The Case for California’s State Public Bank

By Neha Singh

About the Report

This report has been prepared for Rise Economy, a California-based housing, economic and racial justice nonprofit organization that works to remove the historical barriers Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) communities have faced in building generational wealth. It aims to complement and build upon the efforts made by advocates of public banking in advancing the public banking movement.

The author conducted this study as part of the program of professional education at the Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California at Berkeley. This paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the course requirements for the Master of Public Policy degree. The judgements and conclusions are solely those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Goldman School of Public Policy, by the University of California, or by any other agency.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank, first and foremost, Paulina Gonzalez-Brito for bringing me on and giving me the opportunity to learn from them and dive into this important project with support and confidence. I extend heartfelt appreciation to my advisor, Dan Lindheim, whose consistent presence and expertise have been instrumental in shaping my understanding. And finally, I extend deep gratitude to the generous public banking experts and stakeholders who offered me wisdom, experience, and advice throughout this project.

Executive Summary

This report explores the pressing need and strategic framework for transitioning the existing California Infrastructure and Development Bank (IBank) into a state public bank, aligning with the aspirations of public banking advocates. Although AB 310 did not pass in the 2020 session, with the aim to establish a depository bank within the IBank, the need for public banking remains high in California. This demand is especially pronounced amid challenges such as affordable housing shortages, infrastructure deficiencies, and exacerbated climate crises following the pandemic. This research builds upon the intention of creating a state public bank primarily focused on increasing low-cost capital to benefit California communities.

This report presents a series of findings and recommendations on comprehensive research methods, including bill analysis, case studies, comparative analysis, and interviews with over 30 stakeholders. My findings indicate that IBank is currently underutilized and faces risks that prevent it from building capacity and expanding its authority into a depository bank. Operating as a revolving loan fund, it lacks the risk management practices needed for fractional reserve lending, hindering its ability to stimulate the economic growth the state needs. Governance issues, including insufficient board engagement and irregular meeting schedules, raise concerns about transparency and oversight. Moreover, the IBank’s limited mandate for financing housing fails to address the significant market failure concerning affordable housing in California. Allocation of resources, such as establishing a venture capital (VC) arm instead of leveraging existing community organizations, further complicates its ability to meet dire community needs. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensure the IBank’s alignment with its intended objectives and the needs of California communities. The following recommendations are intended for Rise Economy and the California Public Banking Alliance (CPBA) organizers, who possess the capability to advance this initiative in the upcoming legislative cycle.

Recommendations

f Transition IBank to a State Public Bank: Empower IBank by transitioning it into a state public bank that accepts deposits. This would enable fractional reserve lending and better alignwith California’s economic development goals.

f Develop Proof of Concept: Organizers should create a proof of concept demonstrating how a state public bank can offer below-market-rate loans to address market failures, particularly for affordable housing projects.

f Adopt Partner Bank Framework: Follow the Bank of North Dakota’s model and collaborate with specialized entities like Financial Development Corporations (FDCs) to expand effectiveness and support grassroots initiatives statewide.

f Reevaluate Board Composition: Ensure the IBank’s board includes representatives committed to community service and transparency, actively participating in oversight to uphold public trust.

f Prioritize Transparency: Enhance internal controls and explore external audit oversight to build public trust and confidence, aligning with best governance practices.

The recommendations are supplemented with a detailed roadmap for advocacy and implementation, beginning with legislative action to charter a state public bank. However, the risk-averse attitude of public officials toward transformative system change often hinders progress. As we see time and again, the inclination to uphold the status quo exacerbates social and economic inequalities. For this reason, the roadmap stresses strategies to mitigate perceived risks, build political capital, and leverage existing infrastructure and networks within the State Treasury to drive capital access toward projects aimed at improving community conditions.

Establishing a state public bank represents a crucial step toward addressing systemic issues and driving inclusive economic growth in California. By expanding the authority, and building the capacity of the IBank and fostering collaborative efforts, the transition of IBank into a state public bank holds immense potential to serve the needs of Californians and advance equitable development initiatives.

Introduction

This report begins with an introduction outlining the project objectives and underscores the convergence with the ongoing initiatives of public banking advocates. It then moves on an in-depth analysis of the legacy of banking practices and challenges within the current banking landscape. It proceeds with disparities within The California Infrastructure and Development Bank (IBank)’s operations, and a comparative analysis to the Bank of North Dakota, with recommendations based on findings. The recommendations lay the groundwork for the ensuing roadmap, which details actionable items aimed at facilitating expedient and effective consideration by the legislature and State Treasury.

Background and Guiding Research Questions

The public banking movement gained traction following direct action to block the Dakota Access Pipeline through the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. In 2017, Divest LA’s successful demand for the Los Angeles City Council to sever ties with Wells Fargo spurred further advocacy for local public banks across California1. As of 2024, the need for a public bank remains urgent, especially with the challenges posed to small banks after the collapse of institutions like Signature Bank, First Republic Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank. This disparity, where big banks receive bailouts while smaller ones do not, provides significant advantages to large banks in attracting deposits and expanding their business. Today, smaller banks face the dual challenge of paying elevated rates to depositors while experiencing subdued borrower demand. These challenges are particularly severe for Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), which provide financing for projects in low- and moderateincome communities nationwide, but struggle with limited lending capital. A state public bank aims to address these issues by providing funds to CDFIs and local public banks to serve their communities, by fostering economic development, and centralizing risk, administrative capacity, technology, and insurance.

The state of California confronts pressing issues that demand innovative solutions:

f Severe Housing Crisis: California is experiencing a severe housing crisis, which requires immediate action to provide affordable housing without displacement.

f Climate Change Mitigation: Increased local funding is needed to tackle greenhouse gas emissions and enhance access to green energy solutions, aligning with California’s ambitious climate goals.

f Support for Small Businesses: Small businesses, especially those owned by marginalized groups, struggle to access sufficient funding, exacerbating existing disparities and hindering economic growth.

f Promotion of Alternative Ownership Models: Alternative ownership models like worker cooperatives face obstacles in accessing traditional bank funding, impeding their potential for contributing to economic resilience and equity.

This report focuses on IBank as a promising opportunity to address the gaps that neither the private market nor the government has effectively filled. Established in 1994, the IBank aims to finance public infrastructure and private development to promote job creation, economic growth, and improve the quality of life in California communities. The power of credit generation is bestowed upon banks by government-issued legal charters, underscoring the pivotal role of banking’s legal and regulatory frameworks. Historically, risk has been wielded as a deterrent in conversations about advancing a public bank that embeds social values beyond profit. Addressing the issue of risk is crucial, and the following research questions will guide this report:

1 PBS SoCal. “L.A. City Council Moves Toward Divesting from Wells Fargo.” PBS SoCal, 17 Mar. 2024, https://www.pbssocal.org/news-analysis/l-a-city-council-moves-toward-divesting-from-wells-fargo

f How can Rise Economy and organizers strategically establish a public bank within the IBank’s existing infrastructure, addressing concerns about risk to access additional capital?

f How can the IBank expand its authority and build long-term capacity to lead economic recovery efforts for affordable housing, green energy solutions, small business lending, and alternative ownership models in California?

Project Methodology

In conducting this policy analysis, a comprehensive approach is employed to examine the context of California’s public banking initiative:

f AB 310 Bill Analysis: Conducted a thorough review of legislative texts, committee reports and feasibility reports, proposed amendments, and rationale.

f Case Study and Comparative Analysis: IBank’s operations were compared with those of the Bank of North Dakota (BND) to identify similarities, differences, and potential opportunities.

f Qualitative Research: Utilized semi-structured interviews with over 30 stakeholders to gather insights into their perspectives, experiences, and perceptions regarding public banking in California. A detailed list of key informants is outlined in Appendix A.

f Stakeholder Analysis: Identified and examined the interests, positions, and political capital of key stakeholders involved in or impacted by the public banking initiative.

f Policy Mapping Exercise: Outlined the evolution and implementation mechanisms of a conversion of IBank into California’s public bank. This offers an in-depth understanding of the policy landscape and its complexities.

