Editors

Editors

Captain Ananthan Tharmalingam RMN

Director General of RMN Sea Power Centre

Prof. Dr. Wan Izatul Asma binti Wan Talaat

Head of Centre for Ocean Governance, Institute of Oceanography and Environment, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu

Editorial Assistants

Commander Wrighton Buan anak Kassy RMN

Lieutenant Commander Norsaydaeaini binti Che Rozubi RMN

LR ETR Tc. Muhamad Asnawi bin Aminuddin

Published by

RMN SEA POWER CENTRE

Jalan Sultan Yahya Petra

54100 Kuala Lumpur

Email: rmnspc@navy.mil.my

Tel: +603 40160137

First Published in 2025

ISBN 978-967-26093-5-3

Printed by

PERAX KREATIF ENTERPRISE

Level 7, Menara Arina Uniti

Jalan Raja Muda Abdul Aziz

50300 Kuala Lumpur

Disclaimer

The views expressed are the author’s own and not necessarily those of the RMN Sea Power Centre. The Government of Malaysia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statement made in this publication.

Copyright of RMN Sea Power Centre (RMN SPC), 2025

© All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means; electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the RMN SPC.

The Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) remains steadfast championing the Malaysian National Agenda as a Maritime Nation. This book journal marks the continuation of a vital discourse, following Malaysia A Maritime Nation Agenda: Charting the Passage (2021) and Malaysia A Maritime Nation Agenda: Steering the Course (2023). Each edition reinforces our collective commitment to strengthening Malaysia’s maritime identity, economy and security in an increasingly complex and dynamic maritime environment.

As a nation strategically positioned along key global maritime trade routes, Malaysia’s economic prosperity, national security and regional influence are intrinsically linked to the seas. Our maritime domain presents both opportunities and challenges, from economic growth through the blue economy to safeguarding our sovereign waters and ensuring regional stability. As a key maritime security institution, the RMN remains committed to protecting Malaysia’s interests while fostering a whole-of-government and wholeof-society approach to maritime strategy.

This journal continues that mission by bringing together perspectives from policymakers, industry leaders and maritime practitioners to shape a forwardlooking and sustainable maritime agenda. It serves not only as a repository of ideas but also as a catalyst for strategic action and policy formulation.

I hope this publication will drive greater national awareness, inter-agency collaboration and long-term investment in Malaysia’s maritime future. By working together, we can navigate evolving challenges and position Malaysia as a strong and resilient maritime nation.

ADMIRAL DATUK (Dr.) ZULHELMY BIN ITHNAIN CHIEF OF NAVY ROYAL MALAYSIAN NAVY

The initiative to publish this book aligns closely with the Malaysia Maritime Conference, first introduced during LIMA ’19 and subsequently continued through LIMA ’23, culminating in this year’s edition coinciding with LIMA ’25. This ongoing effort underscores Malaysia’s unwavering commitment to promote maritime awareness and advancing its status as a progressive maritime nation.

The significance of this book series cannot be overstated. The inaugural publication, Malaysia A Maritime Nation Agenda: Charting the Passage, emerged in 2021, followed by Malaysia A Maritime Nation Agenda: Steering the Course in 2023. Each volume has progressively explored and expanded upon critical maritime themes to promote the national agenda as a maritime nation.

This third edition, aptly titled Malaysia A Maritime Nation Agenda: Navigating the Horizon , builds on the foundation laid by previous editions while venturing deeper into contemporary maritime challenges, emerging opportunities, and strategic possibilities shaping Malaysia’s maritime future. It is organised around three interconnected thematic areas—Geostrategic Dynamics, Non-Traditional Security Threats, and Blue Economy. Within these thematic frameworks, the book comprises eleven chapters, each providing unique insights and expert analyses into various aspects of maritime affairs.

Distinctively, this latest edition represents a collaborative effort, bringing together insightful contributions from local and international experts across diverse maritime fields. Chapters authored by distinguished academics, experienced practitioners, and military strategists offer comprehensive analyses and practical insights. Readers will find particularly intriguing discussions on pivotal topics such as regional stability, emerging security threats, and the transformative economic potential encapsulated within the Blue Economy, providing unique insights and expert analyses that are invaluable to the maritime community.

We extend our heartfelt appreciation to all contributors whose expertise and dedicated research have significantly enriched this publication. Our thanks also go to the editorial assistants and staff at the Royal Malaysian Navy Sea Power Centre, whose meticulous efforts were instrumental in successfully completing this edition.

Ultimately, our aspiration is for readers to find this book enlightening and stimulating. We hope it inspires reflection on Malaysia’s maritime potential, fostering more excellent dialogue, collaboration, and decisive action towards realising our shared maritime ambitions and reinforcing Malaysia’s role within the regional and global maritime landscape.

CAPTAIN ANANTHAN THARMALINGAM RMN PROF. DR. WAN IZATUL ASMA BINTI WAN TALAAT EDITORS

FOREWORD AND PREFACE

PART I: OVERVIEW AND CONTEXT

INTRODUCTION

Captain Ananthan Tharmalingam RMN & Prof. Dr. Wan Izatul Asma binti Wan Talaat

PART II: GEOSTRATEGIC DYNAMICS

CHAPTER ONE

ASEAN’S COOPERATION WITH THE IORA: STRATEGIC ISSUES AND CHALLENGES IN THE INDO PACIFIC CONSTRUCT

Brigadier General Dato’ Azudin bin Hassan

CHAPTER TWO

LATERAL LEADERSHIP IN THE INDO-PACIFIC: PRESERVING PEACE THROUGH MIDDLE POWER COOPERATION

Dr. Nell Bennett

CHAPTER THREE

THE MILITARISATION OF FEATURES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA: IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL STABILITY

Commander Mohammad Shafiq bin Zainon RMN

CHAPTER FOUR

THE NEED FOR SUBS! ROYAL MALAYSIAN NAVY SUBMARINES DEFENDING MALAYSIA’S MARITIME INTERESTS

Prof. Adam Leong Kok Wey

PART III: NON-TRADITIONAL SECURITY THREATS

CHAPTER FIVE

MARITIME NON-TRADITIONAL THREATS: SOUTHEAST ASIAN’S PERSPECTIVE

First Admiral Dr. Tay Yap Leong

CHAPTER SIX

HIDDEN LINES OF COMMUNICATION: GEOPOLITICS, CYBER THREATS AND UNDERSEA CABLES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA’S MARITIME SPHERE

E Kin Zane Ryan Seow, Karisma Putera Abd Rahman & Fikry A. Rahman

CHAPTER SEVEN

NAVIGATING CHALLENGES IN THE STRAIT OF MALACCA: THE ROLE OF MALAYSIA AND INDONESIA IN REGIONAL MARITIME SECURITY

Commander Syahrum bin Hassim RMN

PART IV: BLUE ECONOMY

CHAPTER EIGHT

HARNESSING THE BLUE ECONOMY FOR MALAYSIA: NAVIGATING OPPORTUNITIES AND GEOPOLITICAL CHALLENGES IN THE INDO-PACIFIC Eimaan Intikhab Qureshi

CHAPTER NINE

MARITIME ARCHAEOTOURISM: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN MALAYSIA

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Hasrizal Shaari and Dr. Nik Nurhalida Nik Hariry

CHAPTER TEN

TOWARDS BETTER OCEAN GOVERNANCE: THE CASE FOR AN OCEAN POLICY FOR MALAYSIA

Nazery Khalid

CHAPTER ELEVEN

NAVIGATING THE MARITIME NATION AGENDA: MARINE SPATIAL PLANNING AS A CATALYST FOR BLUE ECONOMY DEVELOPMENT IN MALAYSIA

Prof. Dr. Wan Izatul Isma binti Wan Talaat

PART V: EPILOGUE

CONCLUSION

Captain Ananthan Tharmalingam RMN &

Prof. Dr. Wan Izatul Asma binti Wan Talaat

INDEX

Ananthan Tharmalingam RMN

Prof. Dr. Wan Izatul Asma binti Wan Talaat

Malaysia, endowed with strategic geography and abundant maritime resources, stands at a pivotal juncture, navigating both opportunities and challenges in a rapidly evolving geopolitical seascape. Historically significant maritime routes such as the Malacca Strait, once traversed by ancient traders connecting East and West, continue to highlight Malaysia’s enduring role in global maritime heritage. Navigating the Horizon is the third instalment of the RMN Sea Power Centre’s insightful exploration into Malaysia’s maritime ambitions, following previous books Charting the Passage and Steering the Course . Building upon these foundations, this volume delves deeper, addressing contemporary maritime issues through three distinct yet interconnected themes: Geostrategic Dynamics, Non-Traditional Threats and the transformative potential of Blue Economy.

Malaysia’s maritime domain—dynamic and fluid by nature—remains central to its identity, security, and economic prosperity. Yet, as previous editions have highlighted, steering an effective maritime agenda demands more than geographical advantage; it requires strategic foresight, coordinated institutional effort, and comprehensive governance. Navigating the Horizon gathers perspectives from military strategists, distinguished academics, industry experts, and maritime practitioners, enriching our understanding of Malaysia’s quest for sustained maritime nationhood.

Geostrategic Dynamics

The journey begins with a broad exploration of the geopolitical currents shaping Malaysia’s maritime future. How can Malaysia effectively navigate complex alliances, assert its influence as a middle-power, and manage the intricate dynamics of regional security? Each chapter unfolds critical strategic insights into these vital questions, providing clarity on Malaysia’s evolving role in an increasingly contested geopolitical landscape.

