40 – Number 10

Pondering Pollard 24: ‘Great Photographers’ by The Editors of Time-Life.

Hon.

Page 6

From your Secretary

Jacky Lee

Acting Secretary, Australian Chapter

It’s a real pleasure to be writing to you in my role as Acting Hon Secretary while Elaine is away. My thanks to her for the trust and opportunity to serve during this period.

Although I’ve been deeply involved in photography for almost thirty years, I’m still relatively new to the RPS family, having joined in 2023 and becoming part of the Australian Chapter Committee in the same year. Within the Society, I also serve as a Content Manager on the RPS International Team under Claudine’s direction, and as a member of the AI Working Group at RPS Headquarters, chaired by Mathew. It has been a wonderful experience learning from such talented and dedicated colleagues across different regions.

At present, RPS Headquarters is reviewing proposals for the forthcoming Five-Year Plan (2026–2030), shaping the Society’s long-term direction. Excitingly, work is also underway to launch the Chartered Photographer designation next year, a development that will provide formal recognition of

professional photographic standards. If you have any questions or thoughts about these initiatives, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

This month, we’re pleased to welcome Dr Wei Hong Liu, who has recently joined the Chapter. A warm welcome! With this addition, our Chapter membership now stands at [Ian, do you know the number?], a reflection of our steadily growing community of passionate photographers across the country.

As several of our committee members have busy schedules, our next Chapter meeting is tentatively planned for December. Many thanks to Ian for coordinating, and I look forward to catching up with many of you then.

Welcome from the Editor

Ian Brown

Editor, Australian Chapter

Congratulations to our secretary, Elaine Herbert ARPS, on being awarded the President's Medal in recognition of an outstanding contribution to the Society. Since I took over as Editor, I have had outstanding support and guidance from Elaine. If you missed it, here is a link to the announcement.

As we approach the end of the year, we have several events coming up.

Later this month, we have the online presentation, 50 Shades of Grey, by Gigi and Robin Williams, and in December, we have the Annual General Meeting (see the notification to the right). As well as all things related to the Chapter, we will also give members a chance to showcase their work. Please take advantage of this opportunity.

In the issue, my thanks again go to Robin Williams for his Pondering Pollard article. We have a new contributor to the Members’ Gallery. Thanks to Charles Yang for his images. I saw them in Michel Claverie’s eCircles Critique, which Charles and I are members of. All it took for Charles to submit some work was for me to ask him to send something through. If it’s that easy, I’ll ask everyone. So, please, send your work

Specifications for contributors

When sending images for the Newsletter, the only requirement is that they are jpeg or png. Images can be 300 ppi and up to A4. Don’t forget you can also add captions for your images. If you don’t include a caption, we’ll assume you don’t need one.

through. You don’t need to write a full article; your images are enough. Having said that, I would have a brief explainer to help put your work in context.

We are so light on contributors this month that I have submitted my own article. So please, keep your work coming in, or I’ll have to keep padding the Newsletter out with my work.

Save the date: RPS Annual General Meeting

3 December 6:00 pm AEST

We will be holding our Annual General Meeting 3 December starting at 6:00 pm AEST.

As well as the AGM, there will also be an opportunity for members to showcase what they are working on at the moment.

We’ll broadcast the Zoom link to all members in the next few weeks.

Email images to ian@bforbrown.com.au and keep those pixels and captions coming in! For non-image files (e.g. PDFs), under 5 MB is preferred and never 10 MB or more. If your images are too big to email, I have created a Dropbox folder you can upload

your images to. Email me for permission, and I’ll grant access to the folder. I will need to delete your images once I have downloaded them.

Deadline for contributions to the next issue is 23 November 2025.

