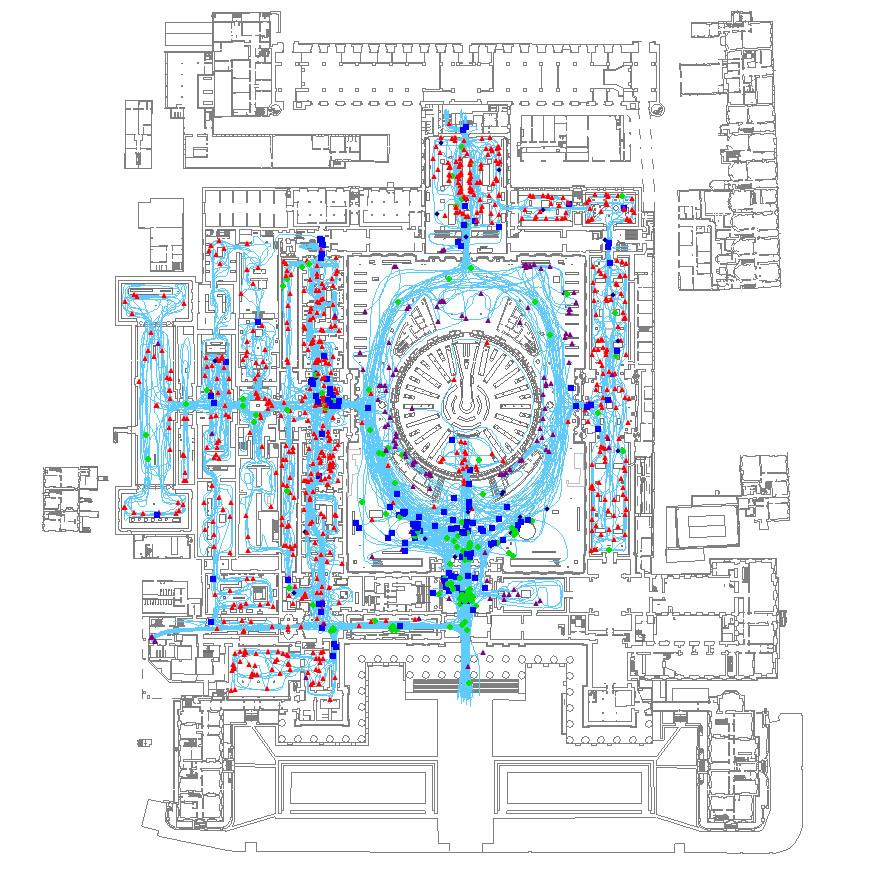

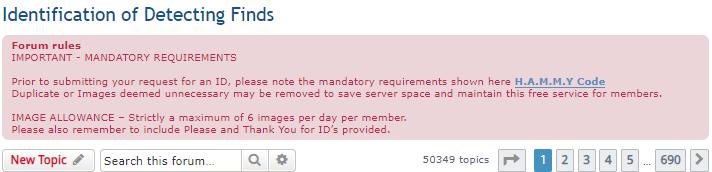

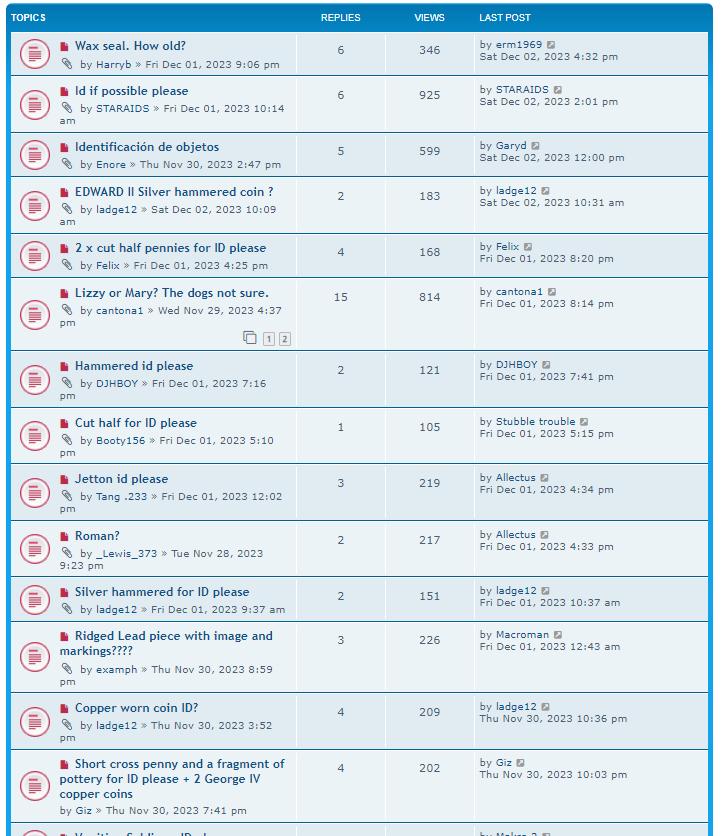

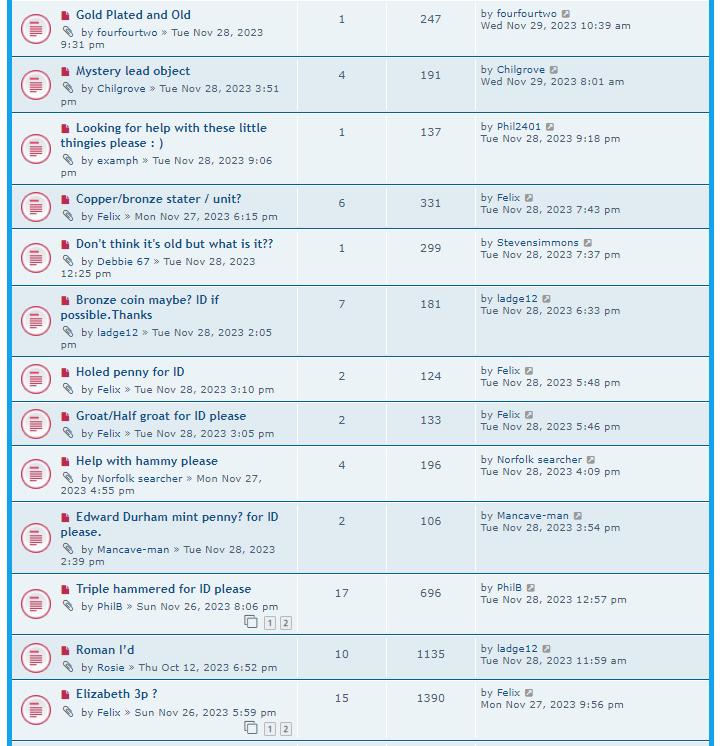

Figure 4: The home page of metaldetectingforum.com, showing (A) the sub-forum catologue, (B) the keyword search, and (C) the latest threads

01 - HANGING ARTEFACTS ON THE ‘WASHING LINE’ - ESTABLISHING THE METAL DETECTING FORUM AS A COMMUNITY ARCHIVE

Firstly, it is important to discuss how the metal detecting forum can be understood as an archive.