Chapter One by Brigadier General Dato’ Azudin bin Hassan sets the scene by examining ASEAN’s cooperation with the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA). Through a clear narrative, it outlines both the opportunities for collaboration and significant hurdles presented by political, economic, and geopolitical tensions,

advocating stronger institutional coordination, trust-building initiatives, and sustained dialogue to strengthen this critical partnership.

Moving from collective diplomacy to individual leadership, Chapter Two by Dr. Nell Bennett introduces lateral leadership within the Indo-Pacific context. Highlighting Malaysia’s potential as a middle power, the chapter vividly demonstrates how creativity, credibility, and strategic diplomacy can preserve peace amid geopolitical rivalry, underpinning Malaysia’s pivotal role in regional stability.

The narrative transitions smoothly into Chapter Three by Commander Mohammad Shafiq bin Zainon RMN, examining the increasing militarisation in the South China Sea. Here, territorial disputes, economic impacts, and environmental concerns are laid bare, underscoring the importance of Malaysia’s strategic naval capabilities and diplomatic interventions to manage regional stability.

Concluding this section, Chapter Four by Professor Adam Leong Kok Wey emphasises the strategic value of submarines in safeguarding Malaysia’s maritime interests. Drawing on historical evidence, it stresses sustained investments and effective operational management of submarine fleets to ensure deterrence and maritime sovereignty.

The maritime landscape is shaped not only by visible threats but also by unseen challenges requiring innovative strategies and heightened vigilance. These nontraditional threats are often intensified by the geopolitical dynamics discussed earlier, as regional rivalries and strategic competitions exacerbate vulnerabilities and complicate responses. This section highlights these emerging non-traditional security threats, examining their interconnectedness with broader geopolitical currents and their collective impact on regional stability and security.

Chapter Five by First Admiral Dr. Tay Yap Leong initiates this discussion by addressing Southeast Asia’s non-traditional maritime threats, including piracy, human trafficking, and environmental risks. It emphasises Malaysia’s Defence White Paper and UNCLOS, calling for robust regional collaboration and coherent policy frameworks to counteract these effectively.

Continuing this narrative, Chapter Six by E. Kin Zane Ryan Seow, Karisma Putera Abd Rahman, and Fikry A. Rahman focuses on strategic vulnerabilities posed by undersea communication cables, crucial for Southeast Asia’s digital economy. It outlines how geopolitical competition and cyber threats expose these vital infrastructures, urging stronger domestic legislation, enhanced regional frameworks, and improved maritime domain awareness.

Chapter Seven by Commander Syahrum bin Hassim RMN navigates the importance of the Strait of Malacca, showcasing cooperative security measures

implemented by regional states, such as the Malacca Strait Patrols and the “Eyes in the Sky” programme. It advocates deeper regional collaboration and standardised maritime law enforcement to sustainably manage this critical maritime passage.

The final section delves into promising horizons of Malaysia’s maritime economic potential. Embracing sustainable practices, this segment highlights innovative approaches to responsibly harness maritime resources. By aligning economic growth with ecological preservation, the Blue Economy presents tangible benefits not only for national policy but also for local communities, fostering job creation, enhancing livelihoods, and securing environmental sustainability for future generations.

Chapter Eight by Eimaan Intikhab Qureshi introduces the transformative potential of the Blue Economy for Malaysia, exploring fisheries, shipping, tourism, and offshore energy opportunities. It addresses governance fragmentation, geopolitical tensions, and environmental sustainability, advocating an integrated national ocean policy and regional collaborations.

From economic aspirations, Chapter Nine by Assoc. Prof. Dr. Hasrizal Shaari and Dr. Nik Nurhalida Nik Hariry transitions to maritime archaeotourism, exploring underwater cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism sector. It confronts challenges such as environmental degradation and public awareness, offering strategic solutions to leverage Malaysia’s maritime archaeological assets fully.

Chapter Ten by Nazery Khalid debates compellingly for comprehensive ocean governance through establishing a unified National Ocean Policy. Drawing lessons from international best practices, it underscores the urgency for integrated management strategies to sustain maritime resources, enhance national security, and foster long-term economic prosperity.

Finally, Chapter Eleven by Prof. Dr. Wan Izatul Isma binti Wan Talaat highlights Marine Spatial Planning as a critical instrument in realising Malaysia’s maritime ambitions, effectively balancing ecological protection, economic development, and social equity through coordinated maritime planning.

Navigating the Horizon involves charting a strategic course, anticipating future tides, and confidently steering towards a sustainable maritime destiny. This book offers thoughtful analyses and actionable insights, reinforcing Malaysia’s commitment to becoming a robust maritime nation thriving in an interconnected world. The strategic insights presented hold broader implications, potentially influencing regional stability, economic development, environmental sustainability, and fostering collaborative international relations across the IndoPacific region.

Brigadier General Dato’ Azudin bin Hassan Malaysian Army Headquarters

Introduction

In today’s context of Indo-Pacific construct, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) are two prominent regional organisations - the maritime corridor connecting these two entities from the Southeast Asia (SEA) to the Indian Ocean has historically been a conduit for trade, culture, and strategic alliances. The strategic value the sea line of communication (SLOC) hold for global powers is also highly significant. Hence, it has always been aimed for both organisations to ensure regional peace, stability, prosperity and cooperation increasingly important (Acarya, 2009 & ASEAN, 2021). Established in 1967, ASEAN promotes economic integration, political stability, and social progress among its 10 member states, while IORA, established in 1997, comprises 23 member states bordering the Indian Ocean, spanning from Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania (Figure 1).

1:

Indo-Pacific - ASEAN and IORA Member States/Dialogue Partners (Source: Adapted from Agathe, 2017)

This paper argues that both ASEAN and IORA have long understood that collaboration between ASEAN and IORA holds significant potential for improving regional connectivity, trade, and maritime security. Today, within the IP, ASEANIORA cooperation is essential especially in strengthening maritime connectivity (Tharishini, 2023). With extensive coastlines and vital maritime trade routes, these regions recognise the strategic importance of leveraging their collective strengths to address common challenges and opportunities. Both entities appreciate the need for a more meaningful economic development and security cooperation within their respective regions and broader regional integration and stability across the region.

Hence, the rise of the Indo-Pacific construct has created avenue to redefine maritime connections and improve the longstanding ties between ASEAN and IORA in all aspects of economic, geopolitical and strategic terms. However, as much as ASEAN and IORA have undertaken various initiatives to promote mutual understanding, cooperation and development in the past, collaboration has been relatively limited despite shared objectives and geographic proximity (Cordner, 2018). The changing dynamics of the Indo-Pacific present numerous maritime challenges, both traditional and non-traditional, making it imperative for both ASEAN and IORA to pay close attention to one and another and cooperate more effectively.

It is in this context that this paper aims to explore opportunities to strengthen both the institutional mechanisms, foster political consensus, and promote pragmatic cooperation to address common concerns and advance shared interests. Through a comprehensive assessment, the study is expected to contribute valuable insights to regional cooperation in the Indo-Pacific construct and offer actionable policy recommendations. This paper is divided into three sections: (1) The driving

factors of cooperation between the ASEAN and IORA, (2) the strategic issues and challenges impeding effective collaboration, and (3) policy recommendations to improve the cooperation.

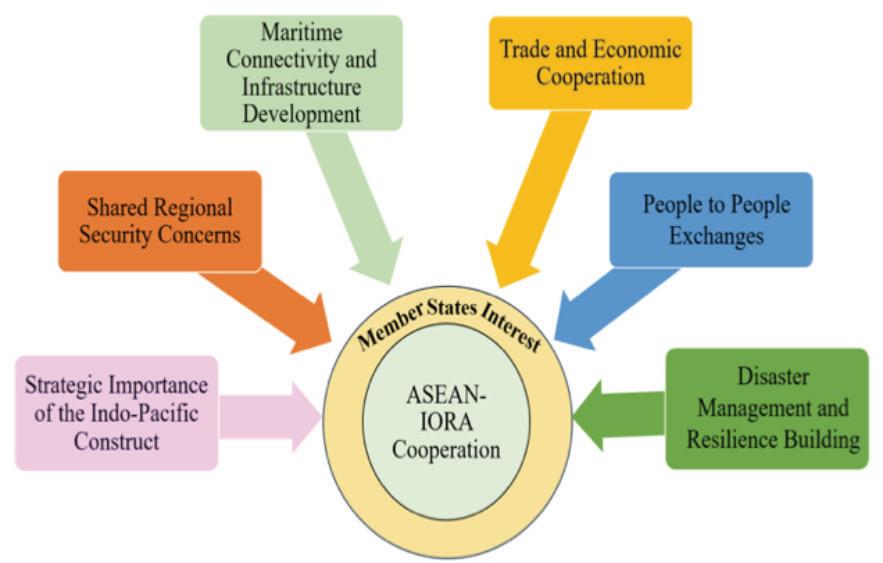

The current cooperation between the ASEAN and the IORA is marked by various initiatives and collaborative efforts to promote regional integration, economic development, and maritime security. While formal institutional linkages between ASEAN and IORA remain limited, member states of both organisations have engaged in practical cooperation and dialogue across multiple domains. Synergizing activities in areas of mutual commitments under IORA and ASEAN would create more comprehensive and inclusive trans- Indo-Pacific arrangements. Figure 2 shows the driving factors that guides ASEAN-IORA current cooperation.