Convenor’s Corner

Rob Morgan ARPS

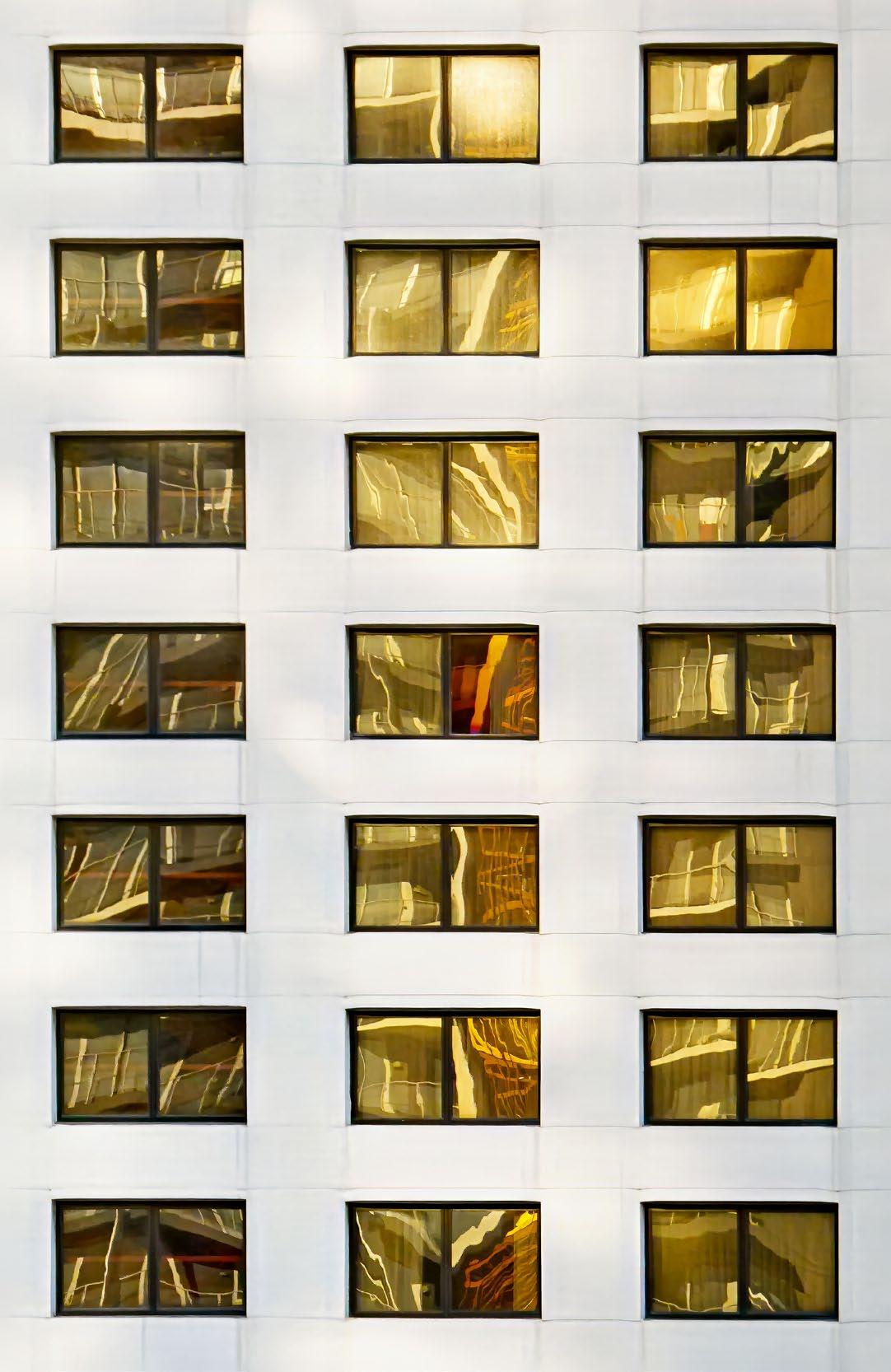

Here is an image I took in Perth in mid-October, while I was there for a conference. Actually, I was not at the conference when I took the photo; the conference was at the hotel in the image (the Pan Pacific), and I was in my hotel nearby, catching up on emails. As the afternoon sun was getting low, I noticed the Pan Pacific’s windows had reflections of lines. Being a traffic engineer, I immediately

thought they were lines from the pavement markings on Adelaide Terrace; I was conjuring up ideas of stop lines, lane lines and bus lanes – until I realised that was not possible, given my angle to the hotel windows (I have squared up the image).

The lines are actually balconies on a nearby high-rise apartment building. It was a reminder of the power of images to create an impression or tell a story for the viewer. For me, it does not matter so much what story an image maker has in mind, or even what the reality is; if an image creates a story or impression in my mind, or it has a great impact on me, that is the measure of a great image. Clearly, many images do have an impact in the way the image

maker intended – such as with great photojournalism – but it need not be that way.

With this image, there can be other stories. Here are 21 windows. What might the people in those rooms be looking out onto? What can they see? What is their perspective? What tales could they tell? In the August Newsletter, our mentoring program was announced. Imagine if there was a Chapter member behind each of these windows. We can’t see them, but they are there. Until we make contact and engage with them, we won’t know what knowledge and experience they can share with us, and we can share with them. The great thing about mentoring programs is how they can have an impact in both directions. So, if you are interested in the mentoring program – either as a mentor or mentee – see pages 24-25, contact our Newsletter Editor, Ian, at ian@bforbrown.com.au

Australian photographer John Pollard FRPS died in 2018, leaving behind not just a grieving family and a substantial legacy of photographic work in public and private collections, but also an eclectic collection of books representing his varied interests over his life. In this ongoing column, I hope to stimulate interest and reflection on various aspects of photography based on the perusal of John’s collection of books. In the process, I also aim to periodically shine a light on John’s career and practice.

Dr Robin Williams ASIS FRPS

Pondering

‘Great

Pollard 24:

Pub. Time Inc, New York, 1974.