In the ‘selective tradition’ Derrida simplifies archives as ‘that place which is their house …that official documents are filed. The archons are first of all the documents’ guardians.’ He goes on to say that in the act of archiving ‘order is no longer assured’4 regarding the institutionalisation of documents, objects, etc, implying that whether an object gets consigned to the archive depends on the biases of the guardians. In a selective tradition, objects get judged by the archons or guardians as whether they have value in the collection, arguably preserving only a fraction of the works in cultural memory. The forum is a storage of digital objects and culture, but challenges this idea of selectivity, removing archontic power and focusing on unbiased, usergenerated content.

A Digital Community Archive

The metal detecting forum is, fundamentally, an online space that contains user-generated threads to discuss topics related to the practice of metal detecting (Figure 4: Labelled C). The platform can be considered a digital community archive because it is managed by a group of people, an administrative team, much like other digital cooperatives and archives. It depends, however, on how the digital space subverts the ‘archontic power’5 of the traditional archive. Within the forum, background moderators create the platform for its member-collaborators. They control the input of these members - so that discussions surrounding artefacts and permissions stay on topic and the threads are useful - but maintain a liberal space for contributions in the style of discussion threads about heritage. The moderators – most often founders of the online metal detecting forum – give legitimacy to the platform as a ‘safe space’ for hobbyists by setting rules for discussion and vetting messages in the online community.

De Kosnik writes in her book Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom about the importance of ‘Archive Elves’ in creating these platforms for creative collaboration – saying that

‘labor that appears to lack three-dimensional form ...is nevertheless real work.’6

The founders and moderators of the metal detecting forums always work voluntarily, but this doesn’t mean that the creation of these discussion channels is merely ‘recreation’ for them – it is labour. A platform with regulations created by ‘moderators’ or ‘admin’ maintains importance for digital cultural memory; voluntary admin act as archons that create a dedicated space for the metal detecting hobby.

Discussion is respectful yet open and preserves the intellectual property of its members.

In De Kosnik’s chapter ‘Archive Elves’, she characterises them as digital stagehands, working backstage to help ‘make the magic happen’ or put works ‘on the line like laundry’7. This comparison frames digital archive moderators as ‘disembodied forces’ - somehow the act of structuring creativity is not to be seen by the collaborators of the archive. Providing contributors with a platform for their work requires smooth, silent operation by the backroom staff. Within the forum, however, moderators can be present within digital discussion channels. Member-collaborators can interact with the founders and share discussions on heritage on an equal footing, implying little hierarchy in this archive, contrary to a selective tradition which has powerful archons at the heart of archive creation.

It is important to use this characterisation of the forum ‘admin’ as it legitimises digital forum labour as a very real form of ‘creative infrastructuring’ – it allows the online forum to be discussed as a digital archive, with members being classed as creative archons that are given a platform to ‘air out’ their treasures and experiences.

Taxonomy and power structures

Amongst this infrastructuring, the forum lacks complete taxonomy within its discussion threads, making it difficult to see certain links between the forum and the traditional archive. Objects of discussion are retrieved through a ‘keyword search’ (Figure 4: labelled B), and these conversations are found through links to subthreads entitled ‘Finds Identification’ or ‘Detecting Research’ for example (sub-forums labelled A). This dismissal of traditional order will be discussed later in the essay, as the text aims to dismantle the power that archons give themselves in inherent structures and discourses within the archive.

4Derrida, Jacques., and Eric. Prenowitz. ArchiveFever:AFreudianImpression/JacquesDerrida;TranslatedbyEricPrenowitz.Chicago ; University of Chicago Press, 1996, 5

5Derrida, Prenowitz, ArchiveFever:AFreudianImpression,pp.3

6Abigail De Kosnik, “Archive Elves,” in RogueArchives:DigitalCulturalMemoryandMediaFandom, MIT Press, 2016, pp.126.

7De Kosnik, “Archive Elves,” in RogueArchives,pp.127

9

Hanging artefacts on ‘the washing line’

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

10

Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

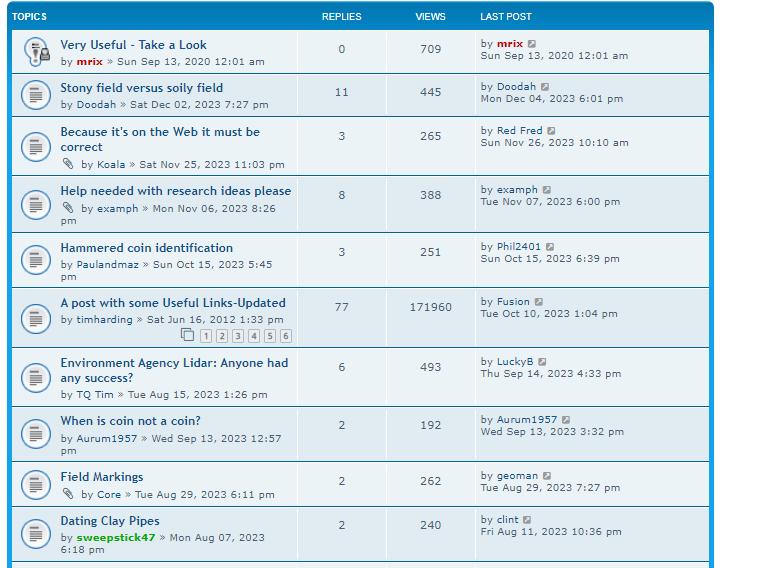

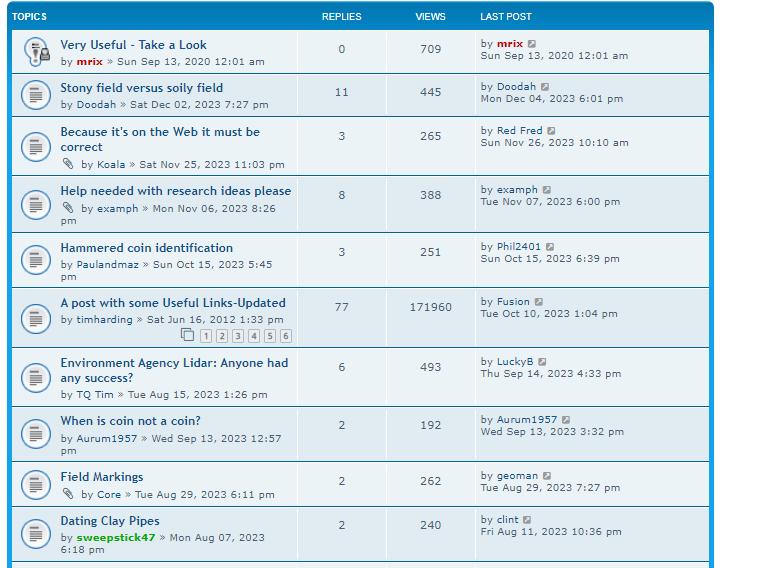

Figure 5: The forum architecture of archontic production, displayed in the ‘similar searches’ section and the threads of Finds Identification with many interactions.

Scavenged

What is the heritage institution? Challenging license and intellectual property through archontic production

02 - WHAT IS THE HERITAGE INSTITUTION?

CHALLENGING LICENSE AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY THROUGH ARCHONTIC PRODUCTION

Mapping the traditional archive

Who owns knowledge? Is there any value in restricting knowledge or being custodians over it? Academic discourse within archaeology is enshrined in ownership, secrecy and carefulness – concealing information about cultural artefacts to protect the landscape context before releasing information in a report or record, or curating heritage artefacts in display boxes.