Scope and Purpose

The recommendations presented in this report are intended for Rise Economy and the California Public Banking Alliance (CPBA) organizers, who possess the capability to advance this initiative in the upcoming legislative cycle. These efforts build upon the groundwork laid by activists who advocated for Assembly Bill 3102 (AB 310), aimed at establishing a state public bank in California. AB 310 proposed significant amendments to the Bergeson-Peace Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank Act3, authored by Assemblymember Miguel Santiago.

AB 310 sought to establish a depository bank within the IBank, requiring the gradual allocation of state funds into the IBank and targeting a 10% investment of the Pooled Money Investment Account’s average daily balance into the IBank. Additionally, the bill aimed to relocate the IBank out of the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO-Biz). COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the 2020 Legislative Session’s timeline hindered AB 310’s review. This bill did not receive a hearing and was never voted on. Moreover, the analysis by the Senate Committee on Governance and Finance4 contemplated the feasibility of the IBank’s conversion by drawing comparisons to the San Francisco Office of the Treasurer and Tax Collector’s Municipal Bank Feasibility Task Force Report. The inadequacies of the assumptions in the San Francisco Municipal Bank Feasibility Task Force Report, which are not attributable to the IBank’s current operations, are detailed in this report.

This report aims to propose recommendations and a roadmap to enhance the capacity

2 AB 310 2019, California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank

3 California Legislature. “Assembly Bill No. 310.”, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_ id=201920200AB310

4 Legislative Counsel of California. “Assembly Bill No. 310.” California Legislative Information. https://leginfo. legislature.ca.gov/faces/billAnalysisClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB310

and broaden the authority of the IBank into a state public bank. While the primary focus is on public banking, it’s essential to recognize that California residents face systemic challenges beyond the scope of public banking solutions. Therefore, this research strives to provide comprehensive context to better understand the broader implications of the recommendations put forth.

Context

In this section, the historical context of banking practices and their disproportionate impact on marginalized communities within California’s financial landscape are outlined. Decades of discriminatory practices, such as redlining, have perpetuated economic marginalization, particularly among communities of color. The emergence of banking deserts, exacerbated by bank mergers and acquisitions, has further limited access to financial services, creating fertile ground for predatory practices to thrive. Despite these challenges, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) play a vital role in financing projects aimed at improving conditions in low- and moderate-income communities. However, CDFIs and other mission-driven local banks face significant obstacles, including limited lending capital and operational funding, exacerbated by the rise of digital banking, which often favors larger institutions.

The Racialized Legacy of Banking Practices

Historical and contemporary banking practices have entrenched racial disparities in access to funding and financial services, amplifying the challenges faced by communities in California. These exclusionary patterns are well-documented, revealing systemic biases within banking operations, particularly evident in the distribution of bank branches and lending practices.

Redlining has left a lasting imprint on California’s financial landscape. This practice systematically restricted access to credit and financial resources for Black and Latinx individuals and households, perpetuating cycles of economic marginalization and exacerbating disparities in wealth and opportunity, particularly in housing5

Banks have consistently favored white communities when establishing and operating branches, leaving communities of color disproportionately underserved. This unequal distribution exacerbates financial inequality, as evidenced by the scarcity of bank branches in communities of color compared to predominantly white areas, both nationally and within metropolitan regions6. Notably, during the Great Recession, banks exhibited higher closure rates in markets serving communities of color, leading to significant branch losses in Black and Latinx neighborhoods7. Consequently, banking deserts have emerged, fostering an environment where predatory financial services like payday lenders and check cashers thrive, perpetuating a cycle of financial hardship and exclusion8

The policy decisions made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic serve as an example of how systemic issues persist within the banking sector. The economic repercussions of the

5 California Attorney General. “Chapter 5: California Reparations Task Force.” Accessed [insert date accessed], https://oag.ca.gov/system/files/media/ch5-ca-reparations.pdf

6 Grigsby, William, Jacob William Faber, and Mark Joseph Stern. “Do Metropolitan Areas Have Equal Access to Banking?” Social Forces 97, no. 2 (2018): 605–632. https://d1y8sb8igg2f8e.cloudfront.net/documents/Do_ Metropolitan_Areas_have_Equal_Access_to_Banking.pdf

7 Song, Yena, and Satoshi Urasawa. “Income Distribution and Macroeconomics Revisited: The Role of Fertility Adjustment.” Economic Notes 47, no. 1 (2018): 63-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecno.12068.

8 Friedman, Lawrence M. “Law and Society Reconsidered.” Annual Review of Sociology 10 (1984): 105-130. https:// www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610441131

COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated racial disparities in the housing crisis9. Business owners of color experienced disproportionate losses in earnings due to COVID-19, with the most significant losses borne by Black business owners10. Additionally, extensive scholarship demonstrates that those who suffer from socioeconomic inequality and housing insecurity are disproportionately affected by climate change11. Despite regulatory efforts, contemporary examples of racial targeting, differential treatment, and disparate impact continue to exist, reflecting the industry’s historical legacy of discrimination. Moreover, these policies underscore the profound consequences of state and local governments relinquishing financial policies to a technocracy of public finance officers and banks. The risk-averse stance of public finance officials toward maintaining the status quo exacerbates ongoing systemic risks and social inequalities, further underscoring the urgency for change.

Consolidation Continuum

In 1994, small banks12 were 84% of all banks in the United States. However, as a result of the rise of interstate banking, deregulation, and the Great Consolidation of bank mergers and acquisitions that followed the 2008 Great Recession, the banking landscape looks very different today. As of 2021, there are far fewer banks, with an almost even split between smaller banks (52%) and larger banks (48%)13. Mergers have been overwhelmingly approved by bank regulators, yet their true assessment of the advantages and drawbacks remains unclear.

The growth within large banks comes from the top 25 institutions, whose combined branch network skyrocketed from 8,740 branches in 1994 to 37,884 branches by 2010 before plateauing. The top 25 banks had been increasing their market share prior to the Great Recession and the subsequent merger and acquisition boom. In the post-crash Great Consolidation, these larger institutions acquired and closed many of the branches that were previously owned by smaller banks. This business practice cut off physical access to face-toface financial services in low-to-moderate income and majority-minority neighborhoods in both urban and rural areas, eventually leading to the banking deserts of today. This hurt rural areas in particular, as NCRC found more than 80 rural banking deserts were created from 2008 through 2016.

The banking sector is also facing significant challenges after Signature Bank, First Republic Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank failed in 2023. Interest rate hikes had a notable impact on the interest rate and liquidity risk of financial institutions. Poor management practices and inadequate regulatory oversight resulted in the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank14 and Signature Bank15. Subsequently, First Republic Bank faltered, driven by a lack of confidence from both

9 CHPC. “Racial Disparities in Housing Security from COVID-19 Economic Fallout.” Center for Housing Policy and Community Development. Accessed May 3, 2024. https://chpc.net/racial-disparities-in-housing-security-fromcovid-19-economic-fallout/

10 U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy. Report on COVID and Racial Disparities. U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy. August 2022. https://advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ Report_COVID-and-Racial-Disparities_508c.pdf

11 Princeton Science Institute. “Racial Disparities and Climate Change.” Princeton Science Institute Tips. August 15, 2020. https://psci.princeton.edu/tips/2020/8/15/racial-disparities-and-climate-change

12 As of January 1, 2021, FDIC and the Federal Reserve categorized a bank as “large” if it had assets of at least $1.322 billion on December 31 of the previous two calendar years. Any bank with less than $330 million in assets for the same period was labeled “small.