This book is part of the LIFE Library of Photography, which consisted of 17 volumes that were published between 1971 and 1974 by Time-Life Inc. (a second edition – smaller in size and less well printed – was

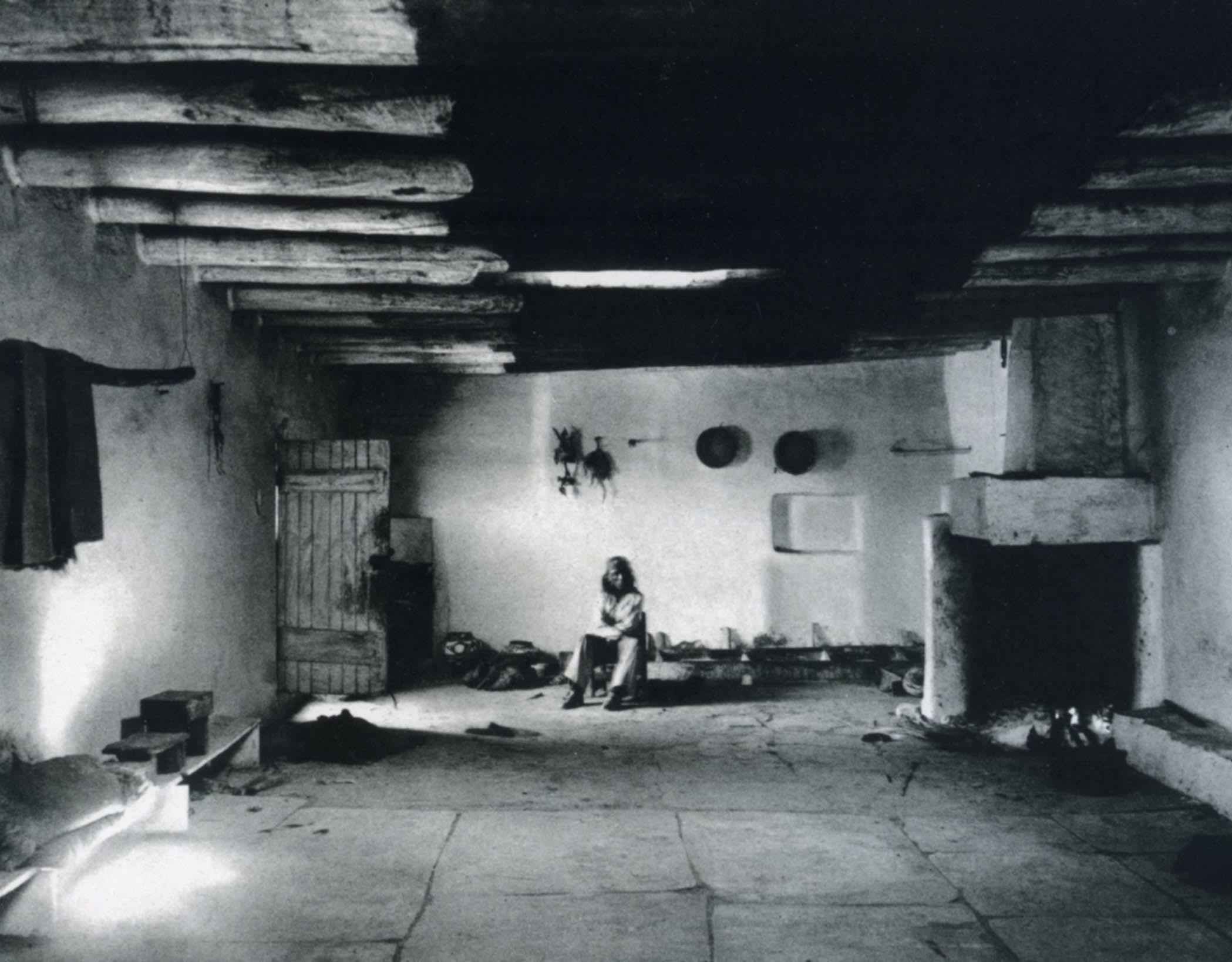

Fig.1 main image: The Kitchen at Vincennes Asylum, Charles Negré, 1860. Negré’s relaxed ‘snapshot’ image actually required his obliging subjects to hold still for the very long exposures.

