8 minute read

In the beginning

Personal recollections of the group’s foundation Eric Houlder LRPS.

The early 1970s was an important time for archaeological photography. After a long period of indifferent site photography, as evidenced in many published reports and the poorly exposed slides seen too frequently at contemporary conferences, a disparate group of enthusiasts was gradually forcing up the picture quality. Meanwhile, improvements in materials and equipment too were enabling those non-photographers responsible for much site photography to achieve higher standards. Several articles in the popular photographic press, by amongst others the present writer, had been well received. Three books, updating though not necessarily improving upon Cookson’s Photography for Archaeologists, were published within a few years of each other demonstrating that there was a demand for instruction in site photography (Matthews 1968, Simons 1969, Conlon 1973). The book by Matthews surprisingly, has no archaeology in it!

Archaeology itself was changing. The Wheeler Box system was gradually giving way to Open Area excavation, whilst the pace of development in town and country was outpacing the older systems of summer digs and haphazard rescue and record. Since before the Second World War, excavations had generally been organised in the summer academic vacations. This was convenient as the organisers were, with few exceptions, academics themselves, whilst the volunteers who did much of the actual digging were often students, teachers, or amateur archaeologists who could choose their work holiday week or fortnight in the summer. Any chance discoveries made by development or agriculture were investigated by the same academics, by local museum curators, or by local enthusiasts. The CBA (Council for British Archaeology) was a co-ordinating body set up in the closing years of the War. It published an annual Calendar of Excavations which carried details of proposed digs and how to join them. In the offseason it carried brief reports of each site for the benefit of participants. I grew up with this system. After digging as a volunteer on a number of local sites, I was befriended by a couple who had both, individually,