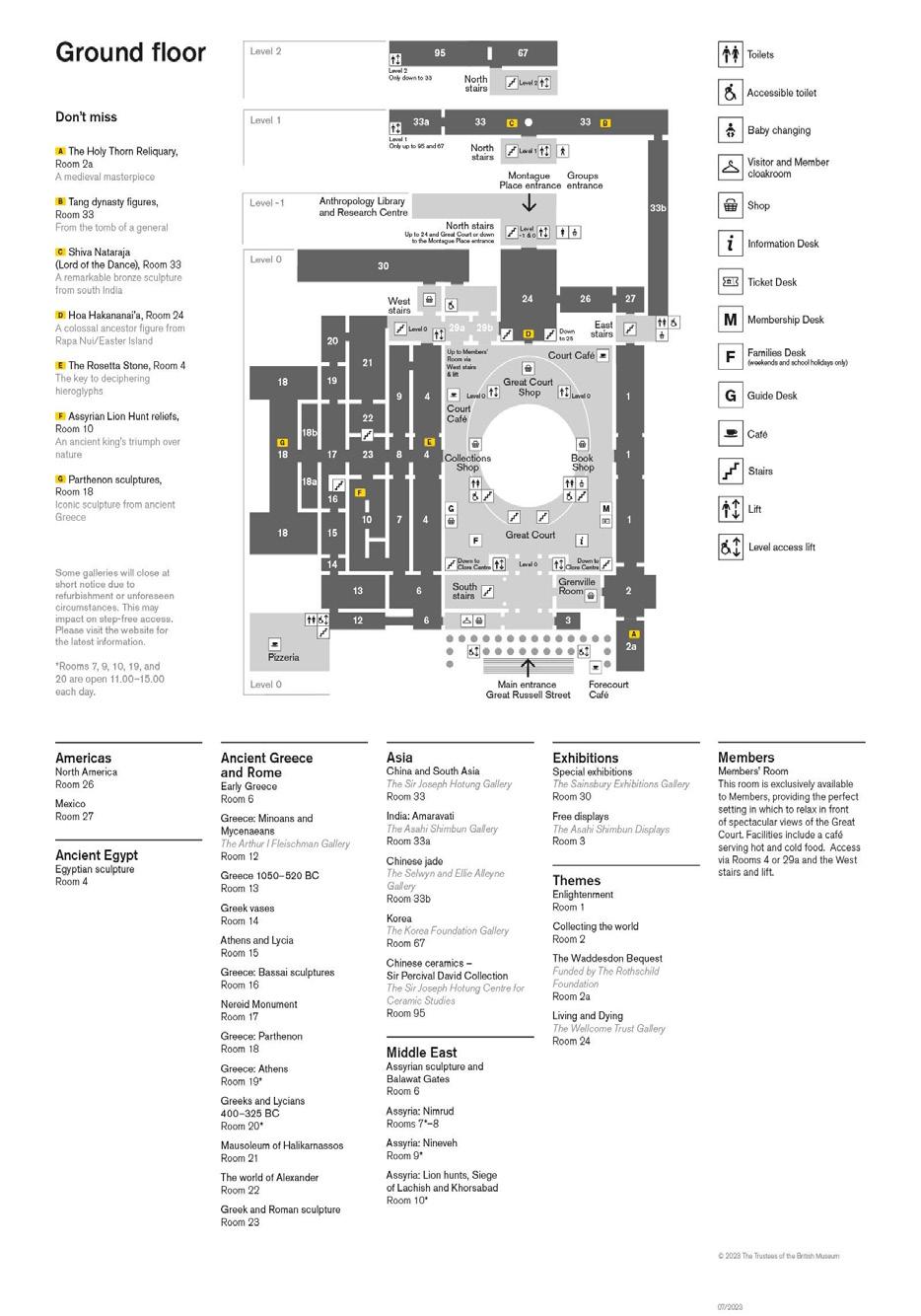

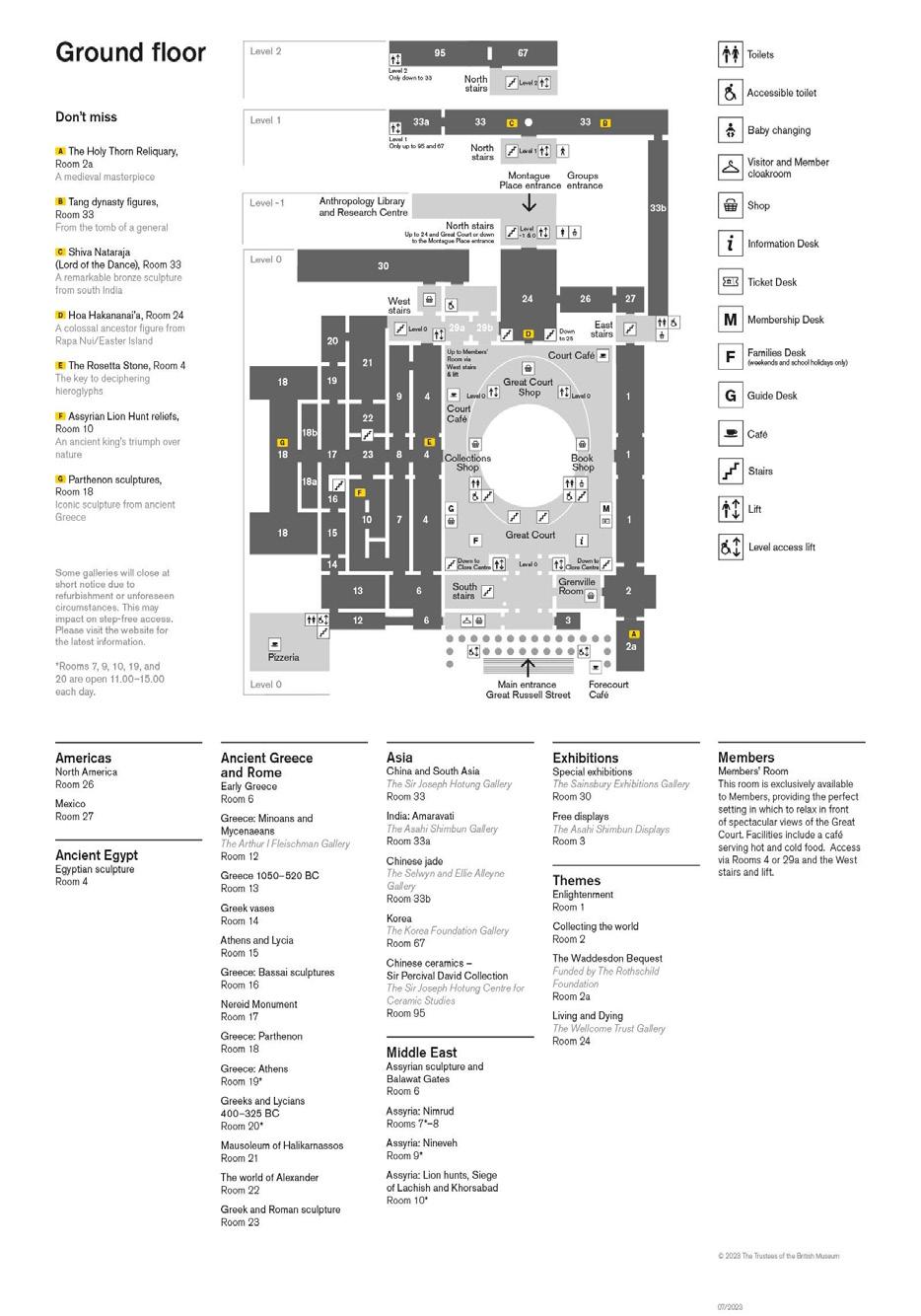

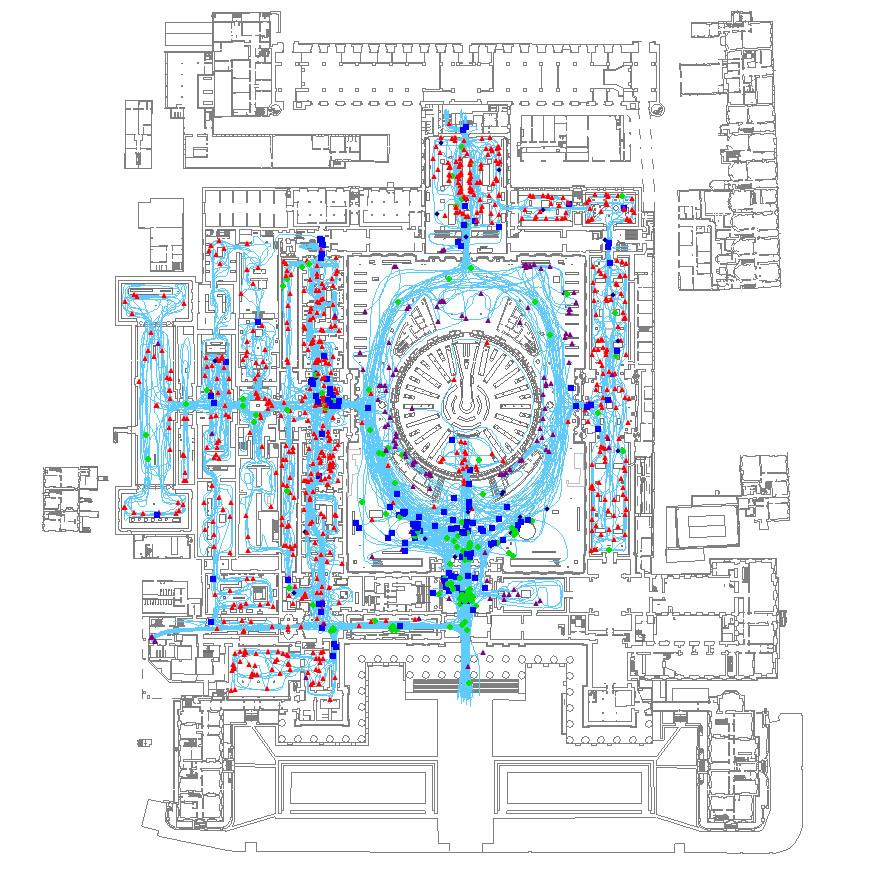

The online forum is an important case study, as it can operate as a launchpad for re-evaluating interactions with the past. It is a liberal medium that counters rigorous privacy and dissolves ‘intellectual property’. The metal detectorist forum can be framed as a community archive as it displays similar characteristics and motivations described by De Kosnik. These digital spaces indirectly question the ‘supremacy and authority of traditional canons’8 of heritage by facilitating liberal discussion in open threads, away from the tight regulation of academic study. What forms this community archive-making is arguably the democratisation of archaeological discourse. If the forum is considered an archive, the members become archons, and the many threads that provide discussion around cultural artefacts become outputs of archontic production.

In Rogue Archives, De Kosnik cites Gaynor Bagnall’s analogy for public experience of the past. Bagnall draws up an image of the traditional cultural institution – the museum – as the primary archive. The initial intention is that consumers ‘map the site physically’9 by moving through the space, and once this initial journey is made, the consumer creates an emotional map of the archive – deciding what they will become ‘fans’ of and what will be used as ‘the bases for their own performances’10. This creates an ongoing ‘Russian Doll’ archival practice which acts as one of the frameworks that users operate within when creating new knowledge topics. De Kosnik wants consumers of licensed works to become users, enabling versioning to occur. To ‘version’ a work is to remix, to appropriate aspects of it to contribute to a repertoire - this transforms the archive from a static place (a place of consignment, of getting rid-of) to a repository of resources to call on for research.

Encouraging a dynamic archive, one which operates as a force for the present, is what the metal detecting forum achieves.

11

Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

What is the heritage institution? Challenging license and intellectual property through archontic production

Scavenged

Figure 6: Map and circulation map of the British Museum

8De Kosnik, “Archival Styles,” in RogueArchives, pp.87.

9De Kosnik, “Archontic Production: Free Culture and Free Software as Versioning,” in RogueArchives, pp.278 10ibid.

The

Forum, Open-source Archiving and Free Culture

Often within a sub-forum entitled ‘Finds Identification’, a thread starter will post an image of an artefact they have found whilst detecting. From this, individuals will post their thoughts on the find, starting a discussion about the object. Users have the opportunity here to talk about their own expertise on finds, as well as discussing their experiences of detecting as a wider hobby. These discussions can then sprout further topics, and then the forum thread can deviate organically. This process of deviation references the ‘concentric rings of archives’ that De Kosnik appreciates. What is produced is a repertoire of expertise and information from a variety of knowledgeable members.