Figure 2: The Driving Factors of ASEAN-IORA Cooperation (Source: Adapted from IORA, 2018; ASEAN.Org, 2023)

Due to economic and geopolitical significance, the Indo-Pacific region has become a focal point of strategic interests for many nations. Spanning from the eastern shores of Africa to the western Pacific Ocean, this maritime space highlights the interconnected nature of sea routes for security and economic growth. When the United States-led Indo-Pacific strategy was introduced, it was aimed to secure Washington a free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) - for continuous peace and stability as well as accessibility across major choke points and SLOCs at sea.

This can be observed with all the key sea lanes within the IP Indo-Pacific facilitate about 60% of global maritime trade, 2/3 of global economic growth, with critical chokepoints like the Straits of Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok being essential for transporting oil and other resources from the Middle East to Asian markets (Storey, 2019) as shown in Figure 3. The security of these passages is vital not only for the United States but for all maritime nations. Besides this, the Indo-Pacific is a realm prosperous in natural resources, including significant offshore oil and gas reserves, and hosts rapidly growing economies such as India and Indonesia. These factors have spurred increased military presence and competition among major powers like the United States, China, and India, each seeking to secure their regional interests.

Figure 3: Indo-Pacific Major Shipping Lan

(Source: Australia Government Department of Defence, 2012 cited in Tharishini, 2019)

The United States’ conscious decision to initiate the Indo-Pacific strategy was largely to realign its policies in responses to its declining influence and the rise of China in the Asia Pacific realm. Emerging and existing stakeholders in the IndoPacific and Indian Ocean regions play crucial roles in shaping foreign policies and expectations (Horimoto, 2020). President Joe Biden during the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) Leaders` Summit 2021 has firmly emphasised the future of their nations and world depends on a FOIP enduring and flourishing in the decades ahead. Part of the United States strategic means are modernised alliances and flexible partnerships.

More importantly is strengthening India’s posture as a leading regional power in the Indian Ocean and reliable Quad. Apart from that, the Indian Ocean is a vital hub for international trade and energy security, linking Asia and Africa. It features strategic chokepoints essential for global trade, drawing interest from the United States and China. Despite their interests, geographical challenges prevent any power from dominating the Indian Ocean (Gilson, 2020). This strategy necessitating a more coordinated approach between ASEAN and IORA.

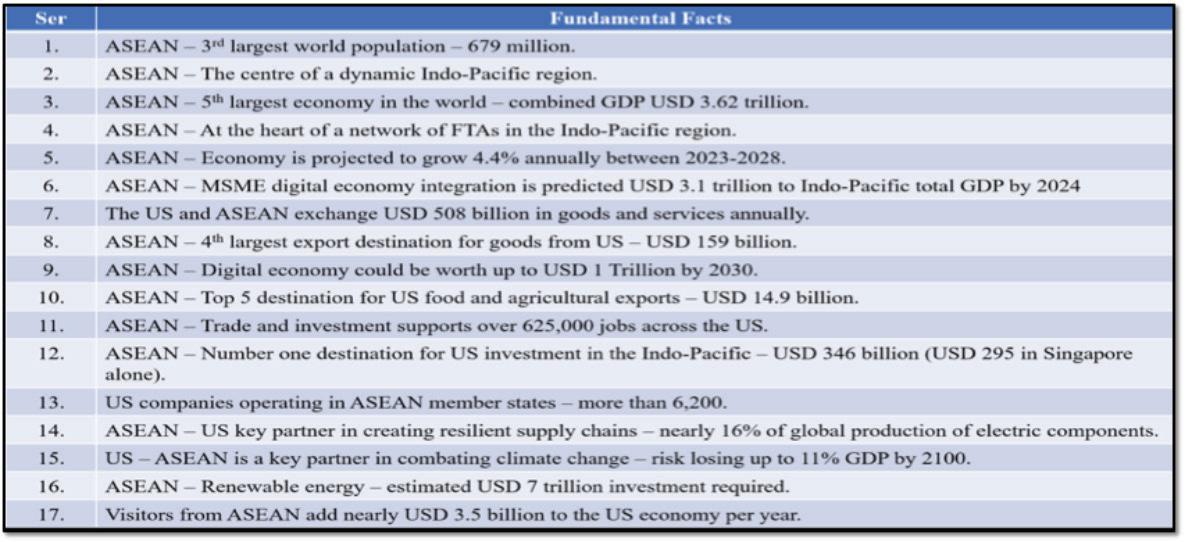

A strong ASEAN is also important for the United States and its allies. Table 1 highlights the importance of ASEAN to the United States. ASEAN with 3rd largest world population is the centre of the Indo-Pacific construct with significant trade and economic relationship with the United States.

Table 1: Why ASEAN Matters for the United States (Source: Adapted from AsiaMattersforAmerica.org/ASEAN, 2023)

The importance of both India and ASEAN along the maritime routes between SEA and the Indian Ocean highlights the strategic shifts the United States adopted to show dominance in the region. As such, it becomes imperative for ASEAN and IORA to play a crucial role in navigating these waters, both literally and figuratively, adapting to the evolving geopolitical landscape to meet emerging challenges and opportunities regionally (Oba, 2019; Koga, 2019; Isa, 2018). In line with this, ASEAN and India have aligned their initiatives more closely with the global strategies to enhance their collective bargaining power and strategic influence.

Both ASEAN and IORA have many common regional security concerns especially in the context of maritime security given the Indian Ocean’s and SEA’s strategic importance for global trade. Forums like the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the IORA Maritime Safety and Security Working Group, for instance, facilitate dialogue and collaborative initiatives to address maritime security threats. Indonesia, a member of both ASEAN and IORA, has actively engaged in maritime security efforts, including hosting the IORA Maritime Safety and Security Workshop in 2018, focusing on enhancing cooperation to combat piracy and transnational crime (Bateman, 2014; IORA, 2024). IORA on the other hand emphasises economic collaboration and quality of life improvements. Its priorities include peace and security, marine science, trade facilitation, disaster management, and promoting good governance (Caballero-Anthony, 2022).

ASEAN and IORA also collaborate on counter-terrorism, recognising the importance of multilateral cooperation in combating terrorism and financial challenges (Ladwig & Mukherjee, 2019). ASEAN’s experience in integrating security through enhancing the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC) principle in the SEA should be a lesson for IORA’s evolving role and impact on international law of the sea and protection of key regional shipping lanes (Elisabeth, 2022). However, despite efforts to address non-traditional security risks, the overall impact of ASEAN and IORA has been limited, with the ARF Regional Security Model struggling to tackle critical issues effectively (Singh, 2017; Aswani et al., 2022).

Maritime cooperation is acknowledged as one of the fundamental areas of cooperation between ASEAN and IORA in ensuring the stability of the seas for the economic development of both regions. This cooperation covers maritime transport, blue economy, and maritime security (Sooklal, 2023). For instance, India’s SAGAR (Security and Growth for all in the Region) policy, which promotes a secure maritime environment in the Indian Ocean through initiatives like the Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) for enhancing regional maritime security cooperation. Duha and Saputro (2022), further explain that, cooperation to boost greater maritime connectivity for trade also includes the development of maritime infrastructure, which is the backbone of economic interaction and connectivity.

Singapore, as a vital member of both organizations, has been active in initiatives promoting port development and maritime connectivity. As a global maritime trade hub, Singapore has championed projects such as the ASEAN Single Shipping Market and the IORA Indian Ocean Maritime Transport Charter to streamline regulatory procedures and improve maritime transport operations efficiency (ASEAN.Org, 2024). Singapore’s involvement in the ASEAN Connectivity Master Plan and the IORA Transport and Connectivity Working Group underscores its commitment in promoting regional connectivity and infrastructure development. ASEAN Connectivity Master Plan 2020’s focus is on the improvement of connectivity in two domains, namely physical and institutional, as well as people’s mobility. An example is Singapore-Kunming Railway Link (SKRL) that aims at linking the South East Asia with China through railways (ASEAN, 2021; IORA, 2021).

On the other hand, there appears to be imbalance in infrastructure development in most IORA member countries, with different levels of development. This situation creates a need for regional cooperation to improve the connectivity of infrastructure among IORA member states and ASEAN member states.

Trade and economic cooperation between ASEAN and IORA have also made significant strides. as another vital member of both organizations, Malaysia has been at the forefront of promoting economic integration and trade facilitation.

Malaysia’s engagement in initiatives such as the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) and the IORA Trade and Investment Facilitation Working Group demonstrates its commitment to enhancing regional economic cooperation. Malaysia’s participation in the IORA Economic Cooperation and Development Working Group has also contributed to initiatives promoting sustainable development and inclusive growth across the Indian Ocean rim (Cordner, 2018).

Since IORA aims to adopt the ASEAN model for engagement in the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly in trade and economy, the complementary interests of significant economies in the Indian Ocean and SEA make cooperation promising. The Indo-Pacific concept has significant implications for Asia, strategically connecting the regions (Pero, 2019; Caballero-Anthony, 2022). ASEAN-IORA trade and economic cooperation present economic opportunities for both regions, essential for ASEAN’s strategic and economic interests. Apart from that, there is an imbalance which exists in the area’s long-term economic development and environmental impact, one which often outpaces the economic and social benefits derive from the oceans. Hence, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IIU) fishing as well as other criminal activities such as piracy can compromise peace and stability as well as hinder global trade and commerce (Chen et al., 2023).