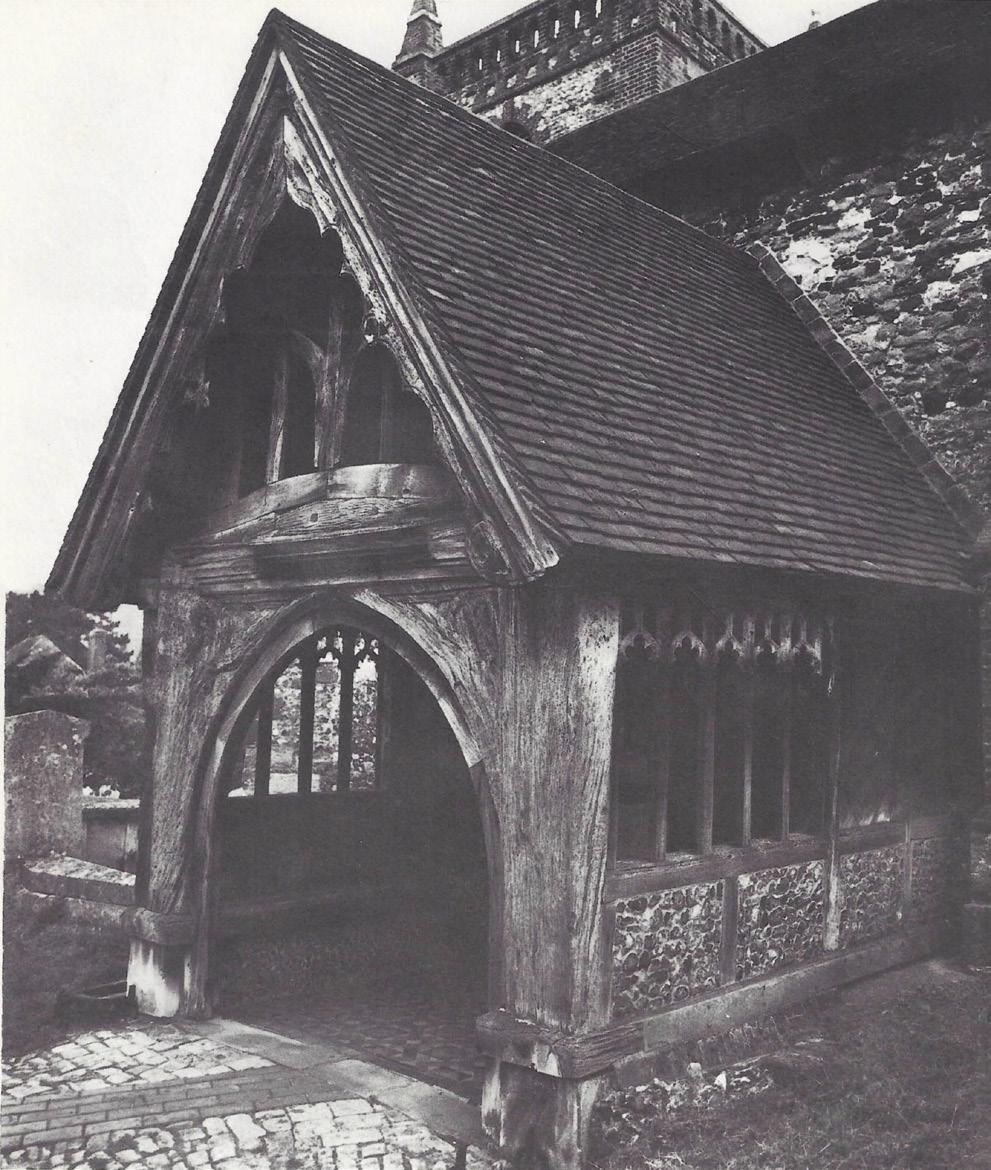

Mr Pinchitraker’s photograph of the Group’s birth in Audley House, London in 1974. Left to Right, Lt Col Derek Knight, MBE Hon FRPS, later President of RPS, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Robert Pitt ARPS, Brian Tremain FRPS, and Kenneth Warr, RPS General Secretary.

The Sutton Hoo Mound One, layed out on the Wheeler Box System with two baulks already removed, and some squares unexcavated. Note that in its day no-one ever called it anything but a grid. Courtesy Dr R Bruce-Mitford & the Trustees of the British Museum.

An Open Area excavation from the tower, Wood Hall, North Yorkshire. Courtesy WHAT Ltd and V Metcalf.

risen up the ranks since before the war. Peggy, or Margaret Markham White, see more in the Trowel Blazers website Women in Archaeology, Geology and Palaeontology (https://trowelblazers.com/), had been a supervisor with Rik Wheeler, whilst Kenneth Wilson her second husband, a published war poet, was Museums Education Officer in Leeds. They trained several younger enthusiasts like me in the Wheeler System. Peggy also knew Cookson, whom she referred to as ‘Cooky.’ She recalled someone tiring of his overenthusiastic ramblings by telling him.

I subsequently directed a number of local and regional digs and then went on the become a supervisor (not yet a photographer, though I did shoot some official pictures) under Paul Ashbee, a top rank archaeologist, who had the distinction of being the first archaeologist to use CCTV cameras on a site, The Wilsford Shaft. I joined him and Dr R Bruce-Mitford on the second dig at Sutton Hoo in 1967. All this whilst heading history departments in local schools, marrying, setting up a home, and having a family. Clearly I had a lot more energy then.

Meanwhile, archaeological site photography had been staggering along largely outside the mainstream of professional photography. The reason, or blame, for this in my opinion lies with Rik Wheeler and his photographer, Maurice Cookson. Cookson always advocated the large format field camera, the larger the better. Wheeler in supporting Cookson also recommended the same. However, whilst producing superb monochrome results in experienced hands, this flew in the face of progress which was firmly in the smaller, metal precision camera camp. Exotic film emulsions like infrared, ultraviolet, and even common or garden colour film was easier and more precisely exposed in the newer instruments, and largely unavailable for the former, except as expensive sheet film. I except from this general criticism those professional photographers working for archaeologists in university and museum environments. These people could squeeze fantastic quality out of even Victorian large format field cameras, and knew instinctively when to use more modern instruments. However, they were a small minority and barely scratched the surface of the vast mass of excavated material. OGS Crawford the aerial photographer was using Rolleiflex instruments, whilst Mercie Lack and Barbara Wagstaffe used Leicas at Sutton Hoo in 1939. Some site photographers already knew about precision cameras even pre-war, but were outnumbered by the ranks of those who read Cookson’s book: Photography for Archaeologists (1954). I purchased this book myself, but already knew enough about photography to realise its shortcomings regarding equipment and materials. Its advice on site preparation was exceptionally good, however, and is still largely apposite. Luckily, my directors were also forward looking. Paul Ashbee, who had known Cookson personally, was using 35mm in the 1960s and probably before, whilst Vincent Bellamy my first ever site director was using two 35mm cameras, for mono and colour, in the mid 1950s.