Despite referencing these rings, the forum-archive is not like the ‘fanfiction’ database that De Kosnik’s research centres around – it is a community archive that re-evaluates the journey of the heritage artefact in cultural memory. Within digital fan-fiction archives, for instance, works that get appropriated by fans have often made copyright claims or lawsuits against those that use the content of the stories. In the forum, issues of ‘copyright’ and ‘intellectual property’ are eliminated because the archive is completely user-generated –heritage and culture are presented in the form of open threads, rather than being institutionalised or curated before public even get exposed to it. Forums ‘cut out the middleman’ by eliminating the ‘archontic power’ of the archaeologists and curators of heritage institutions – that is to say, there is no figure of authority within the community archive, and no singular custodian over heritage.

Free Culture is extremely relevant to this discussion because it talks about how ‘users’ or ‘archons’ challenge the notion of copyright to contribute to a shared cultural database, rather than simply consuming culture that is owned by a singular authority. De Kosnik sees free culture as

‘

…a movement composed of everyday cultural practices, of minor and major appropriations and transmediations performed by individuals and collectives … simply doing what they wished to do with the new media tools, platforms, and networks available to them.’11

This implies that every user having active interactions with heritage, whether that be an archaeologist making a report or a hobbyist making a post online, creates a version - or retelling - of the original historical record. Creating an open-source archive allows the creation of a shared heritage that is always being interpreted in different ways, making the past more relevant and accessible for people.

There is a feeling here that the number of versions or interpretations of cultural artefacts is directly proportional to the significance of an object. Specifically, cultural heritage can be more important if it is consumed more – an artefact gets greater exposure to ‘users’ who appropriate the object for their own discussions or research. Within De Kosnik’s text, there is specific weight placed on the reappropriation of the ‘copyright’ concept to actually enable re-use, rather than imprison information within the private realm. The same regulation that is used for ensuring privatisation of intellectual property, is used to facilitate public versioning – called ‘Copyleft’.

Copyleft encourages an open-source archival practice, and encourages community custodianship over heritage – this follows four ‘essential freedoms’ for open-source activity highlighted by De Kosnik:

‘Freedom 0: The freedom to run a program as you wish.