13 National Community Reinvestment Coalition. “The Great Consolidation of Banks and Acceleration of Branch Closures Across America.” Accessed May 3, 2024. https://ncrc.org/the-great-consolidation-of-banks-andacceleration-of-branch-closures-across-america/

14 Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. (2023). Supervision & Regulation Report. Retrieved from https://www. federalreserve.gov/publications/files/svb-review-20230428.pdf

15 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2024). FDIC Supervisory Insights - Winter 2024. Retrieved from https:// www.fdic.gov/sites/default/files/2024-03/pr23033a.pdf

the market and depositors. Five banks, totaling $548.7 billion, failed in 202316. Although fewer banks failed, the size of these failures marks a historic high, surpassing the magnitude of losses experienced during the 2008-2009 Great Recession.

https://www.fdic.gov/resources/resolutions/bank-failures/in-brief/index.html

In 2023, the collapse of the three regional lenders prompted an exodus of deposits from smaller institutions to larger banks. Following the closings, smaller banks have had to pay higher interest rates on deposits to prevent customers from leaving. Gerald Epstein, an Economics Professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, argues in his latest book that government bailouts of big banks17 over smaller ones grant big banks a notable edge in deposit attraction and business expansion18. This scenario is evident today, with smaller banks facing the dual challenge of paying elevated rates to depositors compared to larger counterparts while experiencing subdued borrower demand19. Among these factors, a recent working paper demonstrates that the rise of digital banking is also tilting deposit-pricing behavior in favor of larger banks20. This research highlights how customer preferences and technological advancements are shaping the way banks set their deposit rates. Contrary to conventional wisdom, which attributes deposit pricing solely to market dominance, this study extends the discussion on why large bank customers are less rate-sensitive. The figures from the study below present the time series of median deposit rates for 19 large banks compared to other banks using RateWatch data from 2001 to 2019. The branch-level deposit rates are collapsed at the bank level, weighted by branch deposit balance. The charts display deposit rates for a $25,000 money market account, $10,000 12-month CDs, and savings accounts below $2,500. The blue lines denote small banks and the orange lines denote large banks.

16 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. “Bank Failures in Brief.” Accessed May 3, 2024. https://www.fdic.gov/ resources/resolutions/bank-failures/in-brief/index.html

17 Smith, John. “First Republic Bailouts and the Future of Democracy.” The Washington Post, May 3, 2023. https:// www.washingtonpost.com/made-by-history/2023/05/03/first-republic-bailouts-democracy/

18 Epstein, Gerald. “Busting the Bankers’ Club and Restoring Democracy.” In Busting the Bankers’ Club: Finance for the Rest of Us, 1st ed., 273–280. University of California Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.8441703.18

19 Reuters. “US regional bank profits to be squeezed by pressure to pay deposits.” Reuters, January 8, 2024.

20 “Why Big Banks Can Pay Less on Deposits.” UCLA Anderson Review. Accessed [insert access date]. URL: https:// anderson-review.ucla.edu/why-big-banks-can-pay-less-on-deposits/

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/should-community-reinvestment-act-consider-race

The challenges faced by smaller banks, particularly in paying elevated rates to depositors while experiencing subdued borrower demand, are particularly severe for Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). CDFIs provide imperative financing for projects in low- and moderate-income communities nationwide, which struggle with limited lending capital. A state public bank aims to address these issues by providing funds to CDFIs and local public banks, thereby fostering community development and centralizing risk, administrative capacity, technology, and insurance.

The Role of Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs)

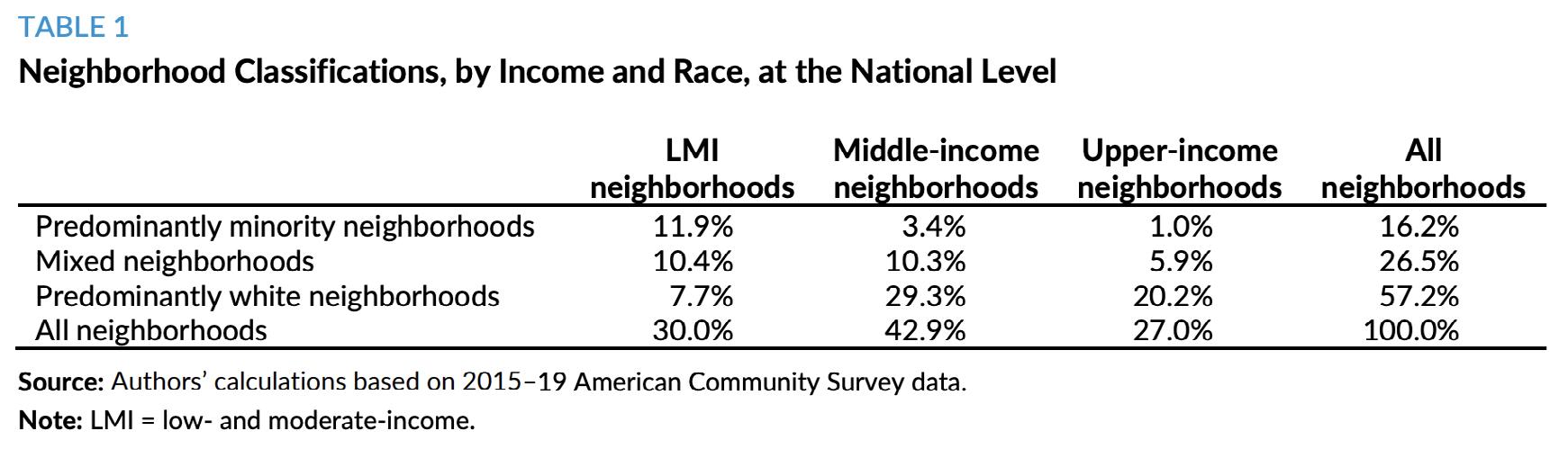

The inception of CDFIs in 1994 marked a pivotal attempt to address economic disparities and foster financial inclusion in the United States. Dating back to the 1880s, when the first minorityowned banks emerged to serve low-income areas, community organizations have long been at the forefront of providing essential financial services21. This evolution saw the inception of credit unions in the 1930s and 1940s, followed by the rise of community development corporations in the 1960s and 1970s and the emergence of nonprofit loan funds in the 1980s. Each of these predecessors to CDFIs aimed to uplift economically underserved markets and improve conditions within these communities. The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was enacted in 1977 to combat redlining, the discriminatory practice of denying mortgages based on race or ethnicity. While the CRA may have emerged from the Civil Rights era to address racial disparities, race is not explicitly mentioned in its original statute, with low and moderate- incomes often used as proxies for race, both for individuals and neighborhoods. Recent analyses by the Urban Institute reveal disparities in lending practices, with minority neighborhoods and borrowers receiving less than their proportionate share of lending from CRA-covered institutions.22 While some improvements have been made, the CRA falls short in adequately addressing racial disparities in homeownership, wealth, and income. For more detailed insights, please refer to Appendix B.

The CDFI Fund was established through the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994. This fund is responsible for certifying various financial entities, including banks, credit unions, nonprofit loan funds, microloan funds, and for-profit and nonprofit venture capital funds, provided they can demonstrate a primary mission of promoting community development. The CDFI Fund mandates that 60% of a CDFIs financial products, such as loans, must be directed towardapproved target markets or eligible

21 Community Development Financial Institutions Fund. Accessed [insert access date]. URL: https://www.cdfifund. gov/

22 Bostic, Raphael W., and Coletta Frenette, “Should the Community Reinvestment Act Consider Race?” Urban Institute, accessed May 3, 2024, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/should-community-reinvestmentact-consider-race

populations. These target markets are defined as specific investment areas or populations in need, ensuring that CDFIs channel a significant portion of their resources toward underserved communities.23 As of December 31, 2023, there are 196 FDIC-insured CDFI bank headquarters across the United States. These banks have almost 1,400 branches, and a combined asset total of over $120 billion. Geographically distributed, these entities serve as pillars for underserved populations, with concentrations notably in regions like California and the Mississippi Delta24

The Challenge Faced by CDFIs

A research report by the Congressional Report Service illuminates that given the target market requirements, certified CDFIs are likely to be principally engaged in risk-based or subprime lending25. CDFIs lend to a distinct customer base that traditional financial institutions often overlook due to the higher costs associated with serving them. These underserved communities encompass individuals and businesses deemed high-risk due to factors such as weak credit histories or above-normal income volatility. Regrettably, regulators and government bodies often fail to acknowledge that this high-risk status often stems from the enduring racial legacy of the banking sector itself.