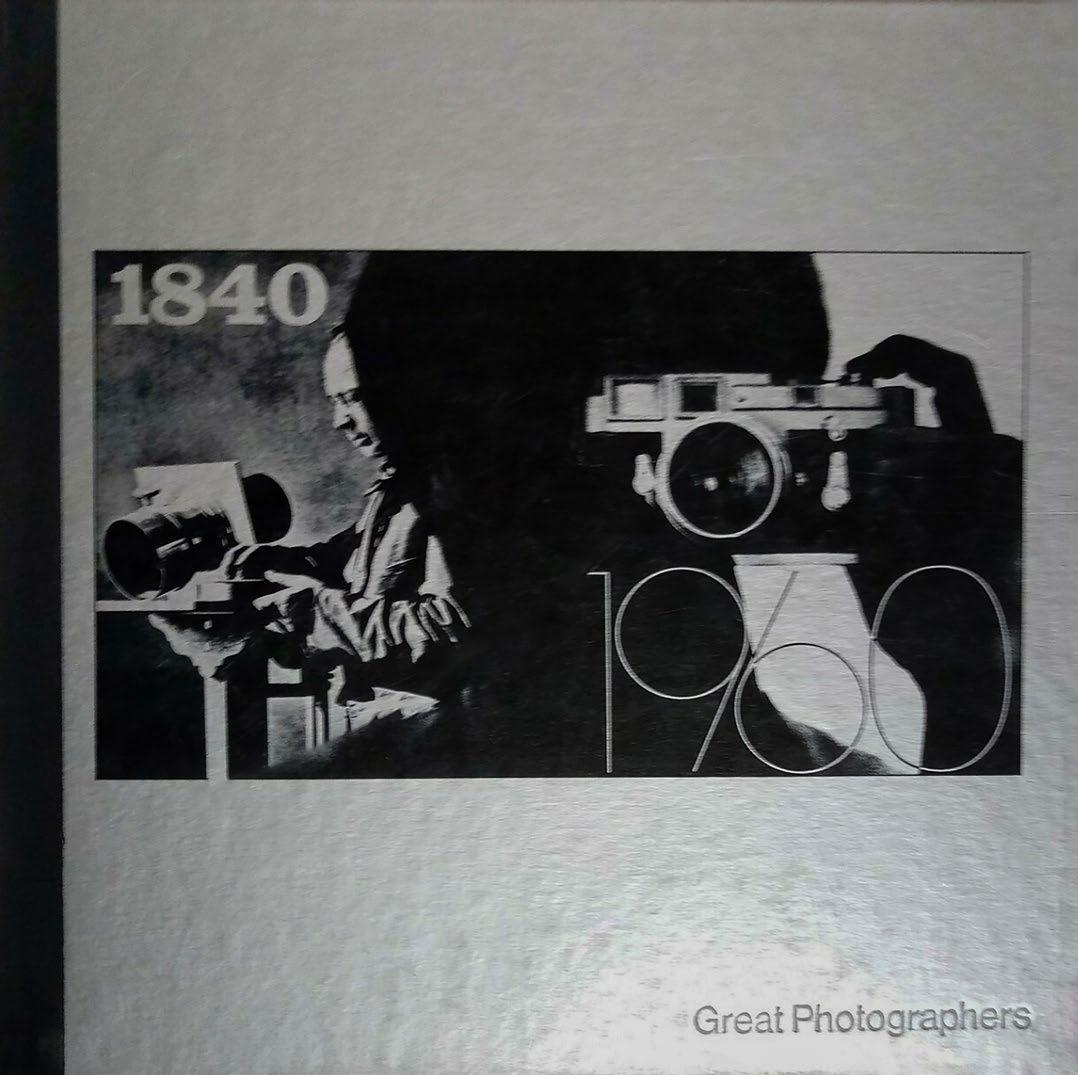

Fig.2 right: Front cover of the book ‘Great photographers’ showing two photographers at work, twelve decades apart, symbolizing the span of time covered by the book.

available in some markets between 1981 and 1982). The series explored all the major aspects of the technology of photography; the techniques of taking pictures; developing film and making prints;

Fig.6: Nude in the studio photographic history; and the aesthetics of photography as an art form. It was published after Time-Life’s incredibly well-received series ‘The Library of Art.’ The Library of Photography series featured duotone printing for its blackand-white reproductions (very high quality for its time) and was able to draw on Life's own vast archive of photographs from virtually every major contemporary photographer. Time-Life Inc. operated a

Direct-to-Consumer model –often referred to as ‘the Book Club’ model – which was very popular in the 1960s and 70s. Customers took out a monthly subscription to receive a new volume in the series each month. With the progressive decline of brick-and-mortar bookstores and the advent of online sellers and electronic publishing (e-readers), Time-Life eventually went out of business. In 2023, without so much as a whisper in contemporary media,

Time-Life ended its six-decadelong existence when the company and its only official online retailer were permanently shut down by its last owner; though the one remaining official website only went ‘dark’ in May 2024. Odd copies of the Library of Photography can often be seen for sale on used-book sites, but complete collections are very rare; I was fortunate enough to purchase a complete collection for my library in 1990. John Pollard had

just two volumes in his collection: this one, ‘Great Photographers’, and the other being ‘Caring for Photographs.’