Freedom 1: The freedom to study the source of the program and change it so that it does the work that you wish (i.e., the freedom to study and change the program’s source code).

Freedom 2: The freedom to distribute exact copies to others.

Freedom 3: The freedom to distribute modified copies to others.’12

This relates to computer programming predominantly, but can be applied to the functionality of the metal detecting forum - where shared photos, maps and stories (Freedom 0) get appropriated (Freedom 1), the user builds on the forum thread and increases the topic’s popularity (Freedom 2) and the discussion is continued and adapted to the queries of each user (Freedom 3).

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

What is the heritage institution? Challenging license and intellectual property through archontic production

11De Kosnik, “Archontic Production: Free Culture and Free Software as Versioning,” in RogueArchives, pp.281

12

12De Kosnik, “Archontic Production: Free Culture and Free Software as Versioning,” in RogueArchives, pp.281-282

03 - HOW TO USE THE FORUM AS A MODEL FOR HERITAGE DISCOURSE

How Archaeologists frame heritage - the motivations of the heritage industry and AR/VR curation

An approach to challenging academic discourse and custodianship needs to include an appraisal of the ways contemporary professionals have engaged communities with heritage.

Privatisation of cultural artefacts and archaeological data is an act of placing the object under custody in the name of protecting heritage. Placing information under a creative commons license is an important way of letting go of these artefacts and acknowledging that communities want to engage with heritage in their own unique way. Sentiments to this effect have been echoed by heritage professionals, to the extent that archaeological teams include a ‘community engagement’ sector:

‘Earlier in the summer we took on a big scheme, which is …on the edge of Poole Harbour and there we found this late prehistoric settlement …. and we’ve set up these sorts of community engagement days where we hire out the village hall.’13 mentioned by an archaeologist in the environment agency in an interview,

‘We have people using VR headsets …and then we took some people out to site and got them to have a go at digging and people could find things and that sort of stuff, which is great for a particular type of person who probably lives nearby and he’s got time to just have a day being an archaeologist…

…But for your normal metal detectorist or somebody that might be living in another part of the country, that is not very accessible.’14

If the intention of the archaeologist is to engage communities with the past, the profession’s dedicated community engagement innovations are not doing enough and are not reaching the appropriate audiences.

13

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices How to use the forum as a model for heritage discourse

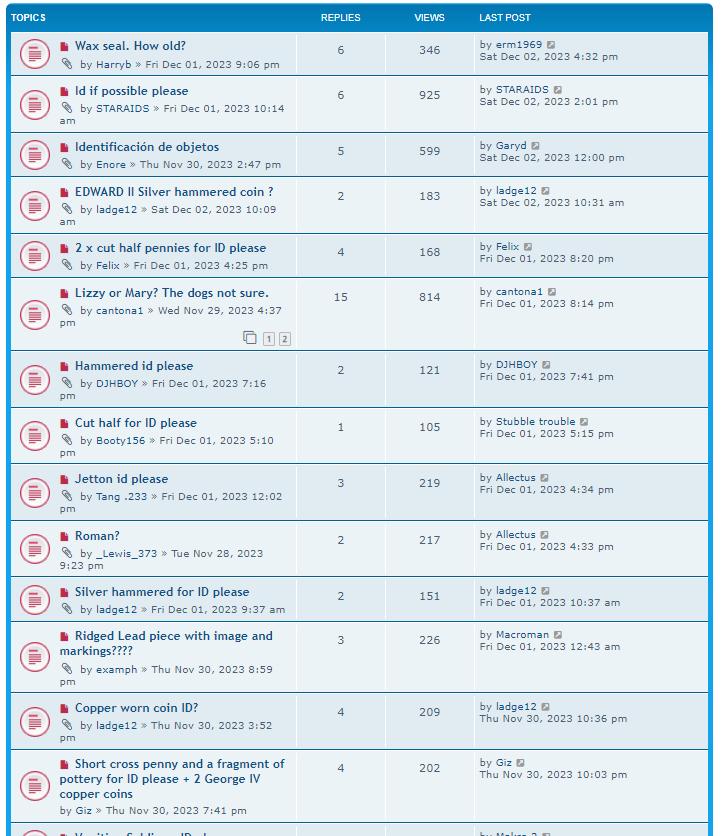

Figure 7: A VR Reconstruction of a Bronze Age Roundhouse by archaeologists. This is the current explorations by archaeologist into making heritage tell a story for contemporary audiences.

13Edward Wilson, video call to author, November 10, 2023 14ibid

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices How to use the forum as a model for heritage discourse

14

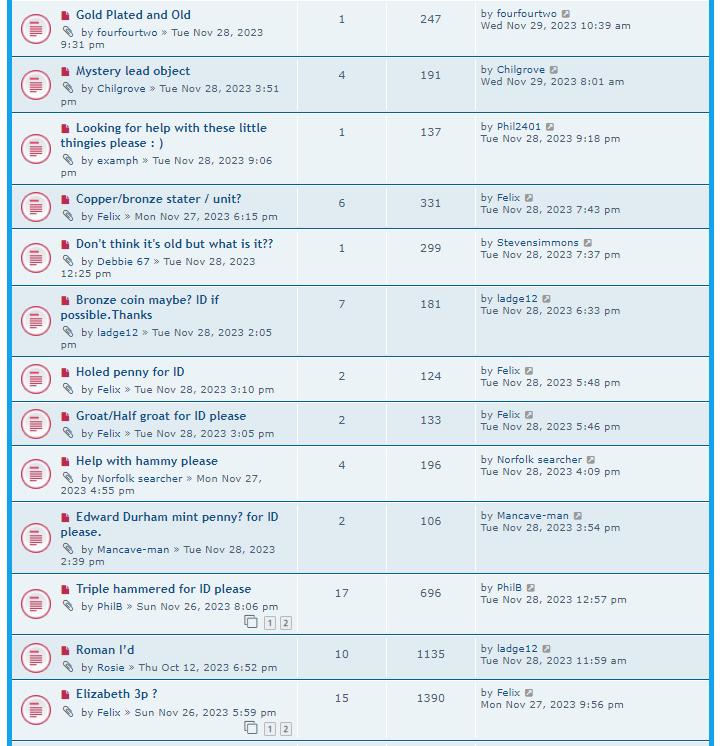

Figure 8: An extracted LiDAR scan of Glastonbury Tor from lidarfinder.com - open-access archaeological data which gets re-appropriated, or scavenged, by metal detectorists in forum threads.

Appropriating Industry Methodologies

Media literacy and the struggle from ‘consumer’ to ‘user’

Bernard Stiegler’s theory of cultural memory enables discussions on how heritage can become relevant to a public consciousness. He understands memory as being constituted of three parts: Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Retention:

• Primary - Present retention, making patterns‘listening to a melody and remembering each note as it passes’

• Secondary - The memory of the object in the imagination – ‘one remembers the melody heard the day before and is able to hear again in imagination by the play of memory’

• Tertiary – Contained memory (books, television, etc) – ‘the identical repetition of the same temporal object’15

Stiegler argues that tertiary retentions are ‘materialized time, which overdetermines the relations between primary and secondary retentions in general, thus, in a sense, permitting their control’ – essentially saying that broadcast methods – forms of capturing primary and secondary retention – create a singular cultural memory because the public ‘tune in’ to the same media representations.

