British farmsteads, post medieval cross-based windmills and World War 2 defensive sites. I eventually got a job as a Field Archaeologist and then progressed to a warm indoor job as the County Planning Archaeologist, responsible for monitoring developments and advising on which archaeological works would be needed to fulfil the planning regulations. After 16 years I left and took the role of a Principal Historic Environment Consultant for Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions https://www.woodplc.com/capabilities/ environment-and-infrastructure-solutions, where I am still happily working today.

My views on heritage photography Throughout my career, photography has never been far away. Indeed, like many, the camera is like an additional limb. To me there are two quite clear focuses for heritage photography and it has nothing to do with professional or amateur status, but the purpose of the photograph being taken. Most field archaeologists are proficient photographers whose reason to take an image is to document as objectively and factually as possible a feature, find, building, structure or feature being excavated. It forms part of the site archive; it allows post-excavation review and permits future revisiting of the site to see exactly how it was in that moment of time. Some of these images can be striking and wonderful in their own right, but the vast majority of images are simple factual records, aesthetics, composition etc. are not required. There are published standards for field archaeology photography, especially when related to recording standing buildings, produced by Historic England that helps ensure consistency of recording across the country (see https://historicengland.org.uk/ images-books/publications/understanding-historicbuildings/). Post-excavation and museum work may involve more specialised and creative photography, especially when documenting and illustrating finds, objects and environmental material (see Simon Hill’s and David Bryson’s pieces in this edition). There are many other skilled photographers in the profession but we don’t see their work due to the limited extent of the final published material, which most often goes into what is called ‘the grey literature’ reports that are not formally published but provided to clients and Historic Environment Records as a requirement of the planning process (see https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/). I hope that the current outreach of the Archaeology and Heritage Group of the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) will encourage many of these people to see their work as a work of art as well as a record and take the steps to have their photographic skills recognised by joining the group to share skills and ideas within the wider heritage photographic community and achieve RPS distinctions. 38

