MALAYSIA A MARITIME NATION AGENDA

Editors

Capt Ivan Mario Andrew RMN Director General of RMN SPC

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nazli Aziz Coordinator of Centre for Ocean Governance, INOS UMT

Editorial Assistants

Cdr Azrul Nezam Asri RMN

Lt Cdr Hafizan Tarmidi RMN

Lt Cdr Danish Asyraff Abdullah RMN

Published by

ROYAL MALAYSIAN NAVY SEA POWER CENTRE (RMN SPC)

Jalan Sultan Yahya Petra

54100 KUALA LUMPUR

Email: rmnspc@navy.mil.my

Tel: +603 2202 7260

First Published 2023

ISBN 978-967-26093-1-5

Printed by Arif Corporation Sdn. Bhd. 42, Jalan Pengasah 15/13, Seksyen 15, 40200 SHAH ALAM, Selangor

Disclaimer

The views expressed are the author’s own and not necessarily those of the RMN Sea Power Centre. The Government of Malaysia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statement made in this publication.

Copyright of RMN Sea Power Centre (RMN SPC), 2023

© All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means; electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the RMN SPC.

This second volume of Malaysia is a Maritime Nation Agenda is compiling various chapters on Malaysia’s past, present and future issues and agendas. It carries the same main title but this volume is focusing on steering the course of the Malaysian maritime agenda. Given the dynamic of maritime agenda at domestic, regional and international levels, the topics addressed in this volume are relevant to understand the strengths, weaknesses, progress, threats, opportunities and challenges that are faced by Malaysia in navigating her direction as a maritime nation.

Surrounded by territorial waters, making sense of Malaysia’s geographical location as a maritime nation is easy. However, steering the course to understand and advance Malaysia’s position as a maritime nation is complicated because of her strategic location. This volume is broad in scope and entails a pluralist-dimensional worldview. It manifests the dynamic and ever-changing perspectives in analysing the nature of different actors interacted at three levels of power authority – domestic, regional and international. The contents in this book has been discussed from historical to current and philosophical to empirical as well as from behavioural to institutional perspectives. The analysis made by the chapter contributors, however, do not necessarily reflect the view of the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN), Universiti Malaysia Terengganu (UMT) and the Malaysian government.

This second volume is organised into six parts. It begins with Part I: Overview and Context, an introductory chapter penned by the editors themselves. Part II contains four chapters that discuss topics on geo strategic and security environment. Consequently, Part III with three chapters addresses topic on Indo-Pacific Strategy and its impacts to Malaysia. As the global agenda has evolved and we are faced the “unconventional” threats, Part IV raises topics related to the border security with four chapters. Meanwhile, Part V comprises two chapters. It touches on blue economy as one of the vital global agenda that intertwined closely with the global development. Finally, Part VI is the epilogue that concludes the topics discussed in this volume.

We would like to extend our gratitude to all chapter contributors. Their valued contributions have enriched our knowledge and permitted this second volume to be published. However, the publication of this book is not intended to exercise ideological and partisan perspectives towards any actors. We also would like to thank everyone who has been involved directly or indirectly in realising this book. Finally, our hope is that the readers of this book would be able to generate new insights related to the efforts in steering Malaysia’s maritime agenda.

Editors, Captain Ivan Mario Andrew RMN Director General, RMN Sea Power Centre (PUSMAS TLDM) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nazli Aziz Coordinator, Centre for Ocean Governance, Institute of Oceanography and Environment, Universiti Malaysia TerengganuPREFACE

PART I: OVERVIEW AND CONTEXT

INTRODUCTION

Editors

PART II: GEOSTRATEGIC AND SECURITY ENVIRONMENT

CHAPTER ONE

MALAYSIA A MARITIME NATION: MAINTAINING RESILIENCE IN MANAGING THE CURRENT STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT

Captain Ivan Mario Andrew RMN

CHAPTER TWO

SHAPING NAVAL POWER: IMPLICATION OF AUKUS TO MALAYSIA’S SECURITY ENVIRONMENT

Captain Ahmad Rashidi Othman RMN

CHAPTER THREE

STRENGTHENING MARITIME SUSTAINABLE AND MARINE ECOSYSTEM PROTECTION THROUGH SECURITY COOPERATION

Commander Azrul Nezam Asri RMN and Lieutenant Mohd Massuoadi Mohd Zukri RMN

CHAPTER FOUR

LABUAN 1846-1963: PORT AND POLITICS OF THE BRITISH MARITIME AGENDA

Nazli Aziz

PART III: INDO-PACIFIC STRATEGY

CHAPTER FIVE

MALAYSIA IN THE INDO-PACIFIC ENVELOPE: THE GREAT GAME 2.0

Captain Mohd Yusri Yusoff RMN

CHAPTER SIX

MALAYSIA’S STRATEGIC RESPONSES TOWARDS THE INDO-PACIFIC CONSTRUCT

Tharishini Krishnan

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE CONCEPTUAL APPROACH: HOW NAVIES CAN SERVE A SHARED INTEREST TO THE INDO-PACIFIC COMMITMENT

Commander Muhamad Zafran Whab RMN

Malaysia a Maritime Nation Agenda: Steering the Course

PART IV: BORDER SECURITY

CHAPTER EIGHT

MALAYSIA’S MARITIME SECURITY CHALLENGES DURING COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Captain Tay Yap Leong RMN and Nor Aini Mohd Nordin

CHAPTER NINE

THE ASEAN’S STRATEGIC VALUE IN ENSURING THE MARITIME SECURITY

Captain Mohd Reduan Ayob RMN

CHAPTER TEN

THE EVER-PRESENT OF ABU SAYYAF IN INSULAR SOUTHEAST ASIA:

MITIGATE BUT NEVER DEFEATED

Abdul Razak Ahmad and Ahmad Zikri Rosli

CHAPTER ELEVEN

THE UNEXPLORED ROLE OF BORDER COMMUNITIES IN BORDER MANAGEMENT

PART V: BLUE

CHAPTER TWELVE

DEVELOPING AND IMPLEMENTING THE BLUE ECONOMY IN THE INDIAN OCEAN: MODEL FOR MALAYSIA

Commander Ang Chin Hup RMN (Retired)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

THE ROLES OF THE NATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC CENTRE IN HARNESSING THE

Malaysia a Maritime Nation Agenda: Steering the Course

“Malaysia is blessed with all the attributes of a maritime nation with continental roots. Our strategic location, between the Indian Ocean and the Asia Pacific region, makes us the focus of global maritime trade, whereby 90 per cent is via shipping…. The maritime sector’s contributions towards the growth and dynamism of our economy will become more significant as we aspire to become a fully developed nation.”

Dato’ Seri Utama Mohamad, Defence Minister said this in his opening speech when officiating the national Langkawi Maritime Conference 2023 (LMC 2023) on 24 May 2023 in conjunction with the Langkawi International Maritime and Aerospace Exhibition (LIMA) 2023. The speech extraction quote above reflects the contents of this book.

Malaysia a Maritime Nation Agenda: Steering the Course is the second series of publications by RMN SPC that discusses Malaysia’s past, present and future issues and agendas as a maritime nation. It carries the same main title but this volume is focusing on steering the course of the Malaysian maritime agenda. Given the dynamics of the maritime agenda at domestic, regional and international levels, the topics addressed in this volume are relevant to grasp the strengths, weaknesses, progress, threats, opportunities and challenges that Malaysia has faced in navigating her direction as a maritime nation.

Surrounded by territorial waters, making sense of Malaysia’s geographical location as a maritime nation is easy. However, steering the course to understand and advance Malaysia’s position as a maritime nation is complicated because of the strong “continental roots” in formulating, and making decisions in directing past, present and future nation development. In an attempt to spark the discussion here, this volume is broad in scope and entails a pluralist-dimensional worldview. It manifests the dynamic and ever-changing perspectives in analysing the nature of different actors involved and interacted at three levels of power authority – domestic, regional

and international in setting the maritime agenda for a nation. The contents in this book have been discussed from historical to current and philosophical to empirical as well as from behavioural to institutional perspectives. The chapter contributors have different backgrounds, from practitioners, academicians, activists and professionals.

This second volume book is organised into six parts. It begins with Part I: Overview and Context, an introductory chapter penned by the editors themselves. Part II contains four chapters that discuss topics on geostrategic and security environment. Consequently, Part III with three chapters addresses the topic of Indo-Pacific Strategy and its impacts on Malaysia. As the global agenda has evolved and we have faced the “unconventional” threats, Part IV raises topics related to border security with four chapters. Meanwhile, Part V comprises two chapters. It touches on blue economy as one of the vital global agenda that is intertwined closely with the global development. Finally, Part VI is the epilogue that concludes the topics discussed in this book.

This book contains 13 chapters. As mentioned above, it addresses four main themes namely Geostrategic and Security Environment (Part II); Indo-Pacific Strategy (Part III); Border Security (Part IV); and Blue Economy (Part V). The arrangement of the chapters as such is to reflect Malaysia’s effort in steering the course in institutionalising a maritime nation. Specifically, there are four chapters in Part II, three chapters in Part III and four chapters in Part IV as well as two chapters in Part V.

In Part II, Captain Ivan Mario Andrew RMN analyses the resilience in managing the current strategic environment of Malaysia as a maritime nation. Since the 21st century is considered as the Asian century, the concerns that perplex the region’s security and progress constitute Malaysia’s resilience in managing the current strategic environment. He argues that the seas are Malaysia’s livelihood, and the security and stability in the South China Sea are critical for Malaysia and Southeast Asian nations. While the territorial dispute in the Southeast Asian region in particular of South China Sea is highly complex, a piecemeal approach would be a pragmatic first step toward a long-term solution. While it is known that practical collaboration, dialogues and trust building are complementary approaches without which effective solutions can be obtained, multilateral cooperation needs to be more steadfast in resolving security concerns.

Captain Ahmad Rashidi RMN discusses the implication of AUKUS to Malaysia’s security environment. In this chapter, he also describes the factors that influence the involvement of Australia and the United States of America (US) with the presence of China as the ‘dragon’ in the region. He highlights that the existence of AUKUS is part of a political and military strategy to balance power in the Indo-Pacific region. Hence, Malaysia needs to be prudent in ensuring that the country’s security and sovereignty are not compromised in the face of the establishment of a military alliance between Australia, the UK, and the US. He adds that in the face of geopolitical challenges involving regional security, it is appropriate that the role of ASEAN through its defence diplomacy be made the focus in the efforts of balancing the influence of major powers.