CDFIs localized and customized loan portfolios also make it challenging to access conventional markets for funding. Instead, CDFIs rely on a combination of public and private subsidies, including grants and donations, to offset the increased costs of serving high-risk customers and pursuing their financial inclusion mission. Private funding fills gaps left by potential cuts in public funding and helps CDFIs serve high-risk customers or endorse their mission-related activities. However, the Federal Reserve’s ongoing survey of CDFIs26 , conducted in collaboration with the CDFI Fund and various industry stakeholders, sheds light on recent challenges. Rising interest rates have pushed the cost of lending capital to the forefront as a challenge for many CDFIs. The survey results highlight a growing demand for CDFIs’ products and services, with almost three-quarters of respondents reporting increased demand from the previous year. However, limited staffing and, notably, lending capital emerge as significant obstacles hindering their capacity to meet this demand adequately. To navigate these obstacles, some CDFIs explore alternative strategies, such as selling loans on secondary markets to free up their balance sheets for additional lending. Operational funding and technology constraints further compound the challenges. Restricted operational funding limits their flexibility in resource allocation, hindering their ability to address staffing shortages and invest in technological upgrades necessary for streamlined operations. The research on deposit rates highlights how customer preferences and technological advancements are reshaping banking practices, shedding light on the complexities that CDFIs are currently navigating in staying competitive.

Robert Villareal, former president of Bankers Small Business CDC of California, provided insights into the challenges confronting CDFIs today He emphasized the impact of the Federal Reserve’s post-pandemic rate hikes, resulting in a highrate environment Previously, CDFIs could lend capital at rates between 1% to 3%, but the shift to lending at rates between 5% to 7% now burdens low-to-moderate income communities with higher capital costs This limitation reduces the capital that’s available to underserved communities

23 See CDFI Fund, The CDFI Fund: Empowering Underserved Communities, https://www.cdfifund.gov/sites/cdfi/ files/ documents/cdfi_brochure-updated-dec2017.pdf.

24 Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “Sizing the CDFI Market: Understanding Industry Growth.”. https://www. newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/newsevents/news/regional_outreach/2023/sizing-the-cdfi-marketunderstanding-industry-growth

25 Congressional Research Service. “Title of the Report.” Report R47217. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/ pdf/R/R47217

26 Federal Reserve Community Development. “2023 CDFI Survey Key Findings.” URL: https://fedcommunities.org/ data/2023-cdfi-survey-key-findings/

Data Limitations

Assessing the performance of CDFIs in facilitating access to capital to their customers poses challenges. The metrics used to gauge their financial strength and performance are less straightforward due to their involvement in more default mitigation activities than traditional institutions. Additionally, data collection gaps hinder the direct correlation between CDFIs’ activities and their customers. The scarcity of reliable research on CDFI outcomes has spurred CitiBank, in collaboration with the Federal Reserve System, to establish a CDFI Research Consortium. This initiative aims to provide support and publishing opportunities for rigorous research on CDFI impact, performance, and strategies. Guided by an advisory board comprising key stakeholders, including the Federal Reserve Bank system, the Consortium seeks to fill the research gap in this field27

Minority Depository Institutions (MDIs) Significance

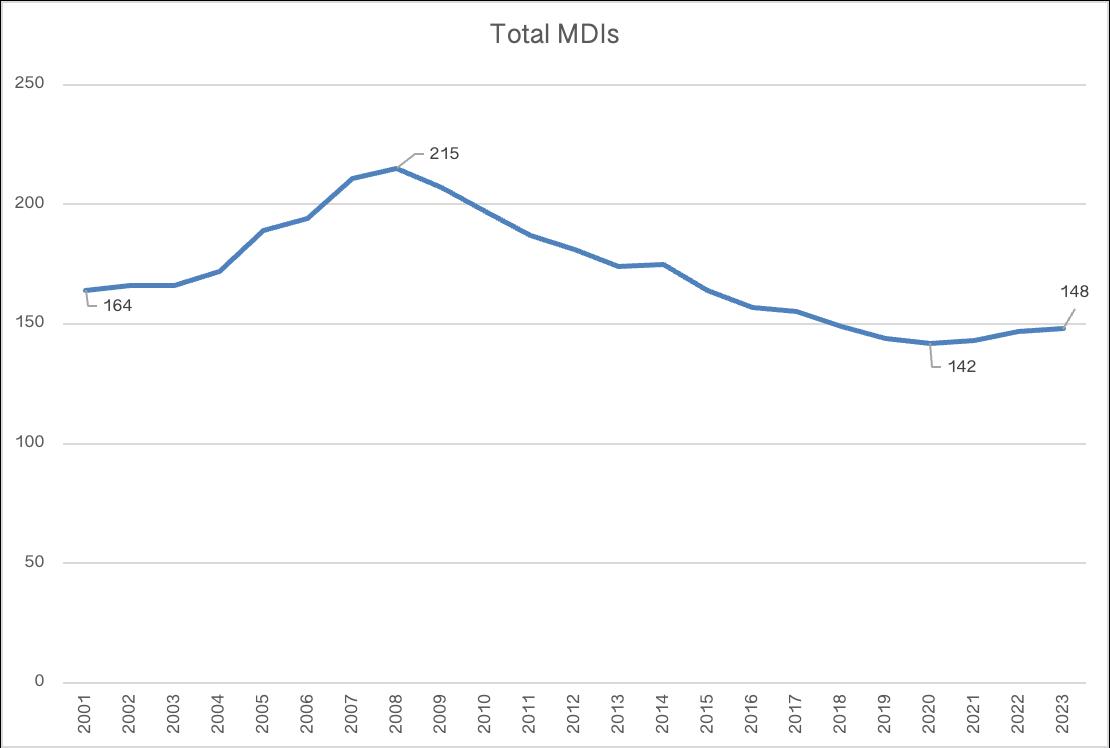

Given the limited research available on CDFIs’ role in facilitating capital access for higherrisk clients, we turn to insights from studies on Minority Depository Institutions (MDIs).

Approximately half of CDFI banks fall under the category of MDIs. MDIs encompass FDICsupervised banks meeting either of the following criteria: (1) federally insured depository institutions with 51% or more of the voting stock owned by minority28 individuals, or (2) federally insured depository institutions where the majority of the board of directors is minority and the served community is predominantly minority.29

Due to their willingness to take on risk to lend to their community, Black-owned banks play a large role in addressing wealth disparities by focusing on low- and moderate-income census tracts. Despite facing fluctuations due to economic cycles, Black-owned banks have consistently increased their lending within these areas, reaching historic highs since 2014. This emphasis on serving marginalized communities underscores the indispensable role Black-owned banks play in supporting Black homeownership and economic empowerment. The FDIC’s data from 2001 to 2023 shows a decline in the total number of MDIs in the United States. Conversely, Black-owned banks categorized as minority status have experienced the most significant decrease, shrinking from 28% in 2001 to 16% in 202330. For more detailed insights, please refer to Appendix C.

Created from the FDIC’s historical MDI data

27 Citigroup Foundation. “Measuring CDFI Impact: A Conversation on the Need for Independent Research.” Accessed URL: https://www.citigroup.com/global/foundation/news/perspective/2024/measuring-cdfi-impacta-conversation-on-the-need-for-independent-research

28 Minority” as defined by Section 308 of FIRREA means any “Black American, Asian American, Hispanic American, or Native American.”

29 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. “Minority Depository Institution (MDI) Definition.”

URL: https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/resources/minority/mdi.html

30 FDIC. “Minority Depository Institutions Program. “https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/resources/minority/mdi.html.

The challenges confronted by CDFIs underscore the urgent need for innovative solutions. Trends in consolidation highlight the diminishing presence of small banks, primarily attributed to market concentration and the technological dominance of larger institutions. This trend is particularly pronounced in the current high-rate environment. Moreover, restricted operational funding limits their flexibility in resource allocation, hindering their ability to address staffing shortages and invest in technological upgrades necessary for streamlined operations. This is particularly problematic given that CDFIs and MDIs cater to distinct customer bases often overlooked by traditional financial institutions, including businesses deemed high-risk due to factors such as weak credit histories or above-normal income volatility. In light of these challenges, establishing a public bank representative of the communities most harmed by these issues holds promise for driving capital access toward funding projects to improve community well-being. Leveraging the infrastructure and experience of an institution like the IBank, with its ability to offer below-market-rate loans, can provide a solid foundation with thepotential to centralize risk, administrative capacity, technology, and insurance for a network of struggling CDFIs.