'Great Photographers’ is a beautiful collection of works of great photographers organised chronologically into six sections: 1840 to 1860; 1860 to 1880; 1880 to 1900; 1900 to 1920; 1920 to 1940; and 1940 to 1960. In each section, outstanding photographers are featured from that period with a bit of biographical information, why

the artists were notable, and plates showing their most famous pictures. In considering such a collection, one has to ask ‘What criteria were used to define a photographer as ‘Great’? In their introduction, the editors explained: ‘The 250 photographs in this book had to run an arduous gauntlet of editorial selection. For each one that was chosen for publication, thousands were examined, some never before seen in this century. Those that survived

represent the work of 68 great photographers; hence the title of the book. What makes a photographer great? Not one great picture. Hundreds of people, by design or by accident, have achieved, or stumbled upon, an image that others consider great. Rather, inclusion in this collection signifies that a photographer accumulated a body of great work during his career. In photography, as in any field, greatness is a quality more

easily demonstrated than defined. Yet, in researching this volume, the editors encountered several factors that, taken in combination, appeared to form a definition. The first is intent. What did the photographer have in mind? When Alexander Gardner shows us an empty Civil War battlefield, he intends us to feel the sense of loss and tragedy he found there. When Lewis Hine poses a child beside an open door, he intends us to ask

the question, ‘Where does the door lead?’ And when Yousuf Karsh shows us the broad brow of Nikita Khrushchev, he intends that we feel the public power, wisdom and aggressiveness that are stored up behind it. The second factor is skill. A great photographer must be able to execute their intention. He has to master all the tools at his command. He must exploit the qualities of light and film, must understand human nature, and know how to be patient at

one moment, spontaneous at another. Without these skills, even the noblest intent remains unfulfilled. Finally, the great photographer must execute his intention with the consistency that lesser photographers cannot approach. The great photograph is no accident in the hands of these men and women. Whenever possible, the editors have looked at the whole life’s work of each photographer represented. With only a few exceptions, the

early pictures and the late ones share the successful mark of their maker. Intent, Skill, Consistency; however different the photographers in this book seem, they all share these three qualities.’ Of the sixty-eight photographers featured, however, only two are women: Julia Margaret Cameron in the 1860-1880 section and Dorothea Lange in 1920-1940. How does a Life photographic survey not include Margaret Bourke-White? (She had featured on the very first cover of Life). I think this is an overall criticism that could be levelled at the entire series – that it is apparently almost inconceivable that a woman would be behind the lens instead of in front! Almost all of the photographers and movements featured throughout the series are male-dominated – a sign of the times, I guess! Nevertheless, there are some great photographers and great photographs in this volume. All of the well-known

photographers are represented in this book: Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Man Ray, Edward Weston, Walker Evans, Cartier-Bresson, Ansel Adams, Irving Penn, Minor White, and so on. Rather than focus on these famous ‘Masters’ I thought it might be more interesting to highlight a few of the less well-known photographers, or at least some images that were not characteristic of the generally known output of a photographer.

The first of these is Charles Negré (1820-1880), a young French painter who specialised in photographing people engaged in their everyday occupations. Working in the early 1860s, he broke with the accepted formal portrait style, which had largely been dictated by the long exposures required. Intending to use the photographs as preliminary studies for his paintings, he roamed the working-class districts of Paris, photographing

chimney sweeps, bargemen and street urchins. Although he converted a few to paintings, he quickly realised that the images were works of art in their own right. They won Negré a place in history as one of the first to see beauty recorded in the scenes of everyday life. Negré was also noticed by the authorities: in 1860, he was commissioned by Napoleon III (who understood well the value of good publicity) to take photographs at the Vicennes Asylum (a facility that had been established by the Emperor for disabled workmen).

Étienne Carjat (1828 – 1906) was a journalist, caricaturist and actor who originally took up photography as a hobby but then made it his profession for over twenty years, specialising in portraiture. By virtue of his ties to the theatrical and literary worlds, he made actors and writers the subjects of many of his portraits. He also photographed celebrities from the worlds of politics and

science. All were superb characterisations; I suspect his images are much more famous than himself. A good portraitist needs both an understanding of the sitter’s character and the ability to put them at ease, and Étienne Carjat obviously had both. One of his peers said, ‘He doesn’t torture them, dislocate their necks, distort their arms or legs …he only asks them to be natural in conversation and thus he achieves a kind of physiognomic tracing that is an

astonishing likeness.’

Hailed today for photographs that show with sympathy and insight Indian life in the American Southwest, Adam Clark Vroman (1856-1916) was a mid-Western railroad man who took his bride to California for her health. The trip was futile –his wife died after only two years of marriage – but Vroman stayed in his adopted Pasadena and opened a bookstore. As an amateur in his spare time, he took up photography. In 1895,

he went on the first of many trips to the Indian lands of the Southwest, where he spent time amongst the Hopi, Zuni and Navajo. He had a remarkable ability to gain their trust, and photographing their rapidly disappearing way of life became Vroman’s life obsession. He returned year after year, bearing gifts of Platinum prints from the previous year’s sessions. It was not until the late 1950s that the elegance, drama and style of Vroman’s ethnographic studies

were recognised with the discovery of 2,500 negatives of Indian life.