De Kosnik, however, believes that publics are more media literate than this theory gives them credit for. ‘Mass media’ can be consumed and then used by a public for their own production of primary and secondary artefacts. To talk about heritage is to locate this conceptual discussion in a political realm, however. De Kosnik acknowledges the political nature of the transformation of the media consumer into the media user, talking about how the marginalised consumer can become liberated from the confines of a dominant discourse:

‘Members of marginalized groups may have maximal incentives to learn how to speak, write, and create from within hegemonic discourses, as appropriating the languages, literatures, and media of the groups who oppress them can be a first step in communicating their radical differences from those groups’16

Speaking the language of the oppressor, or appropriating the academic discourse and methods of professionals, can be the first step to liberation for the marginalised community. Placed within the context of heritage, it is very difficult for a consumer of artefacts to become a user. The marginalized group – the metal detectorists in this case – have followed the path of appropriation to enable engagement with heritage. Examples of this lie in detectorists’ appropriation of landscape tools, predominantly LiDAR, used by archaeologists to understand site contexts.

In an interview with an archaeologist from the Environment Agency, the value of landscape context was highlighted:

‘You know, we used to sell it per tile, and so the planning authorities there were suddenly our best friends because they knew we had this data and we could give it to them…

…so (now) basically anybody can get any lidar tile for their own personal research for free … but what that’s meant is that we’ve lost that ability to have the conversation that goes with that data.’17

Providing creative commons licensing for LiDAR data is seen here as a missed opportunity for crossdisciplinary conversations and exchange. The trouble here is that archaeologists do want that exchange of data between ‘multimodal’ users, but they want to approve how this data is being used. This is understandable, considering the practical notion of job security within the archaeology profession - ‘unless we can demonstrate that we’re giving some public value from what we’re doing, we’re not going to survive as an industry’18. More control over data use allows heritage professionals to have greater legitimacy for their existence – as guardians over a national heritage, perhaps even a national cultural identity.

This essay argues, however, that custodianship over heritage doesn’t have to stay within formal processes of knowledge exchange, and that another way to understand the structure of national cultural identity is by looking at amateur community groups, where LiDAR data is appropriated and combined with the informal research methods of community members, all working together to stitch together an informal heritage.

15 Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

15De Kosnik, “Archontic Production: Free Culture and Free Software as Versioning,” in RogueArchives, pp.300

16De Kosnik, “Archontic Production: Free Culture and Free Software as Versioning,” in RogueArchives,pp.298 17Edward Wilson, video call to author, December 7, 2023 18ibid.

How to use the forum as a model for heritage discourse

How

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices 16

Figure 9: Metal Detectorists detecting on the plough soil - the practice of field walking has an inherent connection with landscape processes, which gets communicated in metal detecting forums alongside more scholarly GIS and LiDAR data.

to use the forum as a model for heritage discourse

Challenging the binary - a new multimodal approach to academic discourse

Marginalised communities, like those in the detectorist forum, appropriate professional data and combine this with their own lived experience of landscape and heritage. As well as this, forum members share links to the PAS and other articles, creating a database of dynamic threads interwoven to create an interactive, informal heritage. This woven approach to knowledge acquisition is synonymous with the scavenger methodology – a composition theory proposed by Judith Halberstam that proposes a queer approach to academic practice.

Within the text ‘Female Masculinity’, Halberstam talks about the importance of valuing contradictions. Stacey Waite references the scavenger methodology as a queer methodology because it challenges the binary in research. Just as dominant discourse has favoured binary genders, academics have split heritage groups into ‘hobbyists’ and ‘professionals’, marginalising the detectorist community and invalidating the types of knowledge they generate.

‘…but that binary logic is precisely the kind of logic that dictates we must either look inside or outside; we must choose either theory or practice; we must either write narrative or scholarship; we must be men or women, scholars or poets.’ 19

Here, the scholarship lies in how detectorists appropriate or ‘scavenge’ archaeologists’ methods, and the poetry lies in the informal story telling of landscape experience and encounters. Interwoven through conversational dialogue on a social network, these opposed ways of knowing enrich each other to create a more well-rounded view of the landscape and build a better picture of the heritage context.

There is power in combining storytelling and scholarship.

The practice of weaving these opposing methods together, Waite would argue, is the practice of the marginalised – it is this group that has been ignored in community engagement with heritage, and it is this group which needs to be nurtured when thinking about the contemporary presence of heritage in public consciousness.

Stacey Waite, a composition theorist, talks about blurring the boundary between scholarly and narrative writing. Waite mentions the ‘civic discourses’ that composition scholars are teaching for and cites Alexander and Wallace by signposting ‘the critical power of queerness’.

A ‘civic’ discourse implies composing an archive about a shared or public heritage – a queer critique would highlight the marginalisation of the detectorist community - and what they bring - within shared cultural memory.

Detectorist forums are intriguing because not only do they propose a new method of researching heritage contexts, but they also demonstrate a new form of heritage – where publics participate in archiving and build on each other’s work. The community archive of the metal detectorist forum sees culture as ‘a repository of resources’ – implying the construction of a repertoire for hobbyists to call on for research.

Understanding how to improve the significance of heritage in a civic consciousness is deeply rooted in disrupting dominant academic discourse. Compositionists, like Stacey Waite and Patricia Sullivan, employ critiques of academic writing norms to push for ‘Multimodal’ media - ‘if form follows function …then we need to investigate new forms.’20 Sullivan cites Patricia Bizzell in pushing for a liberating form of media:

‘…surprisingly, the persona is argumentative, favoring debate, believing that if we are going to find out whether something is true or good or beautiful, the only way we do that is by arguing for opposing views of it, to see who wins. In this view, only debate can produce knowledge.’21

This perspective points out that dominant practice sets up a knowledge claim as something to be contested and fought over – as though knowledge production is about winning. This has elements of Derrida’s perspective on the selective nature of the archive - that archons command what is to be retained in cultural memory by deciding on what needs to be forgotten, as though a piece of knowledge must earn its place in a canon. Rather than being so restrictive in the context of heritage discourse, a way of challenging this ideology would be to shift the knowledge acquisition techniques from reason to emotion.

19 Waite, Stacey. “Cultivatingthescavenger:Aqueererfeministfutureforcompositionandrhetoric.” Peitho Journal 18, no. 1 (2015): 52. 20SULLIVAN, PATRICIA SUZANNE. “EXPERIMENTALWRITINGANDTHEPOLITICSOFACADEMICDISCOURSE:COMPOSITION’SINSTITUTIONS.” In ExperimentalWritinginComposition:AestheticsandPedagogies , University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt5vkdkr.6. 48.

21 SULLIVAN. “EXPERIMENTALWRITINGANDTHEPOLITICSOFACADEMICDISCOURSE:COMPOSITION’SINSTITUTIONS.” In Experimental WritinginComposition , 46.

17

Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

Scavenged

How to use the forum as a model for heritage discourse

04 - TOWARDS A PARTICIPATORY AND INCLUSIVE HERITAGE

The action of scavenging has negative connotations. It evokes images of looting, stealing, and disrupting sensitive landscapes. In reality, these words that detectorists have been branded with can be re-appropriated to become positive, transformative approaches to heritage. It is liberating to view ‘stealing’ and ‘scavenging’ as a practice of cross-contamination between archaeologists’ and detectorists’ methods. The past isn’t dictated by a singular authority, and the archive becomes a place of constant change, rather than a place of storage and forgetting. To be ‘disruptive’ here should be positive - disrupting modes of heritage archiving to create a new way of interacting with the past. The question this essay poses is what is the value of this inheritance if the culture gets protected to death - obscured from the public so its stories and narrative never get communicated in their fullness?