Building Capacity and Expanding Authority of the IBank

In this section, evidence and reasoning are provided to support the establishment of a state public bank. Potential challenges, risks, and objections evident in the operation of the IBank that should be considered by state, county, and local governments, to whom the IBank is ultimately responsible, are addressed. A rationale for identifying areas of mismanagement within the IBank is provided, along with recommendations for envisioning the transition into a state public bank.

As mentioned in preceding sections, market forces, public and private efforts to support CDFIs and MDIs are falling short in addressing California’s urgent challenges:

The state is in the midst of a severe housing crisis, which requires immediate action to provide affordable housing without displacement.

Increased local funding is needed to tackle greenhouse gas emissions and enhance access to green energy solutions.

Small businesses, especially those owned by marginalized groups, struggle to access sufficient funding, exacerbating existing disparities.

Alternative ownership models like worker cooperatives face obstacles in accessing traditional bank funding.

Mission of the State Public Bank

The mission of the state public bank is to lead economic recovery efforts for communities grappling with severe economic strains that continue to be exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recession. This will be achieved by bolstering lending to local banks and expanding credit access to historically marginalized groups, including rural, minority-owned, women-owned, indigenous-owned, and immigrant-owned businesses. Through strategic credit enhancements and active engagement in participation lending with CDFIs and MDIs, the State Public Bank can aim to address the legacy of restrictive practices such as redlining and restrictive covenants perpetuated by traditional financial institutions.

Research Questions

How can Rise Economy and its organizers strategically establish a public bank within the existing infrastructure of the IBank, effectively mitigating risks and positioning themselves to access capital?

In what ways can the IBank expand its authority and bolster long-term capacity to spearhead economic recovery efforts focusing on affordable housing, green energy solutions, small business lending, and alternative ownership models in California?

Criteria

The criteria for evaluating the IBank and proposed recommendations are grounded in the core values established by the Public Bank East Bay, the first public banking effort in the nation to bring on a chief executive officer as of September 2023. Made possible by the success of the California Public Banking Alliance31 (CPBA) passing the California Public Banking Act32 (AB 857), CPBA has been pivotal in driving public banking legislation at regional and city government levels. These state bills, signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom in 2019 and 2021, received support from over 250 civic organizations, local governments, labor unions, affordable housing, and racial and environmental justice groups.

The following core values prioritize the inclusion of disenfranchised communities, such as low-income communities of color and other marginalized groups, as well as emphasize safety, soundness, and financial risk considerations.

Equity

f How does the bank acknowledge and attempt to relieve the contemporary and historical burdens carried by disenfranchised communities, including low-income communities of color and other marginalized groups?

f Are the bank’s lending practices and policies designed to address the specific needs of historically excluded actors, such as rural, minority-owned, women-owned, indigenous-owned, and immigrant-owned businesses?

f Social Responsibility:

f How do decisions regarding loan recipients, sponsored projects, and policy implementation prioritize investing money into the wealth and health of local communities and the environment?

f To what extent does the bank’s operations align with socially responsible practices that benefit local communities and promote environmental sustainability?

Fiscal

Responsibility

f As a steward of public money, how does the bank ensure compliance with directives and policies of state and federal regulators while actively managing risk and making fiscally responsible decisions?

f What measures are in place to maintain the bank in a safe and sound condition while fulfilling its commitment to fiscal responsibility?

Accountability

f How is the bank accountable to the residents of the community it serves, and how does it ensure transparency in its actions and decision-making processes?

f To what extent are stakeholders provided with transparent explanations of the bank’s actions and choices, fostering trust and accountability among the community?

Democracy

f How does the bank’s governance structure promote inclusive and participatory processes that adhere to the values and principles of equity, social responsibility, fiscal responsibility, and accountability?

31 California Public Banking Alliance. “AB857 FAQs.” URL: https://californiapublicbankingalliance.org/wp-content/ uploads/2019/06/AB857-FAQs.pdf

32 California State Legislature. “AB 857, California Public Banking Act.” URL: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/ billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB857

f To what extent are community members involved in decision-making processes, ensuring their voices are heard and their needs are addressed?

The California Infrastructure and Development Bank (IBank)

Purpose

The IBank, established in 1994, operates under the Bergeson-Peace Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank Act within the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (Go-Biz). It is mandated to finance public infrastructure and private development projects aimed at fostering job growth, strengthening the economy, and enhancing the quality of life in California communities. The IBank’s authority encompasses issuing tax-exempt and taxable revenue bonds, providing financing to public agencies, offering credit enhancements, acquiring or leasing facilities, and leveraging state and federal funds.33

Operating as a revolving loan fund rather than a depository institution, the IBank faces a fundamental contradiction: While it extends credit, it lacks the capacity to modulate the currency supply or establish payment structures34. These omissions are notable, as these functions are unique privileges granted to banks through government-issued bank charters. For the purposes of this report, the focus lies on the circulation of the currency supply.

Fractional Reserve Lending

Fractional reserve lending is a foundational practice in banking, where banks are mandated to reserve only a portion of their deposits, allowing them to lend out the remaining funds. The fraction of reserves that banks are required to hold is determined by regulatory authorities. When banks lend out the remaining funds beyond their required reserves, this process effectively creates money. For example, if a bank receives $100 in deposits and is required to keep 10% ($10) in reserve, it can lend out the remaining $90. The borrower then spends the $90, which eventually gets deposited into another bank, allowing that bank to lend out a portion of it, and so on. This process multiplies the initial deposit, creating more money in the economy.

While fractional reserve lending remains a key aspect of the banking system’s operations, Cornell Law Professors Robert Hockett and Saule Omarova challenge the conventional understanding of bank reserves. They argue that the proportion of reserves to total assets is a policy choice rather than an inherent constraint on banks’ lending capacity35. According to this perspective, banks are not restricted by reserves in their lending decisions. Instead, they extend credit based on the demand from credit-worthy borrowers and their assessment of lending risks. Reserves play a minimal role in influencing lending decisions since banks can always obtain reserves from the central bank if needed, typically through interbank borrowing or central bank lending facilities like the Federal Reserve discount window. In this sense, there is an endogenous nature of money creation by banks, where loans create deposits rather than the traditional view where deposits precede lending. Nevertheless, central banks may still use reserve requirements as a regulatory tool to influence bank lending behavior and manage the stability of the financial system.

The Federal Reserve’s decision on March 15, 2020, to reduce the reserve requirement ratios to zero percent in response to the pandemic’s economic fallout, serves as an example that banks not only multiply credit, but they generate it. This power of creditgeneration is bestowed upon banks by government-issued legal charters, underscoring the pivotal role of banking’s legal and regulatory frameworks. These charters essentially serve as licensees to manage public money, consolidating public-private partnership that grants the financial sector control over the creation and allocation of money.

33 “California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank.” iBank, n.d., https://ibank.ca.gov/#

34 Awrey, D. “Unbundling Banking, Money, and Payments.” (2021) URL: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers. cfm?abstract_id=3776739

35 Hockett, Robert C., and Omarova, Saule T. “The Finance Franchise.” (August 8, 2016). 102 Cornell L. Rev. 1143 (2017), Cornell Legal Studies Research Paper No. 16-29. Accessed URL: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2820176

This recognition of the inherent public nature of banking and money serves as a driving force behind the establishment and governance of public banks in numerous countries. Despite their seemingly unprecedented nature in the US, there are currently 910 public banks worldwide, collectively holding $42 trillion in assets.36 The significance of legal bank charters in shaping the monetary system highlights their legal-political design as a critical focus for public banking organizers. Moreover, this perspective shifts away from the narrative that views public money solely as pre-accumulated “taxpayer money,” a notion criticized for reinforcing racist and scarcity-based assumptions regarding public finance. Instead, it redefines money as a public utility regulated and allocated by the banking sector.