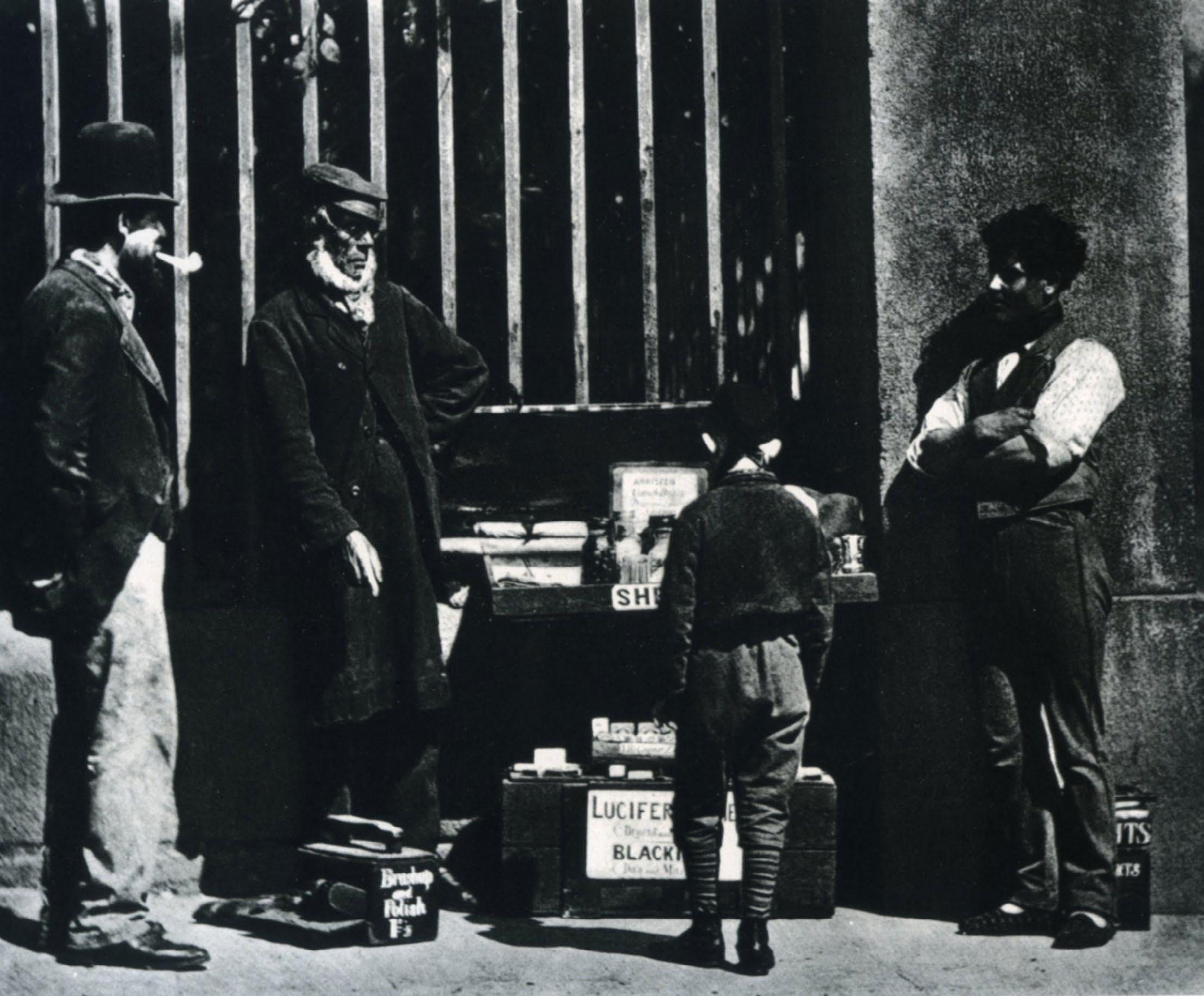

I think that John Thomson (1837-1921) is best appreciated today for his candid documentation of the povertyridden life of industrial London, but during his lifetime, the Scottish-born photographer became famous for his hundreds of photographs of Asians, the fruit of a decade of travel in the Far East. On his return to London, exhibitions of

his pictures won him an enthusiastic following, and he set up a portraiture studio in Mayfair, where he enjoyed a clientele from among London’s well-to-do. He even obtained a Royal Warrant in 1881.

Thomson collaborated with Adolphe Smith, a radical journalist whom he met at the Royal Geographic Society, to produce a monthly magazine, ‘Street Life in London’, from 1876 to 1877. The magazine documented the lives of the

street people of London in text and photographs and was later published in book form in 1878. Thomson’s sharp eye found both the dignity and the pathos of the common man; he could be said to be the father of social documentary photography in Britain.

Paul Martin (1864-1944) stated his aim in photography with characteristic forthrightness: he sought ‘the real snapshot – that is, people and things as the man in the street sees them.’