Commander Azrul Nezam Asri RMN and Lieutenant Mohd Massuoadi Mohd Zukri RMN analyse topics related to strengthening maritime sustainability and marine ecosystem protection through security cooperation. Ocean plays a significant role in aiding a nation to be more prosperous. Through collective efforts, nations are able to manage traditional and non-traditional maritime security and preserve the marine environment effectively. They argue that Malaysia has made noteworthy progress as a maritime nation by investing in personnel and resources while boosting inter-departmental and organizational collaboration. Developing a comprehensive national policy on maritime security and sustainable growth is vital to ensure the issues in the maritime domain are well tackled. This plan should set out the government’s targets and aims for maritime security and sustainable development, as well as the roles and responsibilities of various organizations and stakeholders in achieving these goals. With determination, forward-thinking, and dedicated government entities at all levels, these efforts will be of great worth to the citizens while preserving an area of utmost importance to Malaysia’s future.

The last chapter in Part II is by Nazli Aziz on Labuan Port 1846-1963. Nazli examines the role of a minor port in integrating and consolidating a grand maritime agenda of the British in Southeast Asia with Labuan as a case study. He trances Labuan’s transformation from a natural harbour to a planned port within the regional context. By enlarging the analysis framework of the establishment of Labuan Port from the locality to the region, he illustrates how the port contracting and expanding spheres of influence became part of the larger rhythms of the British political economy. The interaction between ports was often intentional as part of the broader network of markets and trade in order to perpetuate the colonial political-economy powers in the region. There are no such things as “natural” or self-determined ports of the colonials. A port is designed with the purposes and specific features that are pertinent to the area’s interests and the colonial’s needs. As a result, the port interacting under the same ruler has an important impact on the patterns of trade, production and politics which may present new opportunities and setbacks for the development and expansion of particular colonial ports.

Part III deals with Indo-Pacific Strategy. The first chapter in this part is by Captain Mohd Yusri Yussof RMN. He examines the “Indo-Pacific” as an idea that has produced a “mental map” that two traditional oceans i.e., the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean become one ocean. Malaysia is yet to make any official statement on “Indo-Pacific”. This has been generally viewed as “non-action” by certain parties. Even when neighbouring states are seemed to embrace the “Indo-Pacific” geopolitical architecture, Malaysia has remained “inert”. This neutral posture could however be traced through the “set of mechanisms” that Malaysia had used in interpreting the idea. He claims that historically, the history of Malaysia is a history of big power politics and institutionally, Malaysia had seen that being non-aligned is the best policy that it could muster in such situation.

The discussion on Indo-Pacific is further examined by Tharishini Krishnan. She argues that Malaysia must respond to the Indo-Pacific because it is to stay and is shaping the geostrategic discourse and power politics of big powers in the international system. Adopting a hedging position seems to be a logical approach. Malaysia’s strategic response towards the Indo-Pacific construct is one that constitutes neutrality. This approach is driven by the fact that the Indo-Pacific is a systemic rivalry between Washington and Beijing. As a small power, it is illogical and unnecessary for Malaysia to lean towards the Indo-Pacific construct. However, it is not necessarily true that Malaysia is a weak country. Malaysia is bold in proclaiming its position vis-à-vis any rising strategic discourse, for which national interest is prioritised. Malaysia’s decision not to upset China also does not mean that Kuala Lumpur is placating more towards Beijing and less towards Washington. It simply means that Malaysia is smart not to posture against either power because both the US and China are important for its survival, and seeking neutrality provides greater flexibility in its strategic response towards the IP construct.

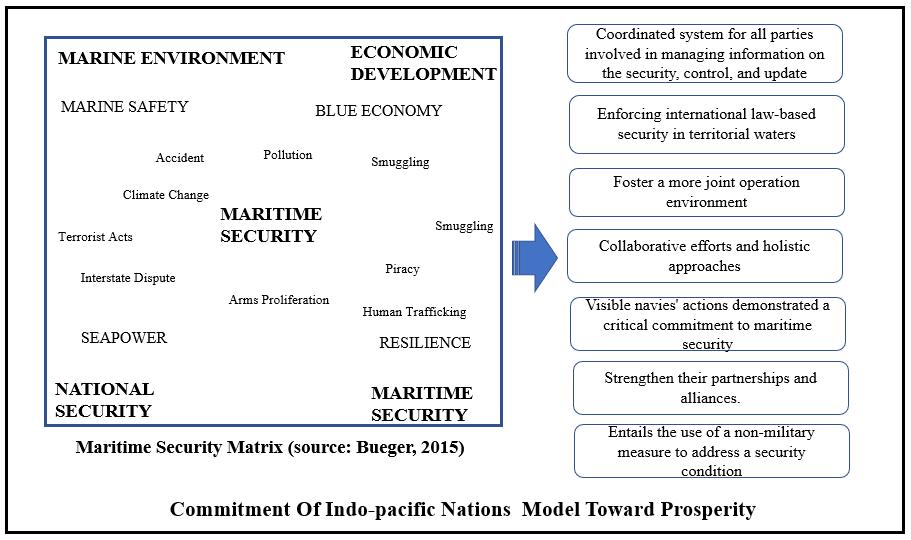

Chapter by Commander Muhamad Zafran Whab RMN is the last article in Part III. His work provides insight into Malaysia’s unique approach to giving the Indo-Pacific nations’ commitment to common purpose, security, prosperity, and order and how it might help Navies best serve the shared interest. Given the recent escalation of the US-China rivalry and its implications for Southeast Asia’s security landscape. He argues that Malaysia’s current involvement in regional dynamics through the lens of the country’s history of dealing with big power competition may be instructive. By examining Malaysia’s foreign policy in the context of its experience in dealing with various long-term security threats and dominant power hegemony, this chapter reveals how the state mediates its position in light of growing competition between China and the US. This situation focuses on security cooperation and the conflict in the South China Sea. He examines how can Malaysians be understood in terms of the country’s traditional approach to regional security, what is Malaysia’s best course of action today, and how Malaysia has navigated the US-China competition.

Part IV deals with border security with four chapters altogether. The analysis present in this part has the tendency to examine non-traditional security issues. The first chapter in this part is by Captain Tay Yap Leong RMN and Nor Aini Mohd Nordin. They study Malaysia’s maritime security challenges during COVID-19 pandemic. They suggest that a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach is the best strategy for Malaysia moving forward in the future be it during a crisis or in peacetime. They claim that the formation of National Task Force (NTF) has clearly shown its benefit in terms of containing maritime security issues as well as increasing overall enforcement and military capabilities. Domestically, threats such as pandemics and illegal immigrants are detrimental to the nation’s social fabric and economy. Hence, Malaysia must start addressing the current issues of existing illegal immigrants that had made the headlines during the pandemic. A whole-of-society approach is also important in imparting information on the importance of reporting illegal immigrants to law enforcement. However, all of

this requires a strong political will at the district, state, and federal levels. Therefore, Malaysians need to understand the consequence that may occur should the country’s maritime security agencies be without proper strategies and capabilities.

Captain Mohd Reduan Ayob RMN studies the ASEAN’s strategic value in ensuring maritime security. He emphasizes that to gain a win-win approach, ASEAN members took a different strategy in addressing the maritime security to avoid losing to one another, which emphasizes argument through dialogue for later settlement and minimal institutionalisation. This chapter highlights the threat resulted from the competition that arises in the South China Sea. As China’s posture attracted global powers into the theatre, ASEAN seeks necessary balancing in protecting sovereignty. The approach taken was to denote the balancing tendency while proposing several outcomes that suit the internal issues within the ASEAN member state. Unity issues must be addressed and subsequently work towards intraregional balancing towards resolving the territorial disputes, directing a balancing effort as a network of resolving conflicts. Several approaches like collaborations and more frequent engagement are highlighted but no matter how serious the maritime security situation is; ASEAN must resolve internal conflicts without outside intervention and consequently adopt a shared solution to address the regional maritime security issues hence ensuring greater economic height.

Using Abu Sayyaf as a case study, Abdul Razak Ahmad and Ahmad Zikri Rosli’s title evidently suggested that this militant group has been mitigated but never defeated. The chapter sheds light on the nature of the threats posed by Abu Sayyaf to Malaysia’s maritime space and recommends ways to counter them. They argue that the essential measure that needs to be undertaken by Malaysia to safeguard its maritime space is to improve its maritime and naval capabilities. They boldly suggest that to achieve this, it is essential to first address the elephant in the room, i.e., the imbalance in the distribution of budgetary provisions. Besides investing in capabilities, the security forces should capitalise on the locals in Sabah as a source of human intelligence and information. Through cooperation with the locals, the authorities can acquire valuable information, such as the presence of unfamiliar faces or suspicious movements noticed by the locals. This chapter demonstrates that ongoing counterterrorism efforts by Malaysia and its neighbouring countries have been relatively effective. Protecting its waters is vital for Malaysia to realise its aspiration as a maritime nation with continental roots. Eradicating the threats of the Abu Sayyaf Group in its maritime space will ensure Malaysia’s maritime security and preserve the well-being of its people and the flow of maritime activities.

The final chapter of Part IV is by Altaf Deviyati Ismail and Tadzrul Adha. They examine the unexplored role of border communities in border management. This chapter underlines that the border communities by virtue of their relationships with the border are an integral part of border management. Their involvement is crucial especially in problem identification and problem-solving because threats and circumstances existing at the local level are shaped by local context and thus may not necessarily align with national level. Knowledge of the views of key

stakeholder groups and the variation within these groups is vital for those who design border management institutions and processes. The notion of border areas is also an important aspect. The border serves as a hard line or a soft zone or even a mixture of both, where stakeholders who work and often live in crossborder communities face similar challenges such as facilitating trade and tourism while at the same time trying to protect their security and cultures. They argue that in order for Malaysia to be fully prepared for the uncertain future ahead, the government should invest seriously in pushing for “total defence” as a means to preserve our national integrity. The holistic approach in looking at our defence capability must no longer rest on the army’s shoulder or the government alone.

Part V is about the blue economy. There are two chapters in this part. The first chapter is by Commander Ang Chin Hup RMN (Retired). In this chapter, he discusses a model for Malaysia on developing and implementing the blue economy in the Indian Ocean. Malaysia is an active member state of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) on blue economy. He argues that the Malaysian blue economy is a balance between economic development and sustainability comprising all economic activities ranging from traditional industries to waste management and desalination. He suggests that the experience of the IORA through its previous chairs’ initiation, planning and implementation by the Member States could serve as a model for Malaysia in implementing the blue economy.