Promoting people-to-people exchanges and cultural diplomacy is central to ASEAN and IORA’s efforts to foster greater understanding and cooperation. ASEAN is constructive, pragmatic, and result-oriented when raising proposals and initiatives for cooperation. Through cooperation between ASEAN and its external partners, people-to-people exchanges play a significant role in connecting relations and consolidate mutual understanding and trust.

Under the Regional Plan of Action to Implement the ASEAN-Partner Strategic Partnership (2011-2015), people-to-people contacts are prioritised for the establishment of a community of nations in the region. People-to-people exchanges are also included in several IORA priority areas. Strengthening understanding and mutual trust among people in the Indian Ocean region is an important driver towards better public awareness and an institutional way to manage regional cooperation (Anantasya, 2023).

As an ASEAN dialogue partner and a member of IORA, India has actively promoted cultural exchange and educational cooperation. Initiatives such as the ASEANIndia Youth Summit and the IORA Cultural Affairs Working Group have facilitated youth engagement, intercultural dialogue, and celebration of cultural diversity (RIS, 2023). India’s hosting of cultural festivals and exhibitions showcases the rich cultural heritage of Indian Ocean-rim countries and creating job opportunities. (Durrance-Bagale et al., 2022: Caballero-Anthony, 2022).

Disaster Management and Resilience-Building

Disaster management and resilience-building efforts have gained momentum within both ASEAN and IORA. Statistically, the Asian Development Bank estimated

ASEAN’s risk losing up to 11% of GDP by 2100 if no serious action to address natural disaster and climate change (AsiaMattersforAmerica.org/ASEAN, 2023). On the other hand, IORA member states from South Asia (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka’s) has 10%-18% of GDP at risk by 2050. Likewise, Central Asia, Middle East, North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa nations face significant losses too (Jones, 2022). As a member of both organisations, Thailand has played an active role in disaster preparedness and response initiatives. It’s engagement in the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management (AHA Centre) and the IORA Disaster Risk Management (DRM) Working Group has facilitated cooperation in disaster response and recovery efforts. In 2019, Thailand hosted the IORA Workshop on Building Resilience to Disasters, which focused on sharing best practices in disaster management (ASEAN Secretariat, 2024).

Both ASEAN and IORA prioritize maritime security and disaster response. Cooperative efforts, such as those in the Malacca Strait and joint disaster management protocols post-2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, highlight regional interdependence in addressing security threats. The IOGA’s (Indian Ocean Global Alliance) DRM programme concentrates on developing the capacity for DRM in the region including prevention, response and rehabilitation One example is the ORA Workshop on Building Resilience to Disasters involving information sharing through experts and policymakers etc. in line with disaster risk management (IORA, 2021).

Theoretical Frameworks in Understanding ASEAN-IORA in the Indo-Pacific Construct

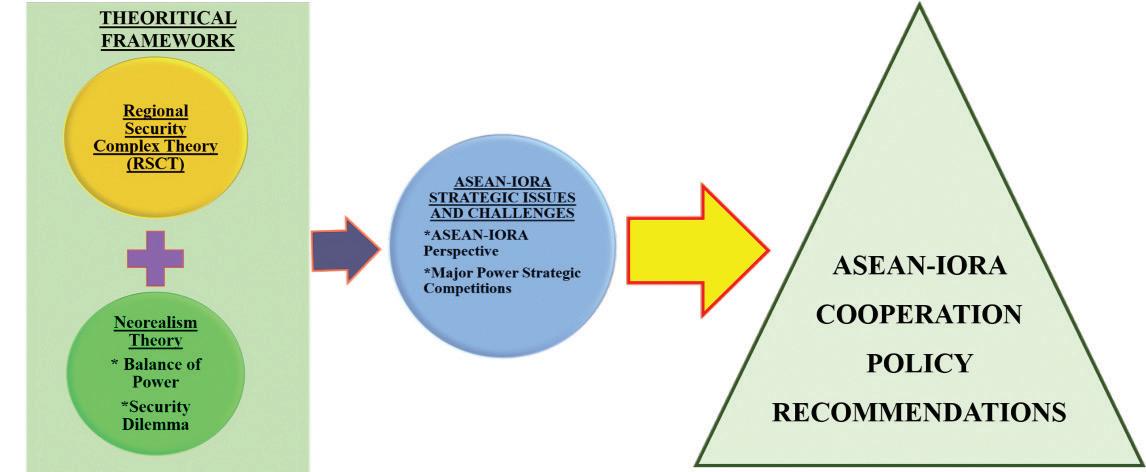

Theoretical support can be useful in evaluating ASEAN-IORA cooperation due to the complexity and dynamic nature of regional security issues. This cooperation encompasses significant major power competition and a vast maritime security domain, including interests in the IP, IO, and South China Sea (SCS). To thoroughly identify and assess the strategic issues and challenges Regional Security Complex Theory (RSCT) and Neorealism, with a focus on the Balance of Power and Security Dilemma supports the analysis as shown in Figure 4

A regional security complex is a group of states with interconnected security concerns, making their national security policies interdependent. Bound by geographical proximity and shared security issues such as political, military and natural disaster threats, these states experience a security threat to one state as a concern for others as well (Buzan & Waever, 2003). They identify various types of security complexes: major power-cantered complexes, standard security complexes, and super complexes formed by overlapping smaller ones. RSCT distinguishes between internal dynamics (interactions within the complex) and external dynamics (interactions with states outside the complex). Changes in global power structures or policies can impact a complex’s stability and character. RSCT emphasizes that global security is the aggregate of these regional complexes, each with unique patterns of amity and enmity, influenced by political, economic, and social factors. Securitization, a key RSCT concept, involves states framing issues as existential threats to justify extraordinary measures. This helps analyse how local security concerns can impact global security (Buzan, 1991 cited in Tharishini, 2015). RSCT is crucial in understanding ASEAN-IORA cooperation and regional stability in the Indo-Pacific where the ASEAN-IORA partnership is notably influenced by regional issues and significant major power rivalries.

Neorealism, contends that the international system operates in an anarchic state, is lacking a central governing authority. In this context, the distribution of power, primarily military and economic capabilities, dictates state behaviours. Driven by rationality and the imperative of survival, states engage in power balancing to prevent any single state from achieving hegemony (Waltz & Kenneth, 1979). In the context of ASEAN-IORA cooperation, this theory suggests that the partnership can be viewed as a strategic move to balance against the influence of major powers like China. By engaging in these regional forums, the United States and its allies seek to counterbalance China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific construct. These major powers rivalry puts ASEAN-IORA member states in a security dilemma situation. Therefore, the cooperation allows smaller states to pool their capabilities and enhance their collective bargaining power, thereby maintaining a balance of power. The security dilemma refers to the situation where actions taken by a state to increase its security (such as forming alliances or building up military capabilities) can lead to increased insecurity among other states, potentially leading to an arms race. However, ASEAN IORA cooperation may help to reduce the security dilemma among member states by fostering trust and cooperation. By creating a platform for dialogue and collaborative security measures, these regional forums can help alleviate mutual suspicions and reduce the likelihood of conflict, thus enhancing regional stability.

The United States, as a significant Indo-Pacific power, acknowledges the region’s vital importance to its security and prosperity. The evolving nature of warfare and international relations has rendered security issues more intricate. Within the regional context, threats to the security of one state impact all states within the complex, influencing regional cooperation. This dynamic also underscores the growing significance of irregular warfare in achieving strategic objectives. What is “irregular warfare” is defined by the United StatesDepartment of Defense (2007) as,

“A form of warfare in which states and non-state actors aim to influence or coerce states or other groups through indirect, non-attributable, or asymmetric activities, either as the main approach or in conjunction with conventional warfare.”

This involves unconventional tactics such as economic dominance, military alliances, influence operations, proxy conflicts and non-state actors to achieve specific political, military, or economic objectives (The United States Department of Defense, 2007; David & Thomas, 2020).

The convergence of state actors, non-state actors, conventional warfare, and IRREGULAR WARFARE presents various strategic challenges that may hinder ASEAN-IORA cooperation. These issues and challenges have been scrutinized from the strategic standpoint of ASEAN-IORA collaboration, and the strategic competition among major powers as depicted in Figure 5

ASEAN-IORA Perspectives

Viewed from the perspectives of ASEAN and IORA, three principal strategic challenges regarding regional cooperation endeavours warrant attention: political disparities among member states, economic disparities within member states, and conflicting regional interests.

A significant challenge for ASEAN-IORA cooperation lies in the political differences among the member states. ASEAN members have diverse political systems, ideologies, and foreign policies, complicating consensus on regional issues. Similarly, IORA members display a wide range of political regimes and geopolitical alignments, reflecting the Indian Ocean’s diversity. These differences can lead to divergent priorities, conflicting interests and varying levels of commitment to regional initiatives, posing significant challenges for ASEAN and IORA. ASEAN’s non-interference and consensus decision-making principle can hinder swift collective action, as seen in the varying national responses to China’s maritime claims (Ishikawa, 2019; Saman, 2015). Collective security and strategic autonomy are central to ASEAN, but often conflicting. For instance, the SCS dispute has caused divisions within ASEAN, with countries like Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia engaged in overlapping claims with China. This may have weakened ASEAN’s unity and credibility regarding China’s actions (ASEAN.Org, 2023; Laila et al., 2015). Similarly, geopolitical rivalries, such as between India and Pakistan, can hinder cooperation within IORA. Resolving these political differences requires diplomatic finesse, consensus-building, and a commitment to constructive dialogue. ASEAN’s principle of non-interference and IORA’s emphasis on dialogue and respect for sovereignty help maintain stability but bridging political divides remains an ongoing challenge.