The son of a French farmer, Martin migrated to England, founded a photographic company and spent all his spare time taking photographs. Martin loved gadgets, and this trait helped him make great photographs unobtrusively; he devised schemes for muffling the shutter noise and even disguised his camera as a stack of books. Martin’s photographic interests were extremely broad, recording many events in addition to the everyday lives of

people. He experimented with photographing at night, during rain, and during snowstorms. His greatest achievements, I think, were his ‘real snapshots’ –devoid of ego but rich in detail.

In 1907, Paul Strand (18901976), the 17-year-old son of a middle-class New York family, who might have been expected to go into business, encountered two of the Masters of American Photography. His life was never the same. The two photographers who so

affected him were Lewis Hine, who taught Paul in his photography course, and Alfred Stieglitz, to whom Hine introduced Strand. Eight years later, Strand walked into Stieglitz’s studio, carrying a portfolio crammed with studies of the people on New York streets. Stieglitz gave him a one-man show and hailed his work as ‘brutally direct.’ Strand spent the following 15 years in close association with the eminent Stieglitz. Meanwhile,

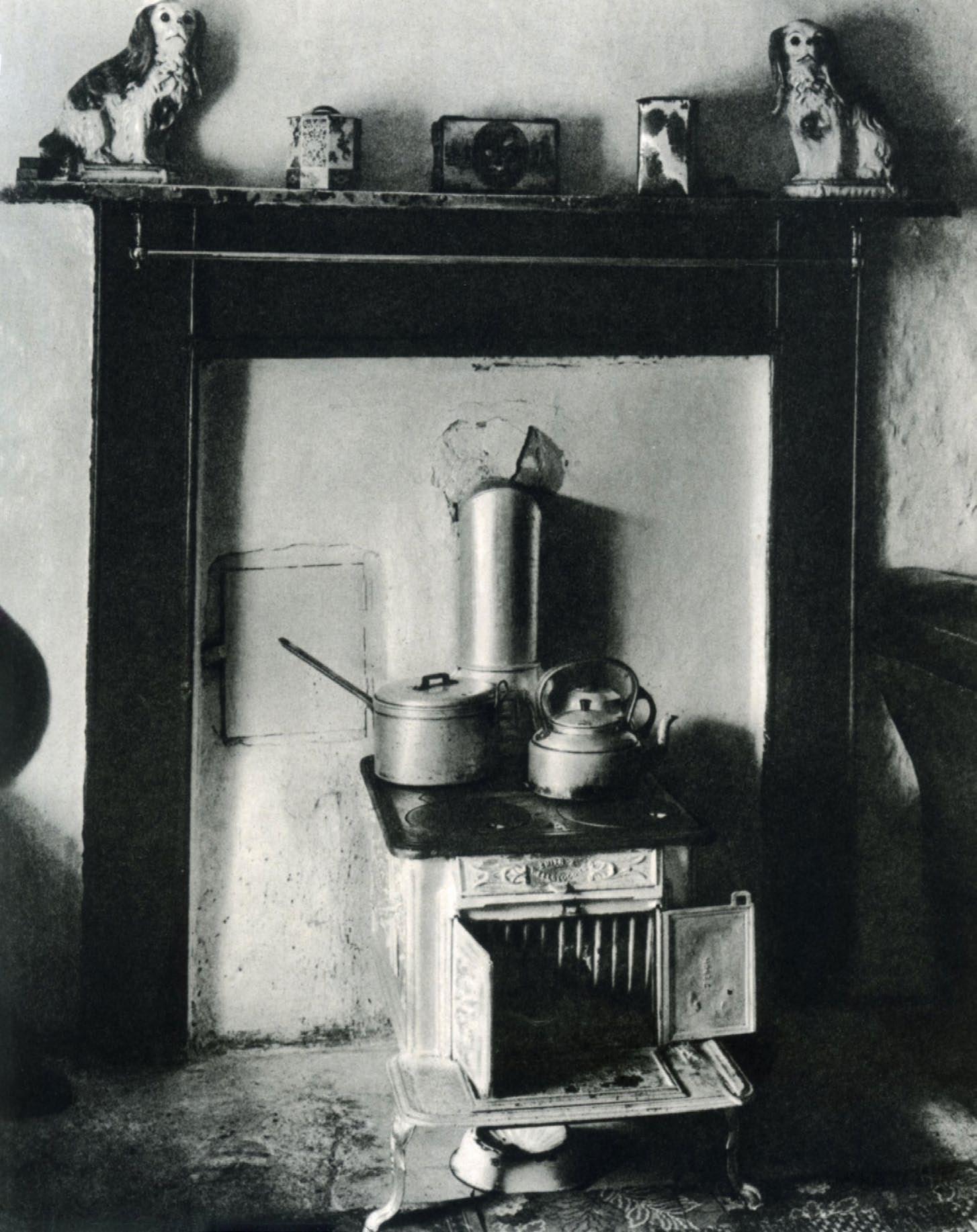

he made a living as a freelance motion picture cameraman. Wherever Strand went and wherever he photographed, he made compositions by associating different textures, a technique that turned many of his portraits into still lifes. Strand is, of course, a very famous photographer, but I chose to feature him here for his littleknown work, in the Outer Hebrides, off the coast of Scotland. Here, he photographed the working

people and their natural settings, still managing to capture textures representationally or metaphorically, lovingly.