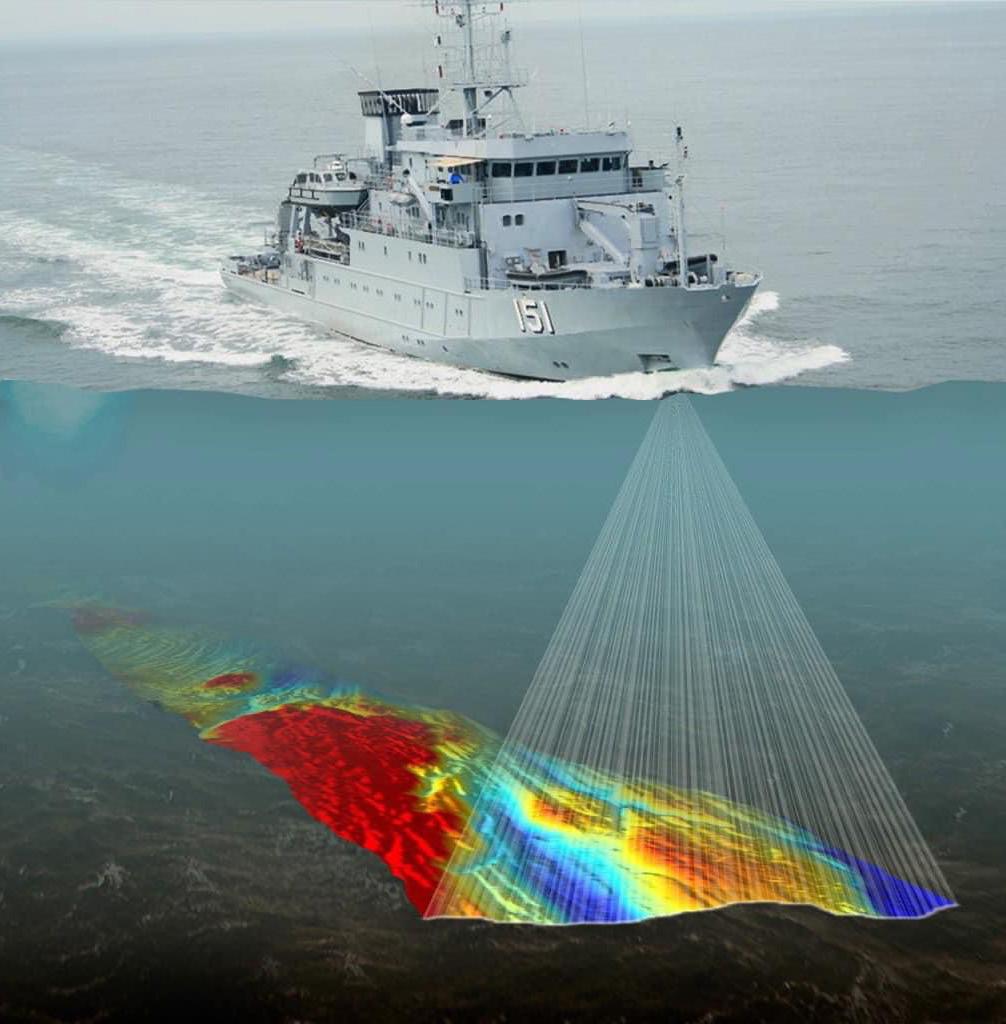

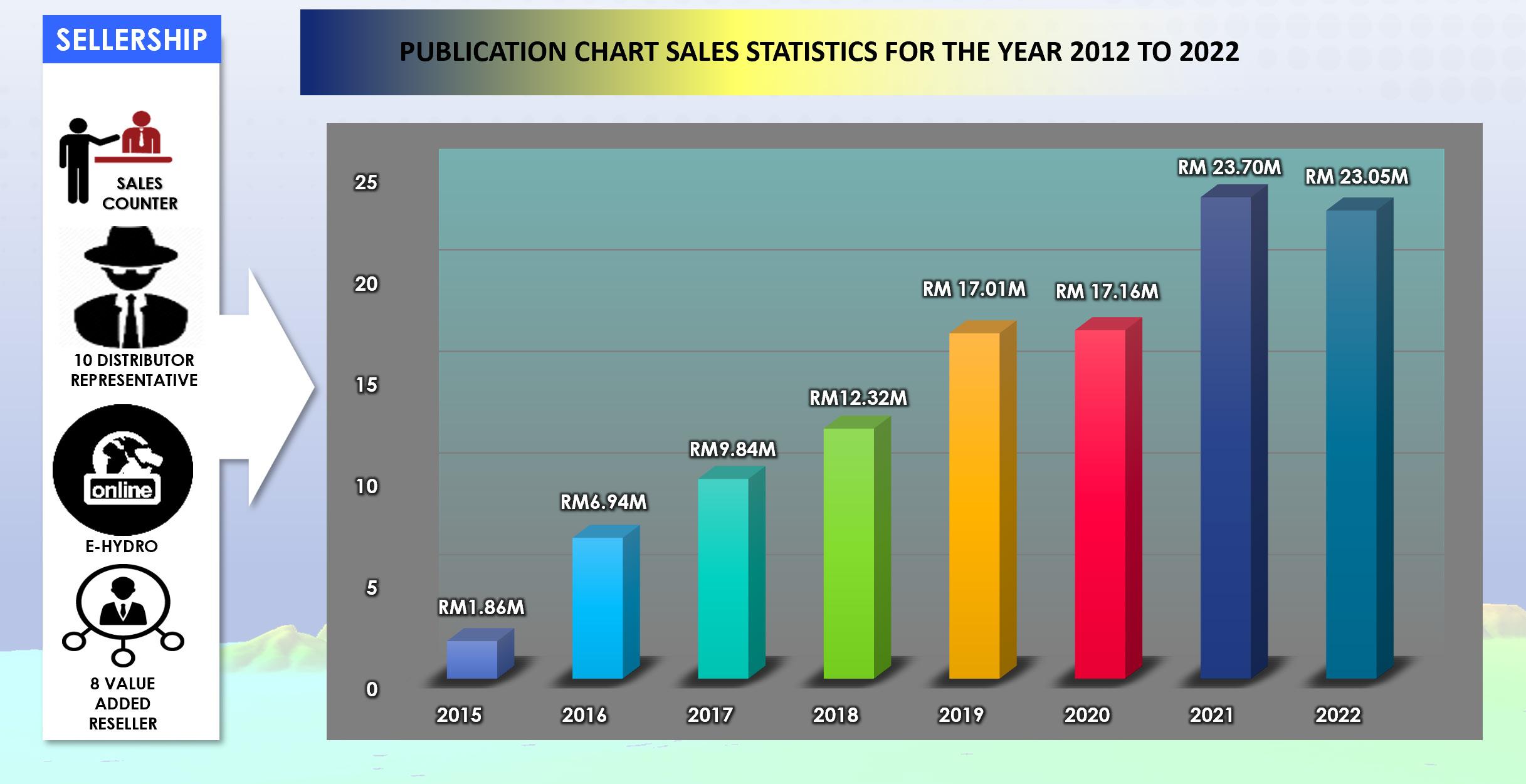

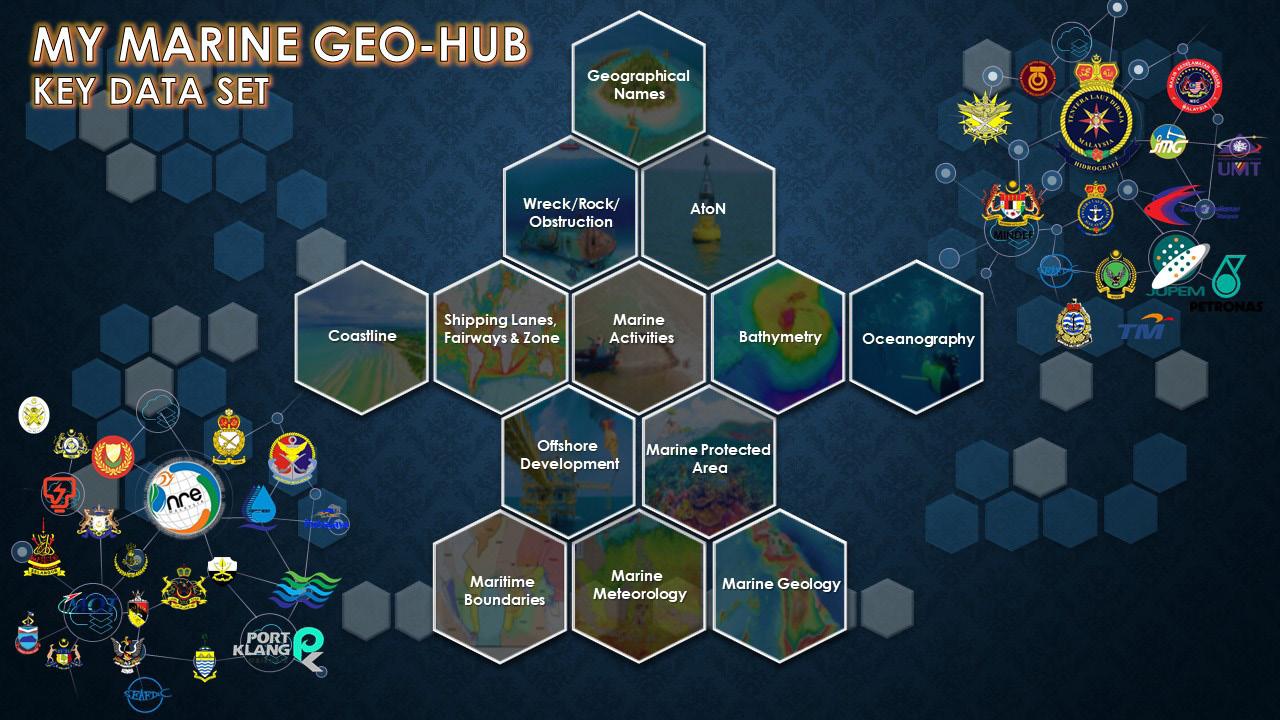

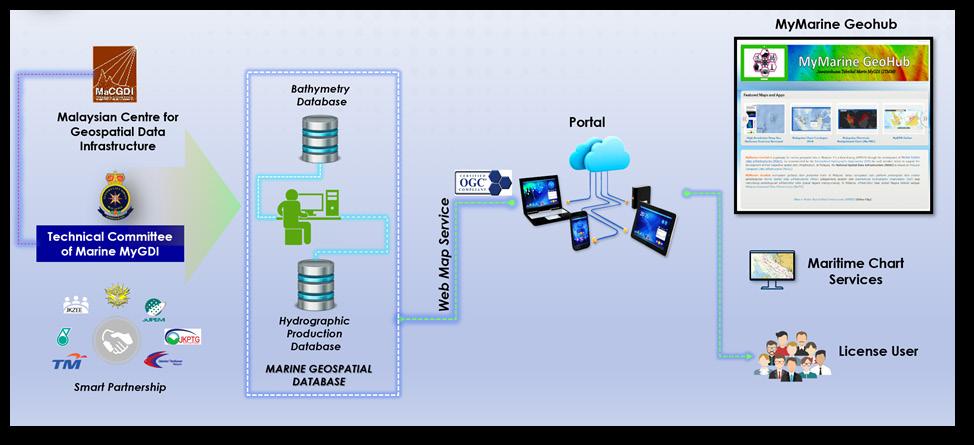

Meanwhile, Rear Admiral Dato` Hanafiah Hassan highlights the roles of the National Hydrographic Centre in harnessing the Malaysian blue economy. As a coastal nation with a maritime territorial zone, Malaysia has to establish hydrographic services to maintain navigational safety and meet technical requirements for delineating national maritime boundaries. The Royal Malaysian Navy hydrographic service has played a crucial role in upholding Malaysia’s commitments and responsibilities as a member of the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) for decades. He argues that if Malaysia wants to advance its blue economy, Putrajaya must first prioritise the completion of a hydrographic audit and economic evaluation analysis. The economic analysis, according to him, aims to demonstrate that utilising hydrographic services can boost productivity and efficiency while reducing the cost structure of many ocean-related activities.

