5 minute read

What is the purpose of

What is the purpose of archaeological and heritage photography?

Chair of the Archaeology and Heritage Group. GWIL OWEN ARPS.

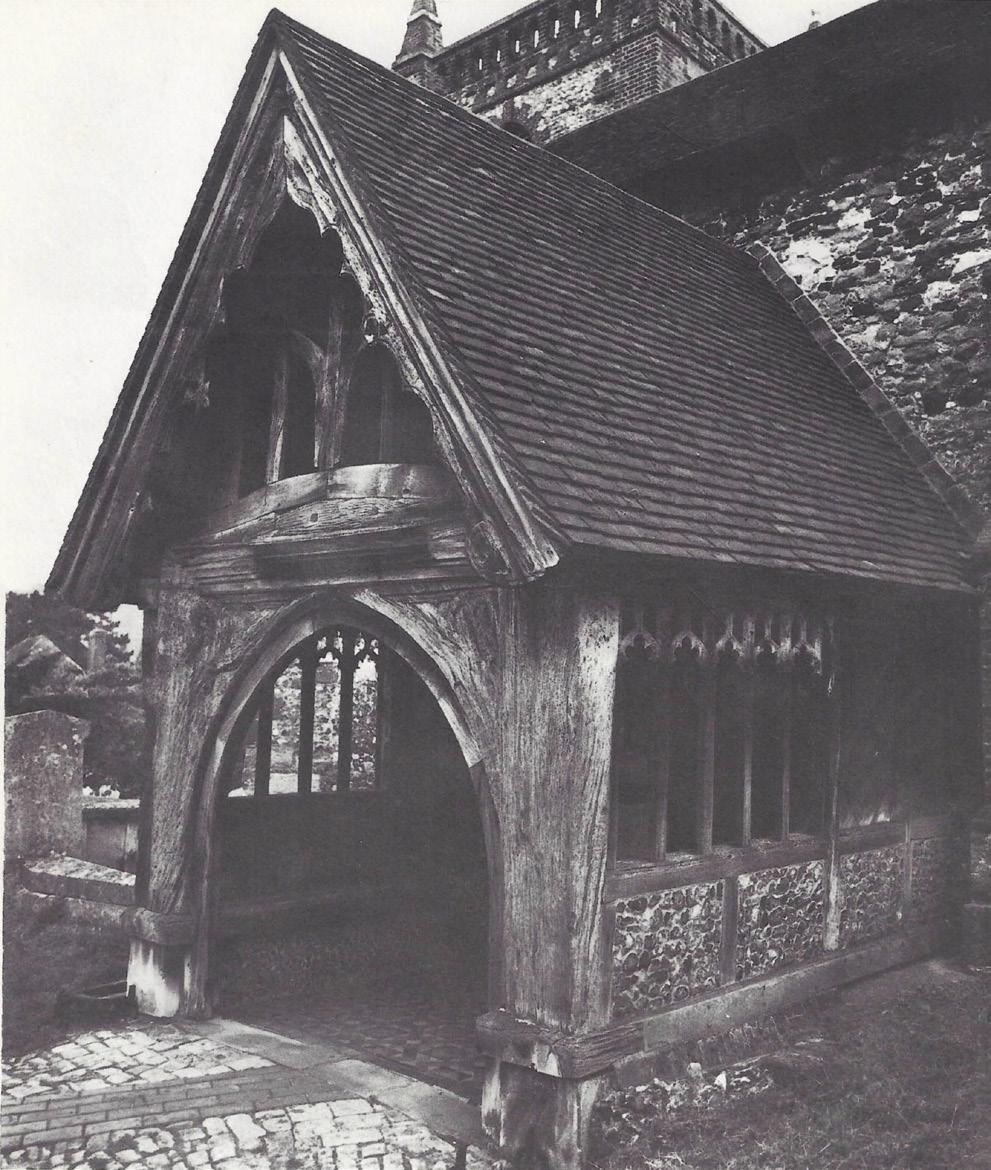

Defining what is exactly Archaeology and Heritage is difficult. Archaeology as a profession, or as a hobby, embraces many activities. They include digging up things (obviously), specialised scientific analyses and the anthropology of earlier societies. This last itself can include my mother’s grave and the art of Neanderthal man. Heritage has been added to our title more recently to reflect an interest in the built environment, particularly the religious landscape. Add to all this museums and prehistoric landscapes and it becomes evident that our photographic recording must be equally diverse. The Archaeology Group was set up in the early 1970s to remedy a perceived lack of photographic tuition within archaeology, in particular within the enthusiastic amateur sector. Archaeology at the time was heavily influenced by the strictures of professional archaeologists, such as Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who considered that photography was, being an objective and scientifically accurate pursuit, necessary for archaeological research. Everything should be recorded for later use as an investigative tool. This was in contrast to many Victorian photographers who favoured the recording of monuments and antiquities from a general art perspective. Photography today - not excluding that within archaeology - is now ubiquitous as a casual endeavour. It is available to all on the simplest mobile phone, in many cases rivalling in its usefulness the output of high end professional cameras. The membership of the A&H group reflects this varied approach, an approach which mirrors the vast range of modern archaeology. Now is a sensible time to reassess the value of photography within archaeology: in what areas can it operate, where does it’s value lie within the range of current archaeological techniques. Sorting out why we use photography in this broad context is key to doing it well: that is doing it informatively. First of all we should recognise that the artistic approach to antiquities has been a consequence of our general cultural values, not necessarily of a specific archaeological approach. Similarly the Wheeler approach, that this all embracing photographic recording to be a vital part of the scientific record is also suspect. The flaw being made obvious by the number of researchers visiting museum sherd collections to find what no-one could see from the period photographs.

Flint “Careful lighting can show differences in use wear”

Human ranging rod “An indication of size can be shown in many ways.”

What can photography offer to archaeology? First and foremost it should be recognised that photography continues to be, with some exceptions, an illustrative device, not a scientific analytical tool. A flint flake can have its use suggested and emphasised by careful lighting. Its formal metrics will be expressed in numbers: its use may be derived from molecular analysis of residues.

Man’s skeleton “The use of a scale prompts ideas of scientific study”