Significantly impact ASEAN-IORA cooperation, ASEAN member states show considerable variations in economic development, income inequality, and industrialisation. For example, Singapore and Malaysia are highly developed, while Cambodia and Laos remain underdeveloped with limited economic diversification (ASEAN.Org, 2018; Ravenhill, 2018). These disparities pose challenges in coordinating regional economic initiatives and addressing the needs of less developed states. Similarly, IORA members face economic disparities, with countries like Australia and South Africa having advanced economies, while Comoros and Madagascar face development challenges and rely heavily on agriculture (IORA, 2024; Lee, 2017). These inequalities hinder efforts to promote inclusive growth, sustainable development, and effective disaster management across the Indian Ocean region and SEA. To address these disparities, initiatives such as the Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI) and the Strategic Action Plan for SMEs aim to support less developed members (ASEAN Secretariat, 2000). Similarly, IORA’s Action Plan and Declaration on Economic Cooperation promote trade, investment, and economic integration.

Posing a significant challenge for ASEAN-IORA cooperation, especially where geopolitical rivalries intersect with regional dynamics. ASEAN members are influenced by external powers like China, the United States, and Japan, each

The major power competitions in the Indo-Pacific mainly between US-ChinaIndia as depicted in Figure 6 is seen to impact regional security dynamics and hindering the ASEAN-IORA effective cooperation. Irregular warfare strategy is currently regarded as the most prevalent instrument employed to surpass their respective competitors.

6: US-China-India Strategic Competition and Implications

Geopolitical Competition in the Indo-Pacific

Geopolitical competition in the Indo-Pacific region is intensifying, marked by the strategic manoeuvres of major global powers and alliances as depicted in Figure 7. seeking to advance its strategic interests in the region (Cordner, 2018). This results in competition for influence, divergent strategic alignments, and conflicting security priorities, complicating consensus and collective action. Similarly, in the Indian Ocean region, major powers such as India, China, and the United States shape geopolitical dynamics and influence regional security architecture. The Indian Ocean’s strategic significance as a maritime trade route and energy corridor has heightened competition for influence, leading to geopolitical rivalries and security tensions. These competing interests undermine regional cooperation efforts on issues like maritime security, environmental protection, and disaster management. Addressing these competing interests requires diplomacy, dialogue and confidence-building measures to mitigate tensions and promote cooperative solutions. ASEAN’s constructive engagement and IORA’s consensus-building and non-alignment approaches help manage competing interests and maintain regional stability, fostering an environment for dialogue, trust-building, and cooperation.

The Indo-Pacific region holds strategic importance for every continent, driven by geopolitical dynamics and economic interests. The United States, along with NATO and its allies, emphasizes a commitment to a FOIP. Security guarantees to Japan, South Korea, and Australia, along with alliances with non-NATO partners like India and the Philippines, reinforce this stance. The Quad alliance, comprising the United States, India, Japan, and Australia, plays a crucial role in addressing shared security concerns and countering China’s growing influence (The White House, 2022). China, meanwhile, has expanded its strategic reach through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), enhancing global trade routes and securing economic and political leverage. This initiative aligns with BRICS’ (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) objectives to challenge Western dominance. Geopolitical competition is further fuelled by issues like the SCS disputes, India-Pakistan border tensions, and China’s claim on Taiwan, complicating ASEAN-IORA cooperation. Meanwhile, India’s investment in Iran’s Chabahar Port enhances connectivity with Central Asia, countering China’s China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) initiative (Shambaugh, 2020; Tripathi, 2016).

The IP’s strategic significance is underscored by SEA’s central position and the Indian Ocean’s role as a vital trade hub linking Asia and Africa. The United Statesand its allies focus on upholding international rules and ensuring maritime security, while China’s initiatives aim to reshape regional connectivity and influence. This competition represents a broader struggle for dominance, with alliances and economic strategies shaping the Indo-Pacific’s future. This strategy incorporates economic influence, and other irregular tactics to consolidate power and counterbalance rivals (Syeda Hibba, 2023). The dynamic interplay between these global powers creates strategic issues and challenges for ASEAN-IORA cooperation, highlighting the region’s critical role in international affairs. Economic Dominance and Dependence

China has strong economic ties with SEA nations with ASEAN working to improve regional connectivity in response. India is also focusing on connectivity with ASEAN through an Act East policy. The major powers and ASEAN rely on economic leverage and coercion, posing significant challenges for ASEAN and IORA member states, often leading to economic dependency on major powers, notably China (Shambaugh, 2020). As evidenced by the BRI, which, while beneficial, has resulted in debt dependencies, allowing China to exert political and economic pressure. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port, developed with Chinese investment, has been cited as an example of “debt-trap diplomacy,” where financial dependency on China led to a long-term lease of the port to a Chinese company, impacting Sri Lanka’s strategic autonomy.

Likewise, India also leverages its economic influence with ASEAN and IORA through projects like the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project, improving regional connectivity. The New Development Bank (NDB) from BRICS supports India’s initiatives, directing funds to bolster its regional sway. However, China’s BRI, exemplified by projects such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), poses competition, binding countries through extensive infrastructure investments (Tripathi, 2016). Apart from that, the trade war initiation is related to US declining influence on world politics and the weaker-than-predicted threats from the global economy. Disputes between the United States and China disrupt the economic stability of ASEAN and IORA members. US-China trade wars and economic sanctions will impact the global economy as it is the second largest and valued at $300 billion. If the trade war continues, the global trade war is expected to increase to $550 billion, over 10% of world trade (Guo et al., 2023).

For instance, the United States-China trade war disrupted global supply chains, affecting ASEAN and IORA member states economies integrated into these chains and leading to economic uncertainty and trade diversion.

Maritime security is crucial for the IORA and the Indo-Pacific region. The ASEANIndia partnership emphasises freedom of navigation and peaceful dispute resolution in the SCS. Particularly those involving China, pose significant security threats in the SCS and the Indian Ocean. China’s construction of military installations on artificial islands in the SCS has heightened tensions with several ASEAN members, complicating regional security cooperation (Elisabeth, 2022; Grare & Saman, 2022). Its deployment of fishing fleets, backed by coast guard vessels, to disputed areas like the Spratly Islands, represents a strategic use of irregular maritime forces to establish a presence without triggering outright conflict.

Significant powers like the United States and India create a strategic military alliances and balancing acts for ASEAN and IORA members, making it challenging to maintain a unified security policy. The United States military presence and defence agreements with ASEAN countries like the Philippines and Singapore establish strategic dependencies. Balancing strategic autonomy with collective

security become a challenge to ASEAN-IORA cooperation. It is a significant challenge for ASEAN and IORA due to differing member states’ priorities and dependencies as seen in the varying national responses to China’s maritime claims (Ishikawa, 2019 & Saman, 2015).