Thus, by the early 1970s there was an increasing interest and competence in site and aerial photography. The founding of Current Archaeology in 1967 was something of a catalyst for site photographers. It was not the only magazine dealing with archaeology in Britain, nor the first. Indeed, Antiquity, originally intended to acquaint the interested general reader with our subject had quickly become something of a specialist journal, whilst the somewhat downmarket – in this context – Archaeological Newsletter had begun post war and finally petered out during the early ‘60s, taking my subscription with it into limbo. So Current Archaeology quickly became the only general magazine for archaeologists in Britain. Like, I suspect, many other archaeological camera users I quickly formed an ambition to achieve a cover image for Current Archaeology, an ambition that took some years to come to fruition. Even before our Group was formed, the RPS had taken an interest in archaeological photography. For example, its Science Committee had sponsored a three day symposium in December 1970 on Photography in Archaeological Research, and many of the prominent specialists in museums and heritage agencies were RPS members. By 1974, the rise of archaeological units and the increasing professionalisation of the discipline left those of us who were in the middle, so to speak, wondering how to maintain our involvement with the subject. In the early months of that year notices appeared in Photography magazine and in Current Archaeology to the effect that the RPS was considering forming an archaeology group, and announcing a special meeting in the Conference Room at RPS Headquarters, 14 South Audley St, London, on 2nd April in the evening. I very quickly joined, sent my apologies for absence to the RPS, and eventually forwarded my group subscription of five shillings (25p). The founder was an Australian photographer, Robert (Bob) F Pitt ARPS who had been working in the Holy Land, which is why most of us had not heard of him before. Sensibly, he had enlisted the help of Sir R E Mortimer Wheeler, known to contemporaries as Rik, short for Eric. The meeting was well attended, and reported upon at length in

A typical pre-war site photographer’s camera with focusing cloth and dark slides holding glass plates. It has a simple reflecting viewfinder of dubious accuracy.

The Photographic Journal (1974), and in an excellent report in Current Archaeology. There were sixty people present when the meeting began, chaired by Robert Pitt ARPS. Luckily, one of those present, RPS member Mr Pinchitraker of Kathmandu, Nepal, took a photograph of the platform group, and though initially printed on coarse brown paper as an insert in The Photographic Journal May 1974, it is reproduced here. Left to right: Derek Knight, RPS President, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Robert Pitt, Brian Tremaine (acting Secretary of the proposed group), and Kenneth Warr, RPS General Secretary. The meeting began with Robert Pitt welcoming Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who entertained those present with a detailed account of his introduction to archaeological photography before the Great War. He described his meeting with the young Maurice Cookson, and their adventures together in attempting to make the camera tell the truth! He closed his address by saying how his friendship with Cookson had taught him much, and how he was surprised that the RPS had not had an archaeology group before. In the discussion which followed numerous questions were asked by amongst many others Henry Cleere, Director of the CBA, Tom Jones ARPS, Photographer to the well known Mucking site, and Andrew Selkirk, Editor of Current Archaeology. A Committee was formed with Brian Tremaine FRPS as its first Secretary. Its task was to assemble a programme of meetings, lectures, workshops and visits. Thus was the Group born.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to my friend, Andrew Selkirk, Founding Editor of Current Archaeology, for unearthing his memories and the relevant Current Archaeology reports. Also to my late friend and mentor Peggy Wilson for remembered quotes

References

Matthews S.K. (1968) Photography in Archaeology and Art, London: John Baker. Simons H.C. (1969) Archaeological Photography, London: University of London Press Ltd. Conlon V M. (1973) Camera Techniques in Archaeology, London: John Baker. Cookson M. B. (1954) Photography for Archaeologists. London: Max Parrish. Editor (1974) RPS Archaeological Group. The Photographic Journal; 114, May: 221.