RECOMMENDATION

Transitioning the IBank into a state public bank that accepts deposits would address its current limitations, empowering it with the authority to engage in fractional reserve lending and effectively modulate the currency supply

The Housing Dilemma

In his book, Epstein explains that mainstream economists often raise the question of necessity, operating under the assumption that the market functions efficiently most of the time37 According to this view, the argument for government intervention or provision must be backed by clear evidence of market failure.

When advocating for government intervention, meeting these standards entails identifying the failure and demonstrating that it arises from a flaw inherent in the market, rather than from individual choices or systemic issues. It is an ironic attempt to address market failure within the United States financial system. As discussed earlier in this section, government actions such as redlining and subsidies to too-big-to-fail banks have significantly shaped the financial sector, disproportionately impeding access to capital for communities of color. Federal government support is fundamental to the very structure of the financial system, as it charters and licenses banks and selectively bails out troubled financial institutions. Therefore, identifying a deficiency or failure within this framework is challenging, given that federal government intervention is deeply entrenched in the functioning of the financial system itself.

Nevertheless, based on research, there is a compelling case to be made for a state public bank that can move the political process forward. The Bergeson-Peace Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank Act outlines the scope of “Economic development facilities,” specifying various infrastructure types but notably excludes housing38. Recent legislation39 (AB1297) expanded IBank’s authority to finance housing when housing is necessary for the operation of the financed project. However, this expansion comes with significant limitations to prevent fund diversion and competition with other housing finance agencies, such as the California Housing Finance Agency and the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

In this context, the absence of a mandate for the IBank to directly engage in housing underscores a significant market failure concerning affordable housing. The shortage of affordable housing units exemplifies where market forces falter in meeting societal needs. When the primary goal of housing development is profit generation, it inevitably leaves unmet demand in areas where profitability cannot be achieved. Research from the

36 Marois, T. (2021). Public Banks: Decarbonisation, Definancialisation, and Democratisation. Pre-release version shared by the author, page 48

37 Epstein, Gerald. “Busting the Bankers’ Club and Restoring Democracy.” Busting the Bankers’ Club: Finance for the Rest of Us, 1st ed., 273–280. University of California Press, 2024. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.8441703.18

38 California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank. “IBank Act.” URL: https://ibank.ca.gov/wp-content/ uploads/2020/06/IBank-Act-California-Government-Code.pdf

39 California State Legislature. “Assembly Floor Analysis of Assembly Bill 1297.” URL: https://trackbill.com/s3/bills/ CA/2021/AB/1297/analyses/assembly-floor-analysis.pdf

Urban Institute underscores this dilemma, revealing that building homes for low-income households lacks profitability for the majority of developers40. The need to charge marketrate rents to offset construction and operating costs poses a significant barrier. Despite decades of efforts, including tax credits, density bonuses, and inclusionary zoning laws, the shortage persists, leaving millions of units short41. In essence, the housing market’s inability to adequately address the needs of low-income households underscores the imperative for legislative intervention. The magnitude of California’s affordable housing crisis exceeds the capacity of financing agencies alone.

The establishment of a state public bank holds immense potential to address California’s affordable housing crisis, surpassing the capacity of existing financing agencies. With the ability to provide funding at a cost feasible for cities and not offered by other lenders, a public bank could significantly bolster housing production, particularly for those with the lowest incomes. This strategic investment would yield far-reaching benefits, including reduced public expenditures and enhanced community well-being. It could lead to savings in healthcare costs by decreasing emergency room visits among the unhoused, improve mental health outcomes for rent-burdened individuals, and foster better education and employment prospects for future generations by ensuring stable housing for children. Moreover, housing constructed with these funds would be designed to withstand natural disasters, thereby increasing safety and mitigating financial risks associated with housing supply loss due to calamities.

RECOMMENDATION

Organizers should develop a proof of concept illustrating how a state public bank can utilize its money supply and offer below-market-rate loans to address market failures

The Partner Bank Model

To underscore the significance of adopting a partner bank framework, we can look to an exemplary model set by the Bank of North Dakota (BND), the sole public bank in the United States. Established in response to the economic challenges faced by North Dakota’s agricultural sector in the early 1900s, the BND emerged as a beacon of resilience. During this time, North Dakotans grappled with recurring challenges such as droughts, severe winters, and unfair business practices by grain dealers and other banks. In response, the state Legislature, influenced by the Nonpartisan League, enacted legislation in 1919 to create the BND and the North Dakota Mill and Elevator Association. With an initial capital of $2 million, the BND instilled a clear mandate and regulatory oversight to ensure its alignment with the state’s economic objectives42

Today, the mission of the BND remains to “deliver quality, sound financial services that promote agriculture, commerce, and industry in North Dakota,” as its vision is to be “an agile partner that creates financial solutions for current and emerging economic needs.43” Over the years, the BND has consistently achieved its mission and vision. The BND has bolstered the state’s economy, particularly during times of crisis like the Great Depression and natural disasters. This includes facilitating small business and agricultural loans, providing mortgages and student loans, and offering infrastructure and disaster relief lending to state and local governments. Following the 2008 global financial crisis, North Dakota stood out with the lowest unemployment rate, lowest default rate, and highest payroll growth rate in the nation, outcomes attributed in part to the presence of the BND. Notably, from 1995 to 2014, the BND

40 Urban Institute. “Cost of Affordable Housing.” URL: https://apps.urban.org/features/cost-of-affordable-housing/

41 CalMatters. “Newsom’s promises to tackle California’s housing crisis fall short on key goals.” Accessed. URL: https:// calmatters.org/housing/2022/10/newsom-california-housing-crisis/

42 Bank of North Dakota. “History of BND.”: https://bnd.nd.gov/about-bnd/history-of-bnd/#:~:text=All%20state%20 funds%20must%20be,collection%20of%20taxes%20and%20fees

43 Bank of North Dakota. “Mission.” URL: https://bnd.nd.gov/about-bnd/mission/#:~:text=To%20deliver%20 quality%2C%20sound%20financial,and%20industry%20in%20North%20Dakota.&text=Bank%20of%20North%20 Dakota%20is,current%20and%20emerging%20economic%20needs.

contributed forty percent of approximately $1 billion of its profits to the state general fund, translating to $3,300 per household44

BND’s collaborative approach with partner banks is instrumental in nurturing North Dakota’s vibrant local banking landscape. Guided by its founding principles, the BND is committed to being helpful, not harmful, to existing financial institutions. Instead of directly serving individual customers45, the BND channels its efforts into supporting local banks and lenders. Not only does this strategy optimize economic growth but it also taps into existing knowledge and community ties.

By serving as a banker’s bank to local lenders, the BND enables these institutions to originate loans that may exceed their legal or internal lending limits46, thereby enhancing their competitiveness against larger out-of-state banks. This partnership ensures that residents of North Dakota have affordable access to financing, so it supports borrowers, but in turn, also strengthens the local banking sector. For a visual representation of a typical business loan transaction, refer to the graphic below:

https://bnd.nd.gov/about-bnd/history-of-bnd/

Due to this collaborative model, North Dakota played an important role in implementing the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) during the pandemic. In a report by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, data analysis from the SBA and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation reveals a sharp contrast in PPP loan distribution between states with many community banks versus those dominated by big banks. North Dakota exemplifies this trend, boasting nearly 10 community banks per 100,000 people, six times the national average. These local institutions, constituting about 80% of the state’s banking market, played a pivotal role in issuing over 11,000 PPP loans, equating to approximately 1,444 loans per 100,000 people. Arizona stands at the opposite end of the spectrum, characterized by the dominance of large banks. With the fewest community banks per capita, approximately 0.2 per 100,000 people, these institutions represent only a minor fraction of the state’s deposits. Consequently, Arizona saw significantly fewer PPP loans, approximately 265 per 100,000 people, highlighting the disparity compared to North Dakota’s extensive community bank network47

44 Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “Bank of North Dakota.” URL: https://ilsr.org/rule/bank-of-north-dakota-2/

45 Although individuals receive student loans directly from BND, they are not targeted for other loans or retail accounts.