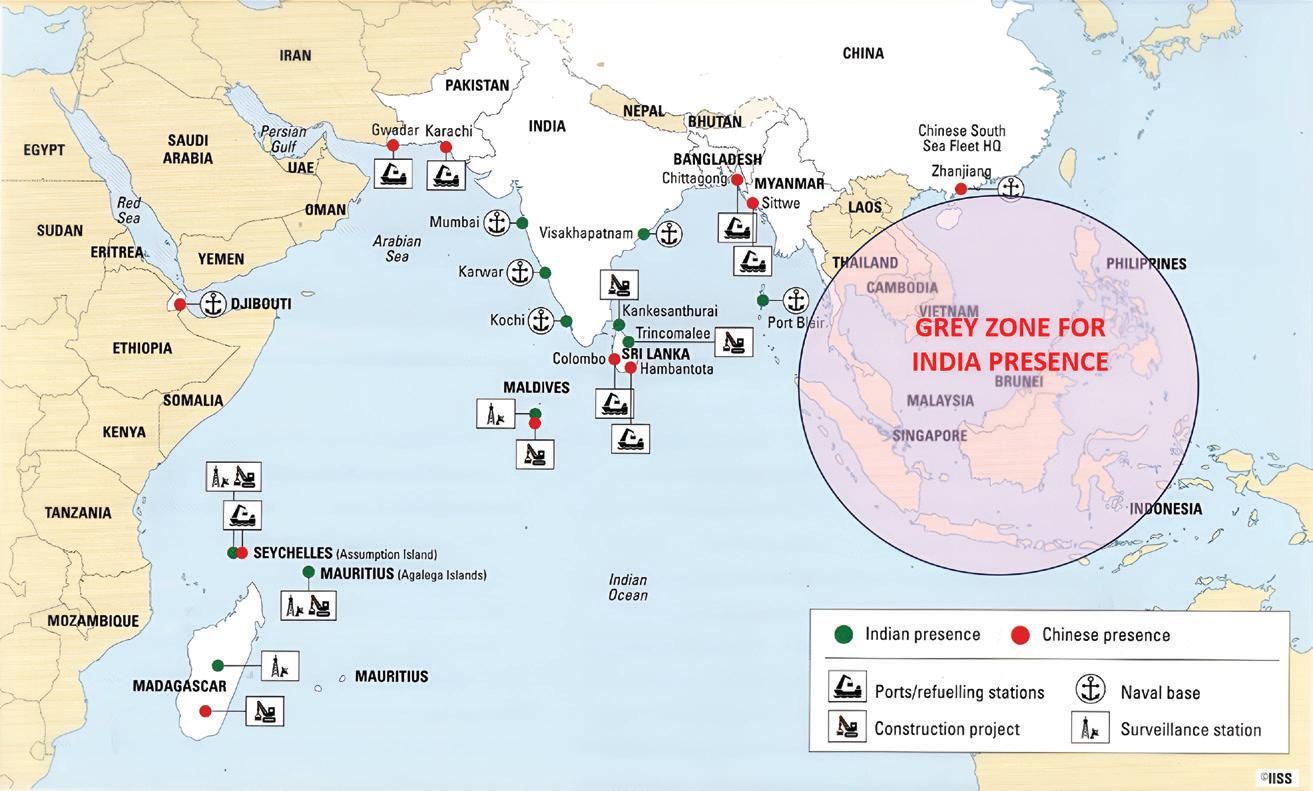

While India’s naval presence in the Indian Ocean aims to counterbalance China’s influence, the Indo-Pacific and the ‘contest for naval influence’ have posed challenges for ASEAN and IORA. This naval power projection has created a security dilemma for their member states in handling significant power influence (Elisabeth, 2022). The Indian and Chinese maritime presence in the Indo-Pacific indicates their clear competition for control over the maritime domain in this region. However, India is somewhat marginalised in this competition, particularly in the Grey Zone areas such as the SCS and the ASEAN nation bloc, as illustrated in Figure 8

Figure 8: Indian and Chinese Maritime Presence in the Indo-Pacific and Grey Zone for India Presence

(Source: Xinhua, 2017; US Department of Defense, 2018 cited in IISS, 2019)

The United States, India, Japan, and Australia have reactivated strategic links with Indo-Pacific states through Quad and AUKUS, which is a trilateral security partnership between Australia, the UK, and the United States intended to “promote a free and open Indo-Pacific that is secure and stable”. The United States aims to drive global rebirth in the Indo-Pacific where through the IndoPacific Strategy 2022, it recognises India as a like-minded partner and leader in South Asia and the IO, and connected to SEA (The White House, 2022; Heritage & Lee, 2020). Strategic alliances exemplify major powers’ complex interactions in the Indo-Pacific, leaving ASEAN and IORA in a struggle for security cooperation with both China and the United States. Meanwhile, ASEAN is central in promoting peace and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific by navigating initiatives like joint military exercises and infrastructure projects that impact regional security dynamics.

Major powers engage in influence operations to sway political decisions within ASEAN and IORA, exploiting existing political divisions. For example, China’s use of economic incentives and political influence to gain support for its SCS claims has created divisions within ASEAN, undermining collective policy responses. ASEAN believes it can play a leading role in establishing regional rules, but the United States’ intervention is seen as premature complicating the situation (Nye Jr, 2020; Ladwig & Mukherjee, 2019).

Irregular warfare strategies are also used such as proxy conflicts and non-state actors’ involvement. This occurs notably in the National League for Democracy with the Arakan Army in Myanmar. Future state-governance challenges will emerge in states facing non-state actors under peace and cooperation rules, as well as human rights, migration, and terrorism rules (Hashmi et al, 2023). Proxy conflicts and the involvement of non-state actors supported by major powers can destabilise ASEAN and IORA regions. The United States and China’s support for different political factions and armed groups in various SEA countries, such as Myanmar, can exacerbate internal conflicts (Ishikawa, 2019; Grare & Samaan, 2022). Myanmar poses a difficulty for both ASEAN and IORA when huge number of the Rohingya’s people flee to most of the ASEAN and IORA countries causing political unrest, social concern and security instability.

To enhance cooperation between ASEAN and IORA, and address the strategic competition especially involving the United States, China, and India and the associated aspects of irregular warfare, ASEAN-IORA cooperation must adopt comprehensive policies as depicted in Figure 9

To deepen institutional, efficiency and effectiveness of ASEAN and IORA, both institutions have to set out strategic direction by developing strategies, enhance multilateral security architecture externally, and ensure regular security review mechanisms. These frameworks should contain elaborate measures for dealing with traditional and non-traditional security threats. Cooperation could encompass combined military operations, and intelligence exchange to improve the capacity of ASEAN and IORA to respond to security threats. One example is the Malacca Strait Patrols initiated by Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand to combat piracy, exhibit successful multilateral engagement.

The ongoing combined exercise and cooperation will help in building defence capability of ASEAN and IORA. They are of a confidence-building nature hence minimizing potential conflicts. For instance, the stepped-up naval cooperation between India and the ASEAN countries has the effect of boosting the security in a given area, and thus, elevating the level of trust. A continuous provision of vulnerability checks and planning for the analysis of the general regional security and cooperation structures is essential. These reviews should encompass the governments, scholars and the civil society so as to guarantee the continued suitability of these frameworks. Strategy review involving stakeholder analyses can tackle emerging issues such as cyber threats. This approach enhances the legitimacy and inclusiveness of policy-making, ensuring diverse perspectives are considered.

To avoid conflicts requires realistic objectives and clear frameworks for collaboration. Clear strategic goals and directive will keep cooperation’s orientation toward results, thus avoiding exploitation by major powers. Setting specific goals helps outline the collaboration process, resource allocation, and achievement metrics, reducing misunderstandings. Mapping out of action plan for disaster response can ensure quick, coordinated efforts during crises. These goals ensure all efforts align with common objectives, enhancing overall effectiveness and value of ASEAN-IORA cooperation.

It is important for ASEAN and IORA members to trust each other. The ASEAN-IORA action plan should promote inclusive dialogue, confidence-building measures, cross-regional partnerships, and people-to-people connectivity. Addressing strategic concerns and confidence-building can be cultivated through inclusive dialogues among ASEAN, IORA members, and major powers. Amplifying venues such as the East Asia Summit (EAS) to embrace IORA members is one way of reducing the security dilemma due to lack of understanding. Confidencebuilding measures, such as joint exercises and information-sharing agreements, can foster trust and stability.

ASEAN and IORA should facilitate cooperation among the member states, universities, research institutes and the think tanks in order to foster cross-

regional cooperation for partnership and exchange programmes. Co-organization of workshops and conferences, common training events addressing interests that include maritime security, environmental protection, disaster response, will enhance knowledge exchange and capacity building. A joint workshop can be organized for member states on the disaster management whereby they exchange the best practices to enhance their disaster management capabilities. Promoting people-to-people connectivity through cultural exchanges, educational programmes, and youth initiatives can foster mutual understanding and solidarity among ASEAN and IORA member states. Programmes like student exchange initiatives between universities in ASEAN and IORA countries can build strong interpersonal and cultural ties, reducing the potential for conflict and promoting a sense of regional community. These soft power initiatives complement hard security measures and contribute to long-term stability.

To further build trust, ASEAN and IORA should establish a regional disaster response mechanism that integrates their efforts. This could include a standing task force and a pooled fund for quick action to natural disasters and humanitarian crises. Given the region’s vulnerability to natural disaster, a well-coordinated response mechanism will ensure a more efficient responses, minimising the human and economic impact. Such cooperation fosters friendly relations and trust among member states, enhancing regional stability.

Concerning the core problems leading to the instability, ASEAN and IORA should focus on integrating sustainability into regional cooperation to improve stability in the Indo-Pacific region. This approach ensures development benefits all member states, creating a more stable and prosperous region. Public policies focusing at blue economy development, sustainable fisheries, and climate change issues can enhance regional resilience. Since socio-economic factors define the long-term security and development, the risk of conflict can be alleviated by addressing socio-economic issues. Blue economy development should be a central theme in ASEAN-IORA cooperation. This includes formulating unified policies to align regional blue economy standards with international benchmarks and encouraging uniform adoption by member states. Capacity building should focus on investing in training and education for marine sectors and establishing R&D centres for blue economy innovations.

To address sustainable fisheries, emphasis should be placed on implementing science-based management plans to prevent overfishing and combat IIU fishing, and establishing regional bodies for enforcement. Strengthening regional cooperation for monitoring and enforcement, engaging local communities in management and decision-making, and educating on sustainable fishing practices are also crucial. Meanwhile, in mitigating climate change impacts, resilience planning is essential. This involves developing climate resilience plans for coastal and marine areas and integrating adaptation and mitigation measures

into development planning. Utilizing renewable energy and establishing regional climate research centres for research and data sharing will effectively address climate change.

ASEAN and IORA should adopt a balanced approach in engaging with the dominant hegemons like the United States and China. Interacting with the two powers in equal circumstance to prevent domination by one or another promotes a multipolar regional order, which is crucial for stability. This way, they can reduce reliance on any single major power, thereby mitigating security dilemma and the risks of entanglement in major power rivalries. Active participation of ASEAN and IORA warrants for interaction with the major powers while maintaining regional independence and encouraging a multipolar system. Given the geopolitical complexities involving the United States and China, these organisations should strive for strategic autonomy and diversified partnerships. Constant participation in diplomatic forums like the ARF and IORA meetings can foster self-sufficiency and balanced relations. Additionally, supporting regional initiatives that promote economic and security cooperation can help in balancing major power influence and ensure a stable, multipolar region.