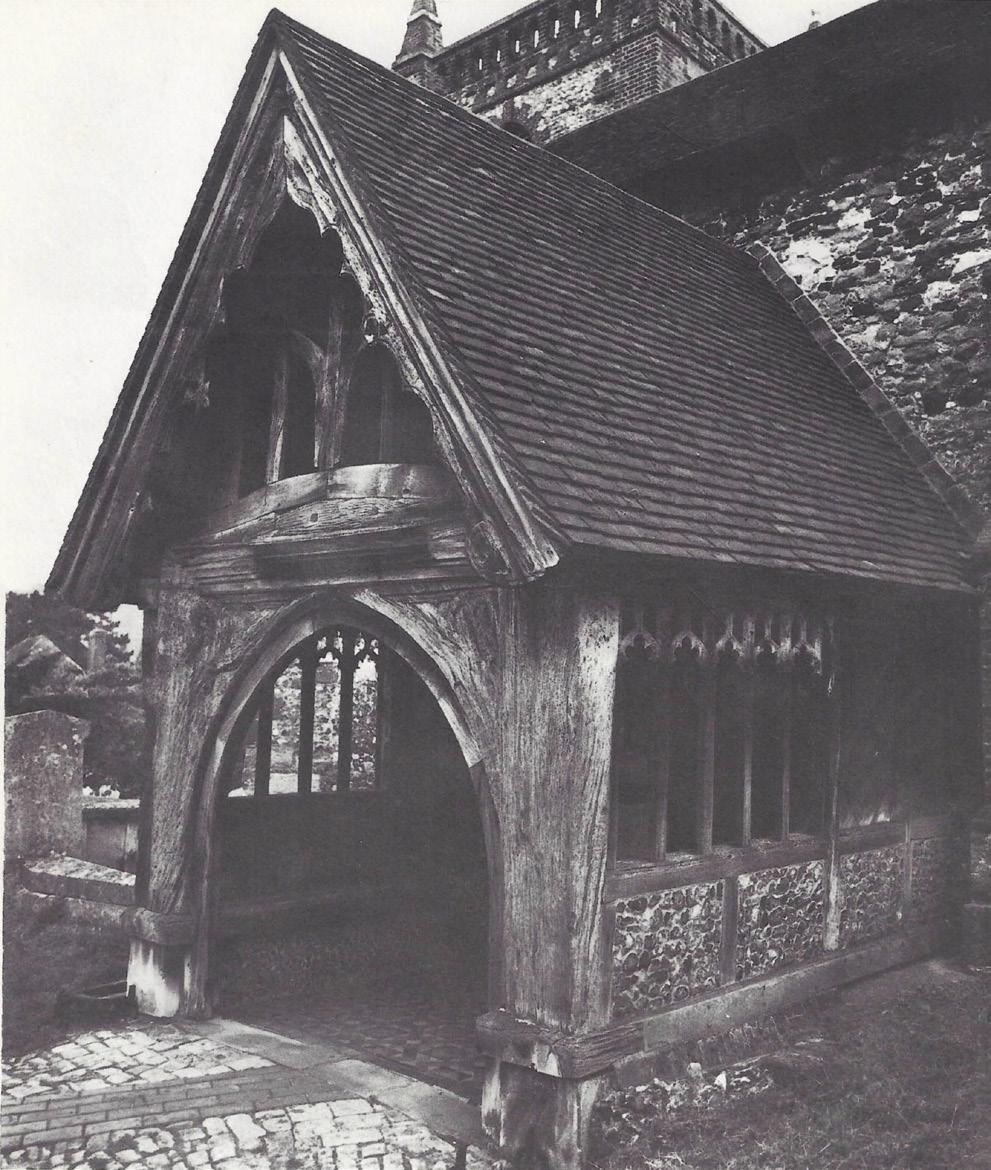

Then there is the aesthetic photography of the historic environment; where the picture tells a story beyond a flat record conveying mood and emotion to helps bring heritage alive. To give an insight into a site or monument that helps explains its purpose, or how it relates to the local people and communities living near the site. This is the specialist photography of the illustrator, the majority of whom do not necessarily work in the heritage sector. These photographs grace the guidebooks and coffee-table books on heritage themes. I find myself in the latter camp. I like to photograph places and structures in a way that expresses the essence of the place or its function. I have started a small project photographing the old field wind pumps that are now a disappearing part of our agricultural landscapes (see back cover). As part of my work I do not need to do the recording side of things, as this is done by specialist field units. I still however take photographs for my job, documenting the field work, and I like to acknowledge and photograph the field staff of commercial units, the unsung heroes of British Archaeology, who do the overwhelming amount of archaeological excavation in the United Kingdom. Recently I trained as a remote pilot for flying drones and am a registered drone pilot with the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). This has enabled me to continue aerial photography, but on a smaller scale, you can’t cover the whole county in an afternoon! You have to check for likely sites on the ground first before taking the camera up. I was fortunate this year to record a large Roman settlement that had not been recorded in full before. Having checked it out I went back a few days later to conduct an automated mapping flight (200 overlapping images). The site had faded a lot, but still proved useful in defining the layout and extent of the site. I am also photographing every one of the 200 parish churches from a low altitude showing the churches in their landscape setting. I am donating a copy of each image to the church to use as they feel fit. I may put them all together in book at the end, I still have 150 to do as Covid-19 put a spanner in this summer’s photography! British Archaeology has changed beyond all recognition from the pre-1980s niche academic specialism to what is now a highly skilled commercial profession employing thousands of archaeologists across the country. Photography has always been and will always be an instrumental tool in fieldwork and post-excavation work, and I hope we can encourage more archaeologists to recognise their talent and work towards a distinction with the RPS.

MIKE GLYDE MCIFA Member of the Chartered Institute for Archaeology