46 Code of Federal Regulations. “Title 12 - Banks and Banking, Chapter I - Comptroller of the Currency, Part 32Lending Limits.” URL: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-12/chapter-I/part-32

47 Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “Banking Consolidation PPP Report.” Accessed [insert access date]. URL: https:// ilsr.org/banking-consolidation-ppp-report/

The IBank, with its growing network, is making strides in this direction through its collaboration with Financial Development Corporations (FDCs)48. These partnerships, as outlined in their 2022/2023 Annual Report, bring a wealth of lending expertise totaling 1,352 years, with 680 years directly supporting the Small Business Finance Center. FDCs leverage diverse funding sources, including federal, state, local, and private resources, to provide innovative community development financing in low- to moderate-income areas. Notably, many FDCs are not only experts in their field but also active lenders who administer various programs for governmental and financial partners49

Given the success of this model, it raises the question: why doesn’t the IBank extend its networks to more local lenders for infrastructure, climate-related, and affordable housing loans, leveraging the expertise of community members who are intimately familiar with local challenges? The evolution of publicly oriented, mission-driven financial institutions in the United States presents an opportunity to expand democratic control of capital. As explored earlier, MDIs and CDFIs play significant roles in this ecosystem. Despite their potential to revitalize underinvested neighborhoods by providing capital for new businesses, affordable housing, and climate initiatives, they often remain resource-constrained, unable to adequately address poverty and investment deficits in urban areas.

On June 27, 2023, the IBank released a press release unveiling the inaugural investment made under its newly launched Expanding Venture Capital (VC) Access program. The initiative aims to foster a more inclusive VC landscape in the state50. The IBank’s decision to invest $200 million in VC funds and businesses in California, facilitated by the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Small Business Credit Initiative is noteworthy. Investing in a VC arm within the IBank’s infrastructure, as opposed to directing funds to establish community-oriented organizations like Pacific Community Ventures (PCV), a current partner of the IBank, raises questions about the optimal allocation of resources. Comparing the intended purpose of the IBank’s VC arm with PCV’s existing initiatives underscores potential disparities. While the IBank’s program is administered in partnership with Cambridge Associates, an external entity headquartered in Boston, PCV is headquartered in Oakland and operates on a local level, directly engaging with small business owners and communities in California. They were founded in 1998 and their theory of change is to “empower small businesses and help impact-first investors more effectively invest in underserved communities51”. PCV’s impactfirst approach, which combines restorative capital and pro bono business advising, aligns closely with the goals of economic, racial, and gender justice. Moreover, PCV’s Oakland Fund Playbook emphasizes community engagement and trust-based outreach, offering a holistic framework for investing in underserved people and places.

The rationale behind the IBank’s decision to create its VC arm instead of channeling federal funds through established community organizations merits further investigation. While outsourcing to Cambridge Associates may offer certain advantages, such as accessing expertise in financial management, it raises concerns about whether this approach prioritizes community impact and local empowerment. The IBank’s potential to assist other financial institutions in stimulating economic development positions it uniquely to promote state programs and collaborate with individuals deeply connected to their communities. By empowering participating lenders and FDCs to handle small business financing, the IBank could further amplify its impact while staying true to its mission of supporting grassroots initiatives.

48 California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank. “Participating Lender List.” URL: https://cdn.ibank. ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Participating-Lender-List.pdf

49 iBank. “2022-2023 iBank Annual Report.” URL: https://www.flipsnack.com/BDF9FFCC5A8/2022-2023-ibankannual-report/full-view.html

50 “California Announces First Investment by Program Designed to Create More Inclusive Venture Capital Ecosystem,” California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank, accessed May 3, 2024, https://www. ibank.ca.gov/california-announces-first-investment-by-program-designed-to-create-more-inclusive-venturecapital-ecosystem/.P

51 Pacific Community Ventures, “About,” accessed May 3, 2024, https://www.pacificcommunityventures.org/about/

RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation: Similar to the BND, the IBank should adopt a partner bank framework to enhance its effectiveness and reach, aligning with its mission of supporting grassroots initiatives and fostering economic development across the state The IBank’s existing collaboration with Financial Development Corporations (FDCs) highlights the potential of partnering with specialized entities to leverage expertise and resources In addition to small business lending, it should offer infrastructure, climate-related, and affordable housing loans, as well as technical assistance, to its partners

While there are lessons to take from the BND partner model, we must also be aware that this model represents a specific historical and political context. The BND has a unique origin story, emerging from the socialist movement brought about by the Nonpartisan League and the agricultural sector. However, despite the historical context shaped by its progressive roots, the current economy of North Dakota is heavily reliant on fossil fuel extraction, and the BND lacks a specific social or environmental mandate. In 2016, the Bank of North Dakota lent nearly $10 million to local law enforcement for their response to protests near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, supporting the suppression of resistance against the Dakota Access pipeline52. Furthermore, a 2019 House Bill provided a contingent transfer of $25.1 million from the strategic investment and improvements fund to the infrastructure revolving loan fund, reflecting the state’s clear dependence on oil and gas revenue53

This underscores that the ethos of any public bank, exemplified by the BND, can reflect the political and ideological landscape of its respective state. In essence, the existence of a public bank does not guarantee alignment with important social values or priorities. It is crucial to recognize that the orientation of the state, along with the governance structure of the institution, the culture, and the tone set by management and the Board are integral in determining the social values and priorities that it upholds beyond what may be apparent in its vision or mission statement. Therefore, in considering the transition from the IBank to a state public bank, careful consideration must be given to its governance framework to ensure alignment with its desired social objectives.

Governance Framework

The IBank currently operates under the guidance of an executive director appointed by the Governor, with a board of directors comprising representatives including the Director of Finance or their designee, the Treasurer or their designee, the Director of the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development or their designee (who serves as chair of the board), an appointee of the Governor, and the Secretary of Transportation or their designee. The members of the board serve without compensation but are reimbursed for actual and necessary expenses incurred in the performance of their duties, along with receiving $100 for each full day of attending meetings of the authority54

Selection to serve as a bank director is often viewed as a privilege, indicating that an individual is recognized for their success in business or professional ventures, is committed to public service, and commands public trust and confidence. However, it is the aspect of public accountability that truly sets the role of a bank director apart from directorships in other corporate entities. The current discrepancies in the IBank’s operations raise concerns regarding the efficacy of its Board.

52 Ellen Brown, “North Dakota’s Public Bank Was Built for the People—Now It’s Financing Police at Standing Rock,” Yes! Magazine, December 14, 2016, https://www.yesmagazine.org/democracy/2016/12/14/north-dakotas-publicbank-was-built-for-the-people-now-its-financing-police-at-standing-rock

53 North Dakota Legislative Assembly, “Committee Memorandum,” accessed May 3, 2024, https://ndlegis.gov/files/ resource/committee-memorandum/21.9224.01000.pdf

54 California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank, “IBank Act,” accessed May 3, 2024, https://ibank. ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IBank-Act-California-Government-Code.pdf

Inadequate Oversight and Engagement: A Lack of Transparency in Director Attendance

Directors’ meetings should be conducted in a businesslike and orderly manner, serving as a crucial aid to fulfilling the board’s supervisory responsibilities.55 Regular attendance, whether in person or via remote access, is essential for directors to stay informed about the bank’s risks, business, and operational performance. However, attendance records of the IBank reveal inconsistency among board members, with many delegates attending in place of designated members56. Discrepancies exist between the board members listed on the website and those attending a majority of the IBank meetings. For instance, in November 2023, Acting Chair Chris Dombrowski, Carlos Quant, Amy Jarvis, and Juan Fernandez attended the meeting, yet the website lists Director Dee Dee Myers, Treasurer Fiona Ma, Director Joe Stephenshaw, and Director Toks Omishakin with their respective biographies. Moreover, certain members’ contributions are infrequent, and there is limited documentation of robust engagement or effective challenge to proposals. These factors suggest a lack of active oversight and engagement, hampering the board’s ability to demonstrate strong management practices.