The idea that archaeological academic discourse presents ‘the dominance of reason over emotional or sensual perception’22 should be confronted, because the ways in which publics interact with the past is arguably through narratives and storytelling – forms that use emotion to generate valuable images of the history and landscape contexts.

Looking back to Waite’s interaction with the scavenger methodology, the author wants to challenge the binary notion ‘that we must look either inside or outside’.23 This notion of looking ‘inside’ oneself speaks to how both personal narratives and scholarly approaches have been given the same level of importance through the metal detecting forum-archive.

It follows that heritage becomes more important to a non-academic audience if heritage institutions are based on collaboration. If amateurs and hobbyists are allowed to assert their inner landscape experiences upon a heritage profession perceived as traditionalist and closed-off, the archive becomes more inclusive - allowing for a broader relevance of heritage in contemporary consciousness.

Practicing archaeology is about ‘doing’ the landscape, not just ‘writing’ the landscape.

A phenomenological process, the archaeologist Christopher Tilley argues, ‘does not start out with a list of hypotheses to be ‘tested’ or a set of prior assumptions about what may, or may not, be significant or important’ 24– this challenges the dominant ideology of knowledge being about winning or being debated. Through the networked forum, metal detectorists produce a collaborative knowledge repository that the community can use to inform their own knowledge of landscape context and help them understand features in the landscapes that they walk. Like Waite’s thesis on composition, the user of the metal detecting forum uses a scavenger methodology to think both within themselves - through empirical observation within the heritage context - and outwardly - this phenomenological experience being narrated to other detectorists through the network.

Heritage has its roots in inheritance - a cultural artefact is passed down by previous generations, with the process being ensured through preservation and custodianship over the artefact. The metal detecting forum frames this inheritance as an ever-expanding repository of resources through the medium of an opensource, open access archive.

To create their own cultural repository means that metal detectorists are disrupting contemporary attitudes - ‘doing’ heritage rather than ‘consuming’ it. Forum threads combine archaeological techniques and storytelling to challenge the power of the traditional heritage institution. This is a wholly participatory, inclusive archive that stimulates a shared custodianship over heritage, redefining the signficance of the past in a public consciousness.

22SULLIVAN. “EXPERIMENTAL WRITING AND THE POLITICS OF ACADEMIC DISCOURSE: COMPOSITION’S INSTITUTIONS.” In Experimental WritinginComposition , 47.

23 Waite.“Cultivatingthescavenger” Peitho Journal 18, no. 1 (2015): 52.

24 Tilley, C. (1997) Aphenomenologyoflandscape:Places,pathsandmonuments . Oxford: Berg. 18

Towards a participatory and inclusive heritage Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

APPENDIX - Conversation with Ed Wilson, Environment Agency

20 Appendix

Consent Form, Ed Wilson, Environment Agency

Ed Wilson

So what we’ve what we find is that if you’ve got, if you’ve got, say, a Roman site and you’ve got Roman coins surviving in a in a in a rubbish pit on that site. The archaeologists will dig down. They’l see the Roman coin. They will recover it. They will know where what layer it came from within the pit, and then they’ll know how that helps to tell the story of that site.

The metal detectorist, though, because of the way a metal detector works, they will just get a ping from that. From that coin, they’ll dig down and they’ll see the pot, the coin, and they’ll recover it, and they’ll have a nice shiny coin. And it’s Robin. And that’s really exciting. And they’ll know what date that coin is and they’ll they’ll get it conserved, potentially, and report it to the portal anticipative scheme. But what they won’t have, they won’t realise that it was in the pit. So you will have lost that ability to tell that part of the story. So if you get an archaeological site that’s been really heavily metal detected, what you actually lose is lots and lots of dating evidence from that site.

Sammy Doublet

I think within my research so far, it’s definitely the idea of decontextualizing something and it’s almost as if archaeologists want you to sort of keep the object in its place before you actually start taking out and celebrating this object because it’s more than just an object, it’s a contextual piece of history.

Ed Wilson

Yeah, so every every layer was called a context, and every context has its own record sheet with its own number. So they you’re absolutely right that that concept of context is really interesting, you know.

Sammy Doublet

Also, I think what I’ve learned a lot about is the idea that when you take away the context, when you take away the object from the context, it’s almost like you commodify, you, commodify that, like they can. It can be commodified. It’s vulnerable to that.

Ed Wilson

You know the Romans or the Saxons that, you know, can see a shiny object which looks amazing. And so that is a very, very accessible thing. Whereas an archaeologist, if they start trying to get you to think about what life is like in the Bronze Age and the role that this object might have played in the Bronze Age and Bronze Age, that’s much more abstract for people and it’s really quite hard for people. If you haven’t really had to engage with that. And so it’s not as accessible and we’re probably as a profession, still, we still struggle to tell those stories because they they require people to think quite a lot.

Sammy Doublet (on the whereabouts of open source data)

I mean, how in your experience, how do these people, I presume these people get wind of these sites through sort of forums and things, or are they local people?

Ed Wilson

The location of the designated sites that information is in the public domain, so you can go online and find a list of all the scheduled HT monuments and each county. So those are the national important sites. Each county also has a thing called a county. Sites and monuments record or a historic environment record. So those sites, a lot of them aren’t legally protected, they are just known our political science, but we put them on the public domain because the the argument is that if local communities know where their local archaeological sites are, they’re more likely to look after them and value them thanif it was just. Yeah.

where their local archaeological sites are, they’re more likely to look after them and value them than if it was just. Yeah.

Sammy Doublet

And what what is important to people in your experience?

Ed Wilson

Yeah, I know that’s good question and you’re absolutely right. Because as archaeologists, we can quite often focus on like a grey literature report, like a hard copy document that describes what was found on that site. And that generally is not very accessible. We. But there are, we are trying to do more accessible things. So we do a lot of on site interpretation. So having a having a story or having an image on site to show what that place might have looked like in the past that’s quite a simple thing that we quite often do.

We do quite a lot just in terms of direct outreach with communities. So we might go into a local community and go to a school or to a village hall and actually show them the objects that have come from their place and have people to just tell that that story.

I was at a community event earlier this summer where we were using VR, so we had VR headsets and it allowed the local community to put headset on and actually walk through the village that we’d designed settlement that we’d excavated where they lived.

Which made it accessible in a different way, but there are some people, there are some people that want the report they want to see a plan they want to see a map. They want to know where they live.

They want to know where the Romans lived. They want to know what the what the landscape was like and the climate was like. And we can do that in a hardcopy report.

But it isn’t very accessible, so those those digital tools are increasingly helping. I had a scheme, a flood defence scheme in Derbyshire where we were building a massive, great big flood wall around this community and we actually we had the remains on the site. We found the remains of a Roman Fort. So we we actually took the wall line of the of the flood defence and followed the shape of the Roman Fort that they have quite distinctive shape and that.

Sammy Doublet

Do you reckon the reason people get into metal detecting is? I mean, what are the reasons people get into metal detecting?