Introduction

Malaysia is blessed to be in a region experiencing peace and tranquillity with rapid economic growth. Now, the country is not beset with any conflicts. However, geopolitical instability and security concerns in the form of Big Power rivalry and their colliding interest in the region, the mistrust of unresolved territorial disputes and non-conventional security issues are shaping and influencing Malaysia’s economic growth and strategic raison d’être.

With the global and economic centre of gravity shifting to Asia, these concerns that perplex the region’s security and progress constitute Malaysia’s resilience in managing the current strategic environment. Primarily, the government views the defence and security of the country as all-encompassing. The country relinquishes the use of force; however, defending the nation’s maritime interest and territories from domestic and external threats is fundamentally its strategic rationale.

The defining feature of the 21st century has been the shift from the global geopolitical centre of gravity to Asia. With a considerable stake in the maritime domain, Malaysia must also be consciously responsible and be the catalyst for peace, security and stability in the region. However, the nature of the following security challenges and the developments in this region over the last few years revolves around questions of whether Malaysia can stay united when national and regional interests diverge and whether it can effectively manage relations with its wealthier, more powerful and influential neighbours which have their particular interest in the region.

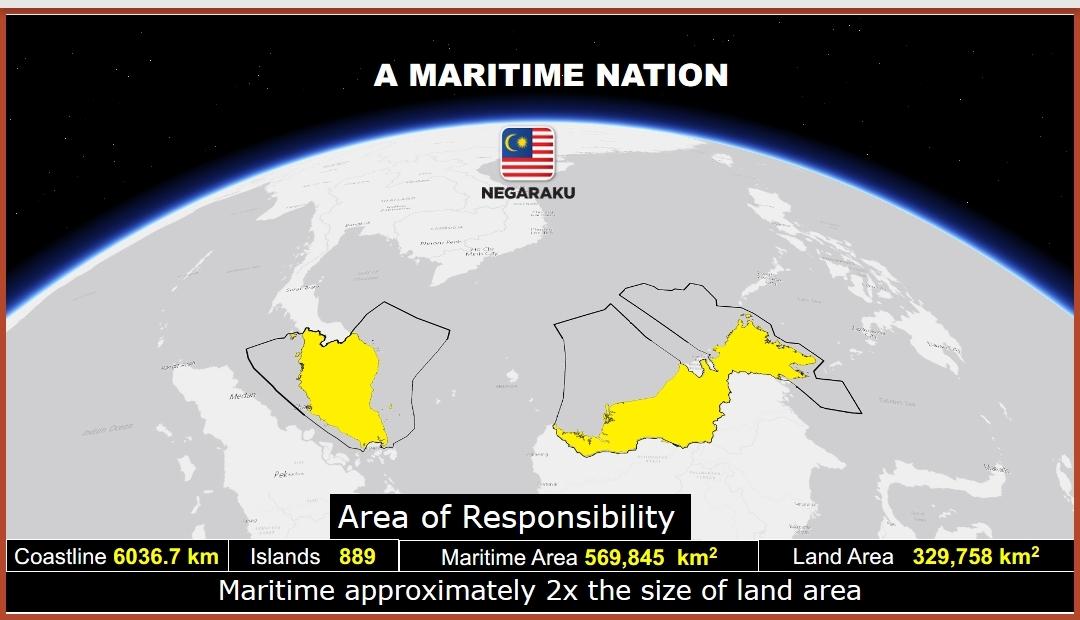

Malaysia must stake its claim for a maritime area twice the size of its landmass. The maritime area covers from the very tip of the Strait of Malacca into the conflictriddled geostrategic South China Sea (SCS) and the Celebes Sea. Furthermore, being in the centre of the busiest waterway linking the east to the west and cognisant of its strategic considerations and interests, the responsibility of safeguarding the country’s maritime geographical area is further divided into three concentric layers (Ministry of Defence, 2020):

a. Core area – Peninsula Malaysia, Sabah, Sarawak and the territorial waters and air space of these land masses.

b. Extended area – Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ) and its airspace.

c. Forward area – beyond EEZ, which is of national interest.

Being the process that integrates the world into one comprehensive system, globalisation has impelled inexorable unification of economic, political and cultural activities beyond borders which have profusely brought prosperity to Malaysia. And, thanks to the acceleration of cyberspace technology, these days’ local activities are influenced by transnational incidences at exponential speed, whereby E-Commerce and the unrestricted Internet have disassembled the barriers to the movement of goods and capital augmented political and economic powers (Solomon, 2008). This has allowed Malaysia to delight in the benefits of this world’s increasing prosperity and most advanced technologies.

Besides changing the global political, societal and cultural environment, globalisation has also brought significant opportunities and risks. Most importantly, economic globalisation has amplified the contemporaneous dependence on seaborne trade, which has exposed maritime assets to security vulnerabilities such as piracy, terrorism and other non-conventional threats. These vulnerabilities, to the esoteric defence intellect, hold weighty security implications and a nation’s decision-making process (Dicken, Kelly, Kong, Olds, & Yeung, 1999). Furthermore, maritime trade depends on the secure use of the world’s Sea Lines of Communications (SLOC). This deliberately entails Malaysia comprehensively estimating the associated maritime security risks that demand its ability to exploit the opportunities ambitiously and counteract the risk pragmatically.

The dawn of globalisation’s technological advancements has revealed an even more complex maritime security environment and impacts the development of sea power globally. Today, technology has enhanced capabilities and significantly impacted maritime agencies’ abilities to address a more complex and dynamic environment. For example, while technology supports operational security measures, simple but

effective technologies like portable radio communications and speed crafts have also helped law breakers tailor their activities effectively undetected. This, therefore, necessitates security agencies to tailor their operations with newer technologies to manage and enable real-time surveillance and monitoring in enforcing law and order. Furthermore, since maritime security threats are non-traditional and transnational, Malaysia’s maritime organisations must increase their capabilities, revisit their maritime strategies and seek comprehensive adaptable approaches towards this complex maritime environment.

The maritime domain has been and will always be a sphere of influence where divergence and cooperation would be the day’s sound bites. This is because it has attracted numerous issues and challenges that have impacted the security and Malaysia’s economic, social and environmental strata. Hence, with the deepening global crisis, these existing security challenges can increase over time.

Malaysia, which centres on the defence of national interests and territories as its fundamentals to sovereignty and independence (Global Security, 2019), sees the inclusivity of its maritime waters’ security and safety as a local issue. Therefore, the end state for this self-preservation rests on the Malaysian Armed Forces (MAF) generally and the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) to focus on the need to protect the nation’s interest in the Strait of Malacca, SCS and the Celebes Sea.

Malaysia’s disputes with its neighbours’ is centred on sovereignty concerns emanating from the apprehensions of insecurity and unresolved maritime borders and boundaries. Contentiously, Malaysia’s serious security challenge can be derived from the complex and multiple territorial disputes in the SCS. However, for the moment, the intensity of the border disputes can be considered low and has remained more at the political and diplomatic level of anger and resentment. The use of force has only been ostentatious, where the presence and role of navies and the employment of the air force have only been tailored to augment the political and diplomatic rhetoric. In short to medium term, an armed conflict seems unlikely, whereby the disputes remain primarily political rather than military. Nonetheless, the risks exist of miscalculations, accidents or unwarranted incidents that can lead to a limited confrontation, which may involve other legitimate forces to a lesser extent.

Malaysia’s interest in the area of contention is due to it being strategic and economically within its EEZ. Strategic and economic value makes littorals compete for territory in the SCS. The area of contention has attracted Big Powers’ presents mainly because some of these Lilliputian squabbles over barren lumps of rock lie in

Malaysia A Maritime Nation: Maintaining Resilience In Managing The Current Strategic Environment

the middle of the most import SLOC where trillions of dollars of trade sail from the west to the east and vice-versa. But more importantly, their presence is vindicated because some of these ‘rocks’ have since been strategically turned into military outposts.

Under UNCLOS III, 1982, Malaysian maritime units have a significant right and duty to exert their presence within the authorised EEZ. Nevertheless, these territorial disputes’ primary challenge is avoiding escalation with claimant countries. In these precarious times, the MAF must continue its maritime and aerial activities with caution. Strategically it will not be wise to agitate any of the Big Powers locked in this rivalry as Malaysia depends on both sides economically or geopolitically. End state, Malaysia must position itself unilaterally well within its EEZ and Continental Shelf while continuing to pursue its claims in the SCS.

In this unpredictable and uncertain environment, the destabilising and geostrategic environment due to these territorial disputes will determine to a certain extent, the world’s future with the apparent interest asserted by Big Powers’ presence and assertiveness for a “free and open sea”. Currently, the disputes are at status quo, contained and managed via diplomatic channels and verbal rhetoric. However, the strategic environment can explode into a crisis if mismanaged.

Now that the COVID-19 pandemic is in its endemic state, the Straits of Malacca, Singapore Strait and SCS are anticipating an increase in traffic density. The high expectations from international users due to the ever-burgeoning traffic in the straits will exert considerable pressure and pose an added security and safety challenge to Malaysia to secure and protect the region’s SLOC. Conflict of any scale concerning the geopolitical complexities within the region’s SLOC will involve various state actors and hamper Malaysia from reaping the benefits of proven and potential riches.

Intractably the pegboard of Big Power rivalry is due to the unfortunate veracity that one feels besieged by the other increased nationalist sentiments towards challenging each other militarily, politically and economically. The presence of warships and aircraft intruding into the waters and airspace of SCS littorals reflects a more significant global security risk that challenges the democratic values of international law. These irrelevant claims and military bullying only further increase the drift in tensions and turbulence, economic competition, superpower logic and populist nationalism, which threatens the region’s security and prosperity (Hawksley, 2018). The continuous strive in Big Power rivalry where no side wants to provoke a conflict, and none is willing to back away either only propagates the many reasons for conflict to emerge and escalate. End state whatever happens in the SCS due to this Big Power rivalry proliferation will define the world’s and Malaysia’s future

correspondingly.