Meeting Frequency and Cancellations

Meetings are frequently canceled without prior explanation or public notice. For instance, the December 2023, February, and March 2024 meetings were recently canceled. Each proposal, which encompasses transactions from both the revolving and climate funds, necessitates board approval. The irregular meeting schedule, sometimes convening only once every four months, raises further questions. Given the significance of climate and infrastructure projects in the state, it is challenging to reconcile the scarcity of proposals with the frequency of meetings. This observation may also be linked to informal outreach efforts.

Insufficient Outreach

The IBank’s reliance on informal channels such as word of mouth and longstanding relationships for outreach, though common in community banking, raise concerns given the IBank’s obligation to serve the entire state. CEO Scott Wu acknowledged the budgetary constraints faced by the IBank as a state entity, which limit its ability to conduct formal advertising or outreach efforts.

However, this approach may exacerbate several critical issues. Informal channels may fail to effectively reach all communities, especially those historically marginalized or underserved, resulting in missed opportunities for economic development. Moreover, depending on longstanding relationships may perpetuate exclusionary networks, reinforcing inequalities and restricting access to resources for marginalized communities. Additionally, informal channels may primarily engage individuals and organizations already familiar with the IBank or with similar backgrounds and interests, leading to a lack of diversity in the applicant pool and limited perspectives in decision-making processes. Finally, without formal outreach efforts, the IBank risks missing opportunities to engage with a broader range of stakeholders, gather feedback, and address the specific needs of different

Holden Weisman, Senior Director of Economic Equity at the Greenlining Institute, highlights the lack of transparency surrounding the IBank, describing it as a “black box” due to the public’s uncertainty about its operations and application processes The IBank’s limited communication with the public and lack of visibility contribute to this perception

55 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Examination Policies Manual. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.fdic. gov/resources/supervision-and-examinations/examination-policies-manual/section4-1.pdf

56 California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank, “2023 Board Meetings,” accessed May 3, 2024, https:// www.ibank.ca.gov/board/2023-board-meetings/

communities. Enhancing outreach strategies is crucial to ensuring equitable access to the IBank’s programs and resources across the state.

RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation: Reevaluate the composition of the IBank’s board to include representatives who embody the values and ethos of a public bank, with a proven commitment to serving their communities and building community power Directors should actively participate in overseeing the bank’s operations to uphold transparency and public trust, while supervising a competent management team

Internal controls

Internal controls play a critical role in maintaining the reliability and integrity of financial operations within banking institutions. The BND demonstrates a robust framework of internal controls overseen by the North Dakota Department of Financial Institutions, incorporating both internal audits and external oversight to ensure compliance with federal banking regulations.

In contrast, the organizational structure of the IBank raises concerns regarding transparency and accountability. The Compliance and Administrative Services division, headed by an unidentified Deputy Director, lacks documented assessments and reports provided to the board. This lack of transparency poses a risk to the institution’s integrity, particularly given its public status. The division’s primary responsibilities include analyzing compliance and risk across all IBank programs, ensuring alignment with relevant laws, regulations, and guidelines. The anonymous Deputy Director also plays a crucial role in evaluating program design, policies, procedures, and conducting risk assessments, compliance examinations, and reviews, encompassing various areas such as human resources management, space planning, procurement, contracts, and other business services. However, there are no documented risk assessments, compliance examinations, or reviews presented to the Board or made public regarding IBank’s policies and procedures.

RECOMMENDATION

To build public trust and confidence, the IBank must prioritize transparency in its internal controls The institution should explore avenues for external audit oversight to mitigate potential conflicts of interest IBank can align itself with best practices in governance and uphold the standards expected of financial institutions, thereby bolstering its credibility and reputation within the public domain

Policy Roadmap

This section introduces a policy roadmap aimed at assisting organizers in advancing the establishment of a state public bank, while simultaneously addressing key issues identified in the feasibility study. The roadmap encompasses legal and regulatory framework development, stakeholder engagement, governance structure establishment, and infrastructure and technology integration. By adhering to this roadmap, advocates can effectively navigate the process of establishing a public bank, ensuring transparency, accountability, and alignment with community needs.

1 Develop a Proof of Concept

RECOMMENDATION

Organizers should develop a proof of concept illustrating how a state public bank can utilize its money supply and offer below-market-rate loans to address market failures

Legislation is required to permit the IBank to convert to a public bank. The current framework does not permit the IBank’s conversion to a public bank under the existing Public Banks Law, specifically Government Code section 57600. Notably, Government Code section 57600(b) (1) delineates the criteria for public banks, mandating complete ownership by local agencies or joint powers authorities, which the IBank does not currently fulfill57. To advocate for the transition of the current IBank to a state public bank, a comprehensive approach is needed, beginning with a compelling proof of concept. Affordable housing is a glaring market failure in California, one that the IBank transition can significantly aid. Despite the urgency highlighted by the lived experiences of Californians and the evident visibility of the growing housing crisis and its impact on homelessness, this effort holds significance when addressing the California Assembly and Senate committees. Despite the apparent disparity, legislative committees often ground their justifications for reform in an economic framework. Therefore, it is imperative that this concept clearly articulates how a state public bank can leverage its money supply to provide below-market-rate loans to affordable housing developers, effectively addressing prevailing market failures.

A promising precedent lies with the work of Emily Ramirez, who conducted pro-forma analyses to test the financial feasibility of developing affordable housing at current interest and capitalization rates. Notably, she conducted this analysis with the Los Angeles Housing Department (LAHD) to include Ordinance United to House LA (ULA) funding in its capital stack58. Ordinance ULA, enacted on April 1, 2023 and crafted through a broad-based community coalition, established the House LA Trust Fund dedicated to funding affordable housing production and homelessness prevention within the City of Los Angeles59

In her analysis of a typical affordable housing project in the Melrose neighborhood, it becomes evident that the current interest rates and underwriting requirements in the private banking and nonprofit lending sector pose significant barriers to meeting the cost to develop affordable housing. The financial breakdown reveals a sobering truth: the development cost for 50 affordable housing units totals around $30 million, equating to roughly $600,000 per unit. Even after utilizing the maximum available funding from the ULA program and factoring in the maximum construction and permanent loans the project could qualify for at the current rate of 7.5% interest and hypothetical 5.5% and 3.5% interest rates there remains a gap in funding60

Moreover, prevailing market interest rates, assumed at 7.5% in the model, exacerbate the financial strain on such projects, undermining their viability. This rate, derived from the conventional banking practice of adding 2% to the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) of 5.3%61, imposes burdens on affordable housing initiatives. The funding gaps necessitate the inclusion of project-based vouchers to achieve break-even or marginal profit for affordable housing development. The scarcity of these vouchers contrasts with the staggering demand for affordable housing in Los Angeles, where an estimated shortage of 500,000 units compounds the urgency of finding solutions62

57 California State Legislature, “California Government Code - Section 1-13150,” accessed May 3, 2024, https://leginfo. legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=GOV&division=5.&title=5.&part=&chapter=&article=

58 Ramirez’s pro forma case study models did not include Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) in their capital stacks. Her work with LAHD focused on testing the financial feasibility of the Alternative Models for Permanent Affordable Housing program - which aims to provide funding for development after scarce LIHTC credits have been maxed out on other projects as well as address gaps in the provision of permanent affordable covenants, often critiqued as a weakness of LIHTC developments.

59 Los Angeles Housing and Community Investment Department, “Uniform Housing Code,” accessed May 3, 2024, https://housing2.lacity.org/ula

60 Ramirez, Emily. 2024. Working Paper: Implementing LA’s Alternative Models for Permanent Affordable Housing. UC Berkeley Goldman School of Public Policy.

61 Sofr Academy, “Current SOFR Rates,” accessed May 3, 2024, https://sofracademy.com/current-sofr-rates/

62 Los Angeles County. (n.d.). Our challenge. Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://homeless.lacounty.gov/ our-challenge/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%202022%20LA,82%2C393%20less%20than%20in%202014

2 Assemble an Engaged Directorate and Competent Management Team

RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation: Reevaluate the composition of the IBank’s board to include representatives who embody the values and ethos of a public bank, with a proven commitment to serving their communities and building community power Directors should actively participate in overseeing the bank’s operations to uphold transparency and public trust, while overseeing a competent management team