Ed Wilson

Alright, I’ll tell you why I did it, because actually that moment of finding an object that nobody’s touched for 2000 years or 1000 years is really, really exciting. There’s something about being the first person to touch something for X thousand years and and there’s also something about revealing the unknown from the soil. So you’ve got a a location which is just a a muddy field, and you’ve got this bit of you’ve got this machine that actually enables you to pick up something that somebody would have held in their hand and that somebody would have valued in the past. And suddenly you’ve got it in your possession, them having lost it or delivery hidden it or what’shappened, and that that is quite an exciting moment. And it’s exciting moment for the metal Tetris and it’s exciting an exciting moment for the archaeologists when they find those things.

21

Ed Wilson

I suppose the difference is that the archaeologists have a mechanism which ensures that information is then shared with as many people as possible, whereas there is a risk with the metal detectors that they’ve got that excitement. And then it goes into a private collection that nobody knows about, or it goes. Or it can be sold and it’s just that that the ability of that object to tell a story for that local community is potentially lost because it’s suddenly taken away from that local community. Without that mechanism for that information to go back.

(on the hobby of metal detecting)

It it is surprisingly hard work as well. I would just throw that into the mix in in terms of actually you hear a lot in the media about people finding amazing things, but you have to walk a very, very, very, very long way with a metal detector in your hand before you find two of those amazing things. And it’s quite physical just in terms of operating that piece of kit for, for, for hours and hours and hours in, in all weathers. It’s quite lonely in that you can’t, speak to anybody really because you’ve got headphones on. So you can’t hear. But the challenge is as much on us as archaeologists, as anybody else to educate people so that they understand the significance of that action and do it in a way which means that that story isn’t lost and there are ways of doing that. As we’ve described, you know, the postpartum scheme is one of them, making sure that you’re not removing material from context is another one.

Ed Wilson

So people are quite protective over that data and it wasn’t really in the public domain. So we could have the members of the public coming in saying I’d like to look at some information on the sites, monuments, record, but actually some of those data sets were withheld.

Then slowly, I suppose, twenty 10s people have started to started putting that some of the authorities started putting their sites when it’s records online, so that anybody at home could access that data and the thinking behind that is that if people know the important thing in their landscape, they are more likely to actually care about it. And actually, there’s a certain amount of local policing that will occur so that the landowner might be a bit more protective over it because they realize they’ve got something quite special.

Sammy Doublet

I also think I wanted to see how much Communication with people on the ground about that kind of stuff (LiDAR)

Ed Wilson

That’s a good challenge actually in terms of the connection we have with those end users, I think because yeah, I suppose because of the the type of archaeological work that I do, where I sit within the process, umm, most of my conversations are either with the local authority or with or with the project team or with the archaeological contractor. We’re increasingly trying to have those conversations with the local communities and to be able to share that information with them, but we we quite often pass that responsibility to the people that are doing that all the time, which is usually for me, it’s usually the archaeological contractor. Earlier in the summer we got a big scheme on more, which is on the edge of Poole Harbour and there’s this prehistoric site in an area where we’re trying to create some mins tidal habitat and we’ve set up these sort of community engagement days where we hire out the village hall.

We have people using VR headsets and then we took some people out to site and got them to have a go at digging and people could find things and that sort of stuff, which is great for the for a particular type of person who probably lives in arm and he’s got time to just have a day being an archaeologist.

You know, we used to sell it per tile, and so the local planning authorities there was suddenly our best friends because they knew we had this data and we could give it to them. And then exchange, we would probably get them to turn up to meetings and get, you know, slightly more positive conversations with them because we were offering them something and then it was a decision was made to make all of that data available on the opensource.gov website.

So basically anybody can get it any lidar tile for their own personal research for free, which is, you know, it’s amazing. And that’s millions of pounds worth of data. Millions of pounds worth of data that we just suddenly made available to everybody. I don’t then get to see how often that’s used by or who that’s used by what they’re what people are doing with that stuff.

Sammy Doublet

Do you feel like do you feel like it’s a bit of a loss when you make that data open source?

Ed Wilson

But what it meant was it just made my life slightly more difficult on a personal level because I used to get to have the conversation, which was really helpful to me in terms of doing my job. It’s a great idea to make it open source, but the the the impact has been that we nowhave even with the planning authorities that we probably don’t have as many conversations as we used to have because every year we give them another set of LIDAR data and it would be a good excuse to have a really good conversation.

22

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edward Wilson, video call to author, November 10, 2023

Uzzell, D.L. (1992) Heritage interpretation. London: Belhaven

Derrida, Jacques., and Eric. Prenowitz. ArchiveFever:AFreudianImpression/JacquesDerrida;TranslatedbyEricPrenowitz.Chicago ; University of Chicago Press, 1996, 1-5

Abigail De Kosnik, RogueArchives:DigitalCulturalMemoryandMediaFandom, MIT Press, 2016

Edward Wilson, video call to author, December 7, 2023

Waite, Stacey. “Cultivating the scavenger: A queerer feminist future for composition and rhetoric.” Peitho Journal 18, no. 1 (2015): 51-71

SULLIVAN, PATRICIA SUZANNE. “EXPERIMENTAL WRITING AND THE POLITICS OF ACADEMIC DISCOURSE: COMPOSITION’S INSTITUTIONS.” In Experimental Writing in Composition: Aesthetics and Pedagogies, 45-75

Tilley, C. (1997) A phenomenology of landscape: Places, paths and monuments. Oxford: Berg.

Figures

Cover Artwork - collage by author

Figure 1: Athens, Art Scene. “‘what If Women Ruled the World?’ at Emst.” art scene athens, December 15, 2023. https://artsceneathens.com/2023/12/15/what-if-women-ruled-the-world-at-emst/.

Figure 2: “Welcome to Our Database!” The Portable Antiquities Scheme. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://finds.org.uk/database.

Figure 3: “Detectorists - Series 1: Episode 6.” BBC iPlayer. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/ b04nqrq5/detectorists-series-1-episode-6?seriesId=b04kf095.

Figure 4: “Forum Group.” Metal Detecting. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.metaldetectingforum.co.uk/index. php?sid=1b7000f7536e38201ce999ecb58b4249.

Figure 5: “Forum Group.” Metal Detecting. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.metaldetectingforum.co.uk/index. php?sid=1b7000f7536e38201ce999ecb58b4249.

Figure 6: “Museum Map.” The British Museum. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.britishmuseum.org/visit/museum-map. and “British Museum - Space Syntax.” Space Syntax - Thriving life in buildings & urban places, December 22, 2020. https:// spacesyntax.com/project/british-museum/.

Figure 7: “Bronze Age Roundhouse Virtual Reality Experience.” Wessex Archaeology, January 1, 2020. https://www.wessexarch. co.uk/our-work/bronze-age-roundhouse-virtual-reality-experience.

Figure 8: “Lidar Finder.” LiDAR Finder. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.lidarfinder.com/.

Figure 9: Hanover Metal Detector Club, LLC (no date) 2022 events, Hanover Metal Detector Club, LLC. Available at: https:// hanovermetaldetectorsclub.com/club-calendar (Accessed: 22 January 2024).

Final Image: Prickett, Katy. “Metal Detecting: ‘I Dream of a Find That Changes History.’” BBC News, September 4, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-norfolk-58001604.

Bibliography

Scavenged Landscapes, Disobedient Practices

23