ASEAN and IORA should commence unity partnerships gearing towards maritime security initiatives encompassing anti-piracy operations, search and rescue missions, and maritime domain awareness. In this regard, establishing a regional maritime security coordination centre, such as a joint ASEAN-IORA task force, will enhance these efforts. Maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region remains a major concern, and joint initiatives will strengthen regional capabilities, improve coordination, and provide a united front against common threats. A regional coordination centre serves as a strategic operation centre for operational collaboration and hub for information sharing.

A joint ASEAN-IORA task force role is to ensure the two organisations engage in extensive communication, planning and cooperation. It is suggested that this task force should consist of ASEAN and IORA members, dialogue partners, international organisations, and civil society groups. It would identify areas of mutual interest, develop joint initiatives, and monitor progress on collaborative projects. By institutionalising cooperation through a dedicated mechanism, ASEAN and IORA can streamline decision-making and promote synergy between their agendas. Joint maritime security efforts can include coordinated patrols, shared intelligence, and joint exercises among ASEAN and IORA members. These common security strategies lead to more efficiency and effectiveness by enhancing preparedness and enforcement in regional waters, thereby improving overall maritime security.

In summary, the cooperation between ASEAN and IORA holds significant promise for advancing regional integration, economic development, and maritime security within the Indo-Pacific construct. The partnership is driven by shared strategic interests such as enhancing regional security, fostering maritime connectivity, promoting trade and economic cooperation, facilitating peopleto-people exchanges, and strengthening disaster management capabilities. These areas of mutual interest provide a strong base for joint initiatives aimed at fostering stability and prosperity across the region. Comprehensive policies as depicted in Figure 9 above would be able to enhance cooperation between ASEAN and IORA, and address the strategic competition especially involving the United States, China, and India and the associated aspects of irregular warfare.

By focusing on strengthening institutional frameworks, building trust, encouraging sustainable development and economic cooperation, balancing relations with major powers, and develop joint maritime security initiatives, these policies would be able to focus on enhancing economic resilience, security cooperation, and political unity while addressing irregular warfare tactics such as economic dominance, political leverage, balancing acts, proxy conflicts, and influence operations. The proposed establishment of a maritime security coordination centre will enhance coordination and streamline decision-making processes. Prioritising connectivity, infrastructure development, cross-regional partnerships, and sustainable development initiatives will further contribute to the longterm well-being and resilience of the Indo-Pacific construct. Through proactive engagement, strategic coordination of actions, as well as pragmatic cooperation, will allow ASEAN and IORA to achieve their full potential and shape a more interconnected and stable Indo-Pacific region.

Finally, embracing opportunities, flexibility, and inclusivity will enable ASEAN and IORA to navigate regional dynamics and promote peace, stability, and prosperity. Through collective action and collaborative efforts, both organisations can shape the future of the Indo-Pacific and contribute to a more peaceful and prosperous world.

References

Acharya, A. (2009). Whose Ideas Matter? Agency and Power in Asian Regionalism. Cornell University Press.

Agathe, M. (Mac, 2017). Rance In the Indian Ocean: A Geopolitical Perspective and Its Implications for Africa. South African Institute of International Affairs. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316081848_FRANCE_ IN_THE_INDIAN_OCEAN_A_GEOPOLITICAL_PERSPECTIVE_AND_ITS_ IMPLICATIONS_FOR_ AFRICA.pdf.

Anantasya, F. A. (2023). South Korea’ New Southern Policy and Its Implications Towards Indonesia and Vietnam. Taiwan Journal

of East Asian Studies. http://tjeas.ciss.ntnu.edu.tw/en-us/shared/ redirect/371?folder=journals&file=South%20Korea%E2%80%99%20 New%20 Southern%20Policy.pdf.

ASEAN. (2021). About ASEAN. https://asean.org/asean/about-asean/.

ASEAN.Org. August 14, 2018. ASEAN Economic Community 2025 Consolidated Strategic Action Plan. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ Updated-AEC-2025-CSAP-14-Aug-2018-final.pdf.

ASEAN.Org. October 2023. OVERVIEW OF ASEAN-INDIAN OCEAN RIM ASSOCIATION (IORA) RELATIONS. https://asean.org/wp-content/ uploads/2023/10/Overview-Paper-ASEAN-IORA-fn.pdf.

ASEAN.Org. (2024). ASEAN Led Implementing Body for Sustainable Infrastructure discusses connectivity and infrastructure cooperation for development. https://asean.org/asean-lead-implementing-body-for-sustainableinfrastructure-discusses-connectivity-and-infrastructure-cooperation-fordevelopment/.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2000). Initiative for ASEAN Integration & Narrowing Development Gap (IAI & NDG). https://asean.org/our-communities/ initiative-for-asean-integration-narrowing-development-gap-iai-ndg/.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2024). NATIONAL EFFORTS RELATED TO ASEAN CONNECTIVITY. https://connectivity. asean.org/resource/cross-borderconnectivity- regional-needs-and-the-role-of-infrastructure-asia/. AsiaMattersforAmerica.org/ASEAN. (2023). ASEAN MATTERS FOR AMERICA MATTERS FOR ASEAN. SIXTH EDITION. Copyright © 2023 East-West Center.

Aswani, S., Sajith, R., & Younus Bhat, M. (2022). Realigning India’s Vietnam Policy Through Cooperative Sustainable Development: A Geostrategic Counterbalancing to China in Indo-Pacific. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Australia Government, Department of Defence. (2012). Australia in the ‘IndoPacific’ century: rewards, risks, relationships. https://www.aph.gov.au/ About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Li brary/ pubs/BriefingBook44p/IndoPacific.

Bateman, S. (2014). Maritime Security in Southeast Asia: Two Cheers for Regional Cooperation. Southeast Asian Affairs, 35-50.

Buzan, B. (1991). People, State and Fear. An Agenda for International Security Studies in the post-Cold Era.

Buzan, B., & Weaver, O. (2003). Regions and Power, The Structure of International Security. United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org. ISBN-13 978-0-511-49125-2 OCeISBN. Caballero-Anthony, M. (2022). The ASEAN way and the changing security environment: navigating challenges to informality and centrality. ncbi. nlm.nih.gov.

Chen, X., Xu, Q., & Li, L. (2023). Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing governance in disputed maritime areas: reflections on the international legal obligations of states. Fishes. https://www.mdpi.com/24103888/8/1/36.

Cordner, L. (2018). Indian Ocean Maritime Security Cooperative Arrangements In: Maritime Security Risks, Vulnerabilities and Cooperation. New Security

Challenges. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3319-62755-7_6.

David, H. Ucko., & Thomas, A. Marks. (2020). Crafting Strategy for Irregular Warfare: A Framework for Analysis and Actions. National Defence University Press. Washington, D.C.

Duha, J., & Saputro, G. E. (2022). Blue Economy Indonesia to increase national income through the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) in the order to empower the world maritime axis and strengthen state defense. JMKSP (Jurnal Manajemen, Kepemimpinan, dan Supervisi Pendidikan), 7(2), 514-527. univpgri-palembang.ac.id.

Durrance-Bagale, A., Marzouk, M., Ananthakrishnan, A., Nagashima-Hayashi, M., Tung Lam, S., Sittimart, M., & Howard, N. (2022). ‘Science is only half of it’: Expert perspectives on operationalising infectious disease control cooperation in the ASEAN region. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Elisabeth, A. (2022). ASEAN Maritime Security and Power Interaction in the Region. In: Khanisa, Farhana, F. (eds) ASEAN Maritime Security. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2362-3_7.

FES Asia Editorial. (2024). Geopolitical Competition in the Indo-Pacific. https://asia.fes.de/news/geopolitical-competition-indo-pacific.html.

Gilson, J. (2020). EU-ASEAN relations in the 2020s: pragmatic inter-regionalism? ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Grare, F. & Samaan, JL. (2022). Rethinking the Indian Ocean Security Architecture. In: The Indian Ocean as a New Political and Security Region. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91797-5_9.

Guo, L., Wang, S., & Xu, N. Z. (2023). US economic and trade sanctions against China: A loss- loss confrontation. Economic and Political Studies. https://ideas. repec.org/a/taf/repsxx/v11y2023i1p17-44.html.

Hashmi, S. K. H., Haider, B. B., & Zahid, I. (2023). Major Powers’ Interests in IOR And Implications for the Region. Journal of Nautical Eye and Strategic Studies, 3(2), 87-103. mul.edu.pk.

Heritage, A. & Lee, P. K. (2020). The Sino-American confrontation in the South China Sea: Insights from an international order perspective. Cambridge Review of International Affairs. kent.ac.uk.

Horimoto, T. (2020). Indo-Pacific Order and Japan–India Relations in the Midst of COVID-19. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

IISS. (2019). ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL SECURITY ASSESSMENT. The International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, UK.

IORA. (2021). About IORA. https://www.iora.int/en/about-us/about-iora.

IORA. (2018). CHARTER OF THE INDIAN OCEAN RIM ASSOCIATION (IORA). Durban, eThekwini, South Africa.

IORA. (2024). PRESS RELEASE IORA and ASEAN Sign MoU to Synergize Work on the Implementation of its Indo-Pacific Outlook. https://iora.int/ sites/default/files/2024-02/press-release-signing-mou-asean-iora%20 %281%29.pdf.

Isa, Rastam Mohd. (2018). Cooperation and Competition in the Asia-Pacific, ASEAN and the Superpower Dynamics Dilemma. Journal of International

Relations and Sustainable Development 11: 90-103. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/10.2307/48573497.