The first time Gyula Halasz (aka Brassai) saw Paris, he was a four-year-old boy from Hungary on a trip with his father. The boy stayed a year but never forgot the city. Twenty-one years later, in 1924, Brassai returned as a working journalist and became obsessed with Paris at night; the immense panorama of drifters,

Fig.8 left: Au Bal-Musette, Paris, Brassai, 1932. In this dance hall Brassai found prostitutes, pimps and delinquents in mixed moods of ennui and merrymaking. Part of the group faces the camera whilst others are reflected in the mirror, giving the viewer the sense of looking at two levels of reality, as in a Cubist painting.

Fig. 9 right: Through the Studio window, Joseph Sudek, date unknown. Looking out and looking in are two of Sudek’s preoccupations. Peering through the ice-frosted glass of his studio window he saw a bird perched in a tree: winter seems to melt away in a pattern both leafy and feathered.

lost old people, concierges, impassive prostitutes, gangsters, lighted fountains, unexpected parks and dingy cafes. An accomplished artist, Brassai had previously looked down on the medium of photography, but now he bought a camera. Night after night, he roamed Montparnasse, becoming so much a part of the scene that people went about their lives oblivious to his clicking shutter. He created a definitive body of

work that captured the very essence of Paris at night between the wars.

To the people of Prague, Josef Sudek (1896-1976), a grey and dishevelled man born near the turn of the century, was a familiar figure. From his little wooden workshop, he peered through his studio windows, which were often crusted with ice or misty with rain. There and on excursions through the town, Sudek humanised Franz Kafka’s City. Sudek lost his right arm in World War I, but that handicap never seriously hindered him. For years, he plodded around Prague, a bowed figure, carrying an old wooden view camera and its tripod over his armless shoulder. His equipment was as unassuming as his appearance. His favourite camera was a Kodak Panoramic, then more than 50 years old. He claimed not to know what a light meter was. But in his studio and away from it, when something caught his attention, Sudek stopped, framed his tired eye within two circled fingers, and waited patiently for the light that he wanted, then made amazing pictures, which made the people of Prague call him their ‘poet with the lens.’

In 1914, when Manuel Alvarez Bravo (1902-2002) was a schoolboy in Mexico City, the sight of cannon and cadavers was a familiar one in the streets there, for the country was deep in the process of revolution. The recollections of the uncertain life around him stayed with him long after nominal peace

arrived. He took up photography and became part of the art colony of the capital, where he came under the influence of artists and revolutionaries who were bent on combining the innovations of modern art with the symbols of Mexican folk mythology. Alvarez Bravo used his camera as his artist friends used their palettes, telling a sombre and sometimes anguished story of grimness and oppression. Bravo was driven by the contradictions he saw in life in general and in his homeland in particular.

In the ongoing battle between straight, ‘realistic’, photography and romanticised, ‘pictorial’ photography, one of the staunch sentinels of realism was Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) of Germany. Opposed to the avant-garde double exposures and photo montages of Man Ray and the Victorian poses beloved by British members of the RPS, Renger-Patzsch produced austere, eloquent photographs of landscapes, forests and industrial artefacts. His volume entitled ‘The World is Beautiful’ (1928) was to become the manifesto of a renewed realism called The New Objectivity. Straightforward as his pictures were, they went far beyond the realism of mere documentation. Whether photographing close-ups of nature, man-made objects, or architecture, he was able to find design in everything he looked at during his long career, which lasted well into the 1960s.

Fig. 10 top left: ‘Good Reputation Sleeping’, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Mexico City, 1938. A nude study that typifies Bravo’s interest in contradictions. The woman seems both sacred and profane. She is secluded by a wall yet threatened by cactus barbs; the coarseness of the seemingly ritual bandages contrasts with her soft flesh.

Fig. 11 bottom left: ‘Hallig man in his boat’, Albert Renger-Patzsch, 1927. Renger-Patzsch’s evocation of detail and design is repeated in his attention to the coiled rope, whitened by the sun and handsomely textured by the sea, lying in the cockpit of this boat from the Halligen Islands along the Frisian coast.

One of only two women to feature in the book, Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) was best known for her work for the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression of the 1930s, which highlighted the plight of the poor. In all her work, Dorothea Lange lived up to the ideal articulated by Francis Bacon, whose words were posted on her darkroom door: ‘The contemplation of things as they are, without error or confusion, without

substitution or imposture, is in itself a nobler thing than a whole harvest of invention.’ Her work photographing the human toll of the depression is well known, but when the depression ended and times changed, so did her subjects. Being a landscapist myself, I have chosen one of her lesserknown landscape images from later in her career to illustrate her contribution.

Save the date: online live presentation 12 November 19:30 AEST