Scales are included in most archaeological contexts but are rarely anything more than a general indication of size or distance. For instance how can we tell from the photograph whether a ranging rod is metric or imperial? Except for details of sections a good idea of size can be derived from vegetation and general landscape features. Defining the different approaches to archaeology can help in choosing the photographic method. Take three simple uses of photography - recording a dig, illustrating an object and suggesting the “human condition” of a past society. The photographic approach is the same for each, the mantra being “viewpoint, timing and lighting” - but not necessarily in that order. For the site photograph choice of camera is not of great importance. Scales and colour patches are useful. Timing depends on what is being revealed. Viewpoint is usually “up or down a bit”. Lighting can be waiting for a cloud to pass or perhaps having the team hold up a large white sheet to provide shade. Objects do not usually depend on timing - though I have had a badly fired pot slump under the camera’s gaze. Lighting and viewpoint can be adjusted to emphasise shape, texture or decoration.

Suggesting the human element of the past is a more tenuous concept. It can be done, for example,

Infant skeleton “Whereas lack of a scale leads to social values and the human condition.”

by putting a dig in its landscape context, or similarly by giving grave goods precedence over skeletal remains.

Lastly photographs can reflect the public attitude to archaeology - its usefulness to society. There are of course some other remote sensing methods analogous to, and sometimes included in the photographic spectrum. Infra red and ultraviolet recording does show what is invisible to the naked eye. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) can add a different perspective from that of conventional

Lidar “Lidar shows landscape forms unaffected by vegetation.”

Amarna visitors “Archaeology can be protected as here by fencing, but is often threatened by development and agriculture as shown in the background”

microscopy. Lidar can reveal landscape features not shown by conventional photography. With it impossible sun angles can be simulated to bring out otherwise unnoticeable topography.

All these methods still fall, or are used, mostly within the general definition of illustration, not analysis. This comprises the majority of archaeological photography. This balance has begun to change. Now, with digital technology developing apace, accurate measurements can be derived, and 3D representations created; colours can be accurately defined. The distinction between illustration and scientific evidence should not be forgotten in enthusiasm for the new.

Despite technological progress photography remains first and foremost a descriptive tool. The key for good photography within archaeology is to recognise what specific attributes an object, or site, has and to make those apparent and appealing both within and without the archaeological community. What is evident to the specialist archaeologist may not be obvious to others however observant or educated they may be.