Big Powers establish their regional presence mainly for national interest through concerted collaboration, dialogues and trust-building efforts. Indeed, this increasing interest and forging of security cooperation and alliances under the ‘free and open seas’ rubric only ramps up the presence. These extra-regional navies skirting around each other suspiciously, basically under the pretext of safeguarding their national interest, practically pave the way for more mayhem than good.

There is only collective defence and little inclusive international cooperation between these Big Powers. Under the gambit of curbing the assertiveness within the region’s SLOC, these alliances present a mixed reaction from claimant nations. For the smaller coastal countries, it would be their strategic economic interest to refrain from agitating these Big Powers. Hence, in dealing with this Big Power’s alliances, Malaysia has to play it safe by siding/not objecting against the right alliances simply because it hasn’t the military might’ to go against them.

The Ukraine crisis has disrupted the world’s economic recovery post-COVID-19 and is likely to persist. Countries directly linked to both countries are the worst affected, with many others feeling the effects of ongoing sanctions, the increase in oil, energy and commodity prices, and the disruption of oil and gas supplies. Significantly this conflict of concern has imported global inflation and disrupted all other related economic transactions and global supply chains. Furthermore, this conflict proves that we are in a situation that depicts the world as unstable and uncertain. Geopolitically, the conflict has also portrayed the division; some are allied with the aggressor, some chose not to side, others are neutral, but many are now shunning the two conflicting countries with blame. Pragmatically, the conflict has placed Malaysia in a position to choose between the competing interest prudently (Bisley, 2022). However, the most intriguing part is that countries are now reassessing their defences, military spending and strategy to not fall into a similar position (The Straits Times, 2022).

Today’s maritime environment has expanded from 3-dimensional domains to now include the evolving cyberspace. Cyber-technological innovation and globalisation have proven to be an overwhelming force for good. However, the threat of falling victim to criminal cyber enterprises remains a clear and present danger, making cyber security an increased global concern that must be dealt with seriously. Firm national and regional resolves are needed because the perpetrators could be anyone,

from individuals launching attacks from the comfort of their homes to militant groups using social media to recruit members and gain sympathisers (Shahrudin, 2017). Therefore, cyber security is a more significant concern than one may realise, which needs Malaysia’s concerted effort to thwart these perpetrators’ Machiavellian intentions.

The maritime domain has attracted unconventional crime, which by far and large, has been dramatically transformed by the revolution in military affairs due to the consequences of globalisation. Besides the evolving nature of unconventional threats, some of the much-debated issues in the maritime environment in this region are cross-border crimes, illegal migration and the manifestation of illegal unregulated and unreported fishing (IUU). These maritime-related vulnerabilities, which include militancy, maritime terrorism, kidnapping for ransom, robbery at sea, and illegal human and drug trafficking, significantly affect and potentially destabilise the country’s maritime security and safety, which restricts the constructive characteristics of economic globalisation (Ong-Webb, 2006).

Although unconventional crime is seen to be dominant on land or ashore, these unconventional modalities may soon become the most common type of maritime threat in the future. Furthermore, as globalisation has made transit among countries easy and ‘borderless’, the world has become a transit point for the terrorist to launch their atrocities.

The changing balance of power dynamics at the regional and global levels has indeed impacted the effective functioning of Malaysia’s ability to secure the country’s maritime interests. The symptomatic fundamental challenges faced, if not curbed, might spiral out of control, become polemic and pit countries against each other. Significantly, more multilateral policies dealing with regional challenges can push Malaysia to look for alternatives in managing the issues with the current and foreseeable deliverables (Rajagopalan, 2021).

The expansion of seaborne trade increases the magnitude of challenges Malaysia must encounter to maintain the safety and security for seafarers to ply the SLOC that borders the nation. Besides individual states’ national security measures, a new idea to effect interaction amongst Southeast Asia (SEA) members adapting to globalisation is collectively realising accruing defence cooperation. SEA nations must unite to establish a comprehensive regional or multinational approach towards preserving the freedom of navigation for economic interdependence and for globalisation to carry on incessantly as their national agenda.

Equally, technological valences due to globalisation, which has prominently transformed and radically reduced time and space regarding military applications, must make Malaysia consider radical solutions germane in this evermore insecure and complex maritime environment. Befittingly, the nation’s maritime forces must be outfitted with compatible equipment that enables big data and intelligence information to be networked, which is the sine qua non for success in any maritime operations while operating with the other major forces. The propagation of commercial equipment utilising military hardware must be widely incorporated to improve maritime interoperability in combating potential threats.

Malaysia’s inaugural Defence White Paper (DWP), formulated in 2019, set the direction of how Malaysia will remain a secure, sovereign and prosperous Maritime nation. Based on the precepts of Si Vis Pacem, Para Bellum (if you want peace, prepare for war), the DWP defines the government’s stance on national defence in line with National Security Policy. Comprehensive consultations with multiple stakeholders within the government agencies, academicians, defence industry players and the public reflect a broad national consensus on the defence force concerning national priorities, policies and resource utilisation.

The DWP outlines three pillars of the National Defence Strategy: interrelated and mutually reinforcing, involving different participants, purposes and processes to help secure Malaysia as a Maritime Nation, which is (Ministry of Defence, 2020):

• Concentric Deterrence, is the principal pillar. It primarily involves the role of the MAF, supported by other national agencies, which serves to preserve our national interests.

• Comprehensive Defence involves the participation of the whole-ofgovernment and the whole-of-society in line with the concept of Total Defence. It is a continuous effort to build internal cohesion, enhance defence preparedness, improve inter-agency coordination, and boost economic capacity and other aspects of national resilience thoroughly and sustainably.

• Credible Partnership refers to bilateral or multilateral defence cooperation with external partners. These partnerships are credible from at least two angles.

• First, Malaysia’s credibility as a dependable partner is the foundation of our defence engagements with countries in the region and the wider world.

• Second, these engagements benefit Malaysia and our partners in terms of defence readiness, security needs and regional stability.

Malaysia A Maritime Nation: Maintaining Resilience In Managing The Current Strategic Environment

The mounting challenges maritime crime brings to the SLOC necessitate adequate security means by the nation to combat them and maintain regional stability. Being positioned uniquely at the heart of SEA that borders the shipping artery linking the west to the Asia-Pacific region, the safety and security of this SLOC is thus a national priority. As a coastal state, Malaysia must provide maritime infrastructure and ensure security and navigation safety in these waterways. Therefore, pooling resources for this common cause becomes necessary, a massive geographical task that only some nations can take sole guardianship. Nonetheless, it is one thing to call for cooperation and quite another thing entirely to make it happen, what more with competing for fundamental concepts of mare liberum (freedom of the seas) and mare clausum (a navigable body of water that is under the jurisdiction of one nation and is closed to other nations) that remains it to be the compelling stumbling block to practical cooperation at this present time.

Competing territorial claims emerge as a serious source of tension and remain intractable in the region, especially in the SCS. Most have consolidated claims by occupying islets militarily and building sophisticated military infrastructure to gain geographic advantage to monitor merchant traffic and, more significantly, during hostilities, to serve as a staging point for interdiction.

The abundance of resources in the form of oil, gas and fish stock in the EEZ further amplifies the maritime sphere’s importance to Malaysia’s economy. The fact remains at large, therefore, that we should acclimatise to the maritime demesne as its strategic rationale and stand firm as a maritime nation and not compromise in defending the nation’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The thinking, working and social culture must place the maritime sector of the utmost importance and preserve our seas in a strategic posture. On the contrary, none of the countries, big or small, in dispute would compromise their claims either. However, rather than resorting to military means, deliberations on a peaceful win-win situation should be sorted out amicably.

The importance of international agreements concerning the use of the sea must be addressed and is needed to balance the competing claims and demands of territorial regimes. These agreements will assist in overcoming the capacity shortfalls, establishing a well-balanced cooperative region and realising the full potential of the convention. Legal frameworks in combating maritime crimes and incidences at sea that would prove effective if implemented, among others, include:

• Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the SCS (DoC). The first step towards legally-binding behaviour and eschewing the use of force in resolving the dispute in SCS is to speed up the negotiations on the Code of Conduct framework agreement (CoC) to replace the 15-year-old DoC of parties.

• United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS III, 1982) provides the overarching legal framework for maritime policy for law and order at sea and managing all coastal states’ security, technology and economic environment. For this reason, nations must ultimately accept subtlety this law as the basis for drawing boundaries and negating disputes over EEZ (although overlapping). However, while UNCLOS exhorts SCS countries to cooperate, the paradox of obtaining maximum benefit from their rights under UNCLOS should not limit the prospects for maritime defence cooperation and regime-building in the region either.

• The adaptation of the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES, 2014) will improve communications, thus enabling each other’s actions in close proximity encounters to be understood to avoid causing miscalculations and unprecedented issues while being involved in their myriad activities at sea. Also, when adapted, this code will come in handy when maritime agencies that do not share a common language are called upon to conduct joint operations in conjunction with the existing SOPs and agreements.

• Convention on the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA Convention, 1988) is the only code with protocols that relates to terrorism and which closes the gap created by the limited definition of piracy. Ratifying this convention will extend coastal state enforcement jurisdiction beyond the territorial limits and, in particular circumstances, allow the exercise of such jurisdiction in an adjacent state’s territorial sea.

Should Malaysia rely on Big Powers as its core allies in SEA to ensure the balance of power in the region? The Big Power’s presence can be seen more as having an enduring utility and an avenue to maintain their defence links to the SEA region as a forward-basing location and gain situational awareness of the SCS and the Indian Ocean. These countries are not obliged to defend the littorals in a war - but presently, they provide the basis for extensive cooperation, shared exercises and communication. Suppose the commitment to a cross-pollination of ideas, practices and experiences in a non-threatening way begins to ebb or be flowed; in that case, Malaysia will still have to rely on regional and local defence solutions to balance and secure itself against the interests of assertiveness in the SCS.

Malaysia A Maritime Nation: Maintaining Resilience In Managing The Current Strategic Environment

While it is essential for Malaysia, it is a concern that alliances with the Big Powers remain the only apparent hedge to ensure the rule-based international order is respected. Nonetheless, choosing sides will be the hardest, and it would be to accept the reality and relevance of the notion and maintain its status as a maritime nation.

Since its inception in 1967, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has contributed significantly to SEA nations’ stability and prosperity. The ‘ASEAN Way’ incorporates unanimous Agreements and Forums and has worked well to avoid armed conflicts between members. Additionally, ASEAN Centrality via institutional mechanisms, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), East Asia Summit (EAS) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), have proven effective as a constructive engagement to manage security issues and economic realities.