Ishikawa, K. (2019). Emphasis on Dialogue and Cooperation: ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. WORLD INSIGHT. https://worldinsight.com/news/ politics/emphasis-on-dialogue-and-cooperation-asean-outlook-on-theindo-pacific/.

Jones, M. (2022). How hard could climate changehit the global economy, and where would suffer most? World Economic Forum. Reauters. https:// www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/04/climate-change-global-gdp-risk/.

KOGA, KEI. (2019). Japan’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” Tokyo’s Tactical Hedging and the Implications for ASEAN. Contemporary Southeast Asia (ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute) 41 (2): 286-313. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/10.2307/26798855.

Ladwig, W. & Mukherjee, A. (2019). Sailing Together or Ships Passing in the Night? India and the U.S. in Southeast Asia. osf.io.

Laila Suriya, Kamarulnizam Abdullah & Siti Darwinda. (2015). The South China Sea Flashpoint: A litmus Test for the ASEAN political-Security (APSC) Building Process. Institute of Diplomacy and Foreign Relations (IDFR), Ministry of Foreign Affairs Malaysia.

Lee, H. (2017). Economic Disparities and Regional Economic Integration in ASEAN and SAARC. Economic Bulletin, 37(4), 2324-2335.

Nye Jr, J. S. (2020). Power and interdependence with China. The Washington Quarterly. viet-studies.com.

Oba, Mie. (2019). ASEAN’s Indo-Pacific Concept and the Great Power Challenge, Rising tensions between the U.S. and China complicate ASEAN’s vision for the region. https://thediplomat.com/2019/07/aseans-indo-pacificconcept-and-the-great-power challenge/.

Pero, D.M. (2019). State Capacity and Leadership in ASEAN and the EU. ncbi.nlm. nih.gov.

Ravenhill, J. (2018). The Political Economy of the ASEAN Regionalization Process. International Organization, 72(4), 840-871.

Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS). (2023). Cultural Diplomacy: Tapping Potential of Traditional Sports. AIC Commentary, No 40, June 2023. https://aseanindiacentre.org.in/sites/default/files/202205/AIC%20commentary%20April%202022.pdf.

Saman, Kelegama. (2015). IORA: Success, Failures and Challenges. Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka, Presentation to the International Conference on India and the Indian Ocean, Odisha, 20-22 March 2015. https:// www.ips.lk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/IPS_SamanKelegama_IORA_ Success_Failures_Challenges. Pdf.

Shambaugh, D. (2020). Where Great Powers Meet: America & China in Southeast Asia. https://books.google.com.my/books/about/Where_Great_Powers_ Meet.html?id=2NQBEAAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y.

Singh, B. (2017). The Emergence of an Asia-Pacific Diplomacy of Counter-Terrorism in Tackling the Islamic State Threat. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Sooklal, A. (2023). The IORA Outlook on the Indo-Pacific: building partnerships for mutual cooperation and sustainable development. Journal of the Indian

Ocean Region. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19480881.2 023.2252189.

Storey, I. (2019). The Importance of the Indo-Pacific: Economic and Security Dimensions. The Pacific Review, 32(4), 495-521.

Syeda Hibba Zainab. (May 20, 2023). The Ascent of India: Aspirations of Regional Hegemony.https://policywatcher.com/2023/05/the-ascent-of-indiaaspirations-of-regional-hegemony/.

Tharishini, K. (2015). Emerging Security Paradigm in the Eastern Indian Ocean Region. A Blue Ocean of Malaysia-India Maritime Security Cooperation. King’s College London.

Tharishini, K. (2019). Navigating Malaysia into the Indo-Pacific Stream. file:///C:/Users/ User/Downloads/NavigatingMalaysiaintoTheIndoPacificStreamSAM UDERASiri12019%20(1).pdf.

Tharishini, K. (2023). The Prospect of Malaysia-India Maritime Connectivity in the Indo-Pacific. Samudera Edition 3/2023. ISSN0127-6700, 8-9.

The United States Department of Defense’s. (2007). Irregular Warfare. Joint Operating Concept (JOC), US.

The White House. (2022). The Indo-Pacific Strategy of The United States. Executive Office of The President, National Security Council, Washington, DC 20503. Tripathi, D. (2016). Indian Aspirations and South Asian Realities; Perceived Hegemon or Emerging Leader? In: Kingah, S., Quiliconi, C. (eds) Global and Regional Leadership of BRICS Countries. United Nations University Series on Regionalism, vol 11. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/9783-319-22972-0_9.

US Department of Defense. (2018). Assessment of US Defense Implications of China’s Expanding Global Access. https://media.defense.gov.

Waltz & Kenneth. (1979). Theory of International Politics. https://archive.org/details/ theoryofinternat00walt/page/n5/mode/2up. New York: McGraw-Hill. Xinhua. (2017). China welcomes Madagascar to join Belt and Road construction. http://www.xinhuanet.com.

Dr. Nell Bennett

Sea Power Centre, Royal Australian Navy

Introduction

The Indo-Pacific region currently confronts a greater range of traditional and nontraditional security challenges than any time over the past century. From territorial disputes to climate change, illegal fishing and marine pollution the challenges are diverse and numerous. Furthermore, all these challenges are in the shadow big power competition in the region. Middle powers have traditionally followed the lead of big powers, especially when confronted with serious challenges. However, the issues that the Indo-Pacific region is facing may be more amenable to a different kind of leadership. This chapter argues that the middle powers of the Indo-Pacific are in a unique position to leverage cooperation and collaboration a build a new model of lateral leadership.

Traditional thinking in International Relations assumes that bipolar systems present middle powers with three strategic options: bandwagoning with stronger powers, balancing against perceived threats, or strategic hedging. More recently a fourth has been added. There has been increasing interest in ‘minilateralism’ – or coalitions of states that come together together to advance specific objectives. Yet there is another alternative available for the Indo-Pacific: middle power leadership. Lateral leadership is a concept that is well established in business studies but one that has received little attention in strategic analysis. Middle

powers, much like middle managers, can promote innovative problem-solving and meaningful change in the absence of top-level leadership. Middle power leadership is different from minileralism in two key ways. First, minilateralism is confined to a single, or small, problem set, while middle power leadership provides a mechanism through responding to a broad set of challenges that are long burning or crises that suddenly emerge. Second, as the name implies, middle power leadership empowers actors to lead with others (including great powers) following rather than working through concensus.

This chapter explores the ways that middle powers, such as Malaysia, can ‘lead from the middle’ and promote norms and governance models that will preserve regional stability. The chapter will first discuss the unique challenges facing middle powers in the Indo-Pacific region. It will then discuss the concept of lateral leadership and the ways that this can be applied to the Indo-Pacific. Lateral leadership is distinguished from minilateralism, which is characterised by its single-issue focus and vulnerability to regime change within participating states. Lateral leadership, by comparison, is a sustainable, long-term model for regional governance. This chapter also discusses the importance of regional dispute resolution mechanisms, such as international law of the sea, mediation and arbitration – not to resolve disputes per se, but as a means of promoting a pre-determined system for managing inter-state relations which provides a sense of regional community that transcends specific disagreements. The chapter will close with a discussion of ways that middle powers can adopt a lateral leadership model and the positive impact this can have on Indo-Pacific stability.

Interest in the role of middle powers has come in waves since the end of the Cold War. In the late 20th century, scholars and foreign policy practitioners predicted the coming of a ‘Pacific Century’ that would be led by middle powers (Foot & Walter, 1999). The belief was that a new regionalism would emerge, based on economic interests, proximity and cultural values. These hopes were dashed by the Asian Economic Crisis, the Global War Against Terrorism, and finally the remergence of great power politics. Middle power cooperation has gradually fallen out of policy and academic fashion.

As the Pacific Century passed out of mind, the new term ‘Indo-Pacific’ gained popularity. The Indo-Pacific provided new conceptual understanding of the ‘region’ – an alternative to the China-centric ‘Asia-Pacific’. As Rory Medcalf maintains, the redefinition reflects ‘the region’s enduring maritime and multipolar character. It is authentically regional rather than narrowly American. The Indo-Pacific serves not to exclude or contain China but to dilute its influence…’ (Medcalf, 2019, p. 83). The implication being that the inclusion of more middle powers inside the region could temper China’s ascendancy and provide viable alternatives for powers that may otherwise choose to align with China.

Despite the attention paid to middle powers, all too often the term ‘middle power’ is undefined (Gill, Lockyer, Lim & Tan, 2024). This can lead to confusion as to which states fall within this category. Middle powers are typically understood to be ‘non-great powers that can influence international affairs in specific instances, shaping their regional environment in significant ways, and resisting the demands of great powers’ (Brattberg, 2021). While there are competing definitions of middle powers, this chapter relies on three key characteristics of middle power: capabilities, status and impact. Middle powers have medium range capabilities, they are respected in the international hierarchy, and they have significant impact at the regional level (Struye de Swielande, 2019, p. 193.).

According to this understanding, Malaysia, Australia, South Korea and Indonesia would be considered middle powers.

Another characteristic that is often used to identify ‘middlepowerhood’ is a preference for cooperation (Harijanto, 2024). This is because middle powers typically support multilateralism and use diplomacy to promote liberal norms (Spies, 2016). These characteristics can be harnessed to address the challenges facing the Indo-Pacific. Former Australian foreign minister, the Hon Gareth Evans (2019) put it in the following terms,