Although ASEAN has had successes in bilateral cooperation and dispute resolutions, further and deeper ties hinge upon recognising common and converging interests – the greatest of which is the stability of the international seaborne trade system. Furthermore, complications arising from some non-ASEAN powers preferring to negotiate with ASEAN one-on-one must be relooked. This is because an outsider that successfully engages ASEAN in such a manner prevents the latter from presenting a united front on shared dispute issues but adversely strengthens the relative position of the former.

Amid territorial disputes and the tensions arising between Big Powers, new terminologies such as the ‘Indo-Pacific’ and multilateral groupings such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) and AUKUS by regional authorities to balance the strategic and geopolitical dynamics of the region has some implications to Malaysia and the region in general (Bisley, 2019). Malaysia’s strategic architecture is still dependent on Big Power-based partnerships, primarily bilateral, as a critical element for protecting its national security and sovereignty from external threats.

Regarding economic, security and strategic resilience, states would prefer to resolve and rely on a single (bilaterally) or fragmented regional organisation that provides better options and solutions in dealing with specific challenges. Based on the thicket of such multilateral groupings, it would be more effective to engage bilaterally, which is presumed to be more exclusive, flexible and functional, attributed to the division in choosing sides or interest-based coalitions of the willing (Yadav, 2022). However, these groupings and the territorial integrity and sovereignty issues involving Big Power states have since brought divisions in recognising the value of economic, security and strategic partnership and engagement. These are why states must choose between these hegemonic and self-apexes Big Powers.

The expansion of cyber technology and the misuse of it by terrorist organisations warrant individual governments to place more resources, allocation and coherent cyber security strategies to combat these increasingly dangerous cyber-attacks. The more Malaysia engages globally with other regional and international cyber security forces, the better the chances to protect the nation and its people from cybercrimes.

No nation can address unconventional threats alone in this’ borderless’ world. Hence, tackling unconventional threats from within and externally requires inter-governmental cooperation. Consequently, with each state having different capabilities and ambitions in projecting power, especially in their confined territorial waters, the challenge of who among the littoral states is to initiate or develop this maritime regime that will share intelligence must first be addressed amicably. Enough intelligence must first be attained; how best but none better than establishing appropriate bilateral and multilateral collaboration. The successful maritime collaboration will also require SEA nations to develop unprecedented shipping protection practices, strategies and doctrines and implement joint maritime operations in mainly territorial waters and within the confined routes/ straits of the littoral states.

As a maritime nation, the seas are Malaysia’s livelihood, and the security and stability in the SCS are critical for Malaysia. The significant expansion of economic globalisation has made geo-economics replace geopolitics, transforming Malaysia’s maritime domain into a global strategic environment. Multilateral cooperation needs to be more steadfast in resolving security concerns. Practical collaboration, dialogues and trust building are complementary approaches without which effective solutions can be obtained.

While the territorial dispute in the SCS is highly complex, a piecemeal approach through ASEAN would be a pragmatic first step toward a long-term solution. The inclusive nature of ASEAN’s centrality should decrease the possibilities of a divided association. Fundamentally, having practised respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity as a tenet, members’ deeds must match its action to avoid a calamity experienced in Ukraine. ASEAN must take the cue from the Russia-Ukraine crisis and continue fostering peace, cooperation and economic independence to avoid a similar disaster. Once conflict happens, devastation ensues, and a cure may be challenging.

Malaysia A Maritime Nation: Maintaining Resilience In Managing The Current Strategic Environment

With Big Powers underpinning security in the region, Malaysia’s strategy and economic and political priorities must remain unswervingly in the regional environs. This is because of its economic interest, which lies heavily concentrated within SEA, where decoupling will negatively affect its survivability. The way forward is to share the commonality of purpose with these Big Powers and regional partners. On the other hand, Alliances generally aid in the peace and security of the region. Still, they can serve as a democratic deterrence against unilateral change to the status quo by force. The Russia-Ukraine crisis is a clear example of whether the alliances in this region can collectively stand up to the would-be aggressor (if it happens). Wittingly, Malaysia must be resilient in managing the current strategic environment. Understanding the region’s security challenges will enable Malaysia to attune its actions and policies to be a secure, sovereign and prosperous Maritime Nation.

Bisley, Nick, (2019). East Asia Summit buffeted by great power rivalry, 3 November, 2019. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2019/11/03/will-great-power-rivalryupturn-this-years-east-asia-summit/ (assessed 23 June 2022, 1547H).

Bisley, Nick, (2022). The Ukraine war threatens Asia’s regional architecture, 21 May 2022.

https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/05/21/the-ukraine-war-threatensasias-regional-architecture (assessed 23 June 2022, 1642H).

Global Security. (2019, August 13). Malaysia National Defence Policy. Retrieved from Global Security: https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/malaysia/ policy.htm.

Goh, T. (2022, May 23). Asia’s current security arrangements better than having one bloc confronting another: PM Lee. Retrieved from The Straits Times: https:// www.straitstimes.com/singapore/asias-current- security-arrangementsbetter-than-having-one-bloc-confronting-another-pm-lee.

Hawksley, Humphrey., Asian Waters – The struggle over the South China Sea & the Strategy of Chinese Expansion. The Overlook Press, New York, (2018), p15.

Ministry of Defence, (2020). Defence White Paper & Key Note Address by Chief of RMN to Malaysia Armed Forces Defence College 2021.

Ministry of Defence. (2020). Defence White Paper. Retrieved from https://www.mod. gov.my/images/mindef/article/kpp/DWP-3rd-Edition-02112020.pdf.

Olds, Kris., Dicken, Peter., Kely, Philip F., Kong, Lily & Yeung, Henry Wai-Chung (1999). Globalization and the Asia-Pacific: Contested Territories. Routledge, London (UK) & New York USA).

Ong-Webb, G. G. (2006). Piracy, Maritime Terrorism and Securing the Malacca Straits. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS).

Rajeswari Pillai, Rajagopalan, (2021). Explaining the Rise of Minilaterals in the Indo-Pacific,” ORF Issue Brief No. 490, September 2021, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/explaining-the-rise-ofminilaterals-in-the-indo-pacific (assessed 23 June 22, 1429H).

Malaysia a Maritime Nation Agenda: Steering the Course

Shahrudin, H. S. (2017, January 17). Country’s Cyber Defence Operations Centre up this Sept, says Hishammuddin. Retrieved from New Straits Times: https:// www.nst.com.my/news/2017/01/204974/countrys-cyber-defence-operationscentre-sept-says-hishammuddin.

Soloman, Hussien (2008). Challenges to Global Security: Geopolitics and Power in an Age of Transition. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, New York & London.

Yadav. Surekha A, (2022). Singapore and Malaysia: Are we really neutral on China? https://malaysia.news.yahoo.com/singapore-malaysia-really-neutralchina-232900929.htm. (assessed Sun, 12 June 2022, 7:29 am).

The Straits Times/ANN, (2022). Lee: NATO-type body not suitable: Asia’s current security arrangements better than one bloc confronting another’. The STAR, Tuesday 24 May 2022.

Introduction

Malaysia has placed nine core security values in its efforts to uphold the state’s Federal Constitution (National Security Council, 2019). The existence of these nine core values that are considered dynamic and complex is aimed at evaluating changes in the current and future security environment. This is important, according to Buzan (1991), who stated that national security involves relatively complex and amorphous entities. According to Waltz (1979), in the structure of the international relations system, security is the primary goal of a state due to the structural pressures and responses to the protection of its security. Every state is exposed to political, economic, environmental, societal and military threats that may create insecurity.

As a sovereign nation, Malaysia defines national security “as a continuous and comprehensive effort in ensuring that Malaysia remains existent, peaceful and prosperous.” The notion is supported by Gariup (2009), who explained that security is a government policy to create peace and protect national interests from enemy threats. It can be described as a state’s responsibility to defend its values of independence and sovereignty and ensure the safety of its people so that they live in harmony and peace (Chandra & Bhonsle, 2015). Therefore, in the face of AUKUS’ establishment, Malaysia must be wise and stand firm in protecting its strategic interests.

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss Malaysia’s stance on the establishment of AUKUS and its implications. This essay also touches on the factors influencing the involvement of Australia and the United States (US) in the region. The Chapter will also mention China’s response to the alliance as influenced by China’s Defense White Paper 2019.

The announcement by the US on its withdrawal from the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan was a shock (Bowman, 2021). The conflict is best described as a long war which began with the September 11, 2011 incident and had to date, resulted in the deaths of 2,461 military personnel and an expenditure of more than USD2 trillion (The White House, 2021). Joe Biden’s administration sees the Afghanistan war as not giving returns to US interests. To the current government, the need to address the rise of China, which is now seen as more dominant in the Indo-Pacific region, is critical as it can undermine the US’ priorities globally (Johny, 2021). Therefore, AUKUS’ launch on September 15, 2021, as a tripartite security partnership involving the US, Australia and the United Kingdom (UK) took place shortly after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. The move is in line with Biden’s statement, which entails that the era of military operations to rebuild other countries is over. The move is also taken as a response by the US towards China’s maritime strategy, which employs the “Island Chain Strategy” concept, as shown in Figure 1 (Office of Naval Intelligence, 2009).

Under this strategy, China has strengthened its assertiveness in the “first chain, “ consisting of the Kuril Islands, Japan’s central archipelago, Okinawa, and the South China Sea (SCS). Meanwhile, China’s presence in the “second chain”, which extends from Japan to Guam, certainly gives an advantage to Beijing in the middle of the Pacific by allowing both dominant and strategic control (Espena & Bomping, 2020).

In the face of this current situation, AUKUS aims to preserve the security and stability of the Indo-Pacific region by equipping the Australian Fleet with nuclear-powered submarines (Macias, 2021). The three-nation alliance sees this security partnership as a collective commitment to developing cyber technology, artificial intelligence, and underwater domain capabilities (Southgate, 2021b). To illustrate its gravity, the Prime Minister of Australia emphasised the matter in one of his statements, saying that “our technology, our scientists, our industry, our defence forces are all working together to deliver a safer and more secure region that ultimately benefits all” (Start Insight, 2021). This arrangement has resulted in various reactions from many countries, with those opposing the existence of AUKUS being among them. Among the most prominent opponents in France since the tripartite agreement has caused the cancellation of a submarine contract with Australia at the cost of 66 billion euros (Baron, 2021).

Although the fundamental goal of AUKUS is to enhance regional cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, it is seen to be more centred on military alliances. Furthermore, Australia’s determination to cancel the project with France invited outrage and was described as a “stab in the back” (Staunton, 2021). The contract, signed in 2016, had promised the supply of 12 conventional diesel-electric submarines, with the first supply expected in 2027 (McGuirk, 2021). Besides, Australia’s agreement on developing nuclear-powered submarine technology with the US and the UK under the auspices of AUKUS is the first in sixty years, as the arrangement was only shared previously between the US and the UK (Holton, 2021). It makes Australia the seventh country in the world to have a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor (Borger & Sabbagh, 2021). The question now is, why did Australia insist on cancelling the submarine manufacturing agreement contract with France and instead accept technical offers from the US and UK to develop nuclear-powered submarines? This issue can be further elaborated on based on the following aspects:

Australia sees China as capable of posing a threat to the country’s democratic system of administration and sovereignty. It is stated in a statement made by the Prime Minister of Australia, Scott Morrison, who said that “China is not only a major trading partner but also a threat to national sovereignty. The dramatic shift shows how the country struggles with China’s growing power” (Needham, 2020). Among the actions seen as a threat to Australia are China’s attempts to influence the decisions of Australian politicians both at the local council and federal parliamentary levels, alongside Chinese students at local Australian universities. Beijing has also intervened in the administration of Chinese-language media in Australia. The situation became increasingly tense, where Australia, among the countries lobbying world leaders to investigate the origins of COVID-19, discovered that the disease first

appeared in Wuhan, China. The situation made Beijing angry, and it retaliated by imposing trade restrictions, technically suspending beef imports, and restricting a $439 million barley trade by imposing an 80.5 per cent tariff on Australian imports (Packham, 2020). In addition, China also withheld shipments of coal and wine by placing those as technical issues under customs.

Australia sees the ability to own nuclear-powered submarines in addition to longrange missiles using US technology as a benchmark in shaping “force projection” (Mao, 2021). This need is also seen as a response by Prime Minister of Australia Scott Morrison, who mentioned that “China has a very strong nuclear submarine development program” (Reuters, 2021). Thus, Australia’s decision to own nuclearpowered submarines is, in essence, a determination to defend itself against China’s assertiveness and aggressive policy regarding airspace, in addition to the issue of overlapping maritime territorial claims. This capability also allows Australia to mobilise its strategic assets to operate remotely and act as a forward base for tactical and preventive advantage. Shown in Figure 2 is a comparison of capabilities between nuclear-powered and conventional-class submarines. Clearly, being equipped with nuclear-powered submarines afford the Australian Fleet many advantages (Sadler, 2021). This advantage will also translate into the technological development of the country’s defence industry.

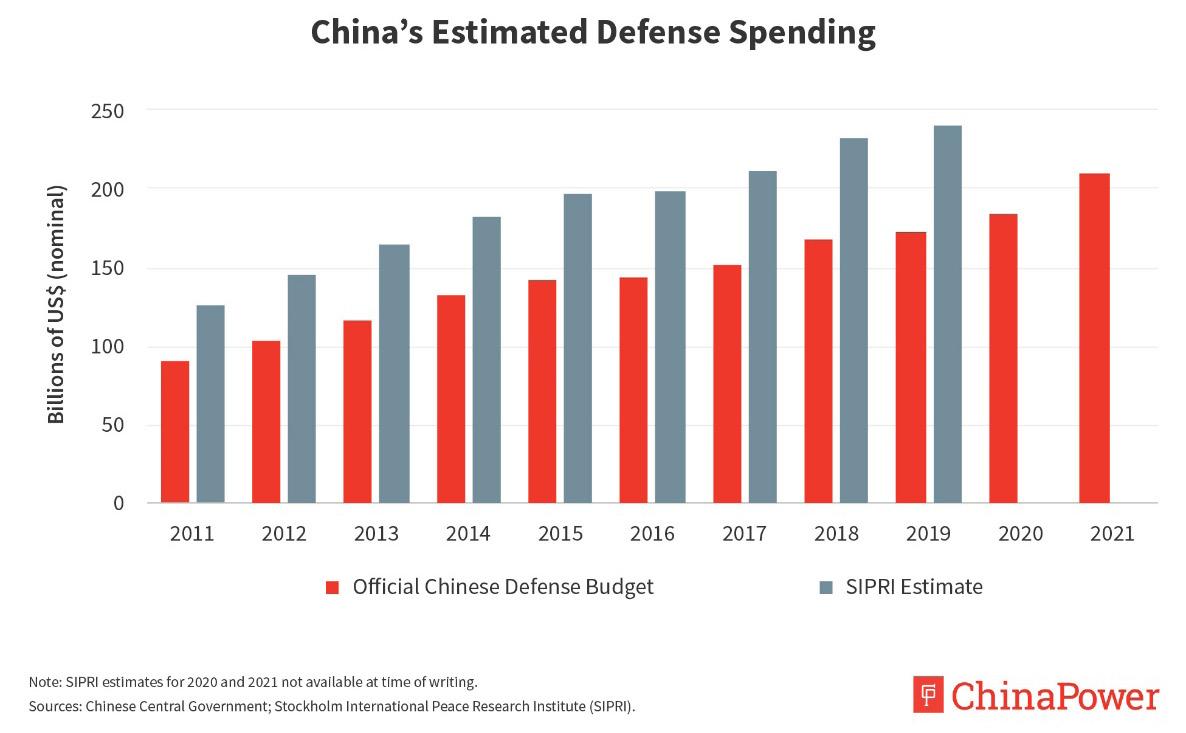

The US’s determination to strengthen its influence in the Indo-Pacific region through AUKUS is undeniably a deterrent signal to China (Patton, Townshend & Corben, 2021). This retaliatory stance is taken in response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which has effectively expanded the nation’s maritime routes across the Pacific and the Indian Oceans, making it easier for the upcoming giant to realise its economic power and strategic ambitions (He & Mingjiang, 2020). Furthermore, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimated that China’s actual military expenditure had reached USD240 billion in 2019, nearly 40 per cent higher than the official budget (USD183.5 billion) reported as shown in Figure 3 (Tirpak, 2021). According to SIPRI, China’s defence expenditure for 2019 is much higher than India, Russia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan (Funaiole, Hart, Glaser & Chan, 2021). The US Department of Defense had also confirmed this, acknowledging that China’s actual defence spending that year could be higher than USD200 billion. Based on the yearly increases in China’s defence allocation, Biden’s administration has foreseen the need to prioritise the Indo-Pacific region by strengthening deterrence to prevent the growing threat of China’s military capabilities (Townshend, 2021).

Given this data, the US realises it needs to build its capacity to curb China’s advance. Thus, one of the essential steps in doing so is to step up its military presence (Carafano, 2019). On the other hand, the US efforts to strengthen the region’s

defence aspect align with a statement by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who stated, “the Indo-Pacific is crucial to our future” (Scott, 2018). Moreover, the Chinese government has criticised the US over its relationship with Taiwan, which it describes as an autonomous island belonging to China (Tanno, 2021). Therefore, China will likely pursue a more assertive approach by developing its nuclear policy capabilities to threaten the US military capabilities in the region (Gallagher, 2019). This can be proven based on the argument that China’s claim over the SCS is due to three main factors. First, it gives China’s Nuclear Ballistic Missile Submarines (SSBN) the advantage of carrying out strategic patrols (Ajansi, 2021). This statement was also acknowledged by President Xi Jinping, who mentioned that the need for nuclear submarines is “to manage the SCS” (Gering, 2021). Secondly, the SCS can act as a buffer zone for China if the US carries out a military attack on mainland China. Third, China’s maritime transportation needs sea routes, which matches the SCS’s role of hosting about a third of global maritime trade.

Additionally, the US worries about China’s nuclear strategic development capability as it has developed relatively fast and is now treated as the primary foundation for protecting China’s national sovereignty and security (Vergun, 2021). Deploying China SSBNs is a critical strategic asset in protecting China’s national security. China is also expected to possess 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030, a target in line with its ambitions to develop its military capabilities. This effort is evidenced by China’s defence budget for 2021, which has increased by 6.8 per cent (equivalent to USD209 billion) compared to the year before (Xuanzun, 2021).

China takes defence cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region seriously, as it deems those in the area irresponsible. China’s Foreign Minister, Zhao Lijian, once voiced that AUKUS can undermine regional peace and stability and intensify the nuclear arms race” (Barber, 2021). This statement was also emphatically acknowledged by Chinese President Xi Jinping, who said that the construction of a U.S.-led alliance would cause a repeat of the Cold War, which took place around the 1970s between the US and Russia (Iwamoto & Yuda, 2021). Also slamming the US’ actions, an international media channel belonging to the Chinese Communist Party mentioned that Washington had lost its mind by gathering its allies to oppose China.

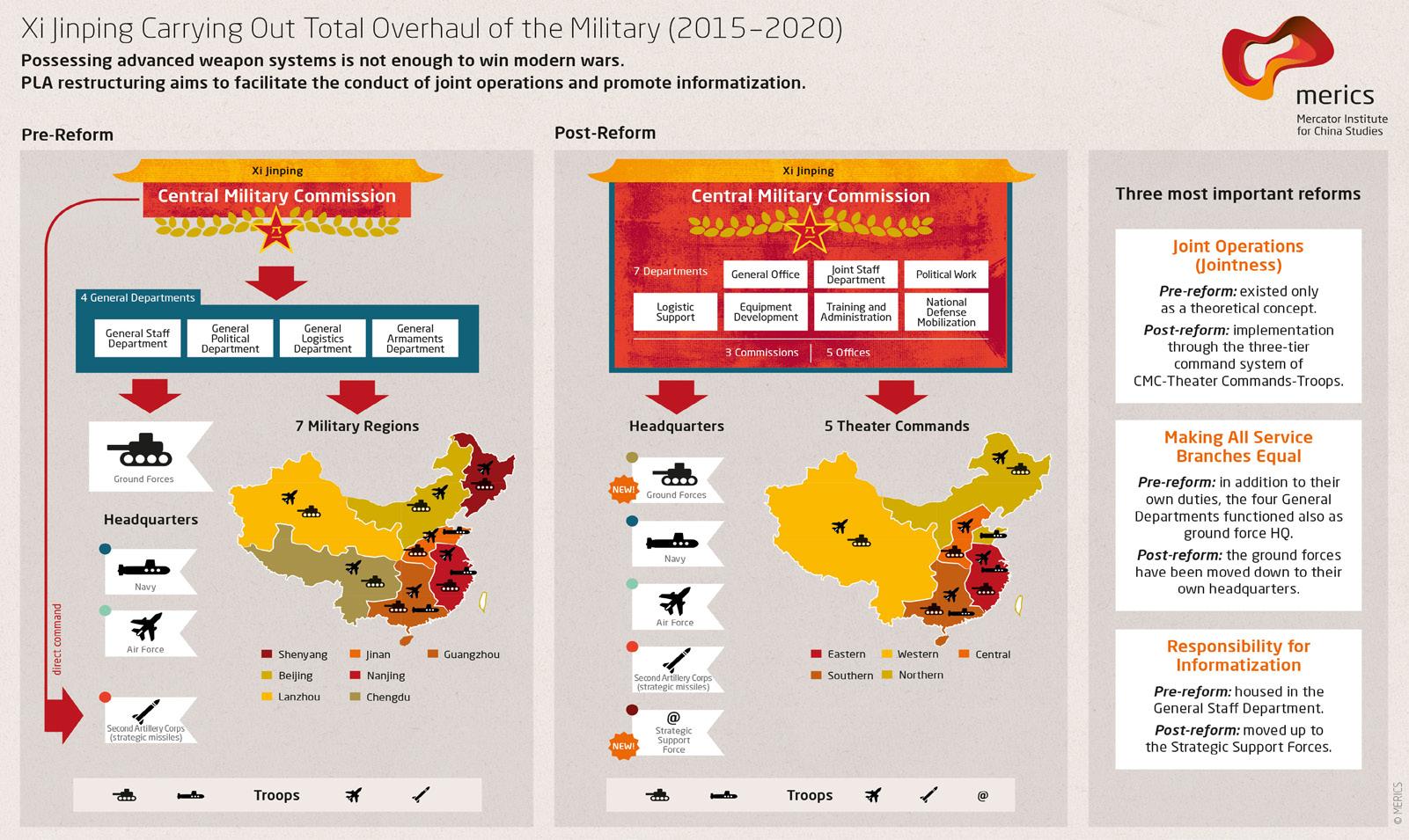

However, it was observed that several Chinese actions were the ones that stimulated the establishment of AUKUS. Primarily, China’s 2019 Defense White Paper stated in detail for the first time the acts of instability by countries such as the US, Russia, EU, the UK, Germany, France, Japan, and India (The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2019,). Moreover, the white paper also contained allegations of the US actions as the leading cause of disruption in the international security order. Besides, the white paper also linked Xi Jinping’s desire to achieve the “China Dream” vision as a critical element to the “strong military dream”, as

Malaysia a Maritime Nation Agenda: Steering the Course

illustrated in Figure 4 (Alsabah, 2016). This was outlined by Xi Jinping in his speech during the 19th Party Congress in 2017, in which he mentioned that he aspires for the Chinese military to become a mechanised force with increased, informative and strategic capabilities by 2020, followed by being fully modernised force by 2035, and a first world-class military by 2049 (US Defence Intelligence Agency, 2019).

Source:

Malaysia has clearly stated concerns over the tripartite cooperation. This was voiced by the Prime Minister, Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob himself, during the East Asia Summit. He stated that “the development of AUKUS could lead to a nuclear arms race and trigger tensions, resulting in regional instability, especially in the South China Sea” (The Straits Times, 2021). Furthermore, Malaysia remains committed to ensuring the Southeast Asian region as a Zone of Peace, Freedom, and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) as delineated in the Declaration and Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapons Free Zone (SEANWFZ) Treaty. Malaysia’s firm stance on the existence of AUKUS can be highlighted based on two things:

The purchases of nuclear submarines by Australia from the US signal that countries in the ASEAN region and the Asia Pacific will also have to strengthen their military systems. This notion is exemplified by China’s transfer of its former diesel-electric submarines to Myanmar in the first transfer of assets involving the two countries

(Yeo, 2021). The move also shows China’s support for Myanmar’s military government against local protests and opposition. China’s move to supply such strategic assets to Myanmar also raises concerns among ASEAN countries, whose foreign ministers unanimously do not support the Myanmar junta’s actions, as they are seen as linked to human rights abuses and the undermining of the concept of democracy (Wang, CNN & Reuters, 2021). The situation is increasingly challenging as Taiwan, which is currently in conflict with China, is also building eight diesel-electric-powered submarines, which are expected to be handed over to the Taiwan Army in 2025 (Ranhotra, 2021). With the acquisition of diesel-electric-powered submarines, Taiwan may also be able to build and own nuclear-powered submarines. What is more worrying is that this submarine development project involves assistance from seven countries: the US, the UK, India, Australia, South Korea, Canada, and Spain.

In addition, if the existence of AUKUS causes a tense situation in the Asia Pacific region, it would undoubtedly be seen as a call for the presence of foreign troops, especially in the SCS. The seas will then effectively be a battleground, a condition that will undoubtedly significantly impact the economic growth of ASEAN countries, as most of their regional and world trade is heavily dependent on the SCS. Additionally, the sea lanes that pass through SCS are the busiest and most important trade routes in the world. In 2016, it recorded the passage of one-third of the world’s maritime trade at an estimated worth of USD 3.4 trillion. It accounts for almost 40 per cent of China’s trade, where 90 per cent is petroleum imports from Japan and South Korea, and 6 per cent is its total US trade (Ott, 2019). In addition, ASEAN is China’s leading investment destination and largest trading partner in manufacturing, agriculture, infrastructure, high technology, digital economy, and green economy. This is proven by strong economic growth in June 2021, where a year-on-year growth of 38.2 per cent was recorded, with investments exceeding USD310 billion and business revenue of Chinese enterprises from project contracts in ASEAN countries approaching USD350 billion (Xinhua, 2021b).

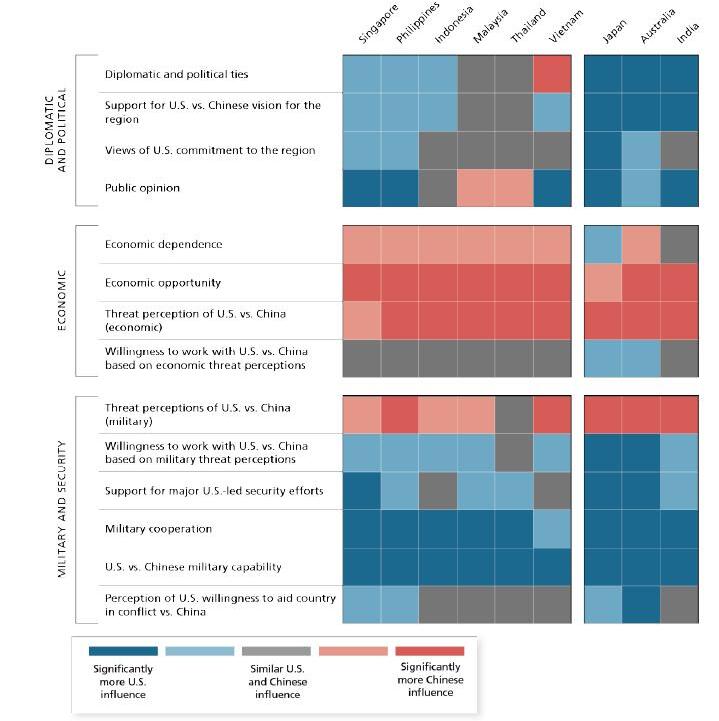

Malaysia uses its international cooperation, external relations, and political, social, economic, and cultural stance to ensure regional stability and security. As a sovereign nation, Malaysia prioritises the spirit of cooperation and goodwill with all countries regardless of political ideology (Ratnam, 1999), which is in line with Malaysia’s policy of neutrality. However, the current situation calls for the country to ensure the region is free from political disputes between major powers, especially the US and China. Table 1 shows Malaysia’s policy concerning the US and China (Lin et al., 2020). In the aspects of political and diplomatic relations, Malaysia adopts a humane approach with both countries to pursue what it perceives as actions that protect national interests (Finkbeiner, 2013). Malaysia is more dependent on China than the US in terms of economy. In 2020, China was Malaysia’s leading trading partner, with a total trade value of RM329.77 billion.

Additionally, a drastic increase in the trade value of RM454.78 billion (USD108.28 billion) was recorded between both nations from January to August 2021 (Hani, 2021). On the other hand, Malaysia has more dominant ties to the US than China regarding security. From 2018 to 2022, the US allocated security assistance of approximately USD220 million, providing equipment, education, training, and other exchange programs to Malaysia. Meanwhile, approximately USD1 million was earmarked for International Military Education and Training Programs parked under a military agreement to bolster and develop human capital between the two countries (Office of the Spokesperson, 2021).

Source: Regional Responses to U.S.-China Competition in the Indo-Pacific by Bonny Lin et al., 2020

Furthermore, one of Malaysia’s principles in resolving international issues is negotiation based on international law. Malaysia has, for now, chosen to avoid any debate, more so those involving force or coercion. This cautious approach can be seen through Malaysia’s effort to call the Chinese Ambassador to express Malaysia’s stance and protest against the presence and activities of Chinese ships in Malaysia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) off the coast of Sabah and Sarawak (Kumar &

staff writer, 2021) as the action is contrary to the EEZ Act 1984 and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982. This firmness of stance demonstrates Malaysia’s commitment to ensuring that every issue of national interest is resolved peacefully and constructively according to international law.

Malaysia can balance the region’s security through its diplomatic ties with China and the US. The relationship between Malaysia and China is generally characterised as a “comprehensive strategic partnership” (Ha, 2021) as it involves close collaboration in various dimensions, enhancement of strategic trust, and sharing of opportunities and joint development plans (Xinhua, 2021a). Meanwhile, the relationship between Malaysia and the US holds a “comprehensive partnership” status as it covers cooperation in politics and diplomacy, economics, education, people-to-people relations, and defence and security (Kuik, 2016). Therefore, Malaysia will continue to enhance and strengthen ties with both countries simultaneously without favouring any country over the other. This approach can indirectly impact Malaysia’s efforts in determining and influencing regional security issues.

Also, Malaysia’s presence in ASEAN influences the region’s stability. As one of the founding nations of ASEAN and a pioneer of the concept of ZOPFAN, which is based on the “principle of peaceful coexistence”, its role in balancing issues related to regional security is huge (Jalil, Perman & Zaaba, 2020). The concept of ZOPFAN, the backbone of ASEAN, was born from Malaysia’s strategy to ensure that Southeast Asia was not involved in major power rivalry during the Cold War (Southgate, 2021a). Thus, Malaysia, which is often seen as the spokesperson for ASEAN, needs to be firm with the AUKUS alliance in asking it to recognise the ZOPFAN concept, which is integral in the regional security structure as a tool that ensures the region is free from nuclear weapons. This stance which explains Malaysia’s determination was voiced by the Senior Minister of Defense, Datuk Seri Hishammuddin Hussein, who said that “Malaysia is in a position to balance the great powers of the region, but at the same time, well respected by both polar powers in the South China Sea” (Azil, 2021).

The existence of AUKUS is part of a political and military strategy to balance power in the Indo-Pacific region. Therefore, Malaysia needs to be prudent in ensuring that the country’s security and sovereignty are not compromised in the face of establishing a military alliance between Australia, the UK, and the US. In addition, in the face of geopolitical challenges involving regional security, the role of ASEAN through its defence diplomacy is appropriate to focus on balancing the influence of major powers. The element of mutual trust between Malaysia and the US in security and defence, in particular, can accommodate the need for stability in the region. This can indirectly influence other allied countries to refrain from acting aggressively.

Malaysia a Maritime Nation Agenda